Exploring Designers’ Practice of Online Example Management

for Supporting Mobile UI Design

Ziming Wu

∗

Hong Kong University of Science and

Technology

Hong Kong, China

Qianyao Xu

∗†‡

The Future Laboratory, Tsinghua

University

Beijing, China

Yiding Liu

∗

Hong Kong University of Science and

Technology

Hong Kong, China

Zhenhui Peng

Hong Kong University of Science and

Technology

Hong Kong, China

Yingqing Xu

†‡

The Future Laboratory, Tsinghua

University

Beijing, China

Xiaojuan Ma

Hong Kong University of Science and

Technology

Hong Kong, China

ABSTRACT

The use of digital examples plays a critical role in mobile UI design.

Yet, it remains unclear how UX/UI designers manage (i.e., collect,

archive, and utilize) examples to facilitate their design processes at

dierent stages, and what possible challenges are imposed on the

design of proper tools to support these practices. In this paper, we

conduct a qualitative interview study with mobile UI/UX designers

(12 experts and 12 novices), deriving the commonality in practices

and analyzing possible dierences across four design phases (Dis-

cover, Dene, Develop, and Deliver) and expertise. In brief, we

nd that there is more diverse and frequent use of examples in the

Discover and Develop phases, and that experts take more diverse

advantage of the information from examples compared to novices.

We further identify the challenges faced by designers when using

existing example management services, and propose potential de-

sign implications for the development of more supportive design

tools in the future.

CCS CONCEPTS

• Human-centered computing → Human computer interac-

tion (HCI); Empirical studies in HCI.

KEYWORDS

Example management; mobile UI design; design practice

ACM Reference Format:

Ziming Wu, Qianyao Xu, Yiding Liu, Zhenhui Peng, Yingqing Xu, and Xi-

aojuan Ma. 2021. Exploring Designers’ Practice of Online Example Manage-

ment for Supporting Mobile UI Design. In 23rd International Conference on

∗

indicates equal contribution.

†

Tsinghua University-Alibaba Joint Research Laboratory for Natural Interaction Expe-

rience, Beijing, China

‡

Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for prot or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation

on the rst page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM

must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish,

to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specic permission and/or a

fee. Request permissions from [email protected].

MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France

© 2021 Association for Computing Machinery.

ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-8328-8/21/09.. . $15.00

https://doi.org/10.1145/3447526.3472048

Mobile Human-Computer Interaction (MobileHCI ’21), September 27-October

1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3447526.3472048

1 INTRODUCTION

Mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets, have become a

pervasive window for users to access information and services, e.g.,

over three billion of people around the world own a smartphone by

September 2018 [

1

]. It is mobile user interface (UI) designers’ goal

to create good interactive experiences for mobile devices’ features,

content, functions, and apps installed. To succeed in this mission,

mobile UI designers often turn to design examples for inspiration,

reinterpretation, and evaluation of ideas [

33

], a common approach

also taken by designers in other domains [

30

]. The typical mobile

UI design examples include but not limited to graphic elements

(e.g., logo, button, and UI animation), case studies (e.g., detailed

design documents), and competitor apps. The visual illustration of

these examples is shown in Figure 1. Despite that emerging online

design repositories, e.g., Dribbble

1

, Behance

2

, and Pinterest

3

, make

it easier than before to search, catalogue, and share digital design

materials [

27

], mobile UI designers still encounter many issues

in their process of managing – collecting, archiving, and using –

examples.

Prior research suggests that design xation, i.e., “a blind adher-

ence to a set of ideas” [

17

], and diculty in articulating query

information are recurrent problems that web, graphic, and prod-

uct designers run into when searching for examples from external

sources [

12

]. Web designers also concern about their diculty in

identifying trustful resources of relevant design examples and about

the inconsistent benets of examples in dierent design phases [

21

].

While mobile UI designers are likely to experience similar hurdles

identied in other domains during example management, those

conclusions in other domains may not be directly applied to mobile

UI design due to the notable dierence between mobile devices and

desktops including the lack of tactile feedback, ubiquity, limited

screen size, etc [

28

]. Designers face additional, unique challenges

introduced by peculiar characteristics of mobile UI design materials,

such as form factors and interaction modalities [6].

1

https://dribbble.com/

2

https://www.behance.net/

3

https://www.pinterest.com/

MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France Wu and Xu, et al.

It is thus necessary to dig into the specic practices of mobile UI

designers to uncover design opportunities for better technological

support [

3

,

22

]. In this paper, we seek to gain deeper insights into

mobile UI designers’ way of dening and applying examples as well

as their experiences with existing online repositories. We are partic-

ularly interested in how their practices may dier across dierent

levels of design expertise and across various design phases. Prior

human-computer interaction (HCI) research indicates that pro-

ciency in design aects how designers treat examples. For example,

compared to novices, expert designers rely less on examples [

25

]

and could evoke a larger number of creative ideas when presented

with examples less similar to the intended design task [

3

]. However,

little is known about the impact of other qualities that expertise

entails, such as role in a project team, on mobile UI designers’ ex-

ample management practices, as well as about how such an impact

spread across dierent design phases.

In short, we aim to explore how designers’ practice of example

management evolves throughout the mobile UI design process, and

how design expertise plays a role within this context. To this end,

we conduct a series of interviews with 24 designers including 12

experts and 12 novices. We compare their means to collect, archive,

and employ examples in four design phases, i.e., Discover, Dene,

Develop, and Deliver introduced in Double Diamond (DD) frame-

work [

5

], to extract similarities and dierences. Double Diamond

framework was developed by Design Council, which has been com-

monly used in the design community. It is the design process model

that was most frequently mentioned by our participants. Moreover,

it has a clear, concise, and detailed denition of each of the four

design phases [

34

]. We thus adopt DD framework in our paper as a

guideline to systematically summarize the participants’ behaviors.

We also gather information about their ways of exploiting the ex-

isting online design repositories, the features they like, the issues

they encountered, and methods for working around technological

barriers, if possible. Our ndings suggest that among all phases,

managing examples takes place more often in Discover and De-

velop. Furthermore, compared to novices, experts discover more

diverse usage of design examples.

The main contributions of this paper include:

•

We provide a deep understanding of how designers manage

(i.e., collect, archive, and utilize) examples in their mobile UI

design practice via a series of interviews with 24 designers.

•

We compare the example management behaviors of the ex-

perts and novices across distinct design phases to uncover

the similarities and dierences.

•

We identify places where current online design material

services fail to meet the need of mobile UI designers, and

suggest opportunities for developing future design support

tools.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Example in Design

Examples involved in creative design process are the materials that

designers constantly refer to. It is a typical type of design collections

[

23

], which may come in various forms, including graphic elements,

sketchy prototype, interaction logic, physical models, etc. [

12

]. They

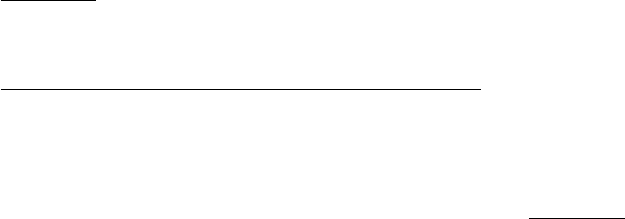

Figure 1: Illustrations of the three types of examples: a) UI

page, b) case study, and c) competitor

provide templates of design solutions, organized ideas, and sources

of inspiration for various perspectives [8].

