GAO

United States Government Accountabilit

y

Office

Report to Congressional Committees

FOREIGN MEDICAL

SCHOOLS

Education Should

Improve Monitoring

of Schools That

Participate in the

Federal Student Loan

Program

June 2010

GAO-10-412

Page i GAO-10-412

Contents

Letter 1

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 7

Appendix I Briefing Slides 9

Appendix II Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 50

Appendix III Comparison of Average Cost of Attendance of

U.S. and Selected Foreign Medical Schools 56

Appendix IV Performance on Licensing Exam by Number of

Attempts on Each Exam Step, and by Nationality

of IMG

57

Appendix V International Medical Graduates and Residencies 60

Appendix VI Summary of Responses by Focus Group Participants

at the Five Foreign Medical Schools We Visited 63

Appendix VII Comments from the U.S. Department of Education 71

Appendix VIII GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 73

Bibliography 74

Related GAO Products 77

Foreign Medical Schools

Tables

Table 1: Residency Programs by State, Academic Year 2008-2009 60

Table 2: Number of Participants in Student Focus Groups, by

School 63

Table 3: Decision to Attend a Foreign Medical School 64

Figures

Figure 1: Licensing Exam Pass Rates by Number of Exam Attempts

on Each Exam Step, 1998 through 2008 57

Figure 2: Comparison of First-Time Pass Rates for U.S. Citizen

IMGs and Foreign IMGs on Step 1 (Basic Science) and

Step 2 Clinical Knowledge, 1998 through 2008 58

Figure 3: Comparison of First-Time Pass Rates for Both U.S.

Citizen IMGs and Foreign IMGs on Step 2 Clinical Skills,

2004 through 2008, and Step 3 (on Delivery of General

Medical Care), 1998 through 2008 59

Figure 4: Percentage of IMGs in Residencies as a Percentage of All

Residents by State, Academic Year 2008-2009 62

Page ii GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Abbreviations

AAMC Association of American Medical Colleges

ACGME Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

AMA American Medical Association

ECFMG Educational Commission for Foreign Medical

Graduates

FFEL Federal Family Education Loans

FSMB Federation of State Medical Boards

HEAL Health Education Assistance Loan

HHS Health and Human Services

IMG International Medical Graduate

MCAT Medical College Admission Test

NBME National Board of Medical Examiners

OB/GYN Obstetrics and Gynecology

USMLE United States Medical Licensing Exam

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page iii GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Page 1 GAO-10-412

United States Government Accountability Office

Washington, DC 20548

June 28, 2010

The Honorable Tom Harkin

Chairman

The Honorable Michael B. Enzi

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor,

and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable George Miller

Chairman

The Honorable John P. Kline

Ranking Member

Committee on Education and Labor

House of Representatives

Each year, the federal government makes a significant financial

investment in the education and training of the U.S. physician workforce.

A quarter of that physician workforce is composed of international

medical graduates (IMG) and they include both U.S. citizens and foreign

nationals. In fiscal year 2008, the federal government loaned $633 million

to U.S. students enrolled in foreign institutions—including medical

students—through the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program.

1

The government also makes a substantial domestic investment in the

graduate training of the physician workforce. For example, in fiscal year

2008, federal support for residency training in the United States amounted

to nearly $9 billion. As with medical students educated in the United

States, this training is required of all IMGs—U.S. citizens and foreign

1

Until recently, these student loans were made through the Federal Family Education Loan

program, which was the only federal student financial aid program in which foreign

schools could participate. Under newly enacted legislation, the SAFRA Act, which was

included in the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, (Pub. L. No. 111-152

(2010)), the FFEL program will terminate June 30, 2010, after which no new loans will be

made under the FFEL program. The SAFRA Act extends the availability of loans under the

William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan (Direct Loan) program to students at eligible foreign

institutions. Thus, beginning in July 2010, students at foreign medical schools will receive

new loans through the Direct Loan program, instead of the FFEL program. Throughout this

report we refer to the federal student loan program in our findings. Where our findings are

specific to the FFEL program, however, we refer to that program by name.

Foreign Medical Schools

nationals alike—who seek to practice medicine without supervision in the

United States.

The Department of Education (Education), which administers the federal

student loan program, must also monitor foreign schools that seek to

participate in the program with respect to specific statutory requirements.

Among these is the statutory requirement that at least 60 percent of their

students who take the U.S. medical licensing exam must pass the exam.

Most recently, Congress increased the pass rate to 75 percent, effective July

2010.

Little is known about IMGs with respect to how much they borrow overall,

or the outcome of their medical studies, leading some policy makers to

question the federal return on investment in IMGs. Therefore, Congress

mandated that GAO study the performance of IMGs educated at these

schools and other aspects of a foreign medical education, including the

potential effect of the new 75 percent pass rate requirement on school

participation in the federal loan program.

2

This report examines the following questions:

1. What amount of federal student aid loan dollars has been awarded to

U.S. students attending foreign medical schools?

2. What do the data show about the pass rates of international medical

graduates on license examinations?

3. To what extent does Education monitor foreign medical schools’

compliance with the pass rate required to participate in the federal

student loan program?

4. What is known about schools’ performance with regard to the

institutional pass rate requirement?

5. What is known about where international medical graduates have

obtained residencies in the United States and the types of medicine

they practice?

2

Pub. L. No. 110-315, § 1101 (2008). A similar mandate was directed at the Department of

Education’s National Committee on Foreign Medical Education and Accreditation. The

committee issued its report to Congress in 2009.

Page 2 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

6. What is known about discipline and malpractice involving foreign-

educated physicians?

On May 26 and 27, 2010, we briefed your staff on the final results of our

analysis in addition to providing interim updates in February and March

2010. This report formally conveys the information provided during the

briefing. (See app. I for the briefing slides.) In summary, we found the

following:

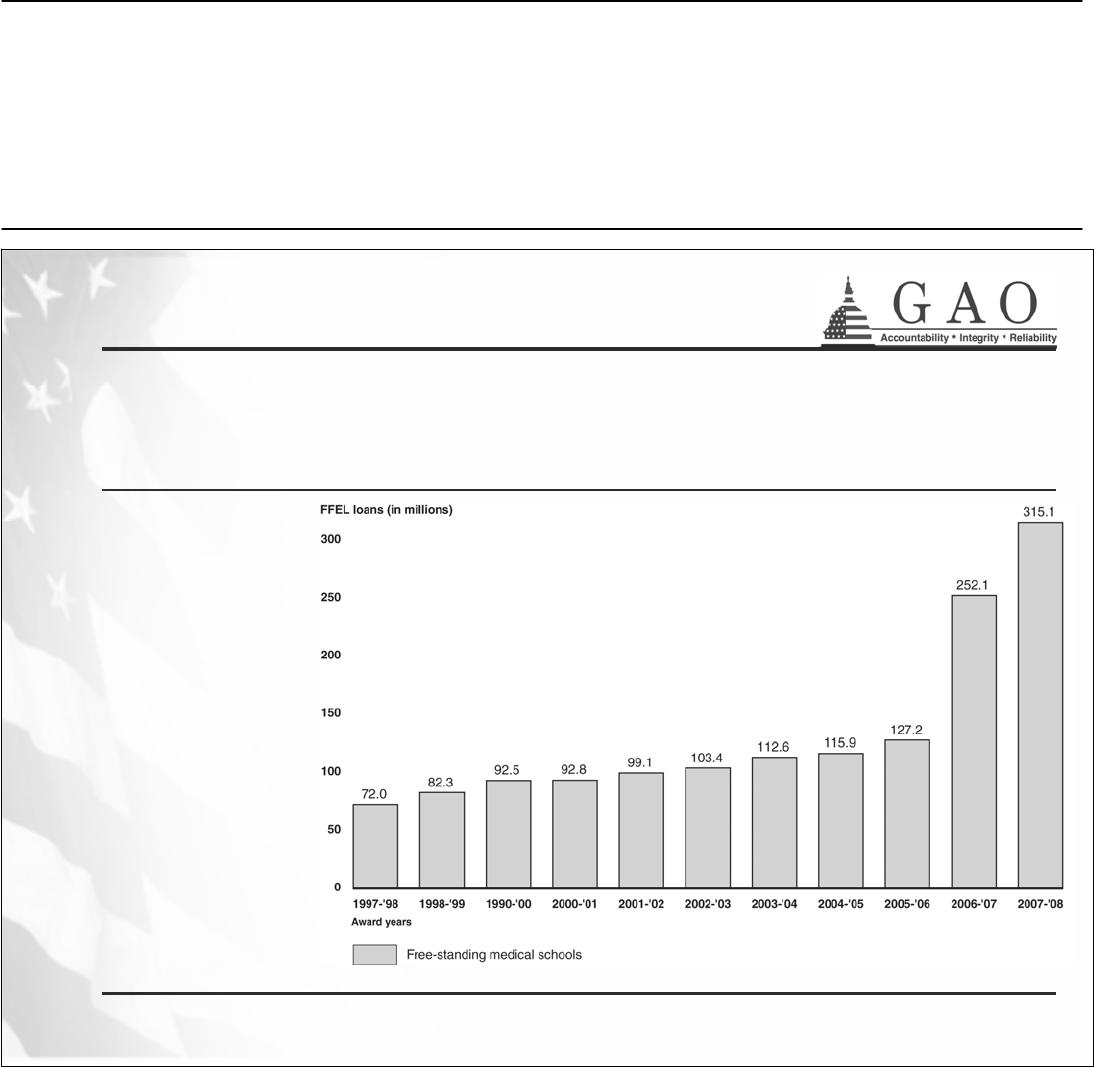

• From 1998 to 2008, U.S. students enrolled at foreign medical schools

borrowed $1.5 billion in FFEL loans to attend free-standing medical

schools.

3

Although this amount represents less than 1 percent of all

federal student loans borrowed during this period, borrowing has

grown significantly, in part because of increases in tuition, student

enrollments, and the availability of additional loan funds for graduate

and professional students.

4

Although our results are not generalizable,

some students who participated in our focus groups estimated that

their student loan debt would range from about $90,000 to $250,000 for

their medical degree alone.

5

In addition, some student borrowers stated

that they lack reliable cost and performance information about foreign

medical schools.

• IMGs, as a group, have consistently passed their medical licensing exam

at lower rates over the past decade than their U.S.-educated peers, but

have narrowed this performance gap for most of the exam steps. In 1998,

for example, average IMG pass rates on the clinical knowledge exam

were 55 percent compared with 95 percent for U.S.-educated graduates.

By 2008, however, IMG rates had increased to 82 percent while they

remained about the same for U.S. graduates. IMGs still lag behind on the

exam step for clinical skills—which involves interaction with patients—

with about a 26 percentage point difference in 2008. They also required

3

Another $1 billion went to students attending foreign schools with a medical program;

however, it is not known what portion of this amount was used to pursue a medical degree

as opposed to some other discipline because the Department of Education does not track

loan volume according to academic discipline.

4

GRADPlus loans are part of the federal student loan program and are non-need-based

loans that graduate and professional students may borrow irrespective of their expected

financial contributions to paying educational expenses. Funds borrowed are limited by

other financial assistance received, such as other FFEL loans, and a student’s cost of

attendance.

5

By comparison, the median loan debt for students pursuing medical degrees in the United

States was $155,000 in 2008.

Page 3 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

more attempts to pass the exam than their U.S.-educated counterparts.

However, pass rates on the additional attempts were lower for both

IMGs and U.S.-educated students compared with pass rates on initial

attempts. Many factors are likely to have affected IMG pass rates,

according to experts and others we interviewed, including students’

proficiency in English and the extent to which foreign schools may or

may not focus on preparing students for the exam.

• Education has not been able to fully enforce the institutional pass rate

requirement needed for continued federal student loan eligibility. The

three private organizations that administer each step of the exam have

declined to release student scores on grounds that the data are

proprietary in nature and should not be used for marketing purposes.

As a result, Education reviews pass rates only when a school applies

for the program, when it periodically seeks recertification, or when

there is a change in ownership. More recently, however, two of the

three testing organizations have begun negotiating with individual

schools for the release of aggregate student performance data. On the

basis of this development, Education officials told us that the

department now plans to require pass rate data annually from all

foreign medical schools participating in the federal loan program.

• Our own analysis of 2008 pass rate data of institutions located in

countries that participate in the federal loan program indicates that

while a majority of foreign medical schools in these countries met the

current 60 percent student pass rate requirement, very few—11

percent—would likely meet the newly required 75 percent pass rate.

Meanwhile, officials from the three testing organizations cautioned

against associating student performance on the U.S. medical licensing

exam with institutional quality, given the variability among students,

the fact that some schools restrict who may sit for the exam, and that

other schools may encourage practice runs.

