0

Which factors affect statement of cash flows restatements and how does the

market respond to these restatements?

Elio Alfonso

Ph.D. Candidate

E. J. Ourso College of Business

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge, LA 70803

Dana Hollie

*

Assistant Professor of Accounting

KPMG Developing Scholar

E.

J. Ourso College of Business

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge, LA 70803

Shaokun Carol Yu

Assistant Professor of Accounting

Northern Illinois University

DeKalb, IL 60115

March 6, 2012

Please do not quote without the authors’ permission.

We thank workshop participants at Louisiana State University for their helpful comments.

*Corresponding Author. Tel.: +1 225 578 6222; fax: + 1 225 578 6201.

0

Which factors affect restatements of cash flows and how does the market

respond to these restatements?

Abstract: The Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has become increasingly concerned with

firms’ misclassification of cash flow activities on the statements of cash flows (SCF). The SEC

has maintained that the proper classification of cash flows gives financial statement users insight

into how a firm generates and uses cash flows. This study investigates the relation between cash

flow restatements, firm characteristics, and corresponding stock market reactions to these

restatement disclosures from 2000 to 2006 In particular, we find that the likelihood of a

restatement is higher for firms with more firm complexity as measured by the number of

reported segments, firms with a BigN auditor, greater debt leverage and discontinued operations.

The overstatement of cash flows from operations (CFO) occurs more likely in firms with a cash

flow forecast, and book-to-tax difference (BTD). Interestingly, the overstatement of CFO occurs

more likely in firms issuing dividends. The changes to total cash flows (TCF) more likely occurs

in firms with BTD, but less likely in firms reporting a loss. Thus, firms with financial distress are

less likely to change TCF in CF restatements. We find that investors react negatively, in some

scenarios, to the SCF restatements. While we find that the market negatively reacts to negative

changes to TCF, we find no significant reaction to positive or no changes to TCF. Interestingly,

we find a significantly negative market reaction to firms with understated CFO restatements but

no significant reaction to overstated CFO restatements. Our findings suggest that financial

analysts, investors and regulators alike should pay close attention not only to an earnings

restatement, but also to SCF restatements.

Keywords: Cash flow restatements, cash flows, cash flow reclassifications, market efficiency

Data Availability: Data are available from sources identified in the paper.

1

Which factors affect restatements of cash flows and how does the market

respond to these restatements?

1 Introduction

Regulators and prior research have shown that investors have suffered significant losses

as market capitalizations have dropped by billions of dollars due to earnings restatements of

audited financial statements (Levitt, 2000; Palmrose et al., 2004). However, to our knowledge,

no study has examined the market effects of restatements of the statement of cash flows (SCF).

As one of the first studies to examine these SCF restatements, our study further contributes to

our understanding of reported cash flows. The statement of cash flows allows investors to

understand how a company's operations are running, where its money is coming from, and how it

is being spent. To the extent that management uses their discretion to opportunistically

manipulate accruals, earnings will become a less reliable measure of firm performance and cash

flows a more reliable and preferred measure. Not only will a firm with more reliable and

transparent statement of cash flows be more aware of its financial standing, but it will also help

investors to make educated decisions on future investments. A firm with reliable cash flow

statements shows more economic solvency, and is more attractive to investors. In this paper,

using a cash flow restatement sample without any concurrent earnings or balance sheet

restatement, we examine the determinants of SCF restatements, that is, whether cash flow

restatements (CFRs) are influenced by particular characteristics of the firm. We then assess the

market’s response to CFRs using the above pure cash flow only restatement sample.

1

1

This study examines only cash flow restatements without concurrent earnings or balance sheet restatements. This

approach allows us to have a “pure” cash flow only restatement sample.

2

“Operating cash flow is the lifeblood of a company and the most important barometer

that investors have. Although many investors gravitate toward net income, operating cash flow is

a better metric of a company’s financial health for two main reasons. First, cash flow is harder to

manipulate under GAAP than net income (although it can be done to a certain degree). Second,

‘cash is king’ and a company that does not generate cash over the long term is on its deathbed”

(Quoted from Rick Wayman, Operating cash flow: Better than net income?, 2010).

2

The SCFs is one of the primary financial statements required to be in accordance with

generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). The Statement of Financial Accounting

Standards (SFAS) No. 95, Statement of Cash Flows (SCF), issued in November of 1987 by the

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) specifies the content and composition of the

statement. The Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has become increasingly concerned with

firms’ misclassifications of cash flow activities on their statements of cash flows. The SEC has

seen an increase in misclassifications on the SCF (Levine, 2005), a presentation problem

affecting firm’s financial reporting transparency. The SEC has maintained that the proper

classification of cash flows gives financial statement users insight into how a firm generates and

uses cash flows. Complementing the

Prior

research has shown that cash flows, a component of earnings, is important because: (1) cash

flows are value relevant (Barth et al., 2001); (2) price-earnings relation depends on the market

perception of cash flow numbers (Barth et al., 2001); (3) analysts explicitly state that forecasting

cash flows is an important objective of firm valuation (AIMR, 1993); and (4) the primary

objective of financial reporting is to provide financial information that aids financial statement

users in assessing the amount and timing of future cash flows (FASB, 1978).

balance sheet and income statement, the SCF, a mandatory

2

Posted Oct 4, 2010 on http://www.investopedia.com/articles/analyst/03/122203.asp#axzz1ibAzKeX1

3

part of a company's financial reports since 1987, records the amounts of cash and cash

equivalents entering and leaving a company. The SCF is distinct from the income statement and

balance sheet because it does not include the amount of future incoming and outgoing cash that

has been recorded on credit. Therefore, cash is not the same as net income, which, on the income

statement and balance sheet, includes cash sales and sales made on credit. Cash flow is

determined by looking at three components by which cash enters and leaves a company: cash

flow from operating (CFO), cash flow from investing (CFI) and cash flow from financing (CFF).

In our sample, approximately 60% (40%) of all CFRs are overstatements

(understatements) to CFO. Firms with overstatements are identified by having downward

restatements to CFO, while understatements are identified by upward restatements to CFO.

Approximately 24% of our observations have nonzero changes from the originally reported to

the restated amounts of total cash flows (TCF). In other words, these firms report restated TCF

differently from their originally reported TCF, which suggest more than just classification

shifting may have occurred. Using a sample of 82 cash flow restatements announced from 2000

to 2006, we find that the likelihood of a restatement is higher for firms with more firm

complexity as measured by the number of reported segments, firms with a BigN auditor, greater

debt leverage and discontinued operations. The overstatement of cash flows from operations

(CFO) occurs more likely in firms with a cash flow forecast, and book-to-tax difference (BTD).

Interestingly, the overstatement of CFO occurs more likely in firms issuing dividends. The

changes to total cash flows (TCF) more likely occurs in firms with BTD, but less likely in firms

reporting a loss. Thus, firms with financial distress are less likely to change TCF in CF

restatements. We find that investors react negatively, in some scenarios, to the CFRs. While we

find that the market negatively reacts to negative changes to TCF, we find no significant reaction

4

to nonnegative changes to TCF. Interestingly, we find a significantly negative market reaction to

firms with the disclosure of restatements with understated CFO restatements but no significant

reaction to the disclosure of restatements with overstated CFO.

Our empirical findings are particularly relevant to academics, financial analysts,

regulators and investors. The results of this study are important to academic researchers because

it focuses on SCF restatements, which has been studied very little in the academic literature. We

do find inconclusive results regarding whether firms with SCF restatements have lower SCF

quality, as indicated by weaker market reactions to positive changes to total cash flows.

Regardless of whether a firm has a negative or positive change to total cash flows, these changes

are an indication of poor quality financial information. Therefore, we expected a negative market

reaction whether the change is positive or negative. Our findings may be of particular interest to

the auditing profession, where the identification of firms with a higher audit risk is extremely

valuable. The evidence in this study suggests that financial analysts, investors, and regulators

alike should pay close attention not only to an earnings restatement, but also to SCF

restatements.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses cash flow

restatement background and the related literature; Section 3 outlines our sample selection criteria

and research methodology; Section 4 presents our summary statistics and empirical findings; and

Section 5 summarizes and concludes the paper.

2 Background and related literature

2.1 Background on cash flow restatements

5

Traditionally, investors have mainly relied on the balance sheet and income statement,

thus focusing more on companies’ earnings as opposed to their cash position. But accounting

scandals in the last decade have changed the landscape of Wall Street. Investors have seen how

easily earnings can be manipulated so they are now focusing a lot more attention on how the

company is doing operationally and cash wise. They pay more attention to non-GAAP measures

such as backlog, bookings, etc. The statement of cash flows has become a more recent focus, and

measures such as “free cash flow yield” have become an indication of financial health. Although

the cash flow statement has become very important, it had been a while since the SEC

announced any regulations strictly concerning the statement of cash flows. Most recently, in

2006, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced a one-time allowance for

firms with erroneous SCF classifications to correct these misstatements without officially

restating their cash flows. Hollie et al. (2011) assesses the impact of this one-time allowance.

