University of Central Florida University of Central Florida

STARS STARS

Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations

2018

An Exploration of Representations of Race and Ethnicity in Three An Exploration of Representations of Race and Ethnicity in Three

Transitional Series for Young Children Transitional Series for Young Children

Sonia M. Balkaran

University of Central Florida

Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Children's and Young Adult

Literature Commons, Elementary Education Commons, and the Language and Literacy Education

Commons

Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses

University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu

This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more

information, please contact [email protected].

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Balkaran, Sonia M., "An Exploration of Representations of Race and Ethnicity in Three Transitional Series

for Young Children" (2018).

Honors Undergraduate Theses

. 409.

https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/409

AN EXPLORATION OF REPRESENTATIONS OF RACE AND ETHNICITY IN THREE

TRANSITIONAL SERIES FOR YOUNG CHILDREN

by

SONIA M. BALKARAN

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements

for the Honors in the Major Program in Elementary Education

in the College of Community Innovation and Education

and in the Burnett Honors College

at the University of Central Florida

Orlando, Florida

Fall Term, 2018

Thesis Chair: Dr. Sherron Killingsworth Roberts

ii

ABSTRACT

This thesis seeks to explore the related research literature surrounding representations and

portrayals of protagonists of various multicultural backgrounds in series or transitional books. As

teachers, it is essential to acknowledge the lack of multicultural characters in children’s literature

among elementary classroom bookshelves and learn how to incorporate literature featuring

strong main characters of varying races and ethnicities so that children can see role models who

mirror their own contexts. Prior studies, such as Gangi (2008) and Green and Hopenwasser

(2017) have examined the deficiency of multicultural literature in the classroom, particularly

among transitional stories, which shows the importance of exploring this topic. Furthermore,

Green and Hopenwasser (2017) emphasize the importance of equal representation of transitional

books with characters of diverse ethnicities, as they act as “mirrors and windows” for students to

reflect upon themselves. These studies argue that to prevent the “whitewashing” of literature for

primary grades, teachers should be cautious while choosing series or transitional books. I

conducted an equity audit on three series or transitional books from different time periods,

commonly found among elementary classroom libraries to explore ethnic and racial

representations of protagonists to the actual demographics of the third-grade student population.

Administering this equity audit also determined that popular series or transitional books are

advantageous to include into classroom libraries when protagonists are portrayed as non-

stereotypical experiencing real-life situations. The findings of this equity audit have the potential

for educators to improve their methods choosing literature with characters of diverse races and

ethnicities and improve methods of integrating multicultural literature into lessons.

iii

This HIM thesis is dedicated to my father, Shamnarine Balkaran, who taught me, from a young

age, the importance of embracing my diverse Guyanese ethnicity and Hindu culture.

To my mother, Ramrattie Balkaran, who instilled my love of children’s literature by reading to

me every single night before bed as a child.

To my sister and brother, Neela and Amit, who are my biggest advocates and supporters.

To my Aja, who instilled in me the importance of giving and receiving a good, quality education.

To Dustin, Dylan, Drew and Savannah Rose, who will hopefully grow up in a world more

inclusive than my own and for whom I strive to become the best educator I can be.

Above all, to Bhagwan (God), through who’s blessings and grace I accomplish all things.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to give a special thanks to my thesis chair, Dr. Sherron Killingsworth Roberts, who

was a guiding light as I completed my thesis, as well as an incredible mentor and role model.

You have been there every single step of the way, through all ups and downs, every bump in the

road, always offering your valuable assistance, advice, and recommendations. I am incredibly

thankful that you chose to chair my thesis during your already busy schedule. I would also like to

thank Dr. Constance Goodman, who’s willingness to share her incredible wealth of knowledge

about diversity in the classroom made my thesis-writing journey almost effortless. Thank you to

Alissa Mahadeo, who remained a steadfast listener and observer as I completed my thesis. Also,

thank you to my family and friends for their encouragement, critique, and steadfast belief in me.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………….1

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE …………………………………………..3

Answering the Question: “What is Multicultural Literature?” …………………………...3

“Mirrors and Windows”…………………………………………………………………...5

“Sliding Glass Doors” ………………………………………………………………….....6

The Influence of Children’s Literature …………………………………………………..7

Importance of Introducing Multicultural Literature in the Classroom …………………...8

CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY ……………………………………………………….11

Selection of Target Population and Transitional Series for Examination ……………….11

Selection of Trends and Themes Examined ……………………………………………..13

Understanding and Eliminating Bias in the Researcher ………………………………...14

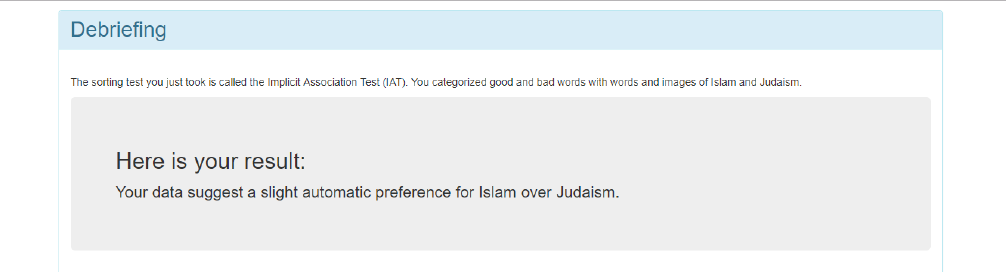

Results of the Researcher's Harvard Implicit Association Tests (IATs) ………………..16

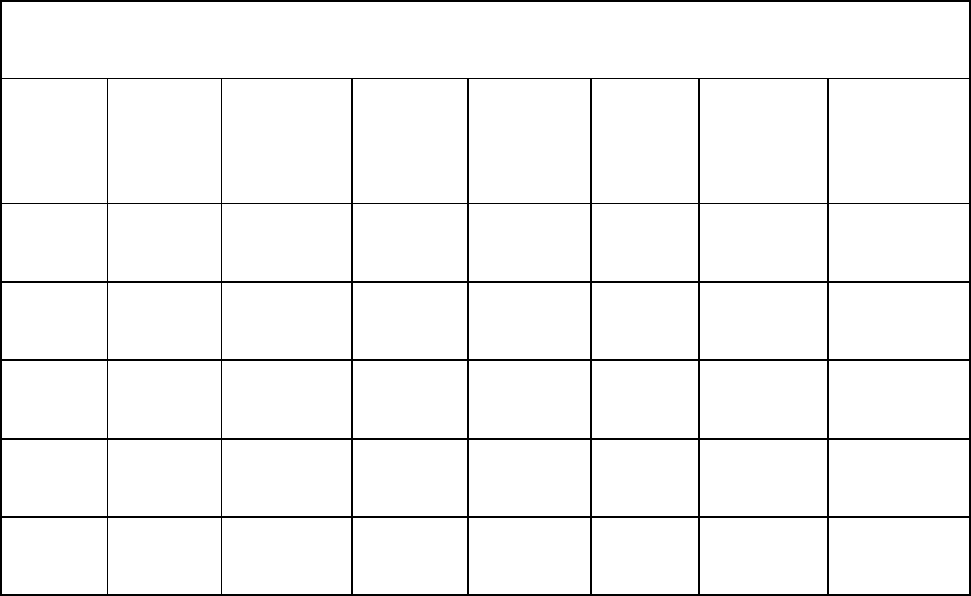

Example of Data Gathering Sheet for Equity Audit …………………………………….20

CHAPTER FOUR: FINDINGS………………………………………………………………….21

Data Sheet Findings for Each Series……………………………………………………..21

Equity Audit of Protagonist in the Following Transitional Series: The Boxcar Children,

The Bailey School Kids and Franklin School Friends …………………………………..32

Breakdown of Equity Audit Comparing Ethnic Protagonists in Transitional Series

Literature to Elementary School Demographics ………………………………………...34

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………..43

Reflections of the Researcher …………………………………………………………...44

vi

Trends and Themes ……………………………………………………………………...45

Research Limitations ……………………………………………………………………48

Next Steps and Future Research ………………………………………………………...48

Educational Implications………………………………………………………………...50

APPENDIX A : COMMON STEREOTYPES AMONG VARIOUS ETHNICITIES AND

RACES …………………………………………………………………………………..53

APPENDIX B: ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………..56

APPENDIX C: RECOMMENDED TRANSITONAL SERIES FOR THIRD GRADE

CLASSROOMS …………………………………………………………………………61

REFERENCES ………………………………………………………………………….67

1

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

The assimilation of different ethnic students in American school systems has come a long

way from the time of segregation as decided by Plessy v. Ferguson, and the Bellingham Riots.

The United States is considered to be a "melting pot of identities among its 323.1 million people,

however, in today's society, the discussion of deporting legal and illegal Americans, denying

refugees to the rights of a free life and education, and building walls between boundaries is

becoming more frequent than the discussion of becoming inclusive. Racial and ethnic

Enrollment in public elementary schools has increased steadily from the early 2000s. From 2004-

2014, there was a 75% increase of Hispanic, African American, Pacific Islander, and Asian

enrollment. By 2014, less than 50% of students enrolled in elementary schools were Caucasian, a

58% decrease from 2004. In 2017, the demographics of American elementary students from

minority backgrounds surpassed the demographics of American students from Caucasian

backgrounds (52% of the population vs. 48% of the population), reinforcing the statement that

the United States is becoming more diverse, primarily in our school systems.

In Florida, all educators acknowledge Florida’s Principles of Processional Conduct for

the Education Profession in Florida, which states that teachers should not discriminate on the

basis of different characteristics, including race, color, and ethnic origin. However, while this is a

mandate teachers must follow, students are not necessarily held to the same standard and may act

ignorant towards their fellow students due to a lack of multicultural education. Especially now, it

is important to teach students, particularly elementary-aged students, acceptance, and

inclusiveness of all types of people. Multicultural transitional series literature with well-

established ethnic protagonists authorizes students to explore worlds both identical and different

from their own. This specific type of literature offers students opportunities to traverse different

2

scenarios with characters whom they can compare against themselves. Through this genre of

books, students are given insight as to why people look, act, dress, and behave differently.

The purpose of this thesis is to perform an equity audit of a current children’s literature

transitional series for elementary age children to identify if it contains protagonists of various

ethnic or racial backgrounds in non-stereotypical roles. Using patterns and trends observed from

a series of equity audits on three sets of transitional series literature, a list of recommended

grade-appropriate multicultural series literature will be constructed and provided as suggestions

for implementation in 3rd grade classroom libraries. This selected list of transitional series

literature was used to generate suggestions for teachers to create a more inclusive classroom

library and incorporate multicultural literature into lesson plans. The necessity of including

multicultural literature and diverse characters in the everyday classroom is shown through the

review of related research literature containing studies that examine the impact this type of

literature has on young children and young children’s attitudes towards (their own and others)

race and ethnicity.

The following chapter will provide an intensive review of the research literature covering

a variety of topics, from multicultural literature, mirrors and windows, the importance of

children’s literature, and the prominence of multicultural literature in the elementary classroom.

These topics influence my research, which is detailed in Chapter Three and Four. Chapter Five

analyzes the results of my research compared to my research of literature, and presents trends

among results, any research limitations, educational implications, and suggestions for future

research.

3

CHAPTER TWO: A REVIEW OF THE RESEARCH LITERATURE

A review of research on multicultural literature for young children highlights the

stereotypes that surround them and the urgent need to start including them in our classrooms. As

more immigrants enter the United States and our classrooms become more inclusive, the age of

introducing and discussing the concept of race and ethnicity gets younger. The majority of the

research reviewed explores the growing inclusion of multicultural literature (literature with

ethnic characters) into the everyday classroom. However, there was little to no reference of any

multicultural literature protagonists of different ethnicities and races in non-stereotypical roles.

The following literature review focuses first on the definition of multicultural literature and the

relating attitudes young children have concerning their own race and ethnicity. It also examines

the possible impact children’s literature has on reinforcing negative views of different races (that

students may have) while indicating the possible reasons of why those views exist and the

influence children’s literature has on positively altering those viewpoints.

Answering the Question: “What is Multicultural Literature?”

To fully understand the importance of multicultural literature, one must first understand

what this term encompasses. Multicultural literature is defined as “literature about the

sociocultural experiences of underrepresented groups,” (Education Wise, n.d, n.p.),

underrepresented groups including those who fall outside the “mainstream” of race, ethnicity,

religion, and language. All genres, both fiction and nonfiction, of literature can serve as essential

tools for addressing diverse issues in the classroom. Although the definition of multicultural

states representations of social experiences of underrepresented groups, some books that qualify

as multicultural literature may make children feel alienated (Davis, Brown, Liedel-Rice, &

4

Soeder, 2005). As students of different ethnicities and races enter school, they are constantly

challenged to “fit-in” and assimilate, in most cases, the texts they read in class do not allow these

students to make connections or achieve proper emotional responses (Robinson, 2013). For the

purpose of this research in analyzing transitional series multicultural literature, an emotional

response is defined as “common emotional reactions such as fears, triumphs, loss, maturation,

childhood recollection, grief, pain, pride, and joy,” (Robinson, 2013, p. 46.). Well-written

multicultural literature with complex, developed characters allows for students of all ages to

experience appropriate emotional responses, including empathy, as well as create a climate that

welcomes racial, gender, and cultural diversity in the classroom.

