Title Page

Title of Project: Patient Reminders and Notifications

Principal Investigator:

James D. Ralston, MD MPH

Other team members:

Jennifer McClure, PhD

Paula Lozano, MD MPH

Linda Kiel, MA

Luesa Jordan

Zoe Bermet

Wanda Pratt, PhD

Jordan Eschler, PhD

Katie O’Leary

Logan Kendall, PhD

Lisa Vizer, PhD

Leslie Liu, PhD

Organization: Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, formerly Group Health

Cooperative

Inclusive Dates of Project:

Initial grant period: 08/01/2013 – 05/31/2016

No cost extension: 06/01/2016 – 05/31/2017

Federal Project Officer:

Shafa Al-Showk, AHRQ

Acknowledgement of Agency Support:

The project described was supported by grant number

1R01HS021590-01A1 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Thank you to

AHRQ for their support. The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do

not represent the official views of AHRQ.

Grant Award Number:

4R01HS021590-03

1

Structured Abstract

Purpose:

To describe patient needs and preferences for a comp

rehensive system of care healthcare reminders

and notifications. This work will inform future development and testing of patient-centered reminder and

notification systems.

Scope:

This study id

en

tified user needs, preferences and capabilities for a health reminder and notification

system by focusing on two populations of patients with disparate chronic and preventive care needs.

One population was women who also manage care for their child under age 12 who had asthma. The

second is patients with diabetes and other chronic health conditions including hypertension and

coronary artery disease.

Methods:

Content and functional specification of reminders and notifications were developed with techniques of

user-centered design and based on the Chronic Care Model conceptual framework.

Results:

User

needs assessment and prototype testing established core design features for improving

healthcare reminders and notifications including minimizing the extensive work of integrating healthcare

reminders into the home environment; accommodating the variation of reminder tools in the home;

tying reminders and notifications to individual’s values and where they carry emotional meaning, like

the memory of hard time or the support of a relationship; matching the design of persuasive reminding

to the individual and task; ensuring that reminders reflect and support collaboration with healthcare

providers: and enabling reminders to support shared tasks and interpersonal ties within social

networks. These design principles can help guide healthcare providers and health information

technology developers towards more effective and patient-centered care.

Key

Words:

patient-pr

ovider communication, chronic illness care, care management

2

!

PURPOSE

The overall goal of the project was to describe patient needs and preferences for a comprehensive

syst

em of care notifications and reminders in two patient groups. The results of this study provide

design specifications needed for further study and development of patient reminder and notification

systems across health care systems.

We had two specific Aims:

• Aim 1: Establish the needs and preferences of patients for notifications and reminders by

stu

dying patient workflow models, user requirements, personal communication patterns, and

contextual factors.

• Aim 2: Build and test a prototype of a patient-con

trolled health reminder and notification

system using iterative rapid prototyping and other user-centered design methods to clarify core

design elements and establish the feasibility of integration with the patient-centered medical

home.

3

!

&

&

&

&

SCOPE

Background

Patient reminders and notifications are effective at helping people reach health goals. They alert people

to schedule medical visits and screenings, remind people how to take complex medical regimens, and

provide a liaison between patients, providers, and the health care system. When combined with fully

functional electronic health records, new communication technologies are an opportunity to contact

patients more often with a more comprehensive set of reminders and notifications than previously

possible.

Despite their promise, reminders and notifications, if poorly designed, can overwhelm or annoy patients

and undermine their effectiveness. Questions also remain about patients’ preferences for receiving

more comprehensive reminders and notifications or using newer communication channels to interact

with their health care providers. Moreover, the effectiveness of such enhanced communication systems

is unclear.

Context

Most studies of reminders have focused on a single health care need or condition and a single delivery

mode, such as postal mail or the telephone. We know little about real-world use of reminder and

notification systems for multiple chronic and preventive health care needs targeting a diverse

population in varied settings. We also know little about how to use new communication tools such as

patient websites linked to electronic health records (EHRs), text messaging, or mobile phone

applications for reminders and notifications. In combination with EHRs, these technologies offer

opportunities for more frequent contact with patients and a more comprehensive set of messages.

However, we do not know the ideal attributes of reminders and notifications including the frequency and

timing of contact or the extent to which patients prefer straightforward reminders versus notifications

designed to encourage and support behavioral action. In addition, reminder and notification systems

have the potential to annoy, overwhelm, or frustrate patients. The impact of individual reminders may

diminish as patients receive multiple reminders and notifications. User needs and preferences must

also be balanced against threats to the integrity, security, and privacy of health care information

involved with newer communication technologies, such as text messaging and social network sites.

