Video Evidence

October 2016

A Primer for Prosecutors

Global Justice Information Sharing Initiative

Global Justice

Information

Sharing

Initiative

Even ten years ago, it was rare for a court case to feature video evidence, besides a defendant’s statement.

Today, with the increasing use of security cameras by businesses and homeowners, patrol-car dashboard

and body-worn cameras by law enforcement, and smartphones and tablet cameras by the general public, it

is becoming unusual to see a court case that does not include video evidence. In fact, some esmate that

video evidence is involved in about 80 percent of crimes.

1

Not surprisingly, this staggering abundance of video

brings with it both opportunies and challenges. Two such challenges are dealing with the wide variety of

video formats, each with its own proprietary characteriscs and requirements, and handling the large le sizes

of video evidence. Given these obstacles, the transfer, storage, redacon, disclosure, and preparaon of video

evidence for evidenary purposes can stretch the personnel and equipment resources of even the best-funded

prosecutor’s oce. This primer provides guidance for managing video evidence in the oce and suggests

steps to take to ensure that this evidence is admissible in court.

2 / Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors

Introduction

The opportunies inherent in video evidence cannot be overlooked. It is prosecutors

who are charged with presenng evidence to a jury. Today, juries expect video to

be presented to them in every case, whether it exists or not.

2

As a result, prosecutors

must have the resources and technological skill to seamlessly present it in court. Ideally,

prosecutors’ oces could form specially trained ligaon support units, which manage all video

evidence from the beginning of the criminal process through trial preparaon and the appellate

process. Short of that, individual trial aorneys

must understand the opportunies and be aware

of the potenal pialls inherent in video evidence.

Further, prosecutors must be diligent to ensure

that law enforcement invesgators have idened

and recovered all exisng video evidence relevant

to a case. In any event, to use video evidence

eecvely in the courtroom, prosecutors must

be familiar with evidenary foundaons to admit

the videos and the technological requirements to

successfully display those videos to the jury.

The purpose of this resource is to provide

prosecutors educaonal material, introduce

helpful resources regarding video evidence,

outline the benets of its use in court, and acknowledge the challenges faced by prosecutors’

oces in handling video evidence. A sample process ow is also provided as step-by-step

guidance on the general procedures and processes prosecutors may follow when preparing and

handling video evidence. It has been designed to correspond to the typical ow of a case from

receipt of evidence through the trial process. Finally, a glossary of terms used throughout this

resource is included, as well as a list of recommended resources for further reading.

This document was a collaborave eort executed through the Global Jusce Informaon

Sharing Iniave (Global), which is supported by BJA, Oce of Jusce Programs,

U.S. Department of Jusce. Global acknowledges that this document does not

address all subject areas of this complex topic but rather provides a high-level

understanding of video-evidence processes to help guide prosecutors.

To use video evidence

effectively in the

courtroom, prosecutors

must be familiar with

evidentiary foundations

to admit the videos

and the technological

requirements to

successfully display

those videos to the jury.

Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors / 3

Examples

of Video-Evidence Sources

The following are examples of sources of video evidence from which video may be recorded or recovered.

• Security cameras/digital video recorders (DVRs) at government buildings, businesses, or private homes

• Trac and toll-booth cameras

• Red-light cameras

• License plate readers

• Video/audio recording technology triggered by gunshots

• Patrol-car cameras

• Body-worn cameras (BWCs)

3

• Law enforcement interviews of witnesses and suspects at police staons

• Social media providers (pursuant to search warrants) and/or screen captures made by law enforcement

• Forensic searches from digital devices (e.g., computer, phone, tablet), pursuant to search warrants

Benefits

of Using Video Evidence

It is important to note that while video evidence may be only one piece of evidence in a case, it can be extremely powerful.

The following are examples of the power of using video evidence in presenng a case to the jury.

• Incorporate into opening and closing arguments (e.g., showing the jury crical parts of the defendant’s recorded

confession)

• Incorporate clips into a slideshow presentaon or trial presentaon soware

• Capture and print slls for use as supplemental exhibits

• Potenal for the in-court idencaon of the defendant as the perpetrator

• Captures the idened defendant in the act of comming the crime

• May corroborate eyewitness tesmony

• May be used to impeach defense witness tesmony

Benefits Challenges

&

Video evidence can come from numerous sources, with both benets and challenges.

4 / Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors

Challenges

for Prosecutors Using Video Evidence

The resource challenges documented below do not come close to the degree of impact that the volume of video from

body-worn cameras will have on prosecutor oce resources, once BWCs are widely adopted across the United States.

4

Aside from these impending challenges, video evidence is subject to a host of other procedures and challenges that

dier from other types of evidence. These include the following:

• Having the proper video players and codecs installed on the prosecutor’s computer

• Having enough me and resources to review video, oen within severe court-imposed charging me constraints

(e.g., 24 to 48 hours) for in-custody suspects

• Obtaining and aording adequate storage

for the video in the prosecutor’s oce

• Developing processes and protocols for the

storage of video in the prosecutor’s oce

• Redacng video for privacy and legal

challenges

• Allocang sucient me for discovery, a

me-sensive and me-consuming process

involving redacon, rendering, and creang

copies of all discoverable video evidence

• The cost of equipment and soware to

review, process, prepare, and share video

evidence

• Ensuring that personnel have the

technical and legal training to comply with

constuonal disclosure requirements,

the Naonal District Aorneys Associaon

(NDAA) Rules of Conduct, Naonal Prosecuon Standards,

5

and all other relevant law

• If a video is edited, it must go through a rendering process. The current state-of-the-art, high-end video

rendering equipment and soware can cost in excess of $100,000. Video rendering can be accomplished with

desktop computers, but at a much slower rate.

Example: A prosecutor may have an eight-hour homicide video interview that the court has ordered to be

redacted to eliminate polygraph references. This can be accomplished by using video-evidence soware or

screen-capture soware. Both processes require rendering. Using a standard desktop, an eight-hour video may

take eight hours or longer to render.

• Responding to novel legal challenges related to the use of video evidence

• Preserving video evidence for appeal

As discussed in this secon, video evidence can come from a host of sources. It can be both

benecial to a case as well as challenging for prosecutors. The following secon will help

prosecutors address these challenges and will provide guidance on the video-evidence process.

Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors / 5

Crime Scene to Courtroom

Video-Evidence Process

This secon provides specic guidance on the procedures

prosecutors follow and the processes they employ for the

receipt, handling, and use of video evidence, whether

that evidence is recovered by law enforcement, by

prosecutors’ oces directly, or by private cizens who

then turn it over to the prosecutor. Regardless of how

the evidence is received by prosecutors, the following

informaon should be helpful.

Video-Evidence Receipt

There are two main methods of transfer of video evidence

from law enforcement to the prosecutor’s oce:

• Cloud Transfer—One method for video transfer

is ulizing a government-approved secure cloud

provider. To the extent that law enforcement

agencies turn to cloud storage for retaining video

evidence, they should avail themselves of the cloud’s

ability to eciently transfer video-evidence les to

a prosecutor. Some cloud soluons also provide

remote viewing for prosecutors that does not

require physically moving the video-evidence les.

In addion, cloud funconality can allow for online

redacon, audit trails, and digital transfer of discovery

to the defense aorney. For more informaon on

cloud technology, refer to the Global Public Safety

Primer on Cloud Technology

6

—a high-level primer

for law enforcement and public safety communies

regarding video evidence and the cloud. Developed

as a frequently-asked-queson (FAQ) guide, the

primer answers straighorward quesons about

cloud technology and includes guidance for agencies

considering cloud vendor contracts. More important,

this resource provides crical informaon on privacy,

security, and data ownership, as well as a glossary

of cloud terminology and a list of recommended

resources.

Agencies may also be interested to learn about the

Federal Risk and Authorizaon Management Program

(FedRamp)

7

—a government-wide program that

streamlines federal agencies’ ability to make use of

cloud vendor plaorms and oerings and introduces

an innovave policy approach to developing

trusted relaonships between federal agencies and

cloud vendors. While FedRamp requirements are

mandatory for federal agencies using the cloud,

the standards and list of FedRamp-compliant

cloud vendors may be of interest to public safety

agencies. FedRamp requires that cloud vendors who

want to secure federal data in the cloud undergo

security assessments to ensure compliance with

the Federal Informaon Security Management Act

of 2002 (FISMA)

8

and with the Naonal Instute of

Standards and Technology’s (NIST’s) Security and

Privacy Controls for Federal Informaon Systems and

Organizaons (NIST 800-53).

9

For more informaon

on FedRamp, refer to www.fedramp.gov. To view

FedRamp-compliant vendors, refer to www.fedramp.

gov/marketplace/compliant-systems/.

• Physical Transfer—Another method for law

enforcement agencies to turn over video les to a

prosecutor is physical transfer via discs, ash drives,

SD cards, portable hard drives, etc., or by providing a

link to les or including in an e-mail aachment.

It should be noted that in most cases, video evidence

is collected from some type of DVR; however, there

are excepons, such as video evidence collected from

smartphones and social media. This resource, however,

addresses how a prosecutor receives video evidence that

law enforcement collects, regardless of its source, format,

or quality.

Law enforcement agencies should provide prosecutors

with two complete copies of the video evidence. The

rst copy should contain the video in its original format

as recovered (with the proprietary video-player soware

included). The second copy should contain the video in

a playable nonproprietary format (e.g., MP4, WMV, AVI,

MPEG).

Note: Some DVRs/devices can export video les to an

MP4 format

10

with the metadata all in one le. These

les can play in the proprietary media player with the

metadata displayed, as well as in a standard media player

with just the video and sound. This is a recommended

format.

6 / Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors

Privacy Redaction

Prosecutors’ oces will need to develop their own

individual policy regarding the privacy redacon of

video when it is shared for discovery and/or Freedom of

Informaon Act (FOIA) purposes. In some jurisdicons,

police departments make the inial privacy redacon on

the discovery copy of the video and then it is reviewed

by the prosecutor’s oce prior to release by the defense.

In other jurisdicons, the prosecutor’s oce prepares

and redacts all video prior to release for discovery to the

defense. In some cases, videos cannot be redacted prior

to release for discovery, and protecve orders may be

necessary.

Video-Evidence Preparation

Whatever process a prosecutor uses to prepare and

render video for trial, the process should be transparent

to the court and, when requested, to the defense. The

following is an example of a video-evidence preparaon

process from a prosecutor’s perspecve—from receipt

of the video to post-trial. It represents a scenario in

which evidence is rst received by the prosecutor’s oce

on disc, ash drive, or portable hard drive. This sample

process ow is provided as step-by-step guidance on the

general procedures and processes prosecutors may follow

when preparing and handling video evidence.

Pre-Trial

• Store and back up video les (e.g., video discs),

including images of any physical wring or labeling

on the outside of the discs,

11

consistent with the

prosecutor’s case management process, policies, and

available resources.

• Review received les to determine whether addional

privacy redacons and/or witness safety concern

redacons are needed.

• Provide a copy of the redacted video les to defense

counsel, pursuant to local discovery rules and

pracces.

• As needed for presentaon in court, prosecutors

should be able to obtain from law enforcement

a copy of the unredacted original video le in

a nonproprietary format (e.g., MP4, WMV, AVI,

MPEG). It is recommended that prosecutors and

law enforcement consult on what video format(s)

work best for use in court. If a prosecutor chooses

to accept only the proprietary format from law

enforcement, he or she may have to use the provided

proprietary soware, when available, or download the

player from the manufacturer to export the video to

a nonproprietary format. Prosecutors also could use

screen-capture soware to render a copy of the video

in a nonproprietary format, assuming the prosecutor

is able to fully authencate the video.

• The nonproprietary video can then be redacted, as

needed, for consideraons of relevance, prejudice,

12

and trial strategy.

• Before trial, create a CD or a DVD of the video

to be marked and admied as an exhibit to be

authencated by the witness(es).

a. Tip: Computers oen freeze when playing videos

from disc drives. It is recommended that video

les be copied from the exhibit disc onto the

hard drive of the computer that will be used in

the courtroom for playback to allow for seamless

playback during court.

Advanced Video Use Tips

Prosecutors may consider using slideshow or trial presentaon soware to present

video evidence in court. It allows for case organizaon, seamless presentaon, and

exibility on direct examinaon and cross-examinaon.

1. Depending on the needs or strategy of the case, a prosecutor may want to have the audio

porons of any video transcribed for use as exhibits in court. Current ligaon soware

allows video les to be synchronized to transcripts for simultaneous viewing in court. It is

important to note that this process can be me-consuming and expensive.

2. Prosecutors may wish to idenfy clips for use in opening, direct, cross, and closing statements

with slideshow soware and/or trial presentaon soware. If necessary, individual clips can

be created with nonproprietary video soware or with screen-capture soware. These clips are made

from video les that have already been provided to the defense counsel. Prosecutors may consider creang a disc

of clips to admit as a separate exhibit with defense spulaon; however, this is not required, since in most cases the

original disc was already admied for the record.

Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors / 7

b. Tip: Avoid using adhesive labels on discs (e.g.,

evidence sckers) to prevent adverse eects on

playback and damage to the data contained on

the disc. The label should be placed, instead, on

the envelope or CD case. However, it is advisable

to write the case number or other idener in

permanent marker on the top of the CD as the

data is on the boom and is unaected by the

wring on top. This will be helpful if the CD

becomes separated from the CD sleeve/case.

• In some cases, one may wish to capture individual

frames (i.e., sll images) from the video that can

be marked as separate exhibits and used in court.

Be sure to provide copies of these to the defense.

Whatever process is used to create the sll images

should be disclosed and placed on the record.

• If any enhancement

13

of the video and/or sll images

is required, this should be completed only by a

qualied expert witness, not the prosecutor.

• Test video playback of all les on the actual device

that will be used to play them in court before

introducing them into evidence.

Trial

• For video les to be introduced into evidence, they

must be authencated. This can occur when an

eyewitness with knowledge teses that the video

le is a fair and accurate representaon

14

of what

transpired, or when no eyewitness is available to

tesfy, the “silent witness theory” can apply.

15

If

introducing video evidence under this theory and

absent a spulaon, it is a good pracce for a

prosecutor to prepare to call, if necessary, a witness

who can tesfy to the operaon of the device that

recorded the video, the witness who recovered the

video and placed it on evidence, any witness with

Trial Tip

An eyewitness to the material on the video may answer quesons about events shown

in the video as it is played for the jury or shortly aer it is played, depending on the

jurisdicon. In addion, a witness who has some specialized knowledge about the video or

the events depicted therein that is helpful to the jury in understanding the video may tesfy

about that knowledge. For example, a person familiar with a subject in the video may idenfy

that person, or an ocer who has viewed the video mulple mes or in slow moon may point

out items in the video that might not be apparent on full-speed inial view. However, neither

the prosecutor nor any witness can give an opinion about what the video shows that does not rest

on special knowledge that the jury does not have. Doing this invades the province of the jury and is

improper.

knowledge, and/or any other relevant chain-of-

custody witnesses.

16

• It is crical for prosecutors’ oces to maintain

technologically current equipment for the display of

video evidence in court.

• At trial, if a prosecutor chooses to play clips of a video,

those clips must be from a video le that is already

admied as evidence (see Advanced Video Use Tips).

• During a trial, if less than the full video is played, the

record must reect what poron of the video (me

sequence or transcript reference) is being played for

the jury.

• It is important to ensure that all of the jury can see

and hear the video while it is being played.

• Jury deliberaon: Requests by the jury for playbacks

of video evidence are common. One common

pracce is to bring the jury back to the courtroom for

any requested playbacks during deliberaons. If the

court orders that the jury have access to the video in

the jury room, a prosecutor should ensure that any

laptop or playback device (1) has no other les on it

other than the soware required to run the video,

(2) cannot be connected to the Internet, and

(3) has been inspected by defense counsel, who has

conrmed this inspecon on the record.

Post-Trial

• It is a good pracce for the prosecutor’s oce to

maintain a copy of all digital exhibits shown to the

jury. Responsibility for maintaining trial exhibits will

vary by jurisdicon.

8 / Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors

Litigation Technology Units and Training

Given the increasing volume of video evidence prosecutors are faced with on a daily basis, prosecutors’ oces should

consider establishing ligaon technology units (LTUs) to support the prosecutor’s preparaon and use of video evidence

at trial. A typical LTU should be supervised by a technically savvy aorney with trial experience. Qualied rered law

enforcement invesgators, legal interns, and clerical sta are examples of personnel who could make up the technicians

in such a unit.

Prosecutors’ oces should pursue training on trial presentaon soware, slideshow soware, video/audio eding

soware, trial advocacy, and courtroom technology.

Conclusion

The growing amount of video now available from security cameras, patrol-car dashboard and body-worn cameras, and

smart devices is creang a signicant strain on budgets and resources across the jusce domain. While the availability

of video evidence can present opportunies for prosecutors who are charged with presenng evidence to a jury, the

complex process of transferring, storing, redacng, disclosing, and preparing video evidence for evidenary purposes is

having a considerable impact on prosecutors’ oces. With video evidence esmated to be involved in approximately

80 percent of crimes, prosecutors must have the resources and technological skill to seamlessly and eecvely present

video evidence in court. To do this, they must have a clear understanding of both the benets and challenges of video

evidence and, more important, the soluons and techniques to address them. This primer provides general guidance

on the procedures and processes prosecutors may follow, from pre- to post-trial, when preparing and handling video

evidence.

Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors / 9

Terms

Original le—A le that is connuous and free from

unexplained alteraons (e.g., addions, deleons, edits,

or arfacts) and is consistent with the stated operaon of

the recording device used to make it. However, Federal

Rules of Evidence (FRE) 1001(d) denes an original of a

wring or recording as “the wring or recording itself

or any counterpart intended to have the same eect by

the person who executed or issued it. For electronically

stored informaon, ‘original’ means any printout—or

other output readable by sight—if it accurately reects

the informaon.”

17

Further, “if data [is] stored [on] a

computer or similar device, any printout or other output

readable by sight, shown to reect the data accurately, is

an ‘original.’” Lorraine v. Markel Am Ins Co, 241 FRD 534,

577 (D Md 2007). FRE 1001(e) states that a duplicate is

“a counterpart produced by a mechanical, photographic,

chemical, electronic, or other equivalent process or

technique that accurately reproduces the original.”

Proprietary video—A video le format that is unique to a

specic manufacturer or product that contains data that

is ordered and stored according to a parcular encoding

scheme, designed by the company or organizaon to

be secret, such that the decoding and interpretaon

of this stored data is easily accomplished only with

parcular soware or hardware that the company

itself has developed. A proprietary format also can be

a le format whose encoding is in fact published but is

restricted (through licenses) such that only the company

itself or licensees may use it. It is important to note

that not all proprietary soware exports the proprietary

players with the video les. If a law enforcement agency

chooses to use a proprietary format, it is a best pracce

for prosecutor oces to encourage the law enforcement

agency to use only proprietary soware players that have

the ability to export video into a nonproprietary format.

Nonproprietary video—A video format that is not

encumbered by any copyrights, patents, trademarks,

or other restricons so that anyone may use it at no

monetary cost for any desired purpose.

Screen-capture soware—Soware that can capture

screenshots of images and videos and save them as

graphic les or record a computer screen and save the

recordings as video les.

Rendering—The process by which video soware and

hardware convert video from one format to another.

Codec—A computer algorithm that controls the

compression/decompression and/or encoding/decoding

of audio and video les. A codec encodes a data stream

or signal for transmission, storage, or encrypon or

decodes it for playback or eding. It is possible for

mulple le formats to ulize mulple codecs. If a video

le will not play, many mes the problem has to do with

not having the correct codecs—a computer program that

both shrinks large movie les and makes them playable on

computers. In some cases, computers try to automacally

download a codec from the Web, but this may be blocked

based on connecvity or security sengs (for example,

some viruses are concealed in codecs). Prior to playing

a video, seek the help of IT personnel to get the proper

codec installed.

