Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

Introduction

1

Guide to Managing

Intellectual Property

and Confidentiality

April 2023

© Crown copyright 2023

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0

except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/

doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team,

The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected].

gov.uk.

Where we have identied any third-party copyright information you will need to

obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at:

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

Contents

Introduction 5

Knowledge Assets and Intellectual Property 5

Intellectual Property (IP) and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) 8

Why is Intellectual Property important? 8

What is Intellectual Property? 8

Making the most of intellectual property 9

Managing Intellectual Property 11

Patents 11

Trade marks 12

Copyright 13

Designs 15

Database Rights 16

Know-How 16

IPR in summary 17

Ownership of IPR 18

IP – Further help 19

Consider this scenario 19

Condentiality 21

Before you share information 21

What to consider when using an NDA 22

Types of NDAs 23

Keep a record 23

NDAs and freedom of information (FOI) 24

Condentiality - Summary 24

Condentiality - Further help 24

IntellectualPropertyCommercialisationRoutes 26

Assignment 26

Licensing 26

ReferencesandFurtherGuidance 28

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

Introduction

5

Introduction

This Government Oce for Technology Transfer (GOTT) Guide explains the basics of intellectual

property (IP) including how it is owned, protected and can be commercialised. It also outlines

when and how to maintain condentiality as well as responsibilities of civil and public servants.

• Civil servants are those employed by the Crown in Crown bodies such as central government

departments and some arm’s lengths bodies (ALBs)

• Public servants refers more broadly to those who work in public bodies such as non-

departmental public bodies

How you handle some IP might depend on the organisation you work for and whether it is a Crown

body or not. A full list of Crown bodies is available on the National Archives’ website.

This document provides links to further reading, including resources available through the

Government Oce for Technology Transfer and the Intellectual Property Oce (IPO). This guide

should be read in conjunction with your organisation’s knowledge asset management strategy and

associated policies.

Knowledge Assets and Intellectual Property

Knowledge Assets (KAs) are intangible assets that have an inherent value to an organisation. KAs

include intellectual property that an organisation holds, the skills and experience of its sta and

its reputation. These include inventions, designs, certain R&D outcomes, data and information,

creative outputs such as text, video, graphics, codied knowledge such as software and source

code, know-how and expertise, business processes, services and other intellectual resources.

It may also include anything that is protected by UK or international intellectual property rights

(patents, trade marks, registered or unregistered designs and copyright), trade secrets, which

have their own form of legal protection, and contractual and non-contractual relationships.

The government has identied KAs as a signicant asset across the public sector and has created

a detailed resource that describes how to develop and deliver a knowledge asset strategy and its

management for organisations and departments across the UK government. This is set out in the

HMG publication The Rose Book.

The UK has a proud history of innovation and creativity, supported by the UK’s world leading

IP system. The Government Oce for Technology Transfer (GOTT) was established in 2022

to support the better management, development and exploitation of the social, economic, and

nancial value of KAs held by the UK public sector. Part of the Department for Science, Innovation

& Technology, GOTT has a remit to increase engagement in and outcomes from KA exploitation

across central government and arm’s length bodies through transforming processes, products and

services.

The Intellectual Property Oce (IPO), is the UK government’s body responsible for the

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

6

administration and granting of IP rights in the UK, and for developing the necessary legislative and

policy frameworks around IP. The IPO:

• Operates and maintains a clear and accessible intellectual property system in the UK, through

IP legislative and policy frameworks.

• Provides guidance and IP learning material about IP rights and responsibilities.

• Supports IP enforcement.

• Grants UK patents, trade marks and design rights.

Introduction

Introduction

Intellectual

Property

and Intellectual

Property Rights

Intellectual property and intellectual property rights

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

8

Intellectual Property (IP) and Intellectual

Property Rights (IPR)

Why is Intellectual Property important?

IP created by civil or public servants and owned by the Crown or your department is a valuable

public asset, and it is the responsibility of civil or public servants to manage it appropriately.

As a civil or public servant, you will be surrounded by IP. It could be a database, new technology

being developed by your team, you may need to control the use of your department’s logo, or

perhaps you use other people’s IP for educational materials, like a presentation, report or booklet.

Managing IP is also about identifying, protecting, commercialising and exploiting its wider value

where appropriate. There may be opportunities to use the IP for other purposes both within

government and in the wider economy. Unique or innovative IP could be useful and valuable to the

private sector, and your department could license the IP for others to use.

Managing your department’s IP can ensure that its value is maximised and not lost or underused.

This value can be measured in terms of public service benets, value to the UK economy, or

sometimes by direct nancial returns generated for the department.

What is Intellectual Property?

Intellectual property or IP is all around you. It cannot be seen or touched but as a civil or public

servant it’s likely you will create, handle, or manage IP every day.

IP is the collective term used to describe creations of the mind. For example: a story, an invention,

an artistic work or a symbol. IP is something that you will create, handle, or manage every day.

The main types are patents, trade marks, designs and copyright.

The IP framework is the legal mechanism that provides protection, through intellectual property

rights, for acts of innovation and creativity. IP is central to innovation and enterprise. IPR’s give

government, researchers, inventors, and businesses the condence to invest in doing something

new.

IP rights can be owned, sold (this if often called assignment), transferred, licensed or given away.

Licensing and selling IPRs is often called commercialisation.

