Overcoming the challenges of informal economic activity requires a combination of policies

tailored to economy-specific circumstances. In countries where informality is predominantly a

reflection of poor governance, an appropriate policy package could streamline regulatory and

tax frameworks while improving the efficiency of public revenue collection and regulatory

enforcement as well as strengthening public service delivery to bolster tax morale. In countries

where informality is predominantly a reflection of underdevelopment, an appropriate policy

package could include measures to expand access to finance, markets, and inputs to foster firm

productivity and growth; better education to facilitate formal sector employment; and

enhanced safety nets to cushion household risks. Several such policy improvements have been

associated with sustained declines in informality.

Introduction

Widespread informality is a common policy challenge in emerging market and

developing economies (EMDEs). Theoretical models present two major reasons for the

emergence of informal economic activity: lack of development (Harris and Todaro 1970;

Loayza 2016) and poor governance (de Soto 1989). These two reasons suggest different

policy approaches to address informality. The former refers to factors such as an inability

of an urban, modern, formal sector to absorb rural migrants; limited financial

development to provide finance for formal sectors; and insufficient human capital that

prevents workers from finding jobs in the formal sector.

1

The latter refers to factors such

as excessively burdensome tax and regulatory frameworks that encourage firms to remain

informal, excessive labor regulations that increase the cost of formal employment, and

poor governance and regulatory quality that discourage formal participation (chapter 2).

The former reason emphasizes the inability to benefit from participating in the formal

sector, whereas the latter emphasizes the costs associated with formal-sector

participation.

2

Many EMDE governments have implemented a wide range of policy reforms in the past

few decades that may have helped to reduce informality (figure 6.1; Jessen and Kluve

2021).

3

These reforms have often been implemented to either increase the benefits of

CHAPTER 6

T

ackling Informality: Policy Options

Note: This chapter was prepared by Franziska Ohnsorge and Shu Yu. Research assistance was provided by

Hrisyana Doytchinova and Lorez Qehaja.

1

See, for example, Amaral and Quintin (2006); Fields (1975); Harris and Todaro (1970); and Loayza (2016).

2

See Loayza (2018); Oviedo, Thomas, and Karakurum-Özdemir (2009); and chapter 2 for a review of costs and

benefits associated with formal (informal) sector participation and how optimizing participants may choose formality

(or informality).

3

Some of these reforms had their roots in the “Washington Consensus” (Birdsall, de La Torre, and Caicedo

2010; Naim 1999; Williamson 2000).

