Bill de Blasio

Mayor

Vincent Sapienza, P.E.

Commissioner

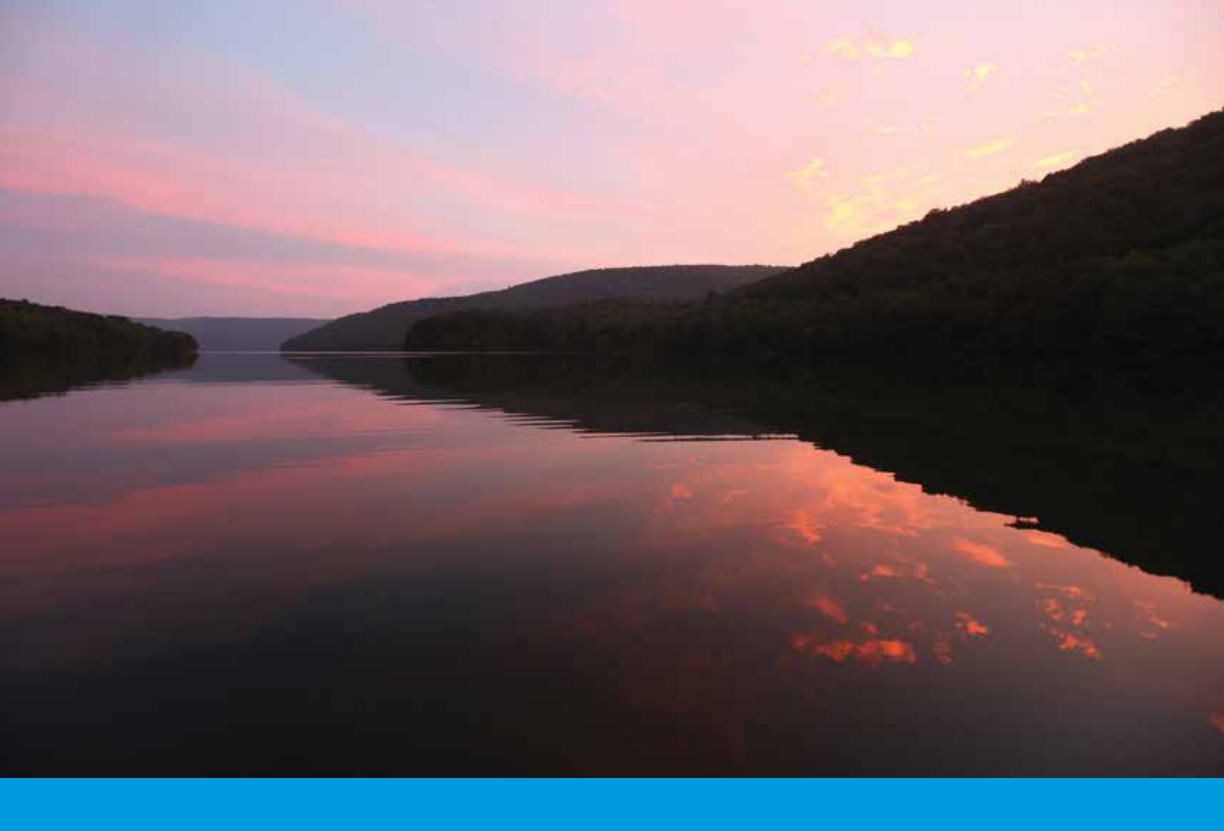

Tunneling through at Schoharie Reservoir

New York City

2018 Drinking Water

Supply and Quality

Report

Esopus

Creek

S

h

a

n

d

a

k

en

Tu

n

n

e

l

PENNSYLVANIA

NEW YORK

NEW JERSEY

CONNECTICUT

CONNECTICUT

NEW YORK

MASSACHUSETTS

New York

Bay

Delaware

River

Hudson

River

Long Island Sound

Delaware Aqueduct

N

ew Crot

o

n

A

q

u

e

d

uct

DELAWARE

COUNTY

SCHOHARIE

COUNTY

GREENE

COUNTY

ULSTER

COUNTY

SULLIVAN

COUNTY

DUTCHESS

COUNTY

ORANGE

COUNTY

NASSAU

COUNTY

CHENANGO

COUNTY

OTSEGO

COUNTY

ALBANY

COUNTY

RENSSELAER

COUNTY

COLUMBIA

COUNTY

PUTNAM

COUNTY

ROCKLAND

COUNTY

WESTCHESTER

COUNTY

West Branch

Reservoir

New Croton

Reservoir

Kensico

Reservoir

Neversink

Reservoir

Pepacton

Reservoir

Ashokan

Reservoir

Schoharie

Reservoir

Rondout

Reservoir

Cannonsville

Reservoir

H

u

dson

R

i

v

e

r

Hillview

Reservoir

N

e

v

e

r

s

i

n

k

R

i

v

e

r

West Branch

Delaware

East Branch

Delaware

Oneonta

Gilboa

Deposit

Liberty

Kingston

Poughkeepsie

Ellenville

White

Plains

Delhi

Walton

Hunter

Phoenicia

Downsville

East Delaware Tunnel

West Delaware Tunnel

Neversink

Tunnel

2

5

M

i

l

e

s

(

f

r

o

m

C

i

t

y

H

a

l

l

)

5

0

M

i

l

e

s

7

5

M

i

l

e

s

1

0

0

M

i

l

e

s

1

2

5

M

i

l

e

s

Croton

Watershed

Croton

Watershed

Atlantic Ocean

Catskill/Delaware

Watersheds

Catskill/Delaware

Watersheds

East Branch

Reservoir

Bog Brook

Reservoir

Croton Falls

Reservoir

Boyds Corner

Reservoir

Diverting

Reservoir

Lake

Gleneida

Muscoot

Reservoir

Middle

Branch

Reservoir

Titicus

Reservoir

Amawalk

Reservoir

Cross River

Reservoir

Lake

Gilead

Kirk

Lake

C

a

t

s

k

i

l

l

D

e

l

a

w

a

r

e

Jerome Park

Reservoir

City Tunnel No. 3

Silver Lake Park

(Underground Storage Tanks)

Manhattan

n

Richmond Tunnel

Brooklyn

Staten

Island

Bronx

Queens

C

a

t

s

k

i

l

l

A

q

u

e

d

u

c

t

BROOKLYN

STATEN

ISLAND

Long Island Sound

East River

Hudson River

Lower

New York

Bay

NEW YORK CITY

WATER TUNNELS AND

DISTRIBUTION AREAS

NY City Line

Catskill/Delaware water service area

Croton and Catskill/Delaware blended water service area

Groundwater supply system (offline)

Richmond Tunnel

City Tunnel No. 3

City Tunnel No. 1

City Tunnel No. 2

Hillview

Reservoir

BRONX

MANHATTAN

Jerome Park

Reservoir

QUEENS

Silver Lake Park

(Underground Storage Tanks)

New Croton

Aqueduct

City Tunnel No. 3 (Stage 2)

Queens/Brooklyn Leg

(Activation Ready)

City Tunnel No. 1

MAP NOT TO SCALE

Croton Water

Filtration Plant

City Tunnel No. 2

Croton Water

Filtration Plant

Cat/Del

UV Facility

Staten Island

Siphon

Dear Friends:

On behalf of my nearly 6,000 colleagues at the Department of Environmental Protection

(DEP), I am proud to report that New York City continues to enjoy some of the best tap

water in the world. In 2018, we continued to deliver more than 1 billion gallons of clean

and delicious drinking water to nearly 10 million people every day.

Many communities throughout the United States remain concerned about the safety of

their public water supplies. Here in New York, we are fortunate to have a water supply that

is well protected and operated by dedicated scientists, engineers and other professionals

who have earned admiration among their colleagues throughout the world.

The evidence of New York City’s high-quality drinking water is in the numbers and on

your taste buds.

In this report, you will see that New York City’s drinking water continued to meet or sur-

pass every national and state standard for quality. These data are based on 53,200 sam-

ples that were collected by DEP scientists throughout our reservoir system, and at nearly

1,000 street-side sampling stations in every neighborhood across the City. Those samples

were analyzed 654,000 times by scientists working in our four water quality laboratories.

Robotic monitoring stations on our reservoirs provided another 1.3 million tests to ensure

DEP was sending the best-quality water to New York City at all times.

The excellent scientic results were validated last summer by our customers and other

New Yorkers. In 2018, New York City earned rst place in the New York State Tap Water

Taste Test competition. That honor was based on hundreds of people who lined up in

New York City and at the state fair in Syracuse to taste water from dozens of cities, towns,

and villages. In the end, New York City earned the blue ribbon for our great-tasting water.

None of these good results happen by accident. Our drinking water system relies on

vast reservoirs, large dams, hundreds of miles of aqueducts, and thousands of miles of

water mains. Steady and focused investment in drinking water infrastructure is key to the

future of New York City. That is why you will also nd in this report news about a number

of infrastructure investments DEP is making now and in the decades ahead. In 2018, we

announced a $1.2 billion tunneling project in Westchester County to improve opera-

tional resiliency and exibility between a key reservoir and treatment facility. The largest

repair project in the history of our water supply system, the $1 billion Delaware Aqueduct

Bypass Tunnel, continued to make steady progress last year as a tunneling machine exca-

vated toward the Hudson River. You will nd details about these and other projects in the

pages that follow.

As we look forward to 2019 and beyond, I want to thank you for entrusting DEP with the

operation, protection, and maintenance of your drinking water supply. We take great

pride in delivering the best water to millions of New Yorkers every day.

Sincerely,

Vincent Sapienza, P.E.

Commissioner

Vincent Sapienza, P.E.

Commissioner

2

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

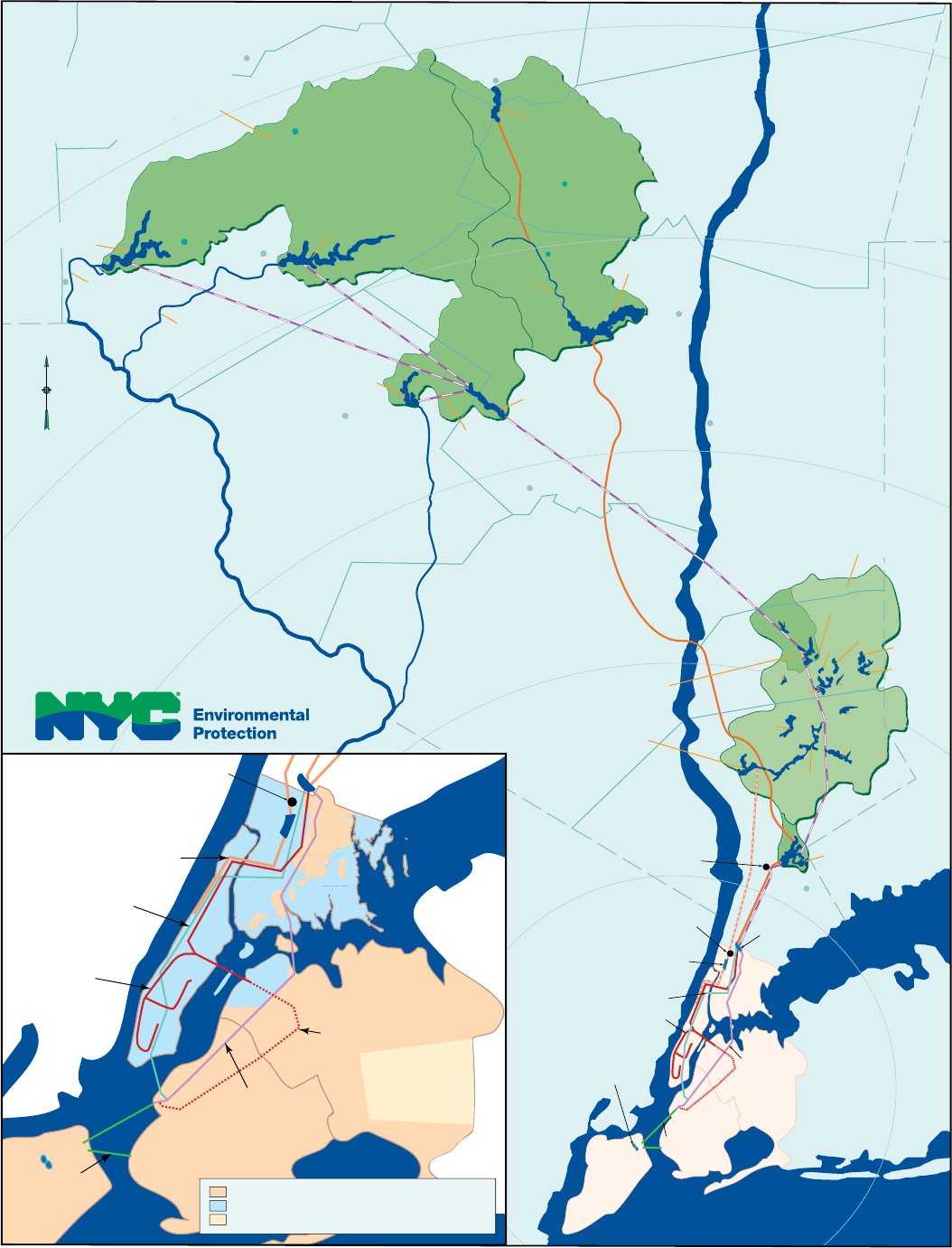

WHERE DOES NEW YORK

CITY’S DRINKING WATER

COME FROM?