They find that, consistent with the SEC’s concerns, firms generally overstated cash flows from

operations and understated cash flows for investing activities, thereby misrepresenting overall

cash flows; and the most frequent line-item reclassifications echoed the SEC’s concerns about

the presentation of discontinued operations and dealer floor plan financing arrangements.

However, insurance claim proceeds and beneficial interests in securitized loans appeared less

problematic than the SEC expected. Overall, their findings indicate that the SEC’s plan was

relatively successful for these firms in that these cash flow restatements only exerted a

marginally negative impact on these firms’ stock prices.

Before 2006, it was last in the year 1987, when FASB issued SFAS 95, Statement of

Cash Flows which required companies to issue a statement of cash flows as opposed to a

statement of changes in financial position, that the SEC announced any new regulation

6

concerning the SCF when the FASB encouraged companies to use the direct method rather than

the indirect method – but they did and still do not require it. As opposed to the large number of

guidelines available concerning earnings reporting, SFAS 95 only focuses on the classification of

cash expenditures between three categories of cash activities: operating, investing and financing.

This lack of guidance allows companies to use some discretion to classify items under these

three categories. Many firms have been using techniques which allowed them to improve their

cash flow situation. Some of the techniques used to inflate cash flow were: stretching out

payables, financing of payables, securitizations of receivables, tax benefits from stock options,

and stock buybacks to offset dilution.

Over the last few years, many of the companies that restated their SCF did so because of

a misclassification of cash flows in their SCF. Many of them have used some of the techniques

mentioned above in order to improve their cash flows from operations. Some examples of the

companies that have used these techniques are General Motors which announced that it would

restate financial results from 2000 to 2005 for GMAC, the automaker’s financial arm.

Apparently, GMAC classified cash flow from certain mortgage loan transactions as CFO instead

of CFF. Loews and its affiliate CAN Financial Corp also announced a restatement due to

misclassification of cash flows. This was actually the companies’ third restatement in one year.

Some cash flow items from operating activities were wrongly classified as investing (“net

purchases and sales of trading securities, changes in net receivables and payables from unsettled

investment purchases and sales related to trading securities”). Another example of CFR is

International Rectifier. The company announced that it would be restating its results for the first

two quarters of 2006 due to a cash flow misclassification of an excess tax benefit resulting from

the exercise of stock options. The company stated that it had presented it as CFO so as a result of

7

the restatement; CFO will decrease while CFI will increase. Linkwell Corporation is another

example in which one of the company’s subsidiary, Shanghai Likang Disinfectant company

bought a building from an affiliate company, Shangai Likang Pharmaceuticals Technology.

Shangai Likang Disinfectant had previously leased some manufacturing space from Shanghai

Likang Pharmaceuticals for about $11,500 per year. Likang Disinfectant paid the $333,675

purchase price for the building by reducing Linkang Pharmaceuticals accounts receivables.

Appendix A provides an example with Lone Star Technologies Inc. (LST). Its SCF restated

period began on January 1, 2003 and ended on December 31, 2004. The CFR disclosure

announcement date is March 6, 2006. LST reported no concurrent earnings restatement with

their cash flow restatement.

With the large amount of restatements occurring, the SEC had no choice but to address

the topic. We investigate the determinants of firms that issue cash flow restatements from three

different aspects. First, we analyze the determinants of firms that issue a cash flow restatement

compared to a control group of Compustat firms. There is very limited prior literature on what

exactly causes a firm to report a cash flow restatement. Second, given that a firm reports a cash

flow restatement, we examine firm characteristics of firms that overstated operating cash flows

instead of understating operating cash flows. Since operating cash flows are often viewed as an

alternative performance benchmark incremental to earnings, managers have incentives to

overstate operating cash flows. If earnings are significantly greater than CFO, investors often

assume that managers are using upward earnings management. This was a major motivation for

many companies, who were eventually caught, to shift financing inflows to the operating section

and to shift operating outflows to investing section. On the other hand, if a firm faces high

political costs, similar to downward earnings management, firms could have incentives to

8

understate operating cash flows. Third, we compare firms that reported an overall change in total

cash flows versus reporting no change in total cash flows in the cash flow restatement. This latter

is important because if the restatement was caused by a simple misclassification among the three

categories in the cash flow statement, we would not expect ex ante a change in total cash flows

reported. A change in total cash flows could be indicative of an unintentional error and/or an

intentional irregularity. Since firms do not usually report the exact cause of the cash flow

restatement and it is difficult to ascertain whether a restatement is due to an error or an

irregularity, this is an important step in understanding the underlying nature of the cash flow

restatement.

2.2 Related Literature on cash flows

Currently, there is limited guidance from prior research regarding cash flow restatements

and little to no research related to the determinants of and market reactions to cash flow

restatements. While we attempt to incorporate prior literature into this study, our study may be

viewed as exploratory in nature and is an early attempt in examining the determinants of cash

flow restatements. Prior research has shown that cash flow is thought to be a fundamental

performance measure for firm valuation (Penman 2001), most research has focused on earnings

(Bowen et al. 1987; Ali 1994; Dechow 1994; Barth et al. 2001, etc.). Nonetheless, examining the

value of reported cash flows is potentially interesting because cash flows are usually viewed as

an attribute of value relevance (FASB 1978; Barth et al. 2001). That is, while prior research on

cash flows generally finds that earnings are superior to cash flows in explaining stock returns,

evidence also suggests that cash flows are incrementally useful in valuing securities (Bowen et

al. 1987; Ali 1994; Dechow 1994). Therefore, this study also focuses on the association between

cash flow restatements and market returns. Within the accounting profession, and among

9

regulators, the debate about the proper format of cash flow statements may have contributed to

classification errors. When finalizing the reporting requirements for cash flow statements, the

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) included interest-related cash flows in the

operating section. In contrast, the AICPA suggested reporting interest payments as a non-

operating cash flow item. Prior research suggests that the format of cash flow statements may be

important to regulators, auditors, and other users of financial statements (Klammer and Reed,

1990; Bahnson et al., 1996; Drtina and Largay, 1985).

The inconsistencies arising when firms report their cash flows in accordance with SFAS

No. 95 have been the focus of several studies. For example, Nurnberg (1993) identifies several

ambiguities within cash flow statements, while Nurnberg and Largay (1996) identify differences

in classifying similar cash flows that may be difficult to resolve. They also provide evidence that

disclosing the nature and reasons for classification policies may enhance cash flow statement

comparability and utility. Some studies have examined the economic implications of cash flow

statement components or items (e.g., Barth et al., 2001; Cheng and Hollie, 2008; Luo, 2008).

Another series of studies (Mulford and Martins (2004, 2005a, 2005b) closely examines

individual cash flow reporting practices at several publicly-traded companies. Mulford and

Martins outline the cash flow problems associated with customer-related notes receivable (e.g.,

dealer-floor plan financing), sales-type lease receivables, and franchise receivables. They

document several companies that classify changes in these types of receivables as investing cash

flows, and argue for their reclassification as operating cash flows. Mulford and Martin’s studies

pre-date the SEC’s actions related to cash flow reclassifications and have been credited with

assisting the SEC in focusing on the issues outlined in Hollie et al., (2011), as well as this study.

10

Chuck Mulford, director of the Financial Analysis Lab at Georgia Tech, led a charge in

2004 and 2005 to get companies to pay more attention to how they classify cash flows, which

prompted the SEC, in 2006, to allow firms to correct their misclassifications in their next

filingperiod without having to formally restate the SCF. Hollie, et al. (2011) investigates the

statement of cash flow reclassifications during this period. To our knowledge, Hollie et al.,

(2011) is the first study to examine statement of cash flows classification and restatements (i.e.,

reclassifications) concurrently. They examine a unique setting in which the SEC allowed

management to avoid penalty for reclassifying its cash flows during a specified period. They also

examine the reclassifications resulting from the SEC’s increased scrutiny of cash flow reporting

during the allowance period. To assess the impact of these reclassifications, they determine the

types of firms affected by this allowance and the types of reclassifications in the operating,

investing, and financing categories of the cash flow statement. They find that, consistent with the

SEC’s concerns, firms were overstating net operating cash flows and understating net investing

cash flows, thereby misrepresenting cash flows. The most frequent line-item reclassifications

were consistent with the SEC’s concerns about the presentation of discontinued operations and

dealer floor plan financing arrangements. Insurance claim proceeds and beneficial interests in

securitized loans appeared to be less problematic than the SEC expected. Overall, their findings

indicate that the SEC’s plan was relatively successful and, for firms that took advantage of the

allowance period, these cash flow restatements had a marginal negative effect on the capital

market.

