S L P P N , A

RESEARCH

RETIREMENT

NEW BRUNSWICK’S NEW

SHARED RISK PENSION PLAN

By Alicia H. Munnell and Steven A. Sass*

I

* Alicia H. Munnell is director of the Center for Retirement

Research at Boston College (CRR) and the Peter F. Drucker

Professor of Management Sciences. Steven A. Sass is an as-

sociate director of the CRR. They would like to thank Keith

Ambachtsheer and W. Paul McCrossan for extremely useful

comments on earlier drafts and Jean-Pierre Aubry for insight on

public plans.

Employer defined benefit pension plans have long

advance. The Netherlands certainly oers one model

been an important component of the U.S. retirement

of risk sharing; this brief discusses an adaptation of

system. Although these plans are disappearing in the

the Dutch approach closer to home – namely New

private sector – replaced by (k)s – they remain the

Brunswick’s Shared Risk Pension Plan introduced in

prevalent retirement plan arrangement in the public

May .

sector. But these public sector defined benefit plans

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first sec-

are currently under financial pressure, as two finan-

tion reviews the problem of risk in employer defined

cial crises since the turn of the century have caused li-

benefit plans. The second section describes New

abilities to soar and assets to plummet. The response

Brunswick’s response – the Shared Risk design and

so far among state and local plan sponsors has been

the regulatory framework for supervising such plans.

to suspend or eliminate cost-of-living adjustments,

The third section discusses the response of union rep-

cut back sharply on benefits for new employees, and

resentatives of workers covered by the new program.

raise employee contributions. Some states have also

The fourth section considers what lessons U.S. plans

introduced a defined contribution component. While

can draw from the New Brunswick approach. The

the cutbacks have sharply reduced future costs, they

final section concludes that the Shared Risk approach

have been ad hoc and unexpected. The question is

is an important evolutionary step, and potentially an

whether a more orderly and predictable way can be

attractive alternative to the traditional defined benefit

devised to share risks, and perhaps head o trouble in

plan design.

LEARN MORE

Search for other publications on this topic at:

crr.bc.edu

Center for Retirement Research

T R D B P

Defined benefit plans promise workers a fixed pen-

sion payment that lasts as long as they live, providing

retirees a valuable source of security when their work-

ing days are done. The cost of these plans, however,

has risen sharply. One reason is that retirees now live

longer: U.S. workers retiring in can expect to

live about four years longer than workers retiring in

.

Most plans also have generous early retire-

ment provisions, with less-than-actuarial reductions

for the increased length of time that early retirees

collect a pension.

