Medical complications

of bulimia nervosa

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

333

A

-- with a history of de-

pression and anxiety presents to your clin-

ic for follow-up after an emergency room visit,

where she had presented 2 days earlier for feel-

ing like she was going “to pass out” during her

college cross-country meet. At the emergency

room, the patient was noted to have a serum

potassium level of 2.9 mmol/L (reference range

3.7–5.1 mmol/L), bicarbonate 35 mmol/L (22–

30 mmol/L), and orthostatic hypotension. She

was given 2 L of intravenous normal saline and

intravenous and oral potassium.

On follow-up, her vital signs are normal.

Her body mass index is 24.5 kg/m

2

. She reports

feeling better but has noted marked swelling

of both her lower extremities, which is causing

her distress. The examination is notable for bi-

lateral 2+ pitting edema and calluses on the

dorsal aspect of her right hand.

■ A SERIOUS MENTAL ILLNESS

WITH PHYSICAL CONSEQUENCES

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is a serious mental ill-

ness characterized by binge-eating followed

by compensatory purging behaviors. It is fre-

quently accompanied by medical sequelae that

affect normal physiologic functioning and

contribute to increased morbidity and mortal-

ity rates.

1

Most people with BN are of normal

weight or even overweight,

2

and are otherwise

often able to avoid detection of their eating

disorder. Thus, it is important that clinicians

familiarize themselves with these complica-

tions and how to identify patients with disor-

dered eating patterns.

Recurrent binge-eating followed by purging

BN is characterized by overvaluation of body

weight and shape and recurrent binge-eating

REVIEW

doi:10.3949/ccjm.88a.20168

ABSTRACT

Bulimia nervosa, a mental illness 4 times more common

than anorexia nervosa, is characterized by binge-eating

followed by compensatory purging behaviors, which

include self-induced vomiting, diuretic abuse, laxative

abuse, and misuse of insulin. Patients with bulimia ner-

vosa are at risk of developing medical complications that

affect all body systems, especially the renal and electro-

lyte systems. Behavior cessation can reverse some, but

not all, medical complications.

KEY POINTS

Most people with bulimia nervosa are young and of nor-

mal weight, or even overweight, making detection and

diagnosis diffi cult.

As a consequence of purging behaviors, pseudo-Bartter

syndrome can develop due to chronic dehydration, plac-

ing patients at risk for electrolyte abnormalities such as

hypokalemia, as well as marked and rapid edema forma-

tion when purging is interrupted.

Electrolyte and metabolic disturbances are the most

common causes of morbidity and mortality in patients

with bulimia nervosa. Hypokalemia should be managed

aggressively to prevent electrocardiographic changes and

arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes.

Diabetic patients who purge calories through manipulation

of their blood glucose are at high risk for hyperglycemia,

ketoacidosis, and premature microvascular complications.

Gastrointestinal complaints are common and include

gastroesophageal refl ux disease.

Allison Nitsch, MD

ACUTE Center for Eating Disorders at Denver

Health, Denver, CO; Department of Medicine,

University of Colorado School of Medicine,

Aurora, CO

Heather Dlugosz, MD

Eating Recovery Center and Pathlight

Mood & Anxiety Center,

Cincinnati, OH

Dennis Gibson, MD

ACUTE Center for Eating Disorders at Denver

Health, Denver, CO; Department of Medicine,

University of Colorado School of Medicine,

Aurora, CO

CME

MOC

Philip S. Mehler, MD, FACP, FAED

ACUTE Center for Eating Disorders at Denver

Health, Denver, CO; Department of Medicine,

University of Colorado School of Medicine,

Aurora, CO

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

334

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

BULIMIA NERVOSA

(consuming an excessive caloric amount in a

short period of time, usually a 2-hour period,

that the patient feels unable to control). This

is soon accompanied by compensatory purging

behaviors that can include abuse of laxatives

and diuretics, withholding insulin (termed di-

abulimia or eating disorder-diabetes mellitus type

1), self-induced vomiting, fasting, and exces-

sive exercise. Some patients also abuse caf-

feine or prescription stimulant medications

commonly used to treat attention-de cit/hy-

peractivity disorder.

Self-induced vomiting and laxative misuse

account for more than 90% of purging behav-

iors in BN.

3

The Diagnostic and Statistical Man-

ual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)

requires episodes of bingeing and compensa-

tory behaviors in BN to occur at least once

per week over the course of 3 months and not

occur during an episode of anorexia nervosa.

3

The complications of purging behaviors found

in BN are identical to those found in the

binge-purge subtype of anorexia nervosa ex-

cept that restriction of calories primarily and

excessive weight loss are not present.

The severity of BN is determined by the

frequency of the mode of the purging behav-

iors (mild: an average of 1–3 episodes of in-

appropriate compensatory behaviors weekly;

moderate: 4–7; severe: 8–13; extreme: 14 or

more) or the degree of functional impairment.

2

Some patients may vomit multiple times per

day while others may use signi cant amounts

of laxatives. Some may engage in multiple

different purging behaviors, which has been

shown to be associated with a greater severity

of illness.

4

Exercise is considered excessive if it

interferes with other activities, persists despite

injury or medical complications, or occurs at

inappropriate times or situations.

2,5

■ ONSET IN ADOLESCENCE,

AND FAIRLY COMMON

BN typically develops in adolescence or young

adulthood and affects both sexes, although

it is much more common in girls and young

women.

6

It affects people regardless of sexual

orientation but has been shown to be more

prevalent in nonheterosexual males.

7

Studies

have found similar prevalence of BN among

different racial and ethnic groups. Individu-

als with BN are generally within or above the

normal weight range.

2

According to pooled data from the World

Health Organization, the lifetime preva-

lence of BN in adults is 1.0% using the older

DSM-IV criteria,

7

which is greater than the

reported prevalence of anorexia nervosa.

Prevalence estimates are higher with the

broadened DSM-5 criteria, ranging from 4%

to 6.7%.

8

There are multiple predisposing and per-

petuating factors—genetic, environmental,

psychosocial, neurobiological, and tempera-

mental. These can include impulsivity, devel-

opmental transitions such as puberty, internal-

ization of the thin ideal, and weight and shape

concerns.