New York City gets its drinking

water from 19 reservoirs and three

controlled lakes spread across a

nearly 2,000-square-mile water-

shed. The watershed is not located

in New York City, but rather upstate,

in portions of the Hudson Valley and

Catskill Mountains that are as far as

125 miles north of the City. A map

of the watershed and reservoirs can

be found on the inside of the front

cover of this report. The New York

City Water Supply System, Public

Water System Identication Num-

ber (PWSID) NY7003493, consists

of three individual water supplies

called the Catskill/Delaware supply,

Pepacton Reservoir

located in Delaware, Greene, Schoha-

rie, Sullivan, and Ulster counties; the

Croton supply, New York City’s origi-

nal upstate supply, in Putnam, West-

chester, and Dutchess counties; and a

groundwater supply in southeastern

Queens. Although the Department of

Environmental Protection (DEP) has

a permit to operate the groundwater

supply, water from that system has

not been delivered to customers in

many years.

In 2018, New York City received a

blend of drinking water from the

Catskill/Delaware and Croton sup-

plies. The Catskill/Delaware supply

provided approximately 94 percent of

the water, and approximately six per-

cent was supplied by Croton.

NEW YORK CITY’S WATER SUPPLY

The New York City Water Supply System provides approximately one

billion gallons of safe drinking water daily to more than 8.6 million resi-

dents of New York City, and to the millions of tourists and commuters

who visit the City throughout the year. The water supply system also

provides about 105 million gallons a day to approximately one mil-

lion people living in the counties of Westchester, Putnam, Orange, and

Ulster. In all, the New York City Water Supply System provides nearly half

the population of New York State with high-quality drinking water.

3

Croton Water Supply located in Putnam, Westchester, and

Dutchess counties

The Croton supply is filtered by the Croton Water

Filtration Plant, located underground in the Bronx. The

plant has the ability to filter up to 290 million gallons

of drinking water each day, which helps to ensure

a sufficient supply of water for the City in the event

of drought, and increases the flexibility of New York

City’s supply against the potential effects of climate

change. The Croton Water Filtration Plant first began

operating in May 2015. In 2018, it was in operation from

May 17 to August 15, September 26 to October 14, and

October 17 until December 31, 2018.

Chlorine

Water is disinfected

with chlorine which is

a common disinfectant

added to kill germs and

stop bacteria from

growing on pipes.

Catskill/Delaware Ultraviolet

(UV) Disinfection Facility

It is the largest of its kind in the world

located in Westchester County. The

facility is designed to disinfect more

than 2 billion gallons of water per day.

NYC Distribution

to the Customer

Other

Treatment

Disinfection

Disinfection

* During 2018, only 0.3 percent of the water produced by Catskill/Delaware supply was not fluoridated.

** During 2018, only 0.06 percent of the water produced by the Croton Water Filtration Plant was not fluoridated.

Catskill/Delaware Supply located in Delaware, Greene, Schoharie, Sullivan, and Ulster counties

Due to the very high quality of our Catskill/Delaware supply, New York City is one of only five

large cities in the country with a surface drinking water supply that does not utilize filtration as

a form of treatment. Rather, the Catskill/Delaware supply operates under a Filtration Avoidance

Determination (FAD), and the water from the supply is treated using two forms of disinfection to

reduce microbial risk.

UV Light

At the UV Disinfection

Facility exposure to UV

light inactivates potentially

harmful microorganisms. UV

treatment does not change

the water chemically, as

nothing is added except

energy.

Other

Treatment

Croton Water

Filtration Plant

Filtration

Chemicals are added to untreated water,

causing particulates to bunch together

and become larger particles called floc.

Coagulation

Fluoride*

Added to water

to improve dental

protection, it is effective

in preventing cavities at

a federally approved

level of 0.7 mg/L.

Sodium

Hydroxide

Added to raise the pH,

it reduces corrosion of

household plumbing.

Food Grade

Phosphoric Acid

Added because it creates

a protective film on pipes

that reduces the release

of metals, such as lead,

from service lines and

household plumbing.

Dissolved

Air

Flotation

Injected air bubbles float the floc to

the top where it is skimmed off.

Sand

Filtration

The water flows through a bed of sand

removing any remaining particles.

UV Light

Chlorine

Food

Grade

Phosphoric

Acid

Sodium

Hydroxide

Fluoride**

HOW DOES NEW YORK CITY TREAT ITS WATER SUPPLIES?

4

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

REGULATION OF

DRINKING WATER

The sources of drinking water (both

tap water and bottled water) include

rivers, lakes, streams, ponds, reser-

voirs, springs, and wells. As water

travels over the surface of the land

or through the ground, it dissolves

naturally-occurring minerals and,

in some cases, radioactive material,

and can pick up substances result-

ing from the presence of animals

or from human activities. Con-

taminants that may be present in

source water include: microbial con-

taminants, inorganic contaminants,

pesticides and herbicides, organic

chemical contaminants, and radio-

active contaminants.

To ensure that tap water is safe to

drink, the New York State Depart-

ment of Health (NYSDOH) and

the United States Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) prescribe

regulations that limit the amount

of certain contaminants in water

provided by public water systems.

The NYSDOH and the federal Food

and Drug Administration’s (FDA)

regulations establish limits for con-

taminants in bottled water, which

must provide the same protection

for public health. The presence of

contaminants does not necessarily

indicate that water poses a health

risk. These regulations also establish

the minimum amount of testing and

monitoring that each system must

undertake to ensure that the tap

water is safe to drink.

DEP’s water quality monitoring

program – far more extensive than

required by law – demonstrates that

the quality of New York City’s drink-

ing water remains high and meets

all state and federal drinking water

standards. Additional information

concerning drinking water can be

found at: www.epa.gov/safewater or

www.health.ny.gov.

DRINKING WATER

SAMPLING AND

MONITORING

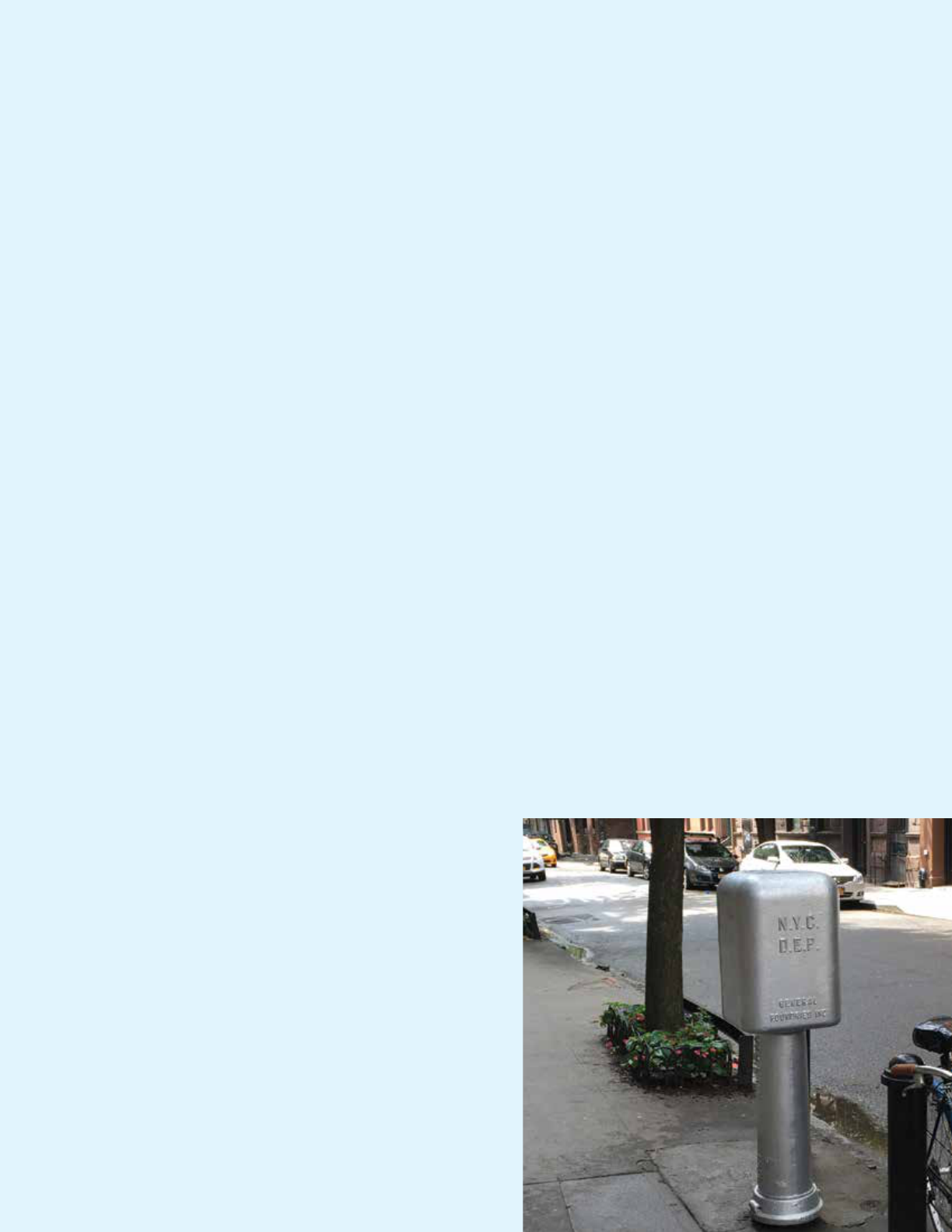

DEP monitors the water in the dis-

tribution system, upstate reservoirs

and feeder streams, and wells that

are sources for New York City’s drink-

ing water supply. To accomplish this

goal, throughout the watershed and

as the water enters the distribution

system, DEP continuously monitors

and conducts analyses for certain

water quality parameters, includ-

ing microbiological, chemical, and

physical measures. DEP also regu-

larly tests water quality at nearly

1,000 water quality sampling sta-

tions throughout New York City. In

2018, DEP performed approximately

414,000 analyses on 37,500 samples

from the distribution system, meet-

ing all state and federal monitoring

requirements. These data are sum-

marized in tables starting on page

10. Additionally, DEP performed

approximately 240,000 analyses on

15,700 samples from the upstate

reservoir watersheds, and took close

to 1.3 million robotic monitoring

measurements to support Filtration

Avoidance Determination (FAD)

watershed protection programs and

to optimize water quality.

DEP scientists in the watershed

DRINKING WATER QUALITY

5

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

New York City’s water is healthy and safe to drink. It is deliv-

ered virtually lead free from our upstate reservoir system

to more than nine million New Yorkers. However, some

older homes may contain lead plumbing that releases small

amounts of lead into the water. Fortunately, residents can

take simple steps to minimize their exposure.

What Are The Health Impacts of Lead?

Lead is a metal that can be harmful, especially to young

children and pregnant women. It is a neurotoxin that can

impact a young child's development, behavior, and ability

to learn. Lead exposure during pregnancy may contribute to

low birth weight and developmental delays in infants. There

are many sources of lead in the environment, most notably

peeling paint, and it is important to reduce exposure to lead

as much as possible.

Can Lead Get In My Drinking Water?

Lead can be released when drinking water is in contact

with older plumbing materials that contain lead, like pipes,

solder, faucets, ttings, and valves. If water has not been

used for several hours, such as overnight, more lead can be

released into the water. DEP treats NYC’s water supply to

reduce this release, and our frequent testing conrms that

it is eective. Nonetheless, that treatment cannot always

reduce lead in every faucet to a safe level all of the time.