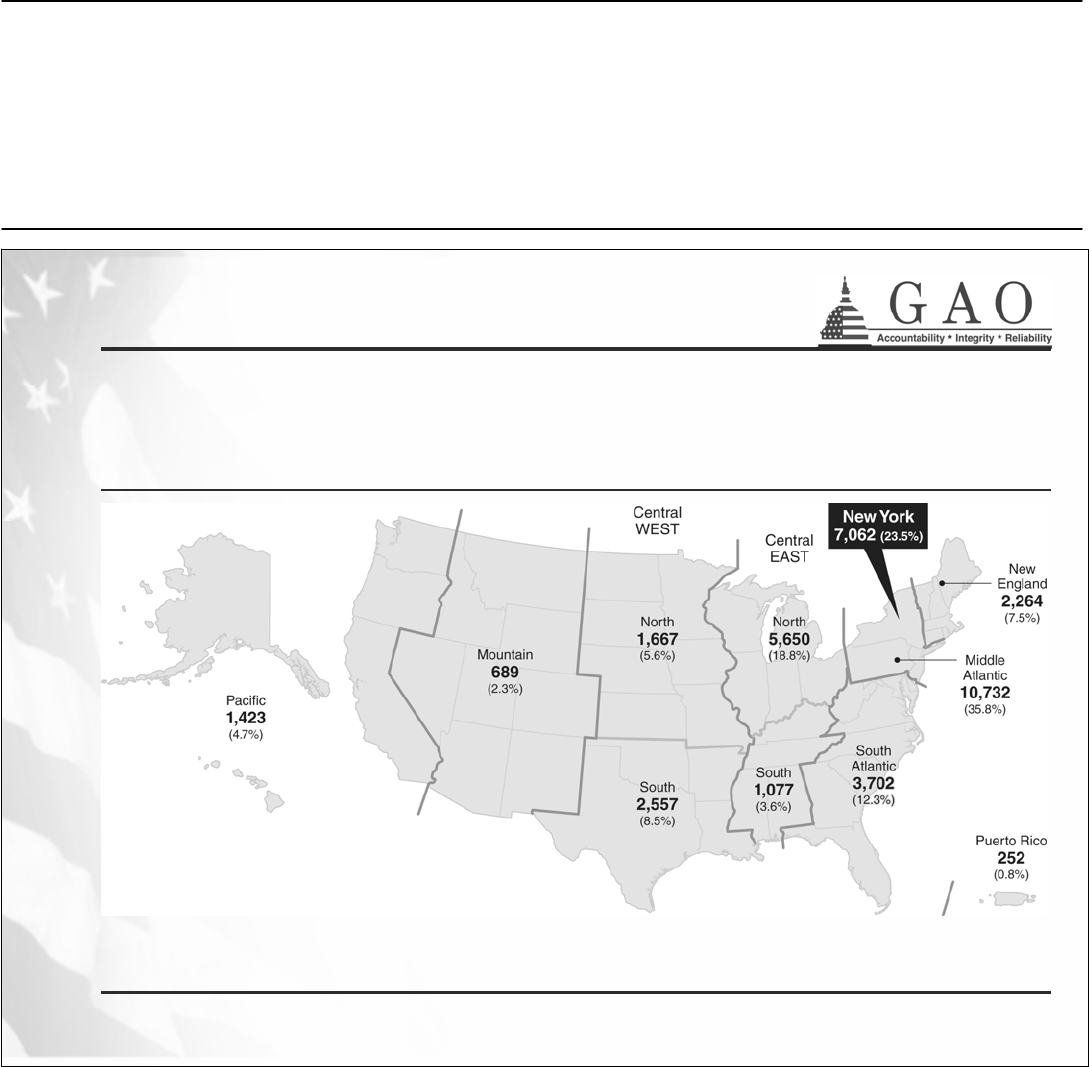

• IMGs have entered into residency programs in all states, though they are

concentrated in the eastern United States, and a larger proportion tend

to practice in primary care than do U.S.-educated graduates. Nationwide,

in academic year 2008-2009 there were 109,482 medical residents, over

30,000 of whom were IMGs (about 27 percent). Of this group of IMGs,

about 78 percent were located in states east of the Mississippi, compared

with 69 percent of all residents. The distribution of IMG residents by

region shows the largest percentage in the Mid-Atlantic and the smallest

Page 4 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

percentages in the Mountain states and Puerto Rico.

6

Several factors can

affect the location of IMGs whether in residencies or in subsequent

practice, such as the geographical distribution of residency programs,

which are largely concentrated in the Mid-Atlantic region and in urban

areas. With regard to medical practice, a larger proportion of IMGs go

into residencies in primary care fields (68 percent compared to 37

percent of U.S. medical graduates in academic year 2008-2009).

Moreover, IMGs increased as a percentage of all residents in core

primary care fields (from 31 to 39 percent) between academic years

2001-2002 and 2008-2009.

7

Research shows that IMGs are also more

likely than U.S.-educated graduates to practice as primary care

physicians after finishing their residency training.

• Overall, few significant differences exist between all IMGs and U.S.-

educated physicians with regard to either disciplinary actions that would

revoke or suspend their licenses or with regard to malpractice

payments

8

—and rates of disciplinary actions are low for physicians as a

whole. Our analysis of national data from 2004 to 2008 on license

revocation and suspension showed that IMGs accounted for a somewhat

larger proportion of these actions than would be expected based on their

share of the physician workforce overall, but it was not a statistically

significant difference. With regard to malpractice, which research suggests

is a weak indicator of physician competence; data on the whole suggest

little difference between IMGs and domestically educated graduates.

GAO is making several recommendations to the Department of Education

concerning the lack of student consumer data on foreign medical

institutions and also the department’s monitoring of pass rates for foreign

medical schools whose students take the U.S. medical licensing exam.

Specifically, GAO recommends that the Secretary of Education

• collect consumer information, such as aggregate student debt level and

graduation rates, from foreign medical schools participating in the

6

The Mid-Atlantic states are New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. The Mountain states

are Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

7

Core primary care specialties are internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, or

internal medicine/pediatrics.

8

Malpractice payments are a monetary exchange as a result of a settlement or judgment of

a written complaint or claim demanding payment based on a physician’s provision of or

failure to provide health care services, and may include, but is not limited to, the filing of a

cause of action, based on the law of tort, brought in any State or Federal Court or other

adjudicative body.

Page 5 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

federal student loan program and make it publicly available to students

and their families;

• require foreign medical schools to submit aggregate institutional pass

rate data to the department annually;

• verify data submitted by schools, for example, by entering into a data-

sharing agreement with the testing organizations; and

• evaluate the potential impact of the 75 percent pass rate requirement

on school participation in the federal student loan program and advise

Congress on any needed revisions to the requirement.

For this report, we analyzed the Department of Education’s loan data for

all foreign medical schools participating in the FFEL program between

academic years 1998 and 2008.

9

To assess the performance of international

medical graduates on licensing examinations, we analyzed trends in exam

data from 1998 to 2008. We evaluated Education’s monitoring of foreign

medical schools’ compliance with the minimum licensing exam pass rate

requirement through interviews with agency officials and analysis of exam

data at an institutional level. We also analyzed graduate medical education

data and interviewed cognizant officials to ascertain where graduates

obtained residencies and to identify their medical specialties. With regard

to discipline and malpractice, we analyzed data from the Department of

Health and Human Services, the Federation of State Medical Boards, and

two states—California and Florida—with high populations of international

medical graduates.

10

We also interviewed experts about the relevance and

availability of these data. Because external data were significant to each of

our research objectives, we assessed the reliability of the publicly and

privately held data we obtained. We determined the data to be sufficiently

reliable for the purposes of this report. Finally, we visited five stand-alone

foreign medical schools in the Caribbean and Europe selected based on

federal student loan volume and other institutional characteristics. At each

school, we interviewed school officials and conducted student focus

groups with a nongeneralizable sample of current students.

9

These academic years were chosen because they coincide with reauthorizations to the

Higher Education Act of 1965.

10

Overall, we interviewed officials from four states—California, Florida, New Jersey, and

New York—and conducted data reliability assessments of their disciplinary data. On the

basis of the outcome of these assessments, we included data from California and Florida in

this report.

Page 6 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

We conducted this performance audit from June 2009 to June 2010 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those

standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient,

appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence

obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions

based on our audit objectives. Our scope and methodology are discussed

in greater detail in appendix II. Additional information related to our

principal findings can be found in appendixes III-VI.

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Education and

Health and Human Services (HHS). We also shared relevant excerpts of

the draft report with the private organizations that administer the licensing

exams. Each of them provided technical comments which were

incorporated into the report as appropriate. Education also provided

additional comments which are reprinted in appendix VII.

Agency Comments

and Our Evaluation

Education agreed with our recommendations and plans to collect

consumer information on foreign medical schools. Education will also ask

these schools to submit pass rate information starting with exams taken

during the award year ending June 30, 2010, and will try to establish a

mechanism to verify pass rates in cooperation with the private

organizations that administer the exams. In addition, Education said that

it has already begun evaluating the potential impact of the 75 percent pass

rate requirement through proposed regulations, and that a notice of

proposed rulemaking inviting public comment is scheduled to be

published in summer 2010.

In its comments, HHS noted that increasing the pass rate requirement will

adversely affect federal student loan availability for future students

attending foreign medical schools, adding that IMGs contribute a

significant percentage of primary care residents in the United States.

Page 7 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

If you or your staff have questions about this report, please contact George

A. Scott at (202) 512-7215 or [email protected]. Contact points for our

Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the

last page of this report. GAO staff members who made key contributions

George A. Scott

to this report are listed in appendix VIII.

Director,

force, and Income Security

Education, Work

Page 8 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

A

ppendix I: Briefing Slides

Page 9 GAO-10-412

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

1

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

Briefing to Congressional Committees:

Education and Labor

House of Representatives

Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

May 2010

Foreign Medical Schools: Education Should Improve

Monitoring of Schools That Participate

in the Federal Student Loan Program

Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

2

Overview

Introduction

Objectives

Scope and Methodology

Summary of Findings

Background

Findings

Conclusions and Recommendations

Page 10 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

Page 11 GAO-10-412

3

Introduction

Each year, the federal government makes a significant financial investment in the

education and training of the U.S. physician workforce. A quarter of that physician

workforce is comprised of international medical graduates (IMG) and they include both

U.S. citizens and foreign nationals.

• In fiscal year 2008, the federal government provided $633 million in federally

guaranteed loans to U.S. citizens enrolled in foreign institutions, including

medical students. These loans were made through the Federal Family

Education Loan (FFEL) program.

1

• That same year, it spent another nearly $9 billion to sponsor the hundreds of

residency programs that train graduates from foreign and U.S. medical schools

alike, and that are required to practice medicine in the United States.

1. To date, the FFEL program has been the only federal student financial aid program in which foreign schools participated. Under newly enacted

legislation, the SAFRA Act, which was included in the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, (Pub. L. No. 111-152 (2010)), the FFEL

program will terminate June 30, 2010, after which no new loans will be made under the FFEL program. The SAFRA Act extends the availability of loans

under the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan (Direct Loan) program to students at eligible foreign institutions. Thus, beginning in July 2010, students

at foreign medical schools will receive new loans through the Direct Loan program, instead of the FFEL program. Throughout this report we refer to the

federal student loan program in our findings. Where our findings are specific to the FFEL program, however, we refer to that program by name.

Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

4

Introduction

Foreign medical schools can differ substantially from U.S. schools in their requirements

for admission and length of study.

• For this and other reasons, the Department of Education, which administers the

federal student loan program, imposes requirements for foreign schools to

participate in the program.

1

• Among these is a statutory requirement that at least 60 percent of IMGs who

take the U.S. medical licensing exam must pass. Recently, Congress

increased the pass rate requirement to 75 percent, effective July 2010.

Little is known about U.S. citizens who study medicine abroad with respect to how much

they borrow in federal loans overall, or the outcomes of their medical studies.

GAO undertook this study pursuant to a mandate enacted in section 1101 of the Higher

Education Opportunity Act.

2

1. To receive federal loan funds, students must be enrolled at eligible institutions located in countries with standards of accreditation of medical schools that

are comparable to the standards of accreditation of medical schools in the United States.

2. Pub. L. No.110-315 (2008).

Page 12 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

5

Objectives

1. What amount of federal student aid loan dollars has been awarded to U.S.

students attending foreign medical schools?

2. What do the data show about the pass rates of international medical graduates on

license examinations?

3. To what extent does Education monitor foreign medical schools’ compliance with

the pass rate required to participate in the federal student loan program?

4. What is known about schools’ performance with regard to the institutional pass rate

requirement?

5. What is known about where international medical graduates have obtained

residencies in the United States and the types of medicine they practice?

6. What is known about discipline and malpractice involving foreign-educated

physicians?

Page 13 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

6

Scope and Methodology

To conduct our work, we:

• reviewed and analyzed federal student loan volume and privately held data on U.S.

licensing exams, residency surveys, and disciplinary actions and malpractice

payments;

• interviewed officials and experts and reviewed information and documents from:

o Department of Education

o Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services

Administration

o Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), the National

Board of Medical Examiners, and the Federation of State Medical Boards

o Selected schools participating in the federal student loan program

o Agencies responsible for licensing and disciplining physicians in four states with high

concentrations of IMGs, and found the data from two of these states to be reliable for

our purposes.

• reviewed relevant literature on IMGs published from 1990 to 2009 by various

associations and individual researchers; and

• reviewed relevant federal laws and regulations.

Page 14 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

7

• conducted site visits to five foreign medical schools:

o American University of the Caribbean (St. Maarten),

o Ross University (Dominica),

o St. George’s University (Grenada),

o Royal College of Surgeons (Ireland),

o Poznan University of Medical Sciences (Poland); and,

• conducted a non-generalizable sample of student focus groups—consisting

primarily of U.S. citizens who were receiving federal student loans—at each school

we visited.

• We determined that the data used to address our research objectives were

sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report.

Scope and Methodology

Page 15 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

8

Summary of Findings

1. From 1998 to 2008, U.S. students borrowed $1.5 billion in federally guaranteed

student loans to study at foreign medical schools. Meanwhile, some student

borrowers stated that they lack reliable cost and performance information about

these schools.

2. Pass rates on the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam have improved for all international

medical graduates, but still lag behind those of U.S.-educated graduates.

3. Education lacks the data necessary to fully enforce foreign medical school

compliance with the pass rate requirement.

4. While a majority of foreign medical schools met the current 60 percent pass rate

requirement in 2008, very few would likely meet the newly enacted 75 percent rate.

5. International medical graduates in residency programs are located primarily in the

eastern U.S. and tend to practice primary care fields.

6. Available data on disciplinary proceedings and malpractice reveal few differences

between international medical graduates and U.S.-educated physicians.

Page 16 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

9

Background

Who Are International Medical Graduates (IMGs)?

• They are physicians who have graduated from medical schools in countries other

than the U.S. and Canada.

1

• IMGs comprise over one quarter (about 244,000 physicians) of the current physician

workforce in the U.S.

• They include both citizens of the U.S. and other countries.

• Of IMGs who practice in the U.S., nearly 20 percent are U.S. citizens or permanent

residents.

1. The definition of IMG may vary. Health workforce experts do not consider Canadian graduates to be IMGs because the accreditor and medical education

standards for Canada are similar to the U.S. Alternatively, the Department of Education’s definition of IMGs includes U.S. students who were educated in

Canadian medical schools. For the purposes of our report, our definition of IMGs excludes graduates of U.S. and Canadian medical schools.

Page 17 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

10

Background

Federal Student Loan Program Requirements for Foreign

Medical Schools

To participate in the program, foreign medical schools must:

• Be located in one of 26 countries

1

whose standards of accreditation are

comparable to those in the U.S. as determined by the National Committee on

Foreign Medical Education and Accreditation;

2

• Meet the statutorily mandated institutional pass rate on certain medical licensing

exams

3

and other specific statutory and regulatory eligibility requirements;

• A few schools have been statutorily exempted from the pass rate requirement in

view of their existing approved U.S. clinical training programs in operation since

1992:

1. According to the Foundation for the Advancement of International Medical Education and Research’s International Medical Education Directory, there were

251 foreign medical schools located in comparable countries, some of which participate in the federal loan program. At various places in this report, the data

presented may pertain to schools that either participate in the federal student loan program or to all foreign medical schools regardless of their participation.

