IK Multimedia MODO Bass

A Technical Article and Sort of Review

Mike Rivers © 2017

Prologue

If you follow my reviews and technical articles, you might well ask “What the heck

is he doing reviewing a software plug-in?” To tell the truth, I’ve wondered the

same thing myself, which is why this article has been a long time coming. Nearly

everything that I record involves real instruments played by real musicians, so

other than just messing around or experimenting, I don’t use virtual instruments,

particularly those of the DAW (Digital Audio Workstation – I used Reaper v5 for

my experiments here) plug-in variety. When I record something with a bass, it’s

nearly always an acoustic bass. I don’t play bass (I’ve played at bass, but that

doesn’t really count) so I don’t really know all the subtleties that a real player

would recognize or find lacking, and I don’t really design sounds, I just make

recordings that sound real.

When my friendly IK Multimedia marketing manager let me know that MODO

Bass was about to be released and asked if I’d like to write a review, I was about

to say “no, thanks” for all of the above reasons, but when I took a closer look, it

occurred to me that it might be a good tool for learning how stringed instruments

make their sounds and what makes one instrument sound different from a similar

one. I figured that the usual reviewers and forum posters would be pretty quick to

tell readers if the program’s sounds were good and useful, something that there’s

no particularly good reason to trust me about. Rather, I could write about the

modeling technology and the flexibility that it offers over conventional synthesizer

or sample-based instruments. So that’s where I’ll be going here.

What It Is

The simple description of MODO Bass (which I’ll occasionally shorten to MODO

here to save my fingers) is that it’s a MIDI-driven synthesizer for electric bass

instruments. It’s a 64-bit application so it requires a 64-bit operating system,

Windows Vista, Mac OS-X 10.9 or newer versions. In the DAW environment, it

runs as a VST2, VST3, AAX, or Audio Units (Mac) plug-in, or it can run as a

stand-alone program for live playing or off-line sound tweaking. What makes

MODO special is that instead of employing samples or conventional synthesis

techniques to produce its sounds, it works by modeling, in real-time, the behavior

of a vibrating string. What this buys you is more accurate response to your

playing that affects the timbre and dynamic characteristics of the notes. Beyond

response to playing techniques, tweaks to the instrument sounds themselves are

in terms of physical things like touch, picking position, string gauge and amount

of wear, rather than boosts or cuts in frequency bands and decays in

milliseconds. Further you can virtually modify the instrument itself in ways that, in

real life, would involve woodworking tools soldering irons.

One thing to know right up front is that it only models “iconic” (IK’s description,

not mine) electric basses – there are no acoustic basses included, hence no

doghouse (upright) bass, no washtub bass, no guitarrón, not even an acoustic

bass guitar. I asked if there was a possibility of adding acoustic models in the

future, and the answer was a pretty straightforward “no.” Acoustic instruments

have more and different variables than what the algorithms used here can model,

so a MODO Acoustic Bass would really be a very different animal. That’s not to

say that it will never happen, but don’t expect an acoustic upgrade to this version.

Modal Non-Linear Physically Modeling Synthesis

This mouthful is the process upon which MODO Bass is based. “Modal,” because

there are several parts that go in to the complete model, and “Non-linear” (that’s

the hard part) because the parts of the instrument that make the sound behave in

a non-linear manner. Here’s an example: The fundamental frequency of a

vibrating string is fixed by its length, mass, and tension – that’s basic physics –

but the overtone structure, and particularly the rate at which individual overtones

decay over time, depend on how the string is excited. The string could be

plucked with a finger, picked with a plectrum (that’s the fancy word for “pick”),

smacked, or even bowed. Each playing technique introduces its own harmonic

signature, and how that varies is interactive with the position along the string’s

length where it’s plucked. Then, since we’re modeling an electric bass here,

there’s a pickup or two. The pickup’s position and its electrical characteristics

affect its signal output, and, to close the circle, the pickup’s magnetic field affects

the vibration of the string.

When a luthier designs a bass, he makes a set of choices based on the sound he

wants to get from the instrument, and hopefully someone else will like that sound

and buy his instruments. What IK has done in developing MODO Bass is to

create a set of mathematical models of the physical parameters that go into

building and playing a bass and how they react to both external stimuli and to

each other. Then, they put a musician-friendly user interface on the tools so that

you can easily experiment with things that affect the sound and put together your

favorite combinations.

The Brass Tacks

I’ll get into how the tools work shortly, but first I’d like to suggest that there are

two ways that you can work with MODO Bass, both equally valid and important.

Twelve instrument models form the basis for all of the sounds in MODO - most

players will recognize most or all of their names. IK has provided 115 preset

combinations of instruments, pickups, amplifiers and effects, built around three

playing styles – finger, pick, or slap, plus a totally off-the-wall set. The partial

listing of presets in the appendix here will give you a sense of the scope and

level of detail that went into preparing them. So one approach is simply to

audition the presets and either choose one and go with it or use it as a starting

point for some further tweaking.

Another approach to using MODO Bass is to build the bass of your dreams using

the tools provided. This is what I find most interesting about this program, so that

will be the focus of this article. But before digging into the toolbox, you’ll need to

what’s available how to find your way around. The most organized way I can

describe MODO’s features and options is through the user interface. So here’s

the $20 tour.

Screens and Controls

This is what you see when you first open the program in both the plug-in and

stand-along mode. The tabs below the row of instruments get you into the inner

workings. The top row of the screen is where presets are selected, loaded, and

new or modified presets saved. By the way, while I’ve reduced these screen

shots to fit the page layout, the full resolution is there. If you can’t read something

clearly on the page of text, zoom in.

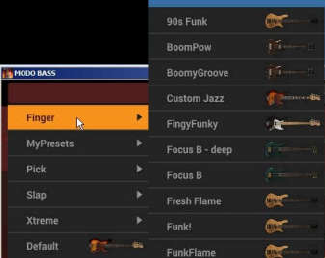

The box in the upper left corner normally shows

the currently active preset, but it’s blank when

the program is first opened. Clicking on the

Preset box brings up the alphabetized category

menu (these are actually folder names), each

containing a bunch of named preset

configurations displayed to the right. From the

factory, the preset categories are defined by the

playing styles - Finger, Pick, and Slap, plus the

wacky Xtreme presets. There’s also Default,

which is a stock ‘60s Fender Precision bass. MyPresets is a folder that I created

to save configurations I used while working on this article.

Clicking on a listed preset loads all of its settings – model, play style, strings,

pickups, and amplifiers – the whole enchilada. The up and down arrows at the

right-hand edge of the Preset box are for scrolling through the whole preset list,

going from one style right on to the next. The SAVE, SAVE AS and DELETE

buttons manage the presets. A word to the wise here: When you come up with a

sound that you like, save it as a preset!!!!

When you begin your sound quest by selecting one of the presets, its name

appears in the box in the upper left corner. If you change anything, an asterisk (*)

follows the preset name to indicate that it’s no longer exactly what you selected.

It’s also a reminder to save your work as you go. There’s no A/B button here, nor

is there a timed auto-save, so if you want to compare your modified preset to the

original or to another preset, If you haven’t saved your work and you select

another preset, your tweaks and trials will go straight to the bit bucket. SAVE AS

prompts you for a new name, while SAVE will ask if you want to replace the

selected preset with your variation – that’s all the warning you get, so heed it.

At the bottom of the screen, there’s the bass fret board and, below it, a piano

keyboard. The lowest octave purple-colored piano keys are notes lower than any

of the modeled basses can play, but they can be used as controls. Stay tuned for

the Control Tab explanation. The gray keys upscale from the purple ones are

inactive for a standard 4-string bass, but switch to white and become playable for

a 5-string bass or one with the E string dropped down to D.

