University at Albany, State University of New York University at Albany, State University of New York

Scholars Archive Scholars Archive

Public Administration & Policy Honors College

5-2016

Demographic Challenges Facing Japan: Is the Solution Demographic Challenges Facing Japan: Is the Solution

Immigration or Family Incentives? Immigration or Family Incentives?

Hui Lin

University at Albany, State University of New York

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_pad

Part of the Public Policy Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Lin, Hui, "Demographic Challenges Facing Japan: Is the Solution Immigration or Family Incentives?"

(2016).

Public Administration & Policy

. 6.

https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_pad/6

This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Public Administration & Policy by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive.

For more information, please contact scholarsarchive@albany.edu.

1

Demographic challenges facing Japan:

Is the solution immigration or family incentives?

Hui Lin

hlin3@albany.edu

Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy

University at Albany

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

degree of Bachelors of Arts from Rockefeller College of Public Affairs

and Policy with Honors in Public Policy

Research advisor faculty: Professor Jeffrey D. Straussman

May 2016

2

Executive summary.

Japan, a super-aging country. It has the highest percentage of elderly population in the

world of 26% as in 2014. The decline of the birth rate and subsequent population drop result

from the imbalance between the younger generation and the older generation. It is facing a

demographic crisis with high potential of the economic threat. The demographic change resulting

a reduction in overall consumption power in japan and left japan will lower revenue to support

their society. This paper examines the possible contributing factors, which discover the equal

access of education opportunity post world war, increasingly expensive education costs and the

challenge faced by contemporary parents to raise children would be the reasons for the decline of

the child births. Also, provide two alternative policies that would be useful for the Japanese

government, the immigration reform and the family incentives policies. Due to historical and

cultural constraints, Japan is unable to import a significant number of immigrants into the

countries. So far, the family’s incentive policies are not effective to achieve the mission of

encouraging more birth, but instead created some barrier for women to raise a child. In order to

be more effective alleviate the issue, the combination of the two policy tools is essential and also

make the certain change of the two policies.

The Significance and Impact of Japan’s Demographic Shift

As early as the 1970s, Japan started to experience sub-replacement fertility rates. This

means that, due to declines in the overall birth rate among Japanese women, the current

generation is less populous than the previous generation. The number of children born per

woman has declined steadily over the last four decades and reached a new low of one point

twenty six (1.26) births in 2005. While that number has inched up slowly (In 2013, the latest

year for which full data is available it was one point forty three) (1.43) it is currently well below

3

the two point one (2.1) births per woman required to maintain current population levels. (World

Bank, 2016) At the same time, Japan has started to experience a sharp decline in adult mortality

rates. The older generation has been growing in number since new medical technologies have

improved the overall health, longevity and life expectancy of its current population (World

Health Organization, 2011).

The decline of the birth rate and subsequent population drop, along with decreases in

mortality rates among the elderly population, has combined to create a society that is aging at

unprecedented speed. Now, Japan is considered a super aging society. It has the highest

percentage of elderly population in the world, 23% in 2009, which continues to grow (Statistics

Bureau, 2010). The development of this demographic shift directly impacts every aspect of

Japanese society. As the cost of social support and benefits for these elders is increasing, the

workforce is shrinking. That means that there is an imbalance between the younger generation

(who can help provide support) and the older generation (who need support). The Japanese

government must shoulder the increasing financial burden of these trends and create new

strategies to deal with this critical issue. They understand that the demographic changes and

resulting reduction in overall consumption power in Japan will mean decreased revenue to

provide essential support systems for an aging society.

This paper focuses on the change in Japan’s demographic patterns post Second World

War to present day. It provides a closer look at past, current and future trends in the total

population of Japan and for each age group. The demographic change is of great importance to

Japan because healthy population growth may determine the strength of the country’s economic

foundation and has a direct impact on the country’s potential for economic propensity in the near

future. Population decline is a serious issue for many developed countries including Japan. The

4

demographic shift in the age of its populace is also a central issue. The government will have to

deal with the impact of these demographic shifts on a national scale. However, in order to

alleviate the issue, it is crucial to understand the contributing factors that triggered the decline of

the birth rate after the Second World War and led to the aging of the population. The Japanese

government also needs to understand the negative and positive economic consequences that the

country will face if the demographic trends continue to move in this direction.

Once the contributing factors to the change in the Japanese demographic structure are

identified, and their economic consequences both for the present and the future are understood, it

may then be possible to identify effective policy alternatives that the Japanese government can

use to remedy the situation. Two potential policy alternatives that have been used in many

countries to address declining populations are immigration reform and pro-family or family

incentive policies. Immigration policy has been used as a tool by many Western countries, such

as the United States, Canada, and Australia, to address labor shortages. However, immigration

reform has not been a popular strategy in Japan. Japan is one of the most homogenous, least

ethnically diverse countries in the developed world and only a very small percentage of its

current population is foreign born. To date, Japan has favored longer term family incentive

policies, which aim to encourage Japanese couples to raise more children by providing various

family care incentives. Rather than relying on immigrants to boost the fertility rate, they want to

encourage young Japanese couples to have more than one child.

The History of the Demographical Shift

From 1945, the year the Second World War formally ended after the Empire of Japan

unconditionally surrendered to the allied troops, to the present day, Japan has experienced two

short baby booms. Japanese researchers Minoru Tachi and Yoichi Okazaki have stated that

5

between the years of 1947 to 1949, when Japan was in its post-war recovery period and soldiers

were returning home and fathering children, Japan experienced it first short baby boom. The

researchers estimate that the annual birth count exceeded two point six (2.6) million in each of

these two years (1969, 170). The second baby boom happened in 1971 once the children from

that first baby boom of 1947-1949 reached adulthood, but the number of births per woman did

not increase (Muramatsu and Akiyanma, 2011).

The birth rate continued to decline for several reasons. First the Japanese government

tried to control any potential overpopulation by encouraging family planning and birth control

and by relaxing abortion laws. Secondly, Japan experienced a significant economic

transformation from 1945-1951 when General Douglas MacArthur, who oversaw the occupation

of Japan, created sweeping changes in the nation. As Japan became less of an agricultural society

and more an industrialized nation, the perceived value of children changed. In an agricultural

economy, children bring greater economic benefits to a family since they provide free labor to

work the land. In essence, children were assets and the more children people had, the better off

they were. However, in a highly-industrialized world this principle no longer holds true. Children

have less economic value. Indeed children become “cost-centers” rather than assets because

parents need to financially invest in their children to secure their future. Children are expensive

commodities in that they have to be fed, clothed nurtured and sent to school so they might get a

decent job. With more children parents face heavier cost burdens and many parents do not have

the means to make multiple investments in human capital (Boling, 1997, 194).

As the Supreme Commander of Allied Power (SCAP), General Douglas MacArthur was

charged with helping the Japanese government rebuild the country after the war. His priorities

during the occupation of Japan were to decentralize the militarization in the Japanese

6

government, create free markets and promote Western ideas. MacArthur prohibited former

military officers from participating in any form of governmental decision-making process (U.S

Department of State, Office of the Historian Milestones: 1945-1952). He also sought to facilitate

economic demilitarization by banning the production of military weapons. The new constitution

for postwar Japan of 1949 stated that Japan must never create a military force and must rely on

its allies to protect the country from outside threats.