9

A history of childhood trauma, in-

cluding sexual, physical or emotional trauma,

has also been associated with BN.

10

More than 70% of people with eating

disorders report concomitant psychiatric co-

morbidity—affective disorders, anxiety, sub-

stance use, and personality disorders are most

common in BN.

11

Psychiatric comorbidities

as well as hopelessness, shame, and impulsiv-

ity associated with the illness may contribute

to challenges with nonsuicidal self-harm,

suicidal ideation, and death by suicide. Indi-

viduals with BN experience lifetime rates of

nonsuicidal self-harm of 33% and are nearly

8 times more likely to die by suicide than the

general population.

12,13

The reported stan-

dardized mortality rates in those with BN

are less than in those with anorexia nervosa

but are still signi cantly elevated at 1.5% to

2.5%.

1

■ MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS

As noted earlier, BN is associated with a

signi cantly increased mortality rate even

though many of these patients are young.

Much of this elevated mortality is attributable

to the medical complications associated with

BN, which are a direct result of the mode and

frequency of purging behaviors. Thus, for ex-

ample, if someone uses laxatives 3 times per

day or vomits 1 time per day, there may be

no medical complications, but many patients

engage in their respective purging behaviors

many times per day, leading to multiple com-

plications.

Self-induced

vomiting

and laxative

abuse account

for more than

90% of purging

behaviors

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

335

NITSCH AND COLLEAGUES

Aside from the electrolyte aberrations

from purging, some of the medical complica-

tions are unique to the mode of purging. Fur-

thermore, BN has been found to increase the

risk of any cardiovascular disease, including

ischemic heart disease and death in females.

14

These same complications may also apply to

patients with anorexia nervosa of the binge-

purge subtype in contrast to those patients

with anorexia nervosa who only restrict ca-

loric intake but do not purge.

We will now discuss, in a systems-based

approach, the medical complications that de-

velop in people with BN as a direct result of

their purging behaviors.

Skin

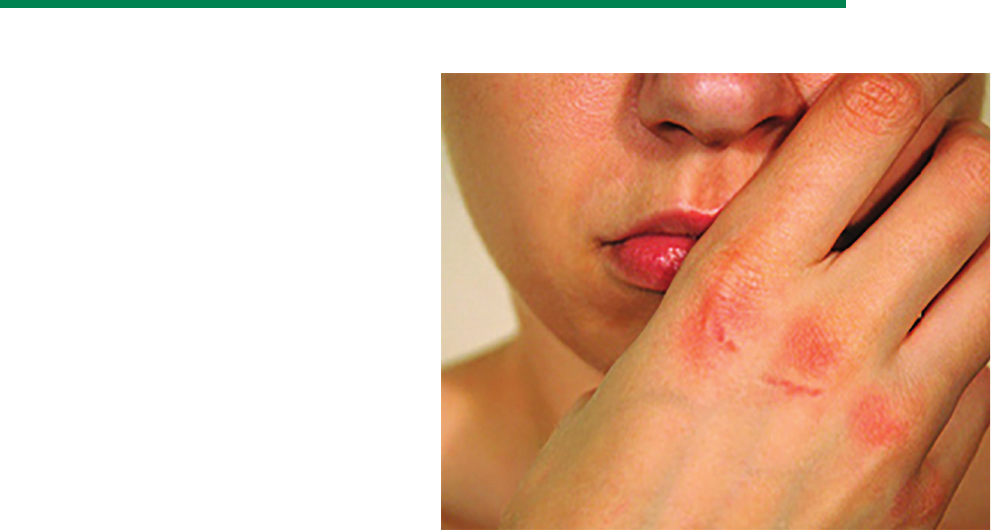

Russell sign (Figure 1), named after Dr. Ger-

ald Russell, who rst de ned the disease BN in

1979, refers to the development of calluses on

the dorsal aspect of the dominant hand.

15

It is

pathognomonic for self-induced vomiting and

is due to traumatic irritation of the hand by

the teeth, from repeated insertion of the hand

into the mouth to provoke vomiting.

15

Russell sign is not commonly seen since

many of these patients are able to spontane-

ously vomit or they utilize utensils to initiate

self-induced vomiting.

Teeth and mouth

Abnormalities of the teeth and mouth, spe-

ci c for purging via vomiting, include dental

erosions and trauma to the oral mucosa and

pharynx.

16

Dental erosion is the most common oral

manifestation of chronic regurgitation. It is

believed to be caused by the teeth coming

into contact with acidic vomitus (pH 3.8), al-

though just how changes in salivary composi-

tion and dietary intake contribute is unclear.

It tends to affect the lingual surfaces of the

maxillary teeth and is known as perimyolysis.

Vomiting also potentially increases the risk of

dental caries.

Trauma to the oral mucosa, especially the

pharynx and soft palate, is also encountered

and is presumed to occur either as a result of

the patient inserting a foreign object into the

mouth to induce vomiting or the caustic effect

of the vomitus on the mucosal lining.

Dental erosions are irreversible once they

have developed. Use of uorinated mouth-

wash after purging and horizontal gentle

brushing are recommended. Ongoing self-

induced vomiting will also damage newly im-

planted teeth as well as dental prosthetics.

Head, ears, nose, and throat

Purging by vomiting increases the risk of sub-

conjunctival hemorrhages from forceful retch-

ing, which can also cause recurrent epistaxis.

Indeed, recurrent bouts of epistaxis that re-

main unexplained should prompt a search for

covert BN.

Pharyngitis is often noted in those who

vomit frequently, due to contact of the pha-

ryngeal tissue with stomach acid. Hoarse-

ness, cough, and dysphagia may also simi-

larly develop. Pharyngeal and laryngeal

complaints can be improved with cessation

of vomiting and the use of medications to

suppress acid production, such as proton

pump inhibitors.

