COMMITTEE ON HOUSE ADMINISTRATION

RANKING MEMBER JOSEPH D. MORELLE (D-N.Y.)

JULY 2024 | 118TH CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

REPORT ON

Voting for Native Peoples:

Barriers and Policy Solutions

COMMITTEE ON HOUSE ADMINISTRATION

RANKING MEMBER JOSEPH D. MORELLE (D-N.Y.)

JULY 2024 | 118TH CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

REPORT ON

Voting for Native Peoples:

Barriers and Policy Solutions

i

Note to the Reader ..................................................................................................................................................iii

PART I: Introduction and Executive Summary ............................................................................... 1

PART II: A History of the Relationship between Native Nations

and the United States and the Path to U.S. Citizenship ....................................................... 4

Colonial Period (1492-1777) ................................................................................................................................ 4

Articles of Confederation (1777-1789) ............................................................................................................ 6

U.S. Constitution and Early Federal Law (1789-1820s) ..........................................................................7

Removal and Relocation Period (1820s-1887) ..........................................................................................10

Stories of Removal ............................................................................................................................................10

Talks of Citizenship ............................................................................................................................................16

Elk v. Wilkins ........................................................................................................................................................19

Subjugation without Citizenship .................................................................................................................22

Allotment and Assimilation Period (1887-1934) .......................................................................................25

Allotment Policy ................................................................................................................................................25

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 ............................................................................................................29

Citizenship Without Its Privileges ....................................................................................................................32

PART III: Present Barriers to Political Participation ............................................................. 40

Extreme Physical Distances to In-Person Voting and Voter Services ......................................... 40

Refusals to Provide In-Person Voting On-Reservations ....................................................................41

Limited Hours for In-Person Voting on Reservations .........................................................................42

Insufcient Ballot Drop Boxes on Reservations ................................................................................. 43

Compounding Barriers to Voting in Person ........................................................................................... 43

Lack of Standard Residential Street Addresses and Sufcient USPS Mail Services ........ 45

Lack of Standard Residential Addresses on Reservations ............................................................ 45

Inadequate USPS Services and Vote by Mail ...................................................................................... 48

Disparate Impact of Voter Identication Laws on Tribal Citizens .................................................. 54

Inadequate Language Assistance ................................................................................................................. 58

Existing Federal Protections ....................................................................................................................... 58

Unmet Needs Under Federal Law ............................................................................................................. 59

Noncompliance with Federal Law ..............................................................................................................62

Vote Dilution and Racial Gerrymandering ................................................................................................. 65

Existing Federal Protections ....................................................................................................................... 65

U.S. Census..........................................................................................................................................................67

Vote Dilution through Discriminatory Districts and Electoral Systems ......................................76

Systemic Barriers Compounding the Direct Barriers ........................................................................... 89

Housing and Socioeconomic Conditions ............................................................................................... 89

Transportation and Physical Infrastructure ...........................................................................................92

ii

Discrimination and Neglect: From Outright Hostility to Failure to

Offer Robust Options for Participation by Tribal Members and

Government-to-Government Consultation with Tribal Nations ....................................................... 96

Ofcials Interfering with Voting and Voter Registration Opportunities ................................... 96

Lack of Opportunity for Government Consultation ..........................................................................102

Hostility in Border Towns, at the Polling Place, and from Government Ofcials ................104

Making It More Difcult to Find and Access Polling Places.........................................................108

Legislative Backlash to Increased Political Power............................................................................109

Hostility Toward Native Elected Ofcials ..............................................................................................110

PART IV: A Way Forward .................................................................................................................................116

Frank Harrison, Elizabeth Peratrovich, and Miguel Trujillo

Native American Voting Rights Act ............................................................................................................... 118

Freedom to Vote Act .............................................................................................................................................119

John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act ......................................................................................120

Further Action .........................................................................................................................................................120

PART V: Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................122

Acknowledgments ..............................................................................................................................................123

iii

Note to the Reader

When this nation took its rst steps onto the world stage, we did so with a deant declaration

that governments are “instituted” among citizens rather than kings, “deriving their just powers

from the consent of the governed.” The wellspring of sovereignty stems from the people

who grant their assent to the rule of law, who lend their faith to the collective efforts of their

neighbors—this is an ever-enduring truth. This conception of liberty is infallible; many of

those tasked with protecting, defending, and expanding that liberty have not been. Those who

have governed have too often misunderstood or ignored their obligations to the people of this

nation. This is why the United States—endowed with such promise—has so often struggled

to live up to the majestic words of our founding documents, to fully earn the consent of the

governed. Our history has been a constant struggle to repair these shortcomings.

This report details one such failing—the repeated refusals of successive state and federal

governments to either respect the unfettered entitlements of national sovereignty or extend

the full rights and privileges of United States citizenship—in particular the right to vote—for

the Native peoples of North America.

As the nation reects on the centennial of the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of

1924, the Democratic members and staff of the United States House Committee on House

Administration publishes this report with the aim of achieving two purposes. First, this report

sets out to establish a concrete record of the voting challenges that Native peoples have

historically faced in this country, produced in recognition of the millions of Native peoples

that Congress currently serves and in acknowledgment of the hundreds of millions that past

Congresses failed so completely. Second, this report demonstrates that Native peoples still

face tremendous barriers to their ability to cast a free, fair, and meaningful ballot in this

country, despite the covenant of citizenship.

Signicant work went into this report—in preparing this record, Committee members and

staff visited reservations or other Tribal lands across six states. Committee members and staff

also spoke to more than 125 individuals or groups dedicated to Tribal governance, organizing,

advocacy, or civil rights, and pored over thousands of pages of historical documents,

congressional records, legal treatises, judicial decisions, and countless other sources. While

the report is not exhaustive—there is so much more relevant history, so many additional

stories that could be included—it is my hope that this report represents a valuable perspective

on the history and current reality of Native voting in this country.

Throughout our efforts on this report, we heard time and again how the federal government’s

repeated breaches of trust and unfullled obligations have fractured our relationship with

Tribal nations and led directly to many of the obstacles this report uncovered. Undeniably,

the barriers Native peoples face to participating in federal, state, and local elections are both

substantial and unique, with each one amplifying the next. It is my belief that a thorough

understanding of this topic will compel any reader—and, hopefully, compel Congress—to

understand the urgent need for strong action to protect Native voting rights and begin to

iv

mend our relationship with Tribal nations and Native peoples. With clear eyes about both the

distressing history of Native voting in this country and the mountainous challenges that remain

for Native voters, this report makes clear that Congress owes bold, effective federal voting

rights legislation to our Native constituents, most pressingly in the form of the Native American

Voting Rights Act, the Freedom to Vote Act, and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

Only then can we hope to say in truth that the just power of the United States derives, nally,

from the full consent of the governed.

