REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

International IDEA’s Constitution-Building Primer 23

© 2022 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specic national or political interests. Views

expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its

Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication

is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-

SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix

and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the

publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the

Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>.

International IDEA

Strömsborg

SE–103 34 Stockholm

SWEDEN

Tel: +46 8 698 37 00

Email: [email protected]

Website: <https://www.idea.int>

Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com>

Design and layout: International IDEA

Copyeditor: Curtis Budden

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2022.32>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-550-5 (PDF)

Contents

Chapter 1

Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5

Chapter 2

What is the issue? .......................................................................................................... 8

Chapter 3

Presidential removal .................................................................................................... 11

3.1. Removal through impeachment .............................................................................. 12

3.2. Removal on grounds of physical or mental incapacity ......................................... 26

3.3. Removal on political grounds (recall) ...................................................................... 31

3.4. Concluding remarks.................................................................................................. 32

Chapter 4

Decision-making questions ......................................................................................... 34

Chapter 5

Examples ...................................................................................................................... 36

References ................................................................................................................... 50

Constitutions ............................................................................................................................ 51

About the author........................................................................................................... 53

About this series ...................................................................................................................... 54

About International IDEA .............................................................................................. 55

4 CONTENTS REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

Constitutions establishing presidential and semi-presidential systems

of government (i.e.systems where the president is directly elected by

the people) are characterized by the parallel popular legitimacy of the

legislature and the president. Presidents in such systems ordinarily

serve a guaranteed xed term of oce (tenure) and are generally not

dependent on the political support (or ‘condence’) of the legislature

(which, in presidential systems, also normally enjoys a xed term).

Only the people can confer a mandate on presidents, and, owing to

this, only they can change incumbent presidents by voting for another

candidate in the next elections. This contrasts with prime ministers in

parliamentary systems who are appointed by parliaments and where

parliament can remove them during their term on purely political

grounds and through regular procedures (i.e.without the need for a

supermajority).

However, many constitutions establishing presidential and semi-

presidential systems of government provide exceptional grounds

and procedures through which a president may be removed before

the end of their term, usually connected with (a)accusations of

serious misbehaviour, corruption or legal/constitutional violations

(impeachment); or (b)physical or mental incapacity. In some cases,

a president is removed to provide political accountability, during

the period between presidential elections, through (c)a recall

mechanism. The grounds for and process of presidential removal

are complex and can be contentious, often involving both legal and

political procedures.

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

5INTERNATIONAL IDEA 1. INTRODUCTION

Constitutional designers in all systems with directly elected

presidents should determine whether, on what grounds and through

what procedures presidents can be removed. Procedures for the

removal of a president may be primarily political or primarily judicial,

depending in part on the grounds for removal. These procedures can

involve various actors at various stages of the process, including,

for example, members of the president’s cabinet, the legislature, the

supreme or constitutional court, medical boards and the people.

The choice of grounds for and processes of removal affect the

degree of diculty in removing a sitting president before the end

of their term. The ease or diculty of removal processes could in

turn affect the relative independence of the executive vis-à-vis the

legislative power—as the legislature is usually involved in initiating

and approving removal motions—and therefore ensures checks and

balances.

The design of presidential removal rules affects ‘both the rate

of removal-worthy actions and events, and also the tendency of

legislatures (and other actors) to engage in impeachment [removal]’

(Ginsburg, Huq and Landau 2021: 143). This Primer seeks to inform

and aid this constitutional design process through a comparative

discussion of the diverse set of rules for presidential removal.

The Primer discusses the grounds and procedures for presidential

removal, the consequences of removal and other related issues. It

deals with presidents in presidential or semi-presidential systems

who are popularly elected (see Electing Presidents in Presidential and

Semi-presidential Systems [Abebe and Bulmer 2019], which considers

the presidential electoral system in the United States as establishing

a direct popular mandate, although technically the president is

elected by an electoral college). Because removal procedures often

involve legislatures, they constitute an exception to the mutual

independence of the legislature and the presidency in presidential

systems (but not always in semi-presidential systems, where the

president sometimes enjoys the power to dissolve parliament).

For a discussion of the mandate and the process of appointment

and removal of non-executive presidents in parliamentary systems,

see Non-executive Presidents in Parliamentary Democracies (Bulmer

2017).

Constitutional

designers in all

systems with directly

elected presidents

should determine

whether, on what

grounds and through

what procedures

presidents can be

removed.

6 1. INTRODUCTION REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

It is important to note that this Primer is based on the rules regarding

presidential removal in the constitutional text, which may not always

be comprehensive. While the most important aspects of presidential

removal rules are commonly regulated at the constitutional level—

with a view to avoiding abuse by transient legislative majorities—

some aspects of removal may also be complemented through

legislation and parliamentary rules of procedure. It is therefore

important to consider all relevant regulations and conventions when

evaluating removal procedures in specic countries.

7INTERNATIONAL IDEA 1. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 2

WHAT IS THE ISSUE?

The presidency is usually the most powerful centre of political

power, enjoys prominent symbolic status and attracts constant

media and popular attention. Rules governing access to and the

exercise and termination of presidential power are therefore critical

to the constitutional framework in presidential and semi-presidential

systems.

The tremendous powers of the presidency come with limited

corresponding accountability mechanisms beyond the potential

for reward with re-election or punishment through electoral loss. Of

these mechanisms, the most notable is the possibility of presidential

removal before the incumbent nishes their term. Presidents

generally enjoy immunity from criminal (and in some cases civil)

proceedings during their tenure. Immunity provisions are ostensibly

designed to insulate presidents from distraction from their crucial

public functions through judicial and other proceedings, and also,

symbolically, to maintain the aura and dignity of the oce of the

presidency.

In the absence of appropriate presidential removal procedures,

presidents could enjoy absolute immunity, which could put them

beyond the reach of the law and accountability. Presidential removal

procedures should therefore be seen as part of the broader objective

of ensuring the rule of law and responsible government, including

against the top oce holder.

The absence of clear and effective presidential removal rules may

not only undermine presidential accountability but also engender

8 2. WHAT IS THE ISSUE? REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

political paralysis. Beyond addressing misbehaviour (or dealing

with bad actors), removal procedures provide mechanisms for a

much-needed hard political reset to revitalize and recalibrate the

political system whenever a country faces systemic challenges in

the political environment and severe inter-branch or other political

deadlock (Ginsburg, Huq and Landau 2021: 143ff.). Moreover,

removal procedures are critical to dealing with situations where an

incumbent becomes incapacitated and, in the case of recall, when

a president becomes deeply unpopular. In all cases, the clarity and

appropriateness of the rules of presidential removal are critical to

making it possible to return to a semblance of relative stability in

politically uncertain and volatile times.

If a misbehaving president does not face consequences, or if there

are no procedures to remove a president who becomes physically

or mentally incapacitated, trust in democracy and democratic

institutions could suffer. At the same time, the abuse and frequent

invocation of removal procedures, which are often pursued along

partisan lines, could undermine political stability (Pérez-Liñán 2007),

democratic legitimacy and presidential effectiveness, as such

processes would sap the focus and energy of sitting presidents.

The challenge for constitutional designers is to balance the value of

presidential removal between elections with the virtues of political

stability and the potential abuse of removal procedures. In seeking

this balance, a number of questions arise, and this Primer aims to

explore the various options to achieve this balance, and, in doing

so, to aid informed decision-making based on comparative design,

scholarship and experience.

The following chapters discuss the questions summarized in Box2.1

and related aspects of presidential removal with examples from

across the world.

The clarity and

appropriateness of the

rules of presidential

removal are critical to

making it possible to

return to a semblance

of relative stability in

politically uncertain

and volatile times.

9INTERNATIONAL IDEA 2. WHAT IS THE ISSUE?

Box 2.1.Key issues to address in the constitutional regulation of presidential

removal

• What degree of incapacity, level of wrongdoing or other reason justies the interruption of

apresident’s popular mandate?

• What processes should be followed to remove a president?

– Should this process involve only political organs (executive and/or legislature) or also

other actors, notably the judiciary (or other independent organ) and the people? If the

latter, how and at what stage should they be involved?

– Are different removal mechanisms necessary to deal with different types of problems

(e.g.judicial or quasi-judicial processes for the determination of wrongdoing, medical

boards of inquiry for removal on grounds of incapacity and popular recall mechanisms for

loss of public condence)?

• What should the consequences be of removal, both in terms of replacing the president and

for the future of the removed president? For instance, should the president still receive a state

pension or be allowed to run in future elections or hold other (prominent) public positions?

10 2. WHAT IS THE ISSUE? REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

In principle, presidents are elected for a xed term. Based on

comparative practice, aside from resignation or death, a president’s

tenure may be terminated only under three broad circumstances:

• impeachment—normally for a crime, serious misbehaviour or other

constitutional/legal violations;

• removal on grounds of physical or mental incapacity; and

• in a few countries, removal on the basis of a recall vote without

specic grounds.

The constitutional regulation of the grounds for and procedure

of presidential removal seeks to provide a predictable legal

and institutional structure for such procedures and therefore to

depoliticize the rules for and process of removal. This is what

formally distinguishes presidential removal procedures covered

in this Primer from no-condence votes in parliamentary systems,

which are purely political. In practice, however, even presidential

removal procedures tend to be highly political. Removal is likely to

be initiated (and to succeed) in countries where the president does

not enjoy signicant support in the legislature, or where divisions

within the president’s party enable a strong cross-party coalition for

removal. Presidents who lack strong popular support, or who have

lost such support, are also more vulnerable to removal initiatives.

Politicization is more likely particularly in cases where courts or

other relatively independent bodies are not involved in the removal

procedure.

Chapter 3

PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

11INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

3.1. REMOVAL THROUGH IMPEACHMENT

Impeachment procedures are designed to disincentivize presidential

misconduct or misbehaviour out of consideration for the

consequences of removal, including potentially opening the way for

further legal proceedings against the removed president. Considering

that, in practice, presidents have signicant powers and distribute

resources, and keeping in mind the diculty of impeachment

procedures in view of partisan politics, calls for impeachment are

common but rarely successful (Samuels and Shugart 2010:111).

An assessment of the formal diculty of or the permissiveness

of constitutions regarding impeachment must consider both the

grounds for and the procedure of removal, notably the number of

institutions that must approve the removal (veto players), and the

strength of the majority required at each stage. Recent comparative

scholarship nds that most constitutions include serious violations

of the constitution or other laws as the grounds for removal, and

they often involve two actors that must decide with a supermajority

(Ginsburg, Huq and Landau 2021: 141–42). Beyond the formal rules,

the context of each country affects the extent to which the formal

degree of diculty corresponds with practice.

3.1.1. Grounds for impeachment

The two most common grounds for presidential impeachment

broadly relate to serious violations of laws or the constitution and the

commission of serious misconduct or crimes, broadly constituting

abuse of presidential power.

Some constitutions specify the nature of the crime, usually related to

treason or atrocity crimes (crimes against humanity, genocide and

war crimes). For instance, in Nigeria, impeachment is possible only

on grounds of ‘gross misconduct’, which the constitution denes as

‘a grave violation or breach of the provisions of this Constitution or a

misconduct of such nature as amounts in the opinion of the National

Assembly to gross misconduct’ (article 143, sections 2[b] and 11,

Constitution 1999, rev. 2011). In the United States, impeachment

is allowed on grounds of ‘treason, bribery, or other high crimes and

misdemeanors’ (article II, section 4, Constitution 1789, rev.1992).

The Algerian Constitution speaks only of high treason (article 191,

12 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

Constitution 2020), while the Mexican Constitution refers to ‘treason

or serious common crimes’ (article 108, Constitution 1917, rev.

2015).

Some constitutions establish grounds that are vague and may lead to

subjective assessments, potentially lowering the overall threshold for

impeachment. In the Philippines, a president can be impeached on

grounds of ‘betrayal of public trust’ (article XI, section 2, Constitution

1987). The Argentinian Constitution lists ‘poor performance’ as one

basis for impeachment (article 53, Constitution 1853, reinstated in

1983, rev. 1994). Ecuadorian presidents may be removed on grounds

of ‘severe political crisis or internal unrest’ (article 130[2], Constitution

2008, rev. 2021). In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the

president can be impeached on grounds of ‘contempt of Parliament’

and ‘infringements of honor or of probity’ (article 164, Constitution

2005, rev. 2011).

In many anglophone African countries, such as Ghana (article 69[b],

Constitution 1992, rev. 1996) and The Gambia, the president can

be impeached on grounds of conduct ‘which brings or is likely to

bring the oce of the President into contempt or disrepute’ (article

67[b], Constitution of The Gambia 1996, rev. 2018). The Chilean

Constitution similarly includes as grounds for impeachment acts

of the administration, and not just acts of the president, ‘which

have seriously affected the honor or security of the Nation’ (article

52[2], Constitution 1980, rev. 2021). In Brazil, attempts against the

federal Constitution, as well as tampering with the budget law and

failure to comply with laws and court decisions, are impeachable

transgressions (article 85, Constitution 1988, rev. 2017).

While legal specicity has the advantage of clarity, potentially

discouraging political manoeuvres, there is no evidence that these

vague grounds have led to more frequent impeachment proceedings.

Instead, such loose or vague standards may have an advantage in

allowing a political reset through the removal of presidents who

have lost popularity or political support to govern (Ginsburg, Huq

and Landau 2021: 144), although they are not guilty of specic

infractions. Nevertheless, this could depend on the procedures for

impeachment, the political party landscape and the relative support

for and patrimonial network of the president. For instance, in Ecuador,

13INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

the procedure for removal on the grounds of ‘severe political crisis or

internal unrest’ is relatively easy, requiring a two-thirds majority in the

National Assembly (article 130[2], Constitution 2008, rev. 2021). But

a president may be subjected to an impeachment process on these

grounds only once in a legislative term and only before their third

year in oce. This combination of vague grounds and relatively easy

removal procedures could generate undesirable levels of political

instability. Indeed, in Ecuador, as a counterweight to this potential

instability, a successful removal through impeachment requires new

elections for both the members of the legislature and the president,

therefore reducing incentives for frivolous impeachment proceedings.

3.1.2. Removal procedure

Stages of the procedure

A comparative overview reveals three distinct stages in removal

procedures: initiation, approval and in some cases conrmation,

usually by a non-political body. Initiation is generally the purview of

the legislature. Similarly, the legislature is generally responsible for

approval, often with a majority higher than in ordinary legislative

decisions (qualied majority). Conrmation could involve either

courts, quasi-judicial tribunals or hybrid bodies composed of both

politicians and judges, which is often common in francophone

countries (sometimes called ‘high courts’) that determine whether

grounds for impeachment exist. The conrmation of the courts or

similar tribunals may still be subject to legislative approval (i.e.the

judicial process may not settle the matter).

In cases where courts or similar quasi-judicial tribunals or hybrid

bodies are not involved, the removal procedure may be seen as

overtly political, even if the existence of the grounds for impeachment

often requires some level of legal determination. The involvement

of courts, quasi-judicial tribunals or hybrid bodies in such processes

adds a legal element to the process but does not eliminate the

political nature of such proceedings, as political action is often

necessary to trigger the impeachment procedure.

Legislative majority required

The legislative majority required to initiate impeachment proceedings

varies. In Romania, impeachment for serious offences that violate

In cases where courts

or similar quasi-

judicial tribunals or

hybrid bodies are

not involved, the

removal procedure

may be seen as

overtly political,

even if the existence

of the grounds for

impeachment often

requires some level of

legal determination.

14 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

constitutional provisions requires approval by one-third of the

members of parliament, while impeachment on grounds of high

treason requires a majority of deputies and senators (articles 95[2]

and 96[2], Constitution 1991, rev. 2003). In Albania, the initiation

requirement is one quarter of the members of the legislature (article

90[2], Constitution 1998, rev. 2016). The initiation rules are often

designed to allow a legislative minority to bring public attention to

the president’s failings, which could encourage accountability and

responsiveness even if the chances of a successful removal are

low. Nevertheless, in some countries, such as the Republic of Korea

(South Korea) (article 65[2], Constitution 1948, rev. 1987), an absolute

majority of members of the unicameral parliament is required to

initiate impeachment proceedings.

In bicameral systems, the power to initiate impeachment tends to

belong to the rst chamber (in rare cases also the second chamber—

for example, Romania, articles 95[2] and 96[2], Constitution 1991, rev.

2003). For instance, in Argentina, a motion to remove the president

requires a two-thirds majority of members present in the rst

chamber, subject to approval in the second chamber by the same

majority in a public meeting where each of the members takes an

oath for the same purpose and that is presided over by the chair of

the Supreme Court (articles 53 and 59, Constitution 1853, reinstated

in 1983, rev. 1994). Comparable arrangements exist in Brazil (which

requires the support of a ‘two-thirds vote of the Federal Senate’

[article 52, Constitution 1988, rev. 2017]) and the United States (which

requires the support of ‘two-thirds of the Members present’ in the

Senate [article 1, section 3, Constitution 1789, rev. 1992]).

Overall, all other things being equal, a higher legislative threshold

makes removal more dicult. Beyond the applicable supermajority,

the chance of success of removal likely depends on the number of

veto points (distinct entities whose consent is required to pass a

decision) involved in the decision and, crucially, whether the president

has sucient allies in parliament to block removal.

It is also important for constitutional designers to clearly dene

whether the majority required should be based on all the seats in a

body or only on those present and voting. In Tanzania, for instance,

impeachment requires support from two-thirds of all members of

15INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

parliament (article 46A[3][a], Constitution 1977, rev. 2005). Similarly,

in the Philippines, the Senate needs a two-thirds majority of all the

members to impeach a president (article XI, section 3[6], Constitution

1987). In contrast, in the United States, the Senate requires a two-

thirds majority of those present (article 1, section 3, Constitution

1789, rev.1992).

Courts in removal proceedings

A legislative decision to remove a president may be subject to further

judicial conrmation. The involvement of the courts, especially those

with a reputation for independence, enhances the credibility and

legitimacy of the legal and factual determinations necessary for the

acceptability of the process. Because judicial procedure creates

an additional hurdle (veto point) in the removal process, it could

diminish incentives for starting impeachment proceedings, although

judicial intervention may not in itself prevent initiatives intended by

the political opposition to bring attention to particular presidential

infractions even when the chances of successful removal are slim.

In South Korea, the impeachment of a president with a two-

thirds majority in the unicameral National Assembly must be

approved by a two-thirds majority (six of the nine justices) in the

Constitutional Court before the president is removed (articles 65,

113[1], Constitution 1948, rev. 1987). Similarly, in Angola, a decision

supported by two-thirds of the members of the unicameral parliament

to impeach a president must be forwarded for approval to the

Supreme Court (for serious crimes) or the Constitutional Court (for

violations of the Constitution) (article 129[3]–[5], Constitution 2010).

In Tunisia as well, a motion of impeachment approved by two-thirds

of the members of the National Assembly requires conrmation

by a two-thirds majority of the Constitutional Court (article 88,

Constitution 2014). In all cases, if the courts nd the accusations to

be unsubstantiated, the president will remain in oce.

In some francophone African countries, a special court made up of

judges and politicians has the power to decide on impeachment.

For instance, in Benin, the High Court of Justice (composed of

all members of the Constitutional Court except its president, six

members elected by the unicameral National Assembly and the

president of the Supreme Court) decides, based on an accusation by

It is also important

for constitutional

designers to clearly

dene whether the

majority required

should be based on all

the seats in a body or

only on those present

and voting.

16 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

a two-thirds majority of the Assembly, on whether the president has

committed treason or other impeachable offences (articles 135–37,

Constitution 1990).

In some countries, the order is reversed: the accusation must

rst be approved by the courts before parliament decides, where

a supermajority is required for the motion to pass. For instance,

in Azerbaijan, the president may be impeached on the grounds

of a conviction for serious crimes by the Supreme Court. In such

cases, the Constitutional Court initiates impeachment proceedings

before the unicameral legislature, which, for the motion to pass,

must approve by a three quarters majority within a maximum of

two months. The resolution of the parliament must be signed by

the Constitutional Court within one week; if it is not signed within

this period, it lapses (article 107, Constitution 1995, rev. 2016). In

The Gambia, when a majority of all the members of the unicameral

National Assembly accuse the president of impeachable misconduct,

the speaker requests that the chief justice convene a tribunal

including a justice of the Supreme Court and four other persons.

If the tribunal nds the president guilty, the National Assembly

may approve the decision with a two-thirds majority (article 67,

Constitution 1996, rev. 2018). In these cases, the judicial decision

needs to be conrmed by political organs, creating the possibility

that a president found guilty could stay in power, which could occur,

considering the political nature of removal proceedings, but would

undermine trust in the rule of law. At the same time, it may make

political decisions to remove the president easier, as the members of

parliament have a judicial ruling to rely upon.

Indonesia has a unique system involving back and forth between the

parliament and the Constitutional Court. Impeachment is initiated

in the rst chamber with a two-thirds majority of all its members.

The decision is then transferred to the Court to determine whether

the president violated the law through an act of treason, corruption,

bribery, or other act of a grave criminal nature or through moral

turpitude, or whether the president no longer meets the qualications

to serve as president. If the Court nds that the accusations are

proven, the rst chamber holds a plenary session to decide on

whether to refer the decision to the second chamber, which can

approve the impeachment with a two-thirds majority (in the presence

17INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

of at least three quarters of the members) (articles 7A and 7B,

Constitution 1945, reinstated 1959, rev. 2002).

While courts are not involved in presidential removal in Zimbabwe,

the Constitution does not leave it to the legislative plenary, which

may be dominated by a single party, thus undermining the voices of

other parties. Instead, it provides for a nine-member parliamentary

committee composed proportionately of all parties represented

in both chambers of the legislature to investigate the existence of

impeachment grounds (as well as for reasons of mental or physical

incapacity). Such a committee is established upon the decision of

half of the members of the two legislative houses in a joint session.

If the committee recommends impeachment of the president, and

if two-thirds of the total membership approve it in a joint session of

the two chambers, the president is removed (article 97, Constitution

2013, rev.2017). The Zimbabwean approach emphasizes the

political nature of impeachment but could generate less condence

and credibility compared with countries where the courts or ad hoc

tribunals make determinations regarding impeachment.

The people in removal proceedings

Presidential removal through impeachment may also involve a

referendum. For instance, in Romania, at the initiation of one-third of

deputies and senators, a joint sitting of the two legislative chambers

can suspend a president with a majority vote on grounds of serious

offences in violation of the Constitution, after consultation with the

Constitutional Court. If the suspension is approved, the impeachment

is referred to a referendum within 30 days (article 95, Constitution

1991, rev. 2003). The involvement of the people of Romania in cases

of serious offences is different from recall procedures, which do not

require specic grounds, as discussed below.

Disincentivizing impeachment

Impeachment proceedings are rare partly because of the powers that

come with the presidency and partly due to procedural diculties.

Beyond these practical and procedural hurdles, however, there are

no direct costs for initiating impeachment processes. But there are

exceptions where a constitution may impose disincentives against

impeachment. Although such disincentives preclude abusive

processes, they could also reduce presidential accountability, as

18 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

opposition groups cannot use the procedure to draw needed public

attention to serious presidential infractions.

The Constitution of Kazakhstan provides that, where an accusation

of high treason against the president fails at any stage, it results

in premature termination of the powers of the deputies of the rst

chamber who initiated the consideration of this issue (article 47[2],

Constitution 1995, rev. 2017). In Ecuador, successful removal on the

grounds of a ‘severe political crisis or internal unrest’ leads to not

only new presidential, but also legislative, elections (article 130[2],

Constitution 2008, rev. 2021).

Impeachment votes

Constitutions differ in their requirements on whether impeachment

votes should be by open or secret ballot. Open ballots encourage

political transparency and accountability. At the same time, open

ballots could put legislators under undue pressure because of fear of

reprisal, particularly if the impeachment motion fails. The possibility

of undue pressure is particularly high for deputies who are from

the same party as the president. Open ballots could also enable

Think point:At what stage should the courts be involved?

Once a decision to involve the courts or other quasi-judicial bodies in the presidential removal

process is taken, constitutional designers must make a second-order policy choice regarding the

particular stage at which such entities should be involved.

Option 1: These entities come at the end of the removal process once a nal decision (often

with a qualied majority) has been taken by the political bodies, and the judicial or quasi-judicial

entities then decide whether the decision should stand or not based on constitutional grounds

(e.g. in South Korea). This option has the advantage of precluding the potential politicization of

professional decisions in a manner undermining expectations of and trust in the rule of law.

Option 2: The courts or quasi-judicial entities come in the middle once an initial political decision

has been taken (e.g. in The Gambia). In this case, a judicial decision conrming the accusation

could be expected to encourage the building of political bridges necessary to enhance the

legitimacy and acceptability of the removal. A decision rejecting the accusation not only would

end the stage but could also reduce the political instability that removal processes often generate

or worsen.

Constitutions differ in

their requirements on

whether impeachment

votes should be by

open or secret ballot.

19INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

corruption, with presidents or their opponents offering benets in

return for veriable support.

The French Constitution requires that the two legislative chambers,

jointly sitting as a high court, vote on an impeachment procedure

through a secret ballot. A decision must be given within one month

of the tabling of the motion (article 68, Constitution 1958, rev. 2008).

Similarly, the Constitution of Côte d’Ivoire requires that the indictment

of the president in parliament, as part of the impeachment process,

be conducted by secret ballot (article 161, Constitution 2016).

The Ghanaian Constitution also requires that legislative votes on

impeachment (as well as for presidential incapacity) be by secret

ballot (article 69[11], Constitution 1992, rev. 1996).

In contrast, the Gabonese Constitution requires that the impeachment

vote in parliament be through a public vote (article 78, Constitution

1991, rev. 2011). The Constitution of Madagascar similarly requires

that impeachment votes, which require the approval of a two-thirds

majority in the National Assembly, be public (article 131, Constitution

2010).

Many constitutions are silent on the issue. In such cases, rules

governing legislative process may be applicable. Whenever there are

disputes, they may be resolved through the courts. For instance, in

South Africa, the Constitution is silent on the impeachment voting

process. During the impeachment process of former President Jacob

Zuma, opposition parties called for a secret ballot to encourage

members of the ruling party to vote freely. Nevertheless, the speaker

argued that she had no mandate to order a secret ballot. The

Constitutional Court ruled that the speaker did have such a mandate

(Constitutional Court of South Africa 2017). Nevertheless, the

Court fell short of requiring a secret ballot, instead leaving it to the

discretion of the speaker, subject to a requirement that the decision

be ‘appropriately seasoned with considerations of rationality’. It

should be noted that, in some countries, this may be regarded as

a matter of non-justiciable parliamentary privilege, in which case it

would be for the legislature to determine.

20 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

3.1.3. Suspension during removal proceedings

Another key issue relates to whether a president is suspended during

the removal process pending nal decisions. In some countries, the

president may be suspended pending nal removal proceedings,

while, in others, there is no such requirement. Suspension is intended

to prevent a president who has been impeached, based on prima

facie establishment of the grounds for impeachment, from tampering

with the process or otherwise taking decisions affecting the nation.

Nevertheless, suspension could create a legal and political vacuum,

and could constitute an abuse of process to ensure the suspension

of a president even if the case for impeachment is weak. Accordingly,

suspension should be considered only at an advanced stage of

the process and subject to procedural protections, such as a

supermajority vote, as is the case in many countries.

Beyond suspension, a president may face restrictions to their power

while removal proceedings are ongoing. For example, in Zambia,

the president may not dissolve the National Assembly while facing

removal through impeachment (article 108[3][b], Constitution

1991, rev. 2016). In Turkey, a president facing an impeachment

investigation may not organize elections (article 105, Constitution

1982, rev. 2017). Other signicant powers that could be restricted

include the right to make appointments to key positions, to invoke

states of emergency and to grant presidential clemency/pardon.

In Brazil, a president is suspended when removal proceedings reach

the Senate or when criminal cases are submitted to the Supreme

Federal Tribunal based on a decision of the rst chamber with a two-

thirds majority (article 86, Constitution 1988, rev. 2017). Similar rules

exist in Colombia (article 175.1, Constitution 1991, rev. 2015).

In Cabo Verde, the president is suspended upon being accused of

committing a crime in the exercise of their duties by a two-thirds

majority in parliament, which leads to an investigation by the attorney

general (article 144[2]–[3], Constitution 1980, rev. 1992). Under the

Egyptian Constitution, impeachment by a two-thirds majority in the

rst chamber leads to suspension and referral of the matter to the

prosecutor general (article 159, Constitution 2014, rev. 2019).

21INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

In South Korea, a president is suspended upon the passing of a

motion of impeachment by the National Assembly (article 65,

Constitution 1948, rev. 1987). The president is removed upon the

armation of the Constitutional Court (article 111[1.2]). Zambia

has similar rules, where a president is suspended as soon as they

are impeached by a two-thirds majority of the National Assembly

(article 108, Constitution 1991, rev. 2016). The suspension becomes

permanent if a tribunal established by the chief justice in consultation

with the Judicial Service Commission nds the president guilty

of the grounds for impeachment, and if the National Assembly

subsequently arms the decision by a two-thirds majority in a secret

ballot. In Tanzania, a president is suspended if the National Assembly

decides, by a two-thirds majority, to establish a special committee of

inquiry to investigate the alleged grounds for impeachment (article

46A[5], Constitution 1977, rev. 2005).

3.1.4. Length of removal proceedings/restrictions on repeated

impeachment motions

Considering the disruptive potential of removal proceedings on

politics and governance, and the potential for partisan harassment,

some constitutions impose specic timelines within which the

process should be completed, starting from the moment the

impeachment procedure is initiated. While a time limit may be

desirable, the appropriate length would depend on the exact nature

of the process itself. Processes involving judicial proceedings could

be expected to require a relatively longer time span. Nevertheless,

the value of a time limit lies in the desire to avoid prolonged political

instability.

For instance, in Angola, an impeachment motion immediately

becomes a priority, and the process, including the decision of the

Constitutional Court, must be nalized within 120 days (article

129[6], Constitution 2010). In Bulgaria, an impeachment proposed by

one-quarter of the members of parliament and approved by a two-

thirds majority is submitted to the Constitutional Court, which must

then decide within a month (article 103[2]–[3], Constitution 1991,

rev.2015).

Constitutions may also impose restrictions on the number of

impeachment proceedings in a given period of time. In Tanzania,

Constitutions may also

impose restrictions

on the number

of impeachment

proceedings in a given

period of time.

22 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

impeachment motions with regard to lowering the esteem of the

oce of the president cannot be tabled until 20 months have passed

following a similar motion (article 46A[2], Constitution 1977, rev.

2005). In the Philippines, the Constitution prohibits more than one

impeachment proceeding against the same ocial within a period of

one year (article XI, section 3[5], Constitution 1987). It is important to

note that the restriction in the Philippines coincides with a relatively

easy procedure for initiating impeachment proceedings. Any member

of the rst chamber can request impeachment. The request is tabled

before the whole chamber within 10 days, and the matter is referred

to the relevant committee within 3 days. The committee reports

within 60 days, and if it approves the request within 10 days by a

majority vote, and if the vote is supported by at least one-third of the

members of the rst chamber, the matter is referred to the Senate

for trial, which, for the motion to pass, must decide by a two-thirds

majority vote (article XI, section 3). In view of the ease with which

impeachment can be initiated, the restriction on repeat proceedings

is understandable.

3.1.5. Replacements in case of removal

The issue of removing a president raises the question of how the

president is to be replaced. Practice in terms of replacement rules

follows two common approaches.

Vice president takes over for remaining term

In countries with a vice president, as is common in presidential

systems, the vice president generally replaces the president upon

removal from oce, particularly where the vice president is elected

on a joint ticket with the president. The vice president also tends to

serve until the end of the remaining term (e.g. Liberia, article 63[b],

Constitution 1986). Constitutions tend to mention only one or two

persons in the line of succession. For example, in Bulgaria, the vice

president takes over for the remaining term. Nevertheless, if the vice

president is not able to take over for any reason, the chairperson of

the National Assembly succeeds, but elections must then be held

within two months (article 97[4], Constitution 1991, rev. 2015).

In Liberia, the term that a vice president serves after replacing a

removed president would not count for the purposes of presidential

term limits (article 63[b], Constitution 1986). The absence of a clear

23INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

rule in relation to the counting of replacement terms can create

legal controversies and even political instability. In 2014, Zambian

President Michael Sata died in oce. Edgar Lungu won in January

2015 the election to nish Sata’s remaining term until September

2016. Lungu then won a second election in August 2016. When he

announced his intentions to run for election in 2021, a case was

led on the grounds that he has served the maximum of two terms

allowed under the Constitution. Lungu argued that the 2015–2016

replacement term did not count. In a 2018 case, the Constitutional

Court ruled that the term he served following the president’s death

did not count for the purposes of constitutional limits (Constitutional

Court of Zambia 2018). A specic rule as in Liberia avoids judicial

controversies as happened in Zambia.

Elections held quickly

In countries without vice presidents, as is common in semi-

presidential systems, the mantle generally passes to the chairperson

of the rst or second chamber of parliament, or in some cases to the

prime minister or top judge. In this case, new presidential elections

are generally held quickly. In South Korea, elections must be held

within 60 days (article 68[2], Constitution 1948, rev. 1987).

In many of these jurisdictions, in view of the absence of a direct

popular mandate, the interim president is proscribed from exercising

certain key presidential powers. For instance, in the Central African

Republic, elections must be held between 45 and 90 days after

the presidency is vacated (article 47, Constitution 2016). The

interim president—who is the chairperson of the rst chamber

or, in their absence, the chairperson of the Senate—is prohibited

from reconstituting the government, leading constitutional reform

or having recourse to a referendum (as well as from running for

president in the next elections).

Ecuador has a unique system where removal leads to not only

presidential elections but also legislative elections (article 130,

Constitution 2008, rev. 2021). In addition to discouraging abuse

of removal processes, this rule ensures that both presidential and

parliamentary elections continue to be held at the same time.

The absence of a

clear rule in relation

to the counting

of replacement

terms can create

legal controversies

and even political

instability.

24 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

It has been noted that removal processes are more likely to serve as

solutions to political paralysis when elections follow the removal of a

president rather than when someone completes their remaining term

(Ginsburg, Huq and Landau 2021: 163). Ginsburg, Huq and Landau

also nd that 74 per cent of constitutions around the world with

presidential and semi-presidential systems provide for immediate

elections in case of presidential removal.

Conditional on length of remaining term

In some countries, whether a replacement election is held or not

depends on the timing of the vacancy. For instance, in Chile, if there

is less than two years left of the removed president’s four-year term,

a replacement president is elected by the plenary of Congress by an

absolute majority of senators and deputies; if there is more than two

years left, general elections are held within 120 days. The elected

president completes the remaining term and is not allowed to run as

a candidate in the next election, in line with the general prohibition

on presidential re-election in Chile (article 29, Constitution 1980, rev.

2021). In Venezuela, where the president serves a six-year term, if a

president is removed or otherwise unavailable within the rst four

years, the vice president takes over, and elections must be held within

30 days; if a vacancy occurs in the last two years of the presidential

term, the vice president takes over for the remainder of the term

(article 233, Constitution 1999, rev. 2009). Similarly, in Comoros,

where a president serves for ve years, if a presidential vacancy

occurs within 900 days of elections, the prime minister takes over,

and elections must be held within 60 days; if a vacancy occurs less

than 900 days from elections, the governor of the island from which

the president originates nishes the term (article 58, Constitution

2018—note that, under the Constitution, the presidency must rotate

between the Islands).

3.1.6. Consequences of removal

Considering the potential seriousness of the grounds for

impeachment, removal could have consequences on a president

beyond losing power. While presidents ordinarily enjoy immunity

during their tenure, they could be prosecuted after the end of their

tenure for crimes committed while in oce. This possibility of

prosecution after leaving oce also applies to removed presidents.

74 per cent of

constitutions around

the world with

presidential and semi-

presidential systems

provide for immediate

elections in case of

presidential removal.

25INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

In addition, removed presidents could be denied benets ordinarily

granted to former presidents. For instance, in Tanzania, a removed

president is denied pension payments and any benets or other

privileges that they would be entitled to under the Constitution or any

other law (article 46A[11], Constitution 1977, rev. 2005). The severity

of these consequences could incentivize incumbents to resign before

removal proceedings are completed. Peruvian President Pedro Pablo

Kuczynski resigned in 2018 under a real threat of removal. Such

early resignation may allow incumbents to avoid the consequences

of removal. Constitutions may, however, allow impeachment of

presidents, even after they have left oce at the end of their tenure

or after resignation, as is the case in Chile where a president may

be impeached up to six months after leaving oce (article 52.2[a],

Constitution 1980, rev.2021).

Another common consequence of presidential removal is the ban

that some removed presidents face on assuming public oce or

other public function. In some countries, such as Liberia (article 43,

Constitution 1986), the ban is permanent. In others, the ban may be

limited in time—for example, for eight years in Brazil (article 52) or for

ve years in Chile (article 53[1]). In Colombia, the impeaching body

decides whether a ban is temporary or absolute (article175).

3.2. REMOVAL ON GROUNDS OF PHYSICAL OR

MENTAL INCAPACITY

The second common basis for the removal of presidents relates

to their permanent physical or mental incapacity to discharge the

functions of the oce. Where the incapacity is temporary due to

being physical in nature, the president is ordinarily replaced for the

duration of the incapacity in line with the relevant replacement rules

(commonly by the vice president or a person designated by the

president). For instance, in November 2021 US Vice President Kamala

Harris served as president for a short while when President Joe Biden

was undergoing surgery (Pengelly 2021).

3.2.1. Procedure for removal for incapacity

The procedure for removal on account of incapacity generally

involves a decision of the legislature and/or the cabinet, and

Removed presidents

could be denied

benets ordinarily

granted to former

presidents.

26 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

examination of the alleged incapacity by a body composed fully or

partially of medical professionals. For this purpose, the president

is generally required to submit himself or herself to a medical

examination—for instance, the Ghanaian Constitution provides

that the president ‘shall be invited to submit himself’ to a medical

examination within 14 days of the establishment of a medical tribunal

for this purpose (article 69[6], Constitution 1992, rev. 1996).

The 2010 Constitution of Kenya (article 144) perhaps has an

elaborate procedure for removal on grounds of incapacity. The rst

chamber of the legislature (National Assembly) has the power to

initiate proceedings on account of incapacity. One quarter of the

members of the rst legislative chamber can initiate proceedings on

account of physical or mental incapacity. If the motion is approved by

a majority of all members of the Assembly, the speaker asks the chief

justice to set up a tribunal composed of three medical professionals,

one lawyer and one member nominated by the president or a close

relative. If the tribunal, which must decide within 14 days, nds the

president to be incapacitated, the speaker must table the tribunal’s

report before the Assembly within 7 days. If a majority of the rst

Box 3.1.Importance of distinguishing temporary and permanent incapacity

The choice of terminology and absence of specic rules in cases of temporary incapacity could

be controversial. For instance, the original version of the Gabonese Constitution (article 13,

Constitution 1991, rev. 2011) referred only to a power vacuum or ‘permanent’ impairment, and

provided that, in such cases, the president of the second chamber takes over, and elections

are organized to replace the president. The Constitution also provided that only the president

or someone authorized by the president can convene the cabinet. When President Ali Bongo

suffered a stroke and fell into a coma in 2018, his incapacity was not considered permanent, and

the succession rules could not be activated. At the same time, under the Constitution the cabinet

could neither meet nor formally take decisions without the president’s authorization. To address

this paralysis, the prime minister requested that the Constitutional Court interpret the Constitution

and allow the vice president to convene the cabinet. The Court effectively, and controversially,

introduced a new provision in relation to temporary vacancy and accepted the prime minister’s

request for the vice president to convene the cabinet (Institute for Security Studies 2018). Bongo

rst reappeared in public 10 months later. A subsequent constitutional amendment expressly

recognized temporary vacancies and provided that, in such cases, a joint body composed of the

presidents of the two legislative chambers and the defence minister would take charge (Ondo and

Moundounga Mouity 2021).

27INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

chamber raties the tribunal’s decision, the president is removed, and

the vice president takes over. If the tribunal nds that the president

is capable, the president continues. The tribunal’s decisions are nal

and may not be appealed. Although Kenya has a Senate, it is not

involved in procedures for removal on grounds of incapacity.

The Constitution of Sierra Leone grants the power of initiating

proceedings on grounds of incapacity to the cabinet (article 50,

Constitution 1991, reinstated 1996, rev. 2013). Accordingly, where

the cabinet resolves that the question of the president’s mental or

physical capacity to discharge the functions of the oce ought to

be investigated, it informs the speaker of the National Assembly.

The speaker, in consultation with the head of the Medical Service of

Sierra Leone, appoints a medical board consisting of no fewer than

ve medical practitioners registered under the laws of Sierra Leone

(interestingly, implying the exclusion of foreign medical doctors).

If the board nds the president incapable of discharging their

functions, the speaker is required to certify the decision and inform

the Assembly. The president is removed, and the vice president takes

over (articles 49[4] and 50[4]).

In the Seychelles, both the cabinet and parliament have the power

to initiate removal proceedings on grounds of incapacity (article 53,

Constitution 1993, rev. 2017). If a majority of the members of the

cabinet or half of the unicameral National Assembly (which must vote

without debate) initiate a proceeding on account of incapacity, the

chief justice establishes a medical board to determine whether the

president is, by reason of an inrmity of body or mind, incapable of

discharging the functions of the oce. If the president is found to be

incapacitated, the matter is referred to the Assembly, which requires

the approval of two-thirds of its members to pass the motion.

In a few countries, such as the United States, there is no requirement

for an independent medical determination of incapacity. In many

others, formal medical approval of incapacity is often a requirement,

usually subject to subsequent political approval (e.g. article 47[1],

Kazakhstan Constitution 1995, rev. 2017, as well as in Kenya

and Seychelles). The subjection of a medical tribunal’s ndings

to legislative approval means that a president found medically

incapacitated could potentially continue if the legislature rejects

28 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

the tribunal’s decision. While this is rare in practice, as is removal

on grounds of incapacity, if it does occur, it could undermine the

legitimacy of the political system. Overall, the absence of the

involvement of a medical tribunal could potentially create risks of

politicization of an alleged medical condition.

In some countries, courts are involved, which may depoliticize

contestations over incapacity. For instance, in Chile (article 53[7]),

the Senate declares, after hearing the Constitutional Court, the

incapacity of the president when a physical or mental impediment

disqualies them from performing their functions. In Bulgaria, a

president is removed on account of incapacity upon a decision of

the Constitutional Court (article 97, Constitution 1991, rev. 2015).

Under the Constitution of Burkina Faso, presidential removal on

grounds of absolute or denitive incapacity is proposed by a majority

of the cabinet and decided by the Constitutional Council (article 43,

Constitution 1991, rev.2015).

Zimbabwe has a unique process that, while political, also seeks to

reduce partisanship. A motion for removal commences with a vote

of at least half of the members in a joint sitting of the two legislative

houses. A cross-house committee composed of nine members

reecting the party composition of parliament is then established. If

the committee recommends removal, the motion is referred to a joint

sitting of the two houses of parliament. If two-thirds of the members

of parliament approve the motion, the president is removed (article

97, Constitution 2013, rev.2017).

Suspension, timelines, replacement, consequences

In some countries, a president may be suspended once incapacity

proceedings commence. Such a suspension, after prima facie

evidence of incapacity is provided, may be justied considering the

seriousness of presidential responsibilities, perhaps even more so

than in cases of impeachment proceedings. Nevertheless, this opens

up possibilities for abuse if the procedure for commencing removal

proceedings is relatively easy, and where there is no timeline within

which a nal decision should be taken. In Sierra Leone (discussed

above), if the cabinet resolves that the president’s capacity in

connection with any inrmity of mind or body be investigated, the

president is suspended from oce (article 50[3], Constitution 1991,

The absence of the

involvement of a

medical tribunal could

potentially create

risks of politicization

of an alleged medical

condition.

29INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

rev. 2013). If the board nds the president to be incapacitated, the

speaker certies the decision, and the president is removed. The

speaker’s certication is nal and may not be challenged in court.

As in the case of impeachment proceedings, constitutions may

provide specic timelines for removal on grounds of incapacity,

considering the political inertia and instability that accompanies such

procedures.

Once a president has been removed on grounds of incapacity, the

replacement rules are generally similar to those applicable for

removal on impeachment grounds. In Tanzania, in case of removal on

grounds of incapacity (or death or resignation) of the president, the

vice president takes over (article 37[5], Constitution 1977, rev. 2005).

If more than three years remains of the ve-year presidential term, the

replacement term counts for the purposes of presidential term limits;

if less than three years remains, it does not count (article 40[4]).

The rules on the secrecy or openness of votes on removal on grounds

of incapacity are also similar to those for impeachment cases.

The serious consequences of removal through impeachment, such

as denial of benets or limits on holding public oce, are generally

absent in the case of removal on grounds of incapacity. This

distinction is appropriate considering the absence of guilt on the part

Box 3.2.Clarity of rules and legal determination

The absence of a medical determination and vague standards and procedures could be

problematic. For instance, in Peru, the Constitution allows the removal of a president by Congress

on grounds of permanent ‘physical or moral incapacity’ (article 113.2, Constitution 1993, rev.

2021, emphasis added). However, the Constitution does not provide a procedure for removal.

Under the parliamentary regulations, presidential removal on this basis can be initiated by 20 per

cent of the members of Congress, and must rst be approved by 40 per cent of the members and

subsequently by a two-thirds vote in the unicameral Congress. Because the Constitution does

not provide for an objective way of determining physical or moral incapacity, the provision has

been frequently invoked to remove presidents and generate political instability. Between 2018 and

2021 alone, one president was removed and another forced to resign, and the country saw several

presidents depart before completing their terms, immersing it in a constant state of political

instability.

The serious

consequences of

removal through

impeachment, such

as denial of benets

or limits on holding

public oce, are

generally absent in the

case of removal on

grounds of incapacity.

30 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

of the incapacitated president. Nevertheless, in cases where moral

incapacity is the basis for removal, as in Peru, the consequences

could arguably be as severe as in the case of removal through

impeachment.

3.3. REMOVAL ON POLITICAL GROUNDS (RECALL)

In addition to cases of removal through impeachment and for

incapacity, some constitutions provide for procedures through which

presidents could be removed without any specic grounds, much like

prime ministers in parliamentary systems. This is effectively a recall

process for presidents. The availability of this option could provide a

valve to resolve political deadlock and instability where a president

has lost political and popular condence and support.

Removal for lack of condence is rare in presidential and semi-

presidential systems but is particularly popular in Latin America,

where it is established in the form of recall. Removals on political

grounds almost always involve a referendum, providing a level of

protection to make up for the absence of reasons for recall. In Latin

America, a recall can be initiated only by citizens. For instance, in

Ecuador, 15 per cent of voters can commence a recall procedure but

only after one year has lapsed since the most recent elections and

before the last year of a presidential term. The National Electoral

Council then organizes a referendum (or a motion to dismiss) within

60 days, and if the motion is approved by an absolute majority of

voters, the president is removed (articles 105 and 106, Constitution

Think point:Should replacement rules vary depending on the grounds for removal?

Allegations of bad behaviour that lead to removal tend to also implicate vice presidents (and

broadly the governing elite or party). Moreover, removal through impeachment is partly seen

as a means to end political paralysis, a situation that does not obtain in case of incapacity.

Accordingly, immediate elections may be more appropriate in the cases of removal through

impeachment (Ginsburg, Huq and Landau [2021: 161] have argued generally in favour of

immediate elections partly also to reduce vice presidential calculations to push for removal

for capricious reasons), while allowing whoever is next in the line of succession to nish the

remaining term may be preferred in the case of incapacity.

31INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

2008, rev. 2021). In Bolivia, a recall can be initiated by at least 15 per

cent of voters but only after half of the presidential term has lapsed

and before the last year of the president’s tenure (article 240[2] and

[3], Constitution 2009). The motion is then submitted to a referendum

(article 204[5]). Bolivia’s Constitution allows only one recall procedure

during a presidential term (article 204[6]). Venezuela has similar

rules but in addition requires that a recall referendum register at least

25 per cent turnout, and more voters than those who voted for the

president must support the recall (article 72, Constitution 1999, rev.

2009).

The Constitution of Iceland, which establishes a semi-presidential

system, allows parliament, by a three quarters majority, to refer the

removal of a president to a referendum (article 11, Constitution

1944, rev. 2013). The president is suspended upon the decision of

parliament, and a referendum must be held within two months of the

decision. With a view to discouraging abuse of the process, if the

vote fails, parliament is dissolved and new elections held. In Egypt

(article 161, Constitution 2014, rev. 2019) and The Gambia (article

63, Constitution 1996, rev. 2018), a vote of no condence is approved

by the legislature by a two-thirds majority, subject to approval in

a referendum. In Egypt, as in Iceland, with a view to discouraging

frivolous referendums, if a referendum fails, the legislature is

dissolved and fresh elections held.

In all cases of recall or loss of condence, if a president is removed,

new elections are organized within a prescribed period (e.g. within

60 days in Egypt, and 30 days in The Gambia). Considering the

political nature of presidential removal, there are generally no

disadvantageous consequences for the removed president beyond

the removal, such as denial of pension or other benets.

3.4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Contestations over the removal of a president have serious

implications for short- and long-term political stability. Constitutional

regulation of and clarity regarding the grounds for removal, as well

as the process and procedures for removal, are therefore paramount.

This Primer has identied a variety of approaches to the regulation

32 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

of presidential removal and discussed the policy reasons behind

diversities in design on key issues. In all cases, however, the objective

is to provide ways of creating genuine possibilities for removing

presidents before the end of their term (a)through impeachment;

(b)on grounds of incapacity; or (c)through recall, while precluding

frivolous and abusive removal proceedings.

Procedurally, the key issue is perhaps whether the courts and/

or other independent bodies should be involved in the three types

of presidential removal processes identied above, and at what

particular stage. In a large majority of countries, judicial and expert

involvement is the norm, but some older constitutions, notably of the

United States and some Latin American countries, do not anticipate

any direct role for the courts. The involvement of the courts and

other formally independent entities could enhance condence in

the removal procedure and reduce excessive politicization. At the

same time, their involvement adds another veto point, which could

undermine the effectiveness of the threat of impeachment as an

accountability mechanism.

In practice, the successful removal of a president, on any grounds,

is rare, particularly in countries where there are well-established,

disciplined parties. Accordingly, while potential removal on grounds

of impeachment could help deter presidential misbehaviour, the

promotion of presidential accountability requires the establishment

of conditions for free, fair and competitive elections. In this regard,

in addition to the complementary role of impeachment procedures,

effective democratic accountability through elections and guaranteed

regular and democratic alternation of power through term limits are

important and could encourage presidents to remain vigilant out of

consideration for the fact that they will face consequences once they

no longer have the protection that incumbency may provide. Crucially,

constitutional designers could enhance the chances for presidential

accountability by avoiding the concentration of power in the oce of

the president.

33INTERNATIONAL IDEA 3. PRESIDENTIAL REMOVAL

Chapter 4

DECISION-MAKING QUESTIONS

1. What grounds are important enough to justify the removal of a

popularly elected president? Impeachment? Incapacity? And/or

recall?

2. What are the potential risks of vague and subjective grounds?

3. What should the purpose of presidential removal through

impeachment be? As punishment for (serious) illegal/bad

behaviour or also to nd a political way out of political paralysis or

ungovernability (political hard reset)?

4. Should the constitution recognize the possibility of presidential

recall on purely political grounds? Through what process?

5. What should the minimum threshold be to initiate a procedure

for removal on grounds of legal violations/misconduct

(impeachment), incapacity or recall?

6. What is the history of presidential abuse, political instability and

presidential removal in the country? What is the political party

system? What has been the trend in terms of parties’ shares

of seats in parliament? How should these factors inuence the

design of the removal process?

7. What rules should be required for decision-making in all these

cases?

8. Does the constitutional framework establish a powerful

presidency, or are there sucient checks and balances that can

reduce the possibilities of presidential misconduct?

9. Should the courts or other independent bodies be involved in the

removal procedure? At what stage of the process?

10. Should there be specic timelines for each stage of the removal

process? What should these timelines be?

34 4. DECISION-MAKING QUESTIONS REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

11. Should votes in the legislature during removal procedures be by

open or secret ballot?

12. Should an incumbent president facing removal through

impeachment, recall or on the grounds of incapacity be

suspended? If so, at what stage?

13. What should happen when a president has been removed?

– If a president is to be replaced by an another ocial, who?

– If a president is to be replaced by the vice president, how should

the vice president be selected (i.e. should the vice president

be appointed by the president or be required to be voted in on

the same ticket as the president to enhance their democratic

pedigree)?

– In case of replacement by an another ocial, would the term

count for the purposes of presidential term limits?

– If elections should be held to replace a removed president, what

time frame should they be held within?

– Would it make sense to decide on the mode of replacement

depending on the period of time left until the next ordinary

elections—that is, elections where the remaining term is long

but replacement by an another ocial where the remaining term

is short (as is the case in Venezuela and Comoros)?

14. What should the consequences of removal be, particularly in the

case of removal through impeachment?

35INTERNATIONAL IDEA 4. DECISION-MAKING QUESTIONS

Chapter 5

EXAMPLES

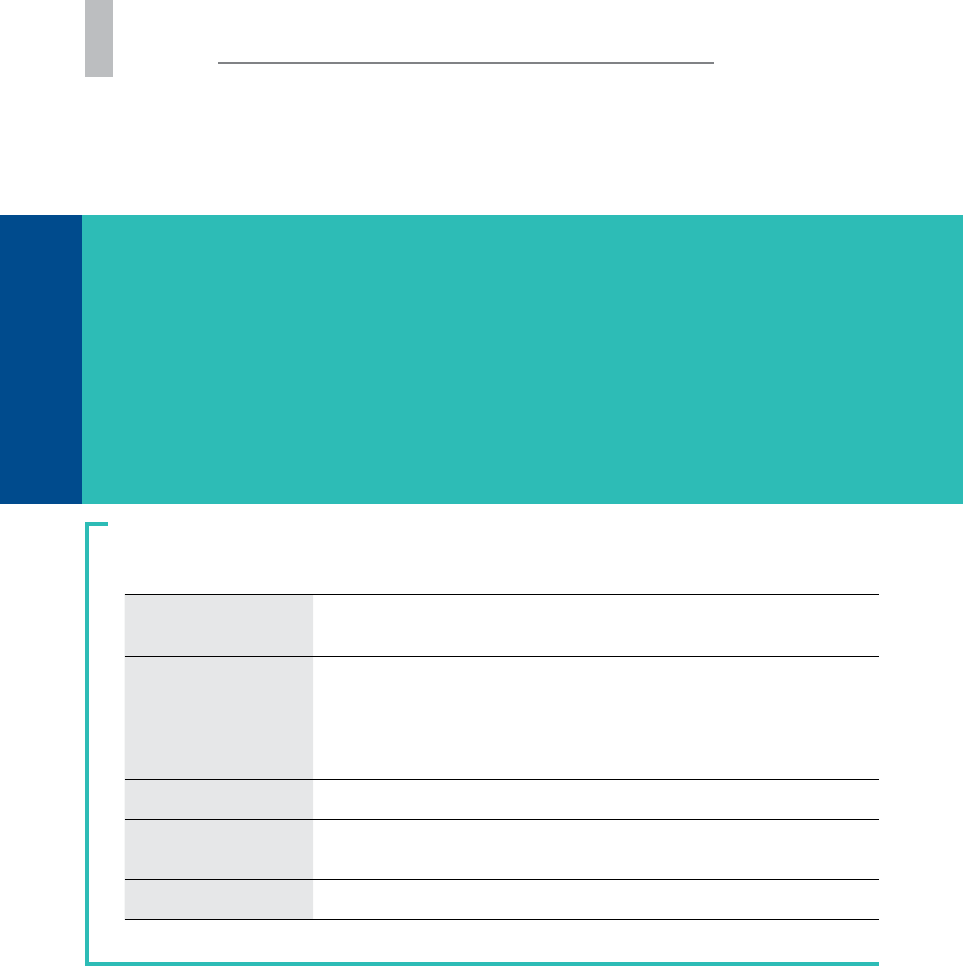

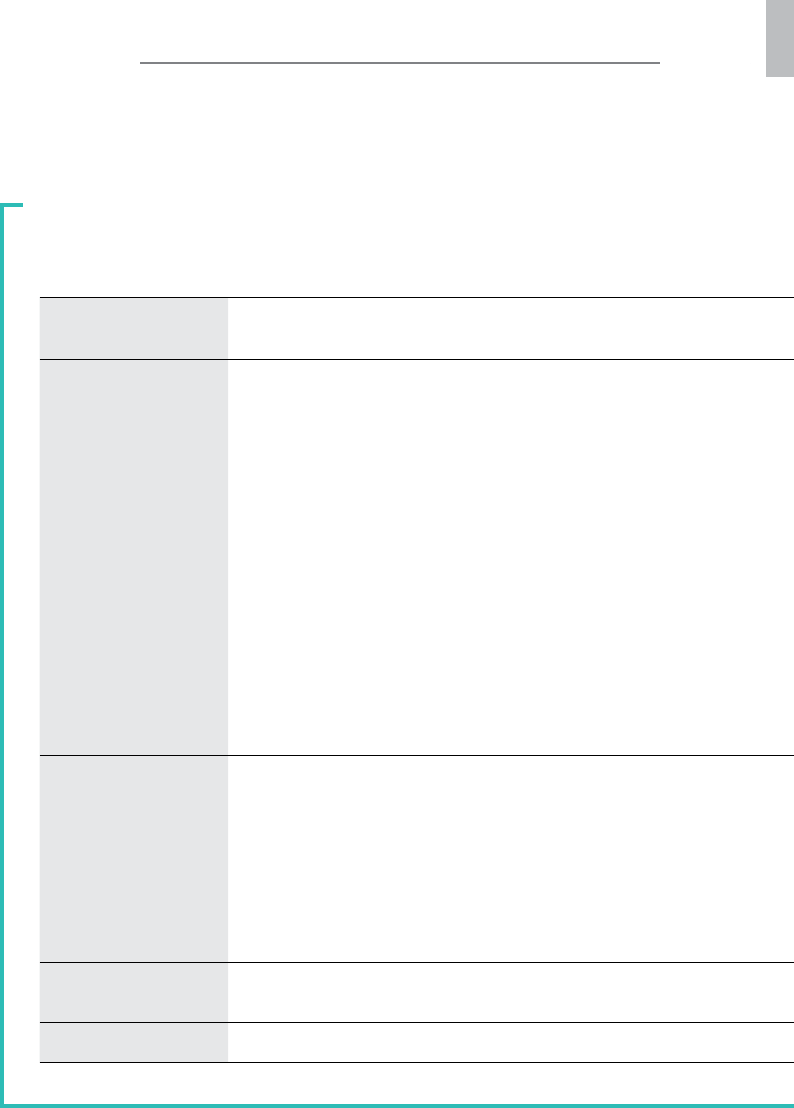

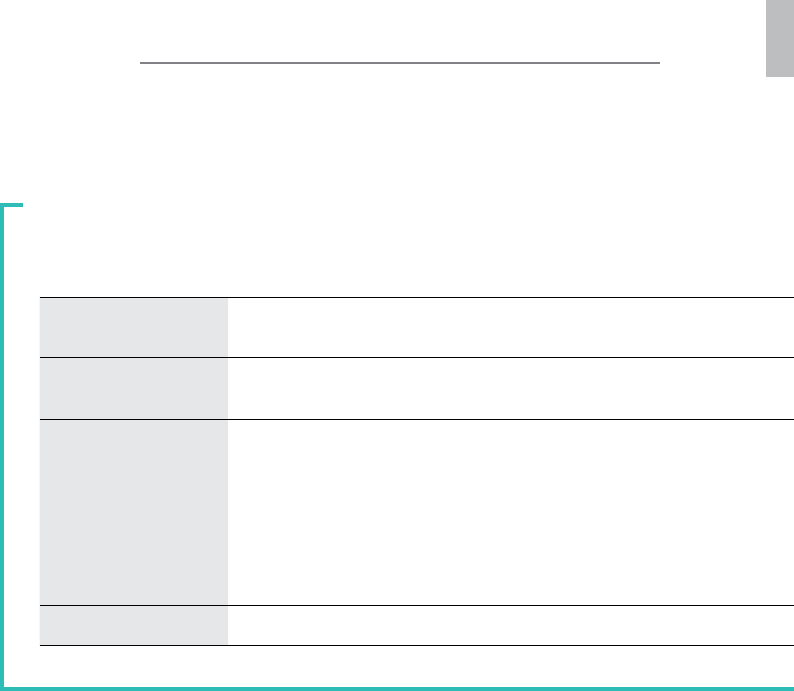

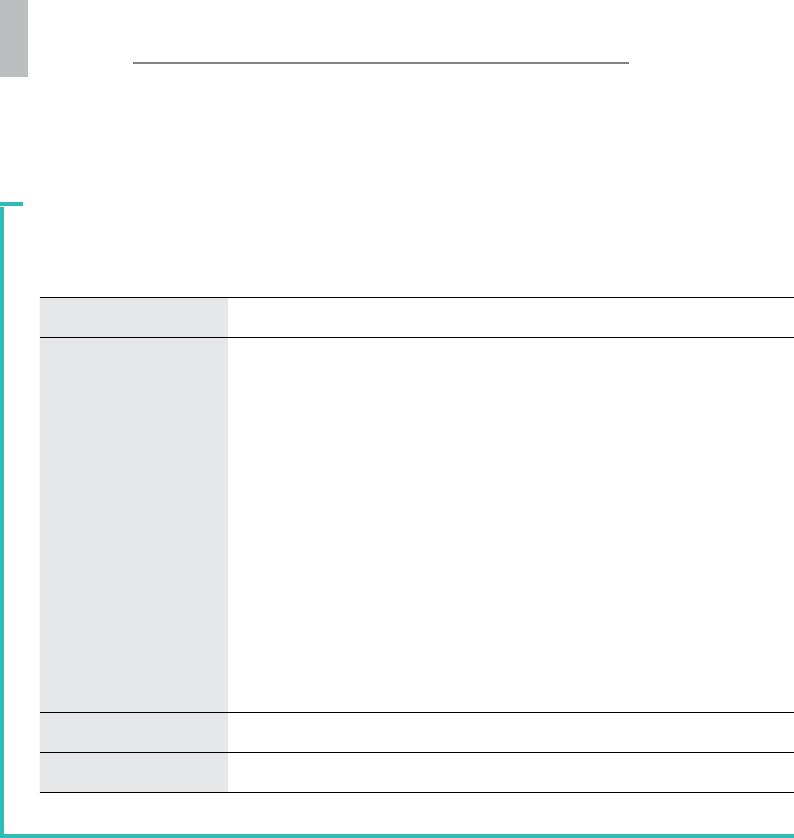

Table 5.1.Impeachment: Argentina, articles 53, 88

Impeachment

grounds

Poor performance; commission of an offence in carrying out duties or

commission of a common crime

Procedure (incl.

timeline if any)

Two-thirds majority of those present in the Chamber of Deputies (rst

chamber) declares the cause for action

Senate approves with a two-thirds majority of those present in a public

session where members swear an oath

Replacement

The vice president nishes the remaining term

Consequences

The Senate could declare the president ineligible to hold any employment of

honour, trust or receiving payment of the state

Suspension

No suspension

36 5. EXAMPLES REMOVAL OF PRESIDENTS

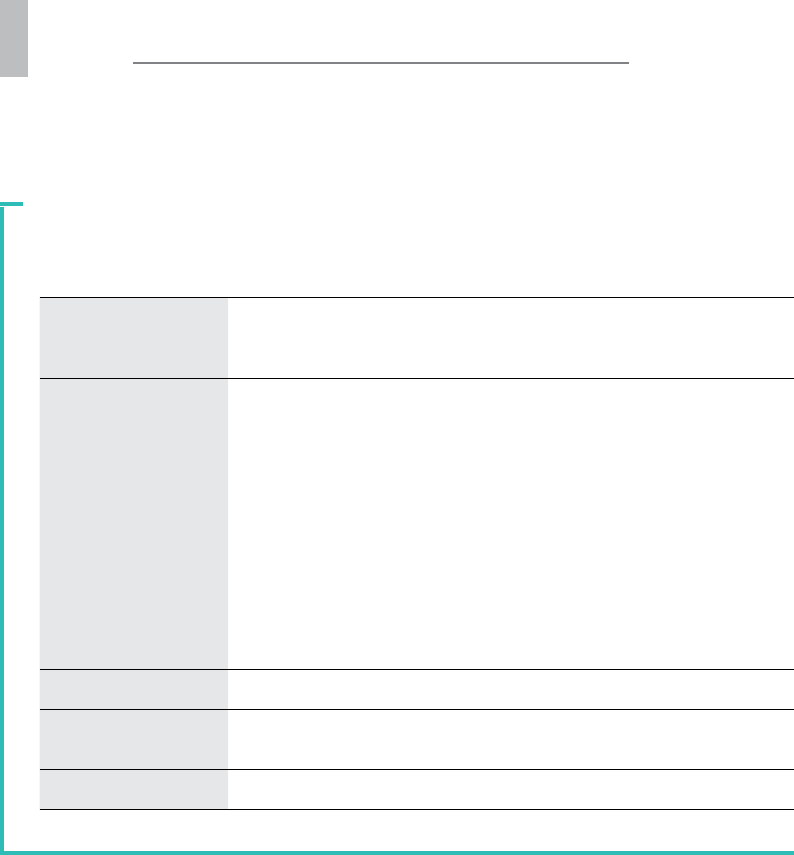

Table 5.2.Impeachment: Ecuador, articles 129, 130, 131

Impeachment

grounds

Crimes against the security of the state; crimes of extortion, bribery,

embezzlement or illicit enrichment; crimes of genocide, torture, forced

disappearance of persons, kidnapping or homicide on political or moral

grounds; taking up duties that do not come under their competence, after a

favourable ruling by the Constitutional Court; severe political crisis or internal

unrest

Procedure (incl.

timeline if any)

Initiated at the request of one-third of the members of the National Assembly

Ruling of admissibility by the Constitutional Court (except for a political crisis

or internal unrest), but prior criminal proceedings are not required

After the procedures provided by law conclude, the president is removed

upon a decision approved by two-thirds of the members of the National

Assembly

A motion to remove the president for taking up duties beyond their

competence or for a severe political crisis or internal unrest can be exercised