[359]

Constitutional End Games: Making Presidential

Term Limits Stick

ROSALIND DIXON

†

& DAVID LANDAU

†

Presidential term limits are an important and common protection of constitutional democracy

around the world. But they are often evaded because they raise particularly difficult compliance

problems that we call “end game” problems. Because presidents have overwhelming incentives

to remain in power, they may seek extraordinary means to evade term limits. Comparative

experience shows that presidents rely on a wide range of devices, such as formal constitutional

change, wholesale constitutional replacement, and manipulation of the judiciary to get around

permanent bans on reelection. In this Article, we draw on this experience to show that, in many

contexts, weaker bans on reelection for consecutive terms, rather than permanent bans on any

reelection, are the best response to the end game problem. Would-be authoritarian presidents are

more likely to comply with term limits that force a temporary exit from the presidency because

they hold open the prospect of an eventual return to power. Furthermore, a ban on consecutive

reelection will allow alternative political forces to strengthen and make substantial democratic

erosion less likely. In this sense, the United States’ oft-cited presidential term limit, which allows

two consecutive terms in office, but prohibits all future reelection, may not be the best model for

preserving democracy.

†

Professor of Law, University of New South Wales (UNSW) (Australia).

†

Mason Ladd Professor and Associate Dean for International Programs, Florida State University

College of Law. For comments on prior drafts or ideas, we thank Mark Tushnet, Mila Versteeg, Eric Posner,

and Brian Sheppard. We also thank Melissa Vogt for outstanding research assistance.

360 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 361

I. WHY TERM LIMITS? TERM LIMITS AND DEMOCRACY ........................... 365

A. DEMOCRACY AND THE ADVANTAGES OF TERM LIMITS .............. 365

B. OBJECTIONS AND DISADVANTAGES ............................................. 369

II. MODELS OF PRESIDENTIAL TERM LIMITS .............................................. 371

III. THE PROBLEM OF COMPLIANCE ............................................................ 376

IV. THE CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF NON-COMPLIANCE .................... 385

A. THE CAUSES OF EVASION ............................................................ 385

B. THE RISKS POSED BY TERM LIMIT EVASIONS ............................. 389

V. SOLVING THE END-GAME PROBLEM: THE ROLE OF CONSECUTIVE

T

ERM LIMITS ....................................................................................... 393

A. CHANGING PRESIDENTIAL INCENTIVES ....................................... 393

B. ARE CONSECUTIVE BANS STRONG ENOUGH? .............................. 398

C. DESIGNING CONSECUTIVE TERM LIMITS: ONE TERM OR TWO .... 402

VI. AVOIDING THE PROBLEM OF SHADOW PRESIDENTS .............................. 403

A. CONSTITUTIONAL DESIGN AND SHADOW RULE .......................... 405

B. CREATING INCENTIVES TO AVOID PARTISAN BEHAVIOR ............ 408

VII. ALTERNATIVE PROPOSALS .................................................................... 409

A. SCRAPPING TERM LIMITS ............................................................. 410

B. POPULAR ENFORCEMENT OF TERM LIMITS .................................. 412

C. PROSPECTIVE-ONLY RULES OF CHANGE ..................................... 414

CONCLUSION ................................................................................................... 416

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 361

INTRODUCTION

Presidential term limits are a common feature in democratic constitutions

worldwide. By our own calculations, over 80% of presidential and semi-

presidential constitutions in force today have presidential term limits.

1

Presidential term limits are common in constitutional democracies because they

are often seen as fundamental for the preservation of constitutional democracy.

Where presidents are able to remain in office indefinitely, comparative

experience shows that they can consolidate enormous amounts of power that

vitiate checks and balances by institutions such as legislatures and courts.

2

While

elections may continue to be held, they often become increasingly non-

competitive, as presidents amass formal and informal resources and use

institutions like the judiciary to undermine the opposition. In the United States,

although formal presidential term limits date only from the Twenty-Second

Amendment, which was passed in 1947, many modern commentators now see

the limits as a core protection of the democratic order.

3

As we will show, despite

its continued reputation as an international gold standard, the U.S. presidential

term limit is vulnerable to term limit evasion in key respects.

Presidents have very strong incentives to circumvent constitutional term

limits in order to remain in power. A study by Mila Versteeg and her co-authors

has recently shown that presidents, since 2000, have sought to evade term limits

in roughly 25% of cases.

4

Where presidents try to evade their term limit, they

succeed about two-thirds of the time.

5

Presidents evade term limits through a variety of routes. Most commonly,

many presidents seek a formal amendment to the term limit; in other cases, they

induce courts to reinterpret the term limits or even to excise them entirely from

1. See infra Table 1. Other studies have reached similar results. For example, Ginsburg, Melton, and

Elkins found that, between 1789 and 2006, about 60% of presidential and semi-presidential constitutions have

had presidential term limits; this rises to over 75% for constitutions in force in 2006. See Tom Ginsburg et al.,

On the Evasion of Executive Term Limits, 52 WM. & MARY L. REV. 1807, 1835–36, 1839 fig.1 (2011). In a study

of 92 presidential and semi-presidential systems between 1992 and 2006, Gideon Maltz found that 87 had some

form of presidential term limit. The relevant 92 countries included almost all key presidential democracies—

those with a population of more than two million people which had minimal norms of political openness. The

99 “regimes” in those 92 countries included 47 democracies and 52 competitive or electoral authoritarian

regimes. Gideon Maltz, The Case for Presidential Term Limits, 18 J. DEMOCRACY 128, 128–29 (2007).

2. See generally David Landau, Abusive Constitutionalism, 47 U.C. DAVIS L. REV. 189 (2013) (pointing

out that there is a degree of abuse of power if the president may remain in office indefinitely); Maltz, supra note

1 (explaining the adoption of presidential term limits after presidential power and the ongoing presidential power

abuse in countries that have yet to adopt a term limit).

3. See, e.g., Aziz Huq & Tom Ginsberg, How to Lose a Constitutional Democracy, 65 UCLA L. REV. 78,

143–44 (2018) (arguing that the Twenty-Second Amendment and Article V cut off one key route towards

authoritarianism in the United States).

4. See Mila Versteeg et al., The Law and Politics of Presidential Term Limits Evasion, 120 COLUM. L.

REV. (forthcoming 2020) (documenting cases and techniques of evasion since 2000).

5. See id.

362 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

the constitutional order.

6

Because of the frequency of evasion attempts,

presidential term limits raise special challenges to democratic constitutionalism.

More than any other feature of a democratic constitution, presidential term

limits create limited incentives for compliance. One of the important insights in

constitutional scholarship in recent years is the degree to which many

constitutional norms effectively become self-enforcing, or self-stabilizing, over

time because they often serve as a basis for valuable forms of coordination

between different political parties or government officials.

7

Life-long bans on

reelection limits, however, remove almost all incentives for presidents to engage

in co-operation of this kind.

Faced with such limits, incumbent presidents face a form of “end period”

or “end game” problem. Compliance with term limits means that, in the short-

run, incumbent presidents are certain to lose the power and privileges associated

with high electoral office, and, in the long-run, gain only limited or uncertain

reputational benefits.

8

In many fragile democracies, political parties will also be

insufficiently strong and independent to exert pressure on a president to leave

office. Instead, they may actively encourage the president to extend their term

in office.

What is the response to this problem? One possibility, as some recent work

has suggested, is to give up the game entirely, and to remove term limits from

constitutions in contexts where they are likely to prove ineffective as constraints

on presidents.

9

But this solution throws the baby out with the bath water. It gives

up on a tool that is important for the preservation of democratic governance

simply because compliance is problematic.

Another response, which we have discussed extensively in recent work, is

to entrench term limits by requiring especially demanding procedures to change

them.

10

In the extreme, term limits are sometimes made completely

unamendable; less dramatically, constitutions can require special procedures

like heightened supermajorities or referenda before term limits can be altered.

These design solutions are sometimes helpful, but do not make the compliance

problem go away. Indeed, in some circumstances, these demanding or special

procedures to amend the term limits may worsen the end game problem because

these procedures heighten the pressure on presidential leaders to seek other

routes to eliminate term limits.

6. See id.

7. See, e.g., Tonja Jacobi et al., Judicial Review as a Self-Stabilizing Constitutional Mechanism, in

COMPARATIVE JUDICIAL REVIEW 185 (Erin F. Delaney & Rosalind Dixon eds., 2018); Daryl J. Levinson,

Parchment and Politics: The Positive Puzzle of Constitutional Commitment, 124 HARV. L. REV. 657 (2011).