2. 20 U.S.C. § 1002(a)(1)(C), (a)(2)(B); 34 C.F.R. § 600.55(a)(4).

3. 20 U.S.C. § 1002(a)(2)(A)(i)(I)(bb); 34 C.F.R. § 600.55(a)(5)(i)(B).

o St. George’s University, Grenada

o Our Lady of Fatima University, the Philippines

o American University of the Caribbean, St. Maarten

o Tel Aviv University, Israel

o Ross University, Dominica

Page 18 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

11

According to Department of Education guidance, students who are enrolled in eligible

foreign medical schools:

• Must generally be U.S. citizens, nationals, or eligible permanent residents to

qualify for federally guaranteed student loans.

• May borrow up to $20,500 in subsidized and unsubsidized loans

1

annually.

Total borrowing through the program for students enrolled in foreign medical

schools is limited to $138,500.

• May borrow additional loan funds up to the cost of attendance minus other

federal assistance in loans for graduate and professional students, available as

of 2006, if they have met the federal student loan program limit.

By contrast, students enrolled in U.S. medical schools may borrow up to $224,000 in

federal guaranteed student loans to replace loan funds no longer available through the

Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Education Assistance Loan (HEAL)

program.

2

Background

Federal Student Loan Program Requirements for U.S. Medical

Students Abroad

1. Federally subsidized student loans are based on financial need. The interest on subsidized federal loans is paid by the federal government while students

are enrolled at least half-time in college and during periods of authorized deferment. The interest for these loans is paid by the student upon graduation.

Interest on unsubsidized federal loans is paid by the student and accrues from the date the loan is disbursed to a student until it is paid in full.

2. U.S. medical students abroad were not eligible to participate in the HEAL program and thus are ineligible to receive the additional loan funds made

available to students attending U.S. medical schools.

Page 19 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

12

Background

How Foreign Medical Schools Differ from U.S. Medical Schools

Foreign medical schools can vary considerably from U.S. medical schools.

• Most students must receive a competitive score on the Medical College Admission

Test (MCAT) to be admitted to a U.S. medical school because of educational

standards and limited slots. Unlike U.S. medical schools, foreign medical schools

do not necessarily require an undergraduate degree or an admissions test; and, if

an admissions test is required, the score need not be as competitive as for U.S.

schools.

• Some foreign medical schools can be highly selective in their admissions though

they do not necessarily require the MCAT.

• Some foreign medical schools are for-profit institutions with shortened academic

timelines. Whereas U.S. medical school students typically complete degrees in

four years, students at some schools in the Caribbean can do so in under three.

Page 20 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

13

Background

Requirements for IMGs to Enter a Residency Program in the

United States

Because medical schools outside the United States and Canada vary in their

educational standards and curricula, ECFMG certification is designed to

assure residency program directors and the public that IMGs have met the

minimum standards of eligibility to enter such programs.

1

• To enter a U.S. residency training program, IMGs must first become

certified by the ECFMG whose requirements include:

1. While there is no limit on the number of times a student may take an exam step, test-takers have seven years from the time they first pass a step to pass

all other steps required for certification.

2. The Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research currently lists more than 2,000 such institutions.

o Passing the first two (i.e. Step 1, Step 2CK and Step 2 CS)

of the three steps of the U.S. medical licensing exam.

1

o Showing evidence of a medical degree from a recognized

medical school.

2

Page 21 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

14

Background

The Steps of the U.S. Medical Licensing Exam

The following exam steps can be taken while attending medical school abroad:

• Step 1 uses a multiple-choice format to assess knowledge and application of

basic science concepts in the practice of medicine.

• Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) uses a multiple-choice format to assess

knowledge of clinical science principles.

• Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) tests students ability to examine and interact with

patients and colleagues.

The final step of the licensing exam is often taken during residency.

1

• Step 3 uses multiple-choice items and computer-based simulations and provides

a final assessment of a physician’s ability to assume independent delivery of

general medical care.

1. According to ECFMG officials, a number of states allow physicians to take Step 3 prior to entering a residency program and a significant

number of IMGs do so.

Page 22 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

15

Background

Discipline and Malpractice

Physicians—whether educated in the U.S. or abroad—who are licensed to

practice, may be subject to various disciplinary actions taken through state

medical boards, or hospitals, and other medical providers.

o License actions: revocations, suspensions, or other restrictions on a

physician’s license based on a review by state medical boards.

o Malpractice

1

: a finding of negligent care, related to services that a physician

provided or failed to provide.

1. Research indicates that malpractice data are of limited value as an indicator of competence or negligence. Possibly no more than 3 percent of medically

adverse events result in malpractice claims. Moreover, of those that do, an estimated 40 percent are found not to have involved error or injury.

Page 23 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

16

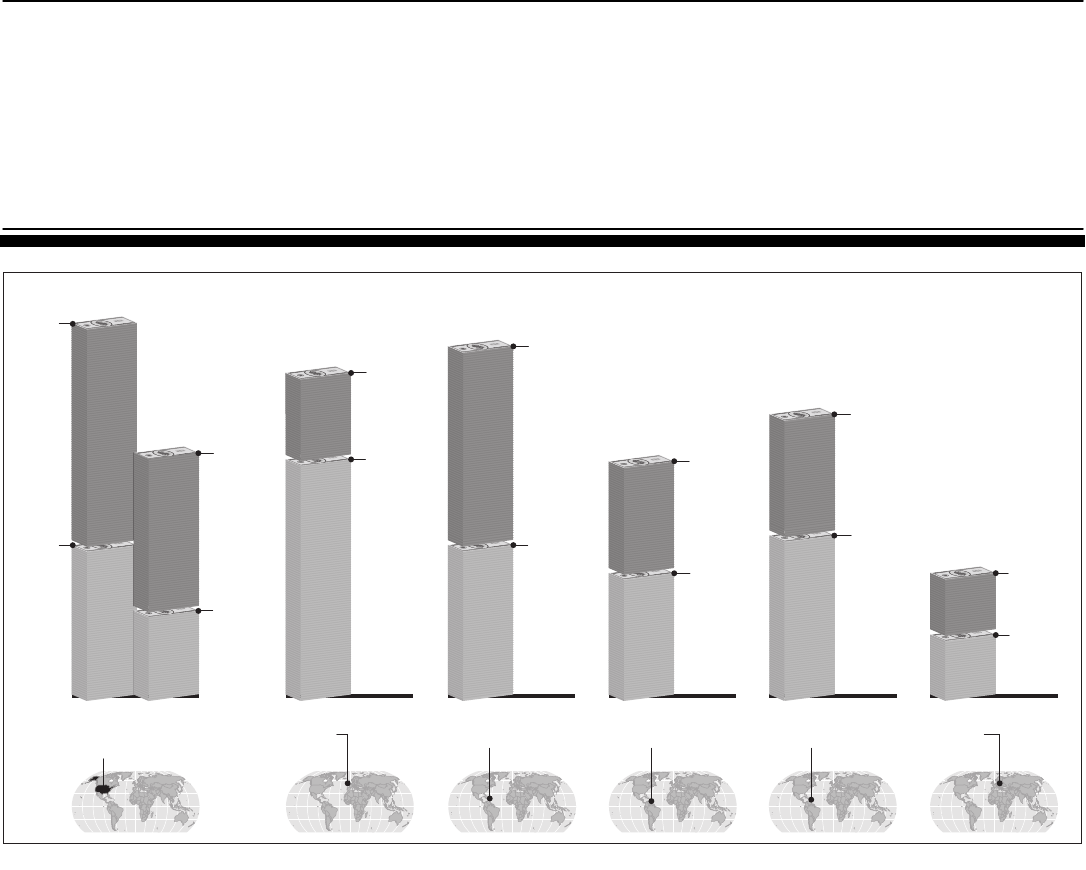

Loans to U.S. Medical Students Abroad Were Concentrated at

Free-standing Medical Institutions

Between 1998 and 2008, a total of 137 foreign medical institutions in 31

countries participated in the FFEL program during at least one academic year.

• School participation has remained relatively constant.

• As of 2008, there were 113 schools.

• Of these, 21 were free-standing medical institutions and the rest were

component schools.

1

From 1998 to 2008, U.S. students borrowed $1.5 billion to study medicine at

the free-standing institutions.

2

• Of that amount, about $1.3 billion (about 90 percent) went to students

at three Caribbean schools (American University of the Caribbean,

Ross University and St. George’s University).

Finding 1: Student Loans at Foreign Medical Schools

1. Free-standing institutions are schools whose principal offering is medical education; whereas, component medical institutions are medical

schools within a larger university system.

2. About another $1 billion was borrowed by students to study at component schools. However, because Education does not capture loan

data by academic discipline, it is unclear what portion of that amount was used to study medicine as opposed to other academic

disciplines.

Page 24 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

17

Borrowing at Foreign Medical Schools Has Steadily

Increased Since 1998

Since 1998,

loans at free-

standing schools

grew by 338

percent

compared with a

154 percent

increase in the

FFEL program

overall.

School officials

we met with

attributed loan

growth to

increases in

tuition,

enrollment, and

the introduction

of graduate and

professional

loans in 2006.

Finding 1: Student Loans at Foreign Medical Schools

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Education data

Page 25 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

18

Importance of Federally Guaranteed Student Loans

Of the students who participated in our focus groups, many reported that they relied

heavily on federal student loans to fund their medical education abroad. The majority

were most likely to categorize federal loans as very important in contrast to other forms

of financial assistance, both private and public.

1

• While little is known about the debt burden accumulated by IMGs, focus

group participants we interviewed projected their student loan debt would

range from $90,000 to $250,000 for their medical degree alone.

2,3

• Officials at the foreign medical schools we visited reported total student costs

ranging from just over $30,000 to about $90,000 per year. Most of the tuition

and fees reported by schools fell within the range of average cost for U.S.

medical schools.

Finding 1: Student Loans at Foreign Medical Schools

1. The findings obtained from our student focus groups cannot be generalized to the student population of international medical graduates.

2. Students participating in the student focus groups did not always indicate whether the loan funds borrowed were federal student loans or

private loans.

3. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, students enrolled in U.S. medical schools incur about $155,000 in student

loan debt for their medical degrees.

Page 26 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

19

Some Focus Group Participants Reported That They Lacked

Reliable Information on Likely Loan Debt and Institutional

Performance

• Some students who participated in our focus groups said that when making their

initial selection of schools, they lacked a centralized source of reliable information

about their likely medical student loan debt or institutional performance such as

graduation rates.

• Many focus group participants said they relied on student-driven websites to guide

their decision-making.

• According to ECFMG officials, IMG oriented websites can vary in both accuracy and

sophistication. Students lack sources that are objective and factual.

Finding 1: Student Loans at Foreign Medical Schools

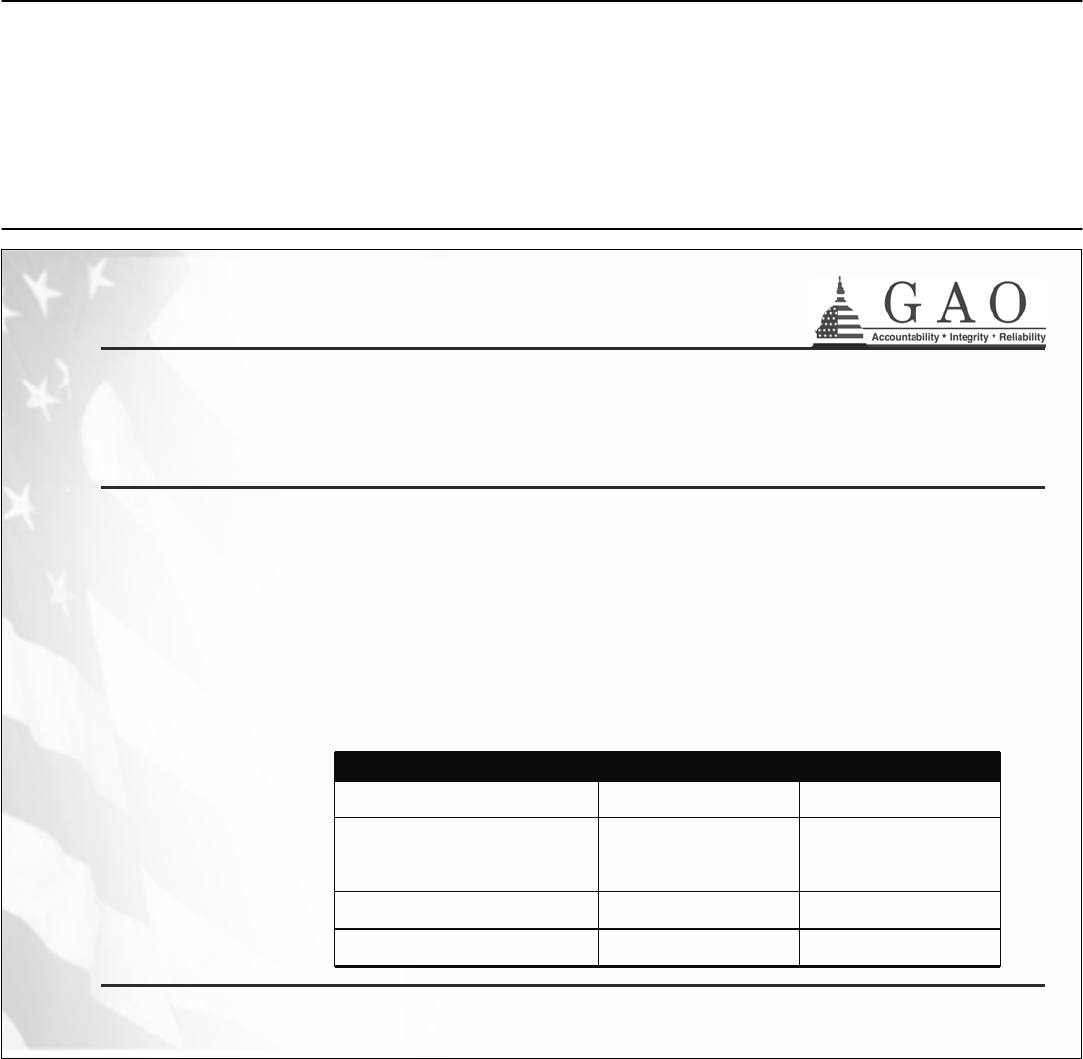

Comparison of

Sources Available for

Decision-making by

U.S.-educated

students and IMGs

Source:

GAO analysis of U.S.

