Sudan Water Policy Review and

Analysis

November 2021

Sudan Water Policy Review and Analysis

Water Productivity Improvement in Practice

November 2021

Prepared by MetaMeta

Prepared by Esmee Mulder and Frank van Steenbergen (MetaMeta), duly acknowledging the review by

Wageningen University and Research and IHE Delft Institute for Water Education

Citation: Mulder, E., van Steenbergen, F., 2021. Sudan Water Policy Review and Analysis. Water-PIP technical

report series. IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, Delft, the Netherlands.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

.

@2021 IHE Delft Institute for Water Education

This report was developed by the Water Productivity Improvement in Practice (Water-PIP) project, which

is funded by the IHE Delft Partnership Programme for Water and Development (DUPC2) under the

programmatic cooperation between the Directorate-General for International Cooperation (DGIS) of the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands and IHE Delft (DGIS Activity DME0121369)

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views

of DGIS, DUPC2, or its partners.

Table of Contents

i

Table of Contents

1 Water resources and agricultural productivity ............................................................................................................ 1

2 Policy review: objectives, process and results ............................................................................................................ 3

2.1 Objectives and process ............................................................................................................................................. 3

2.2 Existing Acts and Policies – Gap Analyses .......................................................................................................... 3

The Irrigation and Drainage Act ........................................................................................................................ 3

The 2005 Gezira Scheme Act ...................................................................................................................... 3

The 1995 Water Law ....................................................................................................................................... 5

2007 Water Policy ........................................................................................................................................... 6

2.3 Water for the New Sudan – Transforming Livelihoods Strategy ................................................................ 8

2.4 Comparative Assessment: Current Status and Future Outlook ............................................................... 10

3 Positioning the new national water policy for improved water productivity ................................................ 15

Policy support for water productivity ............................................................................................................ 16

Policy Relevant Water Productivity Analyses .............................................................................................. 18

4 References ............................................................................................................................................................................ 19

Annex 1: Sudan water acts and regulations drafted in the past decades, but were inadequately enforced.

........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 20

Annex 2: Anchoring pillars of the proposed new national water policy .................................................................. 21

List of Figures

ii

List of Figures

Figure 2-1: Small (1.8 m wide), heavy and ineffective buckets in use by the local private sector in Gezira

Scheme (Credit: MetaMeta, 2019) ............................................................................................................................................ 4

Figure 2-2: New generation, wide (5.5 m) effective buckets currently being produced by the Netherlands

private company Herder that was active in the Gezira Scheme back in the 1990s. The MoIWR has re-engage

with Herder to explore collaboration opportunities (Credit: MetaMeta, 2019) ....................................................... 4

Figure 2-3: Absolute and relative agricultural Research and Development (R&D) spending levels ................ 6

Figure 2-4: Low-cost intake and field canals that contributed to improved field water management and

productivity in Gash seasonal river based agricultural scheme in Sudan (Credit: Amira Mekawi, HRC) ........ 7

Figure 2-5: Cumulative groundwater pumping cost over the 25-year life of solarized systems versus the

existing diesel generator systems (EC-HACP and GSWI, 2017). .................................................................................... 7

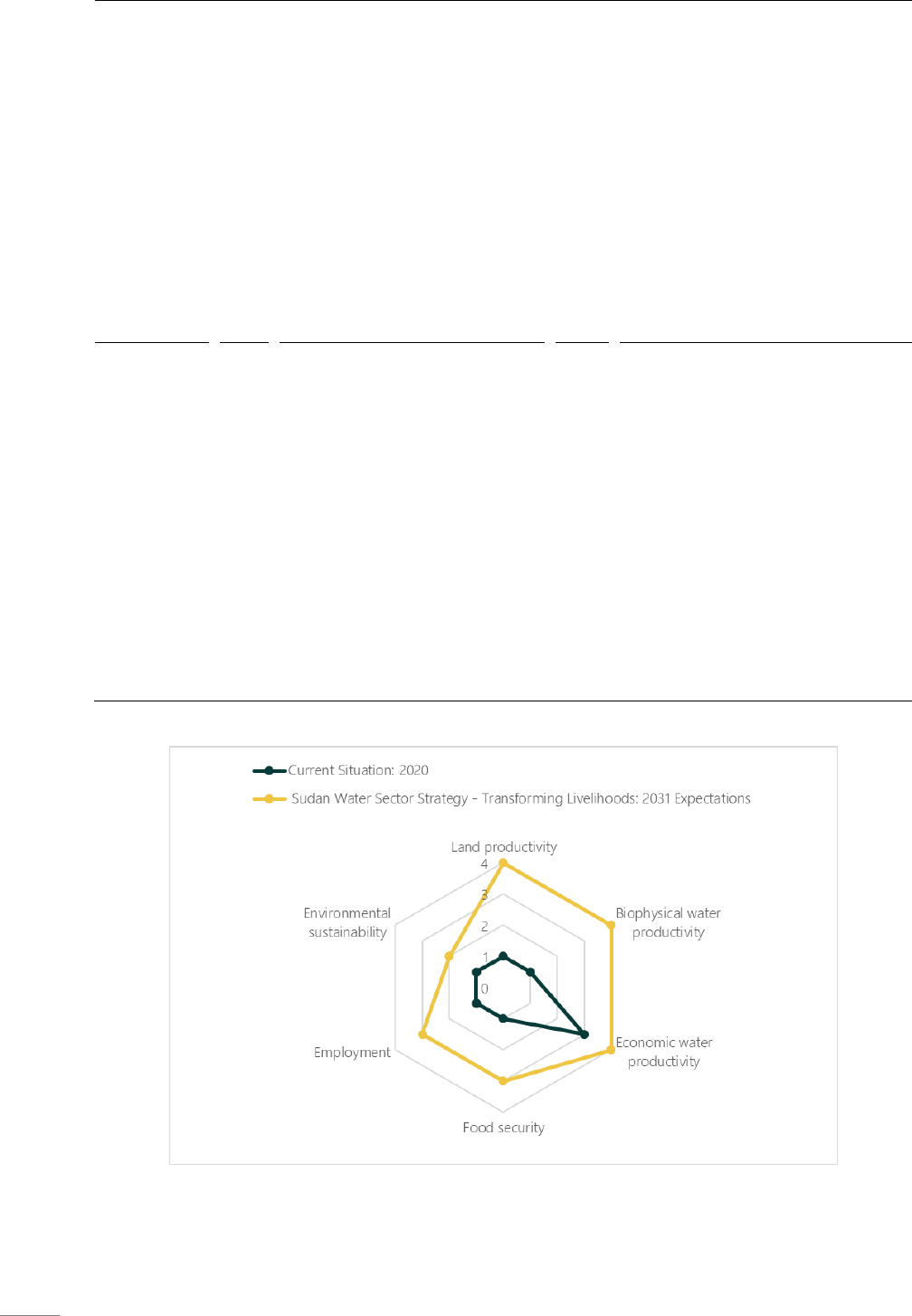

Figure 2-6: Spider diagram comparing the current situation and priorities in the Water for the New Sudan

– Transforming Livelihoods Strategy .................................................................................................................................... 14

List of Tables

Table 2-1: Location and scope of the Medium Size Pump Irrigation Schemes (MoIWR, 2018) ......................... 6

Table 2-2: Overview of indicators used in the assessment ........................................................................................... 10

Table 2-3: Assessment of the current situation and the priorities in the new water sector Strategy ............. 11

Acronyms

iii

Acronyms

ARC Agricultural Research Corporation

EMC Earth Moving Cooperation

HRC Hydraulic Research Centre

FAO Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN

FOP Field Outlet Pipes

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GSA Gezira Scheme Act

GSWI Global Solar-and-Water Initiative

IARP Irrigated Agriculture Rehabilitation Programme

IOD Irrigation Operations Directorate

IRWR Internal Renewable Water Resources

MoIWR Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources

NCWR National Council for Water Resources

NGO Non-Governmental Organizations

NWAP National Water Resources Allocation Plan

O&M Operation and Maintenance

R&D Research and Development

SIWI Stockholm International Water Institute

WAP Water Allocation Plan

WaPOR FAO portal to monitor Water Productivity through Open

access of remotely sensed derived data

WP Water Productivity

WUA Water User Association

Water resources and agricultural productivity

1

1 Water resources and agricultural productivity

Sudan is a water scarce country with the Internal Renewable Water Resources (IRWR) estimated at 32 billion

m

3

/year bringing the per capita water availability below the water stress threshold of 1,000 m

3

/year

(MoIWR, 2021). The Nile river contributes the largest share – 20.5 billion m

3

/year measured at the Sennar

Dam on the Blue Nile (Elamin, 2013). This amount is in line with the 1959 agreement that governs the Sudan

water share of the estimated 84 billion m

3

annual average Nile river flow recorded at the Egyptian Aswan

Dam at the border between the two countries (FAO, 2015). The seasonal streams and groundwater

resources provide about 6.7 billion m

3

/year and 4.8 billion m

3

/year respectively (MoIWR, 2021). Rainfall is

marked by erratic intensity, large seasonal variability, uneven distribution and concentration in a short-wet

season. Average annual rainfall is 200 mm/year, but ranges from 25 mm/year in the dry north up to 700

mm/year in the south (FAO, 2015).

The agriculture sector is the biggest consumer of water resources at more than 90% (FAO, 2015). It is also

the largest potential contributor to the Sudanese economy. It provides livelihoods and job opportunities

for nearly 70% of the country’s estimated 44 million population. Before the oil exports came on line in

1999, agricultural products accounted for upwards of 95 percent of exports and the sector contributed to

nearly 60% of the GDP (Berry, 2015). In the past three decades, however, the agriculture sector has been

on a declining trend due to a combination of factors: neglect by the then government as more attention

went to the oil and services sectors; lack of up-to-date coherent policies and strategies resulting in

inadequate investment, research and capacity building programme (MoIWR, 2019); internal conflicts and

instabilities, particularly in the Western and Eastern agricultural hubs (Mahgoub, 2014).

The agricultural production and productivity is currently low compared to global averages or potential

local targets from the Sudanese Agricultural Research Corporation (ARC). For instance, the 2.4 tons/ha

yield of wheat (FAO, 2019) is 50% of the local target and far below the attainable 6 to 9 tons/ha reported

in the FAO AQUASTAT Database

1

. Wheat is the most important staple and commercial commodity in

Sudan at the moment. In the 2019/2020 cropping season, the 730,000 tons local wheat production covered

just a third of the 2.6 million tons actual consumption. The country is currently filling the gap through

import, which amounted to $500 million draining the meagre national hard currency reserve and triggering

a cascading negative impact on the economy (Ahmed and Mehari, 2020). Importing wheat is also reliant

on international market dynamics, which the country cannot fully control and this has often resulted in

short supply of bread, a very essential staple food for millions of Sudanese. The yield of sorghum (< 1

ton/ha), another major food crop is also low as compared to the achievable 3.5 to 5 tons/ha. Sugar cane,

a highly commercial crop fares far worse at 10 tons/ha – the optimum yield ranges from 50 to 150 tons/ha.

The Water Productivity (WP) of the major crops is also very low. For instance, as documented by the on-

going FAO funded water productivity improvement project in Gezira irrigation scheme, the majority of the

farmers apply nearly twice the wheat irrigation requirement or about 8,000 m

3

/ha (HRC, 2019). At 2.4

tons/ha, this results in 0.3 kg/m

3

, which is significantly below the optimum range of 0.8 to 1.6 kg/m

3

.

Likewise, the WP of sorghum (0.15 kg/m

3

) is just 15 to 25% of the achievable 0.6 to 1 kg/m

3

. This sorghum

WP analyses is based on the 2017 to 2019 flow measurements conducted in the Gash agricultural scheme,

the major source of food and fodder in Eastern Sudan (HRC and MetaMeta, 2020). The Gash farmers supply

6,200 to 7,140 m

3

/ha while the yield rarely exceeds 1 ton/ha.

The February 2019 Water Sector Conference that brought together more than 150 international and local

professionals (the WaterPIP consortium was represented) highlighted lack of coherent policy roadmap as

one of the major factors for the low agricultural production and water productivity. The frequently cited

1

http://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/en/

Water resources and agricultural productivity

2

draft 1995 Water Law and the draft 2007 Water Policy were never officially endorsed due to mainly neglect

by the then Ministry of Water Resources, Irrigation and Electricity. The Conference participants agreed that

the policies are out-dated and do not adequately respond to the Sudan water sector needs of the present

and the future. They accordingly suggested the development a new water strategy and policy (MoIWR,

2019).

The decline in the performance of the agriculture sector has negatively impacted the livelihoods of millions

of Sudanese people, particularly the rural poor farming and herding communities. Sudan currently sits at

the bottom-end of the global food security index, 112

th

out of the 113 countries evaluated

2

. Nearly half of

the total population and three quarters of the vast agrarian communities live in poverty (IMF, 2013).

Since the Peaceful Great Revolution of December 2018, the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources

(MoIWR), the custodian of water resources in Sudan, is working to deliver an inclusive economic growth

that improves the lives and livelihoods of the Sudanese people. The Ministry prepared in the fall of 2020,

a 10-year Water for the New Sudan – Transforming Livelihoods Strategy. This became operational in March

2021. The Strategy is to be followed by the drafting of a National Water Policy in 2021 as well.

These policy efforts by the MoIWR are also in anticipation of the fact that the desire to achieve rapid

economic growth will increase competition for the limited water resources. This is already seen in places

like Kassala, Nyala and El Fasher between agricultural and urban water demands. As competition increases

between various demands on water, strategic plans and policies are needed to inform decisions on water

use, control, protection and development so as to be able to ensure sustainable growth and avoid ad-hoc

planning and implementation.

2

https://foodsecurityindex.eiu.com/

Policy review: objectives, process and results

3

2 Policy review: objectives, process and results

2.1 Objectives and process

The purpose of this review is two-fold. The first part discusses the aspects of the Acts and Policies that

contributed to the current poor status of the agricultural production, water use efficiency and productivity

as well as food security, job creation and other related socio-economic development issues. This second

part presents the future outlook as defined by the ambitions and targets of the National Sudan Water

Sector Strategy: Transforming Livelihoods 2021-2031.

2.2 Existing Acts and Policies – Gap Analyses

Sudan has drafted many water acts and regulations over the past decades (Annex 1). Among these, the

1990 Irrigation and Drainage Act and 2005 Gezira Scheme Act have had the most direct impact on the

current poor performance of the agricultural sector. As indicated earlier, the country does not yet have an

endorsed up-to-date water policy. The most widely cited 1995 Water Law and the draft 2007 Water Policy

are analysed here as several of their gaps could be traced to the decline of the agriculture sector in the

past three decades.

The Irrigation and Drainage Act

The 1990 Irrigation Drainage Act is very much regulatory in nature. Its most prominent provisions stipulate

that any work related to irrigation or drainage needs a permit from the MoIWR and that licensee shall

notify the Ministry to draw water for irrigation, whether from the Nile River or any of its tributaries or any

other rivers or public canals (UNEP, 2012). The Act is relatively silent on the facilitative and enabling aspects

of water management: improved living conditions, providing career paths and capacity development

opportunities for irrigation and water professionals and practitioners and mechanisms to improve irrigation

and related farming services to farmers and other beneficiary groups. This has contributed to poor

operation and maintenance and low crop and water productivity of the four national large-scale irrigation

schemes (Gezira, Rahad, New Halfa and Suki) that cover nearly 2 million ha.

The need to strengthen the facilitative roles of Acts and Policies was recognized in the 2016 international

conference on revitalization of the Gezira irrigation scheme (MoIWR, 2016). Human Resources and Services

(training, improved housing, office and communication facilities) was identified among the top five priority

improvement intervention packages.

The 2005 Gezira Scheme Act

The overarching goal of the 2005 Gezira Scheme Act (GSA) was to transfer significant irrigation water

management and related farming responsibilities from engineers and agricultural officers to farmers. The

specific objectives included ensuring farmers’ right to: (i) effectively participate, at all administrative levels,

in planning and implementation of projects and programs that affect their production and livelihoods, (ii)

manage irrigation operations at field canal level through water users’ associations, and (iii) freely manage

their production and economic aspects within the technical parameters, and employ technology support

to boost production and maximize their respective returns (FAO, 2015).

These rather noble objectives have not been translated into positive impact on the ground and failed to

achieve better irrigation management and improved water productivity. The GSA suffered from hasty, poor

implementation and follow-up. Many irrigation and agricultural experts were relieved of their duties

prematurely as it was then assumed that the WUAs will shoulder much responsibilities. This never

materialized. The nearly 1,500 WUAs established, were not given the technical and financial support to

evolve into mature and viable institutions – almost all are not currently functional. There was also

Policy review: objectives, process and results

4

inadequate coordination among the farmers and the remaining Gezira staff. The majority of the Gezira

farmers started to individually decide what crops, when to grow, and how much area to cultivate. This

action of the farmers and the lack of coordination, which is often directly attributed to a wrong-reading of

the third objective of the GSA, made it impossible to plan and implement a proper irrigation and cropping

schedule. The farmers often cultivated significantly larger area than the design capacity capped at 50% of

the command area of each minor (tertiary) canal at any given cropping season. The Gezira scheme has

1498 minor canals feeding 29,000 field canals. As a result of the ad hoc irrigation scheduling and cropping

pattern, large sections of the scheme, particularly the tail-end areas, often suffered from delayed and

insufficient irrigation (MoIWR, 2016).

Another significant provision of the GSA is the one that granted the private sector the ‘opportunity to play

a leading role in irrigation water management. This provision lacked two major guiding principles: (1)

institutional regulatory capacities of the Irrigation Operations Directorate (IOD) of the MoIWR that oversees

Gezira scheme Operation and Maintenance (O&M) activities, and (2) the technical qualifications and

material capability preconditions for the engagement of the private sector. Presently, the machineries

being used by the private sector and the semi-autonomous parastatal EMC (Earth Moving Cooperation)

are not the most efficient: the de-silting and locally produced mowing buckets are rather small and heavy

and not suitable for regular maintenance. The administrative system is also inadequate: surveyed bill of

quantities, clear measurements or time sheets are not adequately integrated into the workflow. The O&M

is poorly supervised by the IOD, which has outdated facilities to work with – modern land survey

equipment, such as total-stations and GPS devices are not made available. As observed by Smit (2019), the

private companies are often paid by the kilometres cleared of silt and weeds rather than by the quality of

the excavation work. This, as also reported during the Gezira 2016 conference, has contributed to over

digging in some parts, and shallow and wide cross-sections in other areas along the same canal leading

to poor water delivery.

