University of Vermont University of Vermont

UVM ScholarWorks UVM ScholarWorks

UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses

2018

The Meme as Post-Political Communication Form: A Semiotic The Meme as Post-Political Communication Form: A Semiotic

Analysis Analysis

Jacob A. Yopak

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Yopak, Jacob A., "The Meme as Post-Political Communication Form: A Semiotic Analysis" (2018).

UVM

Honors College Senior Theses

. 263.

https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/263

This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at UVM

ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized

administrator of UVM ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected].

The Meme as Post-Political Communication System: A Semiotic Analysis

Jacob Yopak

2

I. History

i. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to provide an analysis of memes. I will use the 2016

American Presidential Election to frame the significance of memes and online communication in

general. A semiotic model will be constructed as well to contextualize the political and social

effects of memetic communication. I will conclude by connecting the semiotic model of the

meme with the political theories of Chantal Mouffe and Hannah Arendt to discuss the potential

for change as the new media form unfolds.

Due to the very contemporary nature of my study most of the literature that I am

discussing will be tangentially related. Memetic communication was originally theorized by

Richard Dawkins as applying the logic of evolution to cultural information. While the name

stuck I will be focusing more on the online phenomenon which does not share many similarities

with Dawkins theory.

Semiotically speaking I draw from Ferdinand Saussure, Mikhail Bakhtin, Valentin

Voloshinov, Umberto Eco, Roland Barthes, and Charles Sanders Peirce. While all of them are

important I mainly use Peirce to discuss the semiotics of memes as his writings privileges the

relationship between the mental concept of the sign and the sign itself. Using the analysis that

Barthes uses in Mythologies may be tempting, but he is more concerned with the creation of

meaning outside the dynamic of the sign and the one person observing it. Both thinkers are

concerned with what observers bring to the table when decoding semiotic structures, but Peirce

is more interested with the small scale meaning network that is more relevant for how memes

function.

3

Instead of being a mere exercise on the modern aesthetics of internet culture,

understanding the meme form can elucidate facts about the nature of modern political dynamics.

Our political discourse has undergone a level of mediation through technological processes

heretofore unseen in humanity’s history. Large social media sites like Facebook and Reddit,

provide users access to the public square without having to see another physical human being.

Facebook alone saw that its 1.65 billion users average 50 minutes of time on the site per day.

That amounts to 82.5 billion minutes clocked on Facebook per day in total. Unlike the famous

squares that have reached international attention, like Tahrir, Tiananmen, and Times (and those

are just the T’s) the online forum has no physical limitation on how many would-be

revolutionaries or passive consumers can gather together in one space. While most of the tech

giants that made the most popular sites in the world were initially satisfied by profiting off their

users, the 2016 American presidential election shows the influential nature of technological

public forums. To best understand what happened online leading up to and during the election,

and why memes as a form of communication are relevant, we must develop a full intersection

between the new media and politics.

In my paper I will also assume that internet communication is structurally speaking

egalitarian relative to traditional media. The internet medium flattens the differences between

content creators and audience members. In addition, the limited access to physical means of

media dissemination- the means to reproduce newspapers or broadcast radio waves- is a moot

point online. Everyone with internet access can add something to the discussion. This leads to a

lot of hand wringing on behalf of those who previously held a monopoly on the flow of

information. On the other side of the spectrum are those who herald the internet as an

uncomplicated democratizing force, which erroneously assumes that the material access to

4

information disseminating technologies is the sole barrier to a fully functioning and unbiased

press. I intend to highlight how the flattening of the material distinctions between the producer

and consumer of media content has created a new landscape for political media, one in which

ideological difference is fostered through a lack of formalized ideological gatekeepers and

postmodern identity politics usurps the traditional national paradigm. Present at this flux of

ideological assertions is the meme, the weapon of choice for the modern trenches of online

political discourse.

ii. What is a Meme?

This first section is to be a history of the meme-form and some basics on how they are used-

especially in connection with online culture and politics.

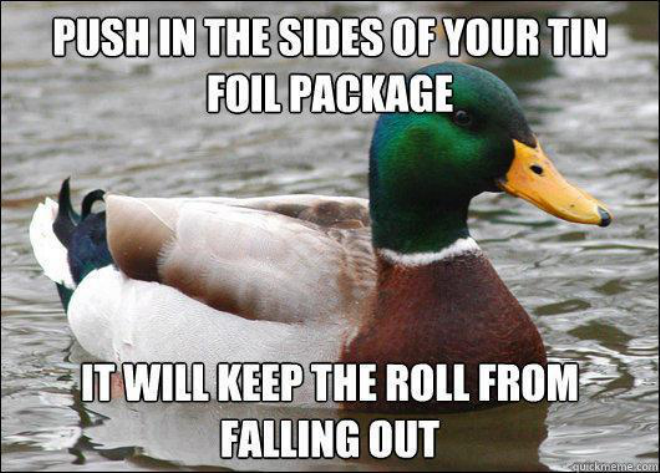

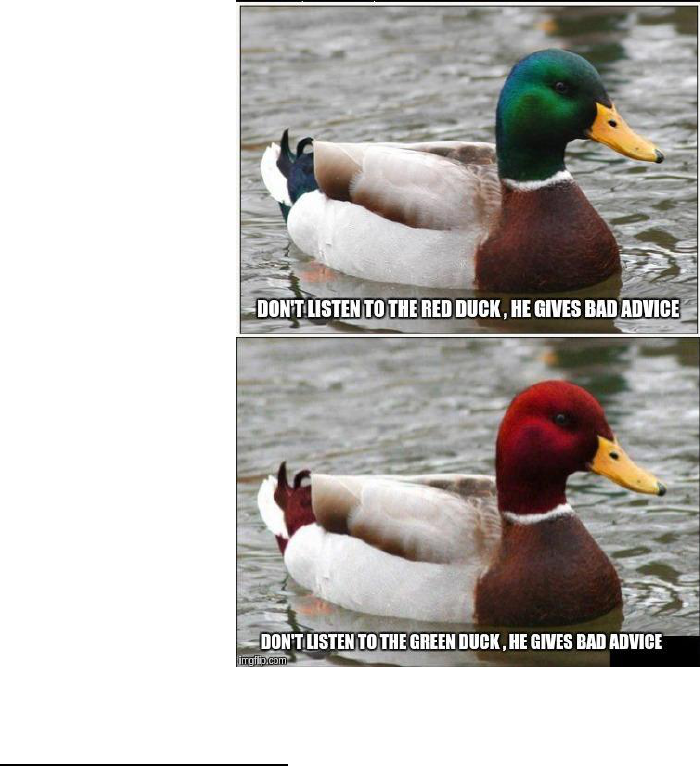

Above is an example of one of the simplest meme forms. The framework entails a static image of

a duck, accompanied with large white all-caps Impact font. The captions give advice or life-

5

hacks, earning the meme framework the name “Actual Advice Mallard.” The image that is

shown above was the first instance of Actual Advice Mallard shared on Reddit in 2011.

1

All

initial derivations of the meme entailed merely editing the text, so each different complete

memes of this class shows the duck giving the reader a different suggestion. The combination of

the name of the framework and the expectations for the edited caption, display how legibility of

the meme depends on an understanding of the meme network. Although there is no objective link

between the photo of a duck and a caption giving advice, the frequency of the connection creates

a larger structure, a socially sanctioned link between the image and the linguistic markers. For