Monitoring Drinking Water for Lead

The federal Lead and Copper Rule was established in the

1990s to require all municipalities to regularly test drinking

water for these two metals, and to take protective measures

if standards are not met. DEP analyzes the drinking water

from hundreds of homes each year, and these samples con-

rm that drinking water meets the federal standards. These

results are presented in the table on page 13 of this report.

How Can I Limit My Lead Exposure?

DEP recommends you take the following steps when using

drinking water for drinking or cooking to reduce lead

exposure:

Run your water for at least 30 seconds or until it gets

cold. Once the water is cold, run it for 15 seconds more.

Use cold water for cooking, drinking, or preparing

infant formula. Hot water is more likely to contain lead

and other metals.

Remove and clean the faucet screen (also called an aer-

ator) monthly, where small particles can get trapped.

Hire a licensed plumber to identify and replace plumb-

ing xtures and/or service lines that contain lead.

How Do I Get My Water Tested for Lead?

If you are concerned about lead in your drinking water, you

can have your home’s water tested at no cost. DEP oers

free testing kits, with prepaid postage, to all New York City

residents. DEP’s Free Residential Testing Program is the larg-

est of its kind in the nation. DEP has distributed approxi-

mately 130,000 sample collection kits since the start of the

program. Call 311 or visit www.nyc.gov/apps/311 to request a

free lead test kit.

Who Can I Contact?

For health-related questions:

Õ Call NYC Health Department – Healthy Homes at

(646) 632-6023

Õ Visit www.nyc.gov/health - Healthy Homes, Lead Poisoning

Prevention

Õ Contact your health care provider if you need a blood test

for you or your child

For questions about lead in drinking water:

Õ Call DEP Lead Unit at (718) 595-5364 or

Õ Email DEPLeadUn[email protected]v

Õ Visit www.nyc.gov/dep/leadindrinkingwater

Õ Call the Safe Drinking Water Hotline (1-800-426-4791) or

visit www.epa.gov/safewater/lead.

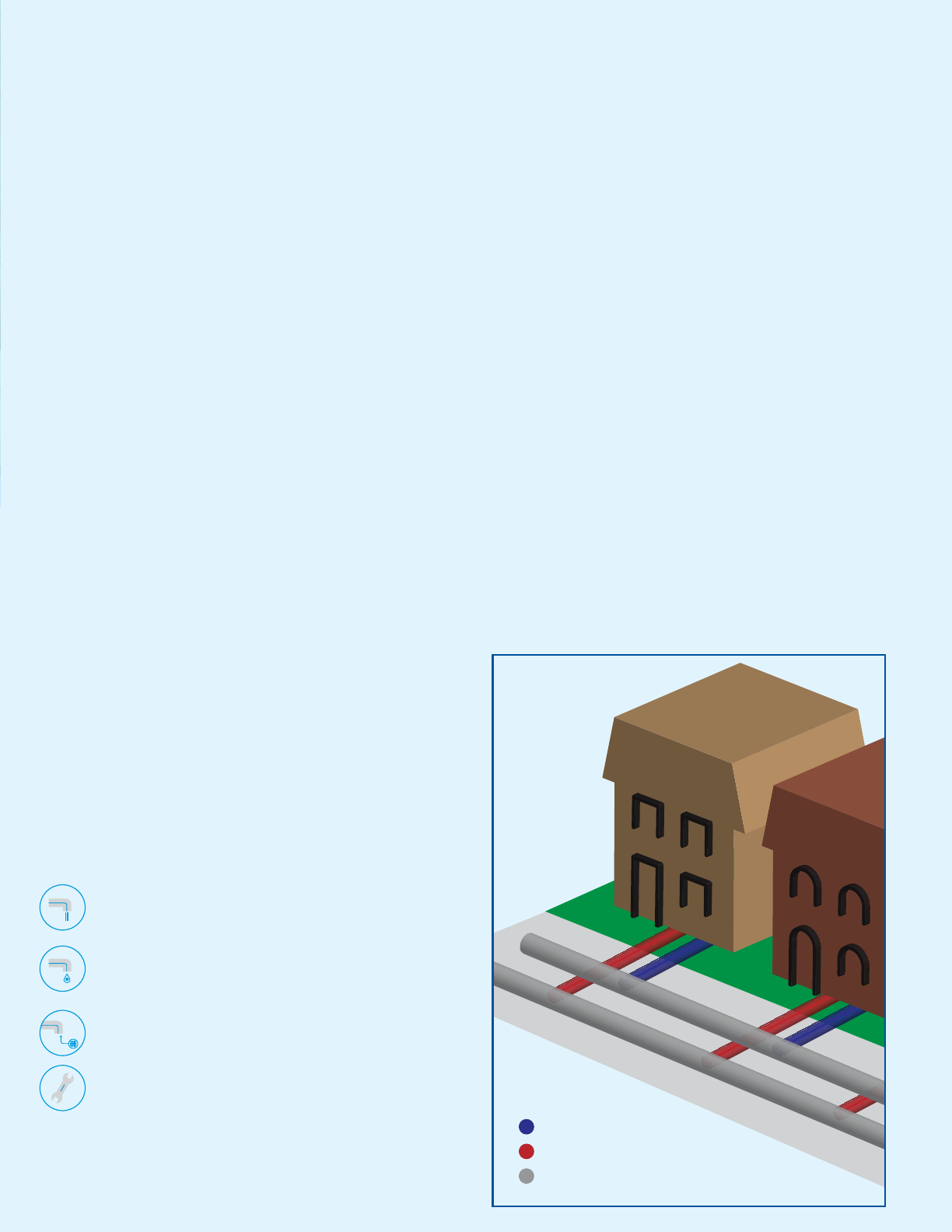

Sewer Main

Water Main

Homeowner’s Water Service Line

Homeowner’s Sewer Line

DEP Water and Sewer Mains

LEAD IN DRINKING WATER

6

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

Fishing in the watershed

WATERSHED PROTECTION

AND POLLUTION

PREVENTION PROGRAMS

Source Water Assessment Program

Federal regulations require states

to develop and implement source

water assessment programs to iden-

tify the areas that supply public tap

water, inventory contaminants, assess

water system susceptibility to con-

tamination, and inform the public

of the results. The states are given

a great deal of exibility on how to

implement source water assessment

programs. These assessments are

created using available information

to help estimate the potential for

source water contamination. Higher

susceptibility ratings do not mean

that source water contamination has

occurred or will occur in the water

supply; rather, they indicate the need

for water suppliers to implement

additional precautionary measures.

In 1993, New York City secured its

rst FAD for its Catskill/Delaware

supply. That was followed in 1997

by the historic New York City Water-

shed Memorandum of Agreement,

which was signed by the City, state,

and federal regulators, watershed

communities, and environmental

advocates. Since that time, DEP has

been implementing a series of pro-

grams to protect our reservoirs and

the streams that feed them from a

variety of contaminants. These ongo-

ing programs operate under the close

scrutiny of both the NYSDOH and

EPA. Because of these eorts, which

are reported in the Watershed Water

Quality Annual Report, NYSDOH does

not deem it necessary to perform a

source water assessment on the New

York City Water Supply. To view the

DEP Watershed Water Quality Annual

Report, visit www1.nyc.gov/html/dep/

pdf/reports/fad_5.1_watershed_monitor-

ing_program-2017-watershed_water_qual-

ity_annual_report_07-18.pdf.

MAINTAINING NEW

YORK CITY’S WORLD-

RENOWNED WATER

SUPPLY

10-Year Filtration Avoidance

Determination

DEP funds and administers a number

of watershed protection and pollu-

tion prevention programs to maintain

the high quality of our drinking water.

These science-based strategies are

designed to protect New York City’s

drinking water at its source by keep-

ing pollution out of our reservoirs

and the streams, creeks, and rivers

that feed them.

In 2017, NYSDOH issued a new

10-year FAD that allows DEP to con-

tinue operating its Catskill/Delaware

supply without ltration through at

least 2027. DEP will commit an esti-

mated $1 billion over the coming

decade to comply with the FAD. That

funding will go toward preserving

watershed lands, upgrading waste-

water infrastructure, implementing

clean water strategies on watershed

farms, and managing streams, for-

ests, and other natural resources that

aect water quality.

Including the new FAD, DEP has com-

mitted more than $2.7 billion toward

its watershed protection programs

since 1993, when the EPA rst issued

the City a waiver from the federal

requirement to lter tap water that

comes from surface sources such as

reservoirs. DEP’s watershed programs

are based on the premise that it is

most cost-eective and environmen-

tally sound to protect the quality

of drinking water at its source. The

ltration waiver allows DEP to avoid

construction of a large ltration plant

7

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

for the Catskill/Delaware supply. Such a

facility is estimated to cost more than $10

billion to construct, which would make

it the largest public works project in the

City’s history.

Over the past 25 years, DEP’s pro-

grams in the watershed have become

a national and international model for

protecting water at its source. Each

year, water utility managers and public

health professionals come from around

the globe to study DEP programs. DEP

has welcomed visitors from Australia,

Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, India,

Singapore, the United Kingdom, and

others who aimed to solve water-quality

challenges by replicating part of New

York City’s protection eorts.

DEP’s source water protection initiatives

and achievements include:

Õ Land acquisition: DEP has preserved

more than 152,000 acres of land

since 1997, in addition to the nearly

45,000 acres of land surrounding its

reservoirs previously owned by the

City. The State of New York owns and

permanently protects 210,000 acres as

parkland or forestland, and other enti-

ties have preserved more than 27,000

acres in the watershed. In all, nearly 40

percent of the watershed is now pre-

served as open space.

Õ Agricultural program: The not-for-

prot Watershed Agricultural Council,

one of DEP’s watershed partners, has

completed more than 450 “whole

farm” plans that incorporate pollution

prevention into the business opera-

tions of local farms. Those plans are

complemented by the installation of

more than 7,800 best management

practices that control runo from

farms and minimize the amount of

nutrients or potential contaminants

entering local streams.

Õ Wastewater treatment plant upgrades:

DEP has completed upgrades on all

private and public wastewater treat-

ment plants in the Catskill/Delaware

watershed.

Õ Septic system repair: The Catskill

Watershed Corporation (CWC),

another partner organization funded

by the City, has invested in the repair

of failing septic systems across the

watershed, with more than 5,500

repairs completed through 2018.

Õ Stream management: DEP has imple-

mented a comprehensive stream

management program to restore the

natural stability and ood resiliency

of streams that feed the reservoir

system. Through 2018, the program

has funded more than 375 projects to

restore stream stability and streamside

vegetation along approximately 44

miles of waterways in the Catskills.

Õ Land management and recreation:

DEP has developed a comprehen-

sive plan to manage the forests on

City-owned land, which naturally

lter the water as it moves toward

the reservoirs. DEP has also opened

nearly 137,000 acres of City-owned

property for shing, hiking, and other

types of low-impact recreation in the

watershed.

Õ Regulatory program: While balanc-

ing the goals of watershed protection

with the needs of the region, DEP

administers a regulatory program to

review and approve new development

proposals in the watershed and works

with local communities to identify

and invest in projects that mitigate

ooding.

The new FAD requires DEP to continue

these core programs. It also requires DEP

fund new eorts to collect and process

wastewater, preserve streams and their

buer lands, and expand our work with

watershed farmers. In addition, the FAD

includes an expert review of the City’s

source water protection programs by

the National Academies of Sciences,

Engineering, and Medicine, which is

expected to be complete in 2020.

More information about the FAD can be

found on the NYSDOH website at:

www.health.ny.gov/environmental/water/

drinking/nycfad.

More information about New York City’s

watershed protection programs can be

found at: www.nyc.gov/watershed.

KENSICO-EASTVIEW

CONNECTION

DEP last year announced plans

for a $1.2 billion tunneling project

in Westchester County that will

improve operational resiliency and

exibility between facilities that

are vital to the treatment of New

York City’s drinking water.

The centerpiece of the project –

known as the Kensico-Eastview

Connection (KEC) – will be a

2-mile-long tunnel between Ken-

sico Reservoir and the Catskill/

Delaware UV Disinfection Facility.

The new aqueduct will provide an

additional conveyance between

these vital components of the

water supply, giving DEP the ability

to take other facilities out of ser-

vice for periodic maintenance or

inspection.

The KEC project will include con-

struction of the new tunnel, facili-

ties to draw water from Kensico

Reservoir and move water into the

UV plant, and other infrastructure

work. DEP has already begun to

collect soil and bedrock samples

from the area to support the

design of the project. Construction

on the rst parts of the KEC project

are expected to start in approxi-

mately ve years; work on the

tunnel itself will start around 2025.

