THE DOG THAT DIDN’T BARK:

LOOKING FOR TECHNO-LIBERTARIAN IDEOLOGY

IN A DECADE OF PUBLIC DISCOURSE ABOUT BIG

TECH REGULATION

JODI L. SHORT, REUEL SCHILLER, SUSAN S. SILBEY, NOAH

JONES, BABAK HEMMATIAN, AND LEEANNA BOWMAN-

CARPIO

1

The internet was built on the techno-libertarian ideology that “information

wants to be free,” and that ideology has played a prominent role in academic

and policy debates about regulating the internet and the big technology

companies that dominate it.

2

Techno-libertarian ideology has generated a

constellation of claims about tech and regulation—from the suggestion that

regulation will stifle innovation in the complex, dynamic tech sector, to the

assertion that the large platform companies are literally not regulable. In

this article, we explore how much traction such claims and ideologies have in

the broader public discourse about big tech and regulation. We employ an

innovative methodology—topic modeling—to track public discourse on the

regulation of big technology from 2010 to 2020. We find that techno-

libertarian ideas about free markets and information freedom play a

surprisingly small role in this discourse. Indeed, we find that the most

common themes in the discourse about big tech and regulation concern: calls

1

Jodi Short is the Associate Dean for Research and the Honorable Roger J. Traynor

Professor of Law at UC Hastings College of the Law. Reuel Schiller is the Honorable Roger

J. Traynor Chair and Professor of Law at the University of California, Hastings College of

Law. Susan S. Silbey is the Leon and Anne Goldberg Professor of Humanities, Sociology

and Anthropology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a Professor of

Behavioral and Policy Sciences at the Sloan School of Management at MIT. Noah Jones is a

2022 graduate of Brown University. Babak Hemmatian is a Beckman Postdoctoral

Research Fellow at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. LeeAnna Bowman-

Carpio is a 2022 graduate of the University of California, Hastings College of the Law.

2

R. Polk Wagner, Information Wants to Be Free: Intellectual Property and the

Mythologies of Control, 103 COLUM. L. REV. 995, 1033 (2003).

The Ohio State Technology Law Journal

2

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

to regulate big tech companies; growing critiques of technology’s influence

in society; and declining discussion of the tech sector as a driver of economic

growth. Our findings should embolden legal and policy advocates to pursue

regulatory initiatives aimed at addressing the social and economic harms

produced by the technology sector knowing that the techno-libertarian

rhetoric likely to be deployed against them may not have sufficient public

traction to win the day.

2022]

SHORT

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 4

II. THE TECHNO-LIBERTARIAN IDEOLOGY .......................... 6

III. TOPIC MODELING ............................................................. 19

A. WHAT IS TOPIC MODELING? ........................................ 19

B. METHODOLOGY ............................................................... 22

C. THE LIMITATIONS OF ALGORITHMIC TOPIC

MODELING ............................................................................ 28

IV. PUBLIC DISCOURSE ON BIG TECH REGULATION:

FINDINGS .................................................................................. 29

V. CONCLUSION ....................................................................... 42

APPENDIX 1: CHOICE OF HYPERPARAMETERS .................. 43

APPENDIX 2: CALCULATING TOPIC CONTRIBUTIONS ...... 44

4

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

I. Introduction

The last fifty years have seen technological innovations that

have dramatically transformed our society. The microcomputer, the

internet, and wireless technology, for example, have changed the way

we consume and communicate in ways that few could have imagined in

1970. Yet the creators of this technology did not simply develop

hardware and software. They also fashioned a system of beliefs. They

have propagated a libertarian ideology that has played a prominent role

in academic and policy debates about regulating the internet and the

big technology companies that dominate it.

Indeed, no industry has been more zealous in crafting and

championing a regulatory ideology than the tech sector. Characterized

variously as technological utopianism, techno-utopianism, or techno-

libertarianism (the moniker we adopt here), this ideology envisions

cyberspace as a domain of “perfect freedom”

3

—a space that promises “a

kind of society that real space would never allow—freedom without

anarchy, control without government, consensus without power.”

4

Techno-libertarianism has generated a constellation of claims about

tech and regulation—that government regulation will stifle innovation

in the dynamic tech sector, that it is unnecessary because market forces

and the tech companies’ own benevolence will prevent social harms,

and that, where regulation is called for, self-regulation is the only

effective way to order the behavior of companies in this complex

industry.

5

Ideologies about regulation shape how—and even whether—

the state regulates.

6

Thus, both advocates and opponents of increased

regulation of the technology sector should want to understand the

ideological and rhetorical landscape upon which these political battles

are occurring. Exactly how much traction do techno-libertarian claims

and ideologies have in the broader public discourse?

To find out, we employ a methodology innovative in legal

scholarship to track public discourse on the regulation of large

3

LAWRENCE LESSIG, CODE: VERSION 2.0, at 3 (2006).

4

Id. at 2.

5

David R. Johnson & David Post, Law and Borders—The Rise of Law in Cyberspace, 48

STAN. L. REV. 1367, 1375 (1996) (“The rise of an electronic medium that disregards

geographical boundaries throws the law into disarray by creating entirely new phenomena

that need to become the subject of clear legal rules but that cannot be governed,

satisfactorily, by any current territorially based sovereign.”); LESSIG, supra note 3, at 31

(statement of Tom Steinert-Threlkeld) (“Some things never change about governing the

Web. Most prominent is its innate ability to resist governance in any form.”); id. (“If there

was a meme that ruled talk about cyberspace, it was that cyberspace was a place that could

not be regulated.”).

6

See Jodi L. Short, The Paranoid Style in Regulatory Reform, 63 HASTINGS L.J. 633

(2012).

2022]

SHORT

5

technology corporations from 2010 to 2020. We use a topic modeling

algorithm to systematically search for discursive trends in a large

corpus of news articles. As we describe in more detail in Part II, topic

modeling is a computational technique that allows for the systematic

study of cultural representations. It is a digitized method for analyzing

textual data to identify common themes and relationships in large

bodies of text, thereby uncovering explicit and latent motifs.

7

Unlike

word-based methods for quantitative content analysis,

8

topic modeling

does not simply count frequencies. Instead, using both the frequency of

particular words and their co-occurrence with respect to one another,

the topic model accounts for the probability that certain words occur

together and for the weight each word contributes to these probability

distributions. The most highly weighted words provide clues about the

significance of particular subjects, or “topics,” which can then be

explored with more conventional interpretative techniques. Because

topic modeling techniques work on large bodies of text,

9

this paper

illustrates how they can prove particularly useful for legal and policy

analysis.

Using topic modeling, we find that techno-libertarian (or even

just plain old libertarian) ideas about free markets and information

freedom play a surprisingly small role in the public discourse, despite

the technology corporations’ relentless emphasis on them. Indeed, we

find that the most common themes in the discourse about big tech and

regulation concern the need to regulate big tech companies. As policy

makers embark on discussions about whether and how to regulate this

powerful sector, they should be aware of these broader trends. The

utopian narratives that big tech companies (and their lobbyists) tell

about themselves do not seem to have captured the public’s

imagination. This fact leaves policymakers with more room to operate

as they craft regulatory responses to the social costs that have

accompanied technological innovation.

The Article proceeds as follows. Part I presents a qualitative

description of the techno-libertarian ideology using source material

produced by or documenting the views of tech companies, their

executives, and their lobbyists. It explores how the ideology developed

and discusses how it shaped the architecture and ethos of internet, as

well as the ideas about how computer technologies should be regulated.

It also documents how techno-libertarian ideas have been deployed in

recent legal and policy debates about the regulation of technology

7

Tim Hannigan et al., Topic Modeling in Management Research: Rendering New Theory

From Textual Data, 13 ACAD. MGMT. ANNALS 589 (2019).

8

See Yla R. Tausczik & James W. Pennebaker, The psychological meaning of words:

LIWC and computerized text analysis methods, 29 J. LANGUAGE & SOC. PSYCH. 24-54.

9

Hannigan et al., supra note 7, at 589.

6

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

companies, including state privacy legislation, municipal regulation of

ride sharing platforms, and proposed Congressional legislation to

ensure the accuracy of ads placed on social media. In doing so, it

highlights how big tech companies have mobilized elements of techno-

libertarian discourse to resist attempts to regulate them. This

qualitative account motivates the empirical question we seek to address

with our topic model: how much do techno-libertarian claims and

ideologies contribute to the broader public discourse relating to the

regulation of major technology companies?

Part II explains what topic modeling is in some detail. It then

describes our empirical study of the public discourse about regulating

large technology corporations and explains our methodology. Part III

presents the results of our study. We find that techno-libertarian

ideologies do not dominate public discourse on the regulation of big

tech. Instead, this discourse is dominated by calls to regulate big tech,

growing critiques of technology’s influence in society, and declining

discussion of the tech sector as a driver of economic growth. This article

then concludes, arguing that the nature of this discourse suggests that

policymakers should not assume that the public accepts the anti-

regulatory premises of techno-libertarianism. Consequently, these

policymakers should realize that they are operating in a more pro-

regulatory political environment than they might have otherwise

believed.

II. The Techno-Libertarian Ideology

The morning of March 3, 1998, was an unusual one for Bill

Gates, then 42-year-old chairman of the Microsoft Corporation. Gates

was in Washington, D.C., testifying before the Senate Judiciary

Committee.

10

Capitol Hill was not a place where Gates felt comfortable.

Unlike many of his colleagues and competitors in the technology sector,

Gates had always sought to avoid political entanglements.

