Co-chair

Co-chair

Commissioners

Table of Contents

Preface

Introduction from Commissioners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Thank Yous and Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

How We Did our Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

Chapter 1- Our Province. Our Democracy.

Voices and Values – New Brunswickers and Democracy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Renewing Democracy in New Brunswick – The Context for Reform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

Toward a Citizen-Centred Democracy in New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

Chapter 2 - Summary of Recommendations

Summary of Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

Chapter 3 - Making Your Vote Count

A Mixed Member Proportional Electoral System for NB . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

Implementing a New Proportional Representation Electoral System for New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .47

Drawing Electoral Boundaries in New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .50

A Fixed Election Date for New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .56

Boosting Voter Turnout & Participation and Modernizing our Electoral Infrastructure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .60

Chapter 4- Making the System Work

Enhancing the Role of MLAs and the Legislature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .67

Improving Party Democracy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .76

Opening up the Appointment Process for Agencies, Board and Commissions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .84

Chapter 5- Making Your Voice Heard

Stronger Voices for Youth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .91

Stronger Voices for Women . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .97

Stronger Voices for Aboriginal People . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .101

A Referendum Act for New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .103

Participatory Democracy and Citizen Engagement in New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .108

Chapter 6 - Recommendation Appendices

A. Policy Framework -- A Representation and Electoral Boundaries Act for New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .117

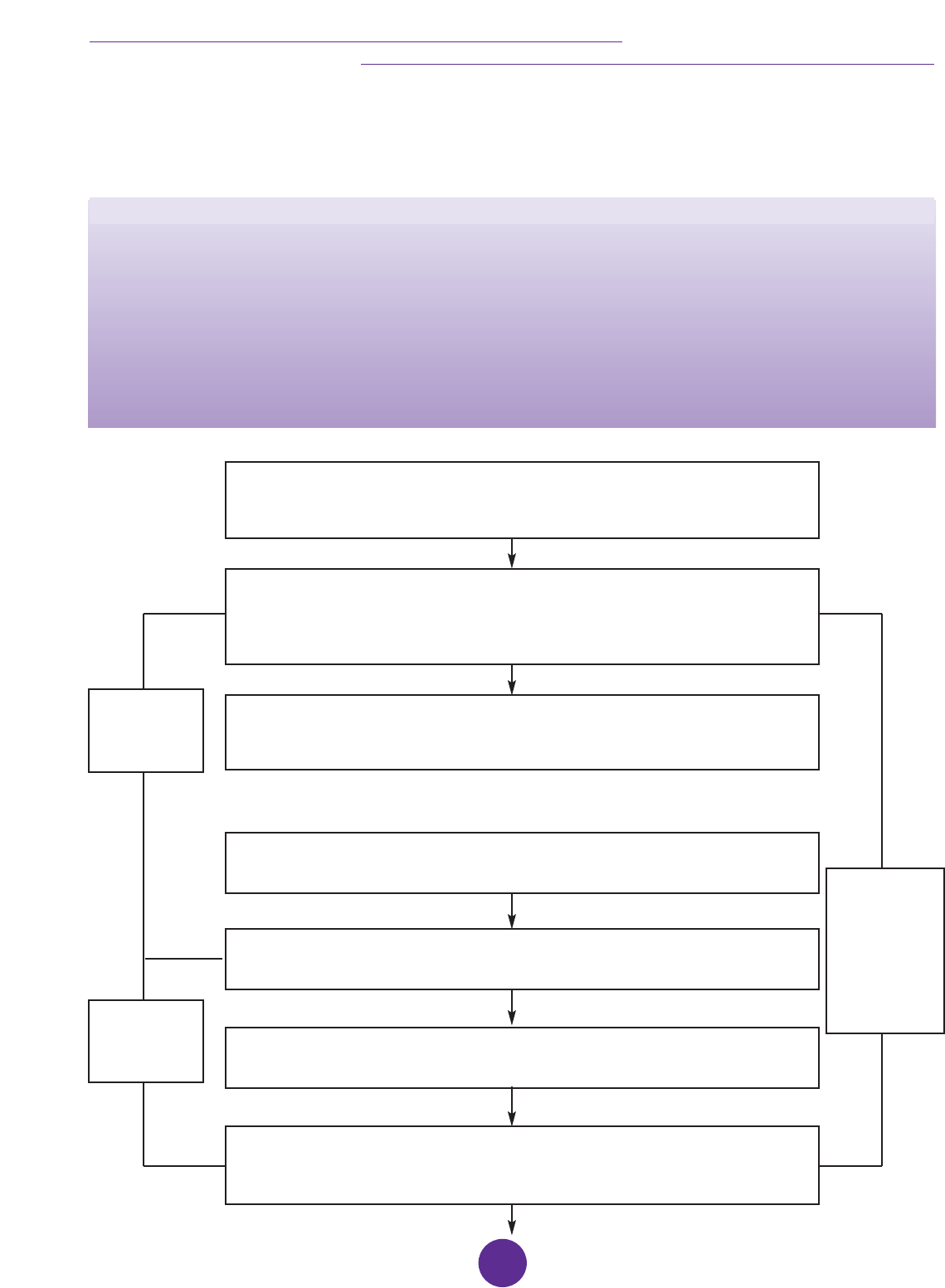

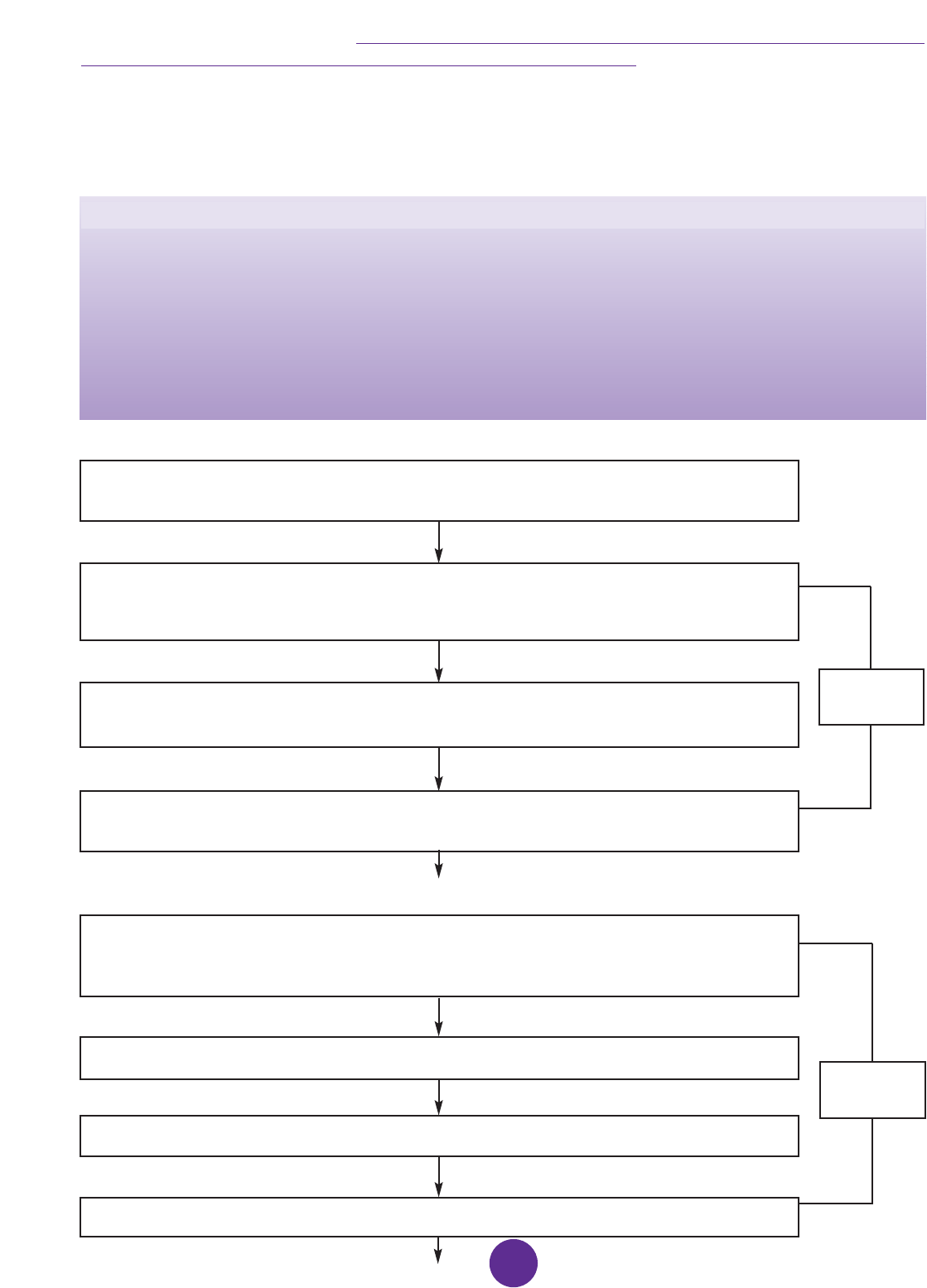

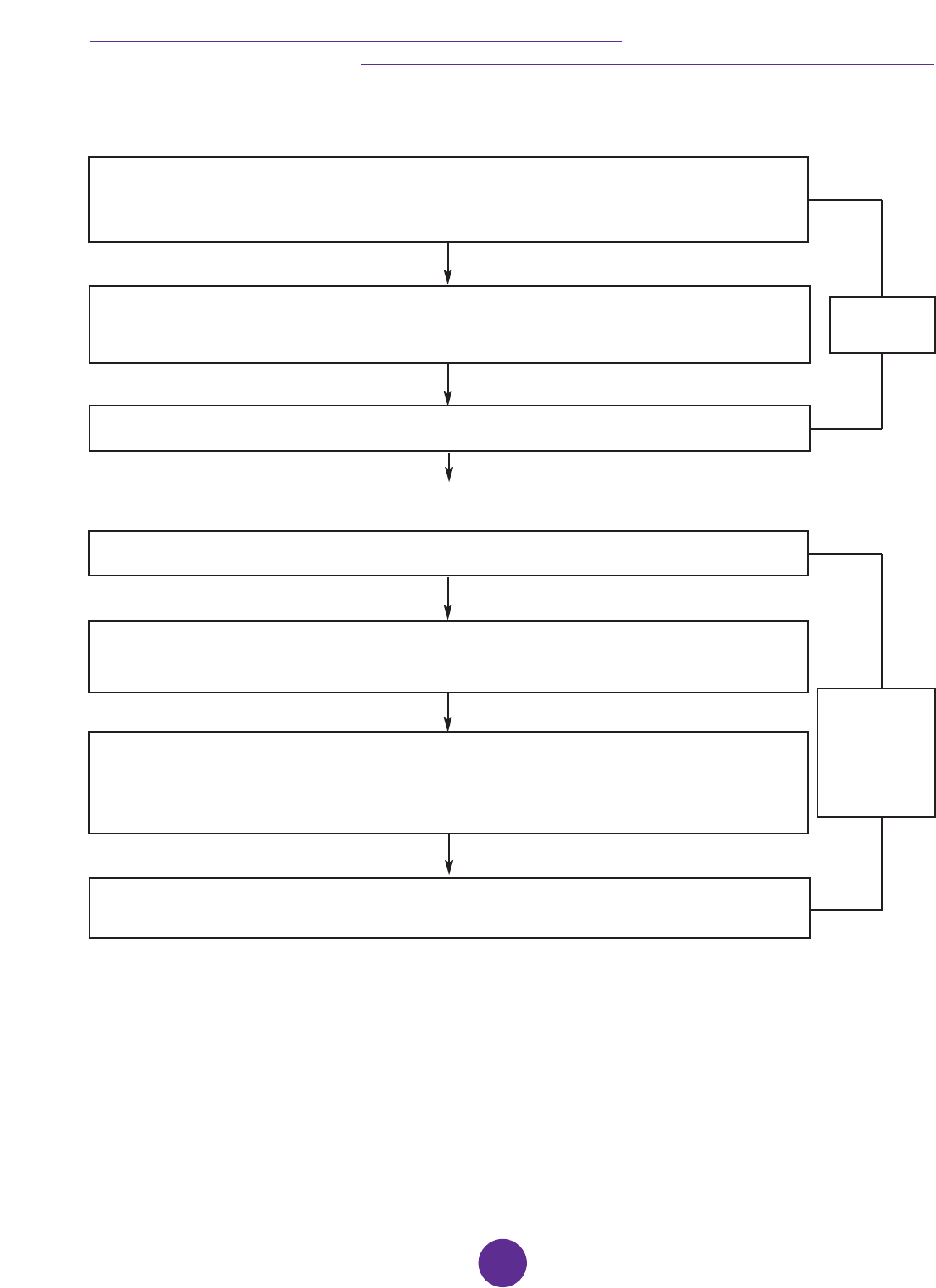

A-1 Flowchart for a Representation and Electoral Boundaries Act Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .123

B. Proposed Mandate – Elections New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .125

C. Policy Framework – The Roles and Duties of an MLA and a Code of Conduct

for Members of the Legislative Assembly of New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .127

D. Policy Framework – MLA Constituency Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .129

E. Policy Framework – Review Committee for MLA Remuneration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .130

F. Policy Framework – Fixed Legislative Calendar Session . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .132

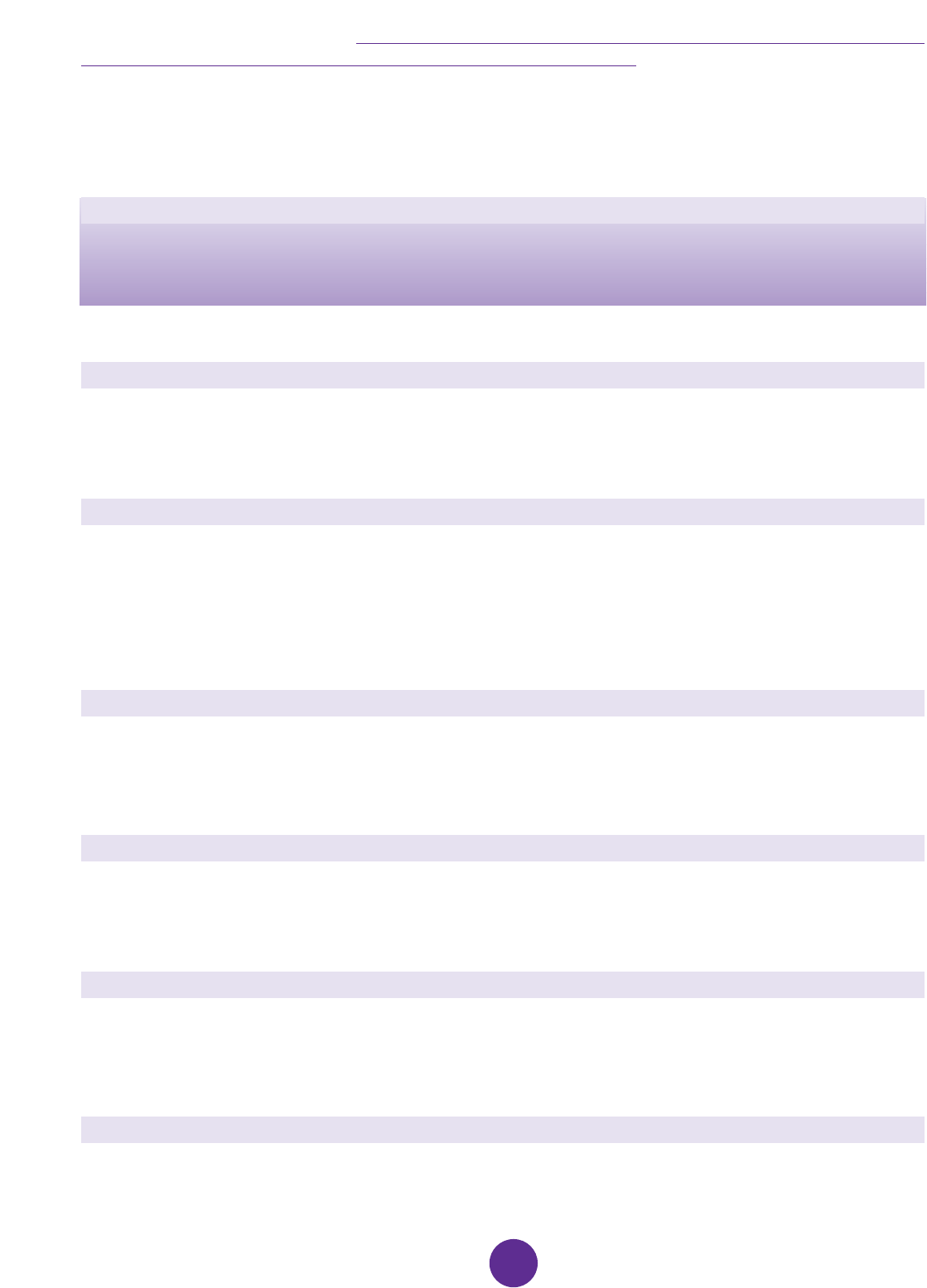

F-1 Possible Legislative Assembly Calendar for 2006 with Committee Days

and Prescribed Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .134

G. Policy Framework – Transparency and Accountability Act . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .140

H. Policy Framework – Improving Party Democracy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .141

I. Policy Framework – Appointments to Agencies, Boards and Commissions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .153

J. Policy Framework – A New Civics Education Program from Kindergarten to Grade12 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .165

K. Policy Framework – A Referendum Act for New Brunswick . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .169

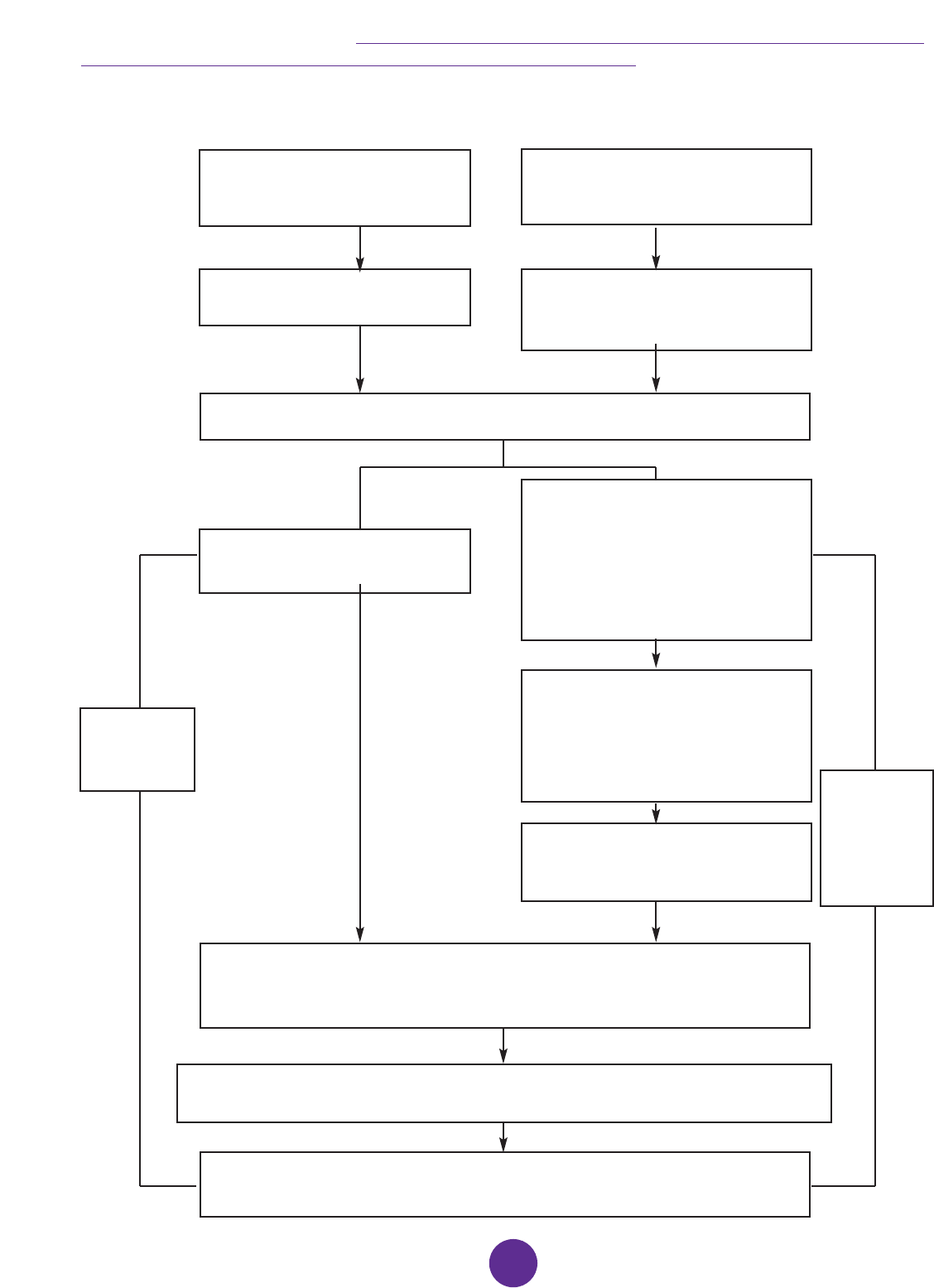

K-1 Flowchart for a Referendum Act Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .178

Chapter 7- Background Appendices

I. Mission, Mandate and Terms of Reference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .181

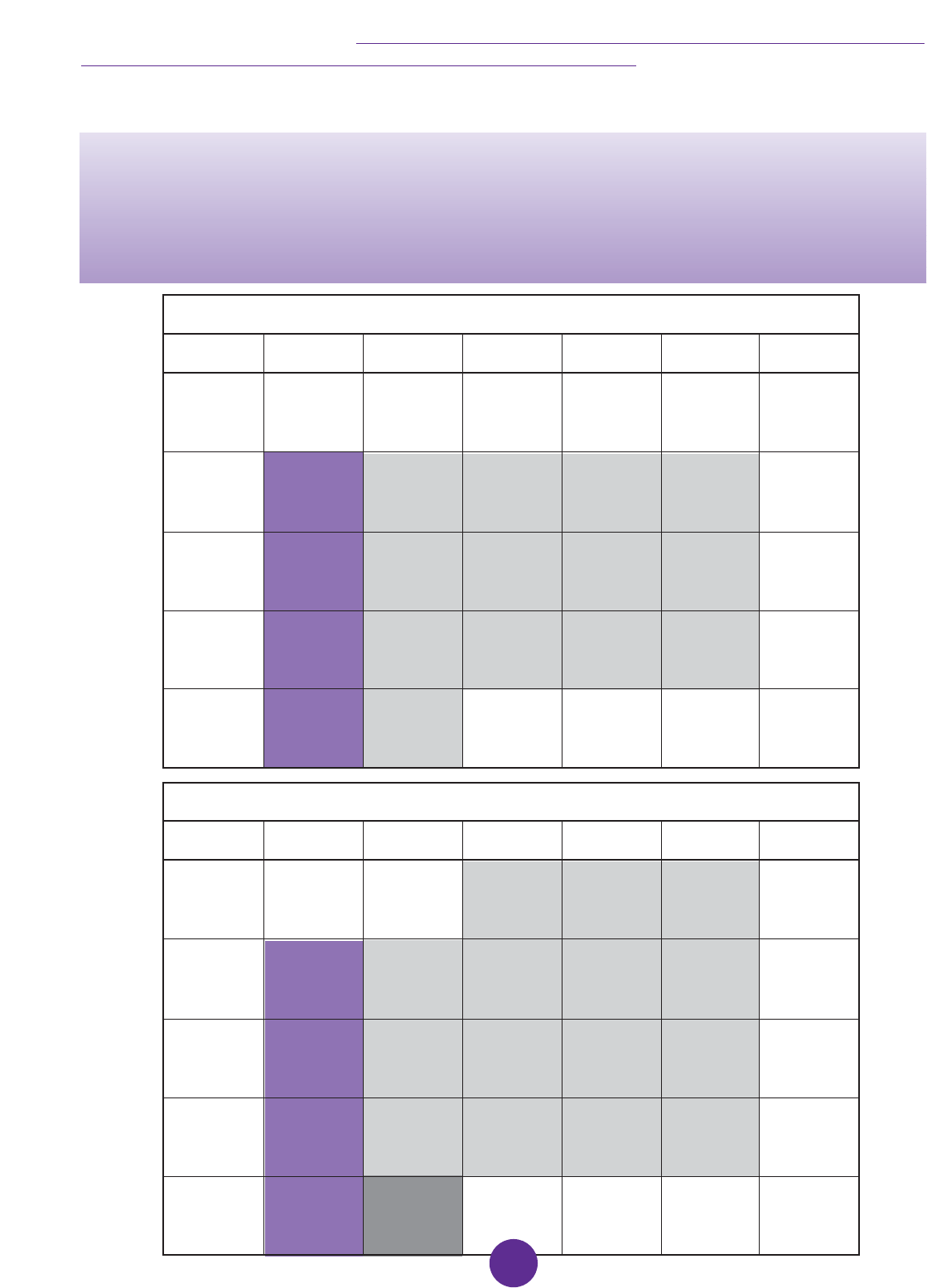

II. Example of a Regional Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) Electoral System in New Brunswick . . . . . . . . .183

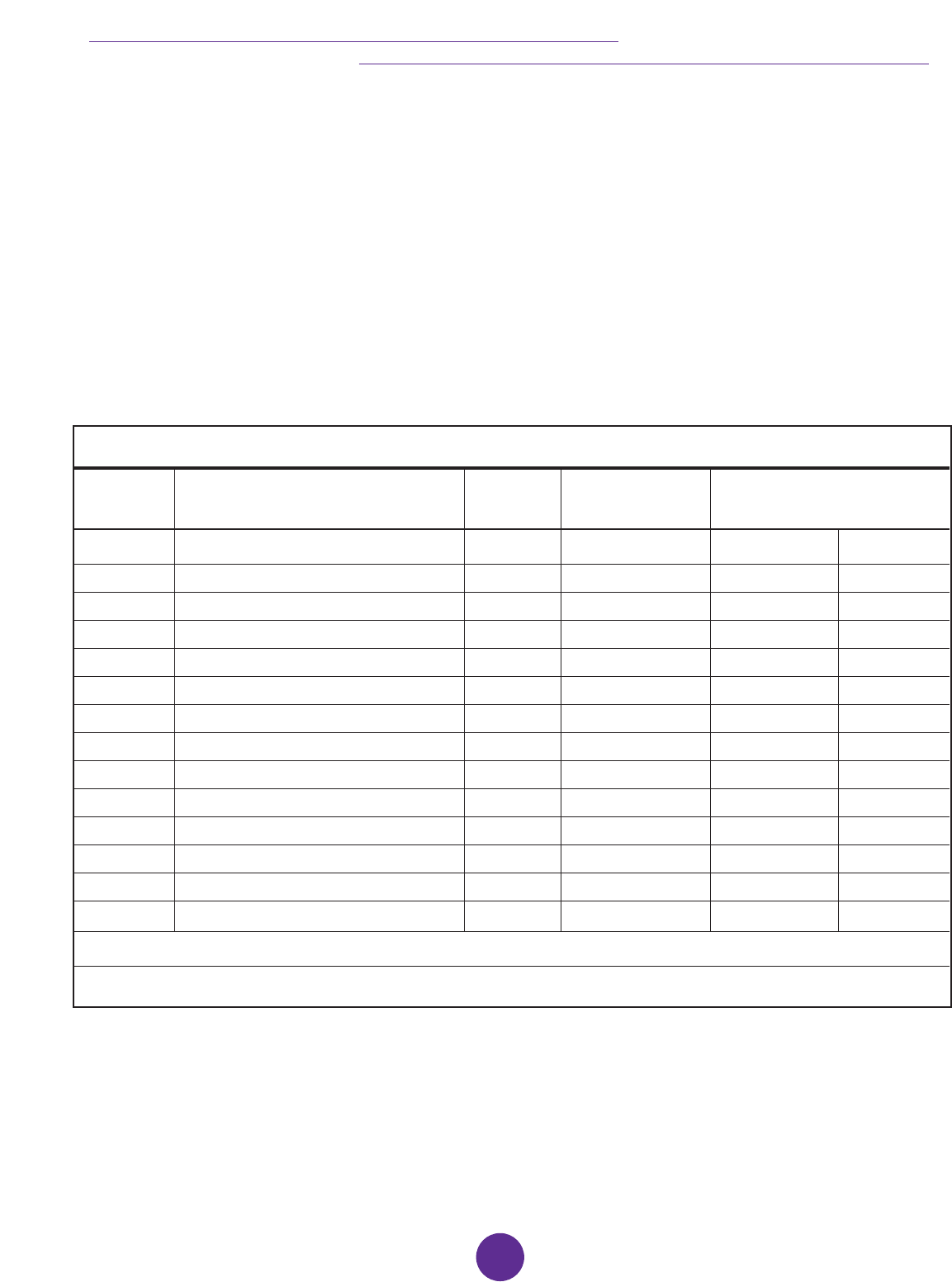

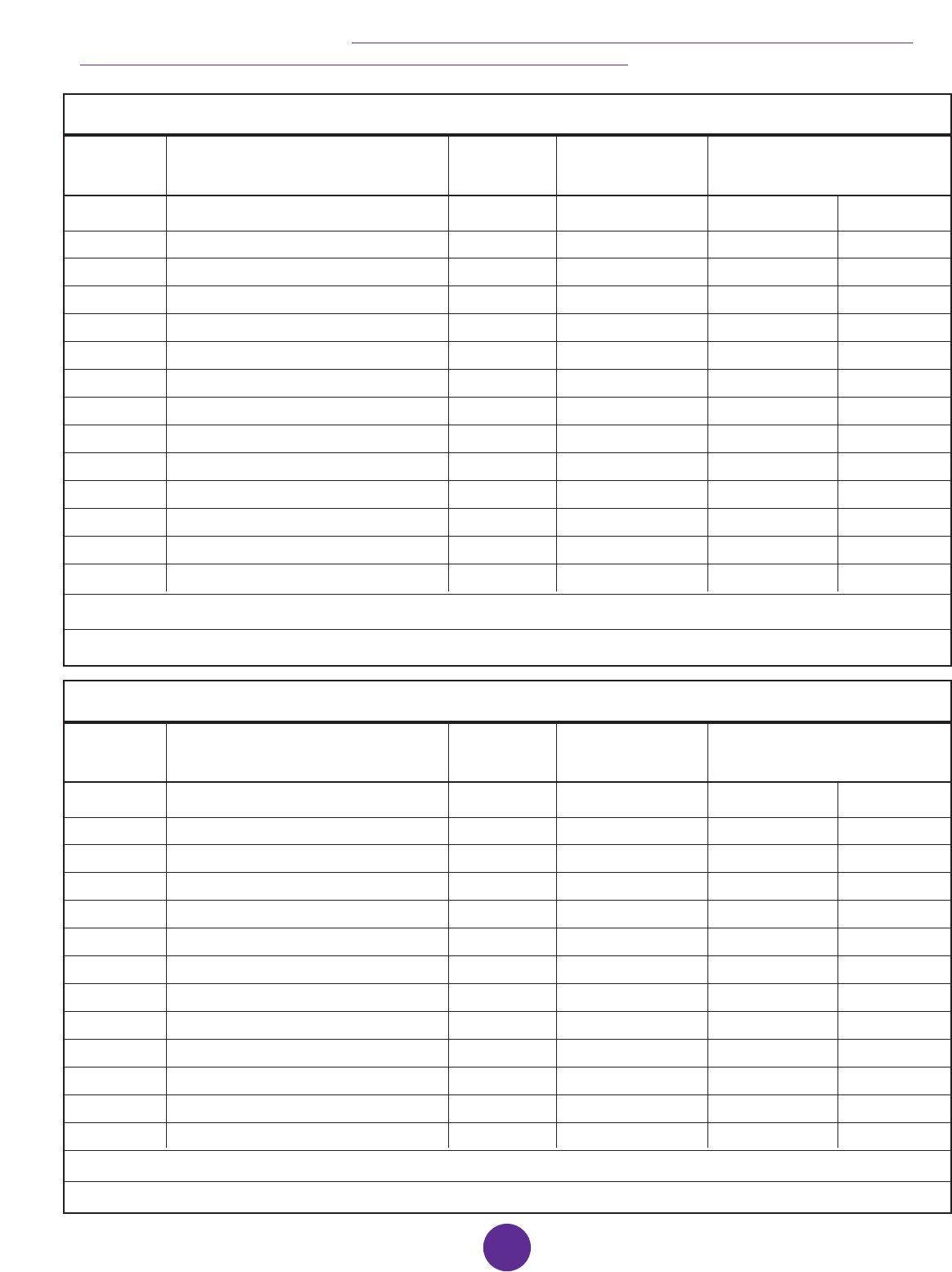

III. Comparison of the New Brunswick MMP Electoral System with SMP Electoral System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .186

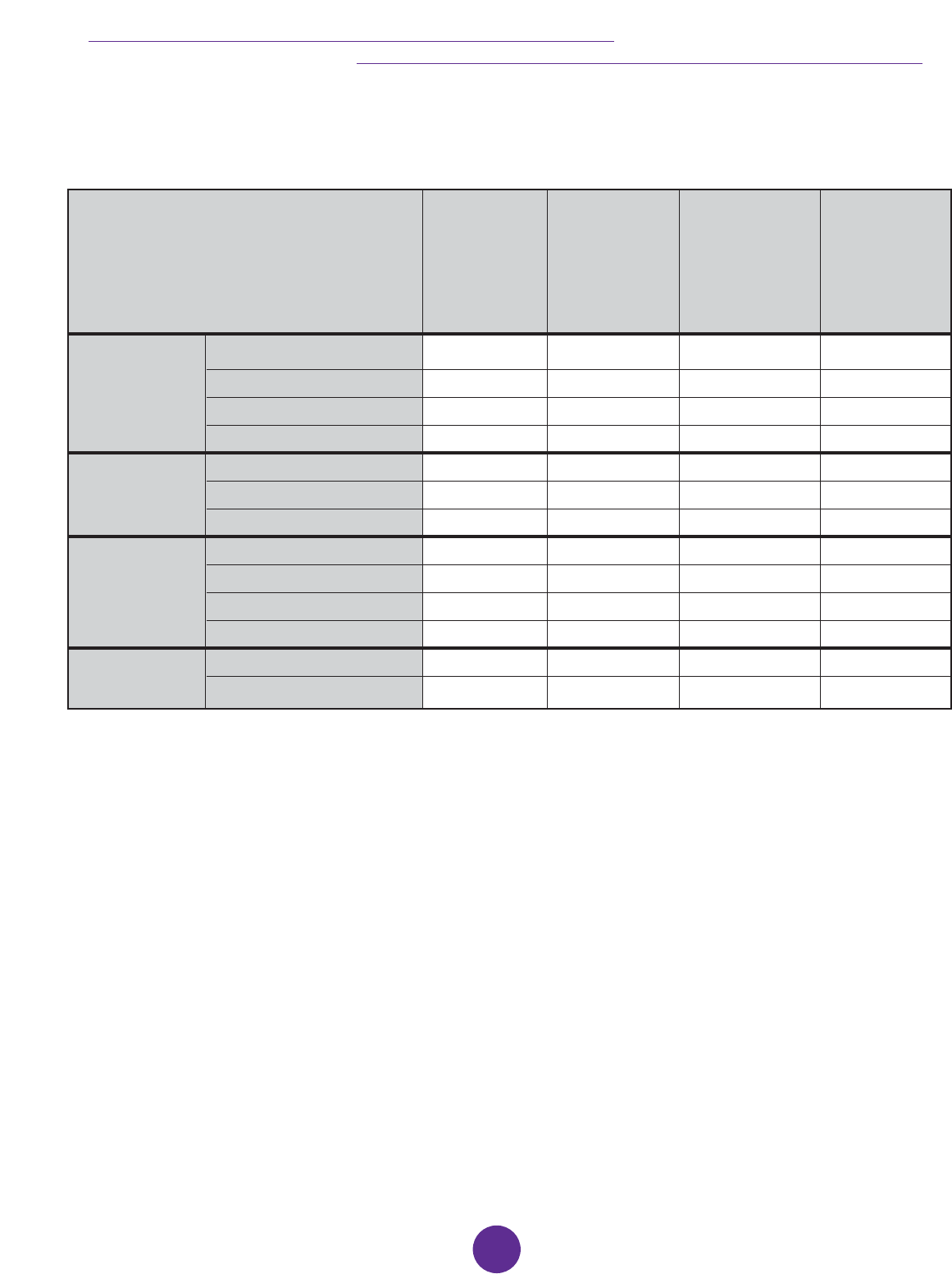

IV. Comparison of Boundaries Legislation Across Canada . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .187

V. Voter Participation – Ranked by Social Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .189

VI. Comparison of MLA Salaries Across Canada . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .190

VII. Comparison of MLA Resources Across Canada . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .191

VIII. Survey of New Brunswick MLAs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .192

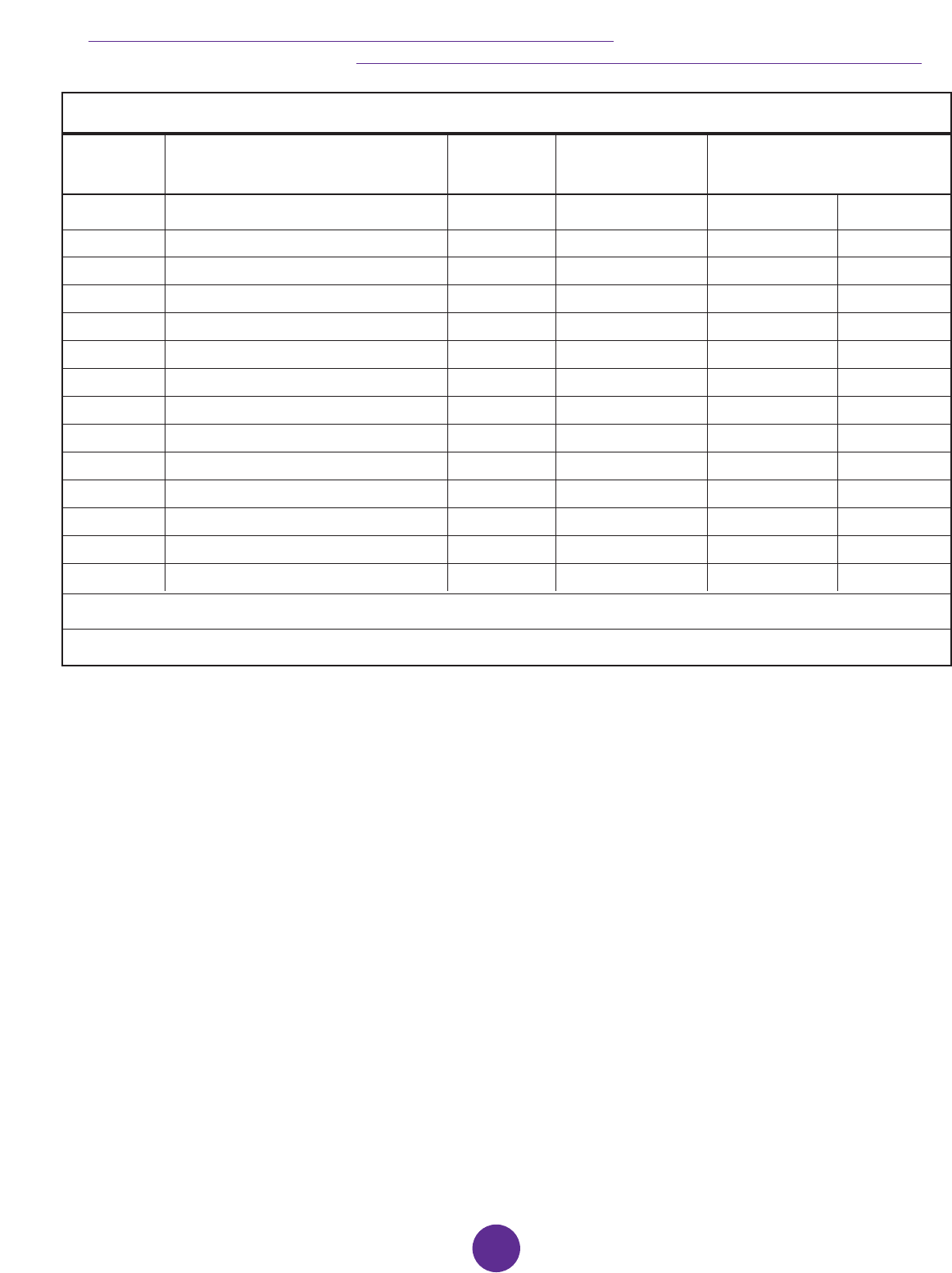

IX. Comparison of Limits on Election Spending Across Canada . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .196

X. Comparison of Disclosure of Contribution Requirements Across Canada . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .198

XI. Comparison of Limits on Contributions Across Canada . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .199

XII. Comparison of Referendum Legislation Across Jurisdictions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .201

XIII. Other NB Electoral and Democratic Statistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .203

XIV. Meetings Held . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .208

XV. Partnerships . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .212

XVI. Academic Research Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .214

XVII. Website and E-consultation Program . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .216

XVIII. Submissions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .217

XIX. Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .219

Chapter 8

Selected Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .223

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

1

Introduction from Commissioners

The Commission on Legislative Democracy, with this report,

concludes a year of exciting challenges, thorough research,

extensive consultation, and thoughtful analysis.

Our mandate was broad, and our time was brief. Although

in this report we confidently and strongly recommend

sweeping changes to our democratic system, we also want

to acknowledge that New Brunswick has grown and

prospered well under our existing system of government,

and we should be thankful to those who have been the

guardians of our government institutions, and served the

public over the last 220 years.

Yet, while our province has achieved great things under the

present system, we feel there is another level that New

Brunswickers can reach if given the right tools, better

information and more effective access to decision-making.

The recommendations that follow are divided into three

broad categories:

In “Making Your Vote Count”, we take on the task of

examining our electoral system and suggesting ways to

more deeply involve New Brunswickers, by developing a

closer connection between the ballots they cast and the

governments they elect. We recommend a move to a Mixed

Member Proportional representation system, while

continuing to honour New Brunswickers’ attachment to local

MLAs who represent them directly.

In “Making the System Work”, we make recommendations

to raise the role of the Legislative Assembly and its

members. We suggest changes to House rules and

procedures, MLA responsibilities, committee work, services,

and a rebalancing of the powers held by the legislative and

executive branches of government.

In “Making Your Voice Heard”, we propose ways to

increase the participation and power of women and youth;

broaden the public’s understanding of and participation in

their local governance institutions; improve access to elected

officials through new technologies; and participate in

important decisions directly through referendums.

The adoption of our recommendations in their entirety would

require many amendments to existing laws, creation of new

legislation, further deliberations by elected officials, and

perhaps even a referendum. Despite those challenges, we

feel strongly that our proposals, if taken together, give each

other more strength.

We therefore hope the government, and the people of New

Brunswick, will consider our report as a complete package.

None of this large body of work would be possible without

the excellent service provided by the Commission’s staff,

headed by its Deputy Minister, David McLaughlin. New

Brunswickers are very fortunate to have such dedicated

people working in the public’s service.

Our thanks are also extended to Dr. Bill Cross, our Director

of Research.

His studies, combined with many submissions from

Canada’s best and brightest academics, give this report a

solid foundation of research that we are sure will become a

valuable record for anyone studying the reform of

government and its institutions.

And, most of all, we Commissioners are grateful to New

Brunswickers who - in groups and individually - took time to

be with us and share their ideas with us at our consultation

meetings, over the Internet, by correspondence, and through

their participation in our surveys. Their dedication to our

province enriches us all. We hope in our report, they will

see themselves and their ideas. We were moved and

enlightened by what they had to say.

Preface

COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE DEMOCRACY

2

Thank You’s and

Acknowledgements

The Commission and its Deputy Minister would like to thank

sincerely and acknowledge publicly the many people

around New Brunswick and across Canada who

participated in our work and helped make this report

possible.

We had many partners in our work and the Commission is

grateful to each of them. We would like to thank Dr. Mary

Lou Stirling, Rosella Melanson and staff at the New

Brunswick Advisory Council on the Status of Women; Ryan

Sullivan, Ivan Corbett and staff at the New Brunswick

Advisory Council on Youth; Rebecca Low, Gina Bishop and

Denis Gaudet at the Centre for Research and Information on

Canada and the Canadian Unity Council; Lisa Hrabluk at

Next New Brunswick; Ghislaine Foulem at the Forum de

concertation des organismes acadiens; and Rick Hutchins at

Policylink NB.

The Commission is particularly indebted to its first-class

academic research team led by its Director of Research, Dr.

Bill Cross, Director of the Centre for Canadian Studies at

Mount Allison University. Participating academics and

researchers included: Dr. Chedly Belkhodja - Université de

Moncton; Dr. Gail Campbell - University of New Brunswick;

Dr. André Blais - Université de Montréal; Dr. Lisa Young -

University of Calgary; Dr. Don Desserud - University of New

Brunswick, Saint John Campus; Dr. David C. Docherty -

Wilfrid Laurier University; Dr. Munroe Eagles - University of

Buffalo; Dr. Joanna Everitt - University of New Brunswick,

Saint John campus; Dr. Sonia Pitre - University of Ottawa;

Dr. Paul Howe - University of New Brunswick; Dr. Roger

Ouellette - Université de Moncton; and Dr. Alan Siaroff -

University of Lethbridge.

The Commission’s work was of great interest across Canada

with those governments and individuals engaged in similar

democratic renewal projects. This new “fraternity” was

helpful in sharing ideas, information and research. We

would like to particularly thank Dr. Ken Carty of University

of British Columbia and Director of Research for the BC

Citizens’ Assembly; André Fortier, Associate Deputy

Minister, Secrétariat à la réforme des institutions

démocratiques du Québec, Government of Québec;

Matthew Mendelsohn, Deputy Minister, Secretariat for

Democratic Renewal, Government of Ontario; Stephen

Zaluski and Stéphane Perrault of the Privy Council Office,

Government of Canada; Hon. Norman Carruthers,

Commissioner, PEI 2003 Electoral Reform Commission, and

Nathalie DesRosiers, past President of the Law Commission

of Canada.

The Commission is grateful to each of its outside speakers

and experts who traveled to New Brunswick to participate

in one of our conferences or roundtables. This includes:

Jeffrey Simpson, National Columnist for the Globe and

Mail; Hugh Segal, President of the Institute for Research on

Public Policy; Hon. Ed Broadbent, MP for Ottawa-Centre;

Peter Dobell, Founding Director of the Parliamentary Centre;

Caroline Di Cocco, MPP, Sarnia-Lambton, Ontario; Geoffrey

Kelley, MNA for Jacques-Cartier, Québec; Ian McClelland,

former MLA, Edmonton-Rutherford, Alberta; Andrew Parkin,

formerly at CRIC; Dr. John Courtney, University of

Saskatchewan; Dr. Stewart Hyson, UNBSJ; Leslie Siedle,

formerly with Elections Canada; and David Moynaugh,

CCAF.

The Commission would also like to thank several New

Brunswick MLAs who met with us or participated at various

events. This includes: Hon. Brad Green, Hon. Keith Ashfield,

Hon. Bruce Fitch, Hon. Joan MacAlpine, Shawn Graham,

Elizabeth Weir, Trevor Holder, Cy LeBlanc, Kelly Lamrock,

Eric Allaby, Milt Sherwood, Jody Carr, Michael (Tanker)

Malley, John Betts, Wally Stiles, and Michael Murphy.

Dr. Keith Culver from the University of New Brunswick

provided welcome advice on the emerging possibilities of e-

democracy and assisted in the development of our “Your

Turn” questionnaire. Two New Brunswick ICT firms, xwave

and CGI, gave us advice, support, and services for our

online questionnaire and discussion forum.

We were very fortunate to have the support of universities

and community colleges in the province in co-sponsoring

several of our events. Thank you to Mount Allison

University’s Centre for Canadian Studies for hosting our first

Academic Conference; the Faculty of Law at the University

of New Brunswick for our Roundtable on Electoral

Boundaries; the Université de Moncton, which hosted our PR

Roundtable and second Academic Conference; and St.

Thomas University for hosting our Youth Forum in

partnership with the New Brunswick Advisory Council on

Youth. As well, thank you to the New Brunswick Community

College network for providing us space and administrative

support at campuses around the province for our spring

consultation process.

This Commission was a ‘start-up’ with no office, staff,

budget or equipment and only a short time to complete our

work. Greg Cook at Supply and Services found us space

quickly. Rick Phillips and his team at Finance set up our

budget and administered all of our requisitions and

payments. The staff at the IT help desk at the Department of

Finance, was a big help at all times. Human resources

assistance and guidance was provided by Cecile Guerrette,

Director of Human Resources, Department of Finance and

Beth Clark at the Office of Human Resources.

Communications New Brunswick performed tremendous

work designing and producing all of our consultation

documents, fact sheets, and other materials with very

compressed timelines. Our website was a very important

part of our consultation process and the CNB website team,

comprised of Bonnie Buckingham-Landry, Kevin Lunn,

Norman Richard, Keehwan Jee and Paulette Stewart, was

innovative and flexible in meeting our needs.

Communications New Brunswick’s Design Services, led by

Michael Côté, was a key player in the production of our

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

3

four public documents. Thank you to Stewart Tower, Lucie El-

Khoury, Ed Werthmann, Jill Wishart and Delia Smith.

Many individuals at various government departments

assisted the Commission in its work by answering our policy

and legal questions, providing data and information, and

giving us advice. The Commission would like to thank the

following persons in particular for their support: Kim

Poffenroth and Heather Hobart (Justice and Attorney

General); Kevin Malone, Judy Wagner, and Greg Lutes

(Executive Council Office); Katherine D’Entremont and

Johnny St. Onge (Environment and Local Government);

Margaret Smith (Education); Mary Ogilvie, Judy Ross

(Service New Brunswick); and Mirelle Cyr

(Intergovernmental and International Relations). Claude

Marquis, Director of the Community Access Centres,

arranged for posting of our consultation papers and

questionnaires on their website.

Sabine Sparwasser, Counsellor of the German Embassy in

Ottawa, provided useful background information on

Germany’s electoral system and arranged for the visit of

Karsten Voigt, a former Bundestag Deputy, with the

Commission.

Thank you to Peggy Scott at Intergovernmental and

International Relations, who was exceptionally helpful in the

early days at finding and organizing a wealth of research

articles and materials.

Peggy Goss and the staff at the Legislative Library were

assiduous in tracking down books, articles, and

monographs on New Brunswick and Canadian electoral

and democratic reform to help us with our research.

The Speaker, the Hon. Bev Harrison, the Clerk of the

Legislative Assembly, Loredana Catalli Sonier, and Peter

Wolters, Donald Forestell and Shayne Davies of the

Legislative Assembly Office were gracious with their time in

meeting with Commissioners and staff, answering our

queries, and providing us with information to complete our

comparative research and policy analysis of the role of

MLAs in legislatures across Canada.

Annise Hollies, Chief Electoral Officer for New Brunswick,

Ann McIntosh, David Owens, and Ron Armitage provided

helpful information and assistance as we studied election

data and results from past provincial elections, and

discussed ideas with us for modernizing our electoral laws.

Mrs. Hollies participated at several conferences and

roundtables contributing her expertise.

Bernard Richard, Ombudsman, was helpful in offering

advice and comments on various ideas being considered by

the Commission, and he also participated at a Commission

event.

Paul Bourque, the Supervisor of Political Financing, met with

Commission staff on the operations of his office, giving us

useful background information.

Thank you to Translation Services who met our very tight

deadlines with courtesy and professionalism. Thanks also to

Interpretation Services and AW Tel-Av for their work

throughout our public consultation process.

Thanks to Julie Legresley who helped get us up and running,

and our summer and co-op students - Kristin Ferguson,

Jessica Holt, and Phillip Gammon.

The most special thanks and acknowledgements are

reserved for the Commission staff without whom none of this

would have been possible - Debbie Hackett (Senior Policy

Advisor); Lisa Lacenaire-McHardie (Policy Advisor); Marie-

Josée Groulx (Director of Communications and

Consultations); and Christyne Duguay (Executive Assistant).

All worked long and difficult hours under the most

demanding timelines to produce exceptional quality work

that was instrumental to the Commission’s learning,

consultation, and deliberations. Their commitment to this

project made a real difference.

Finally, we would like to thank Premier Bernard Lord for his

commitment to the issues of democracy. His willingness to

invite an open and sincere exploration of how our

province’s democracy can be made stronger for citizens is

testament to his own leadership and desire to make New

Brunswick even better.

COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE DEMOCRACY

4

How We Did Our Work

The Commission on Legislative Democracy was formally

established by Premier Bernard Lord on December 19,

2003. It was given approximately one year - until

December 31, 2004 - to report to the Premier and all New

Brunswickers. Speaking in the Legislative Assembly that day,

the Premier set out the Commission’s mandate and invited

all New Brunswickers to participate in its process. He

stated:

“This Commission has a mandate whose scope is

unparalleled in our history as a province. In fact, it

is unique across Canada.”

Specifically, the Commission was instructed to examine and

make recommendations on how to strengthen and

modernize New Brunswick’s democratic institutions and

practices in three main areas:

1. Electoral Reform - changing our voting system;

drawing electoral boundaries; setting fixed election

dates; and boosting voter turnout.

2. Legislative Reform - enhancing the role of MLAs

and the Legislative Assembly; opening up the

appointments process for agencies, boards, and

commissions.

3. Democratic Reform - involving the public more in

decision-making; proposing a Referendum Act.

The Commission’s goal was to present recommendations

that would bring about:

• Fairer, more equitable and effective representation in

the Legislative Assembly;

• Greater public involvement in decisions affecting

people and their communities;

• More open, responsive, and accountable democratic

institutions and practices; and,

• Higher civic engagement and participation of New

Brunswickers.

This large mandate and relatively short time frame set the

stage for how the Commission did its work. While other

jurisdictions are focused on examining single reforms to

their democratic institutions, New Brunswick is unique in

considering each element of democratic renewal fully, at

once, and in an integrated way. A comprehensive

consideration of democratic renewal in New Brunswick was

sought; the Commission was given the challenge to deliver.

To meet this challenge the Commission had to first undertake

significant new research and analysis into each of its

mandate areas. We had to dissect the issues and conduct

our own research and learning. We had to develop

consultation and information documents so New

Brunswickers could participate in our process and give us

their views and suggestions. We had to inform New

Brunswickers about our work as we went along. We had to

hold public hearings and meetings to hear directly from

citizens. Finally, we had to integrate all of this input into our

deliberations to arrive at recommendations that would fulfill

the comprehensive mandate we were given.

Principles

Given the very nature of the topic under study - democracy -

the Commission established four key principles to guide its

work and involve New Brunswickers.

Openness - The Commission’s work and progress would be

as open as possible for all New Brunswickers to follow

through the media, website, and activities.

Participation - New Brunswickers would be invited to

participate in the work of the Commission at each stage of

its progress through as wide a range of events, activities,

and materials as possible, many targeted at specific groups

and communities around the province.

Partnerships - The Commission would establish research or

consultation partnerships with provincial and national

organizations to give it access to additional expertise,

involve even more people in the process, and support our

cost-effective approach to managing the budget.

Research-based - The Commission’s work would be

research-based, giving it a strong independent foundation of

information and learning to assist it in its deliberations.

Three Phases

The Commission undertook three basic phases to its work:

Research; Consultation; and Deliberation.

Research

The Research Phase began with the hiring of Dr. Bill Cross

as Director of Research. Dr. Cross is Davidson Chair and

Director of the Centre for Canadian Studies at Mount

Allison University. He is editor of the Canadian Democratic

Audit series, a published author, and a commentator on

political affairs in Canada.

Dr. Cross directed the Commission’s academic research

program, bringing together noted academic experts from

across Canada and from New Brunswick universities. The

aim of the research program was to ensure the Commission

had access to informed academic research on our mandate,

to stimulate debate and discussion on the subject areas, and

to ensure a specific research focus on the impact and

implications of changes to New Brunswick’s democratic

institutions and practices. Each academic prepared an

original research article for peer-reviewed publication, and

provided important statistical data and insight on each area

of the Commission’s mandate.

The results of their work and expertise were brought

together at two academic research conferences held on

February 5-6, 2004, at Mount Allison University and

September 24, 2004, at Université de Moncton.

Four expert roundtables, focused on specific areas of the

Commission’s mandate, were also held over the course of

2004. These included a Roundtable on the Role of MLAs

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

5

and the Legislature on March 24-25, 2004, held at the

Legislative Assembly in Fredericton; a Roundtable on

Electoral Boundaries held on April 28, 2004, at UNB Law

School; a Roundtable on Proportional Representation held

on September 23, 2004, at the Université de Moncton; and

a Roundtable on Civic Engagement held on October 7,

2004, in Saint John.

Participating in these events were academic experts from

New Brunswick and across Canada; current and former

elected officials from New Brunswick, Québec, Ontario,

and Alberta; community group leaders and activists; the

Chief Electoral Officer of New Brunswick; the Ombudsman;

the Speaker; representatives from various provincial

associations; and public policy experts from the Centre for

Research and Information on Canada, the Institute for

Research on Public Policy, and the Parliamentary Centre in

Ottawa. Each event was open to the public and media,

with simultaneous interpretation.

Consultation

The Commission undertook a broad consultation process

aimed at providing as many New Brunswickers as possible

with the opportunity to give the Commission their views. To

do so, the Commission produced a wide range of fact

sheets and consultation documents, held public meetings for

direct input from citizens, created an interactive website to

encourage online participation, and organized specific

consultation forums for direct dialogue with interested

groups and communities.

Agendas for each Commission meeting were published on

our website. Presentations prepared for Commissioners or

provided by invited experts were also published on our

website for all to read.

Fourteen public hearings were held across the province in

the spring and fall. Eleven Community Leader Roundtables

were also held around the province. Invitations to

participate in Commission events, or visit our interactive

website, were sent regularly to a provincial mailing list that

grew to almost 1,000 names. Given their unique interest in

our mandate, MLAs were specifically invited to participate

in each event. Synopses of each public consultation event

and forum were then prepared and placed on our website

to provide additional feedback to people on what was said,

and to share those observations with as many New

Brunswickers as were interested.

The Commission produced three main consultation

documents: Your Voice. Your Vote (an introductory paper on

the Commission’s mandate); Your Voice. Your Vote. Your

Turn! - Citizen’s Participation Guide (a comprehensive

backgrounder on the issues with an enclosed 50-question

questionnaire); and Options: A Progress Report to New

Brunswickers (a summary of the main options being

considered by the Commission).

The aim of these consultation documents was to, first, inform

New Brunswickers of the mandate of the Commission;

second, provide useful background information on the key

issues we were studying; and third, solicit feedback on the

options and issues for change being considered by the

Commission. This was designed to ensure a fully-transparent

process of consultation with people and obtain the fullest

possible public input at all stages through our public

hearings, Community Leader Roundtables, and our website.

Given the complexity of the issues and the breadth of the

mandate, the Commission decided it was particularly

important to provide a clear sense of its thinking in advance

to New Brunswickers, which we did, through the Options

progress report, in order to receive a direct response from

people on exactly what we were considering.

Copies of the Commission’s three consultation documents

were distributed by e-mail to thousands of New

Brunswickers. Your Voice. Your Vote and Options were also

distributed as newspaper inserts in March and September

2004 respectively, to over 120,000 New Brunswick

households each time.

The Commission organized targeted consultation forums

based on our formal partnerships with the New Brunswick

Advisory Council on the Status of Women, the New

Brunswick Advisory Council on Youth, The Centre for

Research and Information on Canada, Next NB, the Forum

de concertation des organismes acadiens, and others. These

included:

• Youth and Democracy Forum - May 1-2, 2004.

Over 50 youth participated at this forum held at St.

Thomas University in partnership with the NB Advisory

Council on Youth. The provincial forum was preceded

by 13 regional forums in March which brought

together over 100 young New Brunswickers to discuss

youth democratic participation issues.

• Your Voice. Your Generation: Young New

Brunswickers and Democracy Forum -

September 17, 2004. Over 30 university students

participated at this event co-sponsored with Next New

Brunswick and UNB.

• Women and Democracy Forum - September 25,

2004. Over 65 people participated at this forum in

Moncton, in partnership with the NB Advisory Council

on the Status of Women.

• The Reform of Democratic Institutions in New

Brunswick: Issues for the Francophone and

Acadian Communities - June 12, 2004. Over 25

participants from the Forum de concertation des

organismes acadiens representing a wide and diverse

range of Acadian and Francophone associations

discussed the implications of democratic renewal for

their community.

Formal invitations and follow-up reminders to participate in

each event were sent out. All public hearings were

advertised and a news release was distributed to all daily

and weekly newspapers. All events, conferences, and

roundtables of the Commission were open to the public and

media.

COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE DEMOCRACY

6

Each of the 11 public hearings in the spring ran from 4

p.m. to 8 p.m. and included an introductory presentation on

the mandate of the Commission. The three public hearings

in the fall were held on a Saturday or Sunday from 10 a.m.

to 3 p.m. or 4 p.m.

General participation at the public hearings was low.

Participation at the invited Community Leader Roundtables,

by contrast, was generally high. Comments and

interventions were diverse and often detailed in both cases.

Through our consultation process, the Commission was able

to receive important and valuable input from individual

New Brunswickers, students, and a range of provincial and

local groups and associations.

Deliberation

Besides participating in each of the public conferences,

roundtables, forums, and hearings, the Commission

undertook a series of meetings and conference calls to

complete its work. The Commission met 12 times as part of

its overall research, learning, and deliberation process.

Each meeting lasted between two and three days and

involved staff presentations on issues with a discussion and

review of topics and materials. Outside experts sometimes

attended to provide their views on specific issues under

discussion.

In the deliberation phase, the Commission considered input

received from three main sources: First, public comments

and suggestions received through the public hearing

process, the Community Leader Roundtables, e-mails,

questionnaires, and individual submissions. Second, from

the Commission’s own academic research program, staff

presentations and discussions, and expert input generated

from a comprehensive range of meetings conducted by the

Commission. Third, from the various forums and roundtables

held by the Commission.

The deliberation phase of the Commission began over the

summer and was first reflected in the publication of the

Options progress report. Response to Options was an

important part of the Commission’s subsequent

deliberations.

To guide its consideration of issues, the Commission first set

key principles and objectives for each mandate area. It then

developed comprehensive issue documents with supporting

data and materials for discussion at Commission meetings.

Following general discussion on principles and directions,

these were turned into specific recommendations with

supporting policy frameworks.

Conclusion

Our final report and recommendations is very much the

product of the research, consultation and deliberation

process the Commission set out from the beginning. Our

process was open and transparent with New Brunswickers

invited at each step along the way to give us their input.

Many did and their views and suggestions can be found

throughout this report. We believe the research and policy

development work conducted by and for the Commission

provides a strong base of support and integrity that will

serve New Brunswickers well as they consider our report

and recommendations.

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

7

Voices and Values:

New Brunswickers & Democracy

Democracy comes from the Greek words “demos” which

means people and “kratia” which means power. Democracy

is about people having power to take decisions on their

own behalf.

Over the centuries, shape and form have been given to this

powerful principle, leading to a myriad of democratic

institutions, practices, and cultures around the world. There

is no one form of democracy - it is as diverse as humanity

itself. But common elements and principles exist that form

the core of any democracy, whether it is here in New

Brunswick, in Britain, Scandinavia, or even in the post-

Communist countries of Eastern Europe.

Free, fair and regular elections. One person, one

vote. Representative legislatures.

These are the original and most basic foundations of any

democracy. Variations abound, however, for each.

Elections, for example, are held every three years in some

countries; every four, five, and six years in others. Voters

have one vote for a single candidate under our single

member plurality system, but two votes or more under

proportional representation or other preferential ballot

electoral systems. Legislatures can be composed of directly

or indirectly elected representatives.

Each of these variations has emerged in response to a

society’s particular political culture. That culture, in turn, has

evolved from the social and demographic circumstances

and historical experiences of each country. Any form of

democracy is therefore unique and singular to the society

from which it springs.

As societies have become more open, diverse, and

pluralistic, so too have our democracies. Where once

Parliament or the legislature was the locus of authority and

decision-making, new voices and interests outside the

Legislative Assembly are demanding and succeeding in

achieving varying measures of influence. No longer are we

content to choose a representative to travel some distance to

a capital city and take all decisions on our behalf with an

electoral accounting every four years. Accountability of our

legislators and government institutions is demanded at all

times, and independent authorities, such as the Auditor-

General, have grown in stature and influence to ensure this

occurs. Together, this has given rise to a reformulation as to

what constitutes true democracy.

Inclusion. Engagement. Participation.

Responsiveness. Accountability.

These contemporary principles bring a more humanistic and

collective focus to the role of our democratic institutions and

practices. They reflect our expanded notion of democracy

today. For many voters, these have become the new

measures of democratic expectation and legitimacy.

New Brunswick Democratic Values

These principles emerge from the basic values of a society.

For democracy is, at its most central core, really about

values. The shape and form of our democratic institutions

and practices are the expressions, indeed, the vision of

which democratic values matter most to us.

Such is the case for New Brunswick. Deliberately or not,

everything from the way we elect MLAs, to how government

operates, to involving people in decision-making, reflects the

importance we place on one or more democratic value

compared to others.

It is important at the outset of our report to note that, in

large measure, New Brunswick has a strong and successful

democracy. Social and economic progress in our province

since Confederation has been significant. Elections are free

and fair. Our elected representatives are, generally,

sincerely motivated. Public debate occurs on many

important issues. Accountability of government has

increased.

The question before us today is not whether our democratic

institutions and practices have served us well; rather, it is

whether it is time to improve them to meet the changing

needs of our society, to allow us to make even stronger

social and economic progress, and to address the

democratic challenges that exist in our province. The issues

behind this question are summed up in the Commission’s

mandate:

To examine and make recommendations on strengthening

and modernizing our electoral system and democratic

institutions and practices in New Brunswick to make them

more fair, open, accountable and accessible to New

Brunswickers.

What kind of democracy do we want? Answering

this fundamental question begins with determining our

democratic values. Which democratic values matter most to

us, as New Brunswickers, and as citizens?

Early in its work, the Commission posed eight values to

consider when looking at our electoral system, the

functioning of the legislature, and how government makes

decisions.

Chapter 1 - Our Province. Our Democracy.

COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE DEMOCRACY

8

Eight Democratic Values

Fairness - Fairness means that the electoral system

should be fair to voters, parties, and candidates. It

should not benefit one group of voters or one political

party at the expense of another.

Equality - Equality means that all votes should count

equally when electing MLAs.

Representative - Our legislature should not just

represent voters living in a particular geographic area,

but should also represent the diverse faces and voices

of our society.

Open - Openness is the basis of a transparent and

participatory democracy for people. It is an essential

ingredient to help keep government accountable to

citizens.

Effective - An effective government and legislature is

one that is able to take decisions, consider diverse

viewpoints, and respond to changing economic and

social circumstances.

Accountable - Accountability requires governments

and legislatures to justify their actions on a regular

basis, while allowing voters to pass judgment at

election time on the performance of their

representatives.

Inclusive - Inclusion of different types of people and

differing viewpoints is at the heart of a participatory

democracy.

Choice - Choosing candidates, parties, and leaders at

election time is the central democratic action of voters.

Voters must have real choices in a healthy and vibrant

democracy.

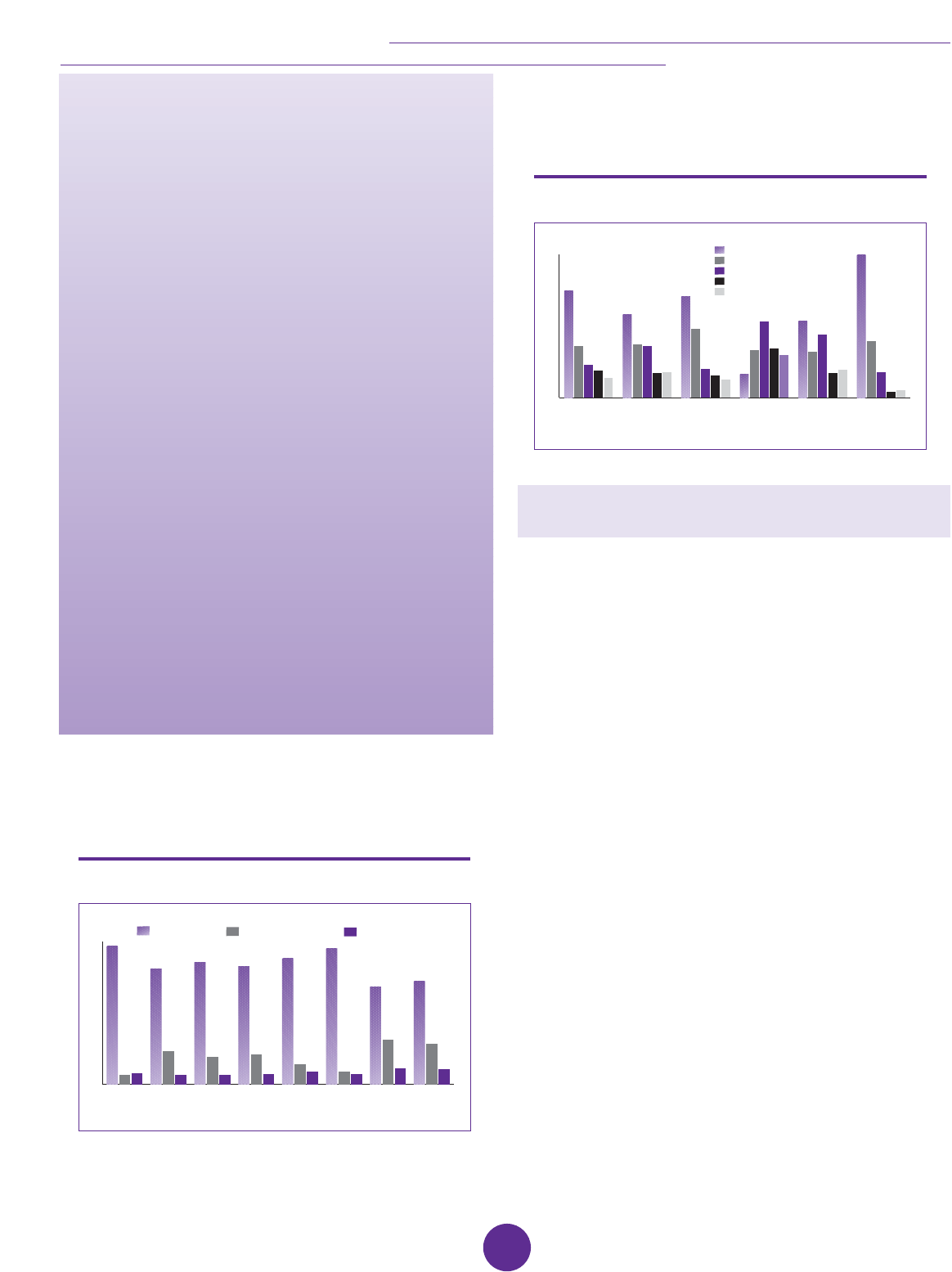

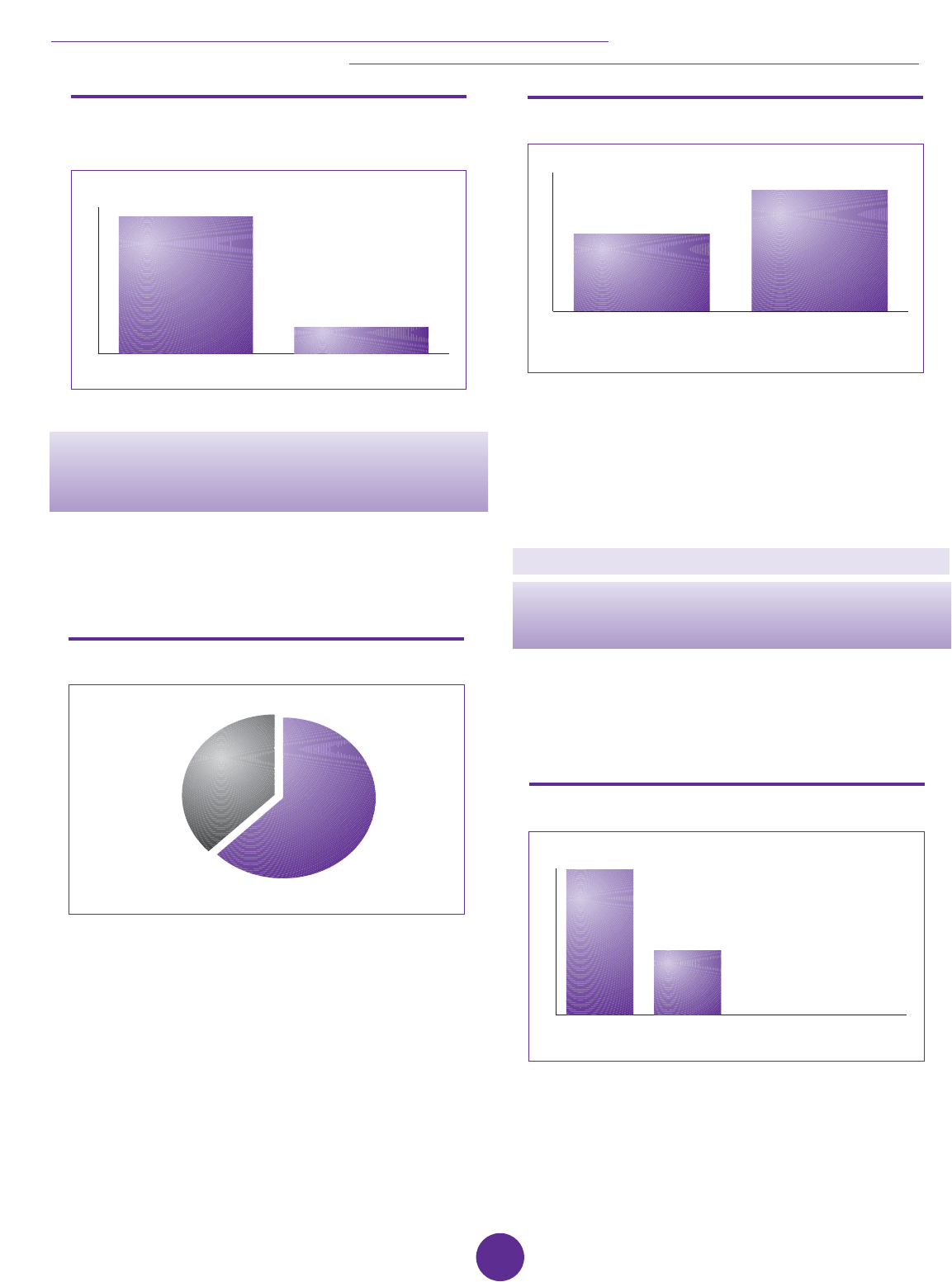

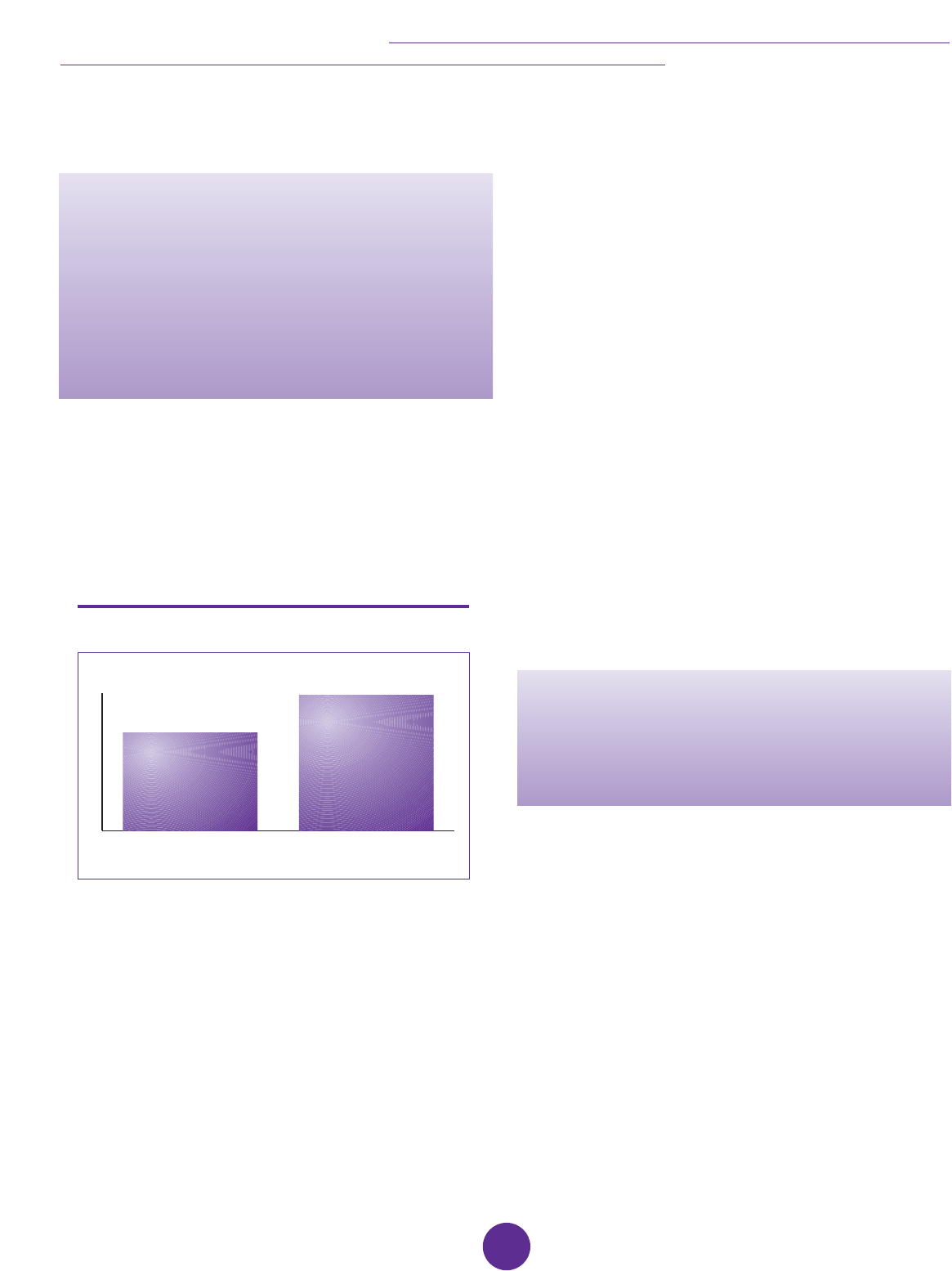

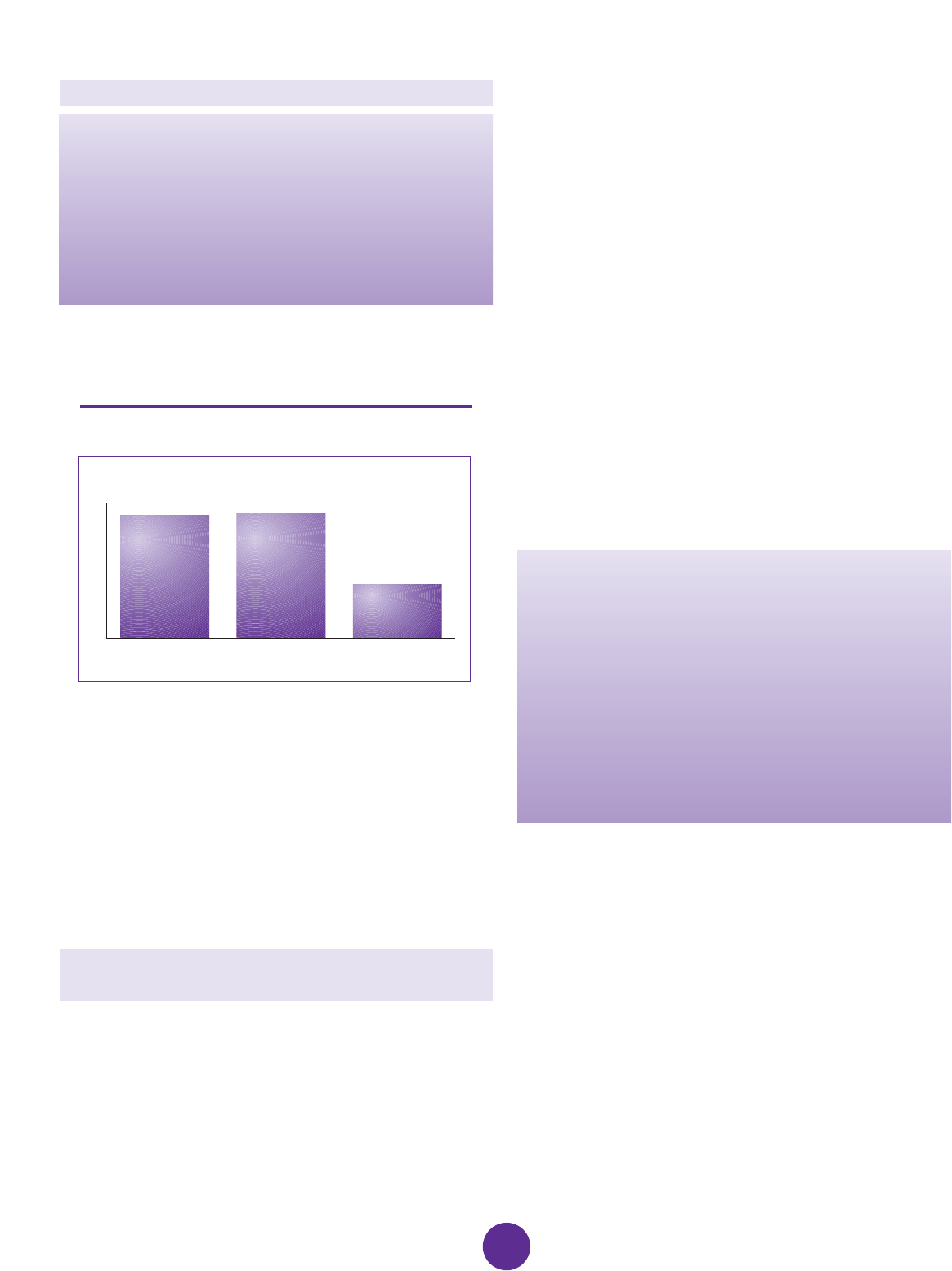

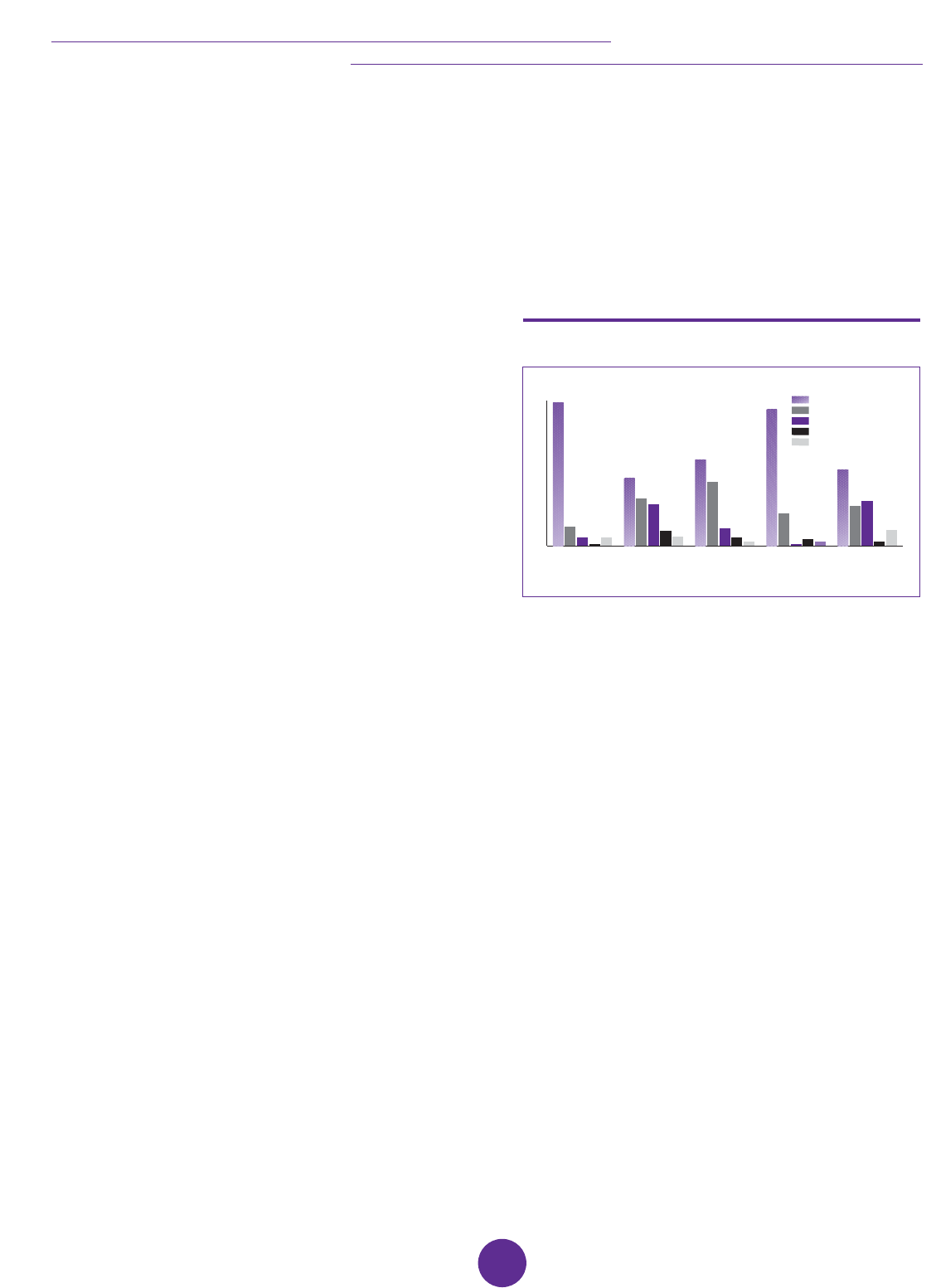

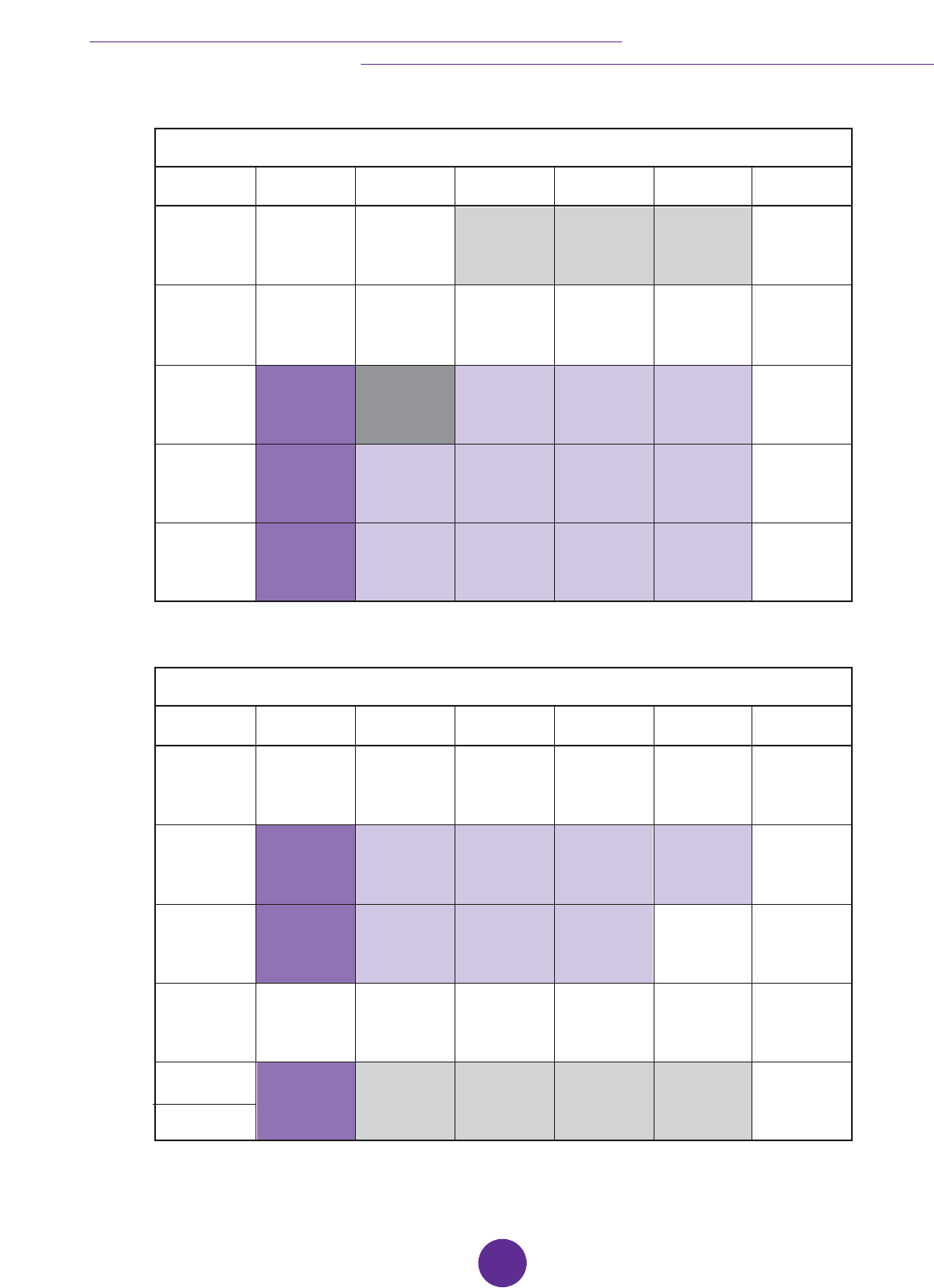

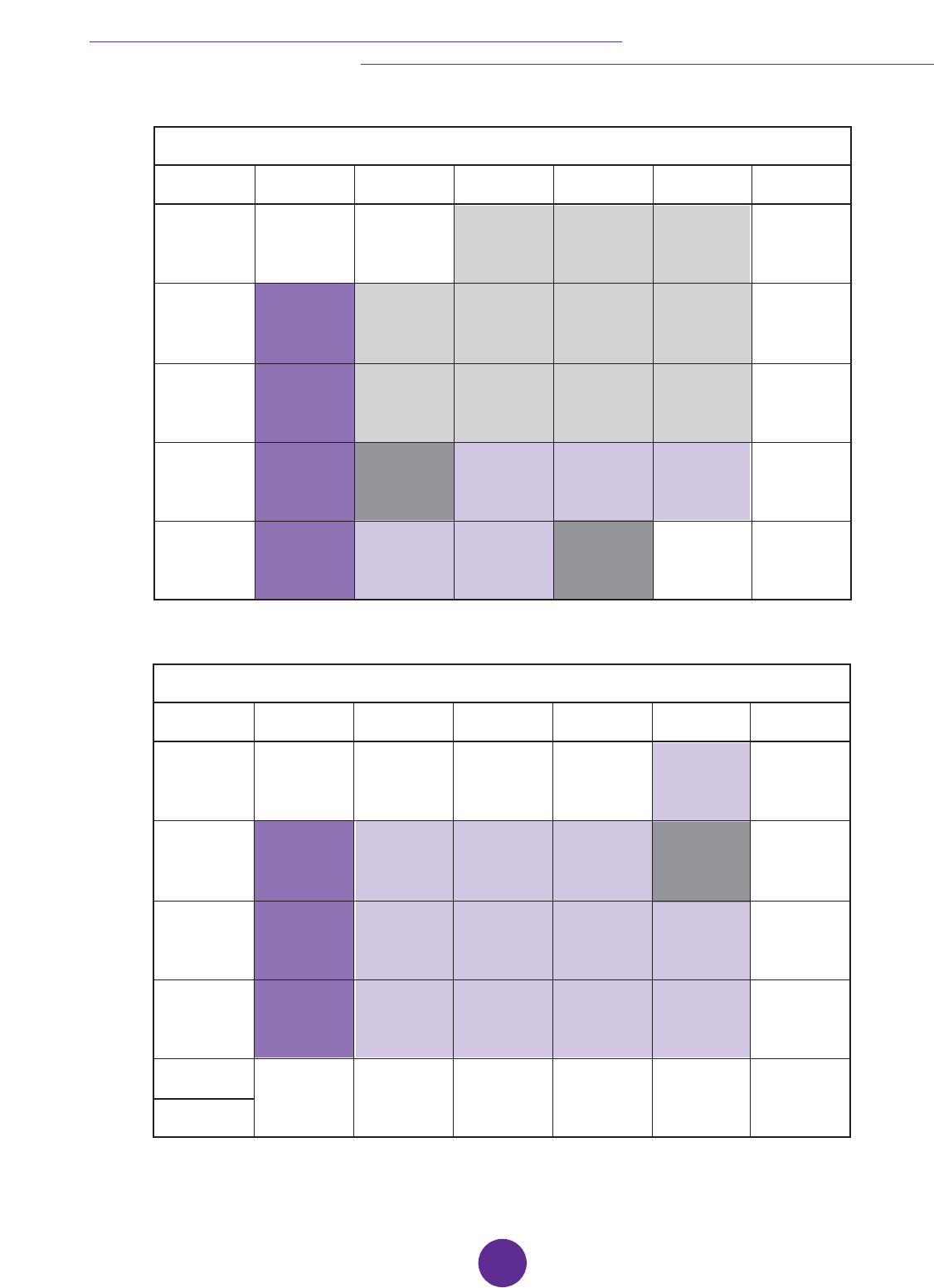

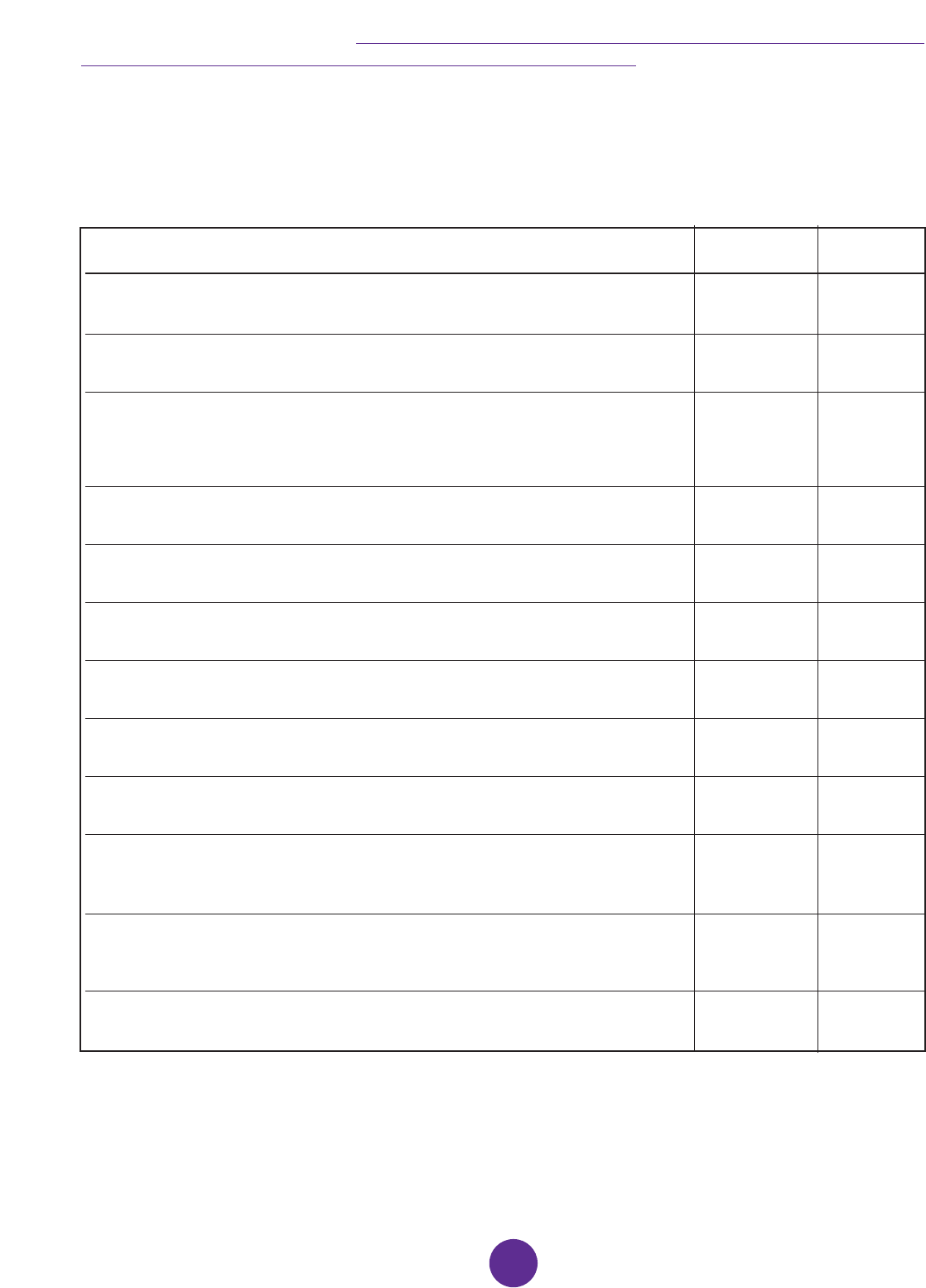

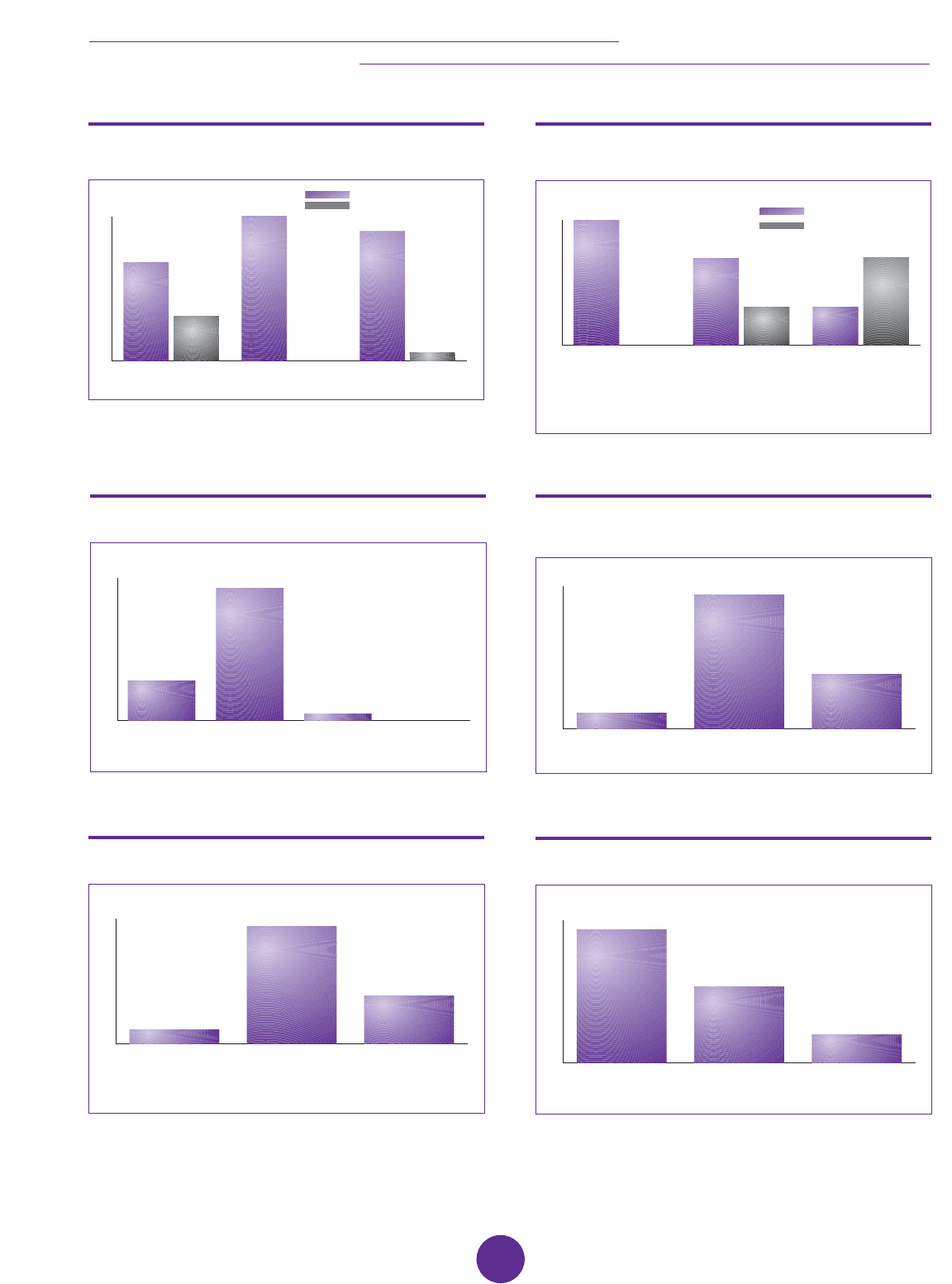

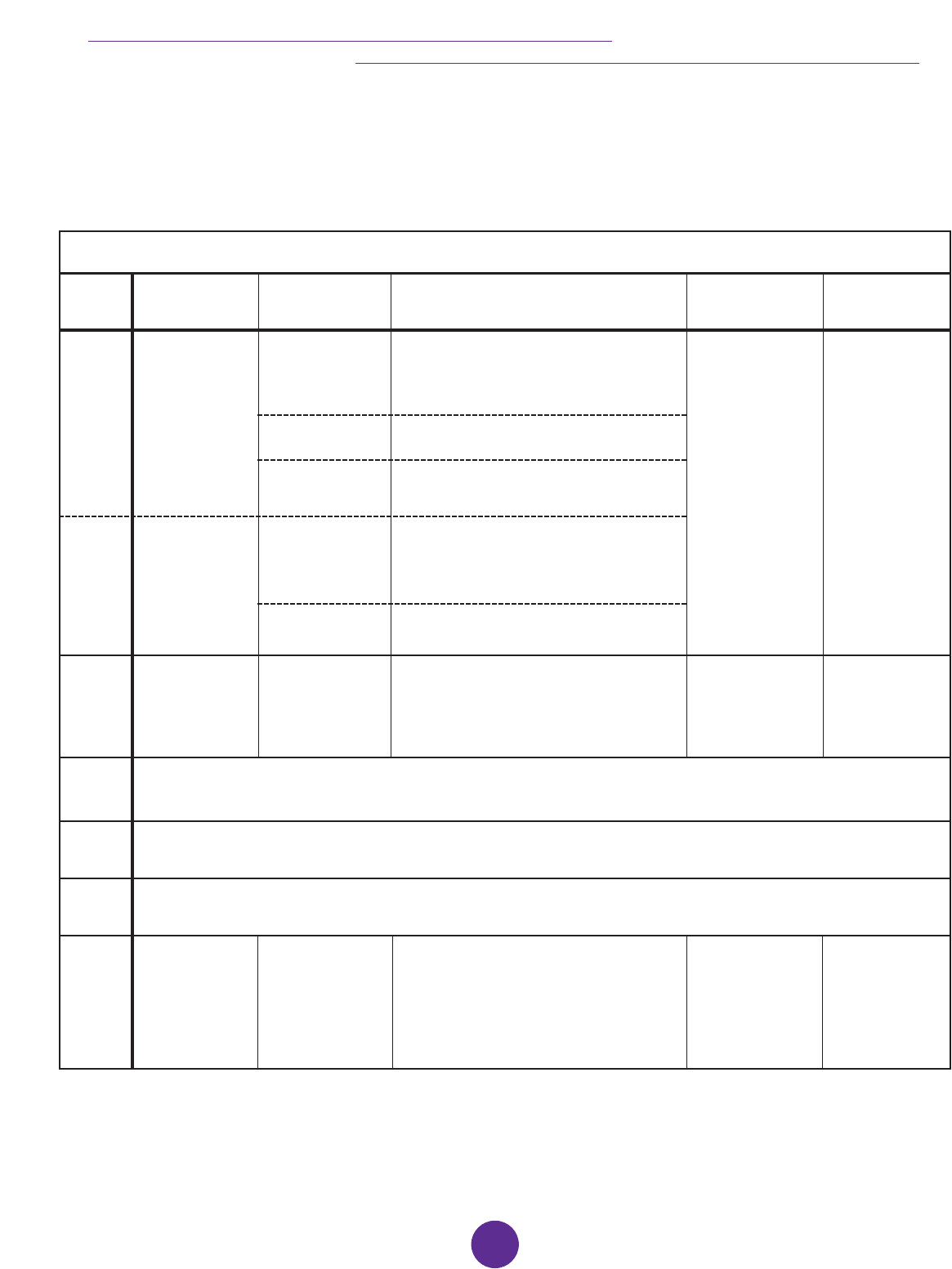

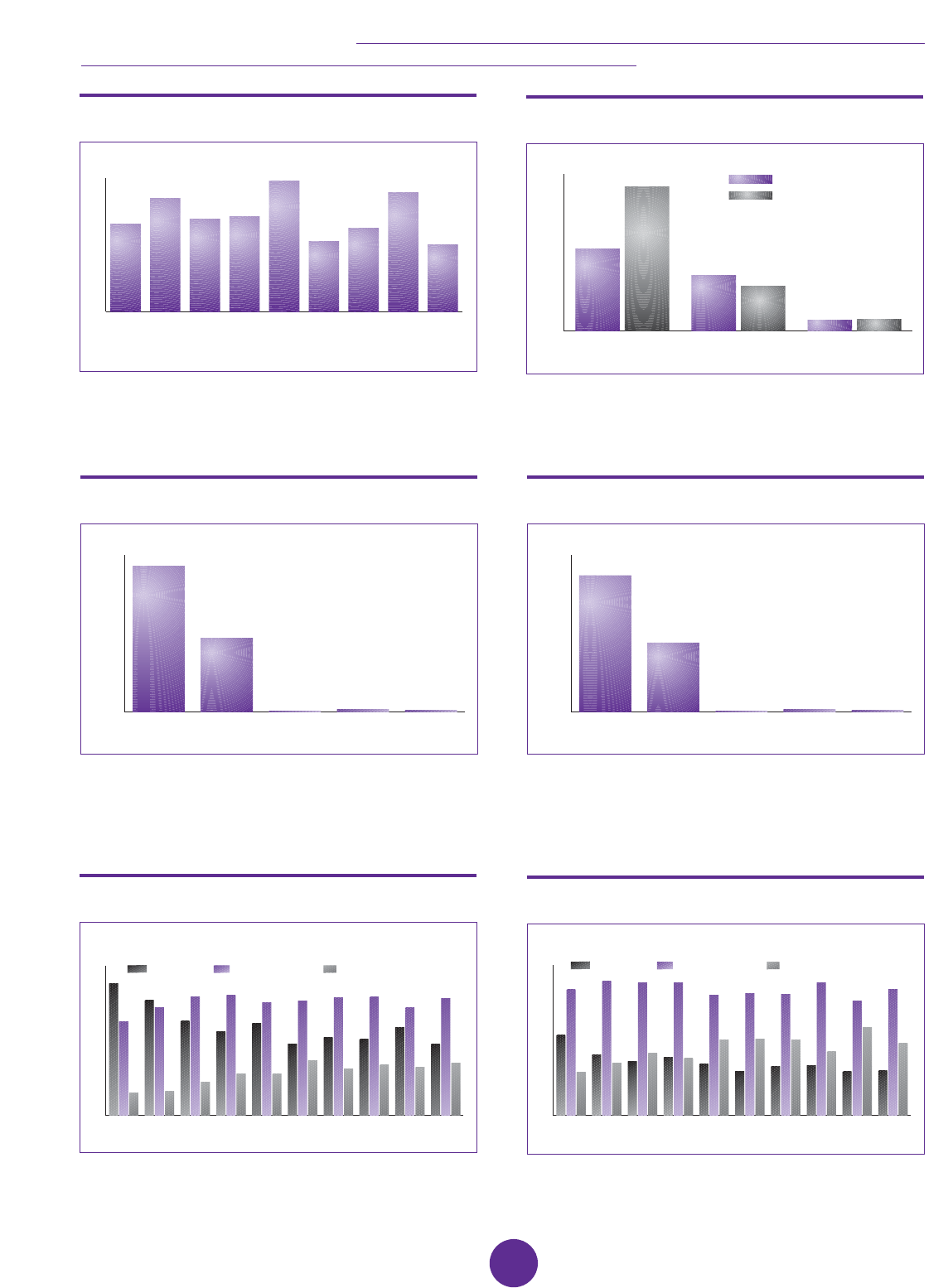

New Brunswickers offered the Commission their opinion on

these values. Voluntary respondents to the Commission’s

questionnaire cited fairness and accountability as their most

important democratic values. As can be seen below, other

values also received significant levels of support.

The importance of accountability as a fundamental

democratic value was reinforced in other responses. When

asked to consider which value was more important to a

strong democracy in New Brunswick, respondents chose

“an effective opposition” more than any other.

Applying Democratic Values to

Democratic Renewal

The Commission believes that it is necessary to address

democratic renewal through a consideration of democratic

values. This is not easy. Values are very personal. Each of

the above values therefore relates to our own personal

conception of democracy. But by considering which values

matter most to us as individual citizens, it helps us determine

more precisely what kinds of changes we need to bring to

our democratic institutions and practices.

Take the case of our electoral system. If fairness or equality

of votes in an electoral system is most important, for

example, then it would suggest a change from our present

single member plurality system which places more emphasis

on effectiveness and accountability. If voter choice rates

high for citizens, then a mixed member PR system allowing

voters to cast two votes, one for the local candidate of their

choice and one for the party of their choice, would likely

come out on top.

The Commission believes that all the democratic values

listed earlier matter, but it is clear to us that when it comes

to making choices about democratic renewal, some values

assume greater importance. Over the course of the past

year, and through our own research, consultation, and

deliberation, the Commission listened to what New

Brunswickers had to say about what was wrong, and what

was right, with our electoral system, the functioning of the

legislature, how decisions are made by government and

many other issues. With the broad mandate the Commission

was given to strengthen and modernize the institutions and

practices of our democracy, it was necessary to apply our

list of democratic values to each area of our mandate in

order to assess both the need for changes and arrive at

specific recommendations.

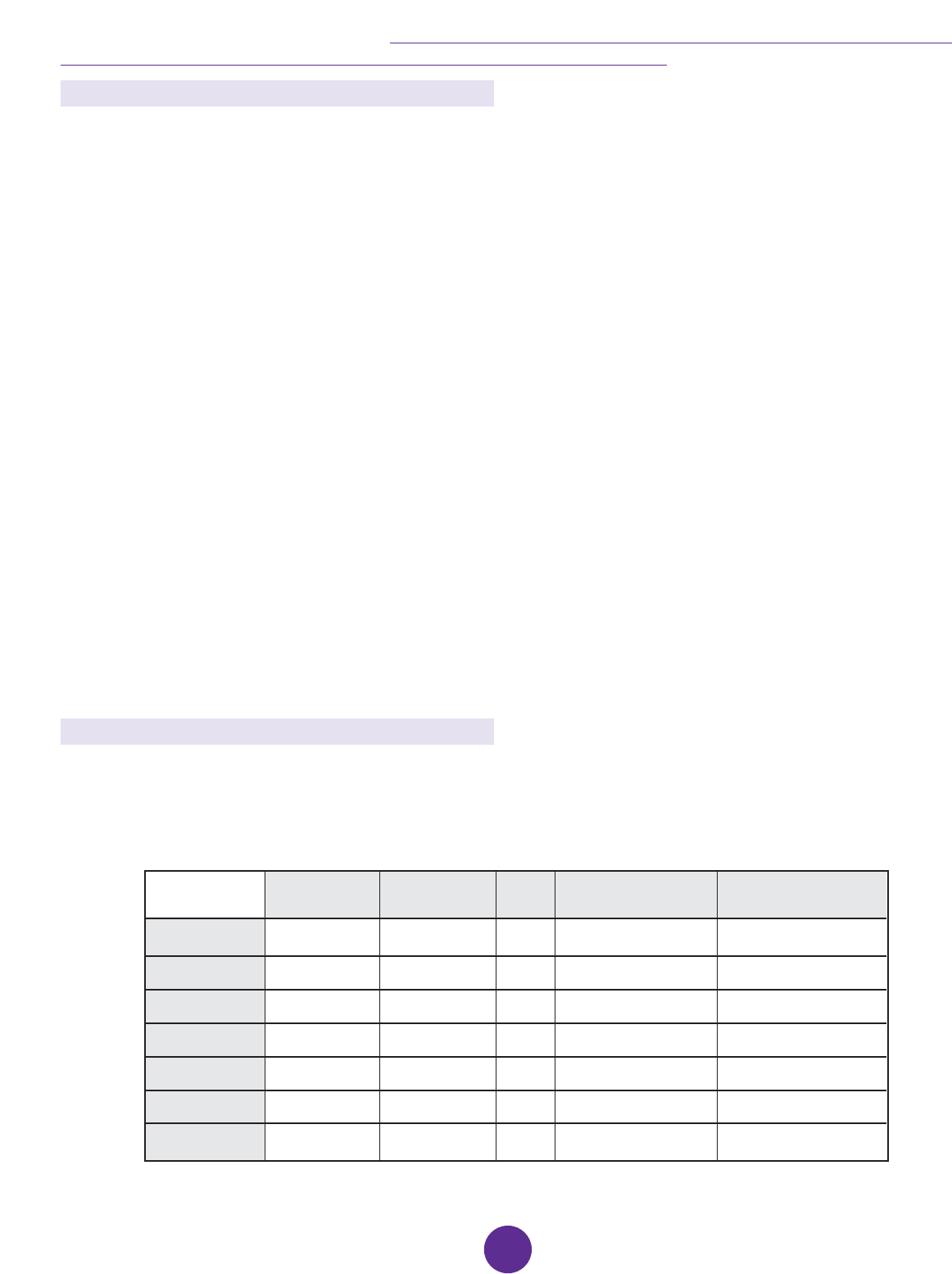

Unimportant

Not that important

Neutral

Somewhat important

Very important

Party seats vs

popular vote

Must win at

least 50%

Smaller party

representation

Strong majority

governments

More women

and minorities

elected

Effective

opposition

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Source: Commission on Legislative Democracy

How important are the following values to a strong

democracy in New Brunswick?

in per cent, based on an average of 277 respondents

Least important

Somewhat important

Most important

Fair Equal Representative Open Effective Accountable Inclusive Choice

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Source: Commission on Legislative Democracy

How important are the following democratic

values to a strong democracy in New Brunswick?

in per cent, based on an average of 276 respondents

Electoral Reform

It is clear to the Commission that the current single member

plurality electoral system is not meeting the democratic

values and needs of New Brunswickers. Fairness and

equality of the vote, which are central to democratic

satisfaction, must be given more weight when votes are

translated into seats. Fortunately, it is not necessary to

discard the values of effectiveness and accountability - key

benefits of our current system - when making a change. The

Commission’s made-in-New Brunswick, regional mixed-

member proportional representation system would continue

to produce effective single party majority governments while

maintaining the direct link between voters and their riding

MLA - a link that helps keep them accountable to voters.

The Commission believes that setting fixed election dates

will reinforce the value of accountability by ensuring that

elections take place at a regular time and date, well known

in advance to voters, rather than at the time and date

chosen by the Premier.

Electoral boundary drawing brings together a number of

different principles. The Commission’s proposed

Representation and Electoral Boundaries Act will ensure that

electoral boundaries in New Brunswick are drawn on the

basis of clear values of equality of votes, fairness to voters

and parties, and ensuring our legislature is representative of

people, communities, and the two official linguistic

communities.

Declining voter turnout is for many a barometer of a

growing and persistent sense of dissatisfaction and

disaffection with our democratic process. Steps being

recommended by the Commission to boost turnout, will lead

to a reinforcement of the values of inclusion and openness;

in particular, to bringing youth back into the process.

Legislative Reform

The Commission believes that its recommendations to

enhance the role of MLAs and the Legislative Assembly - by

reinforcing the independence of the legislature, giving more

authority and resources to MLAs, providing more effective

scrutiny of government - will help make the legislature more

open, effective, accountable, and representative of all

citizens.

Our recommendations for a new appointments process for

positions on government agencies, boards, and

commissions will make that process more open and

accountable to New Brunswickers.

Democratic Reform

More open and inclusive decision-making that involves the

participation of New Brunswickers is the focus of the

Commission’s recommendations in the area of democratic

reform.

The Commission’s proposed Referendum Act is a careful

and measured instrument to involve New Brunswickers in

decision-making. Allowing referendums on an exceptional

basis only with strict financial regulations about spending

and disclosure, as is being recommended, will ensure that

any referendum held in the province is fair, open, and

accountable, while giving voters a clear “yes” or “no”

choice.

Values and Choices

The Commission’s recommendations for a citizen-centred

democracy in our province are based on our New

Brunswick values. These democratic values helped guide the

Commission in its own choices and decisions. Ultimately,

these same values are the test for whether our current

democratic institutions and practices should be changed to

make them stronger for citizens, and how this should be

done.

Renewing the practice of democracy in our province is

essential for the long-term health of our democracy. Each of

us has a stake in the outcome - MLAs, political parties,

communities, and most of all, citizens. None, however, has

a veto on those outcomes, because to do so is to negate the

fundamental democratic values we all share. The

democratic values of New Brunswickers have made it clear

to this Commission what together we need to do.

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

9

COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE DEMOCRACY

10

Renewing Democracy in

New Brunswick - The Context

for Reform

There is a democratic disquiet in New Brunswick.

New Brunswickers are participating less and less in the

electoral process. Voter turnout is declining. New

Brunswickers have less confidence and trust in their political

leaders and institutions. Their attitudes towards government

are increasingly negative. Young people are less engaged

in the democratic process. Their knowledge levels of

democracy and how government works have diminished.

The tone of political discourse and debate has changed.

People are more demanding and expectant about actions

their elected and appointed officials are taking. They are

also more educated and discerning today about choices

their governments and political leaders make. People want

to be heard before decisions are made. They want

feedback on these decisions. And they want the opportunity

to make some decisions on their own that affect them and

their communities. In short, they are less deferential and

more critical towards institutions and traditions than before.

The face of New Brunswick society is changing. We are

more diverse and pluralistic. We are officially bilingual with

two official linguistic communities. Our urban centres are

growing. Information and communications technologies

have taken root, connecting people, governments, and

communities like never before.

As we have changed, so too have the issues facing

governments and legislatures. Issues and challenges have

become more complex and far-reaching. Decisions and

events taking place elsewhere around the world impact us

here at home more than ever before. Our democratic

institutions have less direct control and accountability over

major economic, social, and environmental issues.

New Brunswick has changed and New Brunswickers with it.

The system and practices we inherited from Britain and

adapted as Canadians more than a century and a quarter

ago, do not fully meet the contemporary needs and

aspirations of New Brunswickers. In fact, they remain quite

similar to their original design. While this has served us

well in many ways, certain democratic warning signs are

already apparent. One of our responsibilities as citizens is

to review our democratic institutions from time to time to

ensure they adequately reflect the contemporary values of

our society and the public policy needs of our province.

So, the question we must be asking ourselves is, “Do our

current democratic institutions and practices need to change

to better reflect the voices of New Brunswick, the values we

share, and the issues we must address?”

The Commission believes the answer is “yes”. We believe

the vast majority of New Brunswickers share our view.

Change is not an admission of failure or a sign of

disrespect. It is not a departure from tradition, but an

updating of tradition. The world of our parents,

grandparents and great-grandparents is vastly different from

ours of today. And the world of our children and

grandchildren will be different in turn. We must

acknowledge this reality and deal with it.

We can update our democracy without altering its basic

principles. We can modernize our democracy while

retaining the traditions that underpin it. The value of

democracy is not just what occurs, but how it occurs.

Democratic renewal is never wrong if it is undertaken by

citizens in a democratic way.

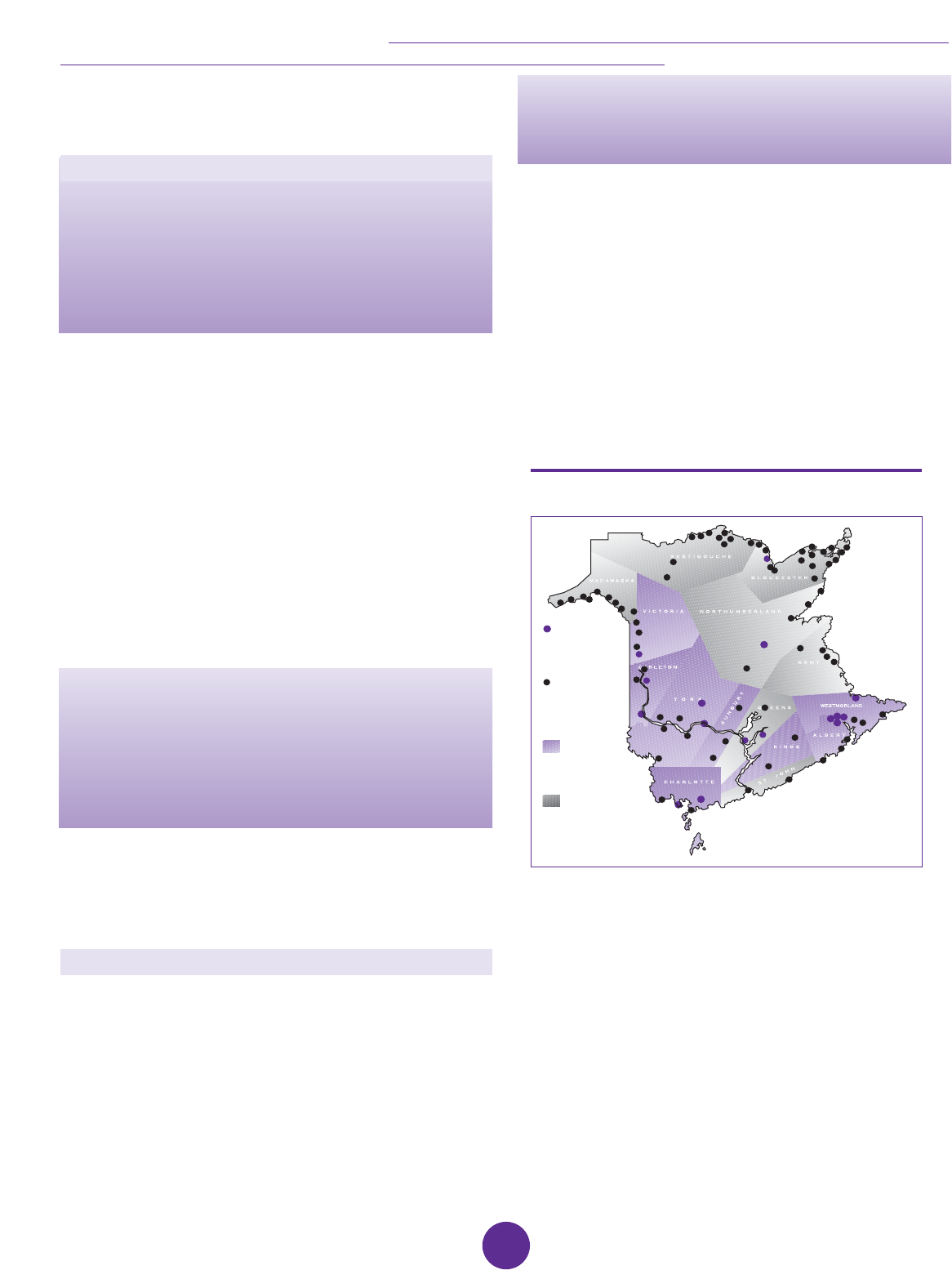

Declining Participation, Engagement and Trust

What is some of the evidence of this democratic disquiet?

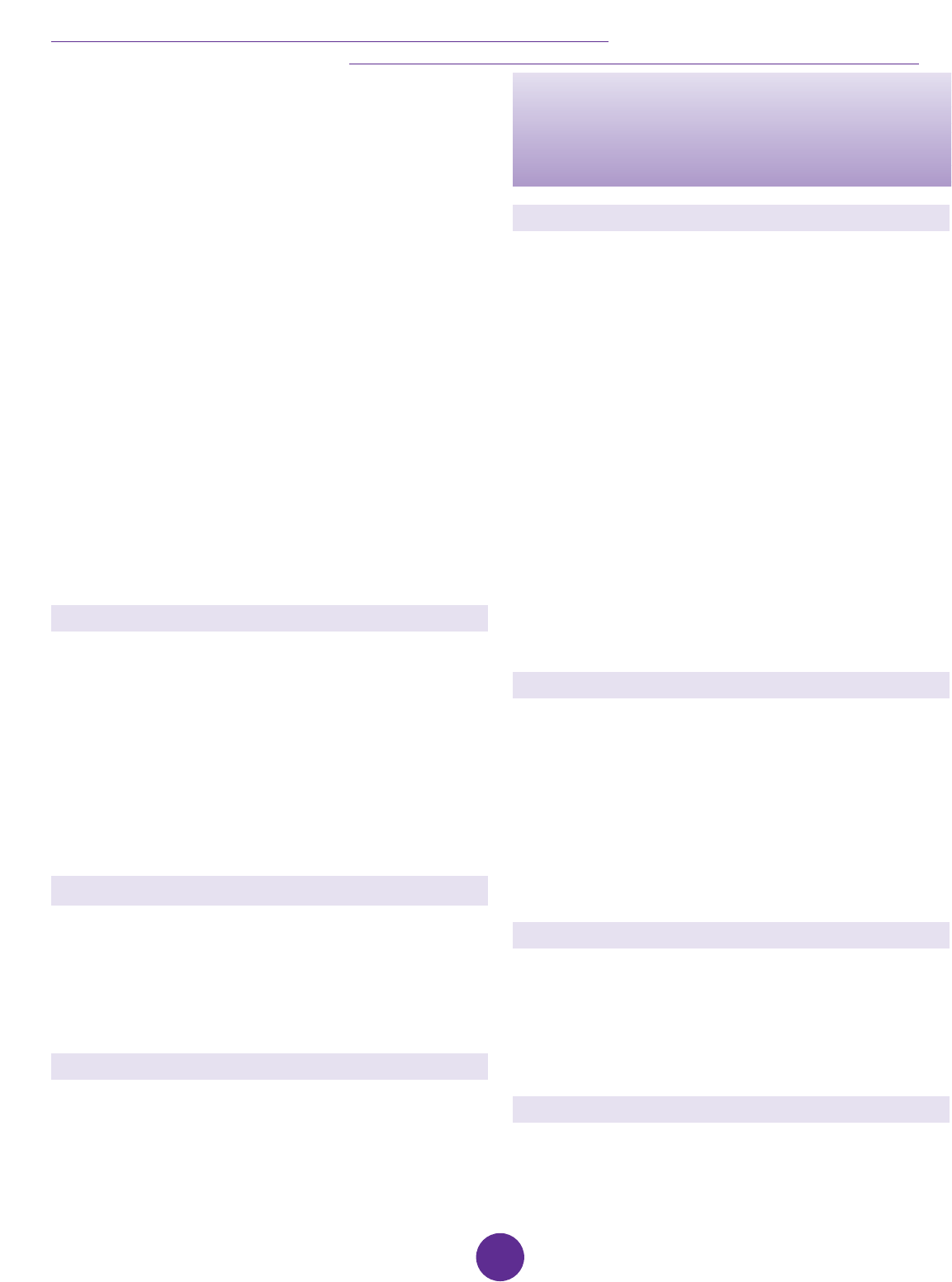

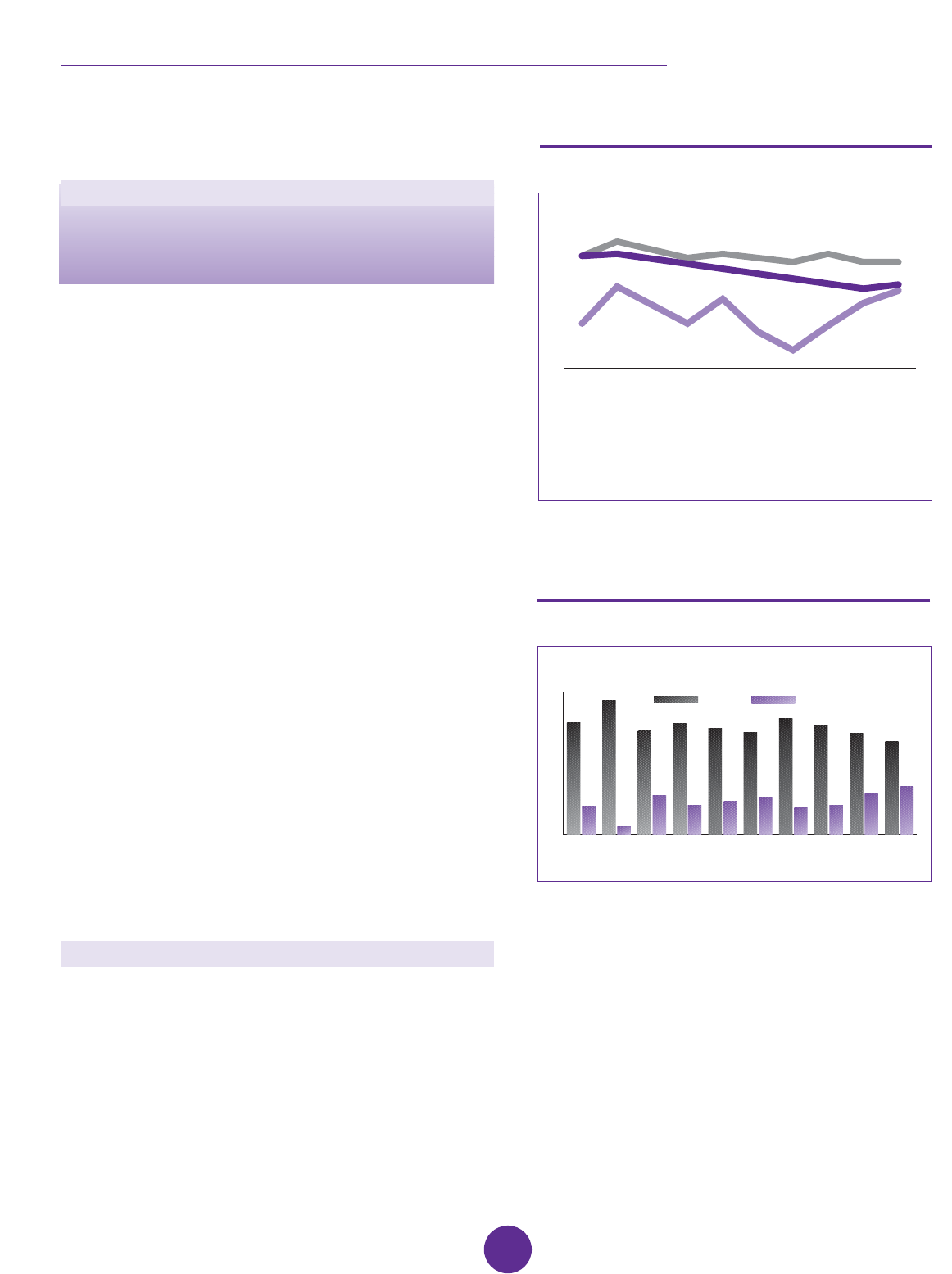

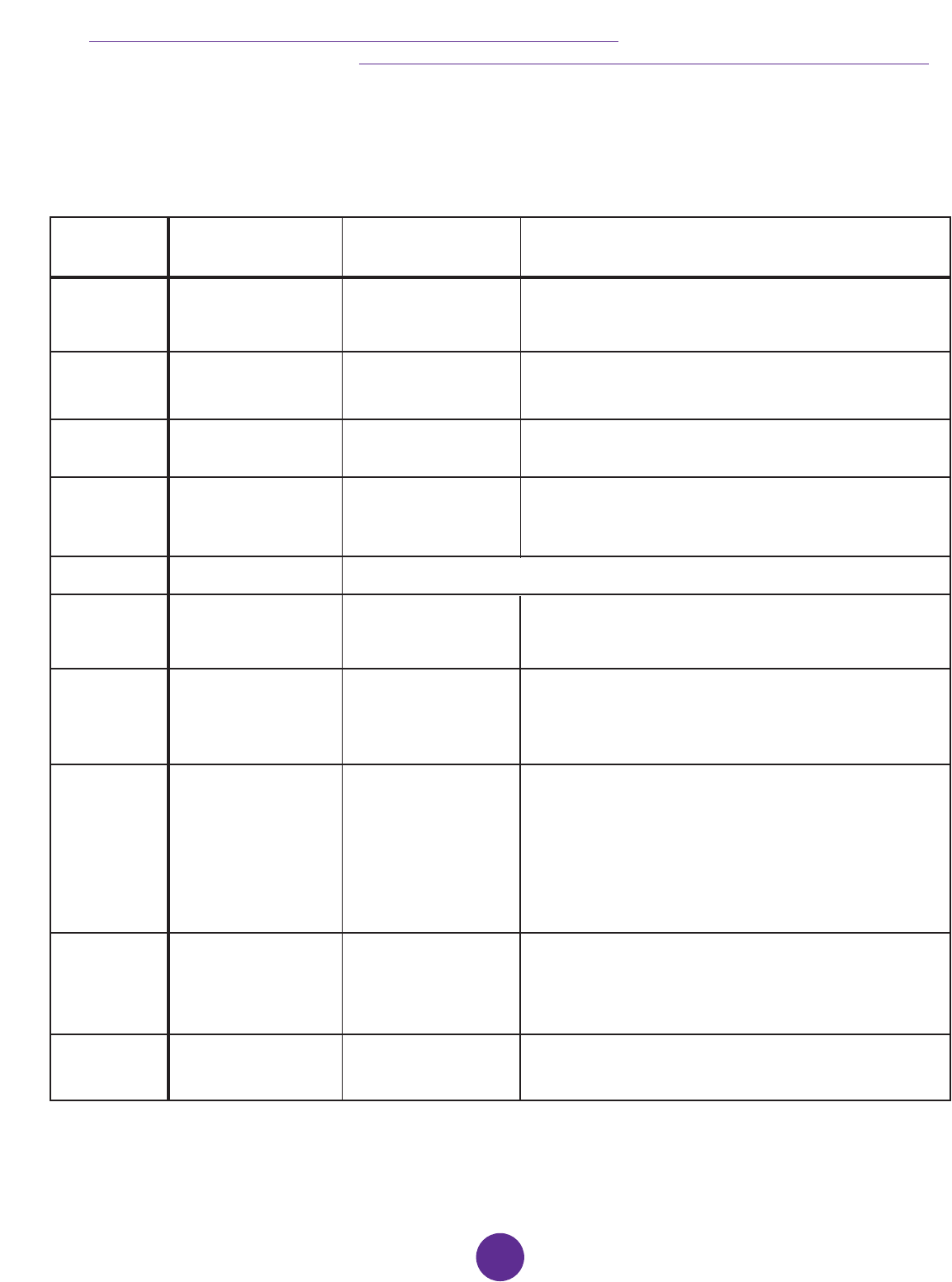

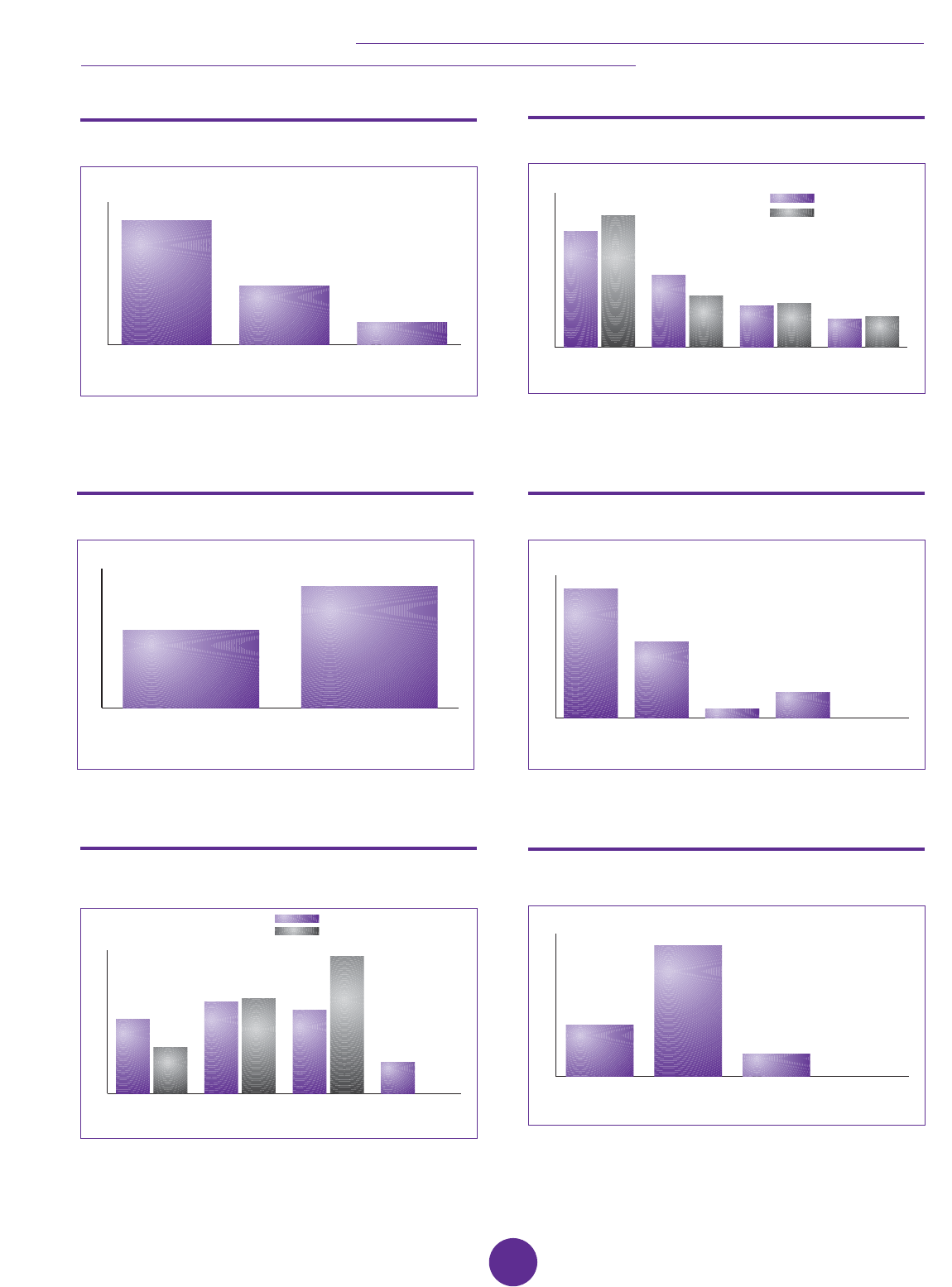

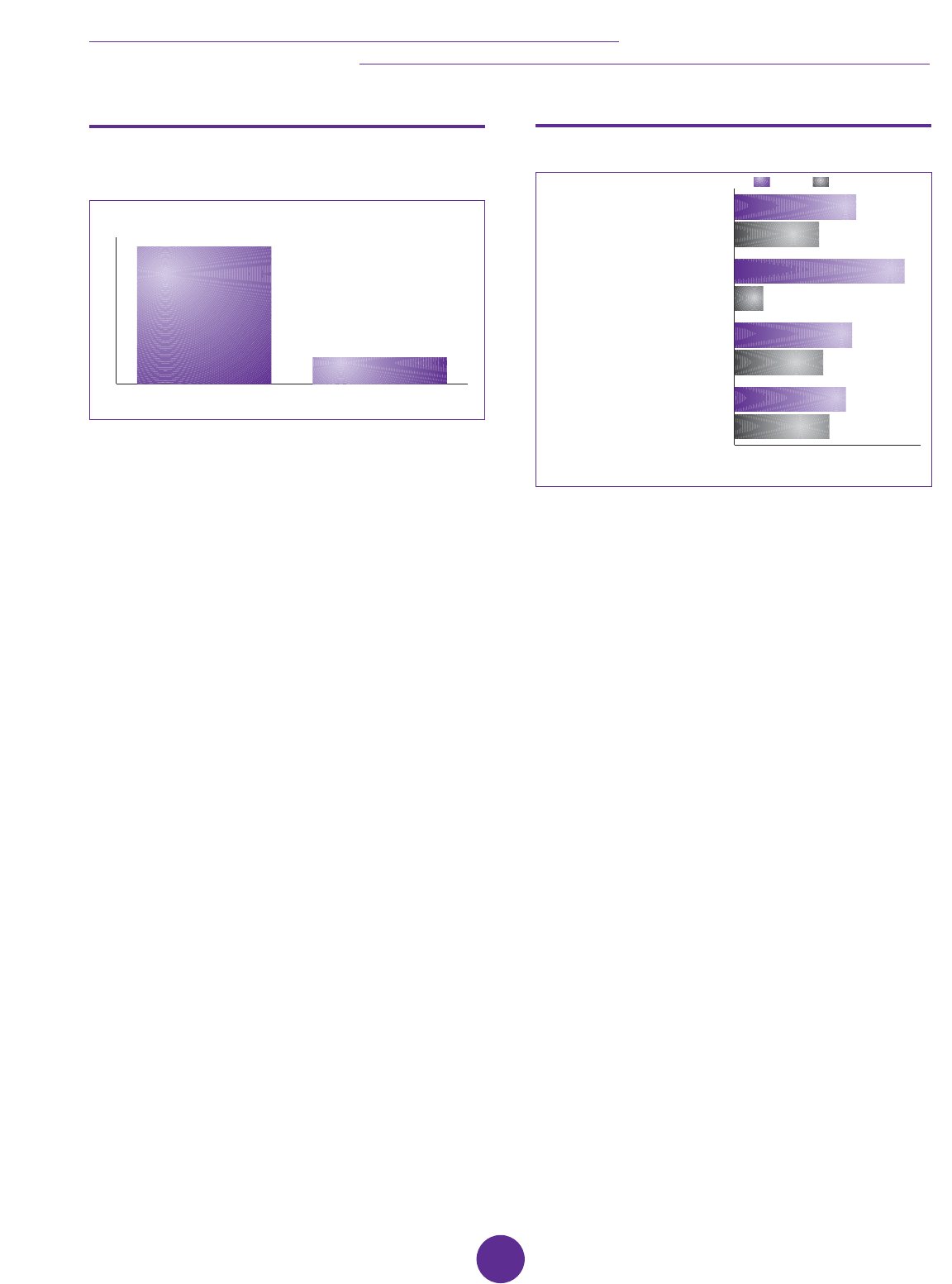

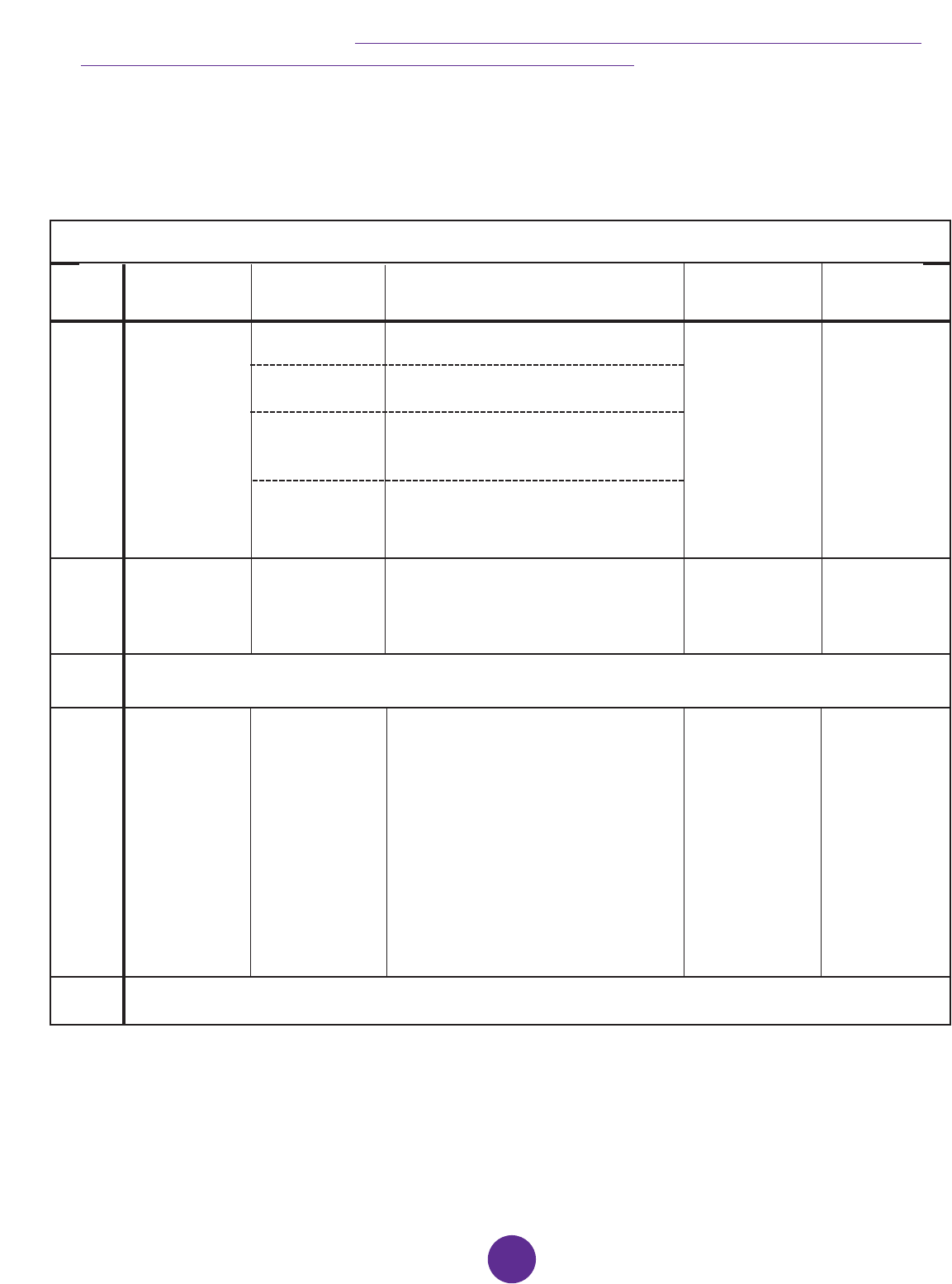

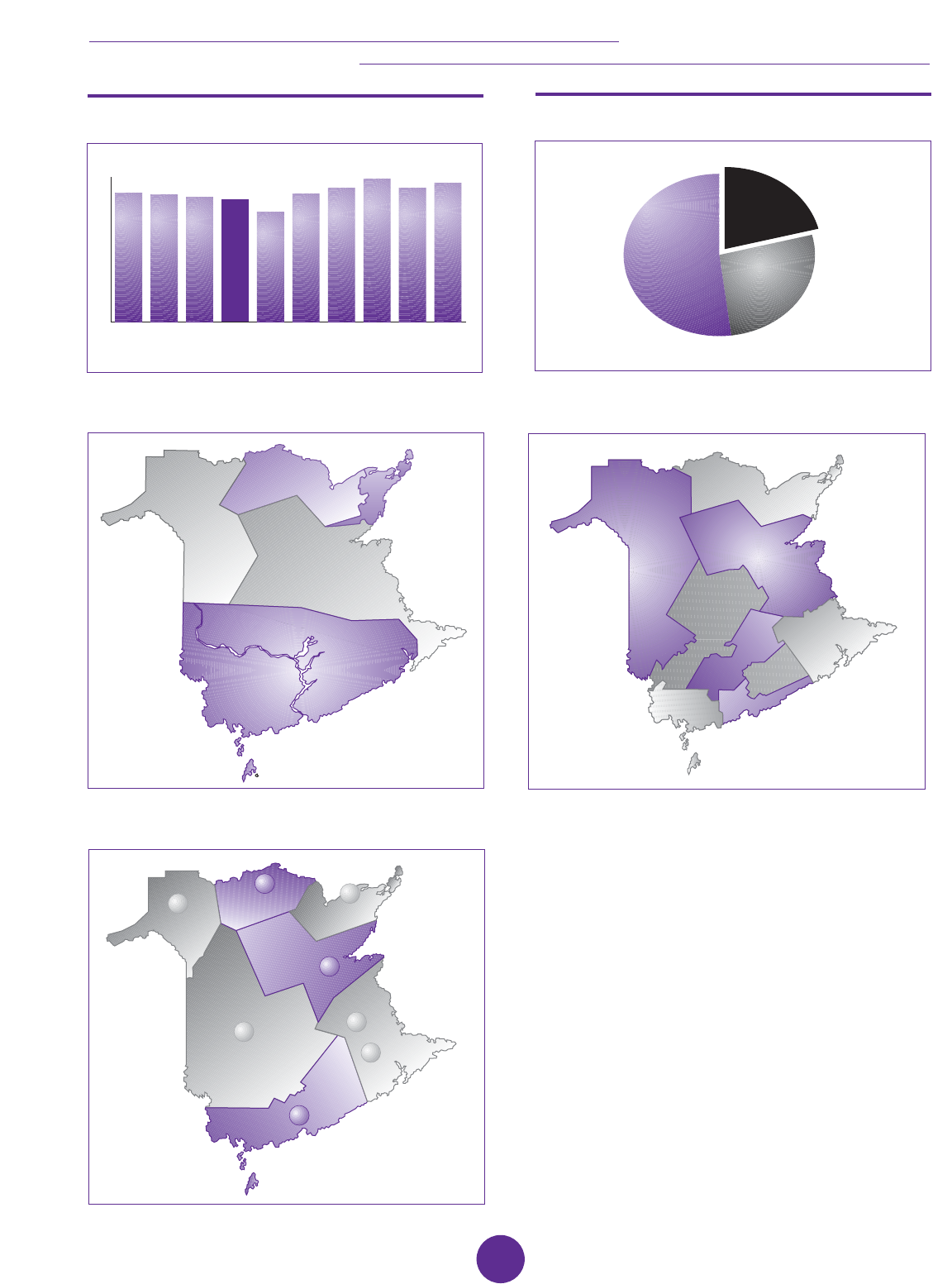

First, fewer New Brunswickers are voting. Turnout in the

2003 provincial election was the lowest ever recorded at

69 per cent. Unfortunately, this is just the lowest point in a

trend that has been developing for many years, as the chart

below indicates.

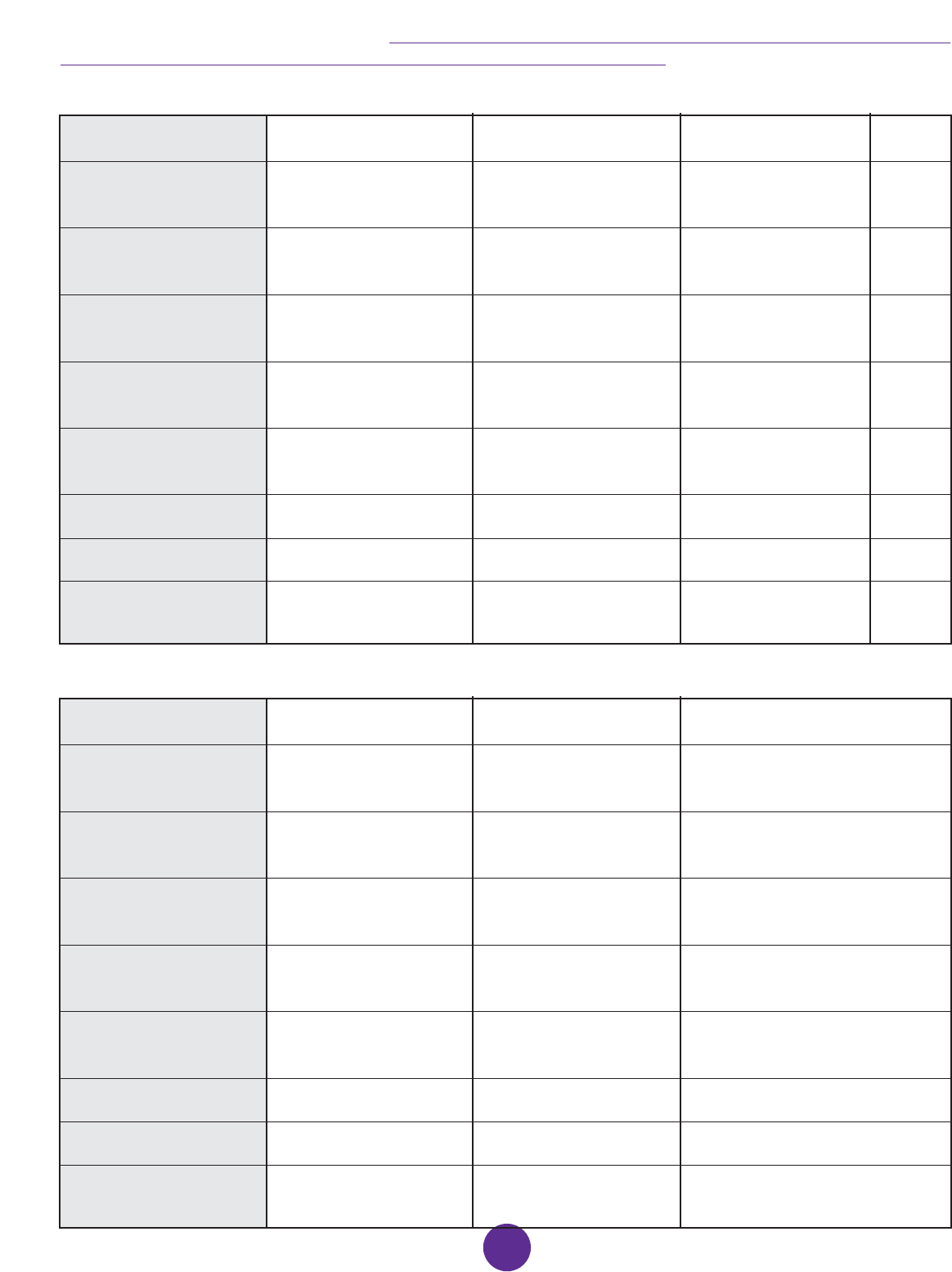

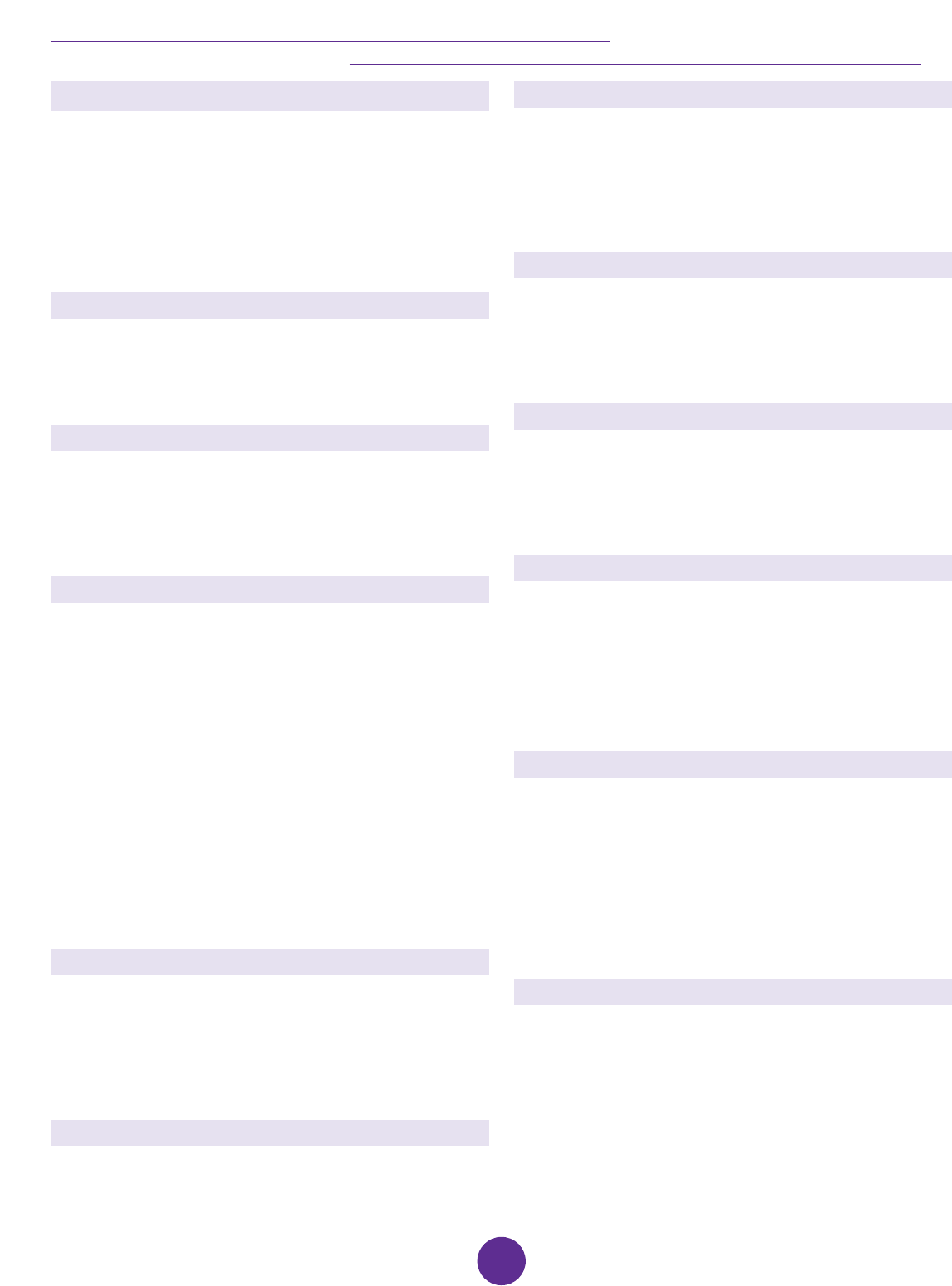

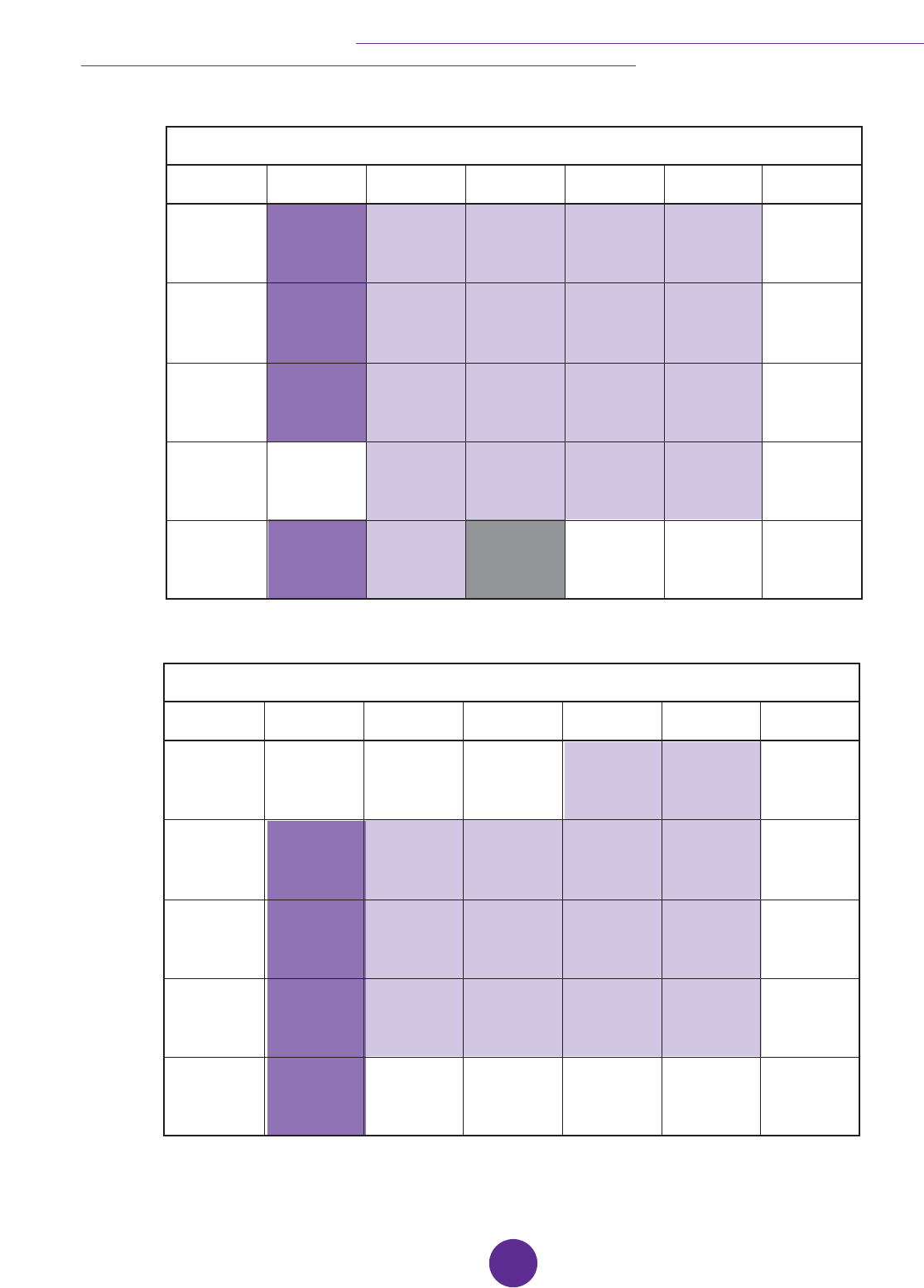

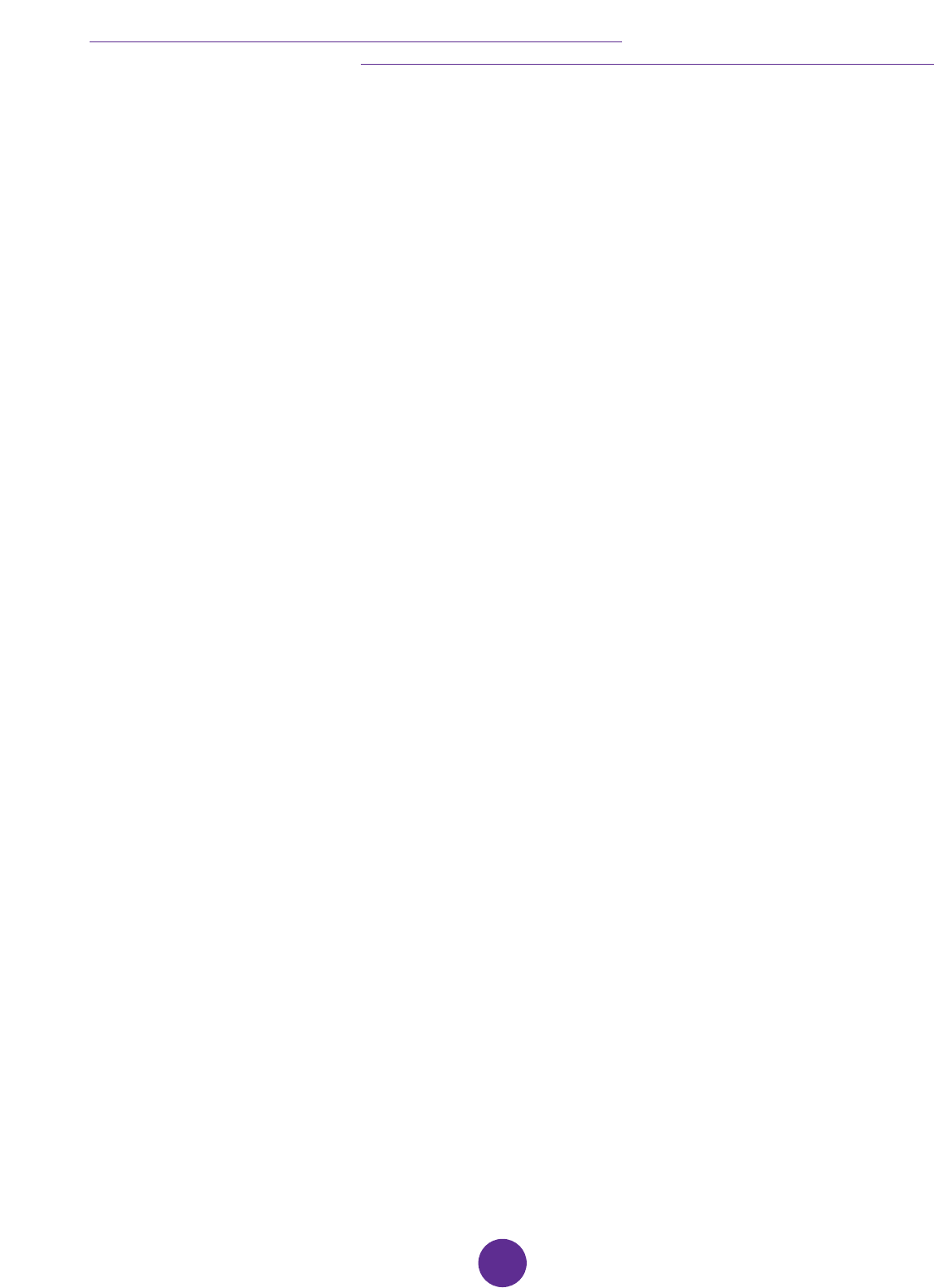

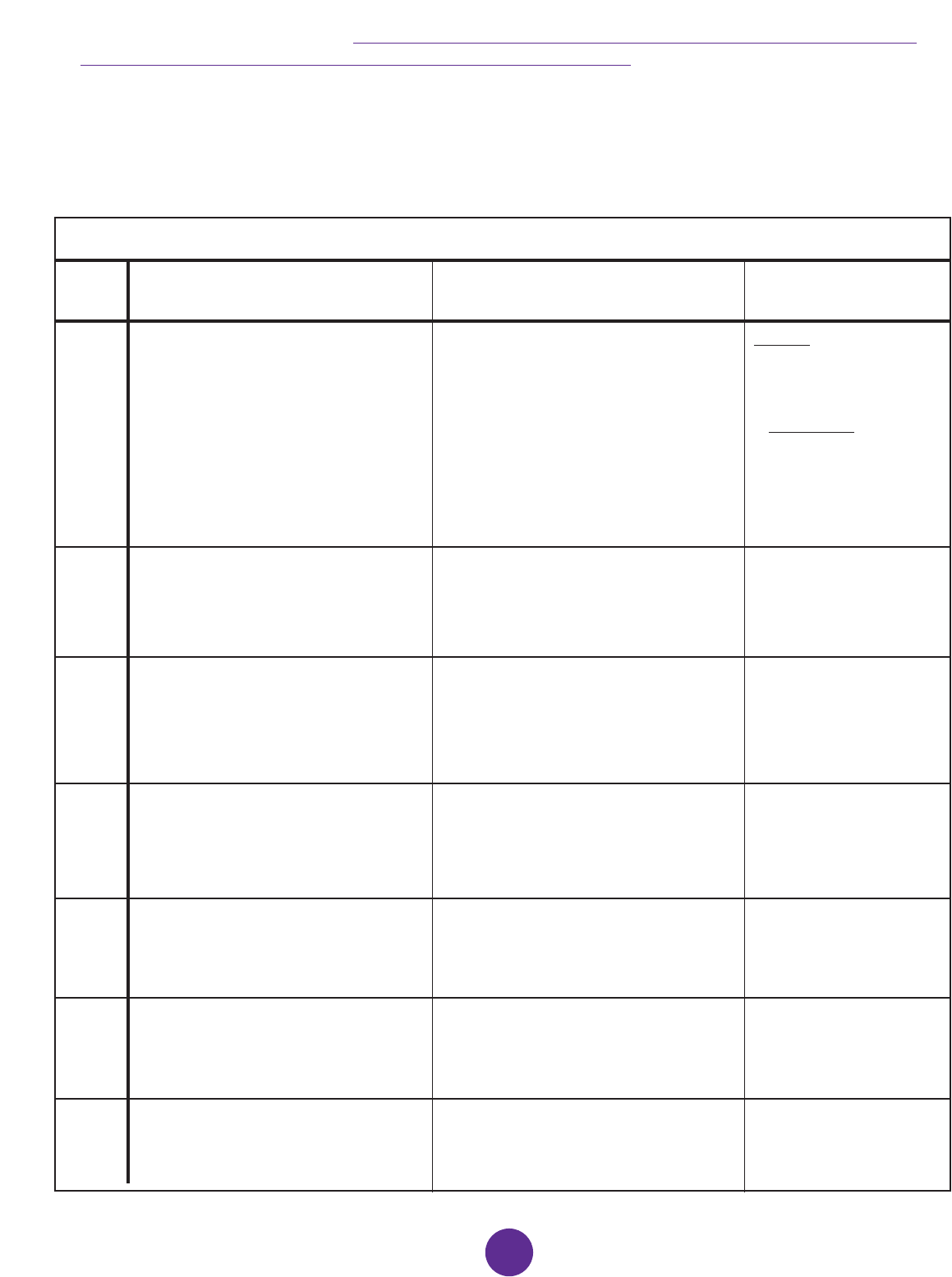

Second, New Brunswickers are not participating in other

democratic opportunities. Many elected positions for District

Education Councils and Regional Health Authorities went

unfilled during the most recent local governance elections,

as the chart below indicates.

60

65

70

75

80

85

Source: Office of the Chief Electoral Officer

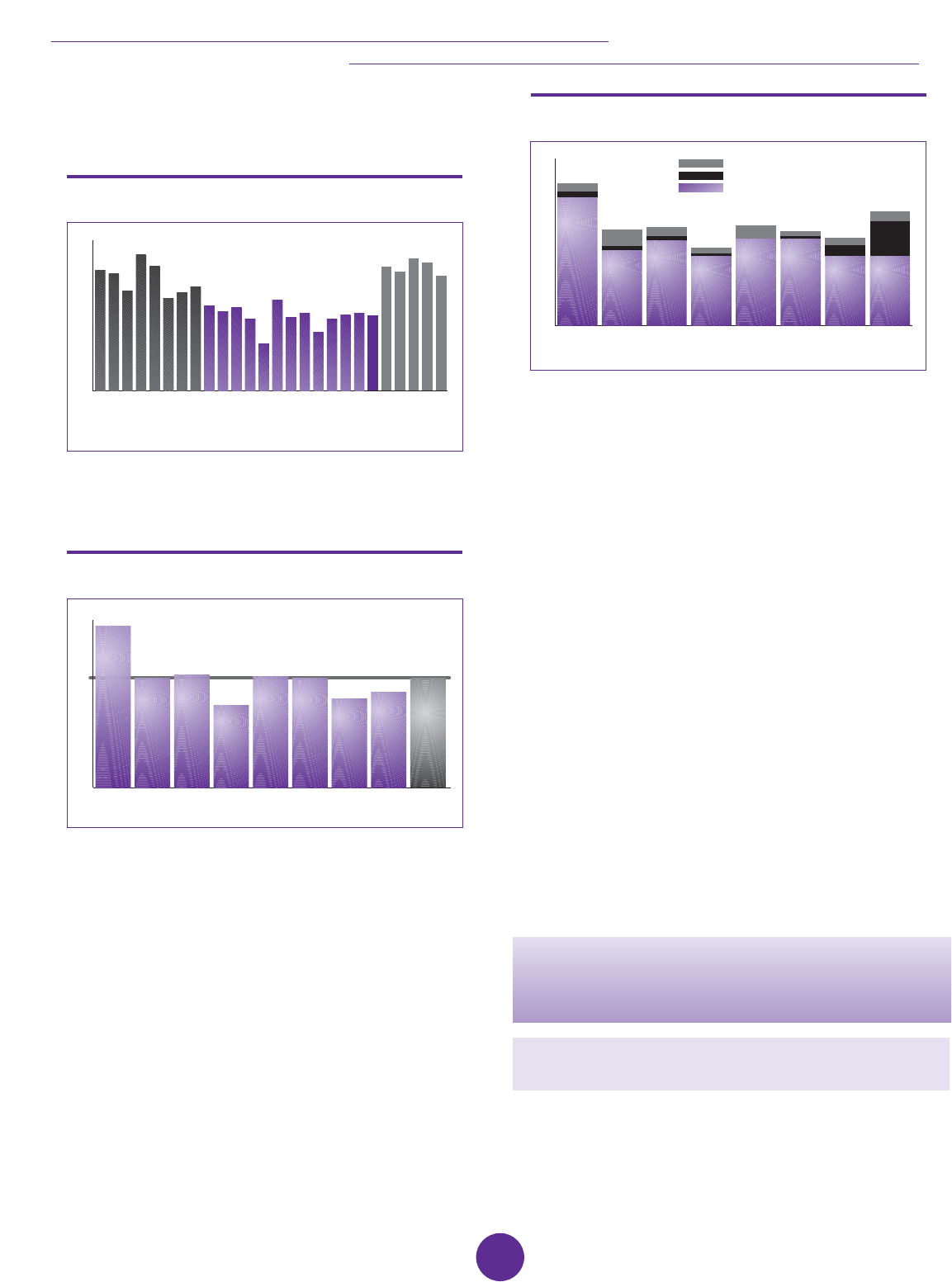

Percentage of voter turnout

Voter Turnout in New Brunswick Elections

1967 1970 1974 1978 1982 1987 1991 1995 1999 2003

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

11

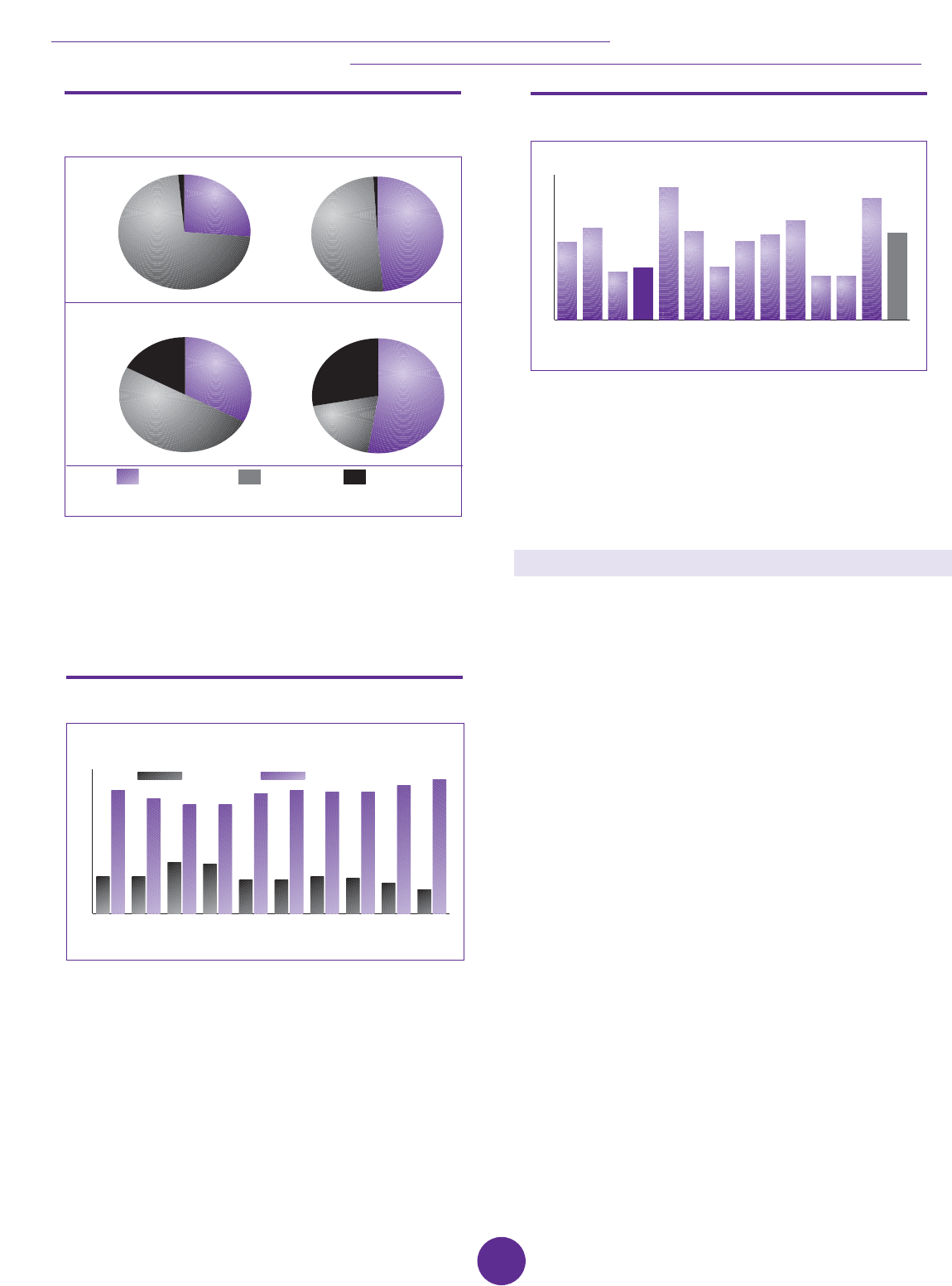

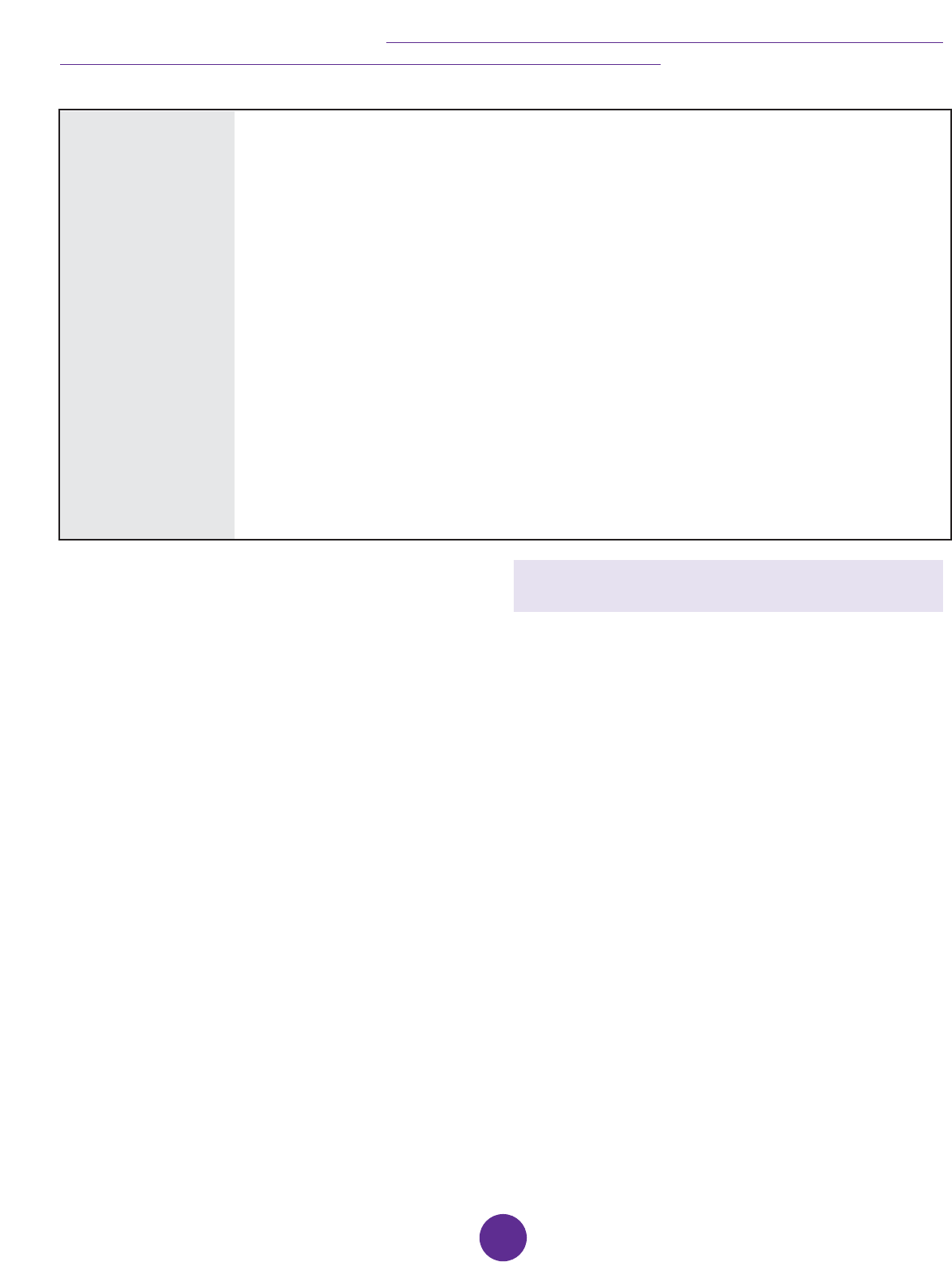

Third, New Brunswickers rate parties and their political

leaders low when it comes to honesty and being connected

to their concerns. Surveys conducted by the Centre for

Research and Information on Canada demonstrate this

below.

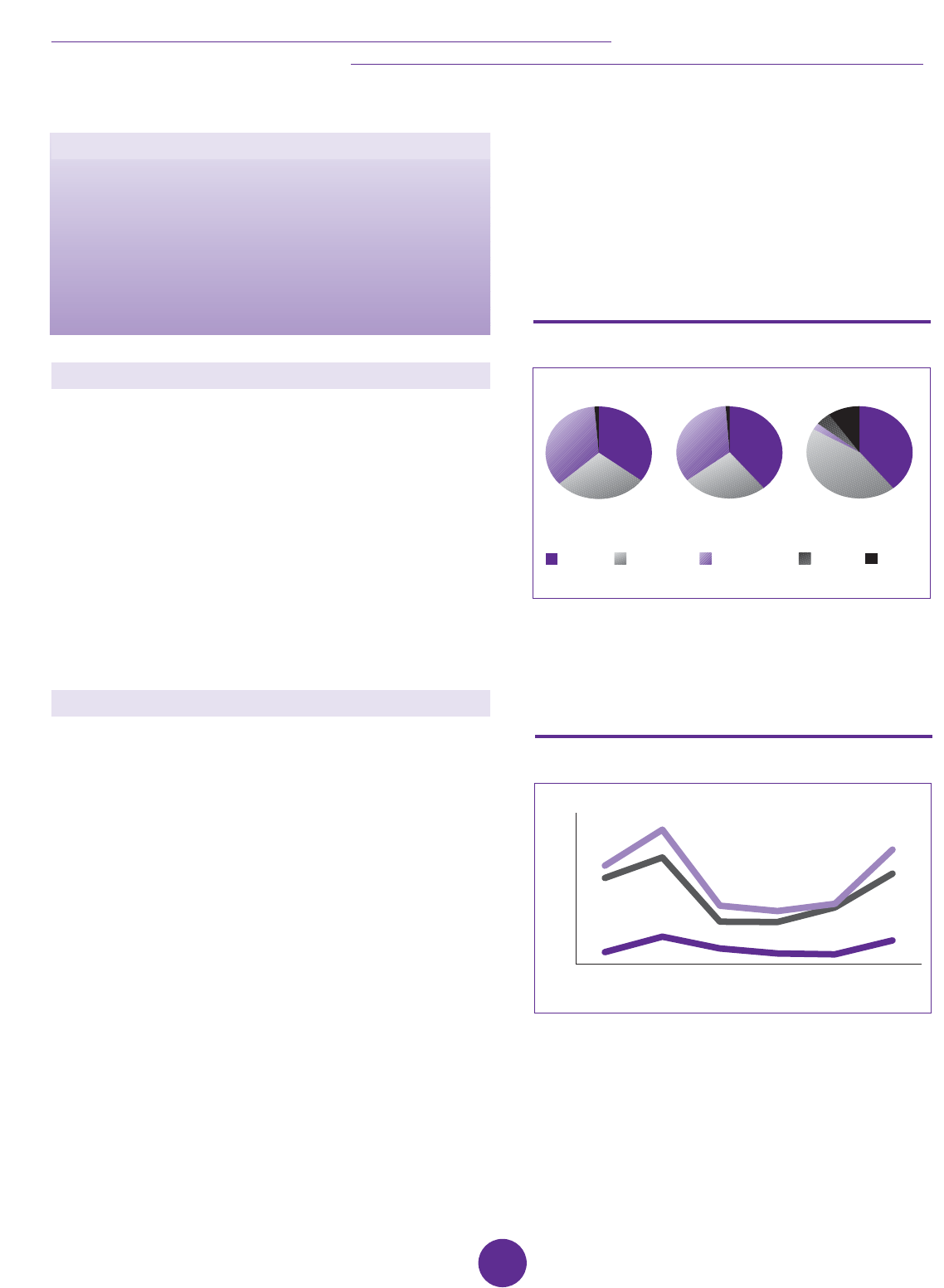

Fourth, there is a severe under representation of women in

the Legislative Assembly. New Brunswick is tied with

Manitoba among provinces as having the second-worst

results in electing women, as can be seen in the chart

below.

It is important to note that not just New Brunswick is

experiencing this phenomenon of political disengagement

and discontent. It is occurring in varying degrees across

Canada. But our challenge, as New Brunswickers, is to

determine what steps we can take to renew our own

democracy, on our own terms.

The Special Challenge of our Electoral System

Democratic renewal requires a special look at our electoral

system. An electoral, or voting system, translates votes into

seats. It is how we determine who will form our government

and who will represent us, as MLAs, in the legislature. Our

most basic democratic values - fairness, choice, equality,

accountability - come together on election night when the

votes are counted. A fair electoral system doesn’t just

produce a government; it produces legitimacy based on

consent. Citizens want to know that their votes count; that

their choices are reflected in the legislature and government.

In short, electoral systems affect citizens’ perception of their

democracy and their satisfaction with it.

New Brunswick’s single member plurality electoral system

(also known as first-past-the-post) has distinct advantages

and disadvantages. Its winner-take-all effect has produced

strong, effective majority governments. This same effect,

however, has produced weak official oppositions with fewer

seats and third party representation than would be awarded

under a more proportional electoral system. Between 1987

and 1999, for example, the opposition never won more

than 20 per cent of the seats in the legislature, despite the

combined opposition parties winning between 40 per cent

and 53 per cent of the vote during this same period. This

has produced an imbalance in our system affecting the

legislature’s ability to hold the government to account.

Original academic research conducted for the Commission

across 20 elections in 19 countries between 1996 and

2001, raises interesting questions about the linkage

between voter satisfaction with democracy and the choice

of electoral system. It shows that the degree of

disproportionality of the electoral system affects citizens’

Nfld. P.E.I. N.S. N.B. Que. Ont. Man. Sask. Alta. B.C. Nun.

N.W.T.

Yuk.

Can.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

Source: Research Centre on Women and Politics, University of Ottawa and

data from various Legislative Assembly websites

in per cent

Percentage of Women Elected to Provincial

Legislatures Across Canada – Last Elections

Contested

Vacant

Regional Health

Authorities

Councillors

Mayors

District

Education

Councils

Acclamation

Source: Office of the Chief Electoral Officer

Contested Positions

Municipal Elections, District Education Councils,

Regional Health Authorities - 2004 Elections

Low Rating

High Rating

Nfld. P.E.I. N.S. N.B. Que. Ont. Man. Sask. Alta. B.C.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Source: Environics Focus Canada / Canadian Opinion Research Archive,

Queen’s University, 2002

Honesty and Ethical Standards of Political Leaders

Generally, how would you rate the honesty and ethical standards of the following leaders

these days? Would you give them a very high rating, a high rating, a low rating, or a very

low rating for honesty and ethical standards?... Political Leaders

COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE DEMOCRACY

12

evaluations of fairness and responsiveness of their

democracy more generally. The more disproportional an

electoral system, the lower the evaluation of the fairness of

the election, the less satisfied people were, and the more

negative were their feelings about the responsiveness of

their elected officials. Changing to a form of proportional

representation could positively impact on New

Brunswickers’ satisfaction with, and participation in, their

democracy.

Electoral and Democratic Reform

Across Canada

It is for these reasons - declining turnout, trust, confidence,

and satisfaction - that several provinces across Canada are

examining their electoral systems and considering changing

to a form of proportional representation.

Following a year’s study, British Columbia’s Citizens’

Assembly is recommending a form of proportional

representation known as the Single Transferable Vote (STV).

This option will be put to voters in the form of a referendum

question on May 17, 2005.

Last year, a Prince Edward Island Commission

recommended adopting a form of proportional

representation known as mixed member proportional. The

government has recently announced its intention to hold a

plebiscite giving all Islanders the chance to vote on a new

electoral system.

The Government of Québec tabled in December 2004, a

bill in its National Assembly, which, if adopted, will change

that province’s electoral system to a mixed member

proportional system. This proposal has been developed

following a consultation process begun under the previous

government. The Minister for Reform of Democratic

Institutions has also released major proposals to reform the

rules and procedures of the National Assembly to enhance

the role of members and the legislative branch.

Ontario has indicated that it will be establishing a Citizens

Assembly within a year to consider whether to change its

voting system to a form of proportional representation. The

results will be put to the people in a referendum. The

Ontario government has established a Democratic Renewal

Secretariat with a minister responsible, to examine a range

of reforms including a fixed election date and political party

financing changes.

The federal government is also considering a public process

such as a Citizens Assembly to examine changing Canada’s

electoral system. This issue is now before a House of

Commons committee. Steps to increase the role of

Parliament and individual Members in policy formulation

and to make government more accountable to Parliament

have already been taken by the federal government.

The impetus for electoral change varies for each jurisdiction,

but all hinge on recent electoral results. In British Columbia

and Québec, there have been recent cases where a party

formed a government with a majority of seats but actually

received fewer votes than their main rival. This was also the

case in New Brunswick in 1974. In four of the past five

elections in PEI, the opposition never won more than five

per cent of the seats. For its part, the federal government is

responding to this wave of provincial reforms and its own

democratic deficit with an assessment of democratic

renewal initiatives.

Together, these reform initiatives indicate that there is a

growing consensus that we must at least consider changing

our electoral system to address the broad-based democratic

discontent felt by many Canadians. Each province is

conducting its examination somewhat differently, but all are

considering a form of proportional representation best

suited to their circumstances as a possible solution. This

indicates that our Commission and province are actually in

the mainstream of Canadian thinking, perhaps even leading

it, when it comes to electoral reform.