Designing optimal systems will involve addressing user needs and preferences for reminders and

notifications, being sensitive to patient confidentiality, and incorporating the capacity of newly emerging

communication technologies such as social media, text messaging, and mobile applications to interact

daily with patients.

Settings&

This study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Washington (formerly Group Health), an integrated

care delivery system with over 660,000 members in Washington and North Idaho. The proposed study

was restricted to the 391,749 members who receive primary care at one of Kaiser Permamente

Washington’s 28 owned-and-operated clinics. At the time of the study, Kaiser Permanente

Washington’s membership includes 55,239 Medicare members, 19,089 Medicaid members, and 11,623

covered by the Basic Health Plan (a state supported insurance program for low-income families). The

Kaiser Permanente Washington’s population is generally similar to that of the surrounding area. Kaiser

Permanente Washington had a slightly higher proportion of women (53%) than the regional community

(50%) and the nation (51%). Kaiser Permanente Washington’s members are also older (46% ≥45

years) than the regional community (38%) and the nation (39%). Compared to the rest of the country,

Kaiser Permanente Washington members are more likely to be Asian or Pacific Islanders (9% versus

4%), but less likely to be African American (4% versus 12%) or report Hispanic ethnicity (4% versus

15%). The Kaiser Permanente Washington racial and ethnic composition broadly represents the Puget

Sound region. In this study, we purposively sampled the Kaiser Permanente Washington population to

simulate the educational status of the U.S. population when possible (approximately 50% with high

school or less educational level) and oversampled racial and ethnic minorities (see Study Population

below for details). Kaiser Permanente Washington uses an ambulatory EHR system (EpicCare) that

4

&

Aim 1:

Aim 2:

N

%

20

N

%

includes clinical decision support features, secure provider-to-provider messaging, and an EHR-

integrated online medical record shared with patients (

www.ghc.org

). Features include secure patient-

provider electronic messaging and online patient access to medical record elements, including results

of medical tests,

af

ter-vi

sit summaries,

and mobile

extensions of the

integrated personal

health record for

iPhone and Android

smart phones.

Currently, at Kaiser

Permanente

Washington, several

reminders are part of

the annual birthday

letter sent out to each

enrollee. Some

reminders also

appear on the patient

website. Like many

US healthcare

systems, notifications

of medical test results

are sent through US

mail letters and email

ticklers

recommending going

to the new test results

on the patient website

or mobile application.

Email notifications are

also sent if a new

secure message from

a provider is present

on the patient's

website.

Table 1: Characteristics of Patient Participants in Needs Assessment

Total

N

40

Asthma

100

Diabetes

20

100

Median Age (Years)

Me

an Age (Years)

54.5

54.

5

37.0

37.

5

64.0

64.

5

Race & ethnicity

Asian

2

0

0

2

10

Black

12

6

30

6

30

Hawaiian

1

1

5

0

0

Indian

0

0

0

0

0

Mixed

1

0

0

1

5

Other

2

1

5

1

1

Unknown

2

2

10

0

0

White

20

10

50

10

50

Hispanic*

2

1

5

1

5

Online health portal use

User

No

n-user

27

13

17

3

85

15

10

10

50

50

Education

>High school

Hi

gh school or less

28

12

16

4

80

20

12

8

60

40

*Hispanic ethnicity designation overlapped with other designations of race; total is > 100%

Participants

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 40 individuals in our needs assessment. As shown in

the table, we purposively sampled individuals with minority racial and ethnic backgrounds in order to

more closely align our participant group with the demographics of the overall US population.

Participants with high school or less formal education level were difficult to recruit, particularly for the

mothers of children with asthma. We were still, though, able to recruit 30% of the overall population with

a high school or less educational level. Since portal use in the KP Washington population had also

grown to over 70% of members overall with even higher use among those with healthcare needs such

as diabetes and asthma, we also changed our initial sampling plan from half portal users to just under

70% portal users.

Aim 2 had four stages of patient and provider engagement in design. In the first stage, we engaged

thre

e cohorts of patients in two sequential sets of futures workshops to help envision ideal reminder

and notification systems; cohorts consisted of patients with diabetes and mothers of children with

asthma. In the second stage, we engaged three cohorts of participants in two sequential participatory

design sessions; cohorts consisted of a mix of patients, mothers of children with asthma and healthcare

5

Study Design

African American

Nat. Amer/Alask.