The exclusion of national military forces in Japan, allowed the country to reserve the

defense spending to invest in economic development (Takada, 1999, 6-7). General MacArthur

introduced economic reforms that benefitted numerous tenant farmers and broke apart big

business to transform the economy into a free market capitalist system. Also MacArthur

promoted the Western idea of gender equality and greater freedoms for women (U.S Department

of State, Office of the Historian Milestones: 1945-1952). This helped support the new free

market economy, because it encouraged more women to enter the Japanese workforce and this

helped meet labor demands. With less military spending, more economic development and a

labor force known for its incredible work ethic, Japan was able to boost its economy shortly after

the war. As japan grown from a devastated country after Second World War and became second

largest economy after the 1960s.

As illustrated in Table 1, the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of Japan

dramatically increased. In 1975, Japan’s GPD per capita was only about 4,600 dollars, but only

ten years later it had almost tripled to 11,000 dollars. The GDP per capita was to keep rising,

becoming an average of 40,000 dollars after 1995 (World Bank). However, as the economy

grew, and incomes began to rise, Japan began to experience a decrease in its population. The

chart shows this negative correlation.

7

Table 1

Sources: the GDP per capita is from the World Bank, and the total population and Rate of

Population change are taking from Japanese Statistic Bureau, MIC; Ministry of Health, Laborer

and Welfare; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism as included in the Japan

Statistics Handbook of 2015.

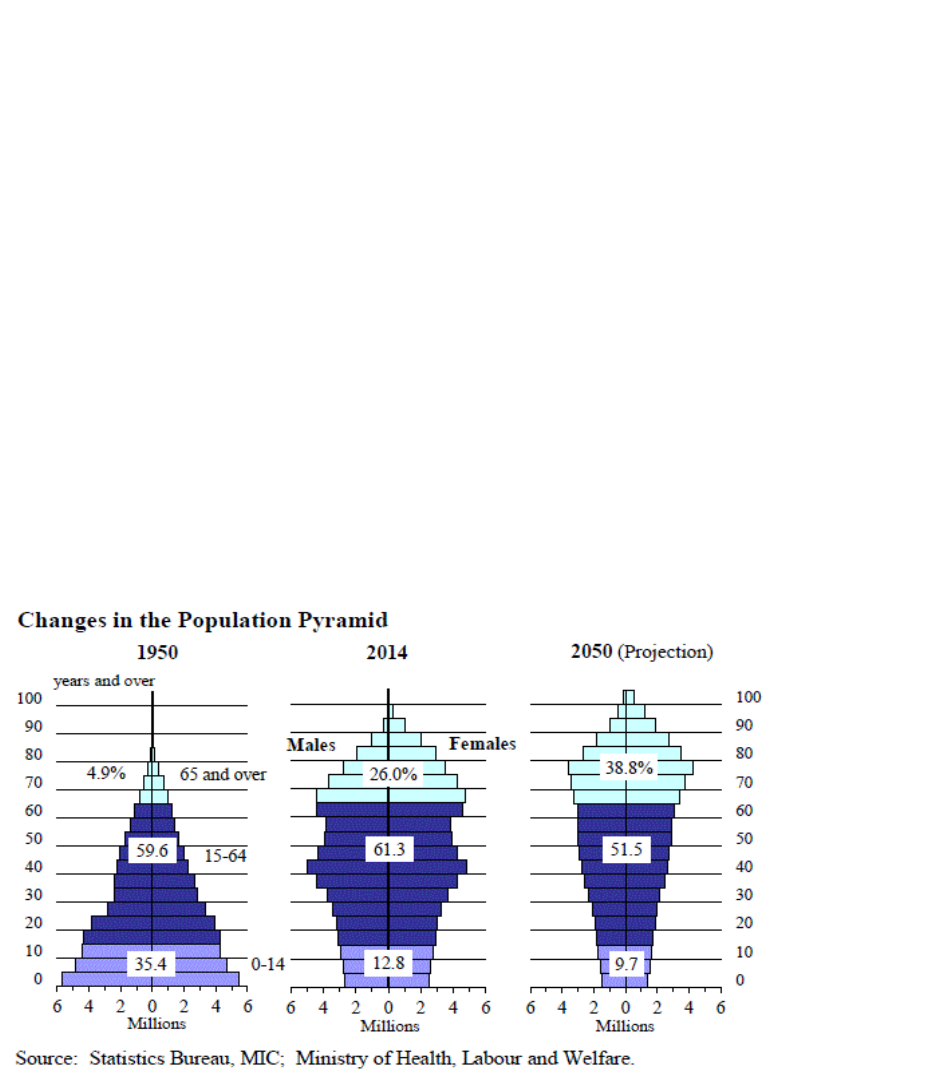

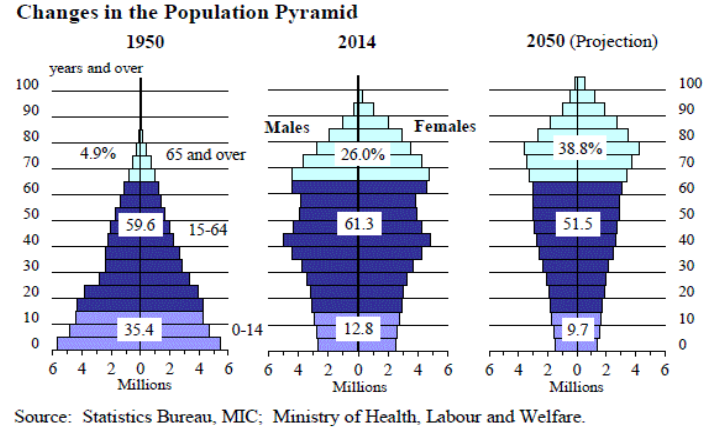

The growth charted in Table 1 led to the changes charted in Figure 1, where we see the

population ratio at each age level. Figure 1 illustrates a clearer picture of demographic trends in

three age groups. The makeup of the population in 1950 was in the shape of a pyramid, where

the child age group from zero to fourteen (0-14) year old is at the base with the largest

percentage share, followed by people aged from 15-64 and with the elderly population

representing the smallest percentage. The population ratio changes quite a bit in 2014, when the

child age population shrinks from 35.4% to 12.8%. The elderly population grows from four

point nine percent (4.9%) in 1950 to 26% in 2014 (Statistical Handbook of Japan 2015, chapter

2 Population).

According to the most recent projections, the percentage ratio will continue to shift. It

will become more of a top down pyramid in 2050. The elderly population, at 38.8% will become

the second largest population and children will only represent about nine point sixth percent

(9.6%) of the total population. To put this into perspective, when we compare Japan to other

countries, we can more see the singularity and significance of such change. “In 2010, the

Japan GDP per Capita ($) Total Popuation (1,000) Rate of Population Change (%)

1975 4,600 111,940 1.35

1980 9,300 117,060 0.9

1985 11,000 121,049 0.67

1990 25,000 123,611 0.42

1995 43,000 125,570 0.31

2000 37,000 126,926 0.21

2005 36,000 127,768 0.13

2010 43,000 128,057 0.05

2014 36,000 127,083 -0.17

8

percentage of the population 65 and older in Japan was 23.0%, exceeding the U.S. (13.1%),

France (16.8%), Sweden (18.2%), and Italy (20.4%), indicating that the aging society in Japan is

progressing rapidly as compared to the U.S. and European countries” (Statistical Handbook of

Japan 2015, chapter 2 Population).

In 2010, Japan had one of the lowest numbers in terms of its child population of 13.2%.

Among these countries, the age of its working-age group is average. However, Japan has the

largest elderly population of 23% of all the other developed counties. In the population

projections of 2050, the child population is down to nine point seven percent (9.7%). The main

workforce age group 15-64 will also decline from 61.3% to 51.5%, and elderly population will

be the highest at 38.8% (Statistical Handbook of Japan 2015, chapter 2 Population).

Figure 1

Education Participation in Post War Japan

The Japanese New Cabinet was formed under the auspices of the Allied Powers in 1945.

Under this new cabinet, a new constitution was drafted with provisions for equal rights for

9

women. These provisions would not only ensure that both genders shared an equal playing field

in society, but would also promote and increase a new source of human capital. As Japan was

transformed to an industrialized country and experienced rapid expansion in its production and

development, the country needed more workers in order to meet the growing demand for labor.

The new constitution included an extension of universal voting rights, allowing Japanese women

who were at least 20 years old, to vote for the very first time. At the same time, an act known as

the Guideline for the Renovation of Woman’s Education stated that there must be equal

educational opportunities for women. In the prewar years, women simply aspired to become

good wives and mothers. Education was not considered relevant in those roles. A woman’s

access to education was therefore limited and any education she might receive was often of poor

quality. The new constitution delivered not only equal access to education and to educational

quality, it also stipulated that there should be mutual respect between men and women who

wanted to pursue higher education (Saito, 2014, 8-9).

In order to successfully implement equal access to education, the Japanese government

eliminated the regulatory barriers that prevented a woman from pursuing higher education.

Women’s universities and coeducational universities were established along with all-girl high

schools. Educational standards at middle schools for girls were brought up to the level of those

for boys. Faculty positions in universities were opened to qualifying women. In order for the

ideal of equal education to be realized, the Japanese government took practical and necessary

steps to ensure that women were prepared to succeed in school from the earliest ages. They

overhauled the kindergarten and early education systems and adopted the principle of

coeducation at all school levels (Saito, 2014, 9).

10

As this “Renovation” was enforced, the percentage of female students in high school

increased significantly. In the early 1950’s, 48% of boys and 36.7% of girls advanced from

middle school to high school. By 1958, the gender gap had closed significantly with 56.2% of

boys and 51.1% of girls entering high schools. Then in 1969, the advancement rates for women

surpassed boys, as 79.2% of boys and 79.5% of girls continued their studies in high school

(Saito, 2014, 10). By the late1990s, almost all women who completed a middle school education

would advance to high school (Shirahase, 2000, 49).

The new system for higher education began in 1949 with the basic mandate that there

should be at least one coeducational university in each prefecture. Of course, the number of

coeducation universities would increase in later years. A junior college system was established

with a greater emphasis on general education. In the early years of education reform, many

women preferred the shorter two-year commitment of a junior college since they thought it

would be easier and certainly much more cost-effective than a university education. Indeed the

female student percentage in junior colleges expanded rapidly from 67.5% in 1960 to 78.8% in

1970 and to 89% in 1980, eventually reaching 91.5% in 1990. Female enrollment in universities

also increased, but at a relatively slow rate compared to junior college. Percentages grew from

12.4% enrollment in 1955 to around 20-25% from 1975 to 1980 (Saito, 2014, 10). However, by

1996 those trends had shifted. In 1997, women's university enrollment reached 26% compared

to 23% enrollment in junior college (Shirahase, 2000, 49). Today women are still more likely to

enroll in a university than a junior college and in recent years, the enrollment ratio of female

students in university had jumped from 32.3% in 1995 to about 41.1% in 2010 (Saito, 2014, 10-

11).

11

The series of actions that the Japanese government undertook to help women access

higher education, move forward in their desired career and enrich their lifestyle, had profound

impacts on society as a whole and on families in particular. According to the Becker, (1981) and

Willis, (1994) stated now families understood that they were expected to invest in their children

and provide them with a quality education (Suzuki, 2006, 6). But over the years, the rising costs

of both public and private educational institutions have become a heavy burden for parents to

carry. Over the years, as enrollment rates of high school, junior college and universities have

risen, so have the costs. A recent educational, financial survey conducted by the educational

policy institute based in Washington D.C and Toronto demonstrated that of 15 developed

countries they surveyed, Japanese students carry the heaviest university financial burden

(Akahata, 2006).

In today’s Japan, national universities charge each student about 820,000 yen (8,200 US

dollars) yearly tuition, and private universities on average charge students about 1,310,000 yen

($13,100 US dollars). Since 1970, the cost of university has increased more than 51 times in

national universities and about six times in private institutions. About 70 percent of Japanese

students are attending private universities because national universities have limited space and

accept fewer entrants. Parents and students are responsible for almost all of the educational costs.

Scholarships are very limited and even were a student to get a scholarship, he or she would likely

have to repay it. In Japan, “scholarships” often charge interest and operate more like U.S. student

loans (Akahata, 2006). As a result, Japanese parents face a serious burden when it comes to their

children’s educational costs (Suzuki, 2006, 7).

The Tension between Work and Family

12

Young Japanese people having grown up in a period of rapid economic expansion and

having been highly educated, they have very high aspirations when it comes to their future lives.

They believe that if they work hard, and put in long hours, they can increase their chances of

getting a good job with prospects for promotion. However, as the global economy faltered, Japan

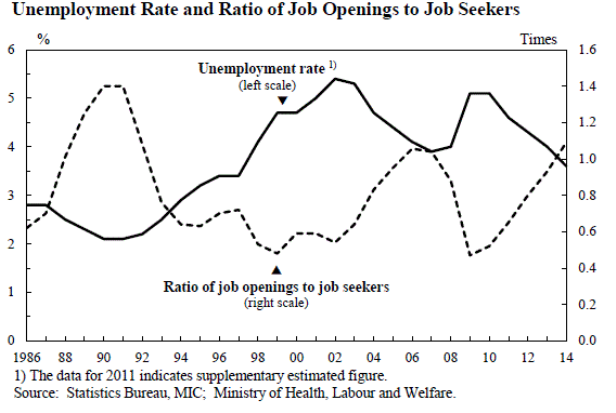

suffered economic hardships around the 1990s and 2008. The unemployment rate increased from

two percent (2%) in 1990 to five percent (5%) in 2003. It declined slightly and jumped again to

five percent (5%) from 2008 to 2010. Figure 2 from the Statistical Handbook of Japan 2015

shows unemployment rate pattern from 1986 to 2014. It indicates the ratio of jobs that are open

to the number of job seekers and it shows the unemployment rate. As we can see, the number of

people who want to work far exceeds the low supply of jobs that are available to the job seekers.

(Suzuki, 2006, 7).

