Project Report

Attitudes and Trust in Leveraging Integrated Sociotechnical

Systems for Enhancing Community Adaptive Capacity: Phase III

Anticipated Willingness to Share Resources in a Disaster Scenario: The Role

of Attitudinal Variables

Prepared for Teaching Old Models New Tricks (TOMNET) Transportation Center

BY,

Katherine Idziorek

Cynthia Chen

Daniel B. Abramson

Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering

Department of Urban Design & Planning

University of Washington

Seattle, WA 98105

December 2020

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE .................................................................. 4

DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................ 5

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................. 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 6

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 7

Research questions .................................................................................................................. 7

LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................................... 8

Willingness to share in a disaster scenario ............................................................................. 8

Place attachment and disaster preparedness ........................................................................... 9

REGIONAL DISASTER PREPAREDNESS CONTEXT AND STUDY SITE .......................... 10

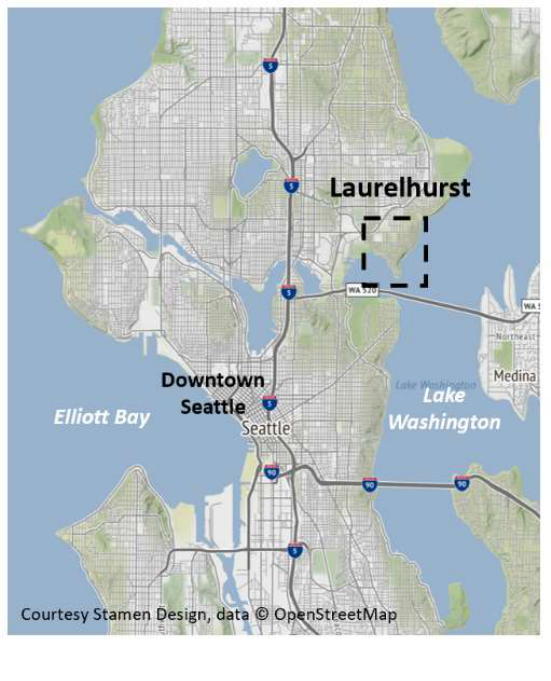

Study site: Laurelhurst .......................................................................................................... 10

METHODS ................................................................................................................................... 12

Community engagement ....................................................................................................... 12

Sample survey ....................................................................................................................... 13

ANALYSIS & FINDINGS ........................................................................................................... 14

Factors affecting disaster preparedness ................................................................................ 15

Attitudes and willingness to share ........................................................................................ 15

Level of concern, preparedness, and anticipated willingness to share transportation

resources ............................................................................................................................... 16

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................................ 17

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................. 19

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Laurelhurst community demographics ........................................................................................ 14

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for key variables ......................................................................................... 16

Table 3. Correlations among key variables (Pearson's r) ........................................................................... 18

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Study neighborhood location ...................................................................................................... 13

Figure 2. Average level of concern about completing everyday activities in an earthquake scenario ...... 19

Figure 3. Average level of preparedness with essential resources .............................................................. 19

Figure 4. Average willingness to share essential resources ........................................................................ 20

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE

1. Report No.

N/A

2. Government Accession No.

N/A

3. Recipient's Catalog No.

N/A

4. Title and Subtitle

Attitudes and Trust in Leveraging Integrated Sociotechnical Systems for

Enhancing Community Adaptive Capacity: Phase III

Anticipated Willingness to Share Resources in a Disaster Scenario: The

Role of Attitudinal Variables

5. Report Date

December 2020

6. Performing Organization Code

N/A

7. Author(s)

Katherine Idziorek, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8130-0536

Cynthia Chen, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1110-8610

Daniel B. Abramson, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5070-8619

8. Performing Organization Report No.

N/A

9. Performing Organization Name and Address

University of Washington

PO Box 352700

Seattle, WA 98195

10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS)

N/A

11. Contract or Grant No.

69A3551747116

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address

U.S. Department of Transportation,

University Transportation Centers Program,

1200 New Jersey Ave, SE, Washington, DC 20590

13. Type of Report and Period Covered

Research Report

(2019 – 2020)

14. Sponsoring Agency Code

USDOT OST-R

15. Supplementary Notes

N/A

16. Abstract

Current work in the area of resource sharing for disaster response and recovery assumes a top- down, centralized

perspective. This study addresses a gap in knowledge about how resources might be shared among community members

when a centralized supply of resources is not available, as might occur in a large-scale event such as a Cascadia

Subduction Zone earthquake. In the case of such a disaster, community members’ willingness to share resources with

one another could contribute to the relative success or failure of communities to be locally self-sufficient if required. This

research draws upon data gathered from a community-scale sample survey set in the Pacific Northwest, a region in which

earthquakes are a certain, though largely unpredictable, hazard. In order to better understand the potential for resource

sharing among community members in the event of an earthquake, we analyze three attitudinal variables related to both

actual disaster preparedness and anticipated willingness to share: level of concern about disasters, place attachment, and

trust. Our findings reveal a negative association between level of concern and actual disaster preparedness, while

willingness to share is most strongly influenced by trust. Additional observed relationships between trust, place

attachment, and community social network size suggest a need for further research in this area. Better understanding

willingness to share and available resources at the community level can help to inform both grassroots efforts and more

formal disaster preparedness organizations regarding targeted interventions for improving disaster preparedness.

17. Key Words

Community Resilience, Sample Survey, Disaster Preparedness, Resource

Sharing, Social Networks

18. Distribution Statement

No restrictions.

19. Security Classif.(of this report)

Unclassified

20. Security Classif.(of this page)

Unclassified

21. No. of Pages

32

22. Price

N/A

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72)

Reproduction of completed page authorized

5

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and

the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated in the interest of

information exchange. The report is funded, partially or entirely, by a grant from the U.S.

Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program. However, the U.S.

Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by a grant from A USDOT Tier 1 University Transportation Center,

supported by USDOT through the University Transportation Centers program. The authors would

like to thank the Center for Teaching Old Models New Tricks (TOMNET) and USDOT for their

support of university-based research in transportation, and especially for the funding provided in

support of this project. TOMNET is focused on advancing the state of the art and the state of the

practice in measuring and understanding traveler attitudes, values, perceptions, and preferences,

and using such data to improve the ability of travel demand forecasting models to predict activity-

travel behavior, mobility choices, and time use patterns under a wide variety of future scenarios.

This project is also supported by volunteers from Laurelhurst Earthquake Action

Preparedness (LEAP) and from the City of Westport, who helped to guide the survey development

by providing community-based perspectives on the research approach.

The team would also like to acknowledge and thank the following additional reviewers:

Patricia Mokhtarian, Georgia Tech Civil and Environmental Engineering; Vicki Sakata, Northwest

Healthcare Response Network ; Carina Elsenboss, Seattle & King County Public Health; John

Scott, University of Washington Telehealth; Maximilian Dixon, Washington State Military

Department Emergency Management Division; Matt Auflick, City of Seattle Office of Emergency

Management; Stephen Burges, University of Washington Department of Civil and Environmental

Engineering; Xiangyang Guan, University of Washington Department of Civil and Environmental

Engineering.

6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Current work in the area of resource sharing for disaster response and recovery assumes a top-

down, centralized perspective. This study addresses a gap in knowledge about how resources might

be shared among community members when a centralized supply of resources is not available, as

might occur in a large-scale event such as a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake. In the case of

such a disaster, community members’ willingness to share resources with one another could

contribute to the relative success or failure of communities to be locally self-sufficient if required.

This research draws upon data gathered from a community-scale sample survey set in the Pacific

Northwest, a region in which earthquakes are a certain, though largely unpredictable, hazard. In

order to better understand the potential for resource sharing among community members in the

event of an earthquake, we analyze three attitudinal variables related to both actual disaster

preparedness and anticipated willingness to share: level of concern about disasters, place

attachment, and trust. Our findings reveal a negative association between level of concern and

actual disaster preparedness, while willingness to share is most strongly influenced by trust.

Additional observed relationships between trust, place attachment, and community social network

size suggest a need for further research in this area. Better understanding willingness to share and

available resources at the community level can help to inform both grassroots efforts and more

formal disaster preparedness organizations regarding targeted interventions for improving disaster

preparedness.

7

INTRODUCTION

In a disaster response and recovery context, most of the current work on resource sharing assumes

a top-down, centralized approach to resource allocation. There is a gap in knowledge in terms of

how to share resources among community members when resources are not at a centralized

location, but at community members’ private locations, such as homes. In this context, community

members’ willingness to share becomes an important factor for exploration. Willingness to share

becomes especially relevant given the isolating effects of many types of disasters on communities

and the subsequent need for localized self-sufficiency. It is also important given the diversity and

potential complementarity among households in terms of the resources they possess.

In this study, the authors address this knowledge gap. We specifically explore the role that

attitudinal factors play in anticipated willingness to share resources, and we compare willingness

to share transportation resources with that of other resources needed to meet people’s everyday

essential needs. We focus on attitudes that relate to disaster preparedness (level of concern about

disasters), community social relationships (trust), and relationship to place (place attachment) in

order to better understand what kinds of community-scale interventions could help to support

disaster preparedness in specific contexts. This research builds upon a previous pilot project

investigating willingness to share and social ties in the same study community (1).

Using data gathered from a community-scale sample survey, we aim to better understand

context-specific needs so as to help inform community-based disaster preparedness efforts. Our

motivation for working at the community scale is driven in large part by the anticipation of a large

seismic event in the Pacific Northwest. In the case of such an event, communities will likely be on

their own for an extended period of time with limited ability to carry out everyday activities, and

they may need to rely on local resources for meeting basic needs. The community scale is also

relevant because many government-led disaster preparedness campaigns target the individual or

household level and do not address preparedness actions that people might take collectively to

prepare their community for disaster.

We look specifically at the findings related to transportation resources. Society relies upon

a functional and resilient transportation systems to support the ability of individuals to meet their

everyday needs. The uncertain and unpredictable impacts of disasters can leave the transportation

infrastructures that supports basic societal functions damaged or non-functioning (2), and

transportation systems are vulnerable to a range of disaster types, including natural hazards,

technological failures, and terrorism (3). If the road network and public transit are compromised

in the event of a disaster, community members could play an important role in supporting

collective mobility at the local scale.