Hispanic

White

High Sch. or less

Some College

4YR College

+4YR College

providers. Table 2 shows the demographics of patient participants in participatory design sessions.

Providers involved in these sessions included 6 primary care providers, 3 medical assistants and 3

nurses

In the third stage of Aim 2, we held two

sequential prototype testing sessions

with 15 patients. Prototypes for the

second session were iterated based on

feedback from the first session. We also

held 2 separate prototype testing

sessions with 15 providers (7 PCPs, 7

MAs, 1 nurse). In stage four, we tested a

series of designs specifically focusing on

new reminder and notification

functionality in the patient portal. This

final stage included prototype testing with

19 patients.

1

Incidence and Prevalence

Measuring incidence and prevalence

was not part of t

his study.

Methods

We used mixed met

hods grounded in a

user centered design approach. Specific

methods included ethnographic

interviews, Q methodology, photo

elicitation, participatory design

workshops, and prototype testing.

Table 2: Aim 2: Participant Demographics for Participatory Design

Mothers of

children with

Asthma

Older adults with

Diabetes

N=11

N=12

Age

Range (yrs)

31-45

54-89

Mean (yrs)

38

73

Race

5

0

0

6

6

0

0

6

Education

2

5

1

3

4

2

2

4

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was only applicable for Q-methodology. All other analyses were qualitative. For Q-

methodology, we used PQMethod software in factor analysis to help identify clusters of individuals with

shared attitudes towards self-management of chronic illness and use of communication technologies.

2

Data Sources/Collection

Data sources included the follo

wing: transcribed interviews; photos by participants; surveys of attitudes

towards communication technologies and self-management of chronic illness; Q data sets; recordings,

artifacts, transcripts and notes from participatory design workshops; audio and video recordings,

transcripts and notes from prototype testing sessions.

Measures and Surv

ey Items

Survey measures were used only for Q meth

odology where we adapted self-reported survey questions

from Davis’ measure of the perceived usefulness, ease of use, and user acceptance of technology

3

; the

patient assessment of chronic illness care (PACIC) and measures of autonomous support.

4,5

Limitations

Our comprehensive approach to remind

ers and notifications did not permit us to target all redesign

processes and follow-up activities involved in chronic care and preventive care. We were also

challenged to make the reminder and notification system simple and visible to a large population of

patients. To address this, we engaged the most diverse set of patients allowed by our methods and

resources.

6

Results

Principal Findings

We su

mmarize our prin

ciple findings by Aim below and then by core design principles. Further details

are in peer reviewed publications (9 published, 2 in process). Results not yet published or in

submission have more detail below.

Aim 1: Establish the needs and preferences of patients for notifications and reminders by studying

pati

ent workflow models, user requirements, personal communication patterns, and contextual factors.

Methods Development:

To begin our work, we published two methods papers to more effectively, efficiently and respectfully

elic

it patient stakeholder input on needs and preferences for designing better healthcare reminders and

notifications. We also published a third paper on the development of Q methodology to help understand

design tradeoffs for tailoring health technologies to different populations. These methods can also be

applied for eliciting patient and family needs for other health information technology applications.

1. Systematic inquiry for design of health care information systems: an example of elicitation of the

patient stakeholder perspective (published).

6

This paper describes the application of the

Vicente theoretical framework to organize qualitative data during our multistage study into

patient engagement with health information technology. The framework helped us develop

interview probes for encouraging patient narratives of engaging with reminders in task cycles in

their home. This approach allowed a more full description of individual and family work rather

only on positive or negative aspects of experiences with reminders systems.

2. Opportunities for empathetic responses in field interview scenarios investigating home health

routines (published).

7

This paper sought to identify and describe effective interview approaches

for fostering empathy with participants during the design process. Empathy with participants

who were living with chronic health conditions was considered essential for building trust and

engaging participants in the design process. The study was performed at midpoint in the data

collection from patient and family interviews in the first phase of Aim 1, which allowed

application of the findings to follow up interviews and other study activities. We identified factors

valuable for enhancing empathy during participant interviews including active listening methods

during expressions of frustration about a diagnosis and feelings of guilt or failure in treatment

and prevention of health conditions.

