1

Good Progress but Challenges Remain:

Achieving Equity in Fairfax County Public

Schools Advanced Academic Programs

Jonathan A. Plucker, Ph.D, Carolyn M. Callahan, Ph.D.,

Dante D. Dixson, Ph.D., and Scott J. Peters, Ph.D.

May 5, 2020

Reported Submitted in Fulfillment of FCPS RFP 3100000390

for Program Review Services for Advanced Academic Programs

2

Table of Contents

Glossary ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3

Description of Task and Supporting Data ………………………………………………………………………………. 5

Methodology ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………........... 10

Literature Review on Interventions ………………………………………………………………………………………. 14

Findings and Conclusions ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 25

Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 42

References ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 47

About the Review Team ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 52

Appendices …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 55

A. Relevant sections of Virginia Code

B. Sample focus group and interview protocols

C. Parent survey

D. NNAT, CogAT, and GBRS score descriptive statistics for all students

E. NNAT, CogAT, and GBRS score descriptive statistics for Level IV-eligible students

F. Parent survey results summary

3

Glossary

Assessment bias: Differences in test scores or teacher ratings across groups do not by

themselves indicate assessment bias. Such mean-score differences, or differences in Level IV

identification rates across two groups, would only be considered evidence of bias if those

differences are due to faulty measurement procedures and not due to real, underlying

differences in what the tests are measuring. Broadly speaking, assessment bias occurs when

there are differences between two parameters that should be equal. An unbiased system can

still produce mean test score differences or differences in rates of gifted student identification

across groups.

Central Selection / Screening Committee: A group of FCPS educators who receive training

about the holistic screening process and review student portfolios in order to make Level IV

eligibility decisions. In 2019, this group met for the district-wide Level IV eligibility review in

December and reviewed 6779 student files.

Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT): A widely-used measure of K-12 students’ reasoning abilities

via quantitative, verbal, and nonverbal batteries. In FCPS, the CogAT is administered to all

students in second grade.

Disproportionality (or underrepresentation): The term disproportionality is commonly used to

refer to the situation in which the proportion of students from a given subpopulation of

students enrolled in advanced learning or gifted and talented programs does not mirror their

proportion in the entire student population in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, home language,

or disability status. Most commonly, it refers to cases where African American or Hispanic

students are disproportionately underrepresented in AAP compared to their representation in

the overall student population.

Excellence Gaps: Gaps in advanced academic achievement or attainment across students of

differing demographics.

Free or Reduced Price Meals: This dichotomous variable is often used as a proxy for a family

experiencing poverty or the stresses or lower family income. For participation in the National

School Lunch Program, families whose combined income is 130% or less of the Federal poverty

line are eligible for free meals at school.

Gifted Behaviors Rating Scale (GBRS): An FCPS-specific measure used by teachers to rate the

frequency of behaviors typical to gifted students / advanced learners. Teachers rate each of

their students every year on the four GBRS items: exceptional ability to learn, exceptional

application of knowledge, exceptional creative / productive thinking, and exceptional

motivation to succeed.

i-Ready Assessment: Diagnostic assessments in reading and mathematics that provide current

achievement level data that can be used for instructional decision-making.

4

Level IV Pool: The group of students who are considered for Level IV services via the Central

Selection Committee. This pool is made up of students who meet NNAT and CogAT criteria in

grade 2 (2

nd

grade screening pool) or who were referred into the pool despite not having

qualifying scores (referral candidates).

Level IV Eligible vs. School Designated: Level IV eligible students are those who have been

identified formally as Level IV students and offered spots in either a Level IV center or local

Level IV program. Level IV school designated students are those who are identified as Level III

students but participate in local Level IV programs if seats are available.

Limited English Proficient Student (LEP – also known as English language learners or ELL): A

student who is not yet proficient in the English language, typically because it is not his or her

native language.

Local Norms: A norm-referenced interpretation is any time a student’s test score is compared

to the test scores of some other group (e.g., “Bobby is the best player on the team” compares

Bobby to the rest of the team). “Local” norms differ from national norms in that the student’s

score is compared to that of her grade-level peers in a particular school building (school norms)

or school district (district norms).

Naglieri Nonverbal Abilities Test (NNAT): A widely-used non-verbal measure of general ability

with limited reliance on English (i.e., no written directions or items). In FCPS, the NNAT is

administered to all students in first grade.

National Norms: A norm-referenced interpretation is any time a student’s test score is

compared to the test scores of some other group (e.g., “Bobby is the best player on the team”

compares Bobby to the rest of the team). In the case of a national norm, the data reported is

most often the percent of a national normative sample that the student performed better than

– for example, a national percentile of 95 means the student scored better than 95% of national

test takers (or a nationally-representative sample).

Twice Exceptional: The term “twice exceptional,” also referred to as “2e,” is used to describe

gifted children who have the characteristics of gifted students with the potential for high

achievement and give evidence of one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state

eligibility criteria (NAGC).

Two-Phase Identification System: A process for identifying students for gifted programming

(e.g., Level IV eligibility) whereby students first take a screening assessment(s) and only those

who pass through the screening phase are put through the program eligibility process. FCPS

uses a two-phase system for Level IV eligibility when all student take the NNAT in first-grade

and CogAT in second grade. Only those students who score high enough on one or the other

are considered by the Central Selection Committee for Level IV placement.

5

Achieving Greater Equity in FCPS Advanced Academic Programs

The study was conducted in response to FCPS informal RFP 3100000390 for Program Review Services for

Advanced Academic Programs. The focus of the proposed review was to combine an analysis of

available FCPS data and documentation with data collected by the review team and state-of-the-art

theory and research to create a set of recommendations for improving equity across all four levels of

FCPS Advanced Academic Program (AAP) services based on the team’s recent research and direct

experience on similar projects.

1

We examined a broad range of data to determine the extent to which equity is an issue at various levels

of AAP participation. We approached understanding the current demographic representation of AAP

students in three ways:

1. Division-generated reports for enrollment in any/all AAP services,

2. Division-generated reports for Level IV eligibility over time,

3. Original analyses, based on student-level data of a single cohort of grade 2 students screened

for level IV services for the from 2018 – 2019 school year and comparing the demographics of

the overall cohort to the sample screened for Level IV services and to the sample found eligible

for Level IV services.

Division-generated Reports for Enrollment in AAP Services

Demographic comparisons across Levels II – IV AAP services are difficult because each level (aside from

Level IV Centers) involves 1) students being selected for participation based on varying criteria across

different schools and/or 2) different service options offered across schools. For example, Local Level IV

services are not available in each building and, even when they are available, schools may use different

criteria for those who actually receive Local Level IV services.

Similarly, principals and local school-level identification committees have more control over

identification of students for placement of into Level II or Level III services. As a general statement, all

racial/ethnic groups are represented in very similar proportions to their representation in the FCPS

population in Level II and III services (see Tables 1-4 and Figure 1 below). For example, White, Asian,

Hispanic, and Black students are represented in Level II services at rates of 13%, 13%, 11%, and 13% (see

Table 2). However, the higher the level of service, the larger the racial disparities, particularly for

Hispanic students. For instance (see Table 4), last year’s cohort of grade 2 students was made up of 9.8%

Black students but they make up just 6.4% of those screened for Level IV services and only 7% of the

cohort identified as Level IV eligible. In contrast, Hispanic students made up 25.3% of the full school

cohort but just 10.6% of those screened and only 12.3% of those who were identified as Level IV eligible.

This stark difference clearly demonstrates the identification gap is larger for Hispanic students than

Black students.

Notably, once a student is identified for one level of service, they represent a student who cannot be

identified for any other level. For example, a Hispanic student identified for Level IV is now one less

1

At various points during the review team’s interaction with FCPS personnel and stakeholders, interpretations of

the contracted task varied widely, including advice that we focus only on Level IV centers, that we address only

Level IV local or center programming, or that we not address Level IV centers at all. However, the goal of the

contract was clarified with FCPS leadership in December 2019, and throughout the project the review team

collected and analyzed data and information related to improving equity at all four levels of AAP programming.

6

student who can be identified at Level III. This is the challenge at looking at demographic enrollment for

each level of service. At the very least, it might also be useful to examine equity for AAP as a whole,

compared to district enrollment, in addition to equity within each level of service. Further, it is

important to emphasize that all of these data provide evidence regarding proportionality – the degree to

which each level of service is or isn’t made up of the same demographic groups in the same proportions

as the Division or cohort of students as a whole. Proportionality and eligibility or readiness are not the

same thing, unless all groups have equal levels of readiness and need for a level of service – something

we discuss at length below.

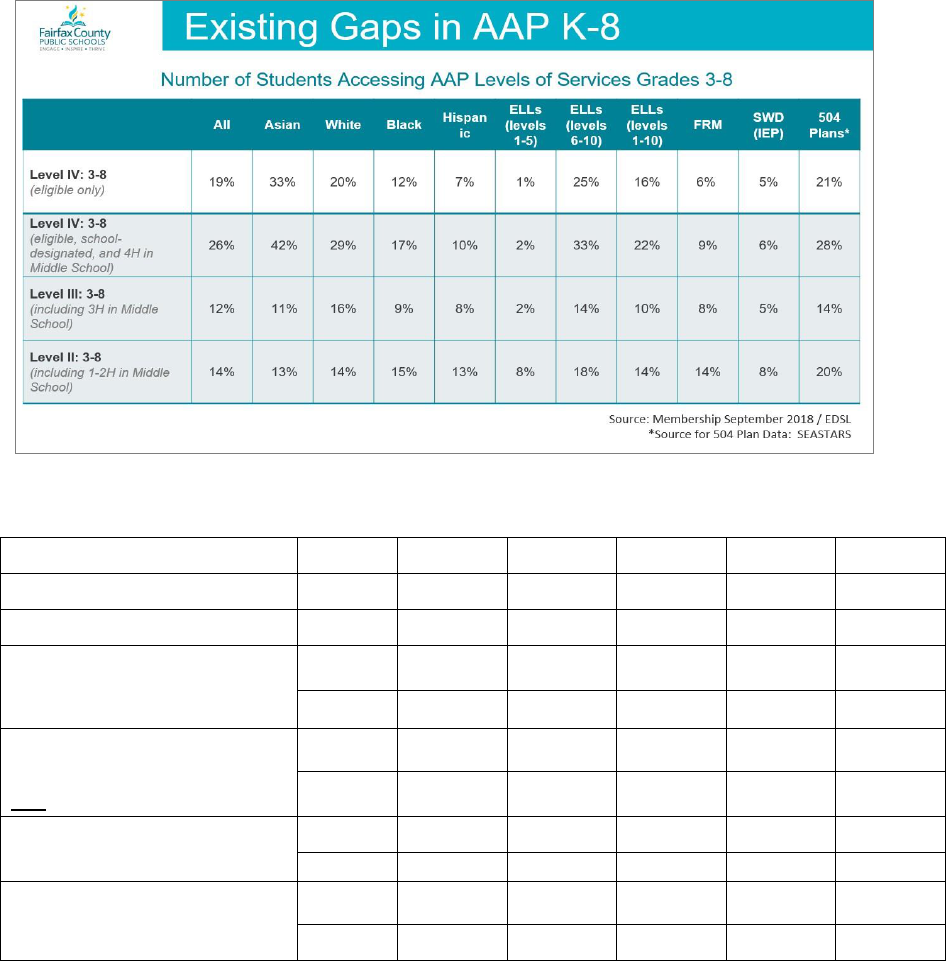

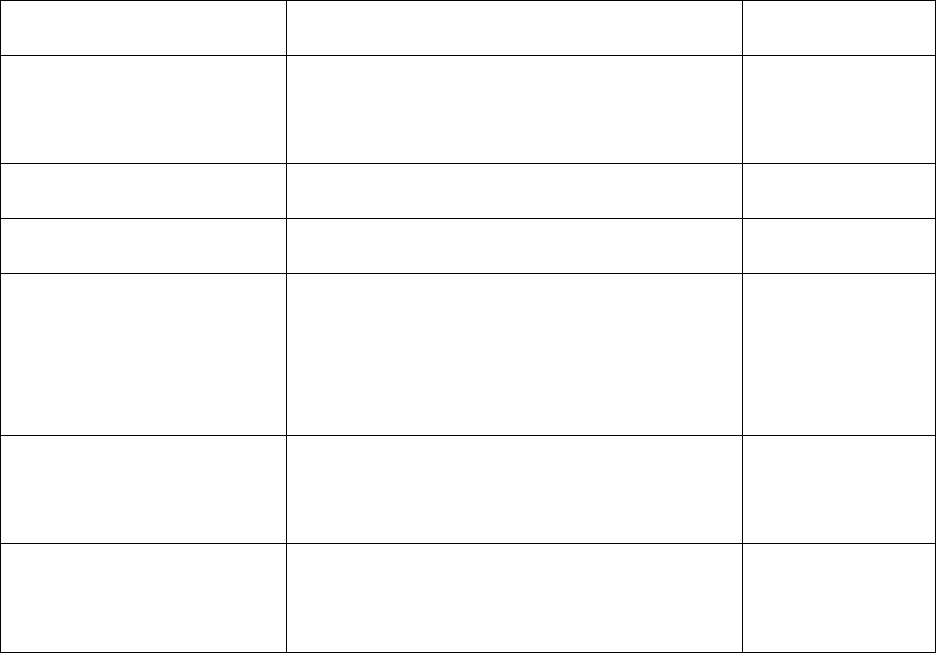

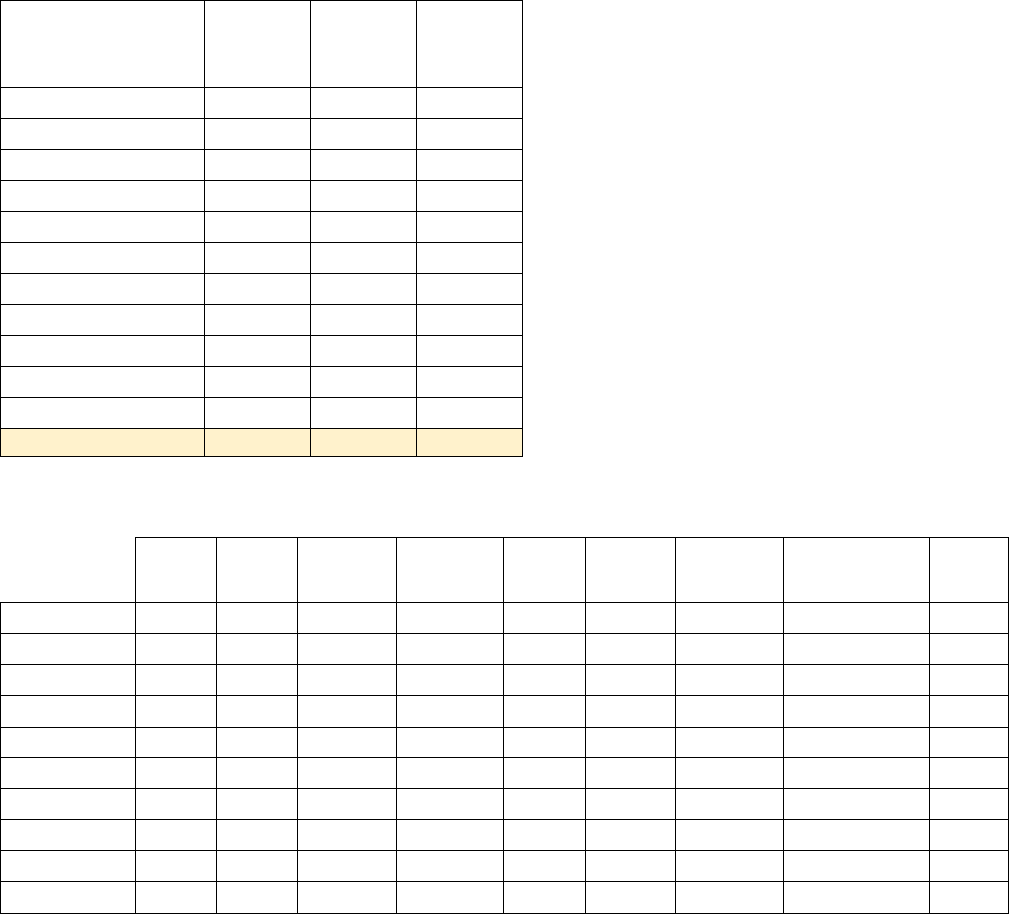

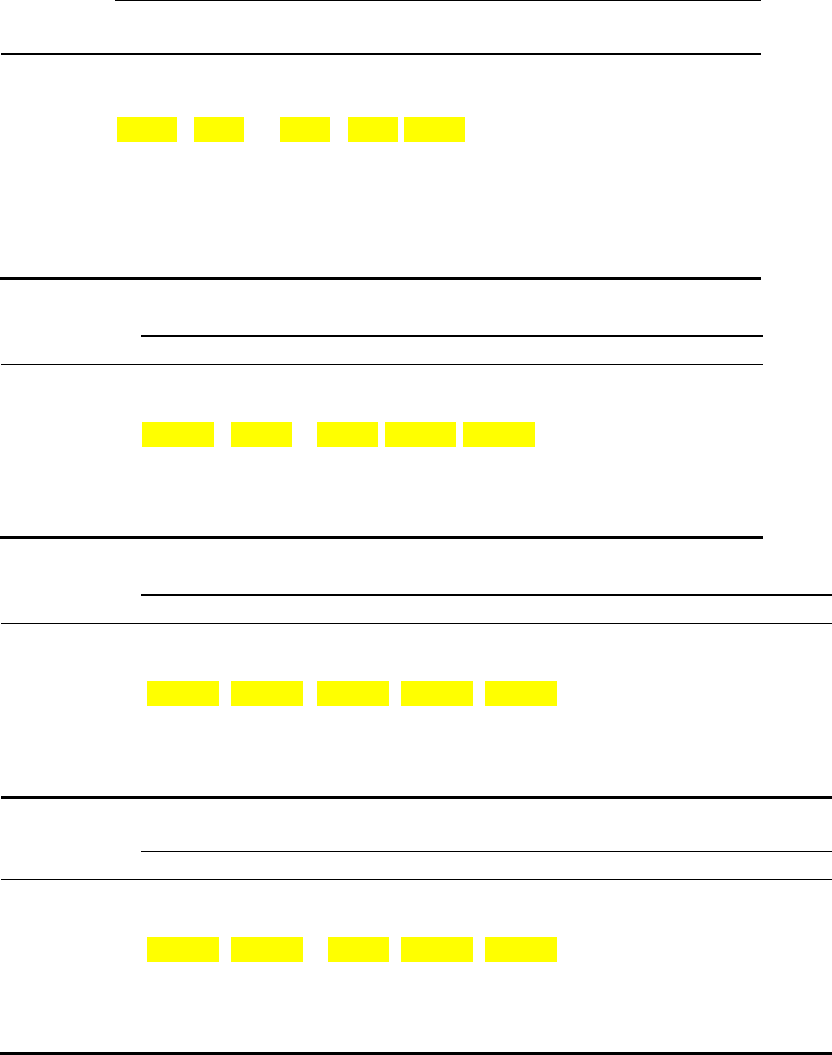

Table 1. Participation Gaps in FCPS Advanced Academic Programs

Table 2. AAP Demographics by Level of Service – Fall 2019:

Percent of each racial group in each level of service

TOTAL

WHITE

ASIAN

BLACK

HISPANIC

OTHER

Total grades K-6

94820

36616

17925

8824

25137

6318

% of grades K-6

100%

38.6%

18.9%

9.3%

26.5%

6.6%

AAP Level IV

(Determined by Central

Selection Committee only)

10152

3998

3468

705

1126

855

10.7%

10.9%

19.3%

8.0%

4.5%

13.5%

AAP Level IV (Determined by

Central Selection Committee

and School Designated)

11209

4435

3788

768

1293

925

11.8%

12.1%

21.1%

8.7%

5.1%

14.6%

Level III services

6719

3288

1326

479

1091

535

7.1%

9.0%

7.4%

5.4%

4.3%

8.5%

Level II services

11672

4762

2237

1133

2733

807

12.3%

13.0%

12.5%

12.8%

10.9%

12.8%

Source: School AAP Enrollment File

7

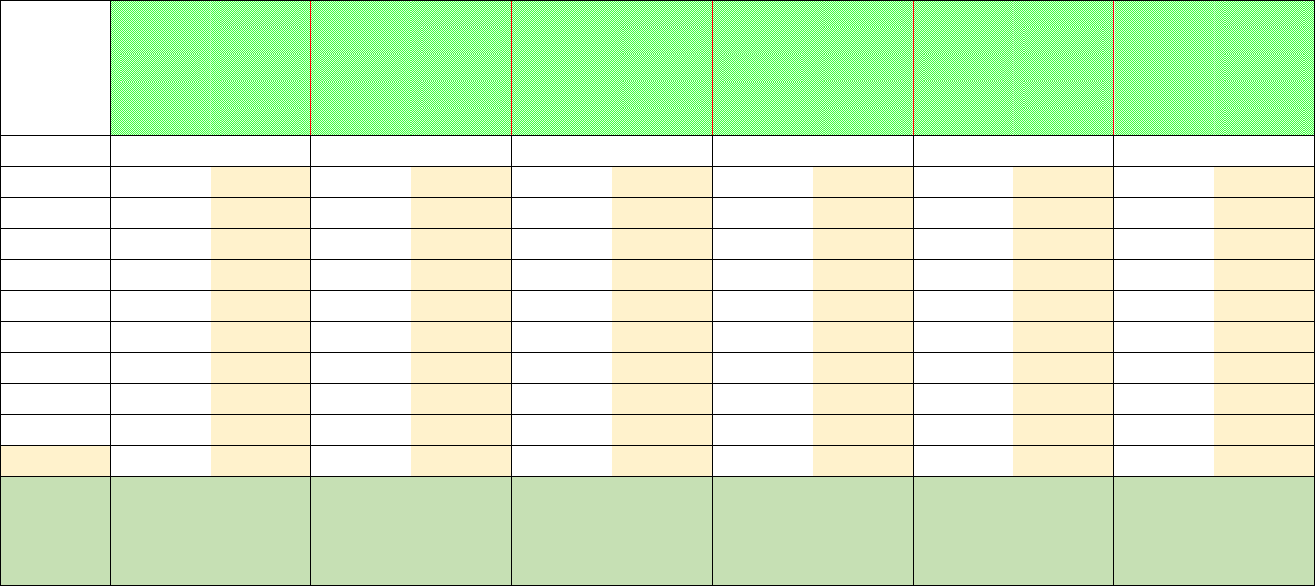

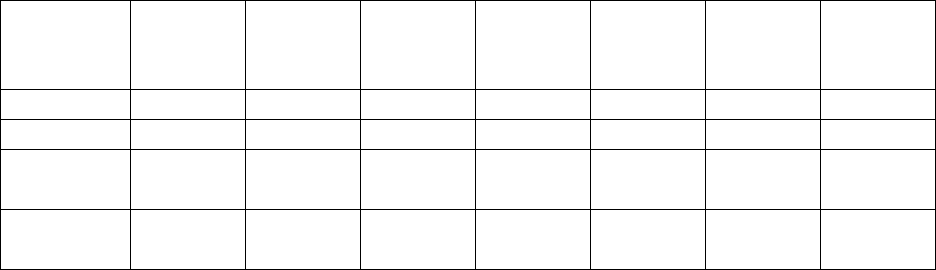

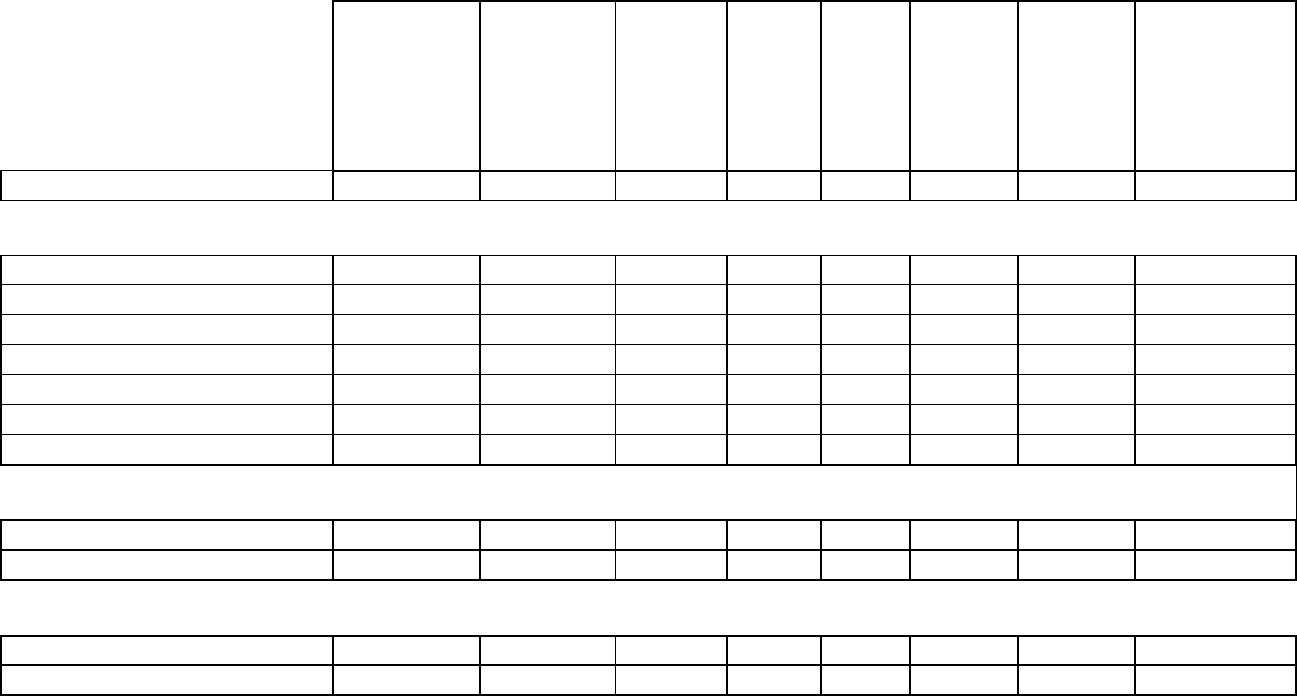

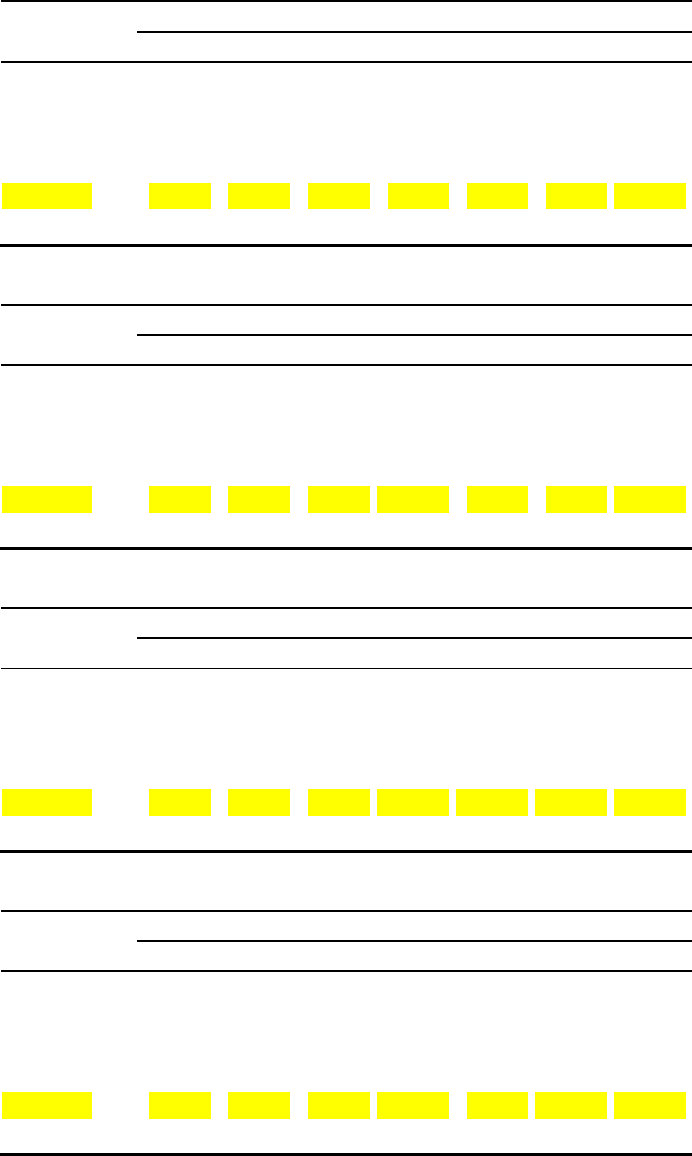

Table 3. Students Eligible for Level IV (full-time grades 3-8) AAP Services Across the Years 2008-2018

Year

White

%

change

from

prior

year

Black

%

change

from

prior

year

Hispanic

%

change

from

prior

year

Asian

%

change

from

prior

year

Two or

More

Races

%

change

from

prior

year

Total

%

change

from

prior

year

2008

5,360

382

403

2,821

703

9,687

2009

5,666

6%

400

5%

438

9%

3,209

14%

746

6%

10,475

8%

2010

5,461

-4%

351

-12%

580

32%

3,341

4%

614

-18%

10,361

-1%

2011

5,776

6%

415

18%

696

20%

3,676

10%

688

12%

11,271

9%

2012

6,763

17%

535

29%

899

29%

4,282

16%

835

21%

13,342

18%

2013

6,989

3%

611

14%

975

8%

4,625

8%

960

15%

14,192

6%

2014

7,089

1%

684

12%

1,142

17%

4,933

7%

1022

6%

14,913

5%

2015

7,062

0%

786

15%

1,231

8%

5,203

5%

1121

10%

15,446

4%

2016

7,174

2%

917

17%

1,452

18%

5,519

6%

1174

5%

16,282

5%

2017

7,294

2%

1,076

17%

1,689

16%

5,788

5%

1254

7%

17,153

5%

2018

6,975

-4%

1,092

1%

1,699

1%

5,728

-1%

1280

2%

16,829

-2%

%

increase

2008-

2018

30%

186%

322%

103%

82%

74%

Note. Subgroups with very small numbers of students removed for purposes of clarity. These include American Indian students (increase from

2008-2018 from 12 to 38 students, +217%) and Hawaiian students (increase from 6 to 17 students, +183%)

8

Demographic Breakdown of 2018-2019 Grade 2 Cohort

As noted above, one of the data sources utilized in this report was the universal screening data set from

the cohort of students who were enrolled in FCPS grade 2 for the 2018 – 2019 academic year. In FCPS,

the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT) is administered to all first-grade students, and the Cognitive

Abilities Test (CogAT) is administered to all second-grade students. These data are used to create the

initial screening “pool” – the students who are automatically considered for Level IV services via a

Central Selection Committee. For the 2018 – 2019 school year, students needed to score a 132 (two

standard deviations above the national mean score) on either the NNAT or composite CogAT in order to

be placed in the automatic pool via the universal screening process (we discuss this process in greater

detail below). Starting in 2019 – 2020, students could be placed in Level IV services if they scores two

standard deviations above the mean on any one CogAT subscale. Our cohort dataset also included racial

/ ethnic information, gender, and scores each student received on the Gifted Behavior Rating Scale

(GBRS) – an instrument completed by each students’ teacher on observable gifted characteristics.

We used this cohort dataset to calculate racial / ethnic demographics for the cohort as a whole, the

population of students placed in the screening pool, and the population of students who were identified

as Level IV eligible. At least with regard to Level IV, this presentation is preferable for understanding

racial / ethnic enrollment differences. These data are presented in Table 4. We also used this dataset to

understand if certain student groups were less likely to be screened or identified when compared to

similarly-scoring peers from other groups.

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

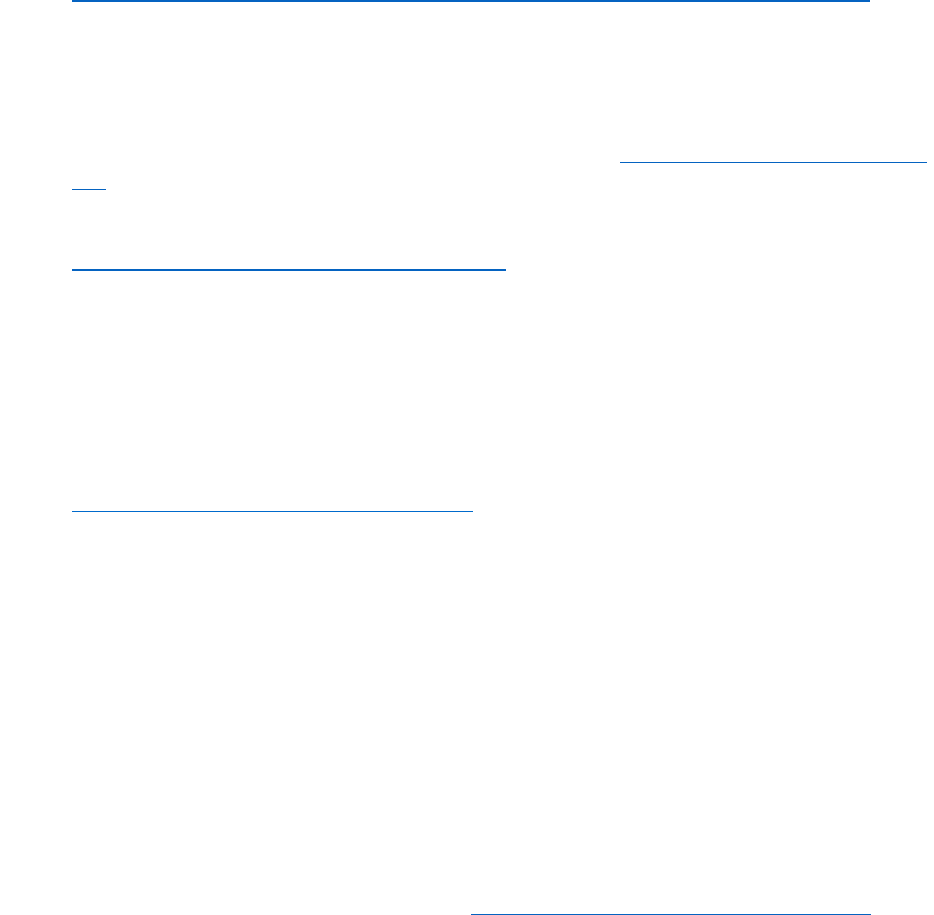

Figure 1. Students Eligible for Level IV AAP,

Grades 3-8, 2008-2017

White Black Hispanic American Indian Asian Two or More Races Hawaiian

9

Table 4. Demographic comparisons across groups – 2018/2019 Grade 2 Cohort (Level IV)

Percentage of Cohort

1

Overall

Population of Students

Screened (pool)

Percentage of

Identified Cohort

African American

9.8%

6.4%

7%

Asian American

18.7%

30.7%

30.8%

European American

39%

43.2%

40%

Hispanic

25.3%

10.6%

12.3%

Multi-racial

6.7%

8.9%

9.6%

Total

100% (13818)

29.3% (3757)

16% (2198)

1

“Cohort” refers to students in FCPS second-grade in 2018 – 2019 school year

Table 4 is a clear illustration of the disproportional enrollment / equity challenges that are common to

the AAP program in FCPS as well as gifted and talented programs across the country. Students from

African American and Hispanic families are disproportionally underrepresented both in the screening

pool as well as among those deemed Level IV eligible (or academically gifted in gifted and talented

programs). In addition, Asian American students are disproportionately overrepresented in the “pool”

and “identified” groups, while European American students are more-or-less proportionally represented

across all three groups. These enrollment rate differences were a motivating factor behind the RFP and

also the team’s investigation and recommendations.

10

Methodology

This section provides an overview of the review team’s approach to data collection, organized by the

four contracted tasks and additional parent survey: (1) a review of existing FCPS policies and related

documents, (2) a review of existing FCPS data analyses and reports, (3) a review of research-based

interventions and best practices, (4) focus groups and interviews with FCPS and community

stakeholders, and (5) a survey of parent attitudes. Each set of activities is described in more detail

below.

Review of Policies and Related Documents

The first data source included any and all policy / procedure documents, school board presentations,

and internal analyses produced by FCPS related to AAP. These were reviewed by the entire research

team through the lens of best practices for gifted and talented student identification and procedures

known to exacerbate or mitigate inequity. Many of the findings from these past data sources are

referenced in this report. This includes a number of tables and figures showing historical demographic

trends. Some of the most important FCPS documents or analyses reviewed include:

1. FCPS Local Plan for the Education of the Gifted 2016-2021

(https://www.fcps.edu/sites/default/files/media/pdf/LocalPlanGifted2016to2021.pdf)

2. FCPS Advanced Academic Programs Identification Procedures Manual: 2019-2020 (see AAP web

site for this and related documents: https://www.fcps.edu/academics/academic-

overview/advanced-academic-programs)

3. 2013 Review of the Advanced Academic Programs authored by Bland et al.

4. May 2018 and May 2019 Advanced Academic Programs Advisory Committee Reports and Staff

Responses to Recommendations

5. Training materials for Level IV Central Selection Committee members

6. 2019 Minority Student Achievement Oversight Committee (MSAOC) History of Reports to the

FCPS School Board 1990 – Present (provided by J. Howard)

7. Data on historical pool benchmark scores for NNAT and CogAT

8. Expansive report on hypothetical alternative identification criteria (e.g., different benchmark

scores, local norms)

9. 2010 – 2019 demographic breakdown of students placed into consideration pool by test scores

10. 2010 – 2019 demographic breakdown of students placed into the consideration pool by referrals

11. Referral data showing the source of AAP referrals by race, ethnicity, gender, ELP, and Young

Scholar participation for 2016 – 2019 school year (called “cohort” above)

12. GBRS instrument and associated training information for teachers

13. Chapter 40: Regulations Governing Educational Services for Gifted Students (§ 22.1-16 of the

Code of Virginia; relevant sections included in the Appendix to this report)

Review of Existing Data and Analyses

In addition to relying on and reviewing existing reports, we also requested and analyzed data from FCPS

staff. In some cases, the, FCPS staff conducted analyses; at our request, we were provided with the raw

data used to conduct our own analyses.

11

1. Primary analyses

a. iReady data on average student achievement by grade level and building

b. Universal screening data (GBRS, CogAT, NNAT) for all grade 2 students in 2018 – 2019

cohort.

We used complete data from the 2018 – 2019 grade 2 cohort in order to conduct a

number of analyses on the identification process. Focusing on a single year / cohort in

this way allowed us to evaluate the formal identification process – in short, to examine

leaks in the pipeline. Analyses included:

i. Comparing mean scores by test by student subgroup

ii. Comparing % of each student subgroup in the overall cohort population,

screened sample, and sample found eligible for Level IV services (Table 4 above)

iii. Measuring the odds of a student being found Level IV eligible by gender and

race / ethnicity after controlling for NNAT, CogAT, and GBRS scores

2. Requested analyses from FCPS

Data on % of students served for each level of FCPS AAP by race, ethnicity, IDEA, and LEP

Data on number and percentage of students screened by attending school

Choice of placement for Level IV eligible students for the past three academic years:

Center, local Level IV, or deferred.

Level IV Center discontinuation rate / placement in year following Level IV Center

placement disaggregated by race, ethnicity, IDEA, ELP, and 504 status

Data on eligibility decision following an appeal disaggregated by race / ethnicity

Data on rates and source of outside testing by race / ethnicity

Data on rates of referral (and referral source) over time

AAP participation data by level of service and race / ethnicity

Review of Research-based Interventions and Best Practices

The team conducted a comprehensive review of the literature to identify empirically-supported

identification and programming interventions for increasing equity in advanced programming. Given

that book-length treatments of these topics are not uncommon (indeed, review team members have

written or contributed to several such volumes), the goal for this review was to highlight key best

practices for achieving equity in advanced programs in the research literature.

Focus Groups and Interviews with Stakeholders

The first step in the process of planning for focus groups and individual interviews was to establish the

stakeholder groups most likely to provide insights into the current state of affairs around issues of

equity in the AAP program. The four reviewers prepared a list of groups of individuals to be interviewed

by role (e.g., parents, AAP teachers, Advanced Academic Resource Teachers (AARTs)) and by committee

assignments within FCPS, representing varying orientations, interests, and perspectives on the issues

(e.g., concerns from members of historically under-represented populations (in gifted programs) or

marginalized groups, twice-exceptional student involvement, identification of gifted students).

We then met with staff from FCPS representing the AAP program, the central administration, and a

liaison from the Office of Research and Strategic Improvement (ORSI) to (1) ensure our list was

12

comprehensive, (2) develop a plan for identifying specific individuals from each group, (3) develop a plan

for communicating with the stakeholders to be invited to participate, and (4) ensure compliance with

guidelines for carrying out such reviews as established by FCPS. The discussion also included an

exploration of ways to ensure representativeness of all groups, development of a viable schedule, and

development of a plan to ensure travel by participants would be manageable and not bias attendance.

We determined that situating interviewers at schools within the different regions across the school

division would minimize travel for school-based participants (e.g., parents, teachers, principals) in focus

groups and interviews, and that other interviews and focus groups would be scheduled at the central

office.

Following the meeting with FCPS staff, we created a spreadsheet to select a sample of representative

schools. We randomly selected elementary schools based on the following criteria:

Group A: Schools in Regions 1 and 2 with high minority representation, a high percentage of

students that receive free/reduced-price meals (FRM), and representatives across all levels of AAP

of programming. At least two schools selected would offer the Young Scholars program.

Group B: Schools in Regions 3 and 4 with relatively high minority representation, a high percent of

students receiving FRM, and representatives across all levels of AAP programming

Group C: Schools from Regions 4 and 5 –mostly 5—with relatively low minority representation,

relatively low percent of students receiving FRM, and representatives across all levels of AAP of

programming

Group D: Schools from Regions 1 and 2 –mixed across all variables noted above

Group E: Schools from Regions 3, 4, and 5- mixed across all variables noted above

Middle Schools were selected to represent all five regions with the inclusion of the one Title I school.

The liaison from ORSI provided school demographic information from which the review team selected

schools from each region. ORSI also assisted with random sampling of teacher, parent, and student

names that were used for focus groups. All principals from schools selected in each region were invited

to attend the focus group at the school selected to be the host school in the region; a random selection

of teachers, AARTs, students identified for AAP services, parents of students identified for AAP, and

members of the local AAP identification committee from each host school were invited to attend focus

group sessions.

Interview Guides. In preparing for the focus group meetings and individual interviews, we created a

series of tailored interview guides (see Appendix). These interview guides were structured to provide a

general framework for questioning. Each guide was comprised of questions to be asked during the

meetings, and the questions were created to reflect issues of equity in the AAP program and to provide

a general sense of the orientation and views of the participants toward the program’s identification

process and service delivery models as they might relate to equity. The guides were prepared to ensure

that the same basic lines of inquiry were pursued with each group or individual. However, additional

questions were added to each guide that would allow us to capitalize on the knowledge and

understandings that a person or group might offer because of their role or experiences with the school

division and/or the AAP program. The guides were used as a framework; however, the interviewer was

free to explore, probe, and ask questions that elucidated or clarified responses or would provide

verification of responses from other people or groups interviewed. Thus, the people who were

interviewing, on occasion, might build a conversation around a particular subject area or word questions

spontaneously or even pursue a new line of questioning if responses suggested the line of questioning

would yield relevant information for the review.

13

Data Analysis. During the focus group and individual interviews, the interviewers took notes on

participants’ responses, particularly focusing on responses that provided insight into equity issues.

Following each visit, the interviewers wrote summary notes of the responses from interviews and focus

groups. These notes were shared with the whole team. The team reviewed the notes and discussed

them with a particular emphasis on comments and observations that suggested a need for pursuit of

any emerging themes at a subsequent visit. The team reviewed the summaries for themes used to

describe the current situation and suggestions for addressing equity issues. At the conclusion of the

visits and follow-up phone interviews, the full set of interview responses were reviewed for additional

conclusions and themes that complemented, extended, or explained quantitative findings and

suggested paths to consider for recommendations.

Parent Survey

The research team designed a parent survey to gather information on perceptions of AAP services,

specifically Local Level IV and Level IV Centers, and awareness of AAP policies and procedures deemed

most relevant to equity. Primarily, we were interested in parental understanding of identification

policies and procedures, parental feelings about how well those procedures were working to identify

students for Level IV placement, and parent feedback on how Level IV services could be diversified or

improved. After initial design by the research team, the AAP office distributed a draft to several parents

as well as FCPS staff for feedback. We integrated this feedback into the final survey instrument. Once a

final version was established (see Appendix), we created seven copies and forwarded them to the FCPS

central office for translation into the following languages: Farsi, Amharic, Spanish, Korean, Arabic,

Chinese, and Urdu. On February 14

th

, all eight surveys were distributed by FCPS. Reminders were sent

out on February 21

st

and 27

th

before the survey was closed the morning of March 2

nd

. As of March 2

nd

,

each survey had the following number of responses: Amharic: 5, Arabic: 17, Chinese: 64, English: 6,071,

Farsi: 2, Korean: 127, Spanish: 154, Urdu: 3. We integrated survey responses throughout the report

rather than in a single section. A summary of results is included in Appendix F.

Limitations

Although our data collection efforts were extensive and went beyond even the ambitious plan in the

accepted proposal, stakeholders should note the review team did not directly observe any classrooms –

either AAP or non-AAP – nor did we speak with a large number of students. Although the plan included

student focus groups, students often did not attend the scheduled meetings, limiting the amount of

student input into the study. However, we believe adequate student input was received, and our

triangulation of other stakeholder perspectives leaves us with a high degree of confidence in our

conclusions and recommendations.

14

Literature Review on Causes of Inequity and Interventions

to Achieve Equity in Advanced Academic Programs

Below we present an overview of the literature on the topic of equity and underrepresentation within

gifted and talented programs. Throughout, we make connections to current FCPS policies and practices

to note where they align and where there is potential for improvement. A summary of these connections

is included in Table 5 on page 24.

For the last 50 years, the field of gifted education has recognized and struggled to ameliorate the

underrepresentation of students from non-European backgrounds in gifted education programs.

Specifically, African American, Hispanic, and Native American youth have been underrepresented in

gifted education services relative to their representation in the student population, while students from

European American and some Asian backgrounds have been well represented or overrepresented. As

most American K-12 students now identify with a demographic racial group other than European

American, the discrepancy in gifted education services is a pressing matter (National Center for

Education Statistics [NCES], 2017). Although perfect proportionality of all subgroups may be unrealistic

given the larger state of inequality in the United States, or for that matter in FCPS, progress (or lack

thereof) is important to investigate. Disparities in the identification of students who have limited English

proficiency or who are served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) are also a

growing issue due to these groups making up a rapidly-growing percentage of the American student

population: currently 9.4% and 13% of American students, respectively (NCES, 2016a; 2016b).

Sources of Disproportional Underrepresentation

In a 2016 analysis, Peters and Engerrand classified the research base surrounding the causes of

underrepresentation into two themes. The first theme presented the view that the assessments

commonly used to make gifted identification decisions are inherently flawed or biased against certain

groups, thereby resulting in disproportional underrepresentation. The response to this argument is best

exemplified by the popularity of “nontraditional” assessments such as the use of non-verbal

assessments of aptitude, use of specific teacher rating scales with language orientated toward the

manifestation of gifted characteristics in under-represented populations; use of alternative assessment

tools such as products and performances, etc. The first-grade FCPS universal screening process uses the

Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT) – one of the most common types of such “nontraditional”

assessments. From this perspective, proportional identification should be expected due to the “culture

reduced” nature of the assessment, and any observed underrepresentation is due to flawed

identification tools. If this is a valid claim, then the call for “less-biased” assessments for identification

makes sense. In addition, if this claim is true, than identification via “culture neutral” tests should result

in more-or-less perfect proportionality across student groups.

Peters and Engerrand (2016) identified a second theme, suggesting the ways in which students are

identified, rather than which particular assessment instruments are used, cause underrepresentation.

For example, teacher recommendations as a tool may be an appropriate data source for student

identification, but if such recommendations are mandatory before any other data points are considered,

then their use could unintentionally exacerbate disproportionality. For example, in 2016, Grissom and

Redding published an analysis of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Kindergarten cohort (ECLS-K),

examining the factors contributing to disproportionality in gifted education. A major finding was that

African American students were far more likely to be identified as gifted in reading if they had a teacher

who was also African American (6.2% vs. 2.1% probability), even after controlling for academic

15

achievement, suggesting that achievement tests themselves were not the source of the problem.

