Report prepared by:

The Campaign for Fiscal Equity, Inc.

May 2011

Taking Attendance Seriously

How School Absences Undermine Student

and School Performance in New York City

The Campaign for Fiscal Equity, Inc. (CFE) is a leading non-profit organization working to

protect and promote the constitutional right to a sound basic education - defined as a

meaningful high school education - for every public school child in the State of New York.

CFE was founded in 1993 by a coalition of concerned parents and education advocates who

filed the landmark case CFE v. State of New York, which established this right. To make this

right a reality, CFE works to ensure that the neediest students in low performing schools make

academic progress, graduate high school and become active civic participants who can

compete in the global economy. CFE works to educate and engage the public and policy

makers to ensure that the historic school budget increases, accountability reform and

meaningful public participation that resulted from the landmark CFE court decision and law

reform are fully implemented.

Helaine Doran

Deputy Director

Board of Directors

Luis Miranda, Chairperson, President, MirRam Group

Edward Fergus, Director, Applied Research, Evaluation and Policy, Metropolitan Center for

Urban Education, Steinhardt School of Education, New York University

Geri D. Palast, Managing Director, JFNA/JCPA Israel Action Network

Dennis Parker, Director, American Civil Liberties Union Racial Justice Program

Steven Sanders, Former Chairman, New York State Assembly Committee on Education

Ocynthia Williams, Parent Leader, NYC Coalition for Educational Justice

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and

School Performance in New York City

Director: Helaine Doran

Author: Dr. Martha Philbeck Musser

Consulting Editor: Phyllis Jordan

The Campaign for Fiscal Equity would like to thank the following supporters whose

grants made this report possible: The New York City Council, the Booth Ferris Foundation,

the Donors Education Collaborative, the New York Community Trust and the

Robert Sterling Clark Foundation.

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 1

INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 7

METHOD .................................................................................................................... 12

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS ........................................................................................ 15

STUDENT PROFILES................................................................................................. 22

SCHOOL PROFILES ................................................................................................... 27

ATTENDANCE AND PERFORMANCE AT THE SCHOOL LEVEL ............................. 34

ATTENDANCE AND PERFORMANCE AT THE STUDENT LEVEL ........................... 37

DISCUSSION .............................................................................................................. 53

RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................... 58

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................ 60

APPENDIX A: TESTS OF DIFFERENCES IN PERFORMANCE AMONG

ATTENDANCE QUINTILES CONTROLLING FOR GRADE 3 PERFORMANCE ......... 62

APPENDIX B: ELA MULTILEVEL MODEL ................................................................ 63

APPENDIX C: MATHEMATICS MULTILEVEL MODEL ............................................. 67

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

Executive Summary

TAKING ATTENDANCE SERIOUSLY:

HOW SCHOOL ABSENCES UNDERMINE STUDENT AND

SCHOOL PERFORMANCE IN NEW YORK CITY

N

early two decades ago, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE) set out to ensure

that New York’s poorest children received the “sound basic education”

guaranteed in the state constitution. A court ruling in 2006 and subsequent

state legislation brought new resources to bear on struggling public school systems, and

the state began to narrow the equity gap that divides our children. Yet we will never

close the achievement gap, even with improved curriculum and instruction, if students

are not showing up for school.

Research has documented that as many as 90,000 New York City elementary students

missed a month or more of school in 2007-08.

1

CFE’s own rigorous study of the city’s

fourth-graders found that this excessive absenteeism is commonplace on elementary

campuses: In nearly 300 schools, at least 20 percent of fourth-graders were chronically

absent last year. Further, the study shows that these absences are dragging down

student achievement, lowering scores on the state’s math and English language arts

tests. Even a child with good attendance suffers a small loss academically when the

school has a high absentee rate, suggesting that excessive absences across the board can

undermine the quality of instruction for all students by creating classroom churn and

leaving teachers mired in review and remediation.

Raising attendance rates can boost test scores, for individuals and schools, the analysis

shows. In fact, the annual predicted test score gain from simply improving a child’s

attendance equals or exceeds the annual gain expected when a child attends a charter

school. Improving attendance and, consequently, increasing instructional time for

children, is a cost-effective intervention that every school in the city can adopt right

now.

CFE’s findings raise several important points for educators:

UÊ Attendance and achievement are inextricably linked. This research, which

focused on the connection between students’ third and fourth grade attendance

and their performance on New York State Testing Program grade 4 assessments,

confirms that student attendance is a statistically significant predictor of

performance. As such, increasing attendance becomes an essential tool for

improving achievement.

1 Nauer, Kim, White, Andrew, and Yerneni, Rajeev. (2008). Strengthening)Schools)by )Strengthenin g)Families:)Community)Strategies)to)Reverse)

Chronic)Absente eism) in)the) Early) Grade s)a nd)Imp rove)S uppo rts) for)Childre n)an d)Families.)Center for New York City Affairs, Milano the New School

for Management and Urban Policy.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

2

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

UÊ Attendance data can be an indicator of students and schools at risk."Researchers

have repeatedly identified chronic absence—defined as missing 10 percent of the

school year as a result of unexcused and excused absences—as a signal that

students are headed off track academically. Our study confirms that poor

attendance puts low-performing students at greater risk of educational failure.

UÊ Improving attendance can reduce the achievement gap."The association between

attendance and performance is found across socioeconomic and ethnic

backgrounds. It is important to note, however, that Black and Hispanic students,

the groups with the highest poverty rates, are more likely than White and Asian

students to be chronically absent. More than one in five Black and Hispanic

students is chronically absent. Similarly, students from low-income families had

lower attendance than their more affluent peers. This suggests that improving

attendance can help reduce the achievement gaps among ethnic and

socioeconomic groups.

UÊ Reducing chronic absence is essential to turning around under-performing

schools. In 298 New York City schools, at least 20 percent of fourth-graders were

chronically absent. These high rates of absenteeism correlated with low

performance. We suspect poor overall attendance reflects the lack of a high

quality, engaging curriculum. Improvements in curriculum and instruction are

critical to school reform. But they aren’t going to help if students aren’t in the

classroom.

WHAT WE DID

National research has established that students who are chronically absent as early as

kindergarten have lower achievement in later grades. To demonstrate that connection in

New York City schools, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity reviewed the attendance records,

state assessment scores and various demographic factors for 64,062 fourth-graders

attending 705 New York City public schools in the 2007-08 school year. We chose to look

at fourth-graders, since the state’s assessments in that grade are longer and, therefore,

considered more reliable than those in third and fifth grades.

The study considered attendance in both third and fourth grades. And we analyzed

other student factors that can weigh heavily on academic performance, including

poverty, ethnicity, disability, English language proficiency, racial or ethnic background,

mobility and past performance. We also considered school characteristics such as

average attendance and test scores, percentage of minority students, and teacher

education and turnover rates. Holding other student and school variables constant to

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

3

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

isolate the role of attendance, we examined the relationship between attendance and

performance at the student level.

To give readers a better understanding of the relationship between student demographics,

attendance and performance in New York City elementary schools, we also present profiles

of student and school statistics on these measures.

WHAT WE FOUND

Overall the best predictor of fourth-grade performance is third-grade performance. But

attendance in third and fourth grade played an important role, as well. In addition to

documenting the relationship between attendance and performance, the study revealed:

UÊ The average fourth-grade student attended school for almost 94 percent of enrolled

school days in third and fourth grades. Half of fourth-graders—about 32,000

students—attended at least 95.4 percent of school days in those grades.

UÊ On the other hand, 18 percent—more than 11,000 students—were chronically absent.

That means they missed more than 10 percent of school days during that period—the

equivalent of at least 19 days in a 185-day school year. Black, Hispanic, and Native

American students were more likely to be chronically absent than White and Asian

students.

UÊ Attendance patterns varied among schools. School average attendance in 2006-07

and 2007-08 ranged from 88.1 percent to 98.8 percent. In the seven schools with the

lowest attendance, the average student attended only 88 percent of enrolled school

days. In the four schools with the highest average attendance, the typical student

attended 98 percent of the time. Thus, students in the highest-attendance schools

received 18 additional days of instruction a year, compared with those in the lowest-

attendance schools.

UÊ Rates of chronic absence varied among schools. In seven schools, no fourth-grader

was chronically absent; in the school with the highest rate, 51.8 percent were chronic

absentees. In more than three quarters (539) of the 705 study schools, at least 10

percent of the fourth-grade class was chronically absent.

WHAT THE TEST SCORES SHOW

The CFE analysis demonstrates that the school-wide attendance rate affects how much of a

boost a student receives from improving his or her own attendance. As such, the research

suggests that students will gain more if their school has a higher attendance rate. If a fourth-

grader at a school with a high attendance rate (96.3 percent) increased his own attendance

rate from 86.8 to 95.4 percent—coming to school 16 more days—we predict he would see a

5.1-point gain in his English language arts score. This may seem modest, but consider that

three years of reform, from 2006 to 2009, raised the city’s average fourth-grade English

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

4

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

language arts score by a total of 6 points. And a study by the New York City Charter Schools

Evaluation Project predicted a 3.6-point annual gain for students in fourth through eighth

grade who attend charter schools.

2

In math, the student would see a 6.9-point gain with

better attendance, compared with a 5-point annual increase at a charter school.

3

For

students at schools with low attendance rates (91.4 percent), the predicted gains are not as

large: 3.5 points in English language arts and 3.7 points in math.

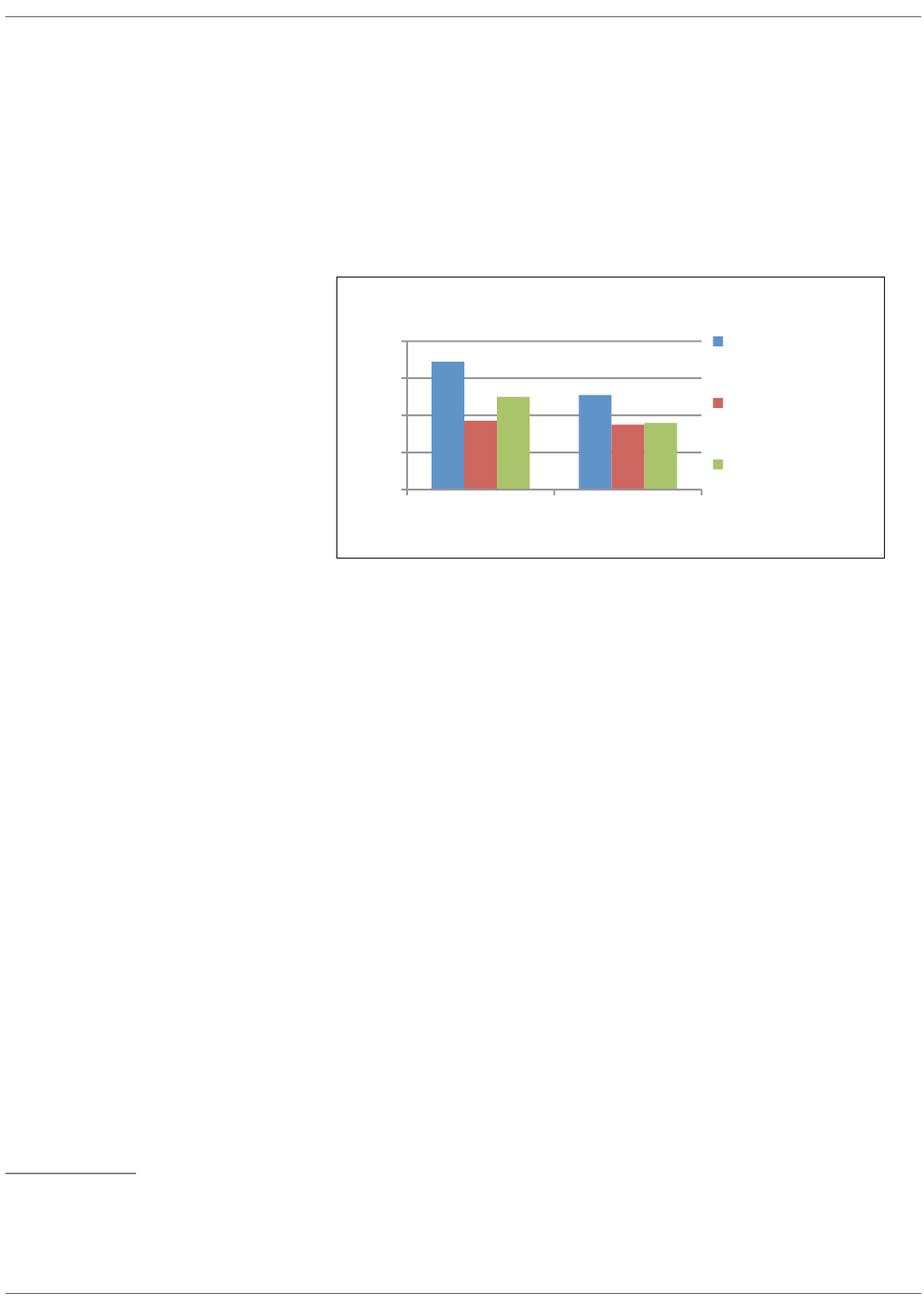

Good attendance can not only

bring better scores for students,

but for schools as well. If the seven

schools with the worst third- and

fourth-grade absentee rates

brought their attendance up from

88 percent to the city average of

93.8 percent, the predicted average

scaled-score gain would be 4.8

points in English language arts

and 6.0 points in math. For some

schools, these gains could mean

the difference between meeting

the standards for yearly progress set under No Child Left Behind and failing.

WHY IT MATTERS

The results of the CFE analysis underscore the vital importance of attending school. A

growing body of research demonstrates the same. In Philadelphia, researcher Michael

Gottfried found similar associations between attendance and standardized test performance

in a study of public school students in third through eighth grade. His research

demonstrated that this association exists independent of other family characteristics, such

as parent education and involvement in school activities.

4

His research strongly suggests that

there is a direct link between attendance and performance.

In 2008, Hedy Chang and Mariajosé Romero at the National Center for Children in Poverty

analyzed U.S. Department of Education data for 21,260 children nationally from

kindergarten through fifth grade. They found that one in 10 kindergarten and first-graders

were chronically absent. By the end of first grade, these children were already slipping

behind in reading, math and general knowledge. Chronic absence in kindergarten was also

strongly associated with lower reading and math performance in fifth grade for poor

children.

5

An analysis that considered New York City students’ attendance from kindergarten

through grade 4 would likely show a stronger correlation of attendance with test scores than

documented by the CFE study.

2 Hoxby, Caroline M., Murarka, Sonali, and Kang, Jenny. (2009). How)New) York) C ity’s)Ch a r te r)S ch o ol s)Af fec t)Ach ie v e me n t ,)Augus t)20 09)Re p or t .

Cambridge, MA: New York City Charter Schools Evaluation Project.

3 Ibid.

4 Gottfried, M. A. (2011). The Detrimental Effects of Missing School: Evidence from Urban Siblings. American Journal of Education, 117, 147–182

5 Chang, H. & Romero, M. (2008). Present,)Engaged,)and)Accounted)for)–)The)Cri tical)Importance)of)Addressing)Chronic)Absence)in)the)Early)Grades.))

National Center for Children in Poverty, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Scaled-Score Gain

Gain

PREDICTED SCALED-SCORE GAIN

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

5

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

Improving attendance and performance are particularly important now that the New

York Board of Regents has instituted tougher standards for proficiency in reading and

math. These new standards resulted in smaller percentages of fourth-graders scoring at

the proficient levels in 2010. The percentage of proficient students decreased 17 points in

English language arts and 22 points in math. Based on historical data, we expect that

fewer of these fourth-graders will be proficient when they reach eighth grade. This is

ominous because a previous CFE study found that high schools with the largest

percentage of entering ninth-graders who, as eighth-graders, had frequent absences and

failed to reach the State learning standards had the lowest Regents diploma rates.

Clearly, test scores are the coin of the realm when it comes to education reform,

measuring school progress and, increasingly, teacher effectiveness. But the value of good

attendance extends far beyond standardized testing gains. For students, attending

school regularly can be a sign that they are engaged in learning, while poor attendance

as early as sixth grade can signal that a student will eventually drop out of high school.

6 7

For teachers, good attendance means working with a full classroom, rather than having

to repeat material for absentee students the next day. For communities, good attendance

has been linked to lower crime rates and higher graduation rates, which in turn bring

better employment and stronger local economies. The consequences of dropping out on

later income, dependence on welfare, and incarceration are widely documented. Each of

these consequences has serious implications for the larger community. Anecdotally,

schools find that good attendance begets good attendance: Students, especially in

secondary school, want to go where their friends are.

Recognizing the value of attendance to school improvement, Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s

office last fall launched a pilot program aimed at reducing chronic absenteeism and

truancy in 25 schools across the city. The program educates parents about the value of

good attendance, offers incentives for children to come to school and provides mentors

for students who are missing 10 percent or more of the school year. The efforts have

already borne fruit: In the first half of the school year, fully 22 of the 25 schools reduced

their absentee rates. The 10 elementary schools saw the best results, with a collective 24

percent decline in the percentage of students who were chronically absent. The seven

high schools showed little change.

CFE believes that this sort of program, as well as the community schools approach used

in many New York City schools, can substantially reduce chronic absence. When

attendance rises, performance will follow. If good curriculum and instruction are also in

place, we can start to make real progress for all of the city’s children.

6 Balfanz, Robert, Herzog, Lisa & MacIver, Douglas J. (2007). Preventing Student Disengagement and Keeping Students on the Graduation

Path in Urban Middle-Grades Schools: Early Identification and Effective Interventions. Educational Psychologist, 42, 223–235.

7 Ou, Suh-Ruu & Reynolds, Arthur J. (2008). Predictors of Educational Attainment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. School )Psychology)

Quarterly,)23,199-229.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

6

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

RECOMMENDATIONS

UÊ Identify and share best practices for improving attendance. We must ensure

that all schools have effective policies for identifying and monitoring chronically

absent students, reaching out to those students and their families and ensuring

that they are on track academically. Most importantly, schools must create a

climate in which all staff, students and families understand the importance of

attendance, set high attendance goals and work to minimize absences.

UÊ Ensure that schools and teachers are looking at the right data. Schools need to

go beyond schoolwide attendance averages to analyze how many absences,

excused and unexcused, each student has accrued and to look for patterns in

neighborhoods, ethnic groups, grades or classrooms. Especially in the early

grades, absentee students often are not willfully skipping school but rather

missing days because of health and safety concerns, frequent moves or

unreliable transportation. Schools should identify these barriers and work with

parents and community organizations to address them.

UÊ Hold schools accountable for attendance and chronic absence rates at the city,

state and federal levels. It is important that schools be held accountable for

improving attendance. To that end, attendance and chronic absence rates should

be publicly available and reported for all federal accountability groups, including

racial and ethnic groups. We recommend that federal, state and city

accountability systems be revised to increase the value of attendance in

assessing school progress. Currently New York is one of five states that does not

include attendance data in its longitudinal student database. The state should

work with school districts to standardize and collect student-level attendance

data, and to develop standard definitions of chronic absence and truancy, so that

comparable measures are used statewide.

UÊ Engage parents and the community in improving school attendance. It goes

without saying that parents play an essential role in getting their children out of

bed and off to school each morning. Often, especially in kindergarten and first

grade, parents simply don’t realize the value of attendance. Community

organizations can help educate parents, support families who need help with

child care or transportation, and provide services to children and families who

need extra assistance.

UÊ Strengthen comprehensive school reform efforts so that when children come to

school they find an excellent curriculum, engaging teachers, a strong principal

and periodic assessments that ensure all students are on track toward meeting

graduation standards.