The Tabs

All of the settings and tweaks are presented as tabbed pages, with the tabs

located below the window showing all of the options and controls available within

that page.

The Model tab

MODO opens in the Model page, displaying the music store’s bass department

stock. Click to select one and the big center window fills with a picture of your

bass along with a list of its default specifications. You can choose an instrument

and just start playing it “off the shelf” but this program is really a tweaker’s

delight. For starters, the yellow triangle with the descending line that you can see

in the overview a page back indicates the picking position, dimensioned in inches

from the bridge. You can drag this around which, as in real life, around alters the

tone, but that’s just a starter.

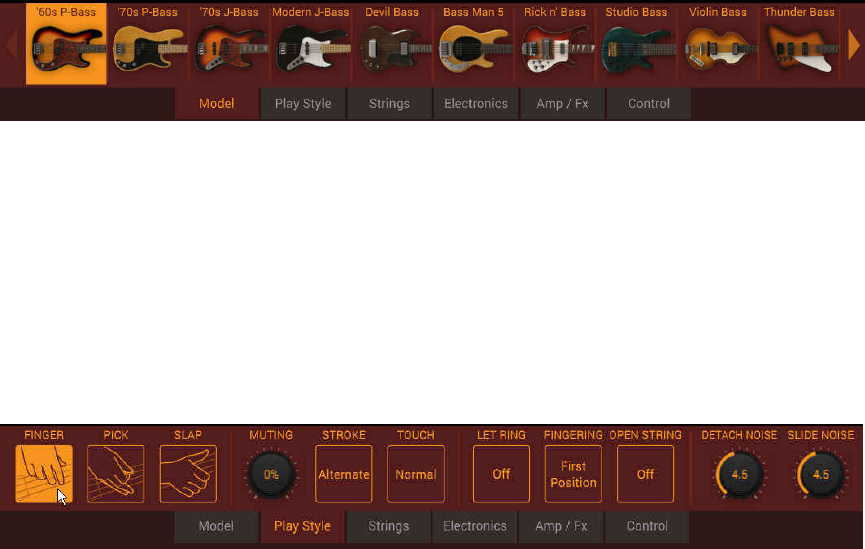

The Play Style tab:

Like many of the control panels in MODO Bass, this one is interactive, with the

choices under the Stroke and Touch buttons changing to go along with the

selected style. For example, for FINGER style, the STROKE button gives you the

choice of plucking the string with the index finger, the middle finger, or alternating

between the two. Clicking on the TOUCH button selects soft, medium or hard.

When the PICK style is selected, your STROKE choices become up, down, or

alternating, and TOUCH becomes SCRATCH, with choices of hard or normal.

From what I hear and knowing something about playing guitar, Scratch seems to

be related to the stiffness of the pick.

SLAP gives you a choice of slapping the string with a thumb, pulling the string

with an index finger, or a combination of both, with MIDI velocity determining

when pulling gets priority over slapping. Play position isn’t defined for the Slap

style – you just wham away anywhere, so the play position marker disappears

from pages that normally show it.

LET RING is an on/off toggle. When it’s off, notes decay pretty rapidly, 25

milliseconds or so, when released. With it turned on, the note will sustain for

several seconds after release, though cuts it cuts off when the next note is

played. This becomes part of a saved preset, and can be pretty annoying for

many styles, so use it frugally. If you like the idea of an occasional sustaining

string as a performance technique, there’s a way to do that under the Control tab,

so stay tuned.

FINGERING translates playing on a linear keyboard to how a real bass player

might get from one note to another. Your three choices are First Position, Easy,

and Nearest. First Position plays everything within the first five frets for

everything below C on the 1

st

string, then plays outside of first position any higher

notes. Easy and Nearest are two different schemes for determining on which

string the next note is played. OPEN STRING allows you to use an open string

rather than fretting the note on a lower string. There are subtle and some not-so-

subtle differences in the harmonic content of a note depending on where it’s

played on the fingerboard, and these two controls offer a degree of

humanization.

DETACH NOISE and SLIDE NOISE are small, adjustable fingering noises that

make your bass less than perfect – or closer to perfect if you look at it another

way. MUTING lays a virtual palm of the playing hand gently on the strings.

The Strings tab:

The STRING button has three options - 4 represents the conventional 4-string

bass standard EADG tuning, 5 adds a low B string, and Drop D switches the

tuning to DADG. The graphics at the bottom of the page change accordingly with

a fifth string appearing when selected, and the white keys (which represent the

notes that you can play) extending downward for the Drop D and 5 string

settings. TYPE selects Round or Flat Wound strings, GAUGE can be Light,

Medium or Heavy, and the AGE of the strings can be New, Broken in, or Old.

Finally, A4 REFERENCE is where you can tune the bass to match tracks that are

off concert pitch. The range is 430 to 450 Hz, or about ±39 cents, not much, but

hopefully enough to get in tune with the piano.

The Electronics tab is about the electronics within the instrument itself:

If you’re building a bass from scratch, this tab opens with the setup for the model

that you select as your foundation. Alternatively, if you’ve started with a preset, it

opens with that preset’s settings. Any bass can have one or two conventional

pickups plus an under-the-bridge piezoelectric pickup, something that’s not

commonly found on a bass, at least not common enough to be on any of the

stock models, though it’s turned up in some presets.

Each pickup including the piezo has its own volume control. For passive

electronics, there’s a single treble-cut Tone control. Active electronics replaces

the single control with individual Bass, Mid, and Treble tone controls.

As in real life, you don’t have to use the

stock pickups. While there aren’t any

aftermarket boutique pickups to choose

from, you can put a pickup from any of the

models on any other model, as well as

adding active electronics to pickups that

were designed before anyone thought to

build a preamp into the instrument body.

Within the physical limits, when this tab is

open, you can drag the pickup positions

around with the mouse.

There’s some fudging (or rather, extended modeling) going on since there’s only

one apparent 5-string pickup, yet when you add the fifth string, the strings are still

evenly balanced with any pickup. There are some restrictions in that some bridge

pickups can’t be installed in the neck position and vice versa. This might be a

mechanical limitation, or it could be that the developers said “Aw, geez, if we

have to model that many combinations we’ll never get the job finished.” Still,

there’s a lot of flexibility here, and one that clearly makes a difference in tone.