Figure 2

The economic downturn has had a significant impact on labor market conditions and has

certainly not given Japanese youth the ability to realize many of their career ambitions. Their

ability to obtain a stable and secure job dropped from 77.8% in 1988 to 55.8% in 2004, and the

number of people in the part time or temporary workforce increased from nine point four percent

13

(9.4%) to 24.6% in the same period (Suzuki, 2006, 7). According to Easterlin, 1979 and Yamada,

1999, young workers who are saddled with student debt and who are finding it hard to achieve

their expected standard of living will hesitate to get married and start a family (Suzuki, 2006, 7).

Therefore, more young people are postponing marriage. As C. Ueno in a 1998 report showed,

education reform and the growth of educational opportunities for women also put pressure on the

job market because it made it more acceptable for women to work outside of the home, and

obtain a professional position (Shirahase, 2000, 48). In the latter part of the 20th century, we saw

an increase in women’s economic power as women pursued education, expanded their career

opportunities, and held more important positions in the workforce. This also impacted population

trends as more women delayed marriage and children to focus on their career. Indeed Japan’s

National Institute of the Population and Social Security Research report of 1998 found that

women in their twenties who have a higher education tend to shift their focus to career goals

rather than pursue marriage. The rise of the working woman in Japan has also had other

consequences. When working women do marry, they face higher divorce rates due to conflict

over the gender-based division of labor in regard to raising children (Becker, 1991, 135-154). As

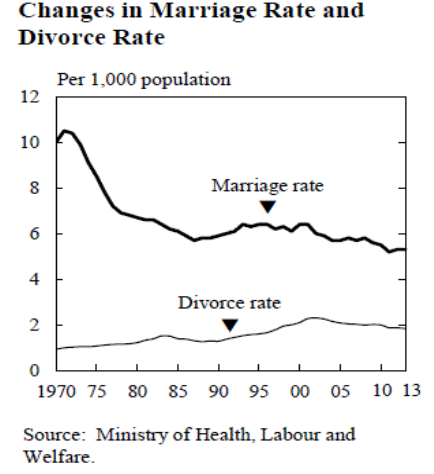

demonstrated in Figure 3 collected from the Statistical Handbook of Japan 2015, marriage and

divorce trends, show significantly different patterns over the decades. In the 1970s, we can see

high marriage rates and low divorce rates. Over the years, marriage rates decline sharply while

the divorce rate steadily increases.

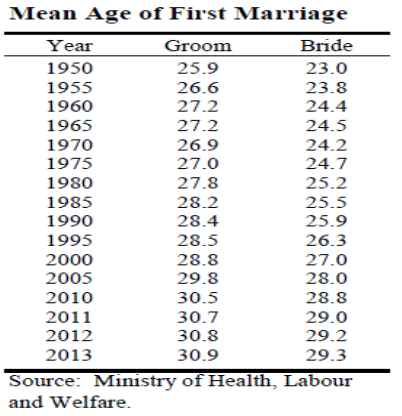

In 1990, according to Robert D. Retherford, Naohiro Ogawa & Satomi Sakamoto, 1996,

presented the average marriage age of a Japanese couple was 28.4 for a man and 25.9 for a

woman, only surpassed by Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Denmark (Boling, 1998,

174). Table 2, also presented from the Statistical Handbook of Japan 2015, shows the average

14

age increase of first marriages for Japanese couples over time. From 1950 to 2013, the rates for

both men and women have increased steadily. In the early 1970s, men married by the age of

25.9. By 2013, the marriage age had increased to almost 31-year-s old. In women the increase

in marriage age is even more profound. In the 1950s women were likely to marry at 23, which is

just one point three (1.3) years younger than the age at which a man might marry. In 2013

women are more likely to marry when they are almost 30. As the age rates have increased both

for men and women, the gap between the average age of a man and woman remains more

consistent. In 2013 it is one point six (1.6) years.

Figure 3

Table 2

15

With marriage age increasing along with divorce rates the National Institute of

Population and Social Security Research shows that throughout the later decades of the 20th

century and the beginning of the 21st century, Japan experienced a serious decline in the total

births of children. The drop in birth rates started in the early 1950s, continued to the mid-1980s

and then accelerated. By the 1970s it had fallen below the population replacement rate of two

point one (2.1) children per woman. These figures suggest a negative correlation between the

increasing advancement of women admitted into higher education studies and the decrease of the

number of children are being born (Shirahase, 2000, 49-50).

The Challenges of Marriage and Childbearing in Contemporary Japan

According to Robert D. Retherford, Naohiro Ogawa & Satomi Sakamoto, 1996 stated

most young people in modern societies, are not in a rush to settle down. They want to enjoy

their youth and the freedom it brings. They also understand practical realities such as the need to

save money in order to afford the expensive down payment on a condominium or house before

marriage. It is very costly to begin married life in Japan, especially for women, In Japan the costs

can be calculated not just in terms money but also in opportunity. In the current working

16

environment in Japan, professional women who going to have a child or had a child are more

likely to be sidelined at work. They are expected to have the majority role in childrearing and

become stay-at-home home moms (Boling, 1998, 174-175). According to a study published by

Retherford, Ogawa and Sakamoto in 1996, women not only have to figure out how to juggle

work and family, they also have to commit to raising their children almost single-handedly. They

will have very little help raising their children as fathers in Japan are often absent when it comes

to the practicalities of childcare. Women will therefore be asked to find the time and energy for

their jobs and for their families (Boling, 1998, 174-175).

The contemporary urban environment of Japan also presents difficulties that may

constrain a young couple’s ability to raise a family. According to Higuchi, Marumoto, Yanson

and Domoto (1991), the majority of couples can only afford to live in very small apartments

where there is little room to raise children (Boling, 1998, 175). In addition the urban

infrastructure is not set up for families. There are a limited number of public parks where

children can play, and the ability to find spaces to play with other children is also limited

(Boling, 1998, 175).

Another factor that may have a limiting effect on the birth rate is that many people are

not in favor of the existing hyper-competitive environment that has been created by the Japanese

educational system. The heavy emphasis on educational success in the one-time school entrance

examination is unfair in that it dictates a student's success in their future life (Boling, 1998, 179).

Students face many examination pressures, because in order to enter a good university they have

to reach a certain score in the school entrance examination and that is the only score that matters.

The consequences of MacArthur’s decision to mandate that women have equal access to

higher education had both positive and negative consequences for Japan. The positives are that it

17

established the idea of gender equality, closed the gender gap between men and women and gave

women the same freedom as men in many aspects of society, from access to education, to

unlimited future career opportunities. The Japanese economy was able to expand as the labor

demand was met by working women. There was also one major negative impact of that social

revolution. When women are educated and become full participants in the labor force they

invariably delay marriage and have fewer children.

The sharp drop in the birth rate in Japan when combined with the aging trend, has had a

serious immediate impact on the overall population. Japan’s total fertility rate first hit below two

(2) in 1975 and then continued to drop. In 1990 it had dropped to one point fifty seven (1.57),

and then to one point forty three (1.43) in 1995, one point thirty nine (1.39) in 1997 and one

point thirty four (1.34) in 1999. In 2001, the Japanese newborn population was reduced by

18,822 compared to 2000, and Japan’s fertility rate hit one point thirty three (1.33). Furthermore,

the number of newborns in 2002 was just 1,156,000, a decrease of about 150,000 from the

previous year (Wang, 2003, 129-130).