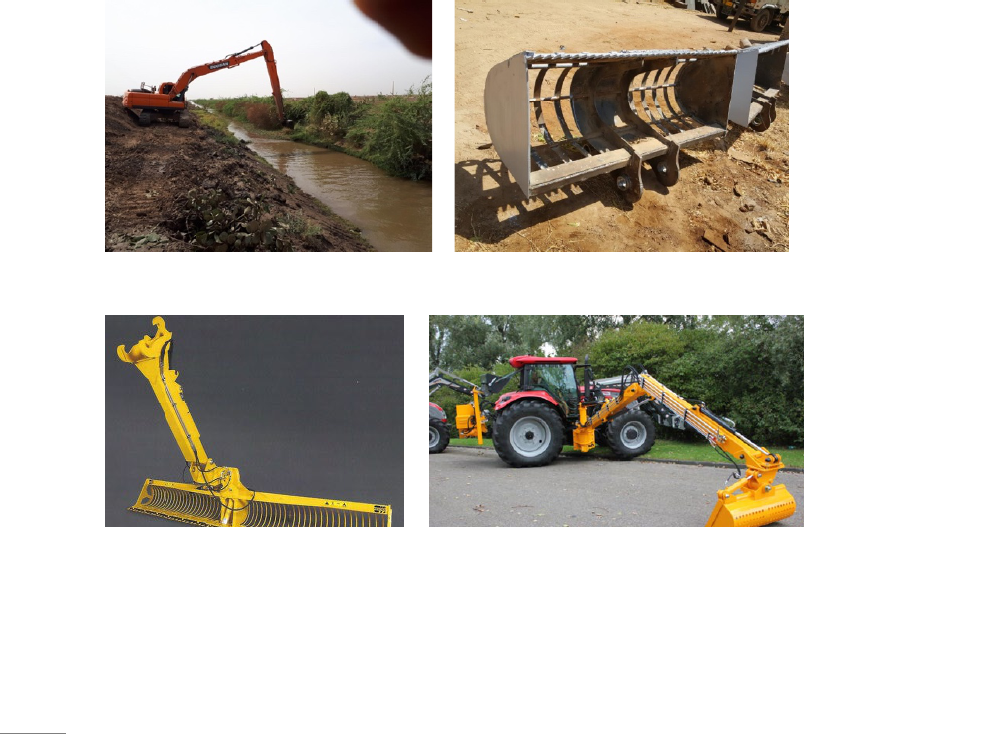

Figure 2-1: Small (1.8 m wide), heavy and ineffective buckets in use by the local private sector in Gezira Scheme (Credit:

MetaMeta, 2019)

Figure 2-2: New generation, wide (5.5 m) effective buckets currently being produced by the Netherlands private

company Herder that was active in the Gezira Scheme back in the 1990s. The MoIWR has re-engage with Herder to

explore collaboration opportunities (Credit: MetaMeta, 2019)

Policy review: objectives, process and results

5

The GSA has since its inception been a subject of much debate and controversy and regularly blamed as

a major contributor to the poor performance of the Gezira Scheme. It is the 2016 International Conference

on Gezira scheme, however, that effectively marked the beginning of the end of the GSA. The conference

participants recommended, among others, to immediately reinstate qualified 70 engineers, 350 gate

operators and up to 1,000 unskilled labourers to bring some order to the irrigation and farming scheduling.

This has been followed through and the GSA has now ceased to play any official role in the Gezira irrigation

scheme management.

The 1995 Water Law

The 1995 Water Law has a number of limitations. It does not embrace the integrated nature of water

resources management and provides little guidance on where to put which waters for best use to meet

concerted peoples’ priorities. There is no emphasis on water management or water productivity as a service

or mention of gender provisions or comprehensive definition of water use. Water quality and pollution

control aspects only get a passing-mention. Public participation and transparency in decision making does

not prominently feature. The Law is silent on the role of States in managing water resources thus leaving

ample room for interpretation on where the responsibility boundary lies with the Federal water agencies

and institutions as well as the local communities. Lack of clarity at best leads to inefficiencies due to

excessive overlap of tasks - it can at worst be a cause for conflicts.

The lack of emphasis on water management or water productivity as a service has had several negative

implications (MoIWR, 2021):

• The National Council for Water Resources (NCWR) that was established by the Law to

operationalize the Law through among others formulating common water resources development

plans and integrated water sector activities, largely remained idle and ineffective institution. It was

inadequately staffed and resourced and its impact remained limited also because there were no

State and catchment level water councils to partner with.

• National Water Resources Allocation Plan (NWAP) was not developed – there is no such a plan

to-date. In the absence of NWAP, the country has not managed to adequately set its water

investment agenda, identify and implement specific programmes of strategic importance to

boosting agricultural productivity and ensuring food security. The NWAP would have also been

instrumental in addressing the priority water resource concerns such as climate change and

disaster risk reduction provisions including early warning systems, risk and migration of vulnerable

communities during extreme events and; conflict mitigation and prevention needs; agricultural

productivity in main agricultural zones; pollution control. Sudan is currently among the 10 most

vulnerable and least prepared countries to climate change impact

3

.

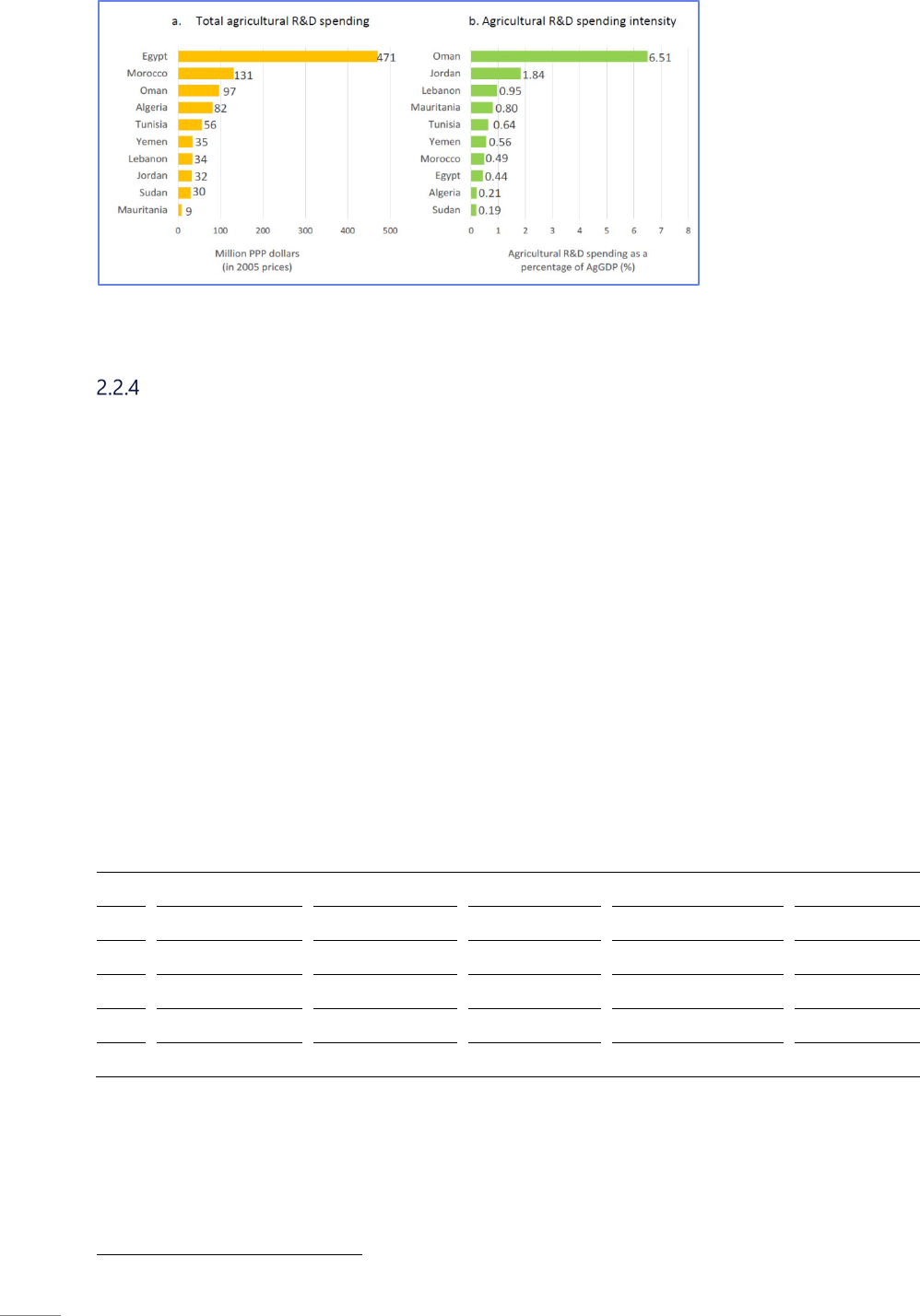

• Research and Development (R&D), one of the stepchildren of the MoIWR has also been

overlooked. Despite the presence of many water specialised research bodies belonging and

affiliated with the MoIWR, they have shown little or no leverage for impact due to the lack of

coordination and limited available financial sources. Absolute and relative data on R&D

investments in the water sector are not available. However, with agriculture being the largest water

consumer, also in the Sudan, a proxy of agricultural R&D spending in 2012 (Figure 2-3) is

appropriate to paint the big picture of fully insufficient attention to R&D in the Sudan.

3

https://gain-new.crc.nd.edu/

Policy review: objectives, process and results

6

Figure 2-3: Absolute and relative agricultural Research and Development (R&D) spending levels

4

2007 Water Policy

At a conceptual level, the draft 2007 Water Policy recognizes the need for integrated water resources

management, but like the 1995 Water Law, it did not address the lack of clarity and coordination of roles

and responsibilities between sectors and across geographic scales, which is prevalent and hampers the

optimal use of limited resources for facilitating and regulating the sector. This is often most evident in the

management of irrigation and drinking water facilities which often deteriorate functionally because of the

lack of clear policies for identifying the responsible entities for O&M.

The inadequate clarity on the roles and responsibilities, coupled with limited provision of resources and

budget for O&M has resulted in fragmented and piecemeal rehabilitation efforts with limited strategic

planning. This has negatively impacted agriculture productivity and sustainability. One documented

example is the deterioration of the infrastructure of the Nile water supplied medium-size pump irrigation

schemes. Some 60% of the nearly 570,000 ha pump irrigation schemes that were rehabilitated some years

back have now exited the production cycle (Table 2-1) due to mainly poor O&M (MoIWR, 2018). These

schemes are nationally significant. They cover a quarter of the roughly 2.3 million ha total area equipped

with irrigation facilities in Sudan and provide livelihoods and food-security for some 130,000 households

or close to one million farming family members.

Table 2-1: Location and scope of the Medium Size Pump Irrigation Schemes (MoIWR, 2018)

No.

State

No. of Schemes

Total area in ha

Cultivated area in ha

No. of Farmers

1 Blue Nile State 34 132,000 41,000 26,238

2 White Nile State 121 147,000 81,000 27,333

3 Nile State 94 141,000 51,000 49,619

4 Northern State 131 146,000 50,000 26,208

Total 380

566,000

232,000

129,398

Insufficient guidance on prioritizing the limited investment that was available for the water and the

agriculture sectors also contributed to the concentration of development interventions in the central parts

of the country endowed with the revenue-rich, easy to develop and use water resources available from the

Nile and its tributaries. This resulted in considerable socio-economic injustice for large segments of the

4

https://www.ifpri.org/blog/agricultural-rd-capacity-arab-world-positive-progress-challenges-remain

Policy review: objectives, process and results

7

population, particularly those in the Eastern and Western fragile regions of the country that rely on seasonal

streams and groundwater resources. These regions are currently the most food insecure. The seasonal

rivers and groundwater resources received meagre investments as they were perceived to be relatively

costly and technically difficult to develop and utilize (MoIWR, 2021).

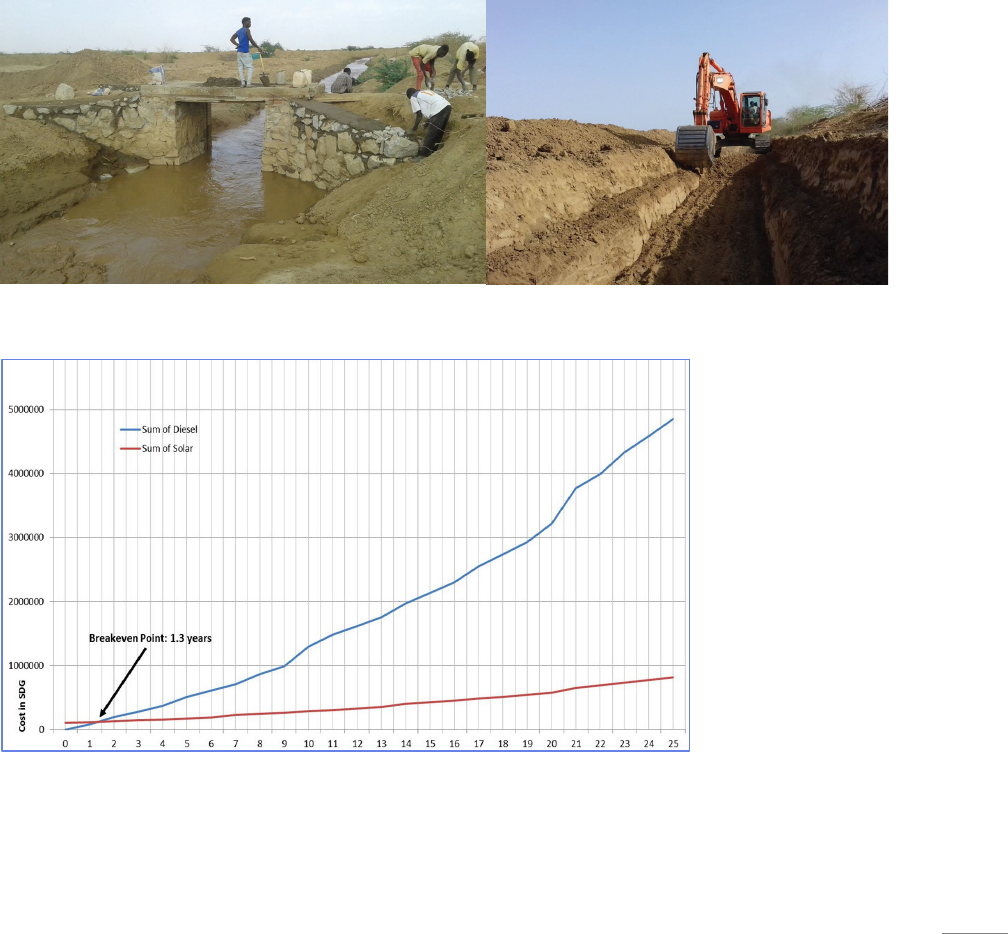

Contrary to this perception, however, there are some evidence-based studies that indicate the viability of

productive investments in seasonal rivers and groundwater-based livelihood systems. One example comes

from the 80,000 ha Gash seasonal river fed agricultural scheme in Eastern Sudan where low-cost (25

USD/ha) field water management interventions in about 3,000 ha doubled the sorghum production to 2

tons/ha while at the same reducing the irrigation demand by a third (HRC and MetaMeta, 2020). The

interventions combined a cross-structure (weir) and improved stone re-enforced field intake to enhance

the floodwater supply; internal earthen bunds to cut by half the size of the mesga (irrigation plot) that is

now large at an average of 250 ha, and 3.5 km long internal earthen canal to irrigate the lower half of the

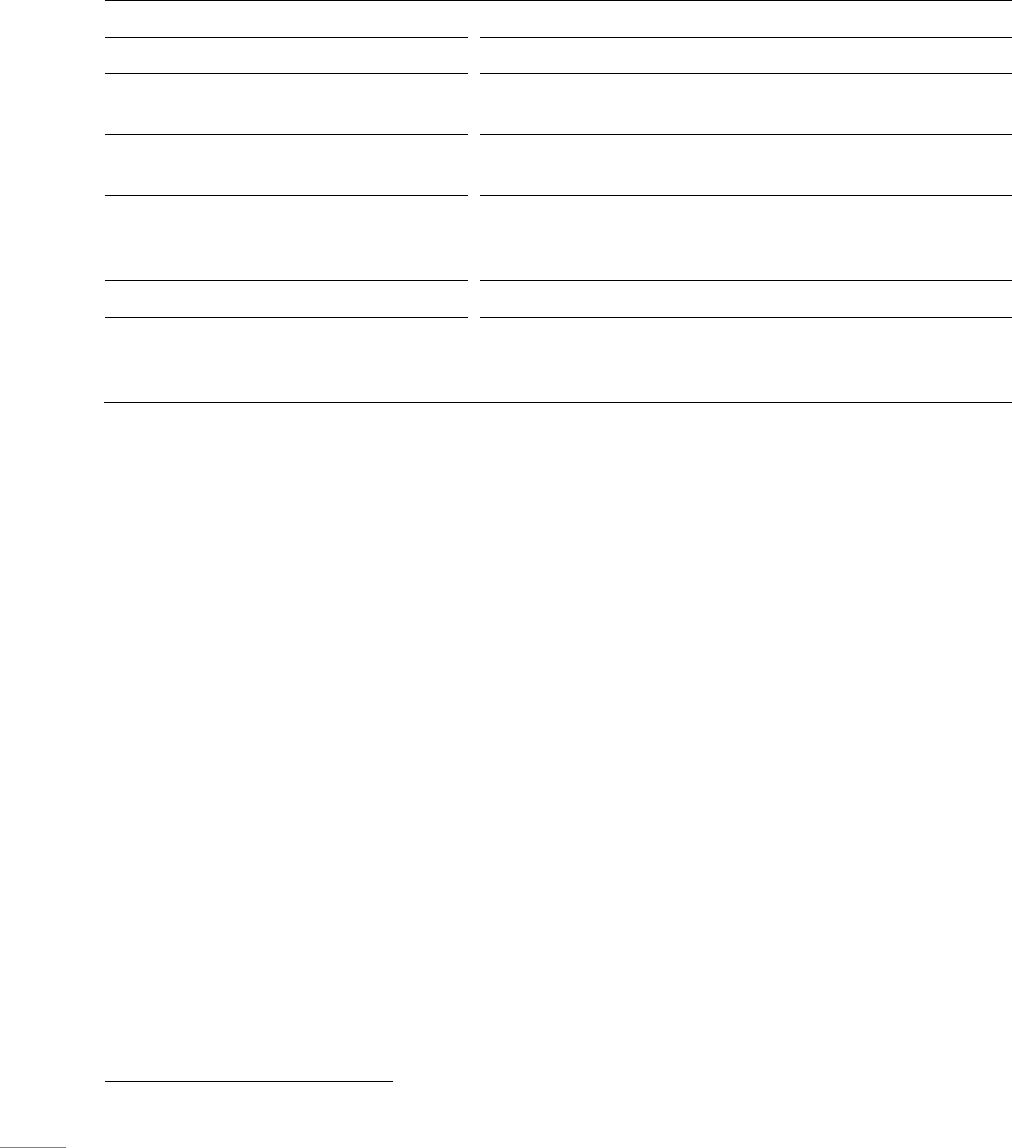

field (Figure 2-4). The second example draws from the 20 multipurpose (irrigation and drinking water