3. Understanding design tradeoffs for health technologies: a mixed methods approach

(published).

8

In order to better tailor reminder and notification systems, we sought to understand

how participants’ attitudes towards use of communication technologies intersected with their

attitudes towards self-management of chronic illness. In this paper, we describe an approach

involving a novel application of the Q-method, a mixed methods approach providing a few key

advantages for health design science including: a structured framework to guide data collection

and analysis; enhanced coding of unstructured data with statistical patterns of polarizing and

consensus view; and elicitation of participants active expression and weighting of competing

values relevant to healthcare design(see below for separate paper on Q method results).

Patient Work, Men

tal Models and Motivation

In a series of analyses, we developed

an understanding of how participants remember what to do

during daily life to inform better design of healthcare reminders and notifications. For these studies, we

viewed healthcare reminders and notifications within the larger context of self-management of chronic

illness.

1. Shared calendars for home health management (pub

lished).

9

Our home visits and interviews

quickly established that home calendars were a central tool for helping participants and families

remember tasks to do each day. This paper described the how 40 of our adult participants (20

each of mothers of children with asthma and individuals with type 2 diabetes) used shared

calendars to support home management. We report on both the diverse systems of home

calendar management, including the common use of multiple calendars within a home, and

failures experienced. We then describe implications for schedule management strategies for

7

individuals and families who need to remember and incorporate the common tasks of caring for

chronic illness.

2. Engineering for reliability in at-home

chronic disease management (published).

10

In this paper,

we examined remembering to perform healthcare tasks in the home from the perspective of

prospective memory theory and systems reliability engineering. Based on participants’

experiences, failures in remembering to perform self-management activities should be viewed

as system failures rather individual failures. Participants also described several design

strategies used to enhance the reliability of systems designs for remembering to perform self-

management tasks. We discuss how these results can be used to improve the reliability and

experience of healthcare reminder systems.

3. Understanding patients’ health and technology attitudes for tailoring self-man

agement

interventions (published).

2

In this publication, we used mixed methods approach (described in

publication #3 under Methods Development) and maximum variation sampling to describe the

intersection between attitudes towards communication technologies and attitudes towards self-

management of chronic illness in 40 of our participants. We found three participant clusters,

“Proactive Techies”, “Indie Self Managers” and “Remind Me! Non-techies” which were

independent of education level, race and age. These results are valuable for informing tailored

design of reminder and notification systems.

4. Designing Asynchronous Communication Tools for Optimization of Patient-Cli

nician

Coordination (published).

2

Since an increasing number of healthcare reminders and notifications

are communicated asynchronously between provider visits, either electronically or through US

mail, we sought to understand how designers can avoid pitfalls and optimize new opportunities

in this growing and evolving form of communication. Key themes emerged associated with both

unsatisfactory and satisfactory asynchronous communication. For good communication, these

themes included the following: enhancing care with followup; reducing uncertainty in plan of

care; and providing an automatic health archive to reference later. Themes of unsatisfactory

asynchronous communication included failing to track issues, including closing the loop on

reminder and notification communications, and exposing patients to inconsistent communication

patterns. Key design recommendations for asynchronous health communications included

incorporating patient preferences for non-urgent information exchange and incorporating status

indicators in asynchronous communications including reminder and notifications.

5. Finding Reminders in the World: How Individuals Support Motivation and Tasks in Managing

Chronic Illness (in revision for submission).

11

In our home visits, we heard clearly that day to day

remembering and performing health self-management tasks can be a tremendous burden for

patients. Motivation to complete these tasks is often a big challenge. After sending our

participants home with Polaroid cameras in the followup phase of the study, we discovered

participants were often appropriating everyday things to both remember and motivate

themselves to perform healthcare tasks. These included artifacts in the home, such as the

display of a cane that prompted a memory of former disability associated with lack of self-

management; and emblems of motivating relationships, such as pictures of loved ones. These

were the most potent reminders we found and highlight new opportunities for providers to

engage patients in identifying and developing a motivating and effective environment for health

in the homes.

Aim 2: Build and test a prototype of a patient-co

ntrolled health reminder and notification system using

iterative rapid prototyping and other user-centered design methods to clarify core design elements and

establish the feasibility of integration with the patient-centered medical home.

1. Persuasive Reminders for Health Self-Man

agement (published).

12

During participatory design

sessions, patients used a combination of storyboards, collages and cultural probes to describe

future reminder systems that could support fulfillment of tasks of managing chronic illness.

