Intellectual Property

& Confidentiality

A Researcher’s Guide

Introduction

2

This Guide is intended to act as a reference for use from time to time

during your academic/research life. Its aim is to provide an overview

of the key issues relating to Intellectual Property (IP) which are likely

to arise during your academic/research career. It explains:

•

The nature of IP, how you may create it, and how to protect it;

•

How to use IP belonging to others safely;

•

How

IP can be commercialised; and

•

The importance of confidentiality.

Your university, NHS Trust or other research institution and/or its

IP commercialisation organisation (or equivalent) will be able to advise

you on these topics and this Guide will act as a prompt for you in these

relationships.

Remember that this is just a guide and does not cover every aspect of IP

nor cover any aspect in great detail nor is it a substitute for you taking

your own independent professional advice. It has also to be read in the

context of your own institution’s published guiding principles, mission

and policy.

This Guide was originally commissioned and created by Mr. Clive Rowland,

Honorary Associate Vice-President, The University of Manchester and Ms.

Janet Knowles, Partner, HGF Law LLP (previously a Partner at Eversheds

LLP).

Contact details

Clive Rowland

The University of Manchester

clive.rowland@manchester.ac.uk

www.manchester.ac.uk

Janet Knowles

HGF Law LLP

jknowles@hgf-law.com

www.hgf.com

©The University of Manchester, HGF Law LLP and Eversheds

Sutherland LLP 2004-2021. All rights reserved.

3

Introduction (The Basics)

Intellectual Property (IP) is something created using your mind, e.g. a story, an image

or invention.

When your concept is produced in a tangible form, say turned into a script, painting

or blueprint, then various IP legal rights (IPRs) are available to prevent others using or

copying that IP so that you can safely market and trade your text, picture or process.

These IPRs attach themselves to your IP.

Reference to IP normally means IP and IPRs therein and those involved in these

creative outputs are variously referred to as Creators or Originators or Inventors.

Some IP is automatic (e.g. copyright) but others require registration (e.g. patents). IP

can be split into main categories as illustrated in Figure 1 on the next page.

In summary, ‘intellectual’ because it is creative, ‘property’ because it is an asset which can

be transacted like any possession and ‘rights’ because recourse to the legal system is

possible.

Confidentiality is about the protection of information.

A variety of information is very important to any business or institution. For example,

employment details, operational performance data and customer target lists. Much

of it will not be generally known and handled privately.

A special type of information is know-how. Know-how is the set of secret, technical

knowledge and activities resulting from experience and testing which usually provides

competitive advantage and is not readily explained or copied. It is often seen as a way

of doing things. Certain types of important know-how will be the most applicable

form of information relevant to you in your research role and will require careful

handling.

Some know-how will be so advantageous, detailed and sensitive it could be considered

a trade secret and afforded special legal protection. A trade secret can be viewed as a

particular class of valuable (confidential) information, such as a chemical formulation,

which is intended to be kept secret and known by only a few trusted employees.

Know-how and trade secrets are akin to property in certain respects and so, whilst they are not

universally defined as IP, it is not inappropriate to include them as an aspect of IP.

The best way to protect any precious information is to mark it as confidential, limit access to it

and, prior to sharing it with others, put in place a written agreement to restrict its circulation or

prohibit further disclosure.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

4

Figure 1

Patents

protect inventions for

products or processes.

The invention must not

be obvious or thought of

before and must be

capable of industrial

application.

You have to apply to the

Intellectual Property

Office to register

patents. They last for 20

years. Also, patent-like

systems are available in

some countries for

‘minor’ inventions

(utility models) and for

new plant varieties.

Copyright

protects items such as

written works, diagrams,

charts, computer source

code, photographs,

music or even

performances. Copyright

arises automatically once

your idea/knowledge has

been expressed in

permanent form. It must

have involved some

element of creation and

skill and not copied

(substantially) from

elsewhere.

Database Rights

protect collections of

works or data (e.g.

results, samples or

patient information)

which have been

systematically arranged

and are accessible

electronically or by

other means. There is

no need to register.

IP

Know-How and

Trade Secrets

Know-how is not

property (IP) as such

but is often treated as

IP. It is an economic

asset and covers

confidential technical

information and

frequently co-exists

with formal IP but can

be stand-alone.

To be a trade secret,

information must not

be generally known but

must be substantial,

valuable and remain

secure.

Designs

protect 3D objects or

designs applied to

them, e.g. laboratory

equipment or the

design of a teapot

or

the design on

wallpaper. They can

arise automatically or

can be registered with

the UK IPO.

Rights also exist for

semiconductor

topographies (layout

designs) also known as

‘mask works’.

Trade Marks

KELLOGG’S, MARS,

MICROSOFT and iPhone

are all successful trade

marks. Their value lies

in the fact that they

denote the origin and

quality of the products

they relate to. Trade

marks can arise

automatically or can be

registered with the

Trade Marks Registry at

the UK IPO.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

5

And in a little more detail...

Patents

Patents protect inventions which relate to a product and/or a process to

make a product. They arise particularly from research & development in

the medical, science, technology and engineering fields.

Once a patent has been granted, it effectively offers the owner a

‘monopoly’ right. This means that only the owner, or someone else with the

owner’s consent, can use the invention for commercial purposes. An

invention will be patentable if: (1) it has not been disclosed publicly

anywhere in the world prior to filing the patent application; (2) it is

inventive; and (3) it is capable of industrial application, (essentially any

commercial, medical or other practical use). Say you have thought of an

invention for a new type of tea bag which can be used 50 times without

losing any flavour! Useful! If you haven’t mentioned it to anyone, it hasn’t

been done before and clearly it’s practical, then a patent sounds possible.

Additionally, some countries have patent-like systems for ‘minor’

inventions (called utility models), giving protection for up to c10 years; and

protection for new plant varieties themselves (known as plant variety rights

or plant breeders’ rights or plant variety certificates) providing cover for 20-

25 years.

If you think your invention is potentially patentable it is essential that the

details of the invention are kept secret until the application for the protection

is made. Disclosure of the key features of the invention before that will make

your application invalid and so may be refused or be open to challenge in the

future if granted.

Methods of disclosure may include publishing details of the invention:

•

in a journal, book, poster or other publication

•

via a website other electronic means

•

in an oral presentation

•

to someone who is not an employee of your organisation, such as

a student, or who is not bound by confidentiality to keep such

information secret or any demonstration or promotion in a public

place.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

6

Intellectual Property Section 1

If the patent/patent application of interest is published in a foreign language

it is possible to check via the Internet or other patent databases to see if an

equivalent document has been published in English in another country such

as the UK, Europe, USA, Canada or Australia, or as a Patent Cooperation

Treaty (PCT) application for example – this is often called “patent equivalent”

searching.

