Oxford American Handbook of

Clinical

Examination

and

Practical Skills

About the Oxford American Handbooks in Medicine

The Oxford American Handbooks are pocket clinical books, providing prac-

tical guidance in quick reference, note form. Titles cover major medical spe-

cialties or cross-specialty topics and are aimed at students, residents, internists,

family physicians, and practicing physicians within specifi c disciplines.

Their reputation is built on including the best clinical information, com-

plemented by hints, tips, and advice from the authors. Each one is carefully

reviewed by senior subject experts, residents, and students to ensure that

content refl ects the reality of day-to-day medical practice.

Key series features

• Written in short chunks, each topic is covered in a two-page spread

to enable readers to fi nd information quickly. They are also perfect

for test preparation and gaining a quick overview of a subject without

scanning through unnecessary pages.

• Content is evidence based and complemented by the expertise and

judgment of experienced authors.

• The Handbooks provide a humanistic approach to medicine—it’s

more than just treatment by numbers.

• A “friend in your pocket,”the Handbooks offer honest, reliable

guidance about the diffi

culties of practicing medicine and provide

coverage of both the practice and art of medicine.

• For quick reference, useful “everyday”information is included on the

inside covers.

Published and Forthcoming Oxford American Handbooks

Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Medicine

Oxford American Handbook of Anesthesiology

Oxford American Handbook of Cardiology

Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Dentistry

Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis

Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Examination and Practical Skills

Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Pharmacy

Oxford American Handbook of Critical Care

Oxford American Handbook of Emergency Medicine

Oxford American Handbook of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Oxford American Handbook of Geriatric Medicine

Oxford American Handbook of Nephrology and Hypertension

Oxford American Handbook of Neurology

Oxford American Handbook of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Oxford American Handbook of Oncology

Oxford American Handbook of Ophthalmology

Oxford American Handbook of Otolaryngology

Oxford American Handbook of Pediatrics

Oxford American Handbook of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Oxford American Handbook of Psychiatry

Oxford American Handbook of Pulmonary Medicine

Oxford American Handbook of Rheumatology

Oxford American Handbook of Sports Medicine

Oxford American Handbook of Surgery

Oxford American Handbook of Urology

Oxford American

Handbook of

Clinical

Examination and

Practical Skills

E lizabeth A. B urns, MD, MA

Professor of Family Medicine

President and CEO

Michigan State University

Kalamazoo Center for Medical Studies

Kalamazoo, Michigan

K enneth K orn, PA-C, ARNP

Adjunct Faculty, Physician Assistant Program

University of North Dakota

Grand Forks, North Dakota

and

Family Nurse Practitioner

Leon County Health Department

Florida Department of Health

Tallahassee, Florida

J ames W hyte IV, ND, ARNP

Associate Professor

College of Nursing

Florida State University

Tallahassee, Florida

with

J ames T homas

T anya M onaghan

1

3

Oxford University Press, Inc. publishes works that further

Oxford University’s objective of excellence

in research, scholarship and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offi ces in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal

Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright © 2011 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

First published 2011

UK version 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press,

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Oxford American handbook of clinical examination and practical skills / edited by

Elizabeth A. Burns, Kenneth Korn, James Whyte IV ; with James Thomas, Tanya

Monaghan.

p. ; cm.

Other title: Handbook of clinical examination and practical skills

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-19-538972-2

1. Physical diagnosis—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Burns, Elizabeth A. (Elizabeth

Ann), 1950– II. Korn, Kenneth. III. Whyte, James, IV. IV. Title: Handbook of

clinical examination and practical skills.

[DNLM: 1. Clinical Medicine—methods—Handbooks. 2. Physical

Examination—Handbooks. WB 39]

RC76.O937 2011

616.07´54—dc22

2010027995

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in China

on acid-free paper

This material is not intended to be, and should not be considered, a

substitute for medical or other professional advice. Treatment for the

conditions described in this material is highly dependent on the individ-

ual circumstances. And, while this material is designed to offer accurate

information with respect to the subject matter covered and to be cur-

rent as of the time it was written, research and knowledge about medical

and health issues are constantly evolving and dose schedules for medica-

tions are being revised continually, with new side effects recognized and

accounted for regularly. Readers must therefore always check the product

information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published

product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and

the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulation. Oxford University

Press and the authors make no representations or warranties to readers,

express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of this material,

including without limitation that they make no representation or warran-

ties as to the accuracy or effi cacy of the drug dosages mentioned in the

material. The authors and the publishers do not accept, and expressly dis-

claim, any responsibility for any liability, loss, or risk that may be claimed

or incurred as a consequence of the use and/or application of any of the

contents of this material.

This page intentionally left blank

vii

Preface (U.S.)

Although we would like to claim the idea for this text as our own, this is

not the case; however, the belief in the text’s adaptability for U.S. medical

providers is. The fi rst edition of this text was developed for use in the

U.K., where a different model of health care exists.

In the United States, the primary care provider role was once the exclu-

sive responsibility of the traditional, medical school–educated MD or DO.

Primary care is no longer the realm of only one type of health-care pro-

vider. No longer is it the duty of only the physician to assess and care

for the patient. Now, collaborative and collegial relationships exist among

various disciplines. Cooperative-care models seek to provide optimal care.

It is from this type of model that the U.S. authors elected to remove the

term doctor from most areas of this text in preference to the term health-

care provider .

Representing the varied disciplines now likely to serve as primary care

providers, the U.S. team of authors illustrates the changing face of U.S.

health care. The authors represent educators and practitioners from

traditional allopathic medicine, nurse practitioner, and physician assistant

disciplines.

This text is not offered as the quintessential text on physical examin-

ation; it is presented, as the title states, as a handbook of physical examin-

ation and practical skills. We also believe that as U.S. health care evolves,

so will this text, with requisite changes and adaptations.

In this text, the important elements that will not change are those that

comprise an appropriate exam and quality care. No matter which discip-

line the provider represents, quality is critical.

Elizabeth Burns, MD

Kenneth Korn, PA-C, ARNP

James White, ARNP

2010

* Out of great respect for the work of James Thomas and Tanya

Monaghan, the U.S. authors chose to leave the following Preface and

Acknowledgments by the U.K. authors unchanged.

Preface

viii

Preface (U.K.)

There are very few people who, in the course of their daily work, can

approach a stranger, ask them to remove their clothes, and touch their

bodies without fear of admonition. This unique position of doctors, med-

ical students, and other health care professionals comes with many strings

attached. We are expected to act “professionally”and be competent and

confi dent in all our dealings. This is hard to teach and hard to learn and

many students are rightly daunted by the new position in which they fi nd

themselves.

We felt a little let down by many books during our time in medical

school, and often found ourselves having to dip into several texts to

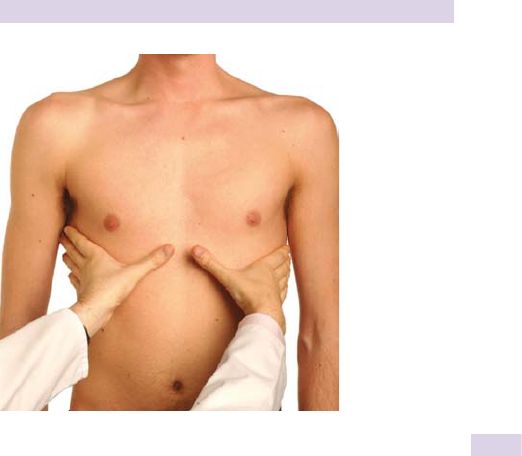

appreciate a topic. This book, then, is the one text that we would have

wanted as students covering all the main medical and surgical subspecial-

ties. We anticipate it will be useful to students as they make the transition

to being a doctor and also to junior doctors. We hope that it will be car-

ried in coat pockets for quick glances as well as being suitable for study at

home or in the library.

The fi rst three chapters cover the basics of communication skills, history

taking, and general physical examination. Chapters 4–14 are divided by sys-

tems. In each of these there is a section on the common symptoms seen

in that system, with the appropriate questions to ask the patient, details

of how to examine parts of that system, and important patterns of disease

presentation. Each of these system chapters is fi nished off with an “elderly

patient”page provided by Dr. Richard Fuller. Following the systems, there

are chapters on paediatric and psychiatric patients—something not found

in many other books of this kind. The penultimate chapter—practical pro-

cedures—details all those tasks that junior doctors might be expected to

perform. Finally, there is an extensive data interpretation chapter which,

while not exhaustive, tries to cover those topics such as ECG, ABG, and

X-ray interpretation that may appear in a fi nal OSCE examination.

Although we have consulted experts on the contents of each chapter,

any mistakes or omissions remain ours alone. We welcome any comments

and suggestions for improvement from our reader—this book, after all,

is for you.

James Thomas

Tanya Monaghan

2007

ix

Acknowledgments (U.S.)

The U.S. authors acknowledge the great work of the U.K. team in the

development of a unique text. The combination of examination, pro-

cedures, and data interpretation into a single handbook-sized resource

represents a new type of resource. It is recognized that this text is a

resource with the potential for substantial enhancement. Your comments

are welcome.

We would also like to thank Oxford University Press (U.S.) for the

opportunity to be involved in this adaptation of this text, with special

thanks to Andrea Seils and Staci Hou for their patience and assistance

during this process.

Colleagues providing specialty review of the Americanization of the

U.K. data and procedures also deserve special thanks.

As always, such projects represent time away from other responsibil-

ities. We acknowledge and appreciate our co-workers and family for giving

us the time to complete this project.

Finally, one last thank-you goes to the fi ne U.K. authors for those

moments of humor while reviewing their text for “Britishisms.”

x

Acknowledgments (U.K.)

We would like to record our thanks to the very many people who have

given their advice and support through this project.

For contributing specialist portions of the book, we thank

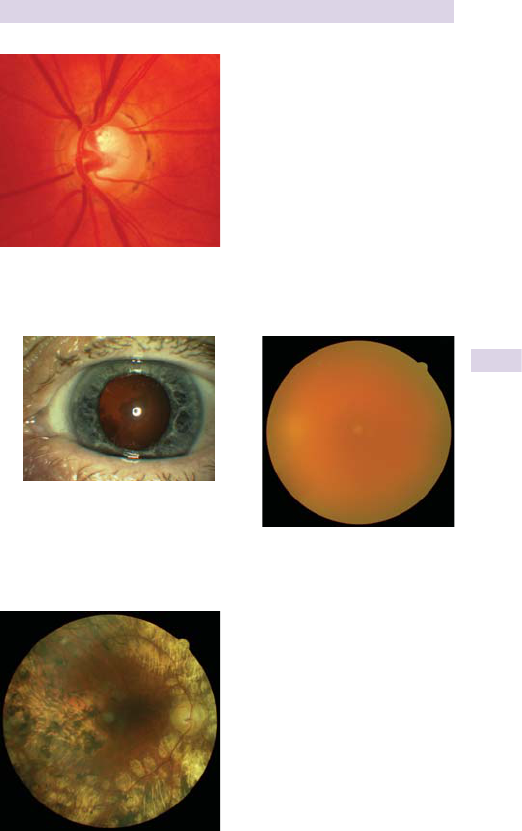

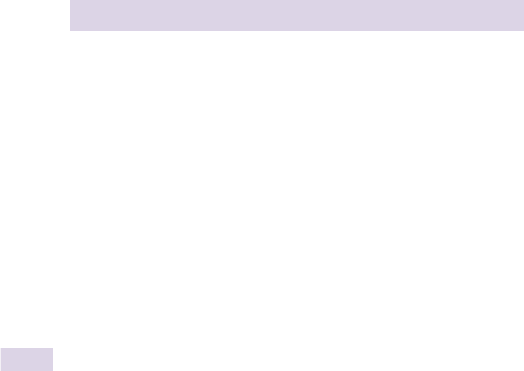

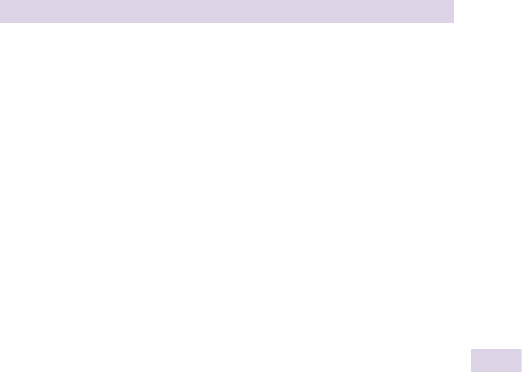

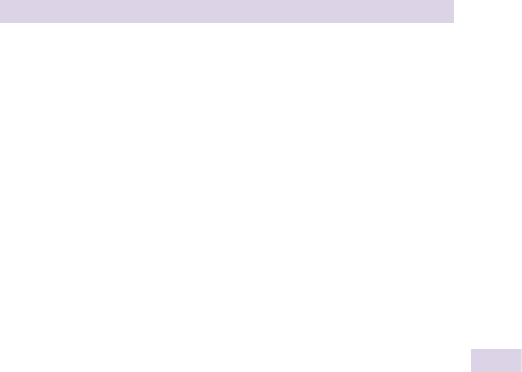

Dr. Tom Fearnley (pages relating to ophthalmology), Dr. Caroline Boyes

(Chapter 16, The paediatric assessment) and Dr. Bruno Rushforth (ECG

interpretation and other parts of Chapter 18). We also thank Heidi

Ridsdale, senior physiotherapist at Leeds General Infi rmary, for her help

with the oxygen/airway pages and for providing all the equipment for

the photographs. Dr. Franco Guarasci and Jeremy Robson read the NIV

and inhaler pages, respectively, for which we are very grateful. We thank

Senior Sister Lyn Dean of Ward 26 at the Leeds General Infi rmary for

reading parts of Chapter 17 (Practical procedures). Our thanks also go to

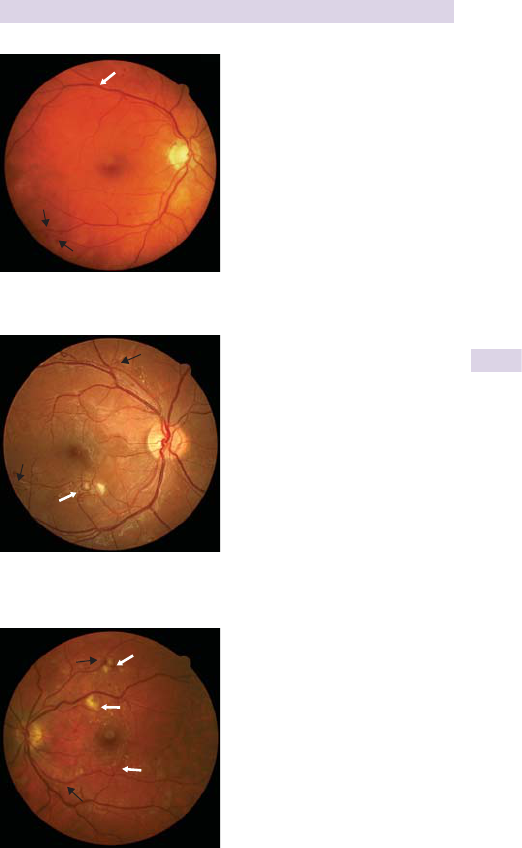

Dr. Jonathan Bodansky, Mandy Garforth, and Mike Geall for providing the

retinal photographs.

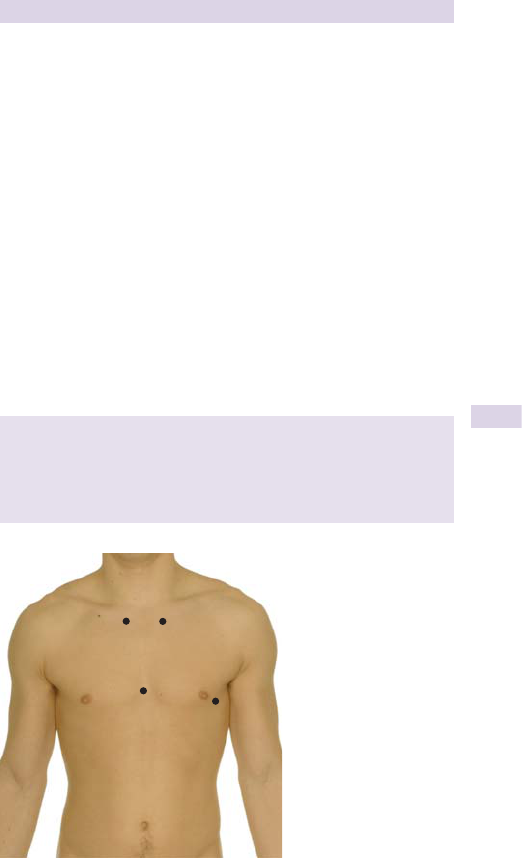

An extra special word of thanks is reserved for our models Adam

Swallow, Geoffrey McConnell, and our female model who would like to

remain anonymous. Their bravery and good humour made a potentially

diffi cult few days very easy. They were a joy to work with. We thank the

staff at the St James’s University Hospital Medical Illustration Studio, in

particular Tim Vernon, for taking the photographs.

We would also like to thank the staff at Oxford University Press,

especially Catherine Barnes, for having faith in us to take this project on,

and Elizabeth Reeve, for her seemingly endless patience, support, and

guidance.

A special word of thanks is reserved for our offi cial “friend of the book,”

Dr. Richard Fuller, who provided all the “elderly patient”pages. Aside from

this, his steadfast and overtly biased support helped carry us through.

Finally, we would like to thank our good friend Dr. Paul Johns. He read

through much of the text and provided invaluable advice and support

from the very beginning. We wish Paul the very best with his own writing

projects and hope to work with him in the future.

Our panel of readers was responsible for confi rming the medical accur-

acy of the text. Most have performed far beyond our expectations, we are

eternally grateful to them all.

Contents

xi

Contents

How to use this book xii

Detailed contents xiii

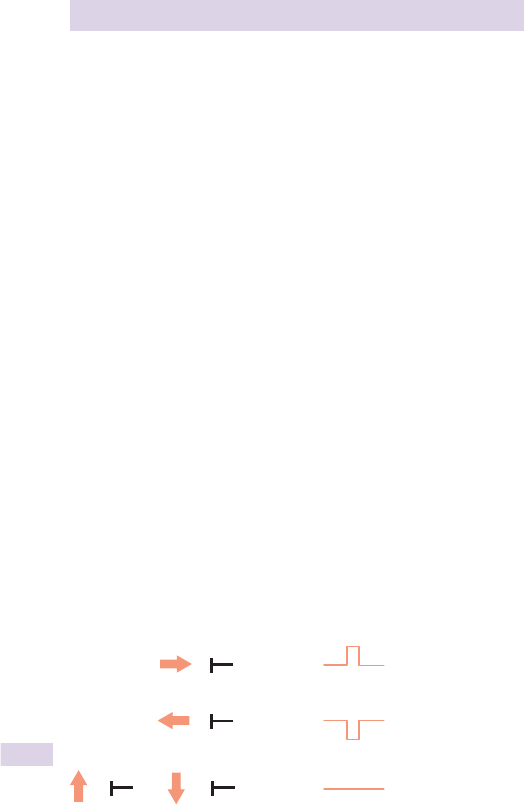

Symbols and abbreviations xx

1 Communication skills

1

2 The history

29

3 General examination

47

4 Skin, hair, and nails

75

5 Endocrine system

95

6 Ear, nose, and throat

119

7 Cardiovascular system

145

8 Respiratory system

181

9 Abdomen

203

10 Nervous system

255

11 Musculoskeletal system 337

12 Male reproductive system 375

13 Female breast 391

14 Female reproductive system 407

15 Psychiatric assessment 449

16 Pediatric assessment 479

17 Examination under special circumstances 507

18 Practical procedures 511

19 Data interpretation 591

Index 673

xii

How to use this book

The systems chapters

In each chapter, there are suggestions of what questions to ask and how

to proceed depending on the nature of the presenting complaint. These

are not exhaustive and are intended as guidance.

The history parts of the systems chapters should be used in conjunction

with Chapter 2 in order to build a full and thorough history.

Practical procedures

This chapter (Chapter 18) describes those practical procedures that the

health-care provider, whether a physician, physician assistant, nurse prac-

titioner, or member of another health-care discipline, may be expected

to perform. Some procedures should only be performed once you have

been trained specifi cally in the correct technique by an experienced

professional.