Innovative activity involves taking risks, be that through investing money in new research and

development (R&D), investing signicant time and resource into writing a book or a piece of music,

or investing in the creation and launch of a new brand.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

9

IP rights, when managed eectively, can mitigate some of the risks involved in these activities

by enabling innovators to protect the fruits of their labour through the provision of a temporary

monopoly. With the security or protection aorded by IP rights, inventors and creators can invest

time, money and expertise into their creative endeavours, and thereby reap the benets of their

hard work.

IP rights support innovation and research and development, which leads to the creation of new

and innovative products. This is important for the UK. The government has a clear ambition to

support and invest in innovation as a key driver of economic growth.

1

Innovation within the public sector can generate signicant benets. Use of intellectual property

leads to further innovation, which may then lead to many wider societal benets, creating jobs and

economic growth (including in the private sector and into new markets).

Here is an example where public sector activity has provided direct, tangible benets for the

general public.

The case studies in this chapter show how there is real potential within government to take known

technical capabilities and public sector innovations and develop and repurpose them to address

new uses and markets. That can be done, as outlined in this document, by careful management of

I P.

Making the most of intellectual property

If you are involved in the creation of intellectual property – or IP – as part of your duties as a civil

or public servant, then it is important that you record, manage and protect it.

If the correct IP rights are not obtained or protected at the appropriate time, then your department

may not be able to protect the IP or benet from it later. You may even nd that someone else

owns the IP, and your department has to pay to use it.

What you need to do will depend on the type of IP that you have created. You can nd out more

1 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-science-and-technology-framework

Case Study

Prince2 was created as the UK government’s internal standard to manage IT projects.

Inspired by an existing project management tool licensed by the government, it was further

developed to become PRINCE2. Launched in 1996 as a generic product management

standard and is currently used in over 150 countries. In 2013, the Cabinet Oce and

Capita plc. formed the joint venture, AXELOS Limited to manage and market PRINCE2.

The Cabinet Oce sold its stake in Axelos Limited in 2021, generating approximately

£185.7 million in revenue for HMG.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

10

about that in the Managing intellectual property section of this document.

Some IP rights are automatic rights, such as copyright. Copyright provides protection against

the copying of original creative works such as books and papers, music, photographs, lm and

animation, art and design.

Some IP rights need to be applied for and registered. This process can require specialist

knowledge. This includes patents which can protect inventions, trade marks which can protect

names and logos, and registered designs which can protect the appearance of goods and graphic

designs.

If you think that you have created or are working on something which could be protected by a

registered right, then your department’s IP expert or legal department will be able to advise. If you

don’t have a local IP expert or innovation support unit, you can also contact the Government Oce

for Technology Transfer. It is important to contact your IP expert at the earliest opportunity.

You must not publish or disclose any invention or design outside of your department before

seeking approval to do so. An unprotected disclosure before taking action to protect the IP, will

prevent it from being protected at all. Your department may miss out on a valuable patent or

registered design right.

Care must be taken when developing or using product names or logos. These must not be

similar to an existing product name or logo as these are likely to be protected by someone else’s

copyright or trade mark or design. You should check with your department’s IP expert before using

any new product name or logo, as you may not be allowed to use it in your work.

Data can appear in many forms and is often highly valuable. Data can be protected in several

ways, through database rights, contractual agreements or through trade secrets. Personal

data is also controlled under the Data Protection Act, and care must be taken to comply with its

requirements at all times. It is important that you always think before sharing data, as a wrongful

disclosure could lead to legal action.

If you are ever unsure about any aspect of IP, then remember to always check with your IP

experts, commercial leads, legal advisor, or where you have one, your innovation team or KA

manager.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

11

Managing Intellectual Property

The main IP rights

There are four main types of IP rights:

• Patents protect inventions.

• Trade marks protect the names of products or brands.

• Copyright is for written work, art, lms, websites, software and databases.

• Designs protect the design or appearance of products.

There are other IP rights and IP related assets such as plant breeders’ rights, performance rights,

database rights, moral rights, know-how and trade secrets, some of which are also covered in this

Guide.

Patents

New and original technical ideas can be protected through a registered patent. Patents are

designed to promote innovation with the reward of a temporary exclusive right. A patent is a

temporary exclusive right granted by the state, for an invention, in exchange for making the

invention public. The patent owner has the right to stop others from using the protected invention

without permission. A patent right lasts for 20 years and functions just like any other property. It

can be licensed, sold, exchanged, kept or mortgaged.

The publishing of inventions is designed to promote innovation – instead of trying to re-invent

something you can search to see what inventions have been made public previously in patent

documents, so you can spend your own creative energy and budget inventing something new or

making improvements to known inventions.

A granted UK patent can stop others making, selling or using your invention in the UK, but has

no inuence elsewhere. If you plan to sell or license your invention abroad, you should consider

protection abroad. If you don’t, anyone can legally make, use or sell your invention overseas.

Criteria for patentability

For a patent to be granted, the invention must be:

• New. It must not have been disclosed anywhere in the world before the ling date of the patent

application for the invention. That means that an invention should be kept a secret before

applying for a patent. Failing to do so may stop you obtaining a patent. See Condentiality.

• Not obvious to someone skilled in the technical area of the invention.

• Have utility. It must also be capable of industrial application, meaning it must be either

something that can be made or used in any kind of industry.

The UK employs a “rst-to-le” system to establish rights. This means that the rst person to le a

patent application for an invention is the one entitled to the patent, not necessarily the rst person

to invent.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

12

It is usual for an applicant to seek professional help before they apply for a patent. A civil or publuc

servant should rst discuss with their departmental IP lead or those responsible for IP policy if they

believe they have a patentable innovation.