If the patent/patent application of interest has only been published in a

foreign language, you can either get a machine translation of the text into

English, a formal translation of the relevant part of the patent or obtain an

English abstract of the patent.

It is a good idea to carry out a patent search before you start a project in

order to try and ensure that your idea has not been disclosed in the general

or patent literature.

If you are not experienced in patent searching you can obtain advice and

assistance from the range of Patent Libraries located throughout the United

Kingdom. There is also a wealth of information on-line. Both the UK

Intellectual Property Office and the US Patent and Trade Mark Office have

on-line services (www.ipo.gov.uk and www.uspto.gov). You can connect

directly to esp@cenet giving access to details of many patents worldwide

(http://gb.espacenet.com) or try Google (www.patents.google.com

).

Alternatively, there are firms and consultants based throughout the UK which

specialise in patent searching and related services. Most firms of Patent Agents

will offer 30-60 minutes of consultation free of charge. If you think you need

this help, contact your IP commercialisation organisation for further help.

Q: How do I know if my invention is already in the public domain?

A: A previous disclosure can include anything from a published patent,

document, information contained in a book, article, journal, TV

documentary, demonstration or even just common practice. Whilst you

cannot expect to find everything, a good starting point is to see if there

are any existing patents which relate to your invention. It is easier than

ever to find patent information as the format of patents has become

increasingly standardised and there are many user-friendly websites that

you can search.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

7

Patenting Process and Indicative Costs

To obtain patent protection for your invention you will need a patent

specification to be written. This describes your invention. This should ideally

be carried out by a qualified Patent Attorney to make sure good patent

protection is obtained. The specification will describe the invention and

define the desired monopoly (in the form of claims). It will usually be initially

filed at the UK Intellectual Property Office.

Although the cost of a UK patent application is fewer than £100, the Patent

Attorney’s time, effort and skill in drafting the patent specification and

formulating the claims has to be paid for too. This can typically cost anything

from around about £3,000 to £5,000 + depending on the complexity of the

technology, the length of the patent specification and the number of claims

filed.

This initial patent filing will only provide protection in the UK. To obtain

patent protection abroad you will need to file corresponding patent

applications to cover all countries that are of commercial importance

to you.

A filing through the PCT route, a year after your UK filing, can delay the possibility

of filing abroad in most countries at a total cost of around £5,000.

There will be other costs along the patent journey, before the patent is granted

(or reduced in scope or rejected) which depend on such things as objections or

international searching and translations.

When the PCT stage ends, choosing in which countries to file your patent,

known as the National Entry Phase, the cost will depend on each country.

For worldwide protection (the major international markets), it is likely to cost

some £25,000 – £30,000.

There are then annual maintenance costs to pay (which continue to be due until

the expiry of the patent).

So, for patent cover in, say, major European countries, the USA and China, the cost,

which will have been defrayed over the first 5+ years from your initial filing,

is likely to be in the region of £40,000 - £60,000.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

8

Know-How and Trade Secrets

R&D projects and course-work can result in extremely valuable technical

information being created. The only way you can really protect your valuable

information (if it isn’t patented) is through confidentiality.

Know-how is a package of useful, non-patented, practical and secret

technical information, resulting from experience.

If information is significant, very sensitive, can be described in detail, has

commercial value, isn’t generally known and reasonable steps are taken to

ensure secrecy, then a trade secret can be asserted without an independent

evaluation or registration process and has an infinite lifespan.

Trade Secrets can be used, for example, if a business doesn’t want to go

through the patenting process, because that involves openly disclosing the

details of the invention.

Copyright

Have you ever written a thesis or article, written up an experiment, drawn

a diagram or even recorded a presentation you have given on a digital file?

All can be protected by copyright.

There is also copyright in music, broadcasts, sound recordings, computer

software, artistic works including photographs, films and typographical

arrangements of published editions. Copyright does not generally protect

against 3D reproduction of items from industrial drawings or plans (e.g.

models created from blueprints). They are instead protected by design

rights or as registered designs (see Designs section on page 11).

Copyright protects the form in which you express your idea but not the idea

itself. For instance, the copyright in the written words of a thesis may belong

to one person but the patent over the invention described in the thesis may

belong to someone else.

Unlike a patent, there is no need to register copyright in the UK; it arises

automatically. All that is required is mainly that the work must be original,

i.e. not copied from another source.

There are different periods for copyright, depending on the type of work, e.g. for

a written article, copyright would last for the life of the writer plus 70 years.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

9

Q: If I write up an experiment, does the fact that the written piece

of work is protected by copyright prevent anyone from using

the results or other information contained in it?

A: No. Copyright only protects the manner in which you have expressed

yourself i.e. the text, style and layout of the written document. It does

not protect your ideas, results or conclusions. Whilst another person

would be prevented from copying your write-up word for word or in

a

manner which was substantially similar to yours, they would not be

prevented from using the results or other information. This can instead be

protected as confidential information (see Know-

How section on page 9) but

you need to keep the written work secret.

Q: I have been recently asked by a publisher to waive my moral

rights in an article I have written. What does this mean?

A: Moral Rights are personal rights which belong to the author of a

piece of work. They are nothing to do with what is right or wrong!

Moral Rights include the right of an author to be identified as such. This

right has to be specifically asserted to be effective i.e. just write on the

work: “Joe Bloggs has asserted his right, under the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.“

Other moral rights include the right to object to derogatory

treatment of copyright work and the right not to have the work of

somebody else falsely attributed to you. These do not have to be

asserted. Moral Rights do not exist in computer software or are

limited in any work created by an employee. Whilst Moral Rights

cannot be transferred, they can be waived. However, there is no

reason why you should automatically agree to waive yours. Always

check with your supervisor or relevant institution representative.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

10

Designs

Designs of or on 3-D objects can be protected by design rights which arise

automatically or they can be registered. There are different types – UK

registered and unregistered designs, and Community registered and

unregistered designs. Community registered and unregistered designs offer

protection throughout the EU, not just the UK. Each type is a little different

in the criteria required for protection and the level of protection available.

A few examples are set out below:

UK Unregistered Design Rights can arise automatically in all or just parts

of a design. The design must not have been copied from another source and

it must not be commonplace in the relevant design field. For example, a

design for some scissors, unless very unusually designed, would likely be

commonplace in the field of cutting equipment. There are exceptions; a UK

unregistered design right will not protect any kinds of surface decoration

(e.g. an engraved design on the scissors). Nor will it protect any design which

is dictated by the way it has been made and any design which has been

created to fit around or inside another object (e.g. a plug and

socket) or to match with another object (e.g. a door panel of

a car). Protection of semiconductor topographies is

a form of unregistered design right in the UK. UK

unregistered design rights will last for the longer of

10 years from when the object was first marketed

or 15 years from the date of the

actual design document.

Q: I have recently compiled a database which holds the

location

reference numbers for all the cytology samples I have

used over

the past 6 months. Is this protected by copyright?

A: Yes, if it involved skill in creating it. It may also be protected

separately by “Database Right” (see Database Rights section on

page 12).

Intellectual Property

Section 1

11

UK Registered Designs can be registered with the Design Registry at the

UK Intellectual Property Office. The registration process is not as expensive

and does not take as long as for patents. UK registered designs can be used to

protect more of the design than would be capable of UK unregistered design

right protection. Surface decoration e.g. any etching, engraving or decoration

on the scissors, can also be protected.

To be registrable, the design must not have been previously disclosed to

the public (unless during a 12 month ‘grace period’ immediately before

the application for the design registration). The design must also have

‘individual character’. This means that the design must not produce any

notion of ‘déjà vu’. Designs which are dictated solely by their function

e.g. indentations on a plastic container to help with grip, will not be

registrable. UK registered designs can last for 25 years.

Community Registered Designs follow much the same criteria as for UK

registered designs. They will also last for up to 25 years.

Community Unregistered Design Rights arise automatically in the same

way as UK unregistered design rights. However, they are slightly different.

Community unregistered design rights only last for 3 years. The same criteria

are applied as for UK and community registered designs i.e. the design must

not have been previously disclosed and must have individual character.

Surface decoration can also be protected.

Database Rights

Database Right protects a collection of independent works, data or other

materials which have been systematically or methodically arranged. They

must also be accessible by electronic or other means. This obviously covers

electronic databases, but could in theory cover biological materials

collections, for instance.

Like copyright, there is no need to register, however, the protection only

lasts for 15 years from when the database was compiled.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

12

Trade Marks

It is difficult to avoid trade marks in day to day life. PEPSI, EASYJET, SHELL,

GUINNESS, iPhone, SELFRIDGES, Mini are all examples. Trade marks denote

the origin and the quality of the products they relate to. A well-known trade

mark is often the most identifiable element of a successful product or service.

They will often make a customer prefer one product over another.

Selecting the trade mark can therefore be crucial and so protection of it is

fundamental. The most successful brands are often those that are

completely distinctive, e.g. Coca-Cola.

Trade marks can be registered in the UK and/or throughout the EU and/or

in other countries/regions. They can also arise automatically if a mark has

been used and has consequently built a reputation. Unregistered trade

marks are, however, more difficult to enforce. If you can, it is always better

to register.

A registered trade mark needs to be able to distinguish the goods or

services of one person from those of another. It must be:

•

distinctive, e.g. “MARS” for chocolate bars;

•

it must not be descriptive of the goods or services to which it is

applied, such as ‘BOOTS’ for shoes; and

•

it must not be deceptive or contrary to public morality.

Objections can be raised to a proposed trade mark, by the owner of an

existing identical or similar trade mark registered for identical or similar

goods or services. Trade marks are registered in different classes, which

broadly distinguish different types of goods or services. Once registered

protection will initially last for 10 years, following which it can be renewed

every 10 years.

Intellectual Property

Section 1

13

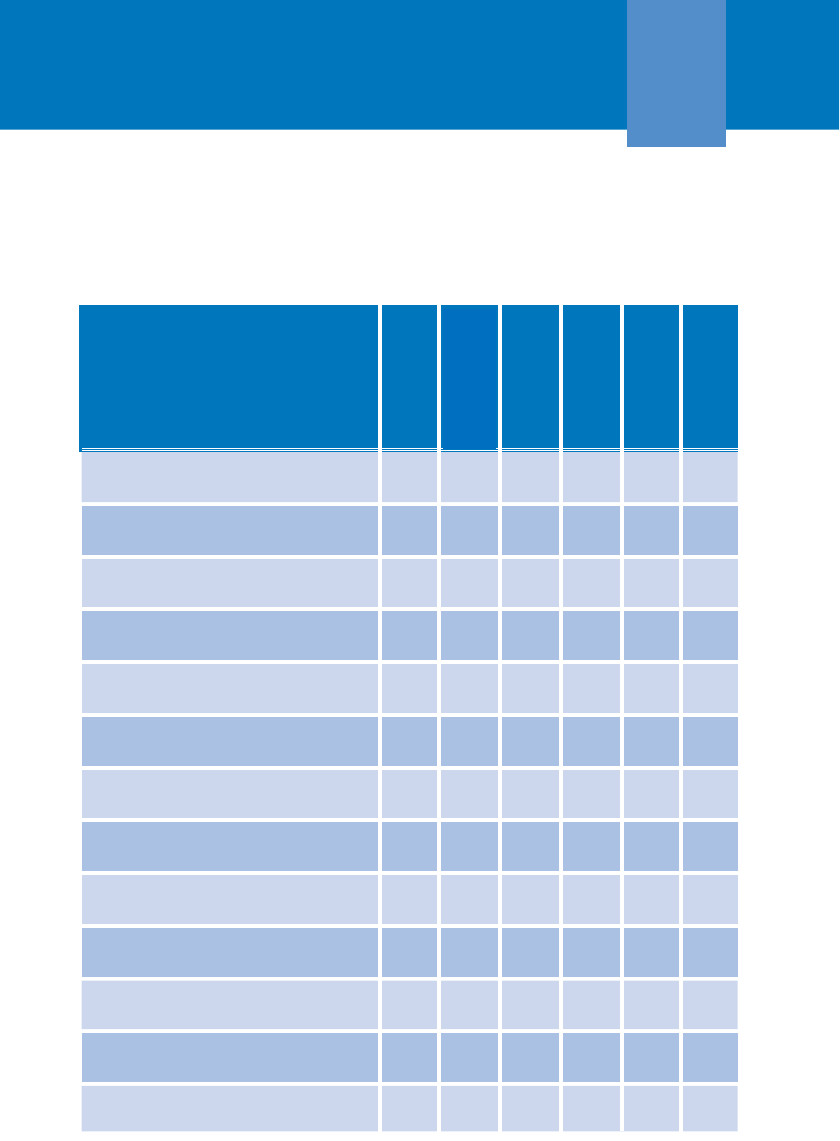

Set out below is a summary of the types of IPRs which might typically

arise in or be affected by activities within a university or other type of

research institution:

Activity

Research Information – preparing

and collating results/methods

Publishing or presenting research,

academic or technical papers

Using others’ research papers

or publications

Market analysis

Industrial design projects

Contract research

C

onsultancy projects

Receiving important confidential

information

Giving out important

confidential information

Using computer software

Developing computer software

Preparing lecture notes

Responding to technical queries

Patents

Know

-How

Copyright

Design Rights

Database

Rights

Trade Marks

IP Ownership

Section 2

14

Will I own the IP I create?