Prior studies have extensively investigated the eects of design

examples. On one hand, as a vital part of design activities, using ex-

amples brings essential benets to the design process [

36

]. Examples

facilitate the creation of a visual framework, the reinterpretation

and evaluation of design ideas [

2

,

31

]. In particular, the designers

tend to generate more diverse and creative ideas if they have more

adequate proper examples [

30

]. Meanwhile, designers can benet

from examples by comparing and evaluating dierent design fea-

tures. On the other hand, examples can cause impediments in terms

of design outcome. Negative eects of exposure to low-quality ex-

amples have been observed, even for experienced designers. More

specically, semantically far inspirational examples can be harmful

in creativity during productive ideation [

4

]. Further, designers can

be xated while facing examples similar to their own artifact to

be designed [

17

]. This is so-called design xation, in which case,

the diversity and originality of the design outputs are limited by

particular examples [26].

2.2 Practice of Example management

Existing HCI research has found that design example usage varies

in dierent stages of design [

12

]. For instance, in the idea genera-

tion stage, example usage helps to deepen the understanding of the

current market, promoting reinterpretation on existing designs and

originality of the proposed design, while in the evaluation stage,

example usage serves as a method to measure the originality and

validity of the design solutions [

12

]. Behavioral dierences have

also been observed between design experts and novices. As experts

have accumulated more design ideas and experience than novices

do in general, they rely less on design example [

25

]. Although with

this fact, it turns out that design xation happens more severely to

experts [

35

]. These existing studies, however, merely focus on one

factor, either design process or design expertise, without taking

both of them into one picture for discussion. Consequently, they

generate limited insight into how to support the novice and expert

in actual design practice. Moreover, while such ndings have iden-

tied the patterns from a general design perspective, they might

not be generalized to a specic domain, mobile UI design, given the

distinct practice across domains [

12

]. The unique design features of

Exploring Designers’ Practice of Online Example Management MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France

mobile devices, such as their ubiquitous nature, small size factors,

and interaction modalities, as well as the existing standardized de-

sign guidelines, signicantly distinguishes mobile UI design from

other design elds [

6

]. To shed light on how computer technologies

might better assist mobile UI designers, we look into the practice

of online example management with existing services. Our work

diers from existing research in coupling the consideration of de-

sign process and design expertise within the context of mobile UI

design.

2.3 Tools and Platforms for Example

management

Multiple ways to nd examples have been identied during de-

sign procedures, such as referring to physical materials and online

resources, meeting people, and so on. Among them, online manage-

ment platform is recognized as a crucial and prevalent channel for

designers to gather information and inspirational materials, espe-

cially with the recent advance of online design repositories [

21

,

25

].

But limited attention has been paid to how those online platforms

support example management and thereby foster creative designs.

The most relevant work is done by Koch et al.[

21

], in which they

conrmed online platforms as a prevalent source of design ideas

through a survey study. By looking at what online materials de-

signers refer to, the authors showed that designers have concerns

about trust and relatedness about online examples. Nevertheless,

they did not touch how these online platforms support example

management and what challenges designers may face in this pro-

cess.

There has been research on developing tools for designers to

support example management, which can be summarized into two

categories. One is to facilitate designers to attain examples in an

ecient and natural manner. For example, Yee et al. introduced a

category-based interface that enables navigation along the concep-

tual dimensions [

39

]. Kang et al. designed Paragon which helps to

browse examples eciently by leveraging metadata [

20

]. A more

recent technology so-called Swire takes designer-created sketch as

input and returns relevant UI examples, providing natural and novel

interaction for example query [

16

]. The other branch of studies

encourages both exploration and exploitation of design examples,

in order to avoid the pitfalls of design xation. A typical work is by

Koch et al. who developed a machine learning supported tool for

interactive ideation assistance, allowing the adaption of exploration

and exploitation strategies [

22

]. Our study is orthogonal to these

work by providing the detailed implications into designers’ needs

for mobile UI design.

3 METHODOLOGY

The ultimate goal of the paper is to explore designers’ practice

of online example management and establish a comprehensive

and systematic understanding of it. To this end, we conduct semi-

structured interviews to address the following research questions:

(1) What types of online examples do designers refer to during

mobile UI design process? How do they collect, archive, and utilize

those materials in practice? (2) How, if at all, does the example

management practice dier by design phases and design expertise?

(3) What are the challenges and opportunities of current example

curation platforms for mobile UI design in the process of example

management?

3.1 Interview Procedure

We recruited interview participants through word-of-mouth and

advertisement on various social media, e.g., Facebook, Twitter, and

WeChat. Among the applicants, we selected 12 expert designers (

E1-E12, who have at least two-year working experience in the in-

dustry) and 12 novices (N1-N12, who are university design students

without working experience) (including 14 females and 10 males,

Age

mean

=

26

.

7). Among the experts, seven work for a company,

three work for multiple clients at an agency, and the other two

work for a university. The participants were all required to have

mobile UI/UX design experience. We conducted semi-structured

interview, either face-to-face or online, with 24 participants. After

getting their consent, we began each interview session by inquiring

about the participants’ recent or ongoing mobile UI design projects,

which serves as a warm-up and oers context for further conversa-

tions about their example management behavior. Discussions about

the interviewees’ current design practice started with one specic

mobile UI project, gathering data about in what design phase(s)

they would use digital examples, and what types of examples they

apply as the design process unfolds. We then asked participants

to describe how and why they typically collect, archive, and uti-

lize examples. They rst derived a general pattern from their own

memories and then referenced their recent design works as con-

crete instances to walk us through specic actions involved in their

actual design process. Subsequently, for each management-related

action identied in the conversations, we asked about their goal

and how they achieved that. More specically, we are interested in

knowing what tools they have been using, what their expectation

are and what barriers they have encountered with existing services.

Further, we posed questions about how the examples they fetch

aected their design outcomes. We asked for additional example

management actions until the participants cannot recall any more

cases. Finally, we closed the interviews with sharing of overall im-

pression about current search tools. Each interview lasted around

90 minutes.

3.2 Thematic Data Analysis

To conduct thematic analysis on the interview data, three of the

authors rst familiarized themselves by going through video record-

ings and transcripts from all sessions to become fully immersed

in the data. Then, the three authors extensively and carefully per-

formed open coding on those data over several rounds. During

this process, the team met regularly to compare and discuss each

other’s codes, consolidating dierent codes into potential overarch-

ing themes related to reoccurring patterns of example management

behavior, including example collection, archiving, and utilization.

Through several rounds of reading, comparing, and rening the

emerging themes, the team generated several sub themes and came

up with an embryonic form of the code book. More specically,

we allowed for new codes to emerge if they do not t clearly into

extracted codes and for the codes to evolve if the denitions are too

narrow or too broad. From there, we dened the themes that we

identied and organized them into a coherent set that t together

MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France Wu and Xu, et al.

to capture the experiences of the participants. When we reported

quotes from participants, we referred to the transcripts and trans-

lated them into English if the interview session was initially carried

out in other languages.

