Washington University in St. Louis Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University Open Scholarship Washington University Open Scholarship

University Libraries Publications University Libraries

10-2021

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington

University in St. Louis: An Ithaka S+R Local Report University in St. Louis: An Ithaka S+R Local Report

Jennifer Moore

Washington University in St. Louis

Christie Peters

Washington University in St. Louis

Dorris Scott

Washington University in St. Louis

Jessica Kleekamp

Washington University in St. Louis

Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/lib_papers

Part of the Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Moore, Jennifer; Peters, Christie; Scott, Dorris; and Kleekamp, Jessica, "Teaching with Data in the Social

Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis: An Ithaka S+R Local Report" (2021).

University Libraries

Publications

. 31.

https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/lib_papers/31

This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at Washington University Open

Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Libraries Publications by an authorized administrator

of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Teaching with Data in

the Social Sciences

at Washington

University in St. Louis

An Ithaka S+R Local Report

Jennifer Moore, Head of Data Services

Christie Peters, Head of Research & Liaison Services

Dorris Scott, Social Science Data Curator and GIS Librarian

Jessica Kleekamp, Head of Assessment & Analytics

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

2

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at

Washington University in St. Louis

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 3

BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................. 3

Subject Librarians ...................................................................................................................................... 4

Data Services ............................................................................................................................................ 4

METHODS ..................................................................................................................................................... 4

Semi-Structured Interviews ....................................................................................................................... 4

Grounded Theory Approach ...................................................................................................................... 5

Coding Strategy ......................................................................................................................................... 5

TEACHING WITH DATA ............................................................................................................................... 6

Data Literacy.............................................................................................................................................. 7

Types of Instruction ................................................................................................................................... 8

Tool-Based Instruction .......................................................................................................................................... 8

Problem-Based Instruction ................................................................................................................................... 8

TOOLS & RESOURCES ............................................................................................................................. 10

Resources for Finding Data ..................................................................................................................... 10

Software ................................................................................................................................................... 10

Tutorials ................................................................................................................................................... 11

CHALLENGES ............................................................................................................................................ 11

Differing Student Skill-Levels................................................................................................................... 11

Finding Data ............................................................................................................................................ 12

Ethical Challenges ................................................................................................................................... 13

SUPPORT .................................................................................................................................................... 15

Instructor Support .................................................................................................................................... 15

Student Support ....................................................................................................................................... 15

Library Support ........................................................................................................................................ 15

LIMITATIONS .............................................................................................................................................. 16

RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................... 17

Finding and Evaluating Data: Build Resources and Workshops on Finding Data in Your Discipline ..... 17

Datasets in a Box: Create a Repository of Teaching Datasets ............................................................... 17

Subject Librarians: Expand Data Literacy Competencies ....................................................................... 18

Workshops and Programmatic Instruction: Data Savvy Program ........................................................... 18

Expand Tutorial Collections ..................................................................................................................... 18

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................. 18

REFERENCES............................................................................................................................................. 18

APPENDIX A ............................................................................................................................................... 20

APPENDIX B ............................................................................................................................................... 22

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

3

INTRODUCTION

Teaching data skills is an essential role for instructors in social science-related fields.

The results from a 2009 survey of employers suggest that by incorporating data firmly

within the curriculum, higher education can better prepare students for productive

careers (Hart Research Associates, 2009). Employers called for greater critical thinking

and analytic reasoning skills, as well as analysis and complex problem-solving skills.

Approximately 70% of respondents wished for students to be better equipped to work in

teams, to be creative, and to be able to locate/organize/evaluate information. Roughly

two-thirds of the employers surveyed were looking for students who could understand

and work with numbers. In the decade since this report was published, the need for skill

development in this area has only increased.

BACKGROUND

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU) is one of twenty institutions contributing to

the Ithaka S+R study Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences (TDSS).

1

This project

builds on Ithaka S+R’s ongoing research program to investigate teaching practices and

support needs across multiple disciplines within higher education. Past projects include

a study to learn more about the support needs of instructors and students in business-

related disciplines and one that examined the support needs of instructors who use

primary sources in the classroom.

The TDSS project explores the teaching practices and support-needs of instructors in

the social sciences who incorporate work with quantitative data into their undergraduate

classes. Particular attention has been paid to identification of the foundational skills that

contribute to success in today’s data-driven world and more particularly to

understanding how the WashU Libraries can better support instructors and students in

the social sciences with their data-related needs. While we do currently provide many

data-related resources and services to meet perceived needs, e.g., data literacy

instruction, access to specialized software, individual consultations, etc., it is unclear to

what degree we are perceived as a data resource on campus, whether instructors are

taking full advantage of our services, and if there are any gaps in the services that we

offer.

1

American University, Boston University, Carnegie Mellon University, Florida State University, George

Mason University, George Washington University, Grand Valley State University, Kansas State

University, Michigan State University, North Carolina State University, Purdue University, Rice University,

University of California Santa Barbara, University of Chicago, University of Massachusetts-Amherst,

University of New Hampshire, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Richmond, Virginia

Polytechnic Institute and State University, Washington University in St. Louis

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

4

There are two groups in the WashU Libraries that offer support for instructors and

students on the Danforth campus who engage in data-intensive research, subject

librarians and Data Services staff.

Subject Librarians

Twenty-four subject librarians serve all departments and schools on the Danforth

Campus at WashU.

2

These librarians provide library-related tools, resources, and

services; develop and offer effective instruction and learning materials; cultivate,

maintain, and manage collections, not only of monographs and journals, but of

increasingly important resources like data sets; and help to support instructors and

students who have data-related needs in their respective disciplines. Subject librarians

often serve as a bridge between faculty and students and the Libraries' Data Services

unit.

Data Services

The Data Services unit serves all WashU campuses through their six core services:

quantitative and qualitative data analysis, data literacy, data management, data sharing

and curation, data visualization, and geographic information systems (GIS).

3

They offer

consultations, talks, demonstrations, and hands-on workshops in each of these areas

with relevant tools. Data Services is also the home of The Research Studio, which is

equipped with collaborative workstations where students can access specialized

software

4

and work on analysis projects. The Research Studio software is also available

to access remotely. It is our hope that this project will help inform future collaboration

between subject librarians and Data Services at WashU.

METHODS

Semi-Structured Interviews

At the beginning of this project, Ithaka S+R TDSS project leaders provided a protocol

and semi-structured interview guide for each university team to use when conducting

interviews with instructors who teach quantitative methods to undergraduates in the

social sciences (appendix 1). After obtaining IRB approval, the team contacted several

key stakeholders on campus who work in the social sciences in order to identify

possible interview subjects. This led to the identification of thirty-seven potential

2

Subject Librarians, A-Z (https://library.wustl.edu/research-support/subject-librarians/librariansalpha/)

3

Data Services (https://library.wustl.edu/research-support/data-services/)

4

Specialized software offered by Data Services: https://libguides.wustl.edu/ds_research_studio/software

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

5

candidates, a list that was narrowed down to fifteen instructors who best fit the desired

candidate profile. Thirteen of those fifteen instructors agreed to the interview.

All interviews were conducted via Zoom, most lasting less than an hour. All participants

verbally consented to participate in the study (appendix 2) and were given the option to

turn off their video if it made them uncomfortable. The audio and transcripts from the

interviews were downloaded and the transcripts reviewed, corrected if necessary, and

de-identified.

Grounded Theory Approach

A qualitative Grounded Theory approach has been used to identify themes in the data

collected from our interviews. Grounded Theory is commonly used in social science

research because it is most suited to efforts to understand the process by which actors

construct meaning out of intersubjective experiences (Suddaby, 2006). Effective

grounded theory requires an interplay between induction and deduction, which some

have labeled as analytic induction:

…Grounded Theory as a research approach is ideal for a field in which

a problem exists for which an explanation (or sometimes a solution) is

missing. It is furthermore ideal for an area in which not much research

and theorizing has been done before, so that there is space left for new

insights and perspectives to be developed (Flick, 2018).

This approach allows researchers to work without assumptions, which means that

categories can be derived from the observation of phenomena and interviewers can go

into each interview as open-mindedly as possible.

Coding Strategy

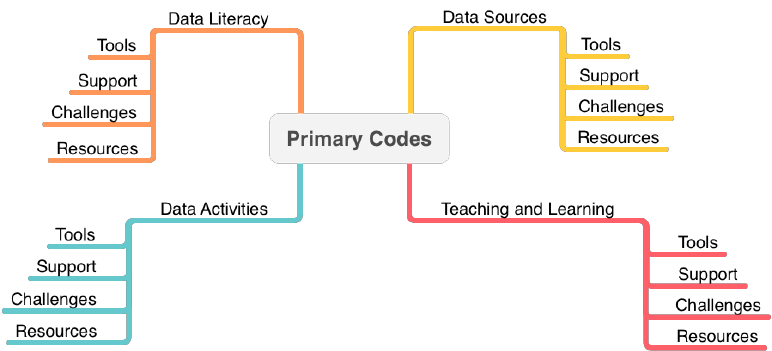

Using a Grounded Theory approach, the project team collectively identified four primary

themes and four sub-themes that emerged from three interview transcripts. Within each

primary theme, the same four sub-themes were coded for (Figure 1). Each team

member then claimed one primary theme to focus on for all thirteen interview

transcripts. Two team members used Atlas.ti and two NVivo, both qualitative data

analysis software, to code the transcripts.