Participant’s ideas and prototypes for these idealized reminder systems identified four key types

of persuasive healthcare reminders: introspective, socially supportive, adaptive and symbolic.

Including these features in reminder design can help support patients to understand why and

8

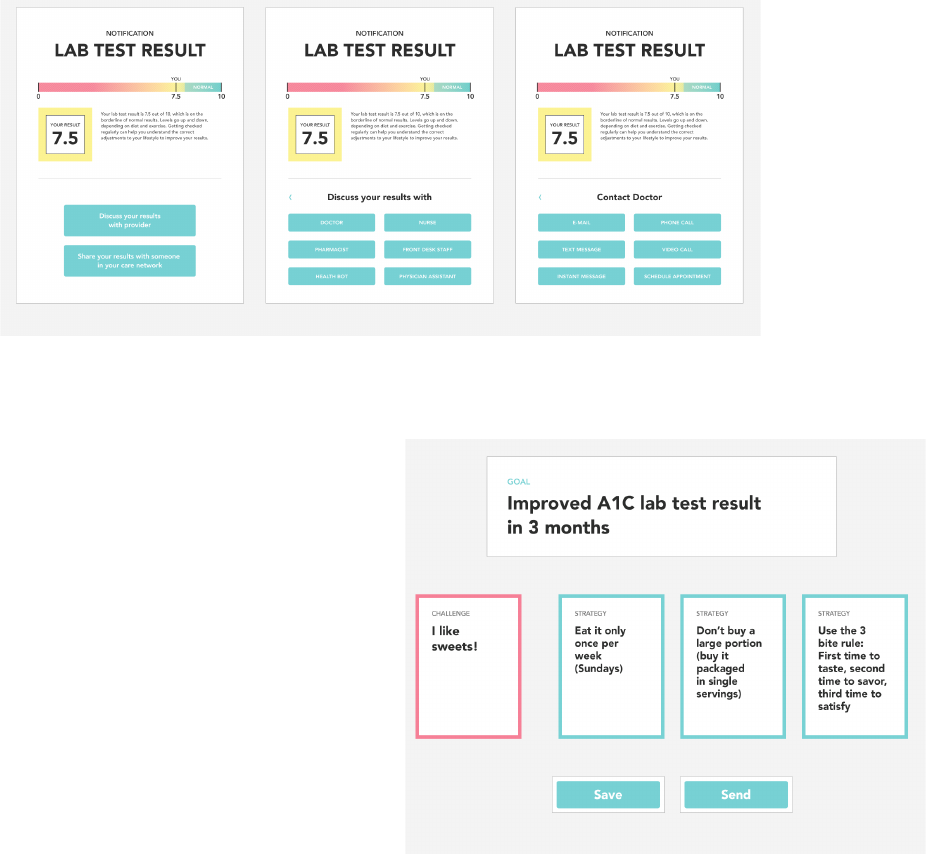

Figure XX: Discovery Tool for Notifications

how to complete healthcare tasks ahead of time.

2. Collaborative Health Reminders and Notifications (drafted for submission). During this final

phase of the project, we iteratively designed and tested prototype reminder and notification

systems in two iterative phases. To develop prototypes, we began with a synthesis of needs

analysis from Aim 1. This needs analysis then fed into value scenarios which were used with

designers in an inspiration workbook. Based on the results, we developed and tested with

participants low fidelity prototypes including a Symbolic Reminder Band, Social Reminder App,

a Reminder Invitation, a Discovery Tool (figure 1) and a Conversational Tool (Figure 2). We

show picture of two of these tools below. The discovery tool was created to explore how

patients gain clarity around their healthcare and how they communicate their need for that

clarity with their provider from outside of the clinic after receiving a notification.

Figure 1: Discovery Tool for Reminders

The conversational tool was created to explore how patients and providers might collaborate in

the clinic on creating reminders around unique patient challenges and strategies to overcome

those challenges.

Preliminary analysis of the results of

prototype testing found that participants

emphasized the importance of

designing collaborative health

reminders and notifications with

particular attention to three domains:

(1) Enable the p

atient-provider

relationship; (2) Support shared action

on health tasks; and (3) Promote

interpersonal ties based on shared

health tasks and goals. Participants

also reported on the potential

challenges of collaborative reminders,

including administering reminders

across social networks.

