1

Journal of Urban Learning,

Teaching, and Research

Volume 17, SPECIAL ISSUE

August 2023

A publication of the AERA Urban Learning, Teaching & Research SIG

2023 Special Issue: Illuminating Effective Practices,

Approaches, and Strategies in Urban Education

2

Examining Discipline Integrity Among Black

Girls in Urban Schools

Tierra M. Parsons

A. Jaalil Hart

Na’Cole C. Wilson

Dr. Chance W. Lewis

The University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Abstract

School discipline has been of primary interest in education over the past six decades.

Examining the expansive body of literature on zero tolerance policies, the school-to-prison

pipeline, and the criminalization and exclusion of Black girls specifically sends a resounding

reminder of the work that remains to be done in the interest of their educational needs,

sustainability and overall well-being. While much has been written about the topic of school

discipline and Black girls, less has been written on the topic of equitable, strength-based

solutions that support their educational advancement, prioritizes the intricacies of their

intersectionalities, and motivates schools to create and maintain cultures of care through

educational policy and practice. Exploring discipline integrity as another valuable, intentional

and inclusive approach can help affirm the worth of Black girls in schools, further empower

stakeholders to make equitable decisions, engage community partners, mitigate educational

risks and address ongoing concerns related to discipline integrity among Black girls in urban

schools.

Keywords: school discipline, Black girls, equity, inclusion, worth, urban schools, discipline

integrity

3

Introduction

The subject of school discipline and its related disparities and controversies has been

of primary interest in education over the past six decades (Children’s Defense Fund, 1975;

Green, 2022, Skiba et al., 2002; Staats, 2014). Many of the interests have been largely centered

on topics concerning zero tolerance policies (Scott et al., 2017), the school-to-prison pipeline

(Hassan & Carter, 2021), the criminalization, victimization, and exclusion of students of color

(Crenshaw, 2015; Lewis et al., 2010), disproportionate discipline sanctions (Blake et al., 2011)

and intersectional violence (Annamma et al., 2019). A large body of literature details the

inequitable discipline experiences of Black boys in urban education; however, the discipline

experiences of Black girls warrant a sustained focus by reason of the outcomes related to their

intersectional complexities. Although much has been documented about the topic, less has

been written about strength-based, equity-focused approaches and solutions that (1) support

the sustainability of Black girls and educators and (2) inspire educational stakeholders

towards cultivating cultures of care in schools through policy and practice. Exploring

approaches such as discipline integrity can help address the discipline and well-being

concerns specific to Black girls in urban schools.

When considering the growing mental health and social-emotional challenges Black

girls face in schools (Cholewa, 2014; Leary, 2019), it is important that educational stakeholders

are made familiar with various approaches to developing equitable school discipline policies

that promote educational reform in the interest of Black girls. These policies must be focused

on centering morality in educational policy. To help dismantle the oppressive mechanisms of

systemic bias in schools that adversely affects Black girls (Ricks, 2014), urban schools should

consider further examining the moral grounding of their strategic approaches when

developing, implementing, and evaluating their operating policies. This critical examination

and commitment to promoting equity in schools through policy have larger implications for

the success and well-being of Black girls, which is the main theme and emphasis of this paper.

One may inquire, isn’t equity in urban education enough when addressing discipline

disparities? Especially when there is a vast amount of equity-focused literature in the field

(Benadusi, 2002; Jurado de los Santos et al., 2020)? First, it is important to operationally define

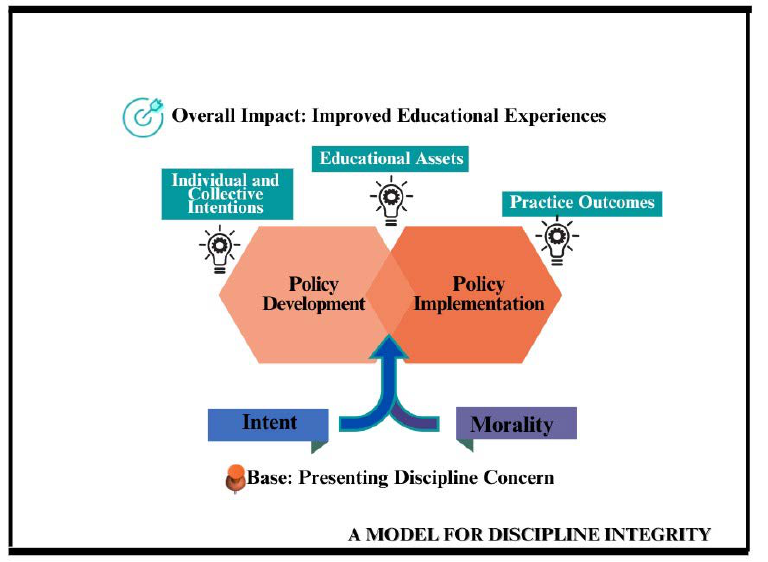

discipline integrity. We define discipline integrity (DI) as an approach to the discipline policy

development and implementation process that intently and morally considers individual and

4

collective intentions, educational assets, and the practice outcomes that impact marginalized

groups rather than in reference to a general or primitive understanding of professional

etiquette and adherence to pedagogical mandates (see Figure 1). For instance, equity when

referring to discipline practices in education has commonly been used to primarily promote

fairness in educational policy and practice in schools (Simon, et al., 2007). This perspective is

also often acknowledged and operationalized in terms of inclusivity and diversity (Ainscow,

2020; Taylor, et al., 2013), resource allocation (Gilbert, et al., 2011) and educational effectiveness

(Kyriakides, et al., 2020). Given the ongoing, disheartening discipline related circumstances

that Black girls have endured in education, equity alone is not enough and discussions around

topics of integrity in school discipline policy development and its implementation.