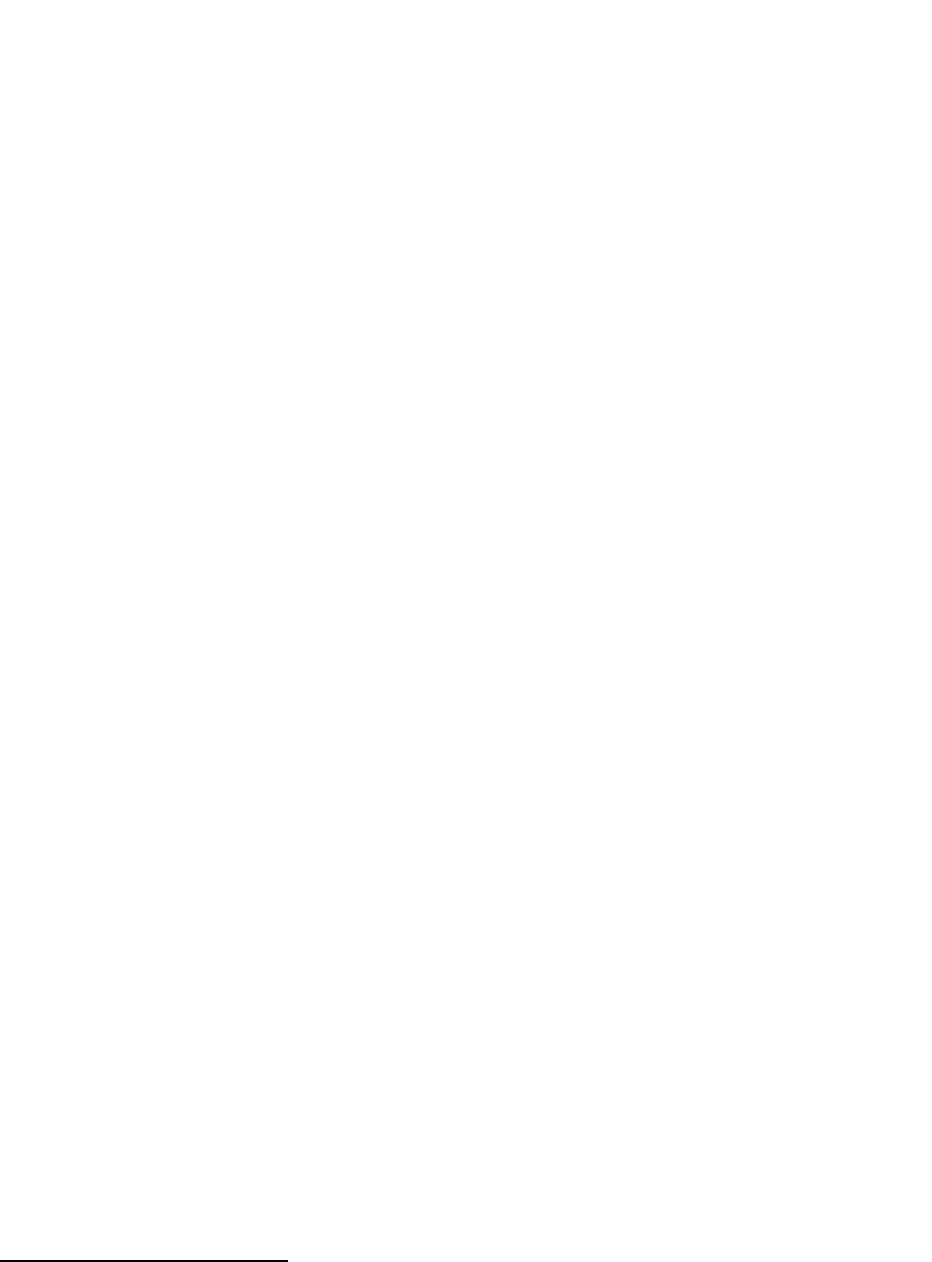

example, below is a “mash-up” of both Actual Advice Mallard and Bad Advice Mallard.

1

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/actual-advice-mallard

6

The meme is akin to the classic riddle, famously depicted in the film The Labyrinth

where there are two guardians of a passageway in the labyrinth and one always tells the truth and

the other always lies. In this meme, both ducks assert that the other gives bad advice. As in the

movie, the version of the riddle depicted in the meme cannot be solved as in the movie and

requires prior knowledge of both forms of mallard memes. While the intentions of this meme’s

original creator are unknowable, it functions by drawing attention to the larger meme networks

of both advice duck memes. Here, any logical reading is predicated of whether the reader has

knowledge of the meme’s framework. I will hold a more detailed analysis of the framework's

impact on meme communication in the Semiotics section of this paper, but a rudimentary

understanding is important here to make the historical and social overview of memes legible.

The example of the two Advice Mallard Memes shows how the boundaries of a meme

framework is constructed. Playing with the boundaries of what is considered a member of any

meme makes the network for that class becomes apparent. For example, the concept of what is

considered an “Actual Advice Mallard Meme” is in flux as meme play with various aesthetic

signifiers of the image or its text. Speaking formally, this is the most constricting definition of

what it takes to be considered a meme. Many images shared on other social media sites behave

socially and virally like a meme but do not share any of its distinct framing. Moving forward

when speaking of memes’ historical import, semiotic particularities, or political influence, I will

maintain that any given meme’s conceptual framework is explicitly at the forefront of its usage

and dissemination.

Considering the meme there are two definitions to account for. The word meme can refer

to a large framework of ideas, phrases, or aesthetic signifiers for example what we expect when

we consider Actual Advice Mallard. This frame then takes shape in the form of a single

7

reference which could be the advice Mallard saying a phrase. This single instantiation of a larger

framework is what most people refer to when they say the word “meme.” Using the word

“meme” to refer to the particular image or concept as well as the larger framework may cause

confusion. To best eliminate ambiguity, I will refer to the instantiation as a meme or complete

meme, and the framework as the meme framework or conceptual network. To be considered a

meme, an instance must clearly reference network of signifiers that any one specific instance of

it can opt into. Then variations of the meme’s framework are constructed as complete memes and

circulated online. Memes are omnipresent online and communicate all sorts of messages in all

sorts of social circles. My discussion will focus on the history of online communication, a

discussion of the current political context that has brought the meme success, a semiotic analysis

of the meme, and finally a political discussion concerned with the implications of the

“memeification” of political discourse.

Internet users construct complete meme through the process of altering or adding to the

meme template. Certain memes are more flexible with regards to what types of content they can

accept; the online meme encyclopedia Know Your Meme refers to this as a meme’s

“exploitability.”

In addition, I will assert that the meme can only function when the connection between its

complete forms and its framework are self-evident to those who are literate in meme-usage.

Memes are only memes when it is clear they are opting into certain signifiers. This may appear

to depend too much on logical circuitousness. The claim that memes themselves constitute their

own frameworks by displaying a trend of signifiers that then construct a legible network lacks

falsifiability. However, since the creation of these connection semiotic structures is arbitrary the

only way to study them is through their connection; I will therefore treat the between framework

8

and complete memes as self-evident. Since a meme’s status as a meme is contingent on it opting

into a framework, any ambiguity as to what larger network it references does not derail its

reading as a meme of a class but rather prevents it from being read as a meme at all. A meme

becomes a meme, as opposed to an image, if the viewer sees it as a member of a larger

conceptual network.

Memes as a medium are primarily an online phenomenon, so many of the behaviors and

vocabulary surrounding them are often new terms for those not of the very-online. Instead of

defining them all in a list here, I will tackle them when necessary as they arise, to make the paper

legible.

Memes on the internet are easy to take for granted. Attempts to tie down a definition only

serves to emphasize their slipperiness. Before I talk about this technically complex method of

communication, I will let a meme do the talking for me. The lengthy quotation that follows is a

“copypasta,” a text-based meme that involves copying and pasting an extended verbose passage

as a non-sequitur often in an unsolicited position.

“You may be onto something here. Memes used to be simple. Relatable. Worth a

chuckle. Then they evolved. New formats, new tag lines, new content that was

then turned into a new meme. Then memes became increasingly meta and self

reflective. They parodied themselves and the users who both made them and

consumed them. They built off of one another. They grew. They morphed into

something entirely novel. This progressed to the point where even that wasn't

enough. They had to become something more than themselves. They became

surreal. They became deep fried and nuked. Each flavor building off of the last

and transforming into a nearly intangible, unknown entity.

Art progressed in a similar fashion. Started off simple, I'm talking cave drawing

simple. Then some pottery and some small abstract sculptures. Subjects everyone

could relate to and understand. Then, as technology allowed for the creation of

cultures and societies, art began to reflect that change and it evolved along with it.

By the Ancient Greeks and Romans, art had become a more advanced version of

the Stone and Bronze Age arts. Better drawings, paintings, and the addition of

mosaics. Sculptures eventually shifted from stylistic expression to naturalistic

representation. Still accessible to everyone, yet more nuanced and complex.

9

After the fall of Rome art stagnated and didn't change very much for nearly a

millennium. Early Christian art dominated for the most part, consisting of murals

and frescos and simple statues. All of which were based on the Ancient styles.

Romanesque and Gothic art also built upon these precedents. This all changed

when the Renaissance attacked.

A cultural explosion changed the art world forever; arguably starting with the

Italian artist, Giotto. He began using techniques like foreshortening and linear

perspective so that the material world could be represented as it appeared to us. A

callback to the naturalistic stylings of the Greeks. Almost like a reference to the

days of yore. A celebration of how art used to be, but with the explosion of new

techniques and technologies, the art grew increasingly diverse. New and improved

frescoes, meticulously crafted sculptures, architectural marvels and the inclusion

of new materials in these works. Instead of tempera, oil was introduced along with

new styles of depicting light and shadow through sfumato and chiaroscuro. These

techniques and stylistic changes, while impressive, were simply an advancement

of pre established art. The Renaissance paved the way for the explosion and

diversification of dozens of art movements that followed.

From prehistoric art to the end of the Renaissance, art was mostly about the same

subjects and used similar techniques to accomplish the goal of producing a work

of art. Yes, the technical proficiency exponentially improved but considering the

centuries in between, few true advancements were made.

Compare this to memes. They were so simple at first and really were nothing

more. Then they got better. More technical. More circumstantial. More media to

create them with. But memes could last years or many months before dying off.

As time went on, the longevity of a meme shortened. This is paralleled in the art

world.

After the Renaissance the Baroque period started. Then the Neo-Classicism,

Romantic, Realism, and Impressionism movements not long after. Still utilizing

the same technical process but the reasoning behind the movements changed. No

longer was it about simply depicting the world around us, it was about prompting

the viewer to consider new thoughts and ideas. Urging them to look past the

image and think deeper about meaning and context. Pushing the boundaries of

what art could be. The Baroque to Impressionism era spanned roughly 300 years.

Compare that to the thousands of years between archaic art and the Renaissance.

It was a huge explosion of self expression. Finally, in the mid to late 19th century

starting with Post-Impressionism, Modern art emerged. This movement focused

on self-consciousness, self-reference, introspection, existentialism, and even

nihilism. I'm talking Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Dada, Abstract Expressionism,

and Surrealism to name the most well known.

These styles changed what art could be. They were no longer about depicting life

as is, or layering a painting with hidden motifs for only the privileged to

understand, they were in and of themselves absurd. Abstract shapes, aggressive

lines and colors, nonsensical dreamscapes. But it didn't stop there.