Figure 2: Conversational Tool for Reminders

3. Integrating the Patient Portal into

Health Management Work Ecosystems User Acceptance of a Novel Prototype (published):

1

. In

this paper, we built on our earlier to work to elicit feedback about reminder and notification

features in patient portals. We used a patient centered approach to design and test prototypes

of new features for managing health tasks within an existing portal tool. We iteratively tested

three prototypes with 19 patients and caregivers. Implications for design based on our findings

included building on the positive aspects of clinician relationship to enable engagement in the

portal including patient reminders; using face to face visits to promote clinical collaboration in

portal use including reminders for healthcare tasks and notifications of test results; and allowing

9

customization of portal modules to support tasks based on user roles.

4. Prototype Feasibility within the Primary Care Setting: In two

group sessions with primary care

team members including PCPs, RNs and MAs, we evaluated the feasibility of three prototypes

developed with patients and described above. We focused on prototypes most amenable

patients and with the most significant potential to impact primary care workflow. The first

prototype focused on a new reminder for getting a retinal screening exam in a patient newly

diagnosed with diabetes, who did not remember why an exam was needed. The prototype

allowed for different options to contact the healthcare provider. Most of the providers

emphasized the value of the reminder existing within an ongoing relationship that includes

educating patients on the importance of recommended healthcare tasks including retinal exams.

While participants endorsed the prototype’s overall concept of easily sending questions to

providers from a reminder, participants were concerned that the patient didn’t sufficiently

remember the value of the exam and identified a missed opportunity for the team to inform the

patient during prior in person visits. In the second reminder, a patient is notified of a medical test

result online and has a followup question. Multiple options for reaching different members of the

care team or a health bot are provided. Primary care team members were concerned about

being overwhelmed with messages from patients in this prototype and liked the possibility of an

automated health bot being the first stop to provide patients with a potential answer. The third

prototype was the conversational reminder tool described above. Overall, providers liked this

tool the most and thought it had potential, as long as the patient was excited to use it. Providers

struggled some, though, with how the tool could be integrated into current primary care staffing

and roles. Several providers thought using a health coach or similar new role would enable use

of the tool rather than adding to the existing roles of nurses or MAs.

Core Design Principles

Based on the combined analyses and publications above, we outline below the study’s core principles

for d

esigning better patient reminders and notifications. We have grouped these principles within four

broad categories of our findings: reminding and notifying within patient and family workflow;

opportunistic reminding; persuasive reminding; and collaborative reminding. Further details describing

these principles are included in our publications.

Reminders and Notifications within Patient and Famil

y Workflow. To integrate with the broad ecology of

calendaring and scheduling, reminder tools in the home should

• Incorporate patient preferences for modality of non-urgent i

nformation exchange.

• Enhance patient followup on reminders and communicate with providers about questions or

conce

rns relating to the healthcare recommendation in the reminder.

• Incorporate status indicators into reminders and other asynchronous communication. Thes

e

indicators would help build shared understanding and accountability between patients, providers

and family members for healthcare tasks and communication.

• Support need for some redundancy in home reminder systems including repeated reminders

and div

ersity of systems used in the home (e.g. paper and electronic)

Opportunistic Reminders. To en

able the most potent reminders we identified in our study,

• Healthcare providers should engage patients in identifying or developing artifacts, activities or

routines that can both remind and motivate for healthful behaviors.

• Heath IT developers should work to move the power of the opportunistic reminders outside of

the h

ome environment and onto mobile applications and into communications with patients and

families.

Persuasive reminders. To help reminders be more meaningful and persuasive, tailor reminder design to

one of

four types to match the task:

• Introspective reminders to trigger reflection goals.

• Socially supportive reminders to enhance motivation and mentoring relation

ships.

10

• Adaptive health reminders that change to meet the shifts in health status, task status and

modality preference.

• Symbolic reminders reminding of personally significant reasons for health behaviors (e.g.

images of a child, dog, garden)

Collaborative Reminders. To

support collaboration and relationships with healthcare providers, family

and friends, reminders should

• Enable the patient-provider relationship. Participants expressed a strong need for reminder to

reflect collaboration with healthcare providers on health goals and tasks and the reminders

themselves should in turn enable the patient-provider relationship.

• Support shared action on health tasks acr

oss social networks including family and friends.

• Promote interpersonal ties based on shared heal

th tasks and goals including both weak and

strong ties.