Figure 1

This model demonstrates the components needed to understand discipline integrity.

Particularly within urban schools, discipline among Black girls has been primarily

associated with criminalization and discrimination and disproportionality (DatiriHines &

Carter Andrews, 2020; Green, 2022). Since there are school policies and practices that are

positioned in anti-Blackness (Wun, 2016), this ideology can be integrated in policy

5

development and practice while subsequently impeding discipline reform efforts and related

restorative practices. Understanding that there may be Black girls in education may not have

experienced the harsh effects of school discipline policies, there are many that struggle

personally and academically because of the way these policies are implemented and

subsequently sustained. According to Morris (2016), the struggles that Black girls face are often

a matter of life and death.

Therefore, it is important that discipline integrity be considered during policy

development and implementation in support of Black girls particularly in urban schools.

According to Weeks (2010), the term “urban” has been acknowledged as a rather complex

concept to define. The author further suggests that although the personal adjective “urbane”

is intermittently used to describe a person, the word urban is broadly defined by the Oxford

English Dictionary as having qualities and characteristics associated with town or city life-

being a part of an urban population. Likewise, the word urban has been described by

researchers throughout the literature as being a nonagricultural, place-based characteristic

with a spatial concentration of people whose lives are organized around nonagricultural

activities (Weeks, 2010). Milner (2015) identified three different conceptual frames for how we

understand the term urban: (1) urban intensive (large metropolitan cities with 1 million people

or more) (2) urban emergent (large cities with fewer than 1 million people) and (3) urban

characteristic (areas smaller than large or mid-sized cities). Bibby & Shepherd (2004)

categorized the term into three dimensions (1) population size (2) physically refined

settlements and (3) economic status and wealth generation and Sorensen (2014) associated the

term urban with industrialization and modernization of societies.

For the past 70 years the advantages for citizens in urban cities have contributed to the

development of urban schooling, privileges that are not common in rural areas (Brint, 2017).

Though many of the individual and community realities are related to the ongoing challenges

that impact students in both urban and rural schools (Theobald, 2005), urban schools warrant

a more concentrated effort due to their significant limitations around access to resources and

opportunities (Milner, 2015). By working specifically with urban schools, educational

stakeholders will have an opportunity to improve the lives and chances of students in this

context with critical educational and individual needs (Friere 1998; Milner, 2015). Using a

Critical Race Feminism (CRF) theoretical lens, this conceptual paper seeks to critically

examine the systemic issues of disproportionate school discipline practices among Black girls

6

in urban schools through the perspective of what the authors term “discipline integrity”.

Further, the dual purpose is to (1) illuminate the worth of Black girls in education and (2)

support the professional development of administrators and other educational stakeholders

as they learn ways to best support and respond to the needs of Black girls. The discussion

from the paper has significant implications and recommendations for urban schools and their

approach to navigating school discipline.

Literature Review

Discipline Integrity and Policy Development

Martin and Smith (2017) argue that in the nearly 70 years post Brown v. Board of

Education, we find ourselves navigating an educational system where Black girls continue to

be disproportionately disadvantaged by structural inequalities, including those related to

school discipline policies. According to McIntosh et al. (2018), many general efforts have been

made to specifically address exclusionary discipline concerns; however, these efforts have not

been shown to sustainably enhance equity in school discipline. In the case of DI

administrators and applicable educational stakeholders in urban schools could adopt DI as a

standard of practice in school discipline policy development and implementation to help

dismantle rigid, systematically biased school discipline policies (Quinn, 2017). The primary

purpose of DI in the context of urban education is to highlight the value of applying a morally

upright, culturally responsive approach to developing, evaluating and implementing school

discipline policies and practices in schools. DI is an important contribution to educational

policy and practice because the approach can (1) help promote the safety, success, and

wellness of Black girls and other marginalized groups by centering their needs and

considering their risk factors (2) morally ground the school policy development and

implementation process and (3) subsequently improve the school climate, operations, and

student outcomes.

According to McFall (1987), integrity is a complex concept with traditional standards of

morality such as honesty and fairness that may conflict with one’s own personal ideals.

Likewise, morality is a guide to behavior for a group or individual that includes accepting a

moral code that avoids and prevents harm to others (Gert & Gert, 2020). Although research

further suggests that morality may not include elements of impartiality regarding all moral

agents and may not be universalizable in any significant way (Gert & Gert, 2020), it is

7

important to establish a common standard that administrators and applicable decision

makers can use as an ethical guide to the school discipline policy development and

implementation process, such as the DI model. In addition, creating an accompanying

checklist as an administrative guide during the discipline policy processes may include the

following questions: (1) have our meeting objectives been pragmatically established? (2) are

our decision-making standards ethically and morally justified (do no harm)? and (3) have

group norms been established for the specification process? (explaining the when, where,

why, how, by what means, to whom or by whom the action is done or avoided) (Teays &

Renteln, 2020). Since research suggests that implicit biases have a significant impact on

decision making and that accountability alone is ineffective in reducing disproportionality

(McIntosh et al., 2018), reviewing a standard checklist as a best practice can prompt a moral

consensus prior to the policy development process and thereafter help dismantle the

perpetual trends of oppression and inequity in the school discipline policy process.

Undeniably, administrators have the challenging task of making tough decisions as it

pertains to ensuring the nobility of their institutional operations. Recognizing that social

acceptability may present a challenge when considering the adoption of DI as a standard to

address bias in policy development (Skiba, 2002), providing specific guidance in making

objective, yet considerate decisions helps people display equitable behavior (McIntosh, et al.,

2018). In addition to the micro and macro expectations of those in various contexts, there is a

high level of vulnerability and accountability associated with making the best-informed

decisions (McIntosh, et al., 2018)-especially related to discipline matters among students of

color. To support administrators in this position, DI provides an opportunity to engage in a

self/group-reflective process that encourages the moral examination of the approach to

inform the school discipline policy process.

Mental Health and Black Girls

One of the most notable influences of disproportionate school discipline practices on

Black girls is the impact on their psychological and emotional well-being (Blake et al., 2011).

Research indicates alarming data and statistics related to the unmet mental health needs of

Black girls. Sheftall et al., (2022) and Lindsey et al., (2019) found that Black girls, regardless of

age, have experienced the largest suicide rate increase compared to Black boys. Additionally,

the worry and stress resulting from some Black girls’ efforts to navigate challenging home and

school environments has been related to increased depression and decreased self-esteem,

8

among other adverse psychological symptoms (Brody et al., 2006; Cholewa et al., 2014). Being

able to exist in schools in the absence of negative stereotypes, strained interpersonal

relationships and exclusionary discipline practices is imperative to helping improve the

mental health conditions and daily functioning of Black girls. The structural inequalities such

as exclusionary discipline practices are likely to impact Black girls by transforming their

environments, influencing their perceptions of school-based discriminatory experiences and

may also have critical implications for their academic and psychological outcomes (Cooper et

al., 2022; Morris & Perry, 2016).

For more than 60 years, the worth of Black girls has been challenged in education

through innumerable disheartening experiences (Annamma et al., 2019; Morris, 2007; Zeiders

et al., 2021). While equity efforts have helped to guide, enhance, and improve discipline

practices, the persistent circumstances that continue to push Black girls out of schools

warrants a more intentional effort in their interest. Crenshaw et al., (2015) encourages those

concerned about the state of Black girls in education to broaden their understanding of the

complexities of their intersectionalities and commit to enhancing resources to ensure that all

youth, including Black girls, can thrive. Considering the benefit of an additional perspective to

address the needs of Black girls in schools, the DI approach can help administrators and other

relevant stakeholders’: (1) center the well-being and matters of Black girls in schools and (2)

enhance current approaches to school discipline policy making and implementation (i.e.,

strategic planning, delivery/communication, follow-up etc.).

Theoretical Framework

Critical race theories are frameworks that denaturalize white privilege in ways that

expose the operations of oppressive social systems (Thompson, 2004). As an extension of

traditional civil rights scholarship, Critical Legal Studies (CLS), and Critical Race Theory

(CRT), Critical Race Feminism (CRF) is a theory that presents a pronounced way of analyzing

and centering the narratives and voices of Black girls and women within various oppressive

and discriminatory societal contexts (Davis, 2000; Wing, 1997; Wing, 2015). According to

Matusda (1987), “those who have experienced discrimination speak with a special voice to

which we should listen” (p. 324). Considering CRF’s legal studies and CRT foundation, it is

important to foreground the significance of their influence on the emergence of CRF.

9

Introduced in the 1970’s CRT emerged as a body of legal scholarship by a community

of mostly scholars and activists of color who were committed to studying and transforming

racism at the intersection of race and power (Bell, 1995; Delgato & Stefancic, 2017). CRT is less

like an intellectual unit consisting of theories and practices but rather one that is comprised of

ways racial power is perceived and expressed in the post-civil rights era (Crenshaw, 2011).

Further, Critical Race Theorists have elevated the influence of CRT through the exploration

of the law's role in the maintenance of social domination, as well as policies that aim to

subordinate minoritized groups (Peller et al., 1995; Milner, 2008). Given CRT’s broad

interdisciplinary influence, the theory can be characterized throughout research and practice

by an expression of commitment to the following basic tenets: (1) ordinariness (disregard for

racism); (2) interest convergence (advancing the rights of people of color when converging the

interests of whites); (3) social construction (race and races are outcomes of social thought and

relations); (4) differential racialization (disparities in treatment of minoritized groups based on

labor market needs); (5) intersectionality (the interconnection of social categories); and (6)

story/counter storytelling and narratives (amplifying voices of color in response to racism)

(Delgato & Stefancic, 2017, 2023). Furthermore, CRT has been viewed to be critical/radical in

nature, with an agenda to champion liberation from racism and critique liberal order (Bell,

1995; Delgato & Stefancic, 2017).

