Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 1 of 39

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

GOOGLE LLC,

Defendant.

Case No. 1:20-cv-03010-APM

HON. AMIT P. MEHTA

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF

PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION TO SANCTION GOOGLE AND COMPEL DISCLOSURE OF

DOCUMENTS UNJUSTIFIABLY CLAIMED

BY GOOGLE AS ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGED

Plaintiffs respectfully request the Court to sanction Google LLC (Google) for its

extensive and intentional efforts to misuse the attorney-client privilege to hide business

documents relevant to this case. Google has explicitly and repeatedly instructed its employees to

shield important business communications from discovery by using false requests for legal

advice. These efforts directly harmed Plaintiffs, undermined their discovery efforts, and

subverted the judicial process. The Court should sanction Google and order the full production of

withheld and redacted emails where in-house counsel was included in a communication between

non-attorneys and did not respond. Alternatively, the Court should hold these silent-attorney

emails are not privileged and immediately order their production.

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 2 of 39

INTRODUCTION

For almost a decade, Google has trained its employees to use the attorney-client privilege

to hide ordinary business communications from discovery in litigation and government

investigations. Specifically, Google teaches its employees to add an attorney, a privilege label,

and a generic “request” for counsel’s advice to any sensitive business communications the

employees or Google might wish to shield from discovery. Google has referred to this practice as

“Communicate with Care.” Documents produced by Google make the existence of this corporate

strategy undeniable and demonstrate the prevalence of this practice throughout the company.

As part of Google’s larger efforts to shield documents from production, Google

employees were expressly directed to add artificial indicia of privilege on all written

communications relating to the exclusionary search-distribution agreements at the heart of

Google’s monopolies. Google’s employees followed the Communicate-with-Care training,

routinely adding in-house counsel to business communications, affixing privilege labels, and

including pretextual requests for legal advice when no advice was actually needed, sought, or

thereafter received. In these email chains, the attorney frequently remains silent, underscoring

that these communications are not genuine requests for legal advice but rather an effort to hide

potential evidence.

Google’s strategy worked. Google’s outside counsel often accepted Google employees’

artificial claims of privilege at face value. After Plaintiffs’ extensive efforts to uncover and

challenge erroneous privilege claims, Google’s outside counsel eventually deprivileged tens of

thousands of documents initially withheld or redacted on the basis of privilege. These efforts,

however, do not—and cannot—cure the misconduct inherent in Google’s efforts to hide relevant

communications. Indeed, many more challenged documents remain outstanding.

Accordingly, the Court should invoke its inherent authority to sanction Google and order

2

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 3 of 39

the production of all emails between non-attorneys where the included in-house counsel did not

reply.

Alternatively, the Court should (1) hold that Google has not, and cannot, make the

necessary showing to support its privilege claims over any email created pursuant to the

Communicate-with-Care program, and (2) order Google to produce withheld emails where the

included in-house counsel did not bother to reply. These silent-attorney emails lack all indicia of

privilege and should be produced. Although Google’s policy of pretextually including attorneys

on business communications has affected a far larger set of documents that Google has withheld

or redacted—and Plaintiffs reserve their rights on this broader set of documents—immediate

production of Google’s silent-attorney emails is the minimum relief appropriate given Google’s

abuse of the discovery process.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I. At Google’s Instruction, Google Employees Deliberately Create Artificial

Indicia Of Privilege To Shield “Sensitive” Business Communications

For years, Google has systematically trained its employees to camouflage ordinary-

course business documents to look like privileged discussions. Google’s efforts to avoid

discovery have included express training and direction on how to imbue “sensitive” documents

(including those documents highly relevant to this case) with the appearance of attorney-client

privilege.

A. Google Directs Employees To Privilege “Any Written Communication”

About Agreements Central To Google’s Anticompetitive Scheme

Google’s documents reveal that Google directs employees to add in-house counsel, make

a pretextual request for legal advice, and apply attorney-client privilege labels to shield

“sensitive” business discussions from discovery, even when the author has no actual interest in

seeking or receiving legal advice.

3

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 4 of 39

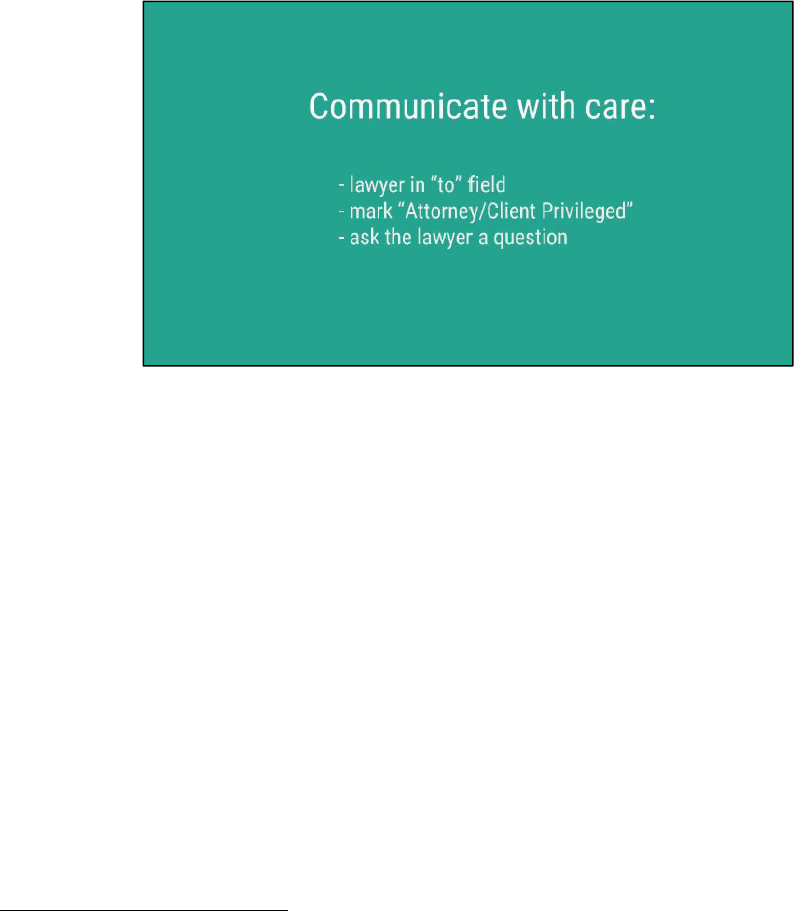

This practice is referred to as “Communicate with Care” and began no later than 2015,

when Google’s new employee orientation included the slide in Figure 1.

1

Figure 1

The speaker notes accompanying this presentation direct new employees: “If you’re

dealing with a sensitive issue, it’s important to communicate with care over email. You can

follow these steps to ensure your email communication is privileged in these circumstances.”

2

There is no discussion about when or whether legal advice is actually needed or should be

sought.

Training of this sort was not limited to new employees. It was also provided to teams

negotiating the search-distribution at the center of this case. In 2016, after the European

Commission opened a formal investigation into Google’s search-distribution practices on

1

Declaration of Meagan K. Bellshaw (Bellshaw Decl.) Ex. 1 (GOOG-DOJ-06890329, at -363)

(per Google’s metadata, date of document is 10/8/2015); Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 2 (Raghavan Dep.

280:1-8, Dec. 14, 2021). Throughout this memorandum, Plaintiffs will refer to this practice as

Communicate with Care as that appears to be how it was frequently referred to by Google. It

may have had different names at different times and to different employees.

