Demographic Research a free, expedited, online journal

of peer-reviewed research and commentary

in the population sciences published by the

Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research

Konrad-Zuse Str. 1, D-18057 Rostock · GERMANY

www.demographic-research.org

DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

VOLUME 11, ARTICLE 14, PAGES 395-420

PUBLISHED 17 DECEMBER 2004

www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol11/14/

DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2004.11.14

Research Article

Marital Dissolution in Japan:

Recent Trends and Patterns

James M. Raymo

Miho Iwasawa

Larry Bumpass

© 2004 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft.

Table of Contents

1 Introduction 396

2 Background 398

3 Data and methods 399

3.1 Data 399

3.2 Adjustment for year of registration 400

3.3 The cumulative risk of divorce 401

3.4 Differences by education 402

4 Results 403

4.1 Trends and levels 403

4.2 Educational differentials 405

5 Discussion 407

6 Acknowledgements 408

Notes 409

References 411

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 395

Research Article

Marital Dissolution in Japan:

Recent Trends and Patterns

James M. Raymo

1

Miho Iwasawa

2

Larry Bumpass

1

Abstract

Very little is known about recent trends in divorce in Japan. In this paper, we use

Japanese vital statistics and census data to describe trends in the experience of marital

dissolution across the life course, and to examine change over time in educational

differentials in divorce. Cumulative probabilities of marital dissolution have increased

rapidly across successive marriage cohorts over the past twenty years, and synthetic

period estimates suggest that roughly one-third of Japanese marriages are now likely to

end in divorce. Estimates of educational differentials also indicate a rapid increase in

the extent to which divorce is concentrated at lower levels of education. While

educational differentials were negligible in 1980, by 2000, women who had not gone

beyond high school were far more likely to be divorced than those with more education.

________________________________

1. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Sociology

2. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Tokyo

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

396 http://www.demographic-research.org

1. Introduction

Over the past 30-40 years, substantial changes in family behavior and organization of

the life course have occurred in all industrialized countries. Often characterized as the

“second demographic transition,” these changes include: (a) delayed marriage and

fertility, (b) increasing cohabitation, divorce, and non-marital childbearing, and (c)

increasing maternal employment (Lesthaeghe 1995; McLanahan 2004). Theoretical

explanations for these changes have focused on increasing economic opportunities for

women, increasing consumption aspirations, declining economic prospects for men, as

well as increasing secularization and growing emphasis on individual fulfillment

(Lesthaeghe 1998). Key empirical features of these family changes include substantial

socioeconomic and regional variation. For example, in her recent presidential address

to the Population Association of America, Sara McLanahan (2004) argued that patterns

of family change are following two different paths depending on social status. Changes

with favorable implications for children (e.g., later marriage, delayed childbearing,

maternal employment) are increasingly concentrated among women with greater

socioeconomic resources whereas changes associated with unfavorable outcomes for

children (e.g., divorce, non-marital childbearing) are increasingly concentrated among

women with fewer socioeconomic resources. Family change associated with the second

demographic transition thus has potentially important implications for social

stratification in general and for growing socioeconomic differentials in the well-being

of children in particular.

Although McLanahan (2004) emphasized the similarity of socioeconomic

differentials in family behavior across a wide range of western industrialized countries,

it is also clear that there is considerable variation across countries in the pace and the

nature of family changes (Lesthaeghe 1995; Lesthaeghe and Moors 2000). In

comparative studies, Japan stands out as one setting in which some family changes

associated with the second demographic transition have been particularly rapid while

others have been slow to emerge. A very early transition to below replacement fertility

and a very late age at marriage place Japan at the forefront of the second demographic

transition. At the same time, some family patterns associated with the second

demographic transition, such as increases in maternal labor force participation and

divorce have remained less prevalent than in most other low-fertility societies (Tsuya

and Bumpass 2004). Despite rapid socioeconomic and normative change, other

behaviors such as cohabitation and non-marital childbearing have been virtually absent

(e.g., Thomson 2003) (Note 1).

The distinctive pattern of family change in Japan likely reflects, in part, a tension

between the social and economic forces of change noted above and the continued

strength of family forms and family values very different from those in most western

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 397

societies (e.g., Mason, Tsuya, and Choe 1998). Previous studies of demographic

change in Japan have linked declining rates of marriage and fertility to relatively

universal social and economic forces of change including increasing educational

attainment, increasing economic opportunities for women, increasing consumption

aspirations, and more tolerant attitudes toward family behaviors such as late marriage

and maternal employment (Raymo 2003; Retherford, Ogawa, and Matsukura 2001;

Tsuya and Mason 1995). Theoretical discussions of the second demographic transition

often place considerable emphasis on the role of increasing individualistic attitudes. A

plausible explanation for the Japanese exception with respect to the most “deviant”

behaviors is that the growth of individualism is at odds with the collectivist orientation

of Japanese society (Atoh 2001). There is, however, some evidence that pressures may

be building for a transition in cohabitation and perhaps even unmarried childbearing

(Rindfuss et al., 2005).

It is also clear that divorce has rapidly increased, with the crude divorce rate

increasing by two-thirds during the 1990s. While this change is reflected in pervasive

attention to divorce in the popular press, demographic analyses of divorce in Japan are

extremely limited. Indeed, existing research consists primarily of descriptions of trends

in crude rates or age trajectories, neither of which speaks directly to the risk of divorce.