Considering the substandard perception of Black girls in schools due to the nature of

their intersectionalities (i.e., gender, race), CRT plays a critical role in challenging oppressive

discipline policies by not only centering their narratives but also focusing on other pertinent

issues of race and racism in education (Annamma et al., 2019). Since scholars assert that

education lacks safe spaces for race, class, and gender discussions (Wiggan et al., 2020), CRT

brings an inclusive analysis that provides a promising pathway to discuss race relations,

systemic bias, and the anticipated solutions in today's urban schools. This perspective directly

challenges racial and structural inequities; however, identifying the need to address gender

related disproportionalities inspired the introduction of Critical Race Feminism (CRF). CRF

adds to CRT by exploring the intricacies of the lived experiences of those who face multiple

discrimination at the intersection of race, gender, and class (Wing, 1996). Likewise, CRF is an

empowering framework that reveals how these factors interact within a white male

dominated system of racist oppression (Wing, 1996), particularly within the context of urban

education. CRF has been instrumental in investigating Black girls’ schooling experiences and

10

identifying development in educational spaces because of their exposure to disciplinary

school policies and the recognizably gendered dynamics of zero tolerance surroundings

(Hines-Datiri & Carter Andrews, 2020). Using the framework’s five tenants: (a) narratives and

counter storytelling, (b) multidisciplinary perspectives, (c) community-focused theory and

practice, (d) intersectionality, and (e) anti-essentialism (Berry, 2010; Shultz, 2009; Verjee, 2013;

Wing, 1997; Wing, 2015), personnel in urban schools have an opportunity to inform the

discipline policies and practices/approaches that shape school dynamics, conversations,

relationships, and outcomes related to Black girls. Further, CRF serves as a useful advocacy

tool when addressing the distinctive situations of Black girls whose lives and intentions may

not comply with a standardizing female voice (Hines-Datiri & Carter Andrews, 2020). If school

leaders and decision makers are inclined to embrace CRF together with the support of

community partners and other educational stakeholders to dismantle systemic oppression

related to school discipline, this effort may be a source of optimism for realizing social justice

and educational reform.

Discussion

An ongoing critical analysis of discipline integrity is important to further

understanding effective, ethical ways to address the perpetuation of school discipline

disproportionately in urban schools among Black girls. With each passing year, the school

discipline narrative remains the same. Countless stories about the criminalization of Black

girls in schools continue to circulate throughout the literature and the news. These girls and

their families continue to navigate the adverse mental health outcomes associated with harsh

discipline policies (Ricks, 2014), yet access to resources for marginalized groups remain

limited. Since the patterns of exclusionary discipline practices involving Black girls are

observed at the national, state, and local levels (Addington, 2021), it is important to consider

the intentions, disposition and actions of policy makers-an influence that is central to ending

these exclusionary patterns and improving the school discipline experience for Black girls.

Change is something that advocates and activists desire to see when addressing the

concerns that Black girls continue to face in schools. Considering the complexities of their

intersecting identities (i.e., marginalization, stereotyping) and the impact of their invisibility in

schools are major concerns that should be a motivating factor to embracing the DI approach

11

to improving school discipline policy development and implementation. Administrators are

encouraged to eliminate bias in their policies and any practice that reinforces oppressive

practices in schools among Black girls (Green, 2022; Morris, 2007). Understanding that Black

girls are often embedded in racialized school contexts that devalue their existence (Cooper et

al., 2022), being intentional about ensuring morality in policy development can help nurture

and protect Black girls from oppressive and discriminatory practices, improve educational

outcomes that are impacted by racism and systemic bias and help strengthen interpersonal

relationships among educators and Black girls that were once damaged by adverse actions

and experiences.

Regarding morality, Abend (2013) asserts that most data and analyses in moral

development research are about a specific action led by a judgment and made in response to a

stimulus. Acknowledging that these judgements and actions are rarely simple and require an

individual to weigh and coordinate moral and nonmoral situational elements (Killen &

Smetana, 2007), morality related to school discipline decisions among Black girls means, for

the purpose of this paper, to make judgments and decisions based on the following criterion:

fairness and non-violence (i.e. absence of excessive force), mental and emotional health (i.e.

valuing well-being and being sensitive to possible trauma), cultural responsiveness (i.e.

consideration of cultural/ethnic background) (Gay, 2018), and inclusivity (i.e. including and

acknowledging minoritized students). Using these benchmarks may well encourage

educational stakeholders to pause and view matters and the subsequent impact of policy

decisions from the perspective of Black girls and their families. Most importantly, these

schools that use this approach can become global models of transformative education through

the development, maintenance, and implementation of morally grounded school discipline

policies and practices.

When teachers, administrators, stakeholders, and community partners use the DI

model as a guide to their policy process, they make an outward commitment to promoting

positive change in schools for Black girls. Everyone that participates in this process would be

responsible for (1) objectively exploring the presenting discipline concern-examining all

personal, social, and academic elements, (2) setting their intent and examining their moral

standards using a common checklist to help guide the evaluation and decision-making

process, (3) ethically create a plan of action in the best interest of the student, and (4) become

champions for positive student outcomes. By doing so, the DI approach-when used as a

12

standard-can help mitigate the risks in the area of school discipline associated with Black girls

(i.e., mental health concerns, criminalization).