10 / Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors

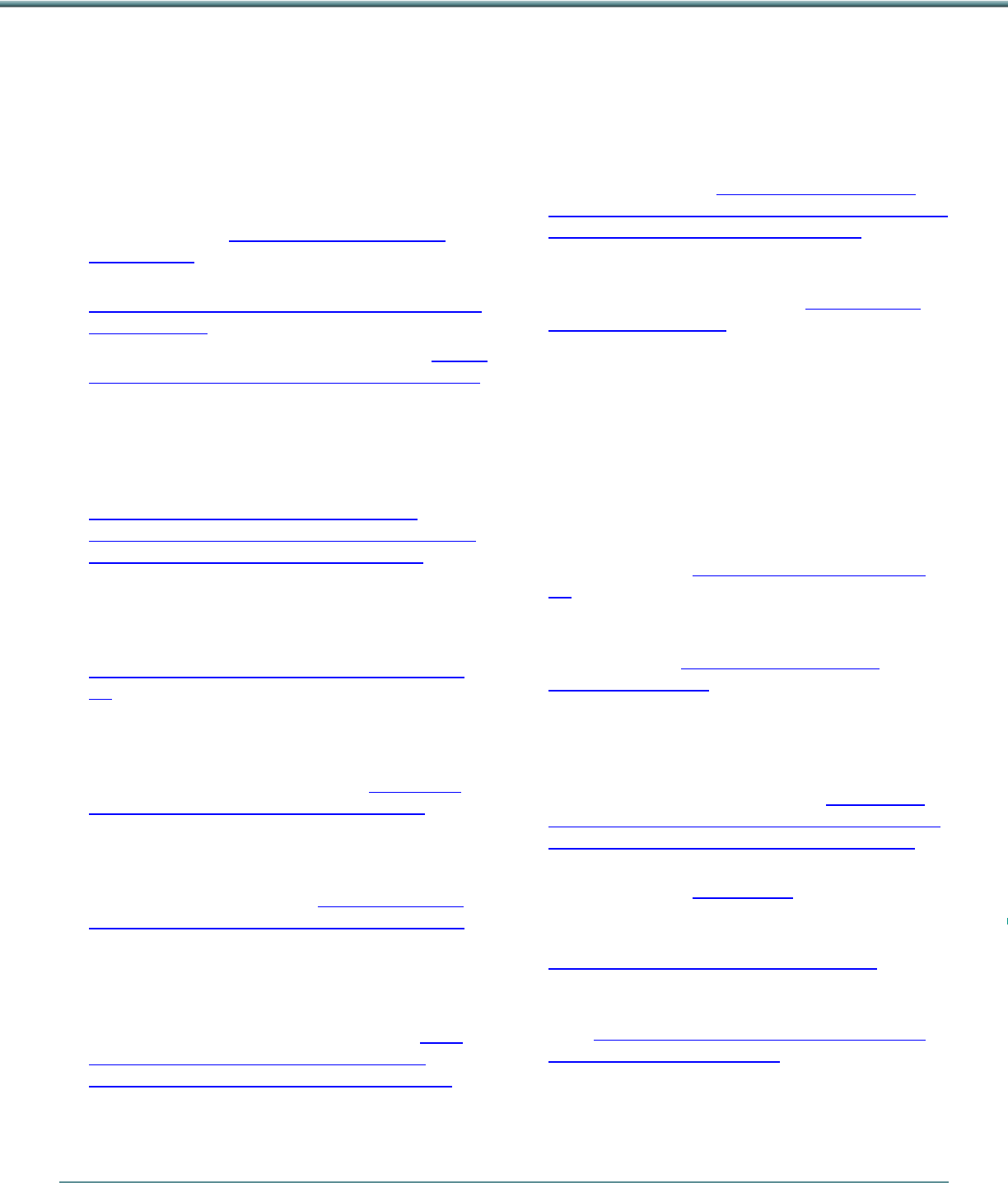

• Video Players, CNET oers links to many of the

video players/codecs needed to play video, such as

VideoLAN Client (VLC), Gretech Online Movie (GOM)

players, and more, hp://download.cnet.com/s/

video-players/.

• Comparison of Video Player Soware, Wikipedia,

hps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_video_

player_soware.

• Producing Camtasia Videos for Local Playback, hps://

www.youtube.com/embed/IM8XxDsOjks?vq=hd1080.

This video contains useful ps on export sengs to

use for rendering in general.

• “5 Tips for Using Mobile Video Evidence in Your

Agency,” PoliceOne.com, April 10, 2014, Panasonic

System Communicaons Company of North America,

www.policeone.com/police-products/police-

technology/mobile-data/arcles/7067437-5-ps-for-

using-mobile-video-evidence-in-your-agency/.

• “A Simplied Guide to Forensic Audio and Video

Analysis,” Naonal Forensic Science Technology

Center, Bureau of Jusce Assistance (BJA), Oce of

Jusce Programs, U.S. Department of Jusce (DOJ),

www.forensicsciencesimplied.org/av/AudioVideo.

pdf.

• “A Simplied Guide to Forensic Evidence Admissibility

and Expert Witnesses,” Naonal Forensic Science

Technology Center, Bureau of Jusce Assistance

(BJA), Oce of Jusce Programs, DOJ, hp://www.

forensicsciencesimplied.org/legal/index.htm.

• “Admissibility of Electronic Evidence: A New

Evidenary Froner,” the Honorable Alan Pendleton,

Bench & Bar of Minnesota, Minnesota State Bar

Associaon, October 14, 2013, hp://mnbenchbar.

com/2013/10/admissibility-of-electronic-evidence/.

— While not a video-evidence-focused arcle, the

“Analycal Framework” for the admissibility of

electronic evidence may be useful.

• “Addressing Video Evidence at Trial,” Doug Wyllie,

Senior Editor, PoliceOne.com, June 24, 2008, www.

policeone.com/police-products/invesgaon/

ps/1706936-Addressing-video-evidence-at-trial/.

• “Best Pracces for Image Authencaon, Forensic

Science Communicaons,” April 2008, Volume 10,

Recommended Resources

This list of resources provides a starng point for prosecutors wanng to learn more about video-evidence processes.

Number 2, FBI’s Scienc Working Group on Imaging

Technologies (SWGIT), www.i.gov/about-us/lab/

forensic-science-communicaons/fsc/april2008/index.

htm/standards/2008_04_standards02.htm.

