1

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

Discussion Draft

Collective Defined

Contribution Plans

______________________________________________________

J. Mark Iwry

J. Mark Iwry is a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings and a visiting scholar at the Wharton School at the

University of Pennsylvania

David C. John

David C. John is a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings, deputy director of the Retirement Security

Project, and senior policy advisor at the AARP Public Policy Institute

Christopher Pulliam

Christopher Pulliam is a research analyst at Brookings

William G. Gale

William Gale the Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Federal Economic Policy and senior fellow at

Brookings, Director of the Retirement Security Project, and Co-Director of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy

Center

This report is available online at: brookings.edu/research/collective-defined-contribution-plans

The Brookings Economic Studies program analyzes current

and emerging economic issues facing the United States and the

world, focusing on ideas to achieve broad-based economic

growth, a strong labor market, sound fiscal and monetary

policy, and economic opportunity and social mobility. The

research aims to increase understanding of how the economy

works and what can be done to make it work better.

September 2021

2

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

Abstract

The long-term shift in the U.S. retirement system from defined benefit pension (DB) plans to retirement

saving accounts such as 401(k) plans and IRAs has transferred significant financial risks to workers, many

of whom are ill-equipped to handle the contingencies. Collective defined contribution (CDC) plans offer a

way to rethink risk sharing. CDCs permit employers to avoid the funding cost and volatility of guaranteed

DB benefits while providing savers and retirees DB-like professional investment management and

pooling, longevity risk pooling, and lifetime income. To be effective, however, CDC plans need to address

issues regarding expectations, equity, transition, and trust. If they can do so successfully, adding

particular CDC features to conventional DB plans or 401(k) plans in appropriate circumstances could

improve outcomes for workers, retirees, and employers. Looking beyond the conventional, traditional DB

and DC plan designs to explore a new, richer, and more nuanced array of risk-sharing and pooling

strategies is a welcome development that will help identify more optimal allocations of financial risks and

retirement benefits.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Arnold Ventures for financial support and Grace Enda and Claire Haldeman for

research assistance.

Financial Disclosure

Iwry periodically provides, in some cases through J. Mark Iwry, PLLC, policy and legal advice to plan

sponsors and providers, government officials, academic institutions, other nonprofit organizations, trade

associations, fintechs, and other investment firms and financial institutions, regarding retirement and

savings policy, pension and retirement plans, and related issues. Iwry is a member of the American

Benefits Institute Board of Advisors, the Board of Advisors of the Pension Research Council at the

Wharton School, the Council of Scholar Advisors of the Georgetown University Center for Retirement

Initiatives, the Panel of Outside Scholars of the Boston College Center for Retirement Research, the CUNA

Mutual Safety Net Independent Advisory Board, a network of advisors to an investment firm, and the

Aspen Leadership Forum Advisory Board. He also periodically serves as an expert witness in federal court

litigation relating to retirement plans. The authors did not receive any financial support from any

organization or person for any views or positions expressed or advocated in this document. They are

currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization that has compensated or otherwise

influenced them to write this paper or to express or advocate any views in this paper. Accordingly, the

views expressed here are solely those of the authors and should not be attributed to any other person or

any organization.

3

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

I. Introduction

Over the past four decades, the U.S. retirement system has largely shifted from defined benefit pension

(DB) plans to retirement saving accounts within the broader defined contribution (DC) category – mainly

401(k) plans – and to individual retirement accounts (IRAs). A key factor driving this change is

employers’ desire to avoid the risks associated with providing guaranteed pension benefits. This

guarantee – a defining feature of DB plans – can entail large funding obligations that can change

unpredictably and can wreak havoc on corporate balance sheets and budgets. But the flight from DB plans

to 401(k)s and IRAs did not make financial risks disappear; instead, it transferred the risks to individual

workers, many of whom are ill-equipped to handle the resulting contingencies.

Collective defined contribution (CDC) plans offer a way to rethink risk sharing between employers and

individuals and among savers and retirees. CDCs and other hybrid retirement plan formats combine DB

and DC elements in different ways. Variants already exist in several countries, are receiving serious

consideration in the United Kingdom, and have counterparts and close parallels in the United States.

1

In CDCs, employers avoid the funding volatility and investment risk of DB plans. Although CDCs are

technically DC plans, they provide some DB-like features for savers and retirees. Compared to 401(k)

plans, which feature individual accounts, participant-directed investing, and typically lump-sum payouts,

CDCs provide DB-style pooling of investments, professional investment management, and lifetime

retirement income. They reduce financial risks for individuals, relative to DC plans, but generally without

guaranteed benefits (Millard, Pitt-Watson, and Antonelli, 2021).

In this paper, we examine the opportunities and challenges associated with implementing CDCs in the

United States. We highlight the advantages of CDC plans as well as several issues that CDC plans must

confront, regarding expectations, equity, transition, and trust. We conclude that, under appropriate

circumstances and contingent on addressing those issues, adding particular CDC features to a 401(k) or a

conventional DB plan can improve outcomes for workers, retirees, and employers. More generally, we

emphasize that evaluations of CDCs depend greatly on the answers to two questions: “Compared to

what?” (e.g., traditional DB plans or 401(k) plans) and “From whose point of view?” (e.g., employees,

retirees, or employers).

Section II compares typical forms of DB and DC plans with a basic type of CDC plan. Section III describes

CDCs and similar plan designs in a number of countries, including the United States. Section IV discusses

the challenges relating to implementing CDC plans. Section V concludes.

