2

AUTHORS

Winnie Khaemba

Raghu Vyas

Inga Menke

CONTRIBUTORS OR REVIEWERS

Down2Earth Policy development Team

Abebe Tadege

Mustafe Elmi

Teun Shrieks

Michael Singer

Ann van Loom

Burcu Yesil

Mark Tebboth

Roger Few

Toby Pitts

CITATION AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication can be reproduced in whole or in part for educational or non-profit

services without the need for special permission from the Down2Earth Project,

provided acknowledgment and/or proper referencing of the source is made.

This publication may not be resold or used for any commercial purpose without prior

written permission from the Down2Earth Project.

We regret any errors or omissions that may have been unwittingly made.

This document may be cited as:

Climate Analytics. 2022. Policy Analysis Report, Down2Earth Project

Supported by:

We would like to thank the EU H2020 for providing the funding for this work

Contract number: 869550

3

1. Executive Summary

Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia continue to be faced with climate change impacts especially

drought and floods that have increased in both frequency and intensity over the past few

years. IPCC projections show that this trend will continue as global warming persists. Impacts

from such changes include worsening water and food insecurity in a region that is mostly arid

and semi-arid. In cognizance of these challenges the countries in the region have put in place

policies on climate adaptation, water and food security at both national and subnational level.

This report presents findings from an analysis of over 60 such policies in all three countries at

national and regional level using a policy triangle approach to consider the context, processes,

content and actors involved in developing the policies.

The analysis reveals that climate change policies have mostly been influenced by international

processes at the UNFCCC. Water policies have been shaped by national and regional

circumstances where water remains scarce and inaccessible to a significant percentage of the

population. Food security policies on the other hand have mostly been informed by continent

wide strategies such as Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Programme (CAADP) as

well as national priorities in ensuring food sufficiency. As a result most policies rank highly in

terms of linkages with other policies and processes averaging 3.3 for Kenya, 2.8 for Somalia

and 2.8 for Ethiopia.

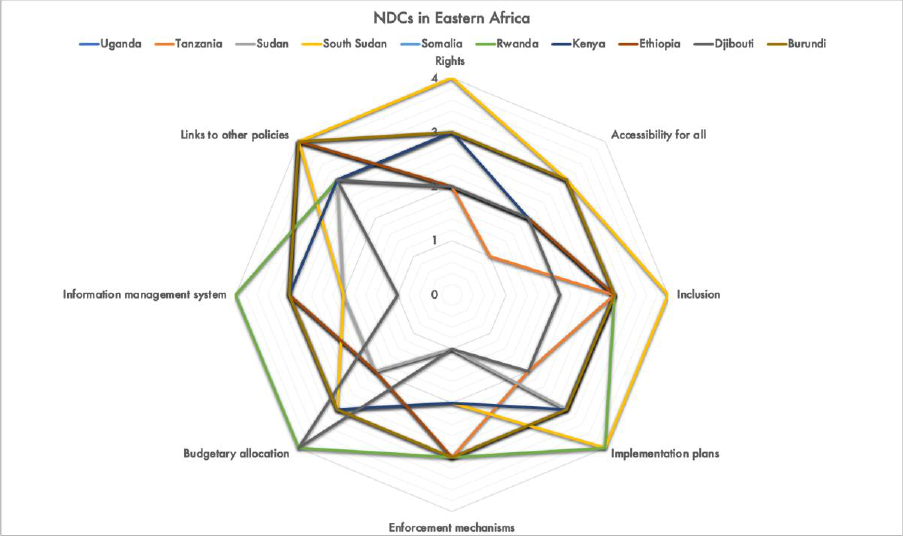

For the NDCs analysis, assessment of 10 Eastern Africa NDCs shows that linkages at 3.6,

implementation plans and inclusion at 3 are the highest rated signaling greater effort to link

with both national, regional and international policies. These policies have an average score

of 2.8. South Sudan’s NDC has the highest score of 3.3, followed by Rwanda and Burundi with

3.1 while Djibouti has the lowest score at 2.1.

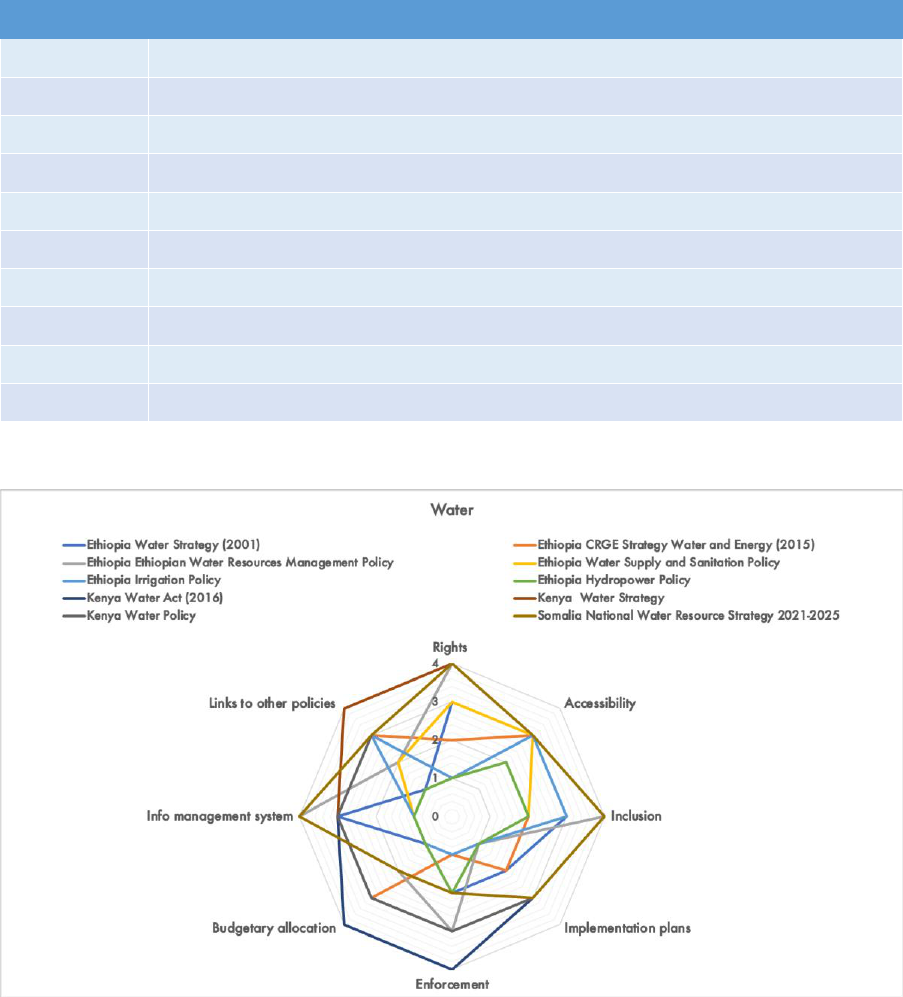

The collective performance of all 3 countries in each sector varies. Water policies average 2.6

for the three countries. Kenya’s water policies rate highly at an average score of 3.4, with the

Water Act of 2016 rated 3.5. This was the highest scoring policy in the entire analysis. This is

followed by Somalia with an average sector-wide score of 3.1, and Ethiopia with an average

score of 2.1.

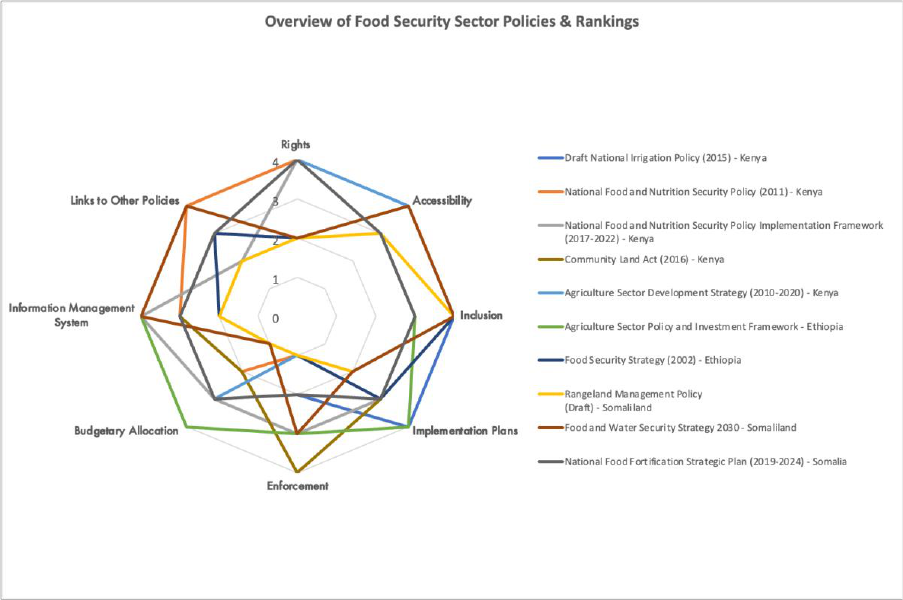

For food security policies, Kenya had the highest-scoring policies, with an average score of

3.3, followed by Ethiopia at 2.9, and Somalia 2.7. Kenyan food security policies scored highest

on inclusion and rights, with all of the country’s sectoral policies scoring a 4 in these

categories. With a score of 3.4, Ethiopia’s Agriculture Sector Policy and Investment

Framework is the highest scoring policy in the food security sector. The Proclamation to

amend the proclamation No. 56/2002, 70/2003, 103/2005 of Oromia rural land use and

administration proclamation 130/2007 followed closely with a score of 3.3.

4

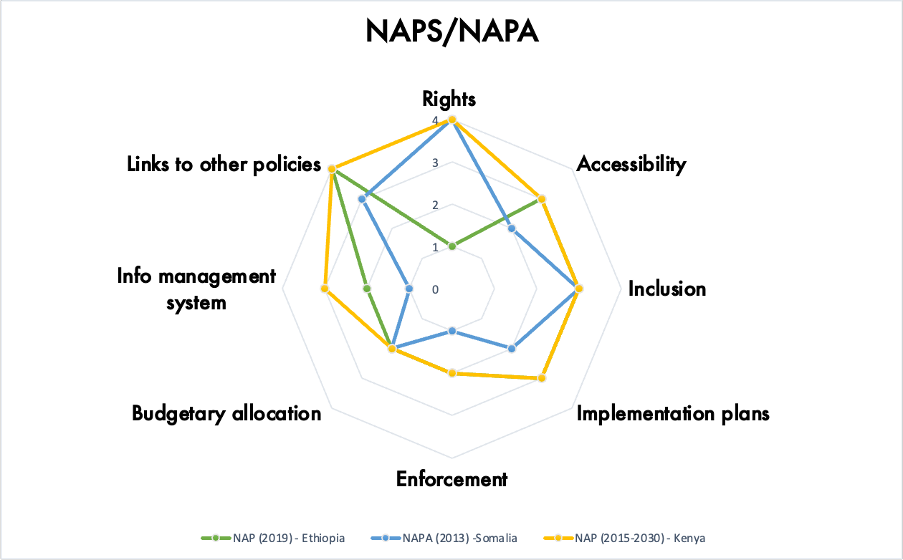

Lastly, the climate change adaptation sector explored the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) or

National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) of each country. With a score of 3, Kenya’s

NAP was the best-performing of the policies analyzed. This was followed by Ethiopia’s NAP

with a score of 2.5, and Somalia’s NAPA with a score of 2.3. In the climate change adaptation

sector, all three policies performed especially poorly with regards to policy enforcement,

scoring an average of 1.3. This was followed by budgetary allocation and information

management systems, both of which had an average score of 2 across all the countries.