Almost nothing is known about the correlates of divorce in Japan, trends in

socioeconomic differentials in divorce, or how these differentials compare to those

observed in other societies. In this paper, we draw upon several sources of data to

begin addressing these major gaps in the literature on family change in Japan. Using

vital statistics data, we describe divorce trajectories for marriage cohorts and construct

synthetic cohort estimates to assess the implications of recent rates. These estimates

provide a clear picture of the extent to which divorce has increased over time and allow

for comparisons with other industrialized countries. Using census data, we examine

educational differentials in the prevalence of divorce and describe how these

differentials have changed over time. Results of these analyses enable us to assess the

extent to which the increasing socioeconomic differentials in divorce found in other

low-fertility societies (McLanahan 2004) are also observed in Japan. Our results raise

several questions regarding the implications of rising divorce rates for social

stratification and the well-being of children and divorced parents in Japan. Importantly,

this study also provides a solid empirical basis for subsequent research addressing these

questions we raise. Before presenting our results, we provide a brief background on

family change in Japan and existing scholarship on divorce.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

398 http://www.demographic-research.org

2. Background

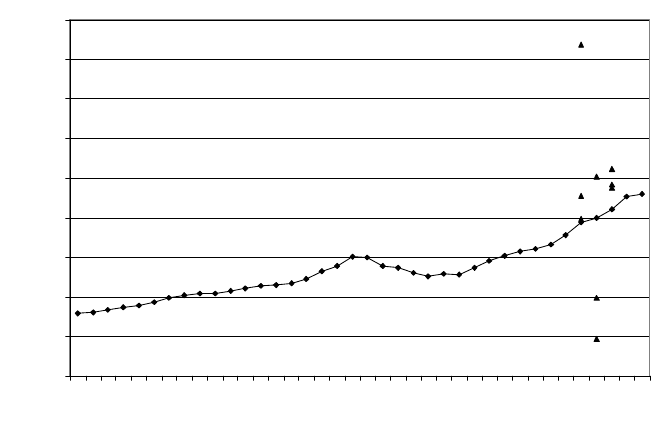

Following steady increases throughout the 1990s, Japan’s crude divorce rate reached

2.3 in 2002 (Figure 1). It is extremely important to recognize that, as illustrated at the

right side of this figure, this is a level similar to most industrialized countries other than

the U.S. The Japanese rate is also much higher than in Italy and Spain, two European

countries with which Japan shares many other demographic similarities (Lesthaeghe

and Moors 2000). As in the U.S., rapid increases in divorce suggest a major

restructuring of the family life course in Japan. It will be important in future research to

compare the consequences of divorce for women and children in Japan to those in other

industrialized countries. The prevalence of extended family residence (Rindfuss et al.

2004) and the importance of family provided care (Ogawa and Retherford 1997) could

moderate these consequences, while the highly asymmetric gender division of labor

among spouses (Tsuya and Mason 1995) and married women’s relatively tenuous

attachment to the labor force (Brinton 2001; Iwasawa 1999) could make the

consequences of divorce even more profound for women and families in Japan than in

other high-divorce societies. The social, economic, and family environments in which

divorce occurs in Japan provide a valuable contrast to the U.S. and other western

countries for studying the correlates and consequences of divorce.

As a non-western society with a very different family tradition, Japan provides an

important test of the generality of McLanahan’s (2004) description of growing

socioeconomic differentials in family outcomes (Note 2). Do relatively low levels of

economic inequality and widely shared normative views of “appropriate” family

behavior restrain such divergence in the experience and consequences of divorce? On

the one hand, the homogeneity of the family life course in Japan’s recent past (Brinton

1992) leads us to expect rather limited socioeconomic differentials in divorce. These

expectations are strengthened by the fact that fertility reduction in the 1950s and more

recent trends toward later and less marriage have occurred rapidly across all social

strata (Hodge and Ogawa 1992; Raymo 2003). On the other hand, we have recently

documented growing socioeconomic differentials in the experience of bridal pregnancy,

an increasingly common pathway to family formation (Raymo and Iwasawa 2004). It is

clear that Japanese women with lower levels of education are increasingly likely to

marry while pregnant relative to their more educated counterparts. Finding a similar

pattern with respect to divorce would provide further evidence of decline in the very

homogeneous family life course in Japan. Although the subject of increasing

socioeconomic inequality has been much discussed in Japan during recent years (Satō

2000; Tachibanaki 2001), very little attention has been paid to the potential role of

growing differentials in family behavior.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 399

Indeed, there is very little academic research on divorce at all. Existing work is

limited to descriptions of trends in crude rates by age and sex (e.g., Koyama and

Yamamoto 2001), analyses of regional variation in crude rates (Fukurai and Alston

1990; Uchida, Araki, and Murata 1993), and synthetic cohort analyses based on age-

specific divorce rates--which ignore differences in marriage duration by age (Beppu

2002, Ikenoue and Takahashi 1994). The scarcity of research on divorce in Japan

presumably reflects the limitations of available data. Complete marriage histories like

those commonly analyzed for the U.S. and Western Europe are not available in Japan

(Note 3). This does not mean, however, that we cannot learn more from the existing

data.

We have three objectives in this paper. The first is to track the experiences over

time of real marriage cohorts up until the duration when they can last be observed. The

second is to use the most recently available period data to make synthetic cohort

estimates of the cumulative proportion of marriages expected to end in divorce by

various durations since marriage. These two results are presented and discussed

together. Finally, we take the observed proportions divorced by ages 35-39 as reported

in the census and make adjustments for differential age at marriage by education

(affecting differences in duration since marriage at the observed ages) in order to

approximate educational differences in the risk of divorce.

3. Data and methods

3.1 Data

The basic data for estimating duration-specific risks are simply the number of marriages

and divorces registered in the Japanese vital statistics system across years. Data on

marital dissolutions classified by the years in which marriage began and ended come

from special tabulations not included in the annual volumes published by the Ministry

of Health, Labour, and Welfare. We adjust these data as described below to reassign

events from their year of registration to the year in which they actually occurred. The

data for estimating educational differentials are census reports of the percent of ever-

married women divorced at ages 35-39, combined with estimates of educational

differences in duration since marriage by these ages.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

400 http://www.demographic-research.org

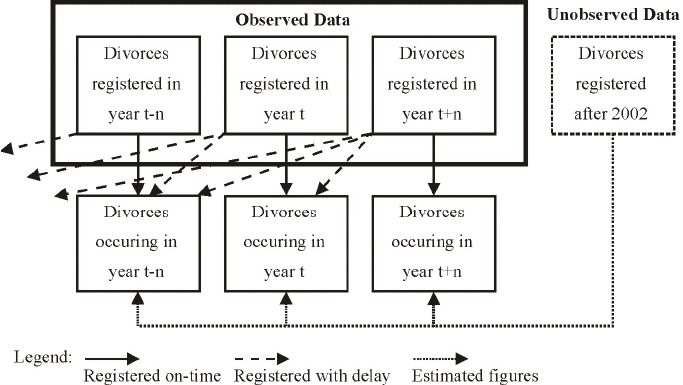

3.2 Adjustment for year of registration

The divorce tabulations classify all divorces registered in a given year (between 1979

and 2002) by the year in which the marriage began and the year in which the marriage

ended. Because roughly 10% of marriages and 30% of divorces are not registered in

the year in which they occur (Ishikawa 1995), it is essential to measure marital duration

using the years in which the union began and ended rather than the years in which

marriage and divorce were registered. The vital statistics tabulations we use allow us to

calculate the number of marital dissolutions by marriage cohort and marital duration by

summing registered divorces in each year occurring to each marriage cohort—as

measured by the years in which coresidence began and ended.

Because the earliest marriage cohort in the data is 1979 and the most recent year of

data is 2002, we can observe divorces registered up to twenty-three years after they

occurred (Note 4). Our counts become progressively less complete for the more recent

years because for each succeeding year a higher proportion of the events will not yet

have been registered. To construct yearly counts of divorce classified by year of

marriage, we use the procedure described in Figure 2. We first subtract from each

year's registered divorces those that occurred in earlier years and add them to the

number events for the year in which they occurred (which have, in turn, had late

registrations subtracted from them and reassigned to earlier years). The count of the

number events for year t is simply the number of events registered in year t, minus

those that occurred n years earlier, and plus those that were registered n years after year

t (where n ranges from 1 to 23). These additions and subtractions of divorces registered

with delay are represented by the bold dashed arrows in Figure 2. This creates a good

count of annual events until the more recent years for which we no longer observe the

large majority of late registrations. However, we can take advantage of the fact that

patterns of delayed registration have been remarkably stable over time to estimate the

number of divorces that have occurred by 2002 but will be registered in 2003 and

beyond.

Using the years for which we have complete counts of events and the years in

which these events were registered, we can estimate the proportion of the events

occurring in a particular year, but that will not yet have been registered by 2002. For

example, to estimate a complete count of marital dissolutions occurring in 1999, we

first add in the late registrations of 1999 divorces as recorded in 2000-2002, and then

adjust that total for the proportion of all divorces from earlier years that were registered

more than three years after they occurred (Note 5). The addition of these estimated

numbers of divorces occurring by 2002 but registered after 2002 is represented by the

thin dotted arrows in Figure 2. To assess the appropriateness of this procedure, we also

worked backwards to estimate the number of duration-specific divorces registered with

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 401

a given delay in the past. In all cases, these estimates were very close to the observed

values.

We use similar techniques to construct yearly marriage cohorts. Vital statistics

tabulations classify all marriages registered in a given year by the year in which the

marriage actually occurred. As with the divorce data, we are thus able to reconstruct

annual marriage cohorts by allocating late-registered marriages from the year in which

they were registered back to the year in which they occurred (Note 6). We adjust the

size of marriage cohorts upward by estimating marriages that have already occurred but

have not yet been registered using the procedure described in the previous paragraph.

With yearly counts of marriages and duration-specific numbers of marital dissolutions

for each marriage cohort, it is straightforward to calculate the cumulative duration-

specific proportions of each marriage cohort to experience marital dissolution.

Rearranging cohort and duration-specific dissolution probabilities as year and duration-

specific dissolution probabilities allows us to calculate the synthetic cohort cumulative

probability of marital dissolution for recent years. Because the earliest marriage cohort

in our data is 1979, we can use observed dissolution probabilities in 2002 to calculate a

synthetic cohort divorce trajectory through 23 years of marriage. For the sake of

simplicity, we ignore mortality in these life-table calculations. This simplification is

unlikely to affect results given the very low levels of young adult and mid-life mortality

in Japan.

3.3 The cumulative risk of divorce

We begin by creating synthetic life-table estimates of cumulative divorce by duration of

marriage. There are several important issues relating to these estimates. The first is

that we use divorce data from 2002. It is important to use the most recently available

data given that the crude divorce rate increased so dramatically during the 1990s—a

decade characterized by very low levels of economic growth, corporate restructuring,

and increasing unemployment (Yamagami 2002).

Second, we improve considerably upon existing synthetic estimates by estimating

cumulative disruption from entry into exposure to risk (marriage) rather than by age,

i.e., we use marital duration-specific dissolution rates rather than age-specific rates.

Age-specific divorce rates reflect two components: a) the risk of divorce by duration

since marriage, and b) the effects of age at marriage on the proportions married at

specific ages, and age differences in duration since marriage. Cumulative estimates

based on age are appropriate when the objective is compare life course experience by a

given age—for example, differences between cohorts in the experience of divorce

before age 30. To evaluate the risk of divorce, however, estimates must be based on

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

402 http://www.demographic-research.org

rates specific to durations since marriage. This difference between age-based and

duration-based estimates is especially important in settings such as contemporary Japan

where marriage timing has changed rapidly (Raymo 2003).