Joseph D. Morelle

Ranking Democratic Member

Committee on House Administration

PART I: Introduction and Executive Summary 1

PART I

Introduction and Executive Summary

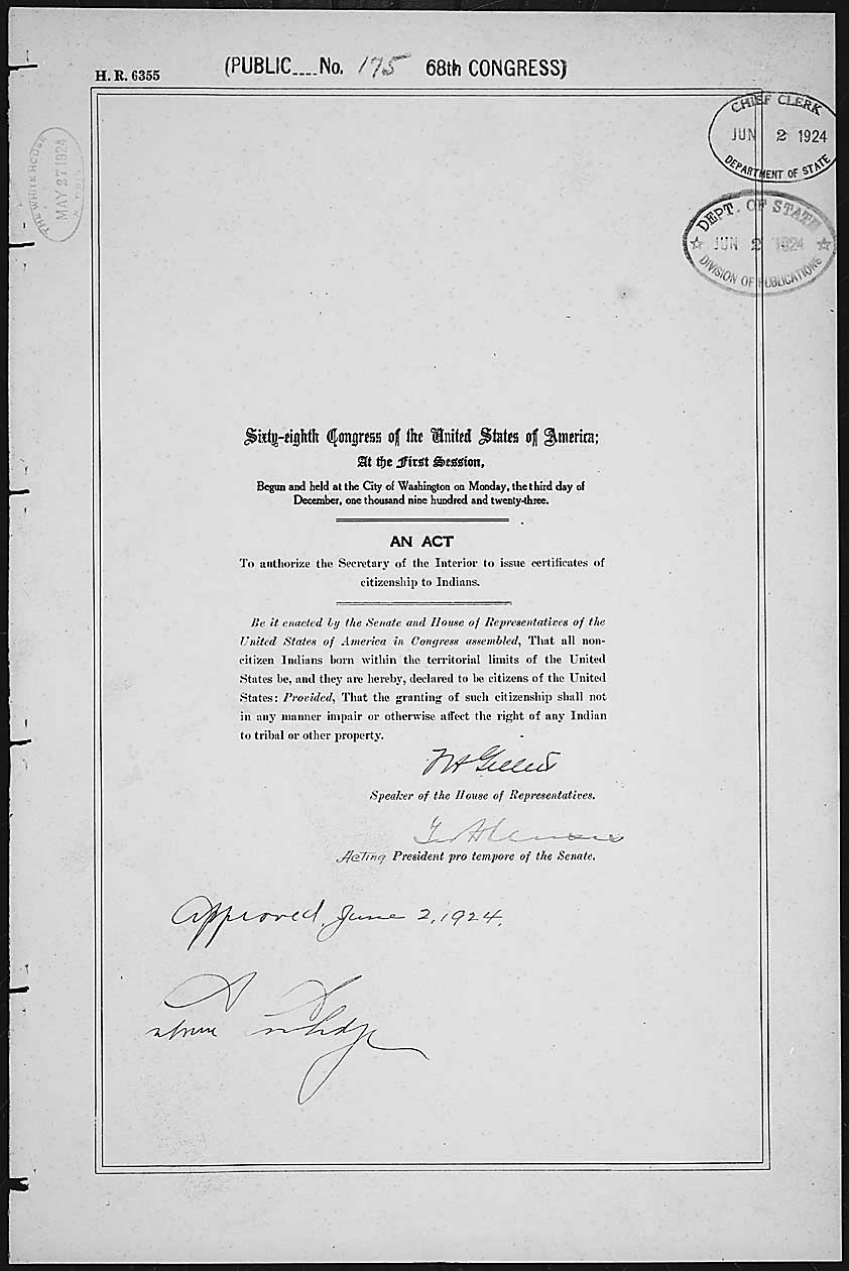

One hundred years ago, the United States Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924

(the “Snyder Act”), statutorily extending U.S. citizenship to Native peoples.

1

The path to U.S. citizenship for Native peoples is a complicated and troubling one. In the nearly

150 years between the United States’ founding and the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act,

the United States persistently attacked the inherent sovereignty of Tribal nations and forcibly

subjected them to increasing federal control.

2

As the edgling nation sought to expand its

territory, it used military force—sometimes supported by coerced treaties—to rid the land it

sought to occupy of Native peoples in order free it for white settlement.

3

To further the United

States’ objectives, Congress and the executive branch carefully designed federal policies that

would allow the federal government to encroach on the jurisdiction of Tribal nations and assert

increasing authority over individual Tribal citizens.

4

At the same time, Congress and federal courts repeatedly refused to recognize Native peoples

as U.S. citizens and extend to them the rights that U.S. citizenship promises.

5

Indeed, Native

peoples did not become U.S. citizens even after the ratication of the Fourteenth Amendment,

which guarantees U.S. citizenship to all persons born within and subject to the jurisdiction of

the United States.

6

Instead, throughout the nineteenth century, and into the early twentieth

century, the federal government considered citizens of Tribal nations “subjects” of the federal

government.

7

When authorities nally extended U.S. citizenship to Native peoples, they granted it on a

piecemeal basis and almost always wielded it as a weapon to undermine Tribal sovereignty

and forcibly assimilate Native peoples into U.S. society.

8

Indeed, before the passage of the

Indian Citizenship Act, the most common way for a Native person to become a U.S. citizen

was through allotment.

9

This process, which forcibly turned land held in common by Tribal

1 Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, Pub. L. 68-175, 43 Stat. 253 (Jun. 2, 1924).

2 See infra, Part I, Articles of Confederation (1777-1789)-Allotment and Assimilation Period (1887-1934).

3 See infra, Part I, U.S. Constitution and Early Federal Law (1789-1820s)-Allotment and Assimilation Period (1887-1934).

4 See id.

5 See infra, Part I, Talks of Citizenship-Allotment and Assimilation Period (1887-1934).

6 U.S. ConSt. amend. XIV, § 1; Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884) (holding that the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of

birthright citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” does not extend to citizens of Tribal

nations because they are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States); see also infra, Part I, Talks of Citizenship-

Subjugation without Citizenship.

7 See Relation of Indians to Citizenship, 7 U.S. Op. Att’y Gen. 746, 749-56 (Jul. 5, 1856); infra Part I, Subjugation without

Citizenship.

8 See infra, Part I, Allotment and Assimilation Period (1887-1934).

9 See id.

2 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

nations for the benet of their citizens into private property, was a key component of the

federal government’s strategy to deconstruct Tribal governments and turn Native peoples into

Americans—whether they consented or not.

10

Unlike the laws that preceded it, the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 promised to convey

protections of U.S citizenship to Native peoples, but crucially ensured “[t]hat the granting of

such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to

tribal or other property.”

11

Today, a century after the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, the full guarantees of U.S.

citizenship have yet to be fully realized. Indeed, Native peoples continue to face persistent and

substantial barriers to the right to vote in federal, state, and local elections.

12

These barriers

include:

● Having to travel extreme physical distances to access in-person voting locations

and voter services, often on dirt or poorly maintained roads and without reliable

transportation.

13

● Lack of standard residential addresses on reservations and failures of states and

localities to make voter registration and voting systems accessible to individuals using

descriptive addresses.

14

● Inadequate mail service by the United States Postal Service on reservations, including

a lack of home mail delivery, slow mail times, and insufcient post ofce boxes.

15

● Voter identication laws that disparately burden Native peoples, including laws that

fail to expressly recognize Tribal ID as valid voter ID, as well as ones that require voters

to present identication displaying a residential address or to obtain inaccessible

underlying documentation.

16

● Inadequate language assistance in Indigenous languages, including due to

noncompliance with existing federal law.

17

● Electoral systems, including at-large voting and district-based electoral maps, that

dilute the voting strength of politically cohesive Native communities.

18

10 See id.

11 Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, Pub. L. 68-175, 43 Stat. 253 (Jun. 2, 1924). Still, some Native nations and Tribal citizens

opposed the unilateral conveyance of U.S. citizenship to Native peoples without their consent. See infra, Part II, The Indian

Citizenship Act of 1924.

12 See infra, Part III, Present Barriers to Political Participation.

13 See infra, Part III, Extreme Physical Distances to In-Person Voting and Voter Services.

14 See infra, Part III, Lack of Standard Residential Addresses on Reservations.

15 See infra, Part III, Inadequate USPS Services and Vote by Mail.

16 See infra

17 See infra, Part III, Inadequate Language Assistance.

18 See infra, Part III, Vote Dilution and Racial Gerrymandering.

PART I: Introduction and Executive Summary 3

● Undercounts by the U.S. census and American Community Survey, which dilute voting

strength when the population counts are used for redistricting and undermine federal

laws that rely on the population counts for enforcement.

19

● Outright hostility toward Native voters by state and local government ofcials, election

workers, and fellow non-Native voters making it more burdensome for Native peoples

to access the ballot and discouraging them from participating in federal, state, and

local elections.

20

● A lack of trust of federal, state, and local governments due to persistent historic and

contemporary discrimination, leading to depressed voter turnout.

21

● Systemic barriers, which compound the direct barriers, including lower socioeconomic

status, inadequate transportation, and poor physical infrastructure.

22

Part II of this report provides an overview of the history of the relationship between Tribal

nations and the United States. Part III details present barriers to the right to vote for Native

peoples. Part IV provides an outlook for the future and describes legislation designed to

remedy many of the voting barriers discussed in this report. Part V concludes this report by

calling on Congress to exercise its constitutional authority to enact meaningful legislation to

protect the right to vote for Native people.

19 See infra, Part III, U.S. Census; id, Inadequate Language Assistance.

20 See infra, Part III, Discrimination and Neglect: From Outright Hostility to Failure to Offer Robust Options for Participation

by Tribal Members and Government-to-Government Consultation with Tribal Nations.

21 See infra, Part III, Lack of Trust and Low Voter Education Leading to Depressed Engagement.

22 See infra, Part III, Systemic Barriers Compounding the Direct Barriers.

4 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

PART II

A History of the Relationship between

Native Nations and the United States and

the Path to U.S. Citizenship

This Part provides a history of the relationship between Native peoples and the federal

government and the ways in which that relationship inuenced debates around U.S. citizenship.

This history is important for its own sake, but it is also the foundation of the contemporary

relationship between Tribal nations and the federal government. Many of the barriers to the

ballot that Native peoples face today can be directly traced to the abuses inicted by federal,

state, and local government actors throughout history.

Colonial Period (1492-1777)

From the beginning of European contact, Native peoples of Turtle Island—a name used for

North America that derives from various Indigenous creation stories about the origin of the

continent

23

—had complex and often formalized relationships with European settlers and

colonial powers. Generally, however, during the Colonial Period (1492-1777), European nations

properly understood Native nations as distinct sovereigns and recognized their inherent

authority to govern their citizens and lands.

24

Native peoples and Europeans generally lived

in “separate communities subject to different

sovereigns.”

25

As distinct sovereigns, Native and

European nations entered treaties, fought wars,

maintained alliances, and engaged in trade with

one another. Native peoples and Europeans were

citizens of their respective nations.

23 See Urban Native Collective, Turtle Island: A Testament to Sovereignty, https://urbannativecollective.org/turtle-island.

24 See Matthew Fletcher, Politics, Indian Law, and the Constitution, 108 Cal. l. Rev. 495, 505 (“Prior to the formation of the

United States, the relationship was one between foreign nations.”).

25 FRank PommeRSheim, BRoken landSCaPe: indianS, indian tRiBeS, and the ConStitUtion 17 (2012) [hereinafter “BRoken landSCaPeS”].

But see Gregory Ablavsky, “With the Indian Tribes”: Race, Citizenship, and Original Constitutional Meanings, 70 Stan. l. Rev.

1025, 1056 (2018) [hereinafter Ablavsky, “With the Indian Tribes”]. At times Tribal nations sought protection from the King

of England against other Tribal nations. Id. In these instances, “Indians were described as subjects too—by both British

Id. But Native peoples’ status as subjects of the King did not threaten their

status as members of autonomous Native nations. Id.

During the Colonial Period (1492-1777),

European nations properly understood

Native nations as distinct sovereigns and

recognized their inherent authority to

govern their citizens and lands.

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 5

After the Revolutionary War, little changed with respect to Native peoples’ citizenship. Despite

the founding generation’s outright hostility toward Native peoples,

26

the nascent United States

generally followed precedent for the nation-to-nation relations set during the Colonial Era.

27

In

a 1789 letter to President George Washington, General Henry Knox, the rst Secretary of War

of the United States, advocated that “[t]he independent nations and tribes of indians [sic] ought

to be considered as foreign nations, not as the subjects of any particular state[.]”

28

Similarly,

Attorney General William Bradford, the second Attorney General of the United States, argued

in a 1794 letter to Secretary of State James Madison that Tribal nations were not subject to

federal jurisdiction on Tribal lands.

29

In line with these views, in the late 1700s and early 1800s,

the United States negotiated distinct treaties with separate Tribal nations, regulated trade

with Tribal nations similarly to the way in which it regulated trade with foreign nations, and

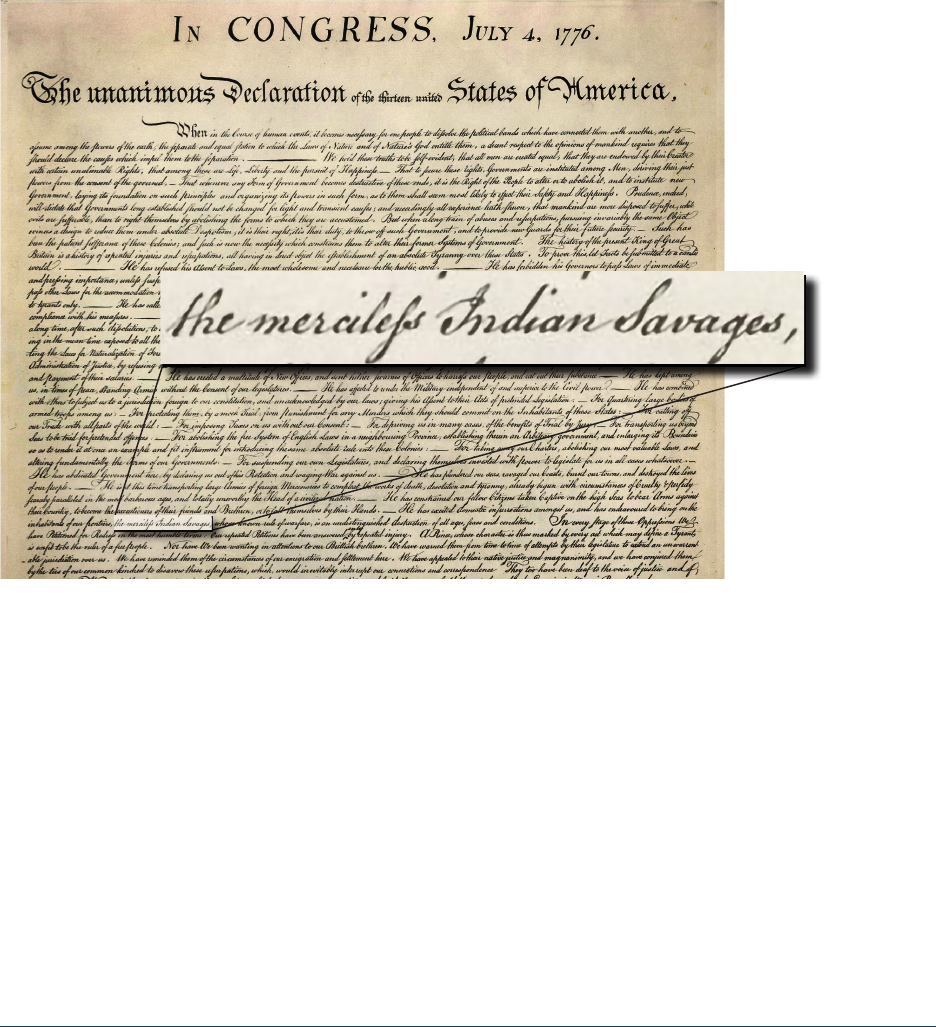

26 The Declaration of Independence, for example, refers to Native peoples as “the merciless Indian Savages, whose known

rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” the deClaRation oF indePendenCe, para.

2. See also James Duane’s Views on Indian Negotiations (1784), in 18 eaRly ameRiCan indian doCUmentS: tReatieS and lawS,

1607-1789, at 299, 299-300 (Colin G. Calloway ed., 1994) (noting in reference to the Haudenosaunee Confederacy that

former Ideas of Independence”).

27 See, e.g., PommeRSheim, supra note 25; Ablavsky, “With the Indian Tribes”, supra note 25 at 1055 (“Despite the new nation’s

[the United States] repudiation of many British precedents, Anglo-Americans largely adopted prerevolutionary diplomatic

practices, which regarded Native peoples not as an undifferentiated mass of “Indians” but as the polylingual, distinct

polities they actually were.”).

28 Letter from Henry Knox to George Washington (July 7, 1789), in 3 the PaPeRS oF GeoRGe waShinGton: PReSidential SeRieS 134,

138 (Dorothy Twohig ed., 1989).

29 See Ablavsky, “With the Indian Tribes”, supra note 25 at 1038 (describing the letter).

Figure 1. The

Declaration of

Independence

referred to Native

peoples as “merciless

Indian Savages[.]”

6 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

appointed agents to act as ambassadors to Tribes, representing the interests of the United

States.

30

Articles of Confederation (1777-1789)

The Articles of Confederation, the United States’ rst charter of government, solidied the

structure of the nation-to-nation relationship, treating Native nations as separate—and

potentially adversarial—sovereigns. Specically, the Articles of Confederation (the “Articles”)

prohibited states from waging war without the consent of the U.S. Congress “unless such

State be actually invaded by enemies, or shall have received certain advice of a resolution

being formed by some nation of Indians to invade such State[.]”

31

The Articles further gave the

U.S. Congress “the sole and exclusive right and power of . . . regulating the trade and managing

all affairs with the Indians, not members of any of the states; provided that the legislative right

of any state, within its own limits, be not infringed or violated[.]”

32

In other words, Tribes would remain separate

nations with whom the national government

would regulate trade and other affairs and

against whom the national government—

and potentially the states—could wage

war.

33

Moreover, while the Articles primarily

left decisions regarding citizenship and

30 Ablavsky, “With the Indian Tribes”, supra note 25 at 1055; see also Trade and Intercourse Act of June 23, 1790; Trade and

Intercourse Act of March 1, 1793, Pub. L. No. 2-19, 1 Stat. 329; Philip J. Deloria, American Master Narratives and the Problem

of Indian Citizenship in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 14 J. Gilded aGe & PRoGReSSive eRa 3, 9 (2015) (“The political mode

was nation to nation, and indeed, the very idea of Indian polities as sovereign nations (in the European sense) originates in

these treaty relations. The United States made that clear through the Trade and Intercourse Act of 1790, which insisted

that states and private entities could not negotiate treaties: those were legal and political acts that took place between

nations.”).

