Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol

and Health: Final Report

This document was published by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction

(CCSA).

Suggested citation: Paradis, C., Butt, P., Shield, K., Poole, N., Wells, S., Naimi, T., Sherk, A., &

the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Scientific Expert Panels. (2023). Canada’s Guidance

on Alcohol and Health: Final Report. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and

Addiction.

© Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2023.

CCSA, 500–75 Albert Street

Ottawa, ON K1P 5E7

613-235-4048

Production of this document has been made possible through a financial contribution from

Health Canada. The funding body did not influence guideline content. The views expressed

herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

This document can also be downloaded as a PDF at www.ccsa.ca

Ce document est également disponible en français sous le titre :

Repères canadiens sur l’alcool et la santé : rapport final

ISBN 978-1-77871-046-9

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 1

About this Document ......................................................................................... 4

Public Summary .......................................................................................................... 5

Technical Summary ..................................................................................................... 6

Aim and Approach ............................................................................................ 6

Risk Associated with Weekly Levels of Alcohol Use ......................................... 7

Risk Associated with Alcohol Use Per Occasion ................................................ 8

Risk when Pregnant, Trying to Get Pregnant or Breastfeeding ......................... 9

Sex and Gender ................................................................................................ 9

Risk for Women ................................................................................................ 9

Risk for Men ...................................................................................................... 9

Youth .............................................................................................................. 10

When Zero’s the Limit ..................................................................................... 10

Reasons for the New Guidance on Alcohol and Health ................................... 10

Alcohol and Cancer ................................................................................... 10

Alcohol and Heart Disease ......................................................................... 10

Alcohol and Liver Disease ......................................................................... 11

Alcohol and Violence ................................................................................ 11

Policy Implications .......................................................................................... 11

Technical Report ....................................................................................................... 12

Introduction .................................................................................................... 12

Awareness and Adherence to the 2011 LRDGs by People Living

in Canada ........................................................................................................ 12

Time to Update ............................................................................................... 13

Aim and Scope of This Report ......................................................................... 14

Part 1: Development of Experts’ Recommendations ................................................. 15

1.1 Defining Research Questions .................................................................... 15

1.2 Estimating the Lifetime Risk of Alcohol-Related Death and

Disability in the Canadian Population ............................................................. 15

1.3 The Evidence Base for Updating the Guidelines ....................................... 16

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances

1.4 Reaching Conclusions and Formulating Recommendations ...................... 17

Part 2: Evidence Used to Construct the Recommendations ....................................... 18

2.1 Global Evidence Review on the Effects of Alcohol on Health .................... 18

2.1.1. Methods ........................................................................................... 18

2.1.2 Results ............................................................................................... 20

2.1.3 Quality of Evidence ........................................................................... 21

2.1.4 Implications ....................................................................................... 21

2.2 Mathematical Modelling of the Lifetime Risk of Death for

Various Levels of Average Alcohol Consumption ........................................... 21

2.2.1 Methodological Principles ................................................................ 22

2.2.2 Results and Implications .................................................................... 24

2.3 Alcohol Use Per Occasion ......................................................................... 30

2.4 Rapid Reviews ........................................................................................... 32

2.4.1 Association Between Alcohol Use, Aggression and

Violence .................................................................................................... 32

2.4.2 Association Between Alcohol Use and Mental Health ........................ 35

2.5 Women’s Health and Alcohol .................................................................... 36

2.5.1 What Are Some Sex-Related Factors? ............................................... 36

2.5.2 What Are Some Gender-Related Factors? ......................................... 36

2.5.3 How Do Sex and Gender Interact and Intersect with

Other Factors? ........................................................................................... 37

2.5.4 How Does Alcohol Affect Reproduction? ........................................... 37

2.5.5 Discussion ......................................................................................... 37

2.5.6 What Are the Key Messages for Women? .......................................... 38

2.6 Views, Preferences and Expectations About Guidelines of

People Living in Canada ................................................................................. 38

2.6.1 Summary of Evidence on Understanding and Response

to Alcohol Guidelines ................................................................................ 38

2.6.2 Public Consultation on Alcohol Guidelines ....................................... 39

2.6.3 Interviews with Stakeholders ............................................................ 39

2.6.4 Focused Discussions with Indigenous People ................................... 41

Part 3: Experts’ Recommendations ........................................................................... 43

3.1 Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health ............................................... 44

3.2 Limitations ................................................................................................. 46

3.3 Moving Forward ........................................................................................ 47

3.4 Future Update of Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health .................... 49

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances

3.5 Conclusion ................................................................................................ 49

References ................................................................................................................ 51

Appendix 1: Lifetime Risk of Alcohol-Attributable Death and

Disability: Shadow Analysis ...................................................................................... 63

Purpose ........................................................................................................... 63

Method............................................................................................................ 63

Summary of the Comparison of Findings ........................................................ 63

Appendix 2: Confidence Intervals for Risk of Disease and Injury ............................. 66

Appendix 3: Specific Messages for Girls and Women to Supplement

the Guidance on Alcohol and Health ......................................................................... 70

Appendix 4: Update of Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking

Guidelines: Open Consultation ................................................................................. 71

Public Summary .............................................................................................. 71

Technical Summary ........................................................................................ 71

Technical Report ............................................................................................. 72

Public Consultation: Summary of Key Actions Taken ...................................... 75

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 1

Acknowledgements

The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) would like to extend its appreciation

and gratitude to the following individuals for their contributions to the project.

Scientific Expert Panels

Members of the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Scientific Expert Panels provided their

expertise and guidance, and made other invaluable contributions.

Co-chairs for the project

• Catherine Paradis, CCSA

• Peter Butt, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan

Members (in alphabetical order)

• Mark Asbridge, Dalhousie Medical School

• Danielle Buell, University of Toronto

• Samantha Cukier, Health Canada

• Francois Damphousse, Health Canada

• Jennifer Heatley, Public Health, Government of Nova Scotia

• Erin Hobin, Public Health Ontario

• Harold R. Johnson, Lawyer and Author

1

• Ryan McCarthy, previously with CCSA

• Chris Mushquash, Lakehead University

• Daniel Myran, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute

• Tim Naimi, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria

• Nancy Poole, Centre of Excellence for Women's Health

• Justin Presseau, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute

• Adam Sherk, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria

• Kevin D. Shield, Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Centre for Addiction and Mental

Health

• Tim Stockwell, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria

• Sharon Straus, University of Toronto

• Kara Thompson, St. Francis Xavier University

1

Harold R. Johnson passed away during the development of this report. We greatly appreciate his important contributions to this process,

and we extend our sincere condolences to his family and friends.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 2

• Samantha Wells, Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, Centre for Addiction and Mental

Health

• Matthew Young, Gambling Research Exchange Ontario, Carleton University and CCSA

The following members and their colleagues led the production of reports and reviews (as indicated)

that informed development of Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health (in alphabetical order):

• Sharon Bernards, Jesus Chavarria, Jean-Francois Crépault, Tavleen Dhinsa, Kathryn Graham,

Bryan Tanner and Samantha Wells: Association Between Alcohol Use and Aggression and

Violence: A Rapid Overview of Reviews to Inform Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines

• Sam Churchill, Tim Naimi and Adam Sherk: Lifetime Risk of Alcohol-Attributable Death and

Disability: Shadow Analysis (Appendix 1)

• Tim Naimi: Per occasion alcohol use

• Nancy Poole and Lorraine Greaves: Sex, Gender and Alcohol: What Matters for Women in Low-

Risk Drinking Guidelines?

• Nancy Poole and Lorraine Greaves: Specific Messages for Girls and Women to Supplement the

Guidance on Alcohol and Health (see Appendix 3)

• Kevin Shield: Lifetime Risk of Alcohol-Attributable Death and Disability

Other Contributors

The project has benefited from the efforts and contributions of the following organizations and

individuals (in alphabetical order):

• Autrement dit: Plain language summary of Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health

• Cochrane Canada: Update of a Systematic Review of the Effect of Alcohol Consumption on the

Development of Depression, Anxiety and Suicidal Ideation

• Cochrane Canada: Update of Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines: Summary of

Evidence on Understanding and Response to Alcohol Consumption Guidelines

• Christine Levesque, Nitika Sanger and Hanie Edalati: Assistance in all aspects of the evidence

review portion of this project

• Jennifer Reynolds: Assistance in overseeing the first public consultation and the stakeholder’s

consultations

• Bryce Barker, Manon Blouin, Patricia-Anne Croteau, Christina Davies, Ahmer Gulzar, Lauren

Levett, Victoria Lewis, Wendy Schlachta, Virginia St-Denis, Sheena Taha, John Thurston and Lili

Yan: Assistance with project management, communications, editing, translation as well as

planning project next steps.

Observers

• Kate Morissette, Public Health Agency of Canada

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 3

Executive Committee

Members of the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Executive Committee generously contributed

their time and expertise throughout this project.

Co-chairs

• Alexander Caudarella, CCSA

• Shannon Nix, Health Canada

• Rita Notarandrea, previously with CCSA

Members (in alphabetical order)

• Ally Butler, Substance Use and Strategic Initiatives, Government of British Columbia

• Ian Culbert, Canadian Public Health Association

• Scott Hannant, CCSA

• Carol Hopkins, Thunderbird Partnership Foundation

• Jennifer Saxe, Health Canada

• Candice St-Aubin, Public Health Agency of Canada

• Robert Strang, Council of Chief Medical Officers of Canada

• Sam Weiss, Canadian Institute of Health Research

Conflict of Interest

The list of potential conflicts of interest for all participants in the project is available on CCSA’s

website: Disclosure of Affiliations and Interests

.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 4

About this Document

This report contains three documents produced for three different target groups.

Public Summary

The Public Summary is a one-page summary intended for the general public.

Technical Summary

The Technical Summary is intended for health organizations, health professionals (e.g., physicians,

nurses, counsellors) and people who would like to learn about the update of the Low-Risk Alcohol

Drinking Guidelines, its key takeaways, the risks associated with alcohol and the implications.

Technical Report

The Technical Report is intended for alcohol scientists, policy makers and healthcare professionals

who are interested in understanding the detailed process followed, the types of evidence and the

way they were used to update the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines.

The three documents in this report were made available for public consultation from Aug. 29 through

Sept. 23, 2022. The report has been modified in response to that consultation. For details on the

comments made during the consultation and the response to those comments, see Appendix 4.

Notes on Sex and Gender Terminology

Alcohol use has risks, effects, influences and consequences specific to sex and gender. In real life

experience, sex and gender interact with each other, and with other intersectional characteristics

to shape the impacts of alcohol use.

The effects and impacts of sex and gender on alcohol use among sub-populations such as

Indigenous Peoples, older people, sexual minorities and gender minorities remain under-

researched or unknown. As evidence about alcohol and social patterns of drinking evolves, it will

be important to continuously reassess the impact of alcohol on all populations, and to create

appropriate public health and health promotion advice for all populations.

Throughout this report, when presenting sex-related risks, the terms female and male are used.

When presenting gender-related risks, the terms women and men are used. When a section or

topic involves the entanglement of sex and gender, the terms women and men are used.

Notes on a Standard Drink

In Canada, a standard drink is 17.05 millilitres or 13.45 grams of pure alcohol, which is the

equivalent of:

• A bottle of beer (12 oz., 341 ml, 5% alcohol)

• A bottle of cider (12 oz., 341 ml, 5% alcohol)

• A glass of wine (5 oz., 142 ml, 12% alcohol)

• A shot glass of spirits (1.5 oz., 43 ml, 40% alcohol)