11

Indeed, the

previous year, the company had donated less than $100,000 to federal

political candidates.

12

Its lobbying operation consisted of a single

10

Rajiv Ch & Rasekaran, Microsoft in Senates Focus, WASH. POST (March 3, 1998),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1998/03/03/microsoft-in-senates-

focus/2a403de5-8088-470b-8485-a40f7229cf3e/ [https://perma.cc/5JKX-3ZZK].

11

Stephanie Simon & Erin Mershon, Gates masters D.C. – and the world, POLITCO

(February 04, 2014, 8:01 PM), https://www.politico.com/story/2014/02/bill-gates-

microsoft-policy-washington-103136 [https://perma.cc/L86V-3P7F].

12

Joel Brinkley, U.S. v. Microsoft: The Lobbying, N.Y. TIMES, Sept. 7, 2001,

https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/07/business/us-vs-microsoft-the-lobbying-a-huge-4-

year-crusade-gets-credit-for-a-coup.html [https://perma.cc/F9GV-4F4U].

2022]

SHORT

7

person operating out of an office in a Chevy Chase shopping mall.

13

Gates seemed to believe that if he ignored Washington, it would ignore

him.

Gates’ appearance on Capitol Hill was not the only unusual

thing about the hearing. Even stranger was how poorly he was received.

Used to kit-gloved treatment by a public that viewed him as the self-

made, boy genius fueling the PC revolution, he was not expecting the

bipartisan drubbing he would receive that day. After a day of defending

himself from accusations of being a greedy, disingenuous monopolist,

the New York Times described Gates as “shellshocked.”

14

What brought Gates to Washington that day was what have

become known as “The Browser Wars.”

15

By the middle of the 1990s,

the Internet had ceased to be merely a tool of academics and computer

aficionados.

16

Through search engines and social networking

platforms, a market for user-friendly software allowing people to access

the World Wide Web had quickly sprung up.

17

Initially, this market was

dominated by Netscape Communications, whose product, Netscape

Navigator, had gobbled up 80% of the browser market by 1996.

18

That

year, however, Microsoft introduced its own browser—Internet

Explorer—and bundled it with its industry-dominant operating system,

Windows 95.

19

As Internet Explorer quickly ate away at its market

share, Netscape brought an antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft,

claiming that it was using its near-monopoly in operating systems to

prevent competition in the market for browsers.

20

As the lawsuit

commenced, Congress invited Gates to the Capitol.

21

The facts alleged

in Netscape’s lawsuit, it seems, put some legislators in a regulatory

mindset.

13

MARGARET O’MARA, THE CODE: SILICON VALLEY AND THE REMAKING OF AMERICA 350

(2019); Brinkley, supra note 12.

14

Lizette Alvarez, An ‘Icon of Technology’ Encounters Some Rude Political Realities, N.Y.

TIMES (March 4, 1998), https://www.nytimes.com/1998/03/04/business/an-icon-of-

technology-encounters-some-rude-political-realities.html [https://perma.cc/3QRW-

2ZAF].

15

For the Browser Wars, see O’MARA, supra note 13, at 341–46.

16

Id. at 287.

17

Id. at 309.

18

Henry R. Norr, Netscape Communications Corp., ENCYC. BRITANNICA (August 28, 2017),

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Netscape-Communications-Corp

[https://perma.cc/TBB7-VBFK].

19

Paul Thurrott, Microsoft to release Windows 95 OSR 2.5, ITPRO TODAY (October 19,

1997), https://www.itprotoday.com/windows-78/microsoft-release-windows-95-osr-25

[https://perma.cc/L6RA-5VHE].

20

O’MARA, supra note 13, at 341–46.

21

Competition, Innovation, and Public Policy in the Digital Age: Hearings Before the S.

Comm. on the Judiciary, 105th Cong. 87 (1998) (statement of Bill Gates, Chairman and

CEO, Microsoft Corp.).

8

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

Gates’ testimony was designed to deflect such impulses. He

delivered a simple message: “The PC industry,” as he called it, was a

goose laying golden eggs.

22

By creating innovative hardware and

software, it generated high-paying jobs, and inexpensive, high-quality

products.

23

Furthermore, American economic growth relied on this

continued innovation, both to keep the technology sector expanding

and to maintain and accelerate other economic sectors that had become

increasingly dependent on technology to compete in a global

marketplace.

24

Government regulation, Gates claimed, would kill the

goose. “To remain competitive and to continue to provide consumers

with high quality, low cost, innovative products . . . software companies

must retain the ability to design their products free from government

interference.”

25

Such “government intervention” “hobbled” the

industry, preventing it from developing “new products that meet the

needs of consumers.”

26

According to Gates, politicians who attempted to regulate

technology industries failed to understand how the industry worked.

No matter how big an existing company was, its products could, at any

moment, be rendered obsolete by individual entrepreneurs— “college

room buddies” working out of “small offices,” “hobbyists” holed-up in

garages, or “innumerable other . . . small entrepreneurs” developing

software at their “kitchen table.”

27

Freedom from government

interference was the key to facilitating this sort of low-capital

competition and innovation. “The software industry’s success has not

been driven by Government regulation, but by freedom and the basic

human desire to learn to innovate and to excel.”

28

Gates was not without allies at the hearings. Tech sector

entrepreneurs Michael Dell and Douglas Burgum echoed his talking

points.

29

The technology industry “started quite literally in the garages,

kitchens, and dormitory rooms of this country. Part of the appeal of this

industry is the freedom to succeed or fail based solely on one’s own

abilities.”

30

Success was thus the product of individual initiative “free

from government regulation . . . .”

31

The venture capitalist/tech

journalist Stewart Alsop, II was even more explicit. “I believe that it is

22

Id. at 90.

23

Id. at 91.

24

Id.

25

Id. at 94.

26

Id. at 96.

27

Id. at 89, 92.

28

Id. at 89.

29

See id. at 113-126 (statements of Michael Dell, Chairman and CEO, Dell Computer Corp.

& Douglas J. Burgum, Chairman and CEO, Great Plains Software).

30

Id. at 125 (statement of Douglas J. Burgum, Chairman and CEO, Great Plains Software).

31

Id.

2022]

SHORT

9

dangerous and potentially disastrous to invite governmental regulation

of the interfaces between elements of the technology we are adopting at

such a remarkable rate.”

32

Dramatically, he likened the hearings to

Joseph McCarthy’s “destructive demagoguery.”

33

He then articulated a

radically antiregulatory stance based on his assessment of the state’s

inevitable regulatory incompetence:

I want to be clear that I also grew up in a time when the

Government proved itself incapable of judicious or expeditious

regulation of the economy as a whole or even of individual

industries, and I learned to distrust a centralized government's

ability to regulate itself or to act in the best interests of its

constituency over the long term.

34

According to Alsop, this hostility to regulation was particularly

appropriate when it came to the regulation of technology. This was

because the personal computer was unlike the earlier technologies—

railroads, petrochemicals, “large-scale manufacturing”—that had

generated previous regulatory impulses.

35

Businesses in those

industries required centralized, hierarchical power that might itself

become oppressive. The tech industry, on the other hand, had no such

potential. Not only did it spring from the initiative of decentralized,

individual entrepreneurs, but it also promoted individual freedom by

destroying hierarchies, both public and private.

The personal computer has challenged corporations’ ability to

control computing resources centrally, empowering

individuals, and breaking down hierarchies. Communications

technologies have made it nearly impossible for centralized

governments to control access to information. The Internet and

the World Wide Web have suddenly removed the structural

costs of gaining access to and managing information in a

fashion unprecedented in human experience.

36

In such a world, regulation was unnecessary. Not only would it stifle

economic growth and technological innovation. It would also

undermine the transformation of the society from a centralized one

based on large, potentially oppressive, institutions to one that was

32

Id. at 128 (statement of Stewart Alsop, II).

33

Id.

34

Id.

35

Id.

36

Id.

10

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

decentralized and egalitarian, driven by networked individuals each

liberated to create, innovate, and flourish.

By the time that Gates, Dell, Burgum, and Alsop appeared

before Congress in early 1998, the tech utopianism that their testimony

reflected was pervasive in American society. In the past three decades

a host of scholars and journalists—Richard Barbrook, Andy Cameron,

Fred Turner, Margaret O’Mara, Scott Galloway, John Markoff, Paulina

Borsook, Alan Lui, Vincent Mosco, Tiziana Terranova, for example—

have described the emergence of this ideology, and the politics that

accompanied it.

37

It took libertarian beliefs—that human society was

best structured by leaving individuals alone to pursue their self-

interests—and linked them to decentralized digital technologies to

explain precisely how this liberation would occur. Personal computers

acted as agents of freedom, promoting liberty and innovation by

creating a hybrid digital-actual society that was free of hierarchical

restraints, be they public or private. In this environment, decentralized

action would generate the best ideas, products, and forms of social

organization. It was a dynamic world of constant, decentralized

innovation in which monopoly was a meaningless concept. Every

corporate behemoth was nothing more than a Goliath waiting to be

toppled by the next David (or Steve, Mark, Jeff, or Elon) whose

unanticipated innovation would soon spring from a Cupertino garage.

Indeed, to the extent that new technologies created social problems,

they would solve these problems themselves. If the internet made

pornography easily available to seven-year-olds, then a filtering

program would solve the problem.