Whilst there is a number of situations in which you will either create or

contribute to the creation of IP, you may not necessarily own the IP in question.

General Position

As a general rule, an originator usually owns any resultant IP from their work, unless:

- the IP was made in the course of their employment;

- there is an agreement to the contrary;

- any other exception applies (e.g. material use of their institution’s facilities).

University employees will usually include academic staff, technicians, research

staff, support staff and administrators. The position of Visiting Professors or

Honorary Appointments can sometimes be unclear unless detailed arrangements

are in place. If you are working within an NHS Trust, it may not always be clear

whether a nurse or doctor who creates IP has done so in the course of their

employment, particularly if their main role is that of a patient carer.

In certain

instances, particularly within NHS Trusts, an individual may be a part-time

employee or jointly appointed with an external organisation.

It is becoming

increasingly common for NHS employment contracts to refer specifically to IP.

Often people involved may have other activities or be part-time.

If you are a student, you will not normally be classed as an employee unless,

in addition to you being registered as a student, you also have a contract of

employment with your university/institution e.g. as a research assistant.

You will however have a student contract to which you should refer.

Always check in what capacity you and your collaborators are engaged in any

project with respect to IP.

IP Policies

Universities or other research institutions have IP policies which are tailored to

their particular missions. They may also have different approaches with different

types of IP. For example, a university may claim ownership of patentable

inventions but not of copyright in certain scholarly materials.

Take time to familiarise yourself with your university/institution IP policy. Your

university’s Registrar or Trust Manager or equivalent will have copies or it may be

on your organisation’s intranet.

IP Ownership

Section 2

15

Originators and Contributors

It is essential in IP law to be certain who was the actual creator of the IP. The

person(s) who have made the creative leap are the originator(s). Different

specific terms are used for the originator(s) of different types of IP. For instance

in the case of patents they are “inventor(s)” and in the case of literary

copyright works they are “author(s)”.

Other individuals may have worked with the originator(s) to develop the

original idea or work, but if they have not created anything new in IP terms,

then they are not originator(s) but simply contributor(s).

Why is it important to distinguish between originator(s) and contributor(s)?

Well, for instance, in the case of patents, only the originator(s) of the invention

are named as inventors on the patent. Any reward sharing, from successful

business applications of the IP under an IP policy, is often only applicable to

the originator(s) and not to the contributor(s), though originators can arrange

to share any financial benefits they receive with collaborators.

Collaborative/Funded Work

If you are working with or for an industrial sponsor or a different university/

institution, check the terms of the funding arrangements e.g. of the grant, the

contract or the collaboration agreement. This is likely to specify who will own

the IP created.

Group Work

Consider whether you have produced work on your own or whether anyone

else has been involved in its creation. It can be more difficult to establish

ownership if a number of other staff/students has been involved in the

same project.

If you write a paper in conjunction with at least one other author, copyright in

that paper will be jointly owned, if your contribution is not distinct. Similarly, if

you develop a patentable invention jointly within a research team, that

invention may also be jointly owned. You will almost certainly need to obtain

the consent of any joint owners if you intend to do anything with that IP.

IP Ownership

Section 2

16

Consider individuals who may have created IP from another research

institution or any other external organisation. IP contributed may either be

owned by the individual or that individual’s research institution or connected

organisation. Check any other university/institution IP policies. Consider any

individuals who may have created IP but then left your team to go elsewhere.

They may have taken IP with them if it belonged to them.

Consultants

Consider whether any external consultants have contributed to the

development of the materials. Consultants are not classed as employees. IP

created by a consultant is likely to be owned by that consultant even if they

have been paid to do the work, unless stated otherwise in the

individual

consultancy agreement. This is particularly relevant in any NHS Trust

environment. A Trust may often appoint medical clinicians. The clinician

may not be an employee of the Trust and therefore IP may belong to the

clinician or their employer.

Why don’t I own the IP which I create?

At the start of a project you may be asked to sign an acknowledgement

which states that any IP you may create during the project shall be owned

by your university/institution. This, and any other situations, where your

university/institution may claim ownership to the IP, is done for a reason.

If an invention is made which is capable of commercialisation, it is very

unlikely that either you created the invention alone or you would have

the funding or resources to patent the invention and take it through to

commercialisation (see Section 6 – Commercialisation). IP

commercialisation and similar organisations are there to help with this

role. If all the IP is in one place, it makes it a lot easier to file applications

and deal commercially with the invention. Universities, in particular, will

often operate some form of policy so that you can share in the rewards of

the commercialisation. Contact your IP commercialisation organisation

for further details.

IP Ownership

Section 2

17

This table summarises some of the different factors which may be used to determine

who owns the IP.

Are you a

Are you a

What type

of IP have

staff?

How and

with whom

did you

Where did

the IP?

Protecting IP

Section 3

18

What can I do to help protect any IP which I create?

Patents

Some practical tips to help protect your inventions, including how to

register a patent are set out below:

Practical tips

If you come up with a new invention, is it patentable

(see Section 1)? Consider whether your invention has

been previously disclosed – e.g. look at existing patents,

key word searches. Use the internet, in particular

esp@cenet.

Keep both originals and copies of all notes, reports,

drawings, lab books etc. relating to the invention in a

secure place. You should try to record as much detail as

possible. Ensure all originals and copies are dated and are

sufficiently detailed (and clear!) to identify the invention

and how it works. Get your supervisor to sign and date

laboratory notebooks on a regular basis.

Keep the invention confidential (see Section 4 for

practical tips on confidentiality). If you need to disclose

any information, you should first speak to your

supervisor.

If, having done your initial searches/investigations you

still think your idea is patentable, let your supervisor

know and contact your IP commercialisation organisation

to set up a meeting.

If it is decided to go ahead, a patent application can be

drawn up, usually with the help of a patent agent, and

filed at the UK IPO. Once filed, you can indicate on any

relevant marketing literature, publications or products

“Patent applied for, No. [NUMBER]”. Do not do this

before you have filed, as it is illegal to do so.

