1

Manhattan, Kansas

African American History Trail

Self-Guided Driving Tour

July 2020

This self-guided driving tour was developed by the staff of the Riley County Historical Museum to showcase

some of the interesting and important African American history in our community. You may start the tour at

the Riley County Historical Museum, or at any point along to tour.

Please note that most sites on the driving tour are private property. Sites open to the public are marked with *.

If you have comments or corrections, please contact the Riley County Historical Museum, 2309 Claflin Road,

Manhattan, Kansas 66502 785-565-6490.

For additional information on African Americans in Riley County and Manhattan see “140 Years of Soul: A

History of African-Americans in Manhattan Kansas 1865- 2005” by Geraldine Baker Walton and “The

Exodusters of 1879 and Other Black Pioneers of Riley County, Kansas” by Marcia Schuley and Margaret

Parker.

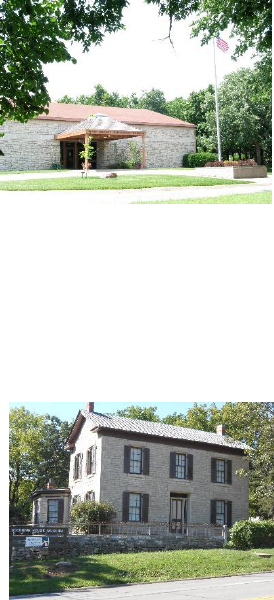

1. 2309 Claflin Road *Riley County Historical Museum and the

Hartford House, open Tuesday through Friday 8:30 to 5:00 and

Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00. Admission is free.

The Museum features changing exhibits on the history of Riley County

and a research archive/library open by appointment. The Hartford House,

one of the pre-fabricated houses brought on the steamboat Hartford in

1855, is beside the Riley County Historical Museum.

2. 2301 Claflin Road *Goodnow House State Historic Site, beside the Riley County Historical Museum,

is open Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00 and when the Riley County Historical Museum is open and

staff is available. (Call 785-565-6490, if you would like to check on availability.) Admission is free,

donations are accepted.

Goodnow House is the 1861 home of Isaac and Ellen Denison Goodnow.

Isaac Goodnow (1814 – 1894) was a founder of Manhattan and Bluemont

Central College (the predecessor of Kansas State University) and was the

first elected State Superintendent of Education. Isaac and Ellen Goodnow

were committed to the Free State cause, advocating that Kansas enter the

Union without slavery.

Leave from the Museum parking lot and turn right (east) on Claflin Road. Go to the entrance to the Riley

County Genealogical Society Library and Pawnee Mental Health. Turn right (south) at the entrance between

RCGS and Pawnee Mental Health. Pause here, or stop in the parking lot.

2

3. 2005 Claflin Road *Platt House. This is the home built for Jeremiah

Everts (who went by Everts) and Jennie Platt in 1871. Everts Platt was

born in Connecticut and grew up in Illinois, where he graduated from

college. He came to Kansas in 1856 and settled at Wabaunsee. While in

Wabaunsee County he was active in the Underground Railroad and was

an ardent abolitionist and Free State advocate. Everts taught school, and

then in 1864, came to Manhattan to teach at Kansas State Agricultural

College (today KSU.) Today, the Platt House is home to the Riley

County Genealogical Society. The Society welcomes visitors during their open hours, call 785-565-

6495 or go to www.rileycgs.com for information.

Leave the parking lot at Sunset Avenue. Turn left (north) on Sunset and go to the corner of Sunset and Claflin.

Turn left (west) on Claflin Road.

As you leave the Pawnee Mental Health parking lot, just ahead is Marlatt Hall, built in 1964 and named

for Washington Marlatt.

Proceed on Claflin Road to the corner of Claflin and College Avenue. Turn right (north) onto College Avenue.

4. 1403 College Avenue, Northwest corner of College and Claflin, *Bluemont

College Marker at Central National Bank. This is the original location of

Bluemont Central College, organized in 1858. The college building was built in

1859, and after 1863 it was accepted by the state as one of the first land grant

colleges in the nation and called Kansas State Agricultural College. In 1875 the

campus moved to its current location by the second KSAC President, John

Anderson. Bluemont Central College welcomed women and African American

students from its founding.

The glacier erratic stone marker was erected by the DAR and the Riley County

Historical Society in 1926 to commemorate the original location of the Bluemont

Central College.