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 5

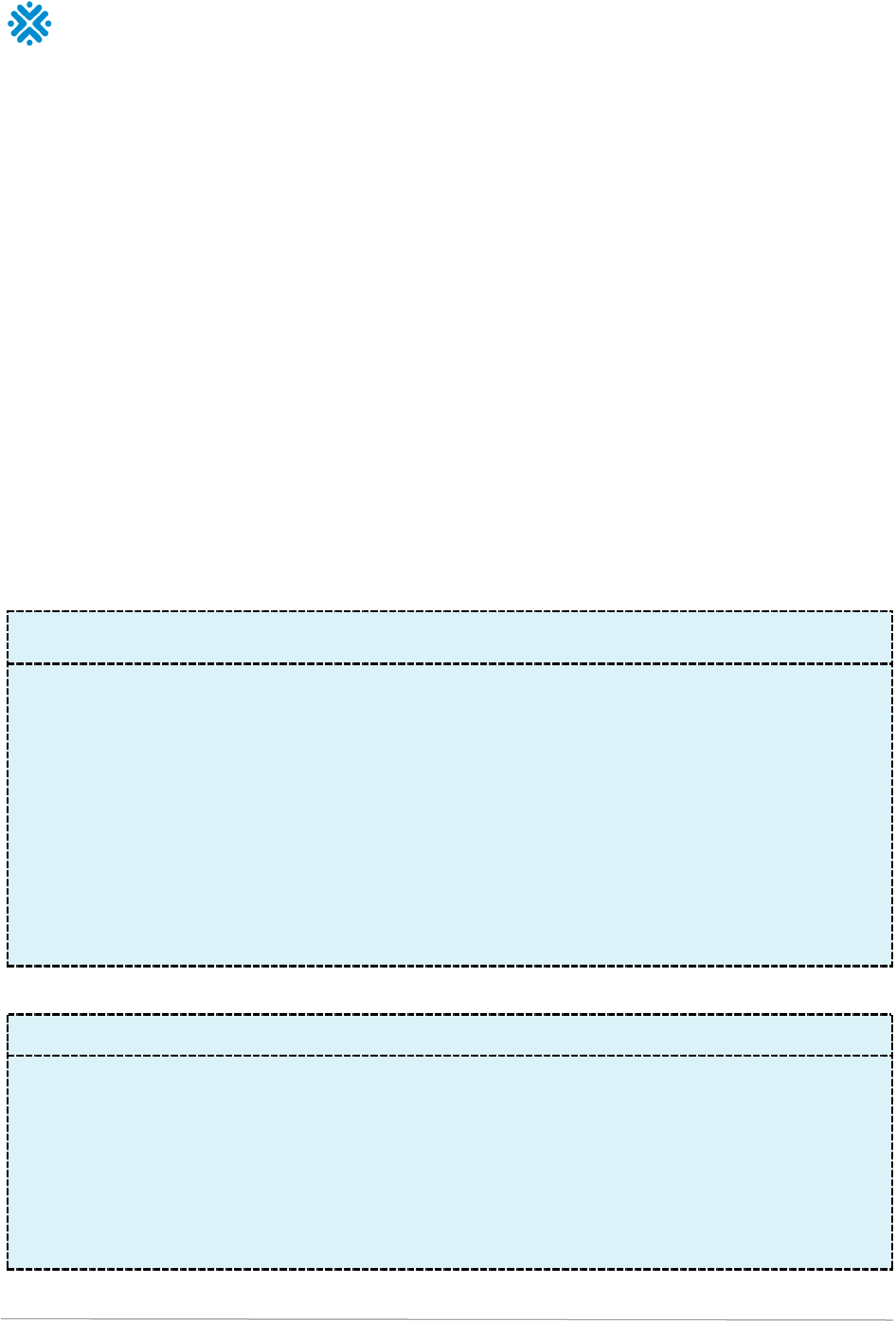

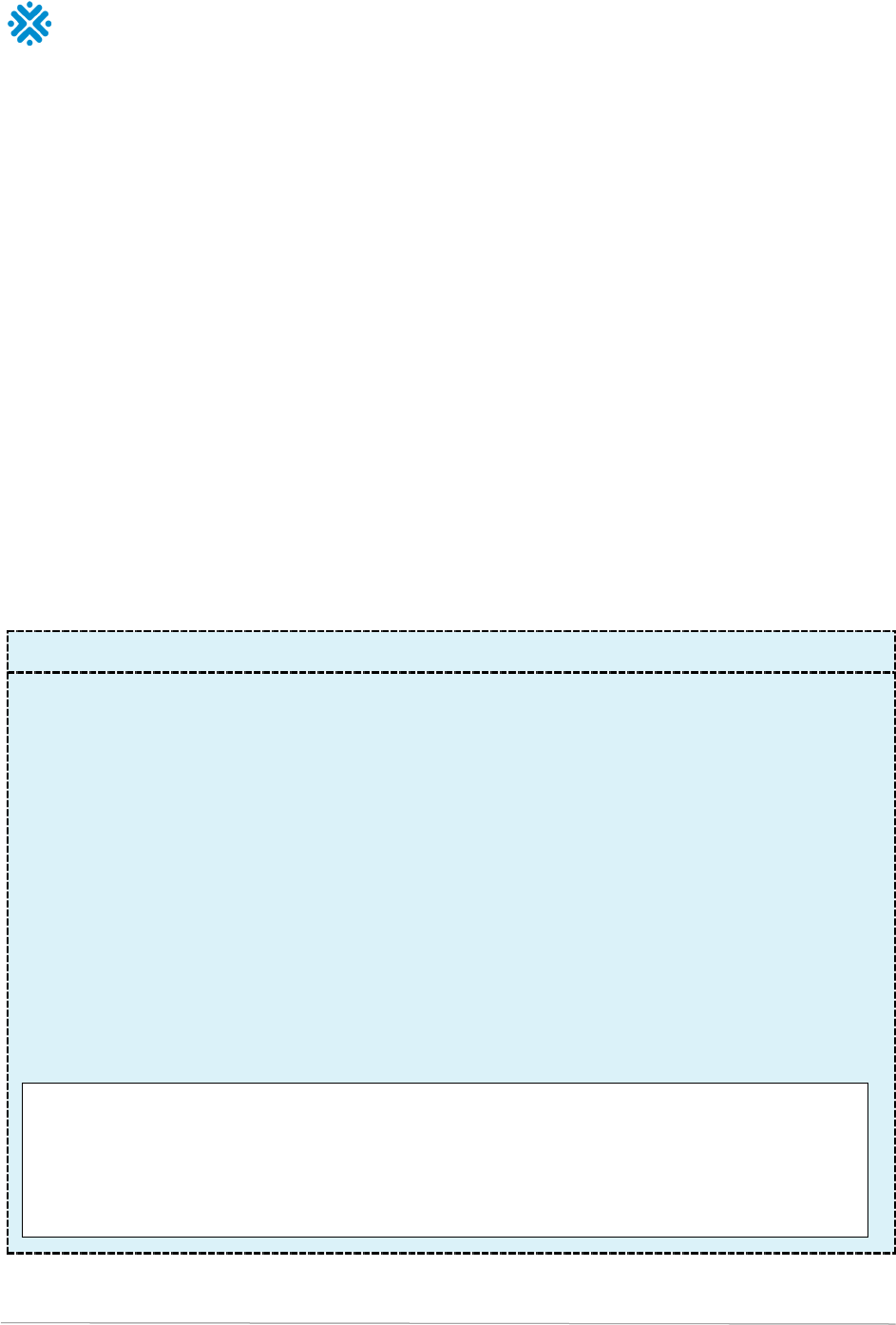

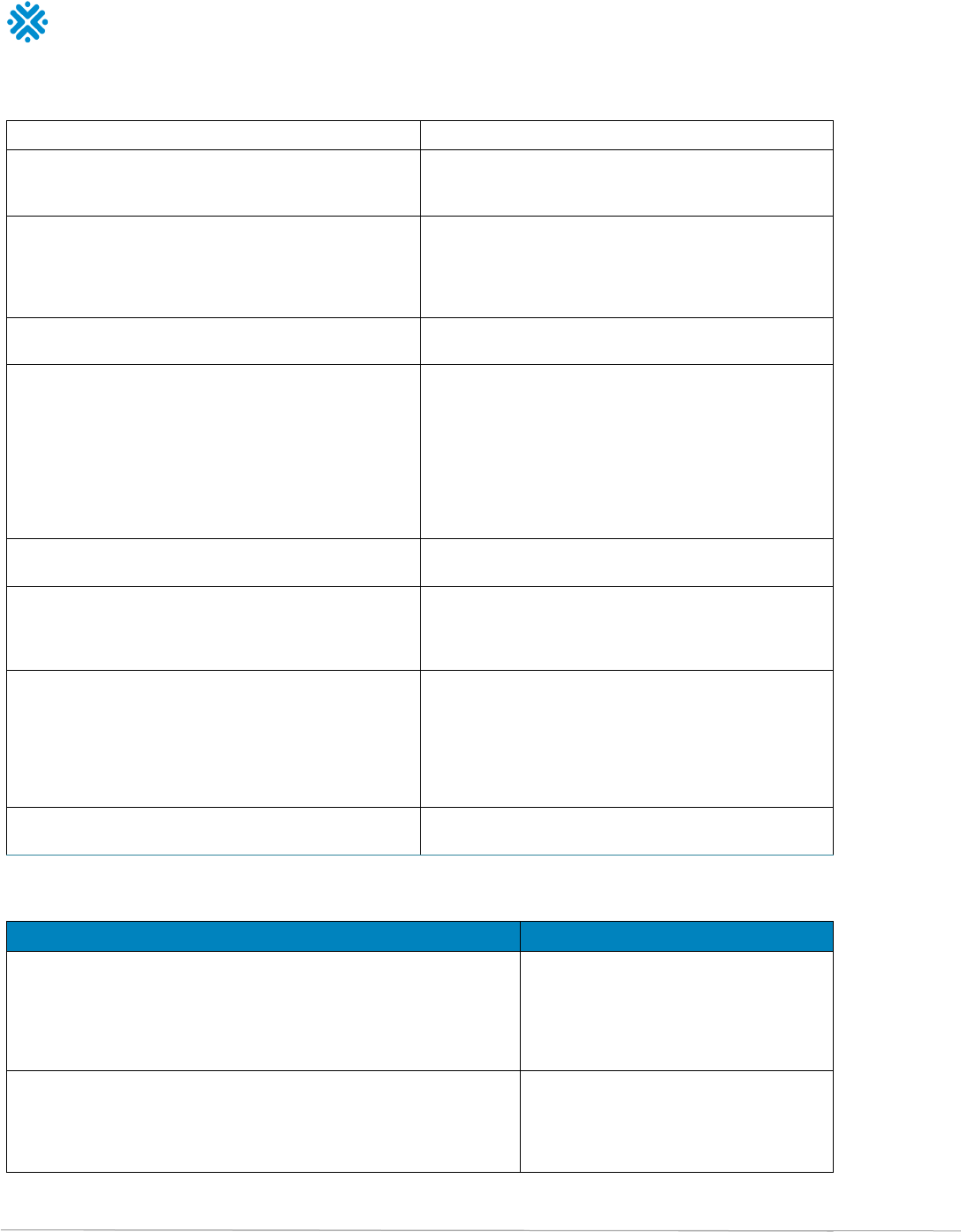

Public Summary

Note. For a PDF of this image, visit https://ccsa.ca/canadas-guidance-alcohol-and-health-public-summary-drinking-less-better-infographic

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 6

Technical Summary

Alcohol is a psychoactive substance used by about three-quarters of people living in Canada. It is

often used in connection with social events or to mark special occasions. However, alcohol can

cause harm to the person who drinks and sometimes to others around them. Alcohol is a leading

preventable cause of death, disability and social problems, including certain cancers, cardiovascular

disease, liver disease, unintentional injuries and violence. In 2017, alcohol caused 18,000 deaths in

Canada. That same year, the costs associated with alcohol use in Canada were $16.6 billion, with

$5.4 billion of that sum spent on health care.

To make more informed decisions about alcohol use, people living in Canada must be aware of

important information about alcohol and health, assess their personal risk and consider reducing

their alcohol use. Taken together

, overwhelming evidence confirms that when it comes to drinking

alcohol, less consumption means less risk of harm from alcohol.

Aim and Approach

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health is informed by a public health perspective. It is intended

to replace Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines. It provides accurate and current

information about the risks and harms associated with the use of alcohol. The guidance should help

people make well-informed and responsible decisions about their alcohol consumption.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health

To reduce the risk of harm from alcohol,

it is recommended that people living in Canada consider

reducing their alcohol use

.

The reasons to do so derive from the following facts:

a. There is a continuum of risk associated with weekly alcohol consumption where the risk of

harm from alcohol is:

•

Low

for individuals who consume

2

standard drinks or less per week;

•

Moderate

for those who consume between

3 and 6

standard drinks per week; and

•

Increasingly high

for those who consume

7

standard drinks or more per week.

b. Consuming more than

2

standard drinks per drinking occasion is associated with an increased

risk of harms to self and others, including injuries and violence.

c. When pregnant or trying to get pregnant, there is no known safe amount of alcohol use.

d. When breastfeeding, not drinking alcohol is safest.

Sex and Gender

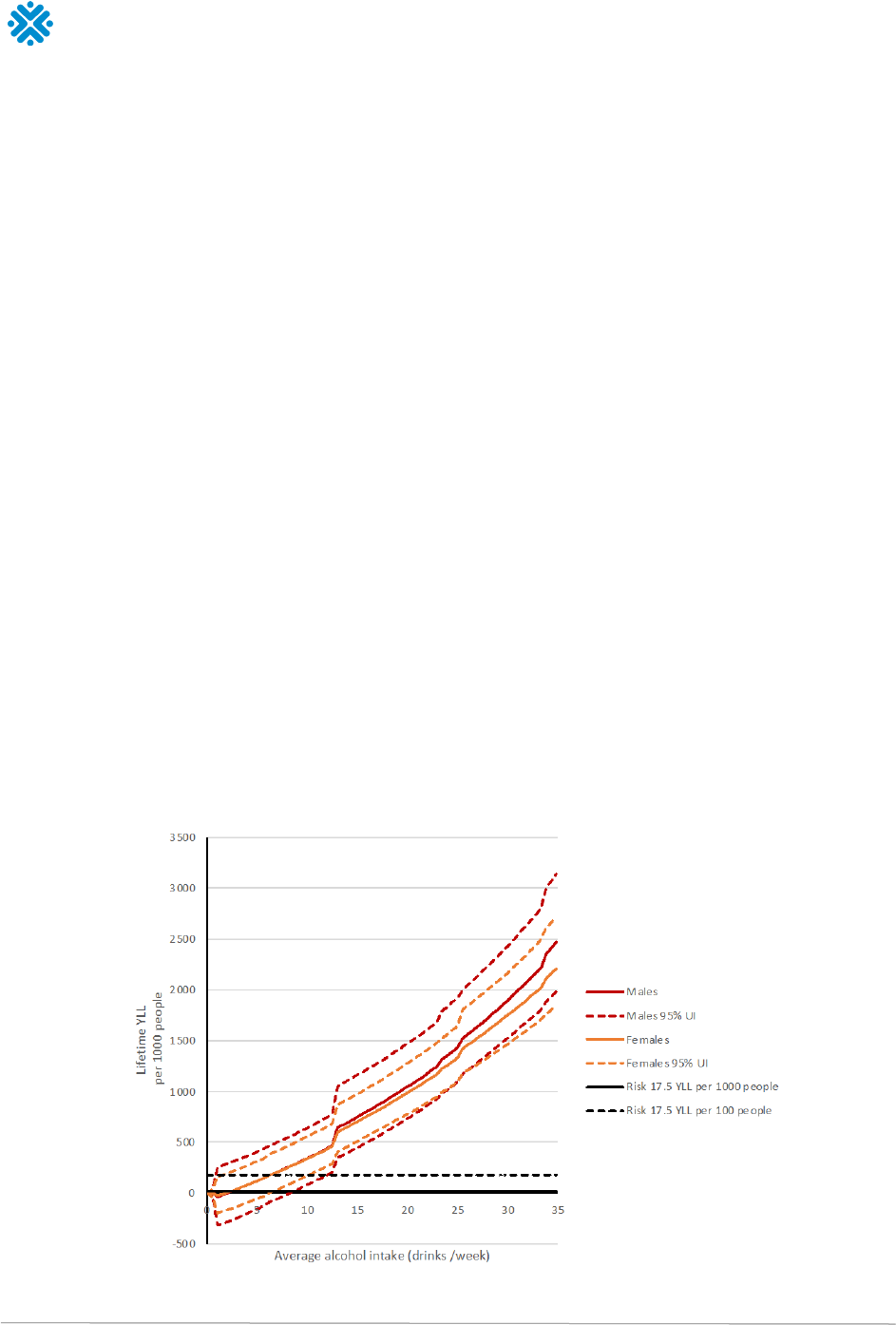

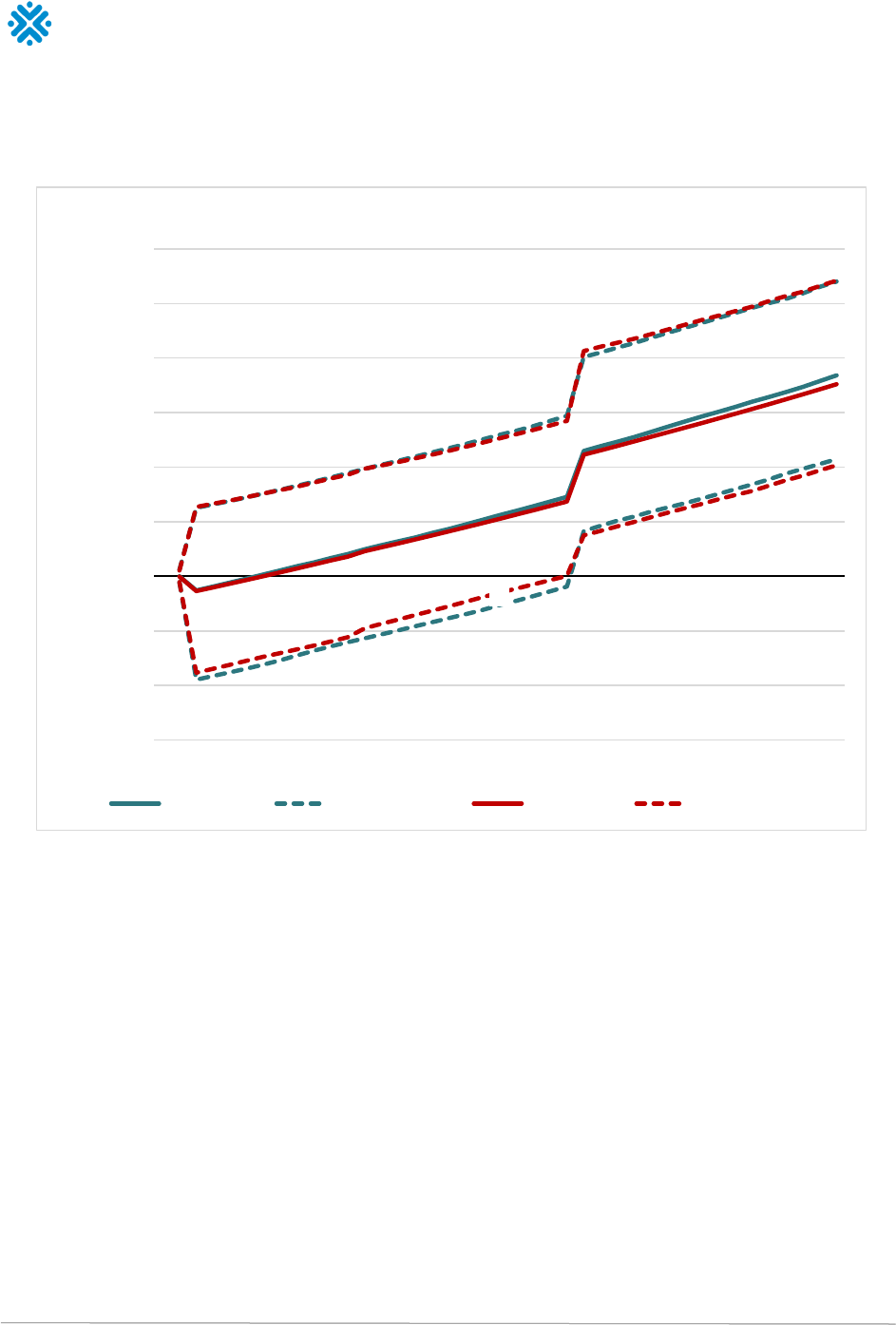

Above the upper limit of the moderate risk zone for alcohol consumption, the health risks

increase more steeply for females than males.