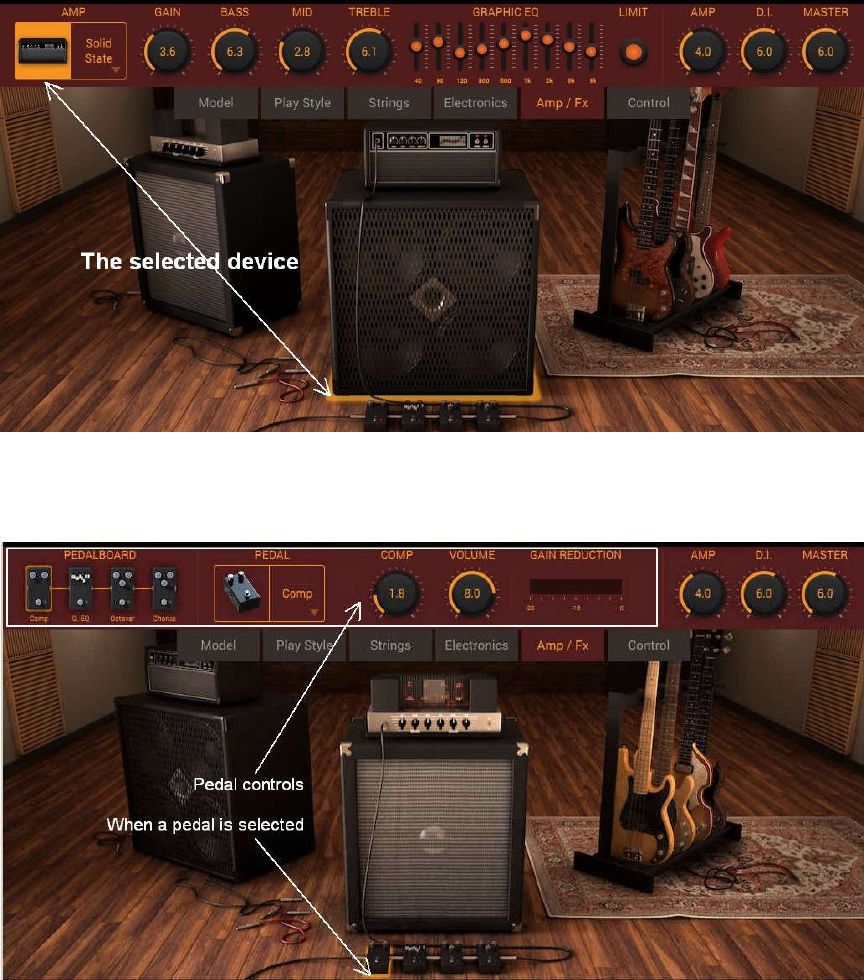

The Amp/FX tab:

While these aren’t integral parts of the physical model of the bass, an amplifier

and effect pedals are often integral parts of a bassist’s sound. IK Multimedia has

many years experience in modeling instrument amplifiers and effect pedals, and

while they aren’t giving away their Amplitube amplifier models here, MODO

includes two generic amplifier simulators based on the Amplitube modeling

technology. One is a tube amplifier graphically reminiscent of the Ampeg B-15.

The other is a solid state amp that doesn’t really remind me of anything in

particular. In addition, there’s a virtual pedal board consisting of four effect

processors selectable from a collection of seven.

Among the two amplifiers and seven effect pedals, there are a lot of different

controls here. What confused me at first was that sometimes it appeared that the

amplifier had a graphic equalizer, sometimes it had a compressor, sometimes

not, and occasionally I found a control that I didn’t expect on an amplifier. It

turned out that sometimes I didn’t notice that what I was seeing was controls for

a pedal rather than the amplifier. It took me a while to recognize what was

selected for control and how to select the controls that I wanted to adjust.

Here’s the big picture for the Amp/FX tab:

And for the effects:

In order to switch between amplifier and effect controls you have to go to the big

picture and click on what you want to adjust. Thinking about this as I’m writing, I’d

find it less confusing if, rather than the combined Amp/FX tab, there was one tab

for amplifiers and another for effects.

Here are the control panels for the two amplifiers:

When working in this panel, you can switch between the tube and solid state

amplifier by from the choices in the AMP box, or, from the big picture, you can

just click on the other amplifier. Either way, the control panel displays the controls

for the amplifier you’ve selected. As a reminder here (to myself, included),

MODO Bass is an instrument modeling program, and the amplifier, while an

important part of the system, is an accessory. The amplifiers work fine and offer

generic control sets, but the models don’t offer the extent of control that’s found

on a more sophisticated amplifier simulator such as microphone type and

position or the load impedance presented to the pickup. But if this isn’t your first

rodeo, you probably already have a couple of amp modelers you like that you

like, and it’s easy to bypass the MODO Bass amplifier and add your favorite to

the DAW’s plug-in chain.

As an FX example, here’s the control panel for the Distortion pedal:

Mouse-clicking on any pedal, either in the big picture or the PEDALBOARD

section of the control panel, displays its controls. A pedal can be engaged or

bypassed by clicking in any of three different places, on the floor, in the

PEDALBOARD section of the control panel, or on the picture in the PEDAL

section of the control panel. A too-tiny virtual red LED indicates that a pedal is

active. The effects offered here cover a pretty wide range of basic functions, but

nothing exotic. There’s distortion, chorus, compressor, delay, envelope filter,

octave divider, and an 8-band graphic EQ.

To arrange the processing order of the pedal board, rather than dragging the

chosen pedals around, it’s necessary to click on a pedal in the chain, then select

the pedal you want in that position. Clicking on the pedal name in the PEDAL box

brings up your list of choices. You can put the pedals in any order, and you can

have multiple instances of the same pedal. You can, for example, run the bass

through four delays if you wish, and in fact there are a couple of presets that

involve multiple delays. There are always four slots and there’s no “blank” pedal.

If you want only one pedal, you have to fill the other three slots and bypass the

unneeded pedals.

Just as in real life, gain structure of the pedal chain matters – you can overdrive a

pedal by turning up the output of the pedal ahead of it. You can also overdrive

the amplifier from the pedal chain. Fortunately, unlike real life, hum and buzz

doesn’t increase when you crank the level in or out of a pedal or amplifier.

The Mixer section (my name for it) is at the far

right end of the Amp/FX control panel. AMP is

the master gain for the amplifier. It interacts with

the amplifier’s input GAIN control in the

conventional manner - turn the input gain up and

the master down for crunch, turn the input gain

down and the master up for clean tones. And before you ask, the controls only

go to 10, not to 11.

Turning up the D.I. knob blends some direct signal in with the amplifier as you

might do in the studio or on stage. The DI output is post-pedals rather than

straight out of the instrument’s jack, and there doesn’t seem to be a way to

change that. Sometimes it’s what you want, or its what you get when plugging in

a hardware DI box just ahead of the amplifier’s input jack (or perhaps the

amplifier has a DI output itself). But in the studio, I generally to take the DI output

directly from the instrument, pre-processing, in order to have complete freedom

to add effects and re-amp it after tracking. When experimenting with pickups and

positioning, I wanted to hear just the direct output. When I was switching from

model to model and comparing sounds, I had to remember to check to be sure all

of the effects were bypassed, since some models have different preset settings,

all of them including a compressor that’s turned on.

Finally, the MASTER knob controls the volume of the amplifier + DI mix.

The Control tab

This one is very different from those we’ve discussed thus far. It offers real time

control of several playing style parameters.

Each of the parameters in this control panel can be assigned to a MIDI

Continuous Controller number. Most have continuous control, and working these

controls while playing can really be fun.

Pitch BEND has a fixed range of a half step up or down with the pitch controlled

by the assigned controller, usually the pitch bend wheel. Adjusting the controller

assigned to SLIDE slides up or down from the currently played note by the

number of frets set by the RANGE control. It’s not a “fretless” slide, however,

since it’s not a fretless bass (that’s on my wish list). VIBRATO depth is adjusted

by its assigned controller, with the vibrato RATE set by its knob.

MUTING applies a bit of virtual palm pressure to the strings. PLUCK POS adjusts

where you’re plucking the string. It’s identical to the dragging the pluck position

pointer with a mouse that’s displayed in the Model, Play Style, and Strings tabs.

If you have one of those screens open and a controller assigned to Pluck Pos,

when you adjust the MIDI controller, the position pointer moves. Cool!

According to the manual, LEFT HAND “controls the left hand position in the neck”

and it seems to come into play when Play Style FINGERING is set to Nearest.

Changing the Left Hand controller moves the block where it tries to find the

nearest place to play the next note to a position of your choosing rather than the

program’s choosing. It’s useful if you want to play a phrase with all of the strings

fretted within a specific area of the fingerboard.

When playing legato, with LEGATO SLIDE engaged (this is an on/off switch, not

a continuous control), you get a slide (again, over the frets) from a held note to

the next note. The speed of the slide is a function of the velocity of the next note.