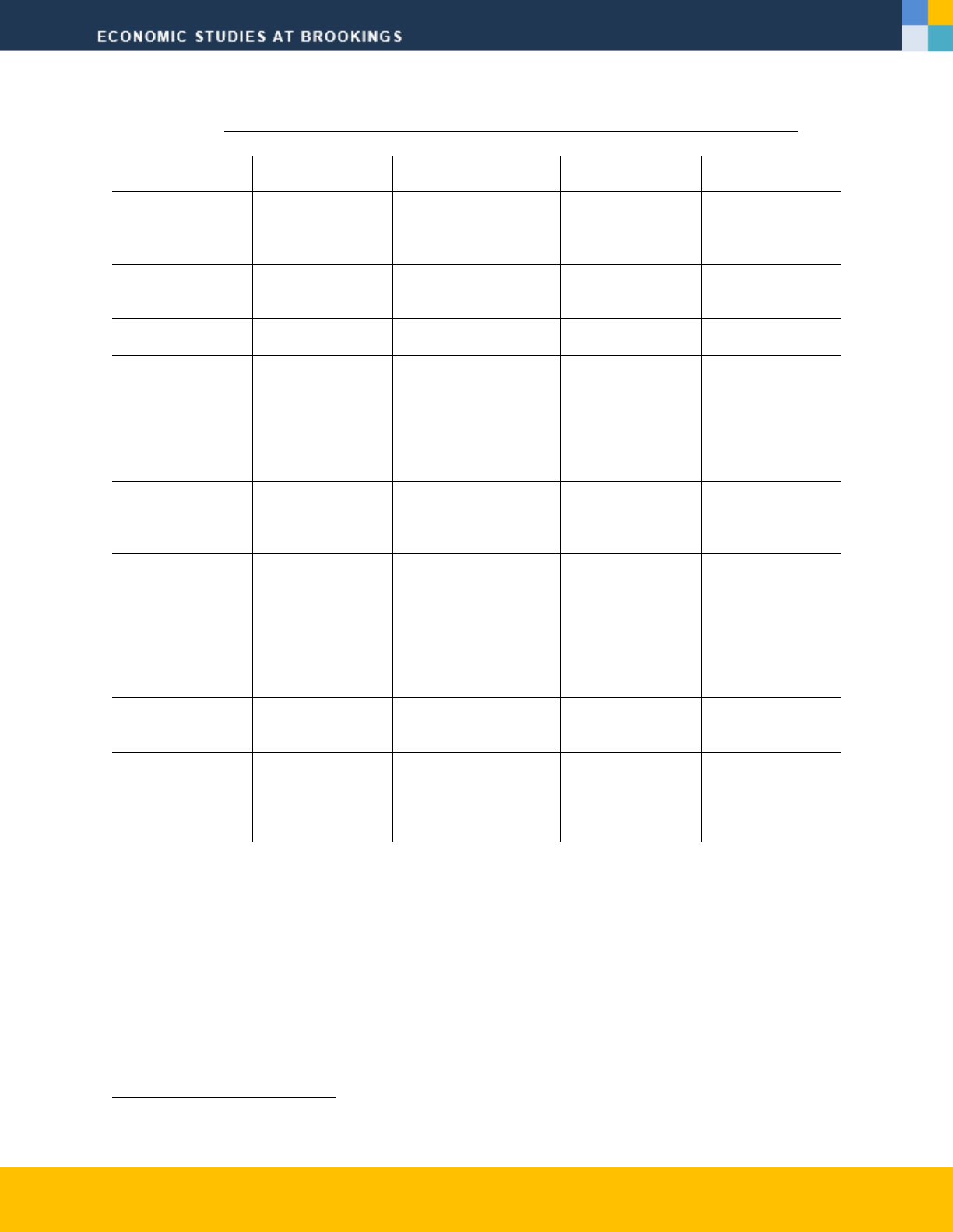

II. Typical retirement plan forms

Retirement plans generally come in three main types – DB, DC, and hybrids. In this section, we compare

and contrast the typical features of basic DB, DC, and CDC plans, a certain type of hybrid. Table 1 provides

summary details.

Defined Benefit Plans

In the typical DB plan, eligible workers are automatically covered and do not make contributions.

Employers guarantee and pre-fund benefits, make investment choices, and bear the financial risks

associated with low asset returns or retirees living longer than anticipated. Benefits are based on

employees’ tenure with the company and a measure of average or final earnings. Benefits are offered and

often paid as an annuity with regular (typically monthly) income guaranteed for the lifetime of the retiree

and spouse, if any. Many DBs, however, allow participants to forgo this longevity risk protection and opt

1

These variants and hybrid plans include “defined ambition” (rather than defined benefit), “target benefit”, “collective money

purchase”, “variable DB”, “variable annuity”, “adjustable pension”, or “shared risk” plans and are discussed below.

4

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

for a lump sum payment instead. There are numerous qualifications and exceptions to this skeletal

description.

2

DB plans offer distinct advantages to employees and retirees. Individuals do not need to make decisions

about, or face the risks associated with, enrollment, contribution levels, investment allocations, and

portfolio rebalancing. The only real decisions a DB participant needs to make are when to retire and start

claiming benefits, and the form in which to take them. Age- or service-based incentives in DB plans,

reflecting employers’ workforce management priorities, are typically strong and can make choices easier.

DB participants benefit from having pooled and professionally managed investments that comply with

strict fiduciary standards.

Nevertheless, DBs have their drawbacks. Even when most widely used, they tended to exclude broad

swaths of the labor force. Because their benefit formulas tend to accumulate benefits on a “back-loaded”

basis, DB plans provide significantly smaller benefits to those, including many women, with interrupted

careers or with frequent job changes and are generally less portable. Private-sector DB plans, and to a

lesser degree government DB plans, often leave retirees exposed to inflation risk. DB participants may

also be exposed to some underfunding risk, although mitigated to a great extent by Pension Benefit

Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) pension benefit guarantees. For employers, DB sponsorship can entail

costly and potentially volatile pre-funding requirements, has a significant regulatory burden, and is seen

as complex and underappreciated by employees.

These drawbacks, combined with several other trends, led to a steady decline in DB plans. First, the

unionized sector and the manufacturing sector – where the DB presence was substantial – have steadily

shrunk. Second, women’s labor force participation rose. Third, DB costs rose as the ratio of retirees to

active workers increased over time.

Defined Contribution Plans

A DC plan maintains an individual account for each participant that sets the participant’s benefit as the

balance resulting from cumulative participant and employer contributions – allocated to individual

accounts based on a stated allocation formula – net of withdrawals and adjusted for the account’s

investment experience. The employee bears all investment risk. The prevalent DC plan design in the

United States is the 401(k) plan.

In 401(k) plans, employers do not face risks related to asset returns, inflation, or retiree longevity, and

typically face low funding costs – often under 3 percent of payroll – compared to DB plans. In addition,

401(k) employer matches of employee contributions tend to be relatively predictable and can be reduced

or suspended in a bad economic climate, thus avoiding funding volatility. Finally, 401(k) plans are simpler

to administer than DBs.