31 Articles of Confederation of 1781, art. VI, para. 5.

32 Articles of Confederation of 1781, art. IX, para. 4.

33 While the Articles of Confederation formally gave the national government the sole authority to manage affairs with Tribal

nations, relying on the Article IX’s prohibition on Congress “infring[ing] or violat[ing]” the legislative rights of the states,

some states asserted their own perceived authority to entreat with Tribes. See, e.g., W. Tanner Allread, The Specter of

Indian Removal: The Persistence of State Supremacy Arguments in Federal Indian Law, 123 ColUm. l. Rev. 1533, 1550 (2023)

these disputes were on full display at treaty negotiations with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Haudenosaunee in

with Native nations and illegally selling Native land.”); Gregory Ablavsky, The Savage Constitution, 63 dUke L.J. 999, 1018-

33 (2014).

Tribes would remain separate nations with

whom the national government would

regulate trade and other affairs and against

whom the national government—and

potentially the states—could wage war.

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 7

naturalization to the states,

34

these provisions make clear that Native peoples were not a part

of the national union.

35

Tribal nations were not members of the confederation of states, and

individual Native people would not be extended citizenship in the new United States.

36

U.S. Constitution and Early Federal Law (1789-1820s)

In 1789, when the 13 inchoate states abandoned the Articles of

Confederation in favor of the modern U.S. Constitution, the United

States reconsidered its relationship with Native nations, choosing

again to bar Native peoples from participation in the newly formed

union. At its inception, the U.S. Constitution expressly mentioned

Native peoples in two places. It rst considered the political

status of individual Native Americans, excluding Native peoples

from the population for the purposes of apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Article I, section 2, clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution provides:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several

States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective

Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free

Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding

Indians not taxed, three fths of all other Persons.

37

Native Americans thus did not receive representation in the newly formed representative

government.

34 See Torey Dolan, Congress’ Power to Afrm Indian Citizenship through Legislation Protecting Native American Voting Rights,

59 idaho l. Rev. 48, 52 (2023). In Federalist No. 42, James Madison cites the lack of uniformity in the citizenship and

The dissimilarity in the rules of naturalization has long been remarked as a fault in our system, and as

laying a foundation for intricate and delicate questions.

. . .

The very improper power would still be retained by each State, of naturalizing aliens in every other State.

greater importance are required. An alien, therefore, legally incapacitated for certain rights in the latter,

may, by previous residence only in the former, elude his incapacity; and thus the law of one State be

preposterously rendered paramount to the law of another, within the jurisdiction of the other. We owe it

to mere casualty, that very serious embarrassments on this subject have been hitherto escaped.

. . .

The new Constitution has accordingly, with great propriety, made provision against them, and all others

proceeding from the defect of the Confederation on this head, by authorizing the general government to

establish a uniform rule of naturalization throughout the United States.

the FedeRaliSt no. 42 (James Madison).

35 See Dolan, supra note 34 at 52; BRoken landSCaPeS, supra note 25 at 30.

36 BRoken landSCaPeS, supra note 25 at 30; Dolan, supra

status as noncitizens, owing their allegiance to another sovereign, mainly Indian polities . . . Being an Indian was contrary to

being a citizen.”).

37 U.S. ConSt.

person. See, e.g., Juan F. Perea, Race and Constitutional Law Casebooks: Recognizing the Proslavery Constitution, 110 miCh. l.

Rev. 1123 (2012).

Native Americans thus did

not receive representation

in the newly formed

representative government.

8 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

The second constitutional reference to Native peoples

considers the regulation of commerce with Tribal nations,

placing their economic status in relation to the federal

government akin to foreign nations and the several states.

38

The Indian Commerce Clause, Article I, section 8, gives

Congress the exclusive authority to “[t]o regulate Commerce

with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and

with the Indian Tribes[.]”

39

This clause recognized Tribal nations as sovereign entities, similar

to states or foreign nations, and “broadly authorized Congress to take the lead on legislative

authority over all aspects of federal, state, and Tribal affairs.”

40

In addition to the U.S. Constitution’s express references to Tribal nations, the Treaty Power

enshrined in Article II, section 2, which gives the President of the United States the “Power, by

and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the

Senators present concur[,]” permits the United States to enter into treaties with Tribal nations

(as well as other foreign nations).

41

Pursuant to this authority, the newly founded federal

government continued the practice that had governed the relationship between Tribal nations

and colonial powers, and later the Union under the Articles of Confederation, and began

entering into treaties with Tribal nations immediately after the Constitution’s ratication.

Between 1778 and the late 1800s, the federal government entered into hundreds of treaties

with Tribal nations, affecting issues such as jurisdictional boundaries, peace and war, water

rights, hunting and shing, and even U.S. citizenship.

42

Professor Matthew Fletcher explains how the Treaty Power governed the United States’

understanding of Tribal nations and the relationships between the sovereigns:

The Treaty Power, and the Indian treaties that arose from the invocation of this

power, further vested powers in the United States, as well as cemented tribal

sovereignty in the new American constitutional system.

43

38 Subsequent caselaw has distinguished Congress’s authority to regulate interstate commerce from its authority

to regulate commerce and affairs with Tribal nations, holding that the latter is far broader. In Haaland v. Brackeen, the

Supreme Court recognized:

We have interpreted the Indian Commerce Clause to reach not only trade, but certain “Indian affairs” too.

Notably, we have declined to treat the Indian Commerce Clause as interchangeable with the Interstate

Commerce Clause. While under the Interstate Commerce Clause, States retain “some authority” over

trade, we have explained that “virtually all authority over Indian commerce and Indian tribes” lies with the

Federal Government.

U.S. 255, 273 (2023) (quoting Cotton Petroleum Corp. v. New Mexico, 490 U.S. 163, 192 (1989); Seminole Tribe of Florida v.

Florida, 517 U.S. 44, 62 (1996)).

39 U.S. ConSt. art. I, § 8.

40 See Matthew Fletcher, States and Their American Indian Citizens, 41 am. indian l. Rev. 319, 323 (2017) [hereinafter, “Fletcher,

States and their American Indian Citizens”].

41 U.S. ConSt. art. II, § 2, cl. 2.

42 See Library of Congress, American Indian Law: A Beginner’s Guide: Treaties, https://guides.loc.gov/american-indian-law/

Treaties.

43 See Fletcher, States and Their American Indian Citizens, supra note 40 at 323-24.

The Indian Commerce Clause

recognized Tribal nations as

sovereign entities, similar to

states or foreign nations.

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 9

9

Thus, in the eyes of the newly formed U.S. government, Tribal nations would remain separate

sovereigns with which the United States—and not the several states—would engage in trade

and enter into treaties.

44

The U.S. Constitution and early federal law demonstrate the

founders’ understanding that Native peoples were not part of

“We the People.”

45

Rather, in the early years of the Republic,

U.S. citizenship was only available to white Europeans and

their descendants. The Naturalization Act of 1790, the rst

federal law providing a process for persons not born U.S.

citizens to attain citizenship, exemplies the early, race-

based understanding of U.S. citizenship.

46

The law expressly

restricted naturalization to “free white person[s] . . . of a good character[.]”

47

Native peoples,

Black people (free or enslaved), Pacic Islanders, Asians, and indentured servants were

ineligible to naturalize.

Not incorporated into the United States, Native nations

enjoyed a sovereign status as distinct political entities, akin

to that of a foreign nation.

48

Likewise, Native peoples were

not U.S. citizens, but instead citizens of separate sovereign

nations who were often uninterested in becoming part of the United States polity.

49

During this

period, the federal government operated primarily through a nation-to-nation relationship with

Tribal nations.

50

Indeed, the edgling United States even used its formalized relationships,

including treaties, with Tribal nations to legitimize its standing on the world stage.

Unfortunately, in the years that followed, the relationship between Native nations and the

United States devolved rapidly and considerably. While the United States government

formally interacted with Tribes through a nation-to-nation framework, some ofcials had

44 See Fletcher, Politics, Indian Law, and the Constitution, supra note 24 at 505 (describing the relationship between the

U.S. and Tribal nations at the U.S. founding as “a relationship between domestic nations when Indian tribes entered into

treaties with the United States in which they each agreed to come under the protection of the federal government.”).

45 U.S. ConSt. pmbl.; see also Jean Schroedel and Ryan Hart, Vote Dilution and Supression in Indian Country, 29 StUd. am. Pol.

dev. 1, 5 (2015) (“While these Constitutional provisions make it clear that the Founders did not consider most indigenous

peoples to be under their political jurisdiction, the question . . . about under what circumstances they could become part of

the polity is left unaddressed.”).

