Phase 2 Project Report

Attitudes and Trust in Leveraging Integrated Sociotechnical

Systems for Enhancing Community Adaptive Capacity:

Phase II

Prepared for Teaching Old Models New Tricks (TOMNET) Transportation Center

By,

Katherine Idziorek

Email: [email protected]

Cynthia Chen

Email: qzchen@uw.edu

Daniel B. Abramson

Email: abramson@uw.edu

Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering

Department of Urban Design & Planning

University of Washington

Seattle, WA 98105

September 2019

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE

1. Report No.

N/A

2. Government Accession No.

N/A

3. Recipient's Catalog No.

N/A

4. Title and Subtitle

Attitudes and Trust in Leveraging Integrated Sociotechnical Systems for

Enhancing Community Adaptive Capacity: Phase II

5. Report Date

September 2019

6. Performing Organization Code

N/A

7. Author(s)

Katherine Idziorek, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8130-0536

Cynthia Chen, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1110-8610

Daniel B. Abramson, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5070-8619

8. Performing Organization Report No.

N/A

9. Performing Organization Name and Address

University of Washington

PO Box 352700

Seattle, WA 98195

10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS)

N/A

11. Contract or Grant No.

69A3551747116

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address

U.S. Department of Transportation,

University Transportation Centers Program,

1200 New Jersey Ave, SE, Washington, DC 20590

13. Type of Report and Period Covered

Research Report

(2018 – 2019)

14. Sponsoring Agency Code

USDOT OST-R

15. Supplementary Notes

N/A

16. Abstract

The project described in this report explores relationships between social attitudes and community-scale disaster

preparedness. Specifically, we are interested in respondents’ knowledge of local resources and their willingness to share

their own resources with others. We report on data gathered from a pilot sample survey focused on community resilience

in an earthquake scenario that was implemented in a Seattle, WA neighborhood. We find that respondents’ willingness to

share resources also depends upon the nature of their social ties to those in need. We look specifically at access to health

care services via different modes of transportation to better understand how people’s means of seeking health care might

change in a disaster scenario. Findings relevant to transportation planning include general uncertainty among respondents

about what transportation options might be available in the event of a disaster such as an earthquake, and few respondents

were prepared with alternative transportation options. This information could be used by municipalities and transit

agencies to help inform community outreach and education efforts relevant to disaster planning. We seek to implement

the survey more broadly across the Pacific Northwest in order to help inform resource matching for disaster preparedness

at a range of scales.

17. Key Words

Community Resilience, Sample Survey, Disaster Preparedness, Resource

Sharing, Social Networks

18. Distribution Statement

No restrictions.

19. Security Classif.(of this report)

Unclassified

20. Security Classif.(of this page)

Unclassified

21. No. of Pages

49

22. Price

N/A

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72)

Reproduction of completed page authorized

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and

the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated in the interest of

information exchange. The report is funded, partially or entirely, by a grant from the U.S.

Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program. However, the U.S.

Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by a grant from A USDOT Tier 1 University Transportation Center,

supported by USDOT through the University Transportation Centers program. The authors would

like to thank the Center for Teaching Old Models New Tricks (TOMNET) and USDOT for their

support of university-based research in transportation, and especially for the funding provided in

support of this project. TOMNET is focused on advancing the state of the art and the state of the

practice in measuring and understanding traveler attitudes, values, perceptions, and preferences,

and using such data to improve the ability of travel demand forecasting models to predict activity-

travel behavior, mobility choices, and time use patterns under a wide variety of future scenarios.

This project is also supported by volunteers from Laurelhurst Earthquake Action Preparedness

(LEAP), who helped to guide the survey development by providing a community organization

perspective. LEAP members John Temple, Amy Fouke, Clair Hector, Louise Luthy and Nancy

Woods provided review feedback that was invaluable to the project.

The team would also like to acknowledge and thank the following additional reviewers: Patricia

Mokhtarian, Georgia Tech Civil and Environmental Engineering; Vicki Sakata, Northwest

Healthcare Response Network ; Carina Elsenboss, Seattle & King County Public Health; John

Scott, University of Washington Telehealth; Maximilian Dixon, Washington State Military

Department Emergency Management Division; Matt Auflick, City of Seattle Office of Emergency

Management; Stephen Burges, University of Washington Department of Civil and Environmental

Engineering; Xiangyang Guan, University of Washington Department of Civil and Environmental

Engineering.

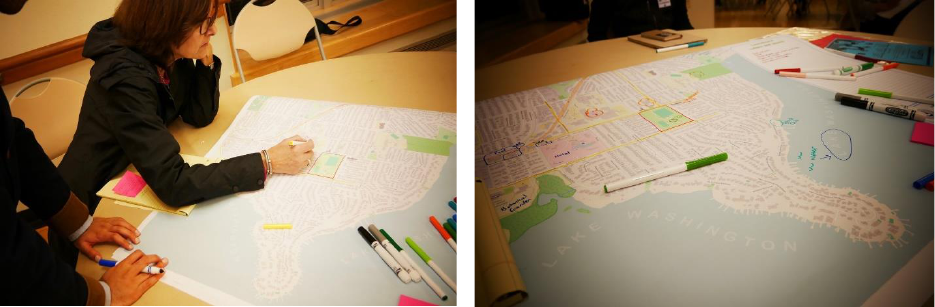

The community workshop activities detailed in this report were facilitated by the authors as well

as by UW doctoral student Lan T. Nguyen and students in Prof. Abramson’s Fall 2018 community

resilience urban planning studio: Helen Stanton, Pegah Jalali, Lauren Kerber, Catharina Depari,

Sreya Sreenivasan and Charlotte Dohrn.

4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................ 3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................. 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 7

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 8

CHAPTER 1: LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................ 9

CHAPTER 2: PILOT STUDY SITE AND REGIONAL CONTEXT ......................................... 12

CHAPTER 3: METHODS ............................................................................................................ 13

3.1 Community Workshop .................................................................................................... 13

3.2 Pilot Sample Survey ........................................................................................................ 14

CHAPTER 4: PILOT SURVEY FINDINGS ........................................................................... 16

4.1 Transportation Preparedness and Level of Concern ................................................... 16

4.2 Willingness to share.................................................................................................... 17

4.3 Transportation, disaster, and health care services ........................................................... 18

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS ................................................................. 21

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................. 23

APPENDIX 1: COMMUNITY WORKSHOPS THROUGH APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY

METHOD ..................................................................................................................................... 28

Introduction and Purpose .......................................................................................................... 28

Partners and Background .......................................................................................................... 29

Workshop Methodology ........................................................................................................... 29

Workshop Activities ................................................................................................................. 30

Activity 1: Asset Mapping .................................................................................................... 30

Asset mapping discussion themes ............................................................................................................ 32

Activity 2: Zone Mapping ..................................................................................................... 33

Activity 3: Disaster Preparedness Resource Matching game ............................................... 35

Workshop summary ................................................................................................................................. 37

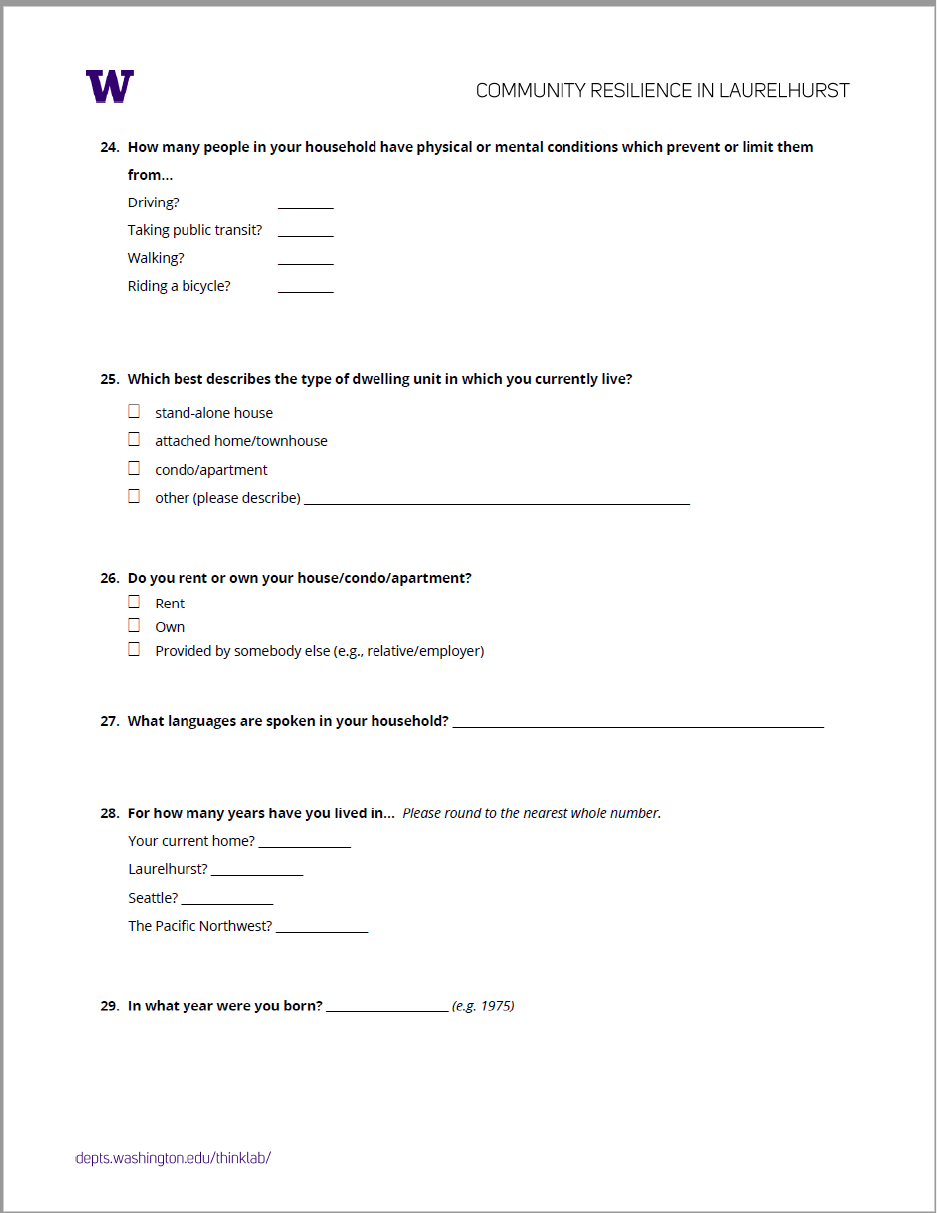

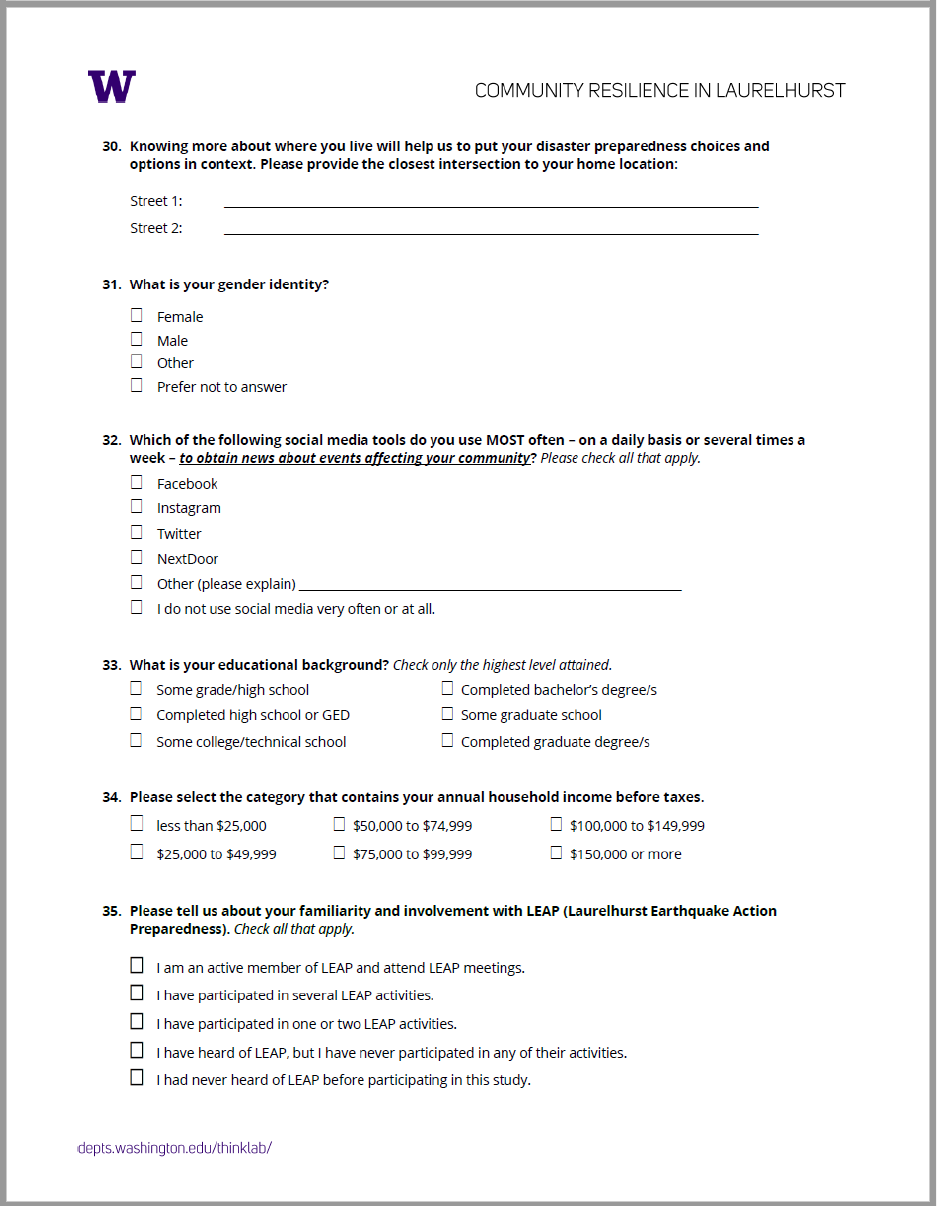

APPENDIX 2: PILOT SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE ................................................................ 39

5

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Where respondents would turn for transportation resources in the case of an emergency ........... 17

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Relative levels of concern about carrying out everyday activities in a disaster scenario ............ 16

Figure 2. Respondent preparedness for carrying out everyday activities in a disaster scenario ................ 17

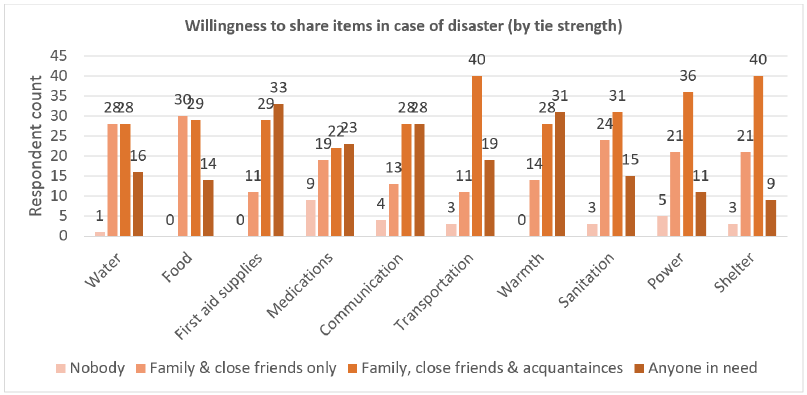

Figure 3. Willingness to share resources in the case of disaster according to strength of social ties ......... 18

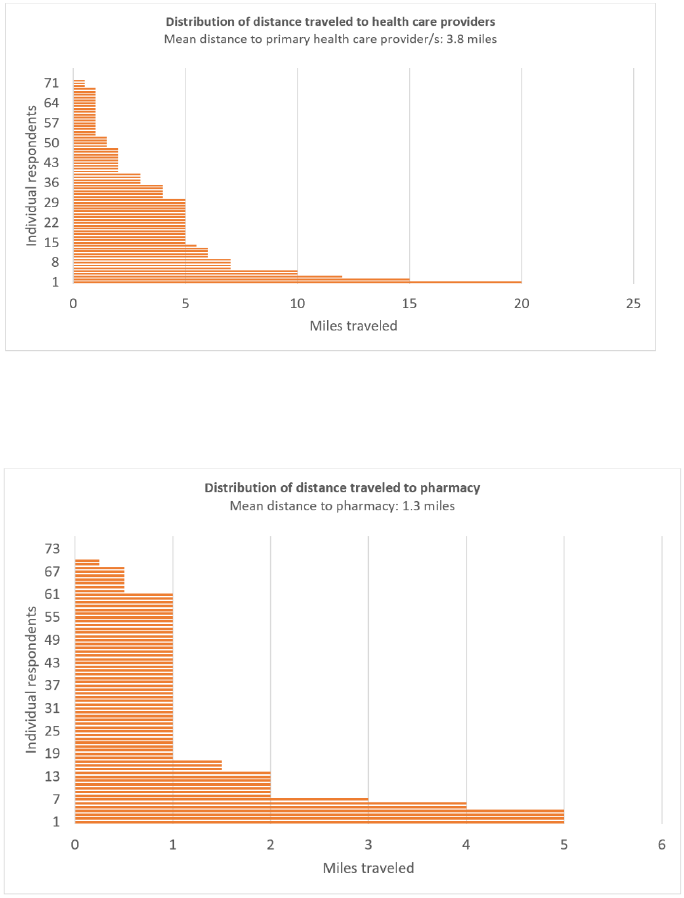

Figure 4. Distribution of distance traveled to primary health care providers ............................................. 19

Figure 5. Distribution of distance traveled to pharmacy ............................................................................. 19

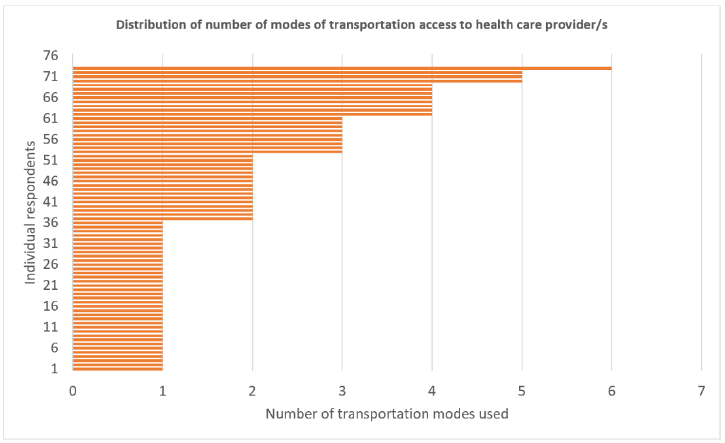

Figure 6. Distribution of number of transportation modes used to access health care services .................. 20

6

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The project described in this report explores relationships between social attitudes and community-

scale disaster preparedness. Specifically, we are interested in respondents’ knowledge of local

resources and their willingness to share their own resources with others. We report on data gathered

from a pilot sample survey focused on community resilience in an earthquake scenario that was

implemented in a Seattle, WA neighborhood. We find that respondents’ willingness to share

resources also depends upon the nature of their social ties to those in need. We look specifically at

access to health care services via different modes of transportation to better understand how

people’s means of seeking health care might change in a disaster scenario. Findings relevant to

transportation planning include general uncertainty among respondents about what transportation

options might be available in the event of a disaster such as an earthquake, and few respondents

were prepared with alternative transportation options. This information could be used by

municipalities and transit agencies to help inform community outreach and education efforts

relevant to disaster planning. We seek to implement the survey more broadly across the Pacific

Northwest in order to help inform resource matching for disaster preparedness at a range of scales.

8

INTRODUCTION

Although much has been written about the likelihood of the survival or failure of physical

transportation infrastructure in disaster situations (for example, see Faturechi & Miller-Hooks,

2014; Soltani-Sobh et al., 2016; or Chang et al., 2012), little research has focused on the

community social and contextual factors that might shape the ways in which transportation systems

transform in both configuration and function as the result of a disaster. In this paper we explore,

through a pilot survey project, the integration of social factors such as attitudes, trust and

willingness to share into a community-level assessment of disaster preparedness with a specific

focus on transportation access to health care services. This research examines transportation-

related issues as they pertain to community-scale disaster preparedness. Given multiple

uncertainties about what kinds of transportation will be useful in a disaster scenario, it is helpful

for community members and disaster preparedness planners to better understand what kinds of

transportation resources are communities equipped with, how might they serve residents in gaining

access to vital resources such as health care services in the case of a large-scale disaster.

The first section of the paper explains the motivation behind such a research agenda,

including a brief discussion of infrastructural interdependency and the place-based nature of

disaster. Because the effects of disaster, especially earthquakes, are inherently geographical (Henry,

2018), we posit that research is needed at the scale of the community in order to better understand

how different places may or may not be equipped to deal with disaster. The second section

specifically discusses the effects of disaster events on trasnportation networks and the varying

roles that transportation infrastructure services play in a disaster scenario. The following section

describes our study site, an urban neighborhood in earthquake-prone Seattle, WA, where we have

partnered with a local organization focused on disaster preparedness to help shape the research

from a community perspective. We then discuss the findings from our pilot survey, followed by

discussion and next steps for advancing a community-scale research agenda.

This work makes two distinct contributions: 1) it introduces a novel, mixed methods

approach to understanding disaster preparedness that integrates community social factors and

attitudes, such as social trust and willingness to share; and 2) it constitutes a first step in the

development of a flexible but rigorous community-scale research methodology that can be adapted

for use in different community contexts. In addition, this work identifies potential gaps that might

be addressed through community education, organization, and outreach to improve disaster

preparedness.

9

CHAPTER 1: LITERATURE REVIEW

The increasing incidence of disaster

In the U.S., disasters are actually quite common, and their impact is increasing (Elliott & Howell,

2017). According to FEMA, the U.S. declared more than 1,000 disasters between 2007 and 2017.

In the fall of 2017 alone, more than 25.8 million Americans are estimated to have been impacted

by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria (FEMA Ready.gov, 2018). The growing number of people

affected by disasters has led to an increased need for individual and family self-reliance during

and following a disaster. The public health consequences of disasters persist long after the event

itself, revealing weaknesses in infrastructure and medical services that often produce many more

casualties than the direct impacts of the event, and creating long-term challenges for communities,

health providers and transportation planners.

The social characteristics of disaster have been widely documented (Quarantelli & Dynes,

1977; Heinberg, 2017; Henry, 2018; Elliott & Howell, 2017; Adger et al., 2005). When physical

infrastructure fails, social relationships serve as a substitute or “backup” to help people survive

and cope with the consequences of the disruption (Freitag et al., 2014; Ritchie, 2017; Klinenberg,

2018). For example, if transportation services were disrupted, people in a community might share

what resources are available locally or provide people with social support that they would

otherwise need transportation (and/or communication) services to access.

Although we recognize that preparing for a disaster involves a great deal of uncertainty, it

is clear that both social connectedness and access to a variety of local resources can help

communities to cope with the consequences of disaster events. In this paper, we explore, via a pilot

survey, the relationship between disaster preparedness and community social networks with a

specific focus on transportation connections to health care services. We also explore how social

attitudes like trust and willingness to share might affect access to different kinds of resources

within a community in a disaster scenario.

The place-based nature of disaster

Disasters are inherently geographical (Henry, 2018). The growing number of people affected by

disasters has led to an increased need for individual and family self-reliance during and following

a disaster. In Washington State, the Emergency Management Division encourages individuals and

families to be prepared to spend up to two weeks without outside assistance after a disaster

(Washington State Emergency Management Division, 2017). Likewise, communities are often cut

off from outside resources and must rely upon internal resources – the collective strengths, skills,

knowledge and material goods - to survive and recover. Most immediate emergency assistance

after a disaster is provided by people within their own communities long before outside help is

available (Henry, 2018). Place-specific factors, such as land use patterns, segregation, violence,

microclimate, poverty, and age of population, can affect the ability of communities to deal with

circumstances caused by disaster (Klinenberg, 2015). Length of residence and knowledge of place

play key roles in how people adapt to disturbances (Connon, 2017), and community organizations

and institutions play an important role in facilitating adaptive actions (Klinenberg, 2015; Henry,

2018).

The interdependency of transportation infrastructure

Disasters affect people and the physical infrastructures upon which they rely due to the

interconnected nature of social and technological systems (Townsend, 2013; Graham & Marvin,

2002); in fact, physical and institutional infrastructures often remain “invisible” until their failures

10

produce social consequences (Graham & Marvin, 2002; Klinenberg, 2015). Deteriorating

infrastructure systems and lack of maintenance have left communities in the U.S. more susceptible

to risk and hazards (Little, 2004a; Flynn & Burke, 2011). Furthermore, the increasing complexity

and interconnectedness of infrastructure systems increases risk of failure (Little, 2004b; Flynn &

Burke, 2011).

In disasters, many of the impacts experienced by communities comprise direct impacts of

failed infrastructural systems (e.g., disruptions in electricity, cellular communications, or

transportation) and indirect impacts, such as the disruption of social and institutional support

systems. Many people are not well-served by these systems in normal, “blue skies” circumstances,

and existing social inequities are highlighted and exacerbated during times of disaster, leading to

inequitable outcomes for the most socially vulnerable (Klinenberg, 2015). This is not to downplay

the extraordinary ways in which communities can come together during a disaster, as described in

Rebecca Solnit’s book, A Paradise Built in Hell (2010); rather, it is to recognize that physical and

technological infrastructure play an important, but often invisible, role in the structure of social

support systems that reinforce everyday community life.

The effects of a disaster can be understood as departures from the “normal” social patterns

of daily life manifested at multiple scales (Chen et al., 2013). At the scale of the community,

emergency response activities become urgent and paramount; at the household level, a new set of

needs, perhaps ensuring the safety of loved ones and procuring basic necessities, replace the set of

“everyday” needs that were previously important (Ibid). Thus, access to transportation services

and the range of people’s daily needs will both change significantly in the case of a disaster, leading

to a new set of conditions under which a community must function by leveraging and matching

locally available resources.

Many people use transportation services on a daily basis to help them accomplish a range

of necessary activities. Transportation services enable people to travel to get to work, to get to

school, to run errands or do shopping, to access services such as day care or health care, and to

participate in recreational or leisure activities. Many transportation activities are organized or

facilitated by information and communications technologies (ICTs), which also enable the

communication necessary to complete a range of tasks, from the transportation-related items noted

above to carrying out work-related tasks to accessing social support.

Although there are many options for combining or substituting transportation and

communications technologies (Salomon, 1986; Mokhtarian, 1990; Lyons, 2009), both often rely

on infrastructure that is susceptible to systemwide failure in the event of a disruption, such as

cellular or transportation networks. In addition, access to many of the transportation services that

facilitate daily activities relies upon the provision of private services and participation in digital

society. In a relatively contained emergency situation that limits transportation options but not

communication services (such as a transit strike, flood, or large planned events) the substitution of

travel by ICT becomes much more attractive, and ICT can accommodate many work, commerce

and social functions if needed (Mokhtarian, 2009). However, the range of scenarios for

transportation and communication technology use and substitution would likely change

significantly in the case of a larger disruption. In the next section, we discuss specifically the

effects of disasters on transportation systems.

Transportation networks and disasters

A functional and resilient transportation infrastructure is necessary for supporting the everyday

needs of society. Disruptions such as disasters, which are uncertain and often unpredictable, can

11

have severely negative impacts on the transportation infrastructure that supports basic societal

functions (Soltani-Sobh et al., 2016). Transportation systems are vulnerable to many kinds of

hazards, including natural events, technological disruptions, and intentional malicious actions

(Faturechi & Miller-Hooks, 2014).

Extreme events like earthquakes are nearly impossible to predict, and their impacts tend to

be underestimated (Kermanshah & Derrible, 2016). Each disaster brings with it unique

consequences, shaped by the magnitude and character of the disaster itself as well as the

geographical, infrastructural and social context in which it occurs. Disasters can involve an array

of different kinds of disruptions; for example, an earthquake might also cause fires, facilitate the

spread of disease, or result in exposure to toxic chemicals (Litman, 2006). Transportation network

damage from earthquakes results from a combination of factors, including ground failure (e.g.,

landslides or ground cracks), faulting (e.g., movement in the horizontal and/or vertical plane of the

roadbed), vibration, and, in coastal areas, tsunami (Kermanshah & Derrible, 2016).

In any large-scale disaster, transportation systems are very likely to be affected, limiting

the availability of service. The impacts that disasters have on transportation systems have

intensified because transportation systems are increasingly complex and interdependent (Faturechi

& Miller-Hooks, 2014). Damaged transportation networks lead to traffic congestion, transit delays,

fuel supply problems, and disruptions to logistics operations (Litman, 2006; Ishfaq, 2012). The

failure of mobile phone and electricity networks can in turn cause the failure of complementary

ICT mobility services as well as more basic transportation infrastructure like stoplights (deJong,

2017). Disrupted transportation systems also result in damage to economic and social systems

(Faturechi & Miller-Hooks, 2014).

The role of transportation in disasters

Transportation systems enable access to critical resources for daily activities as well as in

emergency scenarios, where they can support evacuation, rescue operations, reconstruction, and

recovery. (Faturechi & Miller-Hooks, 2014). Transportation networks and services play different

roles in different types of disasters, including evacuation; delivery of emergency supplies and

services; search and rescue operations; quarantine; and transportation infrastructure repair (Litman,

2006). The success of disaster recovery efforts is often influenced by the relative ease with which

resources can be transported into and out of a community (Soltani-Sobh et al., 2016).

Transportation infrastructure might be appropriated for uses other than their intended

purpose in the case of a disaster. For example, after the 2017 Mexico City earthquake, when

separated bus rapid transit lanes served as emergency transportation corridors because they were

not congested with traffic. In the days following the earthquake, walking, biking and motorcycles

become the primary means of transportation, providing a mobility option for navigating obstructed

streets, enabling the trasnportation of medicines and supplies, and enabling responders to scout

heavily damaged areas (deJong, 2017).

12

CHAPTER 2: PILOT STUDY SITE AND REGIONAL CONTEXT

The setting for this pilot study is an urban neighborhood in the Pacific Northwest, a region recently

attuned to the potential impact and uncertainty of natural hazard events. Although Seattle is

susceptible to several different types of hazards, we focus here on the likely impact of earthquakes,

which in the region might range from more frequent and smaller disturbances to a potential

magnitude 9.0 earthquake as detailed in the highly visible New Yorker article, “The Really Big

One: Earthquake Preparedness in The Pacific Northwest” (Schulz, 2015). A massive Cascadia

Subduction Zone earthquake such as the one described by Schulz and anticipated by the disaster

science community would have a devastating impact on communities throughout the region, both

urban and rural.

The pilot community of Laurelhurst is a relatively wealthy and well-connected urban

neighborhood in Seattle of approximately 4,000 residents. In response to increasing concern about

the potential effects of a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake, a group of Laurelhurst residents

have self-organized to form a disaster preparedness organization, Laurelhurst Emergency Action

Plan (LEAP). The highly educated and mobile residents of Laurelhurst have access to a range of

health care services across the city, including world-class specialist care. Located near the

University of Washington’s Seattle campus, the neighborhood is within close range of the

University of Washington Medical Center, a nationally renowned hospital. Located within the

neighborhood is the main campus of Seattle Children’s Hospital, one of the nation’s top children’s

hospitals, as well as a handful of smaller private businesses and clinics offering a range of health

care services.

LEAP, a community-initiated organization, regularly engages with existing City of Seattle

disaster planning personnel and hosts preparedness events in the neighborhood providing

instruction on a range of topics from how to put together an emergency preparedness kit to how to

stop a bleeding victim from hemorrhaging. LEAP is attempting to organize the entire Laurelhurst

neighborhood into approximately 20-household clusters, each with a cluster captain that can help

to facilitate their group’s preparation for disaster by building stronger social connections within

the cluster. To date, LEAP has not coordinated its efforts with the local health care and wellness

community.

While Laurelhurst is not representative of Seattle neighborhoods, it provides an interesting

test case for comparative purposes. The objective of future research along this line is to engage

additional communities along spectra of both urban-ness and economic status. In addition, the goal

of this research endeavor is not to seek out one-size-fits-all solutions; rather, it is to understand the

ways in which community context and social factors uniquely shape disaster preparedness and

capacity for response. For example, comparing the types resources available between communities

of different economic status could be informative for disaster preparedness planning.

13

CHAPTER 3: METHODS

The research methodology comprised two main components: a public workshop with community

members, and a pilot sample survey. The research team first connected with LEAP members in the

fall of 2016, at which time the two groups discussed their mutual interest in community-scale

disaster preparedness. Discussions focused on better understanding how community assets can be

leveraged to enable resilience in the face of disruptions (such as earthquakes) or other long-term

changing conditions, in ways that also improve everyday community well-being. The research

team began to join LEAP meetings, which led to collaboration on the design of a community

workshop to learn more about assets and values within the Laurelhurst neighborhood.

3.1 Community Workshop

On November 7, 2018, LEAP and the UW research team co-hosted a public workshop at the

Laurelhurst Community Center, creating a forum for neighborhood stakeholders to discuss, via

participatory group activities, the qualities that contribute to a resilient community. The purpose

of the workshop was twofold: 1) to help LEAP recruit new members by spreading the word about

community emergency preparedness; and 2) to build a better understanding of the unique

community values and assets that might contribute to strengthening community resilience in

Laurelhurst. Fifteen community members (including five LEAP members) and the UW team

participated in the workshop.

Working together in small groups, participants were asked to map community assets in

response to the following questions:

• What values or assets make your community unique?

• What are Laurelhurst’s strengths as a neighborhood?

• What characteristics of the neighborhood contribute to everyday quality of life?

Participants were encouraged to think broadly about what might constitute a community

strength or asset. The Community Capitals Framework developed by Emery and Flora (2006) was

used as a prompt for participants to consider natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial

and built capital in the exercise. Transportation-related assets identified by participants included a

nearby light rail station, “lots of bikes,” the road network and access to water and boats via

neighborhood-adjacent Lake Washington. The presence of Children’s Hospital within the

neighborhood was identified as an asset. Social network assets include the fact that many

generations live within the neighborhood; a strong sense of community; people knowing their

neighbors; helpful and caring neighbors; respectful, “dogs on leashes” behavior within the

neighborhood, and low residential turnover resulting in stable neighbors. Transportation emerged

as a primary concern following a potential disaster. Participants voiced their uncertainty about

what transportation infrastructure and travel options would be viable following an earthquake;

some suggested that all-terrain vehicles or bicycles might be more easily used than cars if extensive

damage to roads were incurred.

Gathering this information in the workshop helped the research team to better understand

Laurelhurst’s unique neighborhood context, which in turn helped to shape the survey instrument.

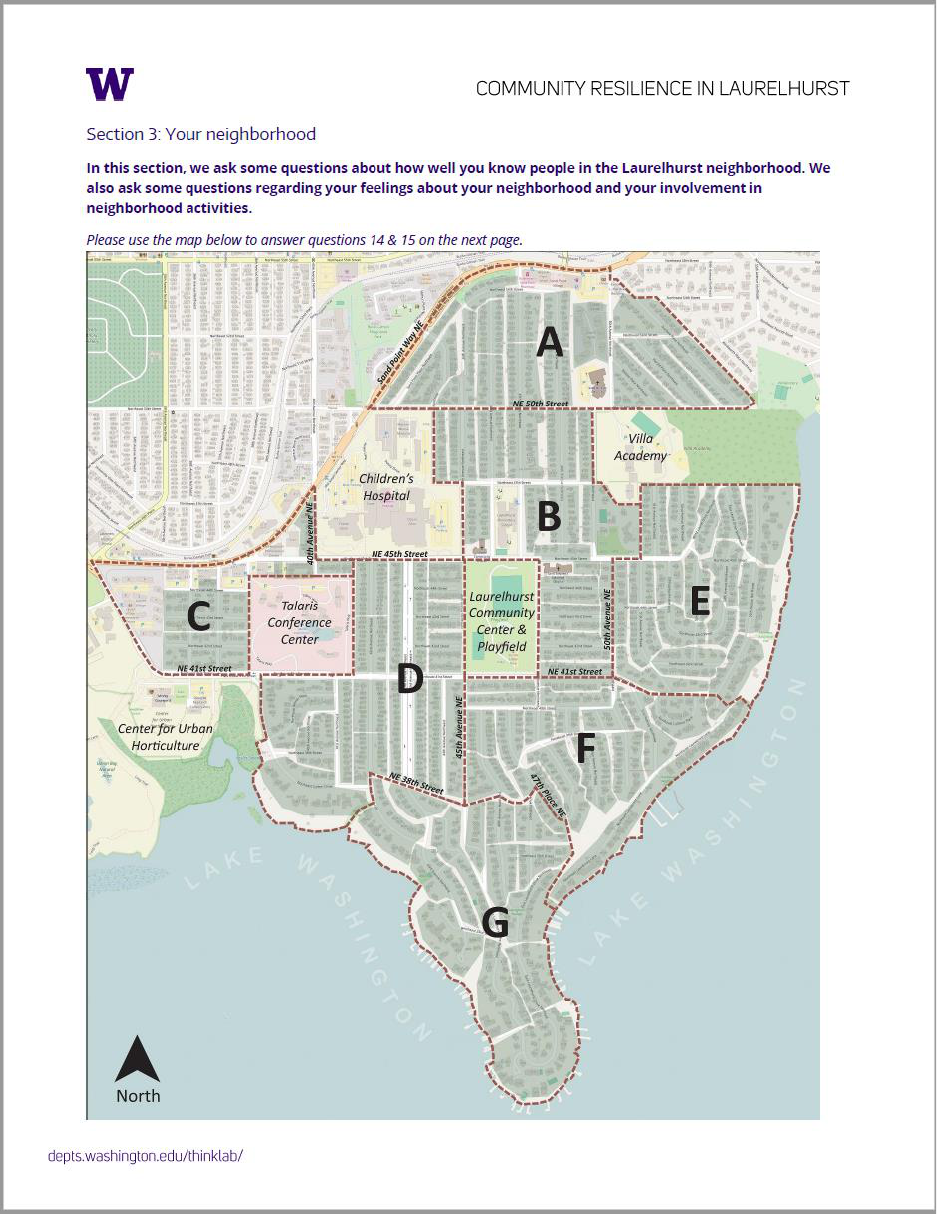

For example, the different neighborhood “zones” outlined on a map contained within the survey

instrument were created using guidance from a workshop conversation about how LEAP might

organize its 20-household clusters into larger zones that could collaborate internally on disaster

preparedness efforts. We were also able to learn about which places or establishments within the

14

community are important to community members and might serve as resources in a time of need.

The information gathered during the workshop also helped with interpretation of survey responses,

particularly in providing context for answers to some of the open-ended questions. After the

workshop, the research team met with LEAP to review the survey instrument and received helpful

feedback that was integrated into the questionnaire for the pilot study.

3.2 Pilot Sample Survey

The pilot survey comprises a random sample of 200 Laurelhurst households. Residential properties

were sampled from within the boundaries of the Laurelhurst neighborhood as defined by the

Laurelhurst Community Club.

Potential respondents were first contacted in April of 2019 via a letter explaining the

importance of the project and directing them to an online survey website. Survey materials were

designed using guidance from Dillman’s Tailored Design Method (2007), and multiple contacts

were made with each potential respondent. Each recipient was given a unique identification

number for logging in to the survey website, and contact information was provided for those who

preferred to request a paper survey. A reminder was sent after two weeks, again highlighting the

online survey website. Finally, after another two weeks, those who had not yet completed the

online survey were mailed a paper copy of the survey booklet. A total of 44 people completed the

online survey, while 34 people completed the paper survey. Three incomplete responses were

discarded for a total of 75 complete and useable responses between the paper and online surveys,

a 37.5% response rate. Responses were collected through June of 2019.

As part of the pilot survey, the research team tested two different incentives: 1) a one-time,

two-dollar cash incentive included in the initial mailing; and 2) a five-dollar e-gift card, which

required respondents to provide their email address. Twenty-seven people who received the two-

dollar incentive completed the web survey, compared to sixteen people who received the five-

dollar incentive. Twelve people who received the two-dollar incentive completed the paper survey

compared to twenty people who received the five-dollar incentive. We found that although the

two-dollar incentive prompted a higher initial response, it was only offered to respondents once,

in the initial mailing, while it was possible to offer the five-dollar incentive with each mailed

communication. In addition, not all respondents who were offered the five-dollar incentive chose

to request it.

The survey instrument was reviewed by members of the City of Seattle’s Office of

Emergency Management, the Northwest Healthcare Response Network, Washington State’s

Emergency Management Division, and the University of Washington Medical Center, as well as

being reviewed by members of LEAP. Some questions from a previous City of Seattle survey on

disaster preparedness were adapted and used as part of the survey instrument.

The survey comprises 35 items, which were a mix of multiple selection and open-ended

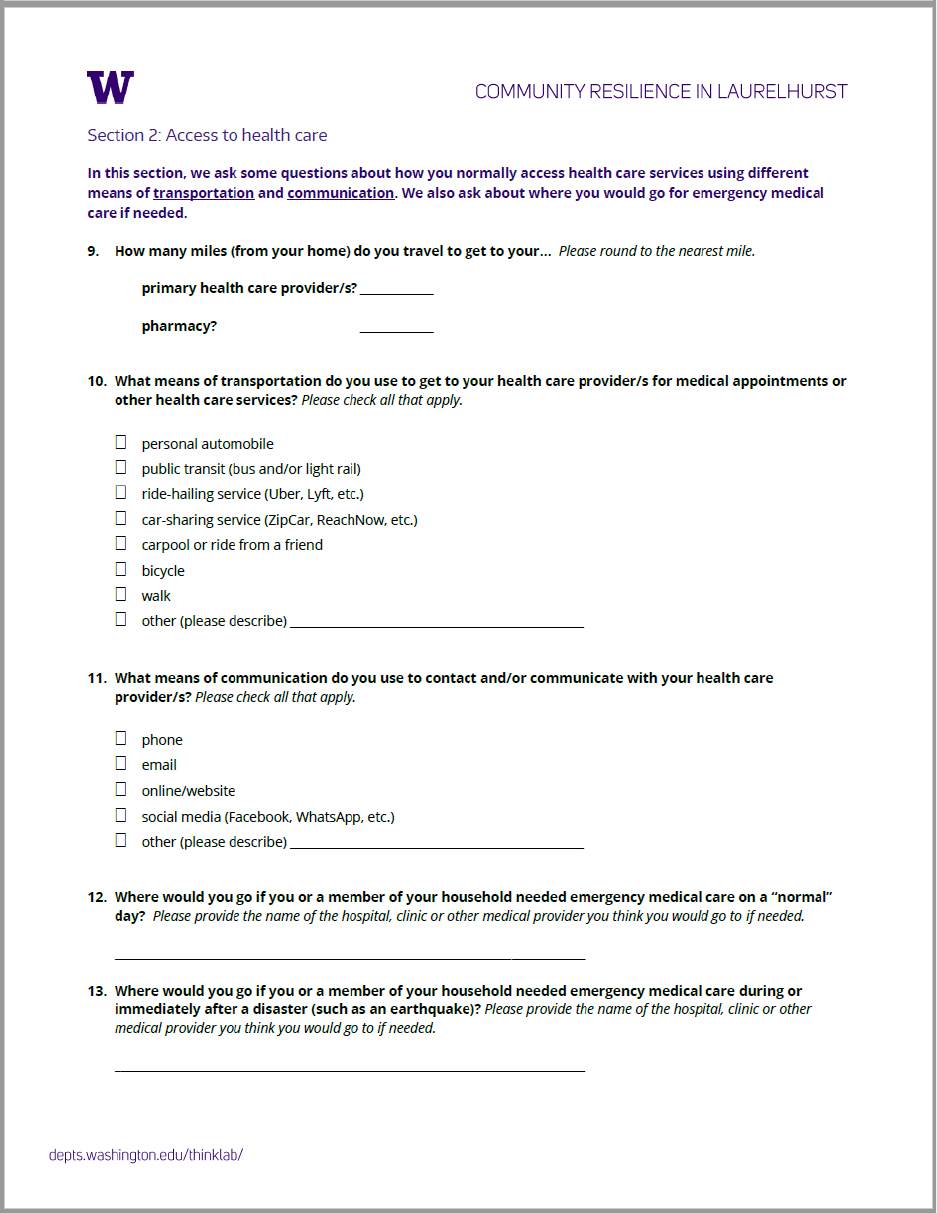

questions and took respondents approximately 20 minutes to complete. The survey was divided

into four modules: disaster preparedness, access to health care, neighborhood connections, and

background information.

The disaster preparedness module asks respondents what preparedness items they have,

what daily activities they are most concerned about carrying out if utility services are lost, and

where they would go to get essential items in a disaster scenario, among other general disaster

preparedness questions. The second module asks respondents specifically about how they access

health care services via different modes of transportation and communication, how far they travel

to access health care services, and how their choice of health care provider might change from a

15

normal, “blue skies” day to an emergency (disaster) scenario.

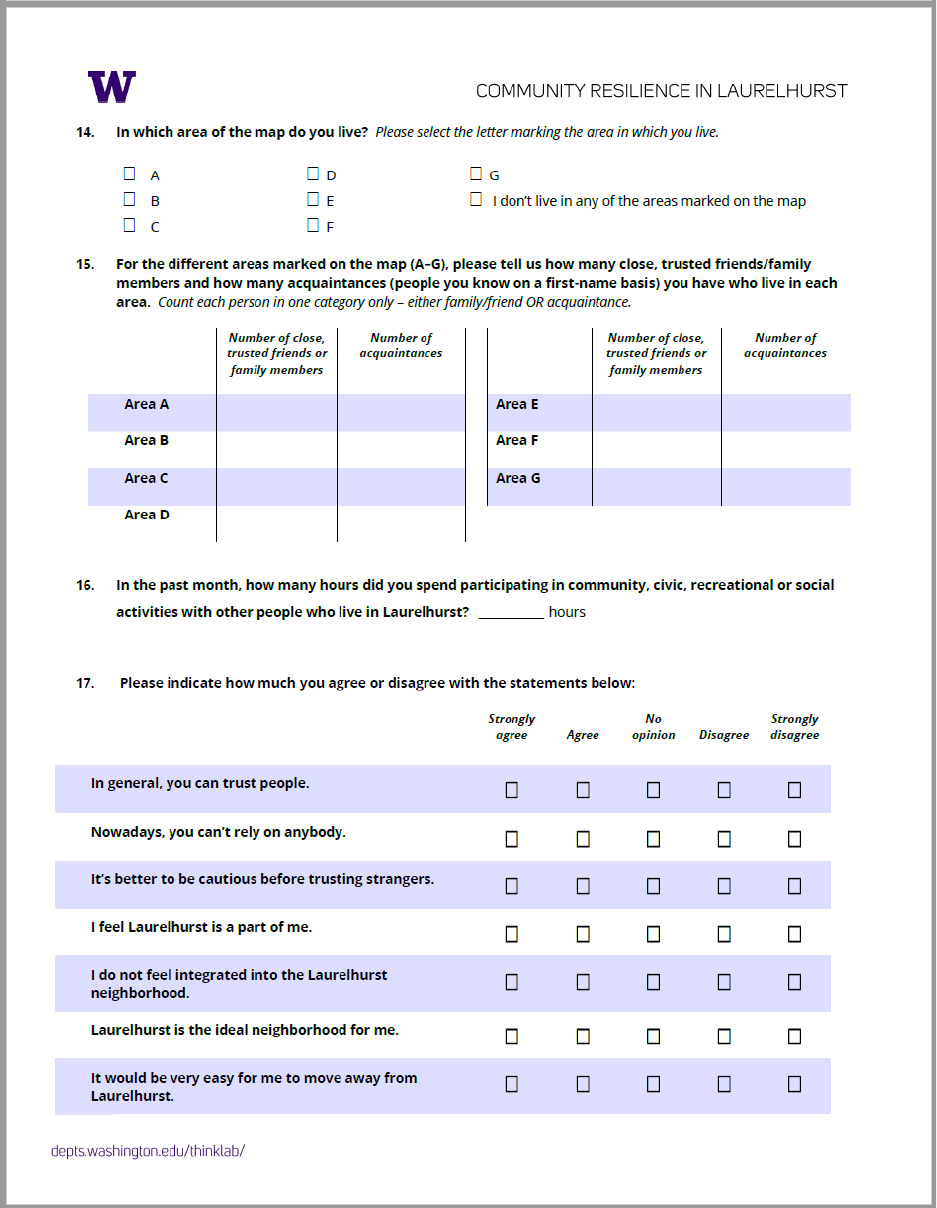

The third module focuses on neighborhood context and social connections. Respondents

were asked to provide the number of core and distant connections within different areas of the

neighborhood (the neighborhood “zones” defined with help from LEAP). This module also

includes a place attachment scale (adapted from Fornara et al., 2010), a social trust scale adapted

from the General Social Survey, and a measure of the number of hours respondents spent engaged

in neighborhood activities each month.

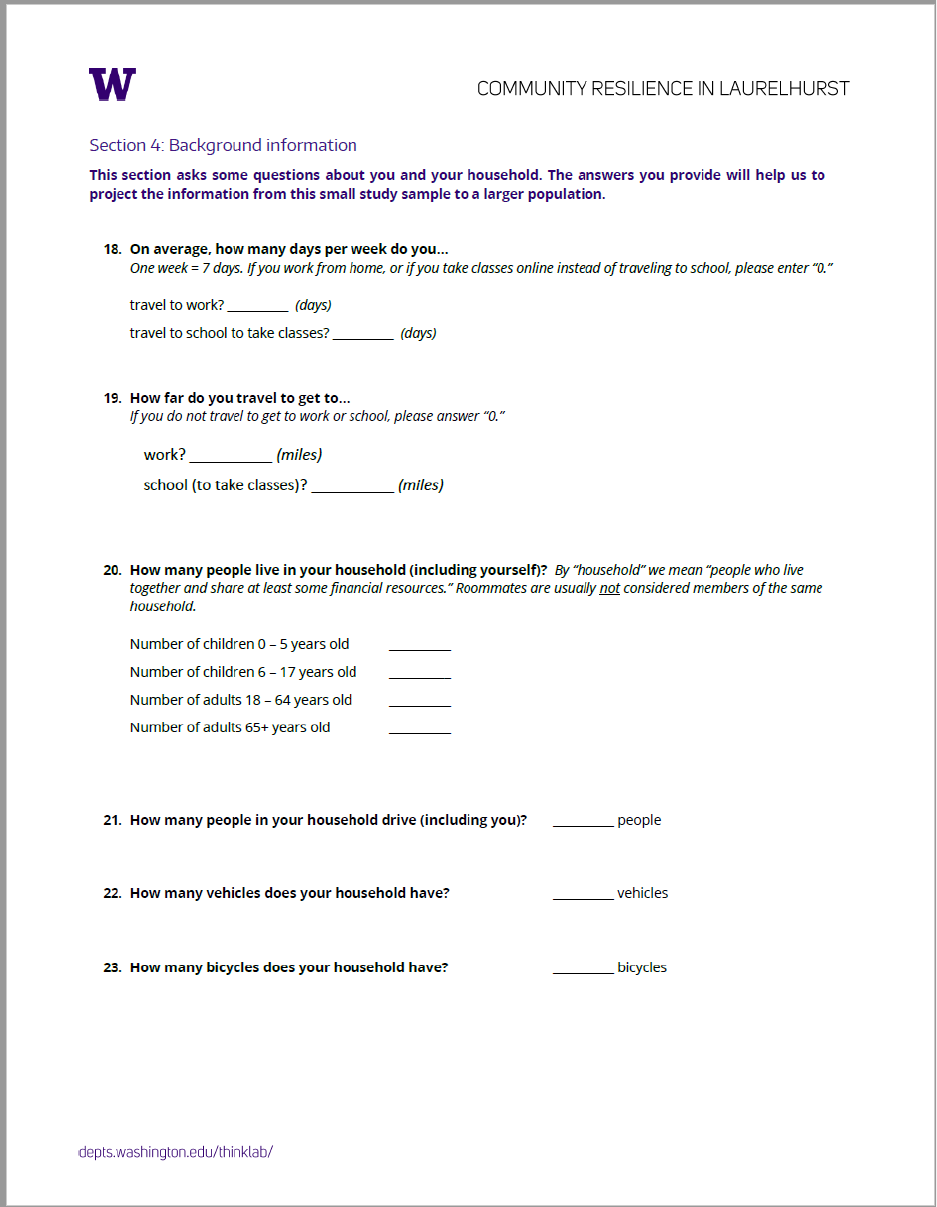

The final module was designed to collect respondent background and demographic

information, including household size and makeup, ethnicity, age, education, income, and rent/own

status. This module also includes questions related to transportation behavior such as number of

commute days per week, commute distance, number of household cars and bikes, and the number

of people in the household with mobility limitations for different modes.

Together, the information gathered from the four survey modules helps to paint a picture

of the ways in which community members have prepared for a potential disaster, what unique

assets are located within the community that might serve as resources in the case of a disaster, a

profile of neighborhood social connectivity, and the ways in which everyday travel behavior relates

to health care access normally as well as during a potential disaster.

Sample Size Calculation

In this survey, key variables such as travel modes, household preparedness measures and

willingness to share are measured in terms of proportions of the survey population.

Within in the study area, there are 1,512 single-family homes and 63 apartments (1,575 households

within the two strata). Assuming 25% variance, specifying a 95% confidence level and accepting

a 5% margin of error for a proportion estimation, the base sample size would be 300 households:

n

0

= .25(1 - .75)/(.05/2)

2

= 300

Adjusting for the finite population correction, we reduce the sample size to 252 households:

n = n

0

/(1 + n

0

/N) n = 300/(1+300/1,575) = 252

Assuming a 20% response rate and a 10% undeliverable) rate, we increase our sample size to

252/.2/.9 = 1400 households. For the full survey, we will sample all 63 multifamily units and 1,337

units from the single-family household stratum to achieve the desired sample size of 1400

households.

For the pilot survey, a random sample of 200 single-family households was drawn without

replacement from the sampling frame using the sample() function in R.

16

CHAPTER 4: PILOT SURVEY FINDINGS

The mean age of respondents was 57, with 48% of respondents identifying as female and 45% as

male (7% preferred not to answer). The neighborhood is very well-off and educated; 65% of

households surveyed have an annual income of more than $150,000, and 63% of respondents had

completed a bachelor’s degree or higher. Just over half of the households speak English only (57%).

An overwhelming majority of respondents (93%) live in a stand-alone house, and 85% own their

homes. The mean tenure of respondents in their current home is 17.0 years, and 20.1 years living

in the Laurelhurst neighborhood. On average, respondents log 2.8 work travel days per week with

a mean commute distance of 5.0 miles. Households have two drivers on average, and just over two

vehicles (2.1).

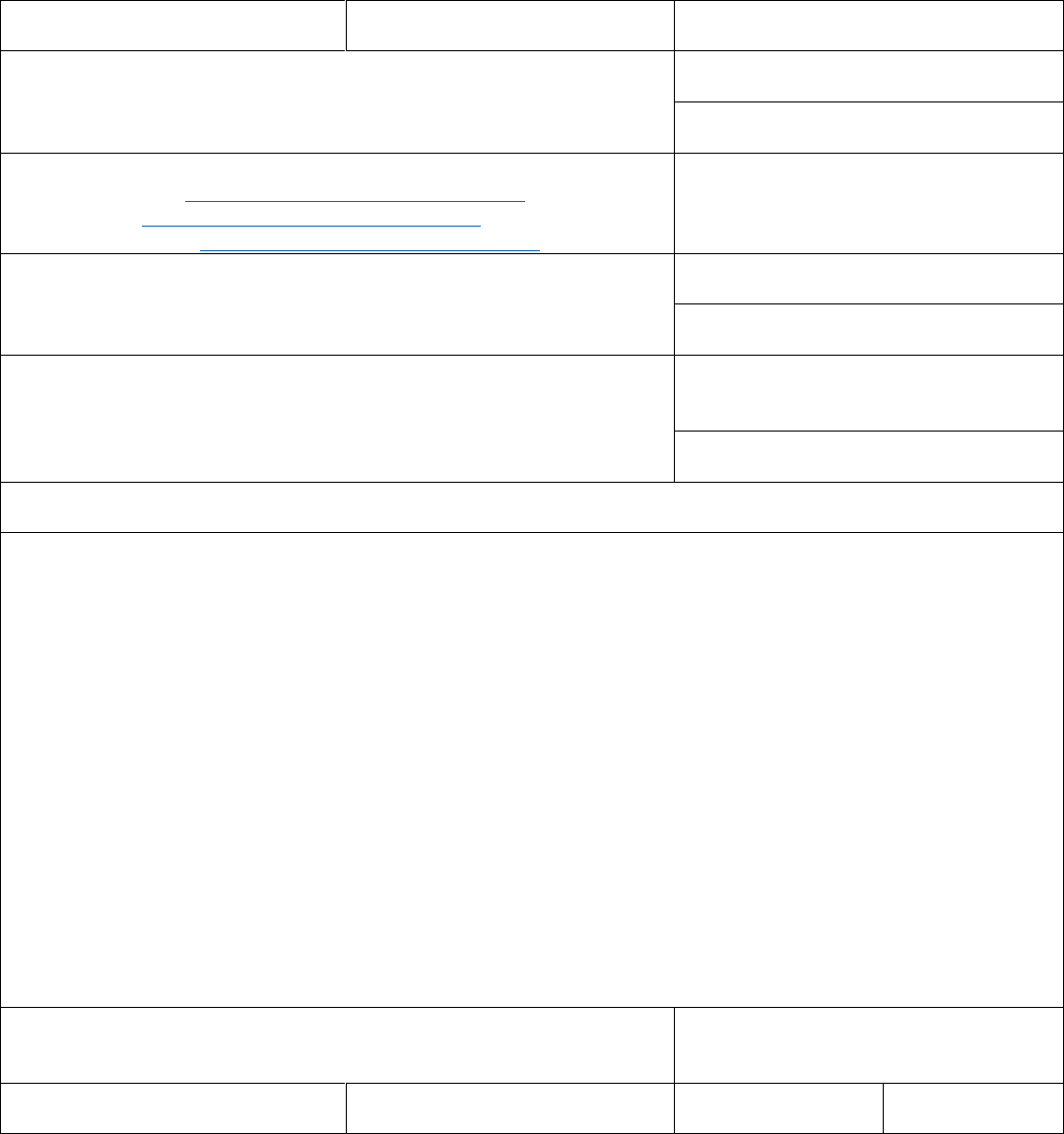

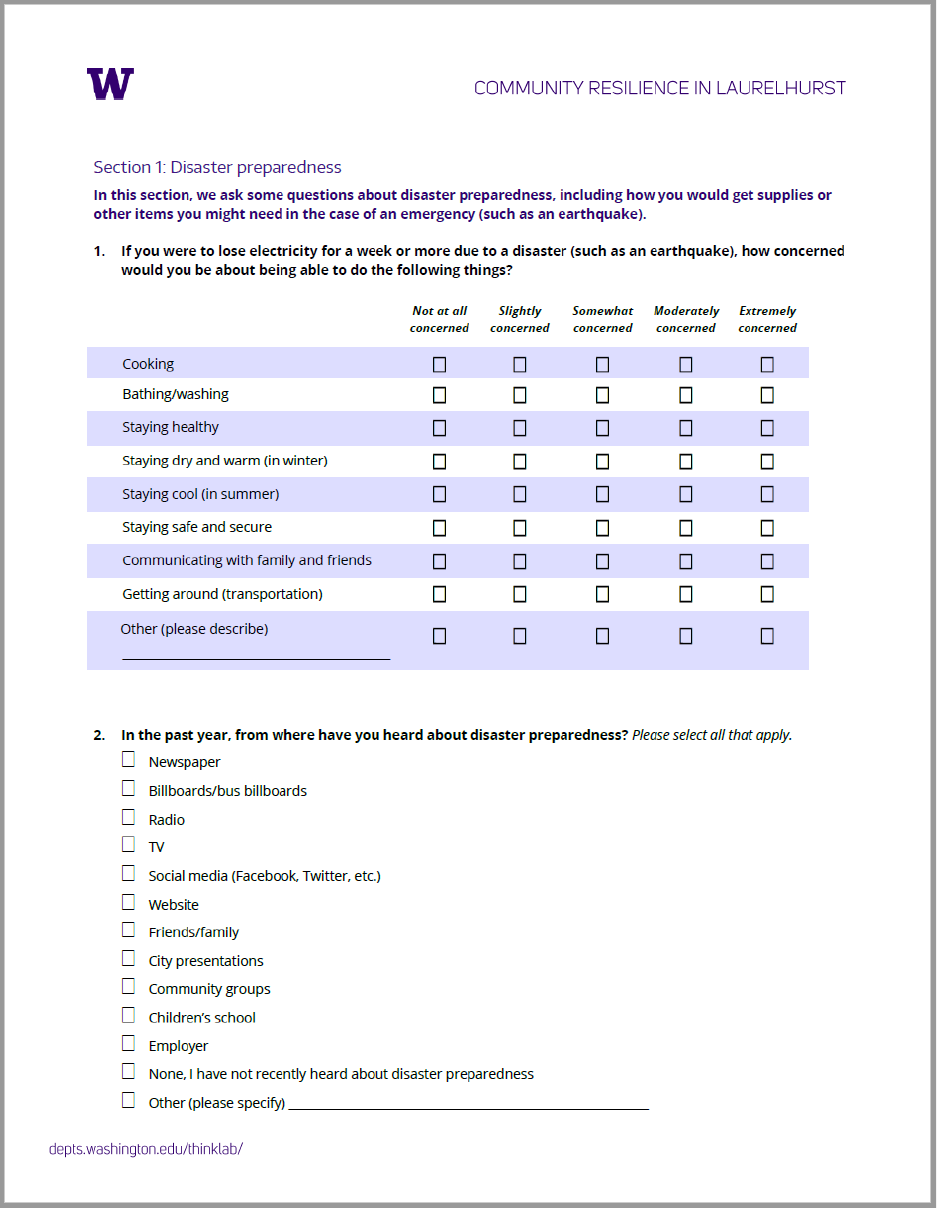

4.1 Transportation Preparedness and Level of Concern

In the survey, we asked respondents how concerned they were about being able carry out a variety

of everyday activities in the case of a major utility outage due to a disaster like an earthquake,

including: cooking, bathing/washing, staying healthy, staying dry and warm in winter, staying cool

in summer, staying safe and secure, communicating with family and friends, and using

transportation to get around. On a five-point Likert scale of “not at all concerned,” “slightly

concerned,” “somewhat concerned,” “moderately concerned,” and “extremely concerned,” the

average response was 2.76/5, or between “slightly” and “somewhat” concerned. Among the eight

everyday needs we asked about, transportation fell sixth in terms of level of concern (see Figure

1).

Figure 1. Relative levels of concern about carrying out everyday activities in a disaster scenario

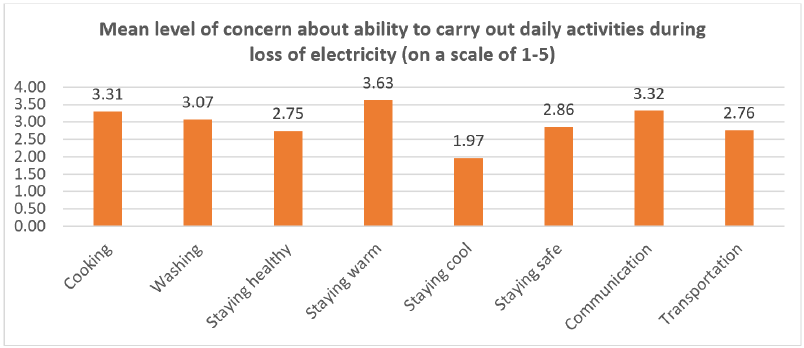

We also asked respondents how prepared they are to survive on their own regarding ten different

preparedness items if there were an extended utility outage in the event of an earthquake (see

Figure 2). Answering on a four-point scale of 0 = “not at all prepared,” 1 = “prepared for 1-3 days,”

2 = “prepared for 4-6 days,” and 3 = “prepared for 7+ days,” the mean level of response for

transportation was 2.55, or preparedness for three to four days. Of the ten items in the question,

transportation fell third in terms of what people felt they were most prepared with, behind warmth

and medications. Every household surveyed had at least one vehicle, and the mean number of

bicycles was 2.5/household, suggesting that people may feel secure in being able to use their

vehicle or a bicycle in the event of a disaster, thus the relatively low level of concern compared to

17

other everyday activities.

Figure 2. Respondent preparedness for carrying out everyday activities in a disaster scenario

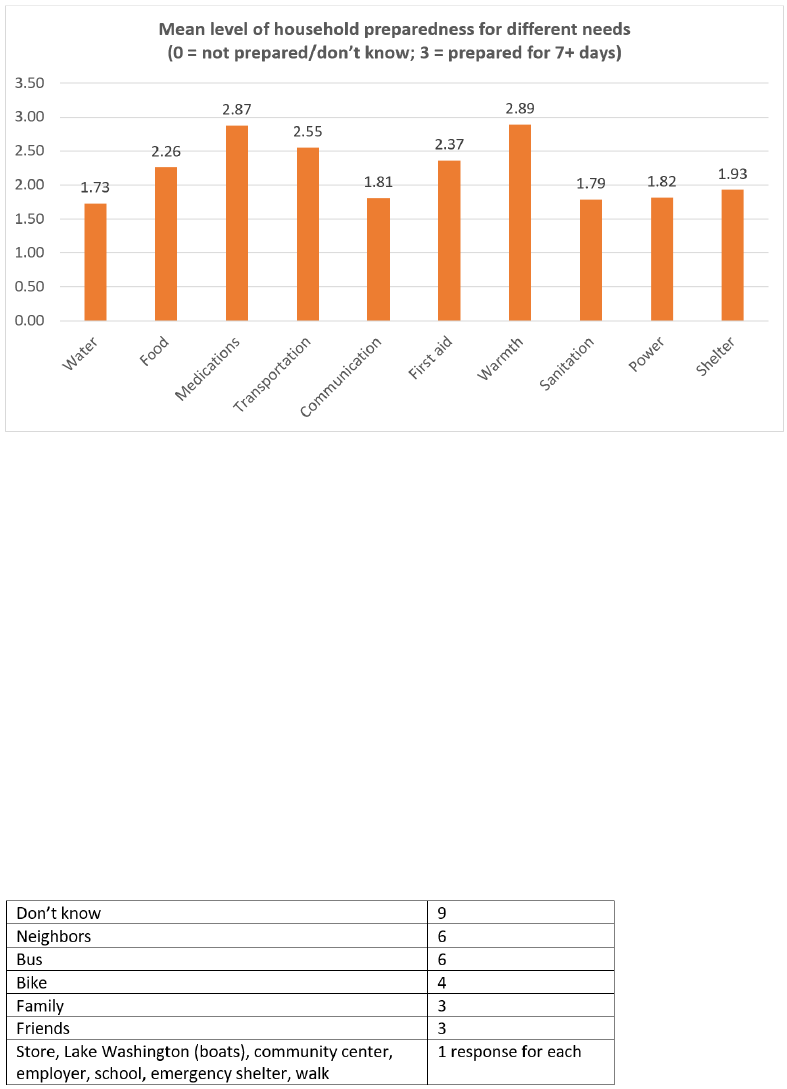

When asked in an open-ended question where they would go to get transportation resources if they

found themselves without a means of getting around in a disaster, many people responded that they

“don’t know” where they would go to obtain transportation (see Table 1). Of the ten items people

were asked about (water, medications, food, shelter, communication, transportation, warmth,

sanitation, power, and first aid supplies), only transportation and sanitation received more “don’t

know” answers than any other answer, suggesting that people may be at a loss in terms of finding

alternative transportation. Only six people said they would turn to neighbors, while another six

thought they might be able to rely on bus service, which limited in the neighborhood even on a

normal day. Walking and biking received relatively few responses. Although in the previous

questions reviewed, people felt relatively little concern about transportation in a disaster scenario

and felt relatively well-prepared, the answers to this question suggest that people may not know

what to do if their own transportation resources (e.g., cars, bikes) cannot be used in the event of a

disaster. We do note that this question had a high rate of non-response, we believe due to its open-

ended nature, thus the relatively minimal response relative to the 75 total respondents.

Table 1. Where respondents would turn for transportation resources in the case of an emergency

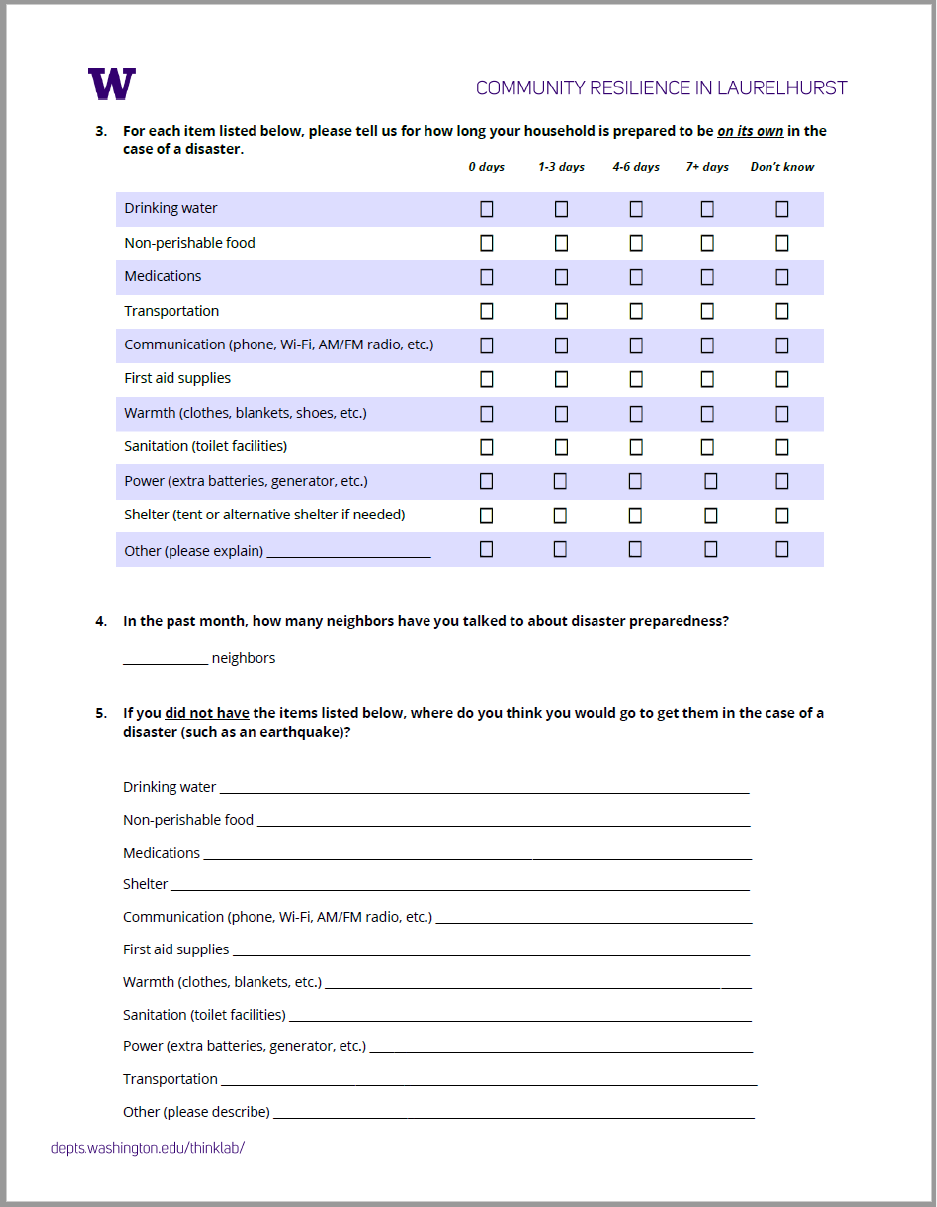

4.2 Willingness to share

Because communities often need to rely on internal resources in the case of a disaster, we were

interested to know how willing people might be to share different kinds of resources in the event

18

of a disaster, and how the strength of social ties might affect that willingness to share. People seem

willing to share transportation with family, friends and acquaintances, but somewhat less with

anyone in need (see Figure 3. Of the 75 total respondents, 51 (68%) indicated that they would

require some kind of social tie in order to share transportation resources with others in their

community (three people indicated they would not share with anyone, 19 indicated they would

share with everyone regardless of social ties, and two did not respond). We did not find a significant

correlation between social trust and willingness to share.

Figure 3. Willingness to share resources in the case of disaster according to strength of social ties

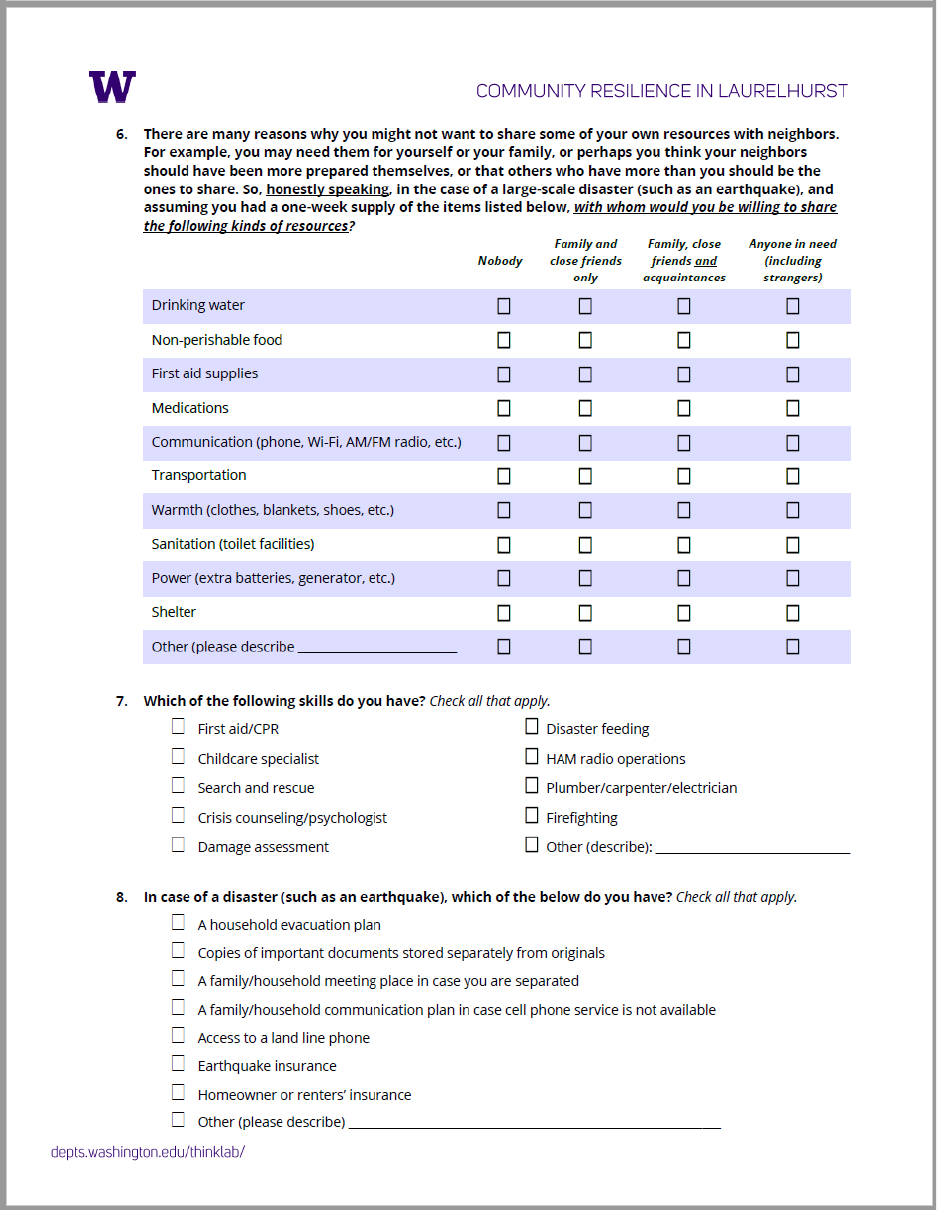

4.3 Transportation, disaster, and health care services

On average, respondents typically travel 3.8 miles to reach health care services and 1.3 miles to

reach their pharmacy. We found that the majority of respondents (76%) travel less than one mile

to their pharmacy, while only 26% travel less than one mile to their primary care provider. This

suggests that it may be feasible for people to reach their usual pharmacy in the case of a disaster,

but likely not their usual primary care provider (see Figures 4 and 5). However, people felt very

prepared with medications because prescriptions tend to provide several weeks’ worth of

medications at one time. We also found that 68% of respondents felt that they would travel to the

same emergency care provider in both normal and disaster circumstances. Whether or not health

care facilities and pharmacies would be functioning in the case of a disaster, however, is highly

uncertain.

19

Figure 4. Distribution of distance traveled to primary health care providers

Figure 5. Distribution of distance traveled to pharmacy

Approximately half (51%) of respondents typically use more than one mode of transportation to

access health care services (we asked about automobile, transit, ride-hailing, car sharing,

carpooling, bicycling and walking), suggesting that familiar alternative modes of transportation

may be available to some people in a disaster scenario (see Figure 6). Just over half of the

respondents (53%) indicated that they have some first aid skills, which might provide an important

community resource if access to health care facilities were limited.

20

Figure 6. Distribution of number of transportation modes used to access health care services

21

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In a very general sense, few everyday activities are completed without leveraging some kind of

transportation resource. The ability to leverage community resources via local knowledge and

social ties is likely to play a significant role in helping people carry out everyday tasks following

a disaster. The literature reviewed suggests that robust social ties serve a critical function when

access to everyday resources is limited (Klinenberg, 2015). As noted previously, disasters are

place-based phenomena, with the implication that characteristics of place will influence the

composition of internal resources available at the community level and levels of interpersonal trust

and connection at the individual level. Because the community capacity necessary to avoid or

recover from a disaster is typically only apparent after a disruption, planning for disaster mitigation

involves a great deal of uncertainty.

Predicting the behavior of sociotechnical systems (such as transportation networks) when they

experience significant disturbance (such as a disaster) is a massively complex endeavor and a task

that remains elusive (Vespignani, 2009). Disaster preparedness planning is rife with uncertainties,

and although models can provide a partial illustration by identifying less stable ground, where the

faults lie, and what infrastructure might be more susceptible to damage, the specificity of the post-

earthquake landscape is largely unknowable.

It is important for planners and communities to be flexible and to think about contingencies in their

earthquake preparedness planning. Despite all the uncertainties involving the built environment in

a disaster scenario, we do know from past experience and research that the social environment of

communities is very important in the hours, days and weeks following a disaster (Freitag et al.,

2014). Social connections often substitute for infrastructural connections when needed (Ritchie,

2017; Klinenberg, 2018), and knowledge of local resources can be critical when communities are

cut off from the outside world. Helping communities to build social ties and enhancing local access

to a diversity of resources is one constructive approach to planning for disasters despite great

uncertainty.

While Laurelhurst, a well-connected urban neighborhood, experiences few if any barriers to

obtaining access to health care and wellness resources on an everyday basis, it will face unique

context-specific challenges in the event of a disaster. Because neighborhood residents have many

options for health care services and are quite mobile, they may have a lack of familiarity with local

health care facilities. In addition, the hospital that is located within the neighborhood provides

specialty care to children and youth, while the population of the neighborhood itself is older than

average, with many retirees. A next step might involve talking to health care institutions about

what they expect to happen in a disaster and about any community outreach plans or actions

regarding disaster preparedness. The steep topography and non-intuitive urban form of the

neighborhood (the community’s meandering streets are so mazelike that public buses often get lost

in the area) are also likely to pose challenges to emergency access, hindering reconnaissance and

rescue efforts in the event of a disaster.

The findings suggest that although people have relatively little concern about transportation in a

disaster scenario compared to other everyday needs, they would not know where to turn for

alternative trasnportation if they could not supply it themselves. Addressing this disparity may

involve education efforts regarding what transportation systems may or may not be available in

22

the event of an earthquake (for example, some people felt that the bus network could serve as an

alternative transportation resource, but this is unlikely due to the nature of earthquake damage).

Community events and activities encouraging the construction and strengthening of social

connections could help to make community members more aware of the disaster preparedness

resources available in their neighborhood (and where the gaps might be).

Remaining gaps and next steps

Mitigation strategies associated with earthquakes have traditionally overlooked the important role

played by transportation systems after disasters (Soltani-Sobh et al., 2016). Research on

transportation in extreme events has also focused on technological applications without revisiting

the fundamental principles of the transportation industry (e.g., design concepts, supporting

technological systems, functionality requirements, capacity) and the ways it is challenged to cope

with risks and uncertainties (Kaewunruen et al., 2016), resulting in a series of repeat failures (with

societal consequences) in the face of extreme events without significant change. Our findings

suggest that incorporating community social factors into transportation planning could provide

helpful information for both “everyday” transportation planning and transportation planning for

disaster preparedness and mitigation.

In addition, another major gap is understanding the needs of vulnerable populations, such as people

who are dependent on transit, in disaster planning and mitigation (Litman, 2006). An approach to

disaster preparedness planning that recognizes the diverse needs of people in poverty, those with

various physical or mental disabilities, those with language barriers and children is required,

pointing to the need for community-scale awareness and research to create inventories of special

needs, available resources, and gaps. It is our hope that moving forward with a research agenda

that integrates community social factors can help to address some of these gaps. Next steps include

testing the workshop and survey protocol in a range of other neighborhoods along spectra of urban-

ness and economic status to better illustrate regional variation in disaster preparedness planning

needs and gaps.

23

REFERENCES

Adger, W. N., T.P. Hughes, C. Folke, S.R. Carpenter, & J. Rockström. (2005). Social-ecological

resilience to coastal disasters. Science, 2005. 309(5737): 1036-1039.

Chang, L., A. S. Elnashai, & B. F. Spencer Jr. Post-earthquake modelling of transportation

networks. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 2012. 8(10): 893-911.

Chen, C., D. Neal, & M. Zhou, M. Understanding the evolution of a disaster—a Framework for

Assessing Crisis in a System Environment (FACSE). Natural hazards, 2013. 65(1): 407-422.

Connon, I. L. C. Extreme weather, complex spaces and diverse rural places: An intra-community

scale analysis of responses to storm events in rural Scotland, UK. Journal of Rural Studies, 2017.

54: 111-125.

de Jong, F. Parks and bicycles were lifelines after Mexico City’s earthquake. CityLab, 2017.

Accessed March 20, 2019 at https://www.citylab.com/environment/2017/09/parks-and-bicycles-

were-lifelines-after-mexico-citys-earthquake/541320/

Dillman, D. A. Mail and Internet surveys: The tailored design method--2007 Update with new

Internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, 2007.

Elliott, J. R., & J. Howell, J. Beyond disasters: a longitudinal analysis of natural hazards’ unequal

impacts on residential instability. Social Forces, 2017. 95(3): 1181-1207.

Emery, M. & C.B. Flora. Spiraling-Up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community

Capitals Framework. Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society,

2006. 37: 19-35.

24

Faturechi, R., & E. Miller-Hooks. Measuring the performance of transportation infrastructure

systems in disasters: A comprehensive review. Journal of Infrastructure Systems, 2014. 21(1):

04014025-1 - 04014025-15.

FEMA Ready.gov. Important Things to Know Before a Disaster, 2018, February 26. Retrieved

from: https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/videos/159970#. Accessed July 15, 2019.

Flynn, S., & S. Burke. Brittle infrastructure, community resilience, and national security. TR News,

2011. 275: 4-11.

Fornara, F., M. Bonaiuto, & M. Bonnes. Cross-validation of abbreviated perceived residential

environment quality (PREQ) and neighborhood attachment (NA)indicators. Environment and

Behavior, 2010. 42(2): 171-196.

Freitag, R. C., D. B. Abramson, M. Chalana, & M. Dixon. Whole community resilience: An asset-

based approach to enhancing adaptive capacity before a disruption. Journal of the American

Planning Association, 2014. 80(4): 324-335.

Graham, S., & S. Marvin. Splintering urbanism: networked infrastructures, technological

mobilities and the urban condition. Routledge, New York, 2002.

Heinberg, R. 8 Lessons for Building Resiliency After the California Wildfires. Citylab, 2017,

November 1. Retrieved from https://www.citylab.com/environment/2017/11/8-lessons-for-

building-resiliency-after-the-california-wildfires/544679/. Accessed July 15, 2019.

Henry, A. How to Prepare Your Community for a Disaster. The New York Times, 2018, February

15. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/15/smarter-living/prepare-your-

25

community-for-a-disaster.html. Accessed January 11, 2019.

Ishfaq, R. Resilience through flexibility in transportation operations. International Journal of

Logistics Research and Applications, 2012. 15(4): 215-229.

Kaewunruen, S., J. M. Sussman, & A. Matsumoto. Grand challenges in transportation and transit

systems. Frontiers in the Built Environment, 2016. 2(4): 1-5.

Kermanshah, A., & S. Derrible. A geographical and multi-criteria vulnerability assessment of

transportation networks against extreme earthquakes. Reliability Engineering & System Safety,

2016. 153: 39-49.

Klinenberg, E. Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, 2015.

Klinenberg, E. Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality,

polarization, and the decline of civic life. Crown, New York, 2018.

Litman, T. Lessons from Katrina and Rita: What major disasters can teach transportation planners.

Journal of Transportation Engineering, 2006. 132(1): 11-18.

Little, R. A socio-technical systems approach to understanding and enhancing the reliability of

interdependent infrastructure systems. International Journal of Emergency Management, 2004a.

2(1-2): 98-110.

Little, R. G. The role of organizational culture and values in the performance of critical

infrastructure systems. In IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (IEEE

Cat. No. 04CH37583), 2004b. 5:4047-4052).

26

Lyons, G. The reshaping of activities and mobility through new technologies. Editorial for special

issue on ICT and the shaping of access, mobility and everyday life. Journal of Transport

Geography, 2009. 17(2): 81-82.

Mokhtarian, P. L. A typology of relationships between telecommunications and transportation.

Transportation Research Part A: General, 1990. 24(3): 231-242.

Mokhtarian, P. If telecommunication is such a good substitute for travel, why does congestion

continue to get worse? Transportation Letters, 2009. 1(1): 1-17.

Quarantelli, E. L., & R. R. Dynes. Response to social crisis and disaster. Annual review of

sociology, 1977. 3(1): 23-49.

Ritchie, L. Social Capital and Transportation: Critical Assets in Community Resilience. TR News,

2017. 311: 27-32.

Salomon, I. Telecommunications and travel relationships: a review. Transportation Research Part

A: General, 1986. 20(3): 223-238.

Schulz, K. The really big one. The New Yorker, 2015. 20(07).

Solnit, R. A paradise built in hell: The extraordinary communities that arise in disaster. Penguin,

New York, 2010.

Soltani-Sobh, A., K. Heaslip, P. Scarlatos, & E. Kaisar. Reliability based pre-positioning of

recovery centers for resilient transportation infrastructure. International Journal of Disaster Risk

Reduction, 2016. 19: 324-333.

Townsend, A. Smart cities: Buggy and brittle. Places Journal, 2013. Retrieved from:

27

https://placesjournal.org/article/smart-cities. Accessed March 3, 2019.

Vespignani, A. Predicting the behavior of techno-social systems. Science, 2009. 325(5939): 425-

8.

Washington State Emergency Management Division. Individuals, Families, & Pets. 2017.

Retrieved from https://mil.wa.gov/emergency-management-division/preparedness/personal.

Accessed February 22, 2019.

28

APPENDIX 1: COMMUNITY WORKSHOPS THROUGH APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY

METHOD

Introduction and Purpose

As part of this project and besides the quantitative survey described in Chapter 3, the team also

conducted community workshops as a qualitative means to understand how a community’s

sociotechnical resources can be integrated for enhancing community adaptive capacity.

Prof. Abramson introduces the workshop activities and provides some background information on

the ongoing UW/LEAP partnership on November 7, 2018.

On November 7, 2018, Laurelhurst Earthquake Action Preparedness (LEAP) and a

multidisciplinary research team from the University of Washington (UW) co-hosted a public

workshop at the Laurelhurst Community Center, creating a forum for neighborhood stakeholders

to discuss, via participatory group activities, the qualities that contribute to a resilient community.

The purpose of the workshop was to build a better understanding of the unique community values

and assets that might contribute to strengthening community resilience in Laurelhurst. Several

community members, a handful of LEAP team members and the UW team participated in the

workshop.

29

Partners and Background

LEAP is a community-based organization in Seattle’s Laurelhurst neighborhood that works to

increase awareness, knowledge, and connections within the community to help minimize the

potential for injury and damage in the case of a major disruptive event, such as an earthquake.

The multidisciplinary UW research team is led by Prof. Dan Abramson (Urban Design &

Planning) and Prof. Cynthia Chen (Civil & Environmental Engineering). Other UW team members

included doctoral student TAs Katherine Idziorek and Lan Nguyen as well as students in Prof.

Abramson’s Fall 2018 community resilience urban planning studio: Helen Stanton, Pegah Jalali,

Lauren Kerber, Catharina Depari, Sreya Sreenivasan and Charlotte Dohrn. The students helped to

facilitate the workshop activities.

LEAP and UW have been working together since the fall of 2017 to better understand how

community assets can be leveraged to enable adaptive capacity in the face of disruptions (such as

earthquakes) or other long-term changing conditions, in ways that also improve everyday

community well-being.

Workshop Methodology

The team adopts the appreciative inquiry-based method for community engagement. Unlike in

most risk assessment efforts, mitigation planning processes, or even pre-disaster recovery plans,

an appreciative inquiry-based community engagement protocol does not begin with presentations

of exposure and vulnerability. Rather, we first ask participants to list the sources of human well-

being (HWB) in their community. What do they like about their community? What makes their

community unique? How do they define quality of life in their community, and what aspects of

their community support quality of life? What brings them joy? Only then do we present the hazard,

or “change agent,” for discussion on how the community might prepare for it, respond to it, recover,

and rebuild. We present recovery as a broad process that depends on built, natural, and social forms

of capital, similar to NOAA’s Roadmap for Adapting to Coastal Risk, which has participants

develop a profile of “the local population” (“societal”), “the built environment” (“infrastructure”)

and “important natural resources” (“ecosystem”). However, the NOAA Roadmap describes a

hazard scenario in detail first and seeks to identify vulnerabilities and strengths primarily in the

context of that specific hazard scenario. Our approach differs significantly in that we present the

hazard or “change agent” only after the participants have profiled the unique attributes of their

respective communities using HWB categories. Moreover, instead of cataloging dysfunctions or

vulnerabilities, we ask questions that lead from the community’s strengths. In effect, we are

applying principles of asset-based community development to disaster planning (Green & Haines,

2012), specifically the idea that creative thinking leads from strength-based positive approaches to

inquiry and action, as expressed in the Appreciative Inquiry (AI) model (Emery & Flora, 2012).

Moreover, a broader, more balanced, and integrative consideration of assets—not just built, but

also natural and social capital—can prompt more adaptive thinking. Communities rely on goods

and services provided by built, natural, and social capital in varying degrees and at different times.

Capital typologies differ; Green and Haines (2012) categorize community capital as physical,

human, social, financial, environmental, political, and cultural. We draw our simpler classification

30

from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment literature (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005)

and particularly from Mulder, Costanza, and Erickson (2006), leaving out human capital

(“personal growth and development”), and define three key categories as follows:

1. Built Capital: Things built by humans for rather specialized purposes, and with significant

ecological footprints. Examples include bridges, buildings, dams, and machinery.

2. Natural Capital: Environmental features that yield a flow of ecosystem services and tangible

natural resources. Examples include forests, wetlands, mangroves, soil, sand dunes,

agriculture, and fossil fuels.

3. Social Capital: Networks and associations of human relationships based on mutual trust,

common interest, or particular skills. Examples include service providers, regular festivals

and gatherings, clubs, and faith-based organizations.

These categories are not exclusive. A park, for example, might be considered a source of ecosystem

services, but if it is engineered for a special purpose (as in a baseball field), it might be considered

“built capital.” If it functions as a gathering place (as in a farmers’ market), it might be considered

“social capital.” The classification allows us to see how the quality of life provided by one type of

asset or capital might be provided by a different type under changed conditions after a disruption.

Workshop Activities

Prof. Dan Abramson and LEAP member Nancy Woods introduced the workshop purpose and

background.

The workshop comprised three primary activities, explained in detail in the following sections:

1) Asset mapping

2) Zone mapping

3) Disaster preparedness resource matching game

Activity 1: Asset Mapping

Participants sat in small groups at tables according to where they lived so that neighbors sat near

one another. Groups were prompted with the following questions:

• What values or assets make your community unique?

• What are Laurelhurst’s strengths as a neighborhood?

• What characteristics of the neighborhood contribute to everyday quality of life?

Participants were encouraged to think broadly about what might constitute a community strength

or asset. The Community Capitals Framework (Emery & Flora 2006) was used as a prompt for

participants to consider natural, cultural, human, social, political, financial and built capital in the

exercise.

Each table worked with a large map of the neighborhood that included space for both mapping

(drawing) and listing assets and values. Each person was asked to quickly write down their “top

three” ideas on sticky notes to get the activity started. Then, using pens and markers, groups spent

about 20 minutes discussing community assets and values and recording them either on the map

31

(for spatial assets/values) or on the list (for non-spatial assets/values).

Participants recorded Laurelhurst values and assets by drawing on neighborhood maps (photos

by Amy Fouke).

Assets listed and mapped during the exercise fell into the following broad categories:

• Shops, restaurants and services: Independent, small businesses in “business district” on

Sand Point Way; University Village; grocery stores (PCC, Metropolitan Market, QFC);

City People’s, Katterman’s Pharmacy, Sand Point Grill, hardware store, gym, good

restaurants

• Parks, nature, open space and recreation: Burke Gilman trail; Laurelhurst Community

Center (sports facilities, views, youth summer programs, meeting place, nature access);

community-developed “Saving Urban Nature” pocket park (NE 47

th

& 47

th

NE);

Magnusson Park nearby; Center for Urban Horticulture (offers birding, public open

space, nature access, education, public meeting space, library, walking); green

neighborhood; natural beauty

• Institutions: Beach Club, churches, private school/pre-schools, hospital in neighborhood,

fire station, NOAA nearby, UW hospital, Children’s Hospital (helipad), ties to UW

(“education pride”)

• Transportation: Light rail nearby (with just “ok” bus access), lots of bikes, road network

(traffic at Montlake Cut mentioned as a negative aspect of neighborhood), water and

boats

• Neighborhood activities and communication outlets: Crime watch, block parties,

newsletter, community blog, NextDoor, Constant Comment, social media (e.g., “Buy

Nothing”)

• Social character: many generations live here, sense of community, people know their

neighbors, neighbors are helpful and caring; “dogs on leashes” behavior, social ties,

static/stable neighbors, feels safe, quiet

• Political/financial/knowledge resources: some residents involved in/have former

experience in politics, many very politically active people (engaged in social issues and

school funding), financial resources, owner-occupied homes, highly educated community,

medical professionals, UW professors/retirees, health care and engineering “know-how”

32

• Built environment: multiple-family dwellings, accessory dwelling units, well-spaced-

out houses, walkable area, gardens in the neighborhood, beautiful neighborhood,

beautiful homes, visibility, no tall buildings, waterfront/water access with street end

public access to waterfront in multiple locations

Although values tended to be more difficult to map than assets, several important neighborhood

values were noted: cross-generational interaction; value of education; access to water and nature;

sense of community; willingness to connect via social activities (block parties, welcoming new

homeowners, “sidewalk friends”); ability to rely on trusted neighbors for communicating

important information.

Asset mapping discussion themes

Several themes emerged during the group discussions as assets and values were mapped. They are

presented here with suggestions for potential follow-up action items by LEAP:

1) Coordination with local institutions

The groups discussed the role that several identified community institutions might play in

a disaster scenario, including schools, churches, the hospital and the community center.

Specific roles mentioned included:

• Laurelhurst Community Center could support evacuation processes and logistics

during a disaster

• Seattle Children’s Hospital might be a source of medical support in a disaster,

including use of the helipad for evacuation

• St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church could potentially act as a neighborhood hub to

provide shelter, power and communication in the case of a disaster

Potential LEAP action items:

• Coordinate (or continue to coordinate, as appropriate) with Laurelhurst Community

Center, Seattle Children’s Hospital and St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church to understand

how (and to what extent) those institutions are able to support the community in the

case of a disaster

2) Transportation and connectivity

Participants emphasized that they value the walkability of their neighborhood, including

access to the Burke-Gilman and other trails. They discussed the proximity to downtown

and the light rail as assets. They suggested that major neighborhood streets (47

th

Ave NE,

NE 45

th

St., NE 41

st

St.) might support evacuation and delivery of medical aid in the case

of a disaster. If cut off or isolated in a disaster situation, boats or kayaks could potentially

be used for transportation.

Potential LEAP action items:

• Understand whether there are designated evacuation routes or strategies for the

neighborhood and how to support community understanding of any designated routes

or recommended actions (coordinate with relevant departments at the City of Seattle)

• Further investigate how boats might be potentially useful for establishing connectivity

with nearby areas or used as rescue conveyances in the case of a disaster

33

3) Disaster skills communication and training

Participants appreciated the skills and knowledge resources of Laurelhurst residents (e.g.,

engineering, health care expertise) that could be very helpful in the case of a disaster if

known and coordinated. It was noted that the role of cluster captains will be very important

for maintaining coordination during a disaster via walkie-talkie (or other communication

devices).

Potential LEAP action items:

• Increase neighborhood skills and knowledge by continuing to support trainings (e.g.,

first aid)

• Create cluster-based “skills inventories” that could be used to understand what

knowledge and skills are available locally and in what areas the community may need

more education or training

4) Engaging local businesses

Participants highlighted several businesses within or near the neighborhood they perceive

as assets: a pharmacy, a hardware store, local restaurants, grocery stores and University

Village. They noted Laurelhurst itself does not have a business core, but there are many

shops and businesses within walking distance. Participants suggested that neighborhood

shops and restaurants could provide logistics, food, or other basic needs for the community

in a disaster.

Potential LEAP action items:

• Engage with area businesses; support disaster preparedness efforts of local employers

5) Leveraging attachment to place

Place attachment, which refers to strength and basis of feelings for a specific place, was a

common theme in several of the workshop conversations about values and assets.

Neighborhood characteristics such as access to water and Laurelhurst’s unique, hilly

topography with views to green spaces evoke the natural beauty of rural areas. These are

important features of the neighborhood that cannot be found in parts of the city dominated

by tall buildings. Likewise, the calmness and quietness of Laurelhurst provide a reprieve

from the noisier and more stressful “urban” areas of the city. Residents enjoy the unique

experience of walking through Laurelhurst offered by its organic, curvilinear streets and

the opportunities this degree of walkability creates to meet and greet neighbors on the

sidewalk.

Potential LEAP action items:

• Organize neighborhood walks or tours to build social capital among neighbors and to

help people get to know the neighborhood better with a focus on unique, place-based

assets.

Activity 2: Zone Mapping

LEAP member Louise Luthy provided background on the intent and importance of creating

34

neighborhood “zones.” LEAP is in the process of organizing the entire neighborhood into

approximately 20-household clusters for the purposes of sharing information that might be useful

in the case of a disaster. Each cluster has a designated captain or captains who are responsible for

disseminating information to cluster members and organizing the cluster’s own internal

information and disaster preparedness resources. Because there are a relatively large number of

clusters across the neighborhood (98 in total), LEAP is interested in creating “zones” that comprise

multiple clusters to help provide another level of efficiency and organization between the clusters

and LEAP itself. The workshop activity provided an opportunity to ask community members,

based on their own knowledge of the neighborhood, what criteria should determine how clusters

are grouped together to form zones.

Participants were given the following questions as a prompt:

1) How many clusters should be in a zone? How large should a zone be?

2) What characteristics should define a zone? (Topography? Transportation networks?

Existing social connections? Land use? Distribution of assets/resources? Information

about hazards?)

In small groups at tables, participants were asked to outline potential zones by drawing on large

maps of the neighborhood showing LEAP’s already-designated clusters. Groups were given

additional maps showing local hazards and neighborhood topography to help inform their

discussion and mapping.

Groups outline zones on maps of LEAP’s neighborhood cluster system.

The groups discussed several factors that could be considered when deciding where zones should

be located and how they should be organized: