MANDATORY

BUILDING

PERFORMANCE

STANDARDS:

A KEY POLICY

FOR ACHIEVING

CLIMATE GOALS

May 2023

ACEEE Report

Steven Nadel and

Adam Hinge

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

i

Contents

About ACEEE ........................................................................................................................................................... v

About the Authors ................................................................................................................................................... v

Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................................... v

Suggested Citation ................................................................................................................................................. vi

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................ vi

Key Takeways .................................................................................................................................................... vi

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 1

The Case for Mandatory Building Performance Standards ..................................................................... 2

Need for Large Savings from Existing Buildings .................................................................................. 2

Limitations of Current Approaches ........................................................................................................... 3

Potential Energy Savings and GHG Emissions Reductions in the United States from

Mandatory Building Performance Standards ................................................................................. 5

Current Mandatory Building Performance Standards ............................................................................... 6

Tokyo .................................................................................................................................................................... 6

Boulder, Colorado ............................................................................................................................................ 8

United Kingdom ............................................................................................................................................ 11

Scotland ............................................................................................................................................................ 14

France ................................................................................................................................................................ 15

The Netherlands ............................................................................................................................................ 17

Reno, Nevada ................................................................................................................................................. 19

Washington, DC ............................................................................................................................................. 22

New York City ................................................................................................................................................. 25

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

ii

Washington State .......................................................................................................................................... 28

St. Louis, Missouri ......................................................................................................................................... 30

Chula Vista, California .................................................................................................................................. 32

Colorado ........................................................................................................................................................... 34

Boston ............................................................................................................................................................... 35

Denver ............................................................................................................................................................... 38

Maryland........................................................................................................................................................... 41

Montgomery County Maryland ............................................................................................................... 42

Vancouver, British Columbia ..................................................................................................................... 44

Summary and Comparison ........................................................................................................................ 45

Geographically Broad Standards .................................................................................................................... 49

U.S. Federal Building Performance Standard ...................................................................................... 49

Europe ............................................................................................................................................................... 50

Pending Proposals................................................................................................................................................ 51

Cambridge, Massachusetts ................................................................................................................ 52

Portland, Oregon ................................................................................................................................... 53

Seattle, Washington .............................................................................................................................. 54

Policies Short of Whole-Building Performance Standards ................................................................... 54

Key Policy and Design Decisions .................................................................................................................... 55

Developing a bps including What input should be sought prior to adopting a bps .......... 56

BPS coverage, metrics and targets ......................................................................................................... 57

Is Energy-Use Benchmarking a Key Foundation for Performance Standards?............... 57

Which Building Types and Sizes Should be Covered? ............................................................. 57

What Exemptions and Accommodations Should be Considered? ..................................... 58

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

iii

Which Metrics Should be Used for Performance Standards? ............................................... 59

Using Multiple Metrics in One Jurisdiction ......................................................................................... 62

Should Specific Provisions be Made for Electrification? ......................................................... 62

How and When Should the Standards Apply? ........................................................................... 63

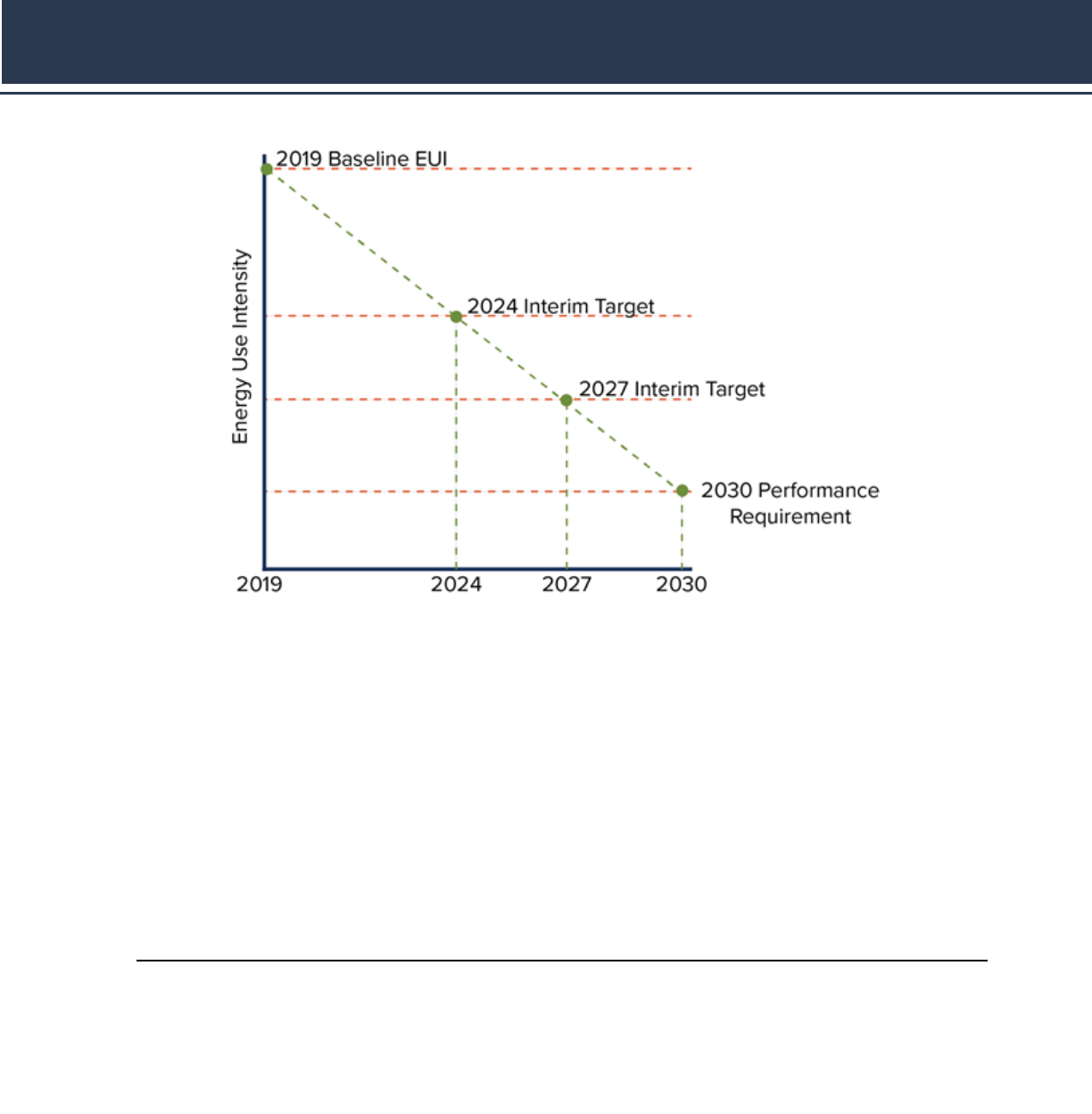

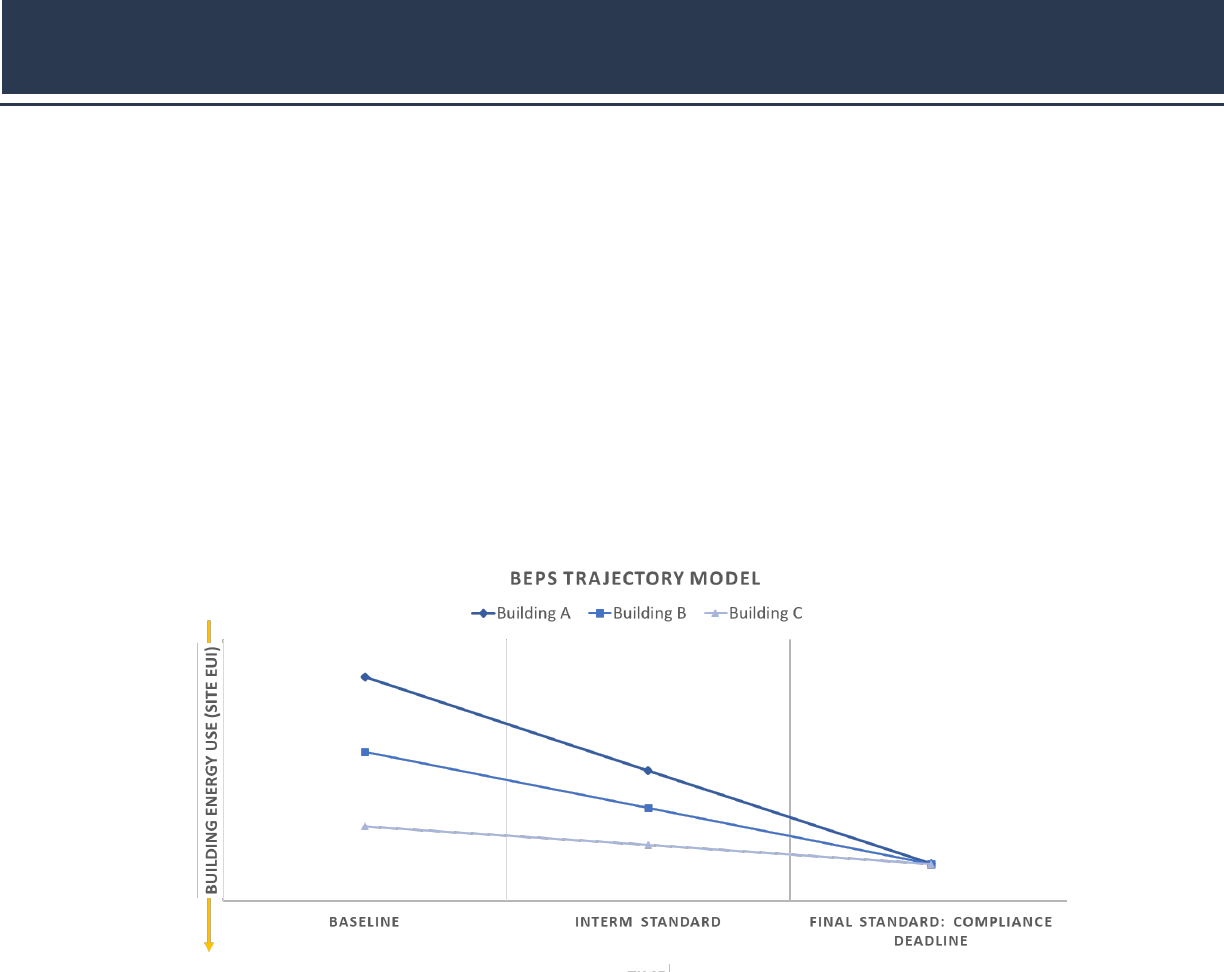

How Stringent Should the Standards Be? Should Only Initial Standards Be Set or

Should Long-Term Standards Be Set with Interim Targets? ................................................. 64

Should Initial Standards Be Set in the Legislation or in Subsequent Regulations? ...... 66

Equity Issues .................................................................................................................................................... 66

What Special Provisions are Needed for Affordable Housing?............................................ 66

BPS and Disadvantaged Communities .......................................................................................... 68

Implementation Specifics ........................................................................................................................... 68

How Much Lead Time Should be Provided? ............................................................................... 68

What level of Staffing and Other Support is Needed for BPS Implementation? .......... 68

What Marketing, Educational and Technical Assistance Efforts Should be Undertaken?

...................................................................................................................................................................... 69

How Do We Build Capacity in the Market?.................................................................................. 69

What Penalties Should be Set? ......................................................................................................... 70

Compliance Options .................................................................................................................................... 70

What Other Compliance Paths Should be Included? ............................................................... 70

Should Trading be Included? ............................................................................................................ 71

Should RECs or Offsets be Incorporated? .................................................................................... 72

Financing Required Upgrades .................................................................................................................. 73

Should Jurisdictions Allocate Funding for Building Upgrades? ........................................... 73

What Role Can and Should Utility Incentives Play? .................................................................. 73

Summary of Building Performance Standard Implementation Information........................... 74

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

iv

Lessons Learned Thus Far .................................................................................................................................. 75

Next Steps ............................................................................................................................................................... 77

Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................................. 78

References ............................................................................................................................................................... 80

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

v

About ACEEE

The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE), a nonprofit research

organization, develops policies to reduce energy waste and combat climate change. Its

independent analysis advances investments, programs, and behaviors that use energy more

effectively and help build an equitable clean energy future.

About the Authors

Steven Nadel has been ACEEE’s executive director since 2001. He has worked in the energy

efficiency field for more than 30 years and has over 200 publications. His current research

interests include utility-sector energy efficiency programs and policies; state, federal, and

local energy and climate change policy; and appliance and equipment efficiency standards.

Steve earned a master of science in energy management from the New York Institute of

Technology and a master of arts in environmental studies and a bachelor of arts in

government from Wesleyan University.

Adam Hinge manages Sustainable Energy Partnerships, a small New York–based

consultancy specializing in energy efficiency program and policy issues. He is involved with a

variety of efforts working toward improving building energy performance around the United

States and globally, including international efforts to share best practices globally on

building energy efficiency policies and programs. Prior to founding Sustainable Energy

Partnerships in 1995, Adam held management positions at Niagara Mohawk Power

Corporation (now part of National Grid) and the New York State Energy Office.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible with the support of project sponsors—New York State Energy

Research and Development Authority, Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance and U.S.

Department of Energy with supplemental support from the Tilia Fund. The authors gratefully

acknowledge the external reviewers, internal reviewers, colleagues, and sponsors who

supported this report. External reviewers were Hayes Jones and Amy Royden-Bloom from

DOE, Cindy Jacobs from EPA, Cliff Majersik from IMT, Josh Kace from LBL, Paul Mathew

(formerly of LBL), Sean Denniston and Jim Edelson from NBI, Josh Putnam from NEEA, John

Lee from NYERDA, Bing Liu and Andrea Mengual from PNNL, and Louise Sunderland from

RAP. External review and support do not imply affiliation or endorsement. We thank Amber

Wood at ACEEE for providing strategic oversite and for drafting the Colorado and Denver

sections. In addition, we are grateful to Louise Sunderland (Regulatory Assistance Project) for

information about the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, and to the managers and other

experts who provided information on their programs and helpful comments on our initial

writeups. Last, we thank Mariel Wolfson for developmental editing; Mary Robert Carter and

Ethan Taylor for managing the editorial process; Jacob Barron for

copy editing; Roxanna

Usher for proofreading; Kate Doughty for help with graphics; and Mark Rodeffer and Nick

Roper for their help in releasing it into the world.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

vi

Suggested Citation

Nadel, S., and A. Hinge. 2023. Mandatory Building Performance Standards: A Key Policy for

Achieving Climate Goals. Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient

Economy.

Executive Summary

KEY TAKEWAYS

• To meet long-term climate goals, substantial energy savings and greenhouse gas

emissions reductions must be obtained from existing buildings. In 2050, an estimated

62% of the building stock will be in buildings built prior to 2023. Although programs

to encourage energy efficiency upgrades to existing buildings have operated for

decades, at current rates, it will take over 300 years to complete whole-building

retrofits on all residences (homes and apartments) and over 50 years to complete such

retrofits on all commercial buildings. New and more-aggressive approaches are

needed.

• Mandatory building performance standards (BPS) can play an important role in

achieving these gains. In some ways, building energy performance standards can be

thought of as the existing-building analog to building energy codes for new

construction.

• BPS are now being successfully implemented in Boulder, Colorado; Tokyo; the United

Kingdom; and the Netherlands.

• In the United States, BPS legislation has been enacted in three states (Colorado,

Maryland, and Washington) and nine localities ranging in size from Reno, Nevada, to

New York City. The number of jurisdictions adopting BPS in the United States has

nearly doubled since 2020. In addition, there are BPS in Vancouver, British Columbia,

and France. Several additional jurisdictions expect to adopt BPS in 2023.

• These jurisdictions are now developing regulations and working with building owners

to prepare for when the mandatory standards take effect. Compliance dates of the

U.S. standards range from 2024 to the early 2030s, varying by jurisdiction and building

size (in many jurisdictions, standards initially apply to the larger commercial buildings,

with smaller buildings applying later).

• To date, most standards cover commercial and multifamily residential buildings above

a size threshold, which ranges from about 10,000 to 100,000 square feet (sq. ft.) of

floor area, varying by jurisdiction.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

vii

To meet long-term climate goals, substantial energy savings and greenhouse gas emissions

reductions must be obtained from existing buildings. At current rates, it will take over 50

years to undertake whole-building retrofits of all commercial buildings, and over 300 years

for all residences (homes and apartments). New and more-aggressive approaches are

needed, such as building performance standards (BPS).

1

BPS are now being successfully

implemented in four jurisdictions. In the United States, BPS legislation has been enacted in

three states and nine localities as well as for U.S. federal buildings. Several additional

jurisdictions either have or expect to adopt BPS soon. Jurisdictions covered in this report are

listed in table ES-1.

1

Depending on the jurisdiction, the names building performance standards (BPS), building energy performance

standard (BEPS) and building emission performance standard (also BEPS) may be used.

•

We find that many different approaches are being tested, in part because each

jurisdiction is different. One of the key issues is whether to base standards on energy

use or greenhouse gas emissions; we discuss pros and cons of each approach.

