No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic or mechanical, for any purpose, without the express

written permission of

U.S. Career Institute.

Copyright © 2012-2013, Weston Distance Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

0201693TB01B-43

Acknowledgments

Editorial Staff

Trish Bowen

Elizabeth Munson

Bridget Tisthammer

Kathy DeVault

Georgia Chaney

Brenda Blomberg

Chris Jones

Joyce Jeckewicz

Stephanie MacLeod

Kelly Brown

Carrie Williams

Meloney Biggerstaff

Design/Layout

Connie Hunsader

Leslie Ballentine

Sandy Petersen

D. Brent Hauseman

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT:

U.S. Career Institute

Fort Collins, CO 80525 • 1-800-347-7899

Lesson 1—The World of Health Care

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 1

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 Daily Activities in the Medical Office

A Day in the Life of the Medical Office Manager

The Doctor’s Point of View

Step 4 A Little Teamwork Goes a Long Way

Physicians

Nurses

Nurse’s and Physician Assistants

Support Staff

Emergency Personnel

Office Professionals

Step 5 Welcome to Your Career as a Medical Coding Specialist!

But Where Will I Work?

Step 6 Personal Qualities of a Medical Coder

Professionalism

Presentation

Adaptability

Step 7 Medical Records

Parts of a Medical Record

The Flow of Medical Information

Step 8 Lesson Summary

Lesson 2—Medical Insurance

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 2

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 The Life Cycle of a Medical Bill

Processing the Bill

Step 4 Insurance

Step 5 Common Insurance Terms

Provider

Claim Form

Deductible

Copayment

Reasonable and Customary

Explanation of Benefits

Electronic Claims

Step 6 Types of Health Insurance

Government Insurance

Private, Traditional Insurance

Managed Care

Blue Cross/Blue Shield

Step 7 Diagnostic Codes—A Piece of the Insurance Puzzle

How Important Is Diagnostic Coding?

Step 8 Procedure Coding—Another Piece of the Puzzle

Step 9 Looking Ahead

Step 10 Lesson Summary

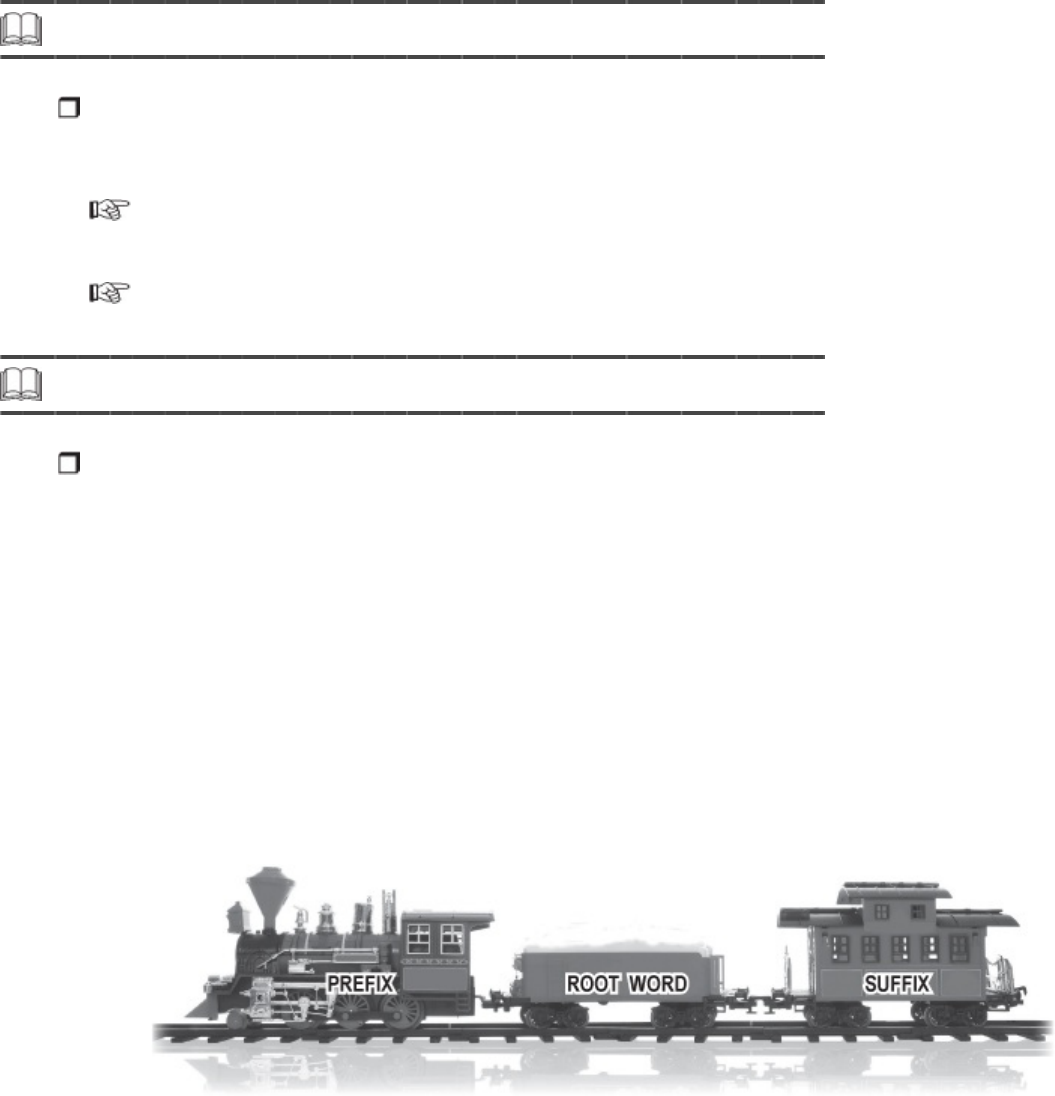

Lesson 3—Introduction to Medical Terminology:

Word Parts

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 3

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 Word Parts

Step 4 Root Words

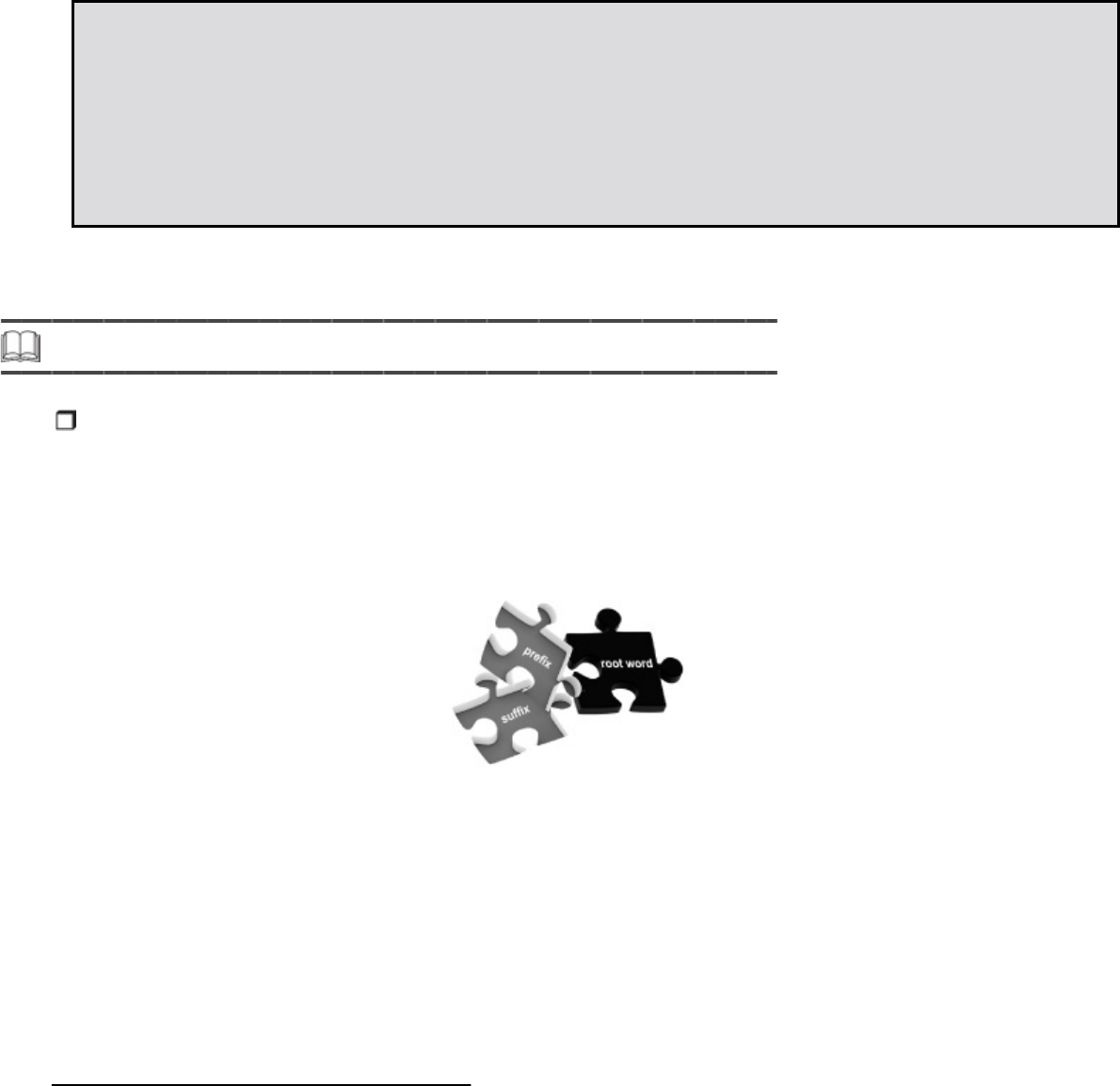

Step 5 Medical Terms

The Combining Vowel

Step 6 Root Words

The Functions of Root Words

Step 7 Pronounce Root Words

Step 8 Write Root Words

Step 9 Meanings of Root Words

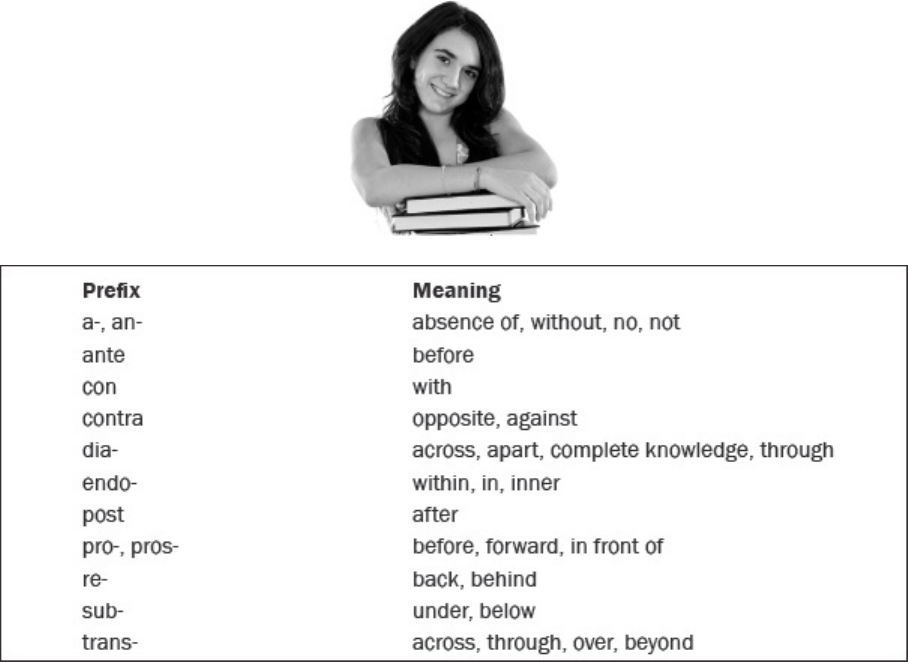

Step 10 Prefixes

Step 11 Pronounce Prefixes

Step 12 Write Prefixes

Step 13 Meanings of Prefixes

Step 14 Suffixes

Step 15 Pronounce Suffixes

Step 16 Write Suffixes

Step 17 Meanings of Suffixes

Step 18 Lesson Summary

Just for Fun

Lesson 4—Medical Terminology:

Dividing and Combining Terms

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 4

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 Dividing Medical Terms

Consonants, Vowels and the Role They Play

A Little Practice

Word Meanings

Step 4 Pronounce Word Parts

Step 5 Write Word Parts

Step 6 Meanings of Word Parts

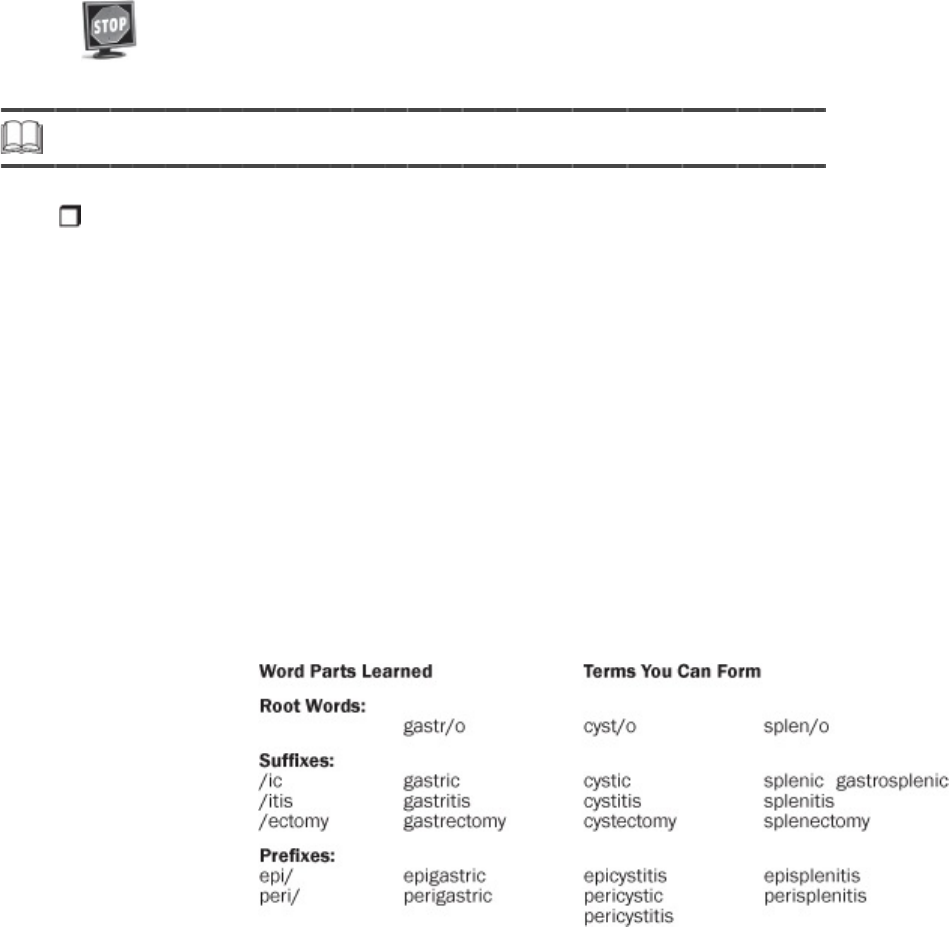

Step 7 Combining Medical Terms

Consonants, Vowels and the Role They Play

Step 8 Pronounce Word Parts

Step 9 Write Word Parts

Step 10 Meanings of Word Parts

Step 11 Lesson Summary

Lesson 5—Medical Terminology: Abbreviations,

Symbols and Special Terms

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 5

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 Abbreviations

Abbreviations in Hospitals

Office Records

Doctors

Pharmacies

Step 4 Learn Abbreviations

Step 5 Meanings of Abbreviations

Step 6 Slang

Medical Slang

English Slang

Step 7 Slang Terms

Step 8 Meanings of Slang Terms

Step 9 Symbols

Step 10 Special Terms

Eponyms

Brand Names

Acronyms

Step 11 Pronounce Acronyms

Step 12 Sound-Alikes and Opposites

Homophones (Sound-Alikes)

Antonyms (Opposites)

Step 13 Medical Plurals

Medical Rules for Plurals

Step 14 Lesson Summary

Lesson 6—Documenting Medical Records

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 6

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 Documentation—The Key Component of Medical Records

Types of Documentation

Commonly Used Narrative Formats

Step 4 The Business of Managing Medical Records

Good Recording Practices

Step 5 Lesson Summary

Lesson 7—Ethics and Legal Issues

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 7

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 Confidentiality

Guidelines for Confidentiality of Medical Records

Guidelines for Faxing Medical Records

Step 4 Medical Ethics

Step 5 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

Step 6 Fraud and Abuse

Preventing Fraud and Abuse

Consequences of Committing Fraud

Step 7 Liability Insurance

Insurance Audits

Step 8 Recovery Audit Contractors

Step 9 Legal Concerns

Subpoenas

Arbitration

Medical Testimony

Step 10 Lesson Summary

Endnotes

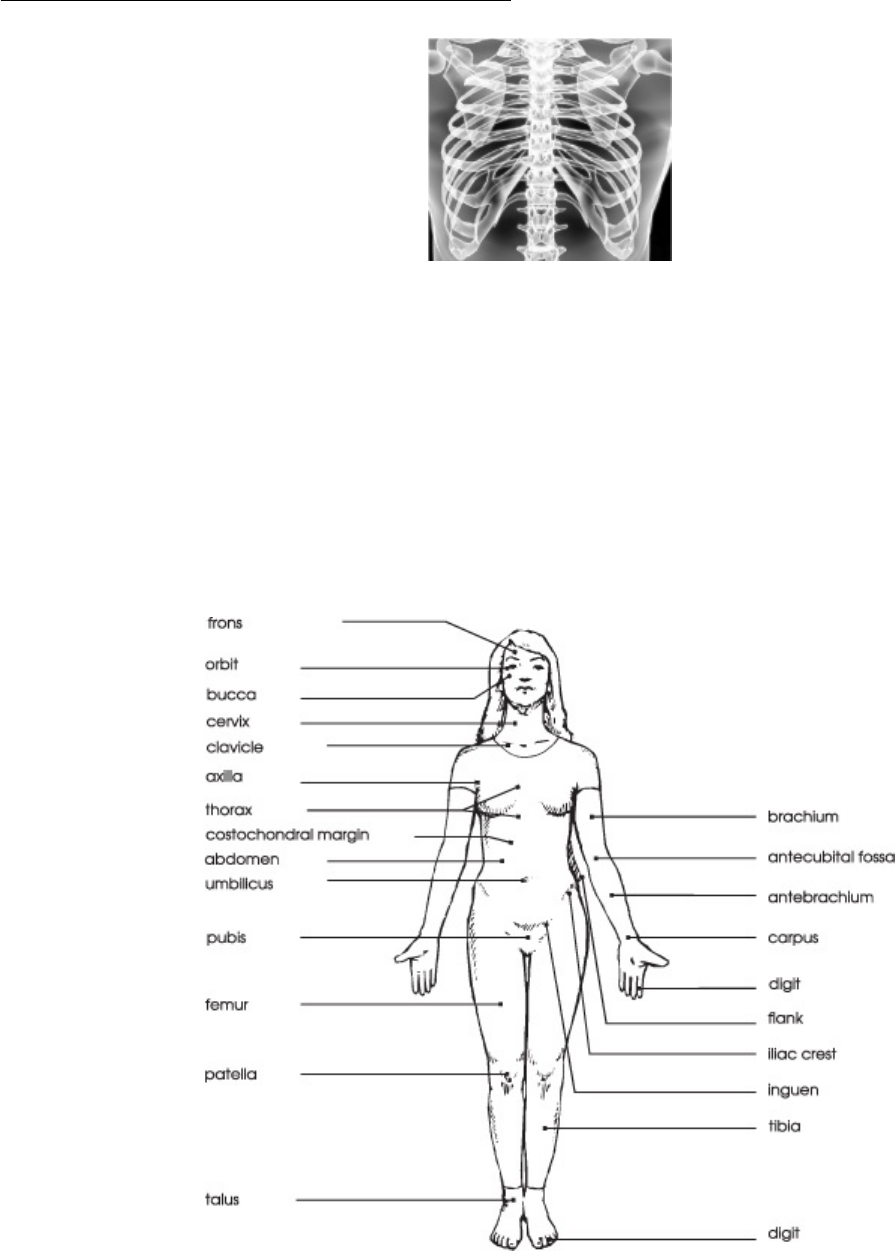

Lesson 8—Introduction to Anatomy

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 8

Step 2 Lesson Preview

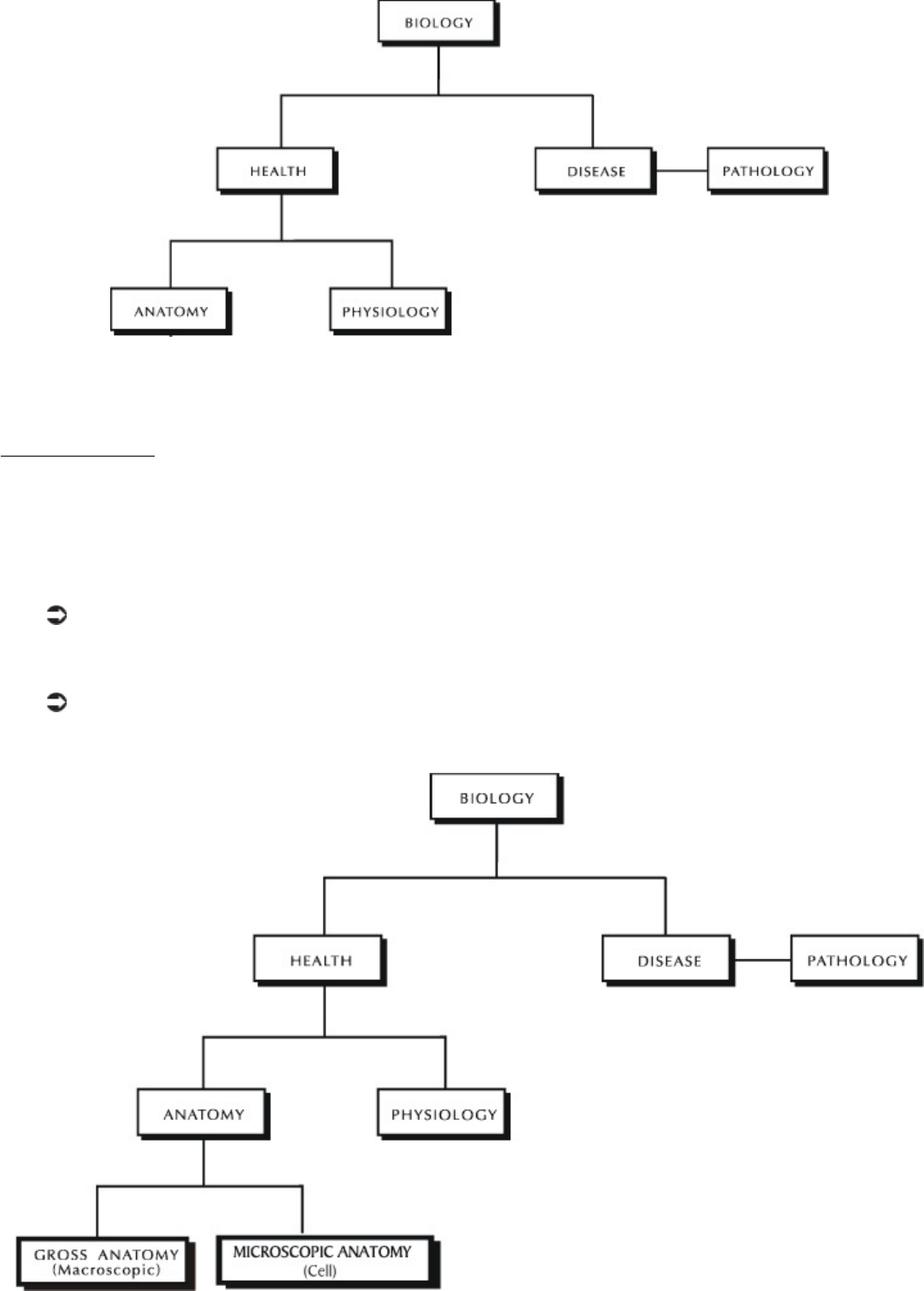

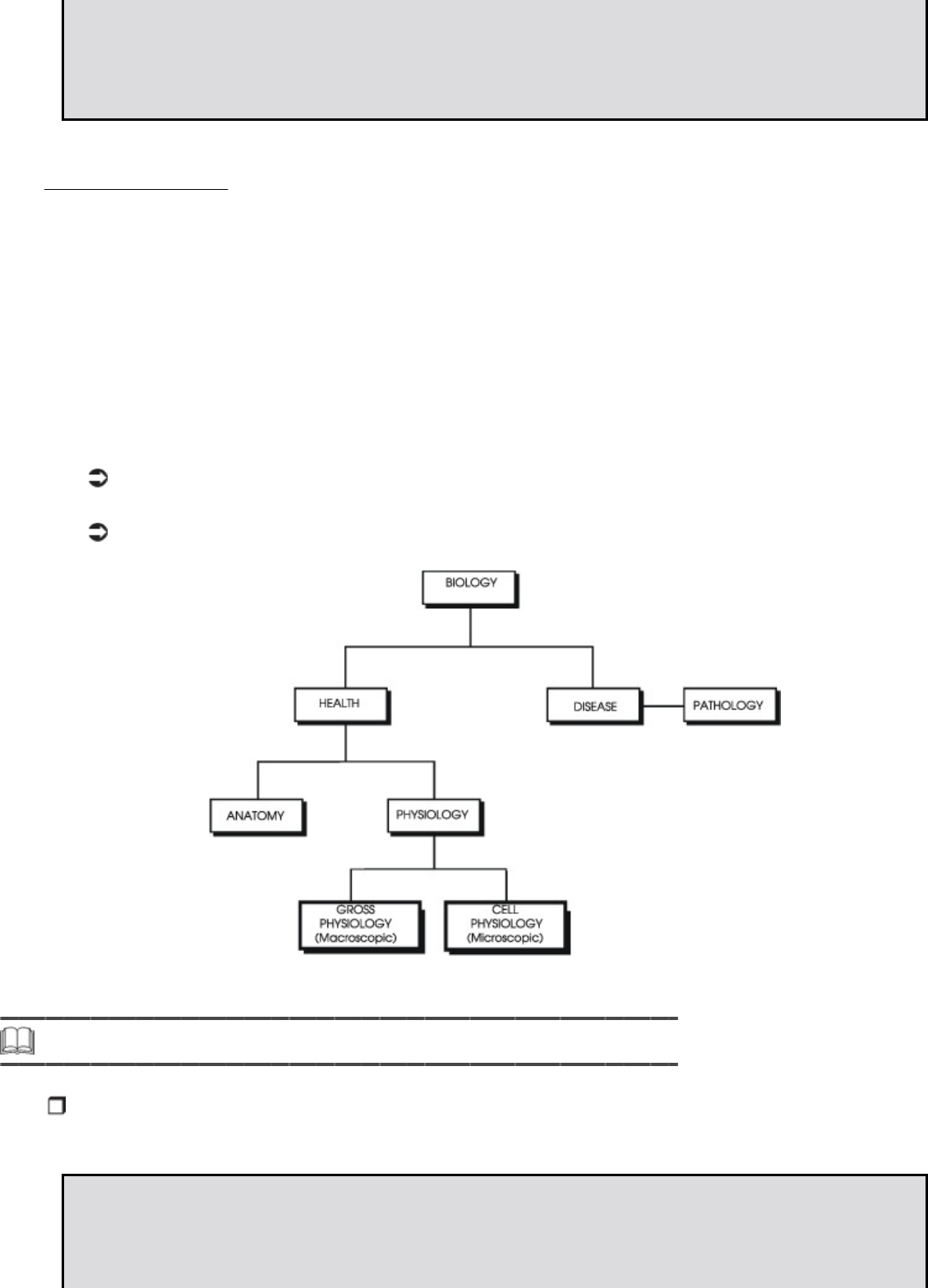

Step 3 Human Biology

What Is Human Biology?