Lee (2011) examines when firms inflate reported CFO in the original SCF and the

mechanisms through which firms manage CFO. She finds that, even after controlling for the

level of earnings, firms upward manage reported CFO when the incentives to do so are

11

particularly high. Specifically, she finds firms manage CFO by shifting items between the CFO

categories both within and outside the boundaries of GAAP, and by timing certain transactions

such as delaying payments to suppliers or accelerating collections from customers. This study

differs from Lee (2011) and contributes to the literature in various ways. First, this study focuses

on both overstated and understated restatements of cash flows. Second, we distinguish between

firms with “pure” classification shifting (which refers to firms that do not have changes to TCF

after restatement) and firms with classification shifting that result in changes to TCF. If the

restatement is purely a function of misclassification (whether intentional or not), we would

expect TCF to remain the same. Third, we assess the markets response to the disclosure of these

CFRs.

3 Research methodology

3.1 Determinants of Cash Flow Restatements

We investigate the determinants of firms that issue cash flow restatements from three

different aspects. First, we analyze the determinants of firms that issue a cash flow restatement

compared to a control group of Compustat firms. There is very limited prior literature on what

exactly causes a firm to report a cash flow restatement. Second, given that a firm reports a CFR,

we examine the firm characteristics of firms that overstated operating cash flows instead of

understating operating cash flows. Since operating cash flows are often viewed as an alternative

performance benchmark incremental to earnings, managers have incentives to overstate

operating cash flows. If earnings are significantly greater than CFO, investors often assume that

managers are using upward earnings management. This was a major motivation for many

companies, who were eventually caught, to shift financing inflows to the operating section and to

shift operating outflows to investing section. On the other hand, if a firm faces high political

12

costs, similar to downward earnings management, firms could have incentives to understate

operating cash flows. Third, we compare firms that reported an overall change in total cash flows

versus reporting no change in total cash flows in the cash flow restatement. This latter is

important because if the restatement was caused by a simple misclassification among the three

categories in the cash flow statement, we would not expect ex ante a change in total cash flows

reported. A change in total cash flows could be indicative of an unintentional error and/or an

intentional irregularity. Since firms do not usually report the exact cause of the cash flow

restatement and it is difficult to ascertain whether a restatement is due to an error or an

irregularity, this is an important step in understanding the underlying nature of the cash flow

restatement. Absent a theoretical model to guide the selection of potential variables which are

associated with the likelihood of cash flow statement restatements, we use variables referenced

in the literature on earnings restatements and cash flows.

Debt

SFAS-95 requires firms to classify uncapitalized interest payments as operating outflows

and capitalized interest payments as investing outflows for both non-financial and financial

companies (FASB, SFAS No. 95). This requirement has led to increased complexity for firms in

choosing how to classify interest payments as it pertains to bonded debt, debt issuance costs, and

capitalized interest (Nurnberg 2006). For example, classifying uncapitalized interest payments as

operating outflows and principal payments as financing outflows leads to at least 4 different

methods of reporting cash flows relating to bonded debt issued at a discount or premium.

Furthermore, classifying capitalized interest payments as investing outflows leads to at least 3

alternative methods of reporting cash flows relating to capitalized and uncapitalized amounts.

Nurnberg (2006) also states that some companies provide cash flow statements “based on largely

13

arbitrary classifications of cash flows that their own spokesmen claim are largely meaningless”.

In addition, Hollie et al. (2011) find that firms with cash flow restatements have a greater debt

ratio than overall Compustat firms with no cash flow restatement. Based on the difficulties in

classifying uncapitalized and capitalized interest payments on the statement of cash flows, we

expect firms with a larger amount of debt to be more likely to issue a cash flow restatement.

Since firms have some degree of flexibility under SFAS-95 in classifying interest payments and

managers have certain incentives to inflate operating cash flows (Lee 2012), we expect firms

with a larger amount of debt to be more likely to overstate CFO, as opposed to understate CFO,

when they issue a cash flow restatement. If the restatement is due to a misclassification of

interest payments instead of unintentional errors, we expect the total change in cash flows to be

unchanged.

Number of Segments

The number of segments is a well-established proxy for firm complexity (e.g., Bhushan

1989; Berger and Ofek 1995; Comment and Jarrell 1995; Servaes 1996; Dunn and Nathan 1998).

As firms engage in more complex transactions and have more diverse operations, we expect the

complexity of the firm to be a driver of restatements. Many companies such as Enron,

Worldcom, and Symbol Technologies used their increased complexity and large number of

segments to disguise shifting of financing cash inflows to operating section of the cash flow

statement and shifting of normal operating cash flow outflows to the investing section (Schilit

and Perler 2010). Since complex firms sometimes use their flexibility in classifying certain

operating, investing, and financing activities with the objective of inflating operating cash flows

(Lee 2012), we expect firms with more segments to be more likely to overstate CFO, as opposed

14

to understate CFO, when they issue a cash flow restatement. If the restatement is due to a

shifting among the three categories on the cash flow statement instead of unintentional errors, we

expect the total change in cash flows to be unchanged.

Discontinued Operations

Levine (2005) refers to the misclassifications that occur when firms lump operating,

investing, and financing cash flows from discontinued operations into a single line item—often

included in the operating section of the cash flow statement—thereby distorting the firm’s cash

flows. SFAS No. 95 and SFAS No. 144 contributed to the misunderstanding by presenting

different interpretations of requirements and different options for reporting cash flows from

discontinued operations. For example, SFAS No. 144 (Accounting for Impairment or Disposal of

Long-Lived Assets) provides “broad criteria” for what should be classified as discontinued

operations, while SFAS No. 95 provides more specific criteria in its application of cash flows

(Whitehouse, 2006). Some companies use discontinued operations in an opportunistic manner to

inflate CFO. For example, in 2006, Tenet Healthcare structured the sale of hospitals and medical

centers but sold everything except for the accounts receivable. Tenet then was able to lower the

sales price by $10 million. When the company collected from its former customers, it reported

the $10 million as an operating inflow instead of an investing inflow, since it was related to the

collection of the receivables (Tenet Healthcare 10-Q, 3/2004). Due to multiple interpretations in

the accounting standards for presenting discontinued operations, we expect a firm to be more

likely to issue a cash flow restatement when it reports discontinued operations. Since it is

possible for firms to inflate operating cash flows, either as a result of ambiguities in SFAS-95 or

managerial opportunism, we expect firms with discontinued operations to be more likely to

15

overstate CFO, as opposed to understate CFO, when they issue a cash flow restatement. If the

restatement is due to a shifting among the three categories on the cash flow statement instead of

unintentional errors, we expect the total change in cash flows to be unchanged.

The alert notes, although not a requirement of SFAS No. 95, that cash flow from

discontinued operations be disclosed separately, companies choosing to disclose them separately

must do so in conformity with SFAS No. 95 and they must be consistent for all periods. Levine

also reiterated the SEC’s preference for the direct method which provides clearer and more

understandable information to investors. Although the indirect method is the most commonly

used by corporations, Levine pointed out that in many cases, when applying this method,

companies start their cash flow statements with income from continuing operations instead of

starting with net income as per SFAS No. 95 guidelines.

The good news for corporations is that the SEC gave them a brief window to rectify their

cash flow classification errors. Firms had to make the necessary corrections in order to comply

with SFAS No. 95 during their next filling period after February 15, 2006 otherwise, they would

have to restate at a later time. This grace period was a great opportunity for companies to avoid

restatement and it reduced the number of companies having to restate their statement of cash

flows. SFAS No. 95 allows companies to choose to report cash flow from continuing and

discontinued operations together or treat them separately. However, companies must remain

consistent in their choice from one period to the other. Unfortunately, many corporations have

not been consistent and have combined them in one period and separated them in another.

Additionally, in many cases, companies are not following the three categories format required by

SFAS No. 95. They often put together all the cash flow from discontinued operations into a

single line item making it difficult to identify which of the three sections (primarily CFO) was

16

affected. The misclassification is somewhat of a presentation issue, which probably explains why

the SEC gave companies a chance to make the adjustment without dubbing it a restatement,

notes L. Charles Evans, a partner with Grant Thornton, LLP”. Some other requirements of this

alert stipulate that companies taking advantage of this opportunity must provide “enhanced

disclosures”. The modified columns in the cash flow statements must be labeled either “revised”

or “restated”, and they cannot use “reclassified”. The information also needs to be disclosed in

the footnotes. According to Professor Mulford from Georgia Tech University, “the increased

scrutiny on this issue is long overdue and that companies had become complaisant in classifying

cash flow from discontinued operations.” In April 2006, the AICPA published another alert

aiming at clarifying things concerning the changes that companies need to make to comply with

SFAS No. This alert focuses on companies with fiscal years which do not follow the calendar

year-end. It provides guidelines on how they can still take advantage of the grace period offered

by the SEC. Since the SEC announcement, companies seem to be more carefully applying the

new guidelines.