258 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

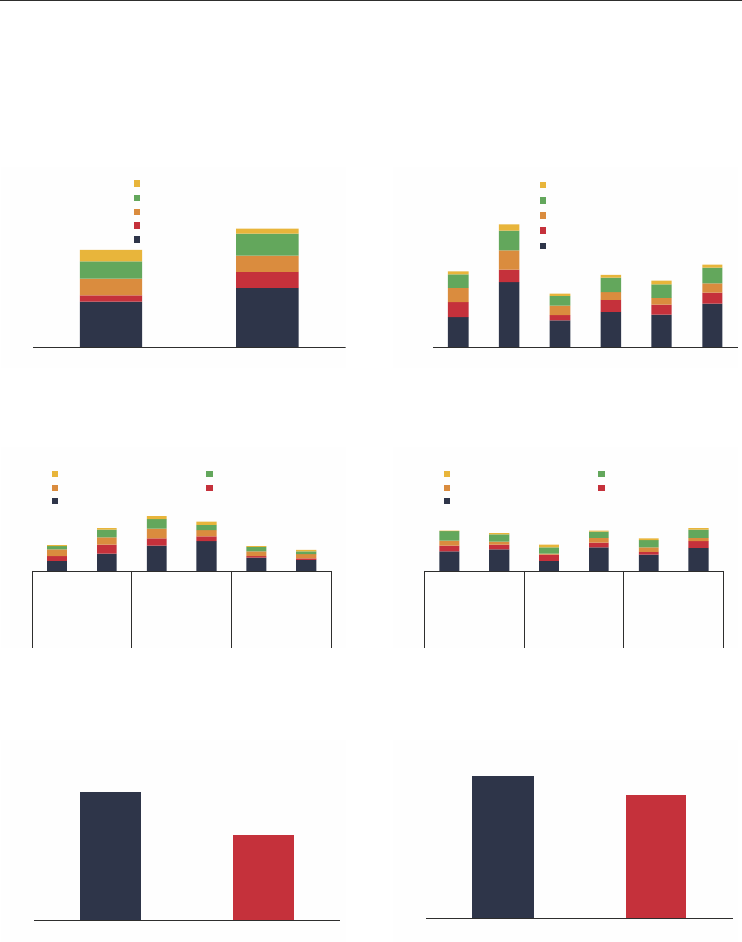

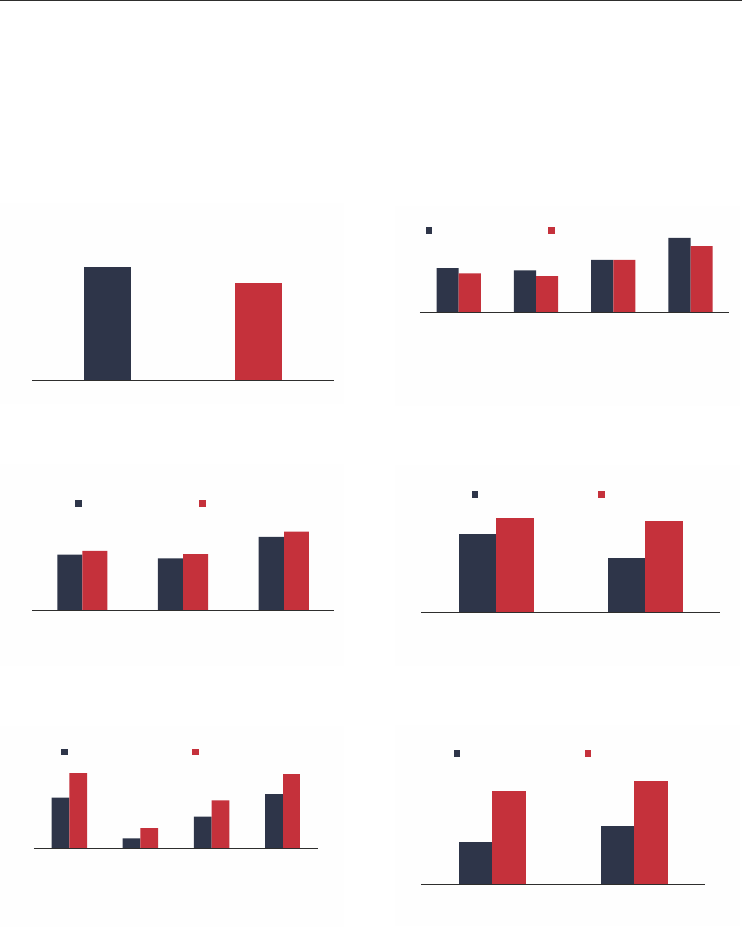

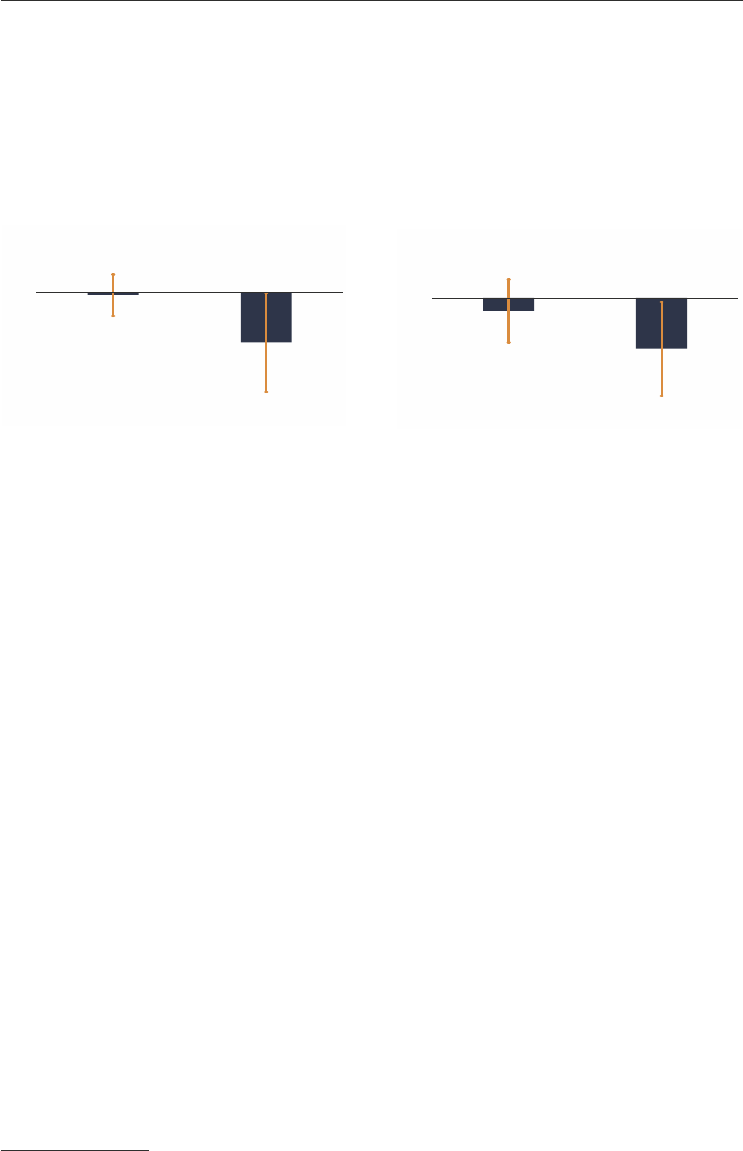

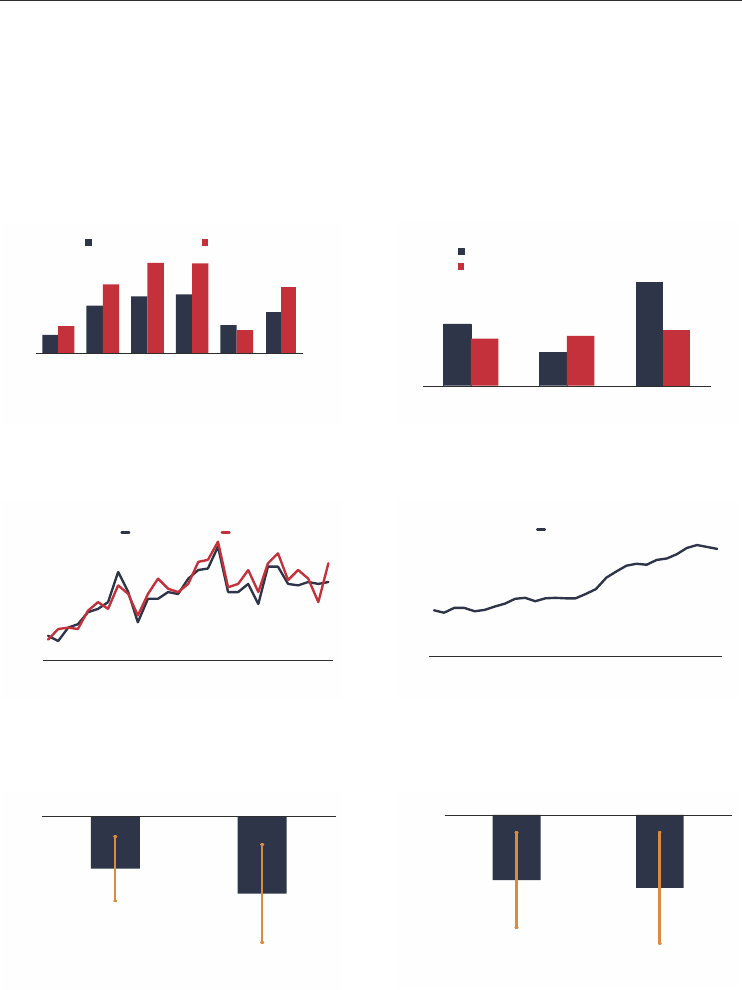

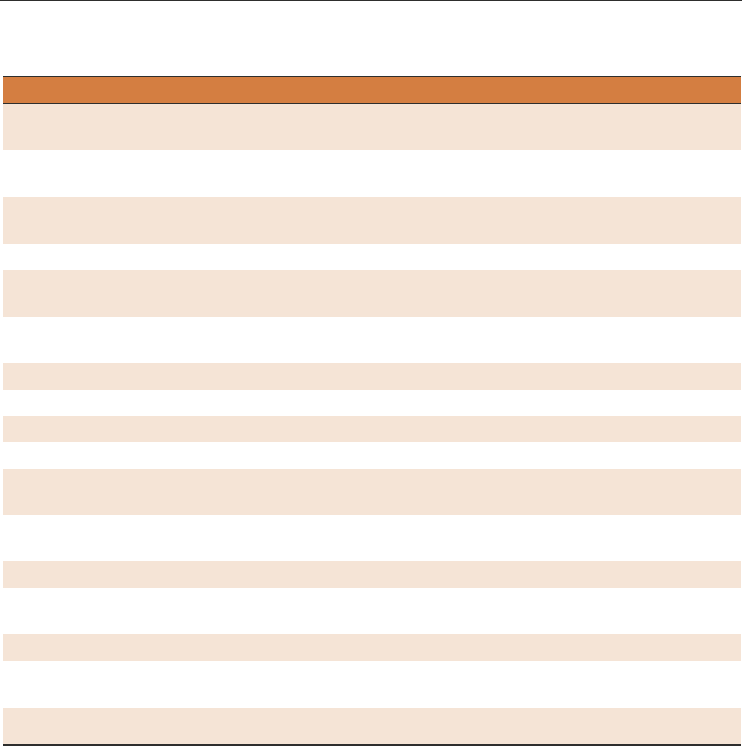

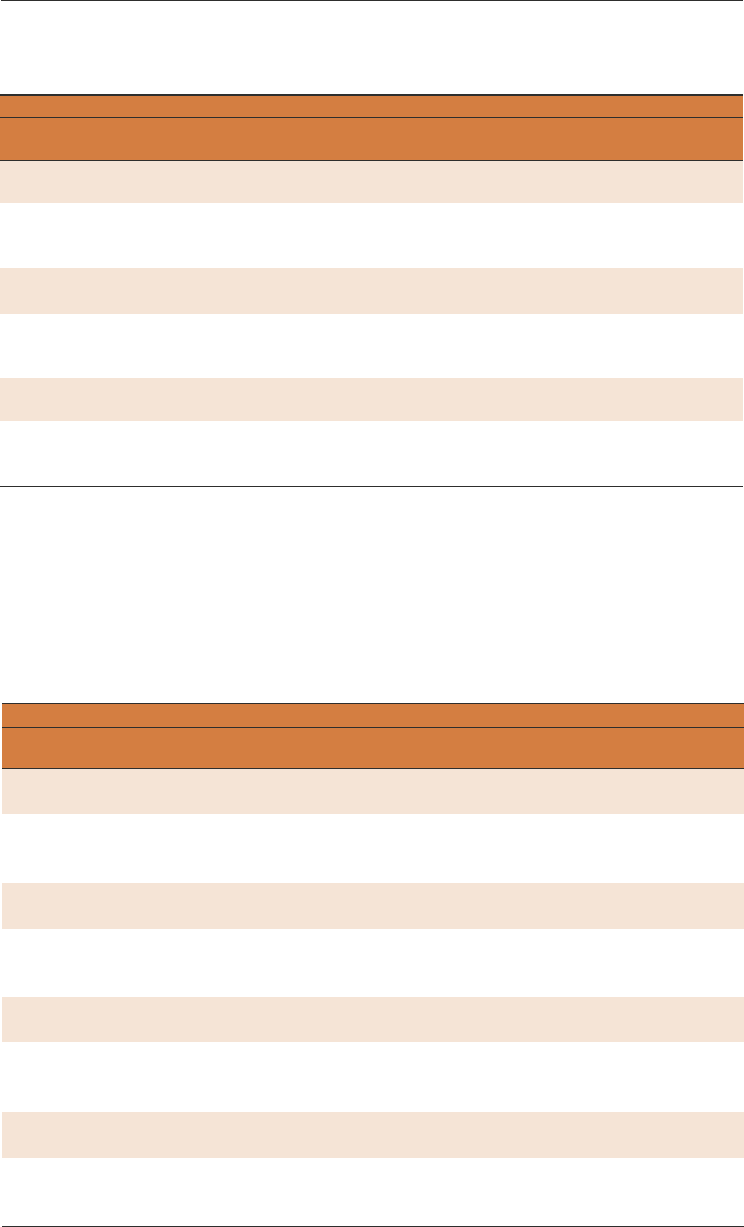

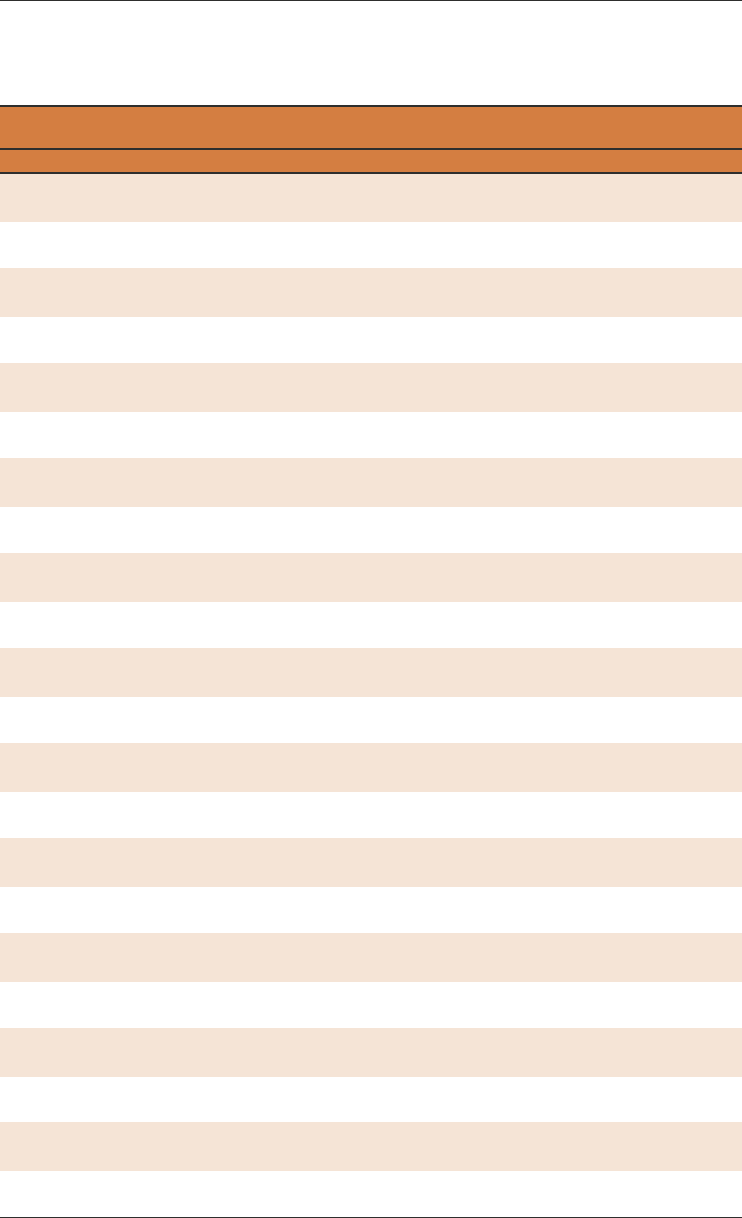

FIGURE 6.1 Policies to address challenges of informality in EMDEs

Governments have implemented a wide range of reforms that could affect informality.

B. Reforms across EMDE regions A. Reforms in advanced economies and EMDEs

Sources: International Country Risk Guide (ICRG); World Bank (Doing Business).

Note: See World Bank Doing Business database for reform details. EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia;

EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MNA = Middle East and North Africa;

SAR = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa.

A.B. For an average economy, the number of policy reforms that have been implemented after year 2008 and are regarded as

“improvement” in the ease of doing business or “neutral” (which applies only to “labor market regulation”) by Doing Business 2008-18.

C.D. For an average economy, the average number of policy reforms per year that have been implemented during 2008-10 in

comparison to the annual average number of reforms conducted during 2016-18 (shown in bars).

E.F. Bars show the shares of economies with improved control of corruption (in E; the ease of doing business in F) between 2010 and

2018.

D. Reforms by EMDE region, 2008-18 (continued) C. Reforms by EMDE region, 2008-18

F. Economies with improvement in the ease of

doing business

E. Economies with improvement in control of

corruption

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

EAP

ECA

LAC

MNA

SAR

SSA

Labor market regulation

Starting a business

Paying taxes

Getting credit

Other reforms

Number of reforms

0

1

2

3

4

2008-10

2016-18

2008-10

2016-18

2008-10

2016-18

EAP

ECA

LAC

Lab mkt regulation Starting a business

Paying taxes Getting credit

Other reforms

Number per year

0

1

2

3

4

2008-10

2016-18

2008-10

2016-18

2008-10

2016-18

MNA

SAR

SSA

Lab mkt regulation Starting a business

Paying taxes Getting credit

Other reforms

Number per year

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Advanced economies

EMDEs

Percent of economies

0

20

40

60

80

Advanced economies EMDEs

Percent of economies

0

5

10

15

20

Advanced economies

EMDEs

Labor market regulation

Starting a business

Paying taxes

Getting credit

Other reforms

Number of reforms

C H A P T E R 6 2

59 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

formal-sector participation or reduce the costs of formal activity. For instance, both

corporate and personal income tax rates in EMDEs have been reduced, from 37-39

percent on average in the early 1990s to about 24 percent in 2019 (Végh and Vuletin

2015). Time spent on paying taxes was cut by about one-third in EMDEs between 2006

and 2020. Value added taxes, which can lower tax burdens through a refund on input

taxes, had been adopted in 71 EMDEs by 2020 (World Bank 2020a). Access to

financial services has broadened, with access to automatic teller machines (ATMs) per

100,000 adults and the share of the population with an account at a financial institution

both increasing by more than 50 percent between 2010 and 2018. Over the same

period, one-third to two-thirds of EMDEs improved their governance and institutional

quality.

A review of past policy reforms indicates that some reforms had unintended

consequences for informality. Policy reforms often had more benign effects on

informality when they were implemented in a supportive institutional and

macroeconomic environment. For instance, trade liberalization programs were often

associated with greater informality in the short term—unless they were accompanied by

greater labor market flexibility and an upgrading of skills in the labor force (Goldberg

and Pavcnik 2003; McCaig and Pavcnik 2015; World Bank 2019b).

The current pandemic has provided a reminder of the developmental challenges posed

by the informal sector. Informal participants have suffered more adverse economic and

health consequences from COVID-19 (coronavirus) than their formal counterparts (box

2.1). The untapped potential of informal sectors, if harnessed to boost income growth

and resilience, can help EMDEs build back better from the severe global recession of

2020. This is especially important against the backdrop of a steady decline in potential

growth, the growth an economy can sustain at full employment and capacity, over the

past decade as all fundamental drivers of growth weakened (World Bank 2018a, 2020b).

Specifically, this chapter addresses the following questions:

• Which fiscal measures can help reduce informality?

• Which other policies can help reduce informality?

• What should be the elements of a comprehensive policy package to tackle

informality?

Contributions. The chapter makes the following contributions to the literature. First, it

offers a systematic review of policies that could affect informality, ranging from fiscal

policies to labor market regulations and policies to encourage financial development. It

covers both policies that are intentionally designed to encourage formalization and ones

that could incidentally affect the informal sector.

Second, the chapter describes novel empirical estimates of the cumulative changes in

informality following various policy changes, obtained using a local projection model.

Policy-related variables examined include tax rates, access to credit by the private sector,

2

60 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

Financial development reduces the costs of accessing external financing and thus

incentivizes firms and households to invest, including in higher-productivity projects.

It also incentivizes participants of the informal sector to join the formal sector. In

emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) with above-median

informality, a significantly larger share of firms relies on internal finance and

identifies access to finance as a major business obstacle than in EMDEs with below-

median informality. Also, in EMDEs with more prevalent informality, a significantly

smaller share of households has access to commercial bank branches, automated teller

machines (ATMs), and credit. Over the past three decades, growing access to financial

services and credit has coincided with a falling share of the informal economy.

Introduction

In recent decades, much research has been devoted to understanding the

determinants of informal economic activity, including the role of financial

development (Loayza 2018; Ulyssea 2020). Financial development can influence

firms’ and individuals’ choices to engage in informal activity and may also,

conversely, be affected by the level of informality (for instance, Capasso and

Jappelli 2013; Elgin and Uras 2013; Straub 2005). Easier access to non-cash-

based payments—whether via mobile phones, cards, or online—can improve the

government’s ability to reach and support informal participants during a

recession like COVID-19 (World Bank 2019c).

a

Firms in the informal sector are typically characterized by small scale, low capital-

to-labor ratios, lack of investment, a low propensity to implement new and even

high-return technologies, and unskilled managers (Capasso and Jappelli 2013;

Dabla-Norris, Gradstein, and Inchauste 2008; Quintin 2008). By influencing

firms’ behavior, financial development can encourage capital accumulation and

productivity improvements, and thus enhance long-run economic growth,

particularly in the presence of informality (Antunes and Cavalcanti 2007).

Against this background, this box addresses the following questions:

• What links between informality and financial development have been

identified by the literature?

• How does financial development differ between EMDEs with high and low

informality?

• How has financial development in EMDEs evolved?

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

Note: This box was prepared by Salvatore Capasso, Franziska Ohnsorge, and Shu Yu.

a. Also see Fang, Kennedy, and Resnick (2020) for detailed examples.

C H A P T E R 6 2

61 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

The box examines the nexus between financial development and informality both

theoretically and empirically. It first provides a short literature review on the

channels through which limited financial development can encourage

informality, followed by a summary of existing empirical evidence. It then uses

both descriptive statistics and regression analysis to show that greater informality

is associated with less financial development, and that better access to finance is

associated with lower informality. The conclusion offers policy recom-

mendations.

Lessons from the literature

Theoretical models suggest that financial development reduces informality,

whereas the existence of informality could also hinder financial development.

Such theoretical findings are supported by empirical studies.

Theoretical models. As informal participants hide all or part of their income and

wealth from the authorities, they face high costs of providing collateral or

signaling their profitability to lenders and are often credit-rationed (Blackburn,

Bose, and Capasso 2012; Capasso and Jappelli 2013). The choice of operating

formally or informally thus involves a trade-off between higher financial costs, as

well as restricted access to public goods, and the benefits of lower tax and

regulatory burdens (Franjo, Pouokam, and Turino 2020; Straub 2005). This

trade-off can be faced at the level of the firm or household (extensive margin) or

at the level of individual transactions within a firm (intensive margin).

Theory predicts that, as financial markets develop, the size of the informal sector

will decrease. Financial development, which involves innovations ranging from

the emergence of new and more efficient monitoring and screening technologies

to more intermediated funds, typically reduces the average costs of accessing

financial resources and incentivizes firms and entrepreneurs to operate formally.

Several mechanisms have been explored.

• Lower collateral requirements. By improving screening and monitoring

technologies, financial development will tend to reduce the minimum

collateral required for borrowing, which will tend to attract entrepreneurs

into the formal sector (Straub 2005).

• Stronger legal enforcement. By strengthening financial contract enforceability,

financial development can lower credit costs, which will also tend to attract

entrepreneurs into the formal sector (Amaral and Quintin 2006; Antunes

and Cavalcanti 2007; Quintin 2008).

2

62 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

• Expanding pool of formal finance. By expanding the pool of formal-sector

funding, financial development can lower the relative cost of formal finance

and attract entrepreneurs into the formal sector (Blackburn, Bose, and

Capasso 2012; Capasso and Jappelli 2013).

• More efficient tax auditing. Financial development can facilitate the

enforcement of tax compliance, which is likely to discourage informal

activity (Guo and Hung 2020).

Conversely, some studies point to informality as holding back financial

development, through several channels.

• Tax evasion. Tax evasion, which is often at the core of informality, erodes

government revenue bases. Countries with pervasive tax evasion have often

used financial transaction taxes to boost revenues. These taxes increase

financial intermediation costs and may slow financial development (Elgin

and Uras 2013; Roubini and Sala-i-Martin 1992, 1995).

• Higher bank monitoring costs. Where informality is prevalent, the lack of

formal, declared incomes and assets may force banks to incur higher

screening and monitoring expenses. This raises borrowing costs (Capasso,

Monferrà, and Sampagnaro 2015).

Empirical evidence. Several measures of financial development have been found

to be statistically significantly associated with smaller informal activity

(Bittencourt, Gupta, and Stander 2014; Bose, Capasso, and Wurm 2012; Gatti

and Honorati 2008). The empirical association has been robust to different

model specifications and estimation methodologies (See table 6B.1 for a detailed

summary).

• Firm-level evidence. Firms that rate financing as a major obstacle to their

businesses have, on average, a 16 percent probability of hiding at least 50

percent of their sales, whereas this probability drops below 6 percent for

firms that consider financing to be a minor obstacle (Dabla-Norris,

Gradstain, and Inchauste 2008). More tax-compliant firms have reported

significantly easier access to credit, and this relationship was stronger in more

formalized economies (Gatti and Honorati 2008).

• Household-level evidence. Italian households reported greater informal activi-

ty, especially in the construction sector, in regions with weaker financial

development (Capasso and Jappelli 2013).

• Cross-economy evidence. Among 137 economies during 1995-2007, both

greater efficiency and depth of the banking sector were associated with

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

C H A P T E R 6 2

63 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

significantly lower informality (Bose, Capasso, and Wurm 2012). Among

150 economies during 1980-2009, faster broad money growth and a smaller

differential between lending and deposit interest rates were associated with

statistically significantly smaller informal economies, even when controlling

for institutional quality and central bank independence (Bittencourt, Gupta,

and Stander 2014).

b

Stylized facts

Firms and workers in the informal sector have less access to credit and financial

services in EMDEs with above-median informality than in EMDEs with below-

median informality.

Methodology and data. A sample of 122 EMDEs for 1990-2018 (or the latest

available year) is split into those with above-median and below-median shares of

informality by output (as proxied by the dynamic general equilibrium model-

based share of informal output in official gross domestic product [GDP]) and

employment (proxied by the share of self-employment in total employment).

c

Financial development is proxied, first, by firms’ reported access to bank credit

and capital markets, their difficulty in accessing credit, and the share of internal

finance used in investment. Second, at the household level, financial

development is proxied by the number of commercial bank branches, ATMs, and

bank credit as well as account ownership and reported use of mobile payment

services. Data are available from World Bank Enterprise Surveys, the World

Bank’s Global Financial Development Database, and the World Development

Indicators. In addition, the International Monetary Fund’s Financial

Development Index and its subcomponents are used as proxies for overall

financial development and for development in “financial institutions” and

“financial markets.”

d

Simple averages of the financial development indicators for

EMDEs with above-median informality and those with below-median

b. Several studies have found nonlinear relationships between informality and financial development.

The impact of financial development on informality is greater in more financially developed economies or

when GDP exceeds a certain level (Canh and Thanh 2020; Gharleghi and Jahanshahi 2020) or may even

be inverse-U-shaped (Elgin and Uras 2013).

c. The results from output informality and employment informality are largely consistent. This box

mainly relies on results from output informality.

d. The “financial markets” development index captures access to, and depth and efficiency of, an

economy’s stock and debt markets, which is less relevant for informal participants in EMDEs. The

“financial institutions” development index measures how developed financial institutions are in terms of

their depth (size and liquidity), access (ability of individuals and companies to access financial services),

and efficiency (ability of institutions to provide financial services at low cost and with sustainable

revenues).

2

64 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

informality (grouped above) are tested for statistically significant differences.

There is no presumption of causality going either from financial development to

informality or vice versa.

Firms. Firms in the informal sector have reported more restricted access to credit

from the banking sector and capital markets, which limits their ability to invest,

including in productivity-enhancing new technologies (Capasso and Jappelli

2013; D’Erasmo 2016; Ferreira-Tiryaki 2008). In EMDEs with above-median

output informality, on average, 36 percent of firms identified access to finance as

a major constraint—about 9 percentage points more than in other EMDEs

(figure B6.1.1). Firms also rely more on internal finance for operating, starting,

or expanding firms in EMDEs with more pervasive informality (Farazi 2014).

On average in EMDEs with above-median informality, 75 percent of firms

depend on internal finance to invest and 19 percent of firms can use bank funds

to fulfill their investment needs, compared with 68 percent and 29 percent of

firms, respectively, on average in EMDEs with below-median informality.

Households. Households in EMDEs with below-median informality have access

to significantly more commercial bank branches, ATMs, and credit than those in

EMDEs with above-median informality (figure B6.1.1). About 50 percent of the

population in EMDEs with below-median informality owns an account at a

financial institution or recently used a mobile money service—about 17

percentage points more than in EMDEs with above-median informality.

Evolution of financial development and its implications

EMDE financial systems have deepened and financial access has broadened over

the past three decades. This has coincided with a steady decline in the shares of

informal output and employment.

Methodology. A local projection model is used to estimate the cumulative

changes in the share of informal output or informal employment over one to five

years following a shift in financial development (annex 6A). Two dimensions of

financial development that are particularly relevant for informal participants are

examined. The first is the ability of individuals and companies to access financial

services, which is proxied by the number of commercial bank branches per

100,000 adults. The second dimension, financial system depth, is proxied by

domestic credit to the private sector in percent of GDP (Svirydzenka 2016;

World Bank 2020c). The estimation controls for per capita GDP. The sample

covers 125 EMDEs over 1990-2018.

Financial development in EMDEs. Measures to improve access to credit have

been a common policy reform in East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

C H A P T E R 6 2

65 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

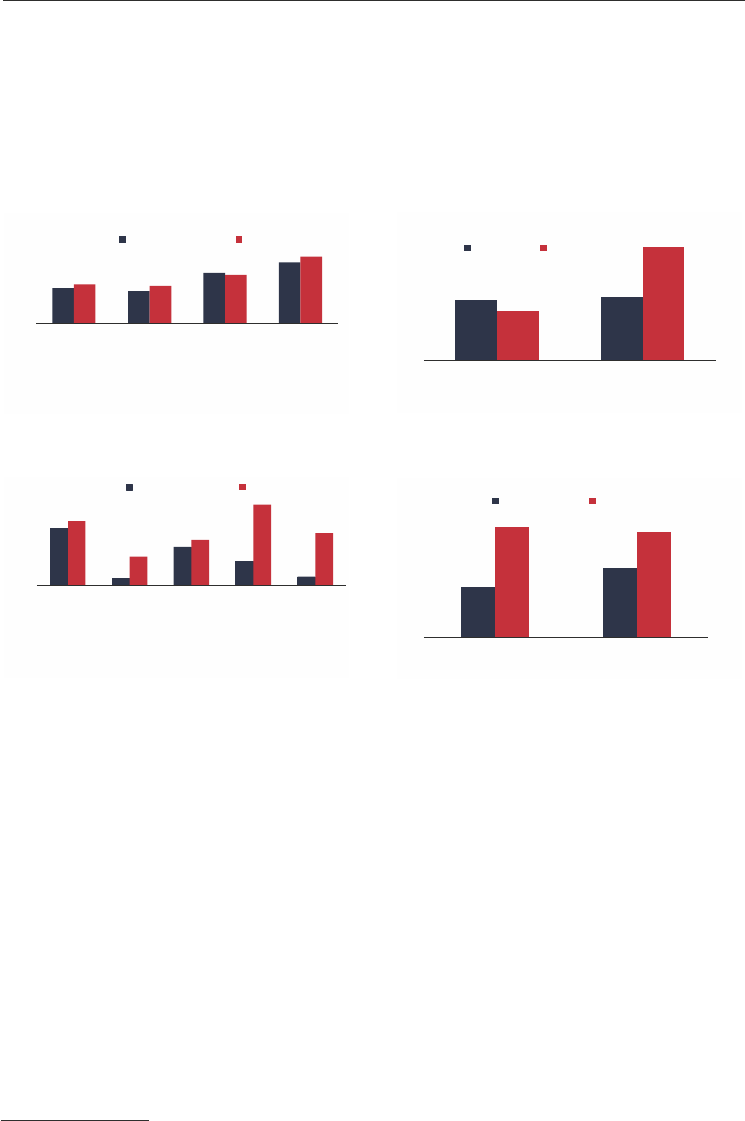

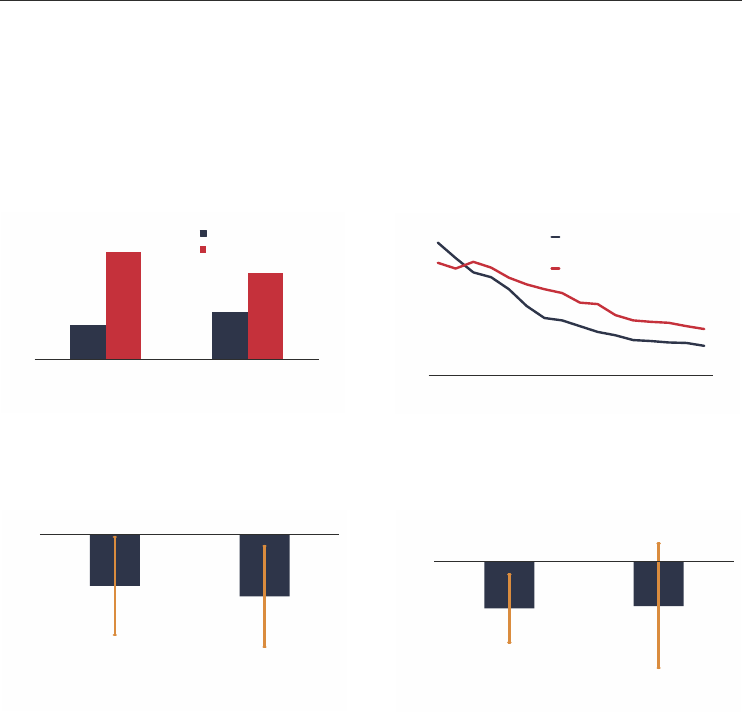

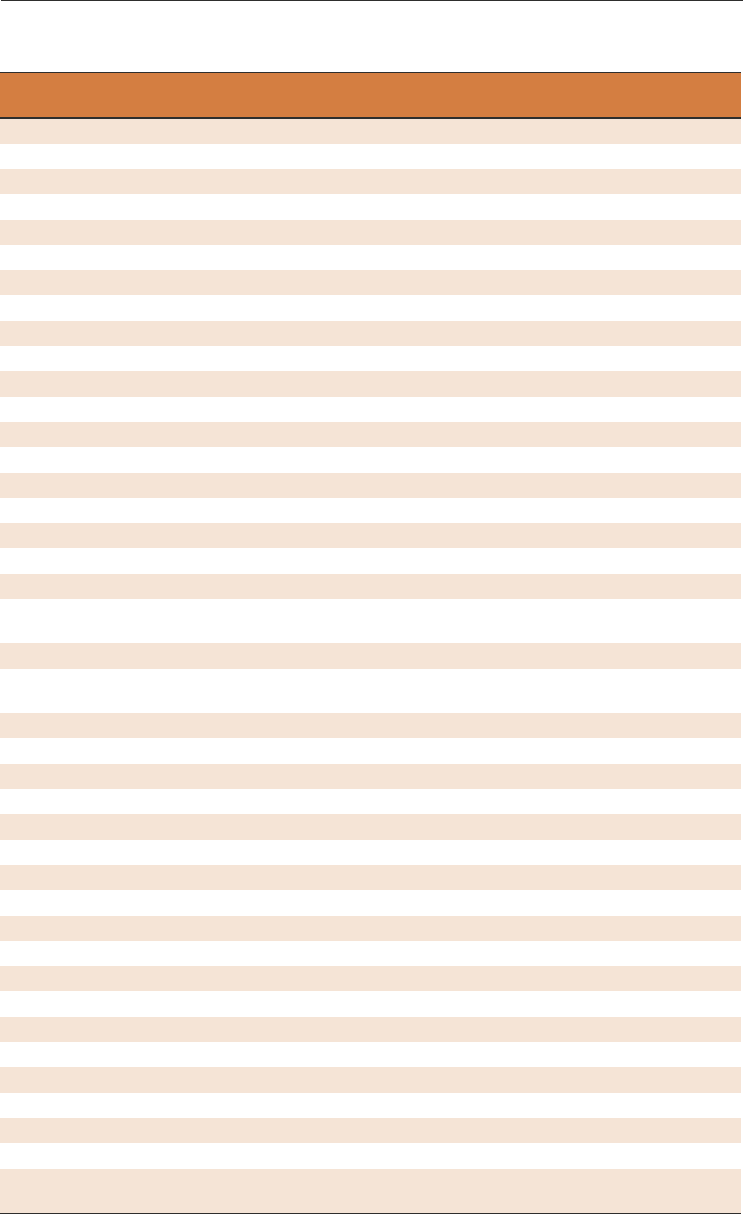

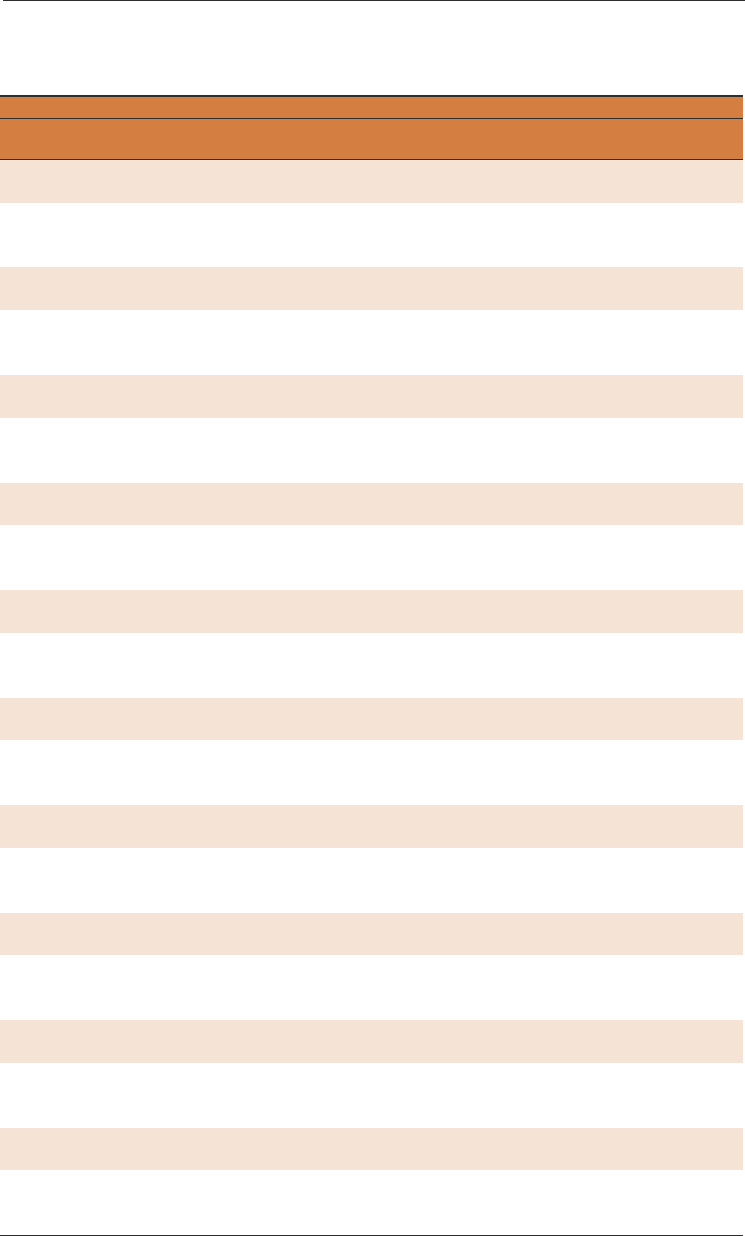

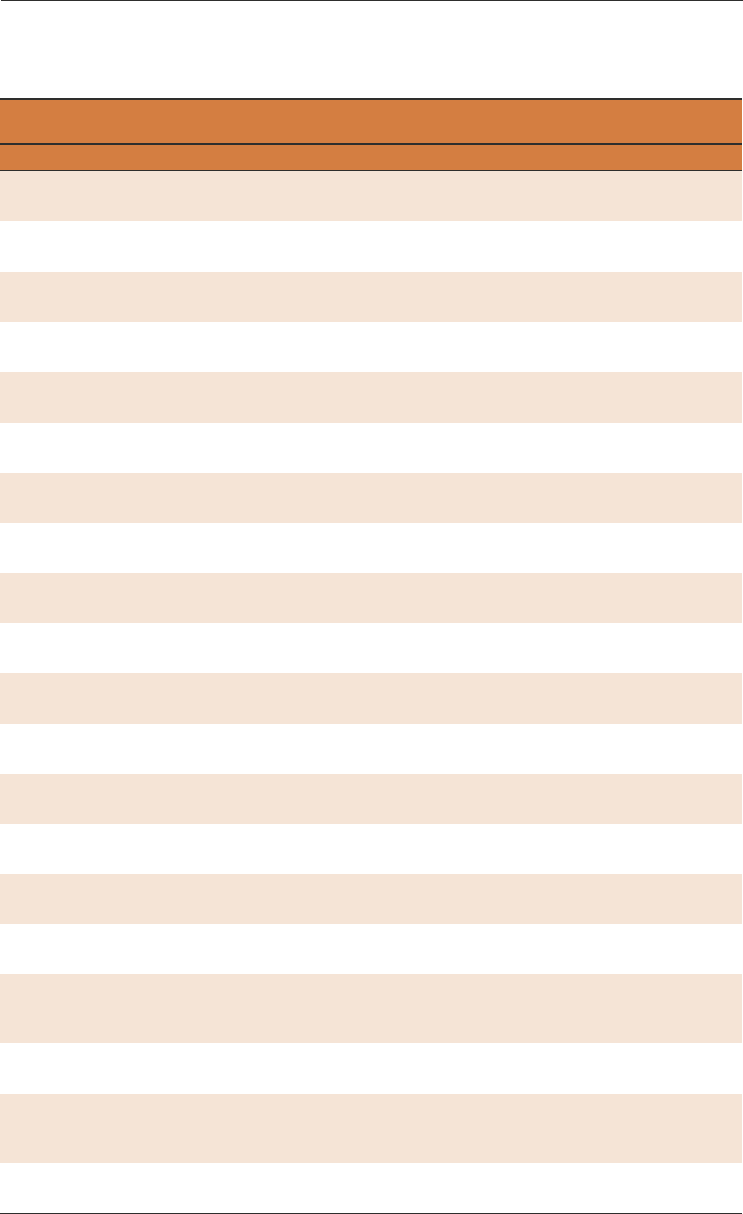

FIGURE B6.1.1 F

inancial development and informality in EMDEs

Firms and workers in EMDEs with more pervasive informality are more likely to be

financially constrained, less likely to obtain bank finance, and more likely to have

limited access to other financial services than those in EMDEs with less pervasive

informality. As a result, firms in EMDEs with more pervasive informality rely more on

internal financing.

B. Financing options facing firms A. Financial constraint facing firms and

informality

Sources: International Monetary Fund (Financial Development Index Database); World Bank (Enterprise Surveys,

Global Financial Development Database, World Development Indicators).

Note: Data are from EMDEs and the period 1990-2018. Output informality is measured by DGE-based estimates on

informal output (in percent of official GDP). Employment informality is proxied by self-employment in percent of total

employment. In A-D, *** denotes that the group differences are not zero at 10 percent significance level. “High

informality” (“Low informality”) are EMDEs with above-median (below-median) DGE-based informal output measure

(or employment informality proxied by self-employment shares) over the period 2000-18 (2010-2018 in C-D). ATM =

automated teller machine; DGE = dynamic general equilibrium model; EMDEs = emerging market and developing

economies; IMF = International Monetary Fund; RHS = right-hand side.

A.B. Bars are simple group means using data from latest year available for EMDEs with “high informality” and those

with “low informality.” “Finance constraint” measures the percent of firms identifying access to finance as a major

constraint in an economy. “Bank finance” measures the percent of firms using banks to finance investment in an

economy. “Internal finance” measures the average share of investment financed internally using personal savings.