Trade marks

Trade marks are the sign under which products or services of the business are sold. A trade mark

needs to be distinctive and help to distinguish the goods or services of one trade from another,

ensuring that the customer knows where the goods or services have come from. A trade mark

must be represented in a clear and precise manner.

Trade marks usually take the form of distinctive words, logos, expressions and slogans, or

combinations of these elements. It is also possible for signs consisting of a colour, the shape of a

product or a sound to act as a trade mark, although these kinds of signs are usually more dicult

to register due to their unconventional nature.

Trade marks can be renewed indenitely, and when registered are represented by an ‘R’ in a circle

®. The sign TM is also used for trade marks, but this doesn’t have any legal meaning in the UK.

All registered trade marks are examined to check they meet the requirements as set out in the

Trade Marks Act 1994.

Once accepted, a trade mark may be registered and renewed indenitely. Renewal costs are due

every 10 years to keep the mark in force.

A trade mark should not:

• Be misleading or oensive. Signs cannot be misleading or contain elements that would be

unacceptable on the basis of accepted principles of public morality (for example, signs that are

discriminatory or excessively profane or vulgar).

• Be exclusively descriptive. For example, the sign ‘pepperoni pizza’ for pizzas would be

unacceptable, as it consists entirely of descriptive words. A sign may contain descriptive words

provided it also contains something distinctive.

• Be non-distinctive or use laudatory terminology or words or shapes in common use in trade.

• Use or denote (without permission) protected emblems such as the ags of other countries,

heraldic symbols, Royal crowns and insignia or the names and images of the Royal family

members.

• Use protected international emblems like the Red Cross or Olympic rings.

• Trade marks can be commercialised e.g. licensed, sold as an asset or franchised.

Practical tips

• Think about whether you need to protect a word, a symbol, a logo, or even a colour as

your trade mark.

• You can search the trade mark database of the IPO to see if there are any similar or

identical trade marks already registered.

• Use the ® symbol once the trade mark is registered. Do not do this before it is

registered – it can be an oence to do so.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

13

Copyright

Copyright is an automatic right, so no formal application is needed in the UK. Copyright provides

protection against the copying of original creative works such as books and papers, music,

photographs, lm and animation, art and design.

It also protects databases and software code, but only the written coding that is used, not what the

coding does.

Generally, copyright protection lasts for the life of the creator plus 70 years, although dierent

rules apply for sound recordings, TV and radio broadcasts and published editions (typographical

layouts).

Copyright is usually owned by the creator of the work. While carrying out your job, however,

copyright will normally belong to the employer. These rights of ownership are governed by

contracts such as an employment contract or a contractor’s contract terms and conditions.

Copyright works produced by ocers or servants of the Crown in the course of their duties

belong to the Crown. It is termed Crown copyright. Examples of this may be laws, government

regulations, Ordnance Survey maps, papers laid in Parliament, government reports, ocial press

statements, academic articles, and many public records.

In contrast to civil servants, public servants who do not work for a Crown body will generally

not generate Crown copyright material in the course of their normal duties. However, it remains

important to check in with your departmental IP lead or those responsible for IP policy in your

organisation if there is any doubt over what rights apply to your work and who owns them.

In Scotland, works produced by ocers or servants of the Crown who operate as part of the

devolved Scottish Administration in the course of their duties, will be held by the King’s Printer for

Scotland.

Typically, a Crown copyright work will enjoy a period of protection of 50 years from the end of the

year in which the work was published, or 125 years if it is not published. Where a work is assigned

(transferred) to the Crown, it will usually enjoy a period of protection of 70 years from the end of

the year in which the author dies.

While the Intellectual Property Oce is the government body responsible for the administration

and granting of IP rights in the UK including copyright policy, the Keeper of The National Archives

(who is also appointed as the King’s Printer for Scotland) is authorised to manage copyright and

databases owned by the Crown.

Copyright can be commercialised through licensing or assignment (sale). It’s worth being aware

that copyright is not automatically transferred to someone who commissions a work, this will need

to be covered in the commissioning contract or agreement.

Understanding Crown copyright

Work created by civil or public servants needs to be handled correctly. If you work for a Crown

body you should always ensure that copyright works such as reports, software, drawings or

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

14

presentations are marked as Crown copyright. If you are a public servant who works for a non-

Crown body, you should mark appropriate works as copyright, or check in with your departmental

IP lead or those responsible for IP policy in your organisation if there is any doubt over what rights

apply to your work and who owns them.

The correct way of marking Crown copyright works is to show the relevant department, followed by

the copyright symbol, followed by the words Crown Copyright, and the date of creation.

Any IP owned by the Crown can be used by sta within government, as and when it is required

in the course of their jobs. Members of the public can also be permitted to use published

Crown copyright material under the Open Government Licensing Scheme and other licensing

arrangements.

Only authorised ocials can permit reuse of Crown copyright works. So, if you are approached by

someone outside of government about using Crown copyright material, or any other IP owned by

the Crown and controlled by your department, then you should refer them to your department’s

lead on IP.

For detailed guidance on Crown copyright labelling and procedures for assignment of works to the

Crown, in the rst instance, check the guidance on the National Archives’ website.

Practical tips

• Keep all originals of your copyright work such as notes, drafts, sketches, drawings,

videos, etc. in a secure place.

• Record the date you created the copyright work, for example, by saving the series of

electronic versions of any works on a computer or storage device to prove the date a

work was created. Alternatively, email the work to yourself or somebody independent,

such as your legal department. The date of the email can be used to demonstrate the

date before which it was created.

• Before using other people’s work, it is important to check that you are not infringing

copyright, and to get the owner’s permission where needed. This includes using

content taken from the internet such as images on websites or search engines.