38

If social networks became

platforms for inflaming ethnic hatreds, then subtle algorithms were the

37

See generally Richard Barbrook & Andy Cameron, The Californian Ideology, 6 SCI. AS

CULTURE 44-72 (1996), http://www.imaginaryfutures.net/2007/04/17/the-californian-

ideology-2 [https://perma.cc/BCE9-VNFH]; FRED TURNER, FROM COUNTERCULTURE TO

CYBERCULTURE: STEWART BRAND, THE WHOLE EARTH NETWORK, AND THE RISE OF DIGITAL

UTOPIANISM (2006); O’MARA, supra note 13; SCOTT GALLOWAY, THE FOUR: THE HIDDEN

DNA OF AMAZON, APPLE, FACEBOOK, AND GOOGLE (2017); JOHN MARKOFF, WHAT THE

DOORMOUSE SAID: HOW THE SIXTIES COUNTERCULTURE SHAPED THE PERSONAL COMPUTER

INDUSTRY (2005); PAULINA BORSOOK, CYBERSELFISH: A CRITICAL ROMP THROUGH THE

TERRIBLY LIBERTARIAN CULTURE OF HIGH TECH (2000); ALAN LIU, THE LAWS OF COOL:

KNOWLEDGE WORK AND THE CULTURE OF INFORMATION (2004); VINCENT MOSCO, THE

DIGITAL SUBLIME: MYTH, POWER, AND CYBERSPACE (2004); TIZIANA TERRANOVA, NETWORK

CULTURE: POLITICS FOR THE INFORMATION AGE (2004).

38

See generally Marie Eneman, Internet Filtering: A Solution to Harmful and Illegal

Content?, IEEE SMARTWORLD, UBIQUITOUS INTELLIGENCE & COMPUTING, ADVANCED &

TRUSTED COMPUTING, SCALABLE COMPUTING & COMMUNICATIONS, CLOUD & BIG DATA

COMPUTER, INTERNET OF PEOPLE AND SMART CITY INNOVATION

(SMARTWORLD/SCALCOM/UIC/ATC/CBDCOM/IOP/SCI) 354-549 (2019),

https://doi.org/10.1109/SmartWorld-UIC-ATC-SCALCOM-IOP-SCI.2019.00104

[https://perma.cc/P2VN-AM66] (canvasing and evaluating the use of Internet filtering for

child abuse material).

2022]

SHORT

11

solution.

39

Worried about on-line privacy? Implement your privacy

settings just so.

The corollary to these beliefs was that decisions made by the

market—the “electronic agora”

40

—were preferable to those made by

the state. Technology had created a pure marketplace of ideas. Thus,

governance generated by the decentralized, technology-enabled

decision-making processes of a networked world would be better than

the decision of any government bureaucrat, no matter how well

intentioned. When Gates, Dell, Burgum, and Alsop made this argument

before Congress in 1998, they were simply articulating what had

become the common wisdom of the denizens of the tech sector for over

thirty years. It was a strange amalgam of ideas constructed out of

classical libertarianism, counterculture communalism, postwar

cybernetic theory, and science fiction inflected-utopianism, but its view

of the state and its role as a regulator was clear. As Esther Dyson,

George Gilder, George Keyworth, and Alvin Toffler wrote in their 1994

tech manifesto, “Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age”:

41

“Today we

have, in effect, universal access to personal computing—which no

political coalition ever subsidized or ‘planned.’” Consequently, “if there

is to be an ‘industrial policy for the knowledge age,’ it should focus on

removing barriers to competition and massively deregulating the fast-

growing telecommunications and computing industries.”

42

Indeed,

such deregulatory impulses should ultimately cast an even wider net.

“[A] ‘mass movement’ for cyberspace is still hard to see . . . Yet there

are key themes on which this constituency-to-come can agree. To start

with, liberation—from . . . rules, regulations, taxes, and laws laid in

place to serve the smokestack barons and bureaucrats of the past.”

43

Techno-libertarian ideology continued to dominate Silicon

Valley’s discourse about itself long after founding entrepreneurs moved

out of their dorm rooms and garages and onto Wall Street. By 2019, the

five largest technology corporations—Apple, Amazon, Facebook,

Google/Alphabet, and Microsoft—had achieved market domination,

their stock worth “more than the entire economy of the United

Kingdom.”

44

Yet the rhetoric remained the same, nurtured by

39

MONIKA BICKERT, FACEBOOK, CHARTING A WAY FORWARD: ONLINE CONTENT REGULATION

(2020).

40

Barbrook & Cameron, supra note 37.

41

TURNER, supra note 37, at 228-232 (Turner describes the writing of this document and

its diverse ideological and theoretical antecedents.).

42

Esther Dyson, George Gilder, George Keyworth & Alvin Toffler, Cyberspace and the

American Dream: A Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age, FUTURE INSIGHT (Aug. 1994)

http://www.pff.org/issues-pubs/futureinsights/fi1.2magnacarta.html

[https://perma.cc/Q3DW-7GGZ].

43

Id.

44

O’MARA, supra note 13, at 1.

12

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

iconoclastic founders and funders like Peter Thiel

45

and Elon Musk,

46

and employed strategically by tech companies to thwart attempts to

regulate them. Thus, faced with the prospect of regulation, big tech

companies repeated the same themes that Gates’ deployed in the

1990s: their industry produced enormous benefits for the public;

47

it

was able to produce these benefits because the government left it alone

to innovate;

48

government regulation would kill innovation and all the

public benefits attendant to it;

49

and whatever social problems novel

technologies created could be solved through self-regulation.

50

In recent years, the industry has had many opportunities to

deploy these arguments as calls for regulation of the technology sector

have gained momentum in response to growing recognition of the

harms the technology sector has caused and the future dangers it

threatens. Platform companies’ relentless surveillance and

expropriation of users’ digital footprint to predict and manipulate user

behavior has raised serious concerns about individual privacy and

human dignity.

51

While social media has been an extremely powerful

tool for the global exchange of information, ideas, and public discourse,

misinformation and disinformation have become rampant,

52

45

Noam Cohen, The Libertarian Logic of Peter Thiel, WIRED (Dec. 27, 2017, 7:00 AM),

https://www.wired.com/story/the-libertarian-logic-of-peter-thiel

[https://perma.cc/38SQ-M9BU] (Thiel, a co-founder of PayPal and the first outside

investor in Facebook, has been characterized as a “public intellectual” and “a trusted

advisor to a new generation of leaders.”); Peter Thiel, The Education of a Libertarian,

CATO UNBOUND (Apr. 13, 2009), https://www.cato-unbound.org/2009/04/13/peter-

thiel/education-libertarian [https://perma.cc/4XC6-ML7V] (Among other things, he has

asserted that internet entrepreneurs create new worlds beyond the reach of government

and expressed hope that Facebook might “create the space for new modes of dissent and

new ways to form communities not bounded by historical nation-states.”).

46

Nick Statt, Elon Musk Says Shelter-in-Place Orders During COVID-19 Are “Fascist,”

THE VERGE (Apr. 29, 2020, 7:30 PM),

https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/29/21242102/elon-musk-coronavirus-fascist-shelter-

in-place-tesla-covid-19-safety-science [https://perma.cc/5YST-68GU] (In a recent

tweetstorm that has since been removed, Musk decried the stay-at-home order imposed by

the California county that hosts his Freemont assembly plant as “forcibly imprisoning

people in their homes, against all their constitutional rights.”); id. (This was, in his

opinion, “breaking people’s freedoms in ways that are horrible and wrong, and not why

people came to America and built this country . . . .”).

47

Competition, Innovation, and Public Policy in the Digital Age: Hearings Before the S.

Comm. on the Judiciary, supra note 21.

48

Id. at 94.

49

Id.

50

Id.

51

SHOSHANA ZUBOFF, THE AGE OF SURVEILLANCE CAPITALISM: THE FIGHT FOR A HUMAN

FUTURE AT THE NEW FRONTIER OF POWER 109 (2019).

52

See Meira Gebel, Misinformation vs. Disinformation: What to Know About Each Form

of False Information, and How to Spot Them Online, BUS. INSIDER (Jan. 15, 2021, 1:02

PM), https://www.businessinsider.com/misinformation-vs-disinformation

2022]

SHORT

13

threatening the integrity of elections, fueling populist violence, and

undermining public health efforts to curtail the spread of COVID-19.

53

Across diverse platforms, the internet actively circulates a broad range

of hard, soft, and child pornography; facilitates sex trafficking, and

enables directly targeted personal threats.

54

The so-called “gig

economy,” unimaginable without the digitally-constructed workplaces

of platform capitalism, has also eroded traditional protections for

employees, resulting in precarious working conditions for many.

55

Governments at every level have proposed regulation to address

these harms. Several U.S. states have imposed privacy regulations on

tech companies.

56

State and local governments have attempted to enact

[https://perma.cc/H2W8-2ZZ6] (misinformation generally refers to false information

presented as fact regardless of the intent to deceive, while disinformation refers to a subset

of misinformation that is intentionally false and intended to deceive and mislead, hiding

the interest and identity of the users).

53

See VIVEK H. MURTHY, U.S. SURGEON GENERAL, CONFRONTING HEALTH MISINFORMATION

(2021), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-misinformation-

advisory.pdf (the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory in July 2021 declaring health

misinformation on social media an urgent threat); Zolan Kanno-Youngs & Cecilia Kang,

“They’re Killing People”: Biden Denounces Social Media for Virus Disinformation, N.Y.

TIMES (July 19, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/16/us/politics/biden-facebook-

social-media-covid.html [https://perma.cc/DCD5-A8G6]; COLLABORATEUP, NEWS

LITERACY AND MISINFORMATION/DISINFORMATION IN THE ERA OF COVID-19 (2021),

https://collaborateup.com/wp-

content/uploads/2021/09/Misinformation_Disinformation_Report_Spreads-2-3.pdf

(disinformation has been widely used to spread inaccurate health information, resulting in

ill-informed decisions about public health measures, use of unproven medical treatments

and vaccine resistance); Press Release, Am. Soc’y for Reprod. Med., New Study Reveals

COVID Vaccine Does Not Cause Female Sterility (June 24, 2021),

https://www.asrm.org/vaccine-does-not-cause-sterility [https://perma.cc/S4CY-AJAW]

(erroneous information on social media about the efficacy and safety of COVID vaccines,

such as claims that the vaccine causes female infertility, has contributed to vaccine

hesitancy).

54

MICHAEL SETO, U.S. DEP’T OF JUST., SEX OFFENDER MGMT. ASSESSMENT AND PLAN.

INITIATIVE, INTERNET-FACILITATED SEXUAL OFFENDING (2015),

https://smart.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh231/files/media/document/internetfacilitateds

exualoffending.pdf; Ross Benes, How Porn has Been Secretly Behind the Rise of the

Internet and Other Technologies, BUS. INSIDER (May 7, 2017, 7:12 AM),

https://www.businessinsider.com/porn-behind-internet-technologies-2017-5

[https://perma.cc/JYC2-L3HC]; Aina J. Khan, Prominent Women Call for Tech Giants to

Act Against Online Harassment, N.Y. TIMES (July 1, 2021),

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/01/world/women-online-harassment.html

[https://perma.cc/3XEC-XDZC].

55

Veena B. Dubal, Economic Security & the Regulation of Gig Work in California: From

AB5 to Proposition 22, 13 EUR. LAB. L. J. 51–65 (2022).

56

See generally IAPP, US State Privacy Legislation Tracker, IAPP (March 3, 2022),

https://iapp.org/resources/article/us-state-privacy-legislation-tracker

14

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

regulation governing ridesharing platforms, like Uber and Lyft, to

provide employment protections for drivers

57

or to address the safety

concerns of passengers by requiring finger-printing and background

checks of drivers.

58

Congress has engaged in vociferous debate about

how to combat misinformation and election meddling on social media

platforms since revelations of Russian interference in the 2016 election

and the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

59

In each of these instances, the

tech industry has responded with familiar anti-regulatory arguments.

Technology companies, the industry argues, continue to lay

golden eggs. They still claim to enhance consumer choice and save

consumers money,

60

but they now claim also to provide an even greater

variety of benefits to the public than when Gates testified before

Congress in 1998. Twitter and Facebook portray themselves as vital to

the functioning of pluralist democracies. They say they are the modern

“public square,” supplying the public with “all the good that connecting

people can bring . . . .”

61

Ridesharing companies claim to keep drunk

[https://perma.cc/V2NP-NH4U] (a periodically updated chart showing the status of

privacy legislation across the United States).

57

Sam Harnett, Prop. 22 Explained: Why Gig Companies Are Spending Huge Money on

an Unprecedented Measure, KQED (Oct. 26, 2020),

https://www.kqed.org/news/11843123/prop-22-explained-why-gig-companies-are-

spending-huge-money-on-an-unprecedented-measure [https://perma.cc/P7MG-TVD7].

58

See Ben Wear, Austin Clerk Validates Petition Seeking Election on Uber, Lyft Rules,

AUSTIN AM.-STATESMAN (Sept. 15, 2016, 12:01 AM),

https://www.statesman.com/news/20160915/austin-clerk-validates-petition-seeking-

election-on-uber-lyft-rules [https://perma.cc/A44F-Z3EK]; Matthew Zeitlin, How Austin’s

Failed Attempt to Regulate Uber and Lyft Foreshadowed Today’s Ride-Hailing

Controversy, VOX (Sept. 13, 2019, 10:52 AM), https://www.vox.com/the-

highlight/2019/9/6/20851575/uber-lyft-drivers-austin-regulation-rideshare

[https://perma.cc/72VJ-VXEY].

59

See Maria Curi, Court Testimony Looms for Zuckerberg in Cambridge Analytica Case,

BLOOMBERG LAW (Oct. 25, 2021, 5:00 AM),

https://www.bloomberglaw.com/bloomberglawnews/privacy-and-data-

security/XABESR2C000000?bna_news_filter=privacy-and-data-security#jcite

[https://perma.cc/3PEE-RT37] (the scandal was over Facebook’s arrangement with

Cambridge Analytica, a once-obscure British consulting firm, which allowed it to access

granular data on 87 million users without their consent for the purpose of targeted political

advertising).

60

ELEC. FRONTIER FOUND., OPPOSITION DOCUMENT ON A.B. 375,

https://www.eff.org/document/opposition-document-ab-375 [https://perma.cc/74ZD-

KCZ9] (last visited Mar. 6, 2022) (regulation would cause “many consumers [to] lose out

on learning about discounts and other offers that would save them money.”).

61

Open Hearing on Foreign Influence Operations’ Use of Social Media Platforms:

Hearing Before the S. Select Comm. On Intel., 115

th

Cong. 19 (Sep. 5, 2018) (statement of

Jack Dorsey, Chief Executive Officer, Twitter, Inc.); Politico Staff, Full Text: Mark

Zuckerberg’s Wednesday Testimony to Congress on Cambridge Analytica, POLITICO (Apr.

9, 2018), https://www.politico.com/story/2018/04/09/transcript-mark-zuckerberg-

testimony-to-congress-on-cambridge-analytica-509978 [https://perma.cc/8YM8-EJYP].

2022]

SHORT

15

drivers off the streets and say that they provide flexible work

arrangements, particularly “for people traditionally marginalized from

the labor market,” including women and people of color.

62

The tech sector continues to argue that its non-stop innovation

generates these public goods, and that regulation would surely stifle

such innovation. As California considered privacy legislation, known as

the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), a lobbying organization

funded by Amazon, Google, and Facebook warned that state-level

privacy regulation “would . . . inhibit organizations’ ability to

innovate . . .” As such, the CCPA would “harm the highly competitive

U.S. digital economy, particularly rapidly-evolving AI and machine

learning technologies . . .” State regulation, according to the industry,

would have an obvious negative consequence: “If one state’s law were

to prohibit an innovative new use of data, an organization might choose

not to pursue that innovation, even if other states permitted it.”

63

Tech

lobbyists made the same argument directly to state legislators. In a

briefing document entitled “Top Ten Reasons to Vote against” the

62

Vote For Prop 1 (@ridesharingatx), TWITTER (May 5, 2016, 6:00 PM),

https://twitter.com/ridesharingatx/status/728388907167932416

[https://perma.cc/G2KG-FAV2]; Vote For Prop 1, Austin’s Bartenders and Owners Are

#FORProp1 Because Ridesharing Cuts Down on Drunk Driving, FACEBOOK (May 2, 2016),

https://www.facebook.com/1521640114830416/videos/1593934660934294

[https://perma.cc/9BWS-HZ65]; Richard Whittaker, Prop 1 Election Results: Uber and

Lyft vs. Austin, the Numbers Through the Night, AUSTIN CHRON. (May 7, 2016, 6:24 PM),

https://www.austinchronicle.com/daily/news/2016-05-07/prop-1-election-results

[https://perma.cc/G6TM-NLBL]; A First Step Toward A New Model for Independent

Platform Work, UBER (Aug. 10, 2020), https://www.uber.com/newsroom/working-

together-priorities [https://perma.cc/4GHF-VBBL]; Lyft, LyftUp | Maya Angelou | Good

Morning | Transportation Access | Lifting Up Communities of Color | 90, YOUTUBE (Aug.

11, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yImMyOkeaKQ [https://perma.cc/66TZ-

XDGX]; Sam Harnett, Prop. 22 Explained: Why Gig Companies Are Spending Huge

Money on an Unprecedented Measure, KQED (Oct. 26, 2020),

https://www.kqed.org/news/11843123/prop-22-explained-why-gig-companies-are-

spending-huge-money-on-an-unprecedented-measure [https://perma.cc/YF7P-UZKS];

Dara Khosrowshahi, I Am the C.E.O. of Uber. Gig Workers Deserve Better., N.Y. TIMES

(Aug. 10, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/10/opinion/uber-ceo-dara-

khosrowshahi-gig-workers-deserve-better.html [https://perma.cc/PFU7-TAY6] (“Unlike

traditional jobs, drivers have total freedom to choose when and how they drive, so they can

fit their work around their life, not the other way around. Anyone who’s been fired after

having to miss a shift, or who’s been forced to choose between school and work, will tell

you that this type of freedom has real value and simply does not exist with most traditional

jobs.”); A First Step Toward A New Model for Independent Platform Work, UBER (Aug.

10, 2020), https://www.uber.com/newsroom/working-together-priorities

[https://perma.cc/N6ZA-232Q].

63

CTR. FOR INFO. POL’Y LEADERSHIP, WHY WE NEED INTERSTATE PRIVACY RULES FOR THE

U.S. 1 (2020),

https://www.informationpolicycentre.com/uploads/5/7/1/0/57104281/cipl_concept_pap

er_-_why_we_need_interstate_privacy_rules_for_the_us__25_september_2020_.pdf.

16

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

CCPA, the industry mentioned “impeding innovation” no less than

three times, explaining that tech companies: “would be hamstrung in

their ability to use information to innovate their products and provide

new services,”

64

and “many consumers would lose out on learning

about discounts and other offers that would save them money.”