Finally, we present data for both real and synthetic cohorts. We are not aware of

any previous analyses of marital dissolution in Japan describing the trajectories of real

marriage cohorts.

3.4 Differences by education

Registration forms for vital statistics do not collect information on educational

attainment, and large sample surveys such as the Current Population Survey or the

National Survey of Families and Households which collect respondents’ socioeconomic

characteristics and marital histories are not currently available in Japan (see Note 3).

Rather than waiting for such data to become available, we believe that it is

important to take advantage of existing data to learn what we can. Consequently, we

use data from the 1980, 1990, and 2000 census publications to describe educational

differences in current marital status and to examine how these differentials have

changed over time. It is important to recognize, however, that examining differentials

in current marital status to shed light on educational differentials in divorce poses two

significant problems. The first is that current marital status understates the actual

amount of divorce because those who have divorced and remarried are simply classified

as married (Note 7). We are thus forced to assume that there are no educational

differentials in the likelihood of remarriage. Growing educational differentials in the

transition to first marriage in Japan (Raymo 2003) suggest that this assumption may be

violated. However, the fact that studies of remarriage in the U.S. and other

industrialized societies have typically not found significant educational differentials in

remarriage (de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003), suggests that the same may be true in Japan.

Data from the Japanese National Fertility Surveys (JNFS), the only large survey

containing information on both educational attainment and experience of divorce,

suggest that educational differentials in remarriage are not large in Japan. However,

because the number of ever-divorced respondents is small for some educational groups,

we cannot confidently conclude from these data that educational differentials in

remarriage are negligible. This caveat should be kept in mind when evaluating our

results.

The second problem is the one we addressed above in comparing life-table

estimates based on duration since marriage rather than simply on age. The available

census data leave us no option but to base our estimate on comparisons of the

proportion divorced at specific ages. Because those in lower educational groups marry

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 403

at younger ages, on average, than those in higher educational groups (Raymo 2003), the

length of exposure to divorce is inversely related to educational attainment. We take a

simple approach to addressing this problem. We first calculate age-specific mean ages

at marriage by education, and we then weight the education-specific ever married

populations by the number of years between mean age at first marriage and the census

date. Dividing the divorced populations by these measures adjusts the prevalence of

divorce to reflect educational differences in age of initial exposure to the risk of

divorce. For each educational group at each census, we are thus able to calculate the

number of currently divorced individuals for each year between initial exposure to the

risk of divorce and the census date.

In order to calculate the education-specific values of mean age at marriage used to

weight the ever married populations in the census tabulations, we use data from the

Japanese National Fertility Surveys. Conducted every five years by the National

Institute of Population and Social Security Research, these surveys provide information

on educational attainment and age at marriage for large nationally representative

samples of married women between the ages of 18 and 49. Measures of mean age at

marriage for 1980 are calculated from the 1982 JNFS, values for 1990 are calculated

from pooled data from the 1987 and 1992 JNFS, and values for 2000 come from the

1997 JNFS. Because tabulations of marital status by educational attainment in the

census are presented by five-year age group, we calculate mean age at marriage for

similar age groups in each of the JNF surveys. In the analyses presented below, we

focus on ages 35-39 because women at these ages will have been married long enough

for many divorces to occur, and yet their experience represents marriages over a

relatively recent period.

We present these analyses and their results in two sections. In the first, we

examine trends and levels in marital dissolution and in the second, we examine

educational differentials in the prevalence of divorce.

4. Results

4.1 Trends and levels

We describe trends in marital dissolution by examining the cumulative probability of

divorce for single-year marriage cohorts beginning in 1980, and a synthetic cohort

trajectory based on divorce rates observed in 2002. The latter spells out the

implications of recent increases in divorce by describing the expected cumulative

proportion divorced at successive durations if a marriage cohort were to follow the most

recently observed duration-specific rates.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

404 http://www.demographic-research.org

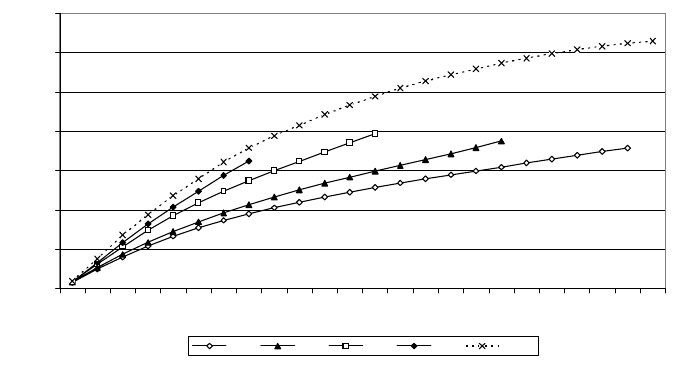

Figure 3 presents five cumulative divorce trajectories. The four solid lines

represent the experience of the 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995 marriage cohorts. The

broken line represents the synthetic cohort dissolution trajectory calculated from

duration-specific dissolution probabilities observed in 2002. The rapid increase in

marital dissolution is very clear, particularly between the 1985 and 1990 marriage

cohorts. The proportion of marriages ending within five years is 50% higher for the

1995 marriage cohort (12%) than for the 1980 marriage cohort (8%). The proportion of

marriages dissolved within 10 years was 12% for marriages begun in 1980 and 17% for

marriages begun in 1990. Despite the somewhat greater gap between marriages begun

in 1985 and 1990, each successive cohort has experienced a higher proportion divorced

at each duration since marriage. The synthetic cohort line continues this pattern with an

increase over the 1995 cohort and then follows a smooth trajectory in which the

proportion divorced by 12 years is about as much higher than the 1990 cohort as the

1990 cohort was relative to the 1985 cohort. This rough equivalence of a 10 year

increase (between 2000 and 1990) to the prior 5 year change (between 1990 and 1985)

suggests some attenuation in the rate of increase, but implies continuing increases in

divorce nonetheless. We estimate the cumulative probability of marital dissolution

within 20 years of marriage to be 30%, a figure that is substantially higher than the

lifetime probability of divorce from earlier age-based estimates (Beppu 2002; Ikenoue

and Takahashi 1994).