• Check that you have the right to use copyright work. This may be checking that you

have the right licence for software, or permissions for the use of an image. A copyright

exception may also cover your use of the work. Check for any copyright terms and

conditions associated with works, for example that may be displayed on websites.

• If you work for a Crown body any work produced by you as part of your role, such as

a report or presentation, should be correctly marked so that anyone who accesses it

knows that the copyright belongs to the Crown. Clear guidance can be obtained from

the National Archives.

• Crown copyright is shown by a C in a circle ©, followed by “Crown copyright”. This

helps to ensure that the Government’s work is easily recognised.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

15

Designs

A design protects the appearance of a product. Designs can be protected through automatic

unregistered protection or by registration, depending on the cover and duration of protection

required.

Registered design

A registered design in the UK protects the appearance of a two or three-dimensional product in

particular, features such as colours, materials, texture, and shape; for example, the shape and

contour of a wardrobe and the surface pattern of a wallpaper. Protection relates to the visual

appearance of a product but does not protect a technical function, what it is composed of, how it is

created, or a form or design that is determined by its function or lacks design exibility.

For example, in the case of the design of an electrical plug, the prongs of the plug would not

themselves be protectable. This is because they are designed to t the socket and as such

perform the technical function of distributing electricity by connecting the plug to the socket and

electrical mains. However, the plug casing may acceptable as it does not have to be shaped in a

certain way.

A registered design is obtained by ling an application and fee with the IPO. The IPO will examine

the design to check it complies with the law. However, the IPO does not check that the design is

new.

A design registration lasts 5 years. It can be renewed every 5 years to keep it protected, up to a

maximum of 25 years.

A registered design can be led within 12 months (the “grace period”) of a design being made

available to the public.

Practical tips

• Keep all originals of your design drawings, sketches, samples, models, and prototypes

in a secure location.

• Record all dates of creation and the dates when you may have disclosed the design,

e.g. at a trade fair or in any publication, as you should with copyright (see above).

Alternatively, email the design to yourself or somebody independent, such as your legal

department. The date of the email can be used to demonstrate the date before which it

was created.

• In the case of unregistered designs, if the owner of the design thinks someone else is

infringing their design, they will need to prove that their design has been copied and

demonstrate the existence of their right. Good record keeping is essential here.

Unregistered design protection

Two forms of unregistered design protection are available in the UK:

• A UK unregistered design right is an automatic right that applies to the shape and conguration

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

16

Database Rights

Database Rights protect a collection of independent works, data, or other materials arranged

methodically or systematically, where there has been a substantial investment in obtaining,

verifying, or presenting the contents of the database.

The database right lasts for 15 years from when the database was completed. There is no need to

formally register a database.

Any person who permanently or temporarily transfers a substantial part of the contents of the

database or makes those contents available to the public by any means, without the consent of

the database owner, will infringe the database right.

Case Study

Celsius Health is a new spin-out company based on an innovative thermal imaging

technology from the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), that allows temperatures to be

read up to ten times more accurately than current diagnostic methods. The initial area

of application is diabetic foot ulcers, where the technology has the potential to transform

treatment. Managing the diabetic foot, coupled with the cost of associated lower limb

amputations, costs the NHS up to £1 billion annually. It is estimated that this technology

could prevent 170 amputations a week in England alone. The underpinning IP and know-

how was developed by NPL scientists and supported through the Government Oce for

Technology Transfer KA Grant Fund.

of three-dimensional designs. Protection lasts for 10 years after the design was rst sold or 15

years after it was created – whichever is earliest. A licence of right must be made available to

somebody who wants one in the last 5 years of protection.

• A supplementary unregistered design, or SUD, is an automatic right which protects the

appearance of two or three-dimensional products such as features of lines, contours, colours,

shape, texture or materials of the product or its ornamentation. SUD comes into existence on

rst disclosure in the UK and protection lasts for 3 years from that disclosure.

Know-How

Know-How covers all forms of information, knowledge and skill, technical or otherwise, e.g. a

procedure, a process, an identiable knowledgeable way of doing something. It has value.

Know-how could be associated with any or all of the IP rights but may not be protectable in itself. It

might encompass material which could go on to be protected by IP, such as a patentable invention

before the patent application has been made. It might be something related to, but not part of, an

IP right, such as specialist knowledge required to operate a machine. Know-how might also be

something entirely separate from IP rights, such as the competitive advantage inherent in having a

more ecient business model than a competitor.

The only way you can really protect your valuable Know-How is through condentiality.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

17

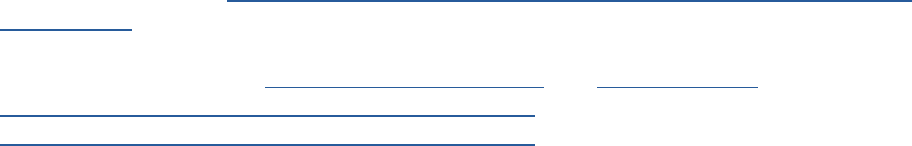

Patents

Protects technical inventions.

Invention must be new, inventive and capable of industrial application.

Invention must not be disclosed before ing for patent protection.

Needs registering.

Requires annual renewal fee.

Duration of the patent right is usually 20 years.

Trade marks

Can be made up of words, logos or a combination or may be a sign consist-

ing of a colour, the shape of a product, or a sound.

Must be distinctive.

Can be registered and renewed indenitely.

Renewal costs are paid every 10 years to keep the mark in force.

Copyright

Protects creative works.

Protection is automatic and doesn’t need registration.

Duration is mainly the life of the creator +70 years.

Crown copyright - Copyright works produced by ocers or servants of the

Crown in the course of their duties belong to the Crown.

Design rights

Designs may be registered or unregistered.

Registered design protects the appearance of a two or three-dimensional

product.

A design registration lasts 5 years, can be renewed every 5 years, up to a

maximum of 25 years.

A registered design can be led within 12 months (the “grace period”) of a

design being made available to the public.

Database rights

Protect a collection of independent works, data, or other materials arranged

systematically or methodically.

Doesn’t require registration.

Rights last for 15 years.

Know-how

Knowledge and expertise.

Cannot be protected.

IPR in summary

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

18

Ownership of IPR

Intellectual property, like any other property, will be owned by someone. The owner of IP can

control its use and take legal actions against anyone who uses it without permission. Knowing who

owns IP is important.

If you buy a book, you do not own the copyright in the content. As the owner of the book, you

can read it and sell it on, you can even destroy your copy, but you cannot copy or reproduce the

contents of the book in any way without the permission of its owner, unless a copyright exception

applies. The owner of the IP may also be the only person authorised to make it available to the

general public, for example on the internet.

The rst owner of IP is usually the person who created it, for example, the author of a book.

However, if the IP is created by an employee as part of their job, then the IP is generally owned by

their employer. IP that you create as part of your role in the Civil Service will be most often owned

by the Crown. For other public sector sta, it is likely your department owns any IP you create,

however this will be dependent on arrangements with parent bodies.

A government department or public body, like any other organisation, must identify and then

manage IP eectively – whether as an owner or a user.

IP and Procurement

It is important to think about ownership of IP when a government department enters into contracts

with third parties to buy in products or services, form research partnerships or collaborate on

a project. Since IP is generally owned by the creator, for procurement the IP produced under

government contracts will be owned by the contractor unless you specify otherwise. So, if your

department pays a contractor to produce IP, such as a report or a computer program, then

unless there is an agreement to the contrary, that IP will be owned by the contractor and not the

government. When entering into a collaboration or partnership an agreement should be signed by

all parties, this agreement will set out IP rights for any new IP which may arise from the work.

Eective management of IP is essential. Whether you are respecting other people’s IP or

maximising the value of Crown or departmental owned IP, being aware of who owns the IP you are

using is vital.

Maintain detailed and accurate records

You may nd you need to prove ownership or authorship of IP, record the basis for your right to

use IP or prove that you have undertaken due diligence. Therefore, it is important that you keep

accurate records of your activities

Be discreet about your innovations

Disclosure can stop you protecting certain types of IP. Condentiality and non-disclosure

agreements are available to help with this process.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

19

IP – Further help

• You can visit the IPO website (opens in a new window) for more information on services. The

IPO can provide guidance on IP education, IP enforcement, rights granting, and operating

overseas (opens in a new window).

• The IPO also provide online support and learning materials (opens in a new window)

including an online IP health check (opens in a new window) which helps with identifying and

safeguarding intellectual property assets.

• The National Archives (opens in a new window) provides guidance and support on Crown

copyright queries and Open Government Licenses.

• The Government Oce for Technology Transfer (opens in a new window) (GOTT) provides

guidance and support to central government departments, arm’s length bodies (ALBs) and

agencies on the identication, management and exploitation of knowledge assets.

Consider this scenario

Alex is a member of your team. They have created a presentation for internal use. Alex

wants to ensure their presentation is engaging, and so has downloaded and used various

images from the internet. The presentation is well received by everyone in the team. Alex

has been asked for a copy of the presentation so that others can use it.

In this scenario:

• Alex has created content in the course of their ocial duties as a civil servant. As

such it is highly likely that IP created in the course of their ocial duties automatically

belongs to the Crown

• Alex is using someone else’s IP when using images from the internet. They will need

to understand and abide by the terms and conditions of use and therefore may need to

ask permission to use them or rely on a relevant copyright exception.

• Alex may not be able to get permission to use these images. Alex may also nd

permission comes at a nancial cost, and it may be that Alex can nd alternatives that

cost less, or indeed nothing, and achieve the same thing. If Alex uses these images

without consent, and the originator becomes aware, there is a risk of a claim of misuse

against Alex’s department, which may cost far more money to address than having

paid for the right to use it in the rst place, both nancially and reputationally.

• Once the presentation has been shared with others, they will need to consider relevant

permissions for use of the images, presentation etc.

Introduction

Introduction

Confidentiality

Condentiality

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

21

Condentiality

If you believe your IP could be potentially patentable or registered as a design, it is important

to consider condentiality. Condentiality is the only way to protect know-how. Condentiality is

especially important when working with potentially patentable IP, for a patent to be granted details

of the invention must not have been disclosed anywhere in the world before the ling date of the

patent application.

