U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

National Institute of Justice

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

N

T

O

F

J

U

S

T

I

C

E

O

F

F

I

C

E

O

F

J

U

S

T

I

C

E

P

R

O

G

R

A

M

S

B

J

A

N

I

J

O

J

J

D

P

B

J

S

O

V

C

Research Forum

Executive Office for Weed and Seed

➤

What Can the Federal

Government Do To

Decrease Crime and

Revitalize Communities?

January 5–7, 1998

Panel Papers

A Message From the

Assistant Attorney General

“What can the Federal Government do to decrease crime and revitalize communi-

ties?” This is a question policymakers, practitioners, and researchers have debated

for more than 30 years. Over the past few years, the Justice Department’s Office of

Justice Programs (OJP) has brought together former administrators of OJP and its

predecessor agencies and a broad range of other criminal justice experts to examine

Federal criminal justice assistance over the past three decades and what lessons this

experience holds as we move to shape criminal justice policy for the future.

In January 1998, OJP posed this question to a group of practitioners and researchers

at a symposium sponsored by two OJP components—the Executive Office for Weed

and Seed (EOWS) and the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). This session brought

together those who are thinking and writing about crime from a practice or research

perspective. It was a result of ongoing collaboration between NIJ, our research

agency, and Weed and Seed, one of the Department’s premiere community-based

initiatives. It marked the first time these two OJP components have come together to

focus on the issue of crime and its impact on communities, and I commend EOWS

Director Stephen Rickman and NIJ Director Jeremy Travis for their vision and en-

ergy in designing this symposium.

I also want to thank the symposium participants for taking the time to ponder and

discuss this critical question—and for their recommendations on how we should be

setting priorities, what role the Federal Government should play, how OJP can best

provide leadership and demonstrate new programs, what approaches are proving

successful, what factors we need to learn more about, and what questions our

research should be trying to answer.

It is so important for those of us at the Federal level to listen to those of you in the

field—to see programs in action, to talk to people on the frontlines, and to get a

better understanding of what’s working, what’s not, and what’s needed. The Attorney

General strongly believes that this kind of engagement is critical if we are going to

keep our Federal programs responsive to the communities they serve, and I have yet

to meet anyone “beyond the Beltway” who disagrees.

These are critical and complex issues we must continue to assess if criminal justice

is to be prepared to meet the challenges of the future. I hope you will find that the

products of our EOWS/NIJ symposium can help make a contribution to this ongoing

debate.

Laurie Robinson

Assistant Attorney General

A joint publication of the National Institute of Justice

and the Executive Office for Weed and Seed

October 1998

NCJ 172210

➤

What Can the Federal

Government Do To

Decrease Crime and

Revitalize Communities?

January 5–7, 1998

Panel Papers

Opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The National Institute of Justice is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the

Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime.

Jeremy Travis

NIJ Director

Stephen Rickman

EOWS Director

➤

➤

iii

Introduction

We are pleased to present this volume of panel papers from the January 1998 Depart-

ment of Justice symposium, “What Can the Federal Government Do To Decrease

Crime and Revitalize Communities,” which was jointly sponsored by the National

Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the Executive Office for Weed and Seed (EOWS).

While NIJ and EOWS often collaborate, this partnership was a unique opportunity

for us to highlight important research, discuss problems facing the Nation’s commu-

nities, and share some of the imaginative solutions to address them that are being

implemented by cities and towns across the country. Conference participants dis-

cussed various ways to effectively address the needs of changing communities and

initiated dialogues that we hope will continue.

We were delighted to host the speakers whose papers are included here. We were

equally pleased with the active involvement of program participants who listened,

questioned, and made observations about the speakers’ presentations.

Teaming with EOWS to achieve the goal of reducing crime and revitalizing commu-

nities is a natural extension of NIJ’s research, evaluation, and development mission

and activities. It also reflects one of NIJ’s strategic challenges that focuses on under-

standing the nexus between crime and its social context. The Weed and Seed strategy

is essentially a coordination effort, making a wide range of public- and private-sector

resources more accessible to communities. With the assistance of the U.S. Attorneys,

the strategy brings together Federal, State, and local crimefighting agencies, social

services providers, representatives of the public and private sectors, prosecutors,

businessowners, and neighborhood residents—linking them in a shared goal of

“weeding” out violent crime and gang activity while “seeding” the target area with

social services and economic revitalization. The strategy combines law enforcement;

community policing; prevention, intervention, and treatment; and neighborhood

restoration. EOWS also provides a range of training and technical assistance activi-

ties to help communities plan, develop, and implement their programs. Combining

EOWS’ community focus with NIJ’s research and development expertise made this

symposium exceptionally productive.

This volume is intended to share the beneficial outcomes resulting from the sympo-

sium. It is our belief that discussions begun between participants at this conference

will lead to action at the community level. It is our hope that these actions will pro-

vide new, creative, and effective approaches to address the issues of crime prevention

and community revitalization that concern all of us.

Jeremy Travis

NIJ Director

Stephen Rickman

EOWS Director

➤

➤

v

Contents

Introduction

Jeremy Travis and Stephen Rickman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii

Panel One: The Context

The Context

Bailus Walker, Jr. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Economic Shifts That Will Impact Crime Control and Community Revitalization

Cicero Wilson . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

The Context of Recent Changes in Crime Rates

Alfred Blumstein . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Luncheon Speaker

Community Watch

Amitai Etzioni . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Panel Two: The Roles of Federal, State, and Local Governments and

Communities in Revitalizing Neighborhoods and in Addressing

Local Public Safety Problems

Revitalizing Communities and Reducing Crime

Robert L. Woodson, Sr. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Cooling the Hot Spots of Homicide: A Plan for Action

Lawrence W. Sherman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Communities and Crime: Reflections on Strategies for Crime Control

Jack R. Greene . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Panel Three: Promising Programs and Approaches

Crime Prevention as Crime Deterrence

David Kennedy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Revitalizing Communities: Public Health Strategies for Violence Prevention

Deborah Prothrow-Stith . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

➤

➤

vi

Lawyers Meet Community. Neighbors Go to School. Tough Meets Love: Promising Approaches

to Neighborhood Safety, Community Revitalization, and Crime Control

Roger L. Conner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Panel Four: What Do We Do Next? Research Questions and Implications for

Evaluation Design

Dynamic Strategic Assessment and Feedback: An Integrated Approach to Promoting

Community Revitalization

Terence Dunworth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Community Crime Analysis

John P. O’Connell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

What Do We Do Next? Research Questions and Implications for Evaluation Design

Jan Roehl . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Appendix A: Author Biographies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

Panel One:

The Context

3

➤

➤

The Context

Bailus Walker, Jr.

within traditional national, State, or neighborhood

borders and have created quality-of-life problems

that have spread among nations at an accelerating

pace. Indeed, the movement of more than 2 million

people each day across national borders and the

growth of international commerce are inevitably

associated with the transfer of health risks, includ-

ing such obvious examples as infectious diseases,

contaminated foodstuffs, and terrorism, which have

multiple dimensions and a broad spectrum of

impacts—some subtle, some overt.

Transnational connections in health imply that

health threats, including violence, can no longer

be contained by national frontiers; most diseases

do not require passports to travel. Due to the ease

of rapid travel, emerging diseases in one country

represent a threat to the health and economies of

all countries. In the United States, local community

leaders are now seeing clear evidence that the

suburbs, which sprang up as an “escape” from the

stress of urban decay, are themselves feeling the

impact of “city ills.” This was clearly delineated in

a recent Wall Street Journal article headed, “More

Suburbs Find City Ills Don’t Respect City Limits.”

1

Demographics

At the same time, the demographic picture is

changing. Demography is the study of the size,

composition, and distribution of human populations.

Although quantitative methods are employed, de-

mography is also centrally concerned with the quality

of human populations, such as their health status. It

should be noted that demographic trends are already

causing an increase in the demand for health services

and altering the character of the demand.

The U.S. Bureau of the Census estimates that the

United States population increased by 2.4 million

people in 1997 to 268,921,733 as of January 1,

1998. The projection is based on the number of

births (3.9 million), the number of deaths (2.3 mil-

lion), and the number of people returning or

This brief discussion will review, in broad outline,

selected health parameters of the context within

which efforts to reduce crime and revitalize com-

munities must be pursued.

My principal underlying thesis is that health condi-

tions, the health status of populations, and the ser-

vices available to address them are among the key

determinants of community stability, economic

viability, and the incidence of crime. Indeed, when

the history of the 1990s is written, health status and

access to health care for large segments of the pop-

ulation in the Nation’s urban centers will appear

repeatedly in many chronicles. Along with pictures

of the homeless, the charts and tables of the rates

of acute and chronic diseases and premature death

among the poor and disadvantaged will illustrate

many texts about crime, community instability, and

family disruption. These data will also illustrate

that the lack of access to comprehensive physical

and mental health care, including health promotion

and disease prevention, has a broad range of social

and economic ramifications that lacerate the civic

fabric and drive people from shared institutions—

subways, buses, parks, schools, and neighborhoods.

Even to casual observers, a discussion of the pre-

vention and control of crime and the revitalization

of communities raises many issues that do not have

a single or unambiguous solution because both

crime and community development are affected by

economic, health, social, behavioral, political, and

scientific factors. Many of these factors are chang-

ing at an unprecedented pace, both in the United

States and abroad. “Abroad” must be emphasized

here because economic, health, and social systems

have become increasingly interconnected and

globalized.

As competition and trade have increased, people

in virtually every country have benefited, and a

remarkable degree of mutual interdependence has

emerged. These changes have also brought risks

that frequently cannot be adequately addressed

The Context

4

➤

➤

immigrating to the United States (867,600) during

the previous year.

2

As the population grows, it will

increasingly become more diverse along many

socioeconomic dimensions. The increasing diver-

sity will create challenges and opportunities for

both the public and private sectors. In addition to

population size, the age structure will be important

in planning for community redevelopment and

crime prevention.

Changes in the Age and Racial

Makeup of the U.S. Population

Today, much attention is being focused on the

“aging” of the U.S. population. Citizens 65 and

older doubled in number between the 1950s and the

1980s. The fastest growing age group is between

55 and 65—now at 21.5 million but expected to

increase to 30 million by 2000 as baby boomers ap-

proach retirement age.