• Initial experience indicates that there are many important issues that must be

addressed including building benchmarking, stakeholder engagement, adequate

staffing, service provider capacity, and technical (and sometimes financial) assistance

to building owners.

• Special attention must be paid to how performance standards apply in critical markets

such as affordable housing.

• As these policies are implemented, jurisdictions must plan for adequate staffing for

implementation, and evaluation will be important to improve them and inform future

decisions on the best approaches.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

viii

Table ES-1. Jurisdictions with BPS standards covered in this report

Countries

States

Localities

Enacted

Expect enactment in 2023

France Colorado Boston, MA Cambridge, MA

Netherlands Maryland Boulder, CO Portland, OR

United Kingdom

Washington

Chula Vista, CA

Seattle, WA

U.S. federal buildings Denver, CO

(EU pending)

Montgomery County, MD

New York City

Reno, NV

St. Louis, MO

Tokyo

Vancouver, BC

Washington, DC

In this report, for each of these jurisdictions we discuss how their BPS are constructed,

implementation progress to date, programs that complement their BPS, and resources for

more information. We also discuss a BPS for federal buildings in the United States and a

pending European Union directive for member states to develop BPS.

Based on progress to date, we then address a series of topics on BPS policy and design

decisions as follows:

• Developing BPS, including what input should be sought prior to adopting BPS

• BPS coverage, metrics, and targets

o Is energy-use benchmarking a key foundation for performance standards?

o Which building types and sizes should be covered?

o What exemptions and accommodations should be considered?

o Which metrics should be used for performance standards?

o Should specific provisions be made for electrification?

o How and when should the standards apply?

o How stringent should the standards be? Should only initial standards be set,

or should long-term standards be set with interim targets?

o Should initial standards be set in the legislation or in subsequent regulations?

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

ix

• Equity issues

o What special provisions are needed for affordable housing?

• Implementation specifics

o How much lead time should be provided?

o What level of staffing and other support is needed for BPS implementation?

o What marketing, educational, and technical assistance efforts should be

undertaken?

o How do we build capacity in the market?

o What penalties should be set?

• Compliance options

o What other compliance paths should be included?

o Should trading be included?

o Should renewable energy certificates (RECs) or offsets be incorporated?

• Financing required upgrades

o Should jurisdictions allocate funding for building upgrades?

o What role can, and should, utility incentives play?

Since implementation is just beginning, it is too early to draw many conclusions. However,

we do find that stakeholder consultation is important both before standards are proposed

and as implementation is proceeding. We find that building benchmarking is generally an

important precursor for performance standards although a few jurisdictions have used

detailed building modeling and other data in lieu of benchmarking data. Most standards to

date apply to commercial and multifamily buildings above a size threshold (which varies

between jurisdictions). Multiple approaches to performance standards are available, and

each jurisdiction must pursue approaches that work for its communities. However, it takes

time to build support and work out details. Experience to date also shows that for standards

to be successful, attention must be paid to implementation, adequate staffing, and

complementing standards with other policies and programs. Complementary activities can

include easily accessible information for building owners on building performance and BPS

requirements, education and technical assistance on ways to reach required performance

levels, and financial incentives and financing to help cover costs to building owners. Special

attention also must be paid to how performance standards apply in critical markets such as

affordable housing. As these policies are implemented,

evaluation will be important to

improve them and inform future discussions on the best approaches.

In concert with complementary approaches, building performance standards can be an

important contributor to efforts to meet energy and climate targets. We are entering an

exciting period of experimentation that will likely teach us many lessons on how best to

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

x

structure and implement such policies to best create quality housing and workplaces while

obtaining large energy savings and emissions reductions.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

1

Introduction

To meet long-term climate goals, substantial energy savings and greenhouse gas emissions

reductions must be obtained from existing buildings. Programs to encourage energy

efficiency whole-building retrofits to existing buildings have operated for decades, and even

the best programs rarely result in the upgrade of more than 1–2% of eligible buildings

annually (York et al., 2015). New and more-aggressive approaches are needed.

One such approach is mandatory building performance standards (BPS)—requiring existing

buildings to meet some performance target (energy or carbon intensity, performance rating,

and so on), with owners having multiple years to bring buildings into compliance. Such

policies are in place for high-energy-use commercial and industrial buildings in Tokyo; rental

buildings in Boulder, Colorado, and the United Kingdom; and offices in the Netherlands.

Commercial and/or multifamily building policies have been adopted in 14 jurisdictions in the

United States and Canada. France has a law for residential performance standards, with

implementing details still being finalized. Similar policies are being considered in several

other jurisdictions.

This paper reviews the rationale for mandatory building performance standards and

summarizes work to date in the specified jurisdictions, including the key decisions they have

made and results where available. We also briefly discuss emerging proposals. This paper

updates a 2020 ACEEE paper by the same name, incorporating many developments and

lessons learned over the past three years. Throughout the paper, we focus on whole-

building performance standards. We do not focus on energy assessment/audit,

retrocommissioning, or lighting upgrade requirements. Many jurisdictions have adopted

these other requirements as a step beyond building benchmarking but short of whole-

building energy performance standards. In some cases (e.g., New York City), jurisdictions

with these other requirements have gone on to adopt whole-building standards. We also

note that the line between whole-building performance standards and partial standards can

be hazy at times. For example, Reno has a whole-building performance standard, but energy

audits or limited upgrades are an alternative compliance path, allowing owners to avoid the

whole-building performance targets. As long as a jurisdiction nominally requires whole-

building performance, we include it in this paper.

2

The various standards differ in their

stringency and impacts, as we discuss toward the end of this paper.

2

The Institute for Market Transformation does not include Reno as a BPS because of the easy alternative

compliance path. Reno is discussed in more detail later in this report.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

2

The Case for Mandatory Building Performance

Standards

NEED FOR LARGE SAVINGS FROM EXISTING BUILDINGS

Buildings account for about 39% of U.S. energy use (EIA 2023) and 31% of U.S. greenhouse

gas (GHG) emissions (the GHG proportion is lower because nonenergy GHG emissions come

disproportionately from other sectors, including agriculture, industry, and transportation)

(EPA 2019). To reach long-term goals to slow climate change, we will need large reductions

in residential and commercial building energy use. Some of these reductions can come from

building more efficient new homes and buildings, actions that are encouraged by advanced

building energy codes that have or are being adopted in many states.