Anatomy

Physiology

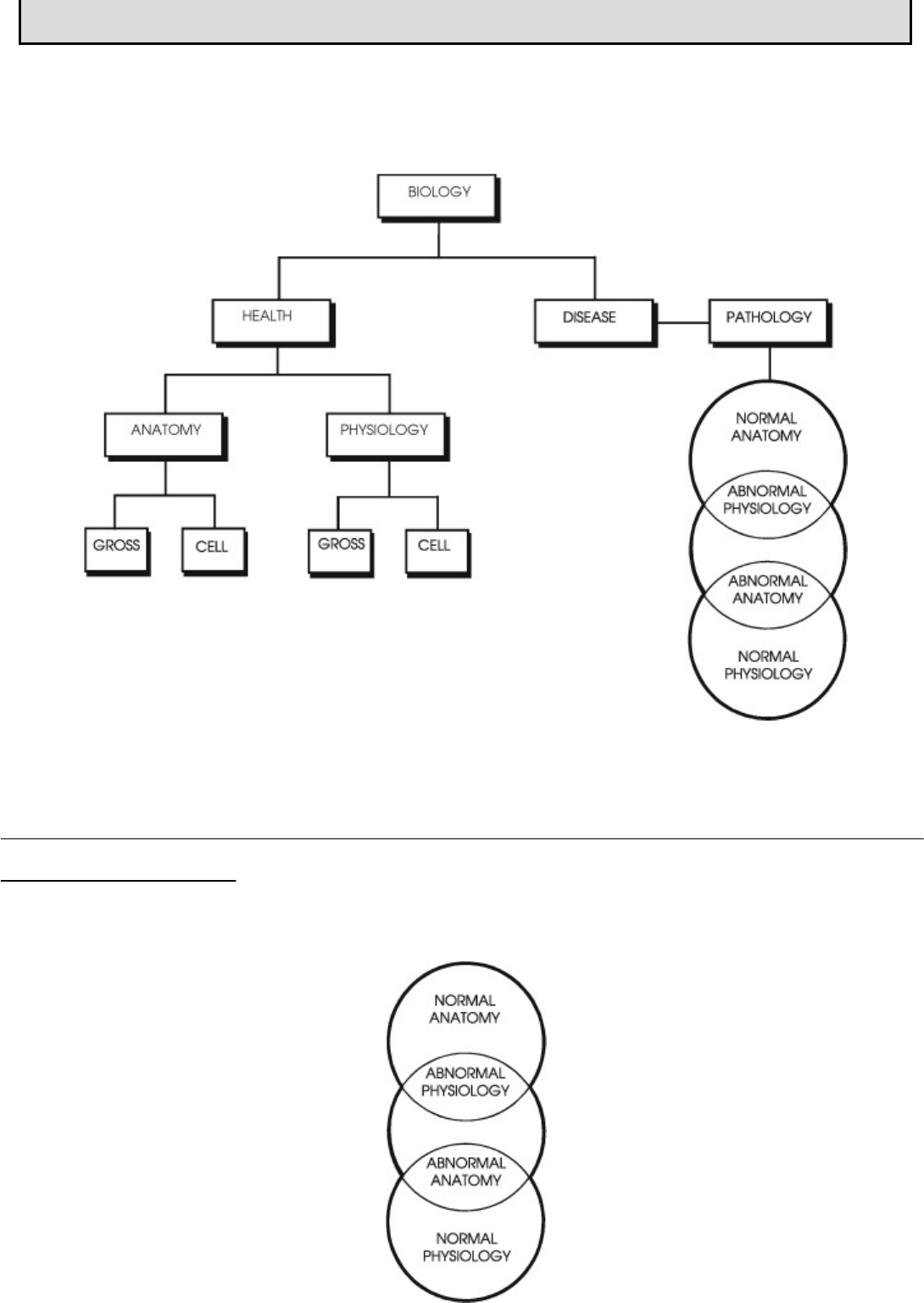

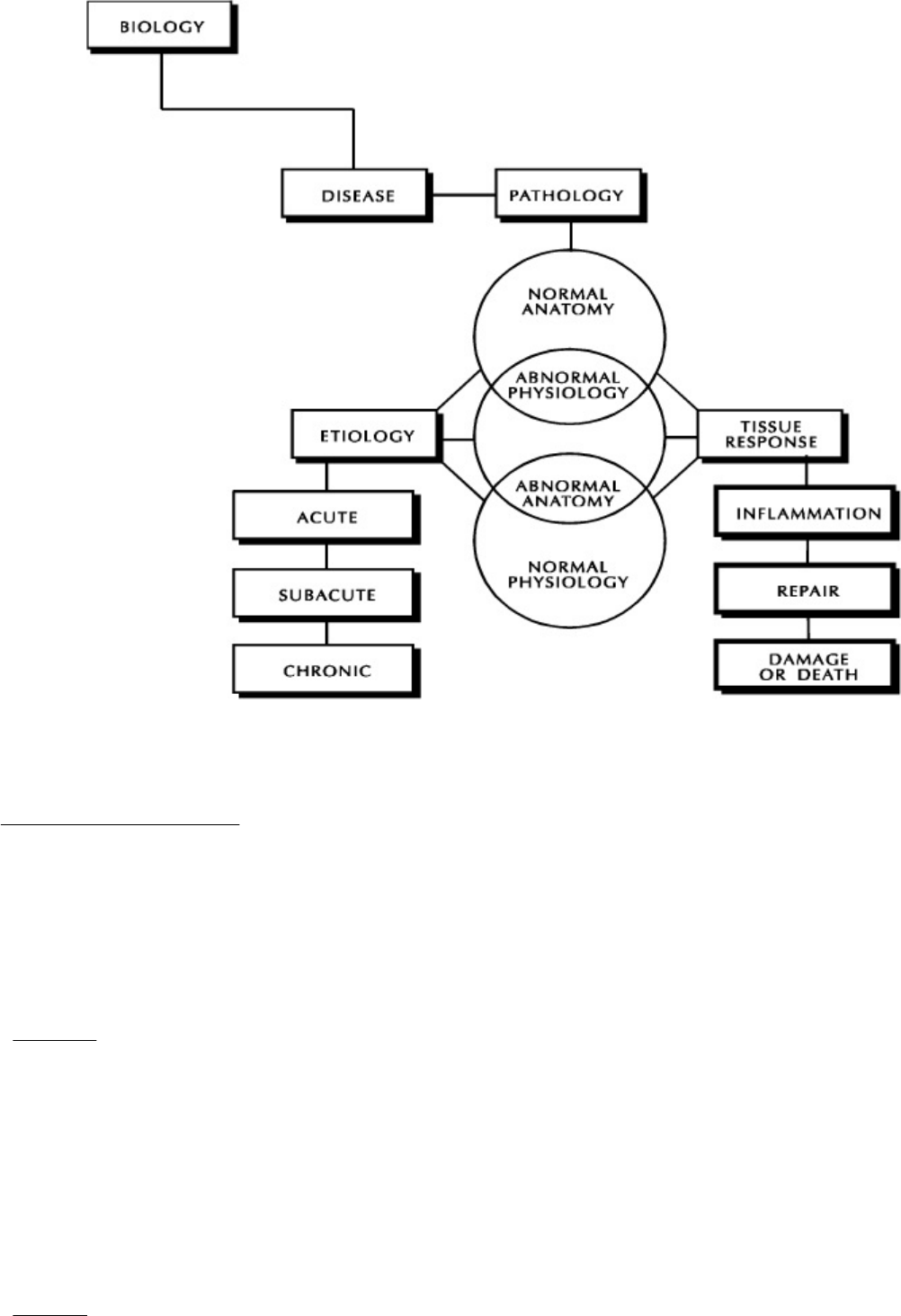

Step 4 Pathology

How Do Anatomy, Physiology and Pathology Relate to One Another?

Step 5 Beginning Anatomy and Physiology Concepts

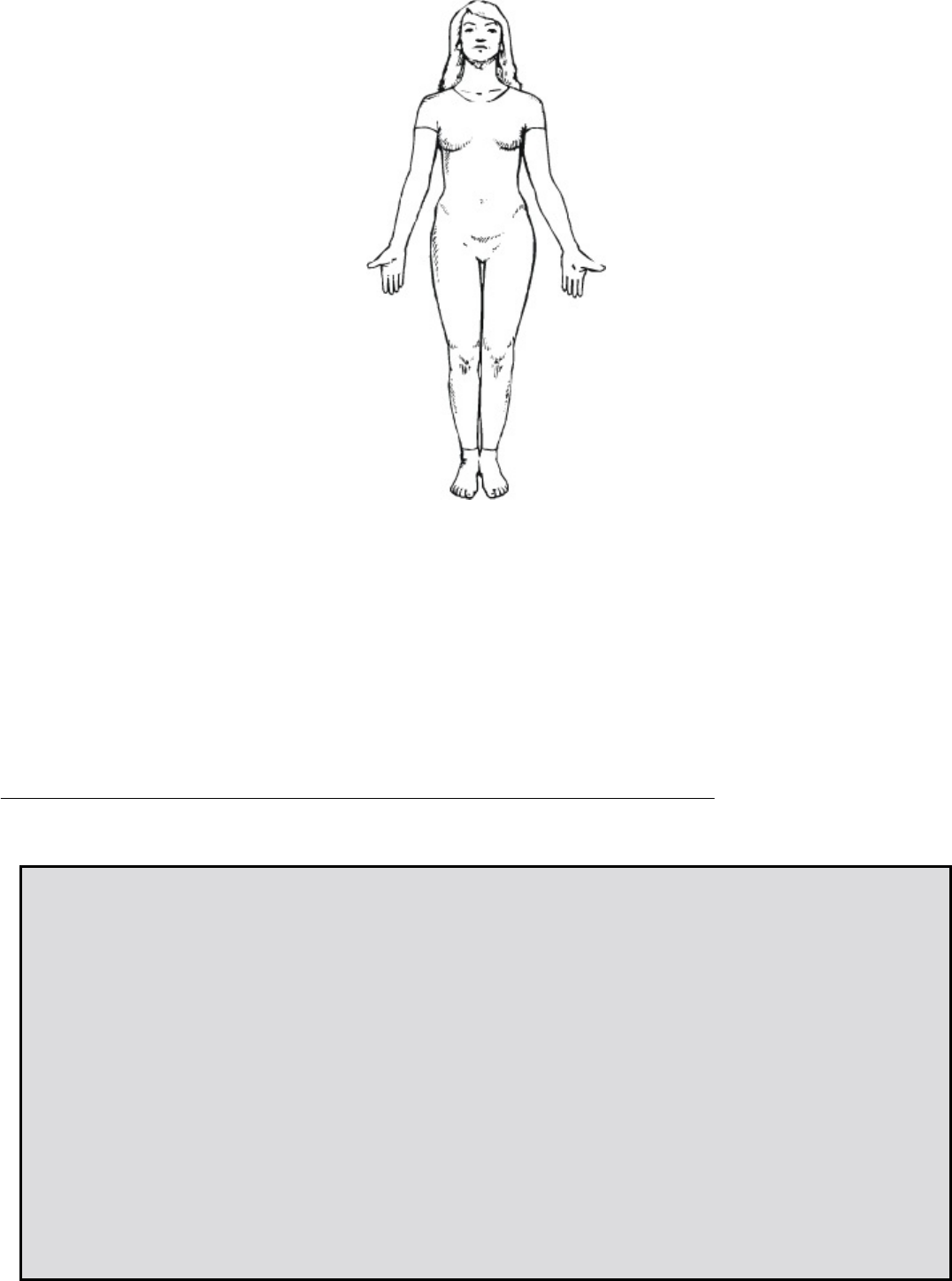

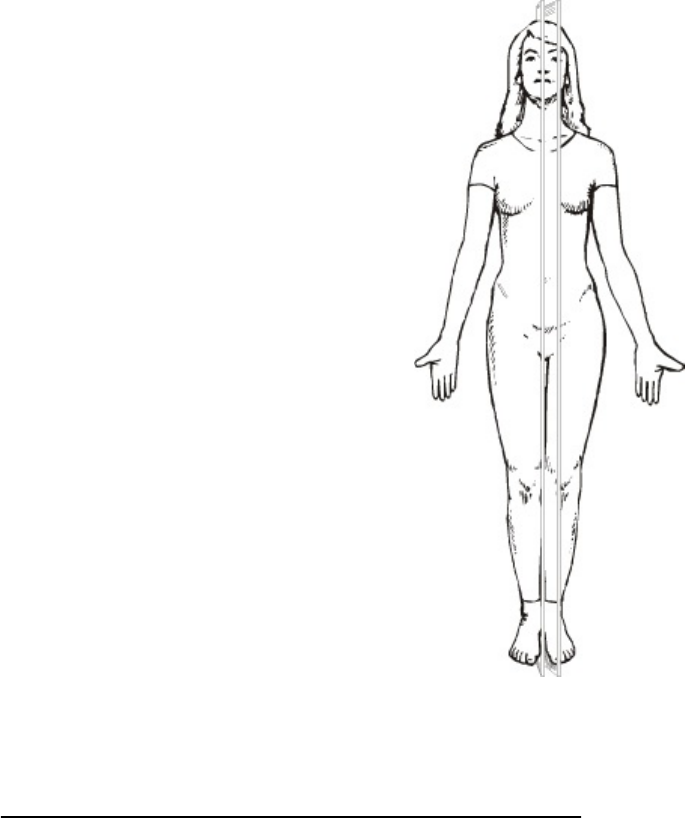

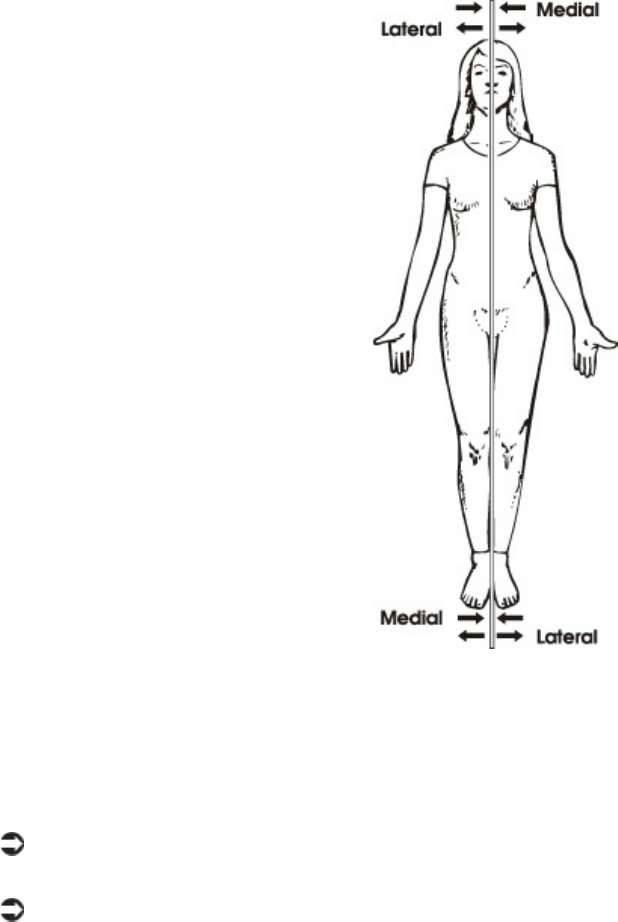

The Anatomic Position

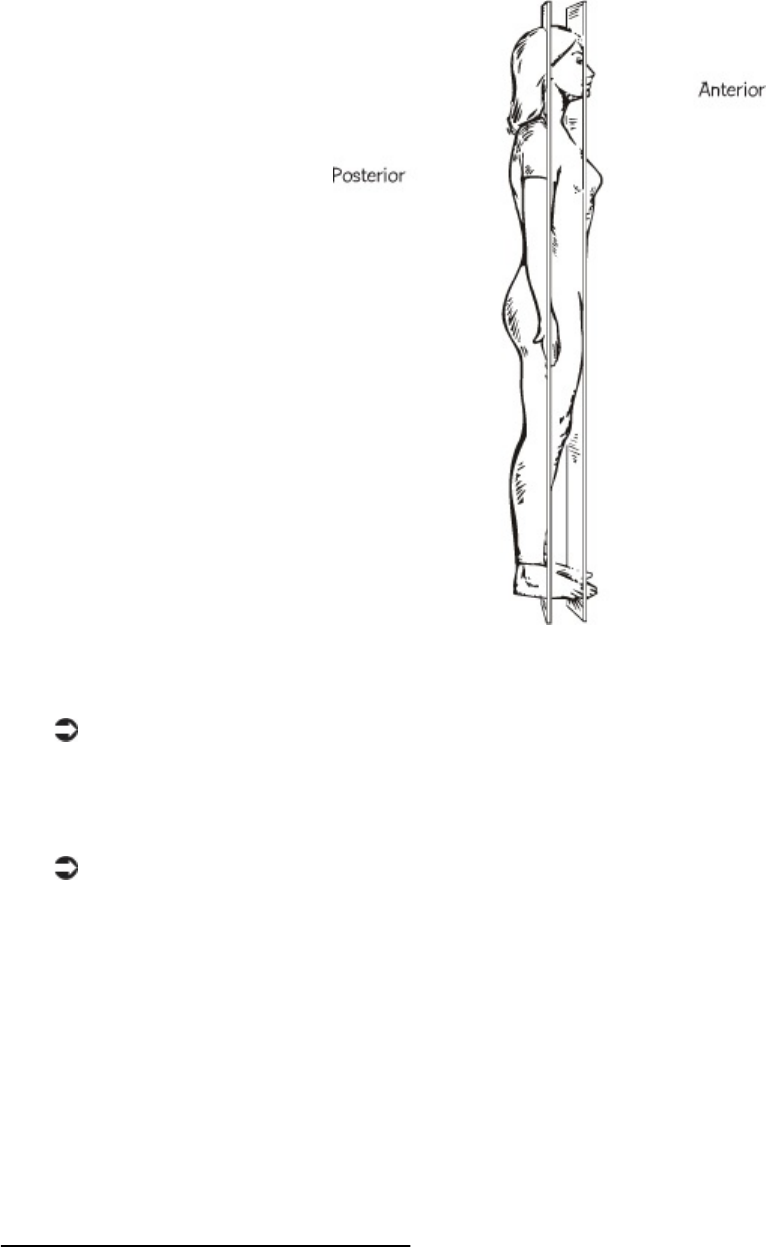

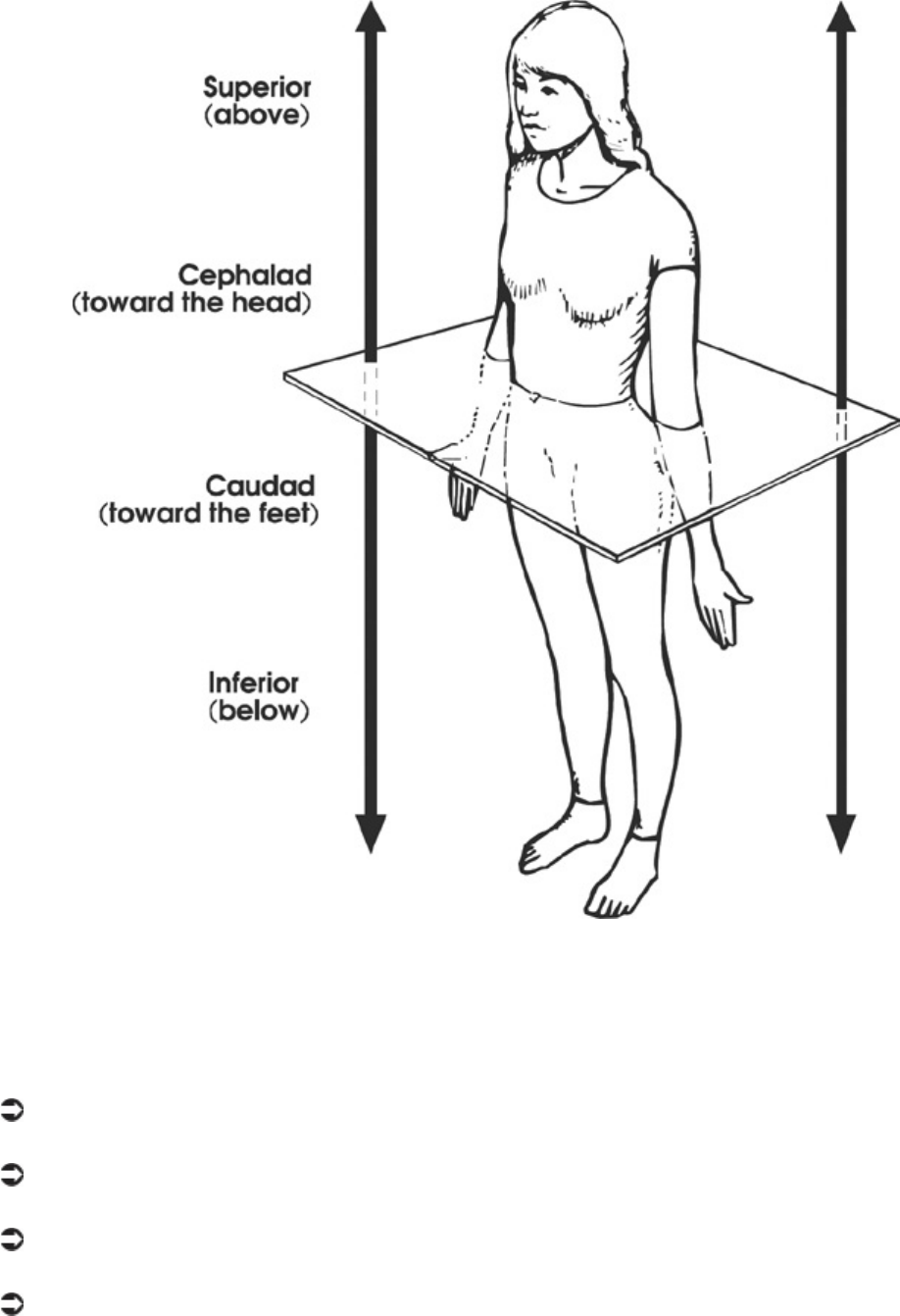

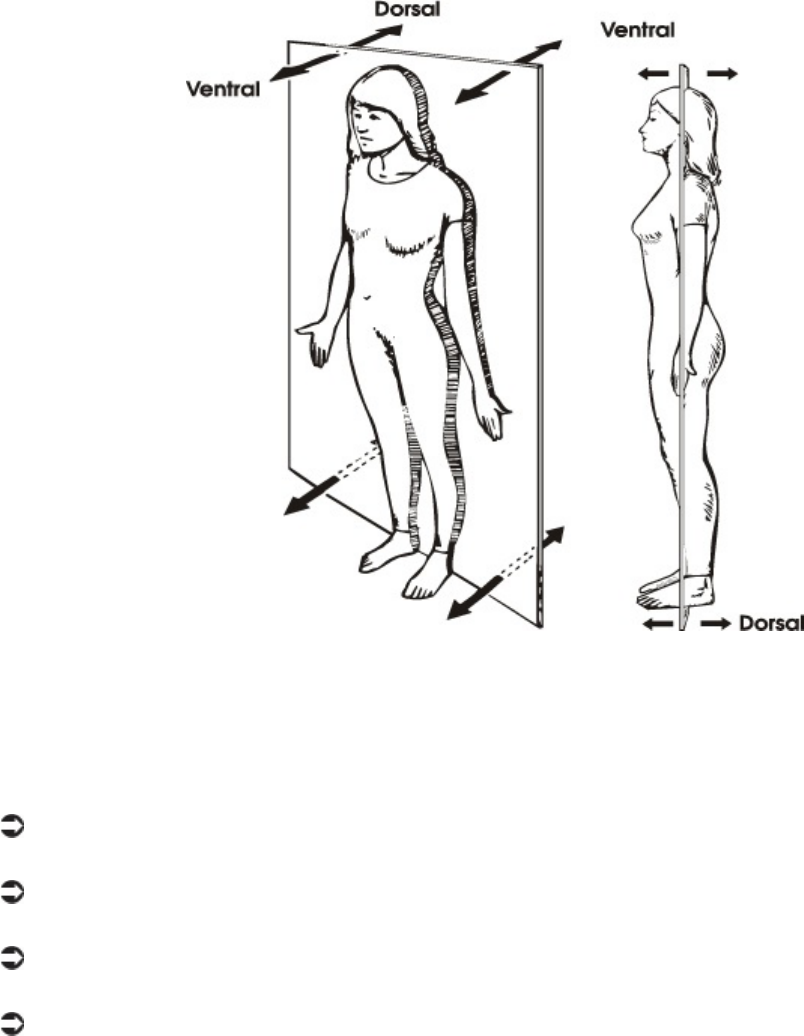

Planes and Sections of the Human Body

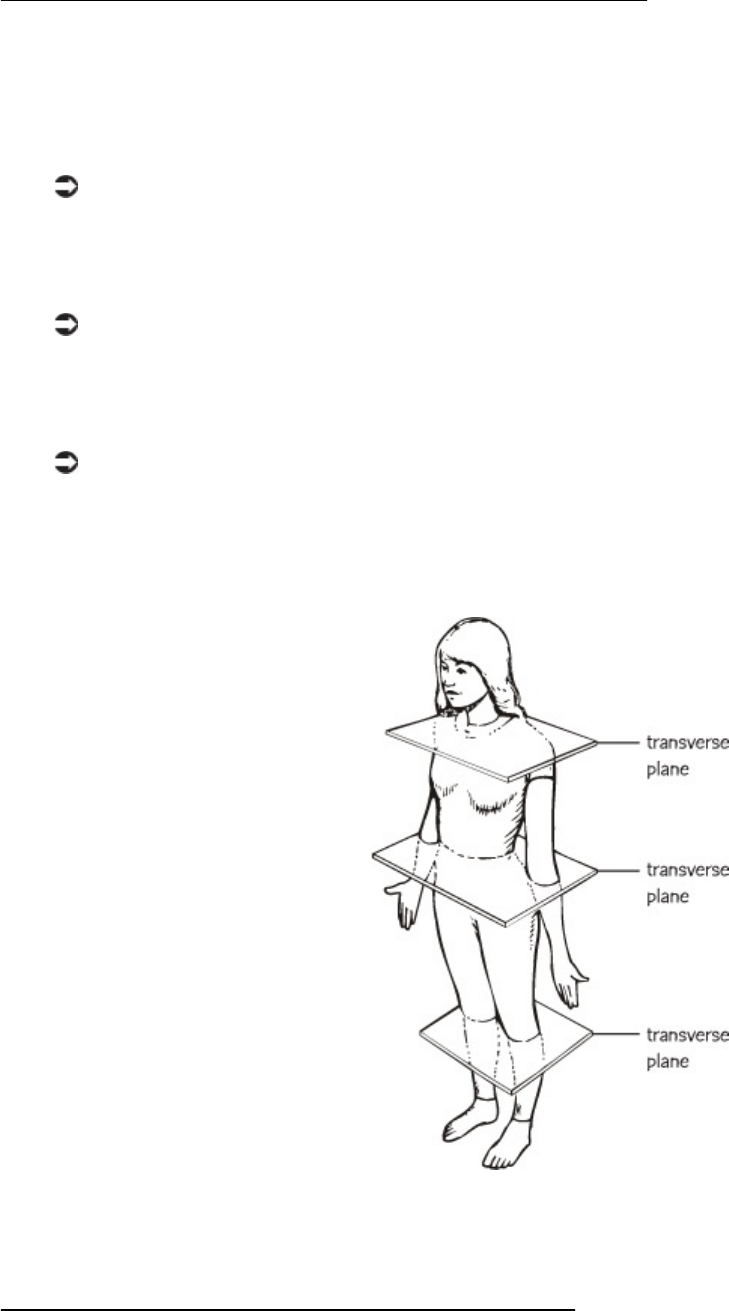

Transverse Planes and Sections

Sagittal Planes and Sections

Coronal Planes and Sections

Planes and Sections

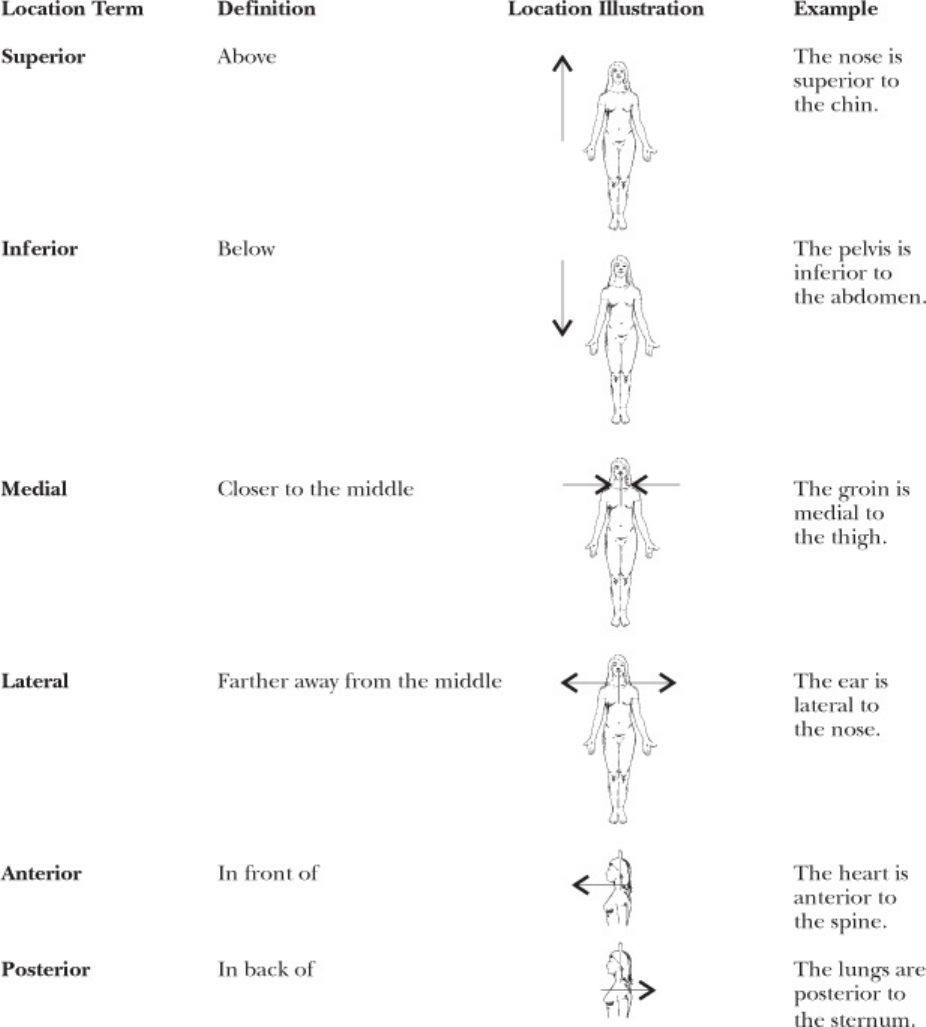

Step 6 Location Terms

Step 7 Pronounce New Terms

Step 8 Write New Terms

Step 9 Meanings of New Terms

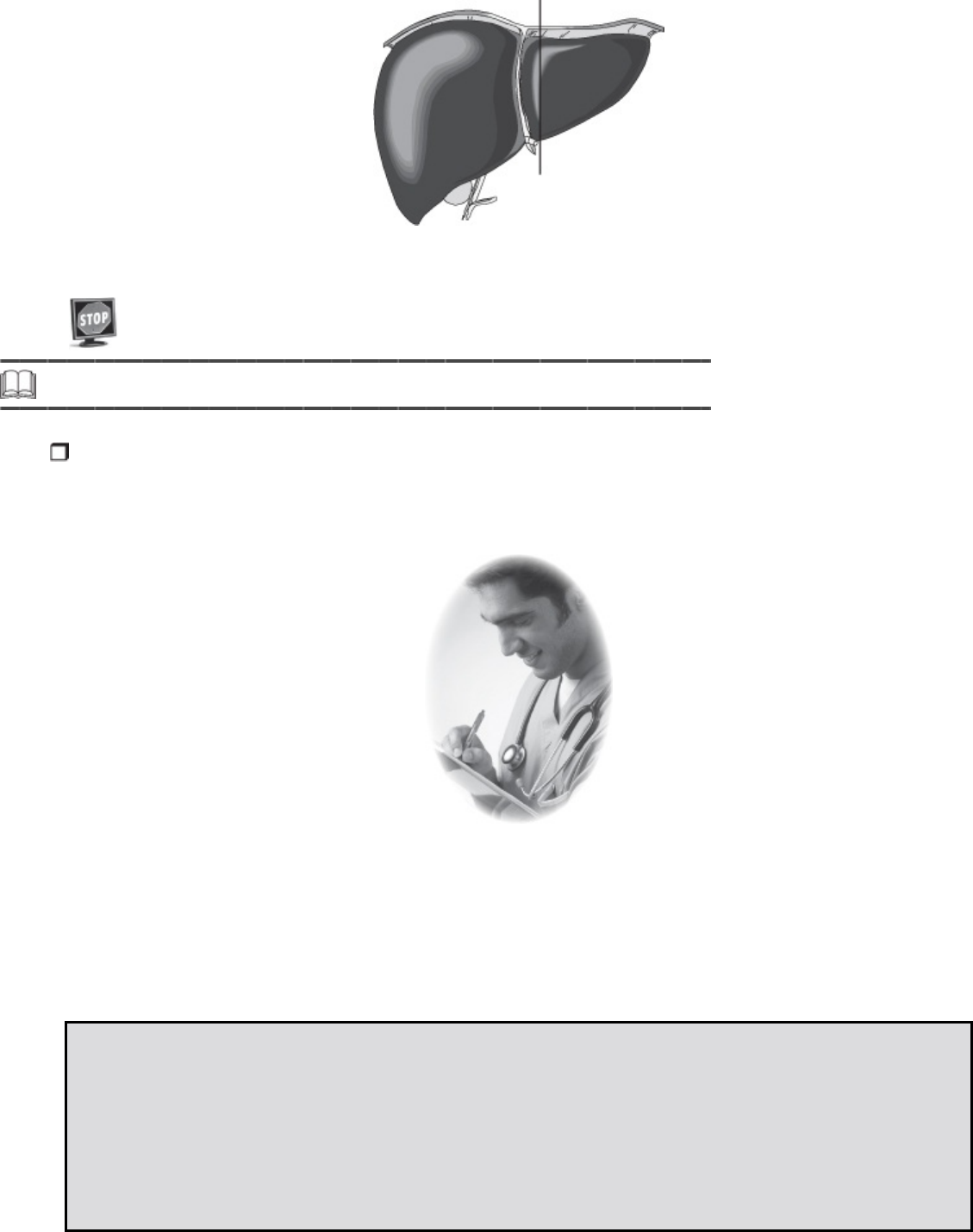

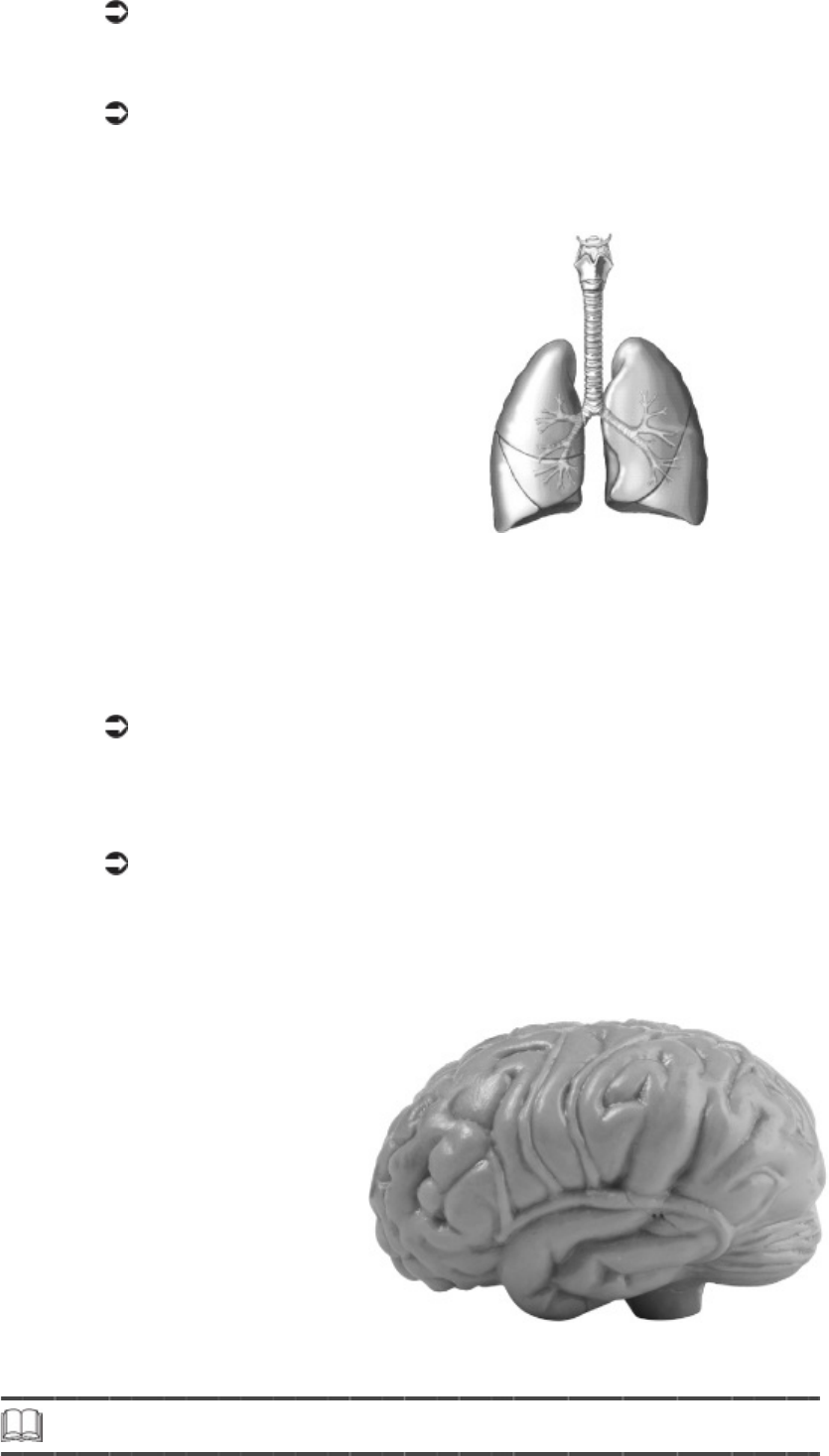

Step 10 Organ and Organ Systems

Respiratory System

Circulatory/Cardiovascular System

Nervous System

Muscular System

Skeletal System

Integumentary System

Endocrine System

Digestive System

Urinary System

Reproductive System

The Immune System

Step 11 Lesson Summary

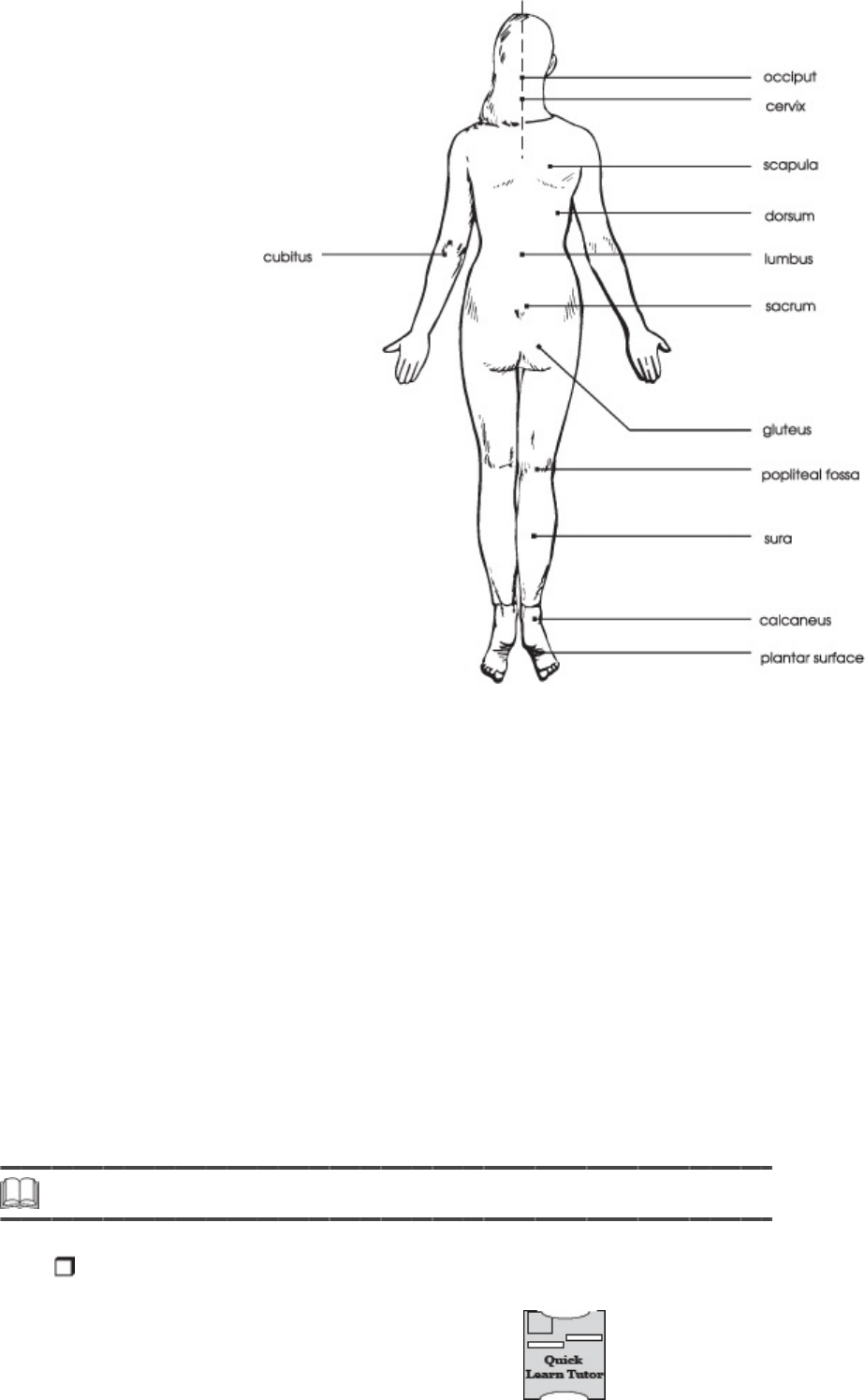

Lesson 9—Anatomy: Landmarks and Divisions

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 9

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 Gross Anatomy

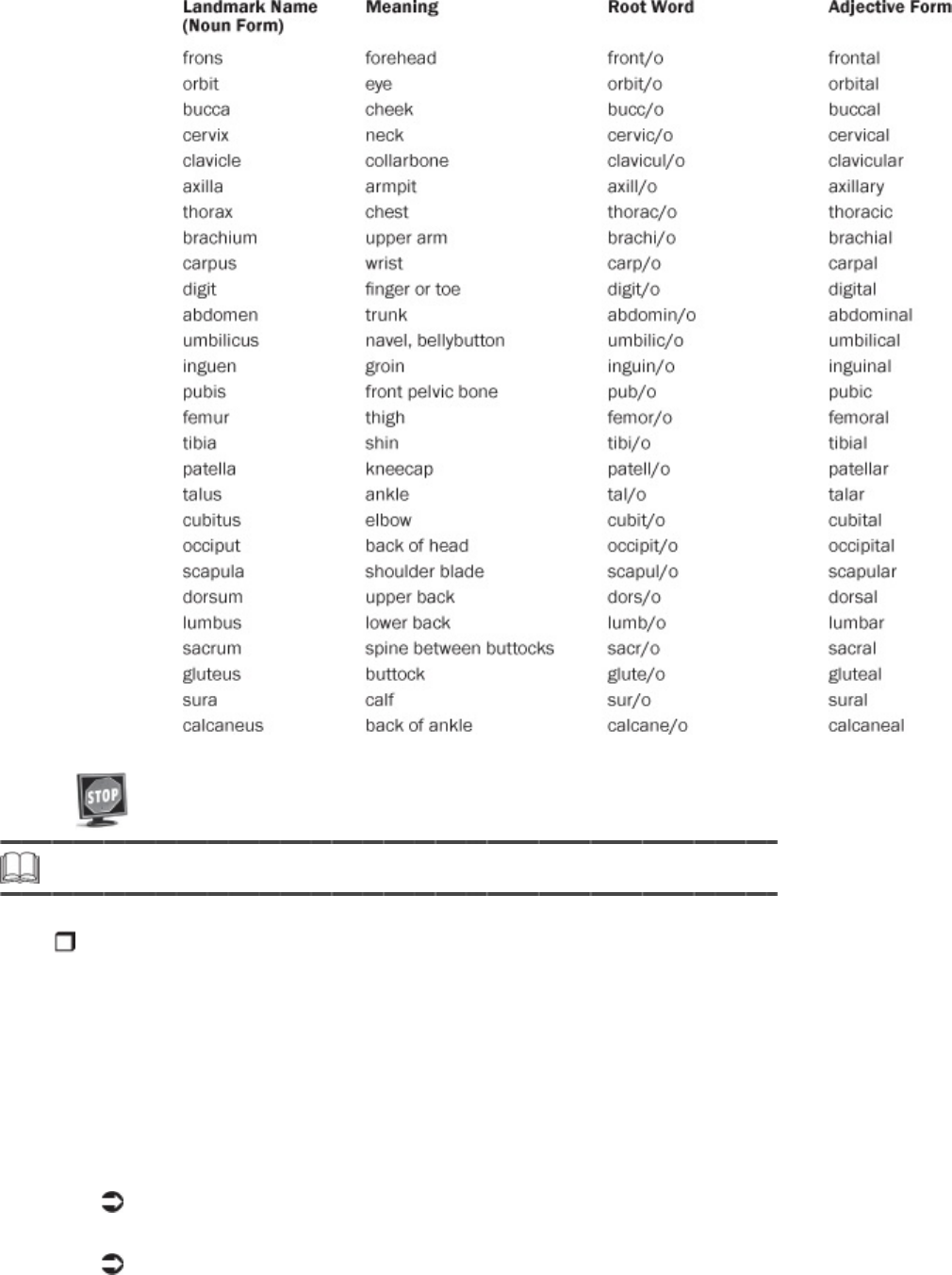

Landmarks and Divisions

Step 4 Pronounce New Terms

Step 5 Write New Terms

Step 6 Meanings of New Terms

Step 7 Adjective Forms for Landmark Names

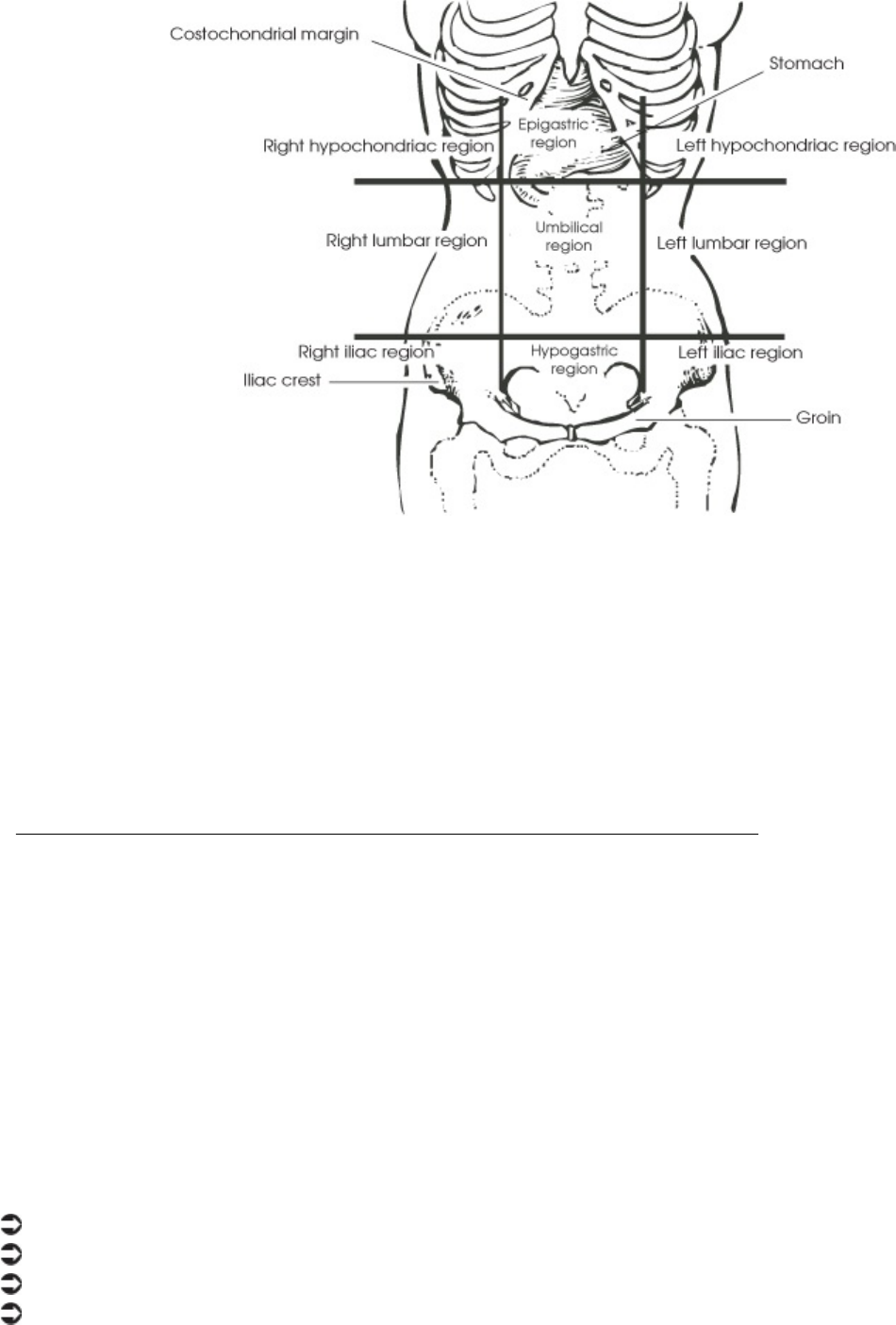

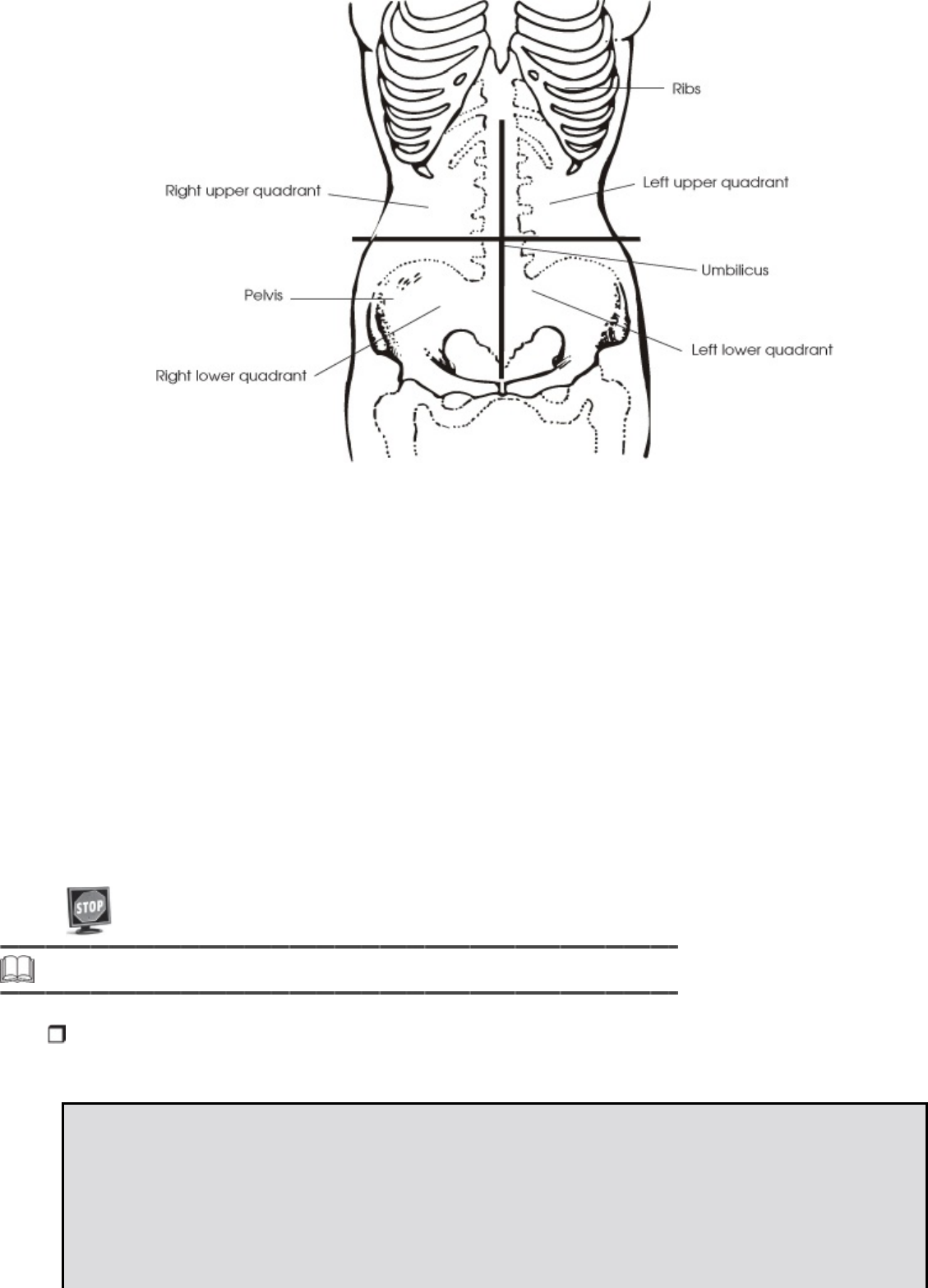

Step 8 Divisions of the Abdomen

An Alternative Division of the Abdomen

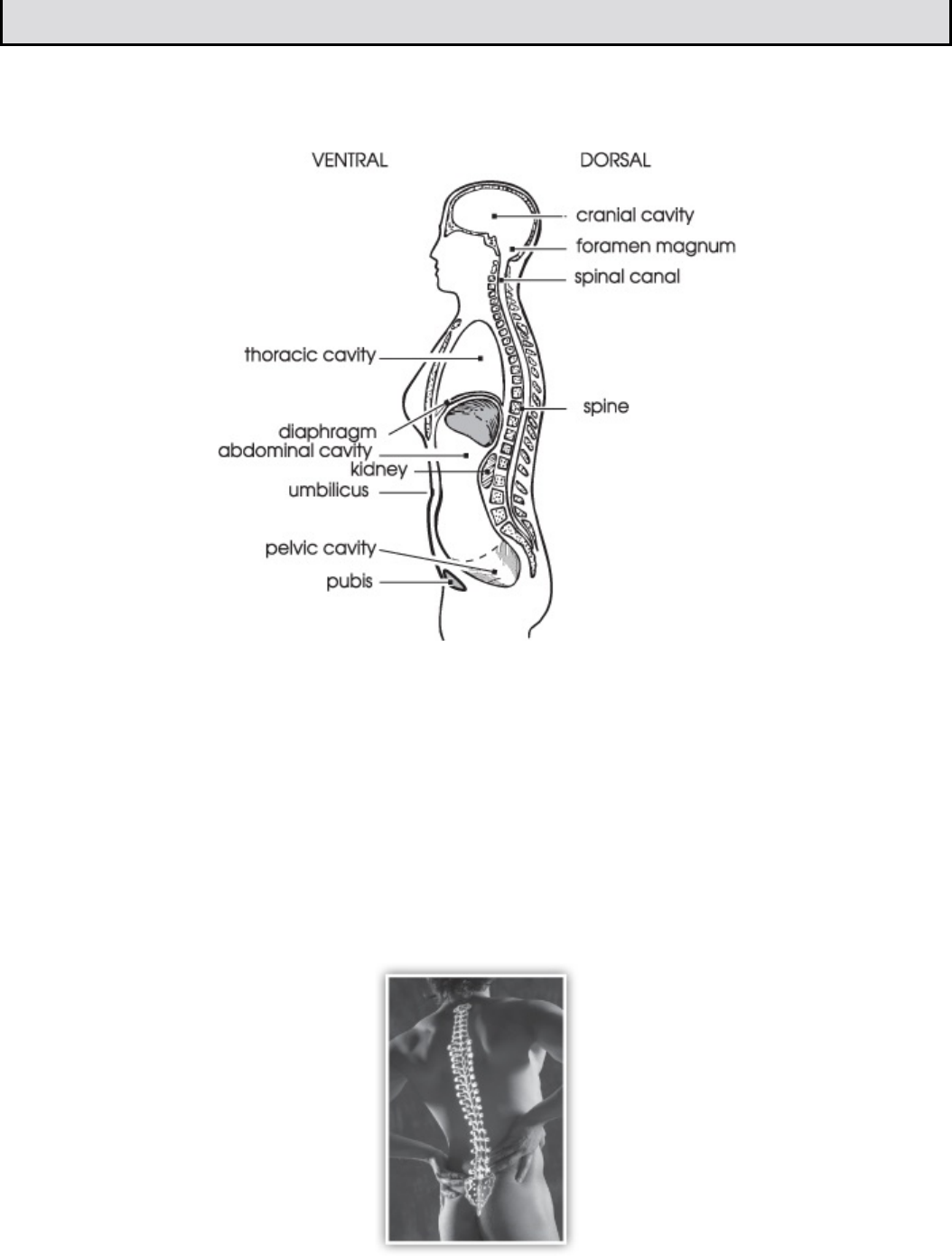

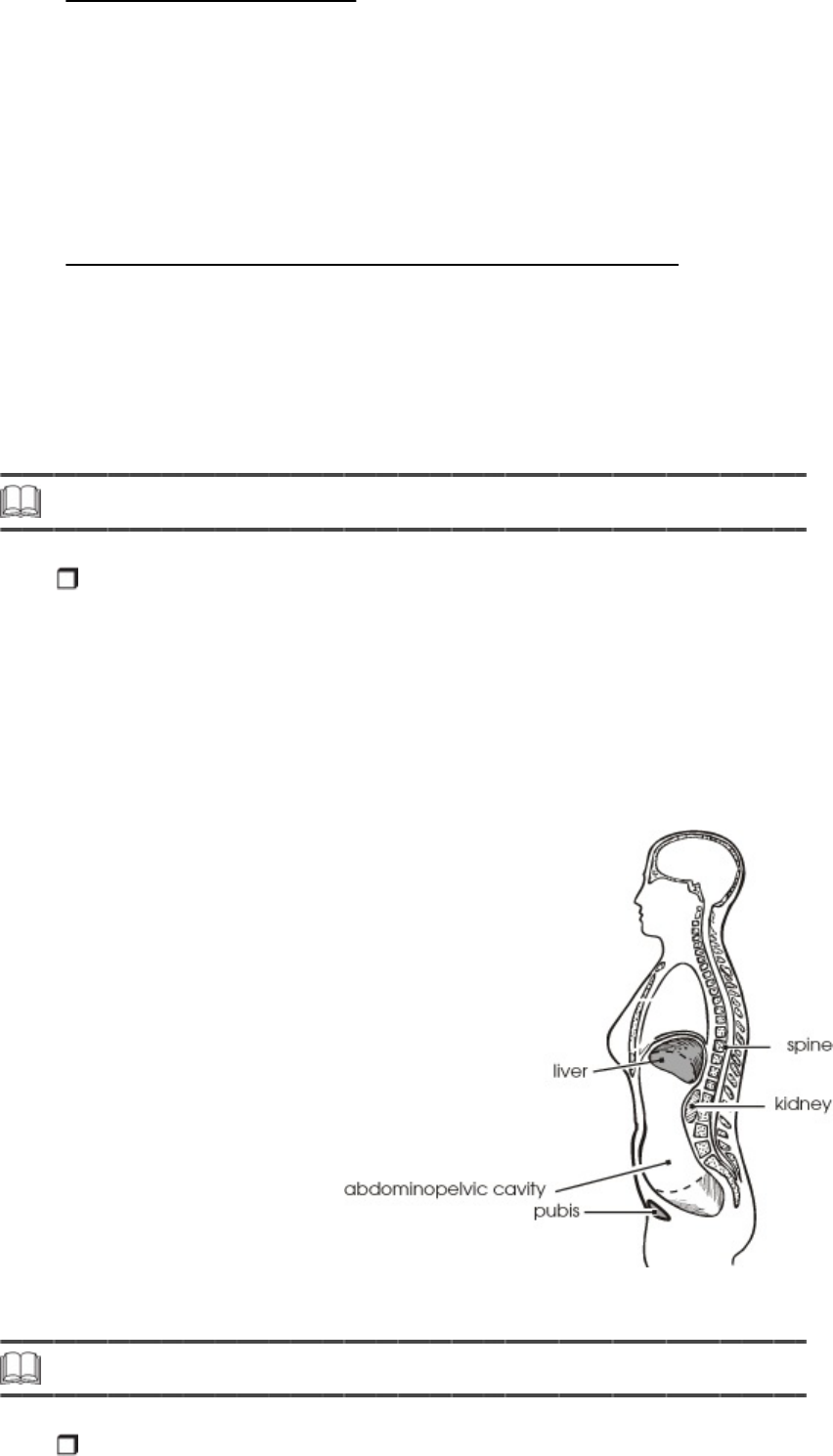

Step 9 Internal Landmarks: The Body Cavities

Step 10 Membranes That Line the Body Cavities

Epithelial Tissue Membranes

Connective Tissue Membranes

Step 11 Retroperitoneal Organs

Step 12 Pronounce New Terms

Step 13 Write New Terms

Step 14 Meanings of New Terms

Step 15 Organization of the Body

Step 16 Lesson Summary

Just for Fun

Lesson 10—Cell and Tissue Anatomy and Pathology

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 10

Step 2 Lesson Preview

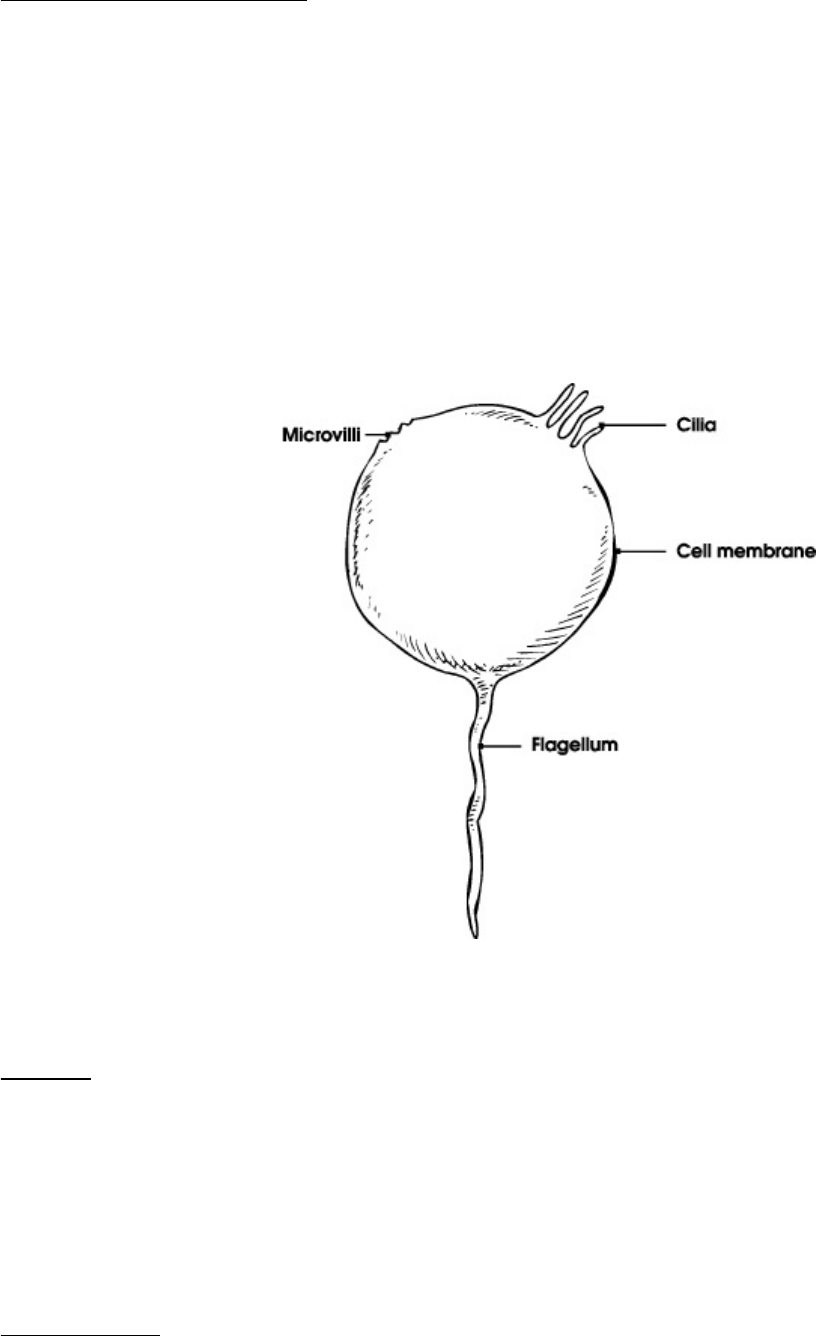

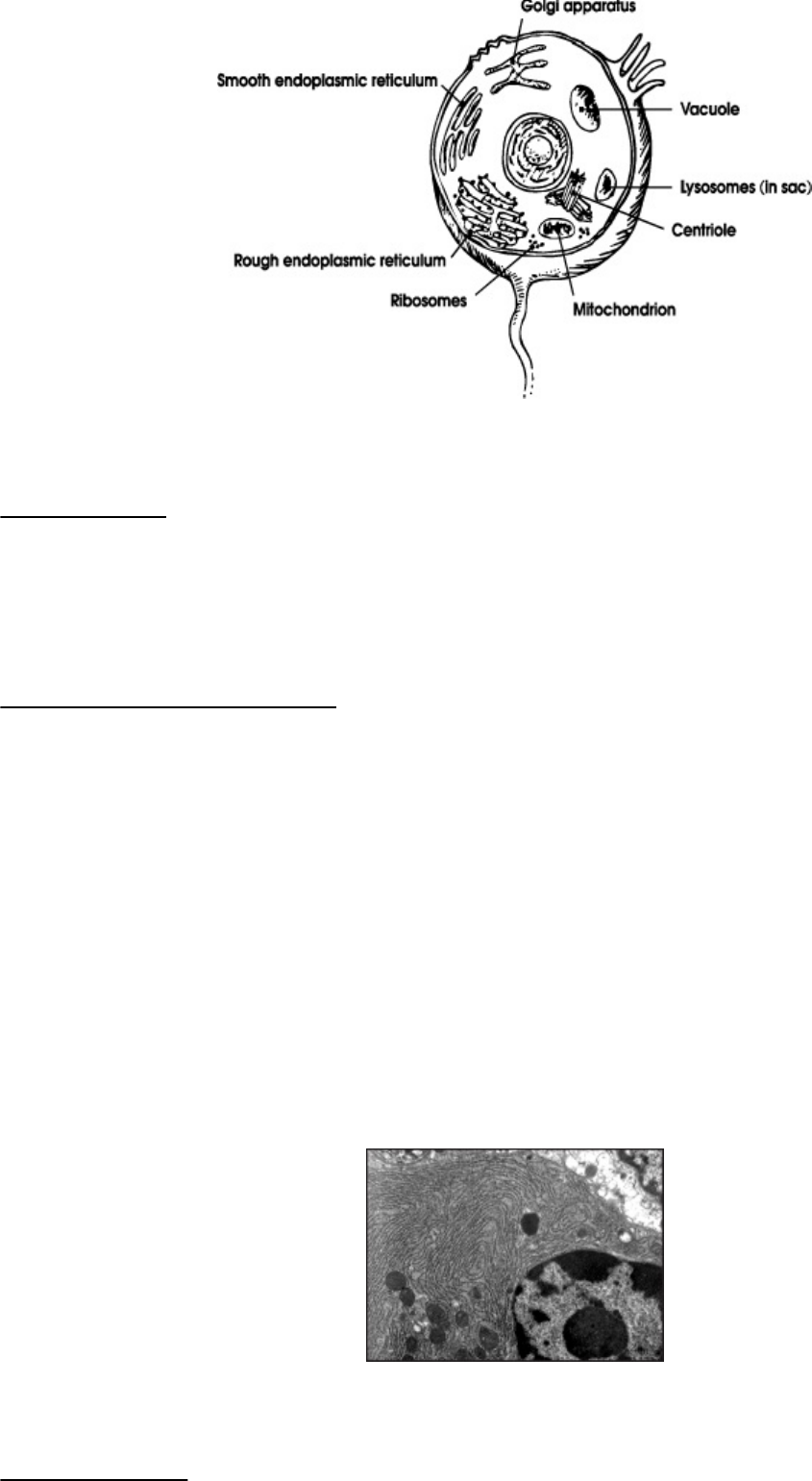

Step 3 Cell Components and Their Primary Functions

Cell Membrane

Cilia

Flagella

Villi

Step 4 More Cell Components and Their Functions

Cytoplasm

Step 5 The Nucleus

DNA

RNA

Nucleoli

Step 6 Pronounce New Terms

Step 7 Write New Terms

Step 8 Meanings of New Terms

Step 9 Cell Pathology

Step 10 Etiologies

Developmental Abnormality

Inflammatory Disease

Hyperplasia and Neoplasia

Metabolic Disease

Vascular Disease

Immunologic Disease

Idiopathic Abnormality

Iatrogenic Abnormality

Nosocomial Disease

Step 11 Cell Damage

Hypoxia and Anoxia

Toxic Agents

Microbial Infection

Allergic/Immune Reactions

Metabolic and Genetic Disturbances

Step 12 Cell Response

Atrophy

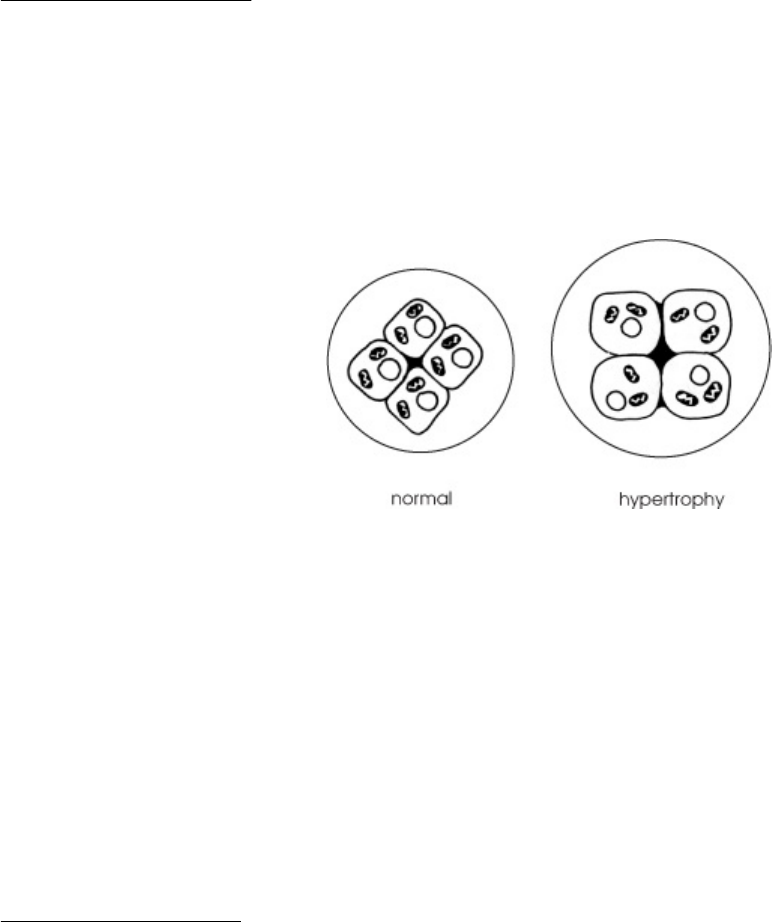

Hypertrophy

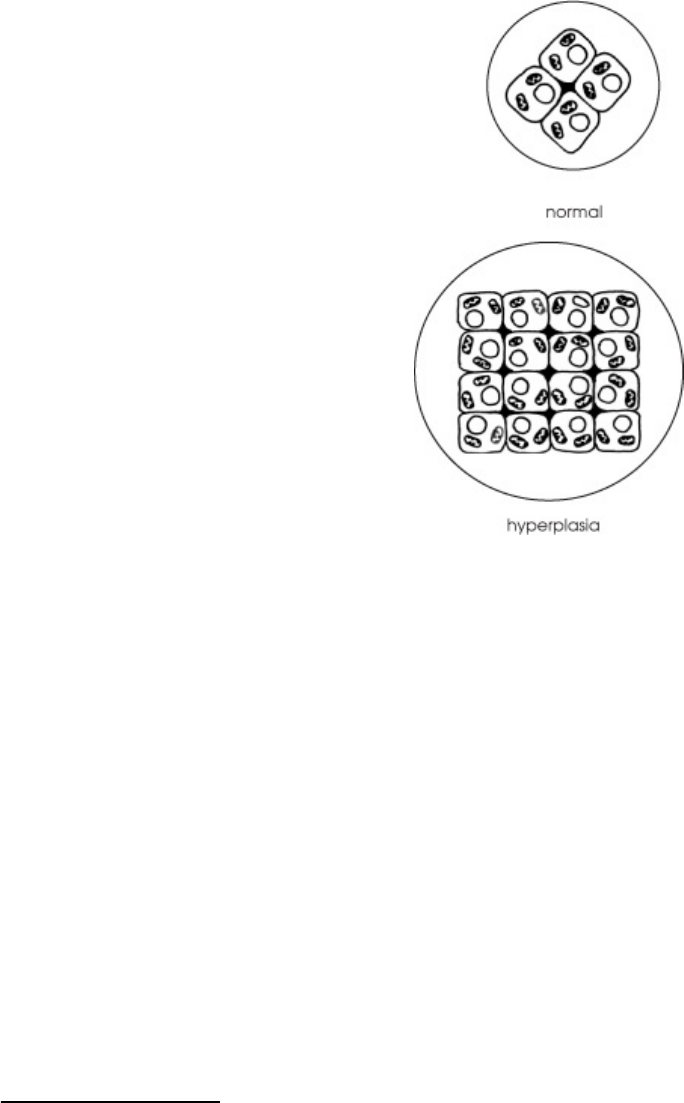

Hyperplasia

Metaplasia

Intracellular Accumulations

Aging

Step 13 Tissue Response

Inflammation

Repair

Damage or Death

Step 14 Pronounce New Terms

Step 15 Write New Terms

Step 16 Meanings of New Terms

Step 17 Lesson Summary

Lesson 11—Diagnostic Coding

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 11

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Step 3 History of the International Classification of Diseases

The WHO

ICD-9-CM

Step 4 Why Code?

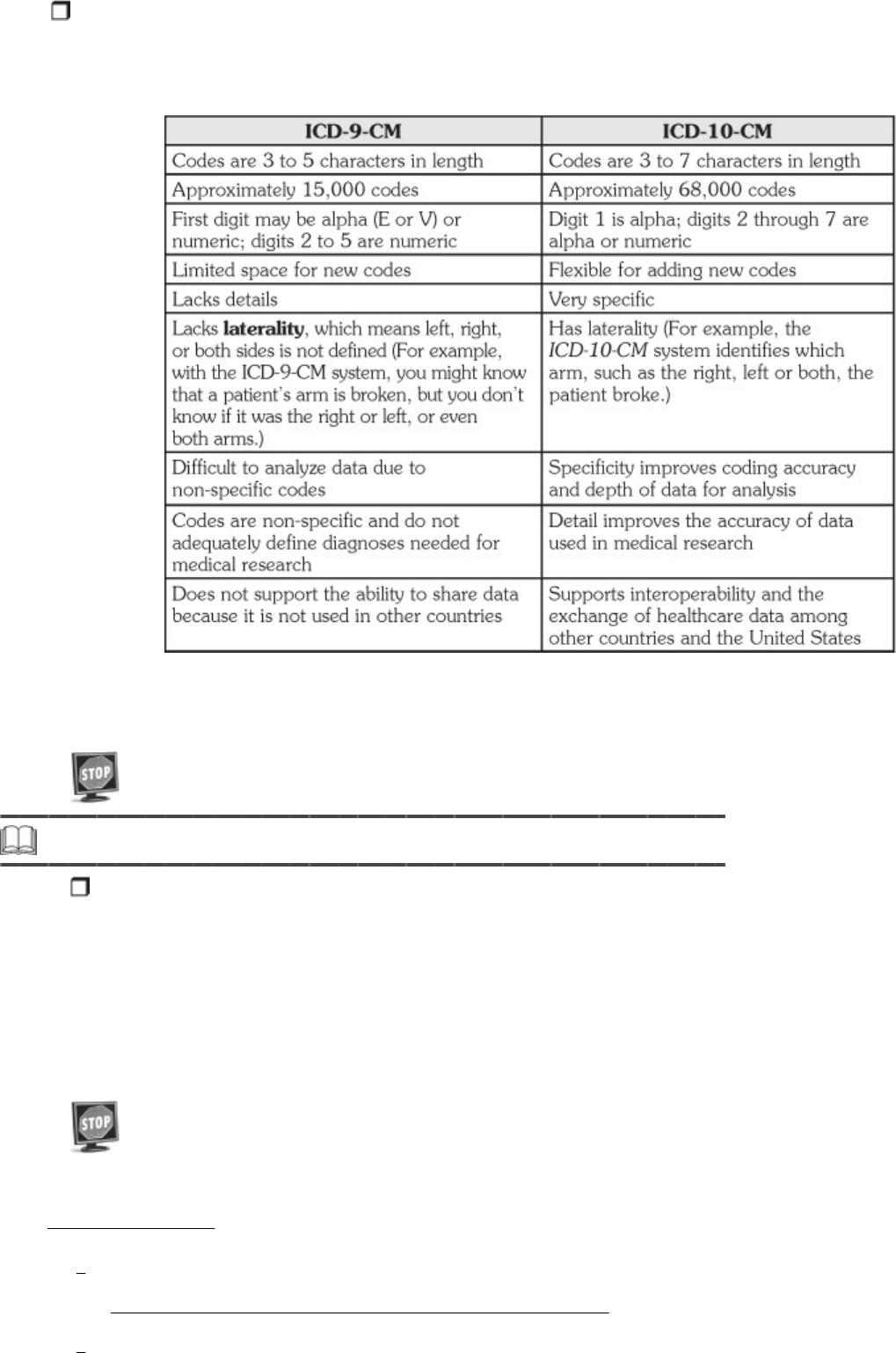

Step 5 ICD-10

Impact for Coders

Step 6 ICD-9-CM vs. ICD-10-CM

Step 7 Lesson Summary

Endnotes

LESSON 1

The World of Health Care

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 1

When you have completed the instruction in this lesson, you will be trained to do

the following:

Explain an average day in a medical office.

List the different types of medical personnel and explain how each role

helps to ensure quality health care.

Describe your role as a medical coding specialist.

Discuss the job opportunities available in your new career.

Identify several types of medical records found in the healthcare world.

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Chances are that you’ve been to the doctor’s office and maybe even your local

hospital a few times in your life (though hopefully not too often!). You’ve seen

doctors, nurses, and office administrators hard at work in these settings, but how

much do you really know about what they do? Well, in this first lesson, we’ll

introduce you to the activities that go on in doctors’ offices.

We’ll introduce you to the activities that go on in doctors’ offices.

You’ll also see where you, the medical coding specialist, fit in! You’ll learn

about your future job duties and see how you will interact with other

healthcare professionals. We’ll also discuss a few of your many job

opportunities. Lastly, you’ll get a look at the medical records that coding

specialists handle on a daily basis.

Did you know that medical coding specialists are in demand throughout

the country because of the vast numbers of doctors and patients? More

doctors are needed now more than ever to take care of our aging

population. This is where you, the medical coder, come into play.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, medical coding is one

of the 10 fastest-growing allied health occupations. Doctors need coding

specialists and are willing to pay well for the services they provide.

Well-trained medical coders make a lot of money. Medical coders often

make $35,000 per year or more. And in time, with practice, patience,

and hard work, you could earn more than $50,000 per year!

You are off to a terrific start by choosing this course as your education for

your exciting new career. In fact, the American Academy of Professional

Coders (AAPC), the renowned coding association, recognizes the

comprehensive quality of this course. This means the AAPC allows graduates