Defined benefit plans have also become increas-

ingly risky as equity holdings have risen and the

maturation process has increased the number of

retirees and older long-service workers relative to the

plan’s funding base. Risky means outcomes can be

good as well as bad. In the s, when the stock

market boomed, the value of pension assets generally

rose well above the value of plan obligations. As a

result, many employers, in both the private and public

sector enjoyed “contribution holidays” and increased

benefits. In the s, when financial markets

tanked, significant underfunding suddenly became

the norm. As a result, employers had to sharply

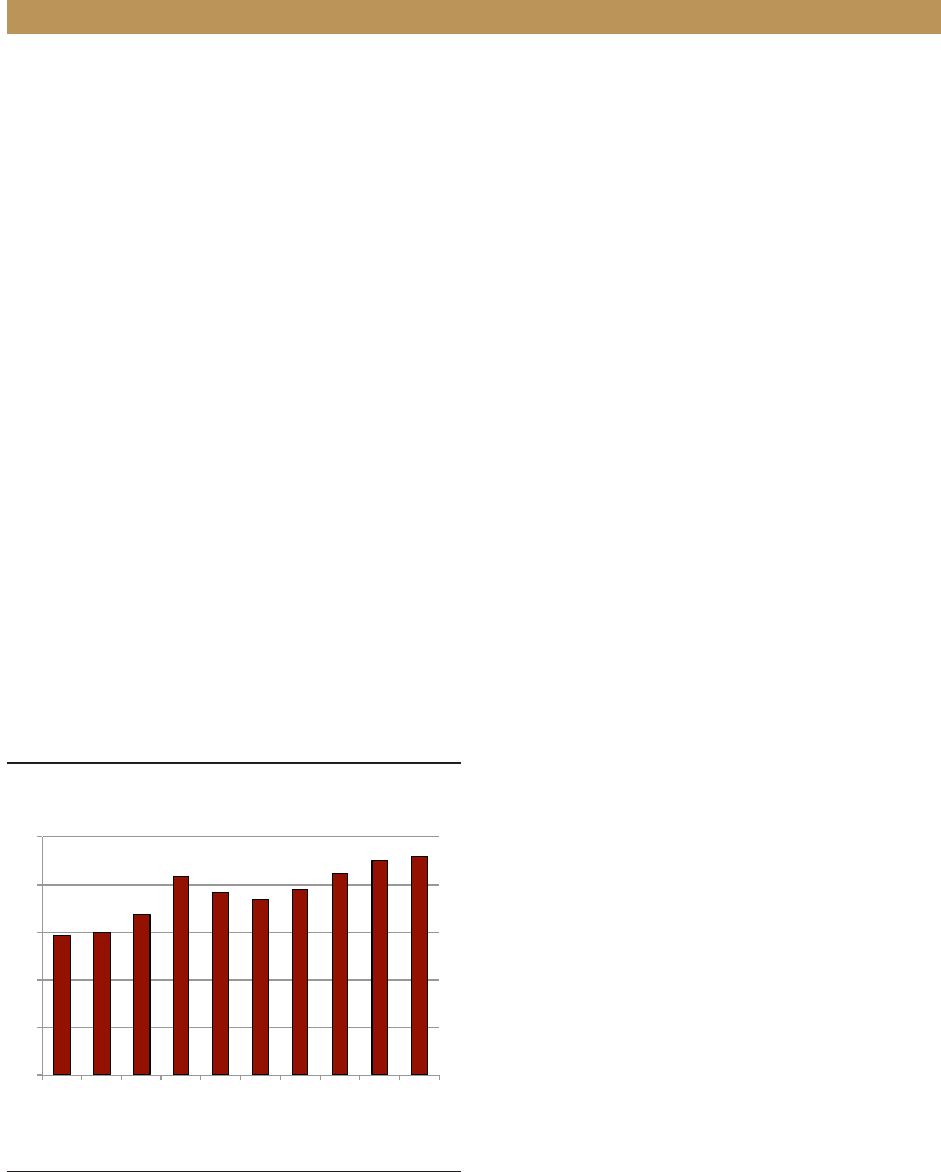

increase contributions(see Figure ).

F . S L P C

P O S R, -

2.9%

3.0%

3.4%

4.2%

3.8%

3.7%

3.9%

4.2%

4.5%

4.6%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Source: Authors’ calculations from U.S. Census Bureau

(-a) and (-b).

In both Canada and the United States, govern-

ment regulations require private employers to

eliminate underfunding within a specified number of

years. As defined benefit risks increased over time,

governments sharply reduced that timeframe – in

Canada from years in the mid-s to five by the

end of the century. This demand for large sums of

cash, when cash is hard to come by, has further in-

creased the risks to sponsors of defined benefit plans.

Given the dicult financial conditions since the

turn of the century, defined benefit sponsors have

been hard pressed to quickly fill funding shortfalls.

The Canadian provincial governments, which set the

minimum funding rules for private defined benefit

plans, responded by relaxing or even exempting

employers from making “required” deficit-reduction

payments. As these make-shift measures dragged

on, the New Brunswick provincial government in

created a “Task Force on Protecting Pensions,”

and added the province’s own public sector plans

to the agenda one year later. The members of the

Task Force then asked for and received a mandate to

“fix” the problem, not just issue a report. Their “fix,”

designed to make both private and public employer

plans “secure, sustainable and aordable for both

current and future generations,” was the Shared Risk

Pension Plan, announced in May .

S R

New Brunswick’s Shared Risk program has three key

elements: ) a new design that splits plan benefits

into highly secure “base” benefits and moderately

secure “ancillary” benefits; ) protocols that require

pre-determined actions to change future benefits,

contributions, and asset allocations in response to

changes in the plan’s financial condition; and ) a

new risk management regulatory framework to keep

these plans on track. The “base” and “ancillary” ben-

efit design is based on the widely admired approach

developed in The Netherlands. The new regulatory

framework is largely based on Canada’s “stress-

test” methods for supervising banks and insurance

companies.

The key innovation is to combine these

elements into a coherent pension program.

N B’ S R P D

The Shared Risk plan guarantees base benefits, but

only grants ancillary benefits if allowed by the plan’s

financial condition. The funding program is then de-

signed to ensure that both base and ancillary benefits

will be paid with a high degree of likelihood. But the

plan sponsor also specifies protocols for responding

to changes in the plan’s financial condition: how to

Issue in Brief

increase contributions, change asset allocations, and

reduce benefits in response to funding deficits; and

how to reduce contributions, change asset allocations

and restore benefits, including restoring previous

benefit reductions, and grant ancillary benefits when

the plan’s financial condition improves.

When the new program was announced, four Ne

Brunswick defined benefit plans – three public sec-

tor plans and one private sector plan – declared that

they were adopting the Shared Risk design. These

plans introduced a new benefit formula that made a

significant portion of future benefits ancillary and de-

pendent on the plan’s financial condition. The plans,

which had initially based benefits on the employee’s

final salary, now adopted formulas that base benefits

on the employee’s much lower career average salary,

but provide much the same “final salary” pension by

indexing employee earnings to wage growth or infla-

tion. These indexing increments are ancillary and

granted only when the plan’s finances exceed speci-

fied benchmarks. For an example, see the Box for th

sequence of steps to be taken in the case of under- or

over-funding for one New Brunswick plan.

,

w

e

N B’ S R R

F

Existing regulations in both Canada and the United

States assess safety and soundness based on a plan’s

current funded ratio. A fully funded plan, with pen-

sion fund assets equal to the present value of plan

obligations, is only required to contribute amounts

needed to cover the additional benefits currently

earned by active workers. Underfunded plans must

eliminate shortfalls within a specified number of

years. This approach ignores how risky a plan’s assets

and obligations might be or how they might change

over time. It makes no dierence whether the plan’s

assets are invested in penny stocks or government

bonds, or whether its obligations could spike, say if

large numbers of workers suddenly claim sweetened

early retirement benefits.

New Brunswick’s regulatory program for Shared

Risk uses a “stress test” to assess the ability of Shared

Risk plans to pay promised benefits. To test the

plan’s ability to pay benefits, each year the plan actu-

ary must run at least , -year simulations using

H R S

This example gives the sequence of actions to be taken by the New Brunswick Hospitals’ plan (Canadian

Union of Public Employees Local ) in response to changes in its financial condition.

If the funded ratio falls below percent for If the funded ratio rises above percent, a

two years in a row or the plan fails to meet the portion of the surplus can be used as follows, if

risk management goals of a Shared Risk plan: the plan can still meet the risk management goals:

. Increase contributions up to percent of . Reverse previous deficit-recovery measures in

earnings, split evenly between workers and the following order:

the employer. a. Reverse any increase in contributions.

. Change the rule for calculating early retire- b. Reverse any reduction in base benefits.

ment benefits, for those not currently eligible c. Reverse any reduction in early retire-

for such benefits, to a full actuarial reduction. ment benefits.

. Reduce “base benefit” accrual rates for future . Index pensions and base benefit accruals up

service up to percent. to the full Consumer Price Index (CPI).

. Reduce base benefits for all members, includ- . Increase individual benefits, as needed, so

ing benefits based on past and future service, that all retirees receive a benefit based on final

in equal proportion until the plan meets the five-year average salary, indexed to the CPI.

risk management goals. . Provide lump-sum payments to oset past

shortfalls relative to a benefit based on final

five-year average salary, indexed to the CPI.

Source: Mann ().

Center for Retirement Research

reasonable estimates of relevant financial parameters.

The simulations must show that over this -year

horizon: ) base benefits will be paid in full at least

. percent of the time; and ) at least percent

of ancillary benefits will be paid, on average, over all

scenarios. Plans that fail this forward-looking test

must modify their investment, funding, or benefit

rules until they pass. This annual review is expected

to identify changes in the plan’s financial condition

much earlier than the traditional funded ratio ap-

proach and produce smoother responses to changing

conditions.

