by John Browne | 06. 12. 2020

2

The DataWindow object is the cornerstone of PowerBuilder application

development. PowerBuilder apps are largely designed around accessing

databases, typically for CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations.

In fact, most business applications—especially legacy client/server applications—

are forms over data: screens contain a host of data-bound controls designed

to build queries against database tables, return results, and allow for CRUD

updates.

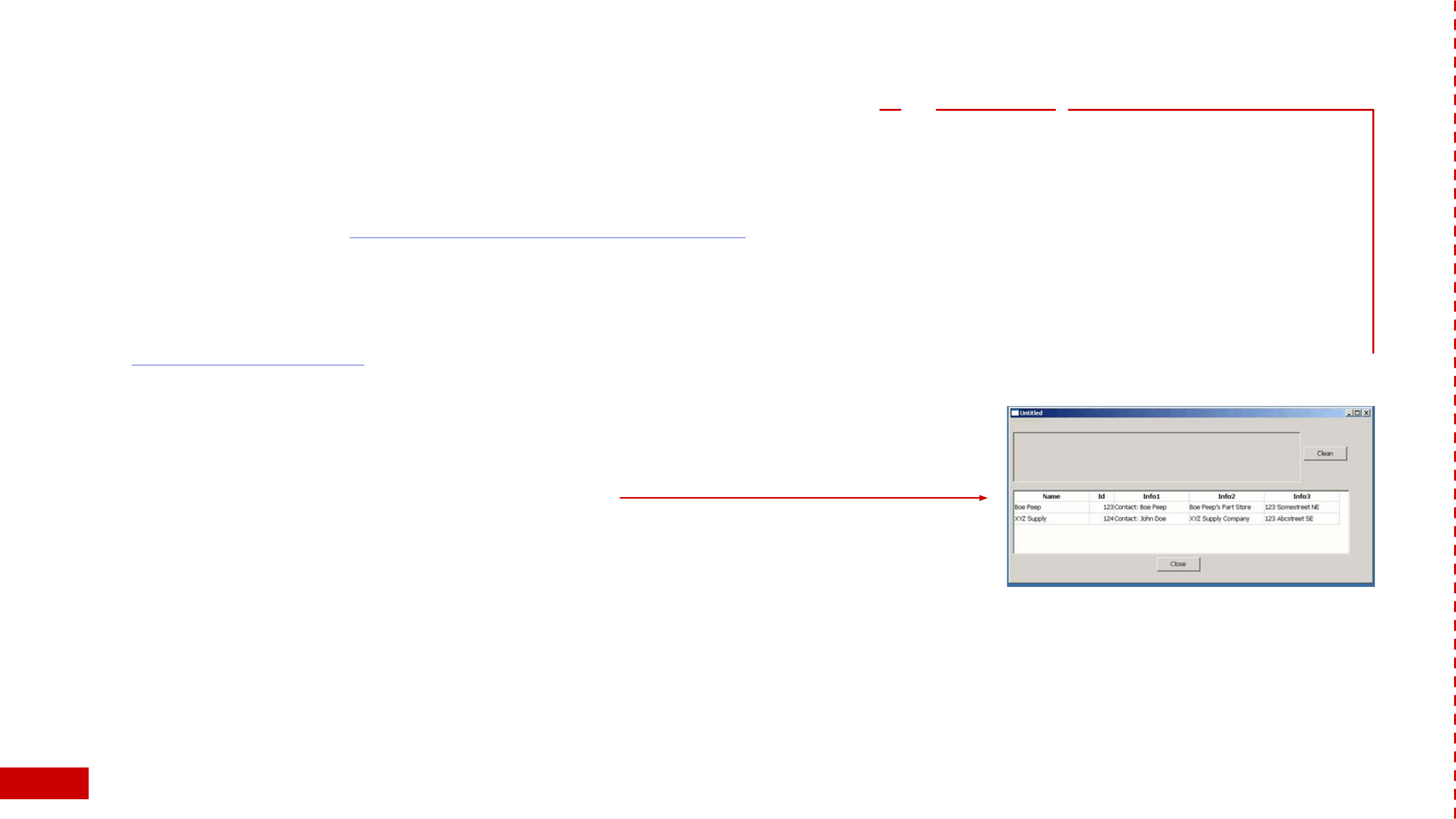

For example, a fairly typical screen for this kind of application might look like this

one:

In this screen—from Mobilize.Net's demo app (Salmon King Seafood)—we have

some text elds for entering search strings, a grid control that returns the

results of a SQL query built from the text box values, another grid control, some

calculated elds displayed as text boxes, and a couple of command buttons. Very

typical.

PowerBuilder was a tool designed to build these kinds of apps quickly and easily,

using an approach that today is known as "low code." With PowerBuilder, you

created windows (forms) with controls and set properties on those controls.

This, in itself, was no different from VB6. But PowerBuilder took the concept as far

as possible, particularly in the use of DataWindows.

3

A DataWindow is an object unique to PowerBuilder.

The window object is bound to a data source, and the results of the

associated DB query can be displayed in a variety of ways or views.

Here, for example, is a DataWindow running in the PowerBuilder 12.5

tutorial—in this case it's displaying data in a grid view:

And here, in the same app, is a second DataWindow displaying the same

query, but in a forms view:

Selecting a row in the rst DataWindow updates the display in the bottom

one:

4

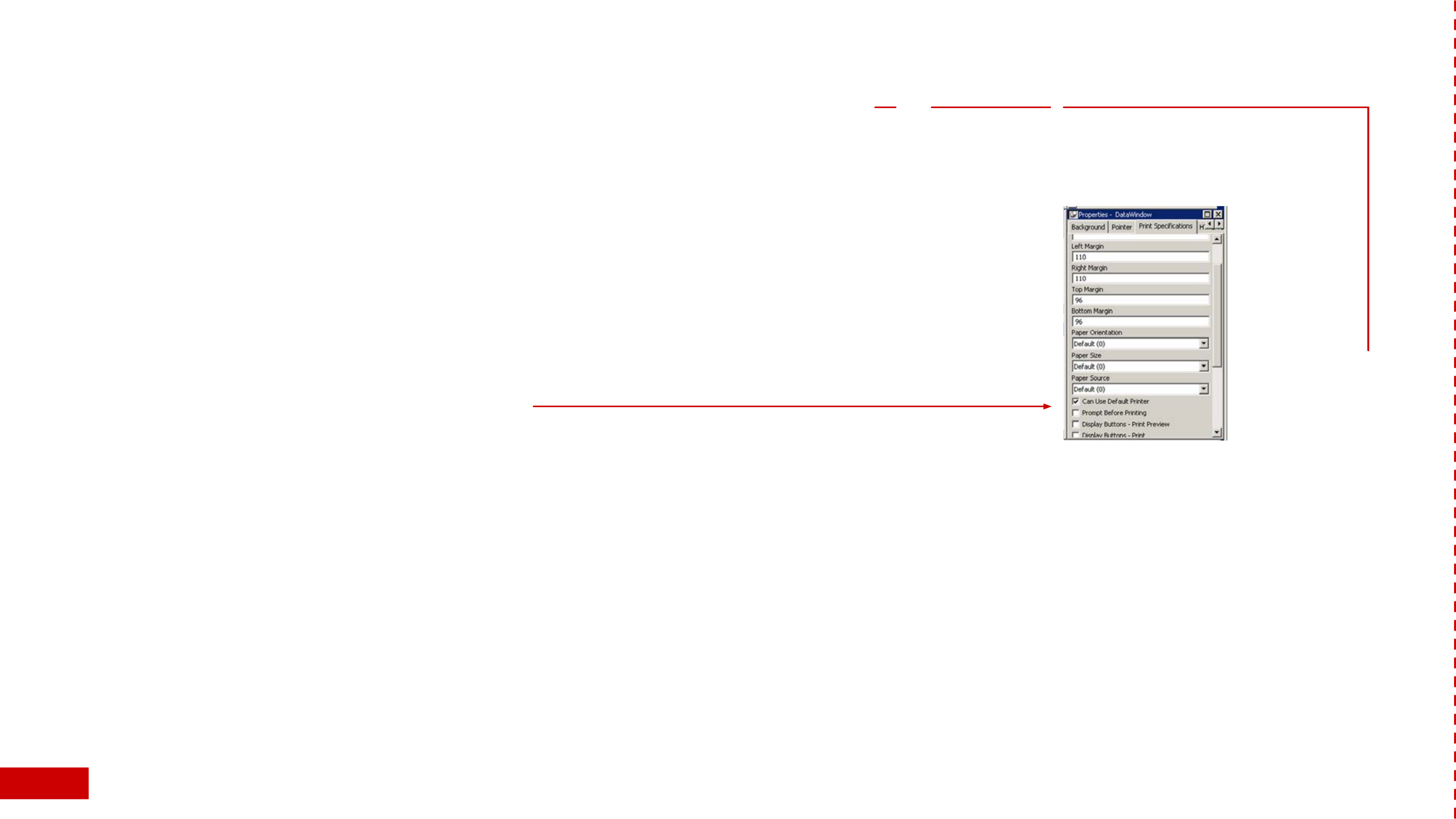

In addition to DataWindows presenting the results of DB queries in a variety

of formats, they also integrate some basic printing concepts directly into the

application user interface.

Remembering that in the 1990s, when PowerBuilder was at its peak of popularity,

paper was still a ubiquitous aspect of ofce life. DataWindows can include

headers, footers, page numbers, and formatting designed for almost any kind of

physical printer. In the DataWindow properties panel, a Print Specications tab

lets you manage all these parameters:

DataWindows can have controls with properties and events, and of course they

can have code that responds to events. So where's the code? The idea behind

PowerBuilder is to minimize the amount of actual coding the developer has to

perform, so as much as possible the integrated development environment (IDE)

allows you to create your application using a more interactive method.

