Improving equity in

transportation fees,

fines, and fares

Findings and recommendations

for northeastern Illinois

April 2021

Contents

Overview .................................................................................................................................................... 2

Why fees, fines, and fares? .................................................................................................................... 10

Equity and mobility challenges in northeastern Illinois ................................................................ 12

Transportation funding challenges ..................................................................................................... 22

Roadways .................................................................................................................................................. 22

Transit ........................................................................................................................................................ 23

Distribution of the cost of public services and infrastructure ....................................................... 25

Equity of Illinois’ tax system .................................................................................................................. 25

Equity of transportation fees, fines, and fares ..................................................................................... 26

Consequences and outcomes of the impacts of fees, fines, and fares ............................................... 49

Existing fee and fare programs .............................................................................................................. 53

Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 55

Improve mobility options ....................................................................................................................... 56

Implement progressive tax strategies ................................................................................................... 57

Make transportation fees for households with low income more affordable ................................. 59

Ensure households with low income can access tools that provide lower costs ............................ 62

Pilot initiatives that coordinate fee and fare collection ....................................................................... 63

Make paying for parking more feasible for both residents and delivery drivers ........................... 65

Implement traffic and parking violation fine reform.......................................................................... 66

Next steps.................................................................................................................................................. 71

Methodology ............................................................................................................................................ 73

Equity in transportation

Page 2 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Overview

Metropolitan Chicago’s transportation system is a literal route to opportunity for the region’s

residents, connecting them to jobs, education, and services. Unfortunately, these opportunities

are not evenly shared in northeastern Illinois. Persistent transportation inequities exist, many

disproportionately impacting mobility options in communities of color and people with

disabilities. These inequities range from the costs of fees and fines to access to efficient

commutes and the high cost of driving. Beyond individual benefits, improving mobility for

residents currently challenged by transportation inequities will help to promote inclusive

growth. This will require significant investments across modes to increase affordability for

residents with low income and connectivity in communities with limited transit, bicycle, and

pedestrian connections.

To begin addressing these issues, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP)

analyzed how residents pay for the transportation system and how the structure of

transportation fees, fines, and fares fits with the financial realities of many households with low

income. While they are just one piece of a household’s transportation costs and overall tax

burden, residents with low income would benefit from reforms that make transportation fees,

fines, and fares more affordable and the overall tax system less regressive. Northeastern Illinois

residents already have several ways they can lower the fees and fares they pay, such as by using

I-PASS accounts and Ventra cards. However, many residents are unable to access these tools,

particularly those without bank accounts.

Residents of northeastern Illinois must also navigate a multitude of public agencies to pay their

transportation fees, fines, and fares. Residents who fail to pay these costs incur late fees and

fines. Fines have a disproportionately high financial burden for households with low income

that can lead to late fees, high debt levels, and other negative impacts. Moreover, data on traffic

safety enforcement indicate that Black residents are more likely to receive citations, leading to

expensive fines.

However, decades of underfunding the transportation system — particularly the public transit

system — have impeded the region’s ability to achieve its mobility equity goals. To ensure the

system is maintained while providing necessary enhancements and expansions, ON TO 2050

recommends securing growing and stable revenue sources to fully fund the transportation

system. To achieve this, new and increased transportation user fees must be implemented so

that travelers pay according to the benefits they receive from system investments.

ON TO 2050 also recommends that new user fees be implemented carefully to avoid undue

burdens on residents with low income. Affordable and accessible mobility options play a key

role in creating pathways to opportunity for people of color and people with disabilities, who

disproportionately live in poverty.

Equity in transportation

Page 3 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

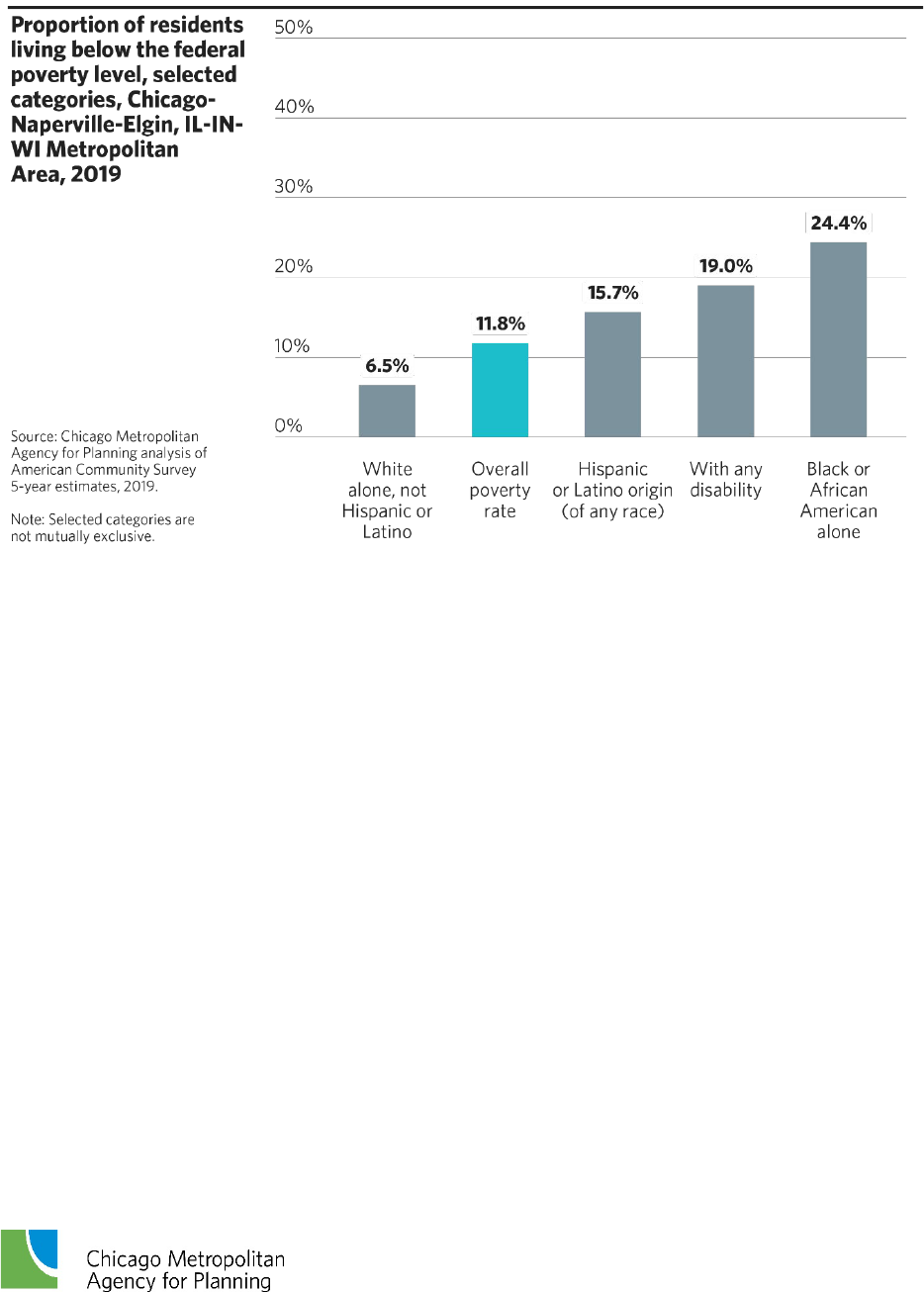

Residents with disabilities or who are Black or Latinx disproportionately live in poverty

For households with low income, it can be challenging to meet basic household expenses,

including transportation costs. The cost of vehicle ownership in particular is high, yet many

households with low income and residents of color lack access to transit options that connect

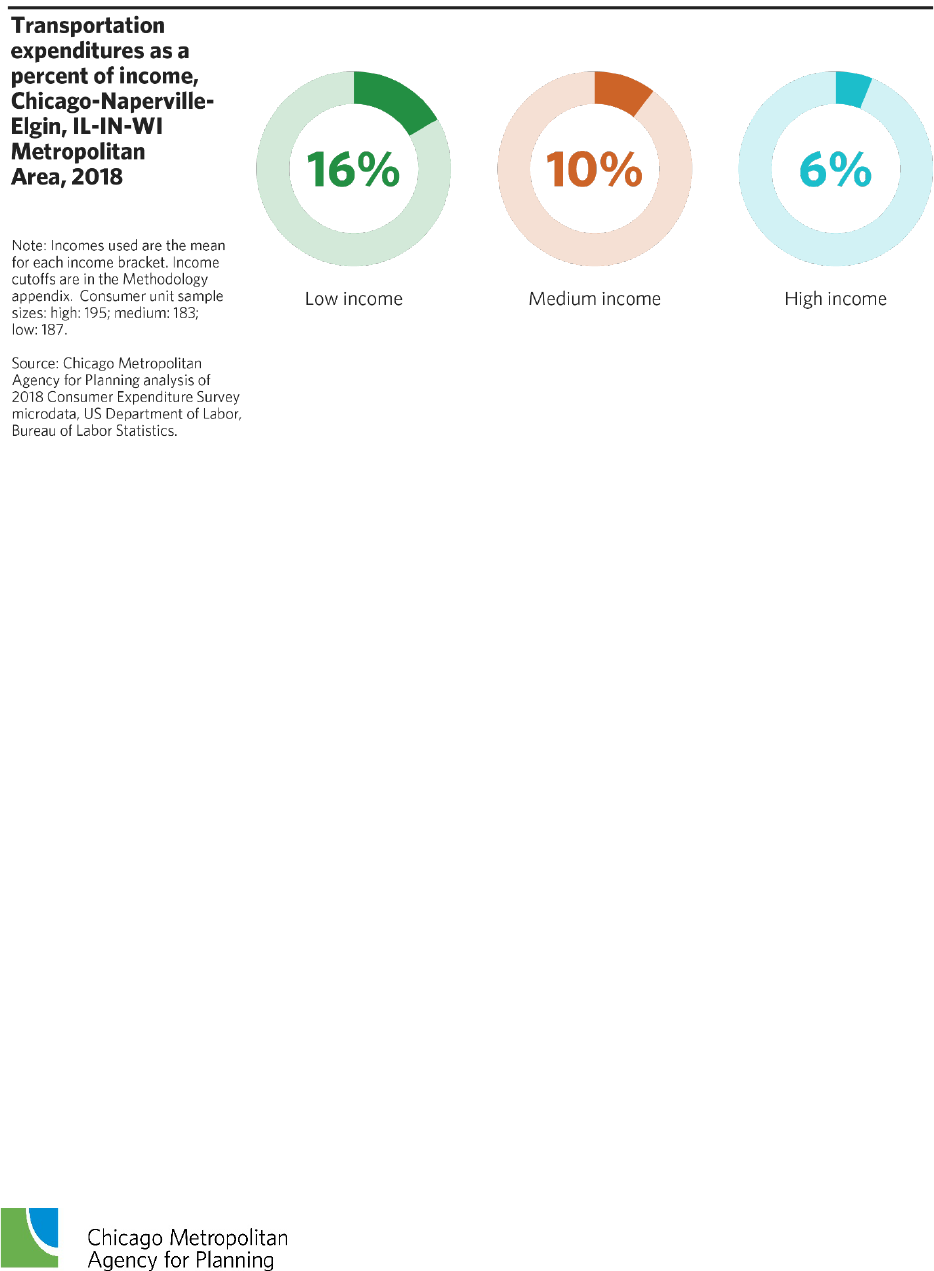

them to jobs within a reasonable travel time. Consumer expenditure data show that those with

low income spend 16 percent of their income on transportation costs, on average, while those

with high income spend just 6 percent.

Equity in transportation

Page 4 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Transportation costs are a larger percentage of income for residents with low income

Project development

To work toward the goal of aligning transportation revenue and equity objectives, CMAP

conducted its first comprehensive analysis on impacts of transportation fees, fines, and fares to

residents and households with low income. CMAP used quantitative data and qualitative

research to understand the challenges of balancing inclusive growth with the need for

transportation revenue.

This project sought to:

• Assess the impacts of fees, fines, and fares on residents in the region with low income

• Evaluate strategies to reduce the financial burden

• Understand the tradeoffs between affordability strategies and other goals and

objectives, including ensuring the transportation system generates sufficient revenue,

including from its users

• Recommend policy changes to reduce inequitable financial impacts experienced by

residents with low income

This report was developed with significant contributions from transportation agencies,

researchers, and advocates. In addition to interviewing many experts on these topics, CMAP

convened a group of partners and stakeholders from across the region to provide feedback on

the analysis and identify policy changes.

Equity in transportation

Page 5 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Assessing equity

Transportation user fees, fines, and transit fares are part of the tax system as a whole, where

every broad-based fee, fine, or fare imposed without regard to income level has the potential to

be regressive. When these fees, fines, and fares disproportionately impact residents with low

income, residents of color may also be disproportionately affected. The following findings

summarize CMAP’s assessment of the affordability of several transportation fees, fines, and

fares and the impacts on residents and households in northeastern Illinois with low income.