Participants also seem to like 401(k)s. For many workers, the appeal of owning growing account balances

seems to outweigh the less tangible, long-term promise of DB post-retirement income. Also, 401(k)s are

more accessible and portable than DBs during times of hardship and job changes.

Over time, as 401(k)s became the primary retirement for more and more people in the United States,

traditional 401(k)s evolved to more recent versions with automated features. Automatic provisions

essentially re-insert some DB-like features into 401(k)s. In a fully automated 401(k), workers are

automatically enrolled, their contributions automatically escalate over time, their accounts are

automatically invested in reasonable ways, and their accounts are rolled over upon job changes.

Participants in an automated 401(k) have full control over these decisions and can override the automatic

2

For example: Private-sector employees seldom contribute to their DB plans, although they often bear the cost of contributions by

receiving lower wages. State and local government plans (where DB remains prevalent) usually require employee as well as employer

contributions. Although employers bear the financial risk, most DB plan benefits are insured by the PBGC in the event of employer

insolvency with unfunded plan benefits.

5

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

settings if they so choose – the rules are defaults not mandates. But participants do not have to make

these choices if they do not want to.

Although they benefit from professionally determined investment options, 401(k) participants don’t

benefit from the diversification gains from additional pooling available in DBs, often face retail pricing of

fees, and still bear the full risk of uncertain asset returns. In addition, 401(k) plans usually receive smaller

employer contributions and pay lump sums, potentially jeopardizing participants’ ability to generate

sufficient retirement income and protect themselves from longevity risk. These shortcomings provide

opportunities for plans like CDCs to maintain the benefits of automated 401(k)s and address their

weaknesses.

Collective Defined Contribution Plans

CDC plans aim to share financial risks in ways that emphasize the strengths and minimize the drawbacks

of DBs and DCs. CDC plans come in many variants; in this section, we focus on a typical CDC plan to

highlight the differences with standard DB and DC plans. In Section III we discuss the variety of hybrid

plans in the United States and other countries that include somewhat similar features.

As in DC plans, it is common for both plan sponsors and/or participating employees to contribute to a

CDC. As in a DB plan, employees generally do not have full 401(k)-style individual accounts (where the

benefit is framed as an account balance resulting from contributions (less withdrawals) and individual

investment returns); however, participants might be seen as having individual accounts in the narrower

sense that certain individual data, such as contributions by and on behalf of individual workers, are

tracked and reported to them. The contributions of an employer’s (or an industry’s) work force are pooled

and professionally managed. The fund managers target future annual benefit levels, but benefit amounts

are not guaranteed.

For plan sponsors, CDCs avoid volatile funding costs by accepting fixed employer contributions correcting

this drawback of DB plans. For workers, CDCs (a) pay benefits in the form of periodic retirement income

(rather than lump sums), (b) pool longevity risk across participants; and (c) provide pooled, professional

investing, correcting these weaknesses of most DC plans.

Paying benefits in the form of periodic income – such as an annuity – and pooling longevity risk helps

people balance the risks associated with either over-consuming early in retirement, thereby risking

running out of funds later, or under-consuming early in retirement, thereby risking having a lower

standard-of-living than necessary. This pooling also enables people to confidently save for an average life

expectancy rather than needing to save for an extremely long one. In addition, CDC plans’ pooling of

investment and longevity risk and lack of guarantee of benefit amounts enables them to provide lifetime

retirement income in-house; they have the option but not the necessity of purchasing commercial

annuities. As a result, they can pay income while avoiding the regulatory, marketing, and profit-margin

costs of commercial annuities.

Pooled, professional investing reduces administrative fees relative to account balances. It increases

participants’ access to a wider range of asset classes, including those that might offer an illiquidity

premium, which are harder for an individual to invest in. It also helps spread a number of risks over time

and across workers, including smoothing routine asset volatility and the sequence-of-return risk and

timing risk associated with having to liquidate assets at a certain point. Some CDC plans, for example, use

reserve funds accumulated from surplus returns in good times to buffer losses during down markets.

Finally, professional investing helps workers avoid “amateur” mistakes – such as overinvesting in the

employer’s stock or failing to rebalance.

For employers, one drawback of CDCs, relative to a DC, is the inability to reduce or suspend contributions

in an adverse economic climate. For workers, the key drawback is that benefit levels are not guaranteed:

employees bear the investment risk, in the form of potential benefit cuts or increased employee

contributions if the plan is doing poorly.

6

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

In addition to pooling among individuals and smoothing over time, these risks have been partially

addressed using a “defined ambition” (DA) design that distinguishes “base” and “ancillary” benefits. Base

benefits are not guaranteed but expected to be paid even under very conservative financial assumptions.

“Ancillary” benefits – such as cost-of-living adjustments or basing benefits on final pay rather than less

generous career average pay – are more explicitly contingent on the plan’s financial condition; if benefits

need to be reduced, they will be cut first.

Is this simply a pyrrhic victory for workers, though, as it reduces “risk” by reducing expected benefits? The

key question, we would suggest, is, “Compared to what?” Compared to a 401(k) plan without investment

or longevity risk pooling or lifetime income, for example, a CDC design would likely benefit participants.

And compared to an unsustainable DB plan, a CDC strategy can establish a systematic, orderly process

that helps workers and retirees manage uncertainty, set reasonable expectations, and plan for retirement.

It is calculated to work in a more professional, fair, and predictable fashion than ad hoc decisions to cut or

suspend benefits made under pressure by plan management or politicians in politically charged

circumstances.

III. Experience with CDCs and related plan designs

The CDC-type and related hybrid pension plans around the world exhibit an array of features.

Understanding how these plans work can help inform discussion of policy reforms in the U.S (Doonan

and Wiley, 2021).

Other Countries

3

Netherlands

The Netherlands has undertaken the largest and most sustained effort to implement a CDC or DA system

on a national basis. The Dutch experience over the past two decades shows how CDC plans can be

implemented at scale and how various challenges and complexities arise and can be addressed.

4

Employee participation is mandatory; employers must participate unless they can offer a better plan. Both

employers and employees make contributions. Dutch occupational-level plans, covering about 80 percent

of the workforce, are collectively bargained, extensively regulated, and professionally managed.

The plans usually target benefits based on an employee’s career average wage, but the actual benefits

depend on the plan’s financial status and therefore are not guaranteed. Participants bear all investment

risk through a combination of potential benefit cuts and increased employee contributions. To help

manage this risk, when the plan’s funding ratio falls below certain benchmarks, it must create a multi-

year recovery program that includes employee contribution increases and/or temporary limits or

elimination of cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), or even cuts in nominal benefits. However, when

benefit cuts actually had to be made several years after the 2008-09 financial crisis, they came as an

unwelcome surprise to many participants. Those risks had not been adequately communicated or

understood, and trust in the system declined.

A key feature of the Dutch DA system has been uniform accruals. Each participant, regardless of age,

accrues the same benefit rights at the same contribution rate. From an actuarial perspective, this means

that younger participants pay more than they should and thus subsidize older participants, who pay less

than they should, yet protecting retirees from current cuts in their ongoing pension payments tends to

have greater political urgency than the need to adequately fund pensions for those whose retirement is

decades in the future. If the plan continues perpetually, and there is always an ample supply of younger

3

In addition to the CDC initiatives described below, Denmark also has implemented similar plan designs.

4

This summary is based on Bovenberg, Mehlkopf, and Nijman(2014), Gérard (2019), Van Popta and Steenbeek (2021), and

Westerhout, Ponds, and Zwanevald (2021).

7

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

workers to support older ones, these intergenerational inequities will even out over each worker’s lifetime.

But this points up a key vulnerability: the sustainability of the Dutch DA system and CDC plans like it

assumes mandatory participation, especially among younger workers, and perpetual existence of the

system.

The Dutch CDC/DA system has been controversial. In 2020, after years of debate about intergenerational

inequities, complexity, and participant perceptions and disappointed expectations, the Dutch government

proposed reforms. These reforms reportedly are strongly supported by the “social partners”, including

labor and employers, and are generally expected to become law (Hoekert, 2021).

The “New Pension Contract” would retain several key elements of the current system – including

mandatory participation; monthly lifetime income without a guarantee of the exact amount; and

collective, professional asset management without direction from individual employees. But it would

make changes that move it closer to a DC model. The uniform accrual and contribution system would be

replaced by an “actuarially fair” system. Benefit rights would no longer be accrued; instead, the accrual or

accounting system would be based on units of value in accounts. The funding ratio would cease to be a

metric: instead, a reserve fund would be mandated to hedge against poor financial performance.

Collective investment returns would be allocated differentially to participants based on a predefined set of

rules. New options would be available for benefit payments, including a lump sum of up to 10 percent of

retirement assets.

The history of the Dutch CDC program illustrates that CDCs have both advantages and potential pitfalls

and may help explain why one commenter opined that a “CDC” actually stood for “Complicated DC” plan

(Lundbergh, 2021).

Canada

The Canadian experience highlights the “compared to what” question noted above. After the financial

crisis of 2008-09, there was significant fear in the Canadian province of New Brunswick that public-sector

DB plans no longer appeared to be politically or financially viable. Faced with that reality, CDC plans were

seen as the preferable alternative to a pure DC approach.

5

As a result, several underfunded public and

private-sector DB plans in Canada moved or are moving to a new “shared risk” program somewhat similar

to the Netherlands’ DA approach. The Canadian “shared risk” model prescribes funding and risk

management goals (including financial stress tests and projected funding ratios) with pre-determined cuts

or increases in benefit payouts and increases or reductions in employer and employee contributions as

well as changes in asset allocations in response to changes in the plan’s financial condition. The plans

maintain an employer guarantee of “base benefits,” defined using career average salary. The difference

between benefits based on career average wages and final wages, together with post-retirement cost-of-

living increases, are classified as ancillary benefits that are not guaranteed but would be provided

depending on the plan’s financial condition.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is considering CDC plans, also known there as “Collective Money Purchase” (CMP)

plans.

6

Subject to extensive regulatory oversight to ensure financial soundness and appropriate plan

design, U.K. employers and employees would contribute to a fund that is professionally managed. Payouts

would be targeted to a specific benefit level but, to make employer costs predictable, would not be

guaranteed and would depend on the plan’s financial status. CDC plan benefits would be expected to be

designed to generally increase over time to keep up with inflation, although they would not be required to

5

From a 2013 government report, “Many in the public complained openly about the generosity of these [DB] schemes and the fact

that they have to pay extra taxes to cover pension deficits for benefits that they cannot afford for themselves” (Government of New

Brunswick, 2013, page 7). Further, a background report on pension reform from the New Brunswick government stated that,

financially, “many [DB] plans as they presently exist are not sustainable in the long term.” (Government of New Brunswick, 2012,

page 1). See also Munnell and Sass (2013).

6

Summary based on Department for Work & Pensions (2021), Thurley and McInnes (2021), and Eagle, Jadav, and Fadayel (2020).

8

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

match inflation every year. In addition, the value of a participant’s expected benefits over time would be

required to at least equal the contributions made by or for the participant.

This framework appears to draw lessons from the Dutch experience, addressing concerns about

intergenerational equity by seeking to prevent excessive cross-subsidization (in either direction) between

new participants and long-time participants and thus between past and future benefit accruals. For

similar reasons, benefit changes must be universal, with any cuts generally smoothed over three years.

United States

The United States has a variety of hybrid plan designs, both actual and proposed. This section describes

these plans, organizing them into three categories: longstanding DC plan designs that have collective

features; recently developed plan designs that are more DB-like with CDC features; and approaches that

use separate DB and DC plans.

Traditional DC-like plan designs with collective features

Money purchase pension plans were originally used as an alternative to DB plans to limit employers’ cost

and potential liability. Money purchase plans are typically funded by employer contributions, usually

made annually and based on a fixed formula (such as 10 percent of salary). Investments are pooled,

professionally managed, and allocated to each participant’s individual account. Benefits are based on

account balances, including both contributions and earnings, so participants bear the investment risk.

The default form of payouts must be an annuity, although the plans can also offer other payout

alternatives.

