Report on

Nonbank Mortgage

Servicing

2024

| I

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................1

1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................3

Box A: Overview of the Regulatory Framework for Nonbank Mortgage

Companies and the Role of Key Market Participants ........................................................5

2 Mortgage Servicers ..............................................................................................................................7

2.1 Servicer Responsibilities .....................................................................................................7

2.2 Servicer Business Models .................................................................................................8

3 The Growth in Agency Securitization and Nonbank Mortgage Companies ...................... 13

3.1 Increased Government and Enterprise Backing of the Mortgage Market ........... 13

3.2 Increased NMC Presence in the Mortgage Market .................................................. 15

3.2.1 Increased NMC Share of Mortgage Originations ....................................... 17

3.2.2 Increased NMC Share as Agency Counterparties .................................... 18

3.3 Increased Aggregate Mortgage Market Exposure to Agency

Securitization and NMCs ........................................................................................................ 20

4 Strengths of Nonbank Mortgage Companies ............................................................................ 21

5 Vulnerabilities of Nonbank Mortgage Companies ................................................................... 24

5.1 Vulnerability to Macroeconomic Shocks ......................................................................24

5.2 Risks Associated with NMC Assets ..............................................................................28

5.3 Liquidity Risk ......................................................................................................................29

5.3.1 Liquidity Risk from Financing Sources .........................................................29

5.3.2 Liquidity Risk from Servicing Obligations and

Repurchase Requests ................................................................................................ 32

5.4 Leverage .............................................................................................................................. 34

5.5 Operational Risk ................................................................................................................ 34

5.6 Interconnections ............................................................................................................... 35

6 Transmission Channels .................................................................................................................... 36

6.1 Critical Functions and Services ...................................................................................... 36

6.1.1 Servicer Financial Stress ...................................................................................36

6.1.2 Servicing Transfers ............................................................................................ 37

6.1.3 NMC Bankruptcy ................................................................................................ 38

6.1.4 Mortgage Origination Disruptions ................................................................. 39

6.2 Exposures ........................................................................................................................... 39

6.3 Contagion and Asset Liquidation .................................................................................40

7 Existing Authorities, Recent Actions, and Council Recommendations ................................. 41

7.1 Promoting Safe and Sound Operations ......................................................................... 41

Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 43

II |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

7.2 Addressing Liquidity Pressures in the Event of Stress ............................................ 44

Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 46

7.3 Ensuring Continuity of Servicing Operations ............................................................46

Recommendation ....................................................................................................... 47

Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................................... 49

List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 51

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | 1

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

Executive Summary

e statutory duties of the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC or Council)

1

include

monitoring the nancial services marketplace to identify potential threats to U.S. nancial

stability; identifying gaps in regulation that could pose risks to U.S. nancial stability; and making

recommendations to enhance the integrity, eciency, competitiveness, and stability of U.S.

nancial markets. In recent years, the Council has identied potential risks to our nancial system

arising from the vulnerabilities of nonbank mortgage servicers.

2

Nonbank mortgage companies (NMCs) carry out critical servicing functions for the residential

mortgage market and originate and service the majority of U.S. residential mortgages.

3

However,

NMCs have key vulnerabilities that can impair their ability to carry out these functions. NMCs’

vulnerabilities can amplify shocks to the mortgage market and thereby pose risks to nancial

stability.

e NMC share of mortgage origination and servicing has increased considerably since the

2007-09 nancial crisis. At the same time, there has also been an increasing share of mortgages

outstanding funded by securitizations guaranteed by the Federal National Mortgage Association

(Fannie Mae), the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), and the Government

National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae), collectively referred to as the “Agencies.” e federal

government provides nancial support to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in conservatorship and

explicitly guarantees Ginnie Mae securitizations. As NMCs have become increasingly important

servicers for the Agencies, the exposure of the federal government and the mortgage market to the

vulnerabilities of these companies has increased signicantly.

NMCs bring some strengths to the mortgage market. NMCs are generally quick to adapt their

operations as market conditions change. Some NMCs have been early adopters of technological

developments and other practices that have helped make mortgage origination and servicing more

ecient and consumer friendly in certain instances. NMCs are also key mortgage originators and

servicers for groups that have historically been underserved by the mortgage market.

However, because NMCs focus almost exclusively on mortgage-related products and services,

shocks to the mortgage market can lead to signicant deterioration in NMC income, balance

sheets, and access to credit simultaneously. NMCs rely heavily on nancing that can be repriced or

canceled by the lender at times when the NMC is under nancial stress. In addition to these liquidity

1 e Council is composed of ten voting members who head the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the Board of

Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve Board), the Oce of the Comptroller of the Currency

(OCC), the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the Federal

Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), and the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), and an independent

member with insurance expertise, plus ve non-voting members. Two of the nonvoting members are the directors of

the Oce of Financial Research (OFR) and the Federal Insurance Oce (FIO). e other three non-voting members

are a state insurance commissioner, a state banking supervisor, and a state securities commissioner designated by

their peers.

2 See Financial Stability Oversight Council. Annual Report. Washington, D.C.: Council, December 14, 2023. https://

home.treasury.gov/system/les/261/FSOC2023AnnualReport.pdf; and Financial Stability Oversight Council. Annual

Report. Washington, D.C.: Council, May 7, 2014. https://home.treasury.gov/system/les/261/FSOC-2014-Annual-

Report.pdf. See also Ginnie Mae. “An Era of Strategic Transformation.” Washington, D.C.: Ginnie Mae, September

2014. https://www.ginniemae.gov/newsroom/Documents/ginniemae_an_era_of_transformation.pdf.

3 is report focuses on one- to four-family property forward residential mortgages.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY2 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

and leverage vulnerabilities, NMCs face signicant operational risk because mortgage servicing is

complex and encompasses third-party and cybersecurity risks.

If these vulnerabilities result in NMCs being unable to carry out their critical functions at times

of market stress, borrowers could experience disruption and harm, the Agencies and other credit

guarantors could experience large losses, and there could be payment delays to stakeholders such as

insurance companies and local governments. Since NMCs have similar business models and share

nancing sources and subservicing providers, distress in the NMC sector may be widespread during

times of strain. e federal government has only limited tools to mitigate and manage these risks.

State regulators and federal agencies have taken steps to mitigate the risks posed by NMCs in recent

years, but the Council is concerned that the combination of various state requirements and limited

federal authorities to impose additional requirements does not adequately and holistically address

the risks described in this report. e Council supports recent actions and continued eorts by state

regulators and federal agencies to act within their authorities to promote safe and sound operations,

address liquidity pressures in the event of stress, and ensure the continuity of servicing operations.

e Council also encourages Congress to promote greater stability in the mortgage market and the

economy by addressing the identied risks. e Council will continue to monitor the evolution of

these risks and may take or recommend additional actions to mitigate such risks in accordance

with the Analytic Framework for Financial Stability Risk Identication, Assessment, and Response

(Analytic Framework), if needed.

1 INTRODUCTION | 3

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

1 Introduction

In 2022, NMCs originated approximately two-thirds of mortgages in the United States and owned

the servicing rights on 54 percent of mortgage balances.

4

NMC market share has risen signicantly

since the low it reached in 2008, when NMCs originated only 39 percent of mortgages and owned

the servicing rights on only 4 percent of mortgage balances. As indicated by their large market

share, NMCs perform critical functions for the mortgage market through their operational capacity

in loan origination and servicing. Although some NMCs specialize only in origination or servicing,

larger NMCs tend to focus on both. While this report explores the vulnerabilities of both these

interdependent activities, the Council’s primary concern for this report is the ability of NMCs to

carry out critical mortgage servicing responsibilities in times of stress.

NMCs bring strengths to the mortgage market. ey are key mortgage originators and servicers for

groups that are historically underserved by the mortgage market. NMCs can specialize in certain

products or operations. For example, some NMCs developed technology platforms that enabled

them to originate mortgages quicker than their competitors. Others expanded into specialty default

servicing for nonperforming loans and loss mitigation.

NMCs are also subject to signicant risks and have key vulnerabilities. Since NMCs only oer

mortgage-related products and services, their protability uctuates with changes in mortgage

demand and mortgage defaults—much more so than for nancial institutions with diversied lines

of business. Likewise, NMCs’ high exposure to mortgage risk means they can experience adverse

eects on their income, balance sheets, and access to credit simultaneously. NMCs’ reliance on debt

that can be repriced, reduced, or canceled at times of stress can lead to signicant liquidity risk,

which is exacerbated by high leverage carried by some NMCs. As a result of these liquidity risks, high

leverage, and other vulnerabilities, rating agencies typically assign speculative-grade credit ratings

to NMCs’ debt obligations. Finally, vulnerabilities are similar across NMCs. As a result, certain

macroeconomic scenarios may lead to stress across the entire sector.

When these vulnerabilities compromise NMCs’ ability to carry out their critical functions, borrowers

may suer from disruptions in the servicing of their mortgages and credit guarantors and insurers

may experience sizeable losses. Commonalities in NMC vulnerabilities and their shared funding

providers and subservicers could lead to contagion. Financial distress at NMCs that is suciently

severe and widespread might lead to a reduction in servicing capacity and in the availability of

mortgage credit.

4 Origination shares for 2008 and 2022 are from data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) by

the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (“HMDA data”). Except as noted, HMDA statistics in this

report for the years 2004 and later are based on closed-end, rst-lien purchase mortgages collateralized by owner-

occupied, site-built one-to-four family properties. Prior to 2004, HMDA data did not include information on lien

status, number of units, or construction type. Data from 2003 and earlier are therefore for all closed-end purchase

mortgages collateralized by owner-occupied properties. HMDA data cover about 90 percent of the residential

mortgage market. Bhutta, Neil, Steven Laufer, and Daniel R. Ringo. “Residential Mortgage Lending in 2016: Evidence

from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Data.” Federal Reserve Bulletin, 103: 1, Washington, D.C.: Federal Reserve

Board, November 2017. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/les/2016_hmda.pdf.

Servicing share is for the fourth quarter of 2022 and is from Inside Mortgage Finance. “Nonbanks and Second-Tier

Servicers Gain Share in 4Q23.” Inside Mortgage Finance (February 2, 2024). It is based on the 50 largest servicers.

Servicing share for 2008 is from Figure 10b in Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC, NCUA. “Report to the Congress

on the Eect of Capital Rules on Mortgage Servicing Assets.” Washington, D.C.: Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC,

NCUA, June 2016. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/other-reports/les/eect-capital-rules-mortgage-

servicing-assets-201606.pdf.

1 INTRODUCTION4 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

In recent years, the federal government has become increasingly exposed to concentration risks

and potential losses stemming from the fragilities of NMCs. e federal government supports the

availability of U.S. mortgages through insurance and direct guarantees of loans nanced through

Ginnie Mae securitizations and through its nancial support for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

(the Enterprises) in conservatorship.

5

e Agencies depend on private rms to service loans, and

those rms are primarily NMCs. From January 2014 to January 2024, the share of Agency servicing

handled by NMCs increased from 35 percent to 66 percent. In total, NMCs serviced approximately

$6 trillion for the Agencies in 2023 and six NMCs serviced Agency portfolios that were each in excess

of $450 billion.

6

With servicing so concentrated in NMCs, state and federal regulators and the Agencies may have

diculty enforcing borrower protections and minimizing taxpayer losses in the event that a large

NMC or several mid-sized NMCs fail. Large servicing portfolios cannot be transferred quickly

because the transfer process is inherently lengthy and complicated. In addition, it might be dicult

to identify another servicer to take over the portfolio. e similarity of NMC business models means

that other NMCs might also have the same issues and be unable to acquire new portfolios. While the

Agencies have backup servicing capacity, that capacity could quickly be exhausted in the event of a

large NMC failure or multiple failures.

As a result, any large nonbank mortgage servicer that failed might need to remain operational while

in bankruptcy for some time to maintain critical mortgage servicing functions. While this could be

done in an adequately nanced bankruptcy under the reorganization chapter of the Bankruptcy

Code (Chapter 11), absent such funding or sucient liquidity just before bankruptcy, the NMC

would likely only be able to sustain operations for a limited period of time. Moreover, because the

risk proles of NMCs are so similar, it is possible that multiple NMCs with common creditors could

be in bankruptcy simultaneously. is situation could create signicant challenges and potential

disruptions to borrowers and the Agencies, as each bankruptcy is oriented toward resolving a single

company. As described in this report, the federal government has only limited tools to mitigate and

manage the risks and ensure that borrowers and taxpayers are suciently protected.