46 Act of Mar. 26, 1790, ch. 3, § 1, 1 Stat. 103, 103 (repealed 1795).

47 Id.

48 See Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94, 99 (1884) (“The Indian tribes, being within the territorial limits of the United States, were not,

strictly speaking, foreign states; but they were alien nations, distinct political communities, with whom the United States

acts of congress in the ordinary forms of legislation. The members of those tribes owed immediate allegiance to their

several tribes, and were not part of the people of the Unite States.”).

49 See Ablavsky, “With the Indian Tribes”, supra note 25 at 1061 (“[M]ost members of Native communities remained both

nonwhite and noncitizens who had little interest in joining the U.S. polity.”); Rebecca Tsosie, The Politics of Inclusion:

Indigenous Peoples and U.S. Citizenship, 63 UCLA L. Rev. 1692, 1707-08 (2016).

50 See, e.g., Allread, supra note 33 at 1551 (“In particular, the [Washington] Administration recognized Native nations as

sovereigns, departing from states’ claims that these nations were conquered peoples. President George Washington and

Henry Knox, the Secretary of War, formulated a policy that focused on pursuing diplomatic relations—treaties—with the

Native nations, protecting the nations’ rights to land, and instituting ‘civilization’ programs that promoted the adoption of

Euro-American forms of agriculture, education, and the market economy.”).

Tribal nations would remain

separate sovereigns with which

the United States—and not the

several states—would engage

in trade and enter into treaties.

Native peoples were not part of

“We the People.”

10 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

already begun to implement policies designed to “civilize” Native peoples in an ill-conceived

effort to provide federal protection from state governments and white settlers, with the

expectation that Native peoples would ultimately become assimilated into white American

society.

51

One of the primary early advocates of this strategy was Secretary of War Henry

Knox. In a 1792 letter to Governor William Blount of the Southwest Territory, Knox argued:

The Indians have constantly had their jealousies and hatred excited by

the attempts to obtain their lands—I hope in God that all such designs are

suspended for a long period—We may therefore now speak to them with the

condence of men conscious of the fairest motives towards their happiness

and interest in all respects—A little perseverance in such a system will teach

the Indians to love and reverence the power which protects and cherishes

them. The reproach which our country has sustained will be obliterated and

the protection of the helpless ignorant Indians, while they demean themselves

peaceably, will adorn the character of the United States.

52

As the U.S. population grew and its military strengthened, so did its desire for more land. As

Professor Frank Pommersheim puts it, by the early 1800s, “[t]he opportunity for Indians and

non-Indians to live parallel lives was rapidly evaporating into a historical mist that itself would

soon be forgotten.”

53

Removal and Relocation Period (1820s-1887)

Stories of Removal

By the early-to-mid-nineteenth century, the federal government, led by President Andrew

Jackson and with signicant pressure from state ofcials, came to view Native nations and

51 See Ablavsky, “With the Indian Tribes”, supra

that portrayed Indians as objects of pity rather than as equals.”); Allread, supra note 33 at 1551-52.

52 Letter from Henry Knox, U.S. Sec’y of War, to William Blount, Governor, Sw. Territory (Apr. 22, 1792); see also Letter from

Henry Knox to George Washington, supra note 28. In the same 1789 letter that Knox advocated to President Washington

for the treatment of Tribes as foreign nations, Knox opined:

had imparted our Knowledge of cultivation, and the arts, to the Aboriginals of the Country by which the

source of future life and happiness had been preserved and extended. But it has been conceived to be

impracticable to civilize the Indians of North America—This opinion is probably more convenient than Just.

the highest knowledge of the human character, and a steady perseverance in a wise system for a series

of years cannot be doubted—But to deny that under a course of favorable circumstances it could not be

incapable of melioration or change a supposition entirely contradicted by the progress of society from the

barbarous ages to its present degree of perfection.

Id.

53 BRoken landSCaPeS, supra note 25 at 19.

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 11

Tribal citizens as the primary obstacle to the United

States’ territorial expansion.

54

The nation-to-nation

relationship was no longer serving the interests of

the federal government. Instead, to remedy what

would come to be known as the “Indian problem,”

55

the

federal government commenced a concerted effort to

eradicate the eastern seaboard of Native peoples in

order to free the land for white settlers.

From the 1820s through 1887—the “Removal and Relocation Period”—the federal government

forced Tribal nations, militarily and through unfair and often coerced or misunderstood

treaties, out of their ancestral homelands and onto reservations a fraction of the size.

Thousands of Native peoples died during the Removal and Relocation Period as a direct result

of federal policy, due to starvation, disease, and lack of shelter. The loss of life and homelands

radically and permanently altered the relationship between Tribal nations and the federal

government. This history continues to shape the contemporary relationships between Tribal

nations and federal, state, and local governments.

56

In 1830, at the encouragement of President Andrew Jackson, Congress enacted the rst

federal law in furtherance of the removal policy, the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The act,

which “provide[d] for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or

territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi,”

57

created the legal authority

for the federal government’s ethnic cleansing of the Native peoples living along the eastern

seaboard whose homelands were highly sought after by white settlers. Once displaced, Native

peoples would be forcibly relocated to lands west of the Mississippi River that would become

known as “Indian Territory.” While the Indian Removal Act plainly subjected Native peoples to

additional authority by the federal government, the law itself conveyed no additional rights to

Native peoples nor did it grant them U.S. citizenship.

58

Once the law was enacted, Jackson and his administration quickly set about negotiating

treaties with Tribal nations for their relocation to Indian Territory. Jackson’s disgust for the

Native peoples his administration displaced is clear from the annual message he delivered to

Congress on December 6, 1830:

54 See Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830, https://history.state.gov/

milestones/1830-1860/indian-treaties (“As the nineteenth century began, land-hungry Americans poured into the

backcountry of the coastal South and began moving toward and into what would later become the states of Alabama

and Mississippi. Since Indian tribes living there appeared to be the main obstacle to westward expansion, white settlers

petitioned the federal government to remove them.”); Library of Congress, Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History:

Removing Native Americans from their Land, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/native-american/

removing-native-americans-from-their-land/; Allread, supra note 33 at 1152.

55 See, e.g., The Indian Problem, ny timeS (Mar. 2, 1879), https://www.nytimes.com/1879/03/02/archives/the-indian-problem.

html; Ray A. Brown, The Indian Problem and the Law, 39 yale l. J. 307 (1930).

56 See, e.g., Katie Smith and Courtney Parker, Song about the Departure of Seminole Indians from Florida for Oklahoma (1892),

.

57 Indian Removal Act of 1830, Pub L. 21-148, 4 Stat. 411 (1830).

58 See id.

The federal government viewed

Native nations and Tribal citizens as

the primary obstacle to the United

States’ territorial expansion.

12 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy

of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the

removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy

consummation.

. . .

The consequences of a speedy removal will be important to the United States,

to individual States, and to the Indians themselves. . . It will place a dense and

civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage

hunters. By opening the whole territory between Tennessee on the north

and Louisiana on the south to the settlement of the whites it will incalculably

strengthen the southwestern frontier and render the adjacent States strong

enough to repel future invasions without remote aid. It will relieve the whole

State of Mississippi and the western part of Alabama of Indian occupancy, and

enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will

separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free

them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their

own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay,

which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the

protection of the Government and through the inuence of good counsels, to

cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian

community.

What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a

few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns,

and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can

devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people,

and lled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion?

59

Despite a erce resistance by many Tribal nations,

60

removal was remarkably successful in

eradicating Native peoples from the southeastern United States. This is in part because when

Native peoples did not leave their homelands willingly, Jackson sent troops to force their

displacement, killing many along the way.

61

For instance, when many Cherokee resisted their

removal that was ordered in the 1836 Treaty of New Echota,

62

Jackson sent Major General

59 Andrew Jackson, Message to Congress on Indian Removal (Dec. 6, 1830), https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5682743.

60 See Protest Petition from Cherokee Nation to the U.S. Government (1836), https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/removal-

cherokee/resisting-removal.html.

61 Library of Congress, supra note 54.

62 Treaty of New Echota, Dec. 29, 1835, 7 Stat. 478. The Treaty of New Echota also guaranteed the Cherokee Nation a

Id. Art. IX (“The Cherokee nation

. . . should be offered to their people to improve their condition as well as to guard and secure in the most effectual manner

the rights guaranteed to them in this treaty, and with a view to illustrate the liberal and enlarged policy of the Government

of the United States towards the Indians in their removal beyond the territorial limits of the States, it is stipulated that

they shall be entitled to a delegate in the House of Representatives of the United States whenever Congress shall make

provision for the same.”). In 2022, the House Committee on Rules held a hearing on the legal and procedural issues with

sending a Cherokee delegate to Congress. See Legal and Procedural Factors Related to Seating a Cherokee Nation Delegate

in the U.S. House of Representatives, Hearing Before Committee on Rules, 117th Cong. (Nov. 16, 2022).