Protecting IP

Section 3

19

Patent granted. You can use “Patent granted, No:

[NUMBER] [2020] [UK]” on any relevant literature,

publications or products.

The UK IPO will perform a preliminary examination

and search of the application to ensure the invention is

new. The Intellectual Property Office would then send

out a detailed search report and the application will be

filed. However a full examination is then required

during which the Intellectual Property Office will

decide whether the application can be granted. This is

a long, painstaking progress which can take 2 to 3

years (longer if you extend to cover countries beyond

the UK).

Protecting IP

Section 3

20

Copyright

There are no special formalities required to protect copyright work in the

UK. This is not always the case in other countries. The good thing about

copyright is that it arises automatically and it is free! However, as there is

no register to refer to, this sometimes makes it difficult to prove

ownership. Some practical tips to help overcome this and protect

copyright are set out below:

Practical tips

Keep all originals of your copyright work such as

notes, drafts, sketches, drawings, videos etc. in a

secure place.

Record the date you created the copyright work: a

good way to do this is put the work in an envelope,

post it to yourself or somebody independent, such as

a solicitor, and leave the envelope unopened. The

postal stamp can be used to demonstrate the date

before which it had been created.

©

Place a copyright notice (for example, ©J.Bloggs 2020

or ©University of Knowledge 2020) on the piece of

work which will act as a useful reminder to anyone

using the work that copyright exists and that action

may be taken.

Try inserting some irrelevant but intentional mistakes

or anomalies in your work (e.g. a repeated line of

source code, or an unusual spelling mistake). This can

be a good way of illustrating that someone has copied

your work if their work also includes the same mistake

or anomaly. Use watermarks.

Protection of work on the internet is more tricky as it

is extremely difficult to police the internet effectively.

Therefore, don’t publish anything on the internet that

you or your university/institution would not wish to

be copied. Perhaps just publish excerpts, and leave

people to come back to you for the main work.

Protecting IP

Section 3

21

Designs

Some practical tips to help protect your designs are set out below:

Practical tips

Keep all originals of your design drawings, sketches,

samples, models and prototypes.

Keep all these materials in a secure location.

Record all dates of creation and the dates when you

may have disclosed the design, e.g. at a trade fair or

in any publication.

Contact your supervisor and/or IP commercialisation

organisation who can help decide what type of

protection is suitable and whether or not to apply

for registration.

22

Protecting IP

Section 3

Database Rights

Some practical tips to help protect your database rights are set out below:

Practical tips

Keep all your notes, records of telephone

conversations and meetings, e-mails, contact details

and other correspondence which you used to collect

and compile the information contained in your

database.

Keep all your working drafts and original copies of

your database in a secure place. If stored

electronically ensure it is password protected.

Record the date when you created the final database:

again, a good way to do this is to put the work in an

envelope unopened.

Alternatively, if stored electronically, e-mail the

database to yourself or somebody independent, such

as a solicitor. The postal stamp or the date of the

e-mail can be used to demonstrate the date before

which it was created.

Place a copyright notice (for example, © J Bloggs

2020 or © University of Knowledge 2020) at the

bottom of the database.

Insert some intentional but irrelevant mistakes or

anomalies in the database.

©

Protecting IP

Section 3

23

Trade Marks

Some practical tips to help protect your trade marks are set out below:

Practical tips

Consider in which countries you would want to

protect your trade mark – i.e. where would the

products or services be sold or used?

Have a look on the Trade Marks section of the UK IPO

website (www.ipo.gov.uk). Click on ‘Trademarks’ and

then ‘Online TM Services’ then ‘Find Trade Marks’

then ‘By mark text or image’. You can then have a

look to see if there are any similar or identical trade

marks already registered.

The same website contains details on how to register

a trade mark. Contact your IP commercialisation

organisation – they may be able to put you in contact

with a Trade Mark Agent to help with the process.

™

Use the ™ symbol when your trade mark is

unregistered.

®

Use the ® symbol when the trade mark is registered.

DO NOT do this before it is registered. It can be a

criminal offence to do so!

Confidentiality

Section 4

24

Could your work or other information or results be useful to someone else

if they ever got hold of it? Could any of your work be potentially patentable

or registrable as a design? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, it

is important to consider confidentiality. Confidentiality is the best way to

protect your information and know-how.

The ‘someone else’ could be an individual from a company, a member of

another research group or someone from another institution or even a

friend or relative. The information may include chemical formulae,

information from laboratory notebooks, experimental techniques,

information concerning the programming of equipment or source code. It

may be personal or commercially sensitive information such as customer

lists or results from market research. These are just a few examples.

It does not matter how informal a conversation or meeting may seem. You

must always consider the nature of the information you are disclosing and

whether, in the circumstances, it is appropriate to disclose. Let’s look at a

few examples.

James has developed the source code for a new computer program. If

someone else is able to access the source code they may well be able to

write a program to undertake the same task but using different code. This

could then be used or developed further into a product which could be

extremely lucrative. The source code is therefore highly-confidential

information and would need to be protected from disclosure.

Mary has invented, in conjunction with her team, a novel technique for

protein analysis. This invention is potentially patentable. One of the criteria

for the grant of a patent is that the invention must be new and must not

have been previously disclosed to the public. If any information relating to

the invention is disclosed before filing a patent application, this would

completely stop a patent from being granted in most countries.

Confidentiality

Section 4

25

Undoubtedly, there will be situations where disclosure cannot be avoided. In

these circumstances you will want to ensure that the person to whom you

disclose the information not only keeps it secret but also does not use it

improperly. If you show someone confidential information for one project,

your agreement should stop them using the information for another project.

Janice has been working on a summer project. The project has been funded

by an industrial sponsor – Inventive Concepts plc. At the beginning of the

project Janice was asked to sign an acknowledgement to say that she

understood and agreed to comply with the terms of the R&D Agreement

between the university and Inventive Concepts plc. She signed. One of the

terms contained in the R&D Agreement stated that any information

generated during the project must be kept strictly confidential and not

disclosed to anyone else who was not directly involved in the project.

Janice must therefore keep the relevant information confidential.

Chris has a consultancy contract with Security Finance Limited relating to

work on cryptography. The consultancy contract contains a confidentiality

clause. Chris needs to be careful not to disclose any of the confidential

information which Security Finance Limited supplies, when carrying out

other work.