INTRODUCTION

7

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

Introduction

N

early two decades ago, the Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE) set out to ensure

that New York’s poorest children receive the “sound basic education”

guaranteed by the State constitution. A court ruling in 2006 and subsequent

State legislation brought new resources to bear on struggling public school systems, and

the State began to narrow the equity gap that divides our children. Yet we will never

close the achievement gap, even with improved curriculum and instruction, if students

are not showing up for school.

Regular school attendance is critical to academic success. National research establishes

that absence as early as kindergarten has an ongoing negative effect on achievement. In

many New York City schools, students are absent far too often and research links these

absences to diminished elementary school performance and lower high school

graduation rates. We also know that chronic absenteeism in elementary schools is

disproportionately a problem in poor and minority communities and contributes to the

achievement gaps among ethnic groups.

This rigorous study of fourth-grade students in New York City public schools documents

that, for individual students, higher attendance predicts higher performance on State

assessments of English language arts (ELA) and mathematics. In addition, higher mean

school attendance also predicts higher student performance. Therefore, the predicted

performance gain from higher individual attendance is greatest for students who attend

a school with high mean attendance. These associations are independent of the

relationships of other student and school variables with performance. That is, when all

other variables are held constant, there is a significant association between attendance

and performance at the student and school level. This report describes the method and

findings of this study and discusses their implications for improving performance in

New York City Public Schools.

ATTENDANCE PROBLEM IN NEW YORK CITY

Too many students in New York City are absent too often. In New York City, one in five

children misses at least a month of school each year—and in many neighborhoods the

number is much higher. According to the Center for New York City Affairs (the Center),

the City’s elementary schools have far more serious rates of absenteeism than had been

previously reported (Nauer, White, & Yerneni, 2008). While City school officials have

long been concerned by poor attendance rates in middle and high schools, an analysis

by the Center found that attendance problems begin with much younger students.

The Center’s analysis of Department of Education (DOE) data found that more than

90,000 children in grades K through 5—or 20 percent of total enrollment—missed at

least a month of school during the 2007–08 school year. They reported that 15.7 percent

INTRODUCTION

8

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

of students in grades kindergarten through 5—and 16.2 percent of students in grades 6

through 8—missed 30 or more days of school in the 2007-08 school year. In 165 schools

serving students in grades kindergarten through 8, at least 30 percent of students were

chronically absent. These schools were concentrated in areas of New York City with the

highest poverty rates.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH FINDINGS

Historically, most published research has examined attendance at the school rather than

the student level. These studies have generally found that higher average school

attendance is associated with higher performance (Roby, 2004). Several recent studies

have documented that for individual students being present at school more days is

associated with higher performance. Michael A. Gottfried’s research, by employing very

rigorous statistical methods, substantially advances our understanding of the link

between individual student attendance and performance. These rigorous methods

allowed him to eliminate alternative explanations of the link between attendance and

performance. One such alternative is that the apparent link between attendance and

performance results from the strong association of each with family characteristics,

such as socioeconomic status, mother’s education, and family involvement in education.

In this view, there is no direct link between attendance and performance. Gottfried’s

research discredits this possibility.

Gottfried has published three journal articles based on his analyses of a comprehensive

data set for elementary and middle school students in the Philadelphia School District

covering the 1994-95 through 2000-01 school years. In one study (Gottfried, 2010),

controlling for student, classroom, school, and neighborhood characteristics, as well as

past student performance, he found that the number of days the student was present

was positively related to both grade point average and standardized test results in the

elementary and middle grades. The relationship was somewhat stronger for middle than

elementary students and for mathematics than reading. The quasi-experimental

approach used in his research supports the premise that there is a causal relationship

between attendance and performance.

Using records for students in second through fourth grade from the same data set,

Gottfried examined the relationship of kind of absence—excused or unexcused—to

performance on reading and mathematics standardized tests (Gottfried, 2009). He found

that higher proportions of unexcused to total absences were associated with lower

performance, particularly in mathematics.

In a third study, Gottfried (2011) sought to isolate the effect of missing school on

elementary reading and mathematics performance. He controlled the effects of family

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

9

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

variables on both the number of days a student is absent and on student standardized-

test performance. Using the Philadelphia School District data set, he tracked five cohorts

of siblings for six school years beginning in the 1994-95 school year. As in previous

studies, he controlled for student, classroom, school, and neighborhood characteristics.

He eliminated family effects by coding each student’s absences and standardized test

scores as deviations from the family average. To illustrate this method in its simplest

form, consider two families. The siblings in one family were absent for four and eight

days and siblings in the second family were absent for 16 and 20 days. In each family,

one sibling was absent for two days more—and one sibling was absent for two days

fewer—than the family average of 6 or 18. The sibling in each family with fewer absences

would be coded -2 and the sibling with more absences would be coded +2. Using this

method, he eliminated family differences that caused the second set of siblings to be

absent for a greater number of days than the first set. By applying the same procedure to

standardized test scores, he eliminated family differences that caused some families to

achieve higher scores than other families. Using these deviation measures, he then

examined whether higher numbers of absences were related to lower test scores. He

found that eliminating the family effects resulted in a stronger relationship between

attendance and performance than he had found in previous studies without this control.

Hedy Chang and Mariajosé Romero (2008) at the National Center for Children in Poverty

(NCCP) reported on the importance of addressing chronic absence in the early grades.

They analyzed U.S. Department of Education national data for 21,260 children from

kindergarten entry in 1998 to grade 5. Chronic absence was defined as missing 10

percent or more of a school year: at least 18 days out of a 180-day school year. They

found that chronic absenteeism is disproportionately a problem in elementary schools

that serve mostly poor Black and Hispanic children. It contributes to the achievement

gap between these children and their White, Asian, and middle-class peers. Students

who have many absences in kindergarten are likely to have similar attendance problems

in first grade. By the end of first grade, these children are already slipping behind in

reading, math and general knowledge. Chronic absence in kindergarten was also

strongly associated with lower reading and math performance in fifth grade for poor

children.

Robert Balfanz and Vaughan Byrnes (2006) analyzed records for four cohorts of middle-

school students (grades 5-8) attending three high-poverty schools implementing whole-

school reform models in the Philadelphia School District. They divided students into two

groups according to whether they were closing the gap between achievement and grade-

level expectations during the middle school years or continuing to fall behind. Students

were counted as closing the gap, if according to standardized test scores, their gain in

grade equivalents was greater than their number of years in middle school. Better

INTRODUCTION

10

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

attendance was among the factors found to distinguish students who were closing the

gap from those who were not. Other factors that achieved similar results were more

years in home rooms where larger percentages of children made high gains, better

behavior marks, and higher self-rankings of effort in mathematics.

The Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE) has completed two analyses of the relationship of

school attendance and school performance. In the first study, we found average school

attendance to be a significant predictor of school grade 4 ELA performance. The study

documented the relationship between attendance and performance on the New York

State grade 4 English language arts (ELA) assessment at the school level. The

explanatory power of attendance was independent of other school variables: percentages

of economically disadvantaged students, English language learners, Black and Hispanic

students, and students with disabilities. These variables accounted for almost 78 percent

of the variation among schools in the performance of fourth-graders, with attendance

and the percentage of economically disadvantaged students being the best predictors of

performance.

CFE’s recent study, Diploma Dilemma: Rising Standards, the Regents Diploma, and

Schools that Beat the Odds

(Campaign for Fiscal Equity, 2010), documented the

importance of attendance in high schools. The study grouped New York City high

schools according to the grade 8 performance of entering ninth-graders. Within each

group of high schools serving similar students, schools with the lowest and highest

Regents diploma rates were distinguished by average daily attendance in the students’

expected graduation year. Schools with the highest Regents diploma rates had, on

average, the highest attendance rates.

RESEARCH OBJECTIVE

Improving performance is a critical goal and attendance is a key element in achieving

that goal. Before 2000, the United States had the largest percentage of college graduates

in the world. By 2010, according to the College Board, we had slipped to 12

th

place out of

36 countries in the percentage of 25 to 34 year olds with at least an associate’s degree. A

recent report released by the State Education Department (2011) showed that only 23

percent of New York City students who entered grade 9 in 2005-06 had graduated by June

2009 with performance that indicated adequate preparation for college; that is, scores of

75 or higher on the Regents English examination and 80 or higher on a Regents

mathematics examination. Our future prosperity depends on better preparing students

to meet future challenges, which will surely depend on higher levels of literacy,

enhanced technical and scientific skills, and greater problem-solving ability. We cannot

afford for students to leave high school without adequate preparation for college and the

workplace, as too many New York City students do today.

INTRODUCTION

11

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

All students now entering ninth grade in New York State except those with disabilities

must meet the more rigorous Regents diploma requirements to graduate. CFE’s research

suggests that entering ninth grade not having achieved the eighth-grade learning

standards substantially reduces a student’s chance of earning a Regents diploma. State

assessment results show that by third grade many students have fallen far behind grade-

level expectations and will fall farther behind without effective interventions, year by

year decreasing the probability of earning a Regents diploma.

The research objective is to document the relationship between individual student

attendance and performance in New York City elementary schools. To achieve this

objective, CFE performed multilevel regression analyses of performance on the grade 4

ELA and mathematics assessments. In examining this relationship, we accounted for the

association between previous performance (third grade) and fourth-grade performance

and for other student and school factors that are simultaneously related to attendance

and performance. These student factors include poverty, ethnicity, gender, disability,

English proficiency, and mobility. The school factors include average school attendance,

average grade 3 performance, percentage minority enrollment, and teacher

qualifications. These analyses define how these explanatory variables are associated

with the performance of individual students and how they vary among schools. We will

use the results to focus the attention of elementary-school staff and parents on the

importance of attendance in enabling students to meet learning standards and to

support the continuation and enhancement of comprehensive school reform in New

York City schools.

12

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

METHOD

DATA

W

e analyzed student data for 705 New York City Public

Schools that served fourth-graders in 2007-08. These

schools enrolled 64,062 fourth-grade students whose

records met the following criteria for study inclusion:

UÊ included scores for the 2006-07 third-grade and 2007-08 fourth-

grade assessments in ELA and/or mathematics.

UÊ indicated enrollment in fourth-grade in a New York City public

school—other than a school in District 75—at the end of the

2007-08 school year.

UÊ included attendance data for 2006-07 and 2007-08.

The New York City Department of Education (DOE) provided the

following data for third-graders in 2006-07 and fourth-graders in 2007-

08: A non-personally identifiable student tracking number; school

identification number where student was registered on October 31 of

each school year; school identification number where student was

registered on June 30 of each school year; gender; ethnicity; grade

level; identifiers of eligibility for free- or reduced-lunch, limited English

proficiency, and disability; days absent, present and released; and

scaled scores and performance levels for the State grade 3 and 4

assessments in ELA and mathematics.

We also obtained data on the teacher characteristics of study schools

in 2007-08 from the State Education Department’s Report Card Data

Base. These characteristics included lack of appropriate certification,

years of experience, graduate education beyond the master’s degree,

and teacher turnover rate.

The achievement data consisted of scaled scores and performance

levels on the 2007 grade 3 and the 2008 grade 4 ELA and mathematics

assessments of the New York State Testing Program. These assessments

measured the performance of students in grades 3 through 8 relative to

the State Learning Standards. In 2008 each of these assessments was

graded on a scale consisting of 280 to 360 points, with a scaled score of

650 indicating proficiency at each grade level. The scale is divided into

four performance levels: Level 1 identifies students with serious

academic deficiencies; Level 2, students partially meeting the

Method

13

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

METHOD

standards; Level 3, students meeting the standards and thus considered proficient; and

Level 4, students meeting the standards with distinction. A great majority of students in

the City and the State perform at Level 2 or 3 on each assessment.