Parotid glands

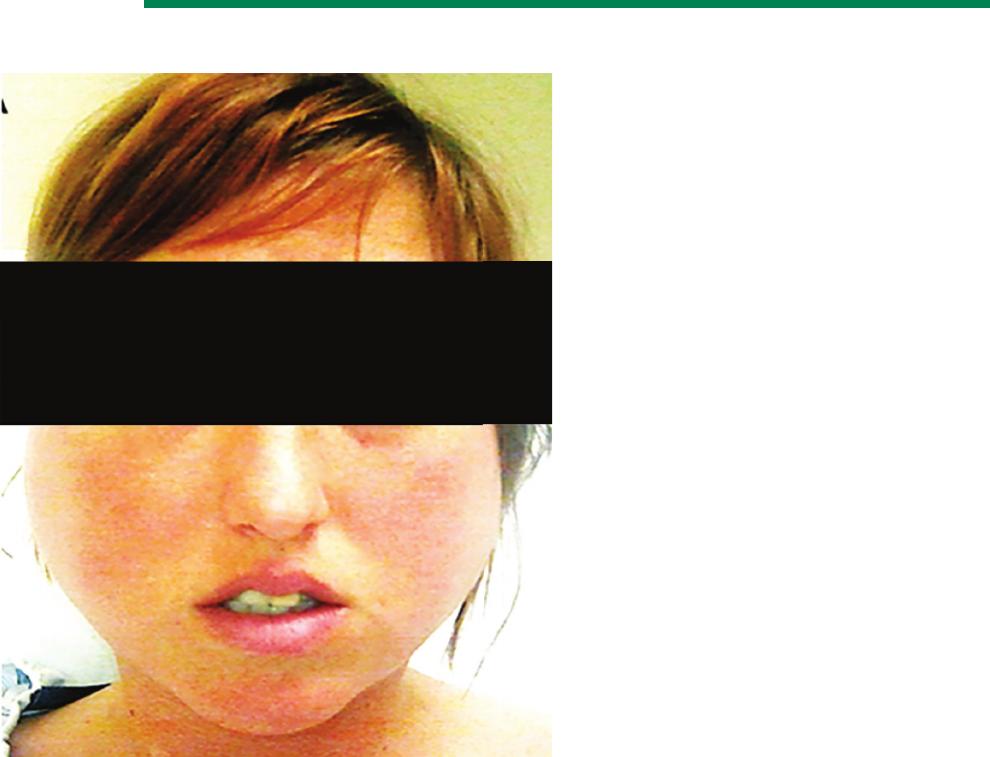

Parotid gland hypertrophy, or sialadenosis

(Figure 2), may develop in more than 50%

of people engaging in purging via self-induced

vomiting.

17

Ironically, it usually develops 3 to

4 days after cessation of purging. Symptoms

include bilateral painless enlargement of the

parotid glands and, occasionally, other sali-

vary glands. It is believed to develop due to ei-

Dental erosion

is the most

common oral

manifestation

due to chronic

regurgitation

Figure 1. The Russell sign.

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

336

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

BULIMIA NERVOSA

ther cholinergic stimulation of the glands, hy-

pertrophy of the glands to help meet demands

of increased saliva production, or excessive

backup of saliva that is no longer needed with

cessation of vomiting.

Pathology study reveals hypertrophied aci-

nar cells with otherwise preserved architec-

ture without evidence of in ammation.

Swelling may subside with cessation of

purging; failure of the parotid gland hypertro-

phy to resolve is highly suggestive of ongoing

purging.

18

Sialadenosis also tends to resolve

with the use of sialagogues such as tart can-

dies. Heating pads and nonsteroidal anti-in-

ammatory drugs also have a therapeutic role

and perhaps should be prophylactically initi-

ated in those with a long history of excessive

vomiting who engage in treatment to stop

purging. In rare refractory cases, pilocarpine

may be judiciously used to reduce the glands

back to normal size.

19

Cardiovascular

The cardiac complications that are speci c

for purging include electrolyte disturbances

as a result of vomiting and diuretic or laxa-

tive abuse. Conduction disturbances, includ-

ing serious arrhythmias and QT prolongation,

are increasingly encountered in those partici-

pating in various modes of purging due to the

electrolyte disturbances that ensue, especially

hypokalemia and acid-base disorders. Also,

excessive ingestion of ipecac, which contains

the cardiotoxic alkaloid emetine, to induce

vomiting can lead to various conduction dis-

turbances and potentially irreversible cardio-

myopathy.

20

Abuse of caffeine or stimulant medications

used to treat attention-de cit/hyperactivity

disorder may cause palpitations, sinus tachy-

cardia, or cardiac arrhythmias such as supra-

ventricular tachycardia. Similarly, diet pill

abuse, which is increased in this population, is

associated with arrhythmias.

21

Pulmonary

Retching during vomiting increases intratho-

racic and intra-alveolar pressures, which can

lead to pneumomediastinum.

22

Pneumome-

diastinum may also be encountered due to

nontraumatic alveolar rupture in the setting

of malnutrition and is therefore nonspeci c in

differentiating patients who purge from those

who restrict.

23

Vomiting also increases the risk

of aspiration pneumonia. Aspiration may be

involved in the heretofore enigmatic patho-

genesis of pulmonary infection with Mycobac-

terium avium complex organisms.

Gastrointestinal

The gastrointestinal complications of purg-

ing depend on the mode of purging used. Up-

per gastrointestinal complications develop in

those who engage in vomiting, whereas lower

gastrointestinal complications develop in

those who abuse stimulant laxatives.

Esophageal complications. Excessive vom-

iting exposes the esophagus to gastric acid and

damages the lower esophageal sphincter, in-

creasing the propensity for gastroesophageal re-

ux disease and other esophageal complications,

including Barrett esophagus and esophageal ad-

enocarcinoma.

24

However, it is unclear if there

truly is an association between purging by self-

induced vomiting and re ux disease. Although

Figure 2. Sialadenosis.

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

337

NITSCH AND COLLEAGUES

research indicates increased complaints of gas-

trointestinal re ux disease in those engaging in

purging, and increased re ux may be present in

those who purge when assessed by pH monitor-

ing, endoscopic ndings do not necessarily cor-

relate with severity of reported symptoms.

24,25

This suggests a possible functional component

to gastrointestinal re ux-related concerns.