DEP expects to nish the project

around 2035.

The nished tunnel will measure

approximately 27 feet in diam-

eter and run 400-500 feet below

ground. It will be large enough to

carry a maximum of 2.6 billion gal-

lons of water each day. Its design

accounts for future growth in New

York City and Westchester County,

the potential addition of treat-

ment facilities in the future, and

the need to periodically take other

aqueducts out of service for main-

tenance or inspection.

8

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

To advance New York City’s position as a global leader

in sustainability, DEP continues to track and reduce

greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to meet citywide

climate change objectives. DEP’s water supply, storm-

water, and wastewater management facilities cur-

rently account for 17 percent of total GHG emissions

from New York City government buildings. To oset

our emissions and provide indirect energy co-ben-

ets, DEP has invested in a number of sustainability

programs, including water demand management.

DEP’s commitment to achieving the Mayor’s OneNYC

goal of reducing GHG emissions 80 percent by 2050

(relative to the 2005 baseline) is driving changes in

the way DEP operates. DEP recently measured the

amount of GHG emissions produced by several of our

traditional facilities, including wastewater resource

recovery facilities (WRRFs). However, DEP did not have

a way to measure the inuence water conservation

and demand management has on the agency’s over-

all GHG portfolio.

To improve our data, DEP began in 2016 a Water-

Energy Nexus Study to calculate the relationship

between decreasing water demand and reducing

GHG emissions. The study was based on a simple

premise – if New York City is using less drinking water,

it must also be using less energy and chemicals to

treat its water and wastewater. The goal was to gure

out how these reductions aected our GHG emis-

sions. As part of the study, experts developed a tool

that accurately estimates the GHG emissions that

are avoided as New Yorkers curtail their demand for

water, allowing DEP to use less energy for treatment.

Utilizing the Water Energy Nexus Tool, DEP discov-

ered that its water eciency programs have also

successfully reduced GHG emissions. As of May 2018,

DEP’s water eciency programs have led to a reduc-

tion of 68 metric tons (MT) CO

2

equivalent (CO

2

e) per

year, resulting from retrots of xtures in 400 schools,

replacing 400 spray showers in City parks, and replac-

ing 12,637 toilets in multi-family residential buildings.

Overall, DEP’s sustainability programs have reduced

carbon emissions by over 480 MT CO

2

e per year,

which is equivalent to 131 standard passenger cars

(10,000 miles per year) or 6,406 60-watt lightbulbs

(used for 8 hours per day, every day).

NEW YORK CITY’S WATER ENERGY NEXUS

– LINKING WATER SUSTAINABILITY TO

GREENHOUSE GAS REDUCTIONS

Water quality testing

8

9

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

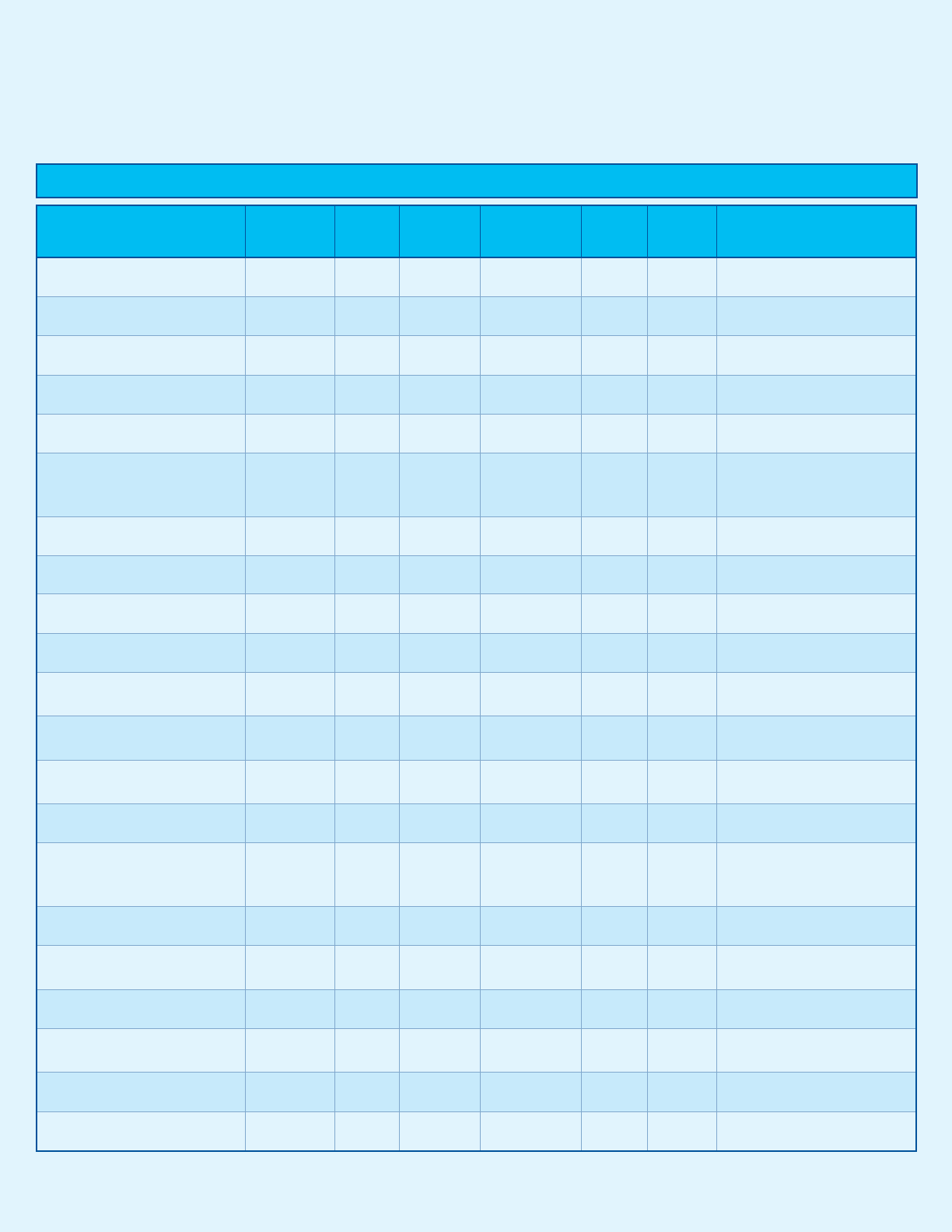

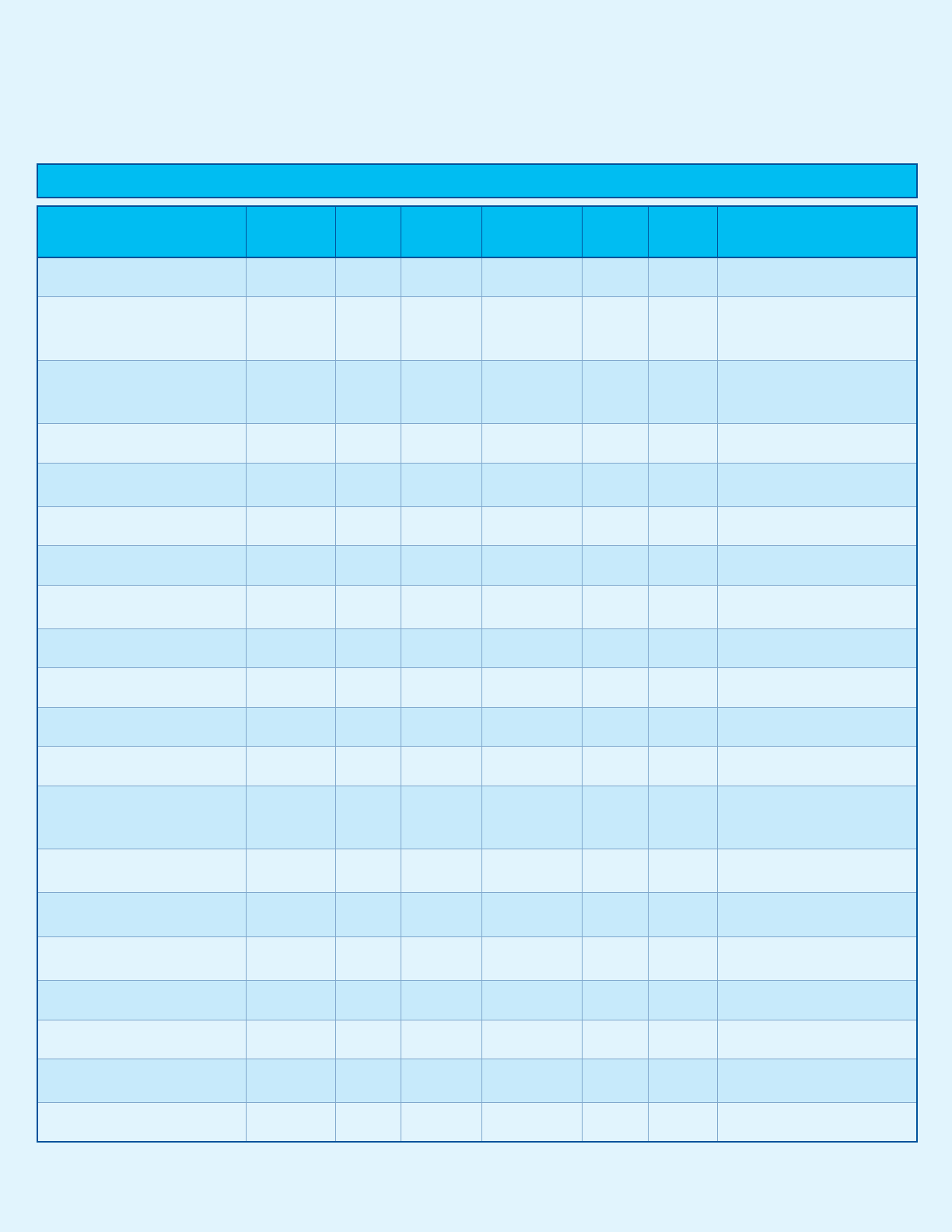

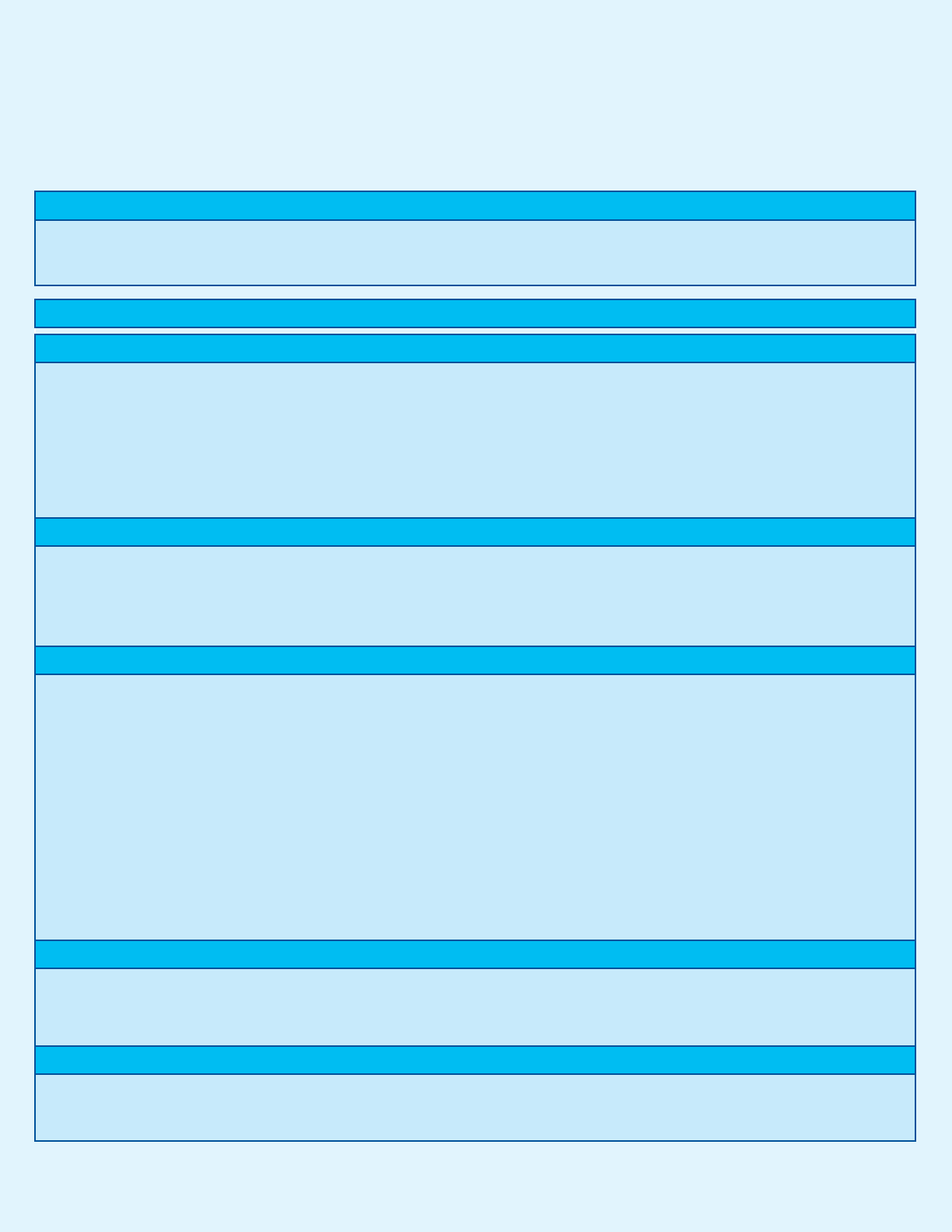

HOW TO READ THE NEW YORK CITY DRINKING WATER QUALITY TESTING RESULTS

The following section of the Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report compares the quality of your tap water to

federal and state standards for each parameter (if applicable). The monitoring results show that New York City’s

drinking water met all drinking water standards in 2018.