The Current Number of Newborns and Its Impact in the Future

According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 2012

report, the number of births in Japan will continue its downward trend and only intensify in the

future. It is predicted that, in the next 50 years, the annual newborn population in Japan will

experience a significant decline from 119 million in 2001 to 67 million in 2050. The Japanese

population reached its peak of 127 million in 2006. After that the annual number of deaths began

to exceed the number of births. In 2027, it is projected that Japan’s population will decline to 112

million, and in 2040 the number will drop below 110 million. The Figure 1 clearly shown the as

to 2014, the elder population is 26% out of the total population. Then, according to projections,

18

in 2050, the elderly population ratio would reach 38.8%, and the average life expectancy of

Japanese men and women will reach 81 and 90 respectively as compared from 70 in 1970. This

means that one in every three people will be an elder (Wang, 2013, 130). According to the Japan

Statistical handbook of 2015, the social security spending has grown from 14,543 billion Yen in

1995 to 31,530 billion Yen in 2015. The spending is most triple in the last 20 years, which is able

equivalent to 33% of the total government expenditures.

Figure 1

The increase in the elderly population of Japan brings with it an increase in the number of

elders who are dependent on the rest of the population for support and an increase in the

financial burdens on the younger generation. As the population ages, more and more seniors

retire from the workforce. They pay less tax and do not create any material wealth. However

seniors continue to consume since they must address their daily needs and they require more

medical and nursing care, which can be very costly. Retirement pensions, medical costs, health

care costs and social welfare costs are escalating rapidly in Japan. The working population must

bear a disproportionate share of these costs and the problem is compounded since the growth in

19

the elderly population is far outpacing the rate at which younger people can contribute to the

social security system. According to the projections already cited from the National Institution of

Population and Social Security Research, if in 2050, every one of three people is an elder, then

the other two Japanese people have to contribute enough to society to take care of this elder. In

all likelihood, some of these people will be children, or students, so the actual workforce will

carry the heaviest social burden. The continuation of this trend will seriously impact the future of

retirement pensions, medical and other social benefit programs in Japan. Therefore, the Japanese

quickly need to solve the problem and find a long-term solution that will help them both to fund

elder care and to address the declining birth rate (Wang, 2013, 130).

Immigration policy, Japan VS Australia and Canada

Given the population shift and decline in Japan, one fundamental economic issue facing

the country is the fact that the workforce is shrinking. One obvious strategic response to this

would be to reform the country’s immigration policy. If Japan was to welcome new immigrants,

those immigrants could help bolster the shrinking workforce and boost the nation’s productivity.

Many Western countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia have historically enacted

immigration reforms when they need to admit new immigrants and solve labor shortages.

Australia experienced an economic boom in the post-Second World War period, when, in

1945, they welcomed about 6 million immigrants. Due to the continual arrival of new

immigrants, the population of Australia has increased from 7 million people to over 20 million.

As author Jock Collins stated in 1991, the immigration policy in Australia was used partly to fill

labor shortages, and also, to add more people to the overall population. Charles Price, an

Australian demographer, characterizes the country as one of the world’s quintessential

immigration countries and indicated that the Australia economy acts like a hungry snake or boa

20

constrictor. It has a great appetite for immigrants during the economic boom years but slows

down its intake of immigrants when faced with a recession. During the post-war period,

Australian immigration policy was primarily driven by the labor market, its purpose being to

fulfill labor market needs (Collins, 2009, 1).

A second post-war economic boom in Australia, driven primarily by globalization, has

led to changes in immigration intakes and given rise to policies that are considered better suited

to Australia’s new economic structure and growing labor needs (Collins, 2008, 244–266). The

immigration policy initiatives now have four major parts that address both the domestic economy

and globalization. The first change was to increase the number of permanent residents admitted

to Australia in accordance with the needs of the business cycle. Secondly, the government chose

to encourage more skilled and professional immigration rather than family migration (which was

prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s). To help solve specific labor shortages it created a list of

occupations in demand so that certain professionals and skilled laborers would be given priority

in their immigration status. Thirdly, Australia increased the number of temporary migrants to

fulfill short-term labor needs. Lastly, the Australian authorities became more aware of the

importance of greater security measures in its immigration screenings as a result of the events of

9/11 and other terrorist acts. The government’s crackdown on illegal immigrants has been

uncompromising. . These four major immigration policy initiatives, which facilitate both

permanent and temporary migration, have helped Australia address the labor shortages in the

market and successfully participate in the new global economy (Collins, 2009, 2).

Japan is one of several countries that face shortages in the labor market. Canada also

faces a similar problem. According to Peter Veress, the president of Vermax Group, a company

that recruits temporary foreign workers, the most obvious solution is immigration. Veress, who

21

served as a former officer of the Department of Immigration, has said that he is thrilled that he is

the leader of a corporate immigration and international recruitment strategy company because of

the opportunities it brings both for his company, for his clients and for countries who need

skilled workers. Veress states that it is a win-win–win solution. He understands the

underpinnings of Canada’s labor situation and cites the fact that population growth is negative,

and the current population is aging. He also notes the greater demand for skilled and professional

workers. Veress says his company effectively solves the labor shortage and skills shortage by

recruiting temporary migrant workers (McNaughton, 2013, 1-4). Raj Sharma of Steward Sharma

Harsanyi Immigration, Family, and Criminal Law states that to employ a foreign worker, a

business needs to show the salary of foreign workers would not create a downward trend in the

labor market. The company cannot just hire cheap foreign workers to replace Canadians.

Additionally, they have to show that they have tried to recruit for the position and demonstrate

that the foreign worker is not likely to take away a job from a qualified Canadian.

Labor shortages can have a critical effect on business growth and development. One can

cite the fact that one of the biggest Canadian Oil and Gas Company, in Alberta faces labor

shortages that are expected to cost the company more than $33 billion over the next few years.

The choice is simple. More foreign workers or the loss of $33 billion in taxable dollars. For

most Canadian capitalists, it is a quick, simple choice (McNaughton, 2013, 5-8).

Canada and Australia faced labor shortages just as Japan does today and the experience

of both countries suggests that overhauling immigration policies might be a solution to the labor

shortage in the Japanese market. However, there is significantly different between Australia,

Canada and Japan, in that Australia and Canada have historically been known as countries built

on immigration, whereas Japan is not. Immigration reform in these two Western countries was

22

supported both by the government and its people. Japan has never been thought of as a country

that either welcomes or needs immigrant. The issue of immigration has been in the background

for decades. Now, however, a combination of economic and demographic changes has brought

the immigration issue to the forefront of Japanese policy debate as well as to the public’s

attention (Papademetriou and Hamilton, 2000, 9).