3

This trend raises concerns

about the economic and social aspects of care for

the elderly and the ratio of elderly dependents to

productive adults, whose caring responsibilities

will shift increasingly from children to the elderly.

Another trend on the demographic landscape is

the growth of the population share of nonwhite

citizens. The minority population numbered nearly

70 million in 1996, about one in four Americans.

By the middle of the 21st century, however, the size

of the minority population should just about equal

that of the non-Hispanic white population. In 1996,

African-Americans made up the largest segment of

the minority population—32 million people, about

12 percent of all Americans. Hispanics followed

closely with 27 million (10 percent).

4

Moreover, because of differential birth rates, a

disproportionate fraction of the country’s children,

adolescents, and young adults will be nonwhite.

Think of the economic and social implications of

an aged population mostly white, combined with a

youth population mostly minority.

New Health Stresses on Women

in the Workplace

Another demographic trend is the large-scale move-

ment of women from the home into the workplace,

particularly into jobs that subject them to health

risks of the kind previously prevalent among men.

In addition to traditional industrial hazards and

workplace pollution, both men and women now

suffer the putative side effects of a range of new

technologies. But our considerations must include

the less overt but long-term impact of job stress on

women’s health along with the psychological and

economic burden of single parenthood.

Women who work outside the home still do most

of the housework as well. Added to the pressures of

long hours of work inside and outside the home are

the time conflicts that emerge when one is both a

homemaker—and usually family caretaker—and a

wage earner. Sick children, school holidays, and ill

elderly relatives all contribute to stress and frustra-

tion in the context of inadequate health and social

services and employers support for working

women. Additional problems include inflexible

work schedules, the trend among employers to

“do more with fewer employees,” and the lack of

high-quality, accessible, and affordable child and

elder care.

Each of these demographic trends has serious

ramifications for social policy, economic planning,

and health care reform. For example, the aging of

Americans clearly implies a need for increased at-

tention to a broad spectrum of geriatric health and

social services. The age group between 55 and 65 is

losing health benefits at a faster rate than any other

group except children. Many in this age group

cannot qualify for health insurance because of the

preexisting health condition criterion imposed by a

number of insurance plans. Another segment of this

population no longer has health coverage because

when they were in early retirement their former

employers canceled their benefits to reduce costs.

Unfortunately, women have a greater chance than

men of being uninsured.

“Social Diseases” and the

Growth of Economic

Inequality

The growth in the nonwhite share of the population

is distressingly bound up with the persistence of,

and even increases in, certain familiar pathologies

of disenfranchisement—substance abuse, teenage

pregnancy, family disintegration—as well as more

recent challenges to the health services system,

Bailus Walker, Jr.

5

➤

➤

such as that of devising, supporting, and delivering

culturally appropriate services to new immigrants

(both legal and illegal) and refugees.

Within this matrix, there is another subset of prob-

lems that might be characterized as new “social dis-

eases.” By social disease, we mean a mixed bag of

pathologies—some physical, some psychological,

some both. They range from homelessness among

veterans and others to child abuse (every 11 sec-

onds a child is reported abused or neglected), with

its long-term neuropsychological impacts from

substance dependency to obesity. Some of these are

pathologies of poverty due to changes in the distri-

bution and location of jobs and in the level of edu-

cation and training required to obtain employment.

5

Let me hasten to insert here that there have always

been homeless people in the United States. As eco-

nomic circumstances have fluctuated, so have the

size and composition of the homeless population.

The homelessness problem has increasingly cap-

tured public attention. Take, for example, Washing-

ton, D.C. Evidence of the problem is not hard to

find in the Nation’s capital. Twenty-five families

spent the Christmas holidays in an emergency

shelter. Many others were housed elsewhere. The

population at the shelter has been growing since it

opened last November. Similar trends have been

identified in other cities, according to a telephone

survey of community leaders conducted in late

1997 by the Joint Center for Political and Economic

Studies.

Of particular relevance to the present discussion is

the fact that many homeless individuals, particu-

larly single young men, have histories of encounters

with the criminal justice system and a glaring lack

of experience with the health care system. Most

disheartening are the cases of adolescents and

post-adolescents who grow out of foster care or

child mental health and mental retardation facilities

because they are no longer eligible for residentially

based services for their age group, yet they have

nowhere to live. They then resort to illegal means

to get food and shelter.

Unfortunately, the otherwise robust economy of

today has helped create the illusion that everyone is

prospering, but that is not the case. Indeed, there is

a rapidly widening gap between rich and poor.

Although it is tempting to add the influence of the

historic legacy of racial segregation and discrimina-

tion, that would only be assigning blame—which is

not a productive exercise—and would blur the chal-

lenges and opportunities to recognize and address

the underlying forces that have provoked economic

stress for many Americans.

In this direction, William Julius Wilson, a long-time

student of economic and social problems of urban

America, writes:

Many of today’s problems in the inner-

city neighborhoods—crime, family

dissolution, welfare—are fundamen-

tally a consequence of the disappear-

ance of work. Work is not simply a

way of making a living and supporting

your family. It also constitutes a

framework for daily behavior because

it imposes discipline.

6

The Troubling Issue of

Mental Health

Then there is the deeply troubling issue of mental

health, a problem so serious that it must be consid-

ered separately. It cuts across boundaries of race,

class, and neighborhood. If it differs from group to

group or community to community, it is in com-

plexity, not in fundamentals. The relevance of men-

tal health to our discussion today was underscored

three decades ago in a 1967 paper of the American

Bar Association (ABA). It is worth quoting at

length:

If one observes both persons who

crowd our criminal courts and the

population of our mental hospitals, one

is struck not by differences between

the two but by similarities. Our pre-

occupation with trying to separate the

“mentally ill” from the “criminals”

may have led us to overlook a more

central reality; both mental illness and

criminality are tributaries of some

deeper mysterious channels. Certainly,

there are differences between “crimi-

nals” and the “mentally ill,” but it

seems possible that the problems of

The Context

6

➤

➤

mental illness and crime lend them-

selves to identical methods of

handling.

7

The ABA report goes on to state that there is a

limited supply of mental health resources and

inefficient use of those that exist.

This resource issue has been brought into much

sharper focus by a recent study that shows that un-

der the pressure of competition and managed care,

two-thirds of the Nation’s private hospitals that are

equipped to take in mentally ill patients dump them

on hard-pressed, financially weak public hospitals.

The study also reports that hospitals discharge

mental patients prematurely, either when their

health insurance runs out or when the cost of their

coverage exceeds the reimbursement rate that

their insurance companies pay hospitals. Among

adolescent psychiatric patients, it is more difficult

for those without health insurance than those with

insurance to obtain needed behavioral health serv-

ices. How many of those who cannot get care

become “students” in the juvenile justice system

is not clear.

Added to this is the shortage of mental health care

professionals. For example, in 1997, the Department

of Health and Human Services—which recognizes

areas with a paucity of mental health care serv-

ices—designated 536 mental health care profes-

sional shortage areas in the United States. This trend

could get worse if the organizational landscape of

health care delivery continues to be rearranged

(i.e., by mergers, consolidations, and alignments of

health care organizations and institutions).

8

Health Care to Meet the

Nation’s Changing Needs

The demographic trend pertaining to women raises

basic questions about what health services are most

critical for female heads-of-household and their

children as well as about how, when, in what set-

ting, and at what cost such services should be

provided. Each of the other demographic trends

previously cited expands or lends weight to a group

with new or greater needs or with needs that have

so far been inadequately addressed in the health and

social services system. These needs have not been

met for a number of reasons. One of the most

prominent reasons is that many members of the

group lack a regular source of health care with an

emphasis on preventive health services. They lack

these services because they do not have health

insurance or other means to pay for care. In a recent

study by the National Center for Health Statistics,

it was found that African-American persons were

four times more likely than whites to report

“no insurance/can’t afford” as their main reason

for poor health.

I will close by underscoring the fact that near the

top of any agenda for revitalizing communities and

reducing crime must be a health care system that

successfully addresses the issue of equity between

the young and aged and among social and ethnic

groups. The health care system must have the

capacity, commitment, and community orientation

to be an active part of efforts to address health care

needs of adolescents, including behavioral disor-

ders and related dysfunctions. It must also address

past inattention to women’s health issues that have

created serious gaps in knowledge about the cause,

treatment, and prevention of disease in women.

Unfortunately, the health care system that exists

today in the United States is not fully prepared to

meet these and other challenges of the 21st century,

as we are constantly reminded by the media,

advocates for the poor and medically underserved,

policymakers, and participants in forums and

workshops.

As managed care has emerged as a principal system

for health care and evidence indicates that the profit

margins of health maintenance organizations are

falling and services may be reduced, it is becoming

increasingly clear that more health care reform is

needed. These organizations are also confronted

with angry consumers demanding better services

and hospitals and physicians determined to resist

further cutbacks in fees.

9

Clearly, health care must be substantially reformed

to meet the changing needs of all stakeholders in a

system so essential to community revitalization and

to a reduction in the incidence of crime and related

social problems.

Bailus Walker, Jr.

7

➤

➤

Notes

1. “More Suburbs Find City Ills Don’t Respect City

Limits,” Wall Street Journal, January 2, 1998, B1.

2. U.S. Bureau of the Census, “U.S. Population Nears

269 Million as 1998 Begins,” Press Release, Washing-

ton, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Bureau

of the Census, December 24, 1997.

3. Day, J.C., “Population Projections of the United

States: 1995–2050,” Current Population Survey,

Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1995.

4. U.S. Bureau of the Census, March 1994 Supplement,

Current Population Survey, Washington, DC: U.S.

Bureau of the Census, 1995.

5. See The Commonwealth Fund, “Survey Finds Missed

Opportunities to Improve Girls’ Health,” The Common-

wealth Fund Quarterly 3 (3)(Fall 1997); Mushinski, M.,

“Teenagers’ View of Violence and Social Tensions in

U.S. Public Schools,” Statistical Bulletin, Metropolitan

Life Insurance Company (July–September 1996);

Children’s Defense Fund, “Key Facts About Children,”

CDF Report, Washington, DC: Children’s Defense Fund,

1995; and Cropper, C.M., “10 Heroin Deaths in Texas

Reflect Rising Use by Young,” New York Times, Novem-

ber 18, 1997, 28.