5

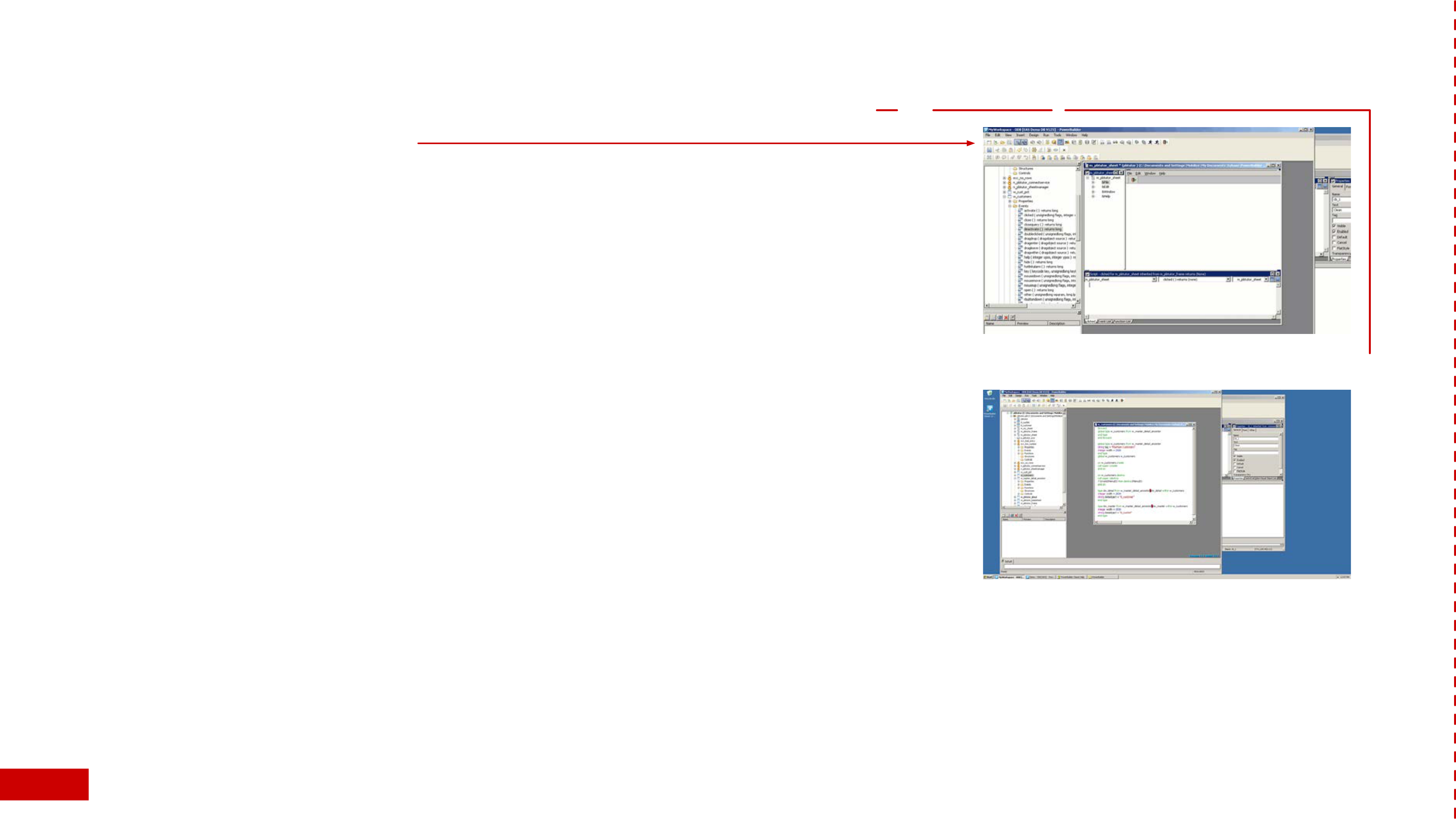

Let's look at an example:

What are we looking at here? On the left side you can see all the available

events for the w_customers DataWindow. The animation shows how

you can get PowerBuilder to add scaffolding for code structures directly

into the script window (PowerBuilder calls code "scripts"). You can see all

the code behind an object, like this w_customers DataWindow, by right

clicking on the object name and selecting "show source":

If we take a closer look at code—this time from a different, simpler, demo

app—we can see it looks pretty straightforward:

If we take a closer look at code—this time from a different, simpler, demo

app—we can see it looks pretty straightforward:

global type w_main from window

end type

type cb_2 from commandbutton within w_main

end type

6

global type w_main from window

end type

type cb_2 from commandbutton within w_main

end type

on w_main.create

this.cb_2=create cb_2

this.cb_1=create cb_1

this.dw_2=create dw_2

this.dw_1=create dw_1

this.Control[]={this.cb_2,&

this.cb_1,&

this.dw_2,&

this.dw_1}

end on

global type w_main from window

integer width = 3374

integer height = 1408

boolean titlebar = true

string title = "Untitled"

boolean controlmenu = true

boolean minbox = true

boolean maxbox = true

boolean resizable = true

long backcolor = 67108864

string icon = "AppIcon!"

on w_main.destroy

destroy(this.cb_2)

destroy(this.cb_1)

destroy(this.dw_2)

destroy(this.dw_1)

end on

...at least, that's what I think they are.

7

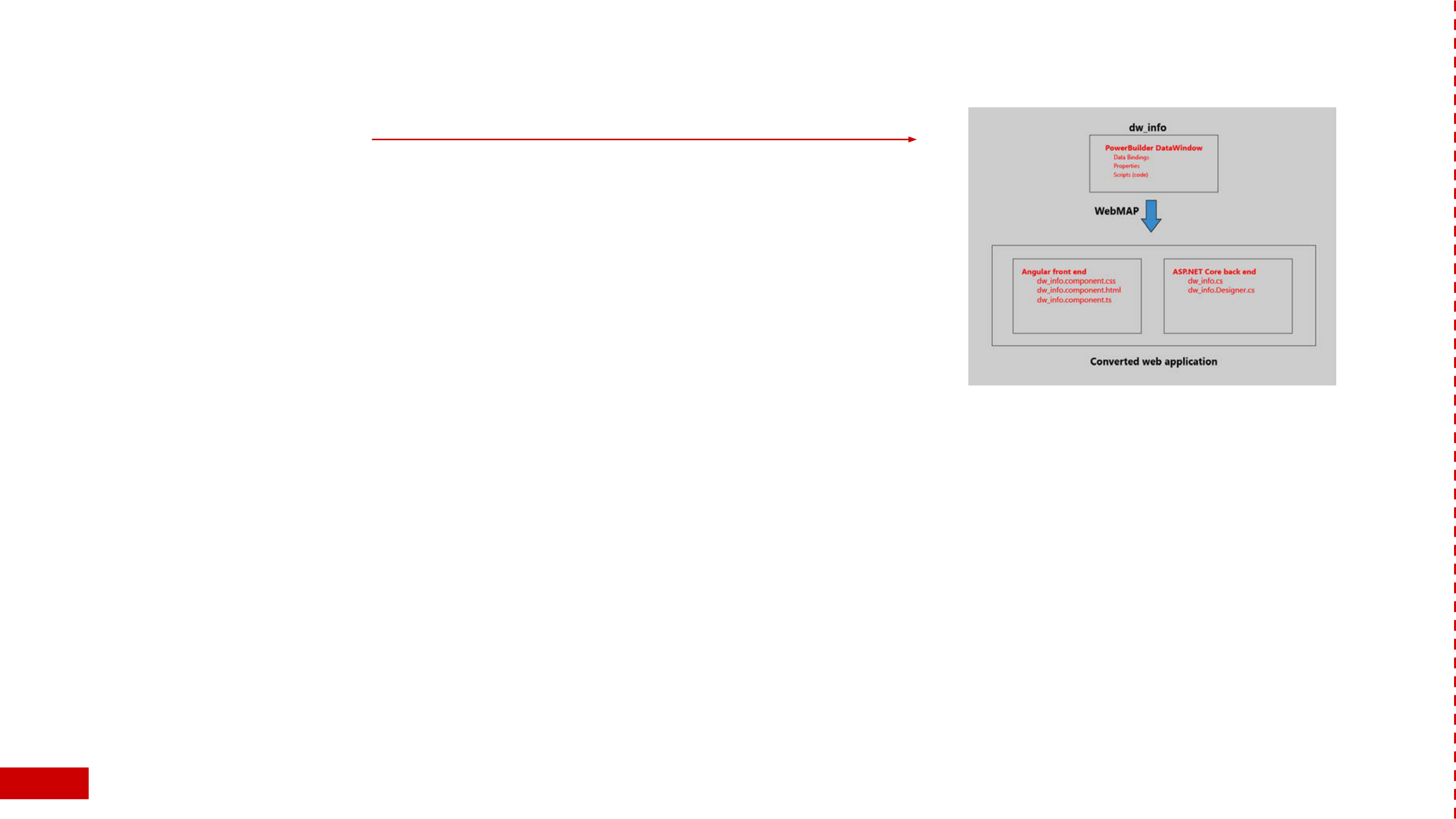

Now that we know more about what PowerBuilder DataWindows look like, how

would we go about migrating DataWindows to the web using non-PowerBuilder

technologies.

Over the last few years, Mobilize.Net has made signicant improvements to

its PowerBuilder migration tools, allowing for modernization/migration from

PowerBuilder to Java or ASP.NET Core.

Both use Angular, HTML, JavaScript, and Kendo for Angular to create a modern,

well-architected web front end and performant back end server. In this case, I'll

show a demo app and how the code is migrated to the web using ASP.NET Core.

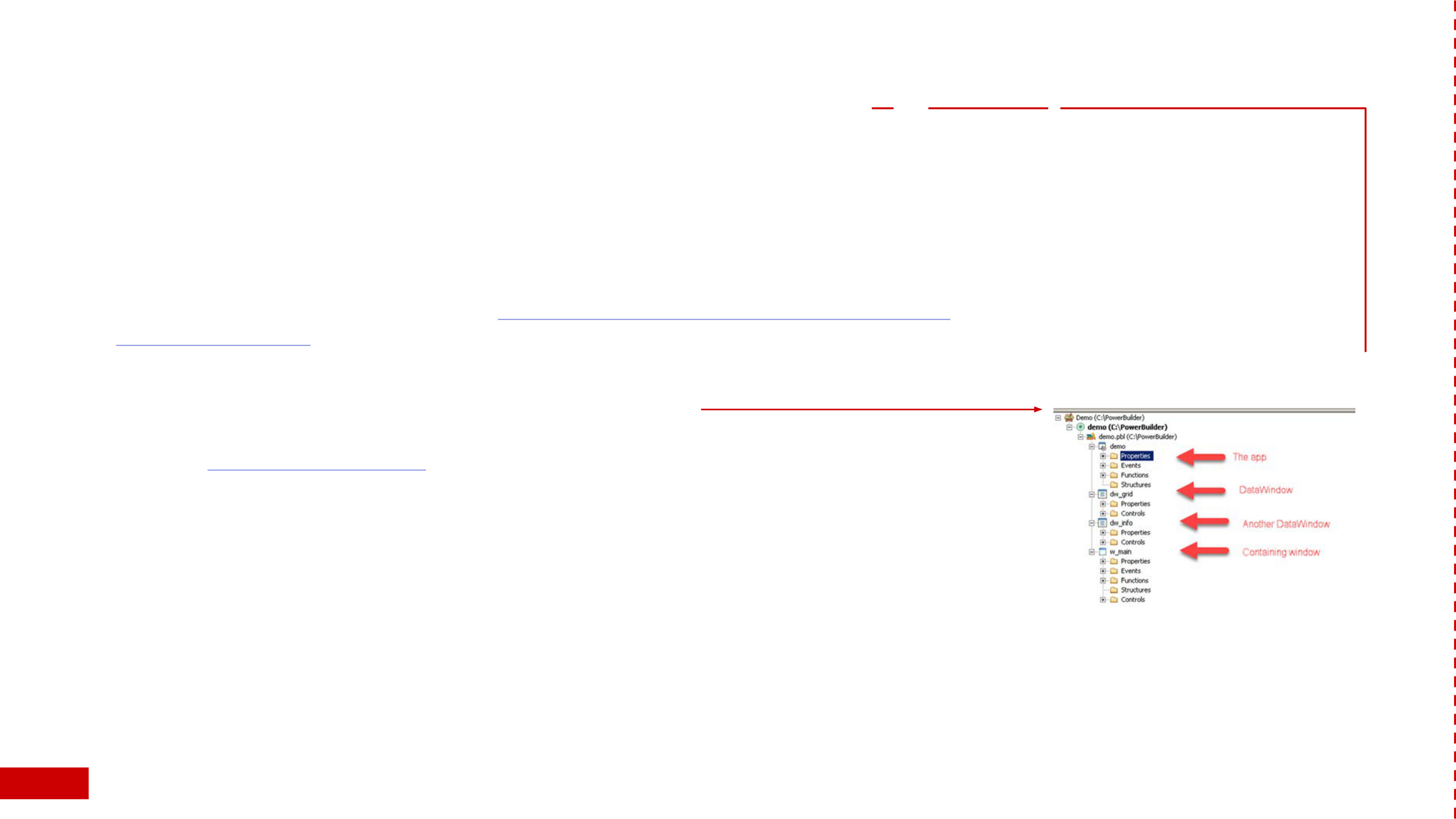

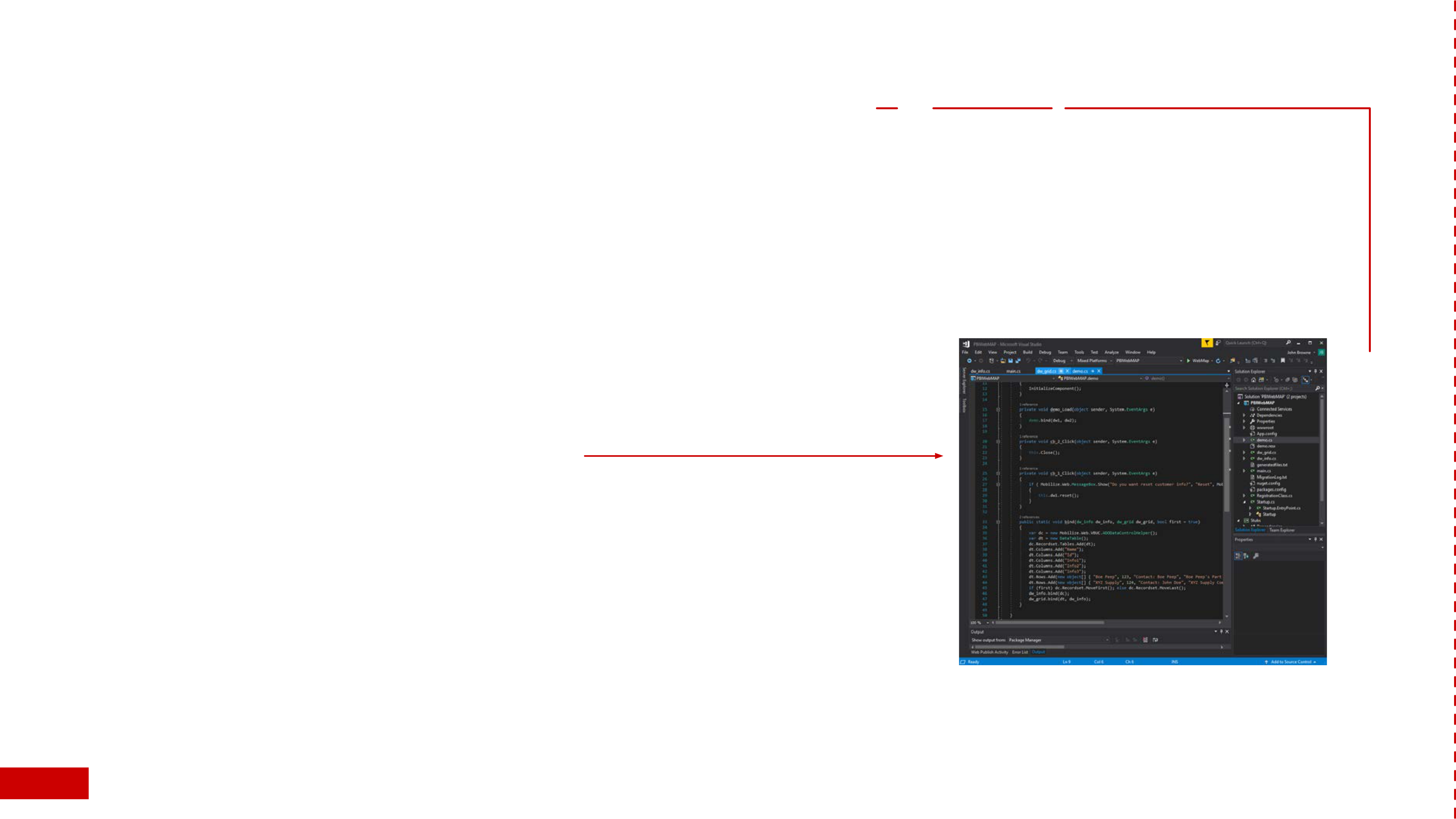

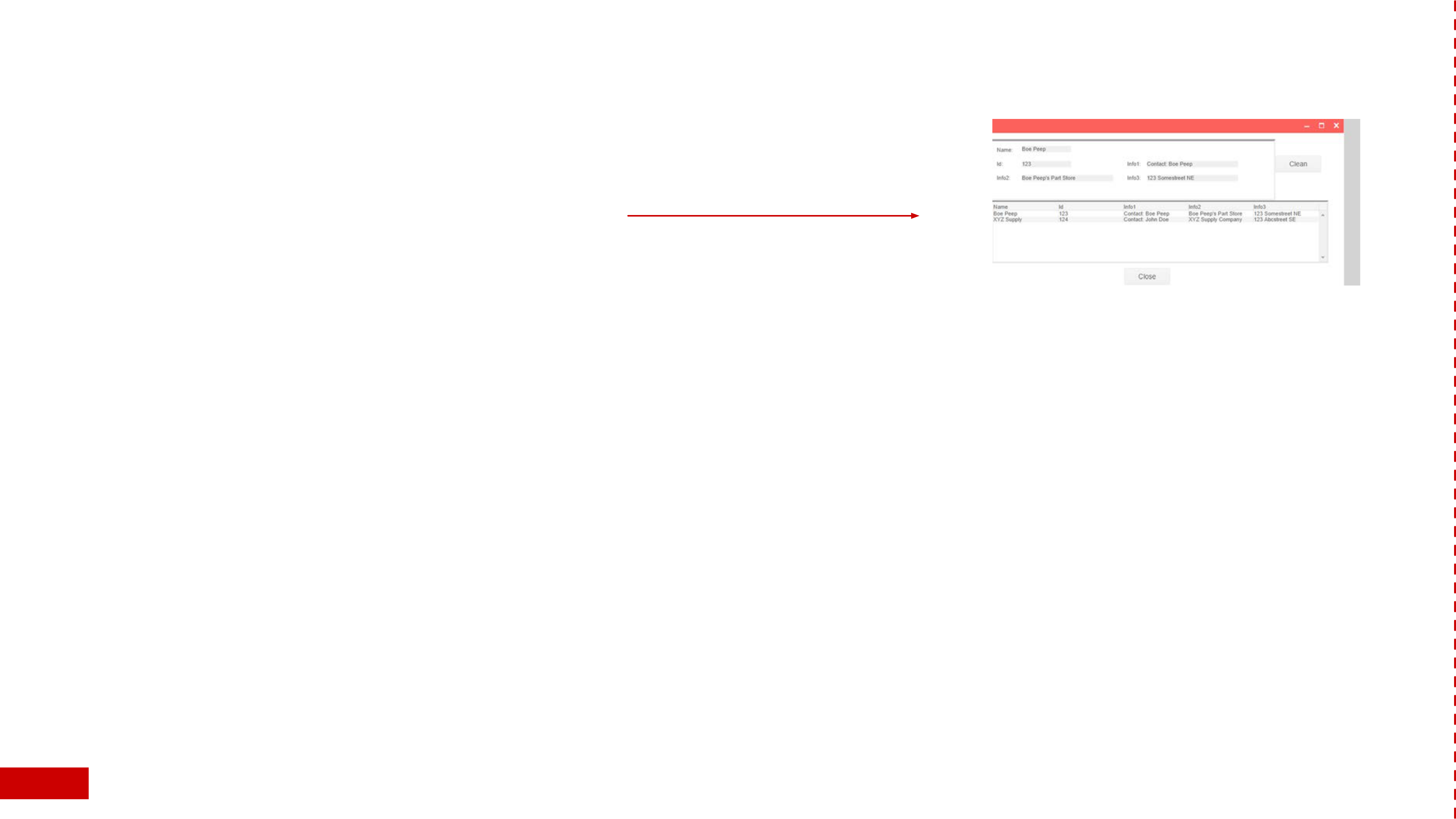

First, let's look at our PowerBuilder demo app:

This looks (and basically is) a trivial example, but there are several interesting

things going on in this demo. First, there are two DataWindows, one a free form

style, and the other (lower) a grid presentation.

Each DataWindow has a command button, and the top command button invokes

a message box (modal dialog). How do these get re-created after migrating these

PowerBuilder DataWindows to a C# web app?

8

Let’s now show how WebMAP can migrate PowerBuilder DataWindows to a

modern web app.

Let's look at the "System Tree" (sort of a solution explorer):

A convention for PowerBuilder apps is to prex the names of things with what they

are (see Hungarian notation).

So the parent window is called a w_main and the DataWindows are called dw_grid

and dw_info respectively.

And because this is so familiar to PowerBuilder developers, we want to keep this

naming convention in the C# code after we migrate it, even though Hungarian

notation is out of favor today.

9

WebMAP is the tool from Mobilize that can convert desktop apps into web apps, working at the source code level.

If you are unfamiliar with our tools, the idea is that you point WebMAP at the root folder of your PowerBuilder

solution and it will generate a completely new folder tree with all new code. Then all you have to do is compile the

new code and voila! There's your modern web app.

If only it were that simple.

In reality, moving from desktop to web—regardless of the source programming language or framework—exposes a

number of disconnects between the two platforms, something I've blogged about in the past. Without some kind

of assistance from automation like WebMAP this kind of effort can take years for signicant apps.

For example, take those DataWindows. As we mentioned before, the presentation of data in a DataWindow can

be formatted like a paper report—in fact, it's a key property of DataWindows. But printing from a web application

is completely different from a desktop app. Desktop (Windows) apps can call Windows services that manage

printers and print queues. They can offer the user a choice of all the installed printers—whether attached or

networked, allow for specic control of the printer, show a preview of the output, and more. The browser can't

even talk to the hardware. So web apps typically handle printing by creating a digital print—like a PDF le—and

offering the user a link to download the le to the local machine for handling (viewing or printing) outside of the

application.

10

Applications with no connections to printers, scanners, cash registers,

or other hardware are arguably simpler to migrate—at least from that

standpoint—than those that have those kinds of connections. (NB: lots of

apps DO have hardware dependencies, and we've developed a way to

connect the web apps to physical devices, but that's a topic for another

blog.)

Our little PowerBuilder demo app doesn't need any hardware, so we can

skip that step in our migration.

Ok, it's done.

Wait, what? Where's the migration step?