Historically, Japan has always been a homogenous society with a singular culture and

unique traditions. It did not welcome international migration in the post war period and its

governmental policies rarely permit foreigners to become Japanese nationals. Due Japan’s 200

years of isolation periods, which not until 1835 when the United State came and connect the

Japan with rest of the world (U.S Department of the State, Office Of the Historian Milestones:

1830-1860) Of course, if the Japanese were to rethink these policies it would have a significant

impact. Current population trends show an approximately 38% decline in every generation since

the 1970s. If this population gap is filled by immigration, the majority of the Japanese population

will be foreign born after only two generations (Retherford and Ogawa, 2006, 35). Therefore, the

Japanese government has taken both direct and indirect actions to limit and tighten immigration

policies while still trying to manage the gaps in their labor force. Primarily policy makers have

depended on three strategies that have met with varying degrees of success. First, Japan has

systematically pursued foreign investments and relocated a great number of production and

assembly jobs overseas, so as to offer some relief from the labor pressure in Japan. Secondly,

Japan made extensive amendments to the 1952 immigration laws in order to welcome certain

categories of foreign workers into the country. These changes expanded new temporary

immigration categories and were designed to encourage foreign workers with in-demand skills to

pursue their professions in Japan. Changes in the 1990 immigration law also permitted people of

23

Japanese descent who are living aboard to immigrate to Japan, and provided additional rights,

job-training programs and other benefits to the children and foreign spouses of Japanese citizens.

The change of this immigration law has attracted about 300,000 Japanese Diasporas to come to

Japan and work and most of them come from South America countries, such as Brazil.

(Kingsberg). This tightly controlled and limited expansion of Japan’s immigration system not

only helped fill some of the vacancies in the labor market, it also helped fulfill some of Japan’s

obligations under the International Trading Regime. Thirdly, the Japanese authorities allowed a

significant number of foreigners in the 1990s to work without legal documentation in many of

the secondary labor markets and in the underground economy. The Japanese government,

however, remains committed to prosecuting illegal immigrants and currently demands that all

workers present appropriate documentation of their eligibility to work. Without it they face

deportation (Papademetriou and Hamilton, 2000, 2-4).

These three strategies successfully limited the number of immigrants entering Japan

while providing some flexibility around foreign labor, however they did not address the central

issue of massive labor shortages in a way that made sense for the long term (Papademetriou and

Hamilton, 2000, 2-4). Many Asian immigrants consider Japan to be an attractive destination,

especially since Japanese wages are often much higher than those in their own countries.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that

pension expenses will double from 1995 to 2020.With social costs like these rising, immigration

seems to be the only sure way that Japan can stay both internationally competitive and address

the domestic costs of population decline. However, the issue is not a simple one. Japan has not

been welcoming to immigrants since the Japanese have a deeply rooted sense of social and

cultural identity and tend to alienate outsiders. This attitude has influenced and limited

24

immigration policy (Papademetriou and Hamilton, 2000, 7). While labor shortages have led

Japan to reconsider temporary migration, many Japanese remain fundamentally opposed to

allowing more permanent immigration (Papademetriou and Hamilton, 2000, 47). This attitude

will take time to change. However change is possible. Even though, the overall foreign

population is about 1.6% of the total population in Japan, one of the lowest of the industrialized

countries, the number of foreigners was increasing up until 2008. Then the global economic

crisis and the Earthquake of 2011 lead to a decrease in the number of foreigners. However the

number of permanent foreign residents is slowly increasing and in 2011 there were one million

foreigners in Japan (National Institute of Population and Society Security Research, 2014, 3).

Family incentives policies since 1970s

While Japanese population decline and labor shortages can be addressed by changes in

the immigration policy and increased admission of both temporary and permanent residents, the

government has also tried to intervene by introducing policies that incentivize Japanese couples

to have more children.. The following chart (Table 3) illustrates some of the family incentive

policies the central government has enacted over the years.

Table 3

Total Fertility Rate Year Government Policies

2.14 1972 Establishment of the Child Allowances

1.54 1991 Enactment of Children Leave Act

1.53 1994 Announcement of Angel Paln for 1995-1999

1.5 1995 Enactment of Childcare and Familly Care Leave Act

1.42 1999 Announcement of New Angel Plan 2000-04

1.34 2001 Amendment to the Employment Insurance Law

1.33 2002 Annoucement of "Plus One" Plan

1.29 2003 Child Welfare Law

1.29 2004 Announcement of New Angel Plan 2005-09

1.39 2010 Child Allowance

25

Sources: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research of 2003 at the Robert D.

Retherford and Naohiro Ogawa, 2005. Total Fertility Rates were accessed from the World Bank

Data of Total Fertility Rate of Japan. The 2003 Child Welfare Law was taken from Child Related

Polices in Japan in 2003. The last two recent Child Allowances were from the 2014 Report of

Social Security in Japan from National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

The Japanese government employed family incentive policies as early as 1972, when it

established child allowances. At that time, the total fertility rate of two point fourteen (2.14)

helped maintain Japan’s population at a time when the economy was still growing. The child

allowance was a lifeline for lower-income couples that wanted to raise a third child. The cost of

the child allowances was funded by all levels of the government, as well as by employers. This

allowance was expanded to cover the second child in 1986, then the first child in 1992. In 1992,

the aim of the government was simply to encourage more births in Japan (Retherford and

Ogawa, 2005, 26).

In 1990, the Japanese government established the inter-ministry committee of “Creating a

Sound Environment for Bearing and Rearing Children” to concentrate on improving the lives

and circumstances of couples who wanted to have children. Under this committee, the Childcare

Leave Act was enacted on April 1st, 1992. The law stated that either the mother or father of a

newborn infant could take up to one year of unpaid leave, if they qualified as a full-time

employee. Temporary workers and part-time workers were not included in the law. The goal of

this law was to make child rearing easier for working women who had to juggle responsibilities

for their children and their careers. The law directly affected companies and organizations that

had more than 30 employees. Companies and organizations with less than 30 employees were

able to opt out of the law until 1995. However, the law did not establish any consequences for

noncompliance. As a result it did not have a significant impact on increasing births as shown in

the total fertility rate of one point five (1.5) (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005, 27-28).

26

In 1994, the Ministry of Health and Welfare introduced an emergency five-year proposal

to improve daycare services. One year later, in 1995 the plan was expanded to a ten-year plan

with an assist from the Labor, Construction and Education Ministries. The plan was officially

known as the plan on “Basic Direction for Future Childrearing Support Measures, but it also

came to be known as the ‘Angel Plan’ (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005, 29). The plan was

conceived to create support measures that would help women balance their work and home lives,

it provided governmental support to help families raise children and offered inexpensive housing

to some families with children. The plan was intended to create a child-friendly environment in

Japan and to relieve some of the financial burdens associated with child rearing (National

Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Child Related Polices in Japan, 14). It

sought to expand day care service centers and reduce work hours for parents. The number of day

care centers that offered infant services was increased by a third, with centers offering longer

hours. Centers that offered temporary or drop-in care were expanded seven fold. There was also

an increase in the number of centers that cared for sick infants, a doubling of the number of after-

school, day care centers, and increases in the number of regional centers offering child-raising

support (Boling, 1998, 5). These newly established daycare centers were funded by the local

government and with appropriations from the national government and the annual budget of the

Ministry of Health and Welfare (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005, 29). The fee for these centers

varied by location and the services they offered were extensive. Some centers provided pick up

services from parents’ homes or local schools; others provided medical care for sick children in

the event that a parent could not pick up their child immediately (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005,

29).