6. Wilson, W.J., “Work,” New York Times Magazine,

August 18, 1996, 28.

7. Matthew, A.R., “Mental Health and the Criminal Law:

Is Community Health an Answer?” American Journal of

Public Health 57 (September 1997): 1571.

8. See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Mental Health, United States, Rockville, MD: U.S. De-

partment of Health and Human Services, 1996; National

Advisory Mental Health Council, Health Care Reform

for Americans With Severe Mental Illness: Report of the

National Advisory Mental Health Council, Rockville,

MD: National Advisory Mental Health Council, 1993;

and Kilborn, P.T., “Mentally Ill Called Victims of Cost-

Cutting,” New York Times, December 10, 1997, A20.

9. See General Accounting Office, Medicaid Managed

Care: Challenge of Holding Plans Accountable Requires

Greater State Effort, Washington, DC: General Account-

ing Office, May 1997; United Hospital Fund, Primary

Care Capacity and Medicaid Managed Care, New York:

United Hospital Fund, 1998; and Knickman, J.R., R.G.

Hughes, H. Taylor, K. Binns, and M.P. Lyons, “Tracking

Consumers’ Reactions to the Changing Health Care Sys-

tem: Early Indicators,” Health Affairs 15 (Summer 1996):

22–32.

9

➤

➤

Economic Shifts That Will Impact

Crime Control and Community

Revitalization

onset of criminal careers by youths. Few criminal

justice reforms and innovations directly address

poverty or the systems charged with addressing

poverty—housing, education, welfare, and employ-

ment and training. In the future, the criminal justice

system must be more proactive in influencing anti-

poverty, community revitalization, family, and edu-

cational programs and policies. To have a stronger

voice in the design of these programs and policies,

economic trends need to be monitored and analyzed

from a crime control and community revitalization

perspective.

Three of the general trends that will influence the

American economic landscape in the 21st century

will have a special impact on crime rates and the

success of efforts to revitalize distressed communi-

ties. These three trends are:

● Increases in populations with higher-than-

average risk of participating in crime, including

long-term unemployed adults and youths,

unemployed ex-offenders, school dropouts,

and children reared in fatherless homes.

● Increases in the number of high-poverty commu-

nities because of failing schools, unemployment,

underemployment, and community abandonment

strategies.

● The continued reliance on ineffective programs

and policies to promote family self-sufficiency

and revitalize distressed communities, including

“deconcentration of poverty” approaches and the

emphasis on income maintenance rather than on

asset-building strategies.

Cicero Wilson

As we approach the year 2000, the United States

is nearing the end of a prolonged period of prison

construction. The growth of violent crime and sen-

tencing reforms in the 1980s and 1990s have led to

record numbers of incarcerated adults and juve-

niles. Although crime rates declined in 1995 and

1996, it is not clear what the long-term crime

and incarceration trends will be during the next

20 years. If crime rates do not continue to decline,

local officials may divert government resources

away from schools, community development,

parks, and other public amenities for prison con-

struction. Two important priorities for our Nation

are to reduce the rate of crime and to minimize

the impact of crime on children, families, and

communities.

Despite improvements in the criminal justice sys-

tem, such as community policing, drug courts, and

increases in prison beds for violent offenders, the

incidence of crime remains high in the United

States. The focus of our attention in the criminal

justice system is on improvements in how we deal

with crime after it is committed. The criminal jus-

tice system must begin to monitor more carefully

economic and community trends that influence the

rate and depth of poverty. The efforts of policy-

makers and practitioners to achieve crime reduction

goals in the next 20 years will require greater atten-

tion to the reduction of poverty. Rates of crime may

be influenced more by rates of persistent poverty

than by criminal justice interventions. Poverty, not

race, sex, or age, still has the highest correlation

with crime and violence.

Poverty helps create and maintain the behaviors and

attitudes that contribute to crime, violence, and the

Economic Shifts That Will Impact Crime Control and Community Revitalization

10

➤

➤

Population Trends

Trend One: For Dropouts and

Unskilled Workers, Finding Family

Wage Jobs With Benefits Will

Become More Difficult

It will be difficult for unskilled and uneducated

labor to find family wage work in the 21st century.

The globalization of the economy and technology

are producing greater productivity, greater competi-

tion, larger profits, and fewer family wage jobs.

Although foreign competition and lower overseas

wages in some countries have cost the United States

jobs, most of our job losses were because of com-

petition from high-wage, high-technology countries

such as Germany and Japan. Technology will have

a greater impact than foreign competition on job

loss and disruption of career paths. Technology will

not only eliminate some jobs in industries such as

banking and manufacturing, it will also change the

educational skills needed for the new jobs.

Another major source of labor market problems

is the corporate culture that promotes maximizing

profits by downsizing, or converting full-time jobs

with benefits into part-time jobs with no benefits.

Jeremy Rifkin, in his book The End of Work,

1

predicts technology and corporate culture will

determine unemployment levels in the 21st century.

If unemployment grows to levels of 20–25 percent

nationally as Rifkin and other authors predict, then

the pressure on all of our social systems will be

enormous. While such dire predictions are far from

guaranteed, these trends must be carefully moni-

tored by agencies and advocates concerned about

reducing crime and revitalizing economically and

socially distressed communities.

Trend Two: The Number of Youths

Failing School Will Continue to

Escalate Without Changes in School

Policies, Tutorial Support Systems,

and Parental Involvement

Youth crime prevention is often deemed synony-

mous with school failure prevention. Unfortunately,

school failure is a growing trend in poor urban and

rural areas. Two sources of school failure are

extremely important to criminal justice and com-

munity development advocates: unaddressed learn-

ing difficulties and school suspension and expulsion

policies.

Unaddressed learning difficulties. Students who

fall behind two grades in school are more likely to

drop out or become involved with drugs, alcohol,

or the courts. Despite the emphasis on education

standards, our schools are still struggling to help

students master basic reading, math, and communi-

cations skills. Many students who are experiencing

learning difficulties have nowhere to go for help.

Working parents, especially single working parents,

have limited time to check homework or tutor their

children. Teachers are overburdened. Most churches

do not offer latchkey or tutorial programs. The

absence of adequate rural transportation is a major

impediment to getting students to programs, if pro-

grams exist.

Without tutorial assistance for students in schools

and juvenile institutions to supplement classroom

instruction, many students will continue to fail and

either drop out or graduate functionally illiterate.

These youths lack the skills needed to succeed in

the 21st-century working world and are at high risk

of becoming involved in criminal activities to sup-

port themselves.

School expulsion and suspension policies. In

response to student disruptive behavior, violence,

weapons, and illegal substances, most schools

have adopted zero-tolerance rules to quickly expel

offending students. Schools penalize minor misbe-

havior with suspensions. However, unlike suspen-

sions of two decades ago, some schools have added

procedures to automatically fail students in courses

in which they have five unexcused absences. A stu-

dent who is suspended for 5 days fails all of his/her

classes for the entire semester. Old policies would

require students to attend afterschool detention and

do more work and suspended students to make up

all assigned work. Today, schools expel students

without adequate provision for alternative schools.

Schools also suspend students so frequently that

they fail enough classes to fall more than 1 year

behind their graduating classes. These students

usually drop out of school. These policies remove

the most troublesome students, but they also push

Cicero Wilson

11

➤

➤

out students who could be helped. These policies

are at odds with everything we know about school

absence, dropouts, school failure, and delinquency.

These school policies are filling communities with

teenagers who are unsupervised most of the day.

These out-of-school youths are at high risk for sub-

stance abuse, teen pregnancy, and criminal activity.

Whatever the sources of school failure, more than

1,100 youths drop out of school every day in the

United States. Many students will graduate without

the basic skills needed to succeed in the rapidly

changing working world. Unabated, this school

failure trend intensifies the problems of unemploy-

ment and poverty, which are primary contributors

to crime rates.

Trend Three: The High Incarceration

Rates of the 1990s Will Result in a

Flood of Unemployed Releasees

From Prisons and Jails in the Next

Two Decades

The efforts of economic and community develop-

ment programs, work force development projects,

and welfare reformers erode when adult and juve-

nile parolees return to the community unemployed.

They attempt to make money through street crime,

drug sales, and extortion from women on welfare.

The current lack of sufficient reintegration pro-

grams, high recidivism rates, and the number of

persons to be released from jails and prisons during

the next 25 years should alarm everyone. Further-

more, large numbers of these releasees are return-

ing to the communities we are trying to revitalize.

The criminal activities of unrepentant parolees

make the neighborhoods inhospitable to efforts to

revitalize the family, community, and local eco-

nomy. Crimes such as carjacking, school violence,

and random shootings have fueled the move of

many families and businesses to communities per-

ceived as safe. Business tax incentives, business

retention strategies, and community development

efforts such as Empowerment Zones are severely

diminished as development tools when businesses

and residents perceive a community or city as crime

ridden. Controlling community crime and violence

is an important prerequisite to community

revitalization.

Trend Four: There is an Increase in

the Number of Fatherless Children,

Who Are More Prone to Delinquency

and Other Social Pathologies

As the incidence of father absence grows, commu-

nity disintegration and crime, especially youth

crime, will continue to grow. Between 1960 and

1990, the percentage of children living apart from

their biological fathers increased from 17 to 36 per-

cent. By the year 2000, half of the Nation’s children

may not have their fathers at home. While the he-

roic efforts of single women to raise their children

alone are laudable, the economic and social require-

ments for raising healthy and productive children

are hard to achieve by poor single parents alone.

Reengaging fathers in the economic and social life

of their children is an important but overlooked

aspect of addressing poverty, community revitaliza-

tion, and crime.

Many of our problems in crime control and com-

munity revitalization are strongly related to father

absence. For example:

● Sixty-three percent of youth suicides are from

fatherless homes.

● Ninety percent of all homeless and runaway

youths are from fatherless homes.

● Eighty-five percent of children who exhibit

behavioral disorders are from fatherless homes.

● Seventy-one percent of high school dropouts are

from fatherless homes.

● Seventy percent of youths in State institutions

are from fatherless homes.

● Seventy-five percent of adolescent patients in

substance abuse centers are from fatherless

homes.