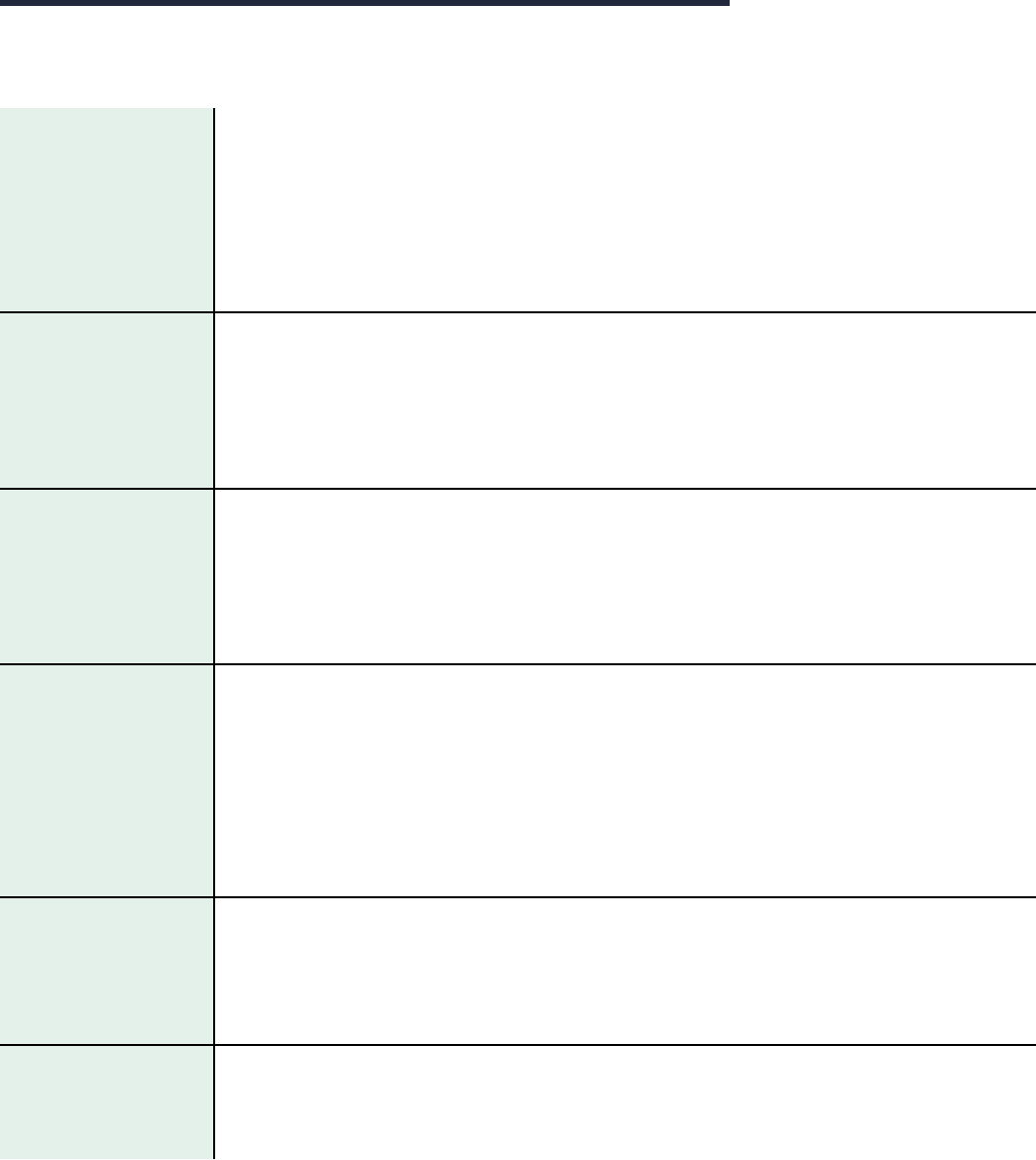

Before you share information

The best way to keep something condential is not to disclose it in the rst place. However, there

will be situations when you need to share information.

You might need to tell people about your idea, project or work outcomes or your commercial

opportunity to explore a collaboration, contract an external expert or get advice. You may need to

share details with a team internal to your organisation or potential external collaborators.

