Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

A report for ANZRP by the Economist Intelligence Unit

February 2015

Sponsored by

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

1

Contents

Executive Summary 2

Introduction 3

What is e-waste? 3

How much e-waste is being generated by the countries studied in this report? 4

What is the outlook for electrical and electronic products? 4

Country summaries 7

Japan 7

Finland 8

Germany 8

Australia 9

Insights for the Australian e-waste system from other advanced economies 11

Consumer e-waste and small devices 11

Scope of e-waste systems 13

Shared responsibility and a systemic approach 14

Conclusions 16

Appendix 18

EPR and Product Design 18

The international trade in e-waste 19

Notes 20

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

2

E

lectrical and electronic waste, or e-waste, is growing rapidly in many countries as the

technological revolution deepens and expands. Indeed, growth in e-waste is set to accelerate

as technologies, especially those geared to consumer communications, extend into new areas and

prices continue to fall. At the same time, stakeholders along the value chain increasingly recognise

that e-waste that ends up in landlls, or is improperly treated, is both toxic for the environment and

to people. Many countries, as a result, have been developing policies and systems to confront the

problem, some of which are becoming ever-more sophisticated.

European countries, in particular, have developed e-waste systems that rely heavily on the principle

of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Essentially, EPR stipulates that the manufacturer of an

electrical or electronic device bears responsibility for that product beyond the initial sale. This is a

core principle of the European Union’s Waste Electronic and Electrical Equipment (WEEE) Directive,

which outlines the producer’s responsibility to manage the collection and recycling of these products.

Crucially, this principle requires the producer to assume the cost of the recycling. Thus, producers of

electrical and electronic devices in Europe have a nancial interest in the life cycle of these products.

Other countries, however, use different approaches. Japan, for example, places the majority of the

cost on the consumer, who pays a fee when recycling.

Compared with these countries, Australia’s e-waste system is in its infancy. It is guided by the

National Waste plan and has at its core the Product Stewardship Act. Like the EU’s WEEE directive,

producers and importers of electrical and electronic devices in Australia bear a nancial responsibility

for the life cycle of their products. But coverage under Australia’s e-waste system, outside of voluntary

schemes, is limited to personal computers, computer accessories and televisions, whereas the EU

directive applies to a much broader range of electrical and electronic equipment. A lesson for Australia,

therefore, is to expand the scope of the products that are covered by the e-waste system.

As e-waste programmes evolve, a number of the countries covered in this report are considering

ways to encourage greater participation of households and consumers. Some countries, including

Japan and Finland, are also making a special effort to encourage the collection and recycling of smaller

devices. Another lesson for Australia, then, is to entice and encourage consumers to become more

active players in the management and recycling of their electronic waste, especially smaller e-waste.

While EPR has put producers at the heart of e-waste systems, it is becoming increasingly important

to promote the “shared responsibility” of all participants. The e-waste system being developed in

Europe, in particular, involves not only national governments, producers and recyclers, but also

consumers, retailers and municipalities. For Australia, a nal lesson refers to a greater role for both

local governments, who can incentivise the e-waste recycling of households, and retailers, who can

provide collection points as the volume of e-waste grows in coming years.

Executive Summary

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

3

Introduction

E

-waste is a global problem that shows no sign of abating. This report is intended to research the

e-waste systems of a select group of advanced economies to develop insights that can be applied

to the Australian market. Other than the focus on Australia, the scope of this research is limited to

three other advanced economies e-waste: Germany, Finland and Japan. Each is regarded as a leader in

developing effective e-waste solutions.

1

Scandinavian and northern European countries have exhibited good cases of policies and

initiatives to tackle the problem. Japan is also strong on recycling and re-use (of recycled

materials). These countries could be seen as benchmarks so far but a number of other

countries also have pilot initiatives to showcase.

Stefanos Fotiou, Asia-Pacic Regional Coordinator,

United Nations Environment Program.

This analysis also focuses on the e-waste system as a whole, rather than solely on e-waste

regulation. Although legislation is an integral part of addressing the e-waste problem, an effective

solution must include consumers, standards, incentives and technology.

What is e-waste?

Different countries dene e-waste in different ways. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS)

2

, e-waste is associated with electrical and electronic equipment that is dependent on electric

currents or electromagnetic elds in order to function (including all components, subassemblies and

consumables which are part of the original equipment at the time of discarding). This includes:

1. Consumer/entertainment electronics (e.g. televisions, DVD players and tuners)

2. Ofce, information and communications technology products (e.g. computers, telephones

and mobile phones)

3. Household appliances (e.g. refrigerators, washing machines and microwaves)

4. Lighting devices (e.g. desk lamps)

5. Power tools (e.g. power drills) excluding stationary industrial devices

6. Devices used for sport and leisure, including toys (e.g. tness machines and remote control

cars).

In discussing the future of the Australian e-waste system, this is the denition that will be used.

“ ”

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

4

How much e-waste is being generated by the countries studied

in this report?

As e-waste has garnered more attention globally, it has become increasingly important to

understand the scale of the problem. That, inevitably, means a better process for collecting accurate,

comprehensive data. This task has been led by a global initiative known as StEP, or Solving the

e-waste Problem, which has created a world map that illustrates the scope of the problem and allows

comparison among countries.

3

The data presented in Table 1, which is derived from StEP, shows the

total and per-capita e-waste that is generated in the four developed countries in this report. While

Australia’s total e-waste is small compared with that of Japan and Germany it is actually the highest in

this sample on a per-capita basis.

What is the outlook for electrical and electronic products?

E-waste shows every sign of growing, and at a rapid rate. Consider, rst, that as developing economies

catch up with those in the rich world, the quantity of electrical and electronic equipment consumed

will also climb. It is not only the domestic economic growth of these developing countries that will

drive this demand, but the increasing need to be connected to other ofces, cities and locations

around the world.

Japan Germany Finland Australia Global

Total (in metric kilo tonnes) 2122 1402 106 447 48,894

Kg per inhabitant 16.6 17.23 19.52 19.71

Source: Jaco Huisman, United Nations University/StEP Initiative

4

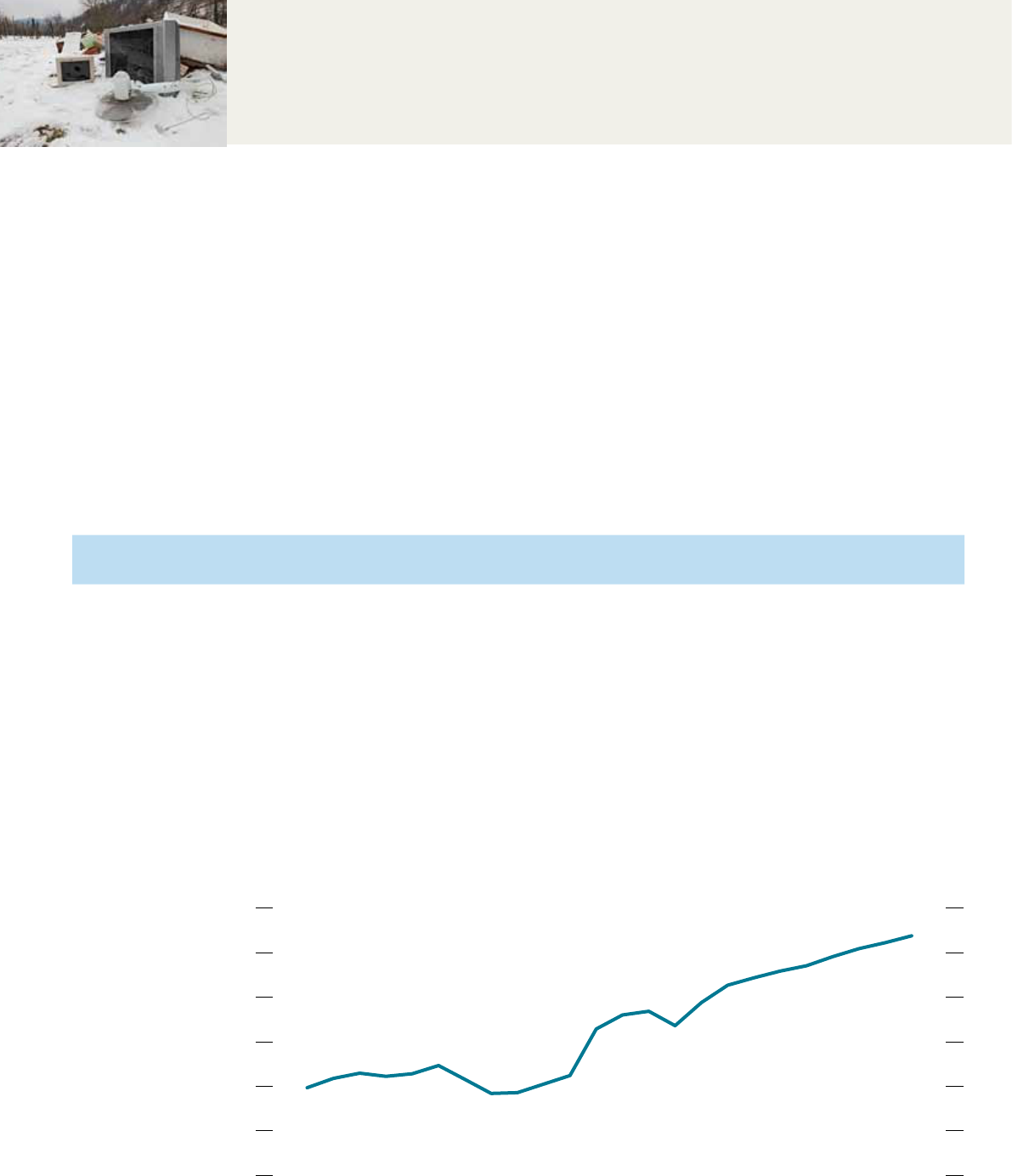

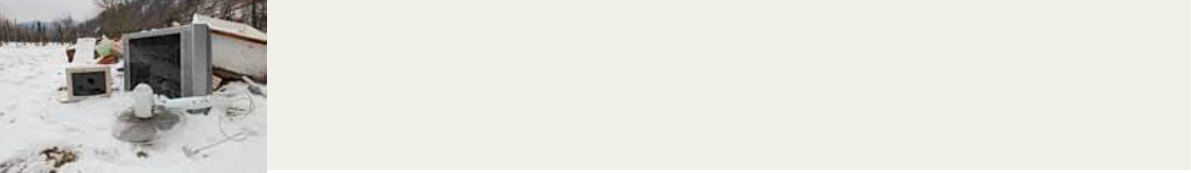

World: IT hardware spending

(US$ m)

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,000,000

1,200,000

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

1,000,000

1,200,000

1817161514131211100908070605040302012000999897961995

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

5

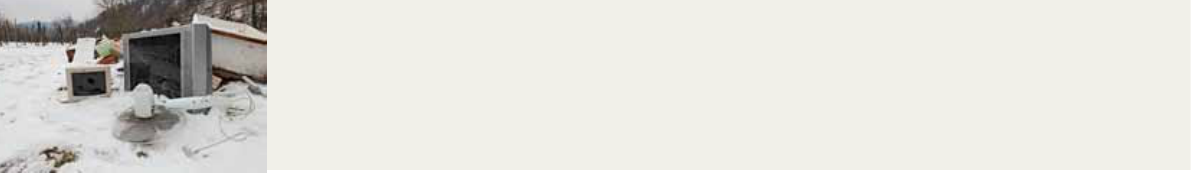

World: mobile subscribers

(per 100 people)

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

1817161514131211100908070605040302012000999897961995

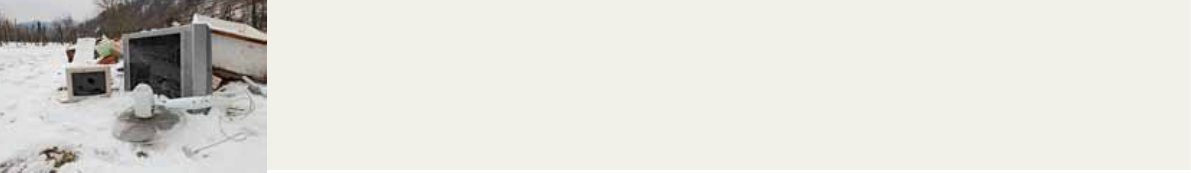

World: personal computers

(stock per 100 population)

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1817161514131211100908070605040302012000999897961995

Second, across both developed and developing countries, consumer preferences regarding these

technologies are constantly evolving. As the processing power of mobile phones and computers

continues to grow, the enhanced capabilities and functionality of consumer electronics accelerates

demand for the next new model and translates into shorter product lifespans.

Third, rapid technological change will not only increase demand for current electronics and

equipment but also result in products that do not currently exist. Some of the consumer electronics

in use today—smart phones and tablets, for example—had not been invented when the rst

electronic recyclers were set-up two or three decades ago, and these devices will not be the last in this

technological evolution.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

6

These trends are evident in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Market Indicators and Forecasts

database. IT hardware spending and use of mobile phones and personal computers is expected to

continue growing globally. Indeed, IT hardware spending alone is forecast to rise by around 60%

between 2009 and 2018. The need, then, for better policy assessments—which will inevitably require

national and international standards that are better aligned—will be an ongoing process.

Whether it is through legislation and standards or education and public awareness campaigns,

efforts to address e-waste are vital. Materials contained in electrical and electronic equipment can

become hazardous to both the environment and people when they end up in landlls. The production

of electronic equipment also has an important sustainability dimension: the manufacturing process

uses a range of resources, from precious metals to rare earths. The responsible use and recovery of

these materials is a key focus of e-waste systems around the world, both from a resource management

perspective—these materials are sometimes in short supply—and because they can be toxic.

Consequently, an effective e-waste system must address every aspect of the electronics value chain.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

7

Japan

Three laws address e-waste in Japan: the Specic Household Appliance Act (1998), the Promotion of

Recycling of Small Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Act (2013) and the Law for the Promotion

of Effective Utilisation of Resources (2001). Set alongside these regulations are public awareness

campaigns and eco-town efforts (eco-towns are focused on reducing carbon emissions and utilizing

waste generated to be used as raw materials in other industries

5

) that result in a broad and advanced

e-waste system in Japan.

The Specic Household Appliance Act, also known as the Home Appliance Recycling Law, requires

consumers to pay recycling fees and dispose of waste at collection points, such as retailers. From

there, the waste is transported to designated sites specied by domestic manufacturers or importers,

who recycle it at home appliance recycling plants. The law covers larger items such as television sets,

refrigerators, air conditioners and washing machines. In Japan’s 2013 nancial year (April-March),

approximately 12.7m units of these four types of home appliances were collected.

6

The Promotion of Recycling of Small Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Act, meanwhile,

expanded the list of covered devices beyond the four categories mentioned in the earlier law. The

new items include digital cameras, mobile phones, game consoles, computers and printers. Unlike

with larger household appliances, consumers do not pay a fee to recycle these smaller items, as the

materials recovered from these devices are expected to be more valuable for the recycler.

7

Japan’s Law for the Promotion of Effective Utilisation of Resources, also known as the Recycling

Promotion Law, encouraged manufacturers to help recycle goods voluntarily and reduce the

generation of waste. One of its main goals was to promote product design that facilitates waste

reduction, recycling and reuse. While this law does cover a wide range of products, including personal

computers, it is not mandatory.

8

The consumer plays an important role in Japan’s e-waste system. Households are obliged to recycle

their e-waste, and in the case of larger home appliances, to pay a fee for doing so. Efforts to improve

consumer participation are supported by public education campaigns and collaborative initiatives

between government and industry. October, for example, is designated “3Rs promotion month” in

Japan (3R refers to reduce, reuse and recycle). Coordinated by eight government ministries, the

campaign involves national promotion and events aimed at public understanding and cooperation.

9

There are also efforts to advance the so-called eco-town concept, with the aim of bringing

government, industry and consumers together to explore environmentally friendly systems at the city

and community level.

10

Country summaries

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

8

Finland

Recycling programmes in Finland are largely based on the guidelines set out in the EU’s Directive on

Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE).

11

As an EU member, Finland added these provisions

to its waste legislation in 2004, via its Government Decree on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment.

The legislation requires producers of electrical and electronic equipment to participate in recycling

these products and makes them liable for the cost of waste management.

12

In line with their WEEE obligations, Finnish producers have established organisations that are

responsible for managing recycling on their behalf, and to which the producers pay a fee. Finland has

ve such organisations: SERTY, ICT Producers Co-operative, Flip ry, SELT ry, and ERP Finland ry.

13

All are

not-for-prot and are supervised by the government to ensure they are meeting their requirements,

which include reducing the amount of waste and the resulting harm caused by electrical and electronic

equipment, enhancing material re-use and recovery, and promoting the recycling of all electrical and

electronic waste.

Since 2005, these producer-funded organisations have maintained more than 400 collection points

for households to dispose of equipment for free. They are also responsible for the transportation of this

e-waste to processing plants and for the recycling of materials. Recent changes to national legislation

also provide for the collection of e-waste by retailers; this has increased the number of collection

points for households to more than 3,000. Consumers can take small, used electrical and electronic

items to retailers for recycling without the obligation to buy a replacement product. Returning large

used items for recycling would, however, require the consumer to purchase a replacement from that

retailer.

