6 "4+374!+(" 3(.-23'$1.1*2 "4+37"'.+ 12'(/

'$.1$(&-.114/31 "3("$2"3.5$1-,$-3.-31 "3.12'$.1$(&-.114/31 "3("$2"3.5$1-,$-3.-31 "3.12

.,/+( -"$1$-#2.++ 3$1 +.-2$04$-"$2.,/+( -"$1$-#2.++ 3$1 +.-2$04$-"$2

$22(" (++(/, -

$.1&$ 2'(-&3.--(5$12(37 6"'..+

)3(++(/, -+ 6&64$#4

.++.63'(2 -# ##(3(.- +6.1*2 3'33/22"'.+ 12'(/+ 6&64$#4% "4+37/4!+(" 3(.-2

13.%3'$.5$1-,$-3.-31 "32.,,.-2

$".,,$-#$#(3 3(.-$".,,$-#$#(3 3(.-

1($9-& /$12'.,2.-$23.$/3

'(213("+$(2!1.4&'33.7.4%.1%1$$ -#./$- ""$22!73'$ "4+37"'.+ 12'(/ 3"'.+ 1+7.,,.-23' 2

!$$- ""$/3$#%.1(-"+42(.-(- 6 "4+374!+(" 3(.-23'$1.1*2!7 - 43'.1(8$# #,(-(231 3.1.%

"'.+ 1+7.,,.-2.1,.1$(-%.1, 3(.-/+$ 2$".-3 "32/ &$++ 6&64$#4

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1924333Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1924333Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1924333

ance programs to ensure they do not run afoul

of the stringent U.S. procurement requirements.

In the past decade, however, as U.S. Govern-

ment contractors continue to expand their global

presence, even the most experienced contractors

have exposed themselves to new risks and compli-

ance requirements. In particular, as contractors

expand their business with government entities

outside the United States, the long arm of the U.S.

Government continues to govern their transac-

tions. Specifically, the Foreign Corrupt Practices

Act prohibits, among other things, the bribery

T

he U.S. Government spent nearly $538 billion dollars in Fiscal Year 2010 for goods and services

provided by private contractors.

1

This astronomical number is the result of the U.S. Government’s

ever-increasing reliance on private companies to keep the Government running. Private companies

that contract with the U.S. Government are subject to an extensive set of rules and requirements

designed to ensure they behave responsibly and to provide taxpayers and the U.S. Government with

the best value for their money.

2

Experienced Government contractors maintain sophisticated compli-

Jessica Tillipman is the Assistant Dean for Outside Placement and a Professorial

Lecturer in Law at The George Washington University Law School, where she

teaches a course in anticorruption law. Dean Tillipman would like to thank

Chris Davis, Leslie Demchenko, and Jessica Henson for their extraordinary

assistance and support in the drafting of this Briefing PaPer.

FCPA Basics & Recent Developments In The Law

■ Antibribery Prohibitions

■ Recordkeeping & Accounting Provisions

FCPA Jurisdiction

FCPA Sanctions

■ Monetary Fines & Penalties

■ Incarceration

FCPA Collateral Consequences

■ U.S. Suspension & Debarment Regime

■ Denial Of Other U.S. Public Advantages

Global Antibribery Enforcement & Collateral Consequences

Debarment By Other International Organizations

Other Costs Associated With FCPA Enforcement

The Road To Settlement

Briefing

papers

second series

®

NO. 11-9 ★ AUGUST 2011 THOMSON REUTERS © COPYRIGHT 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 4-092-350-2

practical tight-knit briefings including action guidelines on government contract topics

IN BRIEF

This material from Briefing PaPers has been reproduced with the permission of the publisher, Thomson Reuters. Further use without the

permission of the publisher is prohibited. For additional information or to subscribe, call 1-800-344-5009 or visit west.thomson.com/fed-

pub. Briefing PaPers is now available on Westlaw. Visit westlaw.com

THE FOREIGN CORRUPT PRACTICES ACT & GOVERNMENT CONTRACTORS: COMPLIANCE

TRENDS & COLLATERAL CONSEQUENCES

By Jessica Tillipman

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1924333Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1924333Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1924333

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

2

of foreign officials to obtain or retain business

with a foreign entity.

3

The United States is currently the world leader

in foreign antibribery enforcement.

4

This is due

to a sharp rise in FCPA enforcement activity in

the past decade.

5

The number of FCPA enforce-

ment actions continues to increase each year,

breaking records not only in the number of cor-

porate prosecutions, but also in total penalties

imposed. In 2010 alone, total penalties resulting

from FCPA enforcement actions topped $1.7

billion.

6

In addition, with over 150 criminal and

80 civil FCPA investigations in the pipeline in

2010, enforcement does not show signs of slow-

ing anytime soon.

7

Indeed, the Department of

Justice has made clear that FCPA enforcement is

a priority, noting that it “remains committed to

prosecuting violations of the FCPA to ensure that

the payment of bribes can no longer be viewed

simply as the cost of doing business in a foreign

nation.”

8

While FCPA compliance is imperative for all

companies subject to its jurisdiction, it is particu-

larly important for companies that contract with

the Government. Given the nature of a Govern-

ment contractor’s business, they are naturally

at greater risk of violating the FCPA than those

companies that do not interact with Government

officials on a regular basis. In fact, in the years

preceding the enactment of the FCPA, the U.S.

Congress singled out Government contractors and

their overseas behavior as particularly troubling.

In the 1970s, a bribery scandal involving Lockheed

Corporation (now Lockheed Martin Corporation),

Northrop Corporation, and oil companies (Gulf

Oil Corporation, Phillips Petroleum Company,

and Ashland Oil, Inc.) was the likely impetus for

legislation prohibiting overseas corruption.

9

The

Government discovered, among other instances

of bribery, that Lockheed had paid millions of

dollars in bribes to foreign governments to secure

contracts, embarrassing both the United States

and the relevant foreign governments.

10

Moreover,

although the company admitted to paying $22

million “under the table to foreign government

officials and political organizations,” the company

refused to identify the recipients of the bribes,

explaining that “identifying its beneficiaries could

hurt its $1.6 billion backlog of unfilled foreign

orders.”

11

The company also refused to promise

to stop bribing foreign officials, stating that the

payments were a necessary cost of doing business

and “consistent with practices engaged in by

numerous other companies abroad.”

12

Govern-

ment investigations and congressional hearings

during this time uncovered a landscape in which

bribery was pervasive and an accepted practice

of the Government’s largest contractors.

13

Thus,

in enacting the FCPA, the Government sought

to deter and prevent Government contractors

and other companies from engaging in corrupt

practices overseas.

Three decades later, the legislation designed

to prevent and punish the bribery of foreign

government officials has become a thorn in the

side of companies that seek to do business with

the U.S. Government. Six of the 10 most prolific

contractors with the U.S. Government, includ-

ing Lockheed Martin Corporation, The Boeing

Company, General Dynamics Corporation, Ray-

theon Company, L-3 Communications, and BAE

Systems, either violated the FCPA or engaged

in activities that allegedly implicate the FCPA’s

antibribery provisions. Moreover, U.S. Govern-

ment contractors that have been investigated by

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

Briefing PaPers

®

(ISSN 0007-0025) is published monthly except Janu-

ary (two issues) and copyrighted © 2011

■ Valerie L. Gross, Editor ■

Periodicals postage paid at Twin Cities, MN

■ Published by Thomson

Reuters / 610 Opperman Drive, P.O. Box 64526 / St. Paul, MN 55164-0526

■ http://www.west. thomson.com ■ Customer Service: (800) 328-4880 ■

Postmaster: Send address changes to Briefing Papers / PO Box 64526 / St.

Paul, MN 55164-0526

BRIEFING PAPERS

Briefing PaPers

®

is a registered trademark used herein under license. All rights

reserved.

Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission

of this publication or any portion of it in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopy, xerography, facsimile, recording

or otherwise, without the written permission of Thomson Reuters is

prohibited. For authorization to photocopy, please contact the Copy-

right Clearance Center at 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923,

(978)750-8400; fax (978)646-8600 or West’s Copyright Services at 610

Opperman Drive, Eagan, MN 55123, fax (651)687-7551.

This publication was created to provide you with accurate and authoritative

information concerning the subject matter covered; however, this publication

was not necessarily prepared by persons licensed to practice law in a par-

ticular jurisdiction. The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal or other

professional advice, and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of

an attorney. If you require legal or other expert advice, you should seek the

services of a competent attorney or other professional.

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

3

the Government for violating the FCPA generally

have not settled cheaply. In fact, the top 10 most

expensive settlements in FCPA history include

eight large U.S. Government contractors: Siemens

AG, Halliburton/KBR, BAE Systems, JGC Corpo-

ration, Daimler AG, Alcatel-Lucent, Panalpina,

and Johnson & Johnson.

14

For contractors that do business with the Fed-

eral Government, these record-shattering FCPA

fines are levied in the shadow of the U.S. Gov-

ernment’s purchasing power. For example, the

companies that settled the three most expensive

FCPA enforcement actions to date, and together

paid approximately $1.8 billion in fines (Siemens

AG, $800 million; Halliburton/KBR, $579 million;

BAE Systems, $400 million),

15

also obtained over

$10 billion dollars in U.S. Government contracts

in FY 2010.

16

These figures demonstrate that the

FCPA creates a substantial risk for U.S. Govern-

ment contractors that want to maintain or grow

their business with certain foreign governments.

If a U.S. Government contractor runs afoul of

the FCPA, it could be subject to a multitude

of penalties beyond those faced by companies

that do not contract with the U.S. Government,

as discussed below. Indeed, U.S. Government

contractors that violate the FCPA face not only

sky-high fines and other monetary penalties, but

also risk being blacklisted and prevented from

bidding on future contracting opportunities of-

fered by its Government customers.

17

FCPA Basics & Recent Developments In The

Law

The FCPA contains two distinct components:

(1) the antibribery prohibitions

18

and (2) the

recordkeeping and internal control provisions.

19

The DOJ is responsible for all criminal enforce-

ment of the antibribery provisions and all civil

enforcement of the antibribery provisions involving

domestic concerns and foreign companies and

nationals.

20

The DOJ is also responsible for the

criminal enforcement of “willful” violations of the

books-and-records provisions.

21

The U.S. Securities

and Exchange Commission is responsible for civil

enforcement of the books-and-records provisions,

as well as for civil enforcement of the antibribery

provisions as applied to “issuers”—any U.S. or

foreign company, or an officer, employee, agent,

or stockholder thereof, that either issues securi-

ties (or American Depositary Receipts) or must

file reports with the SEC.

22

The Federal Bureau

of Investigation now plays a prominent role in

FCPA matters, including through its specialized

“International Corruption Unit” dedicated to the

investigation of overseas corruption.

23

Indeed, all

three agencies have specialized units dedicated

to the enforcement of the FCPA.

24

■ Antibribery Prohibitions

The antibribery provisions prohibit the offer

or payment of money or anything of value to a

foreign official for the purpose of obtaining or

retaining business.

25

The phrase “anything of

value” has always been construed broadly by the

Government and is not limited to money.

26

Gen-

erally, whether an item constitutes “anything of

value” depends on the subjective value attached

by the particular recipient.

27

Moreover, there is

no minimum value that must be met before the

item constitutes an improper gift. Recent en-

forcement actions indicate that even de minimis

payments are prohibited under the antibribery

provisions. For example, the Criminal Informa-

tion charging Panalpina Inc. with conspiring to

violate and violating the antibribery provisions

of the FCPA noted that “[t]he value of the bribe

payments ranged from de minimis amounts to

$25,000 per transaction,”

28

and in the settlement

of Paradigm B.V.’s FCPA enforcement action, the

Government noted that the bribes included pay-

ments or “acceptance” fees of $100–200 dollars.

29

The antibribery provisions prohibit the brib-

ery of foreign government officials—they do not

prohibit bribery of purely commercial entities.

The FCPA expressly defines the term “foreign

official” as officers or employees of a foreign

government, including its departments, agen-

cies and instrumentalities, public international

organizations, or persons acting in an official ca-

pacity for or on behalf of these entities.

30

Similar

to other aspects of the FCPA, the Government

has interpreted the term “foreign official” very

broadly, including low-level employees of state-

owned entities. Although the FCPA’s definition

of foreign official does not expressly mention

state-owned enterprises, the Government has

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

4

argued that state-owned enterprises are merely

an “instrumentality” of a foreign government, as

expressly provided for in the FCPA.

31

In several

recent cases, federal judges have affirmed the

Government’s interpretation of “foreign official,”

including a case in May 2011, where a judge

ruled that a state-owned entity may qualify as

an “instrumentality” of a foreign government.

32

The defendants in that matter, former executives

from Control Components Inc., argued that a

state-owned entity could never be considered an

instrumentality of a foreign government.

33

The

judge rejected this argument, explaining that

the determination regarding whether a company

is an instrumentality is a question of fact that

depends upon various factors, including (a) the

foreign state’s characterization of the entity and

its employees, (b) the foreign state’s degree of

control over the entity, (c) the purpose of the

entity’s activities, (d) the entity’s obligations and

privileges under the foreign state’s law, includ-

ing whether the entity exercises exclusive or

controlling power to administer its designated

functions, (e) the circumstances surrounding

the entity’s creation, and (f) the foreign state’s

extent of ownership of the entity, including the

level of financial support by the state (e.g., sub-

sidies, special tax treatment, and loans).

34

The

court stated that the factors are “not exclusive,

and no single factor is dispositive,” explaining

that they are merely “relevant when determining

whether a state-owned company constitutes an

‘instrumentality’ under the FCPA.”

35

Other recent

cases have also supported the Government’s in-

terpretation,

36

indicating that the Government’s

broad definition of the term “foreign official”

should be a benchmark for companies designing

FCPA compliance policies.

The FCPA provides one limited exception to

the antibribery prohibitions, as well as two affir-

mative defenses. All three are difficult to navigate

and rarely provide an adequate safeguard for a

company once improper payments have been

detected. The facilitating payment exception

states that the antibribery prohibitions do not

apply “to any facilitating payment or expediting

payment to a foreign official, political party, or

party official the purpose of which is to expedite

or to secure the performance of a routine govern-

mental action.”

37

This extremely limited exception

is designed to permit payments used to expedite

“non-discretionary, ministerial activities performed

by mid- or low-level foreign functionaries.”

38

The

exception is so limited, it has even been called

“illusory.”

39

For example, in the DOJ’s settlement

with Noble Corporation for payments it made to

Nigerian customs officials in “special handling

charge[s],” the Government stated that the pay-

ments “were not qualifying facilitating payments

under the FCPA or otherwise legitimate expenses.”

40

Consequently, because the company improperly

recorded the fees as “facilitation payments” in its

books and records, the Government also alleged

that Noble Corporation

created false books and

records in violation of the FCPA

. The U.S. Gov-

ernment’s limited interpretation of the facilitat-

ing payment exception brings it in line with the

majority of other governments, including the

United Kingdom, that do not permit facilitating

payments under their antibribery regimes.

41

As

the Noble matter demonstrates, the facilitation

payment exception has caused confusion among

companies that do business with foreign govern-

ments, especially given the “continued high level

of demand for facilitation payments by foreign

officials, especially customs officers and for the

implementation of operating and maintenance

contracts.”

42

Despite this increasing demand,

facilitation payments continue to create a di-

lemma for companies, given that (1) facilitation

payments are likely prohibited in the country in

which they are being sought, (2) there is little

available guidance regarding when the exception

is applicable, and (3) even if a payment were

to qualify as a facilitation payment, a company

would still need to record it properly in its books

and records. Indeed, failure to accurately record

potentially qualifying facilitation payments has

caused numerous companies to run afoul of the

FCPA’s books-and-records provisions.

43

The two affirmative defenses to the antibribery

prohibitions are similarly limited in scope. Both

provisions provide a defense to liability under

the antibribery prohibitions for payments or gifts

to foreign officials if they are (1) lawful under

the written laws and regulations of the foreign

official’s country, or (2) “reasonable and bona

fide” expenditures incurred by or on behalf of a

foreign official “directly related” to the promo-

tion, demonstration, or explanation of products

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

5

or services or to the execution or performance of

a contract with a foreign government or agency.

44

The first affirmative defense permits payments

only if they are expressly authorized under the

written laws or regulations of the foreign country.

This defense has long been considered relatively

obsolete, but was further narrowed in a recent

court ruling that clarified that this affirmative

defense applies only to laws that render the bribe

itself legal, regardless of whether the law provides

a form of legal amnesty to the defendant under

certain circumstances.

45

The second affirmative defense permits U.S.

companies to pay “reasonable and bona fide”

expenses associated with a foreign official’s visit

to the United States, as long as they are directly

related to the promotion or demonstration of a

product or to the performance of a Government

contract.

46

The DOJ’s FCPA Opinion Procedure,

under which the agency responds to specific

inquiries submitted by companies concerning

the legality of their conduct under the FCPA,

47

continues to provide instructive guidance regard-

ing this affirmative defense.

48

Among many other

Opinion Procedures released in past years, the

first for 2011 outlines “hospitality” best practices,

which include, but are not limited to the following:

(1) companies should pay only for the expendi-

tures of the government officials, not spouses or

other family members, (2) the company should

not play a role in selecting the government official

who will visit, (3) costs should be paid directly

to service providers, (4) companies should not

provide officials with cash or spending money,

(5) any souvenirs provided should have nominal

value, and (6) side trips and other nonbusiness-

related activities should not be funded by the

company.

49

■ Recordkeeping & Accounting Provisions

The recordkeeping and accounting provisions

of the FCPA require issuers of publicly traded

securities to maintain records and accounts that

accurately reflect the company’s transactions.

50

The provisions also require an issuer to maintain

internal accounting controls sufficient to provide

reasonable assurance that its financial statements are

accurate.

51

The purpose of the latter requirement is

to ensure a company detects and (preferably) pre-

vents violations of the FCPA. Moreover, because the

accounting requirements are based on a concept of

reasonableness and not materiality, the provisions

apply to all documents and records, regardless of the

dollar amount involved in the specific transaction.

52

For example, Team Inc., a Texas industrial services

company, disclosed that it was internally investigat-

ing potential corrupt payments totaling at most,

$50,000.

53

Moreover, in its disclosure, the company

explained that the total annual revenues from the

branch of the company involved in the improper

activity represented “approximately one-half of one

percent of our annual consolidated revenues.”

54

Be-

cause there is no de minimis exception applicable to

the books-and-records provisions of the FCPA, the

company found itself spending approximately $3.2

million to investigate payments that were immaterial

to the company’s overall financial situation.

55

This

example makes clear that companies must ensure

their books and records are accurate and must make

internal controls a priority.

The accounting and antibribery sections work

in tandem to prevent companies from hiding

bribes and other improper transactions off-the-

record to conceal misconduct.

56

There is, however,

no requirement that the accounting provisions

must be linked to the bribery of a foreign official.

Consequently, the Government may prosecute a

company for violating the accounting provisions,

even in the absence of a separate violation of the

antibribery provisions.

57

In recent years, the SEC

has taken action against companies pursuant to

the accounting provisions of the Act, even when

the Government is unable to establish a viola-

tion of the antibribery provisions. For example,

in 2011, the SEC settled a civil action charging

NATCO Group, Inc. with violations of the books-

and-records and internal control provisions of

the FCPA.

58

In the NATCO action, the Govern-

ment alleged that the company’s wholly owned

subsidiary, TEST Automation & Controls, Inc.,

“created and accepted false documents while

paying extorted immigration fines and obtaining

immigration visas in the Republic of Kazakhstan.”

Although the company made improper payments,

it was not charged with violating the antibribery

provisions.

59

Instead, the Government alleged

that TEST violated the accounting provisions of

the FCPA when it falsely characterized the pay-

ments as a “salary advance.”

60

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

6

FCPA Jurisdiction

The FCPA’s prohibitions and requirements

have been construed broadly by the relevant

enforcement agencies, especially in regard to

its jurisdictional reach. The FCPA’s antibribery

prohibitions apply to any act “in furtherance of”

an improper payment taken within the United

States, regardless of the nationality of the party

engaging in the improper activity.

61

Thus, the

antibribery provisions apply to both U.S. and for-

eign concerns, if the conduct occurs in any area

over which the United States asserts “territorial

jurisdiction.”

62

Territorial jurisdiction also applies

to any issuer that has a class of securities (includ-

ing American Depository Receipts) registered

pursuant to 15 U.S.C.A. § 78l or that is required

to file reports with the SEC under 15 U.S.C.A.

§ 78o(d).

63

The antibribery provisions’ nationality-

based jurisdiction renders the statute applicable

to acts taken wholly outside the United States,

as long as a U.S. concern or issuer commits the

act.

64

Jurisdiction under the accounting provi-

sions of the FCPA extend only to individuals or

companies that meet the definition of “issuer.”

65

In recent enforcement actions, the Govern-

ment has continued to expand FCPA jurisdiction,

especially in regard to foreign companies and

individuals. Since 1998, the FCPA antibribery

prohibitions have applied to both “issuer” and

non-“issuer” foreign companies and individuals

that commit an act in furtherance of the bribe

while in the territory of the United States.

66

The

Government’s liberal interpretation of the FCPA’s

“in furtherance of” requirement has enabled the

Government to pursue foreign companies and

individuals, as long as they take some act within

the United States that facilitates or furthers the

improper payment.

67

Indeed, eight of the eleven

top FCPA settlements in history involve foreign

companies (or persons).

68

Recent enforcement

actions have demonstrated that the Government

will pursue foreign companies even when the act

“in furtherance of” the improper payment includes

a mere transfer through a correspondent account

in the United States. For example, in 2011, JGC

Corporation resolved FCPA allegations, agreeing to

a settlement including $218.8 million for the bribery

of Nigerian government officials.