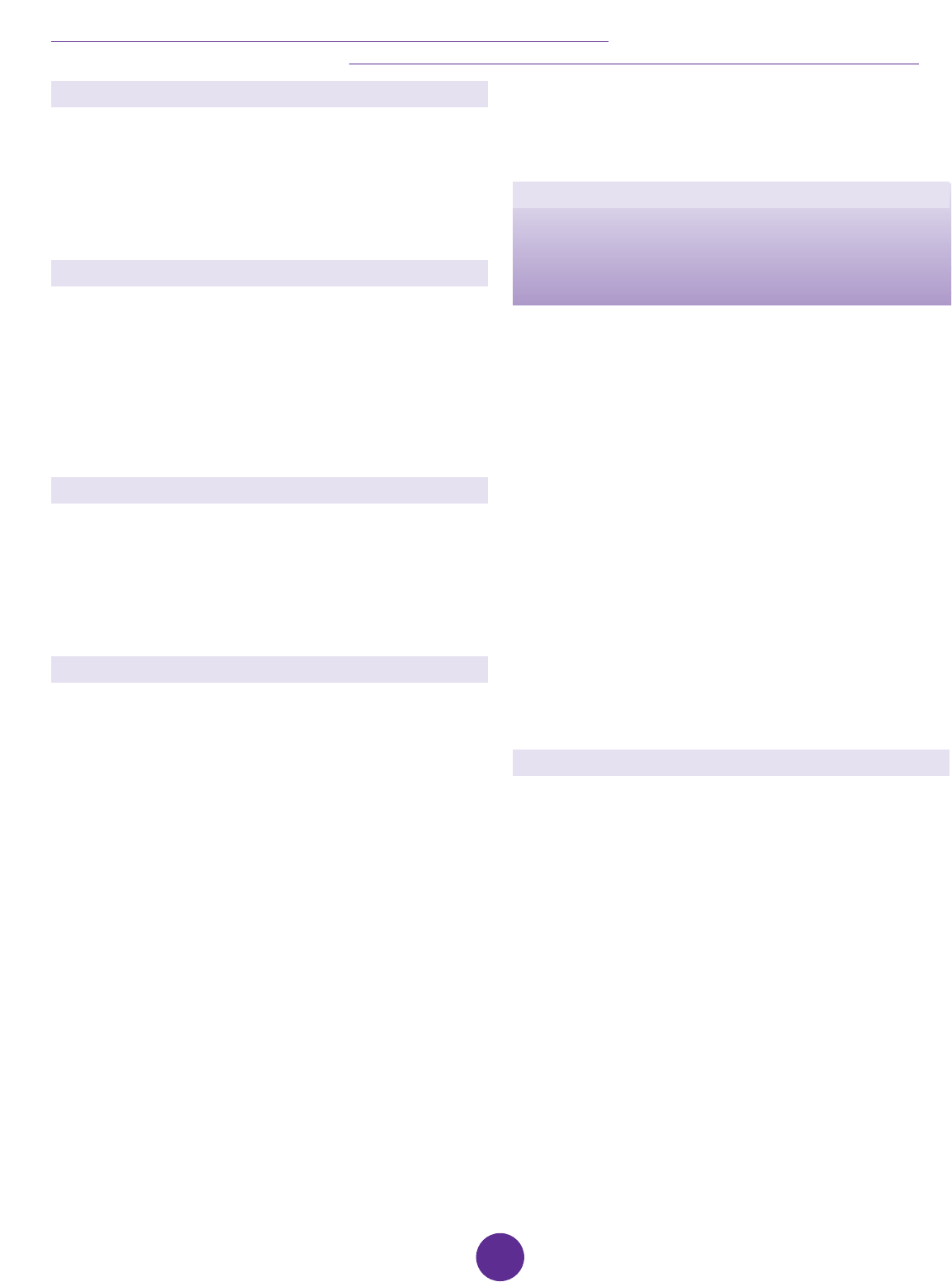

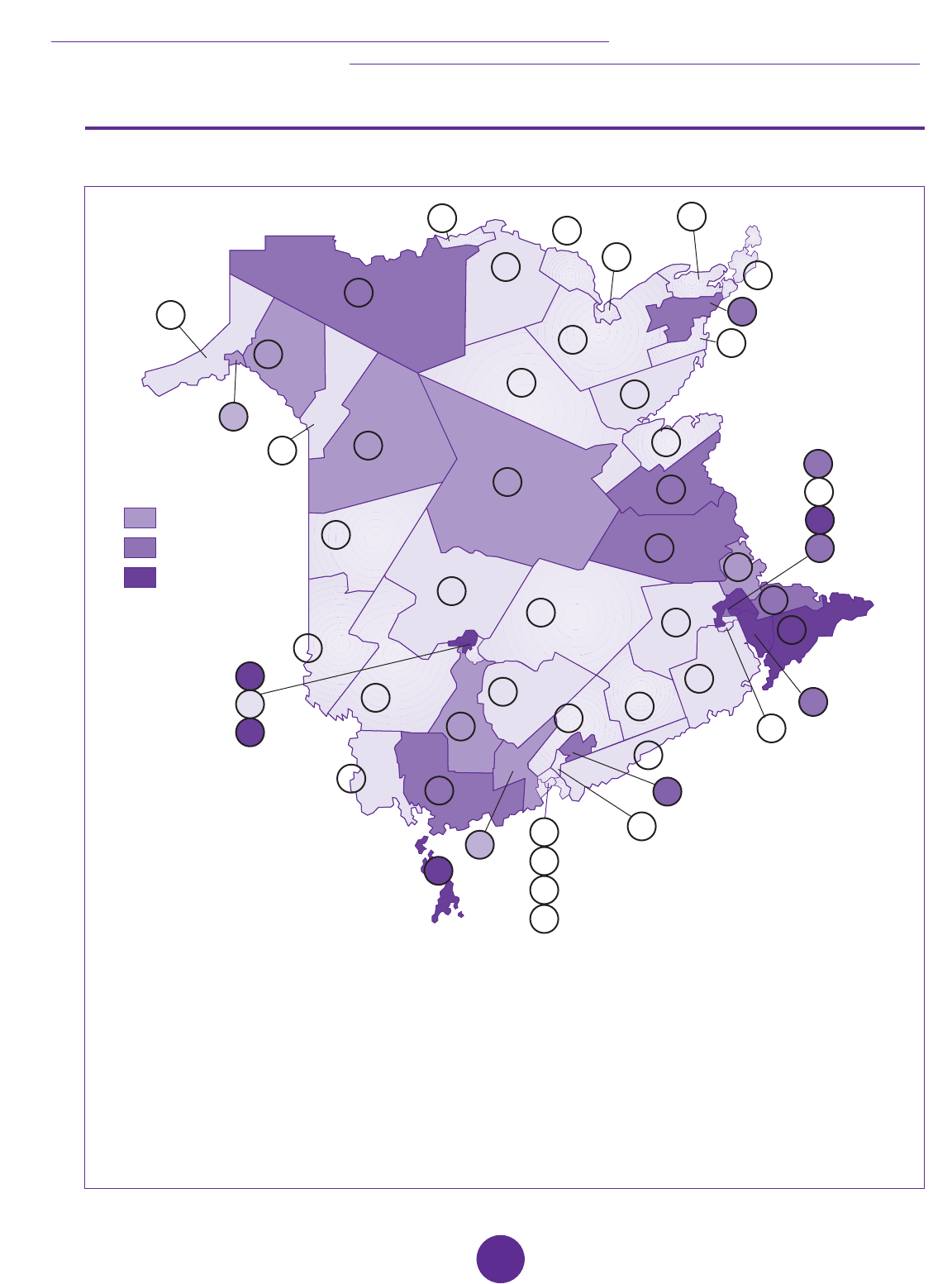

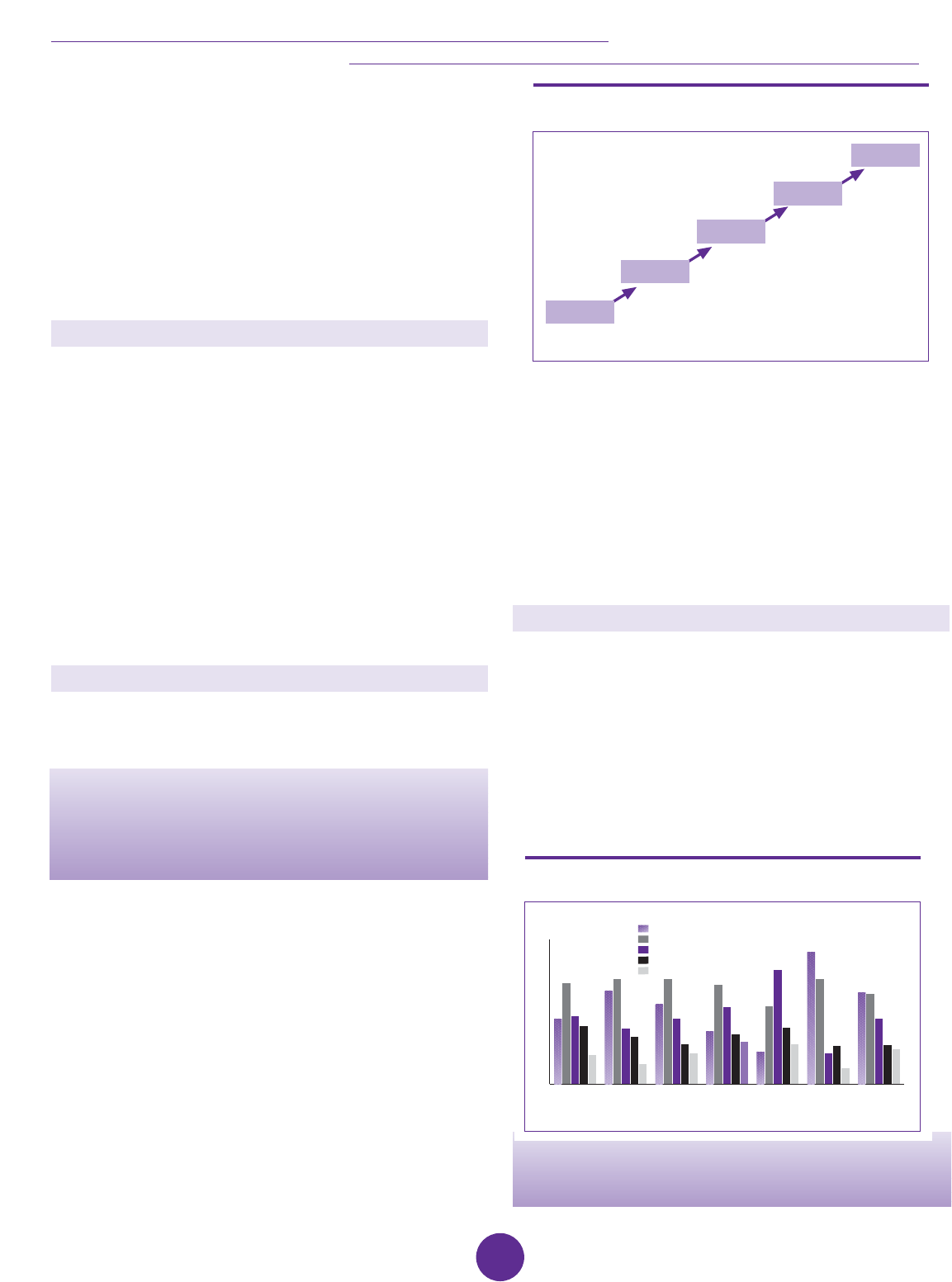

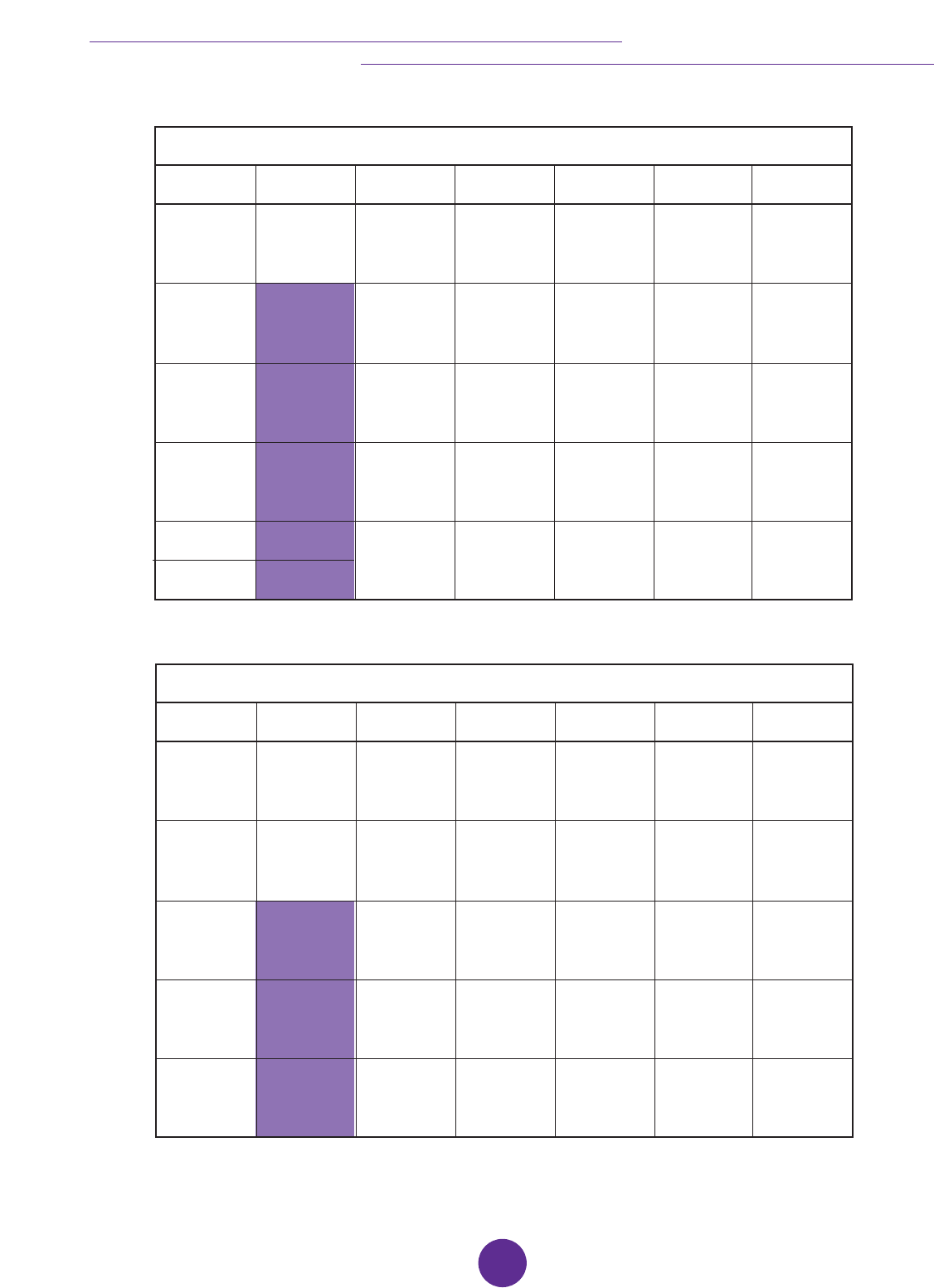

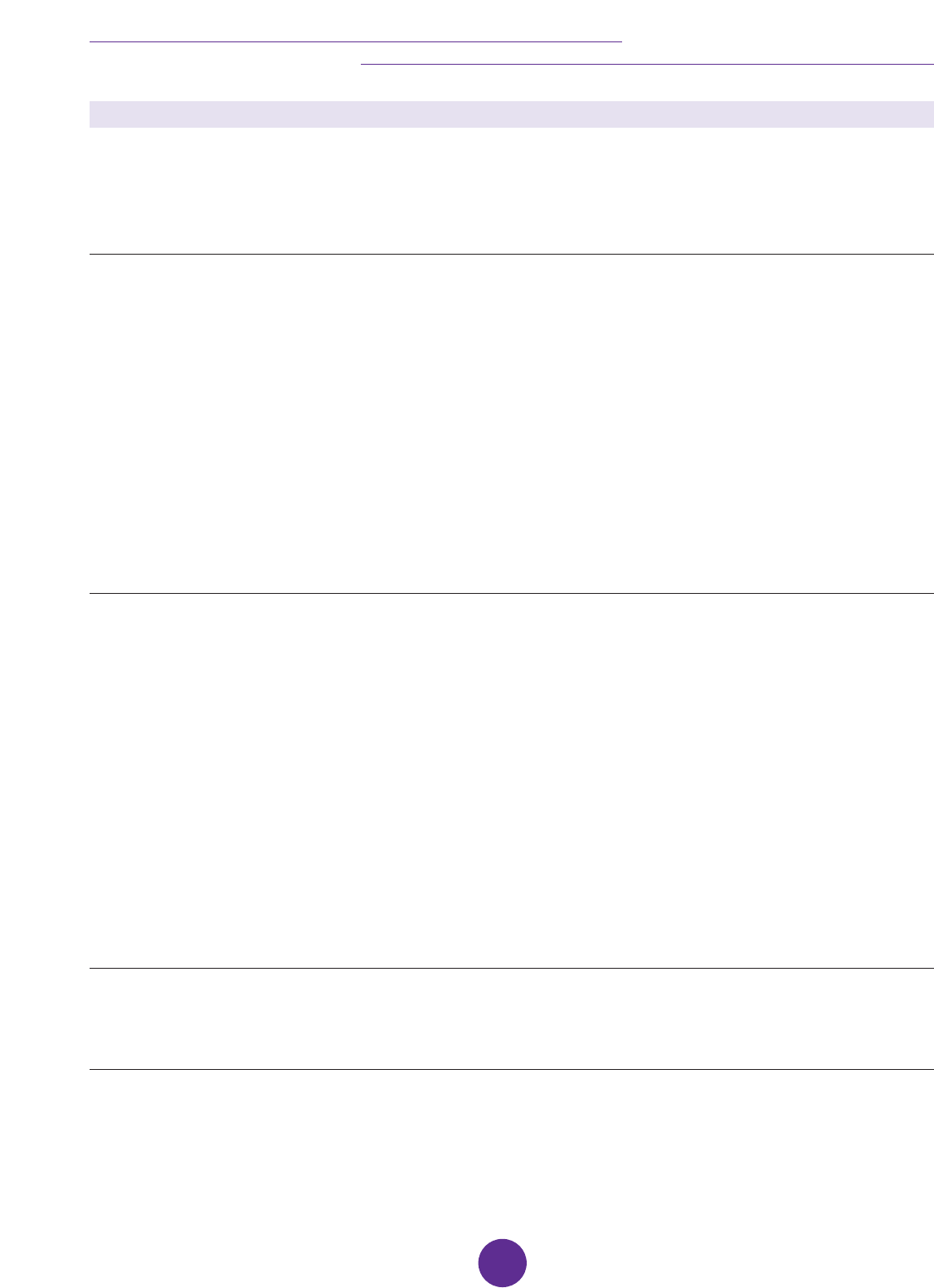

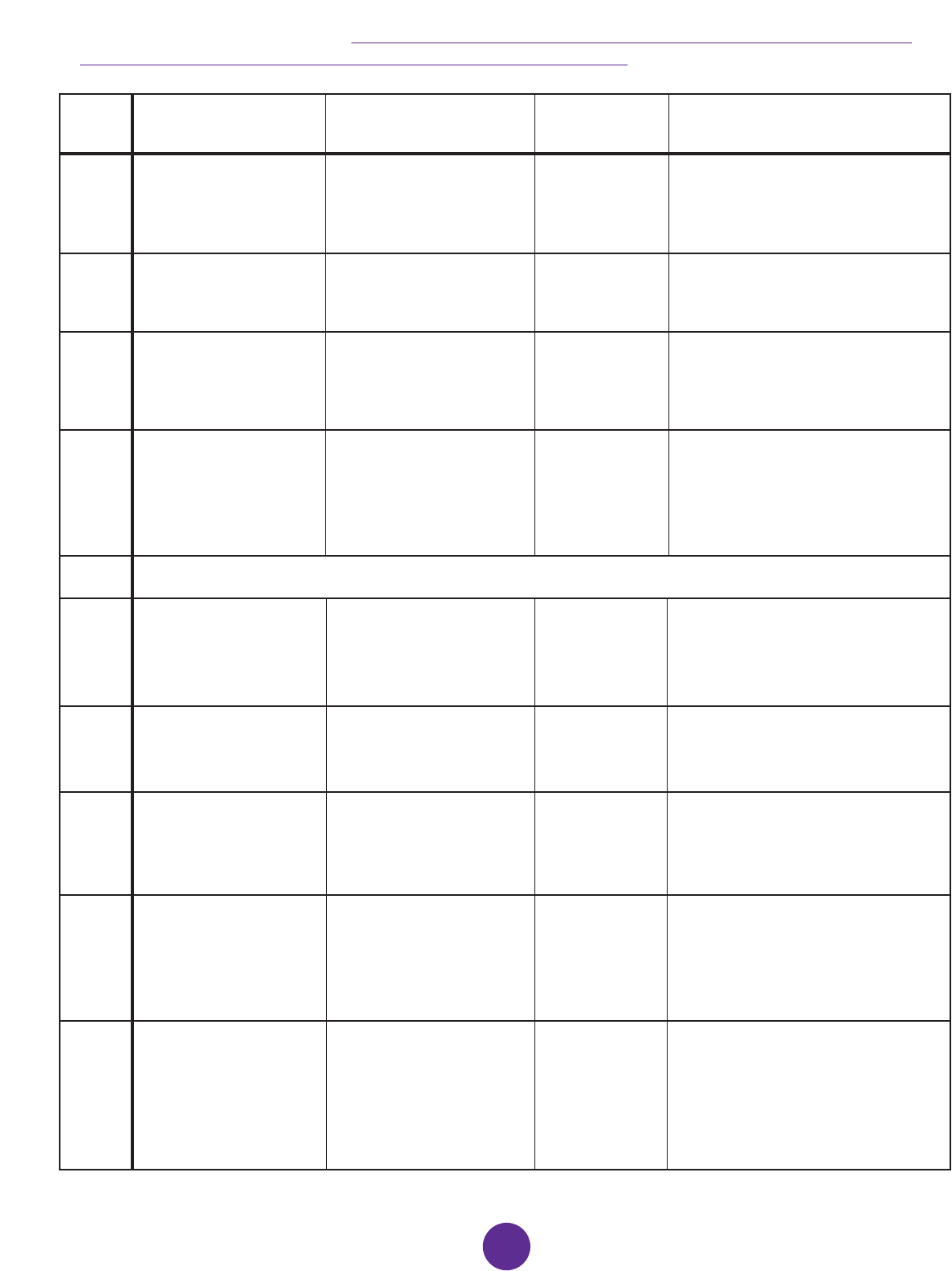

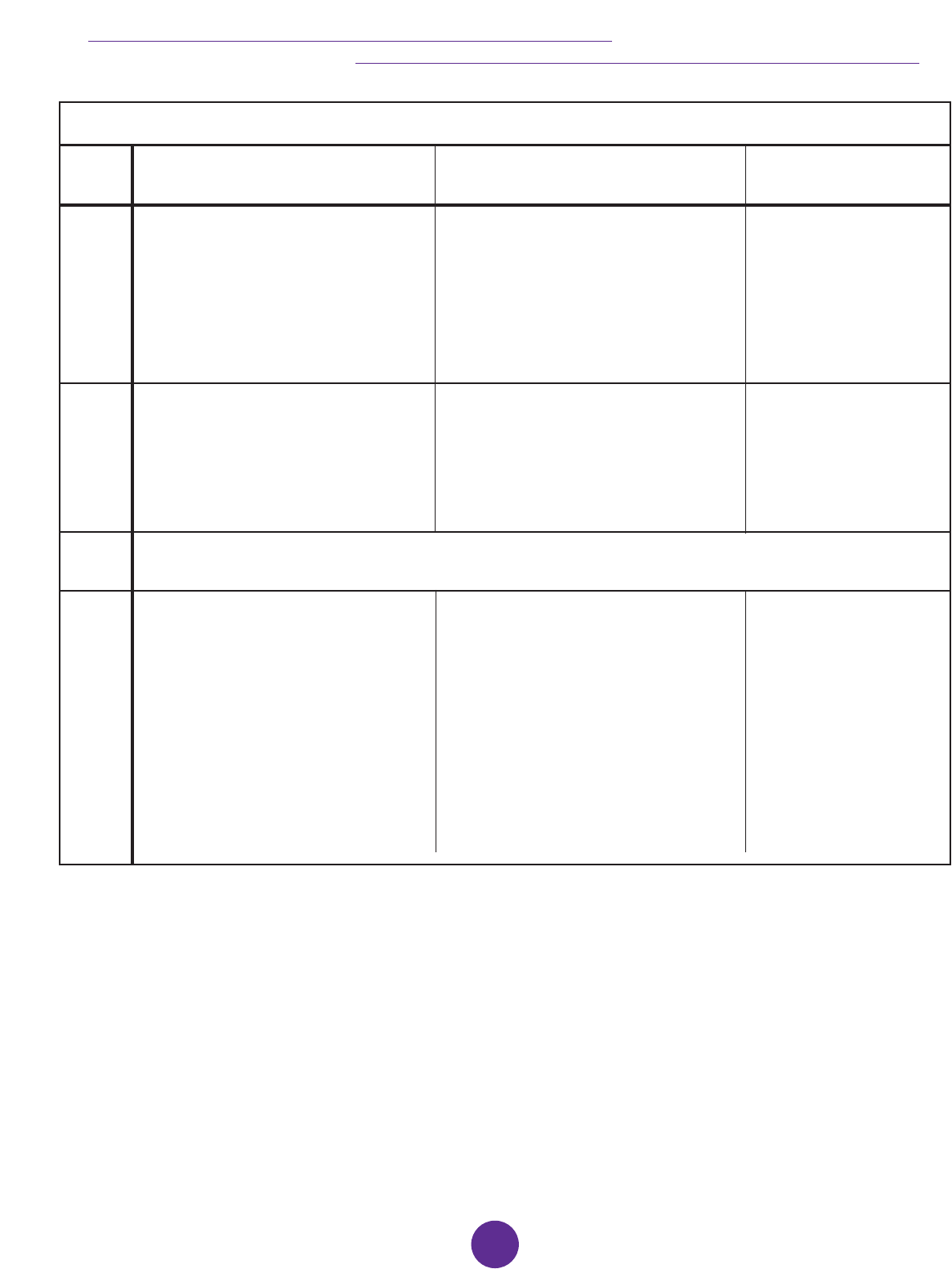

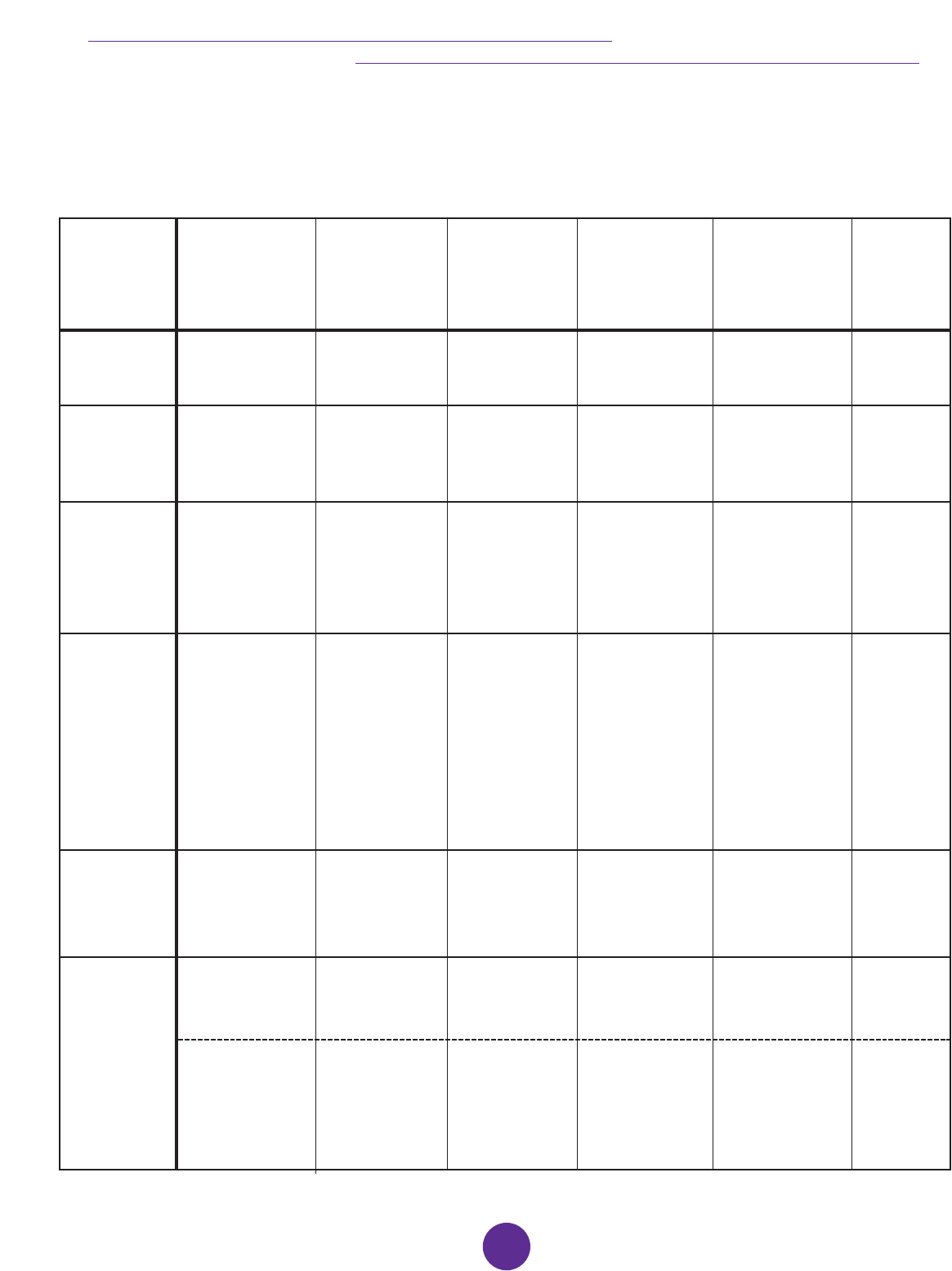

The table on the next page summarizes democratic renewal

initiatives across Canada.

Canada is not alone in these reform initiatives. Other

Westminster-type democracies, such as in the United

Kingdom and New Zealand, have all recently considered

and even undertaken similar reform projects. Scotland and

Wales adopted forms of proportional representation for

their assemblies in 1999. New Zealand adopted a mixed

member proportional representation system in 1993.

Indeed, a comprehensive report on the UK experience with

proportional representation by an independent commission

concluded earlier this year that these new electoral systems

have not produced an adverse reaction from people, are

not too complicated for voters, have produced stable,

effective governments and are now broadly accepted.

The Historical Context

Democratic renewal has always occurred in New

Brunswick. Our democratic institutions and practices today

resemble, but do not reflect, their original shape or intent.

The founders of New Brunswick would recognize some, but

by no means all, of how we practice democracy today in

our province. From the secret ballot in 1855 to universal

suffrage in 1919 to lowering the voting age in 1971, much

has changed in how democracy is practiced in New

Brunswick. The reason is simple: society evolves and with it,

attitudes and expectations about democratic rights. As the

Commission’s academic expert on the history of democratic

reform in New Brunswick, Dr. Gail Campbell of the

University of New Brunswick, stated in her research paper

for the Commission:

“Historically, the tendency to revisit definitions of

democracy has sometimes reflected a genuine shift

in societal attitudes.”

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

13

New Brunswick has not been afraid to embrace democratic

renewal. It is not widely known, for example, but New

Brunswick was the first jurisdiction to adopt the secret ballot

in what would become Canada. It did so just one year after

Australia, which is credited with originating this initiative.

By another measure of democratic reform, Equal

Opportunity in the mid-1960s sought to give citizens equal

access to government services no matter where they lived.

The new Official Languages Act breaks new ground in the

protection and promotion of English and French and the two

official linguistic communities in the province.

Each of these steps expanded our concept of democracy to

make it more inclusive of society and reflective of who we

are. The challenge we are facing today is how the

institutions and practices of democracy, put in place a

century and more ago, can be renewed to keep up with our

expanded concept of democracy and meet the changing

expectations and needs of New Brunswickers.

It is for this reason that the Commission on Legislative

Democracy was created. We have been given a broad and

comprehensive mandate to examine and make

recommendations on the full range of issues affecting

democracy in our province. From electoral reform (changing

our voting system) to legislative reform (enhancing the role

of MLAs) to democratic reform (involving New Brunswickers

more in decision-making) - virtually all aspects of our

democracy was up for review.

This is important since there is no obvious single answer to

any form of democratic malaise. Long-term trends and

attitudes cannot be reversed overnight. It will take time and

effort. However, by focusing on a specific and

comprehensive package of reforms as we are

recommending, this Commission is convinced that New

Brunswick’s democracy can be renewed for its citizens; that

citizens will see real benefits from these changes; that New

Brunswickers will believe their votes truly count; that they

can have a real say in decisions and that government is

listening; and that their elected representatives are

responding to their concerns.

In recent years, over successive governments, New

Brunswick has taken a leading role in the country in

governmental reforms dealing with bilingualism, fiscal

responsibility and tax competitiveness, information and

communications technologies, e-government, quality

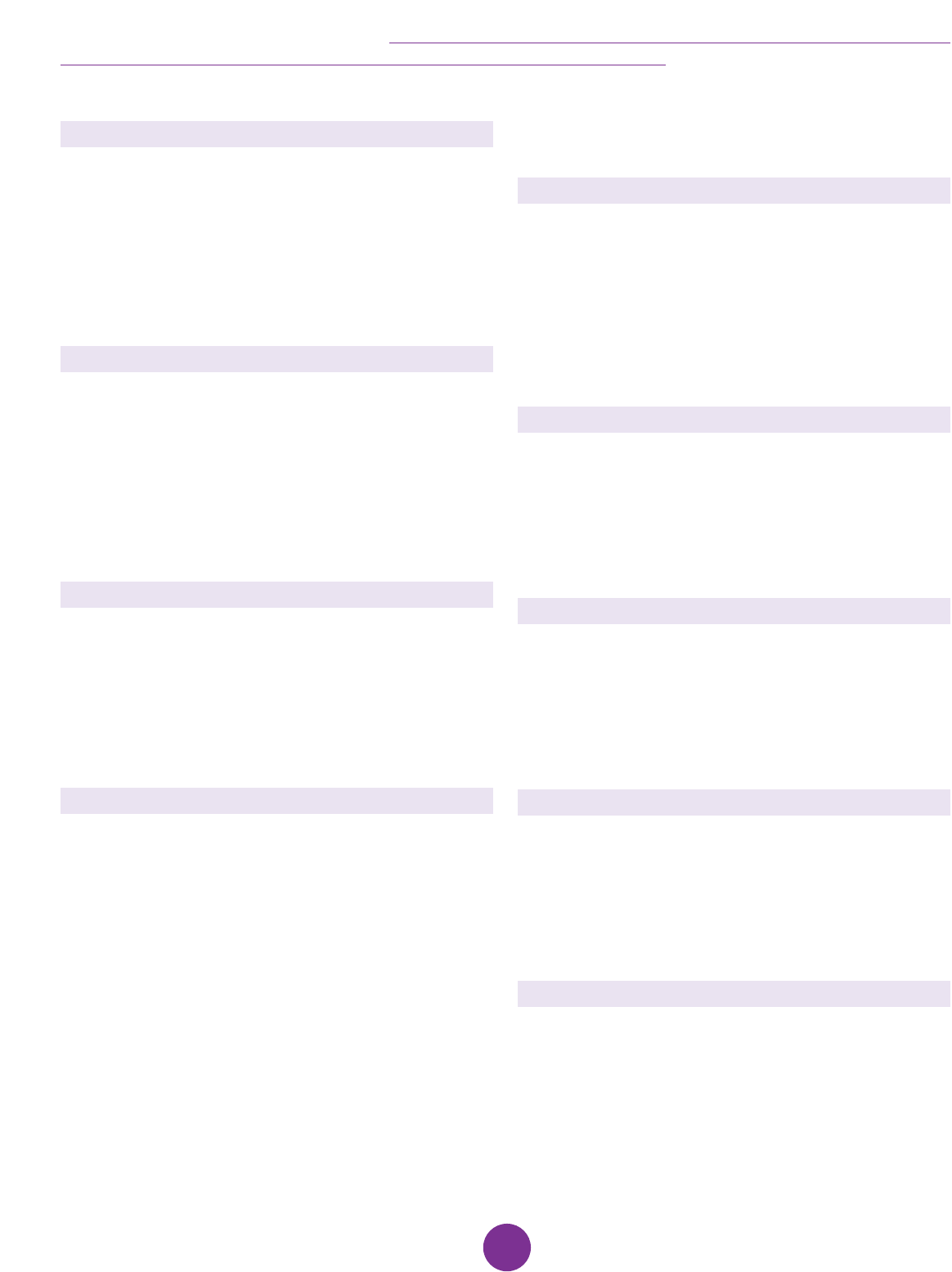

Electoral Reform Enhancing the Role New Mechanisms for Citizen

of Elected Officials Participation in Decision-Making

Key Issues Key Issues Key Issues

• Electoral system reform • Free votes • Citizen’s assemblies/juries/panels

• Increasing voter turnout • More power to committees • Broader consultation powers

• Fixed election dates and backbenchers for Committees

• Electoral boundaries • Increased resources for • Binding referendums

research and consultation • Online town halls

• Increased accountability • Online questionnaires

and ethical standards

Who’s doing it? Who’s doing it? Who’s doing it?

New Brunswick Commission New Brunswick Commission New Brunswick Commission

on Legislative Democracy on Legislative Democracy on Legislative Democracy

Prince Edward Island Québec Democratic Québec Democratic

Commission on Electoral Reform Reform Secretariat Reform Secretariat

Québec Democratic Ontario Democratic Ontario Democratic

Reform Secretariat Renewal Secretariat Renewal Secretariat

Ontario Democratic Government of Canada Government of Canada

Renewal Secretariat Democratic Reform Agenda Democratic Reform Agenda

British Columbia British Columbia

Citizen’s Assembly Citizen’s Assembly

Democratic Renewal Initiatives Across Canada

COMMISSION ON LEGISLATIVE DEMOCRACY

14

education, health care sustainability, and devolution of

decision-making responsibility to regional authorities.

Leading the country in democratic renewal is part of this

strong public policy tradition.

We believe the time has come to renew New Brunswick’s

democracy. The case for renewal is clear. In many ways the

real challenge facing us is how. It is this challenge that is

the main focus of this Commission’s Final Report and

Recommendations.

Towards a Citizen-Centred

Democracy in New Brunswick

“Mission - To identify options for an enhanced

citizen-centred democracy in New Brunswick

building on the values, heritage, culture, and

communities of our province.”

The Commission received not just a mandate, but also a

mission - to make recommendations that would lead to an

enhanced citizen-centred democracy in New Brunswick.

Citizens are the central focus of our work - not parties,

politicians, or even government itself. “Will it lead to a

stronger democracy for citizens?” is the test by which the

Commission evaluated each of its recommendations.

Through the prism of democratic values, we concluded our

deliberations each time by asking whether our proposed

recommendations would lead to an enhanced citizen-

centred democracy. Since democracy is fundamentally a

citizens’ exercise - beginning with the exercise of the

franchise or vote - we believe this gave our mandate an

important and cohesive focus.

The comprehensive mandate of the Commission - electoral,

legislative, and democratic reform - placed virtually all

facets of our democracy on the table. The reason is simple:

they are all linked. Changing our electoral system will lead

to shifts in the roles and responsibilities of MLAs. Involving

people more directly in decisions that affect them will

impact on how government currently functions. An

enhanced role for MLAs will change how decisions are

made in government. It is this integrated examination of our

democratic system that makes the Commission and its

mandate unique to our province and, indeed, the country.

There is nothing piecemeal about this report.

The Three Themes

This focus on citizens led the Commission to develop three

themes from which our recommendations flow. Common to

each is how democracy can be made to work better for

“you, the citizen”.

• Making Your Vote Count

• Making the System Work

• Making Your Voice Heard

Making Your Vote Count

Your vote is the most important democratic expression you

have. It must mean something. For it to mean something, it

must first count. The most obvious counting of votes takes

place on election night when we elect MLAs and choose a

government. But it is really our electoral system and the way

it counts votes that determines who wins and loses by

translating those votes into seats. If you voted along with a

sizeable minority of New Brunswickers for a candidate or

FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

15

party that did not win a seat, did your vote actually count

towards the final result? Under our single member plurality

system, commonly known as first-past-the-post, it counts

principally for the winning candidate. Votes cast for other

candidates are not factored into the results and are thus

‘wasted’. Making your vote truly count means that all votes

must be treated equally and none wasted. As we explain in

our recommendation to adopt a New Brunswick regional

mixed member PR system, this change would clearly make

your vote count far more than now towards electing an MLA

and the party of your choice.

Making your vote count begins with voting for a candidate

in your riding. Electoral boundaries determine the riding in

which you cast your vote. But the composition of a riding

changes over time as population shifts occur. Today in New

Brunswick, some ridings are significantly larger than others,

which means a person’s vote in that riding has less weight

in determining the outcome than a person’s vote in a smaller

riding. Whether riding boundaries fit with communities of

interest can determine whether voters will receive effective

representation. Riding boundaries can be the difference

between a community having legitimate influence in the

riding in which it finds itself, or having its votes

overwhelmed by other dominant, majority interests. And

since your vote is personal and does not belong to a

particular political party, the independence from political

parties of the process by which electoral boundaries are

drawn can have a real effect as well on the results of

elections and who represents you. The Commission’s

recommendations for a new Representation and Electoral

Boundaries Act focus on each of these issues to make sure

that all citizens’ votes count equally.

We vote on election day. But we don’t know exactly when

that date will be. The timing of an election call can leave

some people out of the voting process. Fixed election dates

address this problem. They make your vote count since no

premier can adjust the date of an election to suit his or her

own political preference. The Commission’s

recommendation for a fixed election date every four years

in the fall will help make sure you can plan to vote and you

are not left out.

Voting is a right we share as Canadians. But with that right

comes responsibility. Democracy cannot function without the

consent or participation of voters. Every four years when we

choose a government and elect MLAs to represent us, we

are in reality giving our consent to be governed to a

particular group of representatives. When your fellow

citizens do not vote, they are sending a message that this

choice does not matter to them. When your fellow citizens

do not vote, they are effectively inviting the political parties

to pay more attention to some voices rather than others. The

Commission’s recommendations to boost voter turnout and

participation in the democratic process, particularly by

young people, will encourage New Brunswickers to vote.

Together with changes to the electoral system, and a more

meaningful role for MLAs, citizens will have more incentive

to vote. The resulting higher turnout will convey a greater

sense of legitimacy to the democratic choices citizens will

have made.

For your vote to count, it must first be counted. An effective

and independent electoral infrastructure of laws and

machinery is essential for free, fair, and efficient elections.

Votes should not be lost, or miscounted, or counted twice.

People who have the right to vote should have a place on

the list of electors. The electoral law should facilitate voting,

not place barriers in front of it. The Commission’s

recommendations for a new electoral commission called

Elections New Brunswick, and changes to the Elections Act,