Proceed north on College Avenue. On the right (at College and Dickens), immediately south of the KSU soccer

field, is the Washington Marlatt house and barn. Pause along College Avenue to view.

5. College and Dickens, Immediately south of the KSU Soccer Field. Marlatt House/Barn.

The Marlatt house is the oldest home in its original location in

Manhattan. The Hartford House, on the Riley County Historical

Museum grounds, is older, but it is not in its original location. The

Marlatt house was built in 1856 by Davies Wilson, who was with the

Cincinnati and Kansas Land Company, and arrived in Manhattan on the

steamboat Hartford. Wilson donated the land west of the home to allow

the construction of the Bluemont Central College building in 1859.

Davies Wilson’s widow donated money in his memory to KSU, which was used to build the current

KSU President’s House, located on Wilson Court, on the Kansas State campus.

Washington Marlatt was born in 1829 in Indiana. He had a college degree from Asbury University and

was a Methodist preacher, educator, and abolitionist who arrived in Kansas in 1856. During territorial

Kansas he was a participant (at this location) in the underground railway guiding African Americans out

of slavery. He was a founder of Bluemont College and was its principal. Isaac Goodnow recruited Miss

3

Julia Bailey from back East to assist at the college, and Washington Marlatt married her in 1861. They

lived on this farm most of their lives. The Marlatts had five children who went on to significant

accomplishments, including the nationally recognized entomologist, Charles L. Marlatt, and home

economist, Abby Marlatt. Rev. Marlatt served as a Methodist minister for a while, but most of his life

concentrated on farming.

In 1875 the KSAC campus was moved to its current location.

The old Bluemont Central College building was torn down in

1883. When it was torn down, Marlatt salvaged the letters

spelling out the school name, the used stone, and some of the

timbers from the building to build this barn. The Bluemont

Central School letters are now in the KSU Alumni Association

building.

Kansas State University owns this site now. The Marlatt family

also gave the Top of the World, a scenic overlook, to the

University.

Because of road work in 2020, turn left on Dickens. Turn around and go back to the corner of College and

Dickens and make a right turn (south) on College and go to the corner of College and Claflin. Turn right (west)

on Claflin. Proceed on Claflin to Hylton Heights. Turn left (south) on Hylton Heights Road and go to 1105

Hylton Heights Road and pause to view the Denison house. (Regular directions, with no road work: turn

around in the KSU football stadium parking lot and proceed back south along College Avenue to the corner of

College Avenue and Claflin. At the corner turn right (west) on Claflin. Proceed to Hylton Heights Road. Turn

left (south) on Hylton Heights Road and proceed to 1105 Hylton Heights Road. Pause to view the Denison

house.

6. 1105 Hylton Heights Road, Joseph Denison house. Built in 1859, the home has a basket handle

window just below the peak of the roof, similar to the Bluemont Central College building. Joseph

Denison was Isaac Goodnow’s brother in law. The two men were close friends and came to Kansas

together in 1855 in order to vote Kansas into the Union as a free state. Denison was a Methodist

Minister and served as the President of Bluemont Central

College at the time that it was given to the State of Kansas

as the Land Grant school, and became the first president of

Kansas State Agricultural College. After he was fired in

1874, he had cheese factory at his home here and then was

hired as President of Baker University, a Methodist school

in Baldwin Kansas. He served there a few years and then

returned to the ministry. He died in the Goodnow house in

1900, while visiting his sister.

Continue on south on Hylton Heights to Anderson Avenue. Turn left (east) on Anderson Avenue and proceed

to the corner of Anderson Avenue and Sunset Avenue. Turn right on Sunset Avenue and go to the Sunset

Cemetery gate (on right) turn in.

4

7. Sunset and Leavenworth, *Sunset Cemetery was established in

1860. There are many interesting and important African Americans in

the Cemetery. The stone entry into Sunset Cemetery was built in

1917 by the Women’s Relief Corps of the Grand Army of the

Republic. Architect was E. Arthur Fairman and Charles Alfred

Howell, an African American, received the contract to build the

gateway. The gateway is dedicated to the memory of Riley County

soldiers who served in the American Civil War.

Go to:

Section 4, lot number 143:

8. Grave of Minnie Howell Champe. (1878-1948) Minnie Howell was

the first African American woman graduate of Kansas State, in 1901.

She was a teacher, professor of Domestic Science, and later Director of

the Douglass Center in Manhattan.

9. Grave of Charles Alfred Howell. (1881-1942) Charles Howell was

the brother of Minnie Howell Champe. He was a stonemason who

worked on many local projects, including building the stone entry to

Sunset Cemetery and the stone fence around the cemetery in 1932.

The Howell family came to Kansas from Tennessee. J.M.T. (Jerry) Howell, father of Minnie and Charles,

was a stone cutter and served on the Manhattan City Council. He died in 1897 and is buried near his

children.

Section 7- northwest corner of the section- Potter’s Field.

10. Grave of Hosea McDaniel (unmarked). (ca. 1878-1880) Two year old Hosea died of measles in

Manhattan before the family moved to Wichita, Kansas, where his sister Hattie was born. Hattie

McDaniel was the first African American to receive an Oscar, in 1939, for her performance in “Gone

with the Wind.” She had a long and distinguished career as an actor. The McDaniel family were among

the founders of the Manhattan Bethel A.M.E. Church.

Section 23- Lot A 18

11. Grave of Murt Hanks Jr. (1933-1989) Murt Hanks Jr. was the first

African American to serve as Manhattan Mayor, in 1972. He also

served a second time in 1975. Murt Hanks Jr. was born in a little house

south of the railroad tracks in Manhattan. His father, Murt Hanks Sr.

died in an accident when Murt was only 8 years old. Murt Hanks Jr.

worked to help the family survive. He graduated from Manhattan High

School, attended Kansas State University, and went to work as a

manager for Wallace Kidd’s pest control company. Wallace Kidd was

the first African American elected to the Riley County Commission. Later Murt Hanks Jr. was the first

Equal Employment Officer at Fort Riley.

Leave Sunset Cemetery and turn right (south) onto Sunset Avenue. At Poyntz Avenue, turn left (east) and go to

17

th

Street. At 17

th

Street turn right (south) and go to Yuma Street. At Yuma Street, turn left (east).

5

12. 17

th

Street between Kansas State University and Fort Riley

Boulevard has the overlay name of Martin Luther King Jr.

Memorial Drive. On January 19, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr.

gave an All University Convocation speech in Ahearn Field House

at Kansas State University. The speech was among the last he gave

before his death in April 1968. Ahearn Field House is on 17

th

street,

on the Kansas State campus, and a monument in honor of Dr. King’s

convocation was placed in front of Ahearn Field House. 17

th

Street

was given the overlay name in 2018. Benches along 17

th

in Long’s

Park are marked “A Street Fit for a King.”

Until the 1960’s, most African Americans lived south of Yuma Street and east of South Manhattan Street.

Many African Americans lived further south, beyond the railroad tracks in the “Bottoms,” the low ground closer

to the river, which meant that their homes flooded in high water. Land was less favorable in the Bottoms, close

to the noisy railroad tracks and on low ground that flooded, making the lots less expensive. Housing

segregation in Manhattan was mostly “defacto” meaning it was custom, not law. However, some Manhattan

additions did have covenants that prohibited African Americans. With the fair housing laws in the 1960’s it

became illegal, as well as wrong, to discriminate in housing due to race.

Pause at 1231 Yuma:

13. 1231 Yuma, Jesse Baker Sr. House. Jesse Baker Sr. was born in

1907 and moved to Manhattan from Topeka after the death of his

mother, to live with his older brother, Ernest Baker. He graduated

from Manhattan High School and then played baseball with several

traveling teams. On his return to Manhattan he worked for the

Commonwealth Theaters and played and coached baseball locally. In

recognition of his leadership and significant contribution to local

youth sports, one of the baseball fields in Manhattan City Park was

named “Jesse Baker Field” in 1968. Jesse and Lucille Wilson Baker

had nine children, all of whom obtained college educations.

Go to 10

th

and Yuma. Turn left (north) on to 10

th

Street. Go to Colorado and turn left (west) on Colorado

Street. Pause at 1001 Colorado:

14. 1001 Colorado, Charles A. Howell House. Manhattan stonemason,

Charles Howell, built this house as his personal residence in 1936.

Some of Charles’ other projects include the 1

st

Presbyterian Church,

Waters Hall (West Wing) at Kansas State University, stonework on

the Lyda-Jean Apartments at 5

th

and Houston Street, Griffith Stadium,

Willard Hall at Kansas State University, and the stone fence around

Sunset Cemetery.

