FINANCIAL

INSTITUTIONS

Fines, Penalties, and

Forfeitures for

Violations of Financial

Crimes and Sanctions

Requirements

Report to Congressional Requesters

GAO-16-297

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-16-297, a report to

congressional requesters

March 2016

FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Fines, Pena

lties, and Forfeitures for Violations

of Financial Crimes and Sanctions

Requirements

Why GAO Did This Study

Over the last few years, billions of

dollars have been collected in fines,

penalties, and forfeitures assessed

against financial institutions for

violations of requirements related to

financial crimes. These requirements

are significant tools that help the

federal government detect and disrupt

money laundering, terrorist financing,

bribery, corruption, and violations of

U.S. sanctions programs.

GAO was asked to review the

collection and use of these fines,

penalties, and forfeitures assessed

against financial institutions for

violations of these requirements—

specifically, BSA/AML, FCPA, and U.S.

sanctions programs requirements. This

report describes (1) the amounts

collected by the federal government for

these violations, and (2) the process

for collecting these funds and the

purposes for which they are used.

GAO analyzed agency data, reviewed

documentation on agency collection

processes and on authorized uses of

the funds in which collections are

deposited, and reviewed relevant laws.

GAO also interviewed officials from

Treasury (including the Financial

Crimes Enforcement Network and the

Office of Foreign Assets Control),

Securities and Exchange Commission,

Department of Justice, and the federal

banking regulators.

GAO is not making recommendations

in this report.

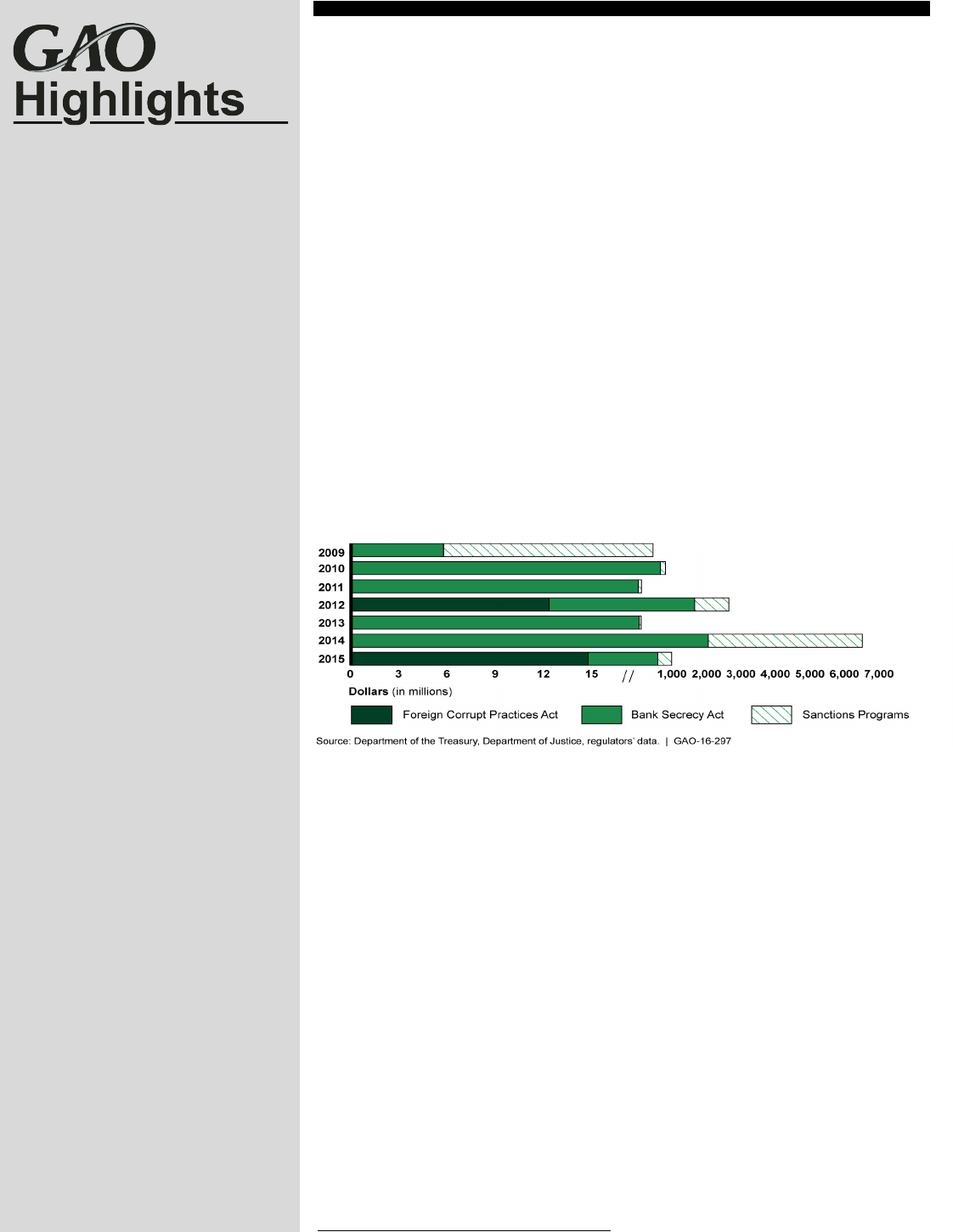

What GAO Found

Since 2009, financial institutions have been assessed about $12 billion in fines,

penalties, and forfeitures for violations of Bank Secrecy Act/anti-money-

laundering regulations (BSA/AML), Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977

(FCPA), and U.S. sanctions programs requirements by the federal government.

Specifically, GAO found that from January 2009 to December 2015, federal

agencies assessed about $5.2 billion for BSA/AML violations, $27 million for

FCPA violations, and about $6.8 billion for violations of U.S. sanctions program

requirements. Of the $12 billion, federal agencies have collected all of these

assessments, except for about $100 million.

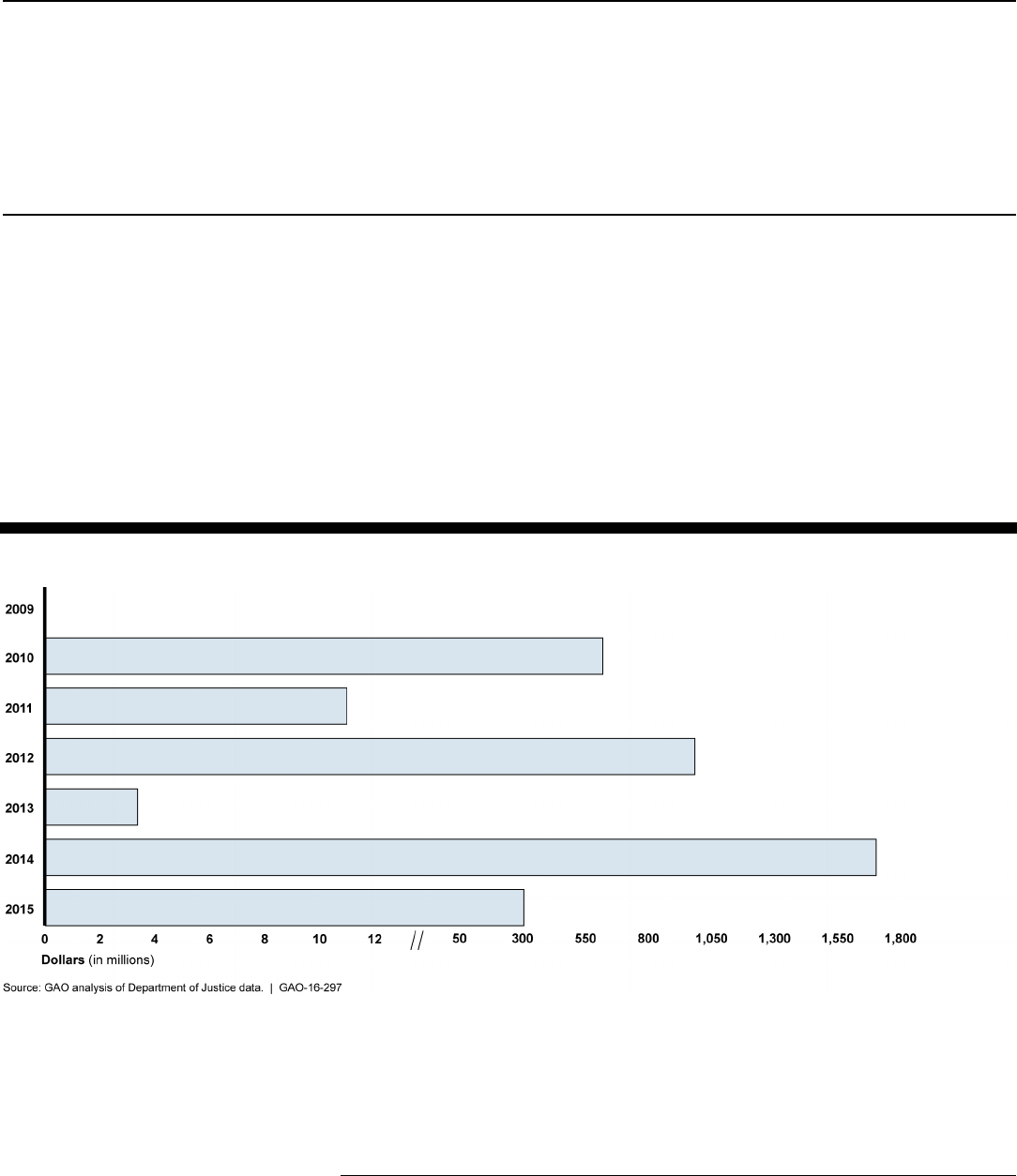

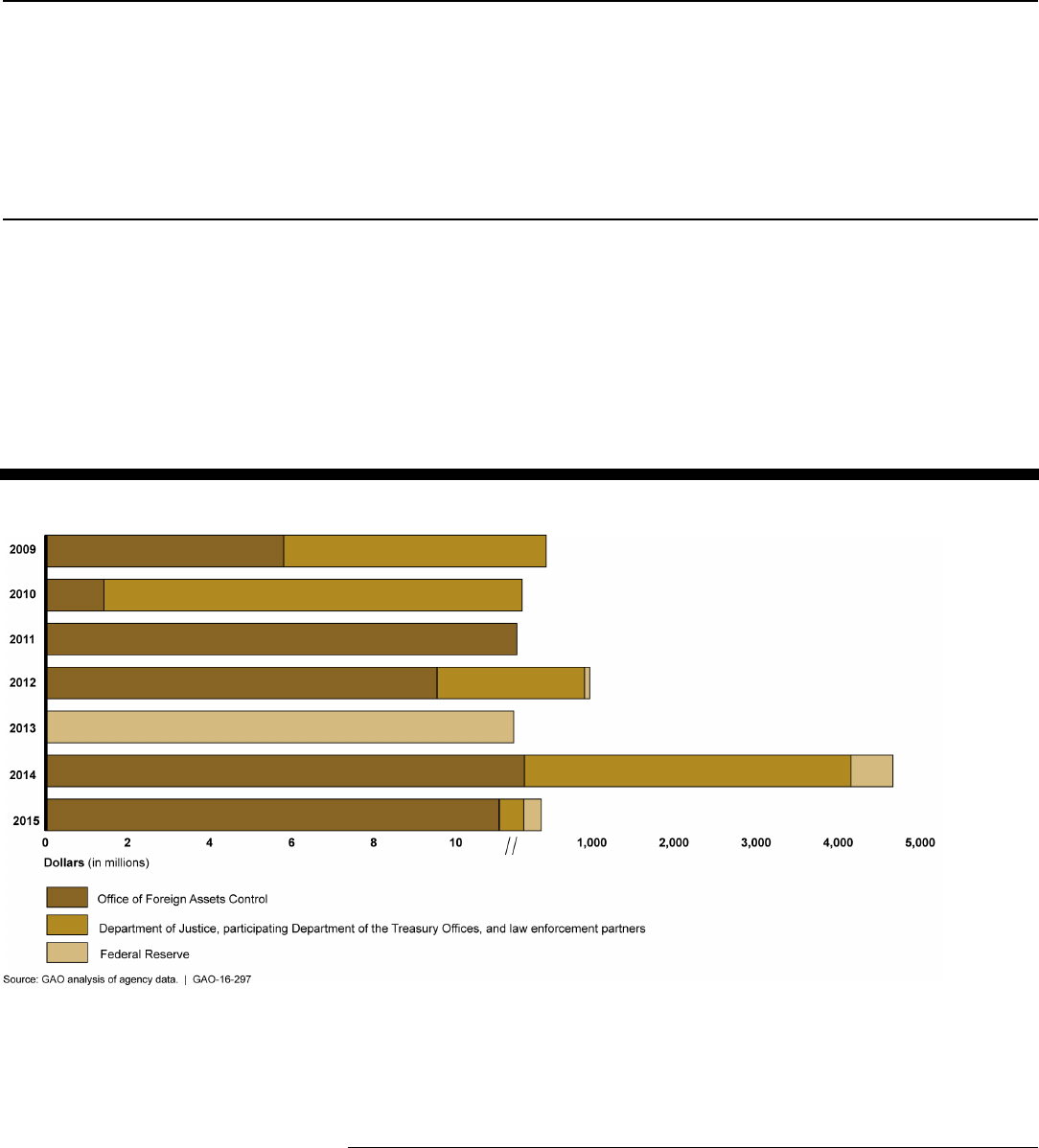

Collections of Fines, Penalties, and Forfeitures from Financial Institutions for

Violations of Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering, Foreign Corrupt Practices

Act, and U.S. Sanctions Programs Requirements, Assessed in January 2009–

December 2015

Agencies have processes for collecting payments for violations of BSA/AML,

FCPA, and U.S. sanctions programs requirements and these collections can be

used to support general government and law enforcement activities and provide

payments to crime victims. Components within the Department of the Treasury

(Treasury) and financial regulators are responsible for initially collecting penalty

payments, verifying that the correct amount has been paid, and then depositing

the funds into Treasury’s General Fund accounts, after which the funds are

available for appropriation and use for general support of the government. Of the

approximately $11.9 billion collected, about $2.7 billion was deposited into

Treasury General Fund accounts. The BSA and U.S. sanctions-related criminal

cases GAO identified since 2009 resulted in the forfeiture of almost $9 billion

through the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Treasury. Of this amount, about

$3.2 billion was deposited into DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture Fund (AFF) and $5.7

billion into the Treasury Forfeiture Fund (TFF), of which $3.8 billion related to a

sanctions case was rescinded in fiscal year 2016 appropriations legislation.

Funds from the AFF and TFF are primarily used for program expenses,

payments to third parties, including the victims of the related crimes, and

payments to law enforcement agencies that participated in the efforts resulting in

forfeitures. As of December 2015, DOJ and Treasury had distributed about $1.1

billion to law enforcement agencies and about $2 billion was planned for

distribution to crime victims. Remaining funds from these cases are subject to

general rescissions to the TFF and AFF or may be used for program or other law

enforcement expenses.

View GAO-16-297. For more information,

contact

Lawrance Evans at (202) 512-8678 or

or Diana C. Maurer at (202)

512

-9627 or [email protected].

Page i GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

Letter 1

Background 5

Financial Institutions Have Paid Billions for Violations of Financial

Crimes-Related Requirements since 2009 11

Collections for Violations Are Used to Support General

Government and Law Enforcement Activities and Victims

Payments 19

Agency Comments 31

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 32

Appendix II GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 37

Tables

Table 1: Treasury Asset Forfeiture Program Components 9

Table 2: Justice Asset Forfeiture Program Components 10

Table 3: GAO-Identified Bank Secrecy Act and U.S. Sanctions-

Related Criminal Cases, January 2009–December 2015 35

Figures

Figure 1: Collections from Financial Institutions for Bank Secrecy

Act-Related Penalties Assessed by Federal Financial

Regulators, Independently and Concurrently with the

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network in January 2009–

December 2015 13

Figure 2: Collections of Forfeitures and Fines from Financial

Institutions for Bank Secrecy Act-Related Criminal Cases,

Assessed in January 2009–December 2015 15

Figure 3: Collections from Financial Institutions for U.S. Sanctions-

Related Forfeitures and Penalties, Assessed in January

2009–December 2015 18

Figure 4: Process for Collecting and Depositing Penalty Payments 20

Figure 5: Justice Asset Forfeiture Program and Treasury

Forfeiture Program Asset Forfeiture Processes 25

Contents

Page ii GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

Abbreviations

AFF Asset Forfeiture Fund

AML anti-money laundering

BFS Bureau of Fiscal Service

BSA Bank Secrecy Act

DOJ Department of Justice

FCPA Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977

FDIC Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

Federal Reserve Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

FinCEN Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

FRBR Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

IRS Internal Revenue Service

NCUA National Credit Union Administration

OCC Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

OFAC Office of Foreign Assets Control

SEC Securities and Exchange Commission

TFF Treasury Forfeiture Fund

Treasury Department of the Treasury

USA PATRIOT Act United and Strengthening America by Providing

Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and

Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

March 22, 2016

The Honorable Michael G. Fitzpatrick

Chairman

Task Force to Investigate Terrorism Financing

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Stephen F. Lynch

Ranking Member

Task Force to Investigate Terrorism Financing

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Robert Pittenger

Vice Chairman

Task Force to Investigate Terrorism Financing

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Over the last few years, billions of dollars have been collected in fines,

penalties, and forfeitures from financial institutions for violations related to

the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977

(FCPA), and U.S. sanctions programs requirements—referred to as

“covered violations” in this report. These requirements are significant

tools that aid the federal government in detecting, disrupting, and

inhibiting financial crimes, terrorist financing, bribery, corruption, and

economic interactions with entities that undermine U.S. policy interest,

among other things. For example, Congress passed BSA and FCPA to

combat money laundering, prohibit U.S. businesses from paying bribes to

foreign officials, and target the financial resources of terrorist

organizations.

1

Similarly, federal agencies have developed regulations

related to U.S. sanctions programs to enforce the blocking of assets and

trade restrictions to accomplish foreign policy and national security goals.

As part of these efforts to stop the illegal flow of funds and to deter

1

Pub. L. No. 91-508, tits. I-II, 84 Stat. 1114 (1970) (codified as amended at 12 U.S.C. §§

1829b, 1951-1959; 31 U.S.C. §§ 5311-5330); Pub. L. No. 95-123, tit. I, 91 Stat. 1494

(codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §§ 78dd-1 – 78dd-3).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

financial crimes, federal agencies—including the Department of Justice

(DOJ), Department of the Treasury (Treasury), and Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC) and other financial regulators—have the

ability to reach settlements, take enforcement actions against institutions

and individuals, and, in the case of DOJ and Treasury, seize assets.

These actions may result in fines, penalties, or forfeitures that the

agencies collect.

2

You asked us to review the amounts of fines, penalties, and forfeitures

federal agencies have collected from financial institutions for violations of

BSA and related anti-money-laundering (AML) requirements (referred to

as “BSA/AML requirements”), FCPA, and U.S. sanctions programs

requirements, how these funds and forfeitures are used and the policies

and controls governing their distribution.

3

This report describes (1) the

amount of fines, penalties, and forfeitures that the federal government

has collected for these violations from January 2009 through December

2015, and (2) the process for collecting these funds and the purposes for

which they are used.

4

To describe the fines, penalties, and forfeitures federal agencies have

assessed on, and collected from, financial institutions, we identified and

analyzed relevant agencies’ data on enforcement actions taken and

cases brought against financial institutions that resulted in fines,

penalties, or forfeitures for the covered violations. Specifically, we

2

Fines and penalties result from enforcement actions that require financial institutions to

pay an amount agreed upon between the financial institution and the enforcing agency, or

an amount set by a court or in an administrative proceeding. Forfeitures result from

enforcement actions and are the confiscation of money, assets, or property, depending on

the violation.

3

With respect to U.S. sanctions programs requirements, we included violations by

financial institutions of U.S. sanctions programs enforced by the Department of the

Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), such as trade and financial sanction

programs and related compliance requirements that are part of federal financial regulators’

examination programs. With respect to anti-money-laundering (AML) requirements, our

review focused on those requirements that financial institutions must implement to be in

compliance with BSA, for example establishing an AML compliance program.

4

The Bank Secrecy Act defines financial institutions as depository institutions, money

services businesses, insurance companies, travel agencies, broker-dealers, and dealers

in precious metals, among other types of businesses. 31 U.S.C. § 5312(a)(2). Money

services business is defined by regulation generally as money transmitters, dealers in

foreign exchange, check cashers, issuers or sellers of traveler’s checks or money orders,

providers or sellers of prepaid access, and the Postal Service. 31 C.F.R. §1010.100(ff).

Unless otherwise noted, we use the BSA definition of financial institutions in this report.

Page 3 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

analyzed publicly available data on the number and amounts of fines and

penalties that were assessed from January 2009 through December 2015

by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal

Reserve), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), DOJ, National

Credit Union Administration (NCUA), Office of the Comptroller of the

Currency (OCC), SEC, and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

(FinCEN), a bureau within Treasury.

5

We also reviewed enforcement

actions listed on Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)

website and identified any actions taken against financial institutions.

6

To

identify criminal cases against financial institutions for violations of BSA

and sanctions-related requirements, we reviewed press releases from

DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section and related court

documents, as well as enforcement actions listed on OFAC’s website. To

determine the amounts forfeited for these cases, we obtained data from

DOJ’s Consolidated Asset Tracking System and verified any Treasury-

related data in DOJ’s system by obtaining information from the Treasury

Executive Office for Asset Forfeiture.

7

We assessed the reliability of the data from financial regulators and

Treasury that we used by reviewing prior GAO evaluations of these data,

interviewing knowledgeable agency officials, and reviewing relevant

5

NCUA officials we spoke with explained that they had not assessed any penalties against

financial institutions for violations of BSA/AML requirements from January 2009 through

December 2015.

6

To identify enforcement actions taken against financial institutions from the actions listed

on OFAC’s website, we applied OFAC’s definitions of financial institutions which covers

regulated financial entities in the financial industry—such as insured and commercial

banks, an agency or branch of a foreign bank in the U.S., credit unions, thrift institutions,

securities brokers and dealers, operators of credit card systems, insurance or reinsurance

companies, and money transmitters, among others. OFAC’s definitions do not include

travel agencies or dealers in precious metals (which are included under BSA’s definition of

a financial institution).

7

We generally identified criminal cases (and related forfeiture and fines) brought against

financial institutions for violations of BSA and sanctions-related requirements by DOJ and

other law enforcement agencies by reviewing press releases on DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture

and Money Laundering Section website and associated court documents, as well as

enforcement actions listed on OFAC’s website. We developed this approach in

consultation with DOJ officials, as their data system primarily tracks assets forfeited by the

related case, which can include multiple types of violations, rather than by a specific type

of violation, such as BSA or sanctions-related violations. As a result, this report may not

cover all such criminal cases, as some may not be publicized through press releases.

However, our approach does include cases that involved large forfeiture amounts for the

period under our review.

Page 4 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

documentation, such as agency enforcement orders for the fines,

penalties, and forfeitures assessed. To verify that these amounts had

been collected, we requested verifying documentation from agencies

confirming that these assessments had been collected, and also obtained

and reviewed documentation for a sample of the data to verify that the

amount assessed matched the amount collected. As a result, we

determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes. We

assessed the reliability of relevant data fields from DOJ’s Consolidated

Asset Tracking System by reviewing prior GAO and DOJ evaluations of

this system and interviewing knowledgeable officials from DOJ. We

determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for purposes of this

report.

To describe how payments were collected for the covered violations, we

identified and summarized documentation of the various steps and key

agency internal controls for collection processes. We also obtained

documentation, such as statements documenting receipt of a penalty

payment, for a sample of penalties. We interviewed officials from each

agency about the process used to collect payments for assessed fines

and penalties and, for relevant agencies, the processes for collecting

cash and assets for forfeitures. To describe how these collections were

used, we obtained documentation on expenditures from the accounts into

which the payments were deposited. Specifically, we obtained

documentation on the authorized or allowed expenditures for accounts in

the Treasury General Fund, Treasury Forfeiture Fund (TFF), and DOJ’s

Assets Forfeiture Fund (AFF) and Crime Victims Fund. We also reviewed

relevant GAO reports, agency Office of Inspector General reports, and

laws governing the various accounts.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2015 to March 2016 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Page 5 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

BSA established reporting, recordkeeping, and other anti-money-

laundering (AML) requirements for financial institutions. By complying

with BSA/AML requirements, U.S. financial institutions assist government

agencies in the detection and prevention of money-laundering and

terrorist financing by maintaining effective internal controls and reporting

suspicious financial activity.

8

BSA regulations require financial institutions,

among other things, to comply with recordkeeping and reporting

requirements, including keeping records of cash purchases of negotiable

instruments, filing reports of cash transactions exceeding $10,000, and

reporting suspicious activity that might signify money laundering, tax

evasion, or other criminal activities.

9

In addition, financial institutions are

required to have AML compliance programs that incorporate (1) written

AML compliance policies, procedures, and controls; (2) an independent

audit review; (3) the designation of an individual to assure day-to-day

compliance; and (4) training for appropriate personnel.

10

Over the years,

these requirements have evolved into an important tool to help a number

of regulatory and law enforcement agencies detect money laundering,

drug trafficking, terrorist financing, and other financial crimes.

8

For prior GAO reports on BSA-related issues and financial institutions, see GAO, Bank

Secrecy Act: Federal Agencies Should Take Action to Further Improvement Coordination

and Information-Sharing Efforts, GAO-09-227 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 12, 2009) and

Bank Secrecy Act: Opportunities Exist for FinCEN and the Banking Regulators to Further

Strengthen the Framework for Consistent BSA Oversight, GAO-06-386 (Washington,

D.C.: Apr. 28, 2006).

9

See, e.g., 31 C.F.R. § 1010.311, § 1010.320, and § 1010.340.

10

In October 2001, the enactment of the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing

Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001 (“USA

PATRIOT Act”) expanded BSA to require that all financial institutions have AML programs

unless they are exempted by regulation. Pub. L. No. 107-56, § 352, 115 Stat. 272, 322

(codified at 31 U.S.C. § 5318(h)). Entities not previously required under BSA to have such

a program, such as mutual funds, broker-dealers, money service businesses, certain

futures brokers, and insurance companies, were required to do so under this act and

related regulations. Moreover, among other things, the act mandated that Treasury issue

regulations requiring registered securities brokers-dealers to file Suspicious Activity

Reports and provided Treasury with authority to prescribe regulations requiring certain

futures firms to submit these reports. § 356, 115 Stat. at 324.

Background

Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-

Money-Laundering

Requirements

Page 6 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

The regulation and enforcement of BSA involves several different federal

agencies, including FinCEN, the federal banking regulators—FDIC,

Federal Reserve, NCUA, and OCC—DOJ, and SEC. FinCEN oversees

the administration of BSA, has overall authority for enforcing compliance

with its requirements and implementing regulations, and also has the

authority to enforce the act, primarily through civil money penalties.

BSA/AML examination authority has been delegated to the federal

banking regulators, among others. The banking regulators use this

authority and their independent authorities to examine entities under their

supervision, including national banks, state member banks, state

nonmember banks, thrifts, and credit unions, for compliance with

applicable BSA/AML requirements and regulations.

11

Under these

independent prudential authorities, they may also take enforcement

actions independently or concurrently for violations of BSA/AML

requirements and assess civil money penalties against financial

institutions and individuals.

12

The authority to examine broker-dealers and

investment companies (mutual funds) for compliance with BSA and its

implementing regulations has been delegated to SEC, and SEC has

independent authority to take related enforcement actions.

DOJ’s Criminal Division develops, enforces, and supervises the

application of all federal criminal laws except those specifically assigned

to other divisions, among other responsibilities.

13

The division and the 93

11

The Federal Reserve, FDIC, and NCUA share safety and soundness examination

responsibility with state banking departments for state-chartered institutions. State

agencies’ assessments and collections are outside the scope of this report. In addition,

BSA examination authority has been delegated to the Commodity Futures Trading

Commission for futures firms and to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for money

services businesses, casinos, and other financial institutions not under the supervision of

a federal financial regulator. See 31 C.F.R. § 1010.810(b)(8)-(9). This report focuses on

Treasury, the federal banking regulators, and DOJ and SEC (which also have FCPA

responsibilities). The roles of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and IRS in

assessing and collecting fines and penalties are outside the scope of this report. However,

included in this report are civil penalties assessed by FinCEN against IRS-examined

financial institutions for BSA violations. We also did not include self-regulatory

organizations in our review that impose anti-money-laundering rules or requirements

consistent with BSA on their members, such as the Financial Industry Regulatory

Authority, because penalties resulting from their enforcement actions against members

generally are remitted to the organizations and not to the federal government.

12

See 12 U.S.C. § 1818 (i)(2). Enforcement actions may also be taken concurrently with

other federal or state authorities.

13

DOJ’s Criminal Division also has other responsibilities, such as prosecuting many

nationally significant cases and formulating and implementing criminal enforcement policy.

Page 7 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

U.S. Attorneys have the responsibility for overseeing criminal matters as

well as certain civil litigation. With respect to BSA/AML regulations, DOJ

may pursue investigations of financial institutions and individuals for both

civil and criminal violations that may result in dispositions including fines,

penalties, or the forfeiture of assets. In the cases brought against financial

institutions that we reviewed, the assets were either cash or financial

instruments. Under the statutes and regulations that guide the

assessment amounts for fines, penalties, and forfeitures, each federal

agency has the discretion to consider the financial institution’s

cooperation and remediation of their BSA/AML internal controls, among

other factors.

14

The FCPA contains both antibribery and accounting provisions that apply

to issuers of securities, including financial institutions.

15

The antibribery

provisions prohibit issuers, including financial institutions, from making

corrupt payments to foreign officials to obtain or retain business. The

accounting provisions require issuers to make and keep accurate books

and records and to devise and maintain an adequate system of internal

accounting controls, among other things.

16

SEC and DOJ are jointly

responsible for enforcing the FCPA and have authority over issuers, their

officers, directors, employees, stockholders, and agents acting on behalf

of the issuer for violations, as well as entities that violate the FCPA. Both

SEC and DOJ have civil enforcement authority over the FCPA’s

antibribery provisions as well as over accounting provisions that apply to

issuers. DOJ also has criminal enforcement authority.

Generally, financial sanctions programs create economic penalties in

support of U.S. policy priorities, such as countering national security

threats. Sanctions are authorized by statute or executive order, and may

be comprehensive (against certain countries) or more targeted (against

individuals and groups such as regimes, terrorists, weapons of mass

destruction proliferators, and narcotics traffickers). Sanctions are used to,

among other things, block assets, impose trade embargos, prohibit trade

and investment with some countries, and bar economic and military

14

See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. § 1818(i)(2)(F); 31 C.F.R. pt. 501, App. A. The actions of criminal

prosecutors are also guided by the application of the Principles of Federal Prosecution of

Business Organizations. See U.S. Attorneys’ Manual, § 9-28.000 (1997).

15

Issuers include U.S. and foreign companies that are listed on U.S. stock exchanges or

that are required to file periodic reports with SEC.

16

15 U.S.C. §§ 78dd-1 –78dd-3; 15 U.S.C. § 78m(b)(42).

Foreign Corrupt Practices

Act and U.S. Sanctions

Programs

Page 8 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

assistance to certain regimes. For example, financial institutions are

prohibited from using the U.S. financial system to make funds available to

designated individuals or banks and other entities in countries targeted by

sanctions. Financial institutions are required to establish compliance and

internal audit procedures for detecting and preventing violations of U.S.

sanction laws and regulations, and are also required to follow OFAC

reporting requirements. Financial institutions are to implement controls

consistent with their risk assessments, often using systems that identify

designated individuals or entities and automatically escalate related

transfers for review and disposition. Institutions may also have a

dedicated compliance officer and an officer responsible for overseeing

blocked funds, compliance training, and in-depth annual audits of each

department in the bank.

Treasury, DOJ, and federal banking regulators all have roles in

implementing U.S. sanctions programs requirements relevant to financial

institutions. Specifically, Treasury has primary responsibility for

administering and enforcing financial sanctions, developing regulations,

conducting outreach to domestic and foreign financial regulators and

financial institutions, identifying sanctions violations, and assessing the

effects of sanctions. Treasury and DOJ also enforce sanctions regulations

by taking actions against financial institutions for violations of sanctions

laws and regulations, sometimes in coordination with the federal and

state banking regulators. As part of their examinations of financial

institutions for BSA/AML compliance, banking regulators and SEC also

review financial institutions to assess their compliance programs for

sanction laws and regulations.

Treasury and DOJ maintain funds and accounts for fines, penalties, and

forfeitures that are collected.

17

Expenditure of these funds is guided by

statute, and Treasury and DOJ are permitted to use the revenue from

their funds to pay for expenses associated with forfeiture activities.

18

Treasury administers and maintains the Treasury General Fund and TFF.

Treasury General Fund receipt accounts hold all collections that are not

earmarked by law for another account for a specific purpose or presented

in the President’s budget as either governmental (budget) or offsetting

17

Funds provide a fiscal and accounting mechanism with a self-balancing set of accounts

which are segregated for the purpose of carrying on specific activities or attaining certain

objectives.

18

31 U.S.C. § 9705(a); 28 U.S.C. § 524(c).

Funds for Depositing

Collections

Page 9 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

receipts. It includes taxes, customs duties, and miscellaneous receipts.

19

The TFF is a multidepartmental fund that is the receipt account for

agencies participating in the Treasury Forfeiture Program (see table

1).The program has four primary goals: (1) to deprive criminals of

property used in or acquired through illegal activities; (2) to encourage

joint operations among federal, state, and local law enforcement

agencies, as well as foreign countries; (3) to strengthen law enforcement;

and (4) to protect the rights of the individual. Treasury’s Executive Office

for Asset Forfeiture is responsible for the management and oversight of

the TFF.

Table 1: Treasury Asset Forfeiture Program Components

Agencies participating in the Treasury

program

Description

Treasury: Internal Revenue Service - Criminal

Investigation

It is a seizing agency for the program and investigates financial crimes such as

money laundering, corporate fraud, and terrorism financing.

Department of Homeland Security: U.S.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement

It is a seizing agency for the program and is responsible for the investigation of

immigration crimes, human-rights violations, and human smuggling.

Department of Homeland Security: U.S. Customs

and Border Protection

It is a seizing agency for the program and seizes property primarily from U.S.

border-related criminal investigations and passenger/cargo processing. Prohibited

forfeited items, such as counterfeit goods, narcotics, or firearms, are held by it

until disposed of or destroyed.

Department of Homeland Security: U.S. Secret

Service

It is a seizing agency for the program and has primary investigative authority for

counterfeiting, access-device fraud, and cybercrimes.

Department of Homeland Security: U.S. Coast

Guard

The Coast Guard participates in the Treasury program, is the lead federal agency

for maritime drug interdiction, and shares lead responsibility for air interdiction with

U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Source: GAO, Financial Institutions: Fines, Penalties, and Forfeitures for Violations of Financial Crimes and Sanctions Requirements. I GAO-16-297

DOJ administers and maintains deposit accounts for the penalties and

forfeitures it assesses, including the AFF and the Crime Victims Fund.

The AFF is the receipt account for forfeited cash and proceeds from the

sale of forfeited assets generated by the Justice Asset Forfeiture Program

(see table 2).

20

A primary goal of the Justice Asset Forfeiture Program is

preventing and reducing crime through the seizure and forfeiture of

19

See GAO, A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process, GAO-05-734SP

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 1, 2005).

20

For prior GAO work on the Justice Asset Forfeiture Program, see GAO, Justice Assets

Forfeiture Fund: Transparency of Balances and Controls over Equitable Sharing Should

Be Improved, GAO-12-736 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2012).

Page 10 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

assets that were used in or acquired as a result of criminal activity. The

Crime Victims Fund is the receipt account for criminal fines and special

assessments collected from convicted federal offenders, as well as

federal revenues from certain other sources. It was established to provide

assistance and grants for victim services throughout the United States.

21

Table 2: Justice Asset Forfeiture Program Components

Department of Justice

Description

The Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering

Section of the Criminal Division

It is responsible for the coordination, direction, and general oversight of the program.

Asset Forfeiture Management Staff

Asset Forfeiture Management Staff are responsible for the management of the AFF,

program wide contracts, oversight of program internal controls, and the Consolidated

Asset Tracking System—the computer system that tracks all assets.

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and

Explosives

It is a seizing agency for the program and is responsible for enforcing federal laws

and regulations relating to alcohol, tobacco, firearms, explosives, and arson by

working directly and in cooperation with other federal, state, and local law

enforcement agencies. The bureau has the authority to seize and forfeit firearms,

ammunition, explosives, alcohol, tobacco, currency, conveyances, and certain real

property involved in violations of law.

Drug Enforcement Administration

It is a seizing agency for the program and implements major investigative strategies

against drug networks and cartels. It maintains custody over narcotics and other

seized contraband.

Federal Bureau of Investigation

It is a seizing agency for the program and investigates a broad range of criminal

violations, integrating the use of asset forfeiture into its overall strategy to eliminate

targeted criminal enterprise.

The U.S. Marshals Service

The U.S. Marshals Service serves as the primary custodian of seized property for the

program and manages and disposes of the majority of property seized for forfeiture.

Marshals also contracts with qualified vendors to assist in the management and

disposition of property. In addition to serving as the custodian of property, it provides

information and assists prosecutors in making informed decisions about property that

is targeted for forfeiture.

The U. S. Attorneys’ Offices

These offices are responsible for the prosecution of both criminal and civil actions

against property used or acquired during illegal activity.

Source: GAO. I GAO-16-297

Note: There are several agencies outside the Department of Justice that also participate in the

Justice Asset Forfeiture Program, including the United States Postal Inspection Service, the Food and

Drug Administration’s Office of Criminal Investigations, the United States Department of Agriculture’s

Office of the Inspector General, the Department of State’s Bureau of Diplomatic Security, and the

Department of Defense’s Criminal Investigative Service.

21

See 42 U.S.C. § 10601(d). See also GAO, Department of Justice: Alternative Sources of

Funding Are a Key Source of Budgetary Resources and Could Be Better Managed, GAO-

15-48 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 19, 2015).

Page 11 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

In addition, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, established a new

forfeiture fund—the United States Victims of State Sponsored Terrorism

Fund—to receive the proceeds of forfeitures resulting from sanctions-

related violations.

22

Specifically, the fund will be used to receive proceeds

of forfeitures related to violations of the International Emergency

Economic Powers Act and the Trading with the Enemy Act, as well as

other offenses related to state sponsors of terrorism.

Since 2009, financial institutions have been assessed about $12 billion in

fines, penalties, and forfeitures for violations of BSA/AML, FCPA, and

U.S. sanctions program requirements. Specifically, from January 2009

through December 2015, federal agencies assessed about $5.2 billion for

BSA violations, $27 million for FCPA violations, and about $6.8 billion for

violations of U.S. sanctions program requirements. Of the $12 billion,

federal agencies have collected all of these assessments, except for

about $100 million. The majority of the $100 million that was uncollected

was assessed in 2015 and is either subject to litigation, current

deliberations regarding the status of the collection efforts, or bankruptcy

proceedings.

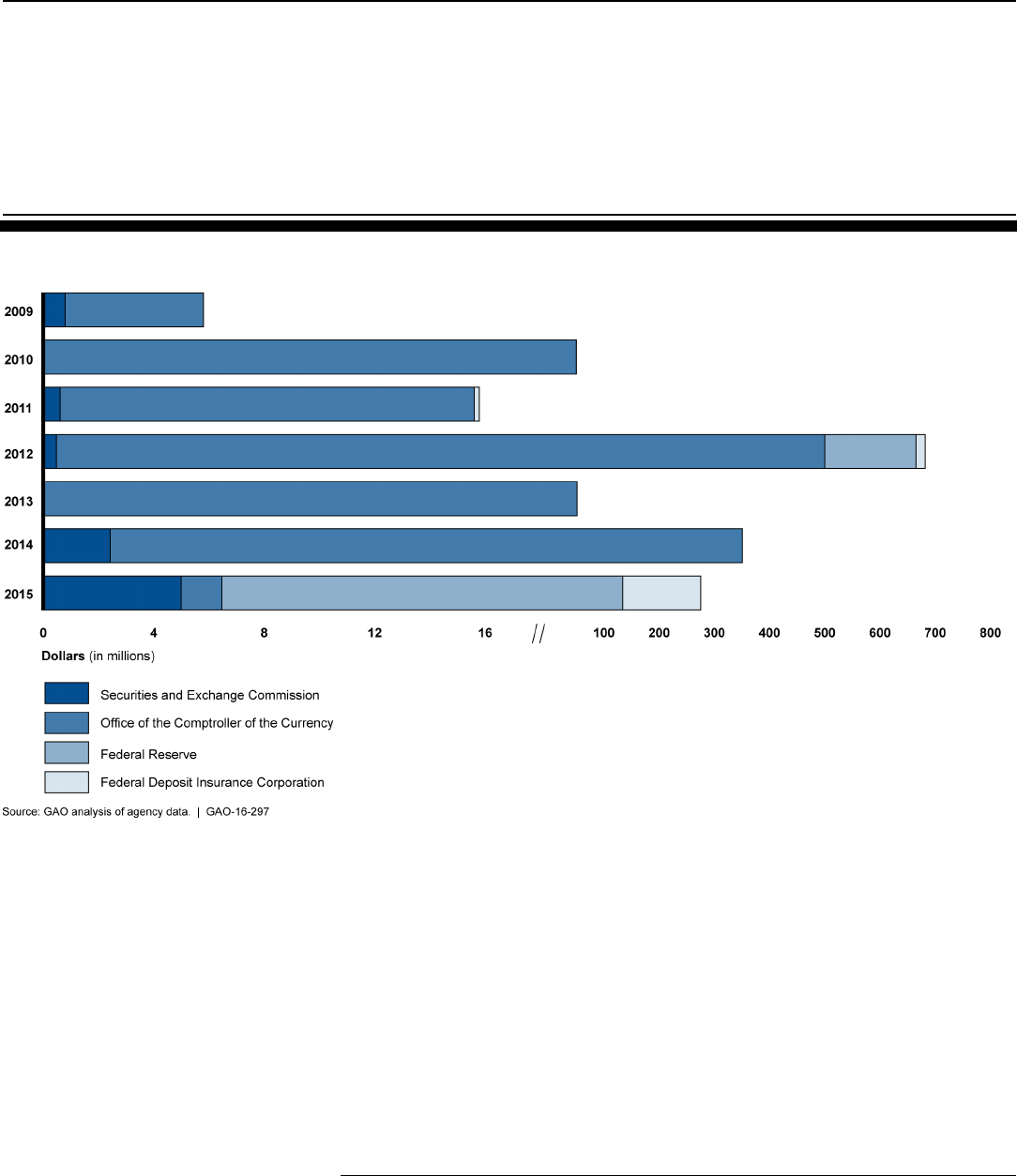

From January 2009 to December 2015, DOJ, FinCEN, and federal

financial regulators (the Federal Reserve, FDIC, OCC, and SEC),

assessed about $5.2 billion and collected about $5.1 billion in penalties,

fines, and forfeitures for various BSA violations. Financial regulators

assessed a total of about $1.4 billion in penalties for BSA violations for

which they were responsible for collecting, and collected almost all of this

amount (see fig. 1). The amounts assessed by the financial regulators

and Treasury are guided by statute and based on the severity of the

violation.

23

Based on our review of regulators’ data and enforcement

orders, the federal banking regulators assessed penalties for the failure to

implement or develop adequate BSA/AML programs, and failure to

identify or report suspicious activity. Of the $1.4 billion, one penalty

(assessed by OCC) accounted for almost 35 percent ($500 million). This

OCC enforcement action was taken against HSBC Bank USA for having

a long-standing pattern of failing to report suspicious activity in violation of

BSA and its underlying regulations and for the bank’s failure to comply

22

Pub. L. No. 114-113, Div. O, § 404(e), 129 Stat. 2242 (2015).

23

12 U.S.C. § 1818(i); 15 U.S.C. § 78u-2; and 31 U.S.C. § 5321.

Financial Institutions

Have Paid Billions for

Violations of Financial

Crimes-Related

Requirements since

2009

Since 2009, Financial

Institutions Have Paid

about $5.1 Billion to the

Federal Government for

BSA Violations

Page 12 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

fully with a 2010 cease-and-desist order.

24

Financial regulators assess

penalties for BSA violations both independently and concurrently with

FinCEN. In a concurrent action, FinCEN will jointly assess a penalty with

the regulator and deem the penalty satisfied with a payment to the

regulator. Out of the $1.4 billion assessed, $651 million was assessed

concurrently with FinCEN to 13 different financial institutions.

25

FinCEN

officials told us that it could take enforcement actions independently, but

tries to take actions concurrently with regulators to mitigate duplicative

penalties.

26

During this period, SEC also assessed about $16 million in

penalties and disgorgements against broker-dealers for their failure to

comply with the record-keeping and retention requirements under BSA.

SEC’s penalties ranged from $25,000 to $10 million—which included a

$4.2 million disgorgement.

27

As of December 2015, SEC had collected

about $9.4 million of the $16 million it has assessed.

28

In the case

resulting in a $10 million assessment, Oppenheimer & Company Inc.

failed to file Suspicious Activity Reports on an account selling and

depositing large quantities of penny stocks.

29

24

In re HSBC Bank USA, Consent Order for the Assessment of a Civil Money Penalty,

OCC Order No. 2012-262 (Dec. 11, 2012).

25

For example, in 2013 OCC and FinCEN assessed against TD National Bank a $37.5

million penalty, which was collected by OCC. See In re TD Bank, Assessment of Civil

Money Penalty, FinCEN Order No. 2013-1 (Sept. 22, 2013).

26

FinCEN officials stated that they decide whether to assess consecutive or concurrent

penalties on the basis of a number of factors, including the seriousness of the violation,

the financial institution’s cooperation, its history of compliance with BSA, and its

willingness to reveal the BSA violation. In actions taken parallel with other regulators,

FinCEN will often consult with these other agencies in determining whether all or a part of

the penalties should be concurrent.

27

Disgorgement is a repayment of ill-gotten gains that is imposed by the court or an

agency on those violating the law.

28

SEC has collected part of the full amount due for two cases during the time frame of our

review. In one case, the debtor has until January 2017 to fully satisfy the payment and has

placed funds in an escrow account to meet the full payment by the due date. In the other

case, the debtor defaulted on the penalty payment and SEC has filed an application in the

United States District Court for the District of New Jersey seeking to require the debtor to

pay the remaining balance of over $2 million in disgorgements, civil penalties, and post-

order interest.

29

In re Oppenheimer & Co. Inc., Order Instituting Administrative and Cease-and-Desist

Proceedings, Exchange Act Release No. 74,141 (Jan. 27, 2015). Oppenheimer also

agreed to pay an additional $10 million to settle a parallel action by FinCEN.

Page 13 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

Figure 1: Collections from Financial Institutions for Bank Secrecy Act-Related Penalties Assessed by Federal Financial

Regulators, Independently and Concurrently with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network in January 2009–December 2015

Note: In this figure, we included collections for actions taken concurrently by federal financial

regulators and FinCEN, as well as actions taken independently by federal financial regulators. The

regulators collect all of the penalties that they assess both independently and concurrently with

FinCEN. This figure does not include any independent assessments collected by FinCEN. Of the

about $1.4 billion assessed from January 2009 through December 2015, almost all of this amount has

been collected except for about $6 million.

In addition, FinCEN assessed about $108 million in penalties that it was

responsible for collecting. Based on our analysis, almost all of the $108

million was assessed in 2015 of which $9.5 million has been collected as

of December 2015.

30

Of the $108 million FinCEN assessed, three large

penalties totaling $93 million—including a $75 million penalty—were

assessed in 2015 and, according to FinCEN officials, have not been

collected due to litigation, current deliberations regarding the status of the

30

The $108 million assessed by FinCEN also includes the assessment amounts of several

partially concurrent enforcement actions that FinCEN took with regulators for which

FinCEN was responsible for collecting.

Page 14 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

collection efforts, or pending bankruptcy actions. FinCEN’s penalty

assessments amounts ranged from $5,000 to $75 million for this period

and are guided by statute and regulations, the severity of the BSA

violation, and other factors.

31

For example, in a case resulting in a $75

million penalty assessment against Hong Kong Entertainment (Overseas)

Investments, FinCEN found that the casino’s weak AML internal controls

led to the concealment of large cash transactions over a 4-year period.

32

We found that institutions were assessed penalties by FinCEN for a lack

of AML internal controls, failure to register as a money services business,

or failure to report suspicious activity as required.

33

Through fines and forfeitures, DOJ, in cooperation with other law

enforcement agencies and often through the federal court system,

collected about $3.6 billion from financial institutions from January 2009

through December 2015 (see fig. 2).

34

Almost all of this amount resulted

from forfeitures, while about $1 million was from fines. As of December

2015, $1.2 million had not been collected in the cases we reviewed.

35

These assessments consisted of 12 separate cases and totaled about 70

percent of all penalties, fines, and forfeitures assessed against financial

institutions for BSA violations. DOJ’s forfeitures ranged from about

31

31 U.S.C. § 5321(a); 31 C.F.R. § 1010.820.

32

In re Hong Kong Entertainment (Overseas) Investments, Ltd., Assessment of Civil

Money Penalty, FinCEN Order No. 2015-07 (June 3, 2015).

33

For purposes of BSA, certain nonbank financial institutions, such as currency exchanges

and check cashing businesses, are considered money services businesses. With few

exceptions, each money services business must register with the Department of the

Treasury.