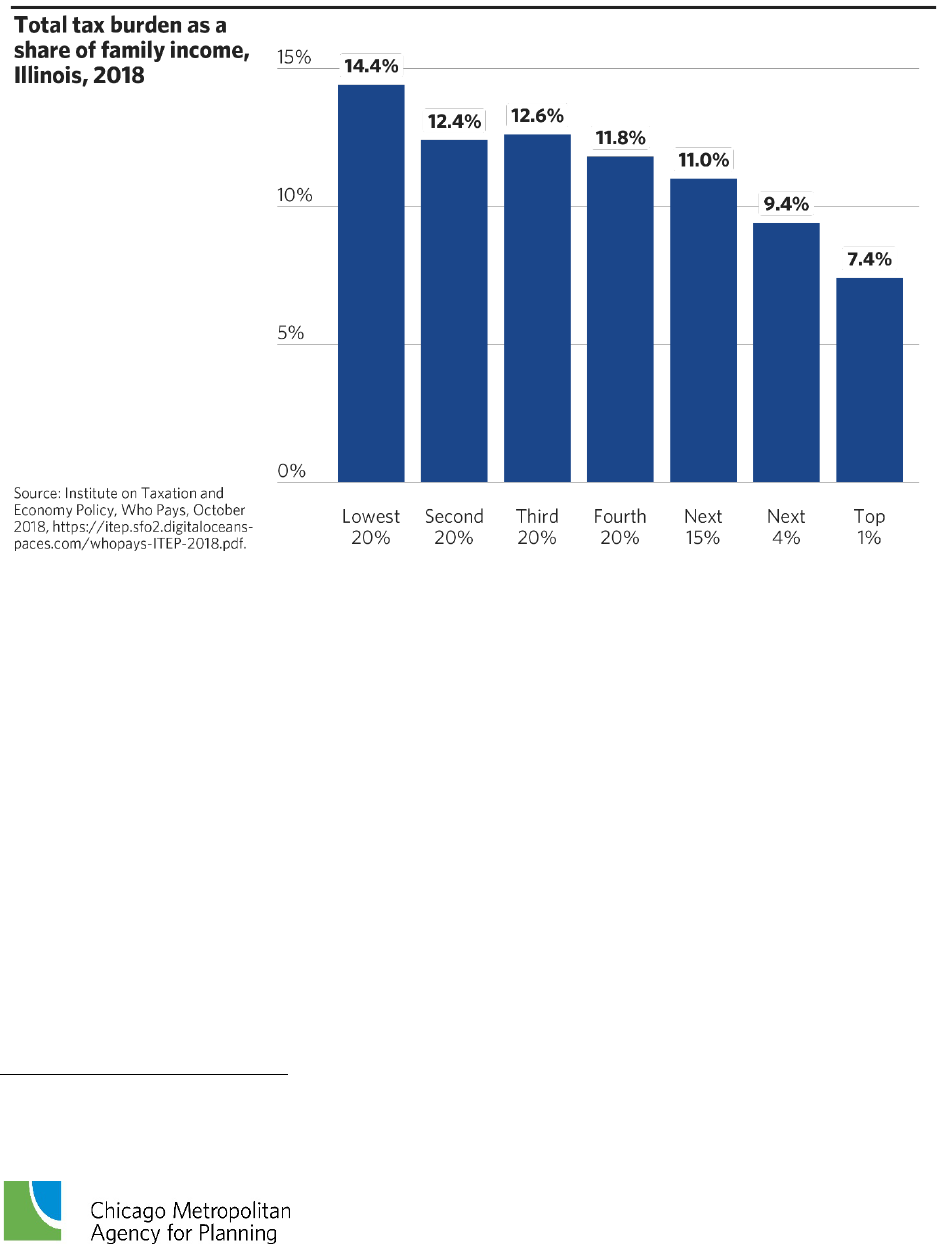

Illinois’ tax system is regressive. Illinois’ overall tax system is regressive, owing to a flat

income tax rate and comparatively low tax exemptions. The 20 percent of non-elderly residents

with the lowest incomes paid 14.4 percent of their income in taxes while the top 1 percent of

taxpayers paid 7.4 percent. States with less regressive structures integrate several features in

their income tax structure to mitigate the impacts of regressive sales and excise taxes like

transportation user fees.

The cost of driving is a burden for households with low income. Driving is the most

expensive mode of travel. This is due to the numerous costs of owning and operating a vehicle,

rather than any associated fees, such as motor fuel taxes or tolls. The larger issue is that

households with low income often lack the money to cover basic household expenses, so any

sort of transportation fee is unaffordable. Depending on where they live, households with low

income may also lack mobility options beyond driving.

Households with low income pay proportionately less in fees associated with driving. The

burden of the state motor fuel tax is borne less by households with low income since they tend

to drive fewer miles. Likewise, households with low income tend to own fewer vehicles, thus

spend less on vehicle registration fees. Tolls are also not a substantial share of transportation

expenses for people with low income.

Equity in transportation

Page 6 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Households with low income have fewer vehicles and drive fewer miles than other households

Some drivers experience challenges accessing lower toll options. The tolling system currently

in place presents challenges to residents without bank accounts. Drivers with an I-PASS can pay

tolls at a lower rate, but many households with low income do not have one, particularly

unbanked drivers.

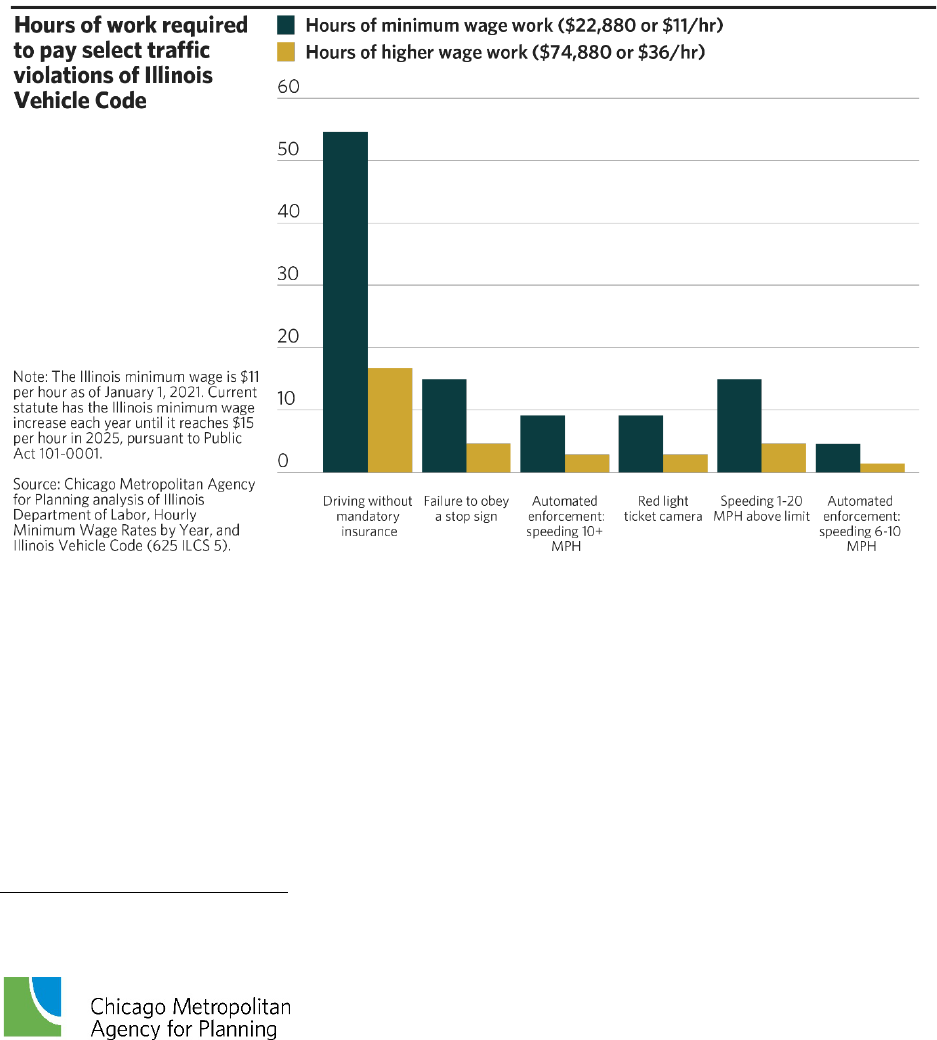

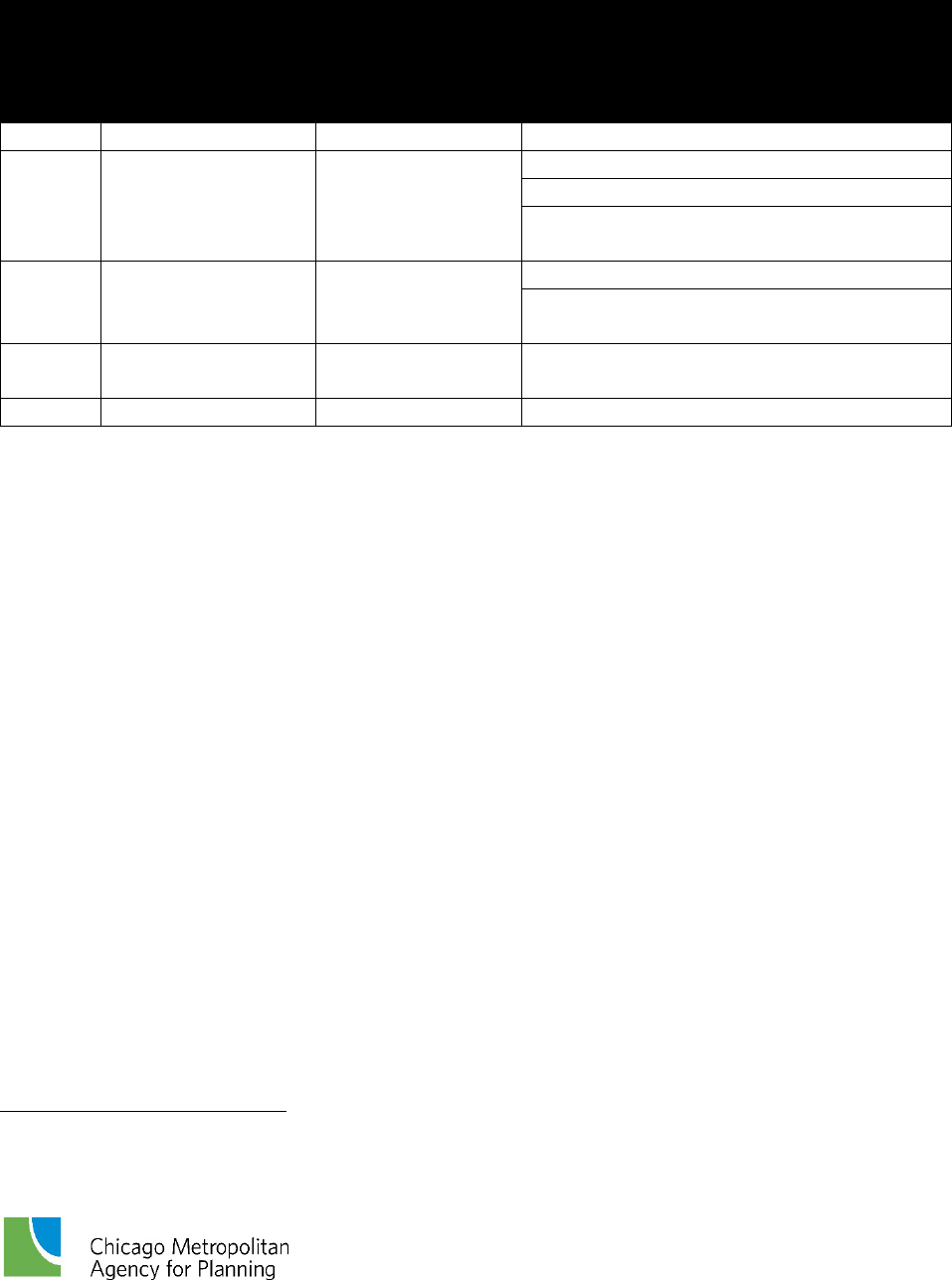

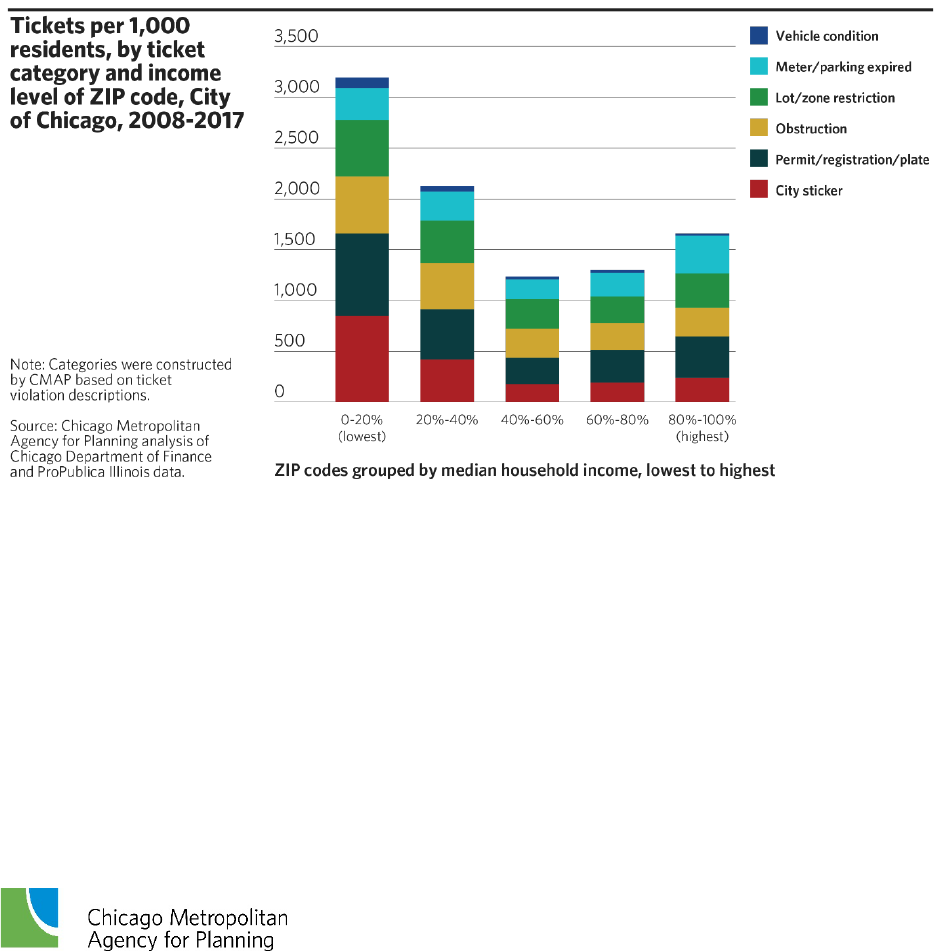

Unpaid fines can be financially devastating. Households with lower income pay a

substantially larger share of weekly wages on a fine than households with higher income.

These fines can compound to become a major source of debt for residents with low income.

When residents with low income cannot pay their fines, they may experience bankruptcy, tax

garnishment, vehicles impoundment, employment prohibition, and credit score damage.

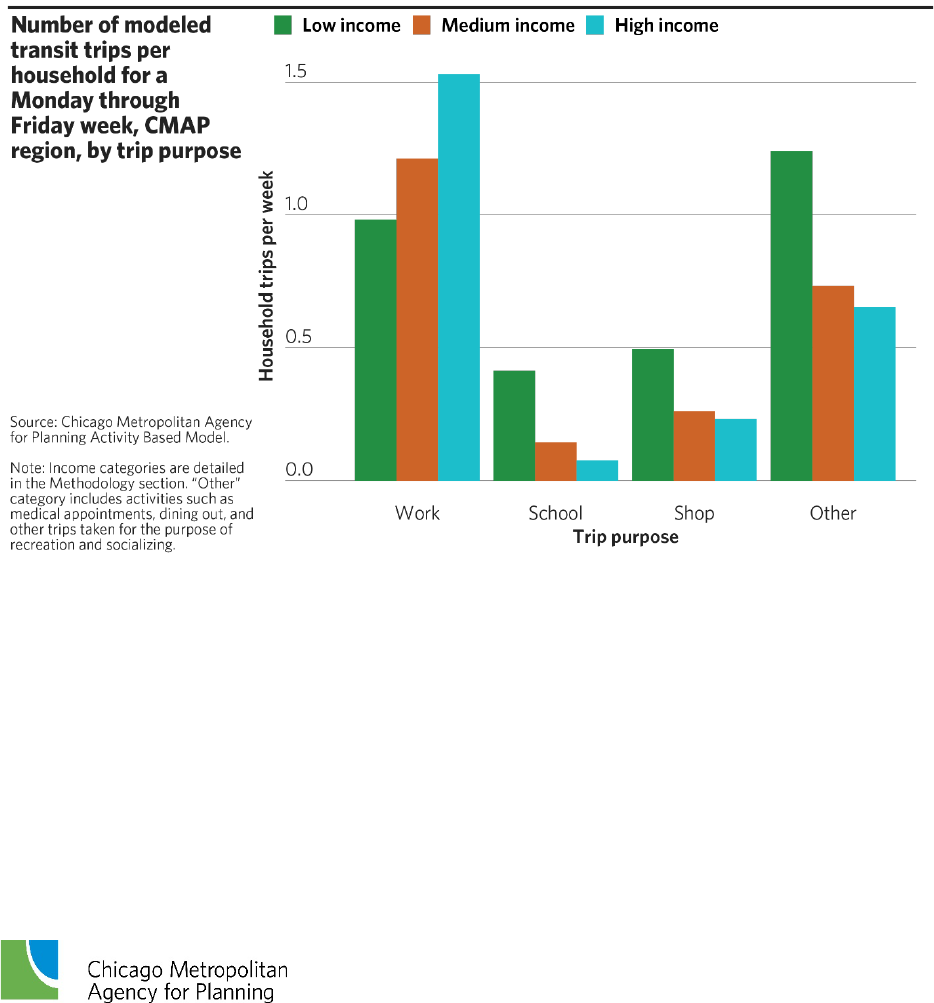

Maintaining affordable fares is necessary so that residents may access economic

opportunities and conduct everyday activities. Residents of all income levels rely on transit.