As we argued in the introduction, Japan’s markedly different family traditions

make comparisons with the Western experience of the second demographic transition

extremely valuable. Figure 4 compares the proportion of marriages expected to end in

divorce by 20 years after marriage in Japan to those estimated for various European

countries by Andersson and Philipov (2001). Our results here are startling. While the

increase in rates of divorce in Japan is well recognized, it has gone unnoticed that Japan

has fully experienced this component of the “second demographic transition.” The risk

of divorce for new marriages in Japan now matches the highest levels in Europe, even

though it is still considerably below that in the U.S. Rates are similar to those of

Germany and Austria, slightly higher than those in Sweden and Finland, and

substantially higher than those of France (30 vs. 19 percent) (Note 8).

Although divorce rates decline steadily over the course of marriage, there is some

increase in cumulative divorce for a cohort even after the duration of 23 years that we

can estimate from our data. On the other hand, the cumulative proportion divorced

increases very little after 30 years, so the proportion divorced by 30 years is a

reasonable indicator of the lifetime probability of divorce. We can make a rough

estimate of this proportion, by applying the ratio of the proportion divorced by 30 years

to the proportion divorced by 20 years duration as reported in other synthetic cohort

studies of divorce in the U.S. and elsewhere. The lowest of these ratios (from the U.S)

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 405

suggests that a third of all marriages in Japan will end in divorce by 30 years after

marriage. This has very substantial implications for family patterns in Japan, especially

in light of evidence presented in the next section showing that the prevalence of divorce

is relatively high among the less advantaged.

4.2 Educational differentials

It is extremely important to understand the extent to which this rapid increase in marital

dissolution has occurred across the socioeconomic spectrum or is increasingly

concentrated among certain groups. As noted above, cross-national studies of family

change associated with the second demographic transition indicate that divorce is

increasingly concentrated among the less educated (McLanahan 2004). We would

expect to observe a similar pattern of change in Japan to the extent that economic

hardship is associated with marital instability and to the extent that Japanese couples

with more limited socioeconomic resources have been most adversely affected by the

economic downturn of the 1990s.

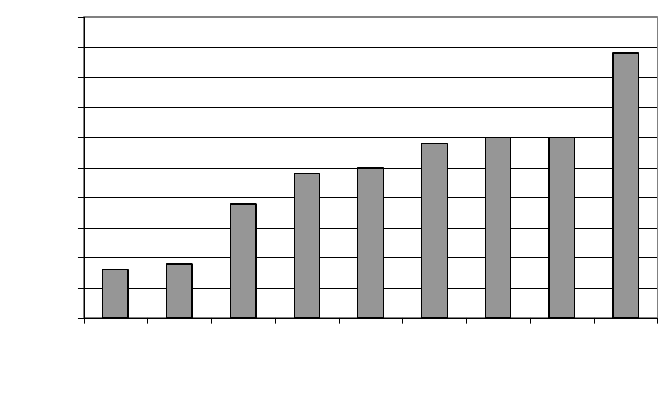

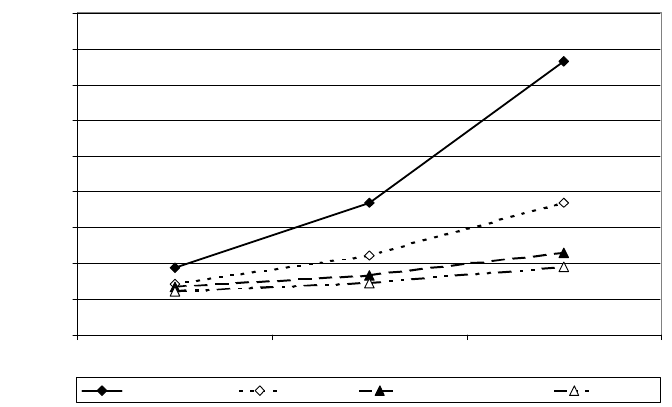

We begin with tabulations of age and marital status by educational attainment for

women in the 1980, 1990, and 2000 census publications. The census contains six

categories of educational attainment: junior high school graduates, high school

graduates, junior college/vocational school graduates, university graduates, in school,

and never attended school. We do not consider the last two categories given the very

small numbers in each and the largely irrelevant nature of the “in school” category

beyond usual ages for schooling. In Figure 5, we present the unadjusted ratios of the

divorced population to the ever married population by educational attainment for 35-39

year old women in 1980, 1990, and 2000. It is immediately clear that the prevalence of

divorce has increased for all educational groups, especially between 1990 and 2000

(Note 9). In 1980, less than 5% of ever married 35-39 year-old women were currently

divorced. By 2000, 15% of ever married women who did not finish high school and

7% of high school graduates were divorced. Increases in the prevalence of divorce for

women with at least a two-year college degree have been relatively small. While it is

important to keep in mind that these figures substantially understate experience of

divorce given that roughly half of those who divorce eventually remarry, it seems clear

that there has been a sharp increase in educational differentials in divorce over the past

two decades.