This thesis has chosen to focus upon transitional series books for young children. Green

and Hopenwasser (2017) state that transitional series literature is written in a straightforward,

predictable, and comprehensible manner, usually for students between the ages of kindergarten

and third grade, containing protagonists dealing with age-appropriate events. If these books are

engaging, well-written and reflective of the reader, children who read transitional series literature

will read for pleasure as an adult (Green & Hopenwasser, 2017, p. 51.). When young students

interact with texts that feature protagonists they can connect with, they can see how others are

like them and are able to make text-to-world connections between the events of the literature and

their actual lives. However, if students do not encounter characters like them, literature will

become more frustrating, rather than pleasurable and entertaining. In the last five decades, the

main protagonists of transitional literature have moved away from the cookie-cutter mold of an

Anglo-Saxon, suburban, American student between the ages of nine and thirteen (Szymusiak &

Sibberson, 2001). By the late 1980s, the multicultural educational movement, a push for equal

5

rights that relates to schools and schooling (Bishop, 1997, p. 2), allowed for the creation of

diverse, complex characters in literature. According to Rudine Bishop:

“Protagonists in literature have slowly been socially and culturally reformed to include

characters of Latinos, American Indians, Asian Americans, the disabled, gays and

lesbians, and the elderly; all of whom felt victimized, oppressed, or discriminated against

in some way by the dominant majority.” (Bishop, 1997, p. 3)

As the American student population continues to diversify and grow, authors of

children’s books seem to embrace multicultural literature and constantly including various

character of different backgrounds and ethnicities; however, a majority of popular elementary

book selections continue to deny underrepresented students realistic images of themselves, and

their families, communities, and cultures. As teachers, one must include engaging and authentic

literature; therefore, this research will explore just how current third grade transitional series

literature for elementary age children strives to reflect the present diverse demographics of

today’s classroom.

“Mirrors and Windows”

With an influx of immigrants attending U.S. schools, it is especially important for

students of all backgrounds to have opportunities to learn and reflect about themselves and others

around them, in and out of school (Tschinda, Ryan, & Ticknor, 2014). Since the population of

American elementary schools is becoming increasingly diverse, transitional series literature

filled with mainly white characters do not allow Caucasian students to reflect on other races, nor

6

does it allow students of other races to reflect upon themselves. However, when used

appropriately in the classroom, multicultural series literature acts as “mirrors and windows”

(Bishop, 1990; Green & Hopenwasser, 2017):

● Mirror Books: Children’s books that allow students to reflect upon themselves

by providing a mirrored view of people from their own culture and ethnicity.

● Window Books: Children’s books that allow students a “window view” of how

people of other cultures and races behave, live, dress, or problem solve.

The exposure to literature can become a shared experience, allowing students to reflect on their

own perspective and individual backgrounds before looking at others. As children learn about

themselves and others, they explore differences and similarities that allow them to learn to

appreciate both theirs and others’ cultures (Lowery & Sabis-Burns, 2007). Considering a

majority of children’s literature in the elementary classroom contains more Caucasian

protagonists than any other race, students of Caucasian ethnicities are exclusively exposed to

literature where they see reflections of themselves and their own lives. For this reason, these

students within the dominant culture view themselves and their lives as being “normal” and view

other people of different ethnicities as “exotic” (Bishop, 1997). Moreover, students of minorities,

who do not see any reflections of themselves, or who see stereotypical, distorted, inaccurate, or

comical depictions of themselves grow to understand that they have little value in their school,

community, and society.

“Sliding Glass Doors”

In 1990, Rudine Sims Bishop coined the new term “sliding glass doors” to describe the

outlooks of diversity that students obtain from children’s literature. In her essay, Mirrors,

7

Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors, she describes these fluctuating phases of children’s literature

stating:

“Books are sometimes windows, offering views of the worlds that may be real or

imagined, familiar or strange. When lighting conditions are just right however, a window

can also be a mirror. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to

walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or

recreated by the author.” (Bishop, 1990)

Books classified as “sliding glass doors” provides students an opening of adventures beyond

their own experiences while portraying protagonists that can look, act, or dress both similarly

and differently than the reader. Reading these types of children’s books may start to become a

means of self-affirmation, where students are constantly seeking representations of themselves

experiencing different encounters in literature that they do not get to experience personally. With

the growing diversity in the elementary school population but only 73.3% of elementary school

books containing Caucasian protagonists, the need to include these “sliding glass doors” is

becoming more frequent (University of Wisconsin, 2017).

The Influence of Children’s Literature

What children read influences how children view themselves, and when children

encounter characters to relate to in text, their comprehension and motivation to read improves

(DeNicolo & Franquiz, 2006). The influence reading will have on a reader is not just affected by

an engaging plot and vivid setting, but also the inclusion of relatable characters. When children’s

books include protagonists, antagonists, and sidekicks of similar racial and ethnic backgrounds to

the students, readers can easily identify and compare themselves to those characters, which

8

furthers their comprehension of the text. Literature, especially children’s multicultural literature,

can contribute to the development of students’ (particularly students of ethnic minorities) self-

esteem by portraying accurate characters that personify students’ images of themselves. When

students select books that elicit empathy and engagement from students of varied cultural

background from different parts of the world, children’s literature can be used as a tool against

challenging stereotypes (Singer & Smith, 2003). It especially allows for Anglo-Saxon,

heterosexual readers to see the world “through other people’s eyes,” despite racial differences.

Diversity in the classroom is growing more meaningful as classrooms continue to

diversify in race and ethnicity. Both preservice and current teachers are inadequately prepared to

understand and handle unique challenges students from different cultural backgrounds encounter

(Robinson, 2013). Teachers hoping to positively impact students’ views of, attitudes towards,

and treatment of individuals with various ethnic and racial backgrounds may turn to multicultural

literature. Therefore, the availability and accuracy of such literature should be examined before

teachers select them for their classroom libraries or as instructional materials. With the current

demographic shifts occurring in the United States due to the influx of immigrants and refugees

(Bigler, 2002), the daily need for cross-cultural understanding is becoming more important.

Importance of Introducing Multicultural Literature in the Classroom

It is critical for teachers to be aware of potential barriers when introducing multicultural

literature in the classroom, however, to do so, educators must first be exposed to this type of

literature themselves. By educating preservice teachers on how to successfully analyze and

choose appropriate multicultural literature, then informing teachers on integrating its use in their

classroom, students are exposed to similar scenarios they may be experiencing and are better

9

equipped to understand people who they encounter at school, in their community, and throughout

the world (Singer, et. al, 2003).

Previous studies, such as ones conducted by Warikoo (2006), and Robinson (2013)

supports the idea that students and teachers alike need to be aware of social and cultural issues

that impact their lives, and that teachers need to find ways of introducing these issues through

literature. Warikoo conducted in-depth interviews on students of Indo-Caribbean descent that

considered three factors to explain differences in ethnic identity: different media images for

South American men and women, a school context of different level of “peer status” perceived

by Indian boys and girls and a gendered process of migration, where women maintain stronger

cultural roots in a new country while men assimilated more. She found, that when entering

school, students often adopt practices of segmented assimilation theory, which suggests that

second-generation of minority cultures (in Warikoo’s case, Indo-Caribbean) youth may

assimilate by adapting their identity to match the “white middle class,” “African-American lower

class,” or may retain ties to their ethnic culture and community (Warikoo, 2006, p. 815.).

Robinson conducted a study on how inservice teachers can best implement multicultural

literature in the classroom by assuming a transformative, critical perspective and posing the

questions:

● What understanding do the students acquire about themselves and others while engaging

critically with multicultural children’s literature?

● What are experiences that allow children to respond critically and emotionally with

multicultural texts? (Robinson, 2013, p. 43)

To complete this study, Robinson implemented a quantitative inquiry completed by collecting

data, locating recurring themes and categorizing and comparing these themes. They were

10

conducted in her classroom, where the demographics consisted of nine European-American, one

African-American, six racially mixed and two Latino students. The author found that

multicultural interactive readings promote critical responses to a text, and that students will draw

on prior knowledge to build upon one another’s comments. By providing students with

opportunities to interact and learn about people whose experiences, cultures, social and economic

situations, and heritages are different from their own, students were given the opportunity to

allow to delve into their prior experiences and verbalize these experiences to focus on their social

and cultural background and make connections between themselves and these characters.

(Robinson, 2013, p. 50.)

In this research, the performance of a series of equity audit of three current children’s

literature transitional series for elementary age children to identify protagonists of various ethnic

or racial backgrounds in non-stereotypical roles will provide both preservice and inservice

teachers a guide on selecting suitable transitional series literature to incorporate into third grade

classrooms. The book list compiled at the end of this research will also provide students options

of representative multicultural transitional series literature for them to compare to their own

cultures, experiences, races, and ethnicities.

11

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this research was to examine the representations and the portrayals of

protagonists with various multicultural backgrounds among three popular third grade transitional

series’. To do so, this research will use an equity audit, similar to one administered by Green and

Hopenwasser (2017) conducted on the first five books of three popular third grade book series to

compare racial representations each books’ protagonists to school demographics of the third-

grade student population. By definition, an equity audit is “a review of inequalities within an

area or of the coverage of inequality issues in a policy, program, or project, usually with

recommendations as to how they can be addressed” (Defined Term, n.d, n.p.). In the past

decade, less than 5% of recommended books for schools were of the multicultural genre (Gangi,

2008), so the results of these equity audits will be used to compile a list of appropriate

multicultural transitional series literature to present suggestions of books and guidelines of

classroom implementation to preservice and inservice teachers so as to integrate literature in

their lessons and classroom libraries.

Selection of the Target Population and Transitional Series for Examination

This research focused on examining transitional series literature appropriate for third

grade students with various reading levels with a multicultural lens. Students respond more

positively to literature containing characters who reflect the reader’s own characteristics (Gangi,

2008); therefore, I chose popular transitional series literature most likely to be in a third-grade

classroom library. Three different transitional series were chosen to be audited based on

popularity among three different time periods and on the amount of racial diversity and attitudes

towards different ethnicities. To narrow down the selection of books from the copious amount of

12

popular transitional series literature, the New York Times Best Sellers List, and the Goodreads

Must-Have Series for ages 6-12 was consulted. From those, The Boxcar Children series by

Gertrude Chandler Warner, The Bailey School Kids series by Debbie Dadey, and Franklin

School Kids series by Claudia Miller were chosen, as they best represented the changing

demographics (1960-2016) of racial ethnicity in elementary-aged children throughout the

decades. These series were published between 1940-2017, so it is appropriate to compare these

protagonists to the period demographics. In each series, only the first five books of the series will

be examined (in the case of Franklin School Friends, there are only five books). Each series

follows the same format:

● Each book examined includes similar sets of protagonists: four in The Boxcar

Children (two boys and two girls) and The Bailey School Kids, five in Franklin

School Friends (two boys and three girls)

○ In The Boxcar Children and The Bailey School Kids, since there are only

four protagonists, each character is the focus of many books. In Franklin

School Friends a new character is introduced each time, allowing for five

protagonists.

● Individual books in each transitional series contains a new plot or “adventure,”

whether it is solving a problem or overcoming a challenge, focused on one main

protagonist but every book will involve all main protagonists in some aspect.

● Each book examined is between 80 to 125 pages.

13

● Each book examined contains about five to seven black and white pictures

throughout the book depicting the main protagonist and characters, the setting,

details of the plot, and any secondary characters

● Each book has a colored, illustrated front cover depicting at least one of the main

protagonists.

Each series was also chosen based on their publication dates, as they were written far

enough apart to show the changing demographic on racial and ethnic characters and how they

were portrayed (or mentioned) in each series. The first five Boxcar Children series books,

published between 1942 and 1960, takes place during a time where segregation between African

Americans and Caucasians are beginning to peak. The first five Bailey School Kids series books,

published between 1991-1992, were written in a time where there was ongoing debate of

whether, genes, environment and ethnicity caused an academic gap between different races. The

first five Franklin School Friend series books, published between 2014-2016, reflects the

growing diversity of America while still alluding to the ongoing stereotypes the nation has of

certain races. The diverse backgrounds of each series allow for a wide selection of themes to be

examined when conducting, comparing, and contrasting this trinity of equity audits.

Selection of Trends and Themes Examined

When conducting this set of equity audits, I examined the “who, what, where, when and

why” of each transitional series to determine the assets and deficiencies of The Boxcar Children

(Warner, 1942-1960, The Bailey School Kids (Dadey, 1991-1992), and Franklin School Friends

(Mills, 2014-2016) and found that two of the three series contributed to immersing third graders

14

in reflective literature. In gathering my data, I examined these third grade book series for

protagonists of Caucasian, African American, Hispanic/Latino, South Asian, Eastern Asian, and

Multi-Racial ethnicities to research equal or unequal representations of ethnicities in elementary

series children’s literature. To compare to reader demographics, I also examined family

dynamics and protagonist character traits (bravery, honesty, fairness) by reading the first five

books in each of the three series, carefully examining the ethnic background (stereotypes,

characteristics, roles, family dynamics, plot, and related actions) of each protagonist.