Post-modernism. Pushing art to the limit of its potential. Pop art, Conceptual art,

Minimalism, Fluxus, Installation art, Lowbrow art, Performance art, Digital art,

10

Earth art. These movements are about skepticism, irony, rejecting grand narratives

and reason and instead embracing the idea that knowledge and truth are the result

of social, historical, and political discourse and subsequently are a subjective,

social construct. It's irreverent and self-referential. It's avant-garde pushed to 11.

But what's next? Post-postmodernism? Metamodernism? Hypermodernity? Who

knows? Only time will tell.

This is where memes are headed. They started off slow but have picked up so

much momentum they're evolving at an exponential pace. They used to hang

around for a couple years at most. Then it turned to months. Then maybe only one

month. Suddenly it was a week tops. While some particularly great memes do still

stick around much like the masterpieces of art in the past, new memes are created

every day, every few hours. New movements of memes are being created all the

time. Anti-memes. Dank memes. Abstract memes. Wholesome memes. Surreal

memes. Deep fried memes. Nuked memes. Even black hole memes, time travel,

and dimensional memes are now a reality. What's going to happen next? A return

to the classics? A new format so brilliant it steals all our hearts and then starts a

whole new movement? I'm excited for the future of memes.

TL; DR: Memes imitate art, art imitates life.

And most importantly we must always remember--- I mean me too thanks lol”

I saw this post for the first time in the early winter of 2017 and it has henceforth become

a popular memetic comment in response to structurally experimental memes. Despite the

meme’s dubious art history, the fact that internet communities treat the mutation of memes with

such gravity shows the degree in which memes have become unmoored from the banal internet

funnies of the mid-aughts to early-teens.

iii. An Introduction to Online Politics

The political contentions in the real world have made their war online, since many people

naturally bring their political ideologies with them when they log on. Most alarmingly in the

modern political landscape is the rise of far-right politics, in the form of the alt-right, Neo-Nazis,

and white nationalist movements. The intersection between online spaces and far-right politics is

11

a complex one. Angela Nagle compiled a detailed perspective on these online political

battlegrounds in her 2017 book Kill All Normies; Online Culture Wars From 4Chan and Tumblr

to Trump and the Alt-Right. Nagle provides a political, philosophical, and historical lens to this

trend. She characterizes this shift as a “backlash” where the new conservative political bloc was

a:

strange vanguard of teenage gamers, pseudonymous swastika-posting anime

lovers, ironic South Park conservatives, anti-feminist pranksters, nerdish

harassers and meme-making trolls whose dark humor and love of transgression

for its own sake made it hard to know what political view were genuinely held

and what were merely, as they used to say, for the lulz. (Nagle 2).

While Nagle tries to remain objective, she minimizes the possible political ambitions of

these various groups. Meanwhile, labeling the anti-feminists as “pranksters” and conflating that

with the myopic brutality they showed in the case of the gamergate controversy begs the

question to what extent do writers like Nagle consider the real-world implications of online

activity. Nagle also introduces a very important topic when considering online communication

and culture: the lulz.

Whitney Phillips offers up the most exhaustive account of “lulz” in her sociological book

on trolls: This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things. Phillips describes the lulz as an online social

fetish that encourages certain trolling behaviors:

Within trolling communities, lulz functions both as punishment and as

reward, sometimes simultaneously. Lulz operates as a nexus of social

cohesion and social constraint. It does not distinguish between friend and

foe, and is as much enjoyed by the trolling spectators as by the active

trolling-agent. This makes the lulz an extremely slippery term, one that

implies active pursuit, lulz don’t amass themselves, they have to be sought

out. (Phillips 28)

12

The lulz are a form of derision or schadenfreude, where there is a perverse enjoyment at

seeing the discomfort of others. An act or gesture can be lulzy to experience this form of

enjoyment, which is the ultimate motivation and goal for those engaging in trolling behavior.

However, the most indicative and pithy take down of what is going on online is a tweet

from twitter user GreytheTick who writes, “I notice the usage of the term Feminazi has dropped

off considerably now that the anti-feminists have decided that Nazis aren’t that bad.” Here, they

highlight a trend that has been occurring across the internet in which formerly garden-variety

misogynists embrace fascist iconography and rhetoric.

While it is likely that this political shift cannot be completely explained through online

terms the importance of the online should not be downplayed. The meme as the vehicle of online

discourse has massive explanatory power in determining what signifiers are being flung about in

the political-ideological battlegrounds of Tumblr, Facebook, and Reddit. Nagle did point to the

liberal consensus that dominated the political psyche before this backlash took place, but never

quite developed the truly material criticism of the rise of modern online fascism. For instance, it

may be easy to place white nationalists and their ideological ilk within the greater potpourri of

13

identity politics. However, as a movement, their platform questions the legitimacy of identity

politics, although in name only. This is complicated by the irony of how the political apparatus

of white nationalism relies on the existence of identity politics to push against. While the

connection between the rise of extreme right-wing politics is not directly connected to memetic

communication, it serves to contextualize the radicalization that is afforded by eschewing

mainstream media options, a phenomenon that will be discussed at length later in the paper.

iv. Modern Meme Politics

The political influence of online communication and memes entered the national and

global consciousness after the 2016 American political election. Where the online right hailed

the power of “meme-magic” to explain their victory, the liberal wing rallied against what they

saw as an army of Russian meme that is an existential threat to American democracy. While I

will consider the meme forms that are employed by the left, I will primarily focus on the memes

and communities that gathered around various right-wing causes (either establishment or not).

My decision to focus more on one side of the political aisle stems from the right-wing memes’

effect on the political consciousness. People online are more aware of the right-wing cohorts

2

of

meme-sharers and I hope to elucidate to what degree this activity translated to electoral success.

Choosing to focus more on the right-wing approach also provides me the opportunity to

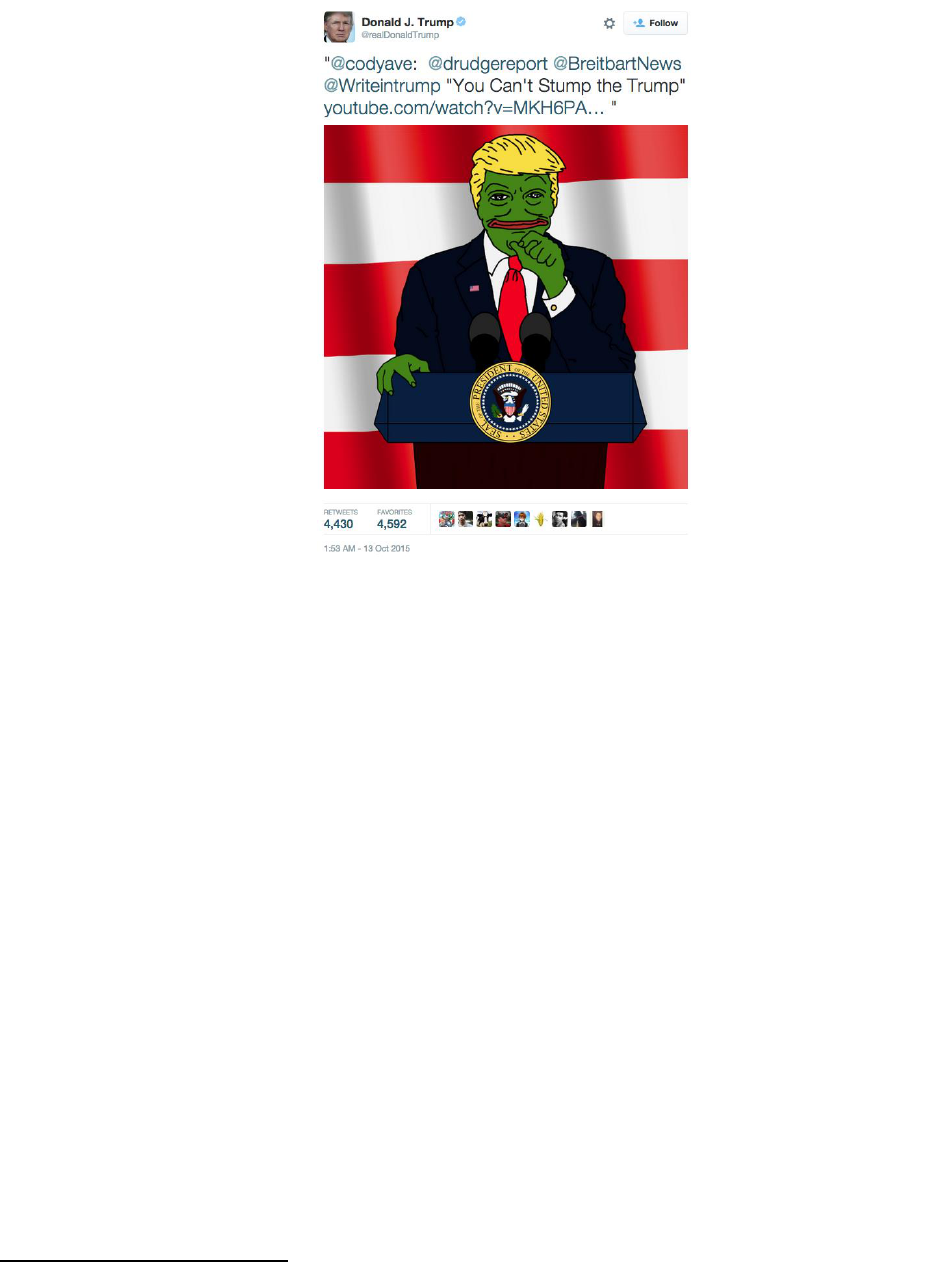

study more closely the most infamous meme during the last election: Pepe the Frog. Pepe as a

case study for the politicization of memes highlights the connection between online aesthetics,

the current state of political discourse, and a case-in-point on how a meme-signifier became a

battleground for the online culture wars. Originated in the comic Boy’s Club by cartoonist Matt

2

http://observer.com/2015/12/15-memes-tumblr-obsessed-over-in-2015/

14

Furie, the image of the sad anthropomorphic frog was hugely popular in the late aughts on online

forums such as Gaia online, Myspace, and 4chan. By 2015, the image was officially tumblr’s

“most reblogged meme” and was still pivotal on 4chan. The normal meme distribution of free

sharing was complicated by a now infamous 4chan post that featured edited Pepe images that

were characterized as “Rare Pepes”. Some of these came with added “seals of authenticity” in

order to legitimize their value. This caused an explosion of “Pepe trading” where files containing

up to several thousand discrete Pepe images were traded. The craze reached the mainstream to

such a degree that celebrities such as Katy Perry and Nicki Minaj were sharing their own Rare

Pepes.