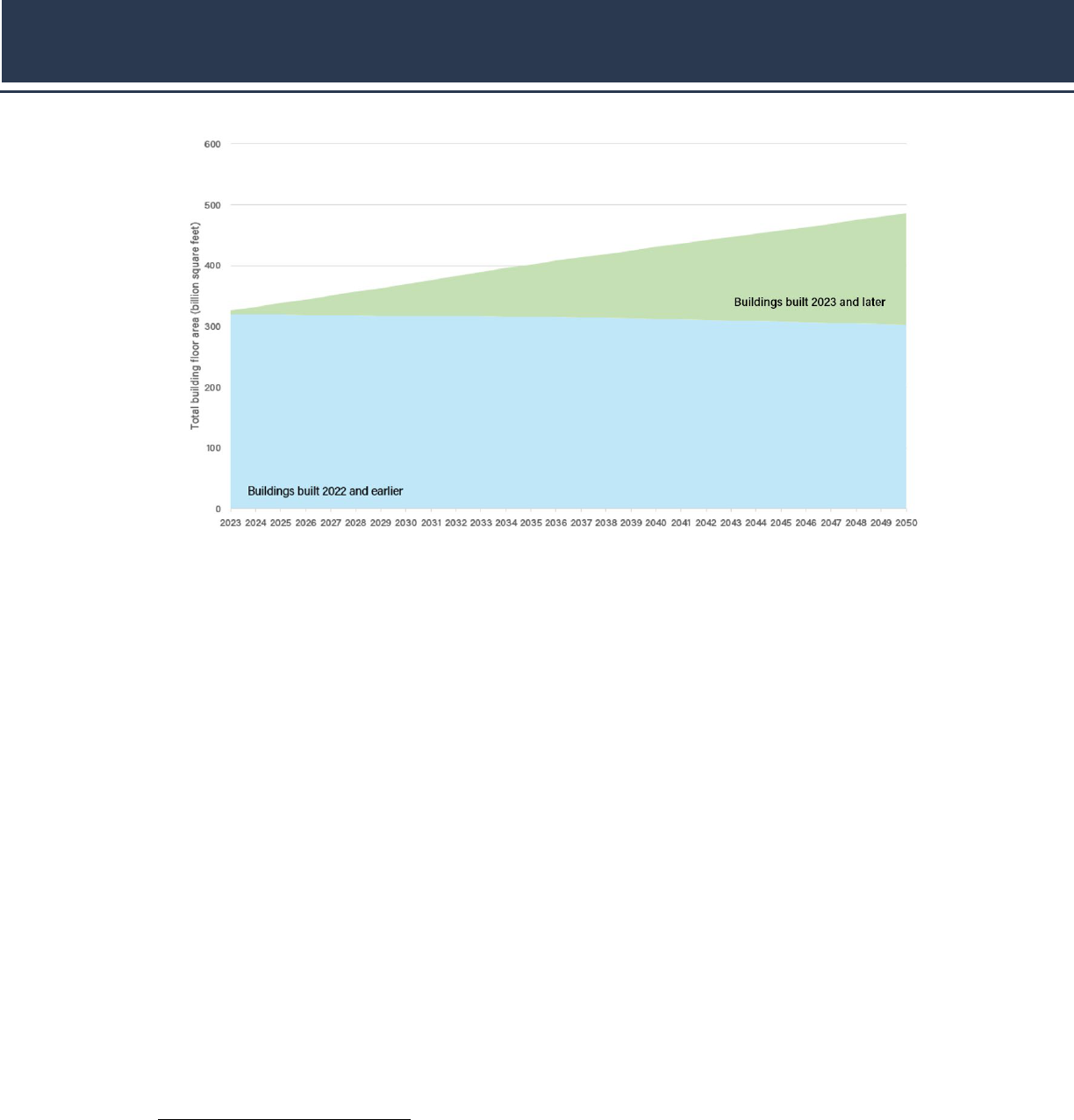

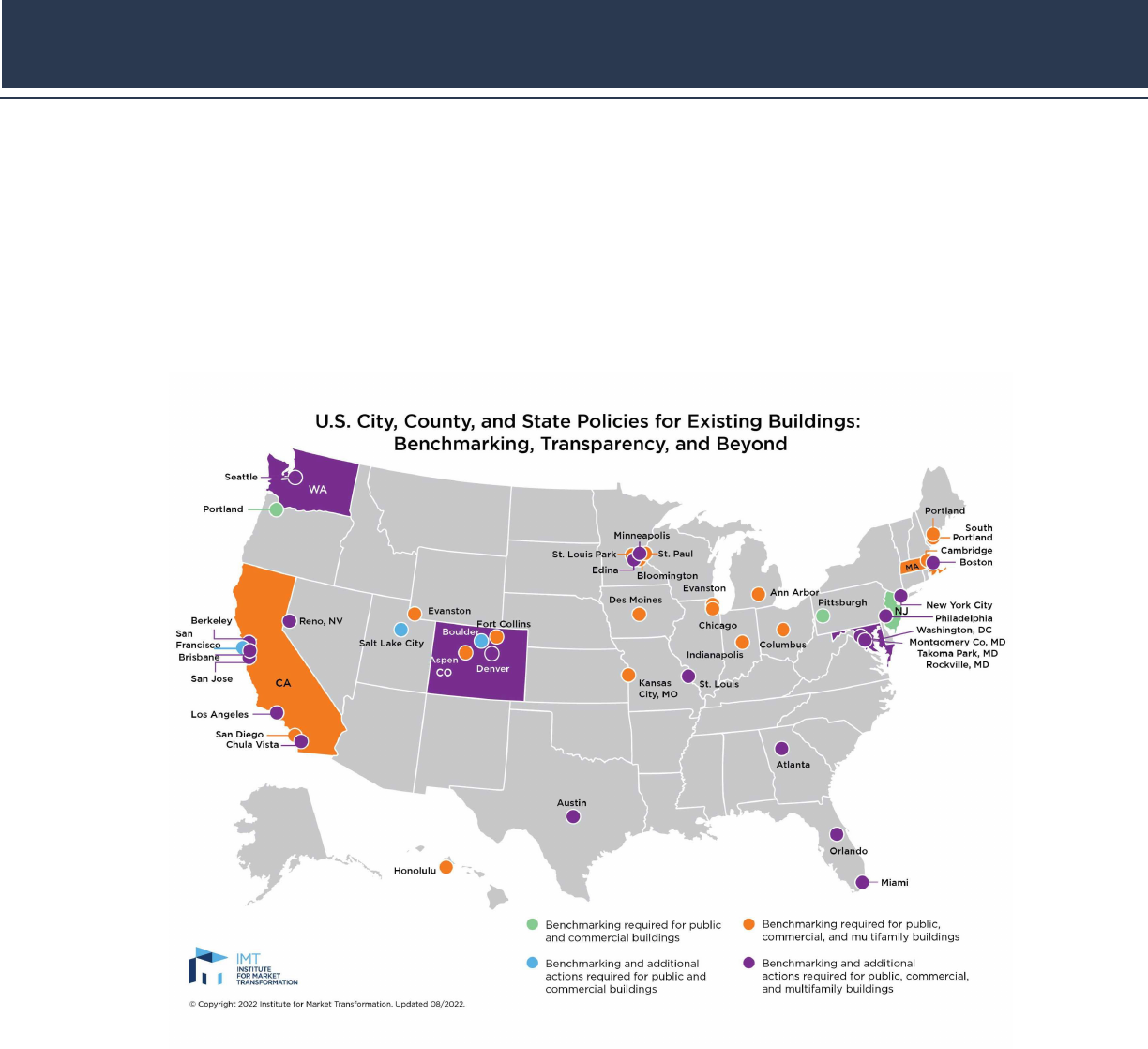

However, since about 66% of the commercial building stock and 60% of the housing

inventory in 2050 will be in buildings that were built prior to 2023 (ACEEE analysis using data

in EIA 2023), retrofitting the majority of existing buildings must be a key strategy (figure 1).

In ACEEE’s 2019 report on how energy efficiency can cut U.S. energy use and GHG emissions

in half, improvements to existing homes and buildings accounted for about 23% of the

energy savings and 18% of the energy-related GHG emissions reductions (Nadel and Ungar

2019).

3

3

These numbers include savings from building retrofits, smart building controls, and half of the savings

estimated in the study from appliance and equipment efficiency standards (the remainder of the appliance and

equipment standard savings apply to new buildings).

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

3

Figure 1. New and existing buildings share of building floor area (residential + commercial) (ACEEE

calculations based on data in EIA AEO 2023–EIA 2023)

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT APPROACHES

While some home and building retrofits now occur each year, it would take centuries to

retrofit all existing U.S. buildings (homes, apartments, and commercial buildings) at current

rates.

In the case of homes, the leading retrofit programs are Home Performance with ENERGY

STAR®, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

collaborative program that works with state and local program operators, and the low-

income Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), a grant program under DOE serving

households with low and moderate incomes. In 2021, Home Performance Program served

124,489 homes (K. Powell, Redhorse Corp., pers. comm., February 3, 2023), and WAP served

at least 64,024 homes (NASCSP 2022). Together, these two programs served 0.13% of the

142.2 million housing units (single family and multifamily) in the United States (Census

Bureau 2023). In addition, a variety of other retrofit programs are offered by states, localities,

utilities, and other agencies of the federal government, and some owners make retrofits on

their own. As a crude estimate, if Home Performance and WAP represent half of U.S. annual

retrofits, then it would take about 377 years to retrofit the current stock of U.S. homes.

4

This

estimate includes only whole-home retrofits. Quite a few homes have received much more

4

The calculation is 142,153,010 units per the Census divided by 188,513 units through Home Performance and

WAP times two (to allow for retrofits beyond Home Performance and WAP) = 377 years.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

4

limited retrofits such as replacing some lightbulbs or upgrading an individual piece of

equipment.

5

For the commercial sector, data from the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA’s)

Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) can help approximate the

building renovation rate. In the 2018 survey (the most recent one published), of the

buildings that were at least four years old, 14–39% have had an efficiency-related renovation

over the preceding 18 years, a simple average of 0.9–2.6% per year.

6

If we take the midpoint

of this range, as a rough estimate, it would take about 56 years to retrofit the current

commercial building stock.

7

This estimate is for buildings to receive upgrades to a few

building systems. It will likely be longer for most systems in these buildings to be upgraded.

According to these figures, to retrofit 80% of the existing U.S. building stock by 2050, we

must increase this annual retrofit rate about 11-fold for residential and nearly twofold for

commercial buildings.

8

And, these retrofits will often need to be more comprehensive than

many current retrofits are. To address these needs, we must dramatically augment current

programs and policies to achieve these large increases. Building performance standards can

play an important role in achieving these gains. In some ways, building energy performance

standards can be thought of as the existing-building analog to building energy codes for

new construction.

9

Furthermore, in both the residential and commercial sectors there is a “split incentive”

problem with rental properties. In these cases the tenant often pays the energy bill but since

5

For example, the 2015 Residential Energy Consumption Survey reports that about 5% of housing units have

received free or subsidized energy-efficient lightbulbs and about 6% have received a tax credit for a new

appliance or equipment (EIA 2018). No time period is provided for when these actions took place.

6

According to table B1 in the 2018 CBECS (EIA 2022), over the past 18 years, 1.006 million buildings have had a

heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) equipment upgrade, which is 17% of the total number of

buildings constructed before 2014. If we also include window replacements and lighting and insulation upgrades,

and assume no overlap between measures, then 47% of buildings received an energy efficiency upgrade. In all

likelihood, some buildings received more than one upgrade, and thus the percentage renovated will be between

17% and 47%. A whole-building retrofit should include multiple systems in a building, and thus the 47% figure is

clearly not whole-building retrofits.

7

The midpoint is 1.7% per year; 1/1.7% = 56 years.

8

For residences: 80% retrofit/27 years/0.26% retrofit rate = 11.4-fold increase. For commercial buildings: 80%

retrofit/27 years/1.7% retrofit rate = 1.74-fold increase.

9

While there are similarities, there are also some structural differences. Building energy codes are triggered at

time of renovation/major work, whereas BPS typically follow specified compliance cycles. Also, BPS are mostly

performance based, whereas most codes are still primarily prescriptive requirements.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

5

they do not own the building, are unable or reluctant to pay for substantial energy efficiency

upgrades. And when the building owner does not pay the energy bills, they do not have a

financial incentive to make investments that reduce energy costs. BPS force owners to make

these upgrades, with the costs incorporated into rents.

POTENTIAL ENERGY SAVINGS AND GHG EMISSIONS

REDUCTIONS IN THE UNITED STATES FROM MANDATORY

BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS

The savings from mandatory building performance standards for existing commercial and

multifamily buildings and homes will depend on the stringency of the standards and the

proportion of the building stock they apply to. As a rough estimate, using data from the

Annual Energy Outlook, if mandatory standards apply to 80% of the pre-2023 commercial

building stock and 60% of the pre-2023 residential building stock and reduce energy use by

an average of 30% (the average retrofit savings estimated by Nadel and Ungar 2019) and

energy-related carbon dioxide (CO

2

) emissions by an average of 60% (higher carbon dioxide

savings due to electrification and use of decarbonized fuels), then savings in 2050 will be

about 5.4 quads of energy and 271 MMT of CO

2

. These results are summarized in table 1.

These reductions are 13% of projected 2050 buildings energy use and 26% of projected

2050 buildings CO

2

in the EIA Reference Case for 2050.

Table 1. 2050 potential savings from mandatory building performance standards

Figures are for source energy, including upstream power-sector losses. Sources: Baseline energy use and

CO

2

and existing building share from commercial sector from EIA 2023. Existing building share

calculated by ACEEE from data in EIA 2023. Proportion of stock covered and average reduction are

rough estimates by the authors.

Variable

Commercial

Residential

Total

Buildings energy use in 2050 (quads)

18.2

23.4

41.6

Buildings energy-related CO

2

in 2050 (MMT) 468 567 1,035

Proportion in 2050 that are pre-2023 66% 60%

Proportion of pre-2023 stock covered

80%

60%

70%

Avg. reduction from performance standards

Energy

30%

30%

30%

Carbon dioxide

60%

60%

60%

2050 energy savings (quads) 2.87 2.54 5.41

2050 CO

2

savings (MMT)

147.8

122.9

270.8

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

6

Current Mandatory Building Performance Standards

We begin this discussion with five standards that are now in effect: in Tokyo (for very large

buildings); Boulder, Colorado (for rental units

10

); the United Kingdom (also for rental units);

France (residences); and the Netherlands (for offices). We next proceed to five standards

where legislation was enacted before our 2020 report was published and where

implementation details have since been largely developed: Reno, Nevada (commercial and

multifamily buildings); Washington, DC (commercial and multifamily buildings); New York

City (mostly commercial buildings); Washington State (commercial buildings to start); and St.

Louis, Missouri (commercial and multifamily buildings). For these jurisdictions we discuss

initial lessons learned. Finally, we discuss an additional eight locations that have adopted

BPS in 2021–2022: Chula Vista, California; Colorado; Boston, Massachusetts; Denver,

Colorado; Maryland; Montgomery County, Maryland; Vancouver, British Columbia; and U.S.

federal buildings. All of this last group cover commercial buildings, and all but Vancouver

cover multifamily buildings.

11

Within the first group, we order our discussion according to

the date requirements begin; for the other standards we order by date of adoption.

TOKYO

Building Performance Standards

In April 2010, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) introduced the Tokyo Cap-and-

Trade Program (TCTP), which sets mandatory CO

2

emissions reduction targets for the largest

energy consumers in the city. The program targets facilities consuming over 1,500 kiloliters

of annual crude oil equivalent (equivalent to approximately 55 billion Btu per year). This

includes approximately 1,400 facilities, comprising 1,100 office and mixed-use commercial

buildings and about 300 industrial facilities. While there is not a direct correlation between

the total annual energy consumption and building size, the buildings covered by the TCTP

are generally from 20,000 to 30,000 square meters or more (approximately 200,000 to

300,000 square feet (sq. ft.) and up) (Satoshi Chida, director, Emission Cap and Trade Section,

TMG, pers. comm., March 9, 2020). Although these facilities represent only about 0.2% of all

commercial and industrial facilities in Tokyo, they account for about 40% of the total CO

2

emissions from those sectors.

A covered facility is required to report its emissions to the TMG every year and must meet an

emissions reduction target by implementing emissions reduction measures and/or

participating in emissions trading. The facility’s baseline emissions from which it must reduce

are an average of any three consecutive years between 2002 and 2007. When the TCTP was

10

Including single-family and multifamily units.

11

Vancouver’s ordinance includes benchmarking of multifamily buildings but does not include performance

standards for these buildings.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

7

launched in 2010, the target for emissions reductions from the commercial and industrial

sectors was 17% by the year 2020. This 17% reduction by 2020 was also the established

target for individual facilities covered by the TCTP.

Reduction targets were specified for the program’s first two five-year compliance periods

(2010–2014 and 2015–2019). Depending on the baseline starting point and some other

factors, buildings were required to reduce emissions 6% or 8% in the first compliance period

and then 15% or 17% in the second compliance period. In early 2019, the TMG finalized the

caps and compliance factors for the third compliance period (2020–2024), which requires an

additional 10% of emissions reductions beyond the second compliance period, resulting in

25–27% reductions from the baseline (TMG 2022).

The TMG decided to use five-year compliance periods as a way to balance its long-term

investment in energy reduction planning while also retaining the ability to adjust regularly if

adequate progress was not being achieved.

The third compliance period introduced a new mechanism allowing covered facilities to

procure electricity or heating from TMG-certified suppliers who document that their energy

supply is significantly less carbon intensive than the normal grid electricity or heat. As of the

end of the first year of the third compliance period (FY 2020), there were 12 certified low-

carbon electricity suppliers and 42 different certified low-carbon heat suppliers.

A significant element of the TCTP is a tenant mechanism that imposes some obligations on

the tenants. Through their “tenants’ obligation and participation scheme,” tenants in covered

buildings must work together with the building owner to implement the energy efficiency

plan. Tenants occupying more than 5,000 square meters (approximately 50,000 sq. ft.) or

using at least 6 million kilowatt-hours (kWh) per year must submit their own carbon

reduction plan.

Companion Programs

The TCTP was preceded by the Tokyo Carbon Reporting Program, which had been

introduced in 2002. This earlier mandatory reporting scheme, now replaced by the TCTP,

provided detailed (and verified) emissions history so that the baselines for mandatory

reductions could easily be set.

The TMG has an array of targeted subsidies and tax credits for various building and business

types, funded from a variety of sources. For example, there are specific subsidy packages to

diffuse green lease practices, including covering a portion of retrofit costs for owners once a

green lease has been agreed upon with a tenant (TMG and C40 2017).

In addition, owners of buildings larger than 5,000 square meters constructed since 2002 are

required to submit a building environmental plan that addresses a wide range of

environmental and energy performance issues.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

8

Beyond companion programs aimed at the biggest emitters covered by the TCTP, many

programs are directed toward smaller buildings, including expansion of the Carbon

Reduction Reporting Program to small and medium facilities. A benchmarking tool has been

developed from the reported data and can enable building owners to understand their

energy use and find potential energy management opportunities.

Results

By 2017, the facilities covered by the TCTP had reduced their emissions 27% relative to the

baseline year, meeting the second compliance target two years early (TMG 2022). The

majority of the reductions were achieved during the first compliance period, with early

reductions driven by electricity supply shortages caused by the Fukushima nuclear disaster

and shutdown of much of Japan’s nuclear generating capacity that drove major conservation

efforts and significant behavior change. These significant reductions offset the impact of

higher carbon intensity of the Tokyo electric grid with fossil generation replacing much of

the nuclear generation. No backsliding from the early deep reductions has been observed,

and additional regular reductions are seen most years.