14

Despite the growing network of recycling points, Finnish consumers have not warmed to the notion

of recycling their smaller used electronics. Small devices account for just 10% of recycled electronics in

Finland, despite the new models, falling prices and high incomes that allow Finns to regularly invest in

new gear.

15

Germany

Germany is one of the EU’s top recyclers overall, and its e-waste system is regarded as both

“comprehensive and forward thinking.”

16

Almost 780,000 tonnes of electrical and electronic waste was

collected in 2010, of which 723,000 tonnes was from households and the rest from businesses.

17

This is

equivalent to 8.8 kilograms of recycled electronic waste per person, which exceeds the 4 kilograms per

person recycling rate stipulated in the EU’s WEEE directive.

The WEEE directive was added to German law in 2005 in the form of the Electrical Products Act

(Elektro-und-Elektronikgeräte-Gesetz), also known as ElektroG. The law is currently being amended to

reect recent changes in the WEEE directive that were approved in July 2012.

18

At the heart of ElektroG is the principle of “divided product responsibility” between the public sector

and device manufacturers. The government is required to establish free recycling collection points

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

9

for all electrical and electronic waste, while manufacturers are responsible for properly disposing

of and recycling this waste. In order for a producer to sell electronic products in Germany, it must

register with the Federal Environmental Agency (FEA), agree to cover the transportation costs from the

collection centres, and oversee appropriate disposal of the waste. Consumers are required by law to

take their e-waste to these municipal collection and recycling points, of which there are around 1,500

in Germany.

The German e-waste system includes a designated clearing house, known as the Old Electric

Appliances Register Foundation.

19

Once a collection centre is lled to capacity, notication is made

to the clearing house, which supervises transport of the waste to the treatment facility. The quantity

of electronic waste a producer must recycle is determined by its market share of the products it sells

in Germany. The clearing house contacts the producer, which in turn contracts out the transport and

recycling services to independent organisations.

Australia

The introduction of the National Waste Policy in 2009 was designed to set the direction of Australia’s

waste management and resource recovery for the ten years from 2010 to 2020. The policy has

several goals, including adherence to international obligations such as the Basel and Stockholm

Conventions

20

; reducing the generation of waste, and ensuring that waste treatment, disposal,

recovery and re-use is safe and environmentally sound. Shortly after, the Product Stewardship Act of

2011 established the framework by which the environmental, health and safety impacts of products,

and in particular those associated with their disposal, are managed. The law included voluntary, co-

regulatory, and mandatory product stewardship, depending on the circumstances.

21

A co-regulatory

arrangement, according to the National Waste Policy, is an arrangement that is designed to achieve

regulated outcomes on behalf of liable parties.

22

The rst co-regulatory product stewardship scheme established under the law was the National

Television and Computer Recycling Scheme (NTCRS). The scheme provides Australian consumers

and small businesses with access to free recycling services for televisions, computers, printers and

computer products (e.g. keyboards, mice and hard drives) regardless of brand or age. It requires

television and computer manufacturers and importers to fund the collection and recycling of a

percentage of their products that are disposed of each year.

23

Under the scheme, the technology

industry was expected to pay for recycling 30% of televisions and computers in 2012-13, rising to 80%

by 2021-22.The recycling target will increase gradually over time until the 80% level is achieved.

Under the law, manufacturers and importers of televisions and computers must join and fund co-

regulatory arrangements. In turn, these approved co-regulatory arrangements administer the scheme

and are charged with achieving results on behalf of their members. Initially, three co-regulatory

arrangements were approved in 2012, and with a further two approved to start operations in 2013, ve

organisations are now able to deliver services under the NTCRS.

24

In 2012-13, its rst year of operation,

the scheme collected approximately 41,000 tonnes of material, more than doubling the estimated

volume that was collected the preceding year, before the programme was launched.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

10

In addition, the Product Stewardship (Televisions and Computers) Regulations of 2011 require that

as of 1 July 2014, approved co-regulatory arrangements operating under the NTCRS recover 90% of

materials used in the products. This gure is the proportion of television and computer by-products

that must be recycled and reprocessed into useable materials.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

11

C

ompared with Japan and the northern European countries, Australia’s e-waste system is in its

infancy. Progress has been made, certainly, since the introduction of the National Waste Plan and

the Product Stewardship Act. But with e-waste in Australia growing three times faster than other waste

streams,

25

the capacity and sophistication of the country’s systems will have to grow and adapt. Based

on our analysis of programmes in Japan, Finland and Germany, Australia could consider three steps to

move its e-waste system forward:

l a greater focus on consumer electronics and small devices

l more expansive coverage

l shared responsibility among all stakeholders

Consumer e-waste and small devices

National and sub-national governments, in countries such as Japan and the Netherlands, have

implemented policies that focus on consumers and small waste. Although the consumer is central to

these schemes, there are differences in the fees and incentives that the consumer faces, as well as the

point at which the consumer engages with the e-waste system. Successful e-waste recycling systems

in Japan and Finland pay special attention to small electronics waste, which is especially relevant

to consumers. They do, however, differ in the way that they incentivise consumers to recycle these

devices. In Finland, the government encourages the recycling of smaller devices by treating them

differently from larger items, in particular by relieving consumers of the obligation to purchase a

replacement product when returning these smaller products to retailers. In Japan consumers do not

have to pay a fee when recycling smaller e-waste, as they do for larger items. Meanwhile, in the US

state of California, consumers incur an advance recovery fee, which is a fee that is paid at the point of

purchase for devices such as televisions and laptop computers.