Recommendations

District-Wide School Discipline Workgroups

Education reform and policymaking are not easy. However, when done intentionally,

these processes have the potential to change the trajectory of students’ lives. In the same way

school districts assemble cadres of stakeholders to examine curriculum and assessment,

establishing workgroups tasked solely with the responsibility of examining, revising, and

creating discipline policies is essential. This work should center the experiences of students of

color, namely Black girls, versus placing their concerns in the margins. In order to promote

ethical policy development and implementation, these teams should first work to build

meaningful and trusting relationships with each other (Schultz, 2019), using protocols that can

be employed in their own schools. Implementing the use of DI in schools when creating,

amending, and implementing school discipline policies can help to dismantle systemic

oppression and prioritize the needs and well-being of Black girls in schools. More

importantly, approaching school discipline in this way shows Black girls that they are worth

the effort and that schools are making every effort to create a new narrative in school

discipline policy on their behalf.

Additionally, it is also important that workgroup members begin to build and deepen

their cultural competence (Ukpokodu, 2011) and engage in a “self-audit” process in which they

begin to unpack any biases, misconceptions, or other factors that may prove to be barriers to

taking a moral approach to improving the experiences of Black girls in the name of school

discipline. Team members can also review their current standards and how those standards

perpetuate discrimination and bias in their policy making process. Each member would be

encouraged to consider the outcomes of their approach on the wellness and success of Black

girls. The overall goal of the SDW is to co-create districtwide discipline policies to address the

disparities for Black girls and other students of color. Members should be well- positioned to

provide insight to both discipline policies and practices that have contributed to the current

plight of Black girls, and therefore, will leverage that positionality in providing insight into

updated policies.

13

Amplifying Student Voice

Salisbury et al. (2019) define student voice experiences as the “opportunities for

students to participate in school-based educational decisions and processes that impact their

and their peers’ lives” (p. 223). However, despite a well-documented history of the impact of

positive student self-advocacy, the voices of students are largely dismissed and excluded from

the education policy-making process (Ginwright & James, 2022). Creating spaces for Black

girls to engage as co-creators of education policy allows students to learn about education

reform. These spaces can include student policy peer councils that review trends in discipline

among Black girls and other marginalized groups. The group could submit their observations

after reviewing student-appropriate, non-identifying reports, as well as identify solutions for

positive change. With their input, administrators and other school leaders can center their

needs and voices during their strategic planning and policy processes. Likewise, and more

importantly, it allows Black girls to uncover potential blind spots in current discipline policy,

identify non-policy-related factors that may impact student behavior (i.e., school culture), and

build relationships with school staff (Mitra, 2018).

Family and School Partnerships

Hart & Butler (2022) proposed the creation and use of a restorative, wraparound

framework to address school discipline disparities in urban schools. A critical component of

this framework is the implementation of family-school partnerships. Scholars and

practitioners have identified several positive impacts of family-school partnerships (Mapp et

al. 2017). Partnering with Black girl and their families could provide further insight into their

cultural background, socio economic needs, mental health concerns and any other factors that

may contribute cause discipline concerns in school. While the need for and implications of

meaningful family engagement are clear, many teachers feel ill- equipped to support this

effort (De Bruïne et al., 2014; Willemse et al., 2018).

Current research begins to highlight several factors that contribute to these feelings of

inadequacy. Grice (2020) identifies a lack of cultural competence as a barrier to familyschool

partnerships and asserts that culturally competent educators can significantly improve the

development of positive and collaborative relationships between schools and families of color.

Creating family school nights to explore meaningful topics aside from academics could

provide schools and families with insight needed to make better decisions around school

discipline. Schools play a critical role in ensuring teachers have the knowledge, skills, and

14

dispositions necessary to implement effective family-school partnerships in support of Black

girls. These groups should work in tandem to provide pre- service, beginning, and veteran

teachers high-quality professional learning activities, to include elements of family

engagement, specifically focused on this area.

Conclusion

Understanding our position in connection to oppressive and privileged systems and

unlearning those systems' protective habits and practices requires an exceptionless, unceasing

commitment (Love, 2019). This level of compassion extends beyond the morning school

greeting, the mandated professional development workshop, and the daily classroom

operations. This sense of compassion and commitment extends to the policy making level.

The concerns that Black girls face in education have been persistent for many years. In

this 21st century, it is time to have real conversations about the challenges with the “source” of

these persistent disparities. Similarly, it is important to explore practical solutions to not only

address and inform the educational system but also the individuals that embody and operate

the system. There is no system without the people that operate it. In order for educational

reform on the behalf of Black girls to become a reality, efforts to improve the policies is

imperative to realizing this change. Discipline integrity provides a pathway for the individuals

and groups that make the decisions about school discipline to use their “point of privilege” to

make decisions that are moral and just-those that support the sustainability, wellness and

success of its students, educators, and stakeholders.