Clear gaps exist in the understanding of social behavioral responses to resource scarcity in a

disaster scenario, including resource-sharing within communities (4). This study contributes to

advancing this exploration by focusing in more detail on anticipated willingness to share specific

types of disaster resources. The findings can be applied practically by disaster preparedness

planners and community-based organizations seeking to prioritize the distribution or development

of disaster preparedness resources within community settings, as we discuss further in our

conclusions.

Research questions

The overarching research goal for this study is to better understand the ways in which the attitudes

of individual community members relate to their potential actions in response to a disaster.

8

Specifically, we seek to understand how respondent attitudes about social trust and attachment to

place influence household disaster preparedness. We also explore how those attitudes shape

respondents’ willingness to share different types of preparedness resources, including

transportation, with others in their immediate community in a disaster scenario. For the purposes

of this study, we define community by identity and physical geography. The community described

in this study is a well-defined Seattle neighborhood in which residents have a clear sense of

neighborhood identity and extent of neighborhood boundaries.

In sum, the overarching research question and sub-questions are as follows:

How are attitudinal factors associated with disaster concern, community social

relationships, and place attachment associated with disaster preparedness?

What attitudinal factors affect actual household preparedness with different types

of resources?

What attitudinal factors affect respondents’ anticipated willingness to share

different types of resources with others in their community in a disaster scenario?

How does willingness to share transportation resources compare to other types of

resources?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Willingness to share in a disaster scenario

In a disaster scenario, people are likely to have limited access to – and a limited supply of –

resources needed to carry out essential everyday activities. These resources range from items that

provide sustenance, like food and water, to items that enable transportation and communication.

In this study, we examine specifically the differences of community members’ willingness to share

various items needed to carry out essential everyday activities and the role that strength of social

ties plays in that willingness to share. While the sharing of resources among non-profit and disaster

response organizations has received much attention (5 – 8), there is little to no mainstream urban

planning research that addresses willingness to share in the context of resources needed for disaster

preparedness from the perspective of community members.

In one study of interagency cooperation during disasters, researchers found communication

and trust building to be critical pre-work for the support of effective decision making and sharing

of resources (9). In another study of interactions between organizations, researchers found that

resource sharing across organizations can help to support coordination, and that organizations with

complementary resources are both more interdependent and more willing to share resources (10).

In a commercial context, willingness to share personal items (e.g., as part of the sharing economy)

decreases as social distance increases (11). Although the same might be true of individuals in

disaster situations, it is possible that different behavior patterns might occur given the uniqueness

and unpredictability of the situation. In a study of people’s anticipated post-disaster social

behaviors and expected survival adaptations in New Zealand, researchers employed a simulated

scenario, finding that as time passed after a simulated disaster, people anticipated being less likely

to offer assistance to or share resources with others and more likely to ask for help or to lie about

their personal level of resources (12).

In a qualitative study of disaster preparedness among aging populations in Australia,

Blakemore and Bevis found that older people tend to be willing to share both experience and

resources in disaster scenarios, highlighting their role as critical community assets (13). While this

study identified willingness to share as a theme of discussion relevant to disaster preparedness

9

research, it did not present empirical findings specific to the topic of resource sharing. Researchers

comparing patterns of resource sharing in tsunami-affected Indian communities found that sharing

networks comprising kin were not as successful as those that were more corporate in nature (non-

kin) (14), suggesting that willingness to share might be enhanced by the presence of more broadly-

defined networks beyond the family or household.

The concept of willingness to share has also surfaced in a developing area of research in

transportation planning involving the assessment of the potential of the sharing economy to

provide temporary shelter and/or transportation options in the case of a large-scale disaster (15,

16). Although the sharing economy has the potential to supplement some public resources in the

case of a disaster, many vulnerable groups still have challenges procuring basic resources like

transportation and shelter (17).

Place attachment and disaster preparedness

Individual households contribute to community resilience through the construction of social

relationships that enable the sharing of information and resources. Place attachment, or the

emotional and cognitive experience linking people to places, has been shown to motivate

participation in cooperative efforts to improve one’s community (18), to build connections between

individuals within a community (19), and to enhance social trust (20). Social trust also plays a key

role in the ability of communities to undertake collective, adaptive action (21, 22).

Place attachment can be predicted by socio-demographic factors such as length of

residence, education, and home ownership (23), and it can be influenced by qualities of place like

land value, community relationships, and available job opportunities (24). In a wide-ranging

literature review, Bonaiuto et al. determined that relatively little is understood regarding the ways

in which place attachment affects disaster risk perception and coping, and they suggest that it

should play a more prominent role in disaster preparedness (25).

Level of place attachment may vary based on community context. A pair of studies focused

on communities living in areas at risk from wildfire in Australia suggest that there may be

somewhat of an urban/rural divide regarding place attachment. One study of fire-risk-prone

communities demonstrated that rural residents generally have a higher level of place attachment

than do urban residents (23). The other study found place attachment to be a motivator for

mitigation and preparation in rural communities, but less so in urban ones (26).

In addition to having an influence on disaster perception and coping, individuals’ place

attachment can also be affected by the experience of disaster. A study of rural Chinese residents

found a complex and somewhat negative association between place attachment and hazard risk

perception, suggesting that greater fear of disaster reduces dependence on place (27). A study of

flood-prone communities in Canada found that the experience of flooding had differing effects on

place attachment (28), and another study found that loss resulting from disasters was associated

with changes in level of place attachment (29).

Many researchers have uncovered evidence that supports the inclusion of place attachment

as a consideration in the study of disaster preparedness and response as well as in the formulation

of disaster mitigation strategies. Researchers exploring the effects of disaster risk on wildfire-prone

communities in British Columbia, Canada argue that the role of place is a critical aspect of the

disaster recovery process as well as an important baseline factor in the construction of social capital

and community disaster resilience (30). In a study of displaced residents post-Hurricane Katrina,

Chamlee-Wright and Storr found that place attachment can play a strong role in residents returning

to an area they have evacuated post-disaster, but essential resources (such as schools and grocery

10

stores) must be available in the community, and community members must have a sense of how

they can contribute to post-disaster community recovery (31).

A study of the dynamics of community disaster resilience in Christchurch suggests that

understanding place attachment and social relationships at a variety of scales can be helpful for

identifying opportunities for both disaster preparedness and recovery (32). Furthermore, research

on high-disaster-risk communities in the Philippines found that place attachment supports stronger

relationships within communities and suggests promise for the development of disaster risk

reduction strategies that leverage collective action (33).

REGIONAL DISASTER PREPAREDNESS CONTEXT AND STUDY SITE

The research project was conducted in the Pacific Northwest, where a variety of hazard types,

including flooding, sea level rise, wildfires, and earthquakes capture the attention of disaster

preparedness organizations and researchers. This study focuses specifically on seismic hazards –

in particular, the potential of a magnitude 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) megathrust

earthquake as described in the attention-grabbing New Yorker article, “The Really Big One:

Earthquake Preparedness in The Pacific Northwest” (34). Anticipated to occur along a 1,000-mile

fault that stretches from Vancouver Island south to northern California where the Juan de Fuca and

North American tectonic plates meet, such an earthquake would devastate communities throughout

the Pacific Northwest and cause a series of cascading failures, including tsunamis and widespread

damage to buildings and infrastructure (35, 36). The disaster science community anticipates there

is a 10%-14% chance of a magnitude 9.0 CSZ earthquake occurring within the next 50 years, and

earthquakes have been identified by Seattle’s Office of Emergency Management as the area’s

riskiest hazard (37, 38).

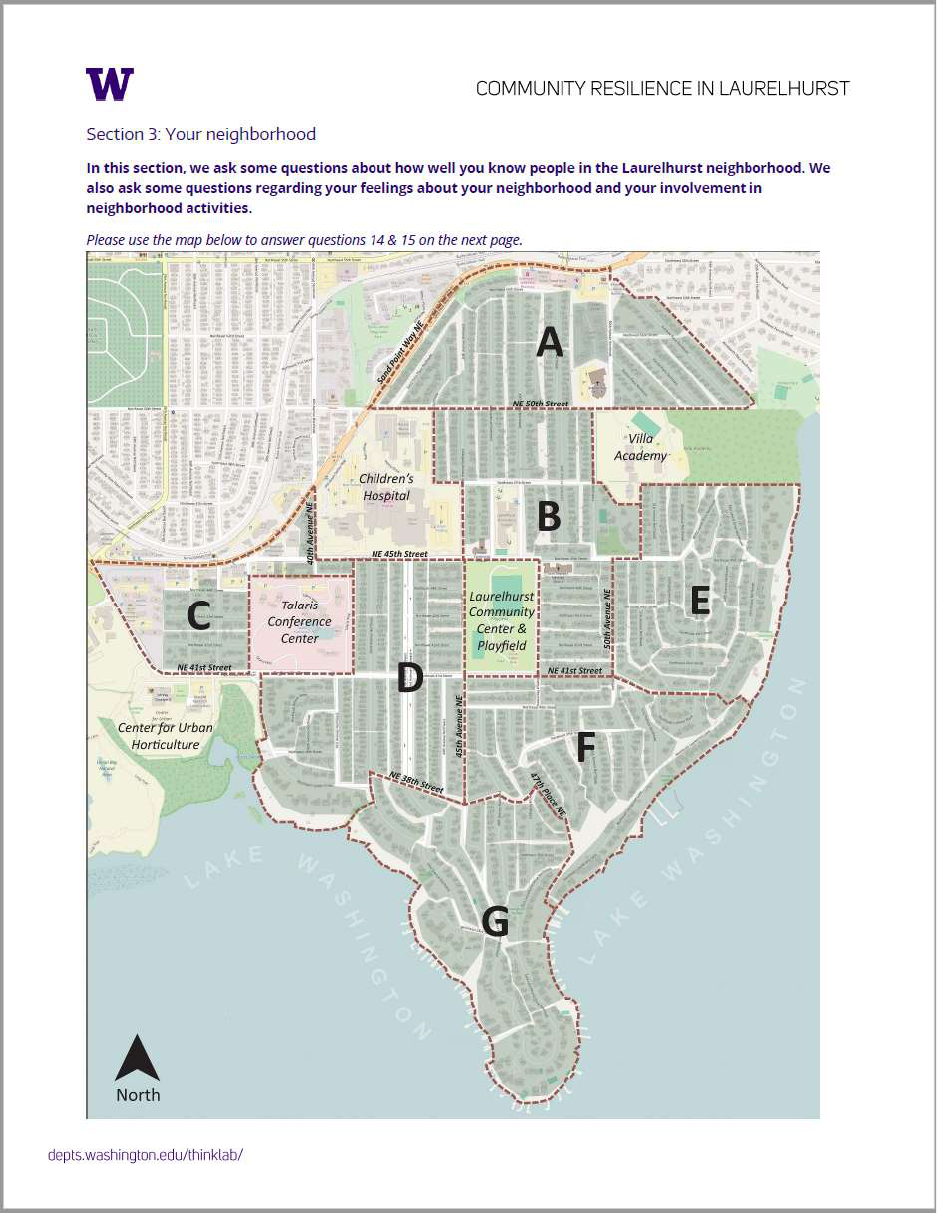

Study site: Laurelhurst

Laurelhurst is a highly educated and relatively wealthy urban neighborhood of approximately