Department of Education,

association, and

independent websites.

No known reliable sourcesMedical college associationMedical School Loan Debt

No known reliable sourcesMedical college associationGraduation Rates

Multiple school websites and

student-led electronic

bulletin boards

Centralized medical college

association website which

allows comparison of

several school websites

Admission Requirements

IMGsU.S. Medical Students

Known Sources Available…

Page 27 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

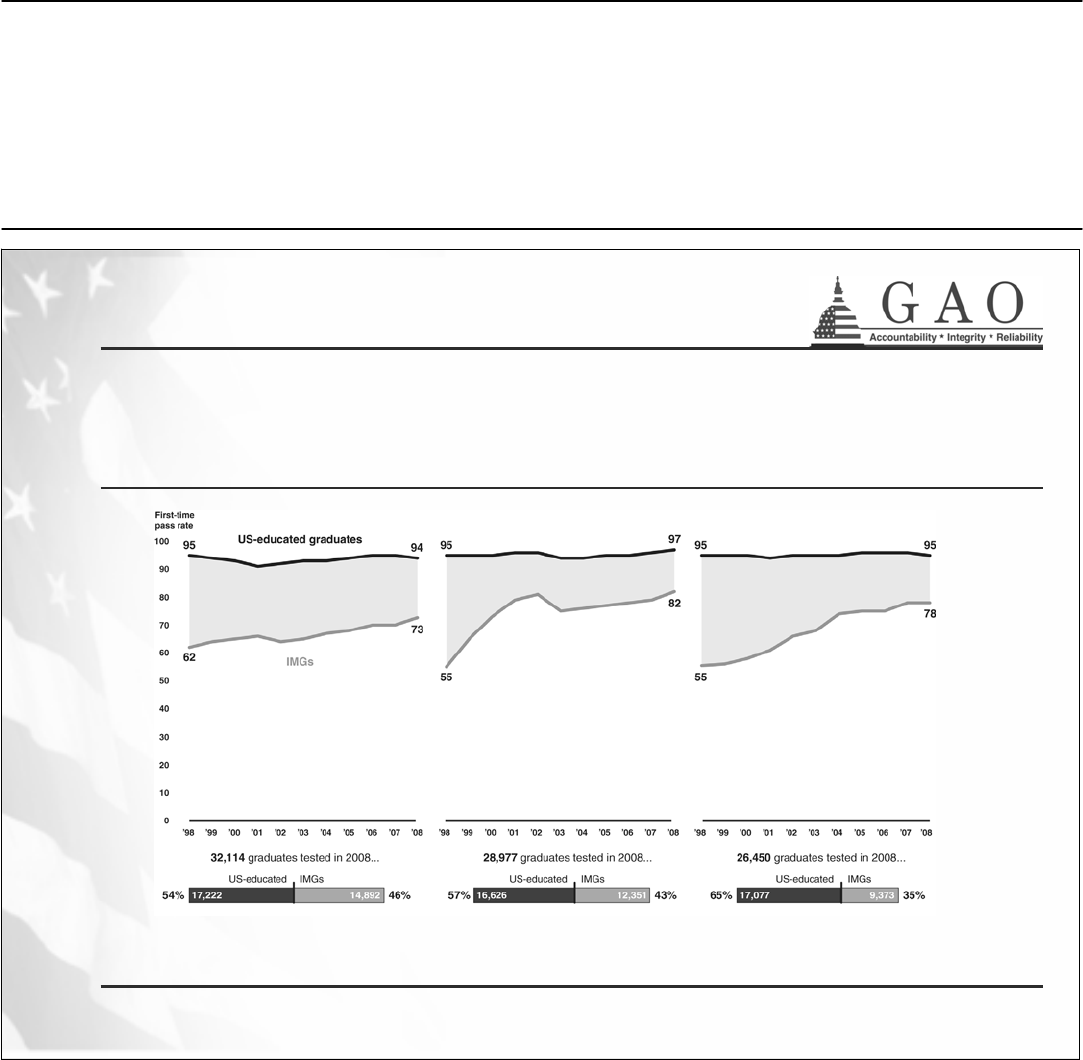

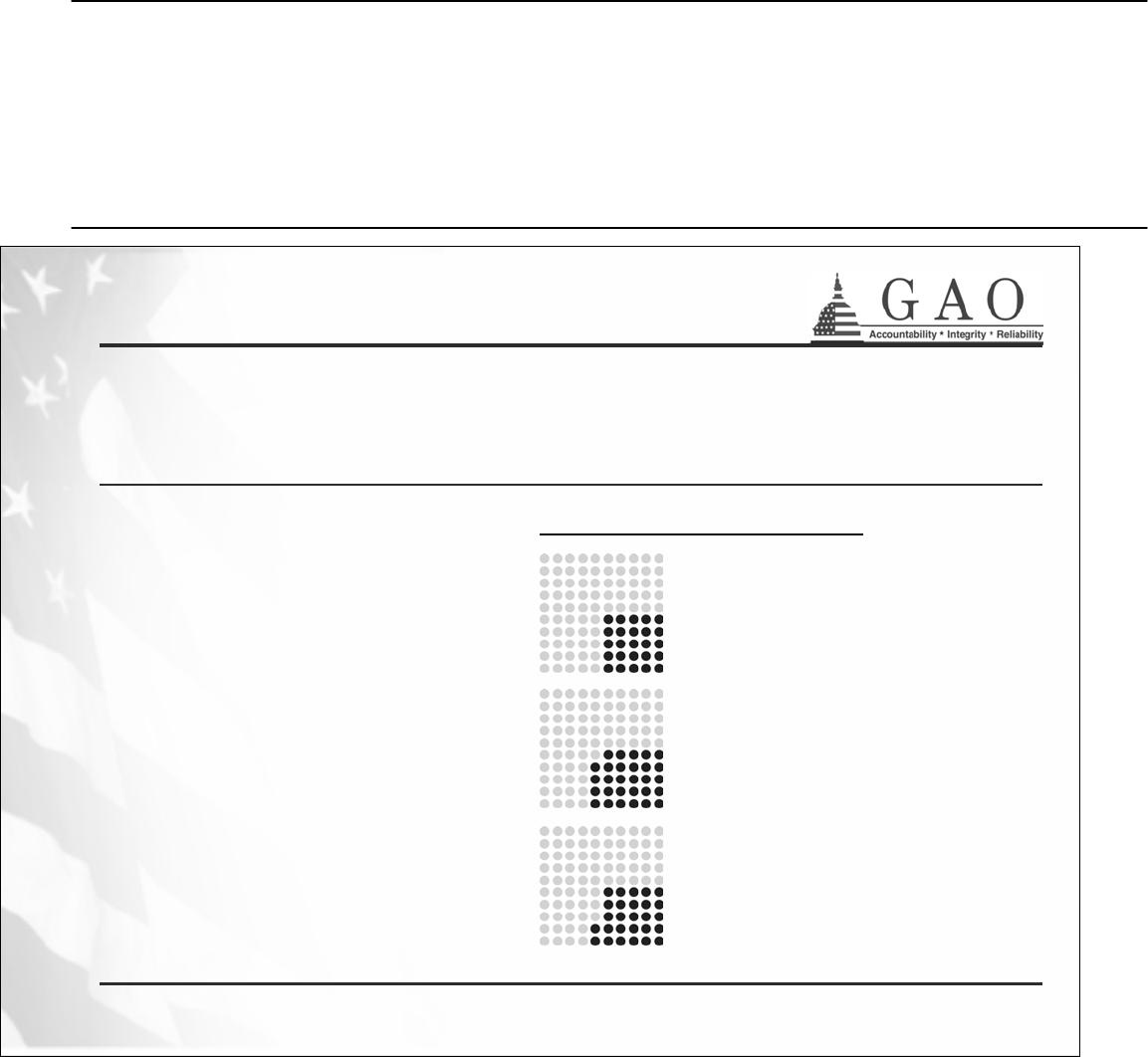

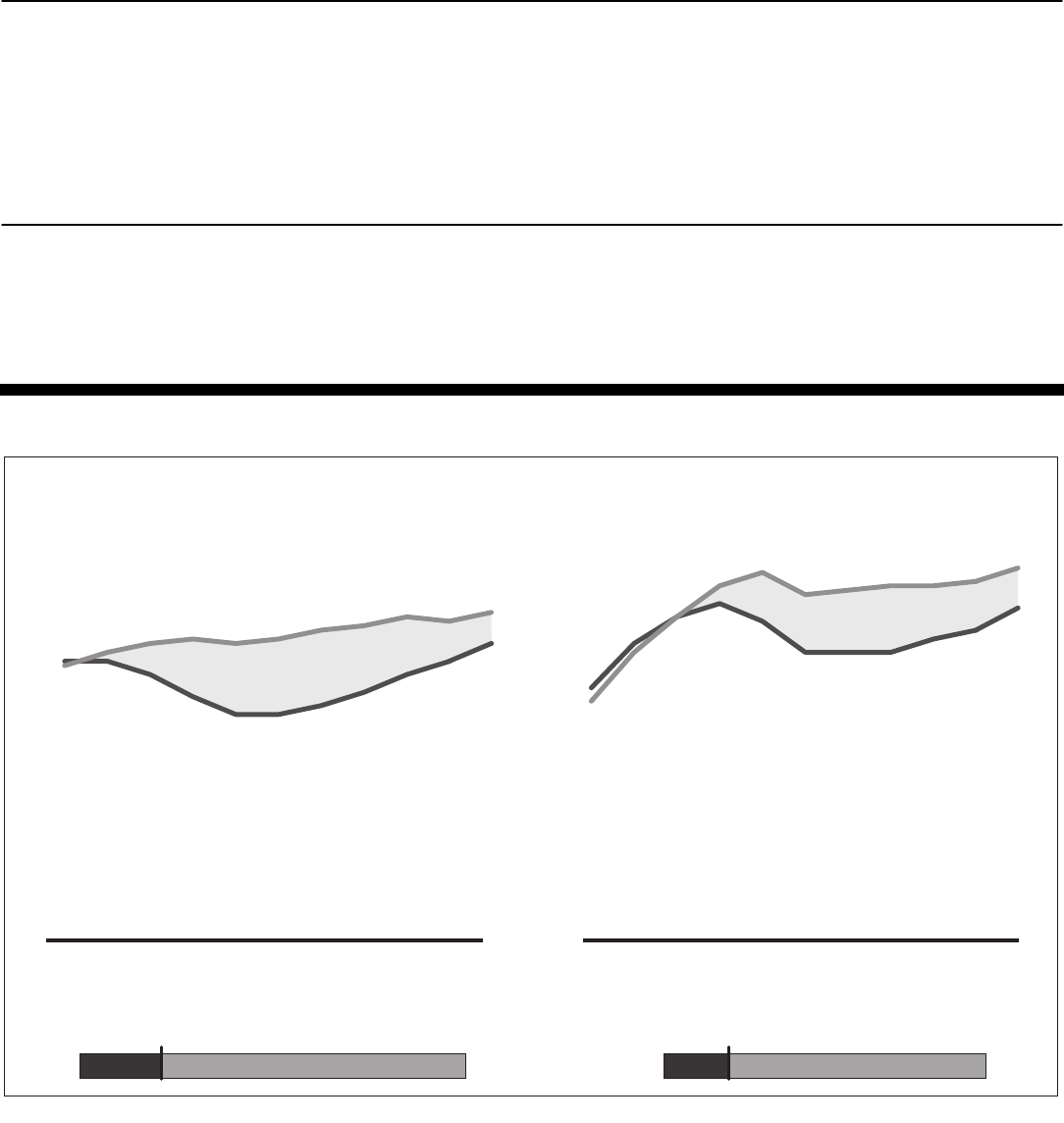

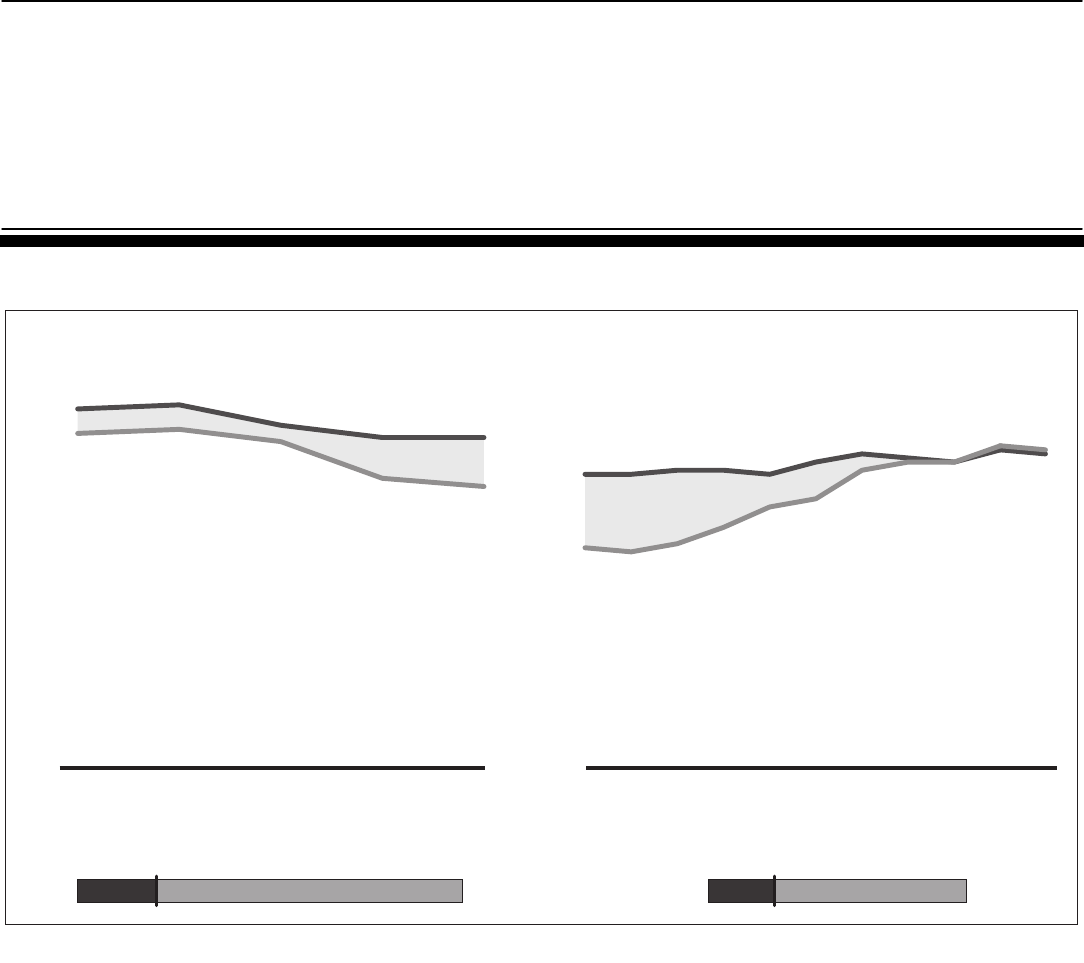

20

Pass Rates for All IMGs Have Improved on Most Licensing

Exam Steps But Still Lag Behind Those of U.S.-Educated

Graduates

Finding 2: U.S. Medical Licensing Exam Pass Rates

Step 1 (on basic science), 1998-2008 Step 2 Clinical Knowledge, 1998-2008

Source: GAO analysis of Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates and National Board of Medical Examiners data.