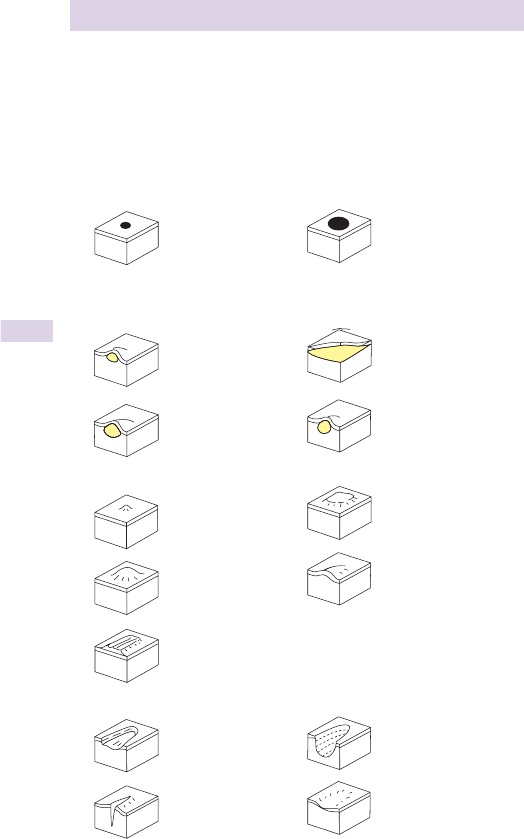

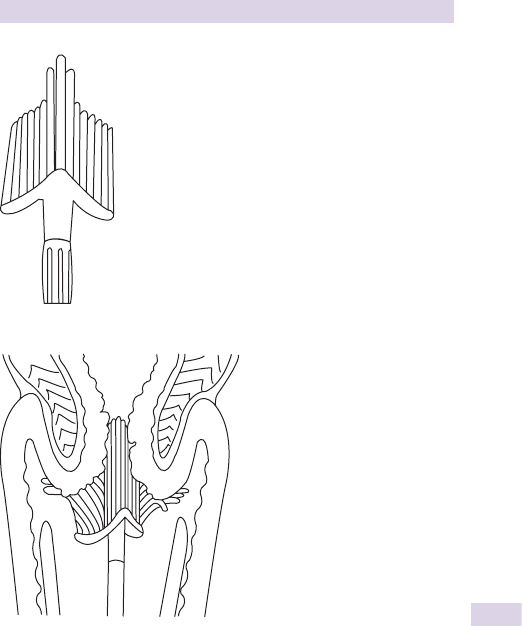

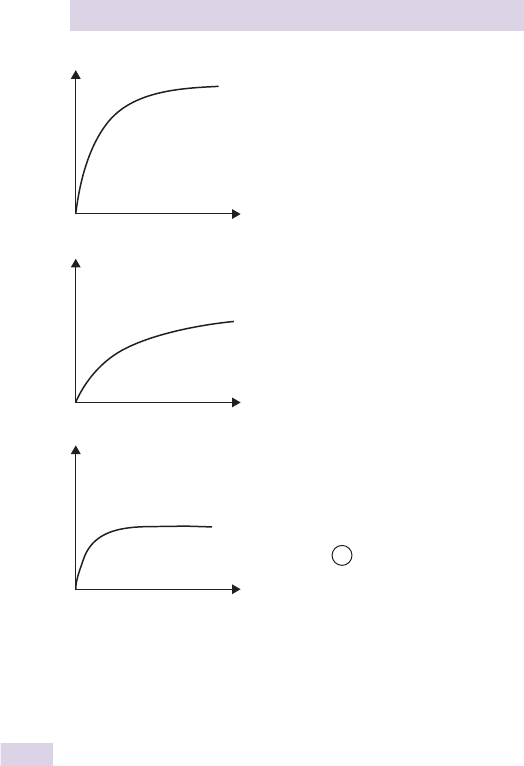

Each procedure has a diffi culty icon as follows:

1 Requires no specifi

c training, and all primary-care provider graduates

should be competent to perform this procedure.

2 Requires some skill. Providers with moderate experience should be

able to perform this procedure with ease.

3 More complex procedures that you may only come across in spe-

cialty practices and will not be required to perform without advanced

training and experience.

Reality vs. theory

In describing the practical procedures, we have tried to be realistic. The

methods described are the most commonly ones used across the profes-

sion and are aimed at helping the reader perform the procedure correctly

and safely within a clinical environment.

There may be differences between the way a number of the procedures

are described here and the way in which they are taught in a clinical skills

laboratory. In addition, local hospitals and clinics may use different equip-

ment for some procedures. Good practitioners should be fl exible and

make changes to their routine accordingly.

Data interpretation

A minority of the reference ranges described for some of the biochemical

tests in the data interpretation chapter (Chapter 19) may differ slightly

from those used by your local laboratory—this depends on the equipment

and techniques used for measurement. Any differences are likely to be

very small. Always check with, and be guided by, your local resources.

xiii

Detailed contents

1 Communication skills 1

Introduction 2

Essential considerations 4

Essential rules 6

Getting started 7

General principles 9

Communicating with deaf patients 12

Cross-cultural communication 13

Interpreters 14

Imparting information 15

The importance of silence 15

Angry patients 15

Telephone and e-mail communication 16

Talking about sex 16

Breaking bad news 17

Body language: an introduction 21

Written communication 23

Law, ethics, and communication 26

2 The history 29

History-taking 30

Using this book 31

Patient profi le

(PP)