3

4chan took the mainstream success of Pepe memes and the Rare Pepe shtick as a

personal attack and an instance of their culture being appropriated. They were furious at what

they viewed as normal people using the meme. 4chan characterizes the folks who do not spend a

lot of time online with the derogatory label of “normie.” In response, the trollish wing of 4chan

purposefully constructed Pepes that were intended to be as inflammatory, offensive, or

distasteful as possible. Pepes with Hitler moustaches or Ku Klux Klan robes were abundant, all

with hopes to make Pepe lose its mainstream appeal. While the trolls wished to “reclaim Pepe as

their own,” the political campaign of Donald Trump was beginning to reach full swing. In a

convenient move to appeal to his very-online demographic, or perhaps to flex his anti-

establishment muscles, Trump tweeted in October of 2015 a Trump Pepe alongside the caption

“You Can’t Stump the Trump.”

3

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/vvbjbx/4chans-frog-meme-went-mainstream-so-they-tried-to-kill-it

15

Trump’s tweet served as vindication for liberals that Pepe was now an official symbol for

Trump and the alt-right, while it simultaneously was an acknowledgment for the online young

reactionaries that Pepe was now a Trump-sanctioned symbol to rally around. The desire to make

Pepe more unattractive for the “normies” and the lulzy political engagement for the grassroots

elements of Trump’s campaign created a perfect storm for flooding forums with Pepes with

various ideological trappings from across the spectrum of reactionary politics. This activity

culminated on September 27, 2016 when the Anti-Defamation League stated that Pepe was now

officially classified as a hate symbol, while conceding that not all Pepes have such malicious

intentions. The reactions on the 4chan boards have been one of bored nihilism who viewed their

effortful campaign as nothing more than a whimsical skirmish.

4

Opposing this shift is Matt Furie,

the original creator of the Pepe character was saddened by the manipulation of Pepe to be used

4

https://yuki.la/r9k/31711843

16

for such harmful intentions and has started an online movement of his own, #savethepepe, in an

attempt to “reclaim” Pepe from its unwholesome associations. This caused outrage on right-wing

forums, especially the subreddit on Reddit called /r/The_Donald, whose members treat Pepe with

the same reverence that is usually only reserved for Trump himself. Many posts called Matt

Furie a cuck while sharing edited Pepes showcasing their crude disapproval.

5

The usage of Pepe for this paper is multi-leveled. Pepe behaves in the classic meme

fashion semiotically speaking. A true semiotic analysis will take place in the next section as well

as determining to what degree the Pepe meme is an exemplar of classic memetic semiotic

structures or not. In addition, Pepe is very historically and politically rich. The purposeful

manipulation of the signification of Pepe asks to what degree the connection between the sad

frog and its most hateful intentions or usages are arbitrary. In a sense, the study will be

determining the legitimacy of those who claim Pepe to be a hateful flagbearer for the American

reactionary right or a simple cartoon frog where any hateful interpretations are purely

coincidental.

I do not want to characterize the meme form as inherently reactionary, fascist, or even

conservative, as that would be equating politics to a structural semiotic system. However, after

the election of Donald Trump many middle-brow liberal publications were trying to determine

how Hillary Clinton could have lost such a winnable election. This lead to some famous online

meme-users to be caught in the political crossfire. One example of this is when Fader, an online

media journal, published an alarmist article criticizing Anthony Fantano, a successful YouTube-

based music reviewer, for what they viewed to be racist meme-usage. The article stated that

Fantano had a side channel that “pandered to the alt-right.”

6

The Needle Drop (the main

5

https://np.reddit.com/r/The_Donald/comments/70xxx8/matt_furie_is_a_cuck_you_cant_kill_pepe/

6

http://www.thefader.com/2017/10/03/needle-drop-deleted-youtube-channel-this-is-the-plan

17

YouTube channel that Fantano posts most of his reviews on) has over a million subscribers and

Fantano keeps most of his music reviews relatively apolitical. His side channel, thatistheplan,

had around 400,000 subscribers prior to its deletion in response to the Fader article. Instead of

earnest music reviews, thatistheplan’s most common videos were filled with bizarrely edited

videos filled with memes and filled to the brim with various online aesthetic signifiers. The

Fader article references several evocatively titled videos of the former channel namely “I

CHANGED MY GENDER BECAUSE OF DONALD TRUMP” and “pepe the frog triggers

hillary clinton,” as examples of what they believe to be Fantano opting into meme culture and

therefore alt-right politics. Unfortunately, the article failed to delve into the actual political

content of the videos in which opting into internet aesthetics rejects the holier than thou

liberalism in order to appeal to the online audience. While Fantano was using signifiers often

associated with far-right online culture, such as air horns and Pepe, they were being used to laud

Obama and Bernie or to support single-payer healthcare. Critics after the fact said that Fantano

should have realized that the aesthetic similarities between him and the alt-right could have made

him seem guilty by association, but all it took was a scroll through his Twitter profile to make

Fantano’s true political positions clear. The music critic asserted in his response video that “there

is nothing inherently right-wing about memes

7

” but, nevertheless, Fantano’s meme-heavy video

channel has been deleted and several of his speaking tours have been cancelled. While Fantano

was correct to say that memes are not inherently right-wing, they are often lumped in with a

transgressive online aesthetic that is deemed asocial. The association between various online

aesthetic signifiers is not objective and is rather a reaction to the electoral defeat of Hillary

Clinton. This reaction characterizes the meme as potentially right-wing, but only to the extent

7

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2UZqIIy7pAk

18

that people believe this association to be true. I will characterize the meme as equal opportunity

with respects to its ideological inflections.

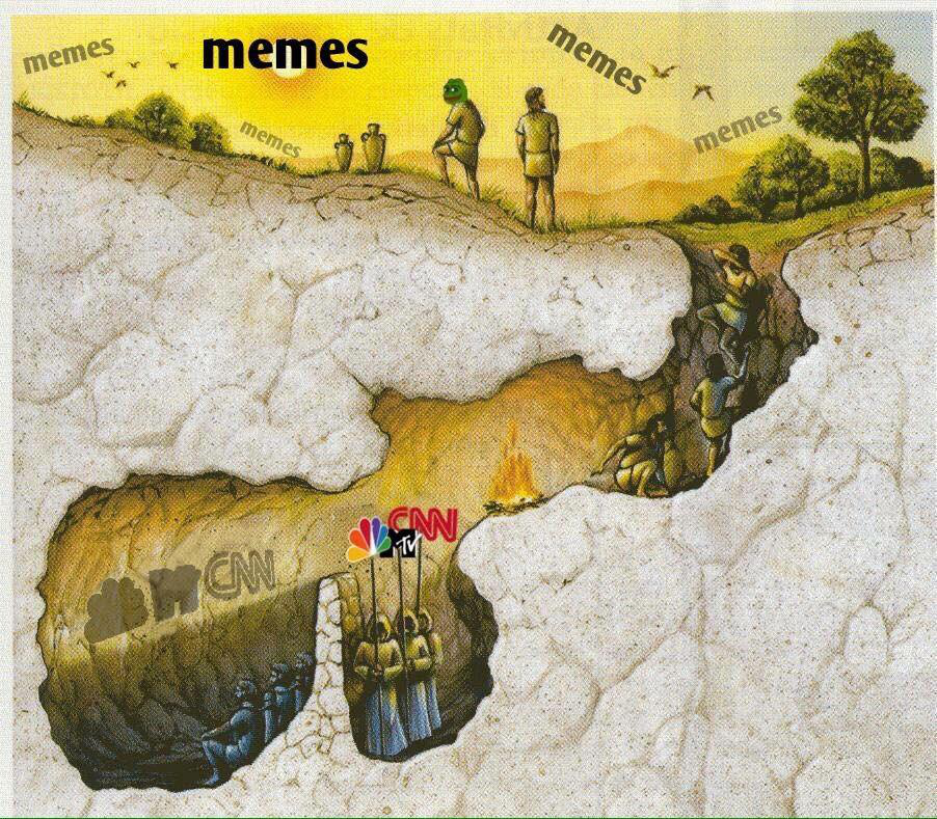

The only inherent politics that are available to the meme form is that of anti-

authoritarianism and a visceral disdain with established mainstream media outlets. Nagle

characterizes the death of old news media institutions as a case of obsolescence and not a

purposeful rejection against the old guard:

The bursting forth of irreverent mainstream-baffling meme culture during the last

race, in which the Bernie Sanders Dank Meme Stash Facebook page and

The_Donald subreddit defined the tone of the race for a young and newly

politicized generation, with the mainstream media desperately trying to catch up

with a subcultural in-joke style to suit to emergent anti-establishment waves of the

right and left. Writers like Manuel Castells and numerous commentators in the

Wired magazine milieu told us of the coming of a networked society, in which old

hierarchical models of business and culture would be replaced by the wisdom of

crowds, the swarm, the hive mind, citizen journalism and user-generated content.