But transit access is especially crucial for residents with low income, as they tend to own fewer

vehicles because of the high cost of driving. Households with low income take 20 percent more

transit trips than other households. When work commutes are excluded, these households take

twice as many trips — indicating that they are more likely to use transit for trips required to live

their daily lives. The cost of a fare varies by many factors, some of which can result in transit

expenses comprising a relatively high share of earnings for a household with low income.

CMAP estimates that expanding reduced fares to all residents with low income would result in

them taking 15 percent more transit trips.

Equity in transportation

Page 7 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Recommendations

Improving mobility for residents with low income will require significant investments in

transit, bicycle, and pedestrian infrastructure, funding to administer programs, and revenues to

recoup losses from reducing fees or fares. CMAP and the resource group considered a variety of

strategies to determine which recommendations would best meet the goals of reducing impacts

on residents with low income, as well as other ON TO 2050 goals. Based on these considerations

and the priorities of the resource group, recommendations are as follows:

• Improve mobility options

• Implement progressive tax strategies

• Make transportation fees more affordable for households with low income

o Expand reduced fare permits

o Expand reduced vehicle registration fees

o Vary state and local vehicle registration fees based on vehicle value

o Ensure any new transportation network company fees support regional

transit goals

• Ensure households with low income can access tools that provide lower costs

o Encourage employers to participate in the Transit Benefit Fare Program

o Bolster efforts that help riders use Ventra

o Develop a lower-cost alternative to I-PASS transponders

o Waive any road usage charge equipment cost

• Pilot initiatives that coordinate fee and fare collection

o Increase availability of I-PASS accounts, including to unbanked households

o Allow local vehicle fees to be paid at the Illinois Secretary of State

o Implement full fare integration across service providers

• Make paying for parking more feasible for both residents and delivery drivers

o Designate short-term loading and standing spaces with reduced transaction

fees

o Ensure multiple payment options for drivers without credit cards

• Implement traffic and parking violation fine reform

o Integrate ability to pay through income-based fines or ability to pay waivers

o Assess appropriateness of fine and late fee amounts

o Report ticketing outcomes and impacts with an equity lens

o Offer alternatives to monetary fines

o Improve repayment plans and collection practices

o End employment prohibitions due to ticket debt

Equity in transportation

Page 8 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Agenda for implementation

In recent years, the State of Illinois and the region have made notable progress on improving

equity in fees and fines. The Illinois Tollway substantially reduced fees for missed tolls in 2020

as part of an initiative to first issue invoices rather than violation notices for unpaid tolls. The

Tollway plans to also expand its I-PASS Assist program in 2021 to additional drivers with low

income as part of its plan to stop accepting cash tolls. The recently enacted Public Act 101-0652

includes provisions rescinding holds on license renewal or reinstatement due to failure to pay

traffic violation fines and suspensions due to failure to pay fines from automated speed and red

light cameras.

CMAP and other regional partners will work to implement these recommendations through

legislation, policy changes, new initiatives, and other reforms. These recommendations require

action and investments by policymakers and transportation agencies like the State of Illinois,

the Tollway, the region’s transit agencies, and local governments. Further, CMAP must

continue to conduct further analysis to pursue policies that ensure the transportation system

promotes equitable outcomes for all residents.

Equity in transportation

Page 9 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Equity in transportation

Page 10 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Why fees, fines, and fares?

Metropolitan Chicago’s transportation system, particularly the public transit system, has

experienced decades of underfunding. To ensure the system is maintained while providing

necessary enhancements and expansions, ON TO 2050, the region’s long-range comprehensive

plan, recommends fully funding the region’s transportation system. ON TO 2050 also

recommends that new user fees be implemented carefully to avoid undue burdens on residents

with low income. The funding decisions that policymakers and transportation agencies make

greatly impact residents’ ability to access the system.

A person’s socioeconomic status, race, or ability should not result in disparate mobility options.

Yet many of the region’s residents who are low income and people of color live in communities

where transit connections from home to work are limited. When people have access to a

multimodal transportation system that connects them to their destinations, it increases

opportunities and improves quality of life. ON TO 2050 seeks to promote inclusive growth by

improving mobility options that spur economic opportunity for low-income communities,

people of color, and people with disabilities.

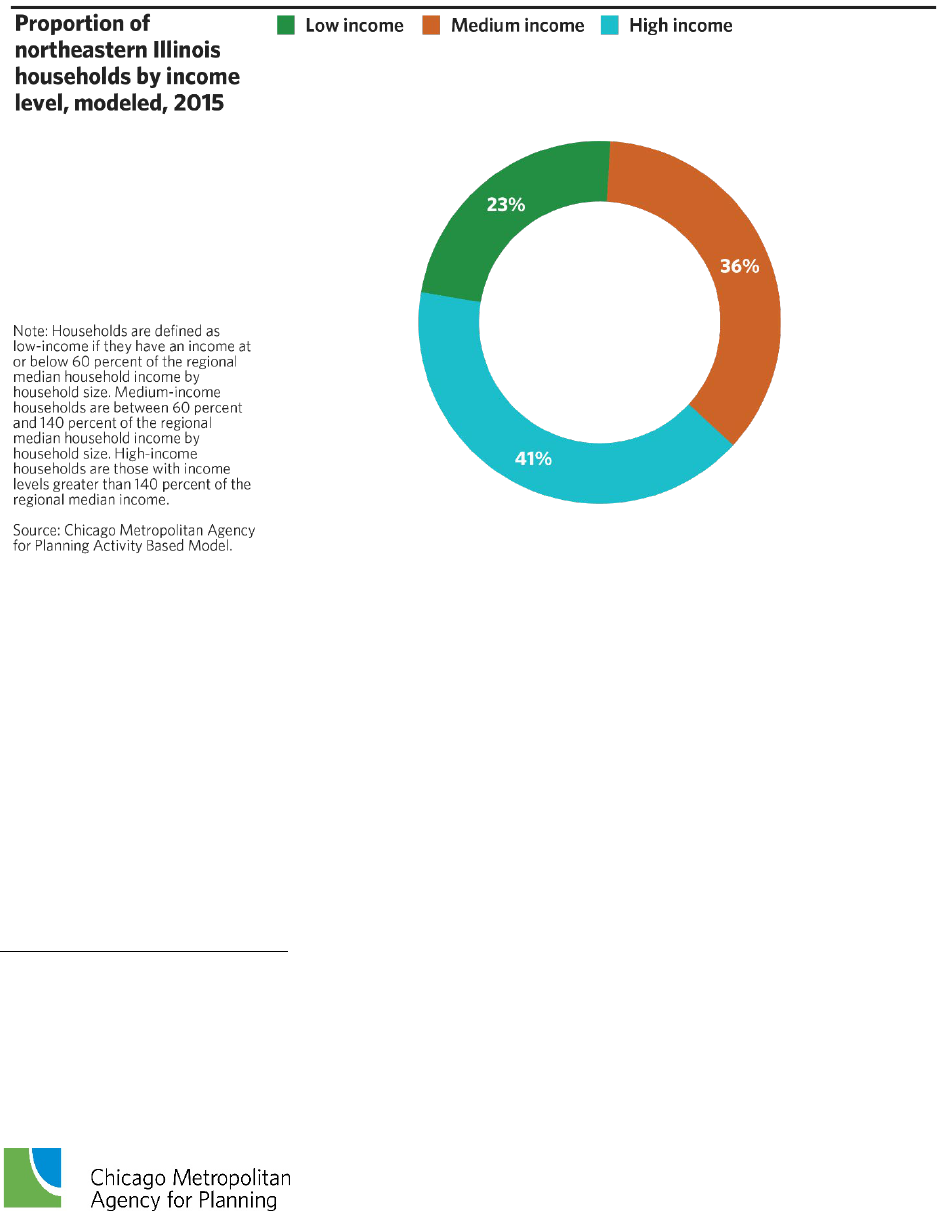

Within northeastern Illinois, CMAP estimates that 22 percent of households have an income less

than 60 percent of the region’s median level.

1

These households are disproportionately

comprised of Black and Latinx residents. Residents with disabilities also disproportionately

have low income and are less likely to drive alone for commuting to work than residents

without disabilities, presenting unique transportation challenges.

2

ON TO 2050 recommends that revenues be collected as direct user fees from those who benefit

from the transportation system. While this helps improve horizontal equity — treating system

users similarly in terms of the costs they pay and benefits they receive — it may not support

vertical equity. Vertical equity refers to the distribution of financial burdens based on a person’s

ability to pay. Horizontal and vertical equity goals can conflict. For example, horizontal equity

requires that a driver with low income pay the same toll as every other driver who benefits

from using a toll road, but vertical equity requires that they pay less than a driver with higher

income. Most transportation user fees have been structured with horizontal equity in mind. But

it is important to make sure that vertical equity and issues of affordability are considered so

they do not unduly impede mobility.

Scope: researching questions and topics

This report seeks to explore equity in transportation fees, fines, and fares; specifically:

• Assess the impacts of fees, fines, and fares on residents in the region with low income

• Evaluate strategies to reduce the financial burden

1

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning analysis of Activity-Based Model results.

2

American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2019.

Equity in transportation

Page 11 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

• Understand the tradeoffs between affordability strategies and other goals and

objectives, including horizontal equity and revenue generation

• Recommend policy changes to reduce the inequitable financial impact experienced by

residents with low income

To undertake this work, CMAP began a process to qualitatively and quantitatively assess the

impacts of several transportation fees, fines, and fares; namely:

• Fees and fines associated with motor vehicle usage:

o Motor fuel tax

o Road usage charges (ON TO

2050 recommendation)

o Motor vehicle registration fees

• Fares on fixed-route public transit

o Priced parking

o Tolling

o Traffic and parking violation fines

o Transportation network company fees

Process: convening partners and stakeholders

This report was developed with significant contributions from transportation agencies,

researchers, and advocates. In addition to interviewing many experts on these topics, CMAP

convened a group of partners and stakeholders from across the region to help provide feedback

on the project. This group met several times between November 2019 and December 2020.

During these meetings, the members discussed and provided feedback on the project’s

objectives and scope; analysis and assessment of the equity of each fee, fine, and fare; evaluation

of strategies to improve vertical equity; recommendations; and priorities for implementation.

The group also discussed gaps in the region’s work on planning-related equity issues, which

CMAP and partners will use to guide future work. The group included representatives from:

• Active Transportation Alliance

• Center for Neighborhood Technology

• City of Chicago, Department of

Transportation

• City of Chicago, Office of Equity and

Racial Justice

• Chicago Jobs Council

• Chicago Transit Authority

• Cook County

• Equiticity

• Equity Institute, YWCA of Evanston

• Heartland Alliance

• Illinois Tollway

• Little Village Environmental Justice

Organization

• Metra

• Metropolitan Planning Council

• Muse Community Design

• Pace

• Regional Transportation Authority

• Union of Concerned Scientists

• University of Chicago Inclusive Economy

Lab

• University of Illinois at Chicago

Equity in transportation

Page 12 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Equity and mobility challenges in

northeastern Illinois

Access to mobility options plays a key role in creating pathways to opportunity for low-income

communities, people of color, and people with disabilities. Yet, persistent transportation

inequities exist in metropolitan Chicago. Historically, policymakers and planners have been

complicit in reinforcing inequities for residents with low income and people of color, especially

Black people. Racism and inequitable distribution of resources have shaped the built

environment through housing policy, zoning codes, transportation planning, urban renewal,

and pollution-generating facilities and roadways.

These inequities have caused mobility challenges. Many residents with low income and

residents of color have limited transportation options that would efficiently connect them to

economic and other opportunities. Transportation costs are rising, increasing the financial

burden on all residents, particularly residents with low and moderate incomes. At the same

time, residents nationwide with low income have experienced slow income growth. Between

2000 and 2018, they saw just 1.8 percent growth in median income, while upper income

households experienced 7.9 percent growth.

3

Black and Latinx residents are especially impacted

by this trend because they are a disproportionate part of the overall population that is low

income. This section will provide an overview of the equity context under which transportation

fees, fines, and fares operate.

Households with low income struggle to pay for basic household needs

Households with low income must use their limited financial resources to meet basic needs.

These expenses include housing, transportation, and food, as well as expenses necessary to

maintain employment like commuting costs and child care. However, national data from the

Federal Reserve indicate that 17 percent of adults were not able to pay their bills in full.

4

These

financial realities mean that even if transportation fees, fines, and fares are a relatively small

part of household expenses, they remain a noticeable daily expense. As a result, they may cause

some residents undue hardship, leading to less efficient mobility decisions, such as additional

driving to avoid paying for parking or tolls, or taking all transit trips in a single day.