Alex has been able to read a thesis from Alex’s university which is subject

to restricted access because of a confidentiality agreement with Future

Research Ltd. Alex wants to use some of the information from it as part of

some other research. If Alex wants to publish the results of the new

research and this includes information from the restricted access thesis,

Alex will need consent from Future Research Ltd. If Alex quotes from the

thesis, consent from the owner of the copyright in the thesis may also

be needed.

Confidentiality

Section 4

26

To whom can I disclose information?

At law employees have duties of confidentiality to their employer. If you are

an employee it is therefore not a problem as such to share your employer’s

confidential information with colleagues who are employed by the same

employer. Remember – students, visiting academics, secondees and

consultants will not necessarily be employees. Accordingly, if confidential

information is to be disclosed to any of them it is always better to try and

have a form of written confidentiality agreement in place. In the case of

students, this may form part of their student contract.

What should I do to protect the information?

You may have heard references made to a ‘CDA’ or ‘NDA’. These are

abbreviations for “Confidential Disclosure Agreement” or “Non-Disclosure

Agreement”. If you have to disclose important information always try and

put a written agreement of confidentiality in place. The best thing to do is

contact your Research Office or IP commercialisation organisation or your

supervisor who will no doubt have a sample confidentiality agreement for

you to use and will be able to help with putting it in place. Remember you

are probably not authorised to sign a confidentiality agreement for your

institution.

These agreements are all to be taken very seriously. Any information and

discussion covered by them must be treated in confidence and not

disclosed to anyone else, except as set out in the agreement. If there is any

breach of any agreement, the other party may be entitled to seek financial

and other compensation (damages) not only from your employer but

possibly from you personally. This is obviously a very serious matter. In an

environment like a university or NHS Trust it is difficult to supervise closely

compliance with all the agreements that have been signed. There is also, of

course, a natural desire to publish and discuss work openly, which may on

occasions give rise to individuals not realising the importance or the extent

of any agreements that have already been signed. Extra care therefore

needs to be taken.

Confidentiality

Section 4

27

Can I present at a conference?

If you disclose the key information about your invention or design whether

at a conference or elsewhere, it can stop you getting IP protection. You

may, however, be able to make some general statements without disclosing

your invention. Discuss this in advance with your IP commercialisation

organisation.

So if you are about to publish at a conference or elsewhere, speak to your

IP commercialisation organisation as early as possible. They will look to file

an application for a patent before publication, if the subject material has

good business prospects.

You can publish openly once a patent application has been filed. However,

there can be some advantage in waiting a little longer before publishing, in

case any claims of your patent are not accepted when they are examined

as part of the patent registration process. These rejected aspects of your

application would then only ever be protected by confidentiality.

Confidentiality

Section 4

28

What else can I do to protect the information?

Practical tips

Consider whether confidential or sensitive information

is accessible by other students or staff. Be careful

about leaving information visible on desk tops. If

necessary keep information in locked cabinets or use

password security for electronic storage.

Keep a record of what has been disclosed during any

meeting/conversation. If a batch of information is to

be passed over, create a list of the information and, if

possible, get the recipient to sign the list by way of

acknowledgement.

Create some minutes or written record of

conversations. This does not have to be overly formal.

Something in bullet point form will suffice. A copy of

this record can then be sent to the recipient.

Top

Secret!

If information is confidential then it never does any

harm to mark it as such. It has the additional benefit

of putting the recipient on notice of the confidentiality

of the information and hopefully reminding them to

treat it carefully. Don’t be afraid to tell the recipient

you expect them to treat it carefully.

Never disclose more information than is necessary. If

an individual or company has refused to enter into a

CDA, instead of disclosing specific details relating to

an invention – just refer to the advantages the

invention would offer the recipient. Whet their

appetite. Hopefully they will then become interested

to find out more and enter into a CDA.

Confidentiality

Section 4

29

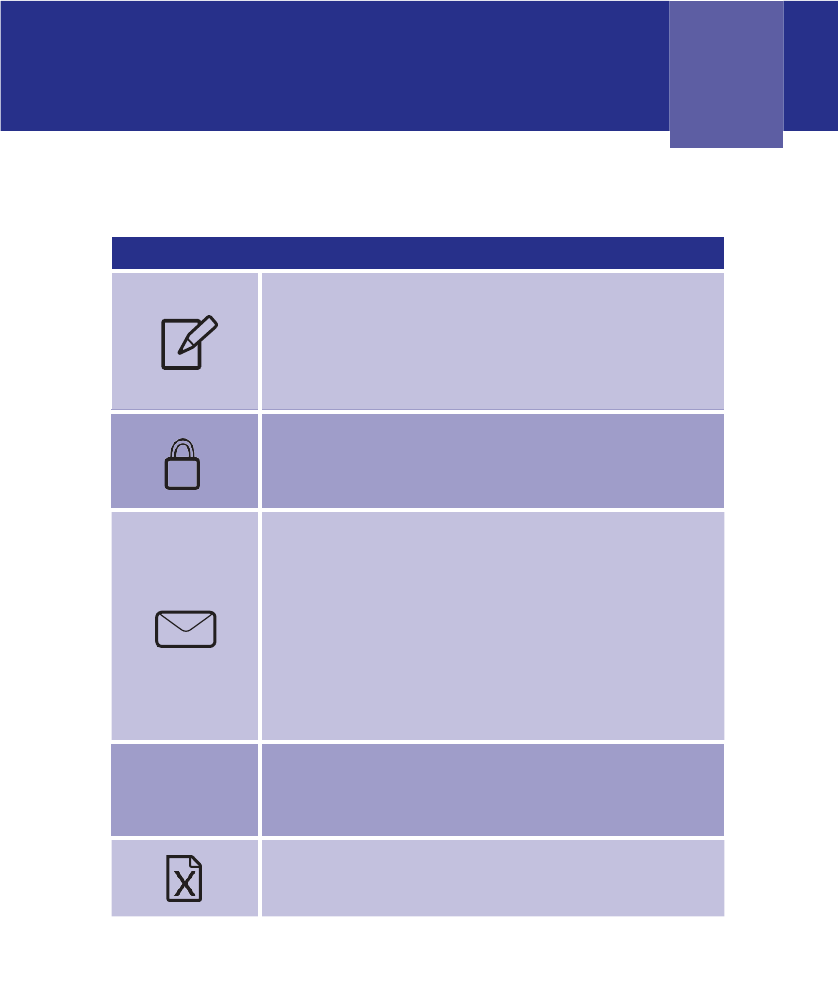

Confidentiality Checklist

•

With whom am I meeting or speaking?

