Global Nomads

A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat-

ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic

and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi-

vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an

invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture,

and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities,

techno-dance culture and globalization.

Graham St John, Research Fellow,

School of American Research, New Mexico

D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the

shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus

on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book

and it is a lot of fun.

Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology

at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor

at the London School of Economics.

Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures,

a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines

the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter-

cultural practice in paradoxical paradises.

Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and

why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative

lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek-

ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of

expressive individualism. These countercultural formations, however, unfold under

neo-liberal regimes that appropriate utopian spaces, practices and imaginaries as

commodities for tourism, entertainment and media consumption.

In order to understand the paradoxical globalization of countercultures, Global

Nomads develops a dialogue between global and critical studies by introducing

the concept of ‘neo-nomadism’ which seeks to overcome some of the shortcom-

ings in studies of globalization.

This book is essential reading for undergraduate, postgraduate and research stu-

dents of Sociology, Anthropology of Globalization, Cultural Studies and Tourism.

Anthony Albert Fischer D’Andrea has recently earned a PhD in Anthropology at

the University of Chicago, where he is Research Associate at the Transnationalism

Project.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Global Nomads

Techno and New Age as transnational

countercultures in Ibiza and Goa

Anthony D’Andrea

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

First published 2007

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2007 Anthony D’Andrea

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic,

mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter

invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any

information storage or retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN10: 0–415–42013–X (hbk)

ISBN10: 0–203–96265–6 (ebk)

ISBN13: 978–0–415–42013–6 (hbk)

ISBN13: 978–0–203–96265–7 (ebk)

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006.

“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s

collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.”