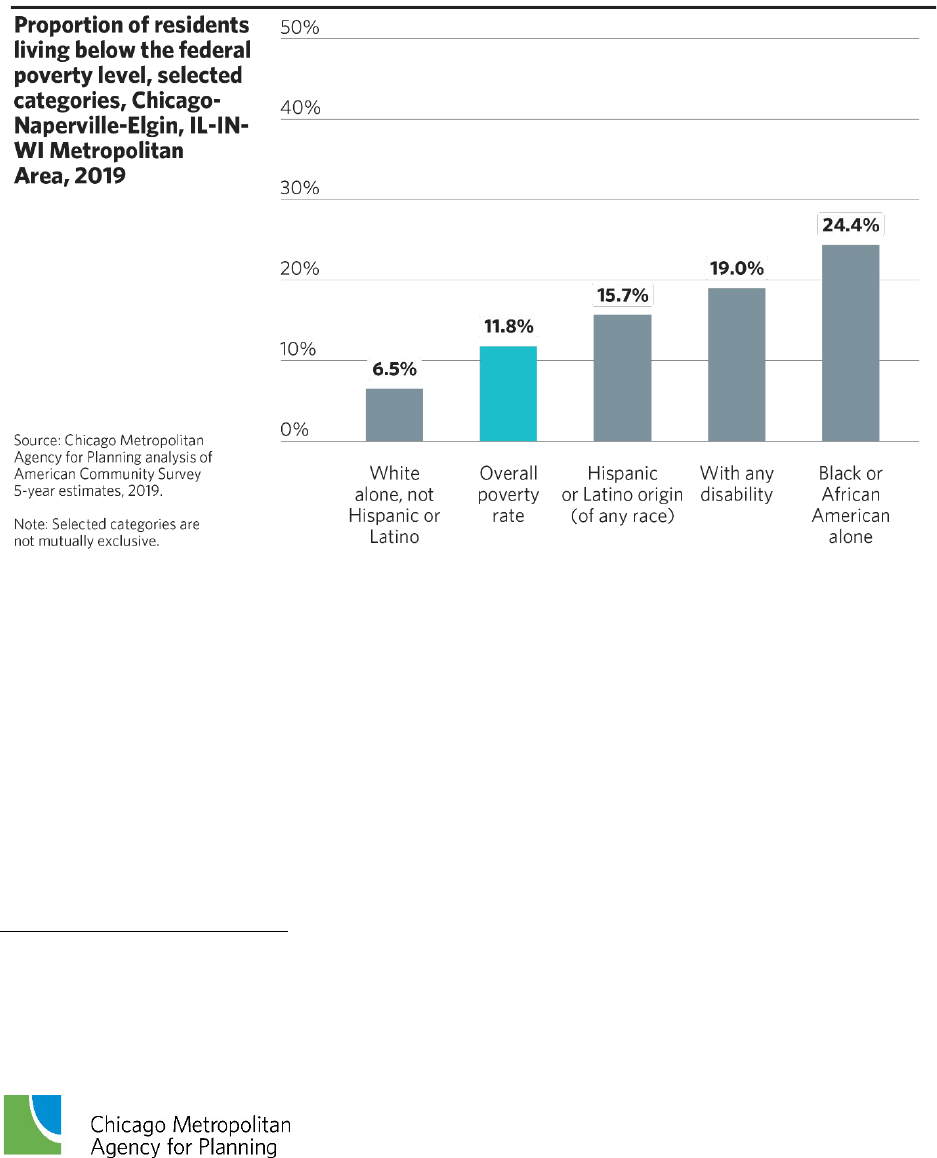

In metropolitan Chicago, 11.8 percent of residents live below the federal poverty level, which is

$25,926 for a household with two adults and two children. Across the larger 15-county

metropolitan area, this equates to 1.1 million residents. Among residents with disabilities, 19

percent live below the federal poverty level, representing a disproportionate share of residents

in the metropolitan area.

3

Pew Research Center, Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call It

a Top Priority, January 9, 2020, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/01/09/trends-in-income-and-wealth-inequality.

4

Federal Reserve Board's Division of Consumer and Community Affairs, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S.

Households in 2018, May 2019, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-economic-well-being-of-us-

households-in-2018-preface.htm

Equity in transportation

Page 13 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 1 illustrates the differences in poverty rates across several categories, showing that the

poverty rate of Black residents is nearly four times that of white residents, while the poverty

rates of residents of Hispanic or Latinx origin of any race are greater than the overall rate.

5

Figure 1.

Finding: Black residents, Hispanic residents, and residents with disabilities are a

disproportionate share of those living in poverty

People of color also disproportionately live in the region’s disinvested communities and

economically disconnected areas.

6

These communities have seen decades of declining

employment, population, and public and private investment, leading to the erosion of tax bases

and public services. Residents of these communities are often denied access to economic

opportunity, resulting in many households having severe financial constraints.

This report will focus on reducing inequity for households with low income, defined by 60

percent of the median household income for the Chicago metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in

2018 (see Methodology). A primary goal is to ensure fees, fines, and fares are not a barrier to

mobility for households with low income, who are disproportionately people of color.

5

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2019. Data are for the Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI

metropolitan area. Population that is Hispanic or Latino includes people of any race.

6

See ON TO 2050 Local Strategy Maps of Economically Disconnected and Disinvested Areas,

https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/2050/maps/eda.

Equity in transportation

Page 14 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

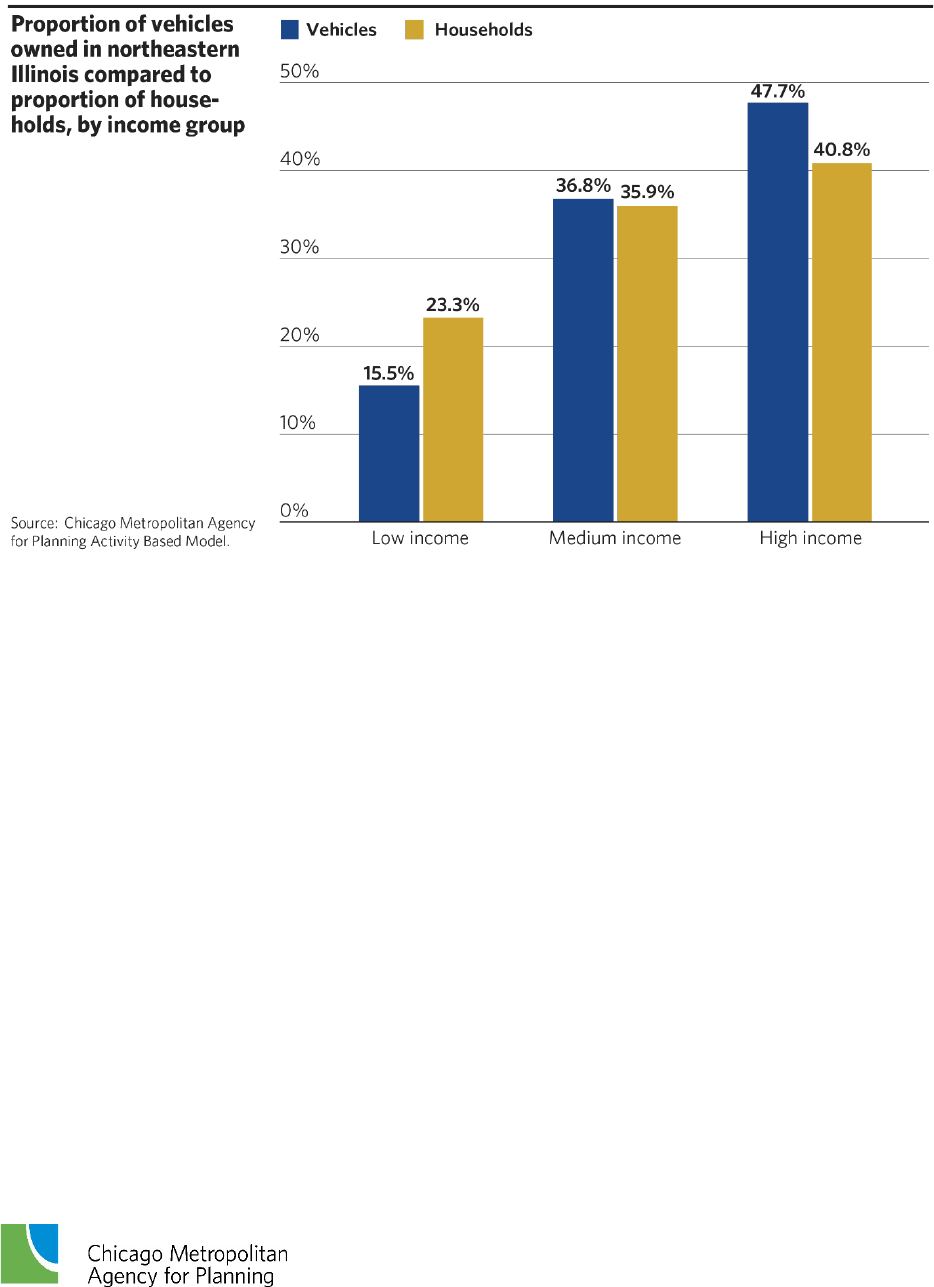

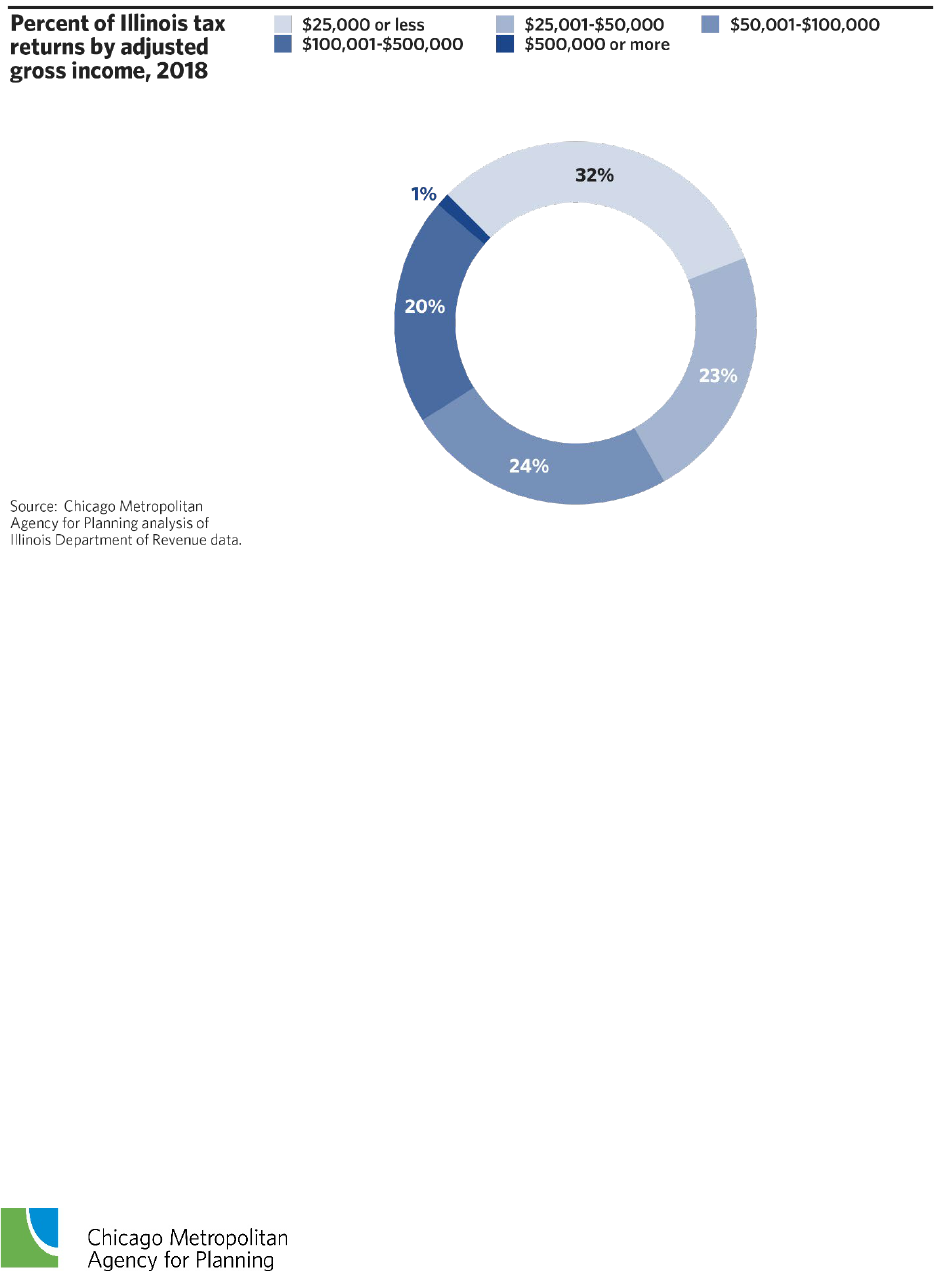

Figure 2 provides an overview of households in each income category used in this report.

Figure 2.

Finding: Among households in northeastern Illinois, 23 percent met CMAP’s definition of low

income

Cost of driving is unaffordable for many households with low income

Consumer expenditure data show that those with low income spend a substantial part of their

incomes on transportation.

7

Figure 3 illustrates the average proportion of income spent on

transportation costs, including driving and public transit.

7

CMAP analysis of U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics 2018 Consumer Expenditure Survey Public-

Use Microdata. In the Consumer Expenditure Survey, a consumer unit consists of all members of a particular

household who are related by blood, marriage, adoption, or other legal arrangements; a person living alone or

sharing a household with others or living as a roomer in a private home or lodging house or in permanent living

quarters in a hotel or motel, but who is financially independent; or two or more persons living together who use their

incomes to make joint expenditure decisions.

Equity in transportation

Page 15 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 3.