The Shared Risk regulatory program also includes

funded ratio yardsticks. However, the measure of

plan obligations used as the funded ratio denomina-

tor excludes ancillary benefits, such as indexing. The

Shared Risk program requires the actuary to project

the plan’s annual funded ratio over the next years.

For new plans, the projected ratios must never be less

than percent of plan obligations. In subsequent

years, the projected ratio must equal or exceed

percent of plan obligations at the end of the -year

planning horizon and must never fall below that level

two years in a row. These requirements, and the

mandatory stress test, eectively raise current fund-

ing targets for Shared Risk plans to about percent

of base benefit obligations.

U S S

R P

It is easy to see why employers would welcome New

Brunswick’s Shared Risk program – the new ap-

proach would allow them to better manage their

finances. Workers, however, were switching from a

defined benefit to a “target benefit” program. Nev-

ertheless, the new plans were adopted with union

support.

The unions embraced the shift to Shared Risk

plans because:

• As private sector workers were losing defined

benefit plan coverage, public employees feared

that taxpayers would target their plans.

• Their defined benefit plans were stressing the

finances of plan sponsors, raising the prospect o

significant benefit cuts.

• Young workers increasingly viewed rising pen-

sion contributions as funding the pensions of

older workers and retirees, not their own

benefits.

f

• The Shared Risk plan oered much greater

security than the likely alternative – a (k)-type

retirement savings plan.

The Government of New Brunswick has been

negotiating with public sector unions to move all of

its plans to the Shared Risk design, and many of these

unions have agreed to the change. Two municipali-

ties, Saint John and Fredericton, have also adopted

Shared Risk plans with union support. In addition,

one private sector plan has applied for registration

as a Shared Risk plan. And a half dozen others are

exploring conversion to the new design.

L U S

U.S. state and local governments have responded

to the large deficits in their pension programs in

dramatic and unpredictable ways. Some states have

cut or eliminated cost-of-living adjustments for cur-

rent as well as future retirees. Some have increased

mandatory employee contributions, sometimes on all

employees and sometimes only on new employees.