6

Pause at 1015 and 1020 Colorado, and then go to 11

th

Street.

15. 1015 Colorado. Former group home for African American Kansas State

College women students in the late 1930’s. Kansas State’s first dormitory,

Van Zile Hall, built in 1926, was open to white women students. All other

students found their own housing, in boarding houses, apartments, rooms in

private homes, or in fraternities or sororities. Many of Manhattan’s student

accommodations were not open to African Americans.

16. 1020 Colorado, Former Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity House. Phi Beta

Sigma, is a historically African American Fraternity founded in 1914. The

fraternity was established at Kansas State University in 1917. It was the first

African American fraternity west of the Mississippi River.

At 11

th

Street turn left (south) and go to Yuma and turn left (east) and proceed down Yuma again.

Pause at 1010 Yuma, then proceed down Yuma.

17. 1010 Yuma. C.V. (Dave) Dawson House. Clinton Van (Dave)

Dawson (1868-1943) family lived in this home. He worked for the

railroad and was a stonemason, helping build many Kansas State

buildings. His two sons were professors and his daughter, Mrs. McCune,

lived in this home until 1974. Later the family of Lazone Grays, World

War II and Korea War veteran, lived in this home. Mrs. Lazone Grays

was honored by the International Women’s Year Commission in 1975 for

her work in rearing children and as a community volunteer.

Pause at 1015 Yuma, then proceed down Yuma.

18. 1015 Yuma. Miles Woods House. Miles Woods (1873-1943) was

among the first group of Exodusters (also known as Exodites) to arrive

in Manhattan in April 1879. The Exodusters were the African

Americans who migrated to Kansas from the South in 1879-1880 in

search of a better, less oppressive life. Miles Woods came from

Mississippi with his step-father, Tom Cruise, mother, and brother. Miles

Woods was the father of Earl Woods (1932-2006) first African

American to play baseball in the Big 7 Conference at Kansas State

University. Earl Woods went on to a distinguished military career.

Earl’s son, Tiger Woods, is a professional golfer.

7

Pause at 930 Yuma and 916 Yuma, then proceed down Yuma.

19. 930 Yuma, Kaw Blue Lodge #107. The Kaw Blue Lodge #107 is a

predominately African American Masonic Lodge. Their building,

purchased in 1974, is the former Second Methodist Church, called Shepard

Chapel. Shepard Chapel was founded in 1866 as a mission of First

Methodist Church and this building was built in 1916. In 1967 Shepard

Chapel merged with the First Methodist Church. African American

Masons have been active in Manhattan since at least the 1880’s.

20. 916 Yuma, Mt. Zion Church of God in Christ. Founded in 1932, Mt.

Zion Church of God in Christ built their current building in 2004.

Pause at 900 and 901 Yuma, then proceed down Yuma.

21. 900 Yuma, *Douglass Center. The United States military was racially

segregated until 1948. During World War I, a recreation center for

white soldiers, the Community House, was built at 4th and Humboldt by

Rotary Clubs and the City of Manhattan. African American soldiers

had recreation space in the basement of the Pilgrim Baptist Church and

the Second Methodist Church (Shepard Chapel.) During the Second

World War, the Community House was again used for white soldier

recreation and the Douglass Center was built, in 1942, as a recreation

center for African American soldiers.

The center became the meeting place for the African American community as soldiers from Ft. Riley

and local citizens all gathered there. Ft. Riley brought some very well-known African Americans to the

area. Joe Louis, Heavy Weight Champion of the World 1937 to 1949, and Jackie Robinson, the first

African American to play in the major leagues in the modern era, and baseball hall of famer, were

among those who came to the Douglass Center during the war years.

Many outstanding people have served as Director of the Douglass Center, including Minnie Howell

Champe, first African American to graduate from Kansas State University, and Dave Baker, former

baseball player, coach, teacher, and son of Jesse Baker Sr..

The City of Manhattan owns and operates the Douglass Center today.

22. 901 Yuma *Douglas School. Douglas School (now correctly spelled

Douglass) was the third Manhattan grade school. (Avenue School was

first, at 9th and Poyntz, where Manhattan High East Campus is today.

The second school was Central School, which was where Woodrow

Wilson is today on Juliette.) In the 1880’s, all Manhattan students

attended the same schools, with African American students in separate

8

classrooms. Douglas School was built in 1903 as the first separate school for African Americans and

opened on January 4, 1904 with sixty students.

In 1902 there was discussion about whether Manhattan should, or should not, have a segregated school.

At the time of the decision the first African American man elected to our school board, Randall Keele,

served on the Board of Education.

After Douglas School was built, all teachers at the school were African American. The teaching staff

were highly educated, excellent teachers. In 1936 the school was expanded with a WPA project.

Douglas School became the heart of the African American community. After grade school, in Junior

High, all Manhattan students studied together. The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka court

case affirmed that segregated schools were not legal and Douglas School closed in 1962. Today

Douglas School is part of the City of Manhattan’s Douglass Center and many educational and

recreational activities take place here.

In 1939 the City of Manhattan, through a depression era works project, built a segregated swimming

pool for African Americans next door to the Douglas School, to the west. This pool was removed in

2005.

Pause at 831 Yuma, then proceed down Yuma.

23. 831 Yuma Pilgrim Baptist Church

The Pilgrim Baptist Church was founded in 1880 by Exodites, or

Exodusters, and was originally called the Second Baptist Church. The

current church building was built in 1917. The architect was Henry B.

Winter, a prominent local architect and early graduate of Kansas State’s

architecture school. The church was expanded in 1982. The Pilgrim

Baptist Church is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Pause at 826 Yuma, then proceed down Yuma to Juliette Avenue.

24. 826 Yuma- George Giles Home

George Giles’s father was member of the 9

th

Cavalry of the United

States Army, known as the Buffalo Soldiers. George’s family moved

to Manhattan around 1910. He attended the Douglas School and went

on to play baseball for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1925. He later

played and managed other teams in the Negro League. He had many

business interests in Manhattan, including a hotel and restaurant.

George Giles (1909- 1992) is buried in Manhattan’s Sunrise

Cemetery. Several famous African Americans stayed in this home as

guests of the Giles family, including Jackie Robinson, Satchel Paige,

Buck O’Neil, Lena Horne, Marian Anderson, and Duke Ellington.

At Juliette Avenue, turn right (south) and go to Ft. Riley Blvd. At Ft. Riley Blvd. turn left (east) and go to 4

th

Street. Turn left (north) on 4

th

Street.

9

Proceed down 4

th

Street and pause in front of Wonder Workshop, 506 S. 4th street and Bethel A.M.E. Church,

southwest corner of 4

th

and Yuma Street. Proceed down 4

th

Street to Poyntz Avenue.

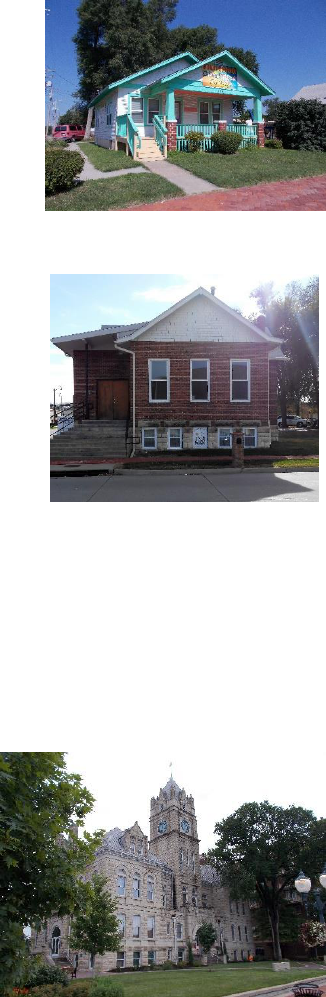

25. 506 S. 4th, *Wonder Workshop Children’s Museum

Wonder Workshop started in 1989 with a three year program to address

the educational, recreational, and social needs of community youth and

their families which was developed by founder and first Director, Richard

Pitts (1955-2020) and others. The Wonder Workshop Children’s

Museum opened in 1994 and the “Outback Camp” at Tuttle Creek Lake

opened in 2000.

26. 401 Yuma, Bethel A.M.E. Church

Bethel A.M.E. Church was founded by the Exodusters in 1879. This is

the third Bethel A.M.E. Church building, built in 1927. The family

(Holbert and McDaniel) of Hattie McDaniel, the first African American to

win an Oscar, were among the founders of this church. The Bethel

A.M.E. Church is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At Poyntz Avenue, turn left (west) and proceed on Poyntz Avenue to Juliette Avenue.

At 5

th

and Poyntz pause at the Riley County Courthouse.

27. 5

th

and Poyntz Avenue, *Riley County Courthouse

The Riley County Courthouse was built in 1906 and opened in 1907.

Holland and Squires were the architects and the building cost around

$50,000.00. Holland and Squires designed a number of other

Kansas Courthouses, including three that have the same design as

Riley County’s Courthouse, the Marion, Osborne, and Thomas

County Courthouses.

Wallace Kidd (1924-2004) was the first African American to serve

as County Commissioner, from 1973 to 1981. He was also the first

African American to graduate at Kansas State in entomology. He

owned and operated Anti-Pest, a pest control company.

Proceed up Poyntz Avenue. At Juliette Avenue turn right (north) and proceed up Juliette and turn right (east)

Bluemont Scenic Drive.

10

Park at the overlook.

Along the way, note the brick streets. Manhattan first paved Poyntz Avenue and Houston Streets.

Brick paving began around 1908. Many of the workmen who did the paving were African American.

Manhattan had a trolley/interurban system from 1909 to 1928. One of the trolley lines ran up Juliette to

the Athletic Field at Bluemont Avenue, where Bluemont School is today. From 1913 to 1928 the

interurban also ran to Junction City.

Bluemont School was Manhattan’s fourth Grade school, built in 1910.

28. The Bluemont Scenic Overlook is at the top of Bluemont

Hill. The hill was named by John C. Fremont when he

explored this area in 1843. Native Americans used the hill

as a burial place. In 1878/79 the burial site was excavated

by Professor B.F. Mudge and others.

On March 24, 1855, Isaac Goodnow climbed to the top of

Bluemont Hill and selected the location for the town he and

his party from the New England Emigrant Aid Society

wished to establish so that they might vote for Kansas to be

a state without slavery in the 1855 Territorial election.

During the Civil War, after Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence in

1863, sentries were placed on Bluemont Hill for security.

In 1879/1880 a mass migration of African Americans came to Kansas. After the Civil War was over,

African Americans living in the American south faced increasing financial and political instability. Few

southern African Americans had hope of owning land or building a prosperous future free from racial

oppression. In 1877, after withdraw of federal soldiers in the south, the safety of African Americans

sharply deteriorated and they looked to Kansas as a possible place of freedom and opportunity.

In 1870 there were 17,108 African Americans in Kansas. By 1880 there were 43,107. This migration

out of the South primarily to Kansas, from 1879 to 1881, is known as the Exodus and the migrants as

Exodusters, or Exodites, taking their name from the exodus from Egypt in ancient times. As many as

40,000 people are thought to have left the South in this period.

In the spring of 1879, thousands of Exodusters left Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and other southern

states arriving in St. Louis, where they overwhelmed that city’s ability to accommodate them. St. Louis

and relief groups paid river passage of the Exodusters to Wyandotte and Atchison, Kansas, in turn

overwhelming those communities. Then arrangements were made for the Exodusters to travel by rail to

any Kansas community which could be persuaded to accept them.

Manhattan was one of the first Kansas towns to accept the Exodusters. During the primary migration,

April 1879 through 1880, around 150 African Americans moved to Manhattan, about doubling

Manhattan’s African American population. It is thought that some of the Exodusters lived at the foot of

Bluemont Hill for a time after coming to Manhattan. Some Exodusters also lived in the old hotel on

Poyntz Avenue, which had come on the Steamboat Hartford in 1855, and others lived in the old paper

mill at Second and Leavenworth Streets. Later, Manhattan’s African American community primarily

established homes south of Yuma and east of South Manhattan Streets.

11

In 1887 Manhattan’s first piped water system was installed. E.B. Purcell gave the land on Bluemont

Hill for the water system and reservoir. Bluemont Hill is still part of the City of Manhattan’s water

system. The water tower on the hill was installed in 1965.

In the 1920’s, Kansas, and the nation, faced a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. In 1924 a KKK rally and

cross burning was held on Bluemont Hill. That rally was the last significant Klan activity in Manhattan.

In 1927 the Manhattan Kiwanis Club built the Manhattan letters on Bluemont Hill. The Kiwanis Club

continues to maintain the letters and in 2019 built the handicapped accessible viewing stand.