ISBN 0-203-96265-6 Master e-book ISBN

Contents

List of figures vii

Acknowledgments viii

1 Introduction: neo-nomadism: a theory of postidentitarian

mobility in the global age 1

Global nomads: instance of cultural hypermobility 1

The significance of expressive expatriation: circuits of

mobility and marginalization 7

Globalization: network, diaspora and cosmopolitanism 10

Aesthetics of the self: post-sexualities in a digital age 17

Neo-nomadism: postidentitarian mobility 23

Nomadic ethnography: methodological challenges 31

Book overview 36

2 Expressive expatriates in Ibiza: hypermobility as

countercultural practice and identity 41

Introduction: ‘fluidity of experiences’ in Ibiza 41

Ibiza contexts: entering the field 44

Spatial and inner mobility: traveling and nomadic spirituality 47

Expatriate media: ‘people from Ibiza’ 58

Expatriate education: ‘international schools’ 61

Expressive lifestyles 65

Conclusion: the aesthetics of centered marginality 75

3 The hippie and club scenes in Ibiza’s tourism industry 78

Counterculture and commodity 78

Utopian sites under siege: Punta Galera 80

The hippie scene: autonomy and tourism 81

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

The club scene: underground and industry 94

Bohemian working class 113

Ibiza imaginary: transgression, nostalgia and diaspora 120

Freak diaspora: the centrifuge island and orientalism 127

4 Osho International Meditation Resort: subjectivity,

counterculture and spiritual tourism in Pune 131

Osho movement: counterculture and commodification 131

Institutional and ideological contexts: the world’s largest

meditation center 134

‘Osho International Meditation Resort’: practices, trajectories

and rituals 139

Culture of expression: psychic deterritorialization and

institutional control 159

Charisma and rationalization: sex, counterculture and

tourism 166

Conclusions: ‘enlightenment guaranteed’ 171

5 Techno trance tribalism in Goa: the elementary forms

of nomadic spirituality 175

Introduction: the psychedelic contact zone 175

The Pune-Goa connection: rebel sannyasins 179

Goa, tourism and ‘hippies’ 181

Day Life: the social organization of the trance scene in

northern Goa 185

Night Life: nomadic spirituality in psychedelic rituals 204

Psychic deterritorialization: madness in India 214

Conclusion: nomadic spirituality and smooth spaces 220

6 Global counter-conclusions: flexible economies and

subjectivities 222

Notes 228

Bibliography 234

Index 245

vi Contents

Figures

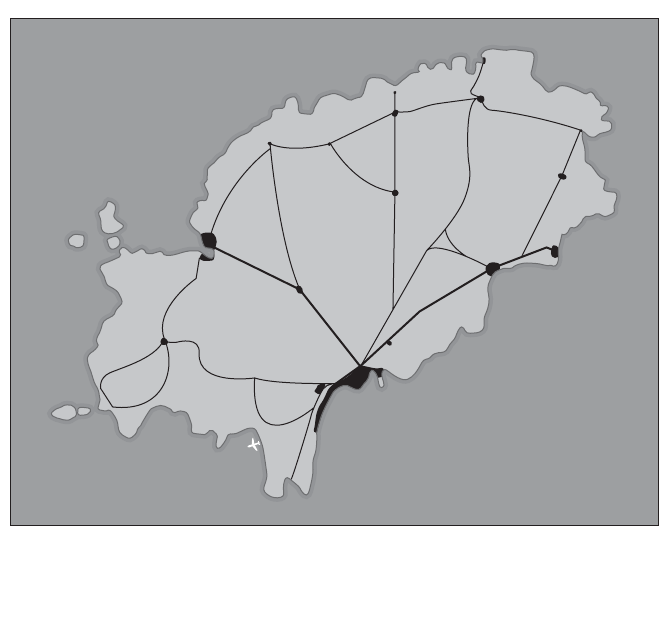

2.1 Ibiza map 42

2.2 Expatriate children 48

3.1 Punta Galera beach 80

3.2 Drum party 82

3.3 World’s largest nightclub 94

3.4 British bar workers 113

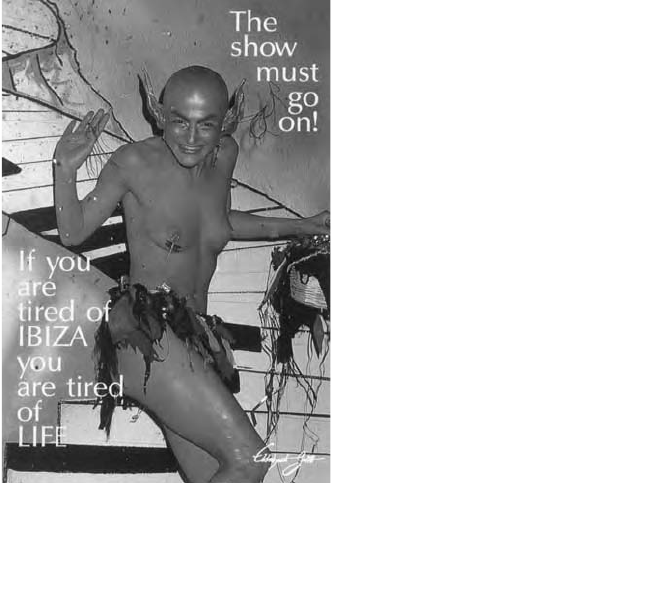

3.5 Postcard of Ibiza 121

4.1 Osho meditation resort 131

4.2 Sannyasins socializing 139

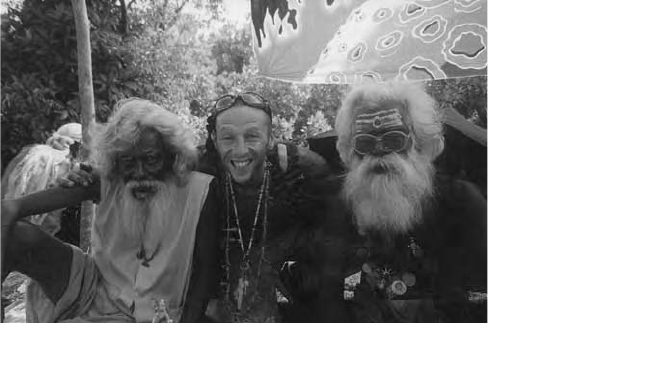

5.1 DJ and sadhus 175

5.2 Trance party in Pune 179

5.3 Anjuna hippie market 185

5.4 Crystal healing practice 202

5.5 Techno bike Amazon 207

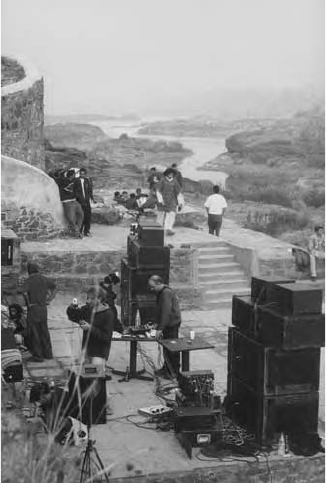

5.6 Trance party near Anjuna beach 210

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Acknowledgments

This book is based on a doctoral research conducted over the course

of several years, places and multidisciplinary incursions. I would like to

thank Elizabeth Povinelli, Saskia Sassen, Joe Masco, Kesha Fikes, Tanya

Luhrmann, Arnold Davidson and Arjun Appadurai for their advice

at former and latter stages of my education at the Department of

Anthropology at the University of Chicago.

From the field, I am grateful to Gary Blanford, Kirk Huffman, Ronnie

Randall and Nora Belton for their contribution to the development of

this project. I also thank Georgia Taglietti, William Crichton, Antonio

Nogueira, Roberta Jurado, Peter Hankinson, Tirry and Toni for their

generous support to my fieldwork in the club scene of Ibiza. In India, I

wish to thank Swami Prasado and Boyan Artac, as well as Dilip Loundo

and Alito Siqueira for interactions at Goa University.

I am also grateful to other friends and colleagues, in particular to

Graham St John and Adam Leeds, who have read parts of my manuscript

and made important comments. I also appreciate the kind permission of

Ronnie and Stephen Randall, Ekki Gurlitt and Krishnananda Trobe to

use photos and an extended quote. Finally, I thank John Urry for allowing

that my work be available in book form.

This research was indirectly funded with a CAPES Foundation fellow-

ship to conduct my doctoral studies at Chicago. I also thank the Center

for Latin American and Iberian Studies and the Gay and Lesbian Studies

Project, both at the University of Chicago, for sponsoring segments of my

fieldwork with travel grants.

While grateful to the sedentary dwellers of Goa, Pune, Ibiza and Chicago,

I wish to dedicate this book to global nomads – expressive expatriates,

New Agers and Techno freaks – who enabled me to learn something

about their lines of flight.

Anthony Fischer D’Andrea

Chicago, January 2007

1 Neo-nomadism

A theory of postidentitarian

mobility in the global age

1

‘The nomad does not move.’

Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Global nomads: instance of cultural hypermobility

Ibiza island (Spanish Mediterranean), summer 1998 – We left Café del

Mar in the busy touristy town of Sant Antoni, and drove north toward

a secluded lighthouse where a ‘Goa trance party’ was scheduled to happen.

‘Goa trance’ is a potent subgenre of electronic dance music developed by

Western neo-hippies (‘freaks’) on the beaches of Goa state (India) in the

early 1990s. My companions that night were four UK and US expatri-

ates who resided in Ibiza or visited the island regularly: two yoga teachers,

a jewelry trader and a journalist, women in their thirties and forties,

wearing light hippie, gypsy-like clothes and a crystal dot on the forehead.

An Italian party promoter had told us about the event. The police busted

his own party a week before, ‘because of the vested interests of big busi-

ness: club and bar owners.’ In Ibiza, Goa and elsewhere, trance parties

are usually illegal, being secretively announced through word-of-mouth

across the alternative populace that, at various levels and degrees, embraces

free open-air ‘tribal parties’ in secluded, natural settings.

In a confusing maze of precarious dirt roads, we joined a caravan of

lost drivers and, having noticed several vehicles suspiciously parked amid

dry vegetation, we decided to stop. The night was absolutely dark. Thin

flashlights and the eerie stomping of techno music afar were our only

leads as we blindly stumbled toward the venue. By the cliff edge, the light-

house projected three solid light beams of mesmerizing beauty. Beside it,

a camp formation with a few tents and banners was dimly lit in fluores-

cent purple. UV lights produced a phantasmagoric glow on colorful fractal

drapes, white clothes, teeth and eyes. A delicate scent of incense pervaded

the air, blending with the acrid smell of hashish smoking. A crowd danced

in front of the DJ (disc jockey) tent located between thundering loud-

speakers, while many others scattered around.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

There were a few hundred people, mostly white young adults. Many

wore hippie or military garments in a fashion resembling psychedelic

guerillas. In their everyday life, they worked in ‘hippie’ (touristy) markets,

nightclubs and bars, and in a variety of informal occupations in handi-

craft, music, wellness, therapy and spirituality. Outsiders readily labeled

them hippies, punks, freaks, ravers or New Agers. However, refusing such

labels, they rather represented themselves as ‘alternative people’: rebel-

lious expatriates from European and American nations. By late autumn,

many would have departed to India and their ambivalently rejected home-

lands, returning to Ibiza next spring.

Trance parties hybridize orientalist and cybernetic elements. Trance DJs

are idiosyncratic men whose personalities well suit anthropological descrip-

tions of witch doctors, now in digital edition. Psychedelic drapes displayed

Hindu, Buddhist and fractal figures in fantastic shapes and colors. From

potent speakers, Techno trance music pulsated in sonic gushes that rever-

berated pleasurably upon the skin. Its multilayered rhythms were extremely

powerful and complex, yet monotonous and hypnotic. Topped by ethe-

real, often spooky arpeggios, the music pumped restlessly throughout the

night. People danced individually, alone but in the crowd, and the predom-

inant mood was joyous, albeit reverential.

As the morning came, the dancing crowd was seen covered in red dust,

floating upward due to continuous feet stomping. Some young women,

fashioned like barbarian warriors, screamed wildly whenever the music

took an exciting shift, like the gears of an unstoppable machine. Some

people danced with closed eyes, drawing gentle tai chi-like movements in

the air. But, after long hours, the crowd was bouncing in a steady, remark-

ably dull fashion, indicating physical tiredness as well as various degrees

of mind alteration. I spotted Shiva, an old blond German hippie, dancing

in a seemingly trance state. Staring aloof into the sky, he jerked as if

musical tweaks electrocuted his body. Recently returned from India,

German Shiva now seemed to be on an ‘intergalactic journey.’ A hairy

Frenchman in chef uniform was selling sandwiches over his rusty scooter,

while a Brazilian drug trafficker observed the frenzy from his ostentatious

Mercedes Benz parked nearby.

The Mediterranean now shined magnificently in bright golden and blue

– a quasi-psychedelic experience in itself. But my friends were tired and

wanted to leave. On the way out, we saw two skinny men dragging

garbage bags, picking a few empty cans and cigarette butts, as usually

done by ecologically minded promoters. Against the incoming flux of

people, I overheard a variety of European languages and also Hebrew.

Someone mentioned that the party would carry on for three days – as

long as the crowd endured, and the police did not show up . . .