Many have sharply reduced future benefits – primar-

ily for new employees – by raising age and tenure

requirements, lengthening the average salary period,

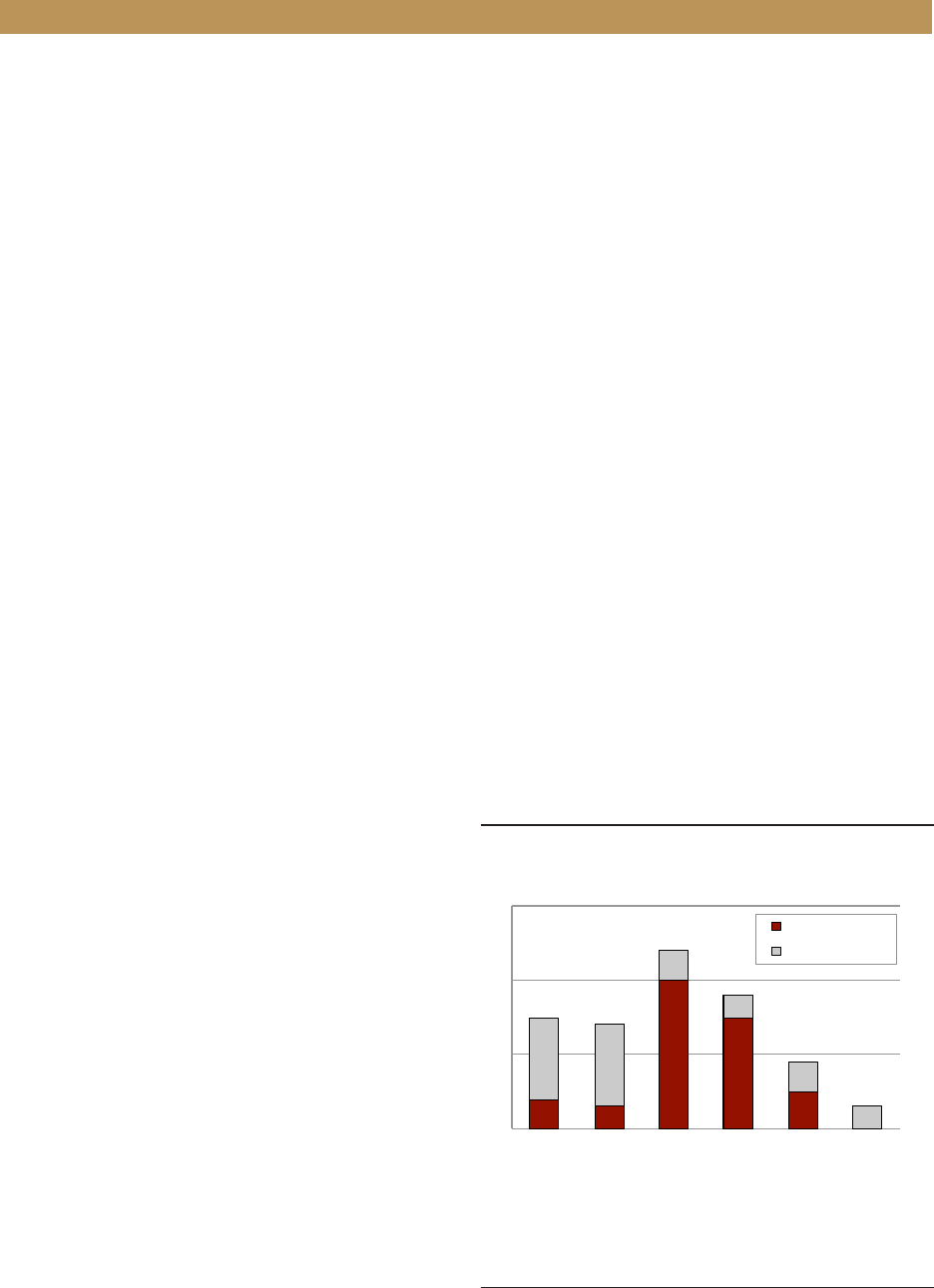

and/or reducing pension benefit factors (see Figure

). In many cases, the cuts for new employees will

produce lower benefits than provided before the

financial crisis.

And just like the permanent benefit

F . P C M S

S-A P, T C

15

14

24

18

9

3

0

10

20

30

New employees

All employees

COLA

Contribution rate

Age/tenure

requirements

Average salary period

Benefit factor

No changes

Source: Munnell et al. ().

Issue in Brief

expansions that occurred during the good times of

the s, nearly all states made the cuts permanent

adjustments to their pension program.

New Brunswick’s Shared Risk program oers a

dierent approach. First, it makes responses to pen-

sion shortfalls far more predictable. The plan design

clearly spells out how the sponsor would respond,

and by sharing the burden among the employer (i.e.

the taxpayer), employees, and pensioners, it moder-

ates the burden borne by each. Moreover, ancillary

benefits not granted in bad years can be expected to

be fully restored in good years. In fact, pensioners

will receive checks in good years that will compensate

for COLAs missed in bad years. Second, the required

risk management tests function as an early warning

system, helping plans minimize the size of any need-

ed adjustments by heading o trouble in advance.

For U.S. state and local plans to adopt a risk shar-

ing approach, sponsors must develop specific rules

for adjusting benefits, contributions, and investment

allocations; these rules need to be fair to workers in

dierent cohorts and income groups; and they need

to be communicated eectively to plan participants.

Establishing such rules is a thorny and dicult

task, but is likely to produce a much more sensible

outcome than lurching toward generous benefit

expansions when times are good and dramatic benefit

reductions when times are bad.

C

New Brunswick’s Shared Risk program is a promis-

ing innovation. It makes changes in benefits and

contributions more orderly, moderate, predictable,

and reversible.

The New Brunswick program does not solve all of

the challenges facing defined benefit plans. A large

enough shock would no doubt also overwhelm the

adjustment rules and risk management procedures of

Shared Risk plans. Nevertheless, Shared Risk plans

could be expected to weather such shocks much better

than traditional defined benefit programs or individu-

als with a (k).