27

As in the child allowance model, the Angel Plan’s services were income-based. Couples

who earned more paid more. The eligibility criteria also varied by region and by demand. In

rural areas, where demand for the services was low, the eligibility requirements were more

relaxed as local governments attempted to attract more couples to use the services. In some

urban areas, where demand was high, supply was low and there were long waiting lists for every

day care spot, many couples with higher incomes simply did not qualify for services (Retherford

and Ogawa, 2005, 29). Lastly, Japan provided free counseling and back up child care support to

first-time parents, especially to couples who were living far away from their families (Boling,

1998, 5). As the result of the Angel Plan, the capacity of daycare centers for children zero to two

jumped to 564,000 in 1999 from 451,000 in 1994 (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005, 28).

The Childcare and Family Care Leave Act of 1995 replaced the 1991 Childcare Leave

Act. Under this new act, full-time workers were granted up to a year of leave for either childcare

or to take care of sick family members. Additionally, employees were able to receive 25% of

their regular salary. These benefits would be provided by the National Employment Insurance

Scheme which had first been created by the central government for the purpose of paying

unemployment benefits. (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005, 29).

The ‘few children’ crisis was broadly debated in the public; however, the issue was not

receiving the same level of responsiveness and attention as that given to the aging of Japanese

society. The Angel Plan and the Parental Leave Act had great aims, but the government did not

provide sufficient funding to assure the success of the policies and they also did not create

appropriate mechanisms to outlaw discrimination against women with children or pregnant

employees (Boling, 1998, 184). Some believed that there was simply not enough money to

support both elder care and childcare adequately (Boling, 1998, 178). By late 1996, officials

28

began to realize that the Angel Plan was unable to fulfill its mission, since local governments

could not provide the proper amount of funding to support the plan. In October 1996, The

Ministry of Health and Welfare declared that the day care center expansion program would be

curtailed and services would be cut, in certain cases by half (Boling, 1998, 177).

In 1999, a new version of the Angel Plan, the New Angel Plan of 2000 to 2004, officially

known as the “Basic Principle to Cope with the Fewer Number of Children” was introduced. It

addressed more specific intentions and goals in the areas of employment, childcare, health

education and housing with eight listed measures. These included: more easily accessible

daycare centers and childcare services; more child-friendly work environments; a proposal to

address changing the traditional view of gender roles and “work first” attitudes in the workplace:

an improvement in maternal and child health services; a proposal to improve local educational

environments and reduce the financial burden on families created by the education of children,

and lastly an emphasis on creating child-friendly housing and public facilities for children to play

(National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Child Related Polices in Japan,

15). It further expanded the number of daycare centers and the capacity of the centers for zero to

two year-old children. The number of day care centers increased from 456,000 in 1990 to

664,000 in 2002. After-school sport and other activities also expanded nationwide with 671,000

children enrolled in 2003. Moreover, it led to the expansion of family supports centers from 82 in

2000 to 286 in 2002. By 2003, about 307 cities and towns received government funding to

support the improvement of babysitting services (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005, 29).

A new amendment was adopted to the Employment Insurance Law. It again sought to

make it easier for employees to take family leave in order to care for their children or family

members. Under this insurance law, full-time employees were eligible to receive up to 40% of

29

their salary rather than 25%. The benefit was still provided under the National Employment

Insurance Scheme. However, this law effectively began to discourage employers from hiring

women as full-time, employees. The statistics show that between the years of 2000 to 2004, the

number of married women, under age 50 who were employed as full-time employees dropped

significantly and the number of part-time workers increased. This trend suggested that married

women would have a harder time securing full-time employment in the future (Retherford and

Ogawa, 2005, 31). It can be safe to assume that such employment trends might have further

discouraged women from getting married and raising children in their 20s, further delaying the

marriage age. The benefit also created a situation where women who did want to have children

would be more likely to have to find part time rather than full time work (Retherford and Ogawa,

2005, 31). In one way, the purpose of government, which was to help working women be able to

take child leave backfired. The government actually created a system that discouraged employers

from hiring women, especially potential mothers, as full time employees.

In 2003, the Child Welfare Law was amended. The new law was designed to address the

welfare of all children, not just children whose parents needed access to affordable childcare.

Under the law, local governments were asked to support childcare activities and provide services

such as counseling for parents, day care centers and childminders (National Institute of

Population and Social Security Research, Child Related Polices in Japan, 17).

Another plan known as “Plus One” officially known as the “Measure to Cope with a

Fewer Number of Children Plus One” was announced in 2002. The government believed that

one of the major factors contributing to the low birth rate was the fact that fathers were

essentially nonparticipants when it came to the issue of child rearing. The plus one suggested that

women would need help in addition to any that might be given by their husbands, and the plan

30

was also designed to encourage men to play a bigger role in the process of raising children. The

plan set out provisions that men could take at least five days of paternal leave from work when

their wife gave birth. It also intended to encourage all full-time employees, not just women to

take childcare leave. The hope was that the plan could encourage parents, especially men to

reduce their work hours so that they might bear more responsibility for child rearing. The New

Angel Plan of 2005 to 2009 wanted to increase the amount of time men spent on their children

and on housework by at least 2 hours and to reduce the amount of overtime worked by men in

their 30s by 25% in the week. Additionally, the plan expanded the number of family day care

centers from 358 in 2005 to 710 in 2010 (Retherford and Ogawa, 2005, 33-34). Additionally, the

plan stated that at least 25% of the eligible men and women who have pre-school age children

should be granted more flexible working schedules and shorter hours. The Plus One was

announced in 2002 and two laws that supported the plan goals were put in place in 2003. One

was the Law for Measures to Support the Development of the Next Generation and two was the

Law for Basic Measures to Cope with a Declining Fertility Society (Retherford and Ogawa,

2005, 32).

The New Generation law targeted large companies with more than 300 workers, no

matter if they are full-time, part-time or contract workers. Any employee who had been working

for the company for more than a year was protected under this law. The law called for companies

to submit a plan to create a family-friendly workplace and to help raise fertility levels and

encourage more births among their employees. The plan was to be submitted to local

government by the time the law was put into effect in 2005. Though no penalties for

noncompliance were stated, companies were urged to submit proposals and address the issue

within the next two to five years. When the action plan was approved the employer would

31

receive a government logo that could be used in advertising campaigns. The process of the plan

was to be evaluated by the Labor Bureau in local government and receive direction from the

Ministry of Health in central government. The target of the law was to increase the percentage to

25% of both men and women who take childcare leave. By doing this the government was

hoping to change the workaholic atmosphere of the workplace and allow employees to feel more

comfortable in taking time off for childcare leave. The Basic Measure Law did not indicate an

action to be taken, but rather set the stage for a future act of the government with the goal of

creating more child-friendly environment both inside and outside of the workplace (Retherford

and Ogawa, 2005, 33-34).

Since 2010, the Japanese government has worked to create a universal child allowance

regardless of income to encourage young couples to raise the child. The child allowances are

designed to provide direct monetary child support for families with children 15 and younger.

With this goal in mind, various kinds of child allowances have been established over the years.

The child allowance that provides monetary support for families with children 15 and younger

has increased from 5000 Yen to 15000 Yen (100 Yen is relatively equal to 1 US dollar). There is

also an allowance for single-parent household and parents of children with disabilities. Each

child allowance has different requirement for eligibilities (National Institution for Population and

Social Security Research, Social Security in 2014).