31

Chief complaint (CC) 32

History of present illness (HPI) 33

Past medical history (PMH) 35

Allergies 36

Drug history 36

Alcohol 37

Smoking 38

Family history (FH) 39

Social history (SH) 41

Review of systems (ROS) 42

The elderly patient 43

The pediatric patient 45

3 General examination 47

Approaching the physical examination 48

First impressions 50

Preparing for the examination 50

Color 51

Temperature 53

xiv

DETAILED CONTENTS

Hydration 54

Edema 55

Nutritional status 56

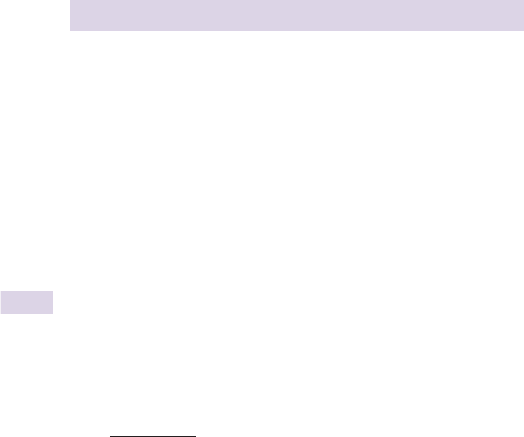

Lymph nodes 58

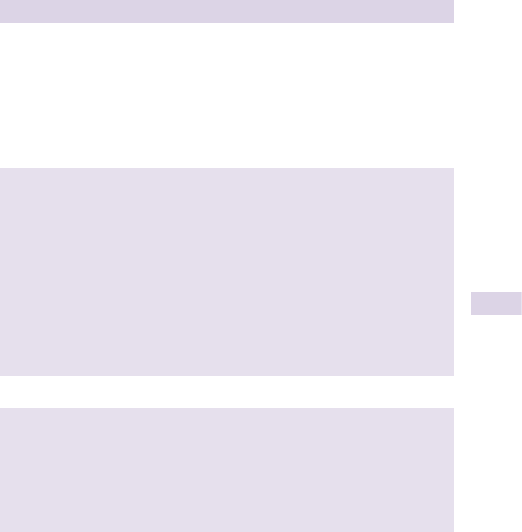

Hands 62

Recognizable syndromes 68

Vitamin and trace element defi ciencies 70

The elderly patient 72

4 Skin, hair, and nails 75

Applied anatomy and physiology 76

Dermatological history 78

Hair and nail symptoms 80

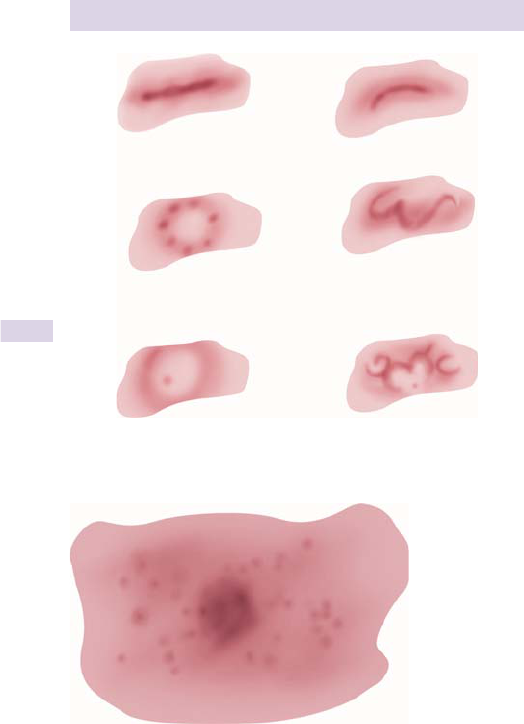

Examining the skin 82

Describing a lesion 84

Examining a lump 88

Examining an ulcer 90

The elderly patient 92

5 Endocrine system 95

Applied anatomy and physiology 96

Presenting symptoms in endocrinology 98

The rest of the history 100

General examination 102

Examining the thyroid 104

Eye signs in thyroid disease 106

Examining the patient with diabetes 108

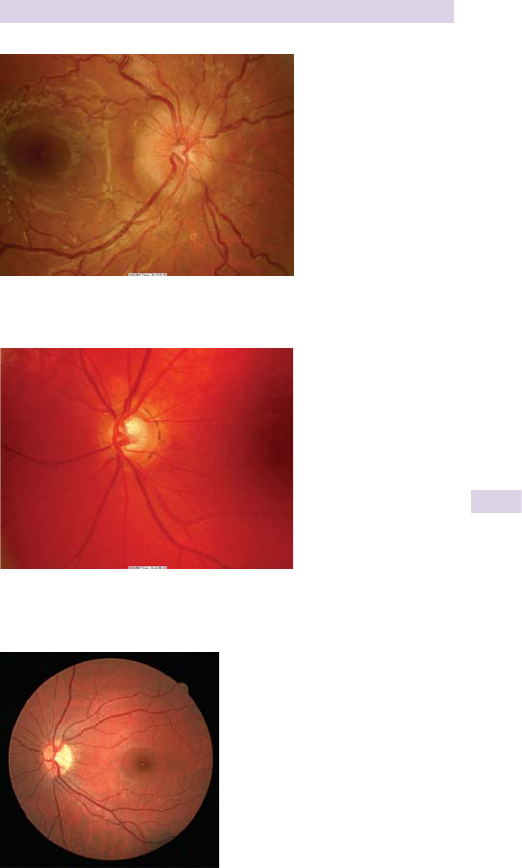

The fundus in endocrine disease 110

Important presenting patterns 114

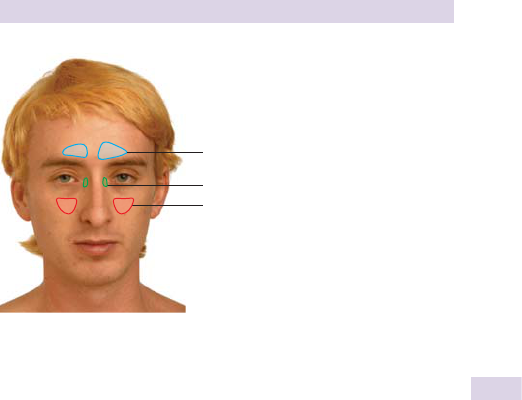

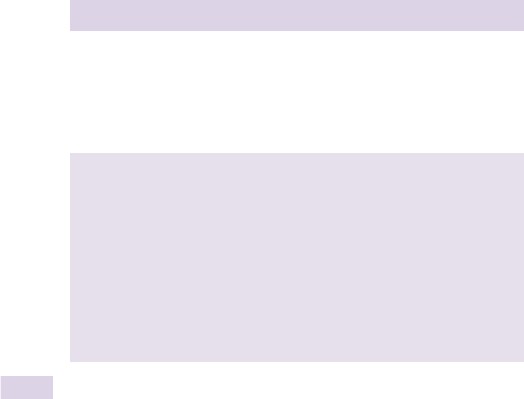

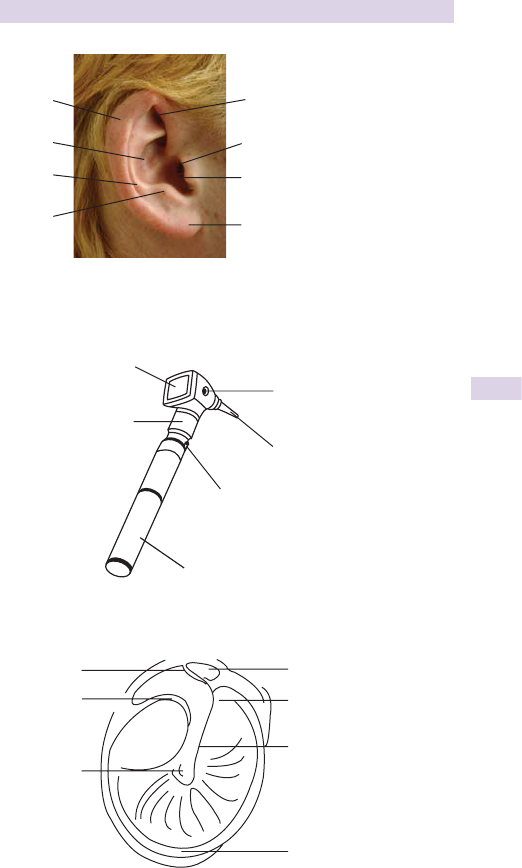

6 Ear, nose, and throat 119

Applied anatomy and physiology 120

Symptoms of ear disorders 122

Tinnitus 124

Symptoms of nasal disorders 127

Symptoms of throat disorders 129

Examining the ear 132

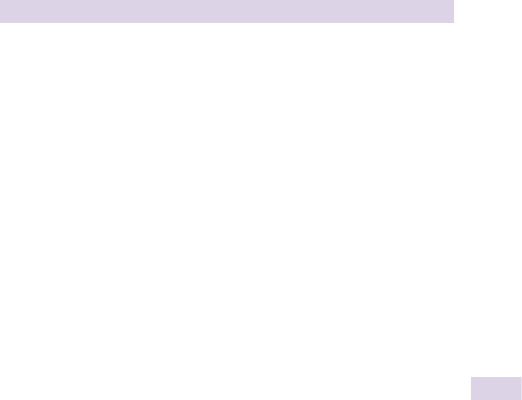

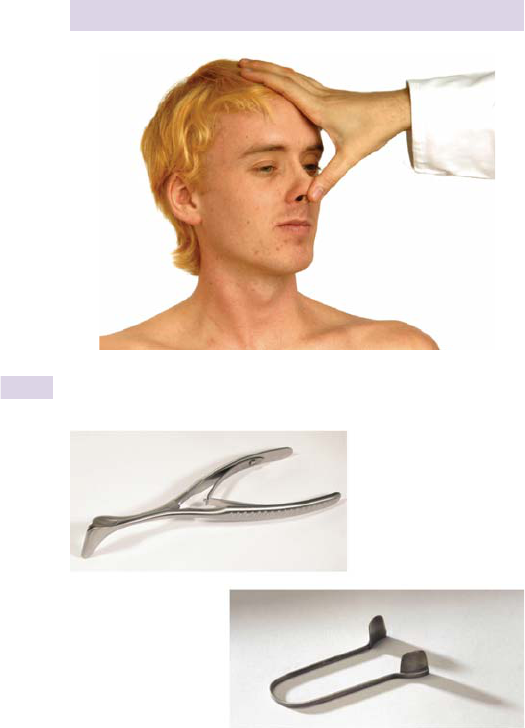

Examining the nose 135

Examining the nasal sinuses 137

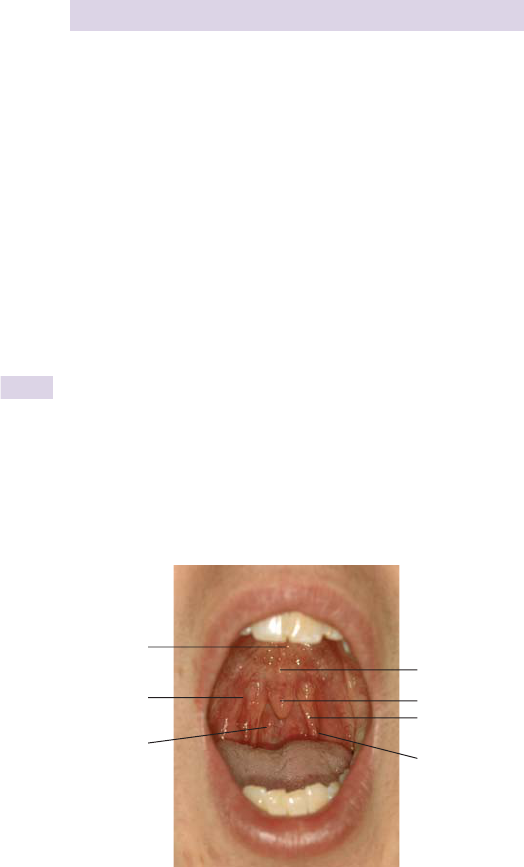

Examining the mouth and throat 138

Important presentations 141

7 Cardiovascular system 145

Applied anatomy and physiology 146

Chest pain 148

Breathlessness and edema 150

xv

DETAILED CONTENTS

Palpitations 152

Syncope 152

Other cardiovascular symptoms 153

The rest of the history 154

General inspection and hands 155

Peripheral pulses 157

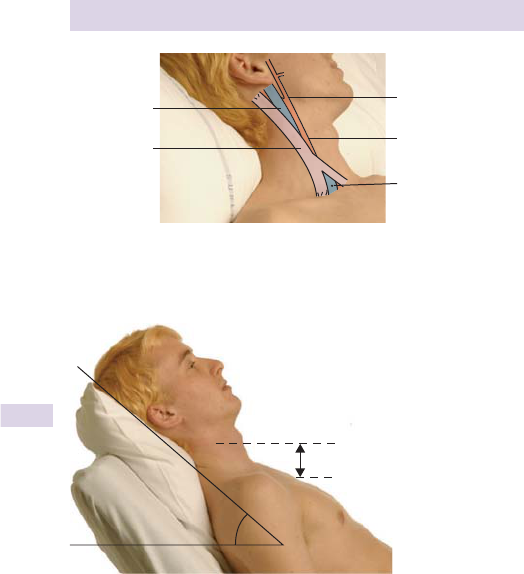

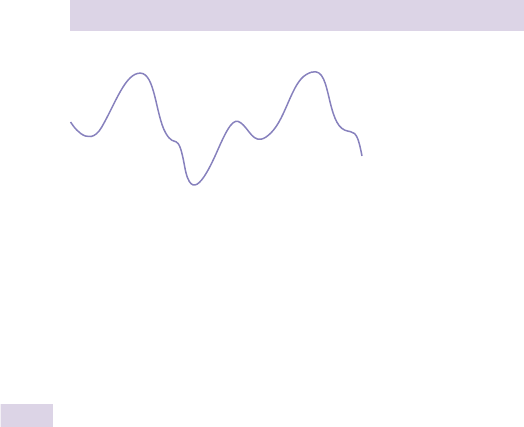

The face and neck 161

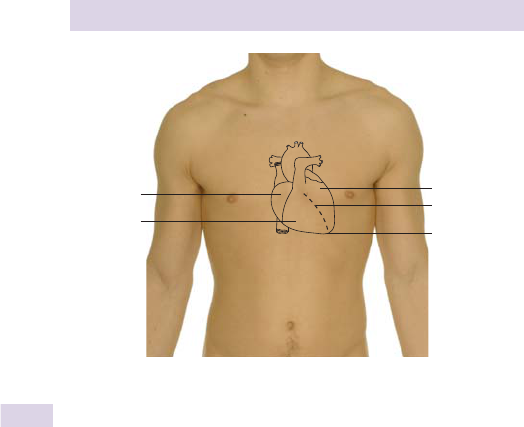

Examining the precordium 165

Auscultating the precordium 167

The rest of the body 173

Important presenting patterns 175

The elderly patient 179

8 Respiratory system 181

Applied anatomy and physiology 182

Dyspnea 184

Cough and expectoration 185

Other respiratory symptoms 187

The rest of the history 188

General appearance 190

Hands, face, and neck 191

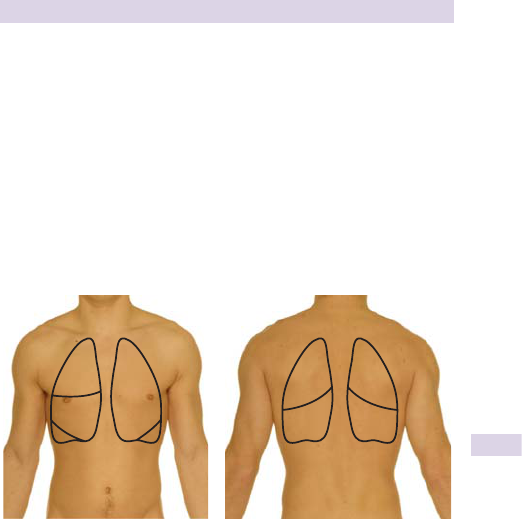

Inspection of the chest 193

Palpation 194

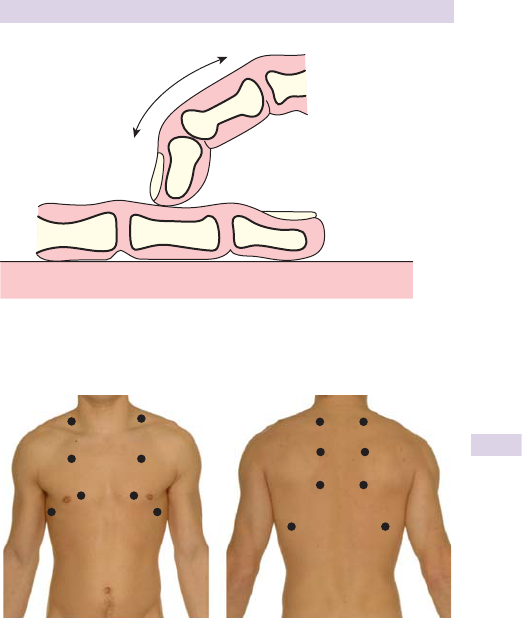

Percussion 196

Auscultation 198

Important presenting patterns 200