As can be seen from the sector-level analysis, Kenyan policies tended to perform

comparatively well overall, followed by Ethiopian policies. Somali policies tended to perform

comparatively poorly on average. However, there is significant variation in the quality and

scoring of policies within each country. These variations can be better understood through

the lens of the sector and/or the elements of the policies being analyzed.

Rights and inclusion are a strength in most policies with a score of 2.9 and 3.3 respectively

across policies where rights to a clean and healthy environment, right to water and the right

to food as well as the recognition of vulnerable groups and how they can be included and

actively participate in planning, decision making and implementation of policies.

Enforcement and budgetary allocation with a rating of 2.2 and 2.4 respectively are two of the

key elements that repeatedly score poorly across most policies including those with well set

out plans. East African countries will need to devise ways in which to enforce set policies to

assure implementation and enhance accountability. For budgetary allocation it is important

that countries ensure that resources are earmarked for policy implementation in whose

absence they may only remain on paper. While international finance is often outlined in

policy, international climate finance remains unpredictable, not additional, and inadequate

thus efforts have to be made to avail this finance for climate adaptation especially by

developed countries that bear the highest responsibility for global warming.

This said the real test is in the implementation of the set policies in these countries. The next

phase of this research will focus on the efficacy of the policies in place where the focus will

be on the progress in implementation of the measures outlined in the policies and the

impact/result of such implementation.

5

Table of Contents

1. Executive Summary 3

2. Introduction 7

3. Methodology 12

a. Background 12

b. Policy Triangle 13

c. Framework of analysis (criteria) 13

d. Policy selection 20

4. Results 21

a. Country level analysis (including stakeholder input) 21

i. Kenya 21

ii. Ethiopia 38

iii. Somalia 50

b. Sectoral analysis (cross-country) 61

i. Water management 61

ii. Food security 64

iii. Climate change adaptation: NAP/NAPA 68

iv. NDC analysis (including additional countries) 70

5. Conclusion 72

a. Key take aways 72

i. Criteria 72

ii. Country 72

iii. Sector 73

b. Recommendations 73

i. Criteria 73

ii. Country 74

iii. Sector 74

6. References 76

6

List of Figures

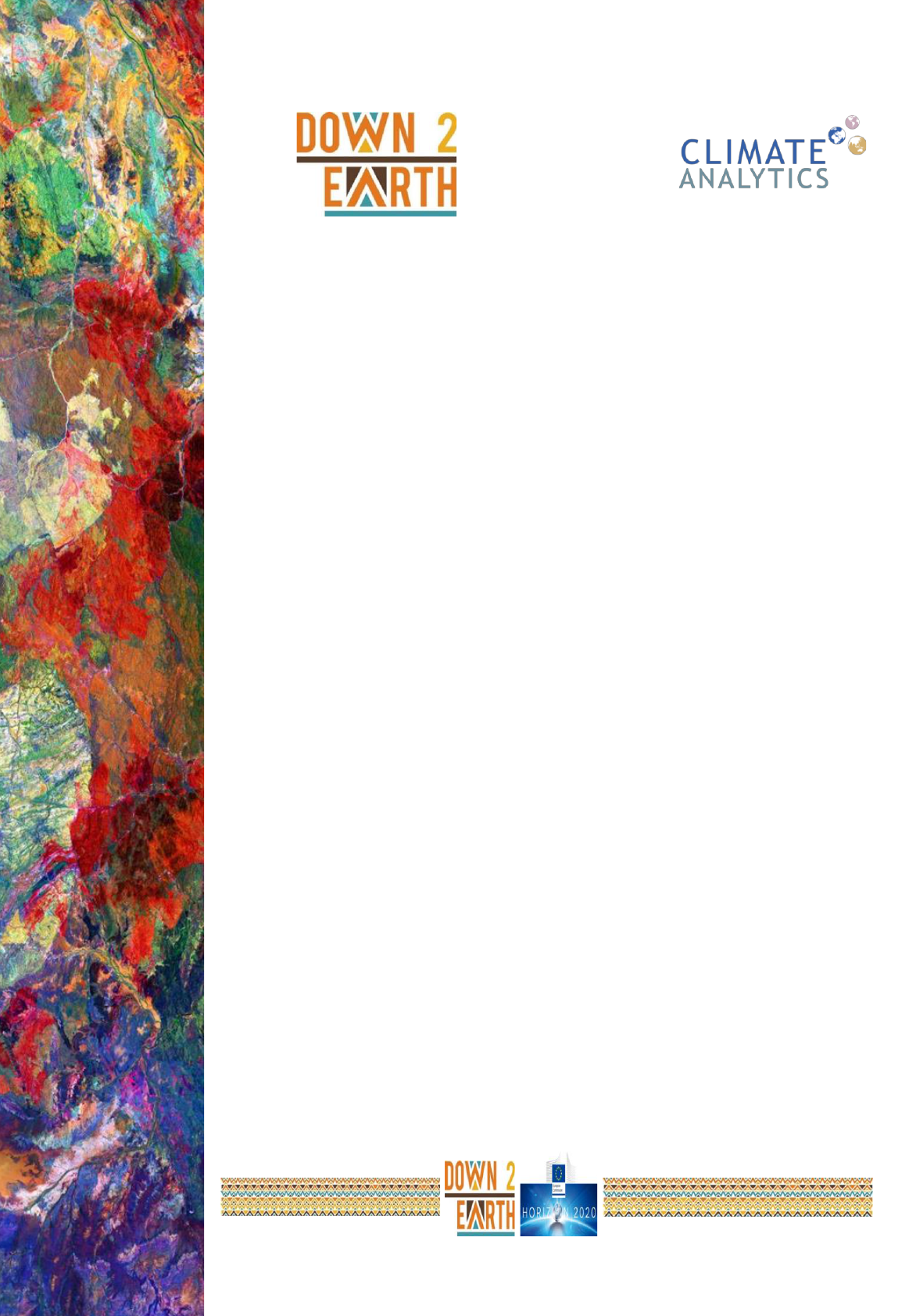

Figure 1: Schematic of the Down2Earth Project ....................................................................... 7

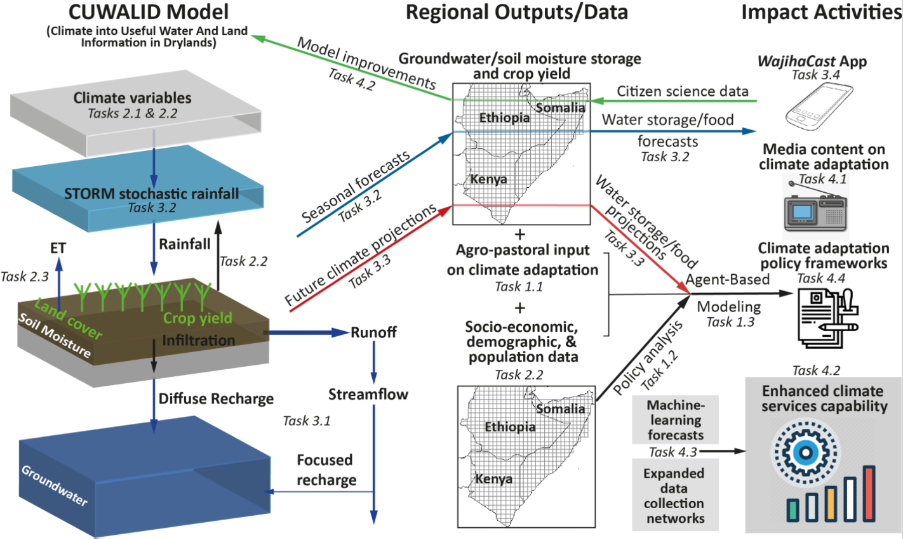

Figure 2: Map of Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia ........................................................................ 8

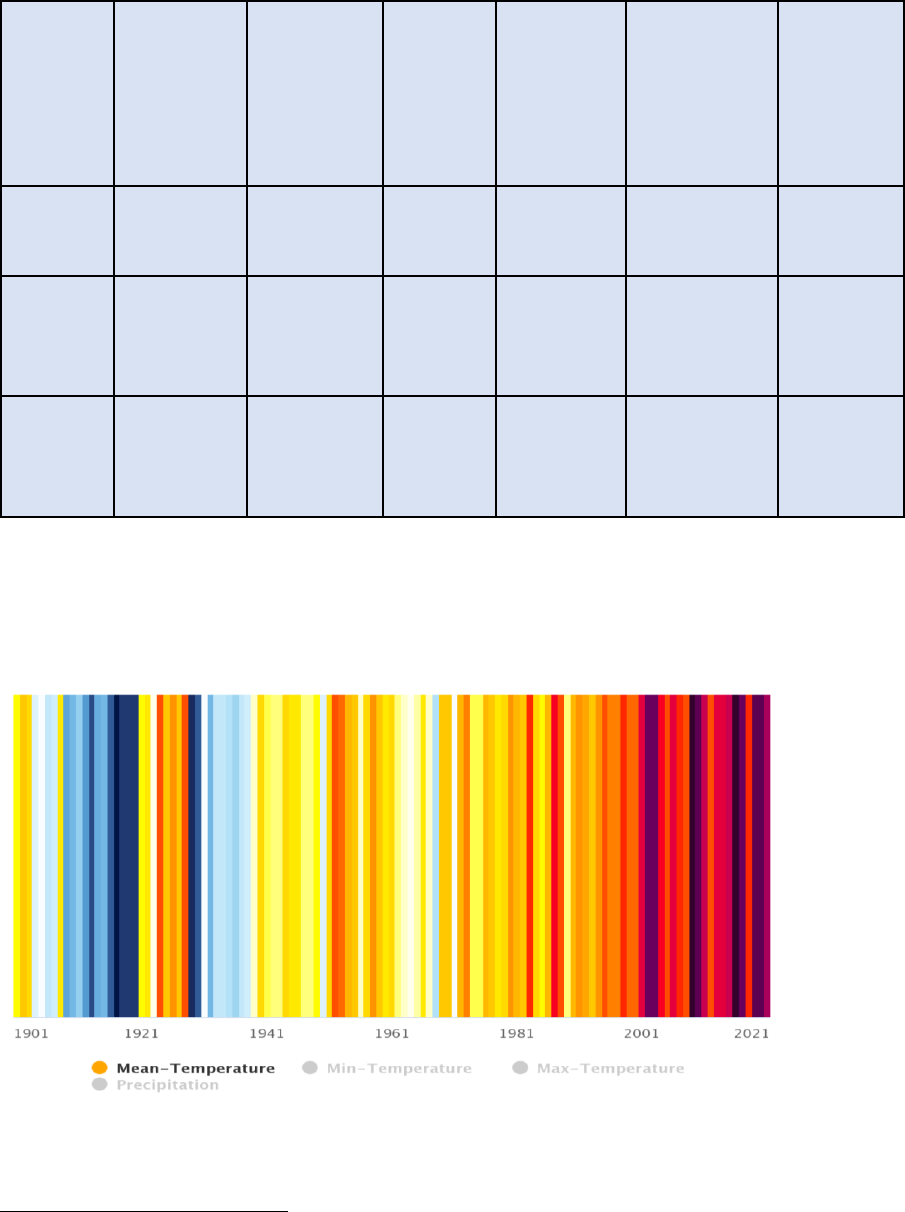

Figure 3: Observed Annual Mean-Temperature, 1901-2021 (Kenya)

6

..................................... 9

Figure 4: Observed Annual Mean-Temperature, 1901-2021 (Somalia)

7

................................. 10

Figure 5: Observed Annual Mean-Temperature, 1901-2021 (Ethiopia)

8

................................ 10

Figure 6: Policy Triangle (Walt and Gilson, 1994) ................................................................. 12

Figure 7:Vertical and Horizontal Interplay (Young, 2002) ..................................................... 13

Figure 8: Policy Analysis Framework (Walker, 2000) ............................................................ 13