This anecdote depicts a rare density of multinational and expressive

elements gathering at the margins of a tiny island. In it, Ibiza appears

as a node of transnational flows of exoticized peoples, practices and

2 Neo-nomadism

imaginaries whose circulation and hybridization across remote locations

suggests a globalized phenomenon. This story also indicates how digital

and orientalist elements may congeal in a ritual assemblage that sustains

alternative experiences of the self. In the convergence of the global and

the expressive, mobility across spaces and within selves becomes a cate-

gory that structures the social life of peoples claiming to embrace the

global as a new home and reference.

By integrating mobility into economic strategies and expressive lifestyles,

I refer to these subjects as expressive expatriates, and, more generally, as

global nomads, notions employed to rethink and stimulate a debate on

globalization and cultural change. The empirical dimension of this research

was based on multi-site transnational fieldwork conducted in Spain and

India from 1998 to 2003, and will be discussed in detail throughout the

book. In this opening section, I will outline the general architecture of

this investigation, summarizing its development in genealogical lines, and

highlighting how its ethnographic horizon has posed specific method-

ological and conceptual challenges to current research and scholarship.

This is a book on cultural globalization, as an effort to understand

how global processes of hypermobility, digitalization and reflexivity inter-

relate with new forms of subjectivity, identity and sociality. Considering

the sheer scale, speed and intensity of transformations being brought about

by globalization, this study is also, and by consequence, an inquiry into

cultural change. In order to enable a clear and efficient strategy of analysis,

I investigate cases of cultural change that appear as explicit, assertive,

and even radical in the scope of contemporary possibilities. I thus selected

the topic of countercultures, which can be tentatively defined as self-

marginalized formations that, in various forms of experimentalism and

contestation, seek to foster a critique that revises modernity within

modernity. In this view, modern countercultures are at least 200 years

old, referring back to Rousseau’s nostalgic reflections on the malaises of

civilization and reason.

In other words, this book investigates contemporary forms of counter-

culture that unfold under the impact of globalization. As I will later

elaborate, Techno dance and New Age spiritual movements seem to pro-

vide lively instances of such a critique of modern institutional-ideological

regimes, but not without their own problematic contradictions and blind

spots, which are also scrutinized in this book.

Much will be said about the spatial and cultural sites of investigation,

but an introductory note is important from the outset. In my preliminary

explorations with Techno and New Age in a number of countries, a series

of apparently serendipitous encounters and discoveries led me to the island

of Ibiza located in the Spanish Mediterranean, a place which turned out to

be as extremely rich as problematic for an empirical investigation of the

interrelations between globalization and counterculture.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 3

In Ibiza, I identified a unique populace of expatriate individuals who

share some defining features, roughly summarized: (1) They reject their

original homelands and seek to evade state–market–morality regimes.

(2) They partake in a cosmopolitan culture of expressive individualism,

manifested in multiple variations of New Age and Techno practice.

(3) They seek to integrate labor, leisure and spirituality into a holistic

lifestyle that romanticizes non-Western cultures, and particularly India.

(4) They overlap with a cultural-artistic elite that establishes a symbiotic

relation with political economies of tourism, entertainment, wellness and

media sectors which appropriate alternative formations in commodity

form. (5) These expatriates engage with practices of mobility that are

pivotal in reproducing the other features.

The mobile feature of expatriate formations introduced a methodolog-

ical challenge to my doctoral fieldwork. While following anthropological

canons that prescribe a locally grounded fieldwork, I realized that Ibiza’s

expressive expatriates periodically depart to other countries where they

stay for extended periods. Due to its material, cultural and temporal

aspects, it became clear that this semi-deterritorialized phenomenon could

not be properly grasped by conventional ethnographic methods alone. In

order to obtain a more accurate picture, I would have to follow these

subjects to places and along practices of mobility crucial to their material

and symbolic reproduction. I had to follow and even travel with my

natives to India. Yet, more than cruising the same pathways, the point

was to foreground mobility as a practice and discourse of identity forma-

tion, considering that meanings and experiences of movement are better

assessed within the movement itself.

Toward a methodology of hypermobile cultures, I sought to combine a

nomadic sensibility for natives’ routes, flows and rituals, with a macro-

ethnography of translocal sites (Clifford 1997; Appadurai 1996). I qualify

this macro-ethnography at three levels: (1) an ethnography of local forma-

tions and subjectivities in a locality or site; (2) the socio-economic con-

textualization of mobile formations in a place (thus corresponding to their

vertical integration); and (3) a translocal ethnography that tracks flows,

nodes, directions and periodicities (thus defining the horizontal integration

across and beyond spaces). These tasks generate multi-layered datasets

which enable the comparison between the vertical and horizontal integra-

tion, thus shedding light on the conditions of (im)mobility. More gener-

ally, the articulation between nomadic sensibility and macro-ethnography

provides the grounds for a ‘nomadic ethnography,’ which embodies a tran-

sition from the Ptolemaic geocentrism of conventional anthropology to an

Einsteinian perception of the relativity of placement and displacement in

a globalizing world.

However, as this methodology allowed me to probe transnational

countercultures as an empirical social phenomenon, the resulting picture

introduced a new order of challenges, this time at a conceptual-theoretical

4 Neo-nomadism

level. As I located my study within the scholarship on globalization and

critical theory, it became clear that none of these intellectual fields alone

would suffice to address the cultural implications and possibilities of

globalization, in particular those related to hypermobility pressures.

In anticipation of a discussion carried out later in this chapter, global

studies currently stumble on two basic problems (Urry 2003; Povinelli

and Chauncey 1999). Global studies have overemphasized the description

of social forms (networks, flows, systems) at the expense of a conceptu-

alization of cultural contents (subjectivities, experiences, desires) that

unravel under the impact of global processes. In this connection, predom-

inant concepts of network, diaspora and cosmopolitanism have been

overused, precipitously crystallizing over the course of a decade in biases

that preclude alternative ways of investigating and conceptualizing cultural

globalization, such as its fluidic and metamorphic components.

In the scope of critical studies,

2

this book draws on Foucault, Deleuze

and Guattari as seminal references whose thought empirically resonates

with the expressive and mobile tropes of global countercultures. To begin

with, in their social and ritual life, Ibiza expatriates fully instantiate

Foucauldian notions of self-shaping/shattering and of aesthetics of exist-

ence. It is almost as if he had written a script that they decided to perform

as their real lives. As will be discussed later, rather than dandyism, the

aesthetics of existence must be understood as an ethics of the self that

opposes dominant biopower regimes, and seeks to engender a holistic

balance of life principles beyond modern fragmentation. However, while

attempting to eschew the tentacles of nation-state regimes, expressive

expatriates problematically replicate aspects of the logic of neoliberal

capitalism. Yet, rather than dissolve the dialectic that permeates the book,

I sought to keep it as a productive tension that is dynamically inscribed

in global countercultures. I thus assessed them in relation to proximate

contexts, rather than imposing some macro-sociological explanation that

determines agency and consciousness, more or less arbitrarily defined by

the intellectual according to their own theoretical affiliation. On the other

hand, under conditions of globalization, it also became clear that the

countercultural aporia vis-à-vis systemic co-optation cannot be addressed

within the scope of critical studies alone. In face of the centrifugal drives

that characterize expatriate countercultures in Ibiza, Foucauldian notions

of aesthetic self-formation are not enough to address the fundamental issue

of hypermobility that structures them.

A dialogue between global and critical studies is a necessary condition

for understanding the cultural implications of globalization. An insight

into this junction derives from the nomadology of Deleuze and Guattari.