Target benefit plans are a variant of money purchase plans that closely resembles a CDC. Unlike other

money purchase plans, target benefit plans define a participant’s benefits as a targeted, not a guaranteed,

amount. The target benefit is the basis for determining how much the employer should contribute based

on reasonable actuarial assumptions (instead of contributing a fixed percentage of payroll). Since

participants’ actual benefits are still determined by the contributions and earnings allocated to their

individual account, they still bear the investment risk. This plan design traditionally has not been widely

used in the United States, although various CDC designs in the United States and abroad are now referred

to as “target benefit plans.”

Profit-sharing plans are more flexible and subject to fewer requirements. Instead of defining required

annual employer contributions, profit-sharing plans allow employer contributions to be discretionary,

and payouts need not be offered as an annuity. Profit-sharing plans can include pooling and professional

direction of investments, but instead often incorporate 401(k) arrangements allowing employees to direct

their own investments.

Both profit-sharing and money purchase plans (including target benefit plans) traditionally provide

meaningful nonmatching employer contributions, such as 7 or 10 percent of salary, as would some other

CDC-type plans. It may be no accident that these traditional plan types, like private-sector DB plans, have

been largely succeeded by 401(k)s and IRAs in the United States, a change that reduces employers’ costs

and risks. Employers have little incentive to offer such larger contributions if employees show equal or

greater appreciation for an un-pooled 401(k) with smaller employer contributions.

During the 1990s and thereafter, a large share of U.S. DB pension plan sponsors converted to a DB-DC

hybrid known as a cash balance pension, and some employers adopted new cash balance plans. The cash

balance plan is presented to participants essentially as if it were a DC plan, but it is actually a DB with

both employer-guaranteed benefits and PBGC insurance. Each participant has an individual account, but

the accounts are notional and are credited with employer contributions equal to a specified percentage of

the employee’s pay that “grow” at a pre-determined interest rate. The employer guarantee of benefits is

effectively limited to the benefit produced by the notional employer contributions and interest credits.

The actual employer contributions are invested on a plan-wide, pooled basis, and not directed by

9

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

employees. Cash balance plans are required to offer lifetime annuity income as the default form of payout,

but many participants elect lump sum payouts instead.

The cash balance experience illustrates the transition risks associated with converting a traditional DB

plan to a hybrid format. For years, the conversions engendered litigation and bitter controversy because

they unexpectedly deprived mid-career DB participants of their anticipated major increases in late-career

benefit accruals provided by traditional, back-loaded DB plans.

DB-Like variable benefit plans, including proposed composites

Recent years have seen significant experimentation with hybrid plans, especially in the U.S. collectively

bargained and state and local government sectors (including, in particular, Maine and South Dakota). The

objective is to manage the shift from traditional DB plans to a plan design that shares risks with

participants in a more collective manner than the individualized 401(k). Labor unions have been

particularly creative in developing and advocating for hybrid pension plan designs that are sponsored and

funded by employers, sometimes have employee contributions, define targeted benefits in a DB-like

manner, invest collectively and professionally without employee involvement, and pool longevity risk to

provide lifetime retirement income. Like defined ambition and CDC plans, these variable benefit plans

protect employers from potentially volatile funding obligations. Although they have DB-like benefit

formulas, some do not guarantee benefits, while others include both a base guaranteed DB component

and a variable component.

The “Variable DB” plan design developed by the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), for

example, combines traditional DB and CDC designs by guaranteeing a DB benefit as a base amount and

providing a potentially higher benefit depending on investment performance of the pension fund.

Investment risk is shared: employers bear the underfunding risk up to the base benefit amount while

employees bear the risk that the variable benefit will not exceed the base benefit. The plan seeks to limit

the employer’s DB funding cost and volatility by designing the guaranteed benefit to be manageable in

amount and by prescribing conservative funding rules to minimize the risk of underfunding that base

benefit.

7

The National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans, a broad-based association of major

business, union, and other stakeholder organizations in the multiemployer pension arena, has proposed a

hybrid plan solution to multiemployer plan underfunding (Defrehn and Shapiro, 2013).

8

Proposed

legislation, which would authorize so-called “composite” plans in the United States, passed the House of

Representatives in 2020, but was not been taken up by the Senate as it aroused considerable controversy,

including strong support and strong opposition within organized labor.

9

Composite plans would be neither DB nor DC. They would not have individual accounts. Assets would be

pooled and professionally invested. Employers would make fixed contributions negotiated between labor

and management, and benefits would be determined by the plan formula and paid as a life annuity.

Employees would bear the risk that adverse investment experience would necessitate benefit reductions.

A composite plan would not be considered fully funded until its projected funded ratio reached 120

percent, and if the plan fell below this benchmark, corrective actions, potentially including benefit

7

The Variable DB design was developed by a UFCW Union task force that concluded in 2006 that continued DB pensions were

unsustainable but rejected a shift to DC because of the extent of the risk that would impose on participants. Participants would

ultimately receive the greater of (i) a DB benefit floor of a specified dollar amount per month for each year of service, guaranteed by

the PBGC, and (ii) a variable or adjustable benefit that could fluctuate based on investment experience. The DB floor would be

determined using conservative interest rates and could be reset periodically as plan demographics changed. Additional investment

returns would accrue to the variable portion of the benefit up to a cap, and any higher returns would instead be set aside in a reserve

to maintain future floor benefits during market downturns. See Blitzstein (2016). This basic approach, which can be used by

multiemployer or single-employer plans, has been adopted thus far by a handful of union plans and by the State of Maine for local

government employees. Maine’s plan features employer and employee contributions that vary based on market performance

(subject to caps and floors) and variable COLAs.

8

The same report by this organization also included the variable DB plan as another promising, innovative hybrid plan design.

9

See GROW Act (2018) and The Heroes Act (2020).

10

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

reductions, would be required. Under the proposed legislation, the joint union-management board of

trustees that manages multiemployer plans would be granted broad powers to provide for benefit

reductions, but increased contributions would be required only if agreed to by both management and

labor.

10

If a plan was doing well, benefits could be increased only subject to extensive conditions and

limitations based on funded ratios and other matters. Because they would not be DB plans, composite

plans would not be insured by the PBGC.