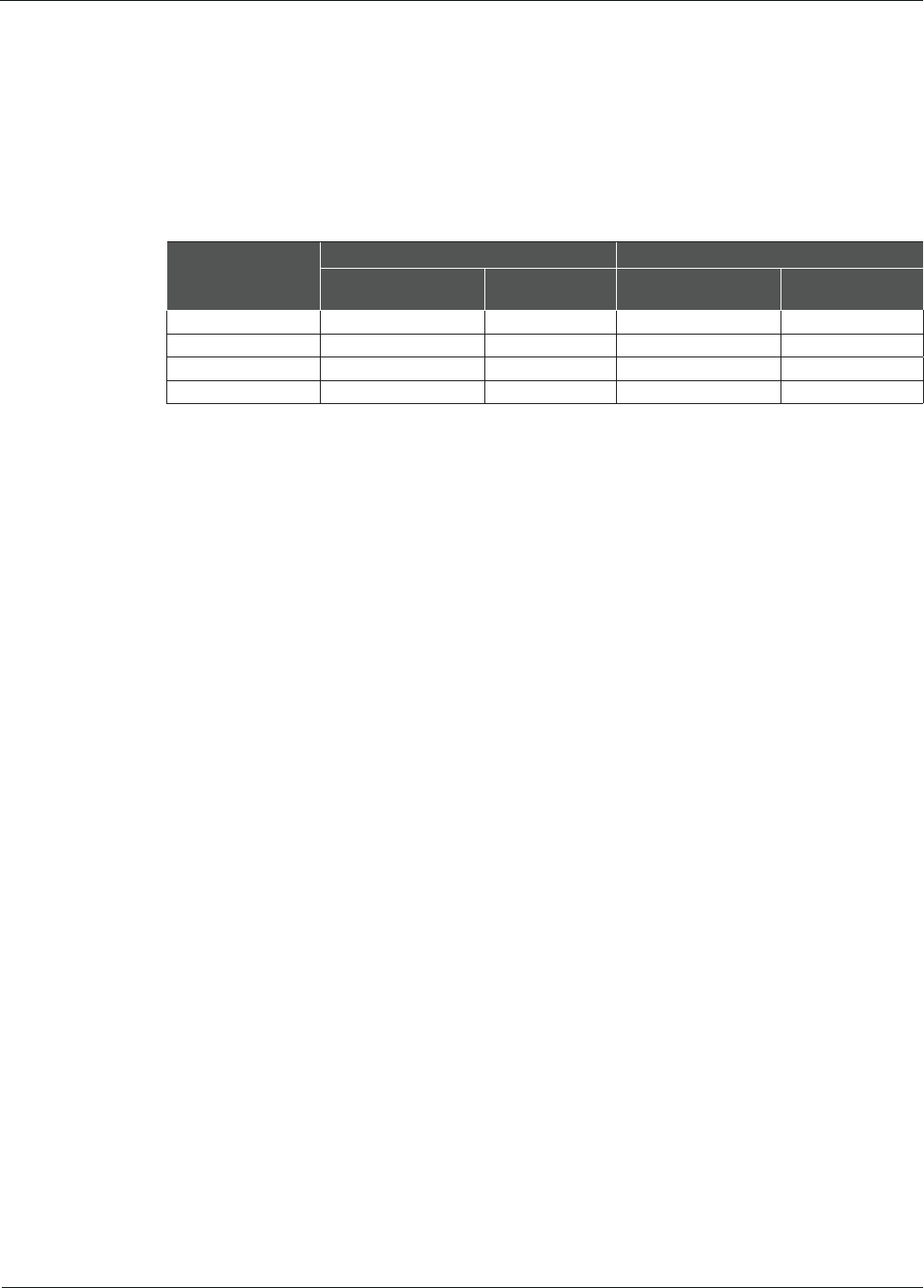

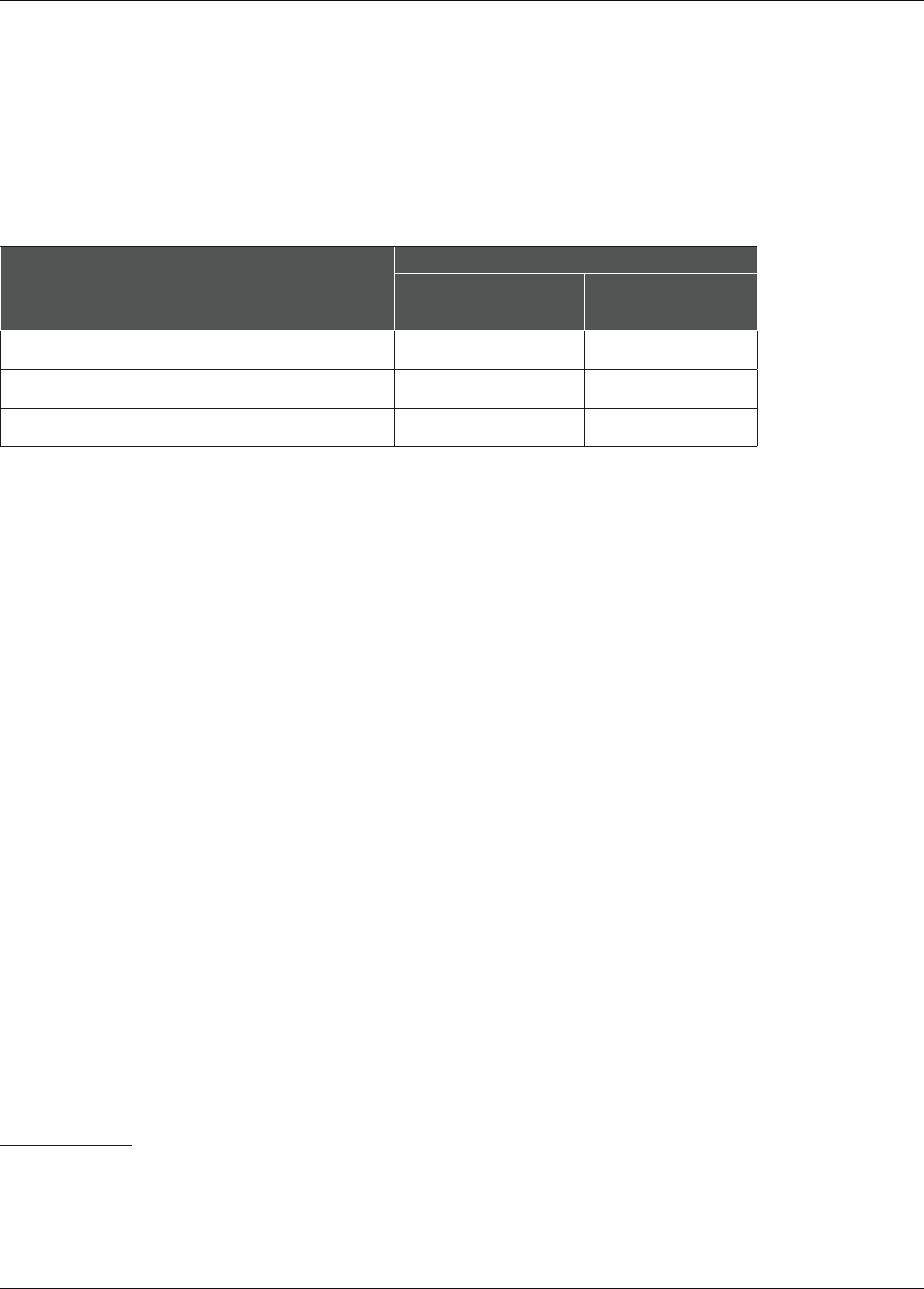

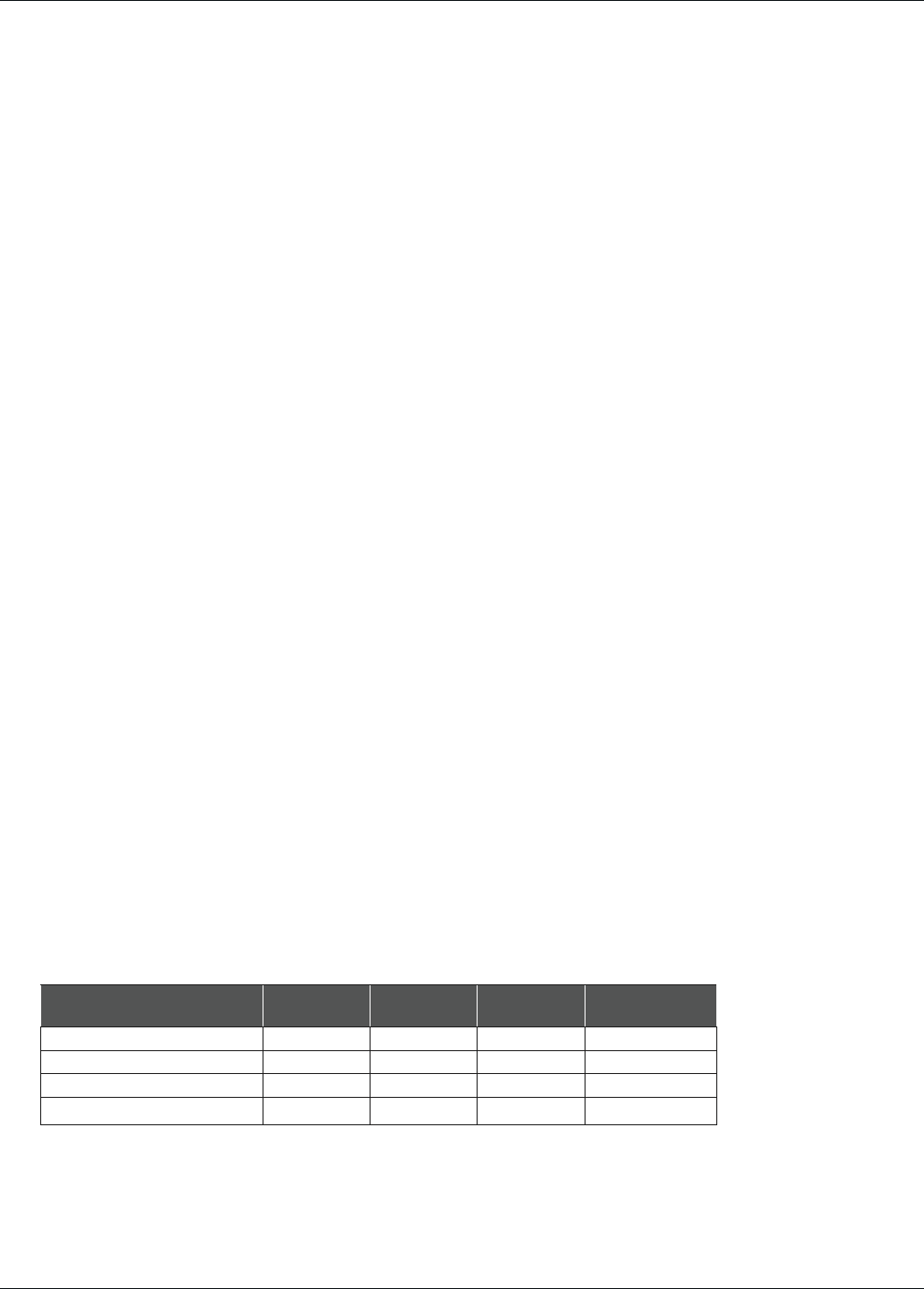

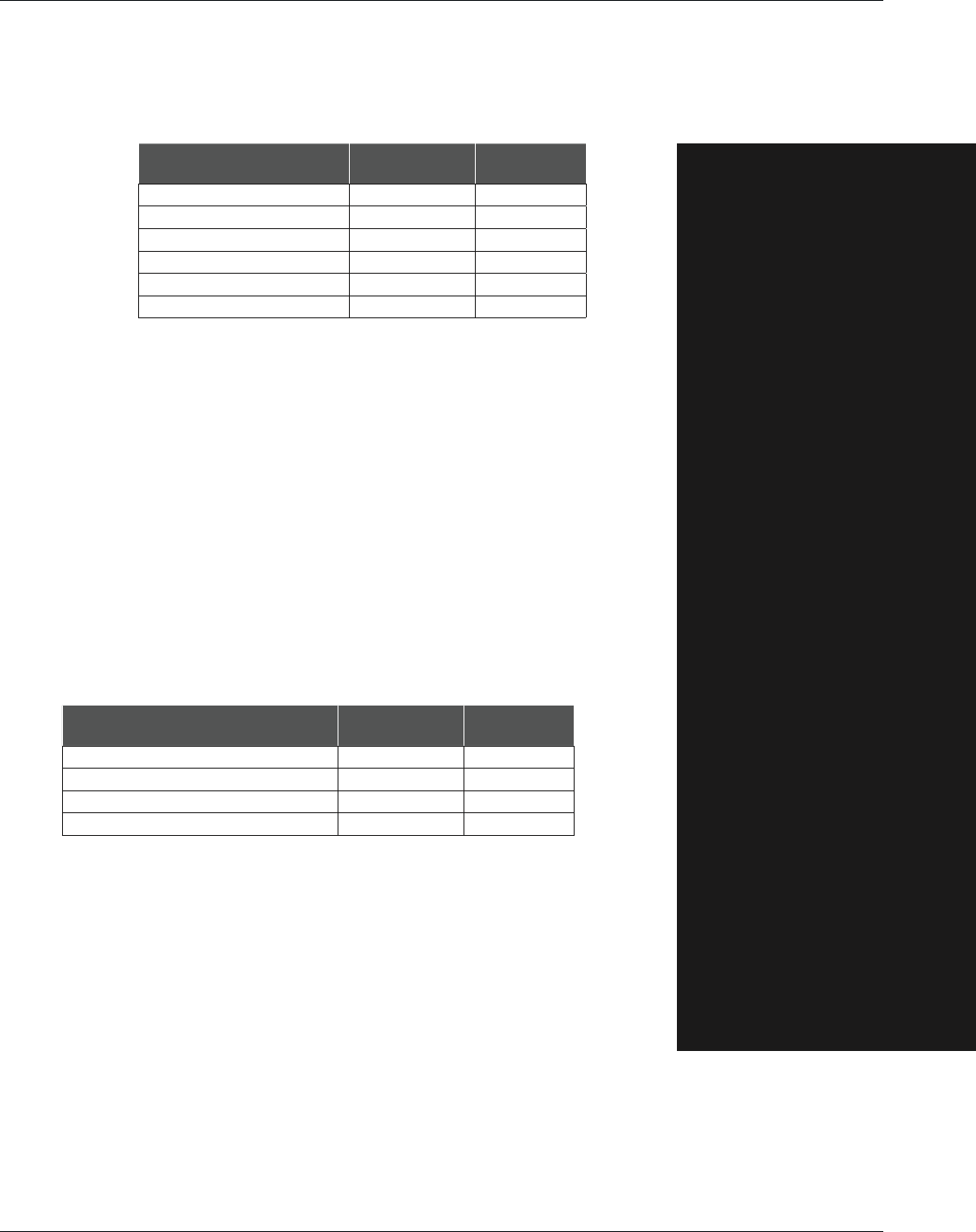

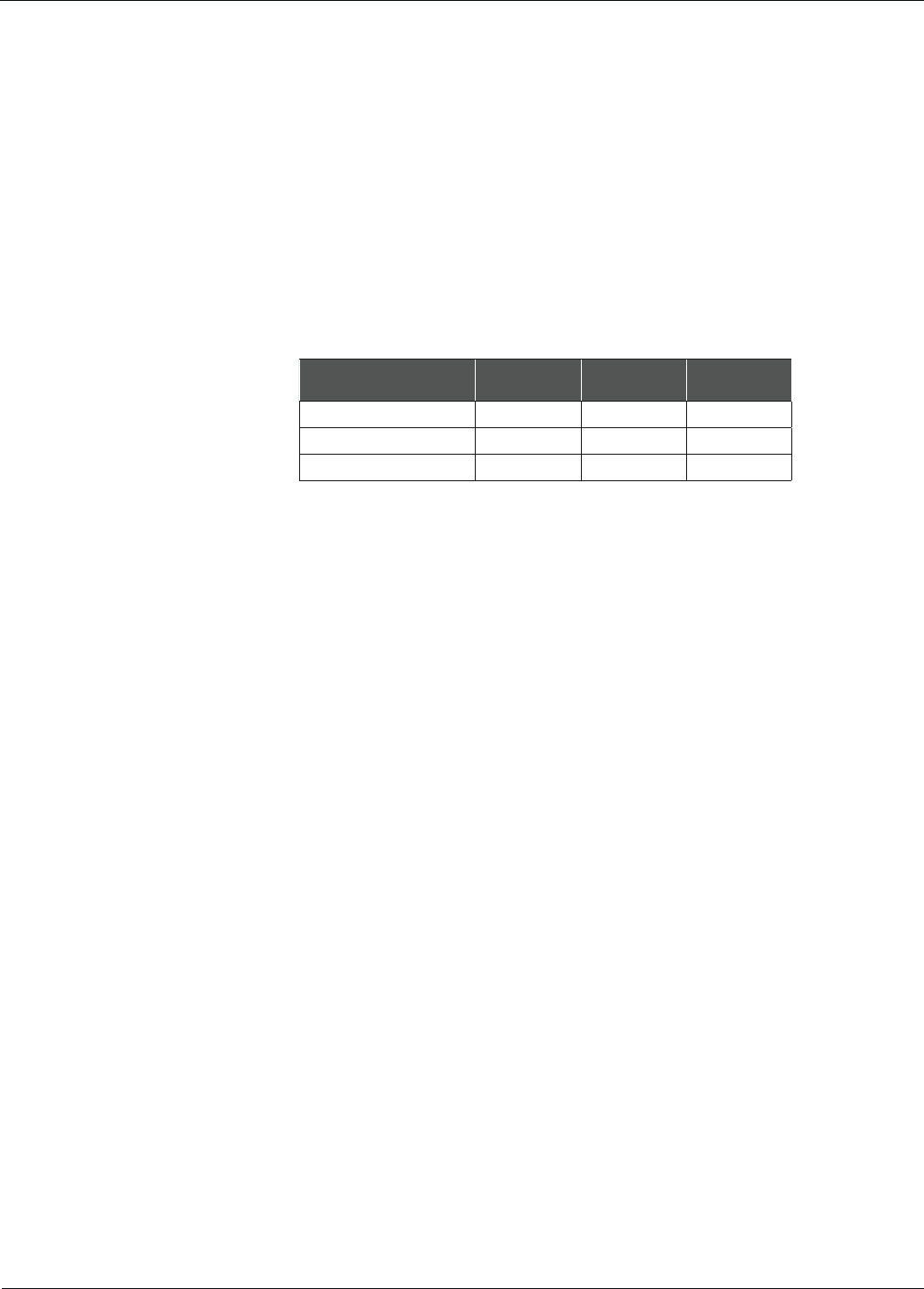

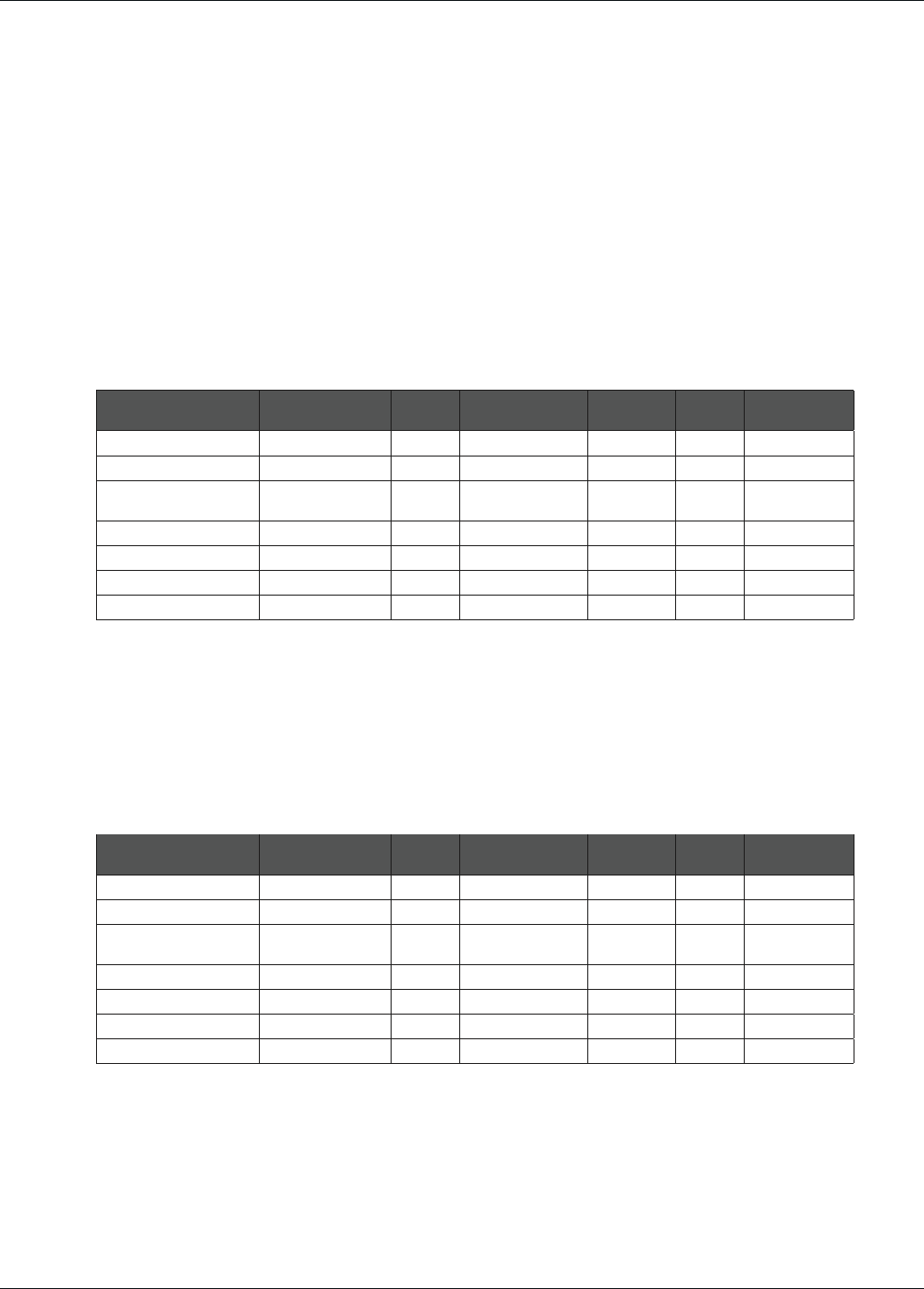

GRADE 4 STATE ASSESSMENTS

Performance Levels, Corresponding Scaled-Score Ranges, and

Percentages of New York City Students Scoring at Each Level in 2007-08

PERFORMANCE

LEVEL

ELA MATHEMATICS

SCALED-SCORE

RANGE

PERCENT AT

LEVEL

SCALED-SCORE

RANGE

PERCENT AT

LEVEL

1 430-611 10.5 485-621 6.3

2 612-649 28.2 622-649 14.1

3 650-715 55.5 650-701 53.4

4 716-775 5.8 702-800 26.2

Using DOE data elements, we calculated the following attendance variables:

UÊ Student Days Enrolled is the sum of Days Absent, Days Present, and Days

Released. (Some students were not enrolled for the entire school year.)

UÊ Student School Year Attendance

was calculated by dividing the number of Days

Present

by Days Enrolled in each school year and multiplying by 100.

UÊ Student Cumulative Attendance was calculated by dividing the sum of Days

Present in 2006-07 and 2007-08 by Days Enrolled in 2006-07 and 2007-08 and

multiplying by 100.

UÊ School Mean Attendance is the arithmetic mean of Student Cumulative

Attendance

for fourth-graders enrolled in the school at the end of the 2007-08

school year.

UÊ A Chronic Absence Identifier was assigned to students who attended school for

fewer than 90 percent of enrolled school days in 2006-07 and 2007-08.

Students were considered to be continuously enrolled if the school identification

numbers on their records indicated that they were enrolled in the same school from

October 31, 2006 until the end of the 2007-08 school year. Continuous enrollment is the

measure of mobility.

ANALYSES

The focus of this research is multilevel regression analyses of the relationships between

attendance and performance on the grade 4 ELA and mathematics assessments. These

analyses are multilevel in that they consider both student and school characteristics in

predicting student performance. This statistical technique allows us to quantify the

association of each explanatory variable with performance, independent of the others.

The most powerful predictor of assessment performance is previous performance.

14

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

METHOD

Therefore, our analyses controlled for grade 3 ELA and mathematics performance.

Including grade 3 performance controlled for the time-invariant characteristics of

students that are simultaneously related to attendance and performance. These time-

invariant characteristics include those components of motivation, ability, and family

support that do not change over time. We also included factors that previous analyses

have shown to be associated with performance, that is, eligibility for free- or reduced-

price lunches (poverty), ethnicity, gender, disability, English proficiency, and continuous

enrollment. Because schools provide the context in which students are educated, school

characteristics can be expected to modify the relationship between student attendance

and performance. Therefore, these analyses also examined the mediating effects of

school contextual factors—mean grade 3 performance, school mean attendance, ethnic

composition, and a teacher quality variable. We selected turnover rate for ELA and

percentage of teachers with 30 credit hours beyond the master’s degree for mathematics

as the best predictors of performance. These analyses produced equations that predict

the grade 4 performance of individual students.

PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS

The next section provides an overview of research findings. The following three sections

provide background information to assist the reader in understanding the multilevel

analyses. “Student Profiles” presents demographic, attendance, and performance

profiles of the 64,062 fourth-graders included in the study. We also present similar

profiles for each ethnic group to show the associations between ethnicity and eligibility

for free-and-reduced-priced lunches, disability, English proficiency, attendance, and

performance. “School Profiles” presents enrollments, demographics, attendance,

performance, teacher qualifications—lack of appropriate certification, years of

experience, graduate education—and teacher turnover rates for the 705 schools included

in the study. This section also examines the relationships of student demographics and

teacher characteristics with attendance. “Attendance and Performance at the School

Level,” examines the relationship of school mean attendance with school mean ELA and

mathematics performance. The final section of findings reports on the multilevel

analyses of the relationships between individual attendance and performance on the

grade 4 ELA and mathematics assessments. The relationship of each explanatory

variable to grade 4 performance is described.

15

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

T

his study is important because unlike previous studies of New York City students

it examines the relationship of attendance and performance at the student level,

while considering other student and school characteristics that are related to

performance. Our multilevel analyses document that both individual attendance and

school mean attendance in grades 3 and 4 are associated with performance on the grade

4 assessments in ELA and mathematics. Higher individual student attendance predicts

higher performance and attending a school with higher mean attendance increases the

predicted performance gain. These associations are independent of the relationship of

other student and school variables with performance. That is, when all other variables

are held constant, there is a significant association, for individual students, between

attendance and performance. These predicted results are based on data for 64,062

students in 705 schools and are highly reliable. The odds that there is no relationship

between attendance in grades 3 and 4 and grade 4 ELA and mathematics performance

are less than one in a thousand.