A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia stands as a powerful

even if intuitive entry into a semiosis of globalization as entailed upon

issues of subjectivity and cultural change. In this connection, I have

sought to integrate predominant tropes of global and critical studies into

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 5

a conceptualization of ‘neo-nomadism’ which can be defined as an ideal-

type that allows us to identify, describe and measure cultural patterns and

effects of global hypermobility. In particular, neo-nomadism addresses

new forms of identity that are based, not on sameness or fixity, but rather

on a principle of metamorphosis (chromatic variation). In other words,

neo-nomadic lifestyles, subjectivities and identities can be addressed as

expressions and agents of the postidentitarian predicament of globaliza-

tion. The point then becomes how we can operationalize this analytical

device at the empirical level.

To this end, I turned to Techno and New Age multiple manifestations,

yet focusing on those segments that produce these forms as a vanguard

predicated on expressivity and mobility. In this book, I examine rave,

therapy and travel as probable expressions of a countercultural regime,

which also embodies and entails the impact of globalization upon self-

identities and socialities. More specifically, Techno and New Age provide

sites of experience, meaning and struggle, by which neo-nomadism mani-

fests itself in two different ways: one as a stabilized form of self-cultivation

(nomadic spirituality), the other as a temporary condition of acute self-

derailment (psychic deterritorialization). In the former, this study verifies

a cultural pattern of religious practice whose nature is multiple, ephemeral

and contingent. It can be captured in the notion of nomadic spirituality,

which operates as an empirical and analytical category that informs how

flexible subjectivities navigate under the volatile conditions of flexible capi-

talism. Nomadic spirituality is empirically detected in most New Age forms

of self-spirituality and other closely related practices of self-development,

while more widely reflecting social processes of multiculturalism, reflex-

ivity and consumerism. Conversely, in the latter, psychic deterritorialization

stands at the intersection of schizoanalysis and the psychiatry of travel,

and it refers to an acute condition of personal derailment by which the

symbolic references of the self are radically uprooted, inferred from

the dramatic alteration of behavioral, cognitive and affective modes of

the subject in relation to its predominantly ordinary states. While varying

in degree, intensity and duration, these cases are frequently reported during

long-haul travel, meditation marathons and psychedelic experiences that

mark ‘contact zones’ intersecting Romanticism, postcoloniality and glob-

alism. Postidentitarian experiences seem more pronounced in spaces of

symbolic power, usually locations embedded in Romantic imaginaries

of exoticism and mystery.

Curiously, back at home the subject quickly regains his or her cognitive

abilities to operate normally in daily life; however, assailed by existential

dissatisfaction, the subject may no longer be willing to cope with conven-

tional routines that structure urban life in advanced societies. Not by coin-

cidence, most expressive expatriates that I interviewed in Ibiza and India

reported that they experienced some sort of personal crisis around the

liminal experience of travel, which consequently prompted them to take

6 Neo-nomadism

their chances in trying a new lifestyle in semi-peripheral locations. In their

utopian narrative of crisis and conversion, traveling can be either symp-

tomatic or etiological of processes of postidentitarian effect. Yet, in the

case of expressive expatriates, spatial and identity mobility have combined

as a neo-nomadic way of life.

Finally, even as cases of nomadic spirituality and psychic deterritorial-

ization require a proper historical contextualization, I would rather argue

that they index the possibility of metamorphic identities which, in turn,

refer to the basic predicament of cultural globalization. They may or may

not become more socially pervasive (although I would argue that such is

the case, due to globalization processes in the rise). In any case, the research

on cultural hypermobility sheds light on crucial aspects of contemporary

life, particularly in sites extensively exposed to global influences.

It is within this general picture that this book seeks to make empirical,

methodological and theoretical contributions. In addition to an empirical

account on expressive expatriation, this study provides an analytical model

that can be employed in the investigation of neo-nomadic formations

and development processes in other paradoxical paradises (such as Bali,

Bahia, Byron Bay, Ko Pangnan, etc.). Furthermore, this research speaks to

a range of topics under the rubric of globalization and cultural change:

expatriation, travel and tourism; countercultures, subcultures and lifestyles;

alternative religiosities, youth and subjectivity formation, in addition to

disciplinary interests in cultural studies and the sociology and anthropology

of globalization. Finally, as mentioned, this research seeks to develop a

conceptual bridge between global and critical studies, which may contribute

to a re-evaluation of a model of identity and subjectivity formation under

conditions of globalization.

As a necessary remark, although touching on a variety of geographical,

topical and disciplinary scholarship strands, the main focus of this research

lies on a populace of neo-nomadic expatriates that navigates those spatial

and cultural sites, and within certain empirical and theoretical contexts.

Within these parameters, I have sought to cover all the relevant studies

about Ibiza, Goa, New Age, Techno, cultural globalization and critical

studies (in addition to parallel incursions in studies on tourism, subcultures,

dance and therapy, among others). I do not claim to have read all the

available references, since this is not only unfeasible but also inefficient

to a certain extent, insofar as the goal of investigating and understanding

the relations between globalization and counterculture remains uncom-

promised.

The significance of expressive expatriation: circuits of

mobility and marginalization

As a counterpoint in migration studies, the terms ‘expressive’ and ‘expa-

triate’ depart with the predominantly utilitarian and essentialized under-

standing of the mobile subject, whether in neoclassical, historical-structural

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 7

or systemic-transnational strains (Castles and Miller 2003). Most studies

have focused on material conditions that propel labor migrants, political

exiles and wealthy expatriates to move geographically, usually against

the restrictive conditions of the nation-state. The scholarship has thus

tended to reify the macro, meso and micro factors that it detects empiri-

cally, thus reaffirming the determinacy of systemic and material conditions

over agency.

Even relatively free-flowing subjects – such as businesspeople, ‘expats’

and other metropolitan subjects – stumble on economic and ethnocentric

orientations that regiment them by systemic regimes. In a classic example,

Aiwa Ong investigates highly mobile Chinese businessmen as agents of a

global flexible capitalism enabling a modular type of citizenship. Within

this logic, flexible citizenship is defined as ‘the localizing strategies of sub-

jects who, through a variety of familial and economic practices, seek to

evade, deflect and take advantage of political and economic conditions in

different parts of the world’ (Ong 1999: 113). Their mobility is determined

by economic interest and political negotiation, maximizing business oppor-

tunities on a transcontinental scale, as well as the basic parameter that

defines their will to be ‘cosmopolitan.’ Cultural capital is thus accumu-

lated in order to facilitate material gain in the arena of international oppor-

tunities. In the analysis of institutional regimes that enable displacement,

Ong detects a type of agency which is propelled by the logic of flexible

capitalism, resulting in a ‘utilitarian post-national ethos’ that combines

economic instrumentalism with familial moralism (p. 130).

In contrast, although conditioned by political economies of postindustrial,

post-welfare societies, global nomads embody a different type of agency,

one that is informed by cultural motivations that defy strict economic

rationale. Many have abandoned metropolitan centers where they enjoyed

a favorable material situation (income, stability, prestige), whereas others

no longer wanted to survive day by day under the exclusionary violence

of neo-liberal economies. In either case, they have permanently or period-

ically migrated to semi-peripheral locations with a pleasant climate, in

order to dedicate themselves to the shaping of an alternative lifestyle. They

retain the cultural capital that would allow them to revert to previous

life schemes if necessary, and, likewise, define new economic goals when

entering alternative niches of art, wellness and entertainment. Nonetheless,

they have accepted the instabilities and hardships that characterize alter-

native careers (parallel to those directly suffered in neo-liberal settings but

not quite the same), insofar as they feel that they can actualize cherished

values of autonomy, self-expression and experimentation. Ironically, these

subjects seem to have reached the apex of Maslow’s hierarchy of human

needs by turning it upside down.