Notes: IMGs include both U.S. citizens and citizens of other countries. As such, IMG pass rates reflect performance for individuals who may or may not have

received federal student loans. All test-takers are referred to as “graduates”; however, students are eligible to take the Step 1, Step 2 clinical knowledge, and

Step 2 clinical skills exams while they are still enrolled in medical school.

Step 3 (on delivery of general medical care), 1998-2008

Page 28 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

21

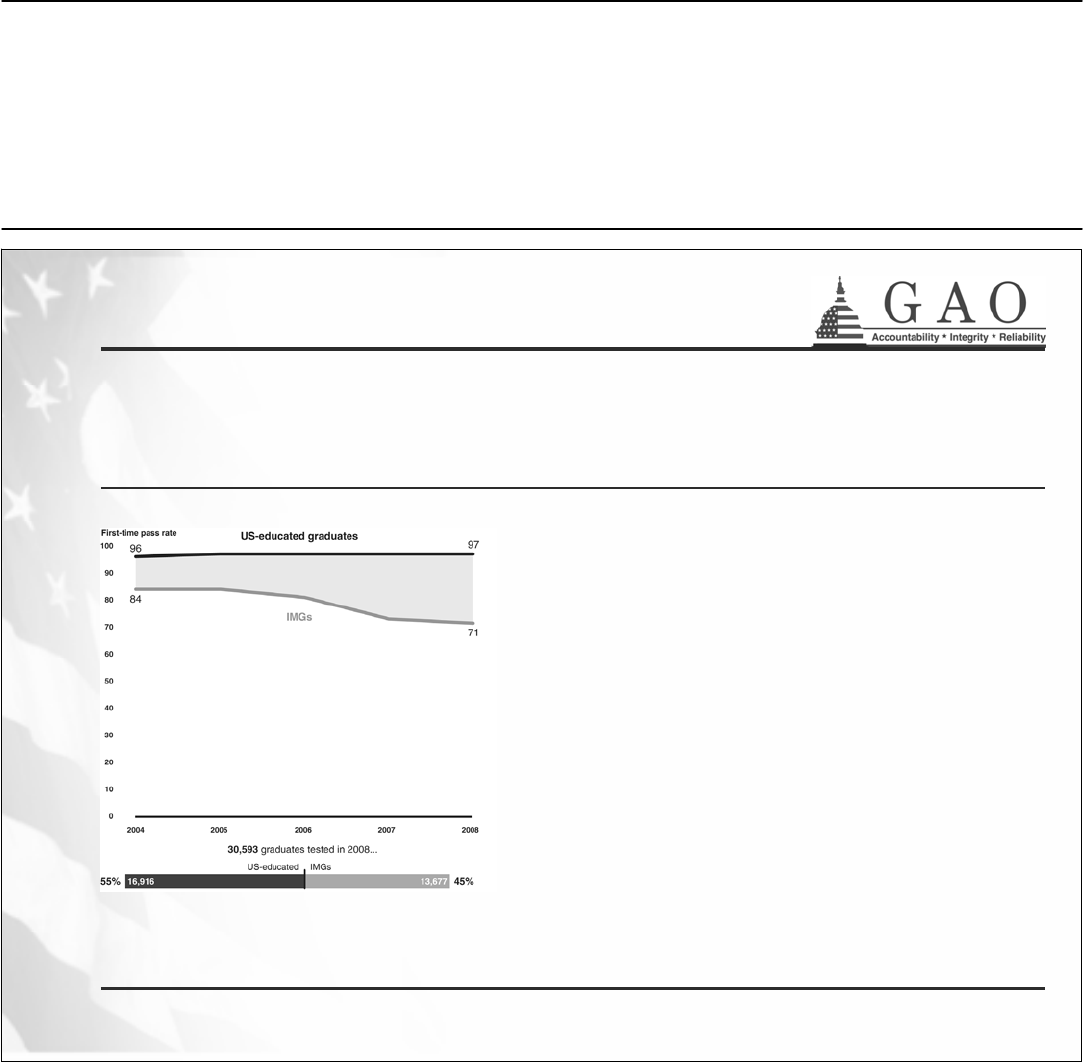

Despite Improvements, IMG First-Time Pass Rates on the

Step 2 Clinical Skills Exam Have Declined

Officials from the two organizations

that maintain licensing exam data told

us that IMG pass rates on the clinical

skills exam, offered since 2004, may

have declined in recent years due, in

part, to increases in the minimum

requirements for passing the exam.

Finding 2: U.S. Medical Licensing Exam Pass Rates

Step 2 Clinical Skills, 2004-2008

Source: GAO analysis of Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates and National Board of Medical Examiners data.

Notes: IMGs include both U.S. citizens and citizens of other countries. As such, IMG pass rates reflect performance for individuals who may or may not have

received federal student loans. Test-takers are referred to as “graduates”; however, students are also eligible to take the Step 2 clinical skills exam. The Step

2 clinical skills exam became a certification requirement on June 14, 2004. Thus, pass rate data for this exam are available only for exam year 2004 and

onward. Prior to that, ECFMG administered the Clinical Skills Exam, starting in July 1998, as a requirement for certification.

Page 29 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

22

IMGs Needed More Attempts to Pass Licensing Exams than

U.S.-Educated Graduates

• IMGs have needed more attempts to pass the licensing exams than their U.S.-

educated counterparts. However, pass rates on additional attempts were lower than

initial attempts for both IMGs and U.S.-educated students. About 27 percent of IMG

test-takers repeated exams during the last ten years, compared to about 6 percent

of U.S.-educated test-takers.

o In 2008, 4,833 IMGs repeated the Step 1 exam at least once and 42 percent

passed on the repeated attempt.

o In the same year, 1,182 U.S.-educated graduates repeated the Step 1 exam at

least once and 69 percent passed on subsequent attempts.

• According to researchers, test takers who require multiple attempts to pass the

licensing exams will likely have difficulty being selected for a residency because they

are viewed by some as less qualified as those passing the exams on their first try.

Finding 2: U.S. Medical Licensing Exam Pass Rates

Page 30 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

23

Factors That May Affect IMG Pass Rates: Limited English

Proficiency and Institutional Focus on U.S. Licensing Exams

• Research indicates that English language proficiency may affect IMGs’ exam

performance on the clinical skills exam, especially in gathering data, sharing

information, and establishing rapport with patients.

1

• Research and experts suggest that other factors are the extent to which exam

preparation is incorporated into a medical school’s curriculum and the proportion of

the school’s students taking the exam.

o Although passing the licensing exam is critical for those seeking to practice in

the U.S., not all schools focus on this as a part of their program.

o Focus group participants at the two European schools we visited told us that

faculty provided limited assistance in exam preparation. Officials at both

schools told us they would provide additional test-preparation support for their

students.

o At the three Caribbean schools we visited, there was significant focus on

preparing students for the exam. Institutional policies at two of the three

schools precluded students from taking the exam if they were not ready and

required successful performance on the exam in order to graduate.

Finding 2: U.S. Medical Licensing Exam Pass Rates

1. According to one study, although research indicates that IMGs who are U.S. citizens are more likely than foreign IMGs to claim English as

a native language and to have received medical school instruction in English, nearly 30 percent of U.S. citizen IMGs are non-native English

speakers. See Boulet, John R., et al, “U.S. Citizens Who Obtain Their Medical Degrees Abroad: An Overview, 1992-2006,” Health Affairs,

vol. 28, no.1 (2009).

Page 31 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

24

Other Factors May Also Explain Lower Pass Rates for IMGs

Who Were U.S. Citizens

• Experts we interviewed suggested that some U.S. citizen IMGs may lack the test-

taking skills of their U.S.-educated counterparts.

• Several focus group participants we spoke with told us that their lower MCAT scores

made them less competitive when applying to U.S. medical schools.

o According to data from the Association of American Medical Colleges, fewer

than one third of 2005-2007 applicants with MCAT scores below 30 were

accepted to U.S. medical schools.

1

• Several focus group participants we spoke with told us that they entered foreign

medical school from other disciplines or applied to medical school years after

finishing college, suggesting that they did not follow the traditional academic

pathway to medical school and may not have had the same exposure to medical

concepts as other students.

Finding 2: U.S. Medical Licensing Exam Pass Rates

1. The highest possible score for all students is 45.

Page 32 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

25

Education Has Not Been Able to Fully Enforce the Pass Rate

Requirement

The three private organizations that administer the licensing exams have not released

their data to schools or to Education on grounds that the information is proprietary and

should not be used for marketing purposes.

• As a result, Education has not been able to collect such data from the schools.

• Education officials said that since federal student loans to foreign medical

schools comprise less than 1 percent of all student loans, they use a risk-based

approach to monitor compliance with the pass rate requirement. They request

the data from schools

1

only when schools:

o apply to participate in the loan program,

o seek recertification for participation—at intervals between 1 to 6 years, or

o change institutional ownership.

• When schools did provide the data, however Education officials noted that they

could not independently verify it.

Finding 3: Monitoring of Licensing Exam Pass Rates

1. Department officials told us that in 2004, when they requested pass rate data from schools, they received data back only sporadically.

Between 1998 and 2008, only one school has lost eligibility based on the pass rate data it provided to Education. Fourteen other schools

have lost eligibility due to not meeting other program rules. Education officials stated that foreign medical schools have been able to obtain

student consent agreements for pass rate data on Steps 1 and 2.

Page 33 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

26

Schools Are Beginning to Negotiate for the Data and Education

Has Recently Reconsidered Its Approach to Enforcement

y

Recently two of the three testing organizations have begun to negotiate, on a

school-by-school basis, to provide the data to schools, which may allow schools to

systematically prove that they are satisfying the pass rate requirement.

o These organizations administer and/or govern Step 1, Step 2CS, and Step 2CK

of the medical licensing exam.

• Education told us that the department will soon fully enforce the pass rate

requirement by requesting schools to provide exam data on an annual basis, but did

not elaborate on how and when it would implement this new approach.

• However, a spokesperson for the testing organization that administers Step 3 said

that the organization would not be entering into such agreements with schools

because it shares exam data only with state medical boards.

• While the National Committee for Foreign Medical Education and Accreditation

recommended the inclusion of Step 3 as part of this requirement, Education officials

indicated that they would not request these data because the testing organization

that administers Step 3 is not specifically covered by the pass rate requirement.

1

Finding 3: Monitoring of Licensing Exam Pass Rates

1. The statutory and regulatory pass rate requirement applies only to examinations administered by ECFMG, which are Step 1 and Step 2. 20

U.S.C. § 1002(a)(2)(A)(i)(I)(bb); 34 C.F.R. § 600.55(a)(5)(B). Because Step 3 is administered by the Federation of State Medical Boards, it is

excluded from the pass rate requirement.

Page 34 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

27

According to our analysis

1

of 2008 institutional pass rate data:

At 60 percent:

A majority (58 percent) of foreign medical schools met or exceeded the current pass

rate requirement.

• For 6 countries, all 30 schools met the pass rate.

• For 3 countries, less than one-third of the 105 schools met the pass rate.

At 75 percent:

Only 24 of 218 schools with test-taking students (or 11 percent) would meet the

newly enacted pass rate were they to post the same performance as in 2008

.

•

Two of the five schools statutorily exempt from the requirement, but which

account for over 50 percent of federal student loans, would not meet the new

standard.

Finding 4: Performance on Institutional Pass Rates

1. The data we obtained from ECFMG and NBME did not allow for the identification of individual schools, but allowed us to look at institutional

performance by country. Because school identities were masked, we could not differentiate between federal loan participants and others. To

the extent that not all schools participated in the federal loan program, our results may be overstated. Our analysis was based on individuals

who took the exam. Because we could not estimate the proportion of students who were allowed to take the exam, we could not identify the

extent to which scores may be overstated.

A Majority of Foreign Medical Schools Met the Pass Rate at 60 Percent

in 2008, But Very Few Would Do So at 75 Percent

Page 35 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

28

Institutional Pass Rates May Be Limited as a Measure of

School Quality

Testing officials cautioned against associating students’ performance on

medical licensing exams with institutional quality for the following reasons:

• Test-takers could be a school’s best or worst students.

• Some schools restrict who may sit for the exam based on student

readiness—thus inflating an institution’s score.

• Other schools may encourage “practice runs” for students who are less

prepared or have no restrictions on who sits for the exams—possibly

lowering institutional scores.

• Performance on Step 3 of the exam—which may occur during residency

training in the U.S.—has little to do with attending school abroad.

1

Additionally, according to some school officials, institutions with small numbers

of test-takers may find it hard to meet the pass rate requirement.

2

1. According to ECFMG officials, a number of states allow graduates to take Step 3 prior to entering a residency program and a significant

number of IMGs do so.

2. Education officials agreed with this assessment and reported to us that they are proposing regulations that would make special provisions for

foreign medical schools that enroll small numbers of U.S. citizens by asking them to provide the data only when the pass rate is based on at

least 8 or more students who took the exam.