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

6

Figure 1. Primary Codes

TEACHING WITH DATA

Our interviews suggest that instructors are teaching with and about data in a number of

different ways and with varying expectations. These efforts include teaching students

how to find data, understand issues surrounding data accessibility and archival erasure,

identify what the research design is in an article and determine if it controls for

confounding variables, determine how trustworthy a study is, and understand how well a

study is conducted in terms of key benchmarks, e.g., validity and reliability of the data,

among others:

I want them to be able to read [quantitative] articles critically and say,

“Hey, you know, they weren’t controlling for this…or the sample they

selected was totally biased and they came up with these conclusions.”

Many instructors recognize how important it is for their students to be data literate and

to learn data-related skills, but they struggle with the magnitude of this endeavor:

There is simply not enough time in class to teach data management,

data organization and analysis, how to deal with assumptions, all of the

different issues in your data, even though it is super important.

Despite the documented need for graduating students to be data literate and the fact

that instructors in the social sciences recognize this need and incorporate some

elements of data literacy and skills into their instruction, Carlson and Bracke (2015) note

that competencies related to working with data are generally not included in the formal

education of students. This begs the question; how can academic research libraries

support both instructors and students as they teach and learn these critical skills?

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

7

Data Literacy

At WashU Libraries, we developed a definition of Data Literacy that includes the

following elements: the ability to find, evaluate, understand, assess, analyze, argue and

communicate with data, and understand the data lifecycle (Table 1). The benefits of

data literacy instruction have been acknowledged, but our findings show that most

instructors find it difficult to build data literacy into the curriculum of a semester-long

class. Reasons include lack of clarity on the part of instructors of what data literacy

entails and what a comprehensive data literacy program in a class setting might look

like. As a result, instructors often bypass teaching some elements of data literacy in the

interest of expediency by providing clean datasets that allow students to easily

accomplish their learning objectives over the course of a semester, pre-evaluating the

suitability of datasets for certain types of analysis, and focusing on activities that are

problem or tool-based:

You know, it's almost like a separate class can be taught on what is

DATA. Even a one credit, one semester, once a week, one hour course

that's like, here's what data is for the social sciences, right?... which

would be interesting...

Table 1. Data Literacy Elements

Element

Definition

Find

Awareness of procedures and considerations when collecting

primary and secondary data

Evaluate

Evaluation of a data source for authenticity, trustworthiness, and

ethical usage

Understand

Comprehension of data formats and tools needed to use data, and

awareness of data documentation (or lack thereof) to guide usage

Assess

Evaluation of the data and methods used in a data argument

Analyze

Analysis of data through query, comparison, and pattern finding

Argue

Understanding, interpretation, and communication of data analysis

Data Lifecycle

Understanding of the various stages through which data moves in a

data project

A number of instructors suggested that research design should be taught before data

literacy. This suggests that students need a better concept of the research process o

contextualize the use of data and why data literacy matters. Teaching the research data

lifecycle is one way to approach these topics together, but time constraints have been

identified as a barrier to incorporating this type of instruction into the curriculum of a

semester-long class. While some instructors do incorporate an original research project

into their classes to teach research design, it results in a lot of work for students over

the course of a semester, especially when they lack familiarity with the process. One

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

8

respondent explained that he has abandoned this type of assignment unless it is a

research-oriented seminar, due to time constraints.

Support for data literacy both within the classroom and without is one way that the

WashU Libraries currently contribute to data-related instruction efforts on campus

though providing instruction and related resources. We further address specific

approaches in the recommendation's section.

Types of Instruction

In our interviews, we identified two different instructional tracts that instructors tend to

utilize in their data-integrated classes; tool-based instruction and problem-based

instruction. It is not clear from our data why they choose one or the other, but one

appears to focus on the research process, and the other on learning specific tasks.

Tool-Based Instruction

Tool-based instruction tends to be task-focused. When instructors use this approach,

data collection generally falls outside the scope of a class. Students are discouraged

from collecting their own data be it primary or secondary, so they can focus on learning

how to use particular tools for data analysis. Data analysis and argument being just two

elements of data literacy. Instructors, in this case, tend to find and distribute datasets

that students can use for manipulation, which results in little-to-no time spent on

learning the important skills of finding and understanding data and critical assessment.

For example, one instructor stated that he prefers giving students datasets because it

allows more time for students to develop data analysis skills:

I would say, the LARGEST percent of work is done with data that I

generate for the class, because a lot of those classes are...I want the

students to focus on getting the skills of the software, and about

thinking about how to use a dataset, rather than bogging it down with

them worried about, like, "Oh my God, how do I find data?" [laughs]

Which I know is the skill, they need. But I do like to focus on the —"So

you have data. Now what?" And that means I can make it really neat

and nice and accessible as well.

Instructor-provided datasets come from a variety of sources, including primary data

generated by the instructor, secondary sources, and data shared by colleagues. Some

instructors use these resources to learn particular types of analysis themselves before

distributing them and teaching these skills to their students, which highlights the need

for tool-based skill development among instructors, as well as students.

Problem-Based Instruction

Problem-based instruction, on the other hand, places emphasis on learning the

research process and related skills, such as establishing the research question, doing a

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

9

literature review, performing research analysis, and assessing the accuracy of the data.

With this type of instruction, instructors focus more on data literacy elements related to

finding, evaluating, understanding, and assessing data. In this case, students are often

tasked with finding their own datasets for class assignments or collecting them through

survey or observation:

...the most difficult part of the creative process is to actually come up

with a question that can be answered in a relatively [short] span of

time...at least something that they can address...Once they achieve

that, then they can start thinking about the kind of data that they will

collect. They build their own surveys.

One instructor encourages students to bring data that they are interested in or have

been working on to his class, which enhances student engagement with the research

process:

Usually, the students do have some data that they are interested in or

have been working on. And then we use that dataset to develop,

actually, a research proposal—essentially a proposal to present a paper

at a conference. So, they have to go through the whole process of, you

know, identifying the research problem, the purpose, literature review,

then developing what type of data they need. And if they have a

dataset, they would be using that-- what type of analysis they were

going to use on it, actually do some analysis and get some findings. So,

it's that whole research process of how you actually conduct your

educational research project.

Another based his course on the critical assessment of archival data and how that data

is structured with no data manipulation expected beyond organization and management

of the data:

...we would as a group, manually scrape these records to extract the details of

incidents that were codified in the database. And so, there would be a—I would

provide students with a codebook, and some initial training around, you know,

what the field narrative means, or HOW to enter data information, or categorical

information about different types [of incidents]. We would also have to talk about

things like duplication, because—two students might be working with two

different sources, but they would mention the same event. So, how do we deal

with that?

A notable exception to our observation that instructors often have students find or

generate data in classes that focus on problem-based instruction comes from two

respondents who provide students with data so they can incorporate it into collaborative

project databases over the course of the semester. The learning objective in these

cases is to allow them to work with and understand data. In one case, the instructor

pulls data from a national database and asks students to enter it into a local project

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

10

database that has a different structure, the challenge being to retain the richness of the

extant data, while forcing it into the limiting structure of the project database. Another

instructor provides students with existing data and asks them to work with and

contribute to it, thereby allowing them to identify relationships and ask other relevant

questions of the data.

While our observations about tool-based and problem-based instruction are not

absolute, they do suggest two very different ways that instructors have their students

work with data in the classroom. Given that different elements of data literacy tend to be

covered in tool and project-based instruction, this suggests that teaching all aspects of

data literacy in a semester-long class is incredibly difficult. Respondents do appear to

recognize the need for additional support in this area.

TOOLS & RESOURCES

Resources for Finding Data

Instructors and students use a variety of resources to find datasets. Some of these

include textbooks, journal articles, primary sources like photographs, letters, and

archival records, previous research, journals, public survey data, websites, data from

local and national organizations and governmental entities, e.g., the National Center of

Educational Statistics and National Park Service, and public opinion surveys, e.g., the

Latinbarometer and European Social Survey.

Shared resources between colleagues are also popular among instructors, such as

lesson plans, problem sets, datasets, and code. It appears that most successful sharing

of resources happens at the departmental and institutional level, with less success

being noted with sharing material between institutions due to data quality issues and

material not being relevant to the course an instructor is teaching. Using shared

resources conveys a number of benefits, including the ability to build upon pre-existing

datasets, a better understanding of how to use these resources for assignments, and

the opportunity to learn how colleagues are using these data resources in their own

classes.

Tools for Collecting & Analyzing Data

Respondents mentioned a wide variety of data tools that they use for collecting and

analyzing data that they use in the classroom, the most prevalent being software and

tutorials.

Software

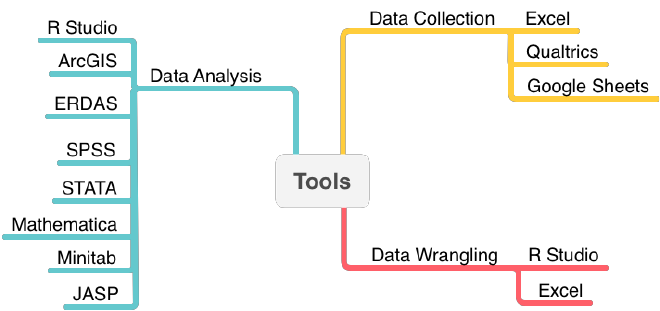

The following software packages (figure 2) are categorized by activity and sorted in

order of prevalence.