Finding: Residents with low income spend 16 percent of their income on transportation costs

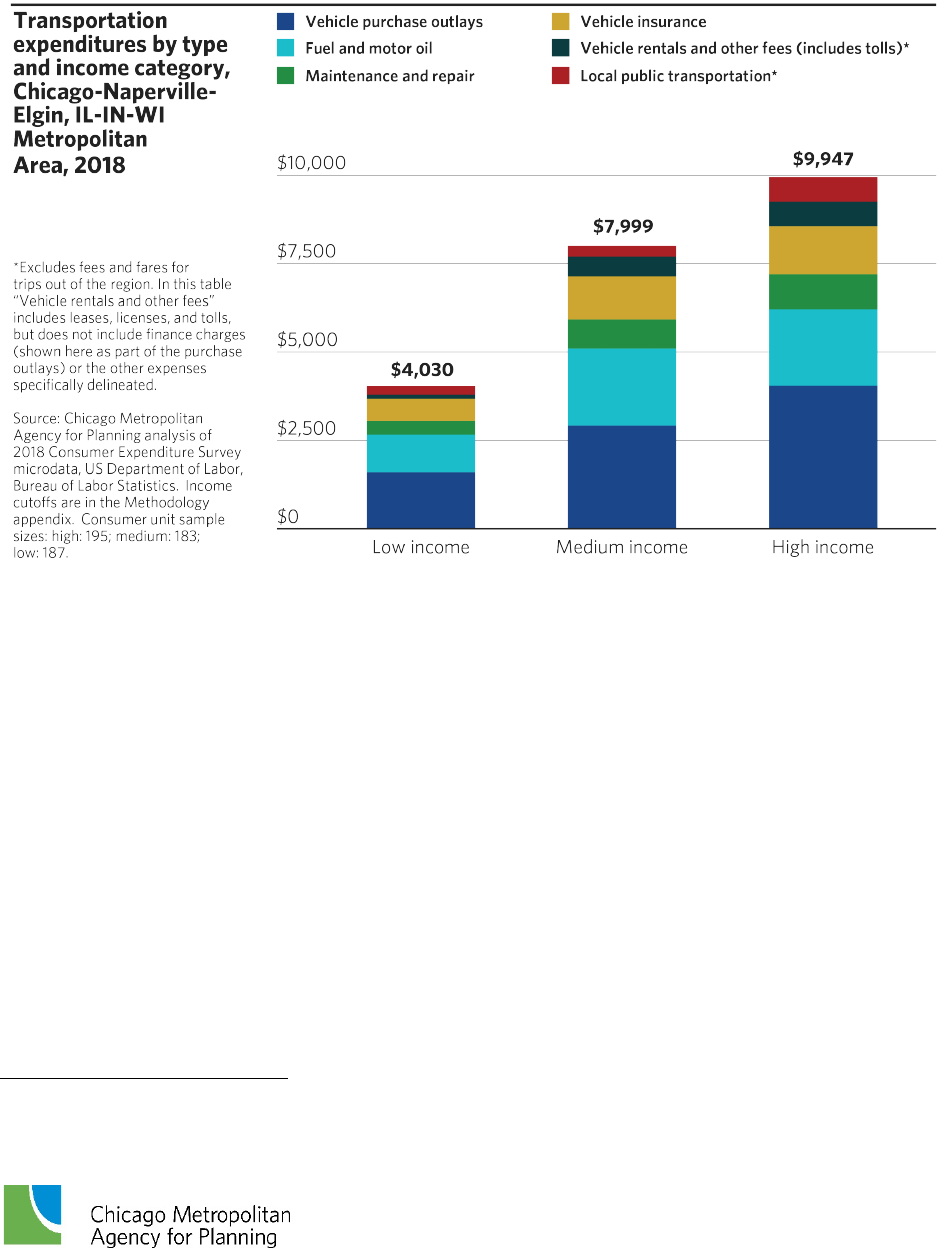

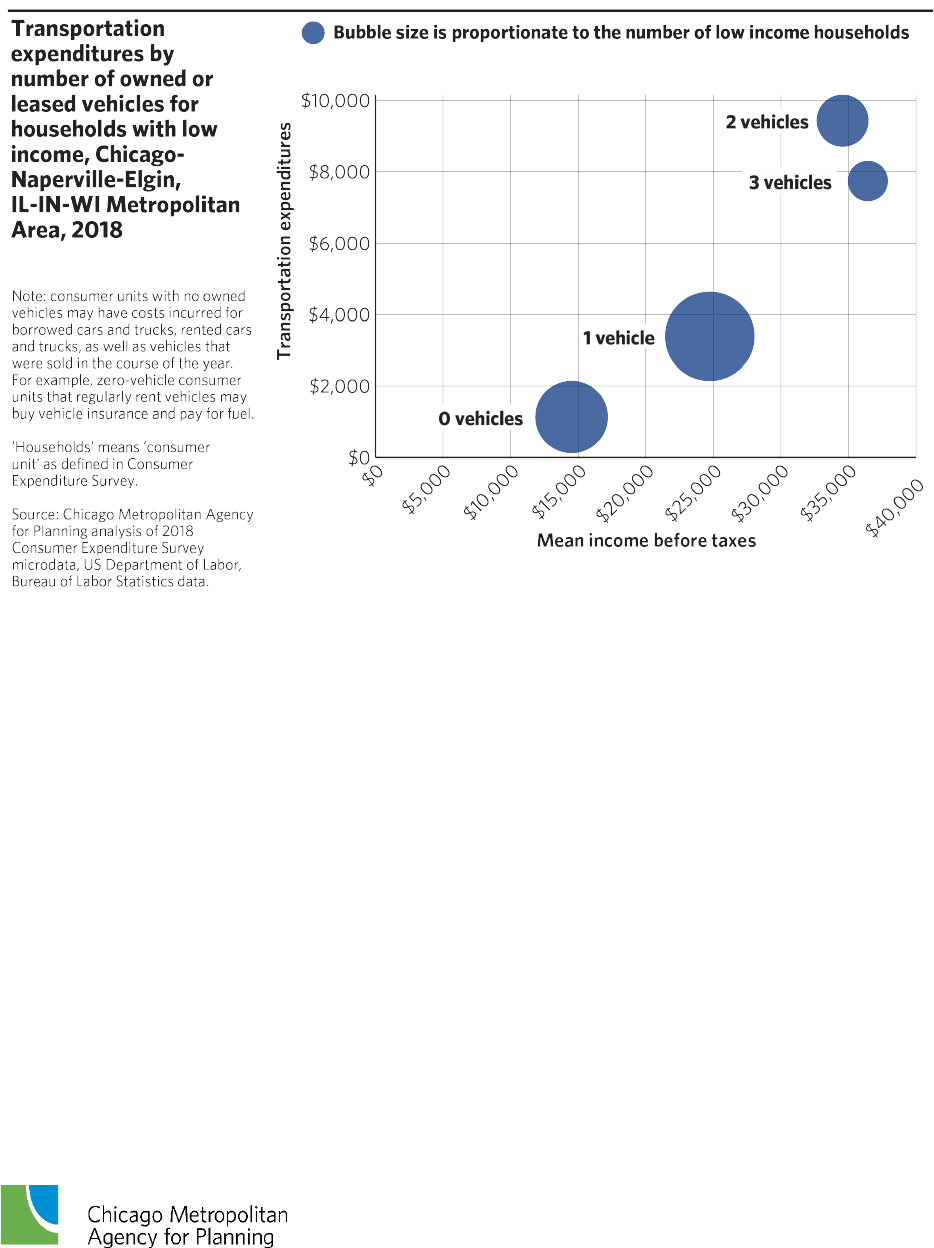

Figure 4 illustrates the ways that vehicle ownership drives expenditures on vehicle purchases,

fuel and oil, and other vehicle expenses (insurance, financing, maintenance, and other vehicle

charges). The Chicago MSA, with its substantial public transportation assets, has lower

transportation expenditures than the United States as a whole, owing partly to lower vehicle

ownership. Primarily, affordability challenges experienced by households with low income are

driven by the numerous costs of owning and operating a personal vehicle, rather than the

associated fees, fines, and fares. The larger issue is that households with low incomes often lack

the income to cover typical base household expenses, so any sort of transportation fee is

unaffordable.

Equity in transportation

Page 16 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 4.

Finding: The costs of owning a vehicle, rather than fees, fines, and fares, account for most

transportation expenditures across income groups

Households with low income spend a substantial proportion of their income on transportation

when they own a vehicle. Households in the low-income group owned an average of one

vehicle, while households in the other income groups owned an average of nearly two vehicles.

However, vehicle ownership rates vary within income groups. Nationally, the Center for

Neighborhood Technology found that Black and Latinx residents living in households with no

vehicles were more likely to be in poverty than white households with no vehicles.

8

Within the

Chicago MSA, Figure 5 illustrates that households with more vehicles have higher incomes on

average, even within the low-income category.

8

Center for Neighborhood Technology, Equity and Smart Mobility, 2019,

https://www.cnt.org/sites/default/files/publications/Equity-and-Smart-Mobility-Report.pdf.

Equity in transportation

Page 17 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 5.

Finding: Even among households with low income, those with more income own more vehicles,

driving higher expenses on transportation

Vehicle owners also incur costs in the form of time spent on paying fees and other related

activities. Drivers need to interact with a variety of facilities to acquire and renew state vehicle

registrations, get state emissions testing annually if their vehicle is more than four years old,

acquire and renew local vehicle licenses, and obtain an I-PASS account, all in addition to regular

vehicle maintenance and motor fuel.

Mobility impacts access to opportunity for residents in economically

disconnected communities

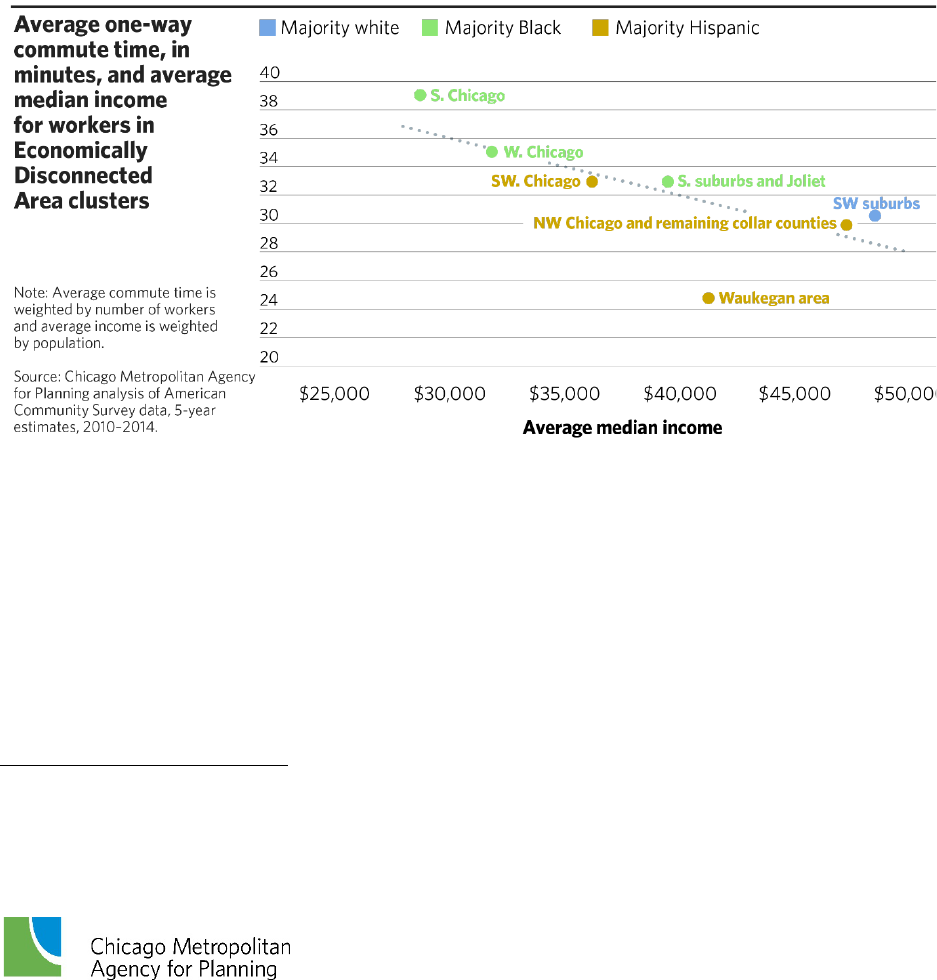

Daily commutes are longer for many residents with low income and residents of color,

especially Black commuters. These lengthier commutes hinder residents’ ability to connect to

available and attainable employment opportunities and reduce overall productivity and quality

of life. Likewise, many residents with disabilities lack sufficient access to mobility options to

commute to work and conduct their daily lives.

This is particularly true for residents living in economically disconnected areas (EDAs) — parts

of the region with concentrated low incomes, limited English proficiency residents, and/or non-

white residents — where access to transit options does not always ensure access to jobs within a

Equity in transportation

Page 18 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

reasonable travel time. Many of these residents must commute to jobs located far from frequent

transit service. In part, this is driven by planning and land use decisions that have not

prioritized affordable housing or commercial and industrial development in infill locations with

transit access. At the same time, these same residents tend to have limited employment

opportunities within their own communities. Differences in commutes depend on what part of

the region a worker lives in, with the longest commutes found for residents of the west and

south sides of Chicago as well as parts of the south suburbs, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Additional time spent driving increases transportation costs, including potentially making a

driver more likely to incur fines.

Figure 6.

Finding: Communities with lower income levels have longer average commutes, even among

economically disconnected communities

In 2017, just 55 percent of residents in metropolitan Chicago lived in areas with at least

moderately high transit availability, while just 53 percent of jobs were accessible via at least

moderately high transit availability.

9

Limited connectivity in the transit network is common in

many of the region’s more rural areas, often making it necessary to own a vehicle. As of 2015,

just 41.5 percent of the region’s population and 38.2 percent of the region’s jobs were located in

areas with “high” or “very high” walkability.

9

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, ON TO 2050, Population and Jobs with at Least Moderately High

Transit Availability, https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/2050/indicators/population-jobs-transit-availability. This is based

on a CMAP-created index that considers multiple factors: proximity to transit stops, frequency of service,

destinations reachable without a transfer, and walkability.

Equity in transportation

Page 19 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

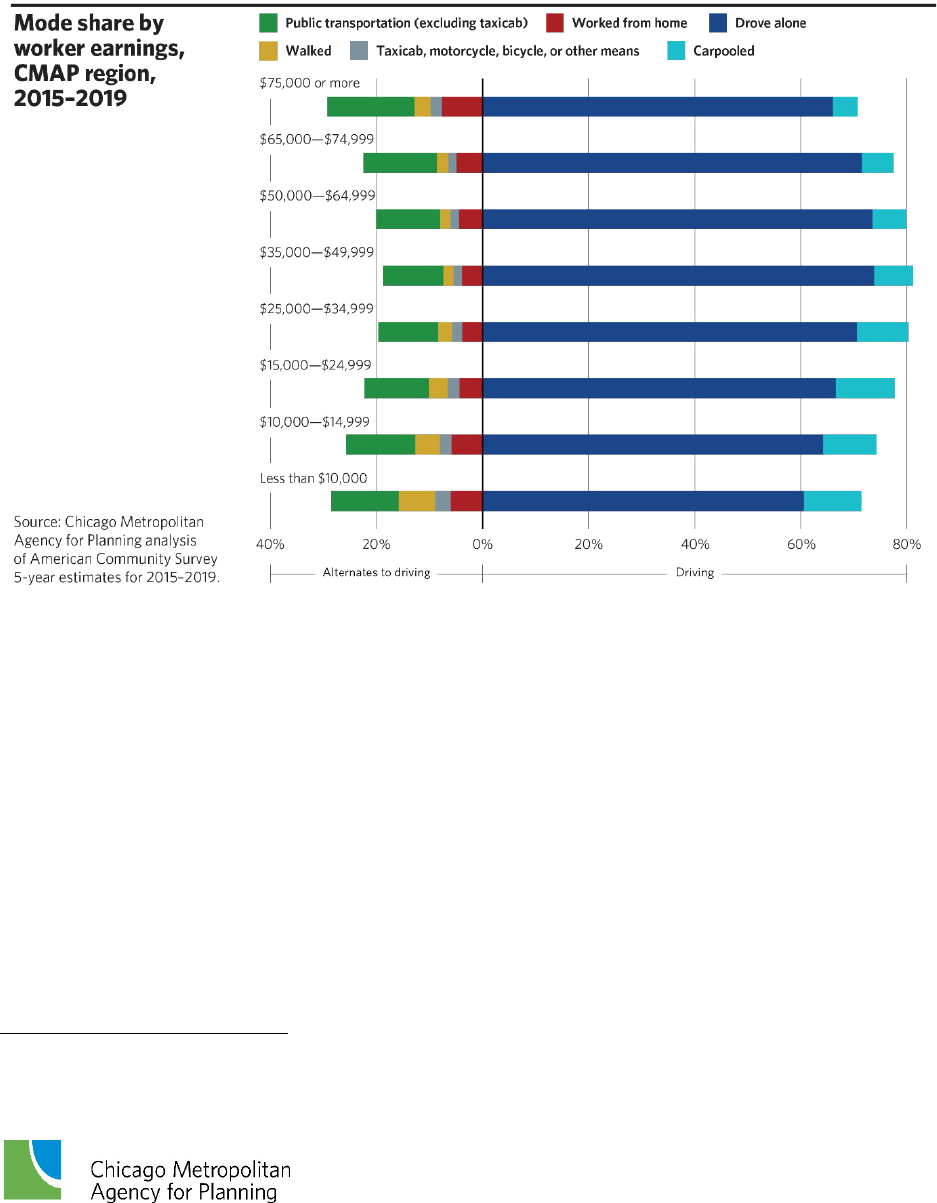

Auto trips represent the vast majority of work trips. Meanwhile, even before the COVID-19

pandemic, transit ridership was declining. Income plays an important role in travelers’ mode

choices for their commutes.