They got their wish, but it’s not quite the utopian vision they were hoping for. As

old media dies, gatekeepers of utopian sensibilities and etiquette have been

overthrown, notions of popular taste maintained by a small creative class are now

perpetually outpaced by viral online content from obscure sources, and culture

industry consumers have been replaced by constantly online, instant content

producers. The year 2016 may be remembered as the year the mainstream media’s

hold over formal politics died. A thousand Trump Pepe memes bloomed and a

strongman larger-than-life Twitter troll who showed open hostility to the

mainstream media and to both party establishments took The White House

without them. (Nagle 3)

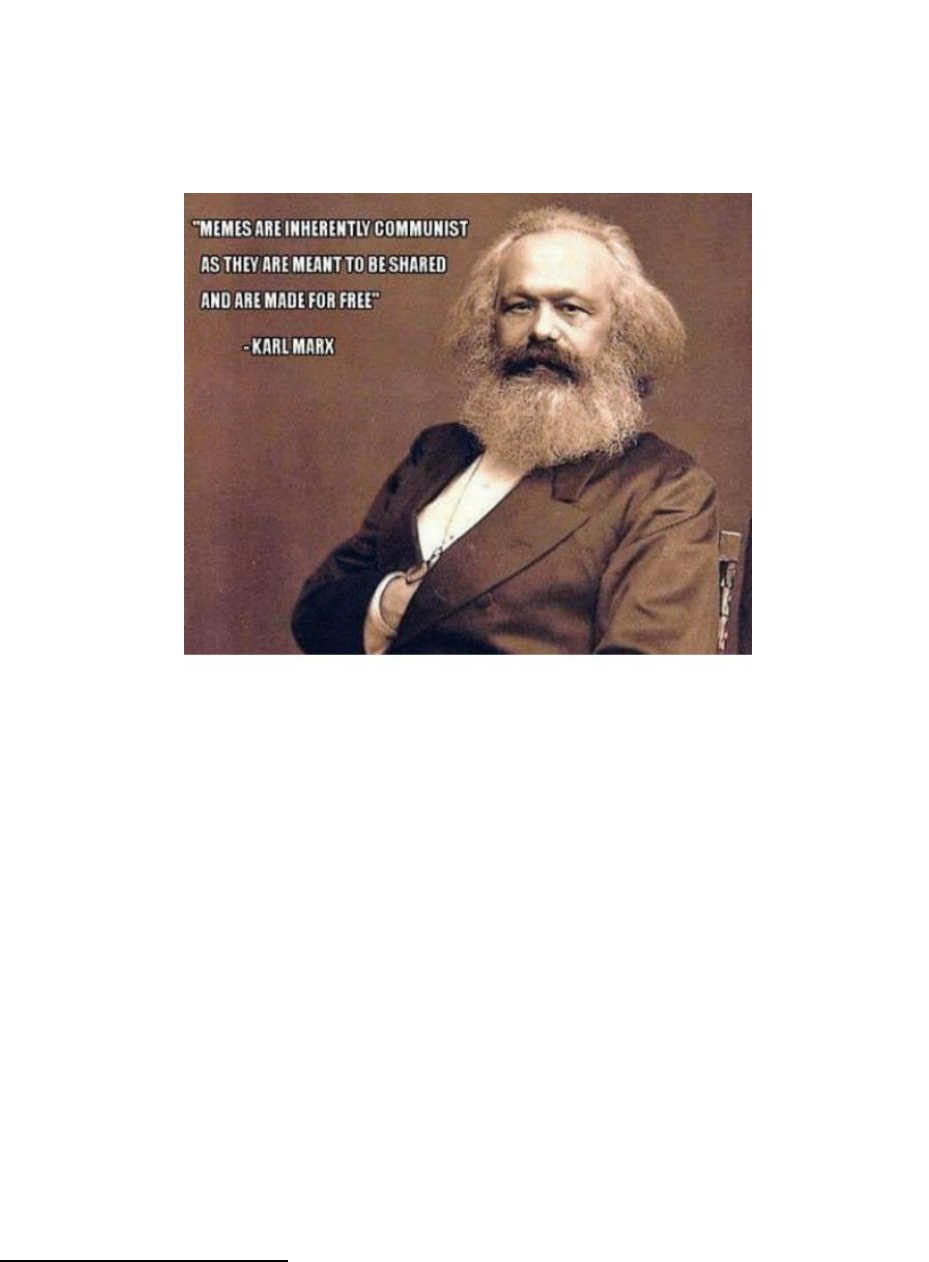

Nagle correctly characterizes the plane of the Trump Pepes and Bernie Sander Dank

Meme pages on Facebook as the modern political media landscape. This new political media is a

network as opposed to top-down and the lines between performer, spectator, and audience

member are thoroughly blurred. Even though there is only anti-authoritarianism that is encoded

in the structures of the online communities, memetic communication, and humor, both sides of

the online political aisle attempt to claim the meme as their own. The Left asserts that the meme

is inherently communist due to its free cost, while the Right make an equally absurd claim that

19

“the Left can’t meme.”

8

The ideological backing here is that the humorless attitude of

establishment liberalism prevents the creation and distribution of any high-quality meme-

making.

“Meme Marx,” found on KnowYourMeme original date and poster unknown

v. The Fake News Specter

Finally, it would be a grave error to ignore the overall political anxiety felt across the

American (and perhaps global) online communities which have been exacerbated by the Russian

hacking scandal and the specter of fake news. The heavily politicized usage of the term ‘fake

news’ was used by the right to smear mainstream journalism outlets, while the liberal center was

concerned with what they saw as rampant fallaciously constructed news stories. In order to

determine the boundaries between the political memes that are the focus of this paper and all

8

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/the-left-cant-meme

20

political content disseminated online, a brief diversion describing the different types of

misinformation and political “spin” often used online will follow.

The politics of the phrase “Fake News” has become a clichéd expression to discredit

journalism that does not follow one’s own ideological persuasions. In addition, the severe

centrist response to the moral failing of the perceived threat of fake news is a reaction stoked by

the anxieties of mainstream journalism outlets, who fear their dying influence over American

political thought. Fake news is not explicitly a creation of the internet; fake news has been

around since the time of the Roman Empire to discredit Mark Antony and was also used to

spread blood libel against medieval Jewish folk. However, accusing the internet of spreading

fake-news is particularly evocative when considering its lack of formalized gatekeepers. To what

degree the “fake-news” story spread due to its own merits, or if it was purposefully stoked by the

fears of the previous gatekeepers of print and cable media institutions is still up for debate.

Zeynep Tufekci, a Turkish intellectual and journalist, is oft-heralded as the “fake-news” expert

and has held multiple Ted talks on the subject. Her book, Twitter and Tear Gas, provides

practical examples of fake news manipulation in both American elections and populist media

platforms covering the Arab Spring. In her book, Tufekci characterizes two different types of

purposefully constructed media manipulation, although she never formally distinguishes between

the two, they are different enough in content and operation to warrant a classification. In her

description of the Arab Spring, Tufekci lauds citizen run media operations in which protesters

can crowdsource journalism online, hopefully to warn their fellow protestors of either

particularly entrenched police positions or to inform them of areas of relative safety. Tufekci

then characterized the notable shift on the efficacy of this networked journalism during the 2016

Turkish coup d'état attempt (whether it was an actual coup or not is not of issue here), where the

21

websites and groups that were originally remarkably effective at informing protestors, became

flooded with misinformation and the site’s organizers were unable to verify or discredit the

information quickly enough. Tufekci highlights their potential power and eludes to their ability

to manipulation as follows:

Nawaat activists did much of their curating and monitoring from abroad, a

practice that seems antithetical to understanding the dynamics of a movement.

However, when social media curating is done correctly, it can be far more

conducive to a comprehensive reporting effort than being in one place on the

ground, amid the confusion, as traditional journalists tend to be. A traditional

journalist can see what is in front of her nose and hear what she is told; a social

media journalism curator can see hundreds of feeds that show an event from many

points of view. Tufekci 41-42.

This form of deliberate misleading, akin to “astroturfing” (a term usually associated with

online marketing), is characterized by the purposeful masking of institutional communications

with the guise of populist or citizen level involvement. In the case of the Arab Spring and

beyond, the implications of this form of astroturfing was a matter of life or death. Astroturfing is

distinguishable from the other form of purposeful distortion, as in this case its power comes from

the illusion of coming from fellow citizens or bottom-up.

However, the other form of “fake news” is a much more salient factor upon the American

political consciousness. Mainstream news publications such as MSNBC covered stories of

teenagers in Macedonia

9

or other nations who are paid to deliberately fabricate news stories

online under the guise of legitimate online journalism. They often went to such lengths as

engineering website headers purporting affiliation with media outlets that do not exist. “The

internet made it easy for anyone to quickly set up a webpage, and Facebook’s user interface

made it hard to tell the legitimate news outlets such as the New York Times or Fox News apart

9

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-38168281

22

from fake ones such as the ‘Denver Guardian’” (Tufekci 298). Here the power to deceive is

enabled by the illusion that the media text is coming from a place of power or authority.