8. See Bruce Baker, Outstaying One’s Welcome: The Presidential Third-Term Debate in Africa, 8

CONTEMP. POL. 285, 287 (2002).

9. See Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1855–66.

10. See Rosalind Dixon & David Landau, Tiered Constitutional Design, 86 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 438

(2018).

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 363

The optimal solution, we assert here, is to focus on temporary or

consecutive, rather than permanent, bans on reelection. Consecutive bans, which

prohibit consecutive reelection after one or more terms, require leaders to leave

power periodically, but allow a return after one or more terms out of power. In

other words, consecutive bans are “soft,” “flexible,” or “weak” term limits that

limit the scope of consecutive presidential reelection but allow non-consecutive

reelection.

11

Consecutive bans, as compared to permanent bans, have a key advantage.

By giving presidents greater incentive to comply with democratic constitutional

requirements, consecutive bans ameliorate the end game problem. Presidents

who know they may be able to return to power later are more likely to leave

power in the first place.

At the same time, pushing powerful incumbents out of power, even

temporarily, will be crucial in preventing the erosion of democracy. When

presidents re-contest an election, they no longer enjoy the benefits of

incumbency, and social and political conditions will often have changed. Voters

may no longer see the president as necessary or indispensable to their well-

being. Other members of a president’s party may also have gained strength and

an independent reputation, such that the party itself has a greater incentive and

ability to support a broader range of candidates.

Following this introduction, this Article is divided into seven parts. Part I

outlines the existing scholarly literature on the relationship between term limits

and democracy. Part II explains the prevalence and design of different kinds of

term limits. Part III outlines the special problems of compliance posed by

presidential term limits, and the empirical evidence of term limit evasion drawn

from around the world over recent decades, particularly in Latin America and

Africa. Part IV explores the causes and consequences of evasions of term limits.

Parts V, VI, and VII deal with solutions. Part V explains and defends our

proposal for weaker, consecutive bans on reelection as a solution to the end game

problem. The proposal is rooted in the successful use of non-consecutive term

limits in several countries.

Part VI deals with an important caveat to our proposal: the problem of

shadow presidents, or, in other words, circumstances where non-consecutive

bans induce presidents to leave power formally but maintain power informally.

For example, consider Russia, where Vladimir Putin temporarily left the

presidency between 2008 and 2012 but continued to exercise considerable power

11. Branko Milanovic et al., Political Alternation as a Restraint on Investing in Influence: Evidence from

the Post-Communist Transition (World Bank Dev. Research Grp., Working Paper No. 4747, 2008). This is in

line with the work of political researchers, such as Cain and Lopez, who suggest that the effectiveness of term

limits is deeply dependent on questions of design and institutional setting. See Bruce E. Cain, The Varying

Impact of Legislative Term Limits, in LEGISLATIVE TERM LIMITS: PUBLIC CHOICE PERSPECTIVES 21, 22 (Bernard

Grofman ed., 1996); Edward J. López, Term Limits: Causes and Consequences, 114 PUB. CHOICE 1, 29 (2003).

364 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

as both prime minister and party leader throughout his “absence.”

12

To be

effective, non-consecutive term limits require the creation of incentives for

presidents to move onto other non-partisan roles and the development of limits

that prevent proxy rule by a president’s family members or close associates.

Part VII briefly discusses three other proposals raised by recent

constitutional design scholarship: the proposal to scrap term limits completely

and rely instead on substitutes; the proposal to focus on popular enforcement as

a way to protect term limits; and the proposal to allow changes to term limits

only on a prospective-only basis such that it does not benefit the incumbent.

While some of these proposals are complementary to our own and have

considerable promise, they all raise problems from the standpoint of

constitutional design.

Finally, this Article concludes by considering the U.S. term limit provision

in light of the arguments developed in this Article. The United States’

presidential two-term limit is highly entrenched because Article V makes the

entire U.S. Constitution extremely difficult to change, and generally gives the

minority party the ability to block that change.

13

However, comparative

experience shows that this very rigidity may increase the incentives of presidents

to find other routes, such as manipulation of the judiciary, to achieve their goals.

Thus, the United States’ presidential term limit is more vulnerable to democratic

erosion than is commonly assumed.

The U.S. Constitution does not deal with the end game problem as

effectively as a weaker, or non-consecutive term limit. This may become a

matter of immediate concern in the United States, given that a myriad of

commentators have noted how the country currently appears to be particularly

vulnerable to democratic erosion.

14

It also suggests that the United States’ two-

term presidential term limit may be a poor model for presidential systems

abroad, despite its popularity (it is one of the most commonly used presidential

term limit found in the world today)

15

and the United States’ continued

reputation for democratic stability.

16

12. See J. L. BLACK, THE RUSSIAN PRESIDENCY OF DMITRY MEDVEDEV, 2008–12: THE NEXT STEP

FORWARD OR MERELY A TIME OUT? 12 (2015); Christian Need & Matthias Schepp, The Puppet President:

Medvedev’s Betrayal of Russian Democracy, SPIEGEL ONLINE (Oct. 4, 2011, 3:51 PM),

https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/the-puppet-president-medvedev-s-betrayal-of-russian-democracy-

a-789767.html.

13. See Huq & Ginsburg, supra note 3, at 143–44.

14. See id. at 165 (arguing that “there is a present danger of constitutional retrogression” in the United

States). See generally CAN IT HAPPEN HERE? AUTHORITARIANISM IN AMERICA (Cass R. Sunstein ed., 2018)

(containing a series of essays on the United States’ vulnerabilities to authoritarianism); STEVEN LEVITSKY &

DANIEL ZIBLATT, HOW DEMOCRACIES DIE (2018) (pointing out various ways in which the United States may be

vulnerable to global pathways of democratic erosion).

15. See Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1836.

16. See infra Table 1.

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 365

I. WHY TERM LIMITS? TERM LIMITS AND DEMOCRACY

Presidential term limits have a wide range of defenders and critics.

Defenders of term limits often point to several arguments in favor of such

limits.

17

A. D

EMOCRACY AND THE ADVANTAGES OF TERM LIMITS

One argument in favor of term limits is that their existence may help draw

more people into office. This argument has more force in some contexts than

others (for example, in local and state elections, where there is a greater chance

of participation by ordinary citizens, than say in national elections) and intersects

with arguments for increasing the representation of women and racial minorities

in political elections.

18

Generally, the argument reflects deeper philosophical

commitments to participatory forms of government and decision-making by all

citizens. As such, the argument is sometimes labelled populist in nature.

19

In the

current climate of illiberal populism, it is perhaps better understood as an

argument for more citizen participation in democratic self-government.

A second argument focuses on the behavior of existing representatives and

their tendency to vote in their own narrow self-interest, or that of their

constituents, as opposed to the broader public interest.

20

Term limits can help

reduce pressure on legislators to vote with reelection in mind because it “frees”

them of “career considerations” or eliminates the need to win reelection. Thus,

legislators are given the scope to engage in reasoned deliberation and decision-

making, or “republican” forms of debate and representation.

21

Some political

scientists further suggest that term limits will reduce overall government

expenditures, especially inefficient forms of expenditure designed to ensure the

reelection of specific representatives.

22

17. See Bruce E. Cain & Marc A. Levin, Term Limits, 2 ANN. REV. POL. SCI. 163, 167–72 (1999).

18. See, e.g., Mark P. Petracca, A Legislature in Transition: The California Experience with Term Limits

19 (Inst. Governmental Studies, Working Paper No. 96-19, 1996).

19. See Cain & Levin, supra note 17, at 168–69; Robert Kurfirst, Term-limit Logic: Paradigms and

Paradoxes, 29 POLITY 119, 123–24 (1996).

20. This, of course, reflects more general tensions within democratic theory about the nature of democracy

and the broader role of legislators. See generally RICHARD A. POSNER, LAW, PRAGMATISM, AND DEMOCRACY

(2003); JEREMY WALDRON, LAW AND DISAGREEMENT (1999).

21. See HARVEY C. MANSFIELD, JR., AMERICA’S CONSTITUTIONAL SOUL (1991); GEORGE F. WILL,

RESTORATION: CONGRESS, TERM LIMITS, AND THE RECOVERY OF DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY (1992); Cain &

Levin, supra note 17, at 170; Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1822; Kurfirst, supra note 19, at 125–26. For

empirical support for this idea, see, for example, Holger Sieg & Chamna Yoon, Estimating Dynamic Games of

Electoral Competition to Evaluate Term Limits in U.S. Gubernational Elections, 107 AM. ECON. REV. 1824

(2017); Daniel J. Smith et al., Long Live the King? Death as a Term Limit on Executives 8–9 (Feb. 22, 2018)

(unpublished manuscript) (on file with authors).

22. See Timothy Besley & Anne Case, Does Electoral Accountability Affect Economic Policy Choices?

Evidence from Gubernational Term Limits, 110 Q.J. ECONOMICS 769 (1995); Timothy Besley & Anne Case,

Incumbent Behavior: Vote-Seeking, Tax-Setting, and Yardstick Competition, 85 AM. ECON. REV. 25 (1995);

Timothy Besley & Anne Case, Political Institutions and Policy Choices: Evidence from the United States, 41 J.

ECON. LITERATURE 7 (2003). But see López, supra note 11.

366 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

The most important modern argument in favor of presidential term limits–

and the one emphasized in this Article—is that term limits have the capacity to

protect democracy and democratic competition by reducing the advantages that

an incumbent possesses in democratic elections and the strength of an

incumbent’s individual personal rule.

23

Incumbents enjoy a range of advantages in democratic elections. For

example, they generally enjoy a stronger reputation or name-recognition among

voters, compared to their competitors. John Lott describes these advantages as

the product of a prior “investment in brand name capital” that is both “sunk” and

“non-transferable,” and that can create an effective barrier to entry by political

challengers.

24

Voters may also be inherently biased toward incumbents because

they may perceive less risk associated with incumbents than with challengers.

25

In addition, incumbents may have greater access to state resources, the

support of the media and interest groups, and the ability to rely on forms of

clientelist or patronage politics to ensure reelection.

26

In hybrid or electoral

authoritarian regimes, incumbents may benefit from the active support of state

media outlets and the ability to use both the civil and criminal law to intimidate

and harass the political opposition and its supporters. The advantages

incumbents enjoy are not the same across all political systems. As Nic

Cheeseman notes, U.S. incumbents often benefit from strong name recognition,

whereas African incumbents rely more heavily on patronage networks.

27

However, there is strong empirical evidence that incumbent legislators and

executive actors enjoy advantages as a result of their incumbency worldwide.

In the United States, the incumbent reelection rate was approximately 97%

in the House of Representatives and 93% in the Senate in 2016.

28

At the state

23. Some political scientists further suggest that this gives incumbents opportunities for “rent extraction.”

Term limits can also potentially limit this kind of rent extraction both directly and indirectly—by reducing

incumbent reelection, and by limiting the timeframe over which incumbents can reach agreements to engage in

log-rolling or rent-sharing behavior. See Barry R. Weingast & William J. Marshall, The Industrial Organization

of Congress; or, Why Legislatures, Like Firms, Are Not Organized as Markets, 96 J. POL. ECON. 132, 138 (1988).

24. John R. Lott, Jr., The Effect of Nontransferable Property Rights on the Efficiency of Political Markets:

Some Evidence, 32 J. PUB. ECON. 231 (1987); see also John R. Lott, Jr., Brand Names and Barriers to Entry in

Political Markets, 51 PUB. CHOICE 87, 89–90 (1986).

25. See M. Daniel Bernhardt & Daniel E. Ingberman, Candidate Reputations and the “Incumbency Effect,”

27 J. PUB. ECON. 47, 49 (1985). The counter-argument is of course that in some elections, voters are looking for

change and will thus, tend to be biased toward challengers.

26. See Nic Cheeseman, African Elections as Vehicles for Change, 21 J. DEMOCRACY 139, 145–46 (2010);

John N. Friedman & Richard T. Holden, The Rising Incumbent Reelection Rate: What’s Gerrymandering Got

to Do with It?, 71 J. POLITICS 593, 596 (2009); Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1820; Maltz, supra note 1, at

131–35.

27. See Cheeseman, supra note 26, at 140, 145–46.

28. Kyle Kondik & Geoffrey Skelley, Incumbent Reelection Rates Higher than Average in 2016,

RASMUSSEN REP. (Dec. 15, 2016), http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/

political_commentary/commentary_by_kyle_kondik/incumbent_reelection_rates_higher_than_average_in_20

16; see also Andrew Gelman & Gary King, Estimating Incumbency Advantage Without Bias, 34 AM. J. POL.

SCI. 1142 (1990).

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 367

level, sitting governors enjoyed an 80% reelection rate.

29

For presidents, the

reelection rate was lower: of twenty-six presidents who ran for reelection in a

general election, only sixteen, or 62%, won a second consecutive term.

30

But

this pattern is not replicated in other presidential systems, where incumbents

seem to have larger advantages.

In Latin America, Javier Corrales and Michael Penfold found that, between

1998 and 2006, sitting presidents enjoyed a 90% chance of winning a second

consecutive term, and an 83% chance of subsequent or indefinite reelection,

such that there was effectively a 62.8% increased chance of reelection for

presidential incumbents.

31

Incumbency also affected the margin of victory in

presidential elections; it increased the margin of a president’s victory over their

nearest rival by approximately 11.2%,

32

and was the strongest factor in

predicting both the probability and margin of victory for presidential elections.

33

In Africa, Gideon Maltz likewise found that, in elections between 1992 and

2006, incumbent presidents were re-elected at a rate of 93%.

34

The incumbent

reelection rate is so high in Africa that, when combined with patterns of ongoing

authoritarian rule, only twelve sub-Saharan countries between 1989 and 2010

experienced a change in presidential leadership through democratic elections.

35

Since then, there have been only three notable instances of a change in

presidential leadership as a result of democratic elections in which incumbents

were eligible to run: Nigeria and Zambia in 2015,

36

and Ghana in 2016.

37

As

Cheeseman notes, this is not simply due to the significant number of electoral or

competitive authoritarian systems in Africa.

38

Even when these countries are

excluded, incumbents won reelection in 64% of elections.

39

29. Kondik & Skelley, supra note 28.

30. See Michael Medved, For U.S. Presidents, Odds for a Second Term Are Surprisingly Long, DAILY

BEAST, https://www.thedailybeast.com/for-us-presidents-odds-for-a-second-term-are-surprisingly-long (last

updated July 13, 2017, 1:20 PM) (reporting 15). President Obama is the 16th. See Michael E. Purdy, Only 30%

of U.S. Presidents Served 2 Full Terms, PRESIDENTIAL HISTORY (Jan. 16, 2013),

https://presidentialhistory.com/2013/01/only-30-of-u-s-presidents-served-2-full-terms.html. Of the other 17

previous presidents, 5 died while in office, 7 declined to run for reelection, and 5 failed to gain their party’s

nomination. PRESIDENTS, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/ (last visited Jan. 24,

2020).

31. Javier Corrales & Michael Penfold, Manipulating Term Limits in Latin America, 25 J. DEMOCRACY

157, 163 (2014).

32. Id. at 164.

33. See id. at 162–64.

34. Cheeseman, supra note 26, at 139–40; Maltz, supra note 1, at 134.

35. Cheeseman, supra note 26, at 139.

36. See Africa’s 2015 Election Experiences Present Dilemmas for 2016 Polls, CONVERSATION (Jan. 26,

2016, 11:02 PM), https://theconversation.com/africas-2015-election-experiences-present-dilemmas-for-2016-

polls-53312.

37. Yomi Kazeem, Ghana Has Elected Nana Akufo-Addo as Its New President, QUARTZ AFR. (Dec. 9,

2016), https://qz.com/858481/ghana-decides-nana-akufo-addo-has-been-elected-as-ghanas-new-president/.

38. See Cheeseman, supra note 26, at 142.

39. Id.

368 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

Term limits can significantly reduce the advantage of incumbency in

democratic elections. In the United States, there is strong evidence that term

limits tend to increase the competitiveness of legislative elections. Kermit

Daniel and John Lott, for example, found that term limits had a strong and

significant effect on a range of measures of competitiveness in state legislative

elections, including who won, who was defeated, the margin between the top

two candidates, and the number of unopposed races.

40

In a global context, there is likewise evidence that term limits promote an

increase in political competition, as well as alternation in individual rule. A

transition in political leadership often weakens the dominant political party in a

competitive authoritarian regime such that it is less able to engage in tactics

designed to undermine true political competition, such as electoral intimidation,

voter registration fraud, and vote tampering.

41

A new leader of a party also

generally has less electoral name recognition and respect than the outgoing

president.

42

New party leaders may even be selected in part because they are not

seen to pose a serious threat to the ongoing power and prestige of the outgoing

president. This gives opposition parties a significantly greater chance of success

in elections against successor candidates than against incumbents.

Two leading examples, highlighted by Maltz, are the changes in political

control of the presidency in Croatia, in 2000, and Kenya, in 2002.

43

In Croatia,

President Franjo Tudjman and his Croatian Democratic Union had been in

power since 1990, but when Tudjman died, his political successor failed to reach

the runoff stage at subsequent presidential elections.

44

In Kenya, President

Daniel Arp Moi ruled from 1978 to 2002.

45

When Moi left office in 2002, at the

end of the formal term limits he agreed to in the 1990s, his party lost control of

the presidency, and Mwa Kibaki was elected to office.

46

Moi’s successor, Uhuru

Kenyatta, did not enjoy the same popular support or appeal as Moi, and many

commentators believe that Moi in fact chose Kenyatta because of this weakness,

understanding that it would make him dependent upon Moi.

47

These patterns are also borne out by quantitative studies of presidential

reelection rates. In Africa, for example, Maltz found that successor candidates

(candidates from the same party as an outgoing president) have a 52% chance of

40. See Kermit Daniel & John R. Lott, Jr., Term Limits and Electoral Competitiveness: Evidence from

California’s State Legislative Races, 90 PUB. CHOICE 165, 181 tbl.7 (1997).

41. Maltz, supra note 1, at 133–34.

42. See Joel Lieske, The Political Dynamics of Urban Voting Behavior, 33 AM. J. POL. SCI. 150, 168

(1989).

43. Maltz, supra note 1, at 131–32.

44. Id. at 131.

45. Id.

46. See id.

47. See id. at 132.

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 369

a successful election, compared to a 93% reelection rate for incumbents.

48

In

competitive democracies, the figure is 50%, compared to 64% for incumbents.

49

The mere alternation in individual presidential rule can help protect

democracy, even where the alternation occurs within an existing party.

Libertarian arguments for term limits, for example, focus on the capacity of term

limits to weaken the power of the legislative or executive branch, and thus,

promote commitments to limited government and individual liberty.

50

These

arguments overlap with democratic arguments for term limits, or at least

executive term limits.

A common hallmark of authoritarian government is an extremely strong

executive branch that has a tradition of personalist presidential rule. Guarding

against the danger of authoritarianism, therefore, will generally require limiting

the powers of the executive branch, especially if there are individual executive

leaders.

51

Term limits are an obvious way to do this because they force a

dominant president to leave office in ways that reduce the informal power of the

presidency. Term limits also undermine the network of clientelist and patronage

relationships that help sustain electoral authoritarian systems.

52

The spread of

presidential term limits in both Africa and Latin America in recent decades

reflects this logic.

53

As John Carey notes, these prohibitions have been

“motivated both by theory and by experiences of individual politicians who

endeavored to entrench themselves in power.”

54

B. O

BJECTIONS AND DISADVANTAGES

Critics of term limits, on the other hand, suggest that they tend to

undermine democracy because they deprive institutions of the professional

expertise and experience needed for success, undermine the incentives and

accountability of elected officials, and deny voters the opportunity to re-elect

their preferred representative.

55

These arguments also have a long lineage—

48. Id. at 134.

49. Cheeseman, supra note 26, at 142.

50. See Cain & Levin, supra note 17, at 171; Kurfirst, supra note 19, at 126–27.

51. See Baker, supra note 8, at 288–89; Maltz, supra note 1, at 130.

52. See Baker, supra note 8, at 288–89, 297–98; Cheeseman, supra note 26, at 150–51; Maltz, supra note

1, at 136–37; Milanovic et al., supra note 11.

53. See John M. Carey, The Reelection Debate in Latin America, 45 LATIN AM. POL. & SOC’Y 119, 122,

127 (2003); see also Ginsburg et al., supra note 1; Maltz, supra note 1, at 131; Denis M. Tull & Claudia Simons,

The Institutionalization of Power Revisited: Presidential Term Limits in Africa, 52 AFR. SPECTRUM 79, 82

(2017).

54. Carey, supra note 53, at 122. Simon Bolivar made an earlier argument for term limits in Latin America

on this basis. See Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1819–20. Note, however, that Bolivar ultimately reversed his

position. See Carey, supra note 53, at 121–22; Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1819.

55. See Cain & Levin, supra note 17, at 182–84; Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1824; Mark P. Petracca,

Why Political Scientists Oppose Term Limits (Feb. 18, 1992) (unpublished briefing paper) (on file with the Cato

Institute) (addressing professionalism).

370 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

many of them were made by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 72.

56

Some

scholarship credit Hamilton’s arguments for defeating proposals to include

presidential term limits in the original U.S. Constitution.

57

Concerns about expertise and electoral incentives, discussed in Part V, can

be addressed by appropriately generous and flexible forms of term limits. The

concern about democracy seems to overlook two key arguments. First, term

limits can play a role in preventing a slide toward authoritarianism or democratic

regression. Second, there are democratic procedural arguments in favor of such

limits (for example, the strong degree of popular support for the enactment of

term limits, and the fact that many term limit provisions are introduced by way

of an amendment proposed or ratified by voters at referenda).

In Africa, for example, public opinion polling by Afrobarometer between

2011 and 2013 found that 75% of voters across thirty-four countries favored a

two-term limit for presidents.

58

Ed Glaeser suggests that this is consistent with

risk aversion among democratic voters due to a preference for “cycling of

ideologies rather than locking into a single ideology,” or a preference for a

degree of ongoing political or ideological alternation.

59

Some scholars further suggest that, at least under certain conditions, term

limits may help promote democratic choice. Term limits solve a coordination

problem among voters in different parties who wish to see, in addition to a norm

of alternation in office, candidates from their own party succeed in elections.

60

We do not suggest that democratic concerns necessarily favor term limits

in all contexts and for all institutions. The strength of the executive in fragile

democracies, for example, is itself often the product of a history of weak

legislatures incapable of imposing any meaningful checks on the executive

branch. A key means of checking the potential for abuse by the legislature will

thus be to increase the power and independence of the legislature. A stronger

legislature will often impose term limits on the executive.

61

Term limits, as

Robert Kurfirst notes, have an important impact not only on the absolute power

of institutions, but also on their relative power and standing.

62

56. See THE FEDERALIST NO. 72 (Alexander Hamilton) (Yale Univ. Press ed., 2009).

57. See Carey, supra note 53, at 120–21.

58. See BONIFACE DULANI, AFRICAN PUBLICS STRONGLY SUPPORT TERM LIMITS, RESIST LEADERS’

EFFORTS TO EXTEND THEIR TENURE 3 fig.1 (2015); see also Adrienne LeBas, Term Limits and Beyond: Africa’s

Democratic Hurdles, 115 CURRENT HIST. 169, 170 (2016) (explaining that Africa is paying heightened attention

to the idea of presidential term limits).

59. See Edward L. Glaeser, Self-Imposed Term Limits, 93 PUB. CHOICE 389, 390 (1997).

60. See, e.g., Andrew R. Dick & John R. Lott, Jr., Reconciling Voters’ Behavior with Legislative Term

Limits, 50 J. PUB. ECON. 1, 8 (1993); Einer Elhauge, Are Term Limits Undemocratic?, 64 U. CHI. L. REV. 83,

85–86 (1997); Glaeser, supra note 59, at 389–90.

61. Some economists likewise suggest that it is important to weaken personal rule so as to promote the rule

of law—this encourages private actors to invest in general rule of law protections, rather than in developing

“clientilistic” relationships with individual political leaders. See Milanovic et al., supra note 11, at 3–4.

62. See Kurfirst, supra note 19, at 129–34. For the argument that term limits on executive and legislative

officials may in fact be symbiotic or complementary in this context, see Michael J. Malbin & Gerald Benjamin,

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 371

Thus, we focus here on presidential term limits. Some countries may

choose to adopt legislative term limits as an additional tool for promoting good

government. However, the case for legislative term limits is more contingent,

especially in cases where they weaken the power of the legislature and, thus,

create an imbalance in the separation of powers.

63

II.

MODELS OF PRESIDENTIAL TERM LIMITS

In constitutional design, arguments in favor of presidential term limits have

won the day in the modern period. However, historically, this tradeoff was not

always resolved in favor of presidential term limits, and term limits have not

always been a standard part of constitutional design. Many early national

constitutions, such as the United States Constitution of 1787 and the French

Constitution of 1791, did not include them.

64

The U.S. Constitution instead

adopted an informal two-term limit, which lasted until President Franklin

Delano Roosevelt ran for, and won, four consecutive terms in the 1930s and

1940s.

65

Following his death, the United States formalized a presidential two-

term limit in the 22nd Amendment, which was adopted in 1951.

66

In recent times, the adoption of presidential term limits has become the

overwhelming design choice in presidential and semi-presidential systems.

67

Public opinion data shows that presidential term limits are generally very

popular.

68

Even where individual presidents are popular, voters do not want

them to remain in office forever. In contrast, term limits for other kinds of actors

are less common. For example, a much smaller number of countries have term

limits for members of the legislature.

69

Similarly, term limits for subnational

officials, such as governors, appear to be less common than for presidents.

70

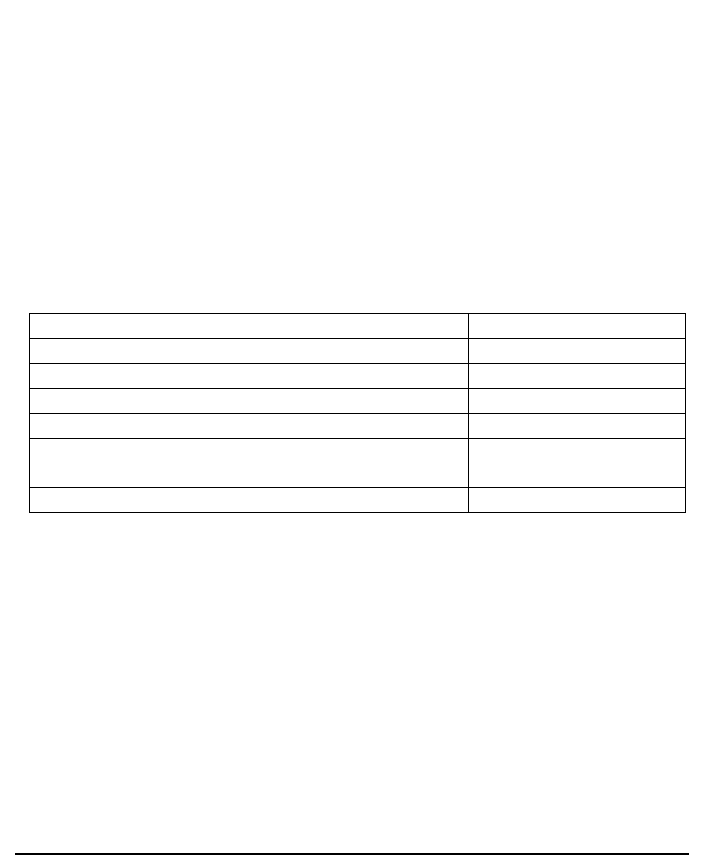

Table 1, based on our own calculations, presents term limits in all presidential

and semi-presidential systems as of 2019. The most immediate point is that most

systems have presidential term limits—only 16% lack them. Moreover, the

characteristics of these countries support an argument that the absence of

presidential term limits tends to erode constitutional democracy. Most of these

countries, such as Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Cameroon, Nicaragua, and

Legislatures After Term Limits, in LIMITING LEGISLATIVE TERMS 209, 220 (Gerald Benjamin & Michael J.

Malbin eds., 1992).

63. In this sense, we take the opposite approach to much of the literature, which tends to be more heavily

focused on legislative as opposed to executive term limits. See López, supra note 11, at 2.

64. As noted above, Hamilton, in the Federalist Papers, argued against them. See THE FEDERALIST NO. 72,

supra note 56.

65. See Peter Feuerherd, How FDR’s Presidency Inspired Term Limits, DAILY JSTOR (Apr. 12, 2018),

https://daily.jstor.org/how-fdrs-presidency-inspired-term-limits/.

66. Id.

67. See ALEXANDER BATURO, DEMOCRACY, DICTATORSHIP, AND TERM LIMITS 32 (2014).

68. See Dulani, supra note 58.

69. See VENICE COMMISSION, REPORT ON TERM LIMITS (2019) [hereinafter REPORT ON TERM LIMITS]

(exemplifying the ongoing debate about whether the legislature should be subject to term limits).

70. See id.

372 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

Venezuela, are ones that observers have argued are hybrid or pure authoritarian

regimes.

71

Table 1: Presidential Term Limits in Presidential and Semi-Presidential

Systems, 2019

Type of Term Limit Percent of Countries

No reelection allowed 8%

Bar on consecutive term after one term 8%

Bar on consecutive term after two terms 7%

Absolute bar after two terms 57%

Ambiguous whether absolute or consecutive bar

after two terms

4%

No term limit 16%

*NOTE: SOURCE: AUTHORS’ CALCULATIONS FROM CONSTITUTIONAL TEXTS.

Initially, constitutions that now lack term limits often included them.

72

But

in order to remain in power, incumbents used constitutional amendments,

through the use of referenda, or other devices such as judicial decisions, to

remove the term limits.

73

The argument in favor of the removal of term limits

generally stressed the importance of continuity in exceptional circumstances.

74

For example, in Venezuela, a 1999 Constituent Assembly dominated by

President Chavez stretched the presidential term limit from one term to two

terms.

75

Later, during Chavez’s second full term, he called for two referenda,

one in 2007 and another in 2009, to remove presidential term limits.

76

The first

effort narrowly failed, but the second succeeded.

77

The argument from Chavez

and his allies was essentially that reelection was a regrettable necessity to keep

71. See Nicolas Cherry, The Abolition of Presidential Term Limits in Nicaragua: The Rise of Nicaragua’s

Next Dictator?, 2 CORNELL INT’L L.J. ONLINE 31 (2014) (discussing Nicaragua); Maltz, supra note 1, at 130,

128, 135 (discussing Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Venezuela); Cheryl Hendricks & Gabriel Ngah

Kiven, Cameroon Presidential Poll Underscores the Need for Term Limits, CONVERSATION (Oct. 8, 2018, 11:19

AM), https://theconversation.com/cameroon-presidential-poll-underscores-the-need-for-term-limits-104583

(discussing Cameroon).

72. See Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, 1835–36; Cheryl Hendricks & Gabriel Ngah Kiven, Presidential

Term Limits: Slippery Slope Back to Authoritarianism in Africa, CONVERSATION (May 17, 2018, 8:44 AM),

https://theconversation.com/presidential-term-limits-slippery-slope-back-to-authoritarianism-in-africa-96796;

Boniface Madalitso Dulani, Personal Rule and Presidential Term Limits in Africa (2011) (unpublished Ph.D

dissertation, Michigan State University) (on file with Michigan State University Library).

73. See, e.g., REPORT ON TERM LIMITS, supra note 69, at 14 (prohibiting use of referenda to override a

constitutional amendment to instate term limits, if adopted); Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1810, 1812, 1847–

48.

74. See, e.g., Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, 1823–27.

75. See Venezuela’s Chavez Era 1958–2013, COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELS.,

https://www.cfr.org/timeline/venezuelas-chavez-era (last visited Jan. 24, 2020).

76. Id.

77. Id.

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 373

his project on track, and the sweeping transformations that his regime was

carrying out could not be entrusted to anyone else.

78

Some countries, about 8% of presidential and semi-presidential systems,

take the strictest possible stance towards presidential term limits and prohibit

any presidential reelection once an incumbent has served a single term in

office.

79

The position taken by these countries obviously stresses the risks of

reelection to democracy, even at the cost of foregoing the expertise and

incentives that reelection may promote.

Of course, the effect of a strict one-term limit will also depend on other

formal and informal aspects of the constitution. The most obvious interaction

here is the length of presidential terms. Globally, presidential terms appear to

vary between four and seven years, and term lengths closer to the latter end of

the spectrum will give presidents more space to pursue their agendas than the

former.

In Mexico, for example, presidents can serve only one six-year term in their

lives.

80

The principle of no reelection is a defining principle of Mexican politics,

even during its lengthy one-party dictatorship throughout most of the 20th

century.

81

In some ways, a lengthy term counterbalances the lack of reelection.

As a result, Mexico has had a series of highly consequential administrations

during the dictatorship, and during and after its transition to democracy.

82

Colombia, in contrast, historically allowed only one four-year term in a

president’s lifetime.

83

In 2005, President Alvaro Uribe amended the constitution

to allow two consecutive terms and won reelection to a second term.

84

However,

his subsequent attempt to amend the constitution again to allow three straight

terms was blocked by the courts.

85

As a result, both Uribe and his successor,

Juan Manuel Santos, were highly consequential presidents who served two terms

each.

86

The former pursued a strategy of “democratic security” to repress the

78. See David Landau, Constitution-Making and Authoritarianism in Venezuela: The First Time as

Tragedy, the Second as Farce, in CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY IN CRISIS? 161–63 (Mark A. Graber et al. eds.,

2018).

79. See supra Table 1.

80. Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, CP, Arts. 82–83, Diario Oficial de la

Federacíon [DOF] 05-02-1917, últimas reformas DOF 09-08-2019 (Mex.).

81. See Jeffrey Weldon, The Political Sources of Presidencialismo in Mexico, in PRESIDENTIALISM AND

DEMOCRACY IN LATIN AMERICA 225 (Scott Mainwaring & Matthew Soberg Shugart eds., 1997).

82. See EMILY EDMONDS-POLI & DAVID A. SHIRK, CONTEMPORARY MEXICAN POLITICS 49–96 (3d ed.

2016).

83. See Rosalind Dixon & David Landau, Transnational Constitutionalism and a Limited Doctrine of

Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendment, 13 INT’L J. CONST. L. 606, 615 (2015).

84. See id. at 615–16.

85. Id. at 616.

86. See, e.g., Alia M. Matanock & Miguel García-Sánchez, The Colombian Paradox: Peace Processes,

Elite Divisions and Popular Plebiscites, DAEDALUS J. AM. ACAD. ARTS & SCI. 152 (2017); Jeremy McDermott,

How President Alvaro Uribe Changed Colombia, BBC NEWS (Aug. 4, 2010),

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-10841425; Maria Alejandra Silva, Alvaro Uribe: The Most

Dangerous Man in Colombian Politics, COUNCIL ON HEMISPHERIC AFF. (Oct. 20, 2017),

374 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

FARC guerilla movement, and the latter sought a peace agreement that took

many years to pursue.

87

Santos, however, re-imposed a one-term, four-year limit

during his second term in office, and it remains to be seen how this will impact

the strength of future administrations.

88

Most presidential and semi-presidential systems around the world take an

intermediate position, balancing the benefits and costs of presidential term

limits. The most common design, implemented by over half of all presidential

and semi-presidential systems, prohibits any reelection after two consecutive

terms in office.

89

This absolute bar on reelection after two terms appears to be

aimed at balancing different aspects of the tradeoff. An absolute two-term limit

allows voters to reward good performance and punish bad performance.

Moreover, successful programs can continue for eight or more years, depending

on the length of presidential term, giving presidents considerable time to develop

their policies. Nonetheless, the term limit forces turnover in office and prevents

incumbent presidents from amassing too much power.

An alternative design choice, one we argue for in this Article, bars

consecutive reelection.

90

A system that bars consecutive reelection allows

presidents to serve one or two terms in office consecutively, but then require that

they sit out for one or more terms before running for election again.

91

Chile, for

example, bars consecutive reelection from presidents after serving one four-year

term, but allows them to return to power after sitting out one term.

92

Former

president Michele Bachelet, for example, served between 2006 and 2010, and

again from 2014 until 2018.

93

http://www.coha.org/alvaro-uribe-the-most-dangerous-man-in-colombian-politics/; Lally Weymouth, An

Interview with Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos, WASH. POST (Aug. 7, 2014),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/an-interview-with-colombian-presidentjuan-manuel-

santos/2014/08/07/3eaff428-1ced-11e4-82f9-2cd6fa8da5c4_story.html.

87. See Matanock & García-Sánchez, supra note 86, at 155; McDermott, supra note 86.

88. See Elizabeth Reyes L., Colombian Lawmakers Approve a One-Term Limit for Presidents, EL PAÍS

(June 4, 2015, 3:59 PM), https://elpais.com/elpais/2015/06/04/inenglish/1433416990_898964.html.

89. See supra Table 1.

90. Ginsburg, Melton, and Elkins find that the most common design of all presidential term limits

historically (as opposed to just those in force today) allowed consecutive reelection after one term in office—

27% of all constitutions used this model, according to their data. See Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1836.

91. As noted in Table 1, there is a small group of countries where it is clear from the constitutional text

that presidents can serve only two consecutive terms in office, but it is unclear whether they are only temporarily

or permanently barred after serving two terms. Taiwan, for example, recently had some controversy about

whether ex two-term President Ma Ying-Jeou could seek a third term after sitting out one term. See Brian Hioe,

Claims by SCMP that Ma Can Run for a Third Presidential Term Are Ludicrous, NEW BLOOM (May 10, 2018),

https://newbloommag.net/2018/05/10/scmp-ma-third-term/. In Malawi, the Supreme Court, in 2009, held that

an ambiguous term limit should be interpreted to bar a potential nonconsecutive third term by former President

Bakili Muluzi. See Muluzi Denied Slot in Malawi Election, UPI (May 16, 2009, 12:50 PM),

https://www.upi.com/Top_News/2009/05/16/Muluzi-denied-slot-in-Malawi-election/88971242492659/?ur3=1.

92. CONSTITUCIÓN POLÍTICA DE LA REPÚBLICA DE CHILE [C.P.] art. 25.

93. See Ernesto Londoño, President Bachelet of Chile Is the Last Woman Standing in the Americas, N.Y.

TIMES (July 24, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/24/world/americas/michelle-bachelet-president-of-

chile.html.

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 375

Until this year, the island country of Comoros allowed presidents to serve

unlimited, non-consecutive five-year terms.

94

Current President Azali

Assoumani previously served as president between 1999 and 2002, as well as

between 2002 and 2006.

95

Brazil requires that presidents sit out for at least one

term after serving two consecutive terms in office.

96

President Luiz Inacio Lula

da Silva (Lula), for example, served as president for two terms between 2003

and 2010, and was planning to run again for a second term in 2019, before being

jailed on corruption charges.

97

The bar against consecutive reelection balances the tradeoff involved in

presidential term limits in a somewhat different way than an absolute bar.

Forcing presidents to leave power may help to break excessive consolidation of

power—even if presidents are able to return later—but still gives presidents

incentives towards electoral accountability, since they may seek a new term in

the future. A bar against consecutive reelection also gives presidents more than

one term to pursue their projects, especially when they are allowed to pursue

two consecutive terms before leaving power.

As we emphasize in Part V, a design that stresses consecutive, instead of

absolute, bans on reelection may reduce the inclination of incumbents to evade

term limits by lessening the costs of compliance, thus reducing what we call the

“end game” problem.

Notably, only one system with any presidential term limits appears to allow

more than two consecutive terms in office. In the Republic of the Congo, a 2015

referendum amended the constitution to allow three consecutive four-year terms

in office.

98

The apparent lack of countries that follow a similar system reflects a

fairly broad consensus, at least at the level of constitutional design, that allowing

more than two consecutive terms in office poses threats to constitutional

democracy that outweigh any gains in electoral accountability and continuity in

policy. Despite this consensus, a number of presidents have managed to use

devices, such as temporary constitutional provisions or judicial interpretation, to

circumvent their term limits and remain in power.

99

94. CONSTITUTION DE L’UNION DES COMOROS [CONSTITUTION] Mar. 24, 2001, art. 13. The new system

allows two consecutive terms. See Comoros Islanders Vote in Presidential Election, BBC NEWS (Mar. 24, 2019),

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-47685991?intlink_from_url=https://www.bbc.com/news/topics/cx1m

7zg0gnlt/comoros&link_location=live-reporting-story.

95. See Former Coup Leader Wins Presidential Race in Comoros, VOA NEWS (Apr. 15, 2016, 8:43 PM),

https://www.voanews.com/africa/former-coup-leader-wins-presidential-race-comoros.

96. CONSTITUIҪÃO FEDERAL [C.F.] [CONSTITUTION] Dec. 2017, art. 14 (Braz.).

97. See Dom Phillips, Brazil’s Lula Launches Presidential Bid from Jail as Thousands March in Support,

GUARDIAN (Aug. 15, 2018, 6:48 PM), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/15/brazil-lula-

presidential-election-campaign-jail.

98. See Philon Bondenga, Congo Votes by Landslide to Allow Third Presidential Term, REUTERS (Oct. 27,

2015, 12:13 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-congo-politics/congo-votes-by-landslide-to-allow-third-

presidential-term-idUSKCN0SL0JW20151027.

99. A very small number of systems combine the logic of consecutive and absolute prohibitions on

reelection. These systems generally require presidents to sit out after serving one term in office, but also limit

376 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

In summary, while the vast majority of presidential and semi-presidential

systems have some kind of term limit to prevent the erosion of democracy,

almost all systems allow presidents to serve more than one term. This reflects

the value that constitutional designers place significant value on other goals,

such as accountability, efficiency, and continuity in public policy.

III.

THE PROBLEM OF COMPLIANCE

There is a strong positive correlation worldwide between the increasing

constitutional entrenchment of presidential term limits and the tendency of

presidents to leave office “voluntarily” as part of a peaceful democratic

transition, rather than through a military coup.

In Africa especially, Daniel Posner and Daniel Young note that many

countries introduced new, entrenched constitutional term limits from the 1990s

onward: thirty-two out of thirty-eight constitutions between 1990 and 2005

adopted or entrenched such limits.

100

During this period, there was a marked

increase in the number of leaders who left “voluntarily,” rather than through

coups, assassination, or other involuntary means. Between 2000 and 2005, only

19% of leaders left power involuntarily, whereas 70–75% did so in the 1960s,

1970s, and 1980s.

101

Of those seventeen leaders that left office “voluntarily”

between 2000 and 2005, nine also departed when they reached the end of their

presidential term limits.

102

The overall pattern globally, however, is not quite so positive. Rather, it

involves a significant amount of non-compliance with presidential term

limits.

103

Tom Ginsburg, James Melton, and Zachary Elkins note that, of the 352

cases in their dataset where presidents had the opportunity to over-stay (in other

words, did not depart early from office), 89 involved an attempt by presidents to

stay beyond their constitutionally permitted term, and 71 of those attempts were

successful.

104

Of these 71 cases, 56 involved formal constitutional amendment

or replacement, 29 and 27 respectively, five involved the suspension of the

constitution, and 10 involved the circumvention or disregard of constitutional

the total number of terms they can serve in their lives. For example, Haiti limits presidents to serving one

consecutive five-year term; they can return to power after sitting out one term, but are limited to serving only

two terms in their lives. LA CONSTITUTION DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE D’HAITI [CONSTITUTION] 1987, art. 134–3 (“The

President of the Republic may not be re-elected. He may serve an additional term only after an interval of five

(5) years. He may in no case run for a third term.”).

100. See Daniel N. Posner & Daniel J. Young, The Institutionalization of Political Power in Africa, 18 J.

DEMOCRACY 126, 132 fig. 3 (2007).

101. See id. at 128 fig.1, 128–29.

102. Id. at 129.

103. For skepticism about compliance, see Daron Acemoglu et al., A Political Theory of Populism, 18 Q.J.

ECONOMICS 771, 792 (2013); Baker, supra note 8, at 285; Javier Corrales & Michael Penfold, Manipulating

Term Limits in Latin America, 25 J. DEMOCRACY 157, 158 (2014); Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, 1847–50; Maltz,

supra note 1, at 129–30; Smith et al., supra note 21, at 6–7.

104. Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1848–49.

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 377

limitations.

105

Moreover, 15 of these “constitutional overstaying” attempts

occurred in countries that were constitutional democracies at the time.

106

Some

of these occurred in the 19th

and early 20th centuries: Costa Rica in 1876,

107

as

well as in 1898;

108

Colombia in 1886;

109

Uruguay in 1935;

110

and Honduras in

1936.

111

Others were more recent, including the Philippines in 1973, Peru in

1995, Argentina in 1995, Brazil in 1998, Venezuela in 2004, Colombia in 2006,

Niger in 2009, and Belarus in 2006.

112

Gideon Maltz likewise notes twenty-six instances in which presidents

chose not to comply with relevant term limits between 1992 and 2006: fourteen

of these instances involved the amendment or repeal of relevant limits, while

twelve involved some form of constitutional “over-staying” or breach of the

relevant limit.

113

Six of these countries were constitutional democracies at the

time of the relevant constitutional non-compliance.

114

In Africa, Posner and Young note the amendment or repeal of

constitutional term limits between 1990 and 2005 in Chad, Gabon, Guinea,

Namibia, Togo and Uganda.

115

The incumbent president in each case ultimately

won the relevant election, such that these changes led to a third consecutive

presidential term for Presidents Idriss Débby of Chad, Omar Bongo of Gabon,

Lansana Conté of Guinea, Samuel Nujoma of Namibia, Gnassingbé Eyadéma of

Togo, and Yoweri Museveni of Uganda.

116

Denis Tull and Claudia Simons extended this analysis to 2016 and found

that, of the thirty-nine presidents in Africa who reached the end of their

constitutionally permitted time in office, eighteen chose not to comply with

relevant term limits, but instead chose to circumvent or to formally amend those

limits.

117

Attempts at formal constitutional change were met with an extremely

105. Id. at 1849.

106. Id.

107. Tomas Guardia Gutierrez, where there was a single term limit with non-immediate reelection not

permitted. Ginsburg et al., supra note 1, at 1851–52.

108. Rafael Yglesias Castro, where there was a single term limit, with non-immediate reelection not

permitted. Id. at 1852.

109. Rafael Nunez, where there was a single term limit, with non-immediate reelection permitted after a full

two-year term elapsed. Id. at 1850 n.213.

110. Gabriel Terra, where there was a single term limit, with non-immediate reelection permitted: two terms

must elapse before the executive can be re-elected. See id. at 1869 tbl.A1.

111. Carias Andino, where there was a single term limit, with non-immediate reelection permitted. See id.

112. See id. at 1869–72.

113. Maltz, supra note 1, at 128.

114. See id. at 130 fig.1 (listing Argentina, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Namibia, Romania and

Venezuela).

115. See Posner & Young, supra note 100, at 132–34. In Guinea, the relevant amendment also repealed all

term limits, thereby allowing President Lansana Conté the possibility of indefinite reelection. See Baker, supra

note 8, at 291–92.

116. Posner & Young, supra note 100, at 133–34. On how changes in Guinea and Burkina Faso have led to

the scope for indefinite reelection in those countries, see Baker, supra note 8, at 291–92.

117. See Tull & Simons, supra note 53, at 83–85.

378 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

high rate of success. For instance, out of the eighteen presidential attempts to

formally amend term limits, fifteen succeeded, compared to only three cases of

failure.

118

Perhaps the most comprehensive study of term limits evasion to date has

been carried out by Mila Versteeg and several coauthors, in which they studied

106 countries.

119

Since 2000, of 234 constitutionally-required presidential exits

from office, there were 60 cases of attempted evasion of existing term limits.

120

Thus, like Ginsburg and Elkins, they find that attempted term limits evasion

occurs about 25% of the time.

121

By far the most common tool to evade term limits is formal amendment to

the constitution, which removes or loosens the term limit.

122

But this is not the

only tool that incumbent presidents wishing to stay in power possess. The study

also outlines other techniques that are used fairly commonly. One is to replace

the entire constitution, which often has the effect of resetting the clock on term

limits.

123

Another is to go to the judiciary and to convince it to reinterpret the

term limit or to throw it out entirely.

124

These latter techniques may actually be

more damaging to the rule of law than constitutional amendment, since they may

have collateral costs to stability or to judicial independence.

Consider the problem through a number of recent cases, drawn first from

Africa. In 2008, the parliament of Cameroon voted to amend its constitution to

remove all presidential term limits, thereby allowing President Paul Biya to

extend his term beyond the twenty-five years he had already served.

125

Similarly,

in 2012 in Senegal, supporters of President Abdoulaye Wade successfully

proposed amending the constitution to allow him to run for a third term, despite

significant public protests.

126

The only silver lining from a democratic

perspective was that the amendment process galvanized a new grass-roots

political opposition movement that defeated Wade’s actual bid for reelection.

127

In 2010, the Djibouti parliament voted to remove presidential term limits

from its constitution, to shorten the presidential term to five years, and to impose

118. See id. at 85.

119. Versteeg et al., supra note 4.

120. See id.

121. See supra text accompanying note 90.

122. See Versteeg et al., supra note 4.

123. See id.

124. See id.

125. LeBas, supra note 58, at 171; Cameroon Parliament Extends Biya’s Term Limit, FR.24,

http://www.france24.com/en/20080411-cameroon-parliament-paul-biya-term-limit-extension (last updated

Nov. 4, 2008, 4:06 PM); Will Ross, Cameroon Makes Way for a King, BBC NEWS,

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7341358.stm (last updated Apr. 11, 2008, 7:08 AM).

126. See Lamin Jahateh, Controversy of Abdoulaye Wade’s Presidential Bid, AL JAZEERA (Jan. 28, 2012),

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/01/201212712295177724.html.

127. See LeBas, supra note 58, at 171.

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 379

a mandatory retirement age of seventy-five for the president.

128

These

amendments paved the way for President Ismael Omar Guelleh to stand for

reelection for a third term in 2011 and a fourth term in 2016.

129

Guelleh was

ultimately re-elected in 2016 with 87% of the vote, against a backdrop of

significant alleged political repression and electoral irregularities.

130

In 2015, the Rwandan parliament passed a constitutional amendment,

which was then approved at a national referendum, to reduce presidential term

limits from seven to five years.

131

In addition, the Rwandan parliament also

created a set of “transitional” arrangements that allowed the winner of the 2017

presidential election to serve an initial transitional seven-year term, and

subsequently be eligible for two additional five-year terms.

132

In aggregate, these

changes created the possibility for President Paul Kagame to stay in office for a

further seventeen years, until 2034.

133

In in the lead up to the 2020 Burundi presidential elections, President

Nkurunziza, who had already served for three terms, proposed changes to the

Burundi constitution to allow him to seek reelection for two more consecutive

terms.

134

Following his reelection to a third term in 2015, he appointed a

commission to consider the possibility of further constitutional amendments.

135

After a process of public consultation, the commission announced its

recommendation to extend presidential term limits from five to seven years.

136

The commission also recommended various parallel changes to the power of the

presidency.

137

Despite criticisms of the commission, and its processes, the

128. See MPs in Djibouti Scrap Term Limits, BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/8630616.stm

(last updated Apr. 19, 2010, 5:57 PM).

129. See Djibouti President Ismail Omar Guelleh Wins Fourth Term, BBC NEWS (Apr. 9, 2016),

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35995628.

130. Id.

131. See Rwanda Changes Constitution to Allow President to Extend His Rule Until 2034, ABC NEWS,

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-12-20/rwanda-changes-constitution-to-allow-president-to-stay-in-

power/7043698 (last updated Dec. 19, 2015, 5:18 PM); Rwandans Vote on Allowing Third Kagame Presidential

Term, BBC NEWS (Dec. 18, 2015), http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35125690.

132. See Rwanda Changes Constitution to Allow President to Extend His Rule Until 2034, supra note 131;

Rwandans Vote on Allowing Third Kagame Presidential Term, supra note 131.

133. Rwanda Changes Constitution to Allow President to Extend His Rule Until 2034, supra note 131;

Claudine Vidal, Rwanda: Paul Kagame Is in Line to Stay in Office Until 2034, CONVERSATION (Jan. 18, 2016,

7:17 AM), https://theconversation.com/rwanda-paul-kagame-is-in-line-to-stay-in-office-until-2034-53257.

134. See Will the 2020 Elections in Burundi Be Bloody?, AFR. NEWS (July 29, 2019, 10:03 AM),

https://www.africanews.com/2019/07/29/will-the-2020-elections-in-burundi-be-bloody/.

135. See Mohammed Yusuf, Burundi Parliament to Review Plan on Scrapping Term Limits, VOA NEWS

(Aug. 29, 2016, 2:12 PM), https://www.voanews.com/a/burundi-parliament-term-limits/3485090.html.

136. Burundi Backs New Constitution Extending Presidential Term Limits, AL JAZEERA (May 22, 2018),

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2018/05/burundi-backs-constitution-extending-presidential-term-

limits-180521134736408.html.

137. Yolande Bouka & Sarah Jackson, Burundi Votes Tomorrow on Controversial Constitutional

Amendments. A Lot Is at Stake, WASH. POST (May 16, 2018, 6:00 AM),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/05/16/burundi-votes-tomorrow-on-

controversial-constitutional-amendments-a-lot-is-at-stake/.

380 HASTINGS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 71:359

proposed changes were subsequently approved by voters at a national

referendum in 2018.

138

Another method used to circumvent presidential term limits in Africa is

through the use of the judiciary. For example, in Burundi, President Pierre

Nkurunziza’s party, in 2015, asked the Constitutional Court of Burundi to find

that the existing term limits did not apply to President Nkurunziza because he

was elected under transitional provisions that provided for indirect,

parliamentary election rather than direct elections.

139

The court upheld the

argument, finding that the transitional provisions operated separately from the

provisions imposing presidential term limits.

140

The court’s decision ultimately

paved the way for President Nkurunziza to be re-elected for a third term.

141

A similar pattern of evasion applies in Latin America.

142

Between 1993 and

2009, Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia all passed formal constitutional changes

that relaxed constitutional term limits and allowed some scope for presidential

reelection.

143

Ecuador and Venezuela formally repealed term limits altogether

so presidents could seek indefinite reelection.

144

In both countries, the changes

were passed despite a tiered constitutional design that required a more

demanding standard when attempting to alter the fundamental structure of the

constitution.

145

In Ecuador, for example, changes to the “fundamental structure,

or the nature and constituent elements of the State” require a referendum,

whereas most other changes can be carried out by Parliament alone.

146

Despite

compelling arguments that the elimination of all term limits would be the type

of fundamental change that would require a more demanding procedure,

147

138. See id. (noting criticisms of the process, and its selectivity, by the Burundi Forum for Strengthening

Civil Society). The referendum itself was also critiqued as tainted by voter intimidation and a lack of

transparency. See Abdi Latif Dahir, Burundi Has Backed Constitutional Changes that Could See Its President

Rule till 2034, QUARTZ AFR. (May 21, 2018), https://qz.com/1284514/burundi-backs-new-constitution-

extending-president-term-limit/.

139. See Stef Vandeginste, Legal Loopholes and the Politics of Executive Term Limits: Insights from

Burundi, 51 AFR. SPECTRUM, 39, 45 (2016).

140. Id. at 52.

141. Clement Manirabarusha, Burundi President’s Commission Says People Want Term Limits Removed,

REUTERS (Aug. 25, 2016, 1:26 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-burundi-politics/burundi-presidents-

commission-says-people-want-term-limits-removed-idUSKCN1100O1.

142. For an overview of judicial decisions in this area, see David Landau et al., Term Limits and the

Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendment Doctrine: Lessons from Latin America, in THE POLITICS OF

PRESIDENTIAL TERM LIMITS 53 (Alexander Baturo & Robert Elgie eds., 2019).

143. See Corrales & Penfold, supra note 31, at 160.

144. See id.

145. See Dixon & Landau, supra note 10, at 448–49.

146. REFORMA DE LA CONSTITUCIÓN, 2008, art. 441 (Ecuador).

147. See, e.g., Carlos Bernal Pulido, There Are Still Judges in Berlin: On the Proposal to Amend the

Ecuadorian Constitution to Allow Indefinite Presidential Reelection, INT’L J. CONST. L. BLOG (Sept. 10,

2014), http://www.iconnectblog.com/2014/09/there-are-still-judges-in-berlin-on-the-proposal-to-amend-the-

ecuadorian-constitution-to-allow-indefinite-presidential-reelection (arguing that the abolition of term limits in

Ecuador should require either a more demanding procedure or a constituent assembly).

February 2020] CONSTITUTIONAL END GAMES 381

presidents in both countries used the less demanding default standard, and the

high courts allowed them to do so.

148

In another class of Latin American countries, courts played a more direct

role and actively removed presidential term limits from their constitution by

holding that the term limits themselves were unconstitutional. This route was

generally taken in cases where presidents lacked the ability to make formal

changes to the constitution that eradicated term limits. In 2009, for example, the

Nicaraguan Supreme Court held that a constitutional term limit that would have

prevented President Ortega from running for a third term in office was

unconstitutional.

149

The court set the term limit aside, allowing Ortega to run for

and subsequently win a new term.

150

Once Ortega had sufficient parliamentary

support, his allies passed an amendment formally removing the term limit, and

he has remained in power ever since.

151

In 2015, the Honduran court used a similar maneuver to remove a

supposedly unamendable term limit,

152

allowing President Juan Orlando

Hernandez to run for, and subsequently win, reelection.

153

Similarly, in Bolivia,

after losing a referendum to extend presidential term limits that would allow