65

Organizations lobbying on behalf of tech companies against

passage of biometric privacy legislation in Montana made similar

arguments. They suggested to state legislators that passage of the

legislation might jeopardize the United States’ status as “the most

innovative country in the world.”

66

Similarly, in response to proposed

federal legislation to strengthen antitrust laws, Google’s Vice President

of Government Affairs and Public Policy insisted that “American

consumers and small businesses would be shocked at how these bills

would break many of their favorite services. . . As many groups and

companies have observed, the bills would require us to degrade our

services and prevent us from offering important features used by

hundreds of millions of Americans.”

67

Of course, in the face of the Cambridge Analytica scandal and

Russian election meddling, leaders in the industry had to admit that

completely unfettered tech libertarianism had created some untoward

large-scale social problems. (“[W]e were way too idealistic,” remarked

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg.

68

) The solution to these problems,

however, was not innovation-killing government regulation. Instead,

the industry could regulate itself, using its technological know-how to

limit the social costs that sometimes accompanied innovation.

69

As

Apple CEO Tim Cook once, tellingly, said: “I think the best regulation

is no regulation, is self-regulation.”

70

64

OPPOSITION DOCUMENT ON A.B. 375, supra note 60.

65

Id.

66

Letter from Ass’n of Nat’l Advertisers, CompTIA, Internet Coal., State Priv. & Sec. Coal.,

TechNet to Chair Alan Doane, H. Comm. on Judiciary, Mont. H.R. (Feb. 22, 2017),

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3553143-SPSC-and-Assns-Letter-Montana-

HB-518-Biometrics.html [https://perma.cc/595Z-EXVR].

67

Ashley Gold, Exclusive: Google’s Salvo Against Antitrust Bills, AXIOS (Jun. 22, 2021),

https://www.axios.com/google-antitrust-bills-house-dae01e6a-2542-4903-bfc0-

a570f024b5b6.html [https://perma.cc/8WNU-JNTQ].

68

Vanessa Romo, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg On Data Privacy Fail: “We Were Way Too

Idealistic”, NPR (Apr. 5, 2018), https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-

way/2018/04/05/599770568/facebooks-sheryl-sandberg-on-data-privacy-fail-we-were-

way-too-idealistic [https://perma.cc/UX8J-BDNT].

69

Peter Kafka, Tim Cook Says Facebook Should Have Regulated Itself, but It’s Too Late

for That Now, VOX (Mar. 28, 2018), https://www.vox.com/2018/3/28/17172212/apple-

facebook-revolution-tim-cook-interview-privacy-data-mark-zuckerberg

[https://perma.cc/FDL3-QDBV].

70

Id.

2022]

SHORT

17

Five days after the Cambridge Analytica story broke, Mark

Zuckerberg issued a statement responding to the situation by providing

a roadmap of steps Facebook would take to regulate itself.

71

He claimed

that the company had already taken steps (in 2014) that would prevent

a similar occurrence and listed additional steps Facebook would take to

secure the platform.

72

He concluded his post by stating: “I'm serious

about doing what it takes to protect our community. . . . We will learn

from this experience to secure our platform further and make our

community safer for everyone going forward.”

73

As calls for regulation

continued to mount, Sandberg insisted that Facebook was “already

adopting the best reforms and policies available.”

74

Indeed, Facebook and other industry actors have repeatedly

deployed claims of their competence at self-regulation to deflect

government attempts to regulate the industry. Facebook defused an

FTC investigation into its privacy practices with an agreement to create

“stringent processes” and “sweeping measures” that it hoped “will be a

model for the industry.”

75

Similarly, in response to legislation

introduced to ensure the integrity of ads posted to social media

platforms,

76

the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB), a lobbying

organization representing companies such as Facebook, Google, and

Twitter,

77

made the case for industry self-regulation in lieu of the

proposed bill. The “economy’s fastest-growing and most dynamic

sector” had “a proven track record” of creating “some of the media

industry’s strongest self-regulatory mechanisms . . . .” Indeed, the only

truly effective way to prevent misleading advertising on the internet

was self-regulation. Internet-based communication was simply too

71

Sheryl Sandberg, FACEBOOK (Mar. 21, 2018),

https://www.facebook.com/sheryl/posts/10160055807270177?pnref=story

[https://perma.cc/A5XY-28EE].

72

Id. (These steps included investigating what apps had access to large amounts of data

before the 2014 changes; further restricting developers’ access to data “to prevent other

kinds of abuse”; and making the platform more transparent to ensure that users

understand which apps have access to their data).

73

Id.

74

Sheera Frenkel, Nicholas Confessore, Cecilia Kang, Matthew Rosenberg & Jack Nicas,

Delay, Deny and Deflect: How Facebook’s Leaders Fought Through Crisis, N.Y. TIMES

(Nov. 14, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/14/technology/facebook-data-russia-

election-racism.html [https://perma.cc/QGE8-7GFE].

75

FTC Agreement Brings Rigorous New Standards for Protecting Your Privacy,

FACEBOOK (July 24, 2019), https://about.fb.com/news/2019/07/ftc-agreement

[https://perma.cc/FVS6-QCQQ].

76

The Honest Ads Act, S. 1989, 115th Cong. (2017).

77

Tony Romm, Tech Titans Support More Political Ad Transparency – But Aren’t Yet

Embracing a New Bill by the U.S. Senate, VOX (Oct. 31, 2017),

https://www.vox.com/2017/10/31/16579880/facebook-google-twitter-honest-ads-act-

political-ads-russia [https://perma.cc/2QU9-F62K].

18

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

rapid and complex to be effectively regulated by the government,

particularly considering the limitations of the First Amendment.

Government regulation was a fool’s errand. Instead, “durable reform

can only happen when the digital advertising community adopts

tougher, tighter, comprehensive controls for who is putting what on its

sites.”

78

The tech industry’s creation and dissemination of the beliefs

described in this section are not new revelations. Shoshana Zuboff has

called these now-familiar tactics—lauding tech’s benefits, suggesting

that government regulation will kill innovation, and advocating for

technology-enabled self-regulation instead—the “cry freedom

strategy.”

79

(Indeed, sometimes that description is literal. “FREE

AMERICA NOW,” tweeted Tesla CEO Elon Musk, as he reopened his

Fremont, California plant in violation of county COVID-19

regulations.

80

) The fact that the tech industry leaders have deployed

this strategy consistently since the 1990s suggests that they believe it is

effective, presumably because they assume its underlying assumptions

are shared by politicians and the public. Yet, this is an untested

assumption that the rest of this paper tests and finds wanting.

In the next section, we describe topic modeling and how we use

it to identify and analyze thematic patterns in news articles published

between 2010 and 2020 to illustrate how big tech regulation is publicly

discussed and interpreted. Then, in section III, we show that, despite

the active promotion of libertarian ideology proclaiming the benefits of

an unfettered internet, ideas about free markets and information

freedom play a surprisingly small role in the public discourse. Instead,

the most common themes in the discourse concern the need to regulate

big tech companies to rein in proliferating social hazards.

78

Oversight of Federal Political Advertisement Laws and Regulations: Hearing Before

the Subcomm. On Info. Tech. of the H. Comm. on Oversight and Gov’t Reform, 115th

Cong. 46 (1983) (statement of Randall Rothenberg, President and Chief Executive Officer,

Interactive Advertising Bureau).

79

ZUBOFF, supra note 51, at 103.

80

Elon Musk (@elonmusk), Free America Now, TWITTER (Apr. 28, 2020),

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1255380013488189440 [https://perma.cc/5573-

6ADM].

2022]

SHORT

19

III. Topic Modeling

A. What is topic modeling?

In order to explore contemporary discourse on the regulation of

large technology corporations, we used computer-assisted topic

modeling, which has significant advantages over conventional

qualitative textual analysis. Traditionally, scholars looking to identify

the use of rhetoric or ideologies in a given policy area must engage in

the time and labor-intensive process of content analysis. This process

requires the researcher to examine a text to identify individual

instances of the content they are interested in.

81

For example, a

researcher interested in public opinion about regulation might read

through a large batch of newspaper articles and extract passages that

articulate pro and anti-regulatory arguments. Once the relevant

passages are identified, the researcher must flag (or “code” or “label”)

the variety of pertinent information contained in them, such as the

substance of the arguments made about regulation or the identity of

those making them.

82

The pieces of text under a single code or label are

collected to form a category or variable that can be treated

quantitatively as data that is then subjected to conventional statistical

techniques.

83

This process identifies the topical patterns within the

overall text.

84

For example, the researcher might be able to

demonstrate that particular arguments tend to be made in conjunction

with one another or that certain arguments wax and wane over time.

There are, however, some obvious limitations to this approach

to content analysis. First, the need for an individual researcher to read

and code each article necessarily limits the number of articles that can

be included in the sample. Second, even the most conscientious

scholars may introduce their own biases and preconceptions as they

read and code the data.

85

Third, the limitations on human perception

mean that researchers may fail to discern certain patterns in the data if

they have been primed to look for different themes.

86

Computer-assisted topic modeling algorithms overcome these

limitations.

87

Beginning with a corpus of text-rich documents, the

81

See Hsiu-Fang Hsieh & Sarah E. Shannon, Three Approaches to Qualitative Content

Analysis, 15 QUAL.HEALTH RES. (2005).

82

Id.

83

Id.

84

See Jodi L. Short, The Paranoid Style in Regulatory Reform, 63 HASTINGS L.J. 633

(2011).