Actually the migration process itself is boring. Pick a source path, an

output path, and push "go." There is literally nothing interesting to see,

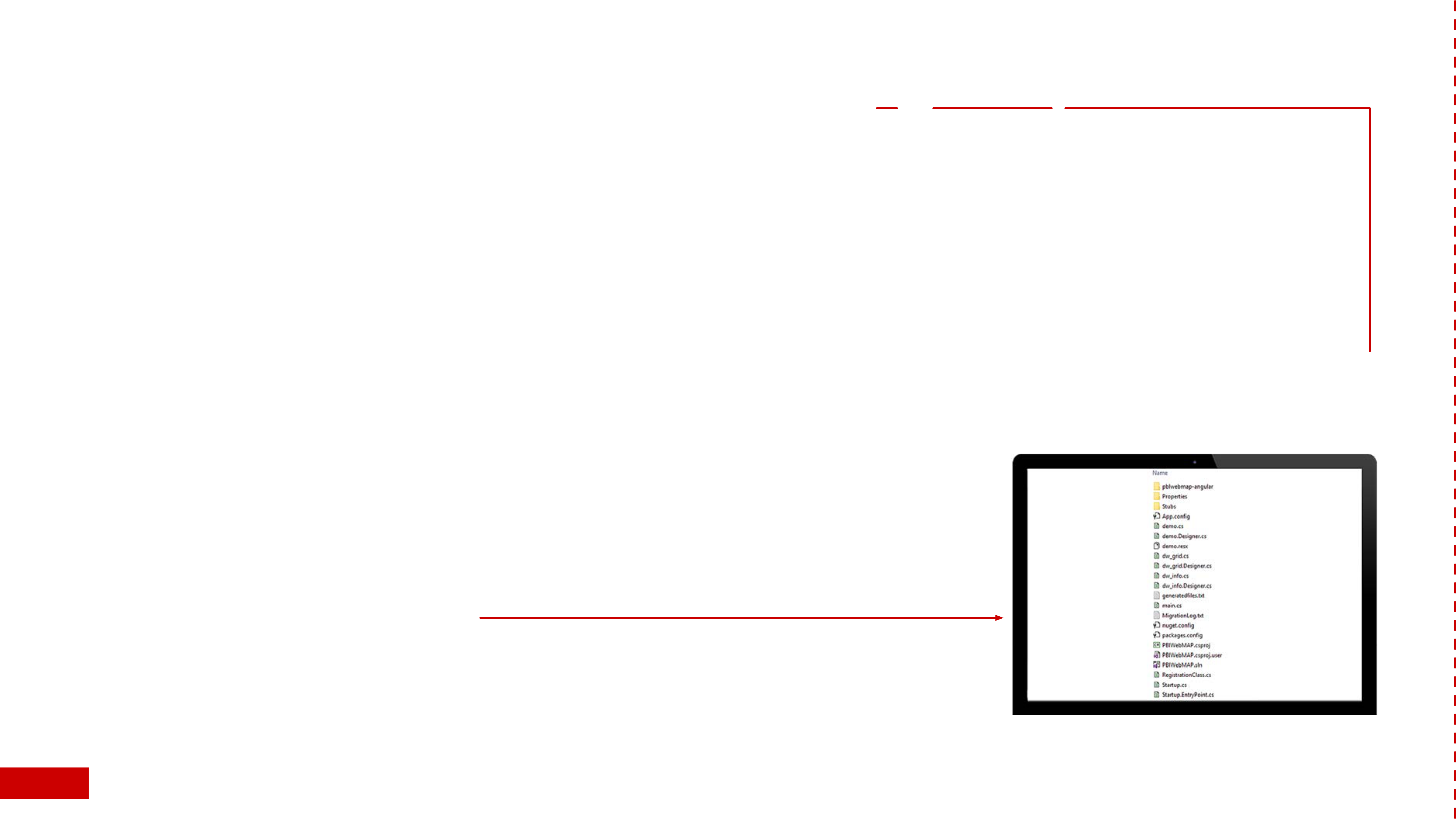

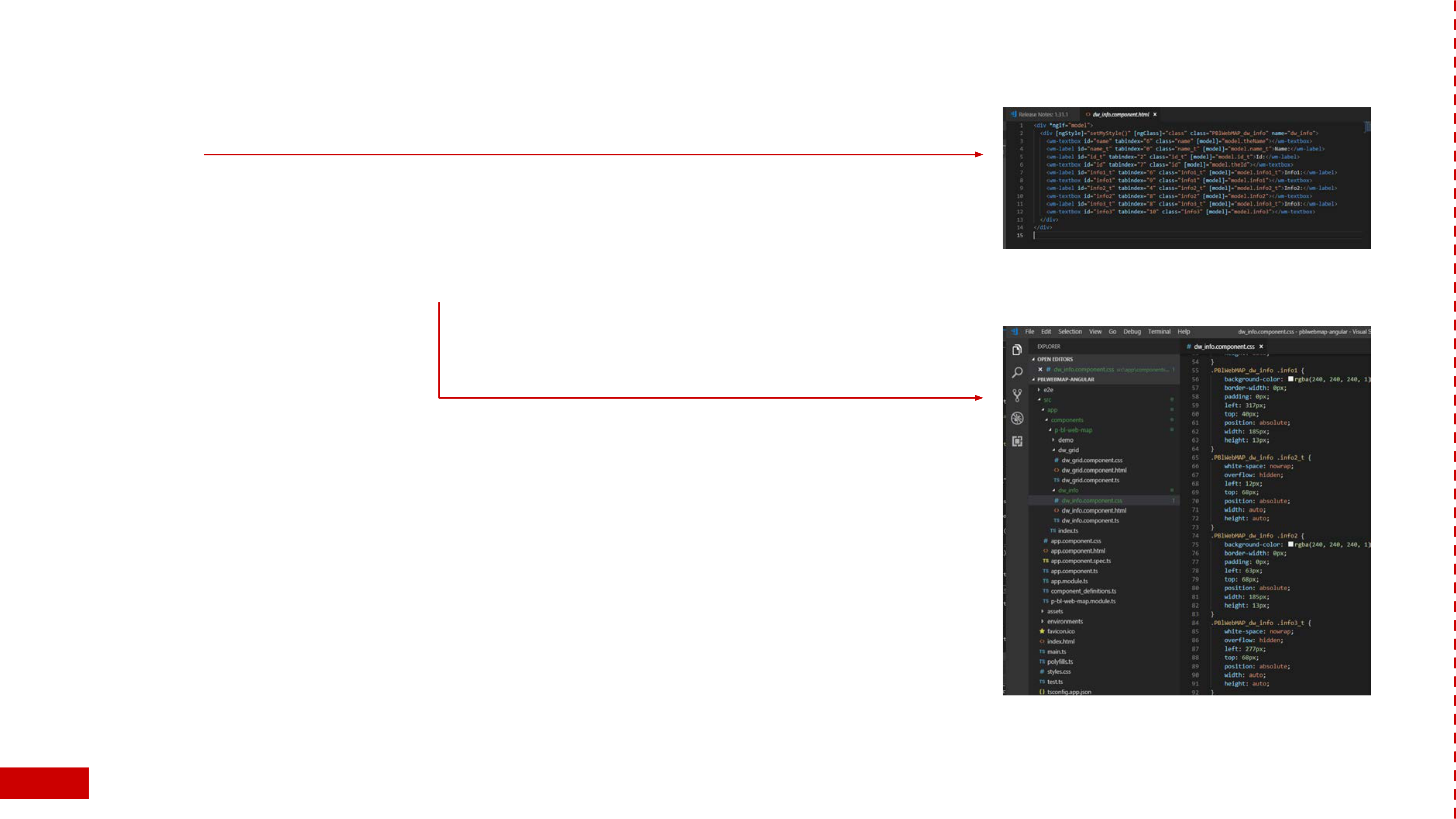

until it's done, then we see this:

11

There are a lot of les there, so let me break it down a bit. Of the three folders,

you can ignore Properties and Stubs (those are support les). The pblwebmap-

angular folder is our front-end (client side) project. We'll come back to that shortly.

Among all the remaining les (at the root) we see a .cs and a Designer.cs le for

each of our PowerBuilder windows: the app (demo) and both the DataWindows

(info and grid) as well as a standard main.cs le.

For various reasons we have split the front-end (client side) code from the back-

end (server side) code in our code tree. At the moment, it's a little easier to work

with Angular, JavaScript, HTML, and CSS using Visual Studio Code (as opposed

to Visual Studio). And, likewise, Visual Studio (not Code) has amazing capabilities

when writing and debugging C# and .NET apps.

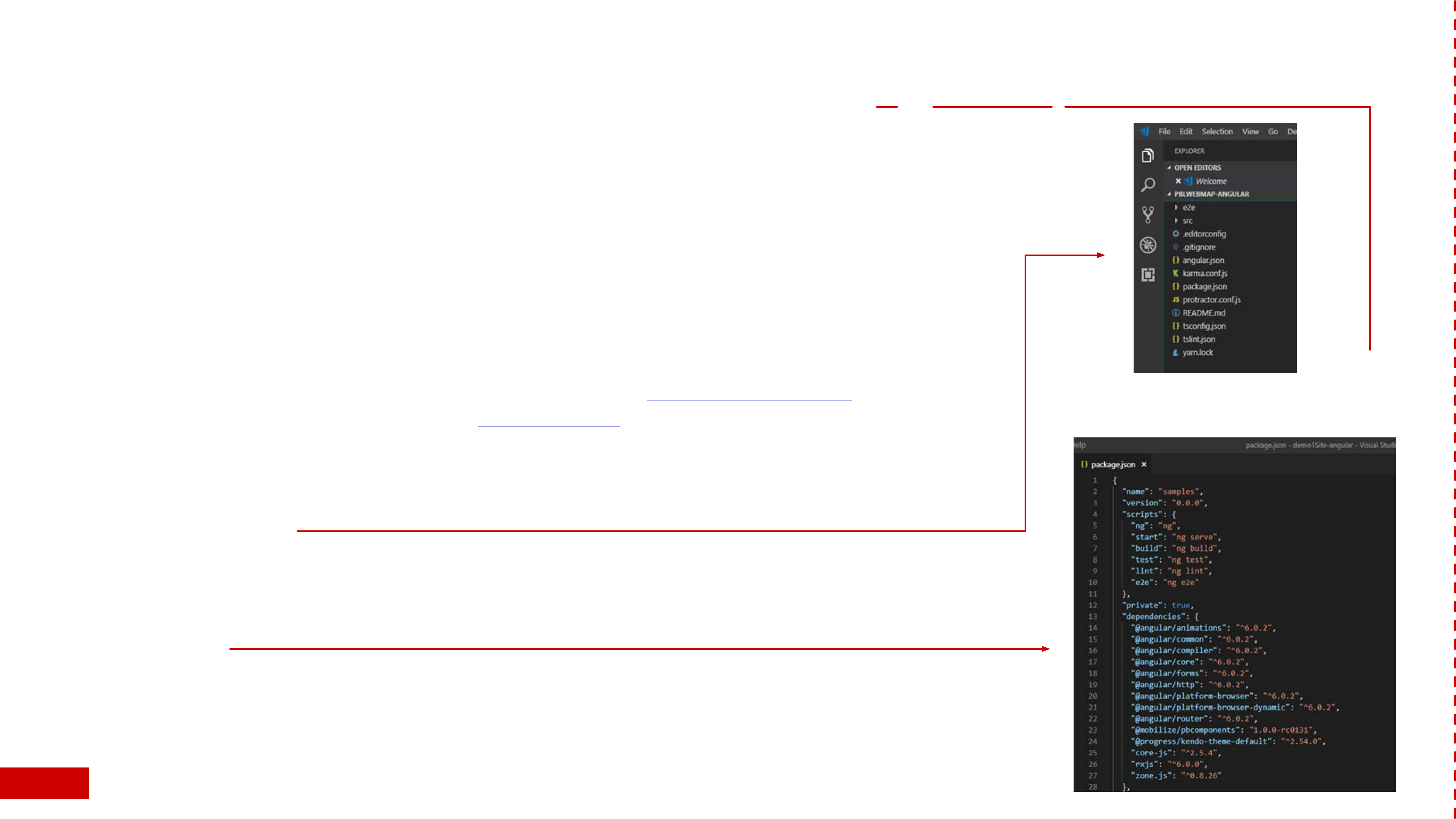

Let's start with the client side code. I'm going to open the demo1Site-angular

folder in Code:

Let's home in on a couple of things we can nd here, starting with the package.

json le:

12

This shows us the dependencies our client-side app requires. What's

notable here is that we're using Angular 7, Kendo UI for Angular, and some

PowerBuilder components from Mobilize.