Making a difference in urban education means studying and applying the elements of

discipline integrity and believing in its impact in schools, specifically on the behalf of Black

girls. Embracing this approach will require a brave commitment to doing the necessary self-

reflection and collaborative work to promote equity and integrity in schools. Future research

on this subject should be focused specifically on how discipline integrity in urban school

policy and practice can enhance the educational experiences of Black girls’ and other students

of color-while encouraging their academic success and overall well-being.

15

References

Abend, G. (2013). What the science of morality doesn’t say about morality. Philosophy of the

Social Sciences, 43(2), 157-200.

Addington, L. A. (2021). Keeping Black girls in school: A systematic review of opportunities to

address exclusionary discipline disparity. Race and Justice.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2153368720988894

Ainscow, M. (2020). Inclusion and equity in education: Making sense of global challenges.

Prospects, 49(3), 123-134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09506-w

Annamma, S. A., Anyon, Y., Joseph, N. M., Farrar, J., Greer, E., Downing, B., & Simmons, J.

(2019). Black girls and school discipline: The complexities of being overrepresented

and understudied. Urban Education, 54(2), 211-242.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916646610.

Hart, J., & Butler, B. R. (2022). Reimagining wraparound supports to address school discipline:

A restorative approach. PDS Partners: Bridging Research to Practice, 17(2), 6-17.

https://napds.org/2022-themed-issue-leveraging-school-university-partnerships-for-

student-learning-and-teacher-inquiry/

Bell, D. A. (1995). Who's afraid of critical race theory. U. Ill. L. Rev., 893-910.

Benadusi, L. (2002). Equity and education. In pursuit of equity in education, 25- 64.

Berry, T. R. (2010). Engaged pedagogy and critical race feminism. Educational Foundations.

24(3-4), 19-26.

Bibby, P., & Shepherd, J. (2004). Developing a new classification of urban and rural areas for

policy purposes–the methodology. Defra.

Blake, J. J., Butler, B. R., Lewis, C. W., & Darensbourg, A. (2011). Unmasking the inequitable

discipline experiences of urban Black girls: Implications for urban educational

stakeholders. Urban Review (43). 90-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-009-0148-8

Brint, S. (2017). Schools and societies. Stanford University Press.

Brody, G. H., Yi-Fu, C., Murry, V. M., Simons, R. L., Xiaojia, G., Gibbons, F. X., et al. (2006).

Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year

16

longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77, 1170–

1189.

Chafouleas, S. M., Johnson, A. H., Overstreet, S., & Santos, N. M. (2015). Toward a blueprint for

trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health, 8(1), 144-162.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Children's Defense Fund. (1975). School suspensions: Are they helping children?

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED113797.pdf

Cholewa, B., Goodman, R. D., West-Olatunji, C., & Amatea, E. (2014). A qualitative

examination of the impact of culturally responsive educational practices on the

psychological well-being of students of color. The Urban Review, 46(4), 574–596.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-014-0272-y

Cokley, K., Cody, B., Smith, L., Beasley, S., Miller, I. S. K., Hurst, A., Awosogba, O., Stone, S., &

Jackson, S. (2014). Bridge over troubled waters: Meeting the mental health needs of

Black students. Phi Delta Kappan, 96(4), 40–40.

Cooper, S.M., Burnett, M., Golden, A., Butler-Barnes, S. & Inniss-Thompson, M. (2022). School

discrimination, discipline inequities, and adjustment among Black adolescent girls and

boys: An intersectionality-informed approach. Journal of Research on Adolescence,

32(1), 170-190. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12716

Crenshaw, K. W. (2011). Twenty years of critical race theory: Looking back to move forward.

Connecticut Law Review, 43(5), 1253–1352.

Crenshaw, K. W., Ocen, P., & Nanda, J. (2015). Black girls matter: Pushed out, over-policed and

under protected. African-American Policy Forum, Center for Intersectionality and

Social Policy Studies, 1-54.

Davis, A. Y. (2000). Global critical race feminism: An international reader (Vol. 40). NYU Press.

De Bruïne, E. J., Willemse, T. M., D’Haem, J., Griswold, P., Vloeberghs, L., & Van Eynde, S.

(2014). Preparing teacher candidates for family-school partnerships. European Journal

of Teacher Education, 37(4), 409-425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.912628

Delgado. R. & Stefancic. J. (2017). Critical Race Theory (Third Edition). NYU Press.

17

Delgado. R. & Stefancic. J. (2023). Critical Race Theory (Fourth Edition). NYU Press.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy and civic courage. Rowman and

Littlefield.

Gert, B. & Gert, J. (2020). The definition of morality. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Edward N. Zalta (ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/morality-

definition/.

Gilbert, R., Keddie, A., Lingard, B., Mills, M., & Renshaw, P. (2011). Equity and education

research, policy and practice: A review. Australian College of Educators National

Conference (Vol. 201, No. 1).

Ginwright, S., & James, T. (2002). From assets to agents of change: Social justice, organizing,

and youth development. New Directions for Youth Development, 2002(96), 27-46.

https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.25

Gray, M. S. (2016). Saving the lost boys: Narratives of discipline disproportionality. Educational

Leadership and Administration: Teaching and Program Development, 27, 53-80.