● Eighty-five percent of rapists motivated by

displaced anger are from fatherless homes.

Without fathers as social and economic role mod-

els, many boys try to establish their manhood

through sexually predatory behavior, aggressive-

ness, or violence. These behaviors interfere with

Economic Shifts That Will Impact Crime Control and Community Revitalization

12

➤

➤

schooling, the development of work experience,

and self-discipline. Many poor children who live

apart from their fathers are prone to becoming court

involved. Once these children become court in-

volved, their records of arrest and conviction often

block access to employment and training opportuni-

ties. Criminal histories often lock these young per-

sons into the underground or illegal economies.

Behaviors related to father absence that directly

contribute to the growth of welfare and the difficul-

ties in creating jobs in communities include:

● Sexually predatory behavior that results in out-

of-wedlock births. (Most teen mothers are

impregnated by older men, not teen boys.)

● Domestic violence that occurs as a result of

arguments over enforcement of child support

payments.

● Welfare pimping, which is the practice of men

collecting part of the welfare check from girl-

friends or the mothers of their out-of-wedlock

children. Some pimps collect from five or six

mothers on welfare per month.

Innovative father engagement programs have had

an impact on child rearing, family economic stabil-

ity, and gang involvement. Unless community revi-

talization and crime reduction programs begin to

address the need for father engagement programs

and services, the cycle of poverty and crime could

continue virtually unabated.

Community Revitalization

Trends

Trend Five: There is an Increase

in the Number of High-Poverty Areas

Socially and economically distressed communities

tend to promote behaviors and attitudes conducive

to crime and dependency. High levels of crime also

help to maintain and increase high-poverty commu-

nities. The 1990 census indicated that the number

of high-poverty census tracts had increased since

the 1980 census. The proportion of poor persons

living in extreme poverty census tracts in the

100 largest U.S. cities tripled between 1970 and

1990, from 12.6 percent to 36.2 percent.

2

Apparently, approaches to law enforcement and in-

come maintenance in extremely poor communities

had limited impact on poverty and crime during the

last two decades. Although current welfare reform

and broken windows approaches to law enforce-

ment appear to have some impact, the underlying

poverty and propensity for crime have been sup-

pressed, not reduced. If recessionary economic

conditions reappear with high levels of unemploy-

ment, the rates of poverty and crime could rise sig-

nificantly. Federal programs and policies that have

an impact on employment and education in poor

communities are very important components of an

effective crime reduction and community revitaliza-

tion strategy.

Federal criminal justice and antipoverty policies

need to consider more effective resource targeting

to reduce the number of high-poverty communities.

However, these policies and programs to combat

the concentration of poverty should not rely on

“deconcentration” or “dilution” approaches. These

dilution approaches deconcentrate poverty by mov-

ing poor families into mixed-income communities.

Generally, these programs do not help families im-

prove their family income, gain economic literacy,

or reduce or eliminate such problems as drug addic-

tion before moving the family. Dilution programs

should not be “problem export” programs. Simply

moving to a better neighborhood will not automati-

cally change destructive attitudes and behaviors.

Trend Six: Community Abandonment

Frustrated criminal justice, housing, and economic

development officials often view communities with

very high rates of crime, housing abandonment,

substance abuse, and gangs as beyond help. Invest-

ing police and economic development resources

in these communities is deemed a waste of limited

resources. This approach is called a “community

abandonment” strategy. The problems with this

approach are numerous. First, these communities

often spread their misery to neighboring communi-

ties. Second, crime and barriers to economic devel-

opment extend far beyond the particular abandoned

community. The presence of such a community

adversely affects the reputation of entire segments

of towns and cities. Third, these abandoned com-

munities also serve as safe havens for criminals

Cicero Wilson

13

➤

➤

who prey on other communities. Fourth, most of

what we have learned about successful community

revitalization has been learned from the efforts of

local residents and their partners in distressed com-

munities. The transformation of the Kenilworth

Parkside Public Housing Development in

Washington, D.C., is one of many successful

transformations.

The frustration and failure associated with revital-

ization efforts in very distressed areas is the result

of weak strategies that do not engage the support

of local residents. These strategies also fail to focus

on asset building and lack strong criminal justice

responses to crime. An example of a good strategy

is the Weed and Seed program. The Weed and Seed

program has a major positive impact on economic

development and revitalization when a coalition of

community and law enforcement agencies work

together to eliminate local crack houses. This

strong law enforcement response, with media cov-

erage of local residents cheering, boosts community

development efforts. This program says to the pub-

lic that something can be done about crime and that

residents of poor neighborhoods want crime elimi-

nated. Without such efforts, community abandon-

ment is viewed as a logical response.

Trend Seven: Without Policies to

Correct Asset Deficiencies, an

Increasing Percentage of Families

Will Not Achieve Self-Sufficiency

and Efforts to Revitalize Poor

Communities Will Continue to

Have Limited Success

Until recently, our approaches to poverty and com-

munity development have been focused on deficits,

problems, and income security programs. Programs

that do not focus on teaching and asset building

consistently fail to reduce poverty and revitalize

distressed communities on a large scale. Asset

building has been the primary vehicle for lifting

individuals and families out of poverty. Assets such

as savings, homeownership, property ownership,

business ownership, and postsecondary education

and training are the resources most Americans use

to become self-sufficient and decrease the likeli-

hood of poverty for themselves and their children.

Asset-building programs increase family income

rather than supplement inadequate income and also

create local jobs and local stakeholders in commu-

nities. Poor families that rise out of poverty through

education and employment often leave poor com-

munities because of crime, poor schools for their

children, and lack of business ownership and home-

ownership opportunities. When these successful

families leave, they take their disposable income,

civic involvement, and examples of positive achie-

vements with them, leaving the familiar concentra-

tion of poor families and problems behind.

Asset-building programs also create a positive eco-

nomic future for youths. Many youths join gangs or

engage in street crime because they feel they have

no other economic options. Programs that provide

youth enterprise skills or education trust funds

influence their view of themselves and their risk-

taking behavior. Crime prevention and treatment

programs as well as community revitalization strat-

egies need to include asset building to be effective.

Poor and working poor families and individuals

can effectively build assets when provided with

specialized programs to help them. By increasing

the availability of these programs and promoting

asset building for the poor, families and communi-

ties can be strengthened. Policymakers and practi-

tioners should explore the expanded use of the

following programs and policies in reducing

poverty and crime:

Economic literacy programs. Economic literacy

programs provide basic budgeting and banking and

savings skills for low- and moderate-income indi-

viduals and families.

Microenterprise and youth enterprise programs.

Microenterprise and youth enterprise programs

provide entrepreneurial training for low-income

individuals. After assessing their talents and inter-

ests, each trainee is taught how to develop a real

business plan by program staff. The program then

makes small amounts of capital available to the

trainees to launch their businesses.

Homeownership programs for low-income fami-

lies. Homeownership programs provide counseling

on the homeownership process and assistance with

budgeting, savings, and the downpayment. These

services create community stakeholders.

Economic Shifts That Will Impact Crime Control and Community Revitalization

14

➤

➤

Individual Development Accounts. Individual

Development Accounts (IDAs) are restricted sav-

ings accounts that can be used for buying a home,

starting or expanding a business, or postsecondary

education and training. Individuals or families are

required to save for their dream, and their savings

are matched by the private, nonprofit, and public

sectors. For example, a family saves $20 a month,

and those savings leverage $80 in matching contri-

butions. IDAs are included in the new welfare law.

The law also allows recipients of income main-

tenance benefits to have these accounts without

affecting their eligibility to receive benefits. Legis-

lation is pending in Congress to provide $100 mil-

lion for IDA demonstrations.

Conclusions and

Recommendations

Our real crime reduction and community revitaliza-

tion challenges involve finding ways to reduce

poverty, the number of high-poverty communities,

family disintegration, and the number of young

people entering criminal careers. Community devel-

opment and crime reduction agencies must not sit

by while employment, welfare, child support, and

school agencies institute rules and guidelines that

increase the difficulty of controlling crime and

reversing community decline. For example:

● Local employment agencies have always put

ex-offenders and youths at the bottom of priority

lists for employment and training services. The

willingness of noncustodial fathers to support

their children is not considered when selecting

participants for training programs. The impor-

tance of employment for noncustodial fathers,

especially ex-offenders, will not become a prior-

ity without Federal guidance.

● New child support and paternity establishment

rules have great potential to increase violence

against women and children. State and local

agencies need guidance in considering how to

reduce these risks.

● Schools not only institute expulsion and suspen-

sion policies that push too many children out,

they also are initially inept at addressing the

emergence of gangs in schools. Information on

best practices to prevent and control gangs and

violence in schools is available at the Federal

level, but few school administrators use it. Fed-

eral incentives to get schools to use this informa-

tion are needed.

The U.S. Department of Justice has developed

accessible databases on best practices in violence

prevention, gang control, victim assistance proce-

dures, and other important areas. In addition, the

Department of Justice has funded demonstrations

and evaluations of important innovations such as

drug courts, community policing, Weed and Seed,

and prison industries. These programs are having

an important impact at the community level.

Greater attention should be given to these databases

and to innovations by other Federal, State, and local

agencies.

Federal agencies with mandates to reduce crime

and rebuild communities need to focus more atten-

tion on asset building, reshaping school suspension

policies, and designing programs and policies to

engage fathers as positive economic and social

agents in families. Without these changes in our

approaches, poverty, employment, school failure,

and family trends will block efforts to reduce crime

and revitalize communities.

Notes

1. Rifkin, Jeremy, The End of Work: The Decline of the

Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market

Era, New York: Putnam Publishing Group, 1995.

2. Kasarda, John D., “Urban Industrial Transition and

the Underclass,” Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science 501 (1990): 26–47. Also see

Wilson, William Julius, When Work Disappears, New

York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1996.

15

➤

➤

The Context of Recent Changes

in Crime Rates

Alfred Blumstein

more buyers and with more transactions per buyer),

there was major recruitment of young minorities

to serve in that role. They were carrying valuable

property—drugs or the proceeds from the sale of

those drugs—and so they had to take steps to pro-

tect themselves from robbery. Because they were

dealing in an illegal market, they could not call

the police if someone tried to steal their valuables.

Their self-protection involved carrying handguns.

Because young men are tightly networked and

highly imitative, their colleagues—even those not

involved in selling drugs—armed themselves also,

at least in part as a matter of self-protection against

those who were armed. That led to an arms race in

many inner-city neighborhoods.

It is widely recognized that violence has always

been part of teenage males’ dispute-resolution

repertoire, but that has typically involved fights,

the consequences of which were usually no more

serious than a bloody nose. The lethality of the

ubiquitous guns contributed in a major way to the

doubling of the homicide rate by (and of) those 18

and under.

The emphasis on the presence of guns as a critical

instrument in this process is reflected in the fact

that gun suicide rates by young people, especially

young African-Americans, escalated at the same

time as homicide rates.

2

There were no comparable

trends in nongun homicides or suicides.

At the same time, the homicide rate for older ages

diminished. For those 30 and older, the reduction

was about 20–25 percent. The growth in the prison

population during that time (a doubling in the incar-

ceration rate between 1985 and 1996) has undoubt-

edly contributed to that reduction, although no one

has isolated that incapacitation effect from other

factors (e.g., a general decline in intimate partner

homicides) that may have contributed to the decline

in the homicide rate by older offenders.

The late 1980s saw a dramatic growth in U.S.

homicide rates, particularly in homicides commit-

ted by young people. Between 1985 and 1992, the

homicide arrest rate for youths and children age 18

and under more than doubled. This gave rise to con-

siderable rhetoric about the “bloodbath” that was

coming and the new generation of “superpredators”

who had to be dealt with in harsh new ways. Fortu-

nately, that growth peaked in the early 1990s and

has declined appreciably since then. Aggregate

homicide rates are now lower than they have been

for more than 25 years, but the rate of homicides by

young people is still well above the stable rates that

prevailed from 1970 through 1985.

In this paper, I would like to address some of the

contextual issues behind the growth in violence of

the late 1980s, examine the decline since 1991, and

explore some of the speculations about the factors

that contributed to that decline. I will then follow

with some suggestions for potential Federal roles

in helping to decrease crime and revitalize commu-

nities.

Growth in Violence in the

Late 1980s

In a recent paper,

1

I examined the time trends in

three measures—youth homicides, handgun homi-

cides by youths, and arrests of nonwhite juveniles

for drug offenses. Each of these rose dramatically

beginning in about 1985 and had more than

doubled by 1992. Similar changes were not dis-

played in adult homicides, nongun homicides, and

arrests of white juveniles for drug offenses.

My hypothesized link among these three trends is

that crack arrived in the mid-1980s, initially in the

larger cities, and spread from there to the smaller

cities. Because crack required many more sellers

to meet the increased demand (composed of many

The Context of Recent Changes in Crime Rates

16

➤

➤

Shifts During the 1990s

The number of homicides by young people leveled

off in the early 1990s and did not begin a signifi-

cant decline until 1994. With the growth in the

homicide rate among young people stopped, the

continuing decline in the homicide rate by older

offenders resulted in a peak national homicide rate

in 1991 and a subsequent decline. That decline was

dominated by the changes in the largest cities—

New York in particular—which displayed very

sharp declines, beginning in 1994.

One explanation that has been offered for the

decline in crime rates is “demographic change.”

This probably harks back to the last time we saw

a significant decline in crime rates, in the early

1980s, when demographic change—the aging of

the baby-boom generation out of the high-crime

ages of the late teens and early 20s—was indeed a

major contributor to the crime rate decline.

3

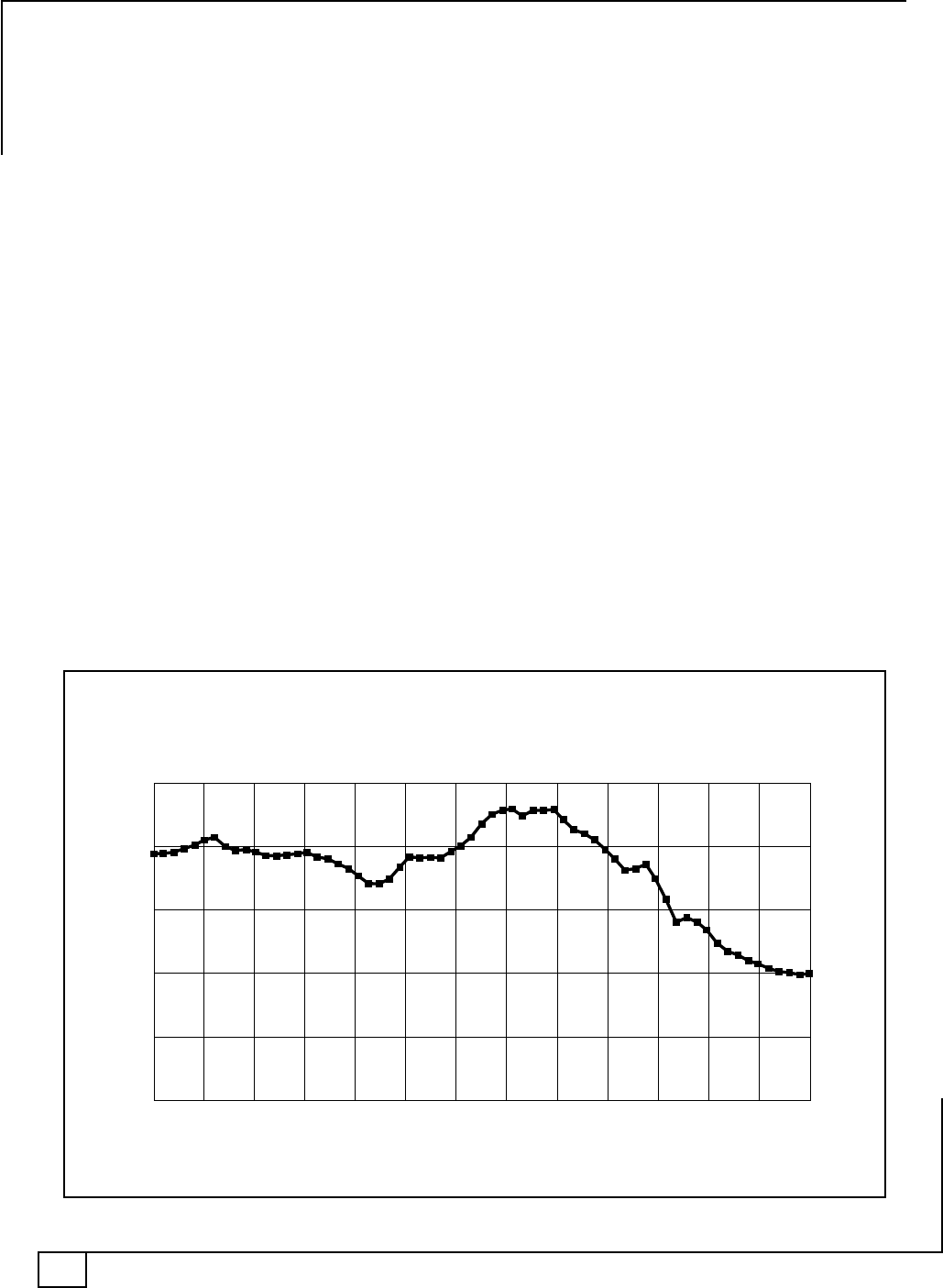

Today,

however, demographic change is working in the

other direction—to increase crime rates. As can

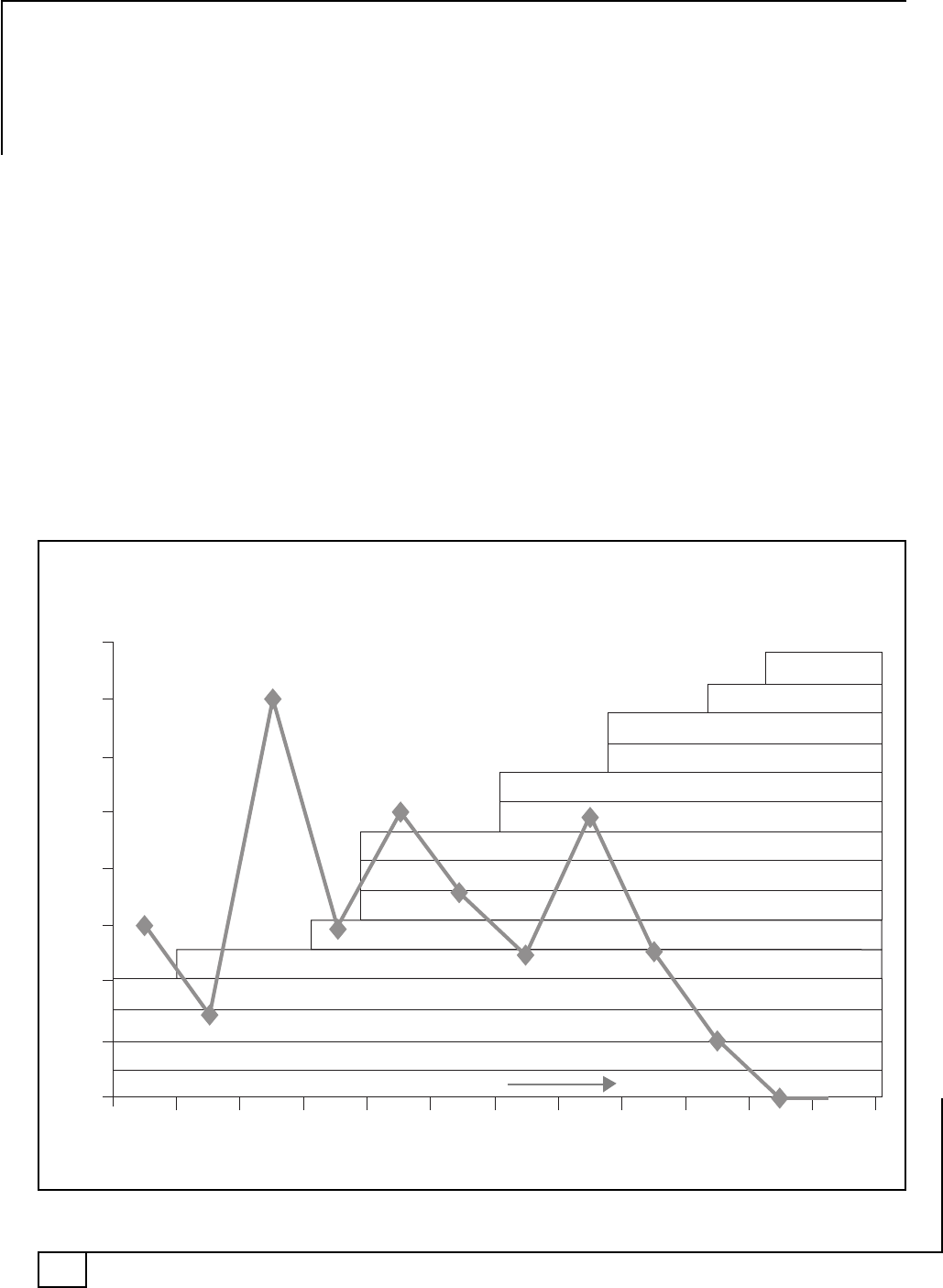

be seen in exhibit 1, which shows the number of

people at each age in the United States in 1998, the

smallest age cohort in the Nation under age 40 is

now about 23. These are the people who were born

in 1975 following the baby boom, which peaked in

about 1960.