In considering the systemic conditions that constrain mobility, it is neces-

sary to take into account the subject’s profile (citizenship, class and race)

in relation to circuits of mobility that include her. Certain nationalities (First

8 Neo-nomadism

World), social class (upper strata), occupations (highly educated profes-

sionals) and ethnicities (white) greatly facilitate international travel.

However, some destinations (tourist-dependent countries), exquisite occu-

pations (artistic, therapeutic, expressive) and mobility trajectories (a copi-

ously visa-stamped passport) may contribute to the movement of those who

do not fit the ideal profile. In this regard, my study provides a contrast with

migration studies which have emphasized conditions of immobility, and it

also questions theoretical studies on cultural globalization that neglect an

empirical fine-grained analysis of meanings and experiences that hyper-

mobility entails.

Mobile peoples (migrants, expatriates, exiles, pastoral nomads, etc.) are

internally differentiated in terms of motivations and life strategies. Most of

them display parochial identities based on homeland nostalgias, reinforced

by contexts of socio-ethnic exclusion (Appadurai 1996; Hannerz 1996):

they are displaced peoples with localized minds. Conversely, expressive

expatriates, such as those seen in Ibiza, reject their own homelands spa-

tially and affectively, resituating national origins in terms of reversed eth-

nocentrism. They make critical assessments about compatriots, tourists and

more conventional expatriates which they deem parochial and conformist:

in effect, expressive expatriates are displaced peoples with displaced minds.

Important to say, this cosmopolitan expatriate type must be considered,

not as an expression of any ‘subculture,’ but rather as an instance of an

ideal-type relating to emerging forms of transnational practice, identity

and subjectivity interrelated with global processes and conditions of hyper-

mobility, digitalization and reflexivity. These subjects inhabit a shifting

nebula of fluidic and blurred sub-styles that evade conventional codes

defined by modern regimes of the nation-state, morality and market. In

this connection, this book more specifically focuses on meanings that lie

at the intersection of mobility and resistance, expressed as self-induced

marginalization.

Despite the number of travelogues and autobiographies written by expres-

sive expatriates (Odzer 1995; Stratton 1994), scholarly references remain

scarce and elusive. Studies on bohemianism and cosmopolitanism make

tangential comments about alternative subjects that, inhabiting the fringes

of modernity, mysteriously overlap with artistic, cultural and economic

elites of the metropole (Blanchard 1998; Watson 1995; Green 1986).

Even the excellent study by Richard Lloyd on neo-bohemians takes place

in the postindustrial city: Chicago (Lloyd 2006). In academic conferences

and informal conversations, I observed that expressive expatriates have

been sometimes compared with ‘bohemian bourgeois’ (Brooks 2000) and

‘hub culture’ (Stalnaker 2002), with whom they appear to share some

basic features, such as the cultivation of expressive individualism, cosmo-

politan tastes and travel experience in the form of leisure or self-discovery

interests.

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 9

However, expressive expatriates sharply depart with metropolitan elites

on crucial topics of consumerism, labor ethics and monadic individualism.

Their critical stance has been more mildly articulated by mainstream

authors, such as David Brooks and Stan Stalnaker. Brooks notes that the

commodification of meaning fosters lack of solidarity, solipsism and even

nihilism in post-suburban environments (Brooks 2000: 221–2). Similarly,

Stalnaker – who writes from the perspective of a global marketing analyst

– warns about the limits of unchecked consumerism: ‘It is at this point, if

you haven’t somehow connected to something larger, past the material

existence, that you find hate and despair’ (Stalnaker 2002: 151). And he

further suggests, ‘In the near future, spiritualism will be a leading factor

in the cultural conversation of the [urban] hubs’ (p. 192).

By problematizing ‘solidarity’ and ‘spirituality,’ expressive expatriates

hinge on crucial conditions of contemporary life, not only from the view-

point of the elected periphery but also from the very center itself. While

consumer societies, according to expatriates and marketing analysts alike,

appear to be blindly marching toward the abyss of spiritual void, cultural

dissent in the West often manifests itself in the will to escape toward

marginal positions and locations. The margin seems to provide some favor-

able conditions for the experimentation of alternative lifestyles that attempt

to integrate labor, leisure and spirituality in ways that are deemed more

meaningful according to those who evade the center.

A curious paradox evinces the significance of alternative modernities.

While attempting to eschew modern systemic regimes, expressive expa-

triates engender spaces, practices and imaginaries that are gradually

captured by capitalist economies (tourism, entertainment, advertising) and

regulated by the state. Places such as Ibiza, Goa, Bali, Ko Pangnan, Bahia,

Byron Bay, San Francisco, Pune, Marrakesh, etc. have become attractive

tourist and trendsetting centers subsequent to the arrival of bohemians,

gays, beatniks, hippies, New Agers, ravers and clubbers (D’Andrea 2004;

Ramón-Fajarnés 2000; Wilson 1997a; Odzer 1994). As it seems, despite

being numerically small, expressive expatriates are disproportionably influ-

ential upon the cultural sphere of mainstream societies, particularly the

youth and other dynamic segments of society. This process of evasion

and capture reveals the ambivalent disposition of desire and confinement

that mainstream (sedentary) societies displays toward countercultural

(nomadic) formations.

Globalization: network, diaspora and cosmopolitanism

This section discusses the main concepts of globalization, noting that they

do not account for the critical features of global nomadism. Globalization

is, at once, an empirical reality, an umbrella term and an analytical para-

digm. It refers to the growing importance of translocal connections in

shaping social life, which becomes disembedded from the determinations

10 Neo-nomadism

of proximate spatiotemporal contexts. It derives from the intensification

of multiple social, economic, political, technological and cultural processes

that complexly interrelate in a manner that is unprecedented in nature,

speed and scale. More empirically, globalization is characterized by:

• the worldwide integration of markets under flexible modes of produc-

tion and volatile financial capital;

• the dissemination of new technologies of communication and trans-

portation;

• the post-Cold War multi-polarity; the rise of transnational actors and

new migration waves as well as the relative decline of the nation-state;

• the reconfiguration of city landscapes, within urban networks and

hierarchies, alongside the rise of the transnationally linked ‘global

city’;

• and the emergence of reflexive and fundamentalist forms of social

organization and identity.

As this picture suggests, the highly disjunctive and hybridist nature of

globalization results in new patterns, risks and opportunities that define

the terms of a post-traditional order (Giddens 1994, 1991). In tandem,

the interaction between local and translocal forces defines the spatiotem-

porality of a given social formation, meaning that an alteration in the

composition of those forces is likely to reconfigure the levels of deterri-

torialization of the society. The difference between ‘transnational’ and

‘global’ is elucidative: the former refers to processes anchored across the

borders of a few nation-states, whereas the latter refers to decentralized

processes that develop away from the space of the national (Gille and

Riain 2002: 273; Kearney 1995: 548). As such, global interaction means

‘not the replication of uniformity but an organization of diversity, an

increasing interconnectedness of varied local cultures, as well as a devel-

opment of cultures without a clear anchorage in any one territory.’

(Hannerz 1996: 102). Composites of local and translocal forces may occur

at ‘border zones,’ shape ‘contact zones’ and constitute ‘global ecumenes,’

all of which can be understood as regions of persistent interaction and

exchange, asymmetries and exploitation, resistance and hybridization

(Clifford 1997: 195; Hannerz 1989: 66; Pratt 1992).