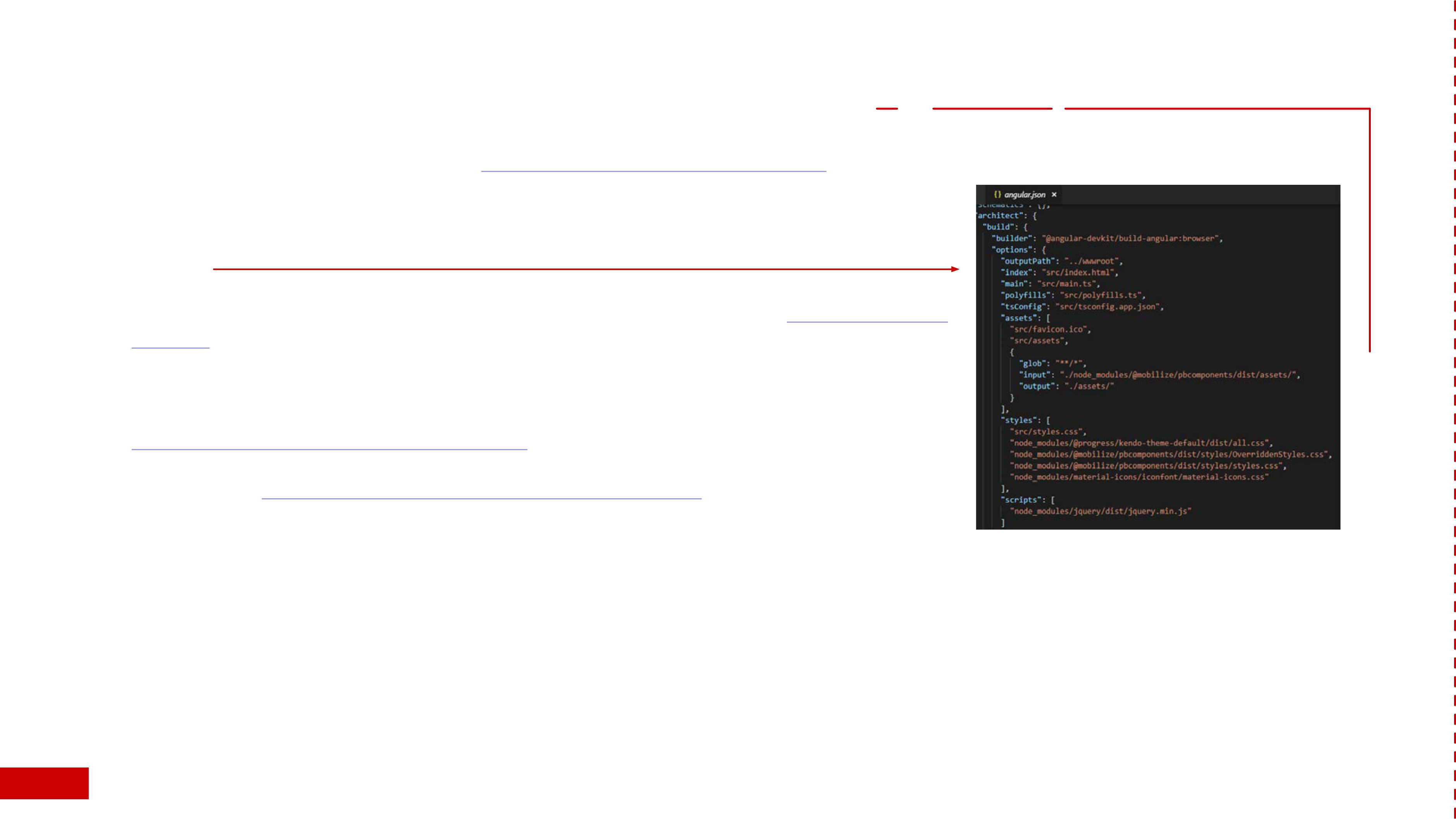

Looking at another key le: angular.json, we see a few more interesting

things:

Note here that the CSS styles that are imported include the Kendo default

theme and some specic CSS les from Mobilize to handle PowerBuilder

requirements.

Progress has three themes for their Angular UI elements that can be

swapped as easily as editing this le here.

Or, you can build your own with their Theme Builder. In any event, having

the UI created in HTML with cascading style sheets gives you a lot of control

over the look and feel of your application.

Note: the standard output for Mobilize.Net's tools attempts to mirror the look and

feel of the source (legacy) application in order to avoid user confusion or the need for

retraining. That doesn't mean it's the right answer for every application, just the one

the majority of our customers request.

13

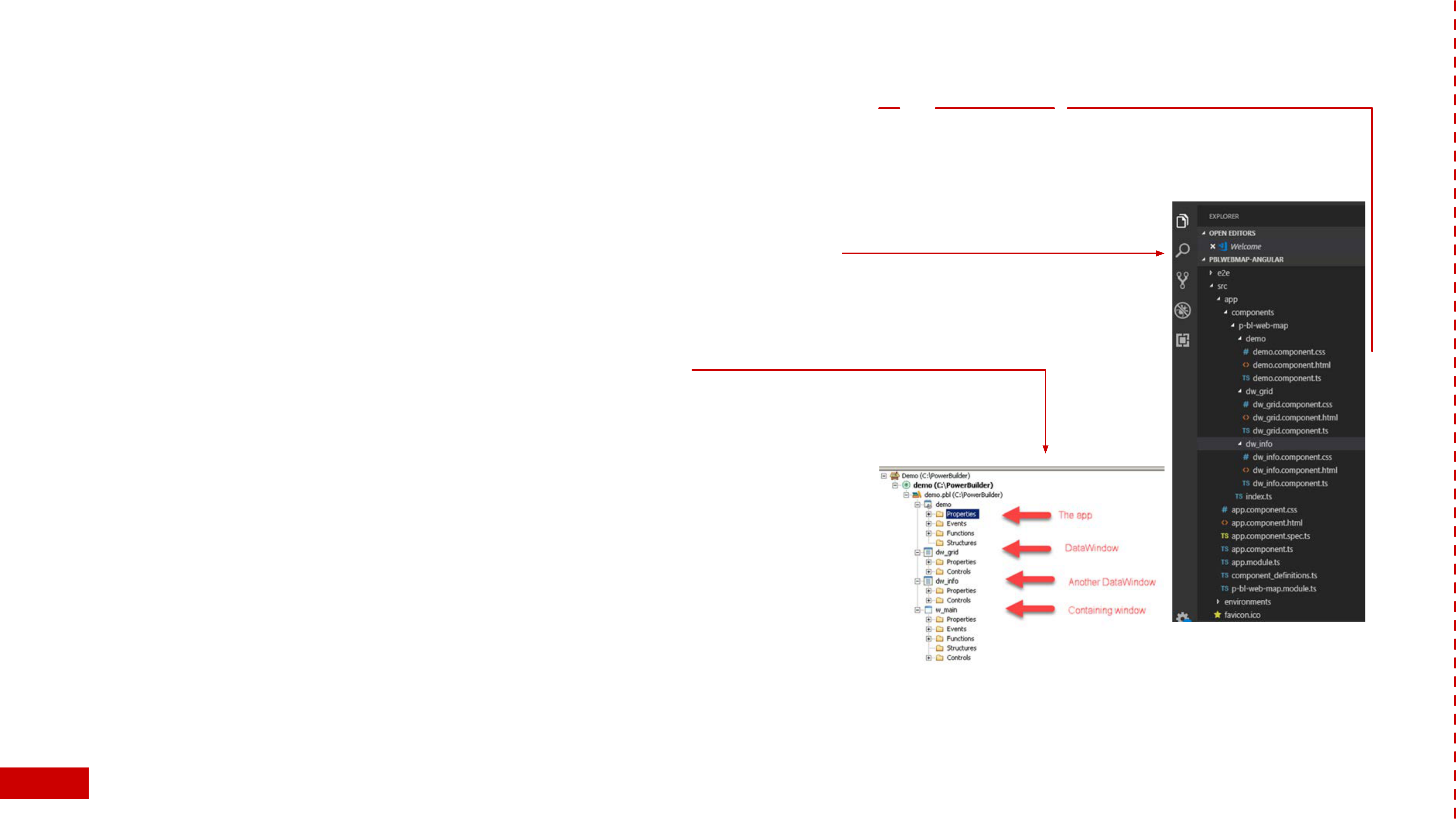

Let's look at the actual code.

The source we want to see is in the \src\app\components directory:

Notice there is a folder for each of our windows: demo dw_grid, and

dw_info. Remember our PowerBuilder system tree?

Where, you might ask, is the w_main component in our Angular

code? The answer is it went into the bit bucket: we don't need a

containing window when we run the app natively in the browser—

we're creating HTML and that's what the browser knows how to

render.

Ok, back to the app structure. I've expanded all three component

source folders, so you can see each has the same pattern of les: a

template (HTML), a style (CSS le), and a TypeScript le that denes

the component, imports, and exports.

14

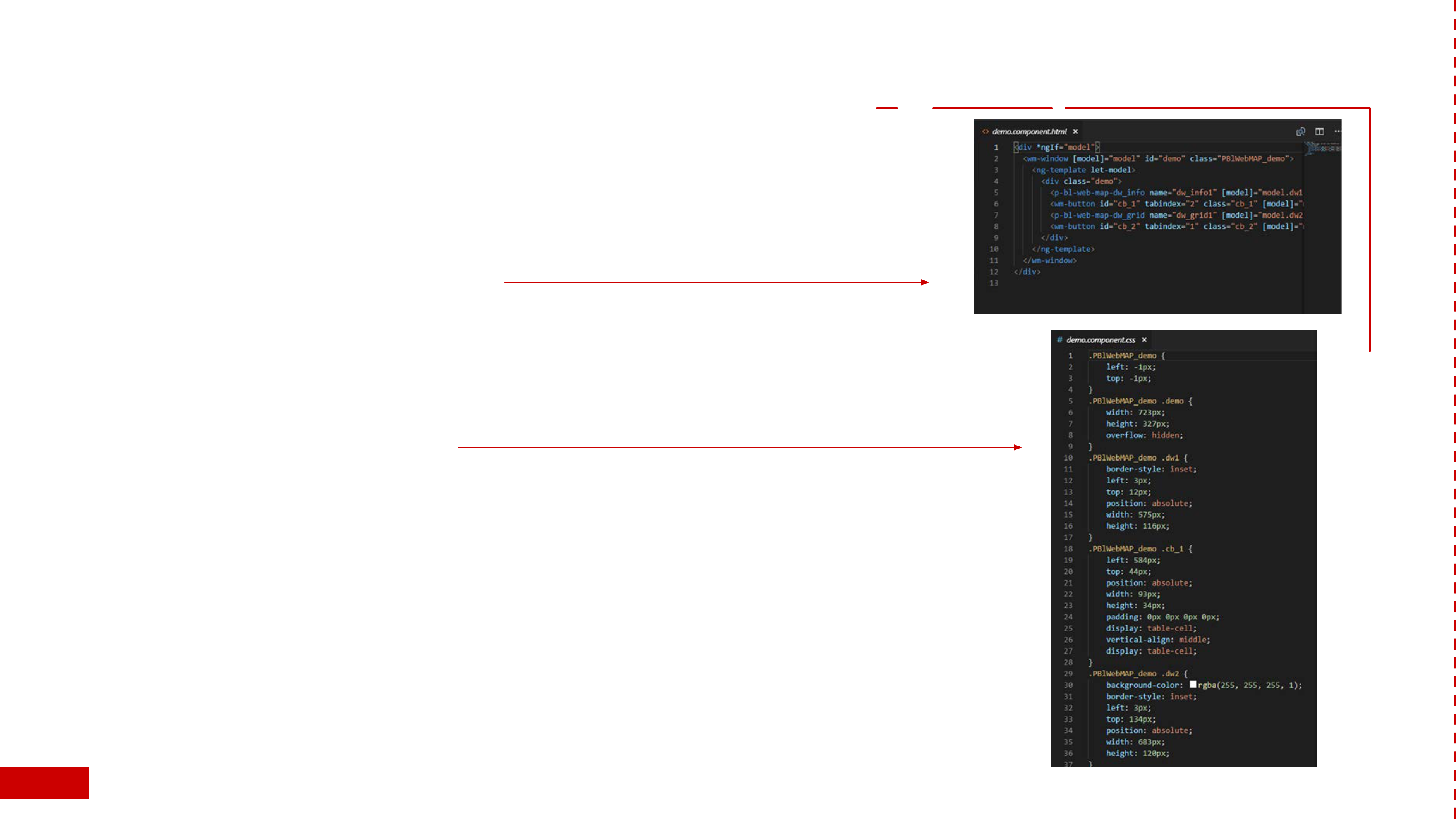

The app (which we'll see in a bit) has two DataWindows inside a

container called demo. Looking at the HTML template, we see it

contains our two DataWindows (dw_info1 and dw_grid1) and two

command buttons (cb_1 and cb_2):

There really isn't much to see here.