2

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 1

4

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 5 of 39

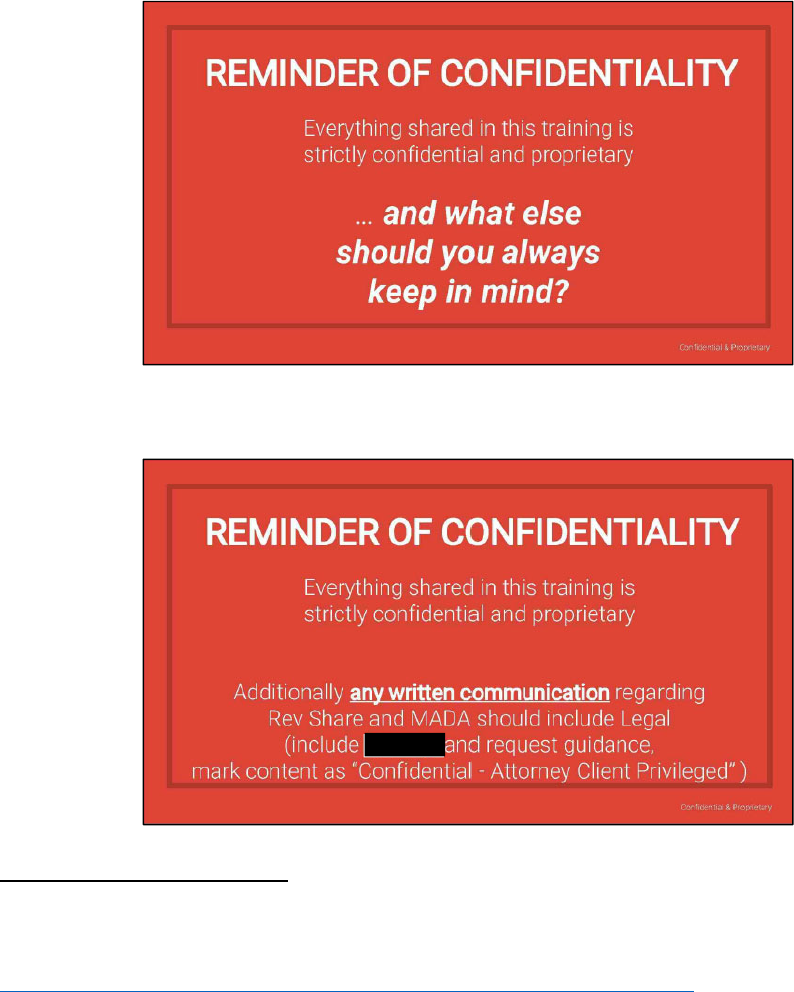

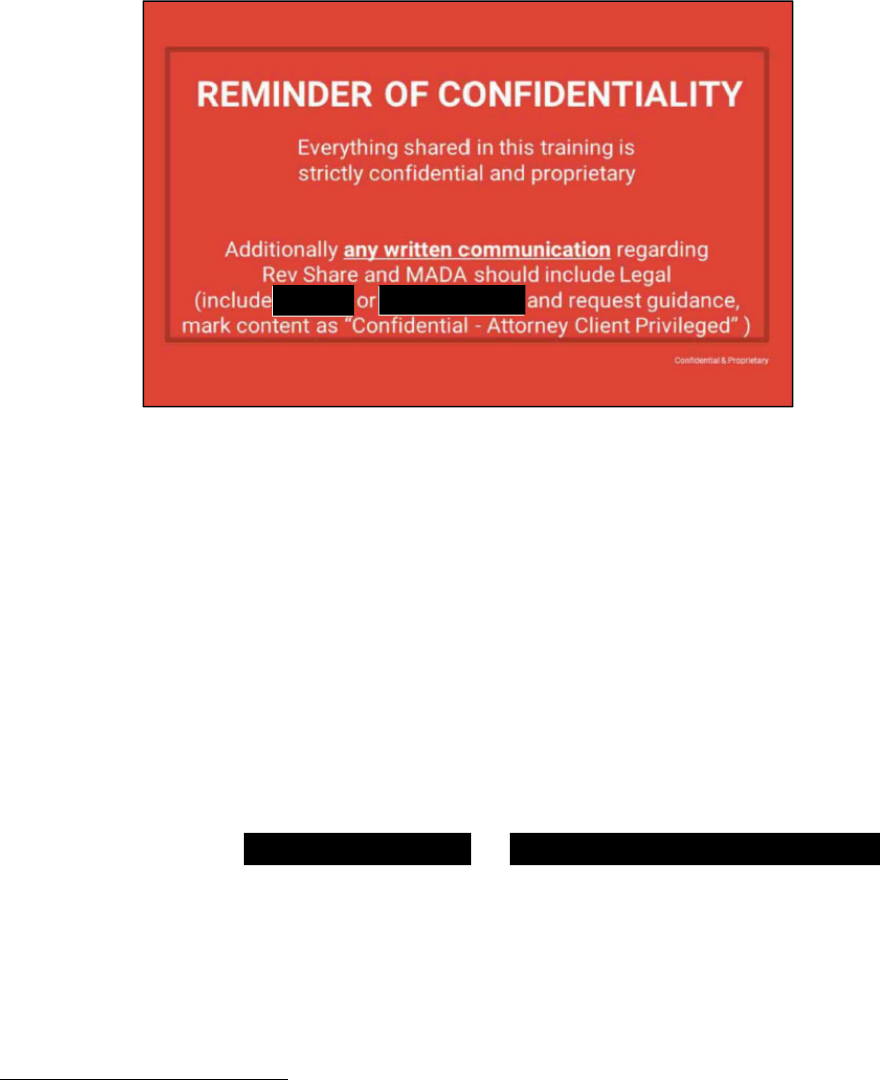

Android,

3

Google held a two-day “Android Mobile Search & Assistant Revenue Share

Agreement Training.” Google presented the slides in Figures 2 and 3 to attendees of this

training.

4

Figure 2

Figure 3

3

Press Release, European Commission, “Antitrust: Commission opens formal investigation

against Google in relation to Android mobile operating system” (Apr. 15, 2015), available at

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO 15 4782.

4

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 3 (GOOG-DOJ-10619658, at -66566) (per Google’s metadata, date of

document is Dec. 7, 2016).

5

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 6 of 39

As the slides show, attendees were asked “what else should you always keep in mind?”

The answer: camouflage “any written communication regarding Rev Share and MADA” to

look like a request for legal advice by adding “Legal” and marking content “Confidential

Attorney Client Privileged.”

5

Google then instructed its employees to “request guidance” from

an attorney.

6

Again, employees were directed to portray business communication as privileged

regardless of whether any legal advice was genuinely sought.

Specific reference to the Mobile Application Distribution Agreements (MADAs) and

revenue-sharing agreements (RSAs) was no accident. These agreements—between Google and

its search distribution partners—are central to Google’s efforts to monopolize the search and

search advertising markets at issue in this case. As Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint explains, the

RSAs and MADAs (along with other supporting agreements) lock up search distribution on

mobile devices and foreclose competition.

7

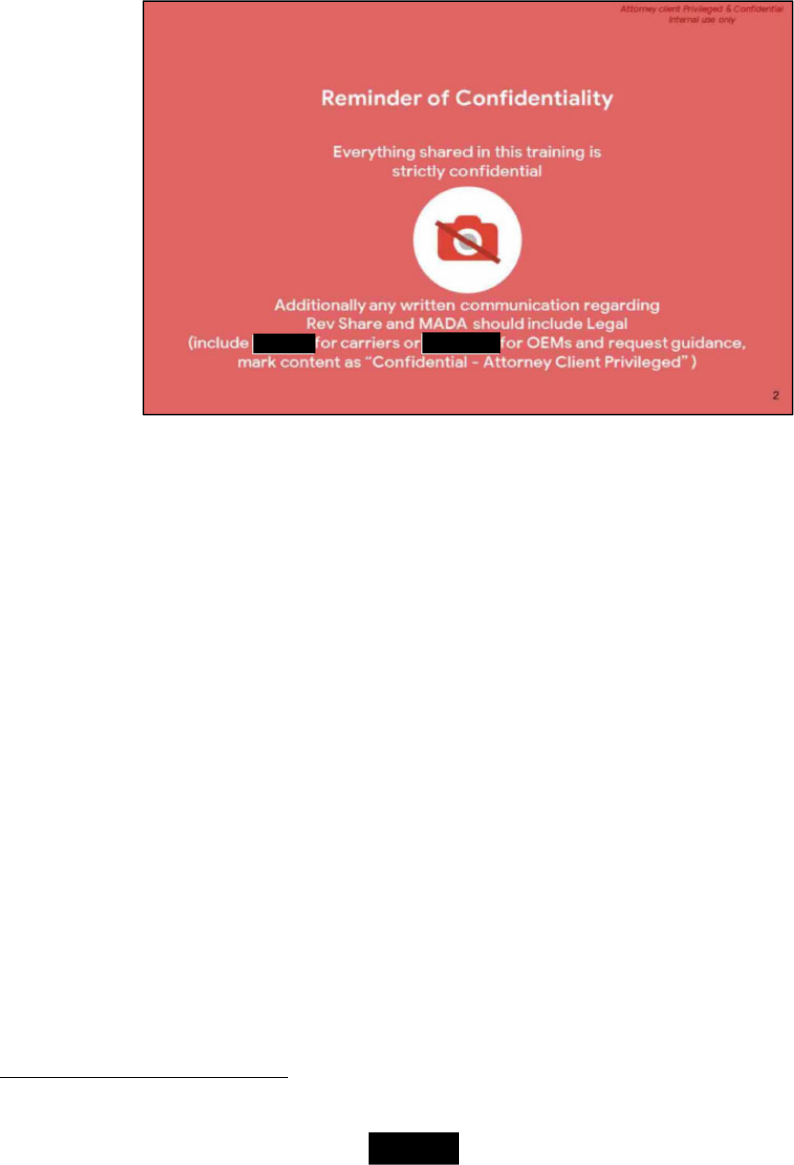

The Communicate-with-Care training surfaced again when the United States began

reviewing Google’s conduct.

8

Six days after the United States Department of Justice issued its

first Civil Investigative Demand in the investigation into Google’s search monopoly,

9

Google

again warned its employees to take steps to immunize from disclosure in discovery “any written

5

Id. at -666 (emphasis in original).

6

Id. Helen Tsao ( ) is in-house counsel for Google. Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 4.

7

Am. Compl. ¶¶ 5287, 166 (ECF No. 94).

8

The Antitrust Division announced the opening of its review of market-leading online platforms

on July 23, 2019. See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, “Justice Department Reviewing the

Practices of Market-Leading Online Platforms” (July. 23, 201), available at

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-reviewing-practices-market-leading-online-

platforms.

9

The Antitrust Division issued its initial Civil Investigative Demand to Google’s parent

company, Alphabet, Inc., on August 30, 2019 (CID No. 30092). Bellshaw Decl. at ¶ 5.

6

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 7 of 39

communication” relating to RSAs and MADAs.

10

Figure 4

As before, Google directed employees to create the appearance of privilege on all written

communications about its search distribution agreements by including counsel on the email,

marking content as “Confidential Attorney Client Privileged,” and requesting “guidance.”

Again, no effort was made to distinguish between authentic requests for advice and efforts to

shield business communications from production.

B. Google Employees Followed The Instructions To Create Artificial Indicia Of

Privilege On Business Communications

Communications produced in response to Plaintiffs’ privilege challenges show that

Google’s employees complied with Google’s instructions to camouflage business

communications. Indeed, Google employees at every level followed the company’s three-step

formula of (1) including in-house counsel on sensitive business discussions, (2) adding privilege

10

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 5 (GOOG-DOJ-21790045, at -046) (per Google’s metadata, date of

document is Sept. 5, 2019). Kate Lee ( ) is another in-house counsel for Google.

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 4.

7

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 8 of 39

headings, and (3) making pretextual requests for legal guidance.

For example, on July 16, 2019, a Google product manager updated two supervisors on

negotiations for Google’s RSA with LG, a mobile-device manufacturer. In the email, the product

manager offered his recommendation and sought input from the supervisors, both non-attorneys,

on the business discussion with LG. Nevertheless, the product manager prefaced the email by

writing “PRIVILEGED & CONFIDENTIAL . . . Kate – please advise as needed.”

11

Kate Lee,

the in-house counsel, was included (as Google taught) on the “To” line but never responded.

12

Google, nevertheless, originally withheld the entire email thread, including the subsequent

emails that dropped the attorney from the discussion and were sent solely between two non-

attorneys.