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 13

Wineld Scott along with 3,000 federal troops and the authority to raise additional state militia

and volunteer troops to eradicate Tribal members from Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee,

and Alabama. In 1838, the military “entered the [Cherokee] territory and forcibly relocated

the Cherokees, some hunting, imprisoning, assaulting, and murdering Cherokees during the

process.”

63

In the fall and winter of 1838 to 1839, on what is now known as the “Trail of Tears,”

an estimated 16,000 Cherokee citizens who survived the onslaught were forced to walk more

than 1,000 miles in harsh conditions to the lands that had been set aside for them in Indian

Territor y.

64

As many as 4,000 Cherokee people died along the way of starvation, exhaustion,

and disease caused by the brutal conditions they were forced to travel in.

65

Other Tribal nations, including the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminoles, and Potawatomi,

amongst others, were similarly forced out of their homelands through actions authorized

under the Indian Removal Act. Tribal nations were also split up into bands as a result of the

Indian Removal Act, with some families resisting removal and remaining in their homelands

and others being relocated.

66

By the end of Jackson’s presidency, he had signed into law nearly

70 treaties under the Indian Removal Act, resulting in the forced relocation of nearly 50,000

people belonging to Tribal nations located along the East Coast.

67

The displaced Tribes lost an

estimated 25 million acres of rich homelands that were quickly opened to white settlers.

68

In 1851, Congress further cemented the federal government’s forced relocation policy with

the passage of the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851, which formalized the reservation system

intended to further subdue Native nations.

69

The act appropriated funding for the federal

government to relocate Tribes to small parcels of land, known as “reservations,” where they

would, in theory, be left to self-govern with support from the federal government.

70

In practice,

Native peoples were involuntarily conned to their reservations, which were often far from

and almost always a fraction of the size of their ancestral homelands.

71

On reservations, the

traditional land and wildlife harvesting practices that Native peoples had used for sustenance

and cultural and religious well-being since time immemorial were severely restricted.

By the 1860s, the forced removal policy had extended well into the West, with the U.S. Army

and private militia acting on the Army’s orders perpetrating countless brutal attacks on Native

63 supra note 54.

64 Id.

65 Id.

66 Some Cherokee peoples remained hiding in North Carolina, evading removal. Likewise, some Potawatomi families

successfully remained in the North while others were removed. This in part explains why some Tribes have numerous

bands in distant parts of the United States.

67 supra note 54; National Archives, President Andrew Jackson’s Message to Congress ‘On Indian

Removal’ (1830), reviewed May 10, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/jacksons-message-to-

congress-on-indian-removal.

68 Id.

69 Indian Appropriations Act of 1851, Pub. L. 31-14 (1851).

70 Id.; see also Nat’l Inst. Health, Nat’l Libr. Med., 1851: Congress Creates Reservations to Manage Native Peoples, https://

www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/317.html#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Congress%20passes%twentiethe,and%20

gather%twentietheir%20traditional%20foods (last accessed Apr. 21, 2024).

71 See Sarah K. Elliott, How American Indian Reservations Came to Be, PBS (May 25, 2015, updated Oct. 18, 2016), https://www.

pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/stories/articles/2015/5/25/how-american-indian-reservations-came-be.

14 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

peoples in an effort to drive them from their homelands. For example, in 1862, U.S. Army

General James Carlton declared in orders to a militia leader, “All Indian men of that [Mescalero

Apache] tribe are to be killed whenever and wherever you can nd them.”

72

In 1863, General

Carlton shifted his focus to the Diné (Navajo), declaring “open season” on the Diné and

setting off a campaign of destruction designed to open Diné bikéyah (Navajo lands) to white

settlement and mining.

73

Carlton ordered Indian agent and U.S. army ofcer Christopher

Houston (Kit) Carson to conduct a “scorched-earth” campaign to burn homes, break up

families, slaughter livestock, destroy water sources, and starve Diné of their resources.

74

The

next year, the U.S. Army drove more than 10,000 Diné, along with about 500 members of the

Mescalaro Apache Tribe, out of their homelands on a 450 mile walk to their forced internment

on the Bosque Redondo Reservation.

75

As many as one in four Diné and Apache people were

killed along the way, primarily due to starvation, dehydration, and exposure.

76

The survivors

were interned on the Bosque Redondo Reservation in harsh conditions for the next ve years,

resulting in countless deaths as well as illness and starvation.

77

Nearby in Sand Creek, Colorado, in 1864, a Colorado volunteer army led by U.S. Army Colonel

John Chivington opened re on lodges of Cheyenne and Arapaho civilians, primarily women,

children, and elderly persons, who had settled in an encampment in Sandy Creek at the

direction and under the expected protection of the U.S. Military while awaiting relocation to

Fort Lyon.

78

The soldiers brutally slaughtered more than 230 innocent civilians during the

eight-hour massacre and afterward spent hours mutilating and committing other atrocities on

the dead.

79

In the late 1800s, the federal government also waged a war against the Tribal nations of the

Great Plains in an effort to take their lands after white settlers learned of gold deposits in

the sacred Pahá Sápa (Black Hills). In the late 1860s and early 1870s, the federal government

attempted to starve Native peoples of the Great Plains by encouraging mass killing of buffalo,

72 Frank D. Reeve, The Federal Indian Policy in New Mexico, 1858-1880, IV, 13:3 n.m. hiSt. Rev. 261 (1938).

73 daniel mCCool, SUSan m. olSon & JenniFeR l. RoBinSon, native vote: ameRiCan indianS, the votinG RiGhtS aCt, and the RiGht to vote

92 (2007).

74 Nat’l Museum Am. Indian, Native Knowledge 360: The Long Walk, https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/navajo/long-walk/

long-walk.cshtml (last visited Apr. 21, 2024) [hereinafter “NMAI, The Long Walk”]; nat’l PaRk SeRv., hUBBell tRadinG PoSt: the

lonG walk, http://npshistory.com/brochures/hutr/long-walk.pdf.

75 See, e.g., Jennifer Davis, Naaltsos Sání and the Long Walk Home, liBRaRy oF ConGReSS (June 18, 2018), https://blogs.loc.gov/

law/2018/06/naaltsoos-sn-and-the-long-walk-home/ (last visited Apr. 21, 2024); diné oF the eaSteRn ReGion oF the navaJo

ReSeRvation, oRal hiStoRy StoRieS oF the lonG walk: hwéeldi Baa hané (stories collected and recorded by Title VII Bilingual

Staff Patty Chee, Milanda Yazzie, Judy Benally, Marie Etsitty, and Bessie C. Henderson; Lake Valley Navajo School pub.,

1991) [hereinafter “oRal hiStoRieS oF the lonG walk”]; James Carleton to Thompson, September 19, 1863, in Navajo Roundup:

Selected Correspondence of Kit Carson’s Expedition against the Navajo, 1863-1865, ed. Lawrence C. Kelly (Boulder, CO:

Pruett Publishing, 1970), 56-57; NMAI, The Long Walk, supra note 74.

76 Davis, supra note 75.

77 Id.

78 Nat’l Park Serv., Sand Creek Massacre: History & Culture, https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/historyculture/index.htm (last

visited Apr. 21, 2024); Nat’l Park Serv., Sand Creek Massacre: The Life of Silas Soule, https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/

historyculture/the-life-of-silas-soule.htm (last visited Apr. 21, 2024); Nat’l Park Serv., Sand Creek Massacre: Joseph Cramer

Biography, https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/historyculture/joseph-cramer-biography.htm (last visited Apr. 21, 2024).

79 See id.

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 15

their primary protein source.

80

In 1868, Major General Phillip Sheridan described the plan to

General William Tecumseh Sherman: the U.S. Army would “make them poor by the destruction

of their stock, and then settle them on the lands allotted to them.”

81

General Grenville Mellen

Dodge famously said of the plan, “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian

gone[.]”

82

That winter, General Sheridan led a campaign against the Cheyenne peoples. U.S.

Army soldiers destroyed their food, shelter, and livestock with “overwhelming force.” In a

dawn raid during a snowstorm in November 1868, Sheridan commanded U.S. Army Lieutenant

Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his 700 troops to “destroy [Cheyenne] villages and

ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, and to bring back all women and children.”

83

The U.S. Army

killed at least 100 Cheyenne people during that attack.

84

In 1874, the federal government amplied its efforts to take control of the Black Hills when

Custer led an expedition of 1,000 U.S. Army soldiers to conrm the presence of gold in the

region.