When CHORD is engaged, it tries to find a way to finger a chord without trying to

play two notes on the same string.

Finally, MASTER is the master volume control, the same control as MASTER in

the Amp/FX tab.

Many of the playing parameters can be controlled by MIDI notes on keys that are

outside the playing range of the bass. These are the purple keys I mentioned

earlier, the lowest octave on the virtual keyboard at the bottom of the main

window. In addition to playing those notes on a MIDI keyboard, you can click on

the on-screen keyboard at the bottom of the screen or you can click on a key in

the key map in the Control tab.

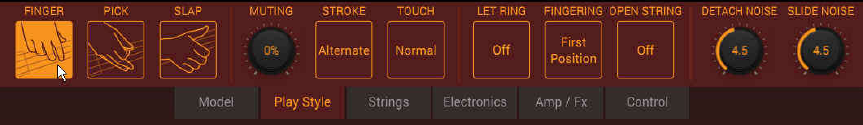

Since several of the Play Style controls are duplicated (sort of) in the Control tab,

here’s the Play Style tab again for reference.

The FINGER, PICK, SLAP, STROKE, and LET RING controls in this panel have

direct equivalent functions in the Control Key Map. The difference between how

the functions work in the Play Style and Control tabs is this: Properties selected

from the Play Style tab are static – they’re stored when you save a preset, and

they stay that way as long as you’re using that preset. Suppose you’ve recorded

a track in your DAW using a Finger style preset and decide that playing the last

chorus with a pick sounds better. One way to accomplish this is to select that

portion of the MIDI track, move it to a new MIDI track with MODO Bass plugged

in, and then select a MODO Pick-based preset for it.

I didn’t intend to get very far into DAW usage here, but since I brought it up, I’ll

tell you that with Reaper, and I suppose any other popular DAW, when you save

a project file with tracks that contain plug-ins, the plug-in settings are saved along

with the project. So if you split a track into tracks that have different presets or

custom settings, they’ll still be there next time you open that project.

But there’s another way to accomplish this.

The control keys can be used to temporarily switch the playing style, which finger

you’re picking with, and whether strings sustain or not. This is really handy when

you’re playing on a full sized MIDI keyboard. Pressing one of these mapped keys

changes the setting to which it’s assigned for as long as the control key is

pressed. When the key is released, setting returns to its previously configured

state. Furthermore, since these controls are sent to the program as MIDI note

messages, they can be embedded in a MIDI track in your DAW.

The Control keys offer a couple of functions that don’t appear in other control

panels. Hammer-on/Pull-off add a bit of extra noise to the attack and release of

notes, but it also does something else. When you play a note, hold it, and

hammer-on the next note, it plays that hammer-on on the same string as the note

you’re coming from, and when you release the hammered-on note, it returns to

the first note if you’re still holding it. It makes for a very accented trill. But even

with OPEN STRINGS engaged, you can’t hammer on from an open string nor

pull off to an open string. As a folk guitarist who plays a lot in first position and

often hammers on to played open string, I found this kind of odd, but then, I’m not

a bass player. What do I know?

The HARMONICS key produces the harmonics you get from plucking a string

while lightly touching it with a fingertip, typically half way between the fret and

bridge. GHOST is kind of a pitched light thump. FORCE _STRING forces notes

to be played on the string you choose rather than moving to another string that

might be a closer reach.

One thing I learned, or rather remembered, from my MIDI experience from 30

years ago, is that not everybody uses the same octave numbering scheme.

When I was trying to switch between fingering and slapping in the middle of a

recorded MIDI bass track as I described previously, I was able to do this using

the keyboard as I was playing, but when I inserted an A#0 note (slap) into the

sequence using Reaper’s MIDI editor, although I could see the control note in the

MIDI track, the picking didn’t change. After tearing out a bit of hair, I tried

recording my live playing, including pressing the low A# key at the appropriate

time. Sure enough, the track played back just what I heard when playing live.

When I looked at the sequence with the MIDI editor, I discovered that Reaper

called that control note A#1 rather than A#0.

A Look Into What Makes It Tick – String Physics

At this point, I could probably simply say: “It works fine and sounds fantastic. Go

play some bass tracks and use your imagination.” But the reason why I chose to

look at this program was because I was intrigued with the method of sound

generation, and what effect changing something had on something that I could

both see and hear. When I review a product, I like to throw some test equipment

at it and learn what’s happening under the hood. Being software, and me being a

hardware guy, there isn’t much in MODO Bass I could put under a microscope.

Two things came to mind, both in relation to the overtones. One was in the way

that changing parameters affected which overtones were most prevalent. This is

a function of resonance, both mechanical and electrical. The other was how

various settings affected the rate at which the different overtones decayed. This

one proved to be most interesting.

In my 1958 high school physics class, when we studied sound, we had a wire

stretched between two hooks on a board, and could observe its vibration under

the illumination of a stroboscope adjusted to flash at the vibrating frequency.

Tuning the strobe light so that the string motion appeared to stop gave us the

frequency. Doubling the strobe frequency made the string’s 2

nd

harmonic come

into view as two stationary nodes. That was pretty cool, but today we have more

sophisticated tools.

A real time spectrum analyzer (RTA) displays what frequencies are present in a

signal, and their relative amplitudes. You’ve no doubt seen such a plot – it looks

like a frequency response graph or sometimes a bar graph. Real time spectrum

analysis is a great tool for frequency analysis when you have a steady input

signal, but, with a plucked string, everything changes, and continues changing,

once the string is left free to vibrate.

One of the ways that a spectrum that changes over time can be displayed is

what’s often called a “waterfall” plot. This is a family of frequency versus

amplitude plots drawn 3-dimensional style as multiple time slices. It’s a good tool

for analyzing the transient response of a loudspeaker or the reverberant

acoustical characteristics of a room, but it became too messy when the time

slices were close enough together to catch the behavior of the vibrating bass

string. So I started looking at spectrograms.

A real time spectrum plot looks like a frequency response curve with frequency

on the horizontal axis and amplitude on the vertical axis, while a spectrogram

plots time on the horizontal axis, frequency on the vertical axis, and indicates

relative amplitude by color or, if in black-and-white, shades of gray.

Here are the three views of a single note, E, played on the 2

nd

fret of the 2

nd

(D)

string, approximately 82 Hz. The model is the 60s P-Bass with the standard

pickup arrangement, plucked with the index finger with a medium touch, direct

output, no amplifier, no pedals engaged.

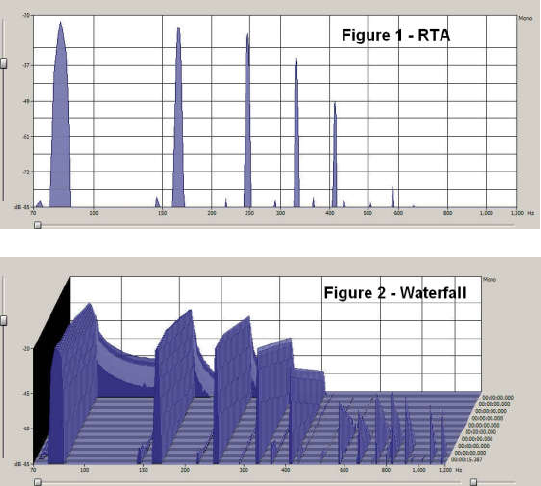

Figure 1 is the RTA plot

averaged over a 5-second

period. Note that the

fundamental frequency,

second, and third harmonics

are nearly the same

amplitude, with the upper

harmonics dropping off fast.