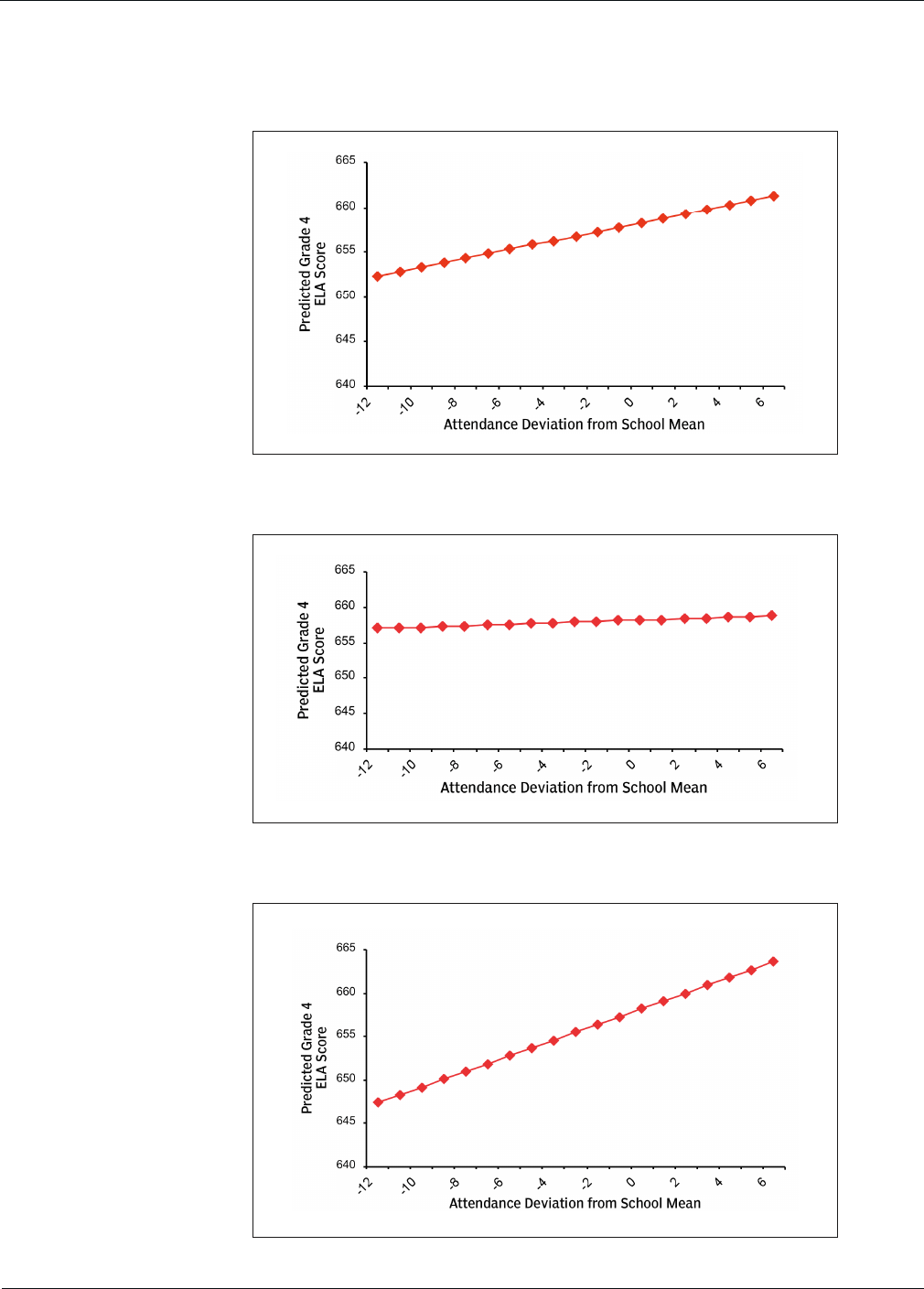

MULTILEVEL ANALYSIS FINDINGS

Individual Student Attendance

Our analyses produced equations that allow us to predict student performance under

various conditions. The relationship of individual student attendance with grade 4

performance is not uniform across schools. The relationship is stronger in schools with

higher average attendance in grades 3 and 4. To illustrate how performance varies

among schools and students with different attendance rates, we compared predicted

fourth-grade scaled scores in hypothetical schools with low-attendance—91.4 percent—

and high-attendance—96.3 percent. Only 10 percent of schools had lower attendance

than 91.4 percent, while 90 percent had lower attendance than 96.3 percent. The average

student in the low-attendance school missed more than twice as many days—16 in a 185

day school year—than the average student in the high attendance school—7 days.

Within each school, we compared the predicted grade 4 scores of three students with

different attendance rates: a chronically absent student (86.8-percent attendance), a

typical student (95.4-percent attendance), and a high-attendance student (99.0-percent

attendance). Students with different grade 3 performance and different demographic

characteristics will have different predicted scores. The predicted gains of students with

the same attendance improvement, however, depend only on their schools’ mean

attendance. For example, students with low and high grade 3 scores attending the school

with high mean attendance can expect the same gain by improving their attendance

from 86.8 to 95.4. The student with the higher grade 3 score will however have a higher

predicted grade 4 score because higher grade 3 performance predicts higher grade 4

performance. Table 1 provides the predicted gains achieved by improving attendance in

schools with the specified mean attendance rates, regardless of the student’s

demographic characteristics and grade 3 performance.

