City University of New York (CUNY) City University of New York (CUNY)

CUNY Academic Works CUNY Academic Works

Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice

2013

Democratizing Indian Popular Music: From Cassette Culture to Democratizing Indian Popular Music: From Cassette Culture to

the Digital Era the Digital Era

Peter L. Manuel

CUNY Graduate Center

How does access to this work bene;t you? Let us know!

More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/296

Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu

This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY).

Contact: AcademicWorks@cuny.edu

14

Democratizing Indian Popular Music

From Cassette Culture to the Digital Era

Peter Manuel

e history of Indian popular music constitutes in itself a signicant

development in modern culture, as this set of genres—especially but

not only in their Bollywood forms—have been cherished by hundreds

of millions of listeners not only in South Asia but internationally

as well. At the same time, the trajectory of Indian popular music

represents a dramatic case study of media culture as well, as its patterns

of ownership, consumption, and even musical structures themselves

have been conditioned by technological changes. Most striking is

the way that a highly monopolized, streamlined, and homogeneous

popular music culture dominated for several decades by Bollywood

gave way in the 1980s and 1990s to a dramatically decentralized

and heterogeneous commercial music culture due to the impact of

new technologies—initially, cassettes. As India entered the digital era

in the new millennium, other media, from VCDs to YouTube, have

intensied the general process of democratization, while adding their

own distinctive dimensions. is chapter (drawing extensively on an

earlier publication

1

) surveys the trajectory of Indian popular music

culture through the cassette era and makes brief observations about

more recent developments in the digital age.

From the early 1970s the advent of cassette technology began to

profoundly aect music industries worldwide. is inuence was

particularly marked in the developing world, where cassettes came to

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 357

replace vinyl records and extended their impact into regions, classes,

and genres previously uninuenced by the mass media. Cassettes served

to decentralize and democratize both production and consumption,

thereby counterbalancing the previous tendency toward oligopolization

of international commercial recording industries.

POPULAR MUSIC AND MEDIA CULTURE IN INDIA

BEFORE 1980

An outstanding feature of the Indian music industry until the 1980s was

its relatively undemocratic structure, as control of its production was

concentrated in a tiny and unrepresentative sector of the population.

From the mid-1930s until the advent of cassettes, commercial lm

music accounted, by informed estimates, for at least 90 per cent of record

output. e dominant entity throughout was the Hindi lm industry,

whose production itself lay in the hands of a small number of rms,

producers, actors, and music producers. Given the vast output of lm

songs, a certain amount of stylistic and regional variety was naturally

evident. Nevertheless, the stylistic homogeneity of the vast majority

of lm songs was far more remarkable, and was most conspicuous in

the overwhelming hegemony, for over 30 years, of ve singers—Asha

Bhosle, Kishore Kumar, Mohammad Ra, Mukesh, and above all, Lata

Mangeshkar. Since vocal style in music is such an essential and basic

aesthetic identity marker, the stylistic uniformity of these singers—

especially of Lata’s several thousand songs—stands in dramatic contrast

to the wide diversity of folk music and singing styles throughout north

India.

2

Further, while regional folk music did contribute to many lm

songs, most lm composers and musicians avoided recognizable folk

elements in an attempt to appeal to a pan-regional market (Chandravarkar

1987: 8). As a result, the overwhelming majority of songs adhered to a

distinctive mainstream style, which, although itself eclectic, was hardly

representative of the variety of North Indian folk music. Song texts

were equally limited in subject matter, dealing overwhelmingly with

sentimental love, again in contrast to regional folksong. In this respect,

however, they were suited to the romantic and escapist nature of Indian

movies themselves, which generally avoided realistic portrayals of the

harsh poverty so basic to much Indian life.

Popular music was apprehended largely through cinema and the

radio; only the urban middle and upper classes had extensive access to

records, due to the expense and power requirements of record players.

358 Ravi Sundaram

His Master’s Voice [(HMV, of Electric and Musical Industries Ltd

(EMI)] enjoyed a virtually complete monopoly in the record industry,

having absorbed or eliminated regional rivals in the early decades of its

appearance in India.

While charming melodies, moving lyrics, and professional production

standards abounded in Indian popular music, what was largely missing

was any sort of armation of a sense of community, whether on the

level of region, caste, class, gender, or ethnicity. It is such a sense of

community that may be said to be an especially vital aspect of folk

songs, which celebrate collective community values through shared,

albeit specic performance norms and contexts, musical style, textual

references, and language. Insofar as lm music succeeded in appealing

to, if not creating, a homogeneous mass market, it did so at the expense

of this armation of community, thereby, it could be argued, reinforcing

some of the alienating aspects of the cinematic fantasies in which it was

embedded.

ALTERNATIVES TO HIS MASTER’S VOICE

While commercial Indian music cassettes began appearing in the early

1970s, it was not until a decade later that they appeared in such quantities

as to restructure the entire music industry. In India as elsewhere, cassettes

and players were naturally preferable to records due to their portability,

durability, low cost, and simple power requirements. Aside from

these advantages, the timing of their spread in India was attributable

to another set of factors. First, the number of Indian guest workers

bringing ‘two-in-ones’ (radio-cassette players) from the Gulf states had

by the 1980s reached such a level that luxuries of this kind had become

familiar throughout the country. More importantly, in accordance with

the contemporary economic liberalization policies pursued by the ruling

Congress Party from around 1978, many of the import restrictions

which had inhibited the acquisition of cassette technology in the 1970s

were rescinded, thereby permitting the import of players and, more

importantly, facilitating the local manufacture of cassettes and players

with some foreign components. irdly, indigenous industry itself,

after decades of infant-industry protection, had improved to the point

that Indian manufacturers were belatedly able to produce presentable

cassettes and players, whether using some imported components or

not.

3

Finally, the aforementioned economic liberalization policies

considerably enhanced the purchasing power and general consumerism

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 359

of the middle classes and even some sectors of the lower-middle classes,

in the countryside as well as the cities. is development, among other

things, greatly contributed to the proliferation of televisions and cassettes

in slums and villages throughout the country.

e advent of cassette technology eectively restructured the music

industry in India. By the mid-1980s, cassettes had come to account

for some 95 per cent of the recorded music market, with records being

purchased only by wealthy audiophiles, radio stations, and cassette

pirates (who preferred using them as masters). e recording industry

monopoly formerly enjoyed by HMV (now Gramophone Company of

India, or ‘GramCo’) dwindled to less than 15 per cent of the market as

over 300 competitors entered the recording eld. While sales of lm

music remained strong, the market expanded so exponentially—by a

factor of 10 in the rst half of the 1980s

4

—that lm music came to

constitute only about half of the market, the remainder consisting of

regional folk and devotional music, and other forms of non-lmi, or in

industry parlance, ‘basic’ pop music.

In eect, the cassette revolution had denitively ended the hegemony

of GramCo, of the corporate music industry in general, of lm music,

of the Lata–Mukesh vocal style and of the uniform aesthetic of the

Bombay lm music producers which had been superimposed on a

few hundred million music listeners over the preceding 40 years. e

crucial factors were the relatively low expense of the cassette technology,

and especially its lowered production costs, that enabled small, ‘cottage’

cassette companies to proliferate throughout the country. e new

small labels tended to have local, specialized, regional markets to whose

diverse musical interests they were able and willing to respond in a

manner quite uncharacteristic of the monopolistic major recording

companies, which, as we have seen, prefer to address and, as much

as possible, to create a mass homogeneous market. In the process, the

backyard cassette companies have been energetically recording and

marketing all manner of regional ‘little traditions’ which had been

previously ignored by HMV and the lm music producers. Rather than

being oriented toward undierentiated lm-goers, most of the new

cassette-based musics were aimed at a bewildering variety of specic

target audiences, in terms of class, age, gender, ethnicity, region and, in

some cases, even occupation (for example, Punjabi truck drivers’ songs).

e smaller producers themselves have been varied in terms of their

region, religion, and insofar as many are lower-middle class, their class

backgrounds as well. Ownership of the means of musical production

360 Ravi Sundaram

thus became incomparably more diverse than before the cassette era. As

a result, the average, non-elite Indian is now, as never before, oered

the voices of his and her own community as mass-mediated alternatives

to His Master’s Voice.

By the early 1990s the cassette producers had come to vary greatly in

size, orientation, operating practices, and other parameters. On the one

hand have been the handful of major rms, namely, GramCo, which,

hampered by ineciency and inability to compete, relied primarily

on its back catalogue of lm music; CBS and a break-away rm,

Magnasound, which specialized in releases of Western music; Polygram’s

Music India Ltd (MIL, formerly Polydor); T-Series/Super Cassette

Industries (SCI), and a newer business founded by the entrepreneur

Gulshan Kumar (murdered, gangland-style, in 1997), with a diverse

catalogue now including much current lm music; Venus, a Bombay-

based concern with a similarly diverse repertoire; and TIPS, which

specialized in cover versions of pop songs. On the other hand have

been the smaller regional producers, which probably came to number

between 250 and 500 nationally.

5

ese themselves range in size from

regional folk/pop producers like Delhi’s Max, Sonotone, and Yuki, with

over a thousand releases each, to operations like Chandrabani Garhwal

Series, whose series, as of 1989, consisted of a single cassette. Beyond

this level emerged numerous provincial entrepreneurial individuals who

would record music and sell copies upon request out of their residences,

dubbing them with simple one-to-one setups.

TECHNOLOGY, FINANCING, AND PIRACY

e expenses and technical resources of the cassette producers naturally

varied in accordance with their size, audience orientation, and other

factors. Both large and small companies would have their own recording

studios and dubbing facilities, and/or they could rely on rented studios

and other duplicators. While a few of the better studios had such features

as 16-track recorders, in the 1990s most professional studios had only

four-track technology. Recorders were almost all imported; dubbing

machinery could be either imported, or might consist of one-to-four

duplicators made by indigenous and generally unlicensed companies.

Similarly, blank tape and cassette shells could either be imported, acquired

from indigenous makers, or, in the case of larger companies like T-Series,

manufactured by the rm itself; smaller producers could assemble the

cassettes by hand. Cassette recorders themselves would range from high-

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 361

delity products of Japanese-Indian ‘tie-ins’ (for example, Bush–Akai

and Orson–Sony) to locally made players, in which only the heads and

micro-motors would be imported.

Recording expenses varied widely. With studio charges and fees

for engineers and musicians, production of a 60-minute tape of mass-

market lm songs and Hindi pop in the 1990s music might on occasion

cost up to Rs 200,000. While the average recording expenses would be

closer to Rs 20,000, many recordings of folk music were produced for

considerably less. Cassette duplication would then proceed in accordance

with demand, with retailers often being able to return unsold tapes to

the manufacturer for re-recording (hence the absence of labels on many

regional cassette shells). Most cassettes would sell for around Rs 18;

HMV’s tapes typically ranged from Rs 24 to Rs 36. Tape delity ranged

from acceptable to worse, with poorer cassettes leaving oxide deposits

on tape heads and wearing out after a few listenings; customers learned

to request to listen to tapes before purchase to ensure that they are not

already defective.

Piracy, or the sale of unauthorized duplications of recordings,

plagued the cassette industry from its inception. e rst half of the

1980s was the worst period in this respect. Extant copyright laws were

unequipped to deal with cassette piracy, while the government showed

little interest in prosecuting oenders. HMV’s inability to reissue its old

lm hits provided the pirate producers with ample repertoire to market.

New companies faced onerous bureaucratic obstacles in legitimately

obtaining licences, including absurd export requirements. Due to high

government taxes on blank tape, and the myopic pricing policies of the

large cassette companies (especially HMV), legitimate tapes cost nearly

twice as much as pirate versions. Further, while most pirate cassettes were

of inferior quality, some, such as the tapes of Goanese music produced

and purchased in the Gulf states by guest workers, were actually superior

to the legitimate cassettes. By 1985, pirate cassettes were generally

estimated to account for 90 per cent of all tape sales. While most of the

piracy was perpetrated by small producers, the edgling T-Series was

widely accused of being a major culprit. Meanwhile, cassette stores and

dubbing kiosks proliferated throughout the country, recording favourite

songs selected by individual customers.

In the latter half of the 1980s, the situation improved somewhat.

Most legitimate producers lowered their prices, making pirate tapes

less competitive. e government, under increasing pressure from

the industry, reduced its various taxes and bureaucratic hindrances to

362 Ravi Sundaram

registration of new companies; more importantly, realizing the extent

of its tax losses, it enacted a more eective copyright act in 1984 and

intensied attempts at enforcement. Legal cover versions of the classic

hits became widely marketed. Consumers gradually became aware of

the advantages of buying legitimate tapes. As a result of these changes,

piracy, although still open and widespread, diminished considerably, at

least in relation to the market as a whole. In the absence of accurate

gures, in the early 1990s I estimated its share at roughly one third of

the market.

THE IMPACT OF CASSETTES ON MUSICAL TRENDS

e cassette vogue played a central role in the owering of a number of

commercial music styles of north India, especially the ‘non-lmi’ genres

that came to rival, if not surpass the popularity of lm music. Film

music, of course, has continued to be the single most dominant North

Indian genre, and cassettes naturally served to disseminate it considerably

more widely than before. Nevertheless, as I have suggested, by making

possible more diverse ownership of the means of musical production,

cassettes came to serve as vehicles for a set of heterogeneous genres

which have provided, on an unprecedented level, stylistic alternatives to

lm music. In the process, relatively new genres of stylized, commercial

popular musics arose in close association with cassettes. e following

discussion, rather than attempting a descriptive survey of these styles,

endeavours to outline the connection between their emergence and

cassette technology.

Ghazal

e Urdu ghazal has played an important part in North Indian culture

since the early eighteenth century. As a literary genre (consisting of

rhymed and metered couplets employing a standardized symbology and

aesthetic), it has been and remains widely cultivated among educated

and even many illiterate north Indians, especially Muslims. As a

musical genre, it emerged as a rich semi-classical style, popularized by

courtesans and, in the twentieth century, by light-classical singers of

‘respectable’ backgrounds. With the advent of lm music, a lmi style

of ghazal emerged, distinguished from its semi-classical antecedent by

characteristics typical of lm song in general, namely, ensemble interludes

between verses, occasional use of Western instruments and harmony,

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 363

absence of improvisation, and a standardized vocal style epitomized by

its main exponents, Talat Mehmood and a handful of other singers,

including, of course, Lata Mangeshkar. While the lm ghazal had

declined after Mehmood’s heyday in the 1950s, in the late 1970s a

new style of ghazal-song owered which was at once commercially

popular, distinct from the earlier lm and light-classical styles, and

lacking direct association with cinema. Indeed, the new crossover

ghazal, as popularized rst by Pakistanis Mehdi Hassan and Ghulam

Ali, was the rst widely successful popular music in South Asia which

was independent of cinema or, for that matter, radio. With its leisurely,

languorous tempo, its vaguely aristocratic ethos, its sentimental lyrics,

and soothing, unhurried melodies, the new ghazal, though disparaged

by purists as restaurant ambient music, came to acquire an audience

far wider than ghazal had ever had before. Much of the new ghazal’s

audience consisted of devotees of the formerly melodious lm songs

who were alienated by the recent lm music trend toward disco-oriented

styles more appropriate to the action-oriented masala (‘spice’) lms of

the 1980s. In the hands of the subsequent ghazal stars—Pankaj Udhas,

Anup Jalota, Jagjit and Chitra Singh, and others—the crossover ghazal

style became even more distinct, with its diluted Urdu, often shallow

and trite poetry, general absence or mediocrity of improvisation, and a

silky, non-percussive accompaniment and vocal style which rendered

it immediately recognizable. As the genre became ever more remote

from its semi-classical antecedent, ‘pop goes the ghazal’ soon became a

journalistic cliché.

What is signicant for the present study is the role that cassettes

played in the popularization of the crossover ghazal. e ghazal vogue

had gathered momentum by the late 1970s, but reached its apogee in

the rst half of the next decade, in tandem with the cassette boom. e

two trends, indeed, reinforced each other, at the expense of vinyl records

and lm music in general. Cassette producers in the rms most closely

associated with the ghazal vogue—GramCo and MIL—saw themselves

as not merely responding to popular demand, but actively promoting, if

not creating the trend. us, MIL vigorously pushed ghazal tapes partly

in order to outank cassette pirates by creating a market for a genre

distinguished by relatively high delity and an auent, yet mass audience

(unlike pirate cassettes, most of which consisted of poor-delity tapes of

lm hits aimed at lower-class buyers).

6

Similarly, a GramCo executive

related, ‘What became necessary [after the decline of melody-oriented

lm music] was to take ghazals and bhajans to a wider market, thus

364 Ravi Sundaram

simplifying them and making them more universally accepted.... Many

such trends can be created.’

7

While our informant was no doubt overstating the ability of the

music industry to create trends outright, it is clear that the deliberate

promotion of ghazal cassettes by the larger recording companies actively

helped popularize both the medium and the music. In the wake of

these developments, commercial cassettes were established as the most

dynamic sector of the music industry by the early 1980s, such that future

developments in the realm of Indian popular music were closely allied to

the new medium.

Devotional Music

If the crossover ghazal boom conrmed the transition from vinyl to cassette

recording, it was the unprecedented vogue of commercial versions of

devotional music that accompanied and fed the extension of the cassette

market beyond the urban middle classes. e devotional music trend did

not, of course, emerge from a vacuum. India, with its vast, diverse and

intensely religious population, continues to host an extraordinarily rich

variety of devotional music traditions. e most widespread of these have

been the various, often collectively performed songs associated with the

Hindu bhakti traditions, which celebrate personal devotion rather than

karma, caste, or formal ritual. Commercial lm versions of bhakti git had

been familiar for decades, and several lm bhajans and artis had acquired

the status of hits, being subsequently sung by devotees throughout the

country (such as the arti ‘Om Jai Jagdish Hare’ from the lm Purab aur

Paschim). Filmi versions of Muslim qawwali had also become a common

feature of Bombay movies. Further, record companies (primarily, of

course, GramCo) had traditionally come to time new releases with the

main Hindu festivals (especially the simultaneous Bengali Durga Puja,

Gujarati Navratri, and Maharashtrian Ganesh Puja), when the public

goes on gift-buying sprees. Nevertheless, the extent of the commercial

bhakti vogue in the early 1980s was quite unprecedented.

e immediate forerunner to the trend was the widely successful

series of recordings by Mukesh consisting of tasteful musical settings of

Tulsidas’s version of the Ramayanaa epic. Although rst released on LP

format, it was not until it was issued on cassette in the late 1970s that

this series achieved mass sales. e phenomenal popularity of subsequent

television serials of the Mahabharata and Ramayana epics played an

even more important role in promoting mass-mediated realizations of

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 365

religious works, including cassette recordings of devotional musics. As

with ghazals, however, the cassette medium itself played the crucial role in

popularizing commercial bhakti git. Cassette producers recognized that

a successful devotional cassette may enjoy a considerably longer ‘shelf

life’ than most other pop music releases, whose sales generally dwindle

after a few months. Further, producers saw that the country’s extant

devotional music traditions constituted a relatively untapped gold mine

of inestimable commercial potential. Accordingly, several commentators

opined that the vogue of pop bhakti music was due primarily to the

advent of cassettes rather than to any resurgence of religious fervour in

the country. us, for example, veteran bhajan singer Purshottam Das

stated: ‘Bhajans have always been popular in certain segments of our

society. But now the catchy tunes have been successful in attracting the

youth. Essentially, it is the cassette medium which is responsible for the

growing sales rather than growing interest.’

8

Similarly, a music journalist

argued, ‘Perhaps the real reason for this manic following of bhajans was

the spectacular rise of audio-visual electronic consumer goods and the

rise of the ghazal’.

9

e variety of commercially marketed devotional musics that

emerged in North India is remarkable. e most conspicuous genre has

been what may be described as a ‘mainstream’ or ‘stage’ bhajan style,

sung by a solo vocalist with light instrumental accompaniment. It

was this genre that started the bhakti boom, in the wake of Mukesh’s

Ramayana and, more importantly, the ghazal vogue. Hence it is not

surprising that in style, instrumentation and leading performers (Anup

Jalota, Pankaj Udhas), the mainstream pop bhajan had marked anities

with the crossover ghazal. While this sort of bhajan continues to enjoy

mass appeal, cassette producers subsequently marketed an extraordinary

variety of religious musics, which, needless to say, come incomparably

closer to representing the rich diversity of Indian devotional musics

than lm musics ever attempted to do. Predominant in the eld,

naturally, are sub-genres of Hindu devotional music, including musical

settings of traditional prayers (for example, Hanuman Chalisa, or the

epics), bhajans devoted to various cult leaders (such as Sai Baba), or to

deities (such as Santoshi Ma), bhajans sung in light-classical style by

classical vocalists like Kumar Gandharva, and all manner of old and

new songs in regional languages. Musics of other religions also came to

be well represented. Qawwali cassettes continue to sell, as do tapes of

semi-melodic discourses by Muslim religious leaders. Sikh devotional

songs—especially shabd gurbani—came to enjoy a large market (and are

366 Ravi Sundaram

remarkable for their avoidance of the stylistic commercialization typical

of many other devotional musics). Christian hymns, Jain bhajans, and

even Marathi Buddhist songs also established their own customers.

While most cassettes, including the mainstream bhajans, are

essentially for recreational listening, others are more functional in

intent and usage. Housewives, for example, may routinely play a

cassette of the Satyanarayan Katha during their occasional ritual

fasting, in place of inviting a pandit to chant the story, or reciting it

themselves. e important thing, in terms of spiritual benet, is that

the story be heard, regardless of whether one recites it oneself or listens

to it while doing housework.

Smaller cassette companies would frequently produce tapes for

specic festivals celebrated annually at shrines or temples. In the years

around 1990, for example, a edgling company in Lucknow would

produce a tape of songs connected with the annual festival in nearby

Deva Sharif, selling some Rs 12,000 worth at the event every year. Such

prots, of course, might be too small to interest the larger recording

companies, but would suce to keep many smaller producers in the

market. Indeed, aside from the appeal of bhajan superstars like Anup

Jalota and Hari Om Sharan, it is the ability of cassette producers to

represent the innumerable ‘little traditions’ that have accounted in

large part for the extent of the devotional music vogue. Perhaps due to

the virtually inexhaustible nature of these traditions, the commercial

bhakti boom, unlike that of the ghazal, shows no signs of abating

at present.

Versions and Parodies: Recycling the Classics

A third important genre in the contemporary cassette-based popular

music scene comprised cover versions of prior hit songs. Such recordings

could be grouped into two broad categories: in one case—that of

the cover version proper, or in modern Indian parlance, a ‘version’

recording—an extant song is re-recorded, generally by a dierent label,

with dierent vocalists; the second category consists of cases where a new

release uses the melody of an extant hit, but set to a new text. e latter

instance, of course, constitutes ‘parody’ (and is commonly referred to as

such in India). Parodies (a term in this usage lacking any comedic sense)

substituting new texts in the same language—a common practice in

modern lm music—are generally not classied in the ‘version’ category,

and lacking direct association with cassettes, will not be discussed in this

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 367

article. Of greater relevance here are those parodies substituting a new or

translated text in a dierent language from the original.

10

Like ghazal and devotional songs, cover versions and cross-language

parodies were neither new nor unique to Indian commercial music; for

that matter, the use of stock tunes is basic to folk music in India and

many other countries. Furthermore, since the mid-twentieth century

Indian folk musicians throughout the country have freely borrowed and

adapted lm melodies. Nevertheless, the extent of the current popularity

of commercial versions and parodies was quite unprecedented in India

and, to my own knowledge, unparalleled in any other country (with

the possible exception of Indonesia, for which see Yampolsky 1989).

e deluge of ‘version’ recordings covering classic lm hits came to

constitute a separate market category that occupied a sizeable niche in

most urban cassette stores. Further, every major hit song of recent years,

regardless of its original language, would spawn several parody versions

in regional languages.

A primary impetus for the vogue of cover versions was the inability

of GramCo to meet the demand for releases of its vast catalogue of past

lm songs. GramCo, by virtue of its longstanding virtual monopoly,

held the rights to essentially all lm songs recorded until the early

1970s. While many of these were forgettable and forgotten, many

others were still in demand, but were not being re-issued, largely due

to the company’s monopoly-bred ineciency. e advent of cassettes

and the subsequent emergence of competing producers provided, for the

rst time, a means of meeting this demand. T-Series founder Gulshan

Kumar was the rst to capitalize upon this situation; since the original

recordings were copyrighted by GramCo, he set out to produce ‘versions’

of the most popular classic lm hits. As the original vocalists were either

prohibitively expensive (Lata), deceased (Kishore, Talat, Mukesh), or

bound by contract obligations to GramCo, Kumar scouted college

talent shows for clone singers, coming up with a stable of inexpensive,

undiscovered vocalists. He then released an ongoing series of ‘version’

tapes entitled Yaaden (‘Memories’), whose labels acknowledged, in

small print, that the singers are not those of the original recordings.

e versions were recorded in stereo, using modern technology, and

thus oered considerably better delity than the originals. Other labels

followed suit, and the category of ‘version’ recordings boomed. Most

of these have been based on Hindi-Urdu lm songs, but some labels

specialized in oering regional-language versions of non-Hindi songs

(such as Sargam’s version series of past Marathi hits). While GramCo

368 Ravi Sundaram

belatedly began reissuing some of its back catalogue, its cassettes, as

noted above, remained considerably more expensive than those of other

labels, including versions.

Critics and acionados often complained that the version singers

were inferior to their models. Nevertheless, the wide sales of these

recordings suggest that the public, when given an alternative, was not

as exclusively xated on Lata and Kishore as lm producers have been.

e vogue of versions also illustrated how cassettes can contribute to

the decentralization of the music industry even where ownership of the

repertoire remains monopolized.

e boom of parody songs in regional languages is another

development intrinsically tied to cassettes and the diversication of

music industry ownership. Of course, Bombay lm music producers

had often borrowed melodies from regional folk music and given them

new or translated texts, generally in Hindi. But the advent of cassettes

and the decentralization of the music scene enabled this process to

occur on an unprecedented scale, and in reverse. First of all, the new

parody recordings were marketed independently of cinema, whether the

borrowed hit melodies originated in lm music or not. Secondly, the

parody songs generally contain new texts in regional languages, rather

than mainstream Hindi–Urdu. us, they have been aimed at regional

markets (Punjabi, Bengali, Marathi, etc.) and in that sense have served

to promote linguistic diversity rather than the hegemony of Hindi–Urdu

in pop culture.

Regional Musics

While pop ghazals, bhajans, and version songs came to form new and

important components of the Indian popular music scene, it was the

commercial recordings of regional folk musics that came to constitute

the most signicant development within the music industry. By 1990,

regional folk musics or stylized versions thereof appeared to account for

around half of all cassette sales in north India.

11

Moreover, it was the

emergence of regional commercial musics which most clearly illustrated

and derived from the decentralization and democratization of the music

industry at the expense of Hindi-Urdu, corporate-produced lm music.

As with the other genres discussed above, commercial recordings of

non-lmi regional folk-pop musics had been extant for several decades

before the cassette boom, but they were limited in quantity and variety,

and their audience was largely restricted to urban middle-class consumers

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 369

who could aord record-players. Mostly they consisted of short, stylized

settings of lively folk songs, or new songs in folk style, accompanied

by instrumental ensembles playing pre-composed interludes between

verses. With the advent of cassettes, modernized versions of such songs

continued to sell, but then came to compete with an unprecedented

variety of other genres. Styles popular primarily among the lower classes,

previously largely ignored by the record industry, came to be represented

on cheap cassettes. Further, unrestricted by the time limits of 78 or 45

rpm records, cassettes could oer a wide diversity of genres which require

longer time to present, and are in many cases more representative of folk

music genres than the short songs formerly marketed on records. us,

for example, western Uttar Pradesh residents could purchase dozens of

cassettes of their cherished kathas, or narrative song-stories (especially

Alha and Dhola), representing dierent episodes sung by dierent

performers. Meanwhile, Rajasthani and Haryanvi listeners could choose

from a few hundred cassettes of old and new kathas in their own dialects.

Extended, narrative genres like Bhojpuri birha also came to be widely

marketed, along with shorter song forms like the Braj-bhasha rasiya,

which had previously been represented by fewer than a dozen records.

Even more dramatic was the vogue of commercial cassettes in

regional languages which had been essentially ignored by the record and

lm industries. For instance, Garhwal, Haryana and the Braj region,

all within 150 miles of Delhi, came to constitute lively markets for

cassettes in their own languages, with several producers, large and small,

issuing new releases each month. Most of these tapes consisted of either

traditional folk songs, or more often, new compositions in more or less

traditional style. Needless to say, while lm music sought to homogenize

its audience’s aesthetics, the cassette-based regional musics were able to

celebrate regional cultures and arm a local sense of community. Unlike

lm songs dealing exclusively with amorphous sentimental love, regional

song texts abound with references to local customs, lore, mores and even

contemporary socio-political events or issues.

Much of the new cassette-based regional music has resisted easy

classication into ‘folk’ or ‘popular’ categories. Many cassettes have

consisted of traditional genres recorded in straightforward traditional

style. Others are ‘modernized’ or ‘improved’ (as producers put it) by

the addition of untraditional instrumental accompaniments. Once

marketed, even traditional songs can sometimes be ‘discovered’ and

enjoy the ephemeral mass popularity of pop hits; for instance, the

Punjabi nonsense song ‘Tutuk Tutuk’, as recorded by the UK-based

370 Ravi Sundaram

Malkit Singh, sold over 500,000 copies. Such sales, however, are

highly unusual for regional folk music, and some indications suggest

that recordings of traditional folk music have declined since the early

boom of the cassette era. Several producers of regional folk cassettes told

me that the majority of their customers were of the older generations,

who were less interested in lm music than the young.

CASSETTES, STYLE, AND FILM MUSIC AESTHETICS

us far, this article has emphasized the ways in which the cassette-based

music industry diered from the lm music industry in oering a much

greater diversity of musics and styles, which more faithfully represented

the variety of north Indian genres and aesthetics. Nevertheless, the

eects of cassette technology were complex and contradictory, and in

some respects could be seen to reinforce, rather than negate, tendencies

manifest within the earlier, corporate-dominated Indian music industry.

Cassettes, after all, are commercial commodities whose production is

subject, in varying degrees, to the same constraints and incentives of

capitalist enterprises in general, such as goals of maximization of prot

and economies of scale. Accordingly, if lm music can be accused of

distorting consumers’ aesthetics by superimposing values deriving from

the inherent structure of the music industry, cassette-based musics could

be seen to perpetuate some of the same tendencies.

An initial constraint is that cassette producers, whether small or large,

will only market those genres that prove protable. us, for example,

because a market must have a certain minimum size, within a given

region it may be only certain genres, or certain styles of a given genre

that were marketed on cassette. A case in point is the commercial music

scene in the Braj area, around Mathura. Most cassettes here consisted of

rasiya, the single most popular folk music genre. Rasiya itself is rendered

in a variety of styles, including village women singing informally in the

evening, a dozen or more devotees singing responsorially in a temple,

a dangal (‘competition’) between two professional groups, a chorus

singing in the Hathrasi style inuenced by nautanki theatre, or a solo

professional accompanied by drum and harmonium. Rasiya commercial

cassettes, with a very few exceptions, presented only the latter kind of

format. Further, while many traditional rasiyas are devotional portrayals

of Krishna and Radha, the vast majority of rasiya cassettes have been

secular, spicy (masaledar) erotica. Some of the best singers continued

to go unrecorded because they sing in styles other than that favoured

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 371

by cassette companies. Producers also tended to avoid vocalists who

perform in peripheral, lesser dialects (for example, Mevati) with smaller

potential markets. us, while cassettes were able to oer incomparably

greater regional and stylistic variety than did lm music, there are limits

to the degree of diversity they could represent.

A particularly conspicuous characteristic of Indian cassette-based

popular musics was the tendency to eliminate improvization. is trend

is especially apparent in ghazal, whose traditional light-classical style was

based on bol banao, or improvized textual-melodic interpretation. While

several cassettes of Mehdi Hassan, Ghulam Ali, and others did feature

some improvization, the majority, like earlier lm ghazals, have consisted

of purely pre-composed renditions whose appeal lay in the xed tune,

rather than in the singer’s skill at improvization. Similar trends could

be observed in other commercialized north Indian genres, suggesting

that the more a genre becomes dependent on the mass media, the less

improvization will be tolerated.

Similarly, cassettes tended to perpetuate the aforementioned practice

of ‘improving’ or ‘decorating’ songs with instrumental interludes

and accompaniments (frequently including chordal instruments). Of

course, many cassettes employed purely traditional instrumentation,

in cases where producers think their more traditional-minded listeners

would disapprove, or when they were disinclined or unable to pay for

extra musicians, arrangers and rehearsal time. But the trend toward

non-traditional instrumental accompaniments, already established in

lm music and radio broadcasts of folk music, was clearly being spread

by cassettes.

Another tendency of Indian popular musics that was reinforced by

cassettes was the promotion of short songs. While as mentioned above,

lengthy narrative song genres were widely marketed on cassette, other

more exible genres (for example, qawwali, rasiya, bhangra, ghazal, and

bhajan) tended to be compressed into four to six minute formats. One

producer of qawwali cassettes told me that in his experience, this format

was the rst thing customers looked for in a cassette. Whether deriving

from the inuence of record format, or from the desire to acquire

several tunes in a single purchase (the favourites of which can always

be replayed), the perpetuation of this custom on cassettes reinforces

the ‘sound bite’ aesthetic in popular musics and extends it to genres

previously uninuenced by the mass media.

While reinforcing a degree of stylistic and formal standardization,

cassettes provided a remarkable stimulus for the creation of new texts

372 Ravi Sundaram

and, in some cases, melodies. Many cassette companies, from T-Series

to several smaller producers interviewed, insisted that their performers,

regardless of genre, sing primarily new material, that is, material with

new lyrics. In the case of regional folk genres like rasiya, a considerable

amount of the familiar traditional repertoire may have been exhausted

in the rst years of the cassette boom, such that the producers’ demand

for new material kept several lyricists occupied (while generating

much verse that acionados nd forgettable). Insofar as novelty is a

virtue in itself, this aspect of cassette impact should not be regarded

as unwelcome.

Similarly, certain genres appeared to have acquired markedly greater

melodic variety in recent decades, although it is dicult to attribute this

development solely to the cassette boom, or, for that matter, to any other

specic factor. Modern renditions of Rajasthani kathas and the Braj-

bhasha dhola are both said to be considerably more sophisticated and

varied in their styles and melodic content than a generation ago. While

professionalism and mass media inuence in general appear to have

contributed to this development, the cassette-based commercialization

of these genres may well have accelerated the process. Another factor

related to this phenomenon was the aforementioned borrowing of lm

tunes, which, of course, had also become a common practice in north

Indian folk music well before the advent of cassettes. Cassettes not only

served as vehicles for such parody tunes, but may have intensied the

practice by increasing demand for new material.

In discussing how cassette technology may reinforce, rather than

oppose certain features of lm music and other related tendencies

within the Indian music industry, we may also reiterate that cassettes

were vehicles not only for the spread of lmi aesthetics and borrowed

lm tunes, but also of lm music itself. In the 1990s lm music still

accounted for around half of cassette sales. Even in stores in provincial

towns, roughly half the shelf space would often be devoted to lm

music. While cassette technology enabled other competing genres to

ourish, some of the same virtues which enabled this development

to occur—low cost, portability, etc.—also promoted the increase of

lm music sales, especially among the lower-middle classes and rural

dwellers. us, while lm music’s share of cassette sales as a whole

dropped signicantly, lm music sales themselves do not appear to

have declined, as the entire market for recorded music has expanded

so dramatically. In this sense, the impact of cassettes was contradictory.

(See Figures 14.1 to 14.3.)

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 373

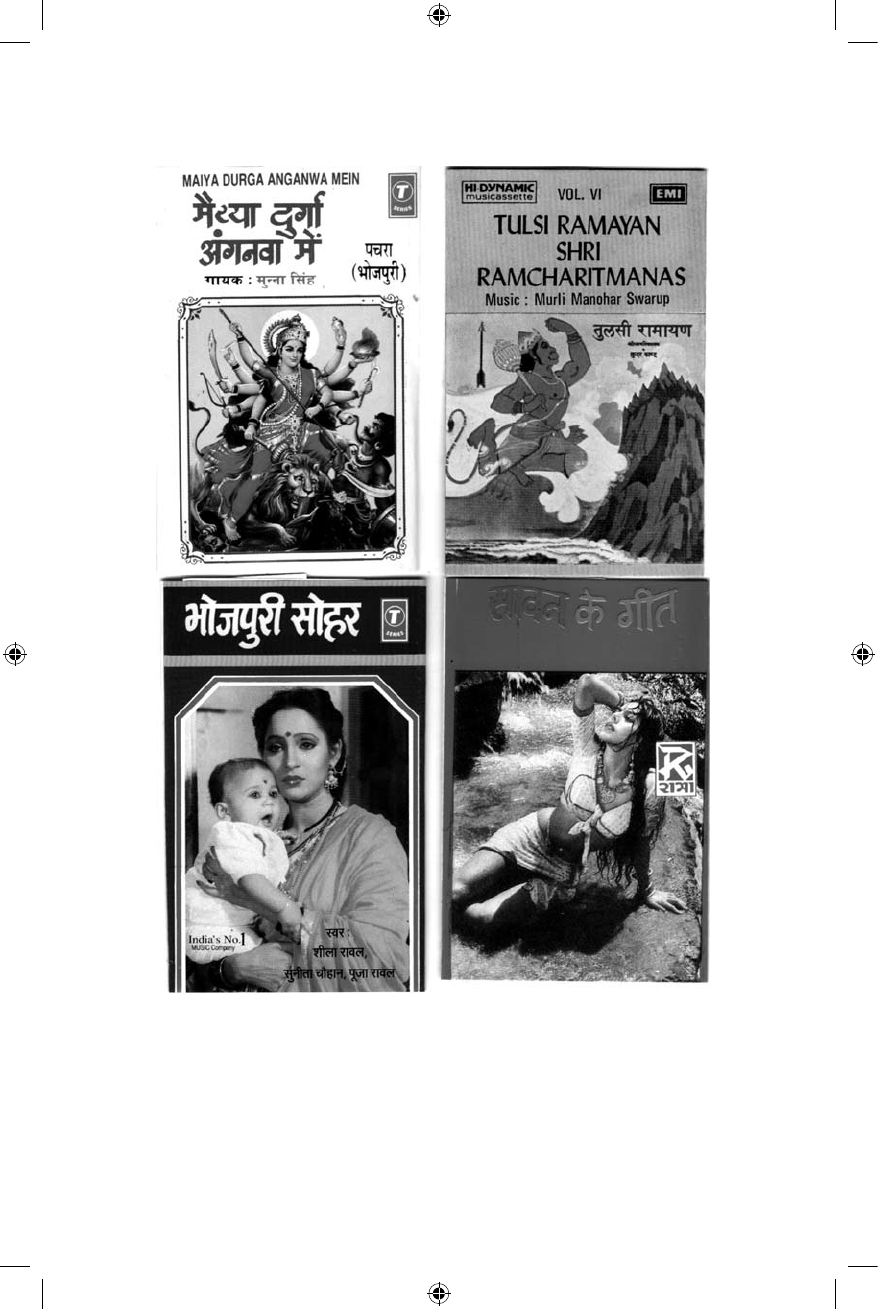

Fi g u r e 14.1 Some Typical Regional Music Cassettes from the

1980s–90s

Source: From author’s personal collection.

Note: Bhojpuri sohar, sâvan, songs to Durga, and a volume of Mukesh’s Tulsi

Ramayana.

374 Ravi Sundaram

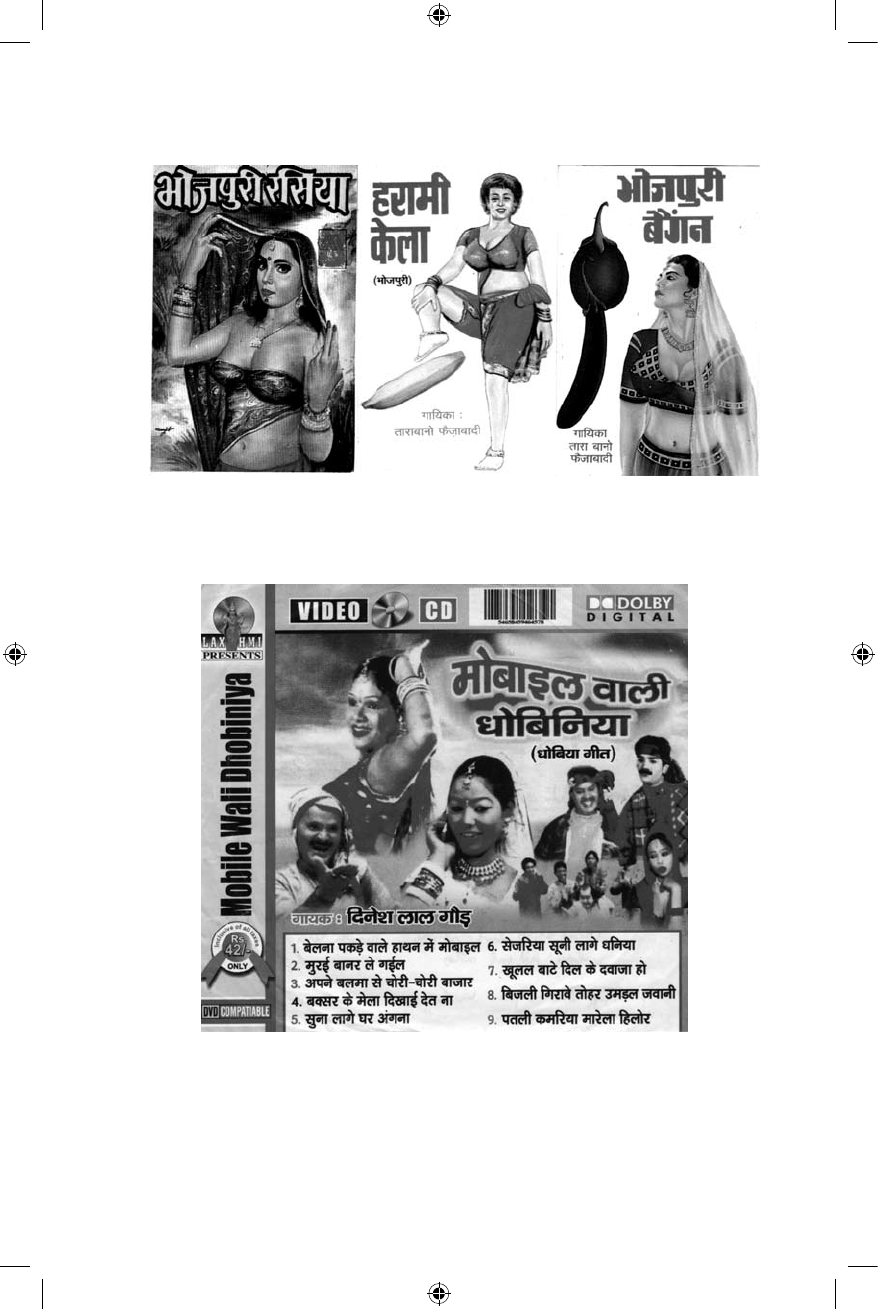

Fi g u r e 14.2 Lewd Bhojpuri Cassette Covers from around 1990

Source: From author’s personal collection.

Fi g u r e 14.3 A Typical Bhojpuri VCD Cover, Featuring the

Titillating Image of the ‘Mobile Wali’

Source: From author’s personal collection.

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 375

INDIAN POPULAR MUSIC GOES DIGITAL

Since the late 1980s the Indian popular music scene has entered the

digital age—unevenly and idiosyncratically, but with prodigious eects.

e impact of digital technologies on Indian popular music culture has

been diverse and profound, and merits expansive scholarly treatment.

is chapter will limit itself to a few cursory observations, relating in

particular to the core themes of decentralization and democratization.

In India, as elsewhere, the initial presence of digital consumer

technology came in the form of music compact discs. By around 1990

CDs had become the dominant audio format in the developed West,

replacing both vinyl and audio cassettes, which had exerted a less

dramatic impact on music culture than in India. Since that period

audio CDs have occupied a stable niche in Indian music culture.

However, their relatively expensive nature has tended to limit their

domain to upper- and middle-class milieus, and to the associated

music genres, such as classical music, high-end Hindi pop, and of

course, lm music. CDs never established much presence in the realm

of regional folk-pop hybrids.

Instead of standard music CDs, two new digital formats came to

dominate the Indian popular music scene, with diverse sorts of eects.

One of these is audio CDs of MP3 les of songs. MP3, as most readers

are aware, is a digital audio format in which audio les are compressed

without excessive loss of delity. An MP3 disc can contain several times

as much music as a normal CD, and its audio delity is considerably

superior. Moreover, both production and duplication costs as well as

consumer playback equipment costs are even lower than those of audio

cassettes. A typical MP3 disc, whether of qawwali or regional folk-pop,

might retail for around Rs. 20–40, and contain a few hours of music.

Accordingly, MP3 discs have increasingly come to replace cassettes,

and many cassette companies (for example, ‘Gathani Cassettes’) have

switched to MP3 production, while retaining their original names.

Audio cassettes are still marketed for purchase by consumers who still

own cassette players, but cassettes are clearly going the way of vinyl.

MP3 discs can be seen essentially as occupying the place formerly held

by cassettes in the market, and being equally conducive to industry

decentralization.

Even more widespread than MP3 discs, and more strikingly new in

their ramications, are video compact discs, or VCDs. VCD consumer

technology started to be marketed in the late 1990s. In the more auent

376 Ravi Sundaram

developed world, VCDs could not compete with DVD video format,

which oered higher quality and longer run time. However, in the

developing world—especially Asia—VCDs became well established in

the early 2000s. In India, VCDs themselves are cheap, typically retailing

for Rs. 25–45, and ‘Walkman’-style players are themselves cheaper than

cassette players, and are easily plugged into the inexpensive televisions

that now abound throughout the country, including in lower-class

communities. While discs can be damaged by being scratched, both

they and players are tolerant of high humidity and generally well-suited

to Indian climate and conditions. ey can also be viewed in regions

or during periods when and where there are no television broadcasts

available. Most advantageous, of course, is that VCDs oer visual as well

as audio data. Music producers have thus found themselves able—and

indeed, obliged—to produce music videos. Unlike in the West, these

videos are not conceived primarily as promotional tools for audio

recordings, but as commercially marketed products in themselves. One

might think that video production costs would signicantly impact

retail prices, but surprisingly, such has not been the case. Rather, VCDs

market for roughly the same prices as MP3 discs, typically Rs. 30–50.

Essentially, video producers have been able to use digital production

techniques and cheap labor to generate picturizations that entertain

viewers without raising retail prices.

Indian VCDs can be seen to some extent as perpetuating trends

established earlier in popular music culture. On the most general level,

the videos themselves perpetuate the well-established tradition of song

picturization standard since the inception of Indian sound lm in

1931. Like cassettes and MP3 discs, they are inexpensive to produce

and purchase, and lend themselves well to decentralized, democratic

production by diverse regional and religious ‘cottage’ industries. A VCD

production company, indeed, might consist of no more than a producer

with a mobile phone, who contracts performers, rents studios, and

orders mass duplication of discs, colorful paper cover labels, and the

like. Just as cassettes could reinforce and revitalize diverse, specialized

forms of Indian vernacular music, so have VCDs enhanced this trend

by adding visual dimensions. A regional-language folksong tradition,

unprecedentedly disseminated on cassette, could now be marketed with

visuals portraying local garb, dances, scenery, and the like. Further, the

VCDs, like cassettes, are at once appreciated as democratic, decentralized

forms of cultural expression while disparaged for their often shoddy

quality and vulgar orientation.

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 377

In other respects, however, the ramications of music video format

inaugurated by VCDs are new. While Bollywood song and dance

scenes might constitute a sort of ideal model for many VCD producers,

most of the latter operate on shoestring budgets obliging them to be

more modest in their picturizations. As might be expected, standard

formulae soon emerged, such that most VCDs, especially on the lower-

budget end, follow what has become a set of familiar norms. A few

VCDs present live concert or stage footage, but the quantity of such

productions is limited by the preference for studio-recorded audio tracks.

More standard is to have the singers, or more photogenic dancers and

models, mouth the lyrics in lip-sync, Bollywood-style. Hence, a qawwali

VCD might show the group singing, with appropriate gesticulations,

in some ‘virtual’ studio setting, with various sorts of computer graphics

interspersed with stock footage of shrines, Mecca, and other religious

imagery. A regional-pop video could portray the vocalist ‘singing’

in various picturesque sites. Often, the video shows the one or two

supposed singers cavorting in a park, perhaps accompanied by dancers

gyrating predominantly in Bollywood style, though perhaps with some

choreographic elements more typical of regional tradition. Dancers’

attire might vary from traditional to contemporary Western, depending

on whether the VCD is a ‘family-oriented’ production or one aimed at

consenting adults, especially young men. Perhaps most engaging are

the various videos that dramatize the narrative content of the lyrics.

For example, the country bumpkin encountering the sophisticated,

scantily clad city girl, or the amorous newlyweds chang under the lack

of privacy in their village home.

One of the very few published studies of ‘VCD culture’ to date is Vishal

Rawlley’s (2007) online essay ‘Miss Use: A Survey of Raunchy Bhojpuri

Music Album Covers’, which also oers information on Bhojpuri VCDs

in general. Rawlley notes that much of Bhojpuri VCD production, like

the regional-language folk-pop cassettes I discussed in my book Cassette

Culture (1993), tends to consist of playfully spicy masala quintessentially

oriented toward young male rural migrants to the cities. Liberated from

village restrictions on comportment, exposed to new mass media images,

and yet still retaining aspects of their regional culture and language, the

VCD consumers are fed fantasies of ‘loose’ women in ‘two-piece’ outts,

dancing to chat-pate lokgeet (‘sweet-salty folksongs’) that are at once

fashionably modern and distinctively regional in language and tune.

Such VCDs become components of a ‘B-industry’ of vernacular urban

media comprising ‘cheaply made porn lms, horror icks, cheesy music

378 Ravi Sundaram

albums, pirated foreign lms’, and the like. As he notes, ‘this B-industry

shares a common pool of talent and facilities—music arrangers, editing

studios, publicity designers, etc.’ Accordingly, some VCDs bear an ‘A’

stamp indicating that they are for adult consumption only.

Such videos are unlikely to be shown on the numerous Indian TV

programs that now broadcast a wide variety of regional songs, especially

in the form of Indian Idol-type amateur competitions. In general, the

eects of stations like Zee TV on popular music culture merit further

study and are too prodigious to be considered here. e cheap VCDs—

whether raunchy Bhojpuri songs or pious Sikh shabd-gurbanis—also

contrast with the smaller number of more sophisticated music videos

that are produced, like their Western counterparts, as promotional

items accompanying commercial audio recordings. Rather than being

marketed to consumers, the videos are generally seen on television or the

Internet. ese are typically more glossy and elaborate productions, and

in some cases tasteful and self-consciously ‘arty’. A popular representative

video in the years around 2006 was that accompanying Rabbi Shergill’s

‘Bulla ki jana main kaun’ (‘Oh Bulla, who am I?’).

It remains to consider the extraordinary impact of the Internet on

popular music culture. While the vast majority of Indians cannot aord

computers or even access to them, a signicant minority—constituting

tens of millions of Indians and non-resident Indians (NRIs)—are

as enthusiastically ‘plugged in’ as are any consumers in the world.

Like other global music scenes, Indian popular music culture is now

enlivened by innumerable websites, online fanzines, and chat groups,

peer-to-peer (P2P) le-sharing networks, and global distribution

outlets. Collectively these at once serve to promote musical micro-

cultures while adding a new dimension of unity to Indian culture,

joining as never before the third-generation Sikh graduate student in

Vancouver with the dhoti-clad clerk sitting in some dusty, sweltering

Internet café in Patiala. Perhaps the most conspicuous medium for

such interactions is YouTube, of which South Asians have made

prodigious use. As many readers of this chapter are aware, YouTube

contains thousands on Indian postings, representing a wide variety of

music genres and formats. Aside from camcorder scenes from local

weddings and other festivities, particularly notable are the hundreds

of music shows from Zee TV and other programs, thousands of

Bollywood song-and-dance scenes, and other thousands of regional

folk-pop music videos uploaded from commercial VCDs. Of almost

equal ethnographic interest are the comments that viewers append

Democratizing Indian Popular Music 379

to YouTube uploads. In many cases, belying the cliché that ‘music

brings people together,’ such comments consist of pages of venomous

diatribes (typically Hindu versus Muslim, or Indian versus Pakistani),

set o by some remark, whether innocuous or deliberately provocative.

e YouTube comments, as a quintessential democratic-participant

medium, reect the full range of human thought about music, from

the inspiringly clever and sublime to the staggeringly ignorant and

sociopathic. YouTube, indeed, has come to constitute a quintessential

new medium, characterized by multi-vocal interaction, decentralized

input of content, and a level of diversity that is not only unprecedented

but was until a few years ago inconceivable.

NOTES

1. Manuel (1993 and especially 1991), from which this work draws

heavily. I use the term ‘popular music’ to comprehend all those genres, including

commercialized folk music, which are marketed as mass commodities and have

been stylistically aected by their association with the mass media.

2. us, while Lata may have recorded in over a dozen languages, she

cannot really be argued to have sung in more than one style.

3. Interview, Anil Chopra, editor of Playback and Fast Forward (a music

industry trade journal), March 1990.

4. See interview, Vijay Lazarus, Playback and Fast Forward, June 1986, p. 30.

5. Anil Chopra, in his interview in March 1990, estimated the number of

cassette companies at 500. A 1987 survey (cited in Playback and Fast Forward,

July 1987, p. 27) listed 256 producers. In 1990 I myself enumerated about 200

in selected regions of North India. Note that the record industry distinction

between ‘majors’, who own production and distribution as well as recording

facilities, and ‘indies’, who generally only record, is not meaningful in reference

to most cassette producers.

6. See, for example, interview, Vijay Lazarus.

7. Interview, GramCo manager Sanjeev Kohli, by Anil Chopra, Playback

and Fast Forward, August 1986, p. 31.

8. Interview, Purshottam Das, by M. Upadhyay, ‘e Bhajan Samrat’,

Playback and Fast Forward, July 1985, p. 15.

9. S. Lalitha, ‘e Business of Bhajans’, e Times of India, 1 October

1988.

10. See articles by music journalist and archivist V.A.K. Ranga Rao (1986)

for a sketch of the history of version recordings in Indian lm music.

11. Interview, Anil Chopra, March 1990. Accurate gures were unavailable

due to piracy, the unreliability of sales reports from the major companies, and

the absence of data from the smaller ones.

380 Ravi Sundaram

REFERENCES

Chandravarkar, B. 1987. ‘Tradition of Music in Indian Cinema’, Cinema in

India, March, pp. 8–11.

Manuel, P. 1991. ‘e Cassette Industry and Popular Music in North India’,

Popular Music, 10(1): 175–203.

. 1993. Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ranga Rao, V.A.K. 1986. ‘Version Recordings: New Controversy, Old Issue’,

Playback and Fast Forward, 26–7 August and 29 September.

Rawlley, Vishal. ‘Miss Use: A Survey of Raunchy Bhojpuri Music Album

Covers’, in Tasweer Ghar: A Digital Archive of South Asian Popular Visual

Culture. Available online at http://tasveergharindia.net/cmsdesk/essay/66/

index_1.html (accessed on 26 September 2012).

Yampolsky, P. 1989. ‘Hati Yang Luka, an Indonesian Hit’, Indonesia, 47: 1–18.