FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF DALLAS

AN ECONOMIC INTERPRETATION

OF SUICIDE CYCLES IN JAPAN

Jahyeong Koo

and

W. Michael Cox

Research Department

Working Paper 0603

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF DALLAS

An Economic Interpretation of Suicide Cycles in Japan

Jahyeong Koo and W. Michael Cox

*

September 15, 2006

Abstract: Suicide rates in Japan have increased dramatically in recent years, making.

Japan’s male rate the highest among developed economies. This study revises the

standard economic model of suicide to accommodate Japan’s experience, focusing on the

change in human capital for the unemployed. We then use the new model and de-trended

data to empirically investigate the relationship between the suicide cycle and the

unemployment cycle. Unlike previous aggregate time series studies, we find that the

relationship between the suicide rate and the unemployment rate is significantly and

robustly positive for both males and females even after controlling for several social

variables.

Keywords: suicide, cycles, unemployment, Japan

JEL classification: I12; J60; E30

*

We thank Genevieve Solomon for excellent research assistant. We also thank two

anonymous referees and seminar participants at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas for

comments on an earlier draft that led to significant improvements in the paper. The views

in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily the views of the Federal Reserve

Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Koo: Economist, Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2200 N.

Pearl St. Dallas, TX 75201. Phone 1-214-922-5179, Fax 1-214-922-5194, E-mail address

Cox: Senior Vice President and Chief Economist, Research Department, Federal

Reserve Bank of Dallas, 2200 N. Pearl St. Dallas, TX 75201. Phone 1-214-922-5150, Fax

1-214-922-5194, E-mail address [email protected]

2

An Economic Interpretation of Suicide Cycles in Japan

I. Introduction

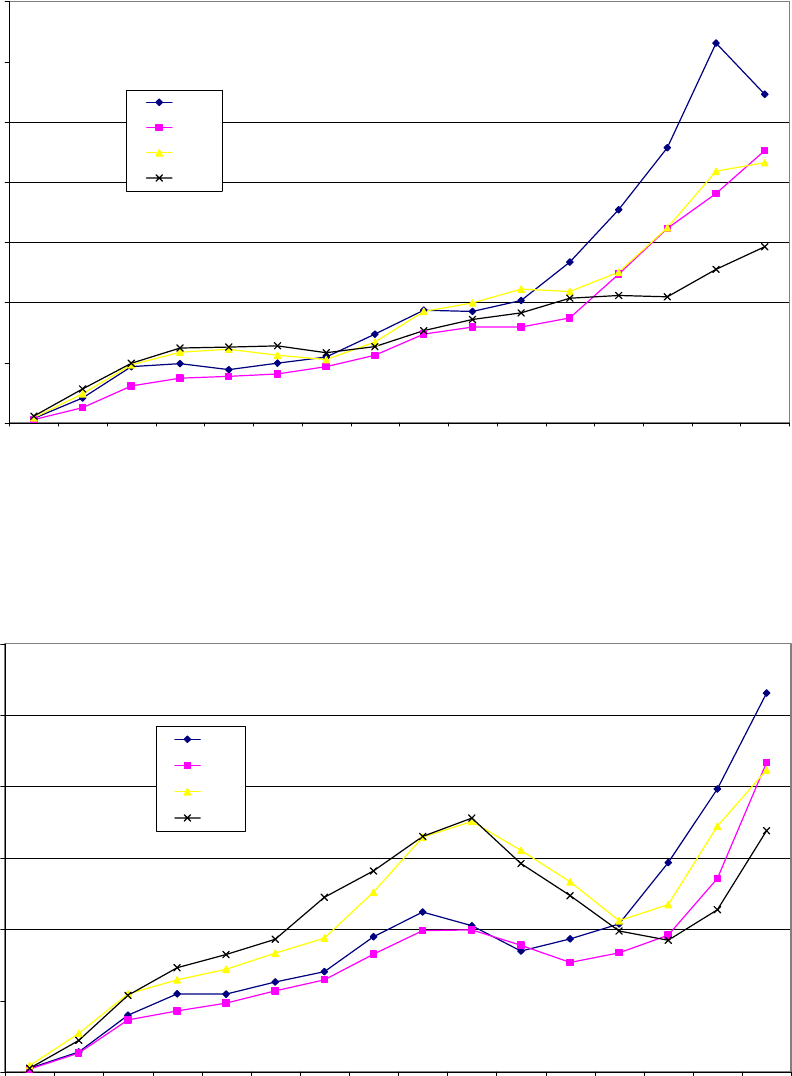

Since the early 1990s, Japan has experienced a tremendous increase in its suicide

rate, especially among middle-aged males. At the same time, most other industrialized

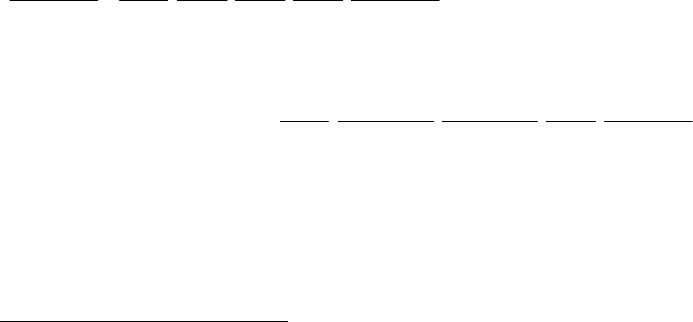

countries have seen suicide rates fall or increase only mildly [Figure 1]. Although Japan

has a culture that is more accepting of suicide than societies with Christian roots, the

recent surge in the suicide rate has drawn the attention of policy makers and economists.

The rate is unprecedented, and the suicide epidemic is probably related to the economic