Based on my previous knowledge and experience with third grade transitional series

literature, I anticipated finding 75% of the books among the three transitional series to contain

protagonists of Caucasian backgrounds, and about 20% of the books observed might contain

protagonists of African American backgrounds. While examining these three series, I found at

least one African American, Hispanic/Latino, South Asian, East Asian, or multiracial character

depicted in roles as secondary and maybe portrayed as stereotypical characters. My previous

knowledge about transitional literature of fueled my inferences for the outcome of this research,

and supported my findings that these sets of equity audits would display data showing a wide

array of protagonists with Caucasian, and African American ethnicities, but would show few or

no characters of Hispanic/Latino, South Asian, East Asian, or multi-racial ethnicities among

Warner’s, Dadey’s and Mills’s third grade transitional series. The following chapter outlines the

findings of this content analysis to compare with my initial predictions.

Understanding and Eliminating Bias in the Researcher:

This researcher read 10 Quick Ways to Analyze Children’s Books for Racism and Sexism

(CITE) to further understand and remove researcher bias when conducting equity audits on

15

Warner’s, Dadey’s, and Mills’s transitional series. This CIBC analysis contains tips on analyzing

children’s books for stereotypes (derogatory implications) and tokenism (identical individuals) in

the illustrations and the author’s perspective. The breakdown of the different components in a

book’s storyline will allow this researcher to examine and determine standards for success or

resolution of problems depending on the race and ethnicity of protagonists and secondary

characters. It also gives suggestions on questions to ask about the lifestyles, relationships among

characters, and the ethnicities of the heroes. As an equity audit analyzes the plot, setting,

illustrations and protagonists, these tips for analyzing bias in children’s literature will be helpful

as it gives short explanations of how to thoroughly analyze these components of children’s

books.

Previously to reading and coding each series, the researcher will create a list of Common

Stereotypes Among Various Ethnicities and Races, located in Appendix A. While filling out the

data sheets and conducting the equity audit on the following three transitional series: The Boxcar

Children, The Bailey School Kids, and Franklin School Friends, the researcher will reference the

list of Common Stereotypes Among Various Ethnicities and Races to check for hidden biases in

protagonists and experiences the protagonists (and secondary characters) encounter.

For this researcher to further understand their implicit biases that may have impacted the

results of this research, I completed a specific set of Harvard Implicit Association Tests (IATs).

An IAT is a social psychological test designed to detect the strength of a person’s automatic

association between mental representations of concepts and evaluations (good or bad) or

stereotypes (Harvard, 2011). To better comprehend any internal multiracial, ethnic, or cultural

biases, I worked to complete Race (Black-White, Native-White American, Asian-European

American, Light-Dark Skin Tone, and Religion IATS. The following IAT scores helped me to

16

keep my bias in check and to keep the results of my analyses into account when conducting the

three sets of equity audits on The Boxcar Children, The Bailey School Kids, and Franklin School

Friends transitional book series.

Results of the Researcher’s Harvard Implicit Association Tests (IATs):

By completing the following IATs, I was able to further understand any implicit biases

they may have in greater detail. This will allow them to acknowledge these biases while

collecting data from each of the chosen transitional book series to complete an unbiased equity

audit. Doing so would also allow the researcher to examine any stereotypes among protagonists.

All IAT results are based on different categorization tasks performed in sets of seven.

The testing candidate sorts through pictures of men and woman of different skin tones, races,

religions, and ethnicities based on different prompts, i.e. “Click I to sort African Americans

when prompted, and E to sort Europeans when prompted. Please complete the sort as fast as you

are able.”

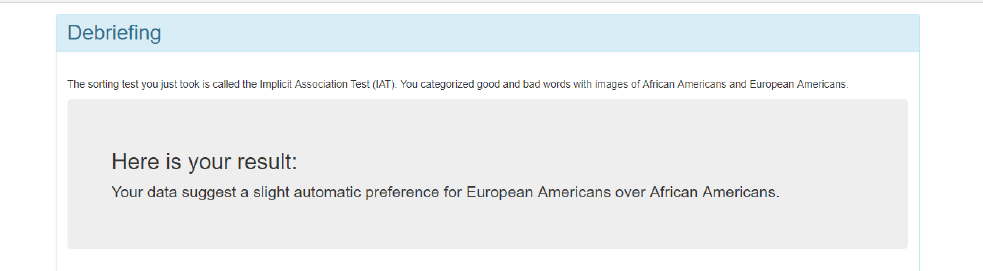

Race (Black-White)

17

The Black-White Race IAT suggested that I have a slight automatic preference for

European Americans over African Americans because I was faster responding when European

Americans and Good were assigned to the same response key than when African Americans and

Good were assigned same response key. The word slight indicates the stregnth of the bias that I

determined.

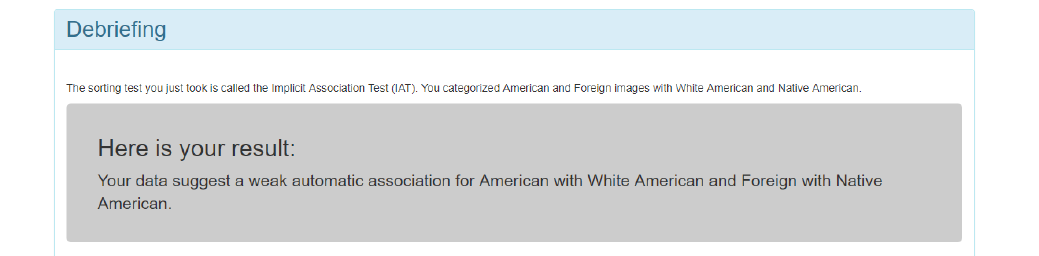

Native-White American

The Native-White American Racial IAT suggested that I have a weak automatic

association for American with White Americans and Foreign with Native American because I

was somewhat faster responding when White Americans and American were assigned to the

same response key than when Native Americans and American were assigned same response key.

The word weak indicates the stregnth of the bias that I have, allowing me to acknowledge and

surpress it.

18

Asian-European American

The Asian-European American Racial IAT suggested that I have a slight automatic

association for American with European Americans and Foreign with Asian American because I

was faster responding when European Americans and American were assigned to the same

response key than when Asian Americans and American were assigned same response key. The

word slight indicates the stregnth of the bias that I have, allowing me to acknowledge and

surpress it.

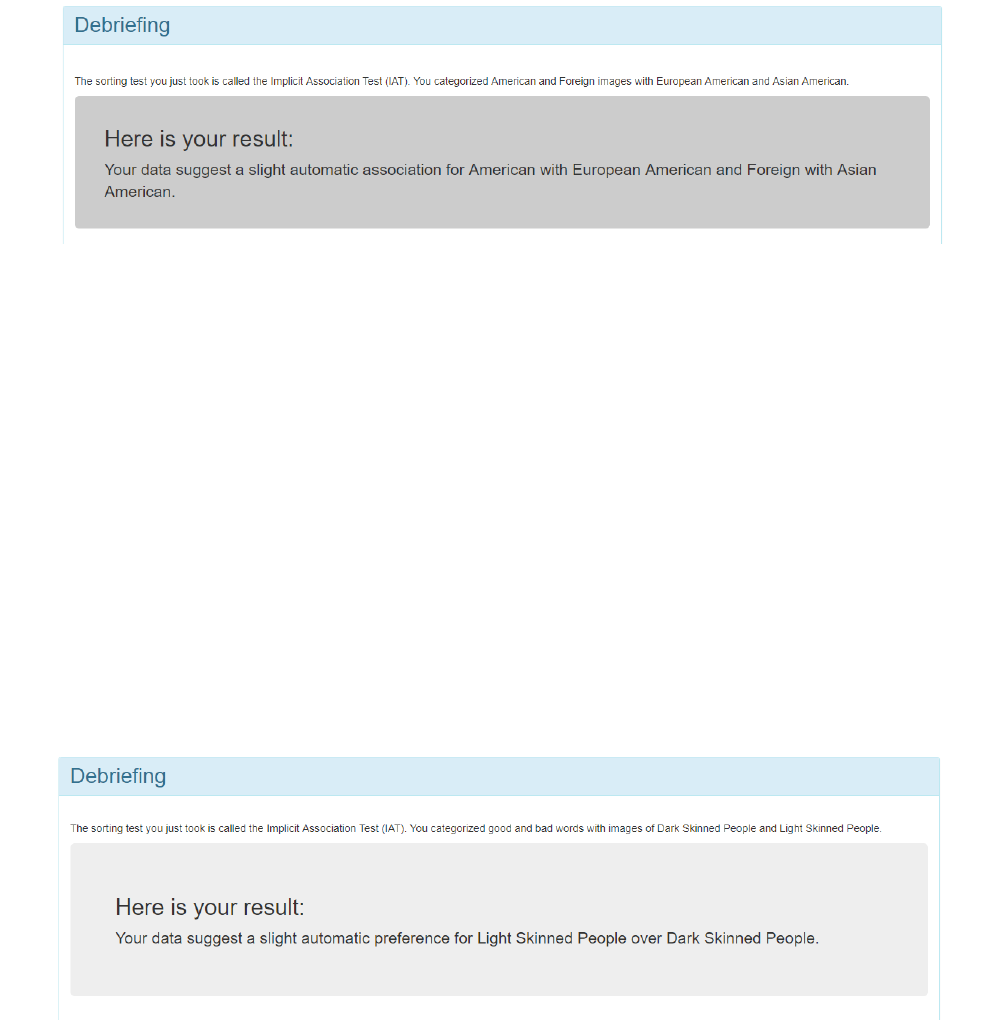

Light-Dark Skin Tone

The Light-Dark Skin Tone IAT suggested that I have a slight automatic preference for

Light Skinned People over Dark Skinned People because I was faster responding when Light

Skinned People and Good were assigned to the same response key than when Dark Skinned

19

People and Good were assigned same response key. The word slight indicates the stregnth of

this bias.

Religion

The Judiasm-Islam Religion IAT suggested that I have a slight automatic preference for

Islam over Judaism because I was faster responding when Islam and Good were assigned to the

same response key than when Judaism and Good were assigned same response key. The word

slight indicates the stregnth of this bias, allowing me to acknowledge it as I conduct the equity

audits.

20

Example of Data Gathering Sheet for Equity Audit:

Name and Author of Transitional Series Examined

Book

Title

Front

Cover

Protagonist

Traits

Family

Dynamics

Stereotype

Ethnicity

Secondary

Traits

Stereotype/

Ethnicity

Book 1

Book 2

Book 3

Book 4

Book 5

*Secondary Traits and Stereotype/Ethnicity will only be used in the cases where it applies.

The following chapter will present the findings of the equity audits taken for the first five

books of these three transitional series, while Chapter 5 will use these results to examine the

trends and themes, research limitations and implications, and opportunities for further research.

21

CHAPTER FOUR: FINDINGS

This chapter will provide a detailed look at the first five books of each selected series and

the appearance or nonappearance of the selected trends and themes. It is important to analyze

each book before analyzing individual concepts and stereotypes that may span across each series

or may be unique to one series. Before conducting a cross-series equity audit, three separate

audits were taken from each transitional series chosen. This analysis is shown with the following

data sheets (Figures 1, 2, and 3). An annotated bibliography of each book selection provided in

Appendix B details all selected transitional series for the reader to better understand findings of

the equity audit.

Data Sheet Findings for Each Series

The first series examined was The Boxcar Children which remains popular despite

original publication dates of 1942-1960. This is one of the oldest and most popular series found

in a third-grade classroom library (Scholastic, 2018). Since this series is extremely prominent in

classroom libraries, and because this series was published decades before educators concerned

themselves with diversity or multicultural education, I wondered what the range of diversity

presented amongst its protagonists might be. Since the original books by Gertrude Chandler

Warner ended publication in 1960, I expected a lack of ethnic protagonists featured in a non-

stereotypical role, as multicultural education had just originated in the 1960s as an effort of

reflect and understand the growing diversity of American classroom (Sobol 1990). However, if

characters of color were included, I wondered what roles they might hold.

Although the original Boxcar Children books by Gertrude Chandler Warner ended

publication in the 1960s, through a partnership with Scholastic, this series continues to be ghost

22

written today, in 2018. However, since most third-grade classroom libraries includes books from

the original series, the following analysis shows trends (stereotypical and non-stereotypical)

among the front cover, protagonists, and family dynamics of the first five books of The Boxcar

Children. For all five books, the four protagonists, Benny, Violet, Jessie, and Henry, range

among the ages of 6 to 14, are brown-hair Caucasian. In the first book, The Boxcar Children, the

children are introduced as orphans who prove to be intelligent, scrappy, and self-sufficient by

making a new life for themselves in a boxcar in the woods. Throughout the book, each child is

given a set of distinguishing characteristics that remain consistent for the rest of the books in this

series.