4,160 residents in northeast Seattle. Located adjacent to the University of Washington campus,

Laurelhurst is served by the University of Washington Medical Center as well as Seattle Children’s

Hospital, a nationally renowned pediatric care facility. Although the neighborhood is primarily

residential, some small businesses and University Village, an upscale lifestyle shopping center, are

located nearby. In part because of its somewhat peripheral location and lack of mixed-use

development, Laurelhurst is not well-served by transit. Most areas of Laurelhurst are located

within a mile or two of the Husky Stadium light rail station at the University of Washington, but

because it is separated from the neighborhood by a number of institutional uses, it is not a walkable

destination for those living in the community. Its geography as a small peninsula on the shores of

Lake Washington, with liquefactable soils to its west and northeast, exacerbates its potential

isolation in an earthquake.

11

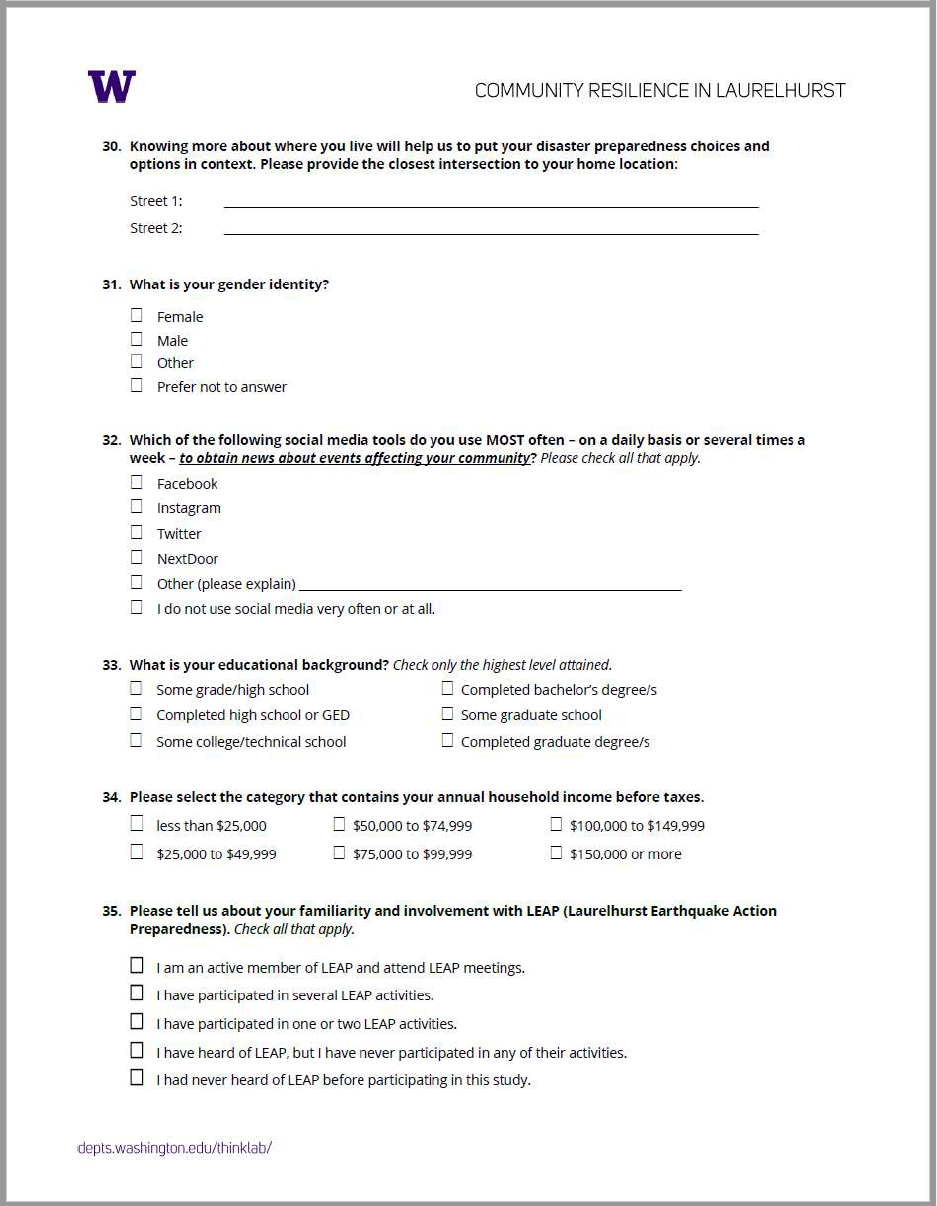

Laurelhurst is home to a grassroots disaster preparedness organization called Laurelhurst

Emergency Action Plan (LEAP). Although originally organized in response to increasing concern

about the potential impacts of an earthquake, LEAP has expanded its mandate to address a broader

range of hazard concerns within the local community and regularly hosts educational community

workshops focusing on disaster preparedness skills and knowledge topics, from putting together

an emergency preparedness kit to stopping a bleeding victim from hemorrhaging. One of LEAP’s

primary goals is to organize the entire Laurelhurst neighborhood into approximately 20-household

clusters, each with a “cluster captain” who can lead the cluster’s disaster preparedness efforts by

building interpersonal connectivity and trust within the cluster.

Although Laurelhurst is not socio-economically representative of Seattle neighborhoods

(see Table 1), its potential for isolation in a major earthquake is typical of neighborhoods in Seattle,

a city of many hills separated by waterbodies and filled wetlands. Data and findings from this

community help to illustrate one local profile regarding attitudes and disaster preparedness

relevant to neighborhood scale self-reliance and intra-household mutual aid. Moreover, additional

in-progress studies will enable a comparison between different types of communities ranging on

spectra of socioeconomic status and urban to rural. Our goal in carrying out this research at the

community level is to look beyond one-size-fits-all approaches to disaster preparedness to better

understand how unique community context and social factors might shape community response in

a disaster scenario.

Figure 1: Location of

Laurelhurst in Seattle

Figure 1: Study neighborhood location

12

Table 1: Laurelhurst community demographics

Survey sample City of Seattle (39)

Age (median) 57.0* 35.5

Ethnicity

White

Black or African American

Asian

Latinx

American Indian/Alaska Native

Other or mixed

No answer

86.4%

0.4%

5.4%

1.6%

0.0%

4.7%

1.2%

68.0%

7.0%

15.1%

6.6%

0.6%

2.6%

Gender female 49.8 49.6%

Household size (mean) 2.6 2.1

Annual HH income

Less than $25,000

$25,000 - $49,999

$50,000 - $74,999

$75,000 - $99,999

$100,000 - $149,999

$150,000 or more

No answer

5.0%

3.1%

7.4%

7.8%

14.0%

51.9%

10.8%

15.0%

15.2%

14.4%

11.6%

17.8%

26.0%

* survey included adults only

METHODS

Community engagement

The research team participated in several LEAP meetings throughout 2017 and 2018 and attended

a series of disaster preparedness workshops and trainings sponsored by LEAP and held within the

Laurelhurst community. In November of 2018, the research team and LEAP co-hosted a public

workshop at the Laurelhurst Community Center, creating a forum for neighborhood stakeholders

to discuss, via participatory group activities, the qualities that contribute to a resilient community.

The purpose of the workshop was twofold: 1) to help LEAP recruit new members by spreading the

word about the community emergency preparedness work they are doing; and 2) to build a better

understanding of the unique community values and assets that might contribute to strengthening

community resilience in Laurelhurst. The workshop was attended by 15 community members.

Workshop activities included asset mapping exercises, which provided valuable background

information regarding what unique resources within the local community might be useful in the

case of a disaster.

All of these activities helped to inform the development of a community resilience sample

survey that was conducted in the fall of 2019. The authors worked closely with LEAP and local

agency partners to refine and test the survey.