Table 1 reects the compliance monitoring results for all regulated and non-regulated parameters, the number of

samples collected, the range of values detected, the average of the values detected, and the possible sources of

the parameters, unless otherwise footnoted. The monitoring frequency of each parameter varies and is parameter

specic. Data presented are for the Catskill/Delaware and Croton supplies, which were the only sources of water in

2018. Table 2 represents those parameters monitored for, but not detected in any sample.

Most of our data are representative of 2018 testing; concentrations of parameters or contaminants do not change

frequently. For previous years' results you can view our reports at: www.nyc.gov/waterquality.

DEFINITIONS

Action Level (AL):

The concentration of a contaminant, which, if exceeded, triggers treatment or other requirements that a water system must

follow. An exceedance occurs if more than 10 percent of the samples exceed the Action Level.

Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL):

The highest level of a contaminant that is allowed in drinking water. MCLs are set as close to the MCLGs as feasible, using the best

available treatment technology.

Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG):

The level of a contaminant in drinking water below which there is no known or expected risk to health. MCLGs allow for a margin

of safety.

Maximum Residual Disinfectant Level (MRDL):

The highest level of a disinfectant allowed in drinking water. The addition of a disinfectant is necessary for control of microbial

contaminants.

Maximum Residual Disinfectant Level Goal (MRDLG):

The level of a drinking water disinfectant below which there is no known or expected risk to health. MRDLGs do not reect the

benets of the use of disinfectants to control microbial contamination.

Treatment Technique (TT):

A required process intended to reduce the level of a contaminant in drinking water.

90

Th

Percentile Value:

The values reported for lead and copper represent the 90

th

percentile. A percentile is a value on a scale of 100 that indicates the

percent of a distribution that is equal to or below the value. The 90

th

percentile is equal to or greater than 90 percent of the lead

and copper values detected at your water system.

UNITS & ABBREVIATIONS

CaCO

3

= calcium carbonate

CFU/mL = colony forming units per milliliter

/cm = per centimeter

o

F = degrees Fahrenheit

µg/L = micrograms per liter (10

-6

grams per liter)

µS/cm = microsiemens per centimeter

mg/L = milligrams per liter (10

-3

grams per liter)

MPN/100mL = most probable number per 100 milliliters

ND = lab analysis indicates parameter is not detected

NDL = no designated limits

NTU = nephelometric turbidity units

/50L = per 50 liters

THE NEW YORK CITY 2018 DRINKING WATER

QUALITY TESTING RESULTS

Water sampling station

10

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

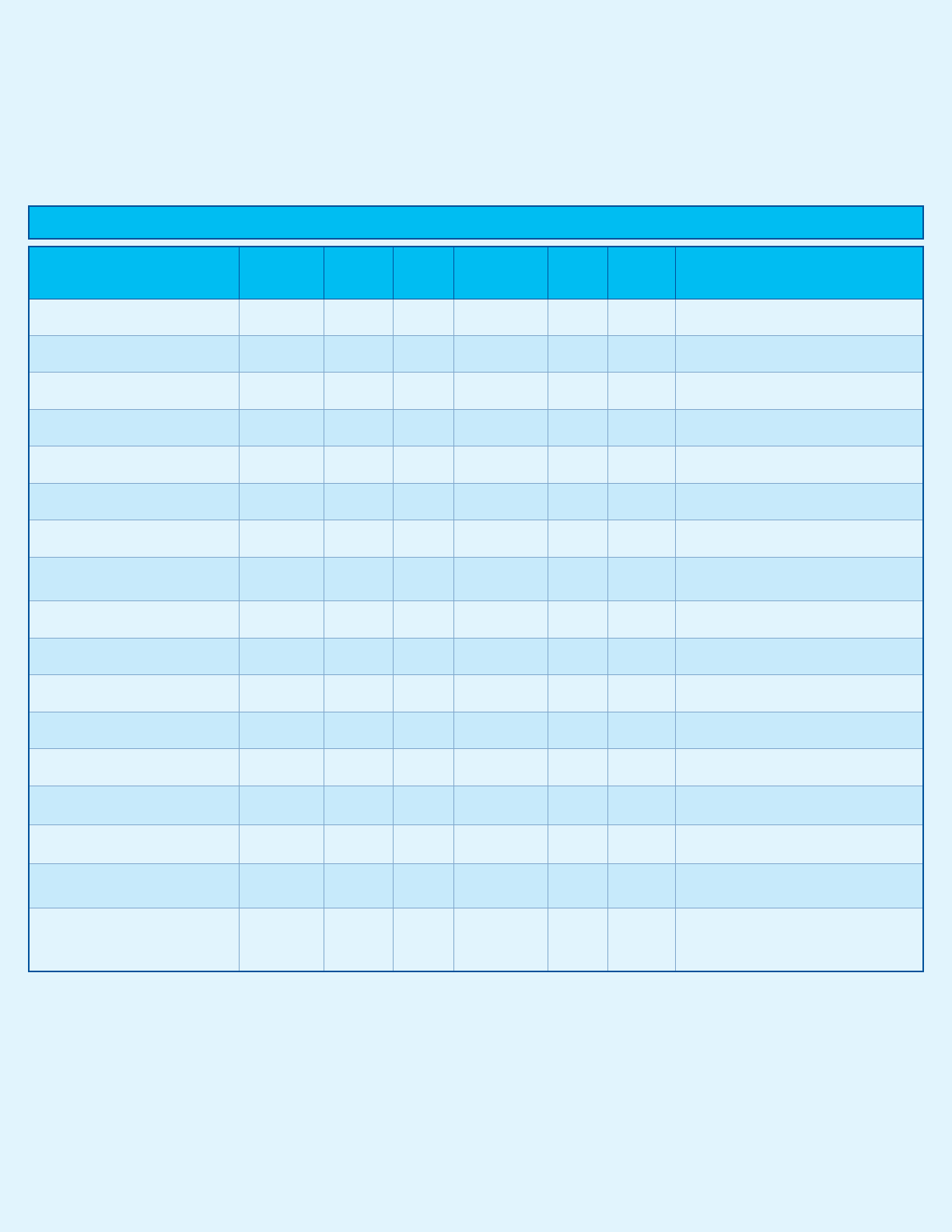

TABLE 1: DETECTED PARAMETERS

THIS TABLE SUMMARIZES MONITORING RESULTS FOR ALL DETECTED PARAMETERS IN 2018

CONVENTIONAL PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PARAMETERS

PARAMETER

NYSDOH MCL

(Highest Level

Allowed)

EPA MCLG

(Ideal

Goal)

# SAMPLES RANGE AVERAGE

MCL

VIOLATION

LIKELY SOURCES IN

DRINKING WATER

Alkalinity (mg/L CaCO

3

) - - 309 14 - 80 21 No Erosion of natural deposits

Aluminum (µg/L) 50 - 200

(1)

- 464 7 - 54 21 No Erosion of natural deposits

Barium (mg/L) 2 2 464 0.01 - 0.05 0.02 No Erosion of natural deposits

Bromide (µg/L) -

(2)

- 6 8 - 35 20.4 No Naturally occurring

Calcium (mg/L) - - 464 5.4 - 29.8 7.6 No Erosion of natural deposits

Chlorate (mg/L) -

(2)

- 32 ND - 0.2 0.06 No

By-product of drinking water

chlorination using sodium

hypochlorite

Chloride (mg/L) 250 - 309 12 - 101 20 No Naturally occurring; road salt

Chlorine Residual, Free (mg/L) 4

(3)

- 16,033 0.0 - 1.3 0.6

(3)

No Water additive for disinfection

Chromium (µg/L) 100 - 464 ND - 3 ND No Erosion of natural deposits

Chromium VI (µg/L) -

(2)

- 32 ND - 0.06 0.04 No Erosion of natural deposits

Color - distribution system

(color units - apparent)

- - 14,700 3 - 35

(4)

6 No

Presence of iron, manganese,

and organics in water

Color - entry points

(color units - apparent)

15

(5)

- 1,333 3 - 14 6 No

Presence of iron, manganese,

and organics in water

Copper (mg/L) 1.3

(6)

1.3 464 0.002 - 0.088 0.008 No

Corrosion of household plumb-

ing; erosion of natural deposits

Corrosivity (Langelier index) -

(7)

- 308 -2.74 to - 0.96 -2.2 No

Fluoride (mg/L) 2.2

(5)

4 2,103 ND - 0.9 0.7 No

Water additive which promotes

strong teeth; erosion of natural

deposits

Hardness (mg/L CaCO

3

) - - 464 18 - 116 27 No Erosion of natural deposits

Hardness (grains/gallon[US]

CaCO

3

)

(8)

- - 464 1.1 - 6.7 1.5 No Erosion of natural deposits

Iron (µg/L) 300

(5) (9)

- 464 ND - 197 32 No Naturally occurring

Lead (µg/L) 15

(6)

0 464 ND - 1 ND No

Corrosion of household plumb-

ing; erosion of natural deposits

Magnesium (mg/L) - - 464 1.1 - 10 1.9 No Erosion of natural deposits

Manganese (µg/L) 300

(5) (9)

- 476 ND - 93 17 No Naturally occurring

Continued on next page

11

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

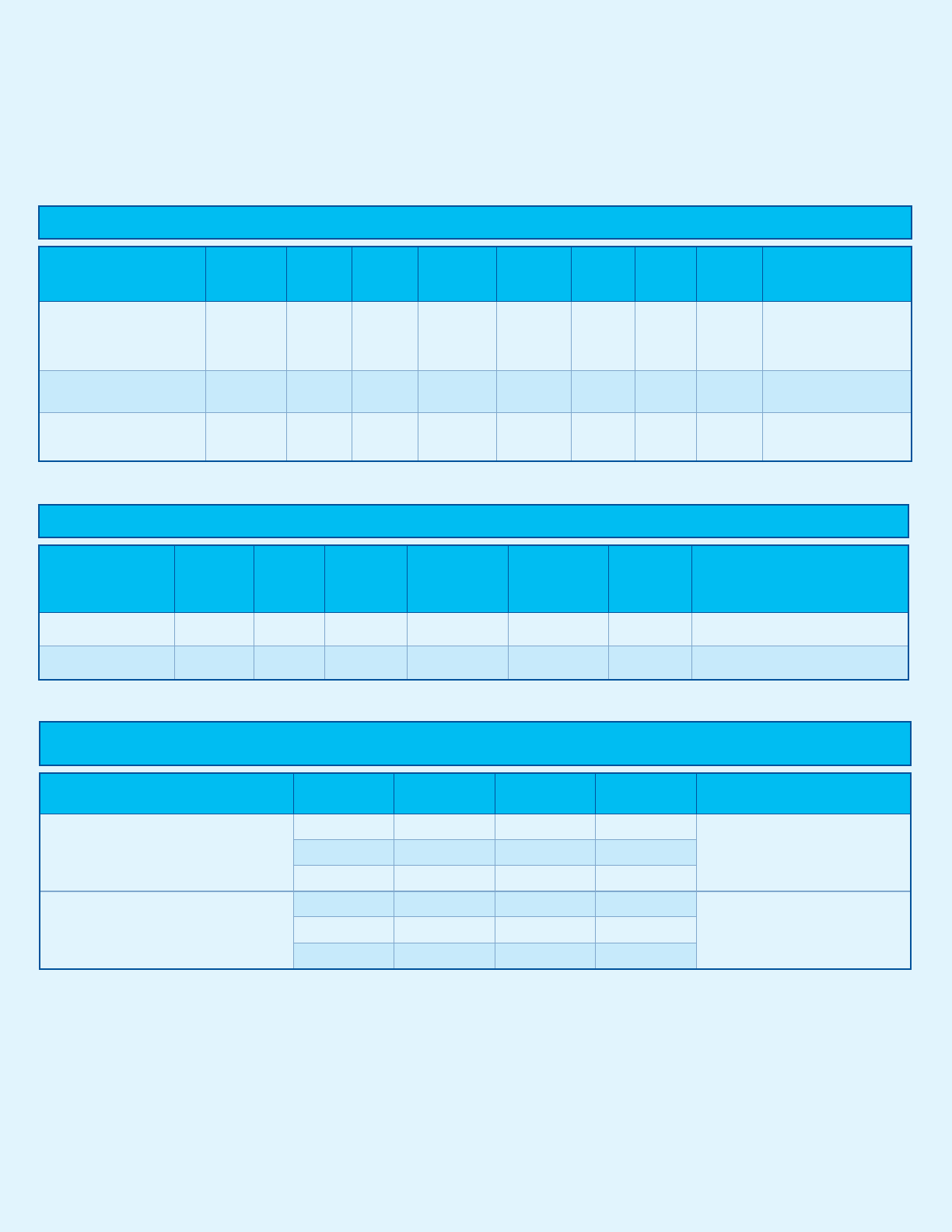

TABLE 1: DETECTED PARAMETERS (CONTINUED)

THIS TABLE SUMMARIZES MONITORING RESULTS FOR ALL DETECTED PARAMETERS IN 2018

PARAMETER

NYSDOH MCL

(Highest Level

Allowed)

EPA MCLG

(Ideal

Goal)

# SAMPLES RANGE AVERAGE

MCL

VIOLATION

LIKELY SOURCES IN

DRINKING WATER

Nickel (µg/L) - - 464 ND - 2 ND No Erosion of natural deposits

Nitrate (mg/L nitrogen) 10 10 309 0.06 - 0.48 0.13 No

Runoff from fertilizer use; leach-

ing from septic tanks, sewage;

erosion of natural deposits

Nitrite (mg/L nitrogen) 1 1 305 ND - 0.002

(10)

ND No

Runoff from fertilizer use; leach-

ing from septic tanks, sewage;

erosion of natural deposits

pH (pH units) 6.8 - 8.2

(11)

- 16,034 7.0 - 10.8 7.4 No

Phosphate, Ortho- (mg/L) 1-4

(11)

- 16,032 0.3 - 2.6 2.1 No

Water additive for corrosion

control

Potassium (mg/L) - - 464 0.5 - 2.8 0.7 No Erosion of natural deposits

Silica [silicon oxide] (mg/L) - - 308 1.7 - 7.5 2.5 No Erosion of natural deposits

Sodium (mg/L) NDL

(5) (12)

- 464 9 - 57 13 No

Naturally occurring; road salt;

water softeners; animal waste

Specific Conductance (µS/cm) - - 16,032 82 - 530 120 No

Strontium (µg/L) - - 464 19 - 99 26 No Erosion of natural deposits

Sulfate (mg/L) 250 - 309 3.5 - 21 5.2 No Naturally occurring

Temperature (°F) - - 16,034 33 - 80 53 No

Total Dissolved Solids (mg/L) 500

(1)

- 310 37 - 295

(13)

72 No

Metals and salts naturally

occurring in the soil; organic

matter

Total Organic Carbon (mg/L) - - 459 1.3 - 2.6

(14)

1.7 No

Organic matter naturally present

in the environment

Total Organic Carbon - source

water (mg/L)

-

(2)

- 6 2.1 - 4.2 3.1 No

Organic matter naturally present

in the environment

Turbidity

(15)

- distribution system

(NTU)

5

(16)

- 14,700 ND - 33.8 1

(16)

No Soil runoff

Turbidity

(15)

- source water (NTU) 5

(17)

- - - 1.6

(17)

No Soil runoff

Turbidity

(15)

- filtered water (NTU) TT

(18)

- - - 0.23

(18)

No Soil runoff

UV 254 Absorbency (cm

-1

) - - 309 0.025 - 0.045 0.032 No

Organic matter naturally present

in the environment

Zinc (mg/L) 5

(5)

- 464 ND - 0.016 ND No Naturally occurring

CONVENTIONAL PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PARAMETERS (continued)

Continued on next page

12

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

ORGANIC PARAMETERS

PARAMETER

NYSDOH MCL

(Highest Level

Allowed)

-EPA MCLG

(Ideal

Goal)

#

SAMPLES

RANGE AVERAGE

MCL

VIOLATION

LIKELY SOURCES IN

DRINKING WATER

Bromochloroacetic Acid (µg/L) 50 - 365 ND - 4.0 1.5 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Bromodichloroacetic Acid (µg/L) 50 - 60 1.7 - 5.1 2.6 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Chlorodibromoacetic Acid (µg/L) 50 - 60 ND - 0.6 ND No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Chloropicrin (µg/L) 50 - 27 ND - 0.5 0.1 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Chloral Hydrate (µg/L) 50 - 24 1.5 - 11.2 5.7 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Dalapon (µg/L) 50 - 309 ND - 1.08

(10)

ND No By-product of drinking water chlorination

1,2-Dibromo-3-chloropropane 50 - 27 ND - 0.09 ND No Used to make fire resistant materials

Diethylphthalate 50 - 93 ND - 7.5

(10)

ND No

Plasticizer used in toothbrushes, toys,

cosmetics, food packaging and aspirin

Haloacetic Acid 5 (HAA5) (µg/L) 60

(19)

- 365 19 - 77 49

(19)

No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Haloacetic Acid 6 (HAA6Br) (µg/L) -

(2)

- 60 2.2 - 9.3 4.3 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Haloacetic Acid 9 (HAA9) (µg/L) -

(2)

- 60 31 - 82 54 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Haloacetonitriles (HANs) (µg/L) 50 - 27 1.1 - 2.9 2.1 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Halogenated Ketones (HKs) (µg/L) 50 - 27 1.2 - 4.5 2.8 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Hexachlorocyclopentadiene 50 - 25 ND - 0.064

(10)

ND No Discharge from chemical factories

Total Organic Halogen (µg/L) - - 283 98 - 281 153 No By-product of drinking water chlorination

Total Trihalomethanes (TTHM)

(µg/L)

80

(19)

- 304 10 - 64 48

(19)

No By-product of drinking water chlorination

1,4-Dioxane

(10)

50

(2)

- 16 ND - 0.08

(10)

ND No

By-product present in paint strippers,

dyes, greases, deodorants, shampoos

and cosmetics

TABLE 1: DETECTED PARAMETERS (CONTINUED)

THIS TABLE SUMMARIZES MONITORING RESULTS FOR ALL DETECTED PARAMETERS IN 2018

Continued on next page

13

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

MICROBIAL PARAMETERS

PARAMETER

NYSDOH MCL

(Highest Level

Allowed)

EPA MCLG

(Ideal

Goal)

# SAMPLES RANGE

# SAMPLES

POSITIVE

AVERAGE

HIGHEST

MONTH %

POSITIVE

MCL

VIOLATION

LIKELY SOURCES IN

DRINKING WATER

Total Coliform Bacteria

(% of samples positive/

month)

5% 0 9,754 - 25 - 0.7% No

Naturally present in the

environment

E. coli (MPN/100mL) -

(20)

0 9,754 - 1 - 0.1% No Animal fecal waste

Heterotrophic Plate Count

(CFU/mL)

TT - 12,640 ND - 2,972 217 1 - No

Naturally present in the

environment

CRYPTOSPORIDIUM AND GIARDIA SAMPLING FROM SOURCE WATER AND RESERVOIR OUTFLOWS

(21)

:

JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2018

PARAMETER

RESERVOIR

OUTFLOW

# SAMPLES

# SAMPLES

POSITIVE

RANGE LIKELY SOURCES IN DRINKING WATER

Cryptosporidium (oocysts/50L)

Kensico 53 5 0 - 1

Animal fecal wasteHillview 53 5 0 - 2

Jerome Park 2 0 0

Giardia (cysts/50L)

Kensico 53 37 0 - 6

Animal fecal waste

Hillview 53 9 0 - 4

Jerome Park 2 0 0

LEAD AND COPPER RULE SAMPLING AT RESIDENTIAL WATER TAPS

PARAMETER NYSDOH AL

EPA MCLG

(Ideal

Goal)

90% OF

YOUR LEVELS

WERE LESS

THAN

RANGE

# SAMPLES

EXCEEDING AL

EXCEEDANCE LIKELY SOURCES IN DRINKING WATER

Copper (mg/L) 1.3 1.3 0.185 0.004 - 0.483 0 out of 481 No Corrosion of household plumbing

Lead (µg/L) 15 0 11 ND - 277 26 out of 481 No Corrosion of household plumbing

TABLE 1: DETECTED PARAMETERS (CONTINUED)

THIS TABLE SUMMARIZES MONITORING RESULTS FOR ALL DETECTED PARAMETERS IN 2018

14

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

TABLE 2: NOT-DETECTED PARAMETERS

THE FOLLOWING PARAMETERS WERE MONITORED FOR,

BUT NOT DETECTED IN ANY SAMPLE IN 2018

CONVENTIONAL PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PARAMETERS

Antimony, Arsenic, Asbestos*, Beryllium, Bismuth-212*, Bismuth-214*, Cadmium, Cesium-134*, Cesium-137*, Cyanide, Gross Alpha*, Gross Beta*, Lead-212*,

Lead-214*, Lithium, Mercury, Potassium-40*, Radium-226*, Radium-228*, Selenium, Silver, Thallium, Thallium-208*, Thorium-234*, Uranium*, Uranium-235*

ORGANIC PARAMETERS

Principal Organic Contaminants:

Benzene, Bromobenzene, Bromochloromethane, Bromomethane, n-Butylbenzene, sec-Butylbenzene, tert-Butylbenzene, Carbon tetrachloride, Chlorobenzene,

Chloroethane, Chloromethane, 2-Chlorotoluene, 4-Chlorotoluene, Dibromomethane, 1,2-Dichlorobenzene, 1,3-Dichlorobenzene, 1,4-Dichlorobenzene,

Dichlorodifluoromethane, 1,1-Dichloroethane, 1,2-Dichloroethane, 1,1-Dichloroethene, cis-1,2-Dichloroethylene, trans-1,2-Dichloroethylene, 1,2-Dichloropropane,

1,3-Dichloropropane, 2,2-Dichloropropane, 1,1-Dichloropropene, cis-1,3-Dichloropropene, trans-1,3-Dichloropropene, Ethylbenzene, Hexachlorobutadiene,

Isopropylbenzene, p-Isopropyltoluene, Methylene chloride, n-Propylbenzene, Styrene, 1,1,1,2-Tetrachloroethane, 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane, Tetrachloroethylene,

Toluene, 1,2,3-Trichlorobenzene, 1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene, 1,1,1-Trichloroethane, 1,1,2-Trichloroethane, Trichloroethene, Trichlorofluoromethane, 1,2,3-Trichloropropane,

1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene, 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene, m-Xylene, o-Xylene, p-Xylene

Specified Organic Contaminants:

Alachlor, Aldicarb (Temik), Aldicarb sulfone, Aldicarb sulfoxide, Aldrin, Atrazine, Benzo(a)pyrene, Butachlor, Carbaryl, Carbofuran (Furadan), Chlordane,

2,4-D,Dicamba, Dieldrin, Di(2-ethylhexyl)adipate, Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, Dinoseb, Diquat, Endothall, Endrin, Ethylene dibromide (EDB), Glyphosate, Heptachlor,

Heptachlor epoxide, Hexachlorobenzene, 3-Hydroxycarbofuran, Lindane, Methomyl, Methoxychlor, Methyl-tertiary-butyl-ether (MTBE), Metolachlor, Metribuzin,