Green, C. (2022). Race, femininity, and school suspension. Youth & Society, 54(4), 685– 706.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X211001098

Grice, S. (2020). Perceptions of family engagement between African American families and

schools: A review of literature. Journal of Multicultural Affairs, 5(2).

https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1064&context=jma

Hardaway, A. T., Ward, L. W., & Howell, D. (2019). Black girls and womyn matter: Using Black

feminist thought to examine violence and erasure in education. Urban Education

Research & Policy Annuals, 6(1).

Hassan, H. H., & Carter, V. B. (2021). Black and white female disproportional discipline K-12.

Education and Urban Society, 53(1), 23-41.https://doi.org/10.1177/001312452091571

Hines-Datiri, D., & Carter Andrews, D. J. (2020). The effects of zero tolerance policies on Black

girls: Using critical race feminism and figured worlds to examine school discipline.

Urban Education, 55(10), 1419-1440.

18

Jurado de los Santos, P., Moreno-Guerrero, A. J., Marín-Marín, J. A., & Soler Costa, R. (2020).

The term equity in education: A literature review with scientific mapping in web of

science. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10),

3526.

Killen, M., & Smetana, J. (2007). The biology of morality. Human Development, 50(5), 241-243.

Kunesh, C. E., & Noltemeyer, A. (2019). Understanding disciplinary disproportionality:

Stereotypes shape pre-service teachers’ beliefs about Black boys’ behavior. Urban

Education, 54(4), 471–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915623337

Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P., Panayiotou, A., & Charalambous, E. (2020). Quality and equity

in education: Revisiting theory and research on educational effectiveness and

improvement. Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). ‘Who you callin’ nappy-headed?’A critical race theory look at the

construction of Black women. Race Ethnicity and Education, 12(1), 87-99.

Leary, K. (2019). Mental health and girls of color. Center on Poverty and Inequality.

https://genderjusticeandopportunity.georgetown.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2020/06/Mental-Health-and-Girls-of-Color.pdf

Lewis, C. W., Butler, B. R., Bonner III, F. A., & Joubert, M. (2010). African American male

discipline patterns and school district responses resulting impact on academic

achievement: Implications for urban educators and policy makers. Journal of African

American Males in Education (JAAME), 1(1), 7-25.

Lindsey, M. A., Sheftall, A. H., Xiao, Y., & Joe, S. (2019). Trends of suicidal behaviors among

high school students in the United States: 1991–2017. Pediatrics, 144(5).

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1187

Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of

education freedom. Beacon Press.

Mapp, K., Carver, I., & Lander, J. (2017). Powerful partnerships: A teacher’s guide to engaging

families for student success. Scholastic.

Martin, J., & Smith, J. (2017). Subjective discipline and the social control of Black girls in

pipeline schools. Journal of Urban Learning, Teaching, and Research, 13, 63-72.

19

Matsuda, M. J. (1987). Looking to the bottom: Critical legal studies and reparations. Harvard

Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Review, 72, 30-164.

McFall, L. (1987). Integrity. Ethics, 98(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1086/292912

McIntosh, K., Ellwood, K., McCall, L., & Girvan, E. J. (2018). Using discipline data to enhance

equity in school discipline. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(3), 146–152.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451217702130

Milner, H. R. (2008). Critical race theory and interest convergence as analytic tools in teacher

education policies and practices. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 332–346.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108321884

Milner, H.R. (2015). Rac(e)ing to class: Confronting poverty and race in schools and

classrooms. Harvard Education Press.

Mitra, D. (2018). Student voice in secondary schools: The possibility for deeper change. Journal

of Educational Administration, 56(5), 473-487. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0007

Monroe, C. R. (2005). Why are "bad boys" always Black?: Causes of disproportionality in school

discipline and recommendations for change. The Clearing House: A Journal of

Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 79(1), 45-50. https://doi.org/10.3200/tchs.79.1.45-

50

Morris, E. W., & Perry, B. L. (2016). The punishment gap: School suspension and racial

disparities in achievement. Social Problems, 63(1), 68–86.

https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spv026

Morris, M. (2016). Pushout: The criminalization of Black girls in schools. New Press

Nelson, S. L., Ridgeway, M. L., Baker, T. L., Green, C. D., & Campbell, T. (2022). Continued

disparate discipline: Theorizing state takeover districts’ impact on the continued

oppression of Black girls. Urban Education, 57(7), 1230–1258.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918805144

Nolan, K. (2011). Police in the hallways: Discipline in an urban high school. U of Minnesota Press.

Peller, G. T. K., Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., Peller, G., & Kendall, T. (Eds.). (1995). Critical race

theory : The key writings that formed the movement. New Press.

20

Peterson, A. J., Donze, M., Allen, E., & Bonell, C. (2018). Effects of interventions addressing

school environments or educational assets on adolescent sexual health: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health,

44(3), 111-131.

Quinn, D. J. (2017). School discipline disparities: Lessons and suggestions. Mid-Western

Educational Researcher, 29(3), 291-298.

Ricks, S. A. (2014). Falling through the cracks: Black girls and education. Interdisciplinary

Journal of Teaching and Learning, 4(1), 10-21.