The elderly patient 201

9 Abdomen

203

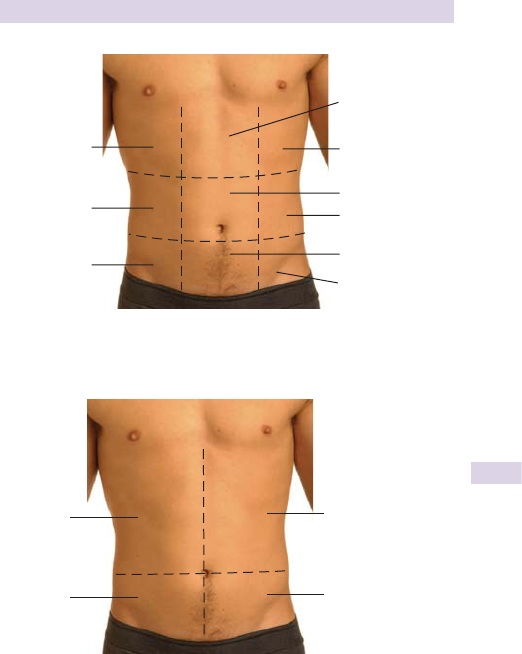

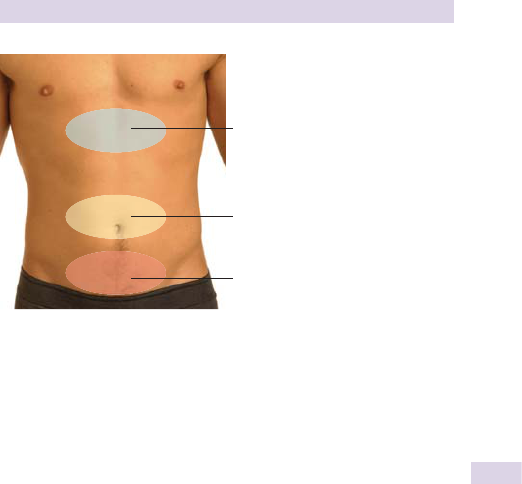

Applied anatomy 204

Esophageal symptoms 206

Nausea, vomiting, and vomitus 208

Abdominal pain 210

Bowel habit 212

Jaundice and pruritus 216

Abdominal swelling 217

Urinary and prostate symptoms 218

Appetite and weight 220

The rest of the history 221

Outline examination 223

Hand and upper limb 224

Face and chest 226

Inspection of the abdomen 229

Auscultation 231

Palpation 232

Palpating the abdominal organs 233

Percussion 239

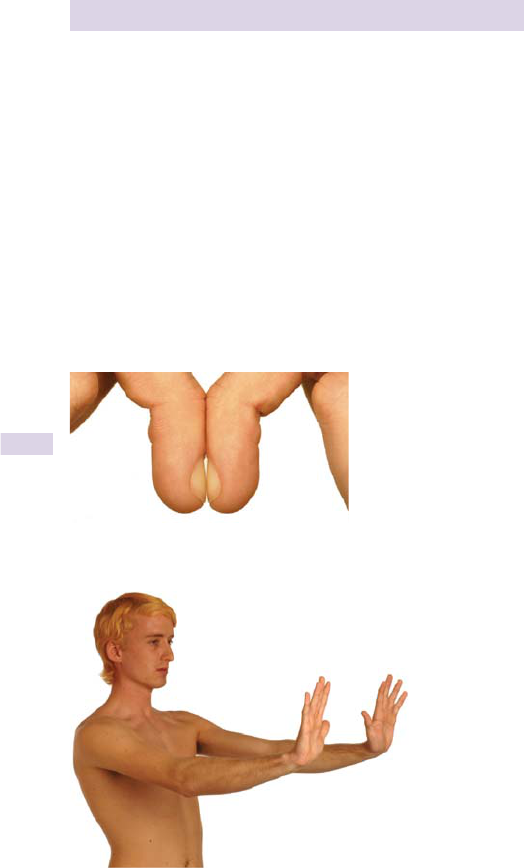

Rectal examination 241

xvi

DETAILED CONTENTS

Hernial orifi ces 243

Important presenting patterns 246

The elderly patient 252

10 Nervous system 255

Presenting symptoms in neurology 256

The rest of the history 258

The outline examination 259

General inspection and mental state 259

Speech and language 260

Cognitive function 262

Cranial nerve I: olfactory 263

Cranial nerve II: optic 264

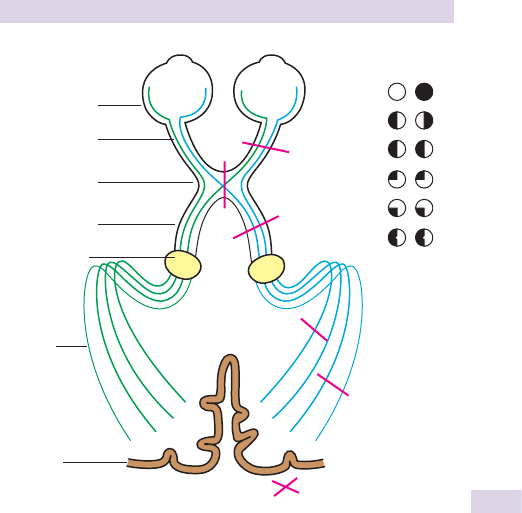

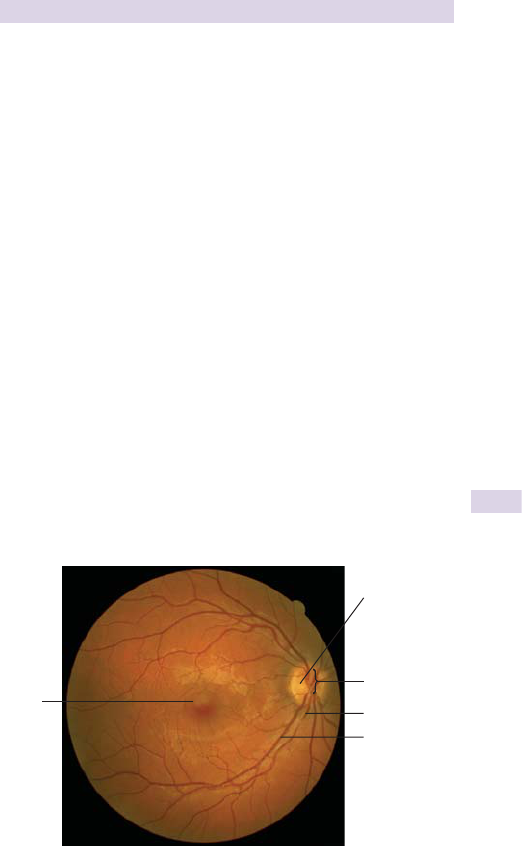

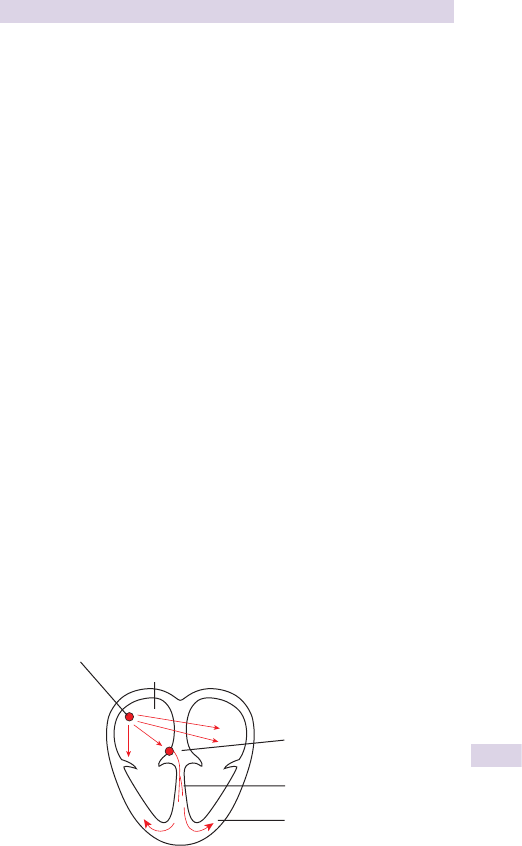

Cranial nerve II: ophthalmoscopy 268

Pupils 273

Cranial nerves III, IV, and VI 276

Palsies of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI 280

Cranial nerve V: trigeminal 283

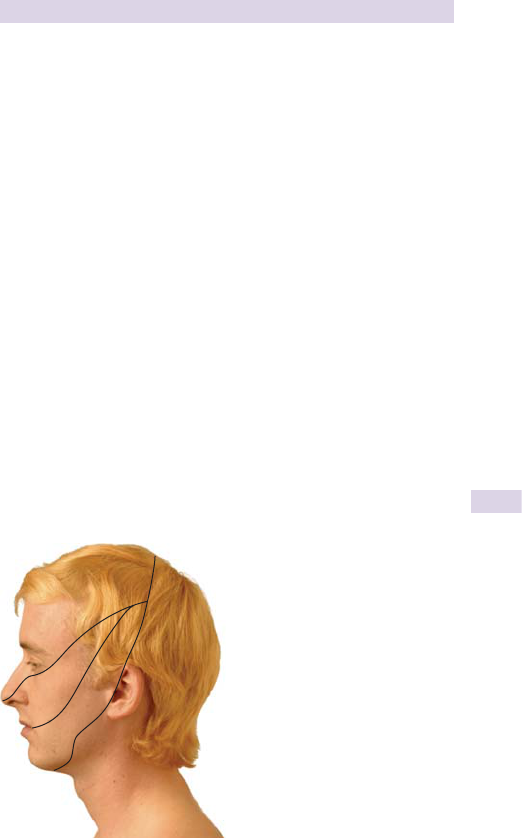

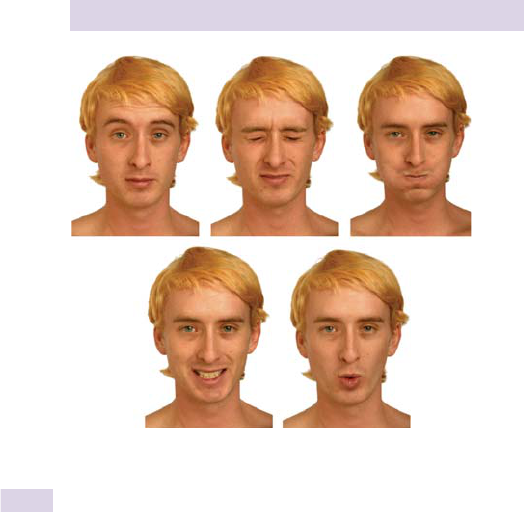

Cranial nerve VII: facial 285

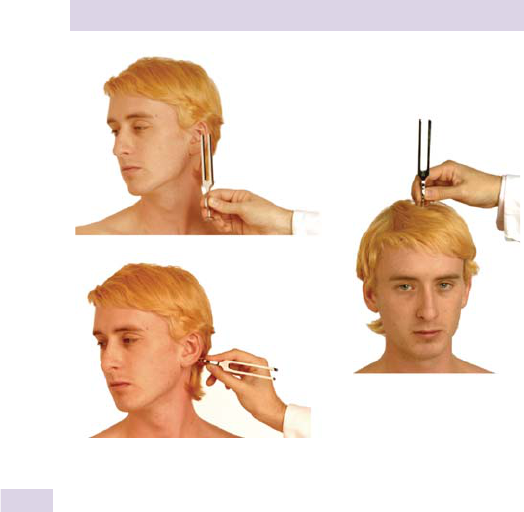

Cranial nerve VIII: vestibulocochlear 287

Cranial nerves IX and X 289

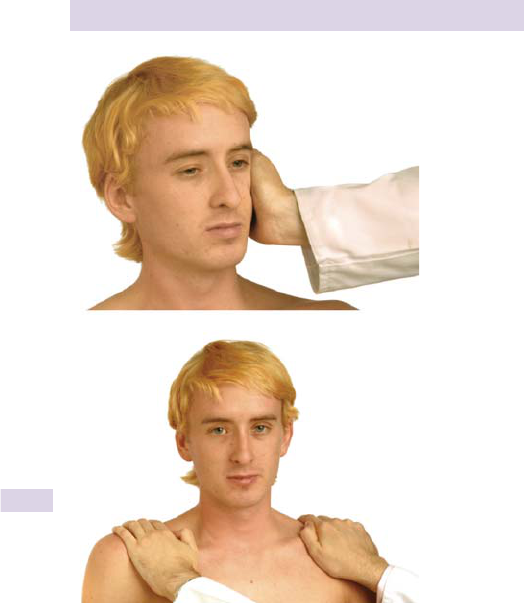

Cranial nerve XI: accessory 291

Cranial nerve XII: hypoglossal 293

Motor: applied anatomy 294

Motor: inspection and tone 296

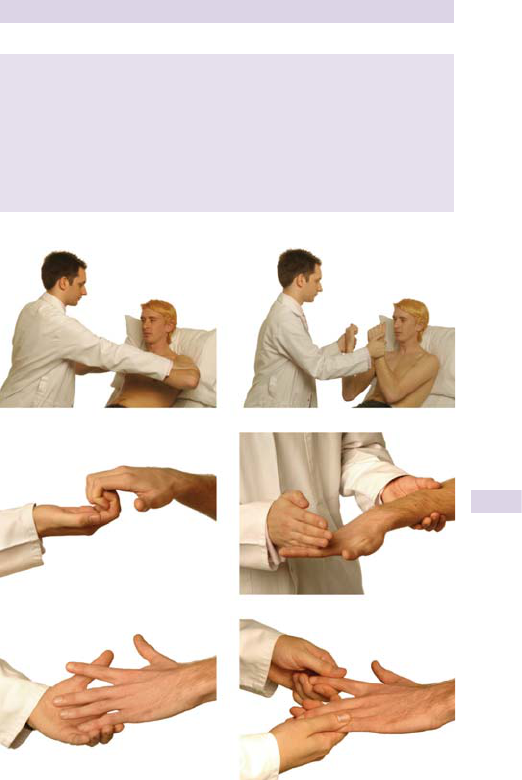

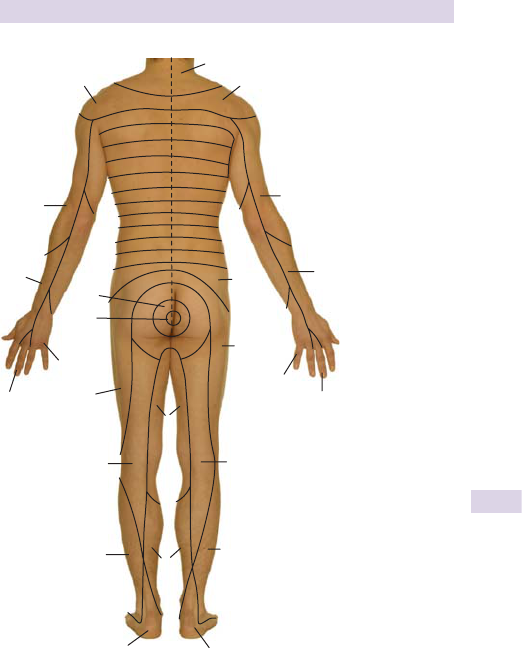

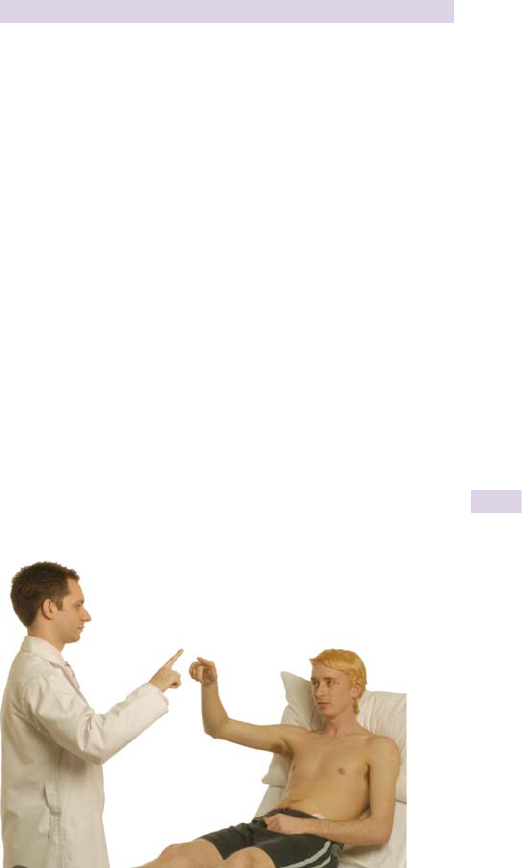

Motor: upper limb power 298

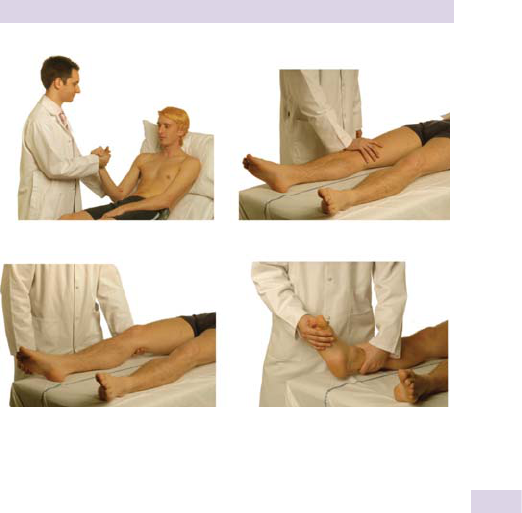

Motor: lower limb power 300

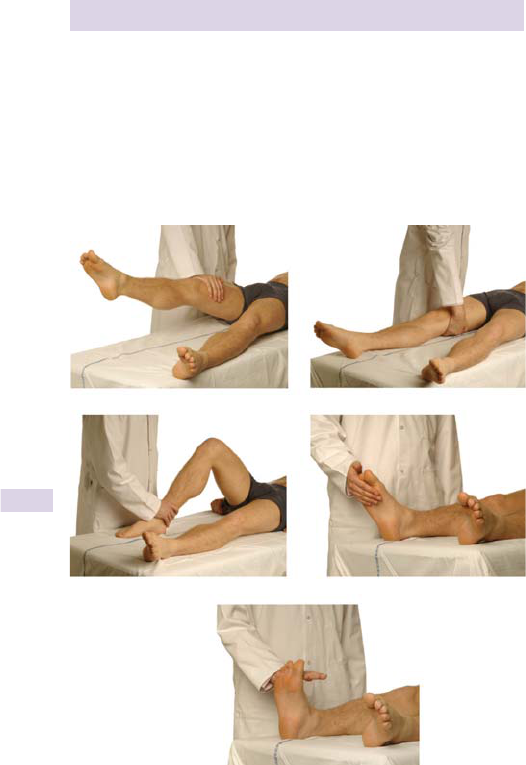

Tendon refl exes 302

Other refl exes 305

Primitive refl exes 307

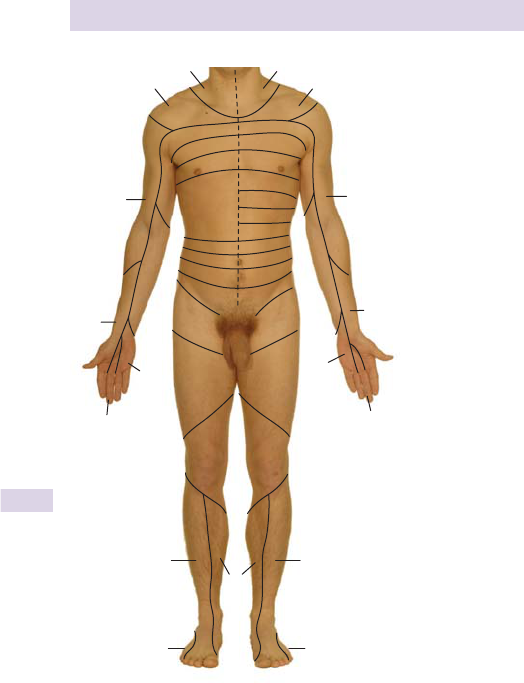

Sensory: applied anatomy 308

Sensory examination 312

Coordination 315

Some peripheral nerves 317

Gait 321

Important presenting patterns 323

The unconscious patient 331

The elderly patient 334

11 Musculoskeletal system 337

Applied anatomy and physiology 338

Important locomotor musculoskeletal symptoms 340

The rest of the history 344

Outline examination 346

GALS screen 347

Elbow 349

Shoulder 351

Spine 354

xvii

DETAILED CONTENTS

Hip 356

Knee 358

Ankle and foot 363

Important presenting patterns 365

The elderly patient 373

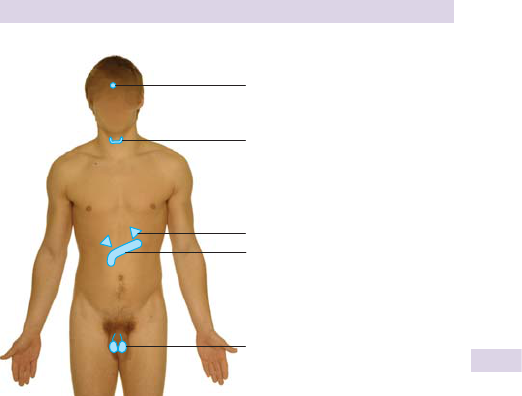

12 Male reproductive system 375

Applied anatomy and physiology 376

Sexual history 378

Symptoms 379

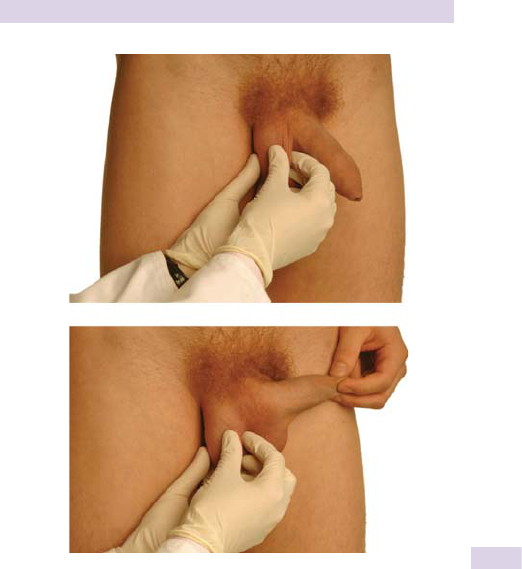

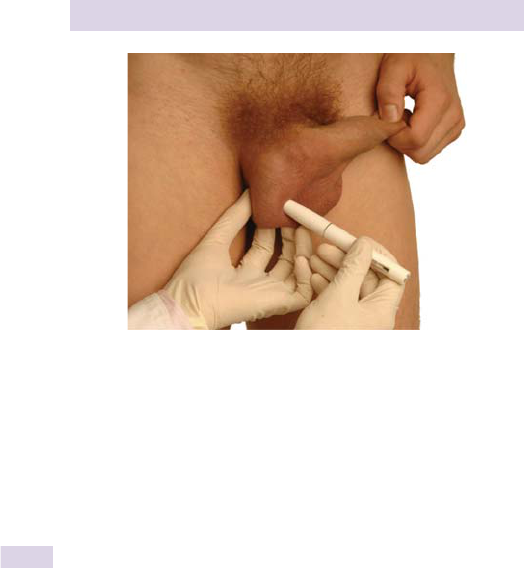

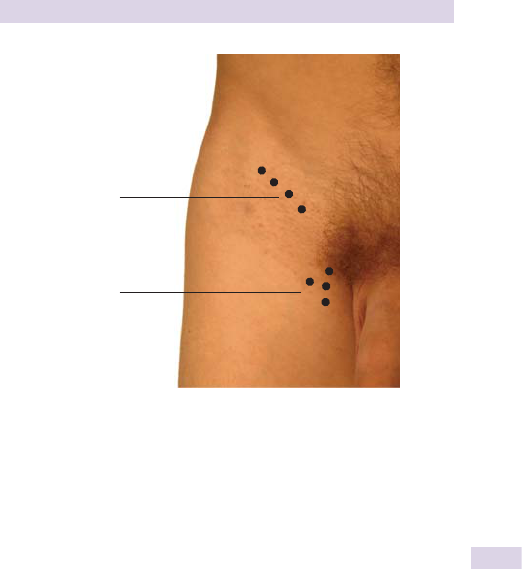