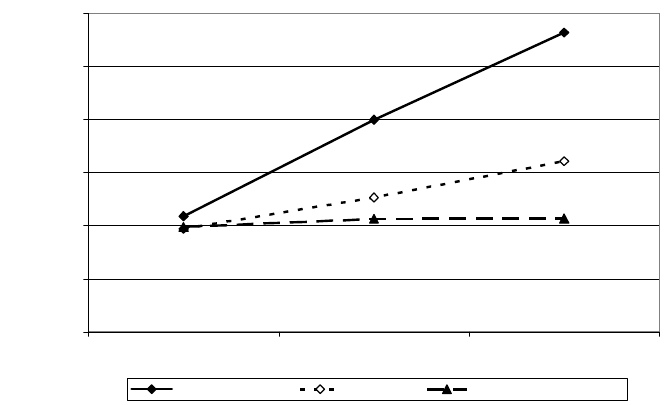

In Figure 6, we describe change over time in the relative prevalence of divorce

after adjusting for educational differences in the mean age at first marriage of 35-39

year old women at each census (as calculated from the Japanese National Fertility

Surveys). This adjustment to account for earlier marriage among women in lower

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

406 http://www.demographic-research.org

educational groups has little impact on the patterns described by the unadjusted data.

Educational differences in the prevalence of divorce were negligible in 1980 but

increased substantially over the following two decades. In 1990, there was a slight

divergence between women with higher education and those who completed high

school and a very large relative increase in the prevalence of divorce among women

who did not finish high school. This divergence between women with and without

higher education accelerated rapidly between 1990 and 2000. In the 2000 census, the

adjusted prevalence of divorced female high school graduates is 1.6 times larger than

for university graduates. Among women who did not complete high school, the

prevalence of divorce is 2.8 times higher than among college graduates. Trends for

women in the lowest educational category may be discounted given the increasingly

small and select nature of this group – in the 2000 census, only 5% of 35-39 year-old

women were classified as junior high school graduates. However, with high school

graduates comprising 51% of 35-39 year-old women in 2000, it is clear that there are

growing educational differentials in the experience of divorce in Japan.

There are two issues that could possibly result in the size of these differentials

being overstated. First, because age at first marriage has increased substantially

between 1980 and 2000, age at divorce has also increased, thus inflating the prevalence

of divorce (i.e., women have had less time to remarry). If this pattern of change has

differed by education, our results may overstate the increase in educational differentials

in divorce. This seems most unlikely, however, since age at first marriage has been

delayed most among the most highly educated women (Raymo 2003). Second, it is

possible that educational differentials in the likelihood of remarriage following divorce

have increased. If highly educated women are increasingly likely to remarry soon after

divorce (relative to their less educated counterparts), the patterns depicted in Figure 6

would overstate the increase in educational differentials in divorce. We are not aware,

however, of any empirical or anecdotal evidence to suggest that this is the case.

In sum, our adjustment for differences in age at first marriage only partially

accounts for differences in exposure to the risk of divorce so we do not place much

weight on the specific values presented in Figure 6. Rather, it is the general pattern of

change that is important. The very clear trends convince us that the growing

educational differentials in divorce are not an artifact of the crude measurement

techniques necessitated by data limitations. The ratio of divorced high school graduates

to divorced university graduates may be more or less than the 1.6 we calculate but it is

surely larger than it was in 1980 and 1990.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 407

5. Discussion

Very little has been known about recent trends in marital dissolution in Japan. It is

clear that crude divorce rates increased sharply during the 1990s, but the absence of

more informative measures of the likelihood of divorce has hidden the scale of current

levels. Furthermore, nothing was known about socioeconomic differentials in divorce.

Our interest in understanding patterns of divorce in Japan is heightened by the contrast

between the very homogeneous nature of the family life course in Japan and evidence

of increasing socioeconomic differentials in family behavior in other industrialized

societies. Is divorce increasingly common across socioeconomic strata, as suggested by

the limited socioeconomic differentials in fertility trends and changes in marriage

timing? Is divorce increasingly concentrated among those with fewer socioeconomic

resources, as in other industrialized countries? In this paper, we have utilized available

data to describe trends in the experience of marital dissolution across the life course and

to examine trends in educational differentials in the prevalence of divorce.

Cumulative probabilities of divorce have increased markedly across marriage

cohorts in Japan. Indeed, our synthetic cohort estimates indicate that roughly one-third

of Japanese marriages are expected to end in divorce. This figure is similar to that

observed in some western European countries and higher than the level in most. Japan

is no longer a society characterized by low levels of marital dissolution. Rough

estimates of educational differentials in the prevalence of divorce indicate that there has

been a rapid increase over the past two decades in the extent to which divorce is

concentrated among those with lower levels of education. While educational

differentials in the prevalence of divorce were negligible in the 1980 census, women

with a high school degree or less are far more likely than their more highly educated

counterparts to be divorced in the 2000 census.

As in the U.S. and most other industrialized societies, it appears that family

changes associated with the second demographic transition may have important

implications for social stratification in Japan. For example, the economic implications

of rising divorce rates for women may be particularly pronounced in Japan where

married women’s attachment to the labor force is far more tenuous than in the U.S. and

many European countries. At the same time, however, the relatively high prevalence of

coresidence with parents following divorce may diminish the economic implications of

divorce for some Japanese women and their children (Note 10). Tabulations of

Japanese census data and data from the National Survey of Families and Households

indicate that the proportion of 35-39 year-old divorced women coresiding with parents

is 25% in Japan but only 2% in the U.S. Does this pattern of post-divorce coresidence

with parents mitigate the economic consequences of divorce for women? Does it

influence the likelihood of remarriage among divorced women? Does it ameliorate the

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

408 http://www.demographic-research.org

negative consequences for children of growing up with a single parent (e.g.,

McLanahan and Sandefur 1994)? In considering these questions, attention will need to

be paid to the potential for even further divergence in family experience. If coresidence

ameliorates the consequences of divorce for some women and children in Japan, these

consequences may be very severe indeed for the majority who do not live with parents.