26

Cessation of purging is the recommended

treatment, although proton pump inhibi-

tors can be tried. Metoclopramide may also

be bene cial, given its actions of accelerat-

ing gastric emptying and increasing lower

esophageal sphincter tone. Endoscopy should

be considered if symptoms continue or have

been present for many years, to look for the

precancerous esophageal mucosal abnormali-

ties found in Barrett esophagus.

Rare complications are esophageal rupture,

known as Boerhaave syndrome, and Mallory-

Weiss tears, causing upper gastrointestinal

bleeds due to the recurrent episodes of em-

esis. Mallory-Weiss tears commonly present as

blood-streaked or tinged emesis or scant coffee

ground emesis following recurrent vomiting

episodes. Usually blood loss from such tears is

minimal. Mallory-Weiss tears appear as longi-

tudinal mucosal lacerations on endoscopy.

Colonic inertia. Individuals engaging

in excessive and chronic stimulant laxative

abuse may be at risk for “cathartic colon,” a

condition whereby the colon becomes an inert

tube incapable of moving stool forward. This

is believed due to direct damage to the gut my-

enteric nerve plexus.

27

However, it is currently

speculative as to whether this condition truly

develops in those with eating disorders and

with use of currently available stimulant laxa-

tives.

28

Regardless, in general, stimulant laxa-

tives should be used only short-term, due to

concerns regarding potential development of

this condition, and should be stopped in those

in whom it develops. Instead, osmotic laxa-

tives, which do not directly stimulate peri-

stalsis, are prescribed in a measured manner to

manage constipation.

Melanosis coli, a black discoloration of

the colon of no known clinical signi cance,

is often reported during colonoscopy in those

abusing stimulant laxatives. Rectal prolapse

may also develop in those abusing stimulant

laxatives, but again is nonspeci c for this

mode of purging as it can also develop solely

as a consequence of malnutrition and the re-

sultant weakness of the pelvic oor muscles.

Endocrine

A potential endocrine complication of BN is

irregular menses,

29

as opposed to the amenor-

rhea frequently observed in both the restricting

and binge-purge subtypes of anorexia nervosa.

Although patients with BN do not appear

to be at a signi cantly increased risk for low

bone mineral density—in contrast to those

suffering from the restricting and binge-purge

subtypes of anorexia nervosa—a bone density

scan with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

may still be warranted to evaluate for bone

disease in those with a past history of anorexia

nervosa.

Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus may

manipulate their blood glucose levels as a

means to purge calories, a condition previous-

ly referred to as diabulimia and now termed

eating disorder-diabetes mellitus type 1.

30

These patients are at risk of marked hypergly-

cemia, ketoacidosis, and premature microvas-

cular complications such as retinopathy and

neuropathy.

■ METABOLIC AND ELECTROLYTE

DISTURB

ANCES

In addition to the above body system com-

plications from purging, each of the common

methods of purging used by patients with BN

can be associated with speci c electrolyte dis-

turbances. These electrolyte abnormalities are

likely the most proximate cause of death in

patients with BN. When a patient simultane-

ously engages in multiple modes of purging be-

haviors, just as their level of psychiatric illness

can be more profound, so too the electrolyte

disturbance pro les can overlap and be more

extreme.

Patients with a history of a known purg-

ing behavior should be screened at increased

frequency for serum electrolyte disturbances,

up to even daily, depending on the frequency

of their purging behaviors.

31

In a study of pa-

tients admitted to inpatient and residential

eating disorder treatment without prior medi-

cal stabilization, 26.2% of the BN patients

presented with hypokalemia (potassium < 3.6

mmol/L) on their admission laboratory test-

Purging

by emesis

increases

the risk

of aspiration

pneumonia

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

338

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

BULIMIA NERVOSA

Chronic

hypokalemia

is often

asymptomatic

and can slowly

be corrected

ing, while 8.5% had hyponatremia (sodium <

135 mmol/L) and 23.4% had a metabolic alka-

losis (bicarbonate > 28 mmol/L).

32

Self-induced vomiting is the most common

method of purging in BN.

33

Patients with self-

induced vomiting or diuretic abuse, or both,

have been shown to present with hypokalemia,

hypochloremia, and a metabolic alkalosis.

34

The severity of the electrolyte abnormalities

worsens with the frequency of vomiting.

Similarly, laxative abuse also results in

hypokalemia and hypochloremia. However,

either a non-anion gap metabolic acidosis or

a metabolic alkalosis may be present, depend-

ing on the chronicity of the laxative abuse.

35

Generally, more chronic diarrhea results in a

metabolic alkalosis. Hyponatremia can also

be present with these 3 purging behaviors.

The hyponatremia encountered is most often

of the hypovolemic type due to chronic uid

depletion as a result of the purging behaviors.

Pathophysiology of hypokalemia

and hypochloremia

The pathophysiologic reasons for hypokale-

mia and hypochloremia seen with all signi -

cant purging behaviors are 2-fold and inter-

related. First, and most obvious, there is loss

of potassium in the purged gastric contents,

excessive stool from laxative abuse, or in the

urine through diuretic abuse.

Second, chronic purging results in intra-

vascular uid depletion. This uid depletion is

sensed by the afferent arteriole of the kidney

as decreased renal perfusion pressure, which in

turn activates the renin-angiotensin-aldoste-

rone system, resulting in increased production

of aldosterone by the zona glomerulosa of the

adrenal glands. Aldosterone acts renally at the

distal convoluted tubules and cortical collect-

ing ducts, causing them to resorb sodium and

chloride in the body’s attempt to prevent se-

vere dehydration, hypotension, and fainting.

Aldosterone also promotes renal secretion of

potassium into the urine and thus hypokale-

mia. This mechanism of potassium loss is ac-

tually a larger contributor to the hypokalemia

than the actual gastrointestinal or urinary

loses from the behaviors themselves.