Finding 4: Performance on Institutional Pass Rates

Page 36 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

29

Some Schools Have Expressed Concerns About the 75

Percent Rate

Some school and medical association officials we interviewed expressed the

view that the new pass rate could discourage loan program participation:

• They noted that because some non-profit institutions are “highly

selective” and only admit small numbers of U.S. students each year,

these schools would find it burdensome and not cost effective to meet

the terms of the provision.

• They also expressed concern that their pass rate performance, given

small numbers of test-takers, would misrepresent the quality of their

program if the school lost eligibility to participate.

1

Finding 4: Performance on Institutional Pass Rates

1. Education officials reported to us that they are proposing regulations that would make special provisions for foreign medical schools that

enroll small numbers of U.S. citizens.

Page 37 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

30

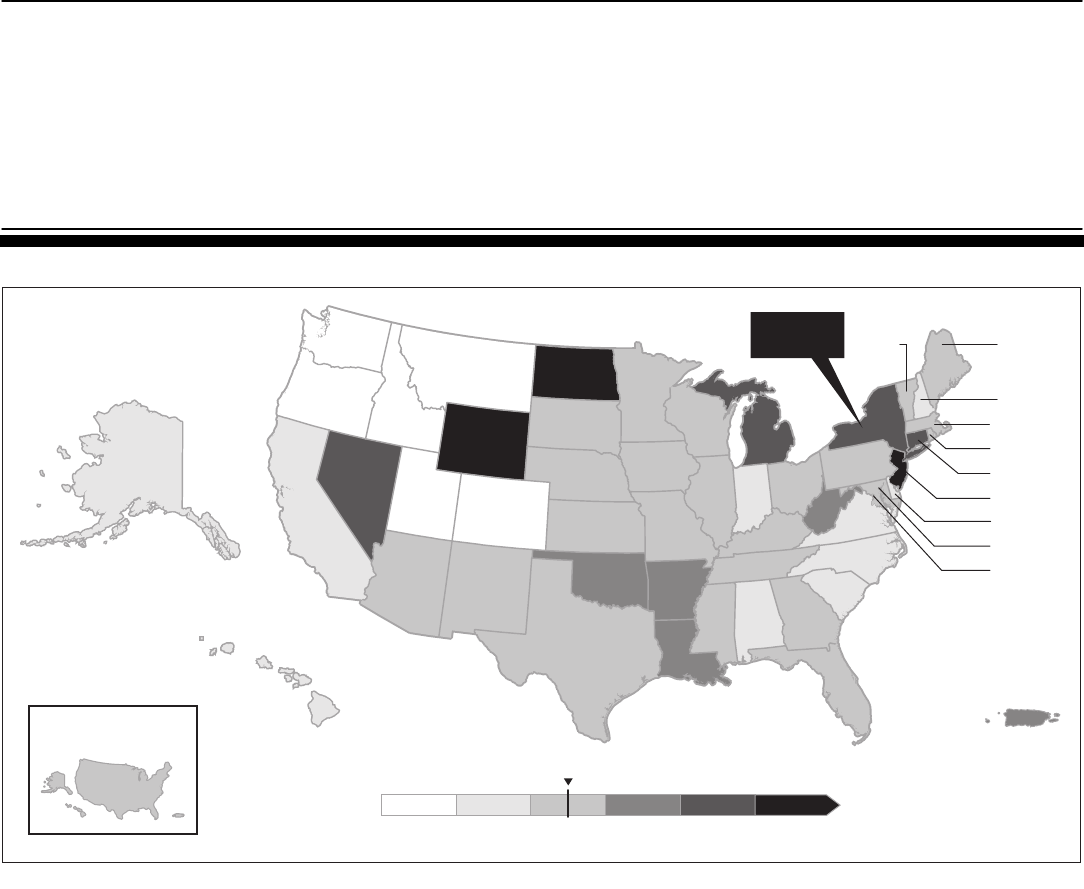

In 2008, a

bout 30,000 IMGs Were in Residencies in the U.S., with 78

Percent of All IMGs Located East of the Mississippi River and 24

Percent in New York Alone

Finding 5: Residencies and Practice

Source: GAO analysis of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) academic year 2008-2009 data.

Note: The geographic location of IMGs in residencies is partly determined by the availability of residency slots in the United States each year.

The map depicts geographic areas as defined by ACGME.

Page 38 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

31

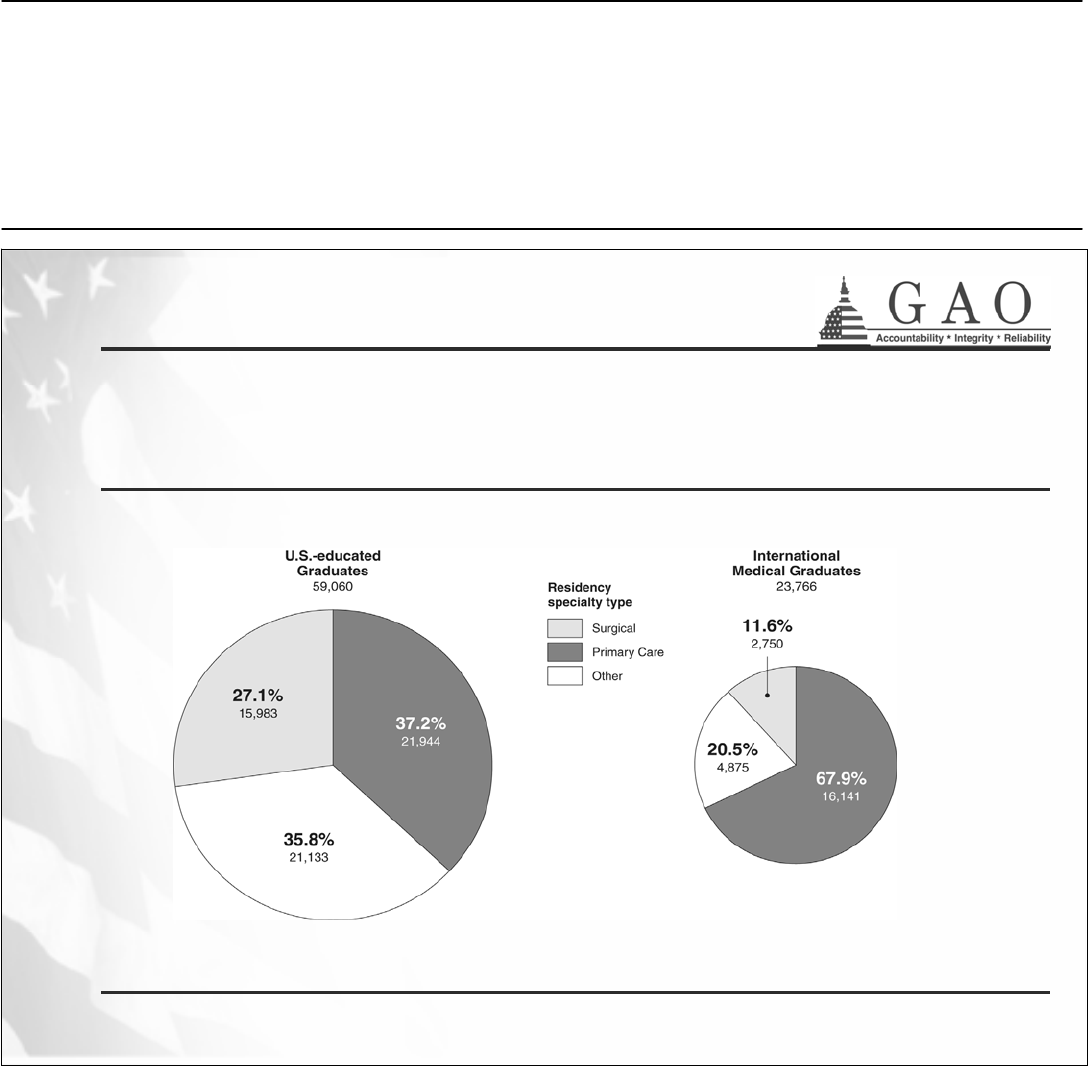

More IMGs than U.S.-Educated Graduates Go into Primary Care-

Related Residencies, And This Pattern Continues into Practice

Source: GAO analysis of ACGME data.

Note: The number of primary care residency slots is determined, in part, by funds available through Medicare payments to hospitals and other

teaching institutions.

Finding 5: Residencies and Practice

Number and percentage distribution of U.S.-educated graduates and IMGs in entry-level residencies,

academic year 2008-09

Page 39 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

32

After completing residencies, some IMGs practice medicine in medically underserved

areas, but it is not known to what extent they do so or whether they are more likely than

U.S.-educated graduates to serve in these areas.

• There are some programs designed to channel foreign physicians into

geographic areas with a shortage of health care professionals.

o The “Conrad 30” J-1 visa waiver allows physicians on Exchange Visitor

(J-1) visas to remain in the U.S. after completing residency, if they agree

to practice for at least three years in an area that is federally designated

as having a healthcare professional shortage.

o These waivers must be requested by a state or federal agency and states

can request such waivers in order to retain foreign physicians for such

designated areas.

Some IMGs Practice in Underserved Areas

Finding 5: Residencies and Practice

Page 40 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

33

Some IMGs Practice in Underserved Areas (continued)

Although J-1 visa waivers for foreign IMGs have been a federal and state

strategy to encourage physicians to practice in underserved areas, HHS,

which defines these areas and coordinates programs for addressing physician

shortages, does not officially collect data on waivers granted or on

placements for physicians who are granted waivers.

1

• According to one estimate, more than 700 foreign IMGs were awarded J-1

visas waivers in 2008 to practice in underserved areas.

2

1. GAO recommended in 2006 that HHS collect and maintain data on waiver physicians in order to better address physician shortages.

According to an official at HHS’ Health Resources and Services Administration, as of September 2008, no action had been taken by HHS

regarding this recommendation. See GAO,

Foreign Physicians: Data on Use of J-1 Visa Waivers Needed to Better Address Physician

Shortages,

GAO-07-52 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 30, 2006).