When considering political or memetic communication online its power to persuade

comes from its perceived earnest intentions when compared with the stuffy political intentions of

classic media institutions. The power of the internet to communicate from peer to peer changed

the media paradigm permanently. As Marcel Danesi stated in his book on The Semiotic of Emoji,

It is obvious that writing does indeed seem to encourage literate people to see

themselves as separate individuals and develop a unique sense of Self. Prior to the

spread of writing, knowledge was the privilege of the few and literacy was left in

the hands of those in power. The growth of literacy substantially reduced the

power of those in authority as written texts could be read “individually” and

interpretations of their content reached subjectively (Danesi 172).

Just as literacy spread and people did not need to depend upon the clergy to interpret

religious texts, now as a different media landscape is constructed there is less dependence on the

traditional media goliaths.

From this point, having established what is at stake when discussing the meme and online

communication, I am going to move forward onto a more specialized semiotic analysis of what

makes a meme. From the semiotic theory a connection to their distinct political ramifications

will come clear.

II. Semiotics

i. Memes are not Language

A semiotic analysis describing the function of the meme as a communication system will

start by comparing them with other relevant sign-systems, namely natural human language and

emojis. Highlighting the differences between memes and other communication forms provides a

23

frame of reference with other sign-systems and it also accentuates their historical import as a

truly different style of communication, rather than just writing them off as nothing more than a

picture that is shared online. I will also talk more in detail about any portions of their semiotic

framework that may be relevant in the discussion of their political potential.

Semiotics started with a linguist, and the relationship between linguistics and semiotics

has always been a close one. Saussure, the progenitor of modern semiotics, used spoken human

language as the sign-system to define the terms that are now omnipresent in semiotics; namely

sign, signifier, and signified. While the goal of semiotics to adequately theorize the intricacies of

the linguistic sign may be semiotics ultimate raison d'etre, a complete history of this pursuit is

not the intention of this paper. Although natural human language is often considered the sign

system par excellence, language is unique when it is compared with other sign systems. While it

is true that memes often have a written language component, it does not provide any significant

connection to the semiotic structures of spoken language. Not only does basically all linguistic

study focus on spoken language, it views written language as a different semiotic system with its

own rules and meaning-making processes.

Saussurean structuralism was motivated by linguistic study- but other than the formal

similarities of the terminology where the sign is the vehicle for communication, any other

perceived commonalities between language and memes begin to break down. The uniqueness of

human language is not a new assertion and many linguists have created theories or benchmarks

proving how either animal communication systems or other human sign systems fail to measure

up to the complexity of natural language. Most compellingly, is Hockett’s design features of

language, where he highlighted that all human languages (regardless of any superficial

appearances of complexity) possess the same 16 “design features” or traits and that no other

24

communication system that we have encountered has matched any human language in this

regard. Although primate communication has been noted to have 9 of the design features they

lack more complex distinctions such as displacement or reflexiveness. Primates do not have the

ability to talk about things or concepts that are not physically present, nor can they use language

to talk about language. This prevents any animal communication system from matching the

complexity of human language. Comparing human language to memetic communication using

Hockett’s design features is very limited in its application. I am not making the claim that memes

are a “new language” and nor do I want to create a paradigm in which memes are a

communication system that does not “measure up” to language. Therefore, another way of

semiotically describing language is necessary to draw an adequate comparison between the two

without the meme immediately becoming just an aberration of language rather than its own

autonomous system.

Although it may be compelling to refer to the online meme-sharing youth as “meme

literate” that does not serve as an indictment to the language qualities of meme-usage. While

meme communication does have its own set of rules, expectations, and sociological norms to

facilitate their usage, it is incorrect to call them a language. Through the combination of both the

visual element and the linguistic ones- meaning is created. The language that is used in memes is

often restricted by its framework to certain types of phrases, for example think of the short

snippets of advice used for the Mallard Memes. Language usage within the meme framework is

as regulated by the framework as the meme’s visual elements. This is significant as it allows the

analysis of the language used in memes to be contextualized by the meme’s framework on a case

by case basis, it is nothing more than a part of the framework as opposed to something outside of

the larger semiotic structure

25

ii. Auto-Semiosis

Moving out of Suassure’s linguistic structuralist approach there was a rich tradition of

linguistic inquiry that rose up after him. Linguists and thinkers such as Valentin Voloshinov and

Mikhail Bakhtin picked up where Saussure left off, expanding upon his coldly structuralist

semiotic analysis. Out of this relatively disparate set of thinkers arose an idea that language was

the only semiotic system that had the ability to undergo “auto-semiosis,” that signs within a

language use themselves and others to create other signs. This observation also showcases how

language is privileged with respects to all other mental processes in humans. I am not attempting

to write a paper analyzing memes through emoji or bricolage, but rather via language. Although

memes are not an inherent communication system that has innate structures within the human

brain, the way in which they relate to one another is like the auto-semiosis capabilities of natural

language.

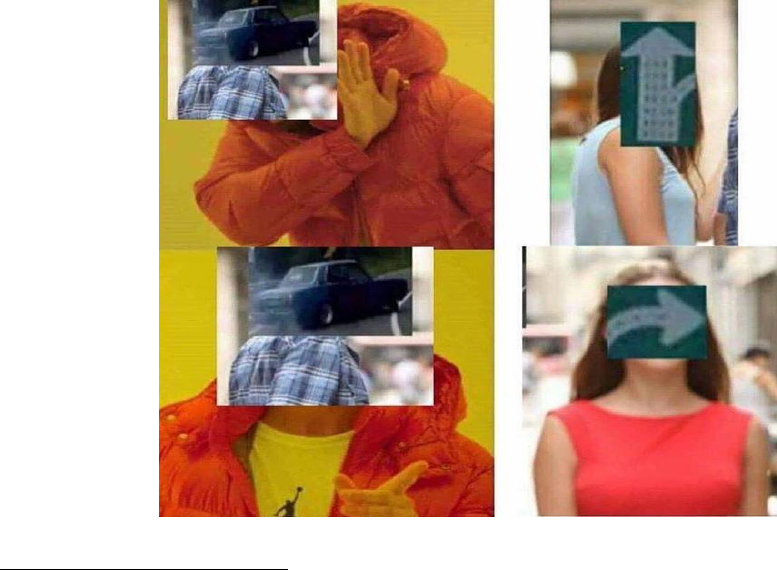

To highlight this similarity, I will use two memes, the Persuadable Bouncer

10

and

Drakeposting

11

memes, both are considered to be “exploitable 4-panel comics.” The structures

within them are similar, in which the form shows either the rapper Drake or the eponymous

Bouncer expressing disapproval about the first image displayed in either comic. Then in the next

pair of images there is a different image which is supposed to be superior (in either an earnest or

ironic sense) that warrants Drake to show his approval or for the Bouncer to let “it in the club.”

Some examples are below:

10

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/persuadable-bouncer

11

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/drakeposting

27

Formally speaking, the memes display very similar semiotic structures, as they are claiming that

one thing, concept, or image is superior to another. At this point, the relationship between the

framework and added content again shows its importance. Compared to other communication

forms they are uncommonly aware of their structures and framing on how they communicate.

Both the information that is added to the template is important, but also the template in and of

itself. There are many memes that display an “A is better than B” relation, including “Distracted

Boyfriend

12

” or “Left Exit 12 Off Ramp.

13

” In this case, the thing that is better is either a person

that is making your head turn or a ramp that requires one to rapidly swerve to take the exit. There

are slight nuances that make each of the different meme templates slightly distinct, but in the end

their structures are quite similar. Meme creation mandates a knowledge of the templates and this

creates “crossovers” or mutations of templates.

12

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/distracted-boyfriend

13

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/left-exit-12-off-ramp

28

Fig: Drakeposting/Exit 12/Distracted Boyfriend Crossover from Know Your Meme poster

NekothePony

Here this meme highlights the similarities between the various templates as Drake, the

car, and the distracted boyfriend are all showcasing their approval/disapproval through the

various elements within the others’ templates. This mashup of meme template and concepts

shows how the meme creators are explicitly aware of the boundaries of any specific meme class.

Memetic communication encourages this type of knowledge where an exhaustive understanding

of the network is needed to make legible memes. The above meme can be viewed as a sort of

memetic “pun.” Just like how language users use similar linguistic units to draw attention to the

similarities and double meanings of words for comedic purposes, this shows that meme-users

often think in similar ways. This sort of usage also muddies the interpretation that memetic

communication is a simple formulaic process but instead characterizes it in a more generative

and creative fashion. While this is not nearly as productive of a process as the auto-semiosis that

is possible through natural language, the ability to play with the templates is a semiotic feature

that is pivotal to the power of the meme.

iii. Distancing Memes from Other Digital Communication Forms

Next, I will distance the meme structures away from another pictographic online

communication system: Emoji. The book on the subject, Marcel Danesi’s The Semiotics of Emoji

takes a decidedly linguistic and semiotic approach to analyzing this sign system. Danesi

purposefully distances himself from calling Emoji usage a language and instead calls it “the

Emoji code.” One of the overarching claims made in the book is that Emoji is used to alter the

29

register of the text-based speech into something that is not meant to be taken too seriously.