Overview of Findings

16

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

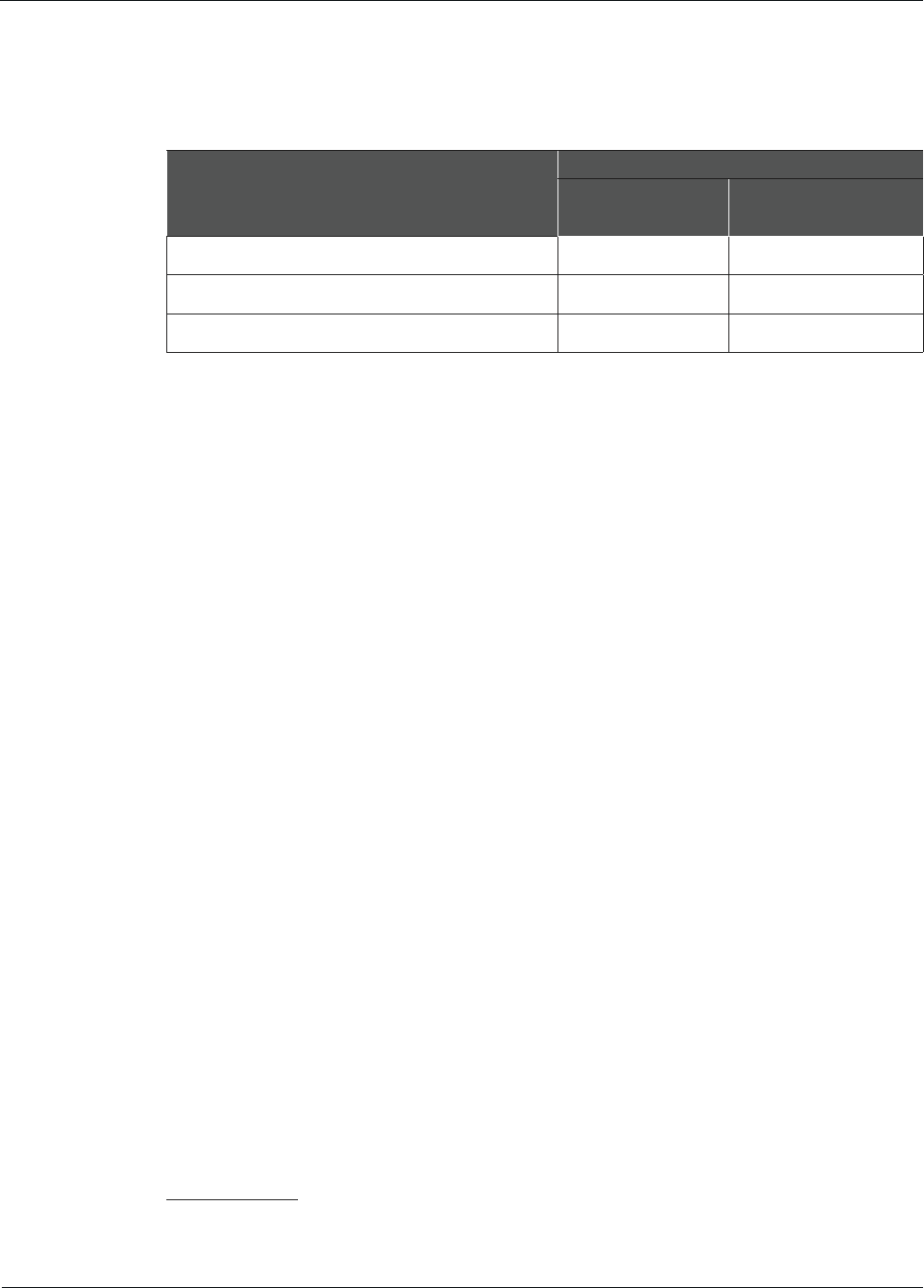

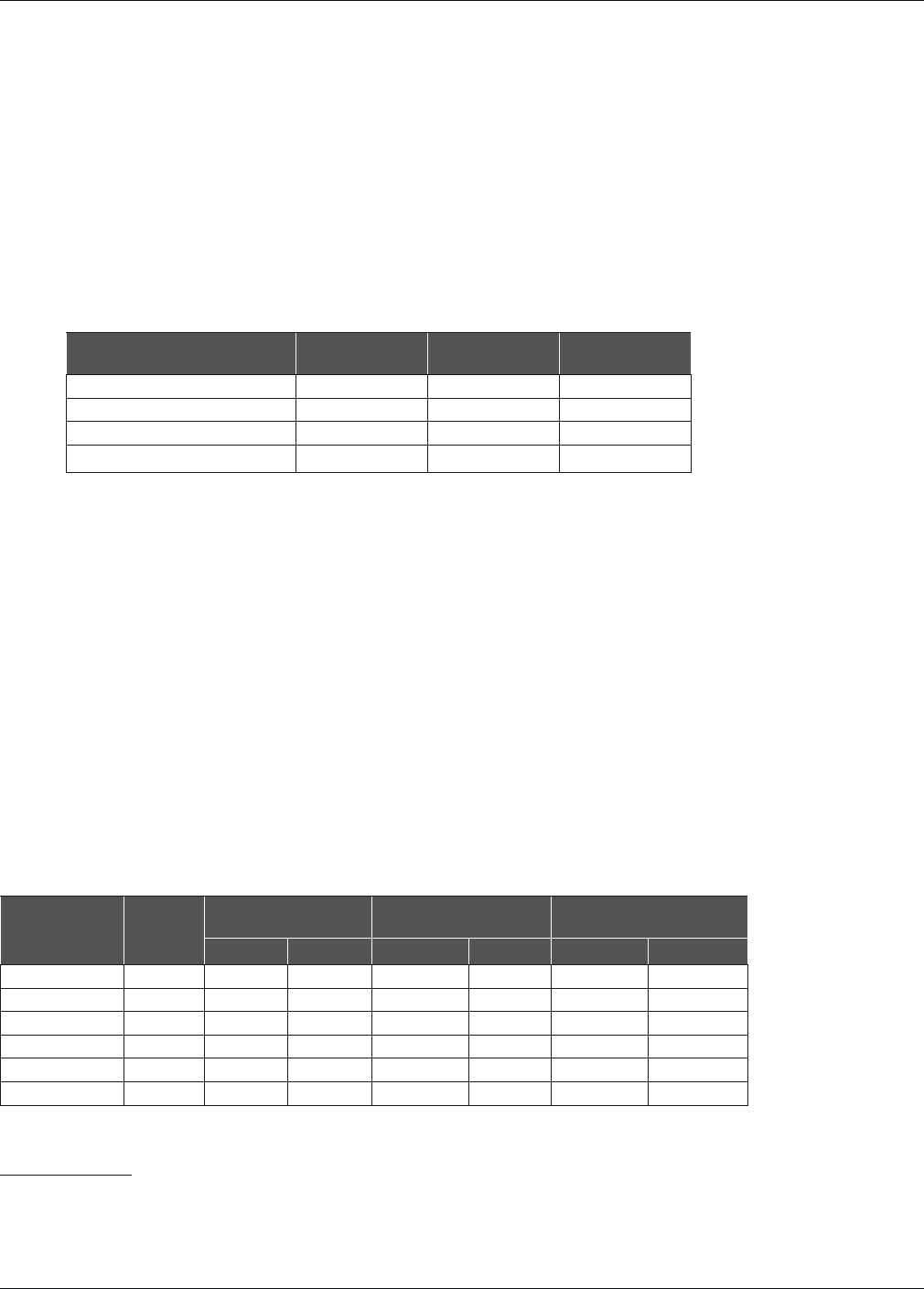

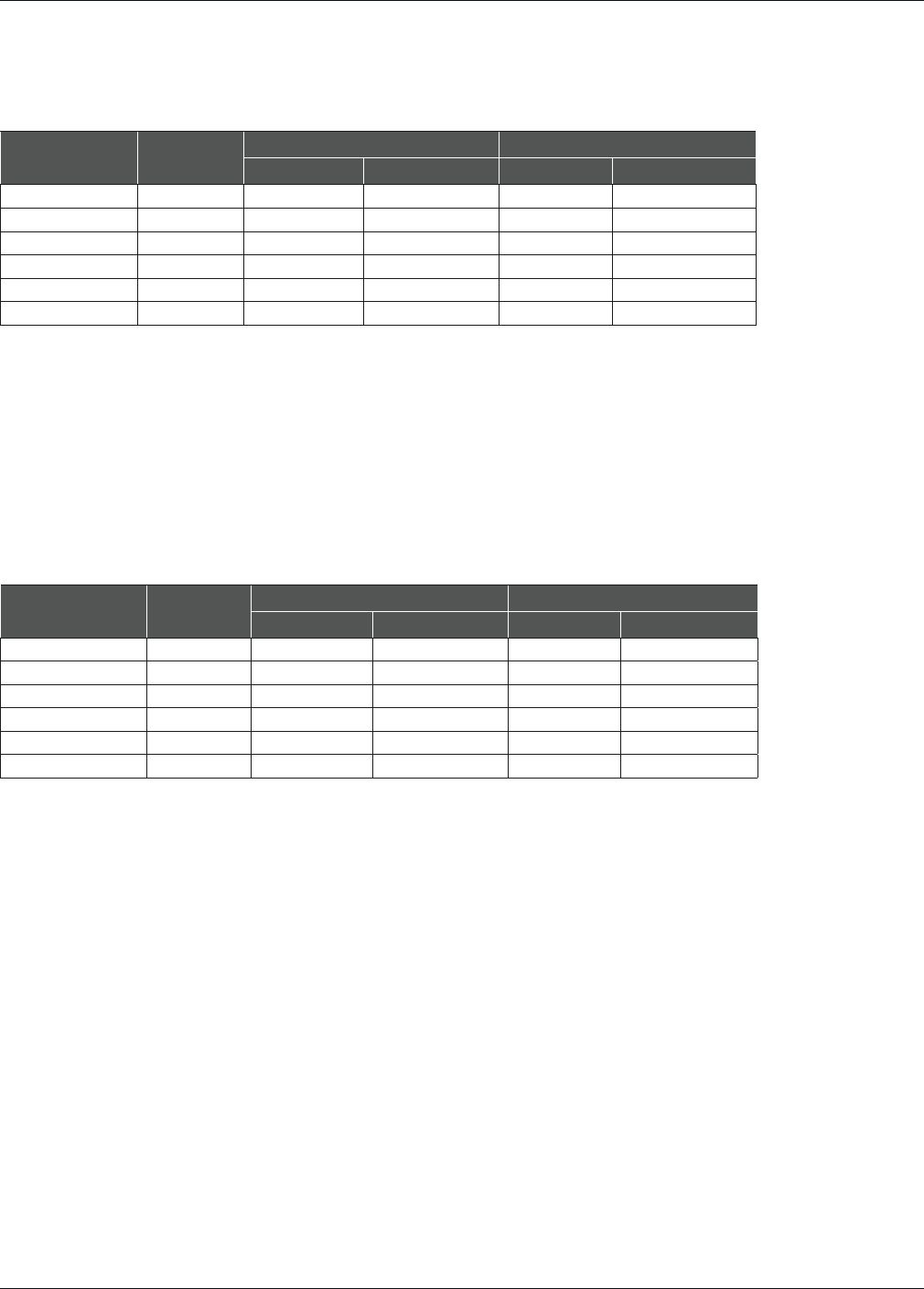

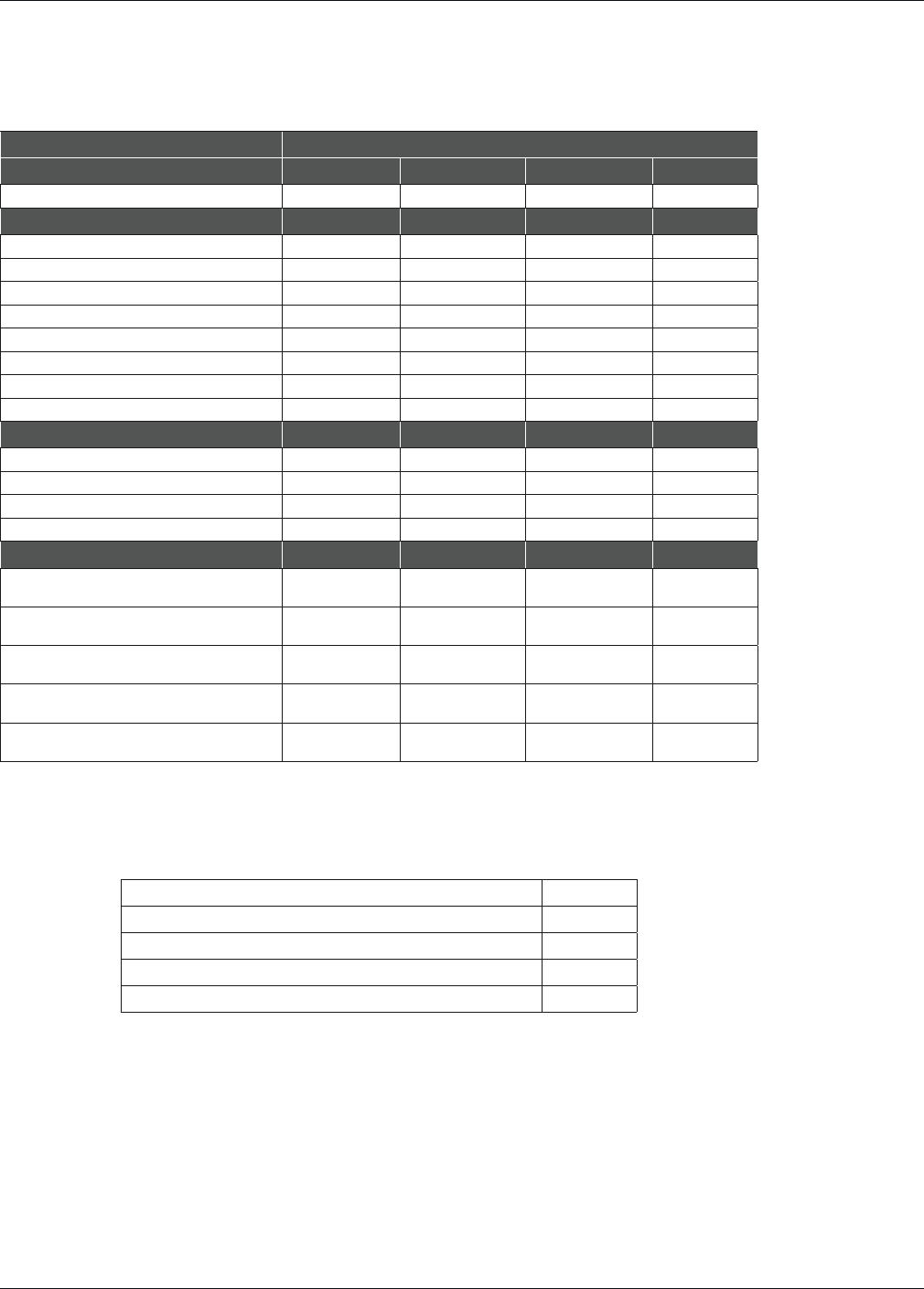

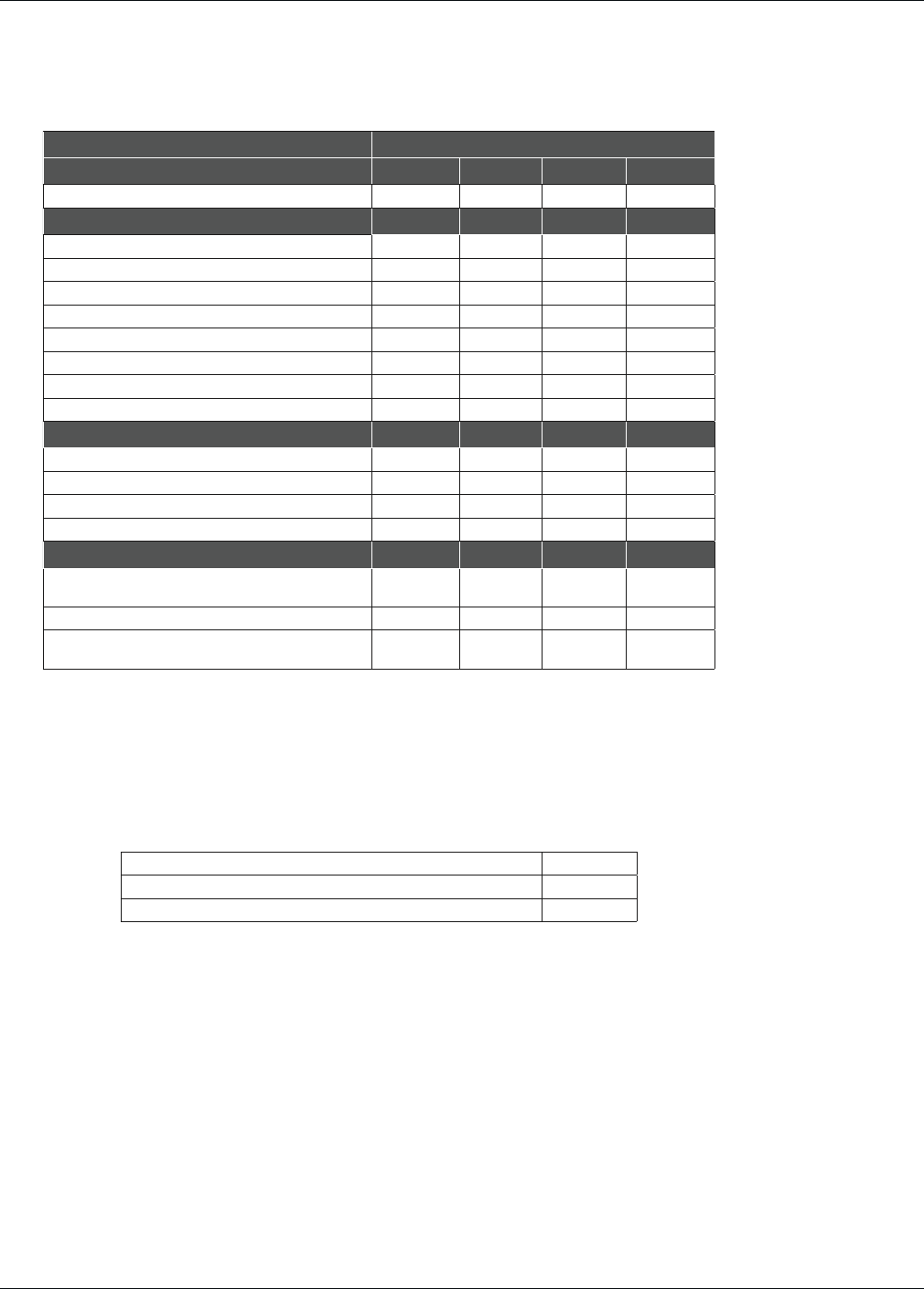

TABLE 1

The Predicted Scaled-Score Gains on the

Grade 4 ELA Assessment as Student Attendance Improves

STUDENT ATTENDANCE

SCHOOL MEAN ATTENDANCE

91.4 PERCENT (169 DAYS

IN 185 DAY SCHOOL

YEAR)

96.3 PERCENT (178

DAYS IN 185 DAY

SCHOOL YEAR)

Gain Predicted by Increasing Attendance

from 86.8 to 95.4 Percent

3.5 5.1

Gain Predicted by Increasing Attendance

from 95.4 to 99.0 Percent

1.5 2.1

Total Gain Predi cted by Increasi ng Attend ance

from 86.8 to 99.0 Percent

5.0 7.2

As shown in Table 1, in the low-attendance school, the predicted ELA scaled-score

difference between the chronically absent student and the student with typical

attendance was 3.5 scaled-score points. A student with very high attendance is predicted

to score an additional 1.5 points compared with the student with typical attendance.

Attendance had a stronger relationship with performance in high- than low-attendance

schools. In the high-attendance school, the predicted grade 4 ELA score of the student

with typical attendance is 5.1 points higher than that of the chronically absent student.

The predicted score of the high-attending student is another 2.1 points higher.

1

These predicted gains can be put in perspective by comparison to other benchmarks.

The predicted ELA scaled-score gain from improving a student’s attendance from 86.8 to

95.4 percent in a high-attendance school is 5.1 points. The mean grade 4 ELA score for

New York City students increased from 657 to 663 between 2006 and 2009; this gain of

six points was seen as indicating improvements in the school system. In 2007-08, more

than one quarter of fourth-graders scored at ELA Level 2, which includes scores from 612

to 649. The expected gain is 14 percent of that range. To cite another benchmark, the

average difference between minority students and White and Asian students on the

Grade 4 ELA assessment was about 30 points. The expected gain is 17 percent of that

difference. Finally, an evaluation of New York City charter schools (Hoxby, Murarka, &

Kang, 2009) estimated that the extra annual gain in ELA scaled score achieved by the

average student in grades 4 through 8 attending a charter school—rather than the

average City public school—would be 3.6 points.

1 Note that school average attendance increases when multiple enrolled students improve their attendance. As the average attendance of

the school increases, so will the predicted performance gain of individual students with improved attendance. If the low-attendance

school succeeds in increasing its average attendance to 92.4 percent, the predicted gain in ELA score increases to 4.5 points and the

predicted gain in mathematics score increases to 5.0 points.

Overview of Findings

17

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

TABLE 2

The Predicted Scaled-Score Gains on the

Grade 4 Mathematics Assessment as Student Attendance Improves

STUDENT ATTENDANCE

SCHOOL MEAN ATTENDANCE

91.4 PERCENT (169

DAYS IN 185 DAY

SCHOOL YEAR)

96.3 PERCENT (178 DAYS

IN 185 DAY SCHOOL

YEAR)

Gain Predicted by Increasing Attendance from

86.8 to 95.4 Percent

3.7 6.9

Gain Predicted by Increasing Attendance from

95.4 to 99.0 Percent

1.6 2.9

Total Gain Predicted by Increasing Attendance from

86.8 to 99.0 Percent

5.3 8.5

In Table 2, we see a similar pattern when we predict grade 4 mathematics scaled scores.

In the low-attendance school, the scaled-score difference between our chronically

absent student and our typical student is 3.7 points. The high-attendance student would

score an additional 1.6 points. Again the relationship between student attendance and

performance is stronger in high- than low-attendance schools. In the high-attendance

school, the predicted score of the student with typical attendance is 6.9 points higher

than that of the chronically absent student. The high-attendance student would score an

additional 2.9 points.

Again we place the gains in perspective. The predicted mathematics scaled-score gain

from improving a student’s attendance from 86.8 to 95.4 percent in a high-attendance

school is 6.9 points. Between 2006 and 2009, the mean grade 4 mathematics scaled score

for New York City students improved from 669 to 688.

2

In 2007-08, almost one in seven

fourth-graders scored at math Level 2, which includes scores from 622 to 649. The

expected gain is 25 percent of that range. Black, Hispanic, and Native American students

scored about 27 points lower than White and Asian students on the Grade 4 mathematics

assessment. The expected gain is about 26 percent of that difference. The predicted

average annual mathematics gain for students attending a charter school is 5.0 points.

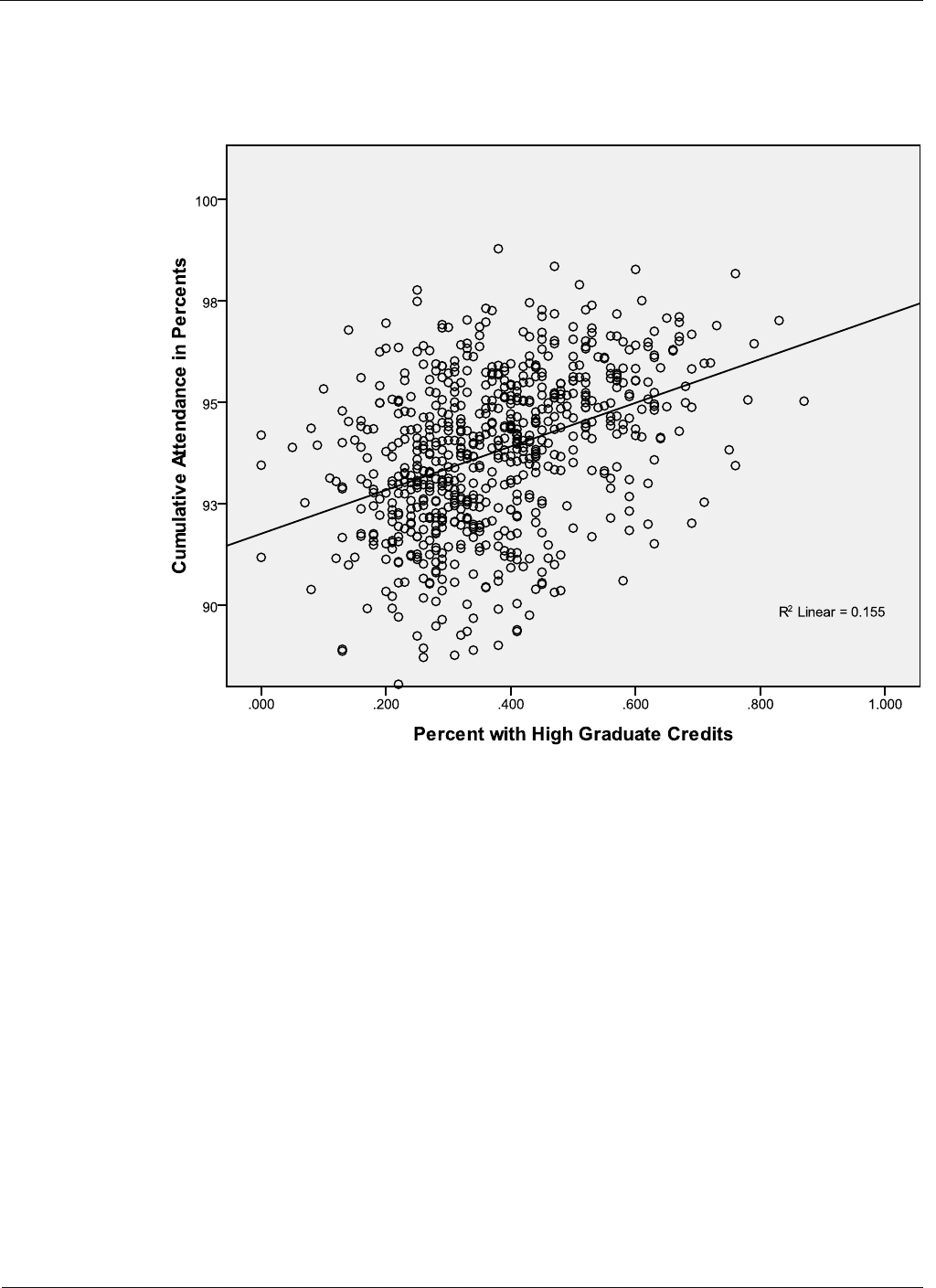

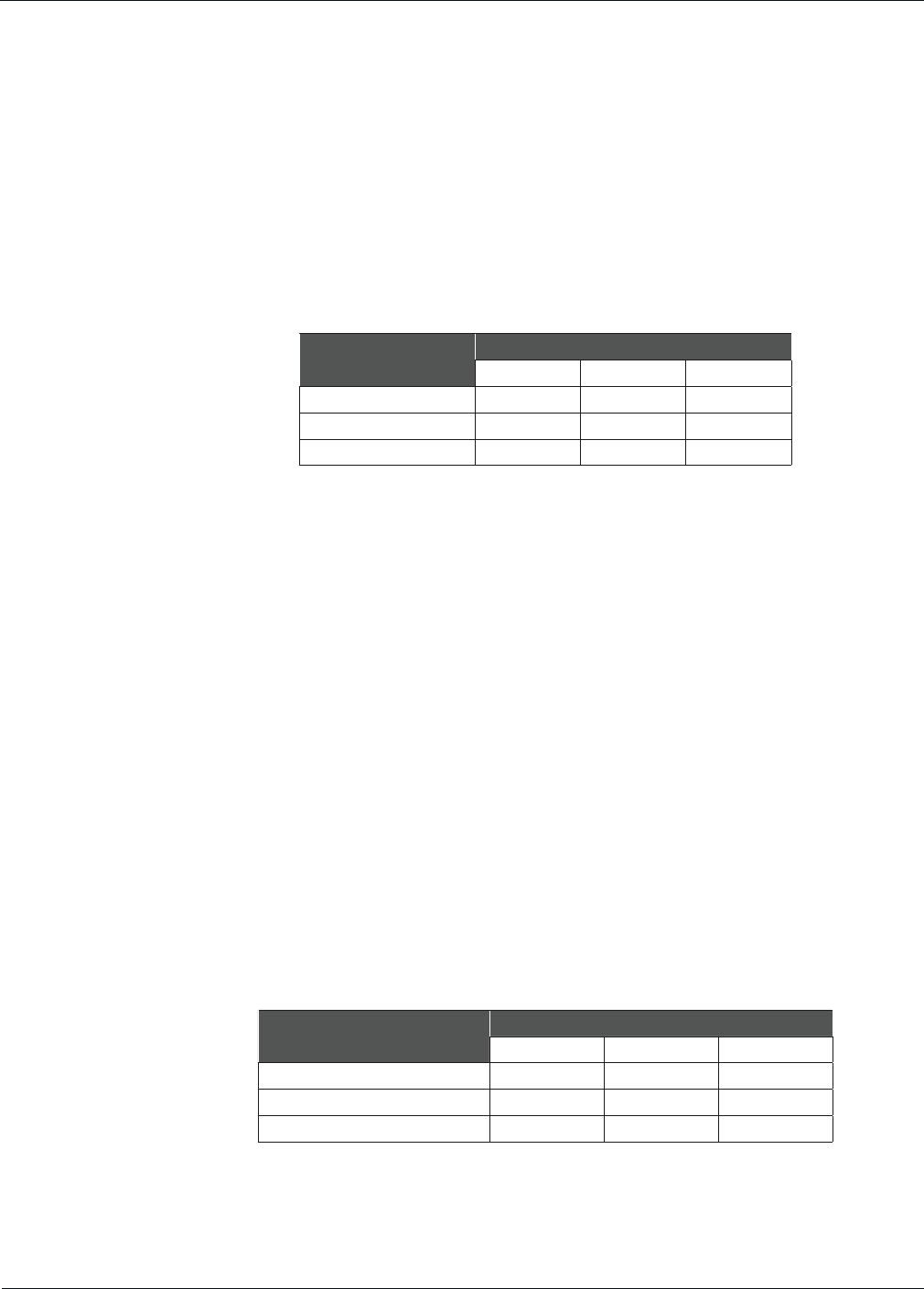

School Attendance

The multilevel analyses results reported above document that higher student attendance

predicts better performance on ELA and mathematics assessments. The analyses also

document that increased school mean attendance predicts higher school mean scaled

scores on these assessments. Each one percentage point increase in school mean

attendance corresponds, on average, to a 0.803-point increase in a school’s grade 4 ELA

mean scaled score. This finding suggests that the seven schools with mean attendance

of only 88 percent could improve their mean ELA scaled score by about 4.8 points by

increasing their attendance to the mean of the schools’ means, 93.8 percent. The

improvement to be gained in mathematics by this increase is even larger: 0.991 points

for each one percentage point increase in school mean attendance. For the seven schools

2 The acknowledged increases in the predictability of mathematics test questions during those years suggest that some portion of that

increase does not reflect real increases in achievement.

18

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

with the lowest attendance, this amounts to a predicted increase of six scaled-score

points.

The multilevel analyses also documented the relationships of student grade 3

performance, student demographic variables, and school variables with grade 4

performance. These relationships are summarized below:

UÊ Student variables. The analysis of ELA data confirmed that eight student

variables are significantly associated with grade 4 performance. Higher

attendance, higher grade 3 performance, being female, and being continuously

enrolled in the same school in grades 3 and 4 predict better grade 4 performance.

Being Black, Hispanic, or Native American; being eligible for free- or reduced-

price lunches; being disabled; and having limited English proficiency predict

lower grade 4 performance. These associations are independent of the

relationships among these explanatory variables.

UÊ School variables. Three school variables, in addition to school mean attendance,

are associated with performance: school grade 3 ELA mean score, percentage of

minority students, and teacher turnover rate. A higher mean grade 3 ELA score

predicts higher grade 4 performance, while larger percentages of minority

students and higher teacher turnover predict lower grade 4 performance.

UÊ Cross-level interactions. Five cross-level interactions are associated with grade 4

ELA performance. For example, the relationship between individual attendance

and grade 4 performance is mediated by school mean attendance. The

interaction increases or decreases students’ predicted scores depending on the

mean attendance of the school they attend. Consider first students whose

attendance is above the school mean. If they attend a school with above average

school attendance, the interaction will result in a small addition to their

predicted scores. For such students who attend a school with below average

school attendance, the interaction will result in a small deduction from their

predicted scores. The opposite is true for students whose attendance is below

their schools’ mean.

UÊ Mathematics. The multilevel analysis of mathematics performance produced

similar findings but showed a stronger association between individual

attendance and performance. Seven of the eight student-level variables have

significant relationships with grade 4 mathematics performance, independent of

all other variables. The association of continuous enrollment with grade 4

mathematics performance is not statistically significant. Being female predicts

lower rather than higher performance. Further, no teacher quality variable is

significantly related to performance, once we account for all other explanatory

variables. Only three cross-level interaction variables meet the statistical criteria

for inclusion in the model.

19

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

OTHER STUDY FINDINGS

The findings listed below provide a context for understanding the results of the

multilevel analyses, summarized above.

The 64,062 fourth-graders in New York City Public Schools in 2007-08 were ethnically

and economically diverse. The prevalence of disability, English proficiency, and mobility

and patterns of attendance and performance varied among ethnic groups. (See “Student

Profiles” for details.)

UÊ The majority of fourth-graders (71 percent) were Hispanic or Black and 84

percent came from low-income families.

UÊ 18 percent of fourth-graders were disabled and 15.2 percent were limited English

proficient.

UÊ About 87 percent were continuously enrolled in the same school from October 31,

2006 to the end of the 2007-08 school year.

UÊ The average student attended school for almost 94 percent of enrolled school

days in grades 3 and 4. Half of fourth-graders—about 32,000 students—attended

at least 95.4 percent of school days in grades 3 and 4.

UÊ Eighteen percent—over 11,000 students—however were chronically absent; that

is, they missed more than 10 percent of school days during that period—the

equivalent of at least 19 days in a 185-day school year.

UÊ Each ethnic group had distinctive demographic characteristics. White students

were much less likely than other students to come from low-income families and

be eligible for free- or reduced-price lunches. Asian students were less likely to be

classified as disabled. Asian and Hispanic students were most likely to be English

language learners. Native American, Black, and Hispanic students were at least

five times as likely as Asian students to be chronically absent. White students

were most likely to be continuously enrolled in the same school in third and

fourth grade.

UÊ The average student scored at the proficient level (650 or higher) on the grades 3

and 4 State assessments in ELA and math in both third and fourth grade.