Discussion

The findings of this project helped address a critical junction in the design and use of patient

noti

fications and reminders. We developed several core design recommendations that can be used by

healthcare providers and policy makers as well as health information technology developers. The value

of our work was emphasized by the enthusiasm received in its publication including nomination of two

of our papers for the outstanding paper award at the Annual American Medical Informatics

Conference

2,12

with one paper winning the award.

2

During and after our presentations, we were also

sought out by health information technology companies for our results and how they might be applied to

current EMRs and patient facing health information technologies. We expect that our results will

continue to help guide both health information technology developers and the design of healthcare

delivery.

Grounding our project in the appro

ach and methods of user centered design allowed us to identify

unexpected challenges and opportunities for designing reminders. We entered the grant believing the

main challenges facing patients related to incorporating multiple reminders across an increasing

number of platforms of communication into daily workflow and management. We came out of the grant

recognizing that the biggest challenges and opportunities focused on designing reminders which better

reflected each patient’s values and goals developed within collaboration with healthcare providers. We

expanded our design probes and prototypes to accommodate this broader set of patient and family

needs.

Our study had

a few limitations. Due to our use of in depth investigation with individual patients, families

and providers, we had a limited number of subjects, all of whom lived in the greater Puget Sound area.

We sought to mitigate this limitation by recruiting a sample which better reflected the overall

demographics of the United States, including greater representation from those with minority racial and

ethnic background and lower formal educational levels. The needs, preferences and abilities for

healthcare reminders and notifications, however, may still be different among populations in other

regions of the United States. Our participants may also have expressed needs and preferences which

may not persist if we had built and deployed a fully functional reminder and notification system within

the patient centered medical home. Although our prototype testing helped attenuate the potential for the

well-known discordance that can occur between expressed and realized needs and preferences, only a

real world testing over months to years would fully clarify the system requirements.

Conclusions

Current healt

hcare reminders and notifications are not sufficiently meeting patients’ needs, preferences

and capabilities. Improving healthcare reminders and notifications will require minimizing the extensive

work of integrating healthcare reminders into the home environment; accommodating the variation of

reminder tools in the home; tying reminders and notifications to individual’s values and where they carry

emotional meaning, like the memory of hard time or the support of a relationship; matching the design

of a persuasive reminding to the individual and task; ensuring that reminders reflect and support

11

collaboration with healthcare providers: and enabling reminders to support shared tasks and

interpersonal ties within social networks. These design principles can help guide healthcare providers

and health information technology developers towards making care more effective and patient

centered.

Significance

This project addressed a

c

ritical junction in the design and use of patient notifications and reminders.

The increasing engagement of patients in care outside of office visits, including through using patient

websites and mobile communication technologies, offers new opportunities to improve care. The

number of potential reminders and patient notifications and the variety of delivery mechanisms also

risks overwhelming and alienating patients. In this study we identified key design principals that can

help keep reminders and notifications meaningful and effective for patients and families. Many of our

findings challenge current approaches to how we remind patients for common health care tasks and

notify them of medical test results and other health information.

Implications

Many of our findings can be applied immediately to the design of both healthcare del

i

very and health

information technology. Simple design changes, such as status indicators on a reminder for a task

received over a patient website or mobile application could substantially improve communication with

patients and may improve the effectiveness of care. Other findings, such as the collaborative reminder

tool, have strong potential to improve how we currently deliver self-management support programs for

chronic conditions including diabetes. These implementations could be done with little impact on

provider workflow and would not require significant changes in staffing or the delivery of care.

The results of our study, h

owever, also highlight many of the larger challenges remaining for the design

of better healthcare reminders and notifications. We heard consistently that reminders for healthcare

tasks need to reflect a patients values and a shared understanding of healthcare goals and tasks

established during collaboration with a personal healthcare provider. Even our best healthcare systems

are ill equipped to create and maintain this level of personalized care. The depth of detail needed for

individual patient and family engagement in this approach to care is beyond the current structure and

financing of healthcare in the United States. These challenges will only grow as the number of

healthcare tasks recommended for individuals continues to rise along with the increasing complexity of

many patients’ care. No health information technology can address these needs on its own. If we are

to build more effective and patient centered reminders and notifications that help patients achieve

better health, we must invest in better staffing and models of primary care.

List of Publications and Products

Publications:

1. O’Leary KO, Liu L, McClure JB, Ralston JD, & Pratt W. Persuasive reminders for health self-

management. Proceedings of the American Medical Information Association, Nov 12-16, 2016.