Far more injuries, violence and deaths result from men’s alcohol use, especially in the case of

per occasion drinking.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 7

The guidance is based on the principle of autonomy in harm reduction and a fundamental idea

behind it is that

people living in Canada have a right to know.

It is hoped that the guidance will be used to develop messaging that speaks directly to the unique

concerns of people with diverse backgrounds and personal experiences. It should serve to improve

alcohol literacy, providing information and suggestions so people are able to make their own choices

about how much they drink. The guidance will support health professionals, family doctors and

nurses who are crucial allies to help people assess their individual risk of harm from alcohol use.

The Guidance on Alcohol and Health is also intended to contribute to an evidence base for future

alcohol policy and prevention resources, with a view to changing Canada’s drinking culture and

curbing the normalization of harmful alcohol use in society.

The production of the Guidance on Alcohol and Health followed a rigorous and transparent approach

to assess the impact of various levels of alcohol use on deaths and disabilities. The analyses were

based on the most recent data and methods, which have evolved since the Low-Risk Alcohol

Drinking Guidelines were released in 2011. Analyses were supplemented by additional reviews on

specific topics and consultations with the public and experts.

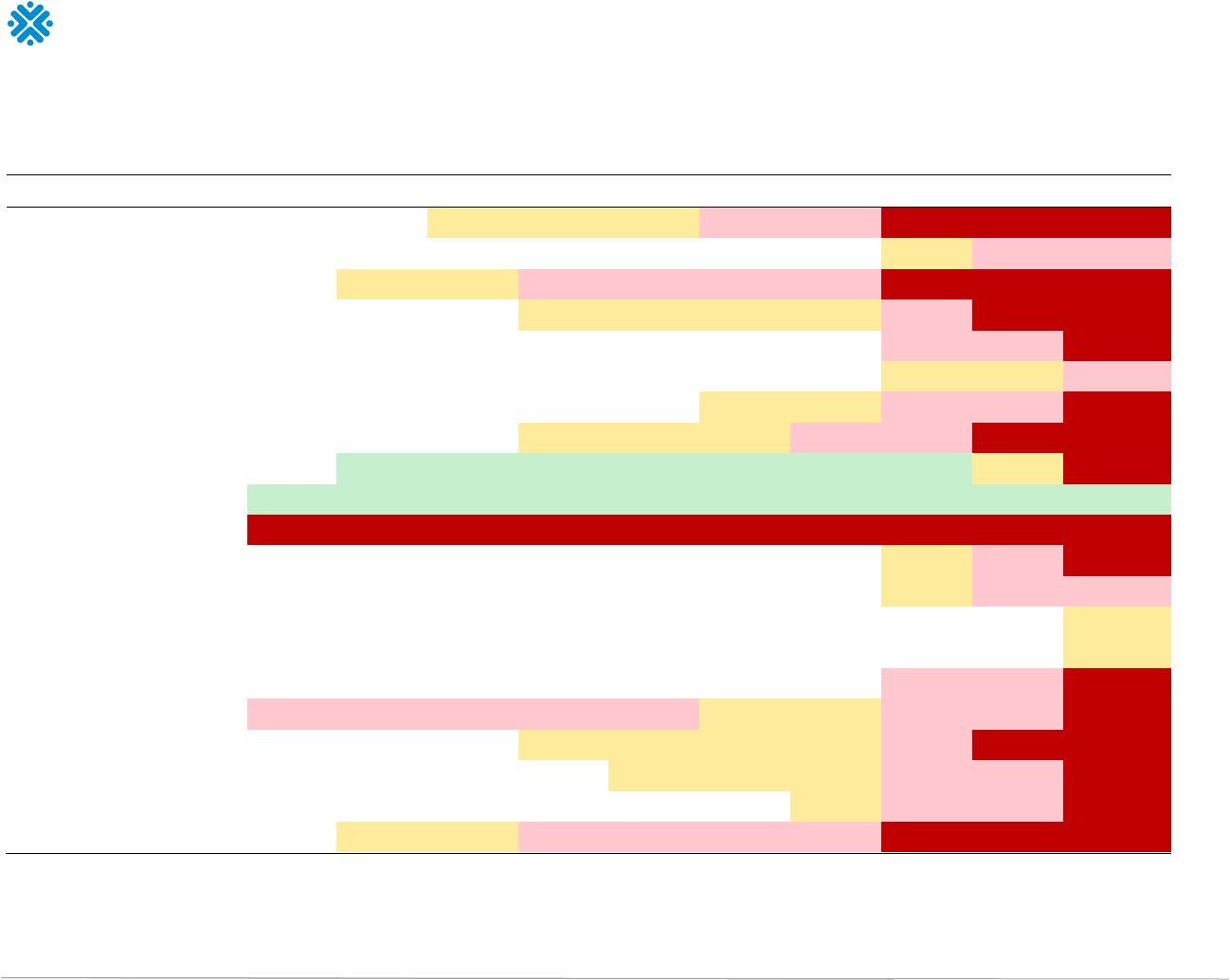

Risk Associated with Weekly Levels of Alcohol Use

Throughout the life course, there are established thresholds of mortality risk that people are willing

to accept. For example, for involuntary risks such as air pollution, a 1 in 1,000,000 lifetime mortality

risk has been used as a gold standard. That is, people are willing to accept a negligible 1 in

1,000,000 risk of premature death when exposed to these risks.

• For risks associated with activities that people undertake deliberately and by choice, such as

unprotected sexual practices, smoking and so on, people may accept a level of risk that is about

1,000 times greater than the one for involuntary risk. Hence, advice and recommendations

made to people about voluntary activities generally use a

low risk level, equivalent to a 1 in

1,000 risk of premature death.

• However, for drinking alcohol, it is not unusual for guidelines to be based on a higher risk

threshold, 10 times that of voluntary activities. Recommendations for alcohol use have often

used a

moderate risk level, equivalent to a 1 in 100 risk of premature death.

Using these different thresholds, this project’s estimates make it possible to put forward a clear

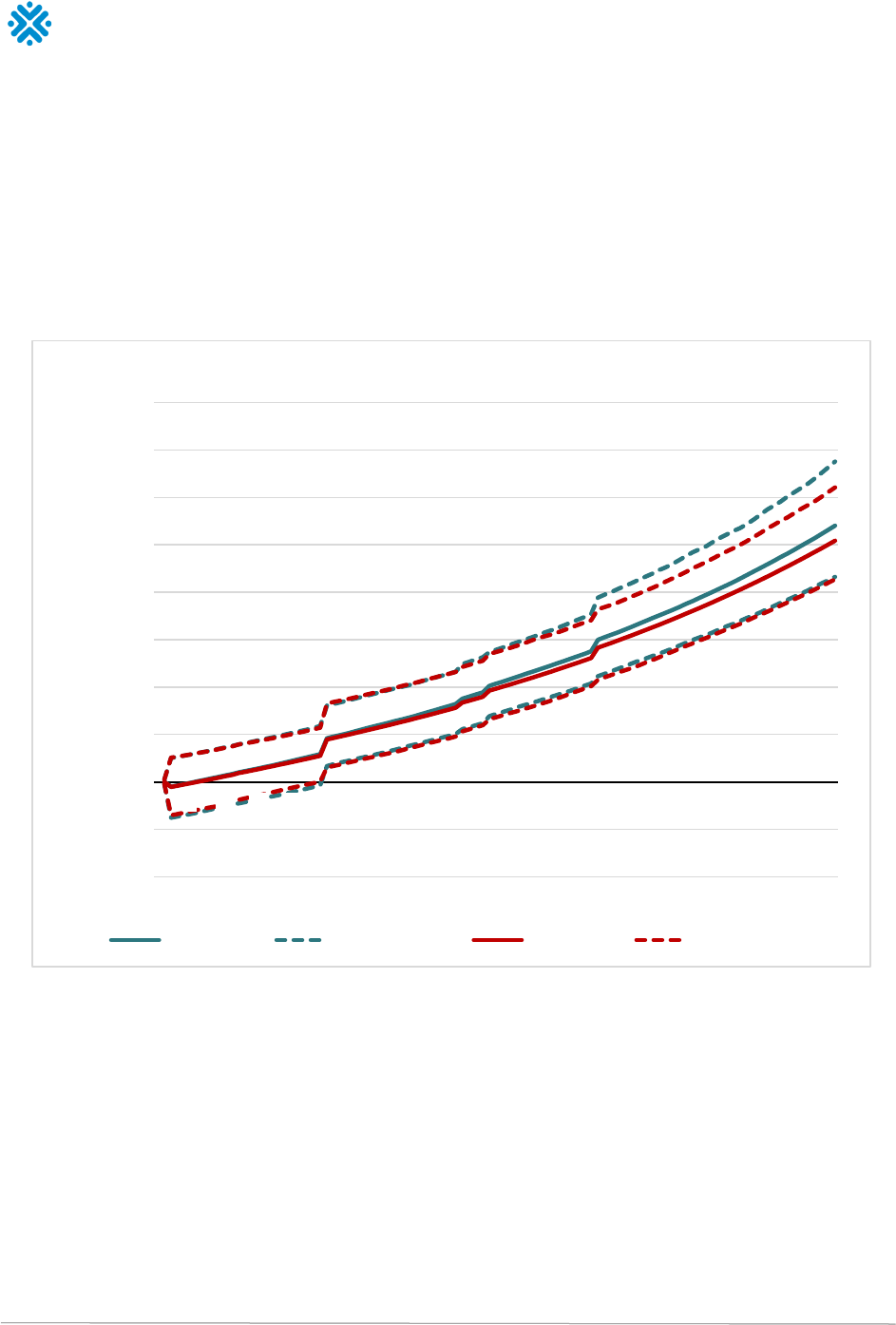

continuum of risk whereby

the risk for those who consume 2 standard drinks or less per week is low,

it is moderate for those who consume between 3 and 6 standard drinks per week, and it is

increasingly high for those who consume above 6 standard drinks per week, with increasing risk

conferred by every additional drink.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 8

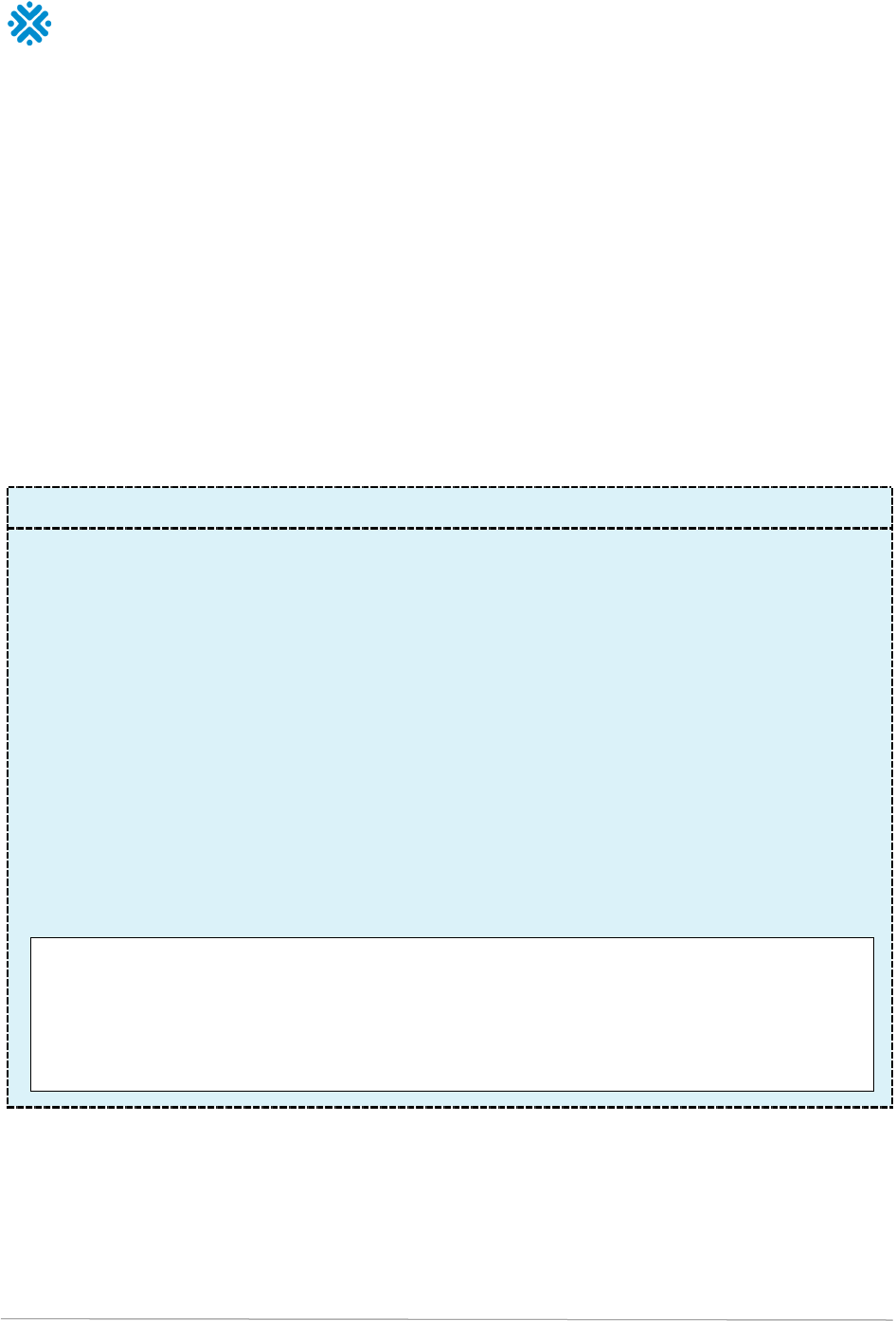

Figure 1. Continuum of risk associated with average weekly alcohol consumption

People should not start to use alcohol or increase their alcohol use for health benefits. Any reduction

in alcohol use is beneficial. This applies even for those who are unable or unwilling to reduce their

risk to low or moderate levels. In fact, those consuming high levels of alcohol have even more to gain

by reducing their consumption by as much they are able.

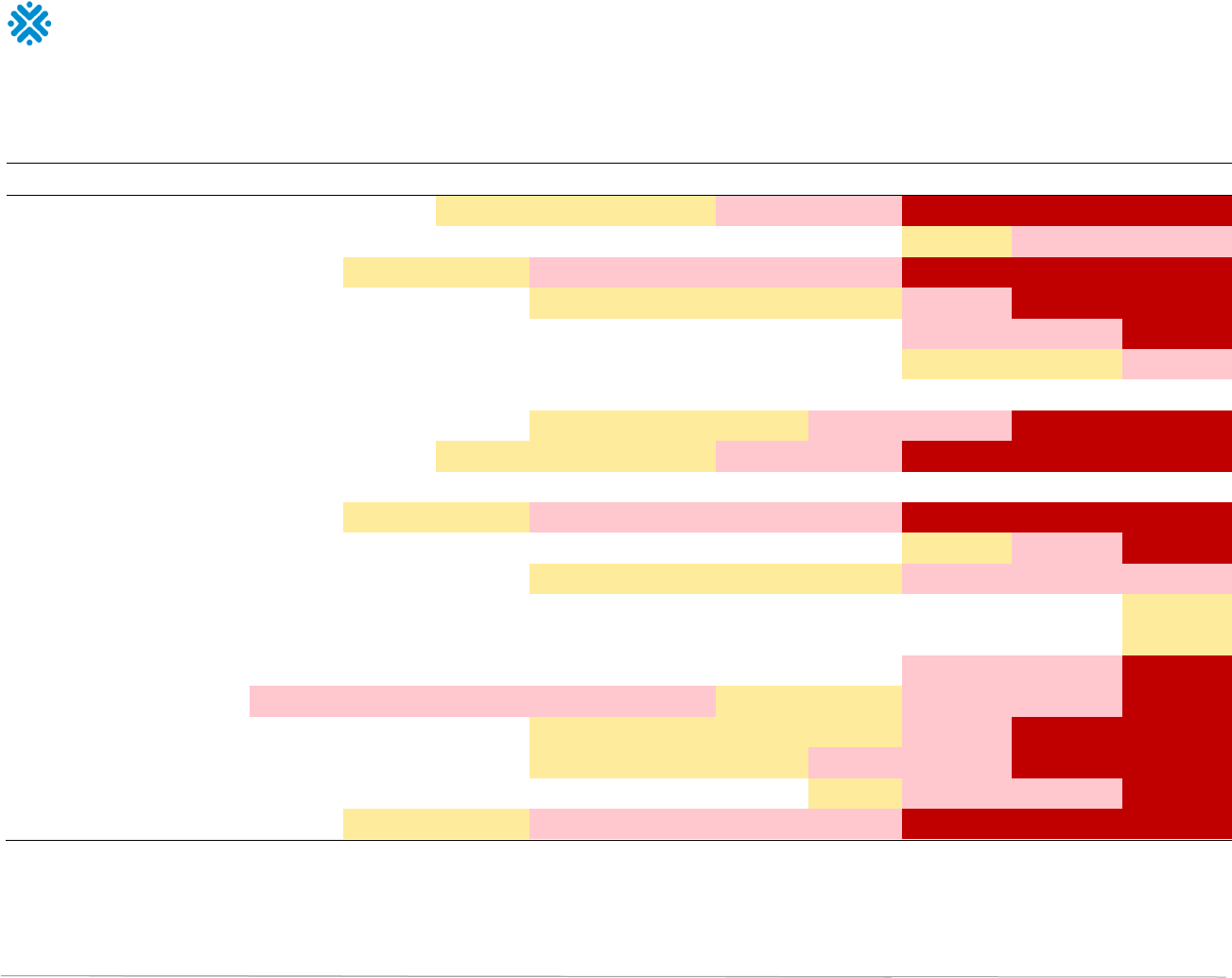

Figure 2. Illustration of examples standard drinks

Risk Associated with Alcohol Use Per Occasion

On any drinking occasion, the risk of acute outcomes such as unintentional injuries and violence is

strongly associated with cognitive and physical impairment from consuming too much alcohol.

The

risk of negative outcomes begins to increase with any alcohol use and consuming more than 2

standard drinks per occasion is associated with a significant increased risk of harms to self and

others.

Binge drinking, usually defined as consuming five or more standard drinks in one setting for men, or

four or more standard drinks in one setting for women, is a pattern of consumption that results in

legal impairment for most people. It is a well-established risk factor for death from any cause,

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 9

including unintentional injuries, violence, heart disease and high blood pressure, and inflammation

of the gastrointestinal system, and for developing an alcohol use disorder (i.e., alcohol dependence).

Many of the complications arising from acute impairment and binge drinking involve second-hand

effects that affect someone other than the person who drinks alcohol (e.g., violence, road crashes,

child abuse and neglect).

Risk when Pregnant, Trying to Get Pregnant or

Breastfeeding

Alcohol is a teratogen or agent that can cause malformation of the fetus. It can lead to learning,

health and social effects with lifelong impacts on the fetus as well as brain injury, birth defects,

behavioural problems, learning disabilities and other health problems typically referred to as fetal

alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). These adverse effects are also observed at low levels of exposure

or short-term exposure to high levels of consumption. For this reason,

when pregnant or trying to get

pregnant, there is no known safe amount of alcohol use. Reproductive health is compromised by

alcohol use. Possible impacts of alcohol on pregnancy and delivery outcomes include increases in

miscarriage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and placental abnormalities.

Alcohol consumption can also negatively impact breastfeeding by causing a decrease in milk

production, early cessation of breastfeeding and effects on infant sleep patterns. Moreover, alcohol

enters breast milk through passive diffusion meaning that breastfeeding infants, who are less able to

metabolize alcohol, can be exposed to it. Therefore

, when breastfeeding, no alcohol use is safest for

the baby. Consuming a standard drink on occasion can be okay, as long as it is planned. It takes

about two hours for the alcohol contained in a standard drink to be eliminated from the body and

leave the breastmilk.

Sex and Gender

Alcohol use and harms are influenced by both sex-based physiological differences, as well as many

gender-related factors, including alcohol marketing tactics, and gender roles, attitudes and

expectations. Many harms from alcohol use are gender-related, including stigma, sexual assault and

intimate partner violence.

Risk for Women

The physiological differences between females and males at low levels of alcohol use have only a

small impact on lifetime risk of death. However, it is unequivocal that

above the upper limit of the

moderate risk zone for alcohol consumption (above 6 standard drinks per week), the health risks

increase more steeply for females than for males. Enzymes, genes, lean body weight and size, organ

function and metabolism are important in processing alcohol and are affected by sex-related factors.

These biological factors enhance the impact of alcohol on females, causing higher blood alcohol

levels, faster intoxication, more risk for disease, including breast cancer, and more long-term harm,

such as liver damage and injury.

Risk for Men

Men drink more alcohol than women and are more likely to drink in excess. Consequently, they are

more likely to be involved in alcohol-impaired driving collisions, to be treated in hospitals and

hospitalized for alcohol-related medical emergencies and health problems, to be diagnosed with an

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 10

alcohol use disorder and to die from alcohol-related causes. Alcohol is also more strongly associated

with perpetration of violence for men than for women.

Men are also more likely than women to take other risks (e.g., use other substances, drive under the

influence) that when combined with alcohol further increase their likelihood of experiencing and

causing alcohol-related harms. Overall,

far more injuries, violence and deaths result from men’s

alcohol use, especially in the case of per-occasion drinking.

Youth

Alcohol use is a leading behavioural risk factor for death and social problems among youth and

young adults, and alcohol is the most common psychoactive substance used by this age group. A

high proportion of alcohol consumed by youth is in the form of binge drinking with its attendant risks

of injuries, aggression, violence and other age-important consequences such as dating violence and

worsening academic performance. In addition, even for the same number of drinks consumed per

drinking occasion, the risk of adverse outcomes from alcohol consumption is greater for youth than

for adults. This may be due to several factors, including greater impulsivity and less emotional

maturity among youth, lower body mass on average, less experience doing complex tasks that are

made more dangerous by alcohol (e.g., operating a motor vehicle) and faster drinking speeds.

For this reason, recommendations related to the risks associated with weekly levels of alcohol use

and alcohol use per occasion do not apply to youth under the legal drinking age. For them, the main

message should be to

delay alcohol use for as long as possible.

When Zero’s the Limit

There are circumstances when no alcohol use is safest. For example, when:

• Driving a motor vehicle;

• Using machinery and tools;

• Taking medicine or other drugs that interact with alcohol;

• Doing any kind of dangerous physical activity;

• Being responsible for the safety of others; and

• Making important decisions.

Reasons for the New Guidance on Alcohol and Health

Alcohol and Cancer

Cancer is the leading cause of death in Canada. However, the fact that alcohol is a carcinogen that

can cause at least seven types of cancer is often unknown or overlooked. The most recent available

data show that the use of alcohol causes nearly 7,000 cases of cancer deaths each year in Canada,

with most cases being breast or colon cancer, followed by cancers of the rectum, mouth and throat,

liver, esophagus and larynx. According to the Canadian Cancer Society, drinking less alcohol is

among the top 10 behaviours to reduce cancer risk.

Alcohol and Heart Disease

After cancer, heart disease is the second leading cause of death in Canada. For many years, the

commonly held belief that drinking in moderation offered protection against coronary artery disease

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 11

has been widely publicized. Research in the last decade is more nuanced with the most recent and

highest quality systematic reviews showing that

drinking a little alcohol neither decreases nor

increases the risk of ischemic heart disease, but it is a risk factor for most other types of

cardiovascular disease, including, hypertension, heart failure, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation

and hemorrhagic stroke.

Alcohol and Liver Disease

Statistics show that liver disease is on the rise in Canada, and alcohol is one of its main causes.

Drinking a large amount of alcohol, even for just a few days, can lead to a build-up of fat in the liver.

This is called alcohol-associated fatty liver. A more severe form of alcohol-related liver disease is

called alcohol-associated hepatitis, which is generally caused by alcohol abuse or, less commonly,

when people consume large amount of alcohol in a short period of time (binge drinking). Eventually,

ongoing alcohol-related liver injury can lead to the development of scar tissue in the liver, termed

fibrosis, which can lead to life-threatening cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Alcohol and Violence

Alcohol is frequently associated with violent and aggressive behaviour, including intimate partner

violence, male-to-female sexual violence, and aggression and violence between adults. Alcohol can

also increase the severity of violent incidents. No exact dose–response relationship can be established

but consuming alcohol increases the risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence. It is therefore

reasonable to infer that individuals can reduce their risk of perpetrating aggressive or violent acts by

limiting their alcohol use. Based on consistent evidence, it is highly likely that

avoiding drinking to

intoxication will reduce individuals’ risk of perpetrating alcohol-related violence.

Policy Implications

To support people living in Canada who will want to drink less, governments, working in close

collaboration with employers, healthcare providers and community stakeholders, need to implement

policies that promote public health. Such policies include strengthening regulations on alcohol

advertising and marketing, increasing restrictions on the physical availability of alcohol, and adopting

minimum prices for alcohol.

As a priority, people living in Canada need consistent, easy-to-use information at the point of pour

to track their alcohol use in terms of standard drinks. They also have a right to clear and

accessible information about the health and safety of the products they buy. A direct consequence

of the current project is that a particular effective policy change could be the

mandatory labelling

of all alcoholic beverages with the number of standard drinks in a container, Canada’s Guidance

on Alcohol and Health and health warnings.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 12

Technical Report

Introduction

Canada’s first Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines (LRDGs) were originally published by the

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) in November 2011 (Butt et al., 2011). The

guidelines were developed by an independent expert working group, with members drawn from

Canadian addiction research agencies. The 2011 LRDGs provided people living in Canada with

advice on how to minimize relative long-term risk of serious diseases caused by the consumption of

alcohol over a number of years (e.g., liver disease, some cancers) and relative short-term risk of

injury or acute illness due to the overconsumption of alcohol on a single occasion (Stockwell et al.,

2012). In addition, specific recommendations were provided for situations and individual

circumstances that are particularly hazardous and for which abstinence or only occasional light

intake was advised (e.g., just before or during pregnancy, teenagers, people on medication). The

guidelines also included tips for safer drinking and the definition of a standard drink. The 2011

LRDGs were a significant step to providing consistent information and messaging for minimizing the

risk associated with drinking alcohol. They have provided the cornerstone for undertaking a variety of

health promotion, prevention and education initiatives across the country (Paradis, 2016).

Still, there were important limitations with the research evidence used to develop the 2011 LRDGs.

In the LRDG technical report

(Butt et al., 2011), the working group noted the under-reporting of

personal alcohol use in self-reported surveys, the failure to take account of heavy drinking episodes

in many epidemiological studies, the misclassification of former and occasional drinkers as lifetime

abstainers, and the failure to control for confounding effects of personality and lifestyle factors

independent of alcohol. In its quality appraisal, using the AGREE II instrument, the Public Health

Agency of Canada (PHAC) further noted limitations, particularly with respect to the rigour of

development and editorial independence, two domains that did not receive the minimum acceptable

score of 60%. Consequently, the 2011 LRDGs received an overall assessment of 60.7% and so did

not meet the criteria for high quality guidelines. They were recommended for use with modifications,

and since then it has been known that careful consideration would need to be paid to these

limitations when developing alcohol guidelines.

Awareness and Adherence to the 2011 LRDGs by People

Living in Canada

Since their publication, the 2011 LRDGs have been promoted to varying degrees across the country

and adopted differently by key demographics. In 2012, just a few months after the release of the

guidelines, a national survey indicated that a quarter (26%) of people living in Canada had seen or

heard of the LRDGs. Since then, a few provincial studies have recorded people’s awareness of the

LRDGs. In 2017, Public Health Ontario surveyed 2,000 adults in Ontario aged 19 and older who

consume alcohol and found that less than a fifth (17%) were aware of the 2011 LRDGs (Public

Health Ontario, 2017a). In 2019–2020, the new Canadian Postsecondary Education Alcohol and

Drug Use Survey (CPADS) surveyed students in colleges and universities in Canada about their

knowledge of the 2011 LRDGs (Health Canada, 2021). Not surprisingly, within this young group,

awareness was negligible with only 16% reporting to have heard about the guidelines and less than

a third of those (28%), being able to accurately report what the guidelines were.