Depository institutions (referred to as “banks” in this report for simplicity) are not immune to

nancial strains and changes in macroeconomic conditions, and federal and state regulators

have identied banks’ servicing errors in both loss mitigation and foreclosure actions. However,

federal and state banking regulators have supervisory and regulatory tools to promote the safety

and soundness of the banking system. Federal and state banking regulators also utilize risk-based

supervision to focus on mortgage servicing risks and safeguard consumer protections. Further,

federal banking agencies have resolution tools to enable core operations, such as mortgage

servicing by a bank, to continue in the event of a bank failure. e federal government’s regulatory,

supervisory, and resolution authorities are more limited with respect to NMCs, although states have

broad authorities.

e Council has raised concerns about the vulnerabilities of NMCs for several years. ose concerns

have become more acute because of the increasing federal government exposure to NMCs and

because the NMCs that originate mortgage loans are currently under nancial strain due to the low

5 See Section 3.1 for further discussion on nancial support provided by the government to Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac.

6 Calculation for total nonbank mortgage servicing balances is based on data from Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, Financial Accounts of the United States. Washington D.C. at https://www.federalreserve.gov/

releases/z1/ and from eMBS at https://www.embs.com/. Calculation of NMCs with Agency portfolios in excess of

$450 billion is from Inside Mortgage Finance at https://www.insidemortgagenance.com/.

1 INTRODUCTION | 5

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

volume of mortgage originations since 2022. Vulnerabilities in mortgage origination can bleed into

servicing operations at rms that both originate and service mortgages.

is report begins with an overview of mortgage servicing. It then describes the mortgage market

shifts toward NMCs, the increased federal government exposure to these rms, NMCs’ strengths

and vulnerabilities, and the transmission channels that could lead to NMC vulnerabilities

amplifying the eect of a shock to nancial stability in a stress scenario. e report concludes with

recommendations that could promote greater stability in the mortgage market.

Box A: Overview of the Regulatory Framework for Nonbank Mortgage

Companies and the Role of Key Market Participants

A combinat ion of state financial regulators, federal agencies, and market participants play dierent roles in

overseeing NMCs. State financial regulators have broad authorities, including prudential regulation, over

NMCs. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has a consumer protection focus but is not designed

to be a comprehensive prudential regulator. Ginnie Mae and the Enterprises, which function as market

participants, can negotiate requirements for their counterparties, including the nonbank mortgage servicers

with which they do business, as a matter of contract. The Federal Housing Finance Agency has regulatory

authority over the Enterprises. Each has dierent objectives regarding their oversight of, or engagement

with, nonbank mortgage servicers.

State Financial Regulators

State financial regulators are the primary regulators of NMCs. They have broad licensing, examination,

investigation, enforcement, and prudential regulatory authority for NMCs that operate within their respective

state. A license is required in each state in which a company conducts business.

7

States can initiate

examinations or investigations at any time, gain immediate access to books and records upon request,

compel production of documents or information through a subpoena, and enforce financial condition

requirements as a condition of holding a license to do business. Through their administrative enforcement

powers, state financial regulators can issue consent judgments or consent orders compelling NMCs to

restructure operations and/or management, cease certain activities, and prohibit the acquisition of new

servicing rights. These administrative enforcement powers allow states to, among other things, require

regular reporting on the status of a loan servicing portfolio, and impose deadlines for compliance with state

and federal consumer protection regulations, as well as financial condition and corporate governance

requirements.

8

States also coordinate multistate supervision through the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS).

CSBS is the nationwide organization of state banking and financial regulators from all 50 states, the District

of Columbia, and the U.S. territories. CSBS also administers the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System

(NMLS) on behalf of state regulators, which includes maintaining all regulatory data submitted by individual

mortgage loan originators and NMC licensees for annual license renewals as well as periodic financial,

activity, banking, and control information at the company level.

9

The quarterly Mortgage Call Report is a

large database dating to 2011 containing activity and financial data for all companies licensed through NMLS

and is largely modeled after the Mortgage Bankers’ Financial Reporting Form (MBFRF) data collected from

the same companies by the Enterprises and Ginnie Mae.

10

The State Examination System is a component of

NMLS that is utilized by states to conduct exams and facilitates multistate exams.

11

7 CSBS. “State Licensing.” State Regulatory Registry, 2024. https://mortgage.nationwidelicensingsystem.org/slr/Pages/

default.aspx.

8 CSBS. “Mortgage Companies – State Authorities.” CSBS, April 1, 2024. https://www.csbs.org/mortgage-companies-

state-authorities.

9 CSBS. “NMLS Modernization FAQs.” CSBS. https://www.csbs.org/nmls-modernization-faqs.

10 CSBS. “Mortgage Call Report.” CSBS. https://www.csbs.org/nmls-modernization-faqs.

11 CSBS. “State Examination System (SES).” CSBS. https://www.csbs.org/aboutSES.

1 INTRODUCTION6 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)

The CFPB has supervisory authority over NMCs to assess their compliance with federal consumer financial

law and enforcement authority to take action against violations of federal consumer financial laws. The

CFPB also has rulemaking authority with respect to federal consumer financial law, including those related

to mortgage origination and servicing. The CFPB has a consumer protection focus; it is not designed to be a

comprehensive federal prudential regulator for nonbank mortgage servicers.

Ginnie Mae

Ginnie Mae is a government-owned corporation of the federal government within the U.S. Department

of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and is subject to annual congressional appropriations for its

salaries and expenses spending. Ginnie Mae provides guarantees to investors in mortgage-backed security

(MBS) programs collateralized by loans insured or guaranteed by other federal government mortgage

lending programs, including the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the Department of Veterans Aairs

(VA), the Rural Housing Service (RHS), and the Public and Indian Housing Program (PIH). In its role as a

guarantor, Ginnie Mae is tasked with providing stability to the secondary market for residential mortgages,

increasing the liquidity of federally-backed residential mortgage investments, and managing federally-

owned mortgage portfolios with minimum loss to taxpayers. Ginnie Mae has the contractual right to set

capital, liquidity, and other eligibility requirements for companies participating in its program, as well as to

conduct compliance reviews of its counterparties. However, it has no direct prudential regulatory authority

over its counterparties.

Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA)

FHFA is responsible for the eective supervision, regulation, and housing mission oversight of Fannie

Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBanks). In this capacity, FHFA may regulate and

supervise the Enterprises’ and FHLBanks’ counterparty credit risk. FHFA has no direct regulatory authority

over NMCs or any other counterparties of the Enterprises. Since 2008, FHFA has served as conservator

for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. As conservator, FHFA has the powers of the management, boards, and

shareholders of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, including authority to set contractual standards for and

exercise contractual rights of each Enterprise with respect to its counterparties.

12

The Enterprises

The Enterprises support liquidity in the secondary mortgage market for housing finance by directly buying

and securitizing mortgages and providing guarantees on MBS backed by eligible conforming loans.

Although the Enterprises are government-sponsored and have a public mission, they are private companies

and are not regulatory agencies. The Enterprises operate as business corporations and do not regulate

seller/servicers. As a matter of prudent risk management, the Enterprises consider possible risk exposure

from contractual relationships with seller/servicers and assess, monitor, and take appropriate actions to

address the risks to which they are exposed in their business relationships. As part of their risk management

processes, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac each have established an approval process for seller/servicers

that includes ascertaining that seller/servicers meet minimum financial eligibility requirements and

monitoring eligibility compliance of approved seller/servicers.

13

12 FHFA. “History of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Conservatorship.” Washington, D.C.: FHFA, October 17, 2022. https://

www.fhfa.gov/Conservatorship/Pages/History-of-Fannie-Mae--Freddie-Conservatorships.aspx.

13 Fannie Mae. “Maintaining Seller-Servicer Eligibility.” Washington, D.C.: Fannie Mae, November 1, 2023. https://

selling-guide.fanniemae.com/sel/a4-1-01/maintaining-sellerservicer-eligibility and Freddie Mac. “Eligibility Criteria.”

Tysons, VA: Freddie Mac, September 30, 2023. https://guide.freddiemac.com/app/guide/section/2101.1.

2 MORTGAGE SERVICERS | 7

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

2 Mortgage Servicers

2.1 Servicer Responsibilities

is report uses the term “servicer” to mean a rm that holds the servicing rights on a mortgage and

records this mortgage servicing right (MSR) as an asset on its balance sheet. Section 5.2 describes

MSRs in more detail. Servicers are responsible for ensuring that servicing functions are carried

out in accordance with the servicing contracts and applicable regulations; as described later,

some servicers carry out these functions themselves and others subcontract them to third parties.

Servicers are also responsible for a variety of cash outlays required under the servicing contract. As

discussed later in this report, for example, if a borrower does not make a mortgage payment, the

servicer may be required to make the missed payment amounts to investors, insurance companies,

and local governments.

Borrowers, guarantors, insurers, and investors depend on servicers to carry out a wide range of

loan administration duties in an accurate and timely way. ese duties include collecting and

recording borrower payments of mortgage principal and interest, taxes, and insurance premiums

and distributing those payments to investors, local governments, and insurance companies. ese

duties also include responsibilities associated with borrowers who do not make their payments,

such as contacting these borrowers and determining available loss mitigation plans. If a borrower

is unable to make mortgage payments even under a loss mitigation plan, the servicer is responsible

for enforcing the mortgage contract and identifying potential liquidation outcomes, such as a short

sale, deed-in-lieu of foreclosure, or foreclosure; evicting the borrower if necessary; and maintaining

the property so that its vacancy does not increase losses for the owner of the mortgage credit

risk. In addition, federal or state governments may establish borrower relief programs in extreme

circumstances that servicers are required to implement, such as the broad mortgage forbearance

provided during the COVID-19 public health emergency.

ese loan administration duties entail considerable interactions with borrowers, including billing,

maintaining escrow accounts, handling customer service, and working with delinquent borrowers.

Borrowers sometimes report frustrations with their interactions with both bank and NMC servicers.

In both 2021 and 2022 the CFPB received approximately 30,000 complaints from consumers about

their mortgages, with about half of those complaints centered on “trouble during the payment

process.”

14

14 CFPB. “Consumer Response Annual Report.” Washington, D.C.: CFPB, March 31, 2022. https://les.consumernance.

gov/f/documents/cfpb_2021-consumer-response-annual-report_2022-03.pdf and CFPB. “Consumer Response

Annual Report.” Washington, D.C.: CFPB, March 31, 2023. https://les.consumernance.gov/f/documents/

cfpb_2022-consumer-response-annual-report_2023-03.pdf.

Mortgage loan administration duties of servicers include:

• Collecting and recording payments.

• Distributing payments to investors, tax authorities, and insurance companies as needed.

• Contacting borrowers (especially for delays or delinquencies).

• Determining available loss mitigation strategies and implementing loss mitigation plans.

• Foreclosing, evicting, and maintaining properties after eviction.

2 MORTGAGE SERVICERS8 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

Some servicers conduct these critical functions in-house, while others contract them out to a

third-party subservicer. is report uses the term “subservicer” to describe a rm that performs

servicing activities on behalf of the servicer based on contractual requirements. Subservicers have

considerable operational risk but less liquidity and funding risk for cash outlays than servicers. Both

banks and NMCs can perform subservicing and use subservicers.

2.2 Servicer Business Models

Servicer business models vary and aect the servicer’s choice of whether to perform loan

administration duties in-house or use a subservicer. Some servicers have active mortgage

origination platforms and carry out the loan administration duties themselves, often to maximize

their interactions with borrowers. A strong borrower connection increases the likelihood that

borrowers will renance their mortgages with their current originators. Originators without an

in-house servicing platform may still value the servicing income and will retain the servicing while

contracting out the loan administration to a subservicer. Other servicers do not have active

origination platforms and own the MSRs as passive investors. Mortgage real-estate investment

trusts, for example, hold MSRs to earn yield and to hedge mortgage basis volatility and slower

prepayment speeds related to other assets in their portfolios. Firms that primarily value these

hedging properties are more likely to outsource loan administration duties to a subservicer.

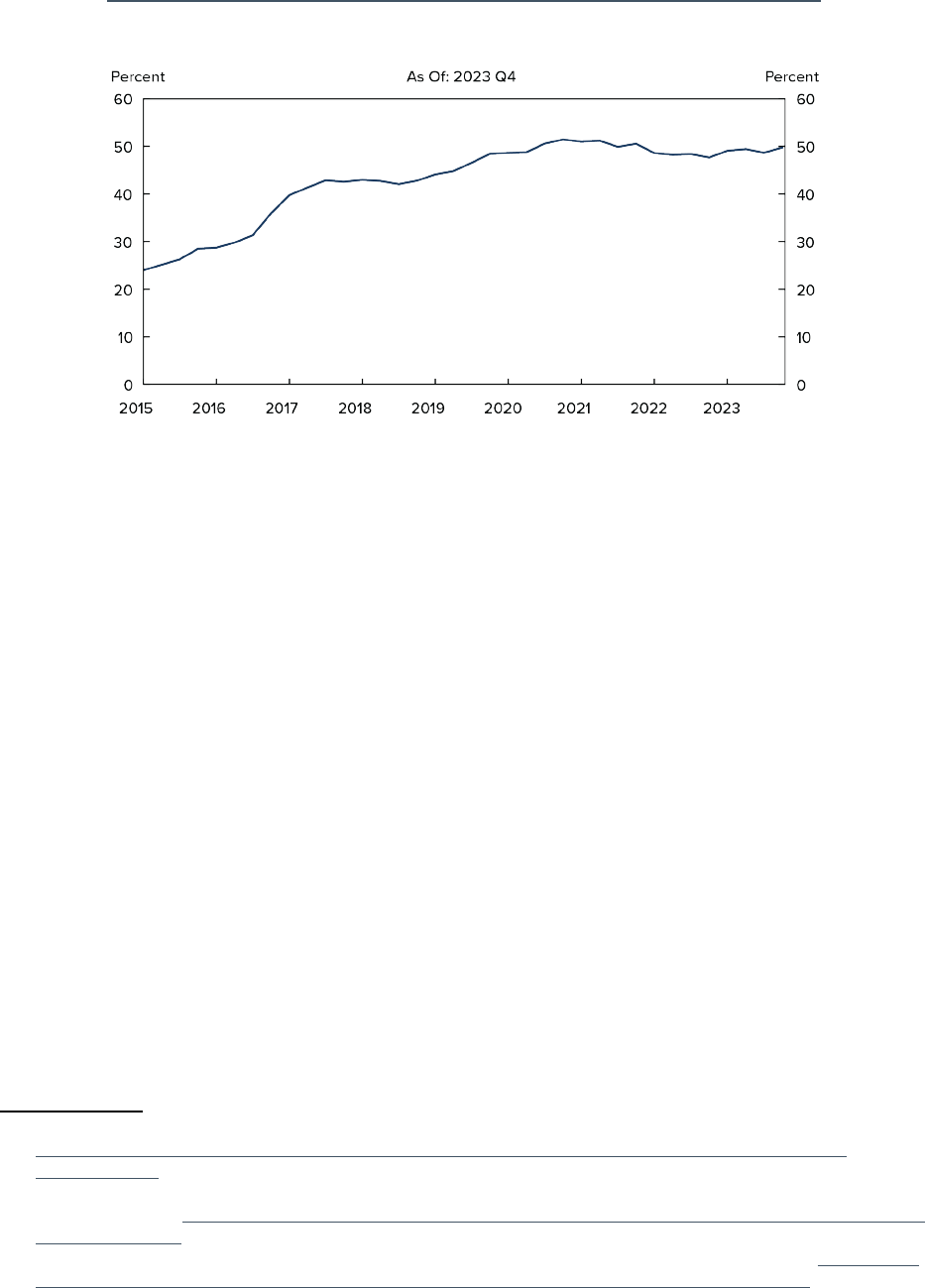

As passive MSR investors have expanded their MSR holdings, there is an increasing share of

mortgages with an NMC holding the servicing rights and contracting out the loan administration

duties to a third-party subservicer. As of the fourth quarter of 2023, of the mortgage balances for

which an NMC held the servicing rights, the administrative duties were handled by a third-party

subservicer for approximately half of those balances (see Figure 1).

15

is share is sharply higher

than in 2015, when subservicers handled the administrative responsibilities for approximately 25

percent of the portfolios of nonbank servicers.

15 Statistics calculated from Mortgage Call Report data collected under the NMLS. Statistics calculated for all mortgages

serviced by NMCs, including some mortgages not funded by Agency securitization.

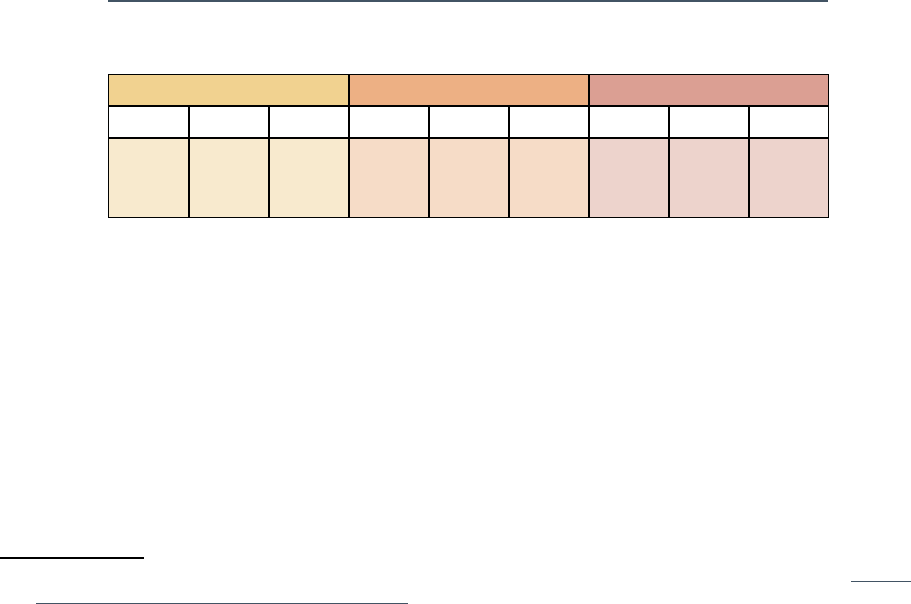

Primary Activity of Servicers and Subservicers

Servicer Subservicer

Hold servicing rights Do not hold servicing rights

Record servicing assets on balance

sheet

Do not record servicing assets on

balance sheet

Retain some (or most) mortgage loan

administration functions

Provide loan administration functions

that are not performed by the servicer

Responsible for cash outlays required

under servicing contract

Not responsible for cash outlays

required under servicing contract

Note: The figure shows the share of all unpaid principal balances serviced by an NMC for

which another firm carries out subservicing responsibilities.

Source: NMLS Mortgage Call Report

Figure 1: Share of NMC Servicing Subserviced by Another Firm

2 MORTGAGE SERVICERS | 9

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

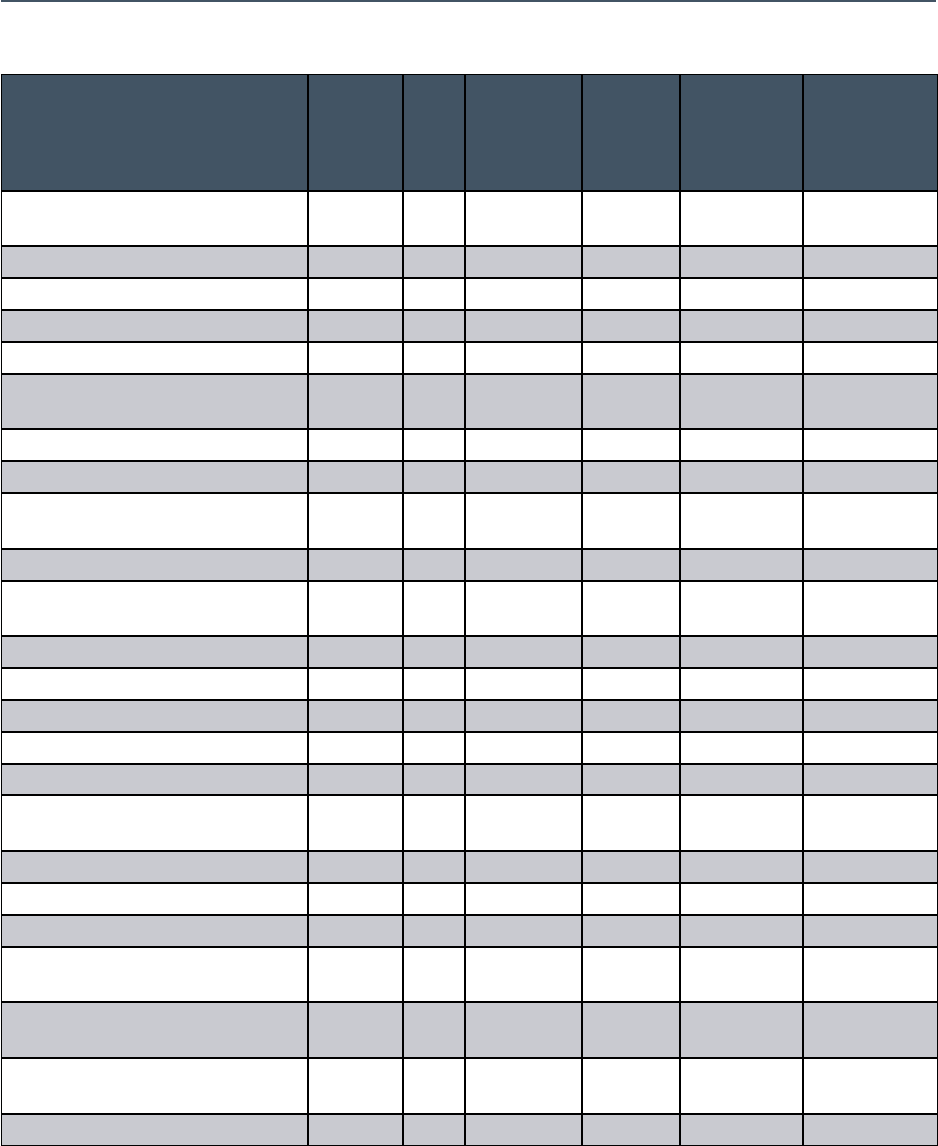

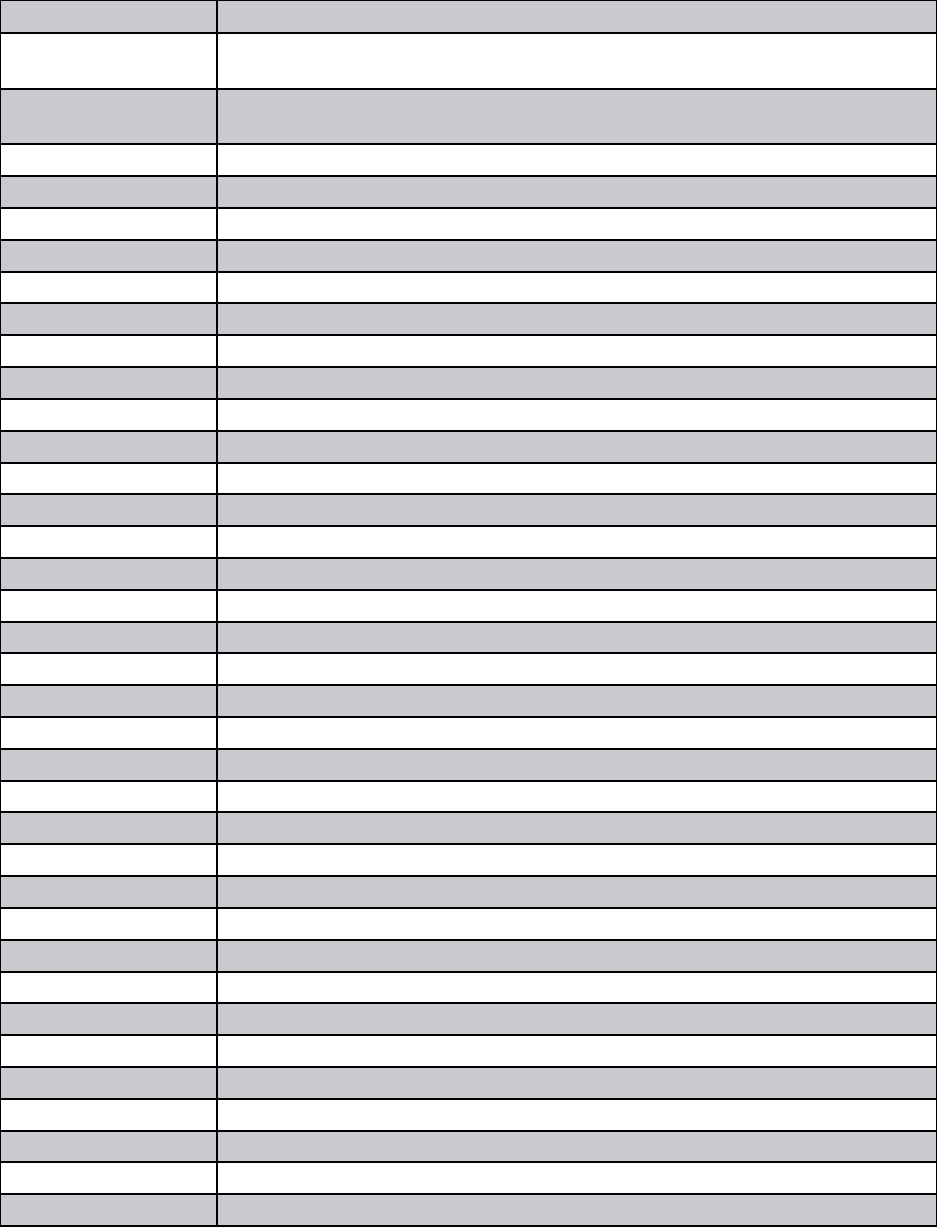

To illustrate why managing nonbank mortgage servicer failures might be challenging for the

Agencies, Table 1 shows data from Inside Mortgage Finance for the 20 largest Agency servicers (both

bank and nonbank) as of the fourth quarter of 2023.

16

e table shows the size of each servicer’s

portfolio, the servicer’s market share, whether the servicer substantially relies on a subservicer for

servicing its portfolio, and whether the servicer acts as a material subservicer for other servicers. A

servicer is dened as utilizing a subservicer if the servicer is not listed in Inside Mortgage Finance’s

“Top Primary Mortgage Servicers” table.

17

A servicer is dened as providing subservicing for

other servicers if it is listed in Inside Mortgage Finance’s “Top Residential Subservicers” table.

18

is classication only captures signicant subservicing relationships; servicers that perform the

loan administration duties for most of the loans in their servicing portfolios may still have smaller

portfolios that are subserviced by other rms.

16 Bancroft, John. “Agency Servicing Ranking Shaped by 4Q MSR Sales.” Inside Mortgage Finance (January 12, 2024).

https://www.insidemortgagenance.com/articles/229895-agency-servicing-ranking-shaped-by-4q24-msr-

sales?v=preview.

17 Inside Mortgage Finance. “Nonbanks and Second-Tier Servicers Gain Share in 4Q23.” Inside Mortgage Finance

(February 2, 2024). https://www.insidemortgagenance.com/products/313275-nonbanks-and-second-tier-servicers-

gain-share-in-4q23.

18 Muolo, Paul. “Some Headwinds for the Subservicing Sector.” Inside Mortgage Finance (March 22, 2024). https://www.

insidemortgagenance.com/articles/230529-some-headwinds-for-the-subservicing-sector?v=preview.

Some servicers conduct these critical functions in-house, while others contract them out to a

third-party subservicer. is report uses the term “subservicer” to describe a rm that performs

servicing activities on behalf of the servicer based on contractual requirements. Subservicers have

considerable operational risk but less liquidity and funding risk for cash outlays than servicers. Both

banks and NMCs can perform subservicing and use subservicers.

2.2 Servicer Business Models

Servicer business models vary and aect the servicer’s choice of whether to perform loan

administration duties in-house or use a subservicer. Some servicers have active mortgage

origination platforms and carry out the loan administration duties themselves, often to maximize

their interactions with borrowers. A strong borrower connection increases the likelihood that

borrowers will renance their mortgages with their current originators. Originators without an

in-house servicing platform may still value the servicing income and will retain the servicing while

contracting out the loan administration to a subservicer. Other servicers do not have active

origination platforms and own the MSRs as passive investors. Mortgage real-estate investment

trusts, for example, hold MSRs to earn yield and to hedge mortgage basis volatility and slower

prepayment speeds related to other assets in their portfolios. Firms that primarily value these

hedging properties are more likely to outsource loan administration duties to a subservicer.

As passive MSR investors have expanded their MSR holdings, there is an increasing share of

mortgages with an NMC holding the servicing rights and contracting out the loan administration

duties to a third-party subservicer. As of the fourth quarter of 2023, of the mortgage balances for

which an NMC held the servicing rights, the administrative duties were handled by a third-party

subservicer for approximately half of those balances (see Figure 1).

15

is share is sharply higher

than in 2015, when subservicers handled the administrative responsibilities for approximately 25

percent of the portfolios of nonbank servicers.

15 Statistics calculated from Mortgage Call Report data collected under the NMLS. Statistics calculated for all mortgages

serviced by NMCs, including some mortgages not funded by Agency securitization.

Primary Activity of Servicers and Subservicers

Servicer Subservicer

Hold servicing rights Do not hold servicing rights

Record servicing assets on balance

sheet

Do not record servicing assets on

balance sheet

Retain some (or most) mortgage loan

administration functions

Provide loan administration functions

that are not performed by the servicer

Responsible for cash outlays required

under servicing contract

Not responsible for cash outlays

required under servicing contract

Note: The figure shows the share of all unpaid principal balances serviced by an NMC for

which another firm carries out subservicing responsibilities.

Source: NMLS Mortgage Call Report

Figure 1: Share of NMC Servicing Subserviced by Another Firm

2 MORTGAGE SERVICERS10 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

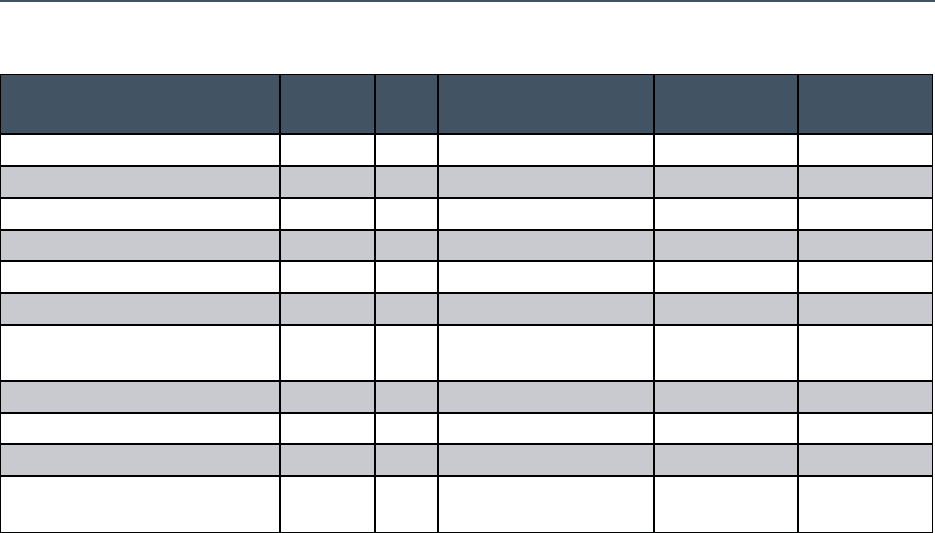

Table 1: Top Agency MBS Servicers, Q4 2023

Firm Type Rank Servicing

UPB

Balance (in

$ Billions)

Market

Share

(Percent)

Utilizes

Subservicer

Provides

Subservicing

Lakeview/Bayview Loan

Servicing

Nonbank 1 644.5 7.3 Ye s No

Chase Home Finance Bank 2 597.0 6.7 No No

PennyMac Corp Nonbank 3 588.5 6.7 No No

Wells Fargo Bank 4 539.9 6.1 No No

Mr. Cooper Group Nonbank 5 531.7 6.0 No Ye s

New Rez/Caliber Home Loans

(Rithm)

Nonbank 6 474.1 5.4 No Ye s

Rocket Mortgage Nonbank 7 463.6 5.2 No Ye s

Freedom Mortgage Corp Nonbank 8 456.7 5.2 No Ye s

United Wholesale Mortgage,

LLC

Nonbank 9 274.4 3.1 Ye s No

U.S. Bank NA Bank 10 220.0 2.5 No No

Matrix Financial Services/Two

Harbors

Nonbank 11 213.2 2.4 Ye s No

Truist Bank 12 210.6 2.4 No No

PNC Bank NA Bank 13 202.5 2.3 No No

Ocwen Financial/PHH Mortgage Nonbank 14 163.0 1.8 No Ye s

Onslow Bay Financial Nonbank 15 150.3 1.7 Ye s No

LoanDepot.com LLC Nonbank 16 134.0 1.5 No No

Carrington Mortgage Services,

LLC

Nonbank 17 126.6 1.4 No Ye s

Fifth Third Bank Bank 18 97.6 1.1 No No

Citizens Bank NA RI

Bank 19 96.3 1.1 No No

CMG Mortgage Inc Nonbank 20 92.6 1.0 Ye s No

Top 10 Agency MBS Servicers

Total

4,790.4 54.1

Top 20 Agency MBS Servicers

Total

6,277.1 70.9

Total Nonbank Agency MBS

Servicers in Top 20

4,313.2 48.7

All Agency MBS Servicers Total 8,847.8

Note: Servicing unpaid principal balance (UPB) is for mortgages in Agency pools only, as estimated by Inside Mortgage

Finance, and may be dierent from other data sources. A firm is classified as using a subservicer if it is not listed in

the Inside Mortgage Finance “Primary Servicer” table. A firm is classified as providing subservicing if it is listed in the

Inside Mortgage Finance “Top Residential Subservicers” table. Sums may not fully match due to rounding.

Source: Inside Mortgage Finance

2 MORTGAGE SERVICERS | 11

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

e data in Table 1 show that nonbank mortgage servicers are among the largest Agency servicers.

NMCs are seven of the 10 largest Agency servicers and 13 of the largest 20 Agency servicers. In

total, the top 20 Agency servicers hold the servicing rights on nearly $6.3 trillion in unpaid balances

on mortgages in Agency pools, approximately 70 percent of the total Agency market. Nonbank

mortgage servicers in the top 20 hold the servicing rights on $4.3 trillion, or almost half, of the total

Agency market.

Table 1 and related data also indicate that many NMCs have large servicing portfolios. In total, 20

NMCs had servicing portfolios with unpaid principal balances in excess of $50 billion in the fourth

quarter of 2023, which is the Agency threshold at which more stringent expanded requirements

take eect.

19

is total includes seven NMCs in addition to those listed in the top 20.

20

Despite the

dierent operating models, since NMCs have similar vulnerabilities and are susceptible to similar

shocks (see Section 5), stress in the mortgage market may be more likely to simultaneously put

multiple NMCs at risk of failure. e failure of several mid-sized servicers could be as disruptive as

the failure of a large servicer.

To provide perspective on how large subservicers can be, Table 2 shows the ten largest subservicers

as ranked by Inside Mortgage Finance. A subservicer is classied as a “subservicer only” if it is

not listed in the Inside Mortgage Finance “Top 100 Firms in Owned Mortgage Servicing” table.

Seven NMCs are among the top 10 residential subservicers, and some of these rms handle very

large balances. Dovenmuehle and Mr. Cooper, for example, have subservicing responsibilities for

portfolios exceeding $400 billion in unpaid principal balances.

19 e Enterprises and Ginnie Mae require a nonbank servicer to meet additional requirements if it holds the servicing

rights on more than $50 billion in unpaid single-family mortgage balances. FHFA. “Fact Sheet: Enterprise Seller/

Servicer Minimum Financial Eligibility requirements.” Washington, D.C.: FHFA, August 17, 2022. https://www.fhfa.

gov/Media/PublicAairs/Documents/Fact-Sheet-Enterprise-Seller-Servicer-Min-Financial-Eligibility-Requirements.

pdf.

20

In addition to the NMCs shown in Table 1, Planet Home Lending, Crosscountry Mortgage, Guild Mortgage Company,

Amerihome Mortgage Company, New American Funding/Broker Solutions, Movement Mortgage, and Provident

Funding Associates had Agency servicing UPBs in excess of $50 billion as of the fourth quarter of 2023 according to

Inside Mortgage Finance. Amerihome is a nonbank subsidiary of Western Alliance Bank.

2 MORTGAGE SERVICERS12 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

Tables 1 and 2 also indicate that servicing and subservicing relationships create considerable

linkages across rms and across the bank and NMC sectors, which is further discussed in Section

5.6. As shown in Table 1, ve of the 20 largest Agency servicers rely on subservicers to handle their

administrative servicing duties, while six of the 20 largest Agency servicers subservice loans for

others. NMCs can use multiple subservicers and can share these subservicers with other NMCs and

banks; subservicers can have many clients.

In summary, the organization of the servicing industry means that nancial strains at both servicers

and subservicers can pose challenges to the Agencies. Servicers provide cash outlays required under

the servicing contract, and both servicers and subservicers perform the critical functions associated

with loan administration. Since some subservicers handle servicing functions for many companies,

vulnerabilities at these subservicers could result in stress being transmitted in the system more

broadly (see Section 6.3). e similarities in NMC business models mean that multiple servicers

could fall into material distress at the same time, which could require the Agencies to manage

several failures at once and could make it challenging to nd new rms to take on the portfolios of

failing NMCs. Some NMC portfolios can be sizeable, and moving these portfolios to a new servicer

can be dicult.

Table 2: Top Residential Mortgage Subservicers, Q4 2023

Firm Type Rank Subservicer Balance

(in $ Billions)

Market Share

(Percent)

Subservicer

Only

Cenlar Bank 1 875.0 21.9 Ye s

Dovenmuehle Nonbank 2 515.0 12.9 Ye s

Mr. Cooper Nonbank 3 403.8 10.1 No

LoanCare Nonbank 4 320.0 8.0 Ye s

Flagstar Bank 5 294.9 7.4 No

ServiceMac Nonbank 6 245.2 6.1 Ye s

Ocwen Financial/PHH

Mortgage

Nonbank 7 139.9 3.5 No

Select Portfolio Servicing Nonbank 8 133.0 3.3 Ye s

M&T Bank Bank 9 115.1 2.9 No

New Rez/Caliber/Shellpoint Nonbank 10 102.5 2.6 No

Estimated Subservicing

Market Total

3,990.0

Note: Estimates include loans held for investment on bank books and loans in private-label securitizations as well as

loans in Agency pools.

Source: Inside Mortgage Finance

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES | 13

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

3 The Growth in Agency Securitization and Nonbank

Mortgage Companies

In the last 30 years, the types of institutions that originate, fund, securitize, and service mortgages

have shifted signicantly. In particular, the share of mortgages originated or serviced by an NMC

and securitized into an MBS guaranteed by the Agencies has increased dramatically, especially since

the 2007-09 nancial crisis. ese trends, combined with the government’s nancial support for the

Enterprises during their ongoing conservatorships, mean that the government’s aggregate exposure

to the fragilities of NMCs has increased substantially.

3.1 Increased Government and Enterprise Backing of the Mortgage Market

e share of outstanding mortgages with a government or Enterprise guarantee has increased since

the 2007-09 nancial crisis. e guarantee takes two forms for investors: protection against credit

losses on the underlying mortgages (“credit” guarantee) and guarantees to receive timely payment of

principal and interest on the securitizations that fund the mortgages (“timely payment” guarantee).

For Ginnie Mae securitizations, Ginnie Mae provides the timely payment guarantee on the security

while the credit insurance or guarantee on the loans is provided by the FHA, VA, RHS, or PIH.

For Enterprise securitizations, the Enterprises provide both the credit and timely payment

guarantees. e Enterprise guarantee is not directly backed by the federal government. In

conjunction with FHFA placing each Enterprise into conservatorship in 2008, the U.S. Department

of the Treasury began providing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with nancial support through the

Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements (SPSPAs), which were executed on September 7,

2008.

21

e SPSPAs, which remain in place, were designed to provide stability to nancial markets

and prevent disruptions in the availability of mortgage nance. However, even in conservatorship,

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac operate as private market participants.

21 FHFA. “Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements.” Washington, D.C.: FHFA, October 17, 2022. https://www.fhfa.

gov/Conservatorship/Pages/Senior-Preferred-Stock-Purchase-Agreements.aspx.

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES 14 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

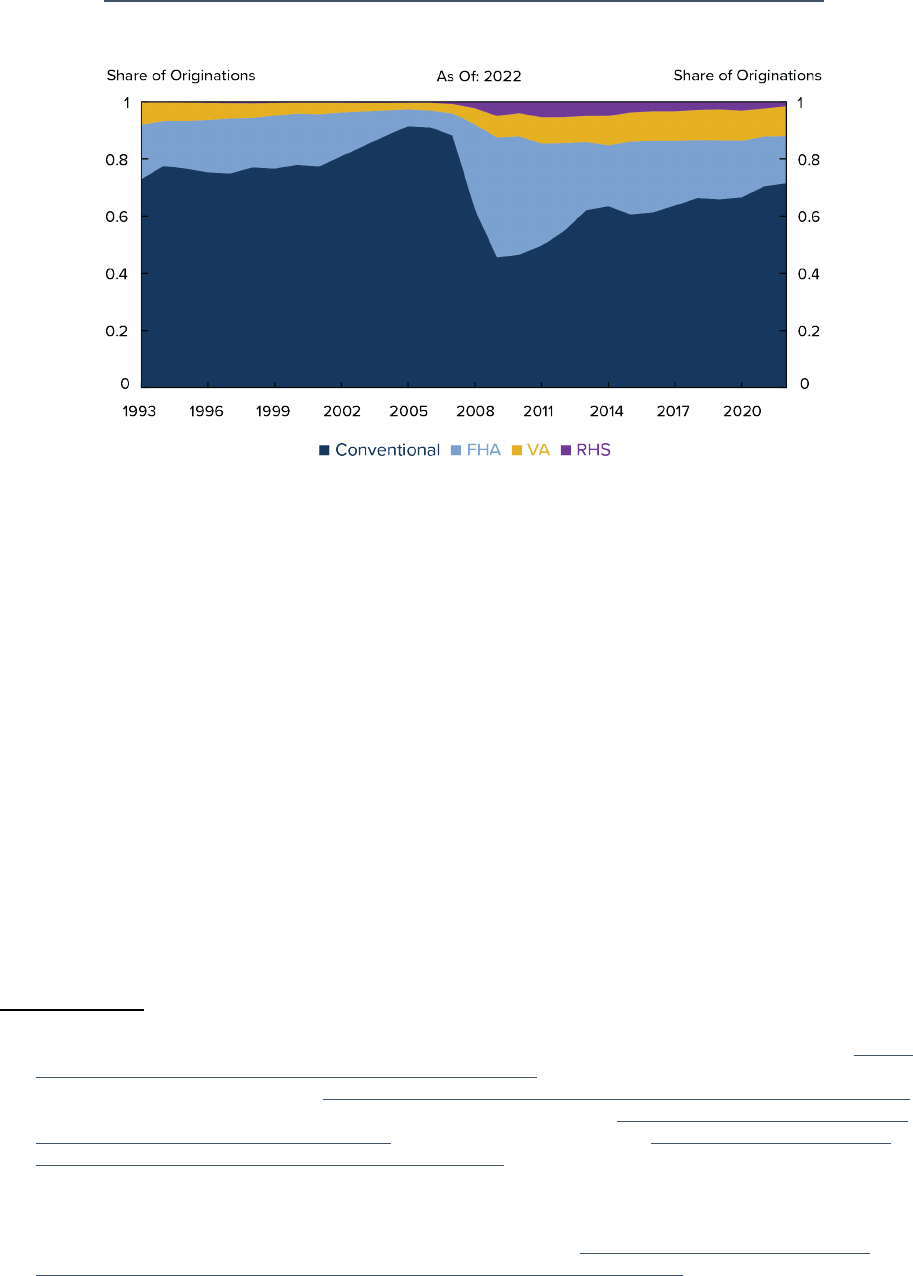

On net, the share of outstanding mortgages funded by Agency securitization rose from 46 percent in

1990 to 68 percent in 2023 (see Figure 2).

22

is upward trend was interrupted in the 2000s as the

emergence of subprime and near-prime mortgage products led to a surge in the private-label

securitization (PLS) market. After the PLS market imploded in 2007, the Agency share expanded

again, led initially by a sharp rise in Ginnie Mae guaranteed securitizations as the FHA, VA, and RHS

programs absorbed some of the origination activity that was funded earlier through PLS (see Figure

3).

23

Increases in the maximum loan size eligible for FHA insurance and VA guarantees also

contributed to the growth.

24

22 Data are from the Financial Accounts of the United States, Table L.218. Data are for residential mortgages

collateralized by one-to-four family properties. Home equity loans are excluded from the calculation. Credit unions

are included in the depository category. Data for the Ginnie Mae component of Agency and MBS pools in the Flow

of Funds Account can be found at https://www.ginniemae.gov/data_and_reports/reporting/Pages/monthly_rpb_

reports.aspx.

23 See Adelino, Manuel, William B. McCartney, and Antionette Schoar. “e Role of Government and Private Institutions

in Credit Cycles in the U.S. Mortgage Market.” Working Paper no. 27499. NBER, July 2020. https://www.nber.org/

papers/w27499 for more discussion of this switch.

24 For more information on the increases in the maximum loan amount eligible for FHA insurance, see Park, Kevin A.,

“Temporary Loan Limits as a Natural Experiment in FHA Insurance,” Working Paper no. HF-021, Washington, D.C.:

HUD Oce of Policy Development and Research, May 2016. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/les/

pdf/WhitePaper-FHA-Loan-Limits.pdf. See also Veterans Benets Administration. “Updated Guidance for Blue Water

Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019.” Circular 26-19-30, Washington, D.C.: Department of Veterans Aairs, November

15, 2019. https://www.benets.va.gov/HOMELOANS/documents/circulars/26_19_30.pdf for increases in the

maximum amount of VA guaranty entitlement resulting from the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019.

Note: One-to-four family residential mortgages excluding home equity loans. Credit unions

are included in the depository category.

Source: Financial Accounts of the United States

Figure 2: Outstanding Mortgage Balances by Sector

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (U.S.), Home Mortgage

Disclosure Act (Public Data)

Figure 3: Loan Origination by Credit Guarantor

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES | 15

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

3.2 Increased NMC Presence in the Mortgage Market

e bank share of mortgage origination and servicing rose substantially at the beginning of the 2007-

09 nancial crisis after many NMCs failed amid a sharp rise in delinquencies and unemployment,

decline in house prices, and collapse of the subprime and Alternative-A securitization market.

Altogether, the total number of NMCs (both independent and bank-aliated) fell by half—a drop

of nearly 1,000 companies—between 2006 and 2012.

25

Some very large NMCs failed, such as New

Century Financial and American Home Mortgage, which received nearly 450,000 and 350,000

mortgage applications, respectively, in 2006.

26

e origination and servicing businesses of New

Century Financial and American Home Mortgage included signicant exposure to mortgages that

were not eligible for Agency securitization.

27

While many of the factors that contributed to NMC failures during the 2007-09 nancial crisis are

signicantly dierent or nonexistent today, it is worth examining similarities in vulnerabilities

given the large market share and reliance on NMCs in today’s market. e NMCs from the pre-

nancial crisis period originated and serviced many subprime and near-prime mortgages that

were poorly underwritten and had opaque and confusing features such as teaser interest rates and

negative amortization.

28

State and federal regulations since the 2007-09 crisis have dramatically

25 Bhutta, Neil, and Glenn B. Canner. 2013. “Mortgage Market Conditions and Borrower Outcomes: Evidence from the

2012 HMDA Data and Matched HMDA–Credit Record Data.” Federal Reserve Bulletin 99, no. 4 (November). https://

www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2013/pdf/2012_hmda.pdf.

26 Applications for 2006 can be found at https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2008/pdf/hmda07tableA1.xls.

27 See these companies’ SEC lings, available for American Home Mortgage at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/

data/1256536/000119312507044477/d10k.htm and for New Century Financial at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/

edgar/data/1287286/000089256906001359/a24944e10vq.htm.

28 For a discussion of the deterioration in underwriting standards, see Mayer, Christopher, Karen Pence, and Shane M.

Sherlund. 2009. “e Rise in Mortgage Defaults,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23, no. 1 (Winter): 27-50. See the

Housing Credit Availability Index in Urban Institute Housing Finance Policy Center. “Housing Finance at a Glance:

A Monthly Chartbook.” Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, March 2024. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/

les/2024-03/Housing_Finance_At_A_Glance_Monthly_Chartbook_March_2024.pdf, for a measure of the role of

product risk in mortgage default risk before the 2007-09 nancial crisis.

On net, the share of outstanding mortgages funded by Agency securitization rose from 46 percent in

1990 to 68 percent in 2023 (see Figure 2).

22

is upward trend was interrupted in the 2000s as the

emergence of subprime and near-prime mortgage products led to a surge in the private-label

securitization (PLS) market. After the PLS market imploded in 2007, the Agency share expanded

again, led initially by a sharp rise in Ginnie Mae guaranteed securitizations as the FHA, VA, and RHS

programs absorbed some of the origination activity that was funded earlier through PLS (see Figure

3).

23

Increases in the maximum loan size eligible for FHA insurance and VA guarantees also

contributed to the growth.

24

22 Data are from the Financial Accounts of the United States, Table L.218. Data are for residential mortgages

collateralized by one-to-four family properties. Home equity loans are excluded from the calculation. Credit unions

are included in the depository category. Data for the Ginnie Mae component of Agency and MBS pools in the Flow

of Funds Account can be found at https://www.ginniemae.gov/data_and_reports/reporting/Pages/monthly_rpb_

reports.aspx.

23

See Adelino, Manuel, William B. McCartney, and Antionette Schoar. “e Role of Government and Private Institutions

in Credit Cycles in the U.S. Mortgage Market.” Working Paper no. 27499. NBER, July 2020. https://www.nber.org/

papers/w27499 for more discussion of this switch.

24 For more information on the increases in the maximum loan amount eligible for FHA insurance, see Park, Kevin A.,

“Temporary Loan Limits as a Natural Experiment in FHA Insurance,” Working Paper no. HF-021, Washington, D.C.:

HUD Oce of Policy Development and Research, May 2016. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/les/

pdf/WhitePaper-FHA-Loan-Limits.pdf. See also Veterans Benets Administration. “Updated Guidance for Blue Water

Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019.” Circular 26-19-30, Washington, D.C.: Department of Veterans Aairs, November

15, 2019. https://www.benets.va.gov/HOMELOANS/documents/circulars/26_19_30.pdf for increases in the

maximum amount of VA guaranty entitlement resulting from the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019.

Note: One-to-four family residential mortgages excluding home equity loans. Credit unions

are included in the depository category.

Source: Financial Accounts of the United States

Figure 2: Outstanding Mortgage Balances by Sector

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (U.S.), Home Mortgage

Disclosure Act (Public Data)

Figure 3: Loan Origination by Credit Guarantor

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES 16 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

improved underwriting standards and restricted or eliminated the use of these product features.

29

NMCs were also heavily dependent on private-label securitization and whole loan sales, which are

less stable funding sources than Agency securitization markets in periods of stress. Today NMCs

focus primarily on Agency securitization. Despite these improvements to the product and market

environment, NMCs in the period before the 2007-09 crisis had liquidity and leverage vulnerabilities

similar to those of NMCs active today, and those vulnerabilities contributed to their demise when

confronted with the market shocks of that era.

30

e NMCs with the largest market share today are

also almost entirely independent, whereas a large share of the NMCs in the period before the 2007-

09 crisis were aliated with a bank holding company and subject to regulation and supervision

from federal and state banking regulators.

In the years after the 2007-09 nancial crisis, banks pulled back from mortgage origination and

servicing in part due to heightened regulation and sensitivity to the cost and uncertainty associated

with delinquent mortgages. On the regulatory front, the revised capital rule issued by the banking

agencies in 2013 imposed stricter capital requirements on MSRs.

31

is rule made mortgage

servicing a less attractive business line for some banks.

32

To the extent that the obligation to service

a mortgage arises from mortgage origination, the revised capital treatment may have dampened

banks’ desires to originate some types of mortgages.

33

Banks perceived an increase in the cost and

uncertainty of default servicing because of developments such as the National Mortgage Settlement,

the Independent Foreclosure Review, prosecutions under the False Claims Act, and private

litigation.

34

While the costs of default servicing rose for both banks and NMCs, banks appeared

to respond more strongly than NMCs to these developments and reduced their exposure from

originating and servicing mortgages to borrowers with a higher risk of default.

NMCs also appear to have gained market share in mortgage originations after the 2007-09 nancial

crisis because they were quicker to embrace new technology that made the mortgage origination

29 CFPB. “Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Publishes Assessments of Ability-to-Repay and Mortgage Servicing

Rules.” Washington, D.C.: CFPB, January 10, 2019. https://www.consumernance.gov/about-us/newsroom/

consumer-nancial-protection-bureau-publishes-assessments-ability-repay-and-mortgage-servicing-rules/. McCoy,

Patricia A and Susan M. Wachter. 2020. “Why the Ability-to-Repay Rule Is Vital to Financial Stability.” Georgetown Law

Journal 108, no. 3 (March 2020): 649-698. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/georgetown-law-journal/wp-content/

uploads/sites/26/2020/03/Why-the-Ability-to-Repay-Rule-Is-Vital-to-Financial-Stability.pdf.

30 For examples, see Dash, Eric. 2007. “American Home Mortgage Says It Will Close,” New York Times (August 3, 2007)

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/03/business/03lender.html and the discussion in Kim, You Suk, Steven Laufer,

Karen Pence, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace. 2018. “Liquidity Crises in the Mortgage Market,” Brookings Papers

on Economic Activity (Spring 2018): 347-428. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/KimEtAl_

Text.pdf.

31 See Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC, NCUA. “Report to the Congress on the Eects of Capital Rules on

Mortgage Servicing Assets,” Washington, D.C.: Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC, NCUA, June 2016. https://www.

federalreserve.gov/publications/other-reports/les/eect-capital-rules-mortgage-servicing-assets-201606.pdf.

32 For some banks, the change in risk weights on MSRs was a relatively small increase from 215 percent to 250 percent.

See ibid.

33 e capital treatment only aects mortgages that are funded through securitization. No MSR is created for a mortgage

held in a bank’s portfolio.

34 See “Joint State-Federal National Mortgage Servicing Settlements.” Joint State-Federal National Mortgage Servicing

Settlements. http://www.nationalmortgagesettlement.com/; Federal Reserve Board. “Independent Foreclosure

Review.” Federal Reserve Board (July 21, 2014). https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2014-independent-

foreclosure-review-background-on-the-independent-foreclosure-review.htm, and U.S. Department of Justice “e

False Claims Act & Federal Housing Administration Lending.” U.S. Department of Justice (March 15, 2016). https://

www.justice.gov/archives/opa/blog/false-claims-act-federal-housing-administration-lending.

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES | 17

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

process faster and more convenient for some borrowers.

35

In addition, NMCs pivoted quicker than

banks after the 2007-09 nancial crisis to develop the expertise to service nonperforming loans. e

extraordinary need for such servicing expertise in the aftermath of the 2007-09 nancial crisis also

helped fuel the growth of some NMCs.

36

e next section describes how this broad shift from banks to NMCs unfolded in dierent parts of

the mortgage market.

3.2.1 Increased NMC Share of Mortgage Originations

From 1993 to 2006, the mortgage origination market was split roughly evenly among banks, NMCs

aliated with banks or bank holding companies, and independent NMCs (see Figure 4).

37

Both

bank-aliated and independent NMCs lost market share to banks during the 2007-09 nancial

crisis. After the crisis, bank-aliated NMCs mostly closed their operations, while independent

NMCs expanded and banks contracted. By 2022, 64 percent of purchase mortgages were originated

by independent NMCs.

35 See Buchak, Greg, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru. 2018. “Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and the Rise

of Shadow Banks.” Journal of Financial Economics 130, issue 3: 453-483, and Fuster, Andreas, Matthew Plosser, Philipp

Schnabl, and James Vickery. 2019. “e Role of Technology in Mortgage Lending,” Review of Financial Studies 32,

issue 5: 1854-1899. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz018.

36 See Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC, NCUA. “Report to the Congress on the Eect of Capital Rules on Mortgage

Servicing Assets.” Washington, D.C.: Federal Reserve Board, FDIC, OCC, NCUA, June 2016. https://www.

federalreserve.gov/publications/other-reports/les/eect-capital-rules-mortgage-servicing-assets-201606.pdf.

37 All statistics in this section are calculated from HMDA data as described in footnote 4. e data series begin in 1993

because HMDA’s coverage of independent NMCs increased in 1993.

Note: Depositories include credit unions. Independent refers to nonbank mortgage

companies. Aliated refers to nonbank mortgage companies aliated with a depository

institution.

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (U.S.), Home Mortgage

Disclosure Act (Public Data)

Figure 4: Loan Origination by Type of Originator

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES 18 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

3.2.2 Increased NMC Share as Agency Counterparties

NMCs have a strong incentive to sell their originations quickly because secondary market sales are a

signicant source of income, and they lack aordable or reliable sources of long-term funding. e

Agencies’ dominant securitization market share means that they are the major source of secondary

market liquidity for NMCs. Some NMCs engage directly with the Agencies to sell or securitize their

loans, whereas others sell their loans to larger banks or NMCs, known as “aggregators,” that engage

with the Agencies.

An originator that funds mortgages through a securitization guaranteed by an Enterprise can

either sell the loans to the Enterprise for cash or exchange the loans for an MBS guaranteed by the

Enterprise. e originator can choose to retain the servicing or release it to be serviced by another

rm. Originators that sell loans to or service loans for an Enterprise are referred to as Enterprise

seller/servicers.

If the originator decides to fund mortgages by issuing a securitization guaranteed by Ginnie

Mae, the originator receives a guaranty on the MBS and retains the servicing unless it transfers

issuer responsibilities through the Pools Issued for Immediate Transfer program. Originators that

issue securitizations guaranteed by Ginnie Mae are referred to as Ginnie Mae issuers. is report

collectively refers to Enterprise seller/servicers and Ginnie Mae issuers as Agency counterparties.

Agency counterparties assume certain responsibilities. For example, if the loan was not

underwritten in accordance with the policies or guidelines of the respective Agency, the Enterprises

or the U.S. government (FHA, VA, or RHS) can pursue the seller for damages or require repurchase

of the loan. Originators that retain the servicing for the loans sold or securitized via the Agencies

must agree to service the loans in accordance with the respective Agency guidelines.

Although NMCs have always originated loans, until the 2010s most nonbank originators were too

small to handle the responsibilities of being an Agency servicing counterparty in a cost-eective

way. Instead, they sold their originations to bank or NMC aggregators. In 2008, independent NMCs

were the sellers for only 10 percent of mortgages in Enterprise securitizations and the issuers for 14

percent of mortgages in Ginnie Mae securitizations (see Figure 5). After the 2007-09 nancial crisis,

some large banks withdrew from the Agency counterparty role for the reasons noted in Section 3.2

and some independent NMCs responded to this market opportunity by expanding their operations

and becoming Agency counterparties. By 2022, independent NMCs were the sellers for 66 percent of

mortgages in Enterprise securitizations and the issuers for 84 percent of mortgages for Ginnie Mae

securitizations.

38

38 is paragraph focuses solely on independent NMCs because they may pose more counterparty risk to the Agencies

than bank-aliated NMCs. Banks and bank holding companies are subject to federal and state supervision and

regulation.

Note: The figure shows the market share for independent NMCs that sold originations to

the Enterprises or issued a securitization guaranteed by Ginnie Mae. In some cases that

NMC was the mortgage originator and in some cases it was a mortgage aggregator.

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (U.S.), Home Mortgage

Disclosure Act (Public Data)

Figure 5: Share of Originations in Agency Pools Contributed by

Independent NMCs

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES | 19

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

3.2.2 Increased NMC Share as Agency Counterparties

NMCs have a strong incentive to sell their originations quickly because secondary market sales are a

signicant source of income, and they lack aordable or reliable sources of long-term funding. e

Agencies’ dominant securitization market share means that they are the major source of secondary

market liquidity for NMCs. Some NMCs engage directly with the Agencies to sell or securitize their

loans, whereas others sell their loans to larger banks or NMCs, known as “aggregators,” that engage

with the Agencies.

An originator that funds mortgages through a securitization guaranteed by an Enterprise can

either sell the loans to the Enterprise for cash or exchange the loans for an MBS guaranteed by the

Enterprise. e originator can choose to retain the servicing or release it to be serviced by another

rm. Originators that sell loans to or service loans for an Enterprise are referred to as Enterprise

seller/servicers.

If the originator decides to fund mortgages by issuing a securitization guaranteed by Ginnie

Mae, the originator receives a guaranty on the MBS and retains the servicing unless it transfers

issuer responsibilities through the Pools Issued for Immediate Transfer program. Originators that

issue securitizations guaranteed by Ginnie Mae are referred to as Ginnie Mae issuers. is report

collectively refers to Enterprise seller/servicers and Ginnie Mae issuers as Agency counterparties.

Agency counterparties assume certain responsibilities. For example, if the loan was not

underwritten in accordance with the policies or guidelines of the respective Agency, the Enterprises

or the U.S. government (FHA, VA, or RHS) can pursue the seller for damages or require repurchase

of the loan. Originators that retain the servicing for the loans sold or securitized via the Agencies

must agree to service the loans in accordance with the respective Agency guidelines.

Although NMCs have always originated loans, until the 2010s most nonbank originators were too

small to handle the responsibilities of being an Agency servicing counterparty in a cost-eective

way. Instead, they sold their originations to bank or NMC aggregators. In 2008, independent NMCs

were the sellers for only 10 percent of mortgages in Enterprise securitizations and the issuers for 14

percent of mortgages in Ginnie Mae securitizations (see Figure 5). After the 2007-09 nancial crisis,

some large banks withdrew from the Agency counterparty role for the reasons noted in Section 3.2

and some independent NMCs responded to this market opportunity by expanding their operations

and becoming Agency counterparties. By 2022, independent NMCs were the sellers for 66 percent of

mortgages in Enterprise securitizations and the issuers for 84 percent of mortgages for Ginnie Mae

securitizations.

38

38 is paragraph focuses solely on independent NMCs because they may pose more counterparty risk to the Agencies

than bank-aliated NMCs. Banks and bank holding companies are subject to federal and state supervision and

regulation.

Note: The figure shows the market share for independent NMCs that sold originations to

the Enterprises or issued a securitization guaranteed by Ginnie Mae. In some cases that

NMC was the mortgage originator and in some cases it was a mortgage aggregator.

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (U.S.), Home Mortgage

Disclosure Act (Public Data)

Figure 5: Share of Originations in Agency Pools Contributed by

Independent NMCs

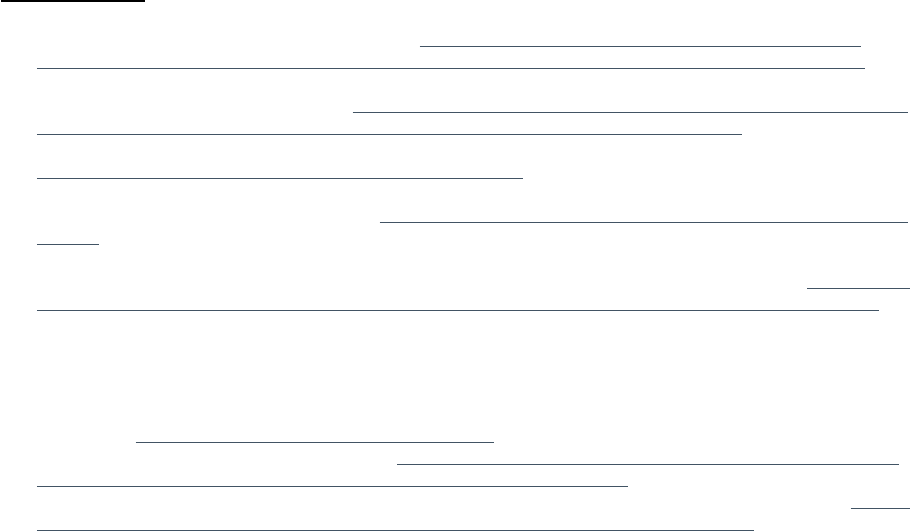

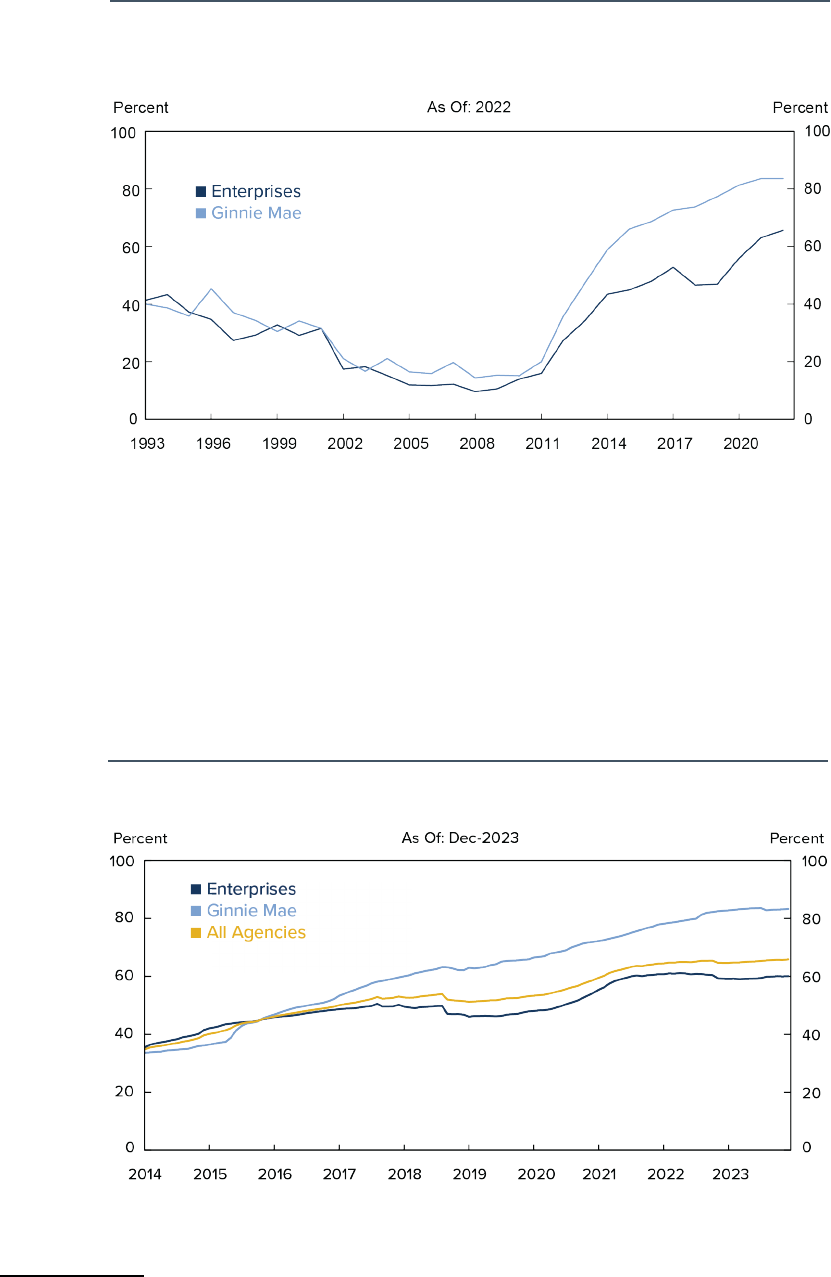

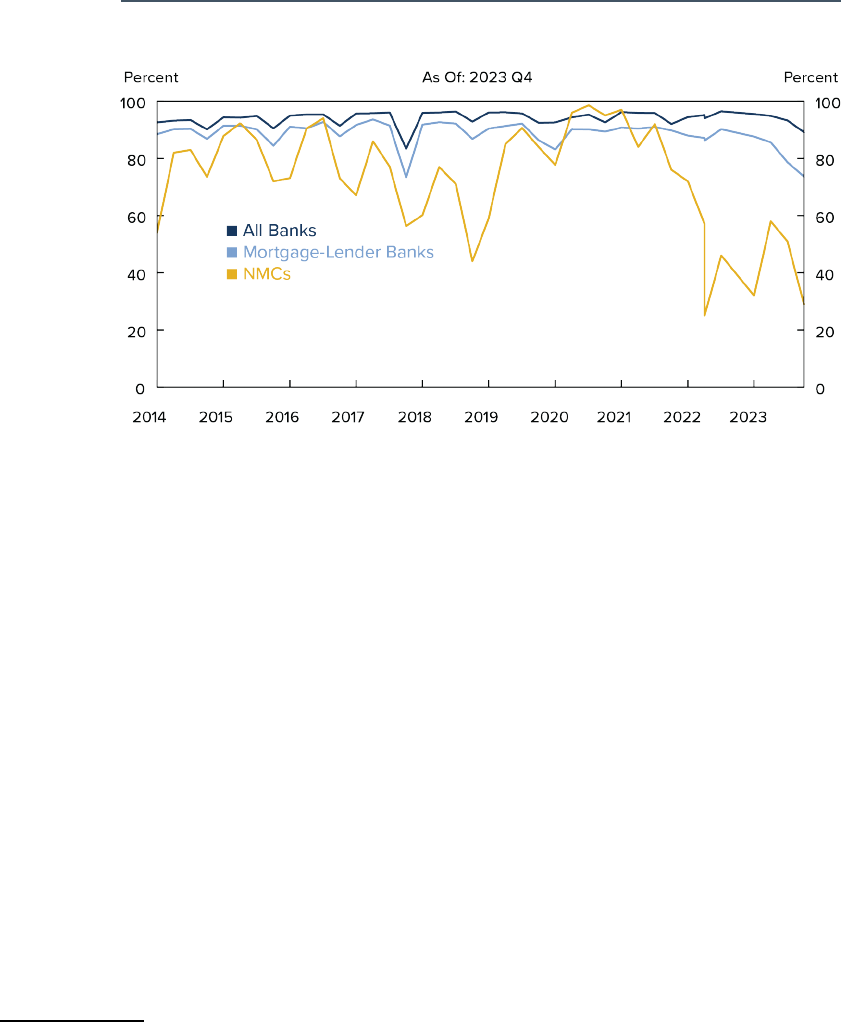

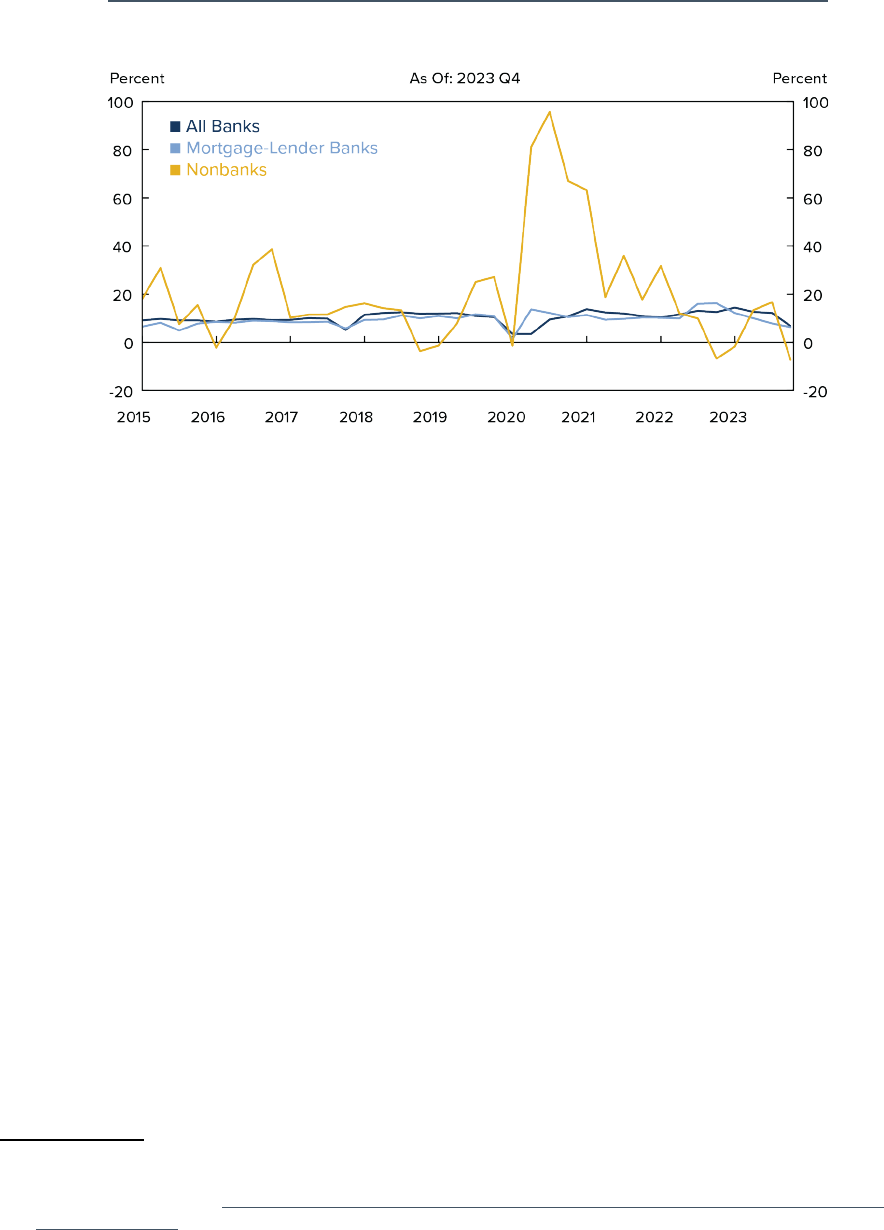

Nonbank rms also expanded their role as Agency servicers (see Figure 6). For the Enterprises,

dierent rms may serve as the seller and servicer of a loan, whereas for Ginnie Mae the functions

are combined. e share of loans serviced by nonbank mortgage servicers for the Enterprises rose

from 35 percent in 2014 to 60 percent in 2023, while the share for Ginnie Mae rose from 34 percent to

83 percent during the same period.

39

39 Statistics calculated starting in 2014 because eMBS data are incomplete in earlier years.

Source: Black Knight eMBS

Figure 6: NMC Share of Agency Servicing

3 THE GROWTH IN AGENCY SECURITIZATION AND NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES 20 |

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

3.3 Increased Aggregate Mortgage Market Exposure to Agency

Securitization and NMCs

As a result of the increased Agency securitization and NMC market share, the aggregate mortgage

market exposure to Agency securitizations with nonbank mortgage servicers has risen dramatically

over time. From 2014 to 2023, the share of all mortgages outstanding that were serviced by NMCs

and had an Agency guarantee grew from 26 percent to 44 percent.

40

In total, the Agency nonbank

mortgage servicer exposure was approximately $6 trillion at the end of 2023.

40 Estimates are for closed-end, one- to four-family residential mortgages and based on data from the Financial

Accounts of the United States and eMBS.

4 STRENGTHS OF NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES | 21

FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing

4 Strengths of Nonbank Mortgage Companies

In some circumstances, NMCs appear to have been more entrepreneurial in their marketing and

market expansion than banks. ey are generally thought to have been quicker to partner with

nancial technology (ntech) companies and leverage their technologies, especially for mortgage

origination activities.

41

In addition, because NMCs focus solely on mortgage-related products, they

may have a greater incentive than banks to adjust their operations when market conditions change.

When interest rates fall and there is greater demand for mortgages, nonbank originators may scale

quicker than banks to meet the surge in demand. In 2020, nonbank originators increased their

market share by four percentage points when mortgage interest rates fell sharply amid the policy

response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

42

As another example, in the aftermath of the 2007-09 nancial

crisis, when a large share of mortgages was delinquent or in foreclosure, some nonbank mortgage

servicers developed greater experience in handling the servicing of distressed mortgages.

43

NMCs have also developed substantial operational capacity, as evidenced by the large market share

that they originate and service. eir origination and servicing platforms are important parts of

the mortgage infrastructure, especially for historically underserved borrowers.

44

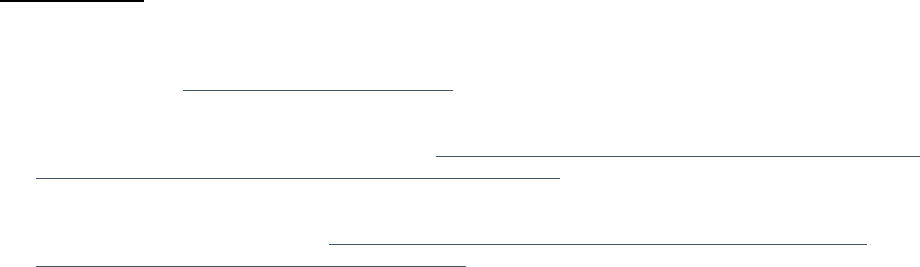

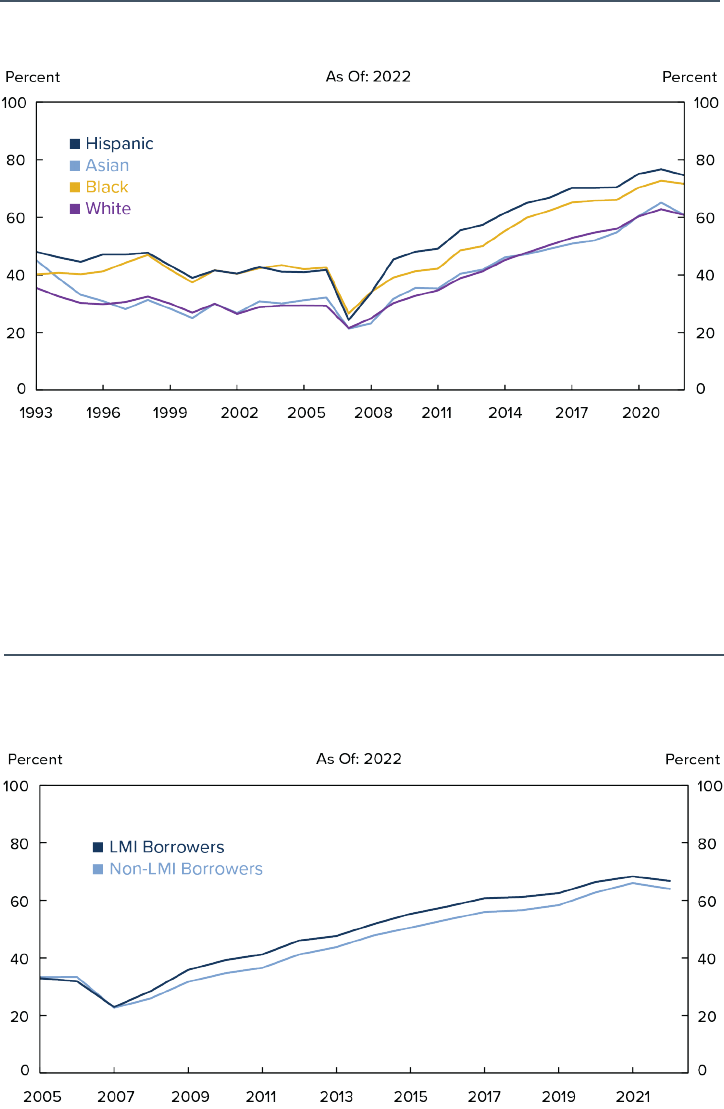

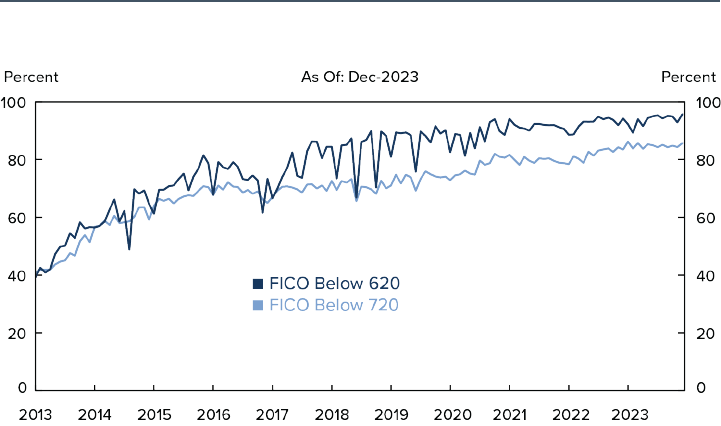

NMCs originated

72 percent and 75 percent, respectively, of mortgages extended to Black and Hispanic borrowers

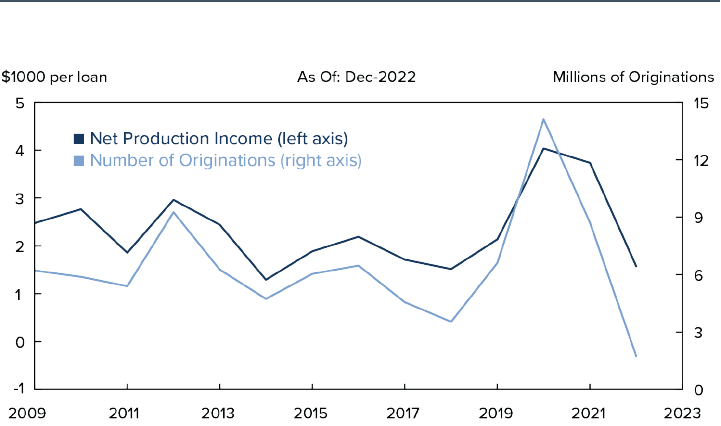

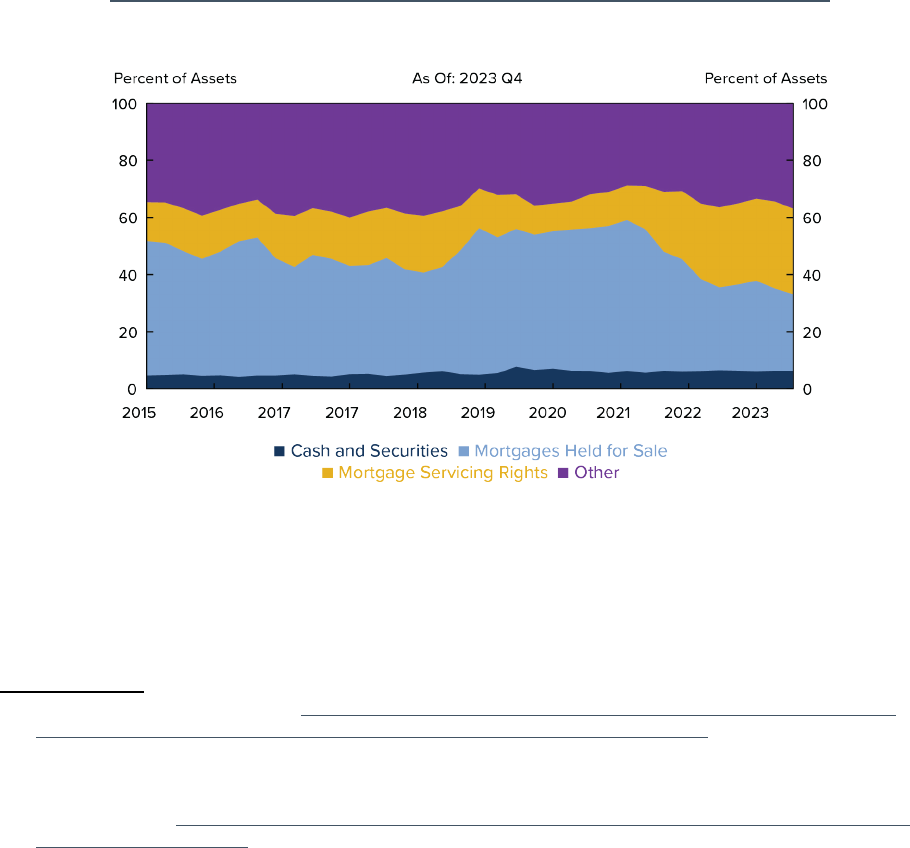

in 2022, and 61 percent of those to Asian and White borrowers; the higher NMC share for Black