Salisbury, J. D., Sheth, M. J., Spikes, D., & Graeber, A. (2019). “We have to empower ourselves

to make changes!”: Developing collective capacity for transformative change through

an urban student voice experience. Urban Education, 58(2), 221-249.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919857806

Salter, P., & Adams, G. (2013). Toward a critical race psychology. Social and Personality

Psychology Compass, 7(11), 781-793.

Schultz, K. (2019). Distrust and educational change: Overcoming barriers to just and lasting reform.

Harvard Education Press.

Schutz, P. A., & Zembylas, M. (2009). Introduction to advances in teacher emotion research:

The impact on teachers’ lives. In P. A. Schutz,!M. Zembylas (eds.), Advances in Teacher

Emotion Research (pp. 3–11). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0564-2_1

Scott, J., Moses, M. S., Finnigan, K. S., Trujillo, T., & Jackson, D. D. (2017). Law and order in

school and society: How discipline and policing policies harm students of color, and

what we can do about It. National Education Policy Center, 1-27.

Sheftall, A. H., Vakil, F., Ruch, D. A., Boyd, R. C., Lindsey, M. A., & Bridge, J. A. (2022). Black

youth suicide: Investigation of current trends and precipitating circumstances. Journal

of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(5), 662– 675.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.08.021

Simon, F., Małgorzata, K., & Pont, B.. (2007). No more failures: Ten steps to equity in education.

OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/no-more-

failures_9789264032606-en

21

Simmons-Reed, E. A., & Cartledge, G. (2014). School discipline disproportionality: Culturally

competent interventions for African American males. Interdisciplinary Journal of

Teaching and Learning, 4(2), 95-109.

Skiba, R. J., Michael, R. S., Nardo, A. C., & Peterson, R. L. (2002). The color of discipline:

Sources of racial and gender disproportionality in school punishment. The Urban

Review, 34(4), 317-342. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021320817372

Sorensen, J. F. (2014). Rural–urban differences in life satisfaction: Evidence from the European

union. Regional Studies, 48(9), 1451-1466.

Staats, C. (2014). Implicit racial bias and school discipline disparities: Exploring the connection.

Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.

https://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/ki-ib-argument-piece03.pdf

Taylor, M. C., & Foster, G. R. (1986). Bad boys and school suspensions: Public policy

implications for black males. Sociological Inquiry, 56(4), 498-506.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1986.tb01174.x

Taylor, C., Fitz, J., & Gorard, S. (2013). Diversity, specialization and equity in education. In

Education and the Labour Government. Routledge.

Teays, W., & Renteln, A. D. (Eds.). (2020). Global bioethics and human rights: Contemporary

Perspectives. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Thompson, A. (2004), Gentlemanly orthodoxy: Critical race feminism, Whiteness theory, and

the APA Manual. Educational Theory, 54, 27-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-

2004.2004.00002.x

Ukpokodu, O. (2011). Developing teachers' cultural competence: One teacher educator's

practice of unpacking student Culturelessness. Action in Teacher Education, 33(5-6),

432-454. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2011.627033

Verjee, B. (2013). Counter-storytelling: The experiences of women of colour in higher

education. Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice, 36(1), 22-32.

Wiggan, G., Pass, M. B., & Gadd, S. R. (2020). Critical race structuralism: The role of science

education in teaching social justice issues in urban education and pre-service teacher

education programs. Urban Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085920937756

22

Willemse, T. M., Thompson, I., Vanderlinde, R., & Mutton, T. (2018). Family-school

partnerships: A challenge for teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching,

44(3), 252-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1465545

Wing, A. K. (1996). A critical race feminist conceptualization of violence: South African and

Palestinian women. Alb. L. Rev., 60, 943.

Wing, A. K. (Ed.). (1997). Critical race feminism: A reader. NYU Press.

Wing, A. K. (2003) Critical race feminism: A reader. New York University Press.

Wing, A. K. (2015). Critical race feminism: Theories of race and ethnicity. Contemporary debates

and perspectives, 162-179.

Wun, C. (2016) a. Against captivity: Black girls and school discipline policies in the afterlife of

slavery. Educational Policy, 30(1), 171-196.

Wun, C. (2016). Unaccounted foundations: Black girls, anti-Black racism, and punishment in

schools. Critical Sociology, 42(4-5), 737-750.

Wun, C. (2018). Angered: Black and non-Black girls of color at the intersections of violence and

school discipline in the United States. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 21(4), 423–437.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.124882

Zeiders, K. H., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Carbajal, S., & Pech, A. (2021). Police discrimination

among Black, Latina/x/o, and White adolescents: Examining frequency and relations

to academic functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 90, 91-99.

23

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

A. Jaalil Hart (he/ him) is a doctoral candidate in the Curriculum and Instruction (Urban

Education) program at the University of North Carolina Charlotte. Focused on practices and

policies in urban education, his research addresses family engagement, teacher education, and

culturally sustaining practices in urban elementary schools.

Na'Cole C. Wilson (she/her) is the Associate Director of Academic Advising in the College of

Health and Human Services at UNC Charlotte. She is also a PhD student in the Curriculum

and Instruction (Urban Education Concentration) program at UNC Charlotte. Her research

interests include examining the best practices of African American academic advisors at

predominantly white institutions and how they manage compassion fatigue.