The proposal lets current multiemployer DB plans transition to composite plans, with the original DB

remaining as a “legacy plan” that is still PBGC-insured. When employers switch from DB to composite,

participants would cease accruing new benefits under the legacy plan and begin accruing new benefits

under the composite plan. Employers would be required to continue funding the legacy plan, but at a

slower pace, with the goal of eventually achieving a 100 percent funding ratio. The proposed risk shift

from employers to employees would also include significant reduction of “withdrawal liability” for

employers that choose to stop participating in the multiemployer plan (Topoleski, 2020). One of the

reasons the composite proposal has aroused controversy is concern about whether it would unduly

weaken funding of the legacy DB plan – another illustration of how new hybrids, including CDCs, can

raise significant transition issues and put a premium on effective plan governance.

Coordinated DB and DC plans

Instead of pursuing the best of DB and DC features by combining the two within a single collective DC or

hybrid plan, similar results can be achieved by using separate DB and DC plans. These can either be

coordinated – for example, by giving participants the greater of the two types of benefits, as in a “floor-

offset” plan – or independent, by giving participants the sum of the two. Both the greater-of and the sum-

of designs permit pooled professional investment and retirement income with longevity risk pooled

among retirees.

11

A third option involving DB and DC plans gives employees the choice to participate in

either one but not both.

IV. Challenges for CDCs

As the discussion above demonstrates, CDC and hybrid plans have made in-roads into pension systems in

the United States and several other countries. Whether they can expand further depends on resolution of

several issues.

First, can participants understand and accept the partial nature of the benefit guarantee? The “defined”

retirement income features of DB and DC plans are clear: in a DB, a specified monthly dollar amount for

life starting at a specified age; in a typical DC, no such guaranteed or targeted monthly retirement income.

Participants in a CDC with benefits that are targeted but not guaranteed might eventually develop

expectations beyond those that are justified by the plan’s terms. The distinction between defined

“ambition” and defined “benefit” is clear in principle, but as a practical matter, may be hard for

participants to live with and for plan sponsors to sustain over the longer term – especially when plan

provisions are complex, potentially nuanced, and ultimately subject to the plan management’s exercise of

discretion. Especially if investment returns are strong for some years, participants might naturally tune

out a plan’s qualifications and caveats and to come to expect and rely on benefits (especially those already

in the process of being paid) being at least equal to those that were targeted. Accordingly, the success of

CDC plans is heavily dependent on accurate and effective plan communications to shape clear and

realistic participant expectations.

Experience could well shed light on whether, and, if so, how, CDC plan design could mitigate the risk of

participant “expectation creep.” For example, in contrast to a purely variable CDC, might a binary CDC

structure with a guaranteed DB benefit and a separate variable targeted benefit naturally reinforce

10

See Internal Revenue Code section 439(a)(2)(B)(i), as proposed to be added by the GROW Act.

11

Another hybrid plan design in the United States. is the “DB-k” plan that combines a DB plan and a 401(k) arrangement, but these

are very rarely used. See IRC section 414(x).

11

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

accurate participant expectations through a clear and consistent demarcation between the guaranteed and

nonguaranteed components (such as a guaranteed benefit versus a targeted but nonguaranteed COLA)?

The risk of “expectation creep” or misunderstanding presents a particular problem in the litigious U.S.

market. In recent years, the U.S. plan sponsor community has become shell shocked by widespread

litigation challenging retirement plan practices and costs. In this environment, employers and their

counsel can be expected to ask whether the efficiencies of CDCs are worth the risk of setting benefit

“targets” that might not be met or well understood by employees. They may fear exposing themselves to

class actions claiming that benefit cuts could have been avoided, that employees were not adequately

warned that cuts might occur, and that particular cohorts were unfairly disadvantaged by transitions to

CDC or other exercises of discretion by CDC plan sponsors. A pure DC model looks clear and simple by

comparison, particularly as Americans seem to have less expectation than others that retirement plans

should and will provide lifetime income.

Second, can CDC plans be designed to meet intergenerational equity considerations? CDCs need to

mediate between different generations of workers, new and old members, and employees versus retirees.

Disparities in treatment – actual or perceived, equitable or not – follow from the inevitable changes over

time in business cycles, investment returns of various asset classes, interest rates, wage levels, and other

factors. These variables affect various plan types and designs. For example, because CDC plans pool

contributions and payouts for workers of different ages, fund managers’ decisions at a particular time to

increase payouts or increase required employee contributions tend to benefit current retirees (who are

receiving payouts but not contributing) at the expense of current workers (who are contributing but not

receiving payouts). In addition, as noted above, in a system where each worker contributes the same

amount, as in the Netherlands, younger participants pay more than they should – from an actuarial

perspective – while older participants pay less. For these and other reasons, CDCs have given rise to inter-

generational tensions and challenging sustainability problems.

Third, can transition effects be managed appropriately at the plan level? Where a CDC or variable DB

starts as an existing DB plan – as composite plans would – transition is critical. As noted, conversions of

traditional U.S. DBs to hybrid cash balance plans created major transition problems. In addition, the

“composite” proposal discussed above, for example, has raised concerns about whether employer funding

of participants’ existing DB benefits would be unduly weakened by relaxation of existing funding

standards for the DB legacy component while adding a composite component competing for a single pool

of assets and funding source. An additional concern is that transitions, such as the cash balance

conversions, almost inevitably generate disparities in treatment of participants by age.

Fourth, can transition effects be managed appropriately at the retirement system level? For several

reasons, CDCs and similar designs may prove more likely to be adopted as replacements for existing DBs

than for 401(k)s. First, employers have already shifted most financial risks associated with retirement

plans to employees and retirees through 401(k)s and IRAs. Second, it may be easier to persuade

employers with DB plans – who face higher costs and risks – than those with 401(k)s that CDCs can help

reduce their costs and risks.

Among employers with 401(k)s, the realistic prospect may be incremental addition of selected collective

strategies or features. These might include help in converting account balances to regular income in

retirement or partial annuitization; enhanced participant access to lifetime income through managed

payout or systematic withdrawal funds; tontine-like mortality credit pooling; or more collective

professional investment including the broader use of institutional or collective approaches.