Thus, we are seeing a growing number of individu-

als entering the high-crime ages of the late teens

and early 20s, and that will continue for at least the

next 10 years. But we should also note that those

changes are not dramatic, with the cohort sizes

expected to grow by about 15 percent in 15 years,

or roughly 1 percent per year. Even when one parti-

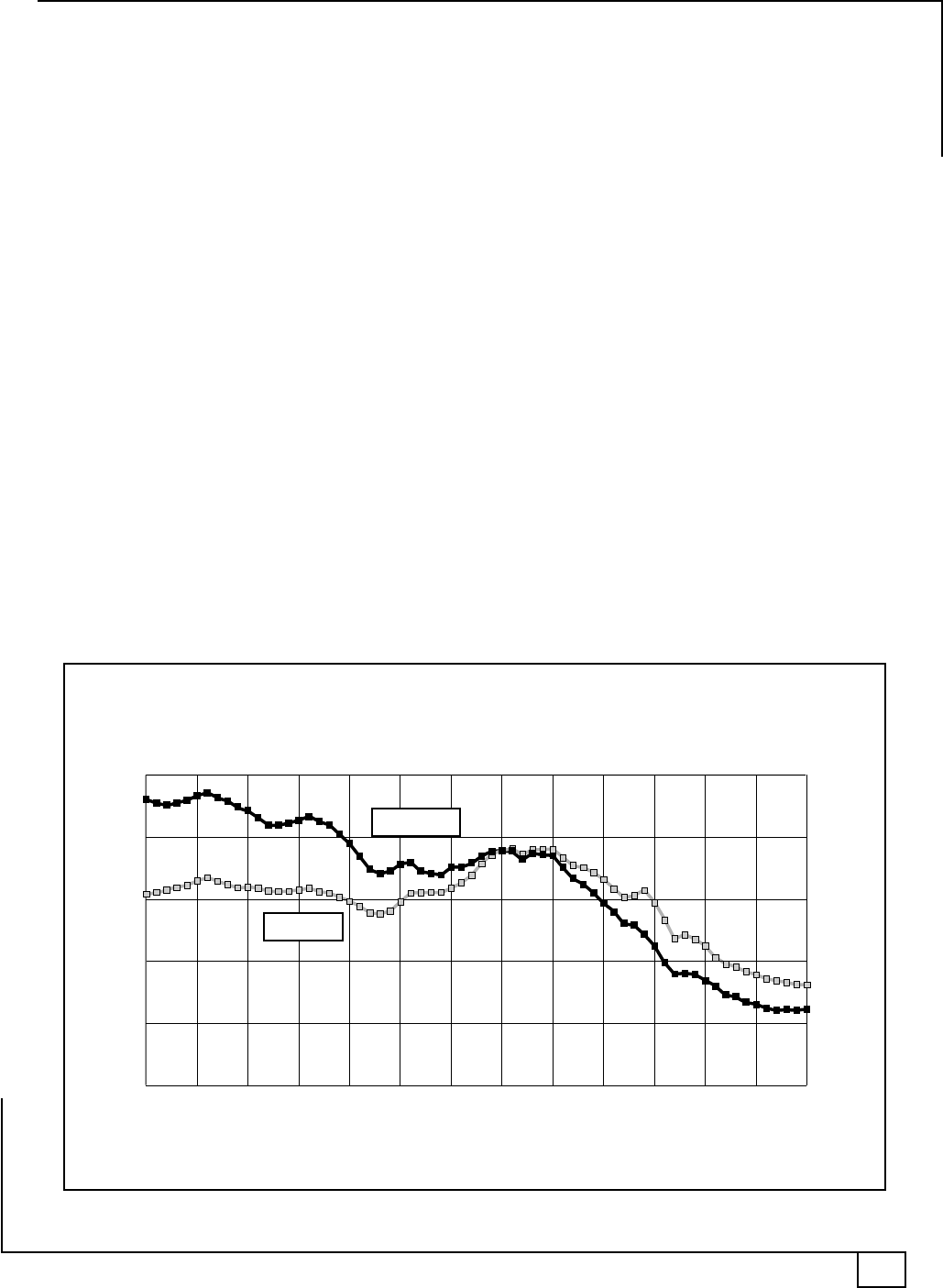

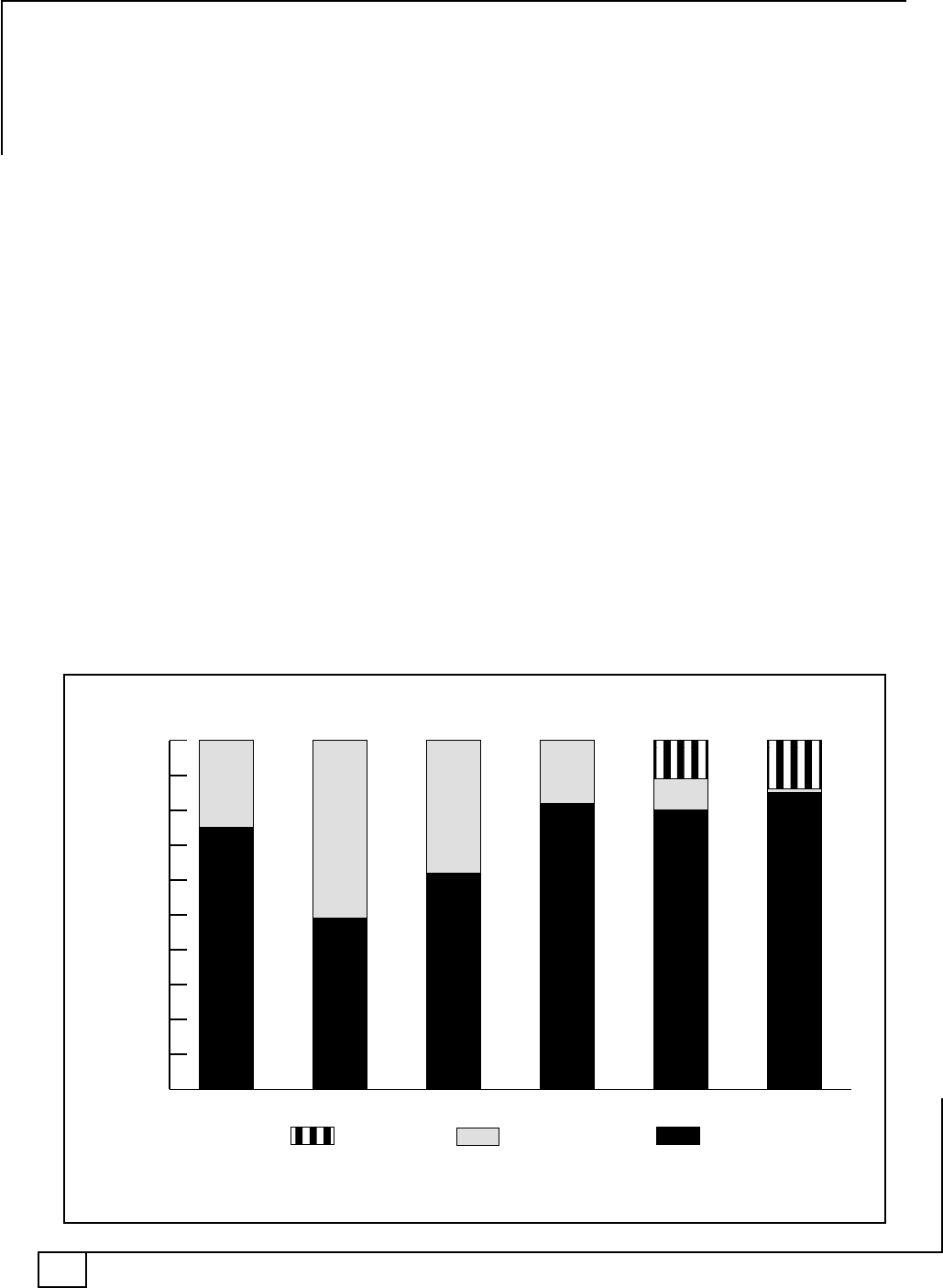

tions this analysis by race (see exhibit 2, which

shows the white and black male populations sepa-

rately by age), we see that the young black male

population (which is multiplied by a factor of seven

to show the comparative growth, since the U.S.

white population is about seven times the black

population) follows a pattern very similar to the

white male population, but with a somewhat faster

rate of growth. Nevertheless, the growth rate of the

black male population is only about 30 percent in

15 years, or about 2 percent per year.

Exhibit 1. Age Composition of U.S. Population, 1998

Number of Persons at Each Age

(Millions)

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census

Age

5 101520253035404550556065

0

1

2

3

4

5

Alfred Blumstein

17

➤

➤

.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

0

5 1015202530354045505560 65

These demographic shifts represent but one factor

contributing to changes in crime rates. If crime

rates within each demographic group stay constant,

then an increase in the size of the demographic

groups with the highest rates contributes to an in-

crease in the aggregate crime rate. But other factors

are contributing to changes in demographic-specific

crime rates well in excess of even 2 percent per

year. During the late 1980s, for example, homicide

rates by young people were growing by 10–20 per-

cent per year. Declines in recent years, especially in

the largest cities, have also been of that magnitude.