In May 2006, Mitcham Industries, Inc announced that it filed its 10K with restated cash

flow statements for the fiscal years ended January, 2004 and 2005 and the first three quarters of

2006. The company stated that the changes in the 10K consist of: (1) eliminating discontinued

operations as a single line item and reflecting cash flows from discontinued operations within

each category of operating, investing and financing activities; (2) reclassifying cash receipts

from the sale of lease pool equipment from operating activities to investing activities and

reflecting the “Gross profit from sale of lease equipment” as deduction in operating activities”;

and (3) reclassified certain of its investments in certificates of deposit from cash and cash

equivalents to short-term investments. More and more companies have followed Mitcham

17

Industries, which shows how eager companies were to comply with the new guidelines if it

allowed them to avoid the stigma of a restatement.

CFO-Earnings Quality

Nwaeze et al. (2006) find that CFO becomes an important component in setting CEO

cash compensation when the quality of earnings relative to the quality of CFO as a measure of

performance is low. This is due to the stewardship information beyond earnings that is in CFO

when the precision of earnings is low. Therefore, we predict that when earnings quality is low

relative to CFO quality, managers will have greater incentives to overstate CFO in order to boost

the cash component of the CEO’s compensation. Likewise, we expect that firms are more likely

to issue a cash flow restatement when the earnings quality is low relative to CFO quality. If

managers are inflating CFO by shifting from either the investing or financing category instead of

unintentional errors, then we expect total cash flows to remain the same.

Book-Tax Differences

Mills (1998) finds that firms with large book-tax differences are more likely to be audited

by the IRS and have larger proposed audit adjustments. If firms have large book-tax differences

and recognize that it is likely they will draw IRS scrutiny, they could be more likely to understate

CFO in order to de-emphasize the significance of the amount of cash that is attributable to their

daily operations. Therefore, we expect firms with larger book-tax differences to understate CFO,

as opposed to overstate CFO, when they report a restatement. However, since there is no clear

association based on prior research between book-tax differences and cash flow restatements, we

do not make a prediction on the likelihood of restatement given a firm’s book-tax difference. If

18

managers are deflating CFO by shifting from either the investing or financing category instead of

unintentional errors, then we expect total cash flows to remain the same.

Agency Conflicts

Jensen (1986) shows that conflicts of interests between shareholders and managers are

significantly greater when there are increased free cash flows being generated in the company. In

addition, Dey (2008) finds that firms with greater levels of free cash flows have higher agency

conflicts. Therefore, we proxy for agency conflicts with a firm’s level of free cash flows. We

expect that a firm with more agency conflicts will provide managers with more opportunity to

inflate CFO since managers have varying incentives to report higher CFO (Lee 2012). Likewise,

we expect a firm with more agency conflicts to be more likely to issue a cash flow restatement. If

managers are inflating CFO by shifting from either the investing or financing category instead of

unintentional errors, then we expect total cash flows to remain the same.

Total Accruals

A firm with a greater level of accruals will, by definition, have earnings that are higher

than the firm’s CFO, holding CFO constant. When there is a wide gap between earnings and

CFO, and earnings are significantly greater than CFO, this is often a “red flag” of potential

earnings management (Wild et al. 2004). If firms are using earnings management and desire to

narrow the gap between earnings and CFO, we expect these firms to be more likely to issue a

cash flow overstatement, versus an understatement, when restating their cash flows. In addition,

we expect firms with higher total accruals to be more likely to issue a cash flow restatement due

to their desire of appeasing investors’ concerns of possible earnings management.

19

Dividends

Beginning in 2003, when the FASB issued SFAS 150, Accounting for Certain Financial

Instruments with Characteristics of both Liabilities and Equity, there was some classification

issues with respect to dividends (Nurnberg 2006). Under SFAS 150, mandatorily-redeemable

preferred stock is reported as a liability in the balance sheet. Previously, companies were

required to report these securities in the mezzanine section between liabilities and stockholders’

equity. However, SFAS 150 changes the cash flow statement classification of dividend payments

on these securities. Mulford and Comiskey (2005) show that since these securities are now

classified as a liability, the dividends payments are now classified as interest payments, and must

be reported as an operating outflow under SFAS 95. Under SFAS 150, the dividend payments

were classified as a financing outflow. Therefore, we expect that, to the extent that firms issue

mandatorily-redeemable preferred stock, a firm that issues dividend payments will be more

likely to have a cash flow restatement, especially after 2003. If indeed firms use the classification

of dividends as a method to report higher CFO, we expect firms to be more likely to overstate

CFO, as opposed to understate CFO, when they issue a cash flow restatement. If the restatement

is primarily due to the shifting of dividend payments between the financing and operating

sections on the cash flow statement instead of unintentional errors, we expect the total change in

cash flows to be unchanged.

Cash Flow Forecasts

Analysts’ cash flow forecasts are important for investors of firms where

accounting, operating, and financing characteristics suggest that cash flows are useful in

20

interpreting earnings and assisting in forecasting the firm’s future performance (Defond and

Hung 2003). Furthermore, Lee (2012) shows that firms with cash flow restatements are more

likely have at least one analyst cash flow forecast during the fiscal year. Therefore, we expect

that firms to be more likely to have a cash flow restatement when they have an analyst cash flow

forecast. If the market rewards firms that meet or beat analyst cash flow forecasts, as Brown et

al. (2010) show, we expect that firms with cash flow forecasts will be more likely to have a cash

flow restatement. In addition, firms will be more likely to overstate CFO, versus understate CFO,

when they have a restatement. If the restatement is caused by shifting among the three categories

of the cash flow statement or unintentional errors will determine whether total change in cash

flows will be unchanged.

Auditor Type

The size of the audit firm is often used as reference to the audit quality. Prior research has

shown that bigger audit firms have better financial resources and research facilities, superior

technology, more talented employees to undertake large company audits than smaller audit firms

and are more likely to be sued (Lys and Watts, 1994; Deis Jr and Giroux, 1992; and Lennox,

1999). Therefore, we expect that firms with a Big N auditor would be more likely to understate

CFO which would be consistent with more conservative reporting.

Political Sensitivity

If managers are using downward earnings management it is likely that CFO will be

greater than operating income. Therefore, despite the direction of earnings management,

managers want to close the gap between earnings and CFO because investors are scrutinizing

21

this gap on the basis that cash is “king” (Wild et al. 2004). Prior literature has found evidence of

downward earnings management when applying the political cost hypothesis (Watts &

Zimmerman, 1986) to larger firms and recent extreme performance (defined by abnormally high

earnings or large losses). We use S&P 500 firms and loss firms as proxies for politically

sensitive and highly visible firms which would have greater political costs on average (Saito

2012). Therefore, we expect S&P 500 firms to be more likely to understate CFO in order to

disguise abnormally high earnings and we expect loss firms to overstate CFO to hide abnormally

low earnings. Even though we acknowledge that the latter is not consistent with managers’ desire

to close the gap between earnings and CFO, this only applies to a special case: loss firms.

Hollie et al. (2011) find that during an SEC restatement allowance period, cash flow

restatement firms tend to have lower operating cash flow and return on assets. Therefore, we

predict that loss firms are more likely to issue a restatement than non-loss firms. Since there is no

clear association based on prior research between firm size and cash flow restatements, we do

not make a prediction on the likelihood of restatement given a firm belongs to the S&P 500

Index. Depending on whether managers are inflating or deflating CFO by shifting among the

three categories of the cash flow restatement versus unintentional errors would determine

whether total cash flows remain the same or not.

3.1.1 Additional Cash Flow Restatement Determinant Variables

Total cash flows differ between restated and originally reported amounts

3

In each of our restatements, CFO is either overstated or understated while total cash

flows remain the same after the restatement. However, in some instances the restated total cash

3

We define total cash flows as the sum of cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities.

22

flows differ from the originally reported total cash flows amount regardless of the CFO

classification shift upward or downward. We suspect that when cash flow totals do not remain

the same the company is less suspect of opportunistic shifting because changing total cash flows

is probably more indicative of underlying errors in the reporting of cash flows. We are more

suspicious of a company that engages in classification shifting among the statement of cash

flows categories and total cash flows remain the same after the restatement. This suggests that

the company may have known what they were doing ex ante and it was not merely a

misclassification error. If this is so, then we would expect this variable to be insignificant in

determining an over/understatement of CFO.

Logistic Regression Models

This study employs three logistic regression models to investigate the determinants of

firms that issue cash flow restatements. The first logistic model tests the determinants of firms

that issue a cash flow restatement compared to a control group of Compustat firms.

RESTATER

it

= β

0

+ β

1

DEBT

it

+ β

2

NSEG

it

+ β

3

DO

it

+ β

4

|∆E/∆CFO|

it

+β

5

BTD

it

+ β

6

FCF

it

+

β

7

ACC

it

+ β

8

DIV

it

+ β

9

GROWTH

it

+ β

10

LOSS

it

+ β

11

CFF

it

+ β

12

BIGN

it

+

β

13

SP500

it

+ ε

it

(1)

The second logistic model tests the determinants for a firm that overstated operating cash

flows versus understated operating cash flows, given the firm reported a cash flow restatement.

A firm that overstated operating cash flows reported a higher amount of CFO on the restated

cash flow statement compared to the firm’s original cash flow statement.

23

CFO OVER

it

= β

0

+ β

1

DEBT

it

+ β

2

NSEG

it

+ β

3

DO

it

+ β

4

|∆E/∆CFO|

it

+β

5

BTD

it

+ β

6

FCF

it

+

β

7

ACC

it

+ β

8

DIV

it

+ β

9

GROWTH

it

+ β

10

LOSS

it

+ β

11

CFF

it

+ ε

it

(2)

The third logistic model tests the determinants of the total change in cash flows reported

in the cash flow restatement. The total change in cash flow is determined by summing the

restated operating, investing, and financing amounts less the original operating, investing, and

financing amounts. The dependent variable is a dummy variable indicating whether or not there

is a difference in the total change in cash flows.

TCF_Differ

it

= β

0

+ β

1

DEBT

it

+ β

2

NSEG

it

+ β

3

DO

it

+ β

4

|∆E/∆CFO|

it

+β

5

BTD

it

+ β

6

FCF

it

+

β

7

ACC

it

+ β

8

DIV

it

+ β

9

GROWTH

it

+ β

10

LOSS

it

+ β

11

CFF

it

+ ε

it

(3)

where,

RESTATER is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm has a cash flow restatement and zero

otherwise. CFO OVER is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm’s restated CFO is greater than

its originally reported CFO. TCF_Differ is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm’s restated

total cash flows differs from the originally reported total cash flows. The variables we use to

determine these three dependent variables and control firms are as follows: (1) Debt/Assets

(DEBT) is estimated as short-term plus long-term debt (item #9 and item#34); (2) The number of

segments (NSEG) is from the Compustat Segment file and is a surrogate for operating

complexity; (3) DO is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm reports discontinued operations,

zero otherwise (item #66); (4) |∆E/∆CFO| is the ratio of the absolute value of earnings change to

CFO change (item #18 and item #308); (5) BTD, temporary book-tax difference, is the sum of

24

federal and foreign deferred tax expense (item #269 and item #270, respectively), and where

missing we use total deferred taxes (item #50), grossed up by the statutory tax rate during the

sample period (35 percent). BTD is a dummy variable equal to one if there is a BTD and zero

otherwise; (6) FCF is free cash flow and is equal to CFO minus capital expenditures (item #308

and item #128; (7) ACC, total accruals, is equal to income before extraordinary items minus

CFO (item #18 and item #308); (8) DIV is a dummy variable equal to one if the firm paid

common dividends, zero otherwise (item #21); (9) GROWTH is the market to book ratio [(item

#199 * item #25)/item #60]; (10) LOSS is a dummy variable obtaining one if earnings for the

quarter are negative and zero otherwise; (11) CFF is a dummy variable equal to one if an analyst

issues a cash flow forecast during the fiscal year and zero otherwise. (12) BIGN is an indicator

variable equals to one if the firm is audited by a big auditor (currently the Big 4); (13) SP500 is a

dummy variable equal to one if the firm is listed in the S&P 500 Index.

In the model, we exclude the variables OCF_RESTATE, ICF_RESTATE, and

FCF_RESTATE. These variables generally cause the complete and quasi-complete separation in

the logistic model. OCF_RESTATE is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm restates operating

cash flows and zero otherwise; ICF_RESTATE is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm

restates investing cash flows and zero otherwise; and FCF_RESTATE is a dummy variable equal

to one if a firm restates financing cash flows and zero otherwise.

3.2 Market Reactions to Cash Flow Restatements

We assess the market’s reactions to SCR reclassification announcements. We examine the

various windows centered on the CFR announcement, allowing for any early news leakage that

may occur on day -1 and any news delay that may occur as a result of a restatement

25

announcement after the close of trading on day 0.

4

We use a market-adjusted returns model

based on a value-weighted market index to estimate abnormal returns. The model subtracts the

CRSP market index return from a company’s daily return to obtain the market-adjusted abnormal

return (AR) for each day and company. The daily abnormal returns are summed to calculate the

cumulative abnormal return (CAR) for a given time period. We further test whether the total

market reactions to the total cash flow restatement for vary based on changes.

4 Summary statistics and empirical findings

4.1 Sample Selection

We identify firms that restated cash flows in the Audit Analytics, Inc., database. We

define a statement of cash flows restatement consistent with that of Audit Analytics (AA) where

we obtain the data for this study. AA restatement data set covers all SEC registrants who have

disclosed a financial statement restatement in electronic filings since 1 January 2001. Annual and

amended filings are analyzed by queuing for analysis those filings which contain any of the

words “restate”, “restatement” or “restated.” Corresponding cash flow restatement information is

extrapolated either from 10-K wizard, SEC filings available in the SEC’s online EDGAR

database, or from a copy of the annual report on the company’s website. The initial study

population comprises 329 unique firms. After removing observations with missing data and

keeping only 10-K restatements, our remaining sample consists of 42 firms each of which

disclosed at least one reclassified cash flow statement between 2000 and 2006. If a firm

disclosed restatements for multiple years, we record each year restated. This resulted in 82

4

We lost six firms from the sample because of market data unavailability. We also searched for prior disclosures of

a cash flow restatement announcement to ensure that we were using the first known disclosure date for our analysis.

26

observations for the 42 firms in our sample. We use all other firms covered in Compustat in the

same period as our control group, which consists of 26,939 firm year observations. Thus, the

total sample size of our study is 27,021 firm year observations ranging between 2000 and 2006.

4.2 Descriptive statistics

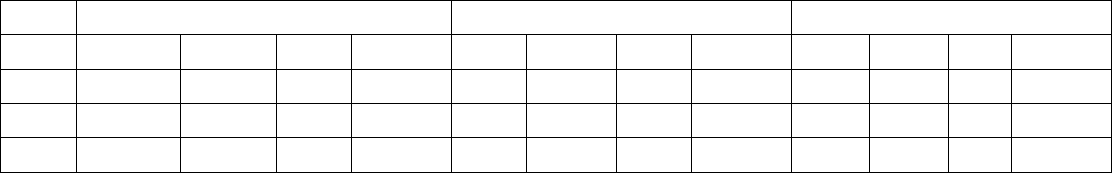

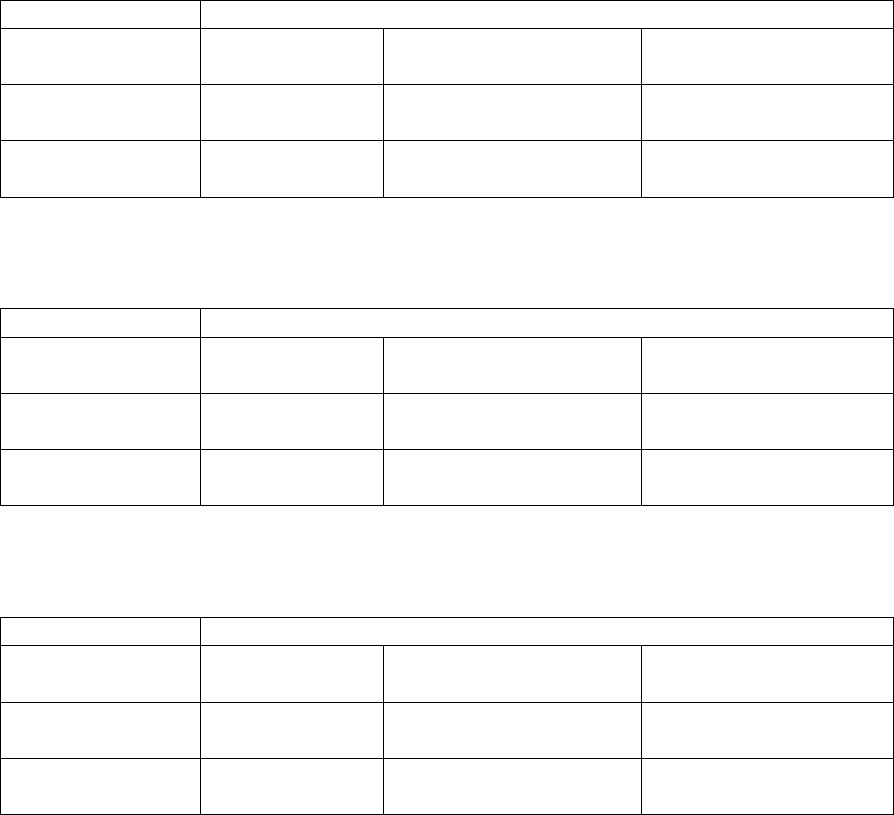

Table 1 presents the summary statistics and comparisons between CFR firms and control

firms samples. The _RESTATE variables by design identify firms that restated its operating,

investing, or financing cash flows, which applies to all sample firms. Each company may have

more than one activity category reclassification. While some firms clearly listed individual cash

flow line-items that had been reclassified, others provided aggregated amounts within activity

categories types. Panel A of Table 1 shows that approximately 94% of the firms with

restatements to the statement of cash flow restated its cash flows from operating activities.