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

11

Figure 2. Tools used for collection and analysis

Tutorials

Several instructors mentioned that they create data-related tutorials for students to use

to help with students with data analysis assignments. These tutorials are readily

available for students to refer to throughout the semester, and they highlight and explain

the steps required to perform required data tasks for their final projects. A good example

comes from an instructor who created a tutorial to help students work through the steps

of a particular type of analysis on a fake dataset. Once the students complete that task,

they are expected to run the same analysis on a real dataset without step-by-step

instructions. At the end of the semester, students are then expected to run the analysis

for their own projects. While the tutorial is created for the fake dataset in particular,

students can watch it throughout the semester to remind themselves of the data

analysis steps.

Instructors also make use of internet resources like MOOCs and YouTube videos for

self-instruction and to help facilitate data-related instruction in the classroom.

CHALLENGES

Finding time to comprehensively teach data literacy has emerged as a significant

challenge that many instructors in the social sciences face. To compensate for this,

many find expedient workarounds, the most common of which appears to be providing a

clean dataset with a code book that allows students to accomplish their learning

objectives without going through all the steps required to find, evaluate, and understand

data themselves.

Differing Student Skill-Levels

The wide range of technical knowledge among students in data-intensive classes poses

a challenge for instructors. In the same class, some students have very advanced

technology and data analysis skills, while others come in with no skills at all. Even

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

12

experience using a seemingly ubiquitous tool like Excel can vary widely within a class.

This influences the pace of a course and the level of expertise that students acquire

over the of a class.

Finding Data

Trouble finding data repeatedly emerged as a challenge for both instructors and

students. General problems include difficulty finding datasets associated with an article;

lack of necessary specificity in a dataset for a proposed project; difficulty finding a

dataset for a particular community; difficulty finding and aggregating relevant data that

exists in different places; narrowing down to a specific dataset when there are many to

choose from on a particular topic; and poor or inconsistent documentation across

datasets.

Pedagogically instructors often struggle to find datasets for different types of research

and analysis. This can be an overwhelming undertaking given the ever-evolving nature

of data-intensive research. This complicates the process of teaching students how to

find their own data. Two examples demonstrate this challenge: I feel like I have a bit of

a gap in MY knowledge and how to find useful datasets. without spending an immense

amount of training in class for them, that would eat up other things. So, I'm not sure how

to approach that, but it seems like a good goal to aim for.

I know that the library has datasets, and you can go through and look at

them, but that is often OVERWHELMING to find specific datasets there,

so I rely on the data that I know about.

When the topic of working with big data came up in one interview, one instructor stated

that their class doesn’t work with big data because he doesn’t know HOW to explore a

dataset from a million users on the Internet.

Adequate time was repeatedly identified as an issue for teaching students how to find

and evaluate data in a single semester-length course:

With the pre-existing dataset that I used in the spring; I didn’t love the

dataset that I gave them. I just didn’t have time to play around with it in

advance, and so most of them didn’t find anything for the questions

they ended up looking at, and I don’t know which ones for them to look

at.

Ideally, datasets are shared with a code book that adequately describes the data for

reuse. While instructors are generally comfortable finding suitable datasets with

codebooks within their disciplines, finding suitable datasets that fall outside of their

discipline can be a challenge. This emerged as a challenge because many students

come into a class with topical interests that fall outside the scope of that particular class

and express a desire to focus on those interests in their projects:

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

13

But for different subject areas besides [mine], you know, they may not

be as readily available. I’m familiar with the ones in [my discipline]. If

they had a special interest in a certain area, it would be up to them to

find it.

Generally, when instructors prefer that students find data themselves, unfamiliarity with

the research process and how difficult it can be to find relevant datasets presents a

challenge to students. This, in turn, presents a challenge for instructors because they

must monitor, support, and encourage students to start the process long before any

deliverables come due. This is evidenced by comments from three instructors.

Students sometimes find HUGE, dense datasets that they then have to

carve out and try to figure out which parts are useful.

Other students have spent, you know, an entire semester just banging

their head against a dataset, a table, and just breaking that table into

something that can then be useful.

There is a really short window where they’ve got a time, “Ok, I need to

go out and get a dataset and figure out what kind of dataset…I need to

do,” and that has to be done early enough in the semester... So, in that

case, I often will be like, “If you want to do this kind of project where you

go out and generate data, I need to know about three weeks into the

semester to help you figure it out.

Ethical Challenges

Ethical challenges in teaching with data in the social sciences take many forms. Our

respondents touched on topics of bias, human subject protection, reproducibility and

transparency, technology outgrowing ethical thinking, and potentially trauma inducing

research. These issues are compounded by big data-mining efforts, in which data is

collected and analyzed and stripped of its context. These instructors expressed concern

that students often don’t know to look for many of these issues.

Maintaining objectivity and understanding data bias were identified as foundational

ethical issues that some of our instructors try to address in data-intensive classes.

Considerations include understanding who recorded the data and for what purpose,

erasure of the archives, and the categorization of individuals reflected in the data. Two

instructors elaborated on these ethical considerations.

The fact that a human being has been transformed in the Census

record into an age, sex, skin color, and nothing else is, in itself, an

ethical issue… and so even the data that we are dealing with, I think, is

just dripping with ethical considerations.

…but you know, I AM teaching how to use data and manipulate data to

answer very important social science questions, and I do forefront

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

14

things like this in my classes, so you know, in GIS we map racial

disparity inequality across our city…I think in some sense, if you are

teaching a—you know, social scientists aren’t necessarily activists, but

we do have a platform to teach students how to use [data] skills to

answer very critical questions facing us today…What is our

responsibility as educators?

Respondents also underscored the importance and challenge of addressing the issues

of data misrepresentation and flawed data in the classroom, both murky areas in

qualitative research. That this is a pervasive problem is supported by the wide variety of

contributing factors that instructors identified during their interviews. Several cited

selective reporting of data, use of misleading proxy data, the replication crisis in the

social sciences, false positive rates in publications, documentation inconsistency across

datasets, drawing unfounded conclusions and inferences, and making up/leaving out

data that skews results as contributing factors. It is important to point out to students

that data misrepresentation is often unintentional. Anyone who models some aspect of

society with data must necessarily make subjective choices about what information to

present. This highlights the importance of transparent documentation in qualitative

social science research.

One instructor highlighted the possibility of negative side-effects that certain types of

social science research may cause for student researchers. Over the course of several

semesters, he came to the realization that students may experience trauma when

collecting and working with data about traumatic events:

One of the challenges that arose in that work, that I was not as

sensitive to as I wish I had been, initially—was the vicarious trauma

involved, you know, in... just, kind of, documenting… one atrocity after

another, and as I became more sensitive to this and the need to be

mindful of the potential harm to student researchers, I basically stopped

using that approach to data entry for that particular line of research, and

I just shut down the development of the database, particularly through

student research assistance.

Most instructors recognize how importance it is for students to learn about and how to

address data-related ethical issues. These skills are essential for students to become

research and data literate. This is a challenge due to the broad scope of ethical

considerations in social science research, which many instructors struggle with

themselves.

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

15

SUPPORT

Instructor Support

Instructors are the first line of data support for students in their classes. Our data

suggest that the primary way that instructors help their students is by identifying,

preparing and providing well documented datasets for class projects and giving

students detailed instructions on how to find similar data themselves. Three supporting

examples demonstrate how instructors provide this type of support. In [my] class, I’m

just handing them data because I want to see if they can make heads or tails of it.

There are four different points in the semester where I provide them

with datasets for different types of analysis.

For my GIS class, I think I’ve pretty much generated most of the data,

or we use Census data, or data from the National Map Viewer, like the

United States Geological Society…

Instructors often help students learn software skills that they use in class for data

analysis, e.g., basic instruction in Excel, instruction on how to set up a Qualtrics survey

and clean survey data, and help writing their first code in R. They also provide

individualized support for students outside of class and suggest useful tutorials or create

relevant tutorials for the class themselves.

Student Support

Graduate teaching assistants (TA) provide support in many data-intensive social

science classes by helping to find datasets for class projects and assisting students

when they experience roadblocks with their projects. Undergraduate peer tutors,

students who have previously taken a particular class, also play a support role in some

classes by providing additional support for students outside of class.

Library Support

As mentioned above, Data Services staff and subject librarians provide a variety of

data-related resources and services at WashU. Some respondents indicated that they

have taken advantage of these resources and services and are pleased with the results.

The Data Services unit has been EXTREMELY helpful in working

particularly with geospatial information and related applications like

ArcGIS.

Others acknowledged that they have not used these services, some confessing that

they had no idea that the Libraries offered data-related services.

In terms of data, I have NOT used any of the library resources.

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

16

Regardless, most of the instructors who we interviewed acknowledged the important

role that the Libraries can play in supporting instructors and students who work with

data in the social sciences. Two instructors spoke specifically about receiving support

from the Libraries:

Mostly by reminding [students] that the library has resources, that there

are help desks, that there are people that can push them further in

learning this software, that even if-- that they should not always expect

like you know, people to just take them by the hand and walk them

through everything, but that they can certainly expect professional

guidance in the library.

I would definitely look for opportunities that specifically offer training [for

instructors] on how to teach students to deal with data, because that is

something where I can teach the software, I can teach the research

design all day long, but, you know, if I had to sit down, and I have to

think, “ok, how do I teach students WHAT data is, and how you

generate data”, that’s trickier. I could DO it, could COME UP with it, but

it would be nice to have guidance on, like a specific, you know, “you’re

a professor who teaches with data. What are some general guidelines

for doing this?” That would be useful, I think.

Our results suggest that some instructors who have worked directly with Data Services

staff to provide data literacy instruction for their classes are generally satisfied. Because

not all instructors have taken advantage of this service yet, the unit also provides

general discipline-agnostic data literacy instruction through the provision of open

workshops and data-related research guides. While this general support is undeniably

important and has helped many students become data literate, our research highlights

the need for data-related instruction that is targeted for specific disciplines. By

collectively reaching out to instructors in their respective areas to identify those who

teach with data, subject librarians can help identify points of need and collaborate with

Data Services staff to develop more targeted data literacy instruction.

LIMITATIONS

The primary limitations of this study center on the lack of experience of the WashU

project team with Grounded Theory as a qualitative research approach and with

developing an appropriate coding strategy. Time limitations due to other pressing

responsibilities prevented the team from spending more time on learning the process

and preparation at the beginning of the project, which became apparent as soon as we

started coding the interview transcripts.

In hindsight, our coding strategy limited the richness of our data. We did not anticipate

the considerable overlap and duplication that using the same sub-themes (tools,

resources, support, challenges) across all four primary themes (data literacy, data

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

17

sources, teaching & learning, data activities) would result in. For example, we each

looked for “resources” as they pertained to our assigned primary theme. Given this

experience, if we started again, we would have reconsidered our primary themes and

not set rigid subthemes.

In the end, we did collect a lot of data pertinent to teaching with data in the social

sciences, but for clarity and to cut down on duplication, we ultimately decided to

combine and organize our findings by sub-theme, all under the overarching primary

theme of Teaching with Data. While we faced several challenges over the course of this

research, we do now have a greater understanding of how to conduct social science

research, including increased familiarity with two common qualitative research software

packages, Atlas.ti and NVivo.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Finding and Evaluating Data: Build Resources and Workshops on Finding Data

in Your Discipline

Researchers have clearly identified the time constraints of a semester-long class as a

barrier to incorporating data-finding exercises into their curriculum. We recommend that

libraries draw upon their existing expertise to develop customized data-finding

resources and instruction to fit individual disciplines.

Datasets in a Box: Create a Repository of Teaching Datasets

Our research clearly suggests that some instructors spend a lot of time searching for

appropriate datasets for their classes. Developing or leveraging an existing repository of

reusable datasets designed specifically for teaching would provide a valuable resource

for instructors teaching with data in the social sciences. Repositories can house

datasets clearly delineated by learning levels, disciplines, and learning goals that

instructors can easily search through. We recommend that libraries assist with the

identification or development, if needed, and promotion of a FAIR

5

(findable, accessible,

interoperable, reusable) teaching-based data repository for instructors who teach with

data:

A repository of problem datasets would be the most helpful. It is hard to

come up with examples aimed at the right level, the right content.

Besides that, you know, there is stuff that I don’t know… It would be

nice to see how other people have TAUGHT that material.

5

GoFAIR: https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

18

Subject Librarians: Expand Data Literacy Competencies

The demonstrated need for data-related support among instructors who teach with data

highlighted by this study has reinforced for us the importance of creating a data literacy

program for subject librarians Because subject librarians are the first line of support

faculty and students in the areas of research, teaching, and instruction, we recommend

that libraries strengthen the data literacy competencies of subject librarians and support

an expansion of the repertoire of data-related services that they offer in collaboration

with other data services libraries have in place.

Workshops and Programmatic Instruction: Data Savvy Program

Some instructors suggest that it would be useful for libraries to conduct workshops for

students on the basics of data literacy, data resources and repositories, specialized

resources for the location and use of discipline specific data, how to use data tools, and

how to interact with data. They are also interested in workshops specifically for

instructors who focus on how to teach students data skills.

Expand Tutorial Collections

departments are creating video tutorials that teach data basics and skills without taking

up precious classroom time. Given time constraints that were repeatedly mentioned

during our interviews, we recommend that libraries work to provide data literacy tutorials

that instructors can leverage.

CONCLUSION

Participating in the Ithaka S+R Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences project has

provided opportunities for our research team to better understand the data needs of

instructors and students on campus. We were surprised by the extent of unmet needs

and challenges that instructors face in this area, particularly in areas of teaching data

literacy. Our research underscores the need for the WashU Libraries to expand the

suite of data services that we offer and continue building the data literacy competencies

with subject librarians so they are equipped to support instructors and students in their

respective disciplines with their data-related needs

REFERENCES

Carlson, J., & Bracke, M. S. (2015). Planting the Seeds for Data Literacy: Lessons

Learned from a Student-Centered Education Program. International Journal of

Digital Curation, 10(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v10i1.348

Flick, U. (2018). Background: Approaches and philosophies of grounded theory. In

Doing Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications Ltd.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529716658

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

19

Hart Research Associates. (2009). Raising The Bar: Employers’ Views On College

Learning In The Wake of The Economic Downturn (p. 10).

