DESIGNING BIOPHILIA INTO INTERIOR ENVIRONMENTAL PRACTICE:

A BIOPHILIC DESIGN ASSESSMENT TOOL DEVELOPMENT

By

BETH LENA SHERMAN MCGEE

A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT

OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

2018

© 2018 Beth McGee

To my Family: I could not have completed this without you

4

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to Dr. Park who took the long journey with me and was the friendly support I

needed at all times and a key to my success. Thank you to my committee who were a very

helpful support system, I am very grateful to you all. Thank you to my husband who is my

support system and my best friend. Thank you.

5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

page

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4

LIST OF TABLES ...........................................................................................................................7

LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................8

ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................9

CHAPTER

1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................11

Theory Building ......................................................................................................................14

Biophilic Design Matrix .........................................................................................................15

2 ESSAY 1 .................................................................................................................................19

Literature Review ...................................................................................................................19

The Original Biophilic Design Matrix ............................................................................22

Design and Assessment Tools .........................................................................................23

Method ....................................................................................................................................25

Research Design ..............................................................................................................25

Phase One: Biophilic Design Matrix Development ........................................................26

Phase Two: Biophilic Design Matrix Testing .................................................................33

Results .....................................................................................................................................36

Research Question One: Perceptions of Biophilia ..........................................................36

Research Question Two: Optimal BDM as a Tool ..........................................................37

Research Question Three: BDM Validity and Reliability ...............................................39

Discussion ...............................................................................................................................40

3 ESSAY 2 .................................................................................................................................44

BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................45

Lighting ...........................................................................................................................47

Materiality .......................................................................................................................49

Color ................................................................................................................................50

Study 1 Method .......................................................................................................................53

Study 1 Results and Discussion ..............................................................................................57

Lighting ...........................................................................................................................61

Materiality .......................................................................................................................63

Study 2 ....................................................................................................................................65

Method .............................................................................................................................65

Results and Discussion ....................................................................................................66

6

4 ESSAY 3 .................................................................................................................................75

Literature Review ...................................................................................................................75

Restorative Environmental Design ..................................................................................79

Studio Education and Biophilic Design ..........................................................................81

Method ....................................................................................................................................83

Participants ......................................................................................................................83

Instruments ......................................................................................................................84

Studio Project and Data Collection .................................................................................85

Results .....................................................................................................................................87

Biophilia Perception ........................................................................................................87

BID-M Helpfulness for Students .....................................................................................91

Discussion ...............................................................................................................................97

5 CONCLUSIONS ..................................................................................................................103

APPENDIX

A ASSIGNMENT SHEET .......................................................................................................111

B BDM SURVEY ....................................................................................................................115

C COGNITIVE INTERVIEW MANUAL ...............................................................................126

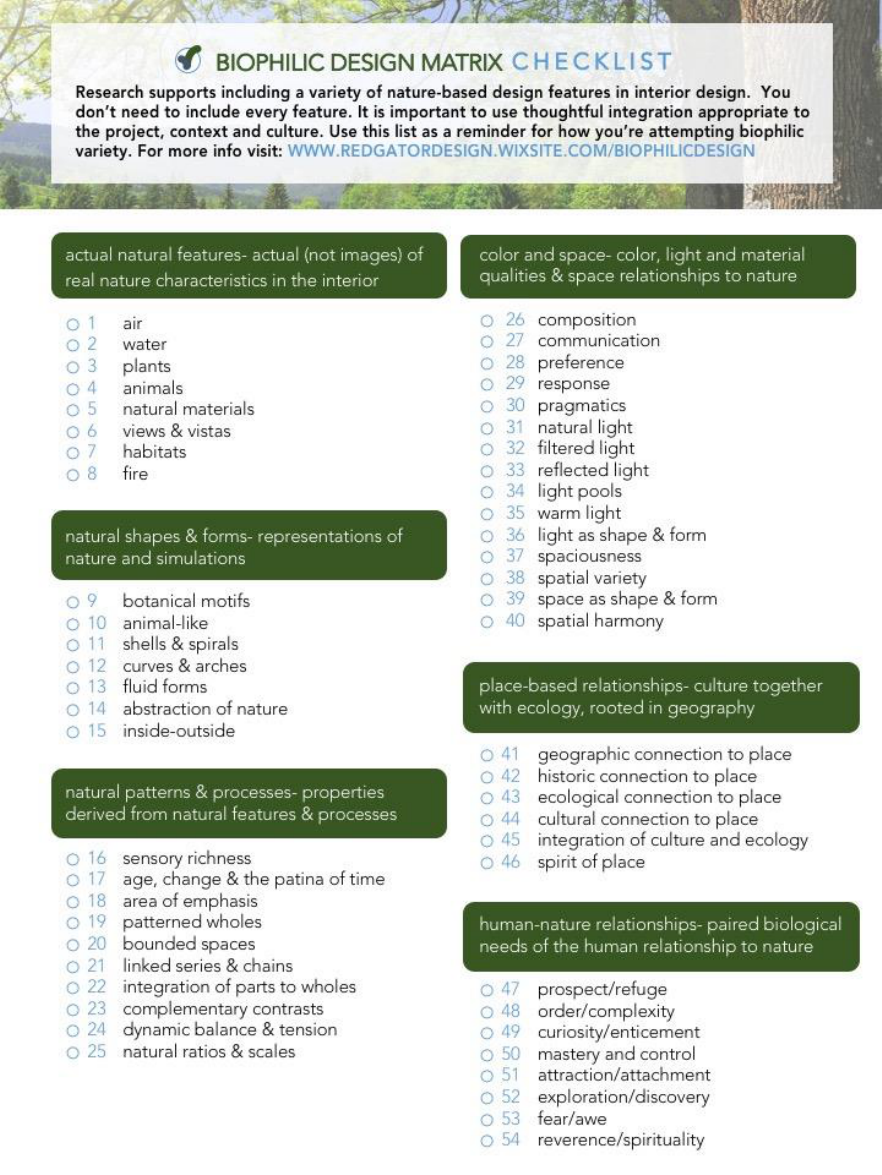

D DESIGNER’S CHECKLIST ................................................................................................130

E EMAIL INVITATION .........................................................................................................131

F FINDINGS FROM THE LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................132

G GUEST EXPERIENCE ASSIGNMENT .............................................................................136

H HOSPITALITY STUDIO PRE AND POST SURVEYS .....................................................138

Pre-Project Assessment Survey ............................................................................................138

Post-Project Assessment Survey ...........................................................................................138

I INFORMATION SHEET (BID-R) ......................................................................................142

LIST OF REFERENCES .............................................................................................................147

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH .......................................................................................................147

7

LIST OF TABLES

Table page

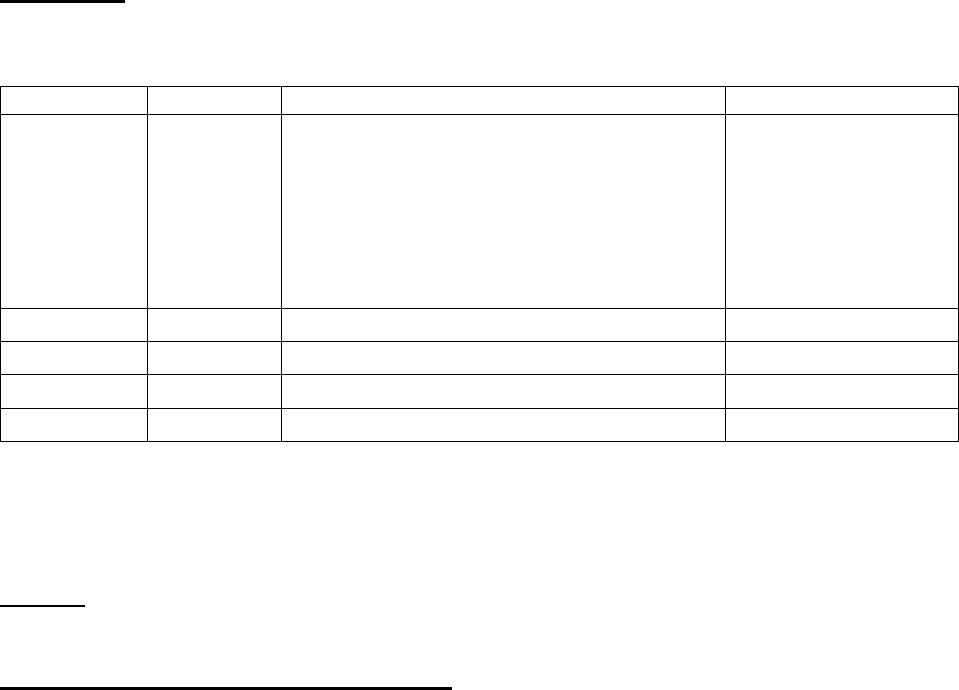

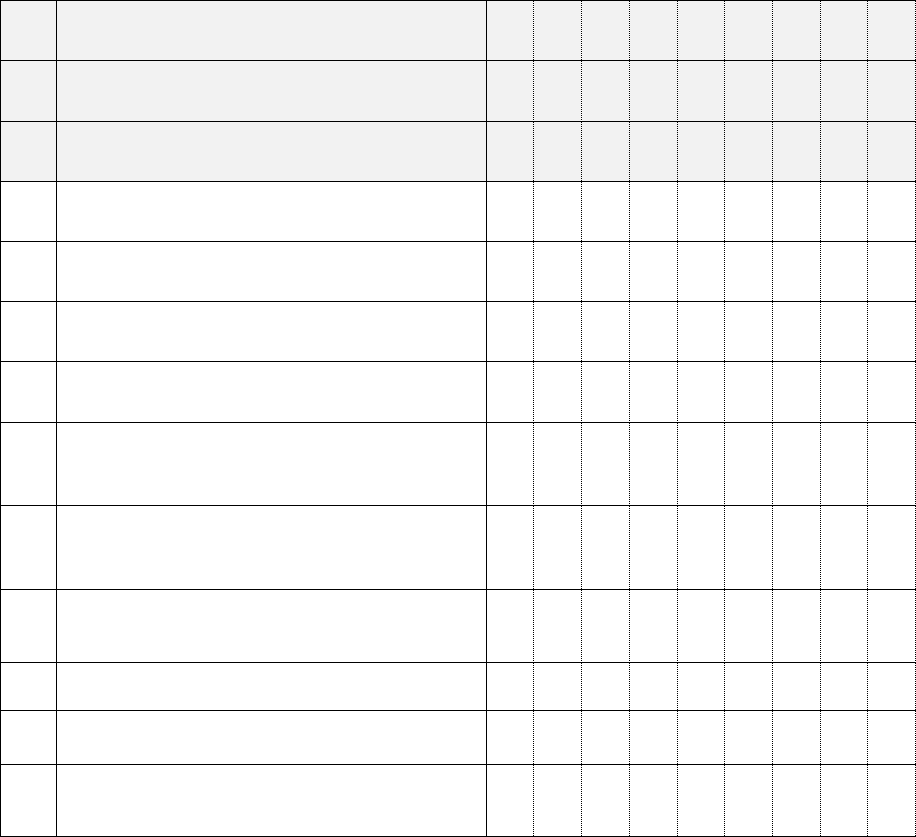

2-1. Cognitive interview overview. ...............................................................................................33

2-2. Biophilic design elements and attributes finalized. ................................................................34

2-3. Demographics of participants. ................................................................................................36

2-4. Pre-BDM practitioner’s perceptions of biophilia. ..................................................................36

2-5. Post BDM open answers, four most common comments. ......................................................37

2-6. Post BDM, future design process uses. ..................................................................................38

2-7. Overall quality of the BDM. ...................................................................................................38

2-8. BDM reliability element and combined results. .....................................................................39

3-1. Biophilic design elements and attributes. ...............................................................................46

3-2. Literature review biophilic design results. .............................................................................56

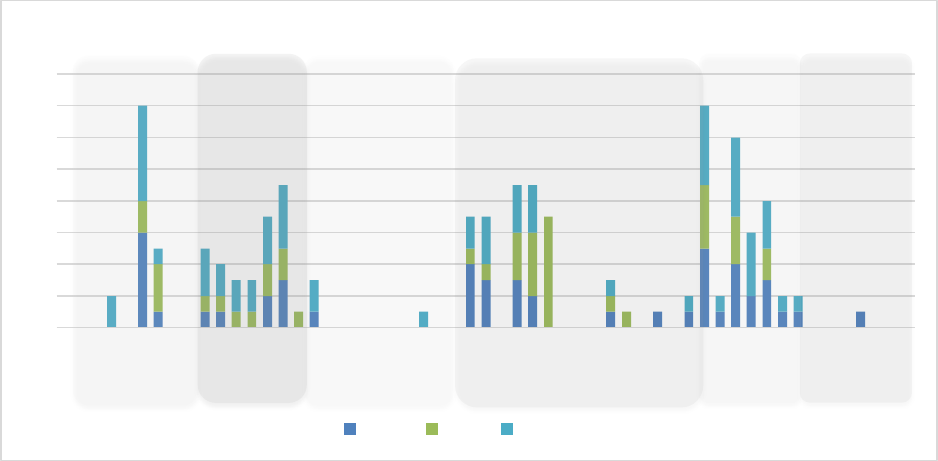

3-3. Biophilic feature frequency in the literature review. ..............................................................58

3-4. Demographics of respondents. ...............................................................................................66

3-5. Frequency of practitioner comments by BID-M attributes, element categories blocked in

color boxes. ........................................................................................................................68

3-6. Frequency of comments by biophilic element. .......................................................................69

3-7. Comparison table ranking highest to lowest frequency of attributes identified in the

literature and by practitioners, top three most frequent attributes. ....................................71

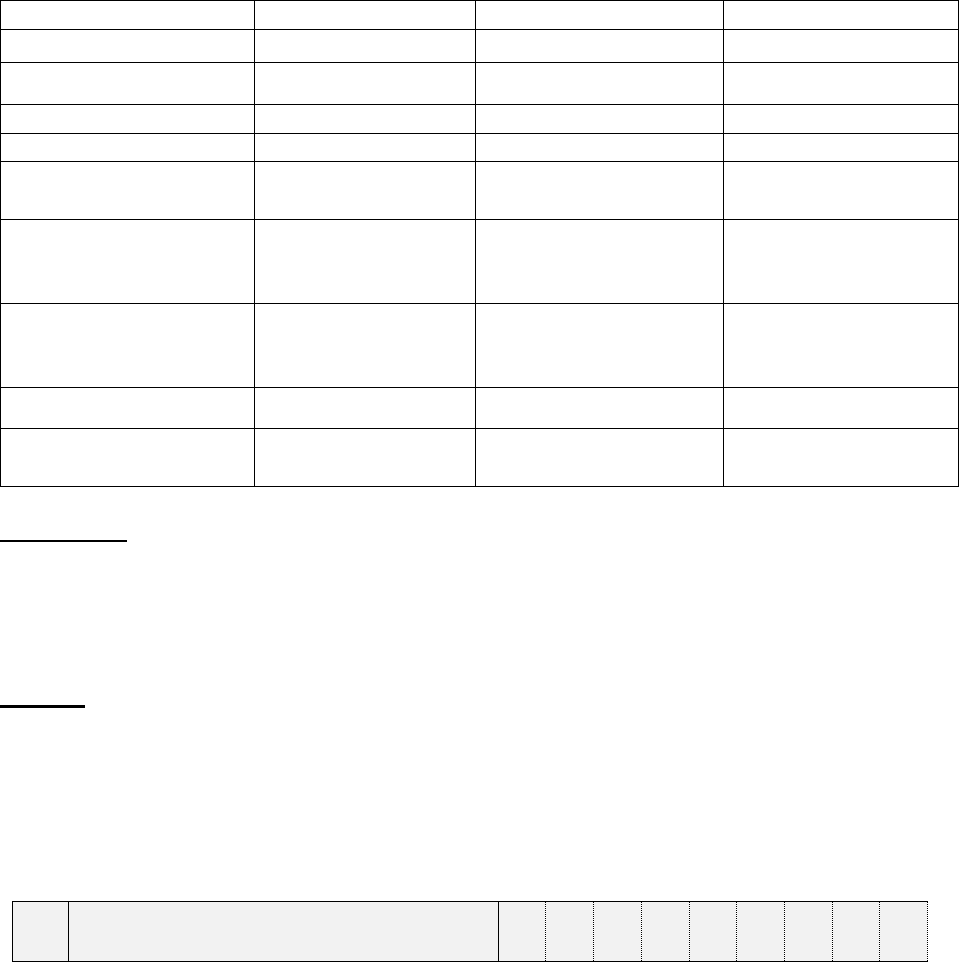

4-1. Biophilic design elements and attributes. ...............................................................................78

4-2. Frequency of open answer themes survey 1, pre-project questionnaire. ................................88

4-3. Perceptions about biophilia throughout project. .....................................................................89

4-4. Jury assessment of student work. ...........................................................................................92

4-5. Inter-rater reliability for the unique jury panels of each day. .................................................92

4-6. Open answer process number of open comments per theme..................................................94

4-7. Challenges and helpfulness of biophilic design. ....................................................................95

8

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure page

1-1. Supporting theoretical framework diagram. ...........................................................................14

2-1. Study process diagram. ...........................................................................................................26

2-2. Site image examples. ..............................................................................................................27

2-3. Proposed restorative environmental design framework diagram. ..........................................43

3-1. Process diagram for both studies. ...........................................................................................52

3-2. Literature review flow diagram. .............................................................................................55

4-1. Study process diagram. ...........................................................................................................84