With the ratcheting down of the cap for the beginning of the third compliance period, and

relatively flat emissions over the five years of the second compliance period, significant

additional reductions will be required by buildings in the third compliance period. For FY

2020, the first year of the third compliance period, total CO

2

emissions from the covered

facilities dropped to 11.04 million tons, a 33% reduction from the base-year (TMG 2022).

The TMG requests information from covered facilities about projections of their obligation

fulfillment for coming years, and it is currently estimated that 75% of facilities will meet the

full third compliance period obligations through their own improvement measures, while

25% of facilities are unlikely to meet the obligations on their own and will likely look to trade

with other facilities.

Sources and Additional Information

• Tokyo Metropolitan Government Cap-and-Trade Program information page:

www.kankyo.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/en/climate/cap_and_trade/index.html

• Urban Efficiency: A Global Survey of Building Energy Efficiency Policies in Cities (TMG

and C40 2017)

BOULDER, COLORADO

Building Performance Standards

In 2010, the Boulder, Colorado City Council adopted the SmartRegs program. The program

requires all licensed rental housing in the city (multifamily and single family) to demonstrate

that they are about as efficient as buildings built to the 1999 Energy Code. In the City of

Boulder, about 52% of housing units are rental and most of the rest are owner occupied

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

9

(TownCharts 2023). SmartRegs builds on an existing City of Boulder rental license program

that requires a rental property to obtain and renew their license every four years. Renewal

entails an inspection for health and safety measures plus additional energy efficiency

requirements. Compliance can be demonstrated in one of two ways: (1) achieve a score of

120 or better through the Home Energy Rating System (HERS), a nationwide scoring system,

or (2) achieve at least 100 points on a prescriptive scoring checklist the City of Boulder

developed based on energy and carbon savings for specific measures. Boulder also requires

two water efficiency points. For large multifamily buildings, a sample of representative

apartment units can be inspected.

In Boulder, property owners were given until December 31, 2018, to bring their units into

compliance. This afforded owners up to two rental license cycles (each license is good for

four years) to implement any necessary upgrades. Inspections are performed by private

inspectors certified by the city. The cost of an inspection is around $120 per rental unit

inspected; however, inspectors are third-party private business owners, so the cost can vary.

Companion Programs

Boulder also offers a companion Energy Smart program that provides technical assistance,

help with selecting contractors for energy efficiency improvements, and financial incentives

beyond those offered by the local utility. Energy Smart is financed mostly by Boulder County,

which provides services to all municipalities in the county. In 2010, Boulder County was a

recipient of a grant from the DOE under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

(ARRA). Additionally, the city contracted with Energy Smart for specific SmartRegs services,

using its Climate Action Plan tax, which is a small city tax on electric service. Energy Smart

also leverages available incentives from their local utility.

Results

For the approximately 23,000 licensed rental units, at the end of 2019 (the most recent data

available), about 22,500 units in Boulder gained SmartRegs compliance. Over the course of

the eight-year compliance timeline, about half of the rental units were found to be

compliant at first inspection, 17% qualified for various exemptions specified in the law, and

most of the rest required upgrades to reach compliance. Nearly all licensed rental units were

inspected using the prescriptive checklist. For those needing upgrades, on average they had

to choose two measures to gain an additional 14 points to reach the required 100 points.

The most common upgrades were attic, crawlspace, and wall insulation. The average

upgrade cost has been $3,022 per unit, of which an average of $579 was paid by rebates. As

of the end of 2018, the city estimated the program had saved about 1.9 million kWh of

electricity, 460,000 therms of natural gas, $520,000 in energy costs, and 3,900 metric tons of

CO

2

. The city estimated total investment at just over $8 million, including nearly $1 million in

rebates (Boulder 2019). RMI (Peterson and Lalit 2018) estimated, on the basis of initial

results, that once

fully implemented, the program will save 4.2 million kWh and 940,000

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

10

therms of natural gas annually. If correct, this is an annual savings of about 566 kWh and 123

therms per unit requiring an upgrade.

12

In our discussions, Boulder officials said they are happy with the program. It has achieved

energy savings and GHG emissions reductions and helped to improve the rental housing

stock. When asked about the impact on the Boulder rental market, they said they have seen

no evidence that the SmartRegs requirements led to either increased rents or a reduction in

rentals. Available evidence says that the market—supply and demand—is what sets the

rental price. They also noted that they will be considering future changes to the SmartRegs

requirements as part of a 2023 update to their overall building stock strategy (C. Elam, senior

sustainability manager, City of Boulder, pers. comm., January 10, 2023, and March 22, 2023).

Sources and Additional Information

• SmartRegs website: bouldercolorado.gov/plan-develop/smartregs

-guide

• A report by the RMI on Better Rentals, Better City (Petersen and Lalit 2018) A report

by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Zimring et al. 2012)

• A paper written by Boulder officials and consultants (Antczak et al. 2016)

• An evaluation of the Boulder DOE grant (Arena and Vijayakumar 2012)

12

Based on 22,500 total rental units and 33% requiring upgrades as discussed earlier in this paragraph.

OTHER RENTAL EFFICIENCY REQUIREMENTS IN THE UNITED

STATES

In addition to the Boulder program, there are two other U.S. cities with more limited

prescriptive energy efficiency requirements for rental housing—Burlington, Vermont, and

Gainesville, Florida.

BURLINGTON

The Burlington standard applies to rental properties that use more than 90,000 Btu for

space heating per heated square foot of floor area. The standard requires insulation of

attics, floors over unheated spaces, water heaters, accessible heating, cooling and hot-

water pipes, and heating and cooling ducts. In addition, sealing of heating and cooling

ducts is required as is air leakage testing and reduction where it exceeds designated

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

11

UNITED KINGDOM

Building Performance Standards

Minimum building energy performance standards were adopted in 2015 and have been in

effect in the United Kingdom since April 2018, such that it is unlawful to let (lease) properties

in England and Wales that do not meet a prescribed minimum level of energy performance

as measured by the building’s Energy Performance Certificate. Scotland has a similar policy

that is about to begin for just the residential sector (see box below at the end of the UK

section). Northern Ireland does not have a program. In the remainder of this section, we

discuss the program in England and Wales.

In England and Wales, all rental properties, both residential (“domestic,” including

multifamily) and commercial (“non-domestic”), that require an Energy Performance

Certificate (EPC) in accordance with the European Commission’s Energy Performance of

Buildings Directive of 2012 are within the scope of this regulation (IPEEC 2017).

The metric for the standard is the building’s EPC, which in the United Kingdom is an A

through G rating based on the calculated (or asset) energy performance rating for that

building (A is the best rating, G the worst).

13

The EPC rating is calculated based on the

building envelope characteristics and permanent energy using equipment (heating and

domestic water heating systems) relying on a standard assessment procedure developed as

part of the regulations. The calculated rating can be improved through installation of capital

measures intended to improve the building’s efficiency, though all based on modeled

performance, not including any impacts of changes to the operation of the building. The

Energy Efficiency (Domestic Private Rented Property) (England and Wales) Regulations 2015

(revised in 2017; UK BEIS 2020a) require that from April 2018 all rented premises within the

13

Most European countries use the EPC label but label details and breakpoints vary between countries. While A–

G is the most common, some countries are A–H and some countries also include A+ and A++ ratings to indicate

superior buildings. In general an A rating means substantially above average but far from net-zero energy.

thresholds and installation of storm windows or double-glazed windows. The cost of

improvements is capped at $2,500 per apartment (Burlington 2021).

GAINESVILLE

Gainesville requires that rental units (single and multifamily) have attic insulation, sealed

duct joints, low-flow showerheads and faucet aerators, insulated hot-water pipes, a

programmable thermostat, and heating/cooling system maintenance at least every 24

months (Gainesville 2020).

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

12

specified scope are expected to meet a minimum energy standard of an EPC rating of E. This

means that any properties with a rating of F or G are not allowed to be re-leased from April

2018 without upgrading to a higher level of performance or registering an exemption.

While the regulations initially targeted buildings at the time of a new, renewed, or extended

lease, beginning in 2018, ultimately all rented buildings must achieve a minimum E rating by

the established deadlines of April 2020 for domestic and April 2023 for non-domestic

buildings.

For domestic buildings, the regulations include a cost cap such that an owner is not required

to spend more than £3,500 (about $4,500) per dwelling unit. This is self-certified by the

building owner or submitting agent. For non-domestic buildings, the cost threshold is

defined to include those investments that pay back within a seven-year period. If the

property cannot improve to an EPC E rating within the cost thresholds, the owner must make

all the improvements that can be made up to that amount and then register an “all

improvements made” exemption with the government, which is valid for five years.