• Henry (14): Calm, hardworking, very protective of his siblings

• Jessie (12): Motherly, tidy, organized

• Violet (10): Sensitive, shy, skilled (at sewing)

• Benny (6): Energetic, cheerful, loves everyone and everything (especially food)

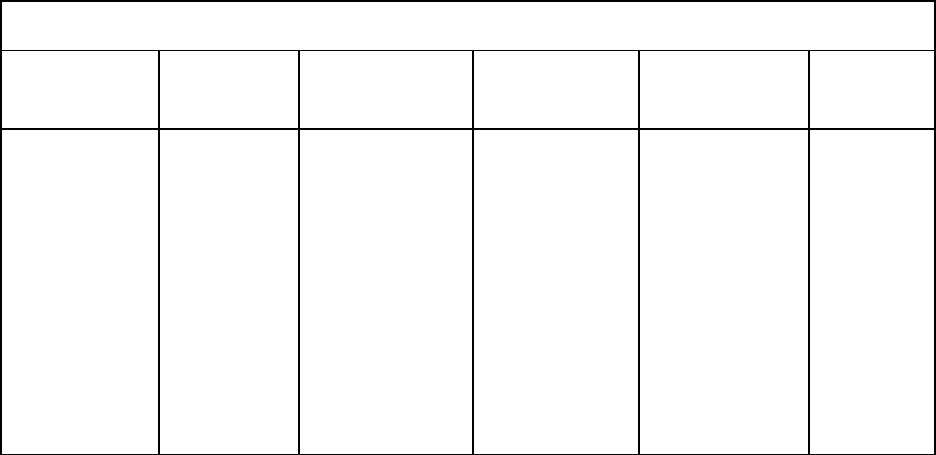

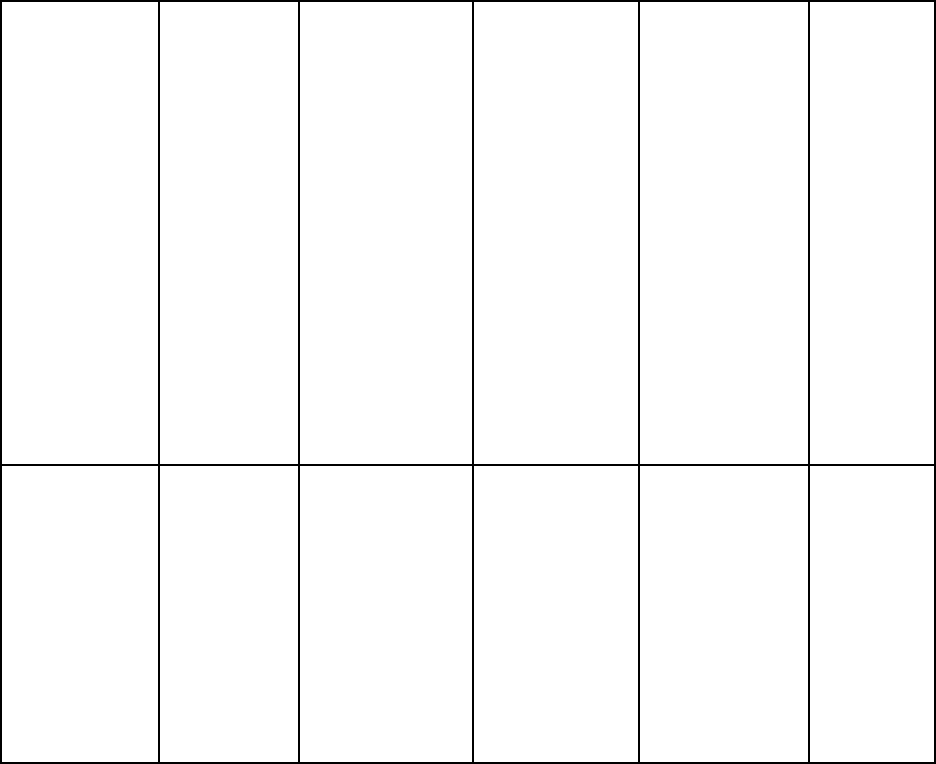

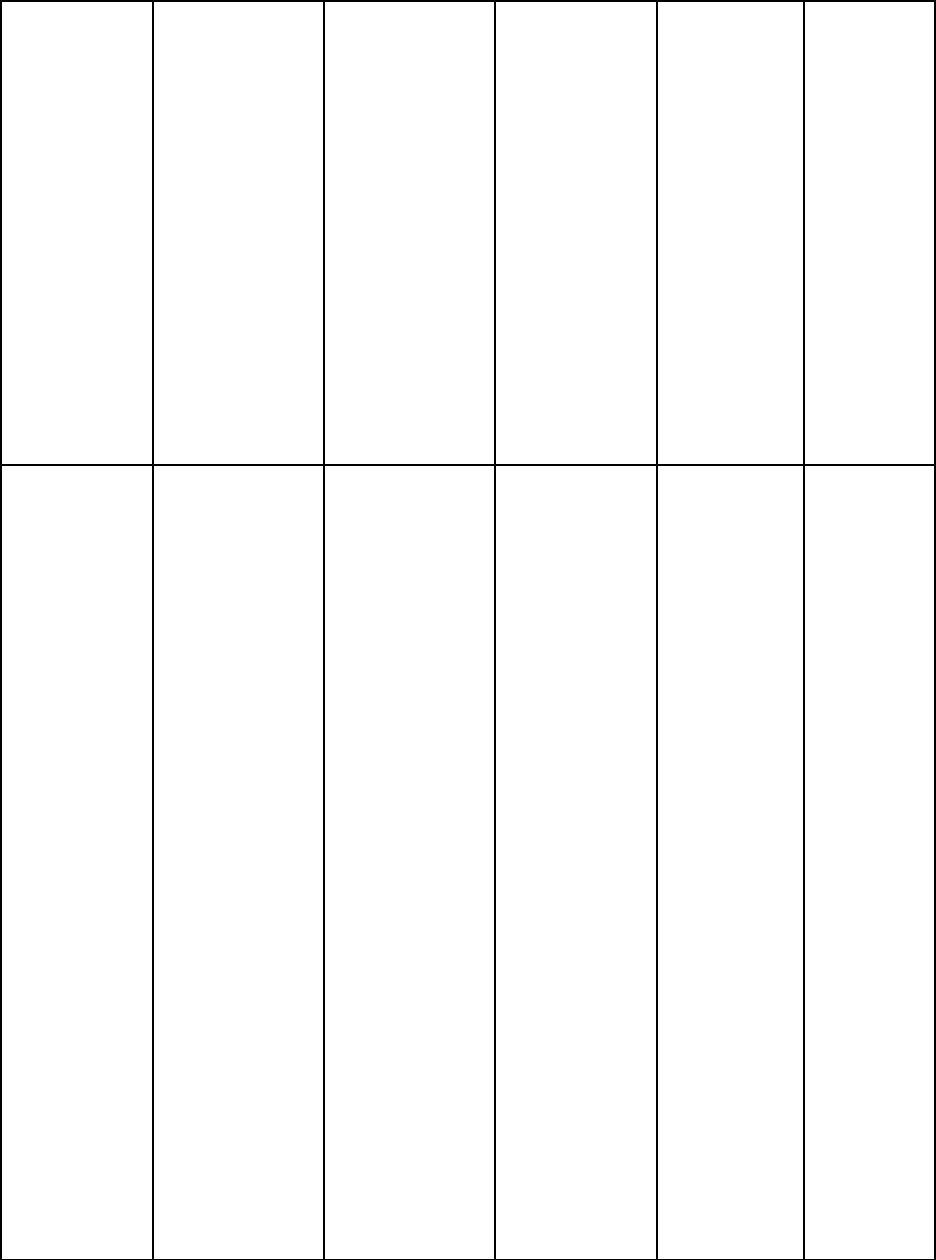

(Figure 1) Data Sheet #1: The Boxcar Children

The Boxcar Children by Gertrude Chandler Warner

Book Title:

Front

Cover:

Protagonist

Traits:

Family

Dynamics:

Stereotype:

Ethnicity:

The Boxcar

Children

Introduction

of Henry,

Jessie, Violet,

and Benny

Alden, the

main

protagonists

-Four

young,

pale-

skinned,

brown-

haired

children

dressed in

clean,

brightly

colored

-Henry, the

oldest at 14, is

calm,

hardworking

and is very

protective of

his siblings

-Jessie, 12

years old,

motherly, tidy,

and organized

-The four

children are

orphaned and

live together

for a majority

of the book.

-They

eventually

move in with

their

grandfather at

-There is a

common

stereotype that

orphans are

resilient and

scrappy,

something the

Alden’s are

-Their

grandfather is

also extremely

Caucasian

23

clothes,

looking

hurried and

scared.

-They are

climbing

into a

boxcar

-Violet, 10

years old,

sensitive, shy,

and skilled at

sewing

-Benny, 6 years

old, loves food

and is very

energetic and

cheerful

the end of the

book and live

with him for

the rest of the

series.

wealthy,

something else

that is a

stereotype to

orphan stories

Surprise

Island

Introduction

of the Alden’s

cousin Joe

Alden

-Four

young,

pale-

skinned,

brown-

haired

children

dressed in

clean

summer

clothes

-They are

climbing

out of a

boat

-Joe Alden is

young adult

friendly, very

into the

outdoors and

enjoys

spending time

with his

cousins

The children

still live with

their

grandfather,

whom Joe is

visiting

N/A

Caucasian

The Yellow

House

Mystery

Introduction

of the Alden’s

cousin Alice,

Joe’s wife

-Four pale-

skinned,

brown-

haired

children

dressed in

clean,

brightly

colored

clothes

-Henry and

Jessie

appear older

here, while

Benny and

Violet look

the same

-Alice is a kind

woman who

marries Joe and

becomes the

Alden’s cousin

The children

still live with

their wealthy

grandfather

N/A

Caucasian

24

Mystery

Ranch

Introduction

of the Alden’s

great-aunt

Jane Alden

-Depicts

and older

Jessie and

Violet,

dressed in

sweaters

and long

pants

-They are

clearly in a

western

town,

driving a

horse-

drawn

carriage

-At first, Aunt

Jane is cranky,

bossy, and

unkind

-Her

disposition is

eventually

sweet and

smart, and she

treats the

Alden’s well

The children

live with their

Aunt Jane

Alden for a

while, as she is

sickly and in

need of care

N/A

Caucasian

Mike’s

Mystery

-Five young

children

dressed in

clean

clothes

appear to be

watching

two dogs

race one

another

N/A

The children

are once again

living with

their

grandfather

N/A

Caucasian

Since this equity audit compares multiple books series to school demographics, the

second book series that was analyzed is The Bailey School Kids. The publication period (1991-

1992) are also dated, but not as far removed as The Boxcar Children, therefore more relatable to

children in 2018. Since multicultural education reform in schools reestablished in 1986

(Tomlinson, 1990), I wondered if the book might highlight more diverse characters represented

in these books published in the early 1990s. As I completed this data sheet, I found that three of

four protagonists were Caucasian, however, this book reveals our first non-stereotypical, African

American protagonist in this series. These characters have crazy experiences and undergo

25

challenges that appeal to students’ sense of whimsical adventure, and that the characters are

relatable to Caucasian and African American students. However, while this book would be

perfect for library shelves of classrooms in 1990, some of the references in the book are no

longer relevant to today’s students, such as Eddie talking to his grandmother on a corded phone

or our protagonists answering math problems at school on the chalkboard. In my experiences

around third-graders in my service learning, some students have no any idea as to what these

things are.

Although The Bailey School Kids have over 30 different books in this series and since

most third-grade classroom libraries includes the first five books from the series, the following

analysis shows trends (stereotypical and non-stereotypical) among the front cover, protagonists,

and family dynamics for these specific books. For all five books, the four protagonists, Liza,

Melody, Howard, and Eddie, are included. Similarly to The Boxcar Children, the protagonists

include two boys and two girls. Throughout the initial book, each child is given a set of

distinguishing characteristics that remain consistent for the rest of the books in this series.