In Quebec, significant resources have been invested to disseminate and promote the 2011 LRDGs

(Paradis, 2016). No study has specifically surveyed Quebecers’ knowledge of the guidelines, but a

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 13

study conducted by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec found that 55% of Quebecers

thought the 2011 LRDGs were adequate, while 37% believed they were too high, that is, corresponded

to larger amounts of alcohol than what they consider to be low-risk drinking (Bergeron et al., 2021).

According to the most recent data from the

Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS, Health

Canada, 2019), a majority of people living in

Canada indicated drinking within the 2011

LRDGs. In 2019, 83% of the people aged 15 years

and older who consumed alcohol in the past year

reported to drink within the guidelines for short-

term risk and 77% within those for long-term risk.

While more females than males reported to drink

alcohol within the guidelines for short-term risk

(85% vs 81%), the percentages were similar for

the long-term risk guideline (76% for males vs

78% for females). Young adults between the ages

of 20–24 were less likely than other age groups to

drink within the guidelines. In 2019, three-

quarters (74%) followed the guideline for short-

term risk of injury and harm while 69% reported to

follow the guidelines for long-term health risk.

While the percentages seem to indicate general adhesion to the 2011 LRDGs, the reality may be

otherwise. The CADS estimates are based on the alcohol consumption in the previous seven days,

meaning that people who consumed alcohol in the past year but did not have a drink in the week

preceding the survey are automatically considered as not exceeding the 2011 LRDGs. This seems

very unlikely given Canada’s timeout culture where people drink to mark special occasions rather

than on a regular daily basis. In fact, a study conducted in 2015 explored adherence to the LRDGs

while attempting to adjust for the under-reporting of alcohol consumption (Zhao et al., 2015). It was

found that 73% of people living in Canada over the age of 15 followed the weekly limits while 61%

followed the daily limits recommended by the LRDGs. In Ontario, the Public Health Ontario survey

found that 39% of people who used alcohol in the Ontario sample regularly exceeded the LRDG daily

limits and 27% the weekly limits (Public Health Ontario, 2017a). According to CPADS , a majority

(88%) of students who use alcohol reported following the guidelines for long-term risk, but only 36%

indicated drinking within the recommendations for short-term risk (Health Canada, 2021). Zhao and

colleagues (2015) also found that, after adjustment for under-reporting, more than 80% of all drinks

consumed in Canada were consumed in a fashion inconsistent with the LRDGs.

Time to Update

There are no set criteria for updating health guidelines to ensure they remain current and evidence

based, but an update is typically recommended when new evidence is identified that is relevant and

important or could alter current guidelines (Vernooij et al., 2014). Over the last decade, several

reasons that justify an update of the 2011 LRDGs have been identified.

First, knowledge on and estimates of relations between different dimensions of alcohol use and

particular diseases, disorders or injuries have been evolving since 2011. Research now confirms the

importance of alcohol use as a risk factor for an increasing number of diseases including at least

seven types of cancers, dementia and sexually transmitted diseases (International Agency for

Research on Cancer, 2012; Lu et al., 2017; Rehm et al., 2017). Second, a Canadian study showed

Canada’s 2011 LRDGs

The 2011 LRDGs recommended people who

consume alcohol to reduce:

• Long-term health risk by drinking no

more than 10 standard drinks a week for

women, with no more than two drinks a

day most days, or 15 standard drinks a

week for men, with no more than two

drinks a day most days.

•

Short-term risk of injury and harm by

drinking no more than three standard

drinks for women or four standard drinks

for men on any single occasion.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 14

that more than 50% of alcohol-attributable cancer deaths in British-Columbia are among former

alcohol users and people using alcohol within the 2011 LRDGs for long-term risks (Sherk et al.,

2020). People living in British-Columbia who use alcohol within the LRDG’s weekly limits also

account for 65% of hospital stays due to unintentional injuries and a substantial percentage of

deaths due to digestive conditions (18%) and injuries (40%), suggesting that reducing the burden of

disease requires revising the 2011 LRDGs (Sherk et al., 2020). Third, countries like the United

Kingdom, France, Denmark, Holland and Australia recently reviewed new evidence on alcohol and

health and released updated guidelines with limits significantly different from the 2011 LRDGs, with

weekly limits ranging from the equivalent of 5.2 to 8.3 Canadian standard drinks for women and

men alike.

2

Finally, given recent reports on the extent to which alcohol use causes social problems

for individuals other than the drinkers themselves (Laslett et al., 2019), there has been curiosity as

to what alcohol guidelines would be if social and mental health harms were also included in addition

to diseases, disorders and injuries.

The Canadian 2011 LRDGs did not include an expiration date but given the limitations and in light of

the new evidence, in early 2019, CCSA, Health Canada, PHAC and members of the Canadian 2011

LRDGs working group engaged in discussions to update the guidelines. In July 2020, Health Canada

confirmed funding to CCSA to update Canada’s LRDGs and make recommendations for knowledge

mobilization to maximize dissemination and application of the updated guidelines. The mandate

specified building on the guidelines from the United Kingdom (U.K. Chief Medical Officers, 2016) and

Australia (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2020), which had provided access to the

underlying evidence base supporting their alcohol guidelines. It was further agreed that CCSA would

be responsible for overseeing and facilitating the updating process. Health Canada would provide

advice, support and guidance through membership on the project’s various committees, plus

administrative support. PHAC would provide methodological advice and support.

Aim and Scope of This Report

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health is intended to replace Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking

Guidelines. It provides accurate and current information about the risks and harms associated with

the use of alcohol. The guidance should help people make well-informed and responsible decisions

about their alcohol consumption. The Guidance on Alcohol and Health is also intended to contribute

to an evidence base for future alcohol policy and prevention resources, with a view to changing

Canada’s drinking culture and curbing the normalization of harmful alcohol use in society.

In the interests of transparency and because developing best practices for defining alcohol drinking

guidelines remains a work in progress (Holmes et al., 2019), this report will describe the updating

process, so that others can learn from the Canadian experience. The report is divided into three

main parts:

1. The construction of experts’ recommendations;

2. The evidence used by the experts; and

3. The experts’ recommendations for updated alcohol guidelines in Canada.

2

Around the world, what constitutes a standard drink ranges from 8 to 20 grams of pure alcohol. In Canada, it is defined as 13.45 grams

(Paula et al., 2020). Some say that Canada’s particular standard drink was chosen because it corresponds to the measure of whisky

traditionally available in Canadian bars (Miller et al., 1991). A more probable reason is that it corresponds to the amount of pure alcohol

contained in 341 ml bottles of 5% beer, which has traditionally been the alcoholic beverage of choice in Canada.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 15

Part 1: Development of Experts’ Recommendations

To update the 2011 LRDGs, four committees were convened. An executive committee with members

from federal, provincial and territorial governments, and national organizations was established to

provide project oversight and advice. Three scientific expert panels were established to review the

evidence for updating the guidelines and making recommendations on how best to mobilize this new

knowledge effectively. One panel focused on the impacts of alcohol consumption on physical health,

a second one on the social and mental health effects, and a third on knowledge mobilization.

To provide scientific support to members of scientific expert panels (hereafter referred to as the

experts), CCSA further established an internal Evidence Review Working Group responsible for

evaluating and summarizing evidence, leading consultations and conducting new research as

needed.

Members of the executive committee and the experts were required to disclose affiliations and

interest, as per Schünemann et al. (2013). The list of potential conflicts of interest was published on

CCSA’s website in Disclosure of Affiliations and Interests

.

1.1 Defining Research Questions

The general research question underlying the 2011 LRDGs update is as follows: To minimize the risk

of developing alcohol-related physical and mental health disorders and social problems, which level

or pattern of use should be recommended to people living in Canada?

For this question to lead to evidence-based guidelines, three more specific questions were

developed, each one specifying a particular target population, the level of exposure to alcohol and

the type of outcomes being considered. (For more information, see

Update of Canada’s Low Risk

Alcohol Drinking Guidelines: Development of Research Questions.) It is these three specific research

questions that have guided this project’s evidence collection, analyses and conclusions:

1. What are the short-term risks and benefits (physical and mental health, and social impact)

associated with varying levels of alcohol consumption (including no alcohol consumption), in

different contexts, associated with a single episode of drinking in the general population?

2. What are the long-term risks and benefits (physical and mental health, and social impact)

associated with varying levels and patterns of alcohol consumption (including no alcohol

consumption) in the general population?

3. What are the risks and benefits (physical and mental health, and social impact) associated with

varying levels and patterns of alcohol consumption (including no alcohol consumption) during

pregnancy or breastfeeding, for fetal, infant and child development?

The specific questions were formulated to encompass all effects, so that studies focusing on both

positive and negative effects could be identified.

1.2 Estimating the Lifetime Risk of Alcohol-Related Death

and Disability in the Canadian Population

From the outset of this project, there was a common understanding among experts that to update

the 2011 LRDGs, the specific research questions would be answered through mathematical

modelling. Modelling had previously been used to establish the 2011 LRDGs as well as alcohol

guidelines in Australia (National Health and Medical Research Council, 2020), the U.K. (U.K. Chief

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 16

Medical Officers, 2016) and France (Santé publique France & Institut national du cancer, 2017).

Moreover, since 2016, the European Union Joint Action on Reducing Alcohol-Related Harm has

recommended the use of cumulative lifetime risk of death from alcohol-related disease or injury as a

common metric for assessing the risks from alcohol at the country level; the metric should also

inform discussions by experts to establish alcohol guidelines (Broholm et al., 2016).

Modelling requires alcohol mortality risk functions for all disease or injury categories causally related

to alcohol consumption. These risk functions can be found in meta-analyses that assess the dose–

response relationship between alcohol and the risk of disease mortality

. The quality of modelling

depends upon the quality of the risk functions and therefore on the identification of the highest

quality meta-analyses. Such identification is a complex and lengthy process that could have gone

over the 21 months allocated to update the 2011 LRDGs. However, the project’s mandate stipulated

that the update should be informed by the 2016 alcohol guidelines from the U.K. (U.K. Chief Medical

Officers, 2016) and the 2020 Australian guidelines to reduce health risks (National Health and

Medical Research Council, 2020). Therefore, a quality assessment of these alcohol guidelines was

performed. (For more information, see

Updating Canada's Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines:

Evaluation of Selected Guidelines.) With regards to its methodology for identifying and selecting

evidence on the risks and benefits associated with alcohol consumption, the Australian guidelines

received top ratings.

Hence, to update Canada’s LRDGs, the global evidence review did not start from scratch, but rather

built upon the rigorous and systematic work previously done by the Australian Alcohol Working

Committee (AAWC), which covered the January 2017 to February 2021 period. (The overall process

is explained in section 2.1.) Besides ensuring the quality of the modelling, the global evidence review

on the risks and benefits associated with alcohol consumption identified areas where high quality

systematic reviews were missing; for these areas, the experts agreed to commission additional

reviews to formulate the updated guidelines for Canada.

1.3 The Evidence Base for Updating the Guidelines

A range of inputs was considered in updating the 2011 LRDGs:

• Global evidence review of the effects of alcohol on health;

• Mathematical modelling of the lifetime risk of death and disability for various levels of average

alcohol consumption;

• Rapid review on alcohol and mental health;

• Rapid review on alcohol and violence; and

• Comprehensive multi-part review of recent literature on women’s health and alcohol.

This project’s mandate also required recommendations for knowledge mobilization of the updated

alcohol guidelines. To this end, a series of activities was undertaken to better understand people’s

views, preferences and expectations on alcohol guidelines. Discussions on formulation and

presentation of the finalized guidelines were further informed by the following activities:

• Summary Evidence on Understanding and Response to Alcohol Consumption Guidelines

;

• Public consultation to hear what alcohol, health and well-being issues matter most and what is

most useful to people in Canada;

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 17

• Interviews with representatives from different health-related organizations that have an interest

in alcohol-related issues; and

• Focused discussions with Indigenous People serving on the LRDG executive committee and

scientific expert panels.

