Progress in the International

Health Partnership & Related

Initiatives (IHP+)

2014

Performance

Report

UNIVERSAL

HEALTH COVERAGE

FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE

HEALTH IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC

REGION

Lorem ipsum

UNIVERSAL

HEALTH COVERAGE

FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE

HEALTH IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC

REGION

September 2017

hera

right to health & development

Laarstraat 43

B-2840 Reet Belgium

Tel +32 3 844 59 30

hera@hera.eu

www.hera.eu

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Pr

epared under contract to UNFPA Asia-Pacific Regional Office

Contributors

Aminur Rahman Shaheen, icddr,b (Bangladesh)

Aroonsri Mongkolchati, Mahidol University (Thailand)

Chean Men (Cambodia)

Josef Decosas, hera (team leader)

Leo Devillé, hera (quality assurance)

Luvsan Munkh-Erdene (Mongolia)

Marieke Devillé, hera (core team)

Marta Medina, hera (core team)

Rita Damayanti, Universitas Indonesia (Indonesia)

Vu Cong Nguyen, PHAD (Viet Nam)

The team acknowledges the valuable support provided by the UNFPA Country

Offices i n B angladesh, C ambodia, I ndonesia, M ongolia, T hailand a nd V iet

Nam, as well as by the UNFPA Regional Office for Asia-Pacific.

Disclaimer

The study of universal health coverage for sexual and reproductive health in

the Asia-Pacific Region was undertaken by hera under contract by the

United Nations Population Fund Asia and Pacific Regional Office. The views

expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of

UNFPA. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of hera.

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

ANC

Antenatal Care

AP

Asia-Pacific

ART

Antiretroviral Therapy

AFPPD

Asian Forum of Parliamentarians

on Population and Development

CBHI

(Bangladesh) Community-based

Health Insurance

CHD

(Mongolia) Centre for Health

Development

CPA

(Cambodia) Complementary

Package of Activities

CPR

Contraceptive Prevalence Rate

CSMBS

(Thailand) Civil Servants’ Medical

Benefit Scheme

DHS

Demographic and Health Survey

DS

Satisfied Demand for Family

Planning

DSF

(Bangladesh) Demand-side

Financing (voucher scheme)

EmONC

Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal

Care

ESCAP

(UN) Economic and Social

Commission for Asia and the

Pacific

GBV

Gender-based Violence

HC

(Cambodia) Health Centre

Health

BPJS

(Indonesia) (social security agency

for health

HEF

(Cambodia) Health Equity Fund

HMIS

Health Management Information

System

HPV

Human Papillomavirus

IAEG

Inter-Agency and Expert Group

ICPD

International Conference on

Population and Development

IDR

Indonesian rupiah

MDG

Millennium Development Goal

MHI

(Thailand) Migrant Health

Insurance

MICS

Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey

MOH

Ministry of Health

MOHFW

(Bangladesh) Ministry of Health

and Family Welfare

MOLSP

(Mongolia) Ministry of Labour and

Social Protection

MOPH

(Thailand) Ministry of Public

Health

MPA

Minimum Package of Activities

MR

Menstrual Regulation

MRM

Medical Menstrual Regulation

(Bangladesh)

NCCD

(Mongolia) National Centre for

Communicable Diseases

NHSO

(Thailand) National Health Security

Office

NIPORT

(Bangladesh) National Institute of

Population Research and Training

NSO

(Mongolia, Thailand) National

Statistical Office

OOP

Out-Of-Pocket (payment for health

services)

OSCC

One-Stop Crisis Centre

PMTCT

Prevention of Mother to Child

Transmission (of HIV)

PNC

Postnatal Care

RH

(Cambodia) Referral Hospital

SBA

Skilled Attendance at Birth

SDG

Sustainable Development Goal

SHI

(Mongolia / Viet Nam) Social

Health Insurance

SHPS

(Bangladesh) Social Health

Protection Scheme

SRH

Sexual and Reproductive Health

SSK

(Bangladesh) (subsidised social

health insurance)

SSS

(Thailand) Social Security Scheme

STI

Sexually Transmitted Infection

THE

Total Health Expenditure

UCS

(Thailand) Universal Coverage

Scheme

UHC

Universal Health Coverage

UNGA

UN General Assembly

UNSTAT

UN Statistics Division

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Summary .............................................2

Effective coverage of sexual and reproductive health services

. 2

Equitable access to sexual and reproductive health services

..3

Financial risk protection for sexual and

reproductive health services

.............................3

Key issues

............................................4

The UN Agenda for Sustainable Development

...............5

Sexual and reproductive health services in Asia-Pacific

......6

The scope of the study of UHC for SRH

....................8

Bangladesh

...........................................9

Cambodia

...........................................13

Indonesia

............................................17

Mongolia

............................................21

Thailand

............................................. 25

Viet Nam

............................................29

Universal health coverage for sexual

and reproductive health

................................33

Effective coverage of SRH services

.......................34

Equitable access to SRH services

........................43

Financial risk protection for sexual and reproductive

health services .......................................47

Conclusions and recommendations

......................53

References

..........................................59

SUMMARY

The study reviewed the progress in six countries of the Asia-Pacific region towards

the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals 3.7 and 3.8.

SDG Goal 3.7: By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive

healthcare services, including for family planning, information

and education, and the integration of reproductive health into

national strategies and programmes

SDG Goal 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk

protection, access to quality essential health-care services

and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential

medicines and vaccines for all

Progress towards the achievement of universal access to sexual and reproductive

healthcare (SRH) was assessed according to a framework proposed in 2010 that

lists 11 key services for comprehensive SRH. Some services, for instance infertility

treatment, were not included in the assessment after consultation with the UNFPA

Regional Office.

Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Mongolia, Thailand and Viet Nam have made

national policy commitments to achieve universal health coverage, each starting

from a different baseline of health service development and health financing, but

each working towards a system of a unified mechanism to pool resources for a

health financing system that would protect households from high levels of payment

for healthcare at the point of service.

Initiatives started in Mongolia in 1994 with the introduction of a mandatory social

health insurance, followed by Thailand in 2002, Indonesia in 2004, Viet Nam in 2008,

Cambodia in 2011 and Bangladesh in 2012. By 2015, the six countries had achieved

different levels of service coverage and financial risk protection. Thailand had

reached a high level of coverage for sexual and reproductive health services with

low point-of-service charges to clients, while Bangladesh was among the Asia-

Pacific countries with the lowest service coverage levels and the highest direct

user charges.

EFFECTIVE COVERAGE OF SEXUAL AND

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH SERVICES

The Asia-Pacific region achieved significant progress in increasing the coverage

of effective sexual and reproductive health services. The maternal mortality ratio

declined by two thirds between 1990 and 2015, the contraceptive prevalence rate at

87.4 percent was three percent above the global level in 2015, and the adolescent

birth rate of 35/1,000 was considerably lower than the global average of 52/1,000.

The coverage of antiretroviral therapy for HIV was however five percent below the

estimated global average of 46 percent. While the HIV prevalence in the region is

low, the incidence of other sexually transmitted infections is higher than the global

average.

These regional statistics, however, hide many details. Some countries in the region

still record very high maternal mortality ratios, low contraceptive prevalence rates,

and very high adolescent fertility. Only a small proportion of sexually active adolescent

girls in Asia-Pacific are unmarried, but access to effective female-controlled methods

of contraception for these girls is particularly low. Furthermore, in four of the six

study countries, adolescent birth rates in 2014 were higher than the levels recorded

in 2005. Among the six study countries, the coverage of HIV antiretroviral treatment

ranged from nine percent in Indonesia to 74 percent in Cambodia.

Access to safe termination of pregnancy and post-abortion care varies among the

countries, depending on the national abortion laws. However even countries with

relatively unrestricted access to pregnancy termination still register large numbers

of unsafe abortions, especially among adolescents. Only Bhutan, Malaysia and

several Pacific Island States have introduced HPV immunisation in their national

immunisation programmes, while in the other countries this service is still in a pilot

phase.

2

National screening programmes for cervical cancer

exist in all six study countries, but only Thailand

records a significant coverage at 60 percent.

Several countries in the region have established

comprehensive one-stop crisis centres for girls

and women who are survivors of gender-based

violence. The centres are integrated in the national

health systems in four countries of the region, in

others they exist as pilots or in an early scale-up

phase.

EQUITABLE ACCESS

TO SEXUAL AND

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

SERVICES

The social equality gap in the use of family planning

and maternal health services has narrowed over

time. In the six study countries, there are no

inequalities in the use of modern contraceptives

among married women, but the gap in adolescent

fertility has not narrowed. Regionally, the difference

in the adolescent birth rate between women in the

lowest and the highest wealth groups increased

between 1998 and 2008. For skilled attendance

at birth, the gap between high and low-income

groups narrowed in Indonesia and Cambodia,

but it increased in Bangladesh. Women resident

in rural areas, remote regions and some island

provinces have lower access and utilisation rates

for reproductive health services, often because of

irregular supplies and stock-outs of contraceptive

commodities. Ethnic minority groups and the large

population of international migrants in Asia-Pacific

(estimated at 27.6 million) face numerous barriers

of access to health services, but information about

utilisation rates and reproductive health outcomes

among these groups is limited.

FINANCIAL RISK

PROTECTION

FOR SEXUAL AND

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

SERVICES

A mix of different financial protection schemes exist

in the six study countries. Efforts to consolidate

them into a single national social health insurance

scheme are furthest developed in Mongolia

and Viet Nam, and relatively far advanced in

Indonesia. In Thailand, however, three parallel

health insurance schemes continue to coexist and

achieve the highest levels of insurance benefit and

population coverage among the six study countries.

Some sexual and reproductive health services in

the other five countries are not included among

the health insurance benefits, but are provided in

public health facilities with varying levels of user-

charge exemptions.

Bangladesh has a fragmented system with a

demand-side financing (voucher) scheme for

maternal health services in 53 sub-districts and

public health provision of family planning services

throughout the country. In Cambodia, financial risk

protection is primarily provided through user-fee

subsidies in public health facilities for poor people,

and through health equity funds that reimburse the

cost of healthcare for the poor. Both countries are

in the early stages of developing a national social

health insurance.

With the exception of Thailand, and more recently

Indonesia, social health insurance schemes do not

provide benefits for family planning services. They

are provided free of charge to targeted populations

through public health services; in Viet Nam, for

instance, to ethnic minority populations; in Mongolia

and Cambodia to poor and vulnerable groups.

Population surveys in Bangladesh document that

many women bypass free public family planning

services in favour of buying services in the private

sector. In all study countries except Thailand, there

is a tendency to focus social health insurance

benefits on medical treatment and hospital

services, while prevention services, including for

sexually transmitted infections, are provided by

public health systems with varying service coverage

and varying levels of user-charge exemptions.

Services that require multi-sector interventions, for

instance services for the prevention and response

to gender-based violence, are generally not covered

by social health insurance. Migrant populations are

excluded from national financial risk protection

schemes in most countries. Only Thailand operates

a health insurance schemes for unregistered

migrant workers, which however only covers about

40 percent of the estimated target population of 3.4

million.

3

KEY ISSUES

• Without questioning the potential of the global UHC goals to contribute to

better services and improved health for all, there is a risk that the UHC

goals will focus decision-makers at national level, as well as international

development partners, on improving treatment services at the expense of

prevention and health promotion. The exclusion of family planning services

from many national UHC schemes is a concern, especially as they affect the

sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent girls.

• Improving sexual and reproductive health requires changes in social norms

to protect the rights of girls, promote gender equality, and improve the

access to information on health and rights among adolescents. Preventing

and responding to gender-based violence requires the participation of many

sectors, including education, justice, social affairs and health. Such multi-

sector responses cannot be wrapped up under a single UHC agenda.

• A history of international, national and local initiatives has left traces

of different types of health financing arrangements in most countries.

Consolidating several initiatives under a single UHC umbrella can create

efficiencies that allow an expansion of coverage and level of financial

protection. Consolidations that are relatively less selective of the type of

beneficiaries are less likely to make errors of omission, without necessarily

generating revenue losses from foregone insurance premiums. Consolidation

should, however, be approached with caution to assure that no essential SRH

service nor any vulnerable population group lose their coverage. By including

prevention and health promotion among the UHC benefits, future costs

for treatment can be reduced and the sustainability of the UHC schemes

consolidated.

• Sexual and reproductive health service coverage for adolescents is lagging

behind the general trend of improved service coverage in the region.

Insufficient financial risk protection may not be the most important reason.

In the development of financial risk protection schemes, however, the

special situation of adolescents should be kept in mind. Adolescents do not

necessarily have ready access to the financial resources of the economic

group in which they are categorised.

• Although there are examples of SRH programmes and financial risk

protection schemes that target vulnerable groups such as ethnic minority

populations, migrant workers or refugees, they are the exception rather

than the rule. There are major service coverage gaps that are reflected in

health statistics. Meeting national targets for sexual and reproductive health

will require that equity gaps be narrowed, including the gaps that separate

migrants from citizens and ethnic minorities from the majority.

• Assessments of progress towards UHC in sexual and reproductive health

that can generate actionable information for national decision-makers are

constrained by important information gaps. They include information about

service quality and about reasons why clients do not always take advantage

of public services provided free of charge; information about the cost-drivers

for out-of-pocket expenditures; information about coverage of migrant

populations; and information about the households among whom out-of-

pocket expenditures for health constitute a serious financial risk.

4

THE UN AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

On September 25

th

2015, the UN General Assembly adopted the Agenda for Sustainable Development entitled ‘Transforming

our World’. [1] It includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030. The third goal is focused on

health and well-being and includes two sub-goals:

3.7 By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-

care services, including for family planning, information and

education, and the integration of reproductive health into national

strategies and programmes

3.8 Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk

protection, access to quality essential health-care services and

access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines

and vaccines for all

An Inter-Agency Expert Group (IAEG) developed the monitoring framework for the SDGs. It presented its final list of

232 indicators in March 2017, including two indicators each for SDG 3.7 and SDG 3.8. [2]

3.7.1 Proportion of women of reproductive age (aged 15-49 years) who have their need for family

planning satisfied with modern methods

3.7.2 Adolescent birth rate (aged 10-14 years; aged 15-19 years) per 1,000 women in that age group

3.8.1 Coverage of essential health services (defined as the average coverage of essential services

based on tracer interventions that include reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health,

infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and service capacity and access, among the

general and the most disadvantaged population)

3.8.2 Proportion of population with large household expenditures on health as a share of total

household expenditure or income

The two SDG goals are closely linked. Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services are essential services and

therefore also included under universal health coverage (UHC). The components of a comprehensive package of essential

SRH services were proposed in 2010:[3]

• Family planning and birth spacing services

• Antenatal care, skilled attendance at delivery, and postnatal care

• Management of obstetric and neonatal complications and emergencies

• Prevention of abortion and management of complications resulting from unsafe abortion

• Prevention and treatment of reproductive tract infections and sexually transmitted

infections including HIV

• Early diagnosis and treatment for breast and cervical cancer

• Promotion, education and support for exclusive breast feeding

• Prevention and appropriate treatment of sub-fertility and infertility

• Active discouragement of harmful practice such as female genital cutting

• Adolescent sexual and reproductive health

• Prevention and management of gender-based violence

The priority SRH needs differ among populations, and the list of essential SRH services must therefore be adapted to

the country context. Furthermore, some of the services in the list are highly aggregated, for instance ‘adolescent sexual

and reproductive health’. When conceptualised within a rights-based framework, the package of activities to promote

and protect the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents expands into many components that extend well beyond

services in the health sector.

The UHC indicator 3.8.1 for monitoring service coverage is based on 16 tracer health services, including three SRH

services, namely family planning, antenatal and delivery care, and cervical cancer screening. But with a total of 126

sub-goals in the SDG agenda, global indicators to monitor any one goal have to be highly aggregated. At the country and

regional level, there is a need for disaggregation, to understand the extent to which commitments to achieve universal

health coverage of essential sexual and reproductive health services are met, including those that are not captured by

the global monitoring system.

5

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

SERVICES IN ASIAPACIFIC

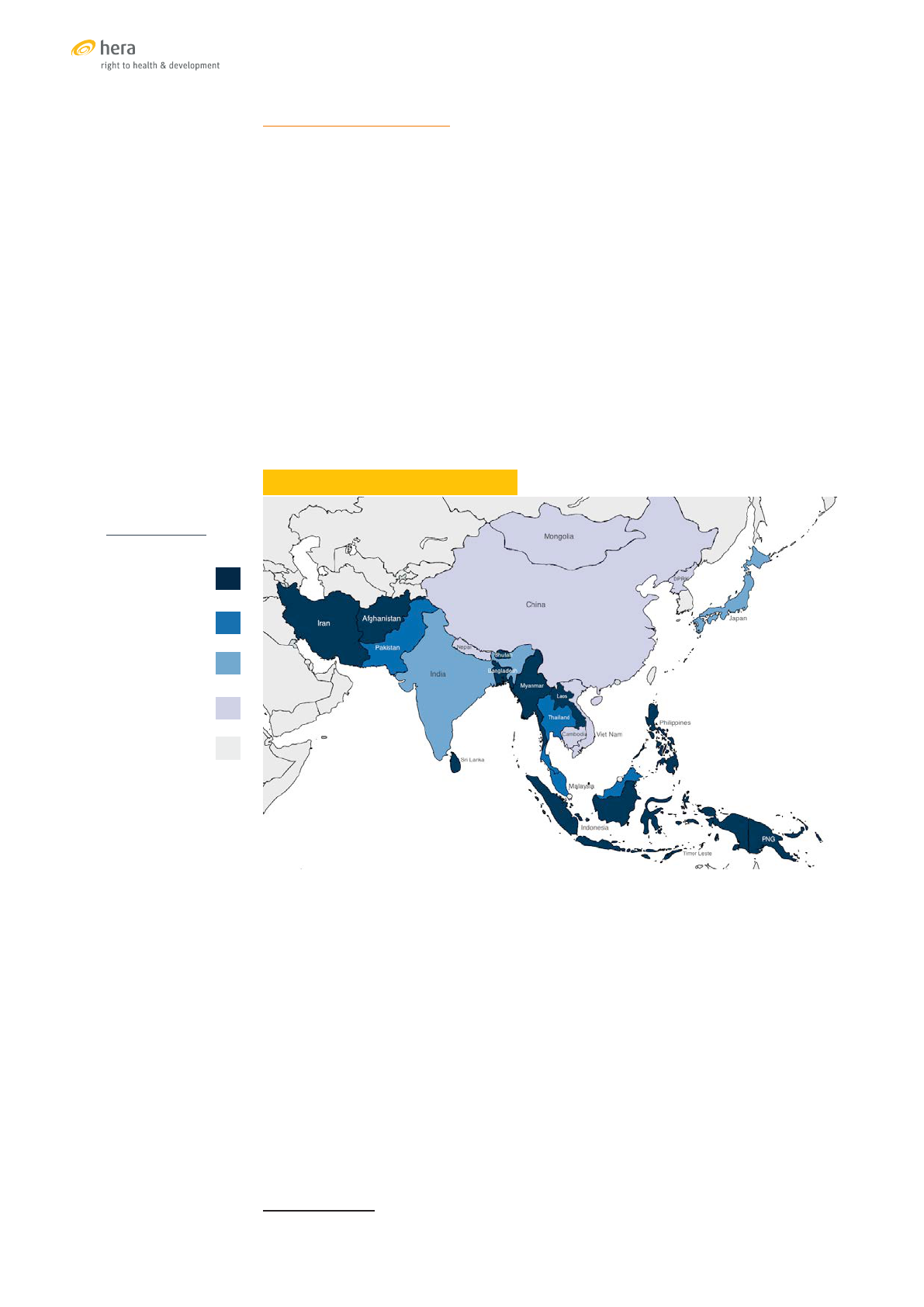

The UNFPA Asia-Pacific (AP) region comprises 37 nation states, including 14 Pacific

Island countries. With a total population of about four billion, it is home to more than

half of the world’s population. The region includes countries that rank in the low,

medium and high range of the UNDP human development index table. Averaging

indicators to establish a regional profile would therefore not be very informative.

Many countries in the Asia-Pacific region are experiencing large international

population movements. The 2015 Asia-Pacific Migration Report estimated that

more than 18 million migrants lived in five countries that are among the ten top

destination countries for international migration in the region (India, Pakistan,

Thailand, Iran and Malaysia). [5] A large proportion of the migrants are young

people whose needs for health care are mostly for sexual and reproductive health.

The extent to which they have access to SRH services and to financial protection at

the same level as the national population is a key equity dimension in the universal

health coverage profile of each country.

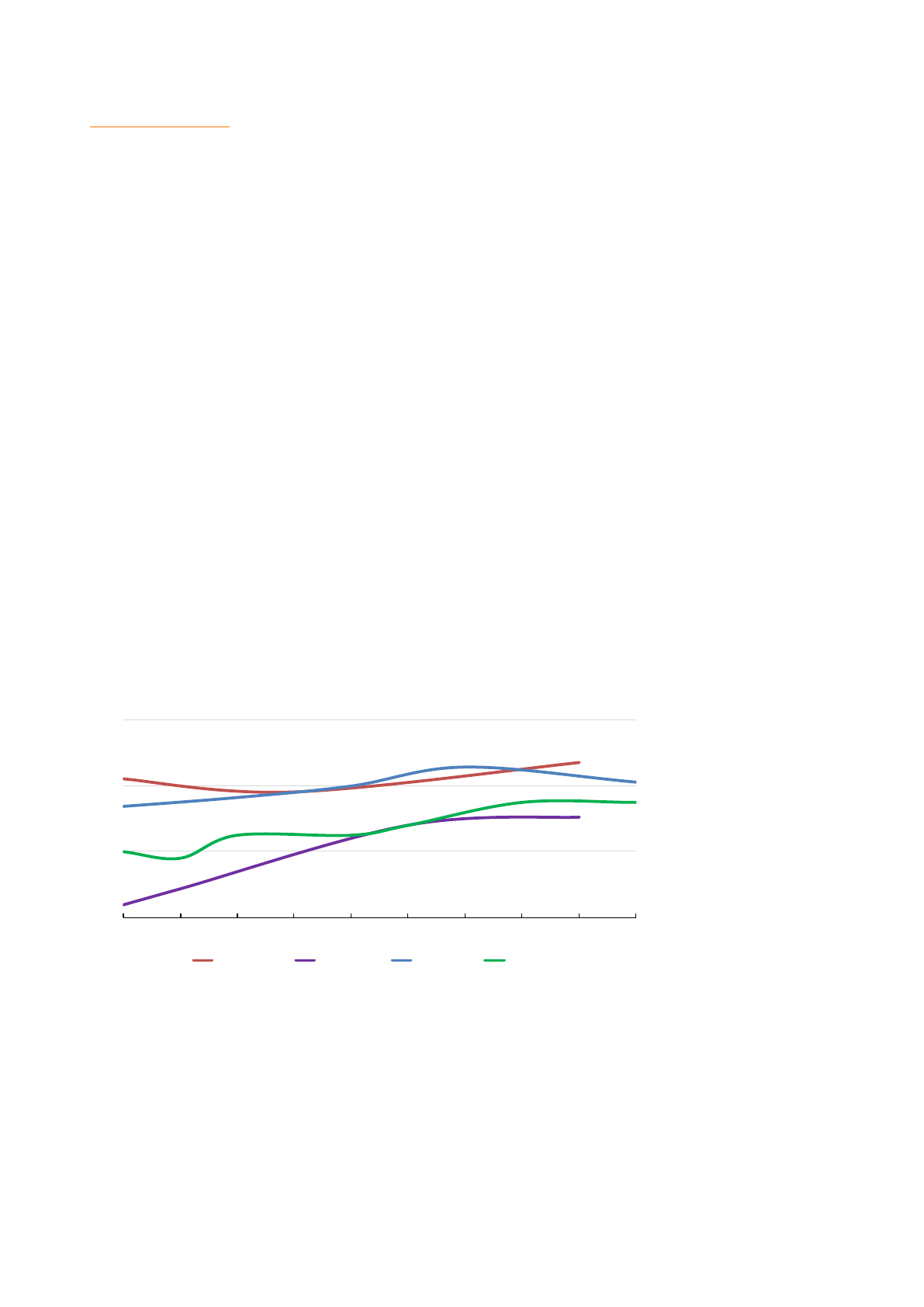

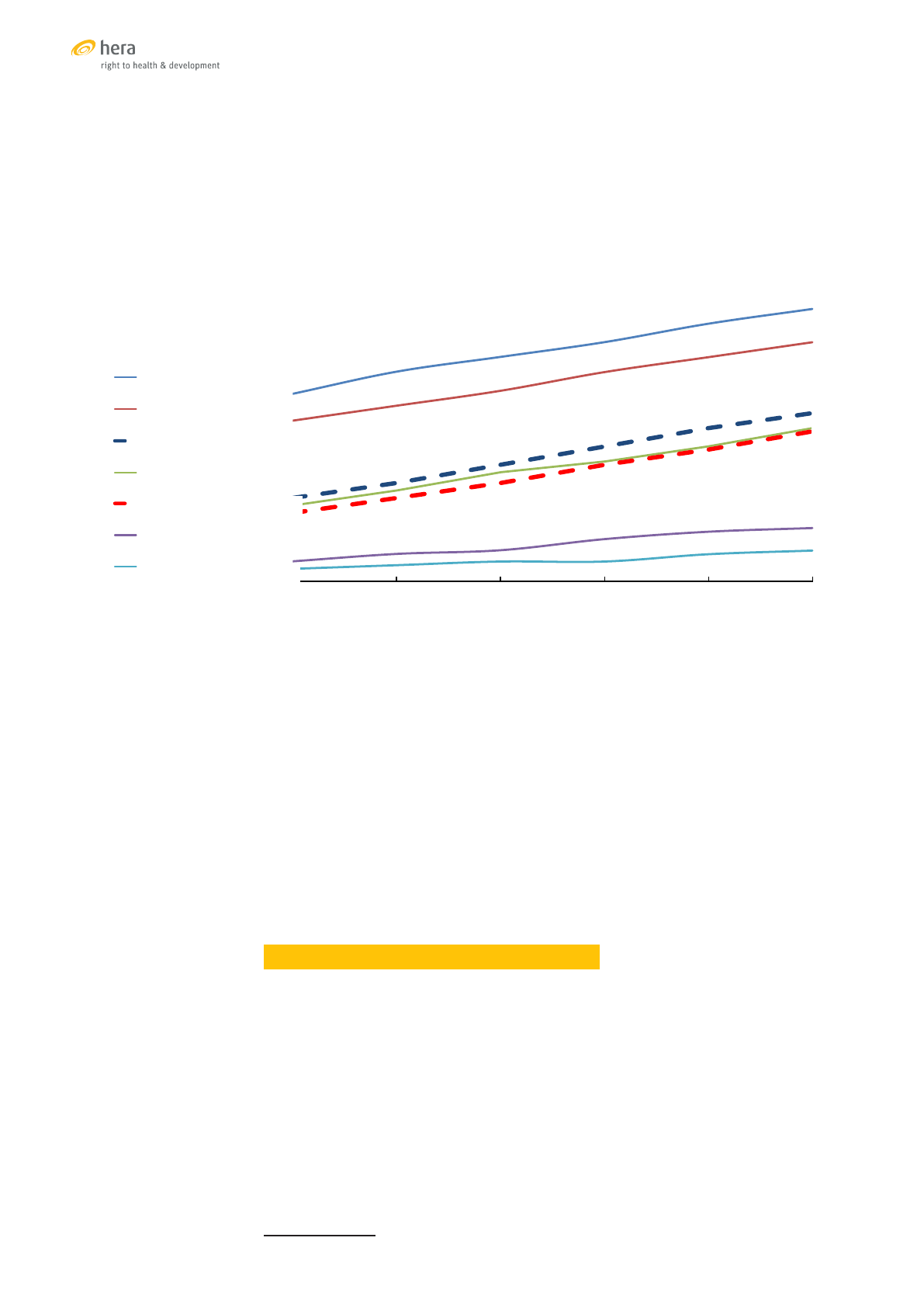

A general overview of the situation of universal health coverage of sexual and

reproductive health services can be presented in a scatter diagram, plotting an

index of SRH coverage on the vertical axis and a financial risk protection index

on the horizontal axis. The SRH service coverage index is calculated from three

indicators that are included among the global indicators for monitoring the SDGs:

• Adolescent birth rate per 1,000 women aged 15 to 19

• Proportion of family planning demand satisfied with modern methods

(women aged 15 to 49)

• Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel

The financial risk protection index should ideally reflect the SDG indicator of

‘proportion of population with large household expenditures on health as a share of total

household expenditure or income’. Data for this indicator, however, are not widely

available. Instead, the proportion of total health expenditure that is paid by patients

and clients out of pocket is used. This is not an ideal indicator, because cash-for-

service requirements differ by type of service. They may be particularly high for

some SRH services that are excluded from health insurance coverage, including

family planning. The indicator also does not reflect uneven coverage for adolescents,

migrants and minority groups who may be uninsured to a much higher degree than

the rest of the population.