12

Fifth, is there enough trust and convergence of interests between labor and management to keep CDCs

financially sustainable and otherwise protective of participants? On an ongoing basis, CDCs’ shift of risk

from employers to participants and added flexibility to reduce benefits have raised questions about

whether they provide too much discretion to make changes adverse to participants without sufficient

guard rails or protections. The more adjustments a plan makes or has discretion to make that result in

12

In recent papers, we have explored issues raised by DC plans’ use of commercial annuities, managed payout and systematic

withdrawal funds, and tontine-like mortality credit pooling, See Iwry et al. (2019), Iwry et al. (2020), and John et al. (2019).

12

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

differential treatment in the pursuit of equity among different classes of participant groups, the greater

the scope for misunderstanding, disagreement, mistrust, and blame. The actuarial calculations and

judgments involved in ensuring CDC financial soundness and sustainability (even with respect to

nonguaranteed benefits) are not naturally transparent or easy for nonexperts to understand. These

concerns lead directly to a heightened need, in variable and adjustable benefit plans, for sound plan

management, governance, and safeguards (Frank 2018 and Ambachtsheer, 2020). The need or authority

to exercise discretion in these plan designs calls for a high degree of transparency and honest brokering

on the part of plan management and often regulatory authorities and policy makers.

Finally, CDCs raise a variety of questions about the tradeoff between pooling and portability when an

employee changes jobs well before retirement. For the most part, DC savings are relatively easy to move

between employer plans. Moving and consolidating DB benefits easily and without loss of value, however,

can be more challenging, and U.S. CDCs are more likely to be DB-like in this respect. If so, when a

participant leaves the employ of the plan sponsor, the CDC presumably would disclose their accrued

target lifetime retirement benefit as well as the lump sum amount available (which could be a refund of

their previous contributions to the plan, with or without interest or earnings) if they cashed out (and

thereby forfeited the retirement income benefit). Following the U.S. DB model, if the former employee left

the benefit in the plan, retirement income might not become available until they reached an early

retirement age such as 55 or 60. If instead they chose the lump sum, they could roll it over tax-free to

another plan or IRA. If a new employee wished to roll over a benefit from another plan into their new

employer’s CDC, the process would depend on that plan’s rules. Those might allow the funds to be

allocated to a separate, rollover account within the CDC plan or used to buy service credits in the CDC

(which might also be offered as an option for others to convert other retirement savings to additional

retirement income from the plan at retirement).

V. Conclusion

While they face significant issues, CDCs and similar approaches that transcend a strict adherence to

traditional DB or 401(k) plan designs can help improve retirement security in appropriate circumstances.

Where a traditional DB plan is well funded by a strong plan sponsor, for example, in the public sector or

in collectively bargained settings, CDCs and similar variable designs might provide some helpful flexibility

such as adjustable COLAs, but could also unnecessarily add complexity, new kinds of uncertainty,

intergenerational equity issues, and potentially unclear expectations for employees and retirees. In the

many situations, however, where the driver of change is the DB sponsor’s unwillingness or inability to

continue bearing costly and volatile investment and funding risks, maintaining an existing DB in its

current form may not be an option. When the alternative is a 401(k) plan, a better solution could be either

to modify the DB to add CDC features and flexibility or to add CDC features to the 401(k), including more

investment pooling and professional investment management, pooling of longevity risk among retirees,

and facilitating the payment of retirement income.

A CDC is also an option for an employer that currently offers a 401(k) but wants to provide a retirement

benefit with better features without the potential expense of a DB. A CDC could provide both higher

benefits and retirement income, rather than forcing new retirees to either incur the cost of a commercial

annuity or determine for themselves how to invest and at what pace to draw down the typical end-of-

career 401(k) lump sum payment.

Looking beyond the conventional, traditional DB and DC plan designs to explore a new, richer, and more

nuanced array of risk-sharing and pooling strategies is a welcome development that will help identify

more optimal allocations of financial risks and retirement benefits.

13

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

Table 1: Summary Comparison of Basic DB, 401(k), and CDC Plan Designs

DB

Regular 401(k)

Auto 401(k)

CDC

Enrollment

Usually no

employee initiative

required to

participate

Eligible employees

participate only if they

sign up

Eligible employees

participate unless

they opt out

Usually, no

employee initiative

required to

participate

Contributions

By employers (and

in some plans,

employees)

By employees (and in

most plans, employers)

By employees (and

in most plans,

employers)

By employers and

often employees

Contributions

pooled

Yes

Occasionally, but

usually not pooled

13

Occasionally, but

usually not pooled

Yes

Investment

Employers/

financial managers

manage on behalf

of employees

Employees choose

among employer-

defined options

Employers set

default investment

choice, but

employees can also

choose among

employer- defined

options

Employers/

financial managers

manage on behalf

of employees

Allocation of risk

Employer bears

investment and

longevity risk

Individual participant

bears investment and

longevity risk

Individual

participant bears

investment and

longevity risk

Employees/

retirees collectively

share investment

and longevity risk

Determination of

benefits

Plan formula

specifies

guaranteed

monthly pension

benefit based on

pay and service

Benefit depends solely

on contributions to

participant’s individual

account +/- investment

experience, less

withdrawals

Benefit depends

solely on

contributions to

participant’s

individual account

+/- investment

experience, less

withdrawals

Plan terms

determine targeted

but nonguaranteed,

variable monthly

pension benefit

Form of benefits

Lifetime income;

often lump sum

option

Usually, lump sum

Usually, lump sum

Lifetime income,

usually variable

Employer Funding

requirements

Yes, because

benefit is

guaranteed by

employer

No but employer might

make defined

contributions

No but employer

might make

defined

contributions

Not like DB, but

employer

contributions

required based on

plan terms

13

An exception is 401(k)s that use investment pools instead of mutual funds.