Instead, a teacher-related variable was at issue. The National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC)

State of the States Report (2015) noted that teacher and parent referrals are a common gate through

which students must pass before being further evaluated for gifted services. The result of this two-phase

identification process is that some students who would meet the identification criteria are never

considered because they never receive the initial referral.

FCPS does use teacher ratings, in the form of GBRS scores, in its AAP identification process. However, it

does so universally, meaning all students are rated by their teachers. This is a strength and avoids one

common problem with teacher ratings. However, although FCPS does conduct universal screening in

first and second grade with NNAT, CogAT, and GBRS, there is a second referral pathway into the

consideration pool for those who know about it. This second pathway consists of parent referrals,

appeals, requests for re-testing, and procurement of outside testing. This second pathway inserts a form

of assessment bias, similar to traditional uses of teacher or parent nominations, whereby those parents

who know about the second pathway and take the initiative to take advantage of it, have a higher

chance of their children getting identified.

A growing body of research points to the use of poorly-designed two-phase identification systems as a

contributor to underrepresentation (e.g., Hamilton et al., 2017; McBee, Peters, & Miller, 2016). Any time

fewer than 100% of students are considered for gifted services (i.e., universal consideration), some

process must be used to determine who is considered and who is not. That process is always imperfect,

but certain factors contribute more seriously to bias in the identification process (McBee et al., 2016). In

gifted education, the most common form of the initial screening phase is the teacher or parental referral

(NAGC, 2015). If students cannot access program eligibility procedures unless first being nominated by a

teacher, then simply improving the quality of the formal identification phase will never solve the

problem, because many students who would (and should) be identified will never make it past the

screening phase.

McBee et al. (2016) gave a second example of a two-phase system wherein students must score at the

90

th

percentile on the phase one assessment(s) to be given the phase two assessment(s). Students must

then score at the 90

th

percentile in phase two to be identified. Even under high reliability assumptions

(.95) with a strong correlation between the phases (.90), approximately 20% of students are missed

compared to universal consideration due to the existence of the conditions in this two-phase system

because some students who would have done well in phase two were blocked by phase one. If the two

cut scores move to the 95

th

percentile, just under 30% of students are missed, with most of the missed

students from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds.

In general, FCPS avoids many of the challenges associated with two-phase identification systems by

conducting expansive universal screening of all students in grades one and two. This is a major strength

over common practice across the country. However, the unequal use of referrals, appeals, re-testing, and

outside testing creates a second pathway to consideration for those who know about it. We discuss this

at length in the findings and recommendations.

Inequality. A factor that was not addressed as a cause of underrepresentation by Peters and Engerrand

(2016), which also contributes to underrepresentation, is the large inequality of educational access and

opportunity in the United States. When approaching the topic of equity in gifted education, it is often

implied that something close to perfect proportionality should exist, and that anything less results from

flawed identification methods (e.g., biased tests or two-phase identification systems), rather than from

16

disparities in educational opportunity. Put simply, this is not a reasonable assumption given the

inequality in educational opportunity in the United States. Exposure to learning opportunities influences

achievement (Lohman, 2005) and measured IQ (Ritchie & Tucker-Drob, 2018). Further, in the United

States, higher-income families generally have greater access to high-quality educational opportunities in

and outside of schools. This is true in many countries but is especially problematic in the United States

(Chimelewski & Reardon, 2016; Finn & Wright, 2015).

In an analysis of nations identified as wealthy by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD), Chimelewski and Reardon (2016) found that the United States had the largest

levels of “poverty/inequality,” as well as some of the largest income-related achievement gaps. The

United States also had the lowest parental support index, and the lowest social welfare policy index.

What all of this means is that broad inequality in the United States persists and is associated with large

achievement differences. Higher family income generally is associated with greater access and

opportunities during the pre-school years, during the school day, and outside of formal education.

Further exacerbating the effect of this inequality is that in 2015, 12% of European American children

lived in poverty compared to 36% of African American children, 34% of Native American children, and

31% of Hispanic children (Kids Count Data Center, n.d.), creating an intersection of race and poverty for

students who have long been under-identified for gifted education services.

In a recent analysis of three states, Hamilton et al. (2017) found that even after controlling for

achievement scores, individual- and school-level free or reduced-price lunch status were negatively

predictive of a student’s probability of being identified as gifted. Their results make clear that individual

and institutional poverty are negatively associated with the probability of a student being identified as

gifted. To be clear, poverty is not the only reason for racial/ethnic disproportionality in gifted

populations. However, in the United States, being African American, Hispanic, or Native American

means one is far more likely to be poor and also face additional institutional barriers related to

race/ethnicity. Thus, proportional representation in the absence of proactive efforts to mitigate the

effects of poverty and racism on access is unlikely to occur.

FCPS is often discussed in gifted education circles as a leader in talent development efforts (discussed

next) to mitigate the effects of inequality on gifted education equity through its Young Scholars program.

What the literature surrounding this topic makes clear is that absent efforts to mitigate the effects of

poverty and unequal opportunity to learn and develop the kinds of skills taught in school,

disproportionality in any advanced learning opportunity will continue.

Talent Development

One of the most promising frameworks with a robust intervention literature is the talent development

framework (Dixson et al., 2020; Renzulli, & Reis, 1985; Subotnik et al., 2011; Worrell et al., 2019). Simply

put, the talent development framework focuses on identifying and developing the academic potential of

as many students as possible, with a particular emphasis on developing the academic potential of those

who are highly motivated and frequently overlooked during the typical gifted and talented education

identification process (e.g., a flawed two-phase identification process; Dixson et al., 2020; Olszewski-

Kubilius & Steenbergen-Hu, 2017; Renzulli & Reis, 1985; Subotnik et al., 2011; Worrell et al., 2018). The

goal of the talent development framework is to help students live up to their highest academic

potential, both within specific domains and generally, to maximize the number of students progressing

through the talent development stages—from potential to competency and from competency to

expertise (Dixson et al., 2020; Worrell et al., 2019).

17

A key way that talent development frameworks deviate from other gifted education frameworks is the

lack of emphasis on who qualifies for advanced academic services, typically determined by a student

obtaining or surpassing an IQ and/or a standardized achievement score above the 90th percentile

(McClain & Pfeiffer, 2012), and the increased emphasis on who would likely benefit from advanced

academics, typically determined by a student displaying potential within an academic domain in early

childhood (Dixson et al., 2020; Worrell et al., 2019). This deviation is critical with regards to equity.

Students from disadvantaged backgrounds (e.g., minorities, students from low socio-economic

backgrounds, English language learners, twice exceptional students) frequently encounter and must

overcome a host of challenges that students from advantaged backgrounds generally do not (e.g., Ford

et al., 2008; Head et al., 2019; Menken, 2010; Olszewski-Kubilius et al., 2017; Worrell & Dixson, 2018).

As a result, students from disadvantaged backgrounds typically have lower academic skills at school

entry and throughout schooling compared to their advantaged student counterparts (e.g., Kettler &

Hurst, 2017; Reardon & Portilla, 2016). This likely leads to the typical identification process missing some

academically gifted disadvantaged students since this process typically focuses on identifying students

displaying high academic talent (e.g., via high IQ and/or standardized test scores), instead of high

academic potential to develop (as is the primary focus of talent development programs). In sum, the

talent development framework makes it more likely for students from disadvantaged backgrounds to be

identified as academically talented and to have their academic potential developed. Correspondingly,

talent development programs tend to display more equity in their representation of students from

disadvantaged backgrounds with disadvantaged students more likely progressing through the talent

development stages (Card & Giuliano, 2015; Dixson et al., 2020; Peters et al., 2019; Peters & Engerrand,

2016).

Effective Talent Development Interventions

Several talent development interventions have been developed and implemented to date. Overall, these

interventions indicate that many disadvantaged academically gifted students are: (a) being missed by

the typical gifted education identification process (e.g., a flawed two-phase identification process; Card

& Giuliano, 2015), (b) would benefit from advanced services when provided the opportunity (e.g.,

Robinson et al., 2018), and/or (c) in many cases have similar outcomes as their advantaged peers when

provided advanced services (e.g., frontloading; see Olszewski-Kubilius et al., 2017). For example, Project

EXCITE is an advanced academics program designed to “support and enhance minority students’ interest

and performance in math and science through extensive supplemental programing, with the ultimate

goal of preparing participants for advanced-level math and science coursework in high school”

(Olszewski-Kubilius et al., 2017, p. 22). Project EXCITE consists of inclusive admission criteria with the

goal of growing/developing their own gifted students from disadvantaged backgrounds. They admitted

African American and Hispanic students (total n = 361) who (a) scored at the 75th percentile or above on

the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT) or a standardized achievement test in reading or math, (b)

exhibited evidence of high motivation (as measured by letters of recommendation and reported work

habits), and (c) displayed evidence of academic potential (i.e., the student’s prior academic

performance; Olszewski-Kubilius & Steenbergen-Hu, 2017).

Project EXCITE’s programing was intensive. It front-loaded its participants starting in the third grade,

providing its participants with approximately 625 hours of supplemental academic enrichment after

school, on weekends, and during the summer. The results of the program are robust. After five years in

the program, the African American and Hispanic Project EXCITE students outperformed their African

American and Hispanic Division counterparts in both math (Hedges g = .42) and reading (g = .51), while

18

also outperforming other African American and Hispanic students that did not participate in Project

EXCITE at their school in math (African American, g = 1.58; Hispanic, g = 1.21), reading (African

American, g = 0.75; Hispanic, g = 0.54), science (African American, g = 1.26; Hispanic, g = 1.07), and

English (African American, g = 1.38; Hispanic, g = 1.06). All effect sizes were in the medium to large

range. Further, Project EXCITE students graduated and attended selective universities (de facto

advanced education programs) at a rate of 50% above the national average for African American and

Hispanic students and at a comparable rate as Asian American students (Ashkenas et al., 2017). Finally,

Olszewski-Kubilius and colleagues reported that after five year in the project, Project EXCITE students

perform similarly to European American students in math (g = -0.02), reading (g = -0.46), science (g = -

0.30), and English (g = -0.31), with all differences being in the small to medium range.