13

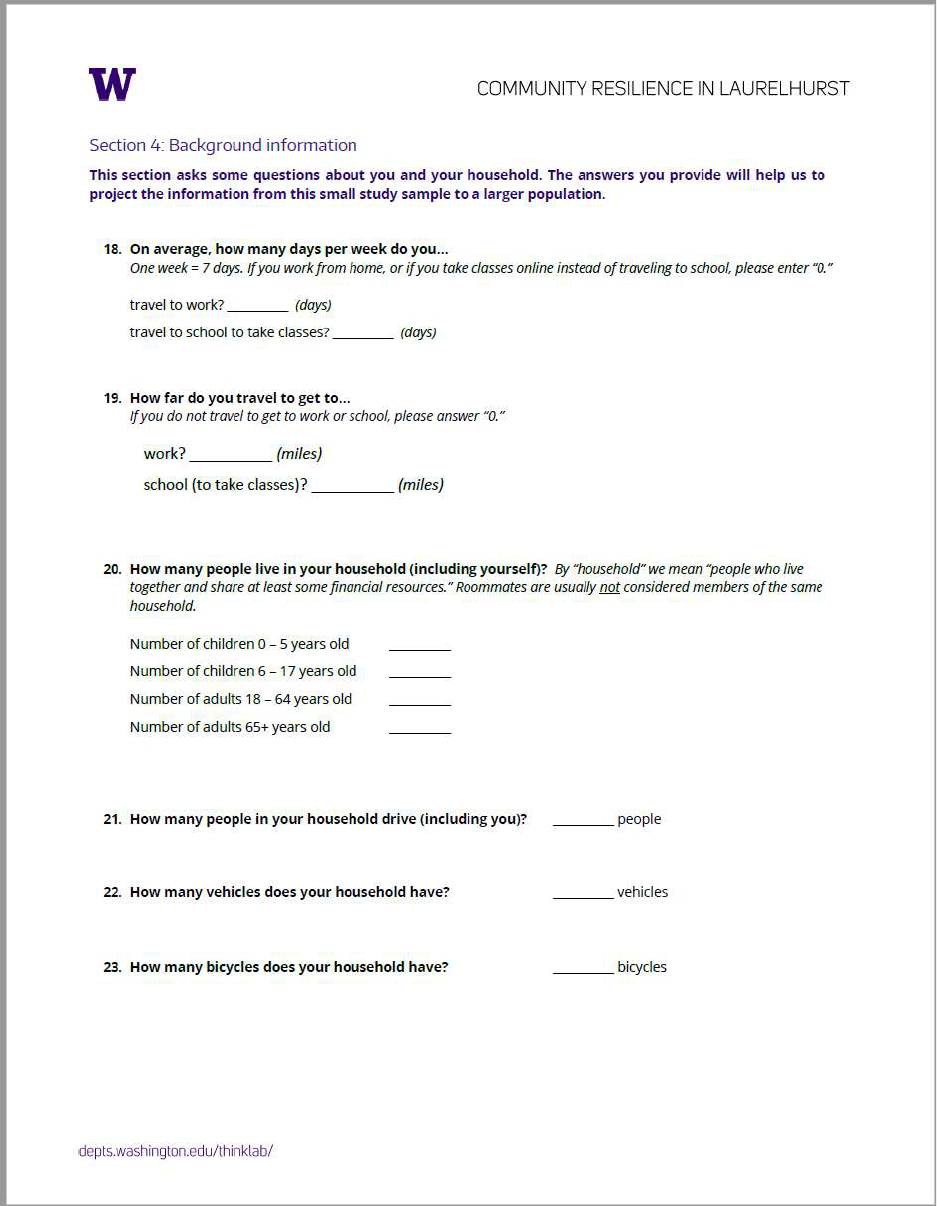

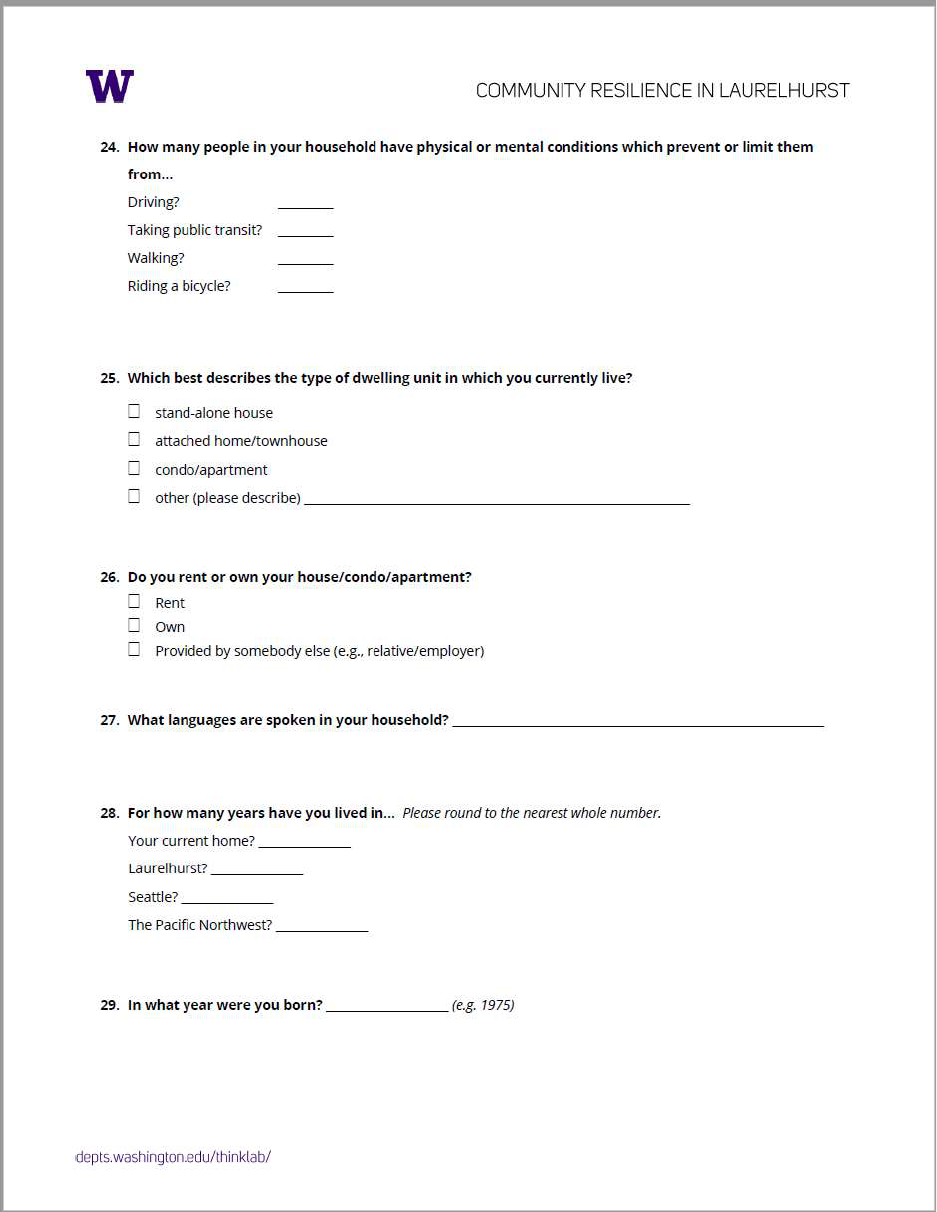

Sample survey

The community resilience sample survey was designed to gather information about relationships

between neighborhood social connectedness, attitudes (such as trust and willingness to share), and

community-level disaster preparedness. Exploratory in its nature, the survey instrument elicits

information from community members not only about how they might be prepared for a disaster

materially, but also about how their attitudes and social connections might contribute to

preparedness at both the household and community scales.

The survey instrument was developed with the help of feedback from members of the City

of Seattle’s Office of Emergency Management, the Northwest Healthcare Response Network,

Washington State’s Emergency Management Division, and the University of Washington Medical

Center, as well as being reviewed by members of LEAP. Some questions from a previous City of

Seattle survey on disaster preparedness were adapted to be used as part of the survey instrument,

and survey items also draw on previous research on trust and place attachment, as noted below.

A pilot version of the survey was pre-tested with members of LEAP before being

distributed to 200 Laurelhurst residents during April of 2018. Some adjustments were made to the

survey based on the pilot, and the full survey was deployed to 733 Laurelhurst households in

October of 2018. Survey recipients were first provided with information on how to access a digital

version of the survey online, and one reminder was mailed regarding the online survey. Those who

did not complete the online survey were sent a paper copy in a third mailing. Respondents were

offered a $5 gift card for completing the questionnaire. An adapted version of Dillman’s “Tailored

Design Method” was used to guide the research team’s survey outreach and communication (40).

We received 145 responses to the online survey and 112 responses from respondents who

filled out the paper booklet (a total of 257 responses). Thirty of the mailings were returned as

undeliverable. Accounting for 19 surveys that were deemed incomplete, the total number of

complete surveys as 238, resulting in a 32.5% response rate.