Approximately 85% of the restating firms restated cash flows from investing. And approximately

46% of the restating firms restated cash flows from financing. Generally firms were restating

operating cash flows downward, while restating investing and financing cash flows upwards.

This finding is consistent with those found in Hollie et al. (2011). In some cases, firms only

restate their total cash flows without making reference to whether the cash flow restatement was

related to the operating, investing, or financing activities of the firm.

Panel C of Table 1 shows that sample firms have significantly more number of segments,

more discontinued operations, more book-tax differences, higher free cash flow, more dividends

paid, more cash flow forecasts, are audited more often by a Big N auditor, and are more often

S&P 500 firms. On the contrary, control firms have greater losses than the sample firms. Most of

these preliminary results are consistent with our predictions. Specifically, firms are more likely

to have a cash flow restatement if they are more complex, have more flexibility in determining

27

discontinued operations, attract higher levels of IRS scrutiny, have more agency conflicts, are

subject to ambiguity in the standards surrounding dividends paid, and are subject to meeting

analysts’ cash flow forecasts.

{Insert Table 1 about here}

4.3 Pearson Correlations

Table 2, Panel A, presents the Pearson correlations for the firms which had a cash flow

restatement. The Pearson correlation between CFO_OVER and BTD is positive and significant

(0.254, p-value = 0.026). The Pearson between CFO_OVER and Big N is positive and

significant (0.356, p-value = 0.002). The Pearson between CFO_OVER and DIV is negative and

significant (-0.218, p-value = 0.057). The majority of the correlations among the independent

variables are statistically significant but their magnitudes are not large. This suggests that

multicollinearity should not be of concern. To verify, we run untabulated tests of

multicollinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and show that multicollinearity does

not pose a problem since all VIFs are below 3 (significantly less than 10 which indicates a

multicollinearity generally).

4.4 Determinants for Statement of Cash Flows Restatements

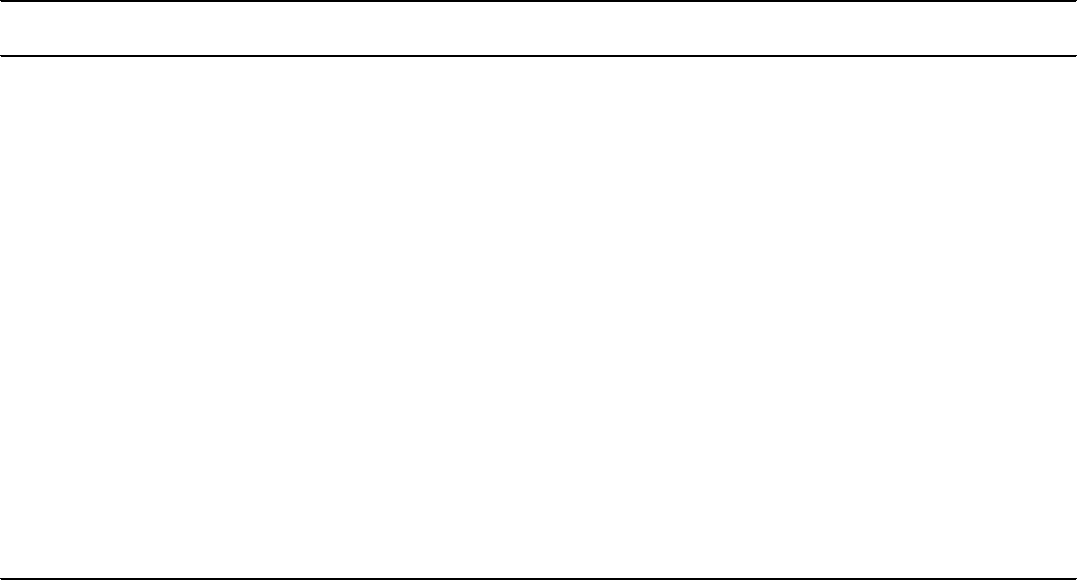

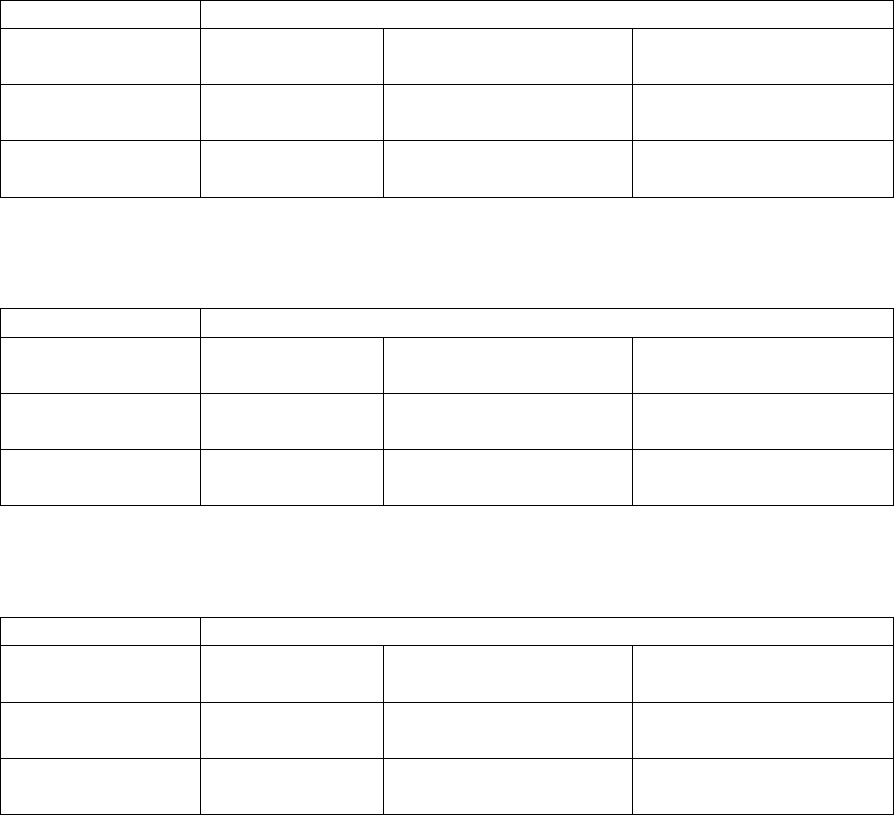

Table 3 provides the results of the logistic regression analysis for firms with cash flow

restatements, where the dependent variable is one for statement of cash flows restaters and zero

for control firms. We find that firms are more likely to have a cash flow restatement when have

higher levels of debt, more number of segments, discontinued operations, and are audited by a

Big N auditor. The positive association between the likelihood of cash flow restatements and

debt is consistent with the difficulties firms have faced in classifying uncapitalized and

28

capitalized interest payments on the statement of cash flows as documented by Nurnberg (2006).

The positive association between the likelihood of cash flow restatements and the number of

segments is consistent with more complex firms using their flexibility in classifying certain

operating, investing, and financing activities with the objective of inflating operating cash flows.

It is also consistent with these firms having more difficulty in making the correct classifications

due to having numerous segments which is compounded by the ambiguities inherent in SFAS95.

The positive association between the likelihood of cash flow restatements and the existence of

discontinued operations is consistent with having difficulties with multiple interpretations in the

accounting standards for presenting discontinued operations. Lastly, the positive association

between the likelihood of cash flow restatements and having a Big N auditor is not consistent

with our expectations since having a Big N auditor would imply higher audit quality and

lessrestatements.

{Insert Table 3 about here}

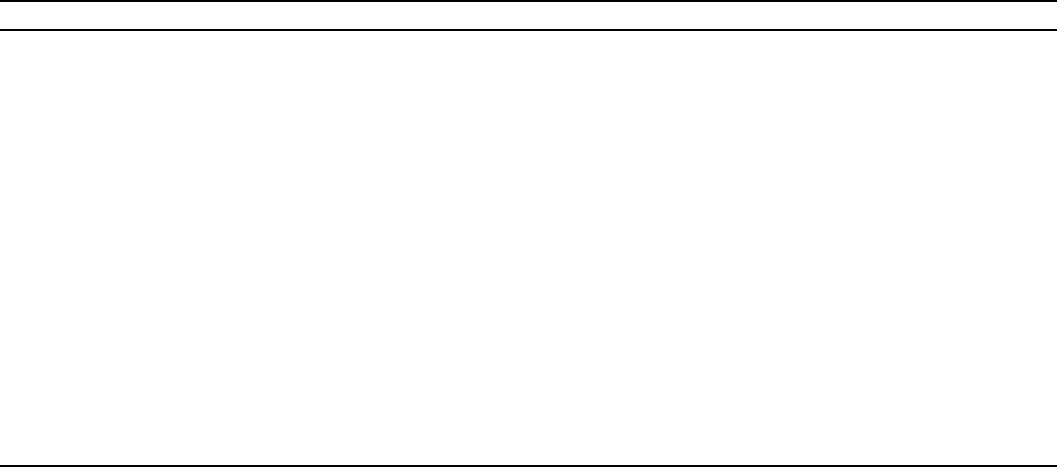

Table 4 provides the results of the logistic regression analysis for firms with cash flow

overstatements as compared to cash flow understatement. We find that firms when firms issue a

cash flow restatement, firms are more likely to have a cash flow overstatement when they have a

book-tax difference and analysts’ issue a cash flow forecast. On the other hand, when firms issue

a cash flow restatement, firms are less likely to have a cash flow overstatement, when they issue

dividends. The positive association between cash flow overstatements and book-tax differences

is not consistent with our expectations. However, the positive association between cash flow

overstatements and cash flow forecasts is consistent with our expectations following Lee (2012).