Examining the male genitalia 381

Important presenting patterns 386

The elderly patient 388

13 Female breast 391

Applied anatomy and physiology 392

Important symptoms 394

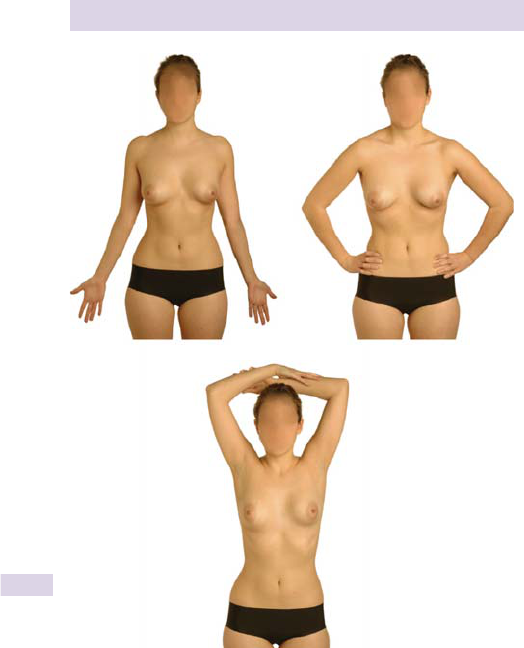

Inspection of the breast 397

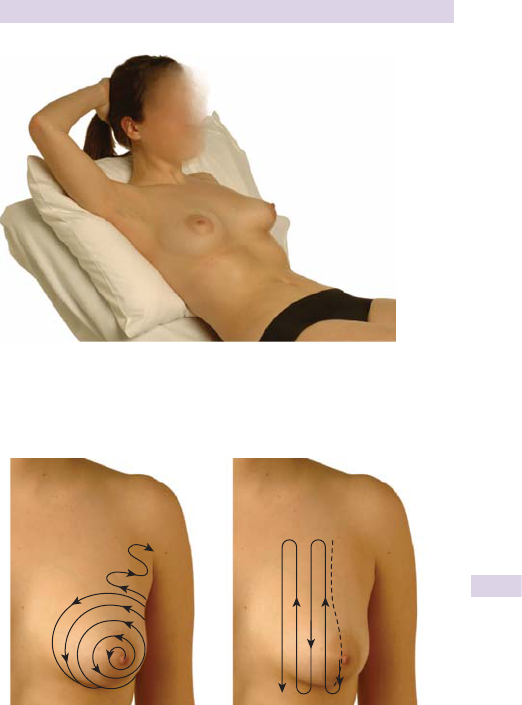

Palpation of the breast 399

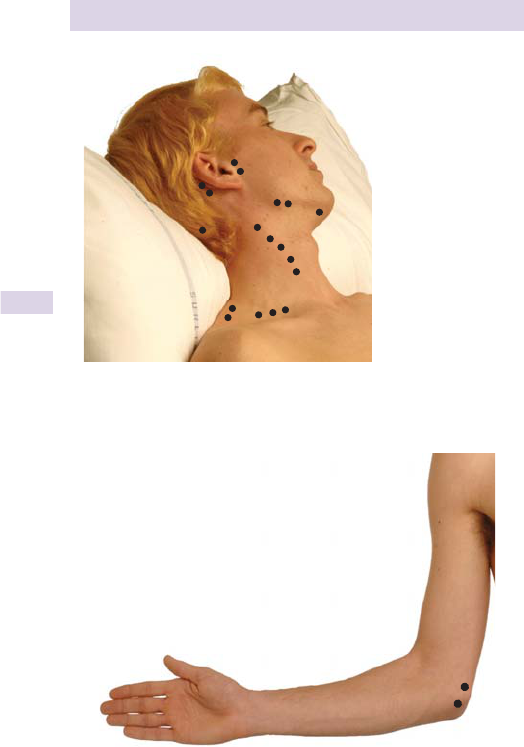

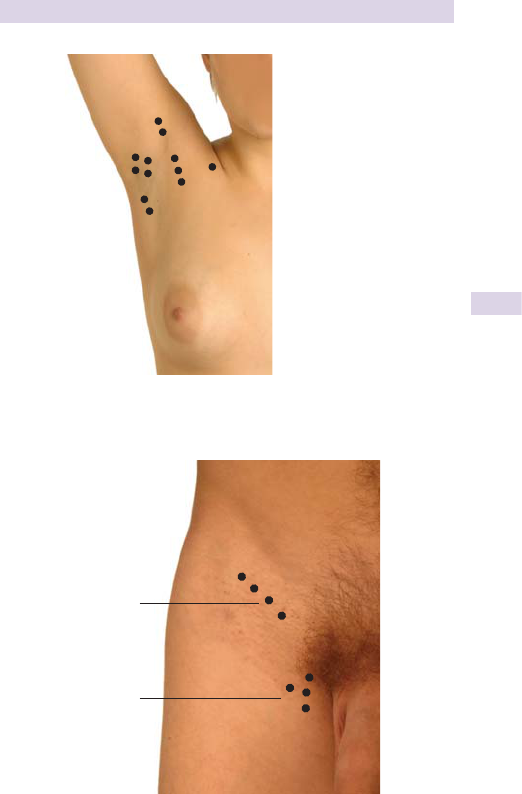

Examining beyond the breast 402

Important presentations 404

14 Female reproductive system 407

Applied anatomy 408

Applied physiology 411

History-taking in gynecology 413

Abnormal bleeding in gynecology 415

Other symptoms in gynecology 419

Outline gynecological examination 423

Pelvic examination 424

Taking a cervical smear 430

History-taking in obstetrics 433

Presenting symptoms in obstetrics 437

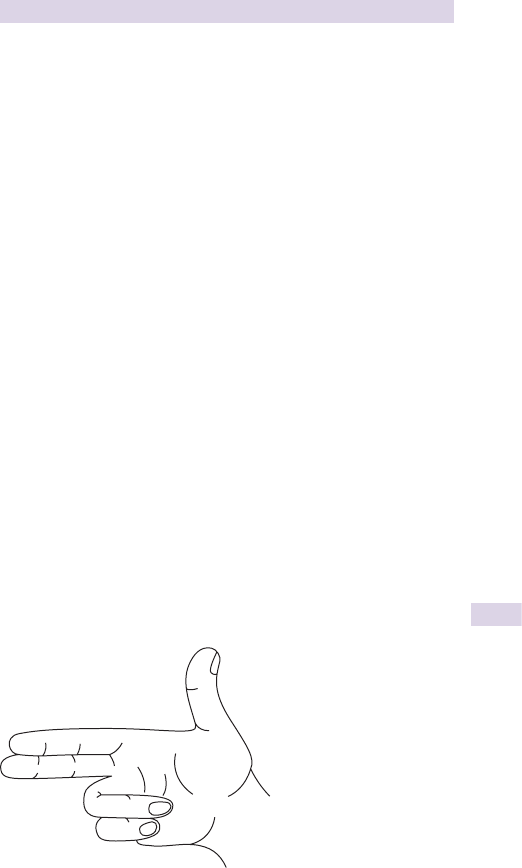

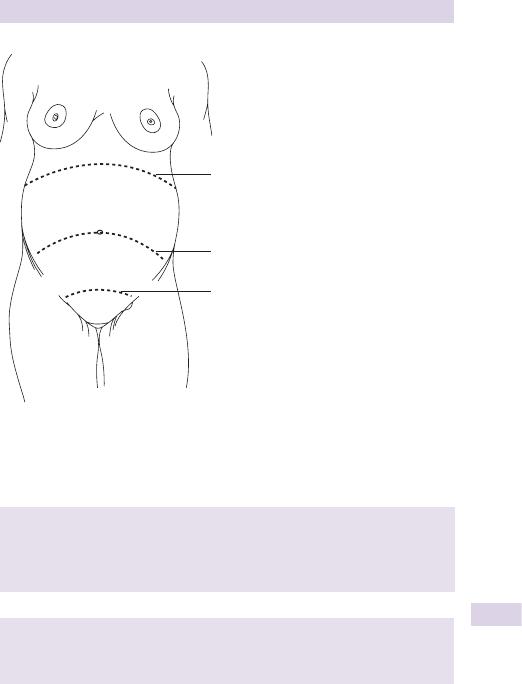

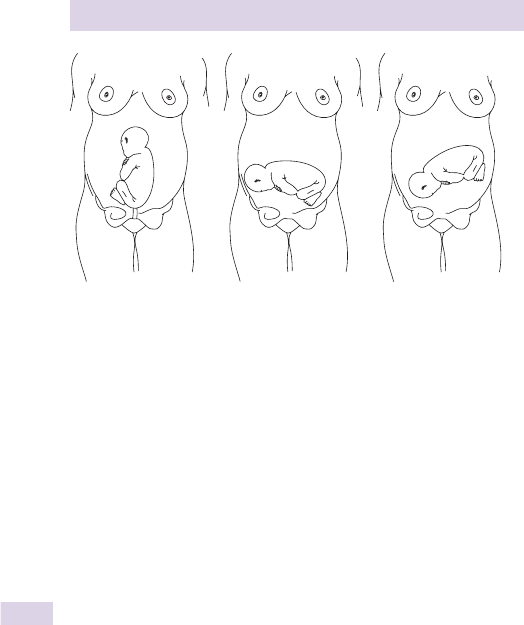

Outline obstetric examination 441

Abdominal examination 442

The elderly patient 447

15 Psychiatric assessment 449

Approach to psychiatric assessment 450

History 452

Mental status examination 458

Physical examination 466

Important presenting patterns 467

Medical conditions with psychiatric symptoms and signs 476

xviii

DETAILED CONTENTS

16 Pediatric assessment 479

History-taking 480

Examination: an approach 482

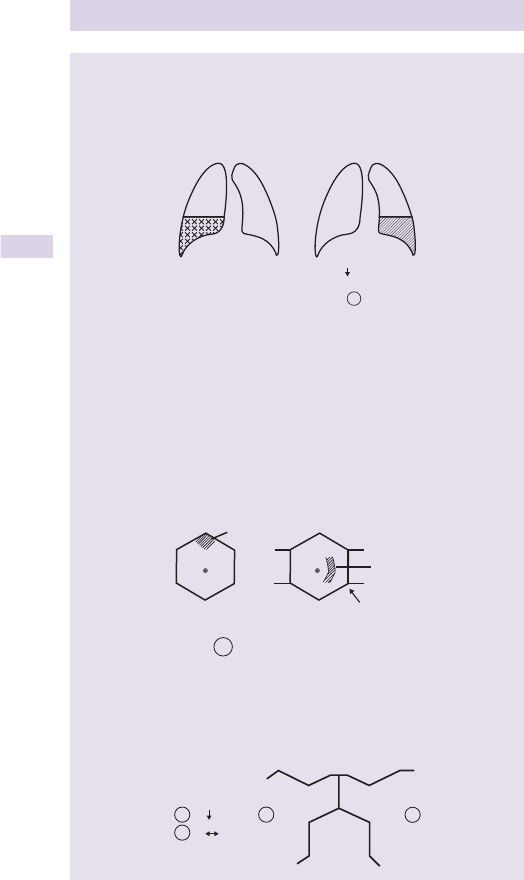

Respiratory system 484

Ear, nose, and throat 488

Cardiovascular system 490

Abdomen and gastrointestinal system 493

Palpation 495

Nervous system 497

Developmental assessment 500

The newborn 502

17 Examination under special circumstances 507

Overview 508

Disasters, terrorism, and public health emergencies 509

Sexual assault 510

Other thoughts 510

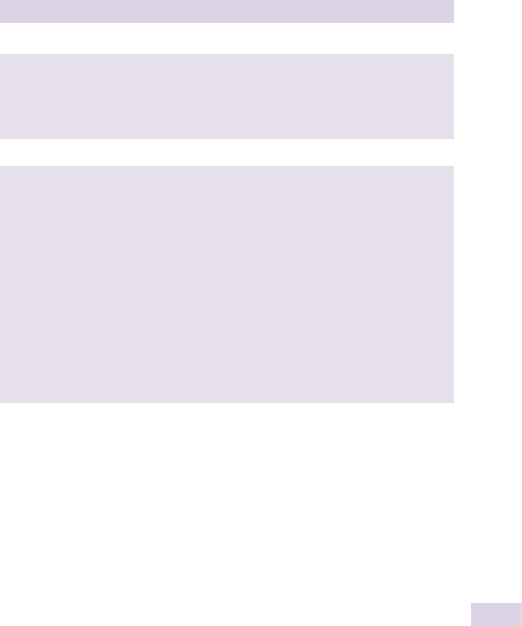

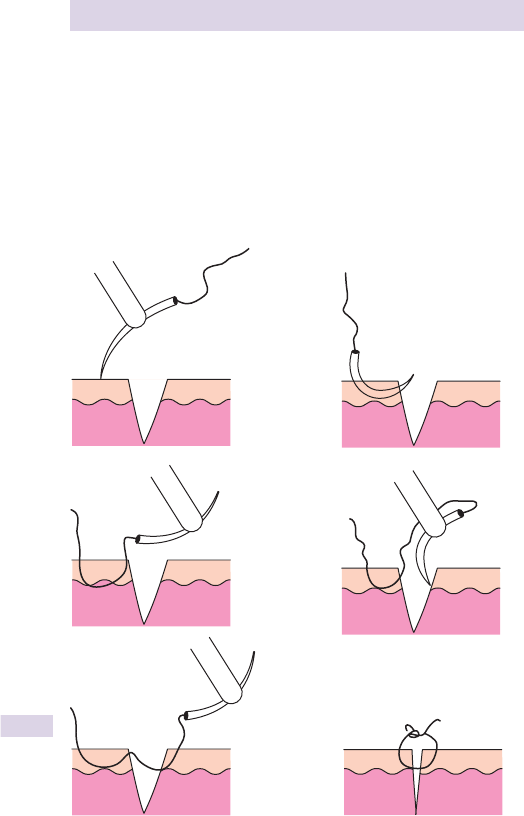

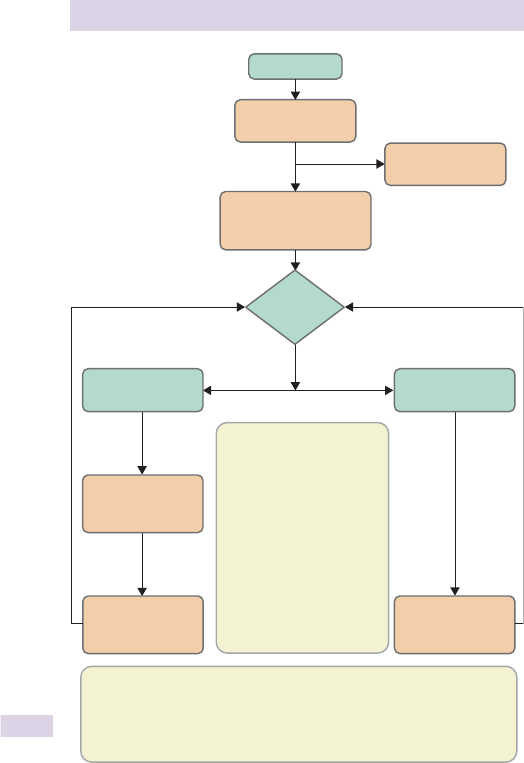

18 Practical procedures 511

Using this chapter 512

Infi

ltrating anesthetic agents

512

Sterility and preparation 513

Hand-washing 514

Injections 516

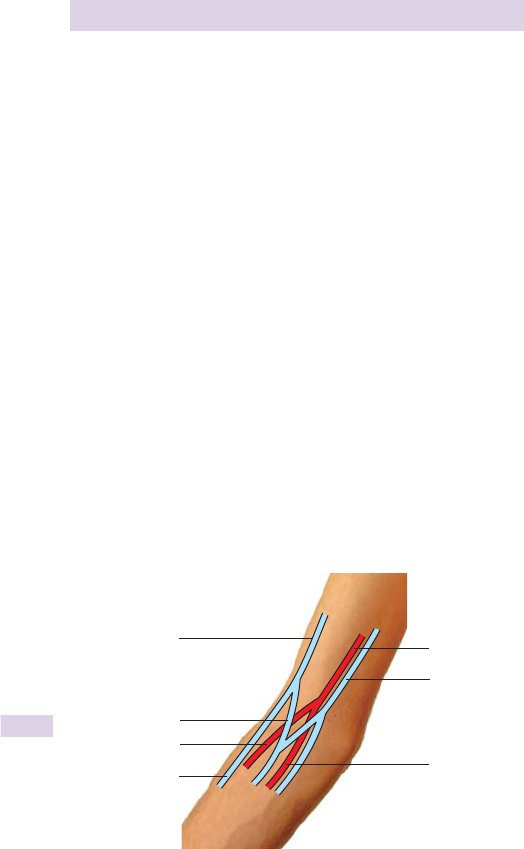

Venipuncture 518

Peripheral IV catheterization 522

Setting up an infusion 524

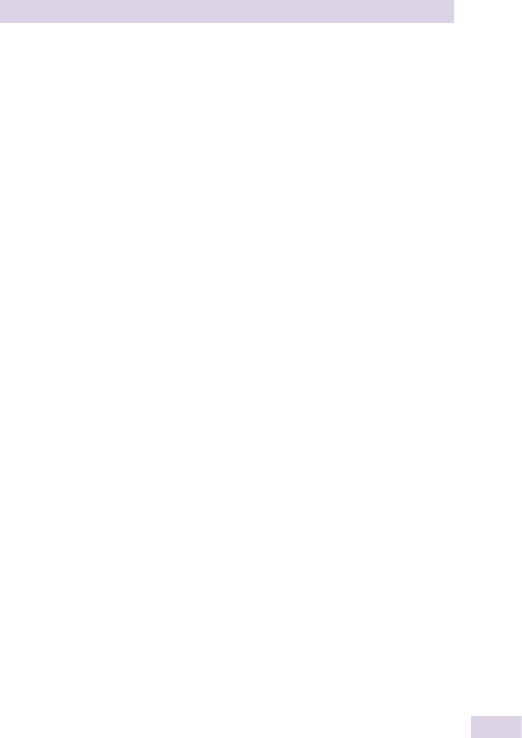

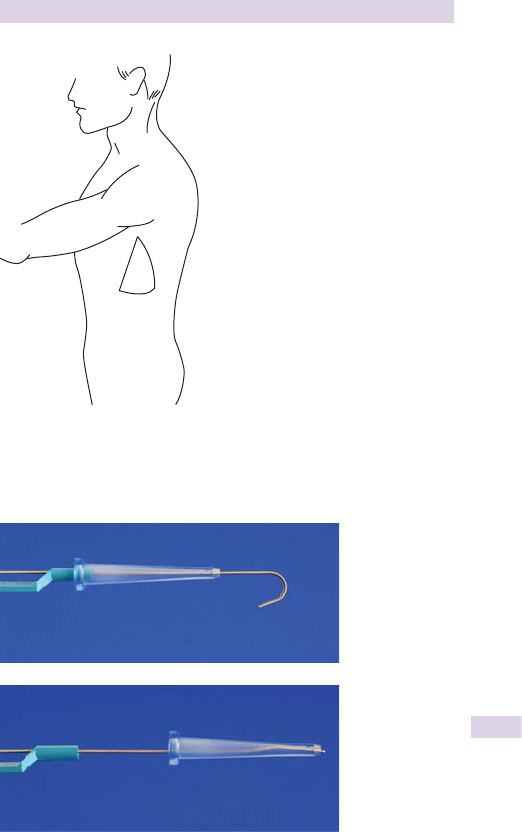

External jugular vein catheterization 526

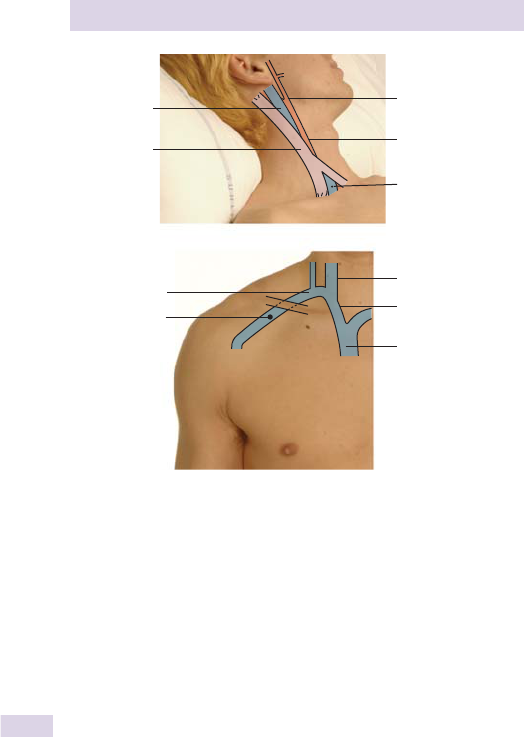

Central venous catheterization 527

Blood pressure measurement 531

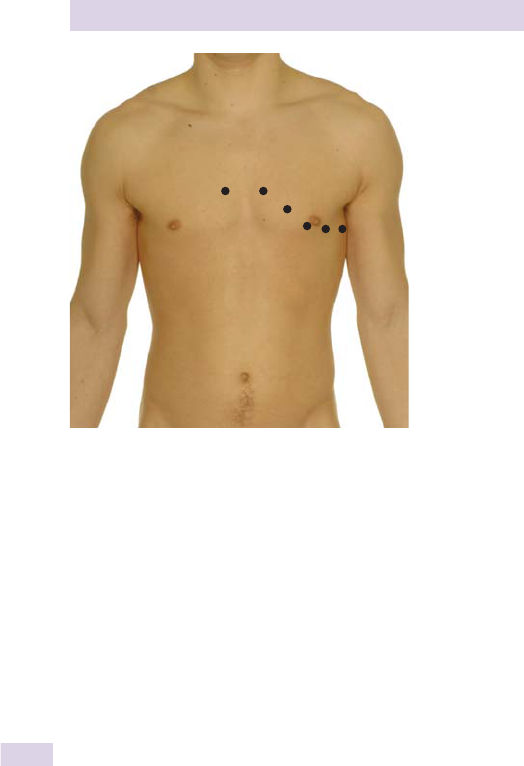

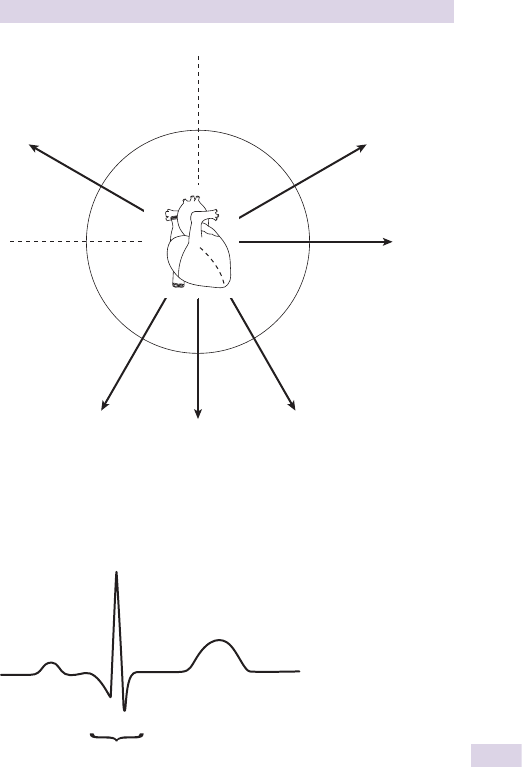

Recording a 12-lead ECG 533

Arterial blood gas sampling 535

Peak fl ow

measurement

537

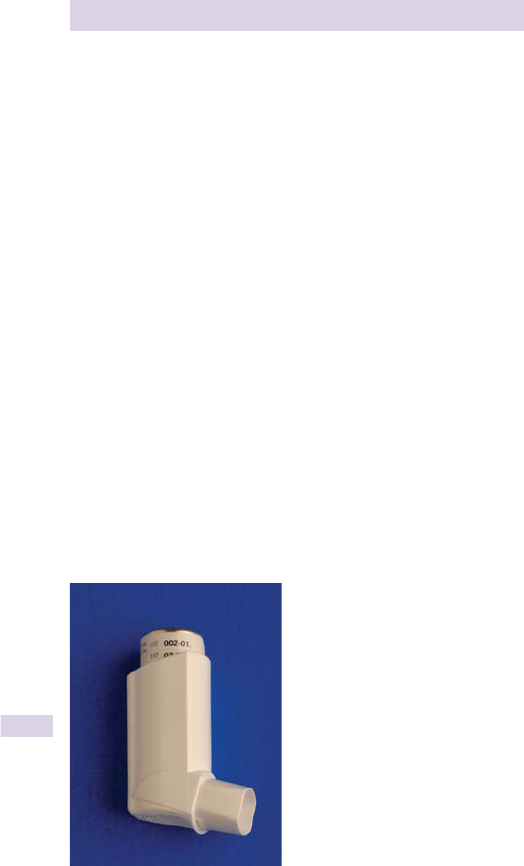

Inhaler technique 538

Oxygen administration 544

Basic airway management 547

Tracheostomy management 555

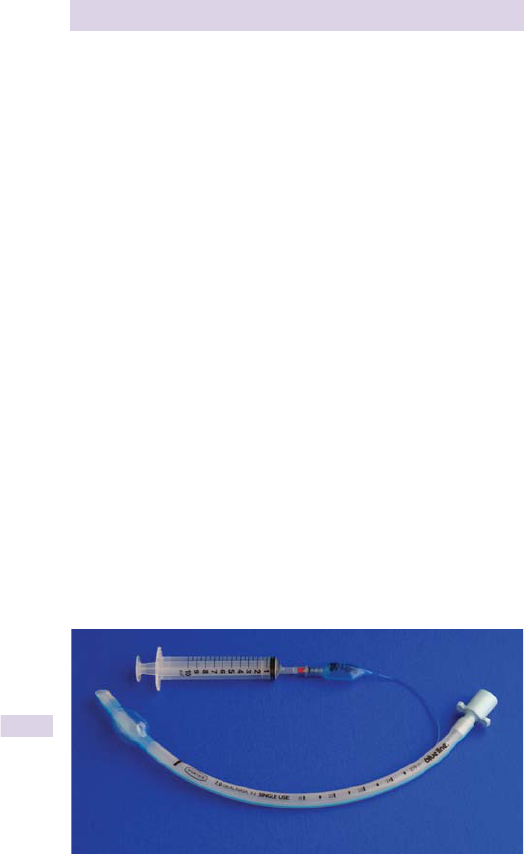

Endotracheal (ET) intubation 557

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) 559

Pleural fl

uid sampling (thoracentesis)