• Liza: the peacemaker, doesn’t like hurting other, and is very timid

• Howard: enjoys school, a logical, level-headed, intelligent thinker

• Melody: brave, athletic, and extremely competitive

• Eddie: mean-spirited (to people who aren’t his friends), boisterous and dramatic

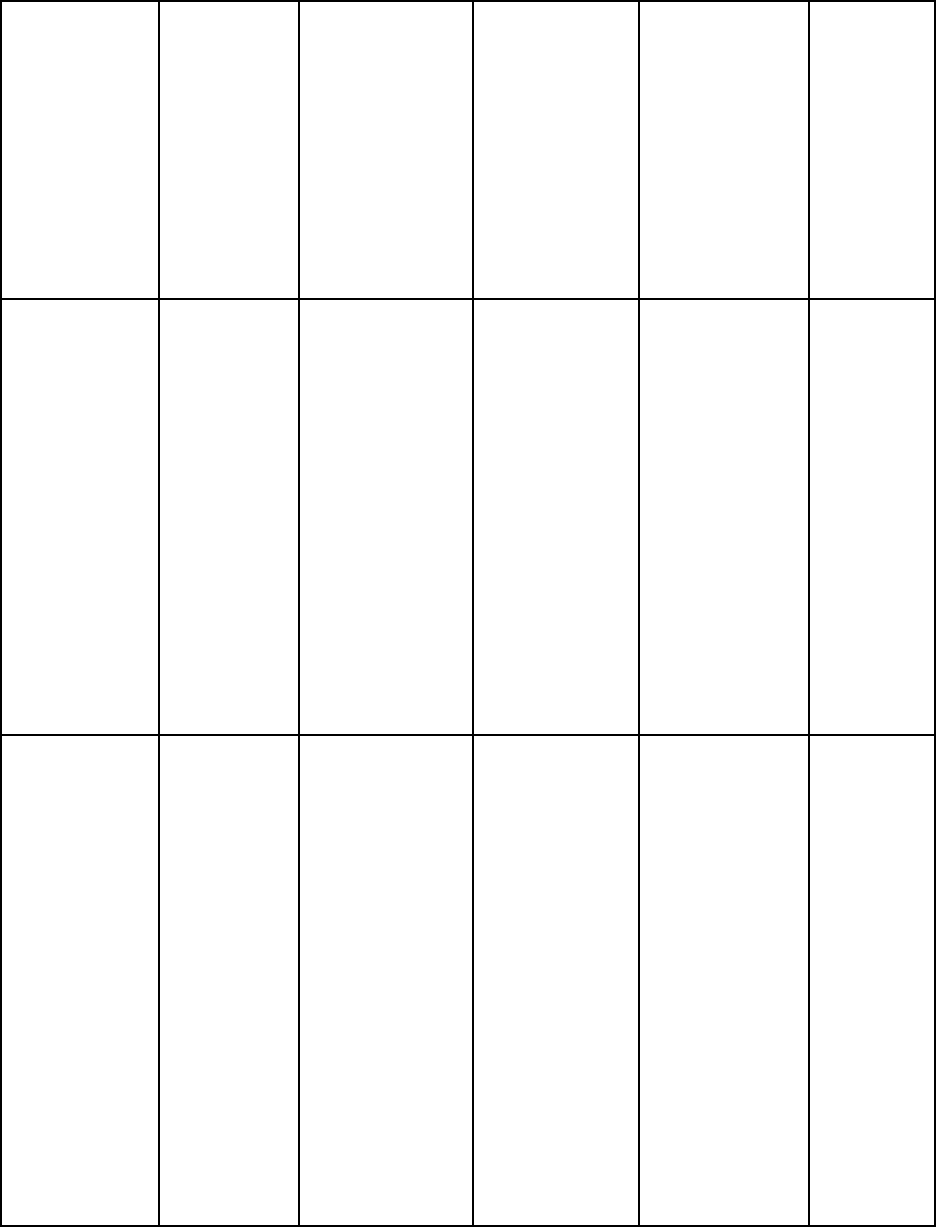

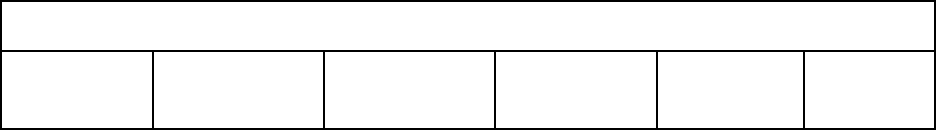

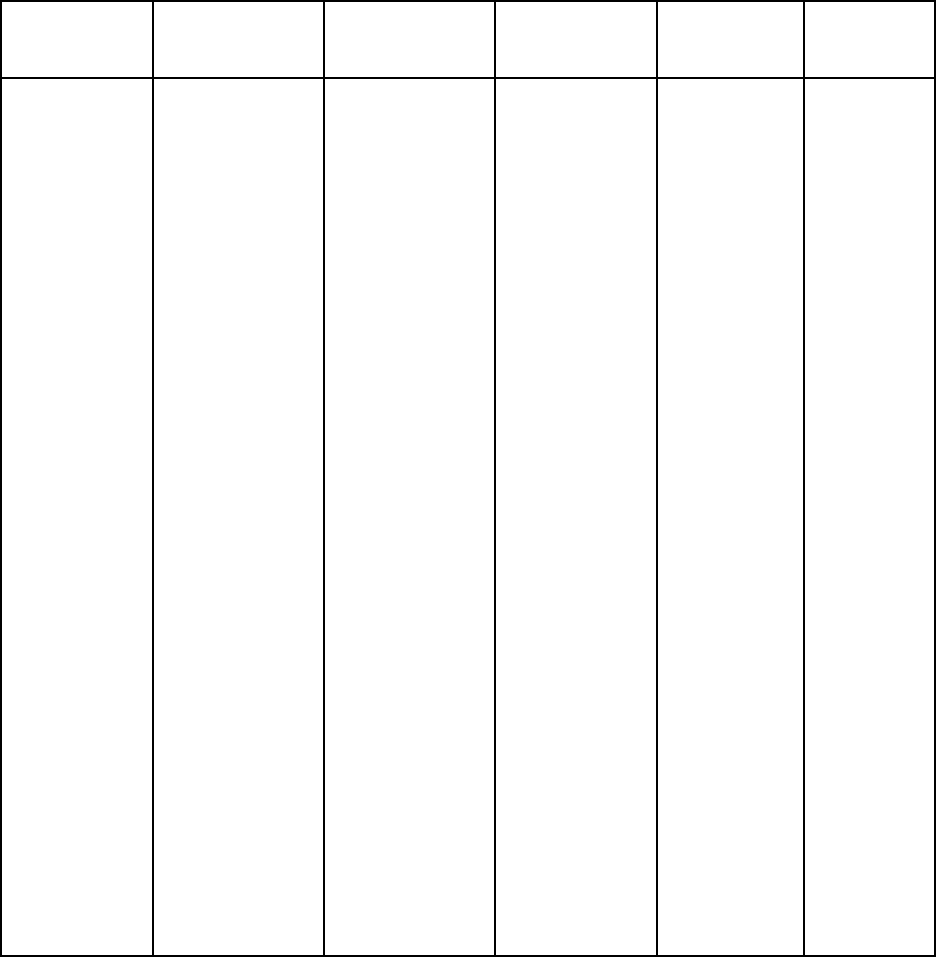

Data Sheet #2: The Bailey School Kids

The Bailey School Kids by Marcia Jones and Debbie Dadey

Book Title:

Front Cover:

Protagonist

Traits:

Family

Dynamics:

Stereotype:

Ethnicity:

26

Vampires

Don’t Wear

Polka Dots

- A traditional

classroom

setting, teacher

is pale-skinned,

class consists

of 8 children,

mostly

depicted as

Caucasian with

blond, red, or

brown hair.

- There is one

boy and one

girl with brown

skin and black

hair

- Liza: the

peacemaker of

the group,

doesn’t like

Eddie’s ideas

that usually

result in

hurting others.

She’s sensitive,

scared around

strangers, and

whimsical

- Howard

(Howie):

enjoys school,

logical, level-

headed and

intelligent

- Melody:

brave, sporty

(plays soccer)

and extremely

competitive

- Eddie: comes

across as mean,

makes fun the

others for

believing in

monsters.

Comes up with

drastic plans to

prove there are

no monsters.

At the

beginning of

this book, the

reader can

clearly see

Melody/Liza &

Howie/Eddie

are pairs of

best friends

-Liza: Mother,

father

(plumber),

and sister

(high school).

She also has a

grandmother.

- Howard

(Howie):

mom, two

sisters, and

dad

(aeronautics

tech station

worker)

Parents are

divorced

- Melody: Dad

(Contractor),

Mom

(Lawyer),

Aunt, great-

aunt and

cousin live

nearby

- Eddie:

Grandmother,

Father, little

sister. Mom is

deceased. He

has an aunt

who lives

nearby.

N/A

Caucasian

African-

American

27

Werewolves

Don’t Go to

Summer

Camp

- Four kids and

a man are

sitting around a

campfire under

a starry night

with full moon.

- The man is

Caucasian,

with brown

hair, a full

beard, wearing

jeans and a T-

shirt.

- Two kids, a

girl and boy,

(Liza and

Howie) are

Caucasian with

blond hair.

- (Melody), the

other girl, is

African-

American with

black hair.

- Eddie, the

other boy, is

Caucasian with

red hair. They

are all wearing

similar clothes

to the man.

SEE ABOVE

Liza: Sensitive

about the fact

that she can’t

swim

SEE ABOVE

N/A

Caucasian

African-

American

Santa Claus

Doesn’t Mop

Floors

-A brick

hallway with a

paperchain

decorating the

wall.

- A man with a

white beard,

muscled legs

and potbelly

(reminiscent of

Santa), is

mopping the

floor.

SEE ABOVE

SEE ABOVE

N/A

Caucasian

African-

American

28

-Three kids in

winter clothes

(Eddie, Howie,

and Melody)

are watching

him.

- Eddie:

Caucasian with

red hair,

- Howie:

Caucasian with

blond hair

- Melody:

African-

American with

black hair

Leprechauns

Don’t Play

Basketball

-A basketball

court, (or

maybe school

gym).

- A old man

with white

hair, sideburns,

dressed in a

green bow tie,

red tracksuit,

and purple

sweater vest is

shooting

backwards

hoops.

- Two girls,

Melody and

Liza, and one

boy, Eddie, are

watching him

Liza:

Caucasian with

blond hair.

- Howie:

Caucasian with

blond hair

- Melody:

African-

SEE ABOVE

SEE ABOVE

N/A

Caucasian

African-

American

29

American with

black hair

Ghosts Don’t

Eat Potato

Chips

An old attic, or

upstairs room.

An old,

transparent

looking man

with white hair

and mustache

is dressed in a

white shirt,

brown suit, red

bow tie, and

brown hat and

shoes. Howie,

Melody, and

Eddie are

walking up the

stairs, they

look shocked at

Howie’s

floating potato

chips

Eddie:

Caucasian with

red hair,

- Howie:

Caucasian with

blond hair

- Melody:

African-

American with

black hair

SEE ABOVE

SEE ABOVE

Caucasian

African-

American

The final series I chose to analyze is Franklin School Friends (2014-2016), one of the

most recent transitional series in third-grade classroom libraries. Unlike the books examined in

The Boxcar Children and The Baily School Kids, Franklin School Friends have five protagonists

instead of four. As it was a fairly recent series, the last book being published two years ago, I

figured that this series would have the largest number of diverse protagonists encountering

30

relatable situations and problems. I fully expected for there to be protagonists of Hispanic,

African American, and Asian American ethnicities, with maybe one or two Caucasian

protagonists, if any. However, a majority of protagonists in this series were identified as

Caucasian, although they were from different backgrounds. Two out of five protagonists were a

race other than Caucasian, (African American and Asian American), although these characters

were portrayed in a stereotypical manner (or had some other stereotypical aspect related to

them). While reading, I thought that Annika Riz, the main protagonist in the second book, would

be classified as a different race, since Annika is not a typical name for a Caucasian girl, however,

there was no mention of her being German or Polish, so I was unable to make that connection.

The following analysis shows trends (stereotypical and non-stereotypical) among the front cover,

protagonists, and family dynamics of the first five books of Franklin School Friends. Unlike the

main characters in The Boxcar Children and The Bailey School Kids, this series had each book

focus on one protagonist and a specific dilemma they have to solve or overcome, although all

five protagonists interact in the book in some way. For all five books, the five protagonists,

Kelsey, Annika, Izzy, Simon, and Cody, are third graders, and range among the ages of 8-9.

Similarly to the protagonists in The Bailey School Kids, each character in this series have a

different outward appearance, even the ones who identify as Caucasian. In each book, each

student are introduced with a certain set of qualities and have to overcome a challenge with their

specific attributes.. Throughout each book, each child is given a set of distinguishing

characteristics that remain consistent for the rest of the books in this series.