The mechanisms by which metabolic al-

kalosis occurs in self-induced vomiting and in

laxative abuse are similar. Initially, hydrogen

ions and sodium chloride are lost in the vomi-

tus or through diarrhea. The loss of hydrogen

ions produces an alkalemic state. Intravascu-

lar volume depletion resulting from the loss

of sodium chloride increases the resorption of

bicarbonate within the proximal renal tubule,

preventing its loss in the urine, which would

normally occur to correct the alkalemia. Hy-

pokalemia, if concurrently present, also in-

creases bicarbonate resorption in the proxi-

mal tubule, further propagating the metabolic

alkalosis. Lastly, increased serum aldosterone

levels, brought about from intravascular vol-

ume depletion, fuel resorption of sodium at

the expense of hydrogen and potassium, re-

sulting in increased loss of hydrogen and po-

tassium in the urine and further maintenance

of the alkalemic state.

In diuretic abuse, the diuretics themselves

act directly on the kidney to promote loss of

sodium chloride in the urine, resulting in in-

travascular depletion and aldosterone secre-

tion. This results in loss of hydrogen and po-

tassium into the urine, resulting in a metabolic

alkalosis. Potassium-sparing diuretics, such as

spironolactone, however, do not precipitate a

metabolic alkalosis, as they inhibit the action

of aldosterone in the kidney.

Table 1 summarizes the electrolyte de-

rangements that occur with BN.

TABLE 1

Summary of electrolyte disturbances in bulimia nervosa

Behavior Potassium Sodium Acid-base

Self-induced vomiting Low Low or normal Metabolic alkalosis

Laxative abuse Low Low or normal Metabolic alkalosis or non-anion gap acidosis

Diuretic abuse Low Low or normal Metabolic alkalosis

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

339

NITSCH AND COLLEAGUES

■ PSEUDO-BARTTER SYNDROME

The aforementioned process of renin-angio-

tensin-aldosterone system activation results

in what has been termed pseudo-Bartter syn-

drome due to resulting serum and histochemi-

cal

ndings on renal biopsy that resemble

Bartter syndrome.

36

However, the ndings are

not due to intrinsic renal pathology but rather

are a result of the chronic state of dehydration

from the purging behaviors. The resultant

elevation in serum aldosterone, an integral

part of pseudo-Bartter syndrome, can result

in rapid edema formation when the purging

behaviors are abruptly stopped. The reason is

that the serum aldosterone levels remain high,

causing salt and water retention even though

the patient is no longer losing uid, as the

purging has ceased.

■ EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT

OF ELECTROL

YTE DISTURBANCES

AND PSEUDO-BARTTER SYNDROME

Covert purging should be strongly suspected

in otherwise healthy young women present-

ing with hypokalemia without an alternative

medical cause.

37

However, hypokalemia alone

is not speci c for underlying purging behav-

iors.

34

If the patient is not forthcoming about

their behavior when confronted, a spot urine

potassium, creatinine, sodium, and chloride

measurement can be obtained to further assess

the source of potassium loss. A urine potassi-

um-to-creatinine ratio less than 13 can iden-

tify hypokalemia resulting from gastrointesti-

nal loss, diuretics, poor intake, or transcellular

shifts. A urine sodium-to-chloride ratio can

also be calculated. Vomiting is associated with

a urine sodium-to-chloride ratio greater than

1.6 in the setting of hypokalemia, whereas

laxative abuse is associated with a ratio less

than 0.7.

36

Chronic hypokalemia is often asymptom-

atic and can be corrected slowly. If the serum

potassium level is no lower than 2.5 mmol/L

and the patient has no physical symptoms or

electrocardiographic changes of hypokalemia,

the hypokalemia can be managed by stopping

the purging behavior and giving oral potas-

sium supplementation.

38,39

Adherence to oral

potassium repletion can be improved by using

potassium chloride tablets rather than liquid

preparations.

38

Aggressive intravenous potas-

sium supplementation places patients at risk

of hyperkalemia and should be reserved for

more critically low serum potassium levels.

Severe hypokalemia (serum potassium less

than 2.5 mmol/L) requires both oral and in-

travenous repletion of potassium. This reple-

tion process is aided by giving isotonic saline

with potassium chloride intravenously at a

low infusion rate (50–75 mL/hour). Correct-

ing the patient’s volume depletion is required

to correct the metabolic alkalosis and inter-

rupt renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

activation. Untreated severe hypokalemia can

result in a prolonged corrected QT interval

on electrocardiography, subsequent torsades

de pointes, and other life-threatening cardiac

arrhythmias. Simply attempting to replete po-

tassium without attention to the concomitant

metabolic alkalosis will be unsuccessful be-

cause of the ongoing kaliuresis due to aldoste-

rone’s ongoing effects on the kidneys. Rarely,

chronic hypokalemia has been associated with

acute renal failure, with renal biopsy demon-

strating interstitial nephritis, termed hypoka-

lemic nephropathy.

40

Mild hyponatremia often will autocor-

rect with interruption of purging behaviors

and oral rehydration. However, if the serum

sodium is less than 125 mmol/L, hospitaliza-

tion is warranted for close monitoring and for

slow correction with isotonic saline—ie, at

a rate that increases the serum sodium by no

more than 4 to 6 mmol/L every 24 hours. This

avoids the serious complication known as cen-

tral pontine myelinolysis.

41

If hyponatremia is

severe (serum sodium < 118 mmol/L), the pa-

tient will likely bene t from admission to an

intensive care unit and renal consultation for

consideration of administration of desmopres-

sin to prevent overcorrection.

Metabolic alkalosis can develop in patients

with BN as a result of decreased intravascular

volume, elevated aldosterone, and hypokale-

mia; it is most often saline-responsive. A spot

urine chloride can be used to inform care. If it

is less than 10 mmol/L, the metabolic alkalo-

sis is hypovolemic and will improve with slow

intravenous saline administration. Clinicians

may also rely on physical examination to help

determine the patient’s volume status.

Mild

hyponatremia

will often

correct itself

with oral

rehydration

and

interruption

of purging

behaviors

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

340

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

BULIMIA NERVOSA

Due to the underlying risk of pseudo-

Bartter syndrome in patients with BN who

abruptly stop purging, care should be taken

to avoid aggressive uid resuscitation. Inter-

ruption of purging behaviors in conjunction

with rapid intravenous uid resuscitation can

result in marked and rapid edema formation

and weight gain, which can be psychologically

distressing. Thus, low infusion rates of saline

(50 mL/hour) and low doses of spironolac-

tone (50–100 mg initially with a maximum

of 200–400 mg/day) should be initiated and

titrated based on edema and weight trends to

mitigate edema formation.