Conclusion

Japan has attempted to address the issue of its declining birth rates and super aging

society by making changes to its immigration policy and to its family incentive policies. Going

forward, both policies have their advantages and weaknesses. The advantage of future reforms to

the immigration policy is that if Japan were to open its doors to more immigrants, it would

32

immediately solve the problem of the country’s shrinking of working workforce. However, the

disadvantage is Japan would need to accept about 600,000 immigrants per year, which currently

is not feasible both politically and culturally. However, one alternative would be to increase the

number of international students allowed into Japan and extend the visas of students who pursue

a professional degree in Japan. Additionally, it could relax the restrictions currently on these

students allowing them both to live and work in Japan permanently. The college student

population would be the ideal immigration population of Japan because this demographic has

specialty and professional skills that are currently in demand in the Japanese workforce. Second,

they are eager to learn and be part of the Japanese culture. The international students are majority

come other Asian countries like China, Vietnam, Korea, Nepal and Taiwan. (Independent

Administrative Institution of International student in Japan 2015) Most of the international

students who study in Japan are interested in learning more about Japanese ways and are open to

adopting Japanese culture (Wang, 2013, 134).

Family incentive policies are designed to encourage domestic young couples to have

more children and to elevate the birth rate in Japan. Unfortunately, various family incentive

policies that have been put in place in Japan have not been effective. The total fertility rate has

remained low for decades. The problem with Japan’s approach to its family incentive programs

is that it was a very fragmented approach with different policies designed to attack different

problems and different stages (Demeny, 1972, 147–161). For example, the enactment of the

Childcare and Family Leave Act, which allowed full-time employees to take up to a year’s

leave to take care of a child or family member and which promised 25% to 50% of the salary

back during the period, backfired. Employers found the policy expensive and this created more

gender discrimination toward young women interested in taking full-time positions. Also, the

33

essential goal of the overall Angel Plan was to expand the number of day care centers. The

expansion of the day care centers, however only solved certain pressures for working women

with children. It did not encourage couples that do not have children to decide to have a child.

The ambitious goal to expand access to day centers was also compromised by the fact that the

government lacked adequate funding to reach its goal. This did not inspire confidence in the

policy. Overall, the most effective policy was that which awarded child allowances to young

couples and helped people who thought they could not afford to have children start families.

However, the initial child allowance was set at around 5000 yen per month. Given the extremely

high costs of education 5000 yen is not a very strong incentive. The current child allowance,

which increased to about 15,000 yen per month in 2012, is a more credible reflection of the

average monthly childcare expenses (Aoki, 2012, 9).

The best solution for the Japanese government if it wishes to alleviate the population

crisis and change the demographic shift is to take advantages of both immigration policies and

family incentive policies. On the one hand, Japan can increase the number of international

students they accept and relax immigration restrictions for workers who have professional skills,

such as nursing, medical, etc. that are in high demand. On the other hand, the Japanese

government must still place a huge emphasis on encouraging more births through family

incentive policies, such as the Child Allowance. Only by employing aggressive interventions will

the Japanese government be able to change its demographic trends, control immigration, assure

an adequate workforce and increase the number of Japanese births.

34

References

1. McNaughton, N. (2013). The immigration Solution for a Domestic Problem. Business in

Calgary, 23(9), 41-47. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from The immigration Solution for a

Domestic Problem.

2. Muramatsu, N., & Akiyama, H. (2011, May 24). The Gerontologist. Retrieved April 15,

2016, from https://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/content/51/4/425.full

3. World Development Indicators. (2016, March 30). Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

https://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_

4. Becker, G. S. (1991). The Demand for Children. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

http://public.econ.duke.edu/~vjh3/e195S/readings/Becker_Demand_Children.pdf

5. Boling, P. (1998). Family Policy in Japan - Homepages at WMU. Retrieved April 15,

2016, from http://homepages.wmich.edu/~plambert/boling.pdf

6. Child related policies in Japan. (2004). Tokyo: National Institute of Population and

Social Security Research.

7. Collins, J. (2009). Immigration And The Australian Labour Market. 23(4), 2-5. Retrieved

April 15, 2016, from Immigration And The Australian Labour Market.

8. Collins, Jock (2008). ‘Globalization, Immigration and the Second Long Postwar

9. Boom in Australia’ Number 61 June 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from Journal of

Australian Political Economy.

10. A. (2006, September 27). Japan's university tuition highest in the world. Retrieved April

15, 2016, from http://www.japan-press.co.jp/2006/2499/education.html

11. International Students in Japan 2015. (n.d.). Retrieved May 04, 2016, from

http://www.jasso.go.jp/en/about/statistics/intl_student/data2015.html

12. List of Statistical Tables Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan GL38020103.

(2010, April 16). Retrieved April 15, 2016, from http://www.e-

stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/ListE.do?lid=000001063433

13. Occupation and Reconstruction of Japan, 1945–52 - 1945–1952 - Milestones - Office of

the Historian. (n.d.). Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/japan-reconstruction

14. Okazaki, Y., & Tachi, M. (1969). Japan's Postwar Population and Labor Force. Retrieved

April 15, 2016, from

http://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Periodicals/De/pdf/69_02_04.pdf

35

15. Papademetriou, D. G., & Hamilton, K. A. (2000). Reinventing Japan: Immigration's role

in shaping Japan's future. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International

Peace.

16. Repatriation But Not "Return": A Japanese Brazilian Dekasegi Goes Back to Brazil 帰

郷」ならざる帰還 ブラジルに戻ったある日系ブラジル人出稼ぎ労働者. (n.d.).

Retrieved May 04, 2016, from http://apjjf.org/2015/13/13/Miriam-Kingsberg/4304.html

17. Retherford, R. D., & Ogawa, N. (2006). Japan's baby bust: Causes, implications, and

policy responses. Tokyo: Nihon University Population Research Institute.

18. Saito, Y. (2014). Gender Equality in Education in Japan. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

https://www.nier.go.jp/English/educationjapan/pdf/201403GEE.pdf

19. Shirahase, S. (2000). Women’s Increased Higher Education and the Declining Fertility

Rate in Japan. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

http://www.ipss.go.jp/publication/e/R_s_p/No.9_P47.pdf

20. Social Security in Japan. (2014). Retrieved April 15, 2016, from http://www.ipss.go.jp/s-

info/e/ssj2014/pdf/SSJ2014.pdf

21. Statistical Handbook of Japan 2015. (2016). Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c0117.htm

22. Suzuki, T. (2006, March). Fertility Decline and Policy Development in Japan. Retrieved

April 15, 2016, from http://www.ipss.go.jp/webj-

ad/WebJournal.files/population/2006_3/suzuki.pdf

23. Takada, M. (1999, March 23). Japan’s Economic Miracle: Underlying Factors and

Strategies for the Growth. Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

http://workspace.unpan.org/sites/internet/Documents/UNPAN95168.pdf

24. The United States and the Opening to Japan, 1853. (n.d.). Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/opening-to-japan

25. Wang, W. (2003). Japan's population trends and their impact on the organization of

society (日本人口机构的变化趋势及其对社会的影响). China Academic Journal

Electronic Publishing House, 127-139. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

26. WORLD HEALTH STATISTICS 2011. (2011). Retrieved April 15, 2016, from

http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS2011_Full.pdf