• Kelsey Green (8): loves reading, dislikes math, extremely competitive

• Annika Riz (8): Loves math, loyal and caring friend

• Izzy Barr (9): Talented Athlete, plays softball and runs track and field, very friendly

31

• Simon Ellis (8): Enjoys school, excels in spelling, tries hard to fit in

• Cody Harmon (9): Polite, well-mannered, enjoys caring for animals, dislikes school

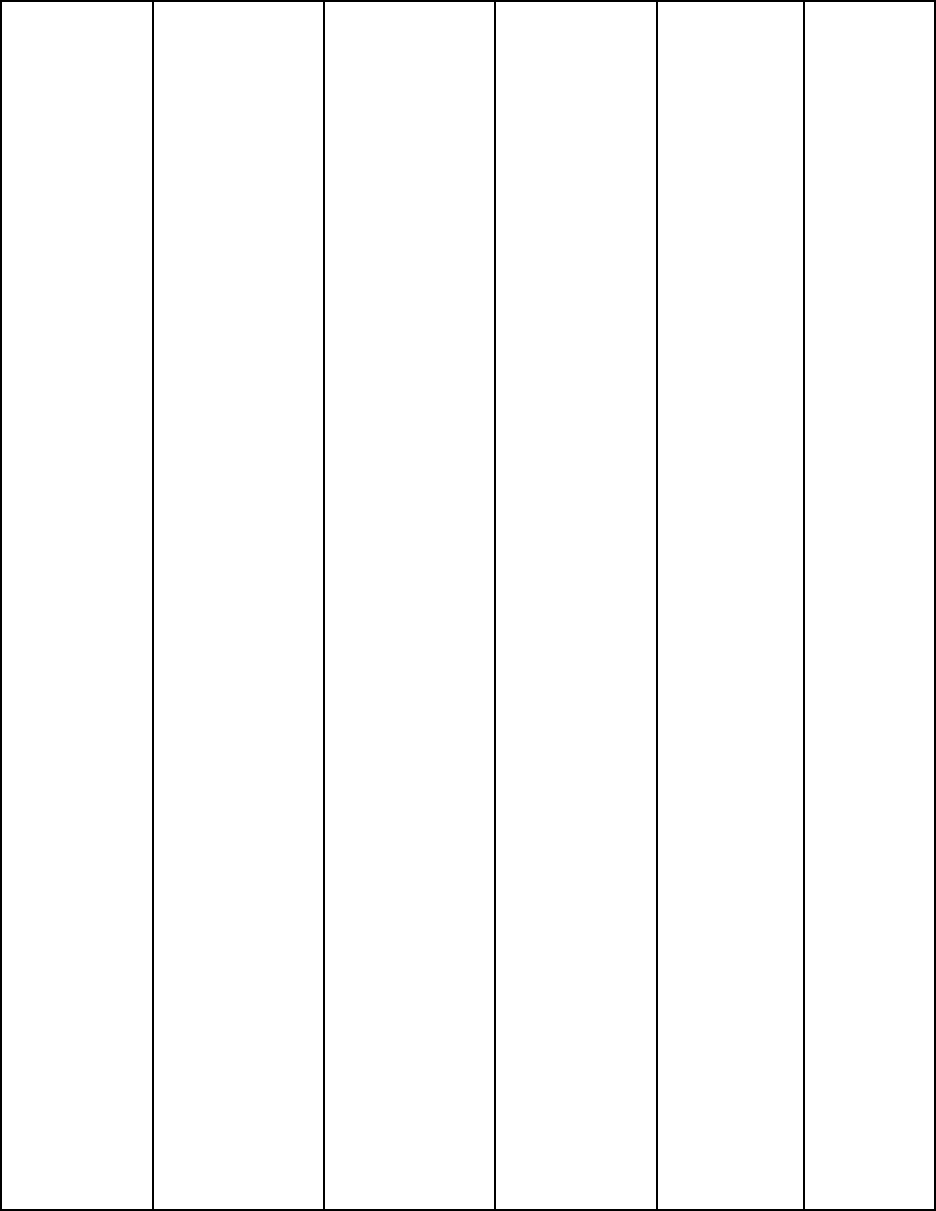

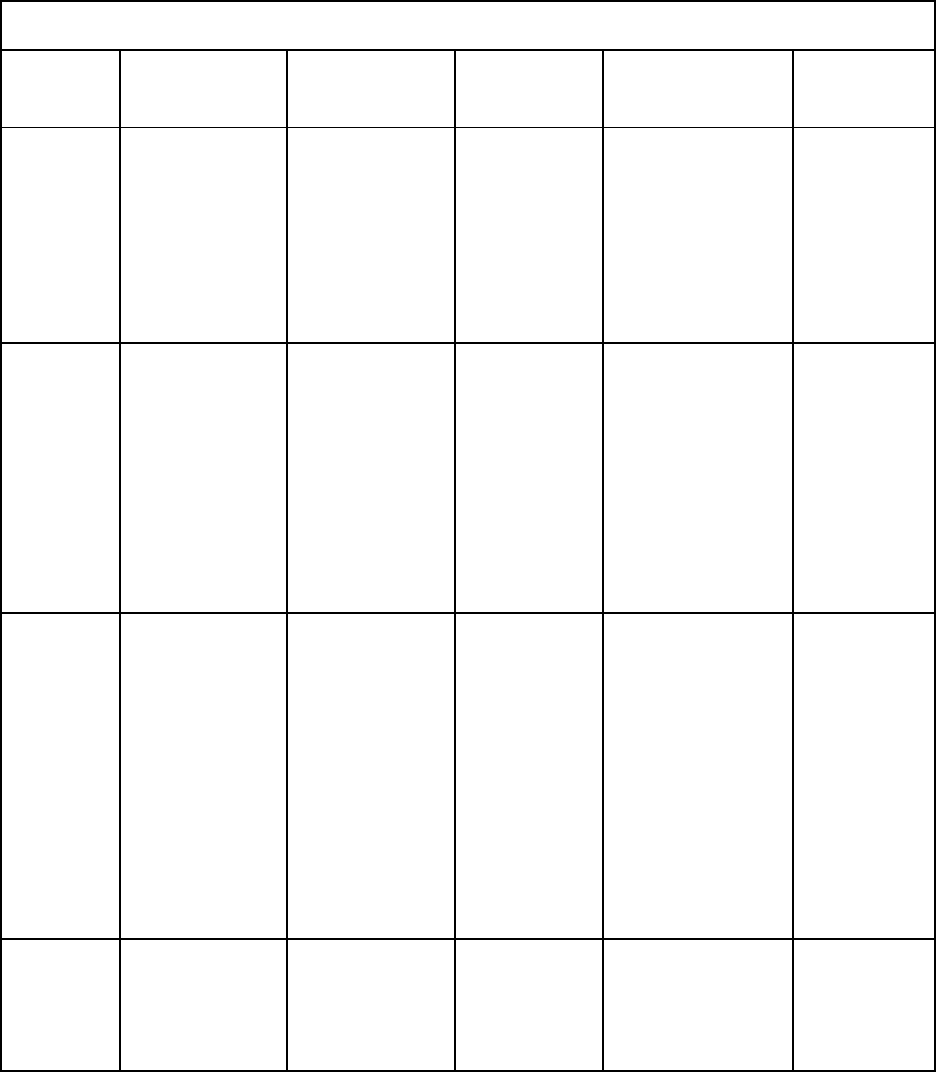

Data Sheet #3: Franklin School Friends

Franklin School Friends by Claudia Mills

Book

Title:

Front Cover:

Protagonist

Traits:

Family

Dynamics:

Stereotype:

Protagonist

Ethnicity:

Kelsey

Green,

Reading

Queen

Pale skinned

girl with short,

brown

shoulder-

length hair, &

her nose in a

book

- Loves

reading: reads

during math

class

- Dislikes math

-Competitive

Dad

Mom (Stay

at Home)

Brother (8th

Grade)

Sister (High

School)

N/A

Caucasian

Annika

Riz, Math

Whiz

Pale skinned

girl with blue

eyes, & long,

blonde braids,

filling out a

sudoku page

-Loves math:

will do sudoku

during recess

-Will whisper

math answers

to her friends

to help avoid

humiliation

Dad (High

school math

teacher)

- family

cook

Mom (Tax

accountant)

Prime

(Family dog)

Refutes the

stereotype:

“blonde girls are

dumb,” as

Annika loves

math, and is a

math genius

Caucasian

Izzy Barr,

Running

Star

Girl with

short, curly,

braided brown

hair, medium

brown skin, &

brown eyes;

running

-Loves sports,

does track &

field and

softball,

encouraging to

others

-Hides her

feelings about

her dad

missing her

games

Dad

(Foreman of

Factory)

Mom

(Hospital

Nurse)

Dustin

(Older half-

brother)

Enforces the

stereotypes that

African

American girls

are better athletes

and of absentee

African

American fathers

African

American

Simon

Ellis,

Spelling

Boy with short

brown hair,

blue eyes, and

pale skin;

-Enjoys all

aspects of

school, and

Dad (very

educated,

plays the

cello)

Enforces the

stereotype that

Asian American

students are

Asian

American

32

Bee

Champ

holding a

pencil and

backpack

excels in

spelling

-Plays the

violin

-Will do

poorly on

schoolwork in

order to

impress his

friends

-Extremely

competitive

Mom (also

highly

educated, is

an author)

smarter and

better at school

subjects than

others

Cody

Harmon,

King of

Pets

Pale skinned

boy with short

brown hair

styled in a

cowlick, &

hugging a dog

-Dislikes

school and

homework

-Enjoys

helping his dad

on their farm

-Loves pets:

takes care of

all their pets

and farm

animals

-Polite, says

“Yes sir” and

“Yes Ma’am”

Dad

(Farmer and

truck driver)

Mom (Stay

at home

mom)

Rex (Family

Dog)

Mr. Piggins

(Cody’s Pet

Pig)

Enforces

stereotype that

farm children are

poorly educated

or dislike school

Caucasian

Equity Audit of Protagonists in the Following Children’s Transitional Series: The Boxcar

Children, The Bailey School Kids, and Franklin School Friends

The following table provides an equity audit of ethnicities among protagonists in The Boxcar

Children, The Bailey School Kids, and Franklin School Friends. It compares the number of

protagonists in each book series among the five common ethnicities counted when taking

elementary school student demographics. These five ethnicities include:

• Caucasian

33

• African American

• Asian American (Southern or Eastern)

• Hispanic/Latino

• Multiracial

• American Indian

As seen in the following chart, both The Boxcar Children and The Bailey School Kids

included four protagonists for each of the five books analyzed. Franklin School Friends

included five protagonists where one main character was the focus for one of the five books,

however, all protagonists appeared in each book (at least) once. In The Boxcar Children

(1942), although the illustrations are completely blacked out, the protagonists, four siblings:

two boys and two girls, are depicted as Caucasian, which is consistent with children in

schools of the time period, however, not consistent with the statistics of students today. In

The Bailey School Kids, one of the four protagonists is portrayed non-stereotypically as

African-American, while in Franklin School Friends, two of the four protagonists are shown

to be of a different ethnicity (Asian American and African American), characterized with

stereotypical qualities. While these books are found on shelves in third-grade classroom

libraries today, the amount of ethnic protagonists are not consistent to the elementary ethnic

and racial demographics the today’s time period.