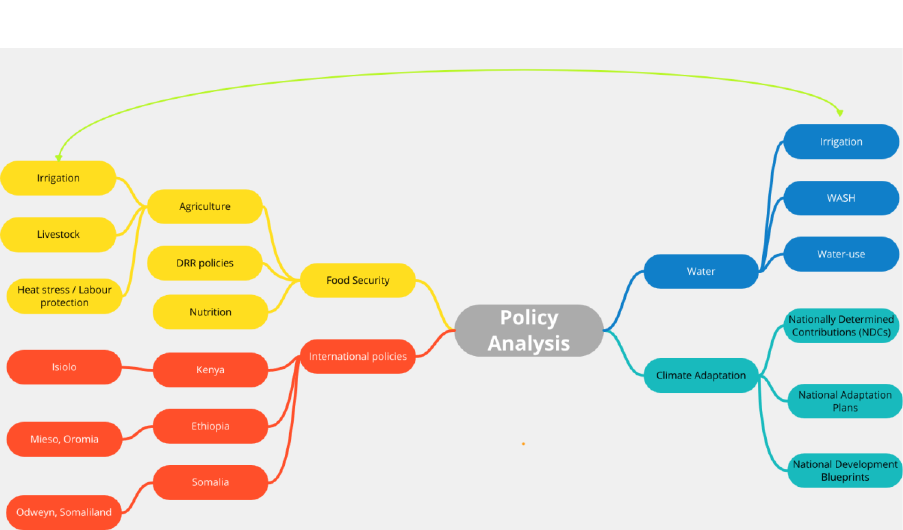

Figure 9: Policy analysis process ............................................................................................. 20

Figure 10: Conceptboard visualization and organization of information for policy analysis .. 21

Figure 11: Rating for Kenya Policies....................................................................................... 23

Figure 13: Rating for Isiolo County Policies ........................................................................... 33

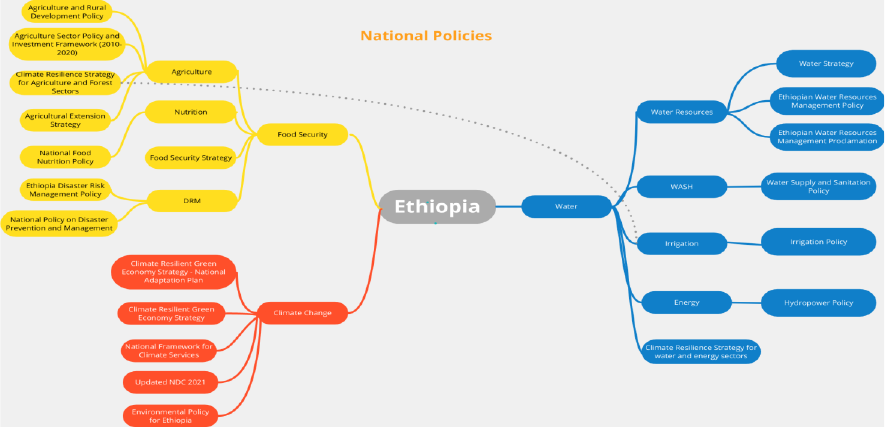

Figure 14: Ethiopia's climate adaptation, food and water security policies ............................. 38

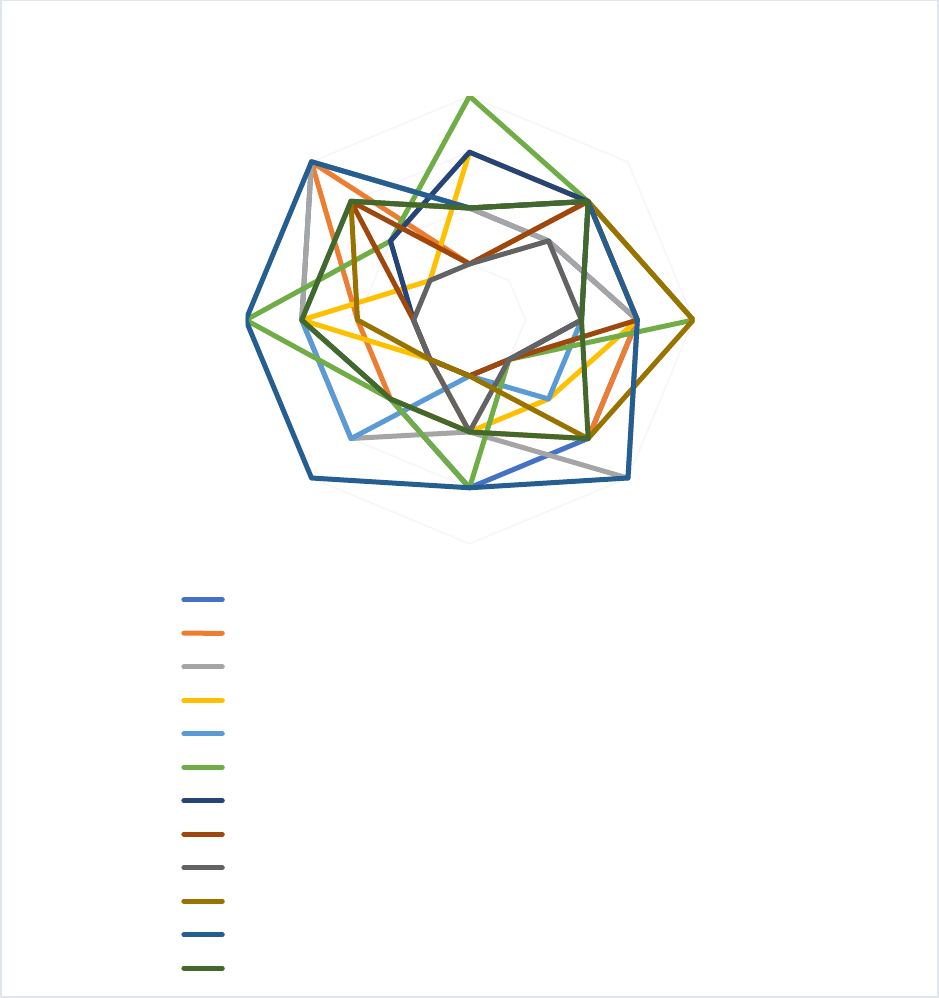

Figure 16: Rating for Ethiopia policies .................................................................................... 40

Figure 17: Rating for Oromia State Policies ............................................................................ 47

Figure 18: Rating for Somalia Policies .................................................................................... 52

Figure 19: Rating for Somaliland Policies ............................................................................... 57

Figure 20: Rating for Water Policies for Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia .................................. 62

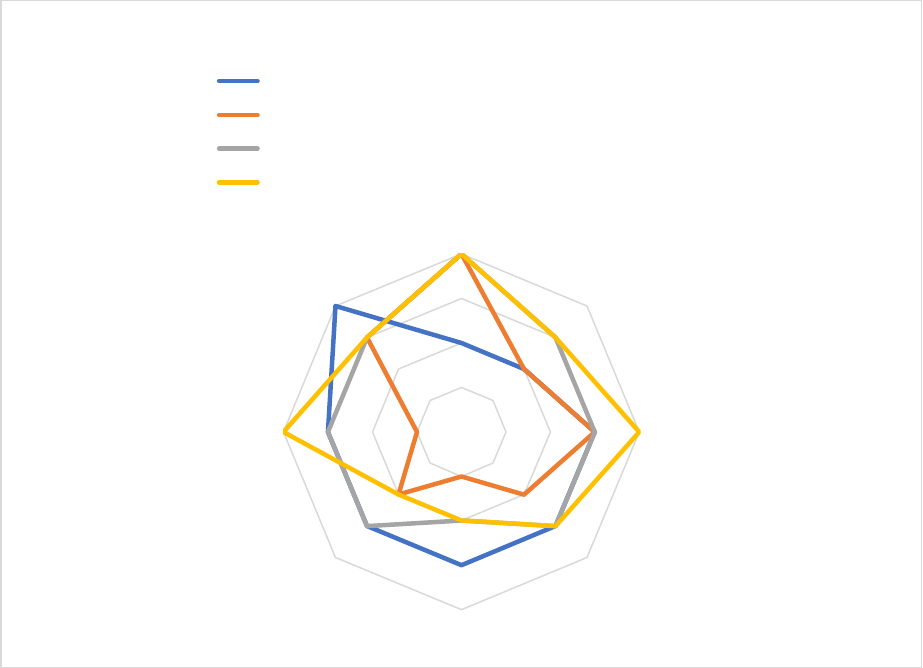

Figure 21: Rating for Food Security Policies .......................................................................... 65

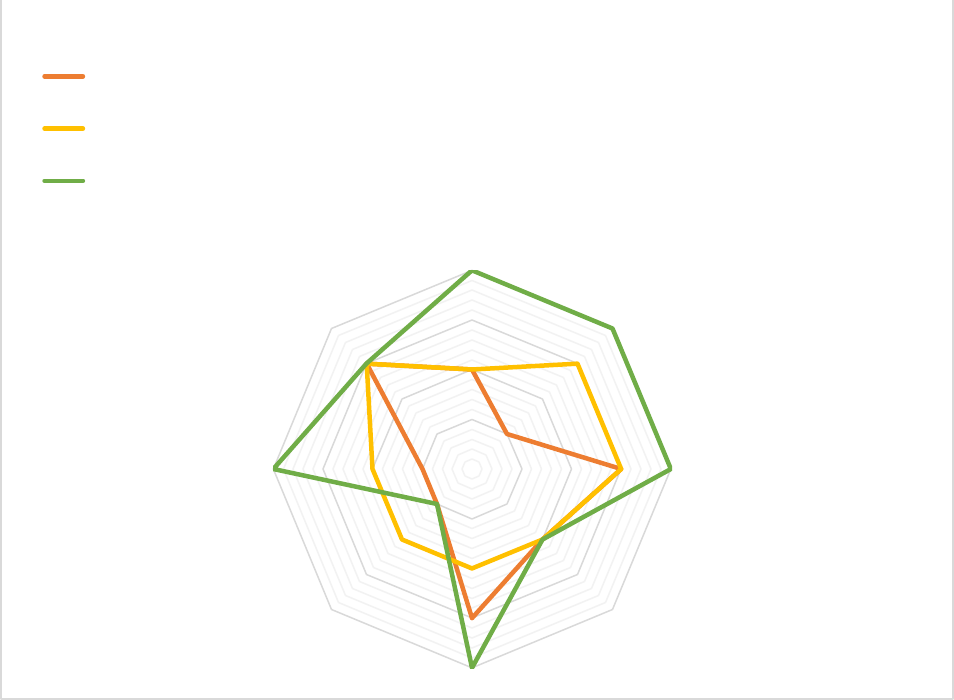

Figure 22: Rating for NAPs/NAPA ......................................................................................... 69

Figure 23: Rating for Eastern Africa Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) ............. 70

List of Tables

Table 1: Key Statistics for Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia ............................................................ 9

Table 2: Components of the Policy Triangle ............................................................................ 15

Table 3: Areas of rating for policy analysis .............................................................................. 17

Table 4: Water Policies ............................................................................................................ 62

Table 5: Food Security Policies................................................................................................. 64

Table 6: National Adaptation Plans/Plans of Action ................................................................ 68

7

2. Introduction

The Down2Earth Project

Climate change continues to impact the Eastern Africa region to a very large extent. The

Down2Earth project

1

seeks to translate climate information for effective adaptation to

climate change. Under this project, Climate Analytics, has conducted policy analysis looking

at different policies relating to food security and water in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia. A

schematic of the overall project and its outputs is shown below.

Figure 1: Schematic of the Down2Earth Project

The policy analysis work is in fulfilment of Task 1.2 on Identifying existing water management

and food security policies and their efficacy in the Horn of African Drylands (HAD). The policy

analysis specifically targeted overall climate adaptation policies and those relating to water

and food security in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia. The aim was to understand existing policies,

assess local-level climate adaptation governance and its linkage with government policies and

assess the efficacy of policies. This will be instrumental in co-developing robust climate

adaptation policy frameworks to support adaptation and foster resilience in a changing

climate.

8

Regional Context: Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia

The Eastern Africa region is among those that are highly vulnerable to climate change

impacts

2

. This is occasioned by its geographical location and physical features including the

fact that much of its land is arid and semi-arid in addition to its high vulnerability and low-

coping capacity. The three countries of focus (Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia) frequently

experience droughts and floods, sea-level rise, cyclones, incidences of pests, heat stress

among other climate extremes. According to the latest IPCC report, such extremes will

continue, increasing in both frequency and intensity as a result of climate change

2

. This has

the result of exacerbating loss of life and livelihoods, biodiversity loss and increasing the

vulnerability of already vulnerable and poor populations especially women

2

.

Figure 2: Map of Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia

9

Table 1: Key Statistics for Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia

Population

(millions)

Area (km

2

)

% of Arid

and Semi-

arid Land

(ASAL)

Climate

change

impacts

% of Pop

without

access to safe

drinking

water

Food

Insecure

Pop. (2022)

Ethiopia

112

3

1,104,300

55%

Drought,

floods

58%

18m

Kenya

47.5

4

582,646

85%

Drought,

floods, sea-

level rise

40%

4.1m

Somalia

15.8

a

637,655

87%

Drought,

floods, sea-

level rise

47%

b

5

7.1m

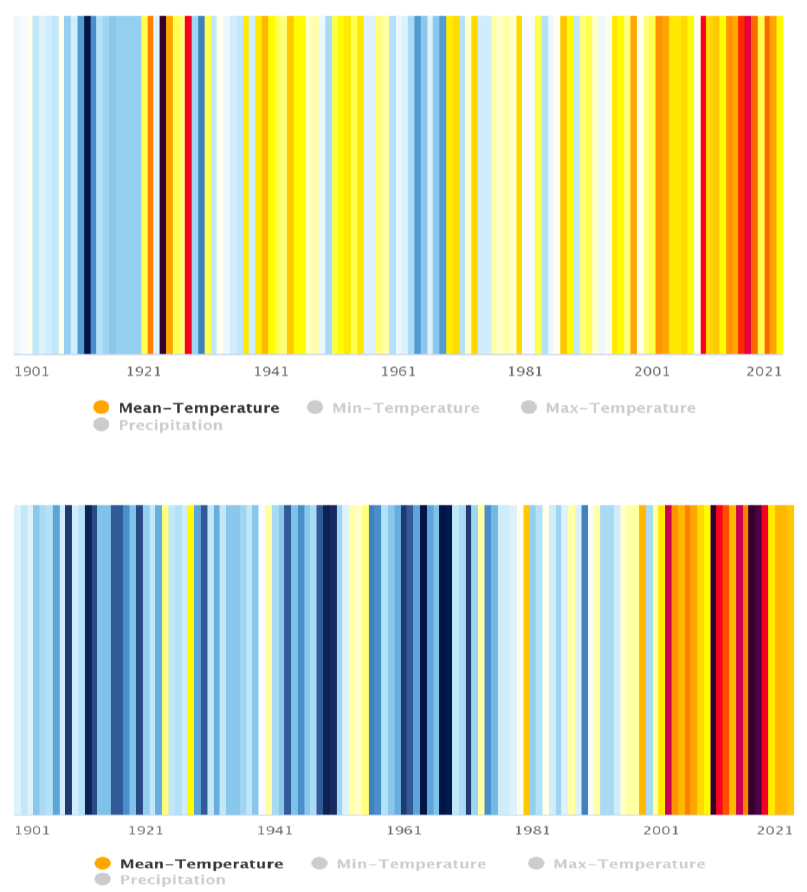

The AR6 WG2 report Africa chapter

2

states that there has been a rise in temperatures in East

Africa of between ‘0.7°C–1°C from 1973 to 2013’ and this is projected to go higher as climate

change impacts increase. Indeed available data shows an increase in mean temperatures as

depicted in the figures below.

Figure 3: Observed Annual Mean-Temperature, 1901-2021 (Kenya)

6

a

Somalia has not conducted an official census since the early 1990’s.

b

The Somali Health and Demographic Survey, 2018-2019 conducted by the Directorate of National Statistics found this to be at 45.7%. In

urban areas those without access are 28.6% as compared to rural areas where 75.8% of the population do not have access. For sanitation

those without access to sanitation services were 57.4% nationally representing a 6.9% improvement since 2000 (the report does not provide

rural/urban statistics for this).

10

Figure 4: Observed Annual Mean-Temperature, 1901-2021 (Somalia)

7

Figure 5: Observed Annual Mean-Temperature, 1901-2021 (Ethiopia)

8

According to the Climate Action Tracker, global mean temperatures are set to surpass 1.5°C

by 2035, 2°C by 2055, and in excess of 3°C by 2100

9

. This will have additional impacts on these

countries already impacted by a warming climate.

Food and Water Security

East Africa’s Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) are host to millions of pastoralists who rely

primarily on livestock for their survival and livelihood. Pastoralists in the region are among

the most vulnerable to climate. Subsistence crop farming in the region (for crops including

maize, wheat, and others) is also predominantly reliant on rainfall which has become erratic

and unpredictable resulting in crop failure and reduced yields. Future projections show

reduced productivity in these crops in the region under various scenarios in a changing

climate

10

since they are sensitive to temperature changes. Maize for instance is particularly

11

sensitive to climate change, which is significant given that the crop accounts for 33.3% and

19.5% daily calories per capita in Kenya and Ethiopia respectively.

IGAD’s Food Crises report

11

shows that Ethiopia had 16.76m people in food crisis between

May- June 2021 and it was forecasted that 18m people will be in food crisis in 2022. Kenya is

also currently experiencing a food crisis with 2.37m Kenyans having faced food insecurity

between November 2021 and January 2022, and 4.1m forecast to have been in a food crisis

between March-June 2022. Somalia had 3.47m people facing food crisis in October –

December 2021 and 7.1m forecasted to be in crisis in June – September 2022. Of these 2.13m

would be in food emergency state and 213,000 in a state of catastrophe (IPC

c

Phase 5). With

the region currently faced with a fifth failed rain season that is compounding an already

ongoing drought

12

this situation is set to make things worse for the region.

All three East African countries are considered water scarce with Kenya having the highest

access to safe water at about 60%, followed by Somalia at 53%

5

and Ethiopia at about 42%

13

.

Ongoing water scarcity is as a result of incessant drought in the region which are set to

increase in intensity and frequency as a result of climate change

13

. Water is an essential

element that supports populations in the region and is inextricably linked to food security as

well as energy. With climate projections showing an increase in temperatures in the region

due to global warming the water scarcity situation is set to grow even worse. Of the three

countries, Ethiopia boasts of higher amounts of inland water as a percentage of its land mass.

The three countries share the 805,100km

2

Juba-Shabelle river basin.

Over the years the three countries have set in place various initiatives including approaches

on integrated water management, poverty eradication, water supply and sanitation

initiatives, conservation of water towers, and several others, in a bid to better manage

available water resources. These will be discussed in detail in the following sections of this

report.

This report is an analysis of access to water, food security and climate adaptation policies in

the three countries to be able to understand their strengths and gaps as well as efficacy of

the policies in place. This understanding will help shape the development of a robust policy

framework that might be applied for enhanced climate adaptation to ensure food and water

security in a changing climate.

c

Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) is an innovative classification system with 5 levels: (1) Minimal/None, (2) Stressed, (3)

Crisis, (4) Emergency, and (5) Catastrophe/Famine

12

3. Methodology

a. Background

Climate change adaptation is vital for developing countries that already face severe climate

change impacts

14

that are also set to increase with additional global warming. The

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2007) defines climate change adaptation

as:

Adaptation to climate change takes place through adjustments to reduce vulnerability or

enhance resilience in response to observed or expected changes in climate and associated

extreme weather events. Adaptation occurs in physical, ecological and human systems. It

involves changes in social and environmental processes, perceptions of climate risk, practices

and functions to reduce potential damages or to realize new opportunities. (p. 720).

In line with this, countries have developed various policies, laws and regulations to adapt to

climate change at different levels. Most of those related to climate change have followed the

national priorities

15–17

, regional priorities and international policymaking

18

. To be able to

understand the policies and analyze them to infer insights on existing gaps, strengths, and

opportunities for enhancement (among other findings), it was necessary to first conduct a

literature review of some of the policy analysis approaches that have been applied as part of

a process to identify a suitable approach.

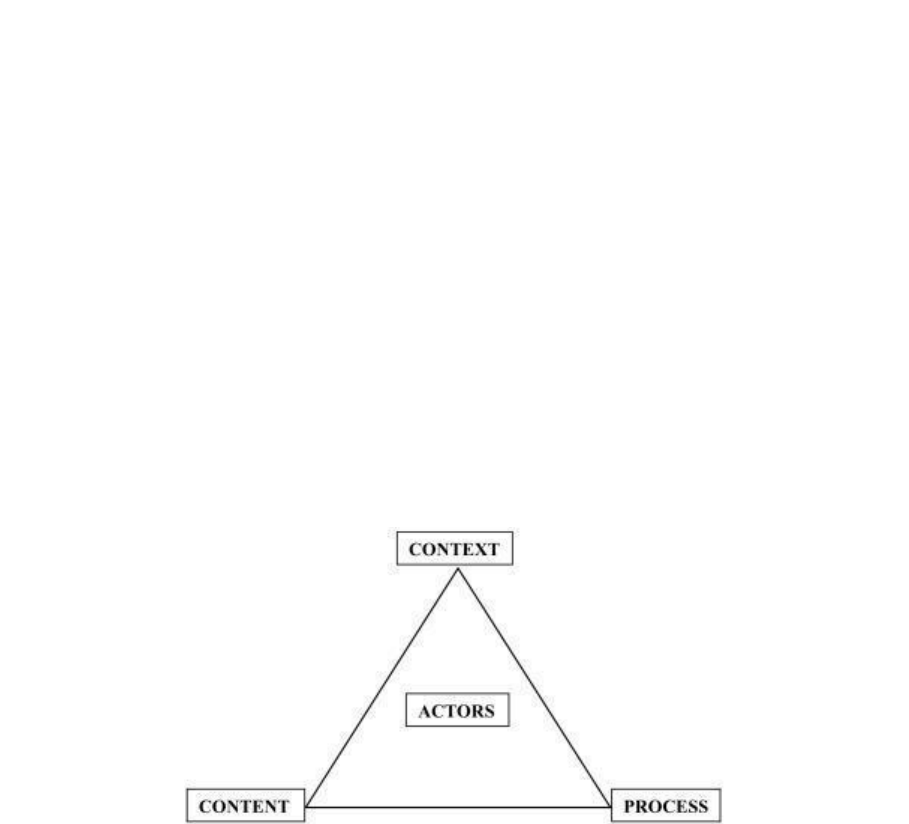

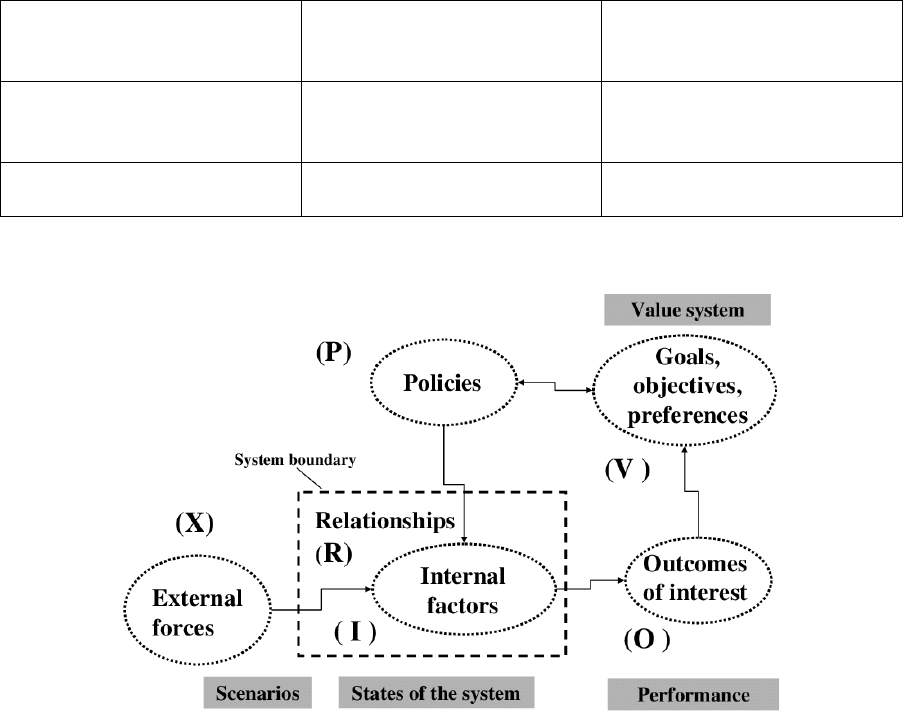

There are various approaches that have been used to analyze policies. To undertake this work,