85

Shortly after, white settlers, with the blessing of the U.S. government, ooded the

lands of the Great Sioux Reservation that had been set aside in the Treaty of Fort Laramie

86

for the exclusive use of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Sioux Nation).

87

By 1876, the federal government

had begun a full scale assault on the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ peoples, attempting to force them

onto much smaller reservations and treating those who refused as “hostiles.”

88

That August,

Congress enacted legislation providing that the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ would receive no funding

for subsistence unless they ceded the sacred Black Hills.

89

The following year, Congress

abrogated the Treaty of Fort Laramie, formalizing the federal government’s cessation of the

Black Hills, and establishing disconnected reservations a fraction of the size of the Great

Sioux Reservation on which the nations of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ would be conned.

90

In 1980,

the United States Supreme Court recognized the federal government’s actions as a “taking of

tribal property, property which had been set aside for the exclusive occupation of the Sioux by

the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868” that “implied an obligation on the part of the Government to

make just compensation to the Sioux Nation[.]”

91

80 See, e.g., J. Weston Phippen, ‘Kill Every Buffalo You Can! Every Buffalo Dead Is an Indian Gone’, atlantiC (May 13, 2016),

https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/05/the-buffalo-killers/482349/.

81 Id.

82 Native Philanthropy, Investing in Native Communities: Annihilation of Buffalo by Military and Hunters, https://

nativephilanthropy.candid.org/events/annihilation-of-buffalo-by-military-and-hunters/ (last accessed Apr. 21, 2024).

83 Gilbert King, Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed, SmithSonian maGazine (Jul. 17, 2012), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/

history/where-the-buffalo-no-longer-roamed-3067904/.

84 Id.

85 United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, 448 U.S. 371, 377-79 (1980).

86 Fort Laramie Treaty of April 29, 1868, 15 Stat. 635.

87 United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, 448 U.S. at 377-81; Nat’l Park Serv., Theodore Roosevelt: The U.S. Army and the

Sioux, https://www.nps.gov/thro/learn/historyculture/the-us-army-and-the-sioux-part-3.htm (last visited Apr. 21, 2024).

88 United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, 448 U.S. at 379.

89 Act of Aug. 15, 1876, 19 Stat. 176, 192.

90 United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, 448 U.S. at 381-83.

91 United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, 448 U.S. at 424.

16 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

These stories of forced removal exemplify the federal government’s policy toward Native

peoples in during the Removal and Relocation Period.

Talks of Citizenship

Throughout the nineteenth century, state citizenship for Native peoples and U.S. citizenship

for Native peoples operated on separate tracks.

92

Even when the Native peoples were largely

excluded from U.S. citizenship, some states chose to convey state citizenship.

93

However,

state citizenship was often highly entangled with race, or more specically whiteness. To

become a state citizen, a Native person generally needed to “prove that they were ‘civilized,’

or had ‘abandoned’ their tribal relations by declaring loyalty to the state or the United States,

relinquishing their treaty rights, paying state taxes, adopting the habits and customs of white

men, or some combination of all of these factors.”

94

The rst formal grants of U.S. citizenship to Native peoples were made in treaties entered

between Native nations and the United States.

95

While these treaties were the direct result of

Tribal governments advocating for the civil rights of their citizens, they generally conveyed U.S.

citizenship to Native peoples only in exchange for some concession of jurisdiction or lands by the

Tribe to the federal government. For example, the 1848 Treaty with the Stockbridge Tribe linked

U.S. citizenship with privatization of Tribal lands.

96

The 1855 Treaty with the Wyandot subjected

the Tribe to the jurisdiction of the Kansas territory.

97

The 1862 Treaty with the Kickapoo was

linked with railroad development through Tribal lands in the West.

98

Through these treaties, the

federal government began its project of using U.S. citizenship as a tool of assimilating Native

peoples into broader U.S. society, whether or not the individual citizen consented.

By the late 1860s, the views of the Nation and the

federal government on citizenship for nonwhite

residents of the United States had begun to shift.

During the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era, as

Congress considered legislation and constitutional

amendments to extend U.S. citizenship and the

92 See Fletcher, States and their American Indian Citizens, supra note 40 at 327.

93 See id.

94 Id. (citing United States v. Elm, 25 F. Cas. 1006, 1007 (N.D. N.Y. 1877) (“If defendant’s tribe continued to maintain its tribal

integrity, and he continued to recognize his tribal relations, his status as a citizen would not be affected by the fourteenth

amendment; but such is not his case. His tribe has ceased to maintain its tribal integrity, and he has abandoned his tribal

relations, as will hereafter appear. . . .”); Anderson v. Mathews, 163 P. 902, 906 (Cal. 1917) (“Neither the members of the

group nor, so far as known, the members of the tribe, were subject to, or owed allegiance to, any government, except

that of the United States and the state of California, and, prior to 1848, that of Mexico.”); Bd. of Comm’rs of Miami County

v. Godfrey, 60 N.E. 177, 180 (Ind. App. 1901) (“So long as he remained an Indian, he was under the control of the United

States as an Indian. But he voluntarily does what the law says makes him a citizen. This change of his tribal condition into

individual citizenship was primarily his own voluntary act. He cannot be both an Indian, properly so called, and a citizen.”)).

95 See Treaty with Stockbridge Tribe, art. IV, Stockbridge-U.S., Nov. 24, 1848, 9 Stat. 955; Treaty with the Wyandot, art. I,

Wyandot-U.S., Jan. 31, 1855, 10 Stat. 1159; Treaty with the Kickapoo, Kickapoo-U.S. June 28, 1862; Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94,

100 (1884).

96 Treaty with Stockbridge Tribe, art. IV, Stockbridge-U.S., Nov. 24, 1848, 9 Stat. 955.

97 Treaty with the Wyandot, art. I, Wyandot-U.S., Jan. 31, 1855, 10 Stat. 1159.

98 Treaty with the Kickapoo, Kickapoo-U.S. June 28, 1862.

The rst formal grants of U.S. citizenship

to Native peoples were made in treaties

entered between Native nations and the

United States.

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 17

right to vote to Black Americans, Congress was also

forced to directly confront the question of whether to

grant U.S. citizenship to Native Americans.

Congress rst took up the issue of whether to convey

U.S. citizenship to all Native peoples in the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, which extended U.S. citizenship to “all

persons born in the United States and not subject

to any foreign power” except “Indians not taxed.”

99

While this restriction excluded most Native peoples, it

would have extended U.S. citizenship to any Native peoples subject to state or federal taxation

by, for example, privately owning land outside of a reservation.

100

President Andrew Johnson quickly vetoed the bill because it would have extended U.S.

citizenship to peoples he considered unt, including some Native peoples.

101

And while

Congress successfully overrode the President’s veto and enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866

into law, President Johnson’s veto message is exemplary of a widespread understanding at

the time that U.S. citizenship should be reserved for white Americans. According to President

Johnson:

This provision comprehends Indians subject to taxation [and other disfavored

races, including Black Americans] . . . Every individual of these races born in the

United States is by the bill made a citizen of the United States.

Johnson then questions whether it is “sound policy” for Congress to convey citizenship to

those he considers unworthy because of their race and concludes:

102

[T]he policy of the Government from its origin to the present time seems to have

been that persons who are strangers to and unfamiliar with our institutions and

our laws should pass through a certain probation, at the end of which, before

attaining the coveted prize, they must give evidence of their tness to receive

and to exercise the rights of citizens as contemplated by the Constitution of the

United States.

103

Following some doubt by proponents of birthright citizenship that Congress had the authority

to grant it through statute, an effort to extend birthright citizenship as a constitutional

right commenced shortly after. In 1868, Congress and the states adopted the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution, which provides in relevant part:

99 Civil Rights Act of 1866.

100 Id.; Dolan supra note 34 at 34; Andrew Johnson, Veto Message on Civil Rights Legislation to the United States Senate (Mar.

27, 1866), https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/march-27-1866-veto-message-civil-rights-

legislation [hereinafter “Johnson, Veto Message”]; Cong. Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Sess. 527 (1866).

101 See Johnson, Veto Message, supra note 100.

102 Id.

103 Id.

Through these treaties, the federal

government began its project of using

U.S. citizenship as a tool of assimilating

Native peoples into broader U.S.

society, whether or not the individual

citizen consented.

18 Voting for Native Peoples: Barriers and Policy Solutions

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the

jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein

they reside.