34

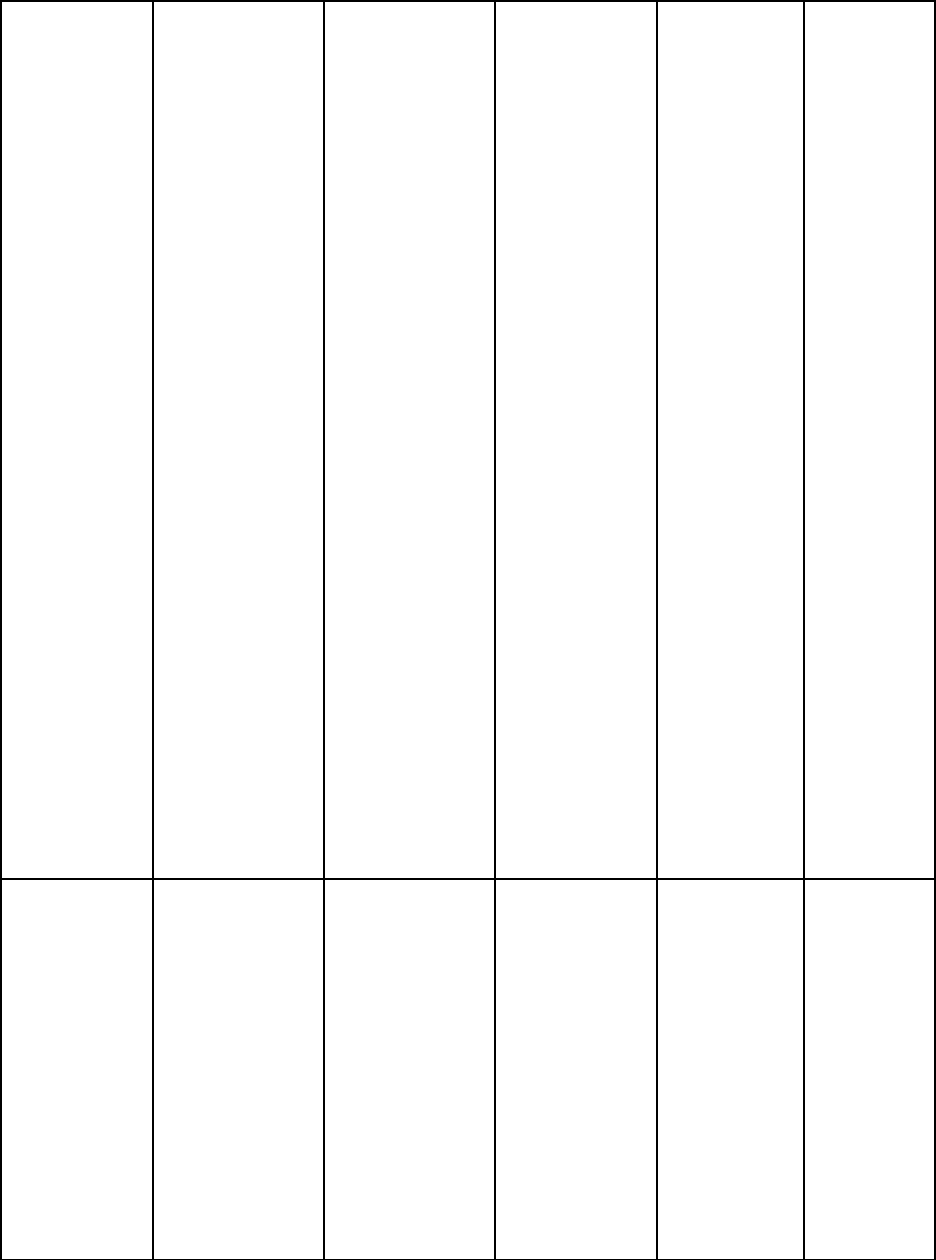

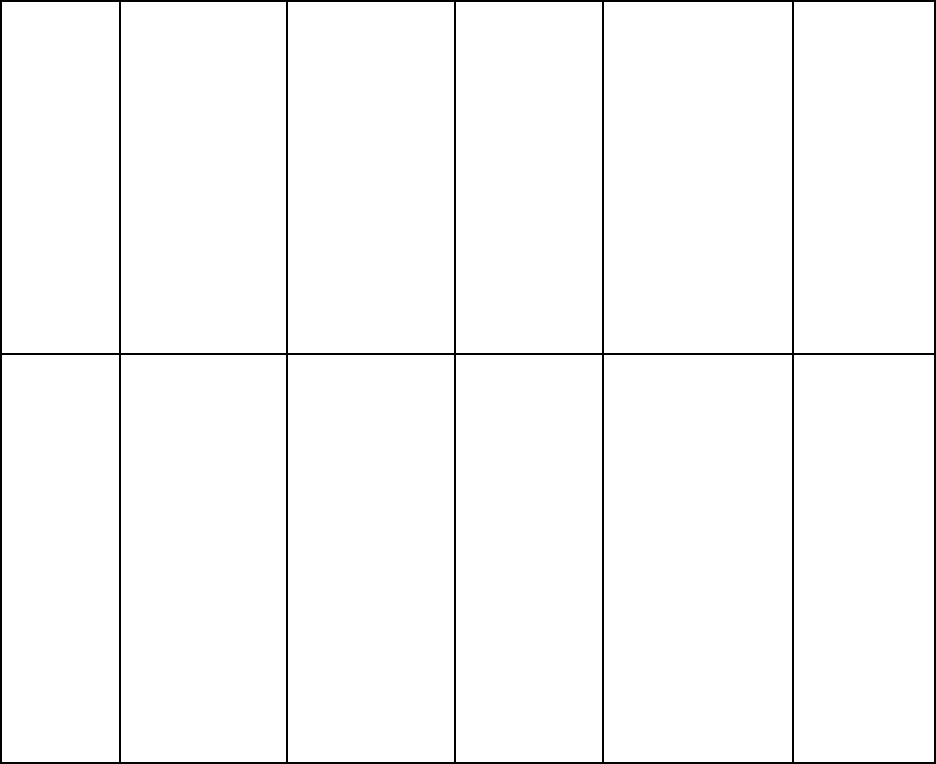

Breakdown of Equity Audit Comparing Ethnic Protagonists in Transitional Series

Literature to Elementary School Demographics

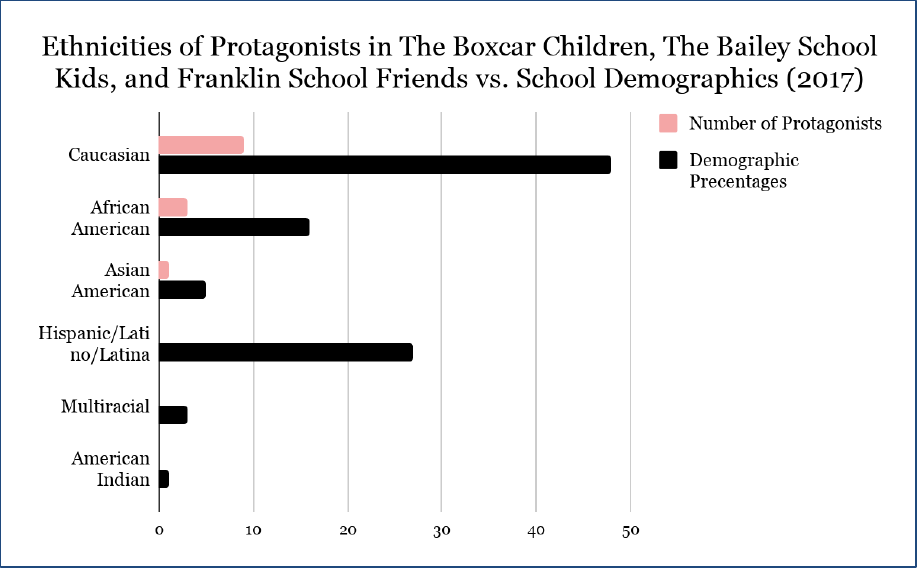

The following charts provide a breakdown of the equity audit taken among ethnicities of

protagonists in The Boxcar Children, The Bailey School Kids, and Franklin School Friends

compared to actual elementary school demographics of the time periods each series was

published. A chart showing the ethnic demographics of elementary students in the time period is

followed by a correlating chart of literary demographics compared to the period demographics.

In this section, one must note see that the diversity of protagonists in transitional series literature

does increase as related to the diversity and ethnic inclusion in the elementary school populations

increases.

35

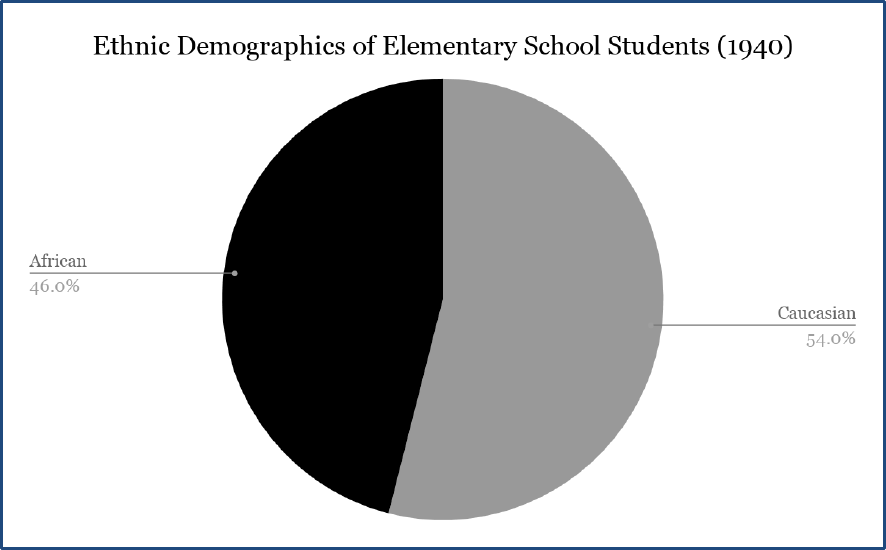

The chart located above shows the elementary school ethnic demographics of students in

the United States in 1940, consistent with the publication of The Boxcar Children series. Here,

the only ethnicities counted were African American and Caucasian, and while the demographics

are fairly even, with Caucasian taking up 54% of the student population while African

Americans take up 46% of the student population, schools in the 1940s were segregated.

Therefore, students in an all-Caucasian school wouldn’t be introduced to any kind of

multicultural literature. While the demographics in African American schools weren’t solely

African American (all minorities would have gone to the same school in the 1940s) the numbers

of those students would be very slight for them to not be counted in the demographics.

36

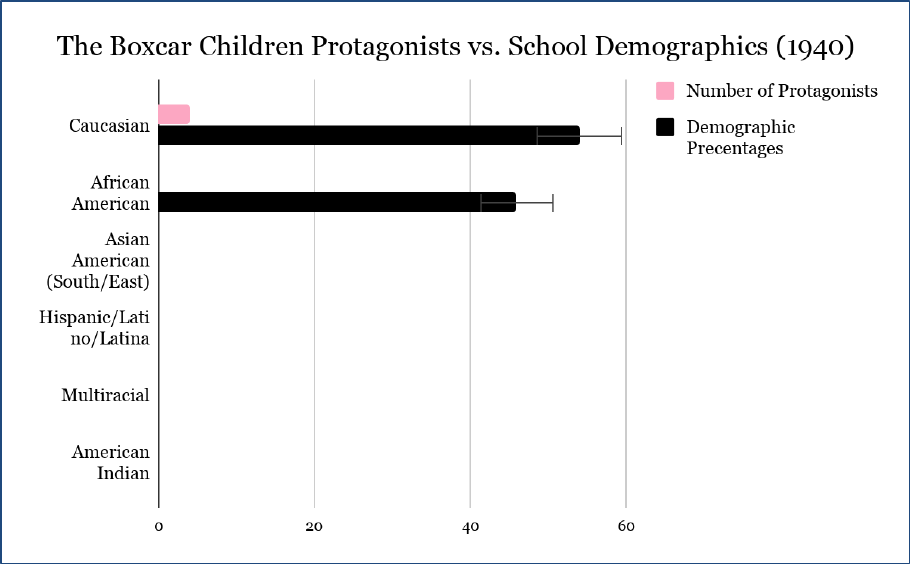

The chart above compares the ethnicities of the protagonists in The Boxcar Children to

the actual elementary school demographics of students in 1940, when the first book in the series

was published. Here, one must note that all four protagonists were identified as Caucasian, which

would be appropriate for students of this time period since schools in the 1940s were segregated.

Due to Jim Crow Laws, segregations of schools required students of Caucasian race to attend

separate schools than students of African American race; therefore, if books from The Boxcar

Children series were on classroom shelves in a 1940 all-Caucasian classroom, students would be

able to relate to the protagonists of Henry, Jessie, Violet and Benny. While segregation isn’t

mentioned in the book itself, no African American (or minority) characters are included in this

series.

37

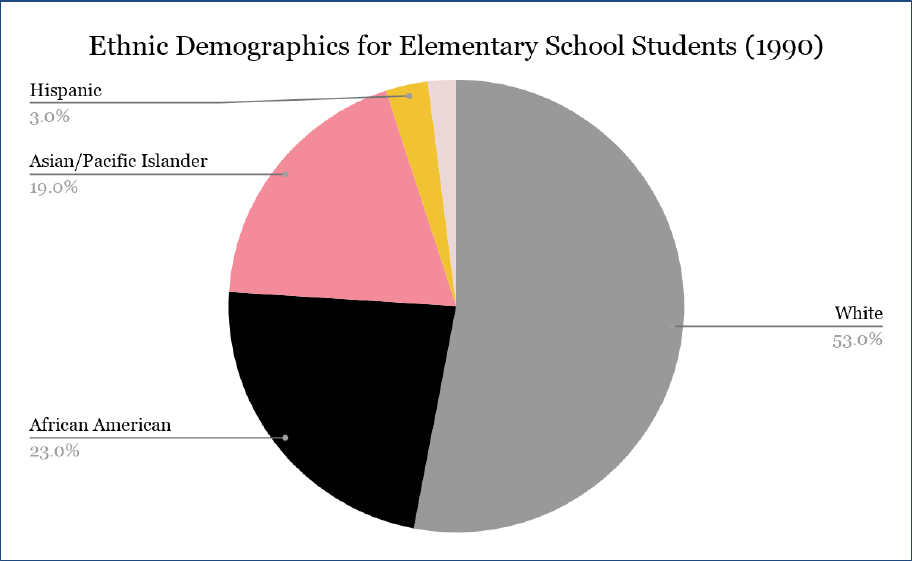

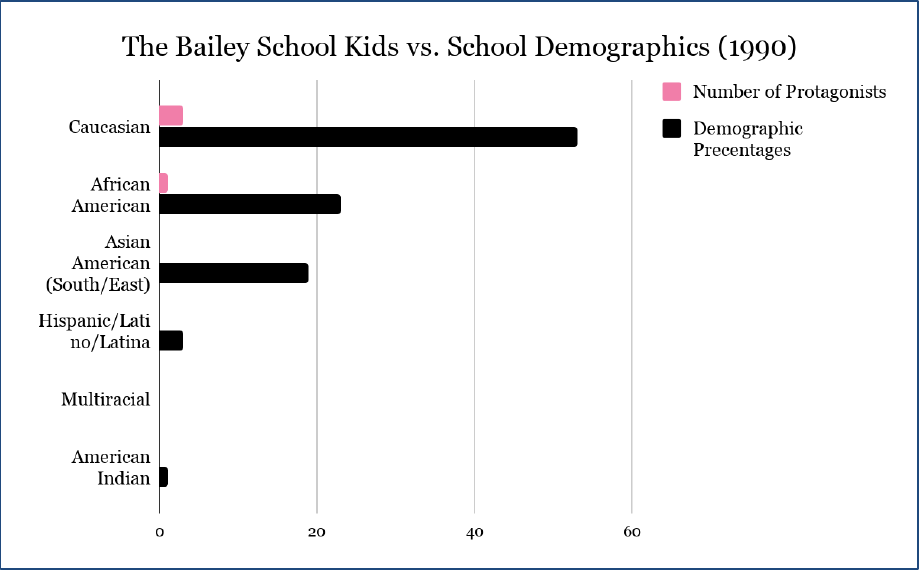

The chart located above shows the elementary school ethnic demographics of students in the

United States in 1990, consistent with the publication of The Bailey School Kids series. Here, the

only ethnicities included increased from only African American and Caucasian: Hispanic and

Asian/Pacific Islander were added. The ethnicities for these demographics of students divided

into the following statistics:

• Caucasian: 53%

• African American: 23%

• Asian/Pacific Islander: 19%

• Hispanic: 3%

Similar to the demographics in 1940, Caucasian students made up a majority of the

elementary school population in the United States. African Americans remained the biggest

minority in American elementary schools, while Hispanic students were introduced as a small-

38

scale minority. Also similar to the 1940 school demographics, the gap between Caucasians as a

majority and the ethnic minorities remains very slight (53% versus 45% in 1990, 54% versus

46% in 1940). From this data the population is slowly shifting to include more minorities.