In globalization studies, the nature of agency and scale varies consid-

erably, according to the object of study and the intellectual purview of

the analyst. Studies that focus on systemic forces (capitalism, science,

modernization) tend to consider actors and places as being subordinate

to contexts of locality-making that lie beyond their control. Analyses of

transnational connections consider actors with an ability to navigate socio-

spatial hierarchies. Diaspora studies, at last, investigate actors that are

more actively engaged in the formation of imaginaries and public spaces

(Gille and Riain 2002: 279).

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 11

However, over the course of a decade, these analytical strands have

rapidly adjusted to issues of replication and normalization, without con-

sidering methodological or conceptual alternatives that could more effi-

ciently and creatively address patterns and complexities of globalization

that remain understudied (Urry 2003: 11–12). More specifically, notions

of network, diaspora and cosmopolitanism have precipitously forged an

understanding about mobile subjects that obstructs the perception of

unknown features and possibilities.

The notion of ‘network’ is the conceptual device most widely employed

in global studies. Comprising related notions, such as ‘flow,’ ‘web’ and

‘circuit,’ its prominence in social sciences reflects the impact of informa-

tion technologies reconfiguring social life as a ‘space of flows’ rather than

a ‘space of places’ (Castells 1996). Assuming different topologies (chain,

hub, channel), a network is a system of interconnected nodes for maxi-

mizing information and energy output. Its potency is defined by the number

of nodes, their interconnections and density, as well as by its relation to

other environs. Networks may overextend insofar as new nodular lines

remain possible. Nodes are not centers but switchers performing func-

tions within a general system that operates through a rhizomatic rather

than a command logic. Nodes vary in importance (depending on loca-

tion, density and energy) but are interdependent and replaceable. Both in

the physical and social realms, a network generates complex intercon-

nections that survive its constitutive elements, extending across time and

space (Urry 2003; Castells 1996).

However, the notion of network has been overused in global studies,

constraining the perception and sidestepping issues of power, meaning and

change. ‘The term “network” is expected to do too much theoretical work

in the argument, glossing over very different networked phenomena . . .

[It] does not bring out the enormously complex notion of power impli-

cated in diverse mobilities of global capitalism . . .’ (Urry 2003: 11–12).

John Urry also notes that the scholarship has relied on a model of

‘globally integrated networks’ (GINs), complex and enduring structures

characterized by predictable connections that nullify time-space constraints.

Transnational corporations and supranational organizations are examples

of GINs. These structures tend to be inertial, rigid and dependent on the

stability of macro systems (international markets, contracts and media/

rumor systems).

Yet, there are networked-like formations that cannot be understood

through the notion of GIN. Urry proposes the notion of ‘global fluids,’

characterized as highly mobile and viscous formations whose shapes are

uneven, contingent and unpredictable. ‘Fluids create over time their own

context of action rather than seeing as “caused”’ (p. 59). Traveling peoples,

oceans, the internet and epidemics are variegated examples of global fluids.

However, Urry does not provide further evidence for advancing his claim

12 Neo-nomadism

that global fluids constitute ‘a crucial category of analysis in the global-

izing social world’ (p. 60).

Neither concept of network (GIN or fluid) can address the meanings

and temporalities of the entities they seek to explain. As an alternative,

the notion of ‘diaspora’ has been largely employed in anthropological

studies of ethnic dispersion. Differing from linear migration and struc-

tured networks, a diaspora includes a full cross-section of community

members spread across diverse regions, while retaining a myth of unique-

ness, usually linked to an idea of homeland, real or imagined (Kearney

1995: 559). A descriptive definition of diaspora includes ‘a history of

dispersal, myths and memories of the homeland, alienation in the host

country, desire for eventual return, ongoing support of the homeland, and

a collective identity defined by this relationship’ (Clifford 1994: 306).

Upon the tension between local assimilation and translocal allegiances, a

diaspora is diacritically shaped by means of political struggles with state

normativities and indigenous majorities (Axel 2002; Clifford 1994: 307–8).

Nonetheless, the relation between diaspora and locality is further frac-

tured by the socio-spatiotemporal disjuncture of globalization, engendering

‘degrees of diasporic alienation’ (Clifford: 315). Under global conditions,

the space and identity of such ethnic dispersions must be reconsidered in

terms of a ‘diasporic imaginary.’ Diaspora is conventionally understood

as being founded on a locus of origin that defines a people as diaspora.

However, ‘[r]ather than conceiving of the homeland as something that

creates the diaspora, it may be productive to consider the diaspora as

something that creates the homeland’ (Axel 2002: 426). As Brian Axel

proposes, ‘My conceptualization of the diasporic imaginary not only repo-

sitions the homeland as a temporalizing and affective aspect of sub-

jectification; it also draws the homeland in relation with other kinds of

images and processes.’ (p. 426).

By breaking the social-spatiotemporal link that constitutes identity,

globalization enables a new form of diasporic imaginary, one whose nature

is post-essentialist. Under these circumstances, diaspora becomes, in the

words of Kobena Mercer, a ‘site of multiple displacements and rearticu-

lations of identity, without privilege of race, cultural tradition, class, gender

or sexuality. Diaspora consciousness is entirely a product of cultures and

histories in collision and dialogue’ (Mercer 1994: 319; see also Clifford

1994). Rather than origin, it values the critical voice in history, estab-

lished by means of power relations and cultural encounters. Although

some historians may note the risk of premature pluralism in this argu-

ment, there is a distinction between historical and essentialist accounts of

diaspora, for globalization introduces conditions of possibility for the

emergence of postidentitarian formations.

In this light, global nomads constitute a negative diaspora, as they see

themselves as part of a trans-ethnic dispersion of peoples that despise

home-centered identities. Their identity as a diasporic formation is not

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 13

based on ethnic or national nostalgias, but rather on a fellowship of

counter-hegemonic practice and lifestyle. For consciously rejecting predom-

inant ethno-national apparatuses, their centrifugal moves do not configure

diasporic alienation; quite the contrary, although perhaps heralding the

ideal of an alternative homeland, their utopian drives are propelled by a

pragmatic individualism, often predicated on reflexive modes of subjec-

tivity formation (Lash 1994; Foucault 1984c, 1984f). Other than making

one’s soul the Promised Land, expressive individualism opposes diaspora

as a basis of personal identity. Therefore, diaspora does not suffice for

addressing hypermobile formations that nest a type of sensibility that, in

the lines of Mercer, tends to reject exclusionary modes of identity forma-

tion based on gender, race, class and religion.

Negative diaspora thus reflects the reconfiguration of self-identity under

the impact of global processes and structures. Media, urban and techno-

scientific apparatuses generate an unprecedented volume of images, signals

and information that gradually undermines the fixity of social roles, iden-

tities and cognitive frames. These have to be renegotiated, as subjects are

forced to make uneasy decisions about their lives: ‘we have no choice but

to make choices’ (Giddens 1994: 187). This condition has been identified

as ‘the problem of inculturation in a period of rapid culture change

[. . .], as the transgenerational stability of knowledge [. . .] can no longer

be assumed’ (Appadurai 1996: 43). Frederic Jameson notes that the emer-

gence of colossal global systems has derailed the human capacity of social

perception and cognition, thus engendering disorientation (Jameson 1991:

45). On the other hand, Anthony Giddens and Scott Lasch are more opti-

mistic in assessing such semiotic excess as, in part, reflecting reflexive

demands which arise from the fabric of social life (Beck et al. 1994). In

this case, the problematization of locality-making becomes a resource

rather than a barrier in the production of meaning, inasmuch as the

aesthetic reflexivity that is entailed by modern reflexivity remains capable

of recalibrating notions of time, space and belonging at the local level

(Appadurai 1996; Lash 1994).