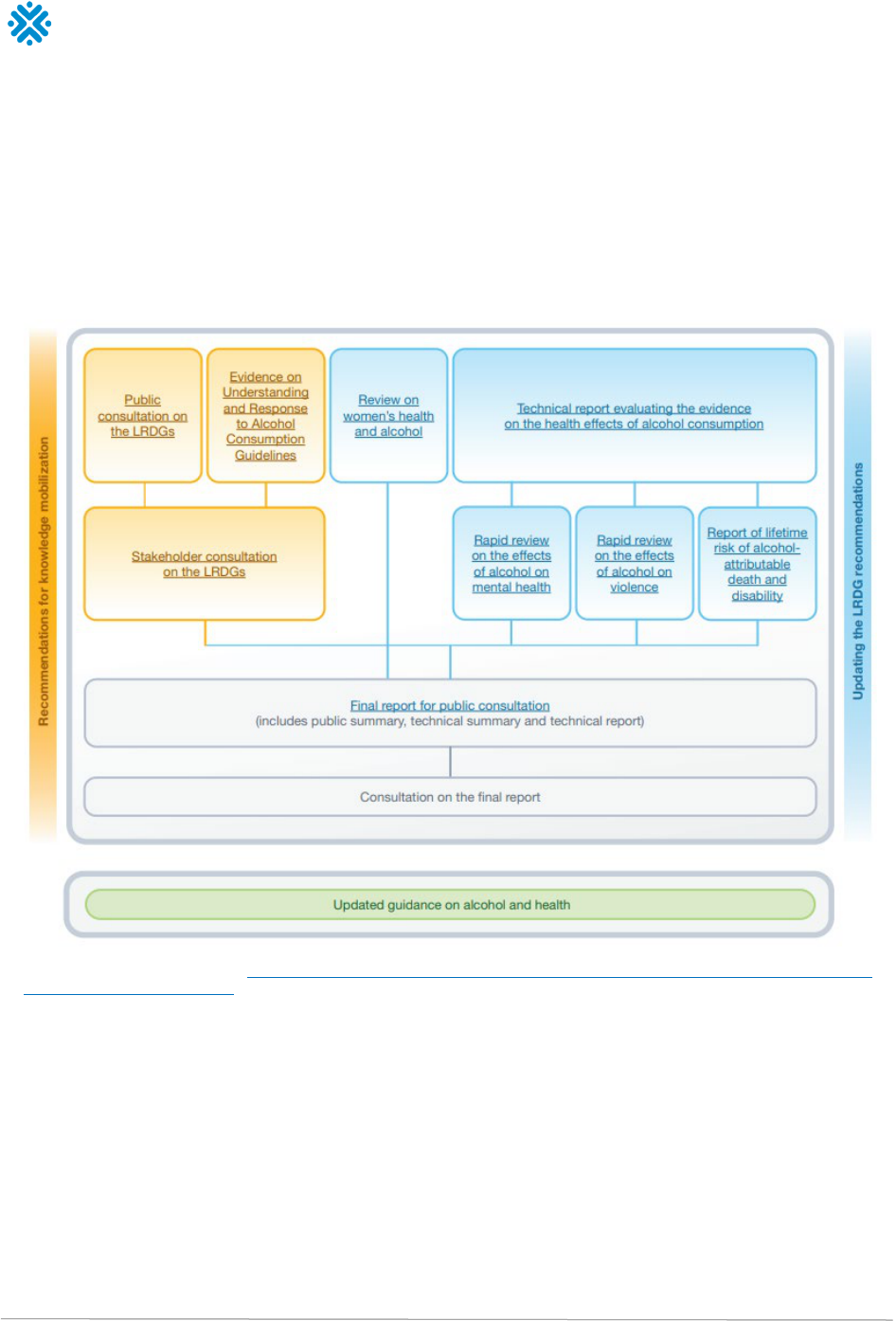

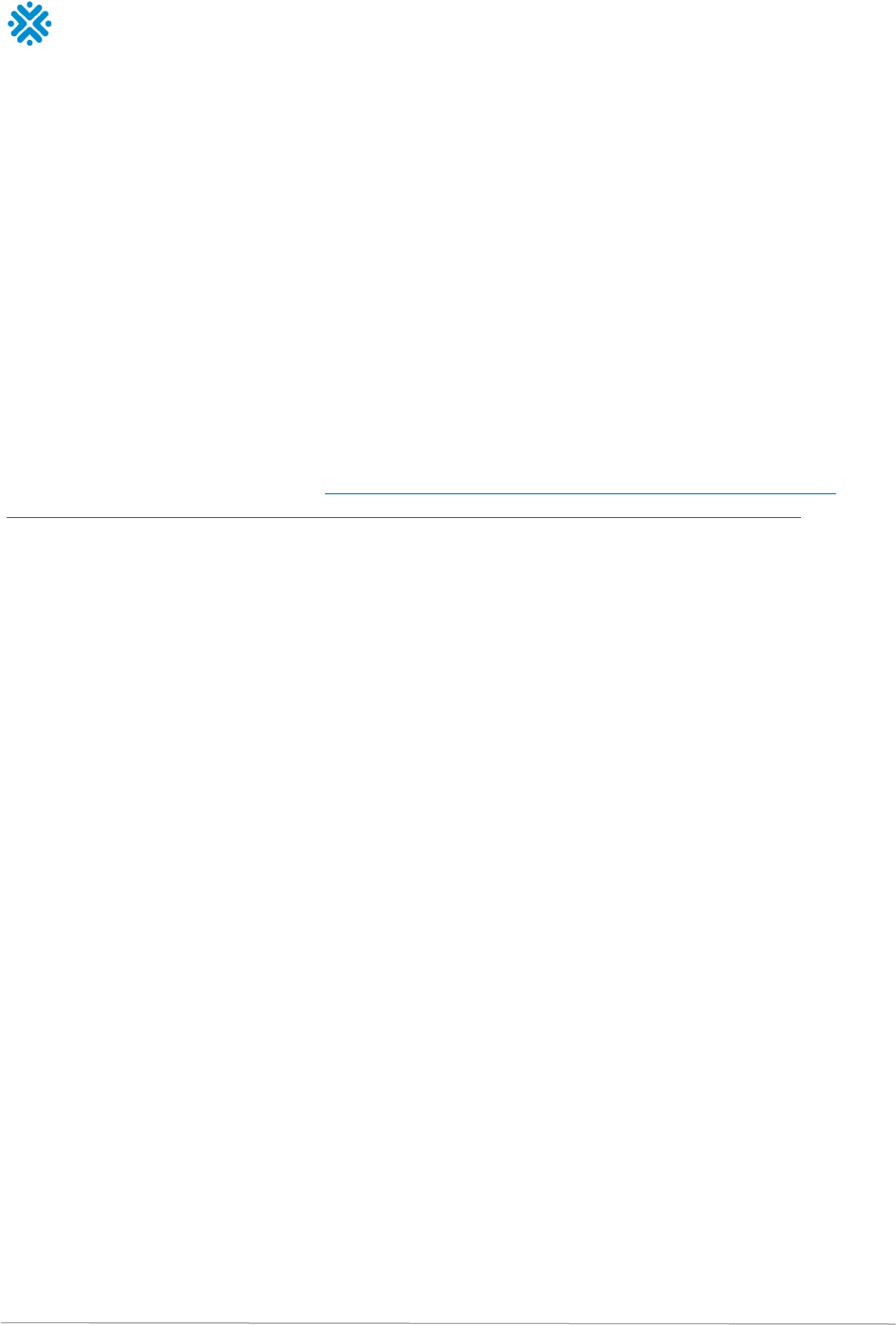

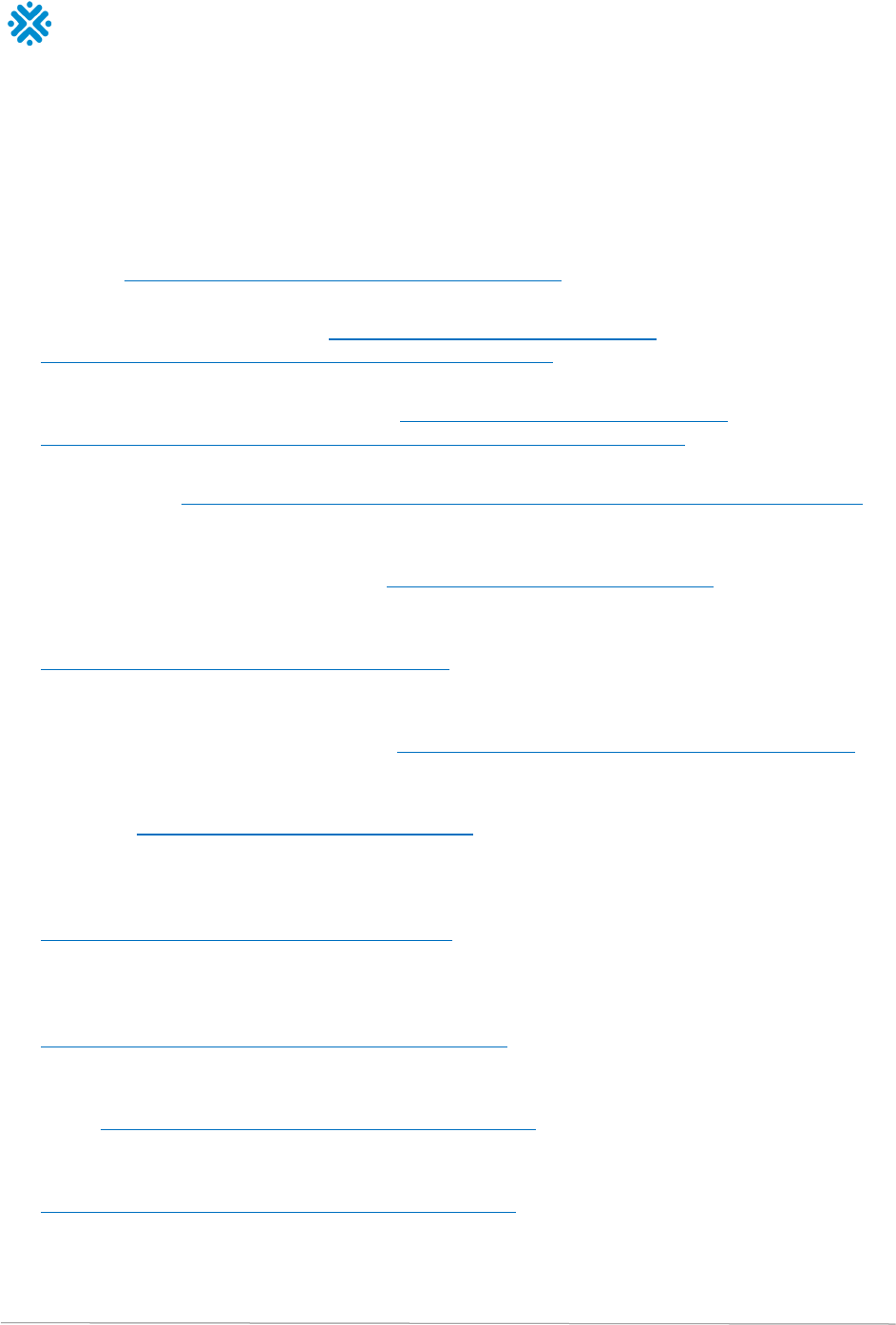

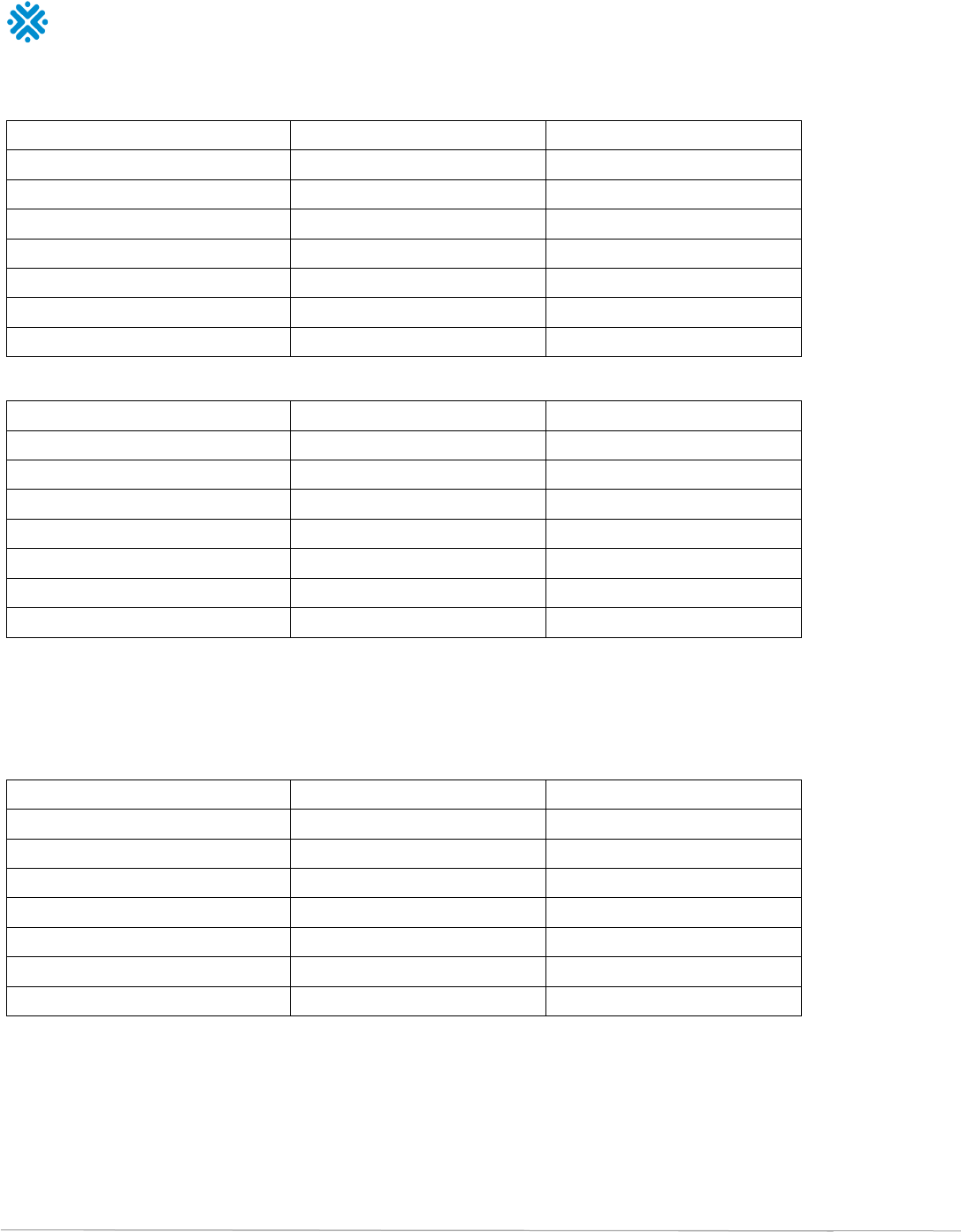

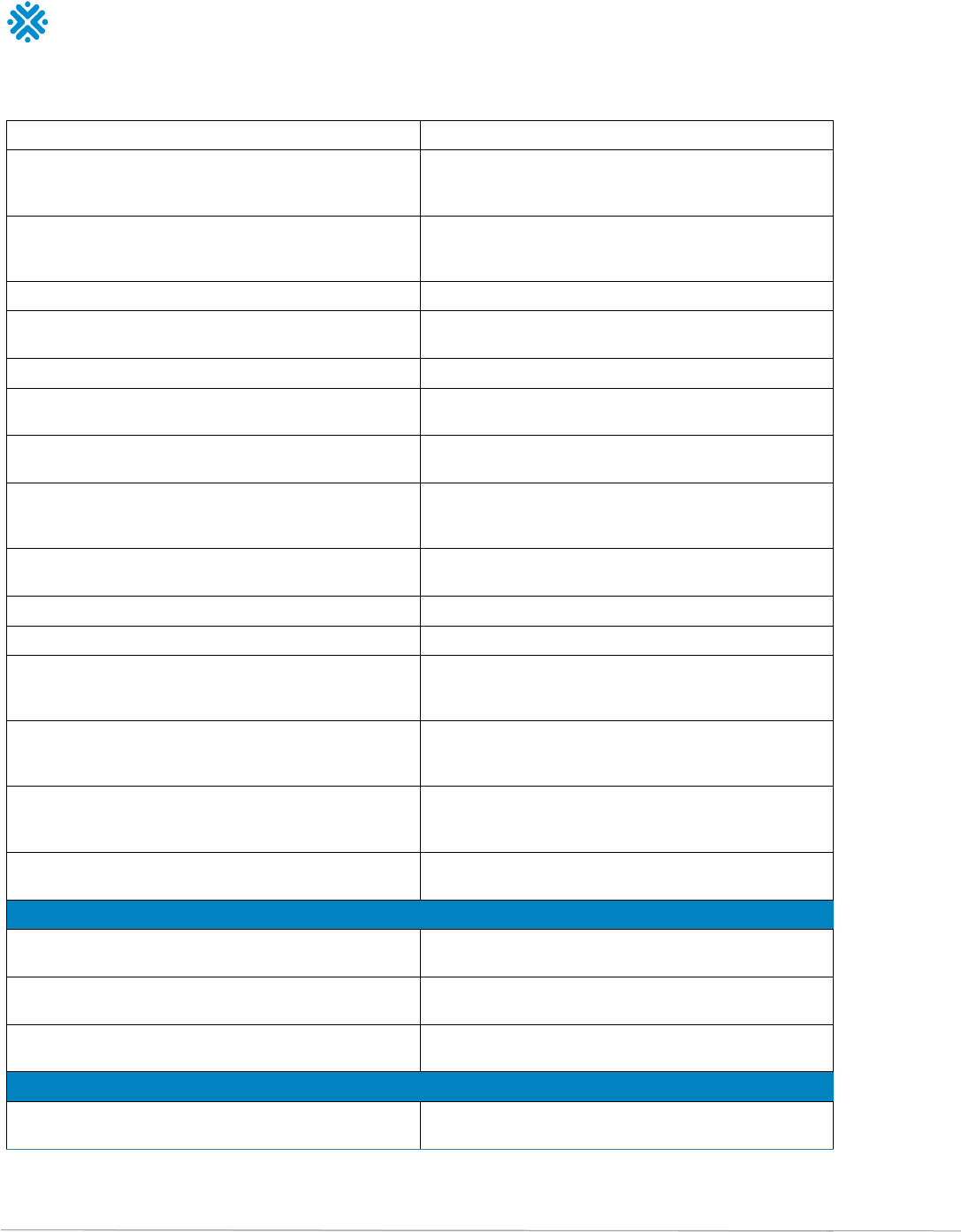

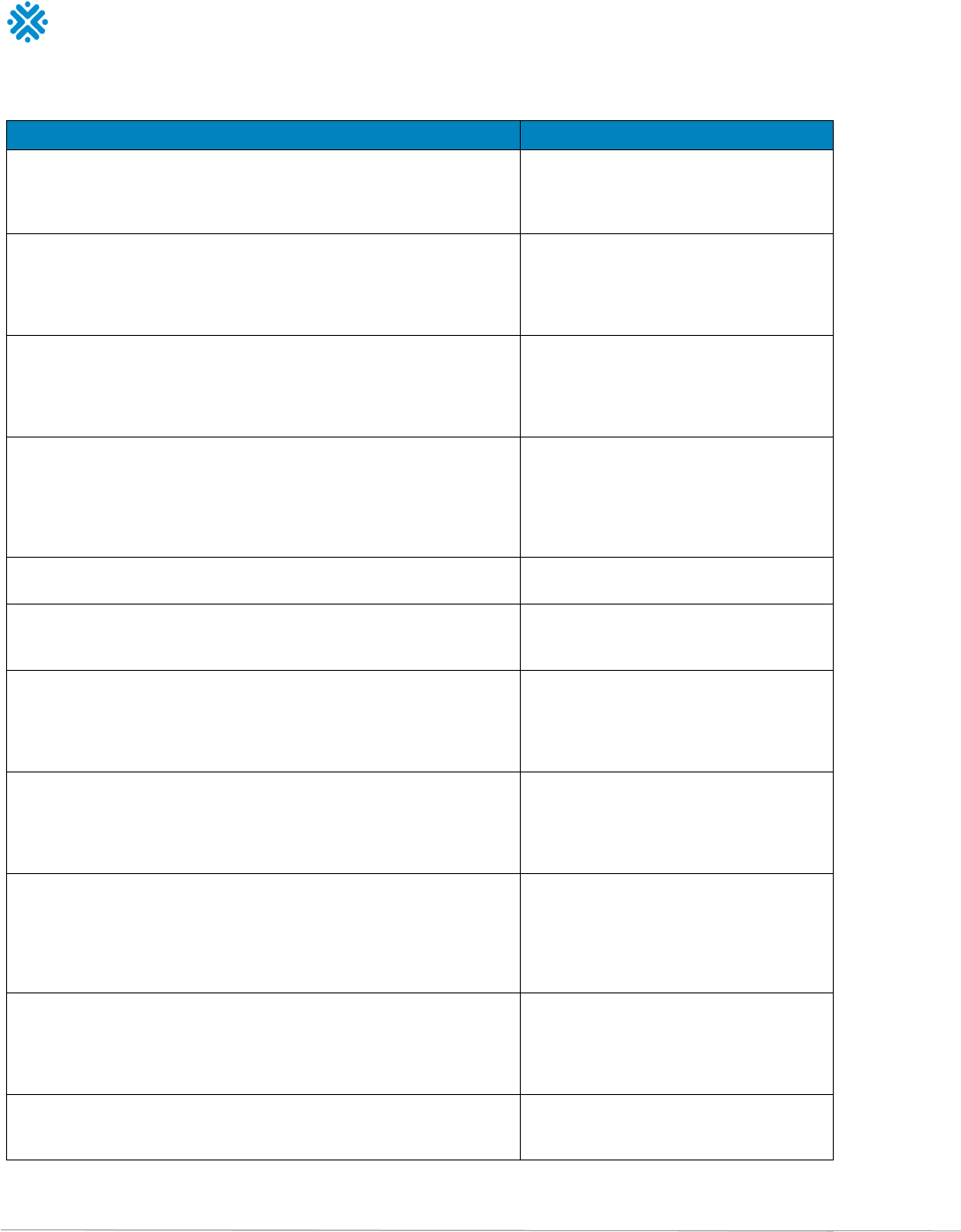

The overall process by which the recommendations were developed is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Process for updating Canada’s LRDGs

Note. For a PDF of this image, visit https://ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2023-01/CCSA-LRDG-Lower-Risk-Drinking-Guidelines-Process-

and-Documentation-2023-en.pdf.

1.4 Reaching Conclusions and Formulating

Recommendations

This project was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated stay-at-home and

travel restrictions. Therefore, all meetings held during this project were conducted online, except the

last three-days meeting to review the results of the open consultation, which was held in-person.

Despite the challenging context, the co-chairs of the scientific expert panels created an online

environment that was conducive to respectful dialogue and the healthy exchange of ideas. The

project comprised three scientific expert panels, but due to the overlap and interest in all the panel

evidence-review activities, experts were invited to attend all panel meetings.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 18

Between September 2020 and October 2022, members of the scientific expert panels met on 18

occasions to discuss the process and the evidence used to develop the recommendations. Efforts

were deployed for panel members to engage in a dialogue and share information for the purpose of

increasing the understanding of the issues and to provide a rationale for choosing a particular position.

The main conclusions and agreement on final recommendations was reached through consensus.

Part 2: Evidence Used to Construct the

Recommendations

The studies and evidence reviews informing the update to the 2011 LRDGs are available on the

CCSA webpage dedicated to this project

. Those interested in understanding in detail the types of

evidence and the way they were used to update the guidelines are encouraged to visit the webpage

to access the full reports. The following sections provide summaries of each report, to give readers

an overview of the material reviewed by the experts to reach their conclusions.

2.1 Global Evidence Review on the Effects of Alcohol on

Health

Several studies have quantified the risk relationships between alcohol use and the occurrence of and

mortality from all disease or injury categories causally related to alcohol consumption. However, the

quality of these studies varies greatly. To provide an answer to this project’s three research questions