42

Spironolactone is

generally continued for 2 to 4 weeks and then

should be tapered by 50 mg every few days

thereafter. Occasionally, in extreme laxative

abusers, proclivity toward edema may persist

and necessitate an even slower spironolactone

taper.

■ MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS

OF BINGE-EATING

The literature on complications of binge-

eating speci c to BN is limited, and thus, we

must look to studies of binge-eating disorder.

However, patients with binge-eating disorder

tend to be overweight or obese, as they do not

purge after binge episodes. Thus, many of the

medical complications in binge-eating dis-

order, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension,

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and metabol-

ic syndrome are obesity-related.

43

In contrast, many patients with BN have

a normal body mass index. Therefore, it is dif-

cult to infer that the medical complications

that occur in binge-eating disorder are the

same as those that occur from binge-eating in

BN. However, the extrapolation does make

sense in some instances. For instance, patients

who binge are at higher risk of nutritional de-

ciencies because food taken in during a binge

tends to be processed, high in fat and carbo-

hydrates, and low in protein. A diet low in

vitamins, including A and C, and minerals in-

creases the risk of nutritional de ciencies. Ad-

ditionally, patients with binge-eating disorder

have more gastrointestinal complaints such as

acid re ux, dysphagia, and bloating, which,

as outlined above, are also seen in BN. Thus,

bingeing may play a role in these symptoms.

Lastly, gastric perforation has been re-

ported in patients with BN in the context of

a bingeing episode marked by excessive stom-

ach distention, resulting in gastric necrosis.

44

Furthermore, gastric outlet obstruction has

also been reported in this patient population

due to formation of a food bezoar.

■ IDENTIFICATION AND MENTAL HEALTH

TREA

TMENT

The Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care

has been shown to effectively screen patients

for disordered eating in a general medicine

setting.

45

It consists of 5 questions:

• Are you satis ed with your eating pat-

tern? (“No” is considered an abnormal re-

sponse.)

• Do you ever eat in secret? (“Yes” is an ab-

normal response to this and the remaining

questions.)

• Does your weight affect the way you feel

about yourself?

• Have any members of your family suffered

from an eating disorder?

• Do you currently suffer with or have you

ever suffered in the past with an eating dis-

order?

Cotton et al

45

found that an abnormal re-

sponse to 2 or more of these questions had a

sensitivity of 100% and a speci city of 71% for

eating disorders.

Standard mental health treatments for BN

include nutritional stabilization and behavior

interruption, monitoring for and appropriate

management of associated medical complica-

tions, prescribing medications as clinically in-

dicated, and psychotherapeutic interventions.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the recom-

mended initial intervention for the treatment

of BN. A recent network meta-analysis sug-

gested that guided cognitive behavioral self-

help and a speci c form of cognitive behavior-

al therapy—individual cognitive behavioral

therapy for eating disorders—may most likely

lead to full remission.

46

No drug has been developed speci cally

for the treatment of BN (Table 2). Fluoxetine,

with a target dose of 60 mg daily independent

of the presence of comorbidities, is the only

medication approved by the US Food and

Drug Administration for BN. This selective

Cognitive

behavioral

therapy is the

recommended

initial

intervention

in the treatment

of bulimia

nervosa

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

341

NITSCH AND COLLEAGUES

serotonin reuptake inhibitor has been shown

to reduce the frequency of binge-eating and

purging episodes signi cantly, more so than

uoxetine 20 mg daily and placebo.

47

Fluox-

etine is recommended for patients who do not

respond adequately to psychotherapeutic in-

terventions.

48

Other selective serotonin reuptake in-

hibitor antidepressants along with the anti-

epileptic topiramate also have been shown to

have modest ef cacy.

49

Bupropion, which has

a boxed warning and is contraindicated in the

treatment of BN, should not be used due to an

increased risk of seizure.

No clinical trials have evaluated the use

of stimulant medications in the treatment of

BN. Often, stimulant medications are discon-

tinued in patients until there is a period of

abstinence from purging behaviors. Following

abstinence, reinitiation of the stimulant could

be reconsidered off-label if bingeing behaviors

persist or attention de cit hyperactivity dis-

order is a comorbidity, or both. There can be

some utility to reinitiation with a clear treat-

ment agreement outlining expectations for

maintaining efforts at purging symptom inter-

ruption and continued stimulant prescribing.

In general, concomitant treatment for anx-

iety or depression should be pursued if these

co-occur with BN. Selective serotonin reup-

take inhibitors such as uoxetine would also

target these symptoms. If a trial of uoxetine

has failed, then sertraline or escitalopram

would be reasonable second-line options.

Typically, citalopram would not be used due

to higher risk of prolonged QT interval than

other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,

especially given the possibility of electrolyte

abnormalities in BN. Paroxetine would not be

used due to the potential for weight gain as a

side effect.

■ PROGNOSIS

Increased risk of relapse has been associated

with greater psychosocial dysfunction and

bo

dy image disturbance.

50

In patients requir-

ing hospitalization, a number of factors have

been shown to predict poor outcome, includ-

ing fewer follow-up years, increased drive for

thinness, older age at initial treatment, and

more impairment in global functioning.

50

Recovery is possible with variable remission

rates, based on the type of study and de ni-

tion of remission, from 38% and 42% at 11-

and 21-year follow-up, respectively, and 65%

of individuals at a 9-year and 22-year follow-

up.

50,51

This reinforces the need to utilize ac-

cessible and effective treatments to achieve

sustained recovery.

■ CONCLUSION

BN is a complex psychiatric disease with myri-

ad medical complications, some of which may

be life-threatening. Most of the morbidity and

mortality in patients with BN is a direct result

of the aforementioned purging behaviors and

their resultant electrolyte and acid-base disor

-

ders. Thus, it is important that clinicians fa-

miliarize themselves with these complications

as most patients with BN are of normal weight

and are otherwise often able to avoid detec-

tion of their eating disorder.