of this recommended program to waive one of the two years of coding

experience needed to become a Certified Professional Coder.

As you go through this program, you can feel confident that you are learning

from the experts. The school has been providing quality home

study

education for more than 30 years. We pride ourselves on our students’

accomplishments! People just like you are working in exciting jobs today

because of the investment they made in their education—we are here when

you need us. If you have a question, contact your instructor. It’s that easy.

Now let’s take those first steps on the path to your new career.

Step 3 Daily Activities in the Medical Office

To fully understand what a medical coding specialist does, you first must

understand how medical office personnel gather information. This information

includes patient data; insurance company information; and doctors’ procedures,

diagnoses and other actions.

To illustrate all of this, let’s take a look at a typical day in a medical office, or

an outpatient setting. (Outpatient settings include clinics, physicians’ offices,

outpatient surgery facilities and hospital emergency departments. Inpatient

settings include hospitals—or facilities where patients are admitted for an

overnight stay.) We’ll get the point of view of the first person to see patients

—the office manager or receptionist—and then we’ll look at the doctor’s

perspective.

A Day in the Life of the Medical Office Manager

Hannah is the office manager for Mercy Medical Center, a busy, family

medical clinic that has three doctors. As the first person to see patients, she

tracks them as they arrive and check in for their appointments. Today, each

doctor is scheduled to see about 15 patients. Hannah’s appointment book

contains a different page for each doctor’s schedule. Her day begins with the

8 a.m. appointments. Each doctor has a bright-and-early patient scheduled.

By 7:55 a.m., two of the three patients are in the waiting room. One is a new

patient at the clinic, and she is filling out the “New Patient Questionnaire.”

The other is an established patient.

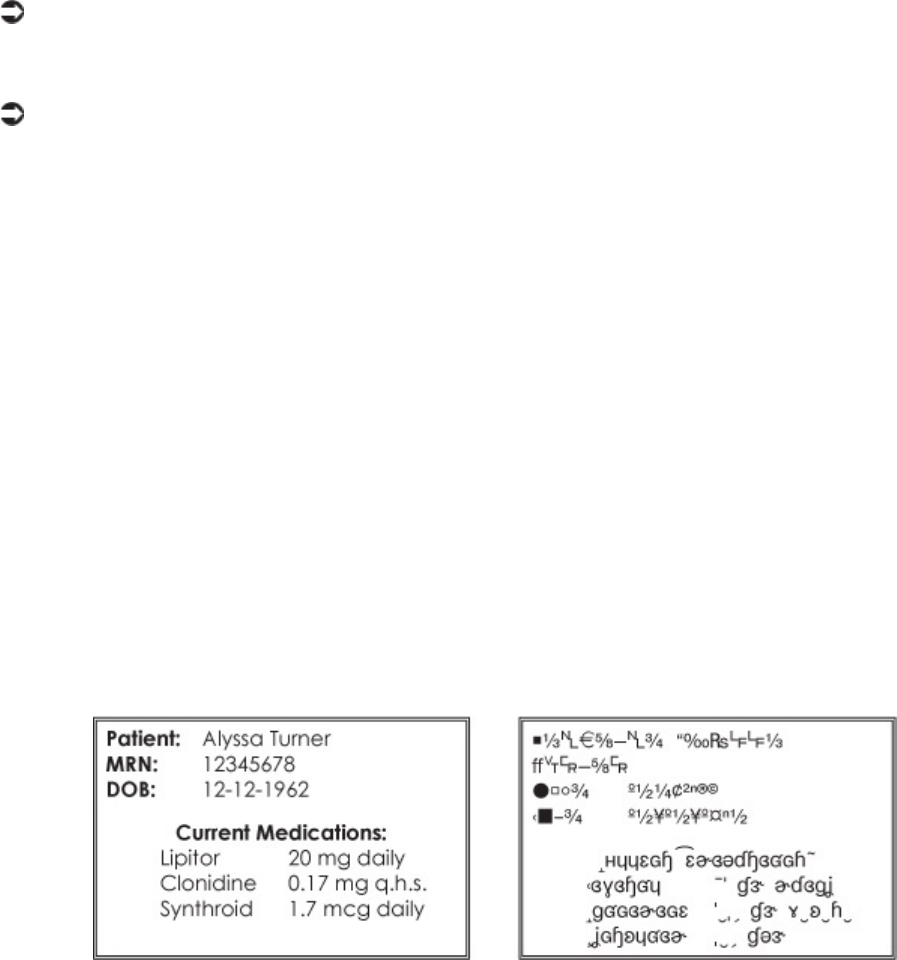

Hannah pulls out the medical files for the established patient. The

medical files are thick, manila folders and are coded on the tab according

to the patient’s last name. She prints an encounter form or super bill for

the established patient and uses a paperclip to attach it to his folder. She

then places the files in the “Patients to See” stack for the nurse of one of

the doctors.

The new patient brings up her completed questionnaire, and Hannah spends

the next few minutes creating medical files for this new patient. Hannah

makes a new folder for the patient, labels it appropriately and places a copy

of the questionnaire in it. Then she takes the original questionnaire and types

the information from it into her computer. This creates two files for the

patient—one in the computer and one on paper. After Hannah has entered

the information about the patient into the computer, she prints an encounter

form or super bill. She then clips the encounter form to the appropriate folder

and places it in the “Patients to See” stack for the appropriate nurse.

It is now 8 a.m., and one appointment has yet to arrive. At 8:04 a.m.,

Hannah receives a call from the missing patient. He is having car trouble and

can’t make it today. Hannah assures the man he can reschedule. She sets up

a new appointment for him and logs it into the doctor’s appointment book. By

8:06 a.m., both of the other appointments are back in the examination

rooms. The 8:15 a.m. appointments begin to arrive. The routine is similar to

the first group of patients except that this time all three appointments arrive.

They all are established patients, so Hannah pulls their files, prints out

encounter forms, and distributes the folders to the correct nurses.

Medical office managers handle multiple tasks.

At 8:10 a.m. the first doctor is finished with his 8 a.m. appointment—

a man named Jim Burgess. Mr. Burgess walks out of the examination

room and gives the encounter form or super bill to Hannah.

Hannah looks at the procedures that the doctor circled and quickly fills in

an amount next to each one. She totals the bill—$187.50—and has Mr.

Burgess sign it. At Mercy Medical Center, most patients are covered by

insurance. In Mr. Burgess’s case the medical office will send the bill to the

insurance company without him paying an initial copayment or the entire

amount of the bill. Therefore, Mr. Burgess signs the bill to give the

insurance company permission to pay the clinic directly and returns it to

Hannah. She rips off the back copy for him.

As Mr. Burgess picks out a lollipop from the basket on the counter, Hannah

quickly files the completed and signed encounter form in her “To Submit,

Current” folder. The nurse has returned Mr. Burgess’s file, so Hannah puts

it in the “To Be Updated” basket. The folders in this basket are waiting for

the doctors’ dictation to be transcribed. Just then the telephone rings. It is

Mercy Medical Center’s medical transcriptionist calling to verify a patient’s

information. Hannah explains she will have to look up that information and

call the transcriptionist back.

Hannah’s day continues this way until she leaves at 5 p.m. During that time,

she continually checks in patients, enters new questionnaires on the

computer, creates files, retrieves files, completes encounter forms, answers

the telephone, and schedules and reschedules appointments.

Now let’s look at the same day’s events from a physician’s perspective.

The Doctor’s Point of View

Dr. Green is one of the physicians for whom Hannah works. He sees his

first patient at 8 a.m. He examines the patient, a woman in her mid-30s,

and determines the cause of her ailment. Dr. Green’s patient has a broken

