0

Recyclers in Product Stewardship

Challenges, priorities, and recommendations from the

recycling sector

Issues paper

Prepared by the

Australian Council of Recycling

April 2024

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the First Peoples and Traditional

Custodians of Australia, and the oldest continuing culture in human history.

We pay respect to Elders past and present and commit to respecting the lands we walk on, and the

communities we walk with. We celebrate the deep and enduring connection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples to Country and acknowledge their continuing custodianship of the land, seas and sky.

We acknowledge the ongoing stewardship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the important

contribution they make to our communities, economies and the environment.

About ACOR

The Australian Council of Recycling (ACOR) is the peak industry body for the resource recovery, recycling, and

remanufacturing sector in Australia. The Australian recycling industry contributes almost $19 billion in

economic value, while delivering environmental benefits such as resource efficiency and diversion of material

from landfill. One job is supported for every 430 tonnes of material recycled in Australia.

Our membership is represented across the recycling value chain, and includes leading organisations in

advanced chemical recycling processes, CDS operations, kerbside recycling, recovered metal, glass, plastic,

paper, organic, tyre, textile, oil, battery and e-product reprocessing and remanufacturing, and construction

and demolition recovery. Our mission is to lead the transition to a circular economy through the recycling

supply chain.

1

Table of contents

Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................ 2

Summary of product stewardship challenges and solutions ............................................................................. 3

Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 4

Product stewardship and extended producer responsibility ......................................................................... 6

Recyclers: The missing link in strong product stewardship outcomes ........................................................... 8

Scheme accountability .................................................................................................................................... 9

ACCC leverage and access .............................................................................................................................. 9

Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................ 11

1. Rethink and restructure product stewardship ..................................................................................... 11

2. Design for recycling and reuse ............................................................................................................. 12

3. Create market demand ......................................................................................................................... 13

4. Enhance collection infrastructure and consumer incentives ............................................................... 15

5. Tighten scheme governance ................................................................................................................. 17

6. Enforce compliance and consequences ............................................................................................... 18

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 21

Appendix 1: Governance arrangements of Australian Government-accredited schemes .............................. 22

Appendix 2: Summary of recommendations .................................................................................................... 23

Case Studies

Case Study 1: Container Deposit Schemes ....................................................................................................... 5

Case Study 2: Dutch Extended Producer Responsibility Textiles Decree .......................................................... 5

Case Study 3: REDcycle ...................................................................................................................................... 6

Case Study 4: Bureau of International Recyclers Position on Extended Producer Responsibility ..................... 7

Case Study 5: Tyre Product Stewardship Scheme ............................................................................................. 8

Case Study 6: Materials Passport and Venlo City Hall ..................................................................................... 12

Case Study 7: Seamless .................................................................................................................................... 13

Case Study 8: B-cycle ....................................................................................................................................... 16

Case Study 9: National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme .............................................................. 19

2

Executive summary

The recycling sector strongly supports an increased focus on producers and distributors (known as ‘brand

owners’) to take greater responsibility across the full lifecycle of products, including at end of use. Product

stewardship and extended producer responsibility can be an effective way to reduce waste and lift recycling

rates—particularly where recycling rates are low, or materials have low or negative value—but only if these

schemes are properly designed in partnership with recyclers.

At present, existing voluntary and co-regulated product stewardship schemes endorsed by the Australian

Government predominantly cater to brand owners. However, it is imperative to recognise that these entities

represent only a part of a product's lifecycle.

Many product stewardship schemes appropriately emphasise the waste management hierarchy priorities of

avoidance, reusability, and designing for repair, yet all products inevitably reach an end of use, where the

ideal outcome is recycling.

Overwhelmingly, when schemes do engage with recycling activities, the focus is primarily on the public-

facing, marketable elements of collection and processing, while underinvesting in the equally critical aspect

of high-value recycling outcomes and demand generation for recycled material.

Too often, cost reduction is prioritised over quality recycling outcomes in such schemes. Not only does this

undermine legitimate recycling operations, but it also erodes community confidence in recycling when the

system fails.

Recent trends indicate recovery rates for household waste have stagnated, while commercial and industrial

waste recovery rates have declined. This pattern underscores the urgent need for a concerted effort to invest

in genuine recycling outcomes.

The establishment of a scheme must not be seen as an end in itself: it must be a means to delivering

sustainable and economically viable circular outcomes, in partnership with the entire supply chain.

Engagement with the rest of the supply chain—especially recyclers, who are the subject matter experts on

recycling—is essential to ensure product stewardship schemes deliver genuine value to brand owners,

government entities, communities, and recyclers, and support the transition to a circular economy.

The recycling sector is concerned that some existing voluntary and co-regulated product stewardship

schemes are not delivering robust recycling outcomes while new schemes are being established without the

correct mechanisms in place to drive effective resource recovery and demand for recycled materials.

With thirteen industry-led government-accredited voluntary and co-regulated schemes, almost one hundred

schemes operating in Australia, and many more in development, now is the time to better align these

initiatives, set stronger targets, adopt better governance and ensure accountability, to deliver genuine

outcomes that support community confidence and proper investment in a robust and competitive recycling

value chain.

This paper outlines the priorities and challenges for recyclers in the current context of a drive towards more

stewardship and extended producer responsibility models. It recommends measures for product stewardship

schemes that will deliver better environmental outcomes and more genuine engagement across the supply

chain, including designing for recycling and reuse, expanded collection and safe disposal measures, ensuring

robust market demand for recycled materials and transparent scheme governance focussing on compliance

and consequences.

Priority areas to deliver better recycling outcomes from product stewardship are as follows:

• Rethink and restructure product stewardship

• Design for recycling and reuse

• Create robust market demand

• Enhance collection infrastructure and consumer incentives

• Tighten scheme governance

• Enforce compliance and consequences

3

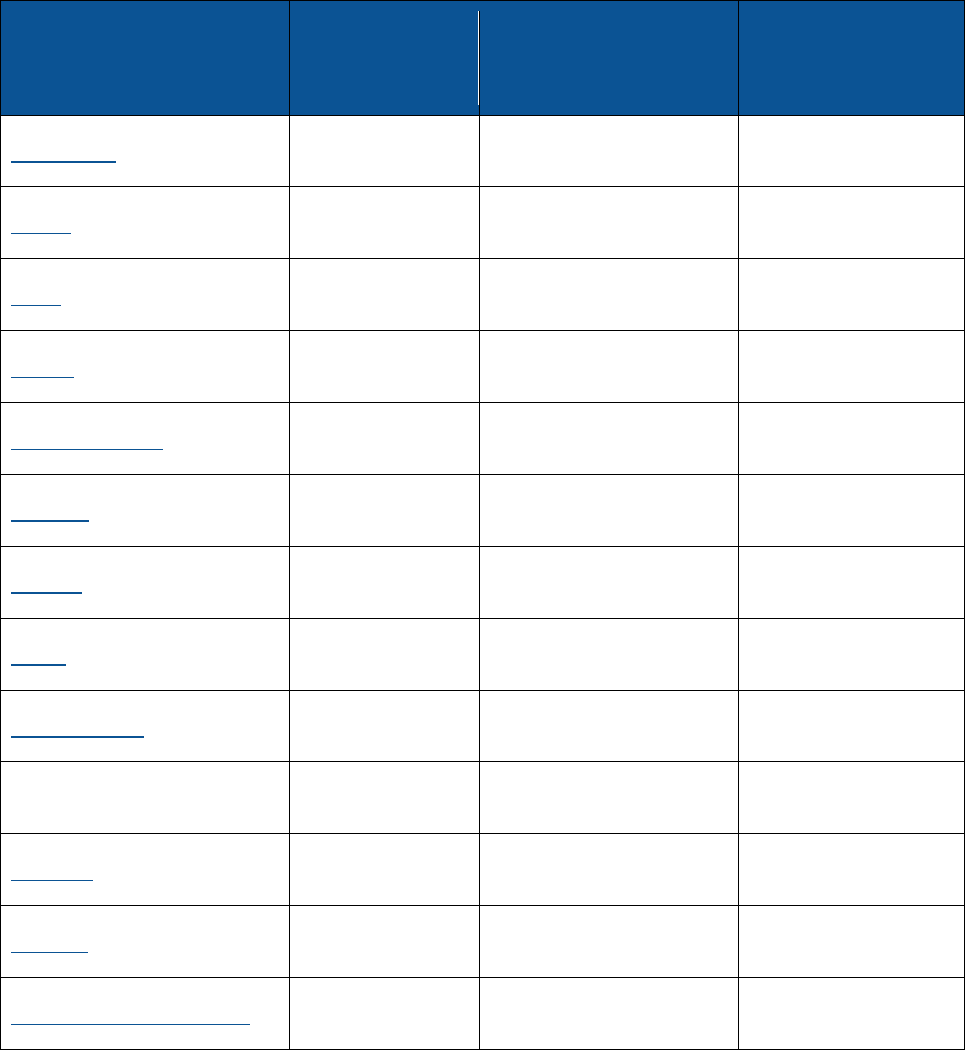

Summary of product stewardship challenges and solutions

Common issues in product

stewardship schemes

Recommendaons

− Underfunding recycling

− Product stewardship

priorised above more

eecve policy and

regulatory levers

− Duplicave schemes

creang ineciency and

confusion

1.1 ‘Trigger Framework’ to determine when a product stewardship

scheme is required

1.2 Assess and embed actual costs of recovery and recycling

2.1 Federal EPR legislaon, iniated by ‘Trigger Framework’

2.2 Evidence-based targets for recyclability, with targets increasing

over me

− Weak end markets for

recycled materials

3.1 Robust end markets for Australian recycled content

3.2 Economic incenves for use of recycled materials

3.3 Minimum thresholds for Australian recycled content

3.4 Cercaon and labelling for Australian recycled content

3.5 Target dumped and subsidised imported material

− Poor governance, including

conicts of interest, and

under-representaon across

supply chain

− Scheme administraon

priorised over recycling

− Lack of appropriate targets

or proporonal

consequences for non-

achievement

4.1 Expand the scope of mandatory e-stewardship, incorporang all

consumer electronic and electrical equipment and loose and

embedded baeries into one comprehensive scheme

4.2 Gap analysis of disposal opons for all electronic and hazardous

waste streams

4.3 Comprehensive network of safe disposal sites

4.4 Incenvise safe baery collecon with deposit refund

5.1 Supply-chain representaon in product stewardship scheme

governance

5.2 Recycling sector expert convenor to engage product stewardship

schemes with recycling sector

5.3 Clearly dened and measurable objecves, rules and targets

5.4 Transparent data about objecves, decision-making processes,

recovery rates, recycling outcomes and material movement

5.5 Ensure scheme's objecves are met with accountability measures

− Poor accountability and

transparency

6.1 Australian Recyclers Accreditaon Program (ARAP)

6.2 Enforce waste export regulaons

6.3 Regulate the export of waste texles, unprocessed scrap metal and

unprocessed e-products

6.4 Tax incenves or priority access to markets for best-pracce

recycling facilies

6.5 Product stewardship schemes to be subject to third-party audits

and/or inspecons

6.6 A naonally harmonised resource recovery framework

4

Background

The Recycling and Waste Reduction Act was passed in 2020, providing a framework for managing Australia's

recycling and waste reduction objectives, which include the development of a circular economy.

1

The Act

identifies voluntary, co-regulatory and mandatory product stewardship schemes as a means to manage the

impacts of products and materials throughout their lifecycle, and enables a more accessible framework for

accreditation of voluntary schemes. The Act provides for the use of the Commonwealth’s logo for accredited

voluntary schemes, promoting the recognition and credibility that government accreditation affords.

2

The Australian Government has signalled a preference for industry action through product stewardship

schemes. The establishment of many government-accredited schemes has also been encouraged by the

Minister’s product stewardship priority list,

3

which identifies products lacking circular or recycling solutions

at their end of use.

The Product Stewardship Centre of Excellence (Centre of Excellence) was established in 2021 with the

support of the Australian Government. The Centre of Excellence maintains the Product Stewardship

Gateway, a directory of product stewardship schemes in Australia, detailing any reporting data product

stewardship schemes disclose.

In 2023, the Centre of Excellence delivered their evaluation of product stewardship and extended producer

responsibility activity in Australia,

4

in line with action 3.3 of the National Waste Action Plan 2019.

5

The

summary report presented a positive view of product stewardship in Australia, despite acknowledging

difficulties in assessing efficacy due to poor reporting from schemes:

Given the inconsistency and gaps in data collection and reporting, only a few of annual

performance indicators could be aggregated. There were also limitations in assessing how

effective initiatives are performing. For example, tonnes of waste products collected for

recovery and materials recovered were not always reported in the context of total waste arising.

Without this data, it is difficult to determine how effective the initiative has been in increasing

recovery or diverting waste from landfill.

6

Some mandatory and well-governed product stewardship schemes have been successful. State-based

container deposit schemes (CDS) will soon be operating nationwide. They are generally considered to be an

appropriately governed and funded approach by recyclers, industry and government stakeholders alike.

These mandatory schemes provide a 10-cent refund for the return of beverage containers, aligning economic

incentives with environmental goals.

1

Australian Government Department of Finance, ‘Recycling and Waste Reduction Act 2020’, Australian Government

Transparency Portal website, accessed March 2024.

2

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, ‘Product stewardship schemes and priorities’,

DCCEEW website, accessed March 2024.

3

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, ‘Minister’s Priority List 2023–2024’, DCCEEW

website, accessed December 2023.

4

Product Stewardship Centre of Excellence (May 2023) ‘Evaluating product stewardship: Benefits and effectiveness,

summary report’, Product Stewardship Centre of Excellence website, accessed March 2024.

5

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (2019, 2022) ‘National Waste Policy Action Plan

2019’, DCCEEW website, accessed March 2024.

6

Product Stewardship Centre of Excellence (May 2023) ‘Evaluating product stewardship: Benefits and effectiveness,

summary report’, p. 10, Product Stewardship Centre of Excellence website, accessed March 2024.

5

Product stewardship and extended producer responsibility schemes are intended to encourage

manufacturers, retailers, consumers, and other stakeholders to take shared responsibility for the

environmental and human health effects of products. They aim to drive environmentally beneficial outcomes

through good design and clean manufacturing, including the use of components and materials that are easier

to recover, reuse and recycle, and often involve strategies such as designing products for recycling, creating

take-back programs for used products, and promoting responsible disposal practices.

However, all products produced or distributed in Australia ultimately reach the Australian waste stream—

including materials banned from export over the last few years. Onshore recycling and the creation of

markets for recycled materials must therefore be an overarching priority across all product stewardship

initiatives.

At a time when resource recovery rates have stagnated,

9

it is vital that recycling is prioritised. The recycling

sector plays an indispensable role in diverting materials from landfill and reintegrating them into the supply

chain, closing the loop in a circular economy.

Recycling operates as an integrated system, comprising collection, processing, and end markets for recycled

materials. In particular, markets for recycled materials are paramount; without robust markets, the system fails.

7

Total Environment Centre (2023) ‘Review: Australian Container Refund Schemes’, TEC website, p. 11, accessed

March 2024.

8

Netherlands Enterprise Agency, RVO ‘Uitgebreide Producentenverantwoordelijkheid UPV’, Business.gov.nl, accessed

March 2024.

9

Blue Environment (2022) 'National Waste Report 2022’, report to the Australian Government Department of Climate

Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, DCCEEW website, accessed March 2024.

Case Study 1: Container Deposit Schemes

Container deposit schemes (CDS) will soon be operang in every Australian state and territory.

These schemes have aracted industry and community parcipaon and substanally reduced beverage container

lier and landlling. The schemes allow for access to quality recovered material, which leads to highest-value

material reuse, such as bole-to-bole recycling. For example, the hot-wash PET ake generated from CDS products

delivers high-quality recycled PET (rPET) for the Australian packaging market. The schemes also deliver

uncontaminated glass for high-value recycling.

Through mandatory product stewardship including a 10-cent refund on returned containers, these schemes have

delivered a naonal average recovery rate of 69%,

7

collecvely resulng in the recovery of over 30 billion beverage

containers, while supporng jobs as well as fundraising for community groups.

More work now needs to be done to improve return rates to internaonal standards, achieve a naonally

harmonised approach and li governance in some schemes.

Case Study 2: Dutch Extended Producer Responsibility Textiles Decree

In the Netherlands, an extended producer responsibility scheme (Uitgebreide Producentenverantwoordelijkheid,

UPV)

8

for textiles came into effect on 1 July 2023. It establishes the following targets for reuse and recycling, which

will ratchet up over time:

• By 2025, 50% of the previous year’s total weight sold must be recovered for reuse or recycling. Of this

percentage, at least 20% must be reused, with at least half reused in the Netherlands. By 2030, it increases to

75% of the previous year’s total weight sold, with at least 25% reused of which 15% must be reused in the

Netherlands.

• By 2025, 25% of all textile fibres of discarded textile products must be used in materials for new products

(fibre-to-fibre recycling). By 2030, this must be 33% of all textile fibres.

• Producers will have to submit an annual report setting out the details of their compliance with the decree, and

are financially responsible for setting up a suitable collection and processing system for discarded textile

products. Non-compliance may be punishable with criminal law sanctions.

6

Currently, many voluntary and co-regulated product stewardship schemes frustrate higher-order recycling

outcomes by compounding a disconnect between manufacturers and recyclers, rather than fostering

partnership. This divide persists partly because manufacturers are hesitant to bear the entire expense of

recycling, which is not a cheap process in Australia, entailing higher costs than other countries in the region

due to factors including labour, energy, logistics and stringent regulations protecting the environment and

human health. Despite the challenges, the recycling sector remains indispensable in fostering sustainability

and responsible material management.

Often, scheme administrators prioritise the establishment of a scheme as an end in itself, with a great portion

of funding dedicated to administration, rather than actual and viable recycling. This emphasis on scheme

establishment rather than delivery of robust outcomes, leads to many inefficiencies, particularly in crossover

markets, as well as aggregation, and overall administration. In this sense, scheme administrators can create

duplicative systems, adding cost to recycling systems without adding value.

Product stewardship and extended producer responsibility

‘Extended producer responsibility (EPR)’ and ‘product stewardship’ refer to management approaches that

emphasise producer responsibility for end-of-use outcomes for the materials and products they place on

market. The terms are often used interchangeably as the sector matures and related initiatives expand and

proliferate, which can create confusion among stakeholders.

For the purposes of this paper, product stewardship will be used to refer to both EPR and product

stewardship unless stipulated otherwise—with a specific focus on voluntary and co-regulated schemes.

Whether EPR, or voluntary or mandatory product stewardship, or neither, is the correct approach for

managing a product at end-of-use will be determined by the nuances such as the material’s inherent value

and properties, the maturity and economic viability of the recycling supply chain and end markets, and

existing policy and regulation.

10

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (30 March 2023) ‘Cooperation proposed to continue on soft

plastics recycling after REDcycle liquidation’, ACCC website, accessed March 2024.

11

Miles, Daniel (30 November 2023) ‘One year on from REDcycle's collapse, Australia remains without soft plastics

recycling program’, ABC News website, accessed March 2024.

Case Study 3: REDcycle

REDcycle was an industry-led program operating from 2011 as a broad-based return-to-store, soft plastics recovery

program in Australia, facilitating the collection and processing of soft plastics into a variety of durable recycled

plastic products. Product manufacturers and major Australian supermarkets partnered with REDcycle to run the

program.

In November 2022, REDcycle announced that it was suspending soft plastics collection, as processing capacity for

soft plastics and markets for recycled soft plastic products became limited.

10

It was later revealed that REDcycle was

stockpiling over 10,000 tonnes of unprocessed soft plastic across dozens of locations Australia-wide.

11

In February

2023, REDCycle was declared insolvent, reflecting broader limitations of the recycling system for soft plastic.

As a product stewardship scheme, REDcycle was fuelled by strong marketing and collection rather than a robust

recycling supply chain and stable end markets. In a market environment where the production of new plastics is still

far outstripping the demand for recycled materials, the collapse of REDcycle underscores the importance of

scrutinising the operational aspects of product stewardship schemes to ensure they are capable of fulfilling their

objectives and contribute meaningfully to circular economy outcomes.

The failure of REDcycle has had a broad impact on public confidence in recycling, with the media often calling into

question the effectiveness of Australia’s broader recycling system, demonstrating that the reputation of the

recycling industry (rather than manufacturers) is most severely compromised by poorly designed schemes.

7

Currently, product stewardship schemes in Australia largely cater to the brand owners above the interests of

the rest of the supply chain, which contains inherent risks and can result in poor environmental outcomes,

for both product stewardship schemes and EPR. These concerns are shared by the Bureau of International

Recyclers (see Case Study 4).

12

It has become increasingly apparent that many EPR and product stewardship schemes have not sufficiently

met expected targets,

13

and too much power given to only one type of stakeholder has resulted in opaque

schemes lacking checks and balances and leading to poor environmental outcomes (see Case Study 9).

12

Bureau of International Recycling (November 2023) ‘BIR Position Paper on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)’,

BIR website, accessed March 2024.

13

Many product stewardship schemes do not report outcomes. Of those schemes required to do so, APCO has

reported that the 2025 National Packaging Targets are on track but will not be met: APCO (2023) ‘Australian packaging

material flow analysis for 2020–21’, APCO website, accessed March 2024.

14

Bureau of International Recycling (November 2023) ‘BIR Position Paper on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)’,

BIR website, accessed March 2024.

What is extended producer responsibility?

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) places legal obligations on manufacturers, importers, or brand owners to

take responsibility for the end-of-use management of their products. If enacted properly, it can be an effective way

to ensure recyclability and fund recycling efforts. EPR schemes can mandate that brand owners take financial or

operational responsibility for the collection, reuse, recycling, or safe disposal of their products at the end of their

useful life.

Broader application of EPR can support greater resource efficiency if carefully implemented to avoid perverse

outcomes. There must be transparency, meaningful and enforceable targets, continuous improvement and the

input and involvement of the recycling industry, with EPR designed to work within, and improve, existing recycling

systems.

What is product stewardship?

Product stewardship schemes can be voluntary, co-regulated or mandatory initiatives, where stakeholders engage

in programs or initiatives to reduce the environmental footprint of products. Product stewardship can devolve

producer responsibility for managing the lifecycle impacts of products onto a broader pool of stakeholders,

particularly retailers, consumers and recyclers.

Case Study 4: Bureau of International Recyclers Position on Extended Producer Responsibility

14

The Bureau of International Recycling (BIR) is a global federation supporting the interests of the recycling industry.

BIR represents over 30,000 companies across 70 countries, through 37 national associations and over 1000 direct

corporate members, covering eight material streams, including ferrous and non-ferrous metals, paper, textiles,

plastics, tyres/rubber, and electrical/electronic equipment.

In 2023, BIR released a position paper on EPR highlighting growing international concern from recyclers about EPR.

Key recommendations outlined in their statement include:

• EPR schemes must not disrupt existing efficient markets, and should be set up only when there is a need and

only once the effectiveness and the intrinsic value of a waste stream have been assessed;

• governments should also consider other policy instruments to increase circularity, such as mandatory design

for recycling and legally-binding recycled-content targets;

• recyclers should be involved in the governance bodies of such schemes to ensure an appropriate balance of

interests among the most relevant stakeholders in the value chain, and;

• ownership of waste should be retained by the recycling company entrusted with the responsibility of

processing the waste, with transparent and fair tenders to avoid monopolies and comply with competition

rules.

8

Recyclers: The missing link in strong product stewardship outcomes

Critical problems arise when a key part of the scheme supply chain is unable to meaningfully engage on costs,

logistics, and the state of end markets. While product stewardship schemes are intended to operate with all

stakeholders working in concert, this is often not the case. In particular, recyclers and remanufacturers are

not sufficiently involved in the establishment or ongoing operations of schemes.

Recyclers can highlight challenges and opportunities in the recycling process, such as recyclability of

materials, components that help or hinder the recycling stream and markets for recycled materials. They are

also positioned to provide expertise into efficient collection, sorting, quality control and processing methods,

improving the overall effectiveness of the stewardship scheme and reducing contamination in recycling

streams.

Currently, recyclers and remanufacturers are under-represented on boards across product stewardship

schemes. Of the thirteen co-regulated and Government-accredited voluntary schemes in Australia, only five

publicly disclose their governance arrangements, and of those, only two show recyclers on the board (as

shown in Appendix 1: Governance arrangements of Australian Government-accredited schemes.

The involvement of recyclers in the governance of product stewardship schemes can help to ensure that

recycling is economically viable and drive market demand for recycled materials. With rising costs across

recycling facilities, it is particularly critical that recyclers are at the table to highlight market failures, to inform

whether, and when, intervention through a product stewardship scheme is necessary.

15

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (May 2018) ‘ACCC re-authorises Tyre Stewardship Scheme’,

ACCC website, accessed January 2024.

Case Study 5: Tyre Product Stewardship Scheme

Tyre Stewardship Australia (TSA), which commenced in 2014, raises a 25 cent per tyre levy from participating tyre

manufacturers, amounting to $7.6 million in 2023. These funds are distributed across three primary functions:

research and development for new end-of-life-tyre (EOLT) products; an accreditation program for collectors,

recyclers and retailers; and consumer marketing.

TSA is a manufacturer-led and governed organisation. There is no recycling industry representation on the board

and little overall strategic engagement with the recycling sector. TSA has no role in the collection and recycling of

EOLTs, and no funds from the scheme are provided to the sector. In the year ending June 2023, while TSA’s levy

income increased by 20%, spending on market development dropped to one-quarter of the company’s spending

(47% went to consultancy expenses, advertising and marketing).

This lack of engagement with the recycling sector has led to some ill-informed decisions. For instance, by

accrediting ‘balers’ (the cheapest disposal option for tyre retailers), prior to the Australian Government’s ban on

the export of whole baled tyres, TSA effectively endorsed many millions of unprocessed EOLTs to be exported to

developing countries in our region and to very poor environmental outcomes such as open burning.

The ACCC recently acknowledged concerns raised by sector stakeholders in relation to the effectiveness of the

scheme, citing insufficient representation on the TSA board, particularly in relation to the tyre recycling sector.

15

Stakeholders identified further concerns stemming from this lack of representation, including the accreditation,

under the scheme, of businesses that were uncompliant with scheme objectives, and insufficient oversight of

unprocessed EOLT’s exported overseas.

ACCC- and Government-endorsed product stewardship schemes are often called on to speak as authorities on

recycling, or are credited with recycling outcomes. TSA, for example, points to increased EOLT recovery rates since

the scheme’s formation as demonstration of its success; however, this change should more appropriately be

credited to tightened state-based regulation: over the same time period, every state substantially reformed

regulation of the storage, transportation, fire safety, end-of-use disposal and other environmental management

aspects of EOLTs. Together, these regulatory changes provided an impactful disincentive to stockpiling EOLTs and

fostered increased recycling investment and activity.

TSA is lobbying the Australian Government to intervene in the sector via regulated product stewardship, despite a

97% collection rate for used passenger and commercial tyres. Since state regulations to limit stockpiling and illegal

dumping have been effective, it is unclear what environmental outcome a regulated scheme would deliver.

9

Scheme accountability

Government-backed schemes must deliver genuine circular economy and recycling outcomes. One way to

deliver meaningful outcomes is to ensure that schemes are advancing progress towards the targets in the

National Waste Policy Action Plan and Australia’s 2025 Packaging Targets,

16

specifically:

• reducing the total waste generated in Australia by 10% per person by 2030

• achieving an 80% average recovery rate from all waste streams by 2030

• phasing out problematic and unnecessary plastics by 2025

• halving the amount of organic waste sent to landfill by 2030

• 100% of packaging being reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025

• 70% of plastic packaging being recycled or composted by 2025

• 50% of average recycled content included in packaging by 2025.

Accountability at present is insufficient to ensure best-practice operations and high-value recycling

outcomes. A history of self-reporting with little benchmarking or consideration for tangible targets appears

to have fostered a culture of accepting any increase in material collection as ‘success’ of some schemes (see

Case Study 5). This self-reported data often goes unchallenged, even where issues are brought to the ACCC’s

attention, leading to reduced confidence and ultimately constraining investment in new recycling capacity

and capability.

17

Product stewardship schemes in Australia are also able to run their own accreditation programs for recyclers,

establishing specific criteria and standards that recyclers must meet to participate in their schemes. These

criteria typically focus on factors such as operational processes, compliance with regulations, the ability to

meet quality standards for recycled materials, and (ideally) environmental impact. Recyclers seeking

accreditation usually undergo assessments, audits, and evaluations to ensure they meet these set standards

before being approved to participate in the product stewardship schemes.

These ‘bespoke’ accreditation programs for recyclers represents a conflict of interest insofar as the priority

of schemes is to keep recycling costs low, rather than ensure best-practice recycling outcomes (see Case

Studies 7 and 9). This is costly and inefficient for both recyclers and brand owners, given that some recyclers

service more than one scheme and are therefore required to be separately accredited. For example, in the

mandatory National Television Computer and Recycling Scheme, recyclers must be approved by each and

every co-regulator that they supply, resulting in duplication of effort.

Product stewardship schemes must ensure transparency, accountability and effectiveness. In particular,

schemes that are accredited by the Australian Government must be required to meet a much higher standard

of governance, transparency and material outcomes.

ACCC leverage and access

Federal accreditation is a six-month process that enables industry-led product stewardship operations to

demonstrate to businesses and consumers that the arrangement has the Australian Government’s stamp of

approval.

18

An ACCC authorisation can also be granted, where schemes can be exempted from competition provisions—

such as those guarding against anti-competitive and cartel-like behaviours—and the ACCC may grant

protection from legal action for conduct that might otherwise breach the Competition and Consumer Act

2010 (the Act). Schemes seek authorisation where they wish to engage in conduct that is at risk of breaching

the Act but nonetheless consider there to be public benefit.

16

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (2019, 2022) ‘National Waste Policy Action Plan

2019’, DCCEEW website, accessed March 2024.

17

Australian Tyre Recyclers Association (2 February 2024) ‘Authorisations register: Tyre Stewardship Australia

Limited’, submission, ACCC website, accessed March 2024.

18

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (March 2023) ‘Product stewardship

accreditation’, DCCEEW website, accessed March 2024.

10

Since product stewardship should align with broader public interest by promoting sustainability, reducing

waste, and safeguarding environmental and public health, ACCC authorisation affords schemes access to a

suite of anti-competitive instruments,

19

such as:

• cartel conduct,

• contracts, arrangements or understandings

containing anti-competitive provisions,

• exclusive dealing,

• misuse of market power,

• secondary boycotts, and

• resale price maintenance.

While ACCC authorisation can support the delivery of public benefit through a product stewardship scheme,

some schemes have elicited commercial in-confidence data from the recycling industry through their ACCC

authorisation, which has subsequently been used to benefit brand owners of the scheme, rather than support

a whole-of-supply-chain stewardship outcome.

20

Some schemes also seek to conflate the achievements of

the recycling sector with those of the scheme (see Case Study 5).

19

Robert Janissen (3 September 2021) ‘ACCC Authorisation for product stewardship schemes’, webinar, Product

Stewardship Centre of Excellence website, accessed March 2024.

20

Australian Tyre Recyclers Association (2 February 2024) ‘Authorisations register: Tyre Stewardship Australia

Limited’, submission, ACCC website, accessed March 2024.

11

Recommendations

1. Rethink and restructure product stewardship

While product stewardship and EPR schemes can have positive outcomes if operated fairly and transparently,

to ensure best practice there needs to be greater critical consideration of the market conditions and

alternative approaches before new product stewardship schemes are established.

Consideration should be given as to whether product stewardship should be the only mechanism to be

instituted. Other effective mechanisms, such as higher landfill levies, landfill bans, product bans and the

enforcement of existing regulation, will be effective in some sectors, and often more cost-effective. Many of

these policy mechanisms are blunt instruments that do not place responsibility and costs on the brand owner.

EPR should be considered amid this range of policy options, and prioritised where adequate funding is not

available for optimum end-of-life solutions, or where there is significant market failure.

Product stewardship schemes should be considered as a mechanism to support the development of

infrastructure and markets for recycled materials, encourage correct collection, and increase end producer

responsibility. If a robust end market exists with adequate investment in recycling and resource recovery, a

scheme could, where appropriate, be wound down.

Product stewardship schemes are more appropriate and effective when applied to new recycling supply

chains—or where collection and recycling rates are low—rather than retrofitting to mature recycling

markets. Uncertainty about how new schemes might be established will deter investment in particular

material streams, with a potential domino effect on investment confidence across broader recycling streams.

There is a need for clarity about where the Australian Government will, and will not, intervene, with a priority

of engaging closely with the recycling sector to ensure that domestic investment is not disrupted or

undermined.

A product stewardship scheme ‘Trigger Framework’ could define clear parameters about when a scheme

should be initiated for a product, or whether a new product or category should be added to an existing

scheme in order to improve efficiency and minimise duplication of effort. Ensuring all parties in the supply

chain know schemes will be triggered once a set of transparent criteria are met—alongside consultation with

relevant supply chain stakeholders, including the recycling sector—will foster market and investment

confidence.

While end markets are key to driving recycling, there will often remain a recycling cost to be covered by a

credible scheme that distributes risk equitably across the supply chain. In sectors where there are low

recovery rates, or the free market does not support an economically viable recycling system, levies must

represent the real cost of recovery and recycling, take into consideration different recycling outcomes that

can deliver lower and higher value outputs, and support recycling development innovation.

Scheme funding that falls short of covering the cost of recycling fundamentally undermines genuine recycling

outcomes.

RECOMMENDATION 1.1 ‘Trigger Framework’ to determine when a product stewardship scheme is

required

In consultation with recyclers, brand owners and sector experts, the Australian

Government should establish a transparent ‘Trigger Framework’ to determine

when a product stewardship scheme becomes necessary: when certain market

conditions exist or recovery rates stagnate or fall. This framework must include

consultation with all supply chain stakeholders, particularly recyclers.

Attached to the ‘Trigger Framework’, an exit conditions metric should be

outlined for every new scheme, dictating under what economic and

environmental conditions and recycling rates a scheme could be wound down,

repositioning some schemes as tools for market rehabilitation and not an end in

themselves.

12

RECOMMENDATION 1.2 Assess and embed actual costs of recovery and recycling

Ahead of endorsing any product stewardship or EPR scheme, the Australian

Government should work with the recycling sector to conduct a comprehensive

assessment of the actual costs of recovery, recycling and remanufacture of

relevant material streams. This assessment should consider the entire recycling

value chain, including collection, logistics, sorting, processing and markets for

recycled materials, and would inform appropriate scheme fees and financing.

Governments must ensure that extended producer responsibility measures

undertaken by product stewardship schemes address actual costs of recovery and

recycling, support genuine and highest-value recycling outcomes, and investment

in Australian recycling.

2. Design for recycling and reuse

One of the biggest challenges to material recovery at end of use is poor design. A key component for every

product stewardship scheme must be to ensure that brands and brand owners design for better material

recovery and reuse, with a priority of procuring recycled materials.

Around the world, innovative closed-loop solutions are being deployed independently of product

stewardship schemes. For example, an aid in the correct sorting of materials for reuse is the ‘materials

passport’.

21

Through smart material choices and designing for disassembly, these materials passports will

make it possible for manufacturers to recoup some of their original investment, as materials can be sold back

into the supply chain, and ultimately used again.

It is understood that relatively few products are manufactured in Australia; however, given that all products

distributed in Australia ultimately enter into Australian waste streams, it is vital that schemes implement

measures to influence design for the Australian market.

Adopting more robust EPR regulations enforces producer responsibility for the entire lifecycle of their

products, including collection, recycling, and remanufacture. This, in turn, encourages the design of products

that are easier to disassemble, reuse, or recycle.

RECOMMENDATION 2.1 Federal EPR legislation, initiated by ‘Trigger Framework’

The Australian Government should implement Extended Producer Responsibility

legislation that holds manufacturers responsible for the end-of-use management

of their products, to encourage circular design and increase the demand for

recycled materials. This EPR legislation should only be initiated when conditions of

a ‘Trigger Framework’ (RECOMMENDATION 1.1) have been met.

21

Cradle to Cradle, ‘City Hall Venlo‘, C2C Venlo website, accessed March 2024.

22

Ellen Macarthur Foundation (June 2021) ‘City Hall from Cradle to Cradle: Venlo’, Ellen Macarthur Foundation

website, accessed March 2024.

23

Kraaijvanger Architects, ‘Municipal Office Venlo’, Kraaijvanger website, accessed March 2024.

Case Study 6: Materials Passport and Venlo City Hall

In the Netherlands, a ‘materials passport’ innovation was deployed during the construction of Venlo City Hall. The

passport records exactly what goes into the building, and will support the correct sorting of materials for reuse.

All components of the building were documented during construction in a materials database—or ‘materials

passport’—that describes the materials and provides an end-of-use plan, such as how to disassemble and recycle or

return them to the manufacturer. By effectively creating a materials bank within the walls of the City Hall and

designing for disassembly, it will be possible to recoup some of the original investment, at a later date, as materials

can be sold back to manufacturers through a ‘buy and buy-back’ scheme, and ultimately used again.

22

Furthermore, during its construction numerous producers and suppliers acquired Cradle to Cradle (C2C)

certifications for their products.

23

13

RECOMMENDATION 2.2 Evidence-based targets for recyclability, with targets increasing over time

Overseen by the Australian Government, product stewardship schemes should set

evidence-based targets for reuse and recyclability within product categories that

are reusable/recyclable and those that are not. Targets for reusability and

recyclability should increase over time, with measures in place to hold brand

owners and distributors to account.

3. Create market demand

Too often, product stewardship advocates appear to consider the establishment of a scheme as an end in

itself—in terms of meeting sustainability obligations—rather than a means to this end. A thriving and scaled

recycling sector is an essential component of a functioning circular economy—and recycling cannot function

without robust markets for recycled materials.

Theoretically, anything is recyclable, but recycling at scale must be economically viable, addressing the cost

of Australian labour, logistics, compliance, infrastructure, research and development, and, most critically,

supporting end markets for recycled materials.

There are significant barriers to strong market uptake of recycled material, including cost competitiveness

with virgin materials and willingness within the supply chain to embrace change. To date, an uneven

approach has been taken by the Australian Government, with a focus on banning the export of ‘waste’

without measures to address imported products that ultimately enter Australian waste streams. Conversely,

there are no drivers to address the import of products that ultimately all become Australian waste, at end of

use, as well as imported virgin and recycled materials that compete with Australian recycled products.

While there must be strong prioritisation of domestic end markets, export markets for processed recycled

commodities should be recognised as a legitimate avenue, akin to any other exported commodity, noting

that the focus must be on domestic processing.

24

Monash Sustainable Development Institute (2022) ‘Textiles: A transitions report for Australia identifying pathways

to future proof the Australian fashion and textile industry’, report, p. 6, Monash University website, accessed April

2024.

25

Australian Fashion Council (18 December 2023) ‘Seamless announces inaugural CEO and Board of Directors’, media

release, Australian Fashion Council website, accessed February 2024.

26

Australian Fashion Council (2023) ‘Scheme Design Summary Report’, Australian Fashion Council website, accessed

February 2024.

Case Study 7: Seamless

Australians are the second-largest consumers per capita of textiles globally, purchasing on average an estimated

27 kilograms of new fashion and textiles each year, of which on average 93% is disposed of.

24

In 2018–2019,

227,000 tonnes of clothing were landfilled in Australia, 105,900 tonnes were exported, 51,000 tonnes were reused

locally, 7,000 tonnes were recycled and 5,000 tonnes went to waste to energy.

The Australian Fashion Council clothing product stewardship scheme, Seamless, launched in June 2023. The Board

was announced in in December 2023,

25

with no representation from the recycling sector.

The scheme design outlined a proposal to reduce this consumption and waste by raising a levy of 4 cents per

garment to be invested in education, scheme administration, and research and development

26

.

This levy does not adequately address the costs of recycling and the scheme design in fact risks potentially locking in a

status quo arrangement in the fashion industry: restricting trade and access to feedstock, and remuneration for recyclers.

The scheme design does not address the economic and regulatory mechanisms necessary to drive resource

recovery: there are no identified end markets for recycled products generated by the scheme and no firm work

plans to develop these markets; no restrictions on the export of textile waste; no landfill bans (noting that some

participants are entitled to a waste levy exemption); and insufficient funding for higher-order recycling.

Under the current design, Seamless will likely raise revenue from consumers while increasing export revenue from

used textiles (including textile waste), without increasing Australian recycling rates.

14

Establishing a circular economy underpinned by a strong recycling sector will require the correct economic

drivers. For example, mandated recycled plastic content in the United Kingdom has catalysed investment in

recycled polymers by creating market demand.

27

Requiring manufacturers to use a certain percentage of

recycled content in their products has created a stable market for recycled polymers, encouraging investment

in recycling infrastructure and technologies to meet this demand.

In Australia, many in the recycling industry advocate for the mandatory implementation of the 2025 National

Packaging Targets set out in the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation. In 2023, the Australian

Government committed to regulate packaging and ultimately enforce these targets:

28

the creation of robust

end markets by 2025, ensuring that packaging incorporates 50% recycled content on average, and achieving

100% reusability, recyclability, or compostability.

29

While not yet defined, it is anticipated that the scope of

this regulation will encompass all packaging sold in Australia, accompanied by consistent benchmarking and

transparent reporting.

Formal government adoption of these targets would provide substantial backing for a flourishing,

competitive recycling sector by mandating recycled content in packaging. This would support the integration

of recycled products and materials into supply chains, fostering resilient and strong end markets.

Circular agreements can also play a useful role in fostering downstream end markets.

30

RECOMMENDATION 3.1 Robust end markets for Australian recycled content

Product Stewardship schemes must prioritise demand generation and play an

active and specific funded role in directly supporting robust and viable end

markets for Australian recycled materials.

RECOMMENDATION 3.2 Economic incentives for use of recycled materials

The Australian Government should create economic incentives for using recycled

materials, such as tax incentives, subsidies, grants, or differentiated regulatory

fees, which can offset the cost difference between recycled and virgin materials,

making the use of recycled materials more financially attractive for businesses.

Incentives to use recycled materials specifically derived from product stewardship

schemes should be considered.

RECOMMENDATION 3.3 Minimum thresholds for Australian recycled content

All Governments should implement strong drivers and mandated procurement

targets to support uptake of Australian recycled content, such as a price signal to

prioritise Australian recycled content over virgin materials and mandatory

minimum thresholds for Australian recycled content.

RECOMMENDATION 3.4 Certification and labelling for Australian recycled content

The Australian Government should work with industry to establish certification

and labelling programs that identify products made from recycled materials to

help consumers make informed choices and increase demand by driving

manufacturers to incorporate more recycled content.

RECOMMENDATION 3.5 Target dumped and subsidised imported material

The Australian Government should support a level playing field for the Australian

recycling market by more strongly targeting dumped and subsidised imported

materials.

27

NetZero Pathfinders, ‘Recycled Content Mandates: U.K.’, Bloomberg website, accessed March 2024.

28

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, ‘Reforming packaging regulation’, DCCEEW

website, accessed March 2023.

29

APCO, ‘Australia’s 2025 National Packaging Targets’, APCO website, accessed March 2024.

30

Steve Morriss (1 February 2024) ‘Circular Contracts: The future of recycling’, Close the Loop blog, accessed March

2024.

15

4. Enhance collection infrastructure and consumer incentives

While some product stewardship schemes have achieved desirable collection rates for end-of-use items, this

is not the case across all product categories. Schemes that provide little incentive for consumers to return

items to away-from-home collection points, and/or haven’t supported a comprehensively accessible and

well-marketed collection network, generally have poor collection rates.

31

Of major concern are items that pose a risk across all other collection and recycling streams, such as those

containing loose or embedded batteries which cause fires in waste and recycling trucks and facilities. The

rapid digitisation and electrification of everyday items, the increasing number of ‘smart’ and disposable items

such as vapes containing embedded and sealed batteries, and a lack of consumer education around their safe

collection, have all contributed to the steep and hazardous rise in batteries in inappropriate waste streams.

32

There is considerable confusion about which items contain batteries and which schemes different electronic

products are subject to. For example, it is not widely understood that vapes and digital thermometers contain

batteries. Also, while there are an array of schemes addressing electronic and electrical products—including

the mandatory National Television Computer and Recycling Scheme (NTCRS), the voluntary Mobile Muster

scheme, and the voluntary B-cycle scheme—many items are not accepted by any of these schemes, leaving

gaps for necessary collection and creating confusion in the community about appropriate disposal options.

Despite this critical lack of access to safe collection locations for these items, to date no comprehensive

geographic mapping of the gaps has been undertaken. Even with a product stewardship scheme in place, if

there are limited accessible safe disposal avenues, the only options for the community are to stockpile, litter

or dispose into incorrect waste streams.

Not only is there insufficient infrastructure to collect such items safely and comprehensively, but there are

also no compelling drivers to divert these types of products from conventional recycling streams (such as

household bins), resulting in major hazards across the recycling sector.

As the Australian Government reviews the framework for e-stewardship, it is essential that all e-products

(including those with batteries) are addressed holistically, rather than the current piecemeal approach.

There must be comprehensive access for collection, as well as compelling incentives for consumers to return

items to appropriate drop-off locations—especially items that pose a risk to human health, the environment

or conventional waste and recycling systems.

Highest-value recycling outcomes are achieved through well-sorted and separated recovered products and

materials.

At a consumer level, there must be a strong incentive to safely dispose of these products through the

introduction of a refund or deposit scheme, similar to container deposit schemes. This will help to drive the

correct collection of products at end of use, which is critically important for items that are hazardous, such

as loose and embedded batteries. Concerns that a refund on batteries might expose consumers to risk can

be addressed by ensuring that refunds are contingent on safe collection practices and appropriate

community education.

31

For example, in 2023, B-cycle’s collection rate of in-scope loose batteries was 12%. See B-cycle (July 2023) ‘Positive

Charge: 2022–2023 Report’, B-cycle website, accessed March 2024.

32

ACOR (December 2023) ‘A Burning Issue: Navigating the battery crisis in Australia’s recycling sector’, ACOR website,

accessed March 2024.

16

RECOMMENDATION 4.1 Expand the scope of mandatory e-stewardship, incorporating all consumer

electronic and electrical equipment and loose and embedded batteries into one

comprehensive scheme

The Australian Government should expand the scope of mandatory

e-stewardship, incorporating all consumer electronic and electrical equipment

into one comprehensive scheme—including any product connected to a plug or

that contains batteries, as well as all loose and embedded batteries, to bring

Australia into line with European standards.

RECOMMENDATION 4.2 Gap analysis of disposal options for all electronic and hazardous waste streams

State and Territory Governments must conduct a detailed gap analysis of disposal

options for all electronic and hazardous waste streams, to help inform future

schemes and policy decisions.

RECOMMENDATION 4.3 Comprehensive network of safe disposal sites

State and Territory Governments must ensure that a comprehensively accessible

network of safe disposal options is provided to all Australians for materials that

are hazardous in conventional waste and recycling streams, such as loose and

embedded batteries, supported by strong community education campaigns.

RECOMMENDATION 4.4 Incentivise safe battery collection with deposit refund

Product stewardship schemes must strongly incentivise safe collection of batteries

at end of use by introducing a deposit refund for safe disposal at appropriate

collection points.

33

Battery Stewardship Council (December 2023) ‘Circular Batteries Australia Position Paper’, p. 7, B-cycle website,

accessed March 2024.

34

Lisa Korycki (29 February 2024) ‘Ecocycle flags e-waste recycling challenges’, Waste Management Review, accessed

March 2024.

35

B-cycle (July 2023) ‘Positive Charge: 2022–2023 Report’, B-cycle website, accessed March 2024.

Case Study 8: B-cycle

B-cycle, which launched in January 2022, is an ACCC-authorised product stewardship scheme for loose batteries,

run by the Battery Stewardship Council.

The B-cycle scheme accepts all small loose and easily removable batteries, including regular AA and other sizes,

button batteries, rechargeable batteries, and small removable batteries from devices like hearing aids, power tools,

e-bikes and digital cameras, but does not accept embedded batteries, batteries over 5 kilograms, mobile phone or

laptop batteries, lead acid batteries or exit lighting. Not all loose batteries are within the scope of the scheme, and

determining which batteries are in or out of scope remains confusing even for those working in the sector.

The authorisation by the ACCC identified that a levy would be applied to imported batteries at a rate of 4 cents per

24 grams, and would be used to fund the scheme and a rebate system for service providers responsible for the

battery’s collection, sorting and processing. However, the scheme only applied a 2 cent levy at its inception, raising

this amount to 3 cents in 2022 and subsequently applying the 4 cent levy at the beginning of 2024.

33

Meanwhile, Australia’s battery recyclers have identified that the B-cycle funding for recycling is insufficient.

34

In

2023, the collection rate was 12% of loose in-scope batteries.

35

Some battery manufacturers and retailers are in competition with B-cycle, in an effort to pursue better recycling

outcomes more efficiently. Those who independently pay for their batteries to be recycled can achieve higher-value

outcomes by paying the recycler directly, rather than paying a levy to B-cycle on one hundred per cent of products

for the lower rate of recycling.

17

5. Tighten scheme governance

Governments and industry are increasingly relying on product stewardship schemes to meet circular

economy principles. A properly functioning circular economy requires participation from every stage of the

supply chain. Currently, these schemes typically represent only one stage of the circular economy supply

chain: producers and distributors (also known as brand owners).

Many existing product stewardship schemes are not neutral bodies, but rather reflect the interests of brand

owners over the rest of the supply chain, including recyclers. To effectively deliver a circular economy,

product stewardship schemes must have a governance structure that equitably represents every stage of the

supply chain.

Product stewardship schemes often exclude the recycling sector—tasked with delivering the scheme’s

ultimate outcomes—from meaningful participation in scheme governance, development and design. It is

essential that the entire supply chain should participate in establishing a scheme’s goals and ongoing

operation, through adequate representation on scheme boards.

Stakeholder governance is increasingly acknowledged as a path for organisations to better address

environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations,

36

with conflicts of interests addressed through

compliance with director’s responsibilities, including fiduciary duties.

37

Scheme governance can also include

community and council representatives. An independent chair may also help to address producer dominance

of schemes.

Effective stakeholder representation in product stewardship scheme leadership is particularly pressing in

light of the ACCC’s recently prioritised focus on environmental claims, and given that every product

stewardship initiative aims to collect and recycle their products. Schemes must deliver genuine recycling

outcomes in order to support a circular economy and community confidence in recycling.

Transparent, objective and consistent data and reporting is also required to assess scheme efficacy against

rigorous targets.

RECOMMENDATION 5.1 Supply-chain representation in product stewardship scheme governance

Product stewardship schemes must have supply-chain representation within

their governance structures. This should comprise an independent Chair, and a

Board that includes representatives and expertise from all stages of a circular

supply chain, with equal decision-making powers and formal channels to provide

expertise. Recycling industry representation should be proportionate to the

operational costs borne for the actual recycling of the product waste stream.

RECOMMENDATION 5.2 Recycling sector expert convenor to engage product stewardship schemes with

recycling sector

To address RECOMMENDATION 5.1, establish and adequately resource a recycling

sector expert convenor, under the auspice of the Australian Council of Recycling,

to facilitate engagement with subject matter experts and leaders in the recycling

sector and provide guidance and board directors to schemes.

36

Zishu Chen (June 2022) ‘Corporate governance: Meet the new champions of stakeholder capitalism’, World

Economic Forum website, accessed March 2024.

37

Various frameworks and guidelines set out directors’ responsibilities regarding environmental outcomes, including

the European Commission’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, the UN's Guiding Principles on Business

and Human Rights, and the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Due Diligence Guidance for

Responsible Business Conduct.

18

RECOMMENDATION 5.3 Clearly defined and measurable objectives, rules and targets

Schemes should have objectives, rules and targets that are clearly defined and

measurable, to track progress, evaluate the effectiveness of the scheme, and

make necessary adjustments over time. Well-defined metrics—especially

regarding recycling and scheme compliance from all parts of the supply chain—

will identify areas for improvement and highlight successes.

RECOMMENDATION 5.4 Transparent data about objectives, decision-making processes, recovery rates,

recycling outcomes and material movement

All stakeholders should have access to information about the scheme’s

objectives, decision-making processes, recovery rates, recycling outcomes and

material movement, reported at a state level. This transparency helps prevent

conflicts of interest when tendering for services and ensures that the scheme’s

actions align with its intended goals.

RECOMMENDATION 5.5 Ensure that the scheme’s objectives are met with accountability measures

Stakeholders within schemes should be incentivised to actively participate in and

contribute to the circular economy, particularly recycling. There must be

mechanisms for holding participants accountable to commitments and actions in

place to ensure that the scheme’s objectives are met.

6. Enforce compliance and consequences

Ensuring compliance with existing regulations must be a priority to increase recycling rates, along with a

harmonised accreditation scheme that supports best-practice recycling outcomes.

‘Bespoke’ accreditation systems for schemes effectively lead to schemes self-reporting, while creating

excessive costs and inefficiencies for both recyclers and brand owners.

Conflict of interest can also go unchecked when schemes develop their own accreditation systems for

recyclers, for example, by emphasising cost-cutting measures over high-quality results.

38

Scheme

accreditations can introduce uncertain and untrustworthy data, undermining confidence and ultimately

limiting investments in expanding new recycling capacities and capabilities.

ACOR has scoped the value of a national accreditation program for Australian recyclers, and is now working

with industry and government to advance the establishment to provide a framework for independent,

objective and consistent assessments that determine whether a recycling site is operating to a specified

standard in a secure, sustainable and resilient manner.

While it is crucial to ensure that recyclers are operating legitimately, it is also a priority to address the

fragmented, variable and duplicative regulatory environment across Australia’s States and Territories. There

must be a nationally harmonised resource recovery framework to prioritise circular economy outcomes,

define ‘end of waste’ and support investment confidence in recycling. There must also be much more

effective enforcement of Australia’s waste export regulation and a broadening of this regulation to address

other materials—including textiles and unprocessed scrap metal—to ensure that Australia’s international

environmental duties are met, and Australia’s recycling capabilities are supported. The cost of this regulation

should be placed on producers and distributors, who are responsible for the products placed on market, not

on the recycling sector.

38

For examples, refer to the included case studies.

19

RECOMMENDATION 6.1 Australian Recyclers Accreditation Program (ARAP)

The Australian Government should support compliance through the

implementation and adoption of an Australian Recyclers Accreditation Program

(ARAP).

40

RECOMMENDATION 6.2 Enforce waste export regulations

The Australian Government should more effectively and proactively enforce

existing waste export regulations, with impactful consequences including fines

and imprisonment. The cost of regulation should be placed on producers and

distributors, who are responsible for products placed on market.

RECOMMENDATION 6.3 Regulate the export of waste textiles, unprocessed scrap metal and unprocessed

e-products

The Australian Government should expand the existing waste export rules to

specifically address waste textiles, unprocessed scrap metal and unprocessed e-

products.

RECOMMENDATION 6.4 Tax incentives or priority access to markets for best-practice recycling facilities

The Australian Government should create incentives, such as tax incentives or

priority access to markets, for recycling facilities that consistently demonstrate

high levels of compliance.

39

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, ‘National Television and Computer Recycling

Scheme’, DCCEEW website, accessed March 2024.

40

Australian Council of Recycling, ‘Australian Recyclers Accreditation Program’, ACOR website, accessed March 2024.

Case Study 9: National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme

The National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme (NTCRS),

39

established in 2011, provides collection and

recycling services for televisions and computers, including printers, computer parts and peripherals. The scheme is

intended to reduce e-waste to landfill, increase the recovery of reusable materials, and provide convenient access

to recycling services for households and small businesses.

Companies who import or manufacture television and computer products over certain thresholds are liable under

the scheme, and are required to pay for a proportion of recycling through membership in an approved co-

regulatory arrangement. These five co-regulators are responsible for the day-to-day operation of the scheme,

including organising collection and recycling of e-waste on behalf of brand owners (known as liable party members

within the NTCRS).

However, the NTCRS has become an inefficient system with a two-tiered marketplace: the five co-regulators

compete to offer the lowest fees to brand owners, forcing prices down to unsustainable levels, while recyclers are

reduced to price-takers. The NTCRS has become a ‘race to the bottom’ for some brand owners at the expense of

best-practice recycling and environmental outcomes.

The drive towards low-cost outcomes has incentivised some co-regulators to reduce accessibility, or compromise

on material recovery rates. There is little transparent downstream verification or reporting of recycling outcomes:

audits in the NTCRS are primarily financial audits, with cursory attention to operational elements.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water is currently leading a redesign of the

NTCRS to broaden the parameters of e-stewardship regulation to likely include all small electrical and electronic

products as well as solar photovoltaic systems. The revised scheme must address the NTCRS’s inefficiencies and

inherent conflicts of interest, while driving a properly comprehensive approach to e-stewardship, incorporating all

consumer electronic and electrical equipment and loose and embedded batteries.

20

RECOMMENDATION 6.5 Product stewardship schemes to be subject to third-party audits and/or

inspections

The Australian Government should require regular independent audits to assess

compliance with regulations and internal policies, holding stewardship schemes to

greater account via more vigilance, auditing and assessment of claims made by

schemes regarding performance, industry data and reporting protocols. Third-

party audits and/or inspections—underpinned by circular principles—should also

be implemented to provide unbiased assessments of compliance and identify

areas for improvement.

RECOMMENDATION 6.6 A nationally harmonised resource recovery framework

The Australian Government, together with State and Territory Governments,

should establish a nationally harmonised resource recovery framework, to

prioritise circular economy outcomes, define ‘end of waste’ and support

investment confidence in recycling.

21

Conclusion

This paper has outlined some of the challenges for recyclers in the current operations and mandates of

product stewardship schemes. As governments and industries look towards greater product stewardship and

extended producer responsibility (EPR) models as a key tool in the circular economy, it is vital that we

encourage a more transparent, inclusive and effective dialogue around their establishment and viable

operations. Greater collaboration will ultimately lead to product stewardship schemes that deliver more

benefits for brand owners, governments, the community and recyclers.

It is essential to the success of any recycling operation, regulation or policy that recyclers and

remanufacturers have a seat at the table, and are consulted often and with intention. In product stewardship

schemes, brand owners represent only a small fraction of the mechanism, but hold the most authority and

decision-making power. As a key part of the supply chain, the recycling, resource recovery, and

remanufacturing sector is essential to ensure product stewardship schemes deliver a circular economy. To

date, this sector’s experience and expertise has largely been overlooked at best, or systematically ignored at

worst.

Ultimately, the key recommendations contained in the paper are an offer from our sector to collaborate,

share our expertise and find a path forward to work together with government and industry to achieve a

thriving circular economy.

22

Appendix 1: Governance arrangements of Australian

Government-accredited schemes

Scheme

Type

Governance

arrangements published?

Recycler on Board?

Activ Group

Co-regulated

No

Unknown

ANZRP

Co-regulated

Yes

No

APCO

Co-regulated

Yes

Yes

B-cycle

Voluntary

Yes