13

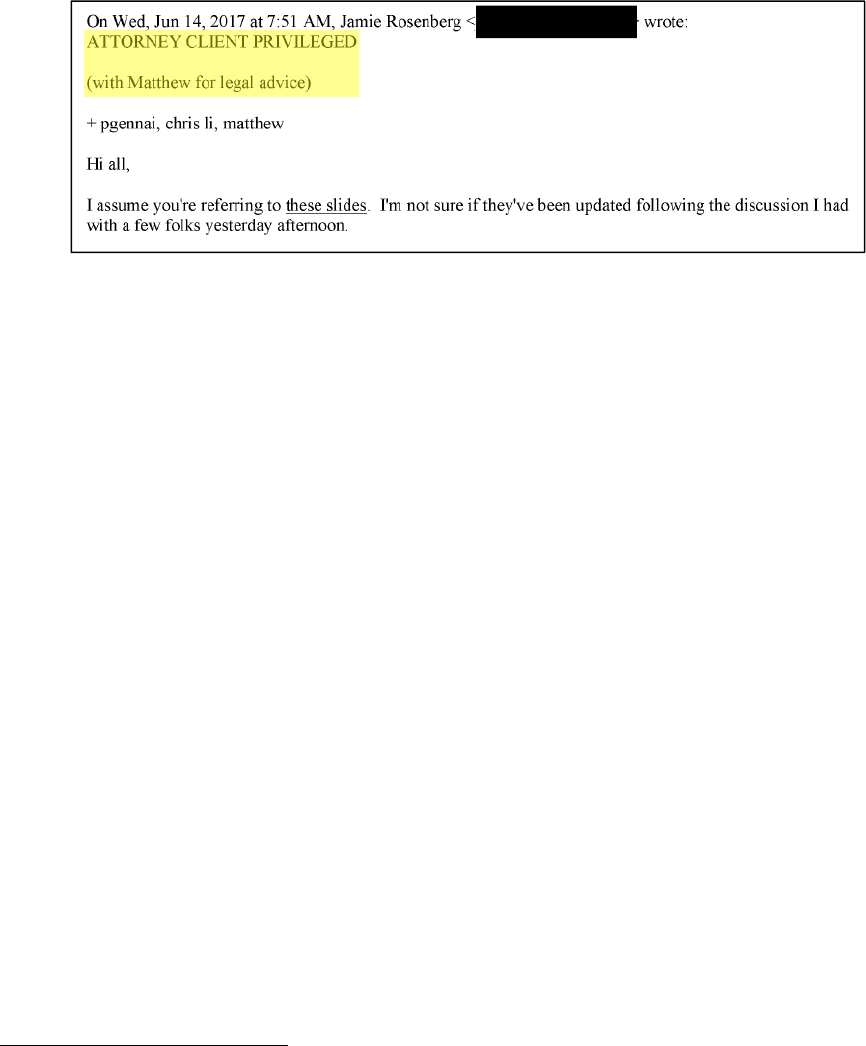

Similarly, on June 14, 2017, a vice president responded to an email discussion about a

slide deck that was being prepared for Google’s CEO Sundar Pichai.

14

The discussion concerned

whether to

. As shown in Figure 5, the

11

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 6 (GOOG-DOJ-28350269, at -271) (emphasis in original); see also

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 7 (GOOG-DOJ-27771584) (showing Kate Lee listed on the “To” line).

12

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 7 (GOOG-DOJ-27771584); Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 8 (GGPL-2060441155)

(Google privilege log entry showing that document was originally fully withheld); Bellshaw

Decl. Ex. 9 (GOOG-DOJ-28350262) and Bellshaw Ex. 8 (GGPL-1081901687); Bellshaw Decl.

Ex. 10 (GOOG-DOJ-28350265) and Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 8 (GGPL-1081901608); Bellshaw Decl.

Ex. 6 (GOOG-DOJ-28350269) and Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 8 (GGPL-1081901607).

13

Id.

14

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 11 (GOOG-DOJ-26758239, at -243).

8

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 9 of 39

vice president followed the Communicate-with-Care guidance:

15

Figure 5

This email, which Google deprivileged only after repeated efforts by Plaintiffs, reflects

all of the hallmarks of Google’s Communicate-with-Care strategy: marking the email as

privileged, copying in-house counsel, and requesting unspecified “legal advice.” Over the next

fifteen hours, the Google employees on this email exchanged eight responses about negotiating

strategy, yet the in-house counsel apparently never responded and no actual legal advice was

sought or disclosed.

16

Nevertheless, Google’s employees included some form of “Privileged”

marking on every subsequent email, including the top-level emails that removed the in-house

counsel from the thread and were sent exclusively between two non-attorneys.

17

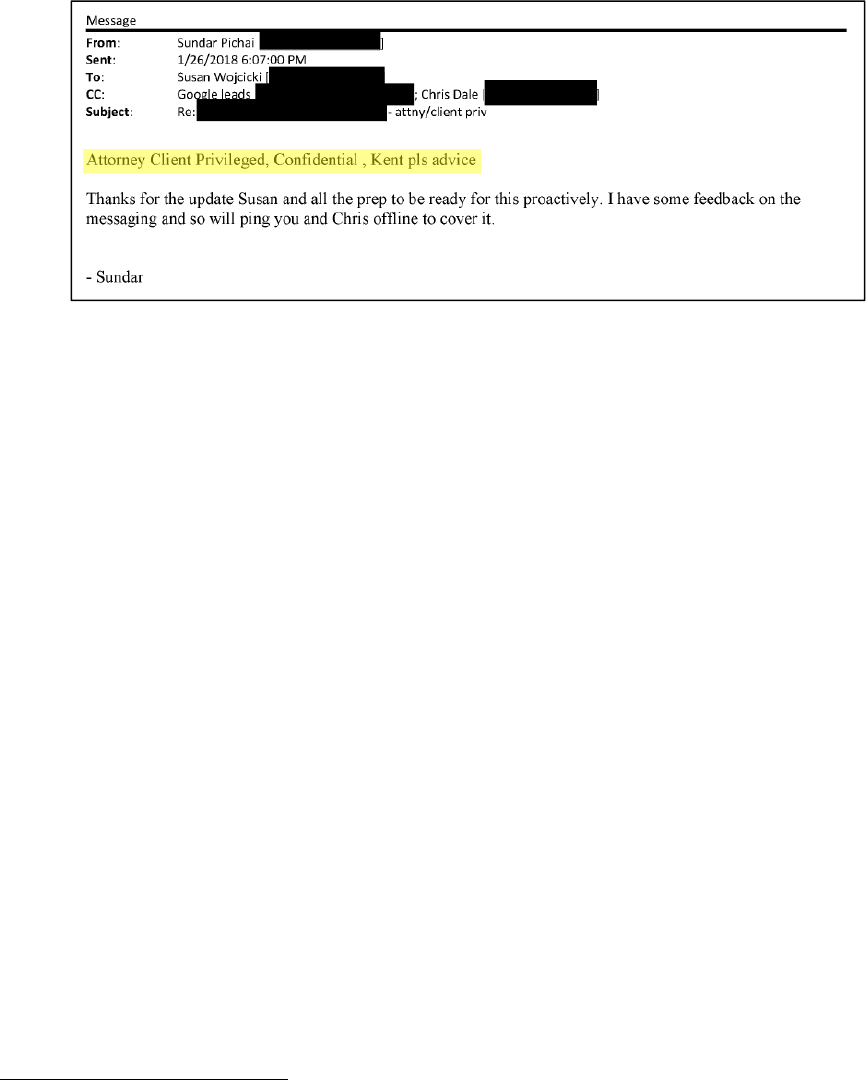

This practice of portraying ordinary business communications as privileged is followed at

Google’s highest levels. Google’s CEO (and now also Alphabet’s CEO), Sundar Pichai sent the

15

Id.

16

Id.

17

Id. Google’s outside counsel initially fully withheld the entire thread, including the top emails

between two non-attorneys. See Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 8 (GGPL-1081174382).

9

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 10 of 39

following email about an upcoming press story to Susan Wojcicki (a non-attorney):

18

Figure 6

Although the email was directed to a non-attorney (Susan Wojcicki) about a non-legal

press issue, Mr. Pichai wrote at the top “Attorney Client Privileged” and “Kent pls advice.” Kent

Walker, a Google Senior Vice President and General Counsel (now Google’s Chief Legal

Officer), apparently never replied to the email thread. This email was initially withheld by

Google and only deprivileged after Plaintiffs challenged.

19

Google’s production contains numerous examples of Google employees carrying out the

Communicate-with-Care directions, where the emails revolve around RSAs, MADAs, and other

“sensitive” issues at the heart of Plaintiffs’ case. Indeed, generic statements such as “[attorney,]

18

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 12 (GOOG-DOJ-28509324, at -324).

19

Id.

10

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 11 of 39

please advise,”

20

“adding legal,”

21

or “adding [attorney] for legal advice”

22

appear in thousands

of Google documents.

23

These emails lack any specific request for legal advice and the attorneys

rarely respond. Tellingly, when Google attorneys fail to respond to these generic requests, the

non-attorneys do not follow-up with more specific requests for advice or even remind the

attorney to respond.

C. Google Employees, Including Its Leaders, Encourage Coworkers To

Communicate With Care By Asking Them To “Make It Privileged”

In following the Communicate-with-Care guidance, Google employees, including

Google’s leaders, frequently express their intent to hide documents from discovery by directing

20

See, e.g., Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 13 (GOOG-DOJ-18636836, at -836) (email from non-attorney,

redacted because top of email includes header “Privileged and Confidential, Seeks advice of

counsel – Kate pls advise,” followed by a business communication directed explicitly to another

non-attorney about the Samsung RSA negotiation); Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 7 (GOOG-DOJ-

27771584, at -854) (non-attorney starts an email sent to other non-attorneys, regarding a

“follow-up conversation with LG” on revenue-share business negotiations, with “Privileged &

Confidential Kate – please advise as needed,” and Google initially withheld the document on that

basis).

21

See, e.g., Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 14 (GOOG-DOJ-24020181, at -182) (Google vice president

starts email to other non-attorneys about business deals with “**attorney client privileged**

adding Legal for counsel,” with no attorney responding to any email in the remainder of the

thread).

22

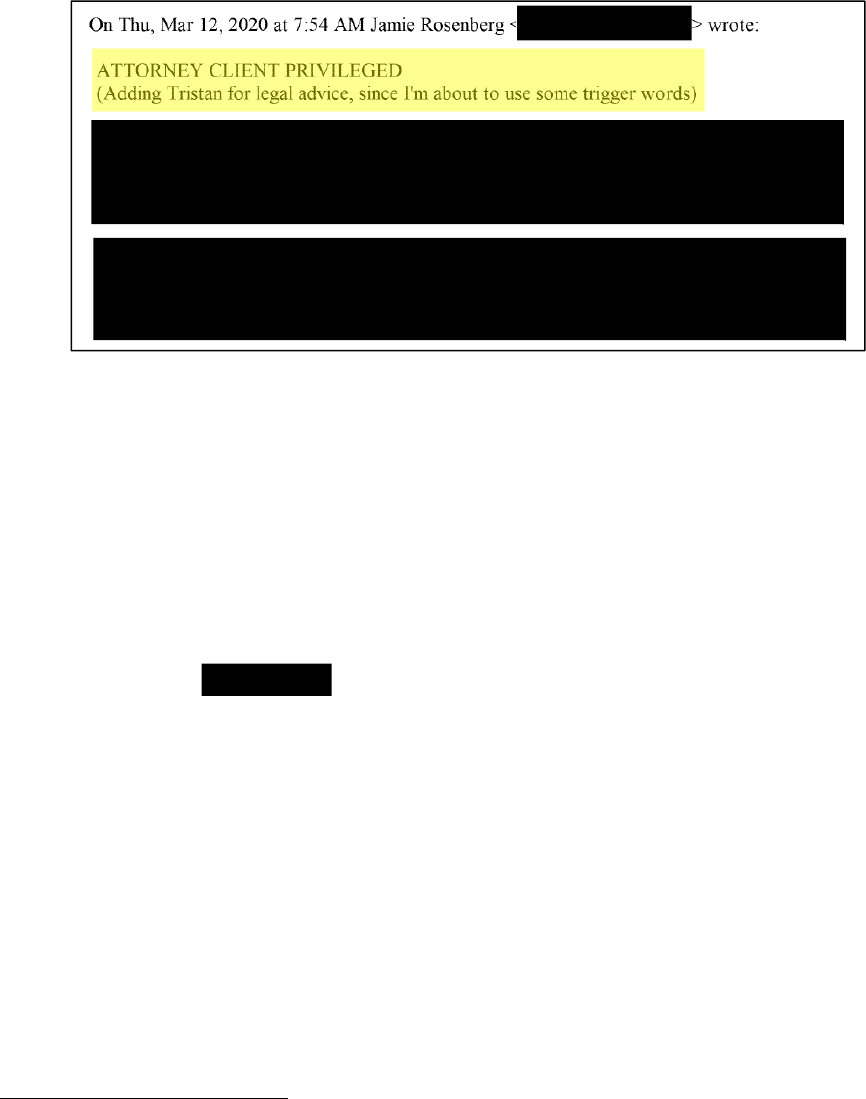

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 15 (GOOG-DOJ-09059783, at -785) (deprivileged communication in

which a Google vice president responds to a thread about Android business issues with