34

DOJ can assess BSA-related forfeitures and fines through prosecutions initiated by a

U.S. Attorney, the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section, or a combination of

both, often in coordination with other law enforcement agencies, including the Federal

Bureau of Investigation, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, IRS-Criminal

Investigation, United States Post Office Inspector General, and State District Attorney’s

Offices. As noted previously, for this report, we identified BSA-related forfeitures by DOJ

and other law enforcement agencies by reviewing press releases on DOJ’s Asset

Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section website, and obtaining and reviewing related

court documents. The $3.6 billion does not comprise the entire universe of BSA/AML-

related forfeitures because DOJ may have made other BSA-related forfeitures not

publicized through this channel. However, our approach does include cases that involved

large forfeiture amounts for the period under our review.

35

As of December 2015, DOJ officials told us that no payment had been collected for one

case with an outstanding amount of about $1.2 million, due in part to the incarceration of

the violator.

Page 15 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

$240,000 to $1.7 billion, and six of the forfeitures were at least $100

million. According to DOJ officials, the amount of forfeiture is typically

determined by the amount of the proceeds of the illicit activity. In 2014,

DOJ assessed a $1.7 billion forfeiture—the largest penalty related to a

BSA violation—against JPMorgan Chase Bank. DOJ cited the bank for its

failure to detect and report the suspicious activities of Bernard Madoff.

The bank failed to maintain an effective anti-money-laundering program

and report suspicious transactions in 2008, which contributed to their

customers losing about $5.4 billion in Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme.

36

For the remaining cases, financial institutions were generally assessed

fines and forfeitures for failures in their internal controls over AML

programs and in reporting suspicious activity.

Figure 2: Collections of Forfeitures and Fines from Financial Institutions for Bank Secrecy Act-Related Criminal Cases,

Assessed in January 2009–December 2015

Note: Of the $3.6 billion assessed in forfeitures and fines against financial institutions for Bank

Secrecy Act-related criminal cases from January 2009 through December 2015, almost all of this

amount was collected, except for $1.2 million.

36

U.S. v. JPMorgan Chase, No. 1:14-cr-00007 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 8, 2014) (information); see

also U.S. v. $1,700,000,000 in United States Currency, No. 1:14-cv-00063 (S.D.N.Y. Jan.

7, 2014).

Page 16 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

From January 2009 through December 2015, SEC collected

approximately $27 million in penalties and disgorgements from two

financial institutions for FCPA violations. SEC assessed $10.3 million in

penalties, $13.6 million in disgorgements, and $3.3 million in interest

combined for the FCPA violations. The penalties were assessed for

insufficient internal controls and FCPA books and records violations. SEC

officials stated the fact that they had not levied more penalties against

financial institutions for FCPA violations than they had against other types

of institutions may be due, in part, to financial institutions being subject to

greater regulatory oversight than other industries. While DOJ and SEC

have joint responsibility for enforcing FCPA requirements, DOJ officials

stated that they did not assess any penalties against financial institutions

during the period of our review.

From January 2009 through December 2015, OFAC independently

assessed $301 million in penalties against financial institutions for

sanctions programs violations.

37

The $301 million OFAC assessed was

comprised of 47 penalties, with penalty amounts ranging from about

$8,700 to $152 million. Of the $301 million, OFAC has collected about

$299 million (see fig. 3). OFAC’s enforcement guidelines provide the legal

framework for analyzing apparent violations. Some of the factors which

determine the size of a civil money penalty include the sanctions program

at issue and the number of apparent violations and their value.

38

For

example, OFAC assessed Clearstream Banking a $152 million penalty

because it made securities transfers for the central bank of a sanctioned

country.

39

DOJ, along with participating Treasury offices and other law enforcement

partners, assessed and enforced criminal and civil forfeitures and fines

totaling about $5.7 billion for the federal government for sanctions

37

OFAC’s website includes all of its independent enforcement actions and any concurrent

actions taken with DOJ or other agencies. In the case of a concurrent action, the forfeiture

or penalty assessed by DOJ or the other agency also satisfied payment of OFAC’s

assessment.

38

31 C.F.R. pt. 501, App. A, III.

39

In re Clearstream Banking, Settlement Agreement, OFAC Order No. IA-673090 (Jan.

23, 2014).

SEC Has Collected

Millions of Dollars from

Financial Institutions for

FCPA Violations

Financial Institutions

Incurred Billions of Dollars

in Fines, Penalties, and

Forfeitures for U.S.

Sanctions Programs

Violations since 2009

Page 17 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

programs violations.

40

This amount was the result of eight forfeitures that

also included two fines. Of the $5.7 billion collected for sanctions

programs violations, most of this amount was collected from one financial

institution—BNP Paribas. In total, BNP Paribas was assessed an $8.8

billion forfeiture and a $140 million criminal fine in 2014 for willfully

conspiring to commit violations of various sanctions laws and

regulations.

41

BNP Paribas pleaded guilty to moving more than $8.8

billion through the U.S. financial system on behalf of sanctioned entities

from 2004 to 2012. Of the $8.8 billion forfeited, $3.8 billion was collected

by Treasury’s Executive Office for Asset Forfeiture, with the remainder

apportioned among participating state and local agencies.

42

In addition to

BNP Paribas, DOJ and OFAC assessed fines and forfeitures against

other financial institutions for similar violations, including processing

transactions in violation of the International Emergency Economic Powers

Act, OFAC regulations, and the Trading with the Enemy Act.

43

From January 2009 through December 2015, the Federal Reserve

independently assessed and collected about $837 million in penalties

40

In October 2015, DOJ and the IRS - Criminal Investigation announced that Credit

Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank had agreed to a $312 million forfeiture for

violating U.S. sanctions programs, of which the bank is to forfeit $156 million to the federal

government (specifically, through the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia for

deposit into the Treasury Forfeiture Fund) and $156 million to the New York County

District Attorney’s Office. However, because this forfeiture was pending as of January

2016, we did not include it in our analysis for this report.

41

U.S. v. BNP Paribas, No. 1:14-cr-00460 (S.D.N.Y. July 9, 2014). The forfeiture order

was signed in May 2015.

42

Of the $8.8 billion enforced by Justice, BNP Paribas is to pay $4.9 billion to state and

local agencies and the Federal Reserve—specifically a $2.2 billion payment to the New

York County District Attorney’s Office and $2.2 billion payment to the New York State

Department of Financial Services. The Federal Reserve separately assessed a penalty of

$508 million against BNP Paribas.

43

OFAC issues regulations pursuant to the International Emergency Economic Powers

Act, Pub. L. No. 95-223, 91 Stat. 1626 (1977) (codified as amended at 50 U.S.C. § 1701-

1705), and the Trading with the Enemy Act, Pub. L. No. 65-91, 40 Stat. 411 (1917)

(codified as amended at 50 U.S.C. app. §§ 3, 5-6). The following regulations were cited in

the enforcement actions for the period of our review: 31 C.F.R pts. 501, 515 (Cuban

Assets Control), 536 (Narcotics Trafficking Sanctions), 537 (Burmese Sanctions), 544

(Weapons Of Mass Destruction Proliferators Sanctions), 550 (repealed Libyan Sanctions),

560 (Iranian Transactions And Sanctions), 594 (Global Terrorism Sanctions), and 598

(Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Sanctions); 15 C.F.R. pts. 730-774; and E.O.13382.

Page 18 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

from six financial institutions for U.S. sanctions programs violations.

44

The

Federal Reserve assessed its largest penalty for $508 million against

BNP Paribas for having unsafe and unsound practices that failed to

prevent the concealing of payment information of financial institutions

subject to OFAC regulations. It was assessed as part of a global

settlement with DOJ for concealing payment information of a financial

institution subject to OFAC regulations.

45

Federal Reserve officials stated

that the remaining assessed penalties related to OFAC regulations were

largely for similar unsafe and unsound practices.

Figure 3: Collections from Financial Institutions for U.S. Sanctions-Related Forfeitures and Penalties, Assessed in January

2009–December 2015

Note: Of the $6.8 billion assessed against financial institutions for U.S. sanctions programs violations

from January 2009 through December 2015, almost all of this amount has been collected, except for

about $2.4 million.

44

The Federal Reserve assessed and collected one penalty against HSBC Holdings for

both BSA and sanctions program violations and did not break down the penalty amount by

type of violation. We included the entire penalty as part of our BSA analysis to ensure that

we did not double count the penalty.

45

U.S. v. BNP Paribas, No. 1:14-cr-00460 (S.D.N.Y. July 9, 2014).

Page 19 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

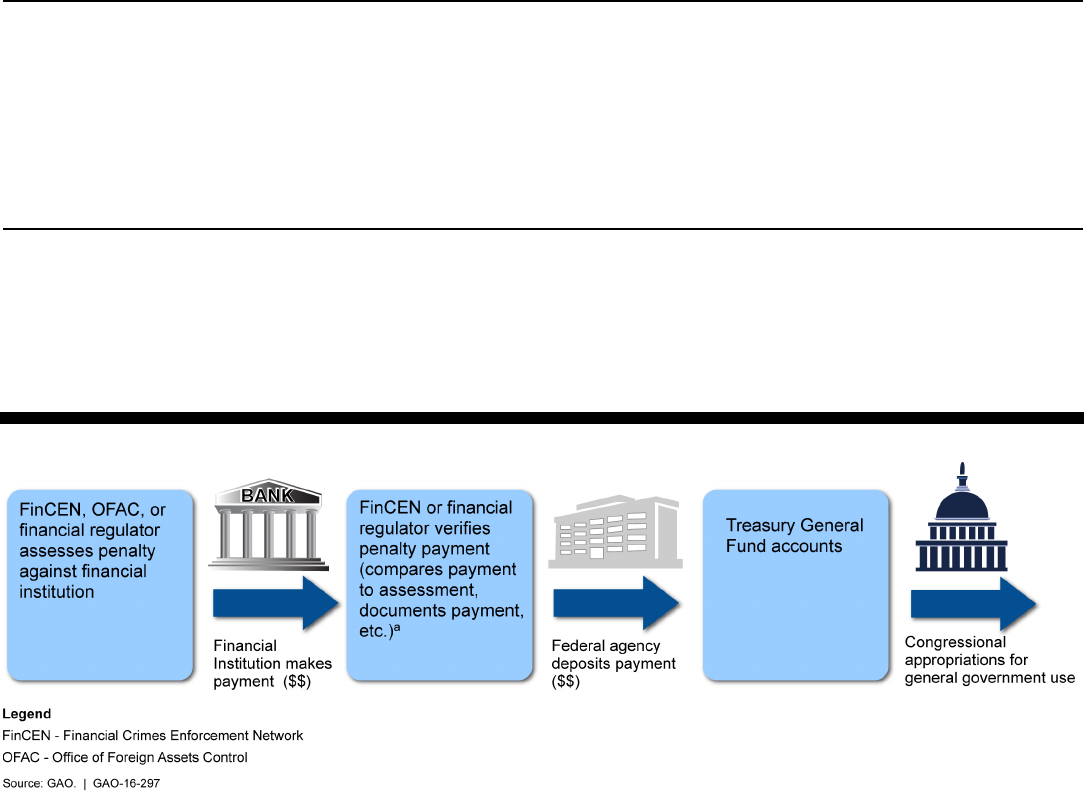

FinCEN and financial regulators have processes in place for receiving

penalty payments from financial institutions—including for penalties

assessed for the covered violations—and for depositing these

payments.