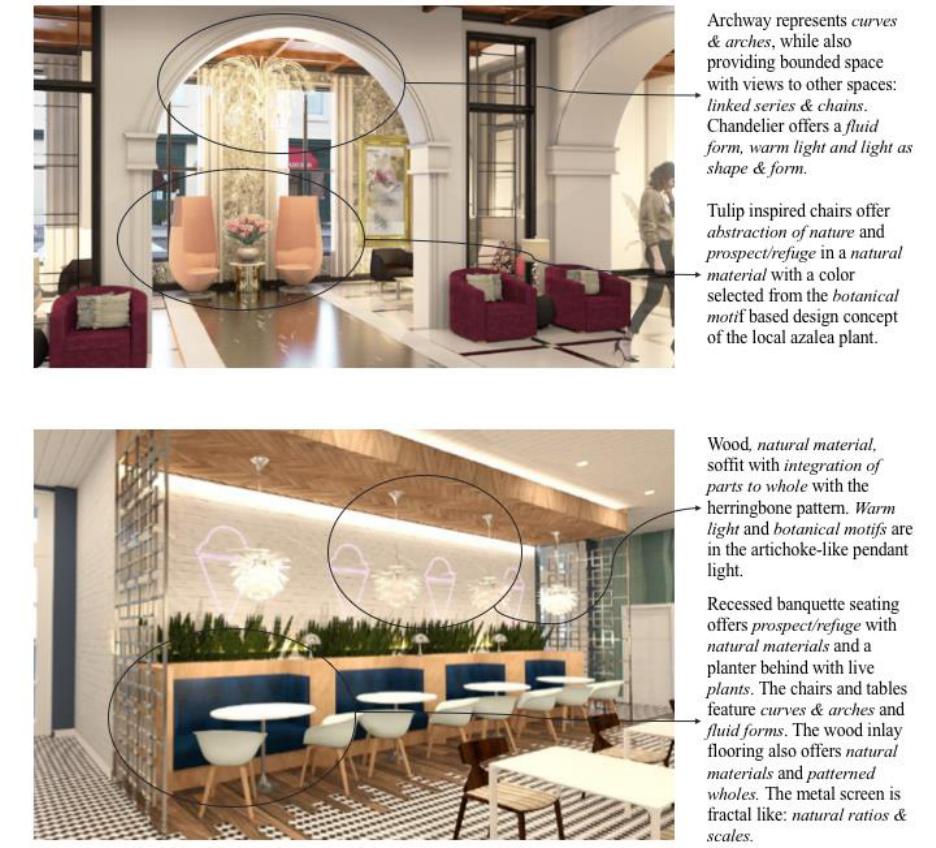

4-2. Student work example of hotel waiting area. .......................................................................101

4-3. Student work example of restaurant seating area. ................................................................101

9

Abstract of Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School

of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

DESIGNING BIOPHILIA INTO INTERIOR ENVIRONMENTAL PRACTICE:

A BIOPHILIC DESIGN ASSESSMENT TOOL DEVELOPMENT

By

Beth Lena Sherman McGee

August 2018

Chair: Nam-Kyu Park

Major: Design, Construction, and Planning

Evidence is growing for nature inclusion in the interior yet there is little support for

helping interior designers integrate it. This study uses the restorative environmental design

(RED) framework to explore the systematic development, testing, and expansion of the Biophilic

Design Matrix (BDM) tool.

In the three essays included, the first essay focuses on the BDM development, which now

contains a total of 54 biophilic design attributes within six element categories. These were

developed through cognitive testing from the original version and then pilot tested with 23

practitioners completing pre and post-questionnaires about their perceptions of biophilia and

experience doing an assessment of a lobby space with the BDM. After BDM use, practitioners

perceived an increase in knowledge of biophilic design. The modified version is now called the

Biophilic Interior Design Matrix (BID-M) which seems to be valid and reliable. The second

essay contributes by linking research to specific attributes through a literature review and

identifying how practitioners are using biophilic design in their practice within color, light and

materiality. Differences and commonalities were found between the evidence for specific

attributes and the actual attributes being used by designers. Essay three explores the BID-M

10

being used in an undergraduate studio course for assessing how it can support conceptual design

and design development to aid students with biophilic integration. Their perceived importance of

biophilic design, confidence in using it and knowledge about it were statistically significant in

the group that had the BID-M throughout the project compared to the group that did not.

Additional comments showed a perceived value to the BID-M in design education and requests

for earlier adoption into the curriculum. This supports the Council for Interior Design Education

standard 7-a to help guide theoretical implications of the built environment with biophilic design

a listed referenced criterion.

Overall, the findings support both practitioners and students using the BID-M to assist

biophilic inclusion throughout the design process. Also, using the checklist as a quick reference

and the online repository, with its growing research base, should be useful to help designers

include thoughtful biophilic variety.

11

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

People's physical and mental well-being remains highly contingent on contact

with the natural environment, which is a necessity rather than a luxury for

achieving lives of fitness and satisfaction even in our modern urban society

—Stephen Kellert

Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life

How can interior design aid people’s connection with the natural world through the built

environment? That is a big question for modern interior design research since Americans spend

an average of more than 90% of time inside (Klepeis et al., 2001; US Environmental Protection

Agency, n.d.; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency & Office of Air and Radiation, 1989) and

this time inside can greatly limit the amount of nature contact (Kellert, 1993). Research shows

positive benefits associated with nature contact (Berman, Jonides, & Kaplan, 2008; Kahn, 1997;

Ulrich, 1984, 1991, 1983), yet questions exist as to how designers of built environments can

tackle nature integration in the interior to facilitate optimal wellbeing.

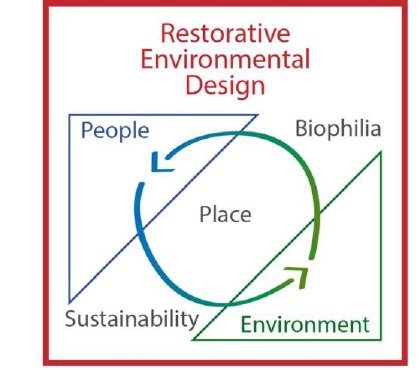

In a design paradigm called restorative environmental design (RED), Kellert (2008b)

defines RED as including both sustainable low-impact environmental strategies, as well as

positive impact (biophilic design) features, that “fosters beneficial contact between people and

nature in modern buildings and landscapes” (p. 5). This paradigm uses the definition of biophilia

as the innate need people have to connect with nature and natural systems (Wilson, 1984).

Interior design is important to the work of RED because it includes the specifying of features that

either provide or do not provide opportunities to reconnect with nature inside of the building

shell and through interior/exterior connections (Kellert, 2008b). Offering nature-based features to

users in buildings should increase biophilia and ultimately wellbeing. Biophilic design is an

12

underexplored area of interior design knowledge. The outstanding problem addressed in the three

papers in this study is the further development of the Biophilic Design Matrix (BDM) tool to aid

interior design identification and application of biophilia. This included the further development

of the design attributes, testing in different settings, using it as an assessment tool and pedagogy

tool and using it with designers of different experience levels. This was all to see how such a tool

could support practice and education in what is termed here as biophilic interior design.

Additionally, the three categories of color, light and materials are key to interior design (Bosch,

Edelstein, Cama, & Malkin, 2012; Dalke et al., 2006), yet they have not had much alignment to

biophilic design approaches for their use. This study begins to address this need as well,

specifically for supporting evidence-based design practice.

Evidence-based design (EBD) is seen as a “process of seeking answers to design

problems not a product that supplies ready answers or standard solutions pulled out of the

practitioner’s files” (Hamilton, 2010, p. 126). The evidence base for design has a history starting

with research around Taylorism and the Hawthorne Studies back in the early twentieth century,

but the landmark study by Roger Ulrich in 1984 connected health with the built environment

through a controlled experiment to start what would be called evidence-based design (Center for

Health Design, 2010).

While evidence-based design is not a new concept, for interior designers there is still a

need for new validated research tools and continued theory development. When such tools are

available they can then be used to aid design decisions that further looks at how people are

benefiting, or not, from the environment (Center for Health Design, 2010). I created the BDM in

2012 to aid biophilic identification, specifically child life play spaces. It was developed based on

the LEED checklist format where a credit is either fulfilled or not. The BDM has been further

13

validated with additional testing (Weinberger, Butler, McGee, Schumacher, & Brown, 2016).

One other tool exists has been proposed that integrates a quadrant overlay on each space for

attempting to count feature frequency with a focus on quantity to assess childcare centers

(Caballero, 2013). How the further integration of biophilic design can best be supported in a

user-friendly version was untested prior to this project.

Biophilia has begun to be supported by evidence from a wide variety of fields. The

evidence shows nature connections offering positive influences on human health, productivity

and environmental attitudes (Beute & Kort, 2014; Kahn, 1997; Louv, 2008; Van den Born,

Lenders, Groot, & Huijsman, 2001). Research shows that active and even passive viewing of

nature can influence health and wellbeing (Kahn, 1997; Tennessen & Cimprich, 1995;

Ulrich,1984). Active engagement with living nature provides optimal restoration, but even

passively viewing nature or natural representations, such as complex fractal patterns and varied

visual surroundings, seems to allow the mind to easily range from directed attention to

fascination as needed for mental and physical wellbeing (Hagerhall, 2004; Joye, 2007; Kaplan,

1995).

Designers have had increasing reason for including biophilic design in the interior since

the beginning of the 1980s with the development of the concept of evidence-based design as an

interdisciplinary approach to building and sharing evidence (Cama, 2009; Ulrich, 1984). The

design field is attempting to incorporate nature into the interior using evidence-based design

(Barnes, 2010; Browning, Ryan, & Clancy, 2014), especially healthcare facilities, however,

research on design has not found vast adoption in practice (Huber, 2016). The development of

tools by the Center for Health Design offers a patient room design checklist and evaluation tool

as well as a safety risk assessment (“chd | The Center for Health Design,” n.d.). The Center also

14

offers case studies that highlight best practices for others to consider. These are very targeted to

performance and specific wellness objectives. The adoption rate of these tools is unknown, and

they are not designed specifically to guide designers with their attempts at integrating biophilia.