Danesi does not want to equate this lack of seriousness with a lack of complexity even when he

states that, “perhaps the emoji code is just another fad… tapping into a comic book or cartoonish

mind-set that is characteristic of pop-culture style in all domains of human interaction” (Danesi

158). Yet he goes on to qualify the previous statement by admitting that the flexibility of emoji is

indicative of “an ever-broadening hybridity of representation that comes from living in the

digital age” (Danesi 158). Although how emojis and memes are discredited as foolish online

kitsch underplays their ability to communicate online messages in a global setting. “Epigenetic

global code” is how Danesi describes online communication; one in which those who are using it

have a significant say in its rules and application.

Formally speaking, the meme and the emoji are distinct. The main difference between the

two systems is that memes are generative while emojis are not. Emojis create meaning by

reorganizing and ordering themselves in specific ways within a closed class of specific images in

a specific medium. “The act of emoji creation” involves adding certain pre-created images to a

text message. There is no opportunity to edit the emojis as they come pre-programmed onto most

cellular devices. Memes do not follow this same logic. The two-fold parts of memes, the

framework and the complete meme, is evidence of their more mutable nature. Meme-making

involves making a new image through editing a preconstructed one. Both communication forms

take advantage of digital technologies ability to reproduce images rapidly; but the meme uses the

computer’s ability to edit content. This difference between the two helps elucidate that although

memetic communication happens online, not all digital communication is memetic.

30

Now that a significant distinction has been made separating online internet memes with

natural language and emoji, I will describe its own semiotic features by discussing the semiotic

peculiarities of memes specifically.

iv. Studying Pepe using the Semiotics of Pierce

When considering memes there are few that stand out more than Pepe the Frog. As

previously stated the politicization of Pepe has reached a high level, with people treating the

once innocent frog as a contemptuous hate symbol or the flagbearer of their entire political

ideology. Starting out to formalize how Pepe communicates, one must first consider how a

concept of a meme is larger than any one instantiation. There are countless Pepe images online,

that have been edited, photoshopped, have added text, or undergone any other alteration

processes. As discussed earlier I will consider that a meme’s membership of any larger network

as clearly defined and self-evident for any one specific meme.

The salience of the meme’s overarching template encourages an analysis outside of the

simple sign/signifier/signified relationship of Saussure’s structuralism. The semiotic theory of

Charles Sanders Pierce is the most compelling analysis in describing the relationship between a

meme’s class membership and any one specific meme. Peirce in the collection Peirce on Signs

complicates the simplicity of the construction of a whole sign from its constitutive parts. He does

this by claiming that a mental concept of the sign intrudes upon the semiosis. “Since a sign is not

identical with the thing signified, but differs from the latter in some respects, it must plainly have

some characters which belong to it in itself” (Peirce 68). While memes are almost always digital

and do not have the natural link that Peirce speaks of, ‘the thing signified’ that Peirce references

could be the mere allusion to the overarching meme class that the meme has membership of.

31

Strictly speaking, Pepe memes only maintain their Pepe status by their likeness. There is no

explicit link connecting any one Pepe meme to the larger Pepe class of memes. In other words, it

is not natural for any image to be associated with Pepe but rather it must purposefully opt into

the Pepe likeness. This act of disruption between the individual instantiations and the meme

framework allows the meme to be more complex than the sum of its parts.

To break this down even further, the act of meme-creation involves adding to or altering

the framework of the meme. When considering the meme’s framework as something that can be

altered, start by thinking of an exemplar of any meme framework, which in the case of Pepe

would be an image of Pepe without any added elements, or for a meme like Actual Advice

Mallard would be just the picture of the duck without text. Then as someone alters the

framework to make a complete meme it is that content used in the alteration process that carries

the brunt of the communicative content. When you see a new Actual Advice Mallard meme the

information that is most noticeable is the added text or any aesthetic shifts that occurred, as it is

where the meme is different from its exemplar. This way of thinking where we notice what

violates our expectations is not limited to just thinking about memes.

For example, I use a computer that is not an Apple product. Although no one would say

my computer is not a computer it still violates the expectation that a computer used by a college

student is likely to be a Mac. When someone sees my computer, a decidedly not-stylish Lenovo

Thinkpad, it is still enough of a computer to be seen as one, yet its non-Apple traits are

exceptionally noticeable.

Focusing on the information that was added to the framework also makes the ideological

claiming of a meme easy. There are countless memes that are often used for political purposes:

32

either Strawman Ball,

14

Daily Struggle,

15

or Hard to Swallow Pills

16

, just to name a few. Being

too numerous to dissect each of them individually, they are often used in political communities

to attacks or point out the contradictions of the other side of the aisle. The point here being that

there is not a meme that only liberals use to attack leftists and vice versa. Memes are equal

opportunity when considering their ability to make ideological assertions.

`

Pepe the frog: taken from Know Your Meme, March 16, 2018, original poster unknown.

Returning to Peirce, who is mostly interested in the semiotic structures of language, he

believes that breaking down natural language elements into its constitutive parts will eventually

reach a dead end, “every thought, however artificial and complex, is, so far as it is immediately

present, a mere sensation without parts, and therefore, in itself, without similarity to any other,

14

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/picardia

15

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/daily-struggle

16

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes/hard-to-swallow-pills

33

but incomparable with any other and absolutely sui generis [unique] (Peirce 70).” Language to

Peirce is not made up of other signs but rather it is natural law, “every thought, in so far as it is a

feeling of a peculiar sort, is simply an ultimate, inexplicable fact” (Peirce 70). Memes of course,

cannot claim to have such lofty origins and often bubble out of the painfully arbitrary; such as a

webcomic for Pepe, or a prematurely dead gorilla in the case of a meme like Harambe. Peirce

never claims that any one individual can change the link between language and the natural world,

which also contrasts with the more mutable, epigenetic qualities of digital communication.

The elevation of the larger framework of the meme complicates the case of Pepe and how

people should treat the famous frog. There are assuredly countless instances of Pepe memes that

are either apolitical or even progressive in their stance, but to what degree they are outliers of the

public perception of Pepe, remains to be seen. In the case of Pepe, that gives the viewer two

options: see the images of Pepe as a meme only to the extent that they know it is a meme or

approach the image with the knowledge that the Pepe class of memes has purposefully

constructed connotations of racism and fascism. To what degree the Pepe-sharers were

legitimately using the frog to disseminate Nazi ideology or racist fearmongering is still a

question, as the manipulation of how the public perceived Pepe to take it back from the normies

was the goal in its own right. I do not have anything in the case of prescriptive rules for judging

the soul of Pepe, nor do I have any attentions to exonerate or indict the meme, as either

redeemable or at the same tier as a swastika.

Concluding my take on the Pepe meme in particular- the slipperiness of the meme’s true

intentions seems to be a feature and not a bug. Alt-right members gathering at protests wear their

Pepe affiliations on their sleeves, whose goofy online aesthetics affords a certain far-right

politics that is given plausible deniability via its arbitrariness. There has not yet been any mass

34

killing perpetrated by followers under a Pepe-flag, but gathering at demonstrations and shouting

“normies out” makes one wonder who is considered a normie

17

and to what extent their political

engagement is beyond the lulz. Using Pepe, or memes in general can be used by anyone from

any political ideology and can be used to try and enact all sorts of political goals. This lack of a

connection to actual political seats of power affords memetic communication to speak truth to

power without putting anything on the line. While there is a decidedly Trumpian wing of online

meme sharing, the sort who were described in Philip’s account treat all politics as a big joke.

Meme’s ability to create a sense of identity around a shared online literacy reflects back to my

statements on the anti-authoritarian internet, which has an endlessly cynical view of power.

Some may claim that the liberal or progressive Pepe’s can serve as proof that the meme is

neutral and is solely what one makes of it. However, it is through the relationship between

memes and their framework that the restrictions and unspoken expectations come forth. When

Matt Furie, the original author/creator of Pepe makes an image of the frog wearing a “Make Pepe

Great Again” hat and urinating on a Trumpian incarnation of the frog, it serves to admit the

corruption of the meme-framework. Additional Pepe memes have been circulating trying to

distance the meme’s network from the alt-right associations.

17

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/23/alt-right-online-humor-as-a-weapon-facism

35

Fig. “Make Pepe Great Again” by Matt Furie. Source: The Atlantic.

Fig: Make Pepe Great Again found on twitter from Rainbow Jedi, original creator/poster unknown.

36

As the perceived meme-framework and understanding of Pepe is that of a far-right icon,

all memes of Pepe carry that association with them. While there may be memes pushing back

against that association, the public at large considers him unwholesome, and hate symbols only

become hate symbols through some concept of consensus. This may seem like a contradiction to

what was stated earlier in the case of meme’s structurally being equal opportunity, but that is not

the case. A meme can have any added content to it that attacks or supports any political ideology

and their flexibility supports this. When considering Pepe as a framework that has associations of

far-right politics it does not remove the possibility of progressive Pepes, as the link between

hatred and the Pepe meme is arbitrary. All non-fascist Pepes are in act of resistance from the

framework and are still completely legible.

This is unfortunately as concrete of an analysis as possible when it comes to Pepe. This

did not feel very satisfying for me after seeing so many Pepes that were among the most racist

and bigoted images I have seen online. Unfortunately, it was the only interpretation that was

honest and that acknowledged the larger political landscape. It is also probable that the racist

Pepes are especially incensing as they juxtapose bigotry with an innocent and even silly original

image. While the swastika provides a historical footing to understand and name the hatred, a

Hitler Pepe treats the slaughter of innocents as a joke. The irreverent treatment of the Holocaust

at the hands of a cartoon frog is much more palatable to mainstream people as it can be written

off as the action of lunatic online trolls. Unfortunately, any legitimate criticisms levied against

racist are often deflected by “it’s just a joke.”

37

Hitler Pepe, from 4Chan, original poster and date unknown.

v. A Semiotic Model of Memes

To synthesize these relatively disparate parts- the comparison with language, Pepe, and

the semiotics of Peirce into a cogent theory, one element loomed over the rest with respects to

relevance. The meme is a communication form in which its network and any instantiations are

held in equal import, and it is only through their confluence is a legible meme created. In

language, the listener brings their language skills and sociocultural information to be able to

decode the information of the speaker. Similarly, in memes, the observer brings their

understanding of the memetic network which elevate the image or concept to “memehood.” This

creates a dynamic in which successfully creating a meme requires an understanding of the

framework. Altering images into a meme template does not always make legible variations

without an adequate understanding of their template. In the conclusion, I will talk about the

political implications of this fact and how the higher barrier of entry for memetic communication

alters the political landscape around in-group/out-group dynamics and performed authenticity.

38

III. Politics

i. Past Understandings of Online Media and Politics

The impact of media and media institutions on the global political landscape has always

been of importance. Freedom of the press is one of the founding tenets of all modern democratic

states. Classic understanding of reactionary or despotic regimes are often characterized as having

a nigh perfect track record of attacking media institutions through the labels of “fake news” or

the classic “lügenpresse.“ Criticisms levied against the press and media (whether legitimate or

not) are often predicated upon a separation between government power, the citizens, and the

media institutions. Institutional power based within the state attempt to construct accusations

brought forth by the media or press groupings as unfounded- that they are a corrupting force

upon the consciousness of the people. For example, Hitler attacking media institutions is only

coherent on the predication that not all of the German citizens were active in constructing the

media narrative. As news media decentralization and digitization occurs, a reading of news

media institutions as a unified body that the state needs to grapple with is outdated. How political

entities negotiate this new territory of citizen-run media is the focus of this section as well as

how internet memes function on the intersection between online political communication and

seats of legitimate electoral power.

The past paradigm of the relationship between media and government has been of two

large distinct institutions engaged in a quarrel of begrudging necessity. Books written before the

2016 presidential election, such as R.J. Maratea’s Politics of the Internet or the essay collection

Culture and Politics of the Information Age, consider the internet as a vehicle to view and share

institutional media communications. The internet’s ability to decentralize media narratives away

39

from a few ideological gatekeepers is often understated by the claim that the sole communicative

act that people consider is the sharing and commenting of articles from corporate media sources.

Maratea however lauds this process and labels it as “meta-journalism” where “commenting and

reinterpreting of new stories online” (Maratea 35) supplies an additional chunk of media

information in the overarching online journalism process. Maratea is right to say that meta-

journalism is a radical shift when comparing it to more traditional top-down and centralized

media paradigms, such as print journalism or radio broadcast. However, it is still an inadequate

representation of the modern media landscape that takes place online. Looking beyond mere

meta-journalism one must consider how internet communication is radically different from other

media forms to allow for a new context of political communication.

ii. “Post”-politics

Many scholars assert that as countries transition to a post-industrial economic mode and

contort to the modern international media landscape, many classically accepted forms of social

relations begin to wither away. This anxiety was present in Frank Webster’s article A New

Politics where he theorizes on a feedback loop of the decay of classic social relations in Western

working-class life. He claims that as the salience of the working class in political and social life

wanes in the face of the decline of stereotypical working-class industry, this begets more

weakening of blue-collar sociality and the further decay of the working class as a social unit,

thus furthering their political impotence. While Webster never explicitly referenced how the

death of local community socialization could lead to a greater alienation with national identity-

the maintenance of any working-class movement at a nationwide level is contingent on the

activity of local communities. Webster then makes the claim that, “in place of community can be

40

identified a postmodern relativism in which values and conduct are regarded as highly

differentiated lifestyle choices, which are incommensurable” (Webster 4). Identity politics then

acts as the replacement for the politics of the nation-state. Webster framed this as a reactionary

move while ignoring how the death of a state-based political consciousness may be a liberation

for those who can now pursue their best interests outside of the nationally mandated Overton

window. A political arena where the stakes are more based on personal performative individual

decisions over inflexible national values is the perfect ideological battleground for a

communication form as flexible as the meme.

A quick aside is needed to push back that a political paradigm that distances itself from

the classic national politics is somehow a regression or any less legitimate. Although many

pundits deride identity politics as a selfish aberration into tribalism- that naively assumes that the

political process focused on the nation-state had everyone’s needs in mind. As identity politics

includes people who were on the political margins, those who were firmly in the center of the

more traditional process accuse this of a dilution of “legitimate” politics. This ignores that

getting more people involved in the political process should, even from a purely numbers

standpoint, make the political arena more legitimate as a public force.

This removal of the nation as a vector that carries political power also changes the

dynamic in which the populace interacts with media corporations. If politics stays within the

boundaries of the nation-state, then viewing the media as the third entity in the triumvirate of

state, citizen, and media is a logical conclusion. As all the nations of the world economically and

politically globalize- it became more complex to determine who the large media corporations

serve and where the loyalties of the people lie. As media becomes instantaneous and identity-

driven an internationalist political arena unfolds on social media. Online there may be more in

41

common between you and someone on the other side of the world who opts into various political

identities and decisions as opposed to your next-door neighbor whose political views are

“unseemly.” Via this removal of the physical impetus of politics, the discussion of political

thought and opinion loses the requirement of institutionally mandated veneer. In fact, the sleek

professionalism of classically respected media institutions is often the first victim of who is

written off as fake news.

18

Most writers and pundits consider this to be a paradise lost of public

debate. That people have been duped into living in a filter bubble,

19

20

21

where people on their

social media feeds receive endless positive affirmation of one’s own political opinion and never

have to even consider the possibility that other people might disagree with them. This of course

ignores the constant and nasty political “disagreements” that occur every second, on every social

media platform. It also shows the discomfort that the traditional media corporations share where

the media landscape is headed, where large top-down “media creators” have a shaky future. The

significance of the shift to meta-journalism showcases that often individuals trust corporate news

only once it has been “digested” by fellow non-institutional sources. The filter bubble canard

also ignores how usual politics is based upon organizing around like-minded individuals in the

party system.

Memes and their online popularity are the communication form par excellence for the

new online political paradigm. Its lack of connection from any national media institution and rich

visual elements allow it to exist internationally and encourage the online virality that is necessary

for any online media form to succeed. This also should not be viewed that due to the comparative

18

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-media-news-survey/trust-the-news-most-people-dont-social-media-even-

more-suspect-study-idUSKBN19D015

19

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2018/01/14/facebook-invites-you-to-live-in-a-bubble-

where-you-are-always-right/?utm_term=.241cf67a69a9

20

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/03/arts/the-battle-over-your-political-bubble.html

21

https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles

42

simplicity of memes that their success should be written off as proof of the dumbing down of the

modern international political discourse. As seen in the previous section on the semiotic

intricacies of memes; that a complete interpretation of them online requires a good deal of

decoding ability.

Of course, the usage of the internet is not just a liberation from the giant restrictive

corporations, but it also winnows public behavior through non-institutional channels. Marcel

Danesi describes it as such,

When the internet came into wide use, it was heralded as bringing

about a liberation from conformity and a channel for expressing

one’s opinions freely. But this view has proven to be specious. In

contrast to the pre- internet print world, it can be said that internet

culture is built on the attainment of a communal consciousness

through artificial means. Living in a social media universe, we may

indeed feel that it is the only option available to us. The triumph of

social media universe, we may indeed feel that it is the only option

available to us. The triumph of social media lies in their promise to

allow human needs to be expressed individualistically, yet connect

them to a common ground – hence the paradox. Moreover, as the

communal brain takes shape in the global village, a form of global

connected intelligence is merging, called by some a “global brain”

(Danesi 174).

This movement to a decentralized media landscape changes the gatekeepers from a

formalized institutional censorship to the specific mores of any one given group. On Reddit this

concept is derided as a “circle-jerk”

22

in which certain topics are either immediately favored or

despised by “the hivemind,” and a topic’s circlejerk takes for granted its positive or negative

traits.

The meme’s mutability allows it to be placed in various social and cultural contexts and

succeed as a legible online communication form. As stated in the semiotic section; memes

22

https://www.reddit.com/r/TheoryOfReddit/wiki/glossary

43

deliver comedy or any other intended content where all the information is contained within the

conceptual framework of the meme, a meme that requires an undue amount of outside

information is either intended for a very strict audience or is being purposefully obtuse. The

meme can either be readable as an image or, if one has prior knowledge of the framework, as a

member of a meme which carries with it all the additional characteristics.

Memes and the behavior they encourage embody the anti-authoritarian attitude afforded

by the internet that treats the political battlefields as one big playground. In Phillips’ This is Why

We Can’t Have Nice Things, she correctly identifies earnest opinion as the antithesis of online

trollish discourse. Phillips notes how it is functionally impossible to actually determine where the

true beliefs of the trolls lie, as even in more formal 1-on-1 interview settings they could be

“trolling the earnest academic.” A great mystery that remains even after the dust settles of the