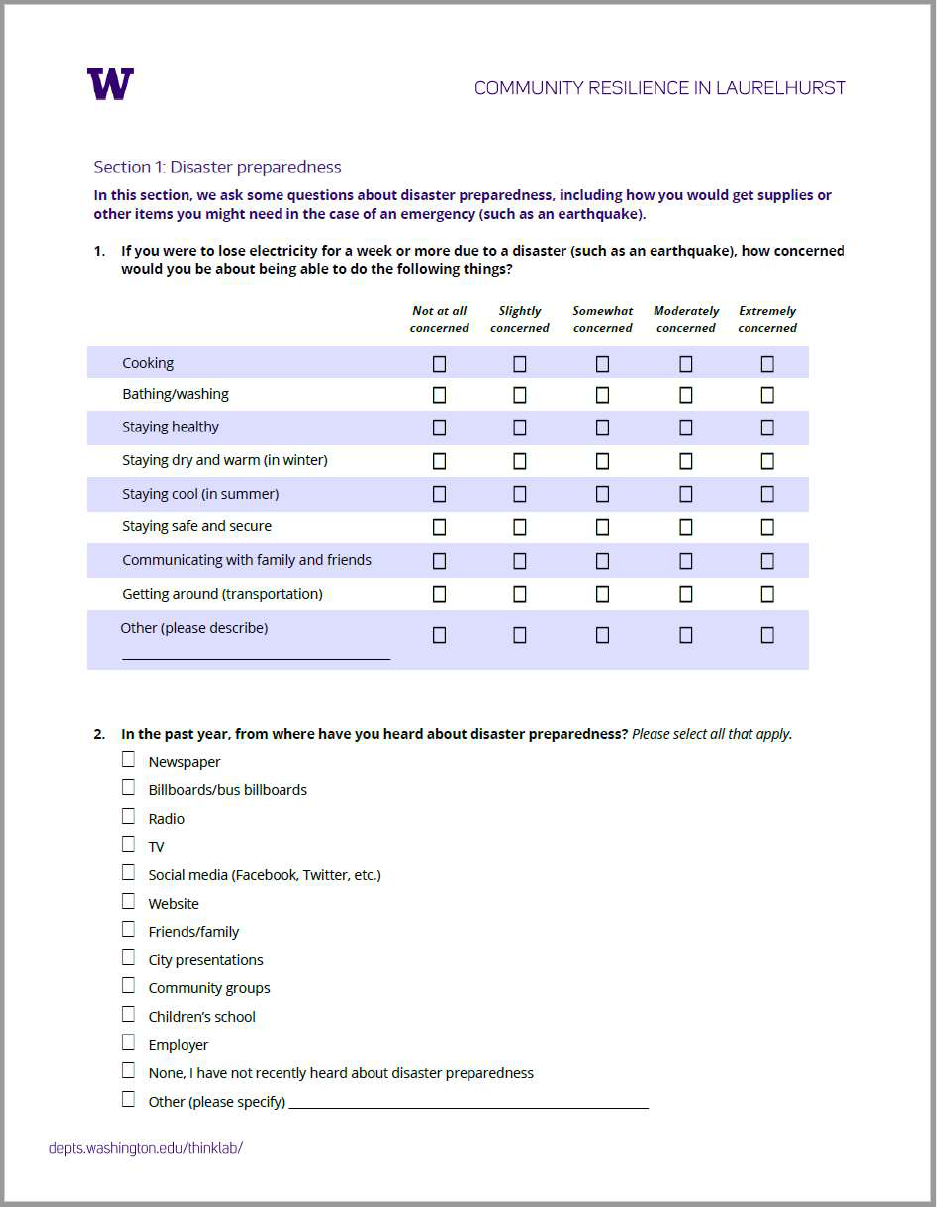

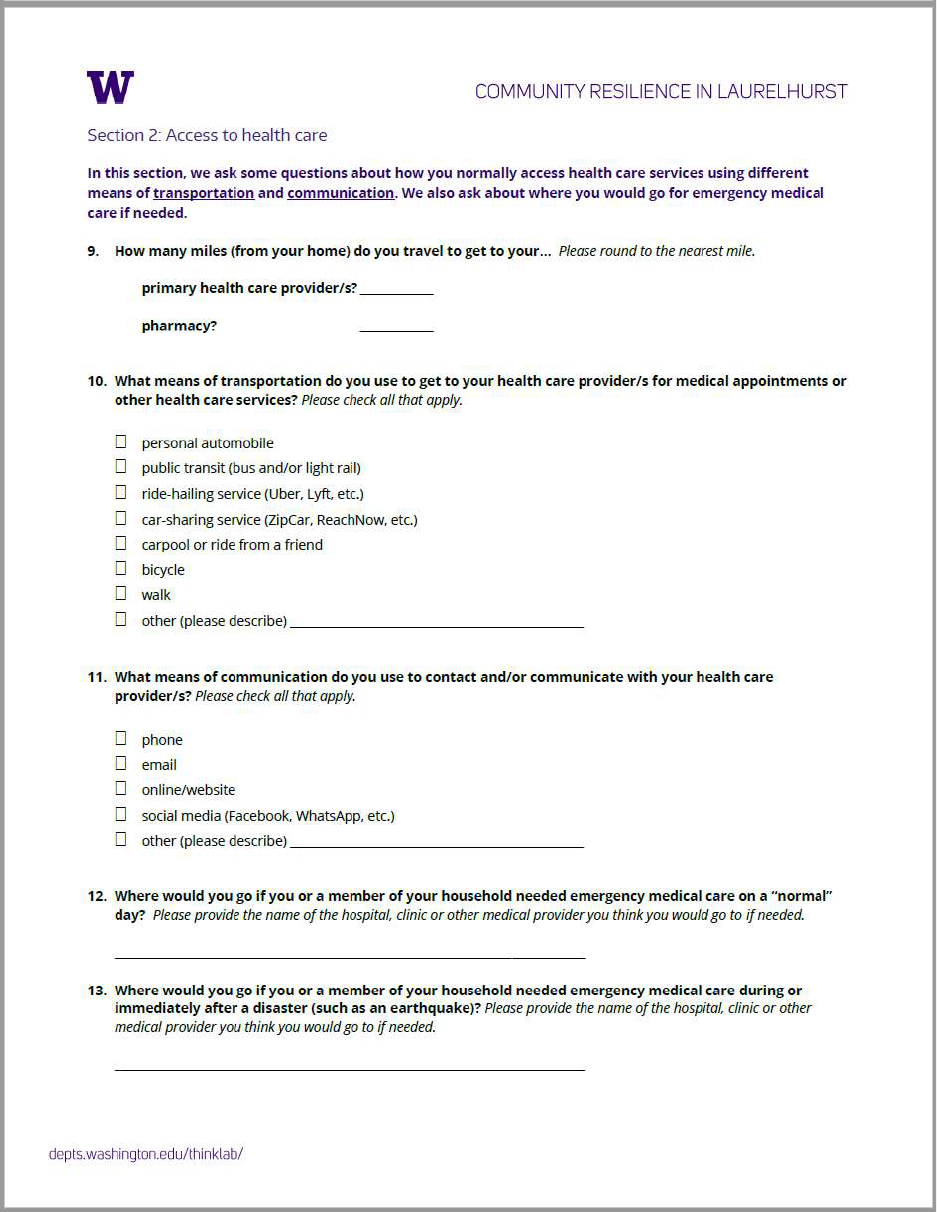

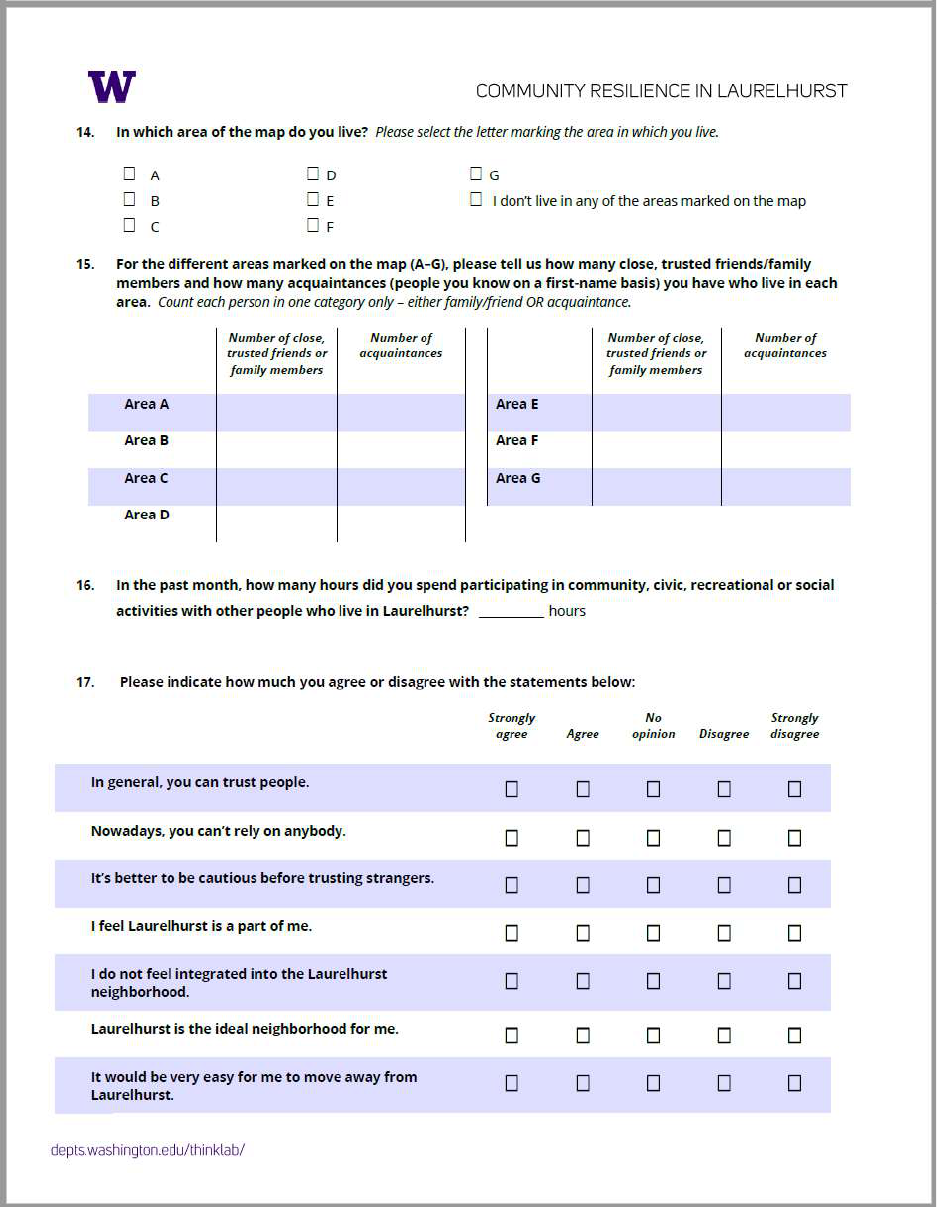

The survey comprised 34 items, which were a mix of multiple selection and open-ended

questions that took respondents approximately 20 minutes to complete. The survey is organized

into four modules: 1) Disaster preparedness, 2) Access to health care, 3) Community and attitudes,

and 4) Demographics. This study deals with data gathered primarily from the disaster preparedness

and community and attitudes modules. We specifically analyze the association of three

independent attitudinal variables (level of concern, social trust, and place attachment) with two

dependent variables (willingness to share and actual preparedness). Based on connections

suggested in the literature, we also assess the relationship of the respondent’s local social network

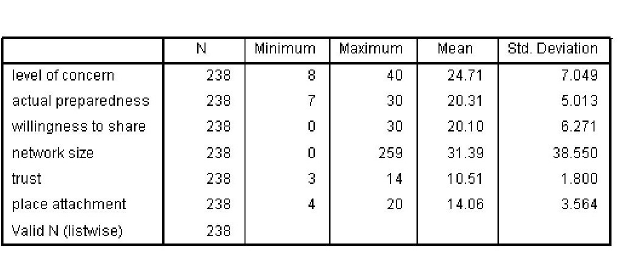

size to these variables. Descriptive statistics for these key variables are included in Table 2.

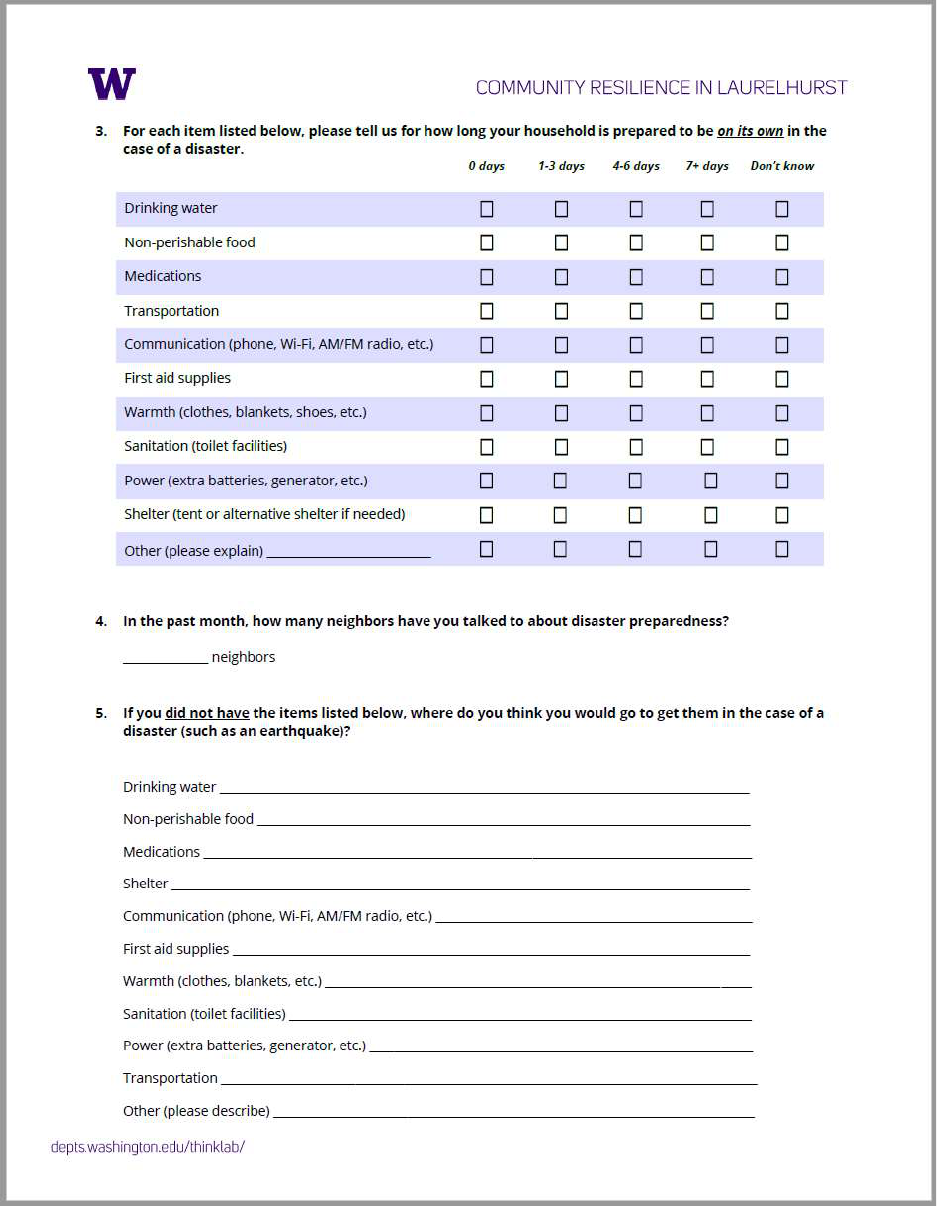

Module 1 (Disaster preparedness) asked respondents to indicate their actual preparedness with

Table

2

: Descriptive statistics for key variables

14

different types of essential items, including water, food, medications, transportation,

communication, first aid supplies, extra clothing, sanitation, power, and shelter. Preparedness was

measured based on the number of days respondents could be self-sufficient with each item (“0

days” to “7+ days”). They were also asked to indicate their level of concern about their ability to

complete essential everyday activities in the case of a disaster, including cooking, bathing, staying

healthy, staying warm/dry, staying safe, communicating with family and friends, and using

transportation to get around.

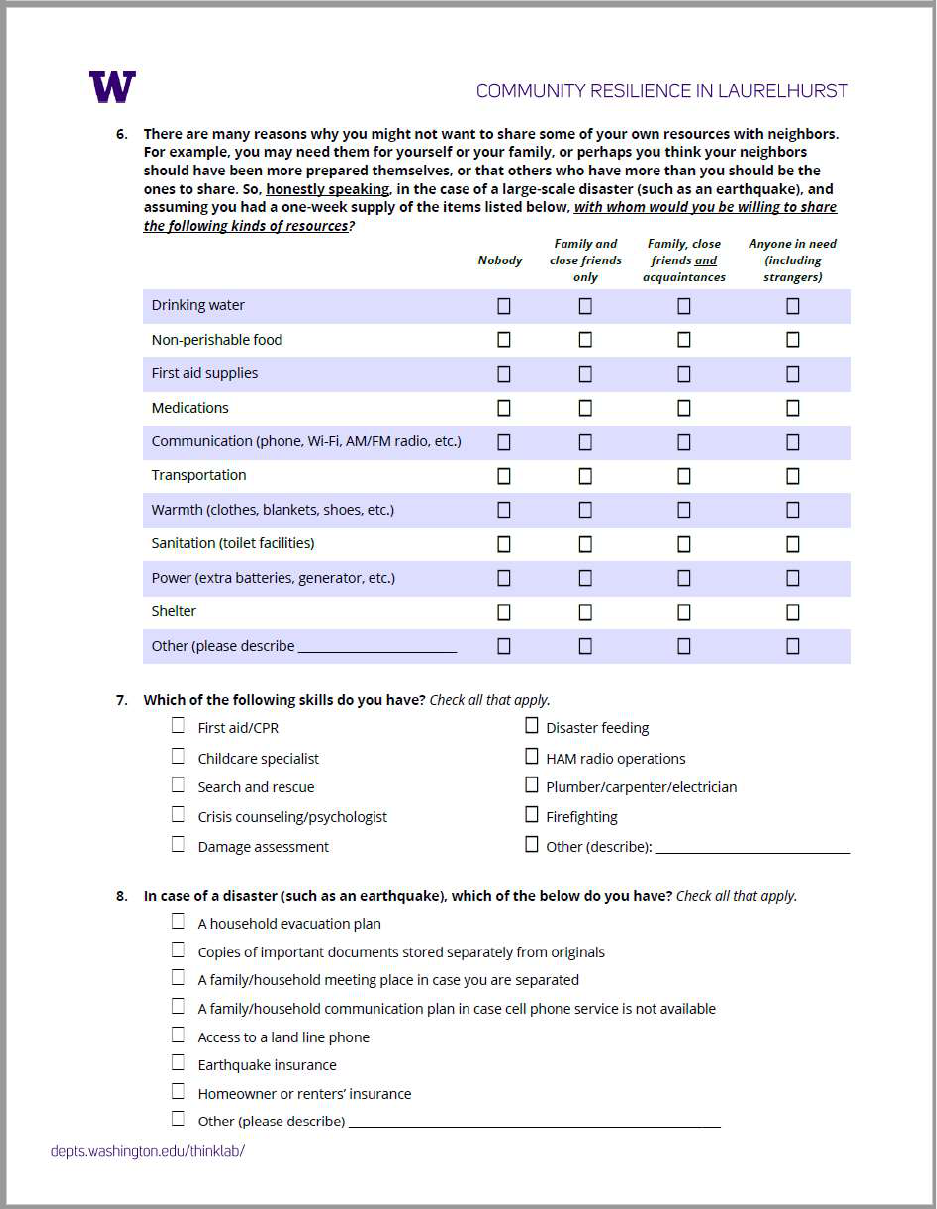

Another section of this module asked respondents about their willingness to share the

different kinds of resources identified in the earlier preparedness question with others in their

community based on the type of relationship people had with the potential recipient (“family or

close friend,” “acquaintance,” or “stranger”). We recognize that this question would likely be

subject to social desirability bias, so we included in the question prompt a number of reasons why

people might be unwilling to share (“perhaps you feel others should be better

1

prepared” or “you

feel you need to keep those items for you and your family”) and asked respondents to provide an

honest answer. We did find that respondents felt differently about sharing different kinds of items,

indicating that they did not feel the need to answer that they would unconditionally share all of the

items with anyone who needed them.

Module 3 (Community and attitudes) focused on neighborhood social connections as well

as attitudes about social trust and degree of place attachment. This module asked respondents to

indicate their neighborhood social network size (family, friends, and acquaintances), and it

included a place attachment scale adapted from Fornara et al. (41) as well as a social trust scale

created using three questions about trust from the General Social Survey (42). The latter two items

were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Half of the scale items were adapted to a negative form of the question to encourage respondents

to carefully consider all items.

ANALYSIS & FINDINGS

For the questions that were evaluated using Likert or other scales (e.g., willingness to share), we summed

the individual responses for each item to create a continuous scale variable. We then evaluated the strength

of association between the variables using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (see Table 3). We use the

interpretation scale adopted by Dancey and Reidy in which Pearson’s r indicates a weak association at 0.1-

0.3, a moderate association at 0.4-0.6, a strong association at 0.7-0.9, and a perfect association at 1.0 (43).

1

For level of concern, respondents were asked to rank, on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all concerned”

to “extremely concerned” their level of concern about their ability to carry out eight everyday activities in the case of

a disaster. For actual preparedness, respondents were asked to estimate for how long they were prepared to be on their

own with ten disaster preparedness items (from “0 days” to “7+ days”). For willingness to share, participants were

asked to indicate with whom they would be willing to share the same ten kinds of resources on a scale of “0=nobody”

to “3 = anyone in need.” For trust and place attachment, respondents were asked to indicate how strongly they agreed

with items on a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

15

Table 3: Correlations among key variables (Pearson's r)

Factors affecting disaster preparedness

We found that level of concern about disasters did have a statistically significant association with actual

preparedness, and that association was both moderate and negative (-.460). In fact, it was the strongest

association we observed among the variables of interest. From this analysis, we cannot know whether there

is causality, but we interpret this to mean that those who are more concerned about disaster feel they are

less prepared for it. It is also possible that people are less worried because they are more prepared. We did

anticipate the possibility of question order bias with this pair of questions and asked about level of concern

first so that respondents’ answers regarding level of concern would be less likely to be influenced by their

stated level of preparedness.