In the absence of joint custody laws, what role do divorced fathers play in the lives of

their children? What are the implications of divorce for father’s well-being?

Subsequent research should address these questions not only to further understand the

family implications of divorce in Japan but also to further understand the ways in which

the consequences of divorce may be moderated by the family, legal, and economic

contexts in which it occurs.

6. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Health and Labor Science Research Grant to the National

Institute of Population and Social Security Research. We would like to thank Naoko

Katsumoto for assistance with data preparation.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 409

Notes

1. Japan’s total fertility rate has been below 2.1 since 1974. In 2002, the mean age at

marriage was 27.4 for women and 29.1 for men, 1.9% of children were born to

unmarried mothers, and 3% of unmarried 25-29 year old men and women were in

cohabiting unions (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

2004a, 2004b).

2. It is worth noting that low levels of divorce are not a “traditional” feature of the

Japanese family. Historical studies (Fuess 2004; Hayami 1973) have documented

very high levels of divorce among Japanese couples in the 19

th

century.

3. Marital history data are available from the National Family Research of Japan

survey conducted by the Japan Society for Family Sociology and from the Japanese

General Social Survey, but both surveys seriously underrepresent divorced

respondents.

4. Vital statistics data obviously provide no information on marriages that were

dissolved but never officially ended by registration of divorce. If “de facto”

divorces are common in Japan, as in the U.S. (Bumpass, Castro Martin, and Sweet

1991), the vital statistics data will understate the incidence of divorce.

Furthermore, if there are socioeconomic differentials in the likelihood of either

registering divorce or self-report of divorce in the census, our analyses may

understate or overstate educational differentials in the experience of divorce.

5. This adjustment procedure very closely resembles that described in Ishikawa

(1995).

6. We use data on all divorces and marriages. We do not distinguish between first

marriages and remarriages. Among women, first marriages comprised 91% of all

marriages in 1979 and 85% of all marriages in 2002 (National Institute of

Population and Social Security Research 2004a).

7. Tabulations of current marital status by experience of divorce among respondents

to the Japanese National Fertility Surveys suggest that roughly 40% of divorced

women and 60% of divorced men remarry.

8. The figures from Andersson and Philipov (2001) are based on data from the late

1980s and early 1990s.

9. The patterns described here are very similar for women in adjacent five-year age-

groups.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

410 http://www.demographic-research.org

10. Mothers receive custody in roughly 80% of divorces involving children (National

Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2004a).

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 411

References

Andersson, Gunnar and Dimiter Philipov. (2001). "Life-Table Representations of

Family Dynamics in 16 FFS Countries." MPIDR Working Paper Series WP

2001-024, Rostock, Germany: Max-Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Atoh, Makoto. (2001). "Very Low Fertility in Japan and Value Change Hypotheses."

Review of Population and Social Security Policy 10:1-21.

Beppu, Motomi. (2002). "An Analysis of the Marriage Life Cycle in Japan Using

Multistate Life Tables: 1930, 1955, 1975, and 1995." Journal of Population

Studies 30:23-40. (in Japanese)

Brinton, Mary C. (1992). "Christmas Cakes and Wedding Cakes: The Social

Organization of Japanese Women's Life Course." In Takie S. Lebra, editor.

Japanese Social Organization. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press: 79-

107.

Brinton, Mary C. (2001). “Married Women's Labor in East Asian Economies.” In Mary

C.Brinton, editor. Women's Working Lives in East Asia. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press: 1-37.

Bumpass, Larry L., Martin Teresa Castro, and James A. Sweet. (1991). "The Impact of

Family Background and Eary Marital Factors on Marital Disruption." Journal of

Family Issues 12:22-42.

de Graaf, Paul M. and Matthijs Kalmijn. (2003). "Alternative Routes in the Remarriage

Market: Competing-Risk Analyses of Union Formation After Divorce." Social

Forces 81:1459-1498.

Fuess, Harald. (2004). Divorce in Japan: Family, Gender, and the State 1600-2000.

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fukurai, Hiroshi and Jon Alston. (1990). "Divorce in Contemporary Japan." Journal of

Biosocial Science 22:453-464.

Hayami, Akira. (1973). Historical Demographic Analysis of Rural Japan in Modern

Times. Tokyo: Tōyō Keizai Shimpōsha. (in Japanese)

Hodge, Robert W. and Naohiro Ogawa. (1991). Fertility Change in Contemporary

Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ikenoue, Masako and Shigesato Takahashi. (1994). “Multistate Marriage Life Tables.”

Journal of Population Problems 50(2):73-96. (in Japanese)

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

412 http://www.demographic-research.org

Ishikawa, Akira. (1995). “Statistical Comparison between Legal and Common-Law

Marriage in Japan.” Journal of Population Problems 50(4):45-56. (in Japanese)

Iwasawa, Miho. (1999). “The Sate of Women’s Life Course in Contemporary Japan:

Focusing on Never-Married Women’s Prospects.” Journal of Population

Problems 55(4):16-37. (in Japanese)

Koyama, Yasuyo and Chizuko Yamamoto. (2001). “Trends in Japanese Marriage and

Divorce: 1996-1998.” Journal of Population Problems 57(3):53-76. (in

Japanese)

Lesthaeghe, Ron. (1998). "On Theory Development and Applications to the Study of

Family Formation." Population and Development Review 24:1-14.

Lesthaeghe, Ron. (1995). "The Second Demographic Transition—An Interpretation." In

Karen O. Mason and Jensen An-Magrit, editors. Gender and Family Change in

Industrial Countries. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press: 17-62.