14

Other

exemptions are described in the references that follow.

It has been proposed through an open UK government consultation, and confirmed in the

UK Government Energy White Paper, that the standards will be tightened with the aim of

having as many homes as possible upgraded to EPC C or above by 2035, where “practical,

cost-effective and affordable” (UK BEIS 2020b). While the consultation closed in December

2020, there has been no update on finalizing the tightening of the standards.

In 2019, the UK government began a consultation process to understand potential changes

to the non-domestic standards to move more aggressively toward their economy-wide

carbon targets. The main proposal from the government (favored option in the consultation)

was to set a trajectory for a new standard of EPC B in 2030 for the non-domestic sector (UK

BEIS 2019b). The consultation closed January 2020, and the government has not yet

responded with their decision.

While there has not yet been a formal proposal from the UK government, in late 2020 the

government confirmed in its Energy White Paper the intention to raise the minimum energy

efficiency standard to an EPC B or above by 2030 (UK BEIS 2020b). This would be

implemented through two compliance windows, the first requiring all privately rented non-

domestic buildings to achieve an EPC rating of C or better by 2027, and the second requiring

an EPC of B or better by 2028. It is not yet clear how soon this proposal will be finalized.

14

Nothing is set out explicitly about what happens after five years, but one UK expert said that logic suggests

that if the exemption expires then the regulation would apply, so a landlord would need to comply with the

standard or seek another exemption.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

13

In addition to the potential change to require an EPC of C or better by 2027 in non-domestic

buildings, there is also a policy change being considered to shift non-domestic buildings

from the current calculated EPC rating (based on modeled energy performance) to have the

ratings more aligned with actual energy use and carbon emissions. Many non-domestic

stakeholders throughout the UK have been advocating for a change to an operational

energy and carbon rating, and there has been a parallel consultation open on that issue

while the final required EPC requirements are being debated.

Companion Programs

At the time that the building performance regulations were established, the government also

introduced a pay-as-you-save finance initiative called Green Deal Finance. Together with

subsidies available for domestic energy efficiency from the utility-funded energy efficiency

obligation, the initiative was intended to ensure that the standard could be reached at no

cost to the landlord. The Green Deal Finance initiative was largely unsuccessful (e.g., see UK

BEIS 2017) and the government has withdrawn its support, so the funding and finance

framework did not materialize as expected.

Funding for energy efficiency measures in domestic properties occupied by low-income

households is available through the Energy Efficiency Obligation (EEO). For domestic

privately rented properties at EPC F and G, the EEO scheme subsidizes selected, higher-cost

insulation and renewable heating measures. Other measures are not permitted for F- and G-

rated properties (UK BEIS 2023). In addition, some subsidies may be available on a piecemeal

basis through individual local authorities.

With dramatically higher energy prices in 2022 and 2023 resulting from the Russian invasion

of Ukraine and resulting energy supply challenges, energy affordability has become the

highest energy policy priority for the residential (domestic) sector, with price caps and

subsidies to protect consumers. It is likely that some of these energy affordability programs

will be expanded to include additional energy efficiency features in the coming years.

Results

In 2021, the UK government issued an evaluation report on the domestic private rented

sector efficiency standard. The evaluation found that it was not possible to definitively

quantify the level of compliance with the regulations. The EPC data for England and Wales

have gaps and data quality issues, and as of April 2020 the evaluation found there were

approximately 130,000 noncompliant properties (out of around 3 million total). The main

energy efficiency improvements made by landlords have been new insulation in combination

with more energy-efficient lighting, and the common mindset was for landlords to have

made improvements necessary to achieve an E rating while minimizing costs (UK BEIS 2021).

Other anecdotal information from some UK experts suggests that there has not been a big

push to renovate buildings, but some buildings have had their EPC ratings recalculated to

obtain better ratings (and therefore be allowed to re-lease the building). The lack of action is

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

14

due at least in part to expectations of significant project funding through the UK

government’s Green Deal finance packages, which did not materialize. In addition, many UK

policies have not been implemented as smoothly as might otherwise be expected because

of turmoil surrounding Brexit, COVID-19, and multiple changes in government leadership

over recent years.

Sources and Additional Information

• Guidance—Domestic Private Rented Property (UK BEIS 2023)

• Guidance—Non-Domestic Private Rented Property (UK BEIS 2019a)

• The Domestic Private Rented Property Minimum Standard (UK BEIS 2020a)

SCOTLAND

As noted above, Scotland has approved regulations very similar to the rental housing

standards in England and Wales. The Scottish regulations differ from the English and

Welsh in that they apply only to domestic privately rented properties and they include a

tightening of the minimum standard from E to D at change of tenancy from 2022 and for

all privately rented homes from 2025. Due to COVID, Scotland proposed to change this to

requiring a C rating for private rental housing as of 2028 “where technically feasible and

cost-effective.” If achieving a C is not technically feasible, then a home or apartment

would need to get as close to Cas is possible and cost effective, with details still to be

developed. In addition, Scotland is developing a regulation for owner-occupied private

housing to reach the C level by 2033. The mandatory standard would apply at time of

property sale and potentially also to homes undergoing major renovations (with major

renovations still to be defined). For publicly owned social housing, initial energy standards

went into effect in 2020 and as of 2021 89% of covered units met these standards. The

standards will tighten to the B level or

equivalent or as much as possible by the end of

2032. Scotland already has a grant program for households in or at risk of fuel poverty,

several energy efficiency loan programs, and a technical assistance and advice program,

all of which would help households comply with the proposed standards (Scottish

Government 2021).

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

15

FRANCE

Building Performance Standards

In 2015, France adopted the Energy Transition toward Green Growth Act (Ministry of the

Environment, Energy and the Sea 2016). This act calls for:

• A 60% reduction in final energy consumption in 2050 compared with the 2010 level

for commercial-sector buildings;

• Renovation of 500,000 homes per year starting in 2017, at least half of which are

occupied by low-income households, aiming for a 15% reduction in fuel poverty by

2020;

• Energy renovation by 2025 of all private residential buildings whose primary energy

consumption exceeds 330 kWh per square meter per year of primary energy.

This last provision is a building performance standard. In France, as in the United Kingdom

and most other European countries, buildings are rated and labeled on an A through G

scale, based on building characteristics (i.e., this is an asset rating and not a performance

rating). The building performance standard in the 2015 law means that ”F-rated and G-rated

residential buildings (about 15% of the housing stock) must upgrade to at least the E level.

This includes both rental and owner-occupied residences. The plan is to steadily tighten

these requirements to bring the entire housing stock to low energy levels (“Bâtiment Basse

Consommation” [BBC] or equivalent) by 2050. This is equivalent to 80 kWh per square meter

per year in primary energy for the regulated loads (heating, cooling, lighting, ventilation, and

hot water). This long-term goal, which corresponds to a B rating, is also part of the 2015 law.

A more recent energy and climate law, adopted in November 2019, sets the goal to achieve

carbon neutrality by 2050 by reducing fossil fuel consumption by 40% by 2030—instead of

the previous 30% target adopted by France—and by closing coal-based electricity

generation by 2022. In addition, the law contains various measures to support the

development of renewable energy and to improve the energy efficiency of housing to

reduce energy consumption by reducing heat loss. Concerning energy efficiency in the

housing sector, the new law calls for retrofitting all “passoires énergétiques” (homes and

apartments not in compliance with the standard) within 10 years according to the following

chronological targets:

• From 2022, freeze rents of “passoire” units. An owner of a passoire will no longer be

able to increase rents.

15

15

Similarly, while not full BPS, in the Netherlands and Brussels, rented homes with the lowest energy performance

ratings are allowed a lower maximum rent (S. Oxenaar, associate, Regulatory Assistance Project EU, pers. comm.,

March 23, 2023).

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

16

• Starting in 2022, each real estate transaction involving a passoire will have to provide

an audit on what work is needed to bring it into compliance. Mention of passoire

status will be compulsory in the real estate advertisements of the dwellings

concerned starting in 2022.

• From 2023, for new rental contracts, the “decency” criteria for dwellings that specifies

minimum requirements (e.g., minimum floor area and free of vermin) is amended to

include a maximum threshold of 450 kWh final energy consumption per square

meter per year (this is the dividing line between an F and G rating). When a rental

falls short of these decency criteria, a tenant can request that the landlord correct the

deficiency.