In addition to Project EXCITE, data from several other interventions provide evidence of effectiveness at

providing increased equity within advanced education programs as well as resulting in improved

outcomes for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. For example, several evidenced-based,

district-specific interventions have reported increased equity and positive outcomes for students from

disadvantaged backgrounds. For instance, Robinson and colleagues (2018) exposed about half their

sample of 1,387 (n = 765, 55.2%) first-grade students to a challenging engineering curriculum and

teachers that were trained for a week during the summer on identifying talent in students from low-

income backgrounds. At the end of one year, teachers in the study referred a substantially higher

percentage of African American (35.1% of total nominations) and low-income (37.5% of total

nominations) students than was typical (Card & Giuliano, 2015). In addition, Robinson and colleagues

reported that students participating in the intervention displayed academic gains, exhibiting higher

academic performance than control group students on an out-of-level science content assessment

(Cohen’s d = 0.28) and engineering knowledge test (d = 0.66). This intervention is similar to several other

gifted education interventions around the country that have reported positive results (e.g., Harradine et

al., 2014; Horn, 2015).

Use of Local Norms

Calculation and use of local norms is another intervention consistent with the talent development

framework that has been found to increase equity within gifted programs as well and has been

identified as a means to attaining positive outcomes for students from disadvantaged groups (Dixson et

al., 2020; Peters et al., 2019; Peters & Engerrand, 2016). Standardized assessments, which include many

of the tests that are used to assess and identify students for gifted programs (e.g., IQ tests, state

achievement tests, the SAT), are normed on a nationally representative sample. This means that when

students take the assessment, their score is compared to a national sample of students (Matthews &

Peters, 2018). National norms are the default because they are useful in several situations such as when

there are a limited number of college admission slots available or a limited number of merit-based

scholarships to award. More succinctly, national norms are typically most useful when one is serving

and/or comparing students from a national pool of candidates.

National norms are significantly less useful for identification for advanced academic program services, as

they are not informed by local information—the district resources, district programs offered, and the

match between specific students’ needs and district resources (Matthews & Peters, 2018). If a school

district has the capacity to develop the academic talent of 20% of its students, why would they limit

themselves to serving only the 5% that have an IQ of 130? In addition, although an IQ at the 99th

percentile nationally may indicate that a student has the ability to efficiently complete advanced

cognitive tasks, it does not indicate whether that student is or has been being challenged academically

19

in his or her classes nor does it indicate whether the student is a fit for the district’s advanced programs

or particular services offered.

Local norms, in comparison, likely provide district decision-makers with meaningful information that is

informed by the local context. Moreover, district gifted education programs do not serve the students

from the entire nation, they serve the students within their school district. As a result, utilizing local

norms would provide a school district information about the academic abilities of its students (relative

to other students within the district), which could be subsequently matched with district services and

programs. More specifically, local norms can help determine which students within a school district or

school building would most likely benefit from their specific advanced services given the available

resources and programs (Matthews & Peters, 2018). For example, a school district may only have the

resources to develop the advanced mathematical talent of 15% of its students. If this district utilized

local norms, they could easily identify the 15% of students with the highest math potential within their

district. Thus, matching academic talent/potential with available district services and resources.

Empirically, local norms have been found to create more racial equity within gifted education programs.

For example, Peters and colleagues (2019) examined the relationship between local norms and

demographic representation in advanced education programs. Their sample consisted of over 3 million

students in third through eighth grade across ten states. They found that when district or school local

norms were used for comparison, African American and Hispanic student representation in the top 15%

of students in both mathematics (% increase ranged from 52%-111%) and reading (% increase ranged

from 54%-99%) meaningfully increased while European American representation remained the same (%

change ranged from -7% to -13%) and Asian American student representation meaningfully decreased

(% decrease ranged from -19% to -26% in math and -20% to -27% in reading). These findings highlight

the importance of implementing local norms and have been argued to relate to positive outcomes for

students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Peters et al. highlighted the problematic decision to not

implement local norms, as it resulted in thousands of African American and Hispanic students not being

identified as academically gifted, thus decreasing their opportunity to readily access an appropriate

curriculum to develop their academic potential. Had the districts utilized local norms, more students

from these backgrounds likely would have had a better chance at a positive outcome. Similar arguments

have been made by other scholars (e.g., Plucker et al., 2017; Worrell & Dixson, 2018).

The application of local norms would identify, at the least, a slightly different group of students than

would national norms. Local norms allow for identification of those who score highest in their school

building compared to those who score high compared to the rest of the nation. Peters and colleagues

(2019) responded to the dichotomy set between these approaches with a “compromise” plan whereby

students are identified if they meet the local norm criteria OR the national norm criteria. Although this

solves the problem of some high-performing students not identified simply because they attend a high-

performing school when local norms alone are applied, it also increases the overall size of the

population in need of services.

Currently, Level IV identification in FCPS is based on a national norm. This creates an equity problem as

scores at this level are often less accurate than they are when closer to average, and because students

who come from less-advantaged backgrounds have had fewer opportunities to develop the skills

necessary to perform at such high levels. Local norms, especially when applied to particular levels of AAP

services, are an area in which FCPS could make progress toward improved equity.

20

In sum, there are several talent development interventions that have been found to increase

representation, opportunity, and positive outcomes for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Nonetheless, no matter the intervention, the elements of a successful talent development intervention

are similar—increased opportunity and appropriate challenge.

Strategies to Increase Equity Within Advanced Academic Programs

In addition to specific interventions noted above that have been implemented to increase

representation and outcomes of students from disadvantaged backgrounds, there are several other best

practice strategies that have been found to increase equity within advanced academic programs. These

strategies include the use of multiple criteria for identification, frontloading, and universal screening.

Frontloading and student support. Gifted education is usually conceptualized as identifying

academically gifted students and subsequently providing them services to develop their academic

talents. A different way to view gifted education within schools, that is consistent with the talent

development model, is to universally frontload students with early learning opportunities. Frontloading

students means preemptively exposing them to advanced or enrichment programming before they are

assessed or identified for an advanced education program. The goal of frontloading is to better prepare

all students for their opportunity to be identified as academically gifted as well as to better prepare all

students to persist in advanced programs should they be admitted (Briggs et al., 2008; Plucker et al.,

2017a; 2017b). In FCPS, frontloading is best exemplified through the Young Scholars program.

This strategy accomplishes its goals in two ways. First, it exposes all students to advanced and/or

enrichment programming, which by definition limits one of the most adverse consequences of being

from a disadvantaged background within the context of advanced education—lack of access to

appropriate advanced programing to develop academic talents (Olszewski-Kubilius & Corwith, 2018;

Peters & Engerrand, 2016; Reis & Renzulli, 1985; Worrell & Dixson, 2018). Second, through the

exposure, it provides all students the opportunity to have their talent developed from an earlier age,

likely leading to a higher portion of students from disadvantaged backgrounds performing better when

being assessed for an advanced program as well as preparing these students for the work and

environment inherent to many such programs (Plucker et al., 2017a; 2017b). The previous points are

particularly important as students thrust into advanced programs without proper preparation are likely

positioned to fail (Plucker et al., 2017a; 2017b; Weiler & Walker, 2009). The failure of disadvantaged

students in advanced programming is particularly detrimental because: (a) many students from

disadvantaged backgrounds are already hesitant to take advanced programming because they likely feel

isolated from their same-group peers who are typically underrepresented in such courses (Francis &

Darity, 2020; Kettler & Hurst, 2017), and (b) students from disadvantaged backgrounds seeing students

from similar backgrounds failing to succeed in advanced academic programs is likely to negatively affect

their own academic self-efficacy relative to being admitted to and persisting throughout such programs

(Dixson, Keltner, Worrell, & Mello, 2018; Usher & Pajares, 2006).

One particular academic paper bolsters the argument for frontloading creating more equity. Weiler and

Walker (2009) discussed a high school that, despite being primarily made up of Hispanic students (62%),

contained an AP mathematics class that was primarily made up of European American students (94.5%).

In acknowledgement of the racial inequity, Weiler and Walker developed and implemented a

frontloading intervention for freshman Hispanic students who were placed in remedial math to begin

their high school math education. They offered them the opportunity to complete an accelerated math

track that would prepare them and ultimately position them to take AP mathematics. The accelerated

21

math track consisted of a summer program intensive in math along with a special math schedule of

courses that included many AP mathematics concepts. They reported that many students not only

excitedly embraced the opportunity, but they excelled throughout their math career at the school,

improving the racial equity within AP mathematics to 30% Hispanic and 70% European American. Put

another way, when advanced math was frontloaded, students were better prepared for advanced

programming later and were more likely to be identified as academically gifted later. This finding is

similar to other findings reported in the literature which outline both the longitudinal and annual effects

of frontloading within advanced academics and the academic context more broadly (e.g., Cuba, 2020;

Olszewski-Kubilius & Steenbergen-Hu, 2017). In sum, frontloading advanced academic material allows

those from disadvantaged backgrounds to have greater access to and success within gifted programs.

Studies of the success of historically under-represented populations in Advanced Placement courses

have also documented the importance of strong support systems for success of under-represented

students in these advanced-level courses (Hanover Report, 2016; Kyburg et al., 2007).