Firms are more likely to attempt to inflate their operating cash flows when analysts issue cash

flow forecasts.

29

{Insert Table 4 about here}

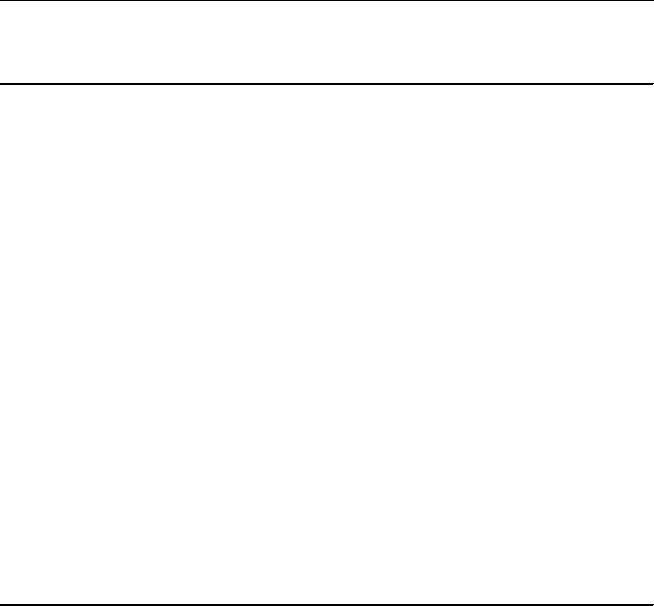

Table 5 provides the results of the logistic regression analysis for firms with total cash

flow changes compared to firms that restate cash flows and have no change in total cash flows.

We find that firms are more likely to have a change in total cash flows when they have a book-

tax difference. On the contrary, firms are less likely to have a change in total cash flows when

they experience a loss. If the change in total cash flows is indicative of an unintentional error

instead of intentional classification shifting, it is possible that this means that firms have cash

flow restatements due to unintentional errors when they have a book-tax difference or experience

a loss. As mentioned earlier, because firms do not disclose the details of the misclassification or

whether it is an error or an irregularity, it is difficult to interpret these findings as evidence of

errors in cash flow misclassification. Nevertheless, we show that the change in total cash flows at

the time of restatement is partially driven by firms that have book-tax differences and losses.

4.5 Market reactions to cash flow restatements

Table 6 shows the abnormal return (AR

t

) and its statistical significance for each day of

the return window (t = -1, 0 and +1, +2), along with the cumulative abnormal return for the entire

three-day window (CAR

-1,+1

). We are currently finalizing the analysis as it relates to the market

reactions to cash flow restatements. We are sure that this analysis will be completed by the

workshop date.

{Insert Table 6 about here}

4.6 Additional analysis & sensitivity analysis to be completed

30

We plan to examine whether any firms have upward restatements to cash flows from

operations. The general inclination is to see downward revisions, however like earnings

restatements, we may find certain situations were upward restatements occur within our sample

period. We will also examine the number of restating firms that employ the direct versus indirect

methods for cash flow statement reporting.

We plan perform sensitivity analysis by deleting all Restaters with more than one

restatement. We will then repeat our main tests separately for cash flow restatements in the

fourth quarter, when an audit is required, and all other quarterly cash flow restatements as one

group. For example, we will look at partial year restatements separately from annual audited full

year restatements. Next, all Restaters’ public announcements between the cash flow statement

disclosure and the subsequent SEC filing dates will be examined to determine if the firm issued a

press release that announced the upcoming cash flow restaement in the SEC filing. We then

examine the robustness of our results to whether revisions are to core or non-core cash flows. We

expect when the restatements are to core items that the reduction in market reactions to the total

cash flow surprise of Restaters as compared to non-Restaters is more pronounced than for non-

core items. These additional tests are sure to give us more insight into the occurrence of

statement of cash flows restatements.

5 Summary and conclusions

To be summarized and concluded when the last of the analysis is completed very soon.

31

Appendix A

Example of a Statement of Cash Flows Restatement

LONE STAR TECHNOLOGIES INC

Original Report

Restatements

Changes

Year

OP

INV

FIN

OP

INV

FIN

OP

INV

FIN

2003

-40.6

-48

0.5

29.5

-39.2

6.4

-32.2

32.2

0

2004

61.7

-71.4

6.4

-8.4

-80.2

0.5

32.2

-32.2

0

Total

21.1

-119.4

6.9

21.1

-119.4

6.9

0

0

0

Note: The variables defined are as follows: OP – cash flows from operating activities, INV –

cash flows from investing activities, and FIN – cash flows from financing activities.

32

References

Abarbanell, J., and V. Bernard. 1992. Test of Analysts' Overreaction/Underreaction to Earnings

Information as an Explanation for Anomalous Stock Price Behavior. Journal of Finance 47:1181-

1207.

Bernard. 1992. Test of Analysts' Overreaction/Underreaction to Earnings Information as an

Explanation for Anomalous Stock Price Behavior. Journal of Finance 47:1181-1207.

AICPA. 2006. Center for Public Company Audit Firms Alert No. 90, SEC staff position

regarding changes to the statement of cash flows relating to discontinued operations.

AICPA. 2006. Center for Public Company Audit Firms Alert No. 98, Update to SEC staff

position regarding changes to the statement of cash flows relating to discontinued operations.

Bahnson, P., P. Miller and B. Budge. 1996. Nonarticulation in cash flow statements and

implications for education, research, and practice. Accounting Horizon 10: 1-15.

Barth, M., D. Cram and K. Nelson. 2001. Accruals and the prediction of future cash flows. The

Accounting Review 76: 27-58.

Berger, P., and E. Ofek. 1995. Diversification‘s effect on firm value. Journal of Financial

Economics 37: 39–65.

Brown, L., A. S. Pinello, and K. Huang. 2010. To Beat or Not to Beat? the Importance of

Analysts’ Cash Flow Forecasts. Working paper, Georgia State University.

Bhushan, R. 1989. Firm characteristics and analyst following. Journal of Accounting and

Economics 11 (July): 255-274.

Cheng, C.S.A. and D. Hollie. 2008. Do core and non-core cash flows from operations persist

differentially in predicting future cash flows? Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting

31: 29-53.

Cheng, C. S. A., Liu, C. S., and T. Schaefer, 1996. Earnings Permanence and the Incremental

Information Content of Cash Flows from Operations. Journal of Accounting Research 34:173-

181.

DeFond, M., and M. Hung. 2003. An empirical analysis of analysts’ cash flow forecasts. Journal

of Accounting and Economics 35 (1): 73–100.

Deis Jr, Donald R & Giroux, Gary A. “Determinant of Audit Quality in the Public

Sector.” The Accounting Review Vol 67, No. 3. (1992).

Dey, A. 2008. Corporate governance and agency conflicts. Journal of Accounting Research

46:1143-1181.

33

Drtina, R. andLargay III. 1985. Pitfalls in calculating cash flow from operations. The Accounting

Review 60: 314-326.

Dunn, K., and S. Nathan. 1998. The effect of industry diversification on consensus and

individual analysts‘ earnings forecasts. Working Paper, CUNY – Baruch College, NY.

FASB. 1978. Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1: Objectives of Financial

Reporting by Business Enterprises. Stamford, Conn.: FASB.

FASB. 1987. Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 95, Statement of Cash Flows,

Stamford, CT.

FASB. 2001. Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 144, Accounting for Impairment or

Disposal of Long-Lived Assets, Stamford, CT.

FASB. 2003. Statement No. 150, Accounting for Certain Financial Instruments with

Characteristics of both Liabilities and Equity. Norwalk Conn.

Hollie, D., C. Nicholls, Q. Zhao. 2011. Effects of cash flow statement reclassifications pursuant

to the SEC’s one-time allowance. Journal of Accounting & Public Policy 30: 570-588.

Jensen, M. “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance and Takeovers.” American

Economic Review 76 (1986): 323–9.

Klammer, T. P., and S. Reed. 1990. Operating cash flow formats: Does format influence

decisions? Journal of Accounting, and Public Policy 9: 217-235.

Lee, Lian. 2012. Incentives to inflate reported cash from operations using classification and

timing. The Accounting Review 87: 1-33.

Leone, M. 2006. Act Now, and Avoid a Restatement. CFO.com, March 20, 2006.

Lennox, Clive S. “Audit Quaility and Auditor Size: An Evaluation of Reputation and

Deep Pockets Hypothesis.” Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 26.

(1999).

Levine, J. 2005.Speech by SEC staff: Remarks before the 2005 thirty-third AICPA National

Conference on Current SEC and PCAOB Developments. Securities Exchange Commission

www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch120605jl.htm

Luo, M. 2008. Unusual operating cash flows and stock returns. Journal of Accounting, and

Public Policy. 27: 420-429.

Mills, L., 1998. Book-tax differences and Internal Revenue Service adjustments. Journal of

Accounting Research 36 (2), 343–356.

34

Mulford, C.W., and Comiskey, E., 2005. Creative Cash Flow Reporting: Uncovering

Sustainable Financial Performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Mulford, C.W. and Martins, M. 2004. Cash-flow reporting practices for customer-related notes

receivable. Georgia Tech Financial Analysis Lab.

Mulford, C.W. and Martins, M. 2005a. Cash-flow reporting practices for customer-related notes

receivable:an update. Georgia Tech Financial Analysis Lab.

Mulford, C.W. and Martins, M. 2005b. Customer-related notes receivable and reclassified cash

flow provided by operating activities. Georgia Tech Financial Analysis Lab.

Nurnberg, H. 1983. Issues in funds statement presentation. The Accounting Review 58: 799-812.

Nurnberg, H. and J. Largay 1996. More concerns over cash flow reporting under FASB

statement no. Accounting Horizons. 10: 123-136.

Nurnberg, H. 2006. Perspectives on the Cash Flow Statement under FASB Statement No. 95.

Columbia Business School: Center for excellence in accounting and security analysis

(Occasional paper series). New York, NY: Columbia Business School.

Nwaeze, T., S. Yang, and Q. Yin. 2006. Accounting information and CEO compensation: The

role of cash flow from operations in the presence of earnings. Contemporary Accounting

Research 23 (1): 227–265.

Palmrose, Z, Richardson, V. J., and S. Scholz. 2004. Determinants of Market Reactions to

Restatement Announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics. 37: 59-89.

Previts, G. J., R. J. Bricker, T. R. Robinson, and S. J. Young. 1994. A content analysis of sell-

side financial analysts company reports. Accounting Horizons 8 _2_: 55–70.

Romero, S. and A. Berenson. 2002. WorldCom says it hid expenses, inflating cash flow $3.8

billion. The New York Times, June 26, 2002.

Roychowdhury, S. 2006. Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of

Accounting and Economics. 42: 335-370.

Saito, Y., 2011. The demand for accounting information: young NASDAQ listings versus

S&P 500 NYSE listings. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting. 38: 149-175.

Schilit, H. and J. Perler. 2010. Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks and

Fraud in Financial Reports. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Servaes, H. 1996. The value of diversification during the conglomerate merger wave. Journal of

Finance 51: 1201-1225.

35

Wayman, Rick. 2010. Operating cash flow: better than net income?

http://www.investopedia.com/articles/analyst/03/122203.asp

Whitehouse, T. 2006. SEC Gives More Guidance On Cash Flow Corrections. Compliance Week,

March 21, 2006.

Watts, R. and J. Zimmerman. 1986. Positive Accounting Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-

Hall.

Wild, J., K. R. Subramanyam, and R. Hasley. 2004. Financial Statement Analysis. New York,

NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

36

Panel A: Descriptive Statistics for Sample Firms

Variable N Mean Std Dev 25th Pctl 50th Pctl 75th Pctl Minimum Maximum

OCF RESTATE 82 0.939 0.241 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

ICF RESTATE 82 0.854 0.356 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

FCF RESTATE 82 0.463 0.502 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

CFO 77 0.364 0.484 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

TCF_Diffe r 82 0.756 0.432 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

DEBT 82 0.420 0.766 0.180 0.364 0.477 0.000 6.989

NSEG 82 2.720 1.597 1.000 2.500 4.000 1.000 7.000

DO 82 0.293 0.458 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

|∆E/∆CFO|

82 5.565 20.301 0.292 0.684 2.459 0.011 140.443

BTD 82 0.793 0.408 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

FCF 82 -0.029 0.173 -0.034 0.022 0.058 -0.638 0.362

ACC 82 -0.110 0.241 -0.122 -0.048 -0.015 -1.671 0.426

DIV 82 0.402 0.493 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

GROWTH 82 2.589 9.414 1.171 1.683 2.825 -37.266 56.731

LOSS 82 0.280 0.452 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

CFF 82 0.305 0.463 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

BIG N 82 0.817 0.389 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

SP500 82 0.146 0.356 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.000

Table 1

Summary Statistics on Variables for Sample and Control Firms

OCF_RESTATE is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm restates operating cash flows and zero otherwise; ICF_RESTATE is a

dummy variable equal to one if a firm restates investingcash flows and zero otherwise; and FCF_RESTATE is a dummy variable equal to

one if a firm restates financing cash flows and zero otherwise. CFO OVERSTATER is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm’s restated

CFO is greater than its originally reported CFO. TCF_Differ is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm’s restated totalcash flows differs

from the originally reported total cash flows. DEBT is estimated as short-term plus long-term debt (item #9 and item#34). NSEG is the

number of segments from the Compustat Segment file. DO is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm reports discontinued operations,

zero otherwise (item #66). |∆E/∆CFO| is the ratio of the absolute value of earnings change to CFO change (item #18 and item #308). BTD,

temporary book-taxdifference, is the sum of federal and foreign deferred tax expense (item #269 and item #270, respectively), and where

missing we use total deferred taxes (item #50), grossed up by the statutory tax rate during the sample period (35 percent). BTD is a

dummy variable equal to one if there is a BTD and zero otherwise. FCF is free cash flow and is equal to CFO minus capital expenditures

(item #308 and item #128). ACC is equal to income before extraordinary items minus CFO (item #18 and item #308). DIV is a dummy

variable equal to one if the firm paid common dividends, zero otherwise (item #21). GROWTH is the market to book ratio [(item #199 *

item #25)/item #60]. LOSS is a dummy variable obtainingone if earnings for the quarter are negative and zero otherwise. CFF is a dummy

variable equal to one if an analyst issues a cash flow forecast during the fiscal year and zero otherwise. BIGN is an indicator variable

equals to one if the firm is audited by a Big 4 auditor. SP500 is a dummy variable equal to one if the firm is listed in the S&P 500 Index.

37

Panel B: Descriptive Statistics for Control Firms

Variable N Mean Std Dev 25th Pctl 50th Pctl 75th Pctl Min Max

CFO OVERSTATER 27052 1.000 0.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000

TCF_Diffe r 27052 1.000 0.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000

DEBT 27052 0.378 0.867 0.017 0.189 0.400 0.000 6.989

NSEG 27052 1.991 1.421 1.000 1.000 3.000 1.000 15.000

DO 27052 0.155 0.362 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.000

|∆E/∆CFO|

26939 5.560 17.952 0.356 1.026 2.917 0.011 140.443

BTD 27052 0.651 0.477 0.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

FCF 27052 -0.206 0.850 -0.119 0.010 0.069 -6.343 0.362

ACC 27052 -0.357 1.501 -0.146 -0.062 -0.017 -12.521 0.426

DIV 27052 0.263 0.440 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

GROWTH 27052 2.504 8.922 0.844 1.718 3.225 -37.266 56.731

LOSS 27052 0.398 0.490 0.000 0.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

CFF 27052 0.201 0.401 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.000

BIG N 27052 0.659 0.474 0.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000

SP500 27052 0.065 0.247 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.000

CFO OVERSTATER is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm’s restated CFO is greater than its originally reported CFO.

TCF_Differ is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm’s restated total cash flows differs from the originally reported total

cash flows. DEBT is estimated as short-term plus long-term debt (item #9 and item#34). NSEG is the number ofsegments

from the Compustat Segment file. DO is a dummy variable equal to one if a firm reports discontinued operations, zero

otherwise (item #66). |∆E/∆CFO| is the ratio of the absolute value of earnings change to CFO change (item #18 and item

#308). BTD, temporary book-taxdifference, is the sumoffederaland foreign deferred tax expense (item #269 and item #270,

respectively), and where missing we use total deferred taxes (item #50), grossed up by the statutory tax rate during the

sample period (35 percent). BTD is a dummy variable equal to one if there is a BTD and zero otherwise. FCF is free cash

flow and is equal to CFO minus capital expenditures (item #308 and item #128). ACC is equal to income before extraordinary

items minus CFO (item #18 and item #308). DIV is a dummy variable equal to one if the firm paid common dividends, zero

otherwise (item #21). GROWTH is the market to book ratio [(item #199 * item #25)/item #60]. LOSS is a dummy variable

obtaining one if earnings for the quarter are negative and zero otherwise. CFF is a dummy variable equal to one if an