arm. When she sees Dr. Green, he listens while she tells him what’s wrong

—this is called the chief complaint. Then Dr. Green looks at her arm and

recommends that x-rays be taken. Finally, since the x-rays show a

fracture, Dr. Green puts her arm in a cast.

This sequence began with a chief complaint—“my arm hurts”—and was

followed by a diagnosis aided by tests—a broken arm as seen on the x-

ray. The sequence is completed with a treatment or procedure—the

fracture care. Doctors perform one or more of these steps with every

patient they see.

Doctors perform many steps when they see patients.

And every time a doctor or nurse performs these duties, the steps must

be recorded into the patient’s history, which is a folder usually called a

chart. The diagnosis and treatment or procedure, along with any tests

done, eventually are coded by you, the medical coding specialist! You will

learn all about coding diagnoses, tests, and treatments as you move

through this course. For now, you just need to understand where you will

gather that information.

After Dr. Green examines the patient, he records some notes about the

encounter. The office’s medical transcriptionist will use this dictation to

transcribe the encounter into a formatted medical report. Dr. Green also

makes some notes on the patient’s history or chart. Now, he is ready to see

his second patient.

Please pause and complete online Practice Exercise 1-1.

Step 4 A Little Teamwork Goes a Long Way

Now you know how information flows in medical settings. You have a basic

understanding as to what some healthcare employees, such as office managers

and doctors, do in a typical day in a medical office. But before we talk about your

role in the healthcare team, let’s identify some of the key players in hospitals and

doctors’ offices and elaborate on what they do.

In most professions, teams of people work together to accomplish goals, and

this is true of physicians as well. In medicine, doctors certainly cannot

perform their jobs alone. Many people work hard, some behind the scenes,

others more visibly, to ensure that the healthcare system runs properly.

When you go to see the doctor, you don’t just see the doctor. You might see

a number of professionals, including a receptionist, an office manager, and a

nurse. Throughout a visit, a doctor may talk to several staff people, including

the medical coding specialist. All of these people are essential members of

the medical care team.

All of these people are essential members of the medical care team.

Physicians

Physicians or doctors are the most prominent members of the medical

care team. They perform life-saving procedures. They cure the sick and

help heal wounds. Becoming a doctor of medicine is one of the most

challenging career paths a person can choose. Not only do doctors earn

four

year college degrees, but they also must complete medical school

and one or more residency assignments. During residency, 85- to 100-

hour work weeks are common. Because of this huge commitment,

doctors deservedly receive much of the attention in the medical field.

Physicians diagnose illnesses and injuries. They prescribe drugs to alleviate

symptoms, treat conditions, and ease pain. They rely on their training to

make quality, accurate decisions. However, as good as physicians are, their

staff ultimately supports them as they provide quality treatment. Nurses are

one essential part of the medical staff.

Nurses

Nurses can give injections.

As professionals who perform a variety of tasks in the medical world, nurses

often must follow through with treatments physicians prescribe. Nurses can

give injections and check a patient’s vital signs, as well as assist in surgery.

It’s also true that nurses must often do the thankless jobs—cleaning up exam

rooms and organizing supplies.

Without nurses, the number of patients a doctor sees in a day would drop

dramatically. Because of their nurses, doctors see more patients and are able

to focus on those patients who require the most care.

Nurse’s and Physician Assistants

Two other categories of personnel in the medical field are nurse’s and

physician assistants. Nurse’s assistants, or nursing aides, help nurses with

daily duties, such as paperwork, general organization and taking a patient’s

temperature, weight, and blood pressure. Some nurse assistants also talk to

patients and make sure they’re comfortable.

Physician assistants or PAs normally are under the supervision of a

doctor, and can perform some of the same functions as a doctor. PA duties

might include stitching up a cut, taking a patient history, and even

performing lab work.

Support Staff

Doctors and nurses rely heavily on support staff to keep a medical office or

clinic running smoothly. As you might guess, each of these positions plays an

important role in the medical world.

Medical Billing Specialists

Medical billing specialists are a perfect example of how interrelated one job is

to the next in a medical office. Remember, coding specialists code what

occurs during a patient’s medical visit, while medical billing specialists use

the codes that a medical coder assigns. Billing specialists then complete the

insurance forms necessary to collect payment from the insurance companies.

These specialists know that the doctor doesn’t get paid unless the form is

completed and filed correctly. Billing specialists have training in medical

terminology, medical records handling, and some basic coding.

Medical Transcriptionists

Do you remember when the doctor in our previous example recorded some

notes about a patient encounter? Well, a medical transcriptionist who

listened to the doctor’s dictation typed what she heard. This then was added

to the patient’s medical record. By using transcriptionists, doctors save time

by speaking their notes.

Medical transcriptionists type the doctor’s dictation.