Let's look at the style sheet le

Again, we're trying to position all the visual elements to resemble as

closely as possible the original runtime UX of the PowerBuilder app. Of

course, since this is CSS you can easily override all the stylings; you can

set global styles with the styles.css le, or add your own JavaScript to

do magical dancing elves. Whatever, it's going to be your app.

15

Finally, here's the component le—note we use TypeScript which gets

transpiled into JavaScript when the app is built for deployment. If

you're unfamiliar with TypeScript, it's just a better JavaScript with stuff

like types and classes.

What do we see here? Looking at the import statements, we see we're

getting a lot of stuff from angular/core, plus some specic Mobilize

WebMAP components. All of these pieces are delivered as packages

when you build the front end.

A complete tutorial on how to build an Angular app is beyond the

scope of this blog; the short version is you have to download/update

all the dependent packages, build the app, and export the minied

results. In our case this becomes a folder called wwwroot, which our

Visual Studio solution le requires. So without further ado, as they say,

let's look at:

16

To be clear: PowerBuilder is not a language per se; it's a 4GL with its

own scripting language. It's familiar looking, certainly readable, but it's

not some ANSI standard programming language. When we migrate

PowerBuilder using WebMAP, we can turn the scripting language—as

well as all the runtime functions, object properties, and events—into

either C# using ASP.NET Core or Java using the Spring MVC pattern.

Today we'll look at converting PowerBuilder to ASP.NET Core. In a

future blog we'll show the Java version.`

Let's open our solution le in Visual Studio:

Let's look at the Solution Explorer—we have our wwwroot folder,

which we talked about above.

Everything the app needs for the front end is in that folder.

We have three C# les: demo.cs, dw_grid.cs, and dw_info.cs.

We also have a main.cs le, which is just an app entry point.

17

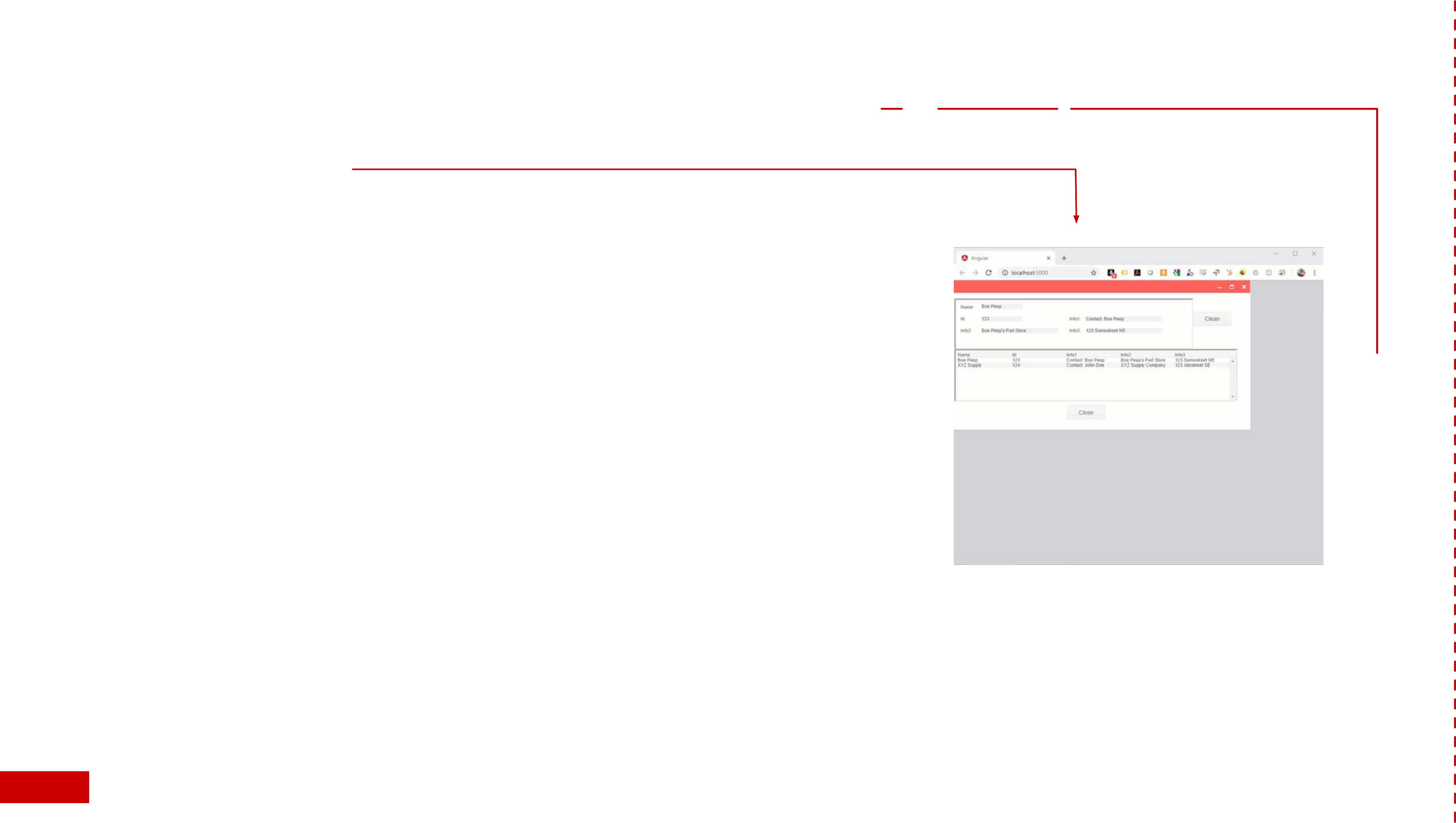

Before we dive into the code, let's see what this migrated app looks like

running in Chrome.

Wow, the same app but running as a native web app in a browser!

Again, it may look trivial, but there's several interesting things going on

in this app.

Let me call your attention to the "Clean" command button—when that

is pressed we see a dialog box asking if we want to reset the customer

information ("Yes" "No"). This is basically a Windows message box—

common on all desktop apps. But on the web it gets tricky—which is

why you don't normally see these in a web application.

The problem with modal dialogs on a web app is that they require a

suspension of action until the dialog is dismissed. On Windows this

isn't an issue.

Windows is a single-user, multi-tasking OS, so each application has its

own process space and thread. Suspension of thread execution doesn't

cause problems for any other process. A web server, on the other hand,

is designed to support multiple user sessions simultaneously: that

single execution thread can't be suspended just because one user can't

make a decision.

18

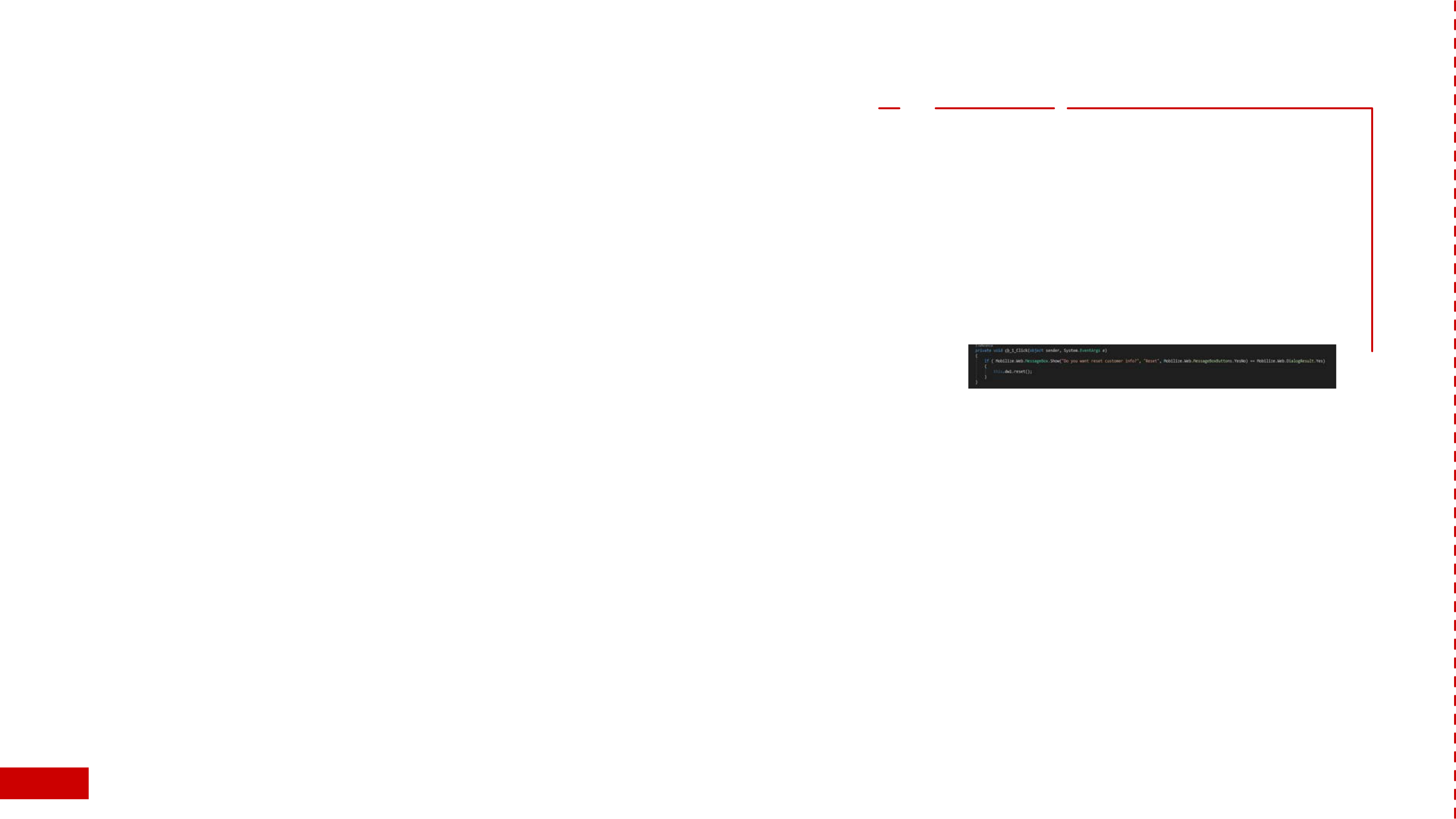

When we migrate PowerBuilder message boxes to the web, we have

to manage that suspension of state in a reasonably elegant fashion, so

that it doesn't damage other session's responsiveness and yet is quickly

retrievable when the user dismisses the modal dialog. I could tell you

how we do it, but then I'd have to kill you.

The beauty of this—from your perspective as a developer—is the

code that you work with. Normally handling a modal dialog, with all

that entails on a web app, would require a boatload of source code.

Instead, through the magic of WebMAP, the code looks like this:

Look familiar? It should, if you've ever written any Windows Forms code

at all. Of course, there's a lot going on behind the scenes to keep the

source code that simple and elegant. We'll get to that in another blog.

As a matter of fact, this one has gone on too long.

In the next step, we get down and dirty with all the code in the new,

migrated web application.

19

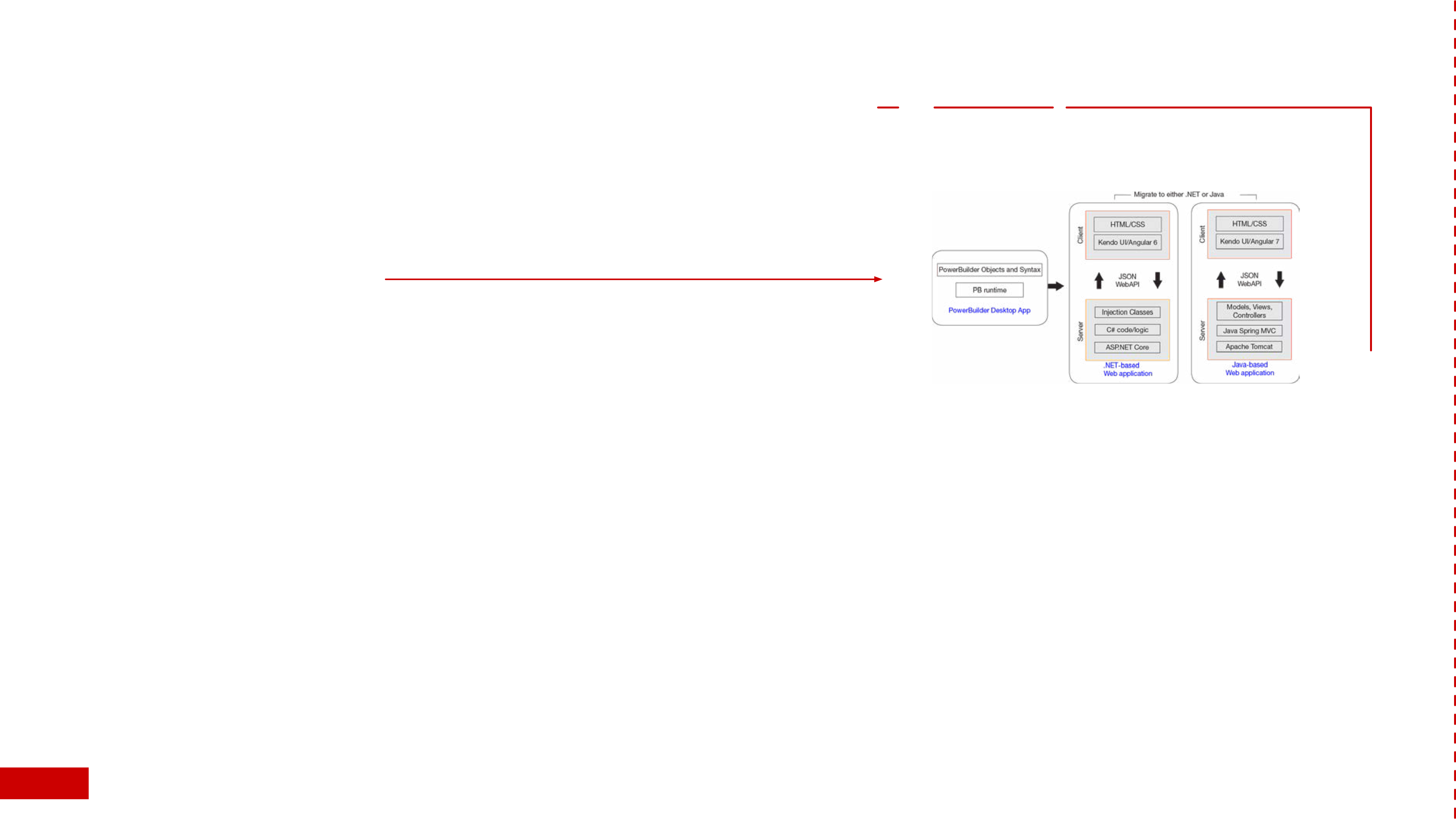

Having migrated our PowerBuilder DataWindows from our sample app

using WebMAP, in this nal chapter we'll take a deeper dive into the

generated code. Let's begin with an overview of what the generated

application looks like:

Notice the option to migrate from PowerBuilder to .NET or

Java. WebMAP can convert your PowerBuilder app—including

DataWindows—to either C# running on ASP.NET Core or Java using the

Spring MVC pattern. In either case, the client-side code is identical,

using Kendo UI for Angular and Angular 7.

In Part 2 we reviewed the front end les, including the component,

template, and styling les. In this post we'll look at the back end in

more detail.

In our original PowerBuilder app, we had two data windows: a grid

presentation (dw_grid) and a form-style presentation (dw_info). Each

DataWindow contained some data-bound controls and a command

button. Each command button had an event handler for a click event.

20

That structure has been preserved in our C#/ASP.NET version as well. Our app consists of four C# les: main.cs,

demo.cs, dw_grid.cs, and dw_info.cs.

The simplest of the four is main.cs, which is just the application entry point. It has just one method:

public

static void Main()

{new demo().Show();

The demo.cs le is a little more interesting: we handle the click events for each of the two command buttons

and dene our data table for the DataWindows:

private void cb_2_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

this.Close();

}

private void cb_1_Click(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

if ( Mobilize.Web.MessageBox.Show("Do you want reset customer info?", "Reset", Mobilize.Web.

MessageBoxButtons.YesNo) == Mobilize.Web.DialogResult.Yes)

{

this.dw1.reset();

}

}

21

public static void bind(dw_info dw_info, dw_grid dw_grid, bool rst = true)

{

var dc = new Mobilize.Web.VBUC.ADODataControlHelper();

var dt = new DataTable();

dc.Recordset.Tables.Add(dt);

dt.Columns.Add("Name");

dt.Columns.Add("Id");

dt.Columns.Add("Info1");

dt.Columns.Add("Info2");

dt.Columns.Add("Info3");

dt.Rows.Add(new object[] { "Boe Peep", 123, "Contact: Boe Peep", "Boe Peep's Part Store", "123

Somestreet NE" });

dt.Rows.Add(new object[] { "XYZ Supply", 124, "Contact: John Doe", "XYZ Supply Company", "123

Abcstreet SE" });

if (rst) dc.Recordset.MoveFirst(); else dc.Recordset.MoveLast();

dw_info.bind(dc);

dw_grid.bind(dt, dw_info);

}

Note that just as in the original PowerBuilder app this demo inserts actual data (two rows) instead of connecting to

an actual database. Sheer laziness but it's just as instructive for this purpose.

22

Notice again the MessageBox.Show method: it looks surprisingly like you would expect to see a "normal" C#

Winforms dialog invocation. Except for the "

Mobilize.Web" namespace decoration, it would be exactly like a

standard .NET Framework

MessageBox() invocation.

How is this possible?

Super short answer: it's complicated. Slightly longer answer: we use code weaving and aspect-oriented

programming (AOP), courtesy of the Roslyn compiler. For a more detailed discussion, check out this three-part

series on the complete WebMAP architecture. An easy way to think about this is that we're just letting the compiler

do the heavy lifting.

A

Mobilize.WebMessageBox()method handles all the issues that make a modal dialog difcult on a web app:

suspending the session (in effect), caching the user state, maintaining all the other sessions with no penalty, and

timing out the invoking session if necessary. Normally you would have to write a bunch of code to handle this

kind of an event on a web app, which is why you don't see them very often. But virtually every desktop app has

this pattern—saving a le, for example. And so moving those desktop apps to web apps presents this modality

problem at least once and more commonly multiple times.

WebMAP, however, makes it simple.

23

We have a new C# le for each DataWindow object that was in the original PowerBuilder project.

Let's look at dw_info.cs rst:

public partial class dw_info : Mobilize.Web.UserControl

{

public dw_info()

{

InitializeComponent();

}

public void reset()

{

this.theName.Text = "";

this.theId.Text = "";

this.info1.Text = "";

this.info2.Text = "";

this.info3.Text = "";

}

internal void bind(Mobilize.Web.VBUC.ADODataControlHelper dc)

{

this.theName.Text = dc.Recordset.CurrentRow["Name"].ToString();

this.theId.Text = dc.Recordset.CurrentRow["Id"].ToString();

this.info1.Text = dc.Recordset.CurrentRow["Info1"].ToString();

this.info2.Text = dc.Recordset.CurrentRow["Info2"].ToString();

this.info3.Text = dc.Recordset.CurrentRow["Info3"].ToString();

}

}

24

+

We inherit from Mobilize.Web.UserControl, which is the parent class

for all our UI objects. Notice that dw_info() is a partial class, which

means that some of the implementation is somewhere else; in this

case it's in a designer file (dw_info.Designer.cs) that we will explore

in a moment.

+

We have three methods in this class: a constructor, reset() which

clears the data, and a bind() method that binds the UI elements to

the database model.

+

The reset() method is called from the click event handler

(see the demo.cs listing above).

It clears the upper DataWindow here:

+

Finally, the database model (the bind() method) maps the model

to the actual client-side UI. Remember our HTML template file (see

Part 2)?

25

Here's what the HTML for this DataWindow's Angular component looks

like:

You can see that the user-interface control names match the model in

the C# le. And if we look in the associated CSS le we'll see the styling

for those UI elements as well:

I noted (above) that the dw_info() class dened in dw_info,cs is a

partial class; partial classes in C# have their implementations spread

over more than one le. In our case the

dw_info() class is also

implemented in the

dw_info().Designer.cs le.

26

Confused yet? Try this:

So turning our attention to the last le we haven't yet looked at

dw_info().Designer.cs), we see the following:

partial class dw_info

{

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

///

/// Required designer variable.

///

private

System.ComponentModel.IContainer components { get; set;

}

protected override void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (disposing && (components != null))

{

components.Dispose();

}

27

}

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Designer]

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.Label name_t { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.Label id_t { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.Label info2_t { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.Label info1_t { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.Label info3_t { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.TextBox theName { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.TextBox theId { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.TextBox info2 { get; set; }

[Mobilize.WebMap.Common.Attributes.Intercepted]

private Mobilize.Web.TextBox info1 { get; set; }

28

Notice the Intercepted attribute used extensively here. Interception in this instance is a way to handle

"cross-cutting concerns" via Aspect Oriented Programming (AOP).

Notice that all the visual objects in the C# version of our DataWindow have only

get() and set()

methods.

The implementation is handled by the interceptors—all this witchery is made possible by the Roslyn

compiler (AKA Visual Studio Compiler Platform) which in turn is why we rely on Visual Studio 2017 or 2019

for the ASP.NET Core code (as opposed to Visual Studio Code).

Roslyn makes it possible to implement AOP in such a way that the code that we actually look at and work on

is de-cluttered.

The good news is you don't have to worry about it.

But if you want to learn more, check out this short video by our own Rick LaPlant explaining how to use

Roslyn to de-clutter your own code.

You can learn more about how WebMAP implements AOP here (PDF) and here (blog post).

29

Let's go back to our running Angular app again:

I don't like the labels of "Info1", "Info2", and "Info3." While they are consistent with

the original PowerBuilder app labels, they don't really tell me what they represent.

I'd like the user to see more representative eld names like "Contact", "Company",

and "Address." And I'd like all the labels to be in a bold font, to make the upper

DataWindow a little easier to read.

Every experienced web developer who is reading along now just snickered and

thought something like, "Well, that's trivial in a web application. Just edit the

HTML and CSS."

Bingo.

So bear with me, because I know that many of our Dear Readers aren't

experienced web developers. So they might enjoy seeing how simple this is.

30

Unlike the original PowerBuilder app, or many legacy desktop apps written in

various languages like Visual Basic or even C/Win32, the view/presentation/user

interface is not part and parcel of the actual business logic.

Instead, the view in this app is handled exclusively by the HTML and CSS, with

Kendo UI and Angular behind the scenes doing the heavy lifting.

The model—the internal business logic representation of all the visual elements—

is in the ASP.NET Core C# code running on the web server. The model doesn't

need to know anything about the view and the view doesn't need to know

anything about the model: we have separation of concerns via the MVC (model

view controller) pattern.

Ok, enough theory. Let's x the UI. Fortunately this is not only easy, it's something

someone untrained in C# or advanced programming can easily do. Here's how I

like to do this.

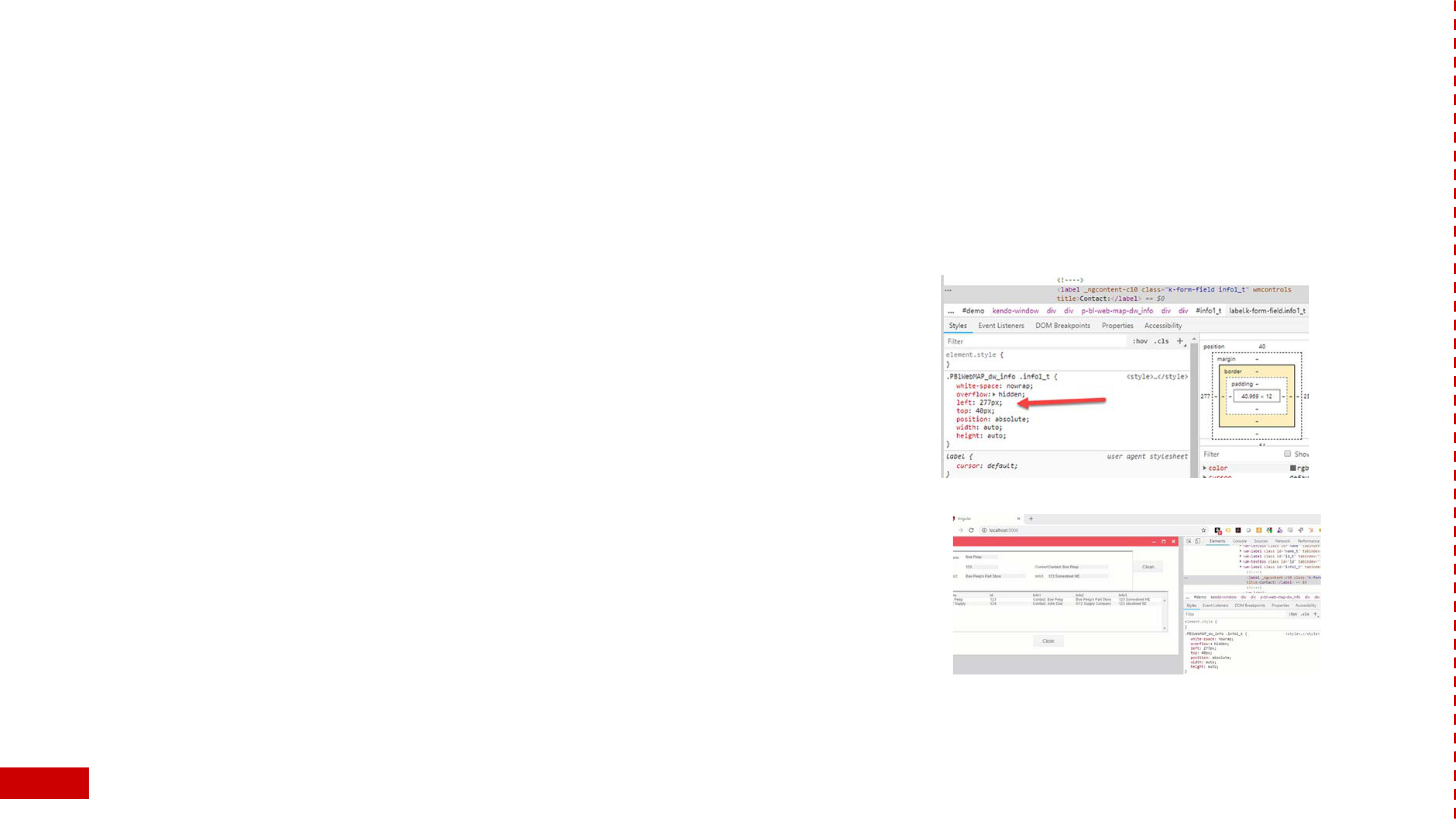

With the app running in Chrome, right click the "Info1:" label and select Inspect.

This opens Chrome developer tools with the focus on that HTML element:

31

On the right we see all the HTML and the blue highlighted code tells us that

the label is a member of the class "k-form-eld info1_t" (k-form-eld being from

the Kendo UI for Angular component library we are using), that it is from the

wmcontrols Angular library from WebMAP, and that the value is "Info1:".

Let's change the label to "Contact":

Zooming in. Changing this:

Changes this:

32

So that's pretty easy—changing the HTML in the Chrome developer

tools lets us see exactly how those changes will change the app

running in the browser.

This is a way to get things how we want them, or play around with the

presentation. Once we know what the changes are, we have to make

them in the original HTML and CSS les and rebuild the client-side

code.

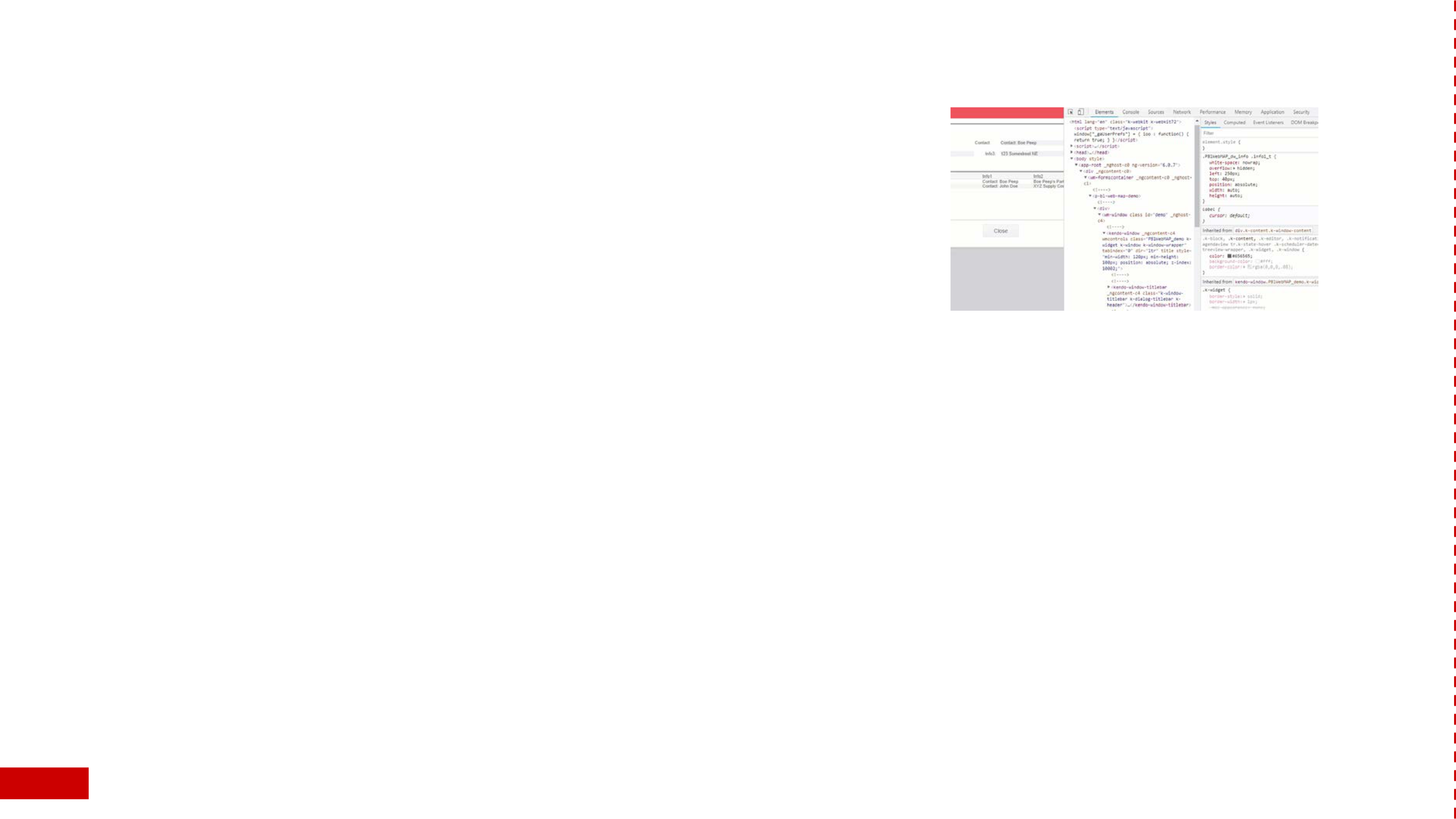

Let's keep going. Notice that our label now bumps into the text

box. Can we change the position? Remember the styling (including

positioning) comes from our CSS le:

33

The controlling factor for our problem is the "left: 277px;" line.

Remember that in order to have the migrated Angular app look

as much as possible like the original PowerBuilder app we have to

position all the elements precisely on the browser window—in this case

these values (left and top) are offsets from the upper left corner of

the browser's area for rendering HTML. If we didn't use the "absolute"

property for the position element, these labels and text boxes could

be scattered all over the browser space.

Since our label .info1_t runs into the text box (info1), we need to shift its

position left. Let's try a value of 250 pixels. How do we do that? It's not

in the HTML, but Chrome developer tools also shows us all the styles, in

their cascading order, like this:

Notice how the CSS matches what's in the view above. We can change

it here to 250 pixels and see if that xes our problem:

34

We can change anything we want if it's CSS: let's make the label bold.

Notice how Chrome suggests things like Visual Studio's "Intellisense":

Clearly, we'd want to adjust everything so it aligns correctly, maybe

make the label font a little larger and prominent, and so on.

And we don't have to make notes about what we did: it's easy in

Chrome to associate the original CSS and HTML source les—in our

Angular folder—with the running app so all our changes are saved back

into our project.

All we have to do then is rebuild the wwwroot folder (using "ng build")

and the app is automatically updated. We don't even have to recompile

the ASP.NET Core solution in Visual Studio.

35

When I talk to developers about PowerBuilder, the rst thing I usually

hear is, "Wow, I can't believe how much PowerBuilder is still out there."

If they have PowerBuilder, the second thing I usually hear is, "It's hard/

difcult/impossible to nd developers anymore."

The world has changed. PowerBuilder belongs to a different, older

world. Today it's all about cloud-native apps. If you've still got

PowerBuilder, I hope this series of posts gives you some useful

information about options to get rid of it.

And have something far, far better.

Mobilize.Net is the world’s authority on automated software modernization.

www.mobilize.net +1-425-609-8458 info@mobilize.net