Chicago, IL.

2. Eschler J, Meas PL, Lozano P, McC

lure JB, Ralston JD, and Pratt W. Integrating the patient

portal into the health management work ecosystem: user acceptance of a novel prototype.

Proceedings of the American Medical Information Association, Nov 12-16, 2016. Chicago, IL.

3. O’Leary K, Vizer L, Eschler J, Ralston J, Pratt W. Understanding patients’ health and tec

hnology

attitudes for tailoring self-management interventions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2015 Nov

5;2015:991-1000. PMC4765611.

4. Eschler J, Liu LS, Vizer L, McClure J, Lozano P, Pratt W, Ralston J. Designing asynchronous

com

munication tools for optimization of patient-clinician coordination. AMIA Annu Symp

Proc. 2015 Nov 5;2015:543-52. PMC4765629.

5. O’Leary K, Eschler J, Vizer LM, Ralston JD, Pratt W. Und

erstanding design tradeoffs for health

technologies: a mixed-methods approach. Proceedings of CHI (Human Computer Interaction).

April 2015.

12

6. Eschler J, O’Leary K, Kendall L, Ralston JD, Pratt W. Systematic inquiry for design of health care

information systems: an example of elicitation of the patient stakeholder perspective. In

Proc

eedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. January, 2015.

7. Kendall L, Eschler J, Lozano

P, McClure JB, Vizer LM, Ralston JD, Pratt W. Engineering for

reliability in at-home chronic disease management. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014 Nov

14;2014:777-86. PMC4419963.

8. Eschler J, Kendall L, O’Leary K, Vizer LM, Lozano P, McClure JB, Pratt W, Ralston JD. Shared

cale

ndars for home health management. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on

Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. March, 2015.

Posters and Presentations:

1. Designing Reminders and Notifications for Patients: AHRQ National Webinar. May 7

th

, 2015

Manuscripts in Preparation:

1. Liu L, O’Leary K,

Pratt W, Ralston JD. Opportunistic Reminders in the World: How Older Adults

Design Everyday Reminders to Manage their Chronic Illness.

2. O’Leary K, Tenghe D, Pratt W, Ralston JD. Designing Reminders for Socialable Use.

References:

1. Eschler J, Meas PL, Lozano P, McClure JB, Ralston JD, Pratt W. Integrating the patient portal

into

the health management work ecosystem: user acceptance of a novel prototype. AMIA Annu

Symp Proc. 2016;2016:541-50. PMCID: PMC5333335.

2. O'Leary K, Vizer L,

Eschler J, Ralston J, Pratt W. Understanding patients' health and technology

attitudes for tailoring self-management interventions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2015;2015:991-

1000. PMCID: PMC4765611.

3. Davis F. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and

Us

er Acceptance of Information

Technology. MIS Quarterly. 1989;13:319-39.

4. Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and

vali

dation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care. 2005;43:436-

44. Epub 2005/04/20.

5. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-det

erm

ination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social

development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68-78.

6. Eschler J, O'Leary K, Kendall L, Ralston JD, Pratt W. Systematic inquiry for design

of health

care information systems: an example of elicitation of the patient stakeholder perspective. In

Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 2015.

7. Eschler J, Ralston J. Opportunities for Empathetic Responses in Fiel

d Interview Scenarios

Investigating Home Health Routines. 2014.

8. O'Leary K, Eschler J, Kendall L, Vizer LM, Ralston JD, Pratt W. Understanding Design

Trad

eoffs for Health Technologies: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Proceedings of the 33rd

Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Seoul, Republic of Korea.

2702576: ACM; 2015. p. 4151-60.

9. Eschler J, Kendall L, O’Leary K, Vizer LM, Lozano P, McClure JB, Pratt W, Ralston JD. Shared

cale

ndars for home health management. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on

Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. 2015.

10. Kendall L, Eschler J, Lozano P, McClure JB, Vizer LM, Ralston JD, Pratt W. Engineering for

reli

ability in at-home chronic disease management. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:777-86.

PMCID: PMC4419963.

11. Liu L. Finding Reminders in the World: How Individuals Support Motivation and Tasks in

Mana

ging Chronic Illness. 2017.

12. O'Leary K, Liu L, McClure JB, Ralston J, Pratt W. Persuasive Reminders for Health Self-

Management.

AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2016;2016:994-1003. PMCID: PMC5333289.

13