2. The Texas Primary Care Office surveys all states annually on their requests for J-1 visa waivers.

Finding 5: Residencies and Practice

Page 41 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

34

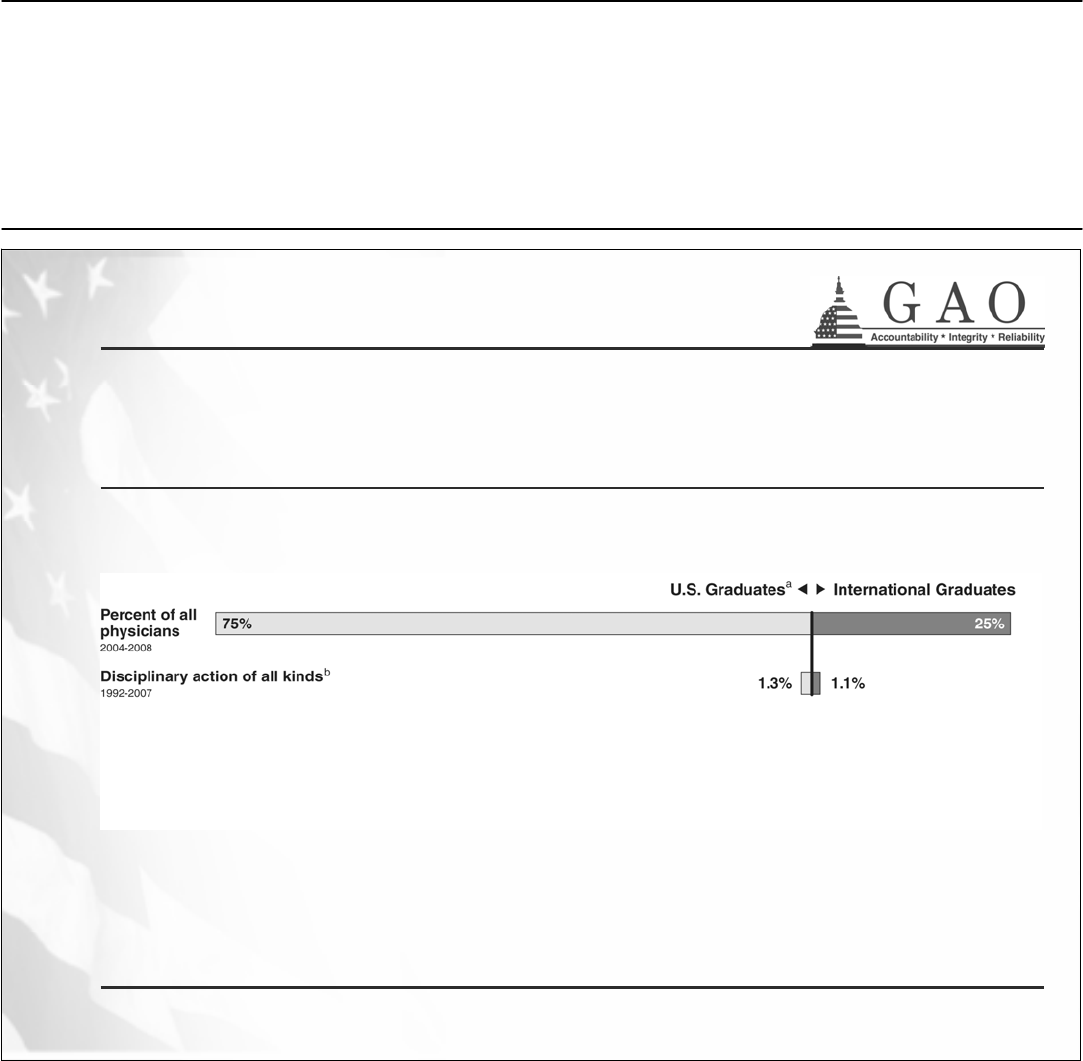

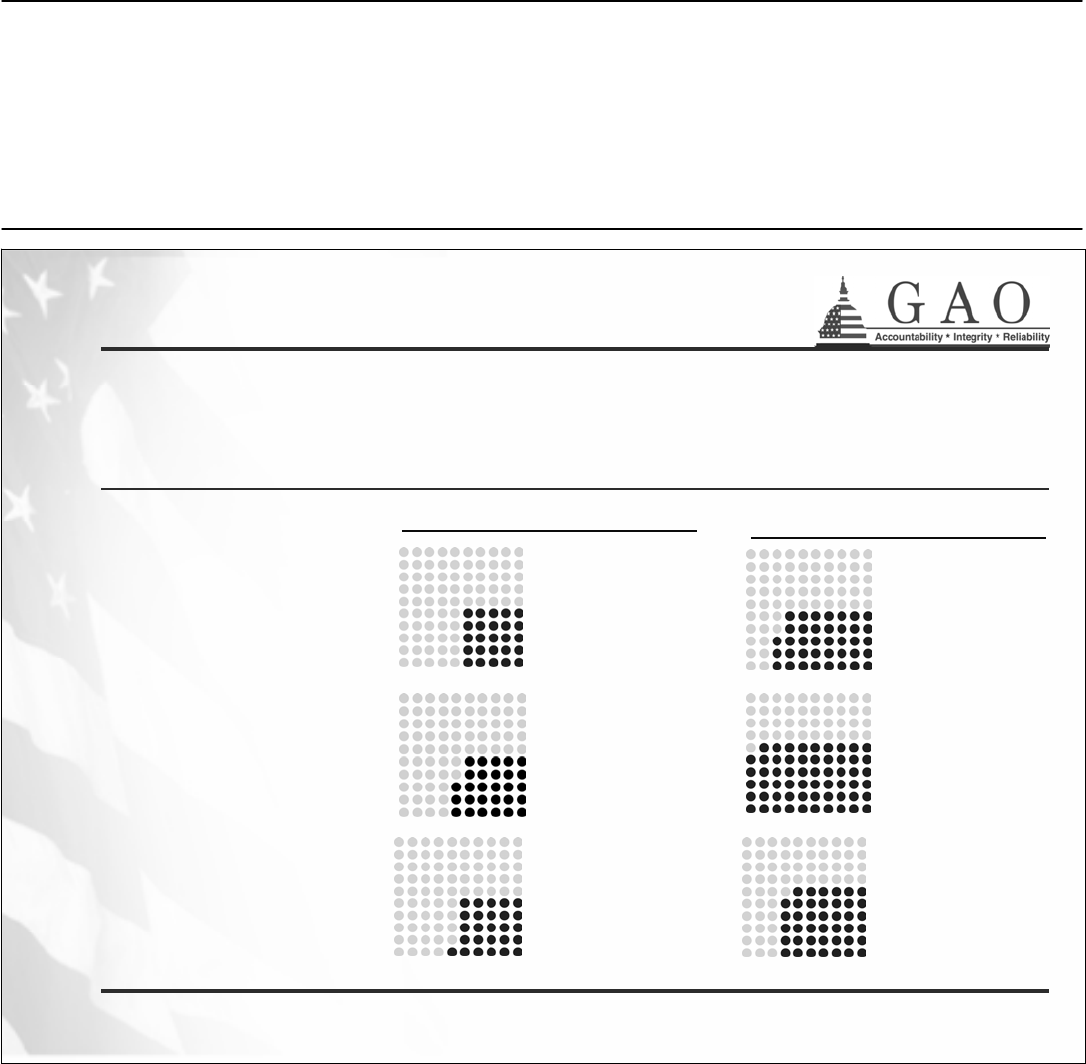

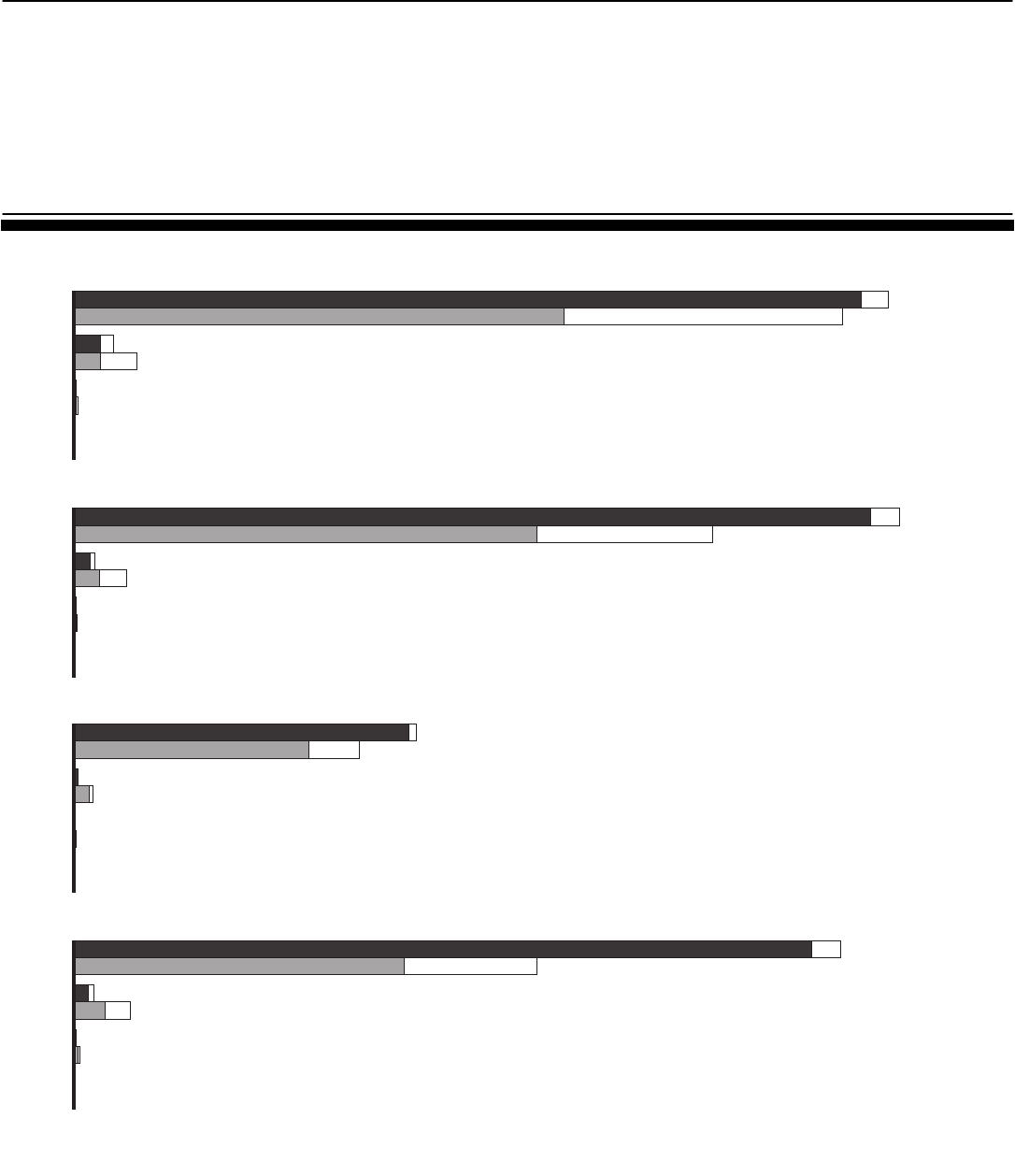

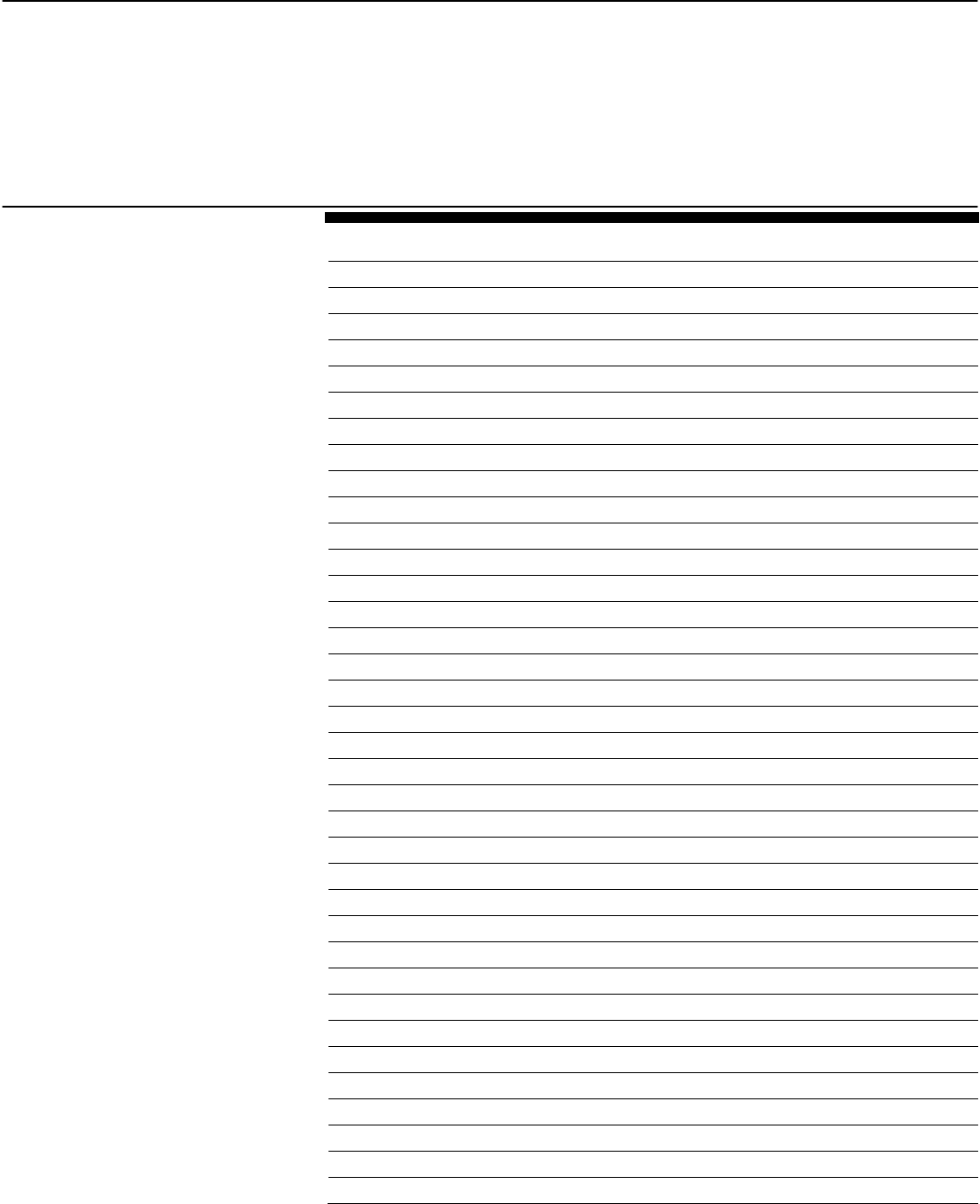

Rates of Disciplinary Action Are Low for Physicians Overall,

Both for IMGs As A Group And for U.S.-Educated Graduates

Finding 6: Discipline and Malpractice

Source: Data on percentage of all physicians by IMG and U.S.-educated status: American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Master File

data as analyzed and reported by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) for 2004 to 2008; discipline data: Federation of

State Medical Boards (FSMB) data prepared for the U.S. Department of Education for 1992-2007.

Notes: a) Canadian medical graduates are counted as U.S. medical graduates for all analyses.

b) “Disciplinary actions” includes license revocations, suspensions, restrictions, and other actions, though not malpractice cases.

Page 42 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

35

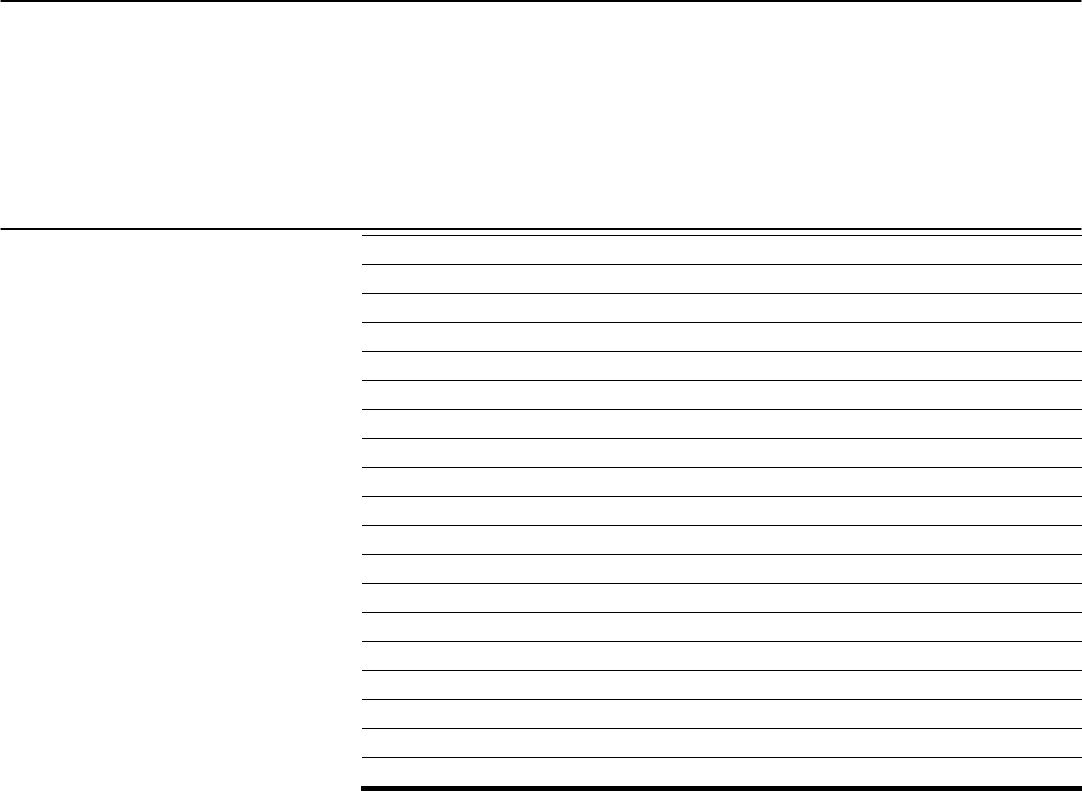

There Are No Significant Differences Nationwide with Regard to

License Revocation and Suspension

Finding 6: Discipline and Malpractice

Source: Data on percentage of all physicians by IMG and U.S.-educated status were obtained from AMA Physician Master File data as

analyzed and reported by the AAMC. License revocation and suspension data were obtained through GAO analysis of FSMB data.

Note: Canadian medical graduates are treated as U.S. medical graduates for all analyses.