Underlying these average scores lies a continuum moving from scores signifying

no mastery of grade-level learning objectives to perfect test performance.

Most of the 705 schools had student enrollments that did not reflect the City’s ethnic and

economic diversity; rather their enrollments were drawn primarily from one or two

ethnic groups and families with similar income levels. Schools varied widely on

demographic indicators, on teacher qualifications, and in attendance rate and

performance. (See “School Profiles” for details.)

20

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

UÊ In half of study schools, 90 percent or more of fourth-graders were Native

American, Black, or Hispanic. In contrast, in 19 schools at least 90 percent were

White or Asian.

UÊ Schools diverged demographically: 5 enrolled no students with disabilities; 44 no

English language learners. In seven schools, all fourth-graders were continuously

enrolled; in six, none was continuously enrolled. In 219 schools, all fourth-

graders were eligible for free- and reduced-price lunches; in one school at the

other extreme fewer than four percent were eligible.

UÊ Attendance patterns varied among schools. School mean attendance in 2006-07

and 2007-08 ranged from 88.1 to 98.8 percent. In the seven schools with the

lowest attendance, students, on average, attended only 88 percent of enrolled

school days in 2006-07 and 2007-08. These students missed about 22 days in the

185-day school year. In the four schools with the highest average attendance,

students, on average, attended 98 percent of enrolled schools days, missing no

more than four days. Students in the highest-attendance schools received 18

additional days of instruction compared with those in the lowest-attendance

schools.

UÊ Similarly, rates of chronic absence varied among schools. In seven schools, no

fourth-grader was chronically absent; in the school with the highest rate of

chronic absence, 51.8 percent of fourth-graders attended school fewer than 90

percent of enrolled days in third and fourth grades; that is, they missed more

than 18 days in a 185-day school year. In more than three quarters (539) of the

705 study schools, at least 10 percent of fourth-graders were chronically absent.

UÊ Schools showed a range of performance on the State ELA and math assessments.

In schools with the lowest performance on the ELA assessment, the average

student barely scored at Level 2, indicating very limited achievement of the

learning standards; in the highest-performing schools, the average student

scored at Level 4. Students, on average, performed better on the mathematics

than the ELA assessment, but the range of performance among schools was

almost as great in mathematics as in ELA.

These differences among schools predict differences in attendance and performance.

(See “Attendance and Performance at the School Level” for details).

UÊ Demographic variables are significantly correlated with attendance at the school

level: larger percentages of fourth-graders who were eligible for free- and

reduced-priced lunches; who were Native American, Black, or Hispanic; and who

were classified as disabled are associated with lower attendance rates. Larger

percentages of students who were continuously enrolled are associated with

higher attendance.

21

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS

UÊ The percentages of teachers without appropriate certification, the percentage

without three years’ experience, and the teacher turnover rate each have small

but highly significant negative associations with school attendance. As each

measure increased, school attendance decreased. The percentage of teachers

with a master’s degree plus at least 30 credit hours is significantly associated

with higher attendance.

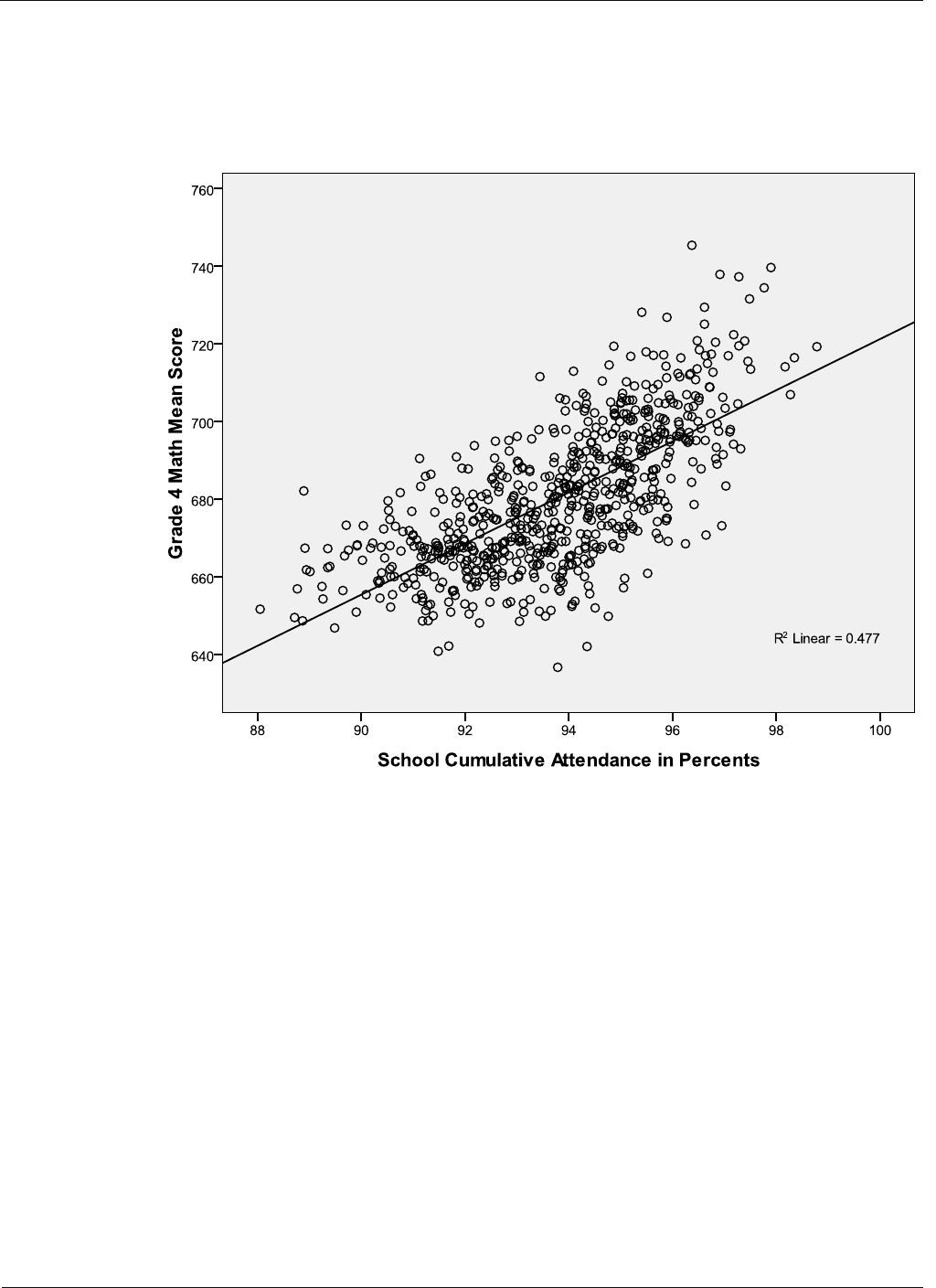

UÊ Both school mean attendance in 2006-07 and 2007-08 and the percentage of

chronically absent students have moderate correlations with mean scaled scores

on the grades 3 and 4 assessments in ELA and mathematics. As average school

attendance increased, performance improved. As the percentage of chronically

absent students increased, school performance declined.

UÊ When schools are ranked according to attendance and divided on attendance

into five groups of equal size, the groups differ significantly on fourth-grade

performance even when third-grade performance is accounted for. The group

with the highest attendance, achieved an unadjusted mean grade 4 ELA score 32

points higher—and a mean grade 4 math score 35 points higher—than the group

with the lowest attendance.

22

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

STUDENT PROFILES

T

hese profiles reveal the diversity of fourth-graders in New York City

Public Schools. Table 3 shows the demographic profiles of 64,062

fourth-graders in 2007-08. The largest ethnic group was Hispanic

(40.4 percent), followed by Black (30.6 percent). The smallest group—with

only 0.4 percent of study group enrollment—was Alaskan Native or Native

American. In later analyses these three ethnic groups were combined and

referred to as the minority group. White and Asian students together made

up 28.5 percent of the study group,

3

which included slightly fewer females

than males.

A great majority of fourth-graders came from low-income families; 85

percent were eligible for free- or reduced-price lunches. In fourth grade, 18

percent were classified as disabled and 15.2 percent were limited English

proficient. Over 87 percent were continuously enrolled in the same school

from October 31, 2006 through the end of the 2007-08 school year. Eighteen

(18) percent—over 11,000 students—were chronically absent; that is, they

attended school for fewer than 90 percent of enrolled school days in 2006-07

and 2007-08—they missed the equivalent of at least 19 days in a 185-day

school year.

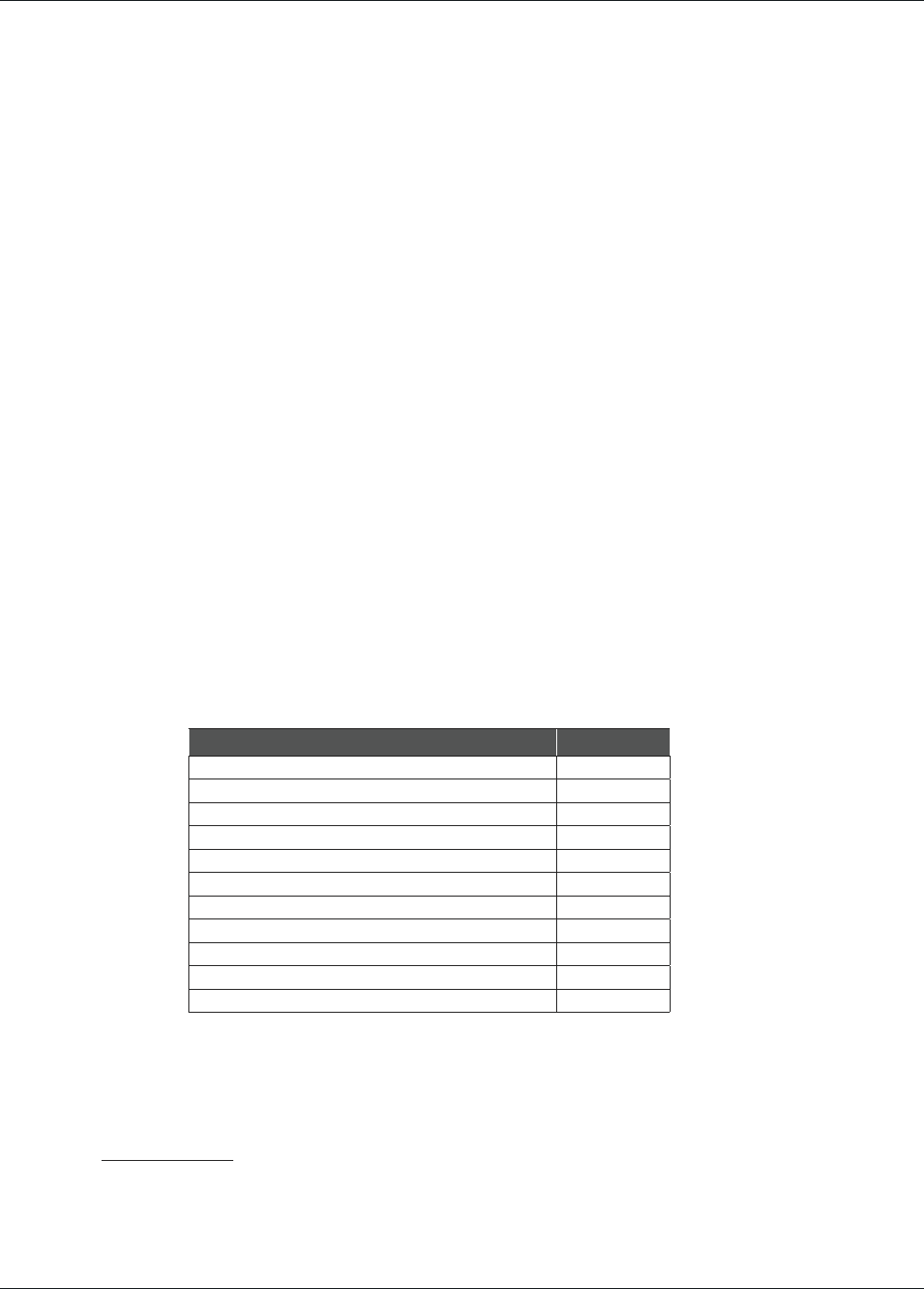

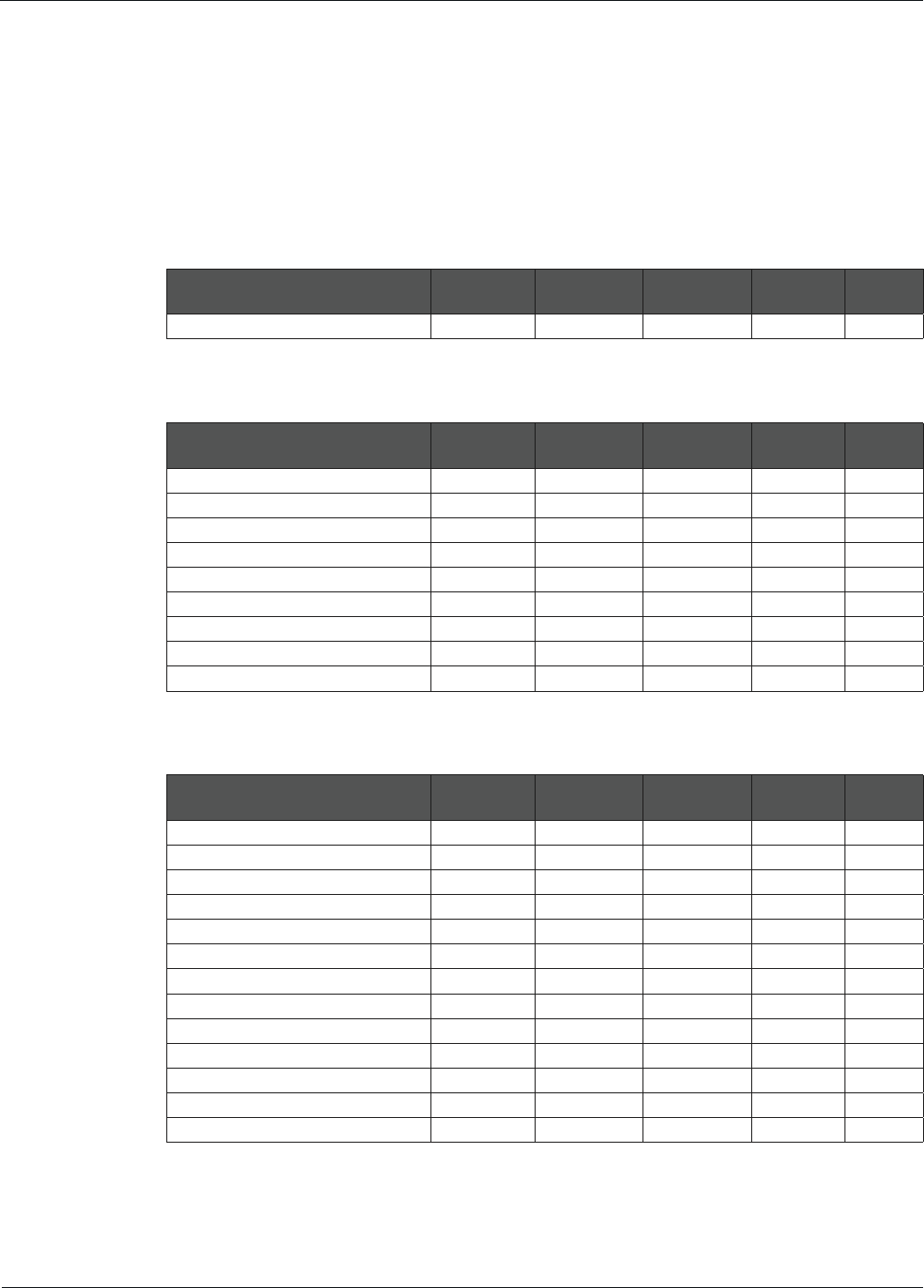

TABLE 3

Demographic Profile of 64,062 Fourth-Grade Students in 2007-08

STUDENT CHARACTERISTIC PERCENT

Native American 0.4%

Black 30.6%

Hispanic 40.4%

Asian 14.0%

White 14.5%

Female 49.5%

FRPL Eligible 85.0%

Students with Disabilities 18.0%

Limited English Proficient 15.2%

Continuously Enrolled 87.3%

Chronically Absent 18.0%

3 All but seven students were identified by DOE as belonging to a single ethnic category as, in compliance with federal

regulations, the State Education Department did not require the multi-racial classification in the 2007-08 school year.

In total, records for 52 students did not have a useable ethnic identity.

Student Profiles

23

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

STUDENT PROFILES

Table 4 shows the mean 2006-07 and 2007-08 attendance rates of students in the study

sample. It also shows their mean cumulative attendance for the two school years. Mean

attendance in 2007-08 was 0.4 percentage points higher than in 2006-07.