While the schemes of Japan, Finland and California focus on the consumer interacting with retailers

and collection points, local initiatives in some Dutch municipalities address consumers within the

household. A recent study of e-waste ows in the Netherlands, conducted by the United Nations

University Institute for Sustainability and Peace, highlighted the potential impact of different waste

policies on the household disposal of electronics.

26

The study examined the difference in household

ows between two distinct forms of local waste policy: a at tax, through which a xed price is paid

for waste services, regardless of the amount thrown away, and a “pay-as-you-throw”, or PAYT system,

in which households pay higher taxes as they throw away more waste. For Dutch households in a PAYT

municipality, there is a strong incentive to dispose of electronics in the appropriate channels, and

not as part of their household waste. Indeed, this is what the analysis showed: the amount of e-waste

Insights for the Australian e-waste system

from other advanced economies

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

12

in general household waste was 50% lower in the PAYT households than in those who paid a at tax.

The fact that around 1kg per inhabitant of e-waste – a large amount when summed across the Dutch

population – was found in household waste in PAYT households emphasises the point that consumers

and small WEEE are a vital part of the e-waste system.

27

Consumer based incentives for small e-waste is not the only challenge to formalising the role of the

consumer. The interaction of consumers and smaller devices also raises the question of the systemic

goals and incentives that relate to these devices.

28

A single recycling target that encompasses all

products in the e-waste system can provide clarity for all stakeholders. However, as noted in a recent

What the world’s leading experts are saying about the role of consumers in an

e-waste system.

“To motivate consumers, we need to educate them from an early age. They must understand that

it is normal to pay for the waste they create”. Jaco Huisman, Scientic Adviser, United Nations

University

“There needs to be both a carrot and stick approach to consumers and e-waste. Sticks may

include fees or nes for dumping electronic devices in the garbage bin; stronger regulation is

needed here. Carrots could involve public and private programmes that create incentives to re-

use products.” Stefanos Fotiou, Asia-Pacic Regional Coordinator, UNEP.

“Increasingly, more metals of the periodic table are being used to increase the functionality of

consumer products. Many of these metals are not as abundant in nature as copper, for example,

or easy to extract and primarily process due to their low concentration. If we want to keep

enabling this increasing functionality of these products, then we need to do more to address

these rare and precious elements and make sure they are recovered and kept in the global

resource loop. Consumers who keep old electronics as back-ups are not helping in this respect”.

Federico Magalini, Industrial Engineer & e-waste expert, United Nations University.

“Regarding the role of the consumer, a shared responsibility model that includes consumer

nancial responsibility is worth investigating. This may include elements similar to the advanced

recovery fee used in California.” Jeremy Gregory, Research Scientist, Massachusetts Institute of

Technology.

“Producer take-back has been a successful strategy. So have local collection points for

consumers. Public information and education is also important. The Swedish system, el-kretsen,

which uses all of these elements, is a good example of how a system can work.” Karin Lundgren,

former consultant at the International Labour Organisation.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

13

StEP White Paper, when assessing the Recast of the EU WEEE Directive, a weight based approach may

have unintended consequences for some appliances, such as small devices. Under a weight based

approach, where the recycling target is based on the tonnes of electrical and electronics products

produced, there is a much greater incentive to recycle larger items like washing machines and air-

conditioners, rather than consumer electronics. For these products, a unit based target or accounting

may be more appropriate as a measure to incorporate into e-waste systems.

Scope of e-waste systems

A signicant difference between the e-waste systems of the northern European countries and Australia

is the overall scope: the EU’s WEEE directive is much more comprehensive than the programme now

in place in Australia. The original EU WEEE Directive covered a range of products, including small and

large household appliances, IT and telecommunications equipment and consumer equipment.

29

The

WEEE Recast, while rening the number of categories, broadened the scope to include all electrical and

electronic equipment, which enables new products and technologies to be included in the future.

30

Compared with the product coverage of the EU WEEE Directive, the Australian e-waste system is

smaller in scope. By construction, the NTCRS is limited to televisions and computers, although there

are voluntary product stewardship schemes that broaden the product coverage. Complementing the

NTCRS, Mobile Muster was established in 1998 as a voluntary scheme and is the only not-for-prot

government accredited mobile phone recycling programme in Australia. It is the mobile phone

industry’s programme to take responsibility for its products at the end of their useful life.

31

Voluntary

product stewardship schemes can be an important aspect of an e-waste approach, but a broader scope

of the Australian system may help to achieve the objectives set out in the National Waste Policy.

The product coverage of the Australian e-waste system could be expanded in regards to both small

and large devices, as well as the categories of products that are covered. The EU WEEE directive covers

large household appliances such as dish washing machines, washing machines and cookers, as well

as small household appliances such as vacuum cleaners, toasters and fryers. Other categories of the

directive, like those that refer to consumer equipment and leisure devices, also show the extent of

small devices beyond mobile phones. Such products include hand held video game consoles, radio

sets and video cameras. As seen in the denition of e-waste from the ABS, the Australian Government

recognises the broad scope of e-waste, and as indicated by a recent report examining the end of life of

refrigerators and air conditioners, the Australian Government may be considering extensions to their

e-waste system.

32

For a country like Australia, with a smaller population than Japan and some EU countries, bringing

more products into the e-waste system will bring additional benets to the system apart from the

collection of more electronic and electrical waste. Firstly, a greater volume of e-waste will encourage

greater efciency in the recycling and material recovery process, and will likely result in a lower cost

per unit recycled. Secondly, with the targets and goals of the Australian Waste Policy, greater e-waste

volumes will incentivise the investment in advanced technologies for the dismantling of products

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

14

and recovery of materials. The additional benets of a broader e-waste system will complement

the schemes already in place and increase the probability of the system’s longer-term goals being

achieved.