The New Brunswick Shared Risk approach pro-

vides an attractive model for governments, employ-

ees, and pensioners that find current procedures for

handling risk in defined benefit plans unworkable,

and for workers who might otherwise end up with a

(k).

Center for Retirement Research

E

U.S. Social Security Administration (). Public sector plans adopting the Shared Risk

design covered workers represented by “Certain

The three members of the Task Force were Susan Bargaining Employees” of New Brunswick Hospitals

Rowland (Chair), a pension attorney with extensive and the Canadian Union of Public Employees, New

experience in restructuring troubled plans; W. Paul Brunswick Hospitals. A private sector plan cover-

McCrossan, former head of the Canadian Institute ing union workers, the New Brunswick Pipe Trades

of Actuaries; and Pierre-Marcel Desjardins, a Ph.D. Pension Plan, also adopted the Shared Risk design.

economist active at the Canadian Institute for Re- The Task Force consulted with unions representing

search on Public Policy and Public Administration. the hospital workers when developing the Shared

The addition of public plans to the Task Force agenda Risk program, and these unions endorsed the shift

in was in part a response to downgrades of New to the Shared Risk design. The pension plan cover-

Brunswick government debt by bond rating agencies ing members of the New Brunswick legislature also

due to the Province’s mounting pension liabilities. adopted the Shared Risk design: the politicians sup-

See Government of New Brunswick (, ). porting the new design felt it important to accept the

same risks borne by other Shared Risk plan partici-

Government of New Brunswick (). pants, a decision supported by an all-party consensus.

The Task Force recommended the conversion of all

For a discussion of the Dutch models and related government plans to the Shared Risk design, and

“Defined Ambition” plan designs, see van Rieland the government also announced its desire to do just

and Ponds (); Ambachtsheer (); Kocken that. The Task Force report also called for changes

(); and Kortleve (). in public sector plans to reduce their costs, including

an increase in the retirement age and reductions in

If all these steps have been taken and the funding subsidized early retirement benefits, albeit introduced

ratio is greater than percent of plan obligations, over a -year period. These changes were accepted

the plan would establish a reserve to cover years’ in the public sector plans that adopted the Shared

contingent indexing; then reduce contributions by Risk program. See Government of New Brunswick

up to percent of earnings; then improve various ().

benefits, including early retirement benefits. The

plan document also suggests more permanent adjust- As the government of New Brunswick noted,

ments could be in order. “Many in the public complained openly about the

generosity of these schemes and the fact that they

Dutch plans strengthened their risk management have to pay extra taxes to cover pension deficits for

methods in the early s, adopting a Value-at-Risk benefits that they cannot aord for themselves.” See

yardstick with a one-year horizon and a confidence Government of New Brunswick ().

level of . percent (Kortleve, Mulder, and Pelsser

). Dutch plans, however, failed to accommodate The New Brunswick government declared its de-

the sharp financial shock that accompanied the Great fined benefit plans to be “no longer sustainable.” See

Recession and, like plans in New Brunswick, were Government of New Brunswick ().

forced to relax their “deficit recovery” rules (Kortleve

and Ponds ). The Canadian Oce of the Su- Government of New Brunswick ().

perintendent of Financial Institutions, which had no

regulatory authority over employer plans, in had Munnell et al. ().

recommended the use of stress tests to manage risks

in defined benefit pension plans. New Brunswick’s Of those plans that have increased employee

regulatory program for Shared Risk plans was the contributions since , only a few have stated that

first to require such tests, at least in North America; the increases are likely to be temporary. Of those

see Government of New Brunswick (, ); that have cut pension COLAs during this period, only

Oce of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions a handful explicitly link future COLAs to the plan’s

Canada (); and McCrossan (). financial condition. One state, Wisconsin, has always

linked its COLA to the rate of return on pension as-

sets.