Figure 7 shows how workers on either end of the earnings spectrum are less likely to travel to

work by car and are more likely to travel by transit. Travelers with lower income are the least

likely to drive alone to work and the most likely to walk, likely in part because auto ownership

can be unaffordable for many commuters with lower income.

In the suburbs, commuters earning lower wages are less likely than commuters earning higher

wages to use public transportation. Rather, many carpool to get to industrial and retail job

centers in more diffuse locations in the region that are not well served by transit. Workers in the

highest earning categories also have lower rates of auto commutes. High earners are afforded

more choice in where to live and may live in areas with better access to transit, such as near

transit connections to Chicago’s central business district. For example, high earners in the

suburban parts of the region are the most likely to use transit, given that they use Metra

commuter rail to reach jobs in the city.

Equity in transportation

Page 20 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 7.

Finding: Workers on either end of the earnings spectrum are less likely to travel to work by car

and are more likely to travel by transit

Systemic racism creates inequities in transportation safety and enforcement

Equity in fees, fines, and fares is impacted by bias in public safety and law enforcement

systems. Beyond improving the transportation system, parallel work must be done to reduce

inequities in how traffic laws are enforced. Although the enforcement system is not the focus of

this analysis, this report outlines the well-documented challenges faced by people of color in

other related systems.

Drivers incur additional transportation-related costs when they are cited for traffic violations.

Traffic violations straddle both the transportation and law enforcement systems. According to a

2018 report by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics, the most common

reason for interaction with the police is being a driver in a traffic stop.

10

10

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Contacts Between Police and the Public, 2018 - Statistical Tables, December 2020,

https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=702

Equity in transportation

Page 21 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

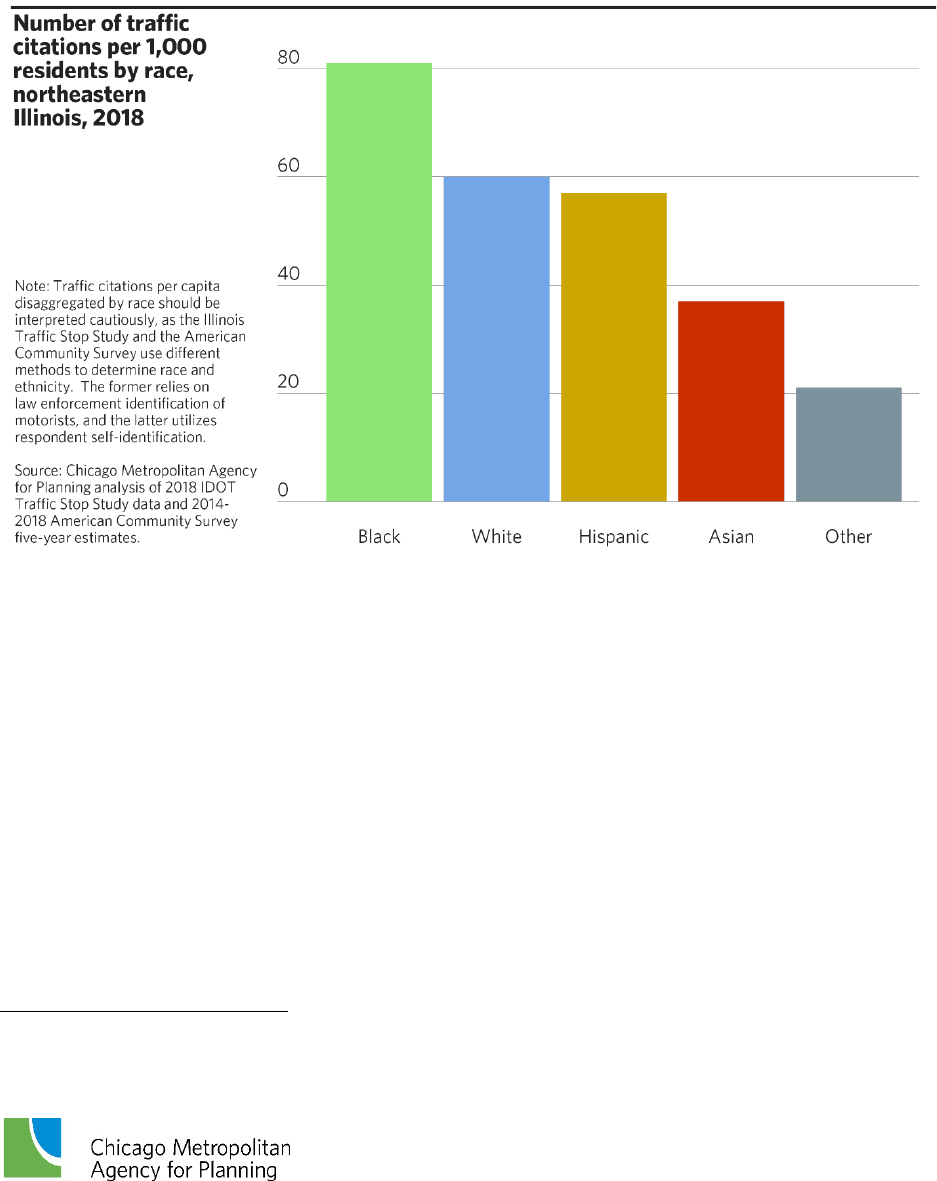

Historically, traffic safety enforcement has had an inequitable impact on communities of color,

with data indicating people of color are involved in a disproportionate share of traffic stops.

11

National surveys show Black adults are about half as likely to have a positive view of local

police performance as white adults.

12

That Black and Latinx communities are at greater risk for

both discriminatory enforcement and traffic violence is not a coincidence; both challenges are

manifestations of systemic racism that is embedded in the built environment.

13

The Government

Alliance on Race and Equity has defined systemic racism as “racial bias among interlocking

institutions and across society, causing cumulative and compounding effects that systematically

advantage white people and disadvantage people of color.”

14

At the same time, higher numbers of pedestrian and bicycle crashes occur in neighborhoods

with greater shares of residents with low income and residents of color.

15

Solving safety

challenges requires comprehensive and context-sensitive solutions. However, many in the

transportation and planning fields have focused on engineering and have not actively engaged

with the role that traffic safety enforcement can play in perpetuating racial and economic

inequities.

These challenges exist in all kinds of communities across the country. ON TO 2050 recommends

that any enforcement mechanisms that address traffic safety disparities in both low-income

communities and communities of color also avoid disproportionate financial and enforcement

burdens on these same communities. Extensive research conducted by the U.S. Commission on

Civil Rights in 2017 revealed the national scope of racial inequity in court debt, fines, and fees,

many of which are traffic-related.

16

ON TO 2050 recommends that any enforcement

mechanisms that address traffic safety disparities in both low-income communities and

communities of color also avoid disproportionate financial and enforcement burdens on these

same communities. The region will need to work together to eliminate inequities in the system

and develop processes, practices, and protocols to ensure equity.

Many households with low income are unbanked and under-banked

One challenge faced by households with low income is a lack of access to or ability to use a

bank account, known as unbanked and underbanked, respectively. Having a bank account or

11

Emma Pierson et al., “A Large-Scale Analysis of Racial Disparities in Police Stops across the United States,” Nature

Human Behaviour 4, no. 7 (July 1, 2020): 736–45, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0858-1.

12

Pew Research Center, The Racial Confidence Gap in Police Performance, September 2016,

https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/09/29/the-racial-confidence-gap-in-police-performance.

13

Vision Zero Network, Vision Zero Equity Strategies for Practitioners, 2017, http://visionzeronetwork.org/wp-

content/uploads/2017/05/VisionZero_Equity.pdf

14

Government Alliance on Race and Ethnicity, Advancing Racial Equity and Transforming Government,

https://racialequityalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/GARE-Resource_Guide.pdf

15

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, ON TO 2050 Recommendation: Improve Travel Safety, 2018,

https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/2050/mobility/safety

16

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Targeted Fines and Fees Against Communities of Color, 2017,

https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2017/Statutory_Enforcement_Report2017.pdf

Equity in transportation

Page 22 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

credit card helps facilitate many transactions, including using modern, electronic methods for

paying transportation fees, fines, and fares. Many entities that collect fees, fines, and fares use

cost differences to incent the adoption of these methods by their customers because of their

collection efficiency. However, it is well documented that people with low income are more

likely to be unbanked and therefore unable to achieve these savings. In Illinois, it is estimated

that 41 percent of households with annual income under $30,000 are either unbanked or

underbanked.

17

With incomes above $75,000, the unbanked rate falls to 1.1 percent of

households and the underbanked rate to 10 percent. From other perspectives, 11.4 percent of

households without a high school diploma were unbanked, while 1.8 percent of households

with a college degree were unbanked.

Among the unbanked, the reliance on cash is significant. Two-thirds of unbanked households

used cash for paying bills in a typical month in 2017. Thirty-nine percent of such households

used nonbank money orders, and 22 percent used prepaid cards. Less than 10 percent of

unbanked households used electronic payments, checks, debit cards, and credit cards.

18

Transportation funding challenges

The region’s transportation system is funded through a variety of federal, state, regional, and

local revenue sources. However, federal and state revenues are not enough to reach a state of

good repair, and underinvestment in capital maintenance has created a significant backlog of

projects. ON TO 2050 recommends that those who benefit from the transportation system fund

it through direct user fees, but this may result in disproportionate impacts on households with

low income.

Making fees and fares more affordable to residents with low income could potentially result in

lower revenues and may require investments in programs or infrastructure. Further

investments in the system could also improve travel times and reliability and even reduce the

need for vehicle maintenance. Given current revenue constraints, this would drive a need to

increase revenues in other ways or reprioritize existing investments toward strategies to help

residents with low income. This section will provide an overview of the region’s transportation

funding system, as well as funding constraints.

Roadways

The state’s roadway system is primarily funded through both federal and state revenues, such

as the state motor fuel tax revenue and state vehicle registration fee. In 2019, the state increased

17

“2017 Survey Results for Illinois: Banking Status for Illinois Households,” Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation,

last updated 2017, https://economicinclusion.gov/surveys/place-data.html?where=Illinois&when=2017.

18

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Division of Depositor and Consumer Protection. 2017 FDIC National

Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, Appendix Tables. October 2018.

https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2017/2017appendix.pdf

Equity in transportation

Page 23 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

several transportation revenue sources, such as its motor vehicle registration fee and motor fuel

tax (MFT) rates, as part of the legislation called Rebuild Illinois. The legislation also provides for

indexing the MFT rate to inflation to limit the erosion of the revenue’s purchasing power over

time. Even with these revenues, estimated to increase available funding by more than $2 billion

annually, resources will be insufficient to make needed investments in maintaining, enhancing,

and expanding the system.

Several forces continue to erode the MFT’s long-term viability as an adequate or fair source of

revenue. The tax revenue depends on how much fuel that drivers purchase — directly related to

how far people drive. Increased fuel efficiency and a lack of substantive growth in vehicle travel

will undermine the ability of the MFT, even indexed to inflation, to keep pace with the cost of

operating and maintaining the transportation system over the long term. ON TO 2050

recommends long-term replacement of the MFT with a road usage charge, which would be

collected as a per-mile fee when driving on public roadways. A road usage charge would

provide a more sustainable revenue source, as it would grow with vehicle travel rather than

motor fuel consumed.

19

At the local level, transportation departments use a mix of state motor fuel tax disbursements

and locally imposed taxes and fees, including motor fuel taxes, vehicle licenses, and priced

parking, as well as property and sales taxes. Local governments may also use fine revenue for

transportation or other purposes, but fine levels should be set to promote safety outcomes and

are not appropriate as a revenue generator.

Transit

The region’s transit system’s operations are funded through transit fares and other operating

revenue, including the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) sales tax, state assistance, a

portion of Chicago’s real estate transfer tax, and limited federal support.

20

Revenues collected

through transit fares and other smaller system-generated revenue supported 39.8 percent of

service operations in 2019.

21

Capital costs are funded primarily through federal sources, as well

as state support from motor fuel tax revenues directed to the RTA and state bonding. Capital

19

A road usage charge would also prevent a growing horizontal inequity related to electric and hybrid vehicles that

will arise if the state continues with an MFT, even with the supplemental $100 electric vehicle fee. Electric vehicle

drivers, as well as hybrid vehicle drivers, will typically pay less than other drivers. In addition, electric vehicle

drivers who drive few miles will pay as much as those who drive substantially more.

20

The 2021 Regional Transit Operating Budget includes 2.3 percent from The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic

Security (CARES) Act and 7.7 percent from other federal relief funding.

21

Regional Transportation Authority. Adopted 2021 Operating Budget, Two-Year Financial Plan, and Five-Year Capital

Program. December 2020. https://www.rtachicago.org/sites/default/files/documents/aboutus/meeting_documents/12-

17-20/Adopted-RTA-2021-Operating-Budget.pdf. Note that fare revenues in 2020 were significantly lower due to

lower ridership due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Equity in transportation

Page 24 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

infrastructure needs are significantly underfunded, with an estimated 34 percent of the region’s

transit assets exceeding their useful life as of 2020.

22

State of Illinois law requires system-generated revenue to recover at least 50 percent of system

operating expenses for CTA, Metra, and Pace and 10 percent for Pace ADA paratransit. State

statute provides for adjustments to calculating the ratio, which explains why actual fare

revenue comes in below the 50 percent mark. To achieve this requirement, the RTA sets a

unique recovery ratio for each service board during the budget process each year.

23

Each

agency’s individual recovery ratio reflects projected income from other eligible operating

revenues, as well as estimated ridership, including revenue from the fares, which vary

depending on several factors.

Revenues from these sources vary between the operators, which is why each agency has a

unique recovery ratio. For example, nearly one out of every three trips taken on Pace is paid for

with a free or reduced fare permit, driving down the total collected fare revenue and requiring

the rest of the system to compensate to reach the region’s required mark. Any changes to fare

policies that reduce revenue need to account for the constrained funding environment with new

sources of revenue or an adjustment to the ratio required of the service operators.

The State of Illinois historically funded mandatory free and reduced fare programs at $34

million annually, although the cost of providing these services far exceeds the reimbursement.

Starting in fiscal year 2015 and for each subsequent year, the state reduced the subsidy by

nearly one half, requiring each agency to recoup revenue for these programs elsewhere.

In addition to reduced funding for statutorily required reduced and free ride permits, the

transit agencies have experienced other decreases in state support.

24

When public funding for

operations decreases, unless there are equal cuts to operating services, the service operators

must compensate with additional system-generated revenues to maintain the region’s recovery

ratio. The State has imposed a 1.5 percent administrative fee for collecting the RTA sales tax, as

well as a 5 percent reduction in state matching funds through the Public Transportation Fund.

In total, these state cuts, in addition to the cuts to the reduced and free fare subsidy, amounted

to a $56 million regional operating reduction in 2019, or 1.8 percent of budgeted revenue, and

were estimated to impact the 2020 operating budgets by $46 million.

22

Regional Transportation Authority. Adopted 2021 Operating Budget, Two-Year Financial Plan, and Five-Year Capital

Program.

23

The 2021 operating budget counts CARES Act and other additional federal relief funding as system-generated

revenue. With the inclusion of these funds, for 2021, CTA’s specified recovery ratio is 54.75 percent, Metra’s is 52.5

percent, and Pace’s is 30.3 percent for suburban service and 10 percent for ADA paratransit.

24

The challenges of insufficient operating funding have recently been compounded by the state’s delinquency on

remitting transit revenues. As of November 2020, the state owed the RTA $193.3 million. Late payments have forced

the agency into short-term borrowing to fill budget gaps, with interest costing $5.2 million in 2019 and $4.6 million

through November 2020.

Equity in transportation

Page 25 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Distribution of the cost of public services

and infrastructure

In the United States, people and businesses pay taxes and fees to fund the cost of public goods

and services. At the state and local level, the overall tax burden and distribution across

taxpayers vary depending on the location. Different states and localities have different tax

structures. The variance is based on reliance on income tax, property tax, sales and excise taxes,

or other taxes or fees, as well as the specific structure of those taxes.

In some states, residents with high incomes pay a higher proportion of their income in taxes

than residents with lower incomes. These tax systems are more progressive and promote

vertical equity. They typically feature progressive elements in their income tax, such as

exemptions or graduated rates. In other states, residents with high incomes pay a lower

proportion of their income in taxes than residents with lower incomes. These systems are

considered regressive and typically feature fewer progressive elements in their income tax or a

higher reliance on sales and excise taxes, which are not based on income level.

Equity of Illinois’ tax system

The distribution of the tax burden impacts Illinois’ broader economic vitality. In 2018, the

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy ranked Illinois’ tax system as the 8

th

most regressive

structure in the United States.

25

The 20 percent of non-elderly residents with the lowest incomes

paid 14.4 percent of their income in taxes, while the top 1 percent of taxpayers paid 7.4 percent.

While Illinois relies on sales and excise taxes to a relatively typical degree, these taxes often

have regressive impacts on the overall tax system. States with less regressive structures

integrate several features in their income tax structure to mitigate the impacts of these taxes.

25

Institute on Taxation and Economy Policy, Who Pays, October 2018,

https://itep.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/whopays-ITEP-2018.pdf

Equity in transportation

Page 26 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 8.

Finding: Taxpayers with the lowest income levels pay a higher proportion of their income in

taxes than higher-income taxpayers

However, Illinois’ income tax structure features a flat income tax rate and comparatively low

tax exemptions. Illinois taxes all personal income at the same rate, rather than a graduated

approach where higher incomes are taxed at higher rates.

26

Currently, Illinois exempts $2,275

per individual from taxable income for filers with income lower than $250,000 ($500,000 for a

joint return). Illinois also provides an Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for households with low

to moderate income that are eligible for the federal EITC. The Illinois EITC is currently 18

percent of the federal EITC and is a refundable credit, meaning that it can be greater than the

amount of tax liability.

Equity of transportation fees, fines, and fares

Transportation user fees, fines, and transit fares are one portion of a resident’s overall tax and

fee burden. They function as part of the tax system as a whole, where every broad-based fee,

fine, or fare imposed without basis in income level has the potential to be regressive. Even when

these expenses are not primary parts of the tax burden, many residents perceive outlays like

26

The Illinois state constitution requires income taxes be at a non-graduated rate. See Constitution of the State of

Illinois, Article IX, Section 3, https://www.ilga.gov/commission/lrb/con9.htm.

Equity in transportation

Page 27 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

tolls or transit fares as substantial relative to other expenses, because they have to pay them on a

more regular basis, particularly if they have to pay in cash.

27

Indeed, particularly noticeable fees

like priced parking are often used as a traffic management tool to drive behavior.

The following section will assess the vertical equity of transportation fees, fines, and fares, and

the impacts on residents and households in northeastern Illinois with low income. When these

fees, fines, and fares disproportionately impact residents with low income, residents of color

may also be disproportionately affected.

28

Policies may not have an overtly racist intent yet

produce inequitable outcomes for people of color.

State motor fuel tax and proposed road usage charge

The State of Illinois imposes a 38.7 cents per gallon tax on motor fuel, with the rate rising with

inflation every July. Only drivers pay MFTs directly and therefore only residents with low

income who drive a car are directly impacted. This would also be true with road usage charges,

when implemented. Current travel patterns and the fuel efficiency of personal vehicles affect

the payments that drivers make in MFT today. Drivers are impacted by the motor fuel tax to the

degree that they use fuel, a function of both miles driven and vehicle efficiency. An average

driver in Illinois pays approximately $200 annually in state MFT and would pay a similar

amount under a potential road usage charge structured to replace the current revenue from

MFT. Drivers would pay a road usage charge solely based on how many miles they drive.

Households with low income incur lower motor fuel tax and likely lower road

usage charge payments

CMAP analysis indicates that communities with median household income under 60 percent of

the region median tend to have lower typical household MFT payments than areas with higher

median household income. These MFT payments totaled approximately $220 per year and $350

per year, respectively, in aggregate for all household vehicles.

29

These communities with lower

income had lower MFT payments because of varying combinations of fewer vehicles per

household and low annual mileage. Differences in MFT payments across communities of

different income levels were not driven by notable differences in vehicle fuel economy. On the

municipal and community area level, no relationship between median vehicle fuel economy

and median household income exists.

27

For example, see Amy Finkelstein, “E-ZTAX: Tax Salience and Tax Rates,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, (2009),

https://economics.mit.edu/files/7878; Raj Chetty, Adam Looney, and Kory Kroft, “Salience and Taxation: Theory and

Evidence,” American Economic Review 99, no. 4 (September 2009),

https://are.berkeley.edu/SGDC/Chetty_Looney_Kroft_AER_2010.pdf.

28

Where possible, the assessment of transportation fees, fines, and fares that follows provides quantitative analysis

on both income and racial dimensions. However, data limitations did not allow a full analysis of the impact of every

fee, fine, and fare by race or ethnicity.

29

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning analysis of American Community Survey estimates for 2011-2015;

odometer readings from the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, 2015-17; and fuel economy estimates from the

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Equity in transportation

Page 28 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

As a result, shifting from a motor fuel tax to a road usage charge would not impose a greater

burden on typical lower-income households relative to typical higher-income households. To

compare the tax burden of a MFT to a road usage charge, CMAP estimated a revenue neutral

rate for passenger vehicles. Under a $0.0195 per mile rate — chosen because it raises the same

amount of revenue overall as the MFT — areas with lower median household income would

experience an $11 typical increase in annual burden, while areas with higher median household

income would experience a $14 typical increase, on average. The higher change in burden is

partially driven by the fact that households in higher-income communities have higher mileage

on average than households in lower-income communities.

Since aggregating to the community level may obscure household-level characteristics, CMAP’s

Activity-Based Model was also used to investigate relationships between income and driving

patterns. The analysis reflects that lower-income households drive fewer miles on average than

medium- and higher-income households, resulting in lower tax payments for the MFT and a

potential road usage charge. While Table 1 compares modeled miles driven by income group

for all households, the results for households that own one or more vehicles are similar. Ninety

percent of all households in the region have one or more vehicles, while 75 percent of

households with low income have one or more vehicles .

30

Table 1.

Finding: Households with low income drive fewer miles than other households

Income level of

household

Share of modeled

households

Share of total miles

driven

Average miles

driven per day

Low

22%

11%

20 miles

Medium

36%

37%

42 miles

High

42%

53%

53 miles

All households

100%

100%

42 miles

Source: Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning analysis of U.S. Census data and CMAP’s Activity-Based Model

Motor fuel taxes do not represent a major cost burden relative to other costs of

driving

Both motor fuel taxes and road usage charges are fees intended to capture funds based on use

of the roadway network. Because they drive fewer miles, lower-income households pay a

similar share of their income in motor fuel tax as higher-income households — approximately

0.2 percent of income for four-person households across each income group. The rate structures

treat drivers of all incomes the same, resulting in a lack of vertical equity for households that

lack sufficient access to other transportation modes. However, it is mostly other driving costs,

such as vehicle purchase, repairs, insurance, and the price of motor fuel itself, not the MFT or a

road usage charge, that make driving unaffordable for some households.

30

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, Activity-Based Model

Equity in transportation

Page 29 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Vehicle registration fees

The State of Illinois imposes a vehicle registration fee, and many municipalities impose their

own vehicle license fees. Vehicle registration fee revenue tends to provide the stability

necessary to fund or issue bonds for multi-year transportation programs. The State periodically

raises these fees to ensure that the revenues are sufficient to maintain and improve the

transportation system. The State of Illinois recently increased registration fees, with annual

passenger vehicle rates increasing from $101 to $151.

31

With 10.8 million registered vehicles,

these fees are the Illinois Department of Transportation’s largest source of state-generated

funding. Nearly 8 million passenger cars are registered in Illinois. Growth in actual passenger

vehicle registrations was just 1.2 percent between 2010 and 2019, which is consistent with

stagnation in the state’s population.

Many municipalities impose annual vehicle fees as well. Within northeastern Illinois, 159

municipalities impose these fees on residents, ranging from $5 to $90. Some municipalities

restrict these revenues for transportation investments, while others use the revenue for general

purposes.

Households with low income own fewer vehicles than other households

State and local vehicle fees are inherently regressive. Because everyone pays the same amount

regardless of income, drivers with low income pay a higher percentage of their income on these

fees than higher-income drivers. Additionally, the annual $151 payments may impose a burden

on low-income households. However, many people with low income are not affected by the fee

because they don’t own a vehicle. Data indicate that households nationwide with less than

$25,000 in annual income account for 13.4 percent of vehicles.

32

Within northeastern Illinois, lower-income communities tend to have fewer vehicles per

household than higher-income communities.

33

In addition, results from CMAP’s Activity-Based

Model indicate that households with low income in the region own 1.1 vehicles on average,

while households with medium and high income own 1.7 and 1.9 vehicles on average,

respectively. In the aggregate, households with low income account for 23 percent of

households in the region but own 16 percent of the vehicles. Figure 9 compares vehicle

ownership by income level in the aggregate for the CMAP region.

31

Electric vehicle registrations were increased from a discounted $35 biennial fee to $251 annually, which is

comprised of the same base registration fee as all vehicle owners, $151, plus an additional $100 fee in lieu of paying

the MFT. As of March 2020, electric vehicles account for 0.3 percent of passenger vehicles in Illinois, with 21,336

active registrations out of nearly 8 million passenger vehicles registered in Illinois.

32

Federal Highway Administration. National Household Travel Survey, 2017.

33

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning analysis of American Community Survey data, 2014-18 estimates

Equity in transportation

Page 30 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 9.

Finding: Households with low income own fewer vehicles than households with medium and

high income

Indeed, not owning a vehicle allows people with low income to avoid paying vehicle fees.

However, in areas with insufficient transit access to employment and services, or bicycle and

pedestrian facilities, not owning a vehicle may not be a reasonable alternative.

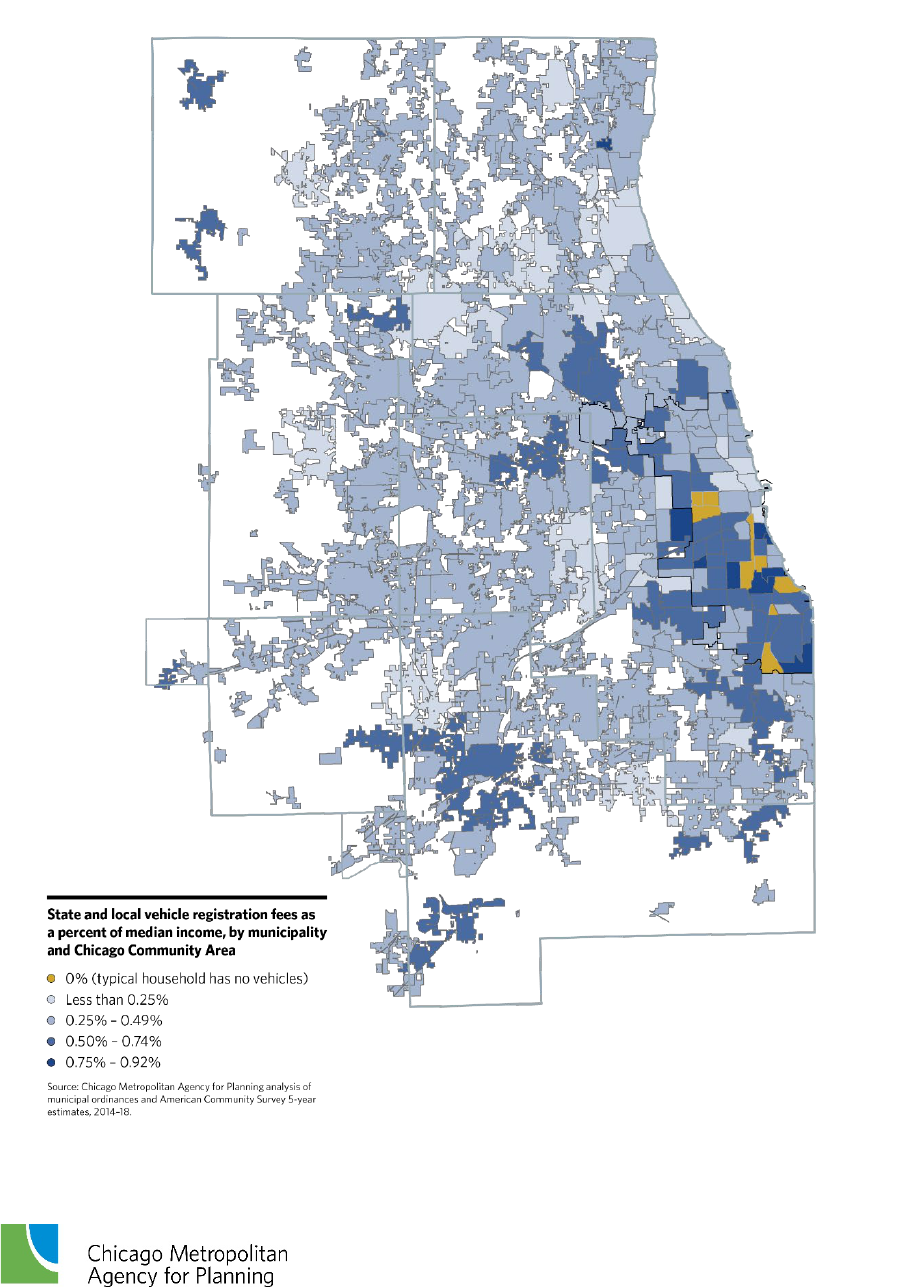

Impact of vehicle registration fees depends on local fees imposed

Across the region, the aggregate effect of state and local vehicle fees varies by both fee levels

and income levels. Figure 10 compares typical household state and local vehicle fees paid, based

on typical household vehicle ownership, to median household income, by municipality or

Chicago Community Area. Although the fees are relatively low compared to income levels,

households with median-level incomes in many Chicago neighborhoods and several suburbs

are paying more than a half a percent of their income annually in state and local registration

fees.