Theory Building

What is unique about restorative environmental design (RED) versus traditional design

practice? “Restorative environmental design, aka biophilic design, provides a more holistic

approach to the design of buildings and environments. It marries green design principles with an

approach that seeks to connect nature and humanity” (2011, para. 3). This can be seen in the

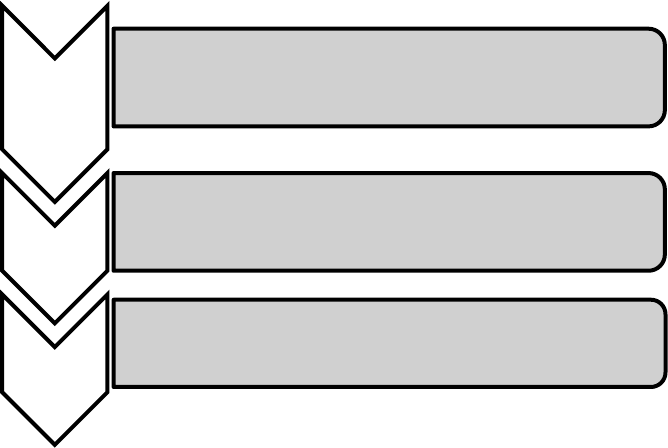

construct diagram, Figure 1, where nature influences people (biophilia) and people influence

nature (sustainability). Where people connect with nature biophilia results. When people build

and act sustainably, then they preserve or even restore nature. When both are present, restorative

environmental design can exist in a symbiotic relationship.

Figure 1-1. Supporting theoretical framework diagram.

Much of the research directed at the restorative part of restorative environmental design

currently comes from environmental psychology. This includes attention restoration theory and

psychoevolutionary theory focusing on stress reduction and attention restoration (Hartig,

Bringslimark, & Patil, 2008; Kaplan, 1995; Ulrich, 1983). This is a view of nature influencing

15

people’s behavior, health and wellbeing. However, these theories fall short of the greater impact

that restoration, as proposed by Kellert in RED, offers. This is the nurturing of nature

connections to facilitate a healthy relationship with nature for both personal wellness and a

global awareness and benefit. Since theory building is an ongoing process “in the discipline of

interior design, researchers should not only be analytical but also engage in a creative process

that requires adjustments and revisions to theoretical propositions and methods” (Clemons &

Eckman, 2011, p. 32). This study does so by seeking evidence for a user-centered

design/assessment tool to guide designers while also allowing understanding how interior design

plays a role in biophilic design. A struggle with design theory application in building design is

well stated by Bardenhagen and Rodiek (2016) specifically regarding health facilities and the

challenges are “to be able to identify which, among the myriad elements available, will best

combine to optimize the intricate human–environment relationships and desired therapeutic

outcomes that exist or are proposed to exist in the space” (p. 149). How designers can include

natural connections is prompting further validation of the BDM.

Biophilic Design Matrix

The Biophilic Design Matrix (BDM) is an evidence-based design tool. The BDM is

aimed to be contextually relevant and useful for designers, because if it is “not contextually

situated, and therefore relevant to the audience that must act on those findings, there will be no

action until the audience finds that contextual relevance” (Barnes, 2010, p. 131). Initial testing of

the BDM involved eight hospitals and 24 child life play spaces (McGee, 2012). The inter-rater

reliability during initial scoring with a test-retest of matrix coding had agreements of 89% by the

first rater and 94% by the second rater. The matrix scores for the 24 spaces (n=24 of 26 child life

play spaces in the state studied) had a mean total score of 21.5 out of 52 attributes. The score

ranged from a low score of 14 and high score of 39. The six elements were: 1) Environmental

16

features- most obvious and well recognized nature characteristics, 2) Natural shapes and forms-

nature representations and simulations, 3) Natural patterns and processes- properties derived

from natural features and processes, 4) Light and space- light qualities and space relationships, 5)

Place-based relationships- culture together with ecology, rooted in the local geography, and 6)

Human-nature relationships- paired biological needs. The BDM had an internal consistency,

Cronbach's Alpha of .804, but showed areas where item development may assist with reliability.

The revised version of the BDM and its use as a design assessment tool now provides a chance to

investigate validation of its contextual relevance for diverse users.

The BDM tool aligns with two worldwide programs that integrate biophilia, WELL

(“WELL v2,” n.d.) and the Living Building Challenge (International Living Future Institute,

2014). Each of these supports biophilia integration in the design of buildings. WELL is a

framework that seeks to advance health and well-being through the built environment (“WELL

v2,” n.d.). It has an indoor plant feature, with a percentage of the wall or floor space needing

coverage, and other options for using nature features, lighting and layout, as well as natural

patterns and outdoor connections. These features are based upon the Living Building Challenge

which is a green building certification program and sustainable design framework seeking ideal

built environments (International Living Future Institute, 2014). There are additional related

features like circadian lighting systems as well. The Living Building Challenge references

Kellert’s original list of biophilic features. However, Kellert’s list of features was not developed

specifically for interior design, so this research aimed to better develop the BDM for clear and

reliable definitions for interior application to relate with frameworks such as WELL and Living

Building Challenge.

17

Besides these few growing sustainable design frameworks, the availability of research

developed tools or frameworks has increased but has had limited adaptation by practitioners

(Browning et al., 2014; Huber, 2016, 2018; Quan, Joseph, & Nanda, 2017). Interior designers are

commonly seeking out research, but they often use fast surfing tendencies when reviewing

information, use familiar sources and do so as quickly as possible (Huber, 2018). There is an

“opportunity to narrow the research utilization gap by making scholarly sources more

approachable” (p. 25). Since interior designers are seeking out more knowledge specifically

about biomimicry/biophilic design, this research used participatory methods for a user-friendly

biophilic interior design language to improve the utilization gap. This led to three areas of focus

in this research. The first, was the BDM being revised through cognitive testing and then further

tested with practitioners in a new context. This was in the hope that these revisions would make

the Matrix more valid, reliable and user-friendly. The second area of focus was the attribute

“color”. It was a key shortcoming of the original version with its definition being “any color”.

This was addressed by adapting the Color Planning Framework (Portillo, 2009) into the Matrix

and was a key improvement. Third, the BDM was used in an undergraduate interior design

studio as a pedagogical tool for teaching and learning about biophilic design as well as aiding its

incorporation.

The research questions of the three essays were:

Essay 1

1. How do designers perceive biophilia?

2. What is the optimal BDM for designers as a design tool for usability?

3. How validly and reliably does the revised BDM appear to measure the variety of

biophilic features present when used by interior designers?

Essay 2

1. What evidence for color, light, and materials can support the biophilic design attributes?

2. How through color, light and materials is biophilia being incorporated into design

practice?

18

3. What are the similarities and differences between the research available and designers’

use of color, light and materials?

Essay 3

1. How do interior design students perceive biophilia?

2. How is the BDM helpful for interior design students?

The Biophilic Design Matrix development process included cognitive testing with

practitioners using a questionnaire with pre- and post-questions surrounding an assessment of a

given healthcare lobby space. They were asked to evaluate the given images of the space for the

presence of the biophilic attributes. Sixty-four features were finalized and then tested with

practitioners using the questionnaire. Furthermore, a literature review linked research to the

attributes through a PRISMA-P modified format. Finally, two groups in a studio project for

undergraduates were compared to investigate how the BDM can aid biophilic design in a

hospitality studio. One half of the class was given the BDM throughout the design process, the

other half was not. At the end, everyone completed an assessment of their own design solutions

and a pre- and post-questionnaire was included. The use of a mixed method approach was

employed for strengthening the BDM to expand the potential for future application.

19

CHAPTER 2

ESSAY 1

A systematic development of the biophilic design matrix attributes, broadened

application and further validation of a biophilic interior design tool: The objective of this

research was to develop the Biophilic Design Matrix. It was originally created to support

designers in identifying and quantifying biophilic features through a visual inventory. This study

continues the process of establishing a formal language for biophilic interior design, as well as

validating the Biophilic Design Matrix. Background: The Biophilic Design Matrix offers a

variety of choices for designer-driven integration of biophilia. It was developed to assess the

variety of biophilic features in the interior. Methods: The original BDM attributes were

reassessed and those appropriate to interior design were put through two rounds of cognitive

testing with pre- and post- questions. The list of features was then refined, definitions developed,

and examples included for each attribute to aid in the ease of biophilic identification. Fifty-four

design features were finalized. The attributes were then further tested with 23 practitioners.

Results: The systematic development and validity testing of the tool resulted in a matrix relevant

to designers. It now offers an expanded application beyond the original setting. Also, its usability

and functionality are attested. Practitioners showed increased perceived knowledge of biophilic

design after use. The six element categories showed internal reliability, as did the Biophilic

Design Matrix as a whole. Conclusions: The revised Biophilic Interior Design Matrix (BID-M)

enhances users’ knowledge of biophilic design and is useful throughout the design process for

guiding creative biophilic design solutions.