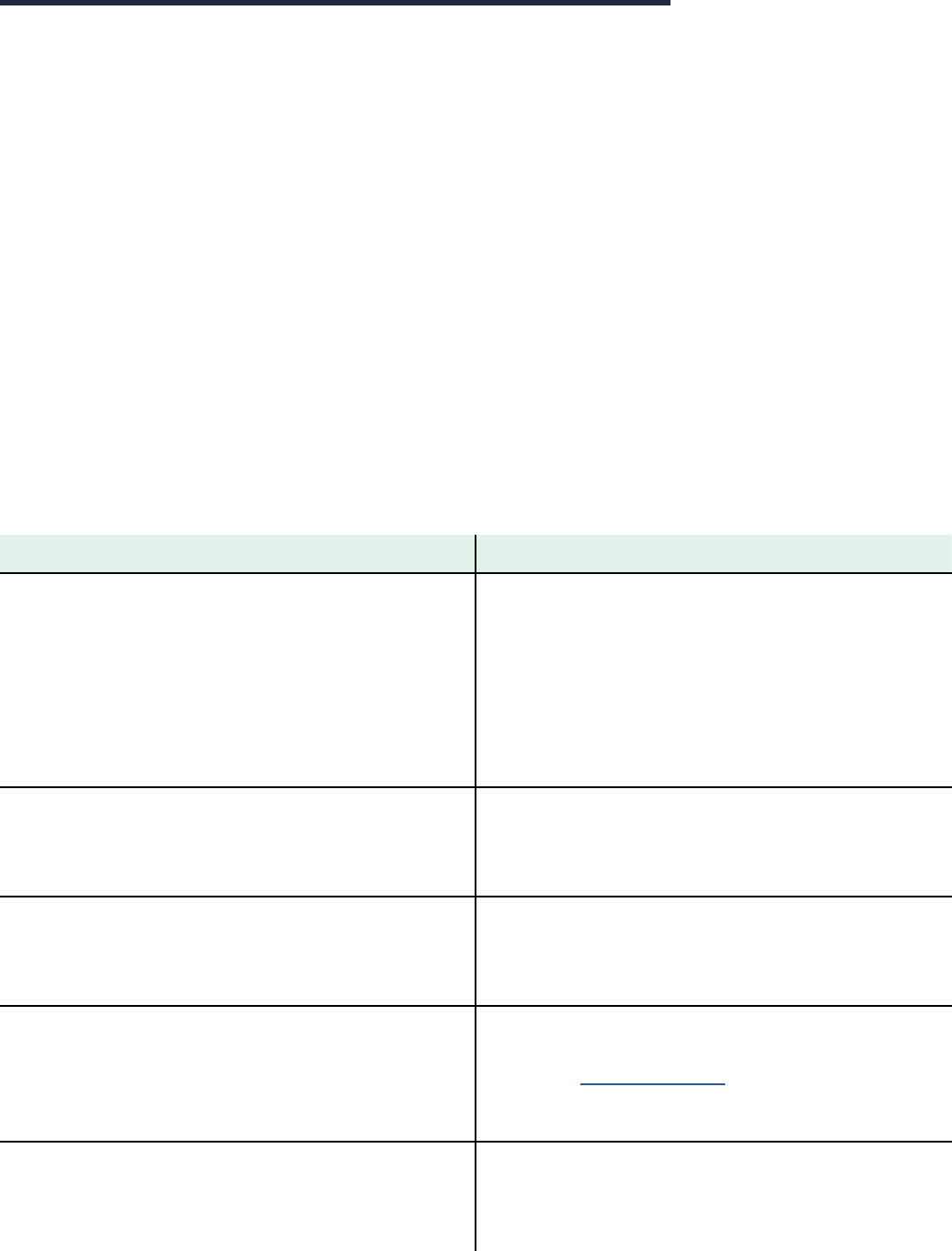

Who are you sharing information with? Howwillcondentialitybehandled?

An internal team or legal advisors/IP attorneys

in your organisation or other parts of the UK

Government

Disclosure internal to your organisation and

the information you share will be kept in

condence.

Disclosure to someone in another government

organisation may not be kept in condence and

it is advisable to check with them rst and with

your IP advisor.

IP attorneys external to your organisation Disclosure with a registered UK IP attorney with

whom you have engaged for their professional

services is kept in condence and does not

require a non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

External experts such as those with knowledge

of your sector or IP opportunity, market

research professionals etc.

External experts need to be covered by

condentiality arrangements directly with

your organisation as part of their contract of

engagement.

Potential collaborators, industry partners or

investors

A condentiality contract (NDA) will need to be

signed. What this is and when it will be used is

discussed in this section.

If you work in a science or technology area

there may be circumstances when you present

your results at a seminar or conferences,

publish a paper or an abstract

The only way to manage condentiality in this

situation is not to disclose the information.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

22

What to consider when using an NDA

If you need to share condential information with someone who is external to your organisation

and is not already covered by a contract of engagement an option to protect condentiality is to

use a non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

An NDA is a legal contract. It sets out how you share information or ideas in condence.

Sometimes people call NDAs condentiality agreements. It may also be referred to as a

condential disclosure agreement (CDA).

Consider at the outset when you need to use an NDA. It may be that in your initial conversations

you can avoid disclosing condential information. For example, if exploring a potential partnership

or licence with a company, it can often be quicker to establish whether there is a mutual interest

in exploring the opportunity further. (You might perhaps just refer to the advantages that working

with you or taking a licence to your IP would oer the recipient). If so, the next step is to move to

signing an NDA before either party shares anything condential. Remember, there is a risk here

and you need to be vigilant and be certain about the limits of what you’re prepared to discuss to

keep your information or IP secret.

As a civil or public servant, you do not need an NDA to be in place to talk to other civil or public

servants in the course of your work, but you should always mark any materials with a relevant

security marking to ensure any documentation is handled and shared appropriately. As well

as being marked appropriately, there should be due consideration of what information needs

to be shared and for what purpose. It is also important that civil and public servants receiving

condential information are made aware of their responsibilities for managing and looking after it.

When you are ready to use an NDA, your legal team or innovation team can advise on

condentiality and draw up an appropriate NDA for you to use. They will need some input from

you. In some cases, your potential partner, particularly if a company, may prefer that you use

an NDA that they have drafted. It’s important that you get this reviewed by your legal oce or

innovation team.

The NDA will be between the external party and your organisation, so you are unlikely (unless

local policy directs otherwise) to have the power to sign an NDA personally. This does not absolve

you from having to adhere to the condentiality terms in the agreement. It’s important that the right

person in the other organisation signs the NDA. They will need to be authorised to do so by their

organisation.

You should decide what your NDA covers. It could protect only information which is recorded in

some form and marked ‘condential’. It can also protect information you share in meetings or

presentations, but only where you can control who is a recipient. For example, this is ne where

your presentation is to one organisation but doesn’t apply where the presentation is to a group of

people from diverse organisations.

A good NDA restricts the use of the ideas and information to a specic permitted purpose. This

could be the evaluation of your idea or the discussion of a joint venture. That purpose should be

specied as precisely as possible in the NDA. You can always widen the permitted purpose later.

You won’t be able to narrow the restriction on the use of your ideas or information later.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

23

You should be realistic. The person you are talking to might need to share your information with

others. This could be their managers, employees or professional advisors. They may also need

to copy your information for this purpose. Make sure that these kinds of disclosures are made in

condence.

Think about how long the condentiality should last. It’s common to see it limited to 3 or 5 years.

After that time, they will be able to use and disclose your information. Once information is made

public in anyway, an NDA can’t be enforced.

Some information could be kept condential forever. Examples of these are:

• non-patentable know-how

• lists of customers

• personal information about the individuals involved in a project

Some companies or organisations could ask you to sign a document agreeing that they will not

have a duty to keep your ideas or information condential. If that is the case, you need to decide

whether to risk disclosing your ideas to them. And then discuss this with your legal department or

innovation team.

As a legal contract, an NDA should be taken seriously. Any information and discussion covered

by it must be treated in condence and not disclosed to anyone else, except as set out in the

agreement. If there is any breach of the agreement, the other party may be entitled to seek

nancial and other compensation (damages) not only from your employer, but possibly from you

personally.

Types of NDAs

NDAs can be one way or mutual (two-way). Use a one-way NDA if only you are disclosing

information and a mutual NDA if both parties are.

If the NDA is one-way only, it may need to be executed as a deed to make it enforceable. This is

easy to do, and it’s important not to make what should be a one-way agreement into an articial

mutual agreement.

If the other party to the NDA is in a dierent country, the NDA will need to state which law governs

the agreement. England and Wales have a dierent legal system to Scotland. It will also need to

state in which courts it can be enforced. It is important that the courts of one country are not given

exclusive jurisdiction. Your organisation may want to enforce the NDA in a dierent country if an

unauthorised disclosure is made there.

Keep a record

You should record what you disclose at meetings or in presentations. Ask people present to sign

a paper copy of a presentation, or a technical drawing to prove they have seen it. Record what

information you disclose in informal situations such as discussions or conversations. Note when

and where that took place.

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

24

NDAs and freedom of information (FOI)

Broadly, public authorities have to make information available to the public if they receive a

specic type of request:

• the Freedom of Information Act 2000

• the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002

• the Environmental Information Regulations 2004 (the FOIA)

There are exceptions which may apply. Check with your legal advisor as to whether this is the

case.

Condentiality - Summary

• Ahead of any meeting or sharing of information with external parties, consider whether you

intend to disclose condential information. If so, you will probably need an NDA – depending on

who you’re sharing the information with.

• Keep records of what has been disclosed (in writing or verbally) as this may be needed to

establish to whom the information belonged.

• If information is condential, it can be useful to mark it as such. It draws attention to the fact.

Do not be afraid to tell the recipient you expect them to treat it condentially.

• Be sure that the right people are signing the NDA. It should be signed on behalf of your

organisation by an authorised signatory.

• Always seek advice from your legal department or innovation team.

• If you wish to present at an event external to UK government, consider carefully what

information you can present. If unsure seek advice from your legal team.

Condentiality - Further help

The IPO has developed a free online tool called the IP Health Check. This helps identify the

necessary practical and legal steps to keep your ideas and information condential.

Introduction

Introduction

Intellectual Property

Commercialisation

Routes

Commercialisation

Guide to Managing Intellectual Property and Condentiality

26

Intellectual Property Commercialisation

Routes

Commercialisation of intellectual property means that it is used or disposed of in return for

payment, whether in cash, in kind or in any other form. This is managed and controlled through

legal agreements such as licences or assignments. These agreements grant rights for third parties

to use someone else’s IP.

Assignment

In the same way as a house can be bought and sold, IP can also be sold or transferred to another

owner. This is referred to as an assignment. Once assigned, the original owner will lose their rights

to the IP. If the original owner continues to use the IP after assignment, they may risk infringing the

rights of the new owner.

Licensing

IP can also be licensed. This is similar to a ‘lease’ of a at. The IP owner permits someone else

(the “Licensee”) to use the IP in return for payment. The owner of the IP remains the same. The

licence can be limited in time and can also be limited in scope:

• An Exclusive licence means that the owner can only permit one licensee to use the IP and

cannot license that same IP to anyone else nor use the IP itself.

• A Non-Exclusive licence means that the owner of the IP can license to more than one licensee.

The manner in which the IP should be used and the eld in which it can be used can be

dened and limited.

In the Civil Service, licensing of copyright and database rights is governed by the UK Government

Licensing Framework (UKGLF) and the Open Government Licence (OGL).

The UK Government Licensing Framework (UKGLF) provides a policy and legal overview of

the arrangements for licensing the use and re-use of public sector information, both in central

government and the wider public sector. It sets out good practice, standardises the licensing

principles for government information, mandates (with exceptions) the Open Government Licence

(OGL) as the default licence for Crown bodies and recommends OGL for other public sector

bodies. A small number of government bodies have delegations of authority in place where a

case has been made successfully to the Keeper of Public Records to adopt alternative licensing

arrangements, principally to support commercial business models such as trading funds and

government-owned companies.

The Open Government Licence (OGL) is a simple set of terms and conditions that facilitates the

re-use of a wide range of public sector information free of charge. There is no need to register

or apply to use the OGL. Users simply need to ensure that their use of information complies with

OGL terms by attributing the source as Crown copyright and not claiming any ocial endorsement

for their re-use.

Introduction

Introduction

References and

further guidance

References and further guidance

References and Further Guidance

1. GOTT has published The Rose Book: Guidance on Knowledge Asset Management in

Government

2. The IPO has developed a series of materials designed explicitly for UK government

practitioners available at www.ipo.gov.uk/ip-support and IP Healthcheck

3. Introduction to Intellectual Property in Government

4. Model Services Contract – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

This publication is available from: www.gov.uk/beis

If you need a version of this document in a more accessible

format, please email [email protected].uk. Please tell us

what format you need. It will help us if you say what assistive

technology you use.