“Attorney Client Privileged (Adding Tristan for Legal advice),” resulting in response emails

using a “Privileged” header even though the added attorney does not respond in any of the

subsequent 11 emails); Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 16 (GOOG-DOJ-28416766, at -768) (largely

deprivileged communication, beginning with “Privileged and Confidential – Adding Tristan for

legal advice Please Don’t Share,” in which a non-attorney emails other non-attorneys about

, but the included attorney does not respond to any of the

subsequent 11 emails that each relate to business considerations).

23

To illustrate, a search of Google’s produced documents (including deprivileged files) for the

generic phrases “please advise,” “pls advise,” “for advice,” “for legal advice,” “for any legal

advice,” “for guidance,” or “seeks advice of counsel” within five words of the first names of five

attorneys from the examples cited in this brief returned 9,329 documents. Bellshaw Decl. ¶ 7.

This is only from the documents that Plaintiffs can currently review. Many more such documents

containing generic and pretextual requests for legal advice are likely still withheld or redacted.

11

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 12 of 39

colleagues to create privileged communications or “m

ake it privileged.”

24

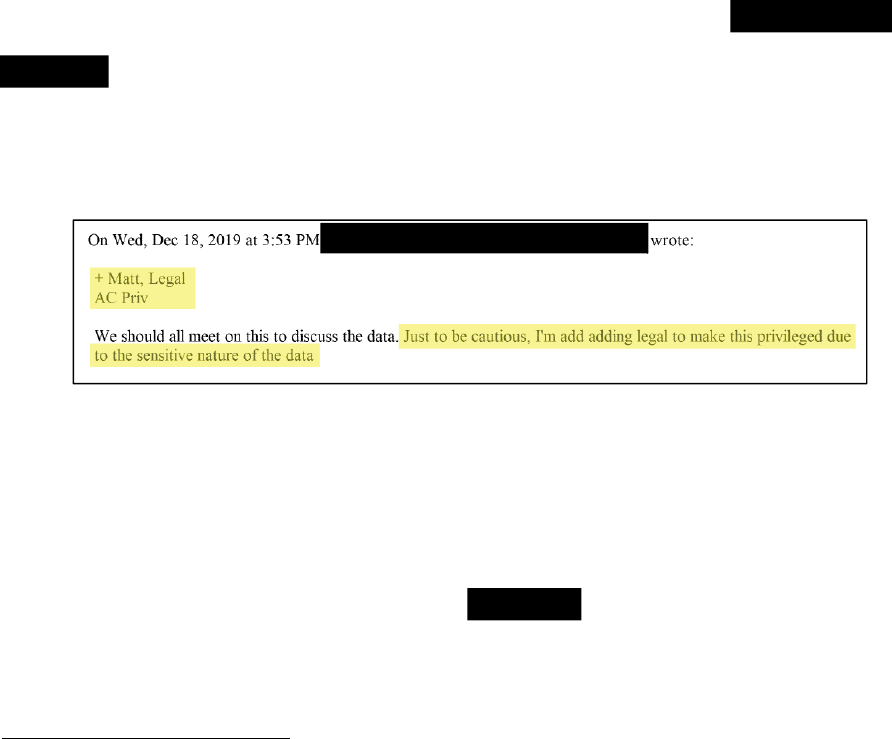

For example, in a 2019

email thread, a Google product-management director asked, “[c]an someone put a lawyer on this

thread and make it ACP by asking for advice?”

25

In another 2019 email thread, as shown in

Figure 7, Google engineers and analysts discussed the business tradeoff of “

.” After reviewing the revenue data, a non-attorney employee added an attorney to the

email “to make this privileged”:

26

Figure 7

The added attorney apparently never responded, confirming there was no legal question to be

answered.

27

Similarly, in Figure 8, a Google vice president explained that he was including an

attorney in an email about business negotiations because his message would contain

“trigger words,” presumably terms that Google employees are taught to avoid (like “leverage”)

24

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 17 (GOOG-DOJ-21646392, at -392) (in an email thread, responding to a

colleague’s request to “threadkill please,” a Google employee wrote “instead of threadkill, please

copy lawyer and make it privileged thread to get internal consultation.”); see also, e.g., Bellshaw

Decl. Ex. 18 (GOOG-DOJ-18895045, at -045) (adding an attorney to an email with meeting

notes “to make this thread Attorney-Client Privileged”); Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 19 (GOOG-DOJ-

09750925, at -925) (“Let’s make the [slide] deck attorney client privileged and share with a

lawyer asap”).

25

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 20 (GOOG-DOJ-23945666, at -668). Google initially produced redacted

versions of the five subsequent emails but then produced an unredacted version of the thread

after Plaintiffs’ challenge. Id.

26

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 21 (GOOG-DOJ-12864417, at -418).

27

Id.

12

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 13 of 39

and that regulators might look for:

28

Figure 8

The included attorney did not respond in any of the subsequent roughly 25 emails in the

string and was eventually dropped from the email thread entirely, confirming that his inclusion

was not for the legitimate purpose of seeking legal advice.

29

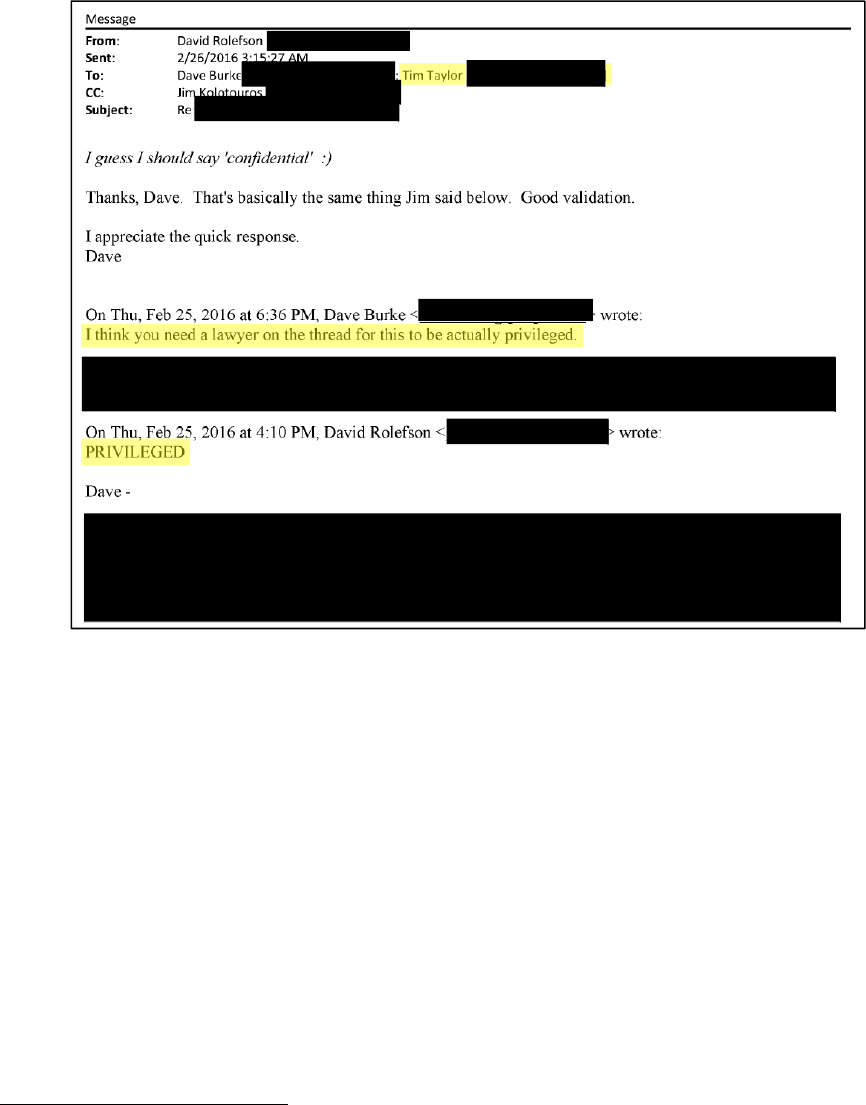

Often, Google employees will correct and discipline colleagues’ misfires in attempts to

claim privilege. For example, on a 2016 email thread in which Google employees discussed a

business negotiation , one employee reminded another that an attorney was needed

for the Communicate-with-Care formula to work (see Figure 9). He warned “I think you need a

lawyer on the thread for this to be actually privileged.” After being reminded, his colleague

replied and, as directed, added in-house counsel, Tim Taylor. Google withheld this document on

28

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 22 (GOOG-DOJ-21815059, at -065).

29

Id.

13

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 14 of 39

a privilege claim until challenged by Plaintiffs.

30

Figure 9

Google’s use of attorneys to shield business communications pervades the entire

company, including its leadership, and continued unabated after the company was on notice of

the Department of Justice’s investigation and even after the filing of the complaint in this action.

For example, after the Department of Justice issued Civil Investigative Demands to

Google, Prabhakar Raghavan, a senior Google executive, sent a list of business ideas to his

non-attorney subordinates. Figure 10 shows that on April 3, 2020, Mr. Raghavan requested a

30

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 23 (GOOG-DOJ-06399233, at -233). Responding several months later to

Plaintiffs’ privilege challenge, Google reproduced the document, without redactions. Id.

14

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 15 of 39

colleague create a “privileged deck” addressing the business issues in the email.