Universal Screening. One of the most common criticisms of gifted education and typical identification

processes is that students from disadvantaged backgrounds are not given an equal opportunity to

demonstrate their academic abilities as are those from advantaged backgrounds due to factors beyond

their control (e.g., racism, economic challenges; Assouline et al., 2017; Elhoweris et al., 2005; Ford et al.,

2008; Grissom & Redding, 2016; Olszewski-Kubilius & Corwith, 2018; Worrell & Dixson, 2018). For

example, Grissom and Redding (2016) conducted a study examining the predictors of gifted assignment

in a nationally representative sample of over 10,000 students. They found that even after controlling for

standardized test scores in reading and mathematics, socioeconomic status (SES), and gender, African

Americans were about half as likely as European Americans to be referred for a gifted education

assessment. Similarly, McBee (2006) found in a sample of over 700,000 students that European

American (5.83%) and Asian American (9.69%) students were at least 2.75 times more likely as their

African American (1.96%), Hispanic (1.36%), and low SES (1.95%) counterparts to be referred by a

teacher for an assessment.

Many scholars have responded to this documented shortcoming by asserting that to increase equity and

close this opportunity gap, advanced academic programs should universally screen all students in the

early grades to both provide them the opportunity to demonstrate their academic potential as well as

provide that opportunity before the effects of being from a disadvantaged background start to mount

(Brown & Abernethy, 2009; Olszewski-Kubilius & Corwith, 2018; Plucker et al., 2017; Worrell & Dixson,

2018). Calls for universal screening are bolstered by studies indicating that universal screening results in

more equity across demographics within advanced academic programs. Universal screening “works” by

not relying on parental initiative or teacher referral. Instead, all students are tested. However, this only

addresses the cause of missed students related to not being referred. It does not address any students

who are missed because of larger, fundamental inequality or lack of opportunity to develop the kinds of

skills the tests are measuring. That is a problem only frontloading can address.

Card and Giuliano (2015) conducted a seminal universal screening study of a school district that

consisted of a diverse group of roughly 40,000 third grade students across 140 different elementary

schools. The district universally screened all second graders with the NNAT. All students who obtained

an NNAT score that surpassed the predetermined cutoff score for the district were referred for a

complete gifted education assessment (full IQ test) by a school psychologist. Card and Giuliano reported

that their universal screening intervention resulted in a 67 percent increase in the total number of

students identified as academically gifted throughout the district (increasing the total percentage from

3.6% to 5.3%), with the overwhelming majority of the additional students identified coming from

22

disadvantaged backgrounds. More specifically, African American student representation in the district’s

gifted program increased by 145%, Hispanic student representation increased by 171%, low SES student

representation increased by 75%, and English language learner representation increased by 150%. It is

important to highlight that all the screening intervention did was provide students the opportunity to be

subsequently assessed by a district psychologist, the criteria to be referred for advanced testing was not

changed nor was the criteria for being identified as academically gifted. The screening intervention

provided access, which resulted in more equity. In sum, universally screening students for academic

talent allows all students the opportunity to demonstrate their gifted abilities, typically resulting in more

equity across demographics within advanced academic programs.

Psychosocial Interventions

One of the current focal points of intervention work in education involves psychosocial interventions.

Psychologists have long posited that motivation, attitude, and the social context of the learning

environment are all strongly predictive of success (CPSE, 2015). Currently, interventions involving

constructs such as stereotype threat, grit, mind-set, and self-affirmations receive significant attention in

education.

The concept of stereotype threat has been considered an especially promising area of inquiry. In

essence, stereotype threat occurs when individuals within a group begin to believe stereotypes about its

members’ abilities and characteristics (Steele & Aronson, 1995). Such stereotypes may limit the

performance on measures of aptitude and achievement and academic success of, for instance, a poor

Hispanic student if she internalizes any stereotypes about the ability of poor Hispanic females to

perform at advanced levels of achievement. If this student does not see advanced achievement as

something that Hispanic students “do” or “are,” then closing excellence gaps will be nearly impossible.

This parallels work to help women overcome stereotype threat related to advanced achievement in

science and mathematics. For over a quarter century, researchers have pointed to negative gender role

stereotypes as a possible cause of female underachievement in STEM areas. Research on stereotype

threat and effectiveness of interventions to counter stereotype threat is still not conclusive (Flore et al.,

2018; Pennington et al., 2016; Spencer et al., 2016) particularly as it might affect particular subgroups of

students.

The potential role of grit, growth mind-sets, positive self-beliefs and other constructs in promoting

advanced achievement and equity has been equally enticing to educators, which is probably one reason

why these constructs continue to be discussed with such enthusiasm in the educational excellence

research community (Clinkenbeard, 2012; VanTassel-Baska, 2013). Furthermore, although the potential

overlap among all of these psycho-social constructs and their effectiveness is still subject to debate (i.e.,

they are currently not well-defined), non-cognitive factors clearly matter in the development of talent

(Abuhassàn & Bates, 2015; Duckworth et al., 2007; Rimfeld et al., 2016).

Despite the potential of psychosocial interventions, research on these constructs have not provided

helpful information for equitably promoting advanced academic achievement. Part of this issue appears

to be the difference between correlation and causation – highly successful students tend to have high

levels of grit, for example, but it may be the case that people who are successful tend to see themselves

retroactively as having been “gritty,” so to speak, when the actual grit construct had little to do with

their achievements.

23

In one of the more exhaustive research programs to date, researchers studied the effects of a brief self-

affirmation in several cohorts of students in a diverse school, beginning in seventh grade (Cohen et al.,

2006; Cook et al., 2012). In the original study and some follow-up research, they found convincing

evidence that such interventions closed racial achievement gaps (as measured by student GPA), with

African American students benefiting from the intervention much more than white students. The

researchers also found evidence that starting the intervention earlier in the school year yielded

significant benefits. But the academic benefits were largely experienced by low-performing and

moderate-performing students, not high-performing students. This suggests that such an intervention

could help close minimum-proficiency gaps, but not equity gaps in advanced programs.

In another follow-up study, the researchers took this work further, investigating the extent to which the

intervention influenced the achievement of students who did not receive it. They hypothesized that the

greater the “treatment density” within each classroom, the greater the spillover effects for all students

in the class (Powers et al., 2015). And that is the limit of what they found, although treatment density

for African American students appeared to be the primary driver of any positive effects. But again, low-

performing students appeared to benefit significantly more than high-performing students. This

research and related studies call into question whether psychosocial interventions are promising

approaches to addressing advanced academics and equity in such programs, partly because stereotype

threat may be less of an issue for high-potential students (Nguyen & Ryan, 2008; Yeager & Walton,

2011).

Plucker and Peters (2016), in a review of the psychosocial research literature, concluded that

psychosocial interventions are not suitable for routine use in schools, and that they may not work at all

regarding the promotion of advanced achievement in equitable ways. Since their review, the research

has turned significantly more negative, with major studies and reviews finding mixed to little evidence

that psychosocial interventions provide learning benefits for any group of students (Burgoyne et al.,

2018; Burgoyne et al., 2020; Burnette et al., 2020; Gandhi et al., 2020; Mehta, 2015; Moreau et al.,

2019; Sisk et al., 2018).

24

Summary

The interventions reviewed above are present in varying degrees in the Fairfax County Public School

division. Table 5 summarizes this information as an introduction to the following sections on Findings

and Recommendations.

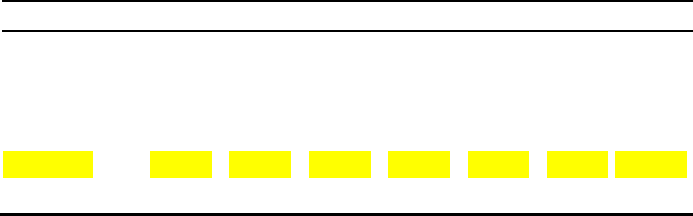

Table 5. Research-supported Interventions for Equity in Advanced Programming

Intervention

Present in FCPS?

Related

Recommendations

Professional development on

advanced learning and

identification for classroom

teachers

High-quality PD available, but decentralized

administrative structure makes access to this PD

infrequently utilized and limited in some regions

and schools

2c, 4a-4e

Universal screening

All students screened at two different grade

levels with multiple measures

2a, 2c, 2d

Use of local norms

The division does not use local norms

systematically

3b

Identification procedures

that minimize advantages of

socioeconomic status

The division has made a sincere effort to

minimize bias in its identification procedures,

but some potential sources of bias remain such

as via the appeals process, requests for re-

testing, and in the procurement of outside

testing

2b, 2e-2h

Frontloading

The Young Scholars program is intended to

provide frontloading, but its implementation is

inconsistent throughout the division and limited

in intensity

3a, 3b

Psychosocial interventions

(e.g., mindset, grit,

stereotype threat reduction

interventions)

Generally NOT supported in the research

literature, but some FCPS leaders talked about

the usefulness of such interventions for

advanced learning

N/A

25

Major Findings and Conclusions

This section highlights our major conclusions from the study. Readers should note that this section

focuses on the contracted task – how to improve equity in FCPS advanced academic programming – and

not a broader set of issues on which we received input. For example, the complications caused by Level

IV Centers within the FCPS pyramid system were often shared with the review team, as were principal

concerns about how state achievement test results are attributed to schools for Level IV Center

students. These and many other issues are important and worthy of being addressed, but they do not

directly relate to the assigned project.

1. AAP programs in FCPS meet the relevant statutory requirements of the Commonwealth of Virginia

and are considered a net positive by the community.

FCPS programming appears to meet the requirements for advanced programs described in

Virginia Code (The Appendix contains relevant sections of the Commonwealth of Virginia Code

regarding gifted education).

AAP is considered a net positive by the community and a key defining feature of FCPS by many

parents and outside stakeholders. Stakeholders described AAP programming as key to the

“identity” of FCPS, sharing stories of how local businesses use the presence of AAP programming

in their effort to recruit employees.

The vast majority of respondents to our parent survey believe that FCPS should continue

offering Level IV Centers as one of its AAP service options. Only 18% of parents believe they

should be discontinued.

2. FCPS has taken a number of steps to increase equity of participation in its Advanced Academic

Programs:

Over the past 10-12 years, FCPS has grown the number of students receiving AAP services

significantly. For example, Table 3 shows a 186% and 322% increase in African American and

Hispanic identification for Level IV services over the last 10 years. This growth is not trivial and is