Attitudes and willingness to share

We found that of the three attitudinal variables (level of concern, trust, and place attachment), only trust

had a statistically significant, though weak, association with willingness to share (.296). We interpret this

to indicate that people are more willing to share disaster preparedness items when they trust others around

them and perhaps feel their actions may be reciprocated in some way. Neither place attachment nor level of

concern had a statistically significant association with willingness to share. Level of actual preparedness

also did not have a statistically significant association with willingness to share, suggesting that willingness

to share has more to do with one’s personal attitudes than with the amount of resources one might have

available to share. We did also find a statistically significant positive association between trust and place

attachment, suggesting that place attachment may play an indirect role in willingness to share that could be

further explored using other statistical methods.

level of

concern

actual

preparedness

willingness

to share

network size trust place

attachment

level of concern

Pearson correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

---

-.460**

.000

-.102

.115

-.036

.578

-.076

.242

-.089

.170

actual preparedness

Pearson correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

---

.052

.426

.065

.317

.026

.686

.044

.502

willingness to share

Pearson correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

---

.033

.618

.296**

.000

.097

.134

network size

Pearson correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

---

.085

.191

.437**

.000

trust

Pearson correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

---

.251**

.000

p

lace

attachment

Pearson correlation

Sig. (2-tailed)

---

N = 238 **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

16

Level of concern, preparedness, and anticipated willingness to share transportation resources

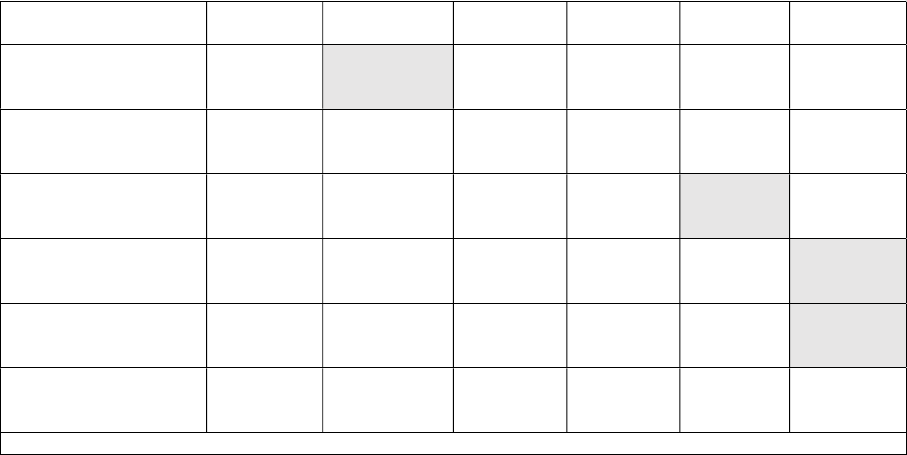

Comparing respondents’ concern about being able to use transportation resources to get around in an

earthquake scenario with other essential activities, we found that the level of concern about transportation

was the lowest of all activities (see Figure 3). This may be because people think they will be able to walk,

ride a bicycle, or even drive in the case of an earthquake. There is great uncertainty regarding what modes

of transportation would be feasible to use after a large earthquake, which might also be a contributing factor

to the low level of concern. Respondents may also feel that relative to the other activities, transportation

will be less essential if the entire region is affected and travel becomes difficult in general.

Figure 2: Average level of concern about completing

everyday activities in an earthquake scenario

Figure 3: Average level of preparedness with essential

resources

17

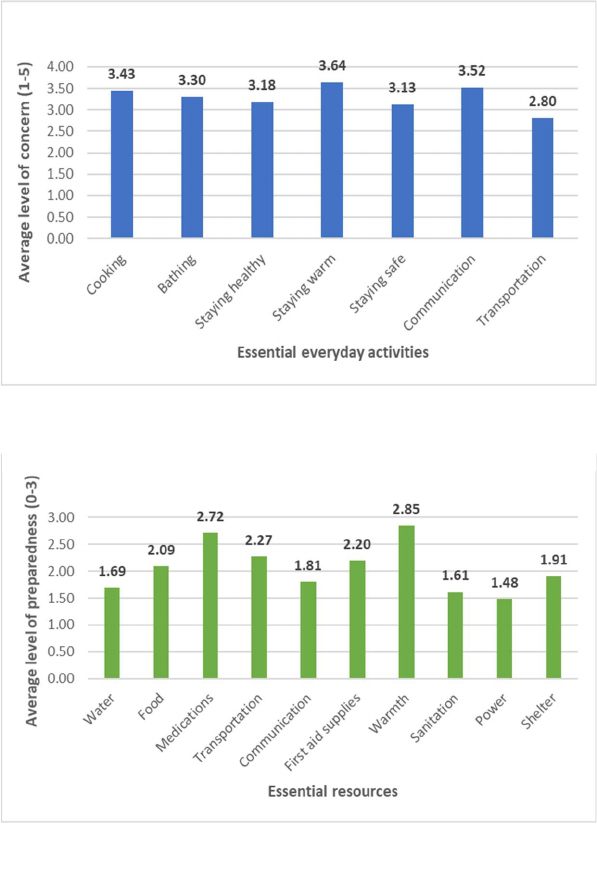

When asked how long they were prepared with a range of essential resources, respondents indicated that

they felt more prepared with transportation than with most other resources (see Figure 4), which aligns with

the findings regarding level of concern. People indicated being more prepared only with “warmth,” which

is understandable because most people have extra clothes and warm blankets, and these are not consumable

resources. People also indicated being more prepared with medications, which is likely because they fill

prescriptions for several weeks’ worth of medication at a time.

Compared to other essential resources, willingness to share transportation ranked fourth out of the ten items

in the survey (see Figure 5). Respondents indicated they were more willing to share warmth, communication

resources, and first aid supplies than transportation. They were more willing to share transportation than

water, food, medications, sanitation resources, power, or shelter. These findings suggest that while people

are somewhat willing to share transportation, they may have some reasons for not wanting to share it with

anyone in need, perhaps anticipation of needing to spend a long period of time in a vehicle with a stranger

or a lesser degree of trust in others regarding sharing this specific resource.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Willingness to share essential resources in disaster scenario is a relatively unexplored topic (12),

and better understanding the factors that influence decision making about sharing resources with

others can help to lay the groundwork for future research on this topic. Practically, understanding

which resources people are more or less willing to share and with whom could help to inform the

disaster preparedness efforts of both community organizations and disaster preparedness planners.

In this study, we found that level of concern about being able to carry out everyday

activities was negatively associated with actual disaster preparedness in terms of self-sufficiency

with essential resources. This likely reflects the feeling that those who are less prepared are more

concerned because they are less prepared, and possibly that those who are more prepared are less

concerned because they are more prepared. One actionable response to this might be targeted

education within the community about how they can best be prepared for a disaster in terms of

both skills and resources.

We also found that greater willingness to share was associated with higher levels of trust,

suggesting that a community with more trusting relationships will be more willing to share

resources with one another in the event of a disaster. Furthermore, willingness to share was not

Figure 4: Average willingness to share essential resources

18

associated with levels of actual preparedness with specific resources. Potential actions responding

to these findings might include framing community-building activities as disaster preparedness

actions and emphasizing the importance of knowing one’s neighbors as part of disaster

preparedness educational activities.

Regarding transportation, our findings suggest that people within the study community

were less concerned about being able to get around after a disaster than they were about being able

to complete a range of other essential daily tasks. Respondents indicated that they felt more

prepared with transportation than with most other resources, and, while people are somewhat

willing to share transportation, they may not necessarily be willing to share it with people with

whom they do not already have an established social relationship. The anticipated use of, and

willingness to share, transportation resources post-disaster is an area of study that should be

examined in more detail.

There are several limitations to the study. One is that, while we gain an in-depth

understanding of a specific place by focusing on the community scale, the findings from the study

are not necessarily applicable to a broad range of communities. The research team is currently

addressing this potential shortcoming by collecting data from two additional Washington State

communities that differ from Laurelhurst in terms of both socioeconomic status and degree of

urban-ness. This further exploration will provide the basis for comparative analysis and, we

anticipate, a more nuanced set of findings.

Another important limitation to note is that we have asked people about their anticipated

sharing behavior in a hypothetical disaster scenario. There are many uncertainties associated with

both aspects of this question. We do not know exactly what will happen in the case of a disaster,

and people cannot necessarily make an accurate prediction about how they will behave in such an

uncertain scenario. We also recognize the potential for social desirability bias regarding the

willingness to share question. We attempted to address this by carefully framing the questions so

that respondents would feel comfortable providing an honest answer. Our finding that people stated

different willingness to share for different kinds of resources does suggest that respondents

carefully considered each resource and that there are at least some reliable relative differences in

willingness to share depending on the resource in question, which can help to inform prioritization

of resource readiness as well as disaster preparedness education.

Finally, next steps include implementing the sample survey described in this paper in two

additional communities to support a comparative analysis. The authors also plan to do further

multivariate data analysis in order to better understand the potential directionality of the

relationships among the willingness to share, trust, place attachment, and disaster preparedness

variables. We believe the findings from this study can be used to help support targeted disaster

preparedness activities in the study community and suggest that in the broader context

preparedness considerations should focus more on building trusting social relationships within

communities

19

REFERENCES

Aldrich, D. P., and M. A. Meyer. Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral

Scientist, Vol. 59, No. 2, 2015, pp. 254-269.

Anton, C. E., and C. Lawrence. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on

place attachment and community participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol.

40, 2014, pp. 451-461.

Anton, C. E., and C. Lawrence. Does place attachment predict wildfire mitigation and

preparedness? A comparison of wildland–urban interface and rural communities.

Environmental Management, Vol. 57, No. 1, 2016, pp. 148-162.

Atwater, B. F., A. R. Nelson, J. J. Clague, G. A. Carver, D.K Yamaguchi, P. T. Bobrowsky, J.

Bourgeois, M. E. Darienzo, W. C. Grant, E. Hemphill-Haley, H. M. Kelsey, G. C. Jacoby, S.

P. Nishenko, S. P. Palmer, C. D. Peterson, and M. A. Reinhart. Summary of coastal geologic

evidence for past great earthquakes at the Cascadia Subduction Zone, Earthquake Spectra,

Vol. 11, 1995, pp. 1–18.

Bonaiuto, M., S. Alves, S. De Dominicis, and I. Petruccelli. Place attachment and natural hazard

risk: Research review and agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 48, 2016, pp.

33-53.

Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup. Cascadia subduction zone earthquakes: A magnitude

9.0 earthquake scenario. Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries; 2013 [cited

2020 July 27]. 23p. Available from:

https://www.dnr.wa.gov/publications/ger_ic116_csz_scenario_update.pdf

Chamlee-Wright, E., and V. H. Storr. “There’s no place like New Orleans”: sense of place and

community recovery in the Ninth Ward after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Urban Affairs,

Vol. 31, No. 5, 2009, pp. 615-634.

Chandi, M., C. Mishra, and R. Arthur. Sharing mechanisms in corporate groups may be more

resilient to natural disasters than kin groups in the Nicobar Islands. Human ecology, Vol. 43,

No. 5, 2015, pp. 709-720.

Cox, R. S., and K. M. E. Perry. Like a fish out of water: Reconsidering disaster recovery and the

role of place and social capital in community disaster resilience. American Journal of

Community Psychology, Vol. 48, Nos. 3-4, 2011, p. 395-411.

Dancey, C. P., and J. Reidy, J. Statistics without maths for psychology. Pearson education, 2007.

Dillman, D. A. Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method--2007 Update with new

Internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, 2007.

Earle, T. C., and G. Cvetkovich. Social trust: Toward a cosmopolitan society. Westport, Conn.:

Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995.

Faturechi, R., and E. Miller-Hooks. Measuring the performance of transportation infrastructure

systems in disasters: A comprehensive review. Journal of Infrastructure Systems, Vol. 21, No.

1, 2014, pp. 04014025-1 - 04014025-15.

Fornara, F., M. Bonaiuto, and M. Bonnes. Cross-validation of abbreviated perceived residential

environment quality (PREQ) and neighborhood attachment (NA)indicators. Environment

and Behavior, Vol. 42, No. 2, 2010, pp. 171-196.

Kapucu, N., and V. Garayev. Collaborative decision-making in emergency and disaster

management. International Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 34, No. 6, 2011, pp. 366-

375.

Haney, T. J. Move out or dig in? Risk awareness and mobility plans in disaster‐affected

20

communities. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2019, pp.

224-236.

Hossain, L., and M. Kuti. Disaster response preparedness coordination through social networks.

Disasters, Vol. 34, No. 3, 2010, pp. 755-786.

Howard, A., T. Blakemore, and M. Bevis. Older people as assets in disaster preparedness, response

and recovery: lessons from regional Australia. Ageing & Society, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2017, pp.

517-536.

Idziorek, K., C. Chen, and D. B. Abramson. Integrating Social Factors into Transportation-Focused

Disaster Preparedness Research. Presented at the 99th Annual Meeting of the Transportation

Research Board, Washington, D.C., 2020.

Jamali, M., A. Nejat, R. Hooper, A. Greer, and S. B. Binder. Post-disaster place attachment: A

qualitative study of place attachment in the wake of the 2013 Moore tornado. Journal of

Emergency Management, Vol. 16, No. 5, 2018, pp. 289-310.

Macagba, S. F. A., J. C. Eligue, and S. Marie. Exploring Social Construct of Place Attachment

among Settlers in Disaster-prone Areas. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied

Research, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2018, pp. 220-233.

Manzo, L., and D. Perkins. Finding common ground: The importance of place attachment to

community participation and planning. Journal of Planning Literature, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2006,

pp. 335-350.

National Opinion Research Center. The General Social Survey. 2016 [cited 2019 December 5].

Available from https://gss.norc.org/

Payton, M., D. Fulton, and D. Anderson. Influence of Place Attachment and Trust on Civic Action:

A Study at Sherburne National Wildlife Refuge. Society & Natural Resources, Vol. 18, No.

6, 2005, pp. 511-528.

Pazirandeh, A., and A. Maghsoudi. Improved coordination during disaster relief operations

through sharing of resources. Journal of the Operational Research Society, Vol. 69, No. 8,

2018, pp. 1227-1241.

Peng, L., L. Lin, S. Liu, and D. Xu. Interaction between risk perception and sense of place in

disaster-prone mountain areas: A case study in China’s Three Gorges Reservoir area. Natural

Hazards, Vol. 85, No. 2, 2017, pp. 777-792.

Petersen, M. D. , C. H. Cramer, and A. D. Frankel. Simulations of seismic hazard for the Pacific

Northwest of the United States from earthquakes associated with the Cascadia subduction

zone, Pure and Applied Geophysics Vol. 159, 2002, pp. 2147–2168.

Ruiz, C., and B. Hernández. Emotions and coping strategies during an episode of volcanic activity

and their relations to place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 38, 2014,

pp. 279-287.

Schreiner, N., D. Pick, and P. Kenning, P. To share or not to share? Explaining willingness to share

in the context of social distance. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2018, pp.

366-378.

Schultz, K. "The really big one." The New Yorker. Vol. 20, 2015.

Seattle Office of Emergency Management. Seattle Hazard Identification and Vulnerability

Analysis; 2019 [cited 2020 July 27]. Available from:

https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/Emergency/PlansOEM/SHIVA/SHIVAv7.

0.pdf

Setiawan E. Can resource sharing improve disaster response effectiveness? Evidence from West

Sumatra earthquake. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering

21

& Operations Management, 2016.

Soltani-Sobh, A., K. Heaslip, P. Scarlatos, and E. Kaisar. Reliability based pre-positioning of

recovery centers for resilient transportation infrastructure. International Journal of Disaster

Risk Reduction, Vol. 19, 2016, pp. 324-333.

Stefaniak, A., M. Bilewicz, and M. Lewicka. The merits of teaching local history: Increased place

attachment enhances civic engagement and social trust. Journal of environmental psychology.

Vol. 51, 2017, pp. 217-25.

Thomas, J. A., and K. Mora. Community resilience, latent resources and resource scarcity after an

earthquake: Is society really three meals away from anarchy?. Natural Hazards, Vol. 74, No.

2, 2014, pp. 477-490.

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey Narrative Profiles: 2014 – 2018 ACS

5-Year Narrative Profile, Seattle City, Washington. 2018 [cited 2020 July 27]. Available

from: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/narrative-

profiles/2018/report.php?geotype=place&state=53&place=63000

Wong, S., J. Walker, and S. Shaheen. Bridging troubled water: Evacuations and the sharing

economy, Presented at the 97th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board,

Washington, D.C., 2018.

Wong, S., and S. Shaheen. Leveraging the Sharing Economy to Expand Shelter and Transportation

Resources in California Evacuations. University of California Institute of Transportation

Studies Policy Brief. 2019 [June 2019, December 10, 2019]. Available from

https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6pw2w52b.

Wong, S. D., J. C. Broader, and S. A. Shaheen. Can sharing economy platforms increase social

equity for vulnerable populations in disaster response and relief? A Case Study of the 2017

and 2018 California Wildfires. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Vol.

5, 2020, 100131.

Winstanley, A., M. Hepi, and D. Wood. Resilience? Contested meanings and experiences in post-

disaster Christchurch, New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences

Online, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2015, pp. 126-134.

22

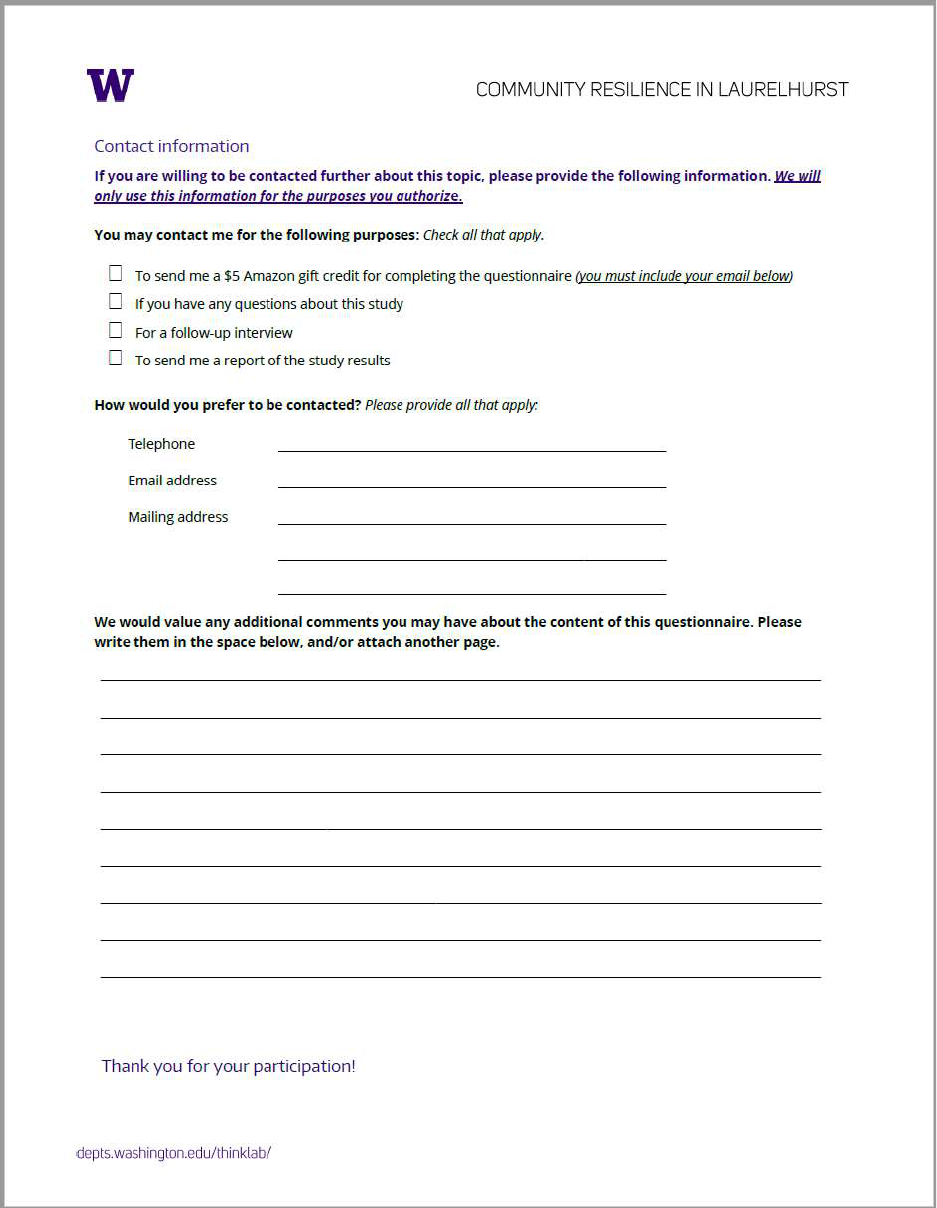

APPENDIX: PILOT SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32