TABLE 4

Attendance Profile of 2007-08 Fourth-Grade Students

ATTENDANCE MEAN

STANDARD

DEVIATION

2006-07 93.7% 5.99%

2007-08 94.1% 5.80%

Cumulative 93.9% 5.51%

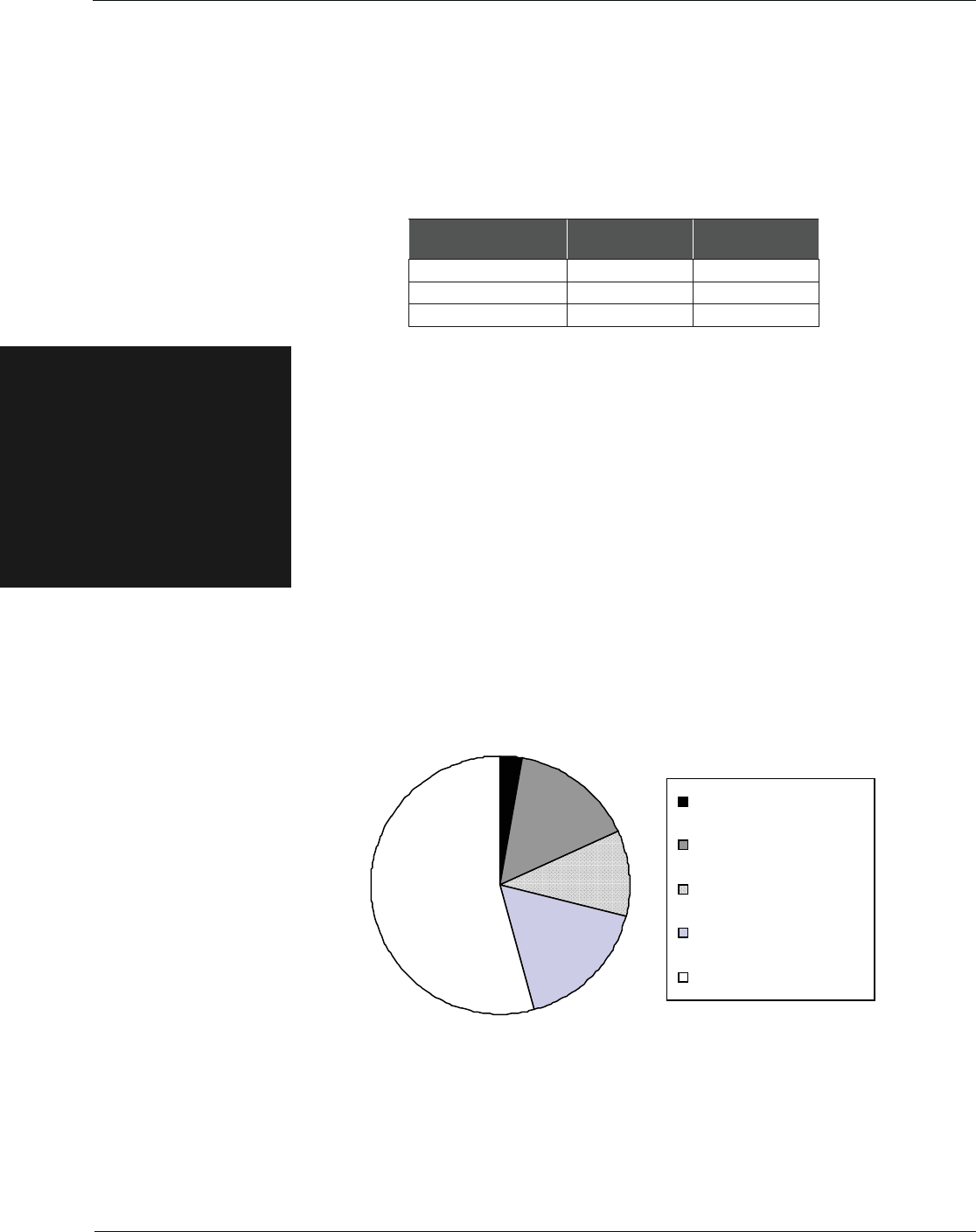

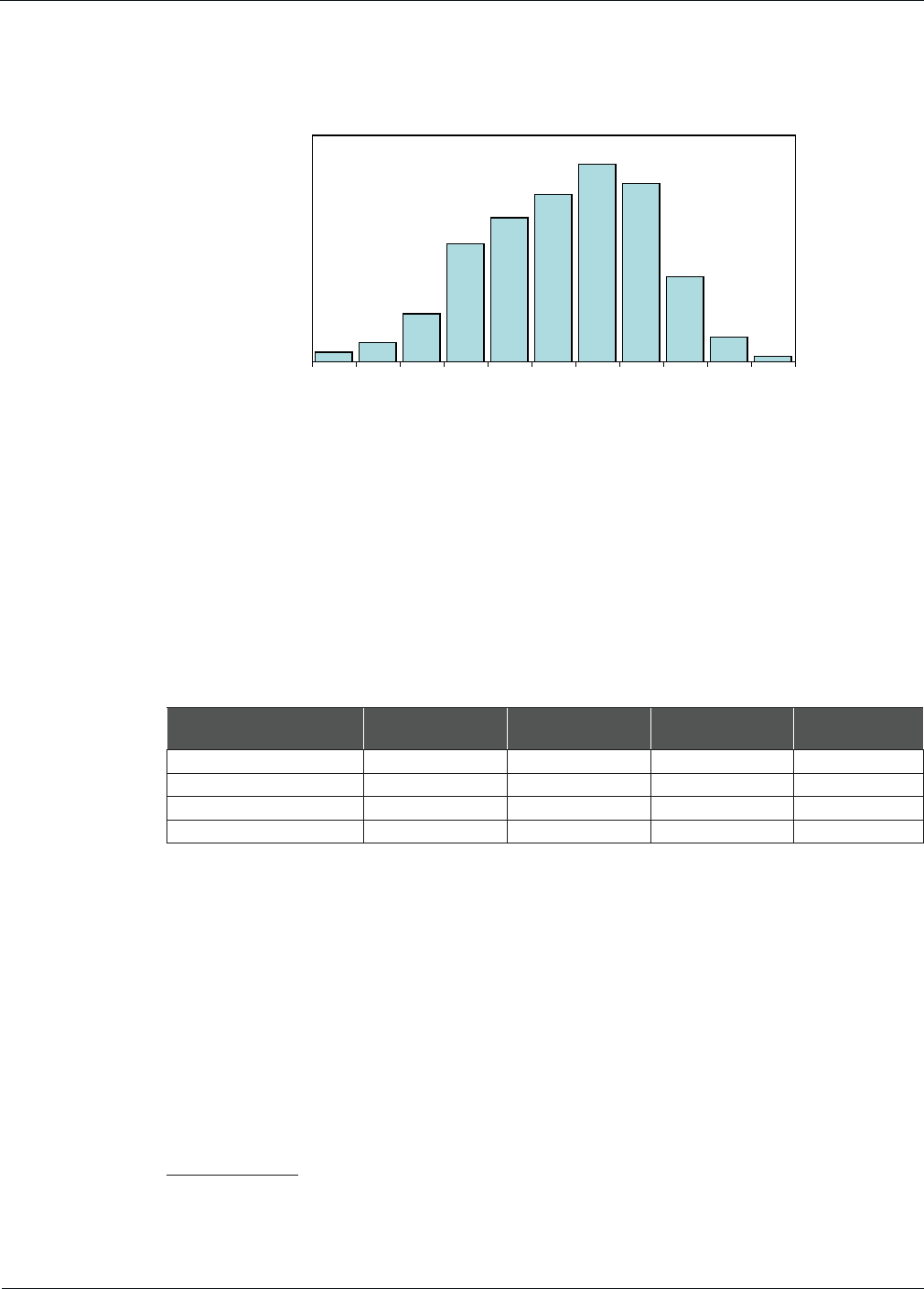

Figure 1 shows the percentage of students at each of five levels of attendance,

ranging from severe chronic absence to good attendance. Three percent of

fourth-graders (1,821 students) had severe attendance problems; they attended

fewer than 80 percent of enrolled days—fewer than 148 days in a 185-day

school year. One student attended only 44 percent of school days in grades 3

and 4. The remaining group of chronically absent students (9,714 students)

attended at least 80 percent—but fewer than 90 percent—of school days. The

third group attended fewer than 92.5 percent of school days; these 7,018

students were not chronic absentees but their low attendance may have

compromised their performance. The fourth group (10,759 students) attended

at least 92.5 but fewer than 95 percent of school days. The final and largest

group, 54.3 percent of fourth-graders (34,763 students) attended school regularly—at

least 95 percent of enrolled days.

FIGURE 1

The Percentage of Students at Each Attendance Level

11%

17%

54%

3%

15%

Less+than+80+percent

80.00+to+89.99+percent

90.00+to+92.49+percent

92.50+to+94.99+percent

95.00+percent+or+higher

THE STANDARD DEVIATION (SD)

measures the variation of values

around the mean value. A small

SD indicates that values tend to

be close to the mean, while a

large SD indicates that the values

are spread over a larger range.

24

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

STUDENT PROFILES

Table 5 reports the mean scaled score achieved by study students on the State

assessments in ELA and mathematics in third and fourth grades. On each test, the

average student scored at the proficient level, 650 or above. In both grades, mean

mathematics scores were substantially higher than mean ELA scores. Note that the

percentages of students meeting the proficiency standards increased substantially

statewide in 2008 and 2009, leading the Board of Regents to raise standards on the 2010

tests. The rationale for this decision is described in the Discussion.

4

TABLE 5

Performance Profile of 2007-08 Fourth-Grade Students

ASSESSMENT

MEAN SCALED

SCORE

STANDARD

DEVIATION

NUMBER

TESTED

Grade 3 ELA (2006-07) 658.8 39.7 62,651

Grade 3 Math (2006-07) 685.8 37.4 63,919

Grade 4 ELA (2007-08) 658.2 39.3 63,778

4

Grade 4 Math (2007-08) 681.0 38.5 64,944

STUDENT PROFILES BY ETHNICITY

Ethnic groups varied substantially in the prevalence of disability, limited English

proficiency, and eligibility for free- and reduced-price lunches. Table 6 shows that White

students were less likely than others to be eligible for free- or reduced-price lunches

(FRPL Eligible

), 52.6 percent compared with 85.0 percent of all students. Asian students

were less likely than other students to be classified as disabled; only 7.5 percent of

Asians were classified compared with 18.0 percent of all fourth-graders. Hispanic

students were more likely than others to be limited English proficient; more than a

quarter of Hispanic students were so identified. The Asian group had the second highest

prevalence of limited English proficient students; 16.9 percent.

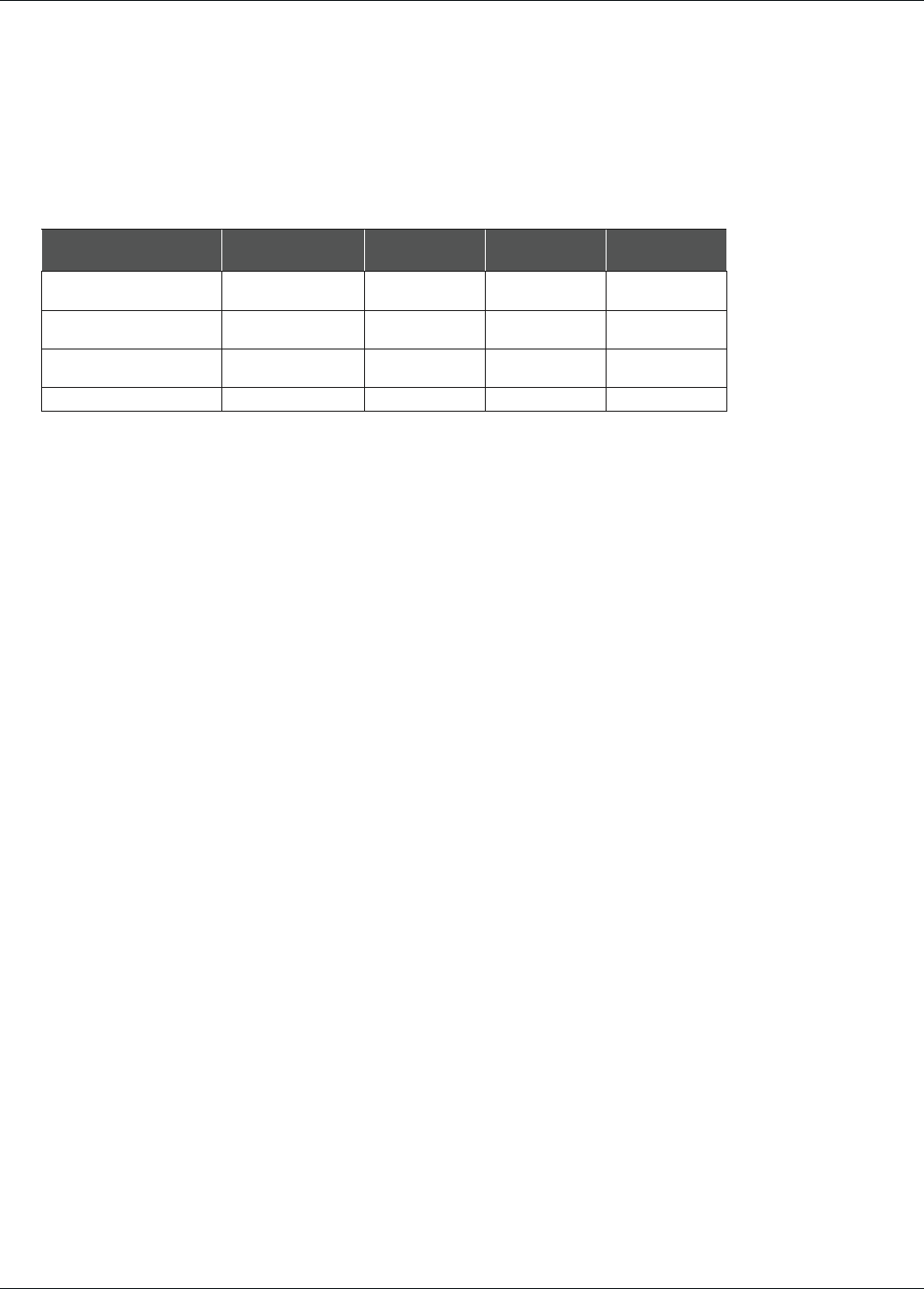

TABLE 6

The Incidence of Free- and-Reduced-Price-Lunch Eligibility, Disability, and

Limited English Proficiency among 2007-08 Fourth-Graders by Ethnic Group

ETHNIC GROUP NUMBER

FRPL ELIGIBLE

STUDENTS WITH

DISABILITIES

LIMITED ENGLISH

PROFICIENT

NUMBER PERCENT NUMBER PERCENT NUMBER PERCENT

Native American 253 224 88.5% 63 24.9% 22 8.7%

Asian 8,993 7,613 84.7% 675 7.5% 1,517 16.9%

Black 19,575 17,497 89.4% 3,706 18.9% 470 2.4%

Hispanic 25,894 24,216 93.5% 5,480 21.2% 7,187 27.8%

White 9,295 4,886 52.6% 1,601 17.2% 544 5.9%

All Students 64,062 54,472 85.0% 11,528 18.0% 9,742 15.2%

4 The increase in the number of students tested in 2008 compared with 2007 can be accounted for by the revised No Child Left Behind

requirement to test limited English proficient students with fewer years of English instruction.

25

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

STUDENT PROFILES

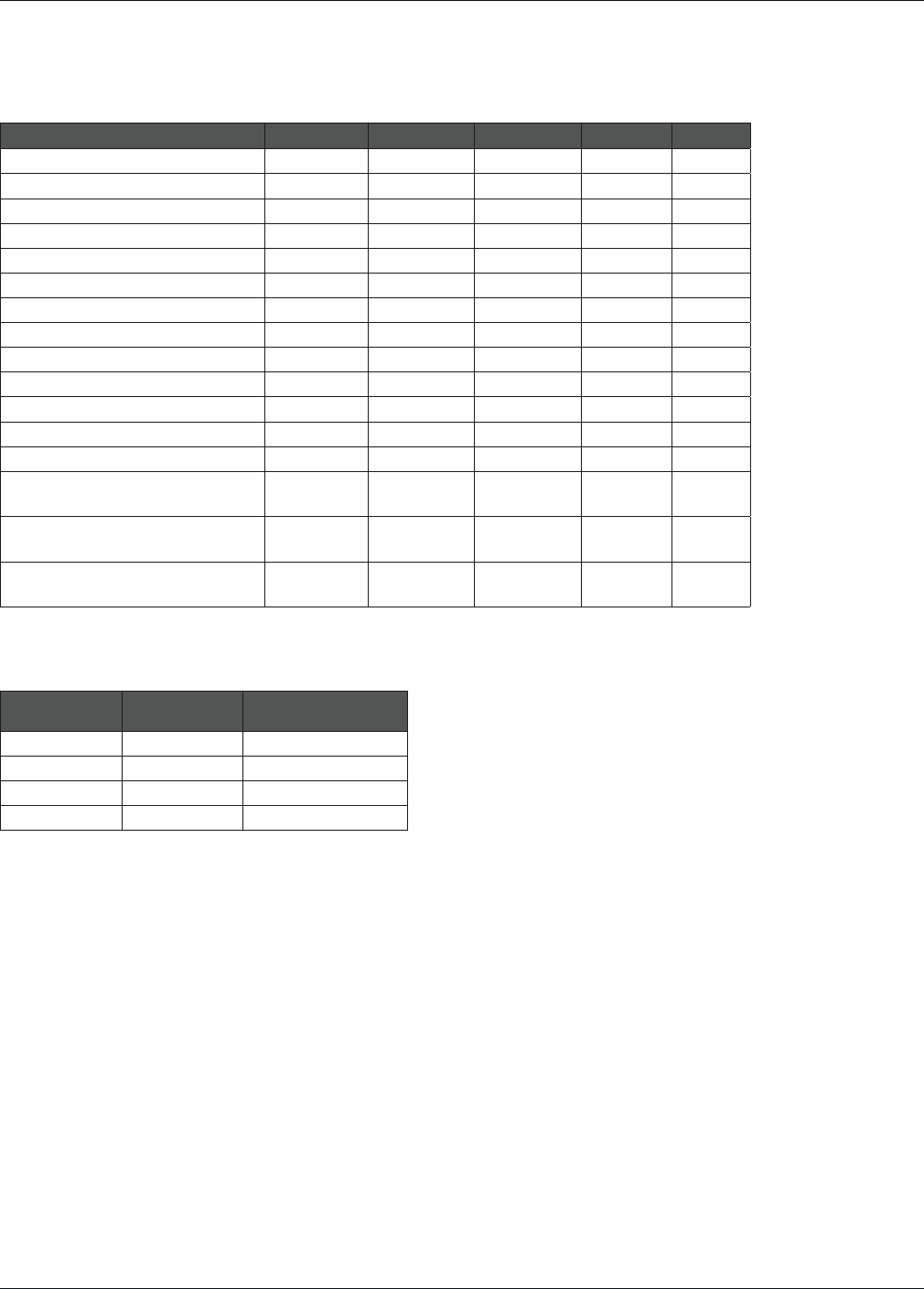

Table 7 shows differences among ethnic groups in the percentage of fourth-graders who

were continuously enrolled in the same school from fall 2006 until the end of the 2007-

08 school year. White students were most likely—and Black students least likely—to be

continuously enrolled.