46

These payments are deposited into accounts in Treasury’s

General Fund and are used for the general support of federal government

activities.

47

From January 2009 through December 2015, about $2.7

billion was collected from financial institutions for the covered violations

and deposited into Treasury General Fund accounts.

48

DOJ and Treasury

also have processes in place for collecting forfeitures, fines, and penalties

related to BSA and sanctions violations. Depending on which agency

seizes the assets, forfeitures are generally deposited into two accounts—

either DOJ’s AFF or Treasury’s TFF. From January 2009 through

December 2015, about $3.2 billion was deposited into the AFF and $5.7

billion into the TFF, of which $3.8 billion related to a sanctions case was

rescinded in the fiscal year 2016 appropriation legislation. Funds from the

AFF and TFF are primarily used for program expenses, payments to third

parties—including the victims of the related crimes—and equitable

sharing payments to law enforcement agencies that participated in the

efforts resulting in forfeitures. For the cases in our review, as of

December 2015, DOJ and Treasury had distributed about $1.1 billion in

payments to law enforcement agencies and approximately $2 billion is

planned to be distributed to victims of crimes. The remaining funds from

these cases are subject to general rescissions to the AFF and TFF or

may be used for program or other law enforcement expenses. DOJ

officials stated that DOJ determines criminal fines on a case-by-case

basis, in consideration of the underlying criminal activity and in

compliance with relevant statutes.

46

In the case of OFAC, Treasury’s Bureau of Fiscal Service collects and tracks payments

for civil money penalties that OFAC assesses, and then deposits the payments into the

appropriate Treasury General Fund accounts.

47

Certain agencies in our review have the authority to seek civil money penalties but do

not have the statutory authority to deposit those penalties into a separate fund. See, e.g.,

28 U.S.C. § 2041 (DOJ); 12 U.S.C. § 1818(i)(2)(J) (FDIC, OCC, and Federal Reserve);

see also 12 C.F.R. § 109.103(b)(2) (OCC). The miscellaneous receipts statute requires

that “an official or agent of the Government receiving money for the Government from any

source shall deposit the money in the Treasury as soon as practicable without deduction

for any charge or claim.” 31 U.S.C. § 3302(b).

48

Of the $2.7 billion, FinCEN, OFAC, and the financial regulators collected approximately

$2.6 billion and DOJ collected a $79 million civil penalty for U.S. sanctions program

violations.

Collections for

Violations Are Used to

Support General

Government and Law

Enforcement

Activities and Victims

Payments

Page 20 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

FinCEN and financial regulators deposit collections of penalties assessed

against financial institutions—including for the covered violations—into

Treasury’s General Fund accounts (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Process for Collecting and Depositing Penalty Payments

a

In the case of OFAC, Treasury’s Bureau of Fiscal Service collects and tracks payments for civil

money penalties that OFAC assesses, and then deposits the payments into the appropriate Treasury

General Fund accounts.

FinCEN deposits the penalty payments it receives in accounts in

Treasury’s General Fund. First, FinCEN sends financial institutions a

signed copy of the final consent order related to the enforcement action it

has taken along with instructions on how and when to make the penalty

payment. Then, Treasury’s Bureau of Fiscal Service (BFS) collects

payments from financial institutions, typically through a wire transfer.

OFAC officials explained that BFS also collects and tracks, on behalf of

OFAC, payments for civil money penalties that OFAC assesses. BFS

periodically notifies OFAC via e-mail regarding BFS’s receipt of payments

of the assessed civil monetary penalties. FinCEN officials said that its

Financial Management team tracks the collection of their penalties by

comparing the amount assessed to Treasury’s Report on Receivables,

which shows the status of government-wide receivables and debt

collection activities and is updated monthly. Specifically, FinCEN staff

compares their penalty assessments with BFS’s collections in Treasury’s

Report on Receivables to determine if a penalty payment has been

received or is past due. Once Treasury’s BFS receives payments for

Penalties Collected by

Treasury and Financial

Regulators Are Deposited

in Treasury’s Accounts for

General Government Use

Page 21 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

FinCEN- and OFAC-assessed penalties, BFS staff deposits the payments

into the appropriate Treasury General Fund accounts.

Financial regulators also have procedures for receiving and depositing

these collections into Treasury’s General Fund accounts, as the following

examples illustrate:

• SEC keeps records of each check, wire transfer, or online

payment it receives, along with a record of the assessed amount

against the financial institution, the remaining balance, and the

reasons for the remaining balance, among other details related to

the penalty. For collections we reviewed from January 2009 to

December 2015 for BSA and FCPA violations, SEC had deposited

all of them into a Treasury General Fund receipt account.

49

• Upon execution of an enforcement action involving a penalty, the

Enforcement and Compliance Division within OCC sends a

notification of penalties due to OCC’s Office of Financial

Management. When the Office of Financial Management receives

a payment for a penalty from a financial institution, it compares the

amount with these notifications. The Office of Financial

Management records the amount received and sends a copy of

the supporting documentation (for example, a wire transfer or

check) to the Enforcement and Compliance Division. OCC holds

the payment in a civil money penalty account—an account that

belongs to and is managed by OCC—before it deposits the

payment in a Treasury General Fund receipt account on a monthly

basis.

• The Federal Reserve directs financial institutions to wire their

penalty payment to the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

(FRBR). The Federal Reserve then verifies that the payment has

been made in the correct amount to FRBR, and when it is made,

FRBR distributes the penalty amount received to a Treasury

General Fund receipt account. Federal Reserve officials explained

that when they send the penalty to Treasury, they typically e-mail

49

According to SEC officials, in general, penalties collected by SEC can be distributed to

three different funds: the Treasury General Fund; the Federal Account for Investor

Restitution Fund, which is a fund that SEC uses to return money to harmed investors; and

the Investor Protection Fund, which is a fund that distributes money to whistleblowers. All

penalties SEC collected related to BSA/AML and FCPA violations from January 2009

through December 2015 have been deposited in the Treasury General Fund.

Page 22 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

Treasury officials to verify that they have received the payment.

They noted that when Treasury officials receive the penalty

payment, they send a verification e-mail back to the Federal

Reserve. According to officials, to keep track of what is collected

and sent to the Treasury General Fund, FRBR retains statements

that document both the collection and transfer of the penalty to a

Treasury General Fund receipt account.

• FDIC has similar processes in place for collecting penalties

related to BSA violations. When enforcement orders are executed,

financial institutions send all related documentation (the stipulation

for penalty payment, the order, and the check in the amount of the

penalty payment) to FDIC’s applicable regional office Legal

Division staff, which in turn sends the documentation to Legal

Division staff in Washington, D.C. If the payment is wired, FDIC

compares the amount wired to the penalty amount to ensure that

the full penalty is paid. If the payment is a check, FDIC officials

make sure the amount matches the penalty, document receipt of

the payment in an internal payment log, and then send the check

to FDIC’s Department of Finance. Once a quarter, FDIC sends

penalty payments it receives to a Treasury General Fund receipt

account.

In addition to the processes we discuss in this report for penalty

collections, SEC, Federal Reserve, OCC, and FDIC all have audited

financial statements that include reviews of general internal controls over

agency financial reporting, including those governing collections.

From January 2009 through December 2015, FinCEN, OFAC, and

financial regulators collected in total about $2.6 billion from financial

institutions for the covered violations but they did not retain any of the

penalties they collected. Instead, the collections were deposited in

Treasury General Fund accounts and used to support various federal

government activities. Officials from these agencies stated that they have

no discretion over the use of the collections, which must be transmitted to

Page 23 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

the Treasury.

50

Once agencies deposit their collections into the Treasury

General Fund, they are unable to determine what subsequently happens

to the money, since it is commingled with other deposits.

Treasury Office of Management officials stated that the collections

deposited into the General Fund accounts are used according to the

purposes described in Congress’s annual appropriations. More

specifically, once a penalty collection is deposited into a receipt account

in the Treasury General Fund, only an appropriation by Congress can

begin the process of spending these funds. Appropriations from Treasury

General Fund accounts are amounts appropriated by law for the general

support of federal government activities. The General Fund Expenditure

Account is an appropriation account established to record amounts

appropriated by law for the subsequent expenditure of these funds, and

includes spending from both annual and permanent appropriations.

51

Treasury Office of Management officials explained that the Treasury

General Fund has a general receipt account that receives all of the

penalties that regulators and Treasury agencies collect for BSA, FCPA,

and sanctions violations. Treasury officials explained that to ensure that

the proper penalty amounts are collected, Treasury requires agency

officials to reconcile the amount of deposits recorded in their general

ledger to corresponding amounts recorded in Treasury’s government-

wide accounts.