Enjoy the views of Manhattan from this historic location.

Turn left on Ehlers Drive and proceed down Juliette Avenue to Ratone Street. Turn right (west) on Ratone and

proceed to N. Manhattan Avenue.

At N. Manhattan Avenue turn left (south) and go to Vattier Street. At Vattier Street turn right (west) on to the

Kansas State campus. Follow Vattier Street up the hill and travel in front of Anderson Hall. Follow Vattier to

the round about and go down Lovers Lane in front of Justin Hall (on the left) and the KSU President’s home (on

the right) back to N. Manhattan.

If you would like to walk through the Kansas State University campus, park on one of the adjacent Manhattan

City streets for free parking, or go to the Kansas State University parking garage (paid parking) at the corner of

17

th

Street and Anderson Avenue. The KSU Alumni Association building is directly across the street (west)

from the parking garage and you may go into the KSU Alumni Association to see the Bluemont College

building letters anytime it is open, generally business hours Monday through Friday.

29. Kansas State University moved from its campus at the

corner of College and Claflin Road to this location in 1875.

Kansas State started as Bluemont Central College, a

Methodist school. The State of Kansas accepted the gift of

Bluemont Central College to establish Kansas State

Agricultural College in 1863, becoming one of the first Land

Grant Colleges in the United States. African American

students were admitted to the college from the beginning and

there have been many notable African American Kansas

State students, including:

George Washington Owens (1875-1950) First African American graduate of Kansas State, in 1901.

He worked at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama with Booker T. Washington, Tuskegee Principal, and

George Washington Carver, Tuskegee Director of Agriculture. He also taught at Virginia Normal and

Industrial School (later named Virginia State College) and organized vocational agriculture training in

Virginia. He was a founder of New Farmers of Virginia, which joined the Future Farmers of America in

1965. A building at Virginia State College was named in his honor in 1932.

Elizabeth May Galloway (1896 - 1994) Kansas State graduate 1919 and 1933. Faculty member of

Prairie View Agricultural and Mechanical College and President of the Texas Association for Negro

Home Economists. In her honor, the School of Home Economics at Prairie View named its new building

the Elizabeth C. May Center in 1958. She was awarded the Alumni Medallion from the KSU Alumni

Association in 1981.

Frank Marshall Davis (1905-1987) Journalist, poet, and American labor movement activist. He

attended Kansas State 1924 – 1927 and in 1929.

12

Claude McKay (1889-1948) Writer and poet, an important figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the

1920’s. His poem "If We Must Die" was adopted as rallying cry by Winston Churchill during WWII:

"If we must die, O let us nobly die, so that our precious blood may not be shed in vain." He attended

Kansas State 1912-1914.

Dr. John Slaughter (1934- ) Engineer, professor, college president, scientist. Dr. Slaughter earned a

Ph.D. in engineering science from the University of California, San Diego, a M.S. in engineering from

the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and a B.S. (1956) in electrical engineering from

Kansas State University. He holds honorary degrees from more than 25 institutions. He is the winner of

the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Award in 1997 and UCLA's Medal of Excellence in 1989. Dr.

Slaughter was also honored with the first "U.S. Black Engineer of the Year" award in 1987 and the

Arthur M. Bueche Award from the NAE in 2004. He served as president of Occidental College in Los

Angeles, and chancellor at the University of Maryland, College Park as well as director of the National

Science Foundation.

Dr. Bernard Franklin (ca. 1953- ) Professor, college administrator, college president, first African

American student body president at Kansas State University, 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in

political science from Kansas State, a Master of Science in counseling and behavioral studies from the

University of South Alabama, and a doctorate in counseling and higher education administration from

Kansas State University. He has served as an administrator in a number of Universities and as president

of Metropolitan Community College-Penn Valley. He was the President of Delta Upsilon International

Fraternity. He was the youngest person to serve on the Kansas Board of Regents and the youngest

person to serve as chair of the Kansas Board of Regents.

This completes the Manhattan African American history trail driving tour. There are many other people and

places in Manhattan and Riley County with significant and interesting ties to our local African American

history. We invite you to explore local history through the Riley County Historical Society and Museum web

sites at www.rileycountyks.gov/museum and www.rileychs.com and by visiting the Riley County Historical

Museum at 2309 Claflin Road Manhattan, Kansas. If you have questions, or comments, please contact us at

785-565-6490 or through our web site.