Shared responsibility and a systemic approach

Many countries have an e-waste policy. The key is implementation, and the willingness

of all stakeholders to contribute to it. In the past, all of the focus has been on producers.

Instead, having a functioning triangle of producers, government and recyclers is key.

Jaco Huisman, Scientic Adviser, United Nations University.

Extended producer responsibility, or EPR, is a consistent theme that informs the e-waste policies of

all of the countries considered here. As Stefanos Fotiou, Asia-Pacic Regional Coordinator for UNEP,

notes, “EPR is the right framework to address these issues.” There is, however, a growing recognition

that EPR alone cannot achieve the desired goals of an effective and comprehensive recycling

framework.

33

As Mr Fotiou suggests, “Shared responsibility is what is needed in addition to ERP. In

other words, ERP is a necessary but not sufcient condition.”

Certainly, governments are already working with producers in the countries analysed in this report,

though in different ways and to different degrees. In countries such as Japan and Finland, the retail

sector also plays a role in managing e-waste. The most important link, however, is the consumer, who is

the ultimate user of these products. Encouraging consumers and households to participate more fully

in e-waste systems will be crucial to accommodating the big increase in waste volume in the coming

decades. For Australia, both the retail and government sectors can play a role in enticing the consumer

into the e-waste system.

While the NTCRS was responsible for recycling 30% of televisions and computers in 2012-13,

Australian states, territories and local governments were responsible for the remaining 70%. With

the NTCRS target rising incrementally to 80% by 2021-22, the interaction of local governments with

the national government e-waste scheme will be crucial. Local governments will continue to manage

general household waste, and with this proximity to the consumer, their importance to the e-waste

system should not be underestimated.

The policies of local governments, therefore, could complement the national e-waste system and

encourage greater recycling of electronic and electrical devices, especially smaller ones. As seen

in some Dutch regions, such policies as PAYT can incentivise the household to reduce the e-waste

that is thrown in the general waste bin. When policies like PAYT are combined with public awareness

campaigns, the household will then have the incentive and the information required to deposit e-waste

into the appropriate waste channel. Other examples of shared responsibility may exist between

different levels of government, but such cooperation and complementarity of policy will only help the

Australian e-waste system meets its mandated targets.

“ ”

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

15

If Australia does embark on a broadening of the scope of its e-waste system, increasing the number

of collection points will be necessary to accommodate the volume of recycled products. Consequently,

it is worth considering the role of the retail sector as another collection point in the system. This may

be especially relevant to smaller devices given the relative ease with which they can be transported

when compared to larger items. At present, there is some involvement of the retail sector with the

targeted recycling of products. Aldi supermarkets in Australia, for example, offer free battery recycling

at their stores. However, if the broader retail sector was to be encouraged to participate in the e-waste

system, a consumer education campaign would be advisable to help inform new consumer habits of

recycling while shopping.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

16

M

anaging e-waste is a multi-faceted challenge, and the associated recycling systems are

inherently complex. As technology constantly evolves, e-waste systems will have to adapt.

This point is embedded in the EU WEEE directive, in which specic dates are set for a review of the

programme’s elements, such as the scope of products covered. As an example of best practice, this is a

feature that other countries should consider. Indeed, each country has its own challenges to confront

as it designs e-waste programmes – from the vast geographical spread of Australia to the concern over

rare-earths in Japan.

34

The need to review, monitor and critique e-waste systems, then, is universal.

Although extended producer responsibility is a necessary part of any e-waste environment, much

more needs to be done. This is best captured by the term “shared responsibility”, in which not only

producers but governments, recyclers, retailers, households and consumers play a vital role. This is

easy to say but difcult to implement. Policymakers globally must balance a number of factors as they

consider a shared responsibility system, some of which may be in conict. This example, covering the

life cycle of a car, is a case in point.

The goal is to keep cars out of landlls, which is admirable. But we need to be careful:

there is also a need to focus on the total environmental impact of the car, including its

use of fuel and its greenhouse gas footprint. Carbon bre vehicles would reduce fuel use,

but are difcult to recycle, so goals can be in conict at times.

Jeremy Gregory, Research Scientist, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Australia, certainly, can do more to advance the idea of shared responsibility. Consistent with that

theme, the consumer needs to be brought more fully into the e-waste system. European countries

have experimented with different schemes to incentivise the recycling behaviour of consumers. The

PAYT system in some Dutch municipalities has led to a reduction in the proportion of e-waste in overall

household waste. Local governments in Australia should consider similar policies that incentivise

household behaviour to separate e-waste, especially smaller devices, from the general waste stream.

The cooperation of all levels of Australian government will be necessary as the e-waste system

transitions to one that is dominated by the national scheme over the coming decade.

In a related area, countries such as Finland and Japan have designed e-waste systems that

distinguish the recycling of small devices from larger ones. They have done this by differentiating how

a consumer interacts with the retail sector when recycling small versus larger items. Consistent with

this theme, Australia should consider the role of the retail sector as a collection point in the e-waste

system. This may be especially benecial for the collection of smaller electrical and electronic devices.

As these systems are monitored and evaluated, valuable insights into consumer behaviour and their

willingness to recycle small electronics will become apparent.

Conclusions

“ ”

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

17

For Australia in particular, expanding the scope of products covered by e-waste systems—from

mainly televisions and computers to more sophisticated IT devices—deserves serious attention, and

could pay dividends by reducing toxic waste, efciently reusing valuable resources and ultimately

reducing costs for businesses and consumers.

Managing—and improving—recycling systems for electronics involves a complex interplay of

economic and social factors, and a sometimes tense relationship between governments, businesses

and consumers. An environment in which responsibilities are more evenly shared, incentives are

clearly laid out, roles are more carefully dened and coverage of products is expanded offers the best

hope for a more effective and adaptable system.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

18

EPR and Product Design

EPR has been portrayed as having two broad roles. Firstly, it was designed to bring the responsibilities

of the producers to the entire life cycle of their products, not simply the initial sale. Secondly, by

establishing EPR as the central theme of an e-waste system, it was thought that this would incentivise

producers to design more recycle-friendly products. Despite some efforts from producers, there is little

evidence that EPR has encouraged the changes in product design that were envisioned.