52

If Treasury finds a discrepancy between the General

50

As noted above, certain agencies in our review have the authority to seek civil money

penalties for general prudential violations but do not have the statutory authority to deposit

penalties into a separate fund. See 12 U.S.C. § 1818(i)(2)(J) (FDIC, OCC, and Federal

Reserve). In general, penalties collected by SEC can be distributed to three different

funds: the Treasury General Fund (see 15 U.S.C. § 78u(d)(3)(C)(i); the Federal Account

for Investor Restitution Fund, created by a provision commonly known as the Fair Fund

provision, which is a fund that SEC uses to return money to harmed investors for specific

cases (see 15 U.S.C. § 7246(a)); and the Investor Protection Fund, which is a fund that

distributes money to whistleblowers and includes any monetary sanction, including civil

money penalties, collected by SEC that is not added to an investor restitution fund (unless

the balance of the fund at the time of the monetary sanction exceeds $300 million)(see 15

U.S.C. § 78u-6(g)).

51

Annual appropriation acts that provide funding for the continued operation of federal

departments, agencies, and various government activities are considered by Congress

annually. Permanent appropriations are appropriations that are the result of previously

enacted legislation and do not require further action by the Congress.

52

Agency general ledgers are required to conform to the United States Standard General

Ledger, which provides a uniform chart of accounts and technical guidance for

standardizing federal agency accounting.

Page 24 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

Ledger and the government-wide accounts, it sends the specific agency a

statement asking for reconciliation. Treasury’s Financial Manual provides

agencies with guidance on how to reconcile discrepancies and properly

transfer money to the general receipt account. Treasury officials

explained that they cannot associate a penalty collected for a specific

violation with an expense from the General Fund as collections deposited

in General Fund accounts are comingled.

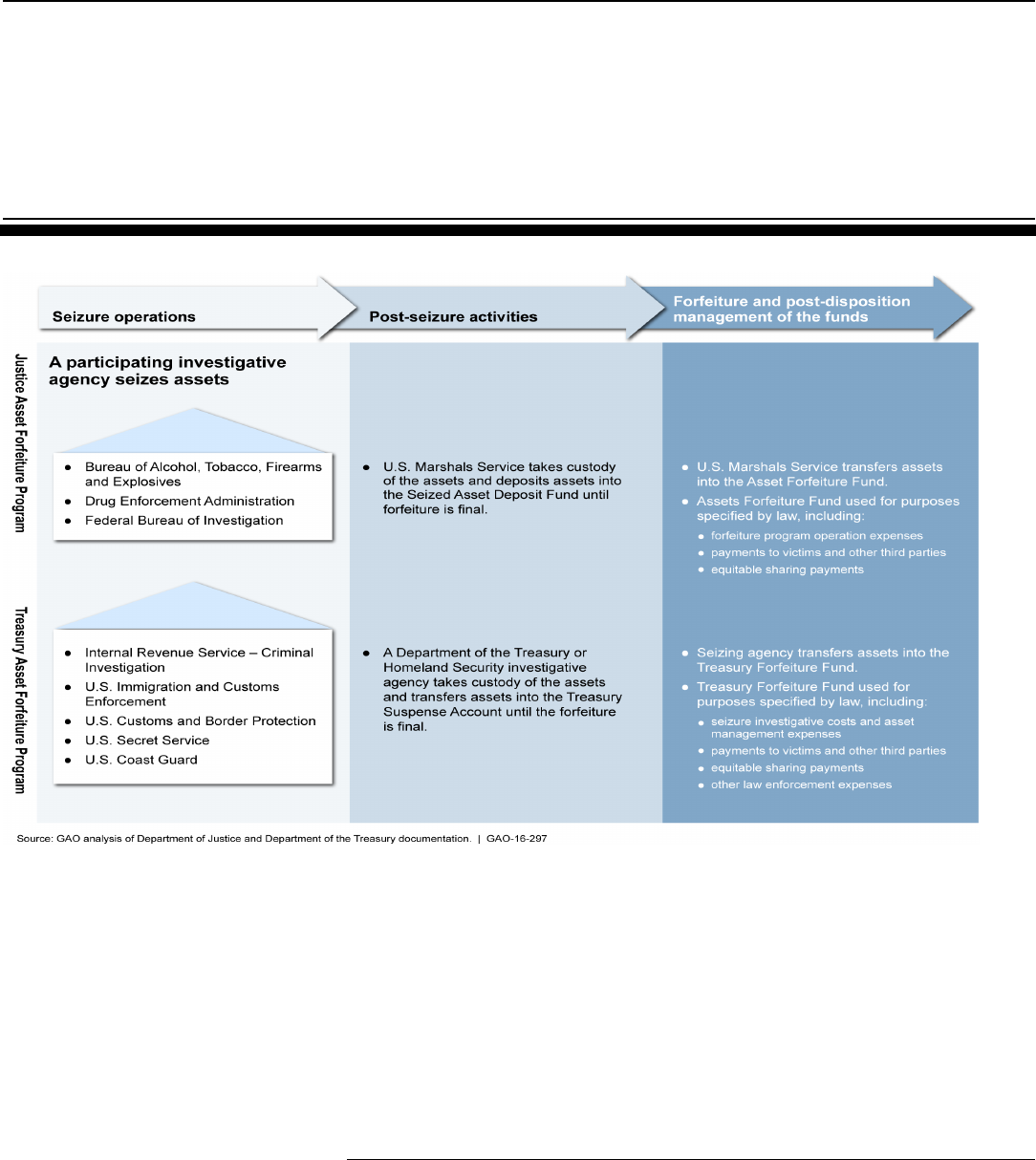

Forfeitures—including those from financial institutions for violations of

BSA/AML and U.S. sanctions programs requirements—are deposited into

three accounts depending in part on the agency seizing the assets (DOJ

and other law enforcement agencies use the AFF, Treasury and the

Department of Homeland Security use the TFF, and U.S. Postal

Inspection Service uses the Postal Service Fund).

53

In the cases we

reviewed, financial institutions forfeited either cash or financial

instruments, which were generally deposited into the AFF or the TFF.

54

Figure 5 shows the processes that govern the seizure and forfeiture of

assets for the Justice Asset Forfeiture Program and the Treasury

Forfeiture Program.

53

In addition, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, established a new forfeiture

fund—the United States Victims of State Sponsored Terrorism Fund—to receive the

proceeds of forfeitures resulting from sanctions violations, Pub. L. No. 114-113, Div. O, §

404(e), 129 Stat. 2242 (2015).

54

In the cases we identified, approximately $100 million of forfeitures from MoneyGram

International also went into the Postal Service Fund. According to DOJ officials, forfeitures

go into this account—which is a fund designed to help the U.S. Postal Service carry out its

purposes, functions, and powers—when the U.S. Postal Service administratively forfeits

assets. Of the $100 million forfeited, DOJ data showed that $62 million had been

distributed to victims of fraud.

Forfeitures Are Deposited

into Accounts with Several

Authorized Uses, Including

Payments to Crime

Victims and Law

Enforcement Partners

Page 25 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

Figure 5: Justice Asset Forfeiture Program and Treasury Forfeiture Program Asset Forfeiture Processes

The Justice Asset Forfeiture Program and the Treasury Forfeiture

Program follow similar forfeiture processes. Under the Justice Asset

Forfeiture Program, a DOJ investigative agency seizes an asset (funds in

the cases we reviewed), and the asset is entered into DOJ’s Consolidated

Asset Tracking System. The asset is then transferred to the U.S.

Marshals Service for deposit into the Seized Asset Deposit Fund.

55

The

U.S. Attorney’s Office or the seizing agency must provide notice to

interested parties and conduct Internet publication prior to entry of an

administrative declaration of forfeiture or a court-ordered final order of

55

Justice Asset Forfeiture Program investigative agencies leading seizures in the cases

we reviewed included the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Federal Bureau of

Investigation. The Seized Asset Deposit Fund is the DOJ holding account for seized

assets pending resolution of forfeiture cases. These processes are described in further

detail in DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture Policy Manual.

Page 26 GAO-16-297 Financial Institutions

forfeiture. Once the forfeiture is finalized, the seizing agency or the U.S.

Attorney’s Office enters the forfeiture information into the Consolidated

Asset Tracking System. U.S. Marshals Service subsequently transfers the

asset from the Seized Asset Deposit Fund to the AFF. Similarly, the asset

forfeiture process for the Treasury Forfeiture Program involves a

Department of Homeland Security or Treasury investigative agency

seizing the asset (funds, in the cases we reviewed). The seizing agency

takes custody of the asset, enters the case into their system of record,

and transfers the asset to the Treasury Suspense Account.

56

Once

forfeiture is final, the seizing agency subsequently requests that

Treasury’s Executive Office for Asset Forfeiture staff transfer the asset

from the Treasury Suspense Account to the TFF. According to Treasury’s

Executive Office for Asset Forfeiture staff, each month, TFF staff

compares deposits in the TFF with records from seizing agencies to

review whether the amounts are accurately recorded.

From January 2009 through December 2015, for the cases we reviewed,

nine financial institutions forfeited about $3.2 billion in funds through the

Justice Asset Forfeiture Program due to violations of BSA/AML and U.S.

sanctions programs requirements.

AFF expenditures are governed by the

law establishing the AFF, as we have previously reported.

57

Specifically,

the AFF is primarily used to pay the forfeiture program’s expenses in

three major categories:

56

Treasury Forfeiture Program investigative agencies leading seizures in the cases we

reviewed included IRS-Criminal Investigation and U.S. Immigration and Customs

Enforcement. Treasury’s Seized Asset and Case Tracking System is the system of record

for the Treasury Forfeiture Program, but some of the participating investigative agencies

also maintain their own asset tracking systems. The Treasury Suspense Account is the

Treasury holding account for seized assets pending resolution of forfeiture cases. These

processes are described in further detail in the Treasury Guidelines for Seized and

Forfeited Property and, according to Treasury officials, in relevant policy directives.

57

28 U.S.C. § 524(c). Additionally, use of the AFF is controlled by laws and regulations

governing the use of public monies and appropriations such as 31 U.S.C. §§ 1341-1353