supply) boreholes in Darfur, Western Sudan. As documented in 2017 by the European Commission

Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (EC-HACP) Department and the Global Solar-and-Water Initiative

(GSWI), the shift from diesel to standalone solar pumping could reduce the water delivery cost by up to

80% (Figure 2-5).

Figure 2-4: Low-cost intake and field canals that contributed to improved field water management and productivity in

Gash seasonal river based agricultural scheme in Sudan (Credit: Amira Mekawi, HRC)

Figure 2-5: Cumulative groundwater pumping cost over the 25-year life of solarized systems versus the existing diesel

generator systems (EC-HACP and GSWI, 2017).

Policy review: objectives, process and results

8

Coming back to the analyse of the 2007 Water Policy, while its regulatory component (monitoring and

evaluation, licences and permits) is weak, the facilitative arm (creating an enabling environment) is even

weaker. As a symptom, human resources development and institutional strengthening has largely been

ignored for the past three decades. There have been limited opportunities for staff career development,

and sparing investment into improving the working environment (housing, communication, transportation

facilities). This eroded the motivation to serve and significantly drained the MoIWR and the country of its

killed and knowledgeable human capital.

The inadequate technical and financial attention to strengthen institutional and human resources capacities

is among the leading factors for the deterioration of the large-scale irrigation schemes in Sudan. The 2016

Gezira consultative workshop, identified several concrete impacts (MoIWR, 2016):

• A large number of tertiary and field canals are either over dug or heavily infested with weeds

and silt as they are rarely maintained;

• Many of the structures, like main canal head regulator gates, intermediate and Field Outlet

Pipes (FOPs), are at best only partially operational;

• Poor water distribution is visible in the scheme. While some areas are excessively irrigated,

some other regions are deprived of water;

• There is over supply in the main and major canal systems. This has created turbulent flow and

erosion of canal embankment, contributed to sedimentation and drainage problems, and

exposes the Gezira Scheme and some villages to flood damage risk during the wet season.

• The drainage infrastructure requires major repair and in some locations in need for

reconstruction. Three out of the five escape drains within Gezira scheme are non-functional,

the majority of the drainage pumps are non-operational, the protective and collective drains

along with their crossings and other structures have aged not to mention that they were not

designed for the current much higher drainage requirements.

The policy also does not adequately address the economic value of water. There are no principles that

govern pricing of agricultural water services. As highlighted during the recent 2019 water sector conference,

water is the least priced as it only accounts for less than 1% of the agricultural inputs. For instance, the flat-

rate irrigation service fees in the Gezira irrigation scheme is 150 SDG (<$0.5 USD) per hectare, which is very

low. As gathered from the field surveys conducted as part of the on-going FAO funded water productivity

improvement project, the average cost of farm inputs in Gezira scheme is currently (2020) nearly $150/ha.

2.3 Water for the New Sudan – Transforming Livelihoods Strategy

The 2021 -2031 Water for the New Sudan – Transforming Livelihoods Strategy is a product of multiple

internal and external reviews and extensive consultations with various national and international water

sector partners of the MoIWR. It has three pillars: Water Resources Management and Irrigation (focus of

this policy review), and Water Supply.

The irrigation pillar has specific targets on the expansion of the irrigated areas, the increase in production

but also on improved water productivity. The Water Resources Management pillar directly addresses the

many gaps of the existing Acts and Policies such as: alignment of roles and responsibilities between Federal

and State levels; strengthening the NCWR, implementing catchment plans, and empowerment of water

councils; the development of NWAP.

The major impacts expected by 2031 in the Irrigation pillar of the Strategy are:

• Improved food and nutrition security, peaceful symbiotic co-existence for some 7 million

farming and herding communities;

Policy review: objectives, process and results

9

• Dignified and rewarding job opportunities for nearly 1.5 million Sudanese, rural youth and

women in particular;

• Strengthened institutions and more competent professionals and practitioners will actively

support the rehabilitation and development of irrigation systems as well as provide better

quality and cost-effective irrigation services to farmers and other clients.

• Solution-oriented and up-scalable research results will enrich and fast-track the expansion,

upgrading and modernization of irrigation systems.

The key 2031 interventions to realize the impacts and address some of above discussed current challenges

of the irrigated agriculture sector are as summarized below:

• Constructing, upgrading and modernizing some 25,000 gender-sensitive and disabled-

friendly basic and safely managed water supply facilities that meet the rural and urban

demands and technology option shares;

• Over a million ha of small-holder irrigated land is technically and institutionally upgraded and

modernized, and adequate arrangements for effective operation and maintenance are put in

place.

• Some 0.5 million ha private sector led new irrigation development;

• At least 50% increase in water and land productivity of 1.5 million ha with ‘low-to-no-cost’

measures such as improving water distribution rules and optimising irrigation duties and water

delivery schedules in terms of water volumes and irrigation intervals. The major irrigated crops

in Sudan (wheat, sugarcane and all vegetables and fruits) have the lowest productivity levels

when compared to that of other countries with similar socio-economic status (see box 1);

• Increase the cropping intensity by at a least a third to boost production for local consumption

and export. Just 40% of the 2.6 Million ha currently equipped with irrigation facilities enters

the cultivation cycle annually;

• Some 50% of the 5,000 staff of the MoIWR including 500 young professionals, and 1,000

farmers’ representatives have enhanced know-how and skills in the irrigation water resources

management and development;

• Institutional capacities of the major directorates of the MoIWR and partner organizations are

strengthened through on-the-job trainings and exchange programmes.

The Water Resources Management Pillar of the strategy has the following 2031 targets:

• Multi-sector development scenario Water Allocation Plans (WAPs) to guide the allocation,

control, use, development and protection of water resources at national, state, catchment-

based community levels;

• Revive and strengthen NCWR and establish state and catchment-level water councils;

• Ministry-wide framework for cost and benefit sharing among varied water users and use is

consultatively developed;

• State and catchment-level governance and conflict management mechanisms, particularly in

fragile water-stressed basins;

• Priority investment and research programmes that address major water resources

management and development issues identified, implemented and upscaled – particular

attention will be given to seasonal streams and groundwater resources;

• Comprehensive water quality and quantity data program established; quality data used for

current and future projections for allocations and development decisions.

Policy review: objectives, process and results

10

2.4 Comparative Assessment: Current Status and Future Outlook

This section comparatively assesses the current status of the water and agriculture sector, which as

discussed in the above, is to a large extent shaped by past acts, policies, strategies and investment

decisions; and the future outlook expected to be defined by the New Sudan – Transforming Livelihoods

Strategy.

The assessment is done based on six indicators summarized below and a scoring matrix ranging from 1

(very low) to 5 (very high).

Table 2-2: Overview of indicators used in the assessment

Indicator

Explanation

Land productivity (kg yield or biomass/ha) Relation between agricultural production and agricultural land

Biophysical water productivity (kg yield or

biomass/m

3

)

Relation between yield (tons) and water consumed

(evapotranspiration)

Economic water productivity ($/m

3

)

Relation between economic value and water consumed

(evapotranspiration)

Food security

Access for all people at all times to enough food for a healthy, active

life either through sufficient local production or reliable and

affordable import mechanism

Employment Number of jobs generated by the agricultural sector

Environmental sustainability Responsible interaction with the environment to avoid depletion or

degradation of natural resources and allow for long-term

environmental quality.

The results of the assessment are given in Table 2-3 and the Spider Diagram (Figure 2-6). The rather

brighter future outlook under the New Sudan – Transforming Livelihoods Strategy is informed by the

following facts and recent developments:

• The New Strategy mentions specific targets on several of the assessment indicators – this is

an imperative first step to ensuring adequate resources allocation – financial and technical.