• “Digital Evidence in the Courtroom: A Guide for Law

Enforcement and Prosecutors,” Naonal Instute

of Jusce (NIJ), DOJ, January 2007, www.ncjrs.gov/

pdles1/nij/211314.pdf. This guide focuses primarily

on digital computer evidence but is useful in guiding

prosecutors through the process of acquision,

integrity, discovery, courtroom preparaon and

evidence rules, and the presentaon of digital

computer evidence.

• “Forensic Imaging and Mul-Media Glossary Covering

Computer Evidence Recovery (CER), Forensic Audio

(FA), Forensic Photography (FP), and Forensic Video

(FV),” Version 7.0, Last Updated July 15, 2006,

Law Enforcement and Emergency Services Video

Associaon (LEVA), www.leva.org/pdfs/GlossaryV7.

pdf.

• “Guidelines for Facial Comparison Methods,” Facial

Idencaon Scienc Working Group (FISWG),

February 2, 2012, www.swg.org/document/

viewDocument?id=25.

• “How to Play a DPD Confession Video,” Prosecutor

Kym L. Worthy, Wayne County Prosecutors Oce,

Michigan. This is an example of a guide made to assist

defense aorneys with playing proprietary police

video les received during discovery. hps://www.

linkedin.com/pulse/sample-how-instrucons-playing-

proprietary-video-le-patrick-muscat?published=t.

• Law Enforcement and Emergency Services Video

Associaon (LEVA), www.leva.org.

• Statewide/Centralized Evidence Laboratories, Naonal

Clearinghouse for Science, Technology and the Law,

hp://www.ncstl.org/resources/laboratories.

• Using and Presenng Digital Evidence in the

Courtroom: Training Material (CD-ROM), NIJ, DOJ,

2008, www.nij.gov/publicaons/pages/publicaon-

detail.aspx?ncjnumber=215094.

—This CD-ROM is an interacve training program on

using and presenng digital evidence in a courtroom

seng.

Video Evidence: A Primer for Prosecutors / 11

Endnotes

1 Dale Garrison, “Advanced Video Forensics,” Evidence Technology Magazine, July–August 2014 Issue, www.evidencemagazine.

com/index.php?opon=com_content&task=view&id=1688&Itemid=49.

2 Ibid.

3 “Body-Worn Camera Toolkit,” Bureau of Jusce Assistance, Oce of Jusce Programs, U.S. Department of Jusce, hps://www.

bja.gov/bwc/.

4 Kay Chopard Cohen, “The Impact of Body-Worn Cameras on a Prosecutor,” Naonal District Aorneys Associaon, hp://

ndaajusce.org/pdf/BWC_Blog_Post_Dra_09%2002%202015_FINAL.pdf.

5 Naonal Prosecuon Standards, Third Edion, Rules of Conduct, Secon 1–1.4, Naonal District Aorneys Associaon, hp://

www.ndaajusce.org/pdf/NDAA%20NPS%203rd%20Ed.%20w%20Revised%20Commentary.pdf.

6 Public Safety Primer on Cloud Technology, Global Jusce Informaon Sharing Iniave, Bureau of Jusce Assistance, Oce of

Jusce Programs, U.S. Department of Jusce, May 2016.

7 The Federal Risk and Authorizaon Management Program (FedRamp) is a government-wide program that streamlines federal

agencies’ ability to make use of cloud services and introduces an innovave policy approach to developing trusted relaonships

between federal agencies and cloud vendors. FedRamp provides a standardized approach to security assessment, authorizaon, and

connuous monitoring for cloud services that secure federal data, www.fedramp.gov.

8 The Federal Informaon Security Management Act of 2002 requires each federal agency to develop, document, and implement

an agencywide program to provide informaon security for the informaon and informaon systems that support the operaons

and assets of the agency, including those provided or managed by another agency, contractor, or other source. hp://csrc.nist.gov/

drivers/documents/FISMA-nal.pdf.

9 Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Federal Informaon Systems and Organizaons, Special Publicaon 800-53A, Revision

4, Naonal Instute of Standards and Technology, hp://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublicaons/NIST.SP.800-53Ar4.pdf.

10 MP4 in PowerPoint, FAASOFT, June 12, 2014, www.faaso.com/arcles/mp4-in-powerpoint.html.

11 In some jurisdicons, it is required to provide the defense with a copy of any wring or labeling on the outside of the disc.

12 People v. Musser, 835 N.W.2d 337 (Michigan Supreme Court, 2013).

13 Forensic Imaging and Mul-Media Glossary Covering Computer Evidence Recovery (CER), Forensic Audio (FA), Forensic

Photography (FP), and Forensic Video (FV), Version 7.0, Last Updated July 15, 2006, LEVA, www.leva.org/pdfs/GlossaryV7.pdf.

14 Authencang or Idenfying Evidence, Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE), Rule 901, hp://federalevidence.com/rules-of-

evidence#Rule901.

15 The silent witness theory is a theory in the law of evidence whereby photographic evidence (as photographs or videotapes)

produced by a process whose reliability is established may be admied as substanve evidence of what it depicts without the need

for an eyewitness to verify the accuracy of its depicon. In People of Illinois v. Taylor, 956 N.E.2d 431, 353 ILL. Dec. 569 (2011),

surveillance video of the defendant comming the crime was captured on a digital medium and transferred to a VHS tape for trial.

The defense connually objected on foundaonal grounds, arguing that it had not been shown that the camera worked properly.

The Illinois Court of Appeals, aer discussing the silent witness theory, found that the tape was inadmissible based on issues

demonstrang chain of custody, conrming the camera worked properly, ensuring the original digital recording was preserved, and

concerns regarding the method used to transfer the video from digital to VHS format. While the Illinois Supreme Court agreed with

the issues the Court of Appeals examined, it disagreed with its analysis and found adequate support for each foundaonal factor

within the trial record and under Illinois law. The tape was ulmately admied and the defendant’s convicon armed. Chain-of-

custody issues in establishing foundaon generally go to weight, not admissibility.

16 Chain-of-custody issues in establishing foundaon generally go to weight, not admissibility.

17 Federal Rules of Evidence 1001(d), hps://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_1001.

About Global

The Global Jusce Informaon Sharing Iniave (Global) Advisory Commiee (GAC) serves as a Federal Advisory

Commiee to the U.S. Aorney General. Through recommendaons to the Bureau of Jusce Assistance (BJA), the GAC

supports standards-based electronic informaon exchanges that provide jusce and public safety communies with

mely, accurate, complete, and accessible informaon, appropriately shared in a secure and trusted environment.

GAC recommendaons support the mission of the U.S. Department of Jusce, iniaves sponsored by BJA, and related

acvies sponsored by BJA’s Global. BJA engages GAC-member organizaons and the constuents they serve through

collaborave eorts to help address crical jusce informaon sharing issues for the benet of praconers in the eld.

IT.OJP.GOV/Global

Issued 10/2016

This project was supported by Grant No. 2014-DB-BX-K004 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs,

U.S. Department of Justice, in collaboration with the Global Justice Information Sharing Initiative. The opinions, findings, and

conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

U.S. Department of Justice.

Acknowledgements

A special thank-you to Global’s prosecutor draing team for their valuable contribuons in authoring and guiding the

development of this resource.

Kay Chopard Cohen

Naonal District Aorneys Associaon

David McCreedy

Appellate Secon

Wayne County Prosecutor’s Oce, Michigan

John Wolfstaeer

Courtroom Technology

New York County District Aorney’s Oce, New York

Appreciaon is also shared for the following individuals and organizaons who contributed to the development and veng of this

resource.

Kevin Bowling

20th Circuit Court, Oawa, Michigan

Represenng the Naonal Associaon for Court Management

Krisne Hamann

Bureau of Jusce Assistance

U.S. Department of Jusce

The Honorable William J. Ihlenfeld, II

United States Aorney’s Oce, Northern District of West Virginia

Represenng the Execuve Oce for United States Aorneys

David Labahn

Associaon of Prosecung Aorneys

Fred Lederer

Center for Legal and Court Technology

William and Mary Law School

Represenng the Naonal Center for State Courts

Patrick Muscat

Violent Crime Unit

Wayne County Prosecutor’s Oce, Michigan

Mark Shlia

Connuing Legal Educaon and Trial Technology

Cook County State’s Aorney’s Oce, Illinois

The Honorable Barbara Mack

Naonal Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges

Mark Perbix

SEARCH, The Naonal Consorum of Jusce Informaon and

Stascs

Raj Prasad

Wayne County Prosecutor’s Oce, Michigan

Sean Smith

New York Prosecutors Training Instute

Christopher A. Toth

Naonal Associaon for Aorneys General

Members of the Criminal Intelligence Coordinang Council

and the Naonal Associaon for Court Management’s Joint

Technology Commiee who parcipated in the veng of this

resource.