National data on license

revocations and suspensions

for the most recent five years

with complete data show that,

while all IMGs represented

about one-quarter of all

physicians, they accounted for

a somewhat larger share of

these disciplinary actions.

These differences were not

statistically significant when

compared to the same

disciplinary actions experienced

by U.S.-educated physicians.

IMGs made up

25 percent of all

physicians in

the U.S. from

2004 to 2008…

… yet accounted

for 29 percent

of license

revocations …

…and

27 percent

of license

suspensions.

NATIONWIDE

(2004 to 2008)

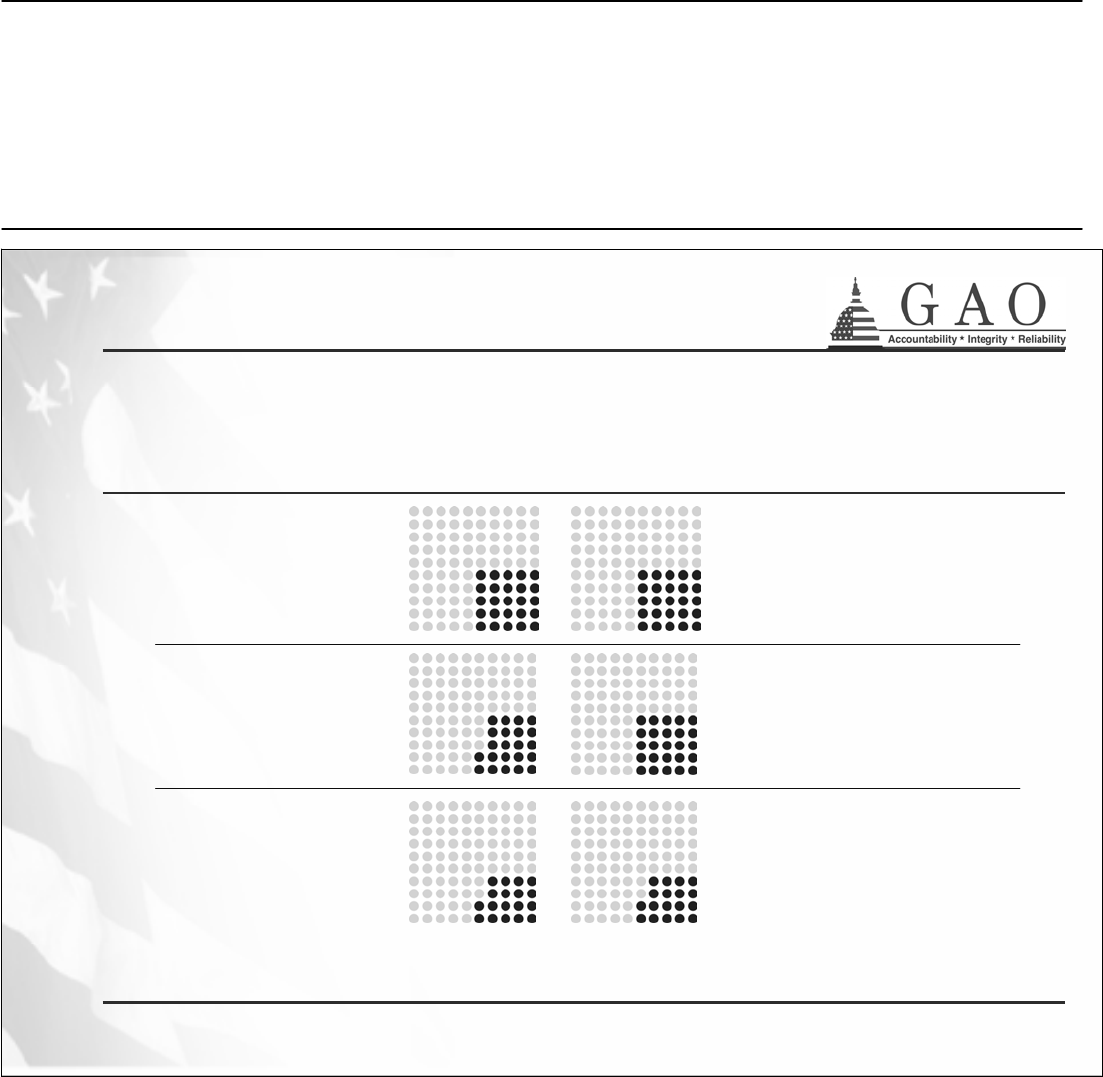

Page 43 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

36

Similarly, for Two Key States, There Are Few Significant

Differences

Finding 6: Discipline and Malpractice

Source: GAO analysis of state license revocation and suspension data, AMA Physician Master File data analyzed and reported by the AAMC.

Note: Canadian medical graduates are treated as U.S. medical graduates for all analyses.

Data from two states

with large numbers of

IMGs generally reflect

the national pattern.

However, our analysis

found significant

differences between all

IMGs and U.S.-

educated physicians in

Florida with respect to

license revocations.

State officials told us

they did not know the

reasons for these

differences.

IMGs made up 25

percent of

physicians from

2004 to 2008,

which is also the

US average…

… yet accounted

for 28 percent

of state license

revocations …

…and

26 percent

of the state’s

license

suspensions.

IMGs made up

38 percent of

physicians, which

is higher than the

U.S. average…

… yet accounted

for 59 percent

1

of state license

revocations …

…and

41 percent

of the state’s

license

suspensions.

CALIFORNIA

(2004 to 2008)

FLORIDA

(2004 to 2008)

1. Denotes a statistically significant difference.

Page 44 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

37

Nationwide, IMGs Did Not Account for A Disproportionate

Share of Malpractice Payments in 2004-2008

1

1. Our analysis of malpractice payments is generally consistent with prior work by GAO and others. See Medical Malpractice: Characteristics of Claims Closed in1984,

HRD-87-55, (Washington, D.C.: April 1987), and S. Mick and M. Comfort, “The Quality of Care of International Medical Graduates: How Does It Compare to That of

U.S. Medical Graduates?” Medical Care Research and Review, Dec. 1997.

2. U.S.-educated OB/GYNs were significantly more likely to have had a malpractice payment during this period than IMG OB/GYNs.

All Physicians

IMGs made up 25 percent

of all U.S. physicians from

2004 to 2008…

… and IMGs accounted for

25 percent of U.S. physicians

with reported multiple malpractice

payments from 2004 to 2008.

Surgeons

IMGs made up 22 percent

of all surgeons working in

the U.S. in 2007…

… and IMGs accounted for

25 percent of U.S. surgeons

with reported malpractice payments

from 2004 to 2008.

Obstetricians/

Gynecologists

IMGs made up 17 percent

of all OB/GYNs working in

the U.S. in 2007…

… and IMGs accounted for

18 percent

2

of U.S. OB/GYNs

with reported malpractice

payments from 2004 to 2008.

.

Finding 6: Discipline and Malpractice

Source: GAO analysis of data reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank.

Note: Percentages have been rounded to nearest whole percentage point. Canadian medical graduates are treated as U.S. medical graduates for all analyses. Malpractice

payments are payments made as a result of a settlement or judgment based on the provision or failure to provide health care services.

Page 45 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

38

Research on IMG Performance Is Limited

Few research studies have compared performance of IMGs with that of U.S.-educated

graduates beyond disciplinary actions, such as on their clinical processes and patient

outcomes.

1

• A 2004 study found IMGs were as likely as other physicians to follow

professional standards.

• A 1991 study found little difference in outcomes for mortality or length of

hospital stay for 16 different medical and surgical conditions.

• A 1990 study found that certain IMGs had higher rates of complications for a

particular surgical procedure.

In addition, a 2004 California study found that of three characteristics—age, gender,

and IMG status—IMG status had the weakest relationship to the likelihood of

professional discipline.

Finding 6: Discipline and Malpractice

1. These studies were among the most recently available research studies conducted on this subject.

Page 46 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

39

Conclusion

While only a very small proportion of all federally guaranteed student loans goes to U.S.

students to study medicine at foreign schools, it does not diminish the valuable role this

funding plays.

• For individual Americans, the loans represent the single most important avenue

available to finance their medical education—without which, they would not

become physicians.

• For the nation as a whole, these loans help assure a steady supply of the U.S.

physician workforce. The fact that foreign educated doctors, including U.S.

citizens, are more likely than their domestically educated peers to practice primary

care medicine fulfills an ever-increasing demand for such physicians.

However, in contrast to those pursuing a domestic medical education, U.S. students

seeking overseas study are at a considerable disadvantage as consumers, given the

absence of reliable information about foreign medical schools—such as their graduation

rates or cost. Yet, the Higher Education Opportunity Act emphasizes the importance of

consumer-based choices.

Page 47 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

40

Conclusion

For policymakers, meanwhile, Education has yet to fully enforce compliance with the

pass rate required for foreign medical schools to participate in the federal loan program

since verifiable data have not been available.

Moreover, while foreign medical schools may soon be able to negotiate access to their

students’ scores, it still remains to be seen whether a specific pass rate is a useful

measure of quality, and, until further evaluation, whether a pass rate of 75 percent is

appropriate.

• Our own analysis of exam scores by country suggests that the new pass rate

requirement may dissuade or even disqualify many schools from participating in

the loan program.

• Such an outcome, would, in turn, severely narrow the choices for U.S. students

who are prepared to undertake the long and difficult road to medical practice.

Page 48 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix I: Briefing Slides

41

Recommendations

To enhance information available for prospective students of foreign medical schools

and strengthen monitoring of foreign medical schools participating in the federal student

loan program, we recommend that the Secretary of Education:

• Collect consumer information, such as aggregate student debt level and

graduation rates, from foreign medical schools participating in the federal

student loan program as recommended by the National Committee on Foreign

Medical Education and Accreditation and make it publicly available to students

and their families;

• Require foreign medical schools to submit aggregate institutional pass rate data

to the Department annually;

• Verify data submitted by schools, for example by entering into a data sharing

agreement with the testing organizations;

• Evaluate the potential impact of the newly enacted 75 percent pass rate

requirement on school participation in the federal student loan program and

advise Congress on any needed revisions to the requirement.

Page 49 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix II: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Appendix II: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Our review focused on the following questions: (1) What amount of federal

student aid loan dollars has been awarded to U.S. students attending

foreign medical schools? (2) What do the data show about the pass rates

of international medical graduates on license examinations? (3) To what

extent does Education monitor foreign medical schools’ compliance with

the pass rate required to participate in the federal student loan program?

(4) What is known about schools’ performance with regard to the

institutional pass rate requirement? (5) What is known about where

international medical graduates have obtained residencies in the United

States and the types of medicine they practice? (6) What is known about

discipline and malpractice involving foreign educated physicians?

With regard to the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program,

program requirements allow only U.S. citizens, nationals, permanent

residents, and certain other eligible noncitizens to obtain these loans. In

view of this fact, our findings for the first objective were limited to U.S.

citizens, nationals, permanent residents, and certain other eligible

noncitizens who were also IMGs. By contrast, our findings pertaining to

the remaining objectives were based on all IMGs educated in medical

schools abroad, including those students who are U.S. citizens or residents

as well as students who are foreign nationals. For these objectives, we

included graduates of Canadian medical schools in the total population of

U.S. medical graduates. According to the body of literature we reviewed,

Canadian schools are generally not considered to be foreign medical

schools since their medical education system is closely comparable to that

of the United States. Similarly, we included graduates of Puerto Rican

medical schools in the total population of U.S. medical graduates because

medical schools in Puerto Rico are subject to the same accreditation

standards as other U.S. medical schools. In addition, our analyses

excluded students in and graduates of osteopathic programs because only

graduates of U.S. osteopathic schools are eligible to become licensed

physicians in the United States.

To determine the amount of federal student loan dollars borrowed abroad,

we analyzed the Department of Education’s loan data for all foreign

medical schools participating in the FFEL program between academic

years 1997-1998 and 2007-2008.

1

We also interviewed Education officials

Objectives

Defining International

Medical Graduates

Data Analysis by

Objective

1

These academic years were chosen because they coincide with reauthorizations of the

Higher Education Act of 1965.

Page 50 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix II: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

about participation in the FFEL program as it relates to foreign medical

schools and their graduates. To aid our discussion on this matter, we

adopted the use of the department’s nomenclature (i.e., free-standing

institutions and component institutions).

2

We reviewed relevant federal

laws and regulations that specify the conditions for compliance with the

FFEL program. To understand how determinations of medical

comparability are made for foreign countries and the impacts on

institutional eligibility, we also observed a meeting of the Department of

Education’s National Committee on Foreign Medical Education and

Accreditation during September 2009. This committee is charged with

reviewing the standards that foreign countries use to accredit medical

schools to determine whether those standards are comparable to those

used to accredit medical schools in the United States. If a country is

determined to have comparable medical accreditation standards (i.e.,

comparable countries), then accredited medical schools in that country

may apply to participate in the FFEL program. Throughout this report we

refer to the federal student loan program in our findings. Where our

findings are specific to the FFEL program, however, we refer to that

program by name.

To determine the performance of IMGs on licensing examinations, we

analyzed medical licensing examination trend data covering the period

1998 through 2008. We interviewed officials of the Educational

Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) and the National

Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) to better understand issues related

to licensing examination pass rates and international medical graduates.

We entered into an agreement with both of these institutions to obtain

their medical licensing examination data. To analyze student achievement

on medical licensing exams, we calculated pass rates by dividing the

number of test takers who passed an exam step by the number of test

takers who attempted this exam step in any given calendar year. We

excluded data from our analysis when information that identified country

and school location was missing. In addition, not all students who attend

foreign medical schools are allowed to sit for the exam. To the extent that

these students are not reflected in the total number of exam takers, our

findings may be overstated. We also interviewed external stakeholders

about factors that may affect IMGs’ pass rates on the licensing exam. In

2

According to Education’s definition, free-standing institutions are schools whose principal

offering is medical education in contrast to component medical schools that are part of a

larger university system.

Page 51 GAO-10-412 Foreign Medical Schools

Appendix II: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

addition, we reviewed literature on IMGs’ performance on the U.S. medical

licensing exam. We also obtained information at selected foreign medical

schools from administrators and students about efforts to prepare

students for the medical licensing exam.

To assess Education’s monitoring of foreign medical schools’ compliance

with the licensing examination pass rate requirement, we interviewed

Education officials about their monitoring activities and reviewed