85

J.B. Ruhl, John Nay & Jonathan Gilligan, Topic Modeling the President: Conventional

and Computational Methods, 86 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 1243, 1279 (2018).

86

Id. at 1274.

87

See id. at 1272–1280 (an excellent description of how topic modeling works in relatively

plain English).

20

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

algorithm can search these documents and produce a set of “topics,” or

probability distributions over words that each express a single theme.

88

These models identify the distribution of topics both within each

document (one document may contain many topics) and across the

entire corpus of documents. The algorithm can reveal motifs in large

collections of documents, both through repetitions of particular words

and associations among words.

89

Thus, within a corpus of text, the

algorithm identifies topics, which are distinguished by clusters of

words that appear together with a high statistical probability.

90

Unlike

88

For this study, we applied the popular Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic model,

commonly used in communication studies, partly based on code developed for the study of

same-sex marriage and marijuana legalization discourse on Reddit in, Babak Hemmatian,

Sabina J. Sloman, Uriel Cohen Priva & Steven A. Sloman, Think of the Consequences: A

Decade of Discourse about Same-sex Marriage, 51 BEHAVIOR RESEARCH METHODS, March

11, 2019; and, Babak Hemmatian, Taking the High Road: A Big Data Investigation of

Natural Discourse in the Emerging U.S. Consensus about Marijuana Legalization, Thesis

(Ph.D.), Brown University, February 12, 2022. The original exposition of LDA can be found

in: David M. Blei, Andrew Y. Ng & Michael I. Jordan, Latent Dirichlet Allocation, 3 J.

MACH. LEARNING RSCH. 993, 993–1022 (2003). Other examples of the method’s use can be

found in, Ilana Heintz, Ryan Gabbard, Mahesh Srivastava, Dave Barner, Donald Black,

Majorie Friedman & Ralph Weischedel, Automatic Extraction of Linguistic Metaphors

with LDA Topic Modeling, PROC. FIRST WORKSHOP ON METAPHOR IN NLP 58 (2013);

Daniel Maier, A. Waldherr, P. Miltner, G. Wiedemann, A. Niekler, A. Keinert, B. Pfetsch, G.

Heyer, U. Reber, T. Häussler, H. Schmid-Petri & S. Adam, Applying LDA Topic Modeling

in Communication Research: Toward a Valid and Reliable Methodology, 12 COMMC’N

METHODS & MEASURES 93 (2018); Hamed Jelodar, Yongli Wang, Chi Yuan, Xia Feng,

Xiahui Jiang, Yanchao Li & Liang Zhao, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and Topic

Modeling: Models, Applications, a Survey, 78 MULTIMEDIA TOOLS & APPLICATIONS 15169

(2019). We chose the LDA approach because past research has shown it can reveal

semantic content of natural language beyond the level of words, allowing for the

differentiation of multiple meanings of a single term. Paul DiMaggio, Manish Nag, & David

Blei, Exploiting Affinities Between Topic Modeling and the Sociological Perspective on

Culture: Application to Newspaper Coverage of U.S. Government Arts Funding, 41

POETICS 570, (2013) (LDA is basically “a statistical model of language”). This model is also

appealing for its ability to identify changes over time in the topics occurring in a large

corpus of natural language data. Both properties are empirically demonstrated in the

published work from which our code base is derived.

89

Ruhl, supra note 85.

90

To improve the quality of our topic model, we applied common preprocessing

techniques to the dataset. We changed all words in our corpus to lowercase to avoid

different cases of the same word being treated as different words and changed different

grammatical forms of the same words to a uniform lemma (a process called

lemmatization). HTML escape codes, uninformative stop words, URLs, new line

characters, punctuation, ubiquitous terms (words that appeared in 99% of the documents),

rare terms (those appearing in a single document), as well as non-alphanumeric characters

were removed from the dataset. We used the lemmatizer from the SpaCy python package

and the set of stop words from the Natural Language Toolkit Bird, Klein, & Loper, NLTK,

(2009), respectively. Our corpus contained 22,692 articles (27,797,084 words in total,

comprising 23,438 unique words) with a mean document length of 1,224 words (median =

536, SD = 2168.7).

2022]

SHORT

21

conventional word-based quantitative techniques in the social

sciences,

91

the topic model does not simply count word frequencies. It

accounts for the probability that certain words occur together and for

the weight each word contributes to these probability distributions.

92

The most highly weighted words provide clues about the subject that

the topic (cluster) represents. For instance, the high weighting of the

words “market, competition, antitrust, platform, consumer” in one

topic relative to other words and other topics as identified by our

algorithm led us to label that theme tech antitrust.

Importantly, topic modeling algorithms like the one used in this

work, are unsupervised, meaning that topics are not chosen ex ante by

the researchers. Therefore, the topics ultimately identified within a

collection of documents are neither known nor searched for in advance.

Instead, the algorithm “learns” the topics and the words from the

corpus of documents that comprise them. The unsupervised nature of

the algorithm makes the coding truly inductive and responsive solely to

the statistical distribution of the words in the text, rather than

deductively derived from existing concepts, theoretical frames, and

possible unreflective biases of a researcher.

93

By discovering both explicit and implicit motifs in a large

collections of documents, the topic modeling algorithm can yield what

social scientists call “frames.”

94

A frame is “a set of discursive cues

(words, images, narrative) that suggests a particular interpretation of a

person, event, organization, practice, condition, or situation.”

95

In

other words, frames convey meanings attached to or associated with

social actions and circumstances—in this instance, rhetoric and

ideologies of the regulation of large technology companies. Thus, by

using topic modeling, we can quantitatively identify salient trends in

the rhetoric that circulate through social discourse.

96

This allows us to

assess whether the techno-libertarian themes so popular within the

tech industry are actually part of the public discourse about tech and

regulation.

91

See Y.R. Tausczik, J.W. Pennebaker, The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and

computerized text analysis methods, JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY, 29

(1), 24-54.

92

Id.

93

John W. Mohr & Petko Bogdanov, Introduction—Topic Models: What They Are and

Why They Matter, 41 POETICS 545, 549 (2013) (arguing that topic models “are methods

that can provide a way to analyze texts (including Big Data’ texts) that is substantively

quicker, more efficient, and more objective than traditional methods of content analysis in

the social and cultural sciences.”).

94

ERVING GOFFMAN, FRAME ANALYSIS: AN ESSAY ON THE ORGANIZATION OF EXPERIENCE

(1974).

95

DiMaggio et al., supra note 88, at 593.

96

Cf. WILLIAM H. SEWELL, LOGICS OF HISTORY: SOCIAL THEORY AND SOCIAL

TRANSFORMATION 152–74 (2005).

22

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

B. Methodology

While unsupervised topic modeling minimizes human

involvement in identifying the topics that permeate a particular body

of data, researchers must identify the appropriate sample corpus of text

to analyze and specify the parameters of the model in order to structure

the study and interpret the results.

97

To construct our sample, we used

a corpus of news articles from the proprietary database Lexis Nexis to

track the evolution of coverage surrounding big tech regulation over the

past two decades. Specifically, we used a sample from the Lexis Nexis

“Data as a Service” platform, which is designed and optimized for big

data analytics and has a search engine dedicated to “News Data.” The

initial sample included any news article that included the keyword

phrase “big tech” and any word in the same lexeme

98

as “regulation.”

99

From this starting point, we filtered the documents to include only

those articles written in English, published in the United States, and

published after the year 2010. Our final corpus contained 22,692

articles, beginning in 2010 with a low of almost zero, to an increase of

several hundred per year between 2014 and 2016, with an increase up

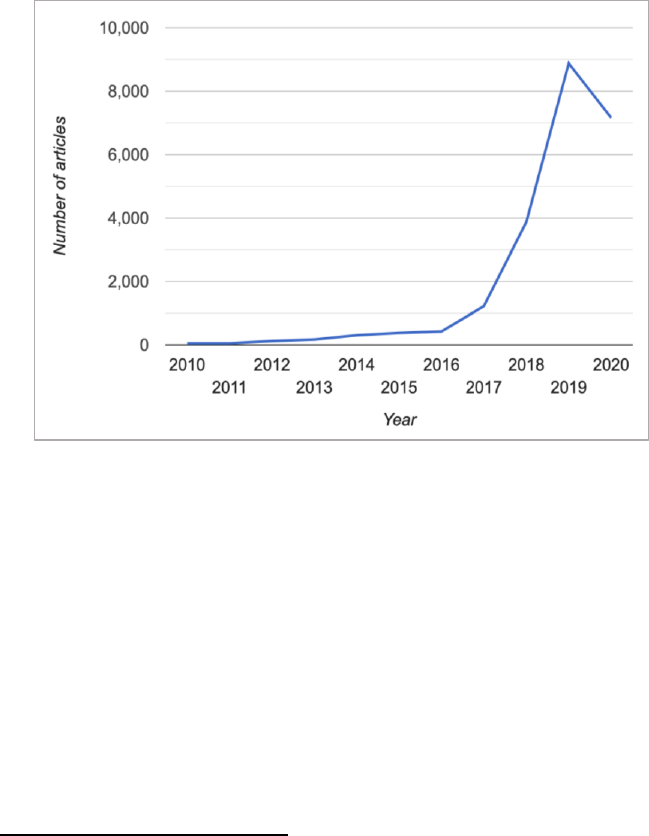

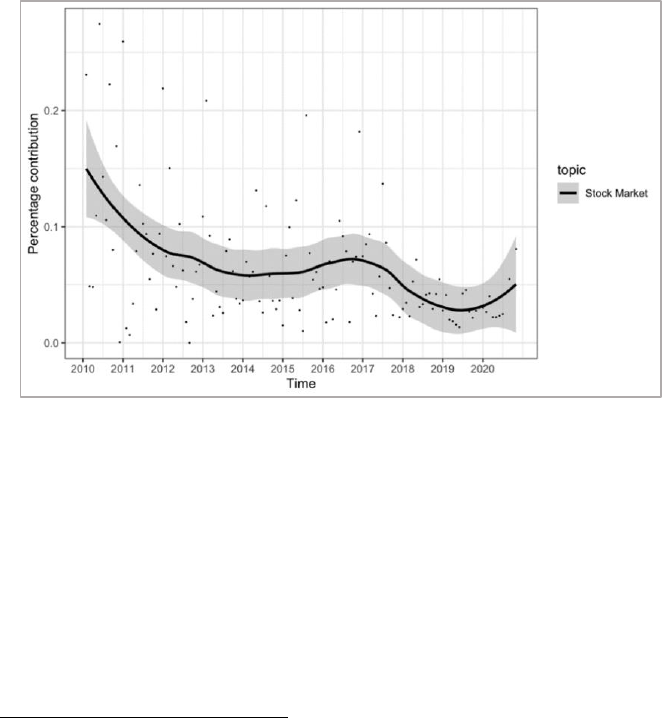

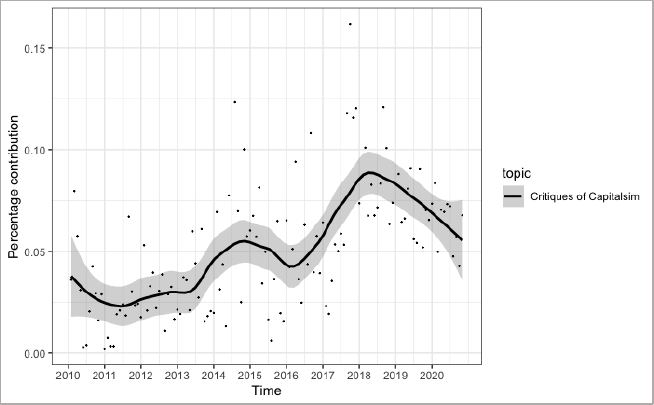

to approximately 9000 in 2019 (see Figure 1 below).

97

Ruhl et al., supra note 85, at 1281.

98

Lexeme, ENCYCLOPEDIA.COM (May 29, 2018), https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature-

and-arts/language-linguistics-and-literary-terms/language-and-linguistics/lexeme

[https://perma.cc/XK8J-WU9Y] (lexeme is a basic lexical unit of a language, consisting of

one word or several words, considered as an abstract unit, and applied to a family of words

related by form or meaning).

99

We used “big tech” as a keyword to balance competing concerns about over- and under-

inclusivity. We wanted to construct a corpus of documents focused on the regulation of

market-dominating platform companies, such as Google (Alphabet), Apple, Facebook, and

Amazon, because these companies have been the subject of the most pointed regulatory

debates, and they have been actively involved in contesting regulation and framing

narratives around the regulation of technology. We saw downsides to using both broader

and narrower terms. For instance, we worried that using a more generic term like

“technology” or “web” or “internet” might pull large numbers of irrelevant documents. At

the same time, we did not want to limit our data coverage exclusively to specific named

companies. The keyword “big tech” allowed us to balance these competing concerns.

2022]

SHORT

23

Figure 1. Sample Document Corpus

We chose to explore news coverage of big tech regulation, rather

than other communication mediums for two reasons. First, news

coverage provides clues to what elites are thinking and doing, especially

when prominent actors (executives, politicians, financiers, for

example) turn their attention to the subjects reported.

100

Because large

technology corporations are some of the most influential actors in our

public sphere, their actions are covered regularly by journalists. In

addition, journalists are well-read, knowledgeable in diverse social

fields, and writing for public audiences.

101

Often using quotes from

institutional actors, journalists embody within their accounts the

language, arguments, and narratives these speakers use to frame,

report and interpret the topic at hand.

102

Second, news coverage of big tech regulation is important

because it influences the views of the reading public.

103

As sociologist

100

Susanne Janssen, Giselinde Kuipers & Marc Verboord, Culture Globalization and Arts

Journalism: The International Orientation of Arts and Culture Coverage in Dutch,

French, German, and U.S. Newspapers, 1955 to 2005, 73 AM. SOCIO. REV. 719 (2008);

Harvey Molotch & Marilyn Lester, News as Purposive Behavior: On the Strategic use of

Routine Events, Accidents, and Scandals, 39 AM. SOCIO. REV. 101 (1974); Stephen D.

Reese, Setting the Media’s Agenda: A Power Balance Perspective, 14 ANNALS INT’L

COMMC’N ASS’N 309 (1991).

101

Paul DiMaggio, Manish Nag & David Blei, Exploiting Affinities Between Topic Modeling

and the Sociological Perspective on Culture: Application to Newspaper Coverage of U.S.

Government Arts Funding, 41 POETICS 570, 573 (2013).

102

Id. at 593.

103

Id. at 573.

24

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

Paul DiMaggio has suggested, news coverage does this in several ways.

It calls readers’ attention to existing interpretations of events and

reinforces those interpretations. It also develops new interpretations

and places them within the broader political, cultural, and social

contexts that people use to interpret such information. In doing so, the

nature of news coverage influences these interpretations by telling and

retelling news events in a selected and directed fashion.

104

Put another

way, news coverage of big tech regulation both reflects and represents

one avenue of dissemination and influence in the formation of public

opinion. For example, if press coverage mentions big tech regulation

topics in association with positive benefits of the companies, these

corporations are likely to enjoy the support of a trusting and benevolent

public. On the other hand, if news coverage uses topics with negative

connotation, public sentiment towards these companies might take a

different path. This may not be directly causal, but the associations are

strong.

105

Ultimately, given the near-instantaneous global spread of

news in the digital age, reported events surrounding big tech regulation

can shape both public opinion and the direction of public policy. Thus,

we explore the news coverage of big tech regulation because news

content holds the unique place of both reporting events and informing

public opinion, which in turn shapes subsequent events.

After selecting the corpus of texts, we had to determine the

number of topics to be identified by the algorithm, optimizing for

predictive capacity and semantic coherence.

106

If the topic model is

asked to identify too few topics, those produced will be so general and

contain such disparate clusters of words that it would be difficult to

make sense of the content or discern any particular frame from the

data. On the other hand, if the algorithm is asked to identify too many

topics, interesting trends might be split up across topics and obscure

their associations and coherence. By identifying an appropriate

number of topics, we can ensure that the algorithm generated topics

that contained words that were clustered in a semantically coherent

fashion without excluding words that logically belonged in that cluster.

To determine the appropriate number of topics for our corpus

of data, we trained multiple models with up to 100 topics in increments

104

Id.

105

Id.; SHANTO IYENGAR, IS ANYONE RESPONSIBLE? HOW TELEVISION FRAMES POLITICAL

ISSUES (Univ. of Chi. Press) (2001); PRICE V & TEWSKBURY D, “NEWS VALUES AND PUBLIC

OPINION: A THEORETICAL ACCOUNT OF MEDIA PRIMING AND FRAMING” IN BARNETT, G AND

BOSTER F. J. (EDS) PROGRESS IN COMMUNICATION SCIENCE, ABLES, GREENWICH CT. (1997).

106

The topic modeling procedures that follow closely match those set forth in see

Hemmatian et al., supra note 88; Babak Hemmatian, Taking the High Road: A Big Data

Investigation of Natural Discourse in the Emerging U.S. Consensus about Marijuana

Legalization (Feb. 12, 2022) (Ph.D. thesis, Brown University) (on file with

ResearchGate.net) (further procedural details can be found in these earlier publications).

2022]

SHORT

25

of 25. For each of these models, we then looked at quantitative

assessments that measured how certain a particular model was in its

predictions of sample testing data,

107

as well as the co-occurrence of

words that belong to the same topic.

108

We also subjected the results of

the alternative models to a qualitative assessment in which we

manually inspected the top 40 words most strongly associated with

each of the topics to ensure that the topics align logically and

experientially with real-world topics.

109

These trial runs suggested that

asking the algorithm to identify 50 topics would yield the most

coherent, analytically useful results.

110

107

As a first quantitative measure, we looked at per-word perplexity for each model. In

machine learning, perplexity is a way of measuring how well a model predicts a held-out

sample, often used for model comparison. Per-word perplexity, in particular, reflects how

uncertain the model is on average when predicting each word in a document, given the

other words in a document. We use the rate at which this uncertainty increases with

incremental additions to the number of topics as a second, more sophisticated measure of

model quality. Weizhong Zhao, James J. Chen, Roger Perkins, Zhichao Liu, Weigong Ge,

Yijun Ding, & Wen Zou, A Heuristic Approach to Determine an Appropriate Number of

Topics in Topic Modeling, 16 BMC BIOINFORMATICS, Sept. 25, 2015(This measure has been

shown to outperform simple per-word simplicity in evaluating model coherence).