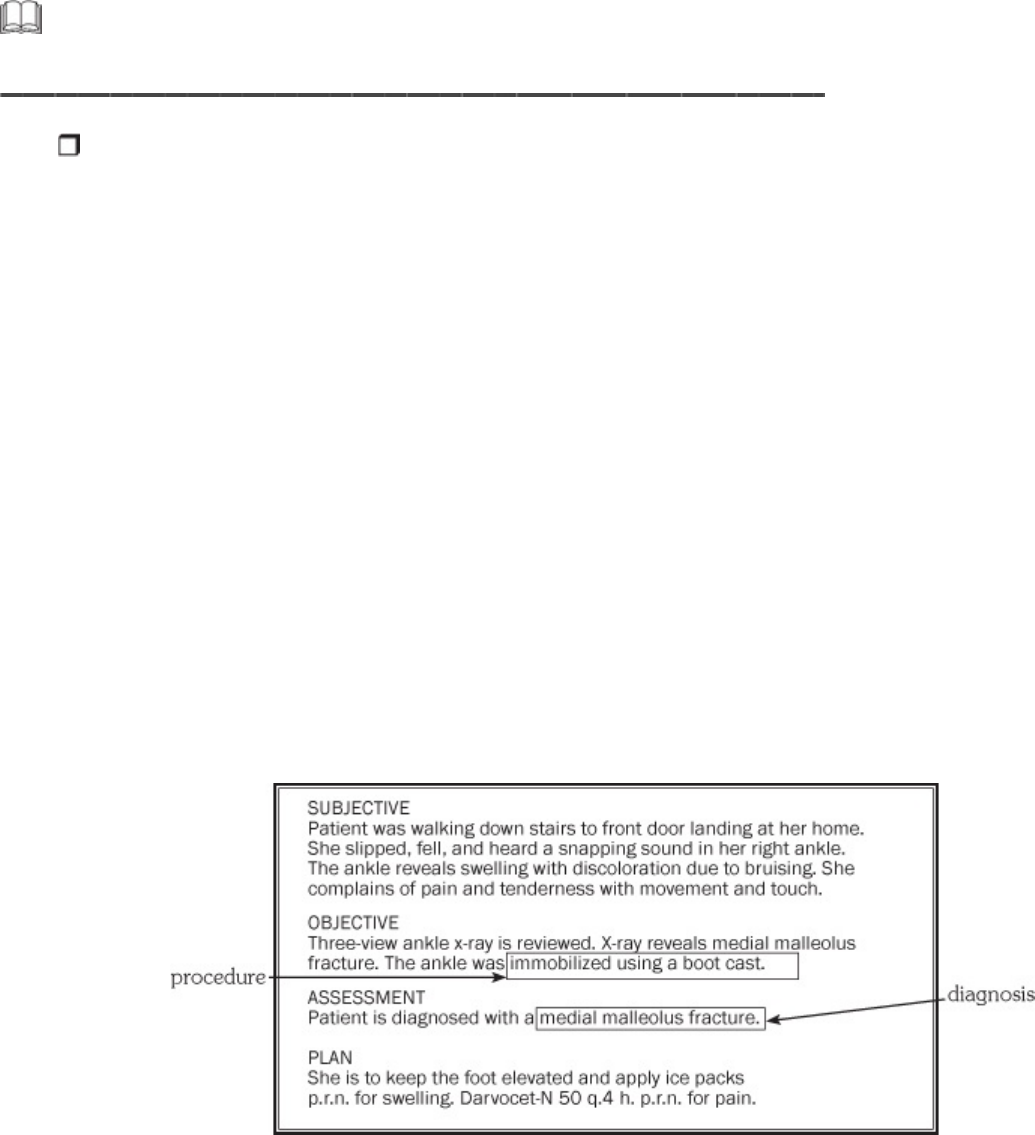

While you don’t need to know every aspect of medical transcription, you

should be aware as to what transcribed reports look like. As a medical coder,

you often will work from these transcribed reports. Two examples of

transcribed reports follow: one for Laura Brown and one for Johnny Cruz.

Study these reports so that you have a better understanding of a

transcriptionist’s role in the medical records process.

Transcribed Report Example One

Name: Laura Brown

#030311

PROBLEM

Upset stomach with vomiting and fever.

SUBJECTIVE

The patient is a 22-year-old female. She went to breakfast with her friends earlier this

morning. She ordered a cream-filled pastry with her coffee. She stated that no one else had a

pastry. About 4 hours later, she started having an abrupt onset of nausea, vomiting,

abdominal cramps, diarrhea, headache and a slightly elevated fever. Since she had the

symptoms for over three hours, she called her family physician and was able to see him this

afternoon.

OBJECTIVE

Physical examination reveals a well-developed, well

nourished female in acute distress.

Blood pressure: 125/85. Temperature: 99.6 ˚F. Pulse: 88. Respirations: 24. Chest is clear.

Cardiovascular examination: Regular rate and rhythm. Abdomen: Positive bowel sounds.

Diffuse tenderness with slight pain. Laboratory results indicated a slightly elevated white

blood cell count. Abdominal x-ray: Normal.

ASSESSMENT

Staphylococcus toxin gastroenteritis.

PLAN

The patient was sent home and told to get plenty of bed rest and begin clear fluids when

nausea and vomiting cease. If the symptoms continue for more than 3 more hours, she should

contact the office.

_________________________________

Robert Snow, MD

D:02-08-20xx

T:02-08-20xx

RS:CJL

Transcribed Report Example Two

Name: Johnny Cruz

#030315

PROBLEM

Sore throat with fever.

SUBJECTIVE

Johnny, a 5 year old, presents to his pediatrician with a sore throat, fever, loss of appetite

and a headache. His mother said that he has been on the couch all morning and refuses to

eat or play.

OBJECTIVE

After examining the patient, the doctor reports enlargement of the lymphatic glands and a

temperature of 103 ˚F. The oral exam reveals a swollen, bright-red throat. A throat culture is

postitive for strep throat.

ASSESSMENT

Acute follicular pharyngitis.

PLAN

Take erythromycin as directed. Temperature to be taken frequently. Children’s Tylenol every

4-6 hours as needed for fever. Encourage bed rest, modify activities and increase fluid

intake. All citrus juices should be avoided until symptoms subside. Call office if symptoms

persist.

_________________________________

Marikit Makabuhay, MD

D:09-15-20xx

T:09-15-20xx

MM:BDD

Medical Record Technologists

Certified medical record technologists control the flow of medical

records to the various people who need to see those records. These

technologists take a certification test that ensures they have the knowledge

to determine what records are needed, who is authorized to see the records,

and how these records are organized. You may find that medical record

technologists, who are certified, are also called Registered Health

Information Technicians or RHITs.

Emergency Personnel

Emergency personnel are a group of professionals with the sole responsibility

of providing immediate medical assistance and transporting the patient to the

hospital for treatment. When someone is hurt and needs an ambulance,

these people respond. Police officers, firefighters, and other rescue

professionals all have some level of medical training.

EMTs can be ambulance crew members.

You probably have heard of emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and

paramedics. EMTs take classes that enable them to stabilize patients who

have a wide variety of emergency medical conditions. They often are

members of ambulance crews and volunteer firefighting organizations.

Paramedics have more training than EMTs. Paramedics are not only able to

stabilize patients, but they can begin treatments to cure patients, such as

administering medication.

Office Professionals

Do you remember Hannah, the office manager from our previous example?

Hannah is an example of an office professional. Without office managers and

receptionists, many medical offices would grind to a halt! These people

organize schedules, record appointments, and answer patient questions.

Office staff members have terrific communication and organization skills.

They also must make a good first impression. The office manager may be the

first person a patient sees upon entering a medical office, and the manager’s

attitude can mean the difference between a pleasant visit and a nightmare

for the patient.

Please pause and complete online Practice Exercise 1-2.

Step 5 Welcome to Your Career as a Medical Coding

Specialist!

Now that you know the job duties of many of those in the healthcare world, let’s

talk about the role that you, the medical coding specialist, will play in the

healthcare picture. From the scenario you read at the beginning of this lesson, you

know that you will be responsible for assigning medical codes to the information

obtained from a patient’s visit to a medical facility. As the coding specialist, you get

the medical record the physician dictated that we talked about previously. You look

over the complaint, the diagnosis and the treatment performed, and then you code

appropriately. To code, you look up the information in a reference book and find

the right set of numbers that describes exactly what occurred.

You can code at home or work in a doctor’s office or hospital, and some

doctors use independent coding specialists. In fact, there are even companies

that hire coding specialists across the country. These remote coders work

online in distant locations, and the company finds work for them to code. So

much depends on where and when you want to work. What’s exciting is that

you’re in control—just as you are in this course, working toward your new

career!

As you already know, medical coding specialists are in demand. Just by

looking at the number of patients doctors see every day, you can imagine

how many coders are needed. Every appointment needs a code attached!

Experienced medical coding consultants can earn impressive salaries.

Surveys indicate that many medical coding specialists earn $35,000 per year

or more. In fact, some medical coding consultants make more than $100,000

per year. Of course, you shouldn’t expect to make $100,000 your first year.

But with work and dedication, you can earn a tremendous salary in a short

time.

But Where Will I Work?

Someone with the knowledge you’re gaining in this course will not be limited

to simply filling out forms. No, the world of medical coding is very diverse

and, as you already know, it offers full- or part-time job opportunities, at

home or in offices.

Medical Coding Specialist

Mercy Medical Center is looking for a part-time Medical Coding Specialist to accurately assign codes to records.

One year of coding experience is preferred, but those who can show they have real-world training in medical

coding also will be considered. Mercy Medical Center is an equal opportunity employer.

Please send cover letter, resume and references to:

Mercy Medical Center

111 Main Street Suite 1

Avery, Ohio 44444

Find Your Future as our Next Medical Coder!

Hart Family Practice is looking for a full-time medical coder to code medical records. Applicant must have

knowledge of medical terminology, anatomy and medical codes. The position offers a generous benefit

package, and salary is based upon experience. EOE

If interested in applying, please send a cover letter and resume to:

Hart Family Practice

222 Skinner Road

Pittman, Louisiana 23232

Medical coding specialists no longer are restricted to the doctor’s office but

now work in hospitals, pharmacies, nursing homes, mental healthcare

facilities, rehabilitation centers, insurance companies, consulting firms, health

data organizations, and their homes. And remember, if you decide you want

to work at home, you set your own work schedule and save on items such as

child daycare and transportation. So how is it possible that one career offers

so many choices? Let’s take a closer look at two different jobs available to

you in this career.

Medical Coding Specialist

A coding specialist typically works in an office or hospital. In some cases the

physician assigns the code, and the coding specialist simply verifies that

these codes are consistent with what the physician has documented. In other

cases the doctor does not assign codes. Instead, the medical coding specialist

translates the doctor’s written diagnosis and treatment into codes. Then the

coder often routes the codes to a medical billing specialist who sends the

claim to the insurance company.

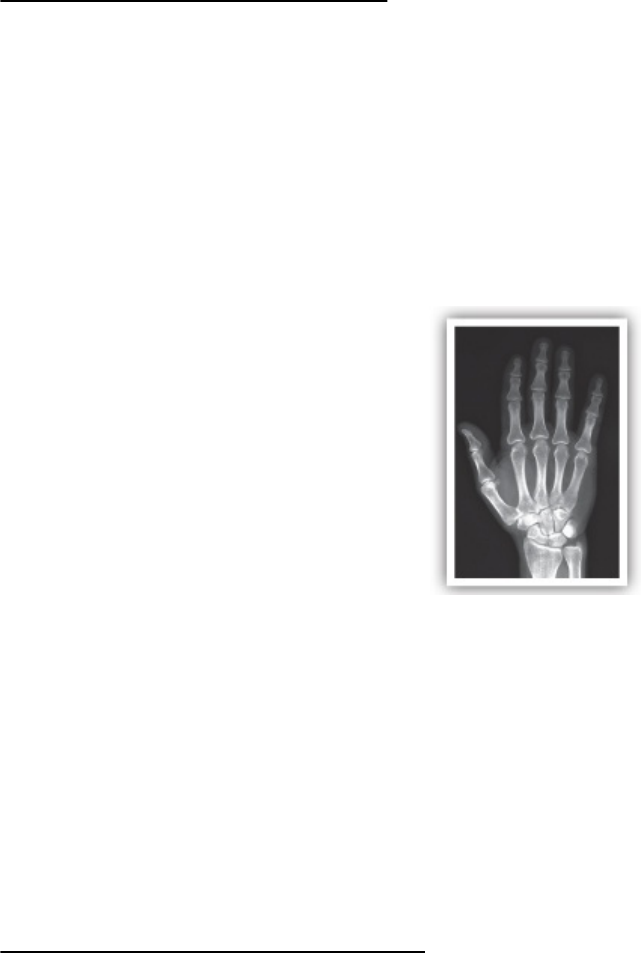

Medical coders apply codes for x-rays.

For example, a medical coder working for a radiologist might have a super bill

indicating a patient came in for a broken finger, as well as transcription

documenting how the x-ray was performed and the radiologist’s reading of

the x-ray. The medical coder would apply the correct codes for the diagnosis

and the procedure, and the medical billing specialist then would send these

codes to the insurance company.

The Medical Coding Service

A medical coding service is the most common at-home employment

opportunity for a medical coding specialist. Medical coding service

providers use a computer to complete the necessary forms and submit them

to the office manager or medical billing specialist. Typically, the self-

employed medical coding specialist charges by the medical record and has

more than one provider as a client.

The work of an independent medical coder doesn’t vary much from that of

those who work in offices and hospitals. The biggest difference involves how

the work gets to and leaves the medical coding specialist. If the coding

service does work for local providers, the work could be picked up and

dropped off every 24 to 48 hours. The medical coding specialist simply takes

the information home, codes it and then returns it to the physician’s office. If

the physician is having his transcription done online, he is set up for online

communication of all work. The coding work can be exchanged online. The

great thing about this route is the medical coding specialist isn’t limited to

clients in her town or even state!

If you’re going to do your medical coding work from home, there are several

items to consider. You’ll have to purchase equipment and set up a home

office, as well as market yourself to find clients. Consult the Medical Coding

Specialist Career Starter Kit included in this course for more guidance in

setting up a home-based business. For now, let’s talk a bit about the personal

qualities that medical coding specialists should possess.

Step 6 Personal Qualities of a Medical Coder

If you think about it, there are a large number of potential clients available in most

towns. Even small towns usually have one or two doctor’s offices and a hospital.

Many times qualified help is hard to find, and because you have a skill that is in

great demand, you have the opportunity to make good money. Though salaries

vary depending on experience, the number of hours worked, and location, we think

you’ll be pleased to discover the amount of money you can earn as a medical

coding specialist. And remember that as your experience builds, you can add to

your earnings while being a vital part of a medical team and doing work that helps

people.

As a part of the healthcare team, medical coders do much of their work

alone; however, coders still are a vital part of that team. The main

thing to remember when you approach a potential client or employer is

that you are the best medical coding specialist for the job. Your

competence means money—their livelihoods—to your employers!

Coders should remember and practice three qualities: professionalism,

presentation and adaptability.

Professionalism

As with any business, the

image you project

is important.

Professionalism is the conduct, aim or qualities that characterize a

profession or a professional person. As with any business, the image you

project is important. You must be professional. This includes how you dress,

talk, and interact with your clients. When you have an initial meeting with

potential clients, your level of professionalism will affect their impression of

you.

When you select what to wear, be conservative but not bland.

When you select what to wear, be conservative but not bland. Your attire

should be clean, wrinkle free and professional. Try to choose something you

feel comfortable wearing. If you are comfortable, you will be able to

concentrate on other important things such as your presentation and

answering any questions your potential client may have. An uncomfortable

outfit, whether in style, color or both, will distract you.

Another facet of professionalism is delivering what you promise. You’ve

probably heard the saying, “Five minutes early is 10 minutes late.” Basically,

this means if you have a meeting at 10 a.m., be 15 minutes early. Never be

late, especially for a first-time interview. Such promptness shows you are

responsible and considerate. If your client is a little late, be understanding.

Just make sure you aren’t the tardy one. When you are asked for work

samples, be prepared. Explain what you know and how you gained your

knowledge. If you ever are asked to complete a test task, do so promptly.

Presentation

Presentation is the act of bringing or introducing something into the

presence of someone else. Often your initial presentation will decide whether

you gain a client or employer. In addition to being on time and dressed

properly for the meeting, your presentation can go a long way in influencing

your client-to-be—both positively and negatively.

Be sure to present a confident image. Your attitude should say, “I know what

I’m doing” without being arrogant or condescending. Remember, this is the

client’s money you’re talking about. Confidence is a must!

Adaptability

Adaptability is the ability to be modified or changed. To be successful,

you must be able to adapt for each client. Some people want tasks done

a certain way. Others may have exactly the opposite requirements.

Insurance regulations change. Forms are altered. If you get too set in

your ways, you might lose clients who require slightly different

approaches.

Step 7 Medical Records

We’ve all had experiences with a doctor’s office. You’ve probably been asked to fill

out a new patient questionnaire in a doctor’s waiting room, or maybe you’ve called

to reschedule a dentist appointment. But you may not be familiar with the contents

of a medical record. Let’s clear up some of these mysteries. As a coder, you’ll

become a pro at explaining these contents.

A medical record is generated when a patient receives medical care. This

record usually begins its life as a questionnaire or patient data sheet—like

the one the new patient filled out in our example. The questionnaire asks

about a patient’s medical history, insurance coverage, and other important

facts. After the patient completes the form, the office administrator takes it

and any applicable insurance information and enters all of this into the

office’s database, either on a computer or manually in a file cabinet. Then a

medical file or record is created.

What is a medical record?

The medical record contains all of a patient’s medical history related

to that doctor and his office. The medical file includes charts, notes, and

information to identify the patient, support the diagnosis or reason for

the appointment, justify the treatment, and accurately document the

results. The record also contains past and present illnesses and

treatments. Every aspect of a patient’s treatment at a healthcare facility

is documented in this file. In other words, the medical record provides a

complete picture of the health care the patient has received.

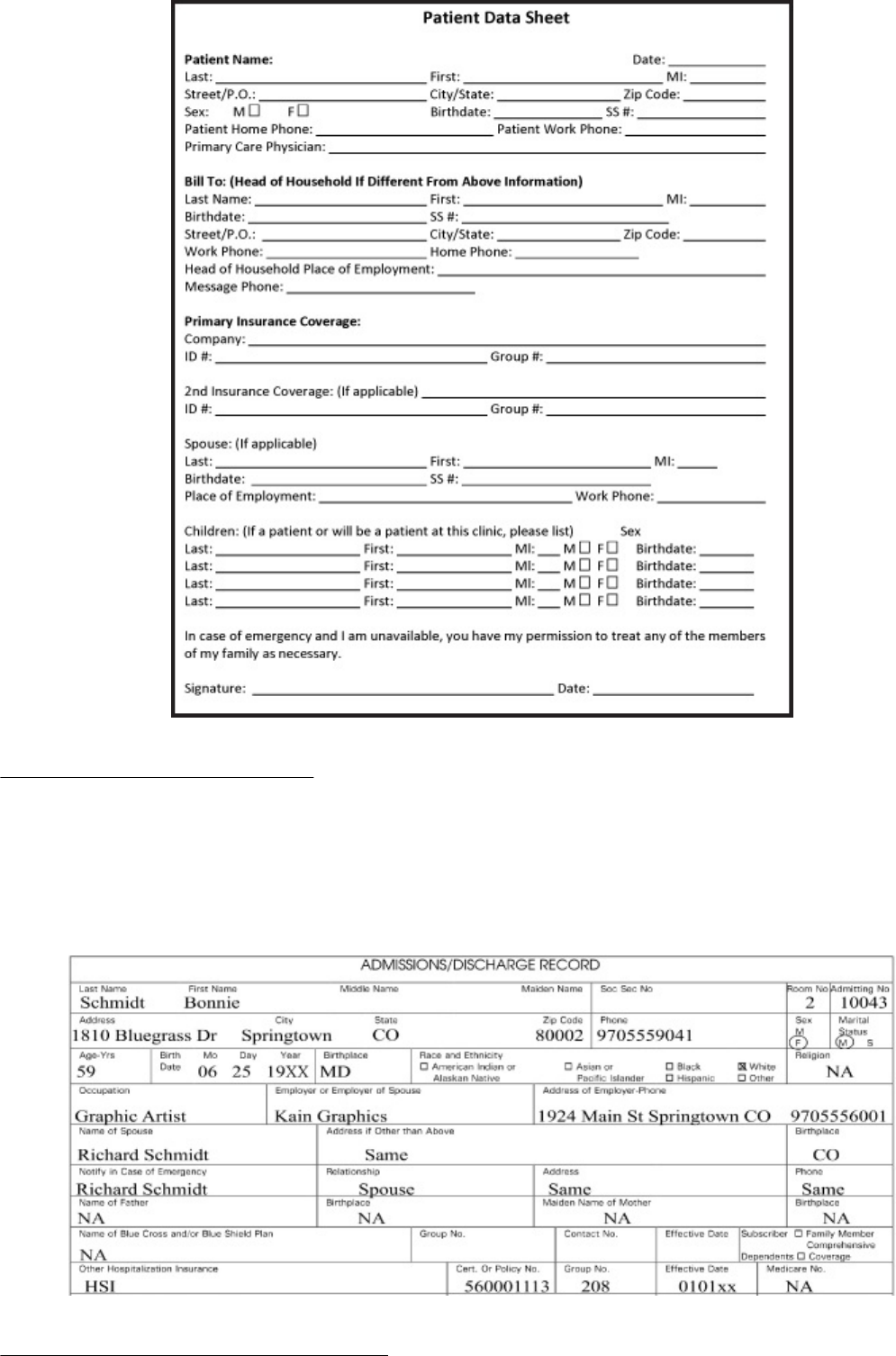

Parts of a Medical Record

The most common parts of a medical record include: The patient

questionnaire, registration/admission form, consent for treatment form,

patient history form, plan of treatment form, and progress report form. Let’s

take a moment to discuss each of these briefly, as well as look at a few

examples.

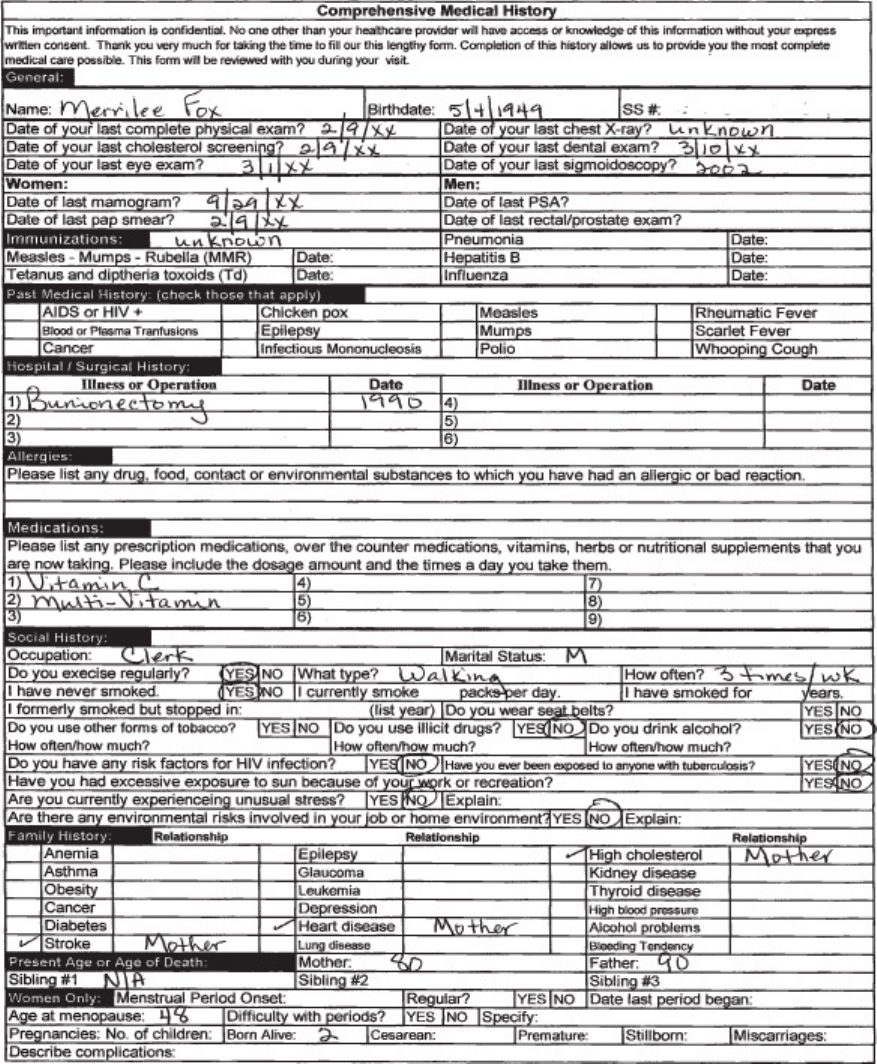

Questionnaire

A medical record is generated when a patient receives medical care. This

record usually begins its life as a questionnaire or patient data sheet. The

questionnaire asks about a patient’s medical history, insurance coverage

and other important facts.

Let’s take a look at an example questionnaire.

Registration/Admission

The registration/admission form is used to record important information,

such as the patient’s name, address and insurance information. This form

may be completed every time a patient sees the provider, or the practice

may keep one on file and update it as necessary.