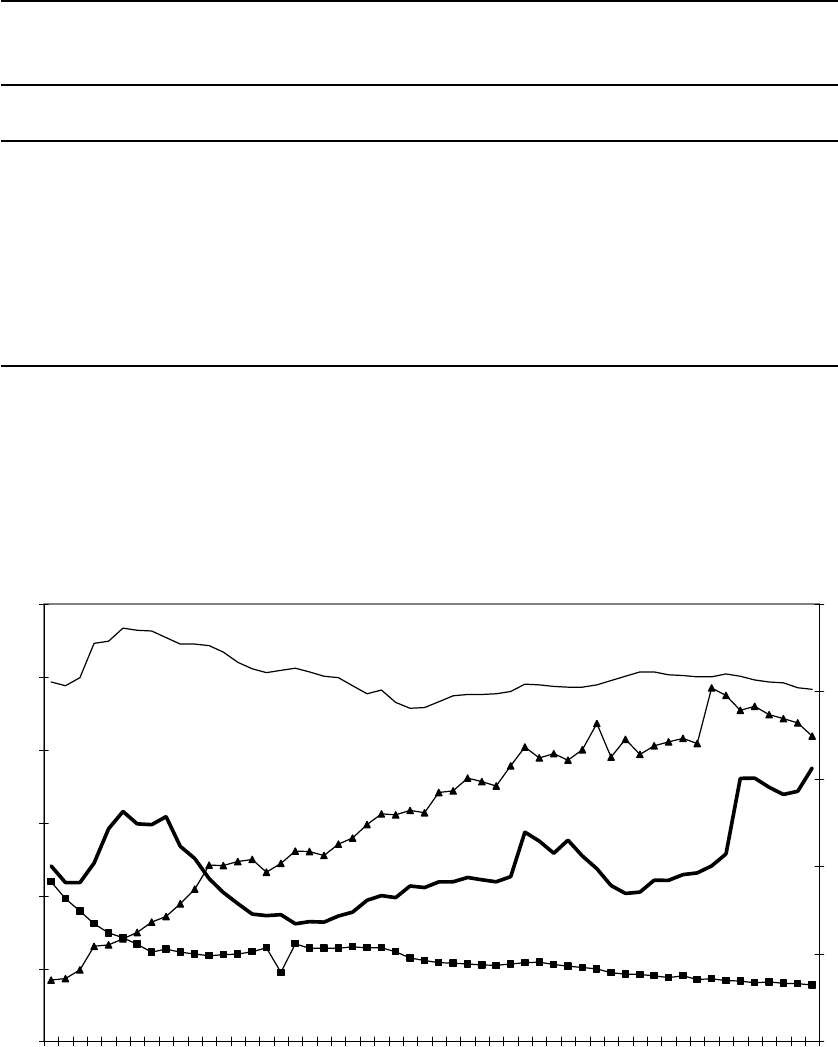

recession that the world’s second biggest economy has suffered [Figure 2].

The male suicide rate in Japan in 2003 was 37.5 deaths per 100,000 persons—

more than twice the U.S. rate of 17.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2002. Japan currently has the

highest suicide rate among developed nations. The male rate is only lower than the

suicide rates of the former Soviet Union and East European countries, which have

endured a long and difficult economic transition, and Sri Lanka, which has suffered a

long civil war. Japan’s male suicide rate almost doubled from 1990 to 2003, a time when

the country was in an economic recession. Japanese unemployment rates increased from

2.1 percent in 1990 to 5.3 percent in 2004. An unemployment rate of 5.3 percent may

look quite healthy from European and U.S. perspectives, but it represents significant

hardship in a country where the average unemployment rate for the last five decades has

been 2.3 percent.

In standard economic models, suicide is considered a decision that a rational,

optimizing agent makes when his expected remaining lifetime utility falls below a certain

2

threshold.

1

Suicide rates, therefore, should be higher when perceived lifetime incomes

decrease. Models that follow the rational choice approach predict that the old age cohorts

will have higher suicide rates, all other things being equal, as the costs of maintaining

health increase with age.

2

Empirical research, however, does not always support the theory. Most of the

work on suicide uses the unemployment rate as a measure of economic hardship and

lifetime earnings because measuring an agent’s perceived lifetime income is not easy in

practice. Empirical tests involving panel data show a strong correlation between

unemployment and suicide (see Platt, 1984; Ruhm, 2000; Gerdtham and Johannesson,

2003), but studies with aggregated time-series data produce mixed results on at least two

key points. First, the relationship between unemployment and suicide tends to be less

sensitive in empirical models that incorporate more social variables, such as age, religion

and divorce rates (Yang 1992, 1994). Second, aggregate time-series research often finds

gender differences in responding to economic hardship. Vigderhous and Fishman (1978),

Yang (1992), Brainerd (2001) and others report that female suicide does not respond at

all (or at best shows little sensitivity) to unemployment compared with male suicide in

the countries they examined.

A monotonically increasing relationship between age and suicide has been

documented since Durkheim (1897) for many countries. However, the relationships have

disappeared as youth suicide rates have surged and overall suicide rates have declined in

1

Hamermesh and Soss (1974) formulate an economic model of suicide that treats individuals as rational,

optimizing agents. Marcotte (2003) extended the Hamermesh and Soss framework to analyze nonfatal

suicide attempts. Cutler, Glaeser and Norberg (2000) and Mathur and Freeman (2002) examine theories of

youth suicide.

2

In the Hamermesh and Soss (1974) setup, the age-specific rates depend upon the distribution of distastes

for suicide and the distribution of permanent incomes.

3

developed countries, including the U.S. and U.K. In the U.S., the suicide rates of young

adults (ages 20-24) are equal to those for prime-age adults (Cutler et. al. 2000). In former

Soviet Union countries, the suicide rates of prime-age adults rose dramatically in the

1990s. This distribution of suicide rates by age follows an observed recent pattern of the

labor markets in former Soviet countries (Brainard 2001).

Revising the Hamermesh and Soss (1984) setup and using filtered time series data,

this article assesses how well an economic model can explain suicide cycles in Japan. An

individual’s economic and social conditions likely play an important role in suicidal

behavior, although we acknowledge the influence of many non-economic and non-

socioeconomic factors on the decision, such as physical and psychiatric illness.

In our revised model, we explain the cases where suicide is not a monotonically

increasing function of age. In Japan, the suicide rate of middle-aged males has surged

more than any other group. The model is also refined to incorporate the relationship

between the suicide rate and the divorce rate, the most frequently examined social

variable. We add the fertility rate, the female labor market participation rate, and alcohol

consumption to control for the role of social variables in estimating the relationship

between economic factors and suicide rate cycles in Japan.

II. Suicide in Japan: An overview

According to the standard model, suicide rates are positively correlated with

income and age. In Japan, however, this simple framework has not served well to explain

the rise in the country’s suicide rates. Suicide trends by sex and age have not followed the

standard theory’s predictions.

4

In Japan, as in most other countries, the female suicide rate is lower than the male

rate during the period we examine (1950 -2003). However, the male suicide rate shows a

distinctive upward trend, whereas the female rate has been declining (Figure 2). The

female suicide rate is not positively correlated with the unemployment rate. We suspect

that improving social conditions for women have led to the downward sloping trend of

the female suicide rate, thus any regression analysis which does not control for the trend

of woman’s status might end up with a negative or insignificant relationship between

female suicide and unemployment

3

. Furthermore, running a regression that invloves non-

stationary variables with trends can result in a complicated econometric problem of

spurious regression.

If we focus on the cyclical components of the time series, even a casual look

reveals a positive correlation between the unemployment rate and both the male and

female suicide rates. During our sample period, Japan experienced three peaks of suicide

rates which correspond to aggregate economic conditions. The first peak was during the

mid-1950s, the second was after the second oil crisis and the third was the result of the

economic recession of the 1990s. The cyclical components of the suicide rate in Japan

were high when the unemployment rate cycles were high.