Equity in transportation

Page 31 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

Figure 10.

Finding: State and local vehicle registration fees reach more than a half a percent of income in

some communities

Equity in transportation

Page 32 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

However, all communities in the region have residents of varying income levels who own

vehicles. Table 2 compares vehicle fee levels by income level, for a four-person household.

Table 2.

Finding: Higher local vehicle fees drive a higher cost burden

Income level, four-

person household

$151 State fee as a

percent of income

State + $25 local fee as a

percent of income

State + $75 local fee as a

percent of income

60% of median income

($51,350)

0.2% 0.3% 0.4%

140% of median income

($119,818)

0.1% 0.1% 0.2%

Source: Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning analysis.

ON TO 2050 encourages municipalities to impose user fees to fund infrastructure that meets

community needs. However, the impact of these fees is greater for drivers in municipalities

with higher fees. While these fees are regressive, they remain a small piece of the overall cost of

vehicle ownership. For typical vehicle costs, these fees represent approximately 2 percent of the

annual cost of owning a vehicle, which can reach $10,000.

Tolling

Tolling allows the high cost of urban expressway construction to be borne by users of those

facilities, rather than the general public. In Illinois, such user fees have allowed Illinois Tollway

facilities to be maintained and improved, while IDOT-maintained expressways have fallen into

disrepair due to a lack of adequate and consistent funding. The need for expanded tolling has

been recognized by ON TO 2050, which recommends IDOT and the Tollway implement tolling

in conjunction with planned reconstruction of existing, untolled facilities. This is meant to

defray the costs of reconstruction and provide a sustainable revenue source for ongoing

maintenance and modernization.

Base charges for the Illinois Tollway vary by facility. The Tri-State Tollway, first constructed

more than 60 years ago, has a price of approximately $0.06 per mile. Newer facilities have

higher rates to cover more of the initial cost of facility construction, rising to approximately

$0.20 per mile on the newly constructed Illinois Route 390.

Likewise, the payment method affects toll rates. The financial viability of toll roads requires that

the cost of collection be substantially lower than the collected revenue. Automated collection via

a transponder costs very little compared to alternative payment methods. As a result, the

Tollway charges more for higher-cost transactions, both to cover costs and, more importantly, to

provide a financial incentive for people to choose payment methods with lower costs to the

Tollway.

Equity in transportation

Page 33 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

More than 90 percent of the Tollway’s transactions are via the electronic I-PASS transponder,

the second-highest electronic collection percentage among peer U.S. toll agencies.

34

That is likely

to increase, as cash tolls are being phased out on the Tollway system. Nearly 70 percent of

Chicago Skyway transactions are electronic, but unlike Illinois Tollway facilities that offer a

discount for electronic transponder payment, cash and electronic toll rates are the same. To

obtain an I-PASS transponder, the account holder must pay $30 up front; $20 is credited to the I-

PASS account and $10 is a refundable deposit. The Tollway’s cost of collecting I-PASS tolls is

significantly lower than pay-by-plate online tolling, used by motorists who did not have an I-

PASS transponder in their windshield.

35

To maximize toll collection efficiencies, the Illinois Tollway has put strong financial incentives

in place to encourage I-PASS use. As compared to I-PASS tolls, a typical toll schedule for

passenger vehicles is double for “pay-by-plate” transactions for 14 days after the toll.

36

To avoid higher tolls and fees, Tollway customers with I-PASS accounts need to keep funds in

their accounts. For customers with credit, debit, and prepaid cards, this is easy through the I-

PASS auto-replenish program.

37

Customers with depleted accounts have 14 days to pay by

plate, or an invoice fee occurs. For customers without auto-replenish, cards may be used online

or over the phone to add funds. Customers can also purchase Illinois Tollway gift cards at

Jewel-Osco using any payment method and replenish their account using the gift card online or

over the phone. Cash, checks, and cards are accepted at four suburban service oases or at the

Illinois Tollway headquarters in Downers Grove. Checks may also be mailed to a processing

center.

Existing tolling does not significantly impact households with low income

At this time, on average, tolls do not appear to be a substantial share of transportation costs nor

a primary driver of transportation outlays for people with low income. Consumer Expenditure

Survey data indicate that other vehicle expenses, which include tolls, make up just 3 percent of

transportation expenses for households with low income and 6 percent for other households.

Rather, vehicle ownership overall is the primary driver of transportation expenses.

34

CDM Smith. Illinois Tollway Comprehensive Study Update. November 2020.

https://www.illinoistollway.com/documents/20184/785978/Traffic+Engs+Rpt+Final+for+IL+Toll+2020A.pdf/5dd2d2ab

-5f65-819d-4eda-c6d4ede75979?t=1610111997297.

35

Illinois Tollway (Mike Colsch), Video Tolling and Collections, March 2017,

https://www.illinoistollway.com/documents/20184/532181/20170313_CSPVideoTolling.pdf/24556ba4-7001-47e0-ad73-

333b83ec3194?version=1.0. In 2015, the cost of collecting tolls was $0.08 per dollar for I-PASS transponder

transactions, including capital expense (gantries, cameras, etc.). Pay-by-plate online tolling, for motorists who did not

have an I-PASS transponder in their windshield, have higher expenses, $0.20 per dollar collected in 2015. Expenses

per dollar collected for cash transactions, which are being phased out, were $0.43 for coin machines and $0.48 for

manual lanes (with an in-person attendant).

36

“Tolling Information,” Illinois Tollway, https://www.illinoistollway.com/tolling-information.

37

“About I-Pass,” Illinois Tollway, accessed March, 2020, https://www.illinoistollway.com/tolling-information/about-

ipass.

Equity in transportation

Page 34 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

The impact of tolling on people with lower income is dependent on several variables. People

with low income tend to have fewer cars than people with high income. In addition, average

annual household miles traveled by auto are higher for people with higher income.

Households with low income may drive fewer miles to avoid the various costs associated with

driving, representing trips suppressed by financial constraints.

While drivers can avoid driving on the Tollway and paying a toll, doing so can make trips

longer. Thus, drivers with low income still use these facilities because they provide a faster

route. While the Tollway serves low-income areas of south suburban Cook County and its

customer base includes drivers of all income levels, much of the Tollway system is in wealthier

suburban counties. In addition, Illinois Tollway per-mile fees are lower than those of many peer

toll agencies nationally, so impacts on lower-income communities have been limited.

Expanding tolling would primarily impact households with moderate and high

income

ON TO 2050’s recommendation to expand tolling to expressways as they are reconstructed may

impact greater numbers of travelers with low income. Using its Activity-Based Model, CMAP

compared a “baseline” 2015 scenario with a “tolling” 2015 scenario, as if the remainder of the

IDOT expressway system in the CMAP region had been tolled at a rate of $0.20 per mile. Under

this scenario, toll revenues would increase by nearly 400 percent. In aggregate, daily toll

revenues would rise from a baseline of approximately $1.8 million to an estimated $8.8 million.

Table 3 indicates that under the expanded tolling scenario, the highest income group would

continue to pay a majority of the tolls collected — and would pay a slightly increasing share.

Table 3.

Finding: Households with low income would pay more in tolls, but a lower share of overall tolls

under expanded tolling

Estimates for

passenger tolls, CMAP

region, 2015

Low income Medium income High income

Baseline

tolling

Expanded

tolling

Baseline

tolling

Expanded

tolling

Baseline

tolling

Expanded

tolling

Share of daily toll

revenues

8%

6%

34%

33%

58%

61%

Daily cost per resident

$0.08

$0.27

$0.44

$0.71

$0.58

$1.20

Source: CMAP activity-based model

While the expanded tolling scenario would result in higher collections from households with

low income, tolls per resident per day would remain lower than those paid by residents with

higher incomes. These model results indicate both lower mileage on the Tollway by drivers

with low income and a lower increase in mileage than households in other income groups.

Lower tolls through I-PASS are less accessible to unbanked households

The tolling system currently in place presents challenges to unbanked residents with lower

incomes who need to access the tollway system. If tolling is expanded, particularly in low-

income areas, equity calls for people with lower incomes to have access to the lowest-cost toll

Equity in transportation

Page 35 of 74 fees, fines, and fares

rates. However, households with low income tend to be unbanked or underbanked, making I-

PASS accounts less accessible to them.

While I-PASS use is already high at the Illinois Tollway, expanded tolling would require

channeling an even greater number of customers to I-PASS transponders so that low-income

households can take advantage of the lowest toll rates available. This is an important task to

meet the needs of households with low income, particularly the unbanked.

Priced parking

Priced parking is recommended in ON TO 2050 as one component of developing more walkable

communities. CMAP recommends pricing to manage demand, so the price would be higher in

areas with higher demand and free in areas with low demand. Parking revenue should not be a

goal in and of itself; it should be considered a benefit of a well-managed transportation system.

In places where the demand for parking is high, using pricing to balance demand allows for a

more efficient use of land, improves travel time reliability by ensuring the availability of open

parking spaces, and facilitates business activity by opening up high-demand spaces closest to

businesses.

There are several potential approaches to pricing parking that have been implemented in

Chicago and some suburban communities. Priced parking is generally found at Metra

commuter stations; on-street in high-demand areas in Chicago, Oak Park, Forest Park,

Evanston, and Hinsdale; or in garages in very high-demand locations near a variety of

destinations. Additionally, residential permit parking is a form of priced parking that addresses

high on-street parking demand. From a regional perspective, broader implementation of priced

parking in appropriate locations could have many positive impacts. But it is also important to

consider the potential negative impacts, particularly equity impacts. These policies can impact

drivers with limited income, particularly those without access to transit or with ambulatory

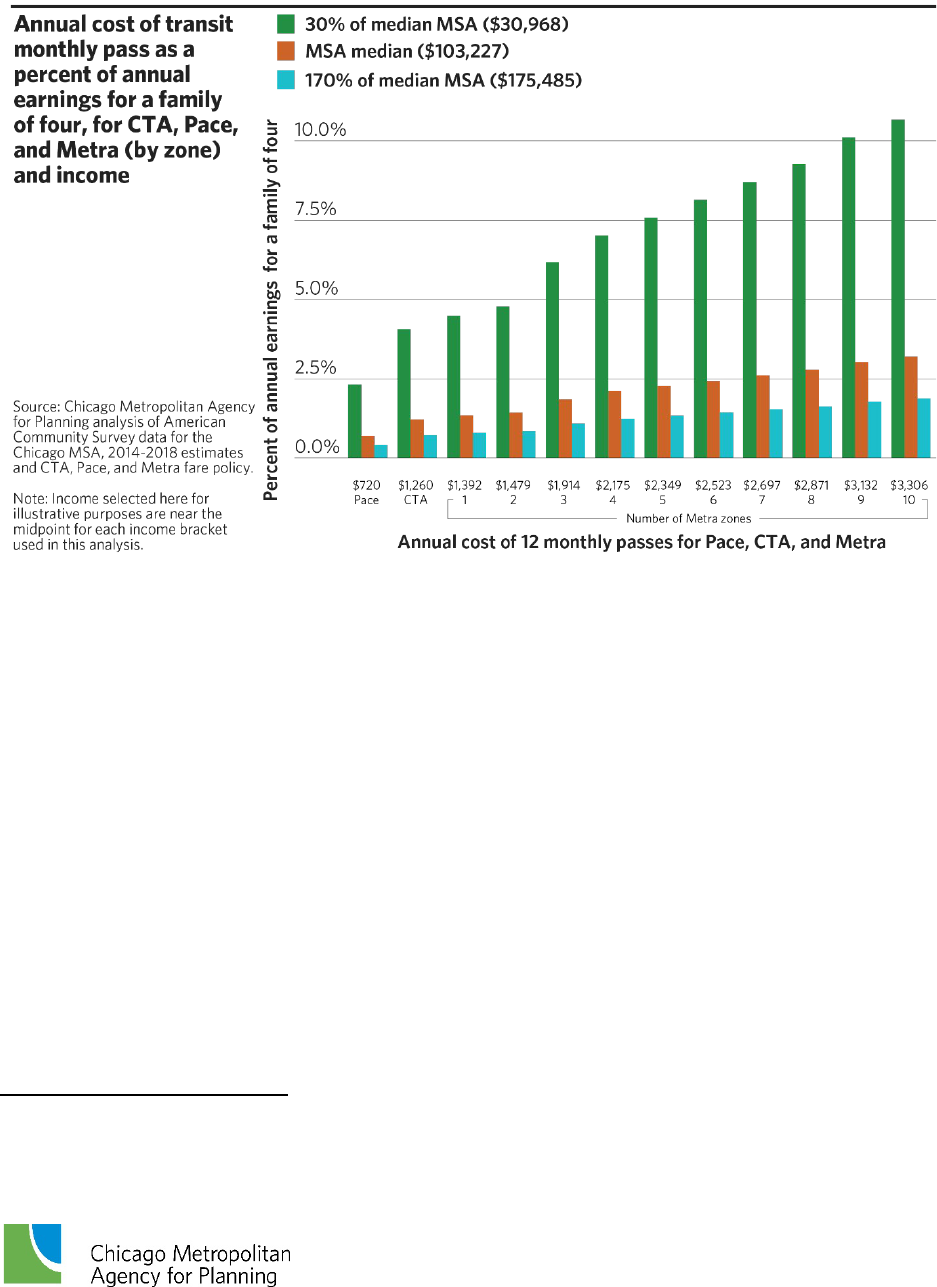

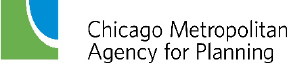

disabilities.