The question then becomes how reflexive subjectivities are constituted

under the deterritorializing conditions of globalization. However, although

dependent of specific objects and scales of analysis, the development of

new methodologies capable of addressing issues of deterritorialization has

been limited, since global studies have privileged the analysis of social

forms over cultural contents:

A troubling aspect of the literature on globalization is its tendency to

read social life off external social forms – flows, circuits, circulations

of people, capital and culture – without any model of subjective medi-

ation. In other words, globalization studies often proceed as if tracking

and mapping the facticity of the economic, population, and popula-

tion flows, circuits, and linkages were sufficient to account for current

14 Neo-nomadism

cultural forms and subjective interiorities, or as if an accurate map

of the space and time of post-Fordist accumulation could provide an

accurate map of the subject and her embodiment and desires.

(Povinelli and Chauncey 1999: 7)

Within current scholarship, one possible way of overcoming this lacuna

involves the deployment of the concept of cosmopolitanism, retooled as a

mediation that translates aesthetic reflexivity into a social disposition that

is malleable to global environments. Cosmopolitanism has been described

as a ‘perspective’ or a ‘mode of managing meaning’ that entails ‘greater

involvement with a plurality of contrasting cultures, to some degree on

their own terms’ (Hannerz 1996: 103). Large cities have been celebrated

as spaces of multiculturalism, but long-haul traveling prevails as the manner

by which one is dramatically exposed to and potentially transformed by

the contact with alterity. According to Ulf Hannerz, ‘genuine cosmopoli-

tanism is first of all an orientation, a willingness to engage with the Other.

It entails an intellectual and aesthetic openness toward divergent cultural

experiences, a search for contrasts rather than uniformity’ (p. 103).

However, this openness usually presupposes material and educational priv-

ileges that are restricted to a few. Most tourists, migrants, exiles and expa-

triates are not cosmopolitans due to a lack of interest or competence in

participating or translating difference: ‘locals and cosmopolitans can spot

tourists a mile away’ (p. 105).

Openness to plurality is not an altruistic gesture, for the main goal of

the cosmopolitan is to understand her own structures of meaning.

‘Cosmopolitans can be dilettantes as well as connoisseurs, and are often

both, at different times. But the willingness to become involved with the

Other, and the concern in achieving competence in [alien] cultures relate

to considerations of self as well’ (p. 103). In a psychoanalytical vein, cos-

mopolitanism exposes an element of narcissism in the development of the

self that is carried out through cultural mirroring (p. 103). In this con-

nection, it can be understood as a ‘therapeutic exploration of strangeness

within and outside the self’ by which ‘detachment from provincial identi-

ties’ alters personal references of self and alterity (Anderson 1998: 285).

However, proponents of a more localized and nativist form of cosmo-

politanism have criticized the predominantly universalist approach as being

tainted with elitism and aestheticism (Robbins 1998: 254; Clifford 1994:

324). These ‘discrepant cosmopolitanisms’ propose a different density of

allegiances that values local worldviews and affirms cultural and historical

specificity. In it, hybridity overcomes translation by subverting colonial

dichotomies and hierarchies. Intellectuals have, in fact, been idealized as

cosmopolitans par excellence (Hannerz 1996; Braidotti 1994), even if their

competence is, more often than not, restricted to sophisticated rationaliza-

tions about the Other. To wit, although noting the performatic dimension

of the intercultural encounter, Ulf Hannerz and Rosi Braidotti claim that

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 15

cosmopolitanism is, above all, a process of management of meaning and

translation. This conception virtually ignores the impact of affective and

visceral engagements with radical alterity in reshaping personhood. Such a

view reduces cosmopolitanism to little more than detached aestheticism, as

more popularly illustrated in bobos and hub influentials’ safe consumerism

of exotic commodities (Stalnaker 2002; Brooks 2000).

Nonetheless, both nativist and universalist schools of cosmopolitanism

neglect three critical issues. First, there is a substantial difference between

aesthetics and aestheticism that debates have overlooked. As will be dis-

cussed in this chapter, aestheticism refers to a form of detached apprecia-

tion as outlined above, whereas aesthetics relates to an ethical orientation

that potentially confronts the fixity of biopower domination while rebal-

ancing life-values. Second, current debates reduce cosmopolitanism either

as a cognitive or as a behavioral capacity, respectively incarnated in sophis-

ticated intellectuals or skillful migrants as iconic examples. Instead, cos-

mopolitanism must be understood as a holistic disposition or attitude (in

social psychology terms), which comprises cognitive, affective and behav-

ioral components altogether. Third, debates on cosmopolitanism are often

anchored on speculative and idealistic assumptions, neglecting empirical

research and validation, particularly by means of cross-cultural analysis.

Among different types of mobile subjects, it seems that the ethical, atti-

tudinal and empirical dimensions of cosmopolitanism tend to overlap in

the figure of the ‘expatriate.’ Hannerz’s observations resonate with the

expressive expatriates foregrounded in this book:

The concept of the expatriate may be that we will most readily asso-

ciate with cosmopolitanism. Expatriates (or ex-expatriates) are people

who have chosen to live abroad for some period [. . .]. Not all expa-

triates are living models of cosmopolitanism; colonialists were also

expatriates, and mostly they abhorred ‘going native.’ But these are

people who can afford to experiment, who do not stand to lose a

treasured but threatened, uprooted sense of self. We often think of

them as people of independent (even if modest) means, for whom

openness to new experiences is a vocation, or people who can take

along their work more or less where it pleases them; writers and

painters in Paris between the wars are perhaps the archetypes.

(Hannerz 1996: 106)

As a writer in Paris between the wars, Walter Benjamin twice fled to

Ibiza in 1932 and 1933. As a forerunner of expatriate life on the island,

Benjamin stayed at a friend’s house in the fisherman parish of Sant Antoni.

3

‘There were only a few foreigners there,’ according to French art historian

Jean Selz, ‘a number of Germans and also some Americans. The foreigners

were often together, so I got to know him. Benjamin was 40, and I was

16 Neo-nomadism

28’ (Scheurmann and Scheurman 1993: 68). In a letter, Benjamin wrote

that Ibiza allowed him to ‘live under tolerable circumstances in a beautiful

landscape for no more than 80 marks per month.’ (Witte 1991: 33). Because

Ibiza was so isolated, his attempts to develop editorial contacts in Paris

proved unsuccessful. Nevertheless, he enjoyed the beauties of La Isla Blanca

amid a lively community of expatriates. Benjamin spotted bohemians in

bars and restaurants, toured with Gaugin’s grandson, and flirted with a

Dutch painter whom he said to have almost included in his ‘angelology’

(Witte 1991). In Ibiza, Benjamin also experimented with opium and hashish

in the context of his interests in surrealism as a countercultural, liberation

movement (Thompson 1997).

In the early 2000s, connectivity would not have been such a problem

for Benjamin. With email and low-airfare jets, he would perhaps have

stayed longer in Ibiza, although intense urbanization and price inflation

have become main complaints among residents more recently. Nevertheless,

throughout the century, Ibiza has been imagined as a utopian paradise,

hosting successive waves of marginal subjects fleeing the metropole: artists,

bohemians, beatniks, hippies, gays, freaks and clubbers. For such a density

of cultural experimentation in a setting of intense modernization as that

island has suffered, French sociologist Danielle Rozenberg has claimed

that, ‘Ibiza is paradigmatic to those who interrogate the development of

contemporary societies’ (Rozenberg 1990: 3). These expressive expatriates

have inadvertently contributed to Ibiza being imagined as an icon of plea-

sure and freedom amid large segments of the Western youth, an icon that

is now rampantly exploited by leisure capitalism, with contradictory effects.

But, while globalization conceals the forces of history, neo-nomadism

embodies a much longer diachrony that can be traced back to the 1960s

counterculture and even further back to nineteenth-century Romanticism.

Aesthetics of the self: post-sexualities in a digital age

The subjects discussed in this book ascribe to a cosmopolitan culture of

expressive individualism. Any practice that allows for the exploration

of personal capabilities in creative, pleasurable and transcendent ways are

of potential interest for expressive expatriates. As such, after fleeing the

homeland, they become personally and/or professionally involved with

therapy, art and spirituality, and their experimentations with hedonism

and sexuality often reflect conscious decisions about transforming their

self-identity modes. These dispositions and their wider circumstances res-

onate with philosophical discussions about an aesthetics of existence which,

according to Foucault, refers to the possibility of an ethics of the self that

is capable of confronting the axiological challenges of modernity. Self-

aesthetics, as a practical lifestyle or philosophical speculation, is predicated

on a fundamental question: how does, can and must one conduct one’s

own life under conditions of moral freedom?

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 17

In this context, self-aesthetics must be considered in its crucial interre-

lations with ethics and politics, schematically considered at three different

levels: (1) aesthetics as an emphasis on forms of coexistence that results

from a world of polytheism of values; (2) aesthetics as a site of resistance

against power-knowledge (biopower) regimes forged by the state and

science; and (3) aesthetics as a lifestyle that sustains alternative experiences

of the self and sociality.

The axiological crisis of modernity is marked by the acute fragmenta-

tion of life-spheres (religion, economy, politics, science, pleasure, intimacy,

etc.) and their gradual colonization by technical reason. The overwhelming

expansion of objective culture undermines the subject’s ability to develop

autonomously (Simmel 1971). To this challenge, Romantic thinkers have

proposed the aesthetic as a realm of self-cultivation (Bildungsideal) by

which a holistic personality can be cultivated against the corrosive effects

of modern specialization. Yet, in face of the imperatives of modernity,

such a view resulted in a withdrawal from the world of action, fostering

a narcissistic style of excessive refinement, formalism and detachment, also

characteristic of cosmopolitan aestheticism.

Within this intellectual context, Max Weber rebuked the Romantic view,

seeing it as a powerless response to the meat-grinding effects of modern

rationalization. In order to tame the ‘iron cage’ of modernity and the

everlasting specters of demagogy and tradition, Weber proposed an ethics

of personhood that integrates vocational specialization with an acute polit-

ical awareness. The self must adhere to a secular ideal of vocation (Beruf ),

which presupposes an ‘irrational’ choice for compliance with one life-

sphere and its core regulatory principle. Nonetheless, Weber soon realized

that the vocational stance is better actualized by means of a political

aesthetics that strives to balance such ends-oriented ethics (embodied in

the principle of conviction, as in science or religion) with a means-oriented

ethics (regulated by the principle of responsibility, as in politics) (Weber

1918). He thus hoped that the cultivated subject would be able to regain

its ability to intervene in reality, while retaining some degree of autono-

mous development.

4

Presenting remarkable similarities with the iron cage diagnosis, Foucault

uncovered how science and state coalesce in biopower regimes, a complex

institutional-ideological apparatus geared toward the administration of

individual and collective bodies. It correlates with the more socially diffused

apparatus of ‘sexuality’ which forges the modern subject of discipline and

interiority.

5

In this light, the subordination of the self to a scientific voca-

tion, as proposed by Weber, would reaffirm relations of domination

entailed by biopower. In other words, by recurring to science and natural

law as sources of legitimacy, liberation gestures, practices and movements

remain entrapped in the epistemic vectors that they ultimately seek to

transcend.

18 Neo-nomadism

Conversely, power-knowledge regimes entail a multiplicity of forces that

escape and resist them. As Foucault noted, mechanisms of subjectification

inadvertently enable tactical resistance, for power is better understood as

modes of relation that are both repressive and productive (Foucault 1976).

The exclusionary logic of the normal-pathologic thus contributes to prolif-

erate abnormalities that unfold both as representation and effect.

Furthermore, the historical decline of moral orthodoxies requires an

ethical response that, in highly reflexive sites, has revolved around the

problematization of the self in relation to itself. As such, once repression

is lifted, the problem becomes how to define and exercise one’s own

freedom in relation to others and to one’s own experience. In the scope

of sexuality, the subject thus becomes a battleground between moralities

of bourgeois interest and of bohemian expression:

A morality of ‘interest’ was proposed and imposed upon the bour-

geois class – in opposition to other arts of the self that can be found

within artistic and critical circles. The ‘artistic’ path [. . .] constitutes

an aesthetics of existence that opposes self-techniques prevalent within

bourgeois culture.

(Foucault 1984a: 629)

This is where latter Foucault meets post-Ascona Weber. The aesthetics

of existence substantially differs from aestheticism. As an ethics of the

self, it has effects of power with a potential for breaking away from

regimes of subjectification that constrain experiences of the self and reality.

It is in this sense that Foucault envisages the aesthetics of the self as a

life politics. ‘“Couldn’t everyone’s life become a work of art?” This was

not some vapid plea for aestheticism, but a suggestion for separating our

ethics, our lives, from our science, our knowledge’ (Hacking 1986: 239).

Liberation movements would not only be aligned with values, methods,

orientations and dispositions that define an ethics of self-mastery (Giddens

1994; Foucault and Lotringer 1989; Foucault 1984a). A post-sexuality

age would also require ‘new forms of community, co-existence and plea-

sure’ capable of nurturing subjective and social modes that redefine terms

of control, discipline and interiority.

How to scrutinize this conceptual horizon empirically is a critical ques-

tion. In this book, I investigate the possibility of a post-sexuality apparatus

being engendered in specific sites of Techno and New Age counterculture

and sustained by expressive expatriates. Yet, a bibliographic search on

the topic is disappointing. Besides a few sociological studies dedicated to

a taxonomy of sectarian subcultures, most accounts have focused on histor-

ical outlooks about the 1960s ‘radicalism,’ the 1970s ‘decline’ and the

1980s ‘co-optation’ (Brooks 2000; Frank 1997; McKay 1996; Roszak

1995; Zicklin 1983; Bellah 1979). The presumed disappearance of counter-

cultures conceals the fragmentation of ‘the sixties’ into a variety of

1111

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1011

1

2

3111

4

5

6

7

8

9

20111

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

30111

1

2

3

4

35

6

7

8

9

40111

1

2

3

4

45111

Neo-nomadism 19

single-issue movements, in turn, paralleled by a host of academic studies:

queer, ecological, feminist; subcultural, new religions, popular studies, etc.

(Clifford 1998). Within a wider socio-historical perspective, nonetheless,

all of these empirico-conceptual formations manifest a basic dissatisfaction

with the promises and rewards of modern civilization.

A note on the notions of ‘subculture,’ ‘counterculture’ and ‘alternative

culture’ is pertinent. These have derived and been questioned from diverse

academic purviews, notably those inspired by functionalism and popular

resistance (Bennett and Kahn-Harris 2004; Muggleton and Weinzierl 2003;

Bennett 1999; Redhead 1997; McKay 1996; Roszak 1995). But, in the

scope of this book, I propose a pragmatic deployment of such definitions.

The notion of ‘subculture’ refers to shared values, symbols and practices of

a group whose members also adhere to or function (more or less normally)

within a larger society. The adjective ‘alternative’ denotes subcultures that

seek some level of autonomy from or replacement of major social schemes.

It connects with the notion of ‘counterculture,’ which differs, nonetheless,

in intensity and amplitude: a counterculture is characterized by more acute