• In the past two years, following the December 2018 Peaceful Revolution, the MoIWR has

aggressively moved to implement the Strategy with some concrete successes:

o The FAO and MetaMeta supported Gezira irrigation scheme productivity improvement

project launched in 2019 has identified a few model farmers who have managed to harvest

4 to 6 tons/ha of wheat and water productivity of about 0.8 kg/m

3

, which is close to the

optimum reported by FAO

5

. Working together with the farmers, the project documented

a compendium of good practices that contributed to such a high yield: 7 to 8 irrigation

turns at a two-week interval, which adds up to an average of 5,000 m

3

/ha; 3 to 4 times

land preparation; 140 to 170 kg/ha seeding rate; 150 to 200 kg/ha and 250 to 350 kg/ha

DAP and UREA fertilizer application respectively; sowing during the period of November

when the temperature is most conducive for germination.

o In the Gash flood-based irrigation scheme, MetaMeta and the Hydraulic Research Centre

(HRC) have successfully introduced on-farm water management practices that combined

internal field bunds and improved intakes and tertiary canals. These interventions in 2,000

ha have doubled the sorghum yield from 0.8 to 2 tons/ha while at the same time reducing

5

https://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/wheat/en/

Policy review: objectives, process and results

11

the water consumption by 30%. The Ministry together with the Sudan International, A UK-

based NGO are working to upscale these interventions into the whole scheme of 80,000

ha.

o The World Bank has approved 300 million USD for Sudan Irrigated Agriculture

Rehabilitation Programme (IARP) that is expected to be implemented in the coming five

years. The programme will benefit some 50,000 ha in each of the Gezira and medium-

sized pump irrigation systems and approximately 60,000 ha seasonal rivers-based

irrigation systems.

o With complementary funding from the French Embassy, preparations are being finalized

to pilot the compendium of good practices at some 10,000 ha in Gezira scheme. This will

also include rehabilitating the tertiary canals most affected with over digging, silt and

weed problems to ensure reliable and sufficient irrigation Supply. The semi-parastatal

EMC financially supported by the MoIWR will support the rehabilitation work with

machinery and personnel.

o With one million Euros grant from the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, capacity

building of irrigation field staff in Gezira and the other large-scale irrigation schemes is

underway. The capacity building is informed by needs assessment jointly conducted with

the relevant irrigation departments. The Ministry has already established a Trading and

Capacity Building Directorate to strategically guide human resources and institutional

strengthening initiatives.

o The Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI) Water Governance Facility has

approved a two-year (March 2021 to Feb 2023), 0.5 Million Euros programme to support

implementation of the water resources management priorities identified in the Strategy.

Among the specific expected deliverables are the development of a NWAP and three

State-level Plans – two covering the fragile Kassala and Darfur regions that predominantly

depend on seasonal streams and floods.

To build on these successes and accelerate investment, research and capacity building programmes in the

decade ahead, the MoIWR has established a dedicated Resource Mobilization and Partnership Unit. While

nobody can predict the future with certainty, the developments in the past two years are indicative of a

promising future for a successful implementation of the New Strategy that is already operational.

Table 2-3: Assessment of the current situation and the priorities in the new water sector Strategy

Indicator

Current situation (2020) largely shaped by past

policies, strategies and investment decisions

The Water for the New Sudan – Transforming

livelihoods strategy: 2031 expectations

Score

Explanation

Score

Explanation

Land

productivity

(kg yield or

biomass/ha)

1

As discussed in Section 1, the land

productivity of the major crops is

currently low.

4 The strategy promotes land productivity

improvement as its top priority. The

proposed technical and institutional

rehabilitation of one million ha is

expected to doubl

e the land

productivity of wheat, sorghum, cotton

and other irrigated crops. Several of the

investment and capacity building

initiatives outlined in the above have the

potential to directly contribute to

improving land productivity. In the past

two years, the irrigation and agricultural

services have improved. Consequently,

as indicated in the above, the FAO and

MetaMeta supported project has

Policy review: objectives, process and results

12

documented up to 6 tons/ha wheat

harvest by some successful farmers,

which is close to the optimum

productivity reported by FAO

6

.

Biophysical

water

productivity

(kg yield or

biomass/m

3

)

1

Biophysical water productivity of the

major crops Sudan is very low (see

analyses in sections 1 and 2).

4 Water productivity is one of the highest

priority targets of the strategy. It

prominently features in the standalone

pillar: “Improving water productivity

with at least 50% more crop per drop”

and also as an integral part of the other

two key pillars, namely ‘upgrading and

modernizing some 1 million ha’ and ‘0.5

million ha new irrigation development.’

In partnerships with FAO, MetaMeta and

other partners, the Ministry of Irrigation

and Water Resources is already

implementing water productivity

improvement project in the largest

Gezira irrigation scheme. Successful on-

farm water management improvement

field trials have also been conducted in

the Gash irrigation scheme that doubled

sorghum yield while at the same time

reducing water consumption by a third.

Furthermore, as gathered by the FAO

and MetaMeta supported project some

model wheat farmers managed about

0.8 kg/m

3

, which is close to the optimum

water productivity reported by FAO

6

.

These are farmers that adhered to a set

of good practices: 7 to 8 irrigation turns

at a two-week interval, 3 to 4 times land

preparation; about 150 kg/ha seeding

rate; 150 to 200 kg/ha and 250 to 350

kg/ha DAP and UREA fertilizer

application respectively; sowing during

the period of November when the

temperature is most conducive for

germination.

Economic

water

productivity

($/m

3

)

3

High commercial crops (wheat, sugar

cane, cotton and several fruits and

vegetables) are produced under the

large-

scale irrigation schemes

supplied from the Nile water. The

very limited investments in the

irrigation sector have mainly been

channelled into t

his Nile water

dependent large-

scale schemes in

the central part of the country. Some

of the bright spots that benefited

from this investment and hence

achieved higher economic water

productivity include the nearly 0.2

million ha Menagil section of the

The strategy foremost aims at

addressing the prevalent socio-

economic disparity between the Nile

water endowed Central region and the

fragile Eastern and Western parts of the

country that mainly depend on seasonal

and intermittent rivers, and temporary

floods. The strategy thus promotes

equal investment to the Nile and non-

Nile water resources as well as cash and

vital food crops.

Assuming the recent successes in

resource mobilization will continue and

perhaps even accelerate driven by the

newly established dedicated Resource

6

https://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/wheat/en/

Policy review: objectives, process and results

13

largest (0.9 million ha) Gezira

irrigation scheme.

Mobilization and Partnership Unit; the

expectation is that investment share of

the revenue-

rich crops will not

significantly decline. Hence, the

Indicator score will score higher because

the strategy specifically advocates for

some low-

cost measures that can

enhance economic water productivity

including market-

oriented cropping

calendar and cropping pattern, and

improved post-harvest techniques and

practices.

Food security 1 As

discussed in Section 1, the

agricultural production and

productivity is currently low and

Sudan sits at the bottom-

end of the

global food security index (112

th

out

of 113 countries).

3 Food security is expected to significantly

improve in the decade ahead

. The

strategy outlines several low-cost

interventions such as improving

irrigation schedules and cropping

patterns to improve productivity as well

as expand irrigable areas to boost

production. Staple at the same time

commercially valuable crops such as

wheat will get the priority. Already a

policy document has been prepared

and resources have been mobilized to

double wheat production to 800,000 ha

in the Gezira irrigation scheme by the

end of 2021 and further upscale this to

over a 1 million ha by 2023. The strategy

also aims at creating rewarding

employment for 1.5 million Sudanese,

rural youth and women in particular. -

this is expected to improve the

purchasing power. Finally, the lifting of

the international embargo will also likely

help in improving the overall economy

that may translate to higher purchasing

power.

Employment 1

Agriculture provides job

opportunities for some 70% of the 44

population of Sudan. The overall

unemployment rate steadily

increased from about 12% in 2011 to

25% in 2020 – it

remained stubbornly

high among the rural youth that rely

on the agriculture sector at over 30%.

The unemployment trend closely

correlates with the loss of oil revenue

following the secession of South

Sudan in 2011 and the weak

agriculture sector left behi

nd that has

never been adequately revitalized

due to a combination of inadequate

policies and strategies and

insufficient investments to support

actionable solutions that boost

production and productivity.

3 Employment in the agriculture sector is

expected to significantly increase. The

strategy has set a target of 1.5 million

job creation (especially among the rural

youth and women) through increasing

water and land productivity in one

million ha irrigated land by at least 50%;

increasing the annually cropped area by

30% or 0.7 million ha; 0.5 million ha new

irrigation development. The 1.5 million

target is based on the estimation that

every 2 ha with 50% productivity

improvement will generate an

additional 1 FTE (full time) employment

and 1 FTE will be generated from each

ha that enters a production cycle. These

values are gathered from the various

consultations undertaken with farmers

Policy review: objectives, process and results

14

and other stakeholders during the

preparation of the strategy.

The 50% productivity improvement is

achievable as for examp

le, there are

already some model farmers harvesting

4 to 6 tons/ha of wheat, which is more

than double the current productivity

level.

Creating an enhanced work

environment (housing facilities,

transportation, communication, etc.) is

also a key target of the strategy. This is

expected to encourage many,

particularly the youth, to enter the

agricultural sector job market.

Environmental

sustainability

1

The need to fast-

track agricultural

development, which is also

symptomatic in many developing

countries,

has pushed environmental

sustainability to the bottom of the

priority list. Water logging is evident

in some parts of the existing

irrigation schemes due to poor

drainage facilities and excessive

water supply; groundwater depletion

particularly in the wate

r stressed

Gash Basin in Eastern Sudan has

reached a concerning level. This is

due to overexploitation and

inadequate attention and investment

to enhance the recharging capacity.

