MORTGAGE

SERVICING

Community Lenders

Remain Active under

New Rules, but CFPB

Needs More

Complete Plans for

Reviewing Rules

Report to the Chairman, Committee on

Financial Services, House of

Representatives

June 2016

GAO-16-448

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-16-448, a report to the

Chairman, Committee on Financial Services,

House of Representatives

June 2016

MORTGAGE SERVICING

Community Lenders

Remain Active under New Rules

,

but

CFPB Needs More Complete Plans for Reviewing

Rules

Why GAO Did This Study

As of September 30, 2015, community

lenders held about $3.1 billion in MSRs

on their balance sheets. Servicing is a

part of holding all mortgage loans, but

an MSR generally becomes a distinct

asset when the loan is sold or

securitized. In response to the 2007–

2009 financial crisis, regulators have

implemented new rules related to

mortgage servicing and regulatory

capital to protect consumers and

strengthen the financial services

industry. GAO was asked to review the

effect of these rule changes on U.S.

banks and credit unions, particularly

community lenders. This report

examines (1) community lenders’

participation in the mortgage servicing

market and potential effects of CFPB’s

mortgage servicing rules on them, (2)

potential effects of the treatment of

MSRs in capital rules on community

lenders’ decisions about holding or

selling MSRs, and (3) the process

regulators used to consider impacts of

these new rules on mortgage servicing

and the capital treatment of MSRs.

GAO analyzed financial data, reviewed

relevant laws and documents from

regulatory agencies, and interviewed

16 community lenders selected based

on size and volume of mortgage

servicing activities, as well as industry,

consumer groups, and federal officials.

What GAO Recommends

CFPB should complete a plan to

measure the effects of its new

regulations that includes specific

metrics, baselines, and analytical

methods to be used. CFPB agreed to

take steps to complete its plan for

conducting a retrospective review of

the mortgage servicing rules and refine

the review’s scope and focus.

What GAO Found

Community banks and credit unions (community lenders) remained active in

servicing mortgage loans under the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s

(CFPB) new mortgage-servicing rules. Among other things, these rules are

intended to provide more information to consumers about their loan obligations.

The share of mortgages serviced by community lenders in 2015—about 13

percent—remained small compared to larger lenders, although their share

doubled between 2008 and 2015. Large banks continue to service more than half

of residential mortgages. Many lenders GAO interviewed said changes in

mortgage-related requirements resulted in increased costs, such as hiring staff

and updating systems. However, many also stated that servicing mortgages

remained important to them for the revenue it can generate and their customer-

focused business model.

Banking and credit union regulators’ new capital rules changed how mortgage

servicing rights (MSR) are treated in calculations of required capital amounts, but

GAO found that these new rules appear unlikely to affect most community

lenders’ decisions to retain or sell MSRs. For example, GAO found that in the

third quarter of 2015, about 1 percent of community banks had to limit the

amount of MSRs that counted in their capital calculations due to the amount of

these assets they held. This may result in some institutions choosing to raise

additional capital or sell MSRs to meet required minimum capital amounts,

depending on banks’ holdings of other types of assets. A few banks with large

concentrations of MSRs that GAO spoke with said they were considering selling

MSRs or other changes to their capital but market participants told us that the

MSR capital treatment was only one of several factors influencing their decisions.

Separate capital rules for credit unions also are unlikely to affect most credit

unions. For example, credit unions told GAO they did not expect to make

changes to their MSR holdings and one credit union explained that it is because

MSRs represented a small percentage of their overall capital.

Banking regulators and CFPB estimated the potential impacts of their new rules

prior to issuing them by, for example, estimating potential costs of compliance.

Banking regulators included the capital rules in a retrospective review of all their

rules required by statute, although this review is to be completed before the MSR

requirements are fully implemented by the end of 2018. Banking regulators also

said they often conduct other informal reviews as needed to evaluate their rules’

effectiveness. CFPB also has a statutory retrospective review requirement, but

its plans for retrospectively reviewing its mortgage-servicing rules are incomplete.

CFPB has not yet finalized a retrospective review plan or identified specific

metrics, baselines, and analytical methods, as encouraged in Office of

Management and Budget guidance. In addition, GAO found that agencies are

better prepared to perform effective reviews if they identify potential data sources

and the measures needed to assess rules’ effectiveness. CFPB officials said it

was too soon to identify relevant data and that they wanted flexibility to design an

effective methodology. However, without a completed plan, CFPB risks not

having time to perform an effective review before January 2019—the date by

which CFPB must publish a report of its assessment.

View GAO-16-448. For more information,

contact

Mathew J. Sciré at (202) 512-8678 or

sciremj@gao.gov

.

Page i GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Letter 1

Background 4

Community Lenders Continue to Service Mortgages as Regulatory

Requirements Increase 14

New Capital Treatment of Mortgage Servicing Rights Likely Will

Not Affect Many Community Banks and Credit Unions 24

Regulators Estimated Impacts of New Rules Using Public Input

and Data Analysis, but CFPB’s Plans for Reviewing Rules Have

Limitations 33

Conclusions 44

Recommendation for Executive Action 44

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 44

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 47

Appendix II Mortgage Servicing Rights Transfer Activity 56

Appendix III Comments from the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection 58

Appendix IV Comments from the National Credit Union Administration 61

Appendix V GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 62

Tables

Table 1: Federal Prudential Regulators and Their Basic Prudential

Functions, as of June 2016 6

Table 2: Median Risk-Based Capital Ratios for Community Banks

by Size and Required Minimum Capital Ratios, Third

Quarter 2015 28

Table 3: Number of Community Banks and Credit Unions

Interviewed, by Size 54

Contents

Page ii GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Table 4: Percentage of Residential Mortgage Transfers of

Servicing Approved by Freddie Mac or Ginnie Mae by

Institution Type, 2010 through 2015 56

Table 5: Net Transfers of Mortgage Servicing Rights Approved by

Freddie Mac or Ginnie Mae by Institution Type and Size

(in billions of dollars of unpaid principal balance), 2010

through 2015 57

Figures

Figure 1: Mortgage Servicing and Creation of a Mortgage

Servicing Right 8

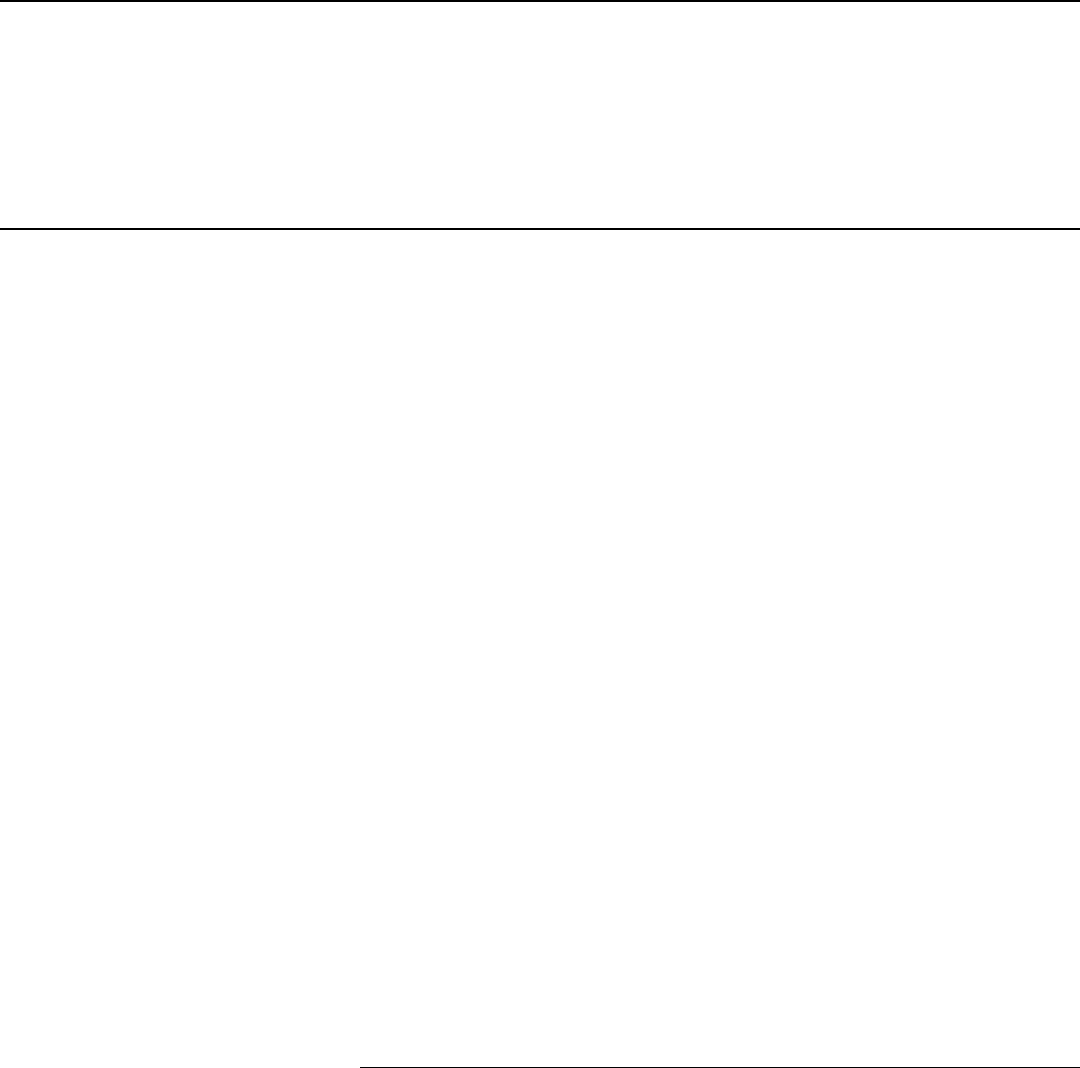

Figure 2: Estimated Share of Residential Mortgages Serviced by

Community Banks, Credit Unions, and Nationwide,

Regional, and Other Banks, First Quarter 2008 through

Third Quarter 2015 (percentage) 14

Figure 3: Percentage of Community Banks, Credit Unions, and

Nationwide, Regional, and Other Banks with Residential

Mortgages on their Balance Sheets by Size, First Quarter

2001 through Third Quarter 2015 (percentage) 22

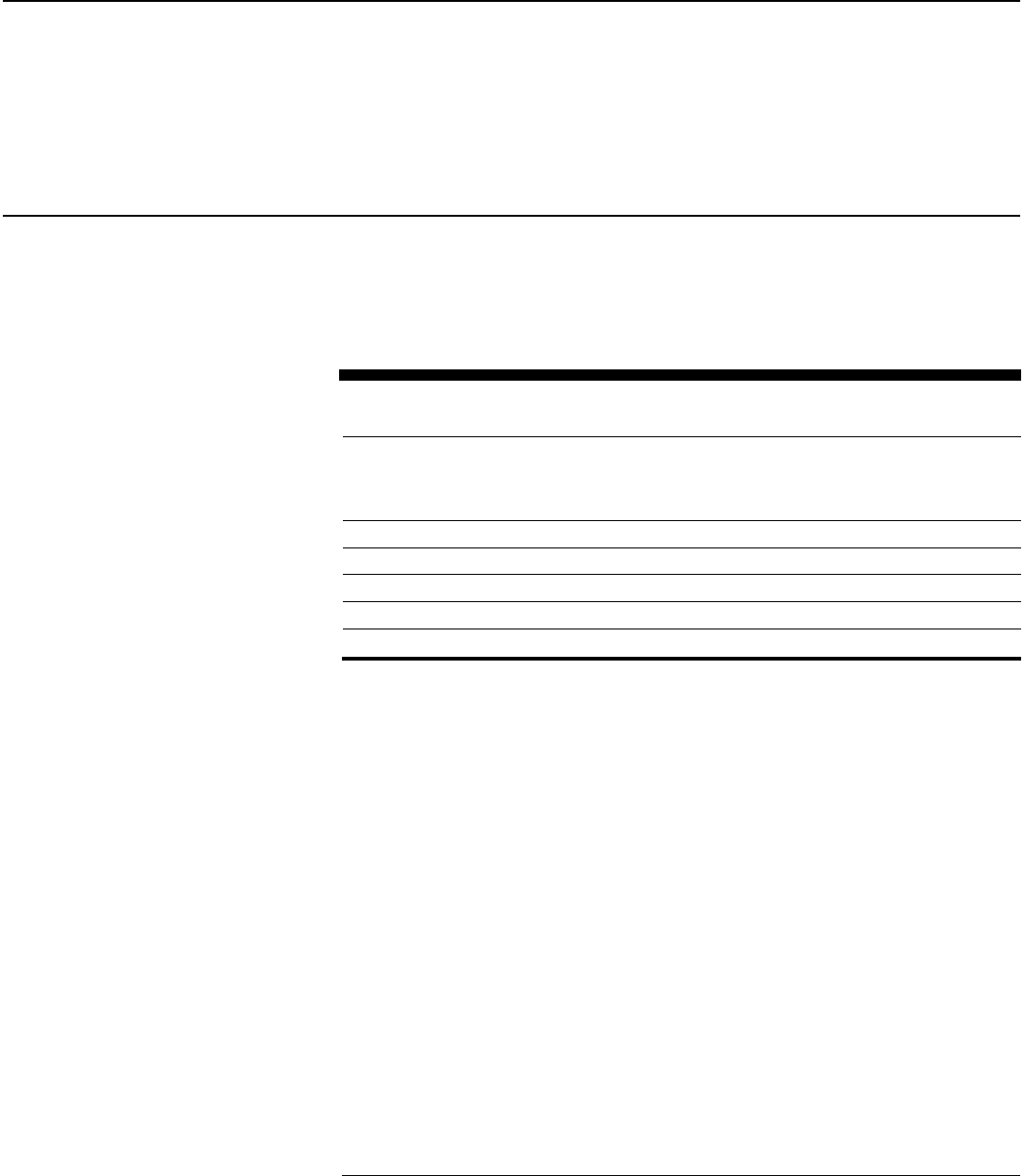

Figure 4: Mortgage Servicing Rights and Risk-Based Capital

Ratios 25

Figure 5: Community Banks’ Capital Treatment of Mortgage

Servicing Rights, 2015Q3 26

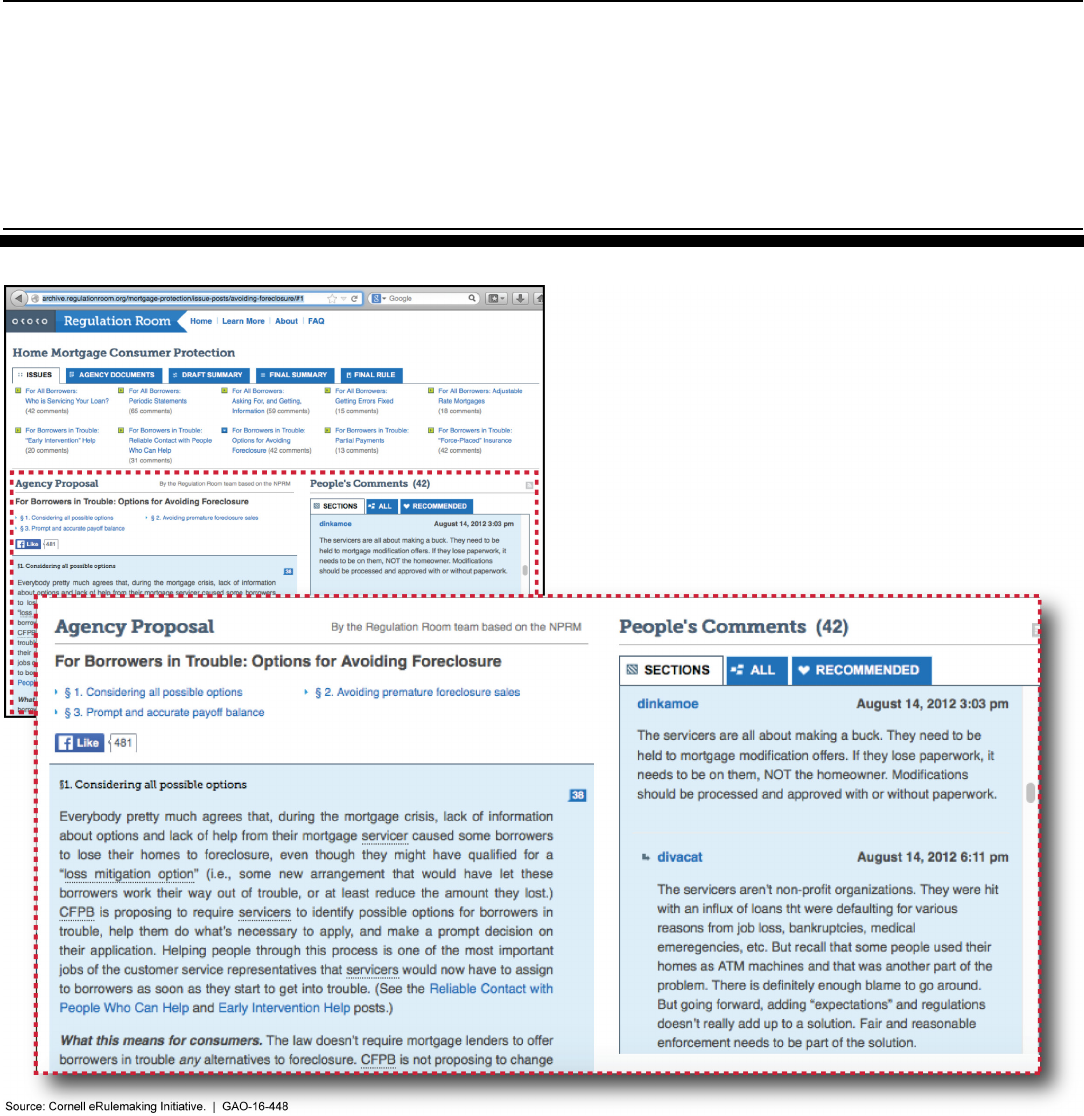

Figure 6: Sample Public Comments from the “Regulation Room”

on CFPB’s Proposed Mortgage Servicing Rule 35

Page iii

GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Abbreviations

ABA American Bankers Association

CET1 common equity tier 1

CFPB Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

CUNA Credit Union National Association

Dodd-Frank Act Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act

EGRPRA

Economic Growth and Regulatory Paperwork

Reduction Act of 1996

FDIC Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

Federal Reserve Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

FFIEC Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council

MBS mortgage-backed securities

MSR mortgage servicing rights

NCUA National Credit Union Administration

OMB Office of Management and Budget

PRA Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995

RFA Regulatory Flexibility Act

SBREFA Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness

Act of 1996

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

June 23, 2016

The Honorable Jeb Hensarling

Chairman

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Chairman:

Many community banks and credit unions (community lenders) view

servicing mortgages as important to maintaining their business and

satisfying their customers. As of September 30, 2015, community lenders

held about $3.1 billion in mortgage servicing rights on their balance

sheets.

1

Recently, these relatively small financial institutions as well as

larger banks have become subject to regulatory changes developed in

response to the 2007‒2009 financial crisis.

These changes are designed, in part, to strengthen the financial services

industry, and some are specific to mortgage servicing. The 2010 Dodd-

Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act)

directed or gave authority to federal agencies to issue mortgage servicing

regulations. In 2013, the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection

(commonly known as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau or

CFPB) issued regulations that require, among other things, prompt

crediting of mortgage payment and early intervention for delinquent

borrowers.

2

Further, also in 2013, federal banking regulators adopted new

requirements for risk-based capital that are based on international

standards (the Basel III framework) developed by the Basel Committee

on Banking Supervision, a global standard-setter for prudential bank

1

Although no commonly accepted definition of a community bank exists, the term often is

associated with smaller banks (e.g., under $1 billion in assets) that provide relationship

banking services to the local community and have management and board members who

reside in the local community. In this report, we use the term “community lenders” to mean

community banks and credit unions. Credit union membership is based on a common

bond, such as residing in a specific geographic area or working in the same profession.

2

Mortgage Servicing Rules Under the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (Regulation

X), 78 Fed. Reg. 10696 (Feb. 14, 2013); Mortgage Servicing Rules Under the Truth in

Lending Act (Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg. 10902 (Feb. 14, 2013).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

regulation.

3

These requirements define how much capital banks must

hold for a variety of activities—including for holding mortgage servicing

rights (MSR), which are distinct assets that generally are created when a

mortgage loan is sold or securitized.

4

Both the mortgage servicing regulations and the regulatory capital

changes for MSRs are relatively new and the effect of these new

requirements has not yet been formally evaluated. Industry and trade

associations have raised concerns about the potential effect of mortgage

servicing regulations on U.S. banks and, in particular, on community

lenders. You asked us to examine the effect of mortgage servicing and

risk-based capital regulations on community lenders and their

customers.

5

This report examines (1) community lenders’ participation in

the mortgage servicing market and potential effects of CFPB’s mortgage

3

Regulatory Capital Rules: Regulatory Capital, Implementation of Basel III, Capital

Adequacy, Transition Provisions, Prompt Corrective Action, Standardized Approach for

Risk-weighted Assets, Market Discipline and Disclosure Requirements, Advanced

Approaches Risk-Based Capital Rule, and Market Risk Capital Rule, 78 Fed. Reg. 62018

(Oct. 11, 2013) (Federal Reserve and OCC) and 78 Fed. Reg. 55340 (Sept. 10, 2013)

(FDIC Interim Final Rule). With minor changes, the September 2013 FDIC interim final

rule became a final rule in April 2014. See 79 Fed. Reg. 20754 (Apr. 14, 2014). The Basel

III framework has no legal force but was issued by the agreement of the Basel Committee

members with the expectation that individual national authorities would implement the

standards.

4

In this report, we use the term “mortgage servicing rights” to mean mortgage servicing

assets that are recognized on a servicer’s balance sheet and are subject to capital

deductions and risk-weighting under the federal prudential regulators’ risk-based capital

rules. Depending upon the facts and circumstances of a given loan sale or securitization

transaction, mortgage servicing rights may or may not actually be recognized on a

servicer’s balance sheet, and when recognized, could actually constitute either a

mortgage servicing asset or a mortgage servicing liability. Also, under U.S. Generally

Accepted Accounting Principles, certain accounting criteria must be met for the sale to

qualify as an accounting sale of servicing assets. For example, the transferor must

surrender control of the financial assets to the transferee.

5

We use the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s practical definition of a community

bank, which incorporates an asset size threshold—generally including banks with less

than $1 billion in assets—and other characteristics, including if it is part of a banking

organization that has loans or core deposits, has limited amounts of foreign assets, has

limited amounts of assets in specialty banks like credit card banks or trust companies, and

is either relatively small or has large amounts of loans and core deposits and a limited

geographic scope. The asset size threshold is not a strict requirement. Larger banks may

be considered community banks if they meet other criteria such as having a loan-to-asset

ratio greater than 33 percent. See Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, FDIC

Community Banking Study, December 2012.

Page 3 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

servicing rules on them, (2) potential effects of the risk-based capital

treatment of MSRs on decisions about holding or selling MSRs, and (3)

the process regulators used to estimate the impact of regulations

addressing mortgage servicing requirements and the risk-based capital

treatment of MSRs.

To address these objectives, we analyzed quarterly data on banks

obtained from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) for the period

from the first quarter of 2001 through the third quarter of 2015, quarterly

data on credit unions obtained from the National Credit Union

Administration (NCUA) for the period from the second quarter of 2002

through the third quarter of 2015, and quarterly data on outstanding

residential mortgages obtained from the Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve) for the period from the first

quarter of 2008 through the third quarter of 2015. We used these data to

estimate the shares of residential mortgages serviced by banks and credit

unions of different sizes, to assess the extent to which banks and credit

unions participate in residential mortgage lending, and to analyze the

potential effect on banks of the capital treatment of MSRs under risk-

based capital rules. We grouped banks into five equal-sized groups, or

quintiles, based on their size as measured by total assets, with the first

quintile containing the smallest banks and the fifth quintile containing the

largest banks. We did the same for credit unions. We assessed the

reliability of the data from FDIC, FFIEC, the Federal Reserve, and NCUA

for the purposes described above by reviewing relevant documentation

and electronically testing the data for missing values, outliers, and invalid

values and found the data to be sufficiently reliable for these purposes.

We also analyzed data on transfers of mortgage servicing rights obtained

from Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae for the period from 2010

to 2015. We analyzed the amount of MSRs associated with mortgage

pools that were sold via bulk sales by banks, credit unions, and nonbank

entities. We assessed the reliability of these data for this purpose by

electronically testing the variables for missing values, invalid values, and

outliers. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable for this purpose.

Finally, we reviewed relevant laws and regulations, as well as past GAO

reports on the financial crisis and the implementation of the Dodd-Frank

Act. We also interviewed officials from a variety of organizations,

including community banks, credit unions, regulators, industry

organizations, credit union service organizations, consumer groups, and

academics and other industry participants such as mortgage brokers. Our

Page 4 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

interviews with a small sample of community lenders and an additional

regional bank provided further insights on their participation in mortgage

servicing and effects of regulations. The responses are not generalizable

to the population of community lenders. Appendix I provides a more

detailed description of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2015 to June 2016 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Various institutions, including banks, credit unions, nonbank entities, and

subservicers, service mortgage loans.

6

These institutions are defined as

follows:

• Banks. Institutions of various types that may be chartered under

federal or state law.

7

One type of bank, community banks, is often

associated with smaller banks (e.g., under $1 billion in assets) that

provide relationship banking services to the local community and have

6

For more information about nonbank mortgage servicers, see GAO, Nonbank Mortgage

Servicers: Existing Regulatory Oversight Could Be Strengthened, GAO-16-278

(Washington D.C.: Mar. 10, 2016).

7

For purposes of this report, banks include bank holding companies, financial holding

companies, savings and loan holding companies, and insured depository institutions,

including any subsidiaries or affiliates of these institutions.

Background

Types of Mortgage

Servicers and Federal

Regulators

Page 5 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

management and board members who reside in the local community.

8

In addition to mortgage servicing, banks offer a variety of financial

products to consumers, including deposit products, loan products,

such as mortgage and auto loans, and credit card products.

• Credit unions. Member-owned cooperatives run by member-elected

boards with an historical emphasis on serving people of modest

means. Like banks, credit unions offer a variety of financial, deposit,

and loan products to consumers.

• Nonbank entities. Entities that are not financial institutions and may be

involved in a variety of mortgage activities, including servicing and

originating loans. Nonbank entities generally do not offer deposit or

credit card products to consumers.

• Subservicers. Third-party servicers that have no investment in the

loans they service. Banks, credit unions, and nonbanks may

outsource loan servicing activities to a subservicer that performs the

same administrative functions the bank, credit union, or nonbank

would to service the mortgage loan.

All U.S. depository institutions that have federal deposit insurance have a

federal prudential regulator that generally may issue regulations and take

enforcement actions against institutions within its jurisdiction. The federal

prudential regulators, which are the Office of the Comptroller of the

Currency (OCC), FDIC, and Federal Reserve, along with the credit-union-

regulating NCUA, oversee depository institutions for safety and

soundness purposes and for compliance with other laws and regulations

8

We use the FDIC’s definition of a community bank, which incorporates an asset size

threshold—generally including banks with less than $1 billion in assets—and other

characteristics, including if it is part of a banking organization that has loans or core

deposits, has limited amounts of foreign assets, has limited amounts of assets in specialty

banks like credit card banks or trust companies, and is either relatively small or has large

amounts of loans and core deposits and a limited geographic scope. The asset size

threshold is not a strict requirement. Larger banks may be considered community banks if

they meet other criteria such as having a loan-to-asset ratio greater than 33 percent. See

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, FDIC’s Community Banking Study.

Page 6 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

that fall within the scope of the relevant prudential regulator’s authority

(see table 1).

9

Table 1: Federal Prudential Regulators and Their Basic Prudential Functions, as of June 2016

Agency

Basic function

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

Charters and supervises national banks, federal savings associations (also known as

federal thrifts), and federal branches and agencies of foreign banks, supervises

subsidiaries of national banks and federal thrifts.

Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System

Supervises state-chartered banks that opt to be members of the Federal Reserve System,

depository institution holding companies (bank holding companies and savings and loan

holding companies), and the nonbanking subsidiaries of those entities.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

Supervises state-chartered banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System,

as well as state savings banks and thrifts and state chartered branches of foreign banks;

insures the deposits of all banks and thrifts that are approved for federal deposit

insurance;

has the authority to conduct insurance or backup examinations for any insured

institutions; resolves all failed insured banks and thrifts; and has the authority to resolve

certain large bank holding companies and nonbank financial companies, if appointed

receiver by the Secretary of the Treasury after the statutory process.

National Credit Union Administration

Charters and supervises federally chartered credit unions and insures savings in federal

and most state-chartered credit unions.

Source: GAO. | GAO-16-448

Note: The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures deposits in insured banks and thrifts

for at least $250,000. FDIC promotes the safety and soundness of these institutions by identifying,

monitoring, and addressing risks to the deposit insurance funds and limiting the effect on the financial

system when a bank or thrift fails.

Additionally, the Dodd-Frank Act transferred consumer financial

protection regulation and some other authorities regarding certain federal

consumer financial laws from other federal banking regulators to CFPB,

to help foster consistent enforcement of federal consumer financial

laws.

10

CFPB has supervision and primary enforcement authority for most

federal consumer financial laws for insured depository institutions with

more than $10 billion in assets and their affiliates as well as certain

nonbank entities. The prudential regulators—the Federal Reserve, Office

9

For a more detailed discussion of the regulatory framework for bank holding companies

and savings and loan holding companies, see GAO, Bank Holding Company Act:

Characteristics and Regulation of Exempt Institutions and the Implications of Removing

the Exemptions, GAO-12-160 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 19, 2012). Nonbank servicers are

subject to different safety and soundness regulation and different capital rules. See

GAO-16-278.

10

These authorities were transferred on July 21, 2011.

Page 7 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

of the Comptroller of Currency, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation,

and NCUA—have primary supervision and exclusive enforcement

authority for federal consumer financial laws for institutions that have $10

billion or less in assets. CFPB also has rulemaking authority to implement

provisions of federal consumer financial law. The Dodd-Frank Act

authorized CFPB to exercise its authorities for a number of purposes,

including ensuring that consumers are provided with timely and

understandable information that will help them make responsible

decisions about financial transactions; protecting consumers from unfair,

deceptive, or abusive acts and practices and from discrimination; and

identifying and addressing outdated, unnecessary, or unduly burdensome

regulations.

11

In the primary market, lenders make, or originate, mortgage loans that are

secured by property or real estate.

12

Originators can choose to hold

mortgages in their own portfolios or sell them into the secondary market.

Servicing is a part of holding mortgage loans in portfolio, but the right to

service a mortgage generally becomes a distinct asset—an MSR—when

contractually separated from the loan if the loan is sold or securitized. In

the secondary market, the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac purchase mortgages that meet their underwriting

criteria and either hold them in their own portfolios or pool them into

mortgage backed securities (MBS) and sell them to investors. Ginnie Mae

guarantees the timely principal and interest payments to investors in

securities issued by approved institutions through its MBS program. Once

the loan origination process is complete, the loan must be serviced until it

is paid in full or foreclosure occurs (see fig. 1).

Servicers perform various loan management functions, including

collecting payments from the borrower, sending monthly account

11

See 12 U.S.C. § 5511(b). CFPB’s rules implementing federal consumer financial laws

apply to all entities within the scope of a particular rule, including smaller banks. See 12

U.S.C. § 5512(b)(4).

12

For a more complete discussion of the primary and secondary mortgage markets, see

GAO, Housing Finance System: A Framework for Assessing Potential Changes,

GAO-15-131 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 7, 2014) and Sean M. Hoskins, Katie Jones, and N.

Eric Weiss, Congressional Research Service, An Overview of the Housing Finances

System in the United States, R42995 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 19, 2015).

Mortgage Servicing

Market

Page 8 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

statements and tax documents, responding to customer service inquiries,

maintaining escrow accounts for property taxes and hazard insurance,

and forwarding monthly mortgage payments to the mortgage owners. In

the event that borrowers become delinquent on their loan payments,

servicers may offer borrowers the loss mitigation options made available

by the owners of the loan, which may include a workout or a loan

modification that permits the borrower to stay in the home or other

options, such as a short sale. In some cases, the servicer is the same

institution that originated the loan. However, servicers may change over

the life of a mortgage as MSRs are sold or transferred to other

institutions.

Figure 1: Mortgage Servicing and Creation of a Mortgage Servicing Right

Note: In addition to banks, credit unions and nonbanks, independent mortgage servicers and

subservicers may be involved in these arrangements. For instance, subservicers—which are typically

nonbanks but can also be banks—may perform some or all servicing functions for the servicer of

record but they do not own the mortgage servicing right.

Page 9 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Mortgage Origination Rules. CFPB issued new rules related to

underwriting of mortgage loans that became effective in January 2014.

13

Generally, lenders making mortgage loans must make a reasonable,

good faith determination of the borrower’s ability to repay the loan. This

ability-to-repay determination requires lenders to meet minimum

underwriting standards, including consideration and verification of a

borrower’s income or assets, debt, and credit history. Lenders are

presumed to comply with the ability-to-repay (determination) requirement

when they make a qualified mortgage, which is a loan that meets specific

product feature and underwriting criteria.

14

Mortgage Servicing Rules. CFPB issued mortgage-servicing-related

rules covering nine major topics that became effective January 10,

2014.

15

According to CFPB, the goals of the servicing rules are to provide

better disclosure to consumers regarding their mortgage loan obligations,

and to inform and assist them with options that may be available if they

13

Ability-to-Repay and Qualified Mortgage Standards Under the Truth in Lending Act

(Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg. 6408 (Jan. 30, 2013). Under CFPB’s ability-to-repay and

qualified mortgage rule, which, as amended, became effective on January 10, 2014, the

agency identified eight underwriting factors a lender must consider in relation to making

the required good faith determination of a borrower’s ability to repay, including a

borrower’s income, assets, employment, credit history, and monthly expenses. In general,

the borrower also must have a total monthly debt-to-income (DTI) ratio, including

mortgage payments of 43 percent or less for the loan to have qualified mortgage status.

12 C.F.R. § 1026.43(e)(2)(vi). The ratio represents the percentage of a borrower’s income

that goes toward all recurring debt payments, including the mortgage payment. Lenders

use the DTI ratio as a key indicator of a borrower’s capacity to repay a loan. A higher ratio

is generally associated with a higher risk that the borrower will have cash flow problems

and may miss mortgage payments.

14

According to CFPB, a qualified mortgage is a category of loans that have certain, more

stable features that help make it more likely that a borrower is able to afford the loan. A

lender must make a good-faith effort to determine that borrowers have the ability to repay

a mortgage loan before it is made. This is known as the “ability-to-repay” rule. A creditor

is presumed to have complied with the ability-to-repay requirements if the creditor makes

a qualified mortgage loan.

15

Mortgage Servicing Rules Under the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (Regulation

X), 78 Fed. Reg. 10696 (Feb. 14, 2013); Mortgage Servicing Rules Under the Truth in

Lending Act (Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg. 10902 (Feb. 14, 2013). The nine topics are:

periodic billing statements; interest rate adjustment notices; prompt payment crediting and

payoff statements; force-placed insurance; error resolution and information requests;

general servicing policies, procedures, and requirements; early intervention with

delinquent borrowers; continuity of contact with delinquent borrowers; and loss mitigation

procedures.

Recent Changes to

Selected Mortgage

Regulations and

Regulatory Capital

Requirements for MSRs

Page 10 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

have difficulty making their mortgage payments. The servicing rules also

aim to ensure that borrowers are protected from harm in connection with

the process of evaluating a borrower for a loss mitigation option or

proceeding to foreclosure.

16

The rules also address critical servicer

practices relating to, among other things, correcting errors, imposing

charges for force-placed insurance, crediting mortgage loan payments,

and providing payoff statements.

17

CFPB included a small servicer exemption from certain parts of the

mortgage servicing rules.

18

Generally, entities that service 5,000 or fewer

mortgage loans, all of which they own or originated, are exempt, for

example, from providing periodic statements. In general, entities that

service one or more loans they neither originated nor own do not qualify

as small servicers, even if they service 5,000 or fewer loans overall.

Regulatory Capital Requirements for MSRs.

19

The Basel III framework

addressed MSRs as part of its effort to improve the banking sector’s

ability to absorb shocks arising from financial and economic stress,

whatever the source; improve risk management and governance; and

16

For complete loss mitigation applications received more than 37 days before a

foreclosure sale, servicers must evaluate borrowers for all available loss mitigation options

and provide notice of decision; borrowers may appeal a denial of a loan modification so

long as the borrower’s complete loss mitigation application is received 90 days or more

before a scheduled foreclosure sale. Servicers are restricted from dual-tracking,

or

simultaneously evaluating a borrower for a loss mitigation option while preparing to

foreclose on the property.

17

Force-placed insurance is hazard insurance obtained by a servicer on behalf of the

owner or assignee of a mortgage loan that insures the property securing the loan.

18

A small servicer is a servicer that (1) services 5,000 or fewer mortgage loans for all of

which the servicer (or an affiliate) is the creditor or assignee; (2) is a Housing Finance

Agency (as defined in 24 C.F.R. § 266.5); or (3) is a nonprofit entity that services 5,000 or

fewer mortgage loans for all of which the servicer or an associated nonprofit entity is the

creditor. 12 C.F.R. § 1026.41(e)(4)(ii).

19

For the purposes of this report, regulatory capital requirements for U.S. banking

organizations related to Basel III capital standards establish more restrictive capital

definitions, higher risk-weighted assets, additional capital buffers, and higher requirements

for minimum capital ratios.

Page 11 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

strengthen banks’ transparency and disclosures.

20

In 2013, the U.S.

federal banking regulators adopted revised capital rules to implement

many aspects of the Basel III capital framework and the Dodd-Frank Act

that apply to banks, savings associations, and top-tier U.S. bank and

savings and loan holding companies. The revised capital rules

significantly changed the risk-based capital requirements for banks and

bank holding companies, applied capital requirements to certain savings

and loan companies, and introduced new leverage standards. These

requirements include provisions related to MSRs that will be fully phased

in by 2018, including:

• An amount equal to MSRs in excess of 10 percent of a bank’s

common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital is deducted from CET1 capital.

21

• An amount equal to the sum of MSRs, certain deferred tax assets

arising from temporary differences, and significant investment in the

capital of unconsolidated financial institutions in the form of common

stock in excess of 15 percent of CET1 capital is also deducted from

tier 1 capital.

• MSRs that have not been deducted from CET1 capital are added to

risk-weighted assets with a 100 percent risk-weight during the

transition period and will be subject to a 250 percent risk-weight once

the revised regulatory capital rule is fully phased-in.

22

In October 2015, NCUA also issued risk-based capital regulations.

23

However, unlike the banking regulators, which applied the MSR

provisions to all supervised banks, NCUA exempted credit unions with

20

See Bank For International Settlements, Basel III: A Global Regulatory Framework; and

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Basel III: International Framework for Liquidity

Risk Measurement, Standards and Monitoring (Basel, Switzerland: December 2010,

revised June 2011). The Basel framework was adopted in 2010 and revised in 2011 and

2013.

21

Common equity tier 1 capital includes in part common shares and retained earnings.

Tier 1 capital, in part is the sum of common equity tier 1 capital and additional tier 1 (which

can include non-cumulative perpetual preferred shares).

22

Prior to the new regulations taking effect, MSRs were included in tier 1 capital up to 100

percent of their remaining unamortized book value (net of any related valuation

allowances) reported on an institution’s balance sheet or 90 percent of their fair value,

whichever was lower. See 78 Fed. Reg. at 62069.

23

Risk-Based Capital, 80 Fed. Reg. 66626 (Oct. 29, 2015).

Page 12 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

$100 million or less in assets from its risk-based capital regulations.

24

Also, all MSRs have a 250 percent risk-weight under the NCUA rule.

According to NCUA’s final rule, the intent is to reduce the likelihood that a

relatively small number of high-risk credit unions will exhaust their capital

to cover their financial obligations and cause systemic losses under the

Federal Credit Union Act, as amended. Under the act, all federally

insured credit unions would have to pay through the National Credit Union

Share Insurance Fund.

25

NCUA’s risk-based capital rules will take effect

on January 1, 2019.

The CFPB and federal prudential regulators face several statutory

requirements in the rule development process, including the Regulatory

Flexibility Act (RFA), as amended by the Small Business Regulatory

Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (SBREFA), and the Paperwork

Reduction Act of 1995 (PRA). The RFA requires that federal agencies

consider the impact on small entities of certain regulations they issue and,

in some cases, alternatives to lessen the regulatory burden on small

entities.

26

The PRA requires agencies to minimize the paperwork burden

of their information collections and evaluate whether a proposed

information collection is necessary for the proper performance of the

functions of the agency.

27

In addition, when promulgating any rule that

would have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of

small entities, CFPB must convene a review panel to collect the advice

and recommendations of small-entity representatives about the potential

24

NCUA defined small institutions in its October 2015 regulatory capital rules as those

having $100 million or less in assets. See 80 Fed. Reg. 66626.

25

The National Credit Union Share Insurance Fund is the federal fund created by

Congress in 1970 to insure members’ deposits in federally insured credit unions. Federally

insured credit unions must maintain 1 percent of their deposits in the Share Insurance

Fund. The purpose of the Share Insurance Fund’s capitalization deposit is to cover losses

in the credit union system.

26

Regulatory Flexibility Act, Pub. L. No. 96-354, 94 Stat. 1164 (1980) (codified as

amended at 5 U.S.C. §§ 601-612). Under RFA, agencies, including financial regulators,

generally must prepare a regulatory flexibility analysis in connection with certain proposed

and final rules, unless the head of the issuing agency certifies that the proposed rule

would not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities.

27

Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995, Pub. L. No. 104-13, 109 Stat. 163 (codified as

amended at 44 U.S.C. §§ 3501-3520).

Rule Development and

Retrospective Review

Processes

Page 13 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

impacts of the proposed rule prior to publishing the required initial

regulatory flexibility analysis.

28

Both CFPB and the banking regulators also have requirements to

retrospectively review rules after rules are in effect. The Dodd-Frank Act

requires CFPB to review its significant rules within 5 years of such rules

taking effect.

29

CFPB is required to assess the effectiveness of the rules

in meeting the purposes and objectives of Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act

and the specific goals stated by the agency, which include ensuring that

consumers receive timely and understandable information to make

responsible decisions about financial transactions and that markets for

consumer financial products and services are fair, transparent, and

competitive. In addition, the federal banking regulators are required by the

Economic Growth and Regulatory Paperwork Reduction Act of 1996

(EGRPRA) to review their regulations at least every 10 years to identify

outdated, unnecessary, or unduly burdensome regulations, consider how

to reduce regulatory burden on insured depository institutions, and

eliminate unnecessary regulations as appropriate.

30

The report from the

first EGRPRA review was submitted to Congress in 2007 and the second

review is underway.

31

The banking regulators have publicly stated they

anticipate completing the current EGRPRA review by the end of 2016.

NCUA conducts a voluntary review of its regulations on the same cycle

and in a manner consistent with the EGRPRA review. Additionally, per

NCUA’s internal policies, NCUA conducts a review of all of its regulations

every 3 years and produces a non-binding memorandum for its board

with suggestions on rules that should be revised or streamlined.

28

See 5 U.S.C. § 609(b). We have work underway looking at CFPB’s Small Business

Review Panel process addressing the extent that CFPB considered small business inputs

into its rulemaking and plan to issue a report later in 2016.

29

12 U.S.C. § 5512(d). Within 5 years of the effective date of each significant rule, CFPB

must conduct an assessment of the rule and publish a report of its assessment.

30

Pub. L. No. 104-208, § 2222, 110 Stat. 3009, 3009-414 (codified at 12 U.S.C. § 3311).

31

Joint Report to Congress, July 31, 2007; Economic Growth and Regulatory Paperwork

Reduction Act, 72 Fed. Reg. 62036 (Nov. 1, 2007).

Page 14 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Many of the representatives from 16 community lenders—9 community

banks and 7 credit unions—that we interviewed noted that they have

maintained their customer-focused business models and continued to

service mortgages over the past 7 years. The total share of all mortgages

serviced by community banks and credit unions has increased since

2008. Some representatives of community banks and credit unions told

us that to manage their increased compliance costs of CFPB’s mortgage-

related rules required under the Dodd-Frank Act, they made adjustments

to certain business practices.

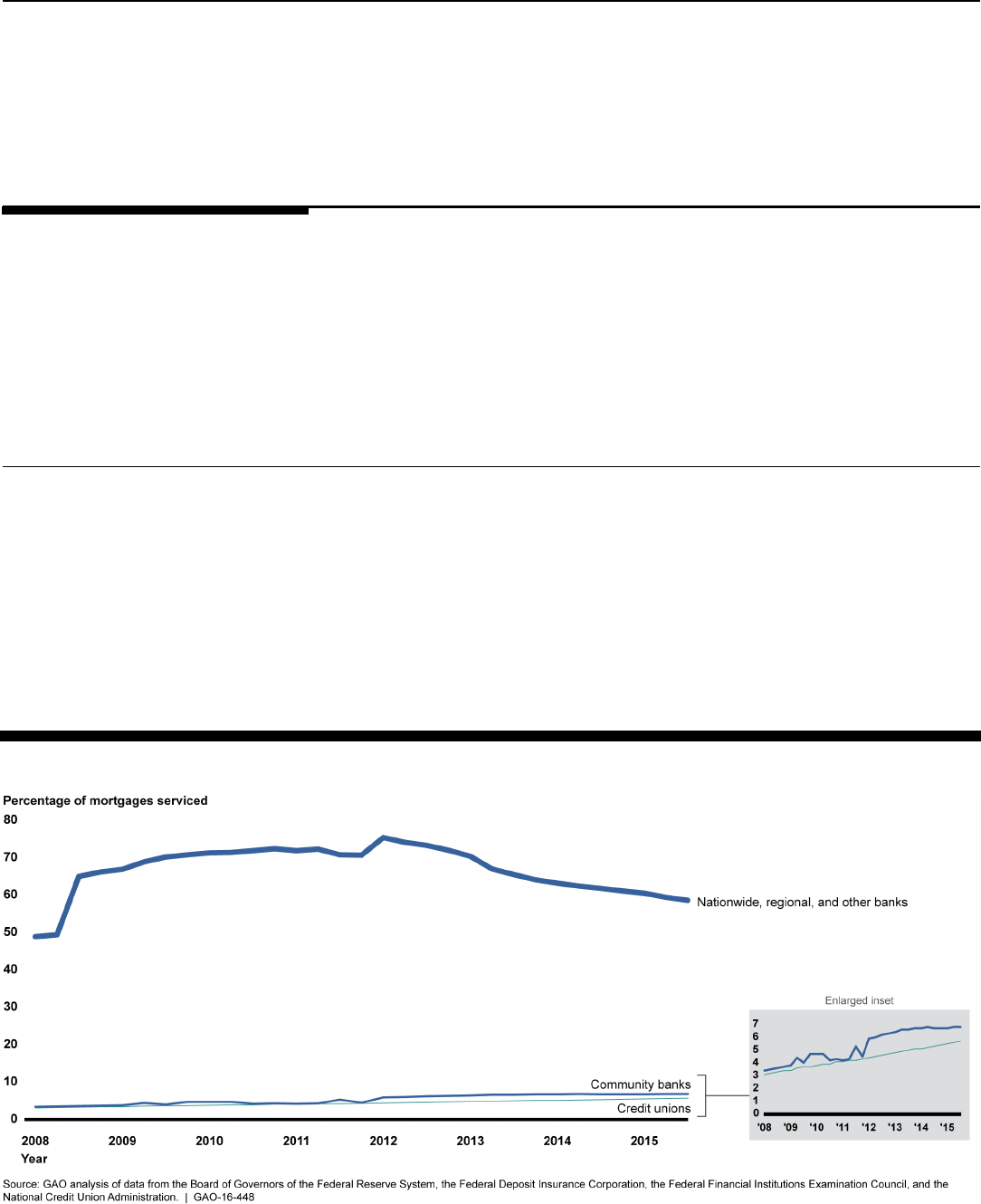

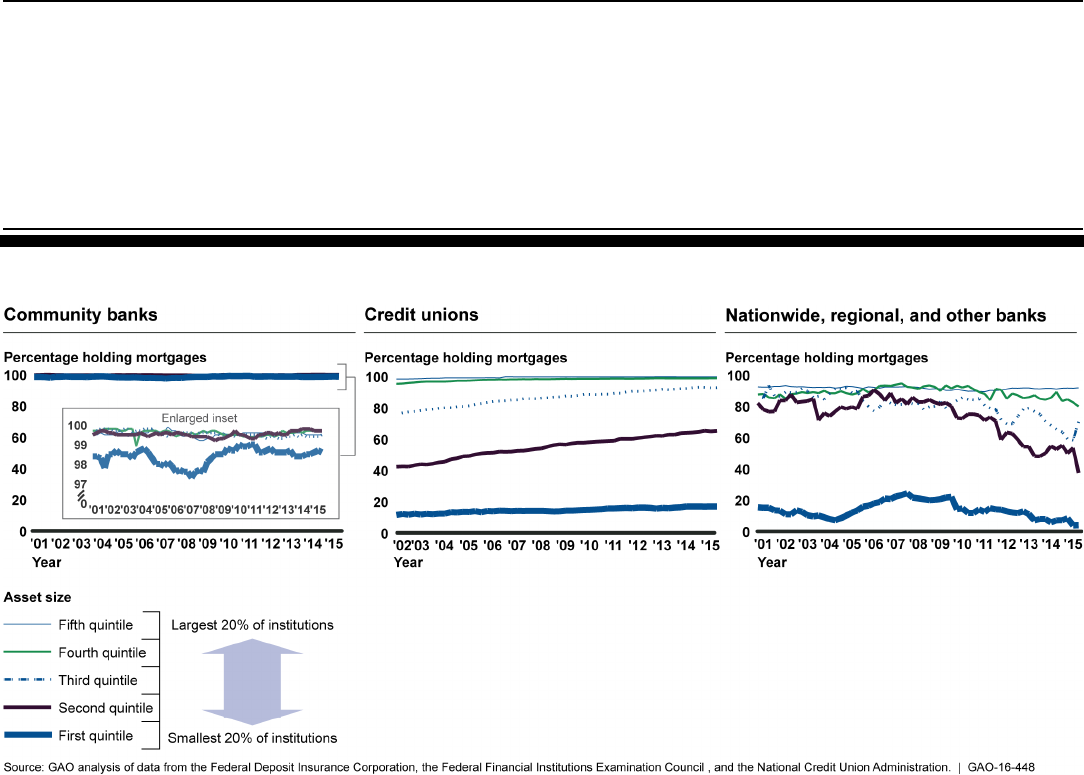

Based on our analysis, the total share of all U.S. residential mortgages

serviced by community lenders increased between 2008 and 2015.

Specifically, between the first quarter of 2008 and the third quarter of

2015, the share of mortgages serviced by community banks increased

from about 3.4 percent to about 6.8 percent, and the share serviced by

credit unions rose from about 3.1 percent to about 5.7 percent (see fig. 2).

The largest community banks and credit unions accounted for most of the

growth in the share of servicing by community banks and credit unions.

Over this period, the amount of residential mortgages outstanding fell

from about $11.3 trillion to about $10 trillion.

Figure 2: Estimated Share of Residential Mortgages Serviced by Community Banks, Credit Unions, and Nationwide, Regional,

and Other Banks, First Quarter 2008 through Third Quarter 2015 (percentage)

Community Lenders

Continue to Service

Mortgages as

Regulatory

Requirements

Increase

The Share of Mortgages

Serviced by Community

Lenders Has Increased

Since 2008

Page 15 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Note: We used data on banks and credit unions that filed Call Reports for the period from the first

quarter of 2008 through the third quarter of 2015. We identified community banks using Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation’s Historical Community Banking Reference Data. Banks that are not

community banks include nationwide and regional banks, internationally active banks, and specialty

banks. We estimated the share of outstanding residential mortgages a bank services by adding the

unpaid principal balance of residential mortgages held for investment, sale, or trading to the unpaid

principal balance of residential mortgages serviced for others and dividing the result by total

outstanding residential mortgages. We estimated the share of outstanding residential mortgages a

credit union services by adding the amount of residential mortgages on its balance sheet to the

amount of mortgages serviced for others and dividing the result by total outstanding residential

mortgages. These estimates may overstate the fraction of residential mortgages a bank or credit

union services because banks and credit unions may not service all of the residential mortgages on

their balance sheet.

Nationwide, regional, and other banks continue to service more than half

of the market. However, nonbank servicers—servicers that are not banks

or credit unions and also are not affiliates of banks or credit unions—have

increased their market presence. We previously estimated that the share

of U.S. residential mortgages serviced by nonbank servicers increased

from approximately 6.8 percent in the first quarter of 2012 to

approximately 24.2 percent in the second quarter of 2015.

32

At the same

time, the share serviced by the largest nationwide, regional, and other

banks decreased from about 75.4 percent to about 58.6 percent.

Many of the 16 community lenders we interviewed, which included

representatives from 9 community banks and 7 credit unions, and several

industry associations we spoke with told us that community banks and

credit unions serviced mortgages held in portfolio or held MSRs because

these activities generated income and allowed them to maintain strong

relationships with their customers. Some of these community lenders and

industry associations noted that holding mortgage loans in portfolio and

servicing these mortgage loans helped with overall profitability. For

example, the servicing revenue can offset a reduction in income from

originating loans when interest rates rise. Conversely, when interest rates

decline, borrowers are more likely to prepay or refinance their mortgage

loans, and servicing revenue may decline, while income from new

mortgage loan originations might increase. Also, representatives at these

institutions and two industry associations noted that servicing mortgages

allowed them to offer customers other revenue-producing products and

services. For example, representatives at one credit union told us that

32

See GAO-16-278.

Page 16 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

servicing mortgages provides it with the opportunity to develop borrowers

into full members with checking and savings accounts and car loans.

In addition to revenue, many community lenders noted that they and their

customers benefit from the close relationship maintained when these

institutions service mortgages. Representatives at several institutions we

interviewed emphasized that they were well positioned to work directly

with customers experiencing hardship to mitigate losses. For example,

representatives at one community bank told us that a customer who could

not make a mortgage payment could meet directly with a bank

representative to develop a payment plan. Customers of community

lenders whose mortgages are serviced by these institutions may

potentially also benefit by not being at risk of errors occurring during a

transfer of servicing, a process that has resulted in violations of consumer

protection laws and other regulations. As we noted in our March 2016

report on nonbank servicers, transfer errors can be especially harmful for

borrowers in delinquency or in the middle of loss mitigation proceedings.

33

Representatives at several industry associations and community lenders

that we interviewed for this report told us that community banks and credit

unions preferred to retain MSRs even if they sold the mortgages in the

secondary market because they were able to maintain close customer

contact should issues arise. A representative at one credit union told us

that it had sometimes needed to step in on behalf of customers to help

resolve issues, such as escrow errors, on mortgage loans they had sold

without retaining the MSRs.

33

See GAO-16-278.

Page 17 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Many community lenders that we interviewed noted that they continued to

service mortgages in their portfolio or to hold MSRs on loans sold to the

secondary market in spite of increased compliance costs of mortgage-

related requirements resulting from new rules instituted pursuant to the

Dodd-Frank Act.

34

These rules cover both origination and servicing of

mortgage loans. They include new requirements, such as minimum

underwriting standards for mortgage loan originators, disclosures to

consumers about their mortgage loan obligations, and loss mitigation

procedures. Some community lenders that we spoke with noted that they

had increased staff, updated their data systems, or hired third parties to

assist with compliance activities to meet CFPB’s servicing rules. Similarly,

in our December 2015 report on the effect of Dodd-Frank Act regulations

on community banks and credit unions, we noted that representatives at

community lenders we interviewed and CFPB stated that the compliance

costs incurred by community lenders to implement new disclosures

included costs of having to work with third-party vendors to update their

loan origination and documentation system software.

35

In an industry

survey of a nonprobability sample of banks in which the majority of

respondents had less than $1 billion in assets, over 80 percent of

respondents noted that increased personnel costs and staff time allocated

to compliance issues were the primary drivers of increased compliance

34

See Escrow Requirements Under the Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg.

4726 (Jan. 22, 2013); Ability-to-Repay and Qualified Mortgage Standards Under the Truth

in Lending Act (Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg. 6408 (Jan. 30, 2013); Mortgage Servicing

Rules Under the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (Regulation X), 78 Fed. Reg.

10696 (Feb. 14, 2013); Mortgage Servicing Rules Under the Truth in Lending Act

(Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg. 10902 (Feb. 14, 2013).

35

GAO, Dodd-Frank Regulations: Impacts on Community Banks, Credit Unions and

Systemically Important Institutions, GAO-16-169 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 30, 2015).

Many Community Lenders

Reported Spending More

in Response to Regulatory

Requirements and Some

Adjusted Business

Activities, Potentially

Affecting Customers

Page 18 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

costs. In addition, nearly 70 percent cited increased costs for third-party

vendor services.

36

Some representatives at community banks and credit unions we spoke

with commented that CFPB’s exemptions for small servicers and creditors

had been helpful to their businesses and customers. Several community

lenders noted that CFPB’s small servicer exemption, which excludes from

certain parts of CFPB’s mortgage servicing rules entities that service

5,000 or fewer mortgages, had been helpful in reducing some of their

compliance requirements.

37

For example, representatives at one

community bank noted that it was nearing the threshold and would have

to create additional processes and install software, but would not

intentionally limit its growth to qualify for the exemption. The community

bank representatives also noted that the bank was preparing for the

additional regulatory requirements by forming a mutual holding company

with another bank to achieve greater economies of scale.

Representatives at another bank noted that CFPB’s small creditor

exemption has allowed the bank to make loans that are considered

qualified mortgages based on the bank’s evaluation of a customer’s debt

36

American Bankers Association, 22nd Annual ABA Real Estate Survey Report

(Washington D.C.: 2015). The 22nd Real Estate Lending Survey had the participation of

182 banks. The web survey was sent out to over 3,000 banks and elicited response from

182 banks for a response rate of 6 percent overall. The data were collected from March 4,

2015, to April 17, 2015, and in most cases report calendar year or year-end results. In

other cases, data reflect current activities and expectations at the time of data collection.

Of the survey participants, 68 percent of respondents were commercial banks and 32

percent were savings institutions. About 77 percent of the participating institutions had

assets of less than $1 billion. Because the survey relies on a nonprobability sample, the

results cannot be used to make generalizations about all commercial banks and thrifts.

37

According to CFPB documentation, this definition covers substantially all of the

community banks and credit unions that are involved in servicing mortgages. Although the

rules exempt small servicers from certain provisions, they require, for example, all

servicers to respond to written notices of errors received from borrowers, and with respect

to loss mitigation, a small servicer is required to comply with two requirements: (1) a small

servicer may not make the first notice or filing required for a foreclosure process unless a

borrower is more than 120 days delinquent, and (2) a small servicer may not proceed to

foreclosure judgment or order of sale, or conduct a foreclosure sale, if a borrower is

performing pursuant to the terms of a loss mitigation agreement.

Page 19 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

and income even though the customer did not meet the specific debt-to-

income ratio required under CFPB’s rule.

38

Some community lenders noted that to manage the increased compliance

costs, they made adjustments to both loan origination and servicing

business practices that could affect their customers’ costs or choices.

These adjustments included raising fees and interest rates and changing

product offerings. Representatives at one credit union noted that while it

had absorbed additional regulatory compliance costs into its general

overhead expenses, it had to raise additional revenue to cover these

additional expenses, such as increasing underwriting fees for mortgage

applications. Several institutions noted that they no longer offered

customers certain products because offering them would require

additional compliance testing to meet regulatory requirements. For

example, a representative at one community bank said that it no longer

offers home equity lines of credit to its customers due to costs associated

with complying with CFPB’s rules related to increased disclosures to the

customer.

39

Representatives at another community bank said it no longer

offered bridge loans—short-term loans typically used when a consumer is

38

Under CFPB’s Ability-to-Repay and Qualified Mortgage Standards Under the Truth in

Lending Act (Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg. 6408 (Jan. 30, 2013) (ATR/QM rule) rule, which,

as amended, became effective on January 10, 2014, generally, lenders making qualified

mortgages must make a good-faith effort to determine that the borrower has the ability to

repay the mortgage loan by documenting a borrower’s income, assets, employment, credit

history, and monthly expenses. The ATR/QM rule sets out several categories of qualified

mortgage: general, temporary, and small creditor. Although small creditors must consider

and verify the borrower’s debt-to-income ratio, these loans are not subject to a specific

debt-to-income ratio, such as the 43 percent or less determination under the general

category. These loans must be made by small creditors and generally held in portfolio for

at least 3 years. Small creditors are generally creditors that together with their affiliates

have less than $2 billion in assets (adjusted annually for inflation) and originated no more

than 2,000 first-lien mortgage loans in the preceding year. Ability-to-Repay and Qualified

Mortgage Standards Under the Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z), 78 Fed. Reg. 35430,

35503 (June 12, 2013) and 80 Fed. Reg. 59944, 59968 (Oct. 2, 2015).

39

A home equity line of credit is a form of revolving credit in which a borrower’s home

serves as collateral. Many lenders set the credit limit on a home equity line by taking a

percentage of the home’s appraised value and subtracting from that the balance owed on

the existing mortgage.

Page 20 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

buying a new home before selling the consumer’s existing home—to its

customers.

40

Other community lenders told us that despite increased mortgage-related

regulatory requirements under the Dodd-Frank Act, they ensured their

customers’ access to credit and maintained close customer contact.

According to an FDIC report, community banks are often considered to be

“relationship” bankers and tend to base credit decisions on local

knowledge and long-term relationships with customers.

41

Representatives

at some community banks and credit unions we spoke with noted that

because of their familiarity with customers, they were retaining mortgage

loans in their portfolios that no longer met tighter credit restrictions in the

secondary market under the Dodd-Frank Act.

42

They explained that

holding these mortgage loans allowed them more flexibility in their

underwriting of these mortgage loans, which facilitated greater access to

credit for their customers. Another community lender told us that although

regulatory compliance costs necessitated having to outsource mortgage

servicing to a third-party servicer, a credit union service organization, for

its mortgage servicing activities, the credit union still speaks directly with

40

Usually secured by the existing home, a bridge loan provides financing for the new

home (often in the form of the down payment) or mortgage payment assistance until the

consumer can sell the existing home and secure permanent financing. Bridge loans

normally carry higher interest rates, points, and fees than conventional mortgages,

regardless of the consumer’s creditworthiness.

41

Community banks tend to focus on providing essential banking services in their local

communities, and are often considered to be “relationship” bankers. This means that they

have specialized knowledge of their local community and their customers. Because of this

expertise, community banks tend to base credit decisions on local knowledge and

nonstandard data obtained through long-term relationships and are less likely to rely on

the models-based underwriting used by larger banks. See Benjamin R. Backup and

Richard A. Brown, “Community Banks Remain Resilient Amid Industry Consolidation,”

FDIC Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 2, 2014 accessed on March 29, 2016 at

https://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/quarterly/2014_vol8_2/article.pdf.

42

The enterprises generally purchase conforming loans, which are mortgage loans that

meet certain criteria for size, features, and underwriting standards. The enterprises’

underwriting includes assessments of measures of the credit risk of purchasing

mortgages, such as borrower credit scores and debt-to-income ratios. For example, the

enterprises have a debt-to-income ceiling of 45 percent.

Page 21 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

borrowers who typically prefer to communicate with the mortgage loan

officer because they have a pre-existing relationship.

43

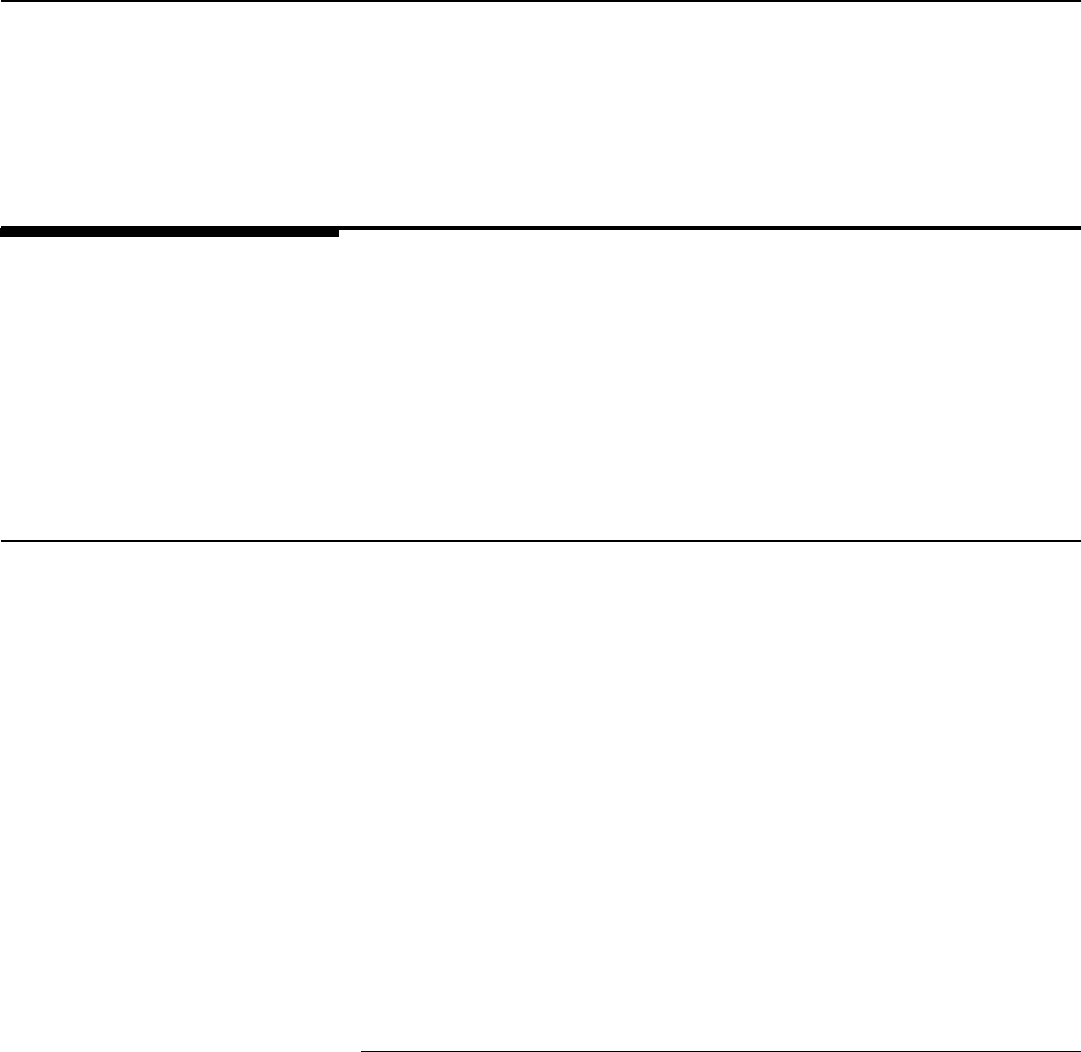

Although new regulations related to mortgage lending and servicing may

increase compliance costs for community banks, our analysis suggests

that these lenders generally appear to be participating in residential

mortgage lending much as they have in the past. We found that for every

quarter from the first quarter of 2001 through the third quarter of 2015,

over 97 percent of community banks of all sizes had residential

mortgages on their balance sheets (see fig. 3).

44

For most community

banks with residential mortgages, these mortgages continued to average

at least 10 percent of assets in their portfolio. Over the period from the

first quarter of 2001 through the third quarter of 2015, median residential

mortgages were 11 percent to 15 percent of assets for the smallest

community banks and 16 percent to 20 percent of assets for larger

community banks.

45

In addition, median residential mortgages as a

percentage of assets have generally increased in the past couple of years

for community banks of all sizes. Thus, community banks generally do not

appear to be shifting their portfolios away from mortgage lending.

43

Credit union service organizations are entities that are owned by federally chartered or

federally insured state-chartered credit unions and that are engaged primarily in providing

products or services to credit unions or credit union members. See 12 C.F.R. § 712.1(d).

44

We used total assets to measure size and we divided all banks—community banks and

nationwide, regional, and other banks—into five equal-sized groups, or quintiles, based on

their size each quarter. The first quintile contained the smallest banks, the second quintile

contained the next largest banks, and so on through the fifth quintile, which contained the

largest banks. In the third quarter of 2015, the largest bank in the first quintile had assets

of about $73.9 million, the largest bank in the second quintile had assets of about $138.5

million, the largest bank in the third quintile had assets of about $250.6 million, the largest

bank in the fourth quintile had assets of about $545.1 million, and the largest bank in the

fifth quintile had assets of about $2 trillion. There were 1,187, 1,248, 1,243, 1,234, and

899 community banks in the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth quintiles, respectively.

45

We calculated residential mortgages as a percentage of assets for every bank and then

calculated the median value of residential mortgages as a percentage of assets for

community banks in each size group, where the median value is the middle or 50

th

percentile value when the values are ordered from smallest to largest.

Community Lenders Are

Continuing Residential

Mortgage Lending and

Have Not Changed Their

Customer-Focused

Business Model

Page 22 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Figure 3: Percentage of Community Banks, Credit Unions, and Nationwide, Regional, and Other Banks with Residential

Mortgages on their Balance Sheets by Size, First Quarter 2001 through Third Quarter 2015 (percentage)

Note: We used data on banks that filed Call Reports for the period from the first quarter of 2001

through the third quarter of 2015 and on credit unions that filed Call Reports from the second quarter

of 2002 through the third quarter of 2015. We assigned banks to groups each quarter using quintiles

based on the distribution of their total assets, where the first quintile contains the smallest 20 percent

of banks, the second group contains the next largest 20 percent of banks, and so on through the fifth

quintile, which contains the largest 20 percent of banks. We identified community banks using

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s Historical Community Banking Reference Data. Banks that

are not community banks include nationwide and regional banks, internationally active banks, and

specialty banks. We also assigned credit unions to groups each quarter using quintiles based on the

distribution of their total assets. Banks that hold residential mortgages are those that hold residential

mortgages for investment, sale, or trading. Credit unions that hold residential mortgages are those

that hold first lien residential mortgages or any other real estate loan or line of credit, which typically

includes second mortgages, and home equity lines of credit, but may also include some member

business loans secured by subordinate real estate liens. Thus, our calculations may overstate the

fraction of credit unions with residential mortgages.

Similarly, the largest nationwide, regional, and other banks (those in the

fifth quintile) generally do not appear to be changing the extent to which

they participate in mortgage lending. Over the period from the first quarter

of 2001 through the third quarter of 2015, over 89 percent of the largest

nationwide, regional, and other banks had residential mortgages on their

Page 23 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

balance sheets.

46

Among those institutions that had residential

mortgages, median residential mortgages were between 13 percent and

16 percent of their assets. In contrast, the percentage of smaller

nationwide, regional, and other banks (those in the first, second, third,

and fourth quintiles) with residential mortgages on their balance sheet has

generally decreased over the period.

Finally, our analysis suggests that credit unions are generally participating

in residential mortgage lending at least as much as they have in the past.

Throughout the period from the first quarter of 2002 through the third

quarter of 2015, larger credit unions were more likely to have residential

mortgages than smaller credit unions.

47

However, for credit unions of all

sizes, the percentage with residential mortgages increased. Among credit

unions with residential mortgages, larger credit unions typically had more

residential mortgages as a percentage of assets than small credit unions.

Median residential mortgages ranged from 6 percent to 10 percent of

assets for the smallest credit unions, and up to 24 percent to 35 percent

of assets for the largest credit unions. While median residential

mortgages as a percentage of assets have decreased for the smallest

credit unions in recent quarters, they have remained constant or

increased in recent quarters for larger credit unions. Like community

banks, credit unions generally do not appear to be shifting their portfolios

away from mortgage lending, with the possible exception of the smallest

institutions.

46

There were 77, 16, 20, 30, and 364 nationwide, regional, and other banks in the first,

second, third, fourth, and fifth quintiles, respectively.

47

As we did with banks, we used total assets to measure size and we divided credit unions

into quintiles based on their size each quarter. In the third quarter of 2015, the largest

credit union in the first quintile had assets of about $5.1 million, the largest credit union in

the second quintile had assets of about $16.3 million, the largest credit union in the third

quintile had assets of about $42.3 million, the largest credit union in the fourth quintile had

assets of about $139.3 million, and the largest credit union in the fifth quintile had assets

of about $72 billion. There were 1,244 credit unions in the first quintile and 1,243 credit

unions in the second, third, fourth, and fifth quintiles.

Page 24 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

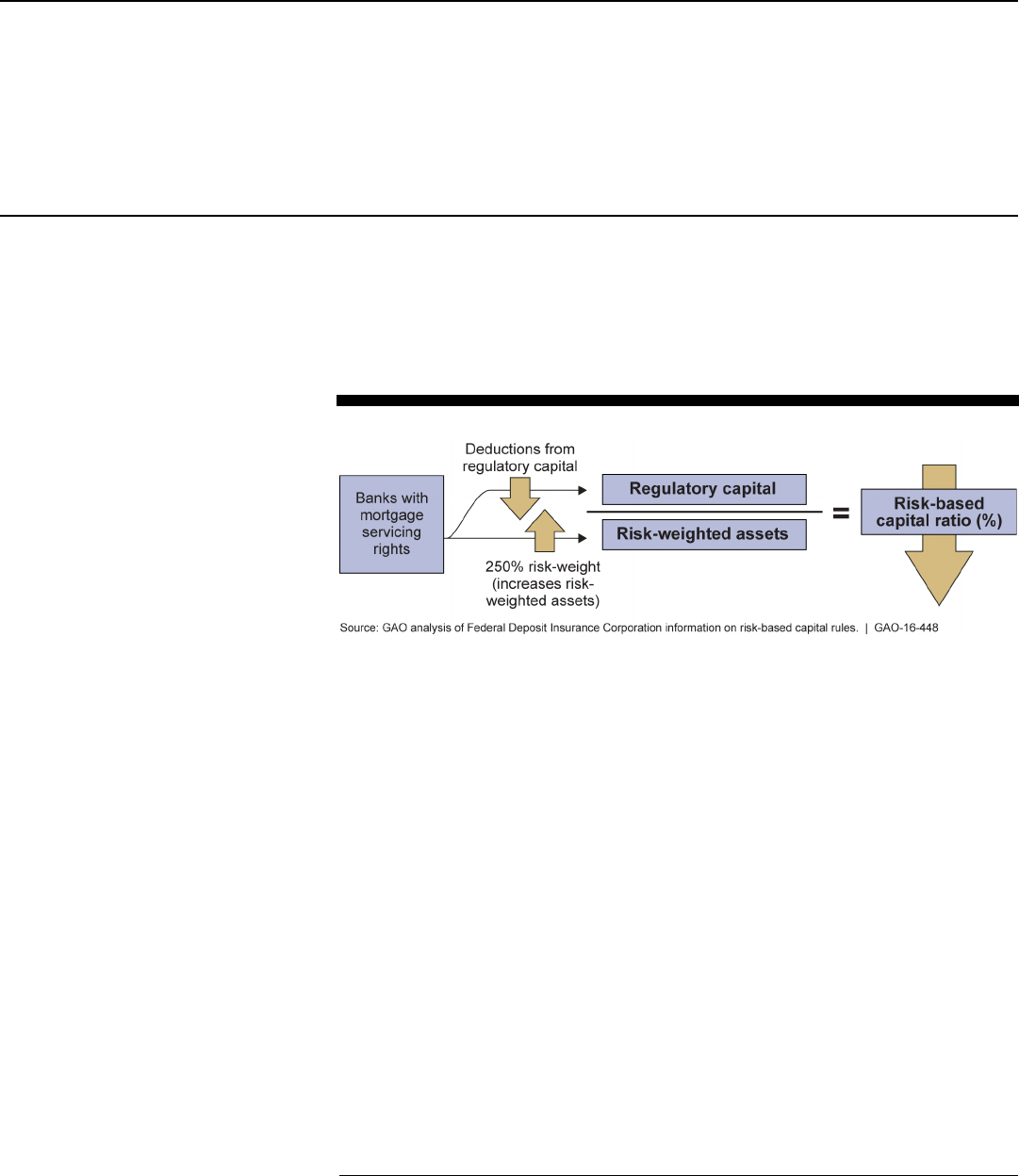

Our analysis suggests that the capital treatment of MSRs would not likely

have a material effect on most community banks because they generally

did not have large concentrations of MSRs. Most community banks we

interviewed confirmed that they did not need to make changes to their

capital because of these rules, but those with large concentrations of

MSRs were considering changes to their capital. We also do not expect

the capital treatment of MSRs to affect most applicable credit unions

based on our analysis and discussions with NCUA and credit unions.

Regardless of type or size, banks with large concentrations of MSRs may

need to raise capital as a result of the new risk-based capital treatment of

MSRs, but our analysis and most community banks we spoke with

confirmed that these new rules were currently not an issue for them.

48

As

stated earlier, new banking requirements being phased in by January 1,

2018, include requiring any amount of MSRs above 10 percent of a firm’s

common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital to be deducted from CET1 capital. In

addition, MSRs, adjusted for amounts deducted from CET1 capital, are

currently assigned a 100 percent risk weighting, which means that every

$1 in these MSRs adds $1 to risk-weighted assets. When the new

requirements are fully phased in, any MSRs not deducted from CET1

capital will be assigned a 250 percent risk weighting, which means every

$1 in these MSRs will add $2.50 to risk-weighted assets (see fig. 4).

49

Some banks may have to increase CET1 capital to ensure that their ratios

of CET1 capital to risk-weighted assets remain above the required

48

Prudential regulators’ capital rules implementing Basel III include provisions related to

MSRs that are to be fully phased in by 2018 and that will affect banks’ regulatory capital

as well as their risk-weighted assets. For a more complete discussion of Basel III, see

GAO, Bank Capital Reforms: Initial Effects of Basel III on Capital, Credit, and International

Competitiveness, GAO-15-67 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 20, 2014).

49

Any amount of MSRs, certain deferred tax assets arising from temporary differences,

and significant investments in the capital of unconsolidated financial institutions in the form

of common stock (collectively, “threshold items”) above 15 percent of a firm’s CET1 capital

must be deducted from CET1 capital. Starting January 1, 2018, any amount of the

threshold items that is not deducted from CET1 capital will be risk weighted at 250

percent.

New Capital

Treatment of

Mortgage Servicing

Rights Likely Will Not

Affect Many

Community Banks

and Credit Unions

Most Community Banks

and Credit Unions Hold

Limited MSRs and Have

Sufficient Capital to Cover

Them

Page 25 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

minimum.

50

Those banks that need to raise capital could face increased

funding costs that they could, in turn, pass on to consumers through

increased cost or reduced availability of credit. However, most community

banks subject to the capital requirements we spoke with said that they did

not expect to need to make changes to their capital because they did not

hold large concentrations of MSRs and had sufficient capital.

Figure 4: Mortgage Servicing Rights and Risk-Based Capital Ratios

Note: Mortgage servicing rights (MSRs) up to 10 percent of common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital will

receive a 250 percent risk weight when the new risk-based capital requirements are fully phased in.

The remaining MSRs are not included in risk-weighted assets.

Based on our analysis, the capital treatment of MSRs likely would not

have a material effect on most community banks because they generally

did not have large concentrations of MSRs. Data on banks’ holdings of

MSRs for the period from the first quarter of 2001 through the third

quarter of 2015 showed that larger community banks were more likely to

have MSRs than smaller community banks and that more community

banks of all sizes were holding MSRs in 2015 than in 2001. However,

these assets were typically a small fraction of total assets. Specifically,

the median value of MSRs as a percentage of total assets has remained

at less than 1 percent in each quarter since the first quarter of 2001.

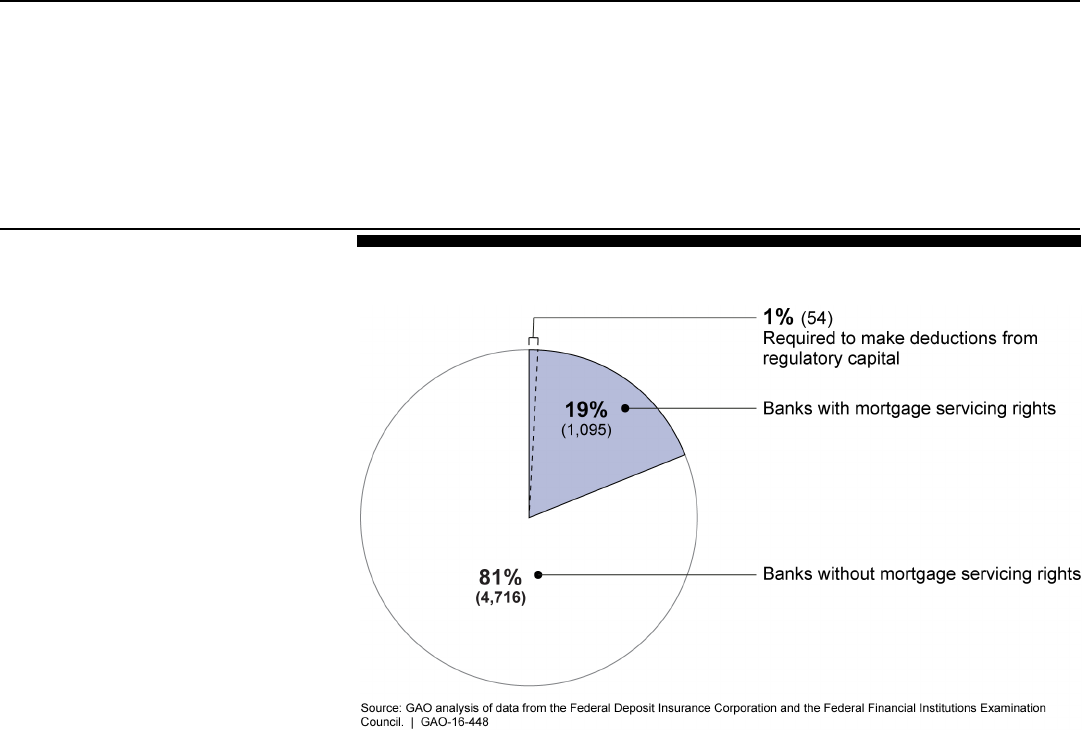

Additionally, our analysis showed that about 19 percent of community

banks held MSRs and about 1 percent made MSR-related deductions

from capital due to the amount of these assets they held as of the third

quarter of 2015 (see fig. 5).

50

Two banking regulators noted that a bank’s capital is a function of its overall risk profile

and not just the MSR amount.

Page 26 GAO-16-448 Mortgage Servicing

Figure 5: Community Banks’ Capital Treatment of Mortgage Servicing Rights,

2015Q3

Note: Estimates of the percentage of community banks holding mortgage servicing rights (MSR) and

the percentage making deductions from their capital because of their MSR holdings are based on Call

Report data from the third quarter of 2015.

Most community banks we interviewed confirmed that they did not need

to make changes to their capital because of these rules, but those with

large concentrations of MSRs were considering changes to their capital.

Institutions with large concentrations of MSRs may choose to raise

additional capital or sell MSRs to meet required minimum capital

amounts, depending on banks’ holdings of other types of assets. Most

representatives of community banks said that regulatory changes to the

capital treatment of MSRs did not require them to sell MSRs or raise