and estimate the impact of alcohol consumption on individuals, a systematic search and review was

performed of meta-analyses that reported alcohol dose–response curves between different average

levels of alcohol use, disease and injuries. The aim was to identify the highest quality systematic

reviews and meta-analyses using a standard set of quality criteria. (For the full report, see

Update of

Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines: Evidence Review Technical Report.)

2.1.1. Methods

A systematic electronic search was performed using PubMed, PsycNET, Embase, Cochrane Library,

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment Database, International

Health Technology Assessment Database, Joanna Briggs Institute, Database of Systematic Reviews

of Effects, and Epistemonikos. The search was limited to articles published from Jan. 6, 2017, to

Feb. 17, 2021. It provided an update to the AAWC systematic review for 2007 to 2017. All articles

included in the Australian’s systematic review were also included in this review (National Health and

Medical Research Council, 2020).

An information specialist screened the search results and removed duplicates and any articles that

were clearly outside of the scope of the project based on titles and abstracts. Two independent

investigators assessed articles for title and abstract, and subsequently for full-text eligibility against:

• The study design and the Population, Exposure, Comparator and Outcome (PECO) criteria;

• Methodological quality criteria selected from A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews

(AMSTAR 2; Shea et al., 2017) and Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews (ROBIS; Whiting et al.,

2013) tools;

• Methods of analyses criteria; and

• Mathematical modelling criteria.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 19

If a particular disease or injury category was considered by more than one systematic review or

meta-analysis, priority was given to the article that met the most methodological quality criteria. In

the event that the same number of criteria were met, the most recent article was given priority.

Finally, the quality of each e

ligible systematic review and meta-analysis was assessed by two

independent investigators using two international standard tools: A MeaSurement Tool to Assess

systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2; Shea et al., 2017), and the Grading of Recommendations,

Assessment, Development and Evaluations system (GRADE; Schünemann et al., 2013). Studies were

also evaluated for the inclusion of sex- and gender-based analysis (Brabete et al., 2020).