69

The Criminal

Information included allegations that JGC aided

and abetted a co-conspirator in causing “corrupt

U.S. dollar payments” to be wire transferred from

a bank account in Amsterdam, “via correspondent

bank accounts in New York,” to bank accounts in

Switzerland, to be used, in part, for the bribery of

Nigerian government officials.

70

The Government

has alleged jurisdiction on the basis of the use of

correspondent accounts in several other recent

enforcement actions as well, including against

Siemens,

71

KBR,

72

and Technip S.A.

73

While most FCPA enforcement actions in recent

years have continued to push the boundaries of

the FCPA’s territorial jurisdiction, a recent case

indicates that there are limits to the reach of

the FCPA. When the U.S. Government charged

Pankesh Patel, a UK citizen, with violating the

FCPA, the Government predicated jurisdiction on

allegations that Patel mailed an original copy of

a purchase agreement relating to alleged corrupt

activity from the United Kingdom to the United

States.

74

The court rejected this argument, granting

Patel’s Rule 29 acquittal motion, and noting that

because the mailing of the agreement occurred

in the United Kingdom, it was not “in the terri-

tory of the United States” and did not establish

jurisdiction under 15 U.S.C.A. § 78dd-3(a).

75

While the Government’s broad interpretations

of jurisdiction are rarely tested, it is possible that

as more companies and individuals test these

theories in court, some limitations to the reach

of the FCPA may be established.

FCPA Sanctions

■ Monetary Fines & Penalties

Recent enforcement actions indicate that a com-

pany’s failure to adequately monitor its business

practices overseas could cost it hundreds of millions

of dollars in fines and expenses. The consequences

are even more problematic for contractors that do

business with the U.S. Government, as an FCPA

violation could harm a contractor’s business with

the U.S. Government and foreign governments.

Contractors have substantial incentive to comply

with the FCPA given the potential penalties that

may result if they fail to do so.

The FCPA’s primary sanction for violations of

its provisions involves monetary fines, penalties,

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

7

and incarceration. Penalties for corporations and

other business entities that violate the FCPA’s

antibribery provisions include a civil penalty of

up to $10,000 and a criminal fine of up to $2 mil-

lion, while penalties for individuals include a civil

penalty of up to $10,000, a criminal fine of up to

$250,000, and five years’ imprisonment, for each

violation of the FCPA.

76

In addition, the “Sentence

of fine” statute permits the Government to fine

persons up to twice the gross pecuniary gain or

loss resulting from the corrupt payment.

77

These

fines and penalties are particularly difficult for

individuals, because employers are not permitted

to pay for their employees’ monetary penalties.

78

Violations of the recordkeeping and internal

control provisions may result in civil penalties of

up to $500,000 for an entity and up to $100,000 for

an individual, or the gross amount of pecuniary

gain.

79

Criminal violations of the recordkeeping

provisions carry a maximum fine of $25 million for

companies, and a $5 million fine and incarcera-

tion for up to 20 years for individuals.

80

The SEC

also typically seeks disgorgement of any ill-gotten

gains associated with the improper activity.

81

Recent FCPA enforcement actions indicate that

the Government is continuing to use monetary

penalties, disgorgement, forfeiture, and incarcera-

tion to deter other companies and individuals

from running afoul of the FCPA. The Govern-

ment will continue to prosecute FCPA actions

in this manner, because “prosecuting individu-

als—and levying substantial criminal fines against

corporations—are the best ways to capture the

attention of the business community.”

82

Indeed,

FCPA enforcement is responsible for nearly 50%

of the $2 billion in settlements and judgments

obtained by the Criminal Division of the DOJ in

2010.

83

The SEC has been similarly active. Since

2010, the SEC has filed 32 FCPA cases and settled

enforcement actions resulting in more than $600

million in penalties, disgorgement, and interest.

84

The Government’s message has been clear: if you

violate the FCPA, you will pay for it. The numbers

support this. In 2010, the DOJ and SEC imposed

over $1.7 billion in penalties and disgorgement

for violations of the FCPA—the highest year for

FCPA fines in history.

85

In the past decade, the

dollar amounts have increased at a dramatic rate.

Indeed, the top 10 FCPA corporate settlements of

all time were imposed between 2008–2011, with

Siemens AG holding the title of “most expensive

FCPA violation” to date.

86

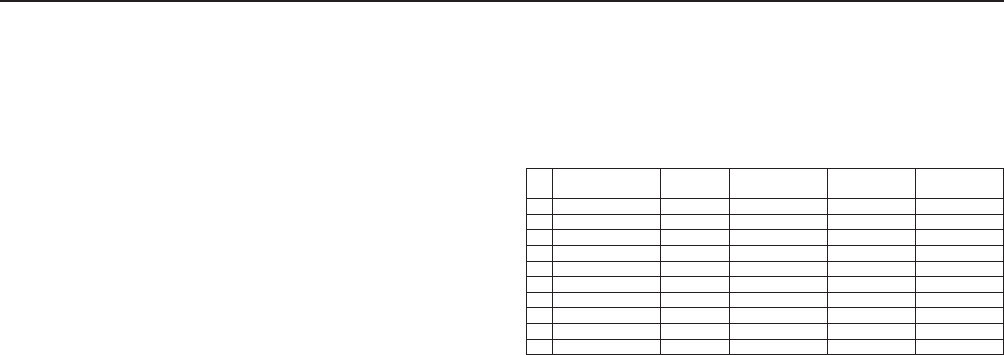

The top 10 corporate settlements total nearly

$3.2 billion in fines and penalties. Fines against

individuals are similarly large. Between 1998 and

October 2010, more than $2 billion in criminal

fines were imposed against individuals.

87

This num-

ber includes several sizable monetary payouts by

individuals, including the eighth most expensive

FCPA enforcement action to date against Jeffrey

Tesler, totaling $148,964,568.

88

The Government also continues to exploit the

other monetary remedies available to it, such as

disgorgement. In fact, from 2004 to date, over $1

billion has been disgorged.

89

Disgorgement is an

equitable remedy used to prevent an entity from

profiting from illegal activities by stripping it of

any ill-gotten gains it may have received as a result

of the improper activity.

90

The SEC currently uses

disgorgement as an enforcement tool in a majority

of the FCPA matters it settles. Because disgorge-

ment is not considered punitive, the SEC may

only disgorge “the approximate amount earned

from the alleged illicit activities.”

91

FCPA-related

disgorgements can total hundreds of millions of

dollars, as with Siemens ($350 million),

92

KBR

($177 million),

93

and Snamprogetti ($125 mil-

lion).

94

The Government may also subject FCPA violators

to another financial blow—forfeiture. “Forfeiture”

permits the Government to seize a wide variety of

assets, including money judgments, property, and

substitute assets.

95

The Government will use “sub-

stitute assets” when the proceeds of a defendant’s

illegal act are unrecoverable as the result of the

defendant’s acts or omissions.

96

Although tradi-

tionally considered to be a rarely used sanction,

recent FCPA enforcement actions suggest that this

Company

Date of

Settlement

DOJ

SEC

Total

1

Siemens

12/12/08

$450,000,000

$350,000,000

$800,000,000

2

Halliburton/KBR

2/11/09

402,000,000

177,000,000

579,000,000

3 BAE 3/1/10 400,000,000 0 400,000,000

4 Snamprogetti 7/7/10 240,000,000 125,000,000 365,000,000

5

Technip

6/28/10

240,000,000

98,000,000

338,000,000

6

JGC Corporation

4/6/11

218,800,000

0

218,800,000

7

Daimler

4/1/10

93,600,000

91,400,000

185,000,000

8 Alcatel-Lucent 12/27/10 92,000,000 45,372,000 137,372,000

9 Panalpina 11/4/10 70,560,000 11,300,000 81,890,000

10

J&J

4/8/11

21,400,000

48,600,000

70,000,000

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

8

is no longer the case. For example, after paying

bribes to Nigerian government officials for nearly

decade to obtain engineering, procurement, and

construction contracts, Jeffrey Tesler, a former

consultant to KBR and its joint venture partners,

pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate the FCPA

and agreed to forfeit $148,964,568—the largest

FCPA-related forfeiture involving an individual

in history.

97

Similarly, when Gerald and Patricia

Green, former Hollywood film executives, were

convicted of nine counts of violating the FCPA

and seven counts of money laundering for their

payment of approximately $1.8 million in bribes

to the former governor of the Tourism Authority

of Thailand,

98

in addition to other sanctions and

remedies, the court imposed a personal money

judgment of criminal forfeiture in the amount of

$1,049,465, plus the amount of each defendant’s

share of their pension plans.

99

The defendants

could not satisfy this order, so the Government

filed a motion seeking substitute assets in the form

of Patricia Green’s West Hollywood residence.

100

The sanctions and forfeiture eventually rendered

the defendants indigent, claiming the couple’s

savings, home, car, company, and pension assets.

101

The Government is also using forfeiture as a

means to recover illegal bribes from the foreign

government officials who accept them. Attorney

General Eric Holder has made clear that through

the “enforcement of [the United States’] asset

forfeiture laws,” recovering the bribes accepted

by foreign officials is “a global imperative.”

102

For

example, in 2010, Robert Antoine, the former

director of international affairs for Haiti’s state-

owned national telecommunications company,

Telecommunications D’Haiti, pleaded guilty to

conspiracy to commit money laundering.

103

In

his plea agreement, Antoine admitted to accept-

ing bribes from three U.S. telecommunications

companies and laundering them through inter-

mediary companies.

104

In addition to a four-year

prison sentence and the payment of $1,852,209

in restitution, the U.S. Government was able to

recover the illegal proceeds of this bribery scheme

by ordering Antoine to forfeit $1,580,771.

105

■ Incarceration

In addition to monetary penalties and remedies,

the most dramatic trend in recent FCPA actions

involves the incarceration of individuals who vio-

late the FCPA. The Government has made clear

that FCPA violations may result in “very serious

penalties, which can include substantial prison

time for individuals who violate the law.”

106

The

prison terms have been significant. In April 2011,

Charles Paul Edward Jumet, an officer of Ports

Engineering Consultants Corporation, received

an 87-month prison sentence—the longest prison

sentence ever associated with an FCPA matter.

107

Jumet pleaded guilty to conspiring to violate the

FCPA by conspiring to pay more than $200,000

in bribes to Panamanian government officials in

exchange for contracts to maintain lighthouses

and buoys along Panama’s waterway.

108

Jumet also

made a false statement to federal agents about

the true nature of a check used to corruptly pay

a Panamanian government official.

109

Similarly,

the former chairman and chief executive offi-

cer of KBR, Albert “Jack” Stanley, agreed to an

84-month prison term when he pleaded guilty to

conspiracy to violate the FCPA and conspiracy to

commit mail and wire fraud.

110

Stanley admitted to

authorizing a joint venture that paid nearly $200

million in bribes to Nigerian officials to obtain

$6 billion in Nigerian construction contracts to

build liquefied natural gas facilities on Bonny

Island, Nigeria.

111

In many cases, judges have ordered prison sen-

tences far lighter than what was initially sought by

the Government. For example, prosecutors in the

case against Patricia and Gerald Green sought a

10-year prison term for both defendants, though

they each received only six-month terms.

112

Leo

Winston Smith, former director of sales and

marketing for Pacific Consolidated Industries,

pleaded guilty to bribing a government official

in the UK Ministry of Defense.

113

Despite the

Government’s 37-month recommendation, Mr.

Smith received a six-month prison term with an

additional six months of home confinement.

114

Prosecutors sought a 168–210 month sentence for

Nam Nguyen

115

for bribing government officials

in Vietnam to secure high-tech contracts, but

he was only sentenced to 16 months,

116

while his

co-defendant An Nguyen received nine months

for his role in the bribery scheme,

117

despite the

87–108 months recommended by prosecutors.

118

While a variety of factors may be the cause of this

frequent downward departure by judges (e.g.,

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

9

health or age of the defendant), judges may be

revealing a bias against lengthy prison terms for

cases involving foreign bribery. What is clear,

however, is that the Government will continue

to seek lengthy prison terms as both a deterrent

against corruption and bargaining chip in its

plea negotiations with individuals.

FCPA Collateral Consequences

While the threat of fines, penalties, disgorge-

ment, and incarceration are sufficient to deter

most companies from bribing officials to obtain

business with foreign governments, companies

that contract with the Government have even

more to lose if they are caught making illicit

payments. For contractors, their livelihood is

at risk, because suspension or debarment from

selling goods or services to the United States

(and other government entities) is a potential

collateral consequence of violating the FCPA.

■ U.S. Suspension & Debarment Regime

The U.S. suspension and debarment regime

is designed to protect taxpayer dollars by ensur-

ing that the Government does business only

with responsible firms.

119

Both suspension and

debarment are extraordinary tools, empowering

the Government with the authority to suspend a

contractor for up to a year

120

or debar a contrac-

tor for up to three years.

121

Neither suspension

nor debarment is meant to be punitive—they are

designed to ensure that the Government does

business only with ethical and honest companies.

A company’s exclusion from the U.S. procure-

ment regime may be as broad or as limited as

the Government deems necessary to protect its

interests, ranging from the debarment of the

entire company to the debarment of a division,

facility, or even a single individual.

122

While the terms “suspension” and “debarment”

are often used interchangeably, they differ in

scope and procedure. The decision to suspend

or debar hinges on the ability to demonstrate

“present responsibility,” which requires, among

other things, a “satisfactory record of integrity

and business ethics.”

123

Suspension is a temporary

exclusion from contracting, triggered by “adequate

evidence” of an offense or misconduct that either

indicates a lack of business integrity or is so seri-

ous that it affects the “present responsibility” of a

contractor.

124

Some agencies consider an indict-

ment of such misconduct, such as the bribery of

a foreign official, to be adequate evidence of a

lack of present responsibility (though it is not

required).

125

In contrast, debarment is a more

permanent status, requiring a “preponderance

of evidence” of misconduct or the commission of

an offense that indicates either a lack of business

integrity or is so serious that it affects the “pres-

ent responsibility” of a contractor.

126

An agency

may debar a contractor based on a conviction

or civil judgment for various offenses, including

the bribery of a foreign official, but neither is

required.

127

Any agency may suspend or debar a contractor,

but once an agency has made that determination,

all agencies must abide by that agency’s decision

(absent negotiated exceptions). In other words, if

a contractor is suspended by the U.S. Air Force,

“it cannot do business with the Navy, [the Na-

tional Aeronautics and Space Administration],

the [General Services Administration], or any of

the other approximately 125 Executive Branch

agencies or departments.”

128

Thus, once a company

is either suspended or debarred, it is completely

excluded from both obtaining contracts directly

with the Government and subcontract work under

prime contracts with the Government.

129

Notably,

because the system is not designed to punish con-

tractors, suspension or debarment only applies

to future contracts, task orders, and options to

extend current contracts—neither suspension

nor debarment affects existing contract work

with the Government.

130

Once a contractor is either suspended or de-

barred, its status as a blacklisted company is made

public through a variety of mechanisms. First,

suspended and debarred contractors are publicly

listed on the Excluded Party Listing Service.

131

All contracting officials are required to review

the EPLS prior to award, and prime contractors

are prohibited from awarding subcontracts to

contractors on this list as well. The EPLS is even

often relied upon by state and local governments,

which often refuse to work with any contractor

listed on the EPLS. While there are no free, pub-

licly available databases that monitor state and

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

10

local debarments, there are privately maintained

databases that are available to the public for a

fee.

132

Even if a contractor is neither suspended nor

debarred, its alleged violation of the FCPA may

be added to the company’s profile in several

other databases. The Federal Government now

maintains a Federal Awardee Performance and

Integrity Information System (FAPIIS), devel-

oped to maintain “specific information on the

integrity and performance of covered Federal

agency contractors and grantees,” such as contract

terminations, past performance, responsibility

determinations, administrative agreements, or

criminal, civil, or administration actions involving

the contractor.

133

Similar to the EPLS database,

Contracting Officers are supposed to use FAPIIS

to review a company’s history, including any past

misconduct, before awarding a contract.

134

In

addition to the Government-maintained FAPIIS

database, the Project on Governmental Over-

sight (POGO) maintains a Federal Contractor

Misconduct Database (FCMD), which contains

“histories of misconduct such as contract fraud

and environmental, ethics, and labor violations.”

135

The FCMD “is a compilation of misconduct and

alleged misconduct committed by the top Fed-

eral Government contractors between January 1,

1995, and the present,” including civil, criminal,

or administrative settlements.

136

No contractor

wants to find itself listed in a publicly available

database alongside companies that have behaved

in a disreputable manner. These databases may

not only harm a contractor’s reputation, they can

also potentially harm a contractor’s Government

business. Contracting Officers tasked to work with

only responsible contractors

137

may be deterred

from working with contractors that have blemished

records. Moreover, because the information in

these databases is available to the public, media

and congressional pressure may influence agen-

cies to avoid contracting with FCPA violators.

What makes suspension and debarment a par-

ticularly complicated collateral consequence of the

FCPA, is that it is not a coordinated regime—the

authority to take such action does not lie with

the FCPA enforcement agencies—it resides with

any one of the procuring agencies and binds all

other agencies to the determination. Moreover,

any agency can suspend or debar a contractor

at any time, regardless of the recommendation

of the DOJ. If a contractor has committed an

offense, such as bribery, an agency is unlikely

to find the contractor “presently responsible,”

unless the contractor can demonstrate that the

bribery was limited to a division or subsidiary of

the company that does not do business with the

U.S. Government. Even then, a contractor must

still convince the Government that the violation

of the FCPA was an isolated incident and has no

bearing on the company’s Government business.

Consequently, a contractor’s behavior following

the discovery of the misconduct, its level of coop-

eration with the Government, and any remedial

measures it has taken, become essential to its

survival.

The risk of suspension and debarment places

contractors in an unfortunate position when an

FCPA violation is uncovered. Because the DOJ

lacks the authority to prevent the suspension

or debarment of a contractor, contractors must

proceed cautiously to avoid any of the likely sus-

pension and debarment triggers. If, for example,

a legal proceeding (such as an indictment) has

been formally initiated by the DOJ, any procuring

agency may suspend that contractor until the legal

proceeding has finished—including any and all

appeals.

138

It is therefore obvious why many U.S.

contractors try to eliminate this risk as quickly as

possible through settlement negotiations.

Notably, while a company may resolve an FCPA

matter with the DOJ by settlement agreement

to avoid a criminal charge or conviction, these

agreements are not a guaranteed shield against

suspension or debarment. The Government

has been clear that neither type of settlement

agreement will preclude a company’s suspen-

sion or debarment, as the agreements bind

only the DOJ.

139

It is, however, possible for the

DOJ to agree to make “representations about a

company’s criminal conduct and remediation

measures to a government contracting agency”

to help the company avoid suspension and debar-

ment.

140

Thus, it is common for the Government

to use the threat of suspension and debarment

to extract extraordinary fines and penalties from

companies in exchange for their support dur-

ing negotiations with debarment officials from

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

11

other agencies. Indeed, if a company agrees to

cooperate, the DOJ may even agree to insert an

affirmative statement in the settlement documents

attesting to a company’s present responsibility.

For example, in 2010, Daimler AG resolved brib-

ery allegations in which the Government alleged

that the company “engaged in a long-standing

practice of paying bribes to foreign officials…in at

least 22 countries…to assist in securing contracts

with government customers for the purchase of

Daimler vehicles valued at hundreds of millions

of dollars.”

141

In its deferred prosecution agree-

ment with the DOJ, the Government included a

provision that stated:

142

With respect to Daimler’s present reliability and

responsibility as a government contractor, the

Department agrees to cooperate with Daimler, in

a form and manner to be agreed, in bringing facts

relating to the nature of the conduct underlying

this Agreement and to Daimler’s cooperation and

remediation to the attention of governmental and

other debarment authorities.

The DOJ’s ability to work with a company to

avoid suspension and debarment is significant

leverage given the potentially devastating con-

sequences that either could have on a company.

Many companies would rather cooperate with

the DOJ than suffer the consequences that might

stem from an indictment or guilty verdict. As

such, it is no surprise that nearly all companies

settle FCPA charges with the Government rather

than challenge them in court.

In recent years, criticism has been levied against

the Government for its failure to use the suspen-

sion and debarment tools when companies settle

FCPA or FCPA-related matters.

143

Specifically, com-

mentators and lawmakers have complained that

when U.S. Government contractors are involved

in an FCPA enforcement matter, “an agreement

by DOJ to intervene on the company’s behalf in

any collateral proceedings, such as suspension and

debarment, is a staple of deferred prosecution

agreements.”

144

While the indignation is currently

directed towards the suspension and debarment

regime in the context of the FCPA, the regime itself,

even in matters unrelated to the FCPA, has long

been criticized as an impotent enforcement tool.

145

It is not surprising that this tool is underutilized,

as the Government depends on a relatively small

number of contractors to supply a majority of its

goods and services. Indeed, “with fewer major,

critical contractors available to compete for the

Government’s most sophisticated requirements, it

seems disingenuous to bar a key player from future

competition.”

146

In fact, although BAE Systems

PLC admitted to (1) conspiring to defraud the

United States by impairing and impeding its law-

ful functions, (2) making false statements about

its FCPA compliance program, and (3) violating

the Arms Export Control Act and International

Traffic in Arms Regulations when it actually (al-

legedly) bribed government officials in exchange

for billions of dollars worth of defense contracts,

the U.S. Government still awarded it over $6.6

billion in contracts in FY 2010.

147

Critics may

continue to gripe about the current state of the

suspension and debarment regime, but the take-

away is clear: companies that provide unique and

important goods and services to the Government

are highly unlikely to be suspended or debarred

as the result of an FCPA violation. As such, the

critics’ demands are not only impractical; they

demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of

the U.S. suspension and debarment regime. The

decision to suspend or debar is a business decision

“that requires a weighing of the risks and benefits

to the Government of contracting with an ethically

questionable firm.”

148

The Government, therefore,

has determined in recent matters that the benefits

to working with contractors that have violated the

FCPA outweigh the risks. Moreover, requiring

the mandatory debarment of companies that are

found to have violated the FCPA could substantially

deter companies from disclosing wrongdoing,

remedying problems, and improving compliance

systems.

149

Indeed, “linking mandatory debarment

to a criminal resolution would fundamentally alter

the incentives of a contractor-company to reach

an FCPA resolution because such a resolution

would likely lead to the cessation of revenues for

a government contractor— a virtual death knell

for the contractor-company.” Similarly, manda-

tory debarment would have a negative impact on

prosecutorial discretion—eliminating the flexibility

necessary to fashion an appropriate resolution

depending on the particular matter.

150

■ Denial Of Other U.S. Public Advantages

In addition to debarment from the U.S. pro-

curement regime, a company that violates the

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

12

FCPA may be ineligible to receive certain other

“public advantages” from the Government, such

as grants, loans, subsidies, or insurance.

151

Like-

wise, a contractor may be excluded from various

other Government programs, such as those found

in agencies like the Commodity Futures Trading

Commission and the Overseas Private Investment

Corporation.

152

Similarly, the Export-Import Bank

may also decline, among other things, applica-

tions for export credit as the result of a company’s

fraudulent or corrupt activity.

153

Another poten-

tial collateral consequence of an FCPA violation

is the possible loss of Government licenses. This

sanction could have an even more devastating

impact on a contractor than debarment, as the

denial of necessary licenses would likely affect

not only a company’s Government sales, but its

commercial sector business as well.

154

In addition,

a company could have its Government security

or facility clearances

155

revoked as the result of

its violation of the FCPA—a sanction that could

render the company ineligible for any current or

future contracts containing such requirements.

The denial of arms export licenses under § 38

of the AECA

156

is another possible outcome when

an applicant has been indicted for or convicted

of violating the FCPA.

157

In addition, § 120.1 of

the ITAR expressly states that licenses or other

approvals may not be granted to entities indicted

for, or convicted of, violating the FCPA.

158

Follow-

ing BAE’s $400 million FCPA-related settlement

with the DOJ, the U.S. Department of State an-

nounced that it entered into a civil settlement

with BAE Systems for 2,591 alleged violations

of the AECA and ITAR “in connection with the

unauthorized brokering of U.S. defense articles

and services, failure to register as a broker, failure

to file annual broker reports, causing unauthor-

ized brokering, failure to report the payment

of fees or commissions associated with defense

transactions, and the failure to maintain records

involving ITAR-controlled transactions.”

159

The

settlement required BAE to pay $79 million in

fines and remedial compliance measures—the

largest civil penalty in State Department history.

160

Because of BAE’s criminal conviction, the State

Department imposed a statutory debarment on

BAE, but concurrently rescinded the order, after

determining that “appropriate steps had been

taken to mitigate law enforcement concerns.”

161

The Department also released an administrative

hold that it had placed on BAE’s license authoriza-

tion requests immediately following the company’s

conviction. The agency did, however, impose a

“policy of denial” on three BAE subsidiaries that

were substantially involved in the activities that

led to the company’s conviction. This means that

there is “an initial presumption of denial” for all

applications from the impacted entities absent a

determination by the State Department that “it is

in the foreign policy or national security interests

of the United States to provide an approval.”

162

Global Antibribery Enforcement &

Collateral Consequences

Government contractors with a global pres-

ence must not only worry about compliance

with the FCPA, they also must be aware of the

antibribery laws in other countries as well. In

recent years, numerous other countries have

implemented more aggressive antibribery regimes

and are actively investigating and prosecuting

bribery cases. For example, the UK Bribery

Act, in force since July 1, 2011, is currently the

cause of greatest concern to companies that do

business in the United Kingdom, because its

provisions are broad, relatively undefined, and

prohibit activities beyond those prohibited by

the FCPA. Similar to the FCPA, the UK Bribery

Act prohibits the bribery of foreign officials,

but it also prohibits commercial bribery and

the failure of a commercial organization to

prevent bribery.

163

Also unlike the FCPA, the

Bribery Act extends jurisdiction over bribe

recipients.

164

The UK Bribery Act is causing

further difficulty for companies that do business

in both the United States and United Kingdom

because it does not permit facilitation payments

or allow an affirmative defense for hospitality

expenditures. As such, companies are strongly

advised to review and update their bribery poli-

cies and compliance programs to ensure they

comply not only with the FCPA, but with the

new heightened standards provided by the UK

Bribery Act (and the bribery laws in any other

country in which the company does business).

In addition to the penalties associated with

the violation of a foreign country’s antibribery

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

13

laws, contractors may also be debarred from

doing business with a foreign government. If a

company violates the FCPA (or another coun-

try’s antibribery laws), debarment from govern-

ment procurement contracts in Europe is also

a potential consequence. Article 45 of the EU

Public Sector Procurement Directive requires

contractors convicted of any of the following

crimes to be debarred from public procurement:

(1) participation in a criminal organization,

(2) corruption, (3) fraud, or (4) money laun-

dering.

165

This is a punitive regime under which

debarment is mandatory and is designed to deter

corruption and bribery in public procurement

activities.

166

The mandatory debarment trigger is

clear: “conviction by final judgment of which the

contracting authority is aware.”

167

This stringent

penalty provides an even greater incentive for

companies that violate antibribery laws to settle

with the Government—they do not want to lose

their contracts with the EU member states. While

there is an exception for “overriding requirements

in the general interest,” it is unclear whether

authorities would permit an exception to the

mandatory debarment rules for a company that

violates the FCPA or other antibribery laws.

168

In

addition, even if a contractor is not “convicted”

of violating such a law, it may still be prohibited

from contracting with an EU member state. Sec-

tion 2 of Article 45 also describes a discretionary

debarment trigger under which contractors may

be excluded for a variety of other reasons, includ-

ing “grave professional misconduct.”

169

The mandatory debarment provisions have been

implemented in the United Kingdom through

Regulation 23(1) of the Public Contracts Regula-

tions 2006

170

and Regulation 26(1) of the Utili-

ties Contracts Regulations 2006.

171

Moreover, in

June 2011, the UK Ministry of Justice published

amended legislation relating to the Bribery Act

making clear that mandatory debarment will be

a likely collateral consequence of a conviction

under §§ 1 and 6 of the Bribery Act—the bribery

of another person or a foreign public official,

respectively.

172

Conversely, the MOJ has stated

publicly that a corporation’s conviction under

§ 7 of the Bribery Act—failure of a commercial

organization to prevent bribery—may only result

in discretionary debarment.

173

Recent FCPA-related settlements have dem-

onstrated that government officials in both

the United States and Europe may go to great

lengths to prevent a valuable contractor from

being excluded by the EU mandatory debarment

provisions, as “there is a growing recognition that

the [European Union] debarment requirement

presents particular challenges for companies

trying to settle cases.”

174

As a result, the Govern-

ment considers “collateral consequences when

structuring settlement agreements.”

175

The Gov-

ernment’s settlement with BAE exemplifies this

issue. Despite widespread allegations of bribery,

neither the U.S. nor UK governments charged BAE

with violating the countries’ relevant antibribery

laws.

Thus, neither settlement agreement trig-

gered mandatory debarment—a clear goal of the

two countries, given that debarment could “ruin

BAE, which employs more than 100,000 people

and is the biggest supplier to the British Armed

Forces.”

176

In this instance, the U.S. Government

extracted an extraordinary $400 million criminal

fine from BAE, the third highest FCPA settlement

in history, in exchange for lesser charges that

would not implicate the mandatory debarment

regime. Indeed, the BAE Sentencing Memoran-

dum expressly explains that the settlement was

structured for this reason, noting that:

177

Mandatory exclusion under EU debarment

regulations is unlikely in light of the nature of the

charge to which BAES is pleading. Discretionary

debarment will presumably be considered and

determined by various suspension and debarment

officials.

The Department will communicate with

U.S. debarment and regulatory authorities, and

relevant foreign authorities, if requested to do

so, regarding the nature of the offense of which

BAES has been convicted, the conduct engaged

in by BAES, its remediation efforts, and the facts

relevant to an assessment of whether BAES is

presently a responsible Government contractor.

Recent settlements with Siemens AG and Daimler

AG were similarly structured to avoid implicating

the mandatory debarment regime.

178

Debarment By Other International

Organizations

Other international organizations may also

suspend or debar contractors if the company or

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

14

individual is found to have violated the FCPA. For

example, the World Bank may debar any firms or

entities that have been found “to have engaged

in fraudulent, corrupt, collusive, coercive or ob-

structive practices.”

179

In fact, “debarment with

conditional release has become the default or

‘baseline’” sanction for such actions.

180

Similar to

the United States, the World Bank also maintains

a list of debarred contractors that renders the

companies and individuals on the list “ineligible

to be awarded a World Bank-financed contract”

for the period of debarment.

181

Historically, the World Bank has demonstrated

that it is far more likely than its government coun-

terparts to debar a company in response to corrupt

behavior. For example, the World Bank exercised its

debarment authority against Siemens after Siemens

settled its FCPA violations with the United States.

182

Specifically, Siemens AG and its affiliates entered

into a settlement agreement with the “World Bank

Group,”

183

under which it agreed to, among other

things, debarment from all projects, programs, or

other investments financed or guaranteed by the

World Bank for at least two years and a payment

of $100 million over 15 years to support global ef-

forts to fight fraud and corruption.

184

In a separate

proceeding, the World Bank debarred Siemens

Russia OOO, a subsidiary of Siemens AG, for four

years for “having engaged in fraudulent and cor-

rupt practices in relation to a World Bank-financed

project”

185

The World Bank Group permitted Sie-

mens to continue working on existing contracts,

though it required the company to withdraw all

bids that had not been accepted by the start of the

debarment period.

186

Similarly, the World Bank

debarred Macmillan, a UK-based publisher, after

it admitted to bribing officials in Sudan to win a

World Bank-related contract to print educational

material.

187

The debarment has rendered Macmil-

lan ineligible from Bank-financed contracts for six

years.

188

Debarment from a multilateral bank is now

even a greater risk to companies that have vio-

lated the FCPA given a recent action taken by

the heads of leading multilateral development

banks to purge corrupt companies and individuals

from their projects. On April 9, 2010, the leading

MDBs—the African Development Bank, the Asian

Development Bank, the European Bank for Recon-

struction and Development, the Inter-American

Development Bank Group, and the World Bank

Group—entered into an “Agreement For Mutual

Enforcement of Debarment Decisions,” under

which a company or individual debarred by one

bank may be debarred from contracting with all

five development banks, as long as the debar-

ment exceeds a period of one year and relates

to corruption.

189

This agreement is made even

more effective by its disclosure requirements: all

five institutions are required to notify each other

when they have debarred a contractor.

190

In addition to MDBs, other institutions may refuse

to do business with a company that violates the FCPA.

For example, a company may be suspended from

doing business with the United Nations Secretariat

Procurement Division if it violates the FCPA.

191

A

year after Siemens settled its FCPA violations with

the U.S. Government, Siemens announced that

the Vendor Review Committee of the UNPD was

suspending Siemens from the UNPD vendor data-

base for a minimum period of six months.

192

Other Costs Associated With FCPA

Enforcement

While the Government has a mighty arsenal of

penalties and sanctions that it can impose on com-

panies that run afoul of the FCPA, they are not the

only costs a company could face should it uncover

evidence of questionable payments. For example,

an internal investigation could cost a company mil-

lions of dollars. In 2009, Team Inc. disclosed that

an internal investigation uncovered questionable

payments totaling no more than $50,000.

193

In a

filing with the SEC, the company noted that it had

spent approximately $3.2 million in investigation-

related expenses, such as legal fees.

194

The SEC

notified Team in 2011 that it did not intend to

impose fines or penalties on the company.

195

The

DOJ similarly indicated that it was unlikely to take

formal action against the company, though it has yet

to formally close the investigation.

196

The company,

therefore, spent $3.2 million—an amount 64 times

greater than the $50,000 the company allegedly

paid to obtain an improper business advantage, to

investigate allegations that the Government did not

deem worthy of prosecution. This example makes

clear that for many companies, the costs associated

Briefing Papers © 2011 by Thomson Reuters

★ AUGUST BRIEFING PAPERS 2011 ★

15

with a discovered FCPA violation may far exceed

any benefit obtained by the bribe.

Similarly, when Avon Products Inc. received

notice of an allegation that “certain travel,

entertainment and other expenses may have

been improperly incurred in connection with

the Company’s China operations,” it launched

an internal investigation that, according to the

company’s own disclosures, has cost them over

$150 million dollars to date.

197

While the initial

allegation involved only the company’s activities

in China, the investigation soon expanded to the

company’s operations in other countries.

198

Thus,

it is possible that by the time Avon finishes its

investigation and begins settlement negotiations

with the Government, the cost of the internal

investigation alone will top $250 million.

199

Other collateral expenses may result from the

disclosure of an FCPA investigation in an SEC

filing. In particular, this type of disclosure may

result in a substantial decrease in the company’s

stock price, profits, or sales, generating yet

another FCPA-related cost. For example, when

Avon disclosed its investigation into bribery al-

legations in China, its shares dropped 8%.

200

When Faro Technologies Inc. disclosed that it

was close to settling an FCPA enforcement action

with the DOJ and SEC, the company directly at-

tributed a drop in profits to its announcement

regarding the pending FCPA settlement.

201

When

weapons maker Smith & Wesson announced an

internal investigation into potential violations

of the FCPA, the company soon discovered that

the announcement negatively affected its sales,

disclosing that “[p]istol sales decreased 25.3%,

driven by the reduction in consumer demand as

well as reduced international shipments related

to our investigation of the FCPA matter.”

202

Companies may also face additional expendi-

tures stemming from collateral civil litigation.

While there is no private right of action under

the FCPA,

203

companies are now finding that after

they announce an investigation into allegations

of improper conduct, or even after they settle

their FCPA-related enforcement actions, they

may become the target of lawsuits, including

but not limited to, securities fraud actions and

shareholder derivative suits. While the success of

these suits has varied, some collateral litigation

has resulted in enormous payouts to the plain-

tiffs: Willbros Group settled for $10.5 million,

Nature’s Sunshine settled for $6 million, and Faro

Technologies settled for $6.9 million.

204

Avon is

also currently the target of a number of securities

fraud and shareholder derivative actions alleg-

ing “breaches of various fiduciary duties for not

properly monitoring the company’s operations

and securities violations for not making proper

disclosure of the problems.”

205

Whether these suits

will be successful remains to be seen, but Avon

stands as a cautionary tale to other companies

that do business overseas. One can only assume

that by the time the dust settles, Avon’s total bill