104

Later, the Fourteenth Amendment excludes “Indians not taxed” from the population count for

the purposes of apportioning seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

105

While Congress likely intended to exclude Native peoples from the Fourteenth Amendment’s

grant of birthright citizenship, there was little consensus about the clause’s true meaning

at the time of its passage. Some members of the 39th and 40th congresses believed the

requirement that a recipient of birthright citizenship must be “subject to the jurisdiction” of

the United States would prevent citizenship from being extended to Native peoples,

106

while

others sought to add additional restrictions to ensure Native Americans would not be granted

citizenship through the amendment.

107

Opponents of birthright citizenship for Native peoples

fell into several categories. Some supporters of Tribal nations believed that U.S. citizenship

was contrary to Tribal sovereignty and would erode the nation-to-nation relationship with

the federal government.

108

Others expressed the racist sentiment that Native peoples were

“uncivilized” and therefore unworthy of U.S. citizenship.

109

Senator James Doolittle of Wisconsin, who sought to add language barring “Indians not taxed”

from becoming U.S. citizens by birthright, exemplies the latter camp:

I moved this amendment because it seems to me very clear that there is a large

mass of the Indian population who are clearly subject to the jurisdiction of the

United States who ought not to be included as citizens of the United States. All

the Indians upon reservations within the several States are most clearly subject

to tour jurisdiction, both civil and military.

. . .

Go into the State of Kansas, and you nd there are any number or reservation,

Indians in all stages, from the wild Indian of the plains, who lives on nothing

but the meat of the buffalo, to those Indians who are partially civilized and

have partially adopted the habits of civilized life. So it is in other States. In my

own State there are Chippewas, the remnants of the Winnebagoes, and the

Pottawatomies [sic]. There are tribes in the State of Minnesota and other States

of the Union. Are these persons to be regarded as citizens of the United States,

104 U.S. ConSt. amend XIV, § 1.

105 U.S. ConSt. amend. XIV, § 2.

106 ConG. GloBe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2893 (1866) (Senator Trumbull noting, “It cannot be said of any Indian who owes

allegiance, partial allegiance if you please, to some other Government that he is ‘subject to the jurisdiction of the United

States.’”).

107 ConG. GloBe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2892-93 (1866) (Senator Doolittle).

108 See Bethany Berger, Birthright Citizenship on Trial: Elk v. Wilkins and United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 37 CaRdozo l. Rev. 1185

(2016).

109 See Dolan, supra note 34 at 34.

PART II: History and the Path to U.S. Citizenship 19

and by a constitutional amendment declared to be such, because they are born

within the United States and subject to our jurisdiction?

Mr. President, the word “citizen,” if applied to them, would bring in all the Digger

Indians of California. Perhaps they have mostly disappeared; the people of

California, perhaps, have put them out of the way; but there are the Indians of

Oregon and the Indians of the Territories. Take Colorado; there are more Indian

citizens of Colorado than there are white citizens this moment if you admit it as

a state. And yet by a constitutional amendment you propose to declare the

Utes, the Tabahuaches, and all those wild Indians to be citizens of the United

States, the great Republic of the world, whose citizenship should be a title

as proud as that of a king, and whose danger is that you may degrade that

citizenship.

110

Some reporting suggests that this choice was made out of respect for the sovereignty of

Native nations as separate from the United States,

111

but the actions of the federal government

at the time tell a different story. At the same time Congress was blocking Native Americans

from becoming U.S. citizens through the Fourteenth Amendment, the federal government,

through its relocation and removal policies, was actively trying to strip away the ability of

Native nations to exist as sovereigns and provide for their citizens. Indeed, even lawmakers

advocating on behalf of Native nations often failed to fully appreciate their sovereignty.

112

Elk v. Wilkins

In 1884, the United States Supreme Court directly confronted the issue of whether the

Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the

United States” would extend to Native peoples.

113

The Plaintiff John Elk, a member of the

110 ConG. GloBe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2892-93 (1866). The opponents to granting the right to vote to Native peoples under

the Fifteenth Amendment were similarly vitriolic. During the debate in the U.S. House of Representatives, Congressman

Charles A. Eldredge of Wisconsin expressed his staunch opposition to the Fifteenth Amendment because of its application

to people of color:

If the . . . the wild Indian [and other disfavored races] are to become a ruling element in this country, then call your

ministers from abroad, bring your missionaries home, tear down your school-houses, convert your churches into

dens and brothels, wherein our young may receive fatal lessons to end in rotting bones, decaying and putrid

ConG. GloBe, 41st Cong., 2nd Sess. 756 (1870).

111 See Berger, supra note 108.

112 See 6 Cong. Rec. 551-53 (1887). In a debate about whether to extend U.S. citizenship to Native peoples in 1877, Senator

Allen G. Thurman of Ohio, who purported to be advocating on behalf of Native peoples’ interests opined:

I do not say the time may not come [to extend U.S. citizenship to Native peoples], I do not say that it is not desirable

that it should come, when what shall be left of the Indians shall be civilized enough to become citizens of the

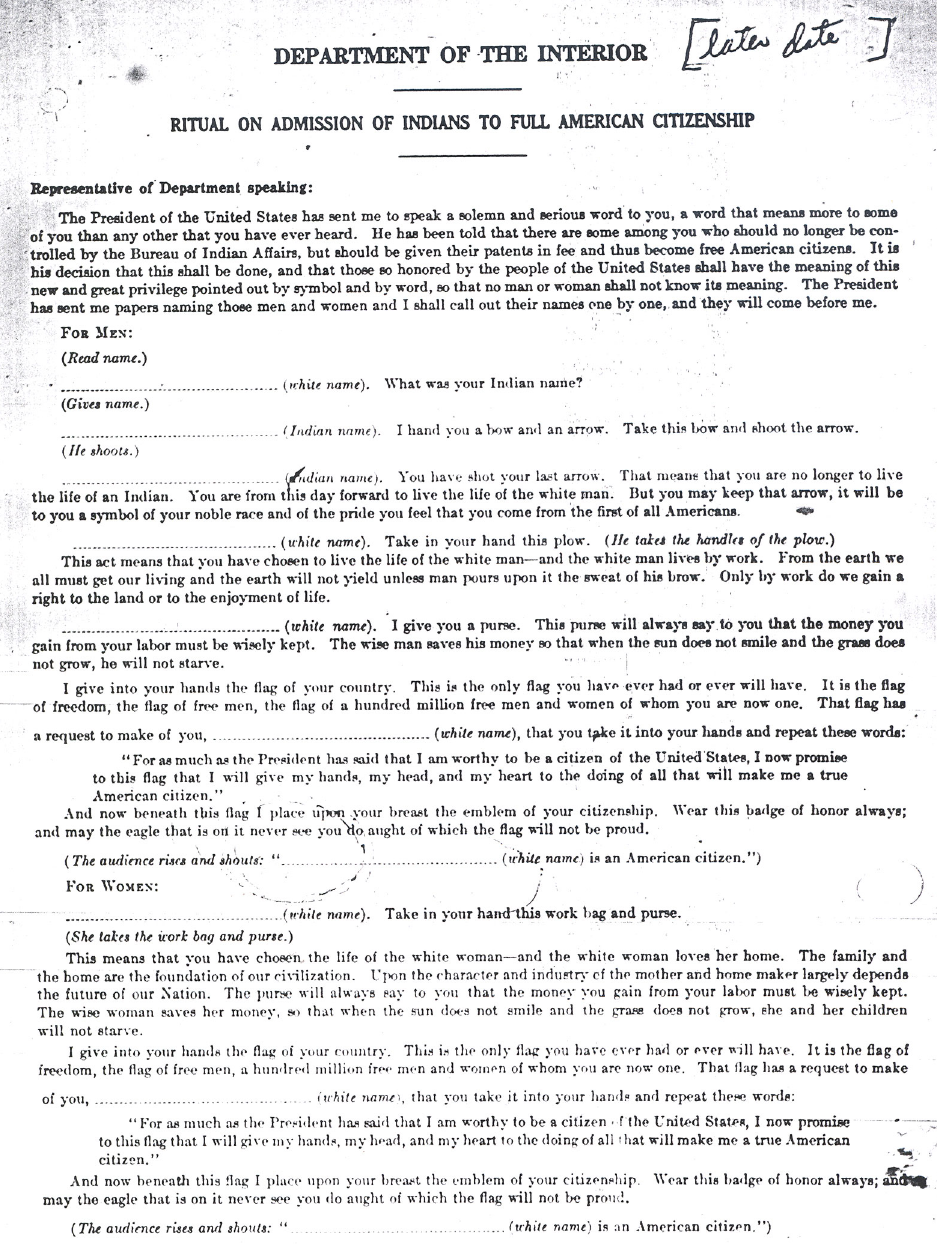

United States and be absorbed in the great body of our population. As to most of them I have no such hope. They