An important avenue to pursue is finding an

explanation for the recent decline in homicides by

young people. Possible explanations include:

● Changes in the nature of drug markets (crack

markets in particular), induced by changes in

the nature of the demand, that has led to less

violence associated with those markets.

● Vigorous police and community efforts in at

least some cities to get guns out of the hands of

young people.

● Police and community efforts to resolve gang

conflicts and encourage disarmament.

● Improvement in the economy that not only has

provided jobs to young people but also has been

a source of improved hope for succeeding in the

legitimate economy.

● Increased incarceration of potentially violent

offenders.

● Improvement in the largest cities that may be

masking a situation that could be very different

in many smaller cities.

These explanations certainly are not mutually ex-

clusive, and different explanations could apply to

different cities. We still need more effort to sort out

these and possibly other contributors to the decline.

Even though the decline in the homicide rate by

young people is encouraging news, it is important

to note that the homicide rate by juveniles is still at

least 60–80 percent above the rate that had pre-

vailed for the 15 years from 1970 to 1985. Thus,

Exhibit 2. Age of U.S. Males by Race, 1997

Number of Males of Each Race at Each Age

(Millions)

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census

Age

White

Black x 7

The Context of Recent Changes in Crime Rates

18

➤

➤

we still have a long way to go in bringing that rate

down.

Incarceration has been the Nation’s dominant strat-

egy against crime over the past 25 years. That has

led to an incarceration rate (prisoners per capita)

that is more than four times the rate that prevailed

with remarkable stability for the previous 50 years.

Incarceration with reasonable sentences is likely to

have an important incapacitation effect on older of-

fenders (ages 25 and older), whose lengthy criminal

careers may reasonably predict future offending.

Such predictions are far more difficult with younger

offenders, so it is important to address opportunities

for investment in crime-prevention efforts targeting

individuals in high-risk situations at an early age.

Even though the payoff from such investments will

take several years to be realized, it is likely to ex-

ceed the fiscal cost—let alone the social cost to the

society and the economy—of widespread use of

long-term incarceration of young people. But no

one can make that assessment definitively because

the evidence on the comparative payoffs is still

poorly known and the payoffs will vary with differ-

ent kinds of interventions with different target

groups. A major national challenge lies in finding

what approaches can be most effective with each of

the different kinds of young offenders. We still do

not have definitive solutions, but it is extremely

important to invest in the research that will enable

us to develop and identify them.

Windows on the Future

As we look to the future, there is little we can say

with certainty. One strong predictor is the demo-

graphic composition of the Nation. It has already

been indicated that demographic trends will con-

tribute to making matters worse, but only at the rate

of about 1–2 percent per year. The other matter of

concern is the greater number of people who will be

unemployed or without reliable sources of income

if the economy turns down—a likely eventuality—

but few people can say with any confidence just

when that will occur. When that happens, we might

see more people resorting to criminal activity

to offset their displacement from the legitimate

economy. One group in particular for whom that is

an important issue is the people who will be dis-

placed from welfare support when their time of

eligibility expires. So far, we have seen an impor-

tant reduction in the welfare rolls by those best able

to move into the legitimate economy, while those

without such opportunities have stayed on welfare.

Within the next few years, more of that latter group

will find themselves without welfare support, and—

especially if there is concurrently a significant

growth in unemployment—there is a serious risk

that they will pursue illegitimate means for their

sustenance.

Another important cloud on the horizon is the con-

cern about the arrival of new drug epidemics in our

major cities. We have seen an ebbing of serious

drug abuse in recent years as young people have

eschewed the crack cocaine that so often did seri-

ous damage to the lives of their parents and sib-

lings. As that awareness fades in coming cohorts of

young people, or if new drugs without the compa-

rable stigma arrive, we might well see a reignition

of some of the serious crime epidemics that charac-

terized the late 1980s. The data to be collected in

75 cities by NIJ’s Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring

(ADAM) program, involving urinalysis of booked

arrestees, should provide some early warning of the

arrival of those problems.

The Federal Role

As one builds on this background to identify an

appropriate Federal role for dealing with these

problems, one is first faced with the complexity of

the division of labor between the Federal Govern-

ment and State and local governments. It is widely

accepted that the primary operational responsibility

for local crime control is inherently State and local.

But there are important aspects of the crime prob-

lem for which the primary responsibility is Federal.

One relates to interdiction of criminal activity in

which interstate transactions are particularly impor-

tant. The most evident of these is the area in which

there is already widespread Federal involvement—

interstate trafficking in drugs. But it is also impor-

tant to focus on another crime-related product,

which is much more directly associated with

violence and one in which the Federal role is still

poorly developed. That relates to the illegal traffick-

ing in firearms, particularly the semiautomatic

handguns that have been implicated as a major

factor in the rise of juvenile violence over the past

Alfred Blumstein

19

➤

➤

decade. Crime-gun tracing by the Bureau of Alco-

hol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) through its Na-

tional Gun Tracing Center has seen some important

growth over the past several years, but the capabil-

ity and the effort applied are still far less than is

needed to become effective in interdicting that

illicit traffic. Better collaboration between local

police and ATF could result in more effective

interdiction of that traffic.

The other general role of the Federal Government

relates to “public goods” that States or localities

need but whose creation is expensive and is broadly

beneficial, so the Federal Government appropriately

becomes the agent to serve the combined interests

of States and localities. These public goods include

creation and maintenance of shared operational

databases such as the National Crime Information

Center (NCIC); fostering and evaluating a wide

range of innovations and disseminating the results

of evaluations of those innovations so that the

successful ones can be replicated elsewhere; and

organizing and sponsoring research and statistical

projects and disseminating the information and new

insights they generate. This last—the research and

statistics function—is the critical one, and it is not

likely to occur without major Federal involvement.

These activities are the province of the U.S. Depart-

ment of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs—NIJ,

the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Bureau of

Justice Assistance, the Office of Juvenile Justice

and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for

Victims of Crime.

Most people see these functions as merely a trans-

fer of Federal money to alleviate local costs. The

agencies’ participation in providing the knowledge

to enhance the overall effectiveness of the agencies

of the criminal justice system is a far more critical

Federal role because the functions could not be

performed without that participation. In view of

their importance, it is astonishing how little money

the Federal Government invests in those functions.

Notes

1. Blumstein, Alfred, “Youth Violence, Guns, and the

Illicit-Drug Industry,” Journal of Criminal Law and

Criminology 86 (1) (Fall 1995): 10–36.

2. See Blumstein, Alfred, and Daniel Cork, “Linking

Gun Availability to Youth Gun Violence,” Law and

Contemporary Problems 59 (1) (Winter 1996): 5–24.

3. See Blumstein, Alfred, Jacqueline Cohen, and Harold

Miller, “Demographically Disaggregated Projections of

Prison Populations,” Journal of Criminal Justice 8 (1)

(January–February 1980): 1–25.

21

➤

➤

Community Watch

Amitai Etzioni*

urges: we all occasionally experience aggressive

feelings, inappropriate sexual desires and selfish

inclinations. The best families and schools can

do—and this is crucial for our understanding of

crime and how to deal with it—is to develop a

conscience that serves as a counterweight. Human

nature is condemned to an eternal struggle between

theses urges (which make us offend mores and

often laws) and our conscience.

Most important, how law-abiding (and good) we

are as adults is very much determined by the extent

to which the conscience we acquired as children

receives external reinforcement. This is particularly

effective when it comes from those in whom we

have an emotional investment: members of our

communities. The stronger the communal bonds

and the more they support pro-social behaviour, the

more we are able to curb our urges, and the lower

the level of crime. This is why we are all so sur-

prised at crime in a small, tight-knit community,

such as Dunblane.

The crimes I am talking about include not merely

street violence, but also child and spousal abuse,

white-collar crimes (embezzlement), corporate

crime and political corruption.

Crime occurs in all social classes, not only in inner

cities. While communities can curb even the most

serious violent crimes, they are particularly effec-

tive in minimising most other crimes, releasing

resources to fight the hard core.

Tony Blair’s anti-crime programme, as drafted be-

fore his election, was successful in deflecting Tory

accusations that Labour was soft on crime. Its focus

on moving police from behind desks to the streets,

“zero tolerance” for petty crimes, and fast-track

punishment for persistent youth offenders, leaves

plenty of room to make it more communitarian.

The government programme could now take into

The way one thinks about and deals with crime

depends on one’s assumptions about human nature.

If one assumes that people are good by nature, as

many liberals do, then one blames conditions in

society on ill conduct. Giving people jobs—well-

paying jobs and not dead-end ones—is the most

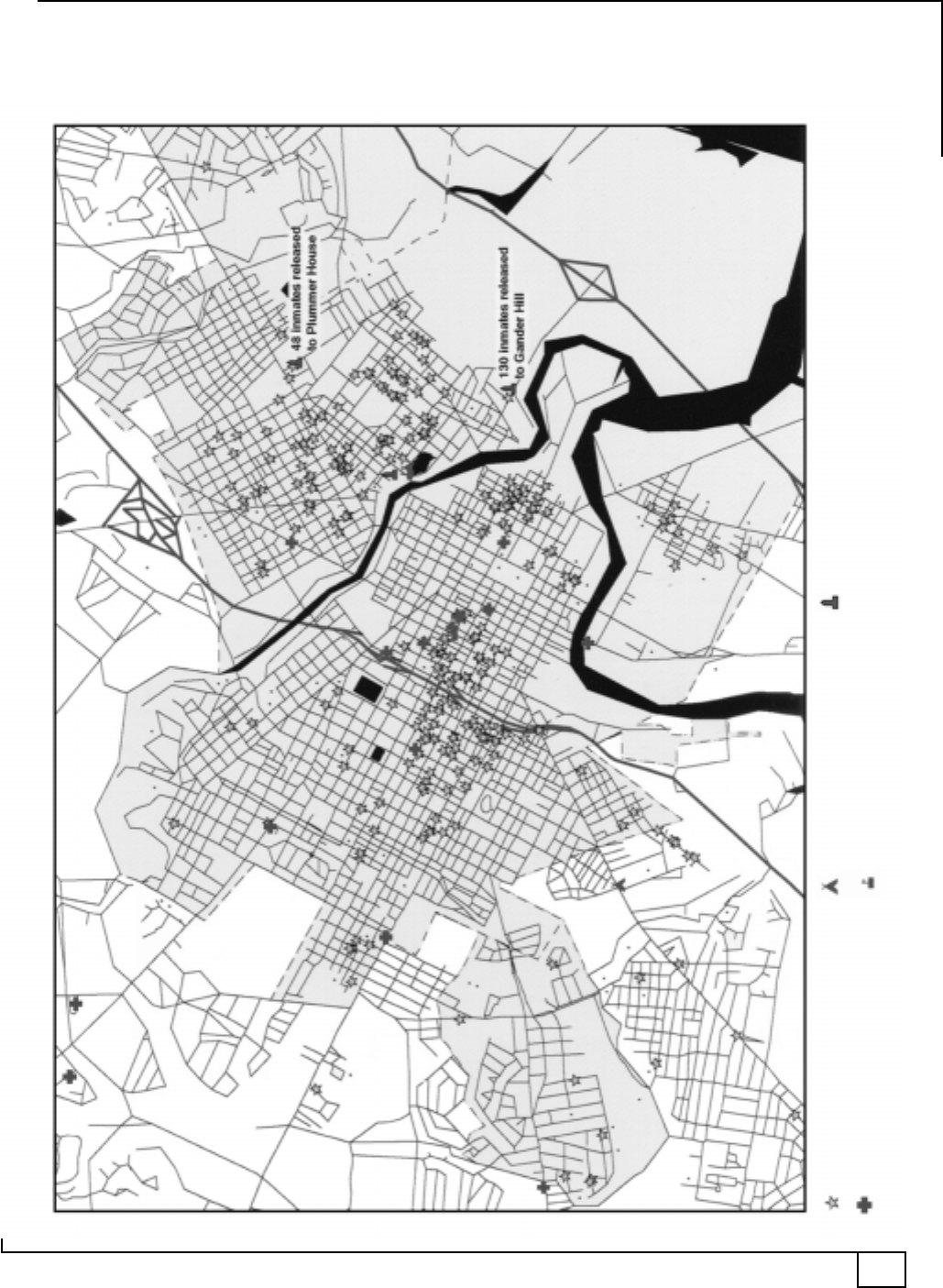

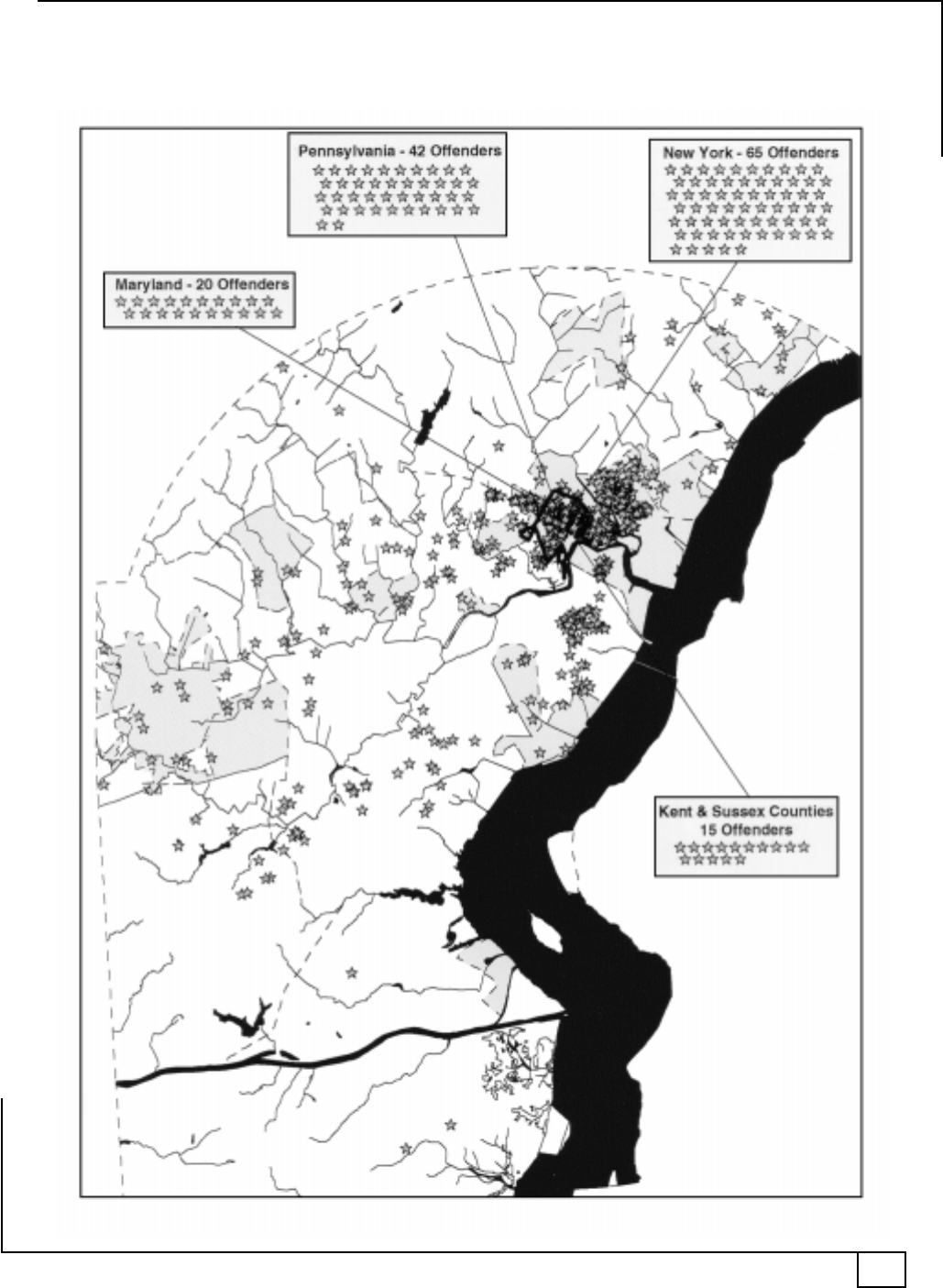

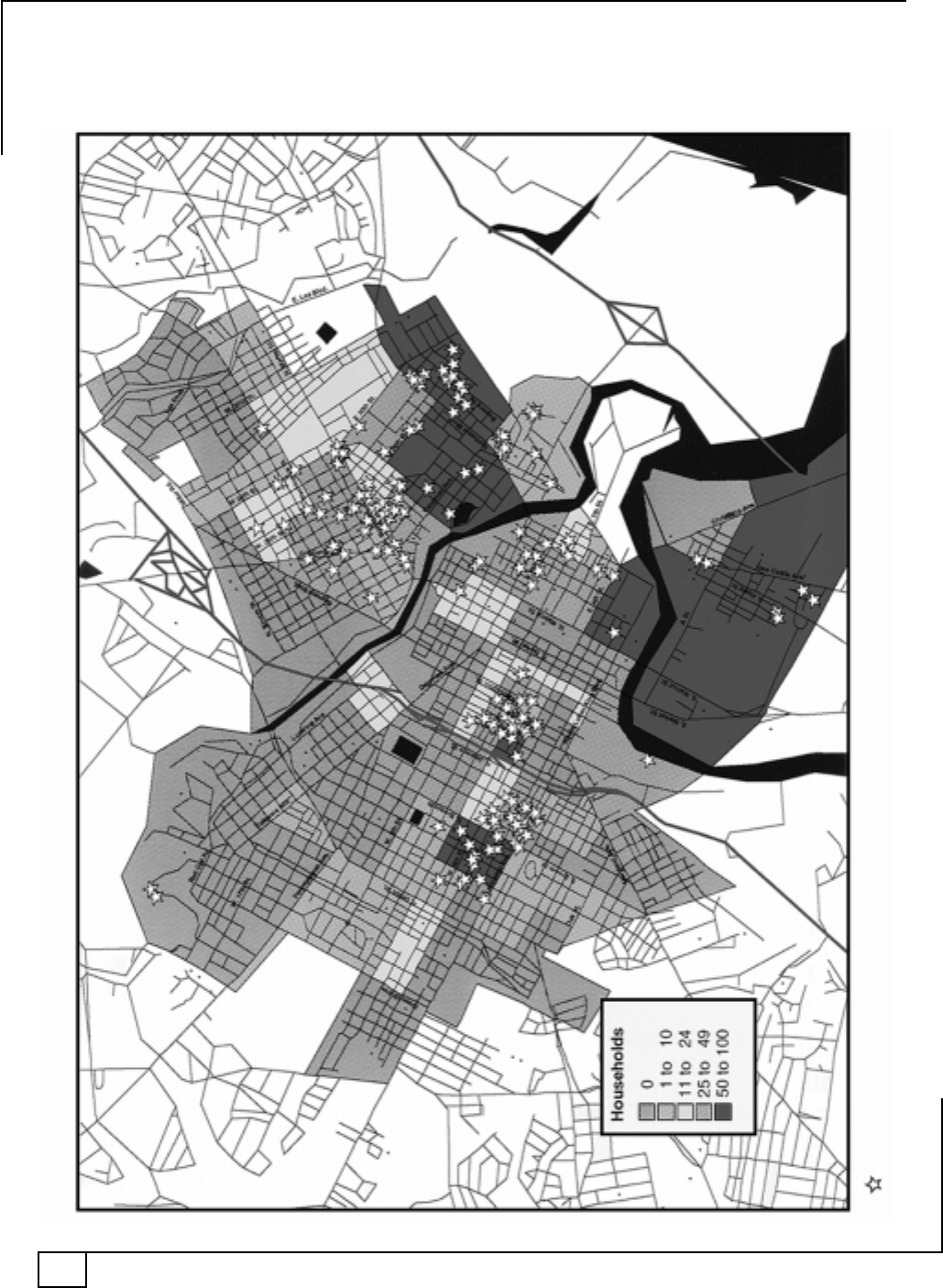

obvious treatment for anti-social behaviour. Educa-