Issue in Brief

R

Ambachtsheer, Keith. . The Pension Revolution: A

Oce of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions

Solution to the Pension Crisis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Canada. . Guideline: Stress Testing Guidelines

for Plans with Defined Benefit Provisions. Available

Government of New Brunswick. . Pension Reform

at: http://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/app/DocReposi-

Background Document. Available at: http://www.

tory//eng/pension/guidance/defined benefitst_e.

gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/corporate/promo/pen-

pdf.

sion.html.

U.S. Census Bureau. -a. State and Local

Government of New Brunswick. . Rebuilding New

Public-Employee Retirement Systems. Washington,

Brunswick: The Case for Pension Reform. Available

DC.

at: http://ppforum.ca/sites/default/files/NB_Pen-

sion%Reform%Case_EN.pdf.

U.S. Census Bureau. -b. State and Local

Government Finances. Washington, DC.

Kocken, Theo. . “Why the Design of Maturing

Defined benefit Plans Needs Rethinking.” Rotman

U.S. Social Security Administration. . Annual

International Journal of Pension Management ():

Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-

-.

Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability

Insurance Trust Funds. Washington, DC.

Kortleve, Niels. . “The ‘Defined Ambition’ Pen-

sion Plan: A Dutch Interpretation.” Rotman Inter-

van Rieland, Bart and Eduard Ponds. . “Sharing

national Journal of Pension Management. (): -.

Risk: The Netherlands’ New Approach to Pen-

sions.” Issue Brief -. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center

Kortleve, Niels and Eduard Ponds. . “Dutch Pen-

for Retirement Research.

sion Funds in Underfunding: Solving Generation-

al Dilemmas.” Working Paper -. Chestnut

Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research.

Kortleve, Niels, Wilfried Mulder, and Antoon Pelsser.

. “European Supervision of Pension Funds:

Purpose, Scope and Design.” Netspar Design

Papers . Tilburg, NL: Netspar.

Mann, Troy. . Personal Communication with

Mann, Director of Human Resources, Corporate

Services Section, Government of New Brunswick.

McCrossan, W. Paul. . “The Whys Behind The

What: New Brunswick Pension Reform Shared

Risk Plan.” Powerpoint delivered at Ryerson

University, November . Available at: http://www.

ryerson.ca/content/dam/clmr/publications/con-

ferences/conf_pensions_paul_mccrossan.pdf.

Munnell, Alicia H., Jean-Pierre Aubry, Anek Belbase,

and Josh Hurwitz. . “State and Local Pension

Costs: Pre-Crisis, Post-Crisis, and Post-Reform.”

State and Local Plans Issue in Brief . Chestnut

Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Bos-

ton College.

A C

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston Col-

lege was established in through a grant from the

Social Security Administration. The Center’s mission

is to produce first-class research and educational tools

and forge a strong link between the academic com-

munity and decision-makers in the public and private

sectors around an issue of critical importance to the

nation’s future. To achieve this mission, the Center

sponsors a wide variety of research projects, transmit

new findings to a broad audience, trains new schol-

ars, and broadens access to valuable data sources.

Since its inception, the Center has established a repu-

tation as an authoritative source of information on all

major aspects of the retirement income debate.

s

A I

The Brookings Institution

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Syracuse University

Urban Institute

C I

Center for Retirement Research

Boston College

Hovey House

Commonwealth Avenue

Chestnut Hill, MA -

Phone: () -

Fax: () -

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: http://crr.bc.edu

Center for Retirement Research

The Center for Retirement Research thanks AARP, Advisory Research, Inc. (an aliate of Piper Jaray

& Co.), Charles Schwab & Co. Inc., Citigroup, ClearPoint Credit Counseling Solutions, Fidelity & Guaranty

Life, Goldman Sachs, Mercer, National Council on Aging, National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association,

Prudential Financial, State Street, TIAA-CREF Institute, T. Rowe Price, and USAA for support of

this project.

© , by Trustees of Boston College, Center for

Retirement Research. All rights reserved. Short sections of

text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without

explicit permission provided that the authors are identified

and full credit, including copyright notice, is given to

Trustees of Boston College, Center for Retirement Research.

The research reported herein was supported by the Center’s

P

artnership Program. The findings and conclusions ex-

pressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent

the views or policy of the partners or the Center for Retire-

ment Research at Boston College.