•

Are

they members of my team, my research organisation or employed by

my employer?

•

What information am I sharing?

•

Is

this

information sensitive or otherwise valuable – could it be misused by

the recipient?

•

Is

this

information potentially patentable or registrable as a design?

•

Am I or is my employer under any obligation of confidentiality not to

disclose this information?

•

Have I asked the other person to sign a CDA?

•

Have I marked any of the information as “Confidential” or “Trade

Secret”?

•

Have

I taken notes of the meeting/conversation from which it can be seen

what I have disclosed and what has been said?

Remember – if in doubt, always speak to your supervisor,

authoriser or IP commercialisation organisation.

Using IP

Section 5

30

Q: When should I be careful when using IP

belonging to others? A: Always!

In the previous sections we have concentrated on what IP is and when and

how you are likely to create it. Don’t forget that other people, including

fellow academics or colleagues you may be working with, may also have IP.

Others’ IP can be extremely useful, but you must bear in mind what you

can and cannot not do with it.

Let’s take patents and copyright as an example. If you make a product or

use a process which has been patented by another person or company, you

may infringe the patent rights of that other person or company. Similarly, if

you copy or share by copying, e.g. online, or adapt a piece of work which is

protected by copyright of another person or company, you may infringe

that person’s or company’s copyright. This is very serious because, if you

are infringing, the owner of the IP may get an injunction to stop you using

the IP anymore and/or may sue you and/or your employer for damages.

There are, however, exceptions, which may allow you to do limited things

without infringing the rights of the owner. Examples are set out below:

You can make a patented product or use a patented process for research

purposes providing it is a research area on the subject matter or the patent.

This means you can also do this to modify or improve the invention to which

the patent relates.

You should and can use patents as a source of information. Much of the

information in patents is never published anywhere else and will often contain

sufficient detail in the text and illustrations so that you, as experts, can

understand how to recreate the invention.

You may want to look through the patents simply for inspiration to prevent you

starting to do research on something that has already been done. You can

search to see what other research has been carried on in the same sort of field

as yours and in addition what progress has been made, on which you might be

able to build.

Always check whether the patent in question has been allowed to lapse. In this

case you can use the invention freely.

Patents: Permitted Actions

Using IP

Section 5

31

Copyright

It is only an infringement of copyright to copy, exhibit or use a piece of

work without the consent of the owner of the copyright. If you are

photocopying or digitising a journal article or book chapter, it is possible

that your university/institution may already have obtained the consent

from the copyright owner through its subscription to a blanket licence

through the Copyright Licensing Agency (CLA) or perhaps another

collecting society. This is also common practice within libraries. Have a

look to see if there are any notices next to the photocopier relating to

this. If you are unsure, contact either the university librarian or your

relevant CLA representative for copyright clearance.

In certain cases you can copy copyrighted work. Usually it cannot be a

substantial part though. Be careful with this – there are no hard and fast

rules on how much constitutes a substantial part. Substantial is about the

quality (importance) of the part copied, not the quantity. There are also

allowances for use of limited sections of work where they are being

copied for the purposes of instruction within a university. Again, have a

look to see if there are any notices next to the photocopier which may

contain some guidelines.

You can also use a piece of a copyright work for non-commercial

purposes if you are using it for research or private study or for the

purposes of criticism and review. You must clearly acknowledge any

reference to the work in question.

Patents: Not Permitted Actions

Using IP

Section 5

32

Unless you have obtained the copyright owner’s consent or your use

falls into any of the categories above, you risk infringing copyright if you

copy the work or permit another person to copy the work.

It is important to remember that in any single web page there can be

dozens of different copyrights. If you want to print out a web page,

or copy and paste anything from a web page the same rules will

apply. Check the copyright notice on the web page, it may be that

the copyright owner has already offered consent. If the copying is

not specifically covered in the page’s own notice then you should

obtain specific permission – this can be done by e-mail. If in doubt,

always refer to your internet policy information or contact your

relevant representative.

Copyright

Whilst there are other situations in which it may be possible to use a

copyright work without infringement, these are more limited in use and

practical application. If you are unsure, it is always best to contact your

library (or other relevant representative) for further guidance.

Q: I was recently provided with a number of tissue samples

from an outside company for my project. I also received a

document referred to as an ‘MTA’ with the samples. What

should I do?

A: MTAs are Materials Transfer Agreements. This agreement is likely to

contain a number of restrictions on what you can and cannot do with

the samples, how you must deal with the results and whether, for

example, you must return any back to the company. It is important to

read through the terms carefully and speak to your supervisor and/or

your IP commercialisation organisation. They will let you know whether

it is appropriate and who is authorised to sign it. You must remember

that when any kind of materials are provided to you it is possible they

may contain confidential information or they may even be protected by

a patent. By using materials which are protected by a patent in a

manner which the owner has not permitted you may risk infringement.

Some MTAs may even try to take ownership of IP created by you.

Commercialisation

Section 6

35

What is commercialisation? Commercialisation is where property is used or

disposed of in return for payment, whether in cash, in kind or in any other

form.

In the same way as a house can be bought and sold, IP can also be sold or

transferred to another owner. This is referred to as an

assignment

.

IP can also be

licensed

. This is similar to a ‘lease’ of a flat. The IP owner

permits someone else (the “Licensee”) to use the IP (or part of it) for a

specified purpose in return for payment. If the IP has been used to make a

particular product, payment will often be made in the form of a “royalty”.

The royalty may be a percentage cut of the price the product has been

sold for by the Licensee.

The table below illustrates some main points to remember:

Assignment

Licence

An assignment transfers

ownership.

Once assigned, the original owner

will lose their rights to the IP. If

the original owner continues to

use the IP after assignment, they

may risk infringing the rights of

the new owner.

You can assign ownership of part

of copyright e.g. English

language rights.

The owner of the IP remains the

same.

The licence can be limited in time.

The licence can also be limited in

scope:

An

Exclusive

licence means that the

owner can only permit one licensee

to use the IP and cannot license that

same IP to anyone else nor use the

IP itself.

A

Sole

licence means the same as an

Exclusive licence except that the

owner of the IP can use the IP itself.

A

Non-Exclusive

licence means that

the owner of the IP can license to

more than one licensee.

The manner in which the IP should

be used and the field/research area

in which it can be used can be

defined and limited.

Commercialisation

Section 6

35

Here are some examples of when a licence or an assignment of IP may

be involved:

•

writing an article for a publisher.

•

franchising

out a set of teaching materials for use by another university or

company.

•

permitting another to use equipment or a specific technique you have

developed.

•

permitting

another access to your results and other data for the purposes of

further development/experimentation.

•

permitting

another to incorporate a product you have developed into

another product

Check that any material used via an ‘open licence’ complies with any terms

and conditions of that licence, for example any obligations and restrictions.

If IP has been developed with a lot of potential for commercialisation, it

may be appropriate to transfer the IP into a separate company which is

dedicated to its commercialisation. These are commonly referred to as

‘spin-out companies’ (or occasionally ‘spin-offs’ or ‘start-ups’).

Your IP commercialisation organisation is experienced in identifying and

putting in place appropriate arrangements and agreements. They have

many contacts and access to professional support. It is not always

straightforward and there are many things to consider. If you think you have

IP which can be commercialised or you are approached by any outside

organisation, you should first contact your supervisor and/or your relevant

IP commercialisation organisation to discuss the options.

Commercialisation

Section 6

35

Case Study

Arnold has just been contacted by an editor from Semi-Conductors

Monthly asking whether he would write an article on his conclusions

from a project he has recently been involved in with his supervisor.

Arnold is asked to sign an agreement before writing the article. Arnold

notices one clause which states “I hereby assign all intellectual property

rights in or relating to the Article”. What should Arnold do?

First Arnold should speak with his supervisor.

Arnold and his supervisor should consider whether there are any results,

conclusions or other information which could be patentable or valuable

to readers for use or further development. Disclosure and publication

would prevent any patent being granted.

Once Arnold has written the article, provided it is Arnold’s own work,

Arnold will be the author of the copyright in the written article. Arnold

should also consider his moral rights in connection with the article (see

Section 1). However, Arnold will not necessarily own the copyright in the

article and should check whether he or his university/institution is the

owner, referring to any relevant IP Policy and the IP commercialisation

organisation. It may be that his university/institution has to sign the

agreement rather than Arnold.

Check if an assignment to Semi-Conductors Monthly could be avoided.

A licence should be sufficient for Semi-Conductors Monthly to use the

article for the purposes of publishing it in a specific edition. An

assignment of all intellectual property rights in or relating to the article

would mean that Semi-Conductors Monthly would become the owner of

the copyright in the article and the university/institution or Arnold

would be unable to reproduce the Article again, even internally, without

asking for consent and possibly having to pay a licence fee.

Section 7

Useful Links/Contacts

•

Your Library Information Service (for literature and patent

database searches)

•

Your employer’s intranet for its IP and various related policies as

well as priorities and guidance notes regarding working with

other organisations, agencies and companies

•

Higher Education Funding Councils for good practice IP reports

and guidance on relevant issues (www.hefce.ac.uk

)

(www.sfc.ac.uk) (www.hefcw.ac.uk)

•

Your

Research

Office and IP commercialisation organisation

•

UK

Intellectual

Property Office website (www.ipo.gov.uk)

•

Esp@cenet Patent website (http://gb.espacenet.com)

•

European Patent Office website (www.epo.org)

•

European

IP Helpdesk(www.ipr-helpdesk.org)

•

Community Trade Mark Searches

(www.oami.europa.eu/CTMOnline/RequestManager/en-

SearchBasic_NoReg)

•

US Patent and Trademark Office (www.uspto.gov)

•

UK

Company

Searches (www.companies-house.gov.uk)

MCR.

IP and Confidentiality Checklist

TYPES OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Copyright

•

Protects items such as writing, music, and

software

•

Protects the expression of an idea, not the idea

itself

•

Protects

original work

•

Arises automatically without registration

•

Duration

mainly life of creator +70 years

Patents

•

Protects

inventions

•

Needs

registering

•

Must

be new, inventive and capable of industrial

application

•

Don’t

disclose pre-application

•

Duration

20 years

UK Unregistered

Design Right

•

Designs

must be original and not commonplace

•

Not protected if surface decoration, dictated by

the way it’s made, made to fit/match another

object

•

Arises

automatically

without registration

•

Duration 10 years from first marketing/15 years

from date of design document

UK/Community

Registered Designs

•

Design

has individual character

•

Not

protected

if dictated by function

•

Don’t disclose more than 12 months pre-

application

•

Duration

25 years

Community Unregistered

Design Right

•

Criteria same as for registered design

•

Arises

automatically

without registration

•

Duration 3 years

Database Rights

•

Protects collection of independent works, data or

other materials arranged systematically or

methodically arranged

•

Arises

automatically without registration

•

Duration

15 years

Trade Marks

•

Denote

origin and quality of goods

•

Not descriptive/must be distinctive

•

Not identical or similar to an existing mark for

similar or identical goods

•

Duration

10 years (renewable)

OWNERSHIP

Ownership

•

IP is generally owned by its creator

•

Employer usually owns IP created by an

employee

•

Consultants generally own the IP they create

•

Student IP depends on the student contract

•

Ownership can be varied by contract

•

IP created jointly may be owned jointly

•

Commissioned designs are owned by

commissioner

PROTECTION

Copyright/Designs/

Database Rights

•

Keep originals of works in a secure place

•

Record all dates of creation

•

Place a copyright notice on each copyright work

•

Insert irrelevant but intentional mistakes or

anomalies in your work

•

Don’t publish on the internet what you don’t

want copied

Patents

•

Check if your invention is new

•

Keep lab notebooks (signed and dated) and

other notes secure

•

Keep invention confidential until filing at least

Trade Marks

•

Use the ™ symbol for unregistered trade mark

•

Use the ® symbol for registered trade mark

•

Set up a watching service

Trade Secrets, Confidential

Information,

Know-how

•

Use written confidentiality agreements

•

File an application before publishing

•

Lock information away

•

Keep notes of meetings

•

Mark information as confidential

•

Disclose as little as is possible

USING IP

Using Others’ IP

•

Can be a source of information

•

Has the period/benefit of protection expired?

•

Do you have a licence?

•

One item can comprise more than one IP right

•

Does an exception apply?

•

Are you copying a substantial (qualitative) part?

•

Have you given appropriate acknowledgement?

COMMERCIALISATION

Commercialisation IP

•

IP is used or disposed of for payment

•

IP can be bought and sold (assigned)

•

IP can be licensed (like a lease)

•

Assignment transfers IP ownership; with

licensing IP owner remains the same

•

Once assigned, original owner loses all rights in

IP

•

Copyright can be assigned in part

•

Licensing allows someone to use IP, often for a

royalty payment

•

Licence can be limited in length, scope and use

©The University of Manchester, HGF Law LLP and Eversheds Sutherland LLP 2004-2020.