a number of approaches were considered starting with the Policy Triangle

19

which considers

context, content, process and actors in the policy process; the vertical and horizontal

interplay

20

that focusses on various intersections at the vertical and horizontal level and how

these influence policies and policymaking; and, the policy analysis framework

21

that looks at

goals and objectives as part of a value system, internal factors as well as external influences

that interact to generate certain outcomes. These are shown in the figures below.

Figure 6: Policy Triangle (Walt and Gilson, 1994)

13

Functional interdependencies

Politics of institutional design and

management

Vertical (cuts across levels i.e.

local, regional, national)

Horizontal (cross-sectoral linkages)

Figure 7:Vertical and Horizontal Interplay (Young, 2002)

Figure 8: Policy Analysis Framework (Walker, 2000)

b. Policy Triangle

The Policy Triangle

19

is an approach that considers actors, content, context and process and

how these interact as already described above. This approach was selected because of its

applicability and usefulness to the current research. Additionally, the horizontal and vertical

interplay

7

in policy analysis was also integrated to capture linkages as well as measures and

goals set out in the policies in recognition of the vitality of these in the implementation and

achievement of desired policy outcomes.

c. Framework of analysis (criteria)

In a bid to streamline and make for effective analysis a detailed framework of key elements

of focus was developed. Within the area of content, the aspects are explored under this

analysis as follows:

Rights: According to the Human Rights Council “climate change-related impacts have a range

of implications, both direct and indirect, for the effective enjoyment of human rights” thus

climate change policies have to integrate human rights incorporating the right-holders -often

14

the marginalized and most vulnerable-and duty bearers

22

. An OHCHR

23

submission to the

UNFCCC COP 21 listed rights most impacted by climate change including the right to food,

water and sanitation, development, life, rights of future generations and of those most

impacted by climate change among others, noting that these have to be protected in climate

policy at all levels. The IOM

24

, Berchin

25

and others consider rights in climate change in terms

of migration and displacement where environmental/climate refugees. (2016)

26

notes that

inclusion of rights in policies creates an accountability element for policymakers.

Accessibility: Access is understood differently in literature. Some studies take it to include

basic needs, basic rights and decisionmaking

27

. In this analysis we take access to mean

availability of information and opportunities to increase knowledge and know-how (including

technological) as well as capacities and be able to take part in or utilize adaptation initiatives.

Inclusion: Inclusion is often taken to mean the participation by women, youth and children,

persons with disability (PWDs), indigenous groups, the elderly and other vulnerable and

marginalized groups. A bulk of the literature on inclusion in climate policy focuses on women

and gender equality, with less literature on youth, PWDs, indigenous groups and others but

all of these note the importance of including these groups to understand and plan for

differentiated impacts, risks and vulnerabilities and ensure equity and just responses to

climate change

14,28

. A 2022 status report on disability inclusion in climate policy

29

showed that

just 35 out of 192 parties to the Paris Agreement mentioned PWDs in their NDCs

d

. The

Adaptation Gap Report emphasizes the need for inclusion, noting that it enhances

ownership

14

and thus communities at local level and other stakeholders have to be included

from the outset.

Enforcement: Enforcement is a key ingredient in ensuring policies work, the IPCC AR4

30

notes

that ‘instruments must be monitored and enforced to be effective’. The Paris Agreement

18

includes a facilitative compliance framework for states to be able to comply with the

obligations set out in the agreement as well as those states have set out for themselves in

their NDCs. Without provisions on enforcement or a compliance framework it may be difficult

to implement policies.

Budgetary allocation: Resource allocation is key in implementation of set policies. Literature

shows that inadequate finances are to blame for the non-implementation of policies

27,31–33

.

International climate regimes such as the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement

5

as well a NDCs have

emphasized the need for predictable, adequate finance for addressing climate change and

various national policies, development blueprints and plans have estimated the costs

required to adapt to climate change underlining the importance of budgets and allocation of

resources for the successful realization of policy goals and objectives.

d

Of the Eastern African countries that are part of the D2E Project, Ethiopia included PWDs in its initial NDC but not in the updated one; Kenya

has PWDs subsumed in ‘other vulnerable groups’; while Somalia does not include PWDs. All NDCs reference women.

15

Implementation Plans: For policies to be successful, implementation plans to operationalize

their objectives are imperative. Implementation plans have to include timelines as well as

those responsible for delivery, indicators and expected outputs and outcomes

14,34–37

.

Information Management System: Systems to manage and monitor information are vital in

management, monitoring and evaluation.

Linkages to other policies: The IPCC AR4

30

states that ‘a combination of policy instruments

may work better in practice than reliance on a single instrument’. This, as a result of the

interconnectedness of climate change issues.

Other components are explored as well as summarized below in recognition that content is

also a product of actors, processes and context. Walt and Gilson (1994)

19

note that ‘focus on

policy content diverts attention from understanding the processes which explain why desired

policy outcomes fail to emerge’ making a case for understanding the varied contexts,

processes as well as actors involved in policymaking.

Table 2: Components of the Policy Triangle

Area

What to look out for

Content (What is included in

the policy?)

▪ Rights, goals for adaptation especially for women,

pastoralists, indigenous people, persons with disability,

youth and other marginalized groups

▪ Accessibility for all

▪ Inclusion

▪ Enforcement mechanisms to ensure implementation

▪ Budgetary allocation to assure implementation – e.g.

funds for capacity building etc

▪ Implementation plans

▪ Information management system

▪ Links to other policies – to integrate the horizontal and

vertical interplay

Context (Political, economic,

social contexts in which policy

is developed)

▪ Power relations between government and people

▪ Public and private sector interests

▪ Cultural considerations

▪ Public information

▪ Constitutional reforms

▪ International processes (SDGs, UNFCCC)

▪ Regional processes (EAC, AU Agenda 2063)

▪ Links to other policies (potential for cross-referencing

etc)

16

Process (How was the policy

developed?)

▪ Inclusivity (or exclusivity) of the processes

▪ The individuals and/or groups that participated in the

policy development process

▪ The extent and nature of public consultations

conducted

▪ The types of evidence used to inform the development

process (IPCC report, review of best practices etc)

Actors (Who are the actors:

groups/individuals involved?)

▪ The levels at which actors were involved (local,

regional, and/or international)

▪ Involvement of:

o Women/gender advocates

o Persons with disability

o Youth advocates?

o Indigenous groups?

o Pastoralists/farmers

o Community elders/ religious leaders

The table below outlines the areas for rating. Allocated ratings are completed separately for

each policy and an explanation of why the rating has been allocated has to be indicated. The

ranking system is based on how concretely (or not) a policy addresses the given issue.

17

Table 3: Areas of rating for policy analysis

High (Score 4)

Medium (Score 3)

Poor (Score 2)

Weak (Score 1)

Rights (clean and healthy

environment, water, food

security) for women,

pastoralists, indigenous

people, persons with

disability and other

marginalized groups that

align with climate

adaptation

Policy explicitly acknowledges

that all citizens have a right to

a (clean and healthy

environment, water, food

security) thus adaptation to

the impacts of climate change,

has a clear goal and

specifically mentions those

who are most vulnerable.

Policy explicitly acknowledges

that all citizens have a right to a

(clean and healthy

environment, water, food

security) thus adaptation to the

impacts of climate change but

does not have clear/explicit

goal but mentions those who

are most vulnerable

Policy explicitly (or even implicitly)

acknowledges that all citizens have

a right to a (clean and healthy

environment, water, food security)

thus adaptation to the impacts of

climate change but does not have

clear/explicit goal and does not

mention those who are most

vulnerable

No mention

of rights, no clear

goals nor mention

of the most

vulnerable

Accessibility for all

Policy fully addresses

accessibility for all groups of

the population to information

and means for adaptation to

the impacts of climate change

(includes FPIC e.g. in cases of

co-benefits from mitigation

action)

Policy mentions accessibility for

all especially those that will be

most impacted but with no

clear focus on what this entails

Policy addresses accessibility but

fails to highlight those most

impacted and how

Policy does not

specifically

mention any of

these

Inclusion

Policy addresses capacity

building, training, technology

transfer, empowerment,

public participation, local

knowledge and scientific

research (ACE, tech transfer)

to ensure that the most

Partially addressed with

mention of the most vulnerable

but with little/no reference to

training, capacity building, tech

transfer etc.

Only addressed implicitly; no

training, capacity building, tech

transfer etc. for most vulnerable

and general population

Policy does not

mention any needs

for inclusive

climate adaptation

18

vulnerable are included in

adaptation to climate change

Implementation plans

Policy has clear plan of action

including specific actions to be

taken and responsible parties

with respect to those that are

most vulnerable to climate

change

● Set out in or in

tandem with the

policy documents

● Actors and targets are

clearly indicated

● Monitoring plan is

clearly set out

● Intervals for

monitoring are

specified

Policy mentions a clear plan of

action with different

components but does not

specify the detail of who does

what, how and when to

monitor and budget guidelines

Policy sets out an action plan but

without any specific mention of

actors, monitoring, budget, etc.

Policy does not set

out any plan of

action or

monitoring plan

Enforcement mechanisms to

ensure equality

Clear enforcement

mechanism is described with

the specific enforcement

agency named;

Clear penalties for non-

compliance (e.g. through an

Act related to the policy);

Not taking proactive steps to

implement the policy is seen

Describes the enforcement

mechanism and contains

penalties but no mechanism for

enforcement is specified in the

policy; there is no mention of

penalties for not implementing

the policy proactively.

Minimal description of an

enforcement mechanism with

minimal penalties and only a focus

on obstruction of the policy

implementation rather than lack of

proactive implementation.