561

Chest tube insertion 563

Nasogastric (NG) tube insertion 567

Ascitic tap 569

Abdominal paracentesis (drainage) 571

Male urethral catheterization 573

Female urethral catheterization 575

Suprapubic catheterization 577

xix

DETAILED CONTENTS

Basic suturing 579

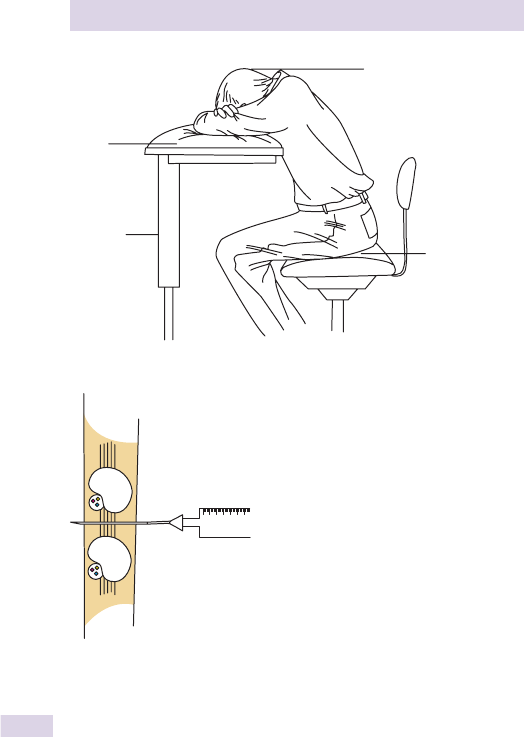

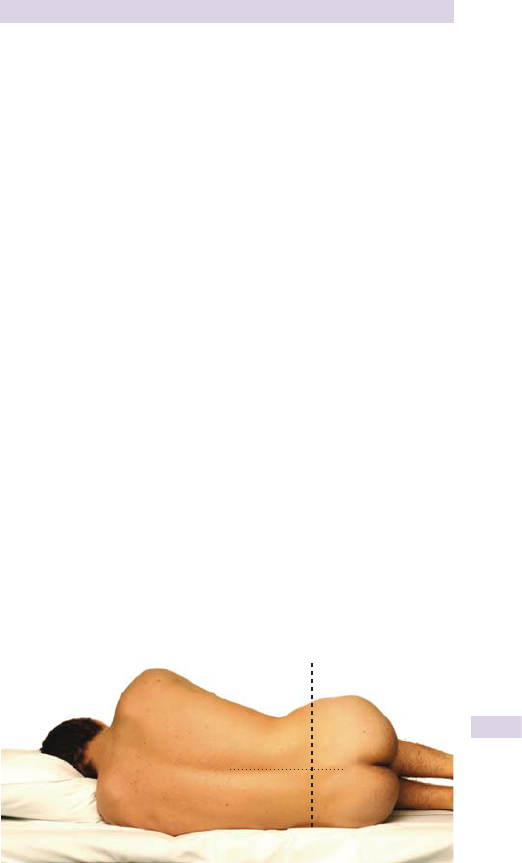

Lumbar puncture 581

Pericardial aspiration 583

Defi brillation 584

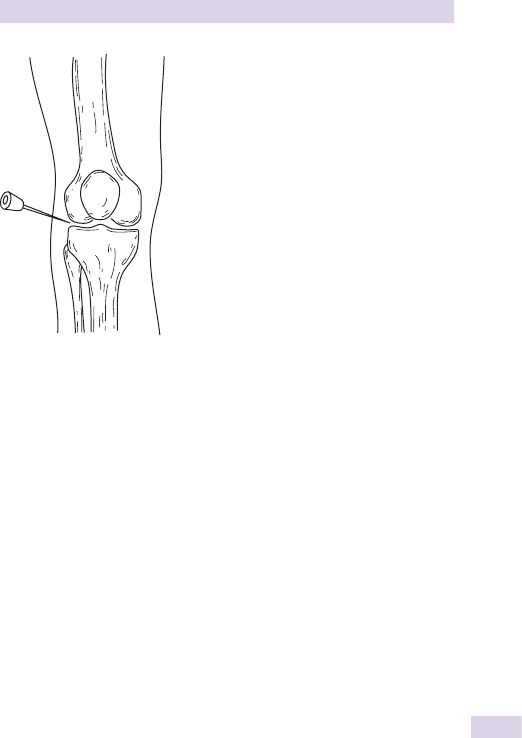

Knee joint aspiration 588

19 Data interpretation 591

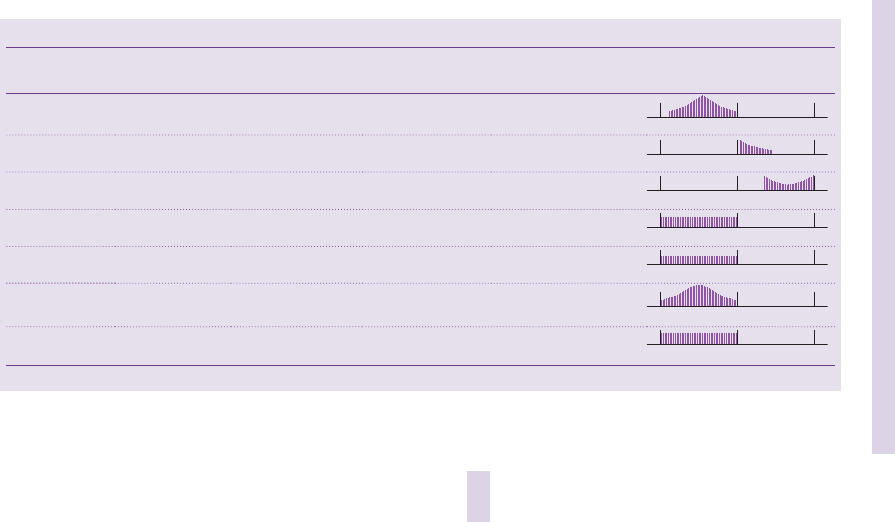

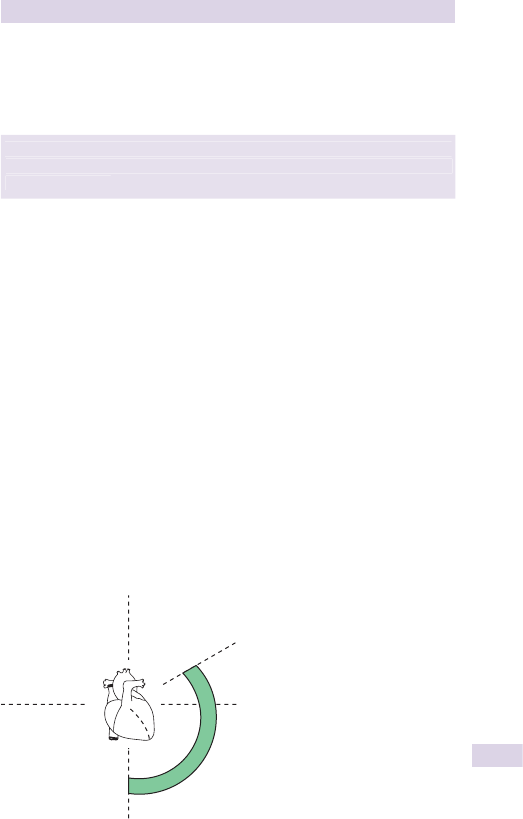

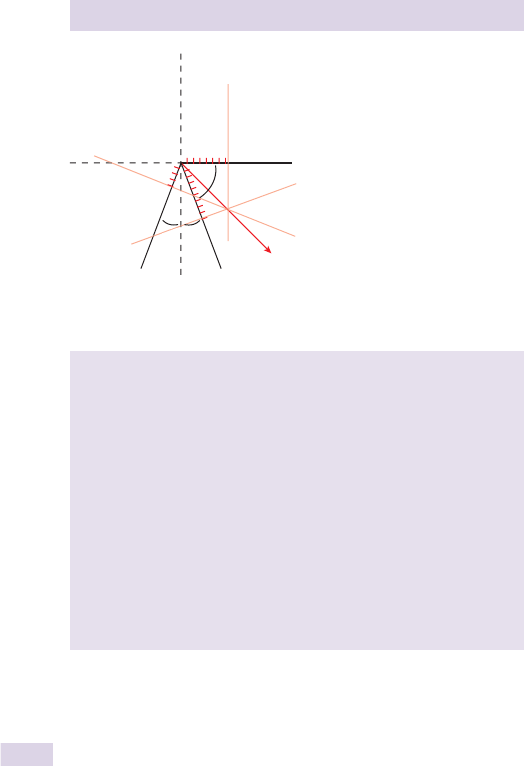

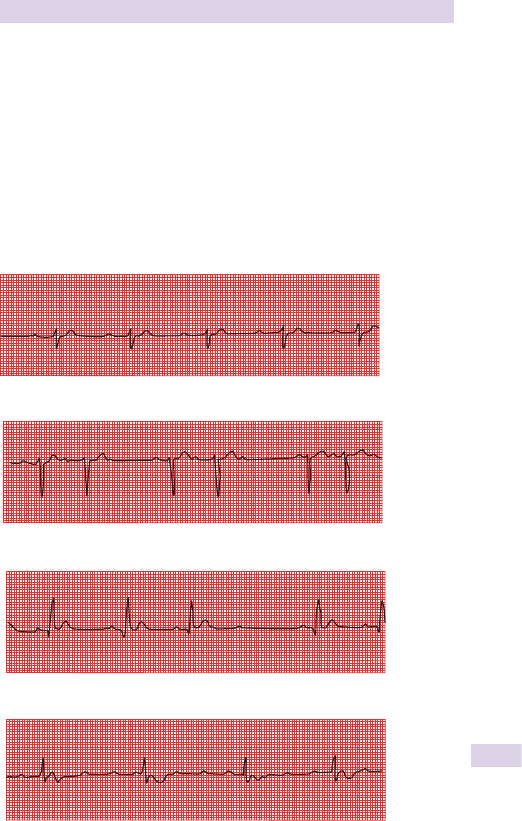

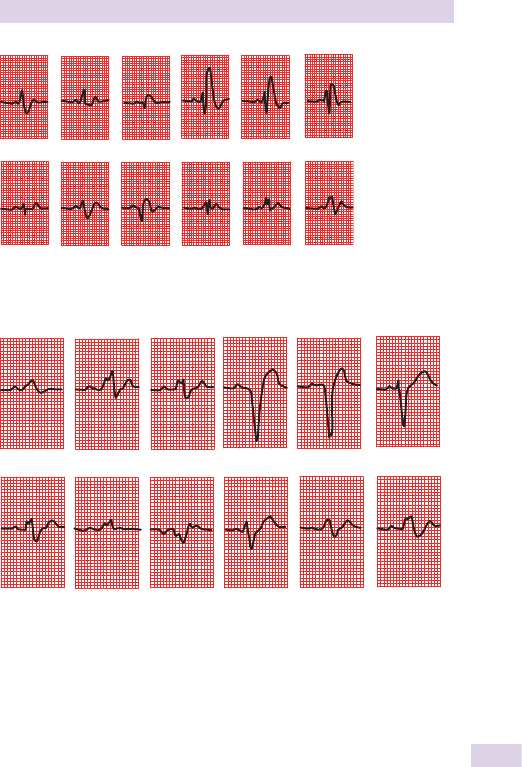

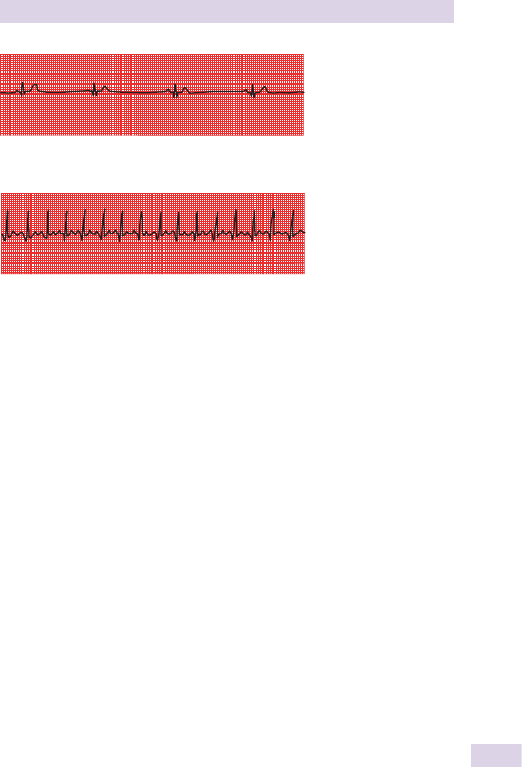

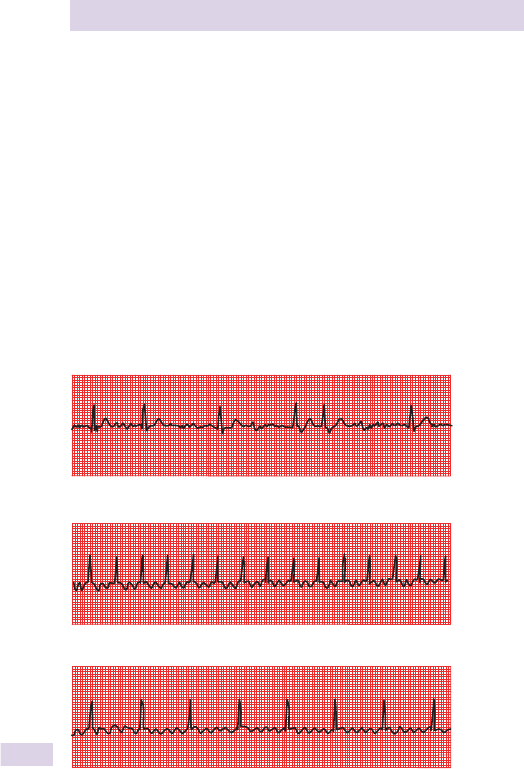

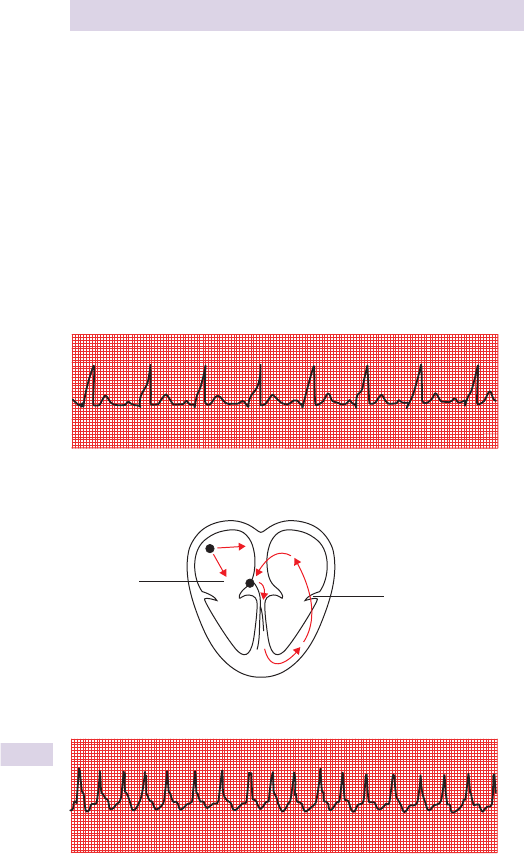

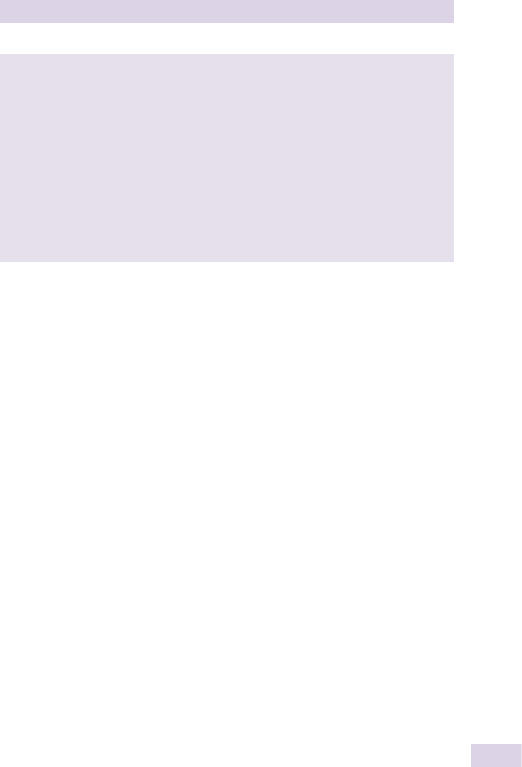

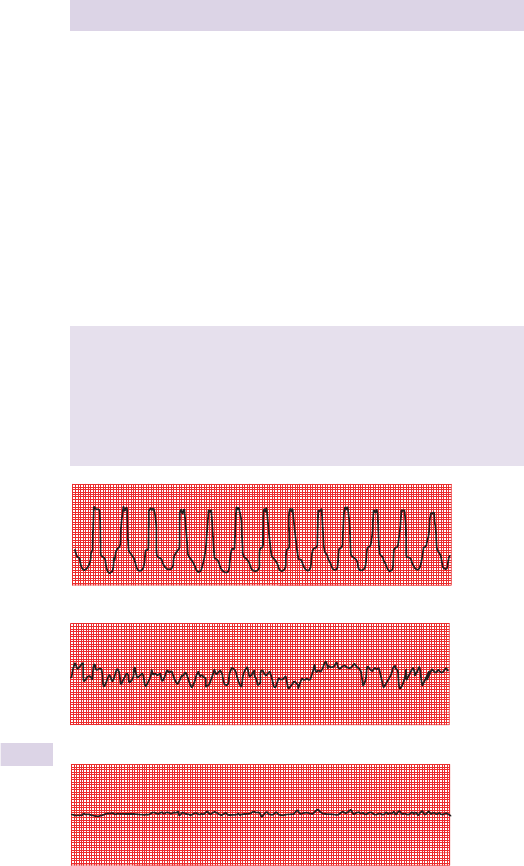

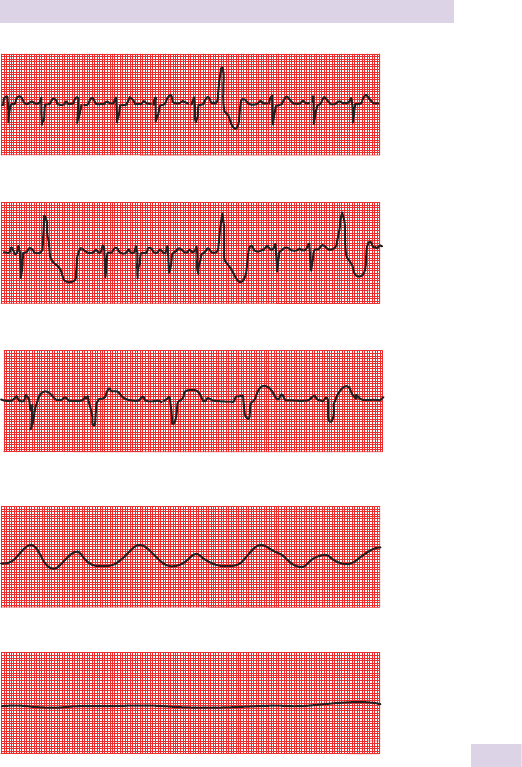

ECG: introduction 592

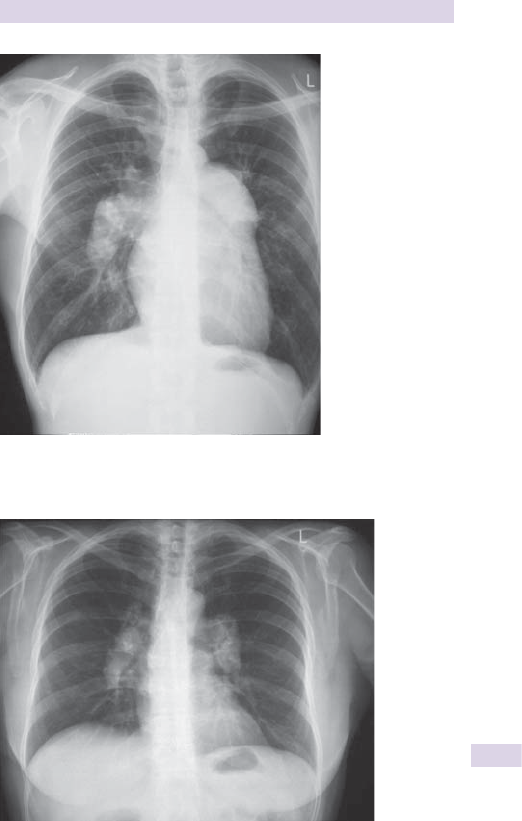

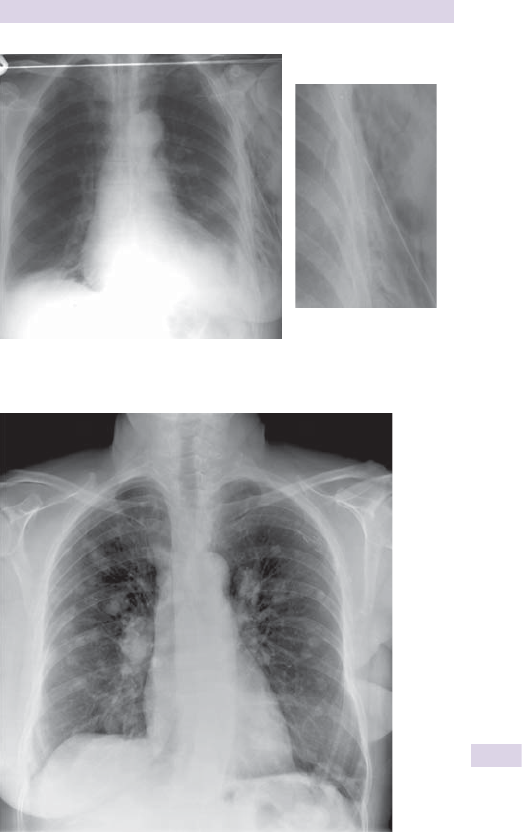

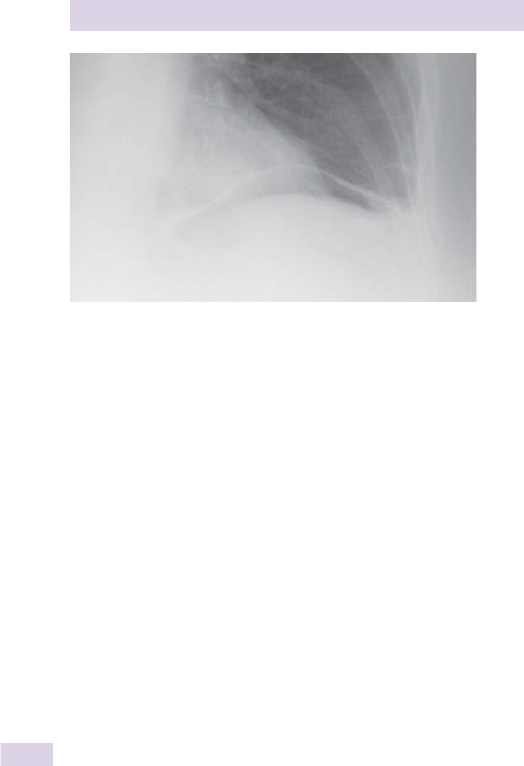

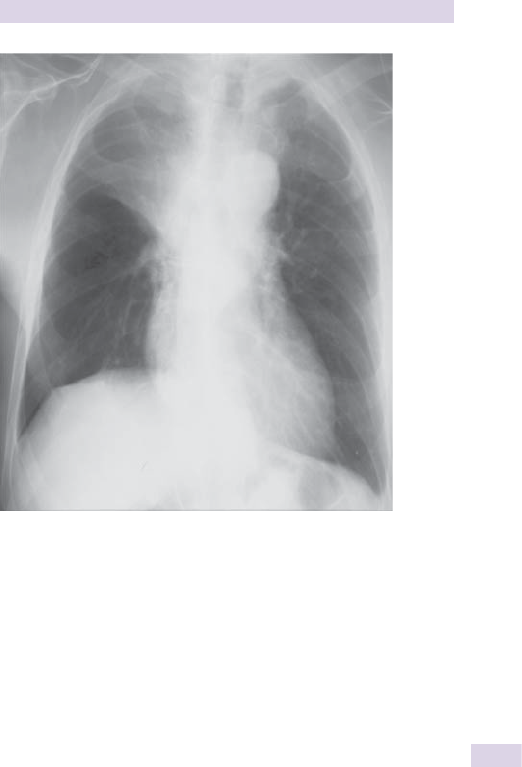

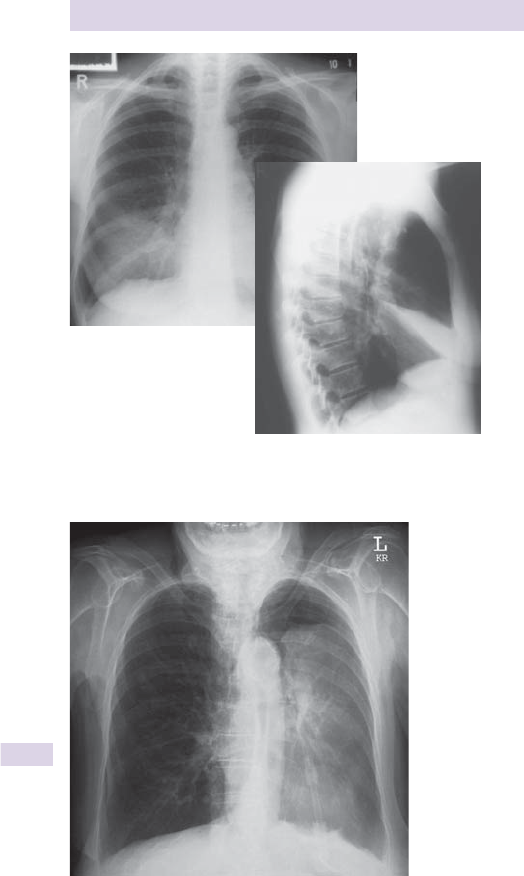

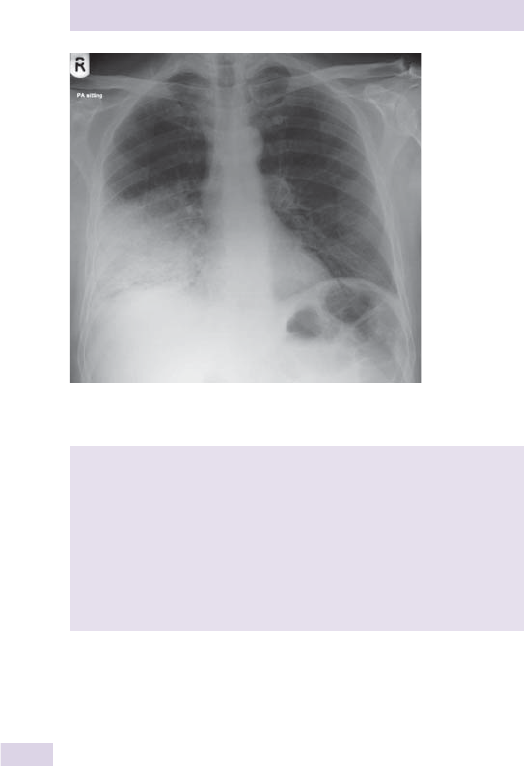

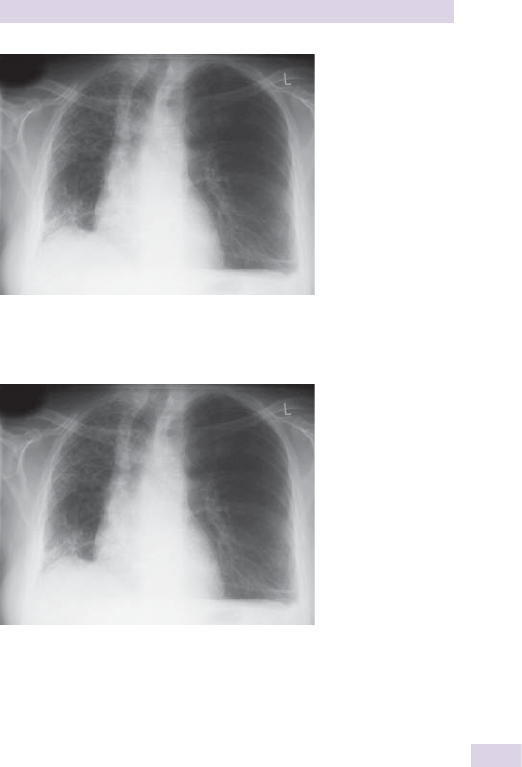

Chest X-rays: introduction 616

Abdominal X-rays: introduction 641

Radiology: pelvis 646

Radiology: hips and femurs 648

Radiology: knees 650

Radiology: shoulder 652

Radiology: cervical spine 654

Radiology: thoracic and lumbar spine 656

Lung function tests 658

Arterial blood gas analysis 663

Cerebrospinal fl uid

(CSF)

667

Urinalysis 669

Pleural and ascitic fl uid 671

Index 673

xx

Symbols and

abbreviations

i increased

d decreased

n normal

7 approximately

b cross-reference

0 warning

2 important

ABC airway, breathing, circulation

ABG arterial blood gases

AC acromioclavicular

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme

ACL anterior cruciate ligament

ACLS advanced cardiac life support

ACSM American College of Sports Medicine

ACTH adrenocorticotrophic hormone

AD Alzheimer’s disease

ADH antidiuretic hormone

ADL activities of daily living

ADP adenosine diphosphate

AED automated external defi brillator

AF atrial fi brillation

AHA American Heart Association

AITFL antero-inferior tibio-fi bular

ligament

AMTS Abbreviated Mental test Score

ANCOVA analysis of covariance

ANOVA analysis of variance

AP anteroposterior

APH antepartum hemorrhage

APL antiphospholipid

ASD atrial septal defect

ASL American Sign Language

ATFL anterior talofi bular

ligament

ATLS advanced trauma life support

ATP adenosine triphosphate

xxi

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

AV atrioventricular

AVN avascular necrosis

AVPU Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive (scale)

AXR abdominal X-ray

BCC basal cell carcinoma

BCG bacillus Calmette-Guérin

bid twice daily

BiPAP bilevel positional vertigo

BMD bone mineral density

BMI body mass index

BMR basal metabolic rate

BP blood pressure

BPH benign prostatic hyperplasia

bpm beats per minute

BPV benign positional vertigo

C cervical

CABG coronary artery bypass graft

CBC complete blood count

CBRNE chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, & explosive

CC chief complaint

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CEA carcinoembryogenic antigen

CF cystic fi brosis

CFS chronic fatigue syndrome

CHD coronary heart disease

CHF congestive heart failure

CHO carbohydrate

CIN cervical intraepithelial neoplasm

CK creatine kinase

CN cranial nerve

CNS central nervous system

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CP cerebral palsy

CPAP continuous positive airways pressure

CPK creatine phosphokinase

CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation

CRF corticotropin-releasing factor

CRP C-reactive protein

CSF cerebrospinal fl uid

CT computerized tomography

xxii

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

CTD connective tissue disease

CVA cerebrovascular accident

CVP central venous pressure

CXR chest X-ray

DEXA dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

DIP distal interphalangeal

DKA diabetic ketoacidosis

DM diabetes mellitus

DO detrussor overactivity

DOB date of birth

DUB dysfunctional uterine bleeding

DVT deep venous thrombosis

EBP epidural blood patch

ECG electrocardiogram

ECRB extensor carpi radialis brevis

ECRL extensor carpi radialis longus

ECU extensor carpi ulnaris

EDD estimated date of delivery

EIA exercise-induced asthma

EIB exercise-induced bronchospasm

EJV external jugular vein

EMG electromyography

EMR electronic medical record

ENMG electoneuromyography

EPAP expiration positive airways pressure

EPB extensor polaris brevis

EPO erythropoetin

ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

ET endotracheal

FCU fl

exor carpi ulnaris

FDS fl exor digitorum superfi cialis

FeCO

2

expired air carbon dioxide concentration

FeO

2

expired air oxygen concentration

FEV

1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

FH family history

FHR fetal heart rate

FMLA Family Medical Leave Act

FPL fl exor policis longus

FRC functional residual capacity

FSH follicle-stimulating hormone

xxiii

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

FVC forced vital capacity

G gauge

GALS gait, arms, legs, spine

GBS Guillain–Barré syndrome

GCS Glasgow Coma Scale

GEJ gastroesophageal junction

GERD gastroesophageal refl ux disease

GFR glomerular fi ltration rate

GH growth hormone

GI gastrointestinal

GnRH gonadotrophin-releasing hormone

hCG human chorionic gonadotrophin

Hct hematocrit

Hgb hemoglobin

HDL high-density lipoprotein

HIPAA Health Insurance Portability & Accountability Act

HPI history of present illness

HPV human papillomavirus

HR heart rate

HRT hormone replacement therapy

HT hormone therapy

HZV herpes zoster virus

Hct hematocrit

IA intra-arterial

IBD infl

ammatory bowel disease

IBS irritable bowel syndrome

ICP intracranial pressure

ICU intensive care unit

ID intradermal

IGF-1 insulin-like growth factor 1

IHD ischemic heart disease

IHS Indian Health Service

IHSS idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis

IIH idiopathic intracranial hypertension

IJV internal jugular vein

ILI infl uenza-like illness

IM intramuscular

IMB intermenstrual bleeding

IOC International Olympic Committee

IPAP inspiration positive airways pressure

xxiv

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

IRMA intraretinal microvascular abnormalities

ITB ilio-tibial band

ITBS ilio-tibial band syndrome

IUD intrauterine device

IV intravenous

IVP intravenous pyelogram

JVP jugular venous pressure

L lumbar

LBBB left bundle branch block

LBC liquid-based cytology

LDH lactate dehydrogenase

LDL low-density lipoprotein

LEP Limited English Profi ciency

LFT liver function test

LH luetinizing hormone

LMA laryngeal mask airway

LMN lower motor neuron

LMP last menstrual period

LP lumbar puncture

LOC loss of consciousness

LSB left sternal border

LSE left sternal edge

LV left ventricle

LVH left ventricular hypertrophy

MALT mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

MANOVA multivariate analysis of the variance

MCL medial collateral ligament

MCP metacarpophalangeal

MC&S microscopy, culture, and sensitivity

MDI metered-dose inhaler

MI myocardial infarction

MLF medial longitudinal fasciculus

MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination

MND motor neuron disease

MPHR maximum predicted heart rate

MRI magnetic resonance imaging

MRSA methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MS multiple sclerosis

MSH melanocyte-stimulating hormone

MTP metatarsophalangeal

xxv

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

MVA motor vehicle accident

NG nasogstric

NIV noninvasive ventilation

NSAID nonsteroidal anti-infl ammatory drug

NYHA New York Heart Association

OA osteoarthritis

OCD obsessive-compulsive disorder

OCP oral contraceptive pill

OSHA Occupational Safety & Health Administration

ORIF open reduction and internal fi xation

OTC over the counter

PA posterior–anterior

PCL posterior cruciate ligament

PCOS polycystic ovarian syndrome

PCP primary care provider

PCR polymerase chain reaction

PCS post-concussion syndrome

PDA patent ductus arteriosis

PE pulmonary embolism

PFJ patello-femoral

PID pelvic infl ammatory

disease

PIP proximal interphalangeal

PMH past medical history

PMI point of maximum impulse

PND paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

PP patient profi le

PPH postpartum hemorrhage

PPRF parapontine reticular formation

PSIS posterior superior iliac crest

PSYM parasympathetic

PTFL posterior talofi bular ligament

PTH parathyroid hormone

Q cardiac output

q4h every 4 hours

qid 4 times a day (quarter in die)

RAPD relative afferent pupil defect

RBC red blood count or cell

RICE rest, ice, compression, elevation

ROM range of motion

ROS review of systems

xxvi

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

RR respiratory rate

RSE right sternal edge

RV residual volume; right ventricule

SA sinoatrial

SAAG serum/ascites albumin gradient

SANE sexual assault nurse examiner

SAH subarachnoid hemorrhage

SaO

2

oxygen saturation

SC subcutaneous

SCC squamous cell carcinoma

SH social history

SI stress incontinence

SIJ sacroiliac joint

SLAP superior labrum anterior to posterior

SLE systemic lupus erythematosus

SLR straight leg raise

SOB shortness of breath

SPECT single photon emission computer tomography

STD sexually transmitted disease

STI sexually transmitted infection

SQJ squamo-columnar junction

SV stroke volume

SVC superior vena cava

SVT sustained ventricular tachycardia

T thoracic

T

3

triiodothyronine

T

4

thyroxine

TB tuberculosis

TBG thyroid-binding globulin

TBI traumatic brain injury

TGA transposition of the great arteries

TIA transient ischemic attack

tid three times daily

TPN total parenteral nutrition

TSH thyroid-stimulating hormone

TURP transurethral resection of the prostate

UAP unlicensed assistive personnel

UMN upper motor neuron

UC ulcerative collitis

UCL ulnar collateral ligament

xxvii

SYMBOLS AND ABBREVIATIONS

URI upper respiratory infection

US ultrasound

UTI urinary tract infection

UV ultraviolet

VEGF vascular endothelial-derived growth factor

VF ventricular fi brillation

VIN vulval intraepithelial neoplasm

VIP vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

VO

2

oxygen uptake

VRSA vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

VSD ventricular septal defect

VT ventricular tachycardia

WBC white blood count

WHO World Health Organization

WPW Wolff–Parkinson–White (syndrome)

Important Notes

0 Write legibly on orders, or print or enter orders via computer.

0 Date, time, and sign all patient care orders.

0 Remember, all facilities should have an approved abbreviations list—

follow it.