■ INITIAL CASE CONTINUED

Y

ou release the patient in the initial clini-

cal scenario from her follow-up appointment

without intervention or follow-up laboratory

testing. You fail to recognize the Russell sign,

and you advise her that the edema is due to

uids administered in the emergency depart-

ment and will self-resolve. She returns to her

purging behaviors with increased vigor due to

perceived weight gain from the edema.

One month later, she experiences a synco-

pal episode during cross-country practice, again

necessitating oral potassium and intravenous

saline administration. On follow-up, her edema

is worse, and you recognize the Russell sign, hav-

ing just read this review article. On follow-up

laboratory testing, you note ongoing mild hypo-

Bupropion is

contraindicated

in the

treatment

of bulimia

nervosa due to

an increased

risk of seizure

TABLE 2

Psychopharmacology clinical pearls

Fluoxetine is the only US Food and Drug Administration-approved

medication for the treatment of bulimia nervosa

Co-occurring anxiety and depression should be managed with therapy

and pharmacologically

Stimulant medications have not been evaluated in the treatment

of bulimia nervosa

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

342

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

BULIMIA NERVOSA

kalemia and screen her for an eating disorder.

The screening is positive, and she discloses to

you not only about her daily self-induced vomit-

ing, but also her abuse of stimulant laxatives and

bingeing episodes.

You initiate a referral to a residential treat-

ment facility for eating disorders, start her on

daily potassium chloride 40 mmol, and plan for

weekly follow-up laboratory testing until she

enters residential treatment.

■

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Ms. Kelly

Maebane for her superb assistance with formatting and edit-

ing of the manuscript.

■ DISCLOSURES

The authors report no relevant fi nancial relationships which, in the context of

their contributions, could be perceived as a potential confl ict of interest.

■ REFERENCES

1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality rates in pa-

tients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-

analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68(7):724–731.

doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

2. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psy-

chiatric Association; 2013.

3. Mehler PS, Rylander M. Bulimia nervosa—medical complications. J

Eat Disord 2015; 3:12. doi:10.1186/s40337-015-0044-4

4. Haedt AA, Edler C, Heatherton TF, Keel PK. Importance of multiple

purging methods in the classifi cation of eating disorder subtypes. Int

J Eat Disord 2006; 39(8):648–654. doi:10.1002/eat.20335

5. Lichtenstein MB, Hinze CJ, Emborg B, Thomsen F, Hemmingsen SD.

Compulsive exercise: links, risks and challenges faced. Psychol Res Be-

hav Manag 2017; 10:85–95. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S113093

6. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, et al. The prevalence and cor-

relates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization

World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry 2013; 73(9):904–914.

doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020

7. Feldman MB, Meyer IH. Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay,

and bisexual populations. Int J Eat Disord 2007; 40(3):218–226.

doi:10.1002/eat.20360

8. Wade TD. Recent research on bulimia nervosa. Psychiatr Clin North

Am 2019; 42(1):21–32. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2018.10.002

9. Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defi ned eating

disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biol Psy-

chiatry 2018; 84(5):345–354. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.014

10. Caslini M, Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Carrà G. Disen-

tangling the association between child abuse and eating disorders: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2016; 78(1):79–

90. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000233

11. Himmerich H, Hotopf M, Shetty H, et al. Psychiatric comorbid-

ity as a risk factor for the mortality of people with bulimia ner-

vosa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019; 54(7):813–821.

doi:10.1007/s00127-019-01667-0

12. Cucchi A, Ryan D, Konstantakopoulos G, et al. Lifetime prevalence

of non-suicidal self-injury in patients with eating disorders: a system-

atic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2016; 46(7):1345–1358.

doi:10.1017/S0033291716000027

13. Preti A, Rocchi MB, Sisti D, Camboni MV, Miotto P. A comprehensive

meta-analysis of the risk of suicide in eating disorders. Acta Psychiatr

Scand 2011; 124(1):6–17. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01641.x

14. Tith RM, Paradis G, Potter BJ, et al. Association of bulimia ner-

vosa with long-term risk of cardiovascular disease and mor-

tality among women. JAMA Psychiatry 2020; 77(1):44–51.

doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2914

15. Strumia R. Eating disorders and the skin. Clin Dermatol 2013;

31(1):80–85. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.011

16. Romanos GE, Javed F, Romanos EB, Williams RC. Oro-facial manifes-

tations in patients with eating disorders. Appetite 2012; 59(2):499–

504. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2012.06.016

17. Garcia Garcia B, Dean Ferrer A, Diaz Jimenez N, Alamillos Granados

FJ. Bilateral parotid sialadenosis associated with long-standing buli-

mia: a case report and literature review. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2018;

17(2):117–121. doi:10.1007/s12663-016-0913-7

18. Vavrina J, Müller W, Gebbers JO. Enlargement of salivary

glands in bulimia. J Laryngol Otol 1994; 108(6):516–518.

doi:10.1017/s002221510012729x

19. Park KK, Tung RC, de Luzuriaga AR. Painful parotid hypertrophy with

bulimia: a report of medical management. J Drugs Dermatol 2009;

8(6):577–579. pmid:19537384

20. Ho PC, Dweik R, Cohen MC. Rapidly reversible cardiomyopathy as-

sociated with chronic ipecac ingestion. Clin Cardiol 1998; 21(10):780–

783. doi:10.1002/clc.4960211018

21. Inayat F, Majeed CN, Ali NS, Hayat M, Vasim I. The risky side of

weight-loss dietary supplements: disrupting arrhythmias caus-

ing sudden cardiac arrest. BMJ Case Rep 2018; 11(1):e227531.

doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-227531

22. McCurdy JM, McKenzie CE, El-Mallakh RS. Recurrent subcutaneous

emphysema as a consequence of bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord

2013; 46(1):92–94. doi:10.1002/eat.22044

23.