Consent for Treatment Form

Whenever a patient agrees to a suggested treatment, the patient must

complete a consent for treatment form. The consent for treatment form

includes a statement indicating the patient has been informed of the

treatment plan, including possible side effects and negative outcomes. The

patient signs the form, indicating agreement to the treatment and awareness

of all possible consequences resulting from the treatment.

Patient History

When a patient sees a provider for the first time or hasn’t seen a

particular doctor for a long period of time, the patient is asked to fill out a

patient history form. The patient history contains critical questions

regarding the patient’s health history. The patient’s responses to these

questions enable the doctor and medical staff to give the patient the best

possible care.

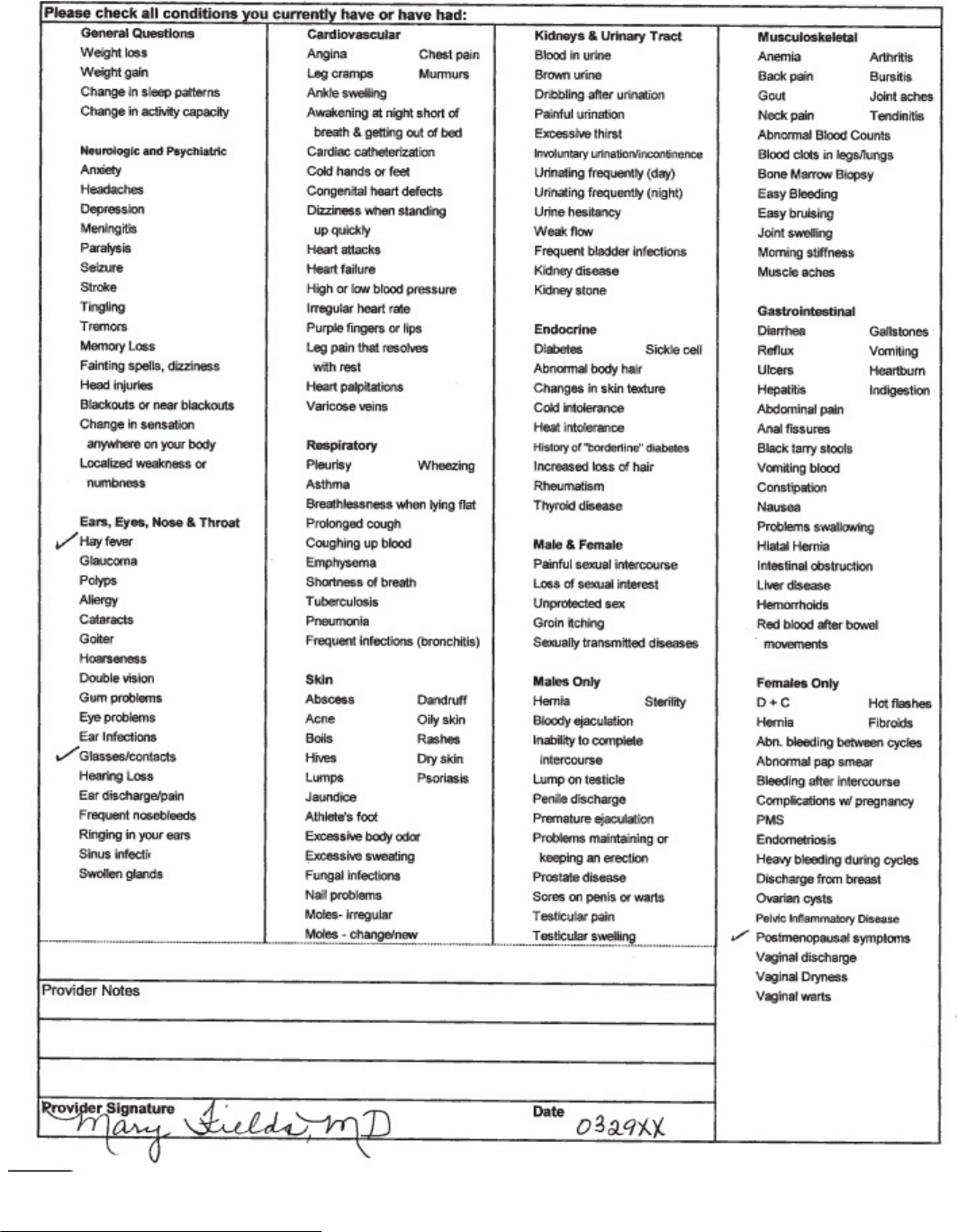

Plan of Treatment Form

The doctor records the orders given to the patient regarding treatment on the

plan of treatment form. In our example, the physician’s instructions are for

discharging the patient. Completion of this form helps establish a plan for

recovery and provides the patient with clear instructions to follow.

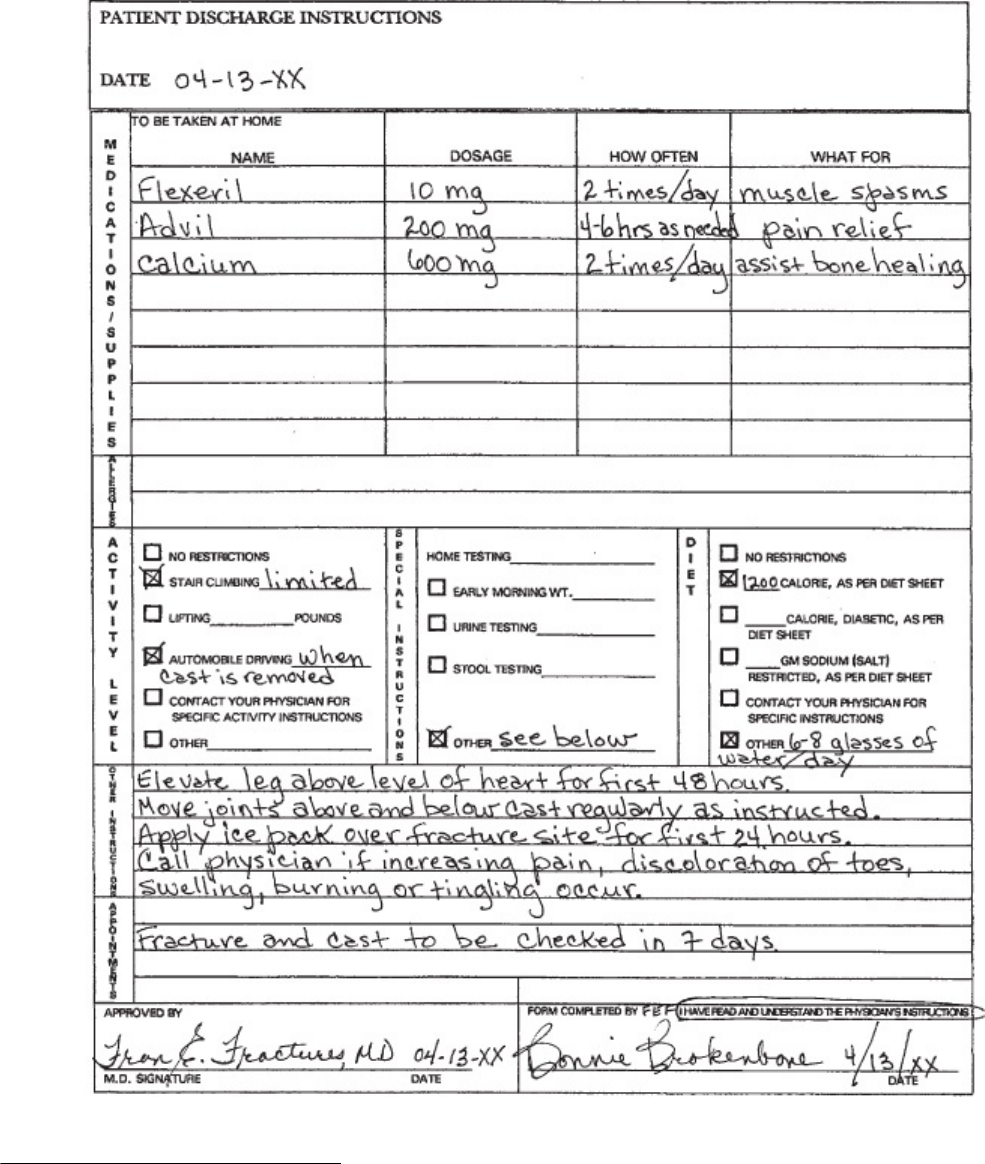

Progress Report Form

As a treatment plan moves along, or as a patient’s condition changes, the

information is recorded on the progress report form. Providers use this

form to chart changes of all kinds in their patients’ conditions. Changes can

include worsening conditions as well as improvements. Every patient has a

progress report form.

The Flow of Medical Information

Doctors, nurses, and other health professionals use the medical record

to provide patient information for the different segments of the patient’s

care. The record helps the various practitioners involved in treating the

patient to communicate with one another. It’s not necessary for a

doctor to individually speak with each healthcare professional. The

medical record keeps the current healthcare providers abreast of the

patient’s treatment and progress. In addition, the record depicts for

future providers an accurate picture of the patient’s previous care. It

enables one doctor who takes over for another to continue to treat the

patient without interrupting care.

Another important use of the medical record is for reimbursements. The

patient’s file supplies information so the patient and third-party payers

can be billed for services and expenses. The medical record

substantiates laboratory tests, medications, and other services listed on

an insurance claim.

The medical record serves other purposes as well. It’s a legal business record

for the healthcare provider. It gives the patient documentation with which to

make legal claims—for example, the extent of injuries from an auto- or

work

related accident. The record can be used to analyze and review the

quality of patient care. It also can be used for research and education and for

healthcare facility planning and market research. And medical records help

determine problems that the healthcare delivery system needs to address,

such as increases in the occurrence of heart disease or breast cancer.

Medical records first were kept in hospitals. Now, virtually every healthcare

provider maintains such records because complete files are necessary to

verify medical expenses, validate the healthcare provided, and meet

government requirements. Although different types of healthcare providers

maintain medical records, all records still are patterned after the hospital

medical record. The format used, and the information recorded in each record

is similar from one facility to another. The box that follows summarizes the

purpose of the information that medical records provide.

Medical Records:

• Identify the patient

• Record results of tests and treatments

• Justify diagnoses and treatments

• Offer information to all providers involved in the patient’s care

• Detail the patient’s previous care for future providers

• Maintain a record of services for billing third-party payers

• Provide the healthcare facility with a legal business record

• Provide tools for evaluating patient care

• Provide documentation for study and research

• Give healthcare providers data for planning delivery of services and

marketing

Please pause and complete online Practice Exercise 1-3.

Step 8 Lesson Summary

Medical coders are an important part of any medical setting, and the scenario at

the beginning of this lesson showed you how information flows through such

settings. This lesson also gave you a firm understanding as to what each member

of the healthcare team does. Coders work with physicians, nurses, office managers,

and others to contribute to the best possible patient care. You learned that this

care occurs in a three

part sequence: chief complaint, diagnosis, and treatment.

The diagnosis and treatment eventually are coded by you, the medical coding

specialist!

We also discussed a few important points for you to remember as you move

toward your new career. You learned about possible employment

opportunities and settings. You also learned the importance of

professionalism, presentation, and adaptability.

Lastly, this lesson discussed medical records. The medical coding specialist

works closely with medical records to assign the correct codes for the

diagnosis and procedure determined during a patient visit. The accuracy of

the codes determines correctly completed insurance forms, thereby obtaining

the proper reimbursement for the doctor.

As you continue this course, you’ll see in greater detail just how important

medical coding specialists are to those who work in and rely on medical

facilities. Medical coding specialists are in demand! The entire field is

expected to grow by more than 46 percent, and the projected growth for

those coders working directly for physicians is 94 percent! By choosing this

course, you have started on an exciting path toward success.

LESSON 2

Medical Insurance 101

Step 1 Learning Objectives for Lesson 2

When you have completed the instruction in this lesson, you will be trained to do

the following:

Explain how insurance works.

Define the terms common to most insurance carriers.

List the types of insurance programs available today.

Discuss how diagnostic and procedure codes apply to insurance.

Determine the basics of filing electronic claims.

Step 2 Lesson Preview

Most people in America qualify for some sort of medical insurance. In addition to

the various government programs available, hundreds of private companies also

provide medical insurance. Fortunately, a few common threads tie all insurance

companies together, for example, the terminology used and the forms required.

These common threads make the medical coding specialist’s job easier.

A few common threads tie all insurance companies together.

It is important to understand medical insurance concepts. With this

knowledge you will be able to communicate effectively with medical billing

specialists. You will work closely with them to secure the highest

reimbursement for the provider’s services. This is why medical coders are a

vital part of the provider’s support staff.

Additionally, the codes you use play a very important role in health data and

research. Did you know that medical codes help track diseases—and cures—

in our country? These codes are entered into a national database, which is

tracked by health researchers. Much government funding for cancer, AIDS,

and other diseases comes from the codes that you will assign. Not only are

you helping health care providers, but your coding work advances research

and treatment development of many illnesses.

In this lesson we will introduce you to the language of the insurance

world. After that, we’ll move into the different programs available. You’ll

be introduced to the various insurance programs. There are government

insurance programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, the managed care

approaches of health maintenance organizations and preferred provider

organizations.

This lesson will introduce two important concepts—diagnostic coding and

procedure coding—and you’ll learn how these codes relate to medical

insurance. And we’ll discuss electronic claims. Chances are you already know

a little about these terms and programs. If you don’t, fear not! We’ll cover

them here. So let’s get started!

Step 3 The Life Cycle of a Medical Bill

You’ve just started the medical bill’s life cycle.

Let’s first review a little about what you learned in the first lesson. Imagine you are

a patient at a doctor’s office. This is the first time you’ve been to this particular

doctor. When you check in with the front desk, the office manager hands you a

questionnaire to complete. This form asks for your name, address, telephone

number, medical history, and insurance information. After you complete the form,

you give it back to the receptionist. With this process, you’ve just started the

medical bill’s life cycle.

Now the office manager enters your information into the computer. The

computer might then produce a patient encounter form, also known as the

super bill. Remember, this is a standard form that contains a list of the most

common procedures the doctor performs at that office. An encounter form

typically lists many types of procedures and diagnoses, such as office visits,

physical exams, x-rays, blood tests, and common illnesses or conditions.

Based on the information you provided on the questionnaire, the computer

prints your name, billing address, insurance company, and policy number on

the encounter form. When you go back to the examination room, your

encounter form is part of the medical file the doctor works with as she

examines you.

When your examination is complete, the doctor circles on the encounter form

the procedures she performed. Usually, more than one procedure is involved.

For example, the doctor might circle the physical exam—new patient

procedure and the x-ray—lower leg procedure if you had to have x-rays

taken. The circled items let the office manager know what to charge you or

your insurance company for your visit. This form is now your bill.

After the bill is created, the next step in its life cycle is processing. Let’s look

at the details involved in that step.

Processing the Bill

Once the medical bill exists, it goes through several steps on its way to being

paid. A patient and medical facility handle bills for medical care in one of

three common ways:

The insurance company might require the patient to pay the entire bill at the time of service.

1. The insurance company might require the patient to pay the entire bill at

the time of service, before the patient leaves the medical facility. Then the

patient submits a claim to the insurance company for reimbursement.

2. The patient might pay a copayment—a flat amount, such as $10,

determined by the patient’s insurance policy—before he leaves the doctor’s

office. Then the doctor’s office submits a claim to the patient’s insurance

company for the remainder of the bill.

3. The patient might pay nothing at the time of the visit to the doctor’s office.

Following the patient’s visit, the medical facility submits a claim to the

patient’s insurance company for the bill. The doctor’s office is reimbursed

by the insurance company for the charges the patient’s insurance policy

covers. The doctor’s office then sends a bill to the patient for the remaining

costs that the insurance doesn’t cover.

How a medical bill is processed varies slightly depending on whether the

patient pays the bill before or after the insurance company pays its portion. If

the patient must pay the entire bill on the day of the treatment, then it also

is up to the patient to send the bill, together with a completed claim form, to

their insurance company. The insurance company then will pay the patient for

whatever charges the insurance covers. For example, if the bill is $100 and

the insurance policy pays 80 percent of those charges, the patient will be

reimbursed for $80 from the insurance company, leaving the out

of pocket

cost for the bill at $20.

If the doctor’s office bills the insurance company first, then the patient can

leave the office either without paying any of the bill or after paying only the

copayment. The insurance company receives the doctor’s request for

payment and pays the covered amount to the doctor’s office. So if the bill

was $100, and the insurance policy covered 80 percent of that, then the

insurance company would pay the doctor $80. The doctor would bill the

patient for the other $20 or for the difference between the $20 and what the

patient already paid as the copayment.

When the insurance company pays for services, whether it pays the patient

directly or pays the doctor’s office, it is reimbursing the patient or the office.

Reimbursement is the process of paying someone back for services already

performed or payments already made.

This entire process—from the initial questionnaire completed in the doctor’s

office all the way through reimbursement—represents the life cycle of the

medical bill. As you’ve probably guessed, a big part of the medical bill’s life

cycle has to do with the insurance part of the process.

Step 4 Insurance

Medical insurance is a contract between an insurance company or carrier and an individual or a group.

In the first lesson we talked briefly about how the medical codes you assign are

sent to insurance companies so that doctors can be paid. But what exactly is

insurance? Well, the terms medical insurance, health insurance, health care

coverage or some other similar phrase all refer to the same thing. Medical

insurance is a contract between an insurance company or carrier and an

individual or a group—the insured. This contract or policy states that in the case of

certain injuries or illnesses, the insurance carrier will pay some or all of the medical

bills of the insured.

In exchange for this coverage, the insurance carrier collects payments or

premiums from the insured. Premiums are paid in advance—they are paid

monthly, quarterly, semi-annually or annually, depending on the contract

between the carrier and the insured. When an insurance carrier pays for

medical treatment, it pays benefits.

It seems like insurance companies pay out lots of benefits, right? Well,

typically the insurance carrier collects premiums from many people and only

has to pay benefits to relatively few. Therefore insurance companies are

generally profitable and are able to provide their services. Every insurance

company requires an itemized list of procedures, pharmaceuticals, and other

materials before they pay benefits. Every procedure and pharmaceutical has

its own code. This is where you, as a medical coding specialist, enter the

picture. You know from what you read in the previous lesson that you must

code what happens during each patient’s visit. When you’ve completed this

course, you will be able to accurately assign diagnostic and procedure codes

for outpatient services.

But first you need to know the language insurance carriers and medical

coding specialists use to communicate. In the next section, you will learn

some of this language.

Step 5 Common Insurance Terms

Liz is an office manager for Dr. Grant. She is great at making appointments and

keeping track of patients. Yesterday, Dr. Grant’s insurance specialist was out sick,

and Dr. Grant asked Liz to check on some insurance information for him. He asked

her to compare the explanation of benefits for three different patients and see how

much each patient needed to pay. Then he asked if any of the three had a

copayment not yet made. Finally, he asked Liz to check the explanation of benefits

to see whether any of the three patients had met deductibles yet.

Liz understands English very well, but these questions all sounded like another language to her.

Liz understands English very well, but these questions all sounded like

another language to her. She dug through some insurance forms, but she

didn’t have a clue about any of the items Dr. Grant had requested. Finally,

she gave up and asked Dr. Grant to wait until the next day when the claims

specialist returned.

Imagine you were Liz. Could you ask someone from an insurance company

questions—and understand the answers? In this section, you will study some

basic insurance concepts that will help you function intelligently when you

come across insurance terminology in your medical coding work. Let’s review

some of the most frequently used terms and what they mean.

Provider

The provider is the person or organization that provides medical services.

Doctors are an example of providers.

Claim Form

The claim form is the completed document that a provider submits to

an insurance carrier. The medical coder’s job is to assign diagnostic and

procedure codes to each claim. The most common insurance forms are

the CMS-1500 and UB-04.

Deductible

The amount of money an individual must pay before insurance benefits

begin is called the deductible. Usually a policy will pay nothing of the

first $250, $500 or $1,000 of medical charges. They then will pay a

percentage of everything above that amount each year.

Any amount that is “applied to deductible” is a covered charge that is

subtracted from the total deductible amount. The insurance carrier does

not pay any money on “applied to deductible” charges.

For example, imagine that Toby has a medical policy that has a $250

deductible and, after the deductible is paid, 80 percent coverage. So far

this year, Toby has spent $200 of his own money on medical care, and

that medical care has been defined as covered under his insurance

policy. For the insurance company to begin to pay 80 percent of Toby’s

covered medical care costs, he must still pay out $50 more for covered

charges. After he has met the $250 deductible, Toby’s medical insurance

benefits will begin, and the carrier now will pay 80 percent of each claim

submitted for covered charges for the rest of the calendar year.

Copayment

A copayment is a flat amount of money paid by the patient at each visit

or for each prescription. Many policies have a copayment for prescription

drugs or office visits to a doctor. That means every time a person fills a

prescription or visits the doctor, it costs her no more than her copayment;

however, she must pay that copayment every time she fills a prescription

or goes to the doctor. Some policies require copayments even after the

deductible has been met. Other policies have no deductible, but a

copayment is required every time any type of medical care is received.

Copayments are paid at the time of service.

Reasonable and Customary

The phrase reasonable and customary or R&C refers to price

guidelines that insurance carriers use for different procedures. Usually a

carrier only will pay up to the maximum on their reasonable and

customary fee, regardless of the actual cost of a procedure to the patient.

For example, if a patient has knee surgery and the doctor charges

$1,000, the insurance company compares that fee to its reasonable and

customary scale.

If the R&C scale gives a $900 limit for that particular procedure, then the

patient may be responsible for the extra $100, depending on the agreement

the physician has with the insurance company. The physician may accept the

R&C scale amount. Fees that exceed the reasonable and customary scale are

disallowed by the carrier.

How much will he have to pay?

Many private insurance carriers have adopted the reasonable and customary

guidelines for their coverage. Many government insurance programs, which

we’ll discuss momentarily, also use reasonable and customary guidelines.

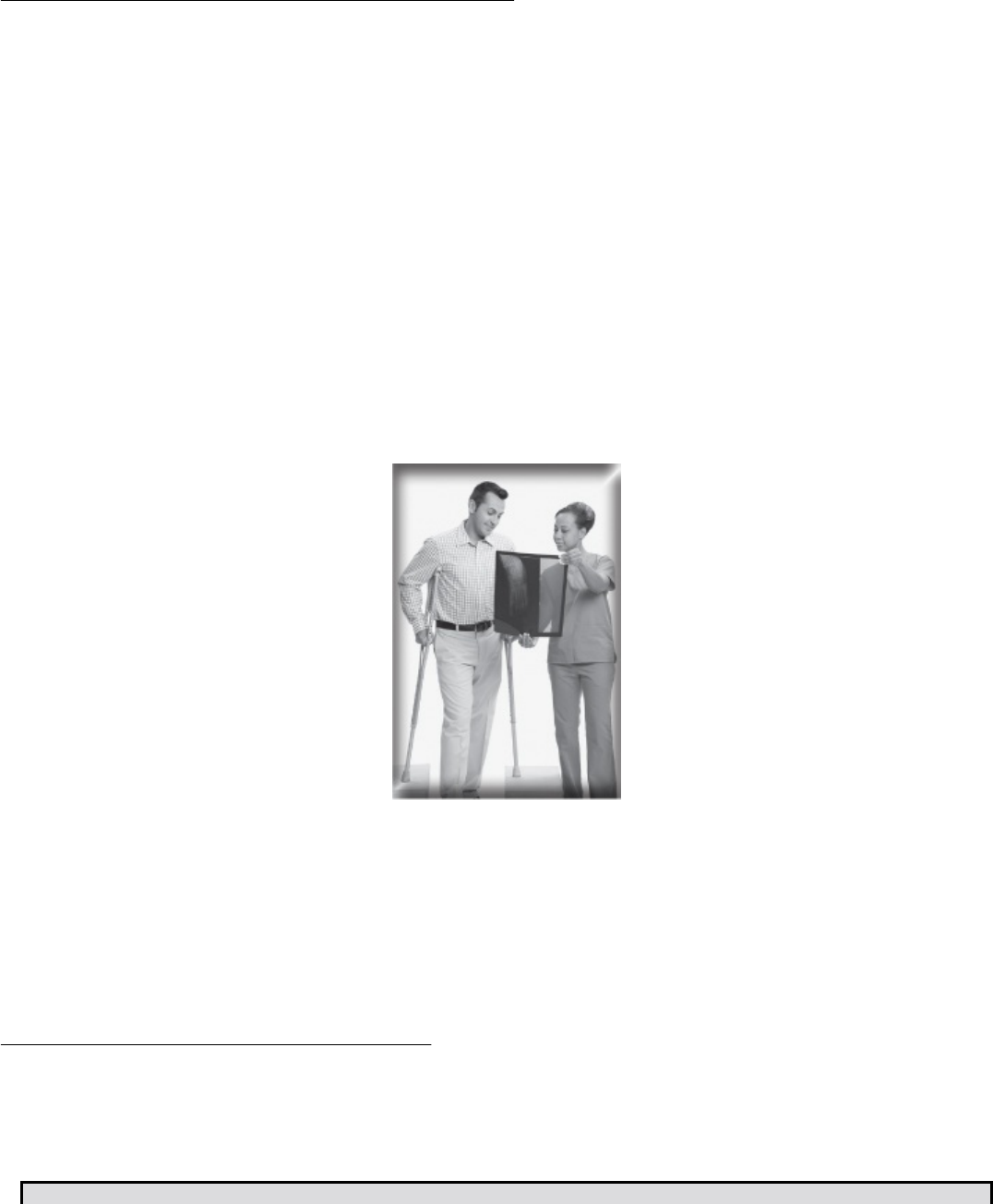

Explanation of Benefits

The explanation of benefits or EOB is a document that explains how much

the insurance company paid and how much it disallowed. Let’s look at two

samples of EOBs.