Suddaby, R. (2006). From the Editors: What Grounded Theory Is Not. The Academy of

Management Journal, 49(4), 633–642.

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

20

Appendix A

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences Interview Guide

Note regarding COVID-19 disruption I want to start by acknowledging that teaching and

learning has been significantly disrupted in the past year due to the coronavirus pandemic. For

any of the questions I’m about to ask, please feel free to answer with reference to your normal

teaching practices, your teaching practices as adapted for the crisis situation, or both.

Background

Briefly describe your experience teaching undergraduates.

» How does your teaching relate to your current or past research?

» In which of the courses that you teach do students work with data?

Getting Data

In your course(s), do your students collect or generate datasets, search for and select pre-

existing datasets to work with, or work with datasets that you provide to them?

If students collect or generate datasets themselves Describe the process students go through to

collect or generate datasets in your course(s).

» Do you face any challenges relating to students’ abilities to find or create datasets?

If students search for pre-existing datasets themselves Describe the process students go

through to locate and select datasets.

» Do you provide instruction to students in how to find and/or select appropriate datasets to work with?

» Do you face any challenges relating to students’ abilities to find and/or select appropriate datasets?

If students work with datasets the instructor provides Describe the process students go through

to access the datasets you provide. Examples: link through LMS, instructions for downloading from

database

» How do you find and obtain datasets to use in teaching?

» Do you face any challenges in finding or obtaining datasets for teaching?

Working with Data

How do students manipulate, analyze, or interpret data in your course(s)?

» What tools or software do your students use? Examples: Excel, online platforms,

analysis/visualization/statistics software

» What prior knowledge of tools or software do you expect students to enter your class with, and what do you teach

them explicitly?

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

21

» To what extent are the tools or software students use to work with data pedagogically important?

» Do you face any challenges relating to students’ abilities to work with data?

How do the ways in which you teach with data relate to goals for student learning in your

discipline?

» Do you teach your students to think critically about the sources and uses of data they encounter in everyday life?

» Do you teach your students specific data skills that will prepare them for future careers?

» Have you observed any policies or cultural changes at your institution that influence the ways in which you teach

with data?

Do instructors in your field face any ethical challenges in teaching with data?

» To what extent are these challenges pedagogically important to you?

Training and Support

In your course(s), does anyone other than you provide instruction or support for your students

in obtaining or working with data? Examples: co-instructor, librarian, teaching assistant, drop-in

sessions

» How does their instruction or support relate to the rest of the course?

» Do you communicate with them about the instruction or support they are providing? If so, how?

To your knowledge, are there any ways in which your students are learning to work with data

outside their formal coursework? Examples: online tutorials, internships, peers

» Do you expect or encourage this kind of extracurricular learning? Why or why not?

Have you received training in teaching with data other than your graduate degree? Examples:

workshops, technical support, help from peers

» What factors have influenced your decision to receive/not to receive training or assistance?

» Do you use any datasets, assignment plans, syllabi, or other instructional resources that you received from

others? Do you make your own resources available to others?

Considering evolving trends in your field, what types of training or assistance would be most

beneficial to instructors in teaching with data?

Wrapping Up

Is there anything else from your experiences or perspectives as an instructor, or on the topic of

teaching with data more broadly, that I should know?

Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

22

Appendix B

Informed Consent Letter

Project title. Teaching with Data in the Social Sciences

Reason for the study. This study seeks to examine social science instructors’

practices in teaching undergraduates with data in order to understand the

resources and services that instructors at Washington University in St. Louis

need to be successful in their work.

What you will be asked to do. Your participation in the study involves a 60-

minute, audio-recorded interview about teaching practices. Your participation in

all or part of this study is completely voluntary. You are free to withdraw consent

and discontinue participation in the interview at any time for any reason.

Benefits and risks. There are no known risks associated with participating in this

study. You may experience benefit in the form of increased insight and

awareness into teaching practices and support needs.

How your confidentiality will be maintained. Interviews will be recorded and

stored as digital audio files by the principal investigator(s) in a non-networked

folder on a password protected computer. Interviews recorded using the Zoom

audio recording feature will be immediately downloaded, stored as specified

above, and deleted from any cloud-based accounts. Audio recordings will be

transcribed by the investigator(s) listed on this protocol and/or a third-party

transcription vendor bound by a non-disclosure agreement. Audio recording files

will be destroyed immediately following transcription. Pseudonyms will be

immediately applied to the interview transcripts and the metadata associated with

the transcripts. Public reports of the research findings will invoke the participants

by pseudonym and not provide demographic or contextual information that could

be used to re-identify the participants.

Questions? You may contact the researchers at any time if you have additional

questions about the study. If you have any questions about your rights as an

interviewee, you may contact the SWAT call service at 314-747-6800.