Jensen VM, Støving RK, Andersen PE. Anorexia nervosa with massive

pulmonary air leak and extraordinary propagation. Int J Eat Disord

2017; 50(4):451–453. doi:10.1002/eat.22674

24. Denholm M, Jankowski J. Gastroesophageal refl ux disease and

bulimia nervosa—a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus 2011;

24(2):79–85. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01096.x

25. Kiss A, Wiesnagrotzki S, Abatzi TA, Meryn S, Haubenstock A, Base

W. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy fi ndings in patients with long-

standing bulimia nervosa. Gastrointest Endosc 1989; 35(6):516–518.

doi:10.1016/s0016-5107(89)72901-1

26. Abraham S, Kellow JE. Do the digestive tract symptoms in eating dis-

order patients represent functional gastrointestinal disorders? BMC

Gastroenterol 2013; 13:38. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-13-38

27. Smith B. Pathology of cathartic colon. Proc R Soc Med 1972; 65(3):288.

pmid:5083323

28. Müller-Lissner S. What has happened to the cathartic colon? Gut

1996; 39(3):486–488. doi:10.1136/gut.39.3.486

29. Gendall KA, Bulik CM, Joyce PR, McIntosh VV, Carter FA. Men-

strual cycle irregularity in bulimia nervosa. Associated factors and

changes with treatment. J Psychosom Res 2000; 49(6):409–415.

doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00188-4

30. Deiana V, Diana E, Pinna F, et al. Clinical features in insulin-treated

diabetes with comorbid diabulimia, disordered eating behaviors and

eating disorders. Eur Psychiatry 2016; 33:S81.

31. Edler C, Haedt AA, Keel PK. The use of multiple purging methods

as an indicator of eating disorder severity. Int J Eat Disord 2007;

40(6):515–520. doi:10.1002/eat.20416

32. Mehler PS, Blalock DV, Walden K, et al. Medical fi ndings in 1,026 con-

secutive adult inpatient-residential eating disordered patients. Int J

Eat Disord 2018; 51(4):305–313. doi:10.1002/eat.22830

33. Mitchell JE, Hatsukami D, Eckert ED, Pyle RL. Characteristics of

275 patients with bulimia. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142(4):482–485.

doi:10.1176/ajp.142.4.482

34. Wolfe BE, Metzger ED, Levine JM, Jimerson DC. Laboratory screening for

electrolyte abnormalities and anemia in bulimia nervosa: a controlled

study. Int J Eat Disord 2001; 30(3):288–293. doi:10.1002/eat.1086

35. Mehler PS, Walsh K. Electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities associ-

ated with purging behaviors. Int J Eat Disord 2016; 49(3):311–318.

doi:10.1002/eat.22503

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from

CLEVELAND CLINIC JOURNAL OF MEDICINE VOLUME 88 • NUMBER 6 JUNE 2021

343

NITSCH AND COLLEAGUES

36. Bahia A, Mascolo M, Gaudiani JL, Mehler PS. PseudoBartter syndrome in eat-

ing disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2012; 45(1):150–153. doi:10.1002/eat.20906

37. Wu KL, Cheng CJ, Sung CC, et al. Identifi cation of the causes for chronic

hypokalemia: importance of urinary sodium and chloride excretion. Am

J Med 2017; 130(7):846–855. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.023

38. Cohn JN, Kowey PR, Whelton PK, Prisant LM. New guidelines for po-

tassium replacement in clinical practice: a contemporary review by

the National Council on Potassium in Clinical Practice. Arch Intern

Med 2000; 160(16):2429–2436. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.16.2429

39. Gennari FJ. Hypokalemia. N Engl J Med 1998; 339(7):451–458.

doi:10.1056/NEJM199808133390707

40. Menahem SA, Perry GJ, Dowling J, Thomson NM. Hypokalaemia-in-

duced acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14(9):2216–

2218. doi:10.1093/ndt/14.9.2216

41. Sterns RH. Disorders of plasma sodium—causes, consequences, and cor-

rection. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(1):55–65. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1404489

42. Brown CA, Mehler PS. Successful “detoxing” from commonly utilized

modes of purging in bulimia nervosa. Eat Disord 2012; 20(4):312–320.

doi:10.1080/10640266.2012.689213

43. Wassenaar E, Friedman J, Mehler PS. Medical complications of

binge eating disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2019; 42(2):275–286.

doi:10.1016/j.psc.2019.01.010

44. Bern EM, Woods ER, Rodriguez L. Gastrointestinal manifestations of

eating disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016; 63(5):e77–e85.

doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000001394

45. Cotton MA, Ball C, Robinson P. Four simple questions can help

screen for eating disorders. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18(1):53–56.

doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20374.x

46. Svaldi J, Schmitz F, Baur J, et al. Effi cacy of psychotherapies and phar-

macotherapies for bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 2019; 49(6):898–910.

doi:10.1017/S0033291718003525

47. Goldstein DJ, Wilson MG, Thompson VL, Potvin JH, Rampey AH Jr.

Long-term fl uoxetine treatment of bulimia nervosa. Fluoxetine Bu-

limia Nervosa Research Group. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166(5):660–666.

doi:10.1192/bjp.166.5.660

48. Walsh BT, Agras WS, Devlin MJ, et al. Fluoxetine for bulimia nervosa

following poor response to psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 2000;

157(8):1332–1334. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1332

49. McElroy SL, Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Romo-Nava F. Progress in de-

veloping pharmacologic agents to treat bulimia nervosa. CNS Drugs

2019; 33(1):31–46. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0594-5

50. Quadfl ieg N, Fichter MM. Long-term outcome of inpatients with bu-

limia nervosa—results from the Christina Barz Study. Int J Eat Disord

2019; 52(7):834–845. doi:10.1002/eat.23084

51. Eddy KT, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, et al. Recovery from anorexia nervosa

and bulimia nervosa at 22-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry 2017;

78(2):184–189. doi:10.4088/JCP.15m10393

Address: Philip S. Mehler, MD, FACP, FAED, Denver Health Medical Center,

723 Delaware Street, Pav M, Denver, CO 80204; [email protected]

on September 12, 2024. For personal use only. All other uses require permission.www.ccjm.orgDownloaded from