• Afghanistan

• Bangladesh

• Bhutan

• Cambodia

• China

• Cook Islands

• D.P.R. Korea

• Federated States

of Micronesia

• Fiji

• India

• Indonesia

• Iran

• Japan

• Kiribati

• Lao P.D.R

• Malaysia

• Maldives

• Marshall Islands

• Mongolia

• Myanmar

• Nauru

• Nepal

• Niue

• Pakistan

• Palau

• Papua New Guinea

• Philippines

• Samoa

• Solomon Islands

• Sri Lanka

• Thailand

• Timor-Leste

• Tokelau Islands

• Tonga

• Tuvalu

• Vanuatu

• Viet Nam

THE UNFPA ASIA-PACIFIC REGION

6

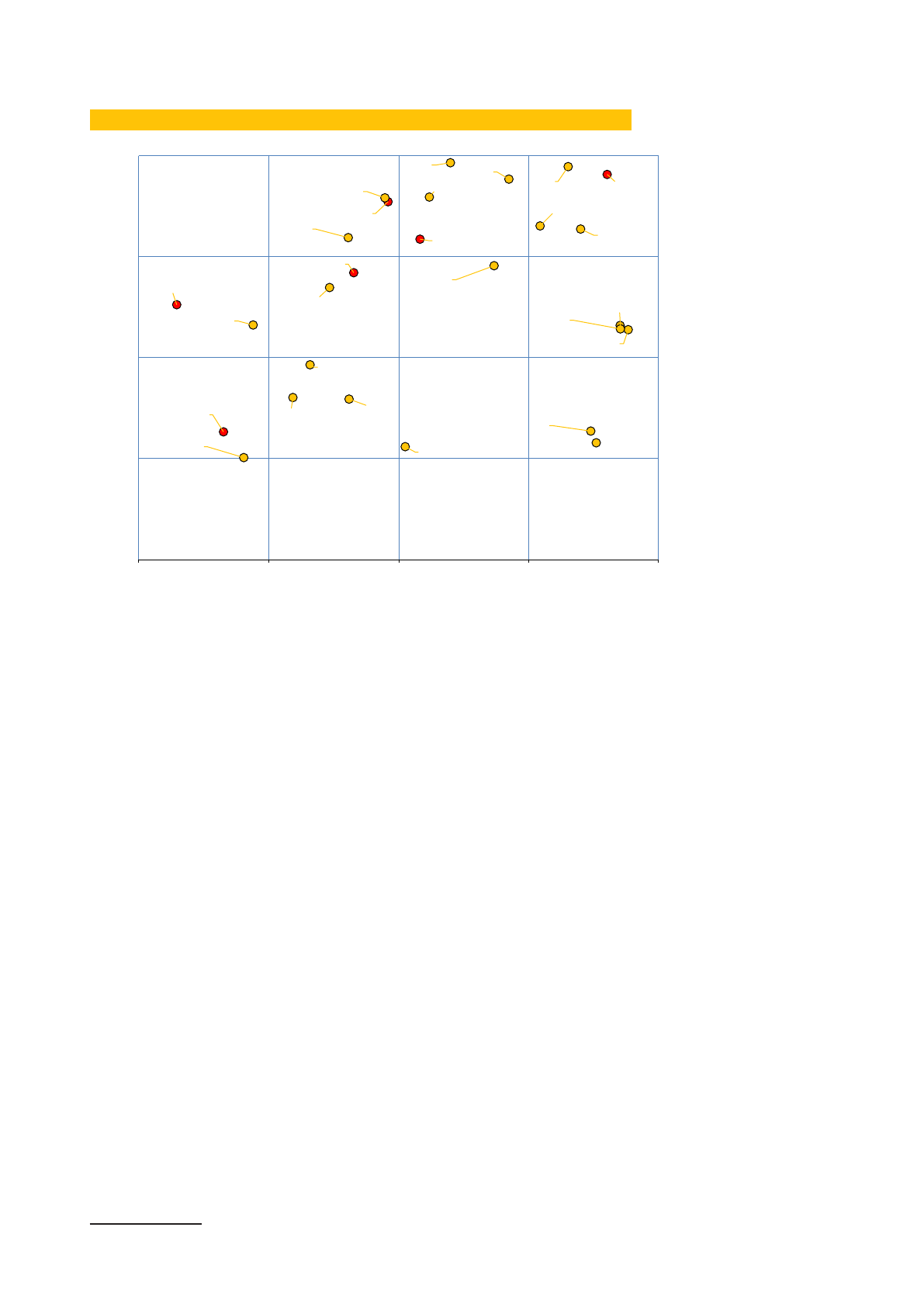

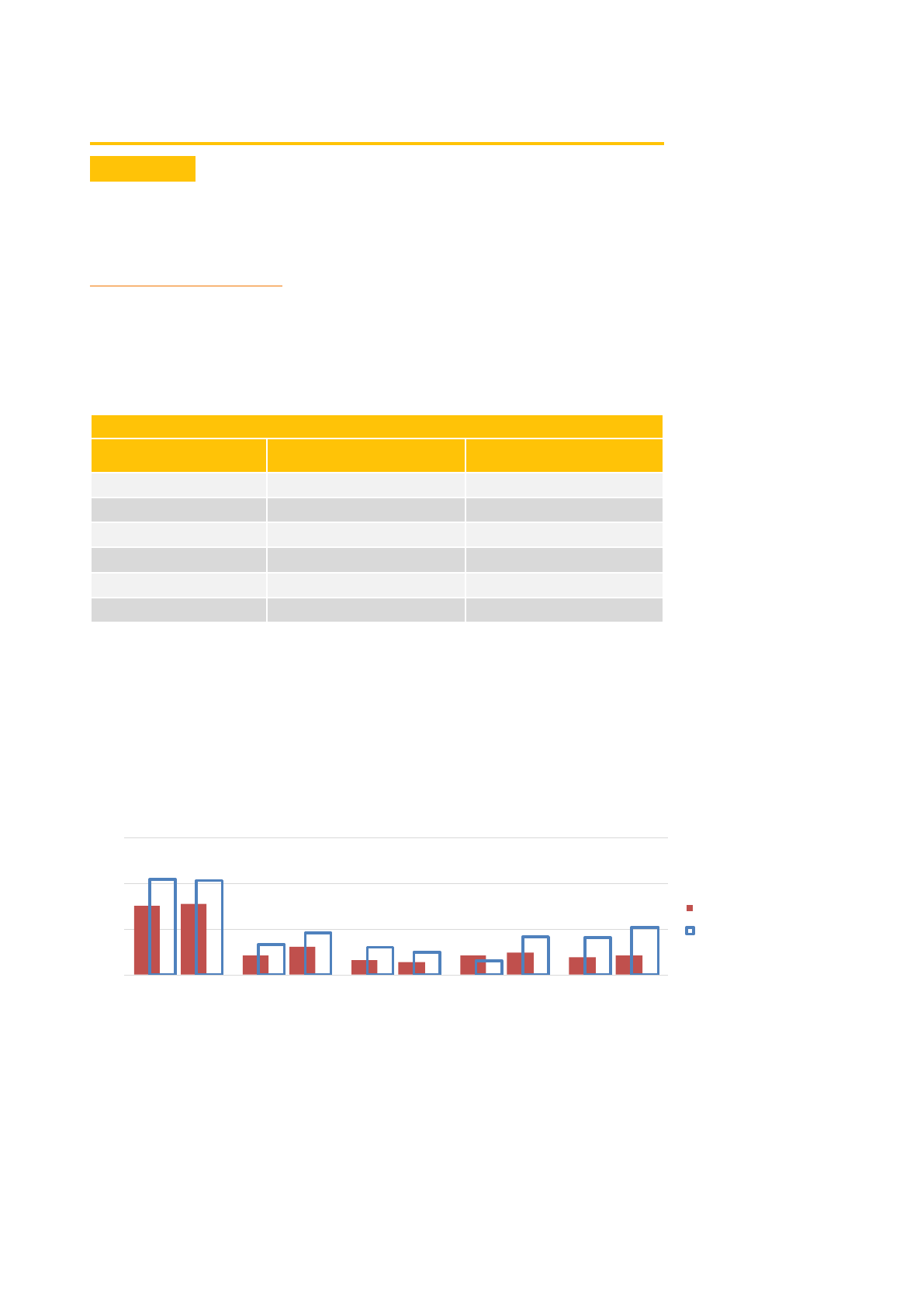

OVERVIEW OF SRH SE

RVICE COVERAGE AND FINANCIAL PROTECTION IN ASIA-PACIFIC

1

Data sources: Ref [6], [7]

An overview as presented in this graphic is useful for orientation. It shows that the

countries in the region map out across a broad range, some with low SRH service

coverage and minimal financial protection and some with high coverage and a high

level of financial protection. Details, however, are lost. Sexual and reproductive health

services range from sexuality education for adolescents to the treatment of cancers

of the reproductive system. The scope is wide, and not all services are provided in

the health sector. Financial risk protection can also take different forms, including

direct public financing of health services; third party payment for services by a

social insurance scheme that may be financed from general tax revenues, insurance

premiums, or a combination of both; a variety of financial risk pooling arrangements

including private health insurance or community mutual funds; and cash transfer or

voucher schemes, typically to offset indirect costs of seeking health care. A detailed

review that covers the range of services, the financial risk reduction schemes, and

the equity of access can only be done at the level of each country.

1 DPR Korea and 9 Pacific Island Countries are not included because of incomplete data

Afghanistan

Bangladesh

Bhutan

Cambodia

China

Fiji

India

Indonesia

Iran

Japan

Lao PDR

Malaysia

Maldives

Mongolia

Myanmar

Nepal

Pakist …

PNG

Philippines

Samoa

Solomon Isl.

Sri Lanka

Thailand

Timor-Leste

Tonga

Vanuatu

Viet Nam

20 40 60 80 100

SRH Service Coverage Index

Financial Risk Protection Index

Low

High

40

Low

Low

High

60

80

7

THE SCOPE OF THE STUDY OF UHC FOR

SRH

For the study, six countries with documented commitments to UHC were selected as

a focus:

Bangladesh

adopted a health financing strategy in 2012 with a roadmap

to achieve universal health coverage by 2032. [8]

Cambodia

adopted the ‘National Social Protection Strategy for the

Poor and Vulnerable’ in 2011 followed by the ‘National Social

Protection Policy Framework 2016-2025’. The long-term

vision presented in these documents is a comprehensive

system of universal health coverage. [9], [10]

Indonesia

initiated a national social security reform in 2004, with

national health insurance as the first of five social security

programmes to be introduced. [11] The national health

insurance programme was launched in 2014.

Mongolia

introduced mandatory social health insurance in 1994, and

in 2013 adopted a long-term strategy for the development of

social health insurance (2013-2022).[12]

Thailand

committed in the National Health Security Act of 2002 to

establish a National Health Security Fund ‘to encourage

access by persons to universal and efficient health service’.

[13]

Viet Nam

introduced a health insurance law in 2008 and revised it in

2014 with a target to reach universal health coverage by

2020. [14], [15]

The six countries are low or middle-income countries with a combined population of

about 600 million, which is almost half of the population of the Asia-Pacific region

excluding China and India.

The scope of sexual and reproductive health services reviewed in the study is

wide but not fully comprehensive. Some essential SRH services are not included,

for instance treatment of breast cancer, infertility treatment, support for exclusive

breast feeding, and health services for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of

sexually transmitted infections (STI) among populations other than adolescents and

pregnant women. This leaves out STI and HIV services for men, transgender and

intersex persons.

Four countries, Indonesia, Mongolia, Thailand and Viet Nam introduced national

health insurance schemes, aiming to achieve a single third-party payment system for

all essential health services. For these countries, the study aimed at documenting

the sexual and reproductive health services that are covered by the insurance, as

well as the inclusiveness and equity of coverage. In Bangladesh and Cambodia,

efforts to establish a national social health insurance are still at an early stage, and

the purchasing arrangements for health services are more fragmented. Several

public and private schemes coexist, together with a public health system that

provides certain services free of charge to users. In these countries, the study aimed

at documenting the different types of schemes and their interactions, including only

those that aim at national coverage and that have a clear objective to protect users

from social hardship. Data were collected in November and December 2016 through

document reviews and interviews with key informants in the six countries.

8

BANGLADESH

9

BANGLADESH

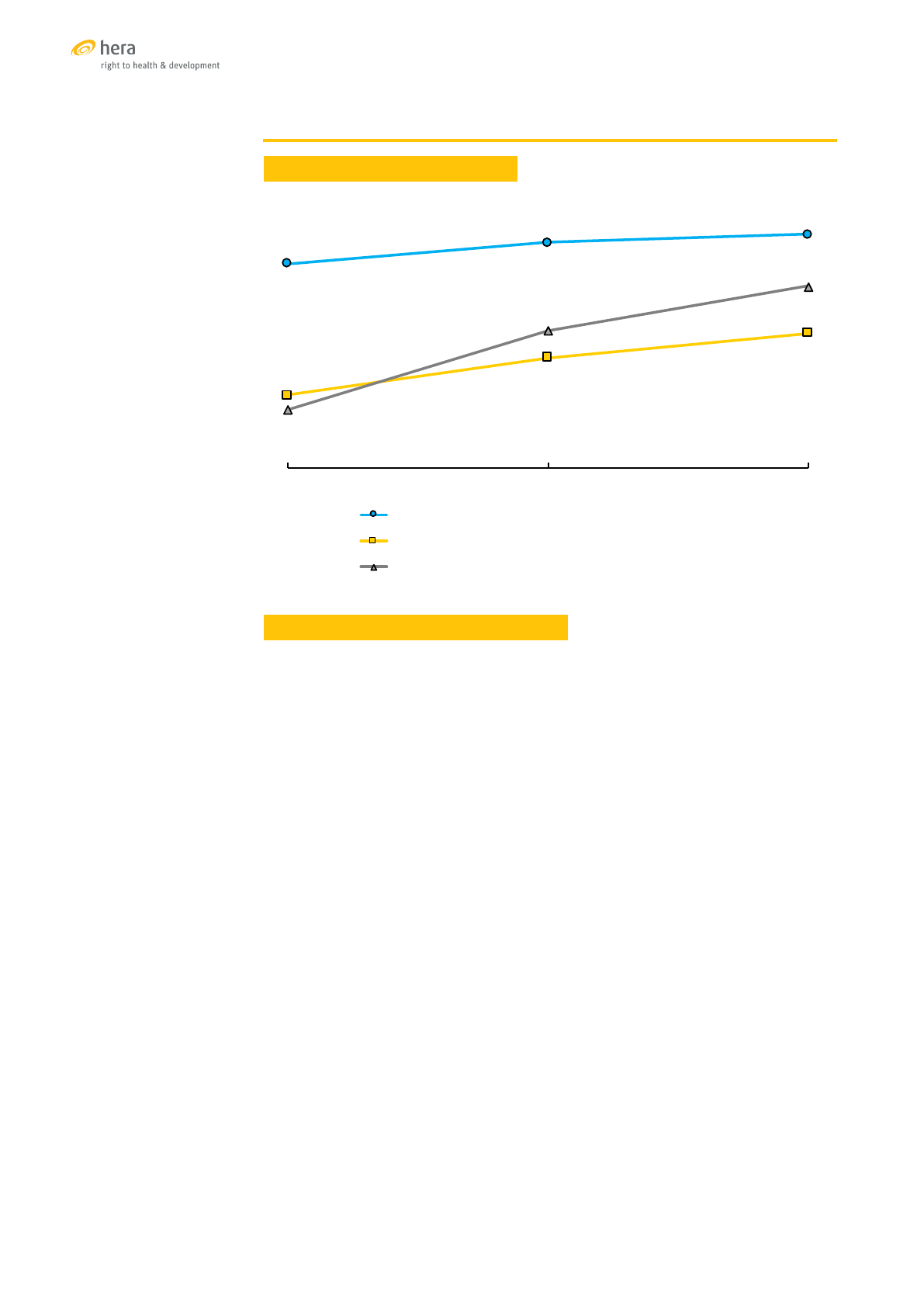

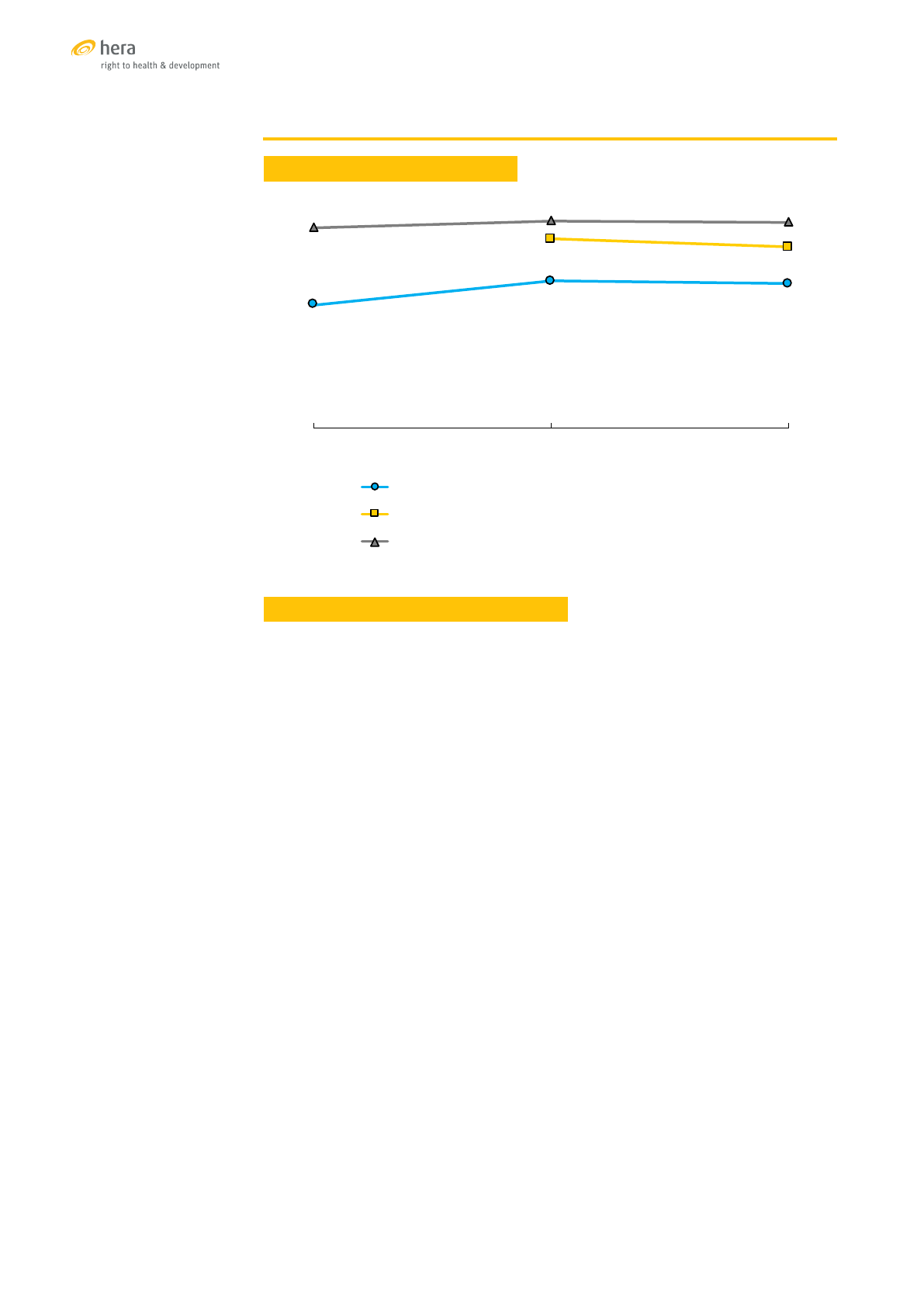

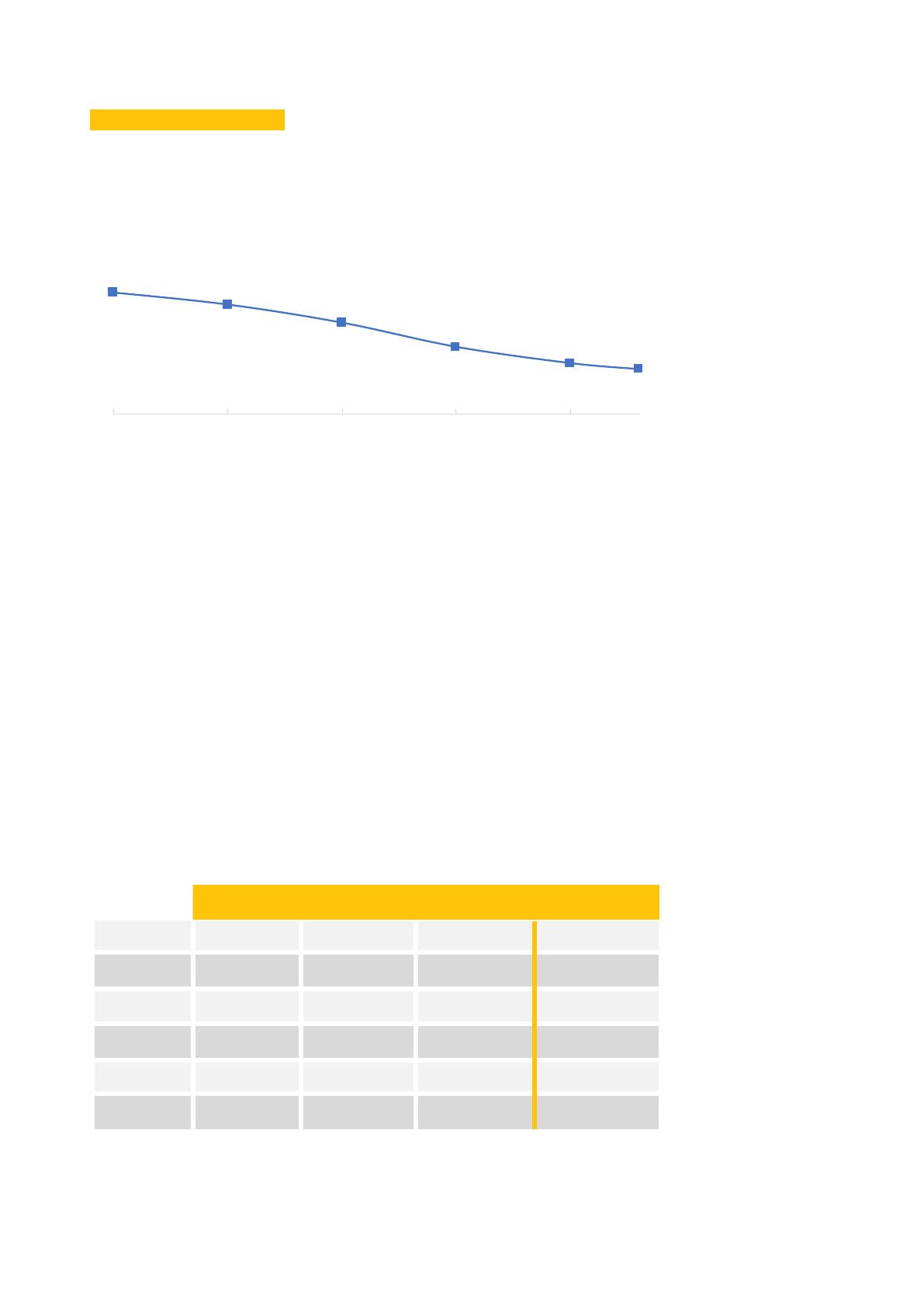

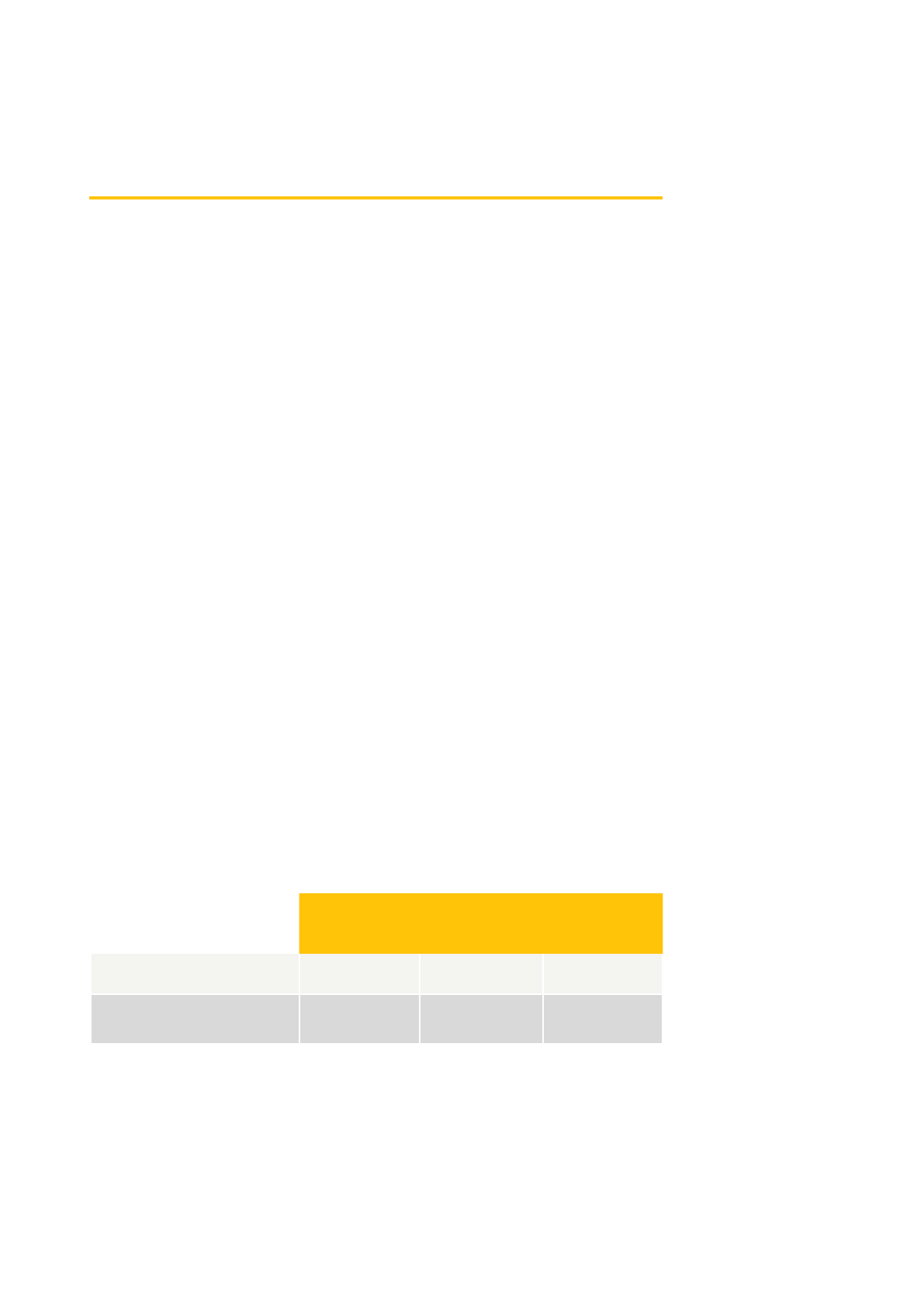

TRENDS OF SELECTED SRH INDICATORS

Sources: [16], [17], [18]

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH SERVICES

Health services in the public sector in Bangladesh are delivered by the Ministry of

Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) through a network of health centres and hospitals

from the primary to the tertiary level. The private health sector is large and has been

growing at approximately 15 percent per year since 2000. In 2013, approximately

half of registered clinic and hospital beds in the country were in the private sector,

and 62 percent of medical doctors were engaged in private practice. [19] Private

for-profit health facilities are concentrated in the urban areas. In addition, a large

number of health facilities for primary and secondary care are operated by NGOs and

confessional organisations, primarily in rural and in high density urban areas.

Although public facilities provide health services without charge to clients or at

subsidised user fees, the proportion of health expenditures covered by out-of-pocket

payments has continued to increase. At 67 percent, it is one of the highest in the

region. Two reasons are cited to explain this trend. Limitations of service quality and

availability in the public sector motivates clients to seek care in the private sector and

accept to pay for services that are perceived to be of better quality. At the same time,

the service offer of public facilities has contracted because of financial shortages.

Medicines and services that were previously provided free of charge are now often

only available at private pharmacies or laboratories. [19]

Contraception: The uptake of family planning was one of the early successes of

population programmes in Bangladesh. Between 1975 and 2014, the total fertility

decreased from 6.3 to 2.3 births per woman. In 2014, about 73 percent of the demand

for modern family planning was satisfied, with small differences between geographic

or socially stratified groups. The adolescent fertility rate, however, did not follow the

trend. After a sharp increase in the 1980s it decreased slowly, but in 2014 it was still at

the high level of 113 births per 1,000, about the same level as in 1975. The main reason

is the early age of marriage among girls in Bangladesh. In 2014, more than half (59%)

of young women were married before the age of 18, with even higher proportions in

rural areas. [18]

Menstrual regulation by vacuum extraction of uterine content to re-establish

menstrual flow in case of a delayed menstrual period has been part of the Bangladesh

national family planning programme since 1979. Menstrual regulation is available free

47%

52%

54%

17%

26%

31%

13%

32%

42%

2004 2011 2014

% married women (15-49) currently using modern contraception

% women with at least 4 ANC visits during their last pregnancy

% of births attended by a skilled provider

10

of charge in public clinics which provide about two thirds of these services. Medical

menstrual regulation through the induction of uterine bleeding by pharmaceutical

means was added more recently in some facilities.

Termination of pregnancy is illegal in Bangladesh under the 1860 Penal Code unless

performed to save a woman’s life. Despite the wide availability of contraceptive

services, including menstrual regulation, the use of induced unsafe abortions is

prevalent. The estimated rate of complications following induced abortions (6.5/1,000)

is comparable to other countries with restrictive abortion laws. [20] Post abortion care

is available in most public and private hospitals.

Maternal health services, including antenatal, obstetric and postnatal care, are

provided in public and private health facilities. A maternal health voucher system

has stimulated uptake of services. The vouchers can be redeemed in public and in

accredited private facilities.

The use of antenatal care has increased, but in 2014 it was still low, with only 31 percent

of women reporting that they had attended four or more antenatal consultations

during their last pregnancy. All increases in antenatal care between 2011 and 2014

were due to an increasing use of the private sector which accounted for 52 percent

of antenatal consultations in 2014. [18] HIV screening, syphilis screening and malaria

prevention are not routinely provided as part of antenatal care.

Deliveries in health facilities increased from 12 percent in 2004 to 37 percent in 2014.

The majority of deliveries, however, still take place in the home. Private hospitals

and maternity homes have become by far the most favoured places of delivery, with

almost twice as many births as in public sector facilities. There have been major

investments under the 2011-2016 health strategy to achieve national coverage of

basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care services, however

not all established centres are able to provide the full range of service, and coverage

in several provinces is still below the recommended minimum density.

The national incidence of delivery by caesarean section of 23 percent of births is very

high. Among women in the higher socio-economic strata, caesarean sections account

for half of all deliveries. A study among 500,000 women who gave birth between 2005

and 2011 found that 73 percent of deliveries in the private sector were by caesarean

section, suggesting that the private sector is driving a high caesarean section rate that

is not always medically indicated. [21]

Diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections are provided in public

facilities and NGO clinics. Statistics about the prevalence of sexually transmitted

infections in key populations such as sex workers and truck drivers are available,

but there is little information about the prevalence of STIs in the general population.

Reports of syphilis screening among pregnant women are scarce. The only available

data come from three tertiary hospitals where one third of the antenatal clients were

tested for syphilis. Among 626 women, two were found to be infected and one received

treatment. [22]

The prevalence of HIV infection is low in Bangladesh. Among people who inject drugs,

female sex workers, and men who have sex with men the prevalence is estimated

at 0.7 percent. HIV programmes primarily focus on prevention among these groups.

Almost all services for HIV, including antenatal testing and PMTCT, are provided by

programmes that rely on international funding. They are not covered by the public

health service. [23] PMTCT services are available in three government tertiary care

hospitals and in a few private facilities. The number of women tested is small, only 13

percent of those who tested positive received anti-retroviral treatment (ART) during

delivery, and only 1.4 percent during breastfeeding. [22]

Immunisation against Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is currently being piloted in

one district, aiming to immunise about 33,000 adolescent girls. The cervical cancer

burden in Bangladesh is estimated at 29.8 per 100,000 women per year. Cancers are

usually diagnosed in advanced stages as access to screening and early treatment is

limited. [24]

Services for the treatment and support of women survivors of sexual violence are

provided by the Ministry of Social Welfare.

11

FINANCIAL RISK PROTECTION

Public health services are nominally free or provided

at subsidised rates. The high level of out-of-pocket

expenditures for health indicates that the public health

service model is not working as intended. A survey in an

urban area of Bangladesh in 2013 reported that between

10 and 18 percent of households experienced an incidence

of catastrophic health costs within the three-month study

period. [25] Two public financial risk protection schemes

are meant to reverse the trend of increasing out-of-pocket

expenditures. In addition, there are a large number of

community-based or micro insurance schemes.

Shasthya Shurokkha Kormoshu (SSK) (subsidised social

health insurance) is the first and only social health insurance

scheme under the MOHFW. It is fully financed from general

government revenues. The long-term vision for SSK is of a

scheme combining risk pooling with a purchaser-provider

split under the stewardship of the MOHFW. In a first phase,

only the poor are covered, and the government pays their

insurance premiums. In the long run, other groups will be

included as paying members. A three-year pilot SSK scheme

opened in March 2016, targeting a population of about 95,000.

It is expected to increase access to hospitals and improve

the quality of services by generating income for the facilities

which they can use for improvements. [26]

The SSK benefits include inpatient care for fifty specified

health conditions in selected public facilities. They do not

include contraceptive and menstrual regulation services; HIV

testing and treatment; cervical cancer prevention, detection

and treatment; and services for survivors of gender-based

violence, child abuse or rape. The main challenges faced

during the pilot phase of SSK include coping with the increased

demand for services while developing reliable procedures to

manage an efficient third-party payment system for providers.

The Maternal Health Voucher / Demand Side Financing

scheme (DSF) started in 2007 as a pilot programme of the

MOHFW in 21 sub-districts. It was scaled up in 2010 to cover

53 sub-districts in 41 districts and a target population of about

26.5 million. At inception, the beneficiaries of the DSF scheme

were pregnant women during their first or second pregnancy

who were considered poor after a formal means test. In nine

sub-districts, ‘universal intervention’ was piloted, extending

the DSF benefits to all women. Vouchers provide a range of

benefits, including comprehensive coverage of antenatal,

delivery and postnatal care, transport subsidies and cash

incentives for mothers who deliver with the attendance of

a skilled provider. Public, NGO and private sector health

facilities that are accredited are reimbursed at a fixed rate for

the vouchers they collect. The total cost of the programme

per voucher distributed was estimated at US$ 41 in 2010.

[27] The programme is primarily financed by international

development partners. Technical assistance is provided by

WHO. Evaluations of the programme in 2011 and 2014 found

that the scheme increased the demand for reproductive

health care among poor women, and that it reduced the

average out-of-pocket costs for normal deliveries from US$

25 to US$ 21 and for caesarean sections from US$ 103 to US$

65. [28],[29]

Community-based and micro health insurance schemes are

managed by NGOs. The schemes are funded with insurance

premiums, cross-subsidisation from other NGO programmes,

and international and national donations. The schemes

target poor and disadvantaged groups as well as members

of the micro-credit groups operated by the same NGO.

Benefits differ among the micro-insurance schemes. Most

of them cover basic and preventive health services including

immunisation, family planning, out-patient consultations, and

normal deliveries. [30]

UNIVERSAL COVERAGE FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

B

angladesh is in the early stages of moving from a public health

service model under which health care is provided by government

and free of charge to users, to a social insurance model under which

health services in the public and private sector are purchased by a

health insurance provider who is funded with insurance premiums

and general government revenues.

Out-of-pocket payments for health care have continued to

increase and there has been a continued drift of patients to

the private sector. This gave rise to the emergence of multiple

community and micro-insurance schemes that provide a limited

amount of financial protection to some. The voucher scheme for

maternity care is a more ambitious initiative, documenting that the

equity and coverage of health services can be increased by offering

payments for services to providers, while protecting users from

expenditures. A large proportion of the increased coverage was

achieved by the private sector, indicating the limitations in service

capacity and quality of the public health sector. The high caesarean

section rates among private sector deliveries, however, suggest

that the scheme generates incentives for performing caesarean

sections without medical indication.

Beyond maternity care, the coverage of SRH services, for instance

for HPV immunisation, cervical cancer screening, or syphilis and

HIV testing in pregnancy, is limited. For services that are available

and provided free of charge in the public sector, for instance for

family planning and menstrual regulation, an increasing number

of women consult private sector providers and pay for the

service. This suggests that these services also face issues about

declining availability and acceptance, despite the substantial

public delivery infrastructure that was established.

The long-term goal pursued in Bangladesh is national coverage

of the entire population with the SSK social health insurance

scheme. SRH services, other than maternity care, are, however,

not included in the benefit package of SSK as it is currently being

piloted. While these services will for now still be offered through

special projects or by the public health service, the offer is limited

and the drift to the private sector will likely continue. This means

that user charges for SRH services will not disappear and may

even rise, as more and more of these services are pushed into

the private sector.

Because the systems for financial risk protection in Bangladesh

are fragmented, the equity of coverage is difficult to determine.

The SSK scheme protects the poor, but only as a pilot programme

with small coverage. The voucher scheme also has a pro-poor

focus, but it covers only about 20 percent of the population. Public

health services theoretically offer universal financial protection,

but they are bypassed by more and more people at all levels of

the socio-economic scale, with the result that they do not deliver

equitable protection from catastrophic health expenditures.

12

CAMBODIA

Creative Commons Photo credit: Clear Path International

https://www.flickr.com/photos/cpi/16775850/

13

CAMBODIA

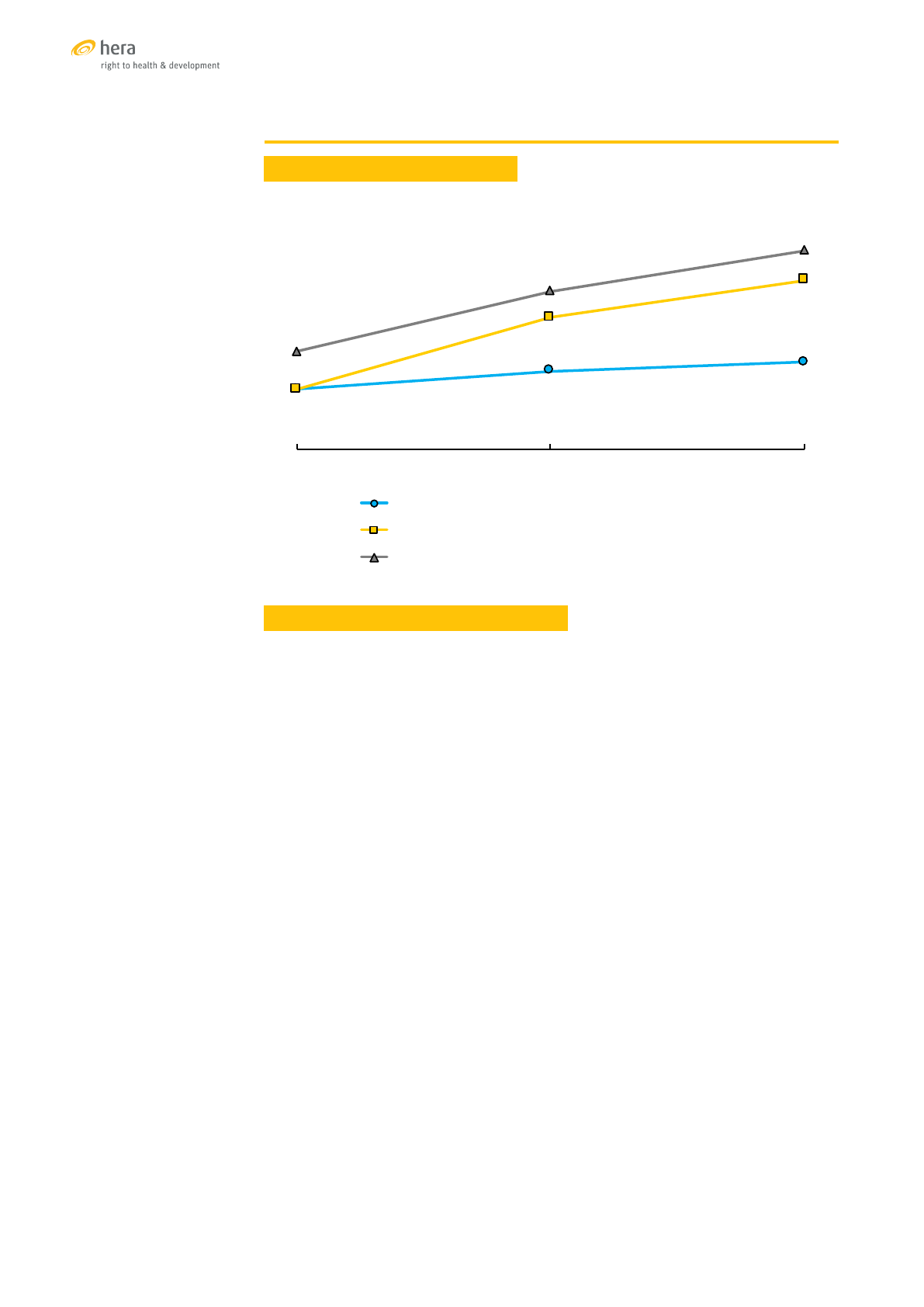

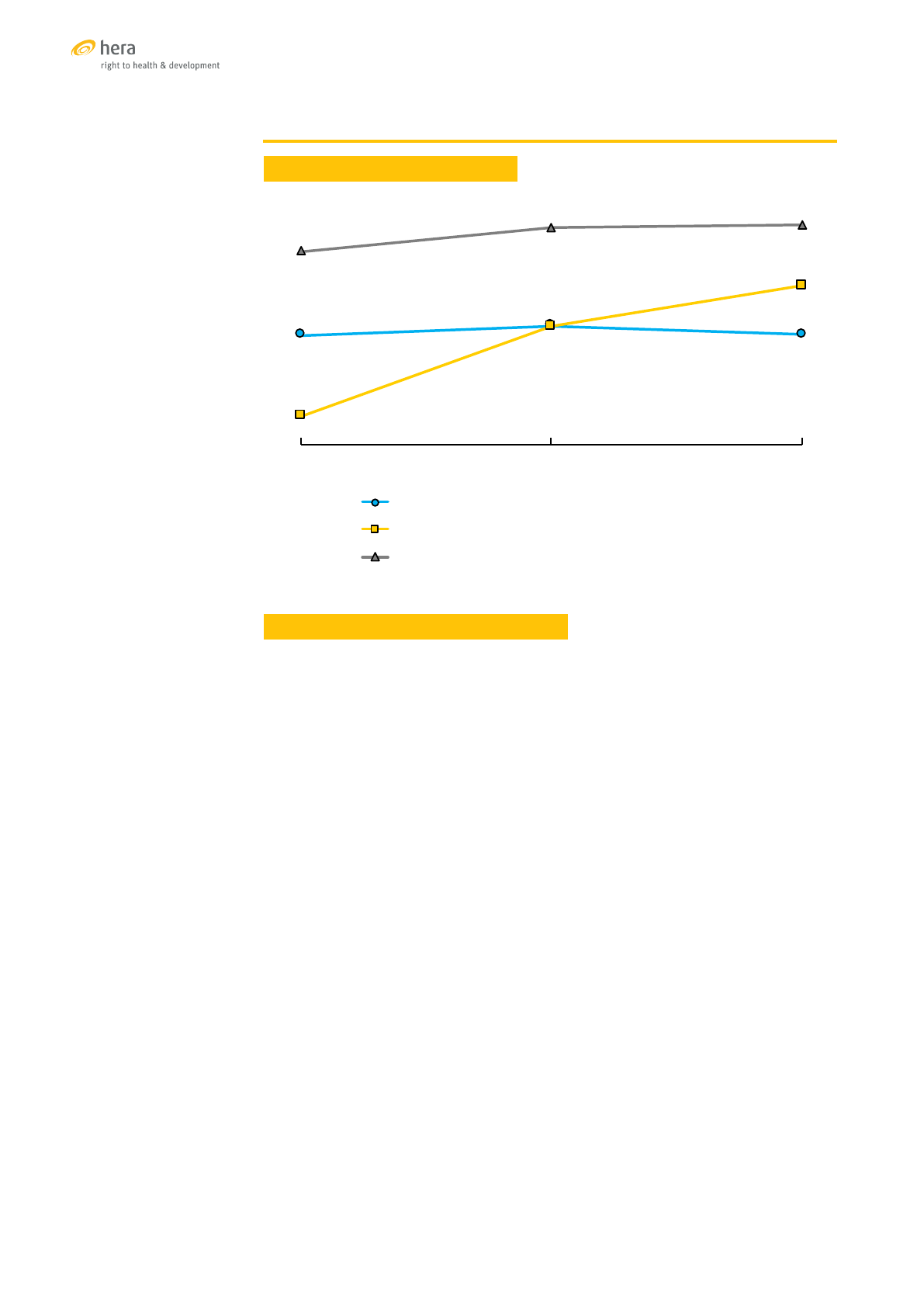

TRENDS OF SELECTED SRH INDICATORS

Sources: [31],[32],[33]

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH SERVICES

Health services in Cambodia are provided in the public and private sector, including

by a variety of NGO-operated not-for-profit health facilities. Two packages of services

have been defined for public sector facilities, the Minimum Package of Activities

(MPA) provided primarily at the health centre level and the Complementary Package

of Activities (CPA) which is available in hospitals. [34]

Contraception, including family planning counselling, provision of implants, IUDs,

pills, condoms, male and female sterilisation, are included in the MPA and CPA.

Utilisation and availability of modern contraception is slowly increasing. The most

widely used methods are contraceptive pills. The uptake of long-acting contraceptive

methods remains limited, but availability in public health facilities is increasing

annually. Emergency contraception was introduced in the public sector in 2012 and

is reported to be available, although there is little information about access and use.

[35],[36] The total fertility rate in Cambodia declined from 3.4 births per woman in

2005 to 2.7 in 2014. The adolescent fertility rate at 57 births per 1,000 women aged 15

to 19 is comparable to other countries in South-East Asia, but shows an increasing

trend over the past years. [33]

Termination of pregnancy in the first trimester was legalised in Cambodia in 1997.

Between 2005 and 2015 the proportion of women who had at least one abortion

within the past five years doubled from 3.5 to 6.9 percent, however deaths related to

unsafe abortions decreased dramatically. In 2005, at least one death was reported

by 10 percent of hospitals, falling to one percent in 2009. [37] Most terminations

(44%) are performed in private health facilities and about 61 percent under the care

of a qualified provider. Vacuum aspiration is the most common method followed

by medical termination. The public sector has a secondary role in the provision of

abortion services. [33],[38]

27%

35%

39%

27%

59%

76%

44%

71%

89%

2005 2010 2014

%married women(1549)currently usingmodern contraception

%women with atleast4ANCvisitsduring theirlast pregnancy

%of births attended byaskilled provider

14

Maternal health services are provided under MPA and CPA. Public sector facilities

dominate in the provision of maternity services with little difference in use according

to social group or residence. Antenatal care consultations, including tetanus

immunisation, provision of folic acid and iron and micro-nutrient supplementation

are available at health centre level through MPA, but laboratory analyses and

ultrasound examinations are only available at referral hospitals. Normal deliveries

and post-natal care consultations are also conducted at health centres, whereas

assisted deliveries, caesarean sections and blood transfusion are only performed in

hospitals. Treatment for fistula and other in-patient hospital services are available at

the referral hospital, covered by the CPA. In 2014, 76 percent of Cambodian women

attended four or more ANC consultations and 89 percent of births were attended by

a skilled health care provider. [33]

Prevention and treatment of malaria during pregnancy is included among the

antenatal services, however the coverage is low. A recent study estimated that 21

percent of the population is at risk of malaria in 20 out of 24 provinces. However,

malaria tests are not routinely conducted during ANC visits as malaria is often not

suspected. Laboratory services are still not strong enough to ensure diagnosis by

quality assured microscopy or rapid diagnostic tests. [39]

Services for sexually transmitted infections are available for pregnant women and

adolescents at health centre level, including HIV testing, counselling, and prevention

of HIV transmission from mother to child. Laboratory analysis of STIs as well as

provision of ARVs are only available at referral hospitals. There are counselling and

testing sites in almost every referral hospital. They are not integrated into general

outpatient services, but they are provided as integral part of antenatal care. [36]

Immunisation against Human Papillomavirus and comprehensive services for

cervical cancer prevention, detection and treatment should be available at the

referral hospitals through the CPA, however, the availability of these services remains

severely limited. There are currently pilot projects for screening and treating cervical

cancer in the provinces but treatment remains concentrated at the district hospital

level. The availability of treatment options for those already diagnosed with cervical

cancer remains limited. Cambodia’s first national cancer centre is expected to be

operational by 2017. [34]

Currently, services available for survivors of gender-based violence are limited to

HIV post-exposure prophylaxis, emergency contraception and STI screening and

treatment. Following the adoption of the national guidelines for the management of

violence against women and children in 2014, the Ministry of Health is undertaking

efforts to build capacity, improve access to forensic services, strengthen referral

systems, and reduce delays in providing care to women who experienced violence.

[40]

15

FINANCIAL RISK PROTECTION

Per person out-of-pocket expenditures for health in

Cambodia are high. They increased three-fold between

2000 and 2014 from US$ 14 to US$ 45, while they

fluctuated as a proportion of total health expenditures

between 60 and 80 percent. [6]

In 2016, Cambodia adopted the ‘National Social

Protection Policy Framework 2016-2025’ with the two

main pillars of social assistance and social insurance.

[10] It is expected to eventually replace a fragmented

system of health financing and financial risk protection

that includes government subsidised and user-fee

financed services provided in public and contracted NGO

health facilities, community-based health insurance,

health equity funds, and voucher schemes. [41]

• Public sector health facilities provide services

defined in the CPA and MPA packages at fixed user

fees with exemptions for the poor. The service

packages include all medical services for sexual

and reproductive health, but the use of public

facilities for these services is variable, ranging

from 16 percent for termination of pregnancy to

76 percent for female sterilisation. [33]

• Health Equity Funds cover approximately 18

percent of the population. They are financed from

a pool of shared government and development

partner contributions. Beneficiaries are identified

according to their household economic situation

through a formal participatory mechanism. The

benefits include partial or full reimbursement of

expenditures for services included in the MPA and

CPA packages, food, transport and funerals.

• Several community-based health insurance

schemes provide similar benefits as the health

equity funds, but target primarily informal

sector workers above the national poverty line.

The coverage is less than one percent of the

population.

• Voucher schemes for reproductive health services

for poor women are operated by a number of

NGOs, but coverage is also very low.

• Social health insurance was recently introduced

to combine existing health insurance schemes

for civil servants and formal sector workers. The

insurance benefits are in line with MPA and CPA

packages.

UNIVERSAL COVERAGE FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE

HEALTH

Cambodia has adopted policies and programmes in key

areas to improve delivery of sexual and reproductive

health services. Laws, standards and guidelines have

focused on supporting universal coverage of maternal

health services and contributed to a rapid increase

in facility-based births and skilled birth attendance.

The provision of family planning improved only slowly.

Although the gap between wanted fertility and observed

fertility closed from 0.6 children per woman in 2005 to

0.3 in 2015, it was still at the level of 0.6 among women in

the poorest segment of the population in 2015, indicating

that they had not achieved the desired access to family

planning. Adolescent fertility rates are increasing,

although this is more related to early marriage than

to access to contraception. The unmet family planning

need for limiting fertility among adolescent women

aged 15 to 19 is quite low at 1.4 percent. [31],[33] Service

coverage for prevention and treatment of cervical cancer

and for addressing violence against women and girls is

still insufficient and requires attention. [37]

Fixed and transparent user fees for sexual and

reproductive health services provide some level of

protection against financial hardship, especially as the

fee levels are set in consultation with communities, and

provisions are made for fee exemptions for the poor. All

SRH services are included in the MPA or the CPA service

packages provided at health centre or hospital level. The

Health Equity Funds provide additional financial risk

protection for the poor. The protection, however, does not

extend to the private sector which delivers the majority

of some sexual and reproductive health services, for

instance for short-term family planning methods and

for termination of pregnancy. The cost of health services

is considered by two thirds of women as a barrier to

access. There is little difference among age groups,

but the financial barrier is higher for rural women and

as high as 79 percent for women in the lowest wealth

quintile. [33]

While Cambodia has achieved impressive progress in

expanding the service offer for sexual and reproductive

health after the almost complete break-down of health

services under the Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s

and 80s, it has not yet achieved a high level of coverage

of financial risk protection. Social equity instruments

such as user fee exemptions and the current nationwide

expansion of the health equity funds have contributed

to narrowing some of the gaps in service utilisation

between poor and rich. But since health equity funds

are reimbursement mechanisms for health service

expenditures, an important financial barrier to service

utilisation remains.

16

INDONESIA

17

INDONESIA

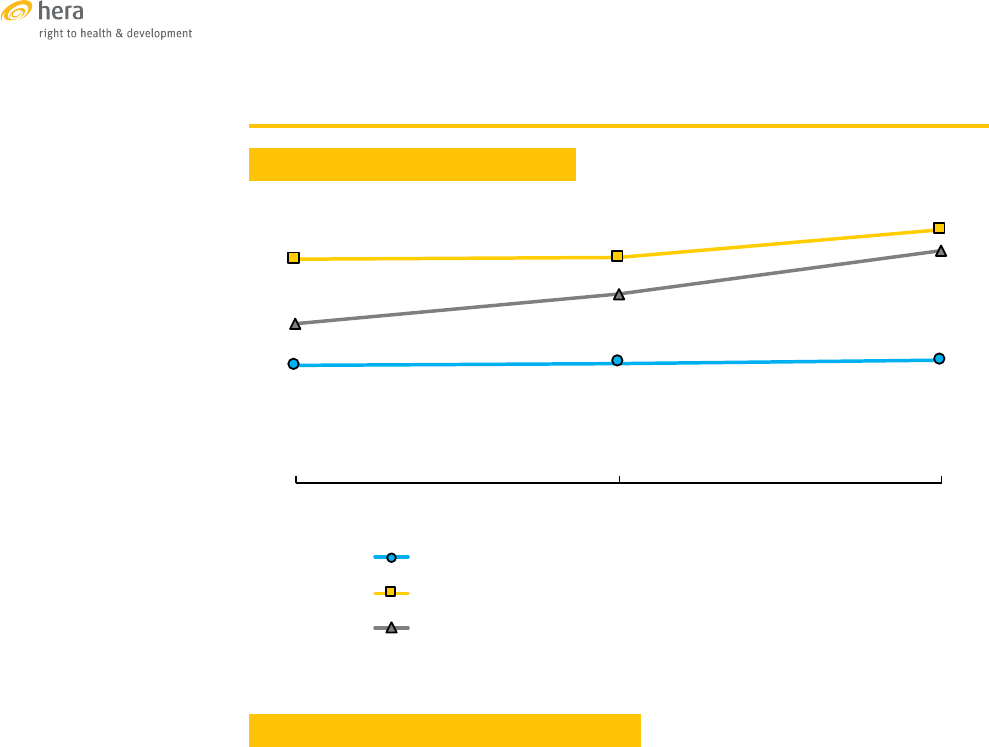

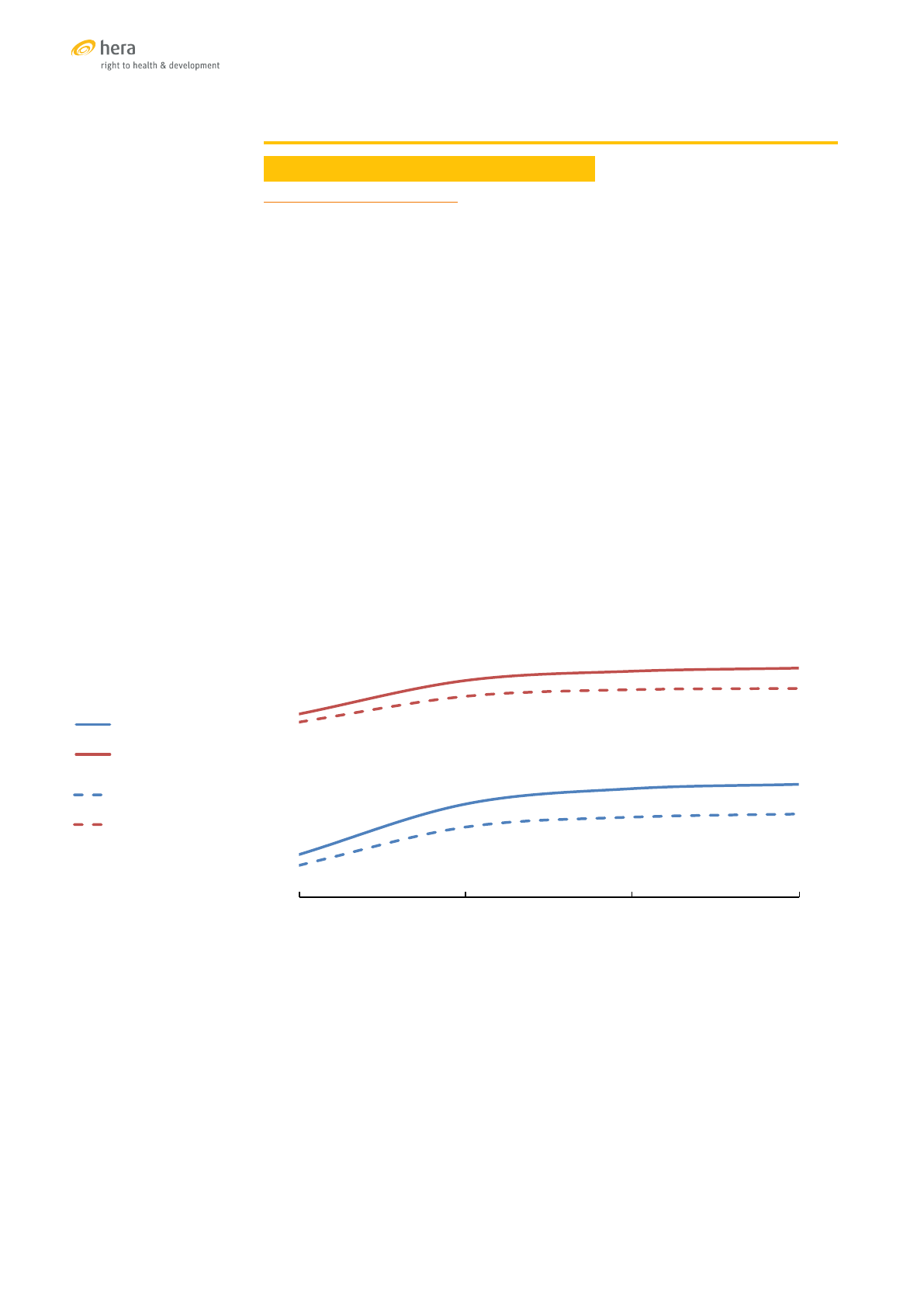

TRENDS OF SELECTED SRH INDICATORS

Sources: [42],[43],[44]

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH SERVICES

The population of Indonesia is served by a mix of public and private health care

providers. Public health centres provide health promotion, immunisation, sanitation

and health care services. The Indonesian health policy requires local governments

to establish one public health centre for every 30,000 inhabitants and one sub-health

centre for every 10,000. There are, however, large differences in service provision

among provinces. A report in 2011 found that 25 percent of health centres country-

wide were without a medical doctor, most of them in remote, poor provinces. [45]

Contraceptive prevalence rates in Indonesia are high and have been for many

years. According to the most recent estimate, 81 percent of married women aged

15-49 have satisfied their need for family planning with the use of a modern method.

[46] The difference between wanted and observed fertility in 2012 was 0.6 children

per woman with little difference according to residence and social status. The

total fertility rate of 2.6 has not changed since 2002. Family planning services are

delivered by the Ministry of Health, and since 2016 they are included among the

National Health Insurance benefits. Contraceptive commodities are supplied by

the National Family Planning Board. Stock-outs of contraceptive supplies in health

facilities and poor quality of family planning services have, however, become an

issue of concern during the past three years. [47]

In 2003, the Ministry of Health started a programme to roll out the provision of

youth-friendly services in primary health centres. About a quarter of health

facilities are currently implementing the programme. However, the access of

adolescents to sexual and reproductive health services remains limited. Guidelines

for health providers stipulate that family planning services should only be provided

to married couples. Adolescent fertility rates have remained unchanged over three

rounds of DHS surveys between 2002 and 2012, each reporting that between nine

and ten percent of women aged 15-19 had started childbearing. [44]

57%

57%

58%

81%

82%

88%

66%

73%

83%

2002 2007 2012

%married women(1549)currently usingmodern contraception

%women with atleast4ANCvisitsduring theirlast pregnancy

%of births attended byaskilled provider

18

According to estimates by the FP2020 programme, there are approximately 2.6

million unintended pregnancies yearly. [46] Indonesia revised its general prohibition

of termination of pregnancy in 2009 under the Law 36 on Health. In Article 75

the prohibition was lifted in case of a threat to the life of mother or foetus and for

pregnancies due to rape. Among the requirements is the consent of both partners

except in cases of rape. [48] The law continues to be restrictive and statistics about

terminations of pregnancy are not available.

Indonesia made significant progress towards expanding maternal health services,

however the 2015 Demographic and Health survey estimated a very high maternal

mortality ratio of 359 deaths per 100,000 live births, an increase of more than 50

percent over the estimate in 2007. [44] In the subsequent strategic health plan (2015-

2019), sexual and reproductive health was therefore flagged as a priority area. [49]

There is evidence that with the launching of the National Health Insurance in 2014,

health service usage and outcomes improved greatly, but available population-

based data mostly predate the health insurance reform. Three subsequent DHS

surveys documented relatively high coverage of some key reproductive and

maternal health services with an increase in skilled attendance at delivery over

the five years preceding the 2012 survey. The surveys document that between 2007

and 2012 about two thirds of women delivered their infants in a health facility. Most

women chose private facilities, but the proportion of deliveries in public facilities

already started to increase prior to 2012 (from 22% in 2002 to 27% in 2012). It is

anticipated that the 2017 DHS will document further increases in deliveries in public

health facilities.

Coverage rates of services for sexually transmitted infections are not known,

however coverage of HIV positive pregnant women with anti-retroviral therapy for

the prevention of mother to child HIV transmission (PMTCT) is low and has been

falling. According to UNAIDS statistics it was 16 percent in 2012, falling to 9 percent

in 2015. Indonesia is not a high HIV incidence country, but because of its large

population there are an estimated 70,000 new HIV infections per year. [50] According

to the 2013 Global STI Surveillance Report, syphilis testing during pregnancy was

reported to be very low in Indonesia, at only 0.1 percent, in the context of a relatively

high rate of positivity of 1.2 percent reported in 2009. [51]

Immunisation programmes against Human Papillomavirus exist only in a pilot

phase. There is no information about the coverage rate. Indonesia has a national

cervical cancer screening programme with a quality assurance structure and a

mandate to supervise and to monitor screening. It does, however, not include an

active invitation for screening, and coverage statistics are not provided. A small

survey between 2007 and 2011 reported that 24 percent of participating women had

undergone cervical cancer screening within the last five years. [52]

19

FINANCIAL RISK PROTECTION

In 2004, Indonesia launched a national social

security reform with the development of a mandatory

national health insurance as the first of five social

security programmes. [11] In 2012, the ‘Road Map

towards National Health Insurance 2012-2019’ was

jointly developed by 14 national ministries and state

agencies with a target to cover the entire population

of Indonesia by 2019. [53] In 2014 a social security

agency for health (BPJS) was established with the task

of merging existing social protection and risk pooling

schemes under a single National Health Insurance

(JKN). Implementation started in January 2014 with

121.6 million members. The majority among them

were social insurance beneficiaries whose premiums

were paid by the State. Since then, there has been an

increasing proportion of contributing members who

joined the JKN through mergers of their civil servant,

military, formal sector or private insurance scheme.

By November 2016, membership was reported at

171 million, about two thirds of the population of

Indonesia. Insurance claims in the 2015 calendar year

were about 18 percent higher than in the first year of

operation in 2014. [54]

Insurance benefits differ among different membership

types and premium rates, but there are plans to

gradually abolish these differences. Premiums start

at 23,000 IDR per month (about 17 US$) which is the

subsidised rate paid by the State for the poor, and are

set at five percent of family earnings for civil servants

and other waged workers. For the self-employed

and those working in the informal economy, three

premium classes exist depending on the level of

services subscribed.

The benefits of the National Health Insurance scheme

launched under the BPJS-Health in January 2014 are

generous, covering most of sexual and reproductive

health services, and also covering some non-clinical

costs such as ambulance referrals and hospital

accommodation. Family planning services were

included in 2016. Not covered are services for the

termination of pregnancy except in special situations.

Care for spontaneous abortion and post-abortive care

are however included.

The JKN scheme is still in the process of expansion,

undergoing adjustments of tariffs, benefit packages

and premiums. According to key informants, it

concluded its first year of operation with a negative

balance, a deficit that increased in the second year.

There are well-founded concerns about the capacity

of government to fund the expansion. Some of the

wealthier cities and districts have introduced pro-

poor programmes to cover additional financial risks,

for instance transport costs.

UNIVERSAL COVERAGE FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE

HEALTH

Between 2014 and 2015, health service utilisation

increased by 60 percent, but changes in service

coverage for sexual and reproductive health are

only just starting to be documented. While coverage

for maternity-related services was already high or

increasing prior to the introduction of the universal

health insurance scheme, some services such as

syphilis screening during pregnancy are lagging

behind.

Access to SRH services for adolescents is restricted

despite the launching of a youth-friendly service at

the primary health care level. The restrictions are

primarily related to service provider regulations and

not to regulations of the National Health Insurance

system.

One of the main obstacles to overcome will be the

regional inequity in service coverage. While the

Capital Region of Jakarta recorded a satisfied demand

for family planning of 82 percent and a rate of skilled

assistance at birth of 99 percent, the corresponding

metrics for the Province of Papua are 48 and 40

percent. [44]

20

MONGOLIA

21

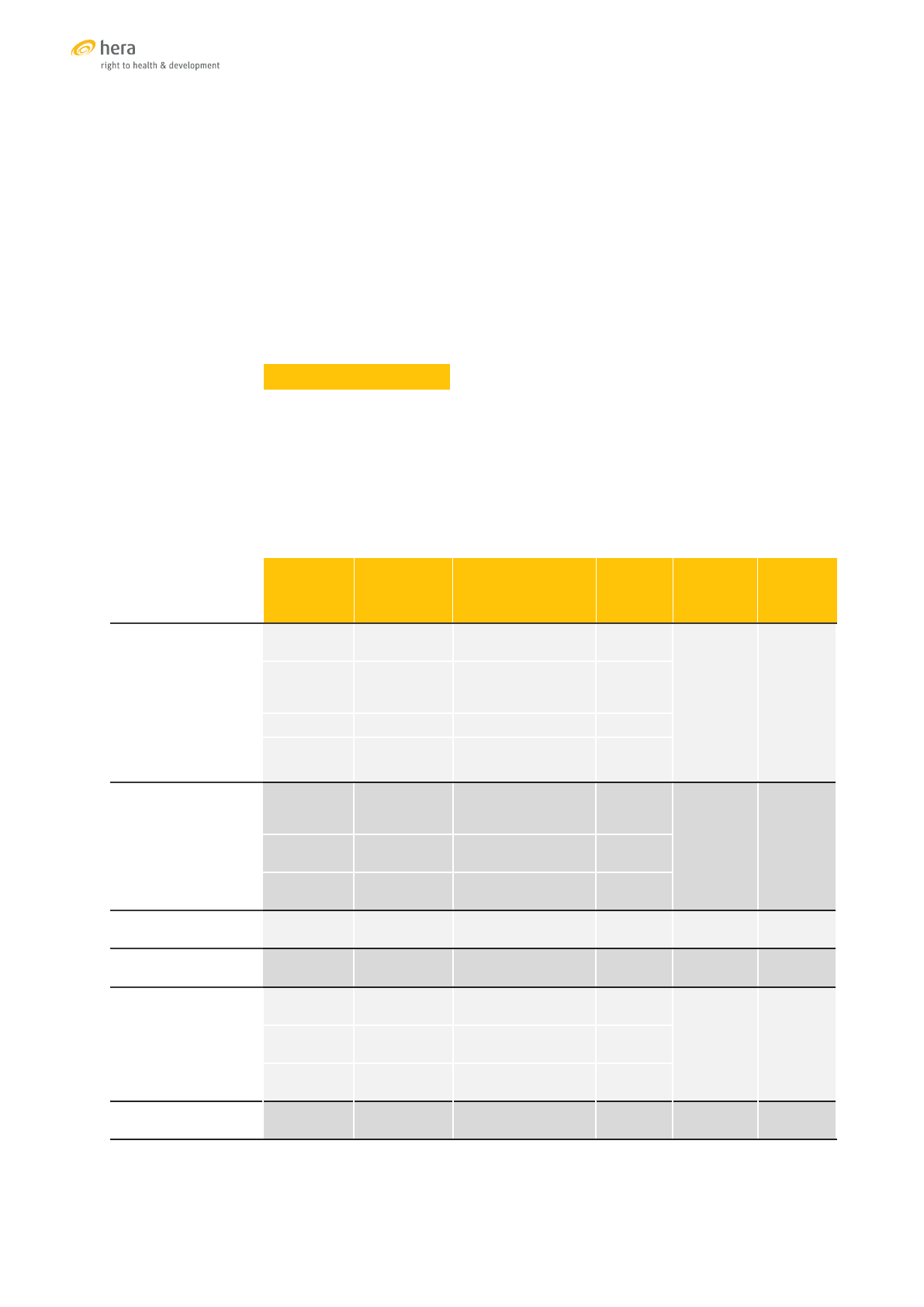

MONGOLIA

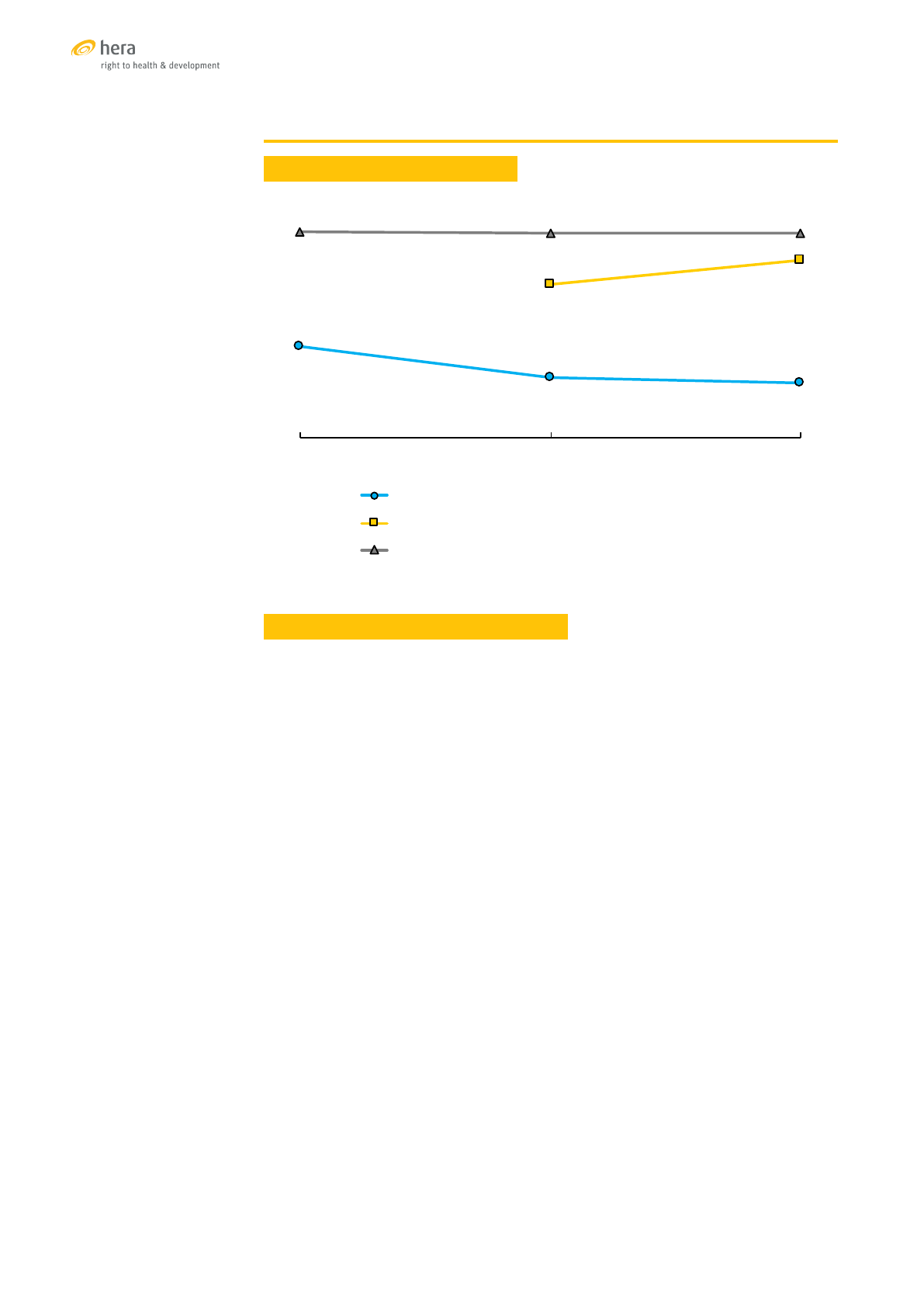

TRENDS OF SELECTED SRH INDICATORS

Sources: [55] ,[56],[57]

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH SERVICES

Health care at the primary level in Mongolia is provided by private and public health

centres, secondary care by public hospitals and private clinics, and tertiary care

by multispecialty central hospitals and specialised centres located in the capital

Ulaanbaatar.

Contraceptive services in the public sector are provided at the primary and secondary

level. In line with a national policy to promote population growth, the service delivery

has deteriorated over the last ten years. Stock-outs of family planning commodities

are common. Even in Ulaanbaatar, all facilities reported stock-outs of family planning

commodities in 2015. The quality of service provision is low, with only 42 percent of

those attending family planning services reporting that they received any counselling.

[58] Contraceptive prevalence with modern methods has been decreasing since 2005,

while the unmet need for contraception also started to decrease in 2010.

In parallel to the decreasing availability and use of contraceptives, the adolescent

birth rate increased from 38 to 40 births per 1000 adolescent girls between 2010

and 2013. In contrast to the general decrease in the unmet need for family planning,

the unmet need among adolescent more than doubled from 14 to 36 percent. The

recently established adolescent health centres that provide counselling and services

for sexual and reproductive health to young people also experienced shortages of

contraceptive supplies. [58]

Termination of pregnancy in the first trimester is legal if performed in a health

facility by a licensed medical specialist. Second trimester terminations require the

permission of a medical committee. Between 2012 and 2013, an estimated 14 percent

of pregnancies ended with an induced abortion. Among never married women the

rate was 30 percent. [57]

61%

50%

48%

81%

90%

99%

99%

99%

2005 2010 2013

%married women(1549)currently usingmodern contraception

%women with atleast4ANCvisitsduring theirlast pregnancy

%of births attendedbyaskilled provider

22

Primary care facilities provide antenatal care and, in rural areas, also attend to

normal deliveries. About 80 percent of deliveries, however, are attended in secondary

level hospitals. Antenatal care coverage (90%) and skilled attendance at delivery

(98%) are high, however the provision of services to migrants and mobile populations

remains a challenge. [57] Mongolia made impressive progress in reducing maternal

mortality from 199 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 26 deaths in 2015.[59] The

national average, however, masks wide geographic and ethnic disparities. Seventy-

five percent of all maternal deaths occur among herdswomen, the unemployed and

unregistered migrants.

HIV testing is mandatory for antenatal care. More than 90 percent of women are

tested, however only 32 percent reported that they were counselled. [57] By 2014, only

seven HIV positive pregnant women had been diagnosed. Coverage rates for PMTCT

services can therefore not be calculated. All anti-retroviral drugs are provided by the

government and dispensed free of charge.

STI services are provided by public and private clinics. STI screening, including syphilis

testing, is mandatory in antenatal care. The high incidence of sexually transmitted

infections is a major concern. Between 2001 and 2013, the syphilis notification rate

increased threefold from 71 to 222 per 100,000. Approximately one third of all cases

of syphilis are diagnosed among pregnant women. One of the challenges of STI

control is the high rate of self-treatment, often with inappropriate medications or

doses. Despite MOH efforts, antibiotics are still dispensed without prescription. [60]

Cervical cancer ranks as the second leading cancer among women in Mongolia

and is the most common cancer in women aged 15 to 44 years. About 320 new

cervical cancer cases are diagnosed annually. [61] A national screening programme

was launched in 2007 and reached a coverage of 29.7 percent in 2008. [62] HPV

immunisation is being piloted in two provinces and two districts of Ulaanbaatar. [63]

Services for survivors of violence against women and girls are limited in the health

sector. UNFPA has piloted the provision of integrated services for victims of violence

through model one-stop centres in Ulaanbaatar and three provinces. [64]

FINANCIAL RISK PROTECTION

The health sector is financed from government resources, Social Health Insurance

(SHI) premiums and out-of-pocket payments. With coverage almost consistently at 90

percent, the SHI has contributed to a stable financing source for the health sector. As

a proportion of total health expenditures, however, government and SHI expenditures

decreased between 1995 and 2014 from 82 to 55 percent, while the proportion of out-

of-pocket expenditures increased from 17 to 41 percent. [6] The long-term health

financing strategy is to reach universal health coverage with a mix of financing

sources of public funds, health insurance funds, and out-of-pocket payments which

are targeted to contribute about 25 percent to total health expenditure.

Health insurance in Mongolia is mandatory. The government fully subsidises the

insurance premiums for about 60 percent of members. About 90 percent of SHI

revenues are through payroll deductions and employer contributions for salaried

employees. The premiums for children under 16, pensioners, mothers of children up

to two years of age, and the poor are paid by government. All others pay a minimum

monthly premium. Government subsidisation of the SHI premiums for students was

removed in 2016. While the system is effective in collecting premium payments in

the formal sector, it is not effective in raising contributions from people who are not

formally employed. [65]

23

The government budget covers prevention activities, primary level health care

services including for maternal and child health, treatment of cancer and diabetes

and treatment of tuberculosis and HIV. The Social Health Insurance benefit package

covers predominantly outpatient and inpatient care in secondary and tertiary public

hospitals, traditional medicine clinics, sanatoriums and rehabilitation centres. Co-

payment requirements at the secondary and tertiary level of care are 10 and 15

percent respectively. Accredited private hospitals can invoice services to SHI and

are allowed to charge user fees at established rates. Outpatient medicines including

contraceptives, diagnostic services above a monthly limit established by SHI, and a

number of specified services, including therapeutic termination of pregnancy, are

not covered by government or SHI and have to be paid for by patients.

This high share of out-of-pocket expenditures in health financing negatively affects

equity, access and use of health services. The poor have difficulties accessing

specific health services, including diagnostic tests and ultrasonography for

pregnant women, even if they are insured by SHI. [66] Among the poorest quintile

of the population, about 95 percent of household health expenditures are for the

purchase of outpatient medicines. [67]

In 2009, an estimated 3.8 percent of households experienced catastrophic health

care costs at more than 40 percent of their household subsistence income. [68] A

more recent study found that this proportion had dropped to 1.1 percent in 2012, but

an estimated 20,000 people were still forced into poverty by the cost of health care.

[69]

UNIVERSAL COVERAGE FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

Mongolia has made impressive advances in reducing maternal mortality, increasing

antenatal care and facility-based deliveries. However declining access and use

of family planning, stock-outs of family planning commodities in public facilities,

rising adolescent birth rates, high abortion rates, a high incidence of sexually

transmitted infections and limited services for survivors of gender-based violence

remain important challenges.

The government subsidises the health insurance contribution for poor and vulnerable

groups, including mothers of children up to two years old and adolescents up to 16

years. There are, however, groups such as the former nomadic households, that are

still uninsured.

Maternity care is provided free of charge at primary health facilities. More

specialised services are covered by the Social Health Insurance at secondary

and tertiary level facilities. Family planning services for most of the population,

ultrasound and other advanced tests during pregnancy, termination of pregnancy,

and out-patient prescription drugs are excluded from the SHI benefits, with the

result that the individuals and families have to pay directly for many SRH services.

The access to SRH services by young people has increased with the creation of the

adolescent health centres, but the initiative has yet to translate into documented

SRH outcomes. Furthermore, the cancellation of government subsidies for the SHI

premiums of students in 2016 may lead to an increase in the loss of health insurance

coverage by young people over the age of 16 years.

24

THAILAND

25

THAILAND

TRENDS OF SELECTED SRH INDICATORS

Sources: [70],[71],[72]

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH SERVICES

Health care in Thailand is provided by the public and private sectors. The public

sector expanded rapidly in the 1960s under the National Economic and Social

Development Plans, which emphasised the coverage of the entire country with

a system of provincial hospitals, district hospital, and sub-district health centres.

Private hospitals are primarily located in urban centres.