In the following sections, we rst describe the themes about

collecting, archiving, and utilizing examples. Next, we report how

example management behaviors dier between expertise and across

design phases. Lastly, we identify the challenges encountered by

designers with existing example-related online platforms for mobile

UI design, and further provide implications on the improvement of

example management services.

4 COLLECTING EXAMPLES

An important topic emerged from the interview responses is about

example collection, including what examples do designers com-

monly use for mobile UI design and how do they retrieve such

examples from a large repository of online design material. We

identify three major types of design examples and three kinds of

search behaviors.

4.1 Example Identication

While standalone UI pages, as mentioned in [

11

], are the kind of

design examples brought up the most by all our interviewees, UX/UI

case studies (75 %) and competitor apps on the market (60 %) are

two other categories frequently exploited to inspire and/or inform

design. Figure 1 showcases these three design types according to

our interviewees. We nd that designers tend to leverage them

for dierent purposes and thus often focus on dierent aspects of

information.

4.1.1 UI Page for Inspiring Graphic Design. A standalone UI page

is a static or dynamic snapshot of a mobile app interface. It can

exhibit dierent levels of prototype resolution, which refers to

the degree of sophistication [

15

], ranging from wireframes to re-

alistic screenshots [

11

] (Figure 1.a). Designers mainly inspect UI

pages for gaining insights into mobile app graphic design (E6,12 and

N6,7,11,12). Some of them focused on the overall graphic design,

such as “the page layout” (E1,3,7 and N1,3,9,10,11), “the graphic

style” (E3,4,5 and N4), and “design trend” (E2,5). In particular, E5

and N10 examined wireframes that illustrate realization of features

through organization of functions and UI pages. N4, instead, scruti-

nized the visual aspects, “In the visual presentation design, I would

imitate the graphic styles and colors of examples. That’s why I

expect their color schemes can match the key visual style of my

own project”. Others (E3,4,5,11 and N2,3,8,12) highlighted the im-

portance of identifying specic static UI components for reference,

including but not limited to icons, buttons, and menus. E3 “would

inadvertently mimic the interactive button, the shadow and the

style of the icon”. N8 added, “When I am not sure which certain

icons might be better, I always nd the examples with those icons

to see how they appear in the actual design”. A few respondents

were also interested in UI animations, the dynamic changes within

each UI page or those between pages (E4,5,11 and N2,12). Since

static pages cannot capture this vital dynamic UI feature, they have

to obtain dynamic snapshots of UI pages saved in animated images

(Gifs), videos, or interactive prototypes. Such UI examples, however,

are rather scarce compared to still images (E7,9 and N9).

Though UI pages are prevalent examples employed in mobile

UI design process, they have several inherent limitations. First,

interaction logic and ow are not explicitly demonstrated. Hence,

some designers try to reverse-engineer the logic from a sequence of

pages. Further with the limited contextual information depicted by

UI pages, it is hard to make sense of and articulate the design ideas.

As E4 described,“When I communicate with developers, using static

documents or scattered pages to illustrate the prototype and convey

the concept is normally time consuming.”To tackle these challenges,

designers would leverage another typical type of examples, case

study, which “ delivers more details and context” (N7).

4.1.2 Case Study for Learning Design Rationale. A UX/UI case study

is a detailed documentation of a successful design project, sharing

the design experience and outlining the issues essential to consider

on projects of dierent kinds and aims [

18

]. It usually conveys the

information about background, functionality, and user research [

18

]

(Figure 1.b). Functionality presented in a case study enables design-

ers to have a design experience with its complete interaction logic,

as pointed out by the majority of the interviewees. According to

N9, “ When designing art museum apps, I will use functions and in-

teraction logics of all the museum’s apps as references to construct

my own.”

In addition, 11 of our designers found the adequate contextual

and analytical information provided in case studies particularly in-

sightful for special purpose-driven design.“The case studies explain

reasons and intentions behind each design decision. They largely

enhance my understanding of the examples and avoid supercial

reference to them.” E6 further demonstrated how he employed case

studies, “When I design a weather data visualization app, I read a lot

of case studies of existing data visualization demo and then apply

the same rationales to backing up my own UI choices.” Moreover,

ve designers indicated the use of case studies to keep up with the

most recent design trends and to study how they arise and evolve.

E5 for instance said that she would “research on case studies or

industry reports to learn the most fashionable design.” Despite their

practicality, UX/UI case studies are not widely available on the

Internet. Perhaps that is why many designers thus turn to existing

applications as an alternative for design reference. E8 mentioned “In

the initial stage of app design, I often research competing products

and try not to miss each update version of them. ”

4.1.3 Competitor for Benchmarking. A competitor app is an exist-

ing mobile application available in Appstore that shares similar,

if not the same, target users, business goals, and/or functions to

the on-hand projects [

13

]. Designers often leverage two pieces of

information of an online app: designers examine the meta data of

the existing apps in appstore, such as “the feature list, the interface

pages, the product description, and user comments” (N1), and a

taste of actual user experience obtained by downloading competitor

apps and interacting with them. Through assessment of competitor

apps, designers could “become more familiar with what is already

available on the market” (N2), which serves as a guidance to their

own projects (E11,12 and N2,7,10). First, in app design, it is critical

to adopt well-accepted design patterns to ensure consistent user

experience [

10

]. As E3 mentioned, “In one of my previous projects,

I was unclear about how to design the log-in page for a particular

type of app. So I looked for the log-in page of the competitor apps

Exploring Designers’ Practice of Online Example Management MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France

and learned from their element composition and layout.” Second,

learning competitors helps foreshadow the eect and acceptance

of certain design feature in reality (E3,5), e.g., “how notication

features are realized through specic salient colors and dynamic

page transitions.” (E3) Third, designers make constant comparison

with competitors to prevent their designs “looking similar to what

already exists on the market” (N6). However, they need to avoid

xating on the existing solutions and patterns of competitors [

26

].

While all types of examples have their own advantages and disad-

vantages, we noticed that the frequency of their usage may vary

between experts and novices.

4.2 Practices in Conducting, Assessing, and

Terminating Online Example Search

We also looked into how designers look for online examples during

mobile UI design and and under what condition they will terminate

the retrieval process.

4.2.1 Behaviors and Strategies of Example Search. From the inter-

view feedback, we identied dierent behaviors our participants

adopt to get examples. Existing studies have classied the explo-

ration of information into a browsing activity (i.e., serendipitous

discovery) and a searching activity (i.e., look for answers to specic

questions). Similar to the previous research [

12

,

14

], we found that

the identied retrieval behaviors can be characterized by these def-

initions and thereby summarize them as browsing and searching

behaviors. Browsing behavior occurs when designers retrieve exam-

ples without particular targets. Designers make browsing retrieval

to gain background knowledge of relevant theme especially in early

stage of their projects. As E9 described, “We collect existing apps

on the market to analyze industry trends, such as the layouts, color

schemes, interaction, and etc.” Unlike browsing, searching behavior

manifests the retrieval process where designers have a clear expec-

tation on the example-targeting search. Therefore, it is normally

done by the support of search engines. As N9 highlighted, “For the

design content I am familiar with, I always have something over my

head to look for. So I just search for the results which exactly match

the picture in my mind.” We also found that most of the participants

would switch between the two types of behaviors. For instance,

when designers conduct exploratory search and encounter some-

thing of interests, they will switch to focused search to dig into that

particular type of examples. As E2 mentioned, “When I look for

arbitrary examples about Map applications on Pinterest, I happened

to see an awesome post. Then I just focus on the recommended

similar designs”.

Within each behavior, designers use dierent strategies which

aid them in getting online examples with existing online services.

One of the most common methods to retrieve online examples is

by searching with keywords (E1,2,3,4). E1 gave an example that “[i]

directly search the keyword ’map’ for navigation Apps when i need

inspiration from their ow and features” while E2 just searched

the name of competitor app recommended by the colleges. They

also search with keywords that describe the expected graphic style,

e.g., “Scandinavian style” when a minimalist scheme was in need by

N7. In addition, some participants used keywords referring specic

components (E1, 3, 4), e.g., E1 searched ‘button status’ to nd out

“how buttons are designed for dierent status”, and E4 collected

an icon for password input via searching ’password’ in Google or

Dribbble. Apart from searching by words, it is also prevalent to

search by images for examples. As E3 stated, “I search on Google

Image or Pinterest with a satisfying image on hand to obtain similar

ones. This also happens when I look for high resolution version of a

low resolution image”. When presented with a large example pool,

designers can utilize restriction functions, normally provided by

the platform, such as tag or lter, to narrow down to more accurate

results.

For instance, in Pinterest the ‘mobile UI’ lter button restricts

the search results into the domain of mobile UI, which provides

“more relevant examples to the App I design” (E1). E2 and N5 had

similar statements during the interviews. In some cases, the lters

and categories can even waive the search keyword when the lter

itself has strictly restrict the results, such as “exploring UI pages in

certain colors” (E4). Other lters provide the criteria capturing social

management information, e.g., user ratings, amount of followers,

and amount of likes, that E5 considered useful.

4.2.2 Termination of Search. Example search can be a labor-intensive

activity. Sometimes people may nd many hits and feel that they

could not exhaust all the candidates. Other times, they may end up

with nothing after rounds and rounds of queries. Hence, to control

the time and eort cost in example searching, designers often preset

an expectation on the spent time and number of good results, to

help determine when to call a halt..

According to the interview results, we found that designers’ ef-

fort required for a retrieval activity is closely related to the time cost.

The retrieval time varies from hours (E1,3,5,9,11,12 and N1,3,4,5,6,7,11,12

) to days (E2). As participants reported, it is highly dependent on the

overall schedule of the project. With an approaching deadline, the

designers would intentionally control the time cost. As E2 stated, “I

don’t go beyond half an hour in case being stuck. Once time is up,

I will just stop and start to decide on strategies for the next step.”

In addition, some designers evaluate the timing by the amount of

visited examples, e.g., E4 usually browses “ve to six screens of

result pages, at most ten ”, before switching the platform or stop-

ping example retrieval, while the others stop the retrieval when

the results become repetitive, which in their opinion indicates “the

exhaustion of novel results.” (E3) Another reason that leads to the

end of a retrieval is the frustrating search trials. Participants might

give up the search after they exhaust the strategies they know but

fail to get what want.

5 ARCHIVING EXAMPLES

After collecting useful examples, designers commonly archive them

for further utilization. In this section, we summarize their archiving

methods based on whether they are integrating examples for direct

or future usage.

5.1 Integration for Situated Inspiration and

Direct Usage

In the archiving process, 14 designers intended to visually integrate

the collected materials into one le, usually in the form of mood

boards or design documents. A mood board is a type of collage

consisting of multiple examples (e.g., images and text) of a certain

topic [9].

MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France Wu and Xu, et al.

Designers including E3 and E4 make a mood board in the archiv-

ing process as it “abstractly depicts the ideal design output, to

provide guidance and inspiration for further desig” (E4). Design

documents, such as Photoshop and Sketch les, are also widely

used by our interviewees. They copied, downloaded or took screen-

shots of the retrieved examples to their own design documents to

simultaneously reference them (E1,3,5,12 and N5,10). In particular,

they often merged the ”directly editable examples into the UI de-

sign documents, to visually evaluate them before storag” (E3) and

”build an mood board of the fashionable UI designs” (N10). Such

documents include “an entire set of UI kits”(E3),“a UI page template

document” (N1), etc.

5.2 Classication for Future Usage

Apart from integration, designers also perform classication of

example documents, into dierent categories. This process can be

carried out online, using archived features of the example manage-

ment platforms, e.g., “Board” in Pinterest (E1,5,6,8 and N3,4,6,7),

“Bucket” and “Like” in Dribbble (E3,4), or using the “Bookmark” of

browsers (E1 and N1,3,4). “I add plenty of examples to bookmarks

before organizing and utilizing them.”(E3) In particular, N8 men-

tioned that using bookmarks can “boost my work eciency”. It can

also be launched oine for various reasons like “worrying about

failed access to online platforms” (E5) or “lack of archived features

on the sites” (E1). “I often download pictures in my favorite styles,

create a folder of collection, and use it when necessary in future.”

(N2) Specically for competitor Apps, seven of our interviewees

installed these Apps on their mobile devices, interacting with and

analyzing them many times (E1,3,5,11 and N2,3,11). I downloaded

‘Google Map’ and ‘Baidu Map’ during the project of a navigation

App. I analyzed and referred to their wireframe with UI pages,

whenever needed” (E1). Additionally, some designers (N2,5,11 and

E7,12) used tools like “Wiznote” and “Eagle” that can classify both

online and oine documents, so that “the examples are saved locally

for utilization while still being accessible any time and anywhere”

(N5). E12 mentioned that she classied examples in “Eagle", which

“allowed sharing with teammates through its cloud service.”

6 UTILIZING EXAMPLES

The interview results suggest that examples can serve dierent

purposes in the mobile UI design process, which we summarized

into two main categories, i.e., construction of feasible design space

and facilitation of specic design generation.

6.1 Constructing design space

Design space refers to the assembly of design points, among which

designers conduct systematic analysis and prune unwanted points

based on relative parameters of interest [

19

]. Designers often switch

between diversifying design ideas and specifying design choices

constantly to rene their design space [

3

]. Within this practice,

examples serve as a critical source for designers to collect back-

ground information to understand user needs, seek inspiration to

diversify design ideas, and validate design choices to narrow down

the design space.

6.1.1 Collecting background information. A starting point to dene

the design space is to collect adequate background information. In

this process, designers conduct research on stakeholders and the

market to fully understand the needs and background of the project.

Designers understand stakeholders’ preference by studying rele-

vant examples, often the stakeholders’ previous products. As E1 said,

“I would check the stakeholder’s previous products in a chronologi-

cal order to learn the characteristics and iteration of their products.”

Through examples, designers also understand stakeholders’ expec-

tation on the product, e.g., “Exploration of examples allows me to

discover the direction in which stakeholders expect the design to be

developed.”(N4) Designers further utilize examples to understand

stakeholders’ preference in the product, e.g., “I often use examples

to conrm stakeholders’ preferred visual design styles and brand-

ing strategy with them.”(N2) In addition, most participants agreed

that gaining background knowledge by examples is important for

establishing a comprehensive understanding of the market. As E3

stated, “Competitor examples deepen my understanding of actual

user need and demanded functions. They also provide marketing

strategies for reference, such as how to bring users and how to keep

them.” Furthermore, by widely studying examples, designers gain

a more precise understanding of the user needs and tastes. As N7

commented, “I like to check the comments left by real users in app

stores because they can reveal what aspects of an app design users

like and dislike.” E1 added, “I spend plenty of time on analyzing the

examples with higher ratings or more downloads because they are

more likely to achieve better user experience.”

6.1.2 Seeking inspiration. Designers seek inspiration in examples

when they do not know where to start and need to become familiar

with the target users or application domain. In particular, four

participant commented that referring to examples can speed up

their design creation, e.g., , E8 mentioned that “when I am stuck at

some point, going over the examples that are similar to my target

design gives me concrete hints to move forward.” Meanwhile, some

designers mentioned that through examples, they can explore more

diverse and new design solutions (E4,5 and N2,4,7,8). N8 commented

that “Examples often bring me new ideas that I cannot come up

with. For example, I recently came across an amazing log-in page

design which was hard for me to imagine without such a hint.”

Examples can also keep them in pace with the design trends (E4,5

and N4), which is critical to professional design practices.

As E5 stated, “I always browse Dribbble to learn what is the

current UI design trend. By going through abundant updated ma-

terial, I establish an impression of the fashionable designs, which

invisibly keeps my designs trendy”. Many designers consider such

exploration as a common routine to expand their design vocabulary

(E11,12 and N2,4,7,8,11). E2 added that “There was a time when the

isometric graphic styles was on trend. I longed for improvement

on my visual design skills, so I learned this new drawing styles by

collecting and mimicking relative examples”.

6.1.3 Validating design choices. After designers accumulate a cer-

tain number of plausible design ideas, examples further assist de-

signers in validating available design options and thereby narrow-

ing down to specic rational design plans. Such validation happens

in two identical situations, adding absent important choices into,

or removing unfeasible ones from, the design pool.

First, some designers leverage examples to avoid missing essen-

tial features. When designers witness adequate successful examples

Exploring Designers’ Practice of Online Example Management MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France

on certain features, which has not been considered yet, they are

likely to add such features to the design pool. For instance, E1 tried

to collect an enormous amount of examples at the early design stage

to ensure “getting exposed to as many awesome ideas as possible”.

Second, the design space consisting of all possible ideas is arguably

large – too large to explore eciently. It is thus necessary to rapidly

narrow down the design space to eventually converge to an optimal

solution by pinpointing the feasible alternatives among available

candidates under given goals. All participants reported that they of-

ten compare dierent UI features appeared in examples of a certain

function and learn from the design rationale behind more suitable

designs. Third, examples can also help designers avoid common de-

sign pitfalls. Since it is dicult to anticipate some mistakes from an

rudimentary idea, designers examine relevant examples to validate

the design choices. If an example shows serious predictable mis-

takes of an idea, designers are likely to eliminate it from the design

pool. As E1 stated, “By carefully studying the design of competitors,

I realize that there will later be severe conicts in the combination

of these two features, so I remove one of them from the design pool

or dene a hierarchy between them in advance.”

6.2 Facilitating design generation

After designers develop a clear design plan, they further utilize

examples for ecient generation of design outcomes.

6.2.1 Speed up design generation. When there are no specic de-

sign guidelines to follow, designers utilize examples also to abstract

common design patterns among similar products. With this strat-

egy, they save the time and eort of creating all features from zero,

e.g., E3 said that “While designing a sports App, I wish to generate

UI styles that are sporty, dynamic and fancy. However, there are

no guidelines for such characteristics. Therefore, I learned from

successful examples to gradually abstract how to design an ideal

sports App UI with proper use of vibrant colors and gradients.” E1

also mentioned that “To quickly nd out common interaction solu-

tions and localization design strategies of navigation App design, I

downloaded more than ten competitor Apps to nd their common

UI features and themes. So I could quickly draft design solutions

of the key features and save plenty of time for further design in

detail.”

6.2.2 Communicating generated designs . Designers also utilize

examples to build common ground in design communication. Ex-

amples are utilized as a “boundary object”, which is a tangible

concept that grounds the conversation between the designers and

other collaborating parties [

24

]. Designs are commonly illustrated

with originated design documents and verbal or textual descrip-

tions. However, originated documents are usually time-consuming,

therefore not suitable for all details of design, while verbal and

textual descriptions are convenient but not comprehensive enough.

Therefore, examples serve as eective and ecient complementary

materials since they are well visualized, some of which are even

interactive, and consume much less time and eort in comparison

to originated design illustration.

Designers use examples for communication to other designers in

the team. In collaboration scenarios, designers utilize examples to

update the design progress and reach consensus among teammates

to improve design eciency, e.g., E7’s colleagues “frequently use

examples to illustrate which feature he/she is working on so that

everyone can keep at the same pace.” With examples, designers can

avoid ’lost in translation’ especially when the designs are complex

or dynamic as designers care about many details of specic design

features and developers do not necessarily speak the design lan-

guage. While delivering the high-resolution prototype to engineers

for implementation, several participants used interactive examples

to demonstrate dynamic UI features and interaction ow (E1,4,7,12

and N4). E4 pointed out that “ Compared to other UI elements, ani-

mations are more ubiquitously standardized and not as specied

among dierent cases. Therefore, I used a lot of animated examples

to show engineers how they are expected to integrate the UI design

into an actual app.” E1 also mentioned that “Sometimes the resolu-

tion of prototypes is not high enough, so I would use examples to

illustrate the designed interaction to engineers.” Another usage of

examples appears in communication with stakeholders, who expect

to see the potential outcome and understand the design rationale

behind though the design process. Once designers scope down

their design options, some participants would take examples as a

tool to communicate the design concepts with their stakeholders.

N4stressed that “I used examples in discussion with stakeholders

to prove the feasibility of my designs.”

7 DIFFERENCE BETWEEN EXPERTISE AND

ACROSS DESIGN PHASES

Based on the interview feedback, we were aware of the dierent

behaviors between experts and novices as well as the dierence

across design phases.

7.1 Dierence between Experts and Novices

7.1.1 Dierent Dependence on Examples. Expert designers we in-

terviewed often expressed that they are rather familiar with existing

graphic design conventions (E6,7,8,10) or have formed their own

style (E1,6,7,10,11). Few novice designers mentioned such patterns.

In other words, the experts rely much less on examples than the

novices when it comes to designing common UI components. For

instance, E1,7 only searched UI examples while facing particular

design challenges, rather than generic issues, as there are both per-

sonal and enterprise UI design library for them to utilize. E1 stated

that “I search for examples mostly when I am facing specic design

problems like a same button in many dierent status, which is not

common in pratice”. E11 mentioned that “Compared to instant ex-

ample retrieval during the design process, I would rather learn from

examples in my spare time to integrate them into my own design

vocabulary. So I can avoid the interruption to the design process by

example retrieval”. In contrast, several novice designers frequently

collect UI examples to gain design inspiration (N6,8,9). According

to N6, “the color theme, page layout, and the functionality of a UI

example can inspire me a lot and help me come up with concrete

ideas for my design.”

7.1.2 Dierent Levels of Example Exploitation. We discovered that

our expert designers tend to take more diverse advantage of the

information from examples compared to novices, perhaps due to the

more critical roles that experts play in a project. For instance, E2,3

were often in charge of a complete mobile app design project and

MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France Wu and Xu, et al.

thus need to examine the local marketing strategy of competitors

to ensure a long-term prosperity of a product. As E3stated, “It is

important to check competitors’ marketing strategy, because I have

to consider how to bring users to my App and how to keep them.”

E3 also studies the target users, problem solutions, and how features

are realized. E5, who is responsible for an entire feature, downloads

competitors and analyzes their users’ feedback to discover design

potentials in her own project. She stated that, “I dig out potential

directions for optimization of my products by carefully reading

users’ comments.” On the contrary, none of novice interviewees

brought up such needs.

7.1.3 Dierent Consistency between Intentions and Behaviors. In

the Develop phase, experts intentionally focus more on target ex-

amples and avoid distraction by exploratory contents, yet such

situation has not been mentioned by novice designers. As E3 stated,

“With a specic design task such as a UI page, I would force myself

to focus on the target examples in result pages, and try not to ex-

ploit results that are not relevant enough, even though they could

be visually attractive.”

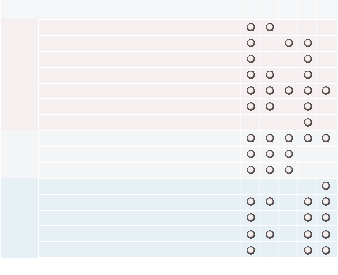

7.2 Dierence across Dierent Design Phases

To attain a deeper understanding of example-related behaviors, we

compare how they vary across design phases, i.e., Discover, De-

ne, Develop, and Deliver. From Table 1, the most example-related

behaviors happen in Discover (42%) and Develop (40%) phases, as

these two phases require more divergence than convergence of

design treatments and background knowledge. Then comes Deliver

(14%) and Dene (4%), of which retrieval behaviors are more con-

vergent. But in Dene, both behaviors take place, though with a

lower frequency.

We specically look into collection behaviors across dierent

phases as it appears more often (49%) than utilization (36%) and

archiving (15%). In the Discover and Develop phases, designers tend

to collect and store broader types of examples than other phases. For

example, they would “download many competitor Apps to learn the

common design solutions and compare their ows” (E1) and “make

mood boards to collect and summarize examples at the same time

to explore proper identities” (E4) for their own design. E4 further

illustrates how he makes a mood board for a tness equipment

App design in this phase, “I make a collage with images of athletes,

dynamic movements, and futuristic UI pages, to depict a modern,

energetic and high-tech image of my product”. In the Dene phase,

designers collect examples mainly for reference to produce graphs

such as “Personas” (E3) and “User Journey Maps” (E5). The common

practice is example classication, either through adding valid posts

to bookmarks, downloading them to local devices or copying them

to the graphic design documents.

In addition, designers conduct more searching than browsing

behaviors in Develop and Deliver phases, when they already have

a focused and converged idea. Such pattern is also reected in

retrieval time, shorter than that of the Discover and Dene phases.

As stated by N1, “In the early exploration stage, it costs more time

to collect relevant materials while in the later Develop and Deliver

stage I seldom browse for more examples”.

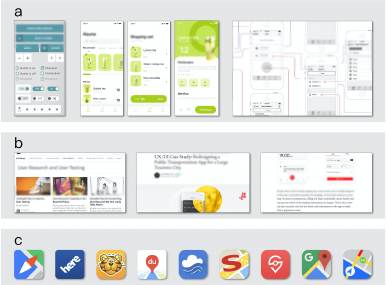

Challenge

cannot search by image

cannot search by author

unclear organization of search results

inaccurate search results

inefficiency to find competitors

lack of example categorization

too many advertisements

extensive effort in labeling examples

cannot bookmark examples

limited support to group examples

lack of copyrignt

outdated examples

lack of interactive examples

lack of UX-oriented examples

low-quality examples

Utilize

Archive

Collect

D B A P G

D: Dribbble | B: Behance | A: App Store | P: Pinterest | G: Google

*

Figure 2: The summary of the typical challenges encoun-

tered by the designers with the existing tools.

8 CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

8.1 What are the barriers encountered in

existing tools?

The unsatised experience reported by the participants are mostly

associated to the negative experience with the low-quality examples

and the limited support they received. We summarized typical

challenges the designers encountered in ve most mentioned tools

(Figure 2).

8.1.1 Exposure to Low-ality Examples. A common problem our

interviewee encountered is frequent exposure to low-quality ex-

amples in online repositories. Due to the limited quality control in

most existing online platforms, a large number of poor examples

may appear in queried results, leading to inecient retrieval ex-

perience. As E2 described, “When I was searching with ‘machine

learning icon’ on Google, the results were very dull and ugly. It

was a pretty tiresome experience to keep facing those weird de-

signs.” That is why some participants (N4,5) favored Dribbble in

which all materials are shared by design professionals and thus

have relatively higher quality. To understand their preference on

examples, we asked about how they evaluate the examples attained

from an online service. Our participants provided dierent criteria,

including visual appeal, feasibility, and richness. Designers would

comprehensively consider these criteria while evaluating the exam-

ples. They are particularly cautious with the examples with high

aesthetic quality but low feasibility. “Many beautiful examples on

Dribbble are too fragmentary. Usually I just take a glance at their

overall graphic style and wouldn’t spend much time on them. Be-

cause they cannot t into real applications”(N4). Moreover, some

interviewees valued the rich contexts and styles of examples (N7

and E8). But the mechanism of some online platforms like Pinterest

tends to present similar design examples with common content or

visual styles, which led to a limitation of diversity.

8.1.2 Ineective Tools for Example Management. Designers also

suer from ineectiveness of existing platforms for example col-

lection, archive, and utilization. From the interviews, we identied

three main obstacles that hinder designers from getting satisfac-

tory examples eciently, including insucient navigation support

Exploring Designers’ Practice of Online Example Management MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France

UI/UX case study

competitor

focused search

search with keyword

search with image

What What

What What

Behavior Behavior Behavior Behavior

How

How

How How

E E E EN N N N

Collect Examples

DISCOVER

DEFINE DEVELOP DELIVER

group competitor Apps group competitor Apps

create mood boards

copy to design documents

create folders as design libraries

classify examples online

add valid posts to bookmarks

download to local devices

copy to design documents

3

1

0

0

0

1 0

0

integrate into mood boards

download the retrieved examples

create folders as design libraries

classify examples online

Archive Examples

0

illustrate prototypes

deliver prototypes to engineers 7

9 8

4

gain background knowledge

understand target users' need

understand clients' need

find out common functions

take creative sources for inspiration

assist designers in validating options

communicate with colleagues

take creative sources for inspiration

speed up design creation

communicate with teammates

follow existing guidelines

avoid common design pitfalls

communicate with clients/colleagues

demonstrate dynamic UI features

Utilize Examples

expand design vocabulary

keep designs in trend

search with keyword

search with image

search by category

search by filter

search by suggestion

search by author

search for page layout

search for color scheme

search for interaction

collect existing Apps

browsing search

focused search

switch between behaviors

UI page

UI/UX case study

competitor

search with keyword

search with image

search by category

search by filter

search by suggestion

search by author

search for page layout

search for color scheme

focused search

browsing search

switch between behaviors

UI page

UI/UX case study

competitor

UI page

competitor

focused search

search with keyword

search with image

search by category

search by filter

1

1

6 5

2

3

2

2

3

10

1

1

0

0

1

1

1

1

1

9

9 6

10 8

12 12

12 11

12 11

0

0

4 2

2

5

6

3

6

4

4

83

4

48

1011

31

11

2

6

4

7 2

1

3

2

0

1 1

1 0

1

0

11

3

2

12

10 11

11 12

1

2

2

1

9

9 5

5

5

7

9 9

4

4

2

1

3

2

3

2

2

2

1

2

4

3

7

2

2

2

1

6

3

3

10 4

3

4

5

6

4

3 1

2 1

1

1

4 1

0

0

11 0

4

4

6

4

3

6

Table 1: Summary of codes extracted from our interviews with 24 designers regarding the behaviors around example manage-

ment.

provided by existing repositories, ineectiveness of the search en-

gines, as well as a lack of archive and utilization feature in online

repositories.

Half of the participants criticized that the limited navigation sup-

port from existing services makes retrieval process inconvenient

and time-consuming, especially given the overwhelming available

examples. In particular, the lack of detailed categorization poses

challenges for designers to dig into a particular type of examples.

N10 complained that “there is no category feature in Dribbble or

Pinterest to avoid irrelevant examples. When I search ‘Mobile UI

for game applications’, instead of mobile UI examples, many game

posters and websites show up in the result.” For other platforms

such as Mobbin and Pttrns, which classify examples in a certain

manner and benet users in example exploration, cannot address

designers’ dierent needs for navigation. “I like the category pro-

vided in Pttrns because it helps me compare the patterns across

dierent types of UI. But it only dierentiates examples based on

their function and doesn’t support other criteria, such as graphic

styles or target users.”(E3) The problem of insucient navigation

becomes more severe in the cases that users have diculty in com-

ing up with keywords for a query. Similar to a prior study [

12

],

we found that many designers feel hard to articulate keywords

accurately describing the examples they are looking for. In such

cases, they are in stronger need of navigation support to help them

narrow down search space.

The performance of the search engine in existing example man-

agement platforms, was challenged by ve of the interviewees.

Compared to professional search service like Google, those plat-

forms have less capacity of providing accurate search results, e.g., “

Dribbble’s search service can somehow handle a broad keyword but

performs badly when given a long and concrete one. On the con-

trary, Google gives much closer examples to expectation”(N2). N1

even “searched for contents of Dribbble by Google” instead of using

the integrated search engine. In addition, some designers expected

those platforms to have Google’s image search function. “There

are a couple of times I would like to use image search to nd the

examples that look similar to my design, but Dribbble and Behance

don’t have such a function so I have to switch to Google.”(N8)

Another hurdle pointed out by our participants is the lack of

eective features supporting example archive and utilization. In

particular, how to help users to organize their collected examples

for later usage is under explored by the existing services(E1,2,and

N2,5,7). “I had to download or copy and paste the examples as local

documents after getting examples online. Manually classifying and

labeling them was very troublesome. Such process could lead to

diculty in later example query(E1).” “It was hard to nd previous

examples since we archived them by name or date, because usu-

ally we could only remember approximately how they look”(N3).

Therefore, some designers expected a feature of the platforms “to

automatically label the examples for convenient and accurate re-

turn visits”(N12). Moreover, our participants were unsatised with

the tedious process searching the same item among diverse ex-

isting online platforms(N1,2,6 and E2). For instance, “because the

online platforms have distinct sources, I had to search with the

same keyword on dierent platforms and chose the best result. The

switching was quite time-consuming and inecient” (N1). So E2

expected that “A new platform would be awesome if it collects the

content of all dierent sources”.

MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France Wu and Xu, et al.

9 DISCUSSION

9.1 Example management in Mobile UI Design

and Other Design Domains – Link and

Dierence

Herring et al. identied the benets of examples in the design

domains of Web, product, and graphic design [

12

]. Our results

suggest that mobile UI designers utilize example in a similar manner.

For instance, like designers in other domains, they also exploit

examples to internalize stakeholder’s needs in the Discover and

Dene phases (i.e., preparation stage in [

12

]), and to validate the

demand and originality of their own UI products in the design

stage. One dierence we identify is that mobile UI designers seem

to employ a broader form of examples. For instance, they prefer to

use mood boards rather than individual visual examples in Discover

stage.

As for the design expertise, similar to the ndings of previous

works on graphic designers [

25

], our expert interviewees in mobile

UI design are more procient at example management than novices.

In fact, they seem to perform less example search on demand com-

pared to those with lower design expertise. For one thing, according

to our interview feedback, managing examples have become a rou-

tine practice of many mobile UI design experts. They have formed

the habit of gathering good examples whenever they encounter one.

When a new project comes, they have had a high-quality collection

of examples to begin with. For another, it is likely that experts

have converted the examples they experienced before to internal

knowledge to a good extent. They may call upon such knowledge

instead of looking for new examples in face of a design request [

25

].

Additionally, dierent from the works in other design domains, we

found that the expert UI designers also take more types of roles in

design process and thus make use of examples in a more diverse

ways than novices. For examples, expert designers (E2,3) who are

in charge of a mobile app design project will look for the marketing

strategies of competitors and will utilize the examples to illustrate

their design thoughts to the engineers. On the contrary, our novice

mobile UI designers are usually responsible for parts of the projects

such as visual design, and they search for those fractional examples

without considering much the budgets and project feasibility.

9.2 Design Implication

We derive the following implications for the future development of

more supportive example management tools.

9.2.1 Compile metrics to filter out low-quality examples. Our study

shows that designers have negative experience with exposure to

low-quality examples in online design material repositories. Even

though platforms such as Pinterest and Behance use social voting

(e.g., ‘like’) to help designers assert the quality of examples, users

often nd this information insucient for decision-making. “A

bunch of returned examples share similar number of likes and it

is hard to pick the good ones from them” (N4). One feasible way

for example repositories to ensure example quality eectively and

eciently is to derive computational metrics to perform automatic

assessment. Our mobile UI designers point out dierent criteria

to evaluate an example, such as “visual appeal”, “richness”, and

“feasibility”. The platforms could rst invite their designer members

to provide comprehensive metrics for the examples and then build

up structured scales to assess the quality of each UI example. Apart

from the criteria mentioned above, other automatic quality metrics

of UI could also be incorporated, such as visual complexity [

29

] and

mobile UI personality [

37

], depending on the need of individual

designers.

9.2.2 Facilitate keywords formulation for search navigation. Search

engines, particularly those employed by mobile UI example reposi-

tories, usually assume that designers already have some targets in

mind when they use their services. However, our mobile UI design-

ers often have no clear thought of what they want and thus have

diculties in articulating search keywords. Under such conditions,

the example-sharing platforms could proactively provide a set of

keywords to help users to narrow down the search space step by

step. For example, the platforms could use the commonly used key-

words to form several example galleries to help users get a sense of

the kinds of available design materials. Once the users show inter-

ests in one specic example (e.g., click on it or have longer dwell

time), the search engine could suggest a set of semantic keywords

that could describe its characteristics from dierent aspects [

38

] to

assist users in consolidating their thoughts and formulating search

queries. Even when the mobile UI designers have a target in mind,

they sometimes are “unable to explain their thoughts in a design

language” (N8 ). In this case, the example search engine could in-

corporate the general search services like Google, which can try to

make sense of not so precise ideas expressed in everyday terms. It

could further incorporate domain-specic crowdsourcing service

[

32

], through which the users can learn how to express their intents

to search engines based on other designers’ suggestions.

9.3 Develop eective features for better

example management

As aforementioned, most of the online platforms fail to support

designers to archive their collected examples. Designers have to

spend extensive manual eorts such as formatting, categorizing,

and labeling examples after they download them. It would become

especially time-consuming when designers face a large amount of

collected examples. The development of automatic example analysis

features (e.g., semantic and style classication, brand recognition,

automatic hierarchical management, etc.) might benet designers

for improving eciency.

Moreover, the disparity between experts’ and novices’ knowl-

edge of and experience with examples imposes a need for the plat-

forms to tailor its example management methods based on user

expertise. For example, if a designer claims to be new to mobile de-

sign area, the platforms can return more diverse types of examples,

e.g., UI page, case study document and competitor apps, to get them

inspired. In contrast, for experienced designers, the platforms could

display more examples of competitor apps and specic features of

a mobile UI.

9.4 Limitation and Future Work

Our study has several limitations. This work focuses mainly on of-

fering a qualitative understanding of designers’ behaviour around

online example management with insights derived from a rela-

tively small sample size. To investigate the statistic detail of the

Exploring Designers’ Practice of Online Example Management MobileHCI ’21, September 27-October 1, 2021, Toulouse & Virtual, France

derived ndings, we will need to conduct further quantitative stud-

ies with a larger number of designers in the future. We organise

our ndings on example management behaviors according to the

Double Diamond (DD) model mentioned by our participants. How-

ever, there are over one hundred design process models other than

the DD model, ranging from short mnemonic devices to elabo-

rate schemes [

7

]. Although it is neither necessary nor realistic to

exhaust all the design process models, we could possibly expand

our research to a few more design models to develop a more com-

prehensive conclusion on example management behaviors, such

as the “ISO 13407 Human-centered design processes for interac-

tive systems”. While we have derived several implications, we did

not test them by implementing an example management tool. We

might design a tool based on the implications for verifying their

eectiveness in actual design scenarios.

10 CONCLUSION

In this study, we present a comprehensive understanding of design-

ers’ behaviors around online example management for mobile UI

design. In particular, we dig into the practice about how designers

collect, archive, and utilize examples by a series of interviews with

12 novices and 12 experts. We compare how their behaviors vary

between expertise and across dierent phases. We nd that there

is a more diverse and frequent use of examples in Discover and

Develop phases. Moreover, compared to novices, experts use de-

sign examples for a more diverse purpose. We further identify the

challenges encountered by designers with existing example man-

agement services, and propose potential design implications for the

future design of more supportive example management tools.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by HKUST-WeBank Joint Lab-

oratory Project Grant No.: WEB19EG01-d and supported by Ts-

inghua University-Alibaba Joint Research Laboratory for Natural

Interaction Experience.

REFERENCES

[1]

2019. Top 50 Countries/Markets by Smartphone Users and Penetra-

tion. https://newzoo.com/insights/rankings/top-50-countries-by-smartphone-

penetration-and-users.

[2]

Nathalie Bonnardel and Evelyne Marmeche. 2005. Favouring Creativity in Design

Projects. Studying Designers 5 (2005), 23–36.

[3]

Nathalie Bonnardel and Evelyne Marmèche. 2005. Towards supporting evocation

processes in creative design: A cognitive approach. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies 63, 4-5 (2005), 422–435.

[4]

Joel Chan, Pao Siangliulue, Denisa Qori McDonald, Ruixue Liu, Reza

Moradinezhad, Safa Aman, Erin T. Solovey, Krzysztof Z. Gajos, and Steven P.

Dow. 2017. Semantically Far Inspirations Considered Harmful?: Accounting

for Cognitive States in Collaborative Ideation. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM

SIGCHI Conference on Creativity and Cognition (Singapore, Singapore) (C&C

’17). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1145/3059454.3059455

[5]

Design Council. 2015. The design process: What is the double diamond. Saata-

vana osoitteessa:< http://www. designcouncil. org. uk/news-opinion/design-process-

whatdouble-diamond>. Luettu 26 (2015), 2017.

[6]

Marco de Sá and Luís Carriço. 2008. Lessons from early stages design of mo-

bile applications. In Proceedings of the 10th international conference on Human

computer interaction with mobile devices and services. ACM, 127–136.

[7] Hugh Dubberly. 2005. How do you design. Hugh Dubberly.

[8]

Claudia Eckert and Martin Stacey. 2000. Sources of inspiration: a language of

design. Design studies 21, 5 (2000), 523–538.

[9]

Nada Endrissat, Gazi Islam, and Claus Noppeney. 2016. Visual organizing: Bal-

ancing coordination and creative freedom via mood boards. Journal of Business

Research 69, 7 (2016), 2353 – 2362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.004

[10]

Vassiliki Gkantouna, Athanasios Tsakalidis, and Giannis Tzimas. 2016. Mining

interaction patterns in the design of web applications for improving user expe-

rience. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM conference on hypertext and social media.

ACM, 219–224.

[11]

Shuai Hao, Bin Liu, Suman Nath, William GJ Halfond, and Ramesh Govindan.

2014. PUMA: programmable UI-automation for large-scale dynamic analysis of

mobile apps. In Proceedings of the 12th annual international conference on Mobile

systems, applications, and services. ACM, 204–217.

[12]

Scarlett R Herring, Chia-Chen Chang, Jesse Krantzler, and Brian P Bailey. 2009.

Getting inspired!: understanding how and why examples are used in creative

design practice. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems. ACM, 87–96.

[13]

Leonard Hoon, Rajesh Vasa, Gloria Yoanita Martino, Jean-Guy Schneider, and Kon

Mouzakis. 2013. Awesome!: conveying satisfaction on the app store. In Proceedings

of the 25th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference: Augmentation,

Application, Innovation, Collaboration. ACM, 229–232.

[14]

Christine Hosey, Lara Vujović, Brian St Thomas, Jean Garcia-Gathright, and

Jennifer Thom. 2019. Just Give Me What I Want: How People Use and Evaluate

Music Search. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems. ACM, 299.

[15]

Stephanie Houde and Charles Hill. 1997. What do prototypes prototype? In

Handbook of human-computer interaction. Elsevier, 367–381.

[16]

Forrest Huang, John F. Canny, and Jerey Nichols. 2019. Swire: Sketch-based

User Interface Retrieval. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (Glasgow, Scotland Uk) (CHI ’19). ACM, New York,

NY, USA, Article 104, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300334

[17]

David G Jansson and Steven M Smith. 1991. Design xation. Design studies 12, 1

(1991), 3–11.

[18]

David S Janzen, Andrew Hughes, and Anthony Lenz. 2016. Scaling Android user

interfaces: a case study of Squid. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop

on Mobile Development. ACM, 31–32.

[19]