Lesthaeghe, Ron and Guy Moors. (2000). "Recent Trends in Fertility and Household

Formation in the Industrialized World." Review of Population and Social Policy

9:121-170.

Mason, Karen O., Noriko O. Tsuya, and Minja K. Choe. (1998). "Introduction." In

Karen O. Mason and Minja K. Choe, editors. The Changing Family in

Comparative Perspective: Asia and the United States. Honolulu, HI: University

of Hawaii Press: 1-16.

McLanahan, Sara. (2004). " Diverging Destinies: How Children Are Faring Under the

Second Demographic Transition." Demography 41:607-627.

McLanahan, Sara and Gary Sandefur. (1994). Growing up with a Single Parent: What

Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. (2004a). Latest

Demographic Statistics. Tokyo: National Institute of Population and Social

Security Research. (in Japanese)

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. (2004b). Attitudes

toward Marriage and the Family among the Unmarried Japanese Youth - The

Twelfth National Fertility Survey. Tokyo: National Institute of Population and

Social Security Research. (in Japanese)

Raymo, James M. (2003). "Educational Attainment and the Transition to First Marriage

Among Japanese Women." Demography 40:83-103.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 413

Raymo, James M. and Miho Iwasawa. (2004). “Premarital Pregnancy and Spouse

Pairing Patterns in Japan: Assessing How Novel Family Behaviors “Fit in” to

the Family Formation Process.” Annual Meeting of the Population Association

of America, Boston, MA (April 1-3).

Retherford, Robert D., Naohiro Ogawa, and Rikiya Matsukura. (2001). "Late Marriage

and Less Marriage in Japan." Population and Development Review 27:65-102.

Rindfuss, Ronald R.; Minja Kim Choe, Larry L. Bumpass, and Yong-Chan Byun.

(2004). “Intergenerational Relations.” In Noriko O. Tsuya and Larry L.

Bumpass, editors. Marrriage, Work, and Family Life in Comparative

Perspective: Japan, South Korea, and the United States. Honolulu, HI: East-

West Center: 54-75.

Rindfuss, Ronald R., Minja Kim Choe, Larry Bumpass, and Noriko Tsuya. (2005).

“Social Networks and Family Change in Japan.” American Sociological Review

(Forthcoming).

Satō, Toshiki. (2000). Unequal Japan. Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Shinsha. (in Japanese)

Tachibanaki, Toshiaki. (2001). Economic Inequality in Japan. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

(in Japanese)

Thomson, Elizabeth. (2003). “Partnerships & Parenthood: A Comparative View of

Cohabitation, Marriage and Childbearing.” Presented at the eleventh annual

National Symposium on Family Issues, The Pennsylvania State University,

College Park, PA (October).

Tsuya, Noriko O. and Larry L. Bumpass. (2004). “Introduction.” In Noriko O. Tsuya

and Larry L. Bumpass, editors. Marrriage, Work, and Family Life in

Comparative Perspective: Japan, South Korea, and the United States. Honolulu,

HI: East-West Center: 1-18.

Tsuya, Noriko O. and Karen O. Mason. (1995). "Changing Gender Roles and Below

Replacement Fertility in Japan." In Karen O. Mason and An-Magrit Jensen,

editors. Gender and Family Change in Industrialized Countries. Oxford, U.K.:

Clarendon Press: Pp. 139-167.

Uchida, Eiichi, Shunichi Araki, and Katsuyuki Murata. (1993). "Socioeconomic Factors

Affecting Marriage, Divorce, and Birth Rates in a Japanese Population." Journal

of Biosocial Science 25:499-507.

Yamagami, Toshihiko. (2002). “Utilization of Labor Resources in Japan and the United

States.” Monthly Labor Review 125(4):25-43.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

414 http://www.demographic-research.org

Sweden

Italy

Canada

Korea

Australia

Germany

France

Spain

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

1965

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

CDR= Divorces/1,000 Population

USA

Figure 1: Trends in Japan’s Crude Divorce Rate and Recent Figures from Other

Countries.

Source: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. 2004. Latest Demographic Statistics. Tokyo: National Institute

of Population and Social Security Research.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 415

Figure 2: Adjustment Procedure Used to Construct Yearly Divorce Counts.

Note: t=1979-2002, n=1-23. All divorces are classified by the year in which the marriage began and ended.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

416 http://www.demographic-research.org

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

Union Duration (years)

Cumulative Probability of Dissolution

1980 1985 1990 1995 2002*

*Refers to hypothetical cohort

Figure 3: Cumulative Probability of Marital Dissolution, by Marriage Cohort.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 417

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Spain

Italy

France

Sweden

Finland

Austria

Germany

Japan

USA

Percent

Figure 4: Proportion of Marriages Expected to Disrupt Within 20 Years: Life Table

Estimates.

Source: Andersson and Philipov (2001).

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

418 http://www.demographic-research.org

0.00

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.10

0.12

0.14

0.16

0.18

1980 1990 2000

# Divorced/#Ever Married

Junior High School High School Jr. College / Voc. School University

Figure 5: Ratio of Divorced to Ever Married 35-39 Year Old Women, by

Educational Attainment: 1980, 1990, 2000.

Source: Population Census of Japan, 1980, 1990, 2000.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 419

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

1980 1990 2000

Adjusted Ratio Divorced (Relative to

University Graduates)

Junior High School High School Jr. College / Voc. School

Figure 6: Educational Differences in the Prevalence of Divorce: Adjusted Ratio of

Divorced to Ever Married 35-39 Year Old Women Relative to University

Graduates, 1980, 1990, 2000.

Demographic Research – Volume 11, Article 14

420 http://www.demographic-research.org