Oxamyl (Vydate), Pentachlorophenol, Picloram, Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), Propachlor, Simazine, Toxaphene, 2,4,5-TP (Silvex), 2,3,7,8-TCDD (Dioxin), Vinyl chloride

Unspecified Organic Contaminants:

Acenaphthene, Acenaphthylene, Acetochlor, Acetone, Acifluorfen, Allyl chloride, Ametryn, tert-Amyl ethyl ether, tert-Amyl methyl ether, Anthracene, Bentazon,

Benzo[a]anthracene, Benzo[a]pyrene, Benzo[b]fluoranthene, Benzo[k]fluoranthene, Benzo[g,h,i]perylene, alpha-BHC, beta-BHC, delta-BHC, Bromacil,

2-Butanone (MEK), Butylate, Butylbenzylphthalate, tert-Butyl alcohol, tert-Butyl ethyl ether, Caffeine, Carbon Disulfide, Carboxin, Chloramben, alpha-Chlordane,

gama-Chlordane, Chlorobenzilate, 2-Chlorobiphenyl, 1-Chlorobutane, Chloroneb, Chlorothalonil (Draconil, Bravo), Chlorpropham, Chlorpyrifos (Dursban), Chrysene,

Cycloate, 2,4-DB, DCPA(Dacthal), DCPA (total mono & diacid degradate), 4,4'-DDD, 4,4'-DDE, 4,4'-DDT, DEF(Merphos), Diazinon, Dibenz[a,h]anthracene,

Di-n-Butylphthalate, 3,5-Dichlorobenzoic acid, 2,3-Dichlorobiphenyl, Dichlorprop, Dichlorvos (DDVP), Diethyl ether, Di-isopropyl ether, Dimethoate, Dimethylphthalate,

2,4-Dinitrotoluene, 2,6-Dinitrotoluene, Di-N-octylphthalate, Diphenamid, Disulfoton, Endosulfan I, Endosulfan II, Endosulfan sulfate, Endrin aldehyde, EPTC, Ethoprop,

Ethyl methacrylate, Etridiazole, Fenamiphos, Fenarimol, Fluoranthene, Fluorene, Fluridone, alpha-HCH, beta-HCH, delta-HCH, 2,2',3,3',4,4',6-Heptachlorobiphenyl,

Heptachlor epoxide (isomer B), 2,2',4,4',5,6'-Hexachlorbiphenyl, Hexachloroethane, Hexazinone, Indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene, Isophorone, Malathion, Methiocarb,

Methyl acetate, Methyl iodide, Methyl paraoxon, 4-Methyl-2-pentanone (MIBK), Mevinphos, MGK264-isomer a, MGK264-isomer b, Molinate, Naphthalene,

Napropamide, 4-Nitrophenol, cis-Nonachlor, trans-Nonachlor, Norflurzon, 2,2',3,3',4,5',6,6'-Octachlorobiphenyl, Paraquat, Parathion, Pebulate, Pendimethalin,

2,2',3',4,6-Pentachlorobiphenyl, Pentachloroethane, Permethrin (cis- & trans-), Phenanthrene, Prometryn, Pronamide, Propazine, Propoxur (Baygon), Pyrene,

2,4,5-T, Simetryn, Stirofos, Tebuthiuron, Terbacil, Terbufos, Terbuthylazine, Terbutryn, 2,2',4,4'-Tetrachlorobiphenyl, Tetrahydrofuran, Thiobencarb, Triademefon,

2,4,5-Trichlorobiphenyl, Trichlorotrifluoroethane (Freon 113), Tricyclazole, Trifluralin, Vernolate

Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR3) Parameters:

(2)

Androstenedione, Bromochloromethane, Bromomethane, 1,3-Butadiene, Chlorodifluoromethane, Chloromethane, Cobalt, 1,1-Dichloroethane, Equilin, Estradiol,

Estriol, Estrone, Ethynylestradiol, Molybdenum, Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS), Perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA), Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS),

Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), Testosterone, 1,2,3-Trichloropropane, Vanadium

Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR4) Parameters:

(2)

Anatoxin-a, 1-Butanol, Butylated hydroxyanisole, Chlorpyrifos, Cylindrospermopsin, Dimethipin, Ethoprop, alpha-HCH, Germanium Total ICAP/MS, 2-Methoxyethanol,

Monobromoacetic acid, Monochloroacetic acid, Oxyfluorfen, Profenofos, 2-Propen-1-ol, Quinoline, Tebuconazole, o-Toluidine, Total Microcystins,

Total Permethrin (cis & trans), Tribromoacetic acid, Tribufos

15

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

(1) EPA Secondary MCL: NYSDOH has not set an MCL for

this parameter.

(2) Monitored for under the Unregulated Contaminant

Monitoring Rule (UCMR), UCMR3 in 2013 to 2016 and

UCMR4 in 2018. UCMR3 included chlorate and chromium

VI, and UCMR4 included bromide and total organic carbon

in source water. No MCL has been established for any of

these parameters and the NYSDOH chromium MCL is for

chromium (total).

(3) Value represents MRDL, which is a level of disinfectant

added for water treatment that may not be exceeded at

the consumer's tap without an unacceptable possibility of

adverse health eects. The MRDL is enforceable in the same

manner as an MCL and is the calculated running annual

average. Data presented are the range of individual

sampling results and the highest of the four quarterly

running annual averages.

(4) An unusual maximum color value of 240 units was

measured at site 52050 (Port Richmond, 10302) on 1/16/18

which was not believed to be representative of normal

conditions. The next sample collected at this site on 1/29/18

had a value of 6 color units.

(5) Determination of MCL violation: If a sample exceeds the

MCL, a second sample must be collected from the same

location within two weeks, or as soon as practical. If the

average of the two results exceeds the MCL, then an MCL

violation has occurred.

(6) Action Level (not an MCL) applies to samples measured

at-the-tap. The data presented in this table were collected

from sampling stations at the street curb. For at-the-tap

monitoring, see the Lead and Copper Rule Sampling at

Residential Water Taps table.

(7) A Langelier Index of less than zero indicates corrosive

tendencies.

(8) Hardness of up to 3 grains per gallon is considered soft

water; between 3 and 9 is moderately hard water.

(9) If iron and manganese are present, the total concentration

of both should not exceed 500 µg/L.

(10) Only detected in one sample: nitrite was detected from

site 47550 (Seaside, 11694) on 10/3/18; dalapon was

detected from site 37950 (East Village, 10003) on 11/7/18;

diethylphthalate and hexachlorocyclopentadiene were

detected from site 1S03A (Wakeeld, 10466) on 5/21/18.

The single detection of diethylphthalate by the contract

laboratory was questionable due to the lab's inability to

reproduce the analysis and an extensive historical record

of non-detection by multiple labs, thus it is believed to be

from sample contamination. The low level detection of

hexachlorocyclopentadiene in the same sample was below

the NYS required reporting limit of 0.1 µg/L. Resampling

and split sampling between two labs on 8/20/18 produced

non-detects for these parameters. 1,4-Dioxane was

detected in only one sample collected for the UCMR3 on

12/8/15 from site 1SCL1 (Van Cortlandt Village, 10463). In all

other samples the parameters were not detected.

(11) NYSDOH established Optimal Water Quality Parameters

(OWQP) under the Lead and Copper Rule which includes

a range for pH and ortho-phosphate which are presented

here. The reported average value for pH is the median

value. The pH was elevated in four samples collected from

site 3ISL4 (Randalls Island, 10035) between 6/20/18 and

12/12/18; in two samples collected from site 51550 (Arden

Heights, 10312) on 7/25/18 and 8/5/18; in two samples

collected from site 23900 (Highland Park, 11207) on

10/24/18 and 11/15/18; in one sample collected from site

56000 (Prince's Bay, 10309) on 11/28/18; and in one sample

collected from site 79450 (South Ozone Park, 11420) on

7/6/18. Ortho-phosphate was below range in one sample

collected at site 3ISL4 (Randalls Island, 10035) on 12/12/18.

(12) Water containing more than 20 mg/L of sodium should

not be used for drinking by people on severely restricted

sodium diets. Water containing more than 270 mg/L of

sodium should not be used for drinking by people on

moderately restricted sodium diets.

(13) An unrealistically low value for TDS of 13 mg/L was

measured from site 10250 (High Bridge, 10452) on 1/3/18;

resample was 49 mg/L on 1/11/18.

(14) An unrealistically high value for TOC of 22.9 mg/L was

measured from site 1S03A (Wakeeld, 10466) on 1/16/18;

resample was 1.56 mg/L on 2/6/18.

(15) Turbidity is a measure of cloudiness of the water. Turbidity

is monitored because it is a good indicator of water quality,

because high turbidity can hinder the eectiveness of

disinfection, and because it is a good indicator of the

eectiveness of our ltration system.

(16) This MCL for turbidity is the monthly average rounded o

to the nearest whole number. Data presented are the range

of individual sampling results and the highest monthly

average from distribution sites.

(17) This MCL for turbidity is on individual readings taken every

four hours at the unltered Catskill/Delaware source water

entry point. Value presented is the highest individual

sampling result.

(18) This is a Treatment Technique performance standard for the

Croton Filtration Plant. The value presented is the highest

single combined lter euent turbidity measurement

which occurred on 12/5/18. In 2018, 100% of turbidity

results were <0.3 NTU while the Croton Filtration Plant was

in operation.

(19) The MCLs for HAA5 and TTHMs are the calculated locational

running annual average. The data in the Range column

are the minimum and maximum values of all sample

sites monitored in the distribution system whether for

compliance purposes or not. The values in the Average

column are the highest locational running annual

averages under the Stage 2 Disinfectant and Disinfection

By-Products Rule.

(20) If a sample and its repeat sample are both positive for

coliform bacteria and one of the two samples is positive for

E. coli, then an MCL violation has occurred.

(21) Samples are collected prior to nal disinfection or ltration

(Jerome Park). Positive results indicate (oo)cyst detection,

not viability or infectivity.

* NYSDOH allows monitoring for these contaminants

less frequently than once per year. These data, though

representative, are from 2016.

FOOTNOTES

16

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

CRYPTOSPORIDIUM AND

GIARDIA

In 1992, DEP started a comprehen-

sive program to monitor its source

waters and watersheds for the pres-

ence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia,

microscopic organisms (pathogens)

that can cause disease. In 2018, DEP

collected weekly samples from the

outow of the Kensico Reservoir,

prior to chlorination and UV disin-

fection, and the outow of Hillview

Reservoir, prior to secondary disin-

fection with chlorine. The outow of

the Jerome Park Reservoir prior to

ltration was also sampled twice in

2018 to complete sampling require-

ments under the Long Term 2

Enhanced Surface Water Treatment

Rule. Samples were analyzed using

EPA Method 1623.1. The Cryptospo-

ridium and Giardia data for Kensico,

Hillview, and Jerome Park Reservoir

outows are presented in the table

on page 13 of this report.

The presence of low levels of Cryp-

tosporidium and Giardia detected

in the source water required no

action on the part of DEP. DEP’s

Cryptosporidium and Giardia data

from 1992 to the present can be

viewed on the DEP website at

www.nyc.gov/waterquality.

While there is no evidence that any

cases of cryptosporidiosis or giar-

diasis have been caused by the New

York City water supply, federal and

state law requires all water suppliers

to notify their customers about the

potential risks from Cryptosporidium

and Giardia. Cryptosporidiosis and

giardiasis are intestinal illnesses

caused by microscopic patho-

gens, which can be waterborne.

Symptoms of infection include

nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal

cramps. Some people may be

more vulnerable to disease caus-

ing microorganisms, or pathogens,

in drinking water than the general

population. Immuno-compromised

persons, such as persons with can-

cer undergoing chemotherapy,

persons who have undergone

organ transplants, people with HIV/

AIDS or other immune system dis-

orders, some elderly individuals,

and infants, can be particularly at

risk from infections. These people

should seek advice from their health

care providers about their drink-

ing water. EPA/CDC guidelines on

appropriate means to lessen the

risk of infection by Cryptosporidium,

Giardia, and other microbial con-

taminants are available from EPA’s

Safe Drinking Water Hotline at

1-800-426-4791.

DEP’s Waterborne Disease Risk

Assessment Program conducts

disease surveillance for cryptospo-

ridiosis and giardiasis to track the

disease incidence, and syndromic

surveillance for gastrointestinal ill-

ness to identify potential citywide

gastrointestinal outbreaks. Persons

diagnosed with cryptosporidiosis

are interviewed concerning poten-

tial exposures, including tap water

consumption. Disease and syn-

dromic surveillance indicates that

there were no outbreaks of crypto-

sporidiosis or giardiasis attributed to

tap water consumption in New York

City in 2018.