Literature Review

Love of life. This is an innate need people have to connect with nature and natural

systems, or biophilia (Wilson, 1984). Modern Americans are spending more time inside with

20

limited direct contact with nature (Klepeis et al., 2001). It has been a growing concern since

connecting with nature has positive influences on human health and wellbeing (Heerwagen,

Judith & Hase, 2001; Kahn, 1997; S. Kellert, 2008; Louv, 2008; van den Berg, Koole, & van der

Wulp, 2003). Research has shown active and even passive viewing of nature can be influential

(Hensley, 2015; Kahn, 1997; Ulrich, 1984). Active engagement with nature is optimal, but even

viewing features found in nature, such as complex fractal patterns, allows the mind to easily

range from directed attention to fascination as needed for mental and physical wellbeing

(Hagerhall, 2004; Joye, 2007; Kaplan, 1995). These views of natural features create a

“neurological nourishment” as our brains effortlessly process complex information from living

or artificial sources (Salingaros & Masden II, 2008). People react negatively to an environment

that is neurologically non-nourishing with distress and anxiety. There needs to be organized

complexity, not too plain and not presenting disorganized complexity. Biophilic design then

needs to mimic this natural complexity. In a recent study, an increase in biophilic variety was

found to parallel an increase in the assessment of “best” playroom by specialists (Weinberger,

Butler, McGee, Schumacher, & Brown, 2017) which may indicate that as natural environments

are varied, so people seek similarly nature-based varied interior spaces. In this way, biophilic

design is serving as a modern “rediscovering” of the connection between humans and the

sensorial environment around them (Salingaros, 2011).

There are also economic advantages of biophilic design across diverse building sectors

that show fiscal disadvantages of ignoring nature, including profit loss (Browning et al., 2012;

Heerwagen, 2010). It can be argued that “incorporating nature into the built environment is not

just a luxury, but a sound economic investment in health and productivity, based on well-

researched neurological and physiological evidence” (Browning et al., 2012, p. 3). A literature

21

review reveled increases in healing rates, learning rates, productivity, property values, reduced

absenteeism, medical costs, stress and even reduced prison costs Browning et al., 2012). These

findings support commercial investment interests.

Restorative Environmental Design

In design people are attempting to help preserve the natural world through limiting

resource use and it has become the standard approach. A new approach to sustainability goes

beyond simple resource reduction and can be seen through a design paradigm called restorative

environmental design (RED) which is a unique concept defined as:

… an approach that aims at both a low-environmental-impact strategy that

minimizes and mitigates adverse impacts on the natural environment, and a

positive environmental impact or biophilic design approach that fosters beneficial

contact between people and nature in modern buildings and landscapes. (Kellert,

2008b, p. 5).

Designers of interior environments are substantially responsible for specifying features

that either provide, or do not provide, opportunities to reconnect with nature both through

interior/exterior connections and interior features (Kellert, 2008b). Offering nature-based

features to users in buildings should ultimately allow people to increase their biophilia and

research shows that such connections can increase health (Beute & Kort, 2014; Hartig et al.,

2011) and wellbeing (Kahn, 1997; Kaplan, 1995; Matteson, 2013; Ulrich, 1984, 1991). The great

amount of time spent in the interior (Klepeis et al., 2001) and the nascent research support

(Green & American Society of Landscape Architects, 2012) requires looking specifically at

biophilic interior design, also how it might support RED.

In RED, a sustainable approach goes beyond minimizing environmental impact to

increasing ecological health. However, it is becoming apparent to many that the next step for the

sustainable design movement is mimicking the natural habitats humans innately prefer (Cama,

22

2013). How interior design can best mimic nature is still a vague and elusive strategy, since

currently there is little support for guiding best practices for how to create such natural spaces.

Kellert first operationalized biophilia in 2008 to guide designers and other building

stakeholders. Based on this list of features, the BDM was applied to interior child life play rooms

in healthcare settings and added a scoring procedure (McGee, 2012). Preliminary reliability was

good but the need to further develop the BDM was apparent. The process of instrument

development typically has an iterative nature. The formulation of concepts and the measurement

process when applied commonly leads to further modification in order to capture a more

adequate representation (Adcock & Collier, 2001). The development of a measurement tool for

biophilic design asked the following research questions:

1. How do designers perceive biophilia?

2. What is the optimal BDM for designers to enhance usability?

3. How validly and reliably does the revised BDM appear to measure the variety of

biophilic features present in a space when used by interior designers?

The Original Biophilic Design Matrix

Opportunities for improvement of the original BDM were noted by the researcher and by

the inter-rater testers as they attempted to use the original BDM. The matrix was not particularly

user friendly and quite time consuming to complete. Many of the attribute definitions adopted

from Kellert’s original list were wordy and difficult.

The attribute color in the original BDM showed no discrimination because it was simply

described as “any color”, as such it was not very informative. Color is complex with direct

relationships with lighting and materiality (Bosch et al., 2012). It seemed of key importance to

develop these three concepts for interior design application. The adaptation of the Color Planning

Framework (Portillo, 2009) was introduced to address this weakness. This framework uses five

categories for an evidence-based approach to color planning and how they impact people and

23

space design. These are now adopted and have been adapted to represent color, light, material

and space concepts more distinctly in the fourth element group of the BDM which is now called

color and light. The new attributes in the element of “color and light” are based on Portillo’s

(2009) five design tactics: compositional (shaping space), communication (creating meaning),

preference (reflecting individuality or market trends), response (arousing feelings and responses)

and pragmatics (responding to resource parameters). To illustrates further, an example of

communication is color selection inspired by the site for telling a visual story connecting the

inside with the outside. This is based on the human need for communicating through design and

interpretive meaning. Regarding color as composition, “working with color compositionally

requires objective problem-solving to integrate color, lighting, and materiality” (Portillo, 2009,

p.7). It needs to be understood individually and with its surrounding composition, such as color

palettes based upon nature. Preference can include such things as personal preference for certain

natural fabrics or colors over synthetic ones. Also, types of art preference varies with more

nature representations preferred (Eisen, Ulrich, Shepley, Varni, & Sherman, 2008) . Response to

the natural environment is an innate reaction and designers can mimic these considerations as

people will have responses to stimuli in the interior. Comfortable seating in an area where you

want a low-stress feeling, is one example. Pragmatic concerns can include sustainability features

and maintenance considerations that increase life cycle as well as safety features, like using

resilient fabrics and lighting in high traffic areas. These 5 attributes adopted from the Color

Planning Framework further develop the BDM as a tool for designers to use in the design

process.

Design and Assessment Tools

Designers are adopting tools in the design process more commonly to support green

building design standards (Edwards, 2010). LEED is the most common sustainable building

24

design standard (Nguyen & Altan, 2011) with little biophilic consideration (Kellert, 2004).

WELL v.2 is a health and well-being focused building design standard that includes both a

quantitative and qualitative biophilia feature (“WELL v2,” n.d.). These address nature

incorporation qualitatively within environmental lighting, layout, natural patterns and direct

interaction. For the quantitative feature, a specific minimum amount of indoor plants is needed.

It also has other related features like a water category, but its goal is specific to health-related

considerations in general, not concerned with experiential connection to nature that addresses

human health, well-being, and spirit. WELL uses the Living Building Challenge as its guidance

for these two biophilic features. The Living Building Challenge v3.1 has similar features without

a plant mandate and are specifically using Kellert’s original definitions for biophilic design that

he proposed in 2008. It is a green building certification program and sustainable design standard

for ideal built environments including integrating people with nature (International Living Future

Institute, 2014). It includes design features that incorporate actual nature, represent nature,

natural patterns, color and light, natural relationships and connections to the place. The Living

Building Challenge creators, International Living Future Institute, also host a biophilic design

initiative aimed to connect people with nature in the built environment and increase access to

resources plus connecting research and researchers with design practitioners (“Biophilic Design

Initiative,” n.d.). This includes access to case studies, a map and links to biophilic examples.

This is helpful in supporting biophilic design. These tools were not developed specifically for

interior designers and relies upon the original language from Kellert to guide biophilic design.

After a review of the top tools available for aiding biophilic design, currently there is a lack of

interior design biophilia focus that could offer specific, user-friendly interior design tactics for

designers to use.

25

Sustainability and evidence-based design do offer models for reference in development of

the BDM. Examples like LEED and the Living Building Challenge are used as both a design and

assessment tool and were used as references to expand the BDM, initially an assessment tool, to

a design tool as well. The BDM can best be symbiotically used with these existing tools in aiding

biophilic design. Many of the items in WELL and Living Building Challenge correspond to

biophilic attributes, so it would be optimal if the BDM were used as inspiration and guidance to

achieve the goals of such building standard programs. This research supports this through adding

improved wording and examples in the revised BDM to guide design application of biophilic

design.

Method

Research Design

This study integrated a mixed-methods approach in an exploratory manner. Social

science exploration is a designed process for “maximizing the discovery of generalizations

leading to description and understanding of an area of social or psychological life” (Stebbins,

2001, p. 3). This study attempted to further operationalize biophilic design for interior design

practice through two phases, Phase one: BDM development and Phase two: BDM Testing

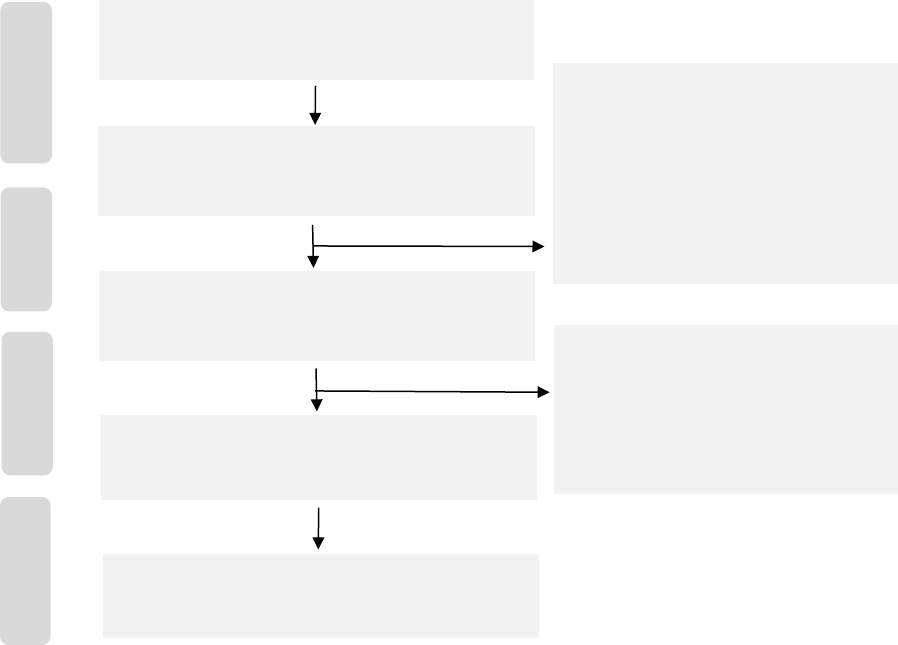

(Figure 2-1).

The online survey used in both phase one cognitive testing and phase two BDM testing

with practitioners used a photoethnography method for completion of the BDM assessment of

the given site. The site images were provided through a link added to the online survey. This

photo-based assessment was a consistent approach with the original instrument development

that proved preliminary reliability and validity (McGee & Marshall-Baker, 2015). The lobby of a

research building waiting areas was used for both phases. This LEED platinum building seemed

an appropriate example to use as it was:

26

Inspired by the principles of the Biophilia Hypothesis, the project emerges from

the inherent human affinity for natural systems and processes. Understanding the

environmental forces of the site, as well as the surrounding context which

includes wetlands, wooded gardens, a parking structure and a cogeneration plant,

informed the programmatic organization, massing and site strategies. The

concept…emerged from the desire to provide sustainable healing, working and

educational environments (“University of Florida Clinical Translational Research

Building,” 2014)

This same site was used for the phase two study.

Figure 2-1. Study process diagram.

Phase One: Biophilic Design Matrix Development

Step one

Phase one had four steps of development. The first step was the preparation needed to

begin the cognitive testing. It started with reassessing the initial list of attributes from Kellert

(2008) to see which ones were appropriate generally to interior environments. Of the 74 features,

66 were included in the first phase of development. The eight not included were exterior focused

Phase 1

BDM

development

•Step 1-Pre-design of BDM and study instruments

• Pre-evaluate attributes

• Created pre and post-questionnaires

• Pilot tested 66 attributes

•Step 2-First round of cognitive interviews

• Interviewed 6 practitioners

• Reivsed language and scale

•Step 3- Focus group with students

•Step 4- Final round of cognitive interviews

• Revised scale again after first tester

• Continued to test, revise, retest

• Interviwed 4 practitioners

• Finalized 54 attributes

Phase 2

BDM testing

• Step 5- Final validation testing included:

• Instruction page

• Demographics page with 4 questions,

• Pre-assessment page with 4 questions

• Picture link and instructions page

• Each of the six element categories followed with the 54

attributes

• Post-questionnaire with 10 questions

27

and/or duplicated in other features. Additionally, four were merged for similarity in interior

design: sensory variability with information richness were merged and simulation of natural

features with biomorphy were also merged. Moreover, the need to further develop color, as well

as its interaction with light and materiality in the interior, were attempted to be resolved by

adapting the Color Planning Framework (Portillo, 2009, see Essay 2).

The definitions were only modified if needed for clarity in the application to interior

design. These were organized in Kellert’s six elements: actual natural materials, natural

representations, natural patterns and processes, light and space, place-based relationships and

human-nature relationships. See Table 2-2 for the element definitions.

The pre- and post-questionnaire and the BDM assessment were created as a single online

survey. The initial questions were developed by creating multiple versions of each to see which

ones seemed to be clear and concise. It was then pilot tested with an interior designer for

readability, use of the site images and general flow of the survey. The feedback helped to revise

the clarity of the instructions and images to prepare for the first round of cognitive testing.

Figure 2-2. Site image examples.

Step two

Step two was then testing the BDM in a round of cognitive interviews. Cognitive

interviews (CI) are the administration of a draft version of an instrument that includes additional

collecting of verbal information about the participant’s survey response and their mental

28

processes (Beatty & Willis, 2007). Cognitive interviewing procedures were used in order to

verify that the tool made sense to the target population and was answerable (Krueger & Casey,

2015), also evaluating the quality of responses and if the question was collecting the kind of

information intended (Beatty & Willis, 2007). This approach emerged in the 1980’s in the

cognitive sciences to add insights into questionnaire design decisions (Campanelli, 1997). The

use of this testing was to make sure everything made sense to the users for gaining valid

information, as such “cognitive testing should be a standard part of the development process of

any survey instrument” (Collins, 2003, p. 229). Additionally, “cognitive interviewing can play an

important role answering the current demand about empirical and theoretical analyses of the

response processes as a source of validity evidence in psychological testing” (Castillo-Díaz &

Padilla, 2013, p. 963). This is important to measurement error and whether respondents

misunderstand questions or concepts. Additionally, it is important to know if people do not know

or cannot recall the necessary information, use incorrect judgment references, hide information

or are only providing a perceived socially desirable answer. The use of cognitive interviewing

can help to identify such issues (Beatty & Willis, 2007).

The two main paradigms since 1984 for cognitive interviews are think aloud and probing

(Beatty & Willis, 2007). The think aloud paradigm asks respondents to report what they are

thinking while they are attempting to answer the question with the interviewer, who is also

prompting for information from the respondent as needed. Notes were taken in the manual, see

Appendix C. These notes were typed up and then guided adjusting the BDM and the

questionnaires. This testing used “think aloud”, as it is a preferred method for being respondent-

driven and a low burden (Collins, 2003). The thinking aloud of answers by the individual was to

see if the items in the BDM seemed confusing when people were trying to answer.

29

The probing paradigm uses interviewer probes regarding comprehension, confidence

ratings and paraphrasing, instead of thinking-aloud. Think-aloud interviews alone may suggest a

problem but not explain what the problem is, and probes address this gap. The blending of the

two original paradigms is a new paradigm (Presser, 2004) and was used in this study where the

participants were asked to think aloud with additional prompting via a post-questionnaire

including a variety of probing types used. The CI probing process can be distinguished in four

key probing types: anticipated, spontaneous, conditional and emergent (Beatty & Willis, 2007).

According to Beatty and Willis, anticipated probes are scripted ahead of time based on

anticipated issues. Spontaneous probes are not scripted and are a response that interviewers make

when looking for potential problems based on their own impetus. Conditional probes are scripted

but are based on a response from the participants. Emergent probes are unscripted and are based

on responses from the participant. Multiple probing types can be used together to address either

expected or encountered problems and useful for identifying the most egregious problems in

groups of participants. CI is finished when interviews are yielding diminishing returns. “There is

always the possibility that one additional interview could yield a significant new insight, or that

an additional interviewer would be more likely to notice additional problems. By the same token,

claims that a questionnaire has ‘no problems’ are impossible—the strongest claim that could be

made is that no problems have (yet) been discovered” (Beatty & Willis, 2007, p. 303). This study

used mostly spontaneous and emergent probes, with some conditional to allow for flexibility and

on-the-spot reactions to the participant.

The cognitive interview selection of participants included establishing a level of expertise

in the field of over ten years of interior design practice and used convenience and snowball

sampling (see Appendix E). Typically in CI, the sampling is used to “reflect the detailed

30

thoughts and problems of the few respondents” (as cited in (Beatty & Willis, 2007, p. 295) and

not necessarily representative of the population. But, again that is not the purpose of CI, as long

as relevant respondents are selected in regard to the topic and have demographic variety (Willis,

2005). The sample size required for CI has been a debated topic with current practice finding that

a small sample of participants reveal most critical questionnaire problems (Beatty & Willis,

2007). While one study found it may take more than 50 interviews to reveal an undiscovered

issue (Blair, Conrad, Ackermann, & Claxton, 2006), generally CI are conducted in rounds of 5 to

15 interviews with repeated revision of questions tested further to eliminate problems (Beatty &

Willis, 2007). Interviews were conducted until relatively few new insights were garnered. While

it might be short of the point when all insights might stop emerging, it is based on the principle

of diminishing returns and a small number of interviews may suffice. Even one interview has

been sufficient (Beatty & Willis, 2007; Charmaz, 2014; Willis, 2005). It has been proposed that:

one potentially useful variation would be to employ an iterative testing approach,

based on rounds of testing with questionnaire revisions between rounds. This

approach is arguably accepted as an ideal practice, and it would be useful to see

whether revised questionnaires are in fact “better,” and how rates of problem

identification decline across revisions (Beatty & Willis, 2007, p. 306).

This is the approach used in this study with two major rounds testing ten participants, six in the

first round and then four in the second round.

All ten participants were interviewed either in person or via a conference call. The first

two participants showed a general appreciation for the BDM and their responses prompted

further testing. Two more sets of two participants were tested with minor adjustments made

between sessions and had similar results. A major revision was needed to fix clarity issues. The

pre- and post-questionnaires also were in need of modification based on feedback from the round

one participants.

31

Step three

The third step of this study included a mid-point assessment of the revised BDM by

students. The major revision of the BDM included adding a scale to the response choices and

fixing the noted repetition among attributes and difficult language. This revision was then tested

in a sophomore undergraduate interior design environment and behavior class to verify if

designers of all level of experience could understand and use the BDM. The use of groups of

students was a type of focus groups. Focus groups have been combined with cognitive interviews

in the same study and complementary (Campanelli, 1997). A focus group is used to better

understand the feeling or thoughts people have about a topic; they gather opinions. Similar to a

standard focus group, the use of a classroom activity collaboratively builds information socially

for increased diversity of perspectives and opinions (“CTI - Collaborative Learning,” n.d.). In the

past using the differing perspectives of students to reveal missing validity issues has also

uncovered issues missed by experts during cognitive interviews (Ding, Reay, Lee, & Bao, 2009).

The interior design students’ considerations proved very insightful during the middle of the

cognitive interview process and aligned with many of the practitioner’s comments. Using

students as a target audience was purposeful in order to assess usability for designers of all

expertise levels.

The process involved the researcher and instructor giving an assignment to the

sophomore class. There were 26 students tasked to use the original version of the BDM with 66

attributes for an assessment of an on-campus game room. After they gathered together for an in-

class activity, they were divided into small groups of 3-5 students and each group was given one

of the six elements (categories), from the original BDM. They were directed to document any

issues they had with attributes in their given element. They were then given the new version of

the same element and instructed to do the same markup process. Each group afterwards shared

32

their findings collectively with the class regarding how the BDM should still be improved and

the differences they saw between the original and modified versions. The assignment aligned

with the environment and behavior course content covering research instrument development.

This information showed the need for further elaboration of the scoring procedure and additional

fine tuning of the vocabulary.

Step four

After the feedback from the students, additional modifications were made, and a revised

BDM version was ready for the second round of cognitive interview testing. The cognitive

interview participants gave insightful feedback after using the BDM. Both the first and second

round of cognitive interviews highlighted the justification for the BDM and its continued

development. For example, CI #7 mentioned “I think this would be a benefit for clients to

understand the long-lasting effects of the feeling of a space through biophilia”. Another

commented regarding how they saw themselves using this list of features (BDM) in the future if

available. They said it could be a “key design driver, to create connection to place, natural and

cultural references” (CI #10). Another designer noted changes they might make in their next

design in how they approach adding color, light and materiality and said they would “Keep it at

the forefront of my brain while designing, always keeping in mind I can come back to my

‘checklist’ to make sure I have covered all categories” (CI #3). The education of the client is an

interesting finding. One designer said “Yes - I think this would be a helpful tool to use with

clients to identify how, not only do they see the space but also how guests/users see and feel in

the space” (CI #7). After the cognitive interview results showed marked improvement with

clarity issues and a shorter time length required, the final survey was sent out to practitioners.

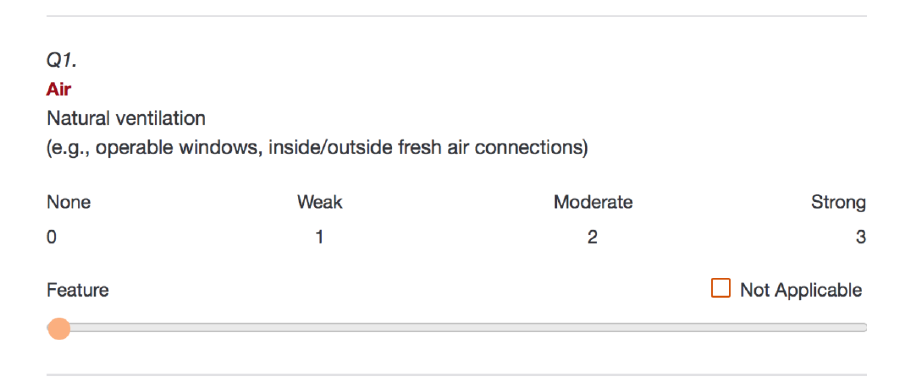

The BDM was finalized with a score range from 0-3: not present at all (0), weak presence (1),

moderate presence (2) and strong presence (3). There was also an option to select “not

33

applicable” for those features difficult to assess in the given site photos. Not applicable was

marked as not present for scoring. See Table 2-1 for the CI participant work experience level,

time to completion of the survey and the number of issues they found.

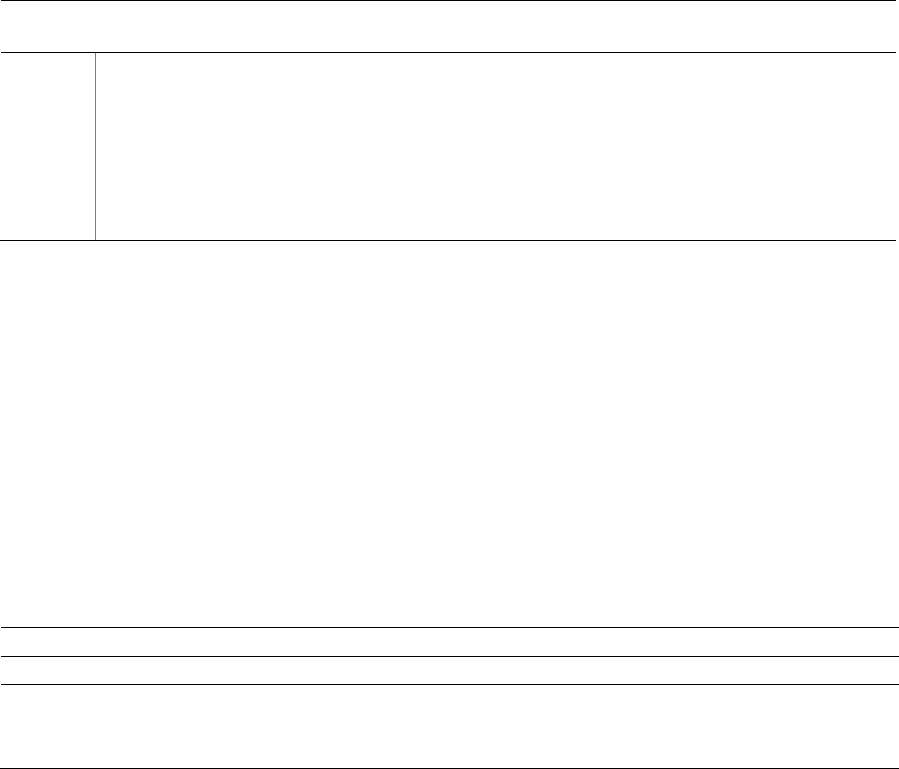

Table 2-1. Cognitive interview overview.

Cognitive

interview order

Tester’s experience

in years

Complete Qualtrics

time/ minutes

# BDM comments:

clarity issues

1

20-25

65

23

2

20-25

63

15

3

10-14

64

14

4

10-14

50

14

5

14-19

87

18

6

14-19

60

27

7

14-19

68

14

8

21-25

45

10

9

26 +

46

3

10

26 +

25

2

Average

20+

57

14

Phase Two: Biophilic Design Matrix Testing

Phase two used the same data collection already tested in phase one, with an online

survey. The practitioners were recruited through direct email, snowball sampling or notification

through social media, such as LinkedIn and Twitter.

Instruments

The goal of step five was to test the BDM with practitioners in order to assess the

perceptions of practitioners regarding biophilia and the improved usability, reliability and

validity of the BDM. The finalized list of attributes is shown in Table 2-2 with the related

elements noted and the attributes numbered for easy reference.

34

Table 2-2. Biophilic design elements and attributes finalized.

Actual natural features- actual (not images) of

real nature characteristics in the interior

1

Air

2

Water

3

Plants

4

Animals

5

Natural materials

6

Views and vistas

7

Habitats

8

Fire

Natural shapes and forms- representations of

nature and simulations

9

Botanical motifs

10

Animal-like

11

Shells and spirals

12

Curves and arches

13

Fluid forms

14

Abstraction of nature

15

Inside-outside

Natural patterns and processes- properties

derived from natural features and processes

16

Sensory richness

17

Age, change and the patina of time

18

Area of emphasis

19

Patterned wholes

20

Bounded spaces

21

Linked series and chains

22

Integration of parts to wholes

23

Complementary contrasts

24

Dynamic balance and tension

25

Natural ratios and scales

Color and light- color, light and material

qualities and space relationships to nature

26

Composition

27

Communication

28

Preference

29

Response

30

Pragmatics

31

Natural light

32

Filtered light

33

Reflected light

34

Light pools

35

Warm light

36

Light as shape and form

37

Spaciousness

38

Spatial variety

39

Space as shape and form

40

Spatial harmony

Place-based relationships- culture together with

ecology, rooted in geography

41

Geographic connection to place

42

Historic connection to place

43

Ecological connection to place

44

Cultural connection to place

45

Integration of culture and ecology

46

Spirit of place

Human-nature relationships- paired biological

needs of the human relationship to nature

47

Prospect/refuge

48

Order/complexity

49

Curiosity/enticement

50

Mastery/control

51

Attraction/attachment

52

Exploration/discovery

53

Fear/awe

54

Reverence/spirituality

Similar to the version tested in phase one, the phase two online survey also included the

BDM and a pre- and post-questionnaire. The pre-questionnaire had four five-point ordinal scales.