2

Given the urgency to deliver quick

economic growth, environmental issues

will struggle to find a front row seat in

water sector investments and

programmes. That said, several of the

low-to-

no cost water productivity

improvement measures promoted by

the strategy will deliver some positive

environmental impacts such as reduced

water logging, soil fertility degradation

and flood damage

Figure 2-6: Spider diagram comparing the current situation and priorities in the Water for the New Sudan – Transforming

Livelihoods Strategy

Positioning the new national water policy for improved water productivity

15

3 Positioning the new national water policy for improved

water productivity

The drafting of the new National Water Policy is at the initial phase of the consultation process. On request

of the MoIWR this section is prepared to initiate dialogue on how best to position the New Policy to support

the achievements of the 2031 targets in the Spider Diagram, particularly with regards water productivity.

Taking stock of the gaps in the existing policies, the ambitions of the Water for the New Sudan Strategy

and the priorities of the Sudanese government, the evolving picture of the new Policy may possibly look

as follows:

• Vision – Overarching Goal

Affordable and reliable water resources of adequate quality and quantity for all Sudanese, in its productive

sense for agriculture and livestock, in its social sense of creating harmony and cohesion, and in its

environmental sense of doing no harm by seeking synergies and complementarities.

• Institutional Goal

The MoIWR and its partner organizations have strengthened human resources and institutional capacity

to reflect peoples’ needs, enable investments in peoples’ institutions and infrastructure, and to mobilise

and deliver value-adding inclusive services to the benefit of all.

• Water Productivity: Contribution to Policy Ambitions

To realize visible and wide impact on the ground, the policy will prioritize actionable solutions that

adequately respond to and harness the promise of the water sector across four priority pillars of the

Sudanese government and the MoIWR: Water for Peace, Water for Food Security, Water for Health and

Water for the Environment (Annex 2 has the details).

Water productivity is a main element of operationalizing the four anchoring pillars. A transformed

agriculture sector that is water efficient, highly productive and employment generating engine, can make

tremendous contribution to socio-economic well-being and peaceful co-existence of the pastoral and

farming communities that account for some 70% of Sudan’s estimated 44 million population. Water

productivity improvement measures such as efficient irrigation scheduling, better drainage and

groundwater recharge, can result in a healthy and sustainable environment.

The new National Water Policy aims at effectively facilitating the following water productivity related targets

contained in the Water for the New Sudan – Transforming Livelihoods Strategy:

• Over a million ha of small-holder irrigated land is technically and institutionally upgraded and

modernized;

• Some 0.5 million ha private sector led new irrigation development;

• At least 50% increase in water and land productivity of the existing 1 million and the new 0.5 million

ha.

• Increase the cropping intensity by at a least a third to boost production for local consumption and

export. Just 40% of the 2.6 Million ha currently equipped with irrigation facilities enters the

cultivation cycle annually.

What is required is to describe how can the policy contribute in practice to making these targets

operational and what additional analyses can be done to inform policy decisions. The Water Sector Strategy

Identified five categories of institutions that are critical for driving the programmes necessary to realize the

Positioning the new national water policy for improved water productivity

16

above outlined targets and operationalizing the activities detailed in the next two sections. These are

summarized below.

• Federal or state level institutions: These institutions may design, appraise, finance, and commission

irrigation and management facilities in accordance with existing standards and menus of

technological options. They are required to provide needed capacity building to establish

community level management structures that are capable of routine O&M and reporting as per

the required standards. Sources of funding may include federal or state-level funds or external

funding channelled through the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning.

• Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs): Accredited NGOs may design, appraise, finance, and

co-implement irrigation and water management programmes in accordance with existing

standards and menus of technological options. NGOs can also play a role in knowledge transfer,

technology adoption, and institutional strengthening to enhance the capacities of communities

and local government to design, implement, and manage programmes. Financing could come

from resources mobilized by the NGOs directly or through international donors.

• Community or civil society institutions: Irrigation and water management initiatives that are

designed and implemented through community cooperation or civil society engagement are yet

another modality. Communities and Civil Societies must inform and report to the local government

institutions about the planning and operation of proposed initiatives to facilitate monitoring of

functionality in the future. Financing of such initiatives may be through community fundraising or

Civil Society contributions. An adequate community level O&M mechanism must be established

to ensure continuity and sustainability of services.

• Private sector: Accredited private sector institutions can contribute to improved O&M of irrigation

and water management facilities. They can also support the establishment and training of

community-level O&M mechanisms. The private sector institutions must engage with federal and

state level governments to ensure appropriate oversight

Policy support for water productivity

Achieving 50% increase in water productivity across 1.5 million ha in the decade ahead is a huge challenge

as it also has to compete for investments with other priorities such as provision of safe and adequate rural

and urban domestic water supply. The policy can play a major role in realizing the target by forcefully

promoting low-to-no cost interventions that often yield immediate results without a long gestation period.

These are often overlooked as often attention goes to huge infrastructural investments. They include:

improving water distribution rules and optimising irrigation duties and water delivery schedules in terms

of water volumes and irrigation intervals; improved drainage (also reusing drainage water), and an array

of smart measures that promote better water management at farmer field level. Besides improving water

productivity, they bring several other benefits: fewer diseases, less back breaking labour, and less

environmental degradation through salinity and water logging.

Another area of policy support is the improvement of economic water productivity that is closely linked to

job creation – unemployment rate in Sudan is currently among the highest among African countries. The

policy could give more visibility to economic water productivity, which is not as explicitly mentioned in the

Water for the New Sudan strategy as the biophysical water productivity. It can also help better orient

resources to interventions such as market-oriented cropping calendar and cropping pattern, and improved

post-harvest techniques and practices (this are contained in the strategy) that can boot economic

productivity.

The policy can also make a significant contribution to water productivity improvement by embracing

‘capacity building and institutional strengthening as the regular order of business”. This has for years been

Positioning the new national water policy for improved water productivity

17

done in ad hoc basis with limited strategic guidance and direction. Inadequate governance and

management of water resources due to weak human resources and institutional capacity is one of the main

reasons for the water productivity levels in Sudan. The policy can enforce several practical measures to

systematically and more efficiently address the issue:

• All investment and development programmes should allocate 5 to 10% of their budget to research

and capacity building; and concerted efforts must be made to ensure that donors and

development banks abide by this.

• Regularly update the knowledge and skills of the MoIWR workforce and mainstream capacity

building in all departments and agencies: each staff member should annually complete at least

one training programme to be eligible for promotion.

• Facilitate applied solution-oriented research with dedicated room for innovation and

experimentation, and water productivity improvement as integral part of capacity building

packages.

• Promote remote sensing, WaPOR and smart ICT technologies for real-time monitoring of water

levels and discharges; and facilitating effective water distribution and management through timely

and reliable mapping of system-wide (from upstream to downstream) variations in irrigation

supply. Other than irrigation water management, the technologies also provide more information

for farmers and policy makers to guide agricultural practices at farm level, in particular information

on status and health of crop growth (diseases, nutrients, etc.). These are important for boosting

land and water productivity. The technologies in particular needed in the mega Gezira irrigation

scheme, but also in the medium-size pump irrigation systems where some individual schemes are

substantial at about 40,000 ha as well as the large-scale seasonal rivers fed irrigation systems such

as the Gash and Toker that cover about 170,000 ha and 100,000 ha irrigated areas respectively.

• Strongly support the initiative by the Water PIP project and similar other efforts to establish

dedicated institutions (service hubs) for real-time monitoring as well as developing products and

services that improve land and water productivity across the 2.3 million ha total area currently

equipped with irrigation facilities in Sudan.

• Facilitate more equitable allocation of financial resources. As discussed earlier, the Gezira scheme,

by virtue of its large size and political status, had monopoly of the investments in the past years.

The policy should unequivocally recognize the fact that the other irrigation systems are equally

important and support the Water Sector Strategy achieve its objective of rehabilitating 400,000 ha

pump irrigation schemes (same target is set for Gezira) and another 300,000 ha seasonal rivers-

based irrigation schemes. The medium-size pump systems, while they only cover two-third of the

Gezira irrigated land, they provide livelihoods and food-security for some 130,000 households or

close to one million farming family members – the same number of target beneficiaries supported

by the Gezira scheme. Likewise, the seasonal rivers-based systems cover about 55% of the Gezira

scheme irrigated area, but they are the major sources of food and fodder for roughly 0.5 million

households or 2.5 farmers and pastoralists (MoIWR, 2021). At operational level, the policy should

endorse and build upon the criteria for equitable financial allocation outlined in the Water Sector

Strategy: a) proportion of inadequately developed irrigation and insufficiently served population,

b) poverty, food insecurity and high unemployment rates; c) vulnerability to climate shocks -

extreme droughts and floods, d) limited resources or funding provided in last 5 years.

Finally, recognizing farmers, herders and producers as solution providers, not just a target group as they

are now often categorised can go a long way in enhancing water productivity. These stakeholders are also

being at the forefront of innovation, knowledge exchange and learning. They are reservoirs of local

knowledge, harnessed through constant strive to address their problems: many have applied such local

knowledge to a greater effect.