31

Figure 10

The requested “privileged deck” involved search advertising—one of the markets Google

is alleged to have monopolized—and was intended for “Sundar,” Google’s CEO. Of note, the

recipient did not respond with a query as to what a “privileged deck” was. The nomenclature was

understood.

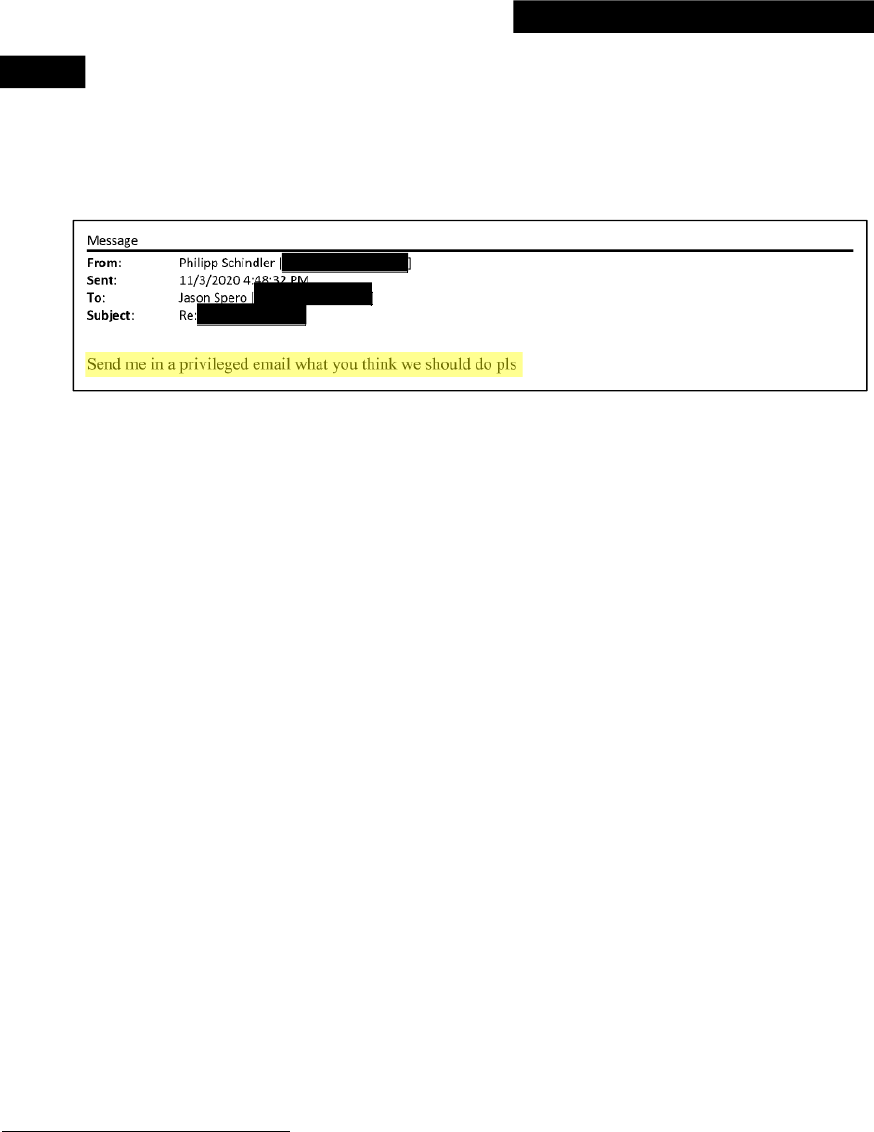

Likewise, one of Google’s most senior executives—Philipp Schindler, Google’s Chief

Business Officer—repeatedly asks for non-legal communications to be relayed to him in a

“privileged” form. On November 3, 2020, after the complaint was filed in this case and Google

had an ongoing duty to produce materials in response to discovery requests, Mr. Schindler

31

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 24 (GOOG-DOJ-20830033).

15

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 16 of 39

received an email from a non-lawyer describing how

. As shown in Figure 11, Mr. Schindler responded, asking for a “privileged email” with

the employee’s perspective:

32

Figure 11

II. Plaintiffs Have Been, And Continue To Be, Harmed By Google’s

Conduct

Google’s strategy of creating the appearance of privilege on sensitive business documents

has had its intended effect: tens of thousands of documents were improperly withheld or redacted

in this litigation and many more challenged documents remain withheld or redacted. The burden

Plaintiffs have faced in seeking the improperly withheld documents and unwinding Google’s

misconduct has interfered with the Plaintiffs’ preparation of their case.

Plaintiffs began challenging Google’s overstatement of privilege claims in June 2021. At

the time, careful scrutiny of Google’s privilege logs showed that tens of thousands of privileged

documents merely included in-house counsel on the carbon-copy line, even though it is well

settled that copying an attorney does not confer privilege. Over the subsequent months, Plaintiffs

repeatedly challenged Google’s privilege claims, even as Plaintiffs worked to understand

32

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 25 (GOOG-DOJ-21476426); see also Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 26 (GOOG-

DOJ-30899052, at -053) (Philipp Schindler asks a non-attorney colleague to send him an update

on a business partner “in a privileged separate email”); Id. (GOOG-DOJ-30899052, at -055 (Mr.

Schindler asks a non-attorney colleague to send more details about a business partner in advance

of a meeting “in a separate privileged thread”).

16

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 17 of 39

Google’s ongoing efforts to falsely claim privilege on common business documents. During this

time, Google has been slow to respond to Plaintiffs’ requests, taking months to reproduce

challenged documents. When Google did concede the veracity of Plaintiffs’ privilege challenges,

the previously withheld documents often arrived after depositions of the relevant Google

custodians.

33

Finally, Google refused to re-review categories of documents directly implicated by

Google’s abuse of the attorney-client privilege.

34

Although Google has, ultimately, deprivileged numerous documents, many other

questionable documents remain fully withheld or redacted.

35

The full universe of unresolved

documents is obscured by the fact that Google has refused, despite repeated requests, to provide

an accounting of which documents it has re-reviewed and which documents it has deprivileged.

36

33

See, e.g., Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 27 (GOOG-DOJ-21672259) (Yuki Richardson email challenged

on November 15, 2021, as improperly redacted, but Google did not produce a deprivileged

unredacted version until January 11, 2022, after the December 15 deposition of Ms. Richardson);

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 28 (GOOG-DOJ-21129755) (email about RSAs with carriers originally

redacted because it included “ATTORNEY CLIENT PRIVILEGED (Kate, please advise)” was

challenged by Plaintiffs on November 15, 2021, but Google did not produce a deprivileged,

unredacted version of the document until January 13, 2022, after the deposition of all three

Google deponents on the thread—Jamie Rosenberg (Dec. 1314, 2021), Adrienne McCallister

(Dec. 13, 2021), and Yuki Richardson (Dec. 15, 2021)).

34

It was not until March 1, 2022, that Google agreed to review a subset of these

communications, and this was only after Plaintiffs informed Google of its intent to file a motion

to compel.

35

See, e.g., Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 29 (GOOG-DOJ-24380202, at -204) (redacted email in which

employee adds attorney Matthew Bye to the “CC” line of an email relating to “Carrier Search

Rev Share” along with several non-attorneys, but Mr. Bye never replies over the course of the

subsequent eight emails between non-attorneys, each of which Google redacted and has not

deprivileged despite Plaintiffs’ challenge on November 15, 2021). For reference, Google has

fully withheld over 80,000 documents where an attorney is merely carbon-copied on an email

between non-attorneys. Because these are fully withheld, Plaintiffs lack any visibility as to

whether an attorney responded with legal advice during the thread.

36

Google has produced tens of thousands of previously fully withheld and redacted documents

as part of its privilege re-review, Bellshaw Decl. ¶ 8, but Google has not provided Plaintiffs with

the necessary information to match newly produced documents to privilege log entries for the

fully withheld version. Plaintiffs repeatedly asked Google for this information in August,

17

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 18 of 39

Google, moreover, has offered no formula by which it can—upon re-review—separate out the

Communicate-with-Care emails from those (if any) carrying a genuine request for attorney

advice. As such, re-review efforts have not remedied Google’s misconduct or the burden and

delay it created.

ARGUMENT

Google’s actions under the Communicate-with-Care program are misconduct that

demand sanction to protect the integrity of the investigative and judicial processes. Even if the

Court holds that Google’s conduct is not sanctionable, the Court should conclude that (1) all

emails created under Communication with Care are not privileged, and (2) Google cannot make

the necessary showing to maintain its privilege claims over the silent-attorney emails. Under

either framework, the Court should order Google to produce all the silent-attorney emails

without redaction.

I. The Court Should Sanction Google For Its Abuse Of The Attorney-Client

Privilege By Compelling Disclosure Of All Silent-Attorney Emails

The Court should exercise its inherent authority to sanction Google’s misconduct by

ordering the production of the silent-attorney emails presently withheld or redacted under claims

of privilege. Specifically, the Court should hold that (1) Google’s conduct is sanctionable, and

(2) an appropriate sanction is the immediate production of all withheld or redacted emails where

no attorney responded to the purported request for legal advice.

A. Google’s Conduct Is Sanctionable Under The Court’s Inherent Authority

The Court should conclude that Google’s years-long effort to hide business

November, and January. See Bellshaw Decl. ¶ 6, Ex. 36 (Plaintiffs’ November 15, 2021 Letter)

and Ex. 37 (Plaintiffs’ January 25, 2022 Letter). Nor has Google updated its privilege logs to

accurately reflect which privilege claims have been withdrawn. As a result, Plaintiffs have no

way to check Google’s work and discern which privilege challenges remain outstanding.

18

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 19 of 39

communications under the cloak of attorney-client privilege is sanctionable misconduct.

1. Google’s Communicate-With-Care Program Is Sanctionable

In Google’s Communicate-with-Care program, new employees were taught to hide

“sensitive” business communications with false requests for assistance from counsel. As part of

their ordinary orientation, these employees were directed to protect sensitive communications by

adding an attorney to the email, directing a pretextual question to the attorney, and marking the

communication privileged. These directions made no allowance for whether legal advice was

necessary or desired. The Communicate-with-Care program had no purpose except to mislead

anyone who might seek the documents in an investigation, discovery, or ensuing dispute.

Indeed, when regulators—including the European Commission and the United States

Department of Justice—began investigating Google’s search-distribution agreements, Google

took steps to ensure its Communicate-with-Care training addressed communications relating to

those agreements. The company explicitly directed its employees to route “any written

communication” relating to RSAs and MADAs—the agreements central to this action—through

counsel with requests for advice included. Google believed that these efforts would facially

support a privilege claim and shield the communications from being produced in future

litigation. Google knew these agreements created significant antitrust risk for the company and

presented significant concerns to antitrust regulators worldwide. The slide in Figure 12 appeared

four times in a single presentation used during the Android Mobile Search & Assistant Revenue

19

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 20 of 39

Share Agreement Training.

37

Figure 12

These directions to misuse the attorney-client privilege were misconduct, as were the

efforts by Google’s employees to follow them—either by falsely seeking legal advice or

instructing subordinates to take a business communication and “make it privileged.”

To be clear, those following Google’s Communicate-with-Care program were not acting

out of an abundance of caution but instead were acting—as directed—to hide specific

communications about subjects being investigated by regulators. For example, in July 2021,

Mr. Schindler—a top executive at Google—reviewed draft notes in preparation for a business

conference on Google’s “ .”

38

37

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 30 (GOOG-DOJ-29824601, at -605, -617, -681, -702).

38

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 31 (GOOG-DOJ-30900278).

20

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 21 of 39

, Mr. Schindler made a request in a comment:

39

Figure 13

Thus, Mr. Schindler—a non-attorney—expressly asked for a business update but one

shielded by privilege. More importantly, Mr. Schindler tips his hand that he wants things routed

through counsel to hide the communications; there is no request for legal guidance. These same

preparation notes included a separate point about a telecommunications company. Mr. Schindler

requested “more details” on this point in a “privileged thread”:

40

Figure 14

These were express efforts by Google’s Chief Business Officer to wrap business

communications in the cloak of attorney-client privilege.

Google’s Communicate-with-Care program was successful: in this case, Google

designated tens of thousands of business communications as privileged and withheld these

documents from Google’s initial production. These over-designations created enormous,

unnecessary costs for Plaintiffs, both (1) in delay in receiving the improperly withheld

documents, and (2) in resources spent investigating and challenging the improper withholding.

Plaintiffs’ efforts to unwind Google’s privilege claims began on June 4, 2021, when

39

Id. at -279.

40

Id. at -280281.

21

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 22 of 39

Plaintiffs sent Google a letter raising a series of privilege concerns based on the first volumes of

Google’s litigation privilege logs.

41

In this letter, Plaintiffs expressed concern over Google’s

withholding of 81,122 documents as privileged where an attorney was merely carbon-copied.

42

Although Plaintiffs had not yet uncovered evidence regarding the Communicate-with-Care

training, Plaintiffs pointed to evidence that Google employees appeared to be adding attorneys to

communications, not for legal advice, but to shield information from discovery. The June 4 letter

cited examples such as emails asking “could we please include a lawyer in the thread and make

the doc A&C Privileged please”

43

and “+ to make this thread Attorney-Client

Privileged.”

44

As Google’s production continued, however, the company advanced the same unfounded

privilege claims for documents identified on subsequent privilege logs. This required Plaintiffs to

send new challenges in July, November, and January.

Subsequently, deprivileged documents revealed that the scope of this abuse was more

pervasive and intentional than Plaintiffs realized. At the time of this filing, Google has reversed

its claims of privilege on tens of thousands of documents. This is no tribute to Google’s efforts to

cure their prior conduct, but a measure of the harm the company’s misconduct has wrought, and

the effort expended by Plaintiffs in challenging Google’s misconduct. This harm continues as

many more challenged silent-attorney emails remain withheld and redacted.

41

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 35 (Plaintiffs’ June 4, 2021 Letter).

42

Id. at 9.

43

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 32 (GOOG-DOJ-07801741, at -741).

44

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 18 (GOOG-DOJ-18895045, at -045).

22

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 23 of 39

2. Google’s Efforts To Hide Relevant Evidence Under The Pretense Of

Attorney-Client Communications Raise The Same Concerns As

Spoliation And Misrepresentation

Sanctions are warranted where “a party has engaged deliberately in deceptive practices

that undermine the integrity of judicial proceedings.” Anheuser-Busch, Inc. v. Natural Beverage

Distribs., 69 F.3d 337, 348 (9th Cir. 1995); see also Leon v. IDX Sys. Corp., 464 F.3d 951, 958

(9th Cir. 2006). Google’s conduct checks all of those boxes. Google engaged deliberately in

deceptive conduct—directing its employees to include pretextual requests for legal advice—for

the purpose of shielding documents from discovery in this litigation. Google’s policy did not

require destroying documents or deleting emails. But orchestrating the use of fraudulent requests

for legal advice to camouflage non-privileged business email has much the same result—

documents that would otherwise be discoverable are denied to plaintiffs—and, if not remedied,

inflicts the same harm on the factfinding process. The discovery process, of course, is essential to

the search for truth in judicial proceedings and ultimately to the Court’s ability to reach

conclusions based on an accurate and complete representation of the facts.

Google’s institutionalized manufacturing of false privilege claims is egregious, spanning

nearly a decade and permeating the company from the top executives on down. The breadth and

calculation of Google’s Communicate-with-Care program renders it commensurate with other

sanctionable conduct, including elements of both spoliation and misrepresentation. Google’s

conduct is cut from the same cloth as actions in the caselaw that have been sanctioned—even if

the fabric is cut in a more intricate pattern.

The Court’s inherent authority enables the Court “to protect [its] institutional integrity

and to guard against abuses of the judicial process with contempt citations, fines, awards of

attorneys’ fees, and such other orders and sanctions as they find necessary, including even

dismissals and default judgments.” Shepherd v. Am. Broad. Cos., 62 F.3d 1469, 1472 (D.C. Cir.

23

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 24 of 39

1995).

When “a party has engaged deliberately in deceptive practices that undermine the

integrity of judicial proceedings,” courts have the inherent authority to impose severe sanctions.

See Anheuser-Busch, 69 F.3d at 348. Here, there can be no doubt Google’s deception was

deliberate and has undermined this proceeding. The requests for legal advice under

Communicate with Care were misrepresentations made when it was foreseeable that the emails

would be relevant to litigation brought by regulators, including the Department of Justice.

Google’s instruction that employees make these misrepresentations increased the likelihood that

a business communication would be withheld as privileged in subsequent government

investigations or litigation. But for the anticipation of litigation, Google’s

Communicate-with-Care instructions serve no purpose.

In Johnson v. BAE Systems, a case concerning both spoliation and misrepresentation, the

court sanctioned the plaintiff, finding that she had “repeatedly obfuscated the truth,” “altered

medical records,” and “failed to preserve and produce relevant documents during discovery.”

106 F. Supp 3d. 179, 189–90 (D.D.C. 2015). Although Google has not destroyed evidence, it has

deliberately obfuscated the truth with each request for legal advice when none was needed,

resulting in a failure to produce relevant documents to Plaintiffs during discovery.

45

The Johnson

court further held that recoverability of destroyed files was “irrelevant” because “[t]he potential

for future compliance with discovery requirements is not an excuse for attempting to destroy

computer files.” Id.

As in Johnson, the fact that Google’s privilege gamesmanship has not destroyed the

45

See Paavola v. Hope Vill., No. CV 19-1608 (JDB), 2021 WL 4033101, at *5 (D.D.C. Sept. 4,

2021) (sanctioning a party that “organized a specific effort to shred documents and dispose of

records while it was actively engaged in litigating this case”).

24

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 25 of 39

relevant non-privileged communications forever is “irrelevant.” Google employees recognize

that adding artificial indicia of privilege has the same effect as deleting documents. For example,

in responding to a colleague’s request to “threadkill please,” a Google employee wrote “instead

of threadkill, please copy lawyer and make it privileged thread to get internal consultation.”

46

Sanctions are appropriate not only to remedy Google’s abuse but also to deter Google and

others from engaging in this deceptive practice in the future. The D.C. Circuit has explained,

“[t]he district court’s interest in deterrence is a legitimate one, ‘not merely to penalize those

whose conduct may be deemed to warrant such a sanction, but to deter those who might be

tempted to such conduct in the absence of such a deterrent.’” Bonds v. District of Columbia,

93 F.3d 801, 808 (D.C. Cir. 1996) (quoting Nat’l Hockey League v. Metro. Hockey Club,

427 U.S. 639, 643 (1976)). If Google’s conduct goes “unpunished, other litigants might be

tempted to abuse the discovery process in the future.” Monroe v. Ridley, 135 F.R.D. 1, 6–7

(D.D.C. 1990).

Neither Google nor any other large corporation with deep pockets and an army of

in-house lawyers should be able to subvert the attorney-client privilege to hide potential

evidence. Google’s efforts to hide documents make a mockery of the attorney-client privilege—a

centerpiece of legal practice. Accordingly, the conduct is particularly problematic and deserving

of proportional sanctions.

B. Compelled Disclosure Of Silent-Attorney Emails Is A Just And Proportional

Sanction For Google’s Misconduct

The Court should order Google to produce the silent-attorney emails as a reasonable

sanction for the company’s misconduct. Specifically, the Court should compel Google to

46

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 17 (GOOG-DOJ-21646392).

25

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 26 of 39

produce all withheld or redacted communications (including attachments and linked documents)

where in-house counsel was included in a communication between non-attorneys but the

in-house counsel never responded.

This sanction is narrowly tailored and proportional to Google’s misconduct. “To be

just . . . the sanction must never be any more severe than it need be to correct the harm done and

to cure the prejudice created to the other party, unless the opposing party’s behavior has so been

so flagrant or egregious that deterring similar conduct in the future in itself warrants the sanction

sought.” Zenian v. District of Columbia, 283 F. Supp. 2d 36, 38 (D.D.C. 2003) (quoting Walker

v. District of Columbia, 1998 WL 429834, at *1 (D.D.C. June 12, 1998)). Here, Plaintiffs seek to

compel the production of documents directly implicated by Google’s abuse of the attorney-client

privilege. Although we seek no more than what is needed to correct the harm done by Google’s

misconduct, the egregiousness of Google’s conduct also warrants this remedy to deter similar

conduct in the future. This sanction is consistent with the caselaw. For example, in Cohn v.

Guaranteed Rate, Inc., 318 F.R.D. 350, 35355 (N.D. Ill. 2016), the court found plaintiff acted

in bad faith and engaged in sanctionable conduct by moving damaging emails to her personal

email account and deleting them before filing suit. Accordingly, the Cohn court granted

defendants “full access” to the plaintiff’s personal email account to permit a transparent

determination of whether any ostensibly deleted emails could be retrieved. 318 F.R.D. at 356.

It is possible that the proposed sanction could result in the production of documents

where individuals genuinely sought legal advice. However, if a few privileged documents are

contained within the set of silent-attorney emails, it is a consequence of Google’s own

misconduct and a warranted penalty. “[P]reventing a party from asserting the attorney-client

privilege is a legitimate sanction for abusing the discovery process.” In re Teleglobe Commc’ns

26

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 27 of 39

Corp., 493 F.3d 345, 386 (3d Cir. 2007), as amended (Oct. 12, 2007). Waiver of privilege is

generally reserved for cases involving “inexcusable conduct” and “bad faith.” DL v. District of

Columbia, 274 F.R.D. 320, 325–26 (D.D.C. 2011). If Google’s intentional misuse of the

attorney-client privilege is not both “inexcusable” and in “bad faith,” Plaintiffs are unsure what

would qualify.

47

Finally, this sanction is necessary as a first step in curing the harm that Google has

inflicted on Plaintiffs and to deter Google from misusing the attorney-client privilege to shield

relevant evidence in the future. Because of Google’s misconduct, Plaintiffs had to wait many

months to receive deprivileged documents. Some deprivileged reproductions even arrived after

the depositions of the relevant Google custodians. Further, Plaintiffs spent significant resources

uncovering and challenging these abuses.

48

Many more challenged documents are outstanding

with limited time in discovery remaining. Immediate disclosure of all the silent-attorney

communications is necessary to correct Google’s abuses. Plaintiffs also reserve the right to seek

adverse inferences and re-open depositions, if necessary.

47

Courts have also held that a party may have a “culpable state of mind” to support sanctions

relating to spoliation “even if the party did not act in bad faith or purposefully destroy records.”

Paavola v. Hope Vill., No. CV 19-1608 (JDB), 2021 WL 4033101, at *12 (D.D.C. Sept. 4,

2021); see also United Med. Supply Co. v. United States, 77 Fed. Cl. 257, 268–69 (2007)

(“Guided by logic and considerable and growing precedent, the court concludes that an injured

party need not demonstrate bad faith in order for the court to impose, under its inherent authority,

spoliation sanctions.”).

48

Courts have held that late and missing productions of documents prejudice plaintiffs. See DL,

274 F.R.D. at 328–29 (holding that plaintiffs suffered prejudice where “delayed production” of

documents “likely left plaintiffs with a compromised trial strategy”); 3E Mobile, LLC v. Glob.

Cellular, Inc., 222 F. Supp. 3d 50, 56–57 (D.D.C. 2016) (“Global has not only incurred

unnecessary costs by having to file a motion to compel and motion for sanctions as a result of

3E’s failure to fulfill its discovery obligations, but Global will also incur additional expenses if it

decides to re-depose witnesses using 3E’s newly-produced documents.”).

27

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 28 of 39

II. Compelled Disclosure Of The Silent-Attorney Emails Is Warranted Because

Google Failed To Establish They Are Privileged Communications

Even if the Court declines to find that Google engaged in sanctionable conduct,

compelled disclosure of the silent-attorney emails is warranted because Google has failed to

meet its burden to establish that these communications are privileged.

A. Documents Created Under The Communicate-With-Care Program Are Not

Privileged And Must Be Produced

Google employees adopting the Communicate-with-Care strategy did not seek actual

advice from counsel. Accordingly, the Court should hold that all emails with pretextual requests

for legal advice where an attorney did not respond are not privileged and immediately

producible.

The D.C. Circuit has adopted the “significant purpose” test to evaluate whether a

document is protected as an attorney-client communication. “Sensibly and properly applied, the

test boils down to whether obtaining or providing legal advice was one of the significant

purposes of the attorney-client communication.” In re Kellogg Brown & Root, Inc., 756 F.3d

754, 760 (D.C. Cir. 2014). Emails adopting the Communicate-with-Care instructions inherently

fail this test. Google’s employees following instructions to “request guidance” or “make it

privileged” are not genuinely seeking legal advice. Instead, these employees are adding counsel’s

name and a mock request for advice merely because they have been directed to do so on all

sensitive communications. Thus, neither seeking nor receiving legal advice is a “significant”

purpose of these emails.

Accordingly, the Court should conclude that any document created under the

Communicate-with-Care rubric cannot be withheld or redacted under a claim of privilege. See

Philip Morris USA, Inc., No. Civ.A.99-2496(GK), 2004 WL 5355972, at *6 (Feb. 23, 2004)

(“[D]ocuments provided to an attorney to keep counsel informed, without an implied request for

28

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 29 of 39

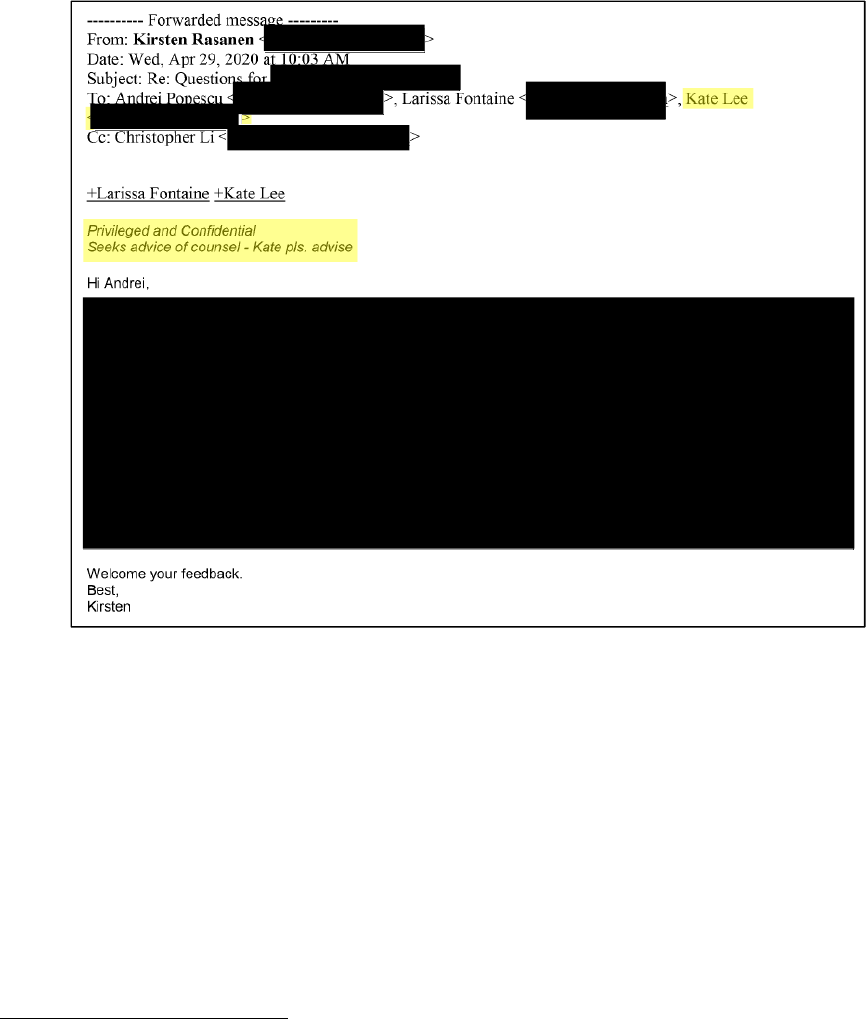

legal advice, will not be privileged”). An example demonstrates the point. On April 29, 2020, a

non-attorney Google employee sent the email in Figure 15.

49

Figure 15

As instructed, the Google employee included the talismanic language of “Privileged and

Confidential” and “Seeks advice of counsel – Kate pls. advise,” but then proceeds to directly

address the non-attorney to whom the email is really directed (“Hi Andrei”). Unsurprisingly, the

non-attorney, rather than the attorney, responds.

50

This email, originally withheld on a claim of

privilege, cannot qualify for privilege protection: the intent was not to obtain legal advice from

in-house attorney Kate Lee but, rather, to use Ms. Lee to shield from discovery the email to

49

Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 13 (GOOG-DOJ-18636836).

50

The included attorney does not chime in at any point in the thread. See Bellshaw Dec. Ex. 33

(GOOG-DOJ-18636847).

29

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 30 of 39

Andrei Popescu.

None of the Communicate-with-Care emails are entitled to privilege protection. Google

“may not shield otherwise discoverable documents from disclosure by including an attorney on a

distribution list.” United States ex rel. Barko v. Halliburton Co., 74 F. Supp. 3d 183, 188 (D.D.C.

2014). The caselaw is clear: an attorney recipient, alone, cannot create a privilege. See Minebea

Co. v. Papst, 228 F.R.D. 13, 21 (D.D.C. 2005) (“A corporation cannot be permitted to insulate its

files from discovery simply by sending a ‘cc’ to in-house counsel.” (citation omitted)).

51

The

D.C. Circuit has warned that, “[i]n cases that involve in-house counsel, it is necessary to apply

the privilege cautiously and narrowly ‘lest the mere participation of an attorney be used to seal

off disclosure.’” Neuder v. Battelle Pac. Nw. Nat’l Lab’y, 194 F.R.D. 289, 295 (D.D.C. 2000).

“[D]ocuments prepared by non-attorneys and addressed to non-attorneys with copies routed to

counsel are generally not privileged because they are not communications made primarily for

legal advice.” Id. (quoting Pacamor Bearings, Inc. v. Minebea Co., 918 F. Supp. 491, 511

(D.N.H. 1996)); see also Western Trails, Inc. v. Camp Coast to Coast, Inc., 139 F.R.D. 4, 13

(D.D.C. 1991) (“As a general rule, ‘corporate dealings are not made confidential merely by

funneling them routinely through an attorney’” (citation omitted)).

Because Google’s employees were not genuinely seeking legal advice, any emails sent

pursuant to the Communicate-with-Care program are not protected by the attorney-client

privilege and must be produced.

51

Nor does privilege attach just because the communication’s author marks the document

“privileged.” See, e.g., In re Domestic Airline Travel Antitrust Litig., No. MC 15-1404 (CKK),

2020 WL 3496748, at *6, 15 (D.D.C. Feb. 25, 2020), report and recommendation adopted, 2020

WL 3496448 (D.D.C. May 11, 2020).

30

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 31 of 39

B. Because Google Cannot Meet Its Burden To Establish Privilege Over Any

Silent-Attorney Emails, All Those Documents Must Be Produced Unredacted

The Court should conclude that Google’s Communicate-with-Care program undermines

the company’s privilege claims on emails where the attorney did not bother to respond to

purported requests for advice. Such emails should be produced unredacted because it is

impossible to establish that such communications genuinely sought legal advice.

“It is settled law that the party claiming the privilege bears the burden of proving that the

communications are protected.” In re Lindsey, 158 F.3d 1263, 1270 (D.C. Cir. 1998). To meet

this burden, a party must “present the underlying facts demonstrating the existence of the

privilege” and “conclusively prove each element of the privilege.” Id. (citations omitted)

For the silent-attorney emails, Google cannot make the necessary proofs. Google has

polluted the record regarding which documents contain genuine requests for legal advice to such

an extent that Google cannot make the necessary showing to maintain privilege over many of its

communications. This, of course, was the entire purpose of Google’s Communicate-with-Care

strategy: camouflage the business communications to look like privileged requests for legal

advice. The result, however, is to throw into doubt all of Google’s privilege claims over attorney

communications. Given Google’s conduct, the fact that an email included an attorney and a

request for legal advice proves nothing. Accordingly, such documents cannot—without more—

be withheld on claims of privilege.

An example will make this clear. On February 27, 2021, after this litigation began, a non-

attorney Google employee (Ariel Spivak) emailed another non-attorney (Philipp Schindler) about

a contract negotiation with a third party and carbon-copied several people, including an attorney,

Kate Lee, one of the attorneys appearing on the Communicate-with-Care slides. This email

31

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 32 of 39

appears on Google’s privilege log as a fully withheld document.

52

If, hypothetically, the email

includes the line “Kate, please advise on any legal issues,” Google’s Communicate-with-Care

program makes the simple privilege review of this email impossible. Was the request for advice

genuine or pretextual? Google, of course, has the burden of establishing privilege; therefore, the

document’s ambiguity—created by Google’s own conduct—must undermine Google’s privilege

claim.

The Communicate-with-Care program also renders Google’s privilege log useless as a

functional tool to evaluate privilege claims. A common entry in the log, as for the Kate Lee

email described in the previous paragraph, is “Email seeking legal advice of counsel regarding

contract interpretation.” This offers no insight into the privilege claim when every email

regarding MADAs and RSAs were designed to look like “Email[s] seeking legal advice of

counsel regarding contract interpretation.”

The most vulnerable of Google’s privilege claims are those where the attorney did not

respond to the email allegedly seeking their advice, i.e., the silent-attorney emails. For example,

in Figure 15 above, an attorney (Kate Lee) was included on the “to” line even though the

communication was clearly directed to a non-attorney (Andrei Popescu). Ms. Lee recognized that

there was no genuine request for legal advice, so she simply ignored the email altogether. Thus,

the attorney’s silence is a clear sign that the email did not actually seek legal advice.

After learning of our plans to file a motion to compel, Google offered to re-review its

privilege log for improper privilege claims. Google’s offer, however, misses the point: how will

Google distinguish between genuine requests for legal advice and those adopted under the

Communicate-with-Care formula? The Court should conclude that the attorney’s response on

52

See Bellshaw Decl. Ex. 34 (GGPL-1060262406).

32

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 33 of 39

these emails is the best indicia of the authenticity of the request for legal advice. In short, the

best, minimum indication of whether Google’s internal communications genuinely sought legal

advice is whether Google’s in-house counsel actually responded.

For the category of withheld documents—the email chains where the attorney stayed

silent—the Court should conclude that Google cannot meet its burden to establish privilege

because Google cannot provide sufficient facts “to permit the court to conclude with reasonable

certainty that the privilege applies.” In re Veiga, 746 F. Supp. 2d 27, 34 (D.D.C. 2010); see also

Bartholdi Cable Co. v. FCC, 114 F.3d 274, 280 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (“We have repeatedly held that

the party claiming privilege has the burden of presenting to the court sufficient facts to establish

the privilege.” (internal citation and quotation omitted)).

Plaintiffs’ proposed remedy is the most reasonable solution; it recognizes the ambiguity

Google has created in the privilege process and provides a solution that does not require

Plaintiffs to devote more resources to tracking and uncovering Google’s misconduct. Indeed, the

requested relief is narrowly tailored to documents directly implicated by Google’s

gamesmanship that do not appear to contain any privileged legal advice.

Accordingly, the Court should order the production of all emails (including attachments

and linked documents) in any email chain withheld under a claim of privilege where the included

counsel remained silent. The Court should hold that Google cannot meet its burden to support its

privilege claims over these silent-attorney emails.

53

53

Nor can Google assert work-product protection over this category of documents for

substantially the same reasons. Google has not provided any evidence that an attorney directed

the creation of these silent-attorney emails nor has Google identified specific litigations for

which these business emails were created. See Fann v. Giant Food, Inc., 115 F.R.D. 593, 596

(D.D.C. 1987) (holding that work-product protection does not shield from discovery documents

33

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 34 of 39

III. Google Must Provide An Updated And Useful Privilege Log

Google’s Communicate-with-Care program has rendered the company’s privilege log

useless. It should be replaced. Moreover, Google has deprivileged documents in response to

Plaintiffs’ privilege challenges without updating its privilege log. This leaves Plaintiffs without

the ability to assess the sufficiency of its efforts.

Whether the Court compels disclosure pursuant to sanctions or Google’s failure to meet

its burden to establish privilege, Google must provide Plaintiffs with the ability to verify

compliance with the Court’s order and the company’s ongoing privilege obligations. Despite

repeated requests, Google has refused to provide Plaintiffs with the ability to assess the adequacy

of Google’s privilege review, one of many reasons why re-review is an inadequate remedy.

Plaintiffs, therefore, respectfully request the Court order Google to provide (1) a single,

comprehensive privilege log that combines all remaining privilege claims Google is continuing

to assert in this litigation—with any corrections they have made—and removes any entries that

Google is no longer claiming; and (2) an index including all documents Google has deprivileged

thus far and all documents it deprivileges as a result of the Court’s order with information

sufficient to match each original privilege log identifier to the new Bates number. Where any

part of a deprivileged document is still redacted, Google also must provide a revised privilege

log entry justifying the redaction.

CONCLUSION

The Court should sanction Google for its deliberate and deceptive misuse of privilege and

order the company to produce, unredacted, all emails wherein counsel does not reply. If the

that were “prepared in the regular course of compiler’s business, rather than specifically for

litigation, even if it is apparent that a party may soon resort to litigation”).

34

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 35 of 39

Court does not sanction Google, the Court should still conclude all emails with pretextual

requests for legal advice are not privileged and Google cannot make the necessary showing to

maintain privilege claims over such emails.

Dated: March 8, 2022 Respectfully submitted,

By: /s/ Kenneth M. Dintzer

Kenneth M. Dintzer

Karl E. Herrmann

U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division

Technology & Digital Platforms Section

450 Fifth Street NW, Suite 7100

Washington, DC 20530

Telephone: (202) 227-1967

Counsel for Plaintiff United States of America

By: /s/ Johnathan R. Carter

Leslie Rutledge, Attorney General

Johnathan R. Carter, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, State of Arkansas

323 Center Street, Suite 200

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Arkansas

By: /s/ Adam Miller

Rob Bonta, Attorney General

Ryan J. McCauley, Deputy Attorney General

Adam Miller, Deputy Attorney General

Paula Blizzard, Supervising Deputy Attorney

General

Kathleen Foote, Senior Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General,

California Department of Justice

455 Golden Gate Avenue, Suite 11000

San Francisco, California 94102

Counsel for Plaintiff State of California

35

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 36 of 39

By: /s/ Lee Istrail

Ashley Moody, Attorney General

R. Scott Palmer, Interim Co-Director, Antitrust

Division

Nicholas D. Niemiec, Assistant Attorney General

Lee Istrail, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, State of Florida

PL-01 The Capitol

Tallahassee, Florida 32399

Scott.Palmer@myfloridalegal.com

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Florida

By: /s/ Daniel Walsh

Christopher Carr, Attorney General

Margaret Eckrote, Deputy Attorney General

Daniel Walsh, Senior Assistant Attorney General

Charles Thimmesch, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, State of Georgia

40 Capitol Square, SW

Atlanta, Georgia 30334-1300

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Georgia

By: /s/ Scott L. Barnhart

Theodore Edward Rokita, Attorney General Scott

L. Barnhart, Chief Counsel and Director,

Consumer Protection Division

Matthew Michaloski, Deputy Attorney General

Erica Sullivan, Deputy Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, State of Indiana

Indiana Government Center South, Fifth Floor

302 West Washington Street

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Indiana

36

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 37 of 39

By: /s/ Philip R. Heleringer

Daniel Cameron, Attorney General

J. Christian Lewis, Executive Director of

Consumer Protection

Philip R. Heleringer, Deputy Executive Director of

Consumer Protection

Jonathan E. Farmer, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, Commonwealth of

Kentucky

1024 Capital Center Drive, Suite 200

Frankfort, Kentucky 40601

Counsel for Plaintiff Commonwealth of Kentucky

By: /s/ Christopher J. Alderman

Jeff Landry, Attorney General

Christopher J. Alderman, Assistant Attorney

General

Office of the Attorney General, State of Louisiana

Public Protection Division

1885 North Third St.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70802

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Louisiana

By: /s/ Scott Mertens

Dana Nessel, Attorney General

Scott Mertens, Assistant Attorney General

Michigan Department of Attorney General

P.O. Box 30736

Lansing, Michigan 48909

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Michigan

By: /s/ Stephen M. Hoeplinger

Stephen M. Hoeplinger

Assistant Attorney General

Missouri Attorney General’s Office

815 Olive St., Suite 200

St. Louis, Missouri 63101

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Missouri

37

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 38 of 39

By: /s/ Hart Martin

Lynn Fitch, Attorney General

Hart Martin, Special Assistant Attorney General

Crystal Utley Secoy, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, State of

Mississippi

P.O. Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Mississippi

By: /s/ Rebekah J. French

Austin Knudsen, Attorney General

Rebekah J. French, Assistant Attorney General,

Office of Consumer Protection

Office of the Attorney General, State of Montana

P.O. Box 200151

555 Fuller Avenue, 2nd Floor

Helena, Montana 59620-0151

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Montana

By: /s/ Rebecca M. Hartner

Rebecca M. Hartner, Assistant Attorney General

Alan Wilson, Attorney General

W. Jeffrey Young, Chief Deputy Attorney General

C. Havird Jones, Jr., Senior Assistant Deputy

Attorney General

Mary Frances Jowers, Assistant Deputy Attorney

General

Office of the Attorney General, State of South

Carolina

1000 Assembly Street

Rembert C. Dennis Building

P.O. Box 11549

Columbia, South Carolina 29211-1549

Counsel for Plaintiff State of South Carolina

38

Case 1:20-cv-03010-APM Document 326-1 Filed 03/21/22 Page 39 of 39

By: /s/ Bret Fulkerson

Bret Fulkerson, Deputy Chief, Antitrust Division

Kelsey Paine, Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General, Antitrust Division

300 West 15th Street

Austin, Texas 78701

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Texas

By: /s/ Gwendolyn J. Lindsay Cooley

Joshua L. Kaul, Attorney General

Gwendolyn J. Lindsay Cooley, Assistant Attorney

General

Wisconsin Department of Justice

17 W. Main St.

Madison, Wisconsin 53701

Counsel for Plaintiff State of Wisconsin

39