New Croton Reservoir

17

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

CROTON WATER

Did you know that even the cleanest

waters can have dierent chemical

and physical properties?

Water hardness is one such attribute

that DEP receives many questions

about when New Yorkers are installing

dishwashers, water heaters, and other

equipment that use water. Hardness

is a measure of the natural minerals –

specically calcium and magnesium

– that dissolve into water as it passes

through soil and rocks. The more dis-

solved natural minerals, the harder

the water.

Neighborhoods in New York City

receive their drinking water from

reservoirs in the Catskill/Delaware

watershed, the Croton watershed, or a

blend from both locations. Water from

the Croton supply is considered “mod-

erately hard,” while the Catskill/Dela-

ware supply is considered “soft” or

“slightly hard.” Citywide average hard-

ness is about 1.5 grains/gallon (CaCO

3

).

In areas of the City where Catskill/

Delaware and Croton water supplies

are blended, the hardness can reach

6.8 grains/gallon (CaCO

3

).

In 2018, DEP increased use of the Cro-

ton System because other parts of the

water supply were temporarily shut

down for infrastructure upgrades.

As a result, water in several areas of

the City may have become harder.

The water is still of excellent quality

and safe to drink. Water hardness,

however, may aect the eciency of

some equipment. Consult the owner’s

manual for the device being operated.

DEP has also compiled some addi-

tional information on water hardness

and its eects at: www.nyc.gov/dep/

water-hardness.

To help homeowners and building

managers determine whether they

are in an area of the City that could

receive moderately hard water, DEP

has posted maps of the water distribu-

tion system that can be found at: www.

nyc.gov/html/dep/html/drinking_water/

croton-water-distribution-maps.shtml.

ADMINISTRATIVE ORDERS

Hillview Reservoir is the nal stop for

drinking water from the Catskill/Dela-

ware System before it enters the City’s

distribution system. On May 24, 2010,

New York City and EPA entered into

an Administrative Order on Consent

that set forth a milestone schedule

to install a cover over the Hillview

Reservoir by mid-2028. The City has

a parallel Administrative Order with

NYSDOH. The EPA Administrative

Order required the City to issue a

notice to proceed to commence site

preparation work by January 30, 2017

at the Hillview Reservoir Site. The

City advised EPA and the NYSDOH

that it was not undertaking that work

pending EPA’s review of the Long

Term 2 Enhanced Surface Water Treat-

ment Rule; thereafter EPA declined

to revise that rule. EPA and the City

are in discussions concerning revised

milestones.

WATER CONSERVATION

DEP operates the largest combined

water supply and wastewater utility

in the United States. DEP employees

work hard to ensure that a reliable

supply of high-quality water is deliv-

ered to about 9.6 million customers

each day, and that about 1.3 billion

gallons of wastewater from the ve

boroughs is collected and treated

every day. Although New York City

has grown by more than 1.6 million

people since 1980, its demand for

water has dropped by approximately

35 percent during that time – making

it one of the most water-ecient large

cities in the country.

The average single-family household

in New York City uses approximately

80,000 gallons of water each year at

a cost of $3.90 per 100 cubic feet of

water (748 gallons), or about $417 a

year. Since nearly all customers receive

wastewater collection and treatment

services in addition to water service,

the combined annual water and sewer

charge for the typical New York City

household using 80,000 gallons per

UPGRADES AT

SCHOHARIE RESERVOIR

DEP continued to make steady

progress on a $400 million pro-

gram to upgrade infrastructure at

Schoharie Reservoir, the northern-

most reservoir in New York City’s

vast water supply system.

Workers this winter “holed

through” on the nal segment

of a 2,118-foot-long tunnel that

will give DEP the ability to release

water downstream from the

reservoir into Schoharie Creek.

The new release works will help

DEP facilitate dam maintenance,

respond to potential emergencies,

mitigate ood risk for downstream

communities, and enhance down-

stream habitat for sh and wildlife.

Construction of the valve chamber

and other elements of the release

works will continue for the next

two years.

DEP also made considerable

progress on its rehabilitation of

the Shandaken Tunnel Intake

Chamber, which draws the City’s

drinking water from Schoharie

Reservoir. Work at the intake

chamber includes the replace-

ment of eight sluice gates that

control the ow of water into the

tunnel by opening and closing

large waterways. Last year, skilled

divers descended about 130 feet

into a ooded shaft to take precise

measurements of the gates and

the grooves that guide them. The

divers will begin to remove and

replace those gates in 2019.

Schoharie Reservoir

18

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

year is $1,080, consisting of $417 for

water service and $663 for wastewa-

ter services, calculated at scal year

2019 rates.

With the creation of an Automated

Leak Notication Program, which

sends alerts to property owners if

there is an unusual spike in water

consumption, more than 290,000

customers have signed up to quickly

nd and x leaks on their property.

To sign up, go to: www.nyc.gov/dep/

leak-notication.

NYC Water Conservation Eorts

Did you know that the average New

Yorker has reduced his or her water

use by nearly half over the past 40

years? Thanks to strategic invest-

ments in our water delivery system

and advances in technology, New

York City is quickly becoming one of

the most water-ecient large cities

in the world.

The proof is in the numbers. The per-

capita demand for water in New York

City peaked in 1979 at 213 gallons

per day. That per-capita demand

by water consumers, however, has

dropped steadily since the 1990s,

falling all the way to the current level

of 117 gallons per day.

So how did New York City shift from

chugging water to sipping it? Two

factors have been key to reducing

our demand for water over time.

Advances in technology have played

a key role. Low-ow xtures that

came onto the market starting in

the 1990s helped the average New

Yorker use less water. Toilets that

ushed with four gallons of water

were replaced by those that ushed

with one gallon or fewer. Low-ow

showerheads, washing machines

and dishwashers also played a role.

DEP has also partnered with other

City agencies, colleges and busi-

nesses to help conserve water.

Recent investments have reduced

overall demand for water by 10 mil-

lion gallons per day, and DEP is work-

ing on plans to conserve another 10

million gallons per day over the next

ve years.

Drinking water conservation eorts

benet the City in many ways. For

one, they have helped to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions related to

operating our water and wastewater

systems by 68 metric tons annually,

as well as limiting sewer overows

into local waterways during rain

events. Reducing the demand for

water also means that New York City

is better protected against future

droughts, as the water stored in our

reservoirs will last longer during

periods of dry weather. And it gives

DEP the exibility to shut down

parts of our water supply system

for repairs, including the 6-month

shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct

that is planned for 2022-2023 to n-

ish repairing a leak in the world’s

longest tunnel.

A comprehensive report on the City’s

water-conservation eorts, One

Water NYC: 2018 Water Demand Man-

agement Plan can be found at: www.

nyc.gov/html/dep/pdf/conservation/2018-

water-demand-management-plan.pdf.

Some highlights of our work in

recent years include:

Delaware Aqueduct Bypass Tunnel

19

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

Õ The installation of timers on 400

spray showers in NYC Parks Depart-

ment playgrounds, saving 1.1 mil-

lion gallons per day in the summer.

Õ Upgrading 30,000 inecient bath-

room xtures in New York City

public schools, saving 3.3 million

gallons per day.

Õ Capital upgrades and modications

of treatment procedures at DEP’s

14 wastewater resource recovery

facilities (WRRFs), saving 1.83 million

gallons per day.

Õ The installation of 500 ecient

toilets and 280 urinals in 10 City

University of New York buildings,

saving 40,000 gallons of water

per day.

Õ Construction of a water reuse facil-

ity at the New York City Fire Depart-

ment’s Randall’s Island Training

Facility, saving 30,000 gallons of

water per day.

Õ Replacement of more than 13,900

inecient toilets in private resi-

dences, saving 560,000 gallons of

water per day.

Õ Distribution of nearly 100,000 home

water saving kits to promote con-

servation, saving 400,000 gallons

per day.

Õ The installation of water meters

and ecient toilets, urinals, show-

erheads, faucets, ice machines and

dishwashers at NYC Health + Hos-

pitals/Harlem, saving more than

90,000 gallons of water per day.

Õ Voluntary challenges with colleges,

hotels, restaurants, and hospitals

throughout the City, each with the

goal of cutting their water use by 5

percent.

Õ Partnering with 10 of its largest

wholesale customers, DEP is devel-

oping and implementing water

demand management plans, under

the Wholesale Customers Water

Demand Management Program.

Implementation of all plans will con-

tinue through October 2022, and

achieve an estimated demand sav-

ings of 4.6 million gallons per day.

DELAWARE AQUEDUCT

BYPASS TUNNEL

DEP has now excavated more than 60

percent of a tunnel needed for the larg-

est repair in the 177-year history of the

New York City Water Supply System.

Workers made substantial progress

on the Delaware Aqueduct Bypass

Tunnel in 2018. The $1 billion project

will repair two leaking sections of the

85-mile-long Delaware Aqueduct, the

longest tunnel in the world. The Dela-

ware Aqueduct delivers about 50 per-

cent of New York City’s drinking water

each day.

The centerpiece of the repair is a

2.5-mile-long bypass tunnel that will

carry water around the largest leak,

which is located in Newburgh, N.Y.

That tunnel is being constructed 600

feet below the Hudson River from

Newburgh to Wappinger. Once n-

ished, both ends of the bypass tunnel

will be connected to structurally sound

portions of the existing Delaware

Aqueduct to carry water around the

leaking section.

After tunneling began late in 2017, DEP

successfully excavated more than two-

thirds of the new tunnel last year. More

than 7,000 linear feet of the tunnel has

been driven through bedrock, and

workers are on schedule to nish exca-

vation by the end of 2019.

Once tunneling is completed, the

bypass will be reinforced with 9,200 lin-

ear feet of steel. The steel liner is made

from 230 individual sections that look

like gigantic soup cans. Each section

of the liner weighs 80,000 pounds and

measures 40 feet long and 16 feet in

diameter. Once tunneling is completed,

segments of the liner will be moved

into the tunnel and welded together

one at a time.

The Delaware Aqueduct will be shut

down for 5-8 months in 2022 to con-

nect the bypass tunnel to structurally

sound portions of the existing aque-

duct. The City’s other surface water

supplies, Catskill and Croton, will meet

the needs of water consumers in New

York City during the shutdown. Repairs

to the Delaware Aqueduct are planned

to be nished in 2023.

Spray showers in NYC park

20

New York City 2018 Drinking Water Supply and Quality Report

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

MY WATER IS A RUSTY BROWN COLOR. WHAT CAUSES THIS?

Brown or discolored water is often related to plumbing corrosion problems inside buildings and from

rusting water heaters. If you have an ongoing problem with brown water, it may be due to rusty pipes.

You should run your cold water for 2-3 minutes if it has not been used for a long period of time. This

will ush the line.

If your water suddenly looks discolored, it might be because of a disturbance to nearby water

mains, including breaks or repairs. This can also happen if there is construction near your building.

Additionally, the use of re hydrants for reghting can temporarily cause brown water. Because the

water mains are pressurized, a disturbance may stir up or resuspend sediments, which causes the

water to be discolored. Discoloration is a temporary condition most often from iron and manganese

particles that have settled to the bottom of the water pipes buried under the roadways. Any sudden

change in the ow of water within the pipes — or outside vibration — may loosen or resuspend the

brownish/red/orange particles of iron into the water. This temporary problem is generally resolved or

reduced when DEP ushes water from nearby hydrants.

SOMETIMES I THINK MY WATER HAS THE TASTE OR ODOR OF CHLORINE?

You may, at times, nd your water tastes or smells like chlorine. DEP is required to maintain a chlorine

residual in the distribution system to prevent the growth of microorganisms. Chlorine is a very

effective disinfectant, and is not considered hazardous or harmful in the amounts used to treat the

water supply.

Chlorine odors may be more noticeable when the weather is warmer. The following are ways you can

remove the chlorine and its odor from your drinking water:

4

Fill a pitcher and let it stand in the refrigerator overnight. (This is the best way.)

4

Fill a glass or jar with water and let it stand in sunlight for 30 minutes.

4

Pour water from one container to another about 10 times.

4

Heat the water to about 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

4

Once you remove the chlorine, be sure to refrigerate the water to limit bacterial growth.

WHY DOES MY DRINKING WATER LOOK CLOUDY SOMETIMES?

Air becomes trapped in the water as it makes its long trip from the upstate reservoirs to the City. As