Positioning the new national water policy for improved water productivity

18

Policy Relevant Water Productivity Analyses

In support of the above outlined and related policy measures to facilitate enhanced water productivity,

several WaPOR (remote sensing) analyses complemented with field research need to be undertaken. Some

of the priority thematic topics include the following:

• Evidence-based documentation of farmers’ field water management and farming practices and

analysing their impacts on water productivity;

• Better identify the various packages of low-to-no cost measures that could result in the highest

possible improvement of water productivity for different crops, agro-climatic conditions, irrigation

methods (large, small, perennial, flood-based) as well as rained and flood-based production

systems;

• Comparative analysis of various scenarios of low-to-no cost measures and investment intensive

infrastructural interventions on water productivity – both biophysical and economic value.

• Impact of various biophysical and economic water productivity improvement scenarios on job

creation, food security and environmental sustainability;

• More attention for sustainable use of water – identifying the most water efficient and productive

measures to realize the proposed increase in crop intensification and new irrigation development;

• Better understanding of the know-how and skills and institutional strengthening interventions that

more significantly contribute to improved water productivity.

References

19

4 References

Ahmed, A.O. and Mehari, A. 2020. Policy Document: Expanding Wheat Production in Gezira Irrigation

Scheme to Meet Local Demand and Reduce Import Dependency. Ministry of Irrigation and Water

Resources (MoIWR). Khartoum, Sudan.

Berry, L. 2015. Sudan: A Country Study. Federal Research Division Library of Congress, United States of

America.

Elamin, A.W.M., 2013. Water Resources in Sudan. International Course on Agricultural Mechanization and

Information Technologies. International Agricultural Research and Training Center (IARTC) in Izmir/Turkey

between 13 – 17 May 2013 Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275016737_Water_Resources_in_Sudan (accessed on November

12, 2021)

European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (HACP) Department and Global Solar-and-

Water Initiative (GSWI). 2017. Visit Report - Solar and Water Initiative for Darfur, Sudan.

https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/solar_water_initative_-_visit_report_to_sudan_-_feb-

march_2017.pdf (accessed on November 14, 2021).

FAO, 2020. Special Report - 2019 FAO Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission to the Sudan. Rome.

FAO, 2015. AQUASTAT Country Profile – Sudan. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

(FAO). Rome, Italy.

FAO, 2008. Recent Developments in Agricultural Research in the Sudan (SRO/SUD/623/mul)

HRC and MetaMeta, 2020. On-farm Water Management in Gash Agricultural Scheme – Final Report.

Hydraulic Research Centre (HRC-Sudan) and MetaMeta Research, the Netherlands.

HRC, 2019. Compendium of Possible Issues and Solutions to Improve Productivity in the Gezira Irrigation

Scheme (Draft Report). Hydraulic Research Centre (HRC). Wad Medani, Sudan.

HRC, 2016. Draft Work-plan and Budget for Upgrading of Gezira Irrigation Scheme. Results of the Expert

Consultation Workshop, 21 to 26 February, Wad Medani, Sudan.

IMF, 2013. Sudan: Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper. International Monetary Fund (IMF), Country

Report no. 13/318.

Mahgoub, F. 2014. Current Status of Agriculture and Future Challenges in Sudan. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet,

Uppsala, Sweden.

MoIWR, 2018. Quick-win Water Sector Investment Projects. Rehabilitation of Medium Size Pump Irrigation

Schemes. Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources (MoIWR). Khartoum, Sudan.

MoIWR, 2019. Conference Report: Harnessing the Promise of the Water Sector for a prosperous New Sudan

18th -19th February 2019. Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources (MoIWR). Khartoum, Sudan.

MoIWR, 2021. Sudan Water Sector Strategy - Transforming Livelihoods 2021 – 2031: The Promise of the

Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources (MoIWR). Khartoum, Sudan.

Smit, H. 2019. Making water security: A morphological account of Nile River development. CRC Press.

UNEP, 2012. Environmental Governance in Sudan: An Expert Review. United Nations Environment

Programme. Nairobi, Kenya.

Annex 1: Sudan water acts and regulations drafted in the past decades, but were inadequately enforced.

20

Annex 1: Sudan water acts and regulations drafted in the past

decades, but were inadequately enforced.

As summarized below, the Acts are very much regulatory in nature and with the exception of the

Environmental Health Act, they offer little guidance on efficient, productive and sustainable use of the

limited water resources of Sudan.

1. Irrigation and Drainage Act 1990: It establishes that any work related to irrigation or

drainage provided needs a permit from the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources. The

licensee shall notify the Ministry to draw water for irrigation, whether from the Nile River or

any of its tributaries or any other rivers or public canals;

2. Water Resources Act 1995: Is a major institutional reform concerned with the Nile and Non-

Nilotic surface waters as well as with groundwater, hence superseding the 1939 Nile pumps

control act that was limited to the Nile waters only. It also establishes the National Water

Resources Council and the need of a license for any water use;

3. Groundwater Regulation Act 1998: Mandates the Groundwater and Wadis Directorate as the

sole government technical organ to develop and monitor wadis and groundwater, and to

issue permits for constructing water points;

4. Public Water Corporation Act 2008: Gives authority to central government for national

planning, research, development and investment in the water supply sector, as well as the

corresponding policies and legislations;

5. Gezira Scheme Act 2005): Effectively transferred irrigation and farming responsibilities from

professionals to farmers. Its main objectives include ensuring farmers’ right to: (i) effectively

participate, at all administrative levels, in planning and implementation of projects and

programs that affect their production and livelihoods, (ii) manage irrigation operations at

field canal level through water users’ associations, and (iii) freely manage their production

and economic aspects within the technical parameters, and employ technology support to

boost production and maximize their respective returns;

6. Civil Transaction Act 1984: Ties the rights to develop and access water resources with land

rights, as long as permission is granted by the respective water authority;

7. Fresh Water Fisheries Act 1954: Is very regulatory in nature and its main provision states: no

person shall introduce any non-indigenous fish into the Sudan except under, and in

accordance with the conditions of, a permit issued by the Minister of Agriculture, Food and

Natural Resources, who may in his absolute discretion refuse such permit;

8. Environmental Health Act 1975: It provides for the conservation of water and the prevention

of the spreading of epidemics. It stipulates that the health authorities, in any Department,

should regularly analyse water samples to ensure its quality and that it is unpolluted. The Act

requires that any person or (institution) responsible for storing or supplying the population

with drinking water, whether belonging to the public or the private sector, should conform

to the health conditions outlined by the Minister of Health;

9. Gash Development & Utilization Act 1992: Provides guidance on, among others, abstraction

and digging of shallow wells licensing; water fees; water resources pollution.

Annex 2: Anchoring pillars of the proposed new national water policy

21

Annex 2: Anchoring pillars of the proposed new national water

policy

Pillar I: Water for Peace

Promoting domestic and regional tranquillity, nurturing cooperation within the water sector community

and facilitating peaceful co-existence among rural and urban communities is a top priority of the

Government of Sudan and the MoIWR. Enhancing food and nutrition security and providing improved

water supply services to post-conflict regions is a critical step to addressing grievances of communities

that have been disenfranchised and marginalized for decades. Making such services available to historically

marginalized communities also presents an opportunity to rebuild the trust and social fabric between

government and communities.

Pillar 2: Water for Economic Growth

A transformed agriculture sector that is water efficient, highly productive and employment generating

engine, can make tremendous contribution to socio-economic well-being of the Sudanese people. For

example, the 2 million ha four national large-scale irrigation schemes (Gezira, Rahad, New Halfa and Suki),

if properly performing, directly and indirectly create over 3 million jobs and contribute immensely to the

improvement of food and nutrition security, raise national income and exports, and boost import-

substitution. Sudan has an estimated 8.5 million ha potential irrigable land. Safe and reliable water supply

for human consumption is critical for having a healthy workforce that can contribute more fully to the

economy. In addition to human consumption, provision of water supply also has the potential to revitalize

the livestock sector and support the lives and livelihoods of millions of herding families.

Pillar III: Water for Health

Severe food insecurity, hunger and undernourishment are direct contributors to poor health including child

mortality and stunting affecting nearly half of the Sudanese population. There are significant regional

disparities with the peace-fragile water stressed eastern and western (Kassala and Darfur) parts of the

country topping the list of the most affected and vulnerable. To address these challenges, there is a need

to introduce a new way of doing agriculture – agriculture that supports diversified and affordable dietary

value chains while being economical with water, and is highly rewarding and attractive to all people,

including women and young people.

Provision of inadequate water supply in both quantity and quality has a profound impact on health

outcomes of Sudanese citizens. Consumption of unsafe water supply directly contributes to high

prevalence of diarrheal diseases that are some of the leading causes of death in Sudan. They also contribute

to malnutrition and stunting in children.

Pillar IV: Water for the Environment

This is a cross-cutting pillar. All new, expansion or rehabilitation programmes and projects for agriculture

and water supply facilities must balance the need to fast-tracking socio-economic development and

realizing environmental sustainability. To have long-lasting impact on peace, health and the economy, the

programmes and projects should adequately identify and recommend mitigation measures for associated

environmental and social risks. Pertinent Environmental and Social Impact Assessments or similar

assessments must be conducted during the design and feasibility studies of the particular investments.