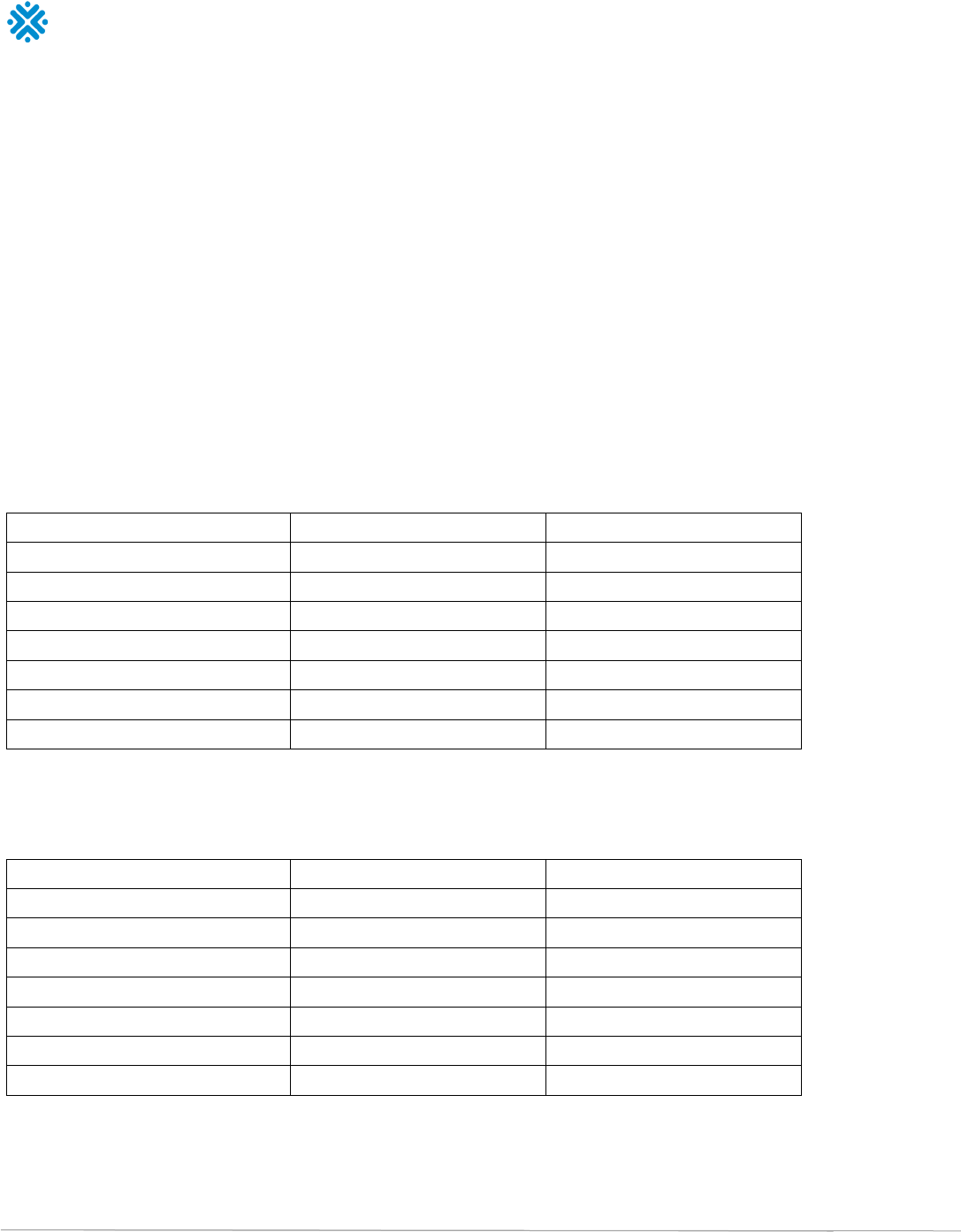

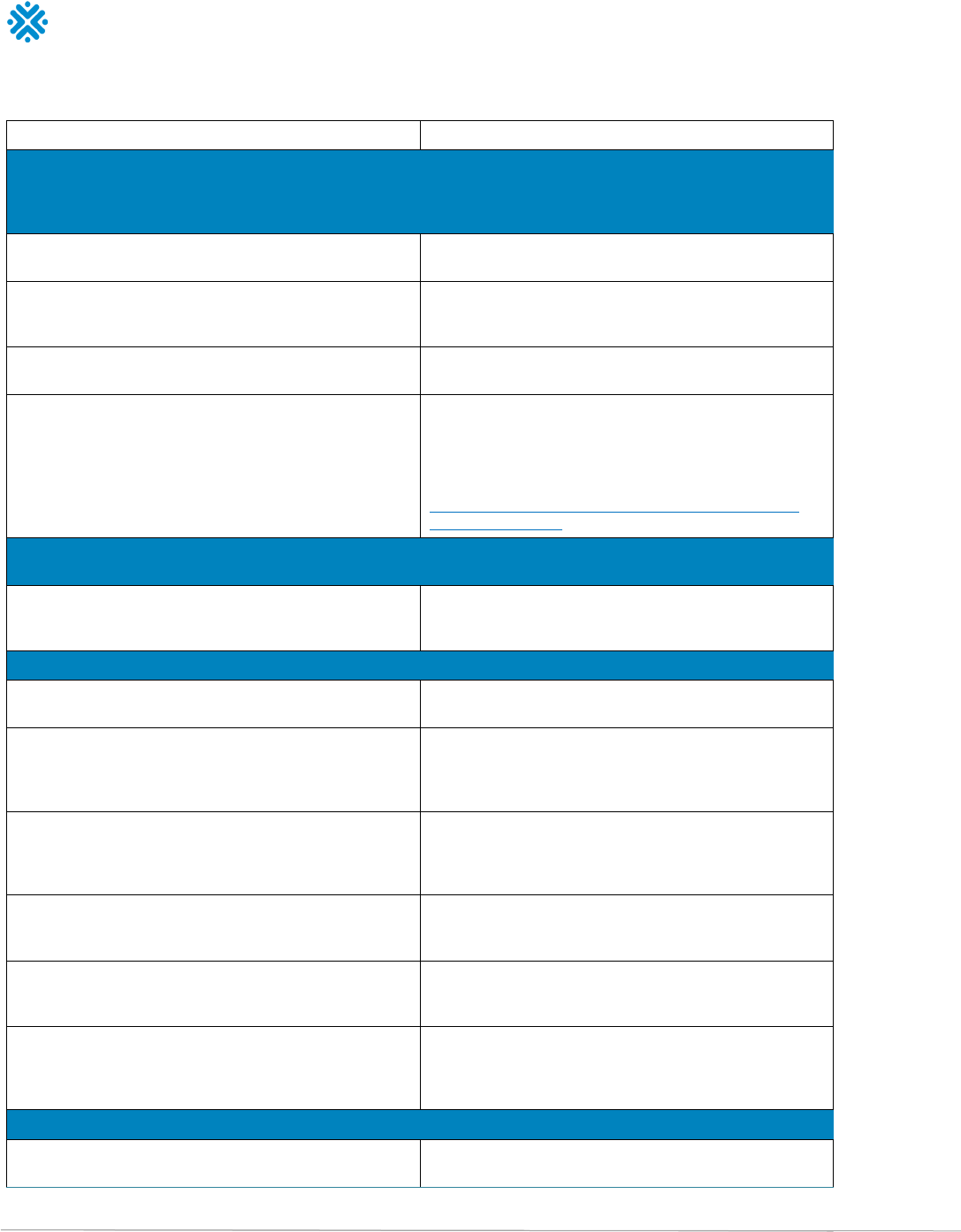

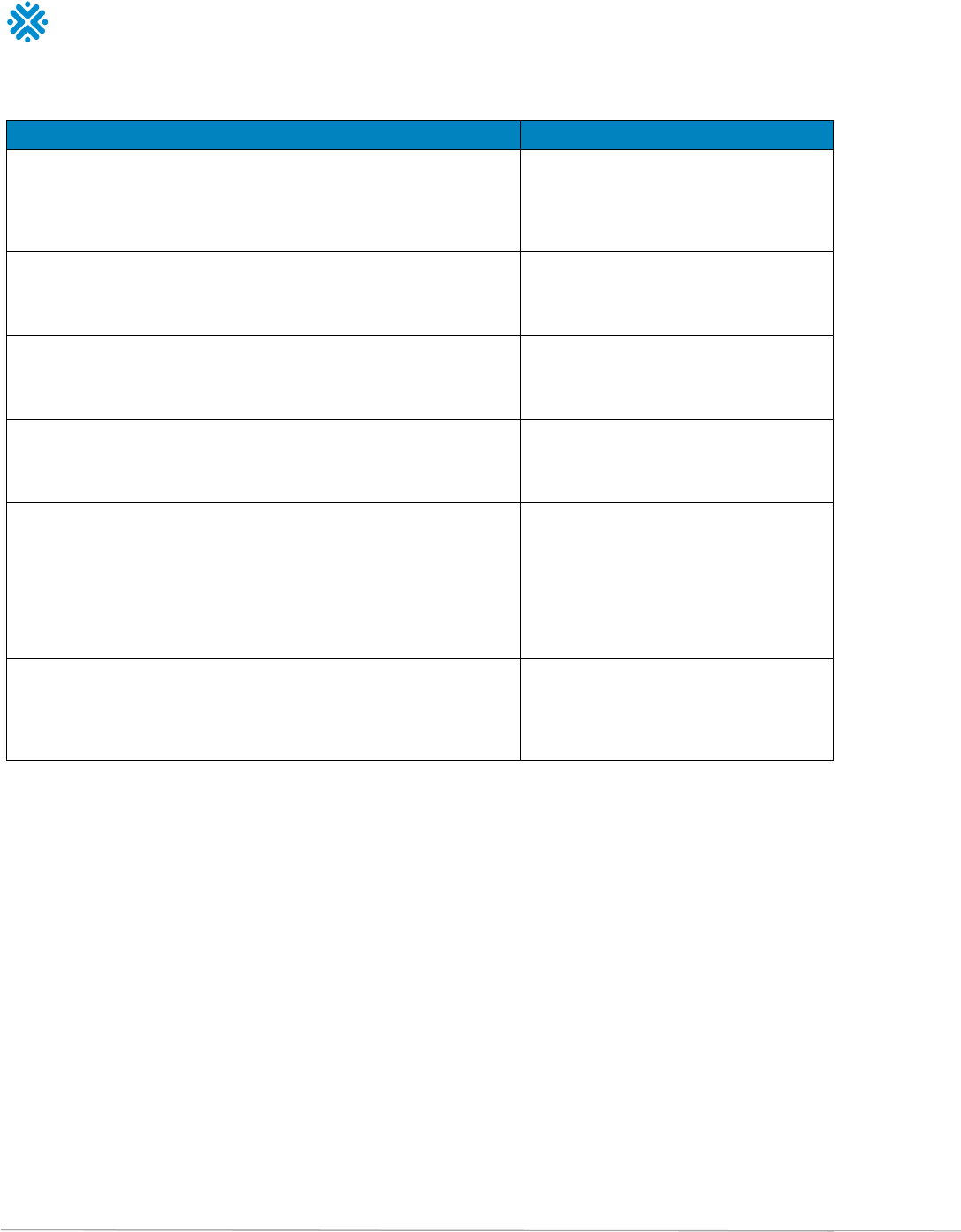

Figure 2. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram

Records identified from:

• Databases (n = 5884)

• Grey literature (n = 31)

• Australian search (n=38)

Records removed by information

specialist:

• Duplicate records removed (n = 325)

• Records outside of the scope of the

project removed (n = 4848)

Records screened

(n = 780)

Records excluded

(n = 541)

Reports sought for full-text retrieval

(n = 239)

Reports not retrieved

(n = 0)

Reports assessed for inclusion eligibility

(n = 239)

Reports excluded:

• Did not met the PEO/study type

criteria (n = 146)

• Methods of analysis insufficient

(n = 11)

• Newer review identified and/or met

more criteria (n = 20)

• No ICD-10 code available (n = 4)

• No dose-response (n = 6)

• No causal relationship with alcohol

consumption (n = 26)

• Reverse causality with alcohol

consumption (n = 1)

• Not a fatal disease (n = 4)

• Alcohol consumption while

pregnant (n = 5)

Reports included in the mathematical

modelling (n = 16)

Identification of studies via databases and registers

Identification

Screening

Included

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 20

2.1.2 Results

In addition to the 38 systematic reviews already identified by the AAWC, a total of 5,915 systematic

reviews were initially retrieved from the updated search. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram presented in Figure 2 illustrates that after

removing duplicates and any articles that were outside of the scope of the project,

a subset of 780

systematic reviews were screened for title and abstract and a total of 239 systematic reviews (37

identified by the AAWC and 202 identified by this update) were subsequently screened for full-text

eligibility.

The 31 reports identified by the search of the grey literature were excluded as PECO and study

design criteria were not met. Most of the grey literature items were found to be informative

brochures, reports, fact sheets and books.

In the end, a total of 16 systematic reviews fulfilled all the inclusion criteria for this project for all

three research questions and were selected for inclusion in the mathematical modelling.

Research Question 1: Short-Term Risks and Benefits

Twenty-nine systematic reviews on the short-term risks and benefits of alcohol were evaluated. Two

systematic reviews were selected for inclusion in the mathematical modelling. One selected review

focused on road injury (Taylor & Rehm, 2012) and the other on intentional and unintentional injuries

(Taylor et al., 2010).

Research Question 2: Long-Term Risks and Benefits

A total of 154 systematic reviews across eight categories of diseases associated with the long-term

health risks and benefits of alcohol were evaluated.

Fourteen reviews were selected for inclusion in

the mathematical modelling. The selected reviews assessed the relationship between alcohol use

and liver cirrhosis (Roerecke et al., 2019), ischæmic heart disease (Zhao et al., 2017; for relative

risks, see fully adjusted relative risks for people 19 to 55 years of age at baseline outlined in Table

3), hypertensive heart disease (Liu et al., 2020), breast cancer (Sun et al., 2020), liver cancer (World

Cancer Research Fund International, 2018), pancreatitis (Samokhvalov et al., 2015), lower

respiratory infections (Samokhvalov et al., 2010a), epilepsy (Samokhvalov et al., 2010b) ischemic

stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage (Larsson et al., 2016), atrial fibrillation

(Larsson et al., 2014), colon and rectum cancers (Vieira et al., 2017), diabetes mellitus (Knott et al.,

2015), larynx cancer, mouth and oropharynx cancers, esophagus cancer (Bagnardi et al., 2015) and

tuberculosis (Imtiaz et al., 2017). The relative risks obtained from systematic reviews were not

adjusted for misestimation of alcohol use. Although there is a hypothesis of a slight underestimation

of alcohol use in medical epidemiology studies (Stockwell, 2018), the direction of alcohol use

measurement bias in cohort studies is unknown (Biemer et al., 2013; King, 1994).

Research Question 3: Pregnancy and Child Development Risks and

Benefits

Twenty-five systematic reviews focusing on the risks and benefits associated with alcohol

consumption during pregnancy or breastfeeding for fetal, infant and child development were

evaluated.

None were selected for inclusion in the modelling because none met the mathematical

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 21

modelling criteria. The studies focused on alcohol-attributable mortality and morbidity to others

rather than the person who consumes alcohol.

2.1.3 Quality of Evidence

The quality of each retained systematic review was assessed with AMSTAR 2 and GRADE. (For the

full AMSTAR and GRADE assessments, see

Update of Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking

Guidelines: Evidence Review Technical Report.)

The systematic reviews used PECO questions and clearly presented inclusion criteria. All were based

on strong and rigorous methods for statistical combination of their results. Retained reviews also

examined dose-dependent relationships through pooled analyses, which is indicative of high-quality

methods. The majority of retained reviews also described the included studies with a good amount of

detail justifying their inclusion. The review search strategies were detailed and many of the studies

conducted the screening steps in duplicate. Most of the retained reviews had no imprecision and

indirectness according to GRADE. However, many of the retained reviews did not assess risk of bias.

Heterogeneity was also reported for many of the reviews and, despite conducting sensitivity

analyses, the source for heterogeneity was seldom identified. Hence, the overall quality score of

most retained reviews was low but this was expected.

Tools used to assess the quality of identified systematic reviews consider randomized clinical trials

the gold standard. However, for examining the association between alcohol consumption and health,

this study design is neither practical nor ethical. For example, it would be unethical to randomize one

group of females to drink alcohol on a daily basis for 10 years and another one to abstain, and then

test who develops breast cancer. In fact, in the field of alcohology most evidence is derived from

cohort and observational studies that have inherent limitations that explain why many systematic

reviews retained for this project did not receive a high-quality score. However, in no way does this

mean that the quality of evidence is insufficient to provide guidance on alcohol and health to people

living in Canada. In fact, there is a high level of confidence among members of the scientific expert

panels and the Evidence Review Working Group that the identified reviews covered in this report are

the latest and most high-quality evidence available to examine this public health issue.

2.1.4 Implications

The global evidence review identified the most recent and highest quality systematic reviews and

meta-analyses available to examine the relationship between alcohol consumption and the various

outcomes covered by this project’s research questions. The methodology used to select these

systematic reviews is based on the Australian guidelines, which received a top score according to a

previous evaluation, further strengthening our certainty that our results are based on the highest

quality evidence. (For more information, see

Update of Canada's Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking

Guidelines: Evaluation of Selected Guidelines.)

Through this work, we identified areas where high quality systematic reviews are currently missing

(e.g., mental health, violence) and for which the experts agreed to commission additional reviews to

complete the LRDG update (see section 2.4). A decision was also taken to commission a report on

women’s health and alcohol that would address, among other things, the issues of pregnancy.

2.2 Mathematical Modelling of the Lifetime Risk of Death

for Various Levels of Average Alcohol Consumption

To establish alcohol guidelines, modelling the lifetime risk of death for various levels of average

alcohol consumption has been recommended (Broholm et al., 2016; Rehm et al., 2014) and applied

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 22

(e.g., in Australia, the U.K., France and Canada). Modelling allows for the estimation of the “excess

risk” of mortality and disability associated with various levels of average consumption and the

specification of the level of risk from negligible to high associated with each level of consumption.

The aim of modelling is not to set a “threshold” of consumption below which there is no risk, but to

provide “benchmarks” based on which recommendations can be formulated.

For this project, the lifetime risk approach was adopted to estimate the lifetime risk of death,

premature death (< 75 years of age), years of life lost (YLLs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)

lost. A full report presenting all analyses is available in

Lifetime Risk of Alcohol-Attributable Death

and Disability. Every estimation and result presented in the report was subsequently the object of a

shadow analysis that confirmed the accuracy of the primary analyses (Appendix 1).

Discussions among experts led to a decision to use risk thresholds associated with YLLs. Compared

to using lifetime risk of death or premature death, YLLs allows researchers to consider the deaths of

older individuals and, more importantly, factors the unequal health loss caused by death among

people relatively younger in age. While DALYs can be an optimal outcome for the measurement of

health loss attributable to alcohol, there is limited data on the DALYs alcohol cause and this project’s

analyses resulted in identical risk thresholds whether they were based on YLLs or DALYs.

3

Since

DALYs is conceptually more difficult to understand than YLLs, the experts fixed their choice on YLLs

estimations. Results are presented and discussed below, after a review of methodological principles.

2.2.1 Methodological Principles

Calculating Alcohol-Attributable Deaths

In epidemiology, the concept of an attributable fraction makes it possible to express the proportion

of risk for a particular health event (in this case death), due to exposure to a particular cause (in this

case alcohol consumption). An attributable fraction is classically calculated from the number of

deaths that could be avoided if the exposure was eliminated.

The proportion depends on the risk of death according to sex and age but also on the “trajectory” of

exposure, which is the history of alcohol consumption before the subject’s death. Establishing

alcohol-attributable deaths in the population requires access to the population’s mortality rate and

knowledge of the individuals’ lifetime exposure to alcohol in standardized terms, such as average

grams of alcohol per day. With this data, alcohol-attributable deaths can be calculated for various

levels of consumption, provided that it is considered identical among individuals and constant over

time for each of them until death. In this model, lifetime abstainers are the reference group in relation

to which the risks associated with different average levels of alcohol consumption are calculated.

By varying the average level of consumption in such a scenario, it becomes possible to summarize

the relationship between the risk due to alcohol and different levels of consumption. In return, this

informs the benchmarks for different levels of risk.

3

For example, there is evidence that DALYs can be influenced by mental disorders such as depression but because the evidence search

did not identify high-quality systematic reviews assessing the relationship between alcohol use and mental health, it is likely that the

current project underestimates alcohol-related DALYs.

Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction • Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances Page 23

Diseases and Injuries Included in the Modelling

A total of 34 cause categories for alcohol-related diseases, conditions and injuries and more than

200 three-digit International Classification of Disease, version 10 (ICD-10-CA) codes were included in

the modelling of alcohol-attributable deaths. To be included, there were three criteria:

1. The disease or injury had to be causally related to alcohol use;

2. A dose–response risk function needed to be available for the risk relationship between alcohol

consumption (measured in grams per day) and the disease or injury of interest that also passed

the GRADE criteria; and

3. Either death or disability needed to be measured specifically for the disease or injury causally

related to alcohol use.

What Evidence Has Changed Since the Release of the 2011 LRDGs?

• Animal, mechanistic and epidemiological evidence published since the publication of the

Canadian LRDGs in 2011 has led to changes in the diseases that are known to be causally

related to alcohol use.

• Alcohol has been found to causally increase the risk of lower respiratory infections

(Samokhvalov et al., 2010a).

• Systematic reviews on the risk relationship between alcohol use and the diagnosis of and

death from cancer have observed no lower risk threshold (Bagnardi et al., 2015; Sun et al.,

2020; Vieira et al., 2017; World Cancer Research Fund International, 2018).

• The risk relationship between alcohol use and hypertensive heart disease has been observed

to have no lower risk threshold (Liu et al., 2020).

• Risks for hemorrhagic stroke have been investigated further, with the risk functions for

intracerebral hemorrhage showing protective effects at lower levels of alcohol use but for

subarachnoid hemorrhage, detrimental effects at lower levels of alcohol use (Larsson et al., 2016).

• Alcohol’s protective impact on ischemic heart disease at lower levels of alcohol use is more

uncertain than previously estimated. The risk is modified by binge drinking (Roerecke & Rehm,

2010; Sundell et al., 2008) and genetics (Chikritzhs et al., 2015; Larsson et al., 2020).

Data Sources

Several data sources were used to make the necessary calculations:

• Data on death and disability for 2017 to 2019 were obtained from Statistics Canada and the