C.D. Bars are unweighted averages of various financial development indicators for EMDEs with “high informality”

and those with “low informality” over the period 2010-18. Output informality is used in C and employment informality

is used in D. “Bank branches” measures the number of commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults. “ATMs”

measures the number of ATMs per 100,000 adults. “Private credit” measures domestic credit to private sector in

percent of GDP. “FD index” is the financial development index from the International Monetary Fund, which measu-

res the overall level of financial development. “Account ownership” is the percentage of survey respondents (aged

15 or above) who report having an account (by themselves or together with someone else) at a bank or another

type of financial institution or report personally using a mobile money service in the past 12 months. “Internal finan-

cing” is captured by the percentage of respondents (aged 15 or above) who report saving or setting aside any

money in the past 12 months to start, operate, or expand a farm or business.

D. Access to finance and employment

informality (households)

C. Access to finance and output

informality (households)

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

0

20

40

60

80

Bank

finance

Internal

finance

Bank

finance

Internal

finance

Output informality Employment informality

High informality Low informality

Percent of firms/investment

***

***

***

***

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Bank

branches

ATMs

Private

credit

Account

ownership

Internal

financing

FD index

(RHS)

High informality Low informality

Various units

***

Index

***

***

***

***

***

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Bank

branches

ATMs

Private

credit

Account

ownership

Internal

financing

FD index

(RHS)

High informality Low informality

Various units

***

Index

***

***

***

***

***

0

10

20

30

40

High Low High Low

Output informality Employment informality

Percent of firms

***

***

2

66 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

North Africa, South Asia, and, more recently, Sub-Saharan Africa (chapter 5).

Measures to expand access to finance have included better personal property

registration to facilitate borrowing by informal firms (for example, Czech

Republic; World Bank 2012) and digital payment systems to encourage a shift

away from informal finance (World Bank 2017).

Overall, access to finance and and the size of financial institutions increased in

more than three-fifths of EMDEs over 2010-18 (figure B6.1.2). The number of

ATMs per 100,000 adults rose from 26 to 40, and the share of population with

an account at a financial institution increased from 33 to 51 percent (Svirydzenka

2016). Domestic credit to the private sector in EMDEs increased by more than 4

percentage points of GDP, on average, over the same period.

Changes in informality following financial development. Financial development

was associated with significant contractions in both output and employment

informality (figure B6.1.3; annex 6A). First, 10 more bank branches per 10,000

adults—about the difference between the averages for EMDEs with above-

median and below-median informality—were associated with a 0.1- to 0.3-

percentage-point decline in the share of informal output in the following one to

five years. The share of informal employment also declined statistically

significantly. Second, a 10-percentage-point-of-GDP increase in domestic credit

to the private sector was associated with a significant contraction in the shares of

output and employment informality in subsequent years.

e

Conclusion

Both theory and empirical evidence indicate that more advanced financial

development is associated with a smaller informal economy, although the

direction of causality remains a matter of debate and may run both ways.

Financial development is considerably weaker in countries with more pervasive

informality. Financial systems have deepened, and access to financial services has

broadened, in EMDEs over the past three decades.

Policy measures to reduce informality, however, need to go beyond improving

the financial system and facilitating access to credit. Evidence suggests that the

impact of financial development on informality depends on the quality of the

legal and regulatory systems, the level of economic development, and financial

e. The results remain broadly unchanged when levels of informal output and employment are used as

robustness checks (see figure 6A.1 for results using levels of informal output). The robust results suggest

that any movement in the informal share of output or employment is determined by changes in informal

activity (the numerator), not by only changes in formal activity (the denominator).

C H A P T E R 6 2

67 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

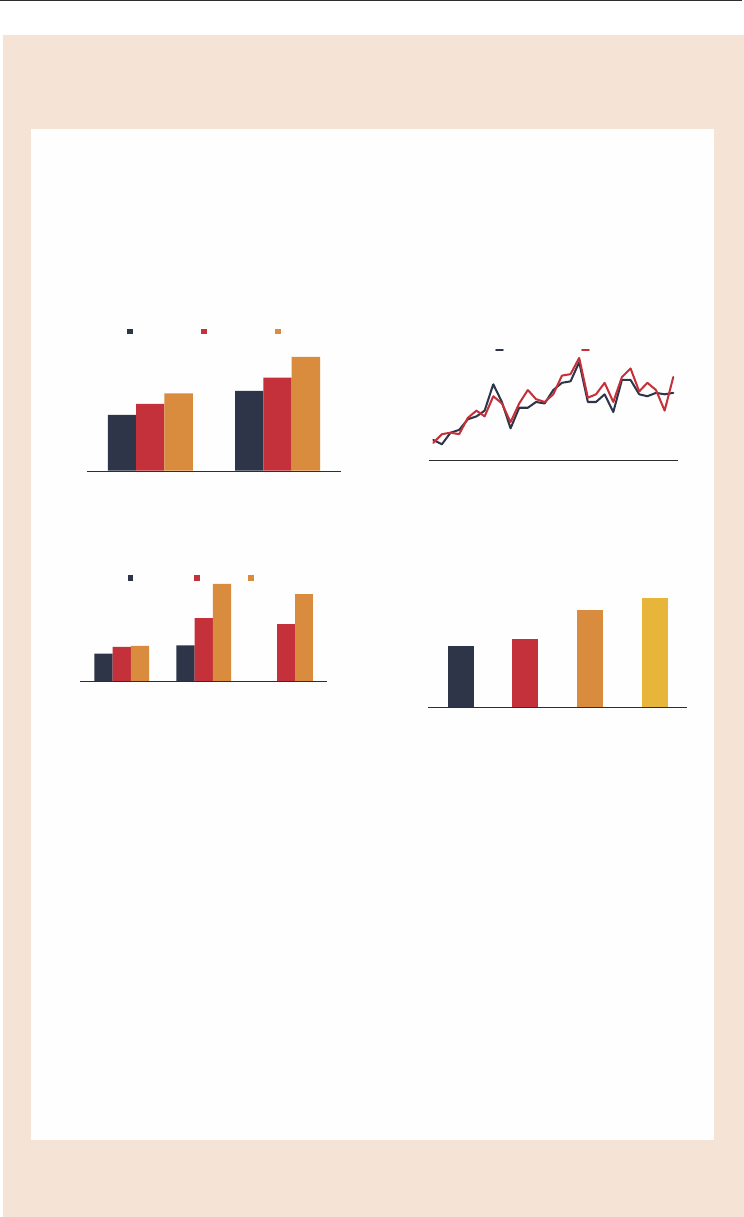

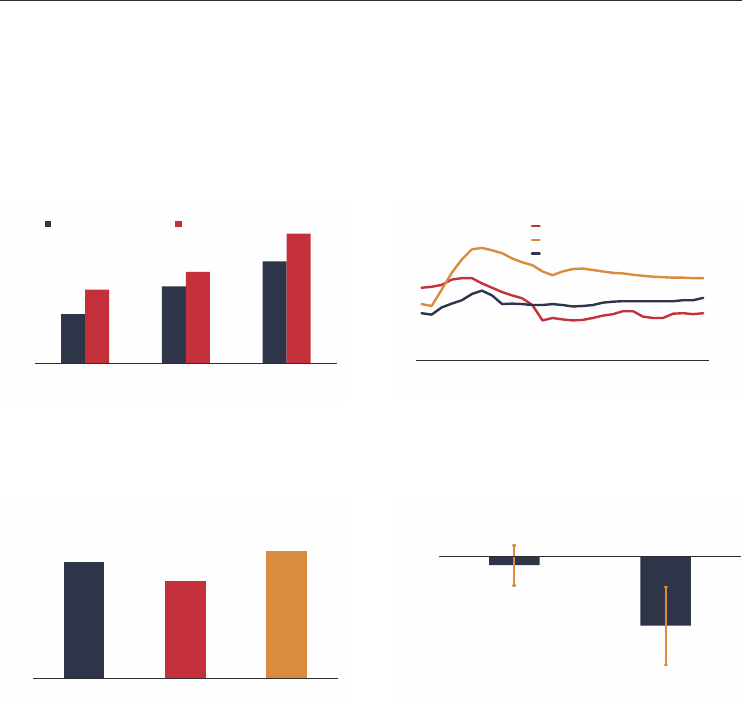

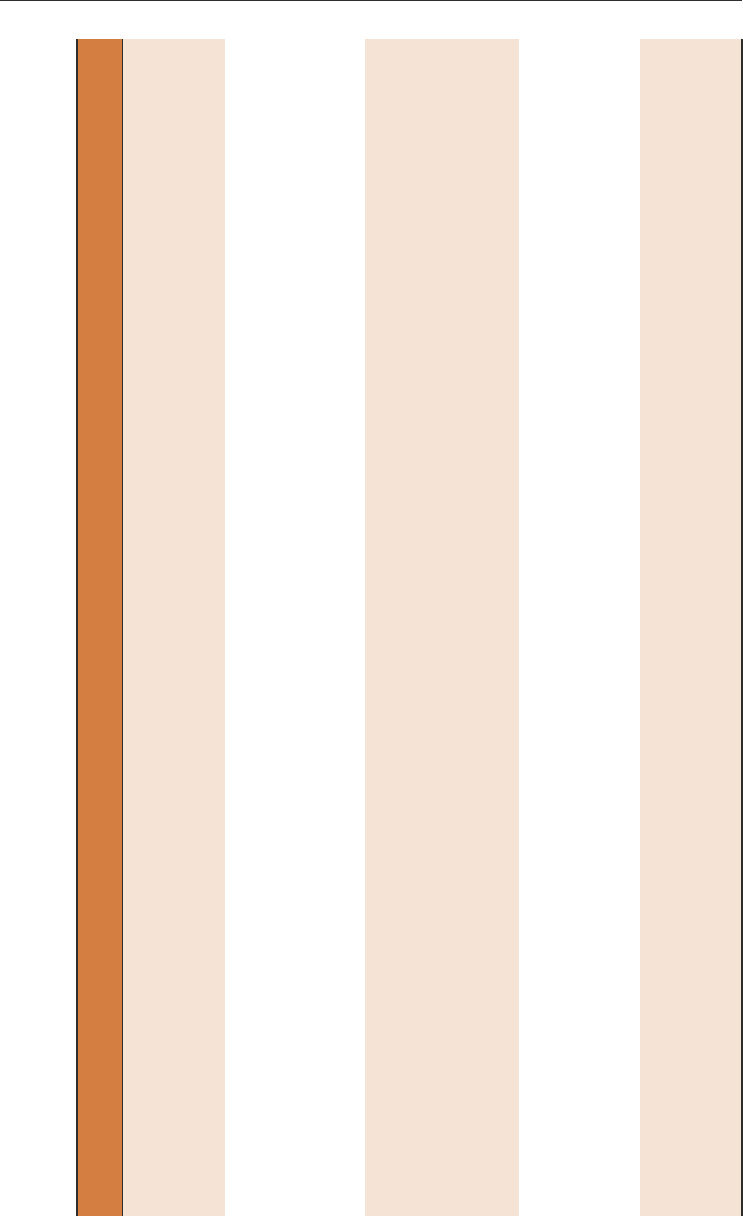

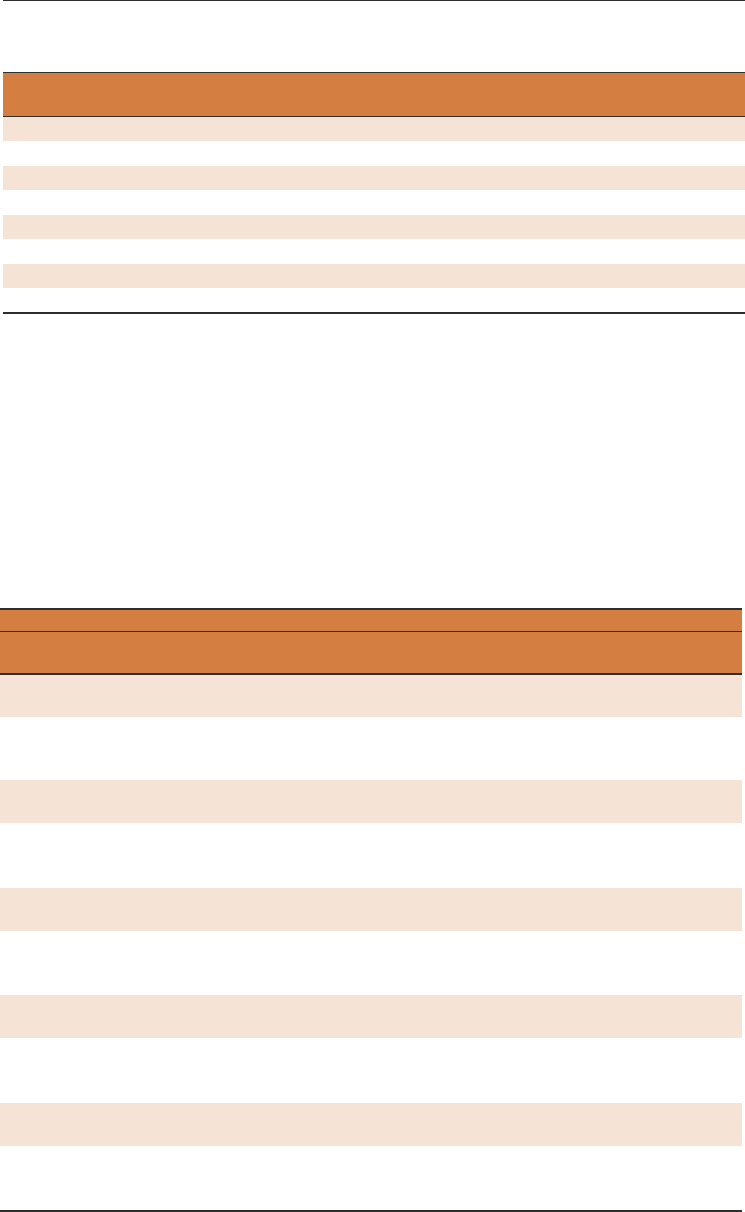

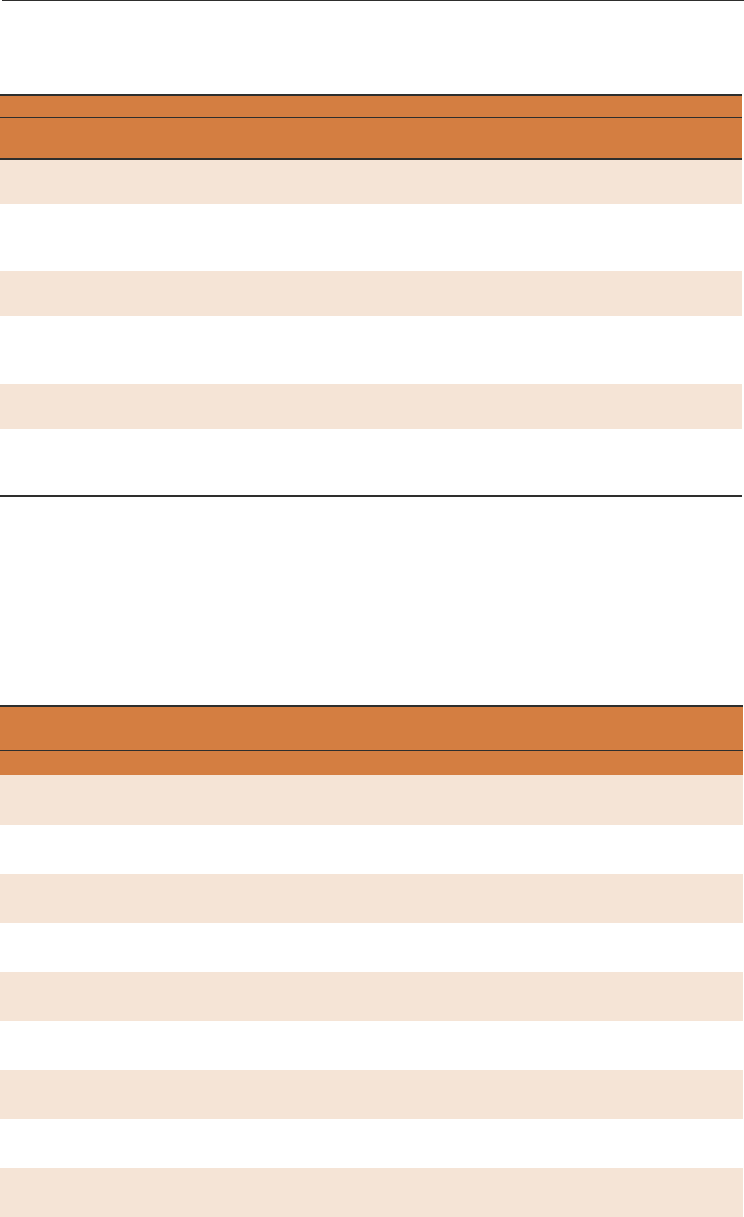

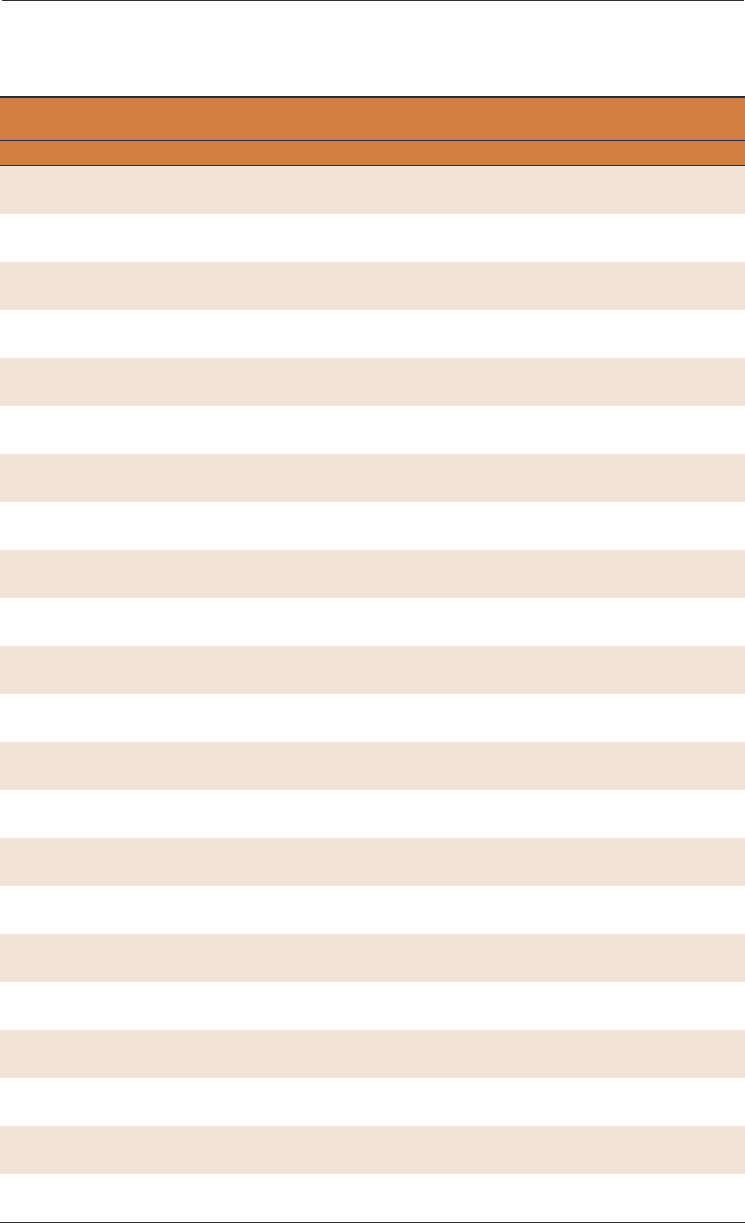

FIGURE B6.1.2 E

volution of financial development in EMDEs

In EMDEs, access to financial institutions and the depth of their activities improved

between 1990 and 2018.

B. EMDEs with improved financial

development

A. Financial development, 1990-2018

Sources: International Monetary Fund (Financial Development Index Database); World Bank (Global Financial

Development Database, World Development Indicators).

Note: Data are from EMDEs and the period 1990-2018. Output informality is measured by DGE-based estimates on

informal output (in percent of official GDP). Employment informality is proxied by self-employment in percent of total

employment. ATMs = automated teller machines; DGE = dynamic general equilibrium model; EMDEs = emerging

market and developing economies; IMF = International Monetary Fund; RHS = right-hand side.

A.B. Bars (A) and lines (B) show simple EMDE averages for corresponding time periods. “Overall” is the aggregate

financial development index obtained from the IMF. It measures the overall level of financial development and

captures development in both “financial institutions” and “financial markets.” The latter is about the access, depth,

and efficiency of a economy’s stock and debt market, which was less relevant for informal participants in EMDEs.

The “Institutions” index measures how developed financial institutions are in terms of their depth (size and liquidity),

access (ability of individuals and companies to access financial services), and efficiency (ability of institutions to

provide financial services at low cost and with sustainable revenues). Some of the subindicators for “Institutions” are

used in C-D to show the access (C) and depth (D) of financial institutions.

C. Bars show simple EMDE averages in earliest possible year (2004), 2010, and 2018. “Bank branches” measures

the number of commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults. “ATMs” measures the number of ATMs per 100,000

adults. “Private credit” measures domestic credit to private sector in percent of GDP. “Account ownership” is the

percentage of survey respondents (aged 15 or above) who report having an account (by themselves or together

with someone else) at a bank or another type of financial institution or report personally using a mobile money

service in the past 12 months. In the case of “account ownership,” data from closest years are used.

D. Bars show simple EMDE averages in corresponding years. The indicators captures domestic credit to private

sector as a share of GDP.

D. Domestic credit to private sector C. Access to finance

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

40

60

80

100

120

1990

1994

1998

2002

2006

2010

2014

2018

Overall Institutions

Number of EMDEs

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

10

20

30

40

Bank branches ATMs Account

ownership

(RHS)

Earliest 2010 2018

Per 100,000 adults

Percent of surveyed respondents

0

10

20

30

40

50

1990 2000 2010 2018

Percent of GDP

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

Overall Institutions

1990-00 2000-08 2010-18

Index

2

68 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

development itself. In addition, the effect of measures to promote financial

development may be temporary and differ depending on the structure of

financial markets.

In particular, improvements in the legal system may be a precondition for

achieving broader access to credit that can draw informal firms into the formal

sector. Measures to improve contract enforcement and investor protection may

be particularly effective in EMDEs, which often fall well behind best practices.

Greater competition and access to markets may foster the productivity gains that

are needed for firms to be able to service debt, one aspect of financial

development. The possibility of reverse causality suggests that, in some instances,

measures to reduce informality by streamlining regulations and improving their

enforcement may create a virtuous circle of lowering informality and spurring

financial development.

BOX 6.1 Financial development and the informal economy

(continued)

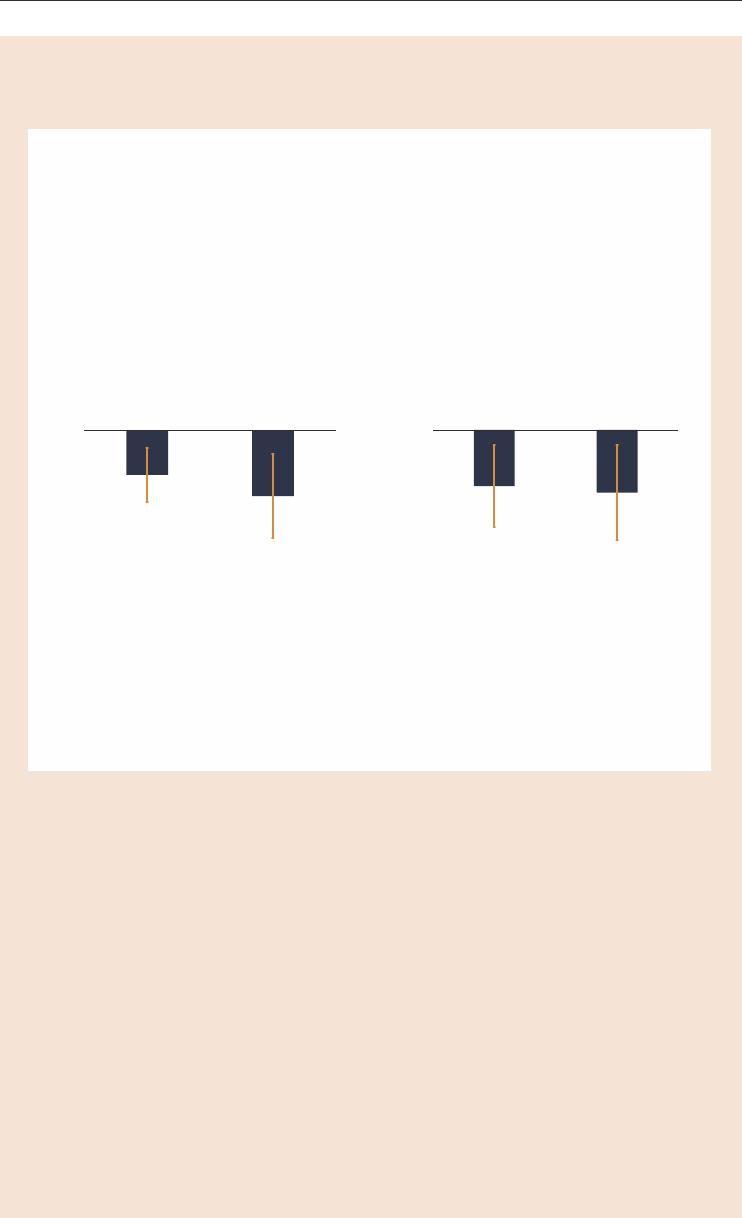

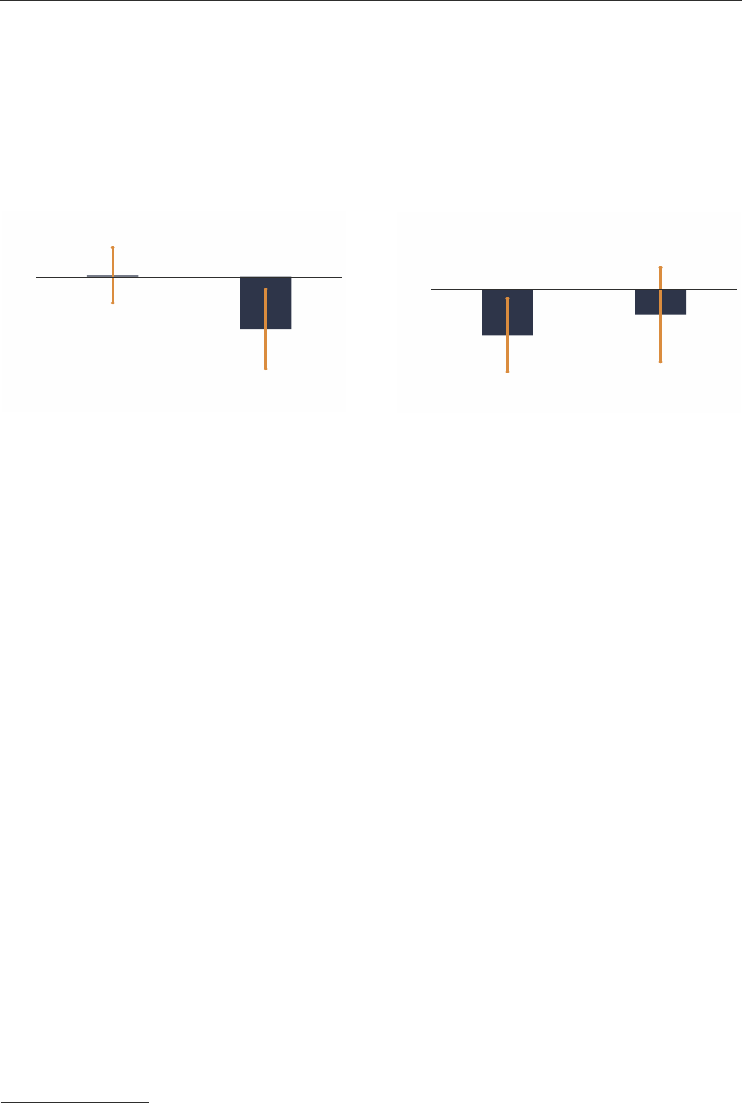

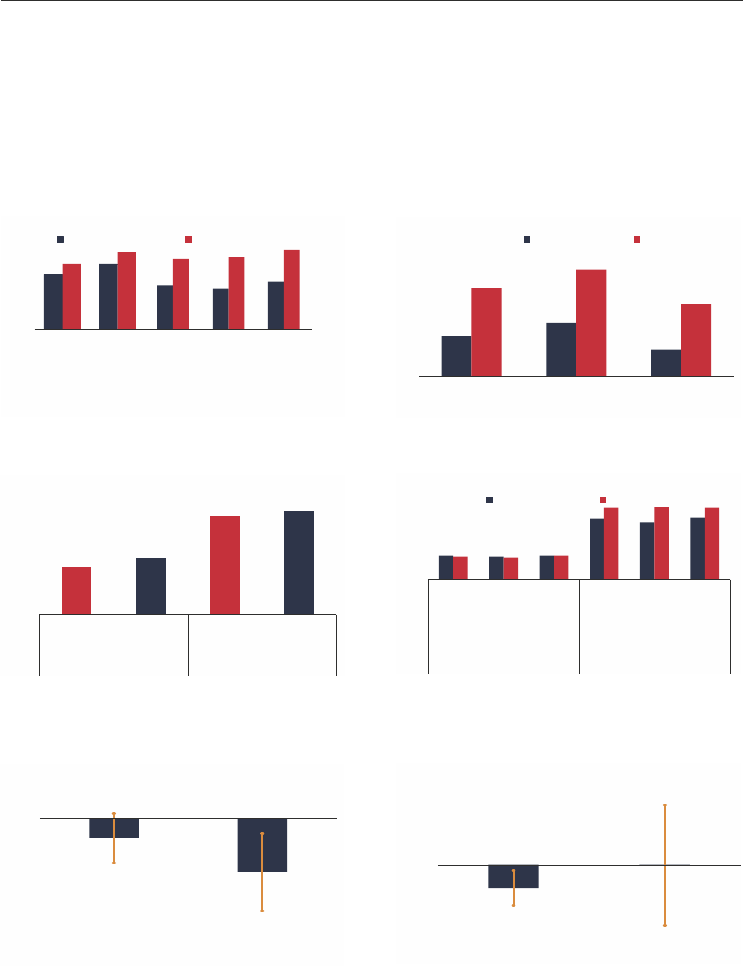

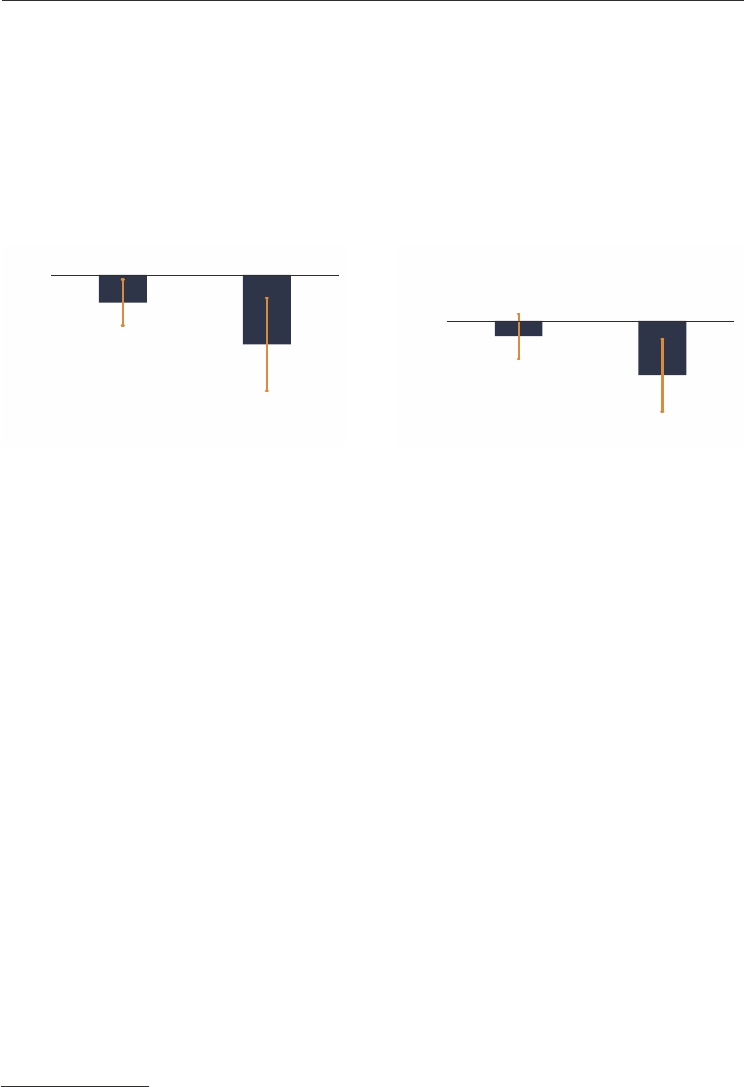

FIGURE B6.1.3 E

volution of output informality following

financial development in EMDEs

Financial development is found to have been associated with significant subsequent

contractions in output informality. Financial development, especially better access to

financial institutions and increased depth of financial institutions, helps reduce output

informality.

B. Cumulative changes in output

informality following a 10-percentage-

point-of-GDP increase in domestic credit

to the private sector

A. Cumulative changes in output

informality following a 10-unit increase in

the number of bank branches per 100,000

adults

Source: World Bank.

Note: Data are from EMDEs and the period 1990-2018. Output informality is measured by DGE-based estimates on

informal output in percent of official GDP. The results are obtained via a local projection method where informality

measures are detrended using Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter. See annex 6A for detailed model specifications.DGE =

dynamic general equilibrium model; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies.

A.B. Bars show the cumulative changes in DGE-based output informality in percent of GDP following a 10-unit

increase in the number of bank branches per 100,000 people (in A) and 10-percentage-point-of-GDP increase in the

share of domestic credit to the private sector in percent of GDP (in B). Whiskers show the upper and lower bounds

of the corresponding 90 percent confidence intervals. “t = n” shows cummulative changes over the n years after the

policy change.

-0.12

-0.09

-0.06

-0.03

0

t = 2 t = 5

Percentage points of GDP

-0.6

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

t = 2 t = 5

Percentage points of GDP

C H A P T E R 6 2

69 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

labor market efficiency, governance, and regulatory quality. This is the first study to

conduct such empirical analysis for a wide range of policies. It is also the first to examine

the share of informality in both economic output and employment: earlier studies have

tended to focus on either informal output, or informal employment, or informal firms.

4

Third, the chapter is the first published attempt to comprehensively examine the link

between financial development and informality both theoretically and empirically (box

6.1). It reviews the literature identifying the channels through which limited financial

development can discourage formalization. It uses both descriptive statistics and

regression approaches to show that informality is associated with lack of financial

development, and that improvements in access to finance are associated with declining

informality.

Main findings. First, macroeconomic policies, governance, and business climates have

become more conducive to lowering informality over the past three decades. Over that

period, EMDEs have reduced tax burdens, improved governance and regulatory quality,

and expanded access to finance, education, and public services.

Second, policies that seek to streamline tax regulation, strengthen tax administration,

and improve public service delivery have been associated with declines in informality.

Separately, policies aimed at invigorating private sector activity broadly, such as

measures to increase labor market flexibility, streamline regulatory frameworks for firm

start-up, expand access to finance, and improve governance have also been associated

with declines in informality.

Third, policy measures can have unintended consequences. For instance, trade

liberalization that raised competition in the tradable sector was sometimes associated

with greater informality in the short run, unless accompanied by measures that increase

labor market flexibility. Also, reductions in informality have tended to be greater for

reforms accompanied by business development and training programs, public awareness

campaigns, and stronger enforcement.

Fourth, financial development has been associated with declining informality (box 6.1).

It reduces the average costs of access to external financing and incentivizes firms to

invest in higher-productivity projects and to join the formal sector. Over the past three

decades, increased access to financial services and increased credit availability have been

followed by declining informality.

Fifth, a comprehensive policy package tailored to country circumstances offers the

greatest chance of success in reducing informality. A combination of measures to

strengthen economic development, boost productivity in both formal and informal

sectors, streamline regulations, and ensure effective enforcement can address multiple

4

See Bosch, Goñi-Pacchioni, and Maloney (2012); Fajnzylber, Maloney, Montes-Rojas (2011); Ihrig and Moe

(2004); and Rocha, Ulyssea, and Rachter (2018).

270 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

sources of informality. The relative priorities will depend on the economy-specific

features of informality.

The rest of the chapter is organized as follows. It first presents a range of fiscal policy

options that may be used to help remove barriers to joining the formal sector. It then

discusses a wide range of policies that can ease the transition from the informal to the

formal sector. The chapter also illustrates the importance of having a comprehensive and

complementary policy package to tackle the challenges posed by informality and how to

implement it successfully. In addition, the chapter describes the implications of digital

technologies for coping with informality. The final section summarizes the conclusions.

Data and methodology

This chapter relies on the database detailed in chapter 2 for measures of output and

employment informality. It applies several statistical tests to quantify the links between a

wide range of policies and informality, without establishing or assuming causality. It

then estimates a series of local projection models to help quantify the cumulative

response of informality to various policy actions over the short and medium terms.

Data. Both output and employment informality are considered here. Output informality

is proxied by estimates based on the dynamic general equilibrium (DGE) model in

percent of official gross domestic product (GDP), and employment informality is

proxied by self-employment in percent of total employment. Both measures are available

for up to 121 EMDEs over the period 1990-2018.

5

For the local projection estimation,

all data series on informality are detrended using the Hodrick-Prescott filter to mitigate

concerns that the results are driven by the declining trend in informality (chapter 2). A

wide range of policy measures is considered here, ranging from changes in corporate tax

rates to actions to improve the ease of doing business (table 6B.2). Detailed data

descriptions are provided in annex 6A.

Empirical strategy. The chapter applies two empirical approaches to assess the links

between informality and policies.

First, differences between average policies in EMDEs with above-median and below-

median informality are tested for statistical significance. The sample of EMDEs is

grouped into those with an above-median share of informal output and those with a

below-median share of informal output, on average during (up to) 1990-2018.

6

For each

subsample, simple averages of policy indicators are generated and the difference between

these two group averages is tested for statistical significance. EMDEs with high

5

In the case of financial development, absolute levels of informal output and informal employment, rather than

their relative share of official GDP or total employment, are used as robustness checks when a local projection

model is estimated (figure 6A.1). Using absolute levels of informal output and informal employment avoids the

possibility that the results are driven by movements in total official GDP or total employment (the denominator)

rather than movements in output or employment in the informal sector (the numerator).

6

The results are the same when EMDEs are grouped according to employment informality (table 6B.3).

C H A P T E R 6 2

71 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

7

The results are robust to using self-employment as ameasure of employment informality (table 6B.5). As

further robustness checks, both ordinary least squares and quantile regressions are performed using the same set of

policy for both output and employment informality measures. The regression results are largely in line with the

findings from the group comparison approach (tables 6B.6-6B.7).

8

In contrast, EMDEs with high or low informality often do not differ significantly in their average statutory

rates for social security contributions nor their revenue collections from such taxes, but they do differ significantly in

the amount of social security they provide (see below).

informality refer to EMDEs with above-median informality, and EMDEs with low

i

nformality refer to EMDEs with below-median informality.

Second, a local projection model as in Jordà (2005), Teulings and Zubanov (2014), and

World Bank (2018a) is estimated to identify the effects of policy changes on informality

over time for a sample of up to 125 EMDEs during 1990-2018. The model estimates

the cumulative changes in informality after policy changes over different time horizons

while controlling for country fixed effects and per capita income levels (table 6B.4).

7

Policy changes are defined as a unit change in the corresponding policy indicator. For

instance, a 1-percentage-point increase in the personal income tax rate is considered a tax

policy change. Annex 6A details the model specification.

Fiscal measures

High tax rates or payments, complicated tax codes, and administrative burdens have

been commonly cited as reasons for informal activity (Auriol and Warlters 2005; Perry

et al. 2007; Waseem 2018). Lax tax enforcement facilitates poor tax compliance

(Slemrod 2019). Poor government services—often underfunded and inefficiently

delivered—will tend to erode tax morale (Awasthi and Engelschalk 2018). In a sweeping

survey of the literature, measures to address such issues have been identified as having

been particularly effective at encouraging a shift into formal activity (Jessen and Kluve

2021; World Bank 2019b).

Tax rates

Higher tax rates in more informal EMDEs. On average during 2010-2018, average

corporate and personal incomes tax rates were significantly higher, by 3 (corporate) to 4

(personal) percentage points in EMDEs with above-median output informality than in

those with below-median output informality. Value added tax (VAT) rates were also

statistically significantly higher in EMDEs with above-median output informality than

in those with below-median output informality.

8

Over time, shift away from income taxes. Since 1990, both corporate and personal

income tax rates have been lowered in EMDEs whereas the use of VAT has expanded.

Average corporate and personal income tax rates in EMDEs have fallen by 13 and 15

percentage points, respectively, from close to 40 percent in the beginning of the 1990s to

about 24 percent in 2020 (figure 6.2). About two-thirds of EMDEs lowered their

statutory personal income tax rates and more than three-quarters lowered their statutory