In 2021, France adopted the Climate and Resilience Law, which modified the building

standards and their effective date, and enabled tenant action against noncompliant

buildings. Under the new law, G-rated buildings must upgrade by 2025, F-rated buildings by

2028, and E-rated buildings by 2034. After 2034, all buildings must be D or better. The new

law prohibits renting out or selling properties with performance below the required levels

and allows the tenant or purchaser to take legal action against the owner and demand

financial compensation.

Companion Programs

To help support these upgrades, France has a variety of complementary programs. Until the

end of 2019, the main form of financial assistance for home energy conservation was an

Energy Transition grant tax credit. Since 2019, this tax credit is being phased out, to be

replaced by a grants system called MaPrimeRénov. This program has two variations—

MaPrimeRénov and MaPrimeRénov Sérénité. The first is for one or a few specific energy-

saving measures while the latter is for comprehensive retrofits that reduce energy use at

least 35% and that are targeted to address energy poverty. These grants are available to

homeowners, landlords, and condominium properties. The level of the grant and work

eligible for a grant are a function of household income and the improvements in energy

efficiency that are obtained. Priority is being given to those on a low-income living in

properties with low energy efficiency performance, and not all households are eligible for all

types of work. This new program is administered by a government department called

“France Renov.”

In addition, the following other programs are available:

• An interest-free Eco-Loan up to €50,000 is available to property owners carrying out

energy renovation work. It can be combined with the grant above.

• The Habiter Mieux Program (Better Housing) targeting fuel poverty and managed by

France's National Housing Agency (ANAH) has increased targets for renovating

homes. In 2021 the target was 75,000 homes per year (total five-year budget of 1.2

billion Euros).

• France Renov Platforms (a kind of national retrofit one-stop shop) provide technical

and financial support to homeowners carrying out energy renovations in

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

17

complement to 450 regional “information service units” that cover the whole of

France.

• The energy-saving certificate scheme (certificats d’économies d’énergie, CEE) has

energy-saving requirements for energy providers (fuel, electricity, gas, heating oil,

and so on) to support energy-saving initiatives. This program targets all households

and businesses, with a specific minimum share for low-income households.

• An Energy Renovation Guarantee Fund provides loans to low-income households,

with a government repayment guarantee.

• Digital maintenance and repair records are being established to compile and store

information on individual homes so present and future owners have ready access to

information that will aid in planning home renovations (Ministry of the Environment,

Energy and the Sea 2016).

Sources and Additional Information

• An English-language summary of the Energy Transition through Green Growth Act

(Ministry of the Environment, Energy and the Sea 2016)

• France section in a report on energy efficiency passports (Fabbri, De Groote, and

Rapf 2016).

• The 2019 law (in French): www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/loi-energie-climat

• The 2021 law (in French) : www.ecologie.gouv.fr/projet-loi-climat-resilience-deputes-

ont-vote-mesures-sur-renovation-des-logements-ca-change-quoi

THE NETHERLANDS

Building Performance Standards

In November 2018, the Dutch government amended their Building Decree to require that

office buildings have an Energy Efficiency Index of at least 1.3 (equivalent to a C EPC rating)

as of January 1, 2023. After that date, noncomplying buildings will no longer be permitted

to be used as office buildings. Dutch EPC ratings are based on calculated energy use, and

tied to an Energy Efficiency Index that does not directly translate to energy consumption

with ratings that range from A+++++ as the most efficient down to G as the least efficient.

Enforcement of the standard is generally by the municipality in which the building is located,

but it can also be delegated to another nominated “competent authority.” As the minimum

standard applies to the use of the office building, the duty to comply can be with either the

tenant or the building owner. Failure to comply will be addressed through administrative

enforcement measures, such as periodic penalty payments, a fine, or the closure of the office

building. The regulations require that measures needed to meet the standard are calculated

to pay back within 10 years. An owner or tenant is required to install measures up to

this

payback threshold but not over, even if a C certification is not reached. A 2016 study

estimated that average payback time to meet this requirement will be between 3 and 6.5

years, with a cumulative total cost of €860 million by 2023.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

18

The Netherlands has around 96,000 offices, 62,000 of which will need to comply with the

standard (the rest are exempt as discussed below). Of these, 39% do not yet have an EPC as

of late 2022 (Dutch News 2022). Of those that do have an EPC, around 50% have an A–C

label and 11% have a label of D–G and therefore will have to undertake work to comply with

the standard, a significant improvement from the situation in 2019 when one-quarter of

buildings needed to make improvements. Regarding exemptions, the standard does not

apply to buildings in which less than 50% of floor area is used for offices (excluding ancillary

functions) or buildings in which only a small floor area (less than 100 square meters) is used

for offices. Exemptions also apply for listed historic buildings, buildings that are only

temporarily used as offices, buildings that do not use energy to regulate indoor climate, and

buildings that are due to be demolished in less than two years.

A tighter target of an A label by 2030 was considered but not introduced. However, the C

requirement by 2023 is expected to be tightened to a higher level in some future year. As of

2022, it is widely expected that the requirement for all office buildings to have an A energy

label by 2030 will be implemented, though there has been no official confirmation from the

government (RWV Advocaten 2022).

A more general requirement for operators of commercial establishments to take up energy

efficiency measures has already laid the foundation for the introduction of the minimum

standard in this sector. The Dutch Environmental Management Activities Law, Decree on

Activities, introduced the “energy savings obligation,” which requires the “operator” of 20

different types of commercial establishments (public and private) that use over 50,000 kWh

of electricity or over 25,000 cubic meters of natural gas to implement all energy savings

measures with a payback less than five years. A list of recognized energy savings measures

with payback in the specified period for each sector is published on InfoMil, a government

knowledge center for resources on environmental legislation and policy (Netherlands

Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management 2023). A provision allows operators to ask

for phased implementation. As of July 1, 2019, all users/tenants had to submit an

environmental report (Wet Milieubeheer) to the municipality covering all processes in the

part of the building they occupy.

Offices are required to comply with both the Class C regulation and this energy savings

obligation.

Companion Programs

The Netherlands Enterprise Agency (Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland, RVO), offers

technical support to building owners to enable them to comply with the standard. It

provides an online tool that enables building owners to explore investment costs, annual

savings, payback times, and CO

2

savings for routes to meeting the standard. A government-

approved register lists energy advisors who can assess and recommend improvements to

meet the standard. Building owners can receive a grant for the cost of this advice if they go

on to install measures.

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

19

The Dutch government also provides tax incentives to partially offset the cost of energy

efficiency measures. For example, the Energy Investment Allowance allows companies to

deduct 45% of specified energy-saving investment costs from taxable profit (Netherlands

Enterprise Agency 2022). The Environmental Investment Allowance is available for

entrepreneurs to make tax deductible investments in a broader range of environmental

measures. In addition, installation of solar thermal and heat pumps is incentivized through

the Renewable Energy Investment Allowance, which provides a partial subsidy of the costs of

the installation. Finally, “green” loans are also available for commercial buildings. These

provide preferential interest rates, often coupled with supporting services such as free

energy consultations.

Results

While implementation is just coming into force in 2023, the program is already having some

impact. For example, the number of investors, mortgage banks, owners, and tenants asking

for more-detailed information about buildings’ energy performance is rising (IGBC 2019b). A

significant increase in investment in the renovation and transformation of commercial

properties has been observed. A growing number of financial institutions are also adapting

their real estate financing measures accordingly. For example, ING, Rabobank, and ABN

AMRO, three leading financial institutions in the Netherlands, have indicated they will stop

financing office buildings with a D label or worse. In addition, ING Real Estate Finance is no

longer refinancing clients lacking a plan to get at least a C label for their office (IGBC 2019).

More recently, it appears that many building owners and consultants are ramping up efforts

to be in compliance with the 2023 requirements and that banks continue to pay attention to

the law. As one bank noted at a recent finance forum, “compliant assets will have high

valuations and good liquidity, while the others will find no financing. We as a bank take this

very seriously” (Dynes 2022).

Sources and Additional Information

• A paper that looks at the potential for minimum performance standards for Europe,

including a case study on the Dutch program (Sunderland and Santini 2020) (this

section draws heavily from this case study)

• An international compilation that provides information on both the office building

and Environmental Management Activities Decree (IGBC 2019)

• The program website (in Dutch):

www.rvo.nl/onderwerpen/duurzaam-

ondernemen/gebouwen/wetten-en-regels/bestaande-bouw/energielabel-c-

kantoren/veelgestelde-vragen

RENO, NEVADA

Building Performance Standards

In January 2019, the City of Reno enacted the Energy and Water Efficiency Program, which

includes both commercial and multifamily building benchmarking and a nominal building

MANDATORY BUILDING PERFORMANCE STANDARDS © ACEEE

20

performance standard for commercial and multifamily buildings 30,000 sq. ft. and larger. We

use the term “nominal,” since as discussed below, the policy includes an easy-to-meet