0 The offi

cial “Do Not Use”list of abbreviations is available at the Joint

Commission Web site at: http://www.jointcommission.org.

This page intentionally left blank

1

Communication Skills

Introduction 2

Essential considerations 4

Essential rules 6

Getting started 7

General principles 9

Communicating with deaf patients 12

Cross-cultural communication 13

Interpreters 14

Imparting information 15

The importance of silence 15

Angry patients 15

Telephone and e-mail communication 16

Talking about sex 16

Breaking bad news 17

Body language: an introduction 21

Written communication 23

Law, ethics, and communication 26

Chapter 1

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills2

Introduction

Communication skills are notoriously hard to teach and describe. There

are too many possible situations that you might encounter to be able to

draw rules or guidelines. In addition, your actions will depend greatly on

the personalities present—not least of which your own!

Using this chapter

Over the following pages, we present some general advice about com-

municating in different situations and to different people. We have

not provided rules to stick to but rather have tried to give the reader

an appreciation of the many ways in which the same situation may be

tackled.

Ultimately, skill at communication comes from practice, self-knowledge

and refl ection, and a large amount of common sense.

Quite a bit has been written about communication skills in medicine and

the health sciences. Most articles suggest a mix of accepted protocols and

traditional approaches—this chapter is no different.

Communication models

There are many models of the practitioner–patient encounter that have

been discussed over the years at great length. These models are for the

hardened student of communication. We mention them here so that the

reader is aware of their existence.

Patient-centered communication

In recent years, there has been a signifi cant change in the way health-

care workers interact with patients. The biomedical model has fallen out

of favor and instead, an appreciation has evolved that the patient has a

unique experience of the illness. This experience involves the social, psy-

chological, and behavioral effects of the disease. Some authors refer to this

approach as the biopsychosocial model, which focuses on the patient in a

more encompassing way.

The biomedical model

• The provider is in charge of the consultation and examination.

• Focus is on disease management.

The patient-centered model

• Power and decision-making are shared.

• Address and treat the whole patient.

The rule is: there are no rules.

INTRODUCTION

3

Box 1.1 Key points in the patient-centered model

• Explore the disease and the patient’s experience of it:

• Understand the patient’s ideas and feelings about the illness.

• Appreciate the illness’s impact on the patient’s quality of life and

psychosocial well-being.

• Understand the patient’s expectations of the encounter.

• Understand the whole person:

• Family

• Social and work environment

• Beliefs

• Find common ground on disease management.

• Establish the doctor–patient relationship.

• Be realistic:

• Priorities for treatment

• Resources

Box 1.2 Confi dentiality

As a doctor, health-care provider, or student, you are party to per-

sonal and confi dential information. While Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations must be followed, there are

also times when confi dentiality must or should be broken (b p. 26).

The essence of day-to-day practice is:

Never tell anyone about a patient unless it is directly related to his

or her care and you have permission.

This includes relatives, which can be very diffi cult at times, particularly if

a relative asks you directly about something confi dential.

You can reinforce the importance of confi dentiality to relatives and

visitors. If asked by a relative to speak about a patient, it is a good idea

to approach the patient fi rst and ask their permission, within full view of

the relative. You can also seek permission from the patient in anticipa-

tion of such queries.

This rule also applies to friends outside of medicine. As care provid-

ers, we come across many amazing, bizarre, amusing, or uplifting sto-

ries on a day-to-day basis, but like any other kind of information, these

should not be shared with anyone.

If you do intend to use an anecdote in public, at the very least you

should ensure that there is nothing in your story that could possibly

lead to the identifi cation of the person involved. If you are in a small

community, it is best to avoid sharing anything, lest you undermine your

reputation as a professional.

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills4

Essential considerations

Attitudes

Patients are entrusting their health and personal information to you—they

want someone who is confi dent, approachable, competent, and, above

all, trustworthy.

Personal appearance

First impressions count—and studies have consistently shown that your

appearance (clothes, hair, makeup) has a great impact on patients’ opinion

of you and their willingness to interact with you. Part of that intangible

professionalism comes from your image.

The white coat is still part of medical culture for students and most

providers. Fashions in clothing change rapidly, but some basic rules still

apply:

• Neutralize any extreme tastes in fashion that you may have.

• Men and women should wear appropriate professional attire.

• Women may wear skirts or slacks but the length of the skirts should

not raise any eyebrows.

• Necklines should not be revealing—no décolletage!

• The belly should be covered—no bare midriffs!

• The shoulders, likewise, should be covered.

• Shoes should be polished and clean.

• Clean surgical scrubs may be worn, if appropriate.

• Hair should be relatively conservatively styled and no hair should be

over the face. Wear long hair tied up.

• Your name badge should be clearly visible, even if you don’t like your

picture.

• Stethoscopes are best carried or held in a coat pocket—worn at the

neck is acceptable but a little pretentious, according to some views.

• Try not to tuck items in your belt—use pockets or belt-holders for

cell phones, keys, and wallets.

2 Psychiatry, pediatrics, and a handful of other specialties require a differ-

ent dress code, as they deal with patients who require differing techniques

for bonding with the health-care professional.

Timing

If in a hospital setting, make sure that your discussion with a patient is not

during an allocated quiet time or disturbing to the patient’s roommate.

You should also avoid mealtimes or when the patient’s long-lost relative

has just come to visit.

2 If you plan to move the patient from the bed to an exam room, ask

the supervising doctor (if not you) and the nursing staff, and let all con-

cerned know where you have gone in case the patient is needed.

Setting

Students, doctors, and other medical providers tend to see patients on

hospital fl oors fi lled with distractions that can break up the interaction.

ESSENTIAL CONSIDERATIONS

5

Often such meetings are necessary during the course of the day. However,

if you need to discuss an important matter that requires concentration

from both of you, consider the following conditions:

• The room should be quiet, private, and free from disturbances.

• There should be enough seating for everyone.

• Chairs should be comfortable enough for an extended conversation.

• Arrange the seats close to yours, with no intervening tables or other

furniture.

Box 1.3 Becoming a good communicator

Learning

As in all aspects of medicine, learning is a lifelong process. One part of

this process, particularly for acquiring communication skills and at the

beginning of your career, is watching others .

You should take every opportunity to observe provider–patient

interactions.

2 You should ask to be present during diffi cult

conversations.

Instead of glazing over during clinic visits or on rounds, you should

watch the interaction and consider if the behaviors you see are worth

emulating or avoiding. Consider how you might adjust your future

behavior.

Select the actions and words you like and use them as your own,

building up your own repertoire of communication techniques.

Spontaneity vs. learned behaviors

When you watch a good communicator, you will see them making friendly

conversation and spontaneous jokes, and using words and phrases that

put people at ease. The conversation seems natural, relaxed, and spon-

taneous. Watching that same person interact with someone else can

shatter the illusion as you see them using the same “spontaneous” jokes

and other gambits from their repertoire.

This is one of the keys to good communication—an ability to judge

the situation and pull the appropriate phrase, word, or action from your

internal catalogue. If done well, it leads to a smooth interaction with no

hesitations or misunderstandings. The additional advantage is that your

mental processes are free to consider the next move, mull over what

has been said, or assess fi ndings, while externally you are partially on

autopilot, following a familiar pattern of interaction.

During physical examination this ability is particularly relevant. You

should be able to coax the wanted actions from the patient and put

them at ease while considering fi ndings and your next step.

It must be stressed, however, that this is not the same as lacking con-

centration—quite the opposite.

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills6

Essential rules

Avoid medical jargon

Medical personnel are so immersed in jargon that it becomes part of their

daily speech. The patient may not understand the words or may have a

different idea of their meaning.

Technical words such as myocardial infarction are in obvious need of

avoidance or explanation. Consider also terms such as exacerbate , chronic ,

numb , and sputum —these may seem obvious in meaning to you but not

to the patient.

You may think that some terms such as angina and migraine are so well

known that they don’t need explanation, but these are very often misinter-

preted. Some examples of such words are given in Table 1.1.

Remember names

Forgetting someone’s name is what we all fear; it is relatively easy to

disguise by simple avoidance. However, using the patient’s name will

make you appear to be taking a greater interest in them. It is particularly

important that you remember the patient’s name when talking to fam-

ily members. Getting the name wrong is embarrassing and can seriously

undermine their confi dence in you.

Aside from actually remembering the name, it is a good idea to have it

written down and within sight—on a piece of paper in your hand, on the

chart, or on the desk. It is a best practice to confi rm the identity of the

patient, using two identifi ers (name, date of birth [DOB]), before you read

results from the chart or electronic medical record (EMR). To be seen

glancing at the name is forgivable; patients would rather have you double

check than bluff your way through an interview.

Table 1.1 Some examples of differing interpretations of medical terms

Word Your meaning Patient’s understanding

Acute Rapid onset Very bad, severe

Chronic Long duration Very bad, severe

Sick Nauseated, vomiting Unwell

Angina Chest pain associated with

ischemic heart disease

Heart attack, shortness of

breath, palpitations

Migraine Specifi c headache disorder Any severe headache

Numb Without sensation Weak

GETTING STARTED

7

Getting started

The start of an encounter is important but is fraught with potential diffi cul

-

ties. Like ever

y

thin

g

else in this cha

p

ter, there are no hard-and-

f

ast rules.

Issues

y

ou should take into consideration include the followin

g

:

•

Are you using a language the patient can understand

?

•

Can the

p

atient hear

y

ou?

Greetin

g

Beware o

f

sa

y

in

g

“

g

ood a

f

ternoon” or “

g

ood mornin

g

.” These

g

reetin

g

s

c

an be inappropriate if you are about to break some bad news or if there is

a

nother reason

f

or distress.

C

onsider instead usin

g

a sim

p

le “hello.”

Shaking hands

A traditional greeting, shaking hands will be readily accepted by most

p

atients, but it can also

p

resent challen

g

es

(

think of

p

atients with severe

a

rthritis of the hands

)

. While physical contact always seems friendly and

c

an warm a

p

erson to

y

ou, a handshake ma

y

be seen as overl

y

formal b

y

s

ome and inappropriate by others. Consider using some other form o

f

touch, such as a sli

g

ht

g

uidin

g

hand on the

p

atient

’

s arm as the

y

enter the

room or a brief touch to the forearm.

(

See also

b

p

. 21.

)

Introduct

i

ons

This is a minefi eld! You ma

y

wish to alter

y

our

g

reetin

g

de

p

endin

g

on the

circumstances—choose terms that suit

you

.

Title—patient

Older patients may prefer to be called “Mr.” or “Mrs.”; younger patients

would

fi

nd this odd. For

f

emale

p

atients whose marital status

y

ou don’t

k

now, you can try using “Ms.,” although some younger or married patients

m

a

y

fi

nd this term o

ff

ensive.

Calling the patient by their fi rst name may be considered too informal

by

some

p

atients. A chan

g

e to usin

g

the

f

amil

y

name mid-wa

y

throu

g

h the

e

ncounter ma

y

a

pp

ear unfriendl

y

or could indicate that somethin

g

has

gone wrong wit

h

t

h

e interaction.

Th

ere are no ru

l

es

h

ere; use common sense to

j

u

dg

e t

h

e situation at t

h

e

time. When unsure, the best option is always to ask.

Title—

y

ou

The title docto

r

has always been a status symbol and a badge of author-

r

ity—within the health-care professions at least. Young doctors may be

reluctant to

p

art with the title so soon a

f

ter ac

q

uirin

g

it, but these da

y

s,

when offi ce visits are becoming two-way conversations between equals,

p

atients may expect equity in t

h

e way t

h

ey are a

dd

resse

d

.

Man

y

p

atients will sim

p

l

y

call

y

ou “doctor

”

and the matter doesn

’

t arise.

We pre

f

er using

f

ormality initially, then using

fi

rst names i

f

circumstances

s

eem a

pp

ro

p

riate. Some elderl

y

p

atients

p

refer—and ex

p

ect—a certain

level of formality, so each situation has to be judged.

“Is it Mrs. or Miss

S

mith

?

” “How would

y

ou like to be addressed

?

”

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills8

Mid-level providers should follow the conventions of the health-care

setting they are in. Formality is appropriate in many settings; however,

most mid-level providers are more comfortable using fi rst names.

Standing

Although this might be considered old-fashioned by some younger people,

standing is a universal mark of respect. You should stand when a patient

enters a room and take your seat at the same time as them. You should

also stand as they leave, but if you have established a good rapport during

the visit, this isn’t absolutely necessary.

You may notice that patients stand when you enter the exam room. Put

them at ease and acknowledge this gesture as well.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

9

General principles

Demeanor

Give the patient your full attention. Appear encouraging with a warm,

open manner. Use appropriate facial expressions—don’t look bored!

Defi ne your role

Along with the standard introductions, you should always make it clear

who you are and what your role is. You might also wish to introduce

your team members, if appropriate. In this era, when patients see so many

health-care providers during the course of a hospitalization, it is helpful to

write the team names down for them.

Style of questioning

Open questions vs. closed questions

Open questions are those for which any answer is possible:

“What’s the problem?”

“How does it feel?”

These enable patients to give you the true answer in their own words. Be

careful not to lead the patient or cut them off with closed questions.

Compare “How much does it hurt?” with “Does it hurt a lot?” The

fi rst question allows the patient to tell you how the pain feels on a wide

spectrum of severity; the second one leaves the patient only two options

and will not give a true refl ection of the severity.

Multiple-choice questions

Often, patients have diffi culty with an open question if they are not quite

sure what you mean. A question about the character of pain, for example,

is rather hard to formulate, and patients will often not know what you

mean (“What sort of pain is it”; “What does it feel like, exactly?”).

In these circumstances, you may wish to give them a few examples, but

leave the list open-ended for them to add their own words. You must be

very careful not to give the answer that you are expecting from them. For

example, a patient whom you suspect has angina (“crushing” pain) you

could ask the following:

“What sort of a pain is it—burning, stabbing, or aching, for example?”

Clarifying questions

Use clarifying questions to get the full details:

“When you say ‘dizzy’, what exactly do you mean?”

“What’s the problem

?

”

“How does it feel?”

“What sort o

f

a pain is it—burning, stabbing, or aching,

f

or example

?

”

“When you say ‘dizzy’, what exactly do you mean?”

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills10

Refl ective comments

Use refl ective comments to encourage patients to continue and reassure

them that you are following the story:

“Yes, I see that.”

Staying on topic

You should be directive but polite when keeping patients on the topic

you want or moving them on to a new topic. Don’t be afraid to interrupt

them—some patients will talk for hours if you let them!

“Before we move on to that, I would just like to get all the

details of this dizziness.”

“We’ll come to that in a moment.”

Diffi cult questions

Recognize potentially offensive or embarrassing questions. Explain why it

is necessary to ask these questions, to put the patient more at ease.

“This may be an uncomfortable question, but I need to know…”

Eye contact

2 Make eye contact and look at the patient when he or she is speaking.

Make a note of eye contact next time you are in conversation with a

friend or colleague.

In normal conversations, the speaker usually looks away while the lis-

tener looks directly at the speaker. The roles then change when the other

person starts talking, and so on.

In the medical situation, while the patient is speaking, you may be

tempted to make notes, read the referral letter, look at a test result, or

check the EMR—you should resist this urge and stick to the customary

rules of eye contact.

Adjusting your manner

You would clearly not talk to another provider as you would to some-

one with no medical knowledge. In much the same way, you should try

to adjust your manner and speech according to the patient’s educational

level. This is can be extremely diffi cult—you should not make assumptions

about intellect or understanding solely on the basis of educational history.

Even the most educated patient can have low health literacy.

A safe approach is to start in a relatively neutral way and then adjust

your manner and speech according to what you see and hear in the fi rst

minute or two of the interaction, but be alert to whether this is effective

and make changes accordingly. Understand that patients want to please

and seem agreeable and may say “yes” when they really don’t understand

“Yes

,

I see that.”

“Be

f

ore we move on to that, I would

j

ust like to

g

et all the

detai

l

s of this dizziness.”

“We’ll come to that in a moment.”

“This may be an uncom

f

ortable question, but I need to know…”

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

11

at all. Having patients explain what they heard back to you (teach back or

“show me” method) is a good way to check their understanding.

Interruptions

Apologize to the patient if you are interrupted in your meeting with

them.

Don’t take offence or get annoyed

As well as being directly aggressive or offensive, people may be thought-

less in their speech or manner and cause offence when they don’t really

mean to. As a professional, you should rise above this situation.

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills12

Communicating with deaf patients

People who are hard of hearing may cope with this problem by using

a hearing aid, lip-reading, or sign language. Whichever technique is used

(if any), some simple rules should always apply:

• Speak clearly but not too slowly.

• Don’t repeat a sentence if it is misunderstood—say the same thing in a

different way.

• Write things down, if necessary.

• Use plain English and be succinct.

• Be patient and take the time to communicate properly.

• Check understanding frequently.

• Consider fi

nding an amplifi er—many geriatric fl oors or clinics will have

one available.

Lip-readers

Patients who are able to lip-read do so by looking at the normal move-

ments of your lips and face during speech. Exaggerating movements or

speaking loudly will distort these movements and make it harder for them

to understand you. In addition to the points above, when talking to lip-

readers

• Maintain eye contact.

• Don’t shout.

• Speak clearly but not too slowly.

• Do not exaggerate your oral or facial movements.

American Sign Language (ASL)

• ASL is not a signed version of English; it is a distinct language with its

own grammar and syntax.

• For ASL users, English is a second language, so using a pen and paper

may not be effective or safe for discussing complex topics or gaining

consent.

• Seek an offi

cial interpreter, if possible, and follow the rules (b p. 14)

on working with interpreters.

13

CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION

Cross-cultural communication

Cultural background and tradition may have a large infl uence on dis-

ease management. Beliefs about the origin of disease and prejudices or

stigma surrounding the diagnosis can make dealing with the problem

challenging.

Be aware of all possible implications of a person’s cultural background.

For example, a Muslim may not take anything by mouth in the daylight

hours during Ramadan. This may have serious implications for medica-

tion management, particularly for chronic diseases such as diabetes or

hypertension.

Even something as benign (to you) as eye contact may have important

cross-cultural implications. For most individuals eye contact is desired,

but for many Native American and Asian cultures, it carries negative

connotations.

Above all, be aware of prejudice—yours and theirs. If you are not aware

of cultural implications when seeing a patient of a different culture, ask for

their input.

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills14

Interpreters

Federal and state laws require the use of interpreters for patients with

Limited English Profi ciency (LEP) and those with hearing disabilities.

Health-care facilities have protocols to follow to meet the LEP regula-

tions; they may have in-house or contract staff or use telephonic services.

Offi cial communicators are bound by a code of ethics, impartiality, and

confi dentiality; friends and relatives are not. It is often impossible to be

sure that a relative is passing on all that is said in the correct way.

Sometimes, especially in urgent situations, the patient’s children are

used to interpret. This is clearly not advisable for a number of reasons.

This places too much responsibility on the child, and the child may not

be able to explain diffi cult concepts. Conversations about sex, death, or

other diffi cult topics are unsuitable for children to take part in; if they do,

this will impede optimal communication.

Using an offi cial interpreter

Before you start

• Brief the interpreter on the situation, and clarify your role and the

work of the department, if necessary.

• Allow the interpreter to introduce themselves to the patient and

explain their role.

• Arrange seating so that the patient can see both the interpreter and

health-care provider easily.

• Allow enough time (at least twice as long as normal).

During the exchange

• Speak to the patient, not the interpreter. This may be hard to do at

fi

rst, but you should speak to and look at the patient at all times.

• Be patient—some concepts are hard to explain.

• Avoid complex terms and grammar.

• Avoid jargon.

• Avoid slang and colloquialisms that may be hard to interpret correctly.

• Check understanding frequently.

• The interpreter may also provide information on the patient’s culture

to assist in the communication.

Finishing off

• Check understanding.

• Allow time for questions.

• Take the time to debrief with the interpreter.

2 If the conversation has been distressing, offer the interpreter support

and let their employer know, if appropriate.

Written information

• If interpreting written information, read it out loud. The interpreter

may not necessarily be able to translate written language as easily.

• Many state and federal health departments and charities provide

written information in a variety of languages—some also provide

recordings. You should be aware of what your locality has to offer.

ANGRY PATIENTS

15

Imparting information

There are some guidelines for imparting any information—good or

bad—to a patient:

• Identify the topic for discussion.

• Identify the people present and ask if there is anyone else that they

would like to be there.

• Establish previous experience and knowledge.

• Keep sentences and explanations short and simple.

• Repeat important information.

• Allow time for feedback and questions, and check understanding.

• Schedule time for follow-up.

• Be honest!

The importance of silence

In conversations with friends or colleagues, your aim is often to avoid

silence, using fi ller noises such as “um” and “ah” while pausing.

In medical situations, by contrast, silences should be embraced and used

to extract more information from the patient. Use silence in order to

listen.

Practice is needed, as the inexperienced may fi nd this situation uncom-

fortable. It is often useful, however, to remain silent once the patient has

answered your question. You will usually fi nd that the patient will start

speaking again, and often provide useful and enlightening facts that you

would otherwise not have gleaned.

Angry patients

With angry patients, use body language to take charge of the situation

without appearing aggressive (b p. 21). Throughout the exchange, you

should remain polite, avoiding confrontation, and resist becoming angry

yourself.

• Look to your own safety fi rst.

• Calm the situation, then establish the facts of the case. Anger is often

secondary to some other emotion, such as loss, fear, or guilt.

• Acknowledge the patient’s emotions through statements such as the

following:

• “I can see that this has made you angry.”

• “It’s understandable that you should feel like this.”

• Steer the conversation away from the area of unhappiness and toward

the positive and plans, to move the situation forward.

• Don’t incriminate colleagues—the patient may remember your throw-

away comments, which could come back to haunt you. Avoid remarks

like “he shouldn’t have done that.”

• Emphasize any grounds for optimism or plans for resolving the

situation and putting things right.

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills16

Telephone and e-mail communication

The essential rule of confi dentiality is that you must not impart personal

information to anyone without the express permission of the patient con-

cerned—except in a few specifi c circumstances (b p. 26).

You must not give out any confi dential information over the telephone

unless you are sure of the identity of the caller. All communication is best

done face to face. This may cause diffi culty if a relative calls to ask about

the patient, but you should remain strict about this rule unless you have

the expressed permission of the patient.

When discussing follow-up communication for test results, obtain the

patient’s permission to leave a message on an answering machine or as

voice mail. Check to see if you have their correct phone number.

E-mail communications can be very problematic, especially if you do not

have a secure, encrypted system. Most health-care institutions have their

own policy regarding use of e-mail, so you should know what the rules are.

Patient’s e-mails should nonetheless be answered. Some providers will call

the patient back, documenting the communication in the EMR or chart.

Others will ask the patient to set up an appointment.

The use of social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) in medicine is still

evolving. It is best not to use these for any patient information.

If telephone communication is essential but you are in doubt as to the

caller’s identity, you may wish to take their number, check it with your

records, and then call them back.

Talking about sex

This can be a cause of considerable embarrassment for the patient and

for the inexperienced professional. Sexual questions are inappropriate to

ask in the presence of friends or relatives, so ask them to leave the room.

Your aim is to put the patient at ease and make responses more forthcom-

ing. Make no assumptions about a patient’s sexual orientation.

• The key is to ask direct, clear questions and show no embarrassment.

• You should maintain eye contact.

• You should also show no surprise whatsoever, even if the sexual

practices described differ from your own or from those that you

would consider acceptable.

• Try to become familiar with sexual slang and sexual practices that you

might not be familiar with.

• A failure to understand slang may lead to an immediate barrier in

the patient interview.

• In general, you should not use slang terms fi

rst. You may wish

to consider mirroring the patient’s speech as you continue the

conversation.

• See b p. 378 for details of taking the sexual history.

BREAKING BAD NEWS

17

Breaking bad news

Students fear breaking bad news, and no one likes doing it. However,

knowing that you have broken diffi cult news in a sensitive way and that

you have helped the patient through a terrible experience can be one of

the most uplifting aspects of working in health care.

Before you start

• Confi rm all the information for yourself and ensure that you have all

the information on hand, if necessary.

• Speak to the nursing staff to get background information on what the

patient knows, their fears, and details of their relationship with any

family or friends who may be present.

Choose the right place

• Pick a quiet, private room where you won’t be disturbed.

• Ensure that there is no intervening desk or other piece of furniture.

• Arrange the chairs so that everyone can be seen equally.

• Hand your pager and cell phone to a colleague or turn it off.

Ensure that the right people are present

• Invite a member of the nursing staff to join you, particularly if they

have already established a relationship with the patient.

• Remember, it is usually the nursing staff that will be dealing with the

patient and relatives after you leave, so they need to know exactly

what was said.

• Would the patient like anyone in particular to be present?

Remember the general principles

See b p. 6 and b p. 9. Avoid using jargon, and speak slowly and

clearly.

Establish previous knowledge

It is essential to understand what the patient already knows. The situa-

tion is very different for a patient who knows that you have been look-

ing for cancer than that of a patient who thinks their cough is due to a

cold.

“What do you know so far?”

“What have the other doctors told you?”

How much do they want to know?

This is key. Before you consider breaking bad news, you have to learn if

the patient actually wants to hear it. Ask an open question, such as:

“Have you thought about what might be causing these problems?”

“Do you know why we’ve been doing these tests?”

“What do you know so

f

ar

?

”

“What have the other doctors told

y

ou?”

“Have you thought about what might be causing these problems

?

”

“Do

y

ou know wh

y

we’ve been doin

g

these tests?”

CHAPTER 1 Communication skills18

You can also ask directly if they want to hear what you might have to

say:

“Are you the sort of person who likes to know all the available facts?”

Warning shots

If they do want to know, you should break the news in a step-wise fash-

ion, delivering multiple “warning shots.” This gives the patient a chance

to stop you if they’ve heard enough or to ask for more information.

Keep your sentences, short, clear, and simple. A conversation may go

like this:

You : I’m afraid the test results show that things are more

serious than fi rst thought.

Patient : What do you mean more serious?

You : Some of the cells look abnormal.

Patient : Do you mean that I have cancer?

You : Yes.

At any point, the patient may stop you, signaling that they don’t want to

hear more about it. Inexperienced practitioners sometimes feel that they

ought to tell the patient the full story, but they must understand that many

people would much rather not hear the words said aloud—this is their

coping strategy and must be respected. More than likely, this will not be

your only opportunity to speak with the patient.

You : I’m afraid the test results show that things are more

serious than fi rst thought.

Patient : Just tell me what we can do next.

You : OK.

Allow time for information to sink in

You should allow time for each piece of information to sink in, ensur-

ing that the patient understands all that has been said and repeating any

important information.

Remember also that patients will not be able to remember the exact

details of what you have said—you may need to reschedule at a later time

to talk about treatment options or prognosis.

Honesty, above all else

Above all, you should be honest at all times. Never guess, predict, or lie.

The patient may break your pre-prepared fl ow of information, requiring

you to think on your feet. Sometimes you simply can’t abide by the rules

above. If asked a direct question, you must be honest and straightforward.

For example:

“Are

y

ou the sort o

f

p

erson who likes to know all the available

f

acts

?

”

Y

o

u

: I’m a

f

raid the test results show that thin

g

s are more

serious than fi rst thought.

P

atien

t

: What do you mean more serious

?

You

: Some of the cells look abnormal.

P

atien

t

: Do you mean that I have cancer

?

Y

ou : Yes.

You

: I’m afraid the test results show that things are more

serious than

fi

rst thou

g

ht.

Pat

i

e

n

t

:

J

ust tell me what we can do next.

Y

o

u

:

O

K.

BREAKING BAD NEWS

19

You : I’m afraid the test results show …

Patient : Just tell me, have I got cancer?

You : Yes, I’m afraid you do.

Don’t rush to the positive

When told of bad news, the patient needs a few moments to let the

information sink in. After the “yes” in the previous examples, you should

preferably wait in silence for the patient to speak next.

The patient may break down in tears, in which case they should be

offered tissues and the support of relatives, if nearby.

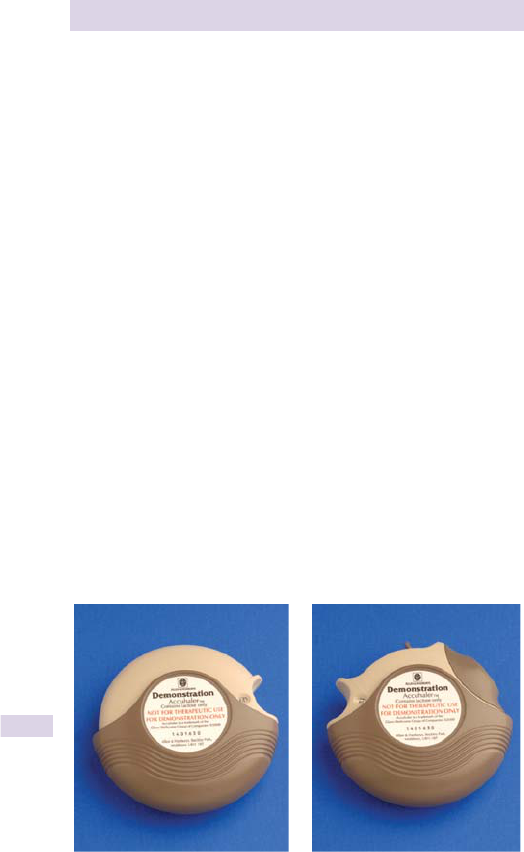

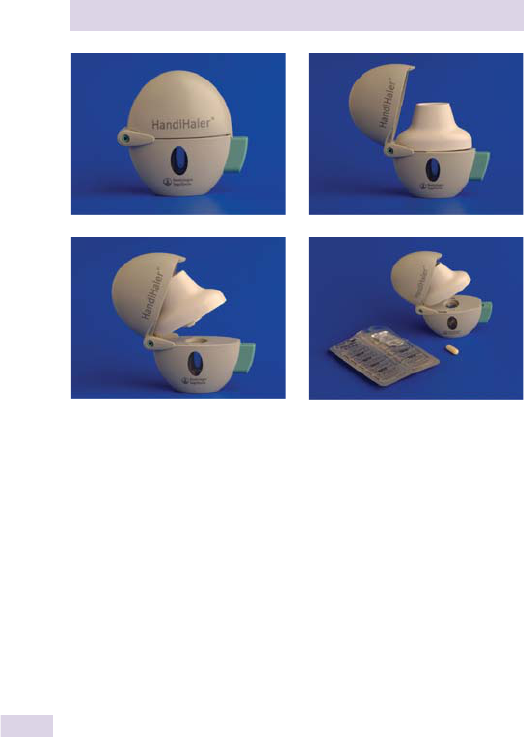

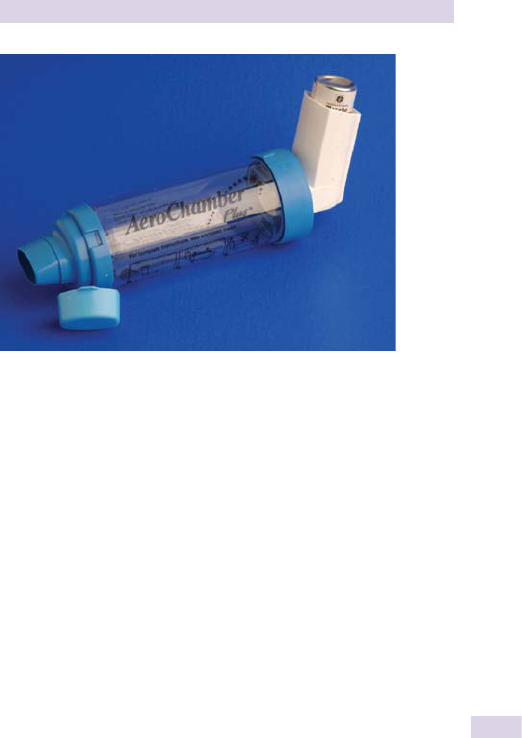

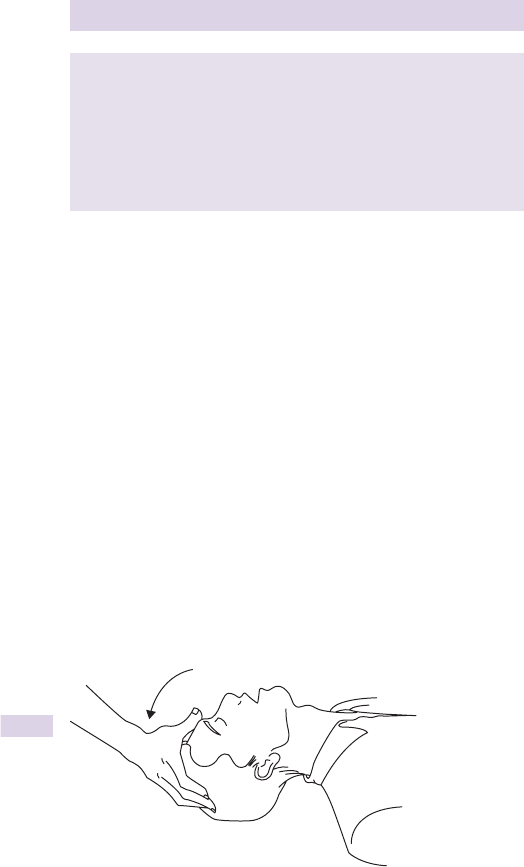

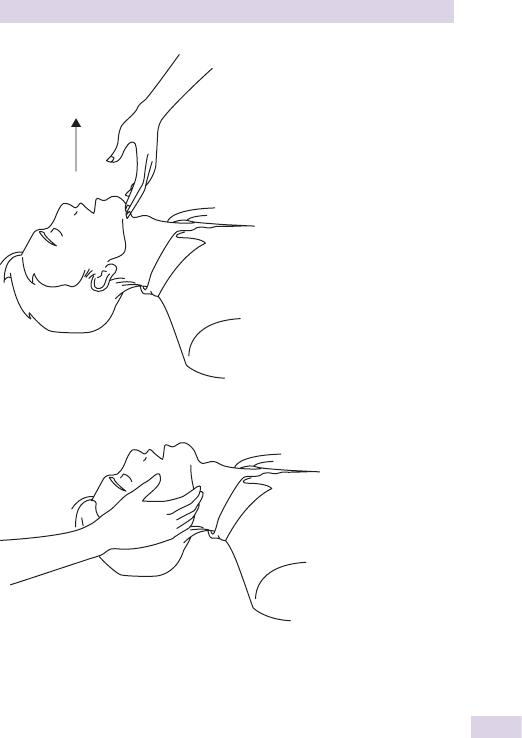

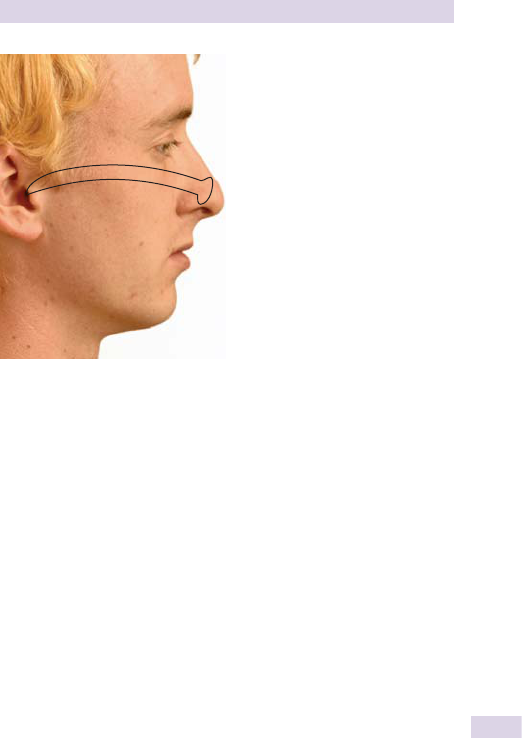

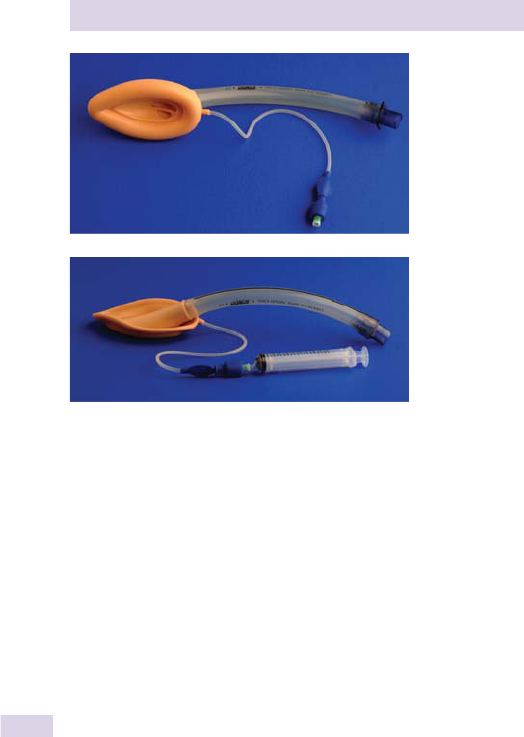

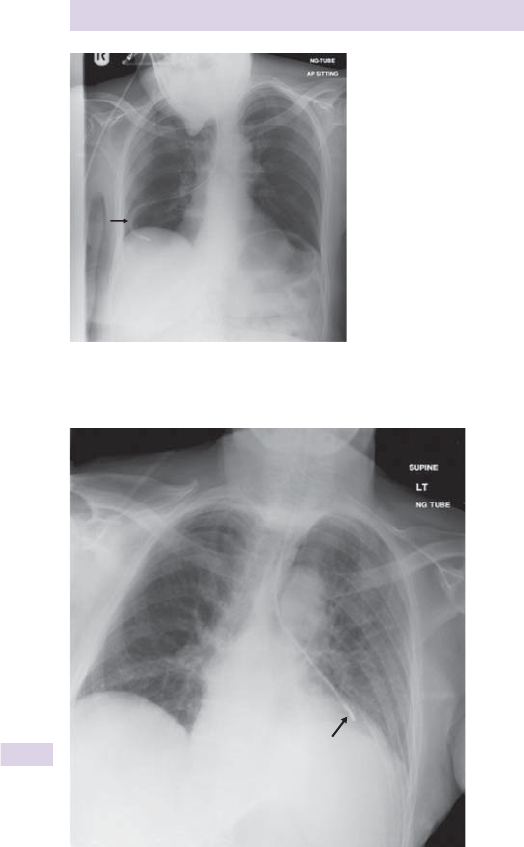

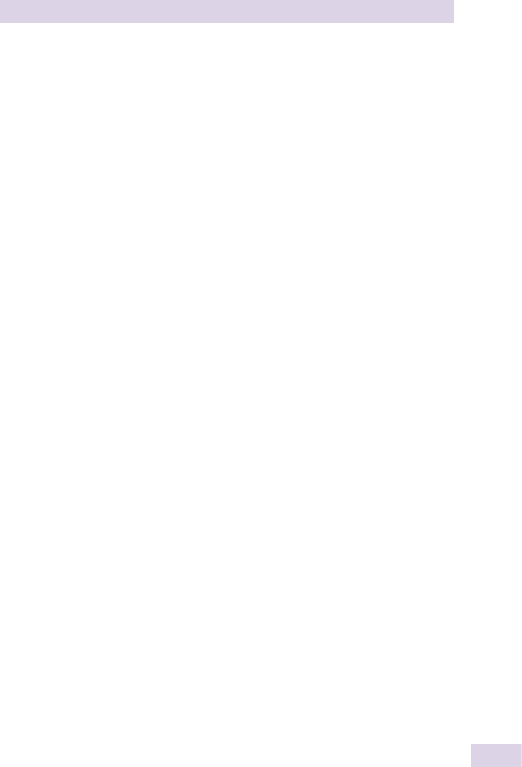

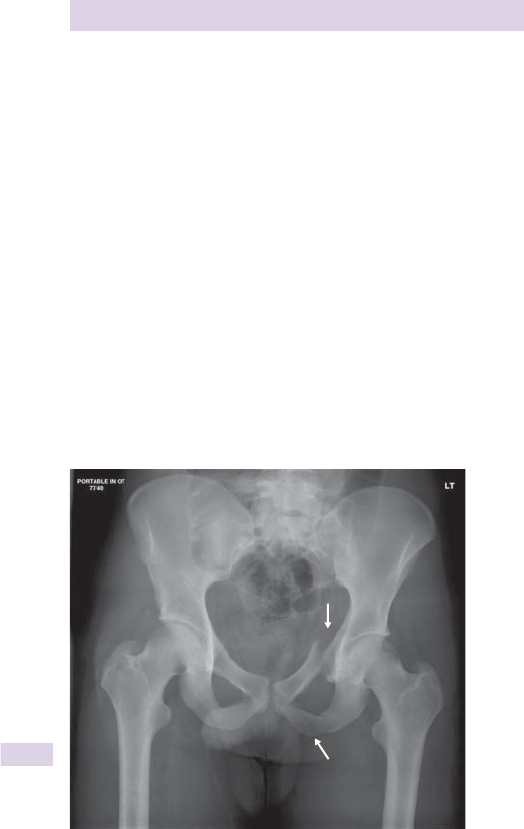

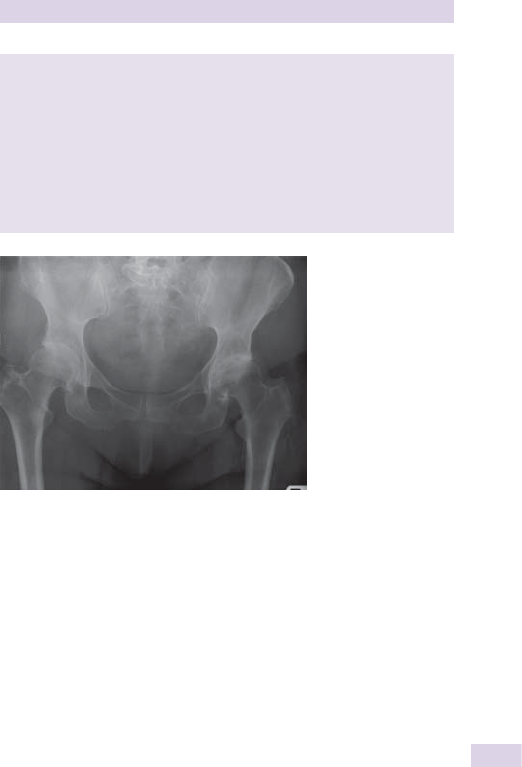

If emotionally distressed, the patient will not be receptive to what