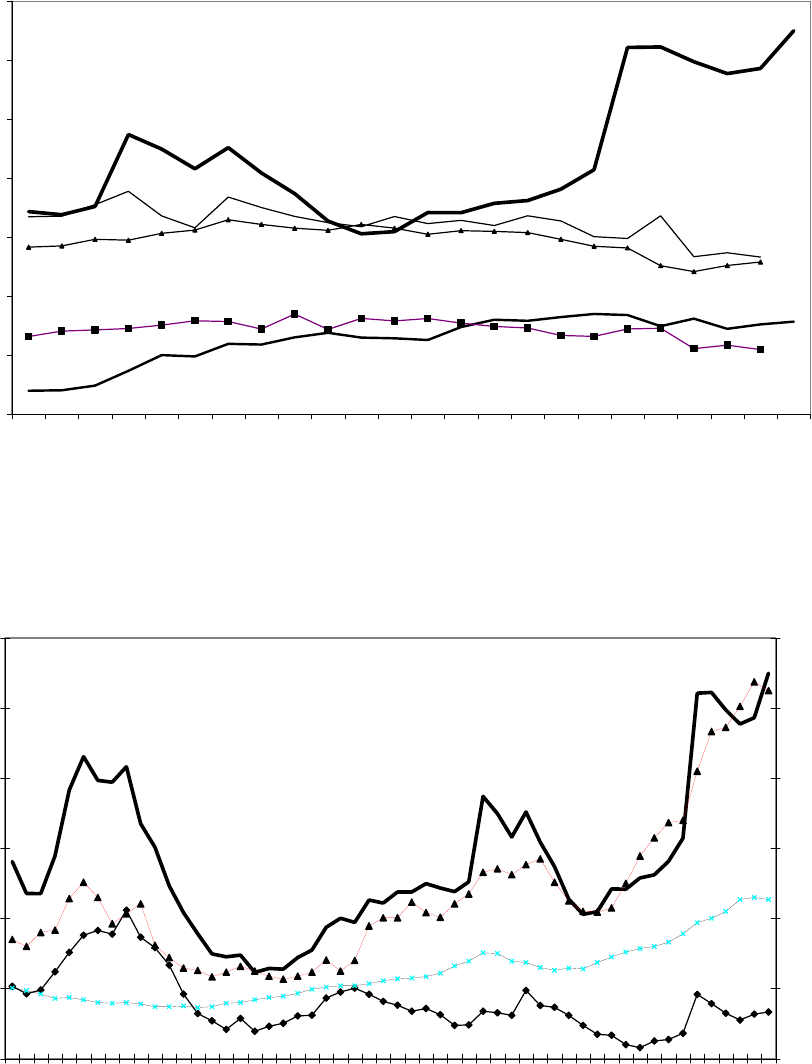

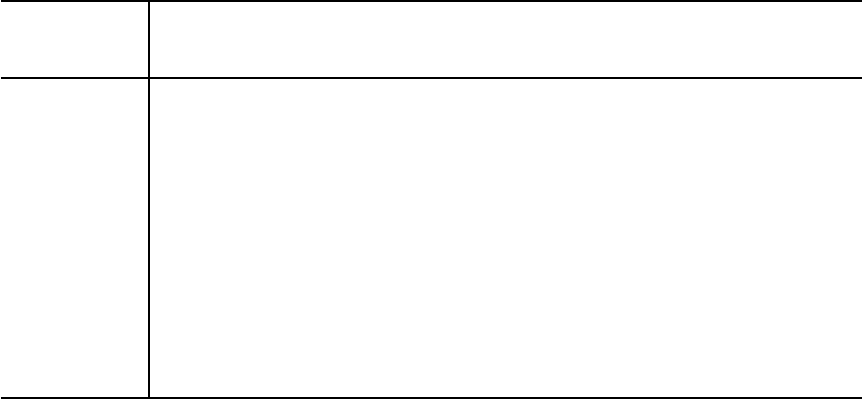

As the standard model predicts, female suicide rates in Japan increase with age.

The patterns do not change when we compare the statistics of 1988, 1993, 1998, and

2003 (Figure 3). Male suicide rates show a significant hump shape for the middle-aged

group between age 45 and 60 during the years 1998 and 2003. This pattern is not found in

3

Durkheim (1897) described women’s suicide in the 19

th

century as a byproduct of ‘excessive regulation’

that manifests itself in the form of women’s their subordinate social status. In China today, the female

suicide rate in the rural area is three times that in the cities. The relatively lower social status of women in

rural area is considered to be a major cause of higher rural female suicide rates (Lee and Kleinman 2000)

.

5

other developed economies and is not clearly predicted by standard suicide models. We

conjecture that changes in the labor market in Japan, including the devaluation of human

capital to older unemployed workers and small business owners, is related to the high

suicide rate of the middle age group.

III. An Economic model of suicide

To accommodate the patterns of Japanese suicide cycles and the distribution of

suicide among age groups, we refine the standard suicide model first laid out by

Hammermesh and Soss (1974) and assess how well our economic model explains the

patterns of Japanese suicide cycles and the distribution of suicide among age groups.

Our revised model follows the framework of the standard model by assuming that

individuals decide to commit suicide if the expected lifetime utility falls below a certain

threshold. The utility function for an individual in the standard model is defined as,

U

m

= U [C (m, Y) – K(m)] (1)

where m is the individual’s age, Y is income that could be devoted to consumption C, K

is the cost of maintaining health in each year (presumably K´ > 0). Then the discounted

present value of an individual’s lifetime utility at age α is:

Z(α , Y) =

e

ω

α

∫

-r(m-α)

U

m

P(m) dm (2)

where r is the discount rate, ω is maximum life expectancy, P(m) is the probability of

living to age m at given age α. An individual chooses suicide when the discounted utility,

Z(α , Y), falls below some critical threshold. Since Z is a decreasing function of α (due to

the increasing cost of maintaining health with age) and an increasing function of Y, the

model predicts that suicide propensity rises with age and falls with income.

6

By modeling the valuation of the discounted benefits and costs of living, this

framework captures the essential element of an individual’s decision to commit suicide.

But with this formulation we cannot explain important aspects of the time series of

Japanese suicide.

First, despite the prolonged recession, per capita real GDP continued to grow in

Japan at an average rate of 1.1 percent a year during the 1990s, and labor’s share of

output peaked in the same period.

4

The observations are contradictory to the model,

because while male suicide rose, average income continued to rise and the income

distribution flattened during the 1990s.

Second, the simple model cannot account for the high suicide rate of middle-aged

males shown in Figure 3B. Lacking any explicit treatment of the link between

unemployment and lifetime income, the simple model fails to explain why the expected

utility of middle-aged males drops so precipitously in the face of worsening economic

conditions.

Third, some changes in social variables, such as the divorce rate, can be partly

explained by rising unemployment. By including social variables, we can test whether

their relationships to suicide are a simple reflection of the change of economic conditions.

To accommodate these aspects of suicidal behavior in Japan, we revise the standard

model. We also extend the setup to account for the indirect impact of unemployment on

suicide through the divorce rate, which is the most frequently mentioned social variable

in the literature.

4

According to Miyanaga (2002), labor’s share in Japan averaged 80.2 percent in 1990s—the highest

among any 10-year window from 1955 to 2000. Labor’s share during the whole sample period averages

76.8 percent.

7

In our revised model, relative income is measured as the distance to the social

mean income at time t. So the suicide rate is not a monotonically decreasing function of

the aggregate income level in time series analysis. It corresponds to the observation that

suicide rates have not necessarily been lower after the decades of rapid economic growth.

Relative income is an increasing function of human capital h, which is constant as long as

an individual is employed. It depreciates if he is unemployed, reflecting the fact that the

unemployed lose the opportunity to maintain human capital through on the job training.

During periods of economic transition driven by technological shocks or regime shifts,

the human capital of the unemployed depreciates faster. The diminished human capital

drives down the expected relative lifetime utility of unemployed individuals faster than

during a normal period.

The equation of discounted present value of an individual’s relative lifetime

utility at age α is;

RZ(α , RY(h)) =

∫

ω

α

e

-r(m-α)

RU [RC(m, RY(h)) – RK(m)] P(m) dm (3)

where RY is relative income which is an increasing function of human capital. RU, RC

and RK are relative counterparts of U, C, and K in equation (1). Human capital declines

when an individual is unemployed. So h

m

= h

m-1

when employed and h

m

= ß h

m-1

when

unemployed ( 0 < ß < 1 ). ß is smaller when the economy is under rapid technological

transformation or regime shift.

The revised model provides the same basic insights into the suicide behavior as

the standard one. It assumes that individuals are more likely to commit suicide when

expected relative lifetime utility falls below a certain level. The suicide rate is related to

income and age. However, the revised model has a novel feature of clearly showing how

8

high unemployment rates lower the expected relative lifetime utility and increase suicide

rates, as seem by

+ + + + −

Unemp

RZ

Δ

Δ

=

U

RZ

Δ

Δ

RC

U

Δ

Δ

RY

RC

Δ

Δ

h

RY

Δ

Δ

Unemp

h

Δ

Δ

< 0 . (4)

The unemployed come to have less human capital than individuals with jobs and

consequently have less relative lifetime utility. Hence, the propensity to commit suicide

will be positively related with the unemployment rate.

The model also can be used to show why the middle-aged group’s suicide rate has

been higher recently in Japan. During a period of economic transition, the technological

shocks quicken the depreciation of human capital for unemployed middle-aged

individuals, who tend to be slower than younger workers in adapting to new labor market

conditions. In a society like Japan, where labor markets are not flexible, the depreciation

of human capital is faster for those age groups that cannot easily find the same quality

jobs once they are unemployed.

5

However, ceteris paribus, the suicide rate increases with

age, just as it does in the standard model (2).

We further extend the model by including the divorce rate. Following Becker

(1974), we assume that marriage has mercenary value. A divorced individual has lower

relative utility and is more likely to commit suicide than a married one. According to the

literature, couples separate when the utility expected from remaining married falls below

5

The Japanese practice of lifetime employment is typically portrayed as providing job security to workers.

But because firms are not able to dismiss workers in response to a business downturn, companies are more

likely to have serious cost overruns and eventually go bankrupt, in which case it is very difficult for

workers to find another job at the same level. The paradoxical result is that workers may in fact wind up

with less security, not more as a result of the lifetime employment practice. It is worth noting that the

Japanese higher education system plays little role in retraining the jobless for alternative professions.

9

the utility expected from divorcing and possibly remarrying (Becker et. al. 1977). Weiss

and Willis (1997) show empirically that the expectation of earnings capacity formed at

the time of marriage does not influence divorce, but surprises concerning the partners’

earning capacity are important in explaining divorce. We consider the reduction of

human capital due to unemployment in Japan as a surprise in earning capacity that is

likely to end in divorce.

6

Then the enriched model becomes:

RZ(α , Y(h)) =

e

ω

α

∫

-r(m-α)

RU [RC(m, RY(h)) – k(m) – Divorce(RY(h))] P(m) dm (5)

where

Divorce is a dummy variable that is positive and constant when human capital h is

below a certain level and zero otherwise. All other things are equal, divorced individuals

have smaller relative utility and are more likely to commit suicide than married

individuals. In the enriched model, unemployment influences relative utility through two

channels. One channel is through low relative consumption RC and the other channel is

through high probability of divorce.

+ + + + −

Unemp

RZ

Δ

Δ

=

U

RZ

Δ

Δ

RC

U

Δ

Δ

RY

RC

Δ

Δ

h

RY

Δ

Δ

Unemp

h

Δ

Δ

+

+ − − + −

U

RZ

Δ

Δ

Divorce

U

Δ

Δ

RY

Divorce

Δ

Δ

h

RY

Δ

Δ

Unemp

h

Δ

Δ

< 0 (6)

If the divorce channel in the second part of equation (6) dominates the relative

consumption channel in the first part, then the relationship between suicide and

6

We assume that high unemployment rates are positively correlated with divorce rates. Weiss and Willis

(1997) show that an unexpected increase in the husband’s earning capacity reduces the divorce hazard,

while an unexpected increase in the wife’s earning capacity raises the divorce hazard so that two effects

work in opposite directions. However, men traditionally have been the major bread earner in a typical

Japanese family and thus we expect the former effect to dominate. We take evidence of the positive

relationship between divorce and suicide rates from Durkheim (1897).

10

unemployment rates will be weaker in the regression analysis that includes divorce rates

as an explanatory variable than in the simple regression with only unemployment rates

7

.

IV. Empirical methodology and Data

A. Empirical methodology

One notable empirical contribution of the extended model is the redefining of

variables in terms of distance from the social mean or trend. It is standard practice

following Lucas (1977) to define the business cycle in terms of deviations from trend.

This convention is preferred by modern macroeconomists and is the one most frequently

employed in empirical macroeconomic studies. Recognizing the importance of de-

trending as well as the lack of consensus about the optimal technique, we operationalize

the cyclical components by employing three different filters.

First, we use a random-walk filter based on first differences of the relevant

variables. Second, we use the well-known Hodrick-Prescott (1997) filter with a

smoothing parameter of 100. Finally, we use a Band-pass filter to produce the

components that correspond to cycles of duration 2-8 years.

Since the filtered series tend to be stationary (Baxter and King 1999), we avoid

the complicated econometric problems that arise when variables with different levels of

integration are included in the same equation. It is worth noting that the trends are

defined operationally, i.e. the measurement procedure defines the concept (Prescott 2006).

In our analysis, we do not rigorously investigate the factors that influence the diverging

trends in Japan’s male and female suicide rates.

7

Using the data of twelve developed nations, Yang (1994) shows that the estimated coefficient on the

unemployment rate is likely to be less significant when the divorce rate is added to the regression. The

analysis however does not separate male and female suicides.

11

B. Econometric models

We concentrate on the de-trended suicide rates and unemployment rates to estimate

their relationship as derived from the model (4). The regressions we estimate take the

form:

Suicide

t

= α + β Unemployment

t

+ε

t.

(7)

Suicide

t

denotes de-trended suicides per 100,000 persons. For example, Suicide

t

= 2

means 2 suicides per 100,000 persons above the trend. Unemployment

t

denotes the de-

trended unemployment rate multiplied by 100. ε

t.

represents the myriad influences on

suicide beyond the influence of economic hardship.

The unemployment-to-suicide channel shown in (6) is tested with the following

regressions.

Suicide

t

= α + β Unemployment

t

+ γ Divorce

t

+ ε

t.

(8)

Divorce

t

denotes de-trended divorces per 1,000 persons, so that Divorce

t

= 2 means 2

divorces per 1,000 persons above the trend. By comparing the regression results of (7)

and (8), we can determine whether the relationship between the divorce and suicide rates

is the mere reflection of economic factors, or whether the divorce rate contains

information about social anxiety not explained by the economic factors.

We extend our econometric model by adding three social variables that are

frequently examined in the suicide literature—the fertility rate, the female labor market

participation rate (FLP), and alcohol consumption.

8

Since the presence of children entails

8

Catholicism strongly disapproves of suicide, viewing it as sin, and this factor is sometimes examined as a

social variable. In Japan, Catholic believers represent only 0.34 percent of the total population and the ratio

has not changed since 1990 (Catholic Bishop’s Conference of Japan, 2005). In view of its size and stability,

we exclude these influences from our analysis as we focus on the cyclical fluctuation in aggregate suicide.

12

family and social ties, it increases social integration and may reduce the likelihood of

suicide. Fertility is, therefore, expected to be negatively related to suicide. Using panel

data, Neumayer (2003) reports a significantly negative relationship between suicide rates

and fertility rates in the U.S. states and Andrés (2006) reaches a similar conclusion for 15

European countries. However, to our knowledge no empirical research examines the

relationship with time series data.

Increased FLP can be associated with higher male suicide rates. Perhaps men feel

challenged in their role as head of the household and are less likely to be comforted by

female partners who also work outside the home (Stack, 1998). This is problematic for

men because they are more likely than women to rely solely on their spouses as their

confidant (McGrath et al., 1990). On the other hand, the association of FLP and female

suicide is not clear. Increased female participation in the labor force may strengthen

social ties with other workers and may help to reduce the female suicide rate. But women

are exposed to the stress of work life, and often face a double burden of outside

employment and unpaid housework. The net effect of a change in female labor

participation on male suicide depends on which of these two effects dominates. The

empirical results are mixed for both cross-sectional and panel data (Chuang and Huang

1997, Neumayer 2003 and Andrés 2005). Heavy alcohol consumption is also reported to

increase suicide rates in cross-sectional analysis (Markowitz et. al 2003, Andrés 2005 and

Brainerd 2001).

The extended econometric model including sociological variables is

Suicide

t

= α + β Unemployment

t

+ γ Divorce

t

+ δ SV

t

+ ε

t.

(9)

The majority of Japanese claim to be a believer of Shinto or Buddhism or both. However, as Shinto and

Buddhism do not have distinctive teachings on suicide and there are no reliable statistics available, we do

not examine the influence of religion in our analysis.

13

SV

t

denotes a vector of de-trended sociological variables, the elements of which are

fertility rates, FLP and alcohol consumption. We measure the fertility rate with average

births from a mother in her reproduction years (ages 15 − 49). FLP is measured by

(female labor force / female population 15 years old and over) x 100. Alcohol

consumption is measured by the net alcohol consumption per adult (age 15 and over).

A comparison of the estimated results of (7), (8) and (9) help us see how well the

enriched explains the suicide cycles in Japan.

C. Data

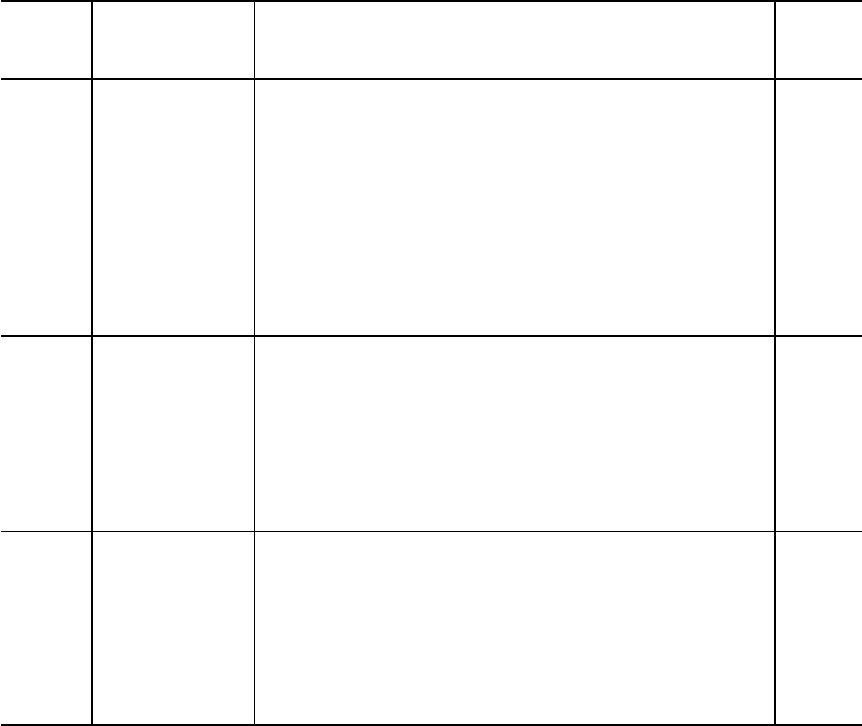

For this study, we use annual data from 1950 to 2003. Table 1 presents the

descriptive statistics of the variables in levels. To control for the influence of the

changing distribution of age groups on suicide rates, the age-adjusted suicide rates based

on the population of 1986 are used. Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare is the

primary source for statistics on suicide, unemployment and divorce. For unemployment

rates from 1950 to 1952, we use the estimates of the Statistical Information Institute for

Consulting and Analysis (www.sinfonica.or.jp

). Fertility rates and FLP come from the

Statistics Bureau of Japan. Alcohol consumption for 1961-2001 comes from World

Health Organization alcohol database (www.who.int). For 1950-1960 and 2002-2003, we

calculated alcohol consumption based on data from National Tax Agency of Japan.

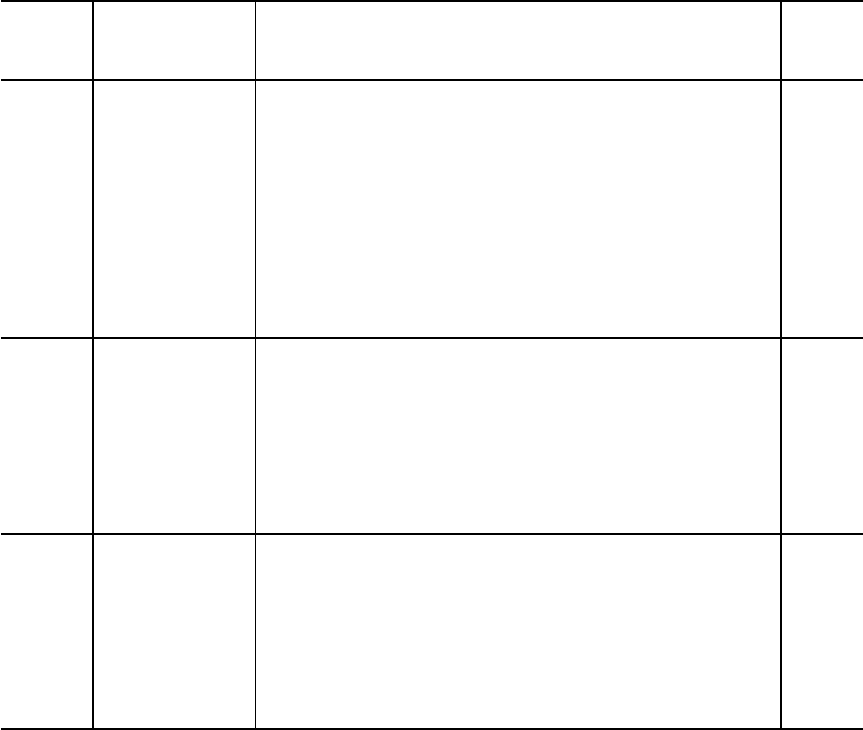

Figure 4 shows the time series of three social variables. The fertility rate is

highest in 1950 at 3.65 children per woman and it has declined since reaching its lowest

point of 1.29 in 2003. The fertility rate tends to decline partly because the opportunity

cost of raising children becomes higher with increased female education. The sharp

14

decline in Japan’s fertility in the 1950s reflects the bust following the post Second World

War baby boom.

In the US, FLP rates have increased with little variation around the trend, rising

from 32.5 percent in 1950 to 59.6 percent in 2003. By contrast, Japan’s FLP rates first

declined from 56.7 percent in 1955 to 45.8 percent in 1976, then increased to 50.7

percent in 1991 declining to 48.3 percent in 2003. The massive migration of farming

families to the cities and rapid economic growth after the Second World War resulted in

an increase of full-time housewives, and consequently lowered FLP in the first part of our

sample. The recession after 1991 lowered the rate, although it is generally considered to

be countercyclical.

Japan’s alcohol consumption per capita increased from 1.4 liters in 1950 to 6.9

liters in 1990, the peak of the bubble economy. Since then, it has fluctuated around the

1990 level. Alcohol seems to be a normal good—with demand increasing with income

before 1990 in Japan. During the 1990s, the fluctuation of alcohol consumption does not

show a noticeable correlation with the rising suicide rate.

Table 2 presents the correlations of the de-trended variables using the random

walk filter. We have to sacrifice the beginning and ending three periods when applying

the band pass filter owing to construction of the weighted moving average. The data are

relatively poorly estimated with the HP filter during the beginning and ending periods. To

have the same period for all of the filters, we report the results using the de-trended data

for the period 1953-2000 after eliminating the beginning and ending three years. The

correlation coefficients of the de-trended variables are not significantly influenced by the

de-trending method used.

15

The de-trended female suicide rate is positively correlated with the de-trended

unemployment rate (0.38) and divorce rate (0.17), even though the correlation

coefficients are smaller than those of the male suicide rate with the unemployment rate

(0.62) and divorce rate (0.52). The divorce rate is positively correlated with the

unemployment rate as our model predicts (0.46). Alcohol consumption does not have a

positive relationship with either male (-0.03) or female suicide rates (-0.02). The fertility

rate has a negative relationship with the male (-0.10) and female (-0.30) suicide rates as

sociology theories predict. FLP is slightly countercyclical (-0.06) and has a positive

relationship with the male (0.25) and female suicide rate (0.24).

V. Empirical Results

OLS estimates of equation (7) with the male suicide rate (the first four rows of

TABLE 3) indicate that the effect of the unemployment rate on the suicide rate is more

pronounced when we focus on the cyclical components of the two variables. Equations

with de-trended variables have larger coefficients for unemployment than equations with

level variables. The coefficient with the random-walk filter indicates that a 1 percentage

point increase in Japan’s unemployment rate will result in 57.6 more male suicides per

million people in Japan—an overall increase of 3,592. The estimate using the HP filter is

the largest. A 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate corresponds to 71.4

more male suicides per million people, an increase of 4,452.

Introducing de-trended variables causes sweeping changes in the estimates of the

female suicide rate. When the variables are not de-trended, the coefficient of

unemployment rate is negative and insignificant. With de-trended variables (the first four

16

rows TABLE 4), the coefficients of the unemployment rate are all positive and significant

at the 1 percent level. The female suicide rate in Japan, however, still responds less than

the male suicide rate to the unemployment rate.

9

Based on estimates with the random-

walk filter, a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate will result in 14 more

female suicides per million people, a total of 902 for the nation.

Taking the average of the three estimates, forecasted total suicides will increase

by 4,774 with a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate over the trend. The

country now has a population of 128 million.

Divorce rates are an important social variable that has more explanatory power

than unemployment rates in some research (Yang 1994). Our model assumes that

marriage has mercenary value and divorce leads to a lower relative income that might

precipitate suicidal behavior. Divorce in our model occurs when couples encounter

unexpected negative income shocks. If divorce were mainly driven by economic factors

and the reduction of utility from divorce were to dominate the reduction from low income

in deciding suicide, the inclusion of divorce should weaken the effect of unemployment

in estimates of (8) compared with (7). Instead, the addition of a filtered divorce rate does

not significantly alter the coefficient of Unemployment. The coefficient of

Unemployment for the male suicide rate declined about 20 percent compared with the

simple regression, but the estimates are still significant at the 1 percent level.

For the female suicide rate, the inclusion of Divorce does not alter the coefficient

of Unemployment. However, the impacts of Divorce on Suicide show distinctive gender

differences. The

Divorce coefficient is positive and significant for Male Suicide, but it is

9

Brainerd (2001) posits that women are more protected from macroeconomic instability in the societies

where women’s non-market work is valued more highly than men’s.

17

mixed and insignificant for Female suicide in the equations using the three different de-

trending methods. R

2

increases about 26 percent for the three filtered variables for the

male suicide rate, but R

2

does not change very much for the female suicide rate. These

findings parallel results for the former Soviet Union countries (Brainerd 2001) and for the

U.S. (Cutler et al, 2000). They also suggest that the mercenary value of marriage is larger

for males than females and factors other than economic hardship also matter

10

.

Including social variables does not alter the size and significance of the

coefficients of the unemployment and divorce rates for both male and female suicide. The

increases in R

2

are moderate − on average 0.053 for males and 0.076 for females. Fertility

is negatively correlated with the suicide rate for both males and females. The coefficient

is significant at the 1 percent level for two out of three de-trending methods regarding the

female suicide rate, but it is significant at the 10 percent level for only one de-trending

method regarding the male rate. The hypothesis that the presence of children, with

promotion of family and social ties, reduces the suicide rate is weakly supported, and the

relationship is more distinct for females than males.

FLP has a positive coefficient for both the male and female suicide rates. The

relationship of

FLP with suicide also shows a gender differential. The coefficient is

significant for all de-trending methods regarding males, but only one for females. The

findings also support the hypothesis that loss of social support due to female participation

in the labor market leads to an increase in male suicide. For females, the double burden of

outside work and housework may be bigger than the benefit of having social ties in work,

but the relation is not robustly significant. Our results coincide with Stack (1987)—at the

10

The utility loss of the mercenary value of marriage via divorce is equivalent in sociological terms to

individual trauma and the lack of social control.

18

aggregate level, the overall FLP affects the male but not the female suicide rate in the

U.S. It is worth noting that even though the coefficient is significant, the impact of FLP

on the male suicide rate is smaller than the unemployment effect. A one standard

deviation increase in the Band-Pass filtered Unemployment variable will be associated

with an increase of 7,131 male suicides, whereas a one standard deviation increase in

FLP will be associated with an increase of only 678 male suicides.

The coefficients on Alcohol are positive but insignificant for males, and mixed

and insignificant for females. However, our results should not be interpreted as saying

that there is no relationship between alcohol abuse and suicidal behavior at the micro

level. The relationship between alcohol consumption and suicide may not be linear. A

recent study by Akechi et al. (2006) using Japanese cohort data shows that the

relationship is U-shaped. Those who do not drink at all commit suicide more than those

who drink occasionally. These results indicate that our time-series data, which aggregate

the cross-sectional distribution of individual alcohol consumption, may not have enough

information to determine the relationship between alcohol abuse and the suicidal

behavior of individuals.

In sum, our initial estimates of the coefficients of the unemployment rate and

divorce rate do not change significantly after controlling for social variables. We may

conclude from these results that the reduction of relative consumption is the major

channel by which relative utility falls and consequently leads individuals to commit

suicide.

11

The divorce cycle is partly correlated to a society’s unemployment cycle, even

11

We explored the effect of using real per capita GDP in the place of the unemployment rate. The

coefficients are robustly significant in all equations estimated, but less significant than those of the

unemployment rate. A simple comparison of correlation coefficients also shows that real per capita GDP is

less correlated with suicide than is unemployment.

19

though non-economic factors influence divorce rates. Our previous results derived from

a simple regression approach (7), thus seem to be reasonable estimates of the relationship

between the unemployment and suicide rates in Japan.

VI. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we tried to extend the research on the economics of suicide in two

ways. First, we revised the standard economic model to analyze the cyclical relationship

between the suicide rate and the unemployment rate. Our model suggests that the recent

surge of middle-aged male suicides in Japan is related to the inflexible labor market that

leads the human capital of the unemployed to depreciate rapidly during periods of

technological shocks and regime shifts. The revised model clearly links the

unemployment and suicide rates and focuses on relative utility rather than the absolute

level. The relative terms conceptually correspond to cyclical components of the variables.

Second, we used three different filters to de-trend Japanese time series. By filtering out

long-term trends from the variables, we are able to illustrate the cyclical relationship

between suicide and unemployment more clearly.

12

Unlike previous research, which

often failed to trace the response of the female suicide rate to economic hardship, our

study indicates that the female suicide rate is also significantly influenced by the

unemployment rate in Japan, even though women are more protected than men from

macroeconomic fluctuations. The results are robust when we include the divorce rate and

three other social variables in the equation. The impacts of social variables show gender

differentials.

Fertility is more clearly related to female suicide, whereas the negative

12

When variables are stationary (as with some U.S. data), the filtered time series approach does not

generally improve estimation.

20

impact of FLP is more distinctive with male suicide. With our aggregate time series data,

we could not find any significant relationship between alcohol consumption and the

suicide rate in Japan.

We conjecture that 4,774 more Japanese will commit fatal suicide anually3 if de-

trended unemployment rises 1 percentage point. Such an acute response of people to

unemployment may be one reason why the Japanese government has been reluctant to

adopt drastic reform measures that could lead to a temporary surge of unemployment

rates during the sustained economic recession that began more than a decade ago.

The theories and empirical results in this paper suggest that government policy to

prevent the depreciation of human capital of the unemployed would help to remedy the

hazard of suicide. Retraining programs for jobless salarymen, tax breaks to encourage the

establishment of temporary agencies, and tax breaks to encourage corporations to hire

temporary workers are policies worth considering in this context.

21

References

Akechi, T., M. Iwasaki, Y. Uchitomi and S. Tsugane. “Alcohol Consumption and Suicide

among Middle-aged Men in Japan.”

British Journal of Psychiatry, 188, 2006, 231-236.

Andrés, A. R. “Income Inequality, Unemployment, and Suicide: A Panel Data Analysis

of 15 European Countries.”

Applied Economics, 37, 2005, 439-451.

Baxter, M., R. G. King. 1999, “Measuring Business Cycles: Approximate Band-Pass

Filters for Economic Time Series.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 81, 1999, 575-

593.

Becker, G. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference

to Education

. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1964.

Becker, G. “A Theory of Marriage.” in

Economics of the Family, edited by T. W. Schultz.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Becker, G. “An Economic Analysis of Marital Instability.” Journal of Political Economy,

85, 1977, 1141-1188.

Brainerd, E. “Economic Reform and Mortality in the Former Soviet Union: A Study of

the Suicide Epidemic in the 1990s.” European Economic Review 45, 2001, 1007-1019.

Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Japan, Statistics of the Catholic Church in Japan 2005,

Japan, 2006.

Chatterji, P., D. Dave, R. Kaestner, and S. Markowitz. “Alcohol Abuse and Suicide

Attempts among Youth.” Economics and Human Biology, 2, 2004, 159-180.

Chuang, H. and W. Huang. “Economic and Social Correlates of Regional Suicide Rates:

A Pooled Cross-Section and Time-Series Analysis.”

Journal of Socio-Economics, 26,

277-289.

Durkheim, L. J. Le Suicide. 1897 [translated by Spaulding, J. A., Simpson G. 1951

Suicide. Free Press, New York]

Cutler, D. M., E. L. Glaeser, K. E. Norberg. “Explaining the Rise in Youth Suicide.”

NBER Working Paper 7713, 2000.

Gerdtham, U., M. Johannesson. “A Note on the Effect of Unemployment on Mortality.”

Journal of Health Economics, 22, 2003, 505-518.

Hamermesh, D. S., N. M. Soss. “An Economic Theory of Suicide.”

Journal of Political

Economy

, 82, 1974, 83-98.

22

Hodrick, R. J., E. C. Prescott. “Post-war U.S. business cycles: an empirical

investigation.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29, 1997, 1-16.

Huang, W. “Region, Culture, Economic and Sociological Correlates of Suicide Rates: A

Cross-National Analysis.” Applied Economics Letters, 3, 1996, 779-782.

Lee, S. and A. Kleinman. “Suicide as Resistance in Chinese Society.” In: EJ Perry and M.

Selden. Eds. Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance. London Routledge, 2000,

221-240.

Lucas, R. E. “Understanding Business Cycles.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series

on Public Policy

, 5, 1977, 7-29.

Marcotte, D. E. “The Economics of Suicide, Revisited.”

Southern Economic Journal, 69,

628-643.

Markowitz, S., P. Chatterji, and R. Kaestner. “Estimating the Impact of Alcohol Policies

on Youth Suicides.”

Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 6, 2003, 37-43.

Mathur, V. K., Freeman, and D. G. Freeman. “A Theoretical Model of Adolescent

Suicide and Some Evidence from US data.” Health Economics, 11, 695-708.

McGrath, E., G. P. Keita, B. Strictland, and N. F. Russo. Women and Depression,

Washington: American Psychological Association, 1990.

Miyanaga, W. “Labor’s Share and the Adjustment of Wages and Employment.” Research

Report no. 27 Development Bank of Japan, 2002.

Neumayer, E. “Socioeconomc Factors and Suicide Rates at large-unit Aggregate Levels:

A Comment.” Urban Studies, 40, 2769-2776.

Newey, W. K., and K. D. West. “A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and

autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix.” Econometrica, 55, 1987, 703-705.

Platt, S. “Unemployment and Suicidal Behavior: A review of the literature.”

Social

Science and Medicine

, 19, 1984, 93-115.

Prescott, E. “Nobel Lecture: The Transformation of Macroeconomic Policy and

Research.” Journal of Political Economy, 114, 2006, 203-235.

Ruhm, C. J. “Are Recessions Good for Your Health?” Quarterly Journal of Economics,

115, 2000, 617-650.

Stack, S. “The Effect of Female Participation in the Labor Force on Suicide: A Time

Series Analysis.”

Sociological Forum, 2, 1997, 257-277.

23

_______. “The Relationship of Female Labor Force Participation to Suicide: A

Comparative Analysis.” Archives of Suicide Research, 4, 1998, 249-261.

Vigderhous, G., G. Fishman. “The Impact of Unemployment and Familial Integration on

Changing Suicide Rates in the U.S.A., 1920-1969.” Social Psychiatry, 13, 1978, 239-248.

Weiss, Y., R. Willis. “Match Quality, New Information , and Marital Dissolution.”

Journal of Labor Economics, 15, 1997, s293-s329.

Yang, B. “The Economy and Suicide: A Time-Series Study of the U.S.A.” American

Journal of Economics and Sociology

, 51, 1992, 87-99.

_______. “The Social Impact of Unemployment.” Applied Economics Letters, 1, 1994,

223-226.

24

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000

Suicides per 100,000 persons

FIGURE 1

Male Suicide Rates in Five Industrialized Countries

Source WHO Mortality database

Japan

Spain

U.K.

U.S.A.

Canada

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Suicides per 100,000 persons

Unemployment Rate (%)

FIGURE 2

Suicide rates, Unemployment rates and Divorce rates in Japan

Unemployment Rate

Male Suicide

Female Suicide

Divorce Rate

Divorces per 1,000 persons

25

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85+

1988

1993

1998

2003

FIGURE 3A

Female Suicide by Age

Suicides per 100,000 females

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85+

1988

1993

1998

2003

FIGURE 3B

Male Suicide by Age

Suicides per 100,000 males

26

Variable

Male

Suicide

Female

Suicide

Unemploy-

ment Rate

Divorce

Rate

Fertility

Rate

FLP

**

Alcohol

Consumption

Unit

suicide/

100,000

suicide/

100,000

percent

divorce/

1,000

b

irth/

1000

*

percent liter

Mean 24.09 14.02 2.33 1.22 1.90 50.24 5.21

Std. Dev. 5.56 2.25 1.08 0.43 0.47 2.72 1.86

Maximum 37.49 20.59 5.38 2.30 3.65 56.70 8.08

Minimum 16.14 10.78 1.13 0.73 1.29 45.70 1.40

*

1000 women with age between 15-49.

**

FLP is the female labor force participation rate.

TABLE 1

Descriptive Statistics

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

0

2

4

6

8

10

Ul tRt(%)

Fi 1 S i id t l t t d di t i J

Female Labor Participation

Male Suicide

Fertility

Alcohol

Consumption

FIGURE 4

Male Suicide and Social Variables in Japan

Suicides per 100,000 persons

FLP (%)

Births per female pop (15-49)

Lliters

p

er

p

ers

o

n

(

15+

)

27

De-trended

Variable

Male Suicide

Female

Suicide

Unemploy-

ment

Divorce Fertility FLP

Female Suicide 0.76

Unemployment 0.62 0.38

Divorce 0.52 0.17 0.46

Fertility -0.10 -0.30 -0.05 0.23

FLP 0.25 0.24 -0.06 -0.12 -0.22

Alcohol -0.03 -0.02 -0.11 -0.24 0.00 0.20

*

Random Walk filtered series (1953-2000)

TABLE 2

Correlation Coefficients of De-trended Variables

*

28

De-trending Method

Unemploy-

ment

Divorce Fertility FLP Alcohol

R

2

Level

2.19

***

(3.48) 0.13

Random Walk

5.76

***

(4.26) 0.38

Hodrick-Prescott

7.14

***

(7.84) 0.55

Band-Pass

5.31

***

(4.22) 0.32

Random Walk

4.51

***

(3.50)

12.64

*

(1.81) 0.46

Hodrick-Prescott

6.04

***

(7.00)

12.70

***

(3.58) 0.62

Band-Pass

4.11

***

(3.71)

22.71

***

(4.52) 0.50

Random Walk

4.34

***

(4.00)

15.99

*

(2.93)

-1.53

*

(1.83)

0.67

***

(4.29)

0.40

(0.61) 0.56

Hodrick-Prescott

5.94

***

(7.84)

11.96

***

(3.07)

-0.69

(0.35)

0.45

**

(2.02)

0.19

(0.27) 0.65

Band-Pass

4.43

***

(4.44)

21.98

***

(4.53)

-0.89

(1.03)

0.47

*

(1.79)

0.05

(0.09) 0.53

TABLE 3

Newey-West heteroskedasticity-autocorrelation consistent t statistics in parenthesis. A *** indicates

significance at the 1% level. A ** indicates significance at the 5% level. A * indicates significance at the

10% level.

Estimates of Male Suicide in Japan

Eq. (7)

Eq. (8)

Eq. (9)

29

De-trending Method

Unemploy-

ment

Divorce Fertility FLP Alcohol

R

2

Level

-1.85

***

(4.45) 0.12

Random Walk

1.40

***

(3.00) 0.14

Hodrick-Prescott

2.06

***

(4.26) 0.23

Band-Pass

1.08

***

(3.14) 0.10

Random Walk

1.41

***

(2.84)

-0.06

(0.02) 0.14

Hodrick-Prescott

2.20

***

(4.31)

-1.62

(0.85) 0.23

Band-Pass

0.95

***

(2.92)

2.34

(1.08) 0.11

Random Walk

1.21

***

(2.81)

1.84

(0.81)

-1.66

***

(4.68)

0.20

*

(2.14)

-0.01

(0.02) 0.27

Hodrick-Prescott

2.13

***

(4.33)

-1.74

(0.86)

-0.57

(0.50)

0.18

(0.98)

0.01

(0.02) 0.26

Band-Pass

0.97

***

(2.77)

2.59

(1.30)

-1.28

***

(3.13)

0.12

(1.29)

-0.10

(0.41) 0.18

TABLE 4

Newey-West heteroskedasticity-autocorrelation consistent t statistics in parenthesis. A *** indicates

significance at the 1% level. A ** indicates significance at the 5% level. A * indicates significance at the

10% level.

Estimates of Female Suicide in Japan

Eq. (7)

Eq. (8)

Eq. (9)