The four questions were on biophilic design and its perceived importance, how much they had

attempted it, their confidence in using it, and their knowledge of it. The post-questionnaire

included one question that asked when they might use the BDM features and could select all that

35

applied. A question with a five-point scale asked about the importance of biophilic design in

interior design. There was another question with five-star rating options (five being the highest

score) and seven categories used to assess the quality of the BDM. Additionally, there were

seven open answer questions with unlimited answer length. The open answer formatted

questions were not limited in the length of response and the coding process used thematic

analysis of the participants’ comments. The comments were coded by the researcher and a

trained research assistant. They agreed on the coding assignment together. Following the coding,

related themes were collapsed, see Table 2-5.

The congruent validity of the answers were tested by looking at item-total correlation and

inter-item correlation with relation to Cronbach’s Alpha (Gliem & Gliem, 2003), since validity

and reliability are key to making sure the findings are truly connected to the construct and are

then relevant for others to build upon. Each step of this iterative method in developing the BDM

builds validity, reliability and discriminatory power into the BDM.

Participants

The final survey assessment of the BDM with practitioners included interior architects

and interior designers. The results included 23 practitioners who completed the BDM

assessment, had a Council for Interior Design Accreditation (CIDA) or National Architectural

Accrediting Board (NAAB) design degree and had been practicing more than 2 years in interior

architecture or design. The demographic breakdown, Table 2-2, showed a variety of experience

length. The most common certification was LEED and the most common specialization was

corporate design.

36

Table 2-3. Demographics of participants.

Results

Research Question One: Perceptions of biophilia.

In general, designers saw biophilia as relatively important (a lot or a great deal of

importance) to interior design (M = 3.39, SD = .72) with a moderate amount of attempted

application (M = 2.26, SD = .92). They were, however, only moderately confident in using

biophilia (M = 2.17, SD = 1.03). See Table 2-4.

Table 2-4. Pre-BDM practitioner’s perceptions of biophilia.

Note: 5-point scale, 5 being high

Designers’ knowledge after using the BDM showed they found the variety of choices

available for biophilic design as remarkable as well as the availability of the tool, see Table 2-5,

column 1. As one designer described it, “There are many subtle ways to bring in biophilic

elements.” Another designer responded that having the BDM “is a valuable reference tool as we

approach wellness goals of the space; the latter are client mindset dependent.”

Practice

years

Frequency

(%)

Certification

Frequency

(%)

Specialty

Frequency

(%)

< 2

0

0

AAHID

1

3

Corporate

9

26

2 - 5

6

26

LEED

12

34

Healthcare

6

17

6 -10

4

17

NCARB

1

3

Hospitality

4

11

11 -15

3

13

NCIDQ

9

26

Institution

1

3

16 - 20

2

9

Well

1

3

Residential

7

20

21-25

1

4

State license

7

20

Other

8

23

≥ 26

7

30

Other

4

11

Pre-BDM assessment

n

M

SD

Skewness

Kurtosis

Importance

23

3.39

.72

-.77

-.59

Attempted use

23

2.26

.92

.21

-.64

Confidence

23

2.17

1.03

.44

-.85

37

Table 2-5. Post BDM open answers, four most common comments.

Research Question Two: Optimal BDM as a Tool

The general perceptions of the BDM was they would use it in the design process or as an

assessment, as shown in Table 2-5 column 2 and 3. One designer said, “It would be a useful

reminder throughout a project and especially in the programming and concept design phases.” It

could be improved by adding more examples, including case studies. Their use of it as a

reference and checklist for ideation was interesting: “this could be a great checklist to share with

clients as part of the design development process”. Another person said, “I could see using the

BDM with a client interested in promoting wellness in their space without direct access to the

outdoor for their employees (in a commercial setting) to create understanding for the importance

of incorporating particular design elements or design decisions.” Another commented “After

using the BDM I feel the need to learn more about it and apply it more into my commercial

projects”.

Post BDM Assessment

Any change in

knowledge of

biophilia

Relative

frequency

(%)

Ways the

BDM can be

improved

Relative

frequency

(%)

Using the BDM in

the future.

Relative

frequency

(%)

Variety of

choices

9

More

examples/ case

studies

6

Design process/

assessment

10

Tool

availability

3

Choices

clarified/

common

language

2

Reference/checklist

3

Increased

knowledge/

desire to learn

2

Qualtrics

format

2

Client justification/

teaching

2

Concept

defined

2

Shorten/chart

2

Teaching aid

2

38

Table 2-6. Post BDM, future design process uses.

One additional question asked more specifically when in the design process they might use the

BDM, see Table 2-6. The majority response (n=15) was that they would use it throughout the

design process with the second highest (n=7) being use in the conceptual design phase. This was

again an interesting finding after their use of it as a post-occupancy evaluation.

Table 2-7. Overall quality of the BDM.

Note: 5-point scale, 5 being high, 54 items, one person did not complete this question.

The BDM quality was rated using a 5-point scale; the mean scores ranged from 3.8 to

4.4, see Table 2-7. Also, the BDM as an assessment tool now has a total possible score of 162.

When might you use the BDM?

Design Phase

Frequency

%

Conceptual

7

21

Programming

5

15

Design dev

5

15

Post occupancy

1

3

All

15

45

Other

0

0

Post-BDM assessments

BD

How would you rate the quality of the BDM as an interior design tool in the following

categories

n

M

SD

Skewness

Kurtosis

Instruction

22

3.82

.97

-.77

.36

Definition

22

3.93

.68

-1.43

2.23

Name

22

4.16

.63

-.97

1.19

Choices

22

3.96

.47

-.58

.04

Comprehen-

siveness

22

4.39

.75

-.63

-.373

Overall

Clarity

22

4.07

.90

-1.21

2.35

Helpfulness

22

3.96

.66

-17.95

3.40

Total BDM score of the given space

BDM score

22

63.00

21.08

4.51

2.01

39

This is based on adding up each attribute’s possible score (0-3). The total score for the

practitioner’s assessment of the given space averaged 63. Several practitioners noted that they

saw the space lacking in biophilic variety and feeling very cold, which may have been

represented in the BDM scores. This is preliminary testing so there is not a set high vs low score,

which may be a future development.

Research Question Three: BDM Validity and Reliability

The element categories were internally reliable as shown in the Cronbach’s Alpha results

of the elements in Table 2-8 with a range α =.77 to .91 (DeVellis, 2017). The overall BDM as a

whole scored α = .94. Additionally, the individual attributes were assessed with the following

criteria:

• Cronbach’s Alpha, greater than or equal to .70

• Inter-item correlations, greater than .15

• Corrected item-scale correlations, greater than or equal .50

• Cronbach’s alpha’s if item deleted, decrease in alpha if item deleted

Table 2-8. BDM reliability element and combined results.

The criteria used excluded 4 attributes: habitats, composition, pragmatic and reflected

light. None of the Cronbach's alpha if item deleted scores for these four items was drastically

different from the element category Cronbach’s Alpha score: habitats (Cronbach’s alpha if item

BDM reliability testing

n

# of attributes

Cronbach’s Alpha

Actual Natural Feature

23

8

.79

Natural Shapes and Forms

23

7

.77

Natural Patterns and Processes

23

10

.79

Color and Light

23

15

.75

Place-Based Relationships

23

6

.91

Human-Nature Relationships

23

8

.86

All elements combined

23

54

.94

40

deleted was .82 up from .79 for the element), composition (Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted was

.76 up from .75 for the element), pragmatics (Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted was .80 up from

.75 for the element) and reflected light (Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted was .77 up from .75 for

the element). Additional rounds of test-retesting of the Cronbach’s alpha by removing these

items and looking at resulting correlation issues increased the Alpha only slightly. These items

should be re-assessed before removing them to see if revised definitions with an alternate

assessment site may provide more rich information and may contradict these findings. The

overall reliability was good, so future testing is needed to expand upon the findings here and

address the potentially biased sampling.

Discussion

Designers see biophilic design as important, however they had only moderate confidence

and previous experience in using it. Future testing with experienced users of the BDM can see if

knowledge increased correspondingly with confidence levels. This would align with other

findings of a correlation between confidence and knowledge in evidence-based practice among

occupational therapy students as experience increased (DeCleene Huber et al., 2015).

After identifying that biophilic design was important, finding out what kind of tool would

support interior designers was even more relevant. The BDM was helpful, had an overall good

quality level and was considered a design aid to the entire design process. It was both relevant

and useful as a design aid but could also be used to teach clients and explain design decisions.

This aligns with Kirk Hamilton’s view on an evidence-based designer being one that makes

decisions with an informed client (2004). In this regard, it is a tool that designers can use to help

clients see the diversity of the needs of building occupants by having conversations with them at

the beginning of a project. This is optimal for working within the building information modeling

process (Azhar, Khalfan, & Maqsood, 2012).

41

To insure the future of the work done here, the concept of biophilic interior design is

proposed, distinct but under the umbrella of biophilic design. To align with this, the name of the

BDM is being changed to the Biophilic Interior Design Matrix with a coordinating toolkit of

parts. The biophilic interior design (BID) toolkit has the following four components now

available at http://redgatordesign.wixsite.com/biophilicdesign:

• biophilic interior design matrix (previously the BDM), BID-M

• biophilic interior design checklist sheet, BID-C

• biophilic interior design reference document, BID-R

• online biophilic interior design research repository

The BDM was overall seen having a good quality and could be used as an assessment tool so it is

now called the BID-M. It was also seen as a design aid so a simplified version without the

scoring feature was created (BID-R) for this purpose, as well a single page list of all the