272 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

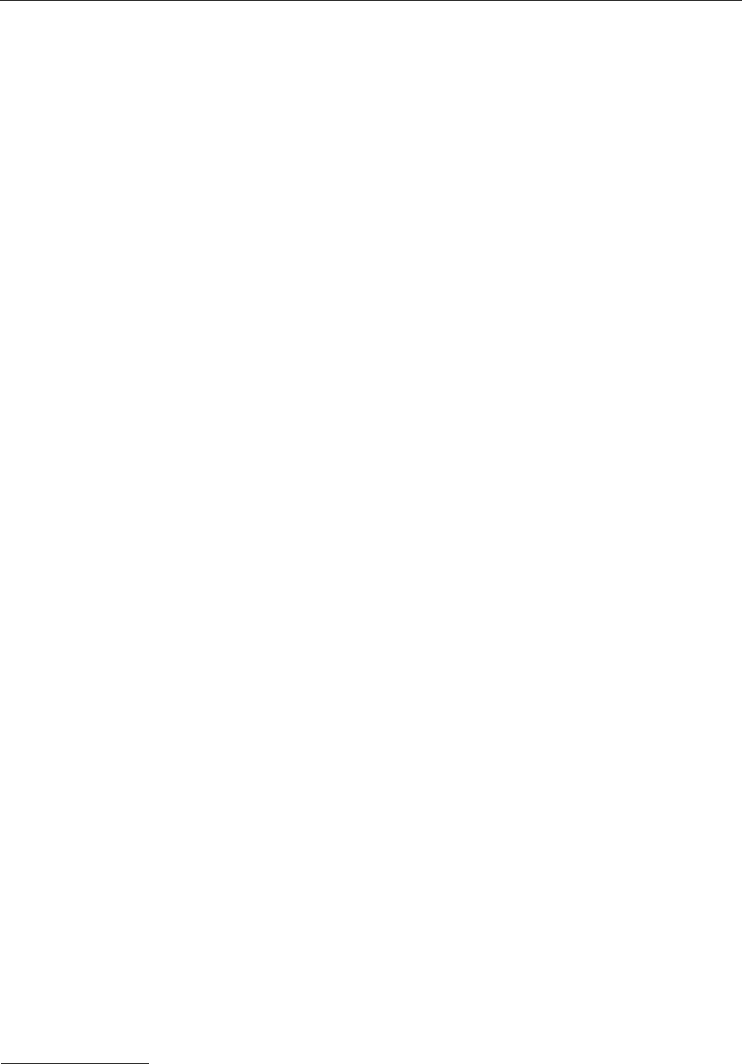

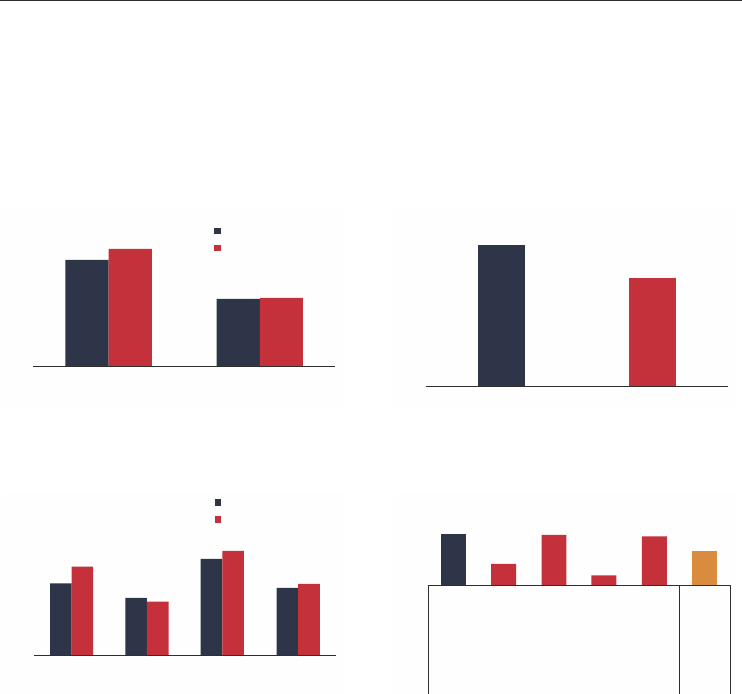

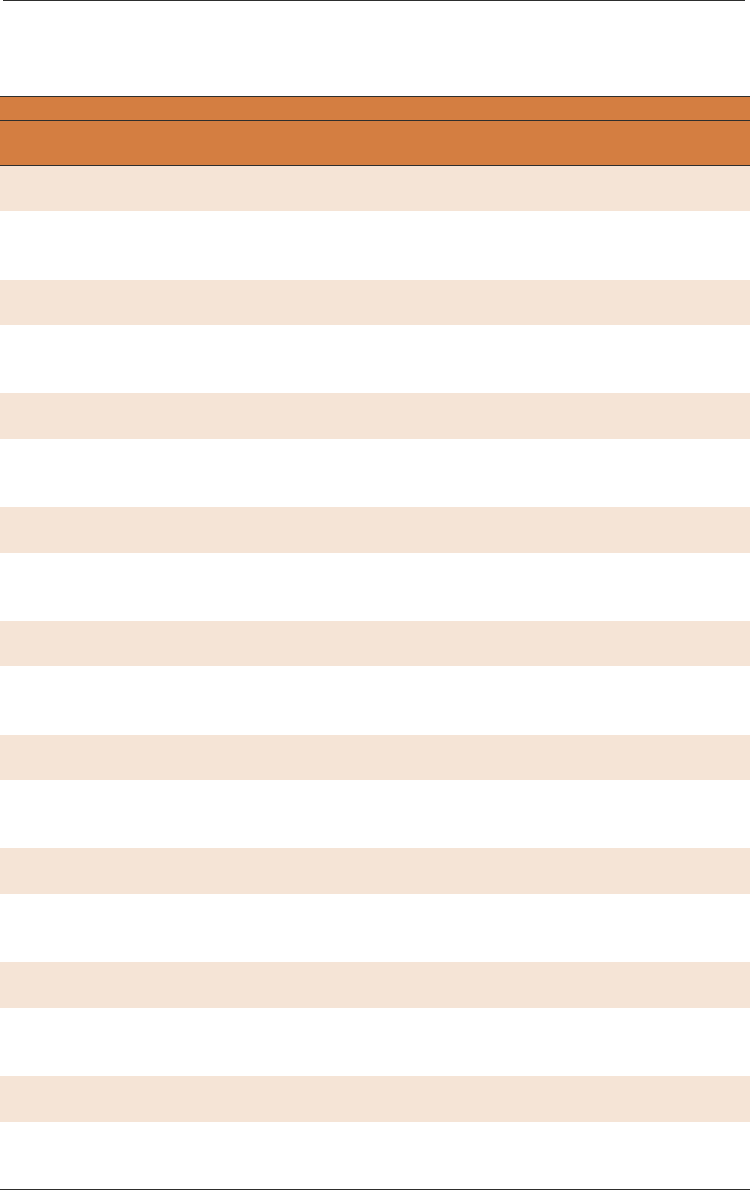

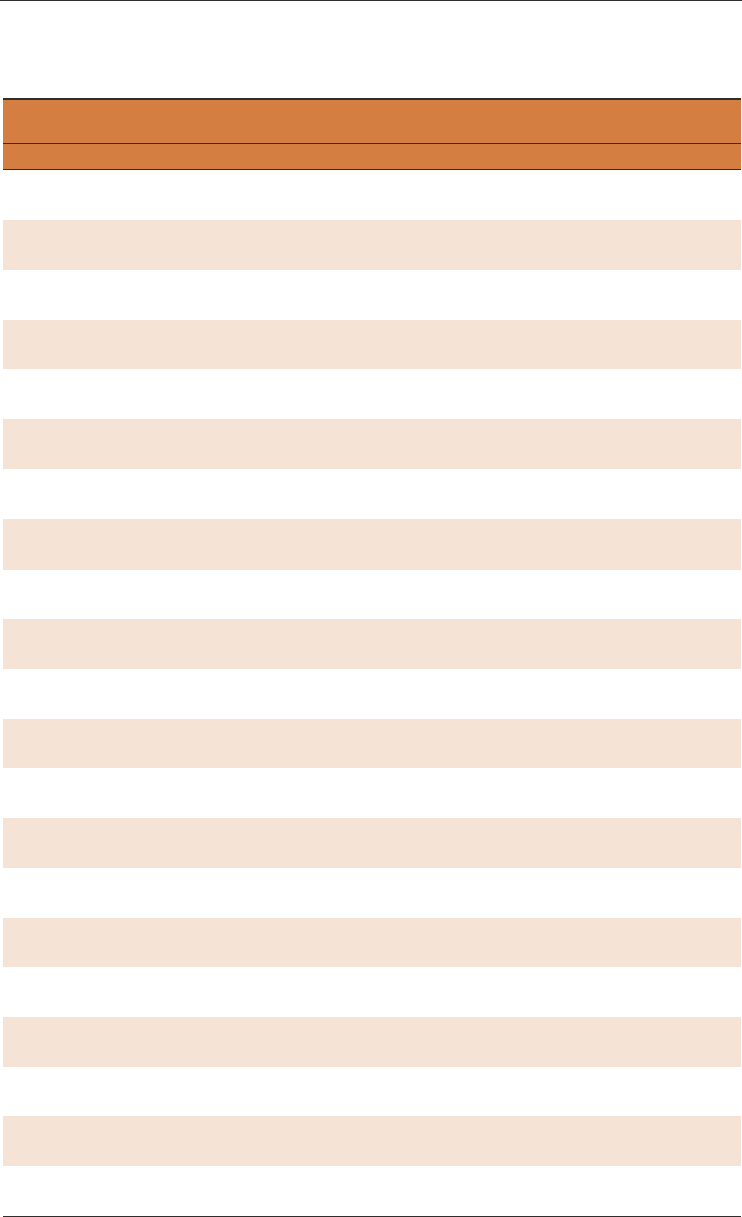

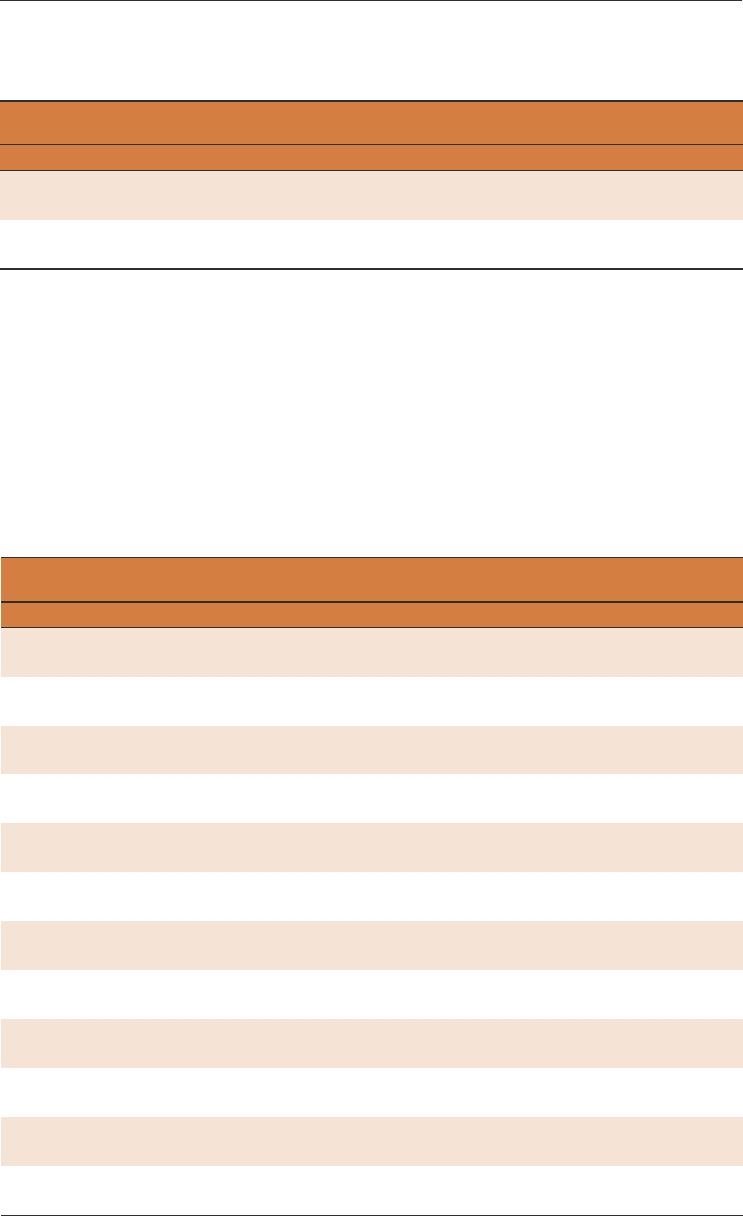

FIGURE 6.2 Tax rates and informality in EMDEs

Income tax rates remain higher in EMDEs with more pervasive informality—

even where

governments have cut rates and shifted toward value added taxation. Informality declined after

income tax rate reductions but not after VAT rate reductions.

B. Tax rates, 1990-2020 A. Tax rates and output informality

Sources: Cnossen (1998); KPMG; University of Michigan; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; Végh and

Vuletin (2015); World Bank (Doing Business).

Note: DGE = dynamic general equilibrium model; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; RHS = right-hand side;

VAT = value added tax.

A. Bars are group means for EMDEs with above-median DGE-based estimates on informal output (“high informality”) or those with

below-median DGE-bases estimates on informal output (“low informality”) over the period 2010-2018. Data are from about 100 EMDEs

(in the case of individual tax rate, China is dropped as an outlier). Bolivia, Georgia, Panama, and Zimbabwe are dropped as outliers.

*** denotes that the group differences are not zero at 10 percent significance.

B. Lines are simple group averages for EMDEs.

C.D., F. Bars show the cumulative changes in DGE-based output informality in percent of GDP following 10-percentage-point increase

in corporate income tax rate (C), individual income tax rate (D), and VAT rate (F). Whiskers show the upper and lower bounds of the

corresponding 90 percent confidence intervals. “t = n” indicates the cumulative changes in output informality over the n years after a

policy change. Data are for EMDEs over the period 2010-18. See annex 6A for detailed model specifications.

E. Bars show the number of EMDEs and advanced economies that adopted VAT.

D. Cumulative changes in output informality

following a 10-percentage-point increase in

individual income tax rate

C. Cumulative changes in output informality

following a 10-percentage-point increase in

corporate income tax rate

F. Cumulative changes in output informality

following a 10-percentage-point increase in VAT

rate

E. Number of economies with VAT

13

14

15

16

17

20

25

30

35

40

45

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2020

Corporate income tax

Individual income tax

Value added tax (RHS)

Percent

Percent

-0.05

0

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

t = 2 t = 5

Percentage points of GDP

0

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

t = 2 t = 5

Percentage points of GDP

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

10

20

30

40

1990 2020 1990 2020

Advanced economies EMDEs

(RHS)

Number of economies

Number of economies

-1.50

-1.00

-0.50

0

0.50

t = 2 t = 5

Percentage points of GDP

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Corporate Individual Value added

High informality Low informality

Percent

***

***

***

C H A P T E R 6 2

73 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

corporate income tax rates over the sample period.

9

These efforts often coincided with a

streamlining of tax regulations and a broadening of the tax base (Kopczuk 2005).

Although income tax rates were lowered, often to reduce distortions that discourage

employment, VAT was introduced, which could be less distortionary than income tax

but may lead to a more regressive tax system (Cnossen 1998).

10

Many economies in

Latin America introduced VAT regimes in the 1970s and 1980s, and their ranks were

joined by a large number of economies in Europe and Central Asia (ECA) during the

1990s. Between 1990 and 2020, the number of EMDEs with VAT systems increased

from 29 to 91 (Végh and Vuletin 2015; World Bank 2020a).

Lower informality after tax rate cuts. Lower corporate or personal income tax rates can

reduce the incentives of firms and households to operate in the informal economy to

lower their costs. In one EMDE, for example, a tax hike in 2010 reduced the number of

formal firms and their sales revenues to such an extent that tax revenues three years after

the hike were lower than they would have been without the tax hike (Waseem 2018). A

sweeping review of past government interventions suggests that tax cuts were particularly

effective in reducing informality (Jessen and Kluve 2021). Similarly, a review of policies

showed that tax simplification and tax cuts were associated with lower informality

(World Bank 2019b).

Meanwhile, the introduction of VAT may strengthen incentives to register in order to

qualify for VAT refunds—or, conversely, may strengthen incentives to operate

informally to offer lower prices excluding VAT. A VAT regime imposes an input tax on

informal firms that do not qualify for refunds but source from formal firms, which in

the right circumstance can motivate them to register, thus raising government revenue

collection (de Paula and Scheinkman 2010; Loayza 2018; World Bank 2018c).

11

A

requirement to digitalize sales receipts for accelerated VAT refunds could further

strengthen incentives to register and correctly report sales (Fan et al. 2020). In one case,

electronic invoicing for VAT purposes was rolled out in waves between 2014 and 2018

and resulted in more than 5 percent higher reported firm sales, purchases, and value

added in the first year after adoption (Bellon et al. 2019).

Indeed, since 1990, a 10-percentage-point decrease in the corporate income tax rate has

been associated with a cumulative decline in output informality of about 0.1 percentage

point of GDP, relative to trend, over the following two years (figure 6.2).

A similarly

sized reduction in the personal income tax rate has been associated with a slightly

stronger, and deepening, fall in output informality in the following five years. Despite

finding significant falls in informality following tax cuts, these falls are generally small in

9

The sample contains up to 53 EMDEs for which data are available in 2020 and 1990.

10

That said, the presence of an informal economy could lead to incomplete coverage and inefficiencies in the

VAT system (Keen 2008; Piggott and Whalley 2001; Emran and Stigliz 2005). In some case, labor informality was

found to be associated with lower overall VAT collection (Caro and Sacchi 2021).

11

Poorer households tend to spend a larger share of their budgets in the informal sector than richer households.

As a result, households in the richest quintile can face an effective consumption tax rate that is twice that of the

poorest quintile (Bachas, Gadenne, and Jensen 2020).

274 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

12

In the case of employment informality, the average annual number of hours spent on complying with VAT

refund requirements amounted to 37 in EMDEs with above-median informality—20 hours per year significantly

more than in EMDEs with below-median informality (table 6B.3).

size, suggesting that cutting tax rates alone is not enough to move all participants from

t

he formal sector to the informal sector. Other policy measures are needed (Loayza

2018). Meanwhile, increases in VAT have not been associated with any significant

change in output informality. This suggests that some informal firms source their inputs

from informal markets that operate outside the VAT system. The results are robust to

using employment informality, instead of output informality.

Tax compliance

More burdensome tax compliance in more informal EMDEs. Beyond tax rates, tax

compliance can be costly and time-consuming and, thus, discourage formal registration

by firms, especially those with poor profitability (Morales and Medina 2016; Rocha,

Ulyssea, and Rachter 2018; Ulyssea 2018). On average, in EMDEs with above-median

informality during 2010-18, it took the average firm 33 hours longer and required

statistically significantly more payments, estimated at 11 per year, to comply with tax

regulations than in EMDEs with below-median informality (figure 6.3). As a result,

despite higher corporate and personal income tax rates in EMDEs with above-median

informality, revenue collections were lower: on average in EMDE with above-median

output informality, personal and corporate income tax revenues were statistically

significantly lower, by 0.6 and 0.8 percentage point of GDP, than in EMDEs with

below-median informality.

Similar administrative challenges have troubled the administration of VAT regimes in

countries with high informality. During 2016-18, firms spent 29 hours a year, on

average, complying with VAT refund requirements in EMDEs with above-median

informality—7 hours more than in EMDEs with below-median informality, though the

difference is not statistically significant.

12

It took about 40 weeks for firms in EMDEs

with above-median informality to receive VAT refunds—significantly longer than the

31 weeks in EMDEs with below-median informality.

Over time, less burdensome tax compliance. Firms’ tax compliance costs have declined

in EMDEs in the past few decades. Since 2006, the time spent by firms on paying taxes

has fallen by 68 hours a year, on average, in EMDEs and the average number of tax

payments per year has declined by one-third, to 26 payments per year in 2020 (figure

6.3). In ECA, the introduction of electronic tax filing and payment systems has reduced

the average tax filing time from 473 hours in 2006 to 225 hours in 2020 (World Bank

and PwC 2019).

Efforts to lower tax burdens have been among the most common policy reforms in

EMDEs, especially in East Asia and Pacific (EAP) and Latin America and the Caribbean

(LAC). Measures to make tax compliance less burdensome have ranged widely (Awasthi

C H A P T E R 6 2

75 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

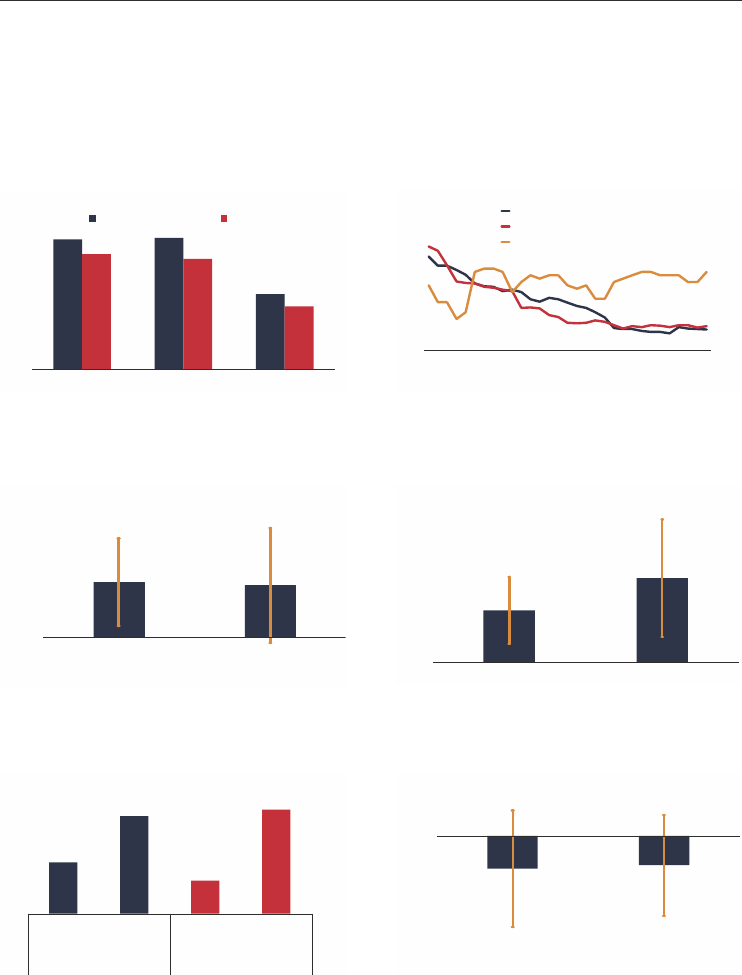

FIGURE 6.3 Firms’ tax compliance burdens and informality in EMDEs

Tax compliance burdens on firms remain higher in EMDEs with more pervasive informality than in

those with less pervasive informality, despite recent declines. Past efforts to lower compliance costs

were not followed by immediate declines in informality.

B. Ease of paying taxes over time A. Ease of paying taxes and output informality

Source: World Bank (Doing Business).