Figure 2 is a 64 time slice

waterfall plot of the same 5-

second note, with each slice

representing a look at the

RTA approximately every

tenth of a second. The slice

in front is the initial attack,

and time moves back toward

the rear of the plot. If you

look along the top of the peaks, you’ll see that the fundamental frequency doesn’t

decay much over the measured time interval – the top of that wedge is fairly flat.

But the 2

nd

and 3

rd

harmonics actually increase a bit after the initial attack before

dropping off. Harmonics beyond the 3

rd

drop off pretty quickly and are more than

60 dB down after the first couple of seconds.

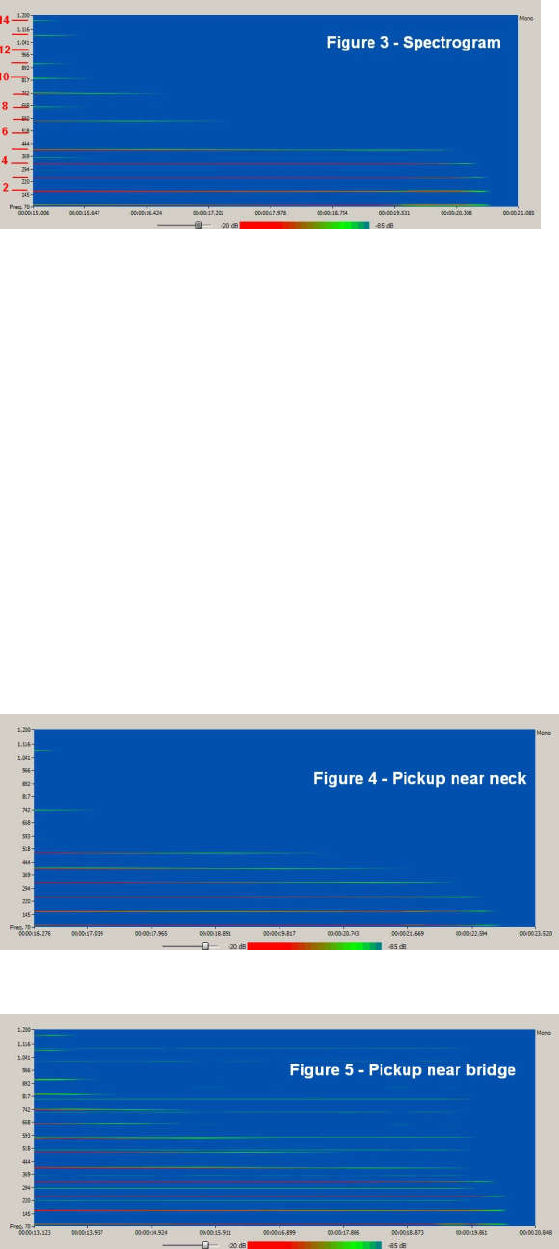

Figure 3 is the spectrogram

of that same note.

Remember that you can

zoom in for more detail, and

there’s more to see here.

Time is on the horizontal

axis, frequency is on the

vertical axis, and amplitude

is represented by the color

with red being loudest and blue being quietest, essentially the noise floor. The

fact that the lines look a little fuzzy and some are mixed colors results from the

string not being mechanically perfect; it’s vibrating frequency varies very slightly

over time. But what’s interesting here is that initially the 2nd harmonic is a little

stronger than the fundamental (more red), the 6

th

and 12

th

harmonics are down in

the noise, and the 8

th

and 10

th

harmonics are stronger than the 9

th

.

Something evident in all of these graphs that I glossed over are the little blips

starting just below the fundamental tone and appearing between all of the

harmonics. That’s D, and it’s not a glitch – it’s repeatable. I suspect that it’s the

sound of the open string before it hits the fret. Lifelike? You bet!

So much for a stock instrument, now let’s look at what happens when we change

something. With so many combinations, I chose to take a close look at

something that’s easy to hear and see, the pickup position.

With the pickup moved as

close to the neck as it will

go (Figure 4), you can see

that there isn’t much

audible above the 6

th

harmonic. There’s quite a

bit of 2

nd

and 3

rd

harmonic,

with the 3rd

nd

harmonic

being stronger than the 2

nd

over much of the sustain period.

When the pickup is moved

as close to the bridge as

possible (Figure 5), the

output is much richer in

harmonics. This translates

to a brighter and harder

tone. Also, not that you’d

really hear it, but notice

that that ghost of a D note

and its harmonics are about 6 dB higher than with the pickup near the neck, and

that they extend out further in the frequency spectrum.

While I don’t encourage anyone to get out a router and start moving pickups

around on your prized ‘60s Precision bass, this is something that you can do in

MODO Bass with just a click and a drag. It also offers some insight in what you

can expect on a two-pickup bass when you start with one pickup off and then

blend it in with the other pickup.

Since IK gave us so many choices for pickups, I thought I’d try a few different

ones on the same body using the same settings as in the pickup position

experiment – direct output, no processing, passive electronics, single direction

pluck with the index finger. For this experiment, I started with the Japan Bass

body with its stock pickup, then swapped it out for the Devil Bass pickup, and

finally the 70s P-bass pickup, all in the neck position, 6 inches from the bridge.

On my first try, I was rather underwhelmed when listening to single notes with

each pickup, held until they died out. While I could hear subtle differences

between the pickups, their spectrograms looked nearly identical. What was most

telling, though, was when I listened to an actual bass track while swapping

pickups – the differences in tone, particularly the attack, were quite dramatic.

What I discovered here was something that probably every bass player knows -

that the most apparent difference in tonal properties occurs at the start of a note,

and five seconds after the attack, every bass sounds about the same.

Furthermore, more aggressive playing makes everything sound brighter. So I

modified my test file to play notes at a pretty brisk MIDI velocity of 100 (range is 0

to 127), and looked at just the first half-second of the note. Some might call this

cheating by adjusting the experiment to achieve the expected result, but it more

accurately reflects what you hear when actually playing the instrument in context.

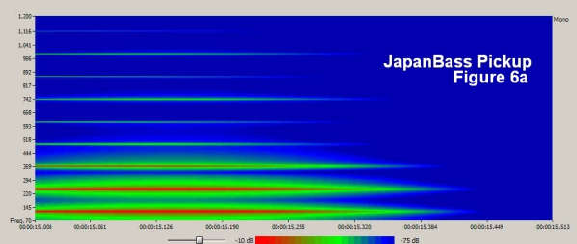

Figure 6 shows the sonograms of a note (in this case B-2, played on the 1

st

string) using each of the three pickups:

Figure 6a is the stock

Japan Bass, but with

passive electronics and

only the neck pickup. It’s

a pretty fat bass sound

with the fundamental,

second and third

harmonics predominant.

Note that the second

harmonic hangs in a bit longer than the others.

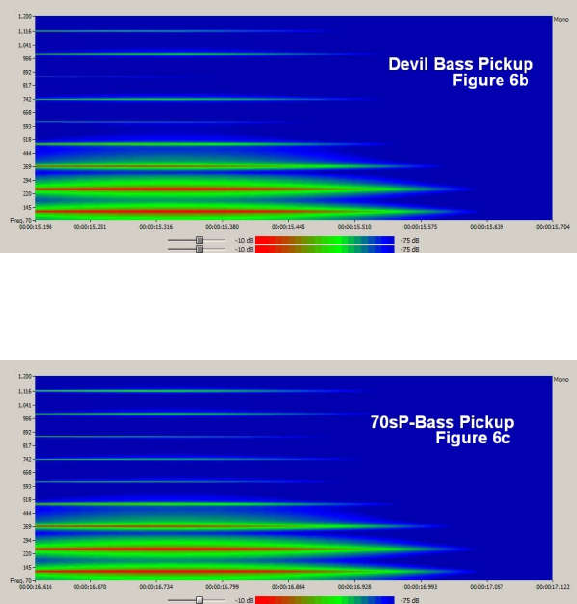

The Devil bass (Figure

6b) pickup’s 2

nd

5

th

and

7

th

harmonics are weaker

the Japan pickup but

there’s some noticeable

9

th

harmonic. This

suggests a slightly

boomier tone than the

Japan pickup due to the

equally strong

fundamental and lower harmonics, but weaker mid-range harmonics, and indeed

it does have a stronger bottom end.

To my ear, the 70s

Precision Bass pickup

(Figure 6c) was the most

balanced of them all,

with a fairly even

distribution of harmonics

over the full range of the

spectrum. Note, also,

that in all of these

examples, the amplitude

peaks about 80 milliseconds after the initial attack.

Latency and the Lightness of Being

Whenever there’s a virtual instrument involved, someone will always ask: “what’s

the latency?” Assuming that you’re playing from a MIDI keyboard, it takes a finite

amount of time for the key press to be converted to MIDI data, then there’s the

time it takes the data to pass through the MIDI driver and get into the workings of

the computer, how long the computer takes to translate the MIDI data into audio

data (that’s MODO Bass’ job), and how long it takes the audio data to get out of

the computer, back to the interface, through its analog-to-digital converter, and

finally out to a loudspeaker. Some of these times are dictated by the hardware,

others by the software, usually expressed casually as “the quality of the drivers,”

and the user-determined size of the ASIO and USB buffers. The data crunching

time is a function of the computer hardware and operating system and will be

faster on some systems than others. What you really want to know, though, is

how long after you’ve pressed a key do you hear the note sound. Many reviews,

or the manufacturer’s data sheet, will state simply that latency is “very low,” but I

like to be more specific than that if I can.

Measuring total latency of this system is

complicated by the fact that the input is

mechanical (a keyboard) and the output is

electrical (audio). In order to try to put a

number on it, I cobbled up a simple test rig

(Figure 7) to generate an electrical pulse when

I hit a key. It consists of a microswitch, a

battery, a resistor and an XLR connector.

Using MODO as a virtual instrument in a

Reaper track, I set up an outboard recorder

(best practice is not to use the system under test as your test equipment if you

can avoid it) to record Reaper’s monitor output on one channel of a stereo track

and the pulse from the microswitch on the other channel. The time between the

starting time of each would be the true latency.

After whacking a few keys with the microswitch, I opened the recording in Sound

Forge, zoomed in on the waveform, and measured the time between the pulse

and where the audio starts as planned. The problem was that I couldn’t get

consistent results because handholding the switch just wasn’t repeatable. It was

a good idea that didn’t work out, but too good of a story to leave behind. Back to

the drawing board.

Next I tried what seemed like an obvious and less complicated procedure. The

plan was to record a MODO Bass MIDI track and, temporarily setting aside my

scruples about using external test equipment, while playing, record the monitor

output of the bass track on an adjacent audio track. With some creative patching

and muting to exterminate feedback loops, I had two adjacent tracks, one with

straight lines indicating the MIDI notes, the other with the bass audio.

With a little cursor dragging, I was able to measure the time between the start of

the MIDI note and the start of the audio. But there was a problem. The audio that

came out while I was hitting the keys was delayed by the latency that I was trying

to measure, but the recorded audio track had the system’s input latency added to

it. I could (and did) measure the full round trip audio latency of the interface going

through Reaper, but I didn’t know how much of that was from the gozouta (that I

wanted to measure) and how much was from the (gozinta), which doesn’t count.

So I rigged up a different way to get an analog pulse at the precise time that I hit

a key. I split the MIDI output from the keyboard with one branch going to the

computer’s MIDI interface to play the plug-in and the other branch connected

directly to one channel of my handy TASCAM DR-44WL recorder. I recorded the

MODO audio output on the other channel of the recorder. Now I had a recording

of what I really wanted – when the key was hit and when the audio started.

The analog signal

derived from the

keyboard’s MIDI Out

was pretty messy due

to the keyboard

sending Active Sense

and me not being able

to find the manual to

see if it could be turned

off. Active Sense is a continuous string of “I’m still here” pulses on the MIDI track,

but zooming in on the recorded waveform made it easy to find the start of the

MIDI note that triggered MODO Bass.

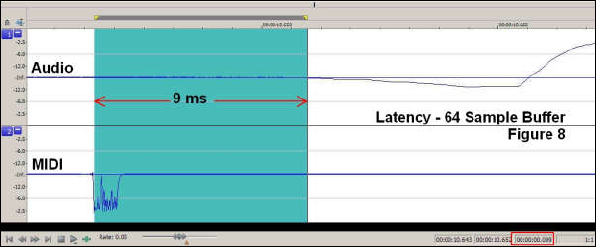

With the computer I was using for my MODO tests, I need an ASIO buffer of at

least 256 samples in order to be confident of stability when recording and mixing.

Since as a rule I don’t monitor through the computer, I usually leave it set up for

512 samples just for safety. I dropped back to 256 samples when I set up MODO

Bass, and that worked just fine. However, this gave me a latency of nearly 30

milliseconds when playing MODO, long enough to be unacceptable to some

players. Reducing the buffer size to 64 samples brought the measured latency

down 9 milliseconds. Latency’s effect on a player’s performance is very

subjective – some are distracted by just a few milliseconds of delay, while others

can tolerate what’s practically an echo. Understand that these measurements are

probably near worst case since I have a pretty slow computer by today’s

standards. Latency through your system will likely be different, probably better.

Other reviewers who are better players and more experienced DAW users than I

have given it good marks in this regard so I’ll proclaim it acceptable.

In order to see how well the plug-in delay compensation worked, I rendered a

MODO MIDI track, creating a new bass audio track from the MIDI track. Latency

compensation is a normally transparent part of the MIDI track rendering process

incorporated into practically DAW these days. It works by delaying all of the other

tracks to match the amount of time the plug-in tells the computer that it needs to

do its thing. Some plug-ins require just a couple of samples worth of time to work,

others, like a convolution reverb, can take tens of thousands. I checked the time

alignment between the original MIDI track and the MODO Bass rendered audio

version and found that the audio was 1 millisecond behind the MIDI track. That’s

enough to get some comb filtering if they’re mixed together, but that’s not

something you’d likely do.

In theory, delay compensation should be perfect, in practice sometimes it isn’t.

Reaper displays the number of samples the plug-in tells it to delay, and with

MODO Bass (as well as for a number of other plug-ins I looked at) it’s zero,

which doesn’t mean that the plug-in is lightning-fast, it just means that Reaper

isn’t displaying a realistic value. There are ways to fine-tune latency

compensation, but I didn’t bother with it here.

I should add that all of these latency measurements were made at a sample rate

of 44.1 kHz. I did some quick checks at 96 kHz and things were about 30%

brisker for the larger buffer sizes, but with a 64 sample buffer, at least on my

system, 9 milliseconds seems to be as short at it can go.

MODO Bass is fairly small and loads quickly, even on my cranky old computer, a

2.8 GHz Core 2 Duo CPU with 4 GB RAM running Windows 7. While the

Windows Task Manager CPU and memory usage monitors aren’t very

sophisticated, it’s comforting to see that with eight tracks of Reaper running

MODO Bass, CPU usage increased by only about 3.5% when playing. Memory

usage is harder to determine since Windows is always doing something and the

memory usage monitor goes wild at random times. As an eyeball average,

playing a fairly busy track with eight instances of MODO Bass with no signs of

stumbling increased the memory usage by about 0.8 gigabytes.

In Use

Every review needs an “In Use” section, but there really isn’t too much to say

here that I haven’t already written in my detailed description of its workings. You

plug it in and it works, just like a refrigerator or a TV set. If I was a normal user

(whatever that means) instead of a reviewer, I’d likely just pick one of the models

that seemed appropriate for the character of the song, load it up, and go.

Everything sounds very good to me right out of the box, but since so often

modern music calls on sound design to make it interesting, the possibilities with

MODO Bass for a unique and Grammy-grabbing bass sound are wide open.

What I can comment on here are some things that I think would make things go a

little smoother when diving into the big pool of modifications.

Presets and Defaults or Presets vs. Defaults

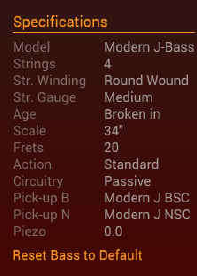

There’s a list of specifications on all of the tabbed pages that show the selected

model bass displayed in big window. At the bottom of the specifications list is a

“Reset Bass to Default” link, which does just that. If anything

that’s on this list has been changed from its original setting,

the “Specifications” title gets an asterisk added to it. Clicking

on Reset Bass to Default restores that model’s original

specifications and clears the asterisk. But be aware that

there are some things on the list that you can’t change, and

things you can change that aren’t on the list. You can’t

change the scale length or number of frets.

If you change the playing position from the standard 6” from

the bridge, the new position sticks for all models. However,

when you switch Play Style from Finger to Pick, the playing position jumps to the

default setting for Pick style, and this sticks for all models until you change it.

All of the models initialize to their defaults (including finger style played 6” from

the bridge) when the program is opened. Closing and re-opening it is the only

way to assure that all defaults are restored. If you want to save a custom playing

position, you can save it with a Preset, but remember that a preset includes the

model, so it will only be that playing position for that particular model with that

particular preset. Due to physical restrictions, not all models can accommodate

the same range of playing positions. If you’re playing one model in a position

that’s too far away from the bridge for another model, it does the best it can by

setting the playing position at the end of that model’s playing range. However,

that playing position sticks for that style on all of the other models until you

stretch it out again. We’re talking about a half-inch difference here, not likely to

matter in practice, but just something to make you wonder if you notice it.

To add a bit of chaos to the confusion, if you’ve saved a preset with a custom

playing position, open that preset, and then change the model, your custom

playing position sticks until you either close and re-open the program or select

the “Default” preset, which takes you back to the ‘60s P-Bass with its defaults.

However, if your preset includes changes that are on the Specifications list,

clicking on Reset Bass to Default resets the strings to their defaults but not the

play style or play position. So the lesson here is that “Default” is for the

instrument itself, and only the instrument.

I’d like to see a “Reset everything” button that gives me the equivalent of a fresh

restart without having to close and re-open the program. Or maybe an “Undo the

last thing you did” button. Sometimes you can get so deep down the rabbit hole

that you don’t know how you got there.

When you recall a Preset, everything is as you’ve saved it, including any pickup

swaps. If you change to a different model, your preset’s strings, playing style and

position settings, as well as the Amp/FX settings are retained, but the pickups

revert to the stock ones on the model to which you’ve just selected. One might

ask: “Why would you want to switch models?” and an appropriate answer would

be “Why not?” Well, one reason why not is that when I played with switching

bodies while keeping everything else including the pickups constant, I didn’t hear

any difference that would make me care. Most of the models have a 34” scale

length, but a couple are shorter, which, it seems, might make a difference since

the vibrating length of the string is different. I didn’t follow through on this and I’m

leaving it as an exercise for the student.

From a cold start, all of the models have strings of the same type and condition,

the same playing style (fingering, stroke, and playing position, and everything

goes through the solid state amplifier with the same settings. However, most

changes that you make with one model are retained when you switch to a

different model.

An oddity with the Amp/FX settings is that, while pedal settings are retained

when switching between the solid state and tube amplifiers, selecting the

alternate amplifier returns its settings to the defaults. If you’ve adjusted the solid

state amplifier to your liking and then want to hear what your bass sounds like

through the tube amplifier, after switching amplifiers, listening, then switching

back to the solid state amp for an A/B comparison, unless you saved a preset

with the amp settings that you liked, you’ll have to reset the amplifier. A notebook

is a good thing to have beside you here to jot down your settings until you decide

to make them permanent with a preset.

Perhaps a method of saving amplifier settings independent of the instrument

settings is in order – or maybe this is IK’s way of encouraging you to buy into

their Amplitube amplifier modeling plug-in (or somebody else’s), which does

provide a place for saving amplifier settings.

The files that define the presets (*.mbp) are stored in folder (for Windows) below

YourUserName\Documents\IK Multimedia\MODO BASS\Presets. You can add,

delete, or rename a preset, but it requires navigating to the Presets folder,

something that users who aren’t terribly computer-savvy might find daunting.

Also, if you rename or add a preset while the program is open, it won’t appear on

the Presets list until MODO Bass is closed and re-opened. I expect that users will

want to share presets, and, in fact I discovered someone who has a set of

presets for sale, so in order to use presets that aren’t installed with the program,

you need to be able to find the folder and not be afraid to change its contents.

Additional buttons to import or delete presets might be a good addition.

Somebody out there must not like dynamics, because the default Amp/FX setup

has the compressor pedal engaged, and the solid state amplifier’s limiter is

switched on. With that as a starting point, setting the amplifier gain structure

(input and output gains) might not work as you expect. Perhaps it’s my studio

bias, but I’d prefer to start with clean amplifier settings, dirty that up first if that’s

what I’m after, and then add the effects.

I’d like to better annotation of the equalizers and tone controls. While it’s not very

common to see meaningful numbers on an instrument amplifier’s tone controls, it

would be nice to see them here, particularly for the tube amplifier’s mid frequency

settings. The frequencies of the graphic equalizer bands on the solid state

amplifier and the graphic EQ pedal are identified, but you have to actually move

a slider in order to see that band’s gain setting. Since I’ve mentioned both

graphic equalizers in the same paragraph, I’ll point out that their frequency bands

are different (the pedal has 8 bands, the amp has 9) and they have only one

frequency, 500 Hz, in common. So if you need some really goofy equalization,

there’s a case for using both.

The Wrap

MODO Bass sounds great, it can be made to sound downright weird, and it offers

ways to adjust tonal characteristics that aren’t possible with samples or

conventional waveform synthesis can’t. But complexity has its price. There’s a lot

to learn here, and, as I discovered while writing the article, it can be an incredible

time sink. There were afternoons when I sat down with the program to check a

function to be sure I remembered it correctly, got sidetracked with something

interesting, and didn’t get away for the next three hours – by which time I’d

forgotten why I dove in initially. I’m easily distracted by toys.

As I mentioned at the opening of this article, you can learn a whole lot about what

goes into making the tone of a string instrument by experimenting with the many

variables that are just a mouse click away. You might be surprised at the

difference new strings make, and how the tone changes as they break in. Some

producers insist on starting a session with brand new strings, others demand

broken-in strings, but you can be the producer with just a few mouse clicks. If you

play bass, MODO Bass might inspire you to pay more attention to where you

pluck the strings and which finger you use, or to consider replacing a pickup or

adding active electronics to a passive instrument.

This plug-in has me dreaming of physically modeled acoustic and fretless

basses, but at this point, I don’t know how far IK is willing to take this concept.

There’s a lot of work involved, and a whole different set of parameters to model

in an acoustic instrument. In the mean time, there’s a lot of fun and great sounds

to be had with the program’s present capabilities.

If you haven’t yet visited the MODO Bass web page, do so, and listen to the

examples there. That’s the best place I can send you to get an idea of the range

of sounds that are possible with this cool program.

IK Multimedia

http://www.ikmultimedia.com/products/modobass/

Retail price: $300 download only, $330 on a USB thumb drive, boxed

If you own certain IK Multimedia software products, there’s a crossgrade deal

that shaves $100 off the cost of MODO Bass, and they sometimes have sale

prices, so check on line for other deals.

Appendix 1 – System Requirements

MODO BASS is a 64-bit application and requires a 64 bit CPU and Operating System.

Mac

®

(64-bit)

Minimal: Intel

®

Core

™

2 Duo, 4 GB of RAM (8 GB suggested), Mac OS X

10.9 or later.

Supported Plug-in formats (64-bit): Audio Units, VST 2, VST 3, AAX.

Windows

®

(64-bit)

Minimal: Intel

®

Core

™

2 Duo or AMD Athlon

™

64 X2, 4 GB of RAM (8 GB

suggested), Windows

®

7, Windows

®

8 or Windows

®

10. Requires an ASIO

compatible sound card.

Supported Plug-in formats (64-bit): VST 2, VST 3, AAX.

Appendix 2 – The Iconic Bass Library

60’s P-Bass

based on Fender Precision Bass®, Alder body

70’s P-Bass

based on Fender Precision Bass®, Ash body

70’s J-Bass

based on Fender Jazz Bass®, Alder body

Modern J-Bass

based on Fender Jazz Bass®, Alder body

Devil Bass

based on Gibson® EB-0

Bass Man 5

based on Music Man® StingRay 5-string

Rick n’ Bass

based on Rickenbacker® 4003

Studio Bass

based on Yamaha® TRB5P

Violin Bass

based on Hofner® Violin

Thunder Bass

based on Gibson® Thunderbird

Japan Bass

based on Ibanez® Soundgear

Flame Bass

based on Warwick® Streamer

Appendix 3 - MODO Bass Presets

- An Abbreviated List of Details

This is a list of all of the 115 preset names. The first group is broken down into

full detail, showing its settings for all of the adjustable parameters. After the first

two in the Finger group, I knew I wasn’t going to last through typing up the whole

set, but I’ve listed all of the categories and their subsets to give you a sense of

how the factory presets are organized and what goes into making your own

presets.

A. Finger – 38 Subsets

1. 90’s Funk

(a) Model - Flame Bass

(b) Play Style – Finger

Muting – 0%

Stroke – Alternate

Touch – Normal

Let Ring – off

Fingering – Easy

Open String – Off

Detach Noise – 3.8

Slide Noise – 1.7

(c) Strings – 4

Standard action

Round wound

Medium Gauge

Broken in

440 Hz pitch

(d) Electronics

Bridge Pickup – Flame BSC

(i) Volume - 0

Neck pickup - Flame NSC

(i) Volume - 10

Piezo

(i) Volume - 0

Active

Tone controls: Bass – 5.0, Middle – 5.0, Treble – 2.8

(e) Amp/FX

Pedal Board

(i) Compressor: On, Comp - 1.8, Volume – 8.0

(ii) Graphic EQ: Bypassed

(iii) Octaver – Bypassed, Blend - 6.0, Volume - 6.2, Texture - 3.0

(iv) Envelope Filter – Bypassed, Frequency – 100, Depth – 10,

Resonance – 5.0, LP – On, BP – Off, HP - Off

Solid State

Gain - 8.3

Tone controls: Bass – 5.5, Mid – 2.8, Treble – 6.1

Graphic EQ

Limiter – On

Mix: Amp – 0.9, DI – 6.4, Master – 8.1

(f) Control – Typical setup

2. BoomPow

(a) Model - Devil Bass

(b) Play Style – Finger

Muting – 0%

Stroke – Alternate

Touch – Normal

Let Ring – Off

Fingering – First Position

Open String – On

Detach Noise – 4.5

Slide Noise – 9.6

(c) Strings – 4

Standard action

Round wound

Medium Gauge

Broken in

440 Hz pitch

(d) Electronics

Bridge Pickup – Devil SC

(i) Volume - 10

Neck pickup – Devil SC

(i) Volume - 10

Piezo

(i) Volume - 0

Passive

Tone: 10

(e) Amp/FX

Pedal Board

(i) Compressor: On, Comp - 5.7, Volume – 5.0

(ii) Graphic EQ: Bypassed

(iii) Octaver – Bypassed, Blend - 6.0, Volume - 6.2, Texture - 3.2

(iv) Envelope Filter – Bypassed, Frequency – 100, Depth – 10,

Resonance – 5.0, LP – On, BP – Off, HP - Off

Solid State

Gain – 5.0

Tone controls: Bass – 6.3, Mid – 2.8, Treble – 6.1

Graphic EQ: Not specified

Limiter – On

Mix: Amp – 6.0, DI – 5.0, Master – 4.8

(f) Control – Typical setup

3. BoomyGroove

4. Custom Jazz

5. FingerFunky

6. Focus B – deep

7. Focus B

8. Fresh Flame

9. Funk!

10. FunkFlame

11. FusionRide

12. Going Grunge

13. Jaco

14. Leeland Softy

15. Metallic

16. Modern Vintage

17. Motown

18. New Bass

19. OctoEagle

20. Old, But Good

21. P-Jam-a

22. PJ Bassy

23. Practice Bass

24. ProPrecision

25. R&B 5-String JB

26. RageFive

27. Really Low

28. RoadWorn

29. StageMaster

30. Stepanyan 5

31. Studio LX

32. StudioSession

33. Sub Violin

34. The ‘50s

35. The Amp Destroyer

36. The Stream

37. Try This

38. Useful

39. Youth

B. Pick – 38 subsets

1. ‘80s Taste

2. Aggressive Pick

3. Anger Increaser

4. BadJazz

5. Bass’aBilly

6. Be A Bit Punk

7. BuzzBuzz

8. Call The Police

9. Can I Call You Floyd_

10. CyberDuck

11. Disco Phunk

12. FarFarAway

13. Fully Loaded

14. Give it up

15. Indi Pendent

16. Jeremy’s Bass

17. Just Works

18. Kick Violin

19. Metallic Side

20. Nasty Punky

21. Near Sine

22. Noisemaker

23. Old Rocker

24. PickNick

25. PowerBall

26. Simple Pick

27. Solid Muted Pbass

28. Solid Picking

29. Stoned

30. Studio Starting Point

31. Teen Garage

32. That 70’s Piece of Ash

33. The Panther

34. Tired Precision

35. TripHop Vintage

36. Try Chords

37. UFO

38. West Coast

C. Slap – 22 subsets

1. 70’s Pump

2. AAA Wanted Slap Bass

3. Acoustic Slap

4. Aggressive Slap

5. Atmo Slap

6. Get Funky!

7. Ghost Notes

8. Gritty Slap

9. Grooovy

10. Growl

11. Jaguar Slap

12. Learning Slap

13. Low End Presence

14. Magnetic

15. ModernSlap

16. Nu Soul Slap JB

17. Precise

18. Simply Good

19. Slap_

20. Slarpeggio

21. Strange Slap

22. Sub Slap

D. Xtreme – 16 subsets

1. Add Vibrato…

2. Attila

3. Broken Amp

4. DnBass

5. Dynotor

6. Hit A Piano

7. InfraViolin

8. Monster Low

9. Near Kick

10. Presynthion

11. Psycodelic

12. SubMarine

13. Synth Funk

14. Triple Chorus

15. Velocity Alien

16. Whales

E. Default