14

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

References

Ambachtsheer, K. 2020. “Governance in Asset Owner Organizations: Still Room for

Improvement.” The Ambachtsheer Letter. KPA Advisory Services LTD. https://kpa-

advisory.com/the-ambachtsheer-letter/view/governance-in-asset-owner-organizations-

still-room-for-improvement

Blitzstein, D.S. 2016. “United States Pension Benefit Plan Design Innovation: Labor Unions as

Agents of Change.” In O.S. Mitchell & R.C. Shea (Eds.), Reimagining Pensions: The

Next 40 Years. Oxford University Press.

https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1093&context=prc_papers

Bovenberg, L., Mehlkopf, R., and Nijman, T. 2014. “The Promise of Defined Ambition Plans:

Lessons for the United States.” In O.S. Mitchell & R.C. Shea (Eds.), Reimagining

Pensions: The Next 40 Years. Oxford University Press.

https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1098&context=prc_papers

Defrehn, R.G. and Shapiro, J. 2013. “Solutions Not Bailouts: A Comprehensive Plan from

business and Labor to Safeguard Multiemployer Retirement Security, Protect Taxpayers

and Spur Economic Growth.” A Report on the Proceedings, Findings and

Recommendations of the Retirement Security Review Commission. National

Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans. https://nccmp.org/wp-

content/uploads/2017/07/SolutionsNotBailouts.pdf

Department for Work & Pensions. 2021. “The Occupational Pension Schemes (Collective

Money Purchase Schemes) Regulations 2021.” Open Consultation. GOV.UK.

https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/the-occupational-pension-schemes-

collective-money-purchase-schemes-regulations-2021/the-occupational-pension-

schemes-collective-money-purchase-schemes-regulations-2021

Doonan, D. and Wiley, E. 2021. “The Hybrid Handbook: Not All Hybrids are Created Equal.”

National Institute on Retirement Security. https://www.nirsonline.org/wp-

content/uploads/2021/05/Hybrid-Handbook-F8.pdf

Eagle, S., Jadav, S., and Fadayel, L. 2020. “CDC – A New Type of Pension Provision Coming to

the UK.” Willis Towers Watson. https://www.willistowerswatson.com/en-

GB/Insights/2020/09/collective-defined-contribution-a-new-type-of-pension-provision-

coming-to-the-UK

Frank, R. 2018. “Collective DC: Let’s Not Go Dutch.” IPE Magazine.

https://www.ipe.com/collective-dc-lets-not-go-dutch/10023436.article

Gérard, M. 2019. “Reform Options for Mature Defined Benefit Pension Plans: The Case of the

Netherlands.” International Monetary Fund.

https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2019/022/article-A001-en.xml

Government of New Brunswick. 2012. “Pension Reform Background Document.”

https://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Corporate/pdf/Pension/Backgrounder_pension.pdf

Government of New Brunswick. 2013. “Rebuilding New Brunswick: The Case for Pension

Reform.” http://leg-horizon.gnb.ca/e-

repository/monographs/31000000047551/31000000047551.pdf

GROW Act. 2018. H.R. 4997. 115

th

Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-

congress/house-bill/4997

Hoekert, W. 2021. “Netherlands: Pension Reforms Postponed for Up to One Year.” Willis

Towers Watson. https://www.willistowerswatson.com/en-

US/Insights/2021/05/netherlands-pension-reforms-postponed-for-up-to-one-year

15

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

Iwry, J.M., Gale, W.G., John, D.C., and Johnson, V. 2019. “When Income is the Outcome:

Reducing Regulatory Obstacles to Annuities in 401(k) Plans.” Brookings Institution.

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2019/07/ES_201907_IwryGaleJohnJohnson.pdf

Iwry, J.M., Haldeman, C., Gale, W.G., and John, D.C. 2020. “Retirement Tontines: Using a

Classical Finance Mechanism as an Alternative Source of Retirement Income.”

Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2020/10/Retirement-Security-Project-Tontines-Oct-2020.pdf

John, D.C., Gale, W.G., Iwry, J.M., and Krupkin, A. 2019. “From Saving to Spending: A

Proposal to Convert Retirement Account Balances into Automatic and Flexible Income.”

Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2019/07/ES_201907_JohnGaleIwryKrupkin.pdf

Lundbergh, S. 2021. “Miracles and Mirages of CDC.” LinkedIn Blog.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/miracles-mirages-cdc-stefan-lundbergh/

Millard, C.E.F., Pitt-Watson, D., and Antonelli, A.M. 2021. “Securing a Reliable Income in

Retirement: An Examination of the Benefits and Challenges of Pooled Funding and Risk-

Sharing in Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) Plans.” Center for Retirement

Initiatives, McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University.

https://cri.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/policy-report-21-03.pdf

Munnell, A.H. and Sass, S.A. 2013. “New Brunswick’s New Shared Risk Pension Plan.” Center

for Retirement Research at Boston College. https://publicplansdata.org/wp-

content/uploads/2014/06/slp_33.pdf

The Heroes Act. 2020. H.R. 6800. 116

th

Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-

congress/house-bill/6800

Thurley, D. and McInnes, R. 2021. “Pension Schemes Bill 2019-21.” Briefing Paper Number

CBP-8693. House of Commons Library.

https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8693/CBP-8693.pdf

Topoleski, J.J. 2020. “Proposed Multiemployer Composite Plans: Background and Analysis.”

Congressional Research Service. R44722.

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44722

Van Popta, B. and Steenbeek, O. 2021. “Transition to a New Pension Contract in the

Netherlands: Lessons from Abroad.” Netspar Industry Series. Network for Studies on

Pensions, Aging and Retirement.

https://www.netspar.nl/assets/uploads/P20210625_Netspar_Occasional_paper_03-

2021.pdf

Westerhout, E., Ponds, E., and Zwanevald, P. 2021. “Completing Dutch Pension Reform.”

Netspar Industry Series. Network for Studies on Pension, Aging and Retirement.

https://www.netspar.nl/assets/uploads/P20210812_Netspar-Design-Paper-179-WEB.pdf

16

/// Collective Defined Contribution Plans | Discussion Draft

The Brookings Economic Studies program

analyzes current and emerging economic issues

facing the United States and the world, focusing

on ideas to achieve broad-based economic

growth, a strong labor market, sound fiscal and

monetary policy, and economic opportunity and

social mobility. The research aims to increase

understanding of how the economy works and

what can be done to make it work better.

Questions about the research? Email [email protected].

Be sure to include the title of this paper in your inquiry.

© 2021 The Brookings Institution | 1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Washington, DC 20036 | 202.797.6000