35

However,

when compared to policy areas such as the scope of the e-waste system and the role of consumers, the

interaction of EPR and eco-design is less relevant for the Australian e-waste system. Primarily, this is

due to the relative lack of technology manufacturing that occurs within Australian when compared to

other countries. Nevertheless, it is still an important debate for all e-waste systems to consider.

One of the world’s leading experts in this eld is Jaco Huisman, Scientic Adviser at the United

Nations University, who has examined the issue of EPR and product design very closely. According to

Mr Huisman, the eco-design of electrical and electronic products should be embedded much more in

the design process than it currently is. While this is something that will take time, Mr Huisman did have

suggestions on the ways that eco-design could be incentivised or encouraged in rms:

There are prevention elements built in various e-waste legislation. However, the waste

phase and design stage are too far apart to enable any feedback loops. There are

attempts like the eco-design directive in the EU to give more guidance. Personally, I

believe eco-design requirements should get much more a ‘process’ related attention

rather than old-fashioned too late product requirements. When companies are directed

to have sustainability criteria incorporated in their bonus system for instance, it may

trigger much more creativity in product development compared to restricting compliance

efforts.

In the EU WEEE Recast of 2012, Article 4 addresses the notion of product design in the WEEE

Directive

36

(emphasis ours):

Member States shall, without prejudice to the requirements of Union legislation

on the proper functioning of the internal market and on product design, including

Directive 2009/125/EC, encourage cooperation between producers and recyclers

and measures to promote the design and production of EEE, notably in view

of facilitating re-use, dismantling and recovery of WEEE, its components and

Appendix

“ ”

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

19

materials. In this context, Member States shall take appropriate measures so

that the eco-design requirements facilitating re-use and treatment of WEEE

established in the framework of Directive 2009/125/EC are applied and producers

do not prevent, through specic design features or manufacturing processes, WEEE

from being re-used, unless such specic design features or manufacturing processes

present overriding advantages, for example, with regard to the protection of the

environment and/or safety requirements.

The effectiveness of eco-design requirements in incentivising product design is an ongoing debate

at present. It is, however, an important consideration for all e-waste systems as they move to become

more sophisticated and better equipped to meet their goals.

The international trade in e-waste

Another theme that was highlighted by the interviewees of this report was that of the international

trade in e-waste. As noted in a research paper from the INSEAD Social Innovation Centre, a

substantial amount of e-waste is being exported to China and Africa where they are either re-sold

or recycled at standards below that of the exporting country.

37

For a detailed discussion of the

complexity of the issues that surround the exporting of e-waste, see the 2013 StEP Green Paper on

the transboundary movements of e-waste.

38

While this is an issue that e-waste systems will continually face over the coming years, it is worth

noting that the EU WEEE Directive (recast) has changed the focus of the responsibility for proving

the functionality of used equipment from the relevant Authority to the exporter. This is addressed in

Annex VI of the WEEE recast, as shown here (emphasis ours):

MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS FOR SHIPMENTS

1. In order to distinguish between EEE and WEEE, where the holder of the object claims that he

intends to ship or is shipping used EEE and not WEEE, Member States shall require the holder to have

available the following to substantiate this claim:

(a) a copy of the invoice and contract relating to the sale and/or transfer of ownership of the

EEE which states that the equipment is destined for direct re-use and that it is fully functional;

(b) evidence of evaluation or testing in the form of a copy of the records (certicate of testing,

proof of functionality) on every item within the consignment and a protocol containing all record

information according to point 3;

(c) a declaration made by the holder who arranges the transport of the EEE that none of the

material or equipment within the consignment is waste as dened by Article 3(1) of Directive

2008/98/EC; and

(d) appropriate protection against damage during transportation, loading and unloading in

particular through sufcient packaging and appropriate stacking of the load.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

20

Notes

1

In a number of interviews conducted for this research, these countries were most often cited as

having advanced policies and thus were considered leaders in the eld.

2

http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/ab[email protected]/Products/4602.0.55.005~2013~Main+Features~Electr

onic+and+Electrical+Waste?OpenDocument

3

http://step-initiative.org/index.php/WorldMap.html

4

Notes from the StEP Initiative on data and denition: Data refers to domestic generation only, thus

excluding import and export of EEE, WEEE, components and fractions. The denitions of EEE and WEEE

include all EU WEEE Directive categories and products, including ALL professional, ALL B2B and ALL

small appliances.

5

http://www.unido.org/news/press/japans-was.html

6

http://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2014/0624_02.html

7

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2013/04/27/editorials/recycling-of-useful-metals/#.

VDdS2fm1Z9V

8

A comparative study of E-waste recycling systems in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan from the EPR

perspective: Lessons for developing countries. 2008. Sung-Woo Chung & Rie Murakami-Suzuki. See

also http://www.meti.go.jp/policy/recycle/main/english/law/promotion.html

9

http://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2014/0930_01.html

10

http://www.unido.org/news/press/japans-was.html

11

http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/weee/index_en.htm

12

http://www.elker./en/tuottajayhteisot_en/tuottajavastuu_en

13

http://www.serty./en/toiminta-ja-jaesenet/membership-in-serty

14

Ministry of Environment, Waste Act, amendments, 4th of July, 2012.

15

http://yle./uutiset/few_nns_recycle_small_electronics_hoarding_rules/7150707

16

Fixing the e-waste problem: An exploration of the sociomateriality of e-waste, Mary Lawhon and

Djahane Salehabadi. 2013. In Solving the e-waste problem: An interdisciplinary compilation of

international e-waste research, Edited by Deepali Sinha Khetriwal, Claudia Luepschen. and Ruediger

Kuehr.