108

As a second quantitative test of fit, we calculated the UMass coherence values for all

models. UMass coherence measures how often the words that comprise a topic actually

appear together in documents. David Mimno, Hanna M. Wallach, Edmund Talley, Miriam

Leenders, & Andrew McCallum, Optimizing Semantic Coherence in Topic Models,

PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONF. ON EMPIRICAL METHODS IN NAT. LANGUAGE PROCESSING 262–

72 (2011) (this is an intuitive measure of topic coherence, because if two words in a topic

really belong together you would expect them to show up together frequently in

documents. Like perplexity, the UMass coherence measures showed a preference for fewer

topics (see Appendix 1 for values). Both measures, per-word perplexity and UMass

coherence, inclined us to choose a model with fewer topics).

109

While perplexity and UMass measures are both suitable approximations of the

interpretability of topics, they sometimes do not align with humans’ intuitive semantic

understanding or actually circulating cultural frames (memes). While quantitative

measures of fit are crucial to optimizing the model, the gold standard of coherence is

aligning the topics identified by the model with human understandings of the subject

matter. Jonathan Chang, Jordan Boyd-Graber, Sean Gerrish, Chong Wang, & David M.

Blei, Reading Tea Leaves: How Humans Interpret Topic Models, 22 ADVANCES IN NEURAL

INFO. PROCESSING SYS. 288 (2009); To choose the top words for qualitative analysis, an

intuitive formula was used that accounts for the baseline popularity of particular words

(see the source in Footnote 72). Keith Stevens, Philip Kegelmeyer, David Andrzejewski &

David Buttler, Exploring Topic Coherence Over Many Models and Many Topics, PROC. OF

THE 2012 JOINT CONF. ON EMPIRICAL METHODS IN NAT. LANGUAGE PROCESSING AND

COMPUTATIONAL NAT. LANGUAGE LEARNING 952, 952–61 (2012).

110

As a robustness check to ensure that the stability of the 50-topic model was not the

idiosyncratic result of the exact number of topics used, we examined models using 45 and

55 topics. These models yielded similar quantitative and qualitative measures of stability

whose similar quantitative and qualitative measures ensured the stability of the 50-topic

model and not the result of the exact number of topics used. A complete list of these topics

and the top words associated with them are available in a digital repository: noah14noah,

Tech_Regulation_Topic_Modeling, GITHUB.COM,

https://github.com/noah14noah/Tech_Regulation_Topic_Modeling.git

[https://perma.cc/A8SF-3LXT] (last visited Nov. 19, 2022).

26

THE OHIO STATE TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL

[Vol. 19.1

Having selected our data set and the optimal number of topics,

we then identified and labeled the most relevant and coherent topics

that the algorithm produced.

111

We identified a subset of top topics by

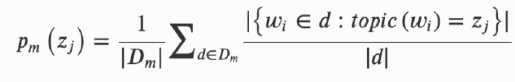

calculating the average contribution a topic made to the overall corpus

in each month and over the life of the sample (see Appendix 2 for

explanation of calculations). We designated a specific topic as top topic

if it met one of two criteria: (1) it was a major contributor to the

discourse overall based on the algorithmic model (> 3% average

monthly contribution);

112

or (2) it demonstrated significant temporal

trends based on the coefficients of a polynomial regression model. After

this initial filtering step, we examined the five most representative

sample articles

113

from each of the top topics to obtain more linguistic

and substantive content that would enable us to identify the theme and

label for each topic. Table 1 presents our top topics and the set of high-

probability words associated with each (referred to as “top words”).

114

111

Even within the optimized, 50-topic parameter, not all topics were equally relevant or

coherent. For instance, we determined that certain topics such CEO Interviews (comprised

of representative articles reproducing interviews with tech company CEOs on a multitude

of topics, with very little discussion of regulation) and Earnings Reports (reproducing

companies’ quarterly earnings reports) were not coherent or relevant in light of the

theoretical concerns of the present study.

112

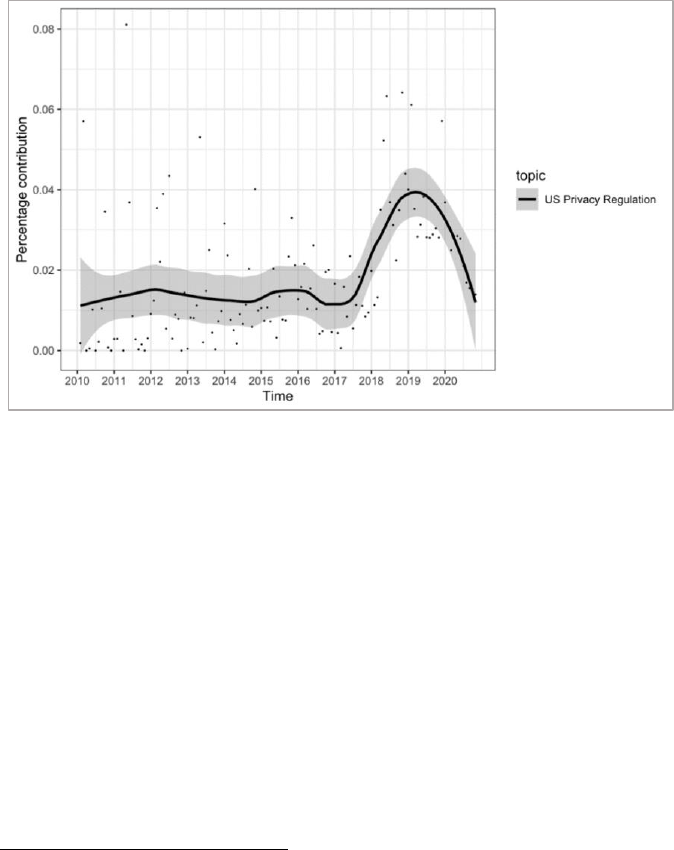

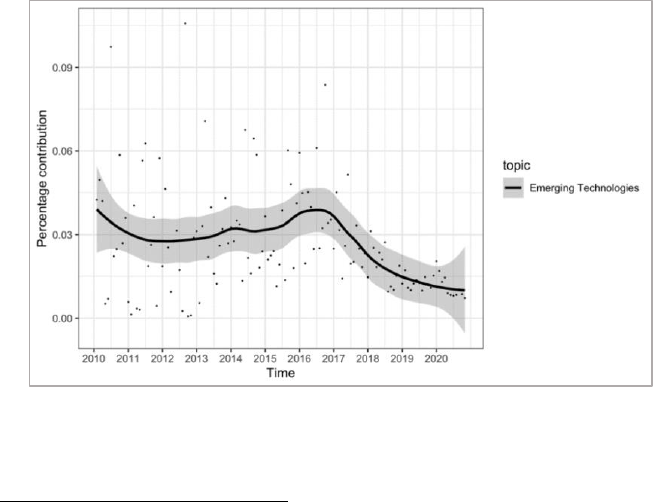

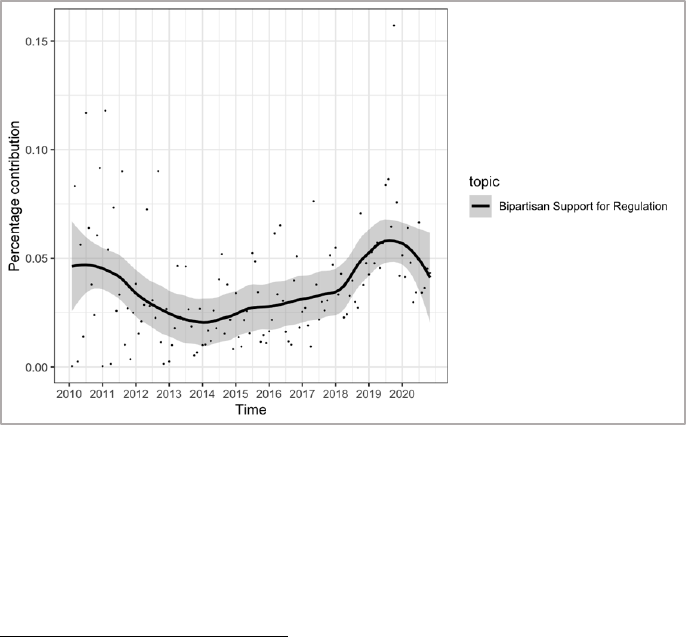

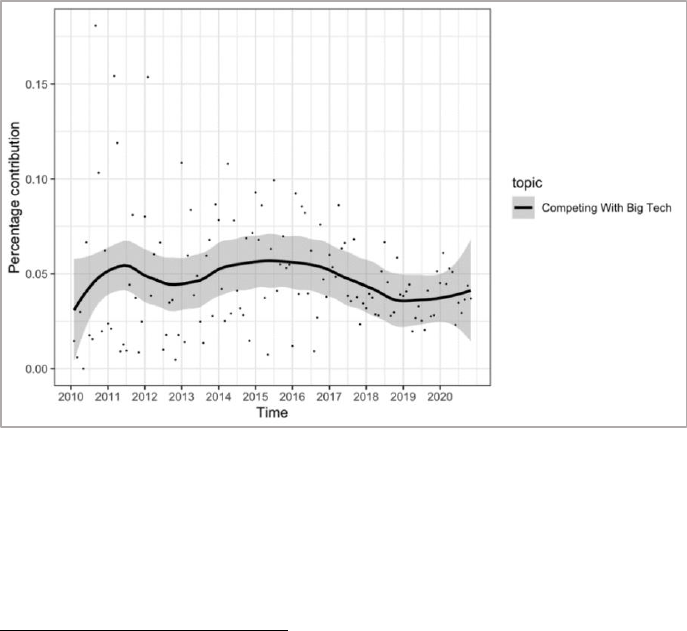

The 3% threshold was selected because it indicates a statistical justification from the