Bill from Doctor: $50

Disallowed: $6

Allowable Charge: $44

Applied to Deductible: $15

Amount due from Carrier: $29

The insurance company sends an explanation of benefits every time you

submit a claim. Even if the carrier is paying nothing on the claim, it still

sends this statement explaining why. As you can see from the example

above, the insurance carrier is paying $29 of a $50 charge, which means the

patient is responsible for the remaining $21.

The following table represents a breakdown of the EOB with a line-by-line

explanation of terms and amounts for the above example:

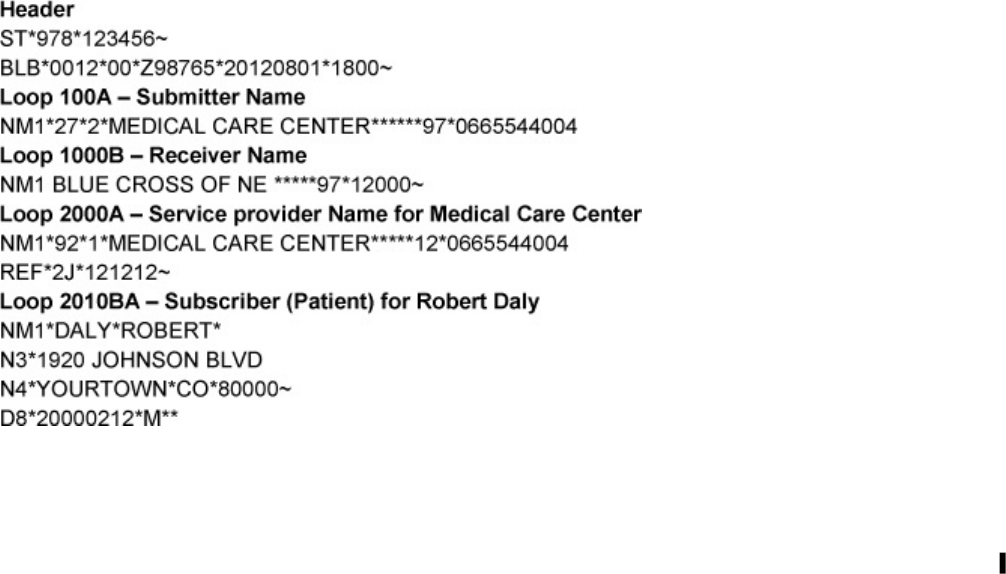

Electronic Claims

Before you dive into specifics, let’s first take a look at how electronic claims

processing works.

The Internet is used to determine eligibility.

Marissa enters her doctor’s office for her appointment. First, the office

manager uses the Internet to visit Marissa’s health plan Web site to

determine Marissa’s insurance eligibility. Next, the office manager prints out

an encounter form for the visit. The doctor sees Marissa, gives her a

prescription, and notes the diagnosis and procedure in her medical record.

Marissa then checks out with the office manager and pays her

copayment. The office manager begins the life of an electronic claim.

During the past several years, electronic claims submission rapidly has

gained popularity. But what exactly is an electronic claim? An

electronic claim is a digitized insurance claim form transmitted from a

computer using a modem and received by an insurance company or

clearinghouse. What does digitized mean? Well, after you, the coder,

code the items for the service, the data is entered into the computer.

Medical billing specialists use computer software to enter patient and

billing information into a claim format. When the data is entered into a

computer record, the information is digitized. That information then is

transmitted to a clearinghouse or insurance company using computer

software and a modem that allows the medical billing specialist’s

computer to communicate with the clearinghouse’s computer.

A clearinghouse is a company that facilitates the processing of claims

information into standardized formats and then submits the claims to the

appropriate insurance companies. Some insurance companies can receive

electronic submission of claims without going through a clearinghouse.

The clearinghouse downloads reports to the medical billing specialist

indicating how many claims it received, and then the electronic claims

are forwarded to the payers. The insurance carriers or payers will report

to the clearinghouse when they receive the claims.

After the insurance company receives the claim from the clearinghouse,

the claim is processed and paid or rejected. As you can imagine,

electronic insurance claims get paid much faster than paper claims.

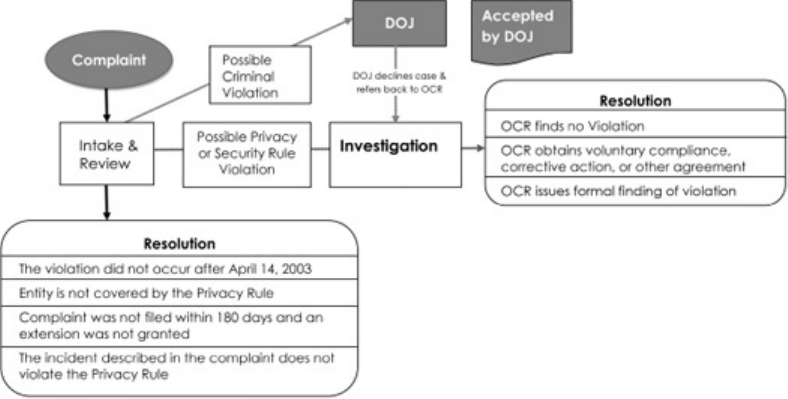

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act or HIPAA

regulates electronic claims, though this is just one of the many services

the act provides. The goal of HIPAA is that all healthcare workers have

similar ease and efficiency in their own communications. Later in this

course we’ll discuss HIPAA and its other facets in a bit more detail. You’ll

also learn exactly how it regulates electronic healthcare transactions.

Please pause and complete online Practice Exercise 2-1.

Step 6 Types of Health Insurance

Hundreds of private insurance companies provide medical coverage for individuals

and groups. These private insurance companies generally follow standards similar

to the government programs we will cover here. This next part of the lesson is

designed to introduce you to the many types of government-sponsored insurance

programs and each program’s requirements for coverage, along with the basic

types of private insurance.

Government Insurance

Unless otherwise noted, these programs are administered by the federal

government.

There are many types of government-sponsored insurance programs.

Medicare

Medicare is a federal health plan that covers people aged 65 and older and

people with disabilities.

Medicaid

Medicaid is a state-sponsored insurance program for low-income people

who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford health insurance.

CHAMPUS

Until recently, CHAMPUS, which stands for Civilian Health and Medical

Program of the Uniformed Services, provided medical coverage for the

families of the various uniformed government services, including the armed

forces. Many changes have taken place in the military healthcare system in

the past several years. The most important of these changes is the transition

from CHAMPUS to the TRICARE healthcare system.

TRICARE

TRICARE is the name of the Department of Defense’s regional managed

healthcare program for military service families. TRICARE provides healthcare

options for the families of active-duty service members. These family

members are called beneficiaries. The service member is called the sponsor.

A sponsor can be active-duty, retired, or deceased. As its name suggests,

TRICARE has three options: TRICARE Standard, TRICARE Extra, and TRICARE

Prime.

TRICARE Standard

This is the new name for CHAMPUS. TRICARE Standard pays a share of the

cost of covered healthcare services obtained from authorized civilian hospitals

and doctors.

TRICARE Extra

This is a PPO-type option that provides healthcare services for eligible

participants on a visit-by-visit basis.

TRICARE Prime

This is an HMO-type option and is currently the least costly healthcare option

offered through TRICARE. Eligible persons must enroll for a year at a time

and agree to seek healthcare from the network of healthcare providers,

hospitals, and clinics. There is a fee for enrollment for retirees; active-duty

service members are enrolled automatically.

CHAMPVA

CHAMPVA, which stands for Civilian Health and Medical Program of the

Veterans Administration, provides medical coverage for veterans with

permanent, service-related disabilities. If a service member dies from a

service

related disability, CHAMPVA also provides coverage to the service

member’s family. Although very similar to TRICARE Standard in terms of

benefits, CHAMPVA is a separate program, distinctly different from

TRICARE Standard.

Workers’ Compensation

Workers’ compensation, a state-run program, pays the medical bills for

people with job-related illnesses or injuries.

Workers can be injured on the job.

In addition to the preceding government programs, many private insurance

companies exist. Private insurance companies can be categorized as either

traditional or managed care. In addition, there is Blue Cross/Blue Shield,

which represents a special case.

Private, Traditional Insurance

Twenty-five years ago, the traditional insurance concept was the only one.

The insurance company contracted with an individual to pay his or her

medical bills based on a fee-for-service concept—that is, whatever the

physician or medical provider charged was the amount on which the

insurance company based its reimbursement.

Private insurance companies are in business to earn profits. They pay out

benefits but also take in much more in premiums.

Managed Care

As healthcare costs skyrocketed, many businesses that held group insurance

policies for their employees began looking for ways to save money and still

provide excellent healthcare coverage. The solution was managed care.

Born in the 1980s, managed care introduced the concepts of Health

Maintenance Organizations, or HMOs, and Preferred Provider

Organizations, or PPOs. In both, groups of doctors contract with the

organization to charge set amounts for procedures. These amounts do

not change, and the patient cannot be charged an additional fee beyond

a copayment.

In HMOs, patients pay a fixed periodic rate monthly, quarterly or

annually. Patients then receive whatever health care they need, but they

must see a physician or medical provider who is part of that HMO. HMOs

encourage their members to practice preventive health care, often paying

for routine physicals and tests designed to catch signs of illness before

the person actually becomes sick. The patient is assigned a primary

physician when she joins the HMO. This primary physician then oversees

that patient.

Patients pay a fixed rate monthly, quarterly or annually.

PPOs contract with many doctors who agree to charge rates according to

the PPO scale. These doctors are not “employed” by the PPO. Instead,

they are independent offices, hospitals, and clinics that have joined the

PPO. When patients in a PPO go to a doctor or clinic who is not part of

the PPO, that patient sees a large reduction in benefits.

Blue Cross/Blue Shield

The oldest and largest prepaid insurance carrier is Blue Cross/Blue

Shield. Blue Cross provides hospital, outpatient, and home-care

coverage. Blue Shield covers physician services and provides dental and

vision-care coverage.

Blue Cross/Blue Shield differs from the other private insurance providers in

that it is not a commercial insurance company. Blue Cross/Blue Shield is a

federation of nonprofit community insurance corporations. Even though Blue

Cross/Blue Shield is not technically a government program, it must receive

state-level government approval before it can raise its rates.

Just as the HMO and PPO managed-care companies do, Blue Cross/Blue

Shield contracts with doctors who agree to charge a set fee for procedures

performed. Blue Cross/Blue Shield then reimburses the doctor directly for all

charges.

Step 7 Diagnostic Codes—A Piece of the Insurance

Puzzle

Now that you know about the different types of insurance programs, let’s take a

moment to discuss medical codes and how they apply to insurance.

After a patient’s office visit, tests, and other procedures, the medical billing

specialist fills out a claim form, which we discussed previously in this lesson.

These forms require special codes—diagnostic codes for diagnoses and

procedure codes for procedures performed. When you write a code on an

insurance form, a bill or a patient’s chart, you are “coding that entry.”

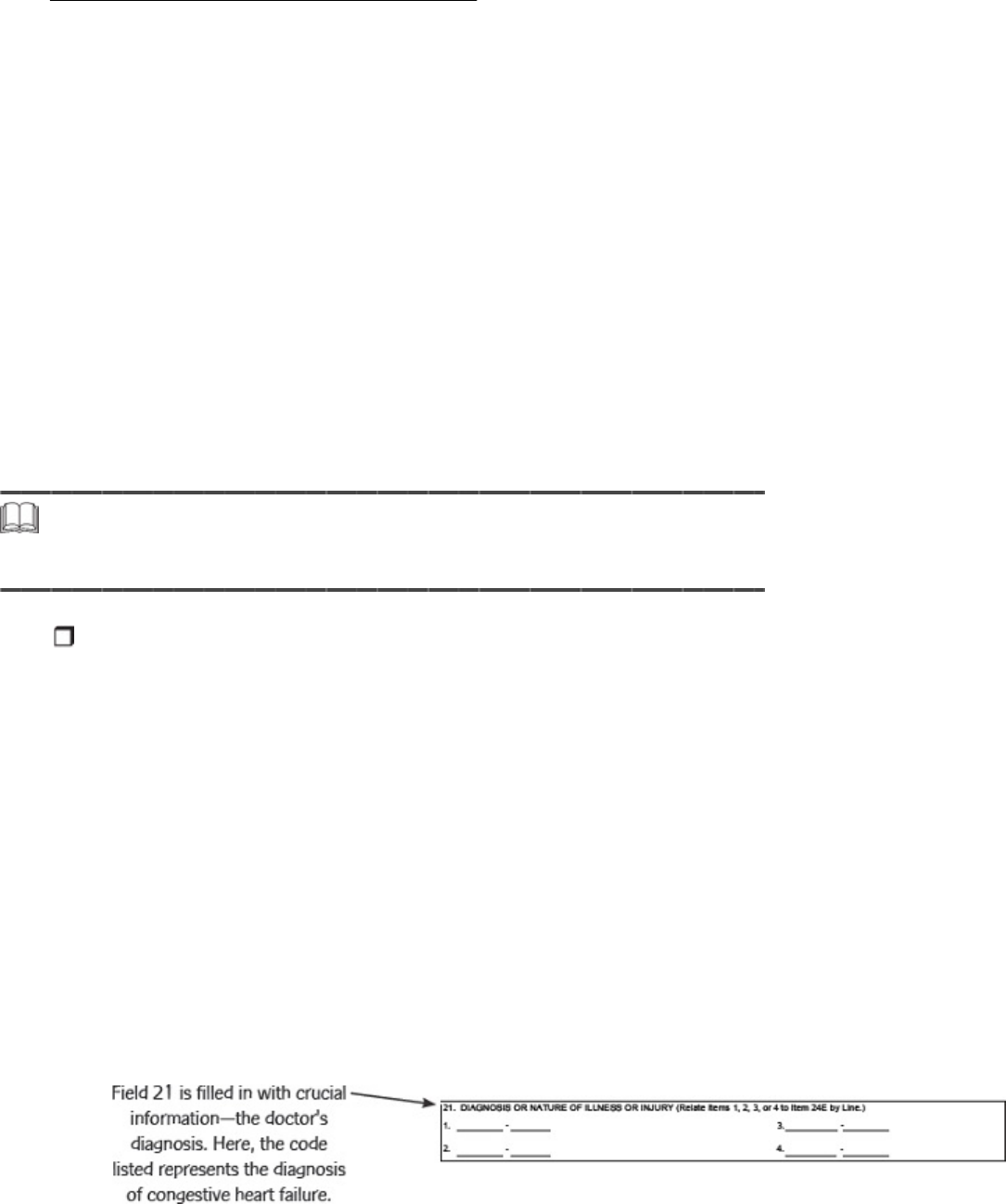

When you look at the CMS-1500 form, there are many fields to be filled.

One of the most important fields is Field 21—Diagnosis or Nature of

Illness or Injury. In this field, you must enter some crucial information.

But what information? Do you write in the doctor’s diagnosis? No. You

must use a diagnostic code.

Field 21 is filled in with crucial information—the doctor’s diagnosis. Here, the code listed represents the diagnosis of

congestive heart failure.

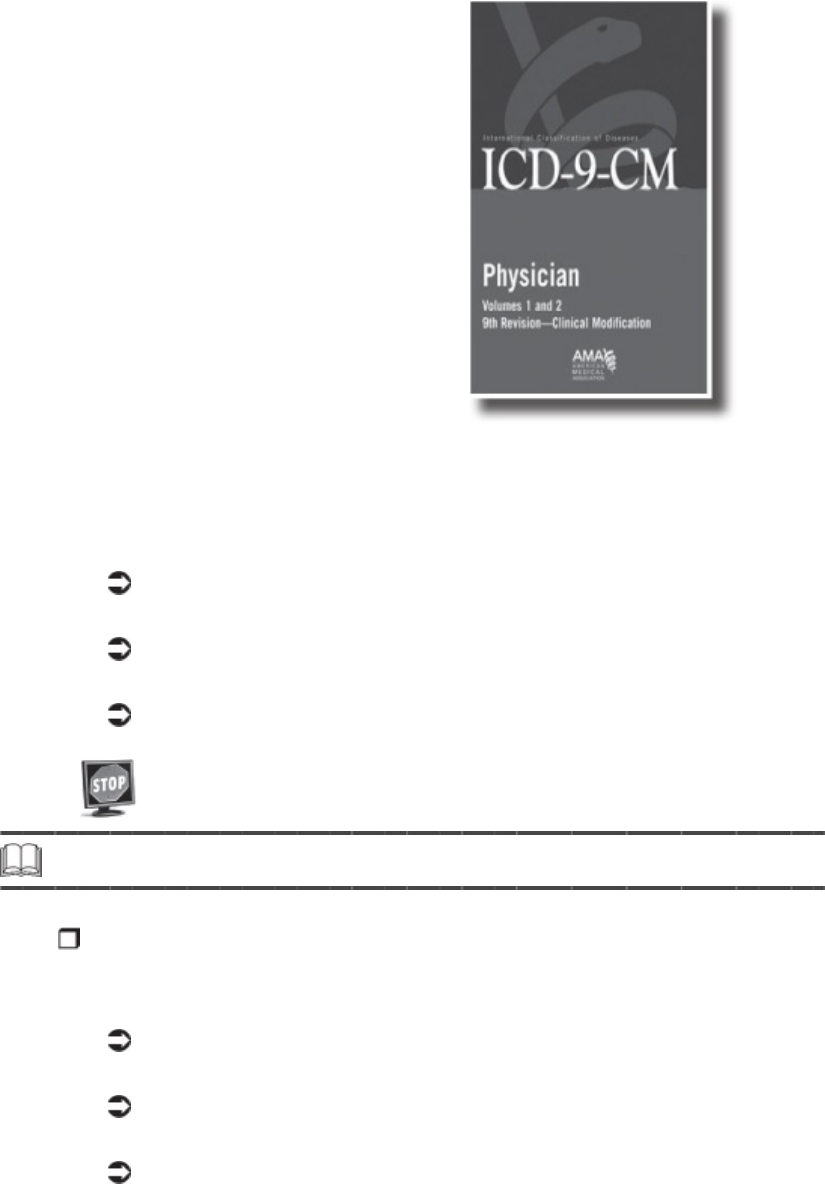

Diagnostic codes are numbers that identify the physician’s opinion

about what is wrong with the patient. This is the physician’s diagnosis.

These codes are not random numbers; they are based on a system called

the International Classification of Diseases or ICD. Hospitals, doctors’

offices, and medical coding specialists use ICD codes.

Often a patient is suffering from more than one symptom. In this case,

multiple diagnoses may apply. The doctor will determine a principal

diagnosis—usually the main cause of the symptoms or the main health

problem. When you code, you always enter the principal diagnosis code

first.

When a physician diagnoses more than one condition, the ones that aren’t principal are called concurrent conditions.

When a physician diagnoses more than one condition, the ones that aren’t

principal are called concurrent conditions. That means these conditions

happen at the same time as the principal diagnosis and might affect how the

patient recovers. For example, if Luke comes to the doctor suffering from a

broken leg—both the lower leg bones in his left leg are fractured—and a

sprained ankle.

How Important Is Diagnostic Coding?

It is your accurate and complete coding that ensures maximum

reimbursement to the provider and provides meaningful statistics to

assist our nation with its health needs. You probably think this seems like

a lot of responsibility, but don’t worry! You are not alone in this.

You know the whole process starts with the doctor and the patient. The

doctor has the responsibility to examine, test, and treat the patient as

needed and then document the services, supplies, and diagnosis.

Following the patient’s appointment, a medical transcriptionist types up

all of the information, and a medical coder then translates that

information into codes that support the procedures performed.

The codes and patient data then are transferred to a claim form and sent

to the insurance carrier for reimbursement to the provider based on the

medical necessity, diagnosis, and procedures involved. The types,

frequency of treatments, and diagnoses gathered from the patient

information provide the statistics necessary to depict health care in this

country. The government and insurance companies use these statistics to

establish guidelines to develop the rates of reimbursement paid to

medical practices in the future.

So you see, it’s the analysis of diagnostic codes that determines whether

insurance carriers will provide coverage for a particular procedure or

service. However, in the past, the diagnostic information that insurance

carriers gather has not been consistent. Therefore, the government now

is developing newer methods for collecting this information.

Now you have a bit of an idea as to how your new role affects insurance

reimbursement. Without your coding skills, doctors would not get

reimbursed for their services! We will cover diagnostic coding concepts

later in the course. Now, let’s look at procedure coding.

Step 8 Procedure Coding—Another Piece of the Puzzle

Diagnosis coding is not the only kind of coding you will do. If you look at the

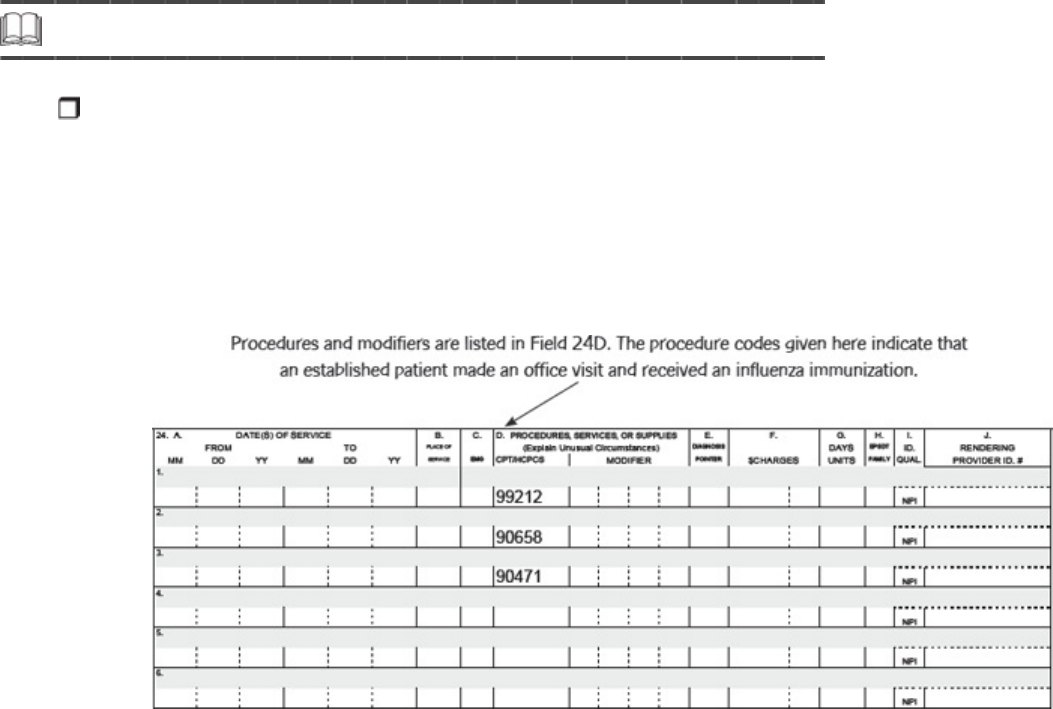

portion of the CMS-1500 form that follows, you will see Field 24D—a column for

Procedures, Services, or Supplies. This column is divided into halves. The first half

is labeled CPT/HCPCS, and the second is labeled Modifier. It is in this field that you

write down the code for the procedures and any modifications of those procedures

or treatments and tests that the doctor performed.