17

http://www.umweltbundesamt.de/en/topics/waste-resources/product-stewardship-waste-

management/electrical-electronic-waste

18

ibid.

19

Solving the E-Waste Problem (StEP) White Paper E-waste Take-Back System Design and Policy

Approaches (2009).

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

21

20

The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary movements of Hazardous Waste and their

Disposal places obligations on Australia to ensure that generation of waste, including hazardous

waste, is kept to a minimum. It also requires environmentally sound disposal facilities to exist and that

waste managers take steps to prevent, and minimise the consequences of, pollution from waste. The

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants further requires the restriction and ultimate

elimination of dangerous long-lasting chemicals. The context of Australia’s National Waste Policy, in

relation to these international obligations, among other aspects, can be seen in National Waste Policy:

Less Waste, More Resources November 2009.

21

http://www.environment.gov.au/protection/national-waste-policy/product-stewardship

22

National Waste Policy Fact Sheet, National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme: Co-regulatory

Arrangements, Australian Government, Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population

and Communities.

23

Department of Environment, National Television and Computer Recycling Scheme, Outcomes 2012-

2013. February, 2014.

24

The three initially approved were DHL Supply Chain (Australia) Pty Limited, Australian & New Zealand

Recycling Platform Limited (ANZRP), and E-Cycle Solutions Pty Ltd. A further two co-regulatory

arrangements were approved in early 2013 to commence operation in 2013–14: Electronics Product

Stewardship Australasia and Reverse E-Waste. TechCollect is a not-for-prot service provided by ANZRP.

25

Electronics Factsheet, Planet Ark.

26

Huisman, J., van der Maesen, M., Eijsbouts, R.J.J., Wang., F., Baldé, C.P., Wielenga, C.A., (2012), The

Dutch WEEE Flows. United Nations University, ISP – SCYCLE, Bonn, Germany, March 15, 2012.

27

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/mar/18/recycling-waste This is an example of a

similar scheme in Neustadt an der Weinstrasse whose recycling rates are the best in Germany. Here, the

town’s citizens are not charged for any waste left out for recycling and the less household waste left

out for incineration the less the household pays.

28

Solving the E-Waste Problem (StEP) White Paper, On the Revision on EU’s WEEE Directive -

COM(2008)810 nal.

29

Other areas included lighting equipment; electrical and electronic tools (with the exception of

large-scale stationary industrial tools); toys, leisure and sports equipment; medical devices (with

the exception of implanted and infected products); monitoring and control instruments; automatic

dispensers

30

Extended Producer Responsibility: Stakeholder Concerns and Future Developments, INSEAD Social

Innovation Centre, written by Nathan Kunz, Atalay Atasu, Kieren Mayers & Luk Van Wassenhove.

31

See Plant Ark ‘Product Stewardship’ Factsheet. Another voluntary product stewardship scheme

in Australia is Apple’s “Reuse and Recycle” programme that gives customers the opportunity to be

rewarded with up to $250 of store credit for their old iPhones and iPads.

Global e-waste systems

Insights for Australia from other developed countries

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2014

22

32

This is a recent release of a product list that outlines products that are under consideration

for regulation, http://www.environment.gov.au/protection/national-waste-policy/product-

stewardship/legislation/product-list-2014-15. A recent report also focused on the end-of-life of

refrigerators and air-conditioners, http://www.environment.gov.au/protection/national-waste-

policy/publications/end-of-life-domestic-rac-equipment-australia

33

For a discussion of the limitations of EPR, see the Special Feature on Extended Producer

Responsibility, Too Big to Fail, Too Academic to Function: Producer Responsibility in the Global

Financial and E-Waste Crises, by Jaco Huisman.

34

Japan is highly dependent on exports of rare earth element from China. For a discussion on the

‘urban mining’ of rare earth elements, see the Research Paper, Urban Mining of Rare Earth Elements in

the United States: A Win-Win Proposition, By Victoria Loewengart, 2011 American Military University.

35

Again, see the Special Feature on Extended Producer Responsibility, Too Big to Fail, Too Academic to

Function: Producer Responsibility in the Global Financial and E-Waste Crises, by Jaco Huisman.

36

Directive 2012/19/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012, on waste

electrical and electronic equipment WEEE. (recast).

37

Extended Producer Responsibility: Stakeholder Concerns and Future Developments, INSEAD Social

Innovation Centre, written by Nathan Kunz, Atalay Atasu, Kieren Mayers & Luk Van Wassenhove.

38

Transboundary Movements of Discarded Electrical and Electronic Equipment, StEP Green paper,

2013. Djahane Salehabadi, Cornell University.

While every effort has been taken to verify the accuracy

of this information, The Economist Intelligence Unit

Ltd. cannot accept any responsibility or liability

for reliance by any person on this report or any of

the information, opinions or conclusions set out

in this report.

Cover image - © ermess/Shutterstock

LONDON

20 Cabot Square

London

E14 4QW

United Kingdom

Tel: (44.20) 7576 8000

Fax: (44.20) 7576 8500

E-mail: london@eiu.com

NEW YORK

750 Third Avenue

5th Floor

New York, NY 10017, US

Tel: (1.212) 554 0600

Fax: (1.212) 586 0248

E-mail: newyork@eiu.com

HONG KONG

6001, Central Plaza

18 Harbour Road

Wanchai

Hong Kong

Tel: (852) 2585 3888

Fax: (852) 2802 7638

E-mail: hongkong@eiu.com

GENEVA

Rue de l’Athénée 32

1206 Geneva

Switzerland

Tel: (41) 22 566 2470

Fax: (41) 22 346 9347

E-mail: geneva@eiu.com