The chart above compares the ethnicities of the protagonists in The Bailey School Kids to the

actual elementary school demographics of students in 1990, when the first book in the series was

published. In this series, the protagonists are more diversified than those in The Boxcar Children,

as they include a protagonist of African American ethnicity. Since African American students are

the largest minority of the elementary school student population, the ethnicities of the

protagonists in this series aligns with the demographics. Although the books in The Bailey

School Kids do not include any other protagonists or secondary characters of Asian American or

Hispanic minorities, this book does remain appropriate to be in classroom libraries in the 1990s.

39

With Caucasian students consisting the bulk of the student population and the main characters in

this series being mostly Caucasian, students were able to relate to these books’ protagonists.

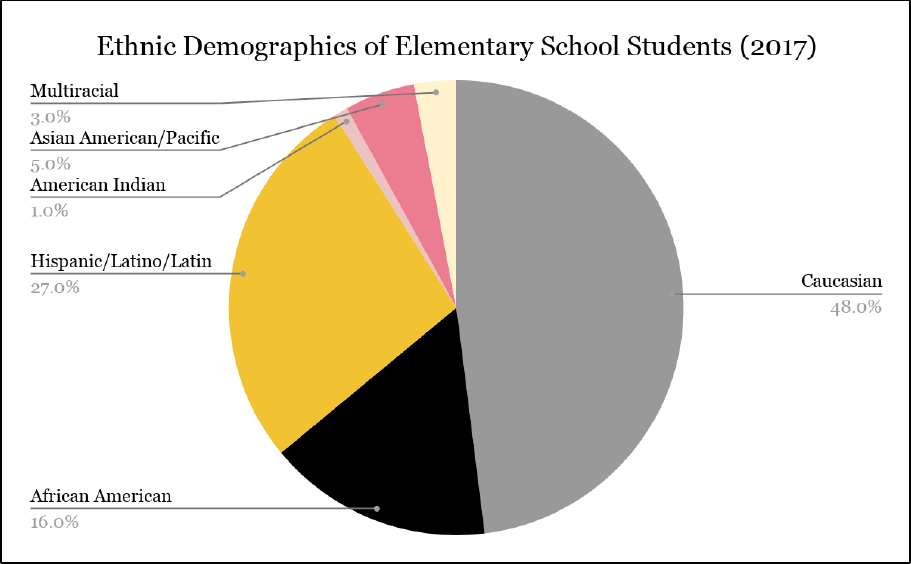

The chart located above shows the elementary school ethnic demographics of students in the

United States in 2017, consistent with the publication of the Franklin School Friends series.

Here, the demographics examined increased from Caucasian, African American, Hispanic and

Asian/Pacific Islander: Multiracial and American Indian students were added. The breakdown

for these demographics of students divided into the following statistics:

• Caucasian: 48%

• African American: 16%

• Hispanic: 27%

• Asian/Pacific Islander: 5%

40

• American Indian: 1%

• Multiracial: 3%

For the first time, the five different minorities make up the majority of students attending

elementary school in the United States; Caucasian students have now become the new

“minority.” African American students are no longer the largest minority subgroup, instead,

Hispanics/Latinos/Latina students makeup the biggest amount of minority students in schools

due to the influx of immigration from countries like Mexico and Puerto Rico. This increase from

3% (1990) to 27% (2017) also accounts for the large number of English Language Learners

(ELLs) in our school systems today. The introduction of a multiracial demographic is only

further evidence of the need to include authentic multicultural literature in the classroom.

41

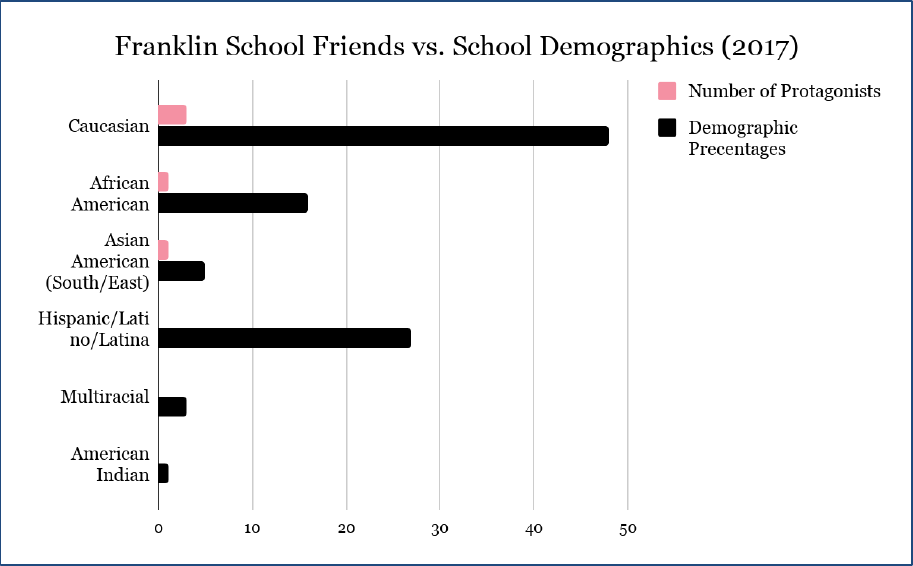

The chart above compares the ethnicities of the protagonists in Franklin School Friends to

the actual elementary school demographics of students in 2017, when the last book in the series

was published. As stated previously, 2017 saw Caucasian students become the “minority” in the

elementary school population, however, most of the protagonists in the Franklin School Friends

series are Caucasian. While two ethnic protagonists are included in the story (African American

and Asian American characters respectively), aspects of their characters are portrayed

stereotypically; not something an educator would want to instill or expose to their students. Also,

even though 2017 demographics show that Hispanics/Latino/Latina students are the largest

minority in elementary school, no character in this series would be relatable to a student of this

ethnicity. For these reasons, while this series would be a fun read for students, books from the

Franklin School Friends series would not be the most appropriate, genuine, or relevant

transitional series literature for a third-grade teacher to include in their classroom library. With a

majority of students in the classroom being from a different minority or race other than

Caucasian, students are not given an opportunity to connect with the characters in these books.

Some expectations are there, for example, an African American student with an absentee father

may relate to the protagonist Izzy Barr, and some Caucasian students will definitely relate to

Cody Harmon, Kelsey Green, and Annika Riz. However, a majority of students will not.

The final chapter will provide a conclusion for this thesis by analyzing the results of my

research and discussing any common trends found among each transitional literature series, as

well as provide a list of acceptable multicultural transitional series (or pilot books of similar

series to come) to include in third-grade classroom libraries. This chapter will also present

research limitations and suggestions for future research and concludes with education

42

suggestions that use research findings to create lesson plans to help teachers use the selected

multicultural transitional series to discuss differences in ethnicity and race in the classroom.

43

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSIONS AND EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS

This thesis is focused on the notable that multicultural transitional children’s literature

plays in shaping how students view themselves, the people, and the world around them. In

schools today, this is especially true, as multicultural demographics have surpassed Caucasian

demographics. As teachers, it is essential to acknowledge the lack of multicultural characters in

children’s literature among elementary classroom bookshelves and to learn how to incorporate

literature featuring strong main characters of varying races and ethnicities so that children can

see role models who mirror their own contexts. The purpose of this thesis was to examine

introductory books of three popular transitional series, using an equity audit, for protagonists of

various ethnic and racial backgrounds in non-stereotypical roles and to outline possible impacts

of trends and themes enclosed within each series. Administering the equity audit also determined

whether popular series or transitional books are advantageous to include into classroom libraries.

Prior studies, such as Gangi (2008) and Green and Hopenwasser (2017) have examined

the deficiency of multicultural literature in the classroom, particularly among transitional stories,

which shows the importance of exploring this topic. Furthermore, Green and Hopenwasser

(2017) emphasize the importance of equal representation of transitional books with characters of

diverse ethnicities, as they act as “mirrors and windows” for students to reflect upon themselves.

These studies argue that to prevent the “whitewashing” of literature for primary grades, teachers

should refrain and be cautious while choosing series or transitional books for classroom libraries.

In 1954, the Supreme Court’s final ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, (racial

segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional) marked the first moment schools

became diversified. Influxes of immigrants from around the world, who make a home in

America, has only added to this diversity, especially in schools. Although demographics of

44

students of multicultural ethnicities and races have surpassed demographics of Caucasian

students, there is still a lack of multicultural literature in classroom libraries that these students

can relate to. With the power that children’s literature has on improving attitudes, invoking

empathy, and opening window and mirrors, classroom libraries should consider adding books

and series that include protagonists of underrepresented ethnicities. While many positive

outcomes can come from utilizing children’s literature, there is also a chance to fall into new

predicaments, such as ethnic and/or racial stereotyping. Therefore, this thesis analyzed three

transitional series popular among third-grade classrooms for trends and themes among

protagonists. The first five books of each series were examined, with the second and third series

selected to remain in third-grade classrooms for containing non-stereotypical ethnic protagonists.

After conducting an equity audit across the three transitional series, I found that the

number of diverse characters in transitional series literature has increased over time, however,

the protagonists of these series do not accurately reflect the demographics of actual elementary

schools and are occasionally portrayed stereotypically. In addition to conducting each equity

audit, I have compiled a list of appropriate multicultural transitional series with suitable ethnic

and multi-racial protagonists for third grade teachers to include in their classroom libraries.

Reflections of the Researcher

Throughout analyzing the research, I reevaluated the purpose and extensions of my

findings. Although underrepresentation of all ethnicities/races and deficiencies of multicultural

literature in schools are broad, important issues, I viewed them as a future educator. Having a

child sees a reflection of themselves in the books they choose to read is crucial towards their

attitude and ability to read (Singer & Smith, 2003). This actuality was the driving force behind

45

me paying close attention to the trends and themes present in the literature I was examining, no

matter how obvious or subtle they were. Focusing on these aspects is important as a researcher of

multicultural literature as to completely understand the strengths and weaknesses of the books

chosen to share among students through our classroom libraries. Addressing ongoing inclusion

of students from all ethnicities, races and cultures is very possible through the addition of

multicultural literature. As educators, teachers to do better in selecting meaningful literature for

all classrooms, among all genres, where students of all ethnicities and races are able to see

representations of themselves and their experiences, not just those of one subgroup.

A miniscule amount of third-grade multicultural transitional series literature is available

for teachers to rotate through and pull from for their classroom curriculum. The biggest

restriction of the research was the limited amount of non-stereotypical literature to examine,

thus, leaving ample room for further research. The lack of available literature made the presence

of trends and themes (both stereotypical and non-stereotypical) seem more intense. Common

trends and themes found amongst each literature series are listed and discussed below.

Trends and Themes:

Trends and themes are found throughout children’s literature, and can range from being

obvious to subtle. However, many times, subtle themes and trends are embedded in diversified

children’s literature. These trends are not isolated to just one book or one series; when one trend

was present, it was likely that multiple were present. As stated previously, a student who is able

to see “mirrors” of self-identity in recommended books will benefit greatly from that reflection

(Bishop, 1990; Green & Hopenwasser, 2017). Protagonists in children’s literature are a critical

aspect when analyzing books because students identify most with main characters, especially

46

those who look, act, and experience similar real-life experiences. The main theme examined for