No mention of

enforcement and

penalties

19

as non-compliance in addition

to obstructing the

implementation

Budgetary allocation to

assure implementation

Budget guidelines for climate

adaptation are clearly

specified in terms of

● What has to be

budgeted for

● Where budget should be

allocated from

● Funding is mandated and

must be made available

Budget guidelines for climate

adaptation are specified in

terms of

● What has to be budgeted

● Where budget should be

allocated from

● But Funding is conditional

(on budget availability)

Budget guidelines are not

specified specifically for climate

adaptation and funding is

conditional on budget availability

No clear budgetary

guidelines and no

mandated

budget for climate

adaptation

Information management

system

The policy specifies clearly

what information should be

collected, by whom, at what

intervals and what indicators

will be used to monitor

progress of climate adaptation

The policy specifies the need for

data and a plan for what

information should be

collected concerning climate

adaptation but with minimal

detail on who should collect it,

when and what indicators

should be used for monitoring

No clear

Information Management System

(IMS) for climate adaptation but

some recognition that data

collection is important for

monitoring

There is no IMS

specified, nor the

importance of

data recognized for

climate adaptation

Links to other policies – to

integrate the horizontal and

vertical interplay

The policy clearly identifies

what linkages exist and how it

builds on those with specific

mention of actions to ensure

the linkages are

strengthened/integration is

achieved to contribute to

climate adaptation

The policy clearly identifies

what linkages exist but with no

mention of specific actions to

ensure the linkages are

strengthened/integration is

achieved to contribute to

climate adaptation

The policy identifies what linkages

exist but there is no mention of

actions to ensure the linkages are

strengthened/integration is

achieved to contribute to climate

adaptation

There is no

mention of the

policy linkages or

how it builds on

those for robust

climate adaptation

20

The entire process can be summarized as shown in the figure below:

d. Policy selection

Lesnikowski et al., (2019)

38

in making a case for a policy mixes approach, argue that

governments normally develop several policy instruments to address issues such as climate

change and that it is difficult to find options encapsulated in a single policy due to the

crosscutting nature of issues such as climate change. Similar views are reflected in other

literature

14,30

with emphasis on the fact that adaptation is a cross/multi-sectoral issue

requiring multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder approaches.

Broader responsive policies development, argues the National Academies Press in their 2011

book (“Advancing the Science of Climate Change,” 2011)

39

is possible with an iterative process

that considers monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL), emerging co-benefits/disbenefits

and the ways in which they interact with each other. This thinking alongside other

considerations informed our choice of policies.

Identification of the relevant policies for analysis

was done consultatively with partners within the

consortium as well as government officials and

other actors who contributed to an initial list of

identified policies. Over 100 relevant policies on

adaptation, water and food security were

identified and listed. These were categorized as

national, regional and local and codified or

uncodified and visualized via an online platform

called Conceptboard. Regional policies from the

specific areas under focus are those for Oromia, Somaliland and Isiolo. Once the selection was

finalized, priority policies for analysis numbering 40 were identified in consultation with the

Down2Earth project partners and other stakeholders. This prioritization was done considering

how relevant the policies were to project objectives and the needs of various consortium

partners in implementing their own tasks under the Down2Earth project.

Policy

Analysis

Approach

Policy Triangle

Content

Rating

Identification

of Policies

Prioritization of

Policies

Policy

Analysis

Broad Categories

Water - irrigation, water

harvesting, resource management

Food Security - agriculture,

irrigation, nutrition

Climate Change - adaptation

Levels

Regional

National

Sub-national

Codified and non-codified policies

Figure 9: Policy analysis process

21

Figure 10: Conceptboard visualization and organization of information for policy analysis

4. Results

The comprehensive policy analysis conducted based on the above research and planning led

to several noteworthy insights on the current state of relevant policies in Kenya, Ethiopia,

and Somalia.

The outcomes of the analysis are summarized below and disaggregated based on the most

noteworthy findings. First, the results are presented at a country-level to provide insights

into the state of key policies in each country and their respective national contexts. This is

followed by a sector-specific analysis that summarizes findings on policies across all three

countries according to specific themes.

a. Country level analysis (including stakeholder input)

i. Kenya

Kenya has made significant efforts in terms of developing its climate change, food security,

and water related policies to address climate change. Some of these policies include the

Climate Change Act of 2016, which is one of the very first pieces of climate change legislation

to come from the region. This act seeks to guide Kenya’s priorities for addressing climate

change focusing on both climate adaptation and climate mitigation. The history of

environmental policymaking in Kenya is long, dating back to the period after independence

with the Sessional paper No. 10 that addressed the control and use of resources noting that

such resources were to be used for the benefit of all

40

. Significant environmental policy was

not developed until the 1999 Environmental Management and Co-Ordination Act (EMCA),

which set out the management of environmental and environmental resources in Kenya. In

22

subsequent years, policies focusing on the various sectors have been developed to address

current challenges guided by the development blueprint, Vision 2030

41

as well as the National

Constitution and other international regimes on climate, water, food security and related

areas.

1. National

Context, Actors and Process

At national level Kenya has the 2016 Water Act

5

, the National Water Harvesting and Storage

Regulations, a Water Masterplan

42

and a draft water strategy. On food security, Kenya has

the Agricultural Sector Development Strategy (2010-2020)

43

to address issues of agricultural

development for food security in Kenya. This has been succeeded by the Agricultural Sector

Transformation and Growth 2020)

44

whose main innovation is the establishment of the

Agricultural Transformation Office as the implementation and enforcement entity for the

strategy. There is also a National Food and Nutrition Security Policy and its implementation

framework.

When it comes to climate adaptation, as mentioned earlier, Kenya has a Climate Change Act

of 2016

45

. There is also a National Climate Change Action Plan

46

, a Climate Change Policy and

a Nationally Determined Contribution updated in 2020

16

, a National Policy for Disaster

Management as well as the National Adaptation Plan and its Adaptation Technical Analysis

Report

47

. Kenya has also embarked on developing a National Framework for Climate Services

and has held several stakeholder meetings to advance this. This is pursued as part of its

commitment to the global framework for climate services.

An analysis of the various policies that Kenya has put in place shows that the country’s climate

adaptation the policies are relatively updated and aligned with existing international laws and

policies. The climate policies were developed in compliance with, and as a response to the

international climate regime, including the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement.

The climate adaptation policies were developed as part of Kenya’s bid to comply with the

international climate policy discussions that have been ongoing since the establishment of

the UNFCCC and its various outcomes, including the 2015 Paris Agreement that set out a

requirement for countries to develop their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). Water

sector policies and laws are a result of water sector reforms initiated to streamline the sector

and ensure access to water and sanitation for all citizens by 2030. Agriculture sector policies

on the other hand are informed by the national priority of addressing food security concerns

in the country in a bid to ensure food security by 2030, as is articulated in Kenya’s Vision 2030.

Policies developed after the implementation of the 2010 Constitution have tended to follow

5

This repealed the 2001 Water Act. It sought to align the water sector to the 2010 constitution as well as Vision 2030 and was preceded by

water sector reforms to the water sector and ensure access to water and sanitation by all Kenyans by 2030.

23

consultative processes with the engagement of a wide spectrum of actors including

community members, civil society, and private sector in a bid to meet the requirements laid

out in the constitution.

Content

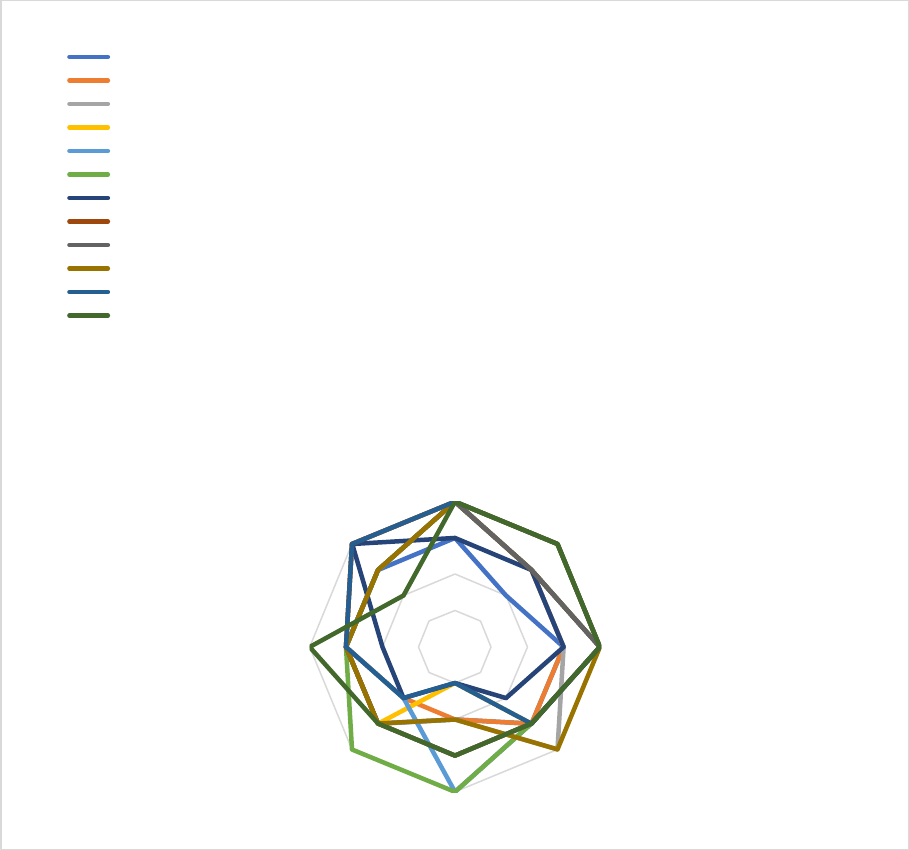

Out of a maximum score of 4, the 2016 Water Act is the highest scoring at 3.5 followed by the

Water Strategy and the Draft Irrigation Policy and the National Food and Nutrition Security

Policy Implementation Framework (2017-2022) each scoring 3.4. The National Disaster

Management Policy is the lowest scoring at 2.5. All policies analysed have a combined score

of 3.2 which is the highest country average for national policies. The scores and areas of rating

are shown in the figure below and discussed in detail thereafter.

Figure 11: Rating for Kenya Policies

0

1

2

3

4

Rights

Accessibility

Inclusion

Implementation plans

Enforcement

Budgetary allocation

Info management

system

Links to other policies

Kenya

NDC (2020)

NAP (2015-2030)

NCCAP (2018-2020)

Agriculture Sector Development Strategy (2010-2020)

Community Land Act (2016)

Water Act (2016)

National Disaster Risk Management Policy (2017)

Water Strategy

Water Policy

Draft National Irrigation Policy, 2015

National Food and Nutrition Security Policy (2011) - Kenya

National Food and Nutrition Security Policy Implementation Framework (2017-2022) - Kenya

24

Rights

Kenya’s 2010 constitution stipulates that every citizen has a right to a clean and healthy

environment. Consequently, policies developed after 2010 all seem to have adopted this

approach stating clearly that ‘citizens have a right to a clean and healthy environment’, a right

to water in the water services policies to meet their basic needs, and access to food as a basic

need.

This is the highest ranked area with a combined score of 3.8 which is the highest for all policies

analysed in this research. The Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and National

Disaster Risk Management (DRM) policy each have a score of 3, while the rest have a score of

4. Rights are especially when thinking about the populations that are more vulnerable to

climate change and will therefore need to be protected under the law and be facilitated to

adapt to the changing climate when it comes to being able to access water as well as food.

Furthermore, Kenya’s NDC specifically talks about the gendered impacts of climate change

for women, youth, coastal communities, and inhabitants of arid and semi-arid areas as being

specifically impacted by climate change. It also highlights the issue of climate refugees and

mentions food security for its citizens as part of its mandate in terms of safeguarding the basic

rights of its citizens. Similarly, the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) of 2015-2030 and the

National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) contain these provisions. The NAP and the

Irrigation Policy, both with a score of 4 in the rights component, quote the Constitution and

Vision 2030 with regards to the provision for the right of all citizens to a ‘clean and healthy

environment’. The NCCAP has provisions on gender equality and, notably, also talks about

traditional practices that may deny women equal rights.

On food security, the Agricultural Sector Development Strategy (ASDS) for 2010-2020 also

provided for ensuring food and nutritional security for all Kenyans, and the strategy itself

aimed at ‘generating high income as well as employment especially in rural areas’. The ASDS

also recognizes that agriculture is the backbone of Kenya's economy, meaning that the

livelihoods of most of the population are drawn from farming activities. Thus, investing in

achieving the ASDS also had the goal of ensuring food security and poverty reduction in the

longer term. An assessment on the performance of this strategy in the literature points to

challenges in its implementation that resulted in it not meeting some of the objectives set

out.

The Community Land Act also mentions issues of rights, referencing the Constitution, human

rights, and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Community members, according to this

Act, have a right to the use and management of their community land and should be able to

participate in decision making. It also mentions the need to take the grazing rights of

pastoralists into consideration when it comes to community land. Additionally, there are

provisions around non-discrimination to ensure that all members within the community have

25

the right to access and use land, including women and children, youth, persons with disability,

and other marginalized groups.

The Water Act also recognizes the ‘right to a clean and healthy environment’ and specifically

highlights the right of Kenyans to ‘access clean and safe water in adequate quantities and

within reasonable standards are stipulated in article 43 of the Kenyan Constitution. Article 7

of the Water Act talks about rights to water resources noting that these ‘are only as prescribed

in the Act’. Water rights here are defined as ‘the right to have access to water through a water

permit’.

The National Disaster Risk Management (DRM) Policy of 2017 is also guided by the bill of

rights in the Constitution and reiterates the same provisions of having access to ‘a clean and

healthy environment’. It also provides for non-discrimination during disaster response.

A common thread that can be seen across all these policies in Kenya is the fact that the rights

to water, the rights to food and the rights to a clean and healthy environment are all included

in the policies.

Access

Access, with a combined score of 3.3, is covered in different ways in the different policies. For

instance, with the NDC of 2020, which has a score of 2, there is reference to enhanced climate

information uptake, but further details are not provided despite the NDC including provisions

for capacity building, awareness, and other measures that might contribute to this enhanced

uptake of climate information. The NAP, which scores 3, provides for citizens’ role in planning,

implementation, and monitoring. One of the actions is enhancing the adaptive capacities of

multiple groups, especially women and children, but there is no detailed plan of action

outlined in the NAP. The NCCAP, with a score of 3, details improved access to water, food

security, and enhanced resilience as some of the measures targeting vulnerable categories of

the population. There is specific mention of using technology, including mobile technology,

for dissemination of early warning to enable groups to make informed decisions and cope

better with the impacts of climate change. However, further details on such measures are not

provided. The ASDS had several relevant key objectives, including identifying priorities for

climate adaptation and mitigation, developing a comprehensive national education and

awareness creation program, and establishing specific cross-sectoral adaptation measures for

vulnerable groups, communities, and regions. There was also provision for periodic reviews

of prevailing climate change threats, conducting risk assessments at national and local levels,

and developing national capacity building frameworks to address climate change. This was

relatively comprehensive, and is the reason for the ASDS’s high score of 4 when it comes to

issues of access. The draft Irrigation Policy, National Food and Nutrition Security Policy (2011)

and the National Food and Nutrition Security Policy Implementation Framework (2017-2022)

26

also score 4 owing to their provisions for access including availing of technology for the

vulnerable, trainings, and other measures to ensure food sufficiency.

The Community Land Act states that land is vested in the community and can consequently

be registered as communal or reserved land for specific purposes set out by the community,

which has access to this land for their own use and benefit. It also spells out benefit sharing

6

and how this will be handled on community land, including provisions for an Environmental

Impact Assessment (EIA) study, compensation, royalties, as well as being able to mitigate

against any negative impacts that might occur. There is also a provision for public education

and awareness to ensure that communities are informed about their rights and community

land. One challenge, however, is that, aside from the measures articulated on benefit sharing,

there is little focus on enhancing resilience of communities to a changing climate through

measures such as enhancing access to technology and provision. This is especially the case for

pastoralists.

The Water Act in Article 9 talks about citizens’ rights to access water and specifically mentions

the poor living in urban areas and those who are living in rural areas. It also addresses benefits

for the poor from financing in various projects that will ensure access to water resources.

There is also a provision that the public should be able to access information about issued

permits, and that broader information generated under this Act should be publicly available

and provided upon request.

For the National DRM policy, which has a score of 3, initiatives are outlined in terms of

collaboration with communities under various areas, including resilience building, early

warning systems to provide information for people to be able to respond to identified risks,

capacity building, and technical training to build community members’ skills to enable them

to adapt to climate change or to respond to any disasters that might occur. The DRM also

emphasizes local management of disasters through what is labeled as a ‘people centered

multi hazard approach’.

Inclusivity

When it comes to inclusion, the policies (which have an average score of 3.7 for this

component) generally mention categories of people that are vulnerable to climate change

impacts and articulate related measures. For example, the NDC (which has a score of 3 for

inclusivity) specifically references local communities, women, youth, and other vulnerable

groups that will be targeted for adaptation technology uptake which integrates both scientific

as well as indigenous knowledge to be able to implement the NDC. It also outlines

involvement by various actors including civil society, county governments, academia,

research, and the private sector. The NAP, which also has a score of 3 for this component,

talks about integrating climate change into the education curriculum through the Kenya

6

These includes benefits from natural and mineral resources or such other utilization of community land.

27

Institute of Curriculum Development. Media is also expected to play a key role in information

dissemination to the public. Vulnerable groups such as women, children, persons with

disability, and the elderly will be specifically targeted. The draft Irrigation Policy, with the

highest score of 4, specifically addresses capacity-building, technology transfer, public

participation, and other measures for enhanced inclusion. The most vulnerable and relevant

groups to irrigation development have been identified, and the interventions demonstrate

how they will be included in and benefit from technology transfer, capacity building, and

other initiatives.

The NCCAP, which also has a score of 3, specifically talks about supporting youth in

innovations as well as local level adaptation action and education on risks and hazards. This

is specifically targeted at young people and mentions capacity building for access to climate

finance as one of the key areas of focus. The ASDS, with a score of 4, focuses on the

strengthening of extension services to further links between research services, local

communities and grassroot farmer organizations to further empower stakeholders in the

sector and provide them with information to facilitate food security. This includes (among

other measures) supporting them with appropriate technologies, training, and having

demonstration centers for practitioners to increase their skills and adapt to climate change.

With a score of 4, the Community Land Act states that community land can be held as

communal, family or clan, reserve, or another category under the Act or in another law. For

this provision it is up to the community to decide how it wants to register the particular land,

and which actors are subsequently included and affected. Customary rights and cultural use

of land is recognized under the Act. The Community Land Act specifically states that any

disposal or alienation of community land has to be agreed to by at least two-thirds of the

registered community land members, which is critical for ensuring that a majority of the

community members are included in decision making on their land.

Under the Water Act, committees and boards that are established must consider a two-third

gender rule as outlined in the Constitution, which facilitates a greater inclusion of women are

in the committees and boards. Water Resource User Associations (WRUAs) are created under

the Act. WRUAs are essentially user associations at sub-basin level that consist of community

members residing there and using the water resources for one use or another. They are

charged with the responsibility of developing their own plans and managing water resources

and access to these. They are also eligible to receive funding, training, and other capacity

building support in their planned activities to ensure they have access to water resources.

The National DRM Policy considers gender mainstreaming, community empowerment, and

public-private and community partnerships as guiding principles. The policy is also cognizant

of nondiscrimination noting that, ‘while providing compensation and relief to the victims of

28

disaster there shall be no discrimination on the basis of tribe, community disability, gender,

religion or political party affiliation’’.

Implementation Plans

For implementation plans, all of Kenya's national level policies score quite well, with an

average score of 3.1. The National DRM Policy of 2017 proved to be an exception, with a score

of 2. The policy talks about its operationalization through legislation guidelines, regulations,

rules, and executive orders but fails to articulate a detailed plan in the document itself,

despite noting that this will be developed at a future date. The plan is still not available, but

there is an ongoing process to finalize the Disaster Management Bill which is currently before

Parliament

7

. The finalization of the Bill is hoped to facilitate the articulation of a

comprehensive implementation plan for the DRM Policy.

The NDC, which has a score of 3, has prioritized adaptation programs covering all the sectors,

and these include specific measures to be undertaken in each sector. The NCCAP, with a score

of 4, provides a detailed implementation plan which includes specific actions, outcomes,

indicators, and the responsible organizations. There is also a timeline and budget for

implementation up to 2023. Monitoring on the delivery of the policy’s interventions is to be

conducted through the National Forest Monitoring System (NFMS) and the Forest Reference

Level (FRL), as well as national performance-based monitoring framework. The NAP further

refined the areas that were prioritized in the NCCAP as well as the Adaptation Technical

Assessment Report (ATAR). These refinements were based on urgency and compatibility with

the action plan and the medium-term plan (MTP) of Kenya’s Vision 2030 and low regret

scenarios

8

. For these, short-term and long-term goals, budgets, and those responsible are

outlined. 17 indicators for monitoring and tracking adaptation measures are articulated in

the NCCAP. Additionally, counties are expected to develop their own respective context-

specific action plans in line with the listed actions, while ensuring that any potential additional

areas of action do not lead to maladaptation.

The ASDS also has a detailed implementation plan, including specific targets such as achieving

an average growth rate of 7% in five years (2010-2015) in the sector, and the increasing

productivity and commercialization competitiveness of agricultural commodities and

enterprises by developing and managing key factors of production. It has a score of 3.

The Community Land Act establishes Community Land Management committees with the

mandate of overseeing the land and related issues, including coordination, conflict resolution,

and setting rules and regulations for use in land management (which must ultimately be

7

The Disaster Bill has been pending since the early 2010’s and has undergone various changes to cater and align to the different agencies

charged with disaster response in Kenya ranging from the NDMA, NDMU and NDOC to the various Ministries and Counties.

8

Low-regret scenario’s here refer to scenarios that will cost the country less both in terms of finance as well as impact on the population

29

ratified by the community). The Act also provides for a procedure on how community land is

recognized and adjudicated.

The Water Act establishes several bodies which have a clear mandate and functions related

to the Act. However, timelines are not clearly indicated, except for a few elements. For

instance, there is the requirement for a water strategy to be developed every five years with

explicit details on the protection and the management of water resources.

Enforcement

With an average score of 2.3 across all the policies analyzed, enforcement is the weakest

across Kenya’s national policies (with the exception of the Community Land Act and the Water

Act, which both scored a 4). For the Community Land Act, there are entities that are directly

in charge of various aspects. These include the community land registrar, who registers

community land, and a community land committee responsible for coordination and

management of community land. The Act outlines a dispute resolution mechanism, including

through traditional systems and structures, community by-laws contained or developed by

the community land committee, and courts of law. There is also a provision for mediation and

arbitration, which can be pursued as a way of dispute resolution. The Act considers unlawful

occupation of community land an offense that attracts conviction for up to three years in

prison or payment or a fine up to 500,000 Kenya shillings. The provision of fines and other

punitive measures serves as a deterrent for non-compliance. However, there are also

procedures that actively encourage and incentivize compliance.

The NCCAP and NAP specifically reference the National Environment Management Authority

(NEMA) as being responsible for their enforcement, but do not provide any further details

about it. The Climate Change Directorate is also charged with the responsibility of

coordination and ensuring implementation of these policies.

The NDC, which has a score of 2, does not clearly articulate measures for enforcement. It

simply states that measures would be undertaken to enhance implementation. This is also

the case for the ASDS and the National DRM Policy, which both have a score of 1, and do not

contain any noteworthy information on enforcement or compliance.

Budget

Budgets are not very well articulated in any of the Kenyan policies, which have an average

score of 2.8. The Water Act ranks highly at 4 because it seeks to establish a Water Sector Trust

Fund in article 113. The Fund will provide funding to counties in marginalized areas for

development of water resources. The Water Sector Trust Fund shall receive resources from

30

government budgetary allocations, the equalization fund, county governments, donations,

grants, and other means.

Even though the DRM Policy seeks to establish a disaster risk management fund, it is not clear

where the funds will be sourced from. The Policy simply noted that this will be from

government and other sources. In the absence of a legal framework, such a fund may be

difficult to set up and operationalize. The current iteration of the Disaster Bill includes a Fund,

which may ultimately be established via an Act of Parliament. The Community Land Act does

not include a budget, but states that the fees and taxes for land registration are to be borne

by those registering. It is thus unclear where the various committees— especially at

community level, such as the community land committees— will draw funds for their

operations from. In practice, such committees rely on member/community contributions to

run their affairs as garnered from stakeholder visits in Nairobi and Isiolo.

The NDC states that the government will provide 10% of the funding for adaptation costs and

21% for mitigation, which translates to an overall commitment of 13% of USD 62 billion

deemed necessary by 2030. There is no specificity on where the funds will be allocated from,

but Kenya has a Climate Finance Policy that may guide and facilitate this allocation.

Furthermore, climate budget codes designed to track allocations to climate change activities

and sectors are expected to mainstream climate in all initiatives and plans. The NAP and the

NCCAP outline adaptation actions, and the ATAR provides further analysis in relation to these,

but no further details are provided on the funding sources for these adaptation interventions.

The ASDS states that implementation will be funded through the medium-term expenditure

framework with financial allocation from the National Treasury. However, the policy also

states that each ministry will have to work out details of its activities and develop a financing

plan that can be acted on.

Information Management System

Information Management Systems, which have an average score of 3, consistently reference

the National Integrated Monitoring and Evaluation System (NIMES) and the County Integrated

Monitoring and Evaluation System (CIMES), which will be used for tracking progress. The NAP

and NCCAP refer to the National Forest Monitoring System and the monitoring, reporting and

verification system (MRV) as part of the information management system that will be used

for monitoring purposes. The ASDS refers to an agricultural sector results framework that

would be used for monitoring.

The Community Land Act provides for an inventory system with the register of community

land, including cadastral maps, names of the community land registered members, the uses

of land, and any other information that may be relevant. However, it is not clear how this will

be managed within a system.

31

The Water Act establishes a national monitoring and information system overseen by the

Water Resources Authority (Article 11). This system is meant to be accessible to the public. In

article 70, the Water Services Regulatory Board (WASREB) is also charged with the role of

establishing an information system and will maintain a national database and georeferenced

information system on water services. In practice, a central system accessible to the public is

not yet in place, but the two agencies maintain internal databases and inventories and

provide information on request with most information also published on their respective

websites. Engagement with WASREB revealed significant progress in fulfilling their mandate

including the presence of a database and reports as well as rules and regulations set in place

to achieve its mandate.

Link to other policies

When it comes to linkages with other policies, the Kenyan policies analyzed score an average

of 3.3 due to the wide range of linkages to, among others, the UNFCCC and its decisions, the

Paris Agreement, the National Inventory Report, Vision 2030, Kenya’s 2010 Constitution,

other sectoral policies, SDGs, AU 2063, and CAADP.

2. Regional

Context, Actors and Process

On regional policies in Kenya, the focus is on Isiolo County which is the site of the Down2Earth

project in Kenya. These policies were developed as a result of devolution where counties are

expected to develop their own policies and laws as a way of cascading relevant national and

international law and policy to local level. In this way policies at county level are expected to

capture their specific contexts, circumstances, capabilities, diversities, priorities and other

intervening factors present at county level.

Under the constitution, policies at county level are supposed to be participatory involving

community members, private sector, women, youth, persons with disability, indigenous

groups, religious organizations among others. As a result, policies at this level have mostly

tended to follow these and generally included these categories of people during consultative

processes to develop their various policies and in committees. In terms of process, typically

policies at county level are discussed at community Baraza’s and other local level meetings

where different stakeholders are able to contribute to the discussions on these policies. The

CIDP and the Isiolo Climate Change Fund Act particularly followed this process with the

involvement of different actors from local level. In fact the Climate Change Fund Act itself

32

creates Ward Climate Change Planning Committees at the ward level to be able to deliberate

on and formulate activities for implementation under the Act.

When it comes to reflection of local contexts, the Isiolo County Customary Natural Resource

Management Bill, 2016 was specifically developed to anchor traditional community resource

management within the law. This is in recognition of the very vital and important role that

communal structures play in the management of resources especially in arid and semi-arid

areas characterized by expansive grasslands inhabited by humans, their livestock and wildlife.

33

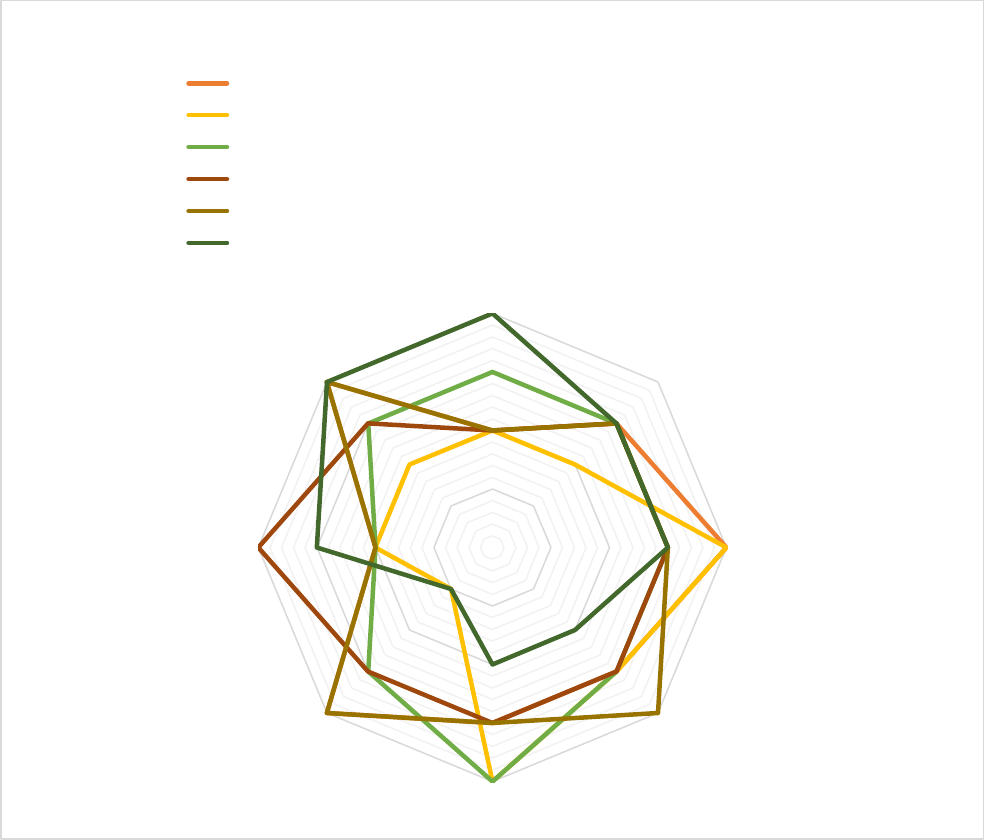

Content

The Isiolo County Community Conservancies Bill, 2021 is the highest scoring at 3.1 followed

by the Climate Change Fund Act (2018), Isiolo County Wildlife Management and Conservation

Bill (2021) and the CIDP all with a score of 3. The lowest scorer is the Isiolo County Customary

Natural Resource Management Bill (2016) at 2.5. The combined score for all county policies

is 2.9. The scores and areas of rating are shown in the figure below and discussed in detail

thereafter.

Figure 12: Rating for Isiolo County Policies

Rights

The various policies have not explicitly captured rights which has the least score of 2.5. The

Climate Change Fund Act (2) for instance mentions vulnerable groups as the ones that would

benefit from some of the projects for implementation at county level and these projects must

incorporate gender, but there is no explicit mention of rights as captured in the constitution.

0

1

2

3

4

Rights

Accessibility

Inclusion

Implementation plans

Enforcement

Budgetary allocation

Info management system

Links to other policies

Isiolo County Policies

Climate Change Fund Act (2018)

Isiolo County Customary Natural Resource Management Bill (2016)

Isiolo County Wildlife Management and Conservation Bill (2021)

CIDP

The Isiolo County Community Conservancies Bill, 2021

Isiolo County Climate Change Draft Policy

34

The County Wildlife Management and Conservation Bill (3) talks about conservation and

management of wildlife for the benefit of ‘present and future generations’, suggesting intra

and inter-generational rights. The draft Climate Change policy has the highest score of 4 since

it reiterates the rights for all to a clean and healthy environment.

The CIDP (3) on its part makes linkages with the Africa Union Agenda 2063, SDG 13 as well as

mentioning the constitution and the rights of the minority and marginalized communities. It

also highlights the fact that it is one of the counties that is vulnerable to climate change

impacts but it does not mention the right to a clean and healthy environment. The community

conservation bill of 2021 only implicitly acknowledges the issue of rights and does not focus

too much on this while on the other hand the draft climate change policy explicitly talks about

rights linking this to article 42 of the constitution on the right to a clean and healthy

environment. It also highlights resource rights and the rights to community land.

Access

On access with a score of 2.8, the various policies provide for access to training and awareness

in the county so as to ensure that people within the county can be able to access and benefit

from the provisions of the policies and laws. The Climate Change Fund Act provides for

training as well as research and providing information that will enable better planning at all

levels as does the draft climate change policy both with a score of 3.

The Customary Natural Resource Management Bill which scores 2 has an objective of ensuring

access for all to natural resources within the county but is silent on issues of free, prior and

informed consent. The County Wildlife Management And Conservation Bill, 2021 with a score

of 3 on its part has a provision on awareness and especially towards conservation and

contains using indigenous knowledge as part of its management regime for natural resources.

Additionally, it provides for a mechanism for benefit sharing with communities living in

wildlife areas. For the Isiolo County Conservancies Bill there are provisions for establishment

of community conservancies where representatives of different categories of people will be

involved to make decisions on how they will be able to access and benefit from the resources

in the conservancies. In terms of early warning this is provided for in the draft climate change

policy which talks about provision of early warning information to communities so that they

can be able to prepare and respond to any changes ahead of time or in time. There are also

provisions for monitoring to ensure that information can be accessed and made available to

the communities especially those who are vulnerable for early action.

Inclusivity

When it comes to inclusivity which has the highest score of 3.3, the policies seem to pay

attention to this, specifically mentioning women, youth and persons with disability,

35

indigenous peoples and local communities inhabiting this area as well as other vulnerable

groups. The Climate Change Fund Act with a score of 4 has a specific provision to have Ward

planning committees composed of these different categories of people as part of the

composition. They are engaged in outreach at the ward level as well as leading the

formulation and development of proposals for projects on climate change adaptation for that

particular ward. In practice, the Ward Planning Committees in Isiolo have all been set up and

some have already developed and submitted their plans for implementation.

For the climate change policy there is recognition of traditional practices used in management

for example the Dedha system amongst the Borana where community elders decide and

agree on use of resources especially in migration patterns at different times during the various

seasons across the year. However, there is no specific role assigned to these traditional

systems within the climate change policy. The final version of the policy incorporated the

other traditional systems as well including those of the Samburu, Somali, Turkana and Meru

that inhabit the area recognizing the traditional system as part of the co-managers of natural

resources that are found within the county and their significant authority and influence on

community matters.

Implementation Plans

When it comes to actions, roles and responsibilities, the policies and Acts all with the

exception of the draft climate change policy which scores 2 have some form of

implementation plan outlining different roles and responsibilities of various actors to ensure

that there is implementation of the specific policy. The combined score for this area is 3. The

county customary natural resource management bill, for example, talks about the role and

responsibility of community elders specifically the Aaba Erega for example who manages the