Note: DGE = dynamic general equilibrium model; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; RHS = right-hand side; VAT

= value added tax.

A.C. Bars are group means using data from latest year available for EMDEs with “high informality” and those with “low informality.”

“High informality” (“low informality”) are EMDEs with above-median (below-median) DGE model-based informal output measure over

the period 2010-18. Data are from about 100 EMDEs. *** denotes that the group differences are not zero at 10 percent significance.

B. Bars show the average number of tax payments per year by a medium-size company. The line shows the average time spent on

paying taxes per year by a medium-size company. Data are for EMDEs.

D. Bars show the cumulative changes in DGE-based output informality in percent of GDP following a 1-point increase in the score for

ease of paying taxes. Whiskers show the upper and lower bounds of the corresponding 90 percent confidence intervals. “t = n”

indicates the cumulative changes in output informality over the n years after a policy change. Data are for EMDEs over the period

1990-2018. See annex 6A for detailed model specifications.

D. Cumulative changes in output informality

following a 1-point increase in the score for ease

of paying taxes

C. Time to comply with and obtain VAT refund and

output informality

and Engelschalk 2018; Slemrod 2019). Tax bases have been simplified in industries with

a high percentage of undeclared workers (for example, domestic work), and tax

regulations have been harmonized across different types of firms (Oviedo, Thomas, and

Karakurum-Özdemir 2009). At the same time, tax enforcement has been stepped up by

expanding the use of information technology and communication tools, encouraging a

switch from cash-based transactions to bank-based ones, and strengthening the capacity

of tax administrations (for example, Nguimkeu and Okou 2019; Prichard et al. 2019).

13

160

200

240

280

320

360

20

25

30

35

40

45

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Tax payments

Time spent on tax payments (RHS)

Number per year Hours per year

0

10

20

30

40

50

Comply with VAT refund Obtain VAT refund

Low informality High informality

Hours/Weeks

***

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0

0.5

1.0

t = 2 t = 4 t = 5

Percentage points of GDP (in 100ths)

260

280

300

320

0

10

20

30

40

Payments Time

(RHS)

Low informality

High informality

Number per year

***

Hours per year

13

See Chodorow-Reich et al. (2018); Crouzet, Gupta, and Mezzanotti (2020); and Lahiri (2020) for the impact

of demonetization.

276 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

Lower informality after measures to facilitate tax compliance. Measures to reduce the

burden of tax compliance or firm registration can lower the cost for informal firms of

moving into the formal sector (Rocha, Ulyssea, and Rachter 2018). Coordination of

minimum tax thresholds across different types of tax, such as personal income tax, VAT,

and social security contributions, could increase tax compliance and improve welfare

(Kanbur and Keen 2014). Measures to harmonize tax provisions or other regulations

across different types of firms can reduce incentives for firms to evade taxation and

remain small and informal (Dabla-Norris, Gradstein, and Inchauste 2018; Harju,

Matikka and Rouhanen 2019). Measures to strengthen tax administration can increase

the likelihood of detection of informal firms that do not comply with taxes (Carrillo,

Pomeranz, and Singhal 2017; Naritomi 2019).

Measures to facilitate tax compliance have been accompanied by statistically significant

declines in output informality (figure 6.3). The effects have not been immediate, being

insignificant in the first year, but have strengthened over time. Thus four years after

reforms that increased the score for the ease of paying taxes by 1 point, the share of

output informality was 0.1 percentage point of GDP lower—a statistically significant

difference.

Tax morale

Weaker tax morale in more informal economies. Tax morale is weaker in EMDEs with

above-median informality. On average, in EMDEs with above-median output

informality, the average household scores 2.5 points on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10

indicating that underreporting of income for tax purposes is always justifiable—that

score is 0.4 index points, and statistically significantly, higher than in EMDEs with

below-median informality (figure 6.4).

Among the many reasons for weaker tax morale is a lack of trust in the government or

dissatisfaction with the quality of public service delivery.

14

Indeed, entrepreneurs in

EMDEs with above-median output informality report significantly poorer access to

government support and programs as well as poorer physical and services infrastructure

than entrepreneurs in EMDEs with below-median output informality (figure 6.4;

chapter 4). Similarly, significantly better access to commercial and professional

infrastructure is reported by businesses in EMDEs with above-median tax morale than

those in EMDEs with below-median tax morale. Coverage of unemployment benefits is

significantly lower, by about 3 percentage points of the population, in EMDEs with

above-median informality than in those with below-median informality. On average , in

EMDEs with below-median informality, social insurance programs can cover about 34

percent of the annual income or consumption of the beneficiary household, which is

significantly lower, by 6 percentage points, than in EMDEs with above-median

informality.

14

See Daude, Gutiérrez, and Mulguizo (2012) for a review of drivers of tax morale. OECD (2019) suggests that

there is a positive association between tax morale and public service provision in Africa, whereas tax morale in Latin

America is more linked with trust in the government.

C H A P T E R 6 2

77 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

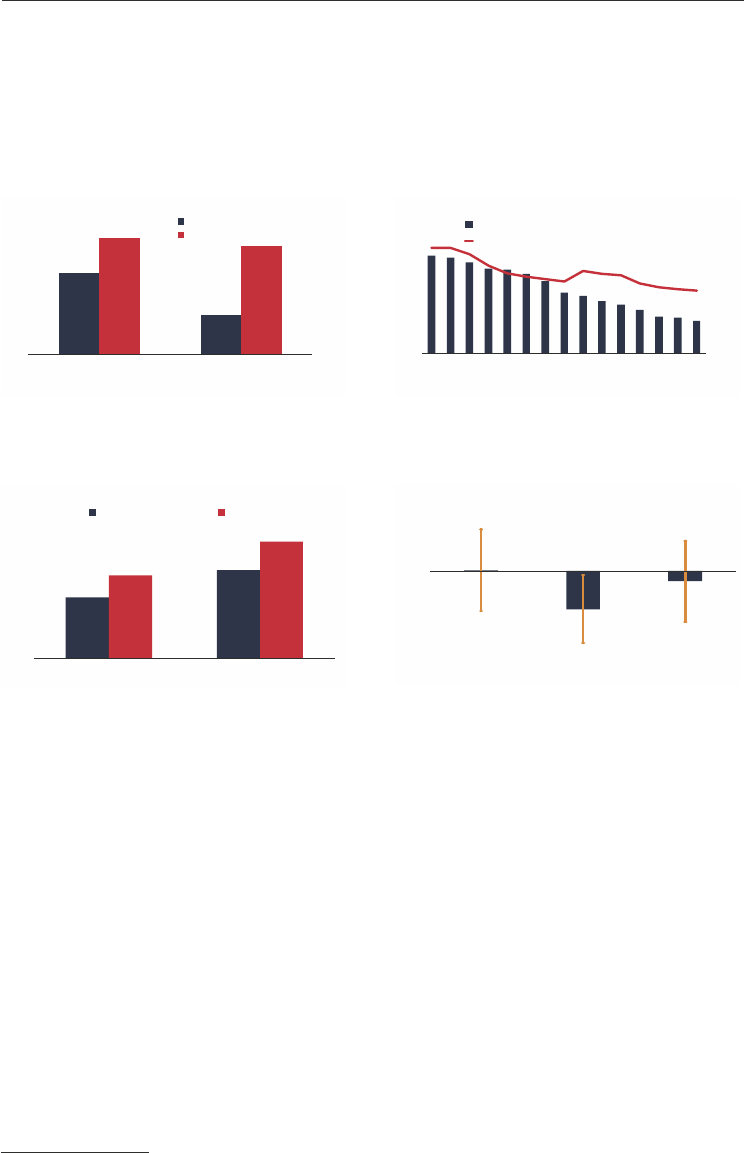

FIGURE 6.4 Tax morale and informality in EMDEs

Tax morale is higher in EMDEs with lower informality. Higher tax morale has been associated with

better government services such as social security, infrastructure, education, and health care

systems.

B. Government support and informality A. Tax morale and informality

Sources: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) database; World Bank (World

Development Indicators); World Road Statistics (WRS).

Note: Data are from EMDEs and the period 1990-2018. “High (Low) informality” are EMDEs with above (below)-mediaDGE-based

estimates on informal output in percent of GDP. All scores on government support and public infrastructure in B and C are for the period

2000-18 and range from 1 (worst) to 4 (best). DGE = dynamic general equilibrium model; EMDEs = emerging market and developing

economies; RHS = right-hand side. *** denotes that the group differences are not zero at 10 percent significance.

A. Bars show simple group averages between 1990 and 2018. World Value Survey asks whether cheating on taxes is justifiable, with a

higher level suggesting that the economy is more tolerant toward the informal sector.

B.C. Bars show simple group averages. “Governmental support and policies” measures the extent to which policies support

entrepreneurship as a relevant economic issue. “Government programs” captures the presence and quality of programs directly

assisting small and medium enterprises (SMEs) at all levels of government (national, regional, municipal). “Commercial and

professional infrastructure” captures the presence of property rights, commercial, accounting, and other legal and assessment services

and institutions that support or promote SMEs. “Physical and service infrastructure” measures the ease of access to physical resources

at a price that does not discriminate against SMEs.

D. Adequacy of social insurance programs is measured as total transfer amount received by population participating in social insurance

programs in percent of total income or expenditures of beneficiary households.

E. Bars show simple group averages.

F. PISA testing scores are for students aged 15.

D. Adequacy of social security and informality C. Tax morale and access to government services

F. Health and education outcomes and informality E. Access to infrastructure and informality

1

2

3

4

Governmental

support and

policies

Governmental

programs

Commercial

and

professional

infrastructure

Physical and

services

infrastructure

Low informality High informality

Score (1 = worst, 4 = best)

***

***

***

1

2

3

4

Governmental

support and

policies

Government

programs

Commercial and

professional

infrastructure

Low tax morale High tax morale

Score (1 = worst, 4 = best)

***

0

2

4

6

8

0

10

20

30

40

Adequacy of social

insurance programs

Coverage of

unemployment benefits

(RHS)

High informality Low informality

Percent of household income Percent of population

***

***

0

20

40

60

0

20

40

60

80

100

Access to

electricity

Internet

users

Paved

road

Mobile

cellular

subscription

(RHS)

High informality Low informality

Percent of population / road

***

Per 100 people

***

***

***

350

370

390

410

430

450

55

60

65

70

75

Life expect-

ancy at birth

PISA

(reading, RHS)

High informality Low informality

Year Score

***

***

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

High informality Low informality

Average response

1 = never justifiable; 10 = always justifiable

278 C H A P T E R 6 T

H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

15

The indicator for tax morale is taken from World Values Surveys, conducted in various years. The current

round of World Values Surveys will complete its data collection in December 2021.

16

Transitions from an employment-based social security system to a well-designed model of risk sharing can

further improve the safety net for informal workers and help protect both formal and informal workers during

economic downturns (World Bank 2013, 2018c).

Education and health outcomes are significantly poorer in EMDEs with above-median

i

nformality, with Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test scores for

15-year-old students in EMDEs with above-median informality being lower by about 10

percent than in those with below-median informality, and life expectancy eight years

lower in EMDEs with above-median informality. The poorer outcomes are partly due to

more limited government expenditures on education and health in EMDEs with more

pervasive informality (chapter 4).

Over time, stable tax morale, despite better government services. In contrast to output

and employment informality, tax morale has remained stable over the past three decades.

In the early 1990s, households in EMDEs gave an average score of 2.5 to the

justifiability of cheating on taxes (where a score of 1 means that cheating on taxes is

never justifiable and 10 means that it is always justifiable)—virtually the same as in

2010.

15

As one of the social capital measures with deep roots in culture, tax morale is

slow-moving by nature (Luttmer and Singhal 2014). In contrast, entrepreneurs in

EMDEs have, on average, perceived statistically significant improvements in government

support or programs for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and in improving

commercial and professional infrastructure available to SMEs (figure 6.5).

Meanwhile, actual government service delivery has improved by several measures. The

adequacy of social insurance programs has risen in EMDEs from an average of 31

percent of household income in the 2000s to 34 percent a decade later. Infrastructure—

for example, road kilometers, access to reliable power, and access to internet services—

has improved considerably since 2000. Mobile cellular subscriptions rose from 28 to 95

per 100 people between the 2000s and the 2010s. EMDEs’ test scores on PISA

indicators of education outcomes have risen significantly, by 17 points, and life

expectancy has risen by four years, on average, in EMDEs.

A range of measures has been introduced over the past three decades to cultivate better

tax morale, including public appeals to declare activities, campaigns to encourage

a culture of commitment to declaration, and efforts to change perceptions of the tax

system’s fairness (Williams and Schneider 2016). Other measures have included steps to

shift the burden of payments of social security contributions from employers to

employees (for example, in Latvia, Poland, and Slovenia), to reduce employers’ social

security contributions (for example, in Bulgaria), and to link social benefits to personal

contributions (for example, in most of the economies in the European Union; Oviedo,

Thomas, and Karakurum-Özdemir 2009).

16

Lower informality after improvements in government services. Improvements in the

perception that tax dollars are spent judiciously—that is, for appropriate objectives and

in an efficient way—can encourage greater tax compliance and lessen informality (Sung,

C H A P T E R 6 2

79 T H E L O N G S H A D O W O F I N F O R M A L I T Y

Awasthi, and Lee 2017). Better education or infrastructure can help raise labor

productivity in both formal and informal activities, thus facilitating a move of previously

insufficiently productive, informal firms into the formal sector.

17

FIGURE 6.5 Government services in EMDEs, 2000-18

Although infrastructure, social security systems, and health care systems have improved in EMDEs

over the past several decades, entrepreneurs’ perceptions of the adequacy of government services

have remained stable and poor.

B. Social security

A. Government support perceived by

entrepreneurs

Sources: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor; Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) database; World Bank (World

Development Indicators); World Road Statistics (WRS).

Note: Data are from emerging market and development economies (EMDEs) and the period 2000-2018. All scores on government

support and public infrastructure in A are taken from the National Expert Survey of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor for the period

2000-18. The scores range from 1 to 4 with a lower score representing poorer entrepreneurial conditions. Bars show simple period

averages for 2000-08 and 2010-2018, correspondingly, with *** indicating that the period differences are not zero at 10 percent

significance level. RHS = right-hand side.

A. “Government support and policies” measures the extent to which policies support entrepreneurship as a relevant economic issue.

“Government programs” captures the presence and quality of programs directly assisting small and medium enterprises (SMEs) at all

levels of government (national, regional, municipal). “Commercial and professional infrastructure” captures the presence of property

rights, commercial, accounting, and other legal and assessment services and institutions that support or promote SMEs. “Physical and

service infrastructure” measures the ease of access to physical resources—communication, utilities, transportation, land, or space—at

a price that does not discriminate against SMEs.

B. Adequacy of social insurance programs are measured in percent of total welfare of beneficiary households.

C-D. PISA scores are for students aged 15. “Paved road” is calculated as 100 minus the share of unpaved road in percent of total road.

“Access to electricity” and “Internet users” are in percent of population. “Mobile cellular subscriptions” and “fixed broadband

subscriptions” are measured as per 100 people.

D. Health and education outcomes C. Public infrastructure

28

30

32

34

0

3

6

9

12

Coverage of

unemployment benefits

Adequacy of social

insurance programs

(RHS)

2000-08 2010-18

Percent of population Percent of household income

0

20

40

60

80

100

Access to

electricity

Internet users

Paved road

Mobile cellular

subscriptions

Fixed

broadband

subscriptions

(in tenths)

2000-08 2010-18

Various units

***

***

***

***

***

380

390

400

410

420

430

440

62

64

66

68

70

Life expectancy

at birth

PISA

(reading, RHS)

2000-08 2010-18

Year Score

***

***

1

2

3

4

Governmental

support and

policies

Governmental

programs

Commercial

and

professional

infrastructure

Physical and

services

infrastructure

2000-08 2010-18

Score (1 = worst, 4 = best)

***

***

***

17

See, for instance, Benjamin and Mbaye (2012); Kim, Loayza, and Meza-Cuadra (2016); Oviedo, Thomas,

and Karakurum-Özdemir (2009); and World Bank (2018c). Better access to education or infrastructure may boost

productivity growth more in the formal sector than in the informal sector, resulting in a fall in the relative share of

informal output in total economic output.

280 C H A P T E R 6 T