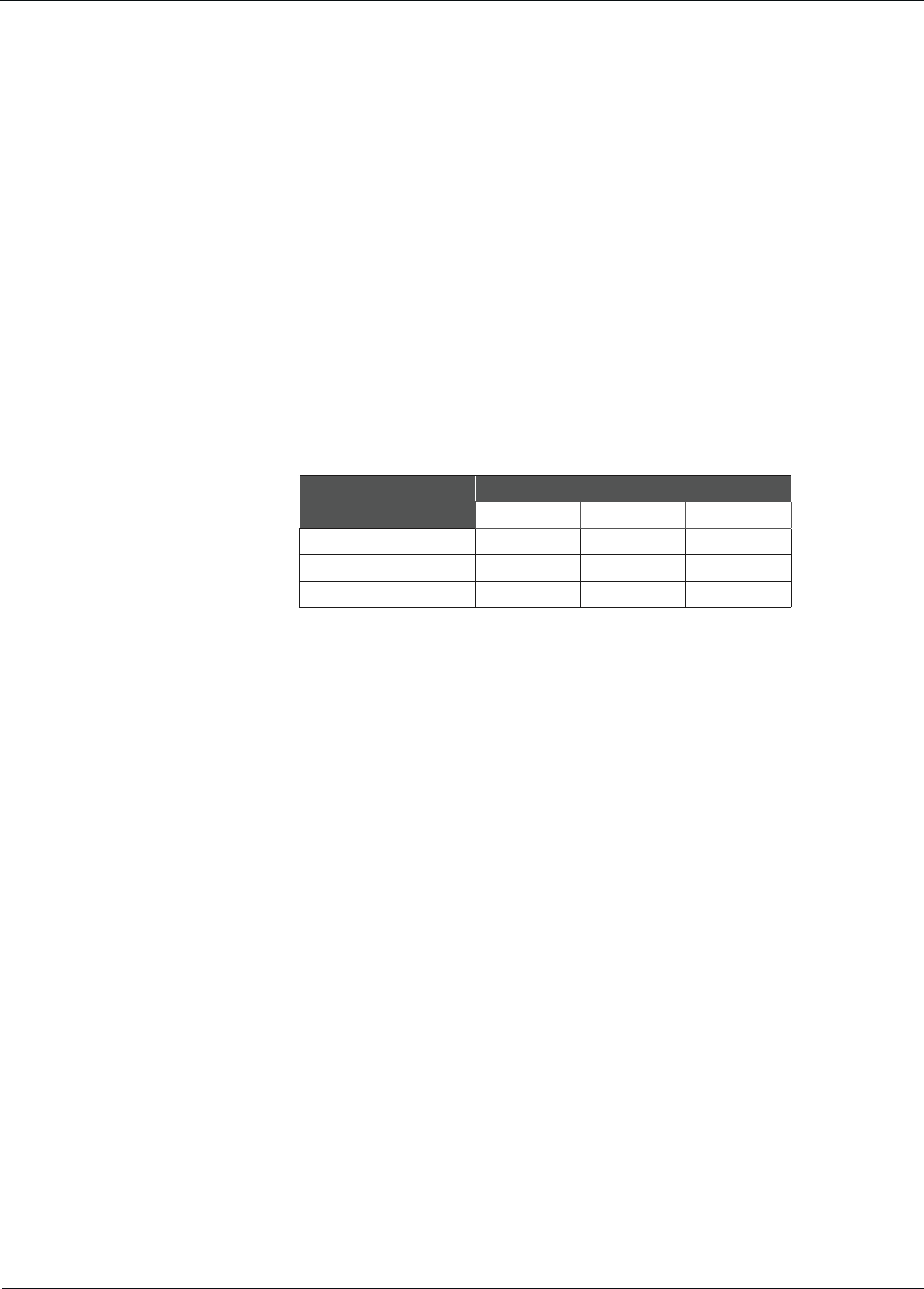

TABLE 7

The Number and Percentage of Continuously

Enrolled Fourth-Graders by Ethnic Group

ETHNIC GROUP

CONTINUOUSLY ENROLLED

NUMBER PERCENT

Native American 225 88.9%

Asian 8,067 89.1%

Black 16,470 84.1%

Hispanic 22,472 86.8%

White 8,675 93.3%

All Students 55,955 87.3%

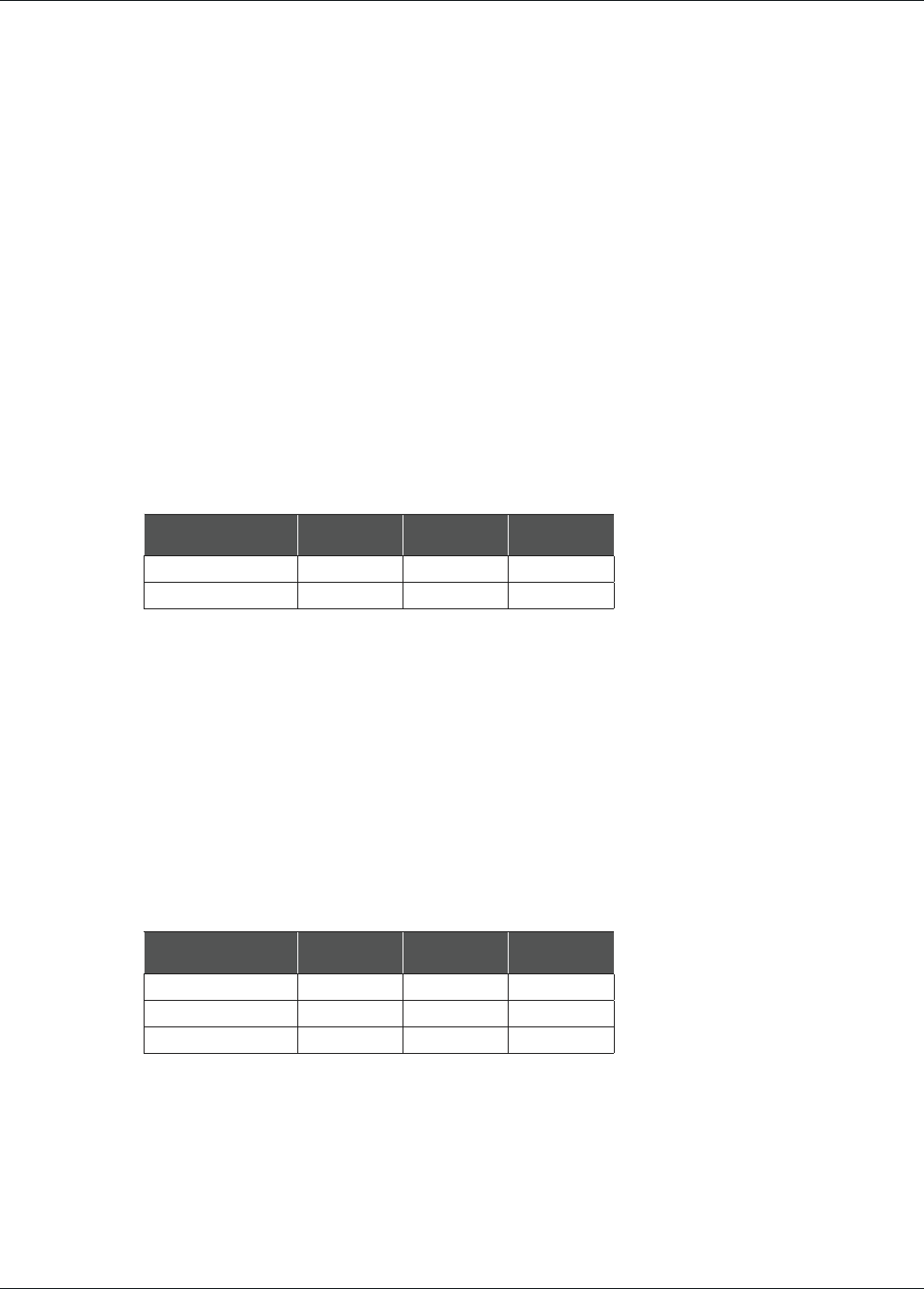

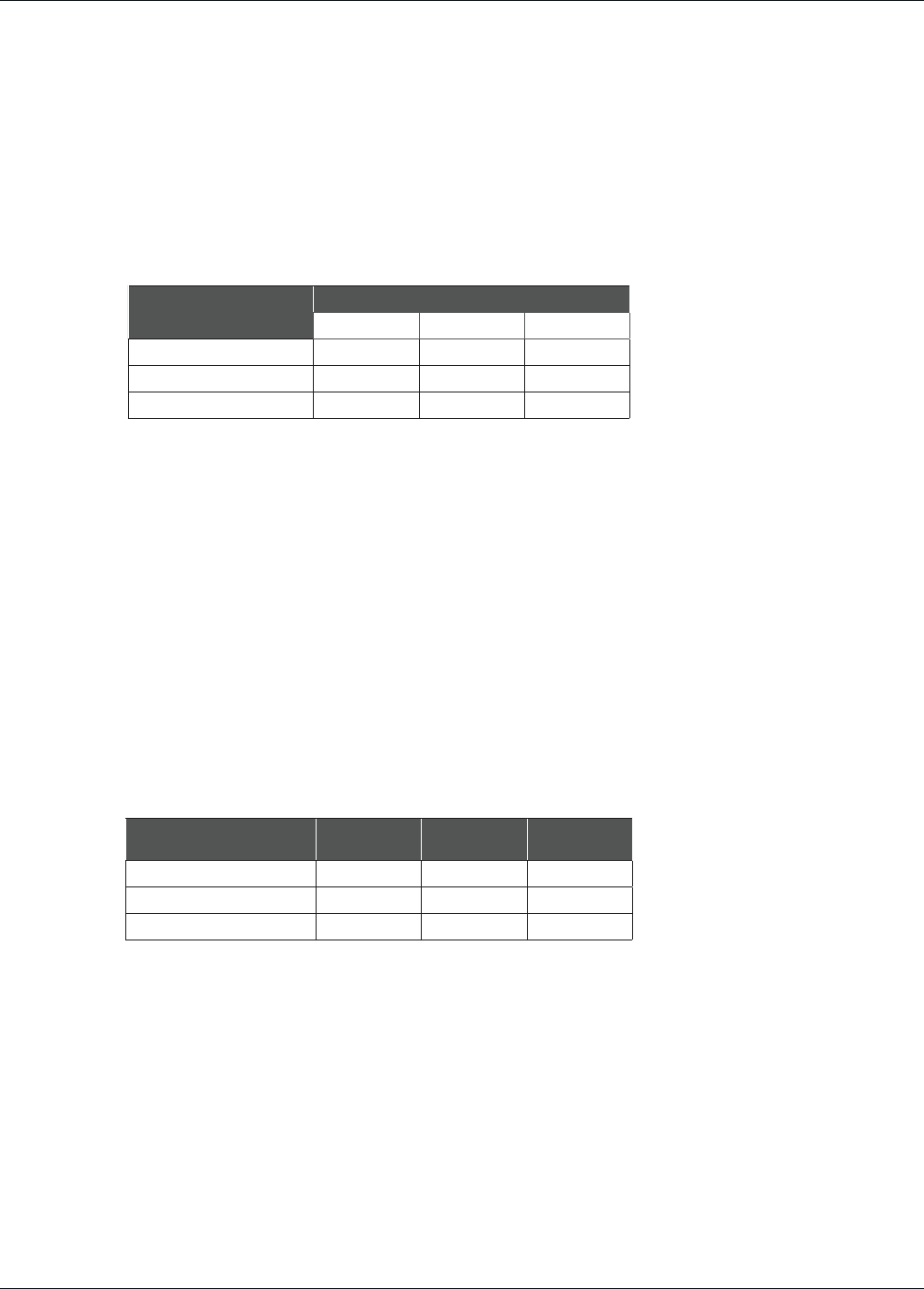

Students of different ethnic backgrounds had different attendance patterns (Table 8).

Asian students had the highest mean and median cumulative attendance and were least

likely to be chronically absent. Half of Asian students attended school at least 98.1

percent of school days. Native American, Black, and Hispanic students were five times as

likely as Asian students and almost twice as likely as White students to be chronically

absent. The Black student group included the largest percentage of students who were

chronically absent. This being said, many students in each ethnic group attended school

regularly. While more than one-fifth of Black and Hispanic students were chronically

absent, almost half (48 percent) of each group attended school regularly; that is, they

were present on 95 percent of enrolled days. While almost one quarter of Native

American students were chronically absent, more than half attended at least 95 percent

of enrolled days.

TABLE 8

Student Attendance in 2006-07 and 2007-08 by Ethnic Group

ETHNIC

GROUP

COUNT

CUMULATIVE ATTENDANCE 2006-07 AND 2007-08

MEAN MEDIAN

NUMBER 95

PERCENT

OR ABOVE

PERCENT

95 PERCENT

OR ABOVE

NUMBER

CHRONICALLY

ABSENT

PERCENT

CHRONICALLY

ABSENT

Native

American

253 93.3% 95.1% 131 51.8% 63 24.9%

Asian 8,993 96.9% 98.1% 7,279 80.9% 381 4.2%

Black 19,575 93.0% 94.8% 9,398 48.0% 4,477 22.9%

Hispanic 25,894 93.3% 94.8% 12,450 48.1% 5,473 21.1%

White 9,295 94.7% 95.8% 5,486 59.0% 1,114 12.0%

All Students 64,062 93.9% 95.4% 34,763 54.3% 11,522 18.0%

26

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

STUDENT PROFILES

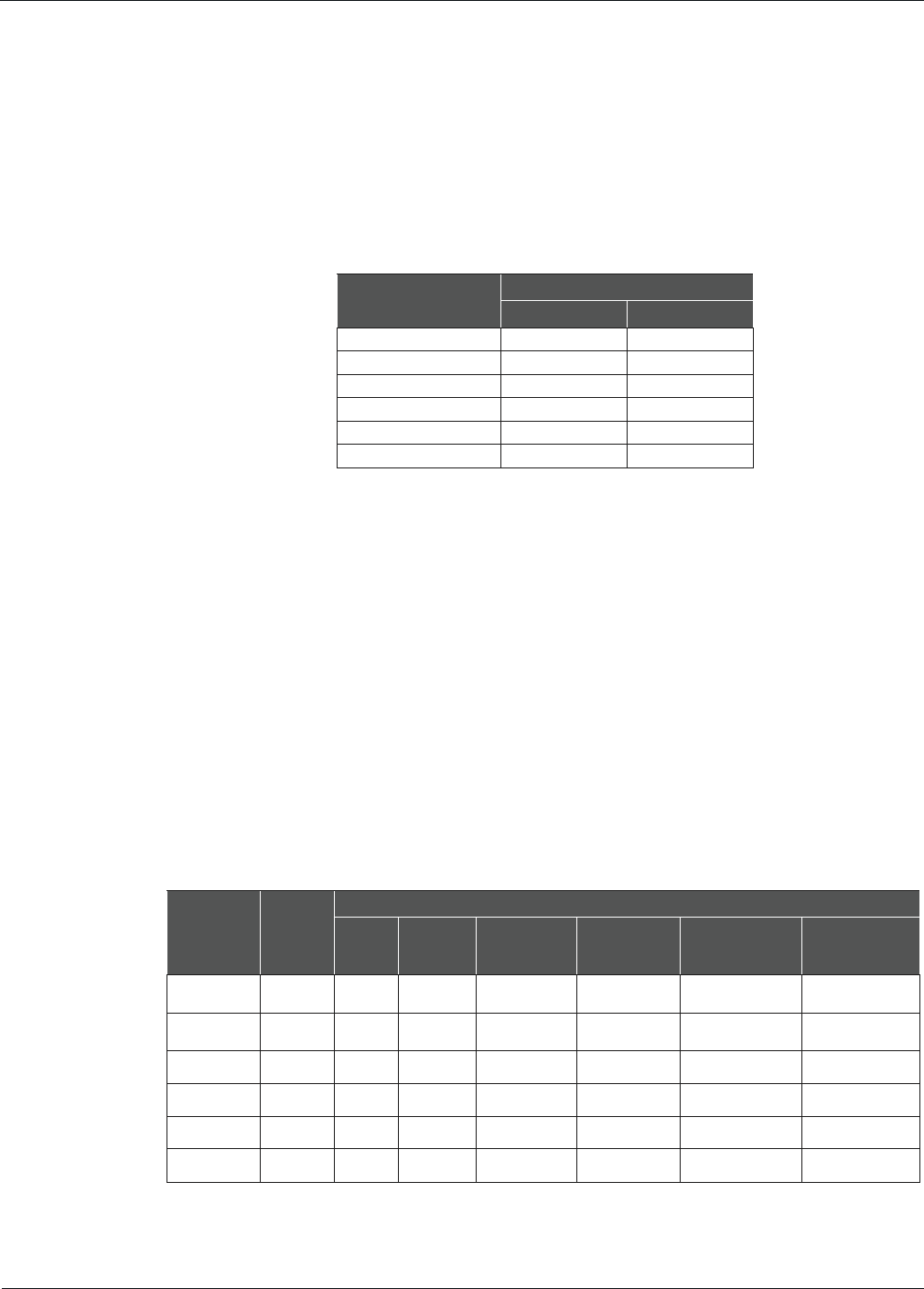

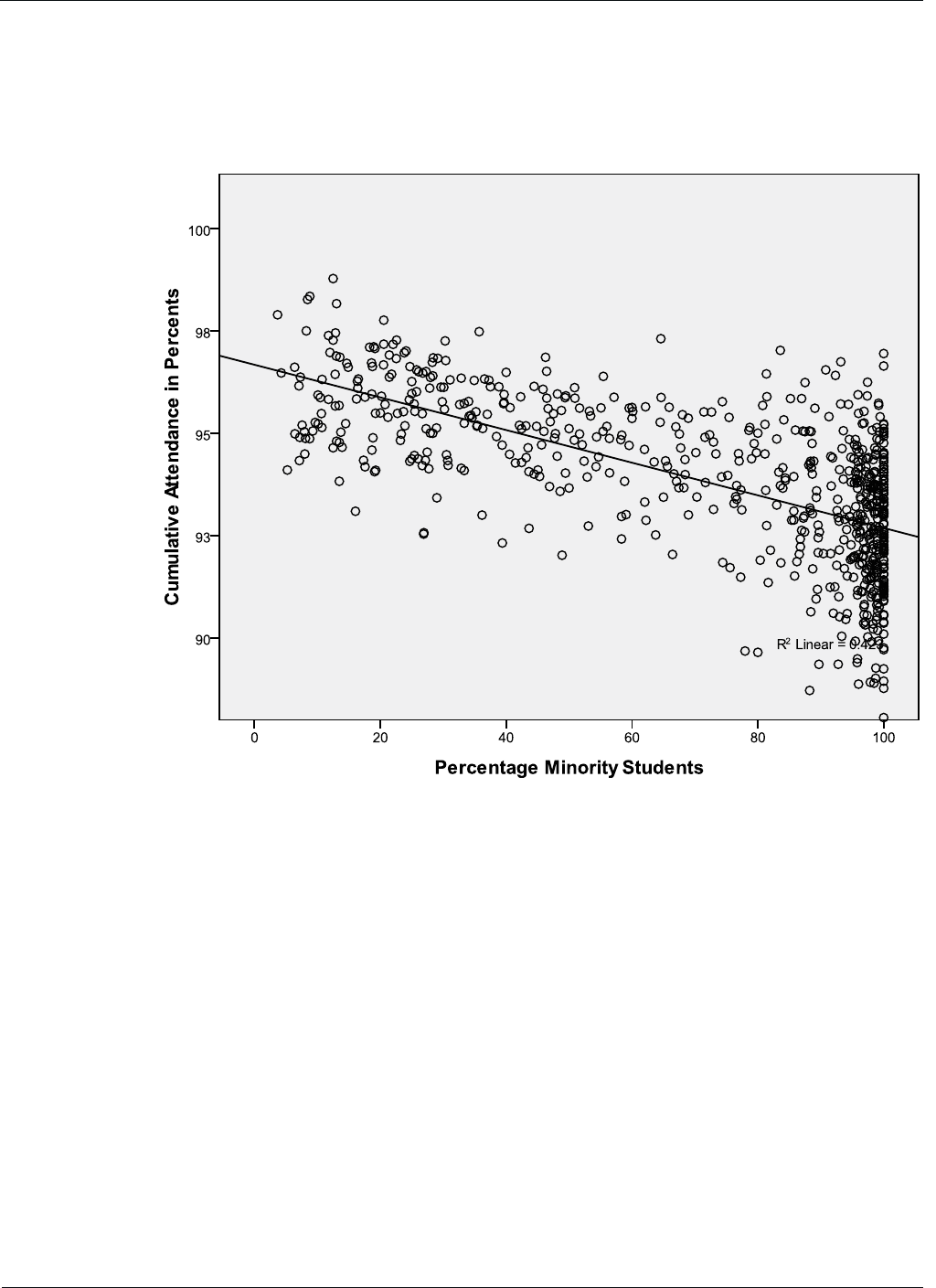

Figure 2 graphically displays the differences in average attendance between students who

are White and Asian and students who are Black, Hispanic, and Native American. White

and Asian students were more likely to attend school regularly—at least 95 percent of

school days—and less likely to be chronically absent than other ethnic groups.

FIGURE 2

Comparison of Attendance Patterns of Students Who Are White or

Asian with Students Who Are Black, Hispanic, or Native American

Asian and White Students Black, Hispanic and Native American Students

8%

22%

70%

22%

30%

48%

95% or higher 90–95% Less than 90%

On average, Hispanic, Black, and Native American students achieved similar scores on the

grades 3 and 4 ELA and mathematics assessments (Figure 3).

5

Their mean scores on each

assessment were 25 to 35 points lower than those of Asian and White students. With the

exception of Asian students, the average score of each ethnic group was lower in fourth

than third grade. The improving scores of Asian students may reflect the increasing

English proficiency of students who began kindergarten as English language learners.

FIGURE 3

Grade 3 (2006-07) and Grade 4 (2007-08) School Mean Scaled Scores

Grade&3&ELA

652.3

675.5

652.5

649.8

680.9

658.8

Native

American

Asian Black Hispanic White All

Students

Grade&4&ELA

648.4

676.9

651.5

649.5

678.7

658.2

Native

American

Asian Black Hispanic White All

Students

Grade&3&Math

678.5

707.2

677.8

678.6

702.1

685.8

Native

American

Asian Black Hispanic White All

Students

Grade&4&Math

673.2

708.1

670.4

673.1

699.4

681.0

Native

American

Asian Black Hispanic White All

Students

5 Performance levels and corresponding score ranges are shown on page 13.

27

Taking Attendance Seriously: How School Absences Undermine Student and School Performance in New York City

SCHOOL PROFILES

